pesquisafapesp

by

Organisms that live for only one day can predict seasonal changes

Brazilian blend

DNA sequencing reveals Indigenous, European, and African ancestry and could democratize access to personalized health care

A prototype device for breast exams does not compress the breast or use X-rays

Elite soccer players are characterized by planning ability and mental versatility

Gas emitted

Amazonian trees accelerates cloud formation

The significance of populational diversity

ALEXANDRA OZORIO DE ALMEIDA Editor in Chief

When the major human genome sequencing projects began in the late 20th century, the belief was that the differences in the genetic composition of different individuals would be minimal. Therefore, to reach the goal of a complete reference genome, little attention was paid to the populational diversity in the samples to be sequenced. It turned out that humans have far fewer genes than expected and that they are not the key to the differences between individuals. Technological advances have made it possible to identify millions of minor changes to the genome—variations that can alter the form and function of proteins or the pattern of activation/deactivation of the genes that they encode. They can be common to populations and have important consequences for public health, such as the propensity to develop a certain disease or how different organisms react to certain medications.

An article published in Science last May sequenced the genomes of 2.7 thousand people from all parts of Brazil. Not only do the results allow a deeper understanding of the genetic diversity of the population, but they also support Brazilian efforts toward precision medicine and its availability in the national health system ( page 6 ).

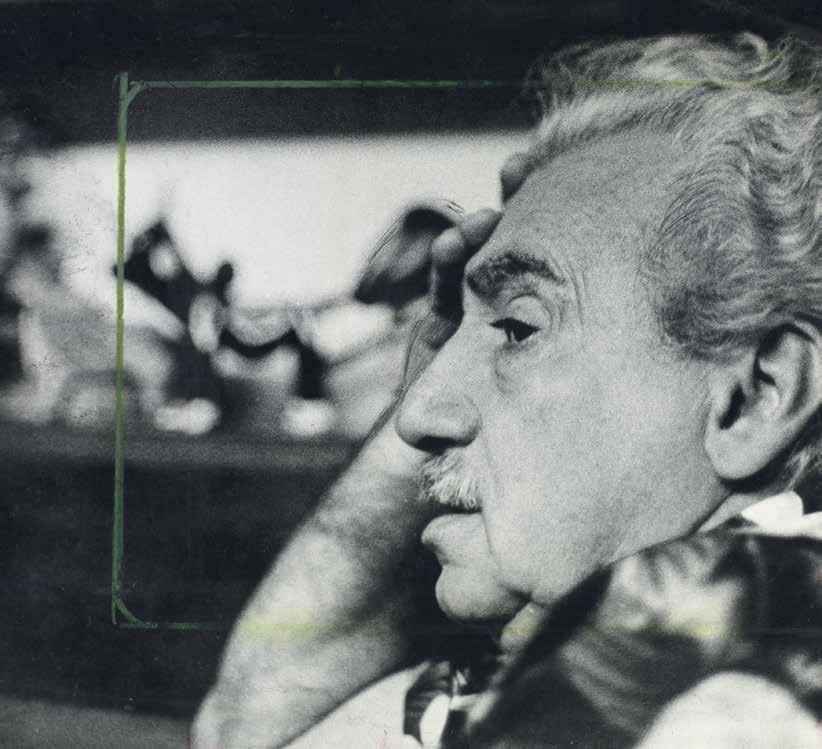

Genetic diversity is also at the heart of another feature, but the subject is cassava, not human genes. Certain cultivation practices used by indigenous peoples such as the Waurá are important for the maintenance of genetic varieties and for guaranteeing food security ( page 37). This edition also offers a diversity of themes, such as research revisiting the works of Jorge Amado (1912-2001), one of the best-known Brazilian writers abroad ( page 58). The technology section offers views from above: nanosatellites for locating shipwrecks

( page 57) and radar-equipped drones that can monitor crops or scan for anthills or buried skeletal remains ( page 40).

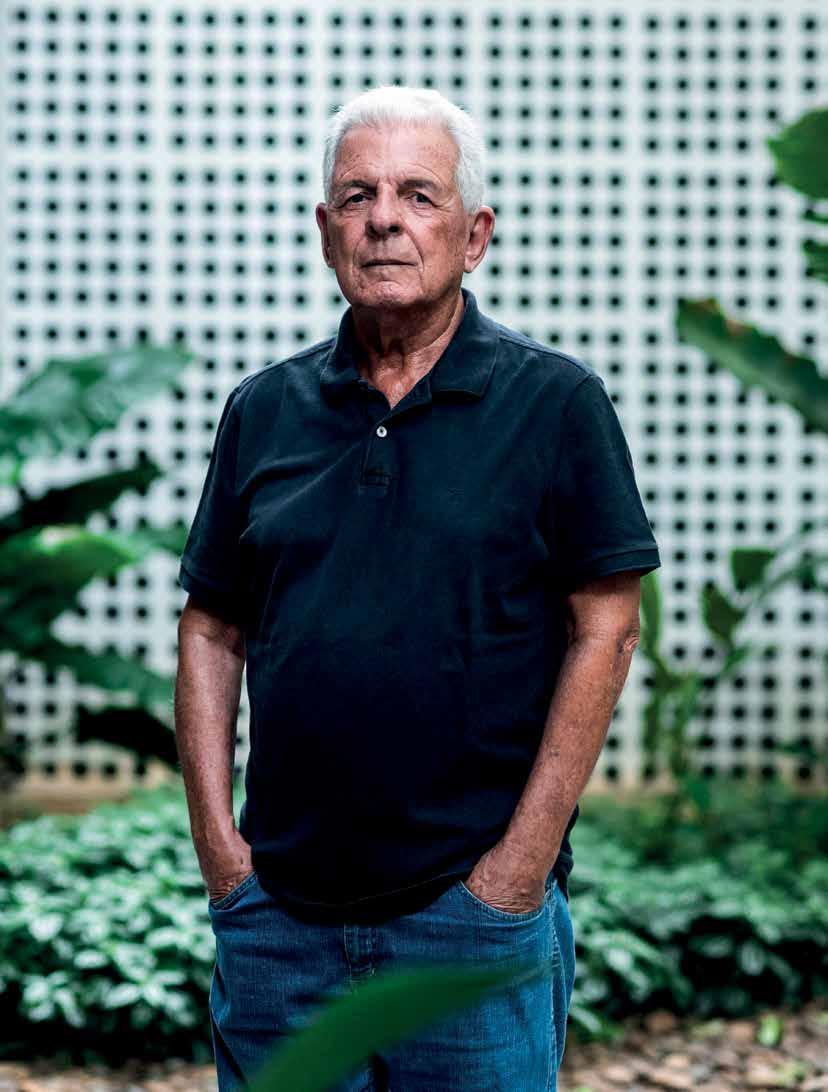

The May edition of Pesquisa FAPESP in Portuguese featured an interview with the philosopher Luiz Henrique Lopes dos Santos of the University of São Paulo. A researcher in the field of logic, Lopes dos Santos has a long track record as an advisor to the Scientific Directorate of FAPESP, the São Paulo Research Foundation. He helped create various research programs, and for 21 years, he was the scientific coordinator of this magazine. It is difficult to summarize his importance in the construction of this publication’s identity. Shortly after granting this interview, Lopes dos Santos was diagnosed with cancer; he passed away last July. His legacy in our newsroom is the daily quest for quality writing combined with scientific accuracy, with a view to engaging a wider audience ( page 16 ).

As we prepare this edition for print, COP30 is taking place in Brazil for the first time. Covering the science behind climate change has always been a staple part of our work. One example is the feature on research that highlights the importance of aerosols, a type of particle, in cloud formation ( page 44). It has been known for some time that aerosols accumulate over the Amazon rainforest. A recent study revealed that isoprene, a gas emitted by trees as a thermal regulatory mechanism, accelerates the formation of these particles, which can travel thousands of kilometers and become cloud seeds.

