Mexico

Mexico

A History

PAUL GILLINGHAM

ALLEN LANE an imprint of

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Penguin Random House UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW penguin.co.uk

First published in the United States of America by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic 2025

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2025 001

Copyright © Paul Gillingham, 2025

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorized edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–0–241–38604–0

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Snježana, who makes so much possible.

History is nothing more than a dream. Those who made it dreamed things that never happened; those who study it dream of things past; those who teach it dream that they own the truth.

Rodolfo Usigli, El Gesticulador

Part One: Inconclusive Conquest, 1519–c. 1650

Chapter One: Invasion and Civil War

Chapter Two: The Quick and the Dead

Chapter Three: Life in the Beginnings of the New World

Part Two: The Viceregal Years, 1535–1821

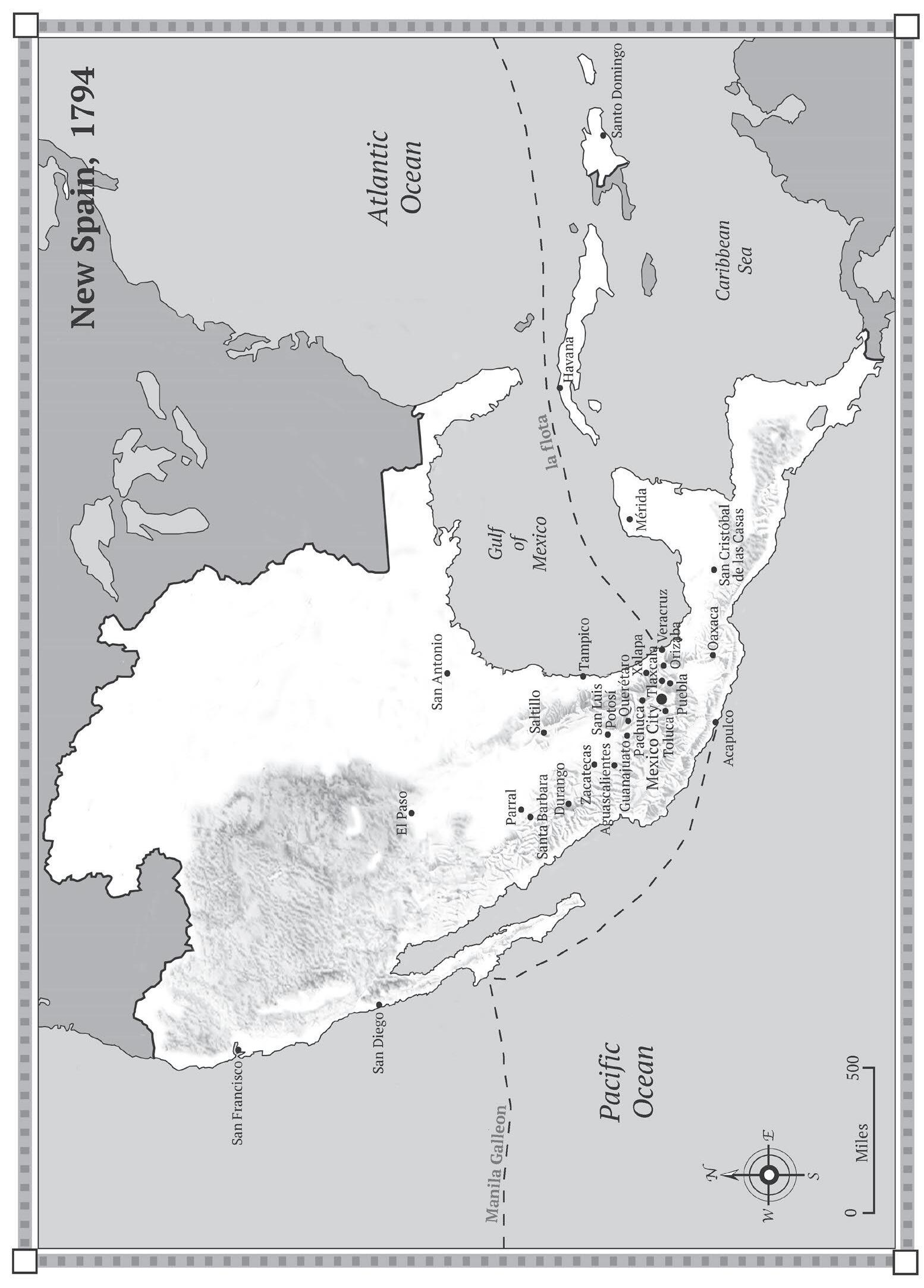

Chapter Four: Distant Masters

Chapter Five: Independence Before Independence

Chapter Six: Traveling, Knowing, and Trading

Chapter Seven: Race, Idealism, and Realism

Part Three: Absolutism and Independence, c. 1750–c. 1877

Chapter Eight: Uncertain Rebels

Chapter Nine: Freedom and Devastation

Chapter Ten: Between Empires

Chapter Eleven: Independence

Part Four: Hedonism and Revolution, 1877–1940 Chapter

Part Five: People and Power, 1940–2020

Chapter

Mexico

Introduction

I n 1534, or maybe 1535, the Spaniards found him among the dead, far to the south in Honduras. He was dark-skinned, pierced, and tattooed, and he had led the Maya people of Chetumal to war for two decades. But he was also in his own way white, a fellow Spaniard called Gonzalo Guerrero, and his three children, born of marriage with a Maya woman, might be seen as the first Mexicans. 1

The history of Mexico, understood as the country and people that grew from such first contacts, began with that Spaniard in 1511, when his caravel foundered on a reef called Los Alacranes, the Scorpions, about seventy miles north of the Yucatán Peninsula. Seventeen men and two women made it off the wreck and rowed toward the nearest land, pushed by the westward ocean current and the prevailing northerlies. After some two weeks in a small boat without food or water, ten made it to shore. The nearest Maya captured the survivors and sacrificed half of them; another three died, of exhaustion, starvation, and grief, according to one chronicler; two endured, the sailor Gonzalo Guerrero and the friar Jerónimo de Aguilar. Both came from the southern Spanish province of Andalusia, like so many others in the New World, and like so many others in the New World both had been born poor. Aguilar came from Écija, a barren town on the Río Tinto; Guerrero came from Niebla, close to Columbus’s port of Palos, a place impoverished enough to have known famine and cannibalism. After their capture both Aguilar and Guerrero learned Chontal Maya and were accepted into Maya society. But thereafter their stories diverged radically.2

Aguilar became a slave who literally counted the days—he ended up off by three—and who according to his own, probably unreliable story rejected paganism and women and consoled himself with a prayer book.3 Guerrero, on the other hand, became a military advisor to the lord of Chetumal, the cacique Na Chan Can, and “taught the Indians to fight, showing them how to make barricades and bastions . . . and by living as an Indian gained a great reputation.” 4 He married the cacique’s daughter. When the Spanish landed on the coast in 1519 Jerónimo de Aguilar escaped to their camp in a loincloth and a canoe, falling to his knees, croaking, “God and Santa María and Seville.”5 By then his Spanish had degenerated to near-pidgin, but even so he became the expedition’s first translator, putting across the diplomacy and menace of the early days of the Spanish landing. By contrast the aptly named Guerrero, “warrior,” told the Maya from the outset that they had to make war on the Europeans, and led by example until he died fighting. In 1527 the Spanish tried to lure him back with a letter reminding him he was a fellow Christian and telling him of his “great opportunity to serve God and the Emperor, Our Lord, in the pacification and baptism of these people.” Guerrero wrote back with the assurance that he did “remember God.” “The Spaniards,” he said, “will find in me a very good friend.” 6 It was a very Mexican irony. He fought on against his countrymen, first in Yucatán and later in Central America, for the rest of his life.

Improbable stories of meetings across oceans hardly start with the Spaniards in the New World. In the Dark Ages the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis told of how Saint Brendan had set off around 500 CE from Ireland to find the Promised Land of the Saints, which he did, returning with accounts of a green and pleasant land somewhere across the open ocean. In 922 the Baghdadi envoy Ibn Fadl ān traveled to the Upper Volga River, where he met some Vikings, recording with ethnographic neutrality their gruesome human sacrifices; less than a century later other Vikings actually made it to the Americas, where they established a short-lived hamlet at L’Anse aux Meadows in grim Newfoundland. By the end of the Middle Ages ships were bigger and navigation better; at the start of the fifteenth century the Chinese Muslim Zheng He took large fleets as far as the Horn of Africa and Zanzibar, conquering Sri Lanka and Sumatra en route. And in the

early sixteenth century the Portuguese progress in the Far East mirrored that of the Spanish in the Americas even down to the year. When the Spanish took Cuba in 1511, the Portuguese took Malacca; as Hernán Cortés settled in central Mexico in January 1520, his forgotten Portuguese equivalent, Tomé Pires, was setting off from the port of Guangdong to Beijing. 7

The difference between these voyages, though, was not that the Spanish won and the Portuguese lost, with the Chinese executing Pires. It was that in the sixteenth century the Spanish were not just explorers, like their Old World forebears. In Mexico they were sometimes raiders, sometimes traders, but above all they were settlers. Individuals might dream of making a fortune and going home to lord it in Spanish society, Iberian nabobs, but collectively the Spanish were colonists from their first landing onward, coming to the New World to found towns and stay. And this was the meeting of two long-separated worlds. The fossil record and genetic analyses establish that ten or so species made it across the Atlantic before the Spanish, including the ancestors of all American rodents and monkeys. An iguana had crossed the Pacific. 8 Yet they made next to no impact on human culture. The two worlds remained radically different in everything from biota—the Indians9 had no livestock to speak of, the Europeans no tomatoes or potatoes—to urban planning. Mexican urbanites had invented public toilets and highly sophisticated hydraulic engineering, but neither steel nor the wheel.

