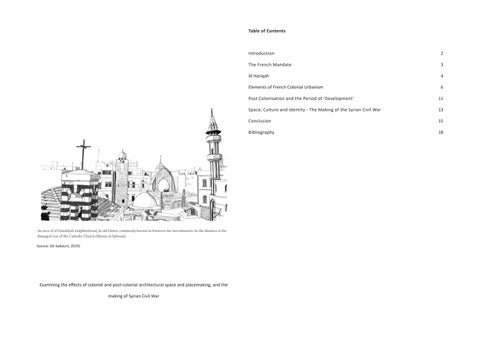

Source: (Al-Sabouni, 2019)

Examining the effects of colonial and post-colonial architectural space and placemaking, and the making of Syrian Civil War

Table of Contents

Introduction

The French Mandate

Al Hariqah

Elements of French Colonial Urbanism

Post Colonisation and the Period of ‘Development’

Space, Culture and Identity - The Making of the Syrian Civil War

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

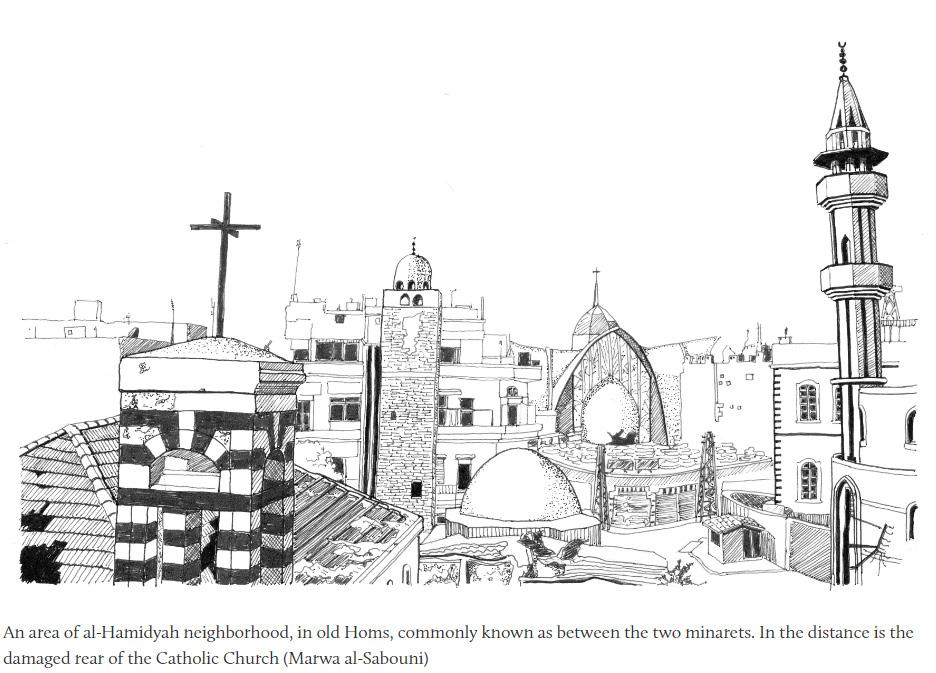

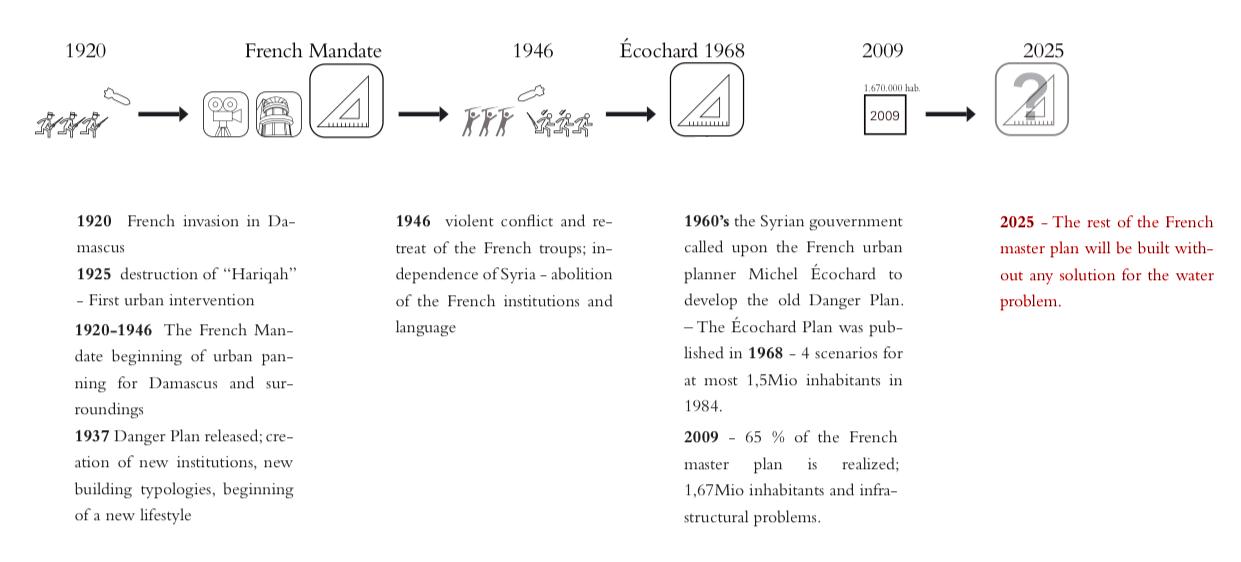

From before the inception of the independent country of Syria in 1946, there have been a multitude of diverse ethnic and religious groups present in the region for hundreds of years (Abbas et al., 2014, 48). Syria has had a longstanding and rich history of “sequenced civilizations which have been layered architecturally within the heart of almost every town and city (Al-Sabouni, 2017)” and has been the central hub of many ancient civilisations, such as the Persians, Greeks, Romans, and the Byzantine to name a few (History.com Editors, 2017). Among the Syrian demographic, there are presently other non-Arab ethnicities like the “Syriac, Assyrian, Kurdish, and Armenian… (with these) cultures integrat(ing) naturally into Syria’s social fabric over time” (Abbas et al., 2014, 52). After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, Syria became a part of the Ottoman Empire from 1516 to 1918. The Ottoman Empire lost control of its territories after the first World War, including the middle eastern regions of the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan), and Mesopotamia (Iraq) (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 5). The British army had aided the local Arab revolutionary groups in Syria in overthrowing the Ottoman government. In the aftermath and at the hands of the British and French Authorities, the Sykes-Picot Agreement divided up the region. By 1920, Syria was underneath the French Mandate, as was Lebanon.

Figure 1: “Mandate Area of French Syria 1920 1946”

Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009)

To understand and assess the repercussions of the French Mandate on Syrian society, the concept of ‘placemaking’ is approached. “Placemaking is the process of creating quality places that people want to live, work, play, and learn in (CNU, 2014).” The concept of space and place are interrelated with personal human connections and interactions. Our surroundings have the power to both define and influence us, meaning that space is more than just its physicality. Therefore, a person’s identity and their spatial environment are interrelated. The French Planners could not anticipate the extent of how their urban interventions impacted the Syrian society. However, through

their own hubris, their schemes when “imposed on a different cultural context, can induce internal conflicts which end up paralysing the internal control mechanism of the community” (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 42). This essay will discuss and examine the effects of colonial and post-colonial architectural space and placemaking, and the making of the Syrian Civil War.