This international edition features a selection of articles originally published in Portuguese between January and June 2025. New content in English is published monthly on our website (revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/en/).

revistapesquisa fapesp

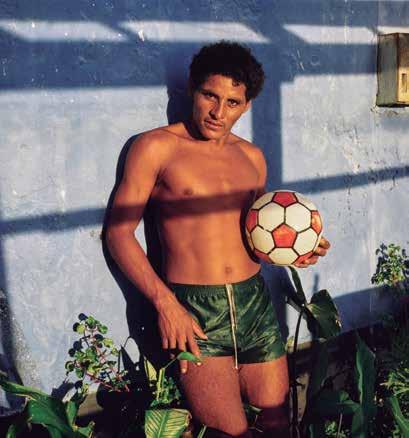

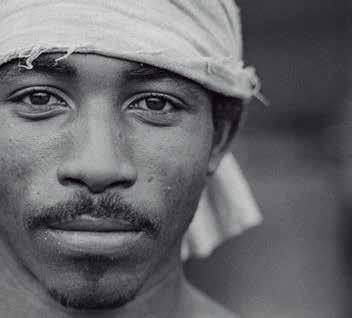

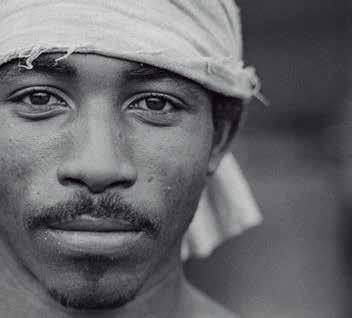

COVER A series of portraits by photographer Luiz Braga , from Pará, illustrates this issue’s cover and cover features. A retrospective of his 50 years capturing the faces of people from the Amazon was exhibited at the Moreira Salles Institute, São Paulo, in 2025

5 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

COVER

6 Sequencing of the DNA of 2,723 Brazilians sheds new light on the country’s mixed ancestry

12 Genome information could pave the way to personalized medicine for all

INTERVIEW

16 Philosopher

Luiz Henrique Lopes dos Santos revisited his academic career and discussed the more than 30 years he devoted to FAPESP

INNOVATION

22 Study details how university laboratories forge partnerships with industry

December 2025

PSYCHOLOGY

26 Elite soccer players have good memories and mental versatility

PHYSIOLOGY

30 Blood vessels release compounds that modulate heart rate and blood pressure

CHRONOBIOLOGY

34 Although cyanobacteria live only for one day, they pave the way for seasonal changes

AGRICULTURE

37 Planting techniques used by the Waurá people in the Upper Xingu region increased the genetic diversity of cassava

AGRONOMY

40 Drone radar monitors crops and locates ant nests and bones underground

ATMOSPHERIC CHEMISTRY

44 Gas emitted by trees in the Amazon accelerates cloud formation

CLIMATE CHANGE

48 Extreme events combining heatwaves, acidification, and chlorophyll shortages have ravaged the South Atlantic

PHYSICS

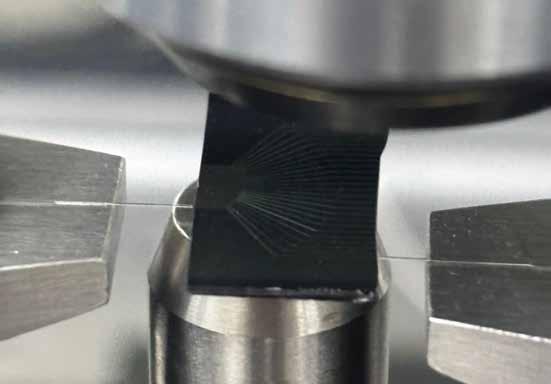

51 The study of the interaction between light waves and mechanical waves could lead to advances in the field of quantum information

HEALTH

54 New breast exam device dispenses with the need for compression and radiation

AEROSPACE ENGINEERING

57 Brazilian nanosatellite has been designed to locate shipwreck survivors

LITERATURE

58 Researchers revisit the work of writer Jorge Amado

MUSIC

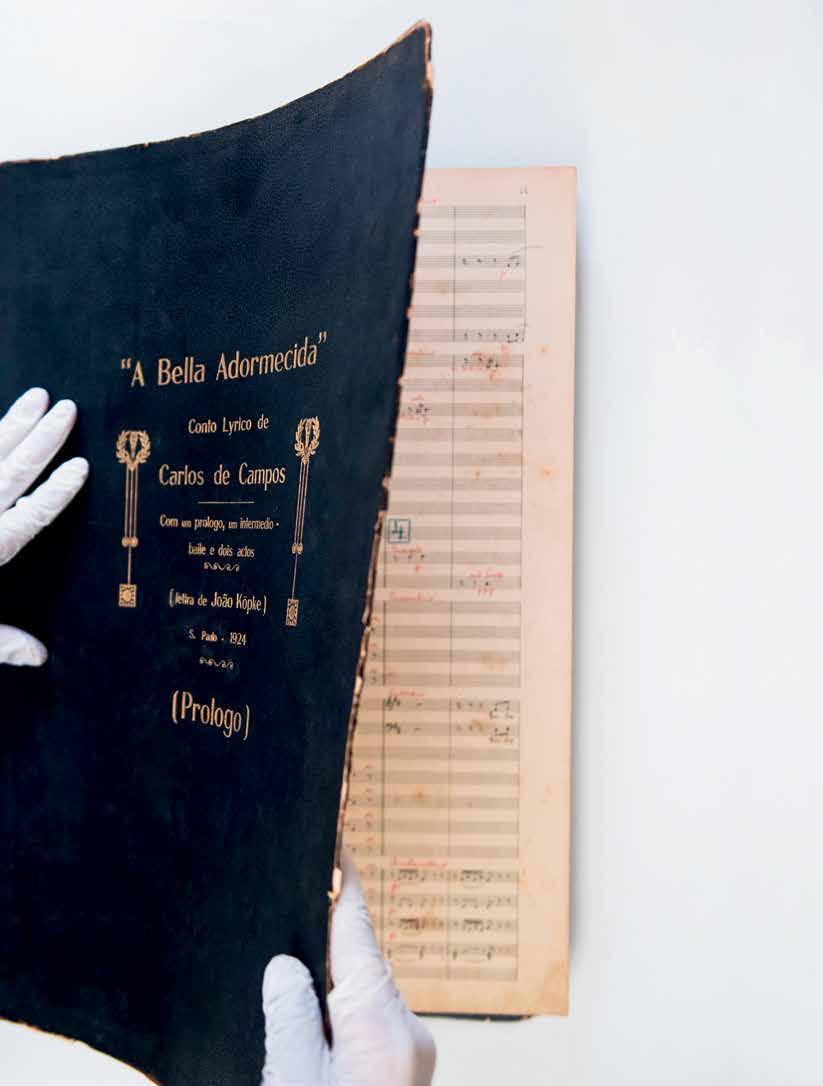

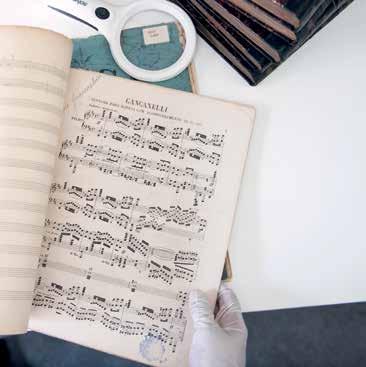

62 Studies uncover rarities and expand access to little-known music collections

66 PHOTOLAB

European father, African or Indigenous mother

DNA sequencing of 2,723 Brazilians reveals a violent legacy behind the interracial mixing that shaped the Brazilian people

GUIMARÃES photos LUIZ BRAGA

MARIA

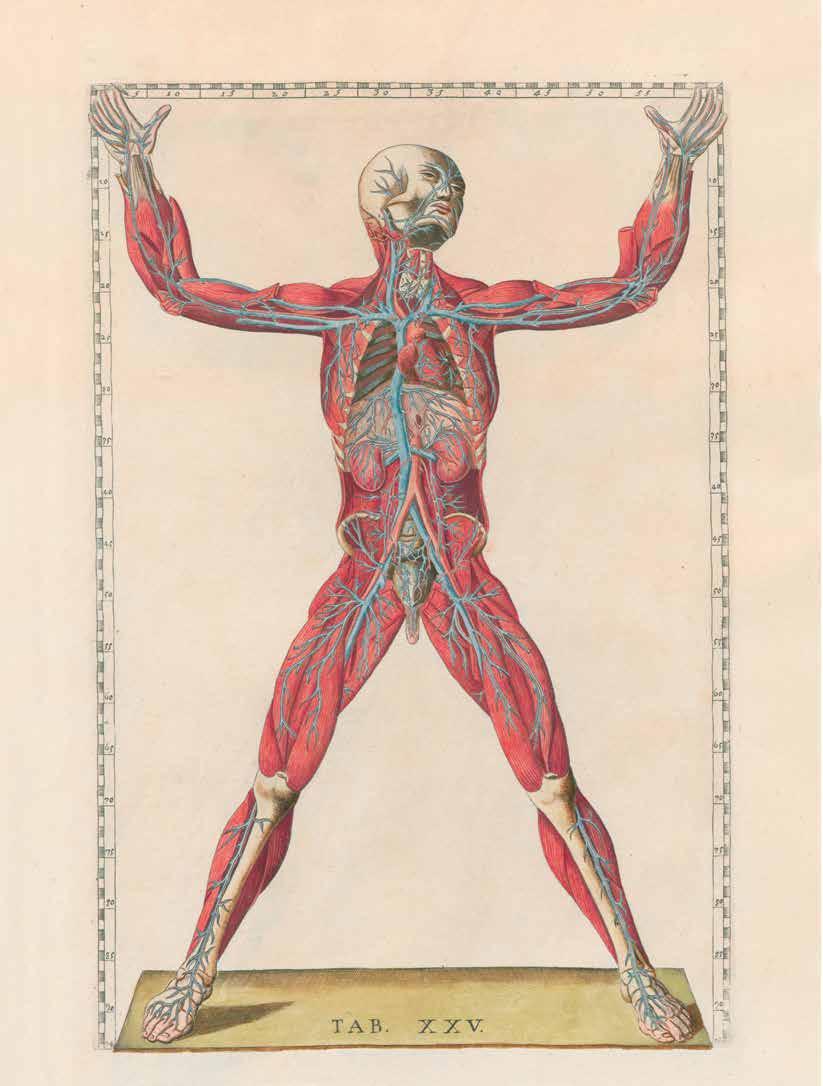

Unsurprisingly, Brazilian people have a mixed racial background, but the details of how this story unfolded and its consequences are only gradually being revealed by geneticists and historians. The latest study, which was published in the scientific journal Science in May, deepened and expanded our knowledge of Brazilians using the DNA sequencing of 2,723 people from across the country. The results reveal strong African and Indigenous ancestry in the maternal lineage, the legacy of widespread violence against women, and an unexpected number of unknown genetic variants with potential health consequences.

