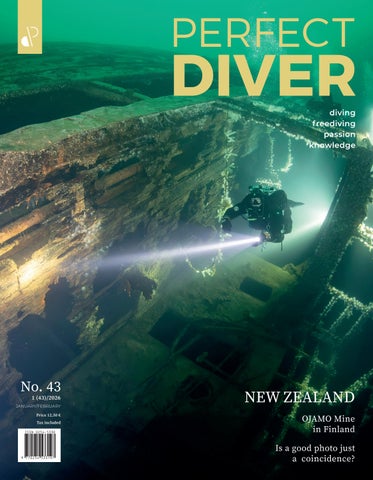

No. 43 1

OJAMO Mine in Finland Is a good photo just a coincidence? diving freediving passion knowledge

NEW ZEALAND

PERFECT FOR DIVING OUTDOORS &

No. 43 1

OJAMO Mine in Finland Is a good photo just a coincidence? diving freediving passion knowledge

Editor-in-Chief

The underwater world is not slowing down – and neither are we. We are delighted to place in your hands a fresh, brand-new issue of Perfect Diver Magazine 1/2026. This is a special edition: we are returning to the glued print format, inviting you to subscribe, and with great pleasure announcing that from this issue onward Perfect Diver is also published in German.

I am not sure whether you noticed, but no sooner had we released our previous issue 6/2025 – featuring a beautiful article on Greenland – than the world quite literally went crazy about it. This time, the opening feature takes us to New Zealand in a story by Dominika Abrahamczyk. We dive around the Poor Knights Archipelago and set off to visit the Hobbits.

In Komodo, together with Sylwia Kosmalska-Juriewicz, we search not only for Komodo dragons, but also for mantas, clownfish, and turtles. In the Red Sea, through the lens of Tomek Kulczyński, we explore the lesser-known wreck of the SS Carnatic. Meanwhile, with Dawid Strączek – making his debut in Perfect Diver – we descend beneath the ceiling of the Ojamo cave in Finland.

Thanks to Marcin Trzciński, who joined Barbara Glenc as a permanent member of our editorial team, a new section has been created: Underwater Photography. From this issue on, all articles – more or less technical – devoted to underwater photography can be found there. The section opens with a photograph of Mr. or Ms. Seal. You will also find a piece by Przemek Zyber on whether taking a great photo is merely a matter of chance and sheer luck, as well as a few words from Krzysztof Brudkowski on night photography.

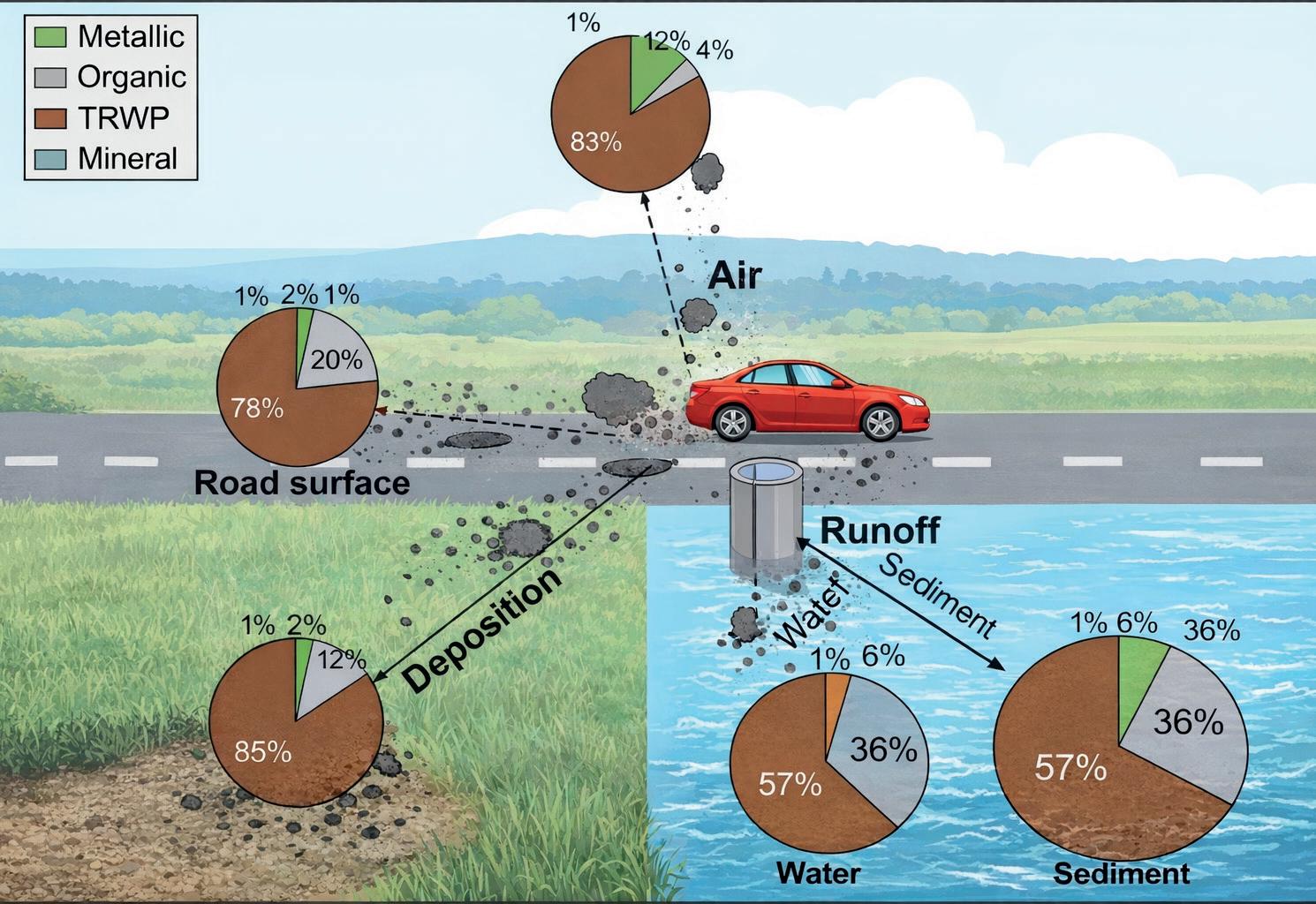

Among the debuts in Perfect Diver is also an article by Ewa Drucis about the very interesting programme “Pojąć głębię” (“Grasping the Depth”). There is Norway in Barbara’s story, along with my own reflections on tyres and their impact on the environment. The issue concludes with an excellent article by Wojtek A. Filip on communication with light. You will see how little separates a quick flash waved in front of a buddy’s eyes to point out another octopus during a night dive from a “shout” for help. It is a good moment to rethink our own approach to these signals – something I have also just done myself.

Did you like this issue? Give us a viral coffee buycoffee.to/perfectdiver Visit our website www.perfectdiver.com, check out Facebook www.facebook.com/PerfectDiverMagazine and Instagram www.instagram.com/perfectdiver/

Publisher PERFECT DIVER Sp. z o.o. ul. Folwarczna 37, 62-081 Przeźmierowo redakcja@perfectdiver.com ISSN 2545-3319

Editor-in-Chief

Technical Diver

World Geography & Travels

Reportage

Image Consulting English Language Translators

Legal Care

Graphic Designer

Advertisement

Wojciech ZGOŁA

Tomek KULCZYŃSKI

Anna METRYCKA

Dominika ABRAHAMCZYK

Waldemar RYDZAK Agnieszka GUMIELA-PAJĄKOWSKA, Arleta KAŹMIERCZAK, Piotr WITEK, Tomek KULCZYŃSKI

Lawyer Joanna WAJSNIS

Brygida JACKOWIAK reklama@perfectdiver.com

THE MAGAZINE IS FOLDED WITH TYPEFACES

Montserrat (Julieta Ulanovsky), Acumin Pro (Robert Slimbach, Adobe), Source Serif 4 (Frank Grießhammer, Adobe)

PRINTING

Wieland Drukarnia Cyfrowa, Poznań, www.wieland.com.pl

www.perfectdiver.pl

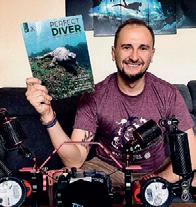

Wojciech ZGOŁA

A man who travels by diving. Connected with water since childhood – from learning to swim, through sailing, to discovering the secrets of underwater lakes, seas, and oceans. Later came a passion for photography and writing, which allow him to share the beauty of the underwater world and the unique stories of each place. He has completed over 900 dives in Poland as well as in remote, exotic warm and cold locations. Each dive is treated as an encounter with nature and history. A lover of Nature in its purest form, he believes that diving is not only a sport, but also a way of building awareness – of the environment, other people, and oneself.

Dominika ABRAHAMCZYK

Infected with a passion for diving by Perfect Diver. She continues to expand her diving skills. Although she definitely prefers warm waters, she dons a dry suit and explores colder bodies of water as well. Her favorite dives are those with plenty of marine life! Recently, she’s been taking her phone underwater in a protective case, trying her hand at amateur photography. She’s also curious about diving medicine. Professionally, she’s a Master’s degree nurse and a surgical scrub nurse.

Tomek KULCZYŃSKI

For Tomek, diving has always been his greatest passion. He started his adventure at the age of 14, developing into a recreational and technical diving instructor, a first aid instructor and a diving industry technician. Currently, he runs the 5* COMPASS DIVERS Pobiedziska Diving Center near Poznań, where he passes his knowledge and skills to beginners and advanced divers, which gives him great joy and satisfaction from being part of their underwater adventure...

Waldemar RYDZAK

“Human! Dive underwater. If the beauty you see down there doesn’t shake you to your core – nothing interesting awaits you in life.”

A diving enthusiast, connected with the water since childhood. She completed her first scuba course at the age of 14 and has never parted with diving since. She wrote her master’s thesis on dive tourism during her geography studies at the University of Warsaw. Starting in 2013, she contributed to the magazine nuras.info and took part in underwater photo shoots. Since 2018, she has been writing articles for Perfect Diver magazine (previously as Ania Sołoducha) and has been part of the editorial team for several years. She pours her knowledge and experience onto the page, sharing and promoting what she loves most – diving. For 13 years, she organized diving expeditions around the world, because working with people and creating new projects is where she truly thrives. She takes part in diving fairs and events, as well as lake clean-ups. She has often had the pleasure of speaking as a presenter at diving expos and conferences and has a number of diving webinars to her name. She has already dived in many places around the globe – and her dream list keeps growing.

