Wellness by Design: A Holistic Approach to Human-Centered Environments

DESIGN INVESTIGATIONS

Defining Wellness

Prioritizing Connections to Nature

Indoor Environmental Quality

Comfort

Thermal Comfort

Daylighting and Visual Comfort

Lighting Design and Control

Acoustics

Ergonomics

Nutrition and Hydration

Activity

Universal Design

Welcoming Atmosphere

Flexibility and Choice

Privacy

Safety

Beauty, Joy, and Art

The Business Case for Wellness

Design Resources

Third Party Certifications

Case Studies

What is Wellness?

Good health is a significant factor, but the concept of wellness is bigger than the absence of illness or injury. It’s an active pursuit that recognizes the interconnectedness of body, mind, spirit, and community. The Global Wellness Institute describes the physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, social, and environmental aspects of wellness, and recognizes that designing for wellness requires a holistic approach.i

Humans spend most of our time inside buildings. Our homes, workplaces, schools, healthcare facilities, worship centers, and gathering spaces all contribute to – or detract from – our wellness. A design process which integrates healthier materials, prioritizes natural light and views, and supports human comfort across a spectrum of experiences will elevate the resulting building for all users.

Many tools and resources exist for mapping out wellness goals before designers even begin sketching design concepts. A visioning discussion at the beginning of the design process is invaluable for guiding owners, designers, and consultants in prioritizing project strategies, and the goals created during this conversation

can serve as touchstones for all future project decisions. The AIA Framework for Design Excellenceiii also offers comprehensive guidance and resources that will enrich and inform these discussions.

In designing for wellness, early moves have big impacts. Opportunities begin with site selection; where a building is situated will influence community connectivity, air quality, and connections with nature. Are there services and amenities nearby, or will building users be dependent on a car to run errands or enjoy a meal? How walkable is the area – is there a nature trail nearby, access to mass transit, or a network of pedestrian-friendly streets? The National Walkability Indexiv and Walk Scorev can provide granular details on walkability, public transit, and cycling options for a site.

Before selecting a site, owners may wish to consider whether air or water quality testing is required. Are there industrial or transportation activities in the area that may impact the air quality, or is any site remediation necessary to remove or encapsulate contaminated soils from previous uses? The definition of “project stakeholders” may extend beyond the building owners and users.

Wellness is an individual pursuit—we have selfresponsibility for our own choices, behaviors and lifestyles— but it is also significantly influenced by the physical, social and cultural environments in which we live.

Global Wellness Instituteii

Thinking beyond the site boundaries, does the project offer any opportunities to improve the community and its ecosystems through strategic development, targeted density, or the right mix of uses?

Designing for wellness continues at the programming stage. The program should account for the right size and mix of spaces to support a variety of wellness components. These might include wellness/respite rooms, mothers’ rooms, kitchens, break rooms, and bike rooms with showers. Note that many of these areas require plumbing and other infrastructure, so tacking them on as an afterthought becomes expensive and inefficient.

The conceptual design stage includes many fundamental decisions that will affect occupant wellness for the life of the building. The building’s orientation, form, and window to wall ratio (WWR) will impact thermal comfort, daylighting, views, ventilation, and glare within the space. In considering occupant wellness from the first iterations, designers can maximize opportunities for daylighting, natural ventilation, strong connections to nature, and occupant comfort

TEN 30

CHARLOTTE, NC

Later design phases will involve many decisions with wellness impacts. Detailing the building, working with consultants on mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) design and life safety plans, navigating product specifications, facilitating building commissioning, and even planning for healthy operations policies; each step of design and construction will provide opportunities to support human wellness.

Prioritizing Connections to Nature

Despite the fact that most of us spend the majority of our time indoors these days, humans evolved within the natural world and remain deeply connected to nature. Substantial research across decades indicates that humans thrive when they have access to natural elements such as daylight, trees, fresh air, and views to the outdoors. A few examples:

A seminal 2003 study showed that students in classrooms with the most natural light progressed 15-26% faster on math and reading tests than those with less access to daylightingvi

A nearly 20-year study of 940,000 medical records showed that living near green spaces significantly reduced anxiety and depression, with the strongest impacts seen in the least affluent neighborhoodsvii

People in buildings with operable windows reported a greater sense of comfort, control, and connection to natureviii

Designing to maximize natural elements within a space – often referred to as “biophilia” – can have measurable impacts on occupant wellness. People in biophilic buildings take fewer sick days, report better moods, have higher productivity, and stay at their jobs longer. This effect has been documented across many project types, perhaps most frequently in classrooms, where test scores serve as a proxy for productivity and concentration. For example, one study showed that students in biophilic classrooms showed three times more improvement in math scores over a seven-month period than those in a control classroom and reported lower stress levels as well.x

The principles of biophilic design are explored in “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design”xi identified by environmental consulting firm Terrapin Bright Green. These principles includexii:

NATURE IN THE SPACE Natural light, views to the outdoors, living walls, plants, and natural ventilation all bring nature into the interior of a building to connect occupants to nature.

Visual Connection with Nature

Example: views to the outdoors

Non-Visual Connection with Nature

Example: birdsong, breezes from outdoors through operable windows or doors

Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli

Example: sounds or sensations from the natural environment that are unpredictable, such as a chirping cricket or the rumble of distant thunder

Thermal & Airflow Variability

Example: natural daily cycles of warming and cooling, or fresh air from an open window

Presence of Water

Example: fountains, fishtanks, or other water features

Dynamic & Diffuse Light:

Example: variable lighting patterns that change with the movement of the earth and support circadian rhythms

Connection with Natural Systems

Example: awareness of weather, site flora and fauna, and seasonal changes

NATURAL ANALOGUES Natureinspired art, materials, patterns, and finishes provide multisensory natureinspired experiences within the building interior and create a sense of place.

Biomorphic Forms & Patterns

Example: a serpentine bench or curved wall

Material Connection with Nature

Example: live-edge wooden countertops or stone hearths

Complexity & Order

Example: fractal patterns in art, floor tiles, or wall coverings

NATURE OF THE SPACE Spaces that safely re-create human experiences in the natural environment provide opportunities for expansive views, privacy, curiosity, and excitement.

