A Complete System for Writing

Responsibly

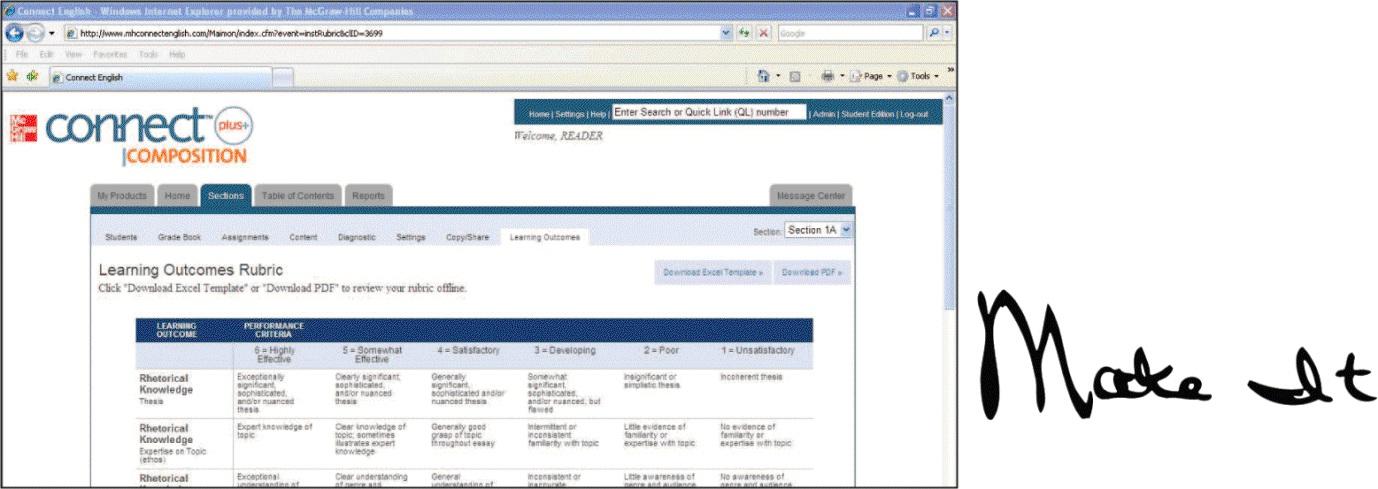

Adaptive Diagnostics develop customized learning plans to individualize instruction, practice, and assessment, meeting each student’s needs in core skill areas. Students get immediate feedback on every exercise, and results are sent directly to the instructor’s grade book.

Results vetted by research. McGraw-Hill’s innovative series of multi-campus research studies provide evidence of improved student performance with the use of Connect, with students in high-usage groups achieving consistently better gains across multiple outcomes. Independent analysis showed that the tools within Connect provided a statistically valid measure for assessing these results.

For more information, visit www.mhhe.com/SCORE.

Palm Beach Community College: Patricia McDonald, Vicki Scheurer

Palo Alto College: Ruth Ann Gambino, Caroline Mains, Diana Nystedt

Pioneer Pacific College: Jane Hess

Rogue Community College: Laura Hamilton

Salem State College: Rick Branscomb

San Antonio College: Alexander Bernal

Seton Hall University: Nancy Enright

South Texas Community College: Joseph Haske

Southern Illinois University–Edwardsville: Matthew S. S. Johnson

Southwestern Illinois College: Steve Moiles

St. Clair County Community College: John Lusk

Page xiii

St. Johns River Community College: Melody Hargraves, Elise McClain, Jeannine Morgan, Rebecca Sullivan

Innovative ideas, effective examples, and good organization …

Barbara Chambers, Jones County Junior College

Tarleton State University: Moumin Quazi

Tennessee State University: Samantha Morgan-Curtis

Texas A + M University Kingsville: Laura Wavell

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Grace Giorgio

University of Maryland—University College: Andrew Cavanaugh

University of Northern Iowa: Gina Burkart

University of Texas San Antonio: Marguerite Newcomb

University of Wisconsin at Marathon County: Christina McCaslin

Valdosta State University: Richard Carpenter, Jane Kinney, Chere Peguesse

Wesley College: Linda De Roche

Westminster College: Susan Gunter

Westmoreland County Community College: Michael Hricik

Wharton County Junior College: Mary Lang, Sharon Prince

Wharton County Junior College: Mary Lang (design designation missing)

Wichita State University: Darren DeFrain

William Woods University: Greg Smith

Design Reviewers

Bakersfield College: Jennifer Jett

Bluefield State College: Dana Cochran

Edmonds Community College: Greg Van Belle

Georgia Perimeter College: Kari Miller

Indian University–Purdue University Indianapolis: Anne C. Williams

McHenry County Community College: Cynthia Van Sickle

Page xiv

Metropolitan State College of Denver: Rebecca Gorman, Jessica Parker

North Idaho College: Amy Flint

Northern Virginia Community College Loudoun Campus: Arnold Bradford

Northwest Missouri State University: Robin Gallaher

Rogue Community College: Laura Hamilton

South Texas Community College: Joseph Haske

Southern Illinois University–Edwardsville: Matthew S. S. Johnson

University of Northern Iowa: Gina Burkart

University of Wisconsin at Marathon County: Christina McCaslin

Westmoreland County Community College: Michael Hricik

Wharton County Junior College: Mary Lang

Components of Research Matters

For Instructors

All of the instructor ancillaries described below, created by Andy Preslar, Lamar State College, can be found on the password-protected instructor’s side of the text’s Online Learning Center. Contact your local McGraw-Hill sales representative for login information.

Instructor’s Manual

The Instructor’s Manual provides a wide variety of tools and resources for enhancing your course instruction, including an overview of the chapter, considerations for assigning, applications for freshman comp and other courses, learning outcomes, strategies and tips for teaching, and exercises and activities.

4 Developing a Sense of Purpose and Context for Your Research 37

a. Recognizing Genre 38

b. Addressing Audience 40

c. Writing with Purpose 41

d. Responding to Context 43

5 Writing a Research Proposal 46

a. Understanding Typical Components of a Research Proposal 46

b. Analyzing the Rhetorical Situation 48

c. Drafting Hypotheses 48

d. Providing a Rationale 49

e. Establishing Methods 50

f. Setting a Schedule 51

g. Choosing Sources Strategically 52

h. Building a Working Bibliography 52

i. Annotating Your Working Bibliography 53

j. Developing a Literature Review 56

k. Formatting the Project Proposal 56

Cite Like an Expert: Reading and Summarizing the Entire Source 58

Page xvi

Part Two Information Matters

6 Gathering Information 60

a. Consulting a Variety of Sources 61

b. Finding Articles in Journals and Other Periodicals Using Databases and Indexes 61

c. Finding Reference Works 67

d. Finding Books 71

e. Finding Government Publications and Other Documents 72

f. Finding Sources in Special Collections: Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Archives 74

g. Finding Multimedia Sources 74

7 Meeting the Challenges of Online Research 76

a. Web and Database Searches: Developing Search Strategies 77

b. Finding Other Electronic Sources 84

c. Finding Multimedia Sources Online 87

8 Developing New Information 88

a. Using Archives and Primary Information 88

b. Conducting Interviews 90

c. Making Observations 95

d. Developing and Conducting Surveys 97

9 Evaluating Information 100

a. Evaluating Relevance 101

b. Evaluating Reliability 102

c. Evaluating Logic: Claims, Grounds, and Warrants 105

d. Evaluating Online Texts: Websites, Blogs, Wikis, and Web Forums 107

e. Evaluating Visual Sources 110

10 Taking Notes and Keeping Records 113

a. Choosing an Organizer to Fit Your Work Style 114

b. Keeping the Trail: Your Search Notes 117

c. What to Include in Research Notes 117

d. Taking Content Notes 117

e. Taking Notes to Avoid Plagiarizing and Patchwriting 119

f. Using Analysis, Interpretation, Synthesis, and Critique in Your Notes 125

11 Citing Your Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism 127

a. Developing Responsibility: Why Use Sources Carefully? 128

b. Understanding What You Must Cite: Summaries, Paraphrases, Quotations, Uncommon Knowledge 129

c. Knowing What You Need Not Cite: Common Knowledge 131

d. Understanding Why There Are So Many Ways to Cite 132

e. Drafting to Avoid Plagiarizing and Patchwriting 133

f. Getting Permissions 135

g. Collaborating and Citing Sources 136

12 Writing an Annotated Bibliography 139

a. Understanding the Annotated Bibliography 140

b. Preparing the Citation 141

c. Writing the Annotation 142

d. Formatting the Annotated Bibliography 142

e. Sample Student Annotated Bibliography (in MLA Style) 142

Cite Like an Expert: Explaining Your Choice of Sources 148 Part Three Organization Matters

Page xvii

13 Writing and Refining Your Thesis 150

a. Drafting a Thesis Statement 151

b. Refining Your Thesis 153

14 Organizing Your Project 157

a. Reviewing Your Prewriting 157

b. Grouping Your Ideas 158

c. Arranging Your Ideas from General to Specific 158

the river in pairs with huge clamor, as if searching for some one who had been drowned. This festival was instituted in memory of the statesman Küh Yuen, about 450 B.C., who drowned himself in the river Mih-lo, an affluent of Tungting Lake, after having been falsely accused by one of the petty princes of the state. The people, who loved the unfortunate courtier for his fidelity and virtues, sent out boats in search of the body, but to no purpose. They then made a peculiar sort of rice-cake called tsung, and setting out across the river in boats with flags and gongs, each strove to be first on the spot of the tragedy and sacrifice to the spirit of Küh Yuen. This mode of commemorating the event has been since continued as an annual holiday. The bow of the boat is ornamented or carved into the head of a dragon, and men beating gongs and drums, and waving flags, inspirit the rowers to renewed exertions. The exhilarating exercise of racing leads the people to prolong the festival two or three days, and generally with commendable good humor, but their eagerness to beat often breaks the boats, or leads them into so much danger that the magistrates sometimes forbid the races in order to save the people from drowning.[384]

The first full moon of the year is the feast of lanterns, a childish and dull festival compared with the two preceding. Its origin is not certainly known, but it was observed as early as A.D. 700. Its celebration consists in suspending lanterns of different forms and materials before each door, and illuminating those in the hall, but their united brilliancy is dimness itself compared with the light of the moon. At Peking, an exhibition of transparencies and pictures in the Board of War on this evening attracts great crowds of both sexes if the weather be good. Magaillans describes a firework he saw, which was an arbor covered with a vine, the woodwork of which seemed to burn, while the trunk, leaves, and clusters of the plant gradually consumed, yet so that the redness of the grapes, the greenness of the leaves, and natural brown of the stem were all maintained until the whole was burned. The feast of lanterns coming so soon after new year, and being somewhat expensive, is not so enthusiastically observed in the southern cities. At the capital this leisure time, when

public offices are closed, is availed of by the jewellers, bric-a-brac dealers, and others to hold a fair in the courts of a temple in the Wai Ching, where they exhibit as beautiful a collection of carvings in stone and gems, bronzes, toys, etc., as is to be seen anywhere in Asia. The respect with which the crowds of women and children are treated on these occasions reflects much credit on the people.

In the manufacture of lanterns the Chinese surely excel all other people; the variety of their forms, their elegant carving, gilding, and coloring, and the laborious ingenuity and taste displayed in their construction, render them among the prettiest ornaments of their dwellings. They are made of paper, silk, cloth, glass, horn, basketwork, and bamboo, exhibiting an infinite variety of shapes and decorations, varying in size from a small hand-light, costing two or three cents, up to a magnificent chandelier, or a complicated lantern fifteen feet in diameter, containing several lamps within it, and worth three or four hundred dollars. The uses to which they are applied are not less various than the pains and skill bestowed upon their construction are remarkable. One curious kind is called the tsao-matăng, or ‘horse-racing lantern,’ which consists of one, two, or more wire frames, one within the other, and arranged on the same principle as the smoke-jack, by which the current of air caused by the flame sets them revolving. The wire framework is covered with paper figures of men and animals placed in the midst of appropriate scenery, and represented in various attitudes; or, as Magaillans describes them, “You shall see horses run, draw chariots and till the earth; vessels sailing, kings and princes go in and out with large trains, and great numbers of people, both afoot and a horseback, armies marching, comedies, dances, and a thousand other divertissements and motions represented.”

One of the prettiest shows of lanterns is seen in a festival observed in the spring or autumn by fisherman on the southern coasts to propitiate the gods of the waters. An indispensable part of the procession is a dragon fifty feet or more long, made of light bamboo frames of the size and shape of a barrel, connected and covered with strips of colored cotton or silk; the extremities represent the

for a good crop, and others of more or less importance, which add to the number of days of recreation.

THEATRICAL REPRESENTATIONS AND PLAY-ACTORS.

Theatrical representations constitute a common amusement, and are generally connected with the religious celebration of the festival of the god before whose temple they are exhibited. They are got up by the priests, who send their neophytes around with a subscription paper, and then engage as large and skilful a band of performers as the funds will allow. There are few permanent buildings erected for theatres, for the Thespian band still retains its original strolling character, and stands ready to pack up its trappings at the first call. The erection of sheds for playing constitutes a separate branch of the carpenter’s trade; one large enough to accommodate two thousand persons can be put up in the southern cities in a day, and almost the only part of the materials which is wasted is the rattan which binds the posts and mats together. One large shed contains the stage, and three smaller ones before it enclose an area, and are furnished with rude seats for the paying spectators. The subscribers’ bounty is acknowledged by pasting red sheets containing their names and amounts upon the walls of the temple. The purlieus are let as stands for the sale of refreshments, for gambling tables, or for worse purposes, and by all these means the priests generally contrive to make gain of their devotion.[385]

Parties of actors and acrobats can be hired cheaply, and their performances form part of the festivities of rich families in their houses to entertain the women and relatives who cannot go abroad to see them. They are constituted into separate corporations or guilds, and each takes a distinguishing name, as the ‘Happy and Blessed company,’ the ‘Glorious Appearing company,’ etc.

The performances usually extend through three entire days, with brief recesses for sleeping and eating, and in villages where they are comparatively rare, the people act as if they were bewitched, neglecting everything to attend them. The female parts are performed by lads, who not only paint and dress like women, but

even squeeze their toes into the “golden lilies,” and imitate, upon the stage, a mincing, wriggling gait. These fellows personate the voice, tones, and motions of the sex with wonderful exactness, taking every opportunity, indeed, that the play will allow to relieve their feet by sitting when on the boards, or retiring into the green-room when out of the acts. The acting is chiefly pantomime, and its fidelity shows the excellent training of the players. This development of their imitative faculties is probably still more encouraged by the difficulty the audience find to understand what is said; for owing to the differences in the dialects, the open construction of the theatre, the high falsetto or recitative key in which many of the parts are spoken, and the din of the orchestra intervening between every few sentences, not one quarter of the people hear or understand a word. The scenery is very simple, consisting merely of rudely painted mats arranged on the back and sides of the stage, a few tables, chairs, or beds, which successively serve for many uses, and are brought in and out from the robing-room. The orchestra sits on the side of the stage, and not only fill up the intervals with their interludes, but strike a crashing noise by way of emphasis, or to add energy to the rush of opposing warriors. No falling curtain divides the acts or scenes, and the play is carried to its conclusion without intermission. The dresses are made of gorgeous silks, and present the best specimens of ancient Chinese costume of former dynasties now to be seen. The imperfections of the scenery require much to be suggested by the spectator’s imagination, though the actors themselves supply the defect in a measure by each man stating what part he performs, and what the person he represents has been doing while absent. If a courier is to be sent to a distant city, away he strides across the boards, or perhaps gets a whip and cocks up his leg as if mounting a horse, and on reaching the end of the stage cries out that he has arrived, and there delivers his message. Passing a bridge or crossing a river are indicated by stepping up and then down, or by the rolling motion of a boat. If a city is to be impersonated, two or three men lie down upon each other, when warriors rush on them furiously, overthrow the wall which they

The morals of the Chinese stage, so far as the sentiments of the pieces are concerned, are better than the acting, which sometimes panders to depraved tastes, but no indecent exposure, as of the persons of dancers, is ever seen in China. The audience stand in the area fronting the stage, or sit in the sheds around it; the women present are usually seated in the galleries. The police are at hand to maintain order, but the crowd, although in an irksome position, and sometimes exposed to a fierce sun, is remarkably peaceable. Accidents seldom occur on these occasions, but whenever the people are alarmed by a crash, or the stage takes fire, loss of life or limb generally ensues. A dreadful destruction took place at Canton in May, 1845, by the conflagration of a stage during the performances, by which more than two thousand lives were sacrificed; the survivors had occasion to remember that fifty persons had been killed many years before in the same place, and while a play was going on, by the falling of a wall.[387]

POPULAR AMUSEMENTS.

Active, manly plays are not popular in the south, and instead of engaging in a ball-game or regatta, going to a bowling alley or fives’ court, to exhibit their strength and skill, young men lift beams headed with heavy stones, like huge dumb-bells, to prove their muscle, or kick up their heels in a game of shuttlecock. The out-door amusements of gentlemen consist in flying kites, carrying birds on perches and throwing seeds high in the air for them to catch, sauntering through the fields, or lazily boating on the water. Pitching coppers, fighting crickets or quails, tossing up several balls at once, kicking large leaden balls against each other, snapping sticks, chucking stones, or guessing the number of seeds in an orange, are plays for lads.

METHODS AND POPULARITY OF GAMBLING.

Gambling is universal. Hucksters at the roadside are provided with a cup and saucer, and the clicking of their dice is heard at every corner. A boy with but two cash prefers to risk their loss on the throw of a die to simply buying a cake without trying the chance of getting it for nothing. Gaming-houses are opened by scores, their

keepers paying a bribe to the local officers, who can hardly be expected to be very severe against what they were brought up in and daily practise; and women, in the privacy of their apartments, while away their time at cards and dominoes. Porters play by the wayside when waiting for employment, and hardly have the retinue of an officer seen their superiors enter the house, than they pull out their cards or dice and squat down to a game. The most common game of luck played at Canton is called fantan, or ‘quadrating cash.’ The keeper of the table is provided with a pile of bright large cash, of which he takes a double handful, and lays them on the table, covering the pile with a bowl. The persons standing outside the rail guess the remainder there will be left after the pile has been divided by four, whether one, two, three, or nothing, the guess and stake of each person being first recorded by a clerk; the keeper then carefully picks out the coins four by four, all narrowly watching his movements. Cheating is almost impossible in this game, and twenty people can play at it as easily as two. Chinese cards are smaller and more numerous than our own; but the dominoes are the same.

Combats between crickets are oftenest seen in the south, where the small field sort is common. Two well-chosen combatants are put into a basin and irritated with a straw until they rush upon each other with the utmost fury, chirruping as they make the onset, and the battle seldom ends without a tragical result in loss of life or limb. Quails are also trained to mortal combat; two are placed on a railed table, on which a handful of millet has been strewn, and as soon as one picks up a kernel the other flies at him with beak, claws, and wings, and the struggle is kept up till one retreats by hopping into the hand of his disappointed owner. Hundreds of dollars are occasionally betted upon these cricket or quail fights, which, if not as sublime or exciting, are certainly less inhuman than the pugilistic fights and bull-baits of Christian countries, while both show the same brutal love of sport at the expense of life.