Handmade Cities

A Toolkit Approach to Urban Village Transformation

Development Proposal Report | Saurav Ashish Chatterjee

Masters in Urban Design | CEPT University

About the studio

The studio has focused on the design aspects of urban transformations within the existing urban areas. The underlying context is that Indian cities are growing rapidly in terms of population and therefore expanding physically. Many urban areas within these cities are dealing with unsustainable levels of stress on infrastructure, resources and public services and are becoming increasingly unliveable. As an attempt to address these concerns, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoUHA) has initiated various schemes that enable planning for developing infrastructure in the brown-field areas through mechanisms such as Local Area Plans (LAP).

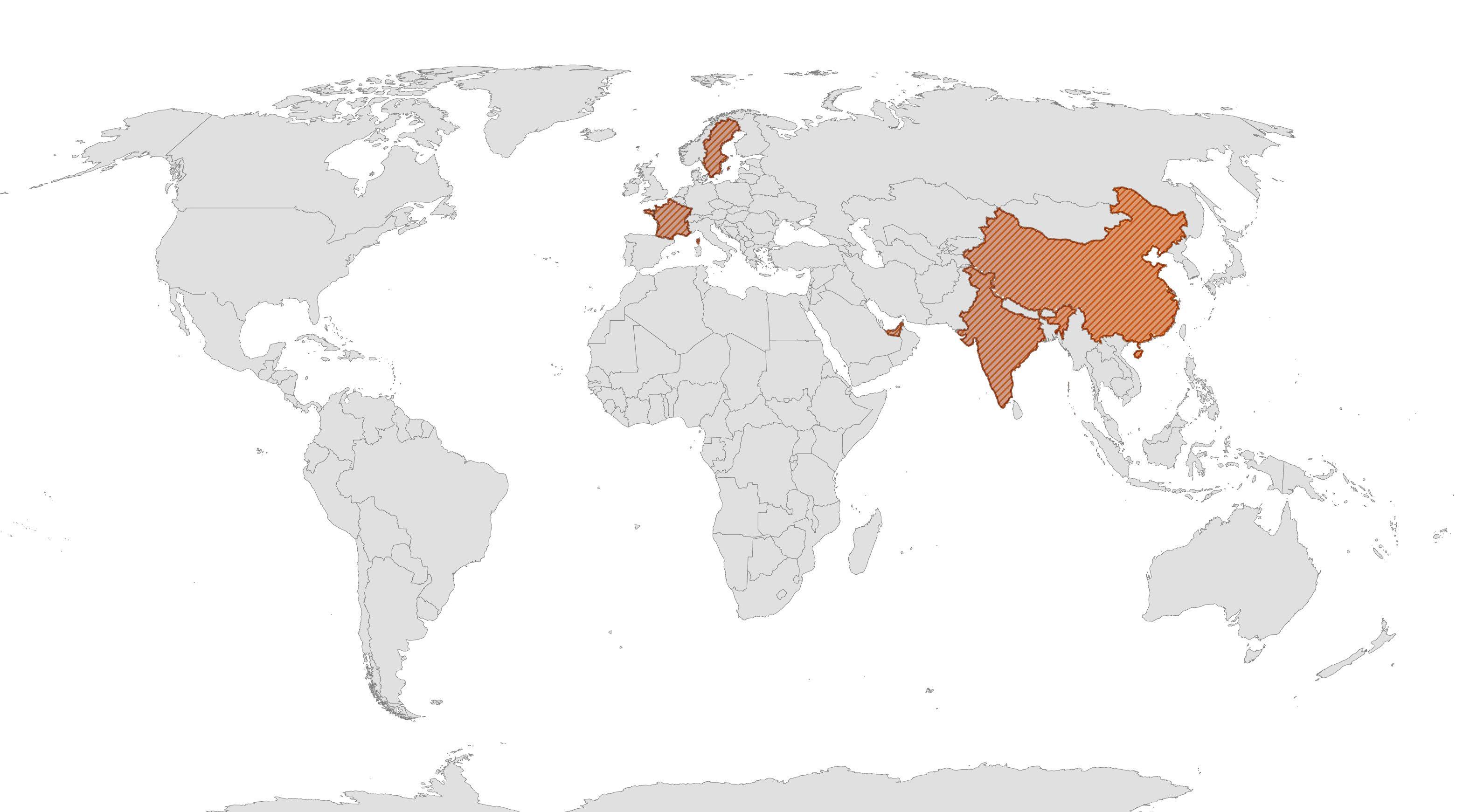

For the purpose of the studio, Urban villages in India are explored as a type. While their role in the cities as havens for new entrants is often glorified, the indifference to include them meaningfully in the planning process is conveniently ignored. In contrast to the proactive approaches around the world towards upliftment of the quality of life & redefining the roles of urban villages, Indian cities have either relocated or cordoned them.

Against the background, the studio examined the position of urban villages in cities today and their possible future roles.

Academic Note

This report is submitted in partial fulfillment of the academic requirements for the award of the Master of Urban Design degree at the Faculty of Planning, CEPT University, Ahmedabad.

The work presented herein is the result of an independent academic inquiry carried out by the author as part of the final semester studio and thesis module. The report explores the transformation of urban villages — specifically Bopal and Ghuma — and critically engages with the regulatory framework governing these settlements, particularly with the General Development Control Regulations (GDCR) as applied in Gujarat.

Through this lens, the report questions the adequacy of existing codes and proposes alternative regulatory approaches aimed at guiding more inclusive, resilient, and context-sensitive urban transformations.

The work is intended as a contribution to the ongoing discourse around Indian urbanism, regulation, and the evolving role of urban designers in shaping emerging city forms.

Abbreviations

AUDA

- Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority

- Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation

- Floor Space Index

- Gujarat Metro Rail Corporation

- General Development Control Regulations

- Local Area Plans

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs

- Special Purpose Vehicle

TPS

- Town Planning Scheme

- Transferable Development Rights

- Transit Oriented Development

ULB

- Urban Local Body

UDPFI

- Urban Development Plans Formulation and Implementation (Guidelines)

Semester 04 | Spring 2025

Tutors : Umesh Shurpalli

Program Chair : Purvi Bhatt

Teaching Assistant : Shivani Singh

Masters in Urban Design Faculty of Planning CEPT University

Executive Summary

Introduction

Background

Premise, Problems and Possibilities

Approach and Structure

Understanding Urban Villages

Defining Urban Villages in India and Ahmedabad

The Role of Villages in Urban Expansion

Literature Review and Theoretical Frameworks

Regulatory Frameworks, Critiques

How the current GDCR shapes these urban villages

Between Regulation and Reality - Conflicts and Contradictions

A Flexible Future - Proposed Strategic Alterations

Precedents and Comparative Models

Overview of selected cases

Analysis and Learnings

Synthesizing an approach

Ideation

Problem to Possibility Vision and Ideation : A Toolkit Approach

Timeline and Phases of Transformation

Existing Site and Anchors

Site Studies

Morphological Matrix Framework Plan

Toolkit in Action

Site Selection Criteria and Rationale Pilot Sites and Design Demonstrations

Phasing, Implementation and Stakeholder Evolution Reflections Bibliography

Understanding Urban Villages

Urban villages represent one of the most paradoxical and persistent conditions in Indian urbanism. Neither wholly rural nor formally urban, they exist as spaces of both resistance and adaptation—absorbed into expanding cities but rarely integrated on their own terms. Often overlooked in master plans and policy frameworks, these settlements challenge the binary of planned versus unplanned, formal versus informal. They are products of their histories, yet deeply entangled with the ambitions and failures of contemporary urban expansion.

In cities like Ahmedabad, urban villages have become the fault lines of growth—sites where the inherited logics of agrarian life intersect with speculative development, fragmented governance, and inadequate regulation. Their compact morphologies, active street life, mixed-use typologies, and intense land value pressures make them critical to understanding how Indian cities actually grow— not just on paper, but on the ground.

Defining Urban Villages

Urban villages in India are a product of fragmented planning, rapid urbanisation, and historical continuity. They are settlements that predate city expansion and become enveloped within the expanding urban footprint—often through planning mechanisms such as development plans and town planning schemes. However, while they are absorbed spatially, they remain administratively and regulatorily out of sync with the surrounding city.

Unlike slums or informal settlements that arise out of necessity or migration, urban villages are legal entities with ownership rights, deep community ties, and sociocultural continuity. Yet, their physical environment— narrow streets, organic plots, informal extensions, and high-density layouts—sits uneasily within the frameworks of modern urban planning.

“Means all land that has been included by the Government/ Collector within the site of village,town or city on or before the date of declaration of intention to make a TP Scheme or Draft DP-2021for Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India”

- Urban Villages as defined by General Development Control Regulations

Fig 02.1. Labour addas function as informal job markets, linking migrant workers with daily wage opportunities in the city

Fig 02.2. Informal street market spilling onto the road, reflecting adaptive use of public space in the absence of planned infrastructure.

They represent a form of embedded urbanism that functions despite being under served, under-regulated, and often misunderstood.

In the context of Ahmedabad, urban villages are the result of a unique interplay between the city’s robust Town Planning Scheme (TPS) mechanism and the limitations of development control regulations. As the city expands, it reconfigures agricultural land into serviced urban plots, yet the original village cores—known as Gamtals—remain untouched. These Gamtals often become dense pockets surrounded by newly urbanised areas, creating a stark contrast in morphology, services, and regulation. They are governed by a separate set of GDCR provisions, many of which are generic, outdated, or ill-equipped to guide meaningful transformation.

Ahmedabad’s urban villages thus become living case studies in how policy lags behind practice. They are spaces of intense transformation—where real estate speculation, population influx, and infrastructure stress converge—but without the tools or frameworks to guide this change meaningfully. The villages of Bopal and Ghuma, once peripheral agrarian settlements, now lie at the heart of this contradiction: fully urban in function, yet governed as anomalies in the planning imagination.

Understanding their definition is not just an academic exercise; it is the starting point for any design or regulatory intervention that seeks to be both just and grounded.

nos.

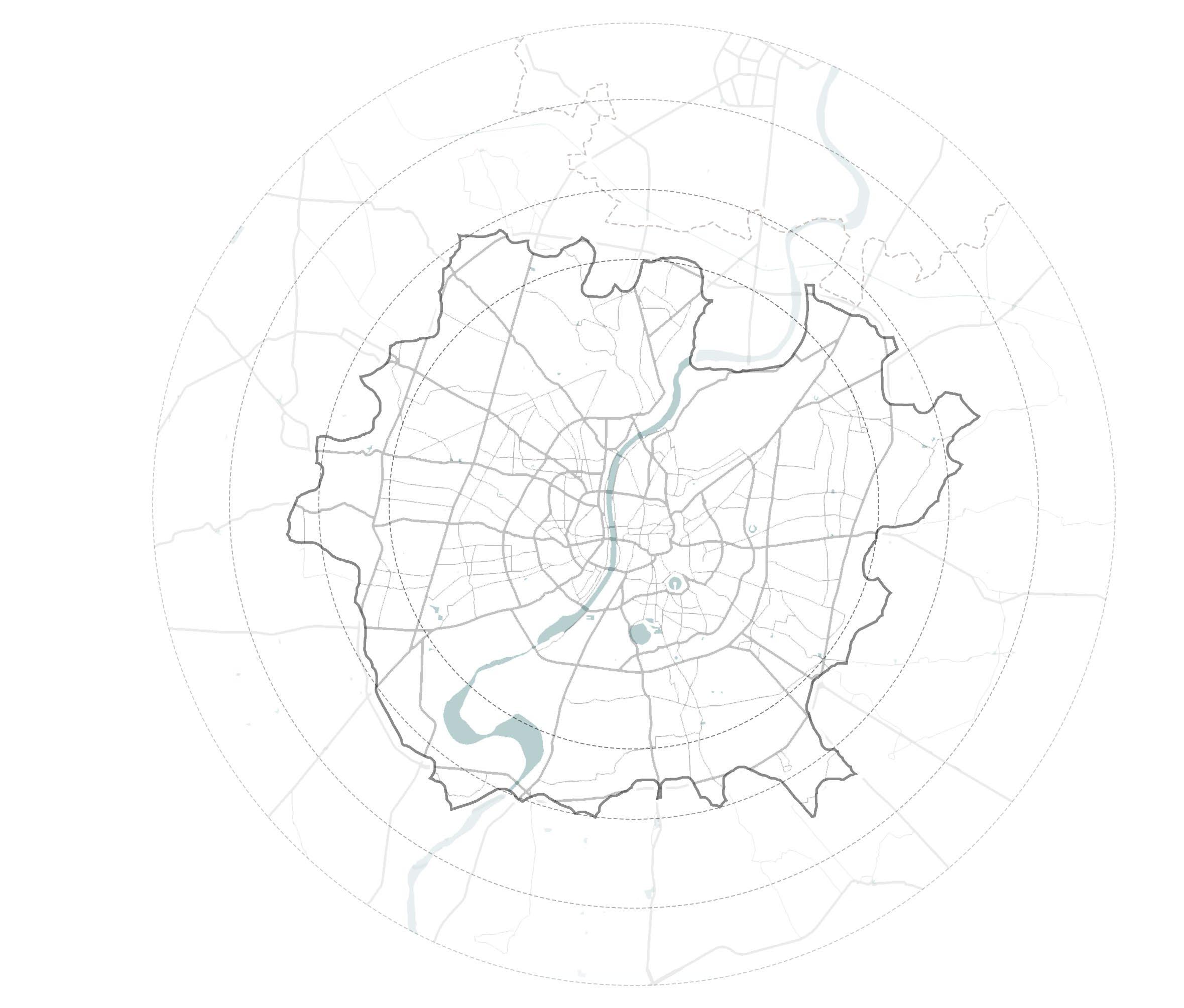

Urban Villages within AMC Boundary limits as of May 2024

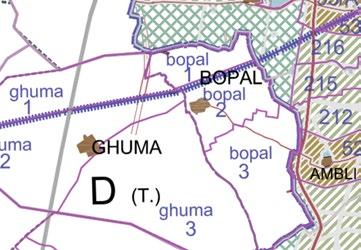

Fig 02.3. Distribution of Urban Villages across Ahmedabad. Historically situated around small lakes and water bodies, the urban villages are strategically distributed equally cross the Municipal limits, well connected to larger road networks and transit systems.

Sabarmati River

CEPT University University Area

Kochrab, Paldi Urban Villages

Bopal, Ghuma Urban Villages

Regulatory Frameworks & Critiques

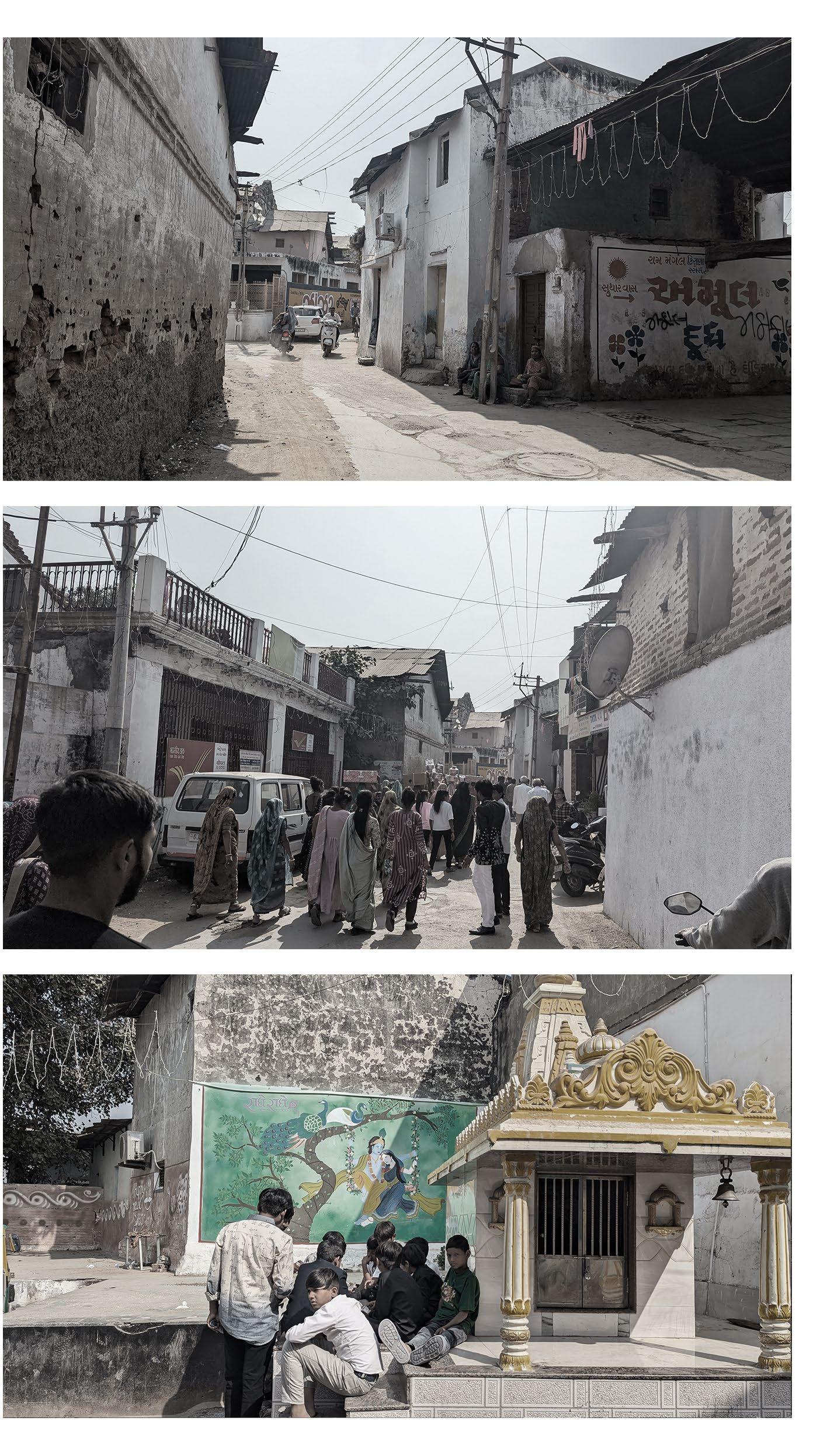

What awaits the migrants

Urban villages lie at the fault lines of India’s planning apparatus—spaces where inherited rurality collides with rapid urbanisation, and where the grammar of everyday life routinely outpaces formal systems of control. Bopal and Ghuma exemplify this condition: intensely built, socially dynamic, and economically vibrant, yet structurally precarious. In these villages, housing is often ad hoc, public infrastructure stretched thin, and the quality of life marked by both resilience and fragility. And yet, amid the chaos, one encounters indigenous, inventive, and deeply appropriate spatial appropriations— from extended otlas that host commerce and kinship to vertical accretions that challenge typological conventions.