For the past few months, she has been the owner of her own company organizing diving and active travel – Umiko Expeditions – with a head full of ideas for the next adventures.

An optimist with a constant smile and an individual approach to every client. Her best life chapter is just beginning! www.umikoexpeditions.pl anna@umiko.pro

+48 516 621 211

He comes from a mining region, where water was more of an exception than an everyday presence. He learned to swim and dive to overcome his fear of water – and, over time, to turn it into curiosity about the world beneath the surface. He has been connected with diving since 2000 (Divemaster, CMAS). He doesn’t chase depth or records; he prefers calm exploration, mindfulness, and the details that are easy to miss when you’re in a hurry. In his day-to-day work, he is a researcher and communication practitioner (Dr hab., Prof. UEP), involved in research and teaching in the areas of creative markets and digital and crisis communication. Within the Perfect Diver editorial team, he supports the crew where content meets technology – on video productions, data analysis, and building the brand strategy.

Wojciech A. FILIP

He has been diving for 35 years. He has spent more than 16,000 hours underwater, most of them diving technically. He has been an instructor and mentor instructor for many organizations including CMAS, GUE, IANTD, PADI. He co-created the training programs for some of them. He is a professional with vast knowledge and practical experience. He has participated in many diving projects as a leader, explorer, initiator or speaker. He was the first Pole to dive the HMHS Britannic wreck (117m). He was the first to explore the deep part of the Glavas Cave (118m). He made a series of dives documenting the wreck of ORP GROM (110m). He has documented deep (100-120m) parts of flooded mines. He is the creator and designer of many equipment solutions to improve diving safety.

Technical Director at Tecline, where, among other things, he manages the Tecline Academy a research and training facility. Author of several hundred articles on diving and books on diagnosis and repair of diving equipment. He dives in rivers, lakes, caves, seas and oceans all over the world.

Laura KAZIMIERSKA

Laura is a journalist, instructor trainer, CCR and cave diver. She has been developing her diving career for over a decade, gaining knowledge and experience in various fields. Her specialty is professional diving training, but her passion for the underwater environment and its protection drives her to explore various places around the world. From the depths of the Lombok Strait, caves in Mexico and wrecks in Malta to the Maldives, where she runs a diving center awarded by the Ministry of Tourism as the best diving center in the Maldives. Laura actively contributes to promoting the protection of the marine environment, takes part in scientific projects, campaigns against ocean littering and cooperates with non-governmental organizations. You can find her at: @laura_kazi_diving www.divemastergilis.com

Zoopsychologist, researcher and expert in dolphin behavior, committed to the idea of protecting dolphins and fighting against keeping them in dolphinariums. Passionate about Red Sea and underwater encounters with large pelagic predators. Member of the Dolphinaria-Free Europe Coalition, volunteer of the Tethys Research Institute and Cetacean Research & Rescue Unit, collaborator of Marine Connection. For over 15 years, he has been participating in research on wild dolphin populations, auditing dolphinariums, and monitoring the quality of whale watching cruises. As the head of the "Free & Safe" project (formerly "NO! for a dolphinarium"), he prevents keeping dolphins in captivity, promotes ethical whale & dolphin watching, trains divers in responsible swimming with wild dolphins, and popularizes knowledge about dolphin therapy that is passed over in silence or hidden by profit-making centers. on this form of animal therapy.

/ Luke Divewalker

A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away there was chaos... …that is, the multitude of thoughts and delights after my first immersion under water in 2005 in the form of INTRO while on vacation in Egypt. By then I had completely immersed myself in the underwater world and wanted it to have an increasing impact on my life. 2 years later, I took an OWD course, which I received as a gift for my 18th birthday, and over time, further courses and skills improvement appeared. "Photography" appeared not much later, but initially in the form of a disposable underwater "Kodak" from which the photos came out stunningly blue I am not a fan of one type of diving, although my greatest weakness at the moment is for large pelagic animals. The Galapagos Islands were my best opportunity to photograph so many species of marine fauna so far. I share my passion for diving and photography with my buddy, who is my wife IG: luke.divewalker www.lukedivewalker.com

I photograph because I love it, I film because it excites me, I write because I enjoy sharing, I teach because I support growth, I travel because I love discovering new things. www.facebook.com/przemyslaw.zyber www.instagram.com/przemyslaw_zyber/ www.deep-art.pl

A graduate of the University of Warsaw. An underwater photographer and filmmaker, has been diving since 1995. A co-operator at the Department of Underwater Archeology at the University of Warsaw. He publishes in diving magazines in Poland and abroad. The owner of the FotoPodwodna company which is the Polish representative of Ikelite, Nauticam, Inon, ScubaLamp companies. www.fotopodwodna.pl m.trzcinski@fotopodwodna.pl

Sylwia KOSMALSKA-JURIEWICZ

A traveller and a photographer of wild nature. A graduate of journalism and a lover of good literature. She lives in harmony with nature, promotes a healthy lifestyle: she is a yogini and a vegetarian. Also engaged in ecological projects. Sharks and their protection are especially close to her heart. She writes about the subject in numerous articles and on her blog www.blog.dive-away.pl She began her adventure with diving fifteen years ago by total coincidence. Today she is a diving instructor, she visited over 60 countries and dived on 5 continents. She invites us for a joint journey with the travel agency www.dive-away. pl, of which she is a co-founder.

I am a traveler and a technical diver, exploring the world both on land and underwater. I have been diving for 16 years. Since I am a professional photographer, a camera has accompanied me from my very first dive. I started with recreational diving, but over time, I obtained full trimix and full cave certifications, allowing me to explore caves, wrecks, and great depths. Underwater, I find a peace that is hard to experience on the surface. Every dive is not just an adventure for me but also an opportunity to capture the extraordinary underwater world through photography. barbaraglenc.foto@gmail.com

By education and profession, I am a nurse and a healthcare manager, and photography is my passion, to which I devote every free moment. Since I started diving in 2019, the camera has become an inseparable element of my underwater adventures. Wanting to capture the beauty of the underwater world in all its glory, I reached for the Canon 5D Mark II SLR, and today my main equipment is the Canon R6. I am constantly looking for new places and challenges to improve my skills. However, my photos would not have been created without the support of friends who have been with me from the beginning and often take on the role of models. I am also strongly connected to the mermaid community in Poland. I specialize in their photography, trying to capture the underwater beauty of this community and convey its unique magic. From the beginning of my diving adventure, I have been associated with the Lublin Diving School Napoleon Arka Kowalika, and since 2025 I have had the pleasure of serving as the DivePro Diving Lighting Ambassador.

@michalmuciek

https://facebook.com/michal.muciek

A graduate of the University of Economics in Katowice and the Warsaw School of Economics. International Diving Federation Course Director, cave diving instructor, and technical diver (OC, CCR). Holds a professional commercial diver qualification. Court-appointed expert in cases related to diving. Active officer of the State Fire Service. Passionate about travel, good music, great food, and positive-minded people.

A legal adviser by profession, trying to help, not win at all costs. A lover of warm climates and blue water. He took up diving in 2018 as an extension of his favorite snorkeling. Now, he plans almost every trip to get his fins wet somewhere. His son Damian is his diving partner. His passion for underwater photography was born from an inner need to capture fleeting memories. Currently, he also tries to use photography to raise awareness of the need to protect marine life and show the impact of climate change in the aquatic environment.

Follow him on Instagram: @mydiving.pl

Founder of the JagnaBlue diving school. She has been a scuba diver since 1993 and has been working professionally in diving for 23 years. She holds instructor certifications with organizations such as PSAI, TDI/SDI, and PADI. Since 2023, she has been a PSAI POLAND Instructor Trainer. She is also an instructor in resuscitation and first aid for adults, children, and infants; holds instructor qualifications in numerous diving specializations; is an instructor of immersion therapy for people with disabilities; and is a certified counselor for summer camps and youth camps. She has logged over 9,000 dives, some of them to depths of 100 meters. Many years of professional experience gained in Poland and abroad enable her to pass on a vast body of knowledge to her students and trainees.

The concept that "the grass is always greener on the other side" used to seem to me like an unnecessary cliché. But when you land in New Zealand – you really discover a new dimension of greenery.

I'm not at all surprised that the Hobbits chose such a place to live :)

Landing in Auckland after a 16-hour flight from Dubai is feels like salvation. The joints seem to crack more than usual, some of us get jet lag, but we start the adventure full of euphoria. At the entrance, we are greeted by beagle dogs –and this is not a sign of total sympathy for tourists, but the best Bio Security alarm system that protects against bringing to New Zealand prohibited products such as fruits, vegetables, seeds, honey, animal products or trekking and camping equipment. All such products are subject to the obligation to declare, under the threat of high fines. And yes – you have to take it seriously, although New Zealanders are extremely helpful and positive towards tourists who communicate culturally and avoid problems. In fact, I don't think I had met people more sympathetic, accommodating, communicative and helpful than New Zealanders. The atmosphere of ubiquitous small-talk bites into the

mind and is sorely missed after returning home and to Europeans closed in on themselves with smartphones in their hands, often not even making eye contact. This different culture is something I miss very much.