But alongside the striking differences came multiple similarities. Both the Spanish and the Aztec empires were patchworks of quite different societies, stitched together in a very recent past. The Iberians were historically divided between two mutually hostile religions, Christianity and Islam; two different language groups, Semitic (Arabic), and Indo-European (Castilian, Catalan, and Portuguese); and the language isolate Basque, unrelated to any other tongue on Earth. Politically they lived in a loose confederation of medieval kingdoms, three of which—Portugal, Castile, and Aragon—preserved their own monarchies as the sixteenth century began. Half the peninsula, the South and East, was culturally and economically embedded in the Mediterranean world; the other half, the West and Northwest, was committed to the fast-growing Atlantic world, with its fisheries, northern markets, and

possibilities in Africa and beyond. The entire assemblage was knit together mythically by the centuries of war that drove the Muslim armies, once dominant, back to the south, and politically by the central kingdom of Castile, whose warlords controlled the production and exchange of wool and wheat, Europe’s two main commodities. Modern Spain was born only at the end of the fifteenth century, when Castile absorbed its junior partners Valencia, Catalonia, and Aragon and seized Granada, the last Muslim stronghold. Only then was the modern Spanish language formalized with its first book of grammar. The country’s very name, España , was first written on a map decades after the conquest of Mexico, at about the same time as people there began to call themselves Mexicans. 10

The Aztec Empire was likewise a recent creation, also dating from the turn of the sixteenth century. Its center lay in the high Valley of Mexico and the city of Tenochtitlán, whose hundreds of thousands of inhabitants made it one of the world’s largest; it had absorbed its own junior partners, the neighboring kingdoms of Texcoco and Tlatelolco, at more or less the same time as the Spanish did theirs. The Aztecs, or Mexica as they more often called themselves, had migrated over generations from the dry Northwest into the temperate central highlands, drawn by the wealth and sophistication of the Nahua cities there and the maize that underlay it all. Outclassed by better-funded and -organized armies, in the thirteenth century the Mexica settled the swamplands of the large central valley and set out to climb from mercenaries to rulers. Two centuries later, their meritocratic flair for dynastic intrigue, engineering, and warfare had brought them dominance over the Valley of Mexico. With that dominance came access to the tax revenues and military resources of the culturally homogenous peoples who surrounded the valley for hundreds of miles, spoke versions of the same Nahua language and believed in the same gods of their own classical antiquity. All of those resources—cultural, economic, and military—became raw materials for dramatic expansion. Thus, in terms of the basic structures of history, mythos, and politics, the Mexica and the Spanish were in some ways poised to understand each other. Both kingdoms were products of a long march south from a harsh North; both were militarized theocracies, their leaders proclaiming manifest destinies. Both had warrior saints as their intercessors

with the divine, Huitzilopochtli for the Mexica and Saint James for the Spanish. Both saw themselves as being caught between barbarians of mountains and drylands—the Chichimeca to the north of the Aztec capital, the Berbers of the Atlas Mountains and the Sahara to the south of Spain—and civilized neighbors too powerful to crush: the Maya for the Mexica, the French and the Ottomans for the Spanish. And in stitching together their empires, both combined elegant centers with piratical frontiers, marriages of nobility and extortion that meant not any single political system but rather a series of defensible strongholds, claims to new ownership, domination of some but not all the people of the new territories.

The meeting of the two places in that first contact between the Maya and the two shipwrecked sailors could be straitjacketed into many meanings. The encounter of the two worlds was bound to happen, and what happened next was not the story of great men or—in the case of Malintzin, an indigenous power behind the conquistador’s throne— great women. Yet the lives of those first two people on the coast of Yucatán, the priest Aguilar and the sailor Guerrero, were apt symbols of much to come: the cosmopolitan and the parochial, the violent and the tolerant, the inevitable and the improbable, the many Mexicos. Above all, their stories evoke an unprecedentedly hybrid place. In its first centuries Mexico was more profoundly, globally hybrid than anywhere else in the prior history of the world, a meeting of hundreds of indigenous peoples with Iberians, with West Africans as numerous as those Iberians for the first century, with half-forgotten Asians who arrived as slaves and melted into local societies. Colonial authorities from the start tried to prevent this promiscuity, at times violent, at times free; everyday people felt differently and ignored them. By the seventeenth century Mexico had become what the United States aspired to be at the end of the twentieth century: not e pluribus unum , but out of very, very many a smaller number of multicultural groups whose members could sometimes move from one to another and who, despite their cultured and legislated differences, were all acknowledged to be fully human.

This was not the beginnings of a deliberately chosen, progressive mingling of races, in Spanish mestizaje . The claim that to be Mexican is to be mestizo is a modern nationalist claim that has propped up an intolerant liberalism, authoritarianism, and even ethnocide. Those who

hawked mestizaje were often disingenuous: While twentieth-century political and intellectual elites boasted of a post-racial Mexico, they secretly aimed to whiten its population with racist immigration policies. 11 Dozens of indigenous societies wanted little to do with such people and fought to remain autonomous for centuries. To some influential thinkers, a “deep Mexico” persisted, México profundo , where a broad swathe of the rural and urban poor hung on against the odds to an unacknowledged pre-Hispanic civilization. 12 Yet while mestizaje is an ambiguous and loaded ideology, it is also an incontestable sociological reality, because Mexico for centuries was the world’s greatest melting pot, in some ways its center, the crossroads of an empire that at its peak stretched from Sicily to southern China and from the Netherlands to West Africa.

This book aims to tell that story from the early sixteenth to the early twenty-first century, with all the predictable caveats. It is a history simultaneously comprehensive and partial, one that seeks to identify the most important phenomena that shaped Mexican lives and then explore them in greater depth. It intersperses chapters that narrate the outlines of a period with chapters that take different perspectives on that same time, aspiring to “a series of [stories] with sliding panels . . . like some medieval palimpsest where different sorts of truth are thrown down one upon the other, the one obliterating or perhaps supplementing another.” 13 The approach of circling the same history from different viewpoints does not mean a loss of causation, however, and I have tried to preserve a hierarchy of the reasons why things happened when they did. I have also tried to avoid our enormous condescension toward the past, recognizing not just differences but also parallels between the history of Mexico and the histories of closer times and places. Mexico has always contained multitudes. 14

Part One Inconclusive Conquest

1519–c. 1650

Chapter One Invasion and Civil War

The numbers in what we call the conquest of Mexico, like the stories, tend not to add up. Most of the invading Spanish were semiliterate; their numbers were often based on enemy estimates or “body counts,” which are always questionable, whether the source is Julius Caesar on the conquest of Gaul or General Westmoreland on the conquest of Vietnam.1

To make matters worse, the Spanish had a flair for melodrama—the conquistadors were passionate about amateur dramatics and put on plays wherever they went2—and good reason to exaggerate the odds they faced and the slaughter they perpetrated. So, whether in the florid prose of their letters and chronicles or in the wooden boasting of probanzas , self-aggrandizing catalogues of services rendered, the Spanish were strategically innumerate.3 In a series of casual asides, they did however include one critical dataset: the vast numbers of indigenous warriors who fought by their side in the wars against the Mexica and the peoples beyond the Valley of Mexico. Figures vary from account to account, but the order of magnitude is always the same: thousands for expeditions to the coasts, deserts, and forests; tens of thousands at the beginning of the siege of Tenochtitlán, the Mexica capital; hundreds of thousands by its end. The conclusion is inescapable: It was not the Spanish but the indigenous peoples of central Mexico who destroyed the Mexica Empire, and the conflict itself was not so much foreign conquest as vicious civil war.

The Mexica, like all empire builders, told stories of manifest destiny. They had been guided to their home on the Valley of Mexico’s central lake by a prophecy, they said, in which an eagle ate a snake

while perched on a cactus. They also told the Spaniards they had been in this promised land for millennia. Yet in reality theirs was a young state, and their island had initially been a wasteland refuge from more powerful and hostile neighbors. The Mexica had been subordinate to the neighboring city-state of Azcapotzalco until 1428, and only took firm control over the central valley in the second half of the fifteenth century, a few decades before the Spanish arrived in 1519. Their first major war of the sixteenth century was against Atlixco, a town just the other side of Popocatépetl, the volcano that rises high above the valley rim. By then, their territories stretched as far east as the Gulf Coast and nearly as far south as Guatemala. But it was a patchwork empire made up of recently conquered and recalcitrant city-states.