These improvisations are not accidents of neglect, but responses to a misfit—a misfit between how people inhabit space and how planning prescribes it. At the centre of this misalignment lies the General Development Control Regulations (GDCR), which carry within them an urban logic calibrated for formal plots, engineered infrastructure, and predictable growth. Urban villages, by contrast, thrive in the realm of informality, with layered histories, non-linear development, and negotiated social contracts.

This chapter takes this friction as its starting point—not to reject regulation outright, but to question its assumptions. When everyday ingenuity clashes with codified rigidity, whose urbanism is legitimised, and whose is marginalised?

Fig 03.1. Precarious tarpaulin and ad-hoc addition shelters mark the migrant’s first foothold in the urban villages.

Fig 03.2. Appropriate appropriations reshape the urban edge as migrants adapt space to meet urgent needs with limited means.

When a settlement resists being “regularised,” what does it reveal about the frameworks that attempt to contain it?

By analysing the effects of the current GDCR on the spatial, social, and economic life of urban villages, this chapter foregrounds the urgent need to rethink regulation as a design tool. It maps the contradictions between policy and practice, highlights the ways in which residents adapt, stretch, or subvert the rules, and ultimately proposes a set of strategic, context-sensitive alterations.

These interventions aim not to formalise informality, but to legitimise existing logics of inhabitation, positioning the code as a living instrument—capable of evolving alongside the city it seeks to govern.

How the Current GDCR Shapes These Urban Villages

The General Development Control Regulations (GDCR) function as a city’s spatial constitution—laying down uniform rules to guide building form, land use, access, and infrastructure provision. However, when applied to urban villages—settlements that precede planning boundaries and evolve outside formal frameworks—the GDCR acts less as a facilitator and more as a rigid imposition. It begins to reshape the village not through sensitive integration, but through compliance-driven transformation that often undermines the very qualities that make these spaces affordable, adaptable, and socially cohesive.

Urban villages—originally agricultural settlements or periurban clusters—undergo dramatic shifts as they are absorbed into the urban fabric. Their land is reclassified, their plot structures regularised, and their activities subjected to urban codes. Yet, the application of GDCR to these dense, fine-grained morphologies often yields spatial conflict. Regulations that assume grid-based planning, wide rightsof-way, and standardised plot depths rarely translate into the intricate patchwork of narrow lanes, courtyard houses, and incremental additions found in urban villages.

In practice, the GDCR begins to shape these areas not by enhancing them but by disabling the very systems they rely on. Rules designed for access and infrastructure—such as fixed road widths or mandatory setbacks—cannot accommodate pre-existing fabric without erasure. As a result, planning interventions are

either enforced through coercive redevelopment or neglected altogether, leading to a regulatory limbo. In many cases, the village becomes a ‘black hole’ on the city’s planning map: visibly urban but legally misaligned.

Moreover, building use norms intended for zoned districts restrict the hybrid and multi-functional life of the village. By enforcing separations between commercial and residential use, or mandating formalities in tenancy, the regulations disrupt the local economies of survival that many urban villagers depend on. The informal rental unit, the shopfront extension, the shared courtyard—all fall outside permissible definitions, despite their essential social and economic role.

Fig 03.3. A dense street of poorly built homes reveals the ever persistent gap between urban growth and urban living.

The GDCR, then, is not a neutral framework—it actively reshapes the physical and socio-economic character of urban villages. It flattens heterogeneity, discourages incremental upgrading, and leaves little room for context-driven solutions. What emerges is

Minimum Area of a Building-unit

Minimum area of a Building-unit shall be 18sq.mts with no side less than 3.0 mts in width.

Intentioned for access, light, and sanitation, can disincentivize small plot, leads to underutilization.

neither a preserved village nor a well-integrated urban quarter, but a compromised hybrid—underserviced, under-legalised, and locked out of formal support.

In this tension between inherited form and imposed regulation lies the starting point of this project. The aim is not to reject the GDCR wholesale, but to reveal its misfit with the urban village context—and in doing so, imagine a regulatory framework that is more enabling, adaptive, and responsive to the specificities of these transitional spaces.

Permissible Building Use

For road widths less than 9 mt, permissible building uses are DW1,DW2,DW3 and M1,M2, restricted to ground floor only.

Set Backs

The Set back of 3.00 m from central line of existing street shall be provided where regular line of street is not prescribed.

The land left open as set back shall be deemed to be part of the street.

Creates asymmetrical streets. No incentive to return space to public realm.

Live Work Typology

Subject to other regulations, uses in a Building-unit shall be regulated according to the width of the road on which it abuts as shown in table no 6.4.

All permissible non-residential uses in residential zones of whatever category may be permitted on the ground floor or any other floor in a residential dwelling if provided with separate means of access/ staircase.

No guidelines to integrate live-work typologies specifically.

Between Regulation and Reality

Across India, as urban villages transition into dense, hybrid settlements within expanding city boundaries, they are subjected to planning regulations crafted for radically different spatial conditions. These villages— evolved through layered histories, social compacts, and economic improvisations—encounter a regulatory framework that neither acknowledges their complexity nor accommodates their inherent logic. The result is not regulatory alignment, but spatial contradiction.

Take, for instance, the GDCR provision that mandates a minimum area for a building unit. While framed around concerns of access, light, and sanitation, this regulation inadvertently penalises small landholders typical of urban villages. The requirement disincentivises development on smaller plots, often leading to vacant, underutilised spaces, or unauthorised incremental extensions. In practice, it stalls the organic densification that these villages are already undergoing—without offering viable alternatives.

Restricts commercial activities to the ground floor for roads less than 6m

Similarly, the permissible building use regulations restrict commercial activities to the ground floor and only on streets wider than 6 metres. While intended to preserve order and circulation, this fails to reflect the live-work reality of village streets, where homes double as kirana shops, workshops, or rental units. By excluding narrow lanes from commercial use, the code isolates a majority of internal street networks from economic vibrancy, directly impacting livelihoods that rely on proximity and footfall.

The absence of specific guidelines for live-work typologies compounds the issue. Villages are not zoned in the conventional sense; rather, they operate on the proximity of domestic and economic functions. But the GDCR’s binary lens—residential or commercial—does not allow for nuanced hybridisation. This results in either unregulated practices or forced conformity, both of which undermine the potential of these communities to evolve sustainably.

Other well-intentioned provisions—like blanket TDR (Transfer of Development Rights) mechanisms for road widening—create further distortions. On paper, they incentivise public improvements; in reality, they often deter landowners from upgrading or redeveloping properties on

narrow lanes due to the disproportionate setbacks and convoluted compensation processes. The transferability becomes an abstract right rather than a usable tool, especially in contexts lacking planning capacity or market uptake. Even the mandatory inclusion of chowks or internal open-to-sky spaces, intended to promote ventilation and light, is often implemented in a blanket, geometrically inflexible manner. The result is a proliferation of poorly proportioned, residual pockets—neither socially vibrant courtyards nor climatically effective voids. Such spaces end up reducing buildable area without meaningfully enhancing its spatial quality.

Together, these contradictions expose a systemic misalignment between codified urbanism and lived urbanity. The regulations seek to bring order, yet in doing so, erase indigenous logics that have allowed villages to remain adaptive, inclusive, and affordable. This isn’t simply a matter of outdated code—it’s a deeper issue of mismatched paradigms. The regulatory gaze must evolve from control to enablement, from universal imposition to contextual calibration, if these urban villages are to transition into equitable and resilient urban futures.

the maximum permissible Floor Space Index (FSI) shall be 2.0, with no provision for chargeable FSI. Capped at maximum of 2.0

Provide an open space or chowk open to sky from plinth level for every 9 meters depth of the building, of at least 5.6 Sq.Mts.

Well-intentioned for street improvement, it often discourages redevelopment or penalizes owners on narrow lanes.

Leads to small courts with poor light and ventilation

Floor Space Index (F.S.I)

Chowks in Gamtals

Rigid and blanket transferable development right provisions.

Fig 03.4 The layered application of GDCR regulations within Gamtals, revealing overlaps, gaps, and spatial constraints.

A Flexible Future – Proposed Strategic Alterations

Minimum Area of a Building-unit

7.1 For plots between 10–18 sq.m., allow 100% ground coverage + shared vertical circulation outside plot boundary.

Permissible Building Use

Allow small scale defined commercial activity where feasible.

- Residents agree on a unified edge line.

- Right to add a shopfront kiosk, otla, or signage.

In light of the systemic misalignments between the current GDCR and the lived realities of urban villages, this project proposes a shift from rigid, top-down regulation to a more responsive, context-specific approach. Rather than rejecting the GDCR entirely, the intent is to strategically recalibrate its provisions—to reinterpret its spirit through a lens that prioritises adaptability, equity, and spatial relevance. These proposed alterations are not sweeping reforms, but targeted, implementable changes that collectively allow the code to respond more precisely to the form and function of urban villages.

One of the foundational changes lies in redefining the Minimum Building Unit provisions. Currently designed to guarantee light, ventilation, and infrastructure access, these rules inadvertently discourage smaller plots or those situated on narrow lanes—conditions typical of village morphology. By allowing for flexible minimum unit sizes within designated urban village zones, and tying

Live-work use permitted on plots up to 100 sq.m., with a maximum of 50% built-up area for small-scale commercial activity.

Shared terraces permitted and excluded from FSI if used for water harvesting, solar access, or communal functions.

them to performance metrics like daylight access or built-to-plot ratios, the code can accommodate organic plot divisions without compromising livability standards.

A similar recalibration is required for Permissible Building Use. In villages, economic life rarely conforms to monofunctional zoning. A household might include a tailoring shop on the first floor, a rental room above, and a shared courtyard for storage. Blanket restrictions on commercial activity above the ground floor—particularly on roads less than 6 metres—are thus unworkable and counterproductive.

Tweak - New Typology

Tweak - Allow Commerce

Tweak - Frontage Rights as Incentive

The land left as setback shall be integrated into the street as shared public space and can be designed as otla.

Controlled vertical mixed use until below 12 m street widths

The project proposes use-based permissions that are lanewidth agnostic, and instead rely on typological thresholds, such as user intensity, noise impact, or fire safety compliance, to guide commercial allowances across floors.

Floor Space Index (F.S.I)

Tweak - Strategic FSI Options

Chowks in Gamtals

Tweak - Common court entitlement Provide more flexible FSI options for a more controlled yet strategic densification

Three or more plots, share a courtyard, grant FSI bonus for plots facing it.

Courtyard must be 36. sqm, all three to have access.

The project proposes use-based permissions that are lanewidth agnostic, and instead rely on typological thresholds, such as user intensity, noise impact, or fire safety compliance, to guide commercial allowances across floors.

The absence of any guidelines for live-work typologies further limits the village’s potential to retain its socio-

The absence of any guidelines for live-work typologies further limits the village’s potential to retain its socioeconomic vibrancy while upgrading its built environment. The proposed regulatory changes incorporate integrated typologies—units that combine residential, commercial, and semi-public functions—with specific design standards for access, ventilation, and safety. This not only legitimises

Fig 03.5 Strategic tweaks to GDCR regulations reimagine flexibility and spatial equity within the fabric of urban villages.

Precedents and Comparative Models

Learning from Elsewhere

Urban transformation—especially in the contested spaces of urban villages—cannot be approached through a single ideological lens or predefined regulatory solution. To critique existing frameworks and to build a more responsive one, it becomes imperative to look outward before we look within. This chapter explores a diverse set of housing typologies, community-led regenerations, and state-supported redevelopment projects across both Indian and international contexts, not with the intention of direct replication, but to extract guiding principles, missed opportunities, and successful negotiation mechanisms.

Unlike conventional precedent studies that merely catalogue typologies, this inquiry is diagnostic in nature. It seeks to uncover how regulations were shaped or challenged by context, how participation was structured, and how spatial resilience was embedded in design processes. These cases—ranging from incremental housing models and inner-city revitalisations to cooperative redevelopment and informal upgrading—allow us to examine how different urban systems accommodate informality, live-work overlaps, and evolving densities.

Some of these models are planned, others evolved; some state-led, others deeply rooted in community agency. The Futian Urban Village in Shenzhen demonstrates how negotiated densification and infrastructure retrofits can preserve social fabric while integrating urban economies. The bedas and vehras of Ludhiana offer indigenous livework housing archetypes that continue to defy formal planning’s rigidity. India’s PMAY-ARHC scheme (Affordable Rental Housing Complexes) reveals the potentials and pitfalls of addressing migrant housing at scale. Meanwhile, Cork City’s foyer housing model presents a dignified response to youth and transitional housing, embedded within urban cores. These cases offer not a singular solution, but multiple fragments of insight—each illuminating what flexible, inclusive, and context-sensitive transformation could look like.

This chapter is structured in three parts. First, a curated overview of selected cases offers a snapshot of the typological and policy landscape across contexts. Second, a comparative analysis unpacks the key learnings—how these projects succeeded or failed, and what they reveal about governance, design, and community. Finally, the chapter synthesises these insights into an adaptable approach—one that does not prescribe, but equips. This synthesis directly informs the toolkit and the strategic alterations proposed to Ahmedabad’s regulatory framework. In understanding what works elsewhere, we sharpen our ability to critique what doesn’t work here—and begin to imagine a regulatory future shaped not by one model, but by many learnings.

Fig 04.1. Formalized under PMAY, the housing block reflects the state’s vision of affordability—uniform, efficient, yet detached.

source : Getty Images, Adobe Stock

Fig 04.2. Futian, once rural, now stands as a example of rapid urbanization, blending high-density development with complex urban fabric

Overview of Selected Cases

To critically assess the shortcomings in current regulatory thinking and to seek alternative directions, this chapter examines a diverse set of precedents. These include both local and international models of urban regeneration, affordable housing, and informal settlement upgrading. While not all are direct parallels to the Indian urban village context, each offers strategic insights into morphological adaptability, policy innovation, and community-led transformation.

The Affordable Rental Housing Complexes (ARHC) under India’s PMAY scheme were launched to address the precarious housing conditions of circular migrants by converting vacant housing stock into affordable rental units. While conceptually progressive, the scheme often falls short in implementation due to lack of spatial integration with employment, mobility, and community networks. Yet, its shift from ownership to rental models represents a crucial step towards rethinking housing for the transitional urban citizen.

The Vehras of Ludhiana, a traditional Punjabi courtyardbased typology, reflect an informal but highly adaptive live-work arrangement. With multiple families cohabiting within tight-knit compounds, vehras support density,

base source : Open Street Maps, Flourish

Vehras Ludhiana, India

ARHC-PMAY-U Ahmedabad, India

Futian Urban Village Futian District, Schezhen, China

Crown Street Regeneration Project Glasgow, Scotland UK

Poundbury Urban Extension Dorset, England UK

Cork City Foyer Housing Model France and the United Kingdom

Affordable Rental Housing Scheme (ARHC)

Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

Futian Urban Village Development

Futian District, Schezhen, China

Informal Rental Housing (Bedas ,Vehras

)

Ludhiana, Punjab, India

Cork City Foyer Housing Model

Parts of France and United Kingdom

Crown Street Regeneration Project

Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom

Features :

Address the housing needs of urban migrants and the poor, the Indian government launched the ARHC scheme under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana - Urban (PMAY-U)

Converting existing government-funded vacant housing into affordable rental units and encourages PPPs to develop new rental housing complexes by offering tax benefits and approval processe

Repurposing unused government buildings maximizes resource efficiency.