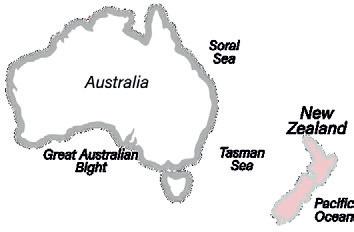

Our goal is to dive around the Poor Knights Archipelago – a place recognized by Jacques Cousteau as one of the best diving destinations in the world. To do this, we have to go to the town of Tutukaka, from where the diving boats depart on Poor Knights. So we rent a car at the airport and set off to our destination. Auckland gives the impression of a very nice and well-kept city, the coastal climate makes the views pleasing to the eye all the time. As we leave the city, it turns out that the roads in New Zealand are very narrow and often wind in serpentines, which is quite a challenge with additional left-hand traffic and, whether you want it or not, triggers some stress

in the initial phase. On the other hand, the circumstances of nature soothe the nerves and after a short time we are able to enjoy watching slightly different flora than the one we see every day. On the way to Tutukaka, we planned a short trek to see the KiteKite waterfall. It is a 3-level waterfall with a height of 40 m to which a picturesque wooden and gravel path leads, starting with a gate for thorough cleaning and disinfecting the sole of shoes. Yes – in New Zealand, great care is taken to protect the unique ecosystem. It takes about half an hour to get to the waterfall, the road leads through the forest, so you will find a bit of shade here.

Dive! Tutukaka is a diving center that is great for organizing expeditions to the Poor Knights. It is worth booking a date in advance by e-mail to be sure that there will be a place for you on the boat. The team at the center is super organized and helpful, we felt taken care of

from the first moments of our stay. First, paper formalities are carried out at the reception, then the designated people help to choose the diving equipment (for such a long journey, we decided not to take most of our equipment and rent it on site) and pack it in a bag. After a short conversation with our guide, we were persuaded to dive in wet suits, which, however, was a mistake at this time of year. The water was only 15 degrees Celsius, so while the first dive was relatively comfortable, the second one gave us a hard time. It is worth bearing in mind that for a small surcharge you can rent a dry suit and lunch on the boat served between dives. Dive! Tutukaka also offers accommodation facilities.

Poor Knights – the name. Where did such a name come from? There are several theories, the most popular being that it comes most likely from Captain James Cook, who during

his travels considered the barren, rocky islands to be similar to "Poor Knights Pudding" – a cheap, English dessert made of bread and eggs, often served with raspberry jam. The islands are overgrown with a plant called Pohutukawa, which in November and December cover the island with a bright red colour – reminiscent of this raspberry jam. The name may be cheap, but life underwater is a blast! Since 1981, fishing has been prohibited here, as it is a marine reserve, cold and warm currents combine here, in addition, spectacular rock formations make life underwater really rich. We can see large animals such as humpback whales, killer whales, dolphins, turtles, ocean sunfish (mola mola) and often even from the boat before we go underwater :) Underwater, you can encounter various species of stingrays (long – and short-tailed stingray and eagleray) and sharks (carpet sharks or bronze whaler), as

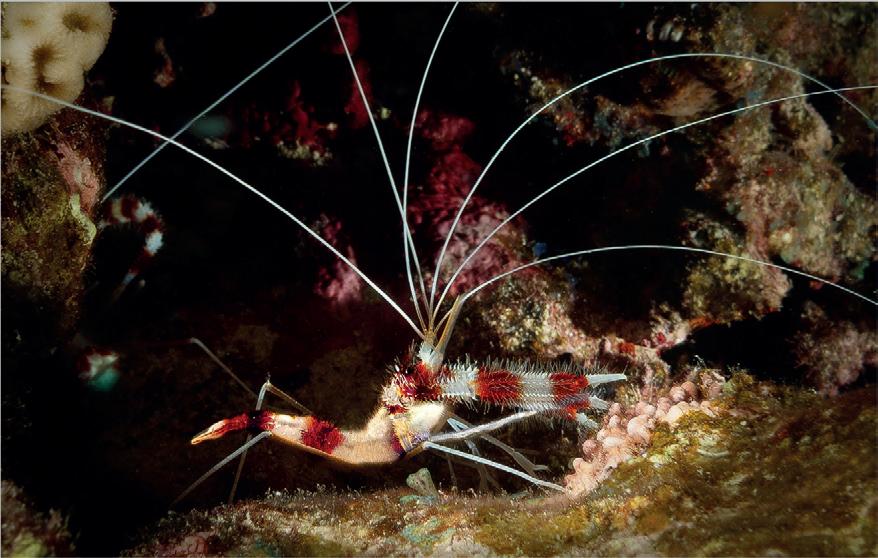

well as moray eels, congers, snappers and many more. For amateurs of macro photography – a colorful snail's paradise from which it is impossible to take your eyes off. To top it off, I will add that all this is surrounded by wonderful walls and rock formations overgrown with sponges, anemones, gorgonian and kelp forest. The multitude of colors and their saturation cause dizziness, and one begins to wonder whether it is reality or a dream, coming to only one conclusion – Jacques Cousteau was right.

The landscape of the Poor Knights Islands is made up of vast caves and numerous rock arches formed by the erosion of volcanic rocks. Most of them have wide entrances and remain well lit with natural light, which allows recreational divers to swim safely. The largest of them, Rikoriko Cave, is considered the largest sea cave in the world and is one of the most characteristic elements of the archipelago. Arches and tunnels act as natural corridors where schools of fish often gather, and the shelter from the waves makes indoor conditions calmer than in open water. It is this clear, legible topography – a combination of vertical walls, caves and arches – that gives the Poor Knights Islands their unique character and importance on the map of the world's dive sites. I think that if the Hobbits could swim – they could easily live in the area of Poor Knights ;)

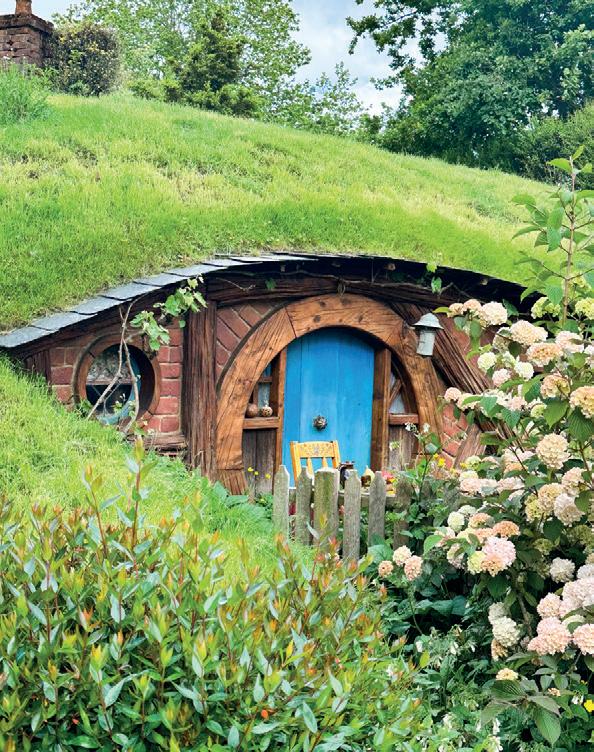

Meanwhile, the next day after the dives, we went to see the real Hobbit village in Matamata, which was built on the grounds of a private sheep farm and was originally built as a temporary set for the movie "The Lord of the Rings". At the moment, it is a ticketed tourist attraction that allows you to perfectly feel the atmosphere of the film and the hobbit idyll. Nasturtiums are blooming, the vegetable garden is teeming with life, interestingly, the light is still burning in many of the hobbit burrows, and the smoke rising from the chimneys and the laundry dried on ropes is an element of the scenery that

is supposed to give the impression that the inhabitants have only left the house for a moment. One of the houses (there are two of them: green and red) can also be seen inside, and the attention to details and little things really gives great satisfaction. The culmination of the tour is a pint of Ale or Cider at The Green Dragon Inn :) A highly commercial attraction, but in my opinion worth seeing.

While planning the trip, we also came across information about the local caves with glowworms. It is one of New Zealand's most iconic natural phenomena, and the Waipu Caves are

among the most accessible and authentic. Unlike commercial grottoes, Waipu remain wild and unlit, allowing bioluminescent glowworm larvae (Arachnocampa luminosa) to be visible in complete darkness like a natural "starry sky". Glowworms use their blue-green light to attract prey, and the damp, cool interiors of caves provide them with ideal conditions. Visiting Waipu requires a flashlight and caution, but it is this austerity of the place that makes contact with this phenomenon less touristy and more direct. When the light of the flashlight goes out, we see an unusual image of a galaxy and millions of stars in the sky. Magical.

New Zealand's North Island lies at the junction of tectonic plates, making it one of the most geothermally active areas in the world. In the area of the socalled Taupō Volcanic Zone, you can observe geysers, bubbling mud cauldrons, hot springs, and steaming crevices in the ground. The most famous place is the area around Rotorua, where geothermal phenomena occur almost in the city center. In fact, while walking around the area, we encounter signs not to deviate from the designated paths, as the surface of the ground can be very hot. Here and there, a cloud of steam comes out of the meadows and grasses, informing us that the signs do not lie.

In Rotorua, you will also find a park with waters and geothermal mud, where you can admire a feast of colors – the intense colors of mineral deposits – from silica white to bright oranges and greens – are the result of high temperatures and the chemical composition of the waters. Geothermal waters and vapors ejected from the crevices of the earth are rich in hydrogen sulfide, and I will only add that the smell in these places is also very characteristic :)

It is astonishing how many diverse attractions can be found on a small area of the northern island of New Zealand. Until now, I only associated it with greenery and a huge number of sheep – which is of course true! But there is much more to it. We were there for only a few days but the sensations, attractions and emotions will be remembered for a long, long time.