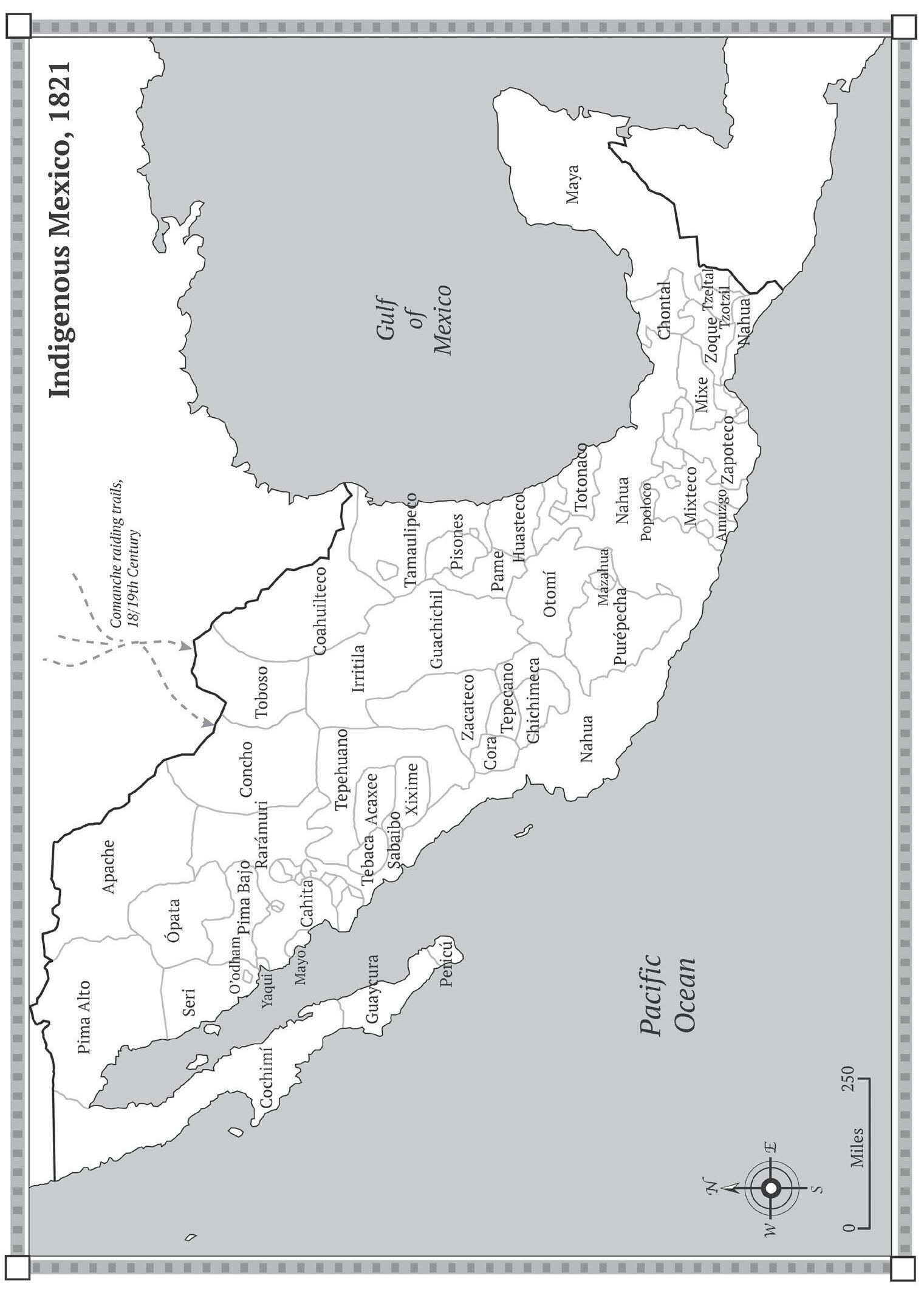

By the time the Spanish arrived it had also reached something like its natural limits, which were far narrower than those of modern Mexico. The Mexica Empire enveloped but did not conquer the kingdoms of the Purépecha of Michoacán and the Zapotecs of Oaxaca, whose accomplished militaries and forbidding mountains preserved their independence during the rise of the central powers. In 1478 some twenty thousand imperial troops died in the last campaign against the Purépecha. 4 Not far to the north were the drylands, where paltry resources and decentralized, mobile, dangerous peoples—the Pames, Guamares, Zacatecos, and Guachichiles, all barbarians to metropolitan eyes—militated against expeditions into what the Mexica called the Great Chichimeca. In the highlands to the east of the Valley of Mexico the small but bellicose city-state of Tlaxcala was still, by the skin of its teeth, free. Mountains did not guarantee survival against Mexica conquest, but when combined with sophisticated enemy states they made the effort of establishing direct rule unappealing.

Above all, the Mexica had yet to push into the lands of the other great sedentary civilization of the time, the Maya. In 1519 the conquest of the Yucatán Peninsula and the country stretching into modern Guatemala was their ultimate strategic goal. It had been done before, in the fourth century, when the central empire of Teotihuacán forcibly installed its ruler in the wealthiest city-state, Tikal. 5 There was compelling reason for such tricky expansionism: The southern city-states, politically divided but culturally quite homogenous, controlled the lucrative trade routes into Central America and beyond. Jade, feathers,

shells, dyes, cacao, and gold were all superb commodities in the indigenous value system, combining portability with low volume and high value; their commerce was the Indian equivalent of the European spice trade. The Maya of the time were some six centuries past their own golden age, the classical period of wealth when major cities such as Tikal housed tens of thousands of people and some of the most sophisticated intellectual, military, and material cultures in the world. Those metropolises collapsed toward the end of the first millennium CE, victims of overpopulation and climate change, severe droughts and tropical storms that devastated southern Mexico and the Caribbean.6 Yet however many centuries past their prime, the Maya of the sixteenth century remained notably accomplished traders and warriors, ensconced in readily defended forest and highland, and they kept the Aztecs confined to the north with a chain of garrisons beyond which only their traders, the pochteca , could go.

So in 1519 a joined-up Mexica state did not stretch as far south as Yucatán or all that far north of its capital; it did not even encompass all of the central highlands. The empire was, like its European contemporaries, a mafia state, demanding privileges and tribute in exchange for peace, and the Mexica had built it with mafia-like ruthlessness and theatrical violence, leaving behind lurid stories of gambling, murder, and human sacrifice on an industrial scale. 7 They were consequently loathed by many of those recently conquered, which makes it unsurprising that so many of their subjects seized the opportunity to rebel when the Spanish landed.

It was not the first Spanish expedition to the North American mainland. The first one reached Yucatán in 1517, a crew of 110 optimists without the necessary funds for even decent water barrels. They came back, according to one pithy sixteenth-century summary, with nothing but wounds. 8 Neither was it the second; that one mapped some of the coast but lost its way in 1518. This was the third expedition, an operation on a grander scale, which set out from Cuba in 1519 under Hernán Cortés. Extraordinary in some ways, Cortés was in many others typical of the first generation of Spanish in the New World. He came from Medellín, a poor place in the southwestern province of Extremadura. He belonged to the impoverished ranks of the lower Spanish nobility: His father, Martín, was a knight of the Order of

Alcántara who chose the wrong side in rebelling against Queen Isabella but survived to tell the tale, or more probably not to tell it. His mother, Catalina, was also from a good family, but without the dowry that would have made them more than the provincial worthies they were, owners of a mill, an apiary, and a small vineyard. Cortés was certainly not upwardly mobile: A small-town refugee, he dropped out of the renowned university in Salamanca without a degree, went back home to live with his parents, fought with them, and slept around. And he was relatively young, twenty-two when he first traveled to the Indies, and only thirty-four when he sailed toward Yucatán. 9

Twelve years in the Americas marked him. Cortés’s first steps came as a settler on Hispaniola, the island at the center of Spanish hopes for wealth from the Indies. Cortés had subsequently been useful to the veteran leader Diego Velázquez in the conquest of Cuba, and he was rewarded with land, Indian slaves, and a series of plum jobs, including a stint as the governor’s secretary and culminating with the mayoralty of the capital, Santiago de Baracoa. According to the myth that Cortés co-authored, he was a brilliant maverick from early on: seducing the wrong woman, being jailed when he dumped her, seducing the governor—platonically—and ending up the natural choice for the next major expedition. According to critics then and now, he was nothing of the sort. His main talents were survival and mythmaking. He was jailed not for sexual swagger but rather for petty crookedness, lifting some of Velázquez’s papers. He was, according to his greatest critic of the time, “an ordinary man . . . very bowed and humble, like the very lowliest crony that Diego Velázquez might wish to favor.” 10 But if that governor was at all competent, and he was, then he would not have appointed an incompetent mediocrity to be his captain on an important and time-sensitive expedition. (Unless he was a relative, in which case in that time and place all bets were off.) And when Cortés lobbied for the job of commanding the third expedition to the mainland, Velázquez gave it to him.

Cortés’s mandate was, however, limited. He was authorized to look for the earlier Spanish mission, to trade for gold with the Indians, and to promote their conversion to Christianity. He was quite explicitly not to be his own man, authorized neither to make war nor to settle. Yet Cortés immediately prepared to do just that. He raised extensive loans

to equip ten ships, arm and train 450 men—nearly a quarter of the male Spanish population of Cuba—and buy himself the sort of clothes he believed any great captain should sport; velvet and gold featured heavily.11 All this unsettled Velázquez. Suspecting—rightly—that Cortés was once more acting the crook, plotting to usurp the new lands and profits, he changed his mind and tried to arrest him. When Cortés found out, he left the island in a hurry and with a flourish, allegedly telling the dithering Velázquez that “these and like things have to be done not mulled over.”12 If he actually said this, the cheek was typical, and so too was his luck. In March 1519, Cortés landed at Cozumel and picked up Jerónimo de Aguilar, the Spaniard who had been shipwrecked there and whom the Maya had captured and enslaved. That meeting alone gave Cortés a translator and valuable intelligence about the Maya. But Cortés’s real stroke of luck came shortly afterward, when the Potonchan Maya gave him twenty teenage girls, one of them a slave called Malintzin.