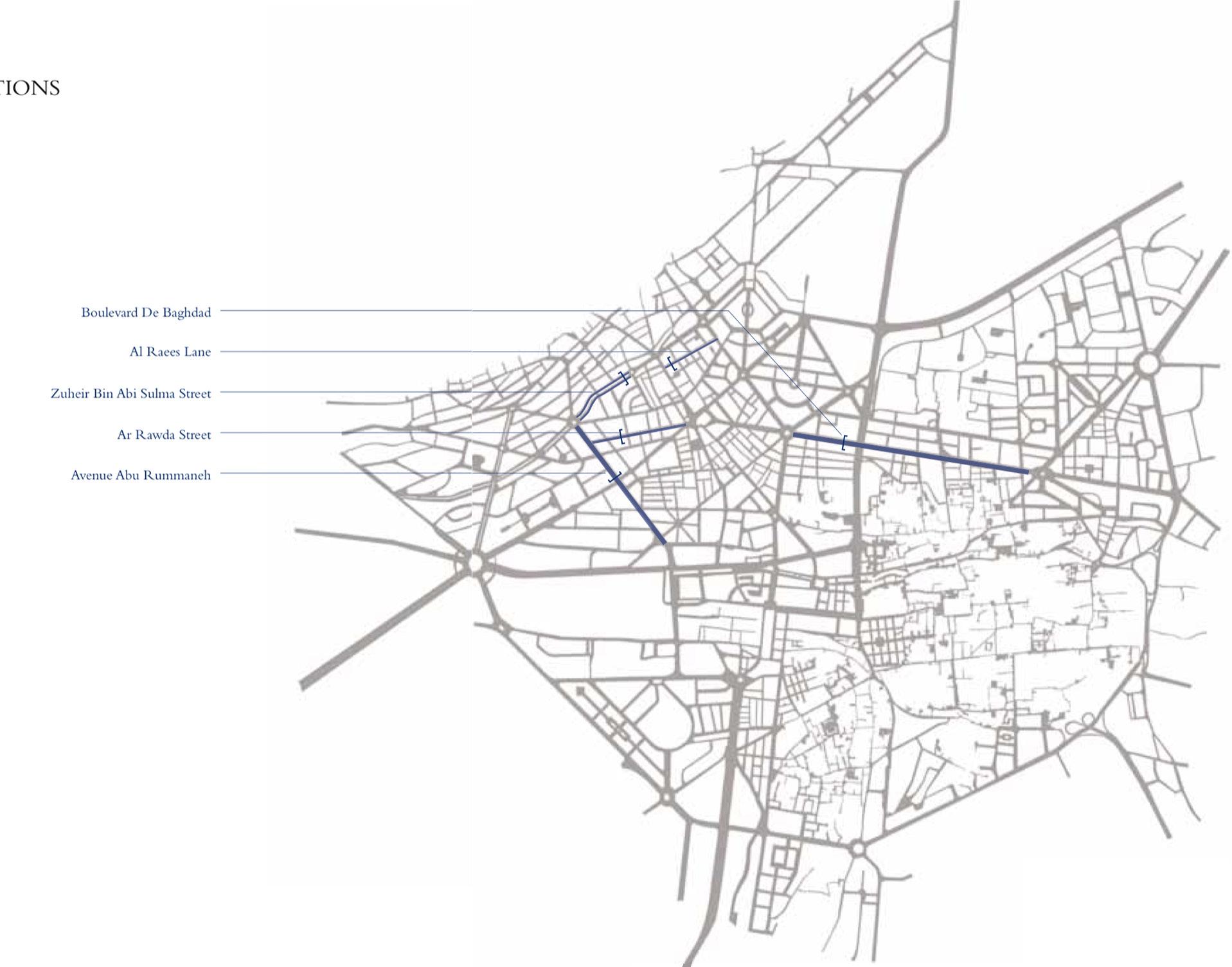

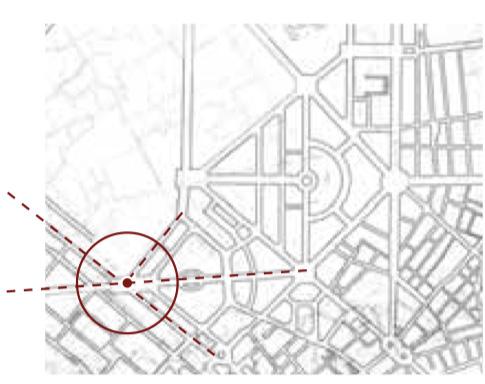

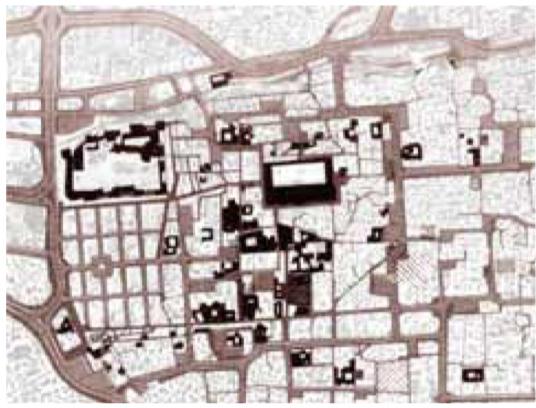

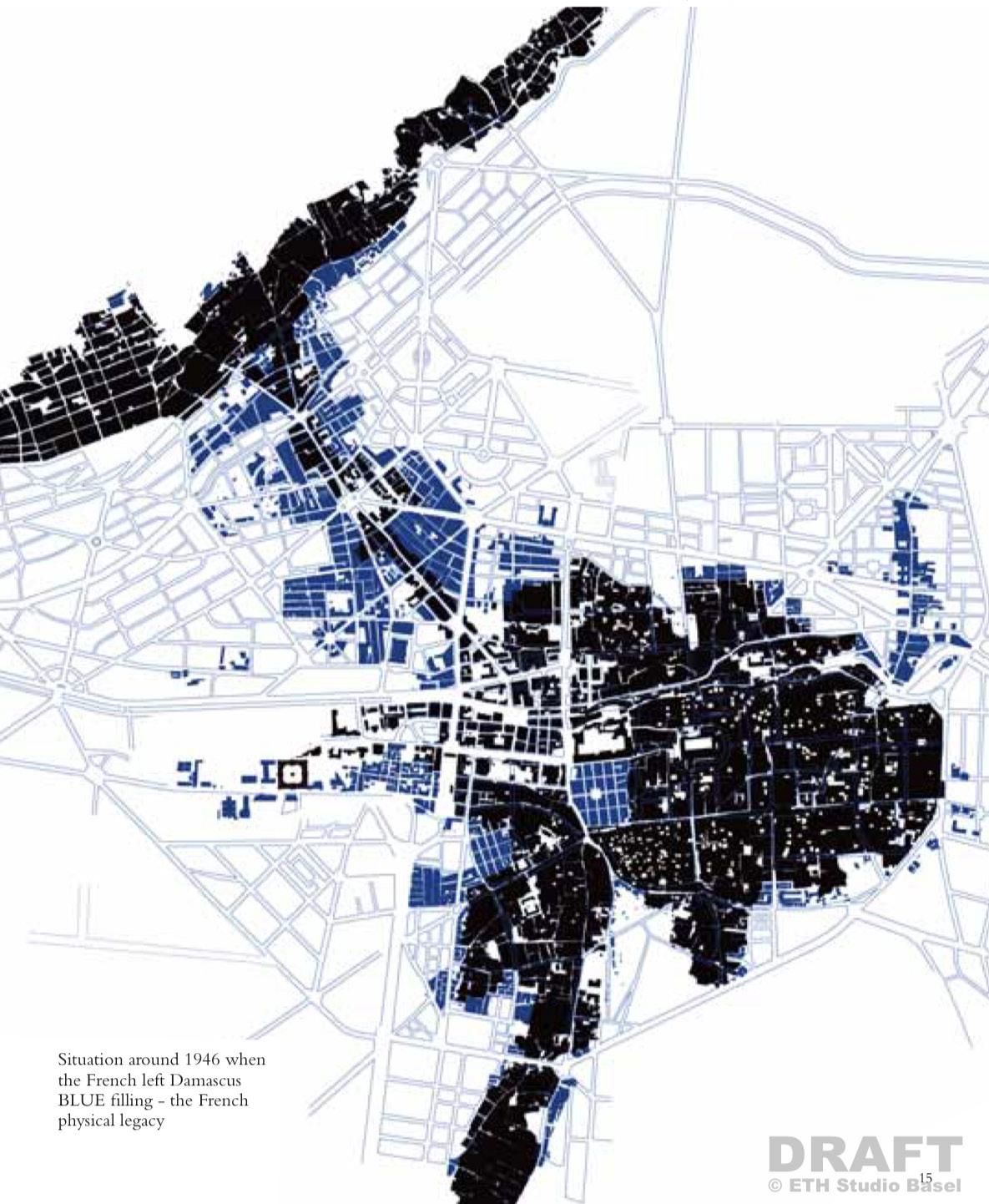

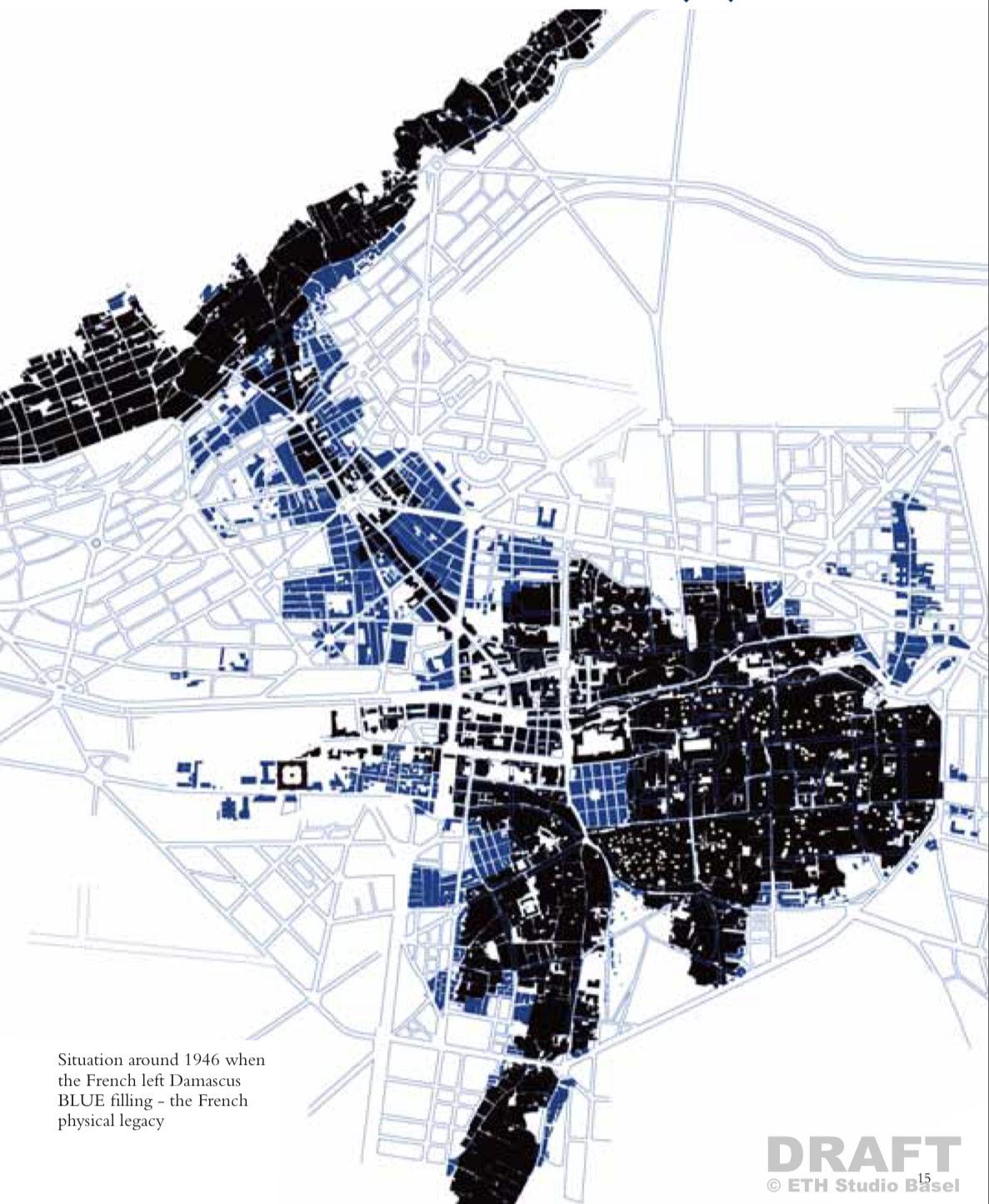

Figure 2: “Masterplan for Damascus” by Danger and Écochard Black - “Urban Fabric of Damascus at the end of the Ottoman Empire” Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 13)

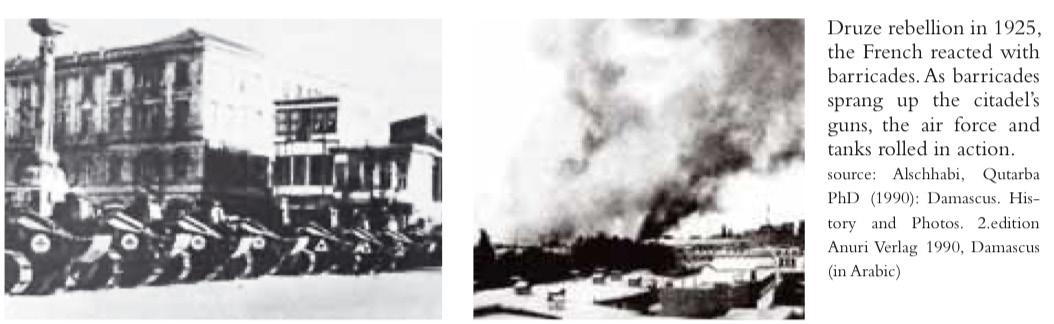

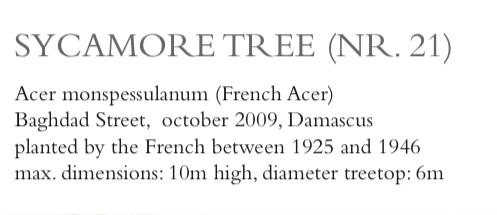

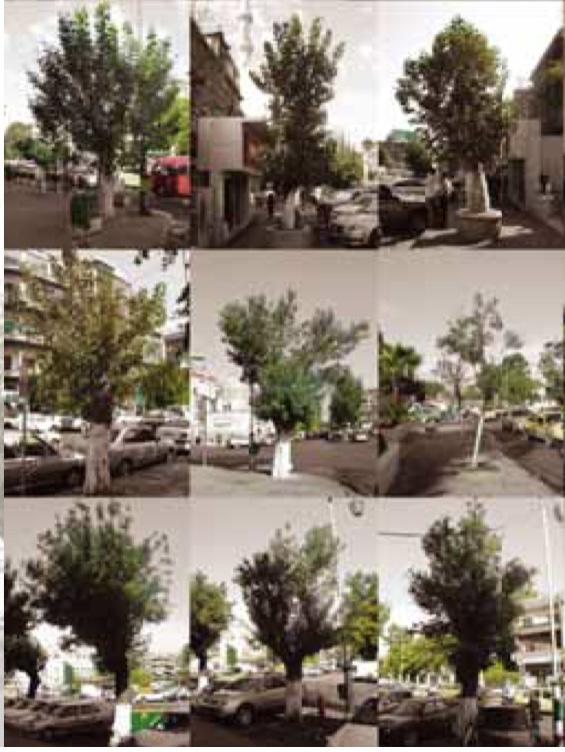

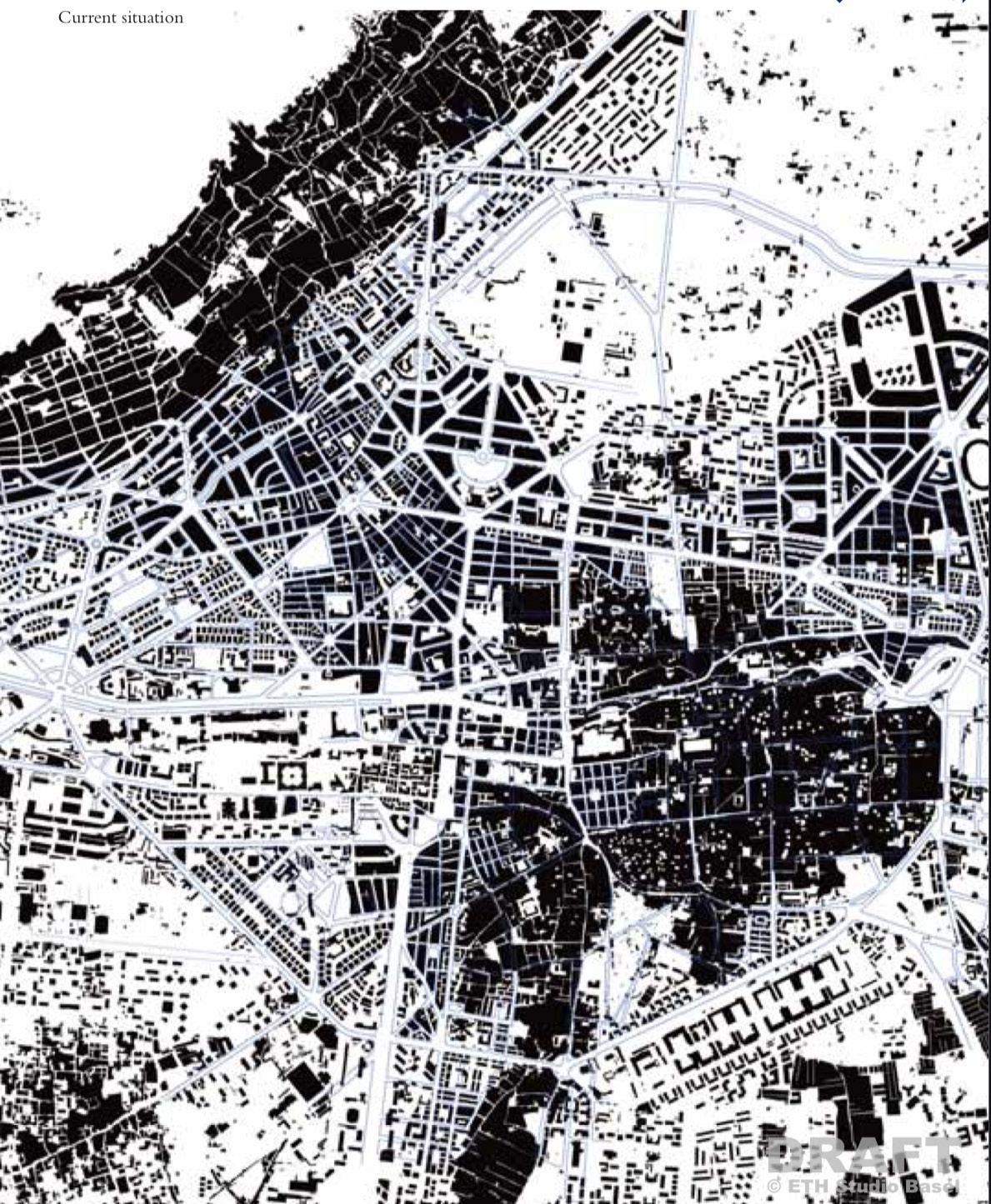

The French Mandate After the end of World War One, the emerging political and religious elite in Syria mainly comprised of Bedouin figures that worked alongside the colonising powers (Omareen & Al Jundi, 2014, page 87). The new ruling figures held their claim to power by “(insisting) on the authenticity of their tribal and clerical lineage… therefore, they possessed a religious legitimacy rather than a civil or political one.” The British and French Authorities during this time, colluded together and drew up an agreement without any representatives of the Syrian demographic, called the Sykes-Picot Agreement (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 5). The French Control was met with opposition and protests, resulting in bombing and destruction of parts of the historical urban fabric (refer to figures 4-10) (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 50). This allowed the French Occupation to introduce their ‘new’ interventions as they “considered the old city as being backward and barbaric” (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 5). Two key architectural figures in the design and implementation of the colonial interventions were René Danger and Michel Écochard. René Danger was commissioned to design a new master plan scheme that implemented ‘modern’ French theories. The interventions of the French urban planners followed the principles “of a Haussmannian city structure”. This included “broad straight streets with tree-lined avenues and residential blocks from four to five floors high with small balconies.” Écochard was employed underneath Danger, and thus was heavily influenced by him. Later in Échochards career, during the 1960’s development boom, he brought many of Danger’s concepts to fruition: “65% of the Écochard plan has been built (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 168).” Haussmann Architecture is the characteristic style attributed to the Parisian aesthetic and city planning, and was developed as a response for improving the living conditions at the time of overcrowding, poor infrastructure, poor hygiene, and disease (Brown, 2022). From Hausmann’s start