Features :

Implemented a comprehensive redevelopment plan focusing on upgrading infrastructure and housing while preserving community network

Public-Private Partnerships: Collaboration between government entities and private developers facilitated resource pooling and expertise sharing.

Resident Compensation: Original inhabitants received fair compensation or rehousing options, ensuring minimal displacement.

Features :

Informal rental housing units known as “vehras,” which are low-cost accommodations.

Affordable Rent: Vehras offer economical housing options, making them accessible to low-income migrants.

Proximity to Workplaces: Strategically located near industrial areas, reducing commute times and expenses.

Community Living: Creates a sense of community among enhancing social support networks

Features :

Designed to accommodate young workers migrating from rural areas to urban centers, later adopted to address homelessness and unemployment

Affordable housing combined with access to education, vocational training, and employment opportunities, facilitating a holistic approach to independent living

Relies on collaborations between government agencies, non-profit organizations, and private sector stakeholders

Features :

Designed to accommodate young workers migrating from rural areas to urban centers, later adopted to address homelessness and unemployment

Affordable housing combined with access to education, vocational training, and employment opportunities, facilitating a holistic approach to independent living

Relies on collaborations between government agencies, non-profit organizations, and private sector stakeholders

Limitations

Lacks adaptation for informal workers’ preferences.

Limitations

Top-down approach.

Resistance from original inhabitants. Loss of culture

Limitations

Not formal developers but operate in the informal market.

Poor Sanitation, health and tenure security

Limitations

High operational costs, low availability and higher demand.

Temporary stay model.

Limitations

Limited Public Transport Integration, Lack of social cohesion and displacement.

Lack of economic diversity – no commerce.

source : Getty Images, Adobe Stock

shared infrastructure, and economic interdependence. They reveal how informal urban morphologies can enable affordability and resilience, challenging formal regulations that often disregard such spatial logics.

The transformation of Futian Urban Village in Shenzhen, China, stands out as a rare example of state-enabled upgrading without large-scale displacement. Rather than demolish and rebuild, Futian underwent selective retrofitting—adding infrastructure, enhancing mobility, and formalising public services—while preserving its highdensity grain and social networks. The case offers a model for integration and negotiated change, especially relevant to India’s urban villages situated in high-growth zones.

The Cork City Foyer Housing Model in Ireland offers transitional housing combined with social support services, targeting young adults at risk of homelessness. It illustrates how design and governance can be aligned to deliver care-oriented housing that bridges vulnerability and self-reliance. Its emphasis on shared spaces, mentorship, and skill-building offers valuable lessons for addressing marginality in peri-urban areas.

Lastly, Crown Street’s urban regeneration in Glasgow demonstrates how fragmented and stigmatised urban environments can be transformed through incremental, participatory planning. Prioritising street continuity, mixeduse blocks, and neighbourhood-scale public spaces, the project avoided large-scale clearance and instead reinstated a livable urban fabric. It exemplifies the long-term value of rooted regeneration over abstract redevelopment.

Together, these precedents collectively inform the project’s design, regulatory, and spatial strategies—demonstrating that a balance between community agency, state support, and morphological sensitivity is not only possible but necessary.

Fig 04.3. In a quest to find the most effective model, each case is weighed against parameters of viability, policy support, community engagement, cultural fit, infrastructure, and tenure security.

Synthesizing an Approach

The analysis of these diverse models—ranging from the vehras of Ludhiana to Shenzhen’s Futian Urban Village and Cork City’s supported housing—underscores that successful transformation is neither purely regulatory nor purely architectural. It lies in the ability to embed flexibility, negotiate density, and structure support systems around human and spatial conditions that already exist.

This synthesis leads to a hybridised approach— not a masterplan, but a methodology. The aim is to develop a transferable, adaptable urban design and regulatory toolkit that operates across morphological, policy, and community scales. Rather than prescribing a uniform vision, the approach frames urban villages

as active test beds for incremental innovation, where regulatory frameworks must be malleable enough to accommodate hyper-local responses, and robust enough to ensure equity and resilience.

From Futian, we borrow the idea of internal upgrading through communal negotiation, layered with state facilitation. From the vehras, we learn to recognise latent housing models that operate efficiently without fitting formal definitions. From ARHC and Cork, we integrate socio-economic programming and alternative tenures, acknowledging the shifting nature of urban dwelling and livelihood. Crown Street shows us the importance of public realm quality and phased growth without displacement.

What binds these approaches is not aesthetics or scale, but a set of principles: enable existing communities to stay and thrive; support density without displacement; bridge formal and informal mechanisms; and design with social infrastructure, not in isolation from it.

These learnings coalesce into the project’s proposed toolkit—a catalogue of spatial interventions, regulatory adaptations, and participatory frameworks. It is not a fixed code but a strategic instrument to guide future transformation across other urban villages. It includes tools such as revised unit size norms, flexible light and ventilation provisions, updated TDR strategies, and site-specific typologies for streets, thresholds, and edge conditions.

In reframing planning from a rulebook to an enabling device, this approach aspires to realign governance with ground realities—to not merely regulate urban villages but to co-create them as equitable, embedded, and evolving parts of the city.

Fig 04.5 Evaluating diverse urban models through a multicriteria matrix to identify patterns of success.

Ideation

Problem to Possibility

The accumulated weight of policies, precedents, and lived realities reveals a peculiar tension in our urban villages: they are sites of both friction and possibility. What appears as dysfunction on paper often sustains everyday life on the ground. Narrow lanes become social corridors. Encroachments double up as economic frontiers. Improvised building forms respond more directly to need than regulation ever has. Yet, these responses are neither recognised by planning tools nor supported by regulatory instruments.

This chapter departs from the idea of villages as “problem zones” and begins to reframe them as latent systems of urban intelligence. Not perfect, but deeply instructive. Their embedded knowledge—of space, community, survival, and entrepreneurship—offers cues for a different kind of urbanism. One that does not arrive with a blueprint, but evolves through scaffolding what already exists.

The ideation, then, is not about correcting the village, but conversing with it.

It begins with re-seeing existing gaps as opportunities for design and governance overlap. The street, for instance, is no longer just a service corridor but becomes an interface of livelihood, mobility, and social infrastructure. Density is not the enemy, but a resource to be optimised with better light, access, and clustering. The housing unit is no longer a fixed prescription, but a flexible frame that can adapt to incremental growth and multi-generational living.

Here, the toolkit emerges—not as a finite set of solutions, but as a dynamic grammar of interventions. It negotiates between regulation and reality, proposing spatial strategies that align with morphologies of the village and the aspirations of its residents. These ideas are not abstract. They have been tested against precedent, policy, and on-ground conditions.

In doing so, this chapter tries to bridge the invisible gap between the informal and the formal—not by erasing difference, but by learning from it. The ideation that follows is less about reimagining the village from above, and more about unlocking what the village already knows, with tools that speak its language.

Vision

This project envisions a future where Gamtals—often viewed as urban remnants or transitional voids—are repositioned as resilient, vibrant, and evolving urban fabrics. Rather than erasing their embedded sociospatial logic, it proposes a framework that works with it: a structured yet flexible toolkit guided by tweaked regulations that enable incremental, community-led transformation. The vision is to shift from top-down impositions to grounded, negotiated urbanism—one that acknowledges the complexities of ownership patterns, the informal economies, and the social fabrics of these villages. Through selective spatial interventions, policy refinements, and a typology-based approach, the toolkit acts as both a design and governance instrument— bridging gaps between lived realities and regulatory frameworks. The aim is not wholesale redevelopment, but a guided evolution that retains the character of these places while unlocking their latent potential. Regulatory tweaks—such as revised unit sizes, adaptable chowk norms, and more nuanced TDR mechanisms—form the backbone of this vision, ensuring that transformation is not only spatially coherent but also socially inclusive and economically feasible. In doing so, the project positions Gamtals as future-ready neighbourhoods—capable of accommodating growth while preserving the dignity, agency, and aspirations of their communities.

a structured yet flexible toolkit to guide the transformation of urban villages —enabling incremental growth, dignified living, and empowered communities.

Incentive FSI

FSI/FAR as an instrument

Building Typologies

Rental Housing Retrofits

Retrofits / Extensions Pre-Approved Retrofit Catalogue

Shared Terraces

Shared Staircase Type 01

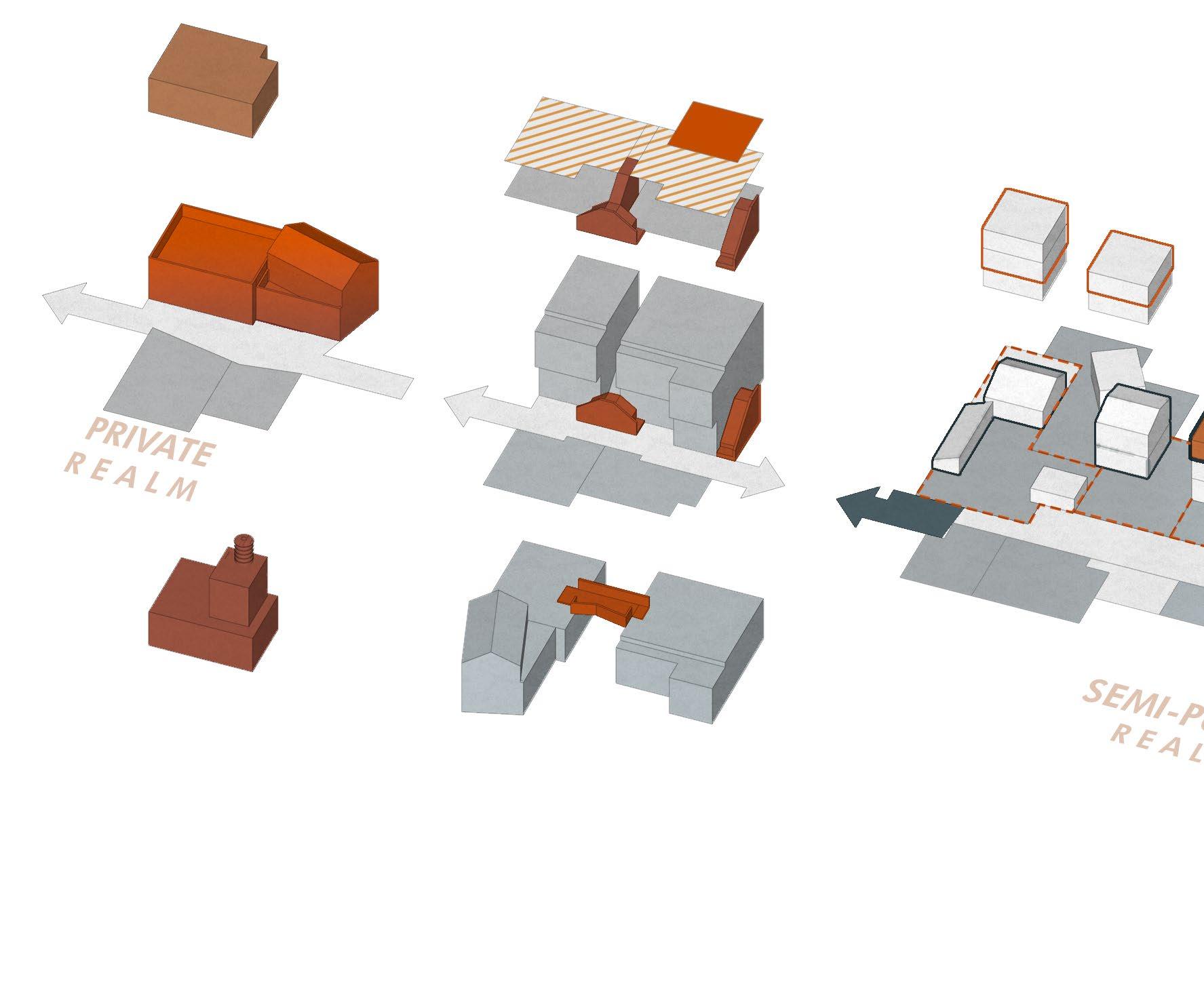

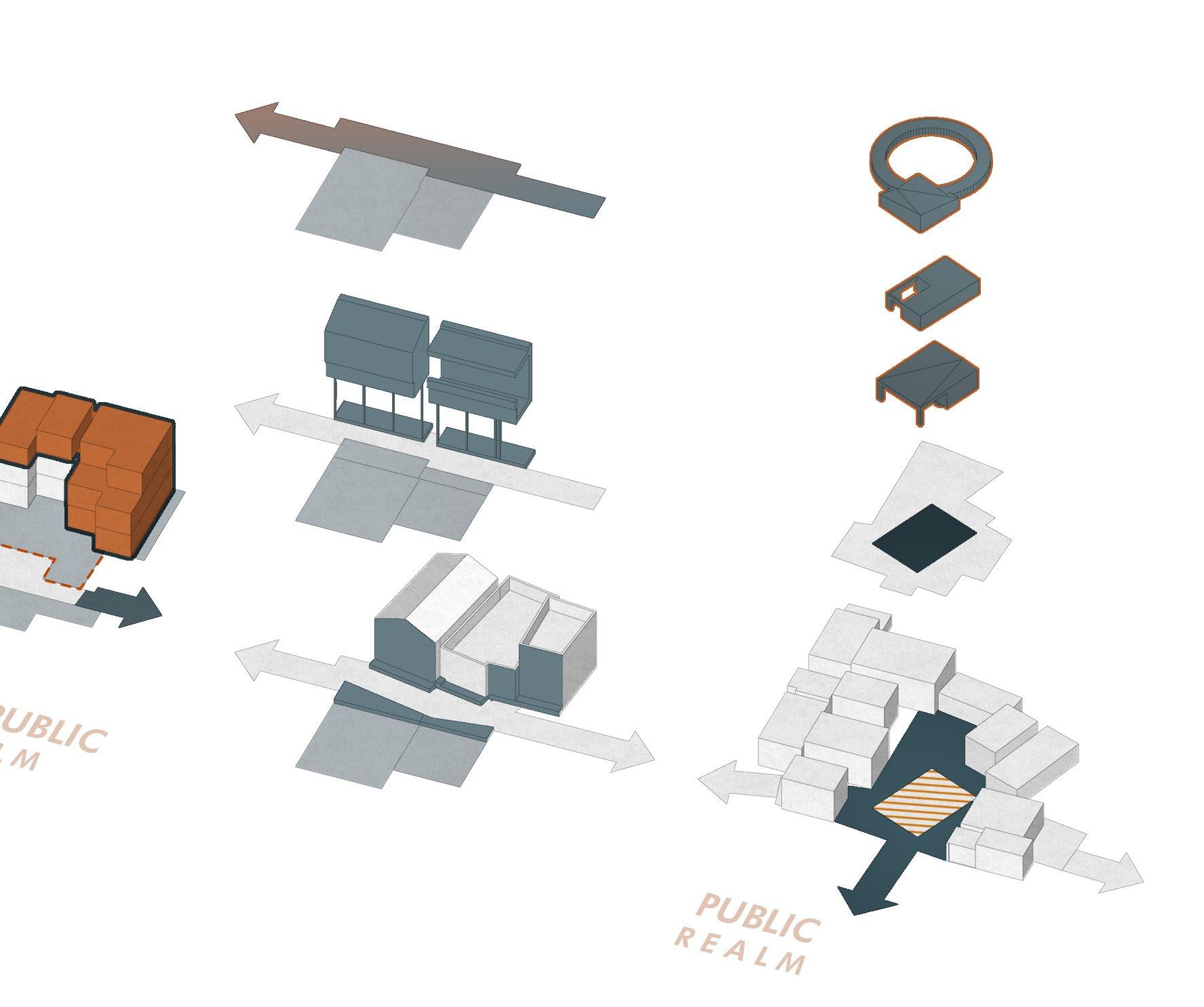

The proposed toolkit is designed to operate across three interdependent realms of intervention—Public, SemiPublic/Private, and Private. This tri-scalar structuring is not incidental but emerges from a close reading of the morphology, land ownership, and social organisation of Gamtals. By strategically working across these domains,

Incentive FSI

Bridge Type A Pre-Approved Retrofit Catalogue

Shared Staircase Type 02

Latent FSI

Underutlised Plots Within a Cluster

Interface / Easements Privately Owned Public Spaces

Fig 05.3 A hybrid model—where top-down regulatory intent is informed by bottom-up spatial and social realities.

This layered approach is the most logical and implementable way forward because it builds on existing conditions rather than erasing them. It allows multiple actors—government agencies, NGOs, local masons, and residents—to operate within their capacities. It does not rely solely on capital-intensive plans or top-down execution, but empowers grassroots transformation through a series of clear, replicable tools.