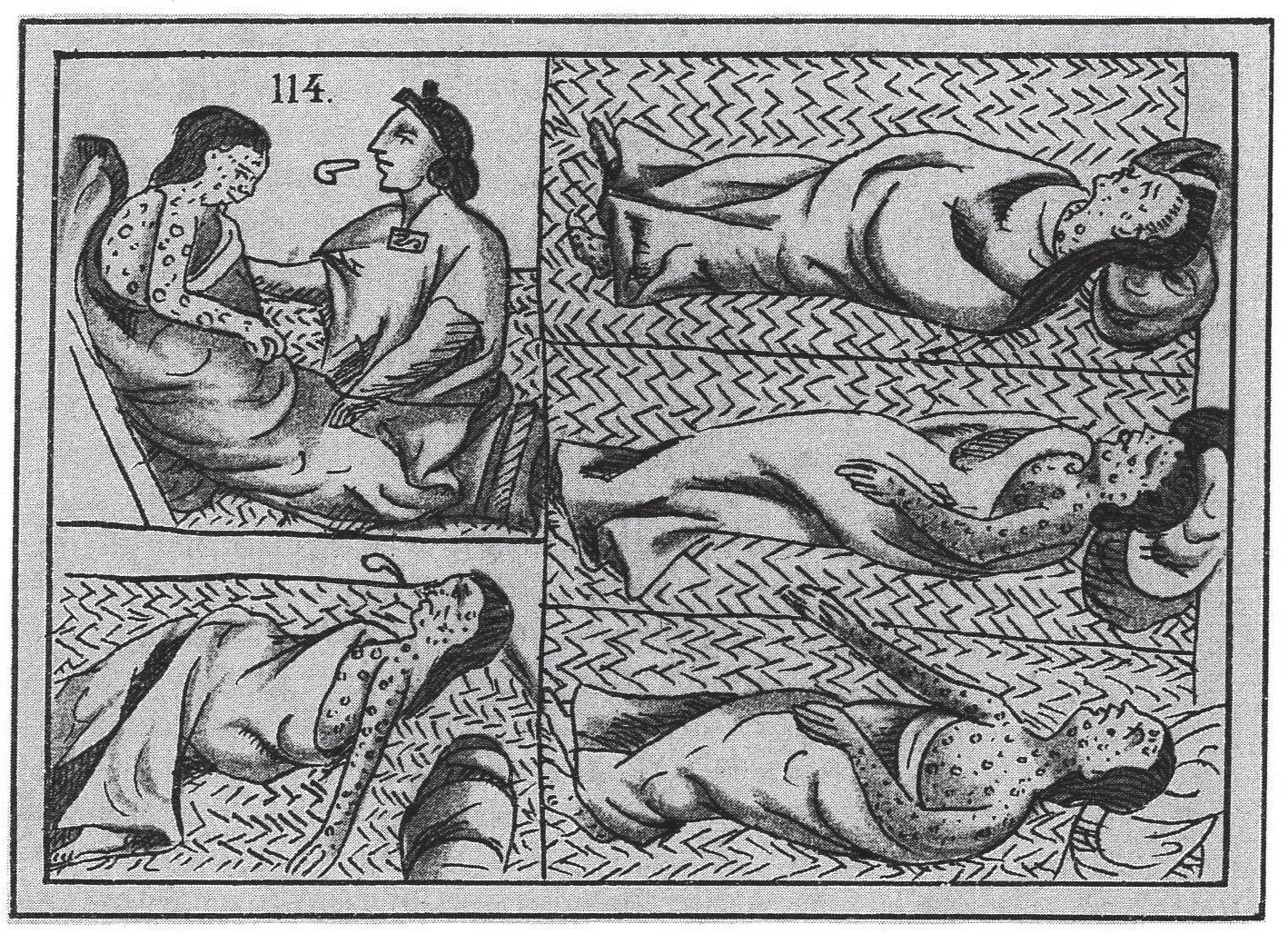

Malintzin was actually Mexica, not Maya, taken before puberty by slave traders from her home on the Gulf Coast in Veracruz—either kidnapped or bought, accounts differ—and rowed down the coast to be sold on. She was beautiful and bilingual in Nahuatl, the language of central Mexico, and the Maya language of the South; she rapidly became fluent in Spanish as well. She became Cortés’s concubine, and a key source of local knowledge and advice throughout the war. In the codices, the indigenous pictogram histories, she appears over and over again next to him, for good or bad, whispering in his ear, fleeing an Indian attack, looking on as he has a mastiff tear a chained native priest to pieces, lecturing a cacique. In the images of some postconquest documents, like the Codex Durán (1579) or the Lienzo de Tlaxcala (1585), her body language and expressions are masterful enough to call into question who was actually making policy, captive or captor.

Malintzin had very little check on what she said to each side in those early days before the Spanish had learned anything beyond crude Nahuatl. At one stage their words passed through three different interpreters and four languages: Spanish to Maya to Nahuatl to Totonac. As a result the Spanish hadn’t a clue what Malintzin was telling the indigenous people they met. Neither do we know much about what she said, felt, and did beyond the outlines of a short obituary. Malintzin was born at the turn of the sixteenth century; picked up by Cortés in

Malintzin and Cortés have an animated discussion at Veracruz, 1519. Codex Durán (1579).

1519; discarded by him in the mid-1520s after bearing his firstborn son, Martín, who was later legitimized by the pope; married off to another conquistador, Juan Jaramillo; and rewarded for her services with a grant of estates in Olutla, her hometown; she had a daughter, María, with Jaramillo in 1526; parted from her firstborn forever when he was sent to Spain at the age of six; and died in early 1529. Her enemies accused her of assorted sins, like money laundering for Cortés, notorious promiscuity, and equally notorious dishonesty in manipulating both sides. One thing is clear: Cortés’s manipulation of indigenous politics, maybe his very survival, is unthinkable without her. 13

Yet there was more than luck or judgment at work. People had been crisscrossing the Caribbean for centuries, and the Spaniards had been doing so for decades. Cortés benefited greatly from the fact that his was the fourth, not first, contact with the indigenous mainlanders. Even his predecessors had been greeted with cries of “Castilian” when they first landed. The peoples of Mexico knew something earthly was in the offing before Cortés turned up: A Maya canoe met with Columbus in 1502, a Spanish ship was wrecked off Yucatán in 1511, and European

clothes and books had already washed up on Gulf shores. 14 So while Cortés was dismissive of the Spaniards he brought with him “of low manner and type, and dissolute with assorted vices and sins” 15—several of his captains had been to Mexico before him, and they were extremely useful because of that. Men like Pedro de Alvarado, Alonso de Ávila, Francisco de Montejo, Bernardino Vásquez de Tapia, and Bernal Díaz del Castillo had the experience Cortés lacked, and provided him with intelligence, confidence, and advice. (Alvarado may have paid for one of the bigger ships into the bargain.) 16 Writing decades later, Díaz carefully deflated the myth of Cortés the brilliant individualist:

And as among us there were such excellent sons, gentlemen and soldiers of such valour and good judgement, Cortés neither said nor did anything without first seeking our very well-considered counsel and agreement.17

Most important of all, the earlier contacts provided him with his critical first interpreter, the bilingual Spaniard Aguilar. He could translate Spanish into Maya; Malintzin could translate that Maya into Nahuatl; and Cortés, consequently, could from the very start communicate with the people he planned to overpower. These linguistic and cultural tools in hand, Cortés wielded them with distinctive guile to manage his own first contacts with the indigenous world. He worked hard to charm and terrify the Indians, encouraging them to believe that both his guns and his horses were hostile living beings, controlled by his goodwill alone. In April 1519, he moved up the coast to central Mexico, where he founded the Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, the Rich Town of the True Cross, later just Veracruz; established good relations with the local people, the Cempoalans; and sent messengers directly to Spain to ask for the royal appointment that would establish his independence from Governor Velázquez in Cuba, entitling him to the leader’s share of any profits. He also received the first messengers from the Mexica capital, Tenochtitlán, and began planning his march there. Finally, he rounded off his coup by beaching and derigging—not burning—his boats, making hasty retreat to the Caribbean islands impossible, and so encouraging his faction-ridden expedition to follow him up into the highlands.18

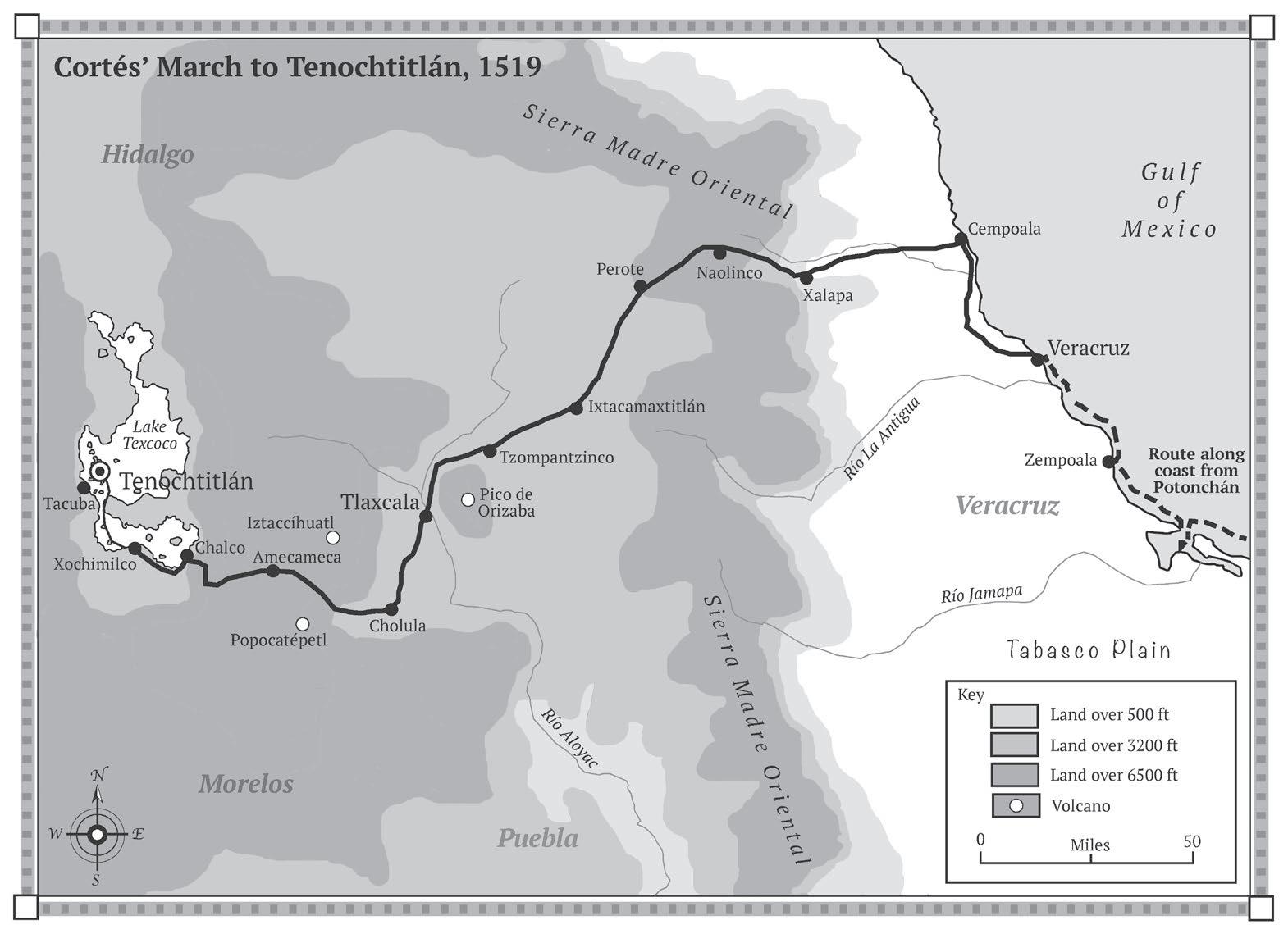

A depiction of one of the many route maps re-creating Cortés’s march to Tenochtitlán, 1519.