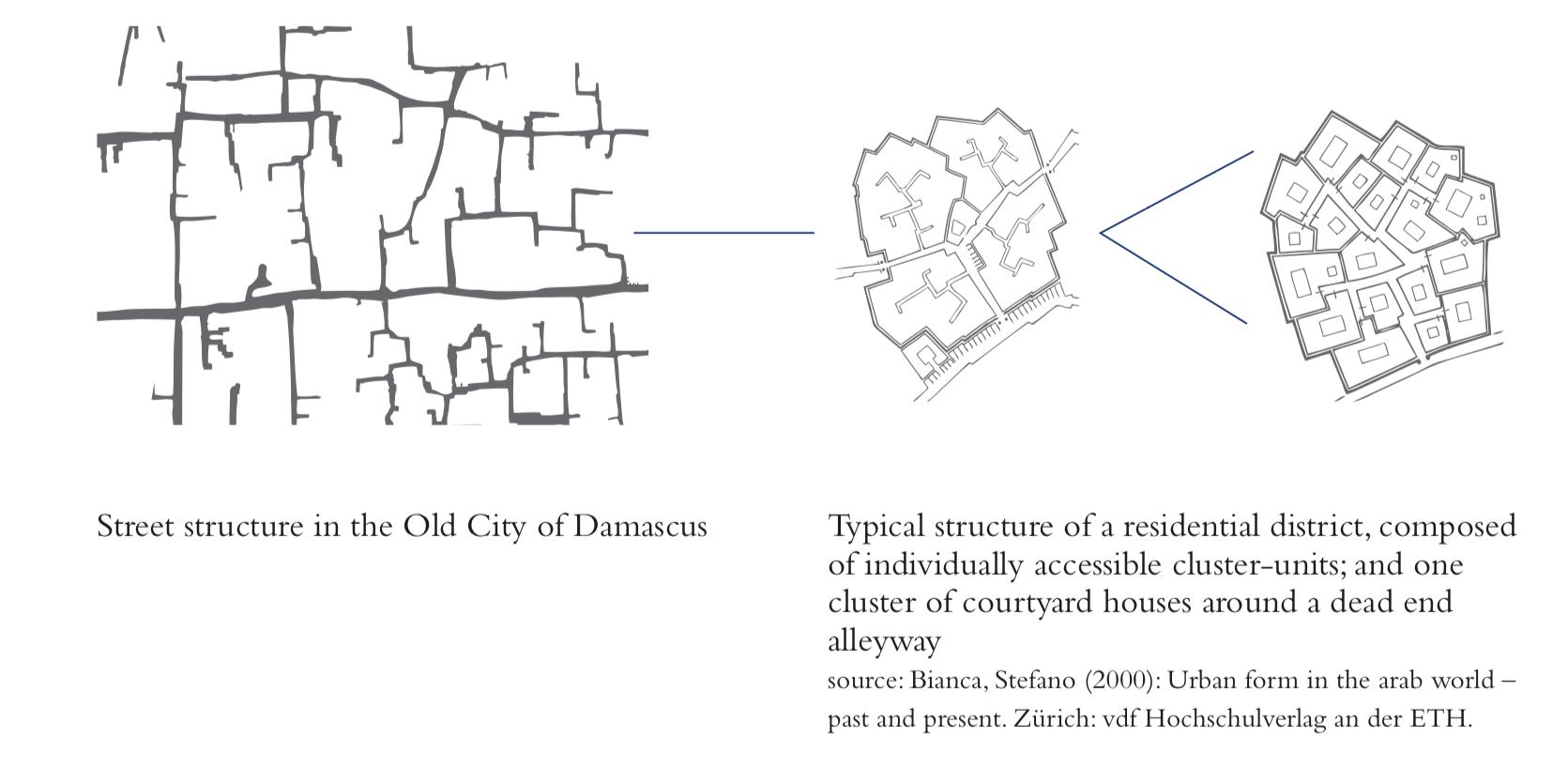

in 1853 until his dismissal in 1870, whole districts and neighbourhoods were demolished to make way for his conceptions: “tearing down of 19,730 buildings and replacing them with 34,000 new ones”. Understandably, Haussmann’s actions were not accepted by many, as stages of architectural history were lost to the demolitions. In addition, his urban scheme essentially gentrified many areas of Paris; prioritising the bourgeoisie and disregarding the poorer class. However, his urban planning schemes were considered ‘modern’ and were valued enough to be implemented into Syria’s urban fabric. It is important to note that Haussmann’s style was envisioned for a European city that craves sunlight and warmth, and had a different history, culture, and social fabric (Karnik, 2019). Historical Syrian and Mediterranean cities in comparison, were designed with smaller scale forms, routes and alleyways to protect and ventilate from the warmer climate conditions.

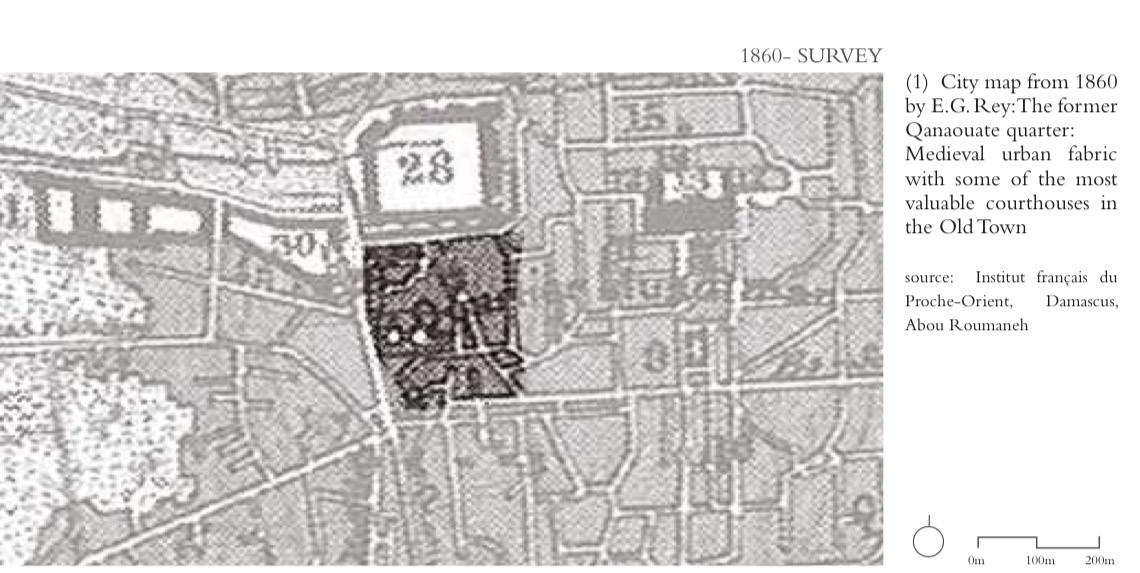

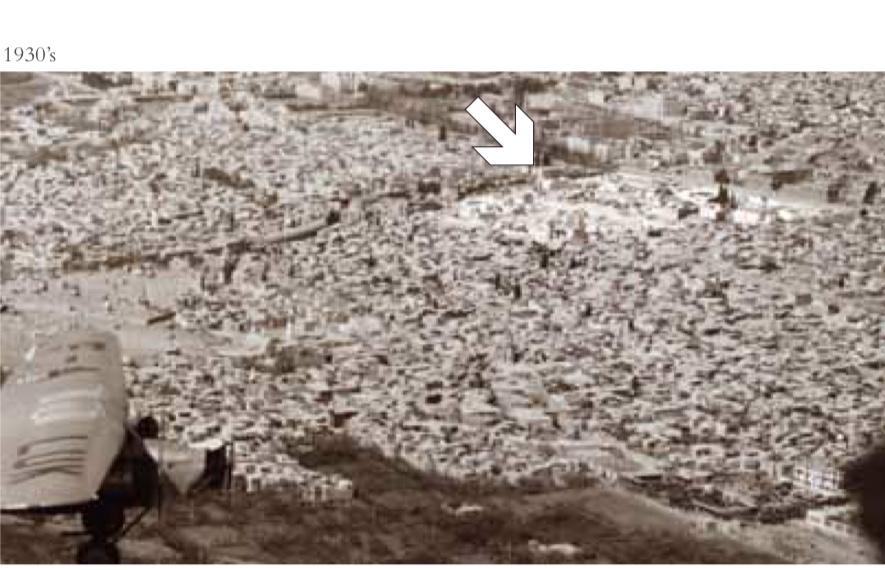

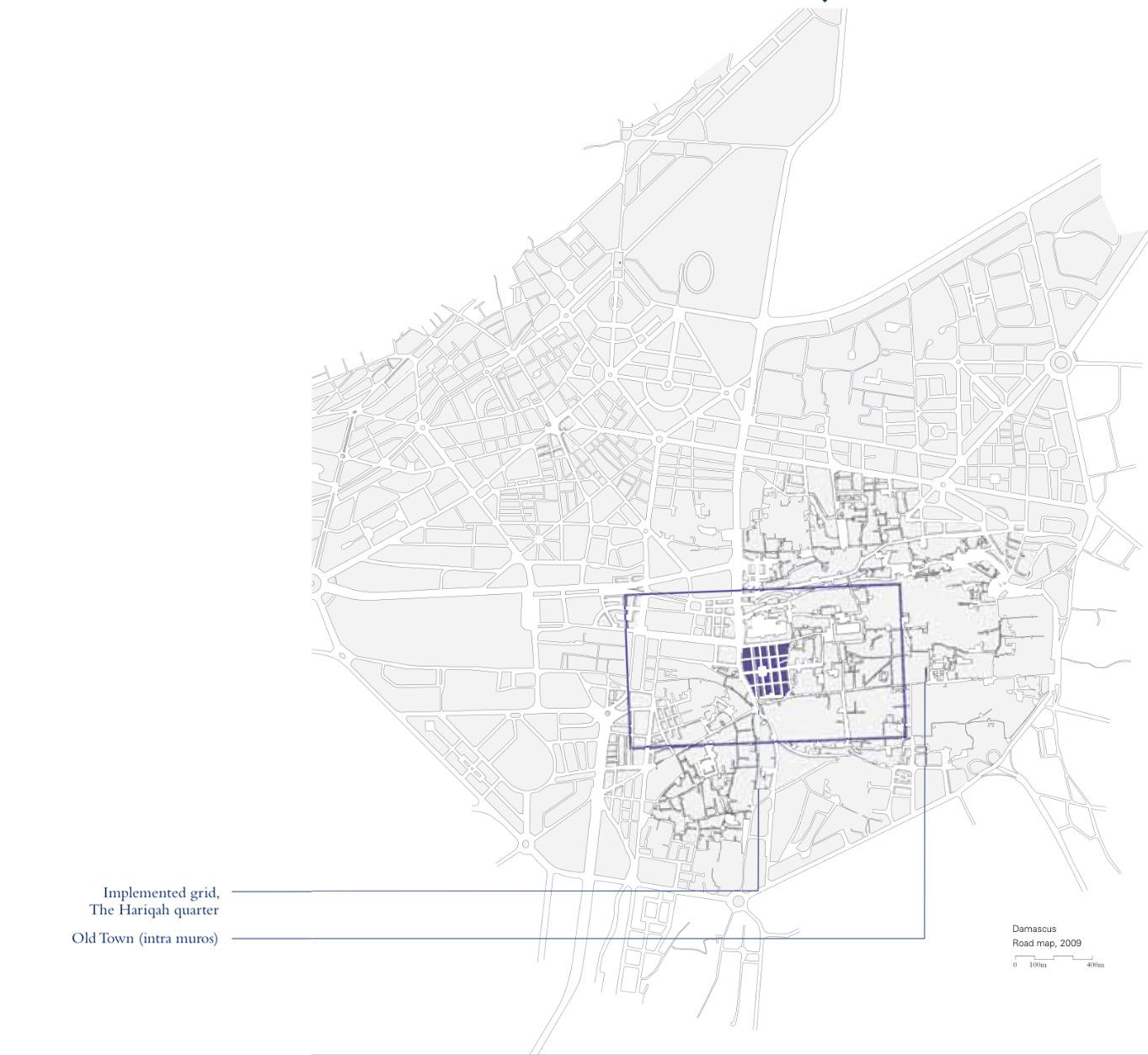

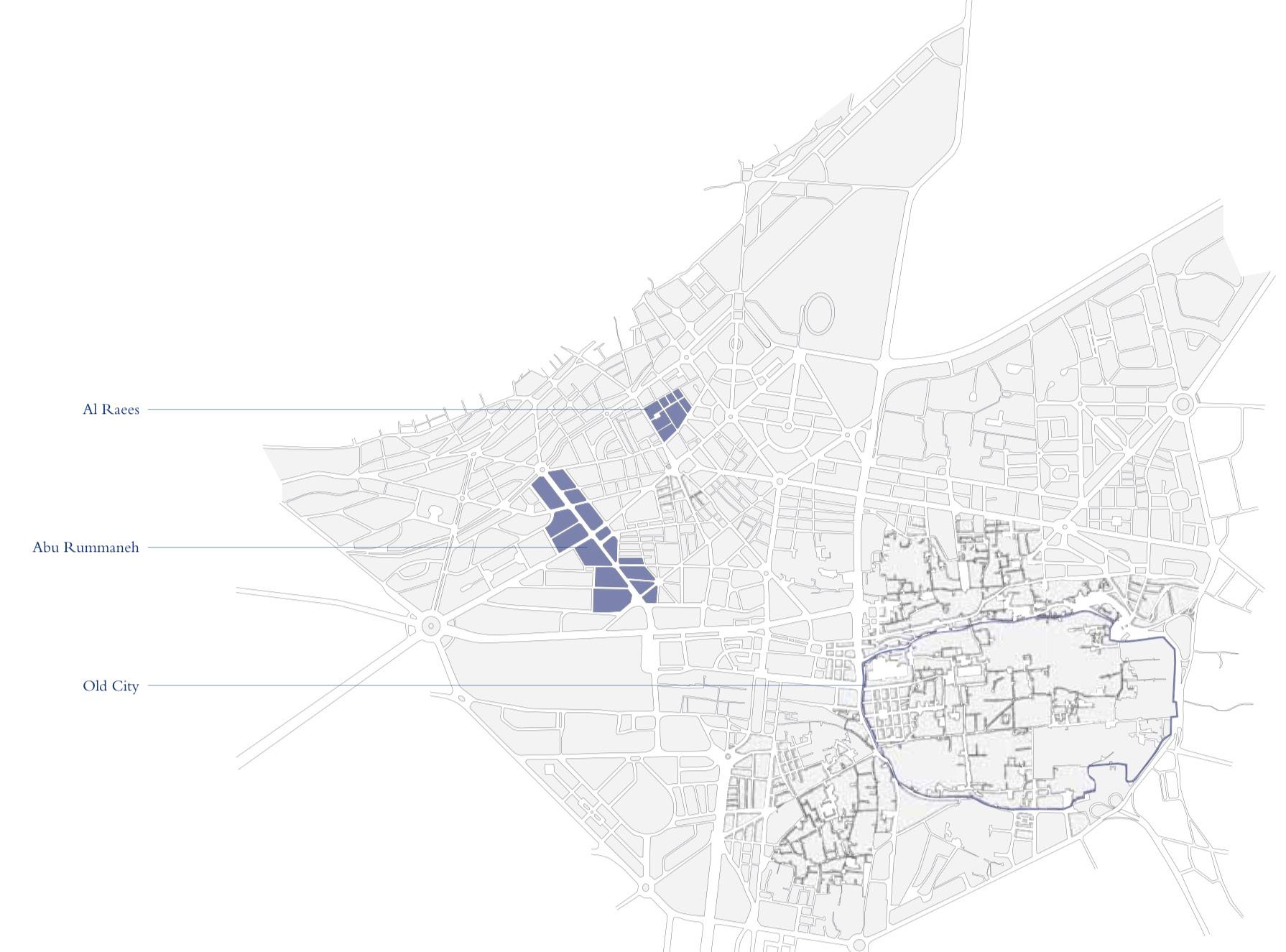

In response to the protests and uprisings by the Druze community, the western part of the Old City was subjected to heavy fire and bombing

(Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 50). Al Hariqah became the first Syrian project of French colonial placemaking.