Prospect

Example: elevated platforms or balcony seating

Refuge

Example: reading nooks, high-backed booths, or respite rooms

Mystery

Example: curved pathways that encourage curiosity to see what’s at the end

Risk/Peril

Safe places to experience thrills: high overlooks or glass walkways

It’s no secret that people tend to prefer texture, patterns, and variation in design, or that people enjoy being near natural elements. People naturally tend houseplants, build stone fireplaces, and love the warmth and texture of wood. Research backs up our intuition and helps us make evidence-based decisions; for example, recent studies have found that merely living near green spaces can add up to 2.5 years to our lives while lowering the risk of dementia,xiii and proximity to trees may reduce vascular damage from pollution.xiv At a minimum, making sure all occupants have access to natural light and views will help regulate circadian rhythm, support eye health, and create more enjoyable indoor environments.

Indoor Environmental Quality

Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ), sometimes referred to as “indoor air quality,” has a significant impact on occupant wellness. IEQ is influenced by many factors, including the design and performance of mechanical systems, the selection of interior finishings and furnishings and their associated Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) that continue to off-gas long after installation, the outdoor air quality in the neighborhood, and whether a space

has the option for natural ventilation. Even the number of people in a space and their level of activity matters, as carbon dioxide builds up faster in enclosed or crowded spaces.

The impact of indoor air quality on human health is well documented. Reducing long-term exposure to particulate matter, for example, lowers health risks for sensitive populations and reduces cardiopulmonary cancer

deaths (as well as deaths from all causes). Research also shows that incremental decreases in particulate matter over the long-term correspond with measurable increases in life expectancy xvi

The human health impacts of better air quality are profound, and so is the economic argument for an investment in IEQ. A 2015 study showed that the cost to double the

ALLY CHARLOTTE CENTER CHARLOTTE, NC

ASHRAE-recommended minimum rate of ventilation cost about $40 a year per employee, but was associated with an 8% increase in productivity–valued at $6500 a year per employee.xvii Other studies have shown slower response times on cognitive tasks as IEQ declines; findings like this impact the workplace, classrooms, healthcare facilities, and anywhere else our cognitive abilities matter (which is everywhere).xviii

Designers should work closely with MEP consultants to determine appropriate minimum ventilation rates, and then consider the benefits of exceeding these rates when setting building performance goals. ASHRAE Standard 62.1 and 62.2 provides guidance on the recommended air changes per hour (ACH) within different types of spaces; these rates may range from 0.35 ACH in a residential setting to more than 10 ACH in a fitness room. MEP consultants will also help to specify the appropriate air filters for the project, while an investment in building commissioning can verify that all systems are performing as expected over time.

The right balance between natural and mechanical ventilation will be influenced by many factors including region, building program, and energy performance goals. Airtight enclosures are, in many cases, better for energy efficiency and indoor environmental

control, and not every site is appropriate for natural ventilation. The Southeast US, for example, is notoriously humid for long stretches of the year, and dehumidification is necessary to stay within generally acceptable ranges for human comfort.

Where natural ventilation is feasible, however, the ability to open windows can reduce dependence on the building’s mechanical systems and thus reduce energy use and costs,xix and many people enjoy the natural variability that comes with open windows and fresh air. When relying on natural ventilation, even seasonally, it is necessary to monitor outdoor air quality for variations in pollution levels. Wildfire smoke, highway pollution, industrial activities, or exhaust from building systems can all degrade air quality and infiltrate the building. Smart building systems such as IEQ sensors may be an option for automatically opening and closing windows when conditions are right to boost ventilation rates.

Interior materials, finishes, and furnishings also have a significant impact on IEQ. Many materials from wall coverings to sealants to flooring to upholstery will off-gas chemicals from the manufacturing process in the form of Volatile Organic Compounds, or VOCs. Designers should specify low- or no-VOC products wherever possible. The International Living

Futures Institute maintains a “red list” of harmful chemicals to avoid in interior specifications. The WELL Building Standardxx and the AIA Materials Pledgexxi also provide guidance on materials selections with an eye towards reducing harm throughout a product’s lifecycle. Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and thirdparty rating systems can assist with healthier building choices.

Indoor plants can impact indoor air quality, but in perhaps unexpected ways. It has long been assumed that indoor plants improve IEQ by removing pollutants from the air. A recent study found that significant IEQ improvement would require 10-1,000 plants per square meter xxii While plants do contribute to biophilia, connections to nature, and enjoyment of the space, other strategies are more effective for IEQ regulation. When plants are incorporated as part of the design, owners should take precautions to prevent mold growth from overwatering and be sure that new plants introduced into the environment have not been treated with pesticides that could impact air quality.

Comfort

Our sense of wellness in a space depends in large part on how comfortable we feel within it – both physically and emotionally. Small stressors can accumulate over time, and tolerance varies widely from person to person. Not every stressor can be eliminated in the built environment, but many common stressors can be anticipated and mitigated through thoughtful and human-centered design.

THERMAL COMFORT When it comes to temperature, the human comfort range is fairly narrow and welldefined. While individual preferences vary, ASHRAE 55-2017 identifies this range as between 67 and 82 degrees Fahrenheit, with an ideal humidity between 30% and 60%. Many factors influence thermal comfort within this range including season, activity level, gender, age, and clothing. How can designers make buildings comfortable for people with diverse needs?

It’s a productivity issue as well as a comfort issue. A 2019 study showed that test scores for women improved significantly when the temperatures rose from too chilly (around 61 degrees F) to comfortably warm.xxiii Conversely, multiple studies show lower performance in overheated spaces; a 2022 study showed greater depression, confusion, and fatigue after heat exposure, impacting cognitive tasks.xxiv

A 2017 study showed that students taking tests in poorly air-conditioned schools on hot days were 12.3% more likely to fail an exam, and 2.5% less likely to graduate on time.xxv

Maintaining temperatures in the human comfort range may involve a tool kit of strategies, from mechanical to natural. The design team should work closely with MEP consultants to determine the appropriate strategies. A well-designed mechanical system will be a critical part of the thermal comfort approach in most Southeastern buildings, which must maintain temperatures during summer’s peak cooling and dehumidification needs as well as the winter heating season.

Designers can take advantage of passive solar design strategies early in the process to reduce heating and cooling loads by taking advantage of the sun. In the Southeast, a long, linear

building oriented with the longest wall facing south (+/- 15 degrees) will allow for the best control of sunlight. Shading strategies can help to allow low-angle winter sunlight into the building to boost warming and block high-angle summer sunlight that adds unwanted heat gain. Awnings, louvers, or bris-soleils can also help reduce hot spots and glare. Note: interior shading strategies such as blinds or curtains are much less effective at reducing solar heat gain during the summer, because once the sunlight has passed into the space, it must be mitigated by building mechanical systems.