“It is really amazing to see in DNA what we already knew from history books,” says geneticist Lygia da Veiga Pereira of the Institute of Biosciences at the University of São Paulo (IB-USP), creator of the “DNA do Brasil” project, which aims to paint a genomic portrait of the Brazilian population by sequencing complete samples collected from all over the country. According to Pereira, until approximately 10 years ago, the genetic diversity of human population samples was very low, around 80% from European ancestry, because most stud-

ies were carried out in the Northern Hemisphere. In Brazil, the focus was on the southern and southeastern regions, where a lower presence of African and Indigenous ancestry was found. Investments in expanding this perspective led to the Genomas Brasil Program at the Ministry of Health’s Department of Science and Technology (DECIT) at the end of 2019, —although the COVID-19 pandemic, which started just a few months later, put a halt to activities for almost two years.

Pereira began to take an interest in the genetic diversity of the population when she realized, approximately 20 years ago, that the discarded embryos from assisted reproduction clinics in São Paulo that she used for her stem cell research were of 90% European ancestry. Those data were not representative of Brazil’s makeup as a whole; it rather reflected the users of those private services. Meanwhile, geneticist Sérgio Pena of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) was studying the DNA of Brazilians from various regions using the tools available at the time, which were much more limited than those in use today. In 2000, he published the results of an analysis of 200 samples from white people in Ciência Hoje and the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Interracial mixing in history

Violence in the formation of the Brazilian people left marks on the genome

1500

On their arrival, Europeans found a population of around 10 million Indigenous people, which was later decimated; sexual violence against women was the norm from the start

17th Century

Genetic markers from 16 generations ago show evidence of mixing between Indigenous women and European men

18th Century

The diamond mining period, which was almost 12 generations ago, brought a large influx of Europeans to Brazil; trafficking of slaves from Africa increased tenfold

Early 19th century

Before the end of the slave trade, around two million slaves were brought over from Africa in the 19th century; eight generations ago was the period of greatest mixing between men of European ancestry and women of African descent

1822 – Independence

Marriages between freed slaves and Europeans were encouraged as a “civilizing” strategy: there was talk of Europeanizing the mixed-race population

1850

Slave trafficking was prohibited 1871

The Law of Free Birth allowed children to be exploited up until the age of 21 but made it illegal for them to be sold. With the loss of market value, slave masters no longer had an interest in having children with enslaved women, and thus interracial mixing declined

1888

Slavery was abolished

Late 19th century, early 20th century

The Brazilian government encouraged the immigration of White men, especially Italians, Germans, Spanish, and Portuguese. The arrival of some four million Europeans is detectable in the genetic makeup

21st century

Most marriages are now between people of similar ancestries

Three in five had Indigenous or African maternal heritage, which was more than expected. The study was reported on by Pesquisa FAPESP in just its second year.

Pena continued to study the topic in more depth and joined forces with another group that was pioneering the study of Brazilian DNA, under the leadership of geneticist Francisco Salzano (1928–2018) of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). Through research led by Maria Cátira Bortolini, which included Tábita Hünemeier's master's degree, the two groups from Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul realized that the African contribution was much broader than indicated by historical records on slavery, which were highly concentrated in Angola, on the west coast of the continent. The western region, where Senegal and Nigeria are located, also made a significant genetic contribution—more in São Paulo than in Rio de Janeiro, indicating asymmetries in the slave trade, according to an article published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology in 2007. “There is no other country in the world with as much interracial mixing as Brazil,” Pena said in an interview in 2021.

The technology has since evolved significantly, leading to a new article published in Science. The paper reveals that European heritage accounts for approximately 60%, whereas African ancestry contributes 27% and Indigenous ancestry represents 13%, in addition to the sexual asymmetry noted by Pena: the paternal lineage, expressed on the Y chromosome present only in men, is predominantly (71%) European. Moreover, the DNA of the mitochondria—the part of the cells passed down only from the mother—comprises 42% African ancestry and 35% Indigenous ancestry.

“The only explanation is four centuries of various forms of violence,” summarizes Hünemeier, currently a professor at IB-USP and one of the leaders of the research. She notes that it is not uncommon to hear older people say things such as “my grandmother was caught by the lasso,” without thinking about what this statement actually means. In more recent generations, marriage between similar ancestries has become more common. According to Hünemeier, the results help debunk the myth of racial democracy that is so often cited as part of the Brazilian identity, since interracial mixing was often something that occurred without consent.

“Brazil needs to reexamine its history and stop saying that we are a country of voluntary interracial harmony,” adds USP historian Maria

Helena Machado, who did not participate in the study. “Our mother is African, our grandmother is Indigenous, and our grandfather is a European who had illegitimate children with her out of wedlock.” Machado is an expert in gender and motherhood during slavery, a system that spanned the entire colonial period and the empire. In 2024, she published the book Geminiana e seus filhos: Escravidão, maternidade e morte no Brasil do século XIX (Gemini and her children: Slavery, motherhood, and death in nineteenth century Brazil; Bazar do Tempo) in partnership with historian Antonio Alexandre Cardoso of the Federal University of Maranhão. “Enslaved women—Indigenous or African—were at the service of their enslavers, making harassment and rape commonplace,” he states.

Women were thus doubly enslaved—forced into being workers and reproducers. “The very bodies of enslaved women were colonized,” Machado explained that Portuguese colonial policies and the policies of Brazil as an independent country from 1822 onwards always encouraged racial mixing and whitening. For example, in 1823, as a member of the constituent assembly, José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva (1763–1838) argued for the formation of Brazilian people through marriages between White men and Afro-descendant or Indigenous women. This approach was part

of a “civilizing” project in which the Black population would be integrated into the European population. With slavery continuing until 1888, however, enslaved women remained subject to those who had control over their bodies. “All of this led to the situation that geneticists now describe,” Machado concludes.

The wide diversity of African ethnicities, as Hünemeier has noticed since the beginning of her scientific career, is also interesting. People who would never have met in Africa because they lived in countries and communities separated by great distances were forcibly placed on the same slave ships and grouped together in slave labor. The objective was to group people from different cultures who did not even speak the same language to minimize the risk of them organizing to fight back against their “masters.” The result is an amalgamation of an entire continent, which can only be found in Brazil. “It is the country with the most African ancestry outside of Africa,” says the geneticist.

In addition to the initial influx of Portuguese from the sixteenth century onwards, European diversity is also high, with a significant flow of immigrants from Germany and Italy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as well as from other countries in lower amounts. One interesting data point was 10 individuals of Japanese descent sampled in São Paulo who showed no signs of interracial mixing, thus revealing a highly restricted and recent contribution to the genetic makeup of the national population.

This article describes the colonization of the Americas as the largest population displacement

Regional ancestry

in human history. In Brazil, some five million Europeans and five million Africans were transplanted to the region, which until then was populated by roughly 10 million Indigenous people who spoke more than 1,000 different languages. These peoples were decimated, suffering a population decline of 83% in the interior of the country and 98% on the coastline between the year 1500 and the present day.

“We expected to find new genetic variants, but the results went far beyond that,” says geneticist Kelly Nunes, who analyzed the data during her postdoctoral fellowship in Hünemeier’s laboratory at IB-USP, alongside three other colleagues with whom she shares the position of lead author of the article: Marcos Castro e Silva, Maira Ribeiro, and Renan Lemes. Variants are differences in a person's sequence relative to the reference genome. “We detected 78 million variants, of which almost nine million were not recorded in any other database.” It became clear that the DNA of the Brazilian population includes a sample of populations that have been neglected from a genomic point of view, especially Africans and Indigenous South Americans. In the near future, with more sampling, it will be possible to better determine the scale of this source of genetic novelties. “We established partnerships to obtain samples from all five Brazilian regions, which gave us greater access to African and Indigenous ancestry,” explains the researcher.

Approximately 36,000 of the nine million new variants described appear to have harmful effects by generating anomalies in their respective proteins, such as loss of function, and may be associated with diseases such as cancer, metabolic dysfunction, or infectious diseases. “What we discover about these variants can be extrapolated

The northeast of the country has more African areas, whereas the southeast and south are more European, and Indigenous heritage is more concentrated in the north

AFRICAN INDIGENOUS EUROPEAN

to peoples that have not been sampled, such as those on the African continent,” proposes Nunes. Knowledge of ancestry and how propensities for certain diseases are distributed across the genome and populations of the world can help make access to precision health more equal, as detailed in the article that follows this one on page 12.

When analyzing genes with signs that they were favored by natural selection (those that occur more frequently than would be expected randomly), many of those genes identified were linked to fertility or the number of children generated, with European ancestral origins. This trait clearly had benefits during the colonization process, during which the Portuguese who settled here quickly increased their presence. Immune response genes of African origin also showed signs of natural selection, reflecting the history of a broad range of pathogens.