After it was all over, indigenous historians and informants recounted how the Cortés expedition had been prefigured for nearly twenty years by auguries of disaster. The emperor Ahuitzótl had allegedly died after banging his head on the lintel of his bedroom, a suspicious story. (He was held responsible for a failure in the city’s water management system, which led to a catastrophic flood: reason enough for discrete murder.) Legend held that the Valley of Mexico had hosted multiple supernatural phenomena. Comets, solar eclipses, temple fires, inexplicable storms, and a string of zoological freaks abounded. A mysterious woman, la llorona , prowled the city by night wailing: “O my sons! We are about to perish.” Most striking of all, Cortés was reported

by these later writers as fulfilling a central Mexica myth, the return of Quetzalcóatl, the feathered serpent god. The Spaniard was white and bearded and came from the East, bringing with him bewildering technological superiority. Quetzalcóatl, similarly white and bearded, had disappeared to the East on a raft after his fall from grace, an indigenous Prometheus who was now honoring his vow to return and reclaim his birthright. 19

These reports were clearly nonsense. Even in his own writing Cortés never claimed to have been taken for the god Quetzalcóatl, and so this particular form of European megalomania does not seem to have had him in its grasp. Neither are the Nahua of the 1520s or 1530s reported as identifying him with Quetzalcóatl.20 The first written version of the story appeared in 1555, in an unpublished draft of a history written by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and some ten tlacuiloani , indigenous scribes, and so the earliest record came a generation after the events were supposed to have happened. 21 This begs the question of why the sons and grandsons of the defeated should subscribe to the myth while the Europeans did not. But there were good political reasons for the conflicting versions. It was not at all in Cortés’s interest to portray himself to the Spanish emperor as a rival theocrat, nor to give the first missionaries room to see him as a heretic. For the Mexica, by contrast, a story of supernatural advantage would help them live with the indignity of defeat by old neighbors and enemies as well as pleasing the Franciscans, with their party line of a divinely justified conquest. The nameless Nahua who collaborated with Franciscan authors had tactical and emotional reasons to shape stories of magic and loss to their teachers’ taste. 22

Yet neither is it impossible that the Spanish collectively were briefly seen as gods. In Mexico their initial identification as one more group of shape-shifting divinities would have made perfectly good sense. The Mexica Empire was a world where multiple unpredictable and violent gods were empirically established and ever-present, a cosmology rather like that of the Old Testament, with God the capo, Archangel Michael the consigliere, and Saint James the soldier, turning up to help the Spanish when things got tough. The Spanish certainly hoped to be seen as gods, and tried to foster the impression. When Cortés first sent an emissary to the Totonacs he chose a battered and ancient-looking

Basque soldier, telling him, “When they see your ugly face they’ll certainly take you for one of their idols.” 23 Yet there is so little firsthand information about the war that it isn’t even clear what Cortés himself looked like: strong-jawed leader to some, syphilitic dwarf to others. 24 If the argument over the question of Spanish divinity in Mexica eyes establishes anything beyond reasonable doubt, it is how the weakness of the chief historical sources—all either geriatric, geographically or historically removed, self-interested, or some combination thereof— allows each age to reinvent the story of the war to its own taste.

Only a handful of Spanish participants in the war with the Mexica wrote books about it: Cortés, in five letters to his emperor; the “Anonymous Conquistador”; Francisco de Aguilar; and Bernal Díaz. The paucity and unreliability are striking. Bernal Díaz wrote the best of them, the revealingly named True History of the Conquest of Mexico , in old age and in disgust at other authors’ mendaciousness. Yet even he was currying favor at court and lying about how much of the war he had seen. Aguilar was even older than Díaz when he wrote his account: He was in his eighties, the conquest sixty years in his past. The influential Francisco López de Gómara was Cortés’s chaplain and never went to the Americas; his Historia general de las Indias , paid for by Cortés’s son, was written in Spain with the conquistador peering over his shoulder. 25 The Franciscan Toribio de Benavente, whom the Mexica nicknamed Motolinía, “the Poor Man,” hadn’t witnessed the wars, and his Historia de los indios de la Nueva España was a social history. Motolinía’s main concerns were the before and after; the war’s narrative interested him much less. The Dominican Bartolomé de las Casas had been in the region and knew some of the conquistadors, but he was more concerned with indicting them than with footnoting his sources. (The title of his work, Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias , says it all.) That Cortés is an unreliable narrator goes without saying. But aside from a scattering of terse mentions in private letters, his first three letters to Charles V were the first widely read versions of the war for Tenochtitlán, and their heroic narrative and persuasive prose poisoned the well for almost all successive accounts.

As for the written indigenous accounts, most came from several generations after conquest. Some of the canonical indigenous historians,

like Hernando de Alvarado Tezozómoc, Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin, and Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, took a step forward in professionalism by specifying their sources. Yet like the Europeans they borrowed from each other (and from the slippery Gómara) and in the main wrote in the early seventeenth century, long after events. Chimalpahín’s closest personal link to the war was his grandfather, who at best experienced it as an infant. Some Nahua writers had their own axes to grind for self-advancement. Ixtlilxóchitl self- identified as indigenous (despite a Spanish father) and over the years became increasingly dismissive of European historians: “Having considered,” he wrote, “the varied and contrary presentations of the [European] authors who have treated the history of New Spain, I did not want to follow any of them.” 26 But he was the great-great-grandson of the king of Texcoco, which made him distant in time but also self-interested in the present in stressing the importance of the Texcocans. Some of the first European historians valued early indigenous sources above Spanish letters, reports, and chronicles. Writing in the 1570s, the Franciscan Diego Durán explicitly chose to believe painted Mexica codices over Spanish books. Yet Indian and Spanish accounts shared some of the same weaknesses. 27

The second big story of the war for Tenochtitlán is dodgy too: that the Mexica leader Montezuma II, shocked by the Spaniards’ unearthly gifts, suffered a nervous breakdown in the face of their advance and surrendered to them at the gates of his city. According to the first indigenous accounts, Montezuma, the tlatoani— emperor, literally “he who speaks”—was remembered as doing next to nothing bar hand-wringing in the face of the Spanish coalition-building and steady advance. As they later told it, “He conceived within himself a feeling that great ills were coming upon him and his kingdom, and not just he, but all those who knew of these tidings, began to fear mightily.” 28 But such a lurch into ineffectuality would have been a surprising shift in character for a forceful, effective, and absolutist ruler. He began his rule by executing all his predecessor’s bureaucrats and replacing them with nobles. He went on to enforce draconian protocol in his relations with the Mexica. It was forbidden to look directly at his face, or to wear shoes or anything but the coarsest clothing in his presence. When he proceeded through the streets, everyone was to bow before him. 29

This authoritarianism was more than a question of style. Montezuma lived up to the literal meaning of his name, “the man who is angered,” by repeated use of arbitrary terror as an instrument of government. His people, he explained to Cortés, “did not like being treated with love but with fear.”30 His people weren’t so sure. Indigenous informants of the priestly Spanish historians Sahagún and Motolinía repeatedly condemned Montezuma as extraordinarily cruel. Yet Montezuma cannot be painted as weak or incompetent until 1519, when, confronted with the growing Spanish threat, he eschewed the strategy of total war that the Maya had (rightly) advocated. The Spanish, whatever else they might have been, were clearly obsessed with meeting the emperor in person; they insisted on it from the first encounter. And they had magical allies in the form of cavalry and cannon, which the indigenous peoples initially believed (and were consistently encouraged to believe by Cortés) to be sentient and intrinsically hostile. But they were also killable, as battles with other indigenous peoples had proven, and they weren’t all that numerous. There was strategic logic behind Montezuma’s policy of wait and see, gathering intelligence, shadowing the Spanish, watching as they were battered in the first major fighting of the expedition, perhaps considering their quest for his city the path into his trap.

But the Spaniards’ battering had been salutary and in the long run critical. They had begun recruiting indigenous soldiers on the coast: Cortés marched up toward Tenochtitlán in company with two thousand Cempoalan warriors. In September 1519 they reached the frontiers of Tlaxcala, the kingdom that had used its uneven mountainland and powerful military to retain a tenuous independence from the Mexica empire. Bloody enmity helped Tlaxcalans to hold together as a unique polity that welded four of the usually individualist city-states, in Nahua altepeme , into a province with a deliberative assembly; they were—as generations of Mexica had realized—formidable opponents.31 The Tlaxcalans’ first reaction to the newcomers was to fight. In the first battle, with his habitual mixture of overstating the odds and understating the costs, Cortés told his emperor that he had faced a hundred thousand Tlaxcalan warriors and battled all day, until an hour before sunset, when they withdrew; and with half a dozen cannon, five or six muskets and forty crossbowmen,

and the thirteen horsemen I had left, I did them great harm, suffering in return only the labor and weariness of fighting and hunger. And it seemed that God fought for us, because among such a multitude of people so spirited and masterful in fighting and with so many different weapons to attack us we got off very lightly.32

In reality the conflict between the Spanish and Montezuma’s longstanding enemies in the treacherous highlands was devastating for both sides. Two major battles and assorted skirmishes left Cortés with only half of his total force alive and in fighting condition, perhaps as few as 350 foot soldiers and horsemen.

