SARI DAYBEDS

Juliana Masiclat

Juliana Masiclat

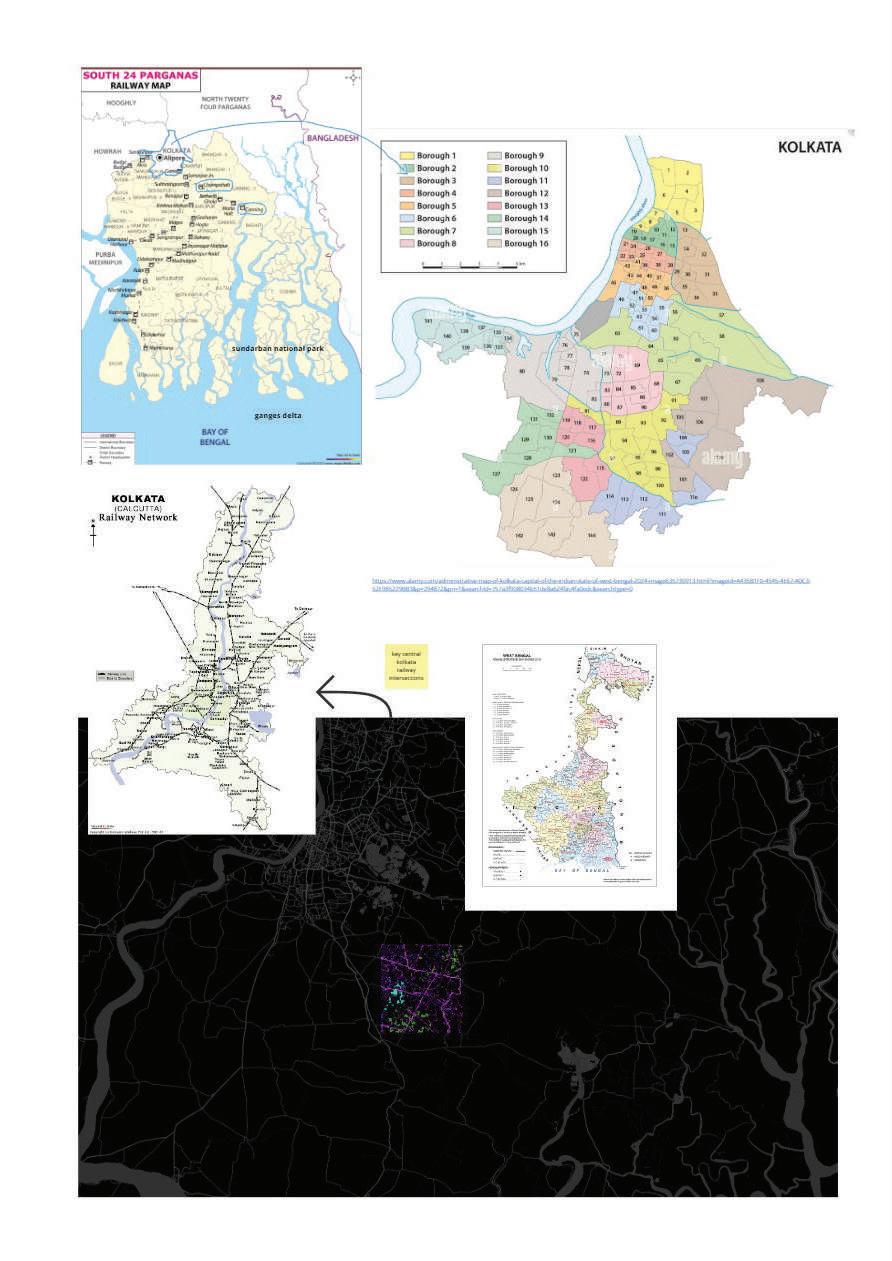

My project explores and expands upon two factors that enable rural households to live remotely in Piali, namely: self-sustenance and proximity to work. Piali is a town located in South 24 Parganas, West Bengal, 40km from central Kolkata and 20km from the end of the train line. Remoteness in this context references the distance from and accessibility to Piali train station, as well as the size of “colonies”, meaning small real estate developments of multifamily, bungalow housing. For the women of Piali that I met in my fieldwork, domesticity is gradually becoming akin to economic productivity. That is, as the area becomes more urbanised, they are now more inclined to provide their daughters formal education, funded through women’s paid labour. Although most women are still homemakers, they now recognise the importance of their personal financial independence mixed with sentiments that only tending to their homes is as good as being idle. Thus, my design research project finds itself in the realm of proposing an architecture for enabling childrearing and running a sari business to take place, simultaneously.

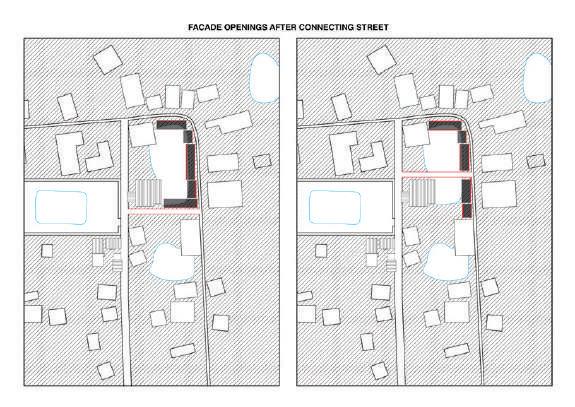

My first strategy utilises an unused plot of private land to combine two sari shops into a singular working space. I also utilise the geometries and proportions of key elements in the shops. Firstly, the daybed as it is a repeated element and a measure for intimacy and conviviality, embodying the social nature of the sari selling experience through its wide and interfacing position of the store. Secondly, the long and sometimes tall storage of the saris that often act as the facade of the shop. They are flanked with a surface such as a daybed to showcase the sari in its entirety, thus creating this dynamic of proportions within the work, social and creative space. Externally, to create an architecture that hosts the

combined sari shops, calls for the activation of the unused plot behind the repair store, as well as a new connecting “shortcut” from the local road to it. To create such a space requires coordination between neighbouring landowners for the benefit of all.

