Eko / Lago de Curamo / Lagos

Once a series of alluvium plains and sandbars along the Atlantic coastline is a part of the city once known as Eko, by the Yoruba Aworis who lived on and cultivated the land. Following the arrival of the colonial interrupters to the West A ican coastal system, the social dynamics and the natural processes of the islands were heavily altered, firstly om the arrival of the Portuguese settlers to Lago de Curamo, and then the subsequent colonial commerce in astructures that were put in place by the British Royal Niger Company in order to establish Lagos as a major West A ican port and a center of trade and commerce.

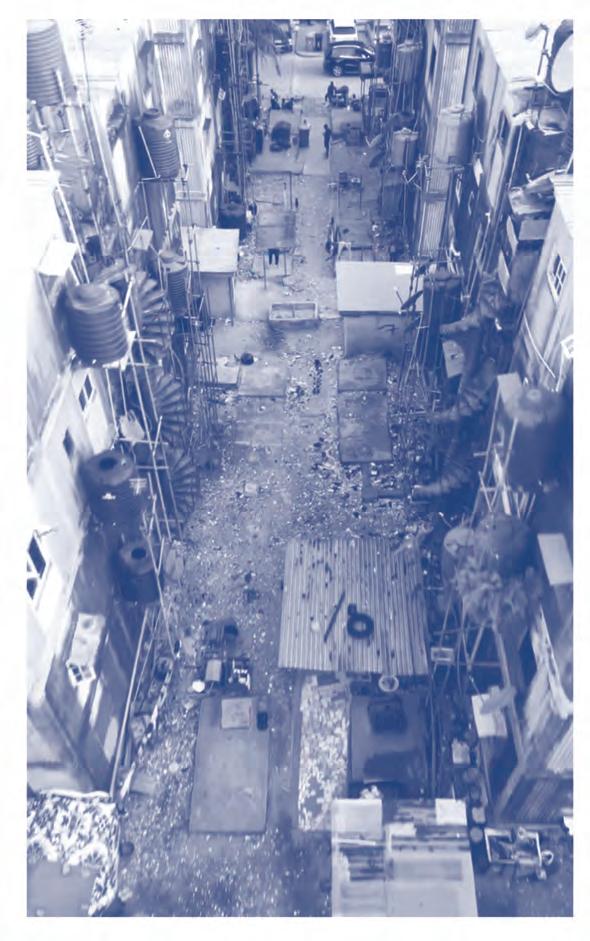

The already rapidly growing urban sprawl exponentially grew northwards om the Atlantic edge between the transition om the colonial era into post-independent Nigeria, which saw Lagos as a key economic center in the region, a center of Yoruba nationalist and political spheres, and subject to the unique Lagosian urbanism that emerged and continues to be transformed and reproduced. Today, the islands are a complicated fabric of transit in astructure, business districts, religious centers, schools, military barracks, overflowing migrant occupied informal settlements, A ica’s rising silicon valley, reclaimed land with the most expensive real estate on the entire continent, and many remnants om the British colonial underpinnings of the making of a Nigerian state.

This project investigates the Lagos Local Community Development Associations (LCDAs) in the four-tier government system that constitutes the “New Geography of post independent Nigeria, and how they negotiate channels of accountability and potential for local management practices to be successful as a paradigm shi into a new mode of environmental politics and discourses of transformation for Lagosians, while simultaneously representing failures in government at the Federal level. While acknowledging the successes of the LCDAs in Lagos Island-Obalende-Ikoyi, this project makes an attempt to navigate the alignment between these LCDAs and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. This critique of an adopted system or singular trajectory for “development” grapples with fugitivity and fugitive epistemologies (Harney & Moten 2013), to present a counter-narrative of how we might learn a new way of knowing about Lagosian ecologies.