6: “City

4: “Druze Rebellion in 1925”

(Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 54)

5: “Aerial View of Al Hariqah Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 54)

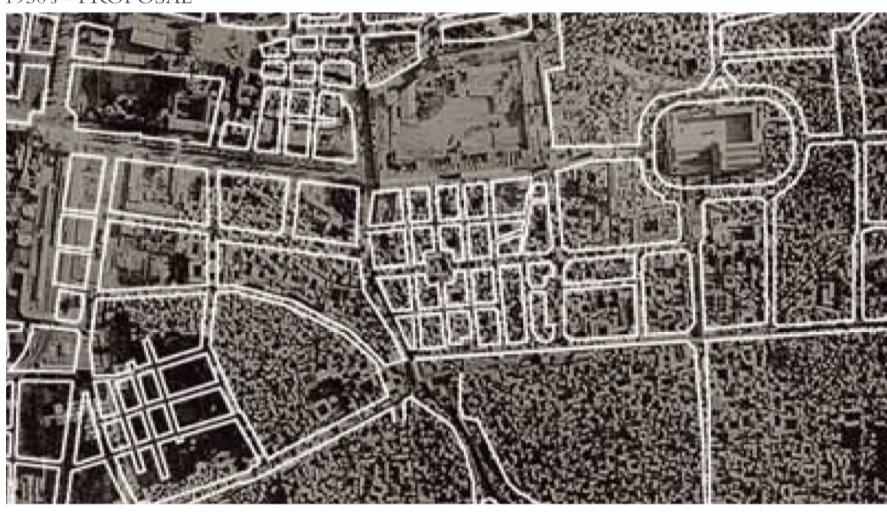

7: “The Danger Plan (1925-37)”

52)

Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 55)

“The bombing of Damascus was welcomed, however, by partisans of ‘modern’ town-planning like Louis Jalabert, who defined it as the ‘development of civilized life’. “[...]The bombardment presented the advantage of allowing certain clearances to be effected (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 50, as cited in Degeorge, 2004).”

Zoning Planning

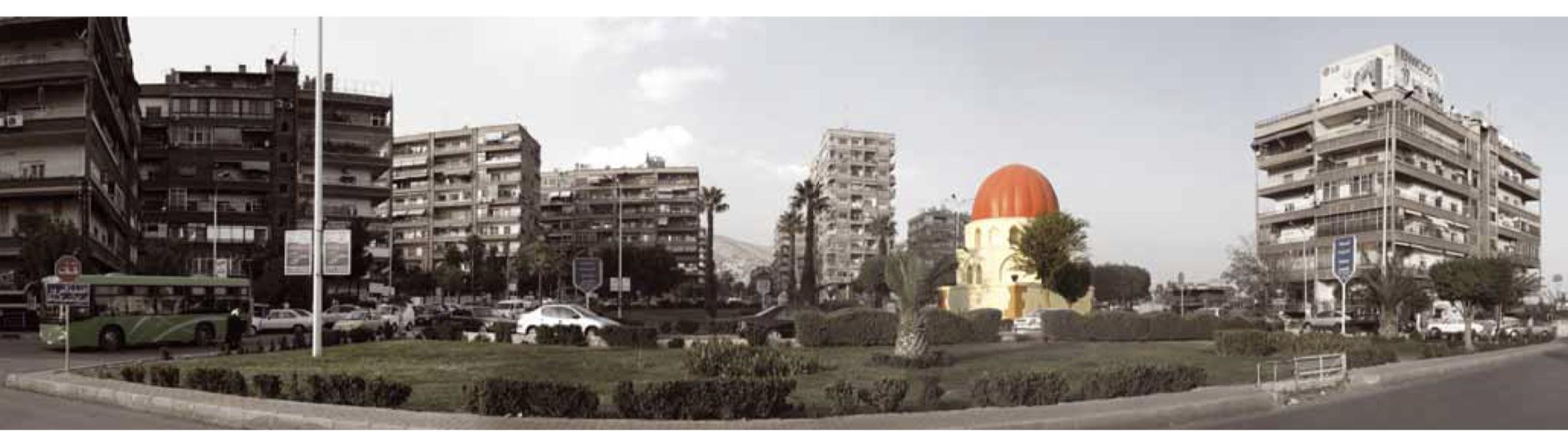

Axis and Roundabouts

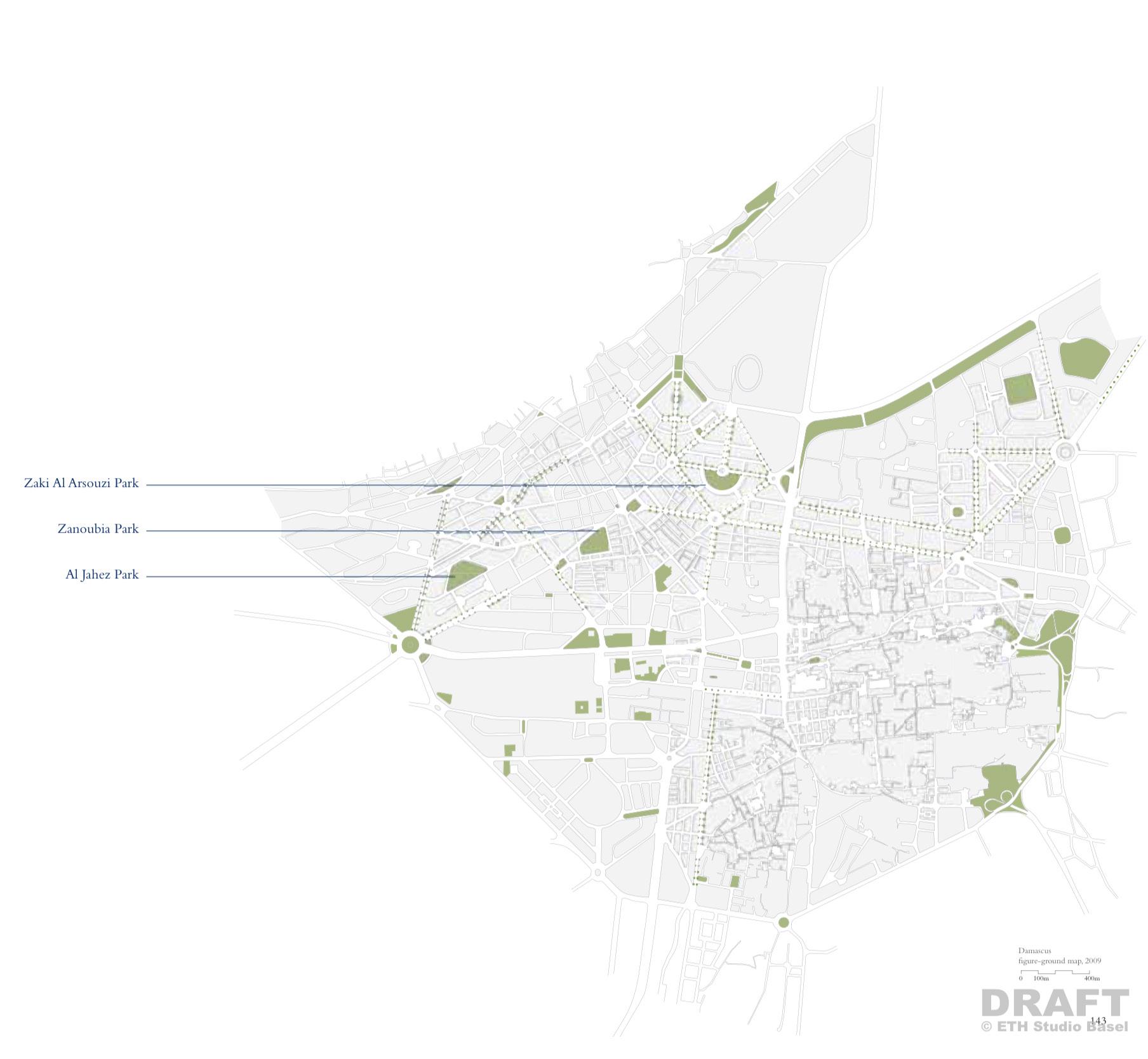

Just as Haussmann demolished and redefined parts of the Parisian urban fabric, so did the French urban planners act in Syria. Following in Haussmann’s footsteps, the colonial planners continued their predecessor’s methods of classist and categorical segregation. The architectural and urban interventions of the French colonial designers are categorised as: zone planning, axes (boulevards) and roundabouts, etoiles and squares, trees, parks and greenspaces, monuments, street furniture and embellishments (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 34).

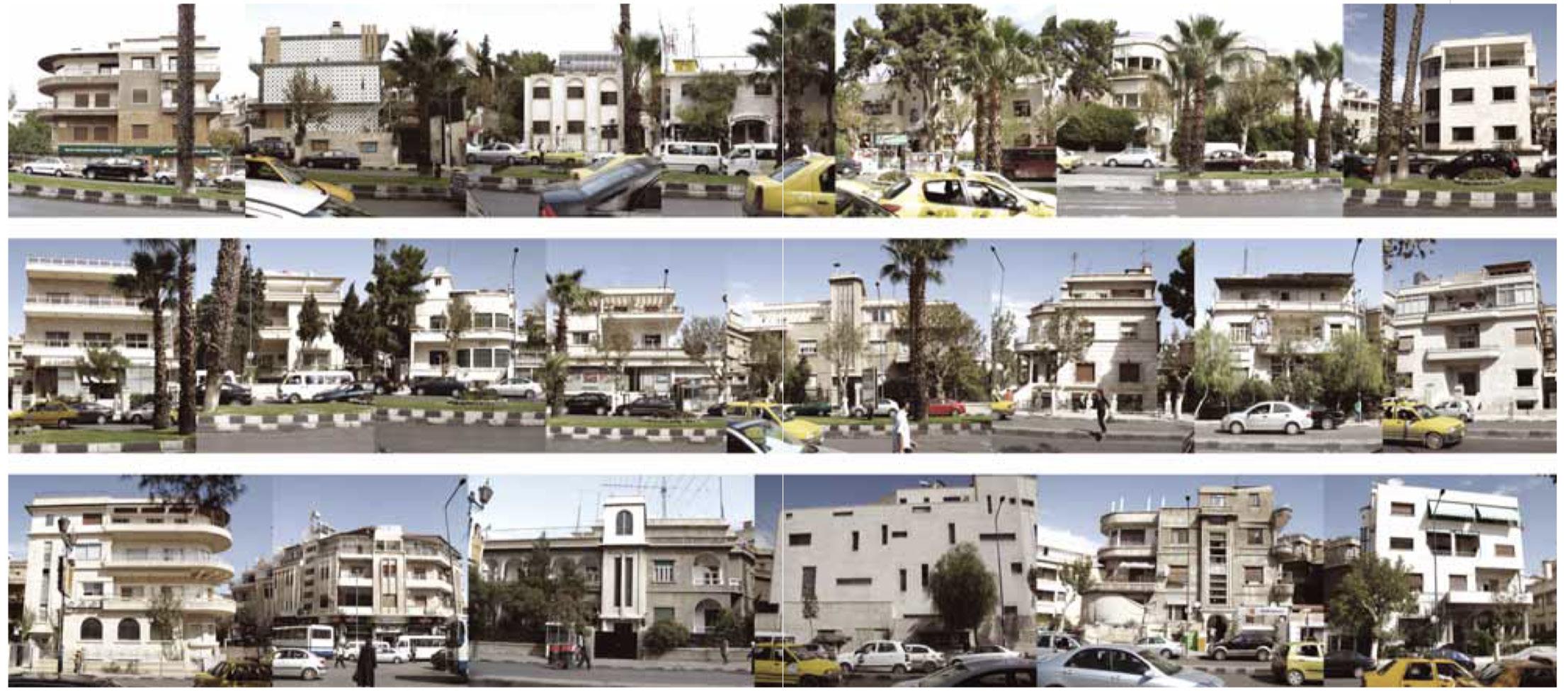

Axes, Boulevards, and Roundabouts

In the masterplan scheme of 1968, Écochard promoted wide spanning streets within the boundaries of the Old City (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 100). Ironically the idea of these wide,

open spaces was “considered as more clean and hygienic”. However, as the planners could not anticipate the popularity and abundance of automobiles, these spaces are subjected to congestion, noise and air pollution. The wide spanning streets, were also militaristic in nature. Allowing surveillance and control of the streets, and access of military vehicles in order to disrupt mass mobilisation, and other forms of protest such as barricading and other means of occupying space.