Street Categorisation

Slow Streets - Schools

Shared Strees - Markets

& Redistribution

Moreover, this strategy allows phased and contextsensitive implementation. Areas with active community participation can begin with public realm upgrades. Sites with tenure clarity can move into private realm modifications. By allowing partial and localised adoption, the toolkit becomes inherently more resilient, adaptable, and politically palatable.

Ultimately, this framework transforms the idea of a toolkit from being a static manual to a living system—capable of reading, responding to, and evolving with the unique challenges and opportunities of each urban village.

Common Courtyards

Community Governed and Operated

Shared Workspaces

Gamtal Follies Women Centres

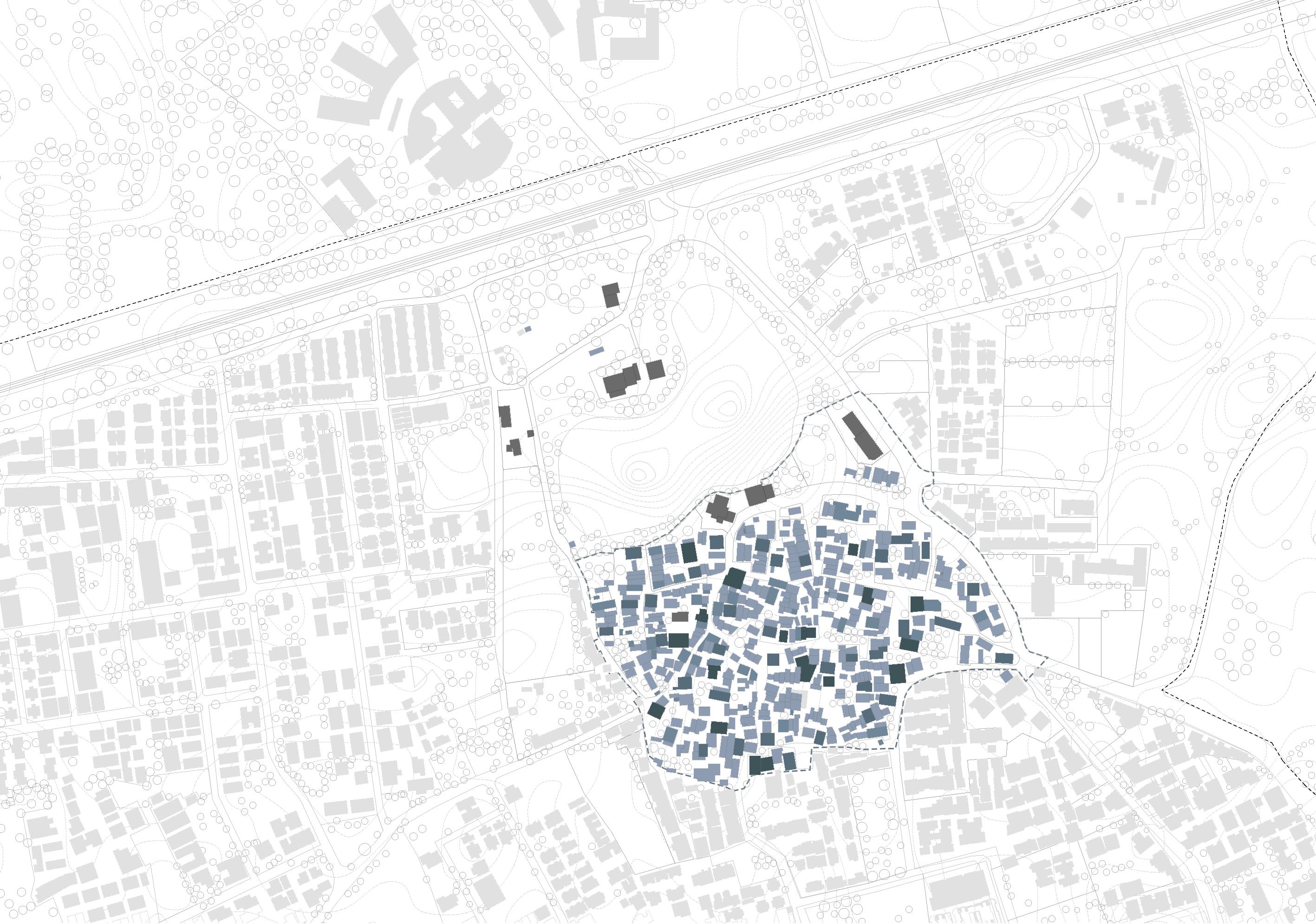

Introduction to Bopal Background

Bopal and Ghuma are two urban villages located on the southwestern edge of Ahmedabad, within the jurisdiction of the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC). Administratively, they fall under the South-West Zone and are part of Bopal Ward, one of the newer wards formed during the 2015 expansion of the AMC limits. Prior to this, both villages were governed by their respective Gram Panchayats and fell under the jurisdiction of the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA).

Strategically located along the BRTS corridor and in proximity to institutions like ISRO, Delhi Public School and a host of private educational campuses, Bopal and Ghuma have become major residential catchments. Yet, their inner morphologies—characterised by dense housing, narrow lanes, and informal mixed-use activities—remain poorly integrated into formal urban plans.

Brief History and Context

Originally agrarian settlements located on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, Bopal and Ghuma were once characterised by farmland, traditional homes, and close-knit village life. Their transformation began in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when Ahmedabad’s rapid westward expansion—fueled by infrastructure investments and institutional growth—triggered a wave of real estate development in and around these villages.

The establishment of educational institutions like the Anant National University nearby, followed by private townships and gated communities, marked the beginning of their urban transition. Yet, despite this growth, Bopal and Ghuma remained administratively rural until their inclusion within the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) and, eventually, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) in 2015.

Their inclusion within AMC marked a significant shift— from a rural governance structure to one governed by urban municipal laws and planning frameworks. This transition, however, has been uneven. While the area surrounding the villages has rapidly urbanised through AUDA-led Town Planning Schemes (TP Schemes), the inner village cores continue to operate with a degree of autonomy and informality, often at odds with the statutory planning instruments like the

General Development Control Regulations (GDCR). Over the past two decades, the area has seen an explosive rise in migrant population, apartment-led densification, and informal layouts driven by plot fragmentation. However, the original village cores—with their narrow lanes, informal housing, temples, and community spaces—still persist, resisting easy integration into formal planning systems.

Fig 06.1 - Most of the roads in the village are narrow, under serviced leading to poor quality of urban living.

Fig 06.2 - There exists a very close socio-cultural dynamic amongst the demographic of the village. Communal activities are an everyday part of life

Fig 06.3 - Many small religious structure dot the village. Due to lack of open spaces, most activities and life proliferate in and around these structure

Fig 06.4 - A montage of the Bopal Lake. Though its the only major site anchor, the lake edge is closed off, with a standard lake front development stamped

Source : Author, Primary Survey

Fig 06.1

Fig 06.2

Fig 06.3

Fig 06.4

Site Profile

Situated along the rapidly urbanising south-western edge of Ahmedabad, the urban villages of Bopal and Ghuma represent a condition where urban expansion collides with rural memory, and where the physical form outpaces institutional frameworks. Forming a part of Ahmedabad’s South West Zone, both villages were incorporated into the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation in 2015, yet still reflect deep-rooted characteristics of informal, self-organised settlement systems.

The spatial condition of the Gamtals is starkly distinct from their surroundings. Here, organic street networks contradict the rigid Town Planning grids that engulf them. Compact, self-built homes often spill into public spaces, otlas and the built form adapts continuously to respond to new social or economic needs. The result is a landscape that is deeply human-scaled but lacks infrastructural parity with its formal neighbours.

Demographically, these areas are home to long-time residents as well as waves of migrant workers, attracted by nearby industrial and service-sector employment.

Source : Author, Primary Survey

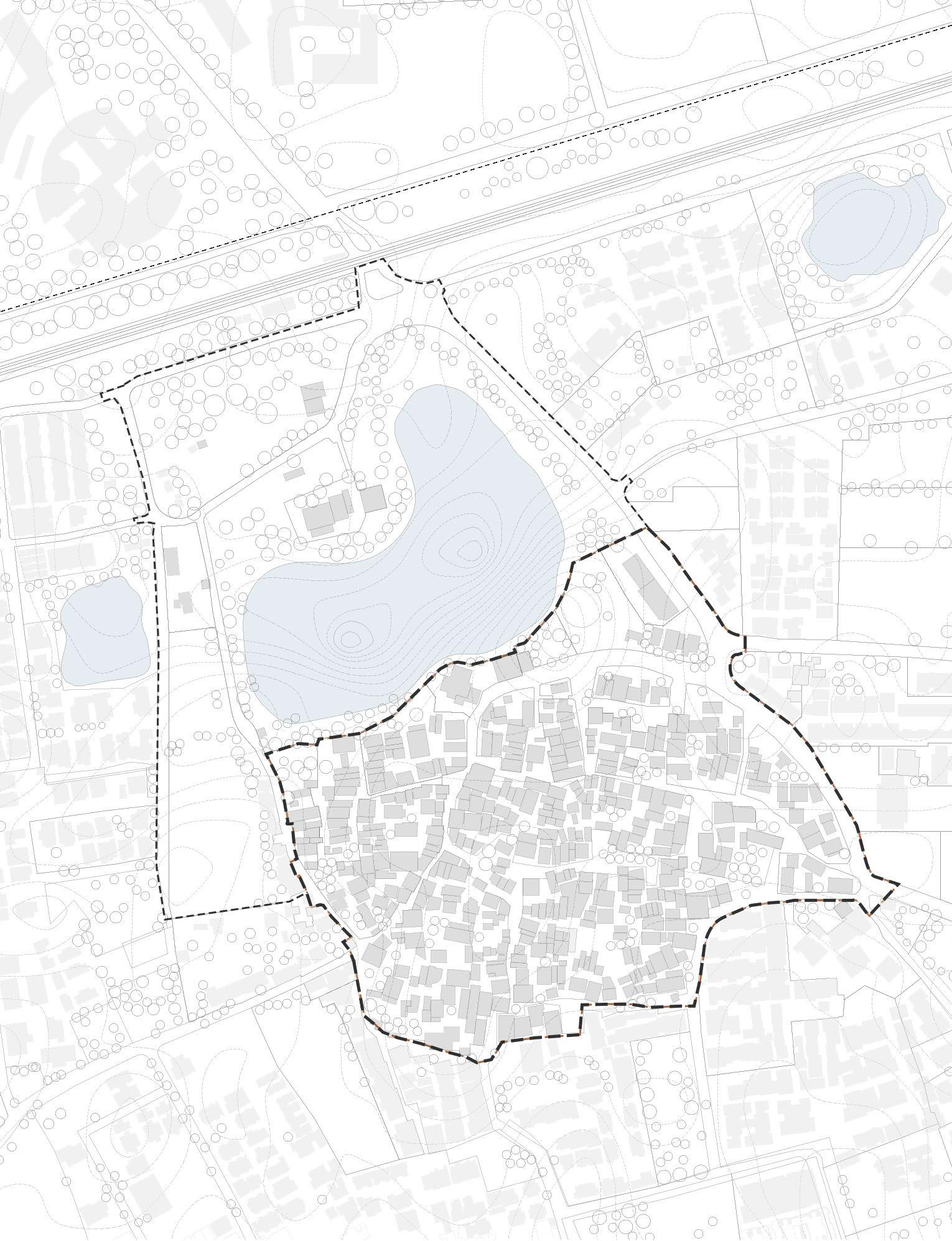

Larger Context

Satellite Map - Bopal Ghuma |

Fig 06.5 - Compact, self-built homes often spill into public spaces, otlas act as thresholds for both interaction and commerce

Fig 06.6 - Newer AUDA TP schemes contradict the organic, smaller compact, self built homes of the gamtals that engulf them.

Phases of Transformation and Brief Timeline

The transformation of Bopal and Ghuma’s Gamtals is shaped by a series of infrastructural and economic triggers that incrementally redefined their morphology. The first major shift began with the completion of the Gandhidham–Ahmedabad railway line in 1969, connecting the villages to broader regional networks and planting the seeds for future urban expansion. However, the real catalyst came in 1982 when Inductotherm set up a major industrial unit in Bopal, attracting employment and prompting widespread land conversions from agriculture to residential and industrial uses.

This industrial presence initiated unregulated peripheral growth, as land was rapidly subdivided and developed without formal planning mechanisms. By the 1990s, the rising land values and real estate speculation in western Ahmedabad further pressured these villages. With institutional zones and residential projects spreading along the SG Highway, Bopal and Ghuma became prime targets for development. However, AUDA’s Town Planning Schemes, designed for greenfield areas, were poorly equipped to handle the dense, irregular fabric of the Gamtals.

The approval of a new TP Scheme in 2008 and the application of the GDCR regulations failed to bridge this gap. Regulations framed for formal, large-plot urban development could not accommodate the nuanced, selfbuilt nature of village morphologies—otlas, mixed-use units, and chowks were seen as violations, not assets. The 2015 inclusion of Bopal-Ghuma within AMC’s limits intensified this mismatch. Infrastructure was laid to formal layouts, often skipping or marginalizing the older cores, increasing disparities in service and governance.

Today, Bopal and Ghuma’s Gamtals remain caught between informal resilience and regulatory exclusion. Each phase—connectivity, industrialization, speculative growth, and municipal inclusion—has added layers of transformation. Understanding this timeline is key to proposing interventions that work with, rather than against, the existing grain of these evolving urban villages.

Landlords start selling off their lands to builders

Bhuj Earthquake Cheap land attracts more buyers in the outskirts

Drive In – Satellite designated as R3 zone Flushes people to periurban zones like Bopal and Ghuma

Bopal Ghuma still not included in AMC, Haphazard development continues. 1966 1974 1980 1996 2002 2015 2020 2019 2021 2025 1969 1982 2001 2004

Development Plan 2021 Revised Development Plan 2022

Capital of Gujarat shifts from Ahmedabad to Gandhinagar Nav Nirman movement rages across Ahmedabad, away from these villages

Earliest traces of agrarian settlements Outside AMC Thakors,

Shalby Hospital, Green City Established Gram Panchayat estd. For administration

Development Plan 2002

Sardar Patel Ring Road completed

Included in AMC limits Bopal Ghuma merged to form a municipality.

Merger with AMC June 2020, part of AMC’s Southwest Zone

Real Estate Market picks up post COVID 19 pandemic

After a speculative wait, the villages are now part of the Thaltej Ward

However, the villages still struggle with jurisdictional ambiguity.

Patels – Landlords Parmar - Labour

COVID 19 Pandemic

Gandhidham–Ahmedabad main line - Completed

Inductotherm Group buys land, first large factory sets

Metrics

Selected Site Area

1.575 sq.kms

Area in acres

Nolli’s Map

Area under roads (%)

Area under built (%)

Unbuilt (%)

58.3 2.0

Ground

20.0 22.0

Area under water (%)

Sub Arterial Roads (%)

Collector Roads (%)

389.1 acres 19.7 3.0

Local Roads (%)

75.0

Connections

Figure

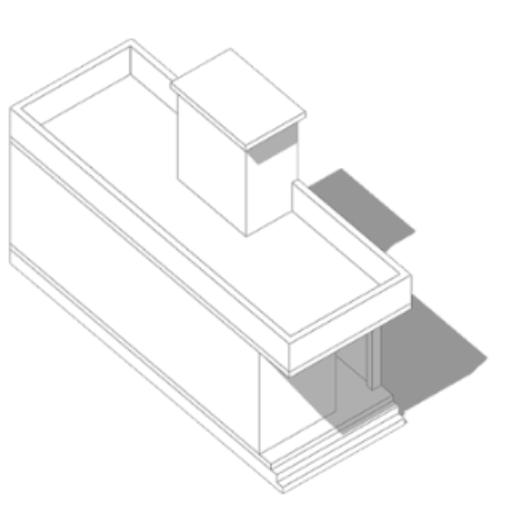

Incrementality Of The Built

In villages like Bopal and Ghuma, the built environment evolves through a process of incremental development, shaped by economic conditions, social needs, and spatial improvisation. Unlike planned neighbourhoods, construction here is self-initiated, informal, and often disconnected from official building bye-laws.

Dwellings typically begin as modest, single-room units with minimal facilities. As families accumulate savings, they expand vertically or laterally—adding rooms, staircases, or utilities as required. There is no standard blueprint; the architecture reflects a direct response to affordability, household size, and opportunity. Extensions are often built in phases, depending on financial liquidity, creating a mosaic of construction styles and stages within a single street.

and an economic support system, contributing to the live-work hybridity that defines the urban village condition. Upper floors are commonly rented out to migrant workers or young families, providing both income and affordable housing. These units are accessed via improvised staircases, often external, and constructed without formal approval—yet they function effectively within the local economy and housing market.