The results also offer genetic clues concerning metabolic diseases concentrated in Indigenous ancestry, which are apparently linked to gradual changes in eating habits. “We started eating processed foods, which creates an environment of natural selection for certain genes,” explains Nunes.

One of the study’s challenges was the data analysis, which relied on cloud computing infrastructure provided by Google. “In Brazil, there were no professionals qualified to deal with this volume of information,” says the geneticist, who claims to have learned a lot from the project, which also trained many other people. Another 7,000 genomes have already been sequenced, expanding the search for representation. The authors promise there will be new results soon. Similar initiatives in other countries in the region could also contribute to our understanding of South American history. “We detected a specific component of pre-Columbian genetic ancestry, present mainly in central-western Argentina,” Argentine geneticist Rolando González-José, a researcher at the Patagonian National Center (CENPAT) and head of the Argentine Population Genome Reference and Biobank Program (POBLAR), who is not a participant of the USP project, told Pesquisa FAPESP by email. “Long-held assumptions about population dynamics in the post-contact period do not sufficiently explain the evolutionary history underlying genetic diversity in modern Argentine populations.” Collaborations with Brazilian scientists, in his opinion, can bear fruit. l

The research project, scientific articles, and book consulted for this report are listed in the online version.

Precision for all

Genome information about the Brazilian population could democratize access to personalized treatments and reduce national health care costs

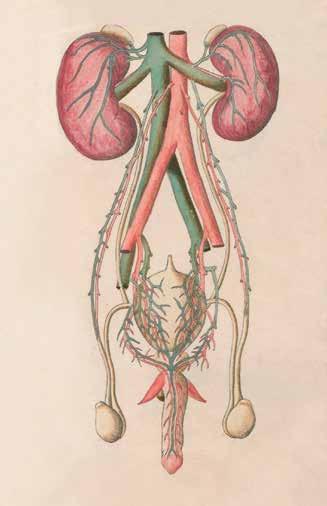

Precision medicine was born out of human genome sequencing and is not a luxury—on the contrary, it enables more accurate diagnoses of some diseases and better and safer medication planning. It is good for the health care system, helping reduce wastage of resources on ineffective procedures, and it is good for patients, who receive the treatment that works best for them, with fewer side effects. However, Brazil suffers from a shortage of the biological parameters needed to know which genetic variants cause which diseases in the country because the sequences used as international references were mostly obtained from people of European descent in the Northern Hemisphere.

The focus on local and regional diversity is not parochialism. Although most of the genome is common to all people, specific modifications can make a significant difference in how genes function, and if defective, they can cause diseases). It is therefore crucial to understand the genetic composition of the Brazilian population, which is why the Department of Science and Technology (DECIT) at Brazil’s Ministry of Health is now creating the National Genome and Precision Medicine Program: Genomas Brasil. In addition to examining Brazilian DNA (see

report on page 6), it encompasses other projects, including Genomas SUS, through which several universities are evaluating the impact of the genome on health.

Started in April 2024, the project aims to sequence the complete genomes of 21,000 Brazilians by November. The goal is to reach 80,000 genomes over the next three years, ensuring the ability to sample a high diversity of ancestries. Additionally, FAPESP has announced a call for proposals to fund the sequencing of an additional 15,000 samples. The aim is to select smaller projects from among scientists who are not currently participating in Genomas SUS. “The foundation will provide a counterpart to the national research,” explains Dr. Leandro Machado Colli of the Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine at the University of São Paulo (FMRP-USP), coordinator of the project. “Samples can be collected anywhere in Brazil, as long as the researchers are based in São Paulo.”

He explains that the strategy adopted by Genomas SUS is to use short-read sequencing, which involves reading the genome from short sections of 150 base pairs, a more cost-effective method. With more complete sequencing to ensure context, the benefits are tangible. “Of the 21,000 samples we already have, we will sequence 200 using long-read technology as a more accurate

MARIA GUIMARÃES photos LUIZ BRAGA

point of reference,” says the researcher. Longread sequencing uses larger sections containing hundreds of thousands of base pairs. In the effort to identify genes linked to diseases, determining the ancestry of each section of the patient's DNA is essential. “We will then know what a certain piece of genetic material in a certain geographic location might say about a person’s health.” The reason is that with sequencing—even the least precise form—it is possible to identify the locations of altered variants on each chromosome and to potentially link them to a propensity for diseases associated with them.

To ensure that the diversity born from interracial mixing is properly represented, Genomas SUS has nine anchor centers across the country: two of them are in São Paulo, and the others are in Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, Paraná, Pernambuco, and Pará. “The Brazilian population has a large representation of peoples who mixed during the country’s formation, including people of Indigenous and African ancestry,” says geneticist Ândrea Ribeiro-dos-Santos, head of the only center in the North region, which is based at the Federal University of Pará and opened in September 2024. “In the Amazon region, Indigenous women were often welcomed into quilombola communities because they knew the secrets and ways of living in the forest,” he explains, based on research results from his group, which identified the sexual asymmetry in genetic contributions.

Just like the center in the Northeast, the Amazon region’s center does not yet have its own sequencing device; thus, the DNA molecules that it collects must be sent for analysis at other centers. To date, 1,800 samples have been sequenced, most of which are from Pará. However, this should change with the inclusion of other states in the region. “Two weeks ago, we were on a health mission in Amapá, where we collected samples in partnership with the state and municipal health departments and the Federal University of Amapá.” Agreements with institutions in Amazonas and Acre are under negotiation, seeking to comply with mandatory ethics issues. The challenges in the region are significant: it can take days to reach some traditional communities, with travel by plane and car followed by days on a boat. However, it is in these remote locations that a unique wealth of the Brazilian territory is found: the genetic and cultural diversity of its human population.

Ribeiro-dos-Santos highlights the importance to the Brazilian national health system (SUS) of

understanding regional or rare genetic variants so that the system can implement treatment protocols for diseases such as diabetes and cancer. There is usually no single gene behind these diseases but a multitude of pathways that can cause dysfunctions in cell replication, leading to cancer, or in metabolism in the case of diabetes, and any altered part can trigger the disease. A successful medication is one that affects the root of the problem. “Without specific knowledge, the patient may die as a result of the treatment, or it may have no effect at all.”

“It is important to know how we can use the genome to understand social inequalities and better diagnose complex genetic diseases,” adds biologist Eduardo Tarazona of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), head of the National Institute of Science and Technology - Genome Ancestry, Diseases, and Bioinformatics in Brazil (INCT-AncesGen) and one of the researchers leading Genomas SUS. “The less European a person is, the less scientists and geneticists know about their diseases.”

One example is an international study in which Colli participated. This study mapped areas of the genome linked to kidney cancer susceptibility and was published in the journal Nature Genetics in 2024. “In previous phases of the study, Brazilian samples were not included out of fear that

racial diversity would reduce the effectiveness of the association analysis,” says the doctor. However, the opposite turned out to be true: when a Brazilian cohort was included in the analyses, a previously unknown genetic variant was found that was present in people of African descent.

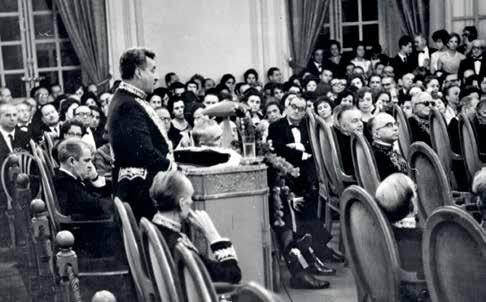

When American geneticist Francis Collins, then director of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), gave a lecture at FAPESP in 2014, geneticist Iscia Lopes-Cendes of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) asked him about the idea of carrying out a population-wide genome project in Brazil. His response was that it was unnecessary since human genetic diversity was already well described. “He was completely wrong. North Americans don’t understand that other Latin populations are not the same as Mexicans,” she laughs, not convinced by the answer. In 2015, Lopes-Cendes founded the Brazilian Initiative on Precision Medicine (BIPMed). “It is the first genome database in Latin America,” she says.

“We have a partnership with the Genomas Angola (GENAN) project, and we have already collected 750 samples,” adds the researcher, who

is supervising an Angolan doctoral student on the project. Lopes-Cendes hopes to find genetic variants that have not yet been described and that could have practical uses in both countries, which have ancestral links as a result of slaves brought over during the colonial period.

“If there is a place where precision health care can be made available to everyone, it is in Brazil,” she says. “We have SUS.” She refutes the notion that the technology would be available only to rich countries and people. On the contrary, she believes that it can be an important tool for preventive medicine. “Personalized health care allows for more efficient treatments, at the right dosages, for the right people, with fewer side effects and lower costs.”

Together with geneticist Thais de Oliveira, a postdoctoral researcher at her lab, she published an opinion piece in the journal Annual Reviews of Genomics and Human Genetics in January, emphasizing the importance of public databases of genome information about Latin American populations. Argentine geneticist Rolando González-José of the Patagonian National Center (CENPAT), head of the Argentine Population Genome Reference and Biobank Program (POBLAR), agrees. “It is important for governments to make agreements on connecting genome databases in the region,” he suggested in an email to Pesquisa FAPESP. Like Colli, he says that short-read sequencing has benefits in regard to optimizing available budgets.

The DNA do Brasil project, which is part of the Genomas Brasil Program, aims to contribute to precision health by providing a detailed overview of Brazilian genetic variation. The pharmaceutical industry could also benefit from these advances. In 2021, USP geneticist Lygia da Veiga Pereira, the founder of the project, used the knowledge that she acquired throughout her academic career to create a startup called gen-t, now funded by FAPESP's Innovative Research in Small Businesses program (PIPE). “We are building a health, lifestyle, and multiomics data infrastructure with 200,000 genomes, which can be used by the industry to accelerate the search for new drugs,” she explains.

The initiative could complement potential implementations of new strategies by SUS. “We are just at the beginning of understanding the impact of genomics on population health,” says Colli. l

Interview Luiz Henrique Lopes dos Santos

The call of logic

A philosopher revisits his academic journey and reflects on more than 30 years working with research funding management at FAPESP

ANA PAULA ORLANDI E FABRÍCIO MARQUES portrait by LÉO RAMOS CHAVES

In 1972, at just 22 years of age, Luiz Henrique Lopes dos Santos became a faculty member in the Philosophy Department at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP), where he had earned his bachelor’s degree and is now a senior professor. At the time, he was part of a group of young researchers invited to fill the gap left by the compulsory and early retirement of professors persecuted by the military regime. Under the guidance of big names such as Otília Arantes, José Arthur Giannotti (1930–2021), and Oswaldo Porchat (1933–2017), Santos forged a career that spanned the philosophy of logic and history of philosophy, and he worked at institutions such as USP, the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), École Normale Supérieure in Paris, Paris Diderot University, and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). His academic production involved mainly the works of German mathematician, logician, and philosopher Gottlob Frege (1848–1925), the topic of his PhD thesis defended in 1989 at USP, and of Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951). One of his most notable contributions was the translation into Portuguese, accompanied by a critical introduction, of Tractatus logico-philosophicus, written in 1921 by Wittgenstein. In addition to his teaching and academic work in philosophy, he was involved in the management of research funding. For more than three decades, he was the philosophy and humanities coordinator of FAPESP's Scientific Board where he assessed thousands of projects proposed by researchers and helped formulate programs for the Foundation. His work at FAPESP included the scientific coordination of Pesquisa FAPESP magazine for 21 years and the formulation of the Foundation’s Code of Good Practices in 2011. On a summer afternoon in February 2025, he granted the following interview. Shortly afterward, Lopes dos Santos was diagnosed with cancer and passed away in July.

Where did your interest in philosophy come from?

When I joined the high school movement, at approximately 15 years old, I began reading political philosophy and soon moved on to philosophy in general. However, when it was time to choose which career to pursue, I was undecided between the more classic route of law, in my case, and philosophy. I come from a family with many lawyers, and my father, who was a stockbroker, wanted me to study law. I took the university entrance exam for both courses, and in 1968, I began law at USP in the morning and philosophy at PUC-SP (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo) in the afternoon.

When did you decide your professional path?

In the 1960s, for an academic career, the natural path for a philosopher was minimally institutionalized. This caused a certain degree of insecurity. The person who put me on the philosophy path was Otília Arantes, who was my professor at PUC and one of my main academic

FIELD OF EXPERTISE

Philosophy of logic and history of philosophy

INSTITUTION

School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP)

EDUCATION

Bachelor’s degree (1971) and PhD (1981) from USP

references. She showed me that such a professional path was possible. When I decided to transfer my philosophy course to USP, mainly because of Otília’s influence, I already felt that the balance was tipping toward philosophy. I took the entrance exam again and enrolled in the class of 1969.

How was the transition to studying philosophy at USP?

It was a little frustrating. At the time, the department had lost professors who had been persecuted by the military regime. In my first month, I had a class with José Arthur Giannotti, who was soon forced into early retirement, just like Bento Prado Júnior (1937–2007). Others had to flee Brazil, such as Ruy Fausto (1935–2020). The department was left completely understaffed. In mid-1969, I went ahead and bravely scheduled an interview with Giannotti at CEBRAP (Brazilian Center of Analysis and Planning), which he helped to fund. I said, “I came to study philosophy at USP because of professors like yourself, who are no longer here. What do I do? Giannotti was preparing an article about Durkheim (1858–1917), who is a sociology theorist, and asked me to read some texts and make a presentation for him. I passed the test, and from then on, I informally began what is now called scientific initiation under Giannotti’s guidance. Every 15 days, I would go to his house to talk about Kant. We became good friends.

Did you graduate in law and philosophy?

For three years, I took both courses simultaneously. It continued like this until Oswaldo Porchat’s assistant, who was my logic professor, accepted a great job offer in financial terms at Banco do Brasil. At the end of 1970, Porchat came looking for me and said that if I finished the course the following year, I could be hired as his assistant. To be able to complete two years in one, I had to give up law, but I left it knowing that I was beginning a career in philosophy. The call from Porchat was decisive because I was undecided between aesthetics and logic.

What was it like becoming a university professor at such a young age?

Of course, I was very nervous. I was 22 years old, younger than most of the stu-

dents. But, as I said, the department was really understaffed. I remember that other professors my age were hired such as Carlos Alberto de Moura, Ricardo Ribeiro Terra, and Olgária Mattos. Some of them were invited by Giannotti to take part in a seminar at CEBRAP, which ran between 1971 and 1973. This experience was truly important for my training because of the high level of the debates.

Did the news of the job leave your father more relaxed regarding your career choice?

He was relieved when he heard the news because he was extremely concerned about my future. Unfortunately, he died soon after, at age 49, at the end of 1971. He was a well-off man, but he was never rich. He preferred traveling to saving money. With his death, my mother, who was a housewife, had to support herself. She went to work with her brother and decided to study social sciences. At around 43 years of age, she passed the entrance exam at USP in the 1970s. We used to cross paths at university, me as a professor and she as a student. After graduating, she went to work at the Support Foundation for Imprisoned Work-

ers, where she remained until she retired in the 1990s. Her role was taking care of the literacy part, and in this job, she had contact with inmates such as Chico Picadinho, the famous serial killer from the 1960s and 1970s. My mother was very dynamic and even back when she was a housewife, she participated in progressive Catholic activism. In fact, her actions even influenced me to join the high school movement in 1964, just before the military coup.

What did you study for your master's degree?

I do not have a master’s degree. I started doing the research for my master’s degree in 1972 at USP on mathematics, logic, and the German philosopher Gottlob Frege under Porchat’s guidance. However, when I was about to start writing the dissertation, Porchat called me to be his righthand man not only at the Center of Logic, Epistemology, and History of Science but also at the Department of Philosophy that he was going to set up at UNICAMP. This was in 1975. On accepting the invitation, he warned me that it would be unfeasible to continue the research for my master’s degree at that time.

How did the idea of the center come about?

When my father died, my mother had to go to work, and at the same time, at around age 43, she enrolled in the social sciences course at USP

Porchat had the idea to create it at USP, but the department of philosophy rejected the proposal because of ideological differences. We were living in a highly polarized environment. Those of us in the field of logic were considered reactionary and were alienated because some people from the department believed that the discipline was linked to capitalism. However, Porchat was a good friend of the then-vice dean of UNICAMP, engineer and physicist Rogério Cesar de Cerqueira Leite (1931–2024). He told the dean of UNICAMP at the time, Zeferino Vaz (1908–1981), that it was a golden opportunity for the university in the field of philosophy. Zeferino fell in love with the idea of an interdisciplinary center and provided the material resources that no initiative linked to philosophy had in Brazil at the time. This made it possible, for example, to bring in visiting researchers from abroad and organize international conferences. The center was founded in 1977 and remains active.

What was its composition?

It was composed of researchers from the Department of Philosophy at UNICAMP and from areas such as mathematics, sociology, physics, linguistics, and theology. I was assigned to make the link to the Institute of Language, where I gave classes between 1977 and 1981.

Was there a community of logicians in Brazil?

There was, but it was, and still is, very small. The most well-known was Newton da Costa (1929–2024), who was at USP at the time but was a major influence on some members of the center, such as Ayda Arruda and Itala D’Ottaviano. At that time, I also became closer to Newton and his paraconsistent logic, after having published a few papers. Beyond its contributions to the realm of logic, the center was fundamental in shaping an academic philosophy community in Brazil. At the time, several centers had very qualified people spread across various states in Brazil. By connecting these islands of knowledge through its activities, the center contributed, for example, to the creation of ANPOF (the National Association of Graduate Studies in Philosophy) in 1983.

What did you study in the PhD program?

My PhD, supervised by Porchat, was an extension of that unfinished research from my master’s degree. I sought to understand how Frege, in the second half of the nineteenth century, caused a break from the Aristotelian model of logic, which had prevailed for approximately 2,000 years. To answer the questions that arose during his research into the fundamentals of mathematics, he was obliged to rethink logic. Thus, he conceived what we today call mathematical logic. I was hired by UNICAMP as a professor with a PhD on the condition of finishing my thesis in 1980, but it was a battle to complete the research. Between 1975 and 1978, I barely touched my thesis because I was immersed in the bureaucracy of the department and center, teaching classes, and holding seminars. In 1978, I returned to my thesis and defended it in 1981. The work was published in 2008 as O olho e o microscópio (The eye and the microscope; Nau Editora]).