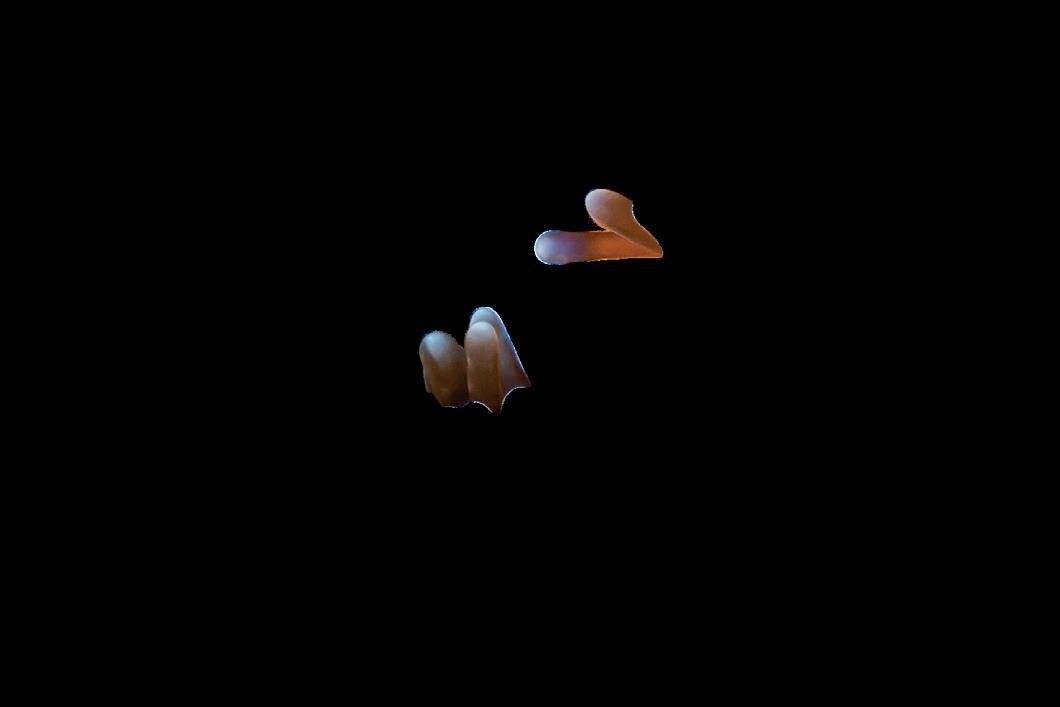

It was already the third day of diving with the seals, and I still hadn’t gotten a good shot. The animals were curious and not particularly skittish, yet they kept what they considered a safe distance the entire time. Combined with the less-than-ideal visibility, capturing a satisfying frame seemed harder than understanding quantum mechanics (or getting a date with Monica Barbaro).

The beginning of the next dive was standard. We swam in a wide line of four, a few meters below the surface, while the curious mammals resting on the seabed lifted their heads to watch us closely. Sure, sometimes they came closer, but only from behind, gently nibbling at our fins. I turned slightly to the left and, floating above the rocky bottom, swam another few dozen meters. And then… right in front of me, face to face (or snout to snout), he appeared. Or she, let’s just say I didn’t check “under the tail.” The seal kept a respectful distance but didn’t flee. In fact, after a moment, it began to swim cautiously around me, gradually closing the gap with each circle. Soon, it was within arm’s reach. I waited through two more laps, then gently tapped the seal on the fin it had extended toward me. Startled, it jumped back and once again maintained its “safe” distance. But after a few seconds, it swam closer again. Another tap, and it jumped back, this time not as far. For a moment, we locked eyes, and then Zenon (his parents would surely be proud if they knew that’s what I had mentally named him) swam toward me again. Only this time… with a flipper extended for another high-five. He circled me, giving me a high-five on each turn, five, seven, ten times. But how many times can you high-five? On the next lap, I surprised him: instead of repeating the tap, I stroked his head. Startled, he jumped back again, but just once. Then he came closer, stretching his head forward and arching his back, inviting more pets.

It was only after several laps that I started taking photos. The first ones, I admit, were taken with my heart in my mouth, worried I might scare Zenon. But surprisingly, the camera flashes didn’t bother him at all. The only condition was ensuring a proper dose of petting. It was a bit overwhelming: stroking, high-fiving, framing the shot, adjusting exposure. My first slightly underexposed shots were corrected by opening the aperture one stop. Then I once again reached out to the seal demanding play. It was magic, probably could have lasted much longer, if not for Wojtek’s sudden appearance (I won’t mention his last name out of respect, but if you really want to know who he is, check the editor’s note on the first page of this magazine; he signed it at the bottom). Zenon froze instantly, then jumped back to what he considered a safe distance. For a moment, he hovered at the edge of visibility, waiting to see how things would unfold. When he saw I wasn’t driving the intruder away, he did a quick flip and swam off, disappearing into the depths…

Æ E xposure settings: Mode M, 1/60 sec, f/6.3, ISO 200

Æ Camera: Olympus OM-D EM10

Æ L ens: Olympus M. Zuiko Digital 14-42 f/3.5-5.6

Æ Housing: Nauticam NA-EM10 + flat port

Æ C onverter: Inon UWL-H100 + dome port

Æ St robes: 2x Inon D2000

Text SYLWIA KOSMALSKA-JURIEWICZ

Photos ADRIAN JURIEWICZ

Between heaven and earth, blissfully suspended, I swing on a white hammock hung on a majestic tamarind tree. The tree grows on the beach and in its wide-spreading crown birds live which, to my joy, have been singing since the morning.

The tamarind tree looks as if it were watching over this place, as if nothing could happen here without its knowledge.

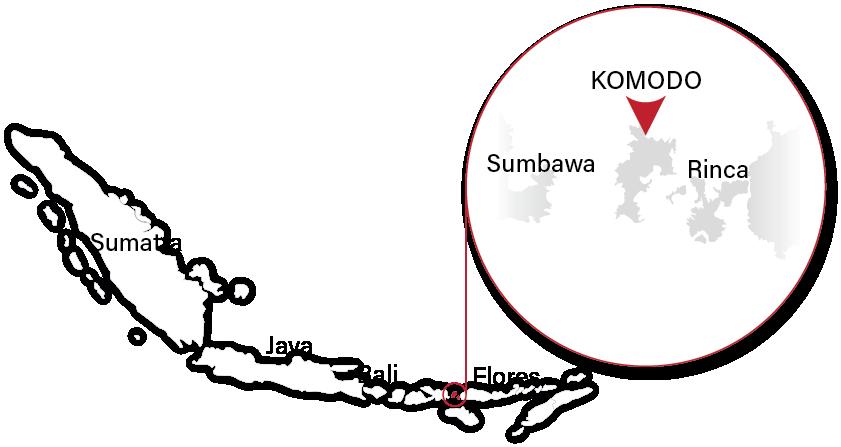

Yesterday, after two weeks of traveling around the islands of Gili and Bali, we flew to Komodo. Early in the morning we landed in Labuan Bajo, a city located on the west coast of the Indonesian island of Flores. From the airport we went to the port, the journey took us ten minutes. During this short ride, we were able to take a closer look at the town: we passed low-rise buildings, small restaurants, warungs, shops and cafes. The street winds like a ribbon, squeezing between buildings and tropical vegetation. After the last bend, a spectacular view of the Flores Sea opened up before our eyes. Turquoise water sparkles like diamonds in the morning sun. Wooden sailboats sway gently on the waves, anchored in the port, and among them a boat that will take us to an island thirty minutes away.

„

boat pass in the blink of an eye. We reach a wooden pier stretching far into the sea. We climb the wooden stairs to the pier. A few people from the staff came out to meet us. With a welcome drink in hand, we head to the reception.

There are places in this world that you visit for the very first time, and yet they feel so familiar, as if you had been there all along.

Magic is the real world here. If you can't understand this, you can't understand Indonesia. Magic is everywhere, magic more than anything else decides about people's lives here.

Tiziano Terzani

The further we sail away from the coast of Labuan Bajo, the more untouched and pristine the landscape becomes. A beautiful panorama appears before our eyes. We pass green, volcanic hills of various shapes and structures, whose rocky slopes steeply descend into the turquoise sea. Over thousands of years, a layer of soil has formed on these rocks, which explodes with greenery during the rainy season. It is the rain that awakens plants to life, turns the barren landscape into a green oasis. The waterway leading to the island is so beautiful that the hours spent on the

This is exactly the thought that appeared in my head the moment I set foot on the pier: "on the island I feel as if I had returned to it, I was an integral part of it". This small piece of land is a true paradise. The word "peace" perfectly captures the spirit of this place. The island is very green, almost a jungle with a fragment of the beach on which there are white, wooden guest houses. Each villa has a spectacular view of the sea. There are palm trees on the beach and one huge tamarind tree that looks as if it was constantly watching over the island. Nothing escapes its attention, it knows when guests arrive and when they leave. In its huge crown live birds, whose singing is carried around the island, and hammocks hang from the branches. The tree protects the space like a good host. There is also a small reception, a restaurant, a spa lounge, a gym, a diving centre and a swimming pool on the island. In front of the cottages, right next to the shoreline, there are sun loungers with navy

blue umbrellas, and in front of the entrance to each villa there are round bowls filled with fresh water to wash your feet of sand before entering the house.

Today, we just enjoy the island. We swim in the sea and dive by the hotel beach. The coral reef surrounding the island is incredibly beautiful. Fish, small sharks, nudibranchs, crabs and corals can be observed even from the pier. The water is crystal clear and acts like a natural magnifying glass. The creatures living in its depths seem to be larger and more magnificent. We dive right next to the pier, which is a natural protection for all underwater creatures that live in its shadow. We dive with great attention between the wooden piles supporting the pier. A school of fish is watching us closely, the fish are as interested in us as we are in them. From above, the pier looks ordinary, gray, devoid of color, built of piles and boards that have long since faded in the sun. For the underwater community, the pier is a real miracle, the most beautiful house in the world, which gives a sense of security, protects against predators and the scorching sun. The crabs shyly emerge and hide in the wooden structure, agilely operating their claws. Schools of fish swirl in a compact formation, they seem to be one organism beating in the rhythm of the same heart. There is so much going on under the surface of the water, and at the same time there is incredible peace, everything is happening in perfect harmony. All creatures are busy with their own affairs, some are hiding while others are hunting. We try to portray all these fleeting moments with a camera and a camcorder to best capture the beauty of this underwater world we love so much.

The next day I wake up early in the morning, even before the local rooster crows, and before the birds start their morning concert. I brew coffee, the smell of it alone makes me smile wide. With a cup of wonderful espresso in my hand, I step out in front of the house, my feet touching the silky, coral sand. I enter the sea and enjoy this magical moment like a child. Mornings are definitely my favorite time of the day. Darkness will give way to light in a moment. In Bali at dawn, I was accompanied by dogs living on the beach, we watched the sunrise together. On Gili I was visited by a patched cat, which gradually took up more and more space on my deckchair, until finally it lay down and fell asleep on my lap. Leaving the house on Komodo at dawn, I wondered who would share this moment with me here. The answer came unexpectedly quickly. A small rodent walked along the beach, a local mouse whose quick, agile movements caught my attention. Before I could get a good look at it, it ran away, disappeared as if it had never been here. The universe has an extraordinary sense of humor.