In such settlements, streets and public space are shaped by the built form, not the other way around. Overhangs, otlas, and balconies project into shared spaces, creating narrow, shaded lanes that reflect community interaction and spatial negotiation.

The pace and pattern of construction are

This form of construction is largely detached from formal building bye-laws, both in spatial logic and in process. Setbacks are often ignored, plots are subdivided without registration, and stairwells or mezzanine levels spill into shared courtyards or over public right-of-way. Far from being chaotic, these are rational, localised decisions made within the constraints of affordability, landownership fragmentation, and the need to accommodate extended or tenant families.

A common pattern is the vertical extension of homes, where upper floors are rented to migrants—particularly single male workers or young families—on informal terms. This process serves both as a housing solution

Development of units varies, largely dependent on the economic condition of families.

largely independent of building bye-laws

engulfed by the imposing grid layouts of rigid TP Schemes. Fig 06.8 - Incremental growth shaped by need, affordability, and adaptation—building the village one room at a time.

Image Source : WRI India

Families expand using saved money. Single rooms with a toilet added. Locality and streets are dependent on the building structures. Whereabouts of every resident is common knowledge and mutual trust is relatively higher.

Migrants take up upper roof top residences on rent.

Built vs. Open Realm

Selected Site Area (Acres)

45.5 26.2 19.5

Building Footprint (%)

The built-to-open ratio in Gamtals is highly skewed toward built-up areas due to incremental densification and lack of planning reserves. Open spaces are typically residual—temple courtyards, dead-ends, or encroached chowks—rather than designed commons. This imbalance limits ventilation, reduces permeability, and constrains opportunities for shared infrastructure or public gathering.

FSI Consumed

% of Plots with FSI higher than prescribed capped limit of 2.0

Despite low-rise morphology, effective FSI consumption in Gamtals is often high, approaching or exceeding statutory limits due to undocumented upper floors and room additions. Vertical extensions accommodate tenants or growing families, creating densities that outpace infrastructure capacity, yet remain under-reported in formal assessments, skewing planning and resource allocation.

Fig 06.9 - Few of the many instances of overconsumption of FSI, as opposed to the mandated blanket restrictions.

Legend

Built Waterbody

Legend

0 - 1.9

2.0

2.1 and above

ISRO Bopal Technical Campus

Sahajanand Bungalows

Village bounds Bopal Talavdi

Vibhusha Society Minor Bopal lake

Agricultural lands

Delhi Public School Bopal

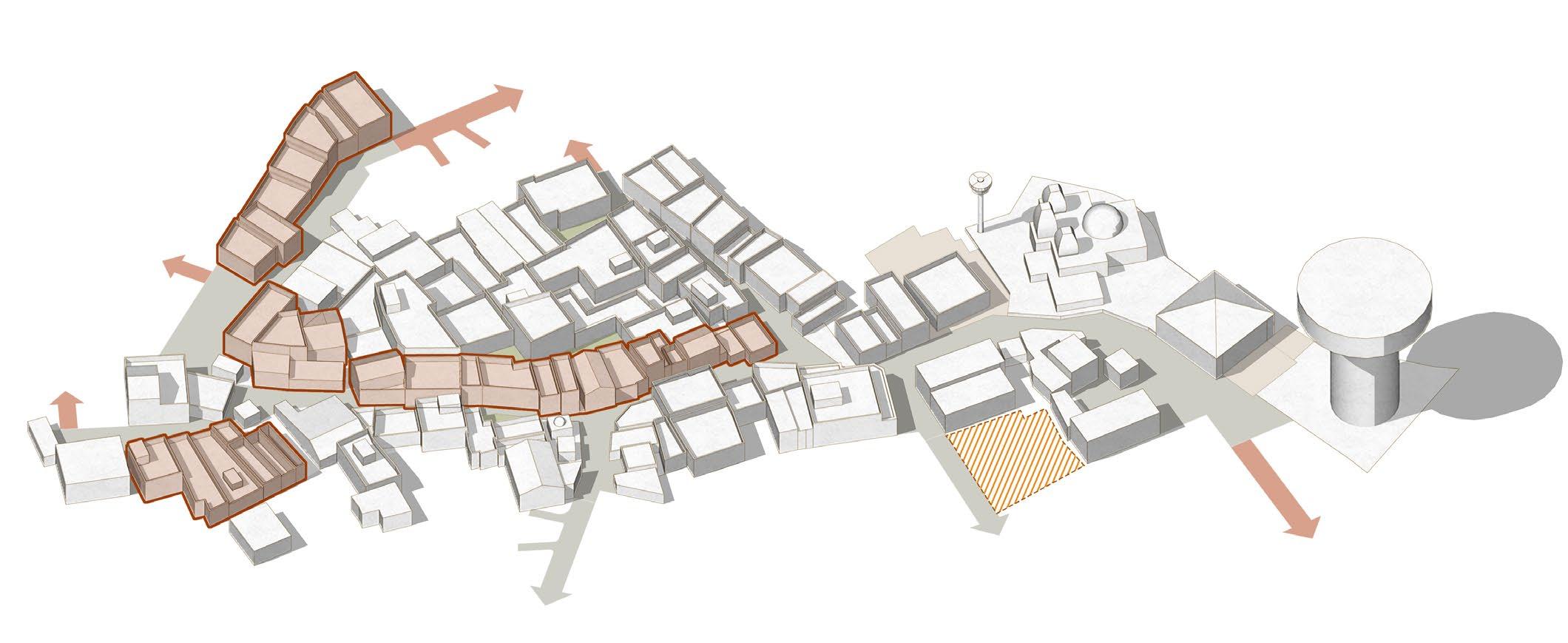

Pilot Street Study

The pilot street study serves as a focused exploration of how transformation can be tested at the scale of a single, representative street within the urban village. It examines built edges, thresholds, public activity, and infrastructure gaps to identify patterns of use, conflict, and potential. Acting as a testing ground for the proposed toolkit, this study helps translate broader strategies into localised, implementable interventions rooted in lived experience and spatial realities.

This segment captures the complexity of everyday life—dense built edges, informal thresholds, mixed-use spillovers, and infrastructure deficits. Through spatial mapping, observational analysis, and typological assessment, the study reveals how incremental transformation can be rooted in existing conditions. It allows for a grounded understanding of the interface between regulation and lived form, offering insight into how change can be both designed and negotiated, rather than imposed.

Selected stretch : 750m

Incoherent Street Character

Problems

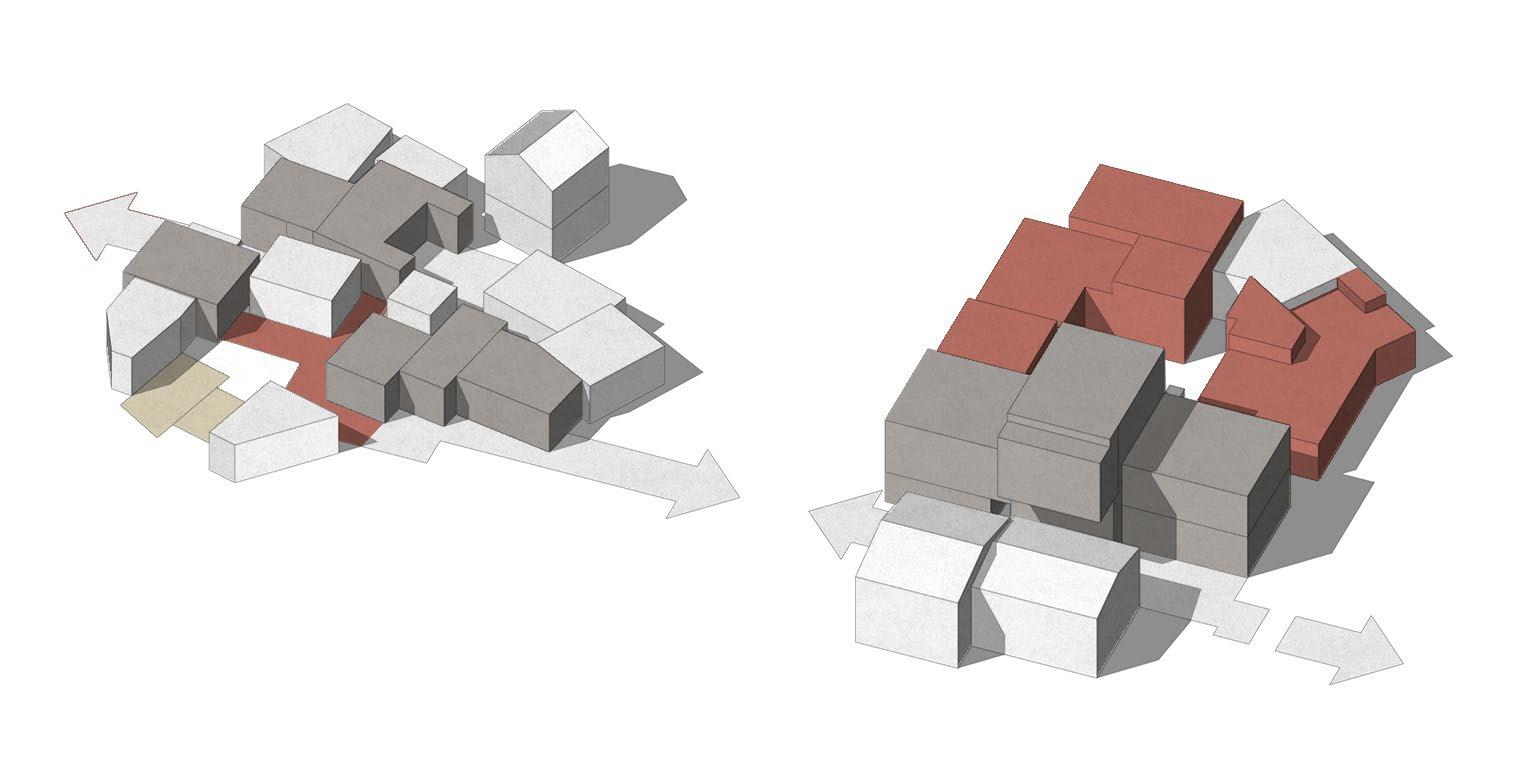

20-50 sq.m plots can be amalgamated

Units with most proclivity to transform

Incentive 0.3 additional FSI

Premise

Rationalize street geometry

Increased public domain

Possibility

Amalgamated built form

Coherent street character

Controlled commercial frontages

Community Chowks

Paid timed parking pockets

Typologies of Domestic Morphologies

The housing fabric in urban villages such as Bopal and Ghuma reveals a complex hierarchy of domestic typologies, shaped by incremental construction, economic necessity, and embedded social structures. These typologies cannot be understood solely through physical form; they must be read as social-spatial systems, ranging from modest single-room units to expansive family compounds with commercial and rental extensions.

At the most compact end of the spectrum are single-room dwelling units, often built at the rear of family plots or on rooftops. Typically occupied by migrant tenants, these units represent a survivalist housing form—minimal in space and services, yet critical to the informal rental economy.

Progressing upward, core family houses form the predominant typology within vaas-based clusters. These are modest ground-floor structures, with 1–2 rooms, attached sanitation, and shared otlas. Their spatial expansion reflects economic growth—vertical additions for rental income, horizontal extensions for new generations. The otla serves as a semi-public interface, mediating domestic life and street activity.

Domestic typologies are not random but ordered by relational proximity, kinship, and negotiated occupation.

Attached shop-houses introduce mixed-use activity into the domestic core. Located along primary streets, these structures incorporate commercial functions on the ground floor—tailoring shops, grocery stores, eateries—while retaining residential use above. These units blur the line between work and home, facilitating embedded livelihood systems.

At the upper end are extended family compounds— multi-storey houses with multiple attached units, often accommodating three generations or renters. These structures assert a form of spatial authority through compound walls, balconies, and distinctive facades, yet remain part of the informal grain.

Collectively, these typologies are clustered into Vaas, which operate as socially governed neighbourhood units. The vaas serves as the organising logic, enabling shared infrastructure, negotiated space, and spatial memory

Large Vaas - Clustered Residence with Small shops

550 sq.m

Vaas (Cluster)

Low rise, low density

350 sq.m

Informal Row Houses (Faliyus)

155 sq.m

Semi Detached with Commercial 105 sq.m

Semi Detached with Rental unit 60 sq.m

Residence with attached Shop 40 sq.m

Tenement with Rental

Room with toilet

Fig 06.15 - There a complex hierarchy of domestic typologies, shaped by incremental construction and economic necessity.

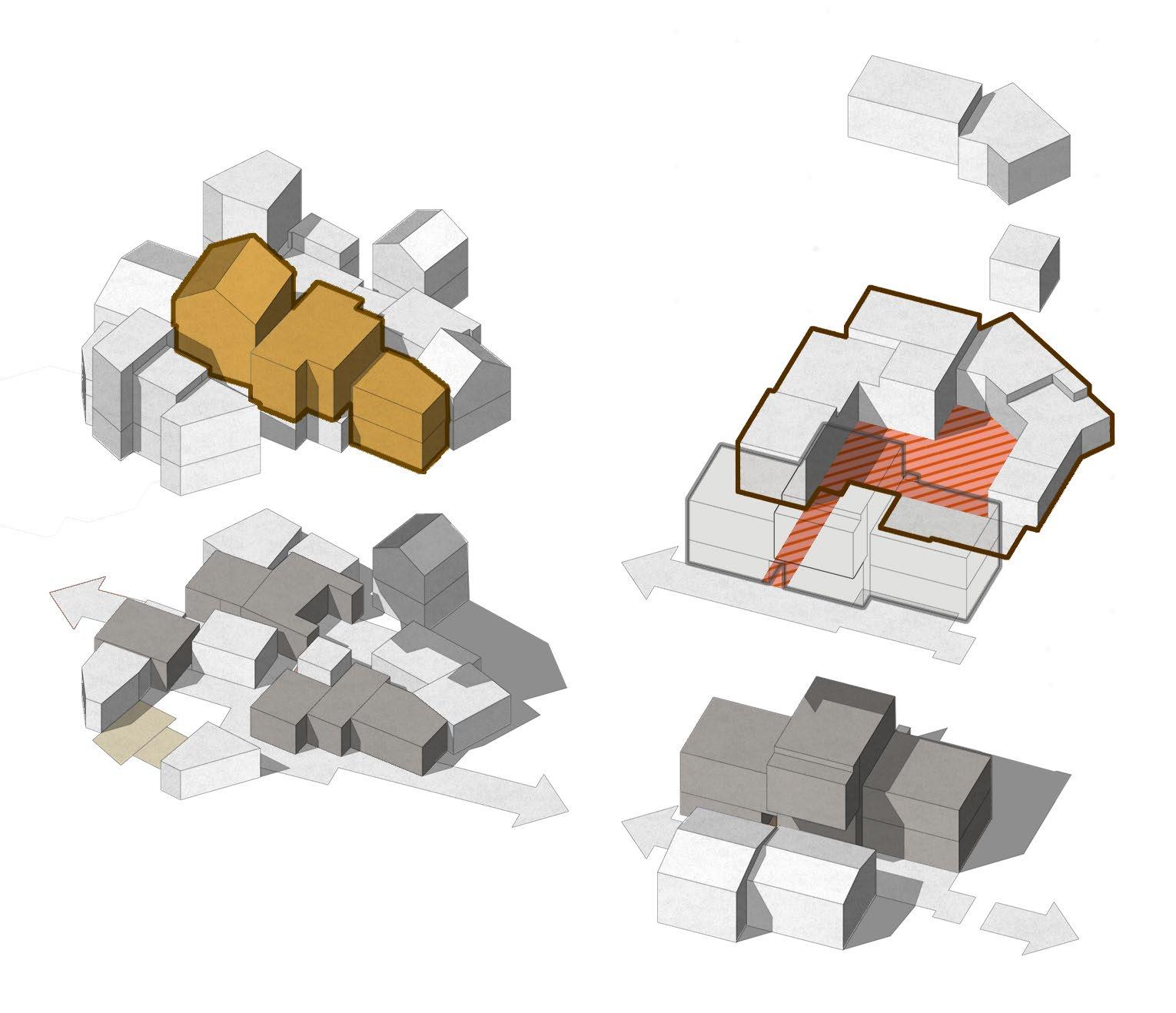

Morphology Matrix

The current condition of the built environment in Bopal and Ghuma’s Gamtals reflects a layered yet fractured urban fabric—where traditional spatial patterns collide with the pressures of urbanisation and the absence of contextual regulatory tools. What emerges is a complex interplay of underutilisation, disconnection, and missed opportunity across both private and public realms.

The built fabric is characterised by dense, low-rise structures, often self-built and incrementally expanded. Despite this density, FSI utilisation remains inefficient, as horizontal sprawl replaces vertical optimisation, primarily due to regulatory barriers and lack of formal financial access. This results in overcrowded ground floors and unused roof terraces, particularly in older homes with aging populations or disintegrating joint families.

