ReWilding

ReWilding

systems approach to climate resilient master planning

The studio introduces a systems-based approach to climate-resilient master planning which emphasizes understanding and addressing the interconnectedness of environmental, social, and economic systems in urban development. By considering the complex interactions between climate factors, natural resources, infrastructure, and human activities, this approach enables urban designers to design cities that are adaptive to changing climate conditions. It incorporates various frameworks to mitigate the growing challenges of urban expansion in our cities in a case of a greenfield development using a Town Planning Scheme (TPS) mechanism when there are multiple land parcels owned by different stakeholders and is directed by the urban development authorities under a Special Purpose Vehicle with specific goals.

This holistic framework ensures that resilience is built into all aspects of urban life, from risk mitigation to longterm sustainability, fostering cities that not only withstand but thrive in the face of climate change. To respond to the demand of expansion in the rapidly growing urban centres, governments facilitate new developments through various development mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my heartfelt thanks to Sahiba Sodhi and Praveen Raj, our tutors. They have both played a crucial role in refining my approach. I am deeply grateful for their dedication and for challenging me to think critically and creatively during this process. I am also grateful for all the assistance provided by Neha Patane whose insightful suggestions have enriched development of the project.

A sincere thank you to Purvi Chhadva for her for their constant guidance and unwavering support throughout the studio and tutors Shashank Trivedi, Shobhit Tayal and Umesh Shurpali for their timely critiques and advices.

This exercise wouldnt have been possible without the mentorship of Chandrani Chakrabarti. Her thoughtful suggestions helped refine the approach and outcomes of my work. I am truly thankful for the time and effort she and her team dedicated to supporting me throughout this journey.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my unit for their consistent collaboration and feedback, of which I am so grateful for because I don’t think it could be possible without them.

...

Tutors : Sahiba Sodhi, Praveen Raj

Teaching Assistant : Neha Patane

Masters in Urban Design

Faculty of Planning

CEPT University

AUDA GUDA

- Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority

- Gandhinagar Urban Development Authority

- Koba Development Corporation Limited

- Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation

- Gujarat Metro Rail Corporation

- Special Purpose Vehicle

- Pandit Deendayal Energy Univerity

- Gujarat National Law University

- Institute of Advanced Research

- Sabarmati River Resiliency Park

Executive Summary

Project Overview

Systems Approach to Climate Resiliency

Vision and Objectives

Manifestation

Reflections

Introduction, Site Profile and Key Drivers

Background

Site Profile and Context

Access and Connectivity

Existing Land Use and Zoning.

Vegetation, Natural Features and Ecology

Precedents

Conceptual Framework

Existing Site and Anchors

Spatial Strategies

Conceptual Framework and selected site

Proposed Master plan

Master

and Metrics

Sabarmati River Resiliency Park

Koba, a village in the Gandhinagar district of Gujarat, India, has a history deeply tied to its geographic and cultural context. Located near the Sabarmati River, Koba has traditionally been a settlement influenced by agricultural practices and trade facilitated by its proximity to Gandhinagar and Ahmedabad.

Historically, the region around Koba was part of the larger cultural and political landscape of Gujarat. During the British colonial period, Koba, like many villages in Gujarat, remained primarily agrarian, with limited direct impact from industrialization or urbanization.

In recent decades, Koba has gained significance due to its location near prominent landmarks such as the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT City), educational institutions, and infrastructure development connecting it to Gandhinagar and Ahmedabad. This proximity has spurred growth in real estate and increased the village’s importance in regional planning and development initiatives.

The establishment of Gandhinagar in the early 1970s, designed as a planned city, marked the beginning of a shift for Koba. Though initially outside Gandhinagar’s urban core, Koba began to see indirect impacts from the administrative and infrastructural focus on the region. Improved road networks and connections between Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar gradually integrated Koba into the broader development framework

The 1990s marked the economic liberalization period in India, which led to rapid urbanization in Gujarat, especially in Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar. Koba started to transition from a purely rural area to a peri-urban settlement. Agricultural land began to give way to small-scale industries, and there was a noticeable shift towards non-agricultural occupations. Improved infrastructure like highways and public transportation linked Koba more effectively to its neighboring urban centers.

The early 2000s saw significant educational and institutional developments in and around Koba. Key institutions such as the Gujarat National Law University (GNLU) were established in proximity, transforming the village into a hub for students and academic activities.

These institutions attracted people from across the state and country, leading to a rise in residential and commercial demand.

During this period, Koba also benefited from its proximity to the Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport and the burgeoning IT and industrial zones around Ahmedabad. Improved infrastructure, such as widened roads and better utilities, began catering to the needs of a growing population.

The establishment and growth of Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT City), located just a few kilometers from Koba, further accelerated the village’s transformation. GIFT City, envisioned as a world-class financial and IT hub, brought significant investment to the region, boosting Koba’s economic and real estate potential.

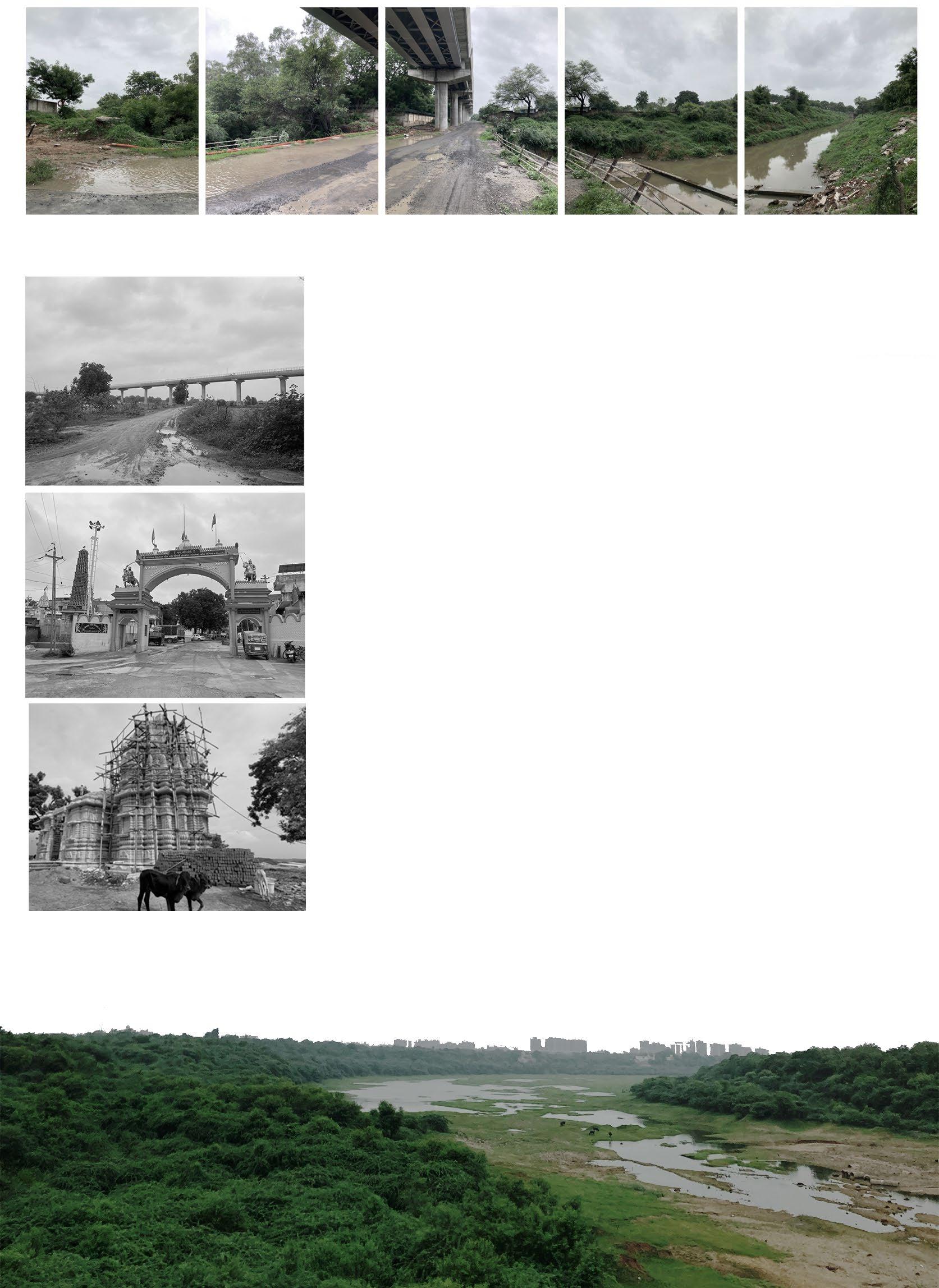

Fig 01.1 - A montage of the sites’ transect showing two major anchors namely, the GMRC corridor, the Southern Drain.

Fig 01.2 - The GMRC corridor is the only major human intervention as of date, on the largely untouched greenfield site.

Fig 01.3 - Entrance to the Juna Koba Gamtal. The gamtal serves as the focal point around which the site’s identity can be woven.

Fig 01.4 - The Kumbeshmar Mahadev Temple. A 500 year old Hindu temple by the banks of the river Sabarmati.

Fig 01.5 View of the site (left bank) as taken from Nabhoi-Karai Sabarmati Bridge. GNLU, IAR seen in the distant background.