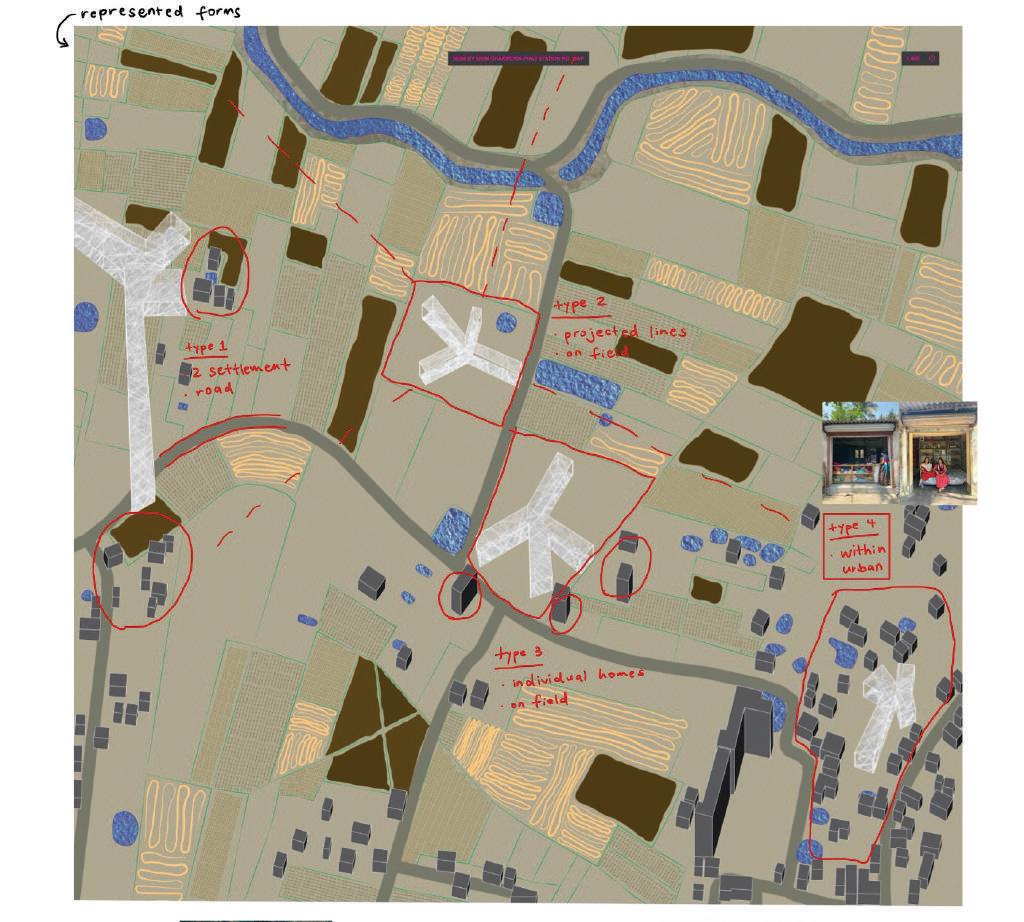

The second strategy imagines the future of sari work collaborations in a new colony as an emblem of exploring a novel remote, periurban settlement logic. Basic elements of a household in Piali consist of a road, a house, a pond and a garden. The plot is former farmland, parcelled into plots, managed and planned by a “promoter” (meaning developer in local parlance). In my project I imagine women as promoters, and this breeds two additions to the basic elements of a household in Piali: a shop and the prospect of combining two or more plots (as demonstrated in my first strategy). As a result in the scenario that i java played out, the hierarchy, volumes and circulation may vary greatly depending on the an=genda of the shop owner, forming a robust colony that provides women agency and empowerment.

In sum, the project speaks to the gradual yet exciting autonomy of women in rural West Bengal. Their remoteness from being confined in their domestic spheres is being activated by the need for local economies in densifying areas. Socially, imagining women shaping novel colonies with their ambitions hopefully introduces avenues to curb post-rural implications to longtime and newcomer residents of Piali.

What you thought and what you found.

Thoughts on social research

A general sense of the demographic’s nature was forefront in conducting the fieldwork. It was especially helpful that Victoria and Dip were greatly aware of Bengali people’s welcoming nature that made it easier to gain momentum on curiosity. There was also a varied type of sampling in each location (Ballygunge Market vs Site vs Koley Market) that gave the research and findings more intentionality. As for fieldwork on site, my experiences in interviewing felt like it was easier to work with natural follow-up questions rather than a questionnaire set. It was also insightful when Dip deliberates the depth of the questions being asked and is aware and experienced in controlling the interview sessions! Additionally, questions that open up the conversation is an important skill that I’ve observed from Dip and Victoria.

Thoughts on researching with unfamiliarity

I was quite comfortable with the unfamiliarity of the landscape, language and situations. The entire fieldwork experience was a constant experience of learning and being present in those situations. What I found which needed more of my energy and attention was unlearning. Dealing with social issues often led me to think of solutions, but it always sent me into a loop of problematizing. Contextualising unlearning in architecture, there were instances that architecture became the antithesis towards social issues. In the city, colonial buildings are megastructures that serve almost no purpose. Schooling in Singapore has taught me the irrelevance of colonial pasts and not to attach nation building with archaic agendas. It was similar in Kolkata where the city has grown in its own manner that puts social issues in the forefront, and often did not care about the aesthetics of architecture.

How it advanced your understanding of architecture and landscape.

It was more palpable that architecture at times exists as a vehicle to achieve social issues. As the studio situated its fieldwork in the realm of social research, it came naturally to relate prior knowledge to conventional ways architecture solves a problem. We saw in a micro scale how selling vegetables in the market requires openness in informal seller’s spaces, thus reconciling with little to no shading when selling their goods. In turn, the power of owning a physical store skews architecture to become not just a commodity but even as a vehicle to gain more sales, as storekeepers can now store, spend longer hours selling and add vertical vantage points for their goods.

Were there moments when something became clear and you changed? - tell a story(s).

The story starts when the studio accidentally took the bus all the way to Howrah station after a muddled exchange with the bus conductor where we said “Howrah?”, he replied “Howrah!”, and we boarded without hesitation. I felt emotional on the bridge crossing back as men and women started pouring out of the station and crossed the bridge on foot to carry goods to sell. In the midst of the crowd was a woman with her son beside her, and she stood out because of her petiteness compared to the men around her with the same sized parcels. I think labour as I know it is no longer a visual aspect, as in cities I visit, work is kept and organised in skyscrapers, hidden. The experience and feeling being in that current made me think why do we work so hard? Who are we working for? Oftentimes work to me is closely tied with family, that I work hard in school to please my parents, and in turn they’ve worked hard creating the life we have now in Singapore. I think mixing these feelings with being on the bridge and having a distanced view from the urban densities combined with the longevity of the river compressed and expanded these feelings at the same time, so that was interesting.

Observations of cropland in the overall site.

Northern Piali that has less built-up surfaces than the South, signalling remoteness.