Morphological Condition

Urban Design Guidelines Possible Toolkit Intervention Toolkit Code Classification Challenges Plot/Unit Range Size

Plots Abutting Main Road.

(6.0m and above)

Building as a Unit

Plots/Built Form Abutting Pedestrian Streets

Plots Abutting Main Road. (6.0m and above)

Cluster - Vaas as a Unit

Plots Abutting Chowks. (6.0m and above)

Smaller plot owners disincentivized.

No model to earn through either FSI.

Unable to leverage potential rental yeilds 10-35 sq.m S

No model to earn through either FSI. 10-35 sq.m, 35-50 sq.m S/M

Enable vertical expansion (up to G+2) through FSI Pooling strategies. Allow rental retrofits with pre approved lightweight prefab additions.

Introduce shared otlas and semi-public thresholds. Allow FSI Pooling within Micro Clusters

Toolkit - Threshold Typologies.

Encourage mixed-use typologies.

Mandate “Flex Space” and “Sakhi Angan”.

Allow FSI Pooling within Micro Clusters

Underutiised public realm.

Ambiguous ownership leads to poor utilization

Plots Abutting Lakes Little community engagement.

Lost ecological/ culture oppurtunity

40-65 sq.m, M

40-85 sq.m 80-120 sq.m, M/L

Gamtal Temple Precinct No cultural identity 300 sq.m and above -

Gamtal Crematorium Precinct Social stigma

No spatial dignity due to proximity in dense urban settings -

Mandate Pocket Parks, Vaas Level Pubic Space. Allow Common Courtyard Entitlement with FSI incentives.

Allow Public Commons Trust / Community Land Trusts

Mandate stipulated boundary walls. Programs for more public engagement with lake. Allow Community Graze grounds.

Mandate Minimal Impact Lake Edge Design

Special Zoning around cultural anchors like Temple. Flexible Open Space Programming.

Renewed Public Space Identity through appropiate place making initiative.

Mandate buffer between urban fabric and crematorium grounds.

Improved access for internments. Program spaces and facilities. Incentivise electronic cremations.

Dedicated ritual waste disposal and defined water access for rituals.

I01-1, I01-2

I01-1,2 S01-R, P01-R

B01-P S01-R, P01-R

B01-P, F01-1 S01-R, P01-R

S01-1, P01-1

S01-1, P01-1

Lack of Cultural Programming

Missed Opportunity for Ecology

Seasonal Drying

Polluted Water Greywater discharge, dumping, or idol immersion.

Conventional, non contextual model of lake front development

Undesignated Open Space

Encroached by Waste/Garbage Disconnected Edges

No Public Realm Identity Gendered Spaces

Generic Open Space Programming

Cultural Programming

realm

public realm

Renewed Public Realm Identity

Flexible, yet programmed Open Space

Temple court

Concrete lake edge Minimal soft scape public realm public realm public

Ghats Access

Cordoned areas around lake as community graze grounds

Wetland edges, native planting Minimal-impact edge design

Placemaking through minimal, low-cost tools. Deepstamb

FSI Pooling models for strategic densification

Introduce hybrid typologies Retrofit for multiple usages

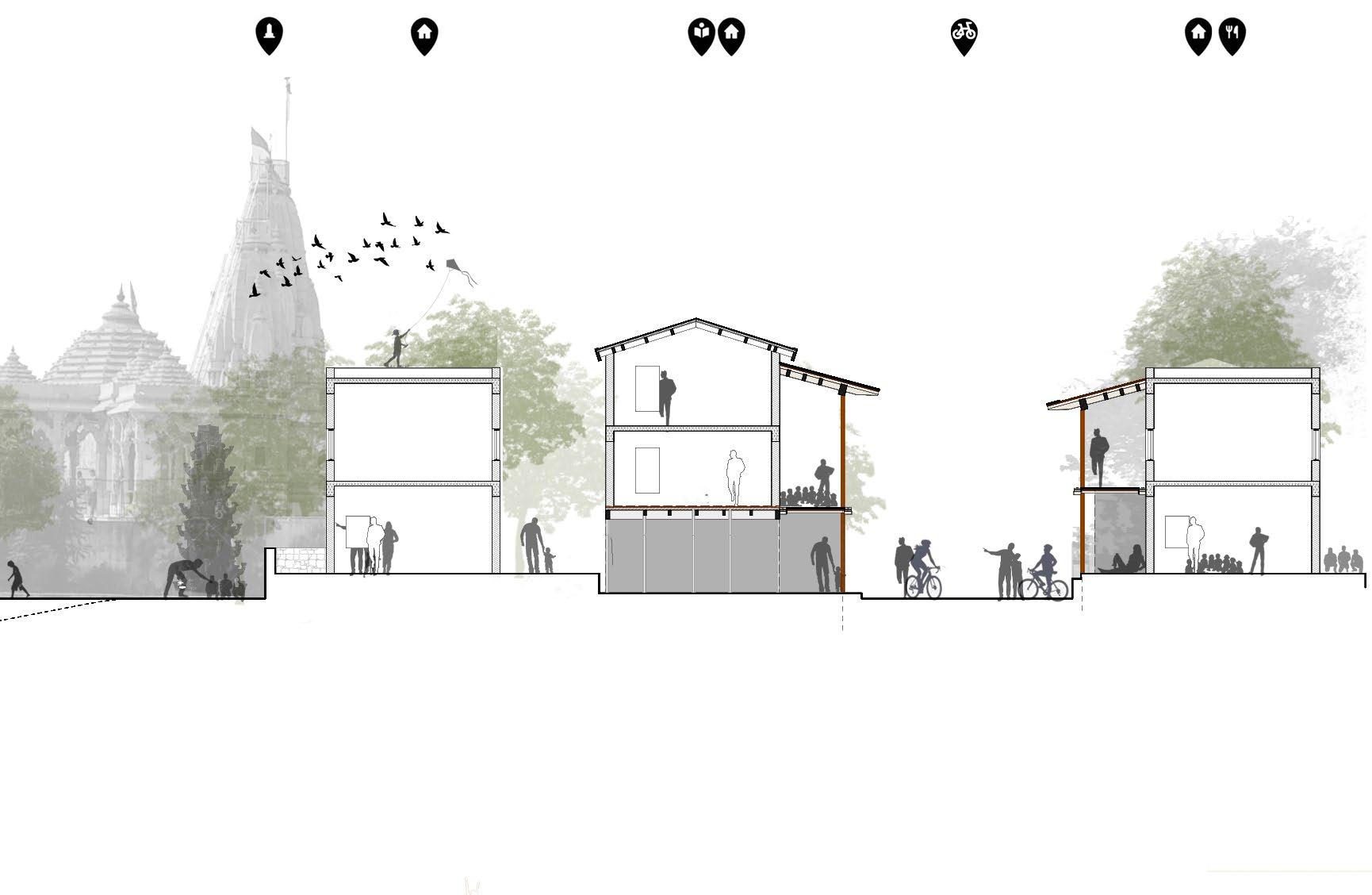

Schematic Section : Existing Village

Mandate Street types

Promoting semi permeable boundaries Activated Frontages Codified Thresholds

Schematic Section : Proposed Transformation

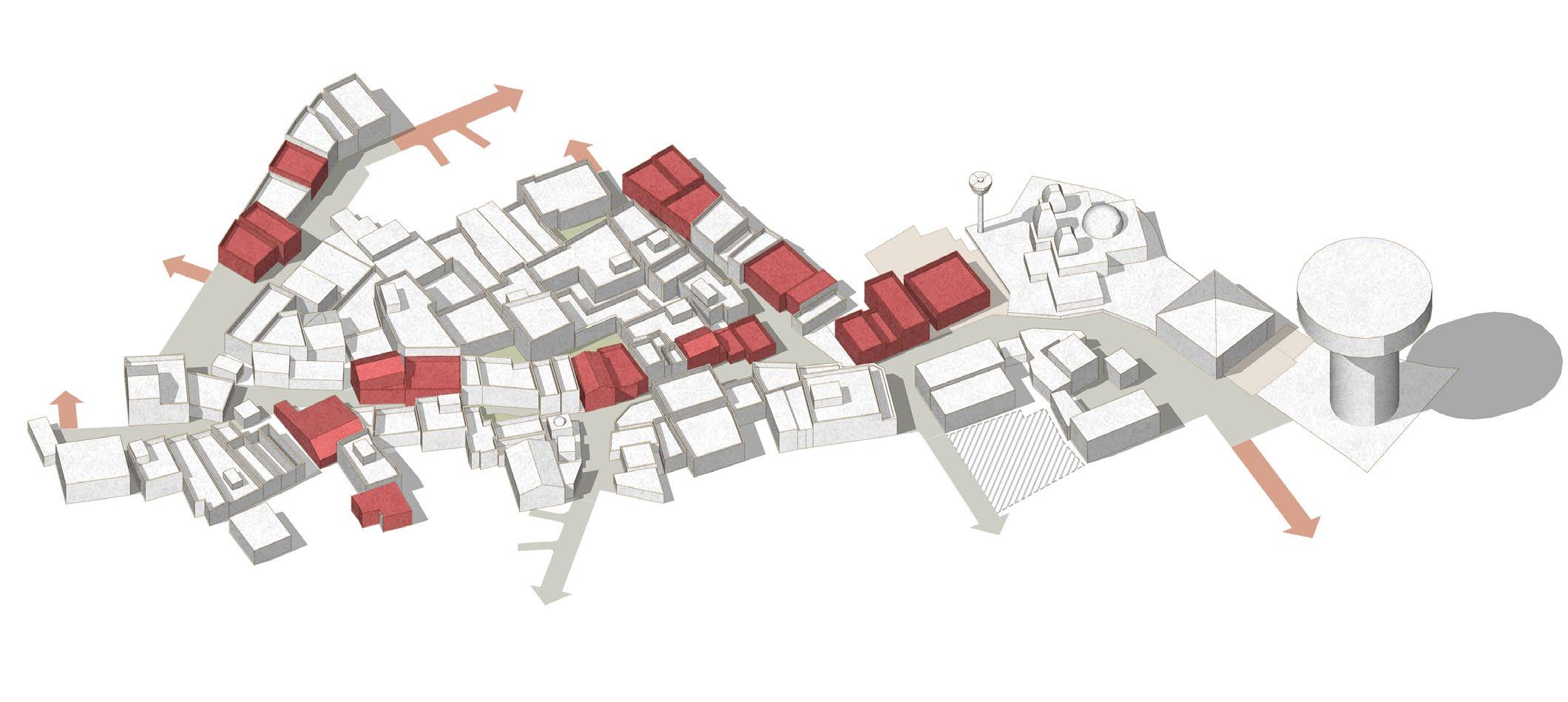

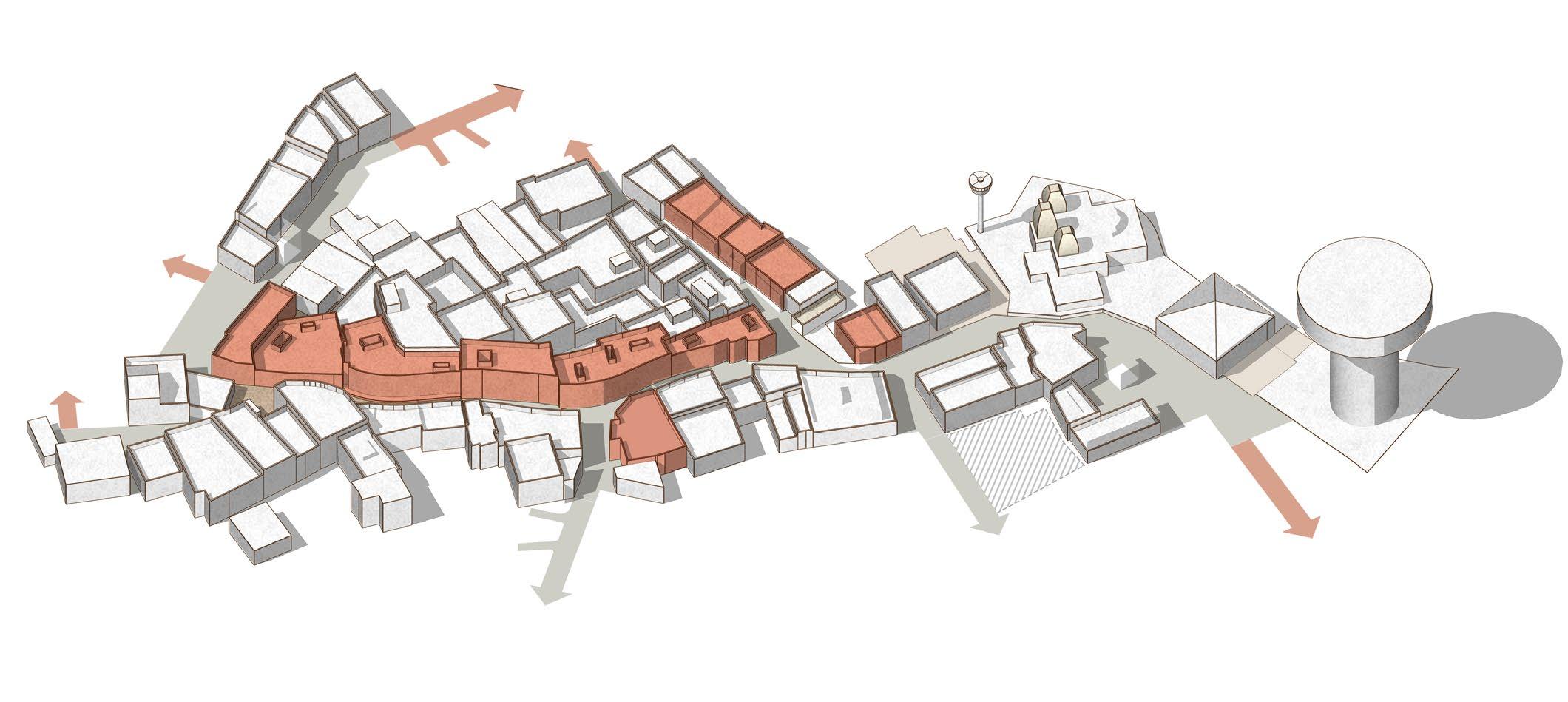

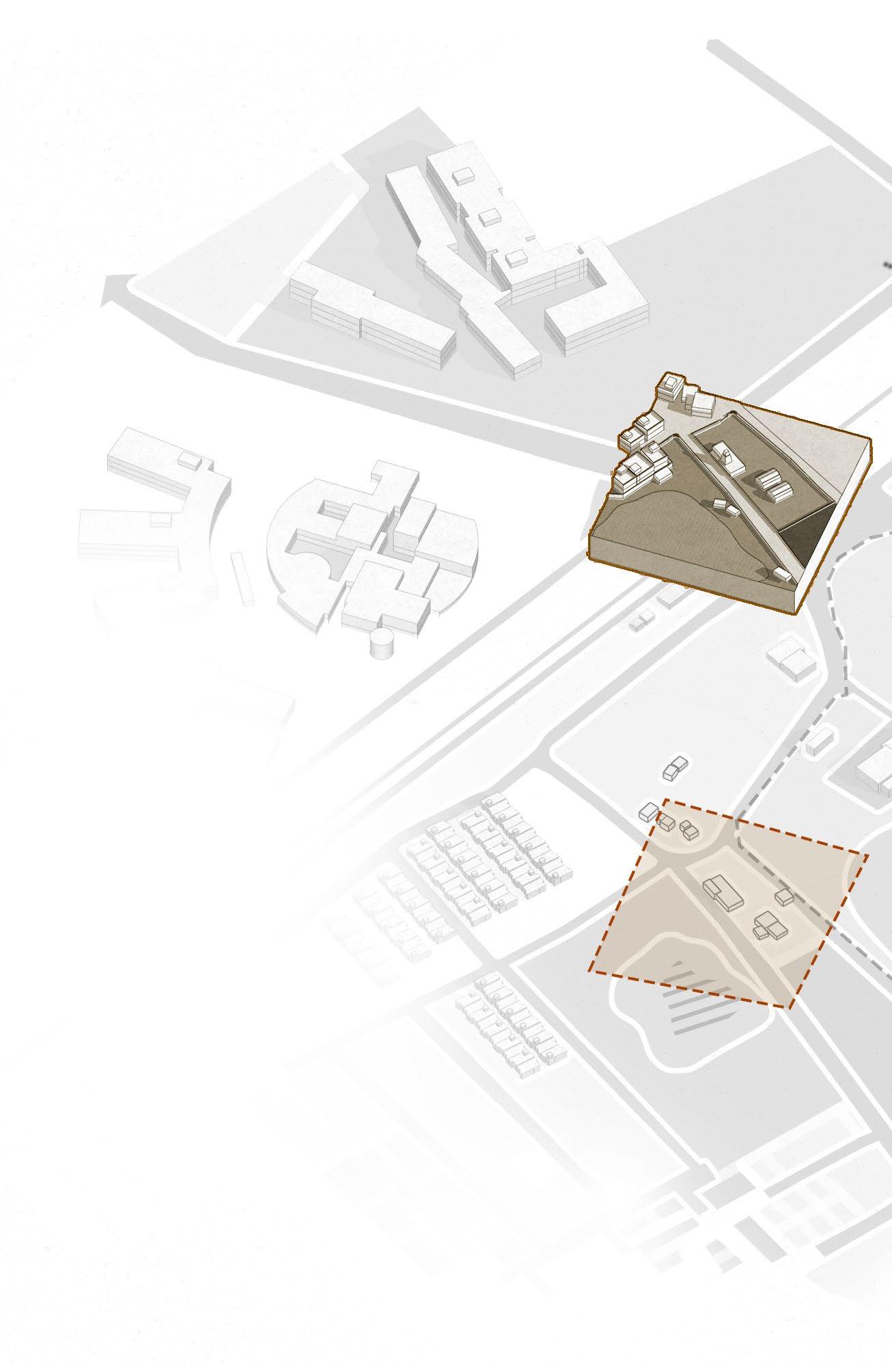

Demonstration Areas

This final chapter transitions the project from conceptual framework to on-ground applicability. While the toolkit operates as a system of design, regulatory, and participatory interventions, its relevance lies in how it can respond to the layered realities of the urban village. Demonstration sites serve as test beds—spatial contexts that reflect the village’s diversity of morphology, social use, infrastructural gaps, and regulatory frictions.