Even in the best-designed buildings, the needs of individual humans will vary. It’s important for building owners to understand how much variety people are willing to tolerate and what seasonal changes mean. For example, it may feel appropriate to add a sweater during the winter, but if people have to wear sweaters indoors during the summer, the building may be overcooled. Could a space be zoned to accommodate a range of options, from cooler to warmer? Is it possible to provide individual controls by room? Or could a building’s badge-swipe system recognize a user’s preferences and adjust temperatures as they move through a building?

GUILFORD COUNTY SCHOOLS PROFESSIONAL & COMMUNITY EDUCATION CENTER GREENSBORO, NC

DAYLIGHTING & VISUAL COMFORT

Daylighting, or the use of natural light to supplement (or even replace) a building’s need for artificial lighting, has been well researched from a wellness perspective. The benefits are intuitive to anyone who’s worked next to a window instead of, say, at a desk in the basement. Research shows that hospital patients recover faster with exposure to natural light,xxvi and that daytime light exposure improves sleep quality and reduces depression symptoms.”xxvi Natural light also helps regulate circadian rhythms, while supporting productivity and better reported moods. xxviii

Early project decisions about building form and orientation can maximize daylighting opportunities. Daylighting is most effective within 30’ of a window, so narrow floor plates work best. In the US Southeast, light from the south is easiest to control and light from the north side tends to be diffuse and desirable, so aligning the longest sides of the building to harvest light from the south and north sides is a best practice (and this strategy works with optimal passive solar design as well). Light from the east and west sides tends to be harder to control in terms of glare and solar heat gain, so limiting exposure on those facades is ideal. Higher window head heights will allow light to penetrate deeper into the building, so opting for higher floor-toceiling heights during the early design

phases is an effective strategy. Light shelves can also bounce light further into the space, while exterior shading strategies can help to mitigate any associated glare. Where floor plates are too deep for daylighting, solar tubes, skylights, or interior courtyards can be used to introduce more natural light.

Beyond daylighting, views to the outdoors are important for visual comfort (and mental healthxxix). Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “the health of the eye demands a horizon,” and this is especially true for people who are using screens for long stretches of time. To alleviate eyestrain from focusing on close-up views such as laptop screens and smart phones, experts recommend a 20-20-20 habit; looking at something at least 20’ away for at

least 20 seconds, every 20 minutes. Access to expansive views makes this process easier and more enjoyable. Research again backs up our intuitive desire for this kind of connection with nature; studies have shown that the lack of a view to nature increases fatigue, and that people who have better views perform up to 25% higher on cognitive tests.xxx

SANDHILLS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CENTER GREENSBORO, NC

LIGHTING DESIGN & CONTROL

Thoughtful lighting design can help to balance daylighting with artificial lighting as needed. Lighting designers will consider the different types of lighting - overhead vs. task lighting, for example. Overhead lighting might provide general illumination, while task lighting can help to reduce eye fatigue and improve visual acuity at workstations. Lighting designers will also focus on reducing glare, which often occurs in high-contrast zones that create light tunnels or hot spots. People experience glare differently depending on their physiology, so a lighting condition that creates mild discomfort for one person might prevent another person from being able to perform tasks at all. xxxii

Where feasible, allowing people to have control over their lighting can improve their experience of the space. xxiii

Some building owners integrate dynamic lighting to adjust light levels and colors over the course of the day. Just as airlines use targeted light frequencies to simulate sleep/wake cycles on a long-haul flight, designers can capitalize on advances in LED lighting to promote focus or relaxation. For example, natural light tends towards warmer frequencies at the beginning and end of the day and cooler frequencies midday; tuning interior lighting to align with these natural rhythms to help regulate circadian rhythms even in spaces where natural light is unavailable.

Artwork, color, and other interior design elements also contribute to visual comfort by providing places to rest the eye and engage the mind. While individual preferences vary, harmonious color palettes, engaging artwork, uncluttered spaces, and a variety of textures and scales add visual interest.

CREDIT ONE STADIUM CHARLESTON, SC

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES CAMPUS RALEIGH, NC

ACOUSTICS Sound can make or break the experience of a space; imagine a restaurant where it’s either too loud to hear the waiter, or so quiet that having a conversation feels awkward. The fact that people respond very differently to noise makes acoustic design even more challenging. Acoustic design can be especially important in healthcare or educational settings, where unwanted noise can impact the speed of healing or the ability to focus on a task. For example, children – particularly those with language or attention disorders, or those learning a new language –show negative academic impacts from persistent unwanted noise.xxxii

In the workplace, research validates why many people love to go to a coffee shop to get work done. The typical noise level in a coffee shop, around 70 decibels, tends to be loud enough to create a pleasant background noise but quiet enough for focus.xxxiii At lower decibel levels, individual noises can create irritation, like one person on the phone or crunching potato chips. At higher decibel levels, the noise can become overwhelming. Creating the right acoustic balance in public spaces might require white noise or noise canceling systems. Designers must also zone program areas to accommodate a

range of functions and noise levels. Focus work areas should be distant from louder zones such as the break room or restroom, and people need places for both private conversations and socializing. MEP consultants will be key partners in a successful acoustic design. Noisy equipment such as air handlers should be strategically located to minimize disruptions to quiet zones such as patient rooms, classrooms, or conference rooms, and ducts should be designed to minimize unwanted noise.