The war ended after eighteen days, however, with the Tlaxcalans convinced of both the threat and the utility of the invaders. They had been divided since the beginning between a hawkish party led by Xicotencatl the Younger from the altepetl of Tizatlán, captain-general of the army, and doves led by Maxixcatzin from the less bellicose altepetl of Ocotelulco, who stressed the military and mercantile advantages of joining the Spanish. Their numerous casualties and the arrival of a delegation to the foreigners from the Mexica, who hoped to egg on the mutual slaughter, led to the doves winning the debate. The four altepeme agreed to ally themselves with Cortés and sent an army of six thousand to join the invasion of the Valley of Mexico (they offered tens of thousands more, but the Spanish, understandably wary, politely declined). 33 The extent of Tlaxcalan influence over the unknowing Spanish was made immediately clear when they diverted the march to Cholula, a city of their bitter enemies, which was out of their way. There they duped Cortés into launching an exemplary massacre, telling him a story of an impending ambush, which probably never existed but served as a casus belli for sacking the city. 34 It was the first demonstration of the intruders’ potential for urban warfare, and it was clearly troubling for Montezuma. For all their losses—of both soldiers and autonomy—the Spaniards had fought the Mexicas’ old enemies to a standstill and then converted them to allies, leveraging an expedition of hundreds into an army of thousands. According to the Nahua accounts from a generation later, Montezuma reasoned that the only viable defense against such aliens was counter-magic. Yet when he unleashed his necromancers in a last-ditch

attempt to keep Cortés out of his city, they were derailed by a drunk from Chalco who prophesied divine abandonment and fiery destruction. The story is one more in Sahagún’s chronicle of doom foretold and psychological collapse; coming from long after the fact, it is similarly dubious. On the other hand, the revisionist idea that Montezuma set out to collect the Europeans, one more species for his extensive zoo, is also inherently dubious. 35 Cortés’s men may have totaled a quarter of one percent of the city’s population, but letting them into its heart out of ethnographic curiosity was the equivalent, in relative terms, of letting four thousand heavily armed alien troops into today’s Manhattan on a whimsy. Since we are left with nothing but unreliable accounts, speculation on the basis of Montezuma’s previous astute war-making is perhaps best. His appreciation of the military capabilities of the Spanish was on the rise. To fight them would mean engaging them on the city outskirts, ravaging the lakeside towns critical for his people’s food supply. If, as the Spanish maintained, they were simply after high-up encounters and gold, then meeting some of their demands and manipulating them into going away, or maybe even turning them against their Tlaxcalan allies, was a subtler stratagem. So the most likely explanation is that the tlatoani opted for diplomacy backed by force. Both curious and wary, on November 8, 1519, he invited the Spanish into his island city and put them up in his father’s palace.

The palace was built of basalt, limestone, and the red lava rock the Mexica called tezontle , which littered the valley floor. Three great volcanic eruptions, the oldest dating back twenty-six million years, had created a deep basin; over geologic time, smaller eruptions part-filled it with lava and ash, and a million or so years ago came the water. When humans arrived from the north about twelve thousand years ago they found that springs, seasonal runoff from the valley slopes, and rivers draining from the west formed marshlands and a large salty lake. 36 These people were few and the wetlands inhospitable, and consequently the first indigenous nomads stayed on the rich soils of the lakeside, surrounded by the sheltering valley rim and the threat of its two live volcanoes, the southern peaks of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl. It was

a good place to live, and about a thousand years BCE they settled in villages that grew into towns that grew into cities. When the Aztecs arrived from the far northwest in the thirteenth century, the only land left was wetland. Over the next three hundred years they moved mud and rock to form a firm central island, and built giant causeways that both connected the growing city to the lakeshore and helped manage the great seasonal floods. The solid causeways also dealt with the problem of drinking water, separating salt- from freshwater lakes, while the Mexicas’ skill in terraforming allowed them to create rafts of floating gardens, the chinampas , to provide food. The story of Tenochtitlán was a story of volcanoes and men moving mud on a massive scale.

Even before they got to Tenochtitlán, the Spanish were groping for parallels for the indigenous cities they found along the way. The higher they climbed up toward the central valley, the harder it became for them to conceive the new world they were encountering. The Anonymous Conquistador thought Tlaxcala quite like Granada, the capital of Muslim Iberia, only bigger. 37 To Bernal Díaz the white walls and high towers of Cholula made it look like Valladolid, the medieval capital of Spain.38 Cortés ran out of comparisons of place and turned to the rhetoric of numbers, telling Carlos V that Cholula had 20,000 houses and some 430 mosques, which would have made it bigger than almost every European city of that time. 39 When the Spanish crossed the valley rim and saw the Mexican capital, there was only one comparison left—Venice—and calling Tenochtitlán an American Venice quickly became a trope. It was not just a question of water management; la Serenissima Repubblica was by far the most populous, powerful, and sophisticated European city-state of its time.

Marching into Tenochtitlán, seeing the buildings rise up out of the water, was “to see things never before heard of nor seen nor even dreamed.” When they settled in town the wonder continued. Montezuma’s palace was duly large and opulent, stuffed with valuables, staffed by hundreds, and home to a zoo and an aviary. Above all it was the everyday city that struck Díaz. The marketplace was vast, packed, and organized; he “had never seen such a thing before.” The array of food, clothes, commodities, and luxuries was beyond words: “If I describe everything in detail I shall never be done.” He tried hard, cataloguing for over a page (he didn’t have enough space for

more, he said) the many slaves, textiles, wild and domestic animals and their hides, building materials, paper, dyes, pottery, knives, axes, and gold measured in goose quills. Climbing to the top of the main temple he saw the straight, paved roads; the canals with their myriad canoes; the bridges and causeways; the aqueduct bringing fresh water down from Chapultepec, the “Hill of the Grasshopper”; the pyramids, squares, courtyards, and orderly houses. From three miles away he could still hear the murmur of the buyers and sellers in the great market. Even the best-traveled of the Spanish said they “had never seen a market so well laid out, so large, so orderly, and so full of people.” 40

Perhaps that was no wonder, because the Spanish who were there were a mixture of provincials and yokels (leavened by a couple of Venetian solders whose names never made it into history). 41 None of the leaders came from Valladolid or Barcelona. There was only one Madrileño. Cortés had lived briefly in Salamanca, a university town with a great plaza, but like his captain, Gonzalo de Sandoval, he was a small-town boy: Medellín had a couple of thousand inhabitants. Bernal Díaz came from Medina del Campo, whose medieval fairs made it a center for wool trading and banking, but it was still at heart a market town. Badajoz and Baeza, home respectively to Alvarado and Cristóbal de Olid, were first and foremost military bases, strategically important, massively fortified, but otherwise small and higgledy-piggledy. None of these bore comparison to the size, complexity, and sophistication of Tenochtitlán. Iberians had lived in sedentary settlements three thousand years longer than the indigenous peoples they were encountering, and they had learned the use of iron, wheels, pulleys, and the Roman arch. 42 But the Mexica, who lacked all those inventions, built a city beyond anything the Spanish had seen.

The first eight months in that city, from November 1519 to June 1520, were surreal even by the standards of such expeditions, which their participants conceptualized in terms of medieval stories of adventure—chansons de geste, Spanish romances, and Christian crusades. (These stories were popular across the whole range of Spanish society: Bernal Díaz was fond of Amadís of Gaul , a 1508 blockbuster, while Queen Isabella preferred the Legend of Lanzarote.)43 While the two sides exchanged labyrinthine courtesies, they plotted against each other in mutual ignorance, suspicion, and mistrust. Each was good at war;

both were afraid; neither was confident that it could win should the tense modus vivendi collapse. The Mexica were, said one of Sahagún’s indigenous informants, “awaiting death, and they talked of this among themselves, saying, “What can we do? Go where we may, we shall be destroyed. Let us await death here.”44 Meanwhile, the Spanish sized up the trap in which they found themselves: a small band of Europeans in the heart of an unknown and warlike society, whose vast army— according to the Tlaxcalans—aimed to eat them slow-cooked with salt, chili, and tomatoes. 45

And so, with the improvisational thuggishness that underwrote much Spanish achievement, Cortés and his captains decided to kidnap Montezuma. They were not the first to use this strategy—the conquistadors of Panama and Nicaragua had captured native rulers to subdue their peoples—but they were undeniably the most ambitious and successful. The Spanish had been in the city for perhaps a week. On the pretext of a Mexica attack on his Veracruz encampment, Cortés and Malintzin visited Montezuma’s palace and offered him the choice of imprisonment or summary death. It was one of several critical moments revealing Montezuma’s helplessness: He went along with Cortés and the fiction that he was doing so freely. He became, at a stroke, a puppet and collaborator. He still legislated in petty affairs of the Mexica and had some freedom; the Spanish took him yachting and even allowed him to continue his human sacrifices. But that did not make him a free man; a European officer might have expected the same treatment (minus the human sacrifice) on parole. Montezuma’s lack of real authority quickly became apparent when Cortés put him in chains and had the captains who had allegedly attacked Veracruz burned alive.