After breakfast with a view of the sea, we went diving. Today, we are planning three descents in different locations. Our diving plan depends largely on sea currents, which can be very strong in the Komodo area. First, we sail to the port, get off the boat, get tickets confirming the park fees, then head to the gates in the port, scan the tickets and go to the other side. After this short walk and completing the procedures, we return to the boat and set sail into the sea. The weather is perfect, the sun is shining, and the water is as smooth as a sheet of ice. After forty minutes, we reach the first dive site of Sebayur Kecil, a small

island located near Komodo National Park. This is the perfect location for a "check dive". The coral reef in this place is beautiful, very diverse and healthy. This is a huge surprise for us, because test dives are usually performed in places that are not the most attractive. The clarity of the water is very good, from the deck of the boat we can see a vast coral garden. We dive along the wall descending in cascades into the sea, we stay at a shallow depth to enjoy beautiful light and the richness of fauna and flora found in this location. We are accompanied by numerous turtles, resting among the corals as if in the most comfortable beds. Schools of colorful fish swim above our heads, and the majestic Napoleon wrass is slowly heading in a direction only well known to itself.

The next dive takes place in Taka Makasar – Manta Point. This location is characterized by a shallow depth, the bottom is covered with white and slightly pink sand and small pinnacles overgrown with corals. Manta rays love this place, they can feed here and indulge in cleaning rituals. We jump into the water and immediately dive, the current is strong, so we don't spend much time on the surface. We notice two huge manta rays that calmly swim below us. They glide with incredible grace, one is black and the other is black and white. Visibility exceeds thirty meters. We stop at the bottom. The current is strong, we begin to drift, surrendering to its force. We look around carefully, look for manta rays or a movement that will attract our attention. We reach a small hill, above which seven manta rays float. They

swim slowly, one after the other spinning in their peculiar dance. Their bodies are cleaned by schools of small yellow and white fish. We stop enchanted by this unusual dance. Their movements are smooth, they move as if they might fly away at any second. We attract their attention, they come very close and turn back just above our heads. We cannot take our eyes off them. We lose track of time. We emerge slowly, absorbing the last moments of this magical meeting.

It's hard to come back to reality after such a spectacular dive. Lunch is waiting on the boat, but no one is hungry, our hearts have been left with manta rays at the bottom of the sea, filled with great joy, gratitude and emotion. We decided to dive again in the same place in two days. Today, however, we sail for the last dive of the day to Tatara Besar. The water seems calm, but in some places it resembles a rushing river. It is the sea currents that cause these changes. We observe a large, wooden boat that has entered the current and begins to rotate around its own axis. Nature shows its strength in a subtle way, thus reminding us where is our place in this huge, beautiful world. Each immersion in the waters of Komodo is a separate beautiful story, told by sea currents, the magic of light and all, even the smallest creatures that play such a significant role in the underwater book of life.

The next day, early in the morning, we set sail for a full-day tour, during which we will visit some of the most spectacular places in the Komodo National Park. The first location we sail to is Padar Island. The place is characterized by a spectacular view of the bay. After an hour of sailing, we reach a wooden pier. The beach on this side of the island is dark and the water is crystal clear. Three timor deer are strolling along the beach after wading in the sea just moments earlier. They usually stay in the interior of the island, where they can take refuge from natural predators, the Komodo dragons. Sometimes, however, they go out to the beaches tempted by coconuts, which tourists buy in small shops located on the pier. After drinking coconut water, the seller cuts open the shell, and the deer eat the pulp from the in-

side, which is a real delicacy for them. After feeding the deer, we start climbing to the top of the hill, which offers one of the most beautiful views in the world. There are over 800 stairs leading to the very top. Heat pours from the sky, and we climb the steep slope step by step. It takes us thirty minutes to get to the top. The reward for the effort of climbing is a breathtaking panorama extending to the island of Padar and nearby islets immersed in turquoise water. We stand in awe staring at the white, black and pink beaches. Nature has created a real masterpiece that we can admire standing at the top of Padar Island.

From the island we sail twenty minutes to the famous pink beach, which owes its color to corals and microscopic organisms called foraminifera. Their shells are pinkish-red in color, when they die the shells are crushed by the waves and mix with white sand. The effect of this combination can be seen on the beach, which has a delicate pink hue. It looks spectacular in the afternoon sun. We bathe in turquoise water in the company

of deer. The sight of these wild animals on the beach is almost surreal and it fills us with indescribable joy.

The next point of the trip is the Komodo National Park, which is famous for the largest living lizards, the Komodo dragons. The boat trip takes us thirty minutes. We hit a concrete pier that leads straight to the entrance, a symbolic stone gate, with the image of two reliefs depicting lizards. We are approached by a ranger (local guide) who has special training in working with monitor lizards. His task is to ensure the safety of tourists and animals living in the tropical forest. In addition to monitor lizards, deer, wild pigs, macaques and various species of birds also live on the island. Monitor lizards (called Komodo dragons) are most active in the morning or late in the evening, during the day they protect themselves from the sun in burrows or dense thickets. We are very lucky and despite the heat, we meet a few individuals. One walks on the beach, another is lounging under a tree, and another has found shelter under a bench, near a souvenir shop. We walk through the rainforest unhurriedly, admiring the mighty trees and lianas hanging from the branches. Colorful butterflies gather at a small spring, created by man, so that the animals living in the forest can quench their thirst. There is a drought here, the forest looks more like a savannah than a humid tropical forest. Monitor lizards are solitary, they swim and move on land very quickly. Males are

larger than females and can be up to three meters long and weigh eighty kilograms. They can smell carrion from a few kilometers away. They feed mainly on deer, wild pigs and birds. Komodo dragons are equipped with venom glands, after a bite the victim suffers a shock and paralysis, and as a consequence dies.

A walk in the monsoon forest is extremely exciting, our senses are sharpened. We listen to every sound that can be an announcement of the appearance of a monitor lizard. We slowly return to the port, have lunch with a view of the sea and sail on for snorkeling with manta rays. It is already late afternoon when we stop at a place called Manta Point. The chance of meeting these majestic creatures is high. The memories of the last dive with manta rays are still alive in our hearts, so we jump into the sea with great hope. We look under the surface of the water, our eyes see an astonishing sight. Fifteen manta rays swim below us. Even snorkeling with these creatures gives us great joy, we dive in and out, enjoying the presence of these magical creatures. We couldn't have dreamed of a more beautiful end to our all-day trip to the Komodo National Park.

Our stay in Indonesia was an extraordinary time that filled us with peace and joy. We will be looking back on these beautiful days for a long time; they are a true testament to how much we have to be grateful for.

Text & photos BARBARA GLENC

Our Norwegian adventure began at the airport in Krakow. Backpacks, diving gear and a lot of excitement – all set for the next adventure.

Direction: BERGEN – a city of rain, fjords and colorful houses that nestled over the bay, like on a picture postcard.

My family and I had arrived two days before the rest of the team, so we decided to use this time to explore the city quietly and taste Norway in our own way. We wandered through the narrow streets of Bryggen, looked into small cafes where the smell of coffee mixed with the sea air.

Bergen welcomed us with the energy of a city perfect for the start of a diving expedition. Trains from the airport run every 5 minutes, tickets are purchased at ticket machines, and the purchase confirmation comes by SMS. The route to the center takes about 45 minutes and costs only PLN 15 (app. 41,62 NOK, 3,55 euro).

Flights from Krakow to Bergen are really cheap – it's worth coming here for at least a few days, seeing a piece of Norway, drinking great coffee, walking between the colorful houses on Bryggen and feeling the atmosphere of the region, which sinks

in rain most of the year, but for us... it had almost two weeks of sunshine.

We also couldn't deny ourselves culinary adventures – reindeer hot dogs turned out to be surprisingly delicious, and fish soups and seafood at the famous market in the city center were a real treat. Every bite tasted like Norway – simple, fresh and with a hint of the coolness of the north.

The rest of the team arrived later, and all the diving equipment arrived in Norway by bus. Thanks to this, we could only fly with hand luggage, which turned out to be a huge facilitation. Without heavy bags and crates with equipment, we could roam freely around the city – enter the Fløyen viewpoint, sit in cafes overlooking the harbor and soak up the atmosphere of Bergen. The two days before the start of the dives were the perfect introduction – calm, full of sun (although this is a rarity in Bergen),

the smell of the sea and the sound of seagulls hovering over the fish market.

The idea for a trip to Norway was born at the Denis diving school from Pszów, which organized a trip to the northern regions of the country. Since we live very close, we decided to join forces – Denis was preparing the main expedition, and we joined with our own plan of reconnaissance and photographic exploration. This combination of spontaneity and experience turned out to be a hit.

This time we did not use the services of any diving center on site – it was supposed to be a reconnaissance. We wanted to check what opportunities Norway offers in terms of independent diving. We had some information from friends

and a few tips found on the Internet – maps, descriptions of wrecks, coordinates of places that someone once visited. That was enough to arouse curiosity. So we packed dry suits, flashlights and cameras, and set off in search of wrecks hidden in the cool, clear waters of the fjords.

We lived in the town of Rutlendar, near the marina from which ferries departed to different parts of the fjords. This made it much easier to move between dive sites – all you had to do was pack your equipment in the car, and in a few minutes you were ready for your next exploration.

We made our first dives literally from the backyard of our house. It was enough to descend the rocky beach to find yourself in clear, calm water. The visibility surprised us posi-

tively – about 15 meters, the water was a pleasant 15°C, and most importantly – there were no currents. Perfect conditions for a warm-up after the trip and the first photos.

The next target was the wreck of Dampskip (Steamboat)

Dampskip wreck (Steamboat) – monumental silence

We started from the shore, calmly descending into the water. It took about 70 meters to swim to the rope leading straight to the wreck and I already knew that this dive would be different. The water was slightly milky, but the visibility allowed me to see every part of the hull and every structure of the wreck.