Source : Author, Primary Survey

Source : Google

6|

Ahmedabad population : 7,922,000*

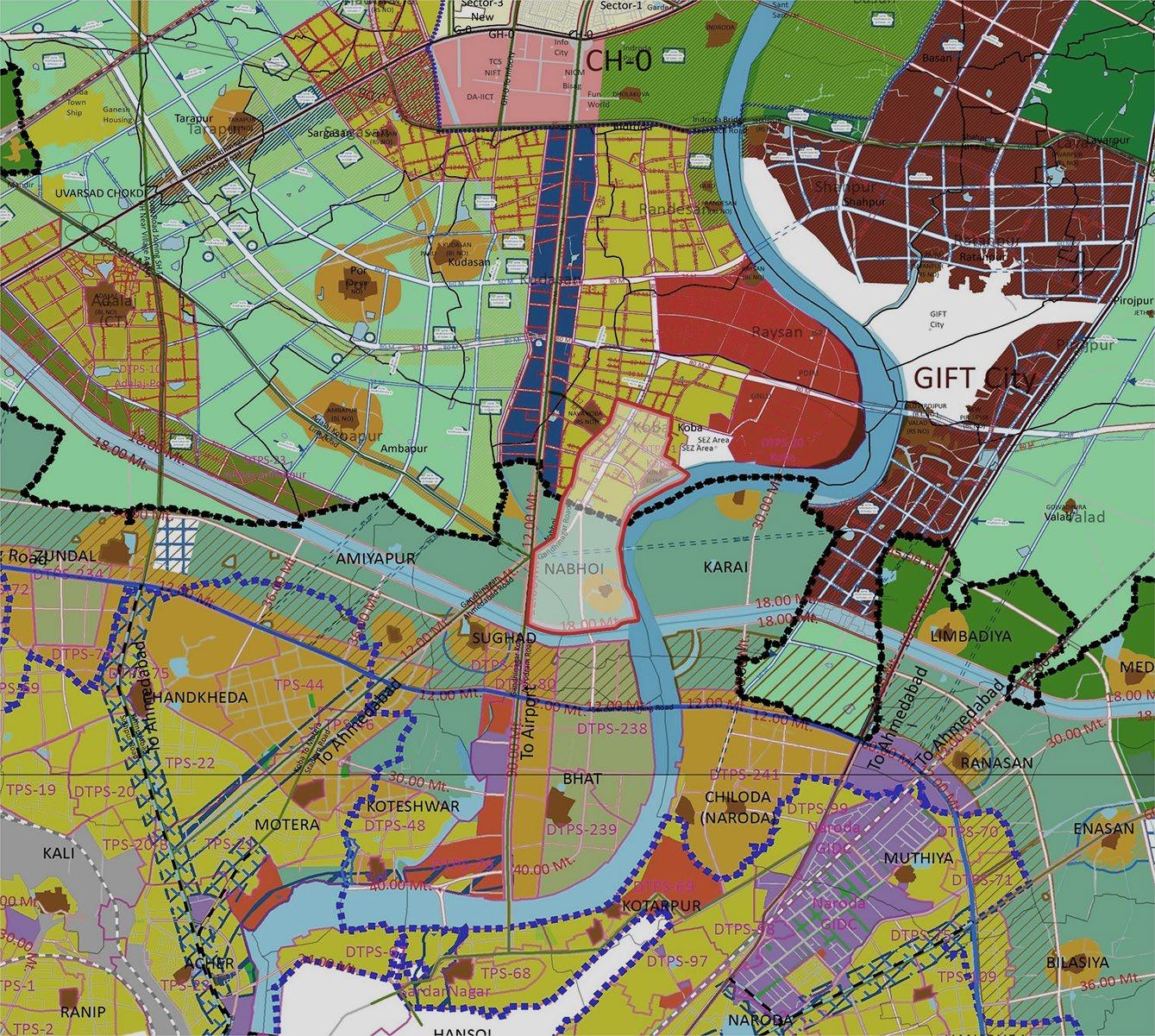

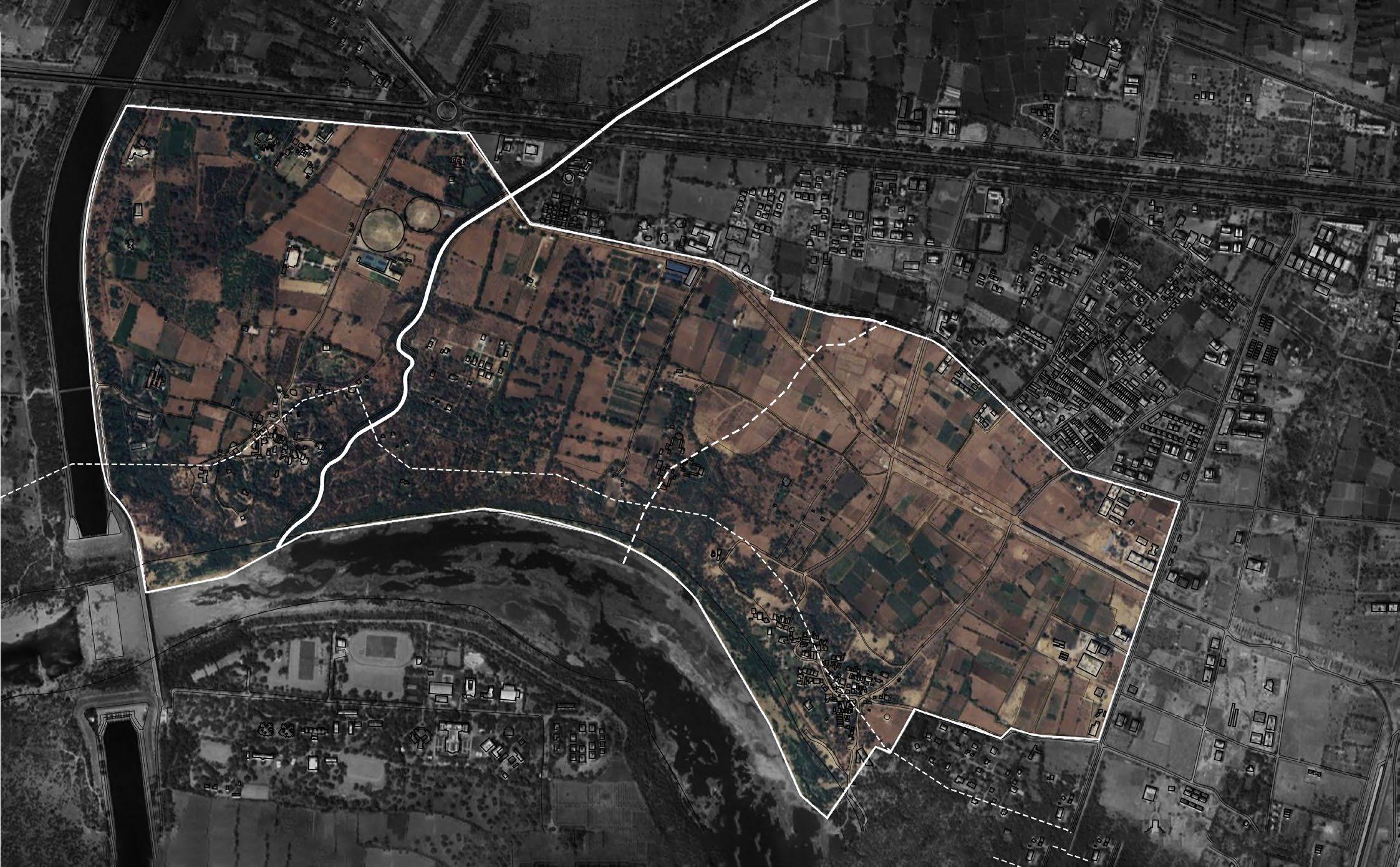

The site is strategically located within the jurisdictional overlap of AUDA (Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority) and GUDA (Gandhinagar Urban Development Authority), creating a unique zoning landscape that severly influences its development potential.

AUDA’s development plan emphasizes industrial and institutional zones, aligning with the TOD zones and SEZs that border the site. Conversely, GUDA focuses on creating a balanced urban-rural mix, with a significant share of land allocated under town-planning schemes.

This dichotomy in the development plans of both the development authorities creates zoning discrepancies, particularly as the site serves as a transition zone between Ahmedabad’s urban sprawl and Gandhinagar’s relatively planned and green framework.

The nearby presence of GIFT City, a prominent employment hub, and institutional zones creates high economic activity within a 2-km radius, promoting land value intensification.

However, critical gaps remain: large tracts of the site are underutilized, with agriculture dominating current use and flood-prone areas along the Sabarmati River limiting construction potential.

The site’s topography and watershed patterns form the foundation of the initial analysis, shaping the design logic of the master plan. Defined by undulating terrain and natural drainage networks, the site is characterized by a gradient that directs water flow toward the Sabarmati River, creating an intricate system of micro-watersheds.

Defined by undulating terrain and natural drainage networks, the site is characterized by a gradient that directs water flow toward the Sabarmati River, creating an intricate system of micro-watersheds. These resultant seasonal water bodies play a vital role in managing monsoonal runoff while supporting the region’s biodiversity. However, rapid urbanization has led to the partial concretization of these watercourses, disrupting natural hydrological flows and increasing the risk of flooding.

More over the larger hydrological and terrain analysis of the site suggest that the entire river edge, both left and right banks is characterized by ravines and broken lands. A large part of the site also falls under this zone, which can severely affect the proposed morphology.

The ravines can be looked at as a tool, rather than a challenge, leveraging them with larger watershed zones to create a system of natural drains to mitigate flooding.

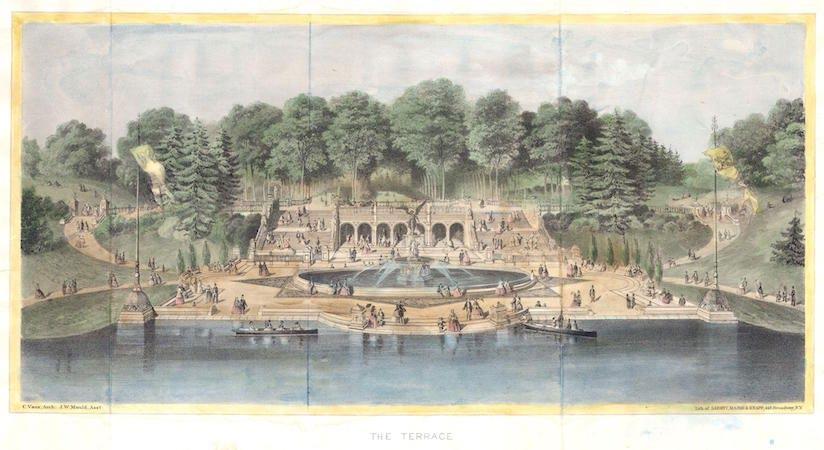

Frederick Law Olmsted, conceived Central Park as an urban sanctuary where all people could reconnect with nature amidst the bustling chaos of New York City. A lithograph done by Vaux, exhibits F.L Olmstead’s vision of a wild, untamed aesthetic of nature, deliberately contrasting with the structured urban grid surrounding it.

In an era where urbanization often distances us from nature, the urban design framework attempts to re-imagine “a city within a park, rather than a park within a city” which offers an alternative idea for the future of urban living.

The premise is to question and re-imagine every aspect/element of our cities and urban life positioning nature as the core framework that drives an economically thriving, resilient urban fabric and quality of life.

The vision challenges conventional urban paradigms by placing nature at the heart of urban development, transforming the built environment into an extension of the natural world. The goal is to redefine the relationship between people and nature, fostering a harmonious coexistence that enhances the quality of life while addressing pressing challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and urban sprawl.

By rethinking urban form and function, it offers an almost utopian alternative to fragmented urban development, demonstrating how cities can grow in tandem with natural systems rather than at their expense.

Almost as if Olmstead would draw a master plan, in place of Bob Moses?

“what if we re-imagine a City within a Park, rather than parks within our cities?”

Shifting our focus to a more granular scale, we now examine the site’s immediate context.

To the north, a minor transportation corridor facilitates connectivity to educational institutes such as the Pandit Deendayal Energy University - PDEU (Formerly PDPU), Gujarat National Law University and the Institute of Advanced Research, University for Innovation, Gandhinagar (IAR), while its west is flanked with smaller cultural institutions such as the Jain Musuem, and dormitories by Mahavir Jain Aradhana Kendra and Shrimad Rajchandra Adhyatmik Sadhana Kendra.

Key site anchors, including the two urban villages of Juna Koba and Nabhoi. Off these villages, eastwards towards the river lies the Kumbheshwar Mahadev Temple. These serve as focal points around which the site’s character and identity can be woven. These anchors not only offer cultural and historical significance but also function as spatial and social connectors, drawing people into the site from surrounding areas.

Additionally, the presence of water features is by far the strongest of the anchors on the site. The meandering Sabarmati River river along the western edge, provides a natural boundary that can be harnessed to strengthen the site’s environmental identity. Another anchor, namely the Southern Drain, cuts across the site. The Southern Drain is an open, concretised storm water channel that empties into the Sabarmati.

The Narmada Siphon and the Narmada Canal form the southern boundary of the site. The Narmada Canal is a 98m wide contour canal in Western India that brings water from the Sardar Sarovar Dam.

Lastly, the GMRC Phase 02 corridor runs across the site North-South, entering off the Koba Circle with two metro stations at Juna Koba and Gujarat National Law University. The metro line itself, the two urban villages of Nabhoi and Juna Koba along with the Southern Drain have been considered as non-negotiable for the master planning exercise.

The varied topography and existing green infrastructure within the site offer further potential for creating distinct zones that cater to both active and passive uses, fostering a sense of place that balances urban life with nature. This juxtaposition of urban and ecological elements creates a opportunities for integrating nature with the built environment.

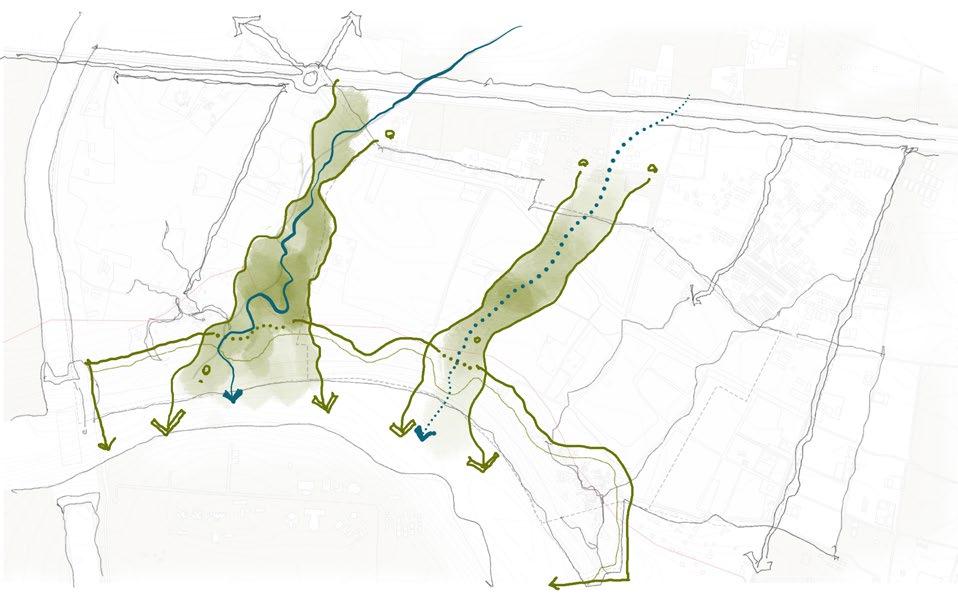

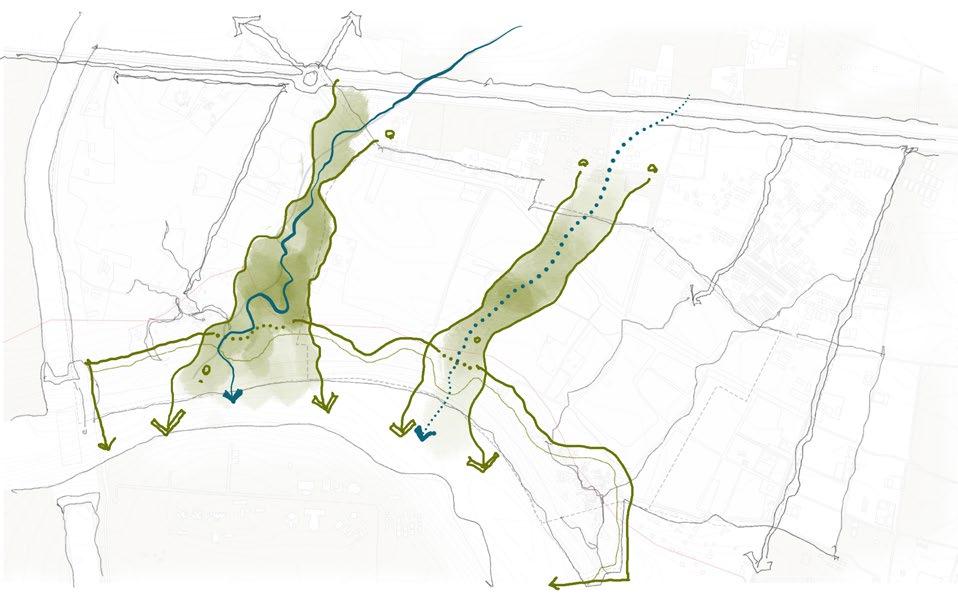

Strengthen the Greens

Identify & strengthen existing ecological corridors

Connect the Twins

Form connections between the cities and villages.

An idea of districts starts to take shape.