In the aftermath of that public execution Cortés offered the emperor the chance to return to his palace, but Montezuma refused—in fear, according to the chronicler Juan de Torquemada, of his own people. 46 Whether this is the case or whether, as Díaz claims, he recognized the speciousness of the offer, hardly matters. What is unimpeachable is that Montezuma’s imprisonment revived dormant tensions among the Mexica. The tlatoani had great, divinely sanctioned, and customarily uncontested power, and Montezuma had been unusually violent in deploying it; but now opposition to his appeasement of the Spaniards crystallized in a hawkish faction of nobles and priests. At first, these

hawks continued to pledge absolute loyalty to the sovereign, restricting themselves to urging war in their daily visits to Montezuma. But the tlatoani’s acts of collaboration grew increasingly compromising. When the Spanish discovered the great treasure of Ahuitzótl concealed within their quarters, Montezuma did not just give it to them; he sent his silversmiths to help them melt it down. Provoked by the kidnapping and then the robbery, Cacamatzin, King of Texcoco, began organizing a surprise attack on the Spanish. Upon learning of the plan, Montezuma had the king arrested and handed over to Cortés, who garroted him. Although the emperor was a deeply religious high priest of the Mexica, he nevertheless allowed the Spanish to set up a chapel to the Virgin Mary in the Great Temple. The tlatoani was clearly eager for his jailers’ approval and gave them gold as well as some of his mistresses. His jailers did not, however, respond in kind: One called him a dog, and another deliberately farted noisily while on guard. Cortés, though, continued to play Montezuma both metaphorically and literally, amusing him with frequent visits for games of totoloque, a form of toss ha’penny played with gold (at which Alvarado, characteristically enough, cheated). 47

Finally, in the spring of 1520, the hawks gave Montezuma an ultimatum, couched in the language of divine command, to declare war on the Spanish. The emperor warned Cortés and temporized, negotiating time for the Spanish to build ships in which to depart. Whether they would have left is a moot point: Before the ships were completed, a fifth Spanish expedition landed on the coast. With at least eighteen ships, over a thousand men, and nearly a hundred horses, it far outnumbered that of Cortés, and it came to stay; the new arrivals brought with them large amounts of merchandise to sell to both Spaniards and Indians. 48 Dispatched by his powerful enemy Diego Velázquez, governor of Cuba, the new expedition was hostile to Cortés and established secret contact with Montezuma. But it was commanded by the uninspiring Pánfilo de Narváez. Gonzalo de Sandoval, one of Cortés’s most politically gifted men, skillfully subverted Narváez’s soldiers, winning over commanders and artillerymen, some of them his relatives, with gold and promises. At the end of May Cortés made a forced march to the coast, leaving Pedro de Alvarado and a small contingent in Tenochtitlán to guard Montezuma. When they reached the coast, Cortés and his men fell

on the new arrivals by night and swiftly defeated them. There were very few casualties, and Cortés incorporated Narváez’s men into his own expedition, trebling his forces. It should have been a moment of triumph and relief. Yet in keeping with the melodrama of the Spanish chronicles, Díaz tells us that “at the very moment of victory news came from Mexico that Pedro de Alvarado was besieged.” The Mexica had finally gone to war. 49

It was bound to happen. But it was no coincidence that the final rupture came in Cortés’s absence. He was a gifted Machiavellian who had steadily increased his demands on the Mexica while maintaining an improbable peace. When he left for the coast, he handed over command to Alvarado, who had Cortesian pretensions, charm, and courage but few of the other abilities. As Cortés afterward recognized, it was a bad choice. The Mexica asked Alvarado’s permission to celebrate the festival of Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, in the main temple. He gave permission and then, at the height of the celebration, launched a carefully planned attack that sealed the temple compound and turned it into a killing ground. There were hundreds, perhaps thousands, of dancers present; almost all were killed. An indigenous survivor left a graphic account:

They surrounded those who were dancing, going among the cylindrical drums. They struck a drummer’s arms; both of his hands were severed. Then they struck his neck; his head landed far away. Then they stabbed everyone with iron lances and struck them with iron swords. They struck some in the stomach, and then their intestines came spilling out. They split open the heads of some, they cut their skulls to pieces; their skulls were cut up into little bits. They hit some on the shoulders; their bodies broke open and ripped. Some they hacked on the calves, some on the thighs, some on their stomachs, and then all their entrails would spill out. And if someone tried to run it was useless; he just dragged his intestines along. There was a stench that smelled like sulphur.50

The motive is baffling; surviving explanations were penned a generation or more after the fact. The late sixteenth-century Codex Ramírez calls it robbery plain and simple, with Alvarado—covetous even by

his peers’ high standards—seduced by the Mexica nobles’ jewelry. The seventeenth-century Texcocan historian Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl has a more complicated and convincing version, whereby the Tlaxcalans duped Alvarado into a preemptive and exemplary massacre with reports of a (nonexistent) Mexica conspiracy, much as they had done in Cholula. The Mexica had regularly sacrificed Tlaxcalans at this festival, and this was their revenge. It was one more chapter in their longstanding civil war.

A mob of Mexica immediately attacked the Spanish barracks and would have overrun them had Montezuma not ordered them to withdraw. At that point, his people still obeyed him. When Cortés reentered the city on June 24, bolstered by Narváez’s men and another two thousand Tlaxcalans, he found the streets empty and the market closed, but the fighting paused. Cortés then compounded Alvarado’s blunder by insulting Montezuma, the only possible mediator, and releasing his younger brother, Cuitláhuac, to negotiate with the nobility. Cuitláhuac was a hawk; predictably enough he never came back. Instead he became the new Mexica leader and launched a massive assault on the Spanish quarters. Cortés supposedly sent Montezuma onto a rooftop to urge a ceasefire that would let the Spanish leave in peace, but the crowd was having none of it; someone down below—according to the Codex Ramírez, his nephew Cuauhtémoc, soon to be emperor—denounced him as a scoundrel and a homosexual and the attack resumed. The Mexica rained darts and stones onto the roof, wounding Montezuma in the head, arm, and leg. He died the next day. It was “quite unexpected,” said Díaz, one of several unexpected deaths of people close to Cortés. Montezuma had outlived his usefulness and might yet have mounted some opposition, and several indigenous historians either hint at or straightforwardly accuse the Spanish of his murder. 51 It is his most likely ending, placing him among the rest of the captive lords, stabbed to death in their chains.

Diplomacy in tatters, the only option left to the Spanish was retreat. Blas Botello Puerto de Plata, the expedition’s soothsayer, foresaw annihilation if they did not leave immediately. This was not a prediction requiring second sight. They faced tens, possibly hundreds of thousands

of Mexica warriors; they themselves numbered around fourteen hundred Spaniards and several thousand Tlaxcalans. On the night of July 1, 1520, they tried to sneak out of the city, carrying what treasure they could and a large portable bridge.

The bridge was vital, for the miles-long causeways leading across the lake out of Tenochtitlán were punctuated by canals, from which the Mexica had removed the bridges. The withdrawal began in a light rain, the column heading west along the Tacuba causeway. They managed to cross the first canal in safety, but a woman saw them and gave the alert and at the second canal the fighting started. The night collapsed into bloody chaos: The Spanish lost their bridge and retreat turned rout. At the canal of the Toltecs, attacked on both sides by canoes and harried by Mexica chasing them down the causeway, the panicking Spanish and Tlaxcalans were forced into the water and were either drowned—many had stuffed their clothes with roughcast bars of gold—or killed in such numbers that those running behind found the gap bridged by corpses. Some at the rear of the column were cut off and turned back into the city, where they made a last stand in their palace before the Mexica captured and sacrificed them. The luckier Spaniards on the lakeshore took a week to fight their way to the safe haven of Tlaxcala, where they took stock. At this unlikely point, Cortés named the country he was losing. Earlier baptisms involved tediously literal Spanish descriptions, saints’ names, or bastardized indigenous words: Puerto Rico, Rich Port, or Tierra Firme, the Mainland; Santo Domingo, for Saint Dominic; Cuba, from the corruption of a Taino noun meaning “great place.” Cortés knew that he had taken a leap beyond these footholds and wanted Emperor Charles V to believe it so that he would send him a proper legal title and even reinforcements. So in October 1520 he wrote Charles a self-aggrandizing letter, toward the end of which he let the emperor know that

from what I have seen and understood regarding the similarity that this entire land bears to Spain, as much in fertility as in grandeur and the cold weather and in many other things that make them comparable, it seemed that the most apt name for this happy land was that of the New Spain of the Ocean Sea, and consequently in the name of Your Majesty I gave it that name.

He hoped, he wrapped up, that His Majesty thought that was acceptable and would sign off on it. 52

The report of a revolutionary future for Spanish power was also meant as distraction and consolation prize for the news of their lethal rout from Tenochtitlán. Cortés watered his defeat down, claiming that he had lost a mere 150 countrymen on that slaughterous night, which became known as the Night of Sorrow, the Noche Triste. But when he mustered his forces in late December there were only 590 men left, and that was after receiving at least 150 fresh troops in the autumn. He had had by all accounts a force of over 1,400 Spaniards before the outbreak of war; consequently, the Mexica probably killed some 900 Spanish that week. 53 As for his indigenous allies, they suffered even more; according to Ixtlilxóchitl some four thousand Tlaxcalans died in the retreat from Tenochtitlán. 54

Yet any Mexica celebrations were short-lived. As the Spanish regrouped in the Tlaxcalan highlands, they gained a new, microbial ally in the form of smallpox. The disease seems to have been brought to Mexico with Narváez by a Black slave, Francisco Eguía; it broke out in Chalco at the end of September. Smallpox was fairly common in Europe, and though it was certainly dangerous to Europeans, the Spanish had a reasonable degree of resistance; the indigenous peoples of the Americas had none whatsoever. As a result, a Franciscan recorded, “among them the sickness and pestilence was so great throughout the land that in most provinces more than half the people died, and in the others little less.”55 This great dying weakened the Mexica armies; it also caused, within months, a generational shift in political leaders across central Mexico. In Cholula, Tlaxcala, and various other towns, it was Cortés who chose successors for the dead caciques, tightening his grip on the region. In Tenochtitlán it fell to the Mexica state council to choose a new leader, because among the dead was the short-lived emperor Cuitláhuac.