UNC GREENSBORO SCHOOL OF NURSING GREENSBORO, NC

ERGONOMICS Every human body is different, and a “standard” chair, desk, or countertop might not be suitable for all users. Adjustable furnishings and equipment are particularly important when people are doing repetitive tasks over time, such as in a workplace or classroom setting. Ergonomic guidelinesxxxiv for various tasks can help people adjust their environment for a healthy posture and minimize strain over time. During the FF&E process, interior designers and furniture consultants will be invaluable in selecting appropriate furnishings and equipment for the end users. In a classroom, millwork may be scaled down to child size; in a clinical space, furnishings will be carefully selected for a range of size and mobility needs; in a residence, a kitchen could be designed with a lower section of countertop and safely located oven knobs for wheelchair users. Workplace design merits particular attention, as people tend to spend long stretches of time at their desks. Adjustable standing desks are an excellent tool for supporting variety over the work day, as studies show that it’s healthiest to alternate between standing and sitting.xxxv

LS3P RALEIGH RALEIGH, NC

ALLY CHARLOTTE CENTER

NUTRITION & HYDRATION

Human bodies need fuel, so adequate space for food preparation and storage is important anywhere people are spending prolonged amounts of time. Hydration is also a necessity so access to drinking water and other beverages is important. The scale of these facilities may vary according to project typology; a student residence hall might require a full kitchen while compact appliances might be sufficient for a small office break room. At a minimum, cold storage, cabinet space, countertop prep areas, and dishwashing facilities will make healthy food choices easier. Dishes and cutlery will help to eliminate plastic waste. The design should also include bins for trash, recycling, and

compost where appropriate. In large buildings, drinking water should be available on every floor.

Owners may consider setting policies to provide healthy and varied food choices for office events and build relationships with a range of vendors for healthy choices. When possible, simply choosing a project site near a variety of food and beverage options can multiply options.

ACTIVITY Building in opportunities to integrate movement can help occupants stay active. Monumental stairs are a popular option for enticing people to walk up a flight instead of taking an elevator; over time, these small choices

add up to significant health gains. To encourage stair use, the stairs should be visible and attractive, ideally in a more prominent location than the elevator. Signage encouraging stair use can provide a subtle nudge as well. (The process of designing for these subtle nudges has been referred to as “choice architecture” and encourages a healthy option without limiting other choices.xxxvi

Selecting a site that promotes walkability (within a campus or through broader community connections) can also encourage more daily activity for occupants through walking meetings, lunchtime errands on foot, or just accumulated steps for a regular afternoon coffee run.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN Feeling

welcome within a space starts with access – can all users safely and comfortably enter, move about, and interact? The principles of universal design go beyond building code to focus on physical, cultural, mental, developmental, and emotional accessibility. xxxvii Designers understand that there is no “standard” body, so accounting for a range of sizes, abilities, life stages, and personalities is key to creating better places.xxxviii

Equitable Use

The space should be appealing and provide the same quality of experience to all users wherever possible.

Flexibility in Use

The space should adapt to the user’s needs, for example left- or right-handedness or preferred pace.

Simple & Intuitive Use

The space should be approachable and engaging for a wide range of skill levels, physical abilities, ages, and literacy/language fluencies.

Low Physical Effort

Use of the space should not tire or tax the user.

Perceptible Information

Any information required to navigate the space should be multisensory (pictorial, verbal, and tactile) and legible for all users.

Tolerance for Error

The design should allow users to engage safely with the space; safeguards should prevent harmful consequences of any unintended uses.

Size & Space for Approach & Use

The design should be user-friendly for people seated, standing, and of various heights and hand sizes. The space should accommodate assistive devices.

Universal design strategies might be tailored to the building’s program or primary audience, while still allowing everyone to feel comfortable and navigate safely. For example:

A children’s museum might be scaled for kid-sized users with furnishings and activities at the appropriate size and height

However, these children might be visiting the museum with their extended family. Grandparents might require places to sit while children are engaged with activities, and these furnishings can be inviting and central to the action. A parent might also be tending to a younger sibling in a stroller, so accessible routes need to be clear and integrated throughout Restrooms with changing tables should be easy to access for parents of all genders. A dedicated lactation room would provide a clean, private space to nurse an infant or pump breast milk. People of all ages might find a family museum outing to be overstimulating at times, so interspersing quieter spaces near the action where people can decompress creates respite areas. While this museum is an excursion for the visitors, it’s also a workplace for the museum staff, so a separate set of “back of house” amenities can provide for their wellness needs over the course of long days working with the public.

In any setting, designers and owners should be mindful that differing needs and abilities might be visible (like a person using a wheelchair or other assistive device) or invisible (like a person with COPD or chronic pain). These differences can include wide variations in sensory processing; the term neurodivergence refers to autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit disorder (ADD), dyslexia, and other patterns of processing information. Neurodivergent individuals may be highly sensitive to stimuli including noises, sights, or smells and may benefit from spaces to decompress.

Designing for neurodivergence is important everywhere, but especially so in healthcare or classroom settings where overstimulation may impact the diagnostic process or a student’s ability to learn. The good news is that strategies that benefit neurodivergent individuals also benefit everyone else. Calmer respite areas near busy spaces; flexible furniture groupings to allow for choice and movement; and careful attention to elements such as acoustics, lighting, and program adjacencies can make a space more comfortable for neurodivergent and neurotypical users alike.

BROADSTONE CRAFT CHARLOTTE, NC

In any project type, restrooms can provide challenges for different physical needs, special situations (such as navigating an airport with luggage), and family configurations. To accommodate a variety of needs, amenities such as changing tables, hygiene products, family restrooms, all-gender restrooms, hooks/shelves for bag storage, and nocontact can go beyond code to create a more inclusive experience.

Workplaces need special consideration because people typically spend long stretches of time there, and their physical needs might vary over the course of the day. Beyond an attractive, welcoming break room with food preparation spaces, workplaces should

provide a dedicated lactation room with sink, refrigerator, comfortable furnishings, and privacy lock. To ensure cleanliness and availability for its intended use, this space should not double as a break room. Ideally, this space should also be reservable so that people who need to nurse or pump in a particular time frame don’t have to compete for space or miss their window. A separate wellness room, perhaps with a couch, dimmable lighting, adjustable thermostat, and sound machine, could serve as a restorative place for all employees. A few minutes in a quiet place could help someone head off a migraine, recover from a hot flash, or just recharge for a few minutes in the middle of a hectic day.

S&ME HEADQUARTERS RALEIGH, NC

WELCOMING ATMOSPHERE What separates a space in which we feel welcome from one in which we feel merely tolerated? Does a space convey a hierarchy, accidentally or otherwise, or can everyone engage equally?

Today’s workplaces tend to strive for design equity with daylight, views, and attractive spaces for all employees; this is a significant change from the days when executives occupied all of the offices with windows and lower-level staff worked in stereotypical cubicles. While some typologies are intended to convey hierarchy (the design of a courthouse, for example), designers can be mindful about creating inclusive, user-friendly places that make all people feel welcome.

FLEXIBILITY & CHOICE Thoughtful furniture selection can allow users to select the configuration that meets their needs. Where space and budget allow, creating groupings in a combination of hard and soft seating can provide options for sitting with a group or sitting solo near the edge of the activity.

Flexible, movable furnishings give people control over their environment. For example, students can reconfigure chairs and tables over the course of the day to switch between teamwork or teacher-led lessons, or guests in a tiered lecture hall could transition from keynote addresses to collaborative workshops in the same space.

In today’s wired world, power access is required wherever people are. MEP consultants will be invaluable in integrating outlets for easy recharging (It’s difficult to take advantage of flexible seating options if your laptop is dying and the only plug is at your workstation.) Many furniture vendors now offer wired furniture options for integrated charging.

Accessible seating is too often an afterthought but should ideally be integrated into the design. Providing sofas or larger chairs interspersed throughout a seating area accommodates larger bodies. Some bodies (and some stressful situations) require more movement; “fidget chairs” in classrooms or task chairs for adults that allow subtle movement in multiple directions can channel energy in nondisruptive ways.

PRIVACY The need for privacy may vary by project type. We might not expect opportunities for privacy in public places where we’re not staying long. In other places – the workplace, the doctor’s office, the university residence hall – people need private spaces to have sensitive conversations or tend to physical needs. Privacy can be both acoustic and physical, so designers must be mindful of both. Designers can work with the owner and consultants to determine the appropriate sound transmission class (STC) for each project type or program space. Employees who work in HR or finance may require spaces with a high STC to safeguard sensitive information,

and the design may include high STC partitions and walls that extend all the way to the next floor to minimize sound transferring between rooms over a dropped ceiling. Even those not handling sensitive information will occasionally need to make a private phone call, so enclosed phone booths or small, flexible conference spaces can accommodate this need.

Physical privacy is paramount in a healthcare setting; patient rooms should be laid out to prevent views into a clinical space when a physician enters the room. As telehealth capabilities continue to expand, the need for private spaces for virtual

appointments in a variety of project types is likely to increase. The ability to conduct a virtual appointment can reduce stress, cost, and travel time for all involved while supporting better health. A college student might have a virtual appointment with a doctor back home and not want to log on from their residence hall where a roommate could walk in, or an employee may schedule a virtual therapy appointment during their lunch break and require a place with acoustic and physical privacy to access the care they need.

SAFETY Safety is fundamental to wellness; this includes both physical and emotional safety. Designers should be cognizant that navigating the world can feel very different for different people, and what might be safe for one group might feel less so for another. Talking to a variety of stakeholders during the design process will inform appropriate strategies and facilitate discussions of relevant policies as well as building design. Safety discussions may include everything from lighting and emergency call boxes in parking lots to HR policies about workplace culture and behavior. Emergency plans and operational policies are part of a comprehensive plan to address building security, and Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) principlesxxxix may be helpful in mitigating safety concerns.

CONFIDENTIAL TECHNOLOGY CLIENT

DELIGHT While our built environment must meet fundamental requirements for life safety, function, and efficiency, we can also create opportunities for surprise, discovery, and joy. Projects of any scale and budget can harness the power of design to build culture, create community, and inspire people. Addressing the needs of the whole person (not just the “worker,” the “student,” or the “patient,”) means designing for beauty, art, and connection.

TEN30 CAMPUS CHARLOTTE, NC

LEGACY

The Business Case for Wellness

Spaces designed for wellness come with measurable human benefits, including healthier and happier occupants. The economic benefits of healthy buildings are measurable, too – and the ROI is significant. According to a recent International WELL Building Institute report:xl

• Over 10 years, the ROI for a highperformance, healthy workplace is $21,172 per employee based on productivity and retention metrics.

• Buildings with a health-related certification command 4.4-7.7% higher rents than non-certified buildings in the same neighborhood.

• Health-focused building elements reduce turnover; tenants stay more than a year longer in healthy buildings.

• Companies prioritizing employee health (based on earning the C. Everett Koop National Health Award) outperformed the S&P Index in studies - by a factor of 3.

• “Investing in holistic employee health can create nearly $12 trillion in global economic value and boost global GDP by as much as 12%, with benefits stemming from improvements in productivity, reduced absenteeism, lower healthcare costs and greater employee engagement and retention.”

An investment in healthier buildings isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s also a smart financial move. People in healthier buildings are more productive, learn better, heal faster, stay longer, and ultimately contribute to stronger communities and more resilient organizations. By prioritizing wellness in the built environment, we’re not only enhancing lives; we’re also building lasting value.

Resources

DESIGN RESOURCES

AIA Framework for Design Excellence

This framework provides design guidance around ten principles including integration, equitable communities, ecosystems, water, economy, energy, well-being, resources, change, and discovery. Multiple categories address human wellness and the built environment.

AIA Materials Pledge

The pledge encourages designers, building owners, and manufacturers to make healthier choices about building materials to support human health, social health and equity, ecosystem health, climate health, and a circular economy.

The Centre for Excellence in Universal Design

The Centre provides educational resources and creates standards for universal design principles originally developed at NC State University in the 1990s.

14 Patterns of Biophilic Design

This frequently used resource developed by Terrapin Bright Green offers a deep dive into the ways biophilia can enhance the built environment.

THIRD-PARTY CERTIFICATIONS

WELL Building Standard

The WELL Building Standard is dedicated to improving the health and well-being of building occupants through scientifically supported design and operational practices. It provides a comprehensive certification system for both new and existing buildings across various sectors, focusing on measurable health-first factors and third-party verification.

The certification structure is point-based, featuring 23 mandatory preconditions and 97 optional optimizations across 10 WELL concepts: Air, Water, Thermal Comfort, Light, Movement, Nourishment, Sound, Mind, Community, and Materials. Certification levels range from Bronze to Platinum, requiring increasing points and concept coverage. WELL Certification is suitable for all space types and locations, including offices, residential, retail, education, industrial, and hospitality.

The certification process involves submitting documentation for third-party review in preliminary and final rounds, with feedback provided for adjustments. Diverse project teams are involved including owners, engineers, architects, contractors, and facility managers, with performance verification conducted by authorized WELL Performance Testing Agents. Achieving certification may involve a substantial MEP investment (both in consultant expertise and equipment).

Enrollment and program fees vary by project type and size, with additional performance testing and administrative fees.

Fitwel

The Fitwel Rating System focuses on the health of building occupants. It offers separate certifications for all building types, with points awarded in categories such as building access, indoor environment, outdoor spaces, and more. There are no prerequisites, and achievement levels range from 1 to 3 stars.

Fitwel is ideal for developers who plan to sell properties quickly, projects with high occupant time inside, and clients prioritizing occupant health. It supports ESG reporting and is most suitable for workplace clients focused on employee retention and amenities.

The system requires minimal coordination with consultants, as most points can be achieved within the architectural scope. Air quality testing is optional. Fitwel is costeffective and can be accomplished on projects with tight timelines, as certification can be completed in 12 weeks and lasts for 3 years. Fitwel works well with other systems like LEED and WELL but is often used as a simpler wellness-focused alternative.

International Living Futures Institute –Living Building Challenge

The Living Building Challenge (LBC) is dedicated to promoting sustainability through a holistic approach that integrates sustainability into the project narrative. Due to its rigorous requirements, LBC is considered one of the highest global standards in sustainable design. The LBC breaks down categories into “petals” of a flower, similar to LEED categories but with higher percentages to meet. Unique aspects of this program include the mandatory requirements for beauty, equity, health, and happiness.

The certification structure is divided into several types: Zero Carbon Certification,

Zero Energy Certification, Petal Certification, Core Certification, and Full LBC Certification. Achievement levels are pass/fail for each category.

• Zero Carbon: 100% of all energy used by the project is offset by renewables.

• Zero Energy: Annual energy usage equals zero through renewables.

• Petal Certified: Focus on a specific petal, like water or energy.

• Core: Reduced LBC requirements, 10 best practices.

• Full LBC: All 20 requirements.

The certification process requires projects to be operational for at least twelve consecutive months prior to the ILFI audit to verify compliance. All team members must be involved for holistic project delivery, and a Living Future Ambassador is required. The ideal clients include homeowners, real estate developers, corporate, institutional, government, and healthcare sectors. The system works well with other systems like Energy Star, LEED, and WELL.

Program fees are calculated on a gross floor area basis (except for single family residences which are charged a flat fee). Fees cover registration, technical support services, third-party audits, and certification; LBC is potentially the most expensive high performance building certification to achieve due to its rigorous requirements.

Green Globes

Green Globes is a comprehensive certification system that evaluates environmental sustainability, health and wellness, and resilience. While not primarily a wellness certification, Green Globes does have many requirements for optimized health and wellness benefits in addition to lower energy, water, and carbon emissions.

The point-based certification structure includes a detailed questionnaire about the project, and point allocations vary based on project type. Certification levels range from One Green Globe (35%-54% of 1000 points met) to Four Green Globes (85%-100% met). Green Globes certification is available for new construction, interiors, existing buildings, and core and shell projects.

The certification process involves input and documentation from diverse project teams, including owners, architects, facilities, HR, management, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineers. Green Globes’ thirdparty assessors interface with project teams and building owners in real-time, offering personalized suggestions to improve sustainable practices. A commissioning agent is required for Green Globes projects and may be hired by anyone on the project team.

Enrollment and program fees vary by project type and size. Most site visits are conducted virtually, but complex projects may require inperson visits with additional travel fees.

CLEMSON UNIVERSITY WILBUR O. AND ANN POWERS COLLEGE OF BUSINESS THREE GREEN GLOBES CLEMSON, SC

LEED v5

The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) version 5 rating system is a comprehensive certification system for sustainable, high-performance design. LEED v5 is focused on the “impact areas” of decarbonization, quality of life, and ecological conservation and restoration. Like earlier versions of LEED certification, the scorecard includes both required prerequisites and optional strategies.

Certification levels are Certified, Silver, Gold, and Platinum. Categories include carbon, energy, water, waste, transportation, materials, and indoor environmental quality. LEED v5 is currently available for Building Design and Construction (BD+C), Interior Design and

Construction (ID+C), and Building Operations and Maintenance (O+M).

Registration and certification costs vary according to project scope and level of certification. In addition to registration and certification fees, consulting fees and documentation expenses can add cost. MEP expenses may also increase with the targeted level of certification and a commissioning agent (separate from other MEP consultants) is required. The owner must also plan for ongoing costs to maintain certification. To maximize opportunity while minimizing costs, clients and teams should commit to project sustainability goals from the earliest project phases, particularly for projects targeting Gold or Platinum levels.

This system is ideal for clients looking for a comprehensive system that addresses many factors of sustainable, healthy building design. LEED certification carries the status of a well-established and rigorous process with significant brand recognition.

For clients pursuing multiple certifications, WELL and LEED now have a streamlined process for projects applying for both, and documentation can be submitted to one place.

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES CAMPUS RALEIGH, NC

MUSC Children’s Health R. Keith Summey Medical Pavilion

The concept of patient-centered care drove the entire design process for this pediatric ambulatory center, informing decisions from site selection through the final finishes. The design focused on the unique needs of young patients and their families to reduce stress and support a collaborative care model. Most notably, the induction rooms for anesthesia are located across the hall from the operating room, allowing parents to stay with their children until a procedure begins without donning surgical “bunny suits” and minimizing stress for all.

The kid-friendly experiential graphic design (EGD) uses local Lowcountry themes to help young patients feel comfortable in the space and enjoy finding their way through it.

LOCATION North Charleston, SC

SIZE 98,000 SF

COMPLETED 2019

case studies

Operating Room

Induction Room

Beaufort County School District

Robert Smalls Leadership Academy

This replacement school celebrating the legacy of a Civil War hero serves Pre-K through 8th grade students in colorful, light-filled spaces designed for discovery and imagination. Students and staff are connected to nature through large windows (including enticing porthole-inspired viewpoints) and ample outdoor amenities; other natural elements find their way into the building through elements such as terrazzo flooring that uses local shells and recycled glass to depict a coastal map, seaweed inspired sun shades, and curved accents. A brightly colored monumental stair encourages activity, and a custom hand-drawn mural encourages school pride and a sense of place.