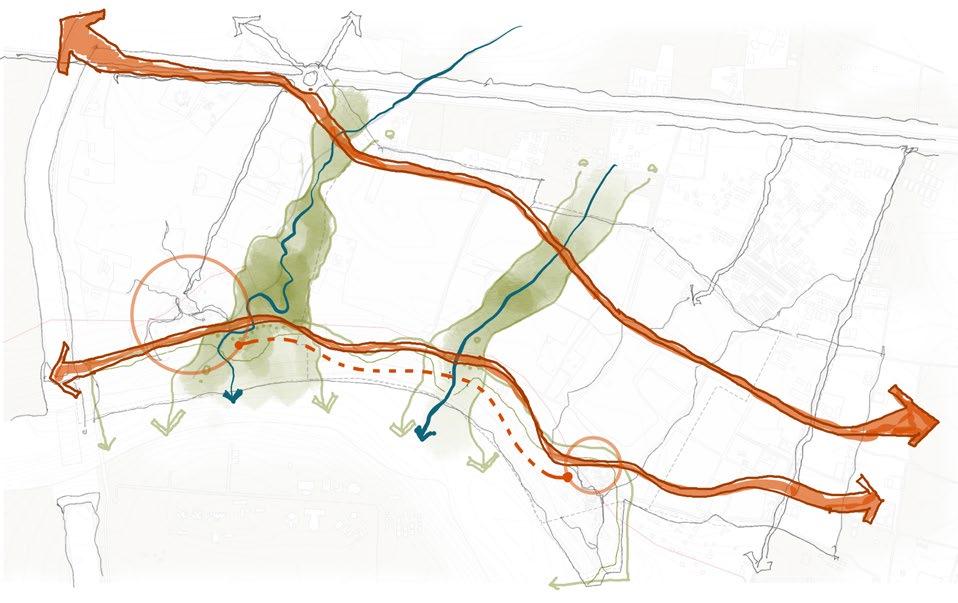

Loop City

A Contiguous Park System that ties it all.

|

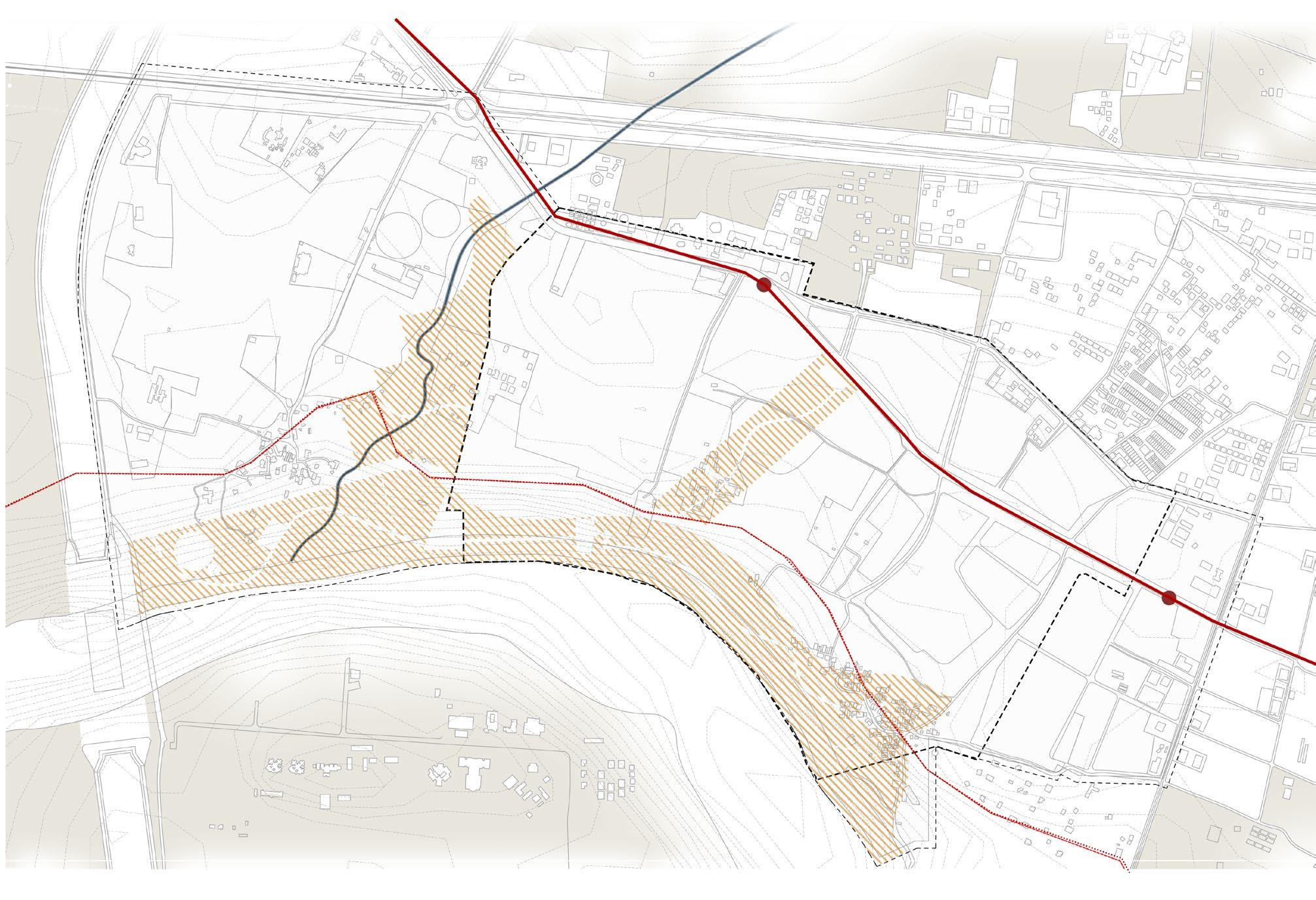

03.2. Satellite map of the site depicts the current fabric around the site. Highlighted in white is the extent of the invasive prosopis and catchments of watersheds and 200m buffer along the Southern Drain. (Source : GoogleEarth)

03.3. The GMRC Phase 02 elevated corridor, urban villages of

and the Southern Drain form the anchors and non negotiables for the masterplan.

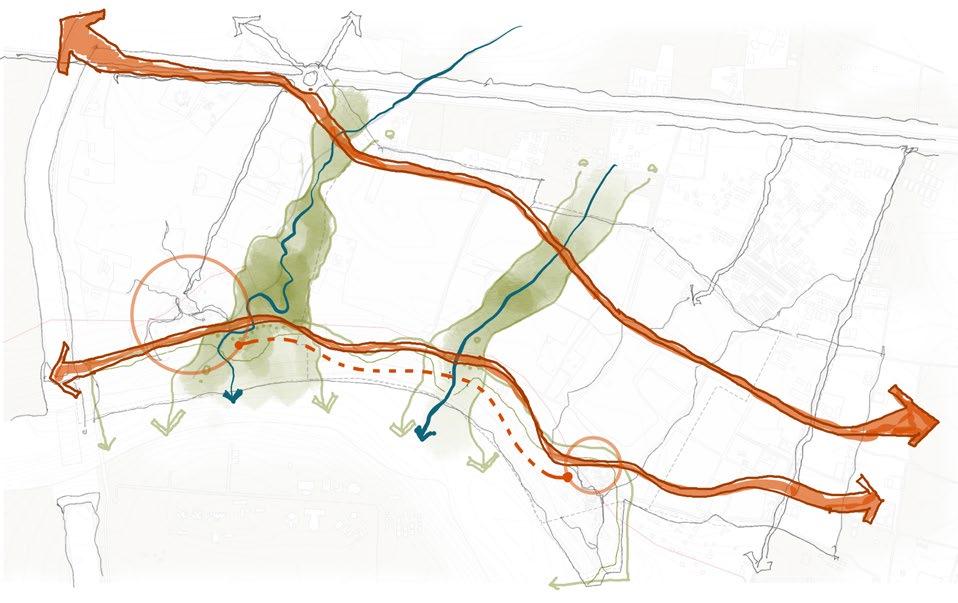

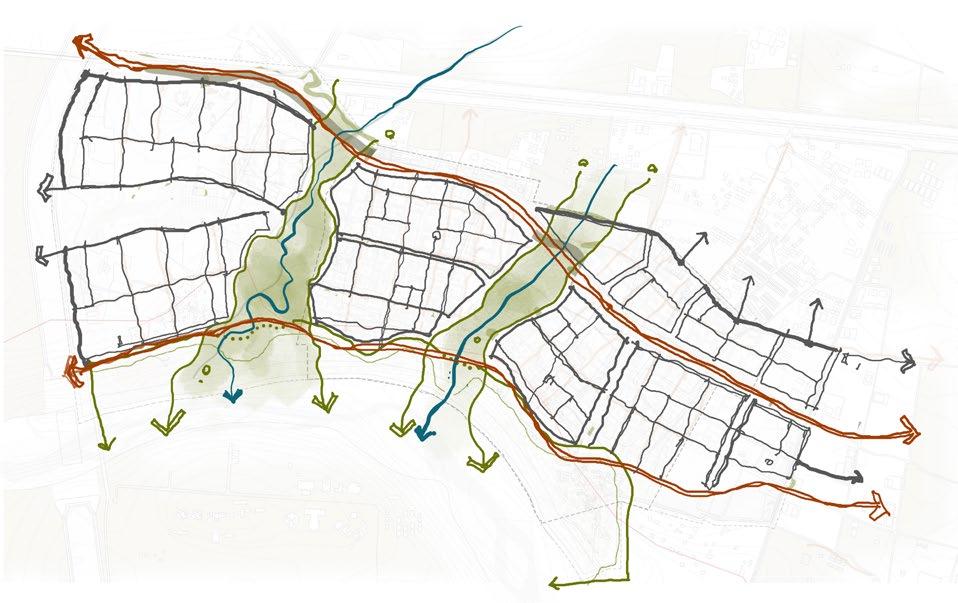

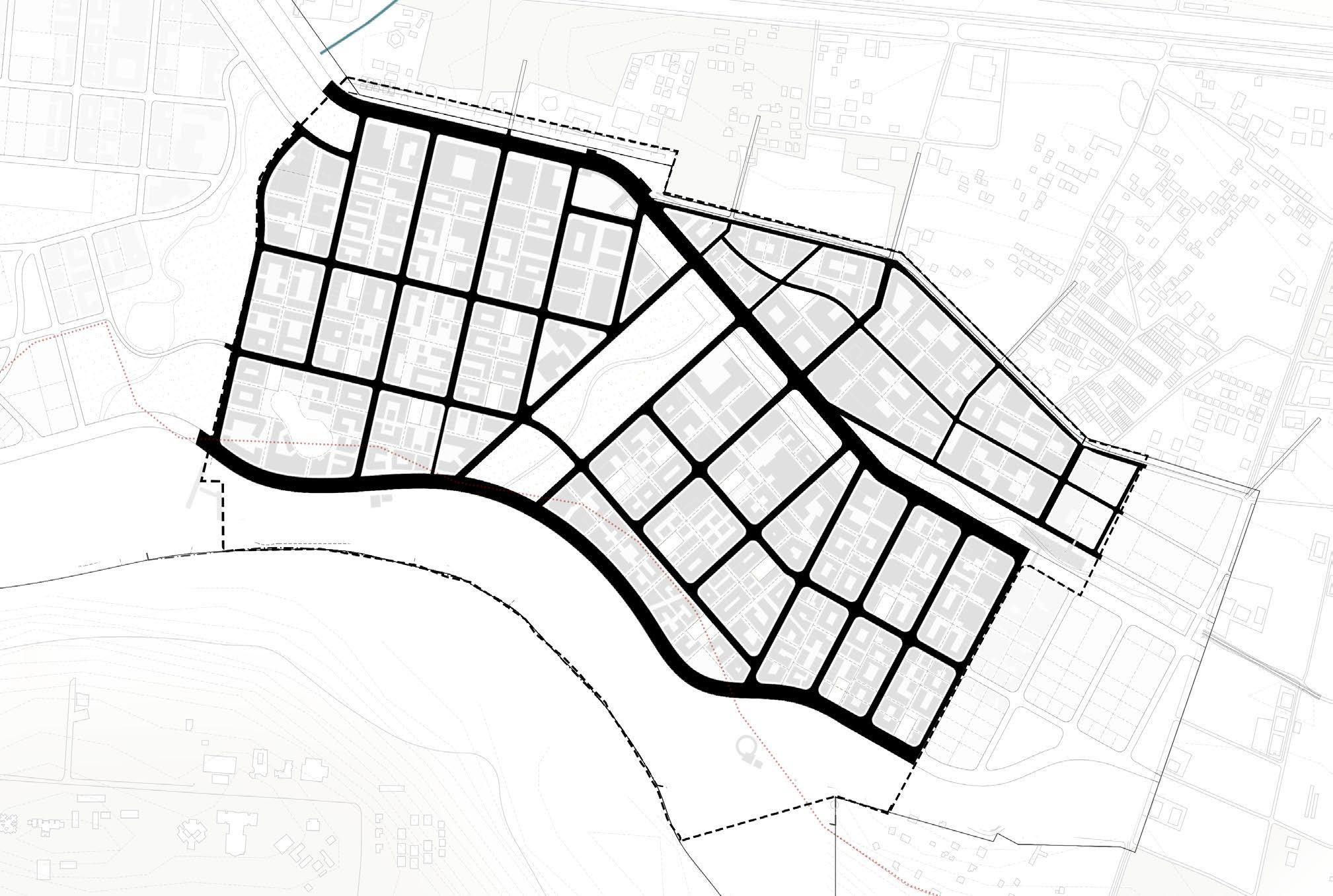

The spatial strategies employed in developing the master plan serve as a critical bridge between site analysis and the final design, translating observations and insights into actionable urban frameworks. These spatial strategies or big moves build on from the strongest of the sites’ aspects to form the first step of the master plan

Existing and lost green and blue corridors are identified and supported with buffers to mitigate risks and enhance resiliency of the site as first line of defense.

Form connections between the cities and villages.

Two major arterial streets lay down the preliminary framework for ensuring a seamless, equitable connection across the site and beyond.

These also rationalize the connectivity between the currently disjointed urban villages and the river edge which is inaccessible due to vegetation.

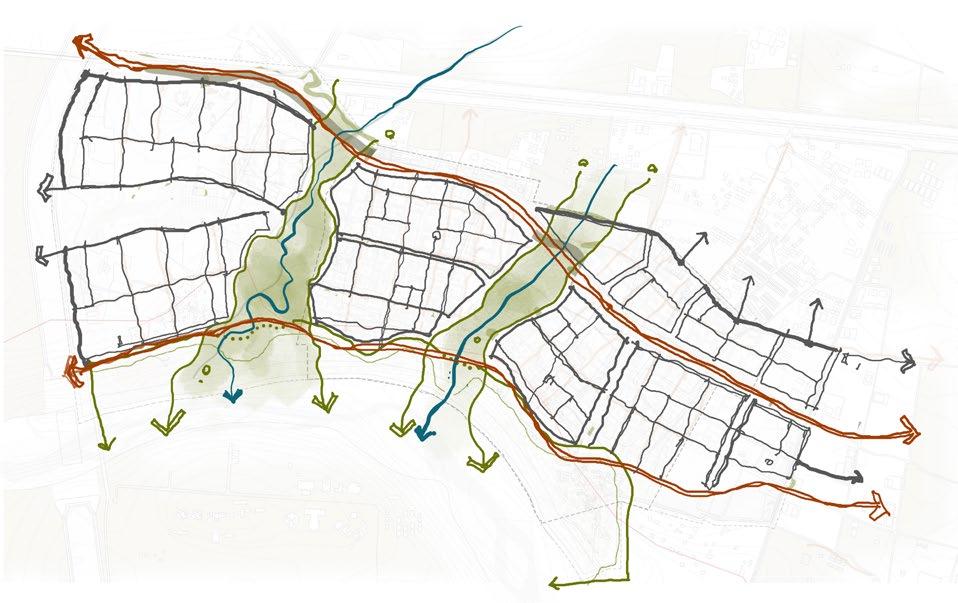

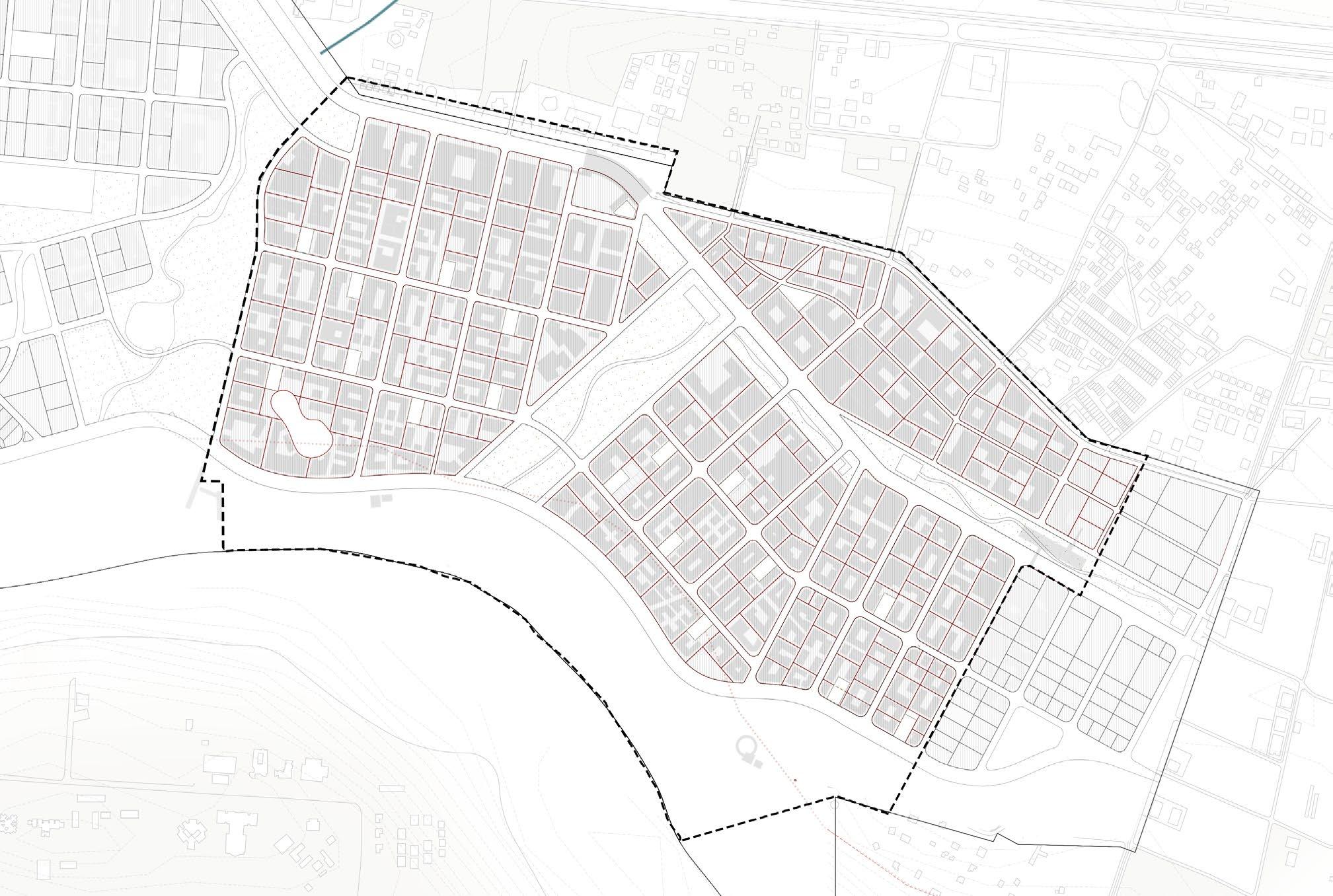

An idea of districts starts to take shape.

A set of distinct, interconnected urban clusters are imagined, each with its own mix of residential, commercial, and civic uses to reduce reliance on distant resources.

Land use intensities transition smoothly from high-density mixed-use centers near transit hubs to low-density residential neighborhoods, preserving community character while optimizing accessibility.

Loop City

A Contiguous Park System that ties it all.

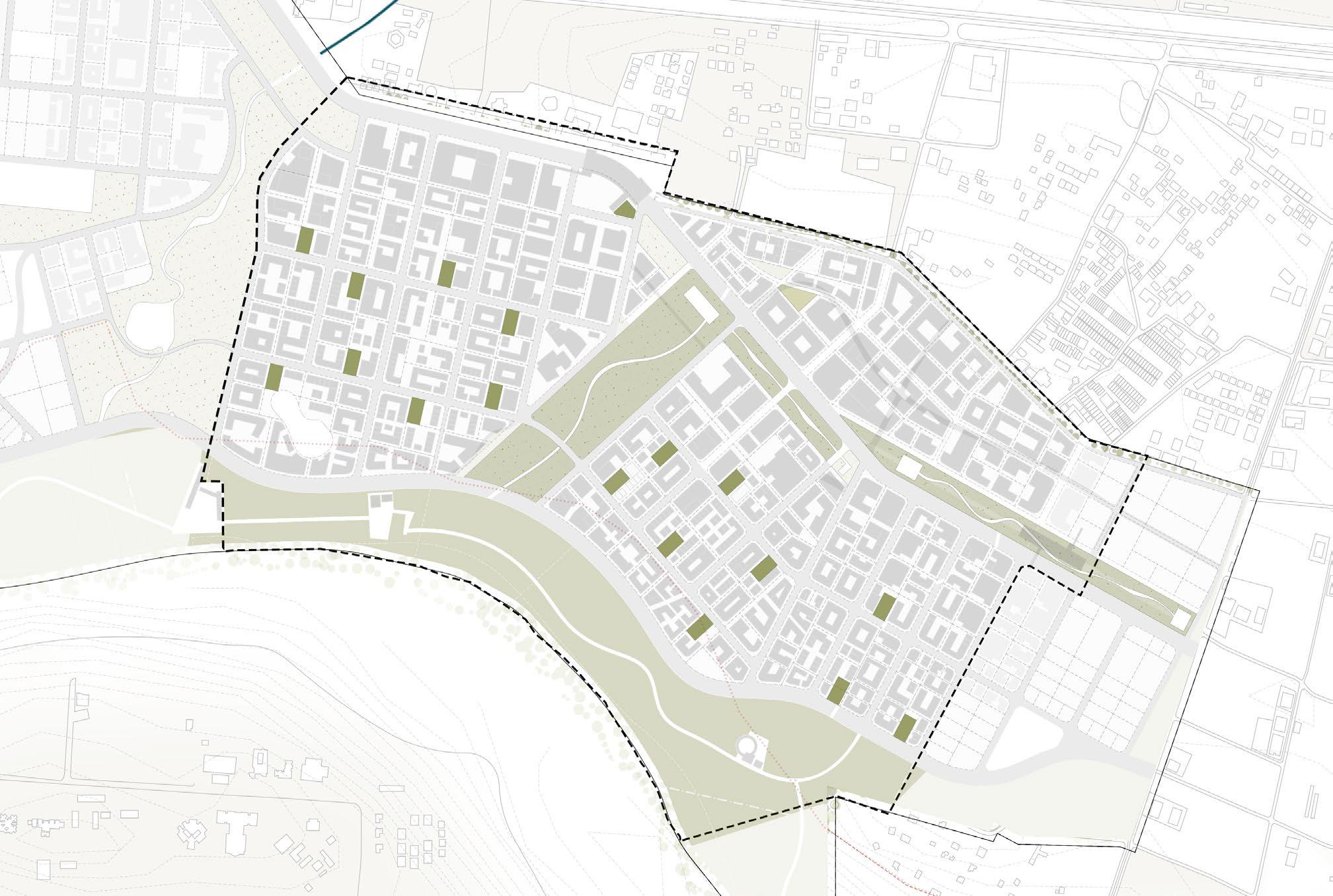

A cohesive system of parks, urban forests, farms and parkways connects the entire master plan ensuring continuous ecological flows and supporting biodiversity and access to open spaces to every resident.

The spatial strategies employed in developing the master plan serve as a critical bridge between site analysis and the final design, translating observations and insights into actionable urban frameworks. The strategies focus on leveraging on natural systems, built environments, and social infrastructure to create a cohesive and adaptable urban fabric. Each spatial strategy is designed to address site-specific challenges while aligning with broader goals of climate resilience, community well-being, and economic vitality.

This leads into a conceptual framework for the entire master plan as an integrative approach that translates spatial strategies into a coherent urban system.

The framework emphasizes adaptability and flexibility into its structure, allowing the city to grow steadily and incrementally. The framework has been conceived for the entire 722 acres of the site.

A proposal for 394 acres, incorporating the Juna Koba urban village has been detailed.

- Koba Circle

- Metro Station

- GMRC Corridor - Highschool - Business district

- Canal Walk

- Community Centre

- Seasonal Reservoir - River Walk - Nature Park - Residential District - Community market - Crematorium

The metrics of the master plan embody a balance between ecological integration, urban efficiency, and community well-being, offering a quantitative foundation for its almost utopian vision. For the ReWilding Koba Master Plan, they illustrate the deliberate integration of natural and human systems. These metrics not only quantify the master plan’s ambitions but also create a road map for its

Connectivity is the backbone of any urban system, shaping how spaces are accessed and activated to form a cohesive whole. In the master plan, the logic of roads and streets extends beyond traditional transportation networks, embracing the systems-based approach that combines transit efficiency and ecological sensitivity. Accounting for 16.7% of site’s area, the roads are imagined to be provide higher efficiencies. Roads, as impervious surfaces, significantly alter the natural hydrological cycle by preventing water infiltration into the soil. Hence, the roads are laid to provide maximum connectivity while increasing the overall surface runoff penetration and ground water recharge.

realization, forming a cohesive framework that guides urban form, mobility, and public realm strategies. With these metrics in place, the transition to detailed design focuses on translating these principles into tangible interventions—crafting spaces, streetscapes, and structures that embody the essence of a city within a park.

Area under roads (%)

16.7

Thoroughfares

Despite a higher ratio of common urban greens, the saleable land parcels cover more than half of the site, constituting 56.7% of the total site area, leaving 43.3% allocated to non - saleable parcels such as roads, open spaces, and public infrastructure.

The non saleable parcels prioritize community needs by integrating green public spaces, ecological buffers, and essential infrastructure into the urban fabric.

This ratio ensures the economic feasibility of the development while reinforcing the vision of a “city within a park” through ample public amenities and green commons.

Saleable parcels (%)

56.7

Non Saleable parcels (%)