In his place the Mexica chose Cuauhtémoc, a talented and intransigent warrior in his mid-twenties. The high priests’ traditional somber admonition to their new tlatoani must have rung particularly bleak:

Perchance you will bear for a while the burden entrusted you, or perchance death will attack you and this your election to this kingdom will be but a dream . . . perchance other kings who despise you

will wage war on you, and you will be defeated and detested, or perchance God will permit that hunger and dearth fall upon your kingdom. What will you do if in your time your kingdom is destroyed, or our lord God unleashes his wrath upon you, sending plague? What will you do if in your time your kingdom is destroyed and your splendour becomes darkness?56

The Mexica’s recent history had been disastrous, and Cortés was gathering allies among their neighbors—this was now a multinational coalition of indigenous peoples from both outside and inside the Valley of Mexico—to assault the city. So the new emperor continued his predecessor’s preparations for war. He dispatched ambassadors to both subject peoples and sworn enemies, even the Tlaxcalans, offering new deals in return for support. He mustered troops and strengthened Tenochtitlán’s fortifications, deepening canals, building walls, digging trenches, and planting stakes in the lakebed. A later chronicle has it that Cuauhtémoc met with Cortés before the siege began. This seems unlikely: Such an encounter would have fit too neatly into the Spanish trope of chivalric warfare to escape every Spanish contemporary’s account. If it did happen it was not the emperor’s idea; as Spanish soldiers reported learning from their Mexica prisoners, “Cuauhtémoc’s intentions . . . were that they would never make peace, but either kill us or die to the last person.” 57

The siege began on May 13, 1521. The Spanish divided their forces to blockade the three main causeways into Tenochtitlán, and broke the pipes that brought fresh water from the springs at Chapultepec. Cortés initially followed a scorched-earth strategy, sallying daily down the causeways into the city, burning houses and defenses, and then retreating for the night. This was painfully slow; the Mexica had the manpower to rebuild their defenses; and the Spanish, sleeping in half-ruined huts, eating grasshoppers, oppressed by heavy rains and continuous fighting, grew impatient. The failure of their first plan seemed clear at the end of June, when Cuauhtémoc made simultaneous night attacks on the Spanish camps before launching a concentrated

assault on Alvarado’s troops on the western lakeshore. The Spanish, very nearly overrun, took heavy losses. In the aftermath they decided to end the war rapidly with a three-pronged attack on the center of Tenochtitlán. It turned out to be a disastrous idea: The Mexica lured Cortés’s men deep into the city and ambushed them. In addition to the many deaths, the Mexica took sixty-six Spanish alive, once more at one of the bridges, and sacrificed them. The effect on Cortés was critical, and he decided to act on his earlier conclusion:

Seeing that those of the city were rebellious and showing such determination to defend themselves or die, I gathered from them two things: first, that we would have little or none of the wealth that they had taken from us, and second, that they . . . were forcing us to destroy them utterly.58

Cuauhtémoc’s leadership—sometimes fighting on the ground, sometimes directing operations from the top of one of the city’s temples— worked well at first. His men nearly captured Cortés in the defeat at the bridge; in the aftermath, the combination of Mexica victory and subsequent propaganda briefly scared off many of Cortés’s indigenous allies. The Mexica, sometimes portrayed as destined to lose because of their sheer incomprehension of their situation, were acutely aware of the novelty—and gravity—of confrontation with the Spanish. They fought with the characteristic sophistication of Mexica warfare, making use of spies, saboteurs, and complex ambushes. They adapted to the new weapons and tactics employed by the invaders. Warriors learned to run in zigzags to confuse the aim of bowmen and gunners, and to throw themselves to the ground and take cover from cannon. Indigenous armorers turned captured swords into scythes and lances; archers learned how to use crossbows. 59 Open spaces such as the market were strewn with boulders to hold up the cavalry. And yet for all that, the Mexica faced certain structural disadvantages that made defeat the most probable ending.

One disadvantage, the least important, was the gap in military technology. The Mexica fought with shield and macquahuitl , a wooden sword edged with obsidian blades; for projectiles they had atlatls , or spear-throwers, as well as bows and slingshots. They were mismatched

against the Spaniards’ early modern tools: steel swords and armor, early small arms called arquebuses, a handful of cannon. In addition to the weapons they imported, the Spanish fabricated more in the course of the war. A giant siege catapult fashioned by a veteran of the Italian wars was comically useless; gunpowder made with sulfur hauled up from the volcano Popocatepétl was not. Yet arquebuses were inaccurate and complicated to load; the few cannon were light. They were impressive as novelties but indecisive as weapons. The Spanish wrote them off as failures in more than one bout of heavy fighting.

As for steel, Spanish armor was hot and cumbersome, and overengineered for this sort of war anyway; most Spanish swapped it for the cotton armor of the Indies. Steel swords were better than anything indigenous, but while obsidian was fragile, it could also be sharpened enough to shave, or to cut open the chest of a human sacrifice. It scared the Spanish; the mysterious Anonymous Conquistador, after Cortés and Díaz the only soldier to write about the war, claimed that the shiny black stone

cut like a blade from Tolosa. One day I saw an Indian fighting with a horseman, and the Indian gave his adversary’s horse such a slash in the stomach that it opened all the way to the entrails. And that same day I saw another Indian deliver a cut to the neck of a different horse, with which he laid him dead at his feet. 60

Gunpowder and steel, in short, were not the advantages they have been made out to be.

Transport was a different matter. Horses were extraordinarily difficult for enemies to deal with, and their value was such that Cortés, describing the death of a mare, expressed more grief than he did in describing many human deaths. When the astrologer Botello asked the spirits about the future, the first question he posed was whether he would survive the war; the second, “If they are going to kill me will they kill my horse too?”61 The Spanish knew their steeds would be critical even before they left Cuba, and thirty years on Díaz could remember every one of the sixteen they shipped over (“a very fine chestnut mare, lively and fast . . . a dappled stallion, chiseled forelegs,

well built . . . a very good stallion, quite a light chestnut in color and a good gallop”). 62

But it was the ships that were, as Cortés put it, “the key to the entire war”: not the ships he left on the beach at Veracruz, but the brigantines he ordered built in the central highlands in early 1521, new hulls mounted with the rigging, sails, and fittings from his original flotilla.63 These thirteen small ships, heavily manned and armed with cannon, gave Cortés control of the lake. The Mexica immediately realized their importance and repeatedly sent saboteurs to burn them. Once the brigantines were launched, the Mexica fleets of canoes were overpowered by these larger, faster, and more heavily armed vessels. In them, the Spanish could raid the outskirts of the city with relative impunity and move reinforcements and materiel quickly between their different camps. Most important of all, the brigantines converted Tenochtitlán’s great defensive advantage, its vast natural moat, into a critical weakness. The city was densely populated and dependent on imported food. By patrolling the lake night and day, the Spanish cut the Mexica supply lines; by mid-July the city began to starve.

To attribute the Mexica’s eventual defeat to this particular form of technological superiority would be, however, to miss the point. The blockade could never have worked without the support of the lakeside towns and villages, and the brigantines could never have been deployed without the manpower of the Tlaxcalans, who built the hulls and supplied eight thousand porters to carry them some fifty miles down to the lakeshore. The entire campaign is, in fact, unthinkable without Cortés’s indigenous alliances, which began with the Tlaxcalans and steadily expanded until they formed a coalition encompassing almost all the central Mexican peoples. The Mexica empire-building of the preceding century had encompassed a systematic terrorism, involving not just conquest but also ongoing sacrifices of human tributes from the defeated. As Montezuma himself said, they had been ruled by fear. When the calculus of fear shifted in favor of the coalition, so did their loyalties. By the end of June 1521, the Mexica were under attack by over one hundred thousand indigenous troops, with more arriving as their erstwhile subjects deserted them.

Not just on the Gulf Coast or in the highlands did history weigh against the Mexica. Their closest neighbors were also quick to turn on

them. Early in the siege Cuauhtémoc called for reinforcements from lakeside towns such as Mixcoac and Xochimilco; the latter sent boatloads of warriors into the city, where, instead of joining the defense, they robbed unprotected houses and carried off slaves; they then went over permanently to the Spanish, completing the capital’s encirclement. Even within the closely allied cities of Tlatelolco and Texcoco there was endemic disunity, as the war fostered violent struggles for power. In Texcoco, prey to a violent dynastic dispute even before the Spanish arrived, Cacamatzin’s successor, suspected of pro-Spanish sympathies, was assassinated by his younger brother. In Tenochtitlán, a purge of Montezuma’s faction began with the new hawkish court hunting down his servants and pages and ended in the execution of any of the dead emperor’s sons who came to hand. The bloody, Shakespearean strife peaked, according to a Tlatelolcan chronicler, immediately before the siege began; its effects were catastrophic.64 While an intransigent Texcocan faction went to the defense of Tenochtitlán, the Spaniards’ puppet sent seventy thousand Texcocan troops to support the coalition. “Your Majesty might well consider,” Cortés wrote to his emperor, “how the people of Tenochtitlán would feel to see coming against them those whom they held to be vassals and friends, relatives and brothers, and even fathers and sons.” 65 It was a literally fratricidal war. It was also a total war. The Spanish were shocked at the intensity of the fighting, even in the dying days of the siege: “The arrows and darts were so thick,” remembered one of Sahagún’s interviewees, “that the whole sky seemed yellow.” Their indigenous allies, Díaz reported grimly, “knew of nothing but killing,” and the standard-bearers were changed daily, for they came off “so badly battered that no one could carry the standards into battle a second time.” Yet while Spanish casualties were high, deaths were relatively low. The Mexica by contrast lost thousands. The first skirmish in Iztapalapa cost them an estimated six thousand dead. By mid-July the combination of bad water, hunger, and disease was killing the Mexica in the tens of thousands. When they began foraging on the city borderlands by night, Cortés planned a dawn ambush that killed and captured over eight hundred of those he described as the most miserable, mostly unarmed women and children. By the end of the siege, broad estimates of Mexica deaths from the fighting alone were upward of one hundred thousand. Such devastation

was off the scale of contemporary European warfare. The Battle of Stoke of 1487, which effectively concluded England’s century-long Wars of the Roses, was fought with a total of about four thousand casualties. The destruction of Tenochtitlán, for more than one chronicler, could only be compared with that of Jerusalem.

The siege was fought to the bitter end. By the last days of July the surviving Mexica were driven to a final stand in a small enclave in the north of the city. For weeks they had eaten whatever came to hand, and not much did: rats, lizards, worms, and marsh grass. They dug up roots and stripped the bark off trees. Running out of warriors, the Mexica armed the women and children and sent them out on the rooftops to fight. Streets and houses filled with corpses; it was impossible to avoid treading on them. A contemporary elegy gives some of the horror of the last days: