ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!

Lu Yixin

Lu Yixin

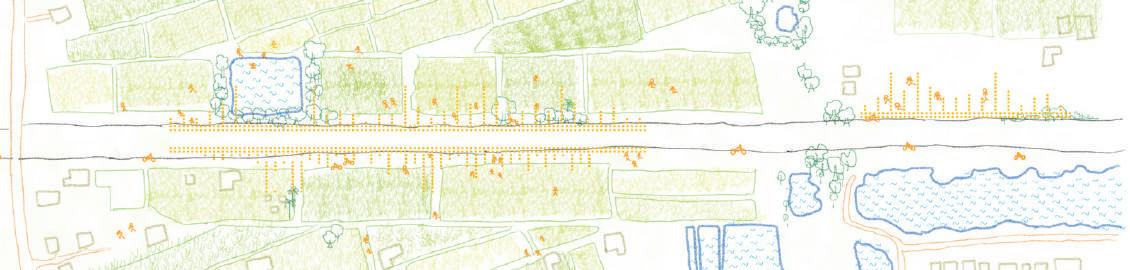

The periurban offers a rich, immersive form of education increasingly lacking in the dense city. In these transitional landscapes— where urban sprawl meets rural life—students learn through direct experience: among paddy fields, banyan trees, and the scent of mango groves. Such environments foster not only ecological awareness and agricultural literacy, but also a slower, more reflective mode of learning grounded in observation, sensory engagement, and seasonal rhythms.

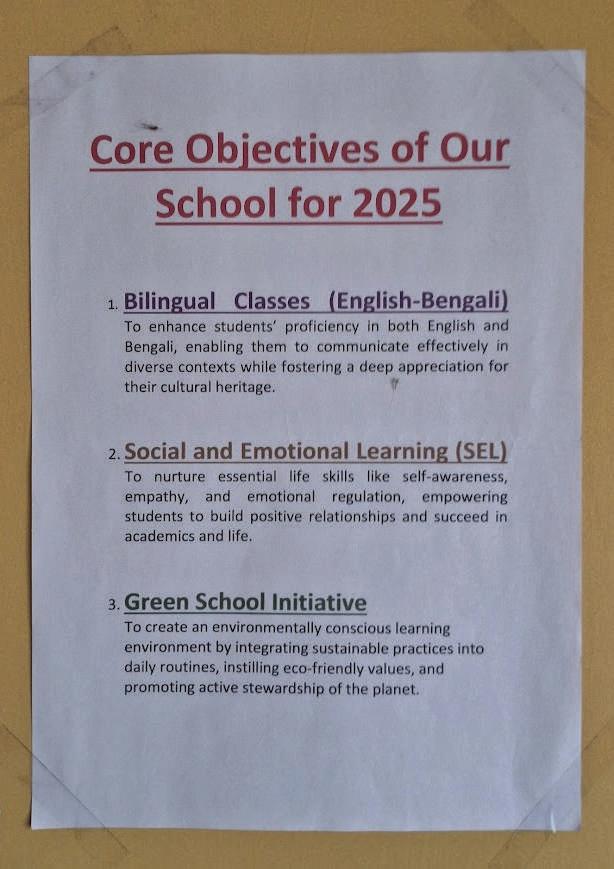

Yet despite this potential, the ordinary periurban school often lack the facilities, resources, and institutional support. Through fieldwork in Kolkata, it was also observed that the periurban lacked dedicated third spaces for schoolchildren. Unlike urban centers with libraries, parks, or youth clubs, the locales of Champahati, Kalikapur and Piali offered few, if any, communal areas where children could gather, play, or learn informally.

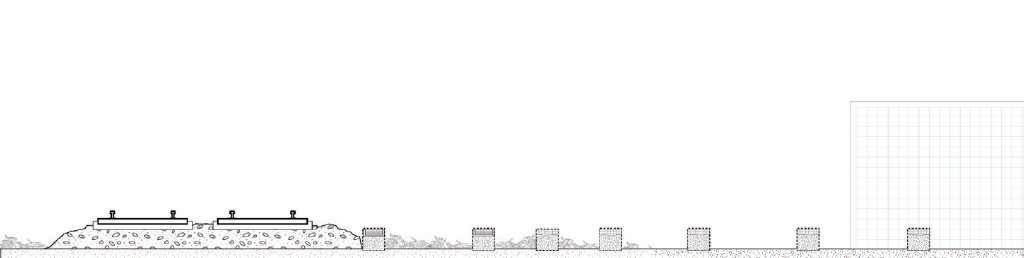

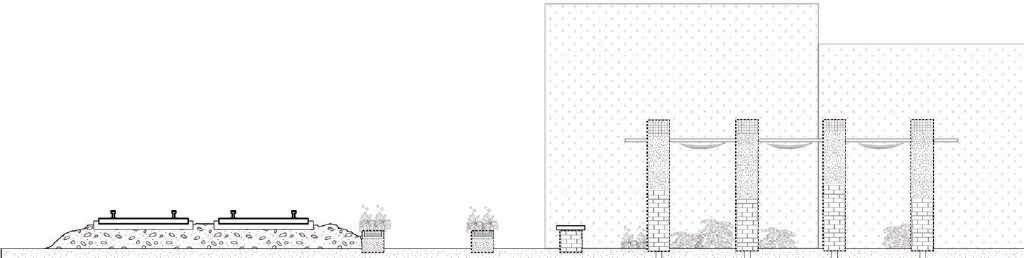

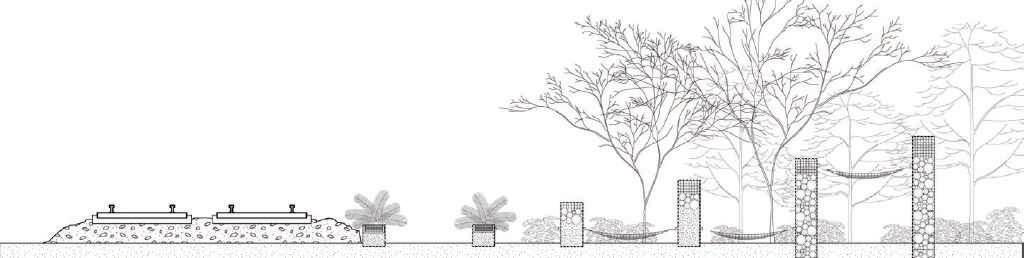

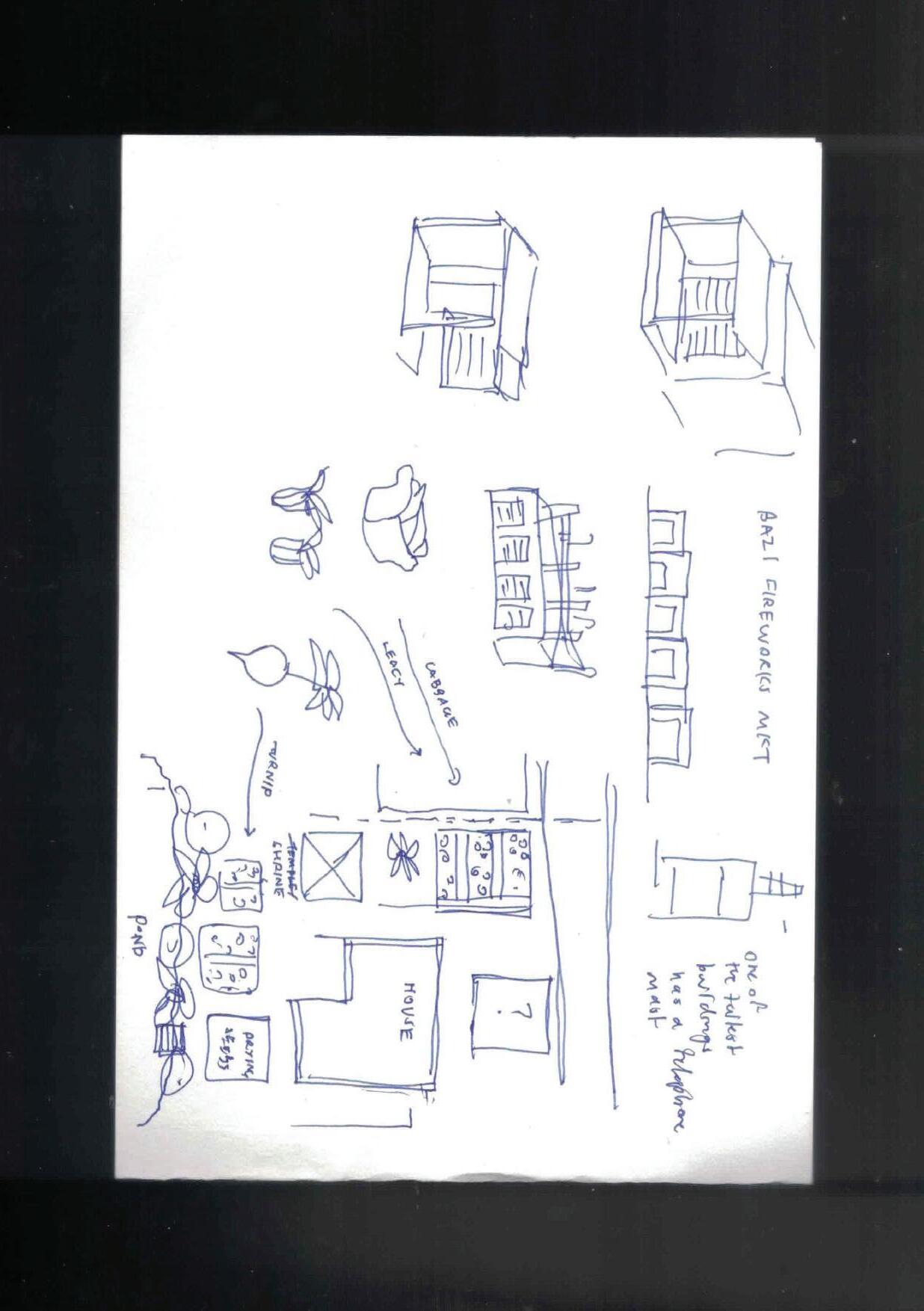

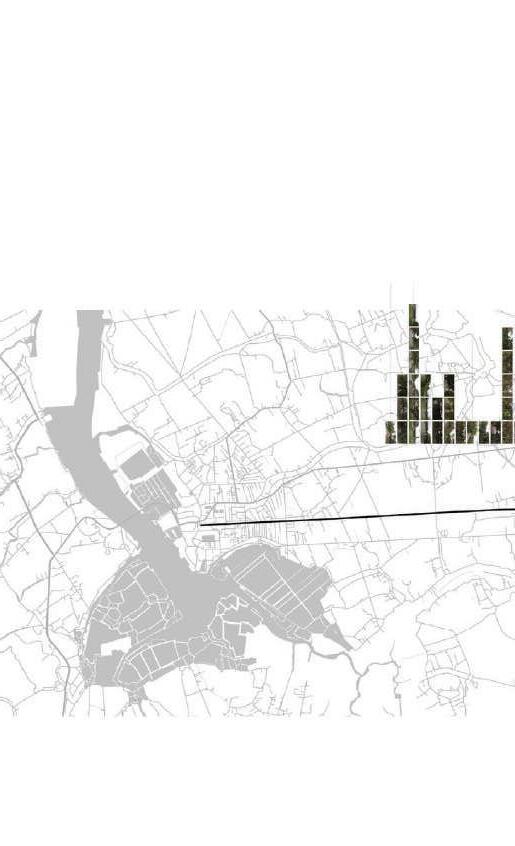

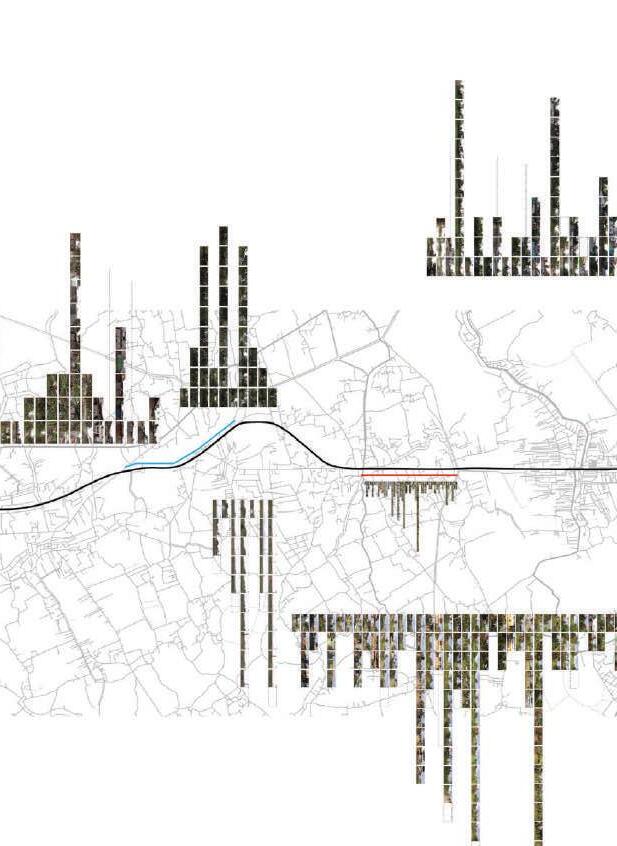

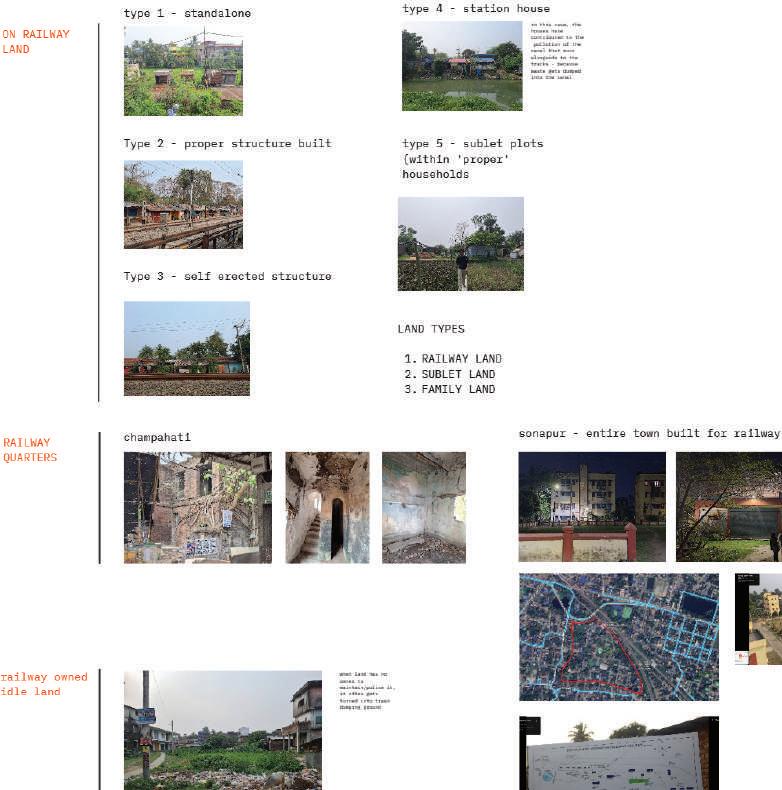

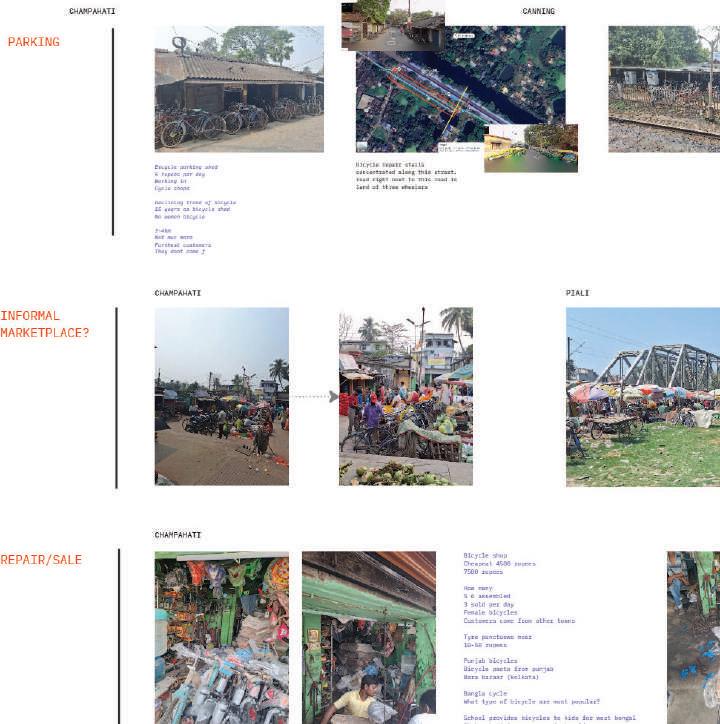

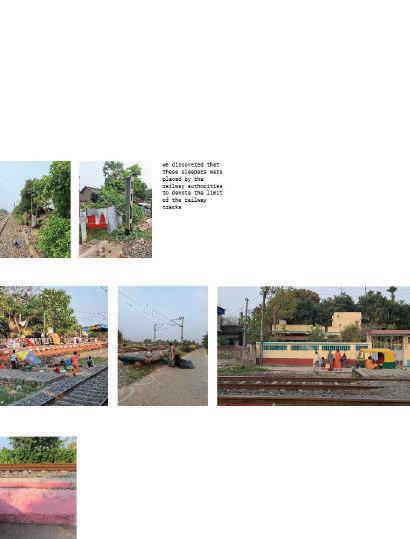

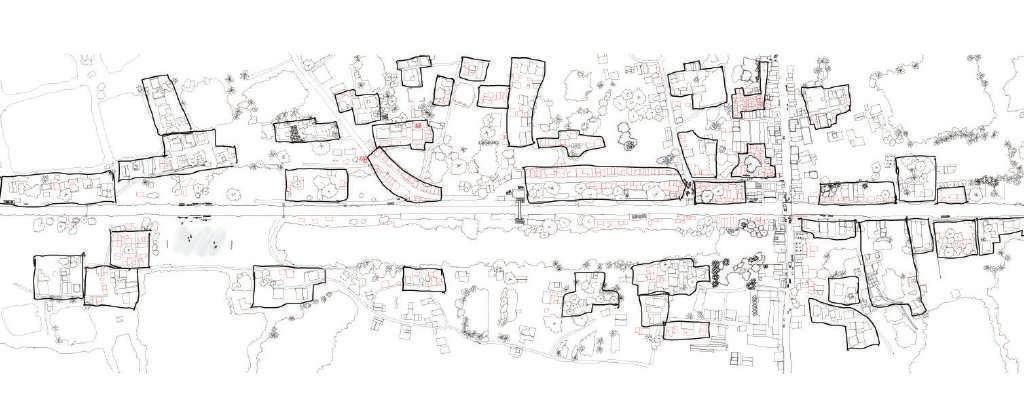

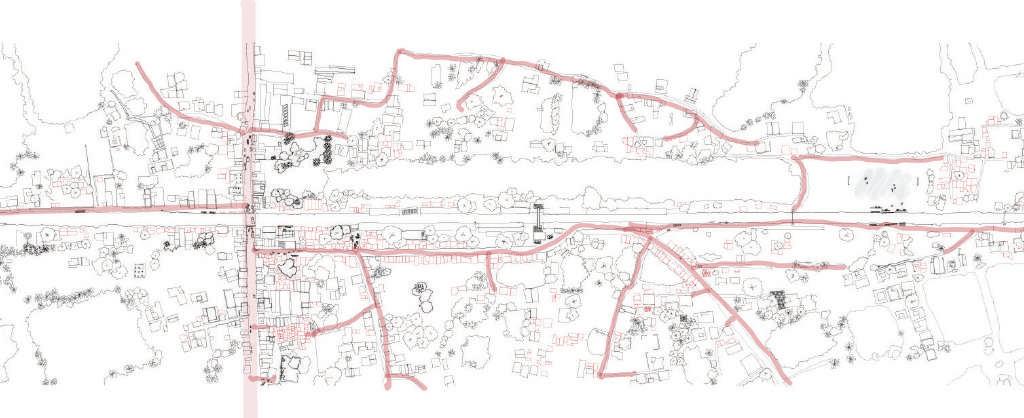

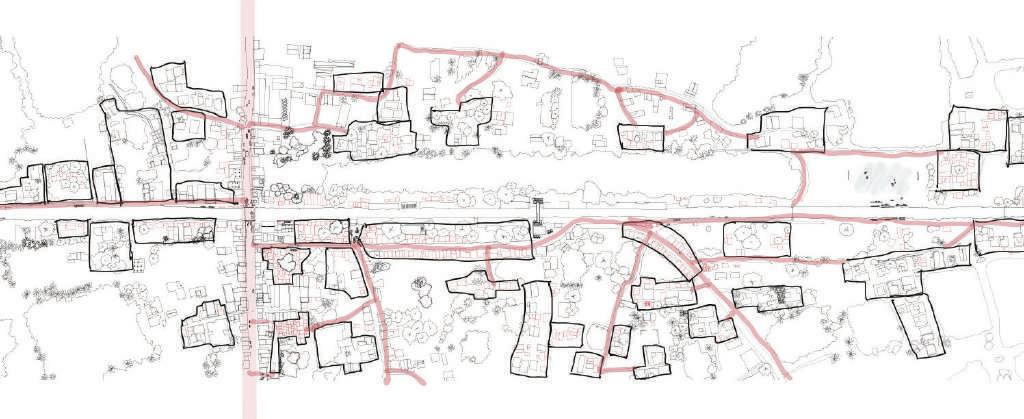

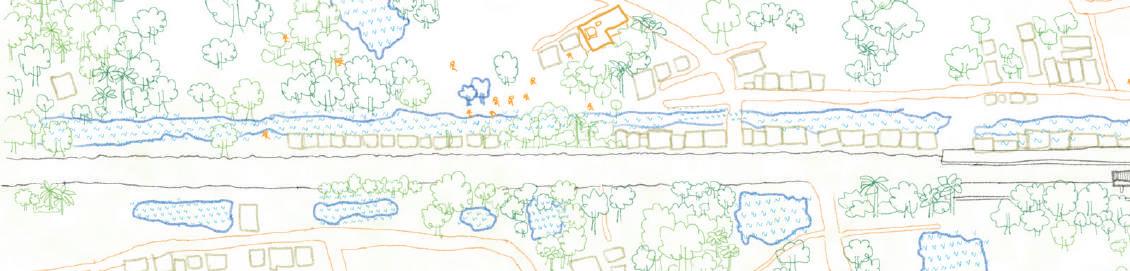

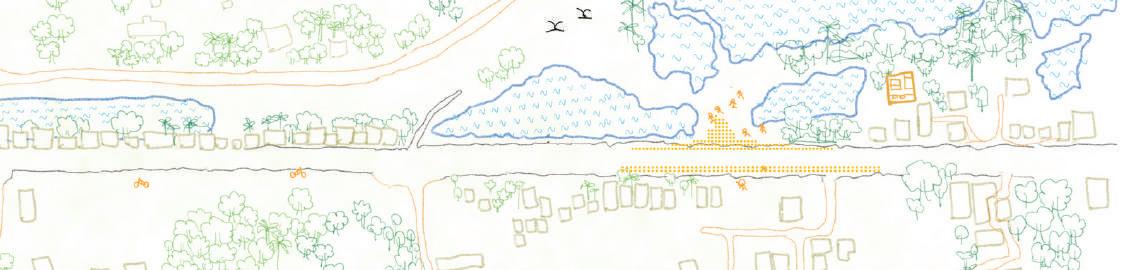

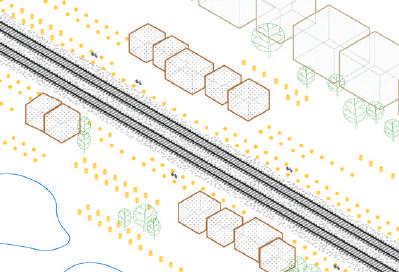

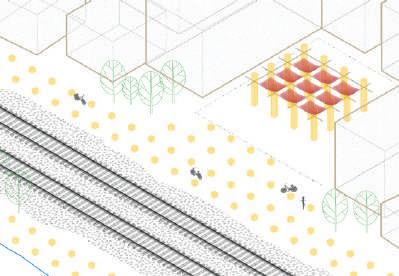

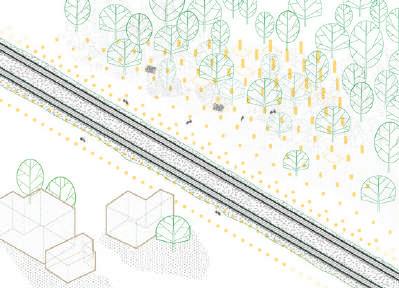

Arise, Children of the Periurban! is a proposal aimed at reimagining and supporting the current state of countryside education. At the heart of the project is a bicycle corridor that runs alongside the suburban railway line, designed to complement existing bicycle distribution programs in West Bengal. Railway authorities allocate sections of land along the tracks to local schools and their students, who are tasked with transforming the harsh, urban edges of the railway into welcoming spaces using gabion cubes, filled with ballast from the train tracks. These nodes, marked by the distinctive gabion cubes, are established and expanded incrementally via bicycles, creating a growing network of child-friendly spaces. Over time, these spaces evolve into vital third places for schoolchildren, offering not just areas for rest and play, but also hosting activities that foster a deep sense of care and reciprocity toward the environment.

Gradually, other ripple effects begin to unfold. The railway track, once a space largely hostile to pedestrians, is transformed into a vibrant, people-friendly corridor. Previously neglected areas, situated between two train stations, start to attract new visitors and activity. Most importantly, the periurban begins to gain recognition beyond its borders as a place of value. No longer simply the area that lies on the outskirts of the city, it emerges as a dynamic space offering unique opportunities for learning, growth, and connection.

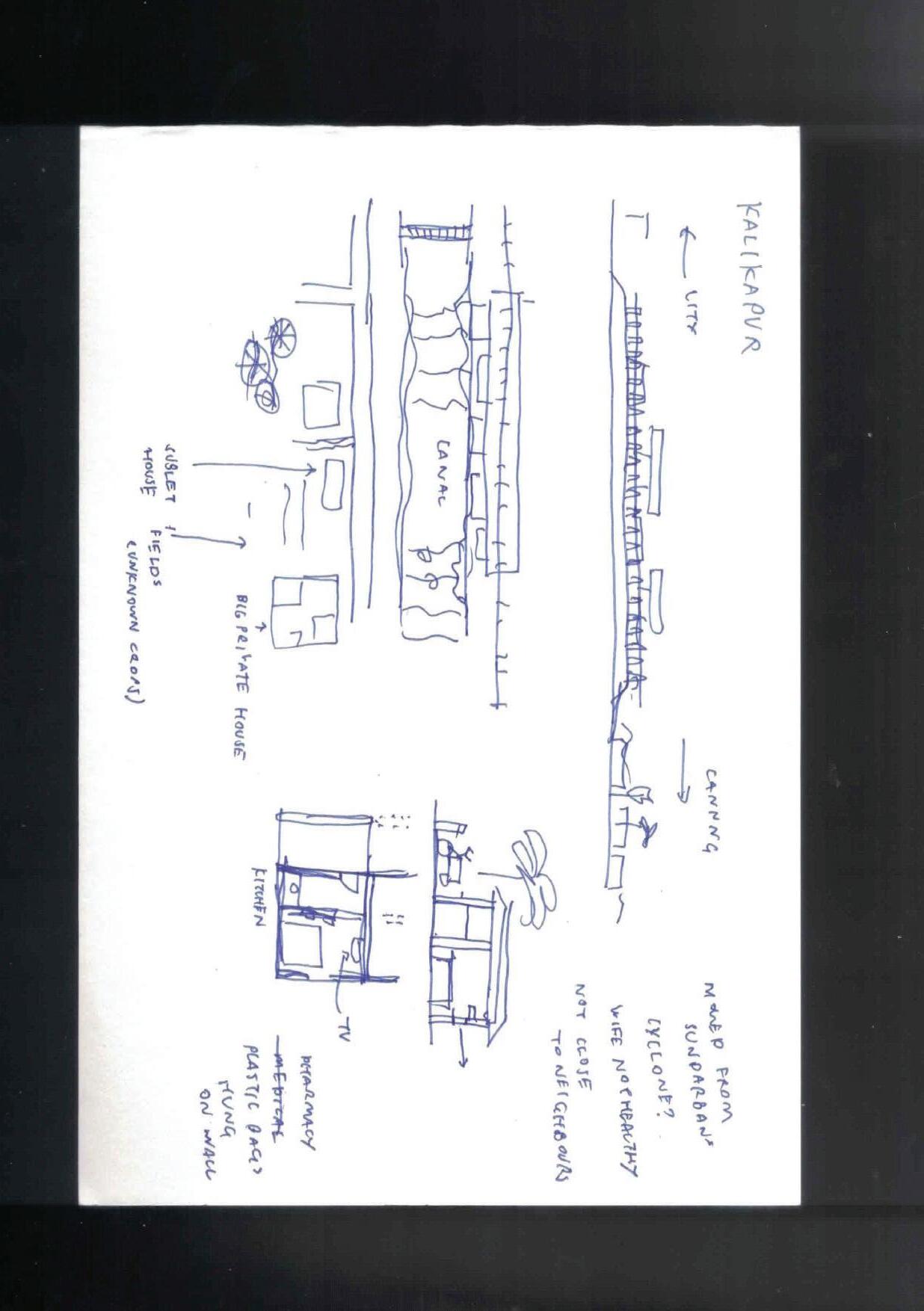

While walking along the railway tracks at Kalikapur, we encountered a young man in his early 20s. He seemed very fashionable (compared to many of the other kalikapur residents we had seen) - with tattoos all over his body and a very up-to-date haircut. When we asked about his job, he told us that he was unemployed. Turns out, he was studying in university (reading a major in history no less) until covid struck, and he no longer had the resources to continue his study. Nowadays, he just spends his time hanging out with his friends in the town of kalikapur.

Most of the people we’ve spoken to so far had been farmers or low skilled workers without too much education - it was surprising to find a university-educated individual. This shattered the illusion that the countryside was just the countryside - it housed people that you would normally find in the city too. We’ve been harping on the idea that the urban and rural are inextricably linked for weeks in studio - but through this encounter, I felt the complexity of that relationship even more viscerally.

Again in kalikapur, we found a man in his late 30s who worked as a home tutor for geography college students. He had graduated a few years ago, and because he was unable to secure a job in the city, he had settled on becoming a tutor (which we found out afterwards, was a fairly common pattern within the rural areas) As we entered his house, we were greeted with the sight of MacBooks and laptops, as his students gathered around the dinner table to got hrough the mechanics of soil sedimentation. The two students he had on that day were both newly minted freshmen at Calcutta University, the alma mater of debanjan, our research assistant. They told us that they lived in the city and would take the train to kalikapur every time they had tuition, choosing this tuition centre in particular over the hundreds of others located within the city. This encounter challenged previous understandings of the countryside being comparatively less ‘desirable’ than the city. We saw individuals co sciously lean towards the offerings of the countryside, even though the city offered those things as well. We’ve heard of suburbanisation, of people moving from the city to the countryside, in search of what the city did not have - but here it is sort of a reverse scenario - the countryside bested the city at what it does best.

3. The plurality of india

In many places - it was hard to pick up a discernable pattern. Perhaps, this was limited by the area we covered - but still, every house had a different story, different background and different lifestyle. Even within markets, the same type of vegetable would have found their way here via a thousand different means. The diversity, in every sense, surpasses that of all other countries I’ve been to. I think about how plurality and multiplicity underscore india as a whole - it’s the first country that I’ve been to that has so many official languages, so much color, so many festivals… so much of everything. Here, things seem to be driven by time-honored habits rather thancold hard efficiency. Vegetables don’t arrive at markets via the fastest possible routes, but instead get passed from one contact to another

4. Time flows differently

Herein lies the next point. Whenever we asked people ‘how long have you been doing this’ or ‘how long have you lived here’, they often minimally quoted 10 years. Most people have been engaged in their currently lifestyles for the last 20-30 years. The same spot at themarket every morning, selling the same onions since their youth.Houses are left unfinished, but unlike projects in the city, there is no rush to finish the houses.I become more and more aware that in order to design, we must be highly conscious of how time flows in periurban kolkata. Many strategies that would work in the city, with clear stages and clear finishing points, may be completely inadequate for the periurban.

5. Fieldwork

I quite enjoyed it! I can’t believe I’ve been doing architecture all my life without even asking people about their lives.

6. Resilience

I have never really liked architecture with a capital A. I like to think of architecture through a more anthropological lens - architecture to me is about material culture, architecture is about how people figure out how to live. At its core, I believe architecture is about resilience - a celebration of our ability as a species to build around whatever difficulty we may come across. Periurban kolkata was a masterclass in resilient architecture - how people came up with creative solutions for their lives, despite limited resources.

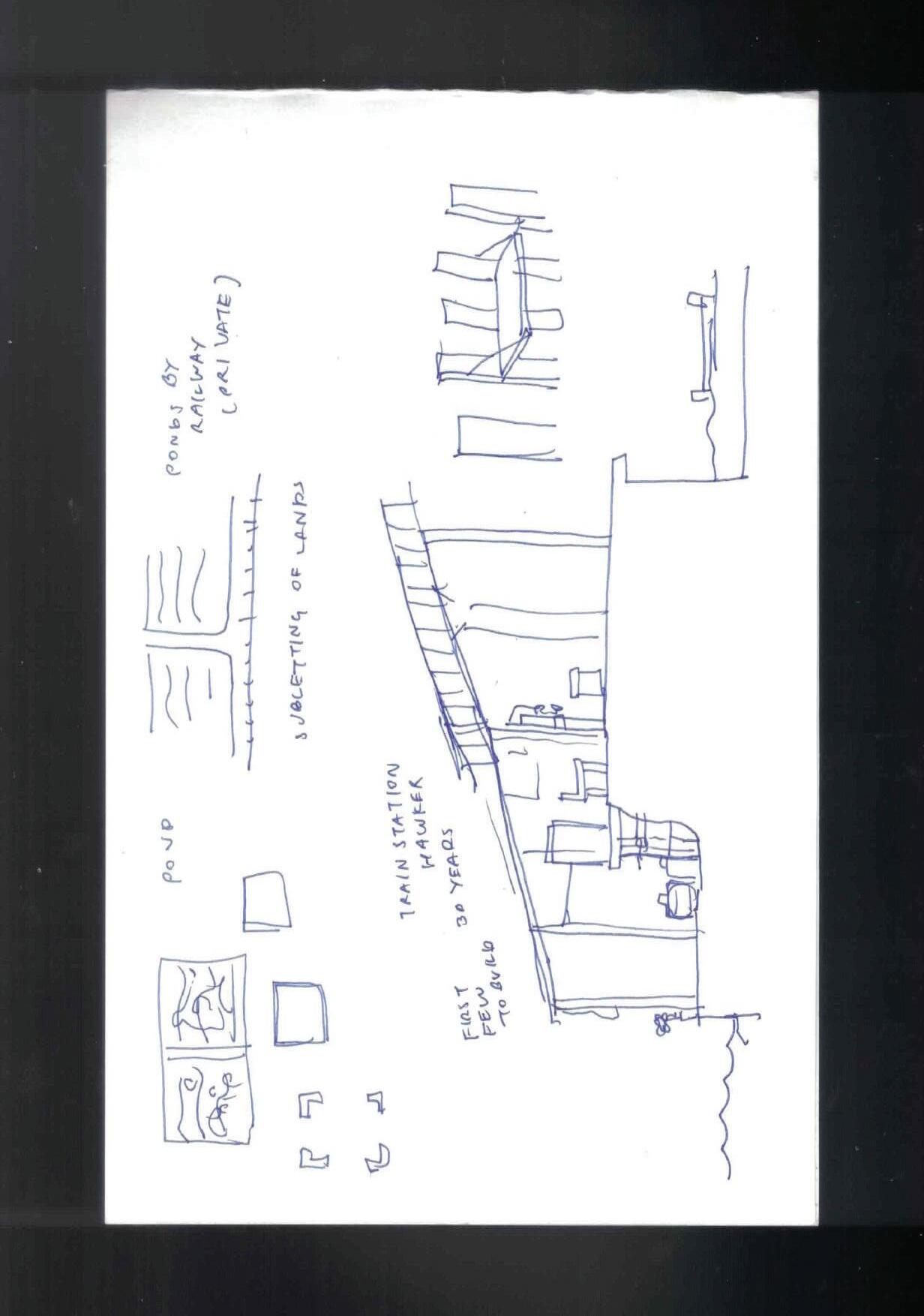

One provision shop located on the platform of kalikapur moved me a lot. The stall wasn’t supposed to exist. The tiny strip of land it stood on was sandwhiched between the train platform itself (which was out of bounds) and a pond. Yet, it found a very sophisticated way to negotiate this lack of space and level difference in the ground. Even the fence of the railway station, something that was meant to keep stalls like this out of the station, was used as a ‘front facade/window’ of sorts, displaying all the snacks the stall had to offer. Architecture existing where people would’ve thought good architecture would have been impossible. Gently and cleverly negotiating around limitations, rather than violently imposing ‘solutions’.

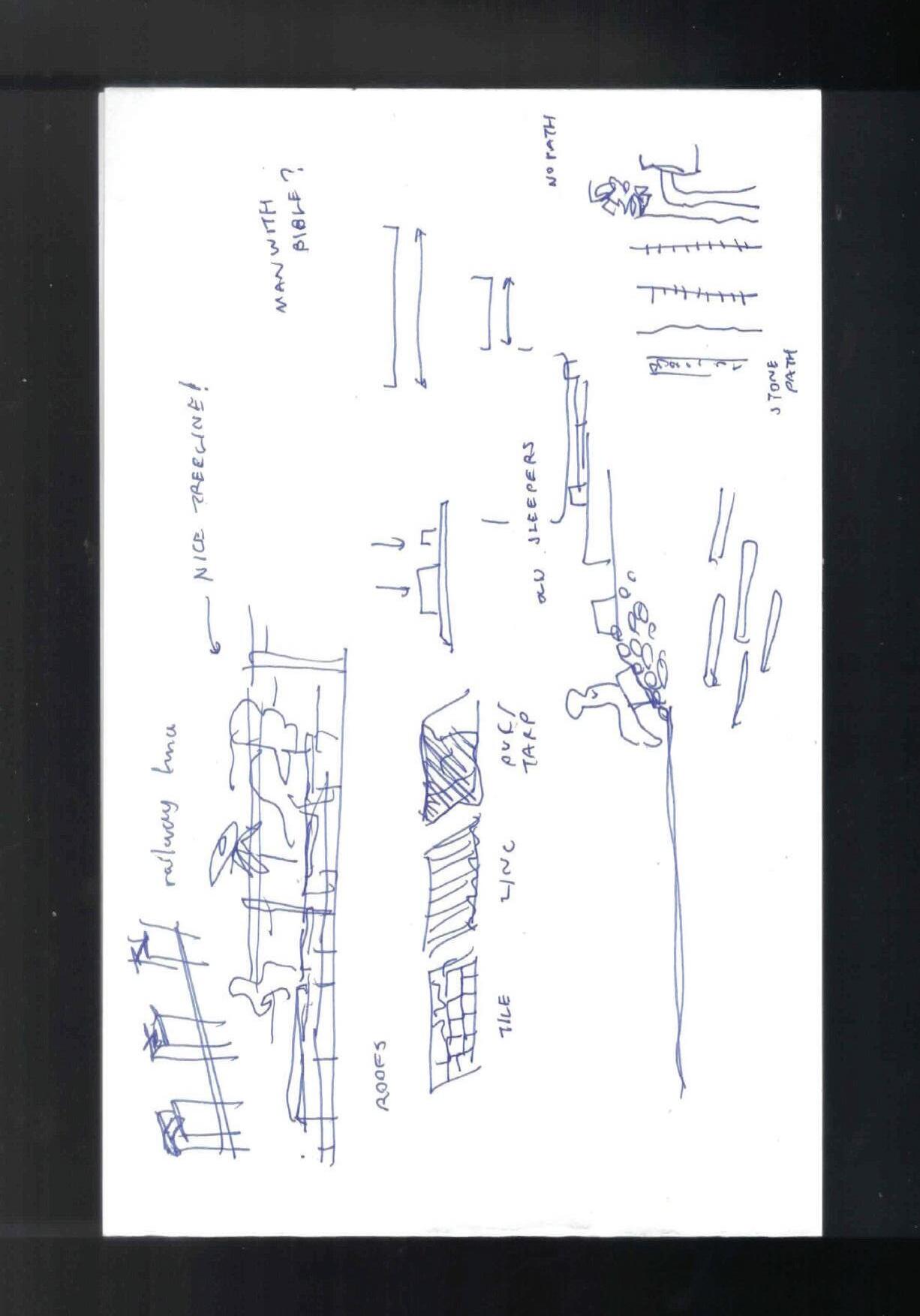

I think I have an idea of where my project will go. I remember on one of the days of fieldwork, we found ourselves walking along the train tracks of champahati during the sunset hours. Champahati’s main roads were loud and chaotic, but along the train tracks, it was nice and peaceful. The sweltering afternoon sun had disappeared. People playing cricket in a large field by the train track. People sitting on sleepers and chitchatting. Trains occasionally zooming by. It was quite beautiful. I’m still trying to find the words to explain this - but I think at the core, I am reminded by these sights to celebrate life, to celebrate the simple things. Often, in designing for a project of this scale, we retreat to the abstract and the large, trying to understand the countryside through conceptual frameworks and theories. But there is something very lived and embodied about the periurban too. It is where people live, where people enjoy living, and there is something joyful about life itself, without (or rather, despite) all of its complexities.

ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!

ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!