The center that we created at UNICAMP in the 1970s was fundamental in shaping the academic philosophy community in Brazil

that I wrote to explain the place of the Tractatus in the history of philosophy is longer than the book itself. Giannotti had already translated this work and written an introduction to it back in 1968. It was the second translation in the world, after the English one, and it was a Herculean task on Giannotti’s part, considering that Wittgenstein had only been dead for 17 years. He was a contemporary, and there was practically no literature on his work. In the 1990s, EDUSP proposed that Giannotti produce a new edition of his Portuguese version.

Giannotti himself said that the work that he did in the 1960s contained many errors. Do you agree?

You stayed at UNICAMP until 1981. Why did you decide to go back to USP? I returned for personal reasons. I had separated from my wife, and my children, who were still small, lived with their mother in São Paulo. Since I did not want to be on the road all the time, I returned to the department of philosophy at USP. At that time, Giannotti had also returned to USP, and together, we taught Introduction to Philosophy to first-year undergraduates. He gave what he called an introductory lecture, and I held seminars with the students while dissecting the texts, reading, and rereading them several times. We educated several generations of philosophers.

In the 1990s, you translated Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus for EDUSP, a book written in 1921 by Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. What were the challenges of this work?

It is not easy translating such complex writing as that of Wittgenstein, who is one of the great philosophers of language, from German to Portuguese. To give you an idea, the introductory study

There were some errors, not so much in the translation from German, but conceptual errors, because there was very little familiarity with the field at the time. This is the case with the specific German philosophy terms from the nineteenth century that related to philosophers such as Franz Brentano (1838–1917), who few people had read in Brazil. Upon receiving an invitation from EDUSP in the 1990s, Giannotti asked me to review the work, but I felt that it would become Frankenstein’s monster and proposed redoing the translation. Giannotti agreed and handed the mission over to me.

Between 1986 and 2007, Giannotti was in charge of CEBRAP’s Professional Training Program. What was your role in it?

This was an interdisciplinary training program aimed at postgraduate students from different fields of knowledge, which was made possible by an agreement between CAPES (the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education) and CEBRAP. It was difficult to enter. Over the course of two years, students participated in activities such as seminars on anthropology, political science, sociology, economics, and philosophy. The meetings were held twice a week, and the teaching staff included Paul Singer (1932–2018) and Ruth Cardoso (1930–2008). I actively participated in the philosophy center until going to Paris in the late 1990s.

You joined FAPESP in 1986. What was the Foundation like at that time?

In 1986, Flavio Fava de Moraes, who was the scientific director at FAPESP, invited me to substitute for João Paulo Monteiro (1938–2016) in the field of philosophy on the Board of Human and Social Sciences. There was no general coordinator, but the role, because of his personality and background, was filled by Leôncio Martins Rodrigues (1934–2021). There was Boris Fausto (1930–2023) in history, Maria Alice Vanzolini in psychology, Cláudia Lemos in linguistics, and me in philosophy.

The workload at the time was small compared to what it is today, right? We would go in on Mondays, and in the first part of the meeting, we would discuss Sunday’s soccer results—Boris, like me, was a die-hard Corinthians fan. We had approximately 15 or 20 proposals to analyze each week. Each of us would get around four. We studied them, produced a report, and decided whether to approve the grant or funding. Then, we went home. It was another world. A change had just taken place that would transform the profile of FAPESP in the shape of an amendment to the State Constitution proposed by congressman Fernando Leça and approved in 1983. It determined that allocations from the Treasury to FAPESP, then fixed at 0.5% of tax revenue, be calculated based on the current year and allocated in twelve monthly installments. Previously, the calculation was made on the basis of the previous year’s revenue, and by the time that the funds arrived, they were eroded by 13 months of inflation. After the Leça Amendment, the Foundation became aware that it had financial power to reach much further. This was completed in 1989, when the new State Constitution increased funding for the Foundation to 1% of the state’s tax revenue.

In practice, how did this ambition materialize?

One of the milestones was the thematic projects initiative. FAPESP had had large projects in the 1960s and 1970s, but they were one-offs, such as the biodiversity survey of the Amazon performed by zoologist Paulo Vanzolini (1924–2013) in the 1960s. Thematic projects were the first regular line of major funding. A discussion arose within FAPESP about whether

it was worth giving so much money to the humanities—it was one thing awarding grants for master’s degrees, but approving the budget for a thematic project was something very different. The credit goes to Fava, who really put his foot down. One of the first thematic projects in humanities was by filmmaker Jean-Claude Bernardet, from USP, whose product was a film. I remained a philosophy coordinator until 1989. Leôncio left, and Fava invited me to take over as adjunct coordinator. Until 1989, area coordinators would go to FAPESP once a week and did not have any organic relationship with the Foundation. With the creation of the adjunct coordinator role by Fava, the adjunct coordinator began to mediate between the area coordinators and the scientific director. In 1993, José Fernando Perez took over the Scientific Board, he asked me to continue, and I accepted.

In 1997, you stepped away from FAPESP to spend a period in France but returned to the Foundation upon returning to Brazil. How was that return?

I spent two years in Paris as a visiting researcher at the École Normale Supérieure

and as a professor at Paris Diderot University. Paula Montero replaced me. When I returned, in early 1999, I was called to work with Paula because there was already the need for two adjunct coordinators in the humanities. Perez had his own creative dynamic and restructured the Scientific Board. He increased the number of adjunct coordinators, and every week, we met for two or three hours in a discussion circle to discuss what was happening. Many FAPESP programs were born from these meetings. The vibrancy of Perez’s tenure came from having people from all areas talking to one another. This was taken to an even larger scale when Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz took control of the Scientific Board in 2005. Everything went through the adjunct coordinators. Once a month, 15 adjunct coordinators met and spent the entire afternoon talking.

How many scientific directors have you worked with?

One of the first thematic projects in humanities was by filmmaker Jean-Claude Bernardet from USP, whose product was a film

There were four. The last tenure, of Luiz Eugênio Mello, was heavily disrupted by the pandemic. He worked miracles. He replaced me as an adjunct coordinator with Ângela Alonso, but I got to know her personally only at the end of his term. He kept the Scientific Board working and accomplished important things such as the effort to create research on COVID-19 and the first projects from the Generation Program, which was aimed at younger researchers still without employment relationships. He also promoted the adoption of equality and inclusion policies. Fava’s administration gave FAPESP greater ambition and created an institutional structure so that the Foundation could work creatively. Perez took advantage of this and was assisted by his personality. He was the embodiment of enthusiasm. When Brito took over, many programs were already in their fourth or fifth year. Brito, also because of his personality of being rational and systematic, brought order, formalized things, and assessed what was working and what was not. He improved and refined the existing programs and began a strong push to internationalize research in São Paulo.

What was your contribution to implementing the Public Education Program?

One of the revolutions that Perez implemented was creating technological research programs, especially in partnership with companies. However, he had the wisdom to consider a broad view of applied research. Research in the humanities can be applied and result in the formulation and implementation of public policies. Perez believed that applied research requires a partner who will potentially use it. From there, the idea emerged of starting with public education and conducting research in partnership with public schools. We called Maria Malta Campos from PUC-SP and the Carlos Chagas Foundation to assist us. I coordinated for a period and passed the baton to Marilia Sposito. Because it was successful, there was demand and partnership; it had everything, and then, the Public Policy Program was launched.

How did Pesquisa FAPESP magazine come about, of which you were the scientific coordinator between 2001 and 2022?

The concept was born out of a conversation between then-Editor-in-Chief Mariluce Moura and Perez. I came on board when it was already in motion because I was in Paris when the idea first came up. From the beginning, the goal was to create a magazine, not for FAPESP, but for scientific communication in Brazil and especially São Paulo. Second, it had to be a journalistic outlet and guided by scientists. For this, it was fundamental for the magazine to be a project linked to the Scientific Board. This enabled the creation of standards that guaranteed the quality that the magazine developed.

Do you mean, for example, that the magazine has a Scientific Committee composed of area coordinators and adjunct coordinators from the Scientific Board?

From the outset, the articles in the magazine were read by the coordinators of their respective areas. The idea was to have a balance between journalistic language and scientific rigor. On the one hand, some people said that the magazine was not rigorous enough from a scientific point of view. On the other hand, it presented things that were difficult for the lay public to understand. Criticism from both sides indicated to us that the

The good practices policy should be pedagogical, but one way of educating is by not allowing the wrong things that happen to go unpunished

which resulted in a text in early 2011 that today is on the FAPESP website. Then, Brito asked me to write a preliminary draft of a Code of Good Practices. For six months, I dedicated myself to this task. I discussed the preliminary draft with Celso Lafer, then the president of FAPESP, who gave it the necessary legal backing. The second version was completed, which Brito circulated among the associate deans and scientific societies. We conducted a wide-scale consultation and published it at the end of 2011. Ten years after the code, all of the public universities in São Paulo have a good practices commission.

Afterward, you began overseeing the cases of misconduct that reached the Foundation.

magazine was on the right path by taking the middle road.

In 2001, you and Professor Perez wrote an article about conflicts of interest in research. Was this the beginning of the debate that would lead to the Code of Good Practices a decade later?