Dampskip made a huge impression on me – 115 meters long, 15.9 meters wide, 4969 GRT. It was lying heavily tilted, touching the bottom with his masts, and his monumental silhouette did not fit into the frame. I slowly moved along the rope, photographing fragment by fragment. Every deck, every side, every engine room – everything seemed to tell its own story.

Built in 1913, also known as Wascana, it sank on April 23, 1945. Diving is possible from a boat or over a steep slope, but the most beautiful thing is to slowly explore its space meter by meter, stopping at the details that still retain the former power of the ship.

There is no fog or dramatic atmosphere of cenotes here –there is monumental silence, raw Norwegian space and the opportunity to create photos that capture the vastness of the wreck and its extraordinary history. Every shot, every frame of the film underwater becomes a part of this story, which you want to explore slowly, in full concentration.

Wrecks Ferndale and Parat

The next place was two wrecks Ferndale and Parat, to which we had to take our boat this time – Denis organized it for us for the whole stay and we had it at our disposal. This greatly facilitated logistics, movement and discovering more places that were not accessible directly from the shore.

The Ferndale Wreck is one of the most popular and most visited wrecks in the region – a classic that attracts divers from all over the world. No wonder: it is spectacular, photogenic and full of life.

After an hour of swimming, we managed to locate the buoy of the wreck. A quick gear up, check of the camera and hop – into the water. Ferndale appeared at 10 meters, but at first the visibility was very limited, only a few meters. A milky haze hovered around the steel structure, creating a surreal atmosphere – just

like in the cenotes of Mexico. Each piece of the hull emerged slowly, timidly, as if the wreck wasn't sure if it wanted to show its entire story.

Over time, the haze began to clear, and Ferndale revealed more and more. A quick glance at the shallows was enough to marvel at the amount of life – colorful anemones, fish and crabs created a colorful, vibrant world.

After a while, we swam through the opening into the interior of the wreck. Breaking through the dark corridors, we swam lower – at 27 meters, where the climate changed completely. The milky haze disappeared, visibility was perfect, and the wreck was covered with white anemones that looked unearthly against the dark background of the metal. It gave an incredible, almost fairy-tale atmosphere.

We dived deeper and deeper, up to 45 meters, where the bow of Ferndale ended. We looked down – and then we saw something that literally took our breath away. Another wreck! Just below us rested the tugboat Parat, visible in all its glory. The steel silhouettes of the two wrecks, lying one above the other, created a mesmerizing sight, as if time had stopped at the exact moment of the catastrophe. This is one of the most magical and emotional dives you can do in Norwegian waters.

We checked out all the bays in the area – the ones that are available, the promising ones, and the ones that are potentially interesting. We assessed the depth, safety and whether the place has diving potential.

In one of the bays found by accident – on our return from the store – we dived. And it was a total success.

After about 15 minutes, we reached a wall overgrown with anemones, full of

fish and crabs. At 9 meters I saw ropes leading down – they stretched into the darkness for as much as 70 meters, maybe more. Visibility exceeded 20 meters, and the water was about 14°C.

This place is ideal for deep, technical dives.

We didn't just dive. Between trips to the water, we picked mushrooms and fished – because how not to take advantage of such clean, wild fjords?

And the views... Norway is beautiful. Fjords, waterfalls, steep cliffs and endless green valleys are extremely impressive.

And the weather! For two weeks, it rained only half a day – an absolute miracle for this region.

Norway is fascinating: underwater and above the surface.

It is a country created for technical divers, wreck divers and for those who are looking for a climate that cannot be counterfeited anywhere else.

Ferndale and Parat – mystical and emotional.

Dampskip – monumental and raw.

New places from the shore – promising, technical and beautifully transparent.

This is a direction to which we will return – without a doubt – in the future.

Text &

TOMASZ KULCZYŃSKI

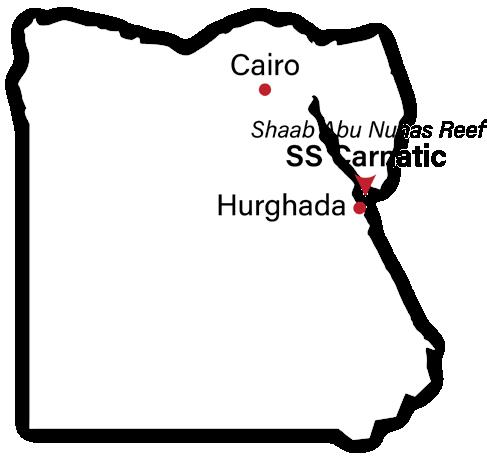

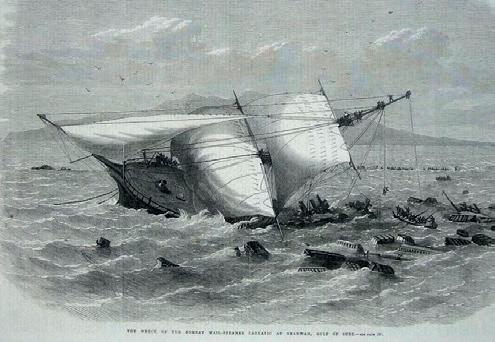

A new year, new plans, winter outside the window… To warm things up a little, today we’ll focus on the wreck of the steamship Carnatic, resting on the bottom of the pleasantly warm Red Sea.

CARNATIC IS A WRECK THAT CONSISTENTLY RANKS AMONG THE TOP SITES IN MOST LISTS, AND AS A RESULT IT’S HEAVILY FREQUENTED.

As always in my articles, I try to give you more than just dry facts, so this time, in addition to the wreck itself, I’d like to take a closer look at the situations and risks that come with diving such a popular wreck. The vessel sank in the 19th century under dramatic circumstances, and its history still fascinates researchers and maritime enthusiasts today.

The ship was built in London at the Samuda Brothers shipyard on the Isle of Dogs between 1862 and 1863. Initially, it was to be

named Mysore, but it was ultimately launched on 6 December 1862 as SS Carnatic and entered service in April 1863. It was owned by the British company Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O).

Carnatic operated on the route between Suez and Bombay, providing a fast steam connection between Great Britain and India even before the opening of the Suez Canal. The journey involved crossing the Mediterranean to Alexandria and then a land

transfer to Suez. The alternative was a long voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, which at that time was economically unviable for steamships.

The ship had a mixed construction – an iron frame with wooden hull planking. It was fitted both with square-rigged sails and a four-cylinder inverted compound steam engine driving a single screw. The engine, designed by Humphrys & Tennant, developed more than 2,400 horsepower.

The use of a compound engine was, at the time, a novelty in the British merchant fleet. Although boiler pressure was limited to 26 psi

due to Board of Trade regulations, the use of superheating made it possible to achieve very good efficiency. Fuel consumption was just over 2 pounds of coal per horsepower per hour, a result comparable with the most advanced vessels of the era.

The disaster occurred on 12 September 1869, when Carnatic struck the coral reef of Sha‘b Abu Nuhas near Shadwan Island, at the entrance to the Gulf of Suez. Captain P. B. Jones initially considered the ship to be safe and refused to evacuate the passengers, assuring them that another P&O vessel – the Sumatra – would soon pass by.

For many hours calm prevailed on board. Only during the night, when water flooded the boilers, did the ship lose power and lighting. After 34 hours stranded on the reef, on the morning of 14 September, the order was finally given to abandon ship. At the very moment when the first passengers were taking their places in the lifeboats, the hull suddenly broke in two. Thirty-one people lost their lives, while the remaining survivors made it to the barren island of Shadwan, from where they were rescued the following day.

Carnatic was carrying a substantial cargo of gold – worth around forty thousand pounds at the time, the equivalent of over a million pounds today. Two weeks after the disaster a salvage operation was carried out and it was officially announced that the entire treasure had been recovered, although rumors of unrecovered valuables still circulate to this day.

After the accident, Captain Jones was called back to England to appear before an inquiry board. Although he was recognized as an experienced officer, it was also concluded that the tragedy could have been avoided had due caution been exercised. His master’s certificate was suspended for nine months, but he never returned to service at sea.

The wreck lies at a depth of 17–25 m and, as I wrote earlier, it is one of the most popular and frequently visited wrecks in the Red Sea. Because it is so popular, it is practically impossible to dive it without at least one other group of divers from other boats in the water… On top of that, you have liveaboard safari boats, which more or less start their trips at the same time, so they are all here either at the beginning of the week or on their way back. Then there are the day boats, which head out from the harbor every morning and return in the evening.

During our dive there were so many boats on site that I could hardly count them. To make things more complicated, they were all moored outside the reef, so we had to reach the wreck by RIB. On top of that it was blowing quite hard, which meant a pretty heavy swell. Taking all of this together, we ended up with a rather explosive mix of circumstances…

To start from the beginning: just getting out to the wreck by RIB was already quite a hassle because of the waves. The ride itself took about ten minutes, but the real problem started once we arrived, because the area above the wreck was swarming with other RIBs – some picking up divers after their dives, others dropping people in. We had to wait another 15 minutes for our turn and, while we were sitting there, water was constantly splashing into the boat, everything was sliding around and, worst of all, most people started to feel seasick… Everyone was already fully kitted up, cylinders digging into our backs and the omnipresent smell of exhaust from the outboard engine hanging in the air…

Once we finally dealt with the surface chaos, we at last got into the water. Our group was fairly advanced, so getting in was straightforward: approach, 1, 2, 3 and splash – everyone in! As I was descending toward the hull I could already see countless streams of bubbles rising above the wreck – it looked a bit like a glass of sparkling water just after you pour it. The biggest problem when diving with such a huge number of people is the very high risk of losing your guide. That’s why I always look for some distinctive feature on

the guide and my buddy so I can tell them apart from everyone else – yellow fins, a mask strap, anything unique. Despite these efforts, every attempt to focus on taking a photo or having a closer look at something ended up with searching for the group – or at least for those who had gone missing. It often happened that, while scanning faces, I’d find one more “lost” diver and suddenly there were two of us looking for the rest. The upside was that navigation on the wreck was child’s play and everyone knew roughly where to look for the group. We finished the dive at the point where the wreck had broken in half, where there are two very thick, twisted mooring lines. We used these lines for our ascent (unfortunately, so did all the other dive groups), so there was a massive traffic jam there! It worked like this: a boat would come in, pick up its divers and move away. In the meantime, another group waited at 5 meters and, as soon as there was space, they surfaced. On the surface the boats circled constantly in the swell, lining up in a queue for the spot with the mooring lines. Underwater all you could hear was the roar of spinning propellers from the boats above…

Have you pictured the situation described above? Then it’s not hard to guess that something had to go wrong at some point. Under strong current and the weight of around twenty people hanging onto it, that thick mooring line tore free from its attachment point and started to drop. It took everyone a moment to realize what was happening. All the guides immediately began trying to fix it and, in an instant, things got pretty chaotic. Most of the divers swam over to the second line, while we, together with our guide, clipped the loose line back in and started our ascent again.

I’d compare it a bit to the checkout lines in a discount supermarket – the moment we had the line fixed, all those people who’d swum over to the other one suddenly started coming back to ours… The only difference was that this time we were first in the queue. Once we surfaced, getting back on the boat was also quite a challenge because of the waves.

What I really want to highlight is this: as we were taking our gear off and climbing back on board, I noticed quite a few heads popping up at the surface, just trying to see what was going on and where their boat was. We all agreed that these people had no idea how dangerous all those RIBs constantly circling while waiting for their groups really were. As we were leaving, we kept shouting nervously to our skipper: “Stop, another one!”

To sum up, I think our dive on the wreck of the Carnatic was a lesson for all of us. Thankfully nothing happened to any of our group, but I honestly can’t imagine less experienced divers out there on a day like that. It’s important to remember that in Egypt people have a different attitude to life and safety, so you really need to factor that in. As for the wreck itself, I agree it is absolutely beautiful and I’d love to have the chance to dive it again – but in better weather conditions and with far fewer divers in the water. As always: safe diving, and see you at the next wreck – maybe the Baltic???

Text DAWID STRĄCZEK

Photos DAWID STRĄCZEK, SAMI PAAKKARINEN, PATRIK GRÖNQVIST

There are dive sites that exist for years somewhere on the border between imagination and the real world – known from films and photographs.

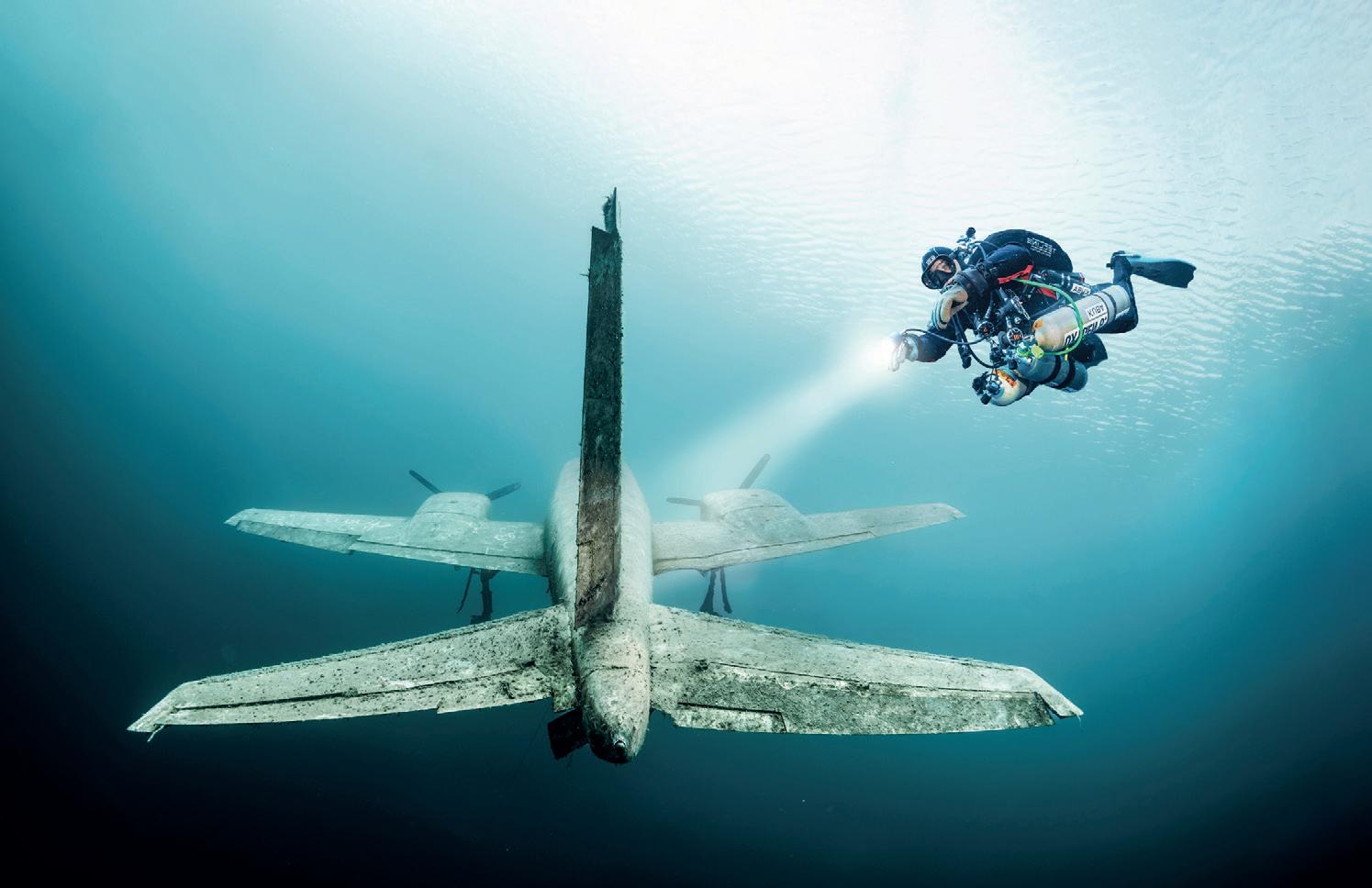

For a long time, one of those places for me was the FLOODED OJAMO MINE IN FINLAND.

Crystal-clear water, absolute darkness, and metaphysical spaces that look more like an alien planet than a former mine – a world that only a few ever get to enter.

Perhaps that’s why it was no coincidence that Ojamo became one of the filming locations for Dive Odyssey, directed by Finnish filmmaker Jan Kasperi Suhonen. This short, visual dive poem had, for years, fired my imagination more than many full-blown reports. Watching Gemma Smith move through vast, shadow-filled spaces had something hypnotic about it – an experience on the border between a dream and a real dive.

For a long time, it was not just a film to me, but an invitation to a place that actually exists.

For many years, however, Ojamo remained purely in the realm of dreams. I only started to seriously think about diving there after one of the big dive conferences, when I had the pleasure of meeting Sami Paakkarinen – a Finnish explorer and instructor who is without doubt among the world’s top technical and cave divers. A short conversation turned into an invitation to dive together, quickly bringing Ojamo down from the level of cinematic vision to something very concrete: planning, logistics, and responsibility.

I almost immediately shared the idea of a trip to Finland with the people I usually dive with. We set up a group chat and started exchanging ideas about everything from logistics and accommodation to objectives and the details of the dive plans. Sami was part of that discussion too, although he never imposed his opinion. He read carefully and asked questions – often the simplest, yet most uncomfortable ones – that more than once called our “perfect” dive plans into question. The conclusion was obvious: Ojamo is not a place that forgives mistakes.

That’s why, although the team was supposed to be bigger at first, in the end only two of us went to Finland – myself and Tomek Iwanicki. And it’s worth stressing this clearly so as not

to sound arrogant: there are many technical divers around me who handle this kind of environment extremely well, but decompression dives under an overhead, on closed circuit, hundreds of metres from the exit and at depths measured in tens of metres require something more than skills and reliable gear – above all, they require complete, unconditional trust in your buddy. On top of that comes a long journey and a lot of time spent together on the surface. Trips like this only make sense when they involve people who not only dive well, but also genuinely enjoy being in each other’s company.

While we were waiting for departure day, curiosity pushed me to dig into the history of the place. The flooded Ojamo mine, located about 60 kilometres west of Helsinki in the Lohja area, has a much richer history than it might seem. Its origins go back to the 19th century, when limestone and marble mining began here. For decades, this raw material was used in construction and architecture, and according to some accounts it even ended up in the floors of the Finnish Parliament in Helsinki. At first the mining was done in an open pit, but over time it moved underground, where an extensive system of tunnels and chambers was created.

In the 20th century the mine continued to operate, including during the difficult period of the Winter War with the USSR, when the Ojamo site was used as a labour camp for prisoners of war. After the war, mining resumed, but in the mid-1960s operations were halted. Falling limestone prices and access to cheaper sources of raw material made further exploitation uneconomical. After the mine was closed, pumping was stopped and the underground workings gradually flooded until the water level reached the surface. Today, from the outside, the site looks like an ordinary forest lake, giving no hint at all of what lies beneath the surface.

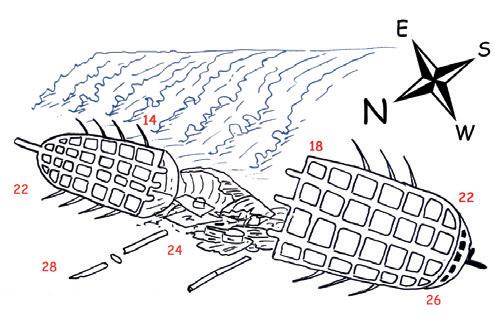

Below the surface, Ojamo forms a multi-level, extensive system of tunnels and chambers that has made it one of the best-known technical and cave diving destinations in Europe. The shallowest level starts at a depth of around 28 metres, the next ones lie at 56 and 88 metres, and the known, explored sections reach down to around 160 metres. The main shaft, dropping to around 250 metres, has still not been fully explored. Long, straight passageways – in places over 1.5 kilometres in length – and huge chambers make an incredible impression even on very experienced divers.

To be able to dive in Ojamo, you need to be aware that it is a site with strictly defined access rules and time slots. The quarry lake at Ojamo is shared with Meriturva – a Finnish training organisation that prepares rescue services, including

fire brigades and water rescue teams. The basin is also used for training purposes by Luksia, a regional training institution that runs commercial diving courses. For this reason, recreational diving takes place mainly on weekends and on weekday afternoons. Access to the water is only possible from the area managed by the Ojamon Kaivossukeltajat Association, which is responsible for organising and coordinating all diving activity at the site.

The entrance to the overhead section is located at a depth of around 28 metres, roughly 200 metres from the entry platform. You can get there by swimming through the open part of the basin, where the water is relatively warm but usually has very poor visibility. For this reason, despite the permanent guideline, the most efficient option is to swim on the surface to the buoy that marks the entrance to the flooded mine.

Once you cross into the mine proper, the conditions change dramatically. The water temperature inside the mine tunnels rarely exceeds 6°C, but the visibility can be truly breathtaking. The main attraction of the first accessible level is a complex of thirteen interconnected chambers known as “the Pearls”. These vast spaces make a huge impression from the very first minutes of the dive.

The deeper levels hide places of an almost metaphysical character, such as “Hell’s Gate” or “Lucifer’s Pillar”. Diving in these sections requires the use of trimix mixtures as well as very

precise planning and solid experience in deep overhead diving. Because of the considerable distance from the entrance and the overall scale of the system, the use of DPVs (diver propulsion vehicles) and closed-circuit rebreathers is strongly recommended – they not only extend your range, but also help maintain an appropriate safety margin.

In Finland, a country associated with pristine nature, thousands of lakes and endless forests, karst terrain is practically non-existent – natural caves are almost nowhere to be found. The local bedrock consists mainly of ancient, hard crystalline rocks such as granite and gneiss, which do not undergo the dissolution processes that lead to the formation of extensive underground systems. This is precisely why flooded mines like Ojamo naturally take over the role of caves, offering Finnish divers an overhead environment in a different, harsher and more industrial guise.

We spread our time at the Ojamo mine over three days of intensive diving. From the outset it was clear this would not be a recreational trip – the priority was training in the use of DPVs in an overhead environment. Every descent had a clearly defined plan and objective, forming part of a larger process rather than an attempt to simply “tick off” a series of locations.

During a dive in Ojamo, the first thing that strikes you is the raw, industrial character of the space. The walls and ceilings

are muted shades of gray and graphite, in places shifting into darker, almost metallic tones. The rock is largely smooth and regular, bearing clear traces of drilling and controlled blasting. Flat planes, repeating shapes, and the geometric order of the chambers make it obvious that this is a space shaped by human hands, not the result of long, natural geological processes.

This mining heritage has its consequences. The rock is stable and “clean” – silt settles mainly on ledges and in depressions, rarely rising into the water column. An accidental fin stroke does not immediately ruin visibility; it usually remains surprisingly good. Combined with the sheer scale of the workings, this creates a sense of space, structure, and control.

During the first dives, there was mostly awe, but also a very palpable respect that at times bordered on fear. The scale of the space, the distance from the exit, and the constant awareness of the overhead made it impossible to forget where we were. With each subsequent descent, that fear gradually gave way to fascination with the place itself – its rhythm, geometry, and calm – always

with a healthy dose of humility toward an environment that does not tolerate carelessness.

The Finns may seem reserved and laconic at first, but once you gain their trust they can turn out to be remarkably warm, helpful, and genuine in their relationships.

Sami Paakkarinen, who ranks among the world’s top technical divers, confirmed his caliber not with declarations, but with a calm, methodical approach, precision, and attention to every detail. He anticipated potential problems and responded

to them in advance, thanks to which all our dives ended safely.

Ojamo does not try to impress with adrenaline or drama. It demands focus, precision, and inner calm. After surfacing, what remained was fatigue, but also a deep sense of satisfaction that everything had gone exactly as it should. It is precisely these emotions – more than the depths, run times, or the names of individual spots – that stay with you the longest and make the thought of coming back appear almost immediately.

Text & photos MICHAŁ MUCIEK

In the landscape of Polish diving, dominated by quarries, the legendary shipwrecks of the Baltic Sea and the depths of the Hańcza Lake, the Łęczna-Włodawa Lake District still appears as a region that has not been fully discovered, although it has crowds of devoted admirers.

Among the dozens of water reservoirs of this region, one lake stands out as the undisputed center of diving tourism in eastern Poland.

Lake Piaseczno, as it is what we are talking about, is a water reservoir that is one of the cleanest in Poland (1st class of cleanliness), which translates into an average visibility of 3 to 7 meters. The best "visibility windows" usually are in June, September and winter – at the turn of December and January,

when the lake can surprise with calm and clear water. However, there are places that do not impress at first glance. Quiet shore, seemingly ordinary water, no spectacular rock formations. And yet, it is enough to dip your face under the surface to understand that Lake Piaseczno is not trying to seduce anyone. It sets the conditions. It is a reservoir that does not impose itself with its narrative. What it does is enforcing it, slowly, consistently, unsparingly. The topography of Lake Piaseczno is simple but ruthless. It teaches you more than many foreign trips: buoyancy control, mid-water work, conscious movement and respect for the bottom, which does not forgive mistakes.

The adventure begins innocently. The beach and the bottom to a depth of about 2 meters – that is, to the border of littoral vegetation – are sandy, ideal for getting acquainted with the water for the first time and for children to play and swim. The bright bottom acts as a natural diffuser, reflecting sunlight and creating an amazing play of lights in shallow water. However, the littoral vegetation marks a clear boundary, beyond which another reality opens up. Below 3.5-4 meters, the bottom becomes muddy. This is the basic information that every dive planning should start with. The silt in Piaseczno is not a defect, it is a feature. It is soft, lightweight and ready to lift with the slightest error. All it takes is one uncontrolled movement of the fin to make the visibility drop to almost zero. This lake does not forgive haste. Every

attempt to "swim" it forcibly ends in frustration. Piaseczno forces your presence, both mental and physical. Therefore, buoyancy ceases to be a theory from the course, and becomes a basic tool for survival and comfort. Here, technique is not an addition to diving, but determines the quality of diving. Calm work with fins, conscious control of the position in the water and planning the route so that you do not return "on your own trail" are sure to turn Piaseczno from being demanding to satisfactory.

Despite the harsh nature of the bottom, Piaseczno is not empty under water. Sunken objects serve as landmarks, but also elements of the tale to be told. A system of handrail ropes and platforms facilitates navigation, guiding the diver through the consecutive stages of initiation.

And what is hidden in the depths? First of all, an extensive underwater infrastructure, created over the years for training, recreation and exploration. From different sides of the lake, there are several logically connected trails, training platforms and landmarks at different depths. It is not a park of attractions in the classic sense, but rather a functional underwater landscape that allows you to plan dives of a very different nature – from calm, shallow dives to more demanding profiles. The whole gives a sense of order, but it also leaves room for discovering and interpreting space. Of course, this is just a summary, the trails hide much more small objects and details. On all of them, we will find training platforms at different depths, as well as remnants of no longer existing bases, unlined but giving a lot of exploratory joy.

And all the routes are connected by one special point – the deepest point of the lake. Officially, it is 38 m, but nature likes to correct tables. With the current drops in groundwater level, the real depth is rather about 36 m. A slight difference, but enough to remind us that underwater it is not the numbers that are most important, but the awareness of the place and conditions. Getting there requires precise planning and a enormous diving culture, one inattentive move can destroy both visibility and the shot.

The story of the sunken German Junkers from World War II has also been circulating in the local community for years. Officially, no one saw it, and unofficially, "someone was once close". And that is why the plane has become the Holy Grail of Piaseczno. The less evidence, the more imagination. The legend lives its own life and gives the lake a hint of mystery, due to which a thought always appears when going under water: what if...?

Today, Lake Piaseczno functions as a full-fledged diving site thanks to its shore facilities. The bases create a coherent map of the entrances to the water, and each of them offers a different atmosphere and standard. Today's image of Piaseczno as an organized diving site was not created as the result of a single project. The first elements of the underwater trail appeared even before the lake gained recognition. It was for practicing technique, orientation and work in limited visibility.

The Profundal Diving Base, run by Leon Staniak, is a base that has been building its reputation for years. It has been operating in its current form since 2014. It is a place for people who val-

ue order and structure. Platforms, a lecture hall, a compressor room and a landing craft form professional training facilities. The base focuses on skill development, including popular sidemount configurations. Profundal does not try to be an "attraction", it is a solid, functional base.

Diving Ranch, the base run by Piotr Tokarski, has a completely different atmosphere. It is an intimate place where diving is combined with camp life. It is selected by people who want to stay at the lake longer. The ranch builds community: it's not just about the number of dives, but about relationships. It offers professional facilities, a compressor room and a wide

training program, ranging from the basic ones to the advanced, closed-circuit rebreather systems (CCR).

"U Gieni" in the landscape of Piaseczno is a special place. A point without extensive infrastructure, but with what is crucial for many: a table for preparing equipment and immediate entry into the water. It is a place of work, raw and simple in its form. Available only through schools and dive centers, it is mainly used for training and underwater work. That is why the teams of the Napoleon Diving School run by Arek Kowalik regularly appear here, for them the calmness, lack of distractions and the ability to fully focus on diving are what counts most.

Right next to it is the base of the Tryton Diving Center with a compressor room and a campsite.

The Dive Service Base located at the Piaseczno resort offers good starting conditions: electricity, shelter and access to recreational facilities.

Looking at contemporary Piaseczno lake, it is difficult to ignore its media coverage. It is a place living in two worlds at the same time. One is the real dive itself: cool water, silt, concentration. The other are the Internet, Facebook and Instagram stories with the note "stunning visibility". Piaseczno lake functions exactly at the interface between these two worlds. On the Internet, the bottom often disappears. The shots are tight, refined, devoid of context. You can see the object, the diver, the beam of light, less often the space around. This is no coincidence. Piaseczno lake does not look good in wide-angle shots. It forces selection and control, and you photograph only what you can control.