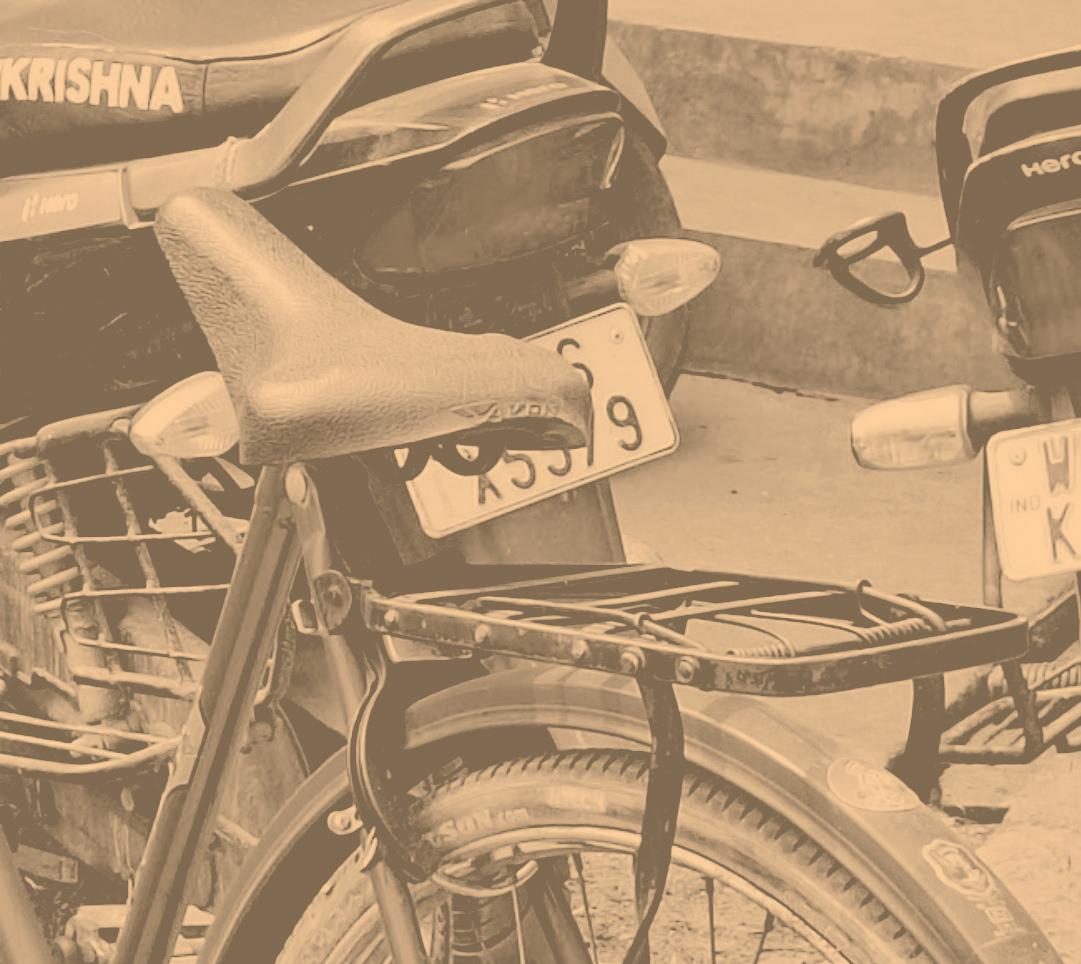

For two years, six days a week, she cycled two hours daily from home to school and coaching classes and back, using a bicycle provided by the state government.

“If I didn t have a cycle, I don t think I could have finished high school. It changed my life,” says Nibha, now 27.

The daughter of a farmer from Begusarai district, Nibha was sent to live with her aunt 10km (six miles) away to attend a nearby primary school. Mobility was challenging for girls and public transport was unreliable.

When Nibha returned home for high school, she hopped on a bicycle, navigating the rough village roads to pursue her education.

“Girls have gained a lot of confidence after they began using bicycles to go to schools and coaching classes. More and more of them are going to school now. Most of them

have free bicycles,” says Bhuvaneshwari Kumari, a health worker in Begusarai.

She's right. A new peer-reviewed published in Journal of Transport Geography reveals remarkable insights about school-going children and cycling in rural India.

The study by Srishti Agrawal, Adit Seth and Rahul Goel found that the most notable rise in cycling in India had occurred among rural girls - increasing more than two times from 4.5% in 2007 to 11% in 2017 - reducing the gender gap in the activity.

“This is a silent revolution. We call it a revolution because cycling levels increased among girls in a country which has high levels of gender inequality in terms of female mobility outside the home, in general, and for cycling, in particular,” says Ms Agrawal.

State-run free bicycle distribution schemes since 2004 have targeted girls, who had higher school dropout rates than boys due to household chores and exhausting long walks. This approach isn t unique to India - evidence from countries like Colombia, Kenya, Malawi and Zimbabwe also shows that bicycles effectively boost girls' school enrolment and retention. But the scale here is unmatched.

The three researchers - from Delhi s Indian Institute of Technology and Mumbai s Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies - analysed transport modes for school-going children aged 5-17 years from a nationwide education survey, looked at

the effectiveness of state-run schemes that provide free bicycles to students and tested their influence on the cycling rate.

the percentage of all students cycling to school rose from 6.6% in 2007 to 11.2% in 2017, they found.

Cycling to school in rural areas doubled over the decade, while in urban areas, it remained steady. Indian city roads are notoriously unsafe, with low urban cycling to school linked to poor traffic safety and more cars on the road.

India s cycling revolution is most substantial in villages, with states like Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, and Chhattisgarh leading the growth. These states have populations comparable to some of the largest European countries. Cycling was most common for longer distances in rural areas than in urban areas, the study found.

India began reporting cycling behaviour for the first time only in the last Census in 2011. Only 20% of those travelling to work outside home reported cycling as their main mode of transport. But people in villages cycled more (21%) than in the cities (17%).

Also, more working men (21.7%) than their female counterparts (4.7%) cycled to work. “Compared to international settings, this level of gender gap in cycling is among the

ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!

ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!

MY BENGAL OF GOLD, I LOVE YOU. FOREVER YOUR SKIES, YOUR AIR SET MY HEART IN TUNE AS IF IT WERE A FLUTE. IN SPRING, O MOTHER MINE, THE FRAGRANCE FROM YOUR MANGO GROVES MAKES ME WILD WITH JOY, AH, WHAT A THRILL! IN AUTUMN, O MOTHER MINE, IN THE FULL BLOSSOMED PADDY FIELDS I HAVE SEEN SPREAD ALL OVER SWEET SMILES. AH, WHAT BEAUTY, WHAT SHADES, WHAT AN AFFECTION, AND WHAT TENDERNESS! WHAT A QUILT HAVE YOU SPREAD AT THE FEET OF BANYAN TREES AND ALONG THE BANKS OF RIVERS! OH MOTHER MINE, WORDS FROM YOUR LIPS ARE LIKE NECTAR TO MY EARS. AH, WHAT A THRILL! IF SADNESS, O MOTHER MINE, CASTS A GLOOM ON YOUR FACE, MY EYES ARE FILLED WITH TEARS! GOLDEN BENGAL, I LOVE YOU.

ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!

THE FRAGRANCE FROM YOUR MANGO GROVES

WHAT A QUILT HAVE YOU SPREAD AT THE FEET OF BANYAN TREES

IN THE FULL BLOSSOMED PADDY FIELD I HAVE SEEN SPREAD ALL OVER SWEET SMILES

ARISE, CHILDREN OF THE PERIURBAN!