It was a localized issue. FAPESP did not have a conflict of interest policy because there had never been a serious problem related to it. There was a serious problem with a research project that assessed the health risks of asbestos. A large amount of money was invested, and the results were favorable to asbestos. It was subsequently discovered that the researcher had a relationship with a company that produced asbestos.

How did the Code of Good Practices come about?

It just came out of the blue for me. In September 2010, I had undergone appendix surgery in Rio, and while recovering, I received a request from Brito to study what existed in the world regarding good practices. I performed this study,

I always insisted, and Brito strongly supported this, that the main axis of the good practices policy must be pedagogical. However, one way of educating is by not allowing the wrong things that happen to go unpunished. It is necessary to have a rigorous and fair system for receiving complaints, investigating, and ensuring the transparency of the results. This requires a lot of work. When you receive a complaint, you have to guarantee time for a defense. It is the institutions that are equipped to investigate what happens on their premises. They can do so impartially and objectively, but there are situations in which they can be swayed by corporatism. In such cases, it is necessary to reject the institution’s investigation, which results in a political crisis. I took care of this from 2011 until 2023. The majority of the cases did not cause confusion, but the few that did were difficult.

Do you divide your time between São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro currently?

Yes. I am a senior professor at USP and supervise postgraduate studies in philosophy. Additionally, I am a collaborating professor at UFRJ, where I participate in seminars and teach short courses. As I am retired, I now have more time to dedicate to academic writing. In the past five years, I have been delving into Aristotle’s way of thinking and have already published some articles on the topic. But I am in no rush. Theoretical production in philosophy is a task that requires patience. l

Linking universities and businesses

Survey maps activities at 240 academic laboratories to understand how they interact with the industrial sector

FABRÍCIO MARQUES

How do universities and companies in Brazil work together to generate knowledge? Two researchers from the School of Economics, Business, and Accounting of the University of Sao Paulo at Ribeirão Preto (FEARP-USP) attempted to answer this question by examining which factors were associated with interaction between companies and 240 public university laboratories in São Paulo State. Some of the study’s conclusions, published in December 2024 in the journal Science and Public Policy, confirmed the results of similar studies conducted in other countries: Compared with laboratories that are less involved with companies, those that have more engagement stand out for their skills in prospecting and attracting private initiative partners, have access to advanced equipment, and

have more permanent researchers to support joint projects. They also receive more support from their departments to facilitate cooperation.

However, there are peculiarities in Brazil, one of which is that the senior level of faculty staff does not interact significantly with industry, an aspect that is more readily observed in the US and Europe with the gradual formation of collaboration networks over professors’ careers. Among the 240 São Paulo State laboratories analyzed, only 55 were led by tenured professors, the highest level in the public academic career, while 114 were led by lecturers or associate professors, and 71 were led by fellow professors. According to the research coordinator, FEA-RP-USP researcher Alexandre Dias, this outcome highlights the marked differences between the science, technology, and innovation (STI) systems in Brazil and those in more developed countries.

“In public Brazilian universities, research and extension are indivisible, and academics at their highest career level usually get closely involved in the management of their units. The predominance of public research funding, the rewards system, and the criteria by which faculty staff are assessed for career progression do not contribute to individual performance aligned with interaction with the industrial sector,” says the researcher, who conducted the survey with Leticia Ayumi Kubo Dantas; he advised on her master’s dissertation, defended in 2023. The two are part of the Center for Research in Innovation, Technological Management, and Competitiveness at FEA-RP-USP.

The key objective of the study was to analyze the degree of “academic engagement” among research laboratories in Brazil. This concept, proposed in 2013 by Markus Perkmann of the UK’s Imperial College London Business School, brings together a set of formal and informal activities that modulate the interaction between universities and the business world. “For a long time, researchers have striven to understand what drives the commercialization of technologies and academic entrepreneurship as phenomena to analyze university–corporation interaction. In the last decade alone, interest has also grown in investigating other channels by which links are forged between universities and companies,” Dias explains.

Laboratory data from seven institutions were analyzed—state-level institutions São Paulo State University (UNESP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), and the University of São Paulo (USP), as well as the federal universities of São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Carlos (UFSCar), and ABC (UFABC), and the Aeronautics Technology Institute (ITA), whose leaders agreed to complete an online questionnaire. In terms of knowledge areas, 20% of the laboratories worked with assorted engineering disciplines—15.8% health sciences, 14.5% biological sciences, 12.5% exact and earth sciences, and 9.6% agrarian sciences; additionally, 27.5% operated across multiple areas.

The research facilities were separated into three categories: The largest group, with 112 laboratories, presented minimal, sporadic involvement with companies. The second group comprised 84 laboratories and demonstrated partial engagement with private initiatives. The third group, consisting of 44 laboratories, stood out for its interaction with companies through different channels: collaborative research (52.3%), research contracts (40.9%) and the expansion of facilities funded by private sources (34.1%). These laboratories also participated in informal interactions, such as postgraduate student train-

Laboratory for New Materials & Devices at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Bauru: Partnership with overseas company

ing in industry projects (15.9%) and consultancy services (22.7%).

The economic value of equipment in these highly engaged laboratories, along with the number of permanent researchers, was found to be three times greater than that in laboratories interacting minimally with companies. Support from departments with which the laboratories are associated was more significant among those engaging significantly: 32% stated that they received sufficient support, compared with 13.4% of those having minimal engagement and 22.6% in the intermediate category. According to Leticia Dantas, the lead author of the study, the research demonstrates the importance of enhancing university laboratories and ensuring a robust structure and larger teams. “This not only boosts academic engagement but also makes laboratories more attractive for partnerships with industry, multiplying the impact of research in the productive sector,” she says.

Economist Eduardo da Motta e Albuquerque, of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) and a researcher at the university’s Center for Development and Regional Planning (CEDEPLAR), who did not participate in the study, agrees that one of the takeaways of the article lies in demonstrating the importance of enhancing research laboratories in the Brazilian university system. “Interaction attracts funds to laboratories and has an impact on the quality of research, bringing new themes for investigation to the university,” says Albuquerque, a specialist in the formation of innovation networks and the forging of links between universities and companies.

“It would also be interesting to widen the survey and find out which industrial segments interact most with the laboratories,” he says. He would bet that there are noteworthy interactions occurring in the agricultural sector, given its economic importance for Brazil, but very little going on with the large pharmaceutical companies, which base their research at overseas headquarters. Albuquerque sees a warning sign in an outcome presented in the article, according to which no correlation was found between the engagement of laboratories with companies and the support provided by the Technological Innovation Centers—offices created under the 2004 Law of Innovation—at public science and technology institutions to manage intellectual property and lend support to university–industry interaction. “The country invested heavily to set up these centers; maybe it’s time to have another look at their function,” he says.

The relationship between universities and companies needs to overcome a series of obstacles, says chemist Elson Longo, an emeritus professor at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) and director of the Center for the Development of Functional Materials (CDMF), one of the Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDC) funded by FAPESP. “Some of the interaction comes through consultancy services offered by researchers to companies. There needs to be more ambitious cooperation to obtain new knowledge and develop innovative products,” he says, giving examples of projects set up by the RIDC in recent decades with the steelmaking and ceramics and cladding industries, which brought changed production methods and productivity gains—the institution currently has partnerships for the development of inputs for cosmetics factories. He also draws attention to the low levels of interest among multinationals in collaborating with Brazilian groups, as a rule preferring to use research and development (R&D) structures at their headquarters.

Emilio Carlos Nelli Silva, of the Department for Mechatronics and Mechanics Systems at the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (USP), sees marked differences between interaction among universities and companies in Brazil and this type of interaction in other countries. “The relationship is more fluid in the United States because companies hire PhDs to work in their R&D centers, and liaising with university groups is done through them. Here in Brazil, as there are still very few PhDs in companies, other actors are involved, and sometimes, there is a lack of understanding that research can come up against obstacles,” he adds.

Funding is another difference. “It’s not our culture here to invest risk capital in promising

Engaged laboratories interact with companies through multiple channels

research, although in certain areas like petroleum and electricity, companies have a legal obligation to invest in R&D, and this creates good opportunities for research partnerships,” he says. Silva is the vice director of the engineering program at the Greenhouse Gases Innovation Research Center (RCGI), one of the Applied Research Centers/Engineering Research Centers funded by FAPESP in partnership with companies—in this case, Shell. The program offers nonreimbursable funds for corporate projects, requires the counterpart funding to be equal to or to exceed the public investment, and engages university research groups of excellence. “The centers create new paradigms for collaboration between universities and companies and bring clear benefits for society.”

According to physicist Carlos Frederico de Oliveira Graeff, of the School of Sciences at UNESP’s Bauru campus, liaising between universities and industry has improved, but there are still things to work out. “Industry doesn’t always get solutions for its problems from academia, just like researchers who make efforts to interact don’t necessarily find companies interested in their expertise,” he says. Graeff runs the Laboratory for New Materials and Devices, which is one of the research facilities participating in the FEA-RP-USP study and is classified among the laboratories with high levels of engagement. The facility, which is currently seeking new materials for use in electronic devices such as solar cells and transistors, is cooperating with two companies: One is a Singapore-based startup seeking uses for the discarded waste of industries that use flies as raw material to produce

animal protein. The challenge is to make use of large volumes of discarded fly exoskeletons (outer shells), which are rich in the biomolecule melanin. Graeff’s group is looking at possible applications for the compound in batteries and capacitors because of its potential for storing energy. The other is a Brazilian company, to which the laboratory transferred useful technology for the production of perovskite solar cells, developed as part of a project supported by Petrobras.