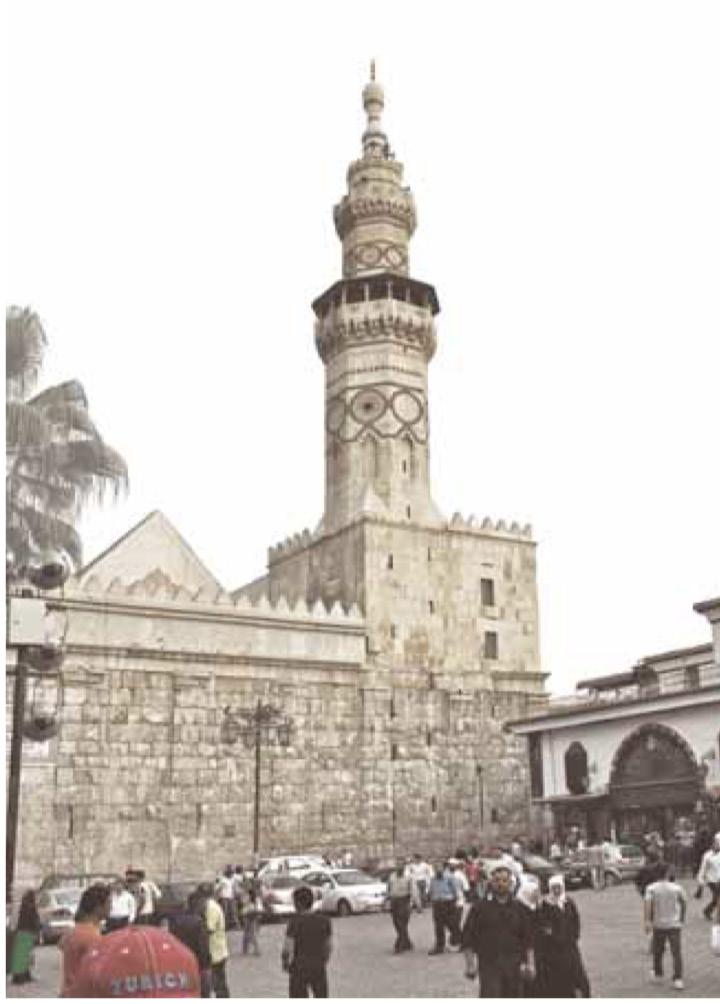

Monuments

Monuments and landmarks were both relocated and manipulated to adhere to the Haussmannian principles (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 80-83). These iconic structures were utilised in public squares, green spaces, and roundabouts to act as grand, isolated displays and as methods of wayfinding. However, the manipulation of these monuments and landmarks were categorised based on their thematic connotations. Different zones were organised for various social classes and their religious beliefs, thus segregating the inhabitants based on their differences and

Figure 14: “Relocation of Maisat Mosque” - The original location is now unknown

Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 86) assigned classifications (Al-Sabouni, 2017). As a result, their environments are represented by their sectarian identity (Abbas et al., 2014, page 48). While previously, there was coexistence amongst the diversity of symbolisms, functional buildings and space, and people. This is evident in the former “closely knit neighbourhoods to the mosques and churches built back to back and face to face…and (the) thriving economies that interconnected the whole city (Al-Sabouni, 2017).”

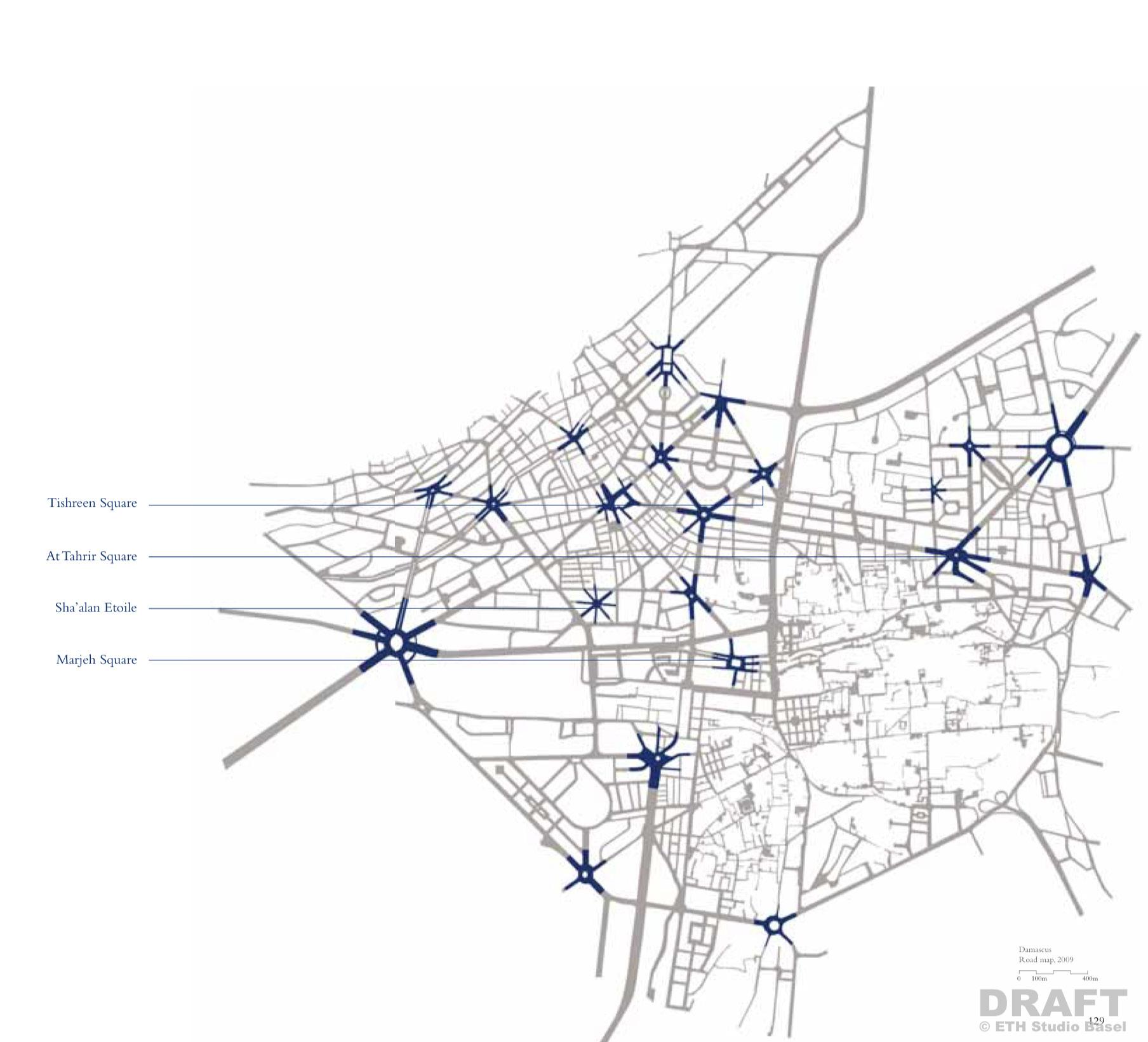

Etoiles and Squares

Etoiles and squares essentially acts as pockets of space that connect different formal urban routes and act as wayfinding landmarks (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, pg 126). The

typical Parisian etoiles and squares incorporate monuments at its centres. If they were left empty, most were later on filled by water features or from the relocation of other existing monuments. At the onset of the Revolution, protests took place within the urban realm.

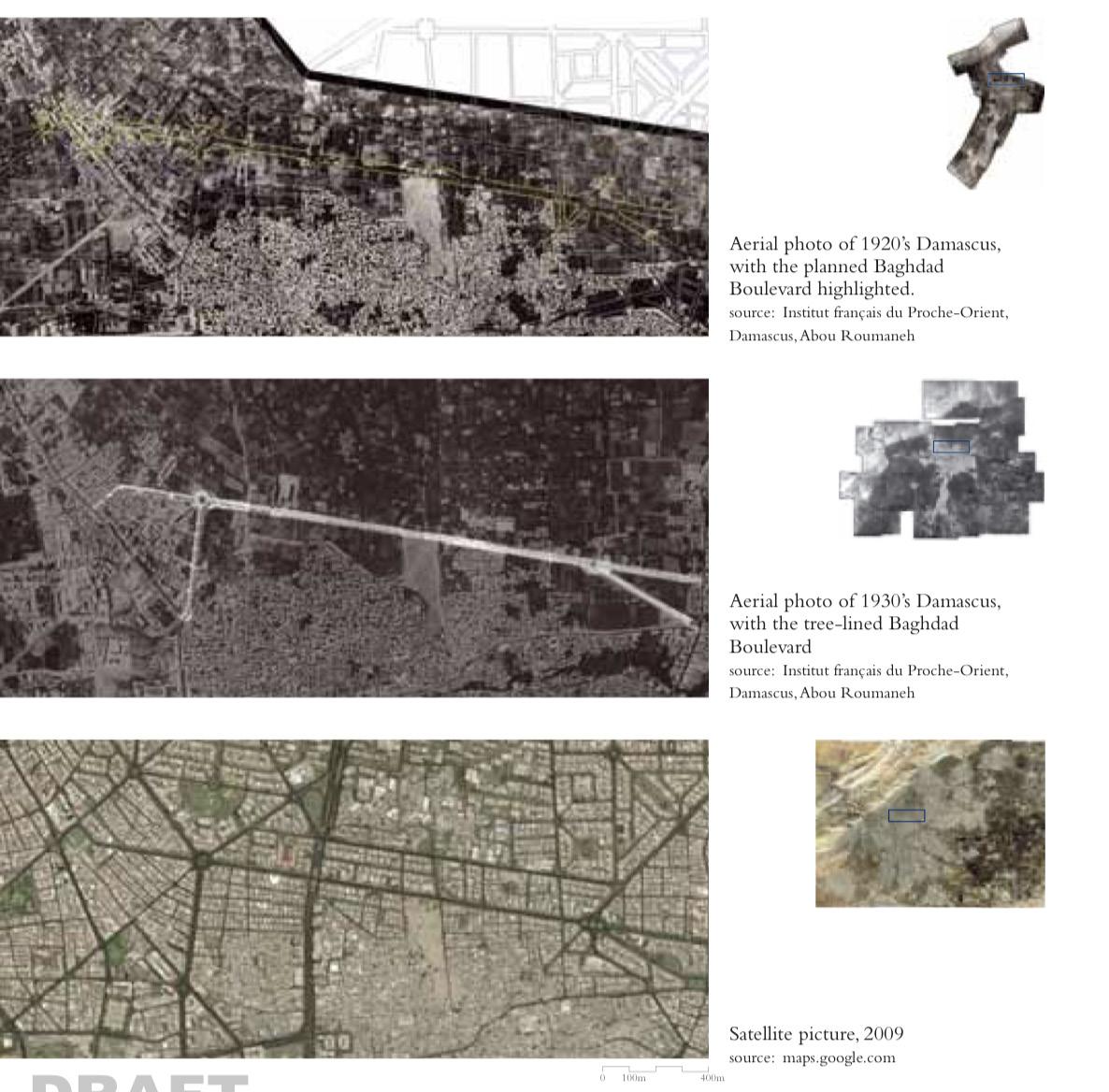

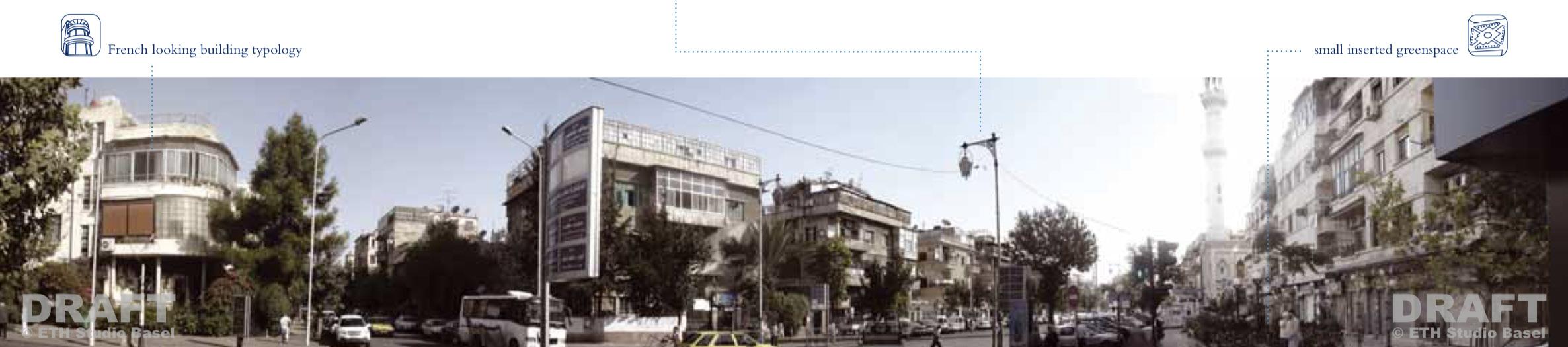

Figures 20: “Tahrir Square - Boulevard De Baghdad”

Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 132-33)

Figure 15: “1930’s Proposal”

Figure 16: “1968 Proposal”

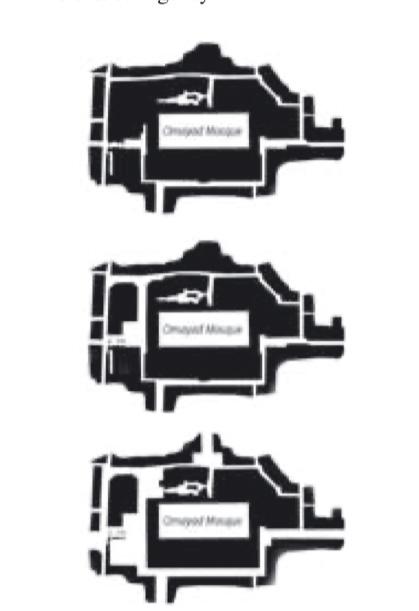

Figure 17: “Isolating Monuments Omayad Mosque”