43.3

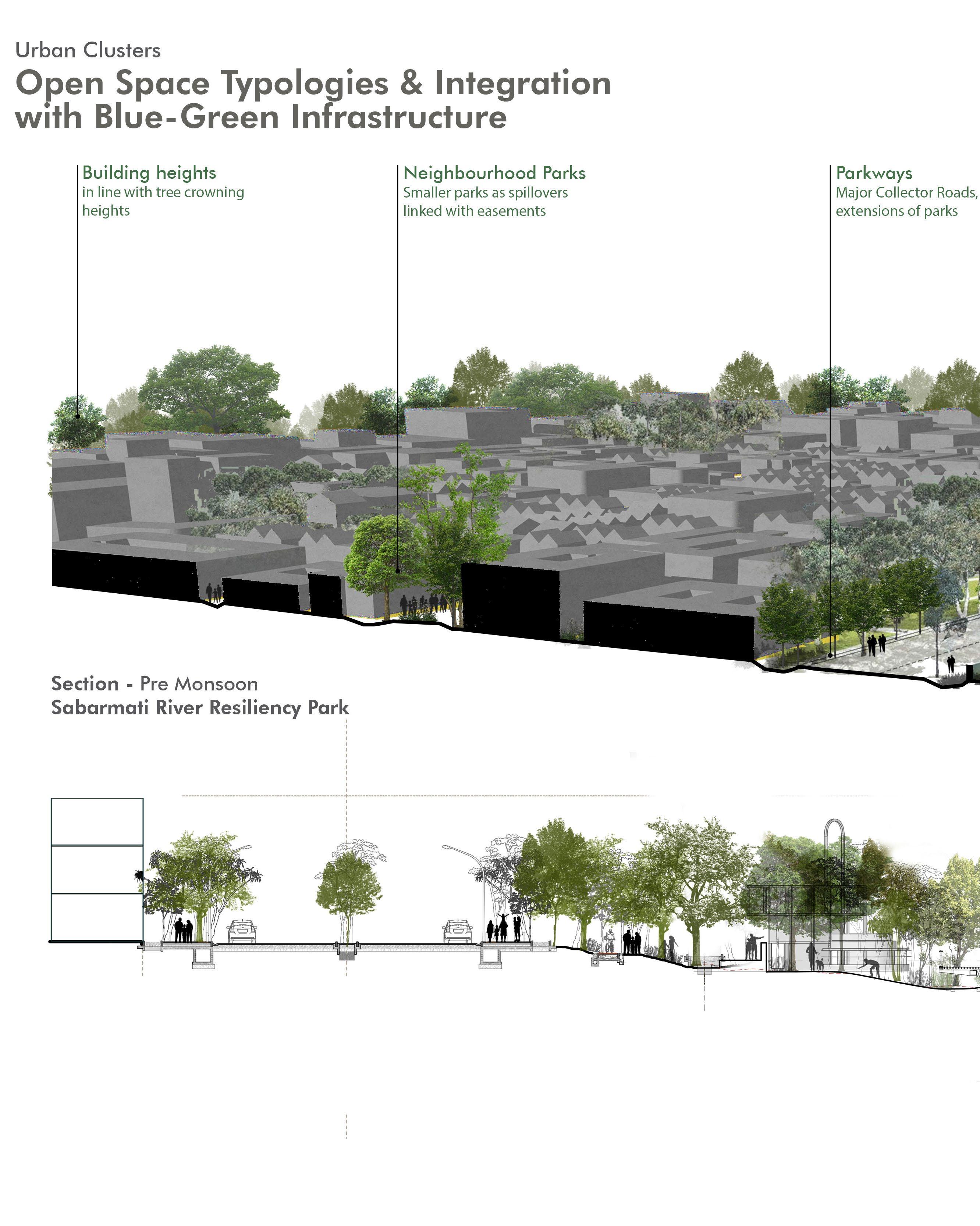

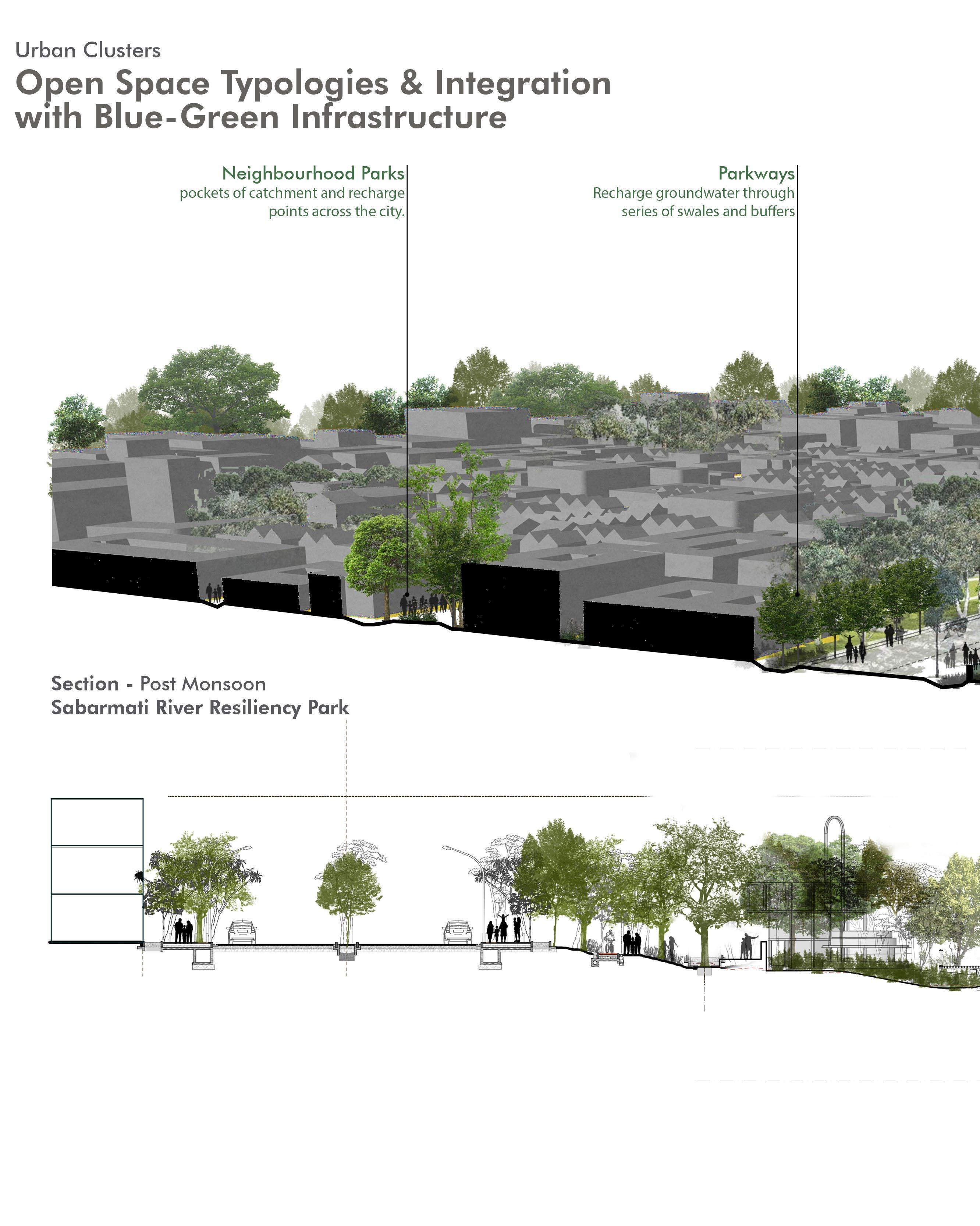

The open space distribution in the urban design master plan embodies the vision of “a city within a park, rather than a park within a city” by integrating a multi-scalar network of green and blue spaces that connect people with nature at every level of the urban fabric.

At the macro scale, expansive green corridors and ecological parks serve as the backbone of the city, linking key urban nodes while providing critical ecological functions such as biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, and storm water management. These large open spaces are complemented by smaller, decentralized green pockets—plazas, gardens, and courtyards—embedded within residential, commercial, and transit-oriented clusters, ensuring equitable access to nature across all neighborhoods.

At the micro scale, pocket parks, bioswales, and rain gardens are strategically placed to activate streetscapes and enhance the livability of local environments. Linear parks and green ways along transit corridors and water bodies double as recreational spaces and ecological buffers, seamlessly blending utility with aesthetics.

These spaces are not merely aesthetic elements but integral components of the ecological and social fabric, designed to optimize carbon sequestration, enhance biodiversity, and support urban resilience. Drawing from Robert Mendelsohn’s thumb rules for maximizing ecosystem services, the master plan emphasizes preserving existing vegetation, re-wilding degraded landscapes, and incorporating diverse plant species with high carbon absorption capacities. Large central parks, urban forests, and green corridors function as “carbon sinks,” absorbing atmospheric CO₂ while providing recreational and climatic benefits.

This hierarchical distribution ensures that every resident is within a 5-minute walk of a green or blue space, promoting physical and mental well-being while reinforcing social cohesion. The varied scales of open spaces—from intimate retreats to community hubs—are designed not only to provide recreation and leisure but also to serve as ecological anchors, embodying the master plan’s commitment to a resilient and harmonious urban environment.

41.6

Carbon Sequestration Potential (kgs/year) Area under Tree Cover (sq.m)

9,55,628.4

*equals 1,053.4 tons annually, based on thumb rules by Robert Mendelsohn

Parkways Neighborhood Parks

Major Green Commons

Open Space Hierarchy |

Fig 03.13. The open space system has three scales of open spaces typologies, namely neighborhood parks, major common greens and parkways binding the master plan together.

Tree Cover and Vegetation Distribution|

03.14. A higher percent of tree cover responds to the lower percentages of tree covers in Ahmedabad and underscores the central vision of the masterplan

As we move into the 21st century, the challenges of rapid urbanization, climate change, and resource depletion faced by our cities today demand innovative planning methods. Traditional compartmentalized approaches to urban development often fail to address the complexity and interdependence of modern urban systems. To bridge this gap, we look at a systems based approach which recognizes our cities as interconnected networks of infrastructure, environment, and community. Globally, cities like Copenhagen, Curitiba, and Singapore demonstrate how systemic thinking integrates mobility, ecology, and urban resilience to create adaptive and sustainable environments.

Looking at our site at Koba, with its close proximity to natural assets such as the Sabarmati river itself and the dense tree cover which prevails as of today, we realize that a systems based approach becomes especially relevant for greenfield developments, where the opportunity exists to holistically design urban frameworks from the ground up, right from the conception.

The ReWilding Koba master plan attempts to re imagine urban living as an extension of the natural environment itself. The frameworks are independent in their conception and function but interdependent in impact, collectively delivering a city that combines the ecological stewardship with economic vitality and human well-being.

The ReWilding Koba master plan employs this approach to envision a city that positions nature at its core. By layering multiple systems such as the mobility, community, landscape, and resilience—it attempts to create an urban fabric that is not only efficient but also resilient and climate-adaptive. This attempt to integrate nature, site and the built ensures that the master plan addresses immediate, pressing urban needs of our cities today, accommodates for the pressures of urbanization due tomorrow while fostering long-term environmental and social sustainability.

While each framework in the ReWilding Koba master plan serves distinct objectives and their effectiveness lies in their interdependence. The mobility networks facilitate accessibility to community anchors, while pedestrian trails connect with green commons, enhancing walkability with

ecological integrity. Landscape systems and transports systems framework complement the resilience framework, ensuring that open spaces, roads double as functional flood mitigation zones.

Districts, in turn are shaped by community systems, host mixed-use spaces that integrate with mobility and landscape strategies allowing for a closer, compact and more sustainable urban living. Leveraging the site and its anchors, the master plan can be delayered into its four key constituent systems framework as follows :

• Mobility Systems Framework

• Community Systems Framework

• Landscape Systems Framework

• Resiliency Systems Framework

By focusing on the relationships between these systems rather than treating individual components in isolation, the approach attempts to achieve an almost utopian vision for Koba. A city where natural processes and urban activities coexist in symbiosis with one another, ensuring that ecological resilience, economic growth, and social well-being are reinforcing for everyone.

The mobility framework can be divided into two of its sub components, the vehicular as well as the pedestrian networks. The vehicular mobility framework ensures that the city is connected efficiently while minimizing the footprint of motorized traffic. The integration of the GMRC elevated metro corridor with multi-modal nodes like public light bus stops creates opportunities for transit-oriented development. Compact arterials and transit-accessible clusters support reduced car dependency, reflecting global best practices in sustainable urban mobility. While the larger transit movement is catered to by the vehicular mobility system, the pedestrian and non-motorized transport (NMT) framework focuses on human-scale connectivity.

The NMT and Pedestrian network actively moves away from major streets and nodes, using easements and shared spaces to separate people from the vehicles. A network of walking and cycling trails is designed to integrate seamlessly across districts, parks, and open spaces. Bike ways use shared corridors and easements, while nature trails pass through protected areas, emphasizing minimal environmental disruption.

Existing Situation & Site Anchors |

Manufacturing, and Lithographic Company

The basic armature provided by the mobility systems results in formation of districts or neighborhoods. These districts become the building blocks of the master plan itself. Each district. The Community systems attempts to organize the urban fabric into distinct districts, each with functional and cultural anchors.

These districts are planned to optimize compactness, connectivity, and accessibility, facilitating mixed-use developments that integrate residential, commercial, and institutional uses. Anchors such as high schools, health centers, and cultural hubs provide essential services while serving as nodes for this social interaction. Community centers, markets, and outreach facilities are placed in an attempt to enhance local participation which helps nurture a sense of belonging. Each district is designed to operate autonomously yet supports adjacent districts through shared resources, reinforcing interdependence within the broader urban system.

What could be considered by far as the most important systems in the framework would be the landscape framework. The framework attempts to strongly define the city’s identity as “a city within a park.” Larger commons like the Sabarmati Resiliency Park and nature reserves anchor the ecological network, providing floodable landscapes, urban forests, and seasonal reservoirs.

These spaces not only conserve biodiversity but also act as urban lungs, sequestering carbon and moderating the micro climate. Complementing these are smaller-scale commons, including parkways, green streets, and neighborhood parks. Parkways, designed as landscaped thoroughfares, double as flood buffers during monsoons. Neighborhood parks function as localized green spaces that are multipurpose and adaptable, serving both recreational and ecological needs. Together, these commons ensure that every urban district is seamlessly integrated into a continuous green network.

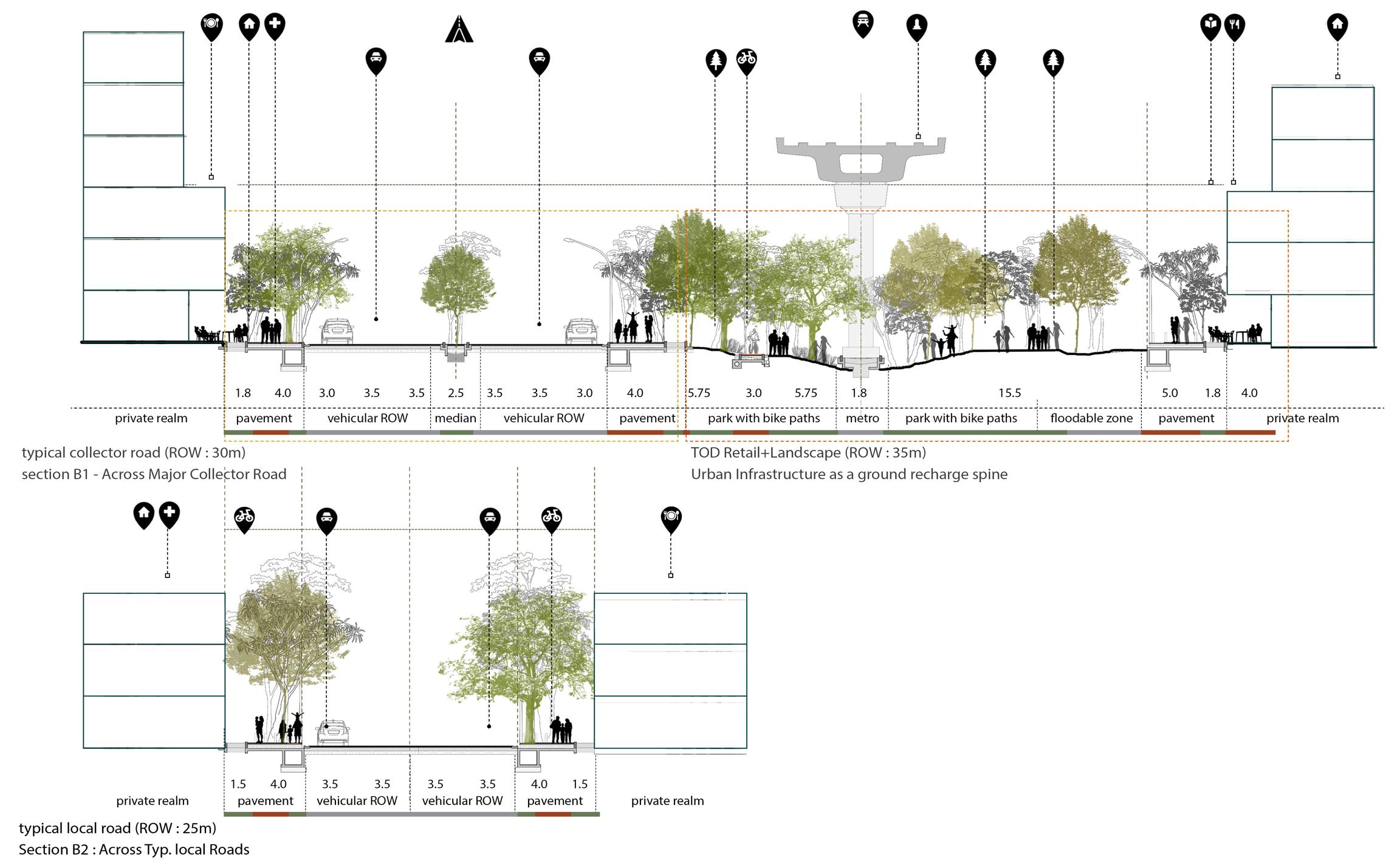

The vehicular mobility framework attempts to ensure that the city is connected efficiently while minimizing the footprint of motorized traffic. With a hierarchy of arterial (ROW 35m), collector (ROW 24m), and local roads, the master plan allows seamless vehicular flow across districts while prioritizing access and convenience.

The integration of the GMRC elevated metro corridor with multi modal nodes like public light bus stops creates opportunities for transit-oriented development. Compact arterials and transit-accessible clusters support reduced car dependency, reflecting global best practices in sustainable urban mobility. Service roads and utility corridors are strategically positioned to streamline functionality without interfering with active public realms.

While the districts form the basic blocks of the master plan the anchors play a pivotal role in shaping the identity, functionality, and vitality of urban districts. They serve as nodes of activity, drawing people together for various purposes and fostering a sense of place within the broader urban fabric.

Strategically distributed, these anchors are imagined to ensure that essential services, cultural amenities, and social infrastructure are accessible to all, creating a collective of almost self-sustained neighborhoods while also helping the master plan to be realized as a collective whole.

Fig 04.04. The community anchors function as the identity as well as the socio-cultural magnets for the residents of the district.

While the larger urban commons mitigate larger ecological concerns and act as the urban lungs, sequestering carbon and moderating the micro-climate, complementing these are smaller-scale commons, including parkways, green streets, larger urban park and a network of minor neighborhood parks.

Parkways, designed as landscaped thoroughfares, double as flood buffers during monsoons. The neighborhood parks function as localized green spaces that are multipurpose and adaptable, serving the immediate neighborhood. Together, these commons ensure that every urban district is seamlessly integrated into a continuous green network.

Seasonal Reservoir to arrest water in temporary water detention and retention ponds

Minor Parkways and Green Streets as a tool to convey water to larger water detention areas in the master plan

Retrofit urban infrastructure to maximize catchment

Lastly, these mobility and landscape systems framework combine to integrate the storm water management into the landscape and road systems. Seasonal reservoirs and constructed wetlands intercept runoff, reducing urban flooding.

Roads function as more than conduits for vehicles; bios wales and permeable medians transform them into recharge spines, enhancing groundwater percolation. Linear parks along canals and riparian trails act as catchment buffers, mitigating peak runoff during storms. This framework emphasizes adaptive design, allowing urban spaces to perform ecological functions while retaining their usability across seasons.

Just as is the case with any city, old and new alike, lies at their core the true reflection of its larger being, at the heart of the ReWilding Koba master plan lies in the composition of urban blocks and clusters. The urban blocks and the resultant, intended urban from that give shape and form to the larger manifestation of its vision of “a city within a park.”

This chapter delves deeper into the micro-level design principles and spatial configurations that bring the earlier mentioned layered systems framework approach to life. Urban blocks here are not just intended as the modular units of land use; they are imagined to be adaptive dynamic spaces where mobility, community, landscape, and resilience frameworks converge to create layered, nuanced, multi functional living environments. Each block is carefully realization of a series of considerations aimed at maximizing accessibility, enhance social interaction, and finer balance of the built and open spaces. All of this, while maintaining a seamless human connection to ecological

and infrastructural networks of the master plan. This warrants a deeper exploration of the nuanced urban design considerations behind these block typologies,

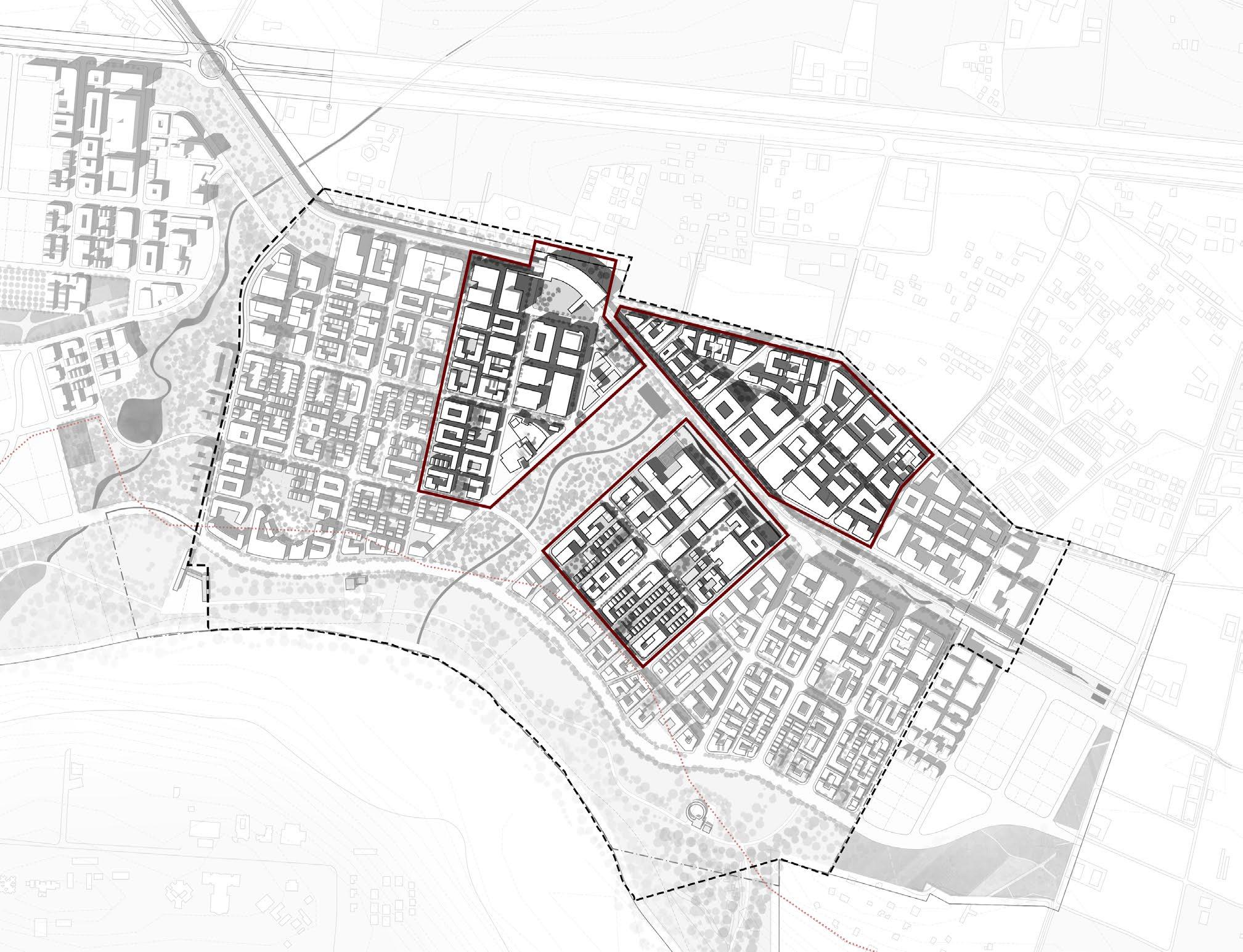

To aid easier comparisons and facilitate better comprehension of the intended urban design considerations and experiences, the select group of three urban blocks is chosen and elaborated upon. This chapter explores the careful selection and design of each of these distinct block types, examining how they interact with each other while contributing to the overall urban framework.

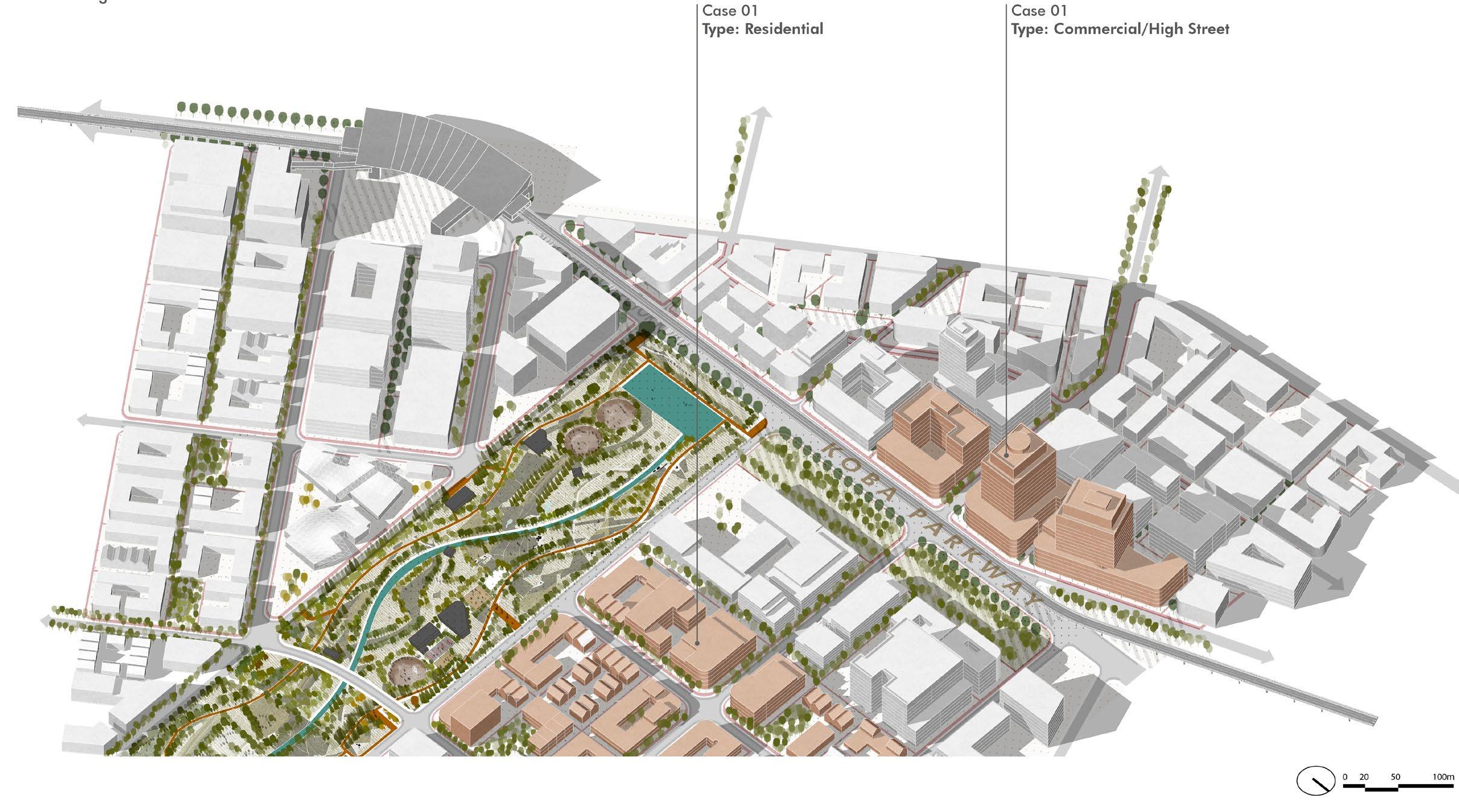

A deliberate clustering logic positions the chosen transit, residential, and high-street/commercial blocks along a single major arterial street, all surrounding a larger, central urban park. This arrangement creates a highly integrated urban environment which could be compared for easy comprehension. By situating these key urban functions in close proximity to one another, the blocks serve as an emblematic example of the entire master plan.

The major arterial street serves as the primary axis of our mobility, linking and offering easy access to all three block types. Throughout the master plan, there are three said hierarchies or typologies of streets.

The major collector road serves as the backbone of the city’s mobility network, providing efficient access to and from key areas within the master plan. With a wider right-of-way of 30 meters, this road is designed to accommodate higher traffic volumes while ensuring safe, comfortable experiences for all users, including pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers.

The GMRC corridor which runs parallel to one of the two major collectors as be re-imagined as a city level bioswales running across the master plan. The underside of the GMRC corridor is an park, and larger floodable shoulder. Activities from the ground floors of surrounding buildings are encourager to spill over the TOD retail zone along this corridor. This typology intends to capitalize on the ‘park’ like nature of the surrounding real estate. The parkways in ReWilding Koba are envisioned as multi-functional spaces that seamlessly integrate pedestrian and non-motorized transport (NMT) networks alongside vehic

ular lanes. Wide sidewalks and dedicated bike lanes encourage active movement, while green buffers between the streets and sidewalks provide natural shade, create visual interest, and reduce the heat island effect.

The local roads, with a right-of-way (ROW) of 25 meters, are intended to provide access to smaller, more residential-scale neighborhoods while maintaining a balanced flow of traffic. These streets are narrower than the collector and arterial roads, which makes them inherently slower, promoting a pedestrian-first environment where walkability is prioritized. In contrast to the larger streets, local roads feature quieter, tree-lined corridors that foster a sense of intimacy and community.

The parkways of Olmstead could be described as the defining philosophy behind the design of streets, sans scale across the entire master plan. Olmsted’s parkway design philosophy centered on the concept of creating green corridors that serve as both transportation routes and natural landscapes. These parkways were conceived as scenic, tree-lined streets that offered a visual and physical connection to nature, even in the heart of a densely built city, something which echoes the very principle of this master plan.

Fig 05.02. The three typologies of streets and the distribution of their right of ways underscores the wide range of their utility. Varied in their scales, all three use Olmsted’s parkways as their central philosophy. Typical Street sections |

The connectivity of the transit, residential, and high-street/ commercial blocks in the master plan is crucial for its vision of a well-integrated, walkable, and accessible city. The transit systems, including buses and Public Light Buses (PLBs), are woven into the urban fabric to ensure seamless movement between these blocks while reducing reliance on private vehicles. Each block type is connected to transit systems differently, reflecting its functional role.

The transit blocks are the most directly integrated with public transit systems, as they are designed to function as hubs of connectivity. These blocks are located adjacent to metro stations and bus terminals, ensuring that they serve as gateways for movement within and beyond the city. Dedicated spaces for bus stops and PLB bays are strategically positioned to minimize transfer distances between modes of transport.

The transit blocks are also directly linked to the arterial street, where buses and PLBs operate on dedicated lanes or prioritized routes, enabling efficient and uninterrupted service. This high level of integration ensures that transit blocks maximize accessibility and convenience for commuters, with transit nodes acting as anchors for mixeduse development and economic activity.

The residential blocks are connected to transit systems in a more distributed manner, emphasizing accessibility without compromising the serenity of living spaces. These blocks are typically located within a short walking or cycling distance from bus stops and PLB routes, ensuring that residents can access transit conveniently. Pedestrian pathways and bike-friendly corridors provide seamless connections to nearby transit hubs, enabling first- and last-mile connectivity.

Unlike transit blocks, residential blocks do not house major transit infrastructure but are carefully positioned to benefit from the proximity of public transit networks. This indirect but deliberate connectivity reduces vehicular dependency among residents while preserving the quiet, community-oriented character of these blocks.