Graeff believes that interactions could be more gainful if Brazil had wider access to multiuser platforms and analytical centers that company researchers could call upon. “Startups need cutting-edge equipment to develop products, and they don’t often have the funds to acquire it,” says Graeff, the former coordinator of Strategic and Infrastructure Programs at the FAPESP Scientific Department. The physicist also considers it pertinent to expand operations at research institutions working with applications at an intermediate level of technological maturity, which still require effort and investments to take a product to market. “The Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) performs this function in agribusiness, and the National Service for Industrial Training (SENAI) has reached out to many different industrial segments through its Innovation Institutes,” he says. Graeff also highlights the model used by the FAPESP Science Centers for Development (CCD), which bring together researchers from state-level institutes, universities, companies, and government bodies in the quest for solutions to issues in society, from agricultural output to urban mobility. “These centers are mobilizing the system around mission-oriented research,” he concludes. l

Laboratory for Fuel Cells and Reactive Conversion at POLI-USP: Innovation and greenhouse gases

Good ball skills and reasoning

The volley by striker Richarlison that sealed the win over Serbia at the 2022 World Cup

Players from elite Brazilian soccer teams present better memory, planning ability, and mental versatility than nonathletes of the same age do

GISELLE

SOARES

On Thursday, November 24, 2022, Brazilians watched attentively as the national team played its opening match against Serbia at the World Cup in Qatar. More than two years later, perhaps few remember the game, which ended with a 2–0 victory for Brazil, but the striker Richarlison’s volleyed goal remains etched in the memories of soccer fans. With his left foot, he cushioned the ball crossed with the outside of the boot by Vinicius Junior and, in a choreographed leap, struck a precise shot with his right foot past the opponent’s goalkeeper. Chosen as the goal of the tournament in a public poll by the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA), the moment illustrates the athlete’s profile on one of his social media accounts.

Moments such as these, which captivate even those who do not follow the sport, do not rely exclusively on luck or extraordinary physical ability. In addition to a deep technical understanding of the game, athletes who pull off such moves demonstrate superior abilities in processing information and making decisions than individuals of the same age and educational level do, according to a study published in January in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)

In this study, an international group of researchers that included Brazilian Alberto Filgueiras, of Central Queensland University in Australia, investigated the personality traits and cognitive abilities of 153 players from teams in Brazil’s top league, Série A, and 51 players from the top division of Sweden’s national league—the athletes ranged from 17 to 35 years of age. According to the authors, this is the most extensive psychological and cognitive assessment conducted on the largest number of elite players to date.

Previous studies included few athletes at the peak of their careers and only some of the tests.

In the study published in PNAS , each player underwent three sets of neuropsychological tests. The first defined the personality traits of the participants. The other two tests, one of which was developed by Filgueiras and colleagues and published in 2023 in the journal BMC Psychology, measured their cognitive abilities—characteristics such as creativity, mental flexibility, and shortterm memory—as well as the ability to sustain attention, plan and solve problems, and inhibit inappropriate responses.

For all the cognitive tests, the soccer players achieved higher average scores than the reference values for individuals of the same age group or for members of the control group, which was composed of 124 Brazilians from the same age range and educational level who did not play soccer.

The superiority of the soccer players in terms of these cognitive characteristics, important for quick reactions, changing strategies, or creating chances in the heat of the game, was complemented by personality traits that also favored self-confidence and teamwork. Compared with the participants in the control group, the athletes presented higher levels of extraversion, openness to new experiences, and conscientiousness (a trait linked to ambition, self-discipline, focus, and self-control). In turn, the control group scored higher than the athletes in characteristics such as agreeableness and neuroticism, with the latter referring to the tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anxiety, anger, frustration, and guilt.

These results, according to the researchers, suggest that elite soccer players tend to be more sociable, disciplined, and adaptable than individuals in the control group are. In contrast, compared with soccer players, nonathletes demonstrated greater emotional instability and

a greater tendency to follow social norms without questioning them.

As a continuation of the study, the authors used the personality traits and cognitive performance of all the participants to teach two artificial intelligence programs to distinguish elite soccer players from nonathletes. They also used one of these programs to identify which personality traits and cognitive abilities contributed most to recognizing who was a top-level soccer player. Afterward, exclusively based on the personality data and cognitive test results, they asked the program to select who were the elite athletes— the algorithm chose correctly 97% of the time.

For the final stage of the research, to verify whether these characteristics could predict the players’ on-field performance, the researchers compared the psychological profiles and the cognitive abilities of the Brazilian athletes with their actual performances (goals, shots on goal, passes, and dribbles) during the 2021 season of the Brazilian Championship, the Copa Sudamericana, and the Copa Libertadores da América—the Swedish players were excluded from this phase because of a lack of data. The players who scored higher on the scales of conscientiousness and openness to new experiences scored more goals, whereas those with better memory successfully completed more dribbles.

“Our results show that cognitive abilities, such as planning and mental flexibility, are directly linked to performance in soccer, influencing metrics like goals, dribbles, and assists,” said Italian psychologist and neuroscientist Leonardo Bonetti, a professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, a researcher at the University of Oxford in the UK, and lead author of the study in PNAS, to Pesquisa FAPESP. A graduate in classical guitar and psychology with a PhD in neurosciences, Bonetti studies the brain mechanisms behind memory and cognitive abilities.

“Our article aims to identify a typical cognitive and personality profile of elite athletes,” explains Filgueiras, coauthor of the study. “Until now, we have known that elite athletes have better physical abilities and technical-tactical knowledge than the rest of the population, but we were always met with the stereotype of the unintelligent athlete, who only has physical skills,” he says. The researchers have shown that their mental characteristics, particularly personality and executive functions, differ from those of the general population. “It would be a sort of sports intelligence, focused on solving problems and making effective decisions on the soccer field.”

One finding that attracted the attention of researchers was the low level of agreeableness among elite athletes; in other words, a tendency to question direct orders. “This makes us reflect on the role of the coaches, who often give a lot of instructions and commands. Interestingly, these athletes do not obey them automatically. They question them and need to be convinced that the instructions make sense before following them,” says Filgueiras. “This is not about impulsiveness but rather about autonomy and confidence in their own decisions. If a coach says, ‘Do it this way,’ the response will likely be ‘Why? The other way seems better,” the Brazilian psychologist adds.

This trait, according to the researchers, could be linked to what is commonly known as “game intelligence,” a skill that involves not only awareness of the environment but also the ability to adapt to sudden changes and maintain stable performance. Ricardo Picoli, psychologist at Esporte Clube Bahia and coordinator of the Specialization Program in Exercise and Sport Psychology at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), states that this ability is particularly relevant in practical situations, such as changes in formation or shifts in game scenarios. “Players with this more developed capacity are able to better assess long-term career opportunities, avoiding choices that may seem attractive initially but could be harmful in the future,” adds Picoli, who did not participate in the study.

The authors of the study from PNAS argue that the results could be used by clubs and coaching staff to improve training methods by incorporating cognitive and psychological testing into player evaluation and development. “Analyzing these skills allows for a more precise approach

A dispute for the ball between Felipe Luis, of Flamengo, and Carlos Palacios, of Internacional, in a Série A match during the 2021 Brazilian Championship

to be taken in selecting athletes, defining roles within the team, and refining training strategies,” affirms Bonetti. “Success in soccer depends not only on physical attributes but also on psychological traits and cognitive abilities, which play an essential role in the performance of high-level players.”

Using psychological assessments to try and understand and improve athletes’ performance is not new. In recent decades, sports psychology has sought to map how psychological factors influence a player’s performance and how they can be applied to enhance training, explains sports psychologist Kátia Rubio, a senior associate professor at the School of Physical Education and Sport of the University of São Paulo (EEFE-USP) and coordinator of the Olympics Study Group (GEO-USP), in an earlier study published in 2007 in Revista Brasileira de Psicologia do Esporte

In high-performance sports, these factors were identified through psychodiagnosis, which assesses the athletes’ personality traits and emotional state during training and competition to identify intervention strategies that alleviate symptoms of suffering and improve emotional well-being. “With the result of the diagnosis, conclusions can be made about individual or group characteristics that support the selection of new athletes for a team, adjusting training, individualizing technical-tactical preparation, choosing the strategy and

tactics to use in a competition, and optimizing psychological states,” writes the researcher in the article from 2007.

In an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP, Rubio, who did not participate in the study led by Bonetti, says that the search for psychological profiles in sports began between the 1960s and 1970s, when psychology tried to establish itself as a science through psychometrics. “In the context of the Cold War, sports were seen as a way of demonstrating power, and there was a lot of interest in making it more predictable, including trying to identify profiles of elite athletes,” recalls the researcher. “However, more than five decades later, there is still not a definitive model that can predict, categorically, who will be a champion. Sporting performance is multifactorial, influenced by psychological, environmental, and social aspects,” he ponders.