Figure 18: Omayad Mosque

Plan Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 82 - 83)

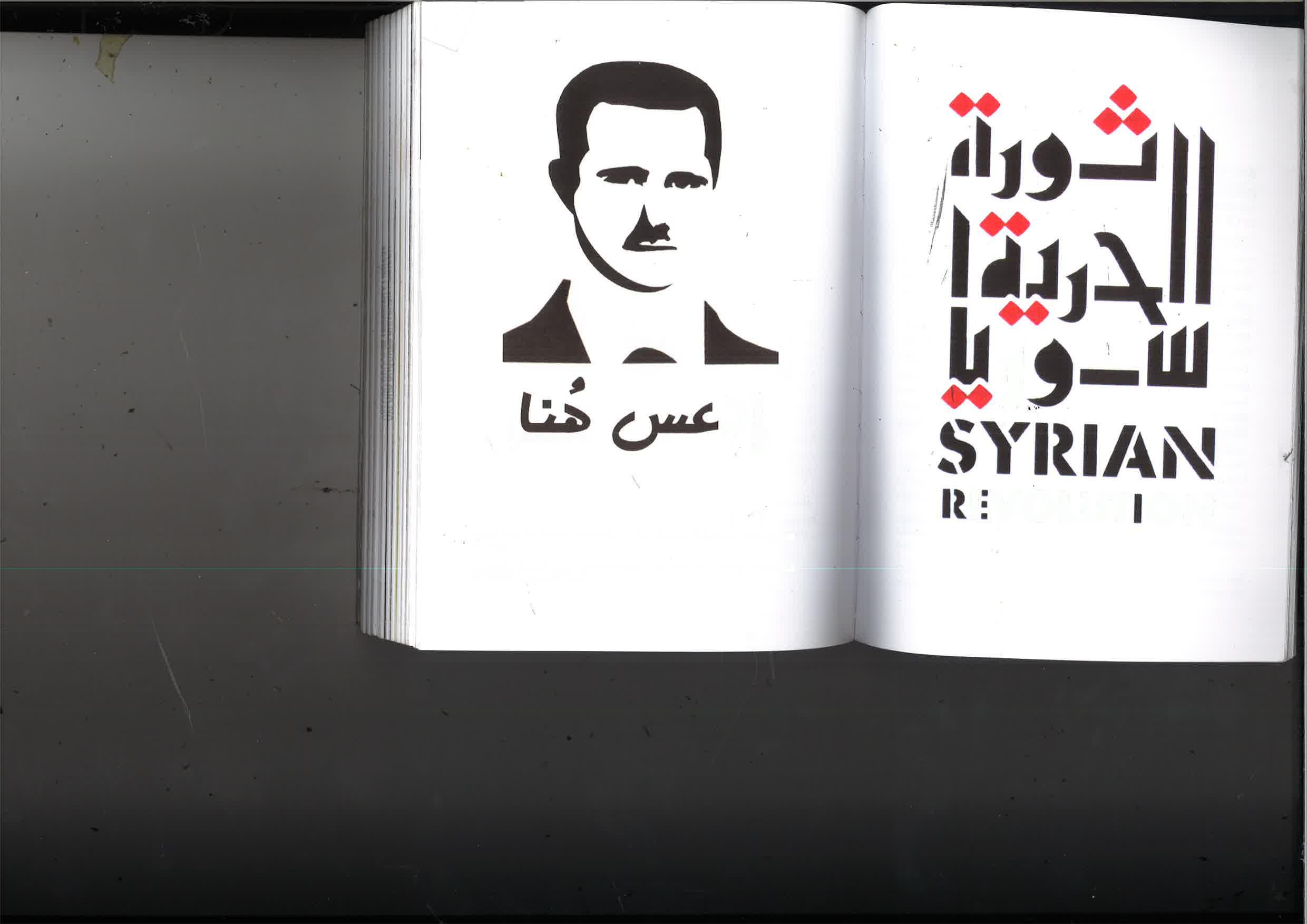

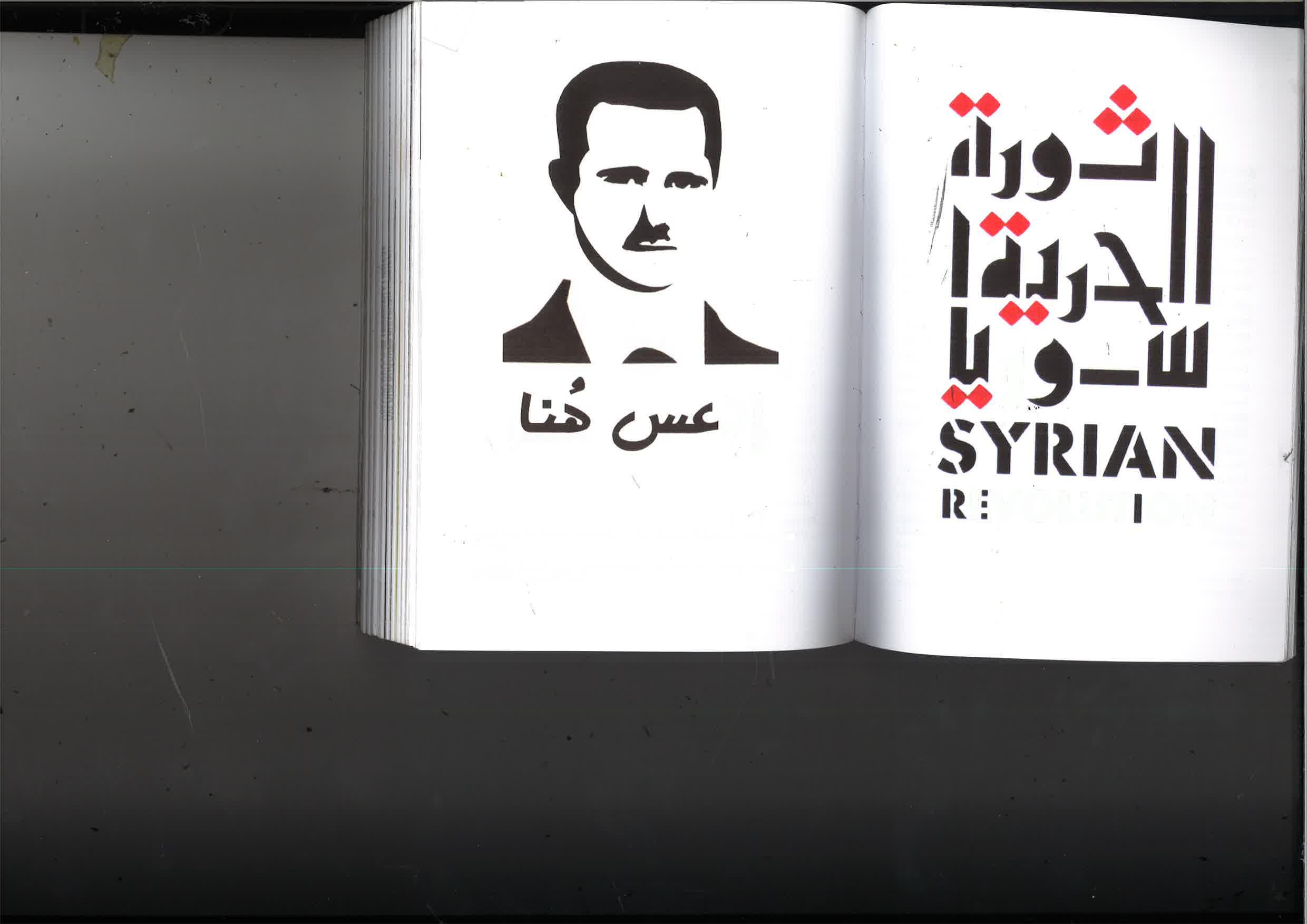

“The people’s reclamation of public space…” (refer to figures 33-34) were both physical and symbolic, with the eradication of totalitarian propaganda: pictures of the Assad family, and statues of the late Hafez Al Assad (Omareen & Al Jundi, 2014, page 97-98).

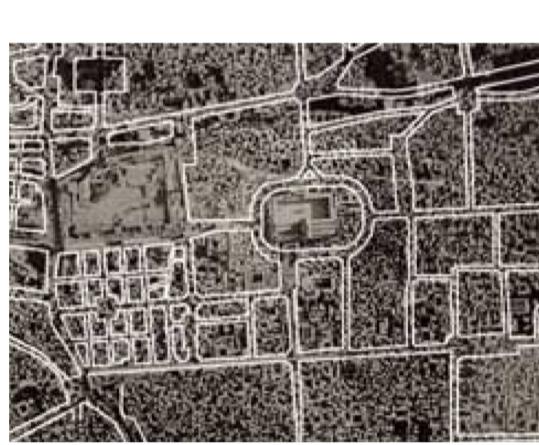

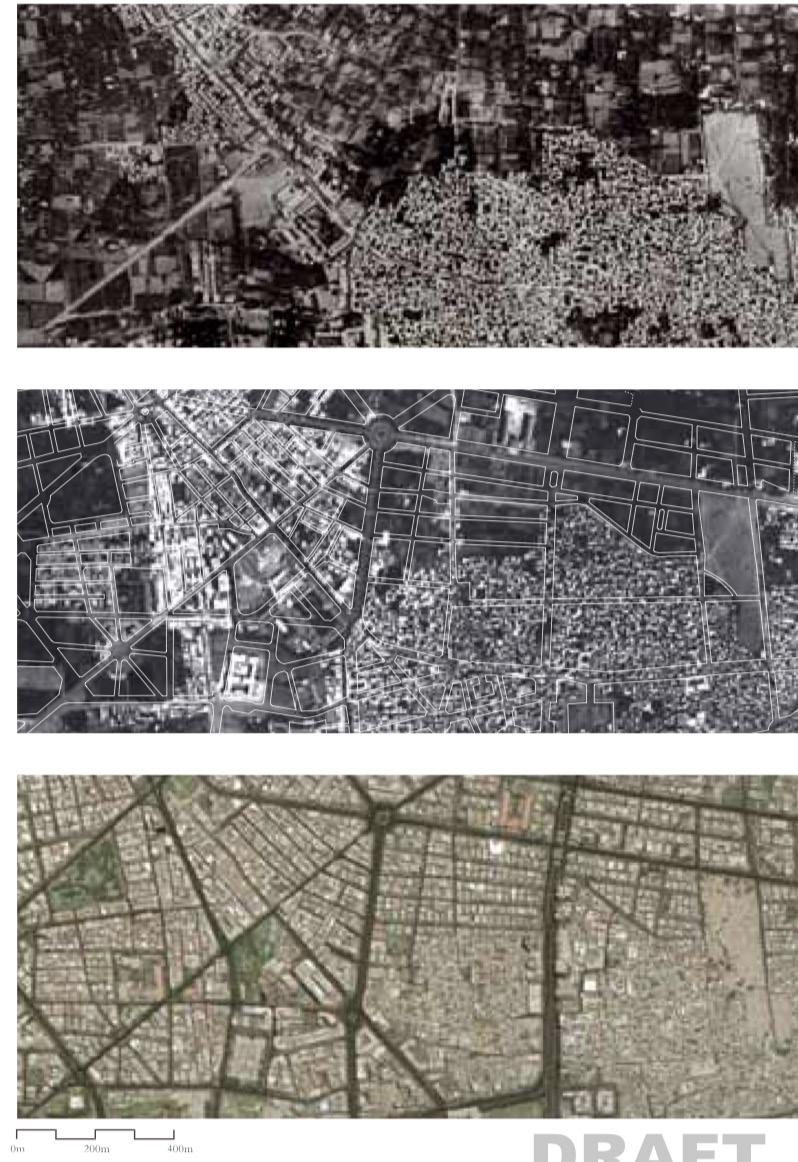

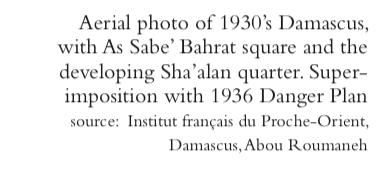

Figure 19: Aerial and Satellite Images

Source: (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 127)

Figure 21: “DamascusEtoiles and Squares”

Source: (page 128-29)

Post Colonisation and the Period of ‘Development’

The process of gaining independence from the French occupation in 1946 had fuelled a militant approach and nationalistic mindset. This can be anticipated due to the creation of a national army in order to repel the colonising powers. Similar instances have also occurred in other Arab countries where ruling figures have adopted a face, or symbolic ‘Leader’, and used religion as their cogent method of propaganda (Omareen & Al Jundi, 2014, page 93).

These ‘Leaders’ embodied both a militant and fatherly spirit. It is necessary to mention the first version and epitome of the Arab Leader, General Gamal Abdel Nasser (Omareen & Al Jundi, 2014, page 89). Firstly, because during a short-lived period of time, Syria and Egypt had combined into a joint nation called the United Arab Republic (1958-61) (Salibi et al., 2022).

For almost four years, General Nasser was acting President over the Syrian territory. Secondly, as mentioned earlier, Nasser was the epitome of the Arab Leader and thus influenced future copies (Omareen & Al Jundi, 2014, page 90). Namely in this case, Hafez Al Assad whose tyrannical reign started in 1970 and was succeeded by his son, Bashar Al Assad, after the former’s natural death. The UAR was a response to Pan-Arabism and Arab Nationalism which in turn were post-colonial ideologies and an attempt in the creation of the Arab nation and collective identity, separate from imperialist rule (Pan-Arabism 2020). Regardless of these attempts of decolonisation, to this day Syria’s juridical system is based on Islamic as well as French principles (Hamidé et al., Government and Society - Justice, 2022). Furthermore, Michel Écochard was reemployed by the newly established government, to help accommodate the housing shortage and to complete his earlier urban vision from the period of colonial rule.

Hafez Al Assad’s Ba’athist regime, consisting mainly of Alawite members, was widely

accepted by the Syrian society during this period of ‘development’ as the movement of

modernisation brought about many new reforms, a more stable economy, better employment opportunities, and an improved military power (Ochsenwald & Commins, 2022). One of Bashar’s many honorary titles, or one of the marketing schemes for his public image, include the ‘Leader of Development and Modernisation’ (Omareen & Al Jundi, 2014, page 94). The housing boom that ensued after colonial rule, was a result of the new surge of labour coming into the growing industrial cities (Al-Sabouni, 2017). The movement of industrialisation itself is an influence of colonial rule. To keep up with the demand, mass-development projects were approved by government authorities to move forward with “the construction of low-income flats in the cities” (Hamidé et al., Government and Society Housing, 2022). These previously foreign high-rise structures, that lacked any local characteristics, now encompassed the existing historical cities in their “sprawling” pattern and in their conceptual formation were designed to segregate based on sects (Al-Sabouni, 2017). Thus, fuelling further alienation among neighbouring communities: “...diversity (does not condemn) societies to division and dismemberment. Rather the successive governments that ruled the Syrian state failed to manage this diversity adequately…” (Abbas et al., 2014, page 48).

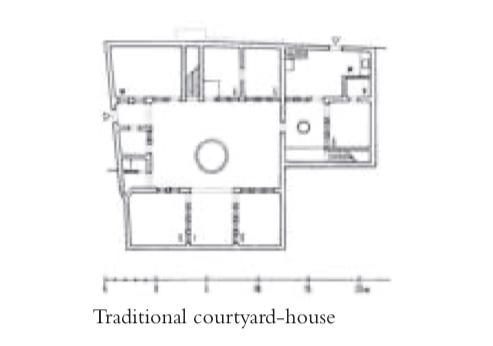

Urban Morphologies and Building Typologies

Space, Culture and Identity - The Making of the Syrian Civil War

Before the start of the revolutionary protests in 2011, the Syrian society had identified themselves and were affiliated to their respective sects (Abbas et al., 2014, page 48). This was

as a result of the colonial ‘zoning’ schemes or urban segregation of the different cultural groups and classes. It was therefore subconsciously indoctrinated into the collective mind because of their architectural, and therefore social, environment. Abbas defines ‘culture’ as “all forms of relationships that individuals or sets of individuals united within a group build with the world” (Abbas et al., 2014, page 49). This definition is distinctly similar to the definition of placemaking by the CNU (2014) as mentioned earlier on in the research. Therefore, this concept of ‘culture’ corresponds with the argument that the impacts of French colonial placemaking has led to the making of the Syrian Civil War.

As “people are influenced by a myriad of cultures”, the systemic architectural segregation implemented by the French urban planners was historically unnatural within the Syrian collective (Abbas et al., 2014, page 49). Syria had embodied a space and platform for diverse cultures and religions, and had subsequently deformed into the prevalent mindset of the singular person, identifying with their own individual sects as the ‘collective’ (Abbas et al., 2014, page 50). These cultural associations constitute a person’s moral code, traditions, beliefs, and hence their identity. When these communities are separated based on their cultural affiliations, the lack of diversity further alienates and isolates those who: do not conform to the majority within the community, and the community itself with the outside world. This can be defined as a “sectarian culture”. “This is how a culture of religious affiliation transforms into a culture that rejects difference, rejects the Other, and celebrates the superiority of the collective”.