Rural Piali

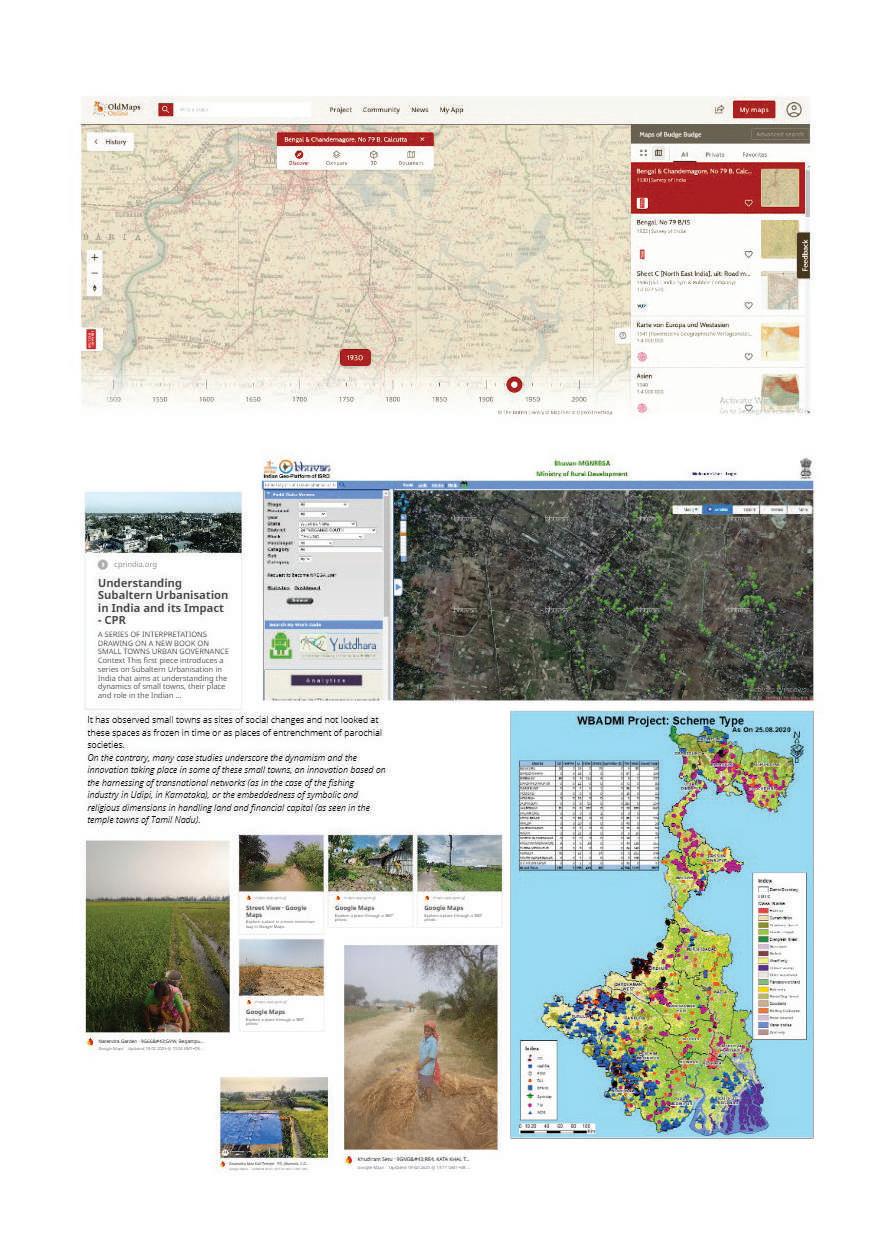

Researching rural Piali encompasses the demographic data across gender, age and occupations that cannot be seen through mapping the built-up surface areas and croplands. Eventually, the focal point of discussion and further research lead to the feminisation of labour in periurban scapes. This meant probing the narrative of various definitions of productivity amongst Piali women.

Surveying the working women in Piali showed that homes are vehicles for work to coexist, to maintain domesticity yet instigate financial independence from their spouses.

Such an arrangement calls for rethinking what remote means to a single homemaker; and it meant creating their own community of women in their periphery where time and domestic work are shared.

Learning from existing long-term residents’ livelihoods and domestic routines allowed further exploration about the more remote yet growing areas of inner Piali. Strategy A encapsulates the interdependent relationships between Piali residents on a linear street layout, and how the built environment shifts accordingly, such as incremental housing additions and how leftover space is an opportunity for shared ownership.

Applying similar logic to a potential colony not only involves further improvements of setting one up, but as well as opening up to a new way of settlement. Imagining a community of women setting up shop in the scale of a colony and manoeuvring other components of pond, garden and living could be a new means of periurban space.

JULIANA MARIE JUMIG MASICLAT