The high-street/commercial blocks are positioned along major bus and PLB routes to maximize accessibility for shoppers, employees, and visitors. Bus stops and PLB bays are located at intervals that align with the high foot traffic expected in these blocks, ensuring frequent and convenient access. The ground floor designs of buildings in these blocks include wide sidewalks and open plazas that integrate seamlessly with transit stops, enhancing the pedestrian experience.

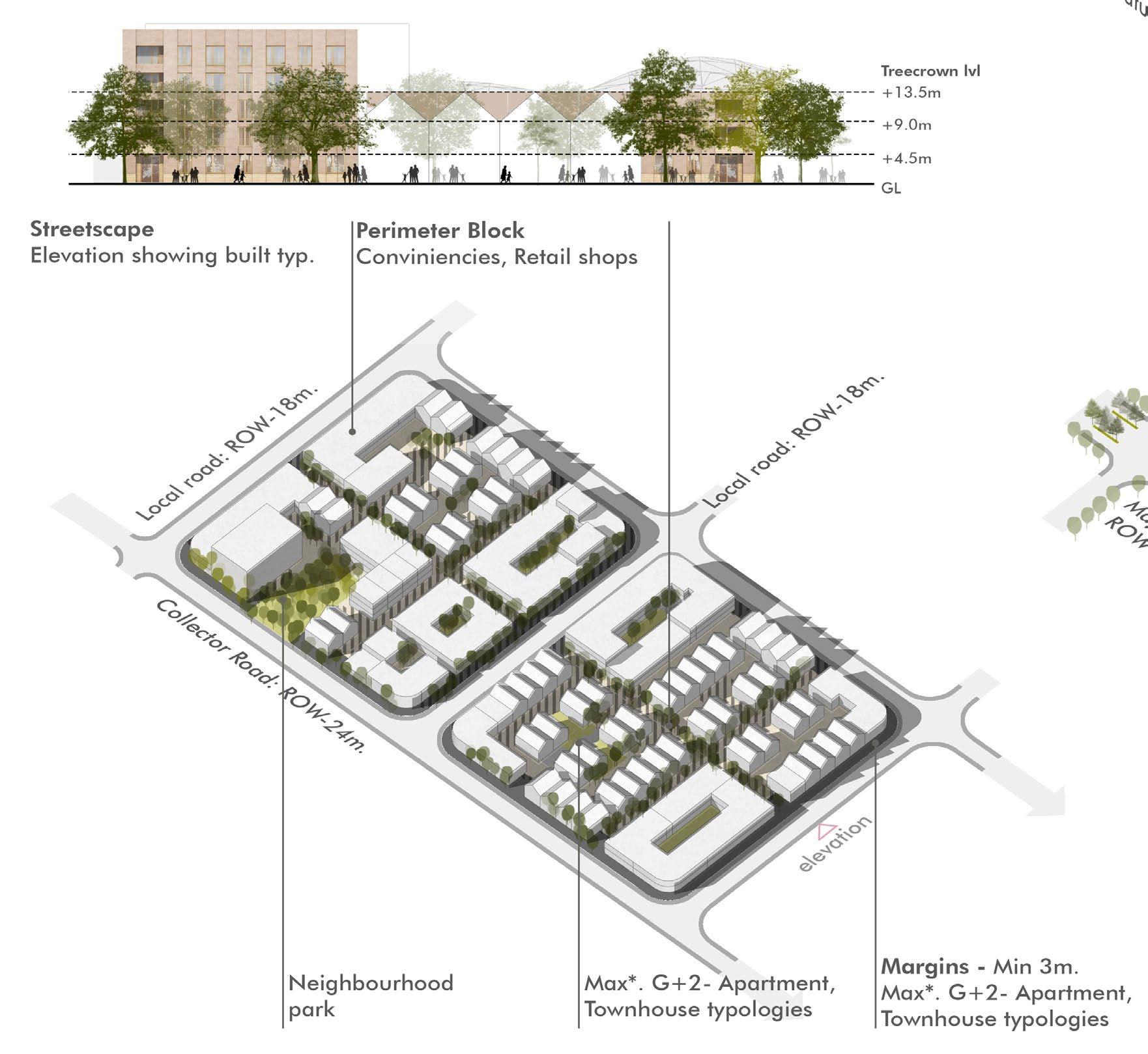

While this master plan challenges the conventional urban model by embedding green and blue infrastructure as the guiding framework for development, its success lies in this manifestation to reflect in the individual, resultant buildings. To delve deeper into the detailed urban design guidelines, two representative cases have been selected from the residential and commercial blocks, each highlighting distinct building typologies that embody the master plan’s vision.

From the residential blocks, a mid-rise apartment complex serves as an example of medium-density housing designed to balance livability, accessibility, and integration with green spaces. Its layout demonstrates how shared courtyards, tree-lined pathways, and open spaces are used to foster community interaction while ensuring privacy and natural ventilation.

Similarly, from the commercial blocks, a high-street retail and office complex exemplifies the dynamic interplay between active ground-floor retail and upper-level commercial spaces. This typology emphasizes vibrant public realms through wide sidewalks, outdoor seating, and landscaped plazas, seamlessly integrating the building with adjacent streets and the urban park. These cases provide a lens to explore the detailed strategies for scale, built form, materiality, and interface with the public realm that guide the master plan’s urban design.

The urban design guidelines for a typical commercial cluster in the “ReWilding Koba” master plan emphasizes flexibility, connectivity, and adaptability. Commercial clusters are designed with comparatively larger, adaptive plot sizes ranging from 5,000 to 7,000 square meters, accommodating diverse retail and non retail typologies, including towers and apartments for higher densities.

Such building types are characteristically conceived by a mixed-use mid-rise building typology, which the proposed master plan strives to achieve its economic objectives without compromising the active use of public space. The ground floor of the complex is designed for retail and café spaces that open into landscaped plazas and wide pedestrian walkways making them vibrant and active at

the street levels. The upper portions, however, are allocated for offices, which decorate the economic activity of the block without exceeding to residential or transit blocks.

Typical sizes range between 60m x 100m, going as high as 135m in come cases. Step backs are proposed after G+3 floors, to lower the impact on pedestrians. Urban design guidelines mandate datums for buildings to follow which would result in an homogeneous urban fabric, regardless of the building type. The complexes are also configured with shared easements, shaded seating areas, green buffers, and collective open spaces with direct access to the abutting buildings in the vicinity resulting in an almost contiguous ground floor shared by all.

The urban design guidelines for a typical residential cluster in the “ReWilding Koba” master plan emphasizes compactness, connectivity, and integration with nature. Residential clusters are designed with smaller, adaptive plot sizes ranging from 2,000 to 4,000 square meters, accommodating diverse housing typologies, including townhouses and apartments for higher densities, rather than stand alone single family units.

The maximum height of the buildings is limited to G+2 to G+6 to maintain a sense of humanity and to blend in with the tree canopies so as to create a park-like setting in the area. The intra-residential streets are designed for the provision of walking and cycling only accompanied by developed back thus developed back roads separated by vehicular barriers.

The plots are intended to develop without the notion of walls, allowing abutting plots to share margins and provide larger, wider easements.

Each residential block measures 40m x 80m, at its most largest plotting, with easements at every 50m for easy access. This helps generate a block thats walkable within 10 min radius. Plots are programmed as adaptable modules allowing greater efficiencies. This helps smaller plots to capitalize on their ability to amalgamate if such an event should occur.

Lastly, every residential block has a dedicated open space in form of an neighborhood park tucked between plots, measuring 27m x 50m. This provides for an much needed release between continuous building facades.

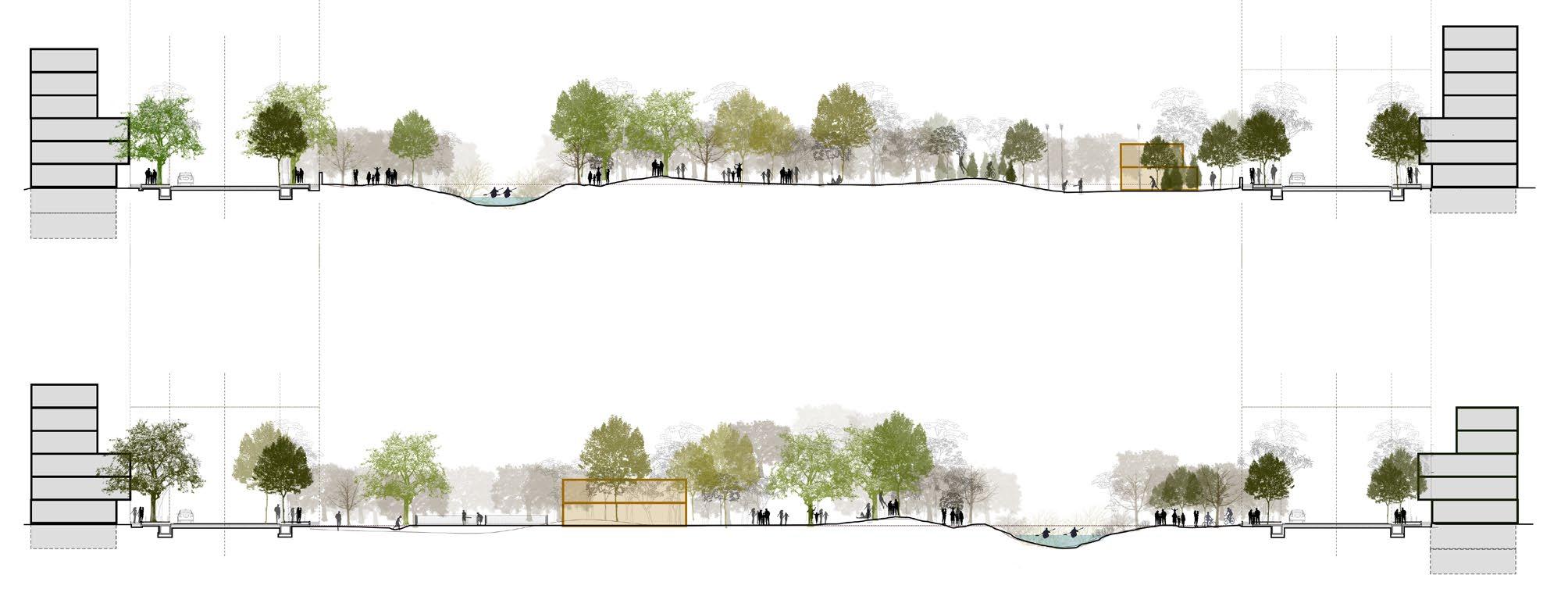

The Koba Urban Forest Park, spanning 89 acres, serves as the keystone of the master plan’s armature. The site of the park, falls primary in the ridge line of potential watersheds which makes its location perfect for a city level flood mitigation. Strategically located at the intersection of key transit, residential, and commercial blocks, the park is

imagined as a multi functional green space that supports ecological resilience, social interaction, and recreation. The park itself measures 620m x 135m at its widest, with about 68% of its area under a direct tree cover. The park is programmed with cultural centers, sports facilities along with walking, jogging and bike tracks

The park integrates a mix of programmed and passive spaces, including amphitheaters, event lawns, and cultural nodes, which host community events and outdoor gatherings. Walking trails, bioswales, and rain gardens are seamlessly woven into the design, enhancing storm water management and groundwater recharge.

Edges of the park respond to the land uses nearby at every point. The park also features a 14m wide rivulet which could be canoed upon, taking no longer than 25 mins to reach from one end to the other.

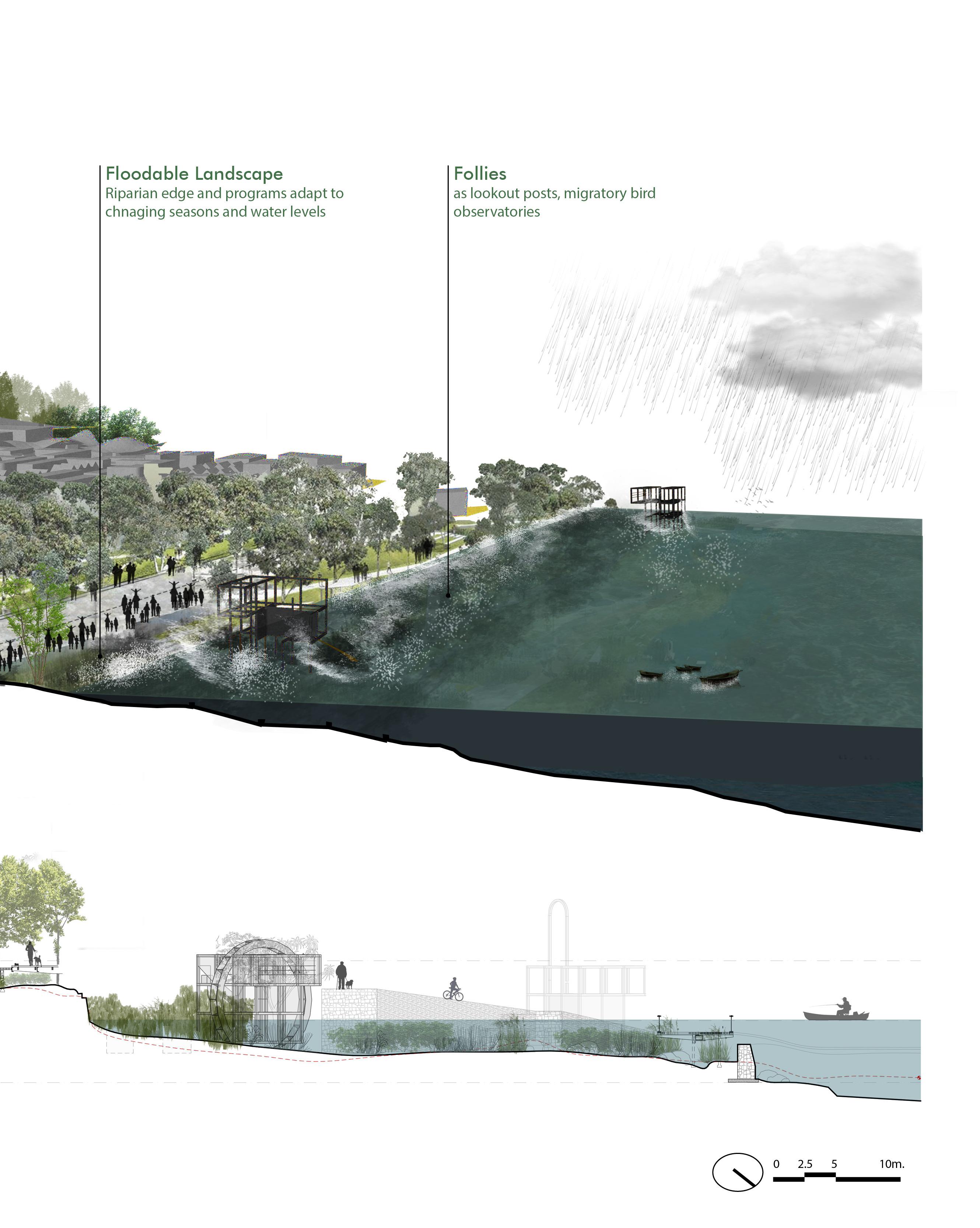

The Sabarmati River is undoubtedly the strongest of the sites’ anchor, an natural asset of historic, cultural and ecological significance. The river flows through the city of Ahmedabad, culminating at the site on its northern edge. While being a silent of victim of forced river training for much of its course through the city, the site remains one of the last ecological sensitive zones throughout its entire course before the GIFT City limits begin.