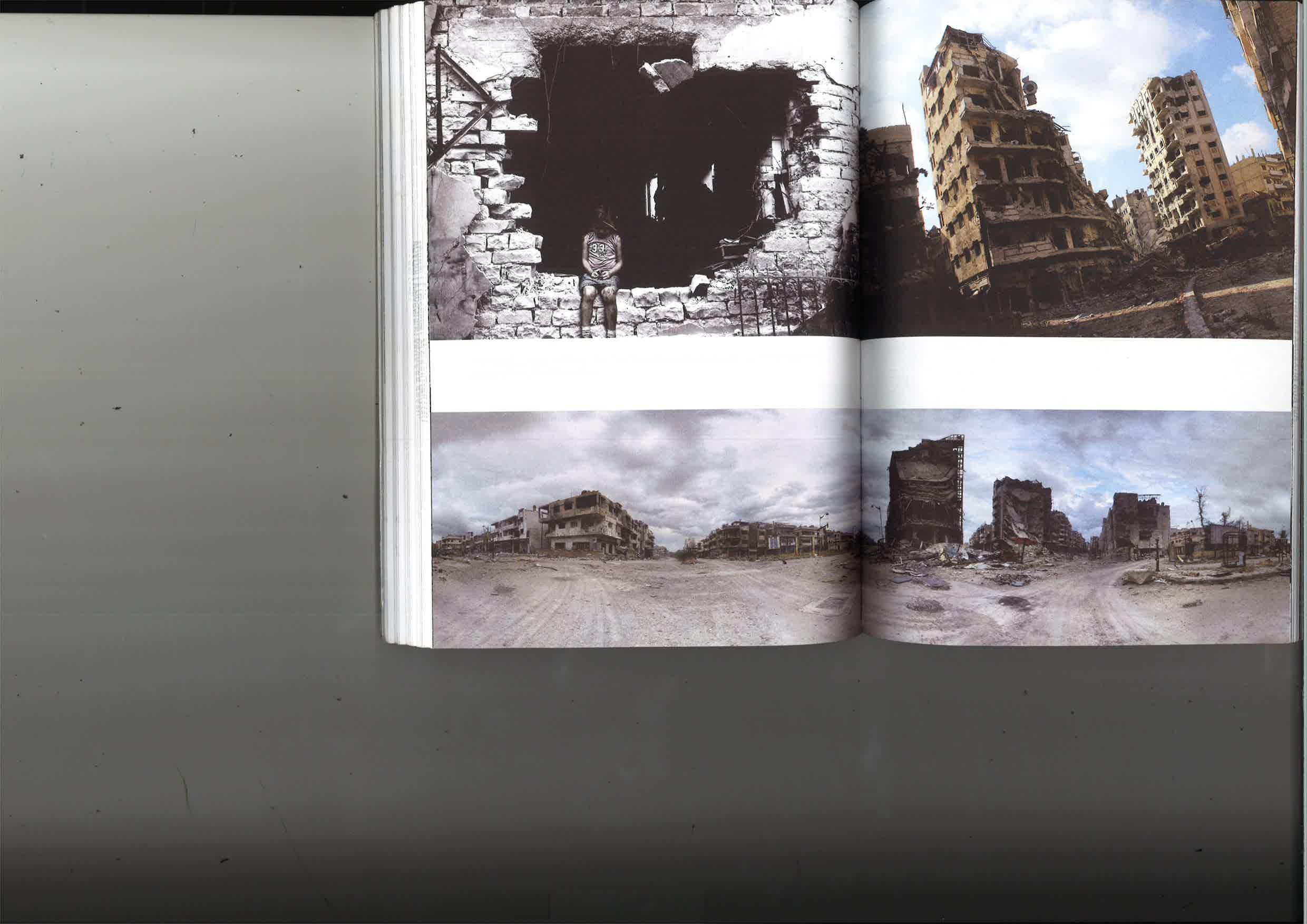

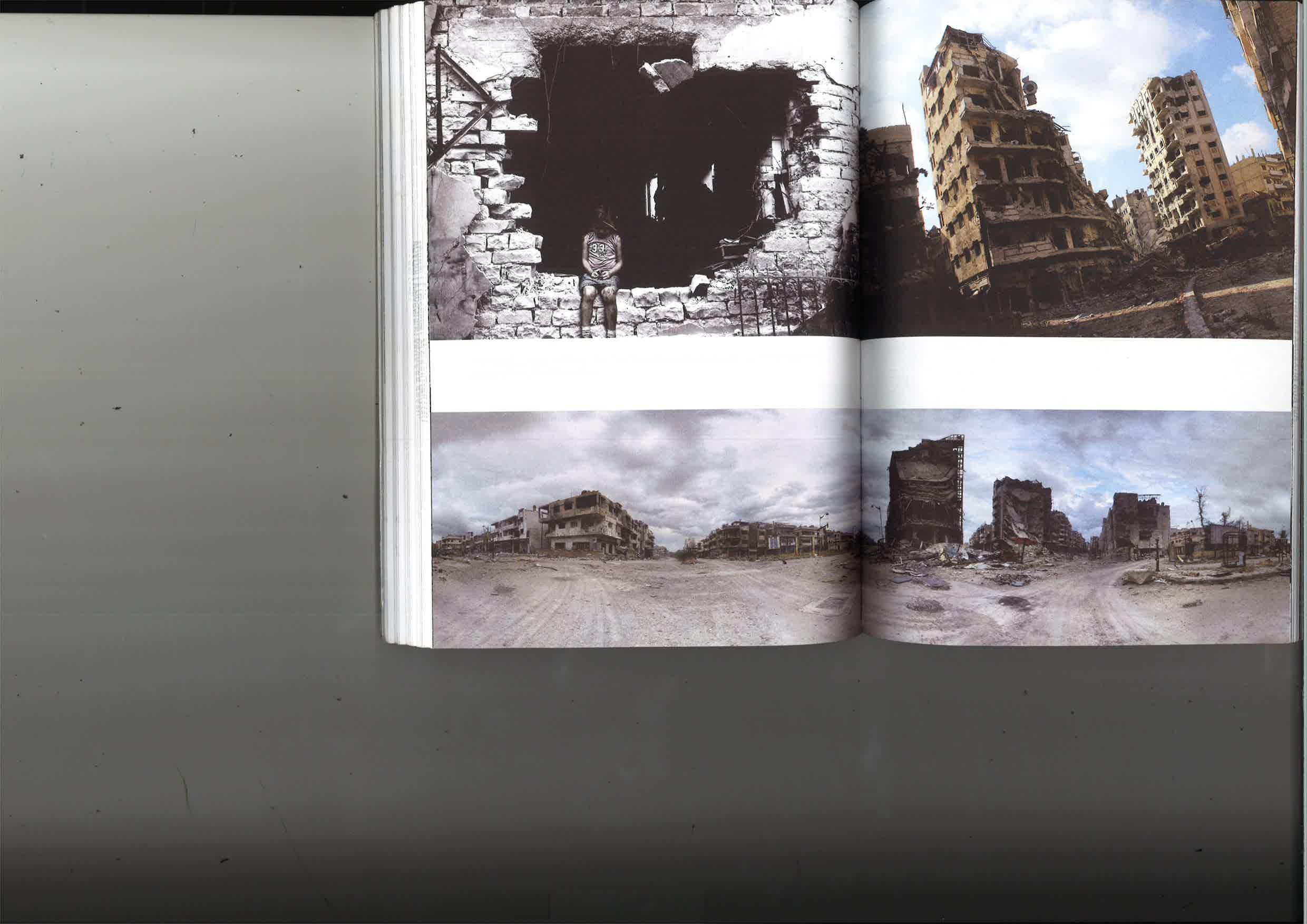

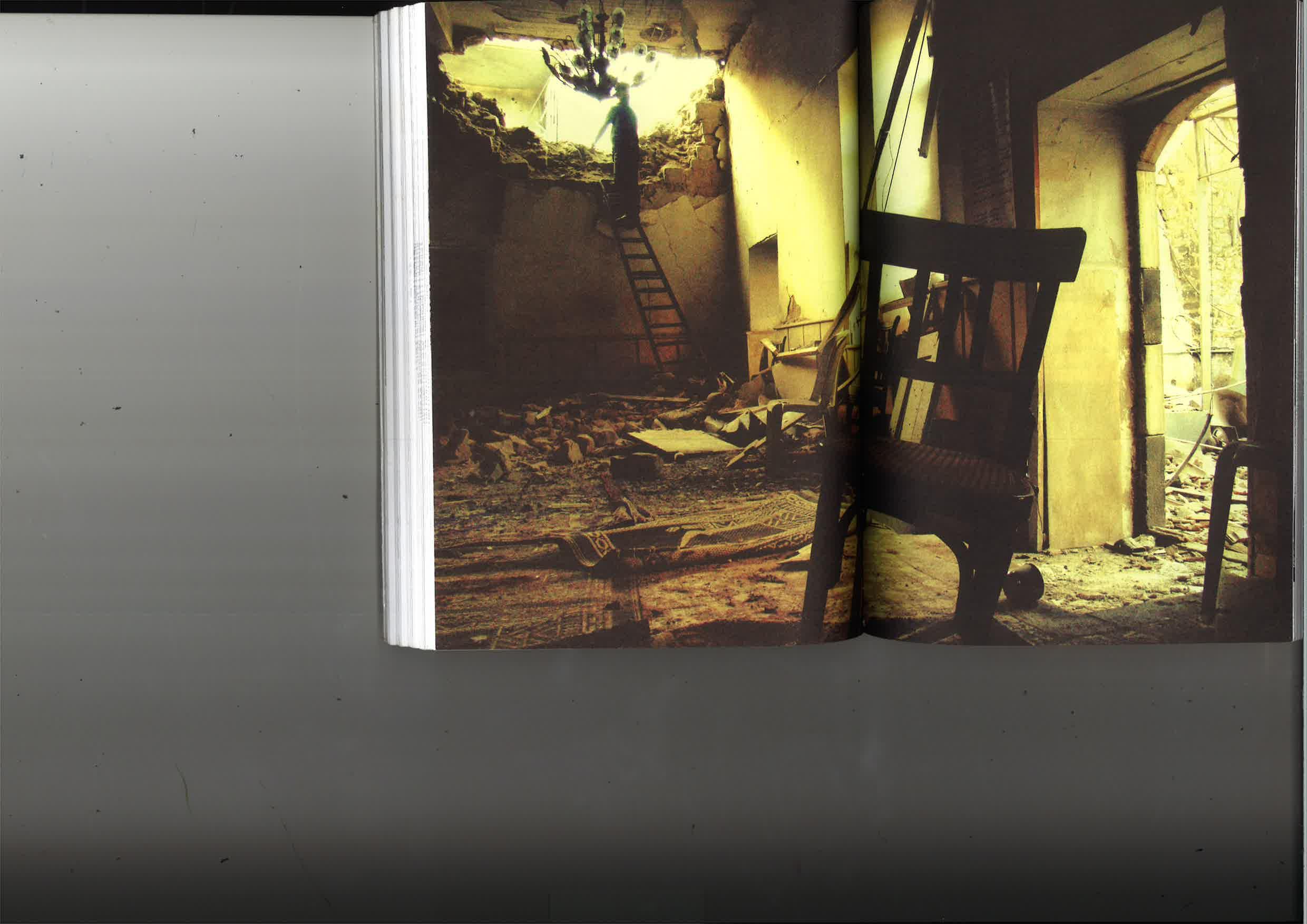

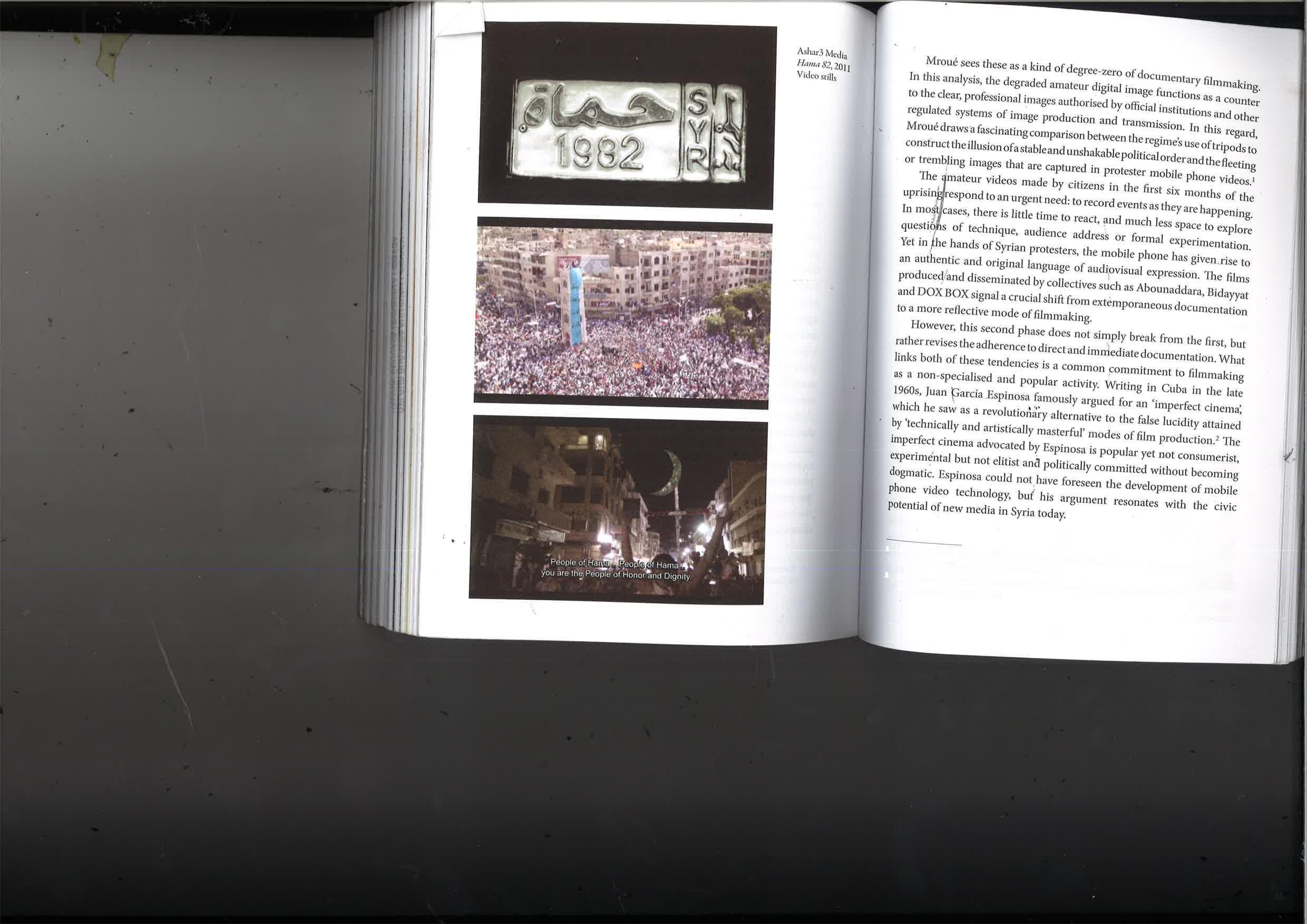

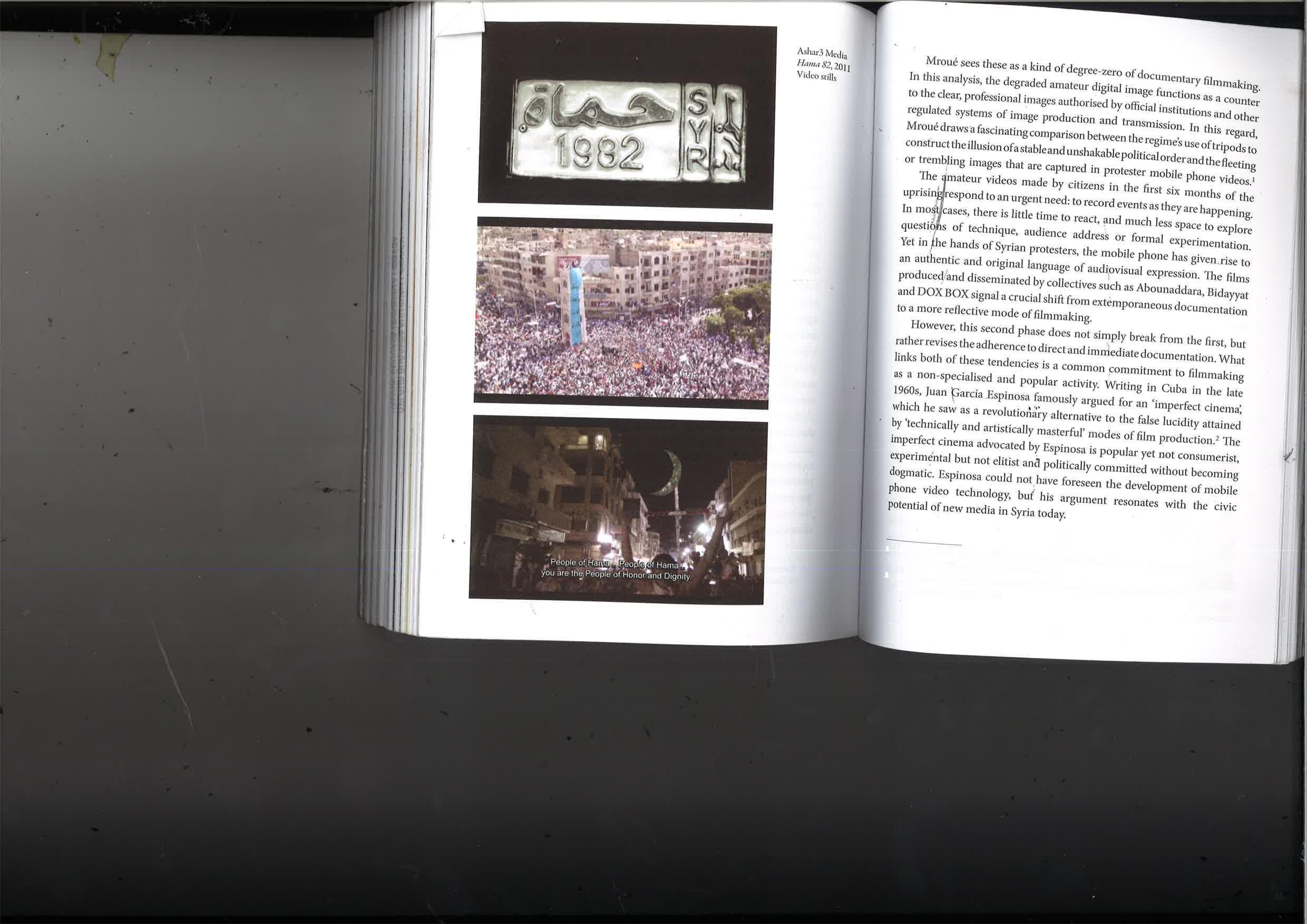

The Syrian Revolution had initially started out as a series of peaceful protests, with the people calling on their rights for a different government body and system. In response to this, the Syrian Regime retaliated with violence and divisive propaganda. A spokesperson of the Assad Regime had expressed “a scheme to create sectarian chaos” (Abbas et al., 2014, page 52). Fundamentally, the French colonial placemaking had inadvertently created the foundations of the regime’s tactics of dividing the voices of the revolution. Attacks on civilians by the Syrian Armed forces, were also calculated to adhere to the “sectarian rhetoric”; the regimes violence itself would target different sects, and that would subliminally register within the minds of the people. Undeterred by their opposition, the Syrian Revolution’s recognised rallying cry is ‘One, one, one: the Syrian people are one’ (Abbas et al., 2014, page 53). This evokes hope that despite the colonial repercussions and the regime’s efforts, the people see themselves as one unified identity: Syrian.

35: “Syrian Freedom Revolution”

Conclusion The research compiled and presented by Stockhammer and Wild (2009), was extremely fundamental in understanding the spatial dynamics of the French urban interventions. The research acknowledged that those interventions were not entirely successful. However, the research lacked a critical analysis of the causations of colonial rule and the societal impacts of those interventions. At one point, they had expressed that “the French Mandate in Syria was… too short and Damascus became an excellent example of how a city can react to different ideas in a short period” (Stockhammer & Wild, 2009, page 42).

Abbas refers to the “culture of citizenship” as the answer to the “sectarian culture”; one unified Syrian identity. However, that is easier said than done as in order to do this, the whole framework of the Syrian legal system, colonial notions and policies would have to be completely erased to start over. As well, it does not consider the architectural revival of the bombarded, barren cities. Perhaps, with the current Syrian diaspora, their similarities and their differences, the common fact that they have been displaced and integrated into different cultures, could be the one unifying driving force. A “culture of citizenship” would hopefully establish a ubiquitous cooperation between the Syrian citizens, expressed in how they would communicate amongst each other and within their shared urban realm.

Some aspects of placemaking that can constitute a functional and ‘human’ space include

“preservation of historic structures”, “respect (of) community heritage”, and an environment for “arts, culture, and creativity” to flourish (CNU, 2014). As architects, we need to assess that any interventions and constructions should be contextualised and related to its urban environment. When successful, these interventions could create an urban setting that makes

its inhabitants feel comfortable, safe, and connected. Therefore, when assessing the impacts of French colonial placemaking, the researcher is of the opinion that there was very little consideration towards the social and cultural aspects that made up the Syrian society, almost an erasure of their culture and identity, and a lack of respect towards their historical built environment.

• Abbas, H., McManus, A.-M. and Zyiad, L. (2014) “Between the Cultures of Sectarianism and Citizenship,” in Syria speaks: Art and culture from the frontline. London: Saqi Books, pp. 48–59.

• Al Sabouni, M. (2019) Al-Hamidyah Neighborhood, Middle East Eye. Middle East Eye. Available at: https://www.middleeasteye.net/sites/default/files/an_area_of_al-hamidyah_neighborhood_in_old_homs_commonly_known_as_between_the_two_minarets._in_the_distance_ we_can_see_the_damaged_rear_facade_of_the_catholic_church_marwa_al-sabouni.jpg (Accessed: November 2022).

• Al-Sabouni, M. (2017) “From a model of peace to a model of conflict: The effect of architectural modernization on the Syrian urban and social make-up,” International Review of the Red Cross, 99(906), pp. 1019–1036. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/s181638311900002x.

• Brown, R. (2022) Haussmann architecture: Defining the elements of this iconic style, Homedit. Homedit. Available at: https://www.homedit.com/haussmann-architecture/ (Accessed: November 2022).

• CNU Staff (2014) “Four types of placemaking,” Better Cities & Towns [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/four-types-placemaking#:~:text=The%20simplest%20definition%20is%20as,exactly%20is%20a%20Quality%20Place%3F (Accessed: November 2022).

• Elias, C. and Omareen, Z. (2014) “Syria’s Imperfect Cinema,” in Syria speaks: Art and culture from the frontline. London: Saqi Books, pp. 257–268.

• Hamidé, A.-R., Ochsenwald, W.L. and Commins, D.D. (2022) Government and Society - Justice, Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Available at: https://www.britannica. com/place/Syria/Local-government#ref29982 (Accessed: December 4, 2022).

• Hamidé, A.-R., Ochsenwald, W.L. and Commins, D.D. (2022) Government and Society - Housing, Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Available at: https://www.britannica.

com/place/Syria/Local-government#ref29982 (Accessed: December 4, 2022).

• History.com Editors (2017) Syria, History.com. A&E Television Networks. Available at: https:// www.history.com/topics/middle-east/the-history-of-syria (Accessed: November 2022).

• Karnik, P. (2019) The Haussmann Plan by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann: Transforming City of Light, Rethinking the Future. Rethinking the Future. Available at: https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/case-studies/a2695-the-haussmann-plan-by-baron-georges-eugene-haussmanntransforming-city-of-light/ (Accessed: November 2022).

• Halasa, M. et al. (2014) “Lens Young,” in Syria speaks: Art and culture from the frontline. London: Saqi Books, pp. 118–129. Lens Young is an unofficial group of citizen-photographers.

• Halasa, M., ʻAmrīn Zāhir and Maḥfūḍ Nawārah (2014) “Stencilling Martyrs - Graffiti Starts a Revolution,” in Syria speaks: Art and culture from the frontline. London: Saqi Books, pp. 284–289.

• Ochsenwald, W.L. and Commins, D.D. (2022) Emergence and fracture of the Syrian baʿath, Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/ place/Syria/Emergence-and-fracture-of-the-Syrian-Baath (Accessed: November 2022).

• Omareen, Z. and Al Jundi, G. (2014) “The Symbol and Counter-symbols in Syria,” in Syria speaks: Art and culture from the frontline. London: Saqi Books, pp. 84–101.

• Pan-Arabism (2020) Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pan-Arabism (Accessed: November 2022).

• Salibi, K.S., Polk, W.R. and Ochsenwald, W.L. (2022) The union with Egypt, 1958–61, Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/ place/Syria/The-union-with-Egypt-1958-61 (Accessed: November 30, 2022).

• Stockhammer, D. and Wild, N. (2009) The French Mandate City A footprint in Damascus. Draft, ETH Studio Basel Contemporary City Institute. Draft. Basel, Switzerland: ETH Studio Base. Available at: https://archive.arch.ethz.ch/studio-basel/projects/beirut/damascus/student-work/thefrench-mandate-city-(damascus).html (Accessed: November 2022).