The intent is not to propose an idealised solution, but to operationalise the toolkit across representative conditions—each site becoming a pilot for incremental transformation rooted in lived form and adaptive logic. These sites offer opportunities to visualise how strategic regulatory tweaks and spatial interventions can work together to enhance density, improve public interfaces, re-activate commons, and legitimise informal adaptation.

To ensure relevance and replicability, site selection follows specific criteria:

(1) diversity of built typologies and edge conditions, (2) observed tension between regulation and lived use, (3) presence of latent socio-economic activity (4) potential for scalable impact within the broader village fabric.

These criteria ensure that the demonstration is not isolated, but embedded—speaking to the broader ambitions of the project while remaining deeply grounded in the everyday.

Edge Precinct Crematorium

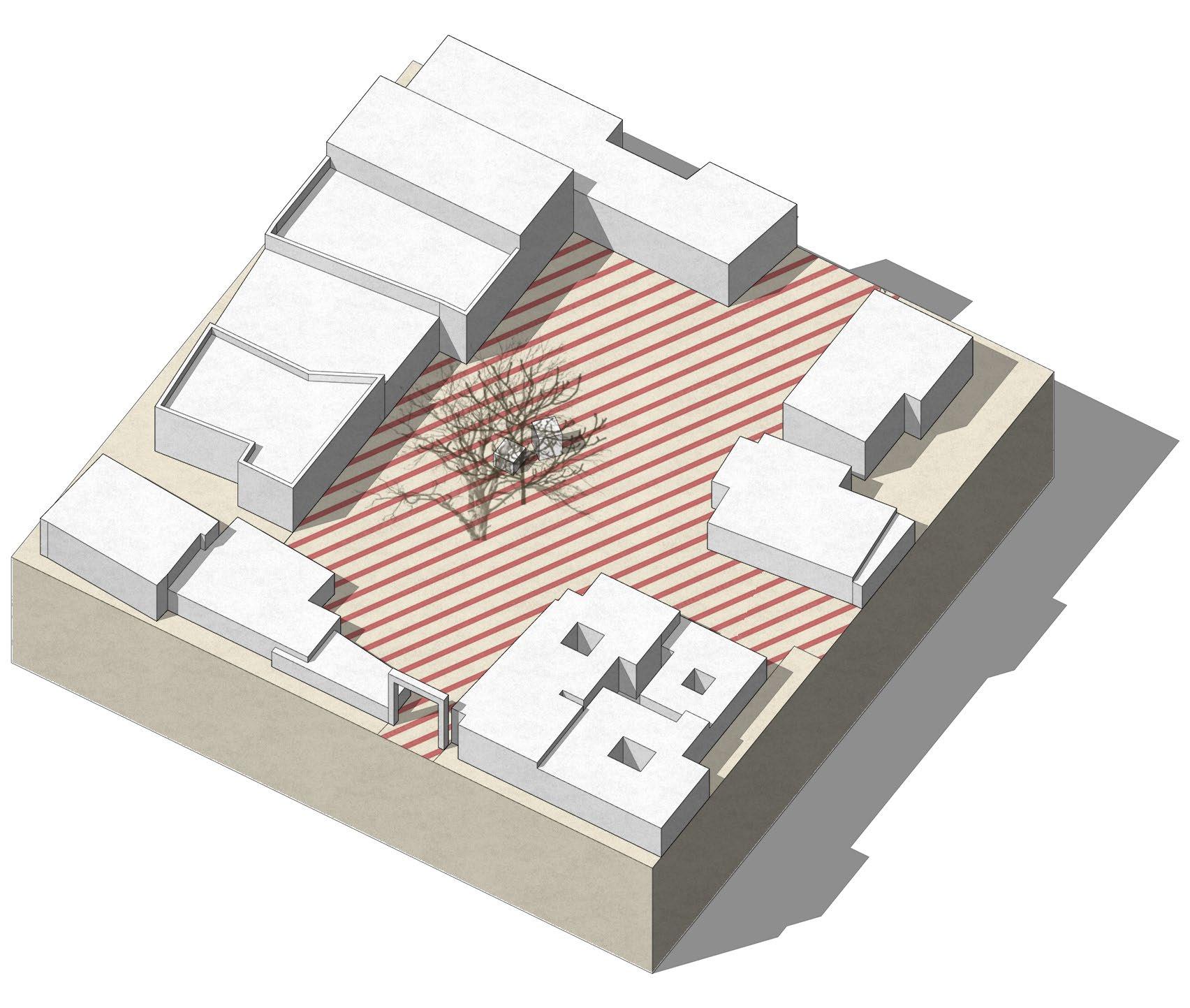

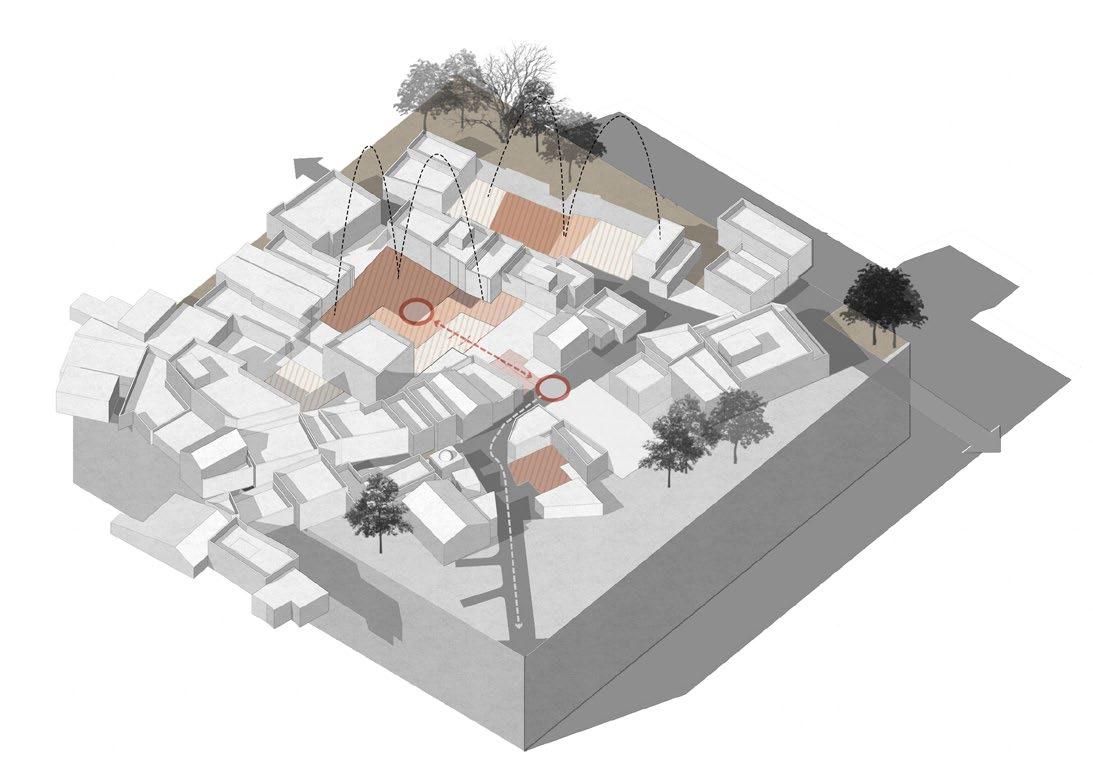

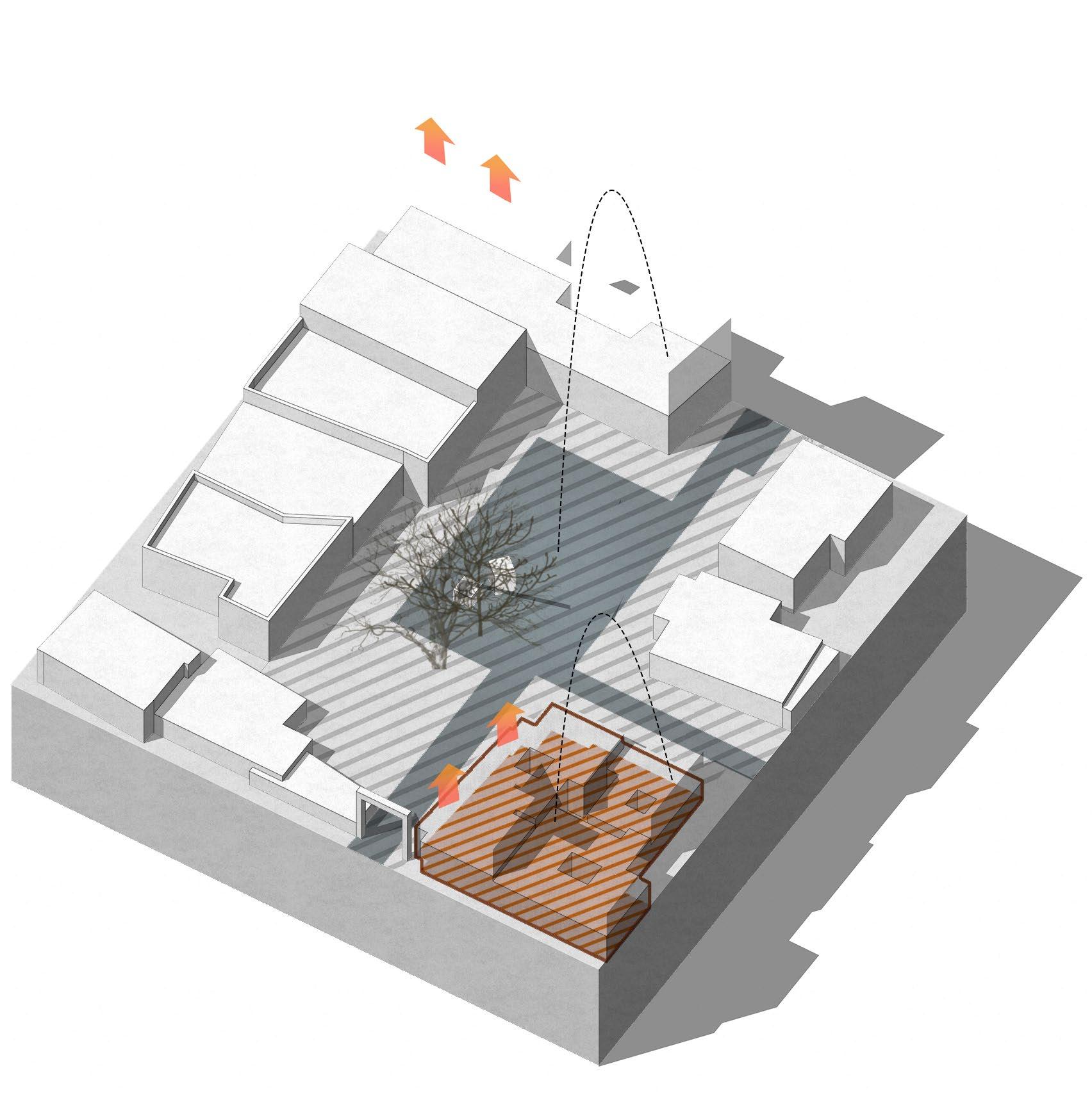

Fig 07.1 - Isometric view of the urban village showing selected sites for pilot projects and their relationship with each other.

Vaas Level Park

Village Lake Precinct Temple Precinct

Cluster of Vaas

Fig 07.1

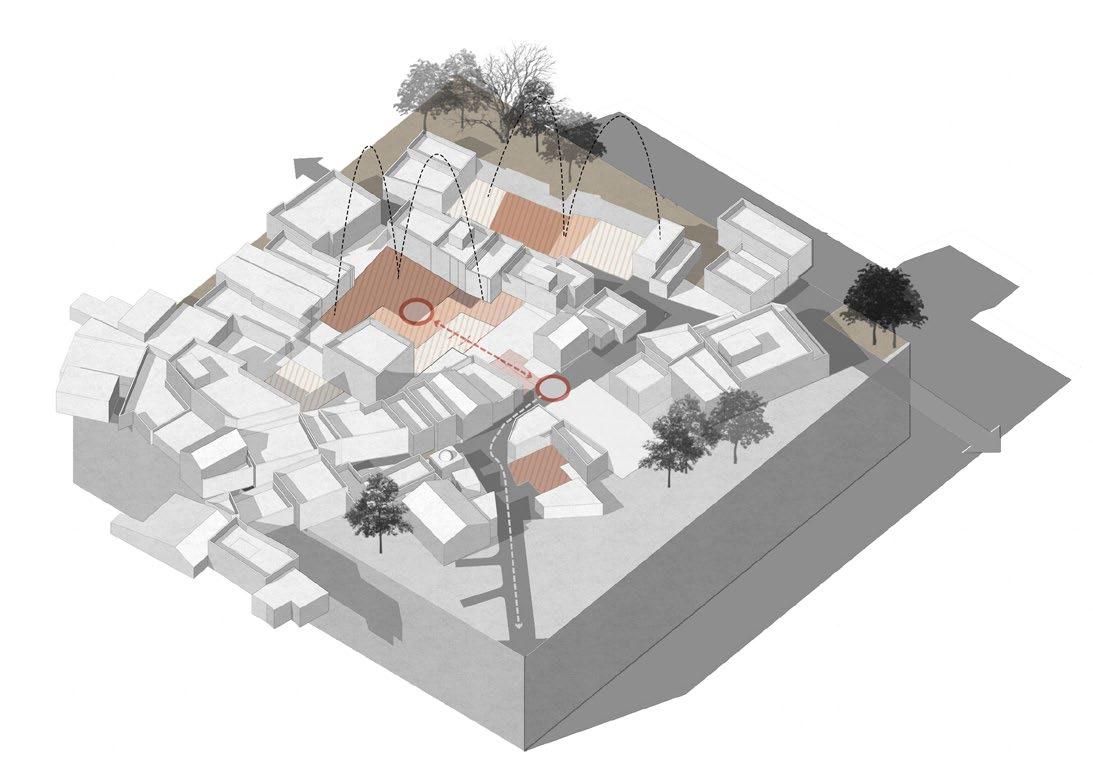

Vaas as Unit of Neighborhood

A dense cluster of titghtly packed homes organized along narrow, shared streets and inner chowks, traditionally designed to support tight-knit communities, the vaas today faces challenges from unregulated transformations, strained infrastructure, and eroding spatial logic.

Location Criteria

• Site reflects the typical internal residential grain of the urban village, including narrow lanes, organic layout, and a mix of old and new housing forms.

• The area has dense habitation, active doorfront use, and visible layers of everyday life — making it an ideal site to test public-private edge management strategies.

Vaas as a basic unit of gamtal Revitalize

A close-knit cluster of houses belonging to families of the same caste or community. It is shaped by kinship, caste, and customary use.

Drop off Gateway to the Vaas

Flexible “Flex” Space:

Open areas that can adapt based on community needs, times of day, seasons : nurseries, sports fields, gardens, plazas, markets, etc.

Transforming the Vaas means upgrading it without erasing its cultural grain.

Unorganized development limits footfall and property value

Poor Access Management

Multiple random entry points and parking without organization. Missed Potential

Unrealized retail potential

Underutilized commercial opportunities due to regulations

Uncoordinated Frontages

Broken, ad-hoc extensions and patchy, mismatched setbacks

Blank Compound Walls

Dead frontages reduce surveillance, and pedestrian comfort

Encroached Public Realm Shops extend onto footpaths informal vending spills

Unsafe additions

Temporary structures that are poorly maintained

Fig 07.2

A dense cluster of titghtly packed homes organized along narrow, shared streets and inner chowks, traditionally designed to support tight-knit communities, the vaas today faces challenges from unregulated transformations, strained infrastructure, and eroding spatial logic.