Acey offers an exploration of contemporary challenges facing Lagos as development projects offset practices of dispossession and repossession which give rise to a unique Lagosian informal urbanism and volunteer ecologies that respond to governmental failures to ameliorate the acute housing and in astructure crisis facing its more than 15 million residents (Acey 2019, 52). This analysis of the human scale of displacement in Lagos and across Nigeria in colonial and post-independence development schemes that threaten and regard as temporary, illegitimate and subject to clearance (Acey 2019, 56), while simultaneously and urgently giving rise to voluntary in astructures (slums) and alternative ways of living that are continuously and robustly reproduced in the urban form.

By considering the nature and role of the state and the legacy of exclusionary visions that are residual om the era of colonial rule, Acey precisely locates the political context that gave rise to the four-tier system of self-governing organizations that operate locally that Ojo, Vickers, and Ballas delineate in their investigation of the variables and methodological approach employed in The Segmentation of Local Government Areas: Creating a New Geography of Nigeria (Ojo et al. 2012). Their argument that this geo-demographic model for segmentation is beneficial in the developing world is similarly put forth in Horowitz’s political ecological assertion that co-management

Agents & Institutions: A Political Ecological Framework (2022)

practices and “participatory conservation” (Horowitz 2015, 240) enable the organizing of local communities in service of ensuring their agency in imagining or determining the criteria of their trajectories for socio-ecological change, economic growth and in astructural development (Horowitz 2015, 239-240).

In this amework, Horowitz considers the “ever-tightening linkages between small-scale land-use practices, inevitably steeped in local knowledge, and an increasingly global political economy” (Horowitz 2015, 237) that this segmentation model (Ojo et al. 2012) produces. This supports the argument that such systems reveal social and spatial inequities and relationalities, and is put in place to strengthen the building of policy inter and intra regionally where many believe that post-independent Nigeria is too diverse to co-exist, and to encourage concepts of a Nigerian national identity (Ojo et al. 2012, 47).

Much of the discourse in cultural and architectural theory and urban studies reflects this notion of modern Nigeria as a nation in crisis, a contentious political imaginary underpinned by the purposeful destabilization of local socio-political powers leading into the creation of a Nigerian state by the British in 1960. In Learning om Lagos, Gandy grapples with how while much of the socio-spatial difficulties in approaching Lagos can be traced back to the colonial era, the trajectories of the military dictatorships that were instigated under the guidance of the World Bank and the United Nations International Monetary Fund (Gandy 2005, 42) further served to give rise to the vast informal economies that weave through the fabric of the city.

This intent for a post-colonial exploration of Lagos’s amorphous urbanism suggests that while “informal networks and settlements may meet immediate needs for some, and determined forms of community organizing may produce measurable improvements, grassroots responses alone cannot coordinate the structural dimensions of urban development” (Gandy 2005, 52). While Western planning experts have concluded that Lagos “lacks all the basic amenities and public services deemed essential in traditional urban studies” (Gandy 2005, 40), and fixes Lagos as a failure to be a city, Gandy asserts that this view is blatantly reductive and more importantly, implores that the ongoing legacy of imposed 19th century power relations be considered in order to assemble alternative modes of sense making for 21st century Lagosian urban ecologies (Gandy 2005, 47).

In order to further unsettle Lagosian political ecologies, this nod towards new ways of looking at or arriving in the seemingly endless entanglements of shi ing impermanence that constitutes Lagos, resonates with the notion of fugitivity (Harney & Moten 2013) as an interdisciplinary, decolonial gesture imbued with critique of modern epistemologies (Akomolafe 2020) which perpetuates the dilemmas of the capitalist and neoliberal structures that centralizes rationality, and instrumentalizes the nonhuman world as a resource for humankind. Akomolafe elaborates on this notion and postulates that to know fugitively is to come alive to other senses, to lose our way om the political imaginary of the Human and towards alternative design forms and fugitive ecologies in a more than Human world. This shi towards the fugitively as a way of knowing does not simply seek escape om the organizations and logics that hold us (Harney & Moten 2013, 11), but rather implore us to pursue alternate modes of inquiry that can respond to the “crisis” of urban form, in order to move beyond presentist,

instrumental, problem-solving approaches to design (Foster 2018, 8) and move towards navigating a new set of intelligences that reconceptualizes and honors the robust agility of Lagosian urbanism.

Ultimately, the fourth-tier government system that constitutes the “New Geography of Post-Independent Nigeria” (Ojo et. Al) enables community elected councils near autonomous control over the development planning for transit, health, education, and commercial in astructures. The goals of the LCDA, and their notions of Nature and Environment(s) are intrinsically tied to the Sustainable Development Goals outlined under the UN 2023 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Atanda-Lawal 2022). This project investigates how the introduced Local Community Development Associations negotiate channels of accountability and potential for local management practices to be successful as a paradigm shi into a new mode of environmental politics and discourses of transformation for Lagosians, while simultaneously representing failures in government at the Federal level. While acknowledging the successes of the LCDAs in Lagos Island-Obalende-Ikoyi, this project makes an attempt to navigate the alignment between these LCDAs and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. This critique of an adopted system or singular trajectory for “development” grapples with fugitivity and fugitive epistemologies (Harney & Moten 2013), to present a counter-narrative of how we might learn a new way of knowing about Lagosian ecologies.

Acey, Charisma. 2019. “Rise of the Synthetic City: Eko Atlantic and Practices of Dispossession and Repossession in Nigeria.” In Disassembled Cities: Social and Spatial Strategies to Reassemble Communities, edited by Elizabeth L. Sweet, 51-61. N.p.: Routledge.

Ajibade, Idowu. 2017. “Can a Future City Enhance Urban Resilience and Sustainability? A Political Ecology Analysis of Eko Atlantic City, Nigeria.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 28:85-92.

Akomolafe, Bayo. 2020. “Coming Down to Earth.”

Akomolafe, Bayo, and Alnoor Ladha. 2017. “Perverse Particles, Entangled Monsters and Psychedelic Pilgrimages: Emergence as an Ontoepistemology of Not-Knowing.” Ephemera 17, no. 4 (November): 819-839.

Dipeolu, Adedotun Ayodele, Eziyi Offia Ibem, and Joseph Akinlabi Fadamiro. 2021. “Determinants of Residents’ Preferences for Urban Green In astructure in Nigeria: Evidence om Lagos Metropolis.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 57.

Fadamiro, Joseph Akinlabi, and Joseph Adeniran Adedeji. 2016. “Cultural Landscapes of the Yoruba of South-Western Nigeria Demystified as Solidified Time in Space.” Space and Culture 19 (1): 15-30.

Folayan, Bolu J., and Oluwaseun Dokunmu. 2019. “Participatory Communication as a tool in all-inclusive grassroots governance: A study of Selected Community Development Associations (CDAs) in Lagos and Ogun States.” Nigerian Communications and Information Technology Journal 1 (1).

Foster, Jeremy. 2018. “Landscape Criticism: Between Dissolution and Objectification.” Journal of Landscape Architecture 13 (3): 8-11.

Gandy, Matthew. 2005. “Learning om Lagos.” New Le Review 33 (June): 37-53.

Gundaker, Grey. 2016. “Design on the World: Blackness and the Exclusion of Sub-Saharan A ica om the ‘Global’ History of Garden and Landscape Design.” In Cultural Landscape Heritage in Sub-Saharan A ica, edited by John Beardsley, 15-60. Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Haber, Alejandro F. 2009. “Animism, Relatedness, Life: Post-Western Perspectives.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (3): 418-430.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. N.p.: Minor Compositions.

Ikioda, Faith Ossy. 2013. “Urban Markets in Lagos, Nigeria: An Examination of Complex Urban Retailing Environments.” Geography Compass 7 (7): 517-526.

Jones, Yinka, and Venessa Williams. 2022. “Achieving Affordable Public Transport in Lagos and NMT.” Lagos Urban Development Initiative.

Kadiri, Folashade. 2021. “Lagos and Community Development.” The Guardian Nigeria.

Maier, Karl. 2000. This House Has Fallen Midnight in Nigeria. New York: Public Affairs.

Mendelsohn, Ben. 2018. “Making the Urban Coast: A Geosocial Reading of Land, Sand, and Water in Lagos, Nigeria.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, A ica, and the Middle East 38 (3): 455-472.

Muriithi, Samuel. 2022. “List of 37 LCDA in Lagos State and their chairmen in 2022.”

Ogwu, Matthew Chidozie. 2019. The Geography of Climate Change Adaptation in Urban A ica. Edited by Michael Addaney and Patrick B. Cobbinah. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ojo, Adegbola A., Daniel Vickers, and Dimitris Ballas. 2012. “The Segmentation of Local Government Areas: Creating a New Geography of Nigeria.” Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy 5 (1): 25-49.

Osanyintuyi, Abiola John, YongHong Wang, and Nor Aieni Haji Mokhtar. 2022. “Nearly Five Decades of Changing Shoreline Mobility Along the Densely Developed Lagos Barrier-Lagoon Coast of Nigeria: A Remote Sensing Approach.” Journal of A ican Earth Sciences 194.

Phillips, Alexandra. 2014. “A ican Urbanization: Slum Growth and the Rise of the Fringe City.” Harvard International Review 35 (3): 29-31.

Robbins, Paul. 2015. “The Trickster Science.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by Gavin Bridge, Thomas A. Perreault, and James P. McCarthy, 89-101. N.p.: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Rocheleau, Dianne, Barbara Thomas-Slayter, and Esther Wangari. 2013. “Gender and Environment: A feminist political ecology perspective.” In Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experience, edited by Dianne Rocheleau, Barbara Thomas-Slayter, and Esther Wangari, 3-23. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis Group.

Shakiru Akin, Akinyemi. 2020. Understanding Factors That Increase Citizens’ Participation in Community Development Projects in Lagos, Nigeria. N.p.: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

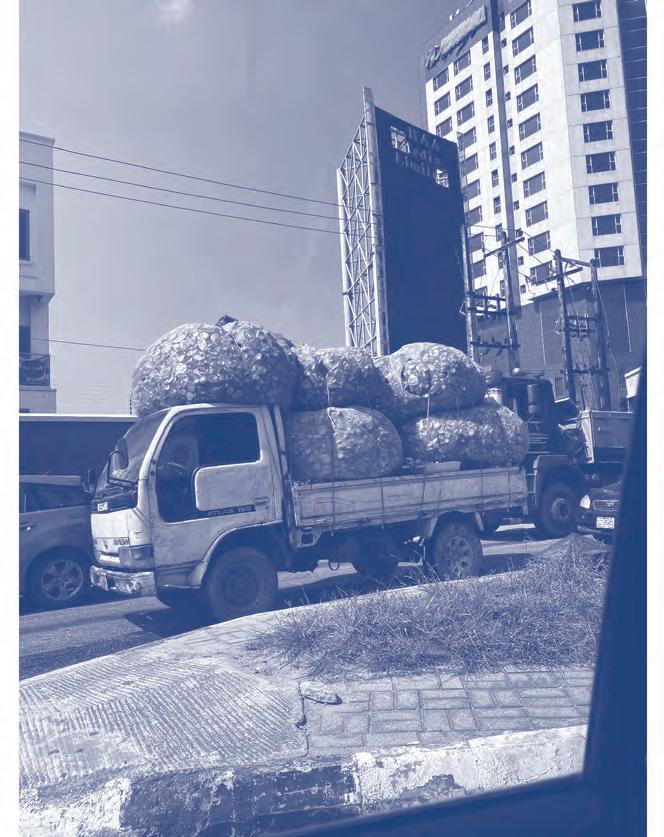

Maybe this is a call to articulate a different sense of what these waste landscapes mean, and to think about what my activism could mean here? Maybe this project provides an opportunity to articulate a way of looking at a landscape that has more to go with grief, and celebration, and fugitivity. And to notice plastics for their agency, having the power to shape and be shaped by our landscapes.