LOCATION Beaufort, SC

SIZE 149,000 SF COMPLETED 2023

case studies

Clemson University Wilbur O. and Ann Powers College of Business

The student-centric design includes a mix of formal and informal spaces that encourage collaboration, spontaneous interaction, and immersive learning. The design team creatively turned a challenging 40’ grade change into an opportunity for movement, connection, and views reminiscent of Rome’s Spanish Steps. A grand interior stairway mirrors the outdoor stair, activating the atrium space with places for seating and spontaneous interactions. Natural light, flexible furnishings, and a goal for the building to serve as a campus hub for all students all contribute to a sense of inclusivity and welcome.

Designed in partnership with LMN as Design Architect, LS3P as Architect of Record

LOCATION Clemson, SC

SIZE 176,000 SF

COMPLETED 2020

case studies

Alliance Residential Company

Broadstone Developments

Broadstone residential developments are known for their high-design, place-based residential complexes that tell authentic stories about their communities. LS3P has provided interior design services for a number of Broadstone developments’ amenity spaces. These amenities feature engaging social spaces designed to encourage connection; shared program spaces tailored to tenant needs at each location; and bold patterns, textures, finishes, and features for high impact and visual interest.

case studies

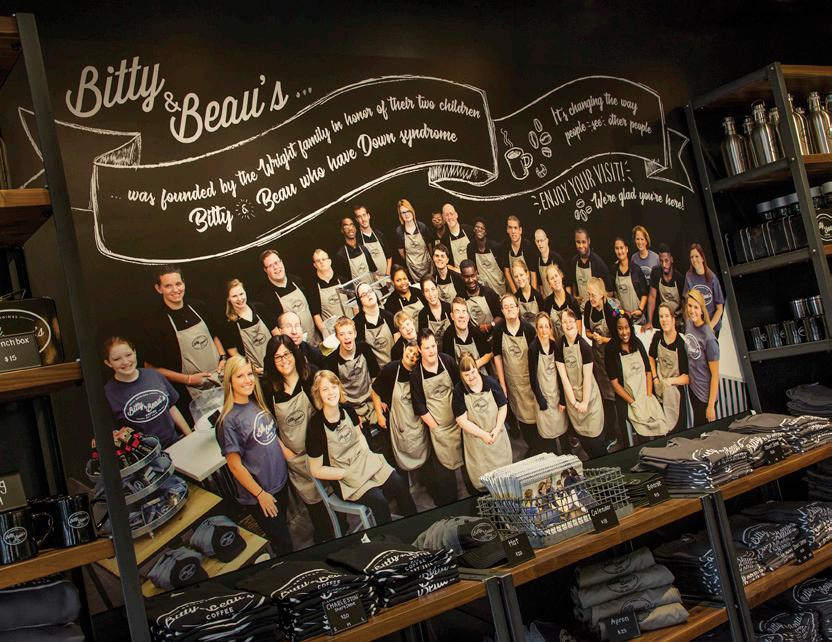

Bitty & Beau’s Coffee

Bitty & Beau’s Coffee, founded on value, inclusion, and acceptance, changes the world for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), and the lens through which we view them. Nationwide, over 70% of people with IDD are unemployed; Bitty & Beau’s reverses that statistic by giving its enthusiastic IDD staff meaningful work while integrating team members into the community.

The company’s stores offer inviting, relaxed community spaces where everyone is welcome. The experiential graphic design (EGD) explains the company’s mission and underscore the company’s mantra that “It’s More Than a Cup of Coffee.”

case studies

Ally Charlotte Center

The client’s “people first” ethos led to a workplace design focused on wellness, spontaneous collaboration, and activity-based work areas. Amenity spaces on every floor range from golf and NASCAR simulators to giant chess games, a music room, and a library. A barista area with grab-and-go food options doubles as a popular gathering and meeting space. Natural light, expansive views, flexible seating, enticing stairways, a living wall, and sustainable product choices all contribute to a welcoming workplace.

Designed in partnership with SmithGroup as Associate Architect

LOCATION Charlotte, NC

SIZE 60,614 SF

COMPLETED 2022

case studies

iGlobal Wellness Institute. “What Is Wellness?” Global Wellness Institute. Accessed September 24, 2025. https:// globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/.

iiGlobal Wellness Institute. “What Is Wellness?” Global Wellness Institute. Accessed June 16, 2025. https:// globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/.

iiiAmerican Institute of Architects. “AIA Framework for Design Excellence.” AIA, https://www.aia.org/design-excellence/ aia-framework-design-excellence. Accessed September 24, 2025.

ivU.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National Walkability Index. ArcGIS Web Map. https://epa.maps.arcgis.com/home/ webmap/viewer.

vWalk Score. “Cities & Neighborhoods.” Walk Score. https://www.walkscore.com/citiesand-neighborhoods/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

viHeschong Mahone Group. Windows and Classrooms: A Study of Student Performance and the Indoor Environment. California Energy Commission, 2003. https://efiling.energy. ca.gov/GetDocument.

viiEngemann, Kristine, Ulrik S. N. Andersen, Lars Arge, Charlotte G. Monrad, Peter Hjorth, Carsten Bøcker Pedersen, Jens-Christian Svenning, and Christina B. M. Nordentoft. “Residential Green Space in Childhood Is Associated with Lower Risk of Psychiatric Disorders from Adolescence into Adulthood.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116, no. 11 (2019): 5188–5193. https://doi. org/10.1073/pnas.1807504116. Accessed September 24, 2025.

viiiU.S. Green Building Council. “Thermal Comfort Reference Guide (IDC).” U.S. Green Building Council. https://www.usgbc.org/ node/2758273. Accessed September 24, 2025.

ixRyan, Catherine O., William D. Browning, and Dakota B. Walker. The Economics of Biophilia: Why Designing with Nature in Mind Makes Financial Sense. 2nd ed. New York: Terrapin Bright Green, LLC, 2023. https://www. terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/eob-2/.

xDeterman, Jim, Mary Anne Akers, Tom Albright, Bill Browning, Catherine MartinDunlop, Paul Archibald, and Valerie Caruolo. The Impact of Biophilic Learning Spaces on Student Success. American Institute of Architects, October 2019. https://www. brikbase.org/sites/default/files/The%20 Impact%20of%20Biophilic%20Learning%20 Spaces%20on%20Student%20Success.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xiBrowning, William D., Catherine O. Ryan, and Joseph O. Clancy. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design. New York: Terrapin Bright Green, LLC, 2014. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/ report/14-patterns/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xiiBrowning, William D., Catherine O. Ryan, and Joseph O. Clancy. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design. New York: Terrapin Bright Green, LLC, 2014. https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/ report/14-patterns/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xiiiPatel, A. “Aging Green Spaces Are Good for Your Health. But They Need Help.” The Washington Post, June 28, 2023. https:// www.washingtonpost.com/climatesolutions/2023/06/28/aging-green-spacesnature-health/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xivUniversity of Louisville. “Living Near Trees May Prevent Vascular Damage from Pollution.” UofL School of Medicine, https:// louisville.edu/medicine/news/living-neartrees-may-prevent-vascular-damage-frompollution. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xvWorld Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/ item/9789289002134.