Fig 07.2 - Existing Vaas shows poor consumption of FSI, access management and ad-hoc extensions to the built.

Fig 07.3 - Toolkit introduces hybrid typologies with codified otlas. Strategic densification while increasing public realm.

P-04

Follies used as congregation space community events

B-02

Rental Housing Retrofits

B-01 Hybrid Typology

C-03

Shared Staircase - Type 02 Adoption incentivised with FSI

I-05

Upper Level Commercial Veradah

Allow small commercial activities

P-01

Common Courtyard Entitlement Shared courts

Toolkit Intent

Densifies the area in a controlled manner, enhancing land use efficiency, Frontages defined; small commercial inserts.

07.3

B-02

Rental Housing Retrofits

I-01

Codified Otlas as per ground floor use

FSI Incentives

C-01

Shared Terraces

I-04

Datum for commercial/ vending to spill over in controlled manner

Fig

Toolkit Response

• Controls on plot depth, building alignment, and height ensure visual coherence. Setbacks and buildto lines shape a consistent street edge and protect light access.

• Design templates for rental or co-living units with shared courtyards.

• Support mechanisms for multi-tenant dwellings to participate in incremental redevelopment.

Fig 07.4 - Final transformed Vaas realises untapped potentials without loosing the essense of traditional living.

Fig 07.5 - Existing Street and Vaas.

Fig 07.6 - First phase of transformation, with better legible streets.

Safer, Legible Retrofits

Additions like staircases, bridges as per pre approved catalogue

Activited Heart of Vaas legible space for congregations and activities with ‘flex’ space

Shared Terraces

Continous Terraces become secondary level of public realm, incentivised FSI additions

Newer Hybrid Typologies

Small scale commerical activities on upper levels, for streets lesser than 6.0m

Continous Thresholds

More interactive edges and street frontages

Active Street Fronts constant eyes-on-the-street and street-level engagement.

public spaces designed around temples and chabutras

better FSI utilization and compact built form

Fig 07.4

Fig 07.5

Fig 07.6

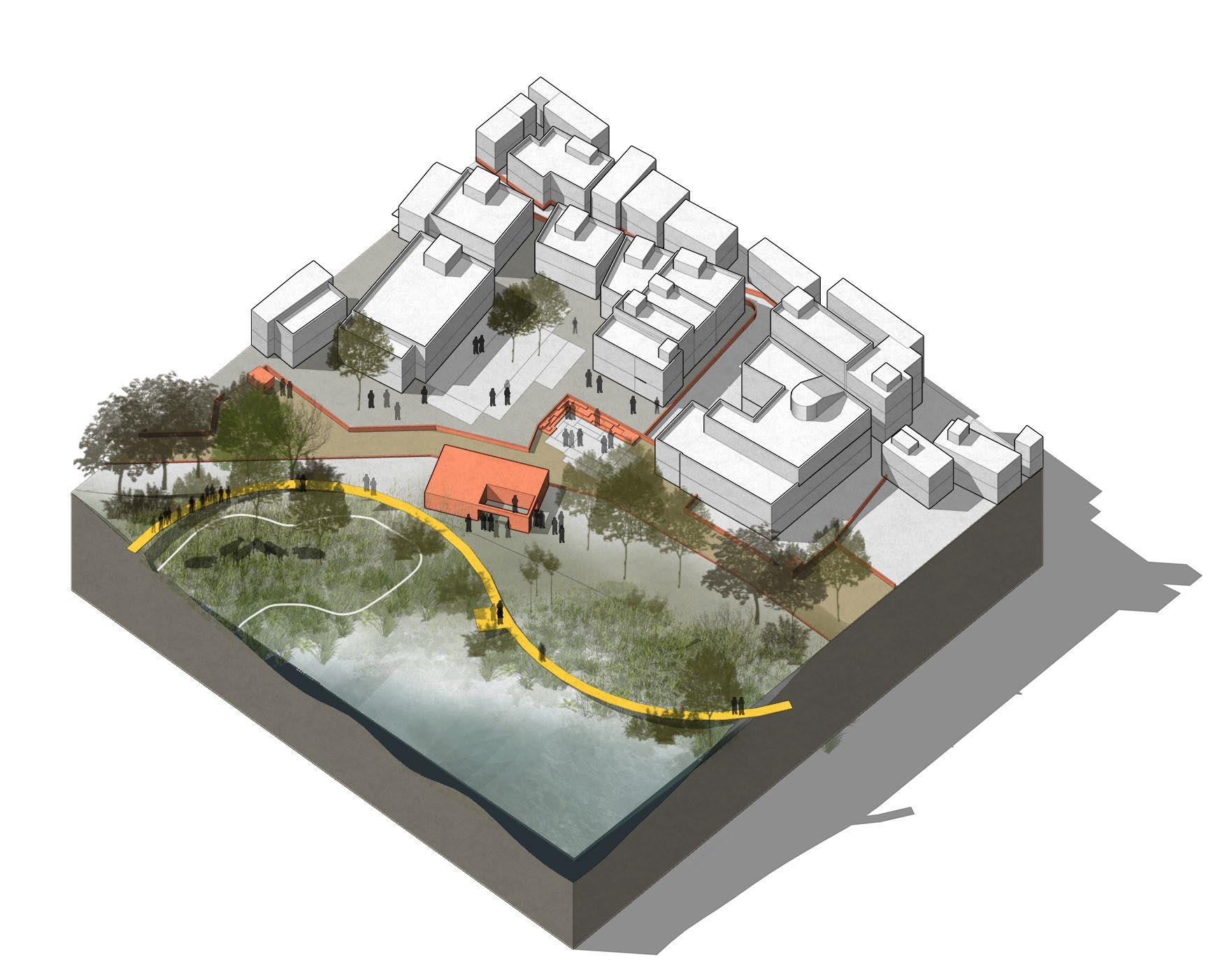

Lake Precinct

Often neglected or encroached upon, these water bodies hold immense potential as socio-ecological anchors within peri-urban settlements. Reimagining the lake as a shared public realm can catalyze environmental restoration, enable microclimatic comfort, and strengthen community identity in areas grappling with unplanned growth.

Location Criteria

• Site must include or lie adjacent to a lake, pond, or seasonal water body with ecological, cultural, or historical relevance.

• Preference for sites with available land parcels under municipal or public ownership to reduce land acquisition complexities.

Least Invasive park design

s while allowing gentle public access

Boundary designation

Reclaim lost lake edge and remove encroachments

Shared access for local communities.

Encroachment plots often extend impermissibly into the lake margin

Compound Wall

Interface treatment

Shared easements, ensure continuous public access, no boundary walls.

Community graze grounds

preserving traditional livelihoods while promoting ecological stewardship

Vehicular Road

Entry

Controlled access, visitor center, podiums for more public engagement with lake

Environmental Degradation discharge greywater and solid waste directly into the lake, exacerbating pollution

Loss of Ecological Interfaces

Hard infrastructure replaces natural riparian buffers

No Visual or Physical Relation with the Lake Discontinuous and unsafe public realm

No Programmatic Engagement missing opportunities for enhancing urban vitality and experience

Underutlised private realm private plots fail to leverage the visual and experiential value of the lake economically

Stamped lakefront model

Forced, non contextual and often alienating lake front models copied.

Elevated boardwalks to preserve natural terrain

Fig 07.10

Strategic, replicable framework to reclaim, restore, and reprogram lake edges in urban villages as resilient public spaces. Empowers local communities and local authorities to guide informal transformation through smallscale, phased interventions.

I-01

Interface and Easements Privately Owned Public Spaces

F-02

FSI Pooling and Redistribution in lieu of open spaces

P-01

Public Commons by partnering trust Community/ Trust maintained and financed public spaces.

07.10 - Existing plots abutting lake edge suffers a lack of physical and visual connection with the lake.

Fig 07.11 - Toolkit introduces ecological buffer zones, promenade framework while returning spaces for community activities.

Programmatic Engagement reimagine proximity with lake as a civic asset to capture economic oppurtunities

Promenade Framework continuous, universally accessible pedestrian promenade that ensures connectivity

Toolkit Intent

Uses the lake as a spatial anchor with program to stitch disparate informal developments and catalyze neighborhood cohesion.

Ecological Buffer Zones prescribed non-buildable setbacks along the lakefront reserved for public use

Urban Form Guidelines

Mandate stepped building frontages with active ground-floor uses

Flood mitigation

Employ graded slopes, permeable surfaces, and native vegetation to stabilize banks

Inclusive Programming

Designated community grazing grounds along lake edges for community

Minimal Impact Lakefront Design Mandate least invasive design strategies like boardwalks to restrict damage to the lake edge

Fig

Fig 07.11

Vaas Level Park

Serves as an embedded micro-open space within the dense residential grain, strategically introduced to enhance community well-being, restore ecological balance, and address the chronic deficiency of accessible green infrastructure at the neighbourhood scale.

Location Criteria

• Identifies vacant, fragmented, or informally encroached land parcels that can be reclaimed and reprogrammed for public use.

• Positioned to ensure equitable access within a 2–3 minute walking radius from surrounding homes, prioritizing children, elderly, and women.

Internal Competition, Not Collaboration

Each owner acts independently, no shared investment in upgrades

A close-knit cluster of houses belonging to families of the same caste or community. It is shaped by kinship, caste, and customary use.

Open areas that can adapt based on community needs, times of day, seasons : nurseries, sports fields, gardens, plazas, markets, etc.

Special areas for only women not just as physical retreats, but symbolic assertions of spatial equity in gamtals. Typically include visual screening, their own set of amenities like bathroom.

Neglected Interstitials Dead leftover spaces between buildings

Unmaintained semi-open areas (garbage dumping, informal parking)

Lack of Coherence

Different building heights, setbacks, styles, chaotic streetscape

organized pedestrian pathways

No mechanisms for pooled maintenance or public realm improvements Poor Accessibility Confusing or blocked access for loading/unloading,

Prescriptive regulations minimum OTS sizes just enough to “clear” ventilation rules

Flexible “Flex” Space: Sakhi Angan - Recognizing Women

Vaas as a basic unit of gamtal Revitalize Flexible Space

Transforming the Vaas means upgrading it without erasing its cultural grain.

Sakhi Angan Drop off

Local Street Gateway to the Vaas

Vaas Gate

Fig 07.14

Open spaces are often residual, unplanned, and lack clear boundaries or collective identity, reducing their usability and meaning.

Many open spaces are isolated, not visually or physically linked to primary or secondary movement corridors.

Fig 07.14 - Existing Vaas open courts shows degradation of space, garbage dumping and poor circulation.

Fig 07.15 - Toolkit introduces programmatic inserts like Sakhi Angan, to activate these interstitial spaces.

P-04

Sakhi Angan - Women Centre Follies used as congregation spaces

more formal civic structure that symbolizes gendered access to space. It houses visual screening, seating, shade, and hygiene facilities, which helps reinforcing the equity lens

Toolkit Intent

Activate and formalize Vaas-level open spaces as shared community assets support daily life,and reclaim land for collective use.

F-01

Phased Incremental Uplift Participation in phased upgrade program, certified by ULB

Bonus FSI:+0.1 per phase(up to +0.5)

Phasing : Paving - Lighting - FolliesSoftscaping

Street categorisation Establish internal movement Corridors.

P-01

Common Courtyard Entitlement Shared courts I-03

F-03

These plots receive FSI incentives in exchange for sharing maintenance and visual openness.

Fig 07.15

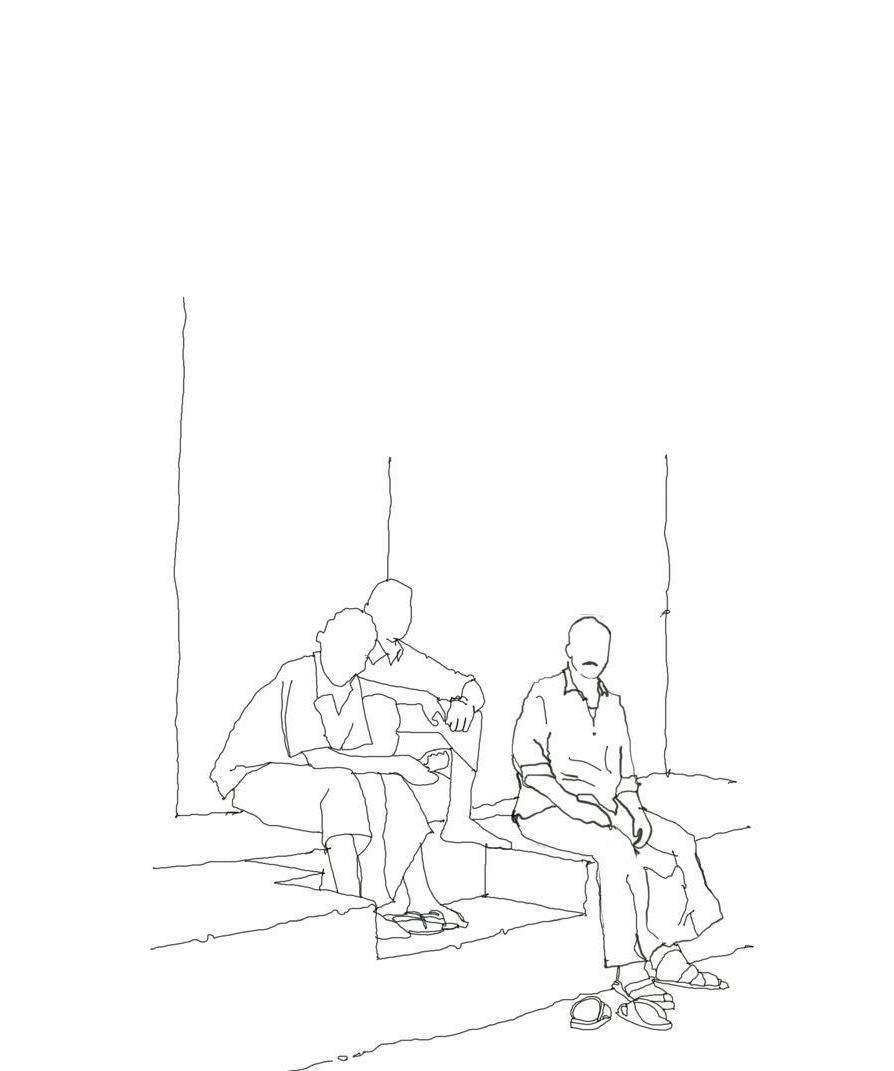

Previously underutilized and fragmented, the space has been reconfigured through participatory design processes to support intergenerational use, with specific emphasis on gender-inclusive access and everyday social routines. The spatial intervention includes shaded seating niches, permeable surfaces, and native planting that together improve microclimatic comfort, while the inclusion of low-height edges and visual permeability ensures safety and passive surveillance. Importantly, Sakhi Angan functions not merely as a recreational space but as a

Fig 07.16 - Final transformed Vaas court introduces Sakhi Angan to address community values yet remedy gendered spaces.

Fig 07.17 - Existing open courts within villages lack programming and are often encroached by illegal parking.

Fig 07.18 - Proposed transformation returns the public space back to people, while deterring encroachments.

Cluster-level urban design codes

Unified façade treatments, signage guidelines, stepped height controls

hybrid commons—a flexible node for informal gatherings, women’s association meetings, and seasonal celebrations. Anchored by local stewardship and culturally embedded design, this transformation exemplifies how small-scale, distributed interventions can recalibrate the quality of life and social cohesion at the neighbourhood scale.

Phased Upgradation Map

cluster transformation templates to raise property value steadily

Women Centre

Special areas for only women not just as physical retreats, but symbolic assertions of spatial equity in gamtals.

Internal mobility layouts

Define shared service lanes, pedestrian-only alleys

Flex Space

Open areas that can adapt based on community needs, times of day, seasons - nurseries, plazas, markets, etc.

Common Court Entitlement

Plots share a courtyard, granted FSI bonus for plots facing it. min. 36 sqm, all plots to have access.

Fig 07.16

Pocket park toolkit low-cost landscape upgrades, tree planting modules, community seating

Vaas Gate/

Fig 07.17

Fig 07.18

Catalyzing Change through Phasing

Urban transformation, particularly in complex, informal environments such as Gamtals, cannot be achieved through singular, large-scale interventions. Rather, it requires a temporal logic—a deliberate and strategic sequencing of actions that respond to socio-spatial readiness, institutional capacities, and evolving community aspirations. Temporal sequencing allows change to unfold incrementally, enabling learning, trust-building, and resource mobilization at each phase before scaling up.

The concept of phasing as a design and planning strategy gains critical importance in these contested contexts, where residents have historically experienced marginalization, infrastructural neglect, or abrupt topdown redevelopment.