Being a seasonal river, the Sabarmati experiences large variations across the year. The high flood line, last marked during the survey for the Dharoi Dam records at 61.5m from the MSL. Being largely straight in its path for much of its course through the city, the Sabarmati meanders heavily near the site forming two large ox bows before flowing outside the GUDA limits.

All of these observations, point strongly in a direction that is perhaps shies away from most market driven responses of riverfront projects undertaken for the river in the city.

The Sabarmati River Resiliency Park is an embodiment of these learnings. Stretching for 2.3 kilometers along the Sabarmati River and covering 89 acres, stands as the

largest ecological and recreational elements of the ReWilding Koba master plan. Designed as a multi functional green corridor, the park exemplifies the integration of resilience, ecology, and public engagement, addressing critical environmental challenges while creating a thriving urban commons.

The park’s primary function is flood mitigation, achieved through a system of constructed wetlands, floodable landscapes, and a seasonal reservoir that captures and retains excess storm water during monsoons. These elements work together to manage runoff, recharge groundwater, and protect the city from urban flooding. Alongside its hydrological role, the park supports biodiversity, with riparian buffers and designated conservation zones providing habitats for native flora and fauna, including migratory birds.

The entire park is imagined as a wild-scape, taking over the currently inaccessible, invasive prosopis juliflora laden water edge. To scale this vast landscape park, a series of urban installations, inspired by Tschumi’s follies from Paris are arranged in a grid.

Urban Installations |

the expanse of the park.

The entire park can be phased out, with the part closest tot he Southern Drain and the seasonal reservoir taken up first. The follies, series of trails, nilgai preserve and bird observatory are few of the programmatic constituents of the Sabarmati River Resiliency Park.

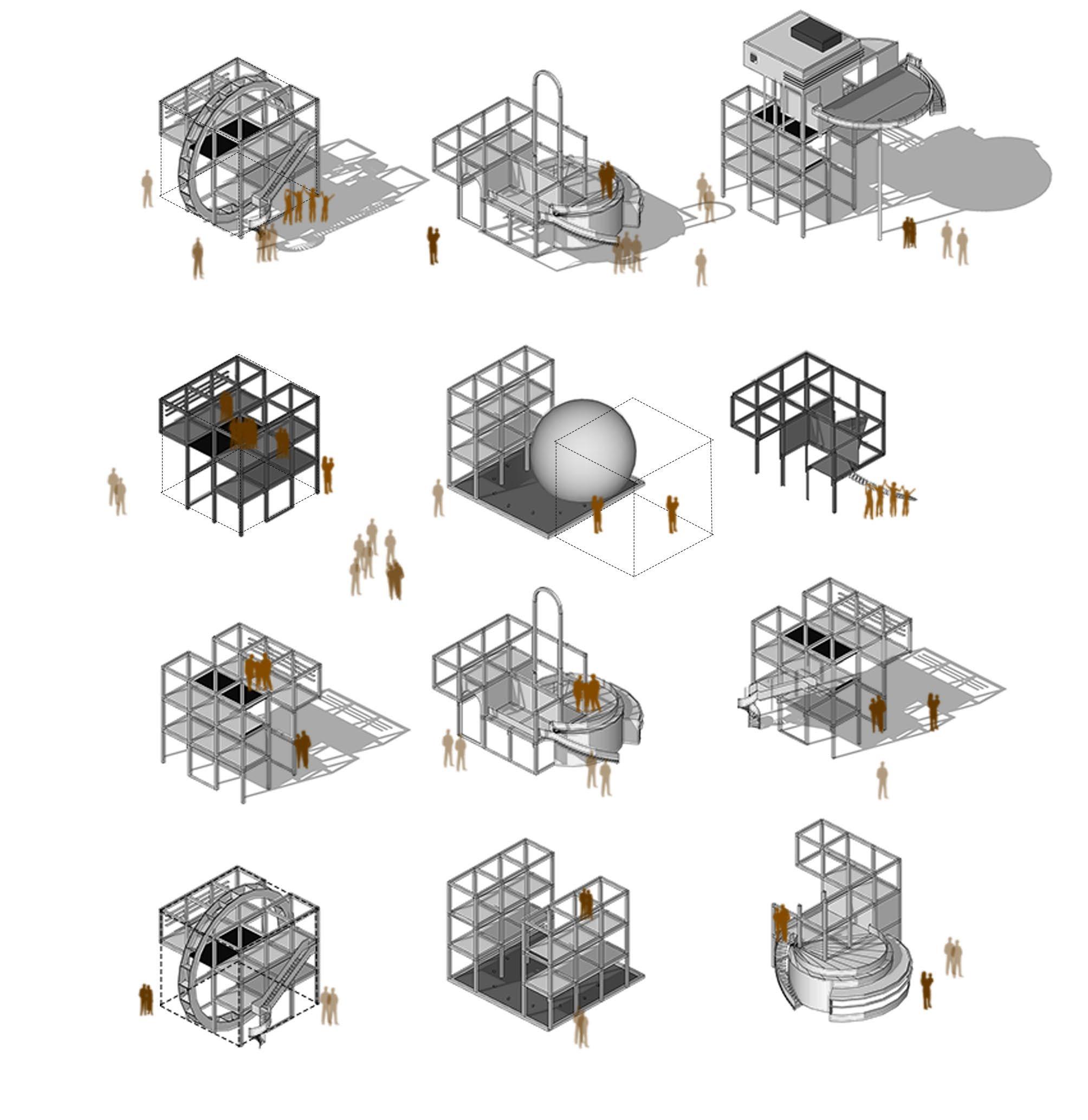

The re.create urban installations are a network of installations aimed at scaling down the Sabarmati River Resiliency Park. Each of the installations, arranged at strategic location shall be programmed to serve specific purposes. A series of pathways, trails shall tie all the installations together.

The installation’s design starts with a cube of 9m x9m x9m volume of a space. The design of the installations themselves is imagined to be highly porous in nature and very simplistic it its expression and form.

Mimic almost like the frameworks of larger, simpler shapes such as cubes and spheres, the installations can be allowed to be taken over by humans and nature alike.

Public conveniences like dedicated washrooms, baby stations, police chowkeys, restrooms, observation towers, way finders, kiosks, shops, interpretation centers, bike and cycle stations form the basis of their programs

Fig 06.4. The simple form of the installations derived from the pure shapes posses a range of possibilities, both in their expressions and programming potentials. Urban Installations - Possibilities|

Much of Sabarmati River Resiliency Park is imagined as an floodable bank, an extent to the river itself. The design is painstakingly made to resemble a natural shrub land.

Series of park trails, board walks and trails tie the strategic points of the park together, with installations dotted amidst them. Much of the design is intended to glide or hover of the natural lay of the riparian edge.

primary function is flood mitigation, achieved through a series of constructed wetlands and floodable landscapes.

While the park and its programs make the water edge now accessible, the program and its edge respond to changing seasons and water levels as well.

During events of heavy rains or flash floods, a solitary river wall protects the edge of the master plan from the floods. During peak monsoons or an unlikely event of a 50 year flood, the parks edge would stand resilient as the city’s first line of defense.

The ReWilding Koba master plan represents a bold and transformative vision for the future of urban design—one that redefines the relationship between cities and nature. At its core lies the principle of creating “a city within a park,” a reversal of conventional urban paradigms that often marginalize green spaces. This nature-centric approach not only addresses contemporary urban challenges like climate resilience, ecological degradation, and social inequity but also sets a benchmark for sustainable and inclusive urban development.

From its foundational systems approach to its detailed block designs and phasing strategies, the master plan reflects a holistic and future-ready framework for urban growth. By weaving together mobility, community, landscape, and resilience systems, the master plan ensures that the city functions as an interconnected whole, where each layer supports the others. The Sabarmati River Resiliency Park, Koba Central Urban Park, and network of neighborhood parks exemplify how green infrastructure is integrated at every scale to enhance livability, ecological health, and urban resilience. These open spaces are not just passive amenities but active participants in the city’s hydrology, biodiversity, and social life.

The diversity of urban blocks—transit-oriented, residential, and high-street/commercial—further emphasizes the master plan’s commitment to creating multifunctional and adaptable urban spaces. Transit blocks anchor the city with hubs of connectivity and economic activity, residential blocks provide vibrant and nature-integrated living environments, and high-street/commercial blocks foster economic vitality and social interaction. Together, these block typologies create a dynamic urban fabric that balances density and accessibility with ecological integrity.

The phasing and implementation strategies underscore the master plan’s practicality, ensuring that its ambitious vision is realized through systematic and manageable steps. The phased development approach focuses on prioritizing infrastructure, public spaces, and community services early in the process, enabling the city to grow organically and sustainably. By aligning shortterm actions with long-term goals, the phasing plan ensures that the master plan remains adaptable to future needs while staying true to its overarching vision.

The ReWilding Koba master plan represents a bold and transformative vision for the future of urban design—one that redefines the relationship between cities and nature. At its core lies the principle of creating “a city within a park,” a reversal of conventional urban paradigms that often marginalize green spaces. This na Reflecting on the journey of designing ReWilding Koba, it becomes clear that this master plan is not just a response to urbanization but a re-imagining of what cities can aspire to be. It challenges the conventional dichotomy of urban and natural, proposing instead a harmonious coexistence where nature is not relegated to the fringes but embedded within the city’s core. It envisions a city that is resilient to climate change, equitable in access to resources, and vibrant in its cultural and social life.

As the project transitions from vision to realisation of a masterplan, the ReWilding Koba master plan serves as a blueprint for how future cities can be designed in the face of global challenges. Its principles—integrating ecological systems, prioritizing unbuilt spaces, and creating inclusive urban environments—offer a model for urban design that transcends its immediate context. It is a city that breathes with nature, adapts with resilience, and thrives with its people, setting a new standard for sustainable and innovative urban development.

In the broader context of urban design and planning, ReWilding Koba exemplifies the possibilities that emerge when cities are designed with the environment as a partner, not an afterthought. It is but an humble attempt to leaves behind a legacy of hope and innovation, challenging cities, her makers and the citizens to rethink the potential of our built environments and to aspire to cities that nurture both humanity and the planet.

As this journey concludes, one hopes that the realization of Koba can be so much more than we see around us today. As a living, breathing testament to the promise of our ‘ReWild-ed’ urban futures.

• Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960.

• Gehl, Jan. Cities for People. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2010.

• Olmsted, Frederick Law. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: The Formative Years. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

• Alexander, Christopher, et al. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1977.

• Copenhagen City Council. Copenhagen Climate Plan 2025: A Green City. Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020.

• Curitiba Urban Planning Agency (IPPUC). Integrated Transport and Green Space Development Report. Curitiba, Brazil, 2018

• Urban Land Institute. Principles for Creating Vibrant Open Spaces in Cities. Washington, DC: ULI, 2015.

Indian Green Building Council (IGBC). Guidelines for Green Infrastructure in Urban Areas. Hyderabad, India, 2020.

• IPCC. Climate Change and Cities: The Role of Urban Areas in Climate Adaptation. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC, 2021.

Mendelsohn, Robert. Designing Landscapes for Climate Resilience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard GSD, 2019.

• World Economic Forum. “The Future of Cities: Reconnecting Urban Life with Nature.” Accessed October 2024.

• UN Habitat. “Urban Resilience Principles for Sustainable Cities.” Accessed October 2024.

Fig 01.A. The systems approach leverages strong site anchors in an attempt to realize spatial strategies as a base for a resilient master plan.

Fig 01.1. Satellite Map shows the site and its proximity with the twin cities of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar. The sites’ strategic location, along with the Sabarmati forms the major anchors for the master plan.

Source : Google Earth

Fig 01.1 - A montage of the sites’ transect showing two major anchors namely, the GMRC corridor, the Southern Drain.

Fig 01.2 - The GMRC corridor is the only major human intervention as of date, on the largely untouched greenfield site.

Fig 01.3 - Entrance to the Juna Koba Gamtal. The gamtal serves as the focal point around which the site’s identity can be woven.

Fig 01.4 - The Kumbeshmar Mahadev Temple. A 500 year old Hindu temple by the banks of the river Sabarmati.

Fig 01.5 View of the site (left bank) as taken from Nabhoi-Karai Sabarmati Bridge. GNLU, IAR seen in the distant background.

Source : Author, Primary Survey

Fig 02.1. Satellite Image showing the site’s context in the 3km radius. Larger site level anchors include the GIFT City, Indroda Park

Source : Google Earth

Fig 02.2. The development plans of AUDA and GUDA demonstrate a stark dichotomy and conflicting zoning. The jurisdictional bounds of both the authorities pass right through the center of the site. This creates an opportunity to aptly shape the pressures of urbanization.

Source : AUDA, GUDA

Fig 02.3. Despite being in close proximity to Sabarmati river, there is a dearth of larger ecologically sensitive zones, reiterating the urgent need for ecological interventions.

Source : Author, Primary Survey

Fig 02.4. The site falls between two larger regional level watershed zones (yellow) creating multiple smaller seasonal run offs along the site. By leveraging this and directing these stray run offs into a system of flood mitigation strategies, site’s resiliency can be strengthened.

Source : Author, Primary Survey

Fig 03.1. “The Terrace.”, Colored Lithograph, Major and Knapp Engraving, Manufacturing, and Lithographic Company (1869) Source : The Library of Congress Collections Website (2022)

Fig 03.2. Satellite map of the site depicts the current fabric around the site. Highlighted in white is the extent of the invasive prosopis and catchments of watersheds and 200m buffer along the Southern Drain. (Source : GoogleEarth)

Saurav Ashish Chatterjee

Masters in Urban Design

Faculty of Planning

CEPT University