xviCorreia, Andrew W., C. Arden Pope III, Douglas W. Dockery, Yang Wang, Majid Ezzati, and Francesca Dominici. “Effect of Air Pollution Control on Life Expectancy in the United States: An Analysis of 545 U.S. Counties for the Period from 2000 to 2007.” Epidemiology 24, no. 1 (2013): 23–31.

xviiMacNaughton, Piers, Usha Satish, John Spengler, Jose Vallarino, Joseph Allen, and Suresh Santanam. “Associations Between Cognitive Function Scores and Green Building Design Features in Office Workers: A Pilot Study.” Environmental Health Perspectives 123, no. 7 (2015): 700–708. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3757288/.

xviiiCedeño Laurent, Jose Guillermo, Piers MacNaughton, Emily Jones, Anna S. Young, Maya Bliss, Skye Flanigan, Jose Vallarino, Ling Jyh Chen, Xiaodong Cao, and Joseph G. Allen. “Impacts of Indoor Air Quality on Cognitive Function.” Healthy Buildings, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, September 9, 2021. https://healthybuildings. hsph.harvard.edu/impacts-of-indoor-airquality-on-cognitive-function/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xixRuotsalainen, R., R. Rönnberg, J. Säteri, A. Majanen, O. Seppänen, and J.J.K. Jaakkola. “Indoor Climate and the Performance of Ventilation in Finnish Residences.” Indoor Air 2, no. 3 (1992): 137–145.

xxInternational WELL Building Institute. WELL Building Standard. https://standard. wellcertified.com/well. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxiAmerican Institute of Architects. “Materials Pledge.” AIA, https://www.aia.org/designexcellence/climate-action/zero-carbon/ materials-pledge. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxiiCummings, Michael B., and Bryan E. Cummings. “Potted Plants Do Not Improve Indoor Air Quality: A Review and Analysis of Reported VOC Removal Efficiencies.”

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 30, no. 2 (2019): 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-019-0175-9.

xxiiiAubrey, Allison. “How Office Temperature Affects Cognitive Performance.” NPR, May 26, 2019. https://www.npr. org/2019/05/26/727108363/how-officetemperature-affects-cognitive-performance. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxivBlatchley, Barbara. “The Effect of Temperature on Cognitive Function.” Psychology Today, March 31, 2022. https:// www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/ what-are-the-chances/202203/the-effecttemperature-cognitive-function. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxvPark, Jisung. Heat and Learning. NBER Working Paper No. 24639, revised July 2020. https://www.nber.org/papers/w24639. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxviBeauchemin, K.M., and P. Hays. “Sunny Hospital Rooms Expedite Recovery from Severe and Refractory Depressions.” Journal of Affective Disorders 40, no. 1–2 (1996): 49–51.

xxviiLam, Raymond W., Ariel J. Levitt, Robert D. Levitan, et al. “Efficacy of Bright Light Treatment, Fluoxetine, and the Combination in Patients with Nonseasonal Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA Psychiatry 73, no. 1 (2016): 56–63. https:// doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2235.

xxviiiPhipps-Nelson, J., J.R. Redman, D.J. Dijk, and S.M.W. Rajaratnam. “Daytime Exposure to Bright Light, as Compared to Dim Light, Decreases Sleepiness and Improves Psychomotor Vigilance Performance.”

Sleep 26, no. 6 (2003): 695–700. https://doi. org/10.1093/sleep/26.6.695.

xxixLevoy, Gregg. “The Value of Looking at Long-Distance Views.” Psychology Today, October 2023. https://www.psychologytoday. com/intl/blog/passion/202310/the-valueof-looking-at-long-distance-views. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxxHeschong, Lisa, and Doug Mahone. Windows and Offices: A Study of Office Worker Performance and the Indoor Environment. California Energy Commission, 2003.

xxxiStone, P., and S. Harker. “Individual and Group Differences in Discomfort Glare Responses.” Lighting Research & Technology 5, no. 1 (1973): 41–49.

xxxiiMacNaughton, Piers, Usha Satish, John Spengler, Jose Vallarino, Joseph Allen, and Suresh Santanam. “Associations Between Cognitive Function Scores and Green Building Design Features in Office Workers: A Pilot Study.” Environmental Health Perspectives 123, no. 7 (2015): 700–708. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3757288/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxxiiiGaskell, Adi. “What Is the Ideal Noise Level for the Office?” Forbes, March 21, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ adigaskell/2023/03/21/what-is-the-idealnoise-level-for-the-office/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxxivMayo Clinic Staff. “Office Ergonomics: Your How-To Guide.” Mayo Clinic, May 25, 2023. https://www.mayoclinic.org/ healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/ office-ergonomics/art-20046169. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxxvBuckley, John P., Alan Hedge, Thomas Yates, et al. “The Sedentary Office: An Expert Statement on the Growing Case for Change Towards Better Health and Productivity.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 49, no. 21 (2015): 1357–1362.

xxxviThaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Vol. 47. New York: Penguin Group, 2009.

xxxviiNorth Carolina State University. “Defining Universal Design (UD).” Disability and Multimodality, https:// disabilityandmultimodality.wordpress. ncsu.edu/universal-design-ud/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxxviiiCentre for Excellence in Universal Design. “The 7 Principles of Universal Design.” National Disability Authority, https:// universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design/ the-7-principles. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xxxixInternational CPTED Association. CPTED. net. https://www.cpted.net/. Accessed September 24, 2025.

xlHartke, Jason, Katie Worden, Mingyang Yang, and Whitney A. Gray. Investing in Health Pays Back, 2nd Edition: The Business Case for Healthy Buildings and Healthy Organizations. International WELL Building Institute, 2025. https://www.wellcertified.com/health-paysback/second-edition. Accessed September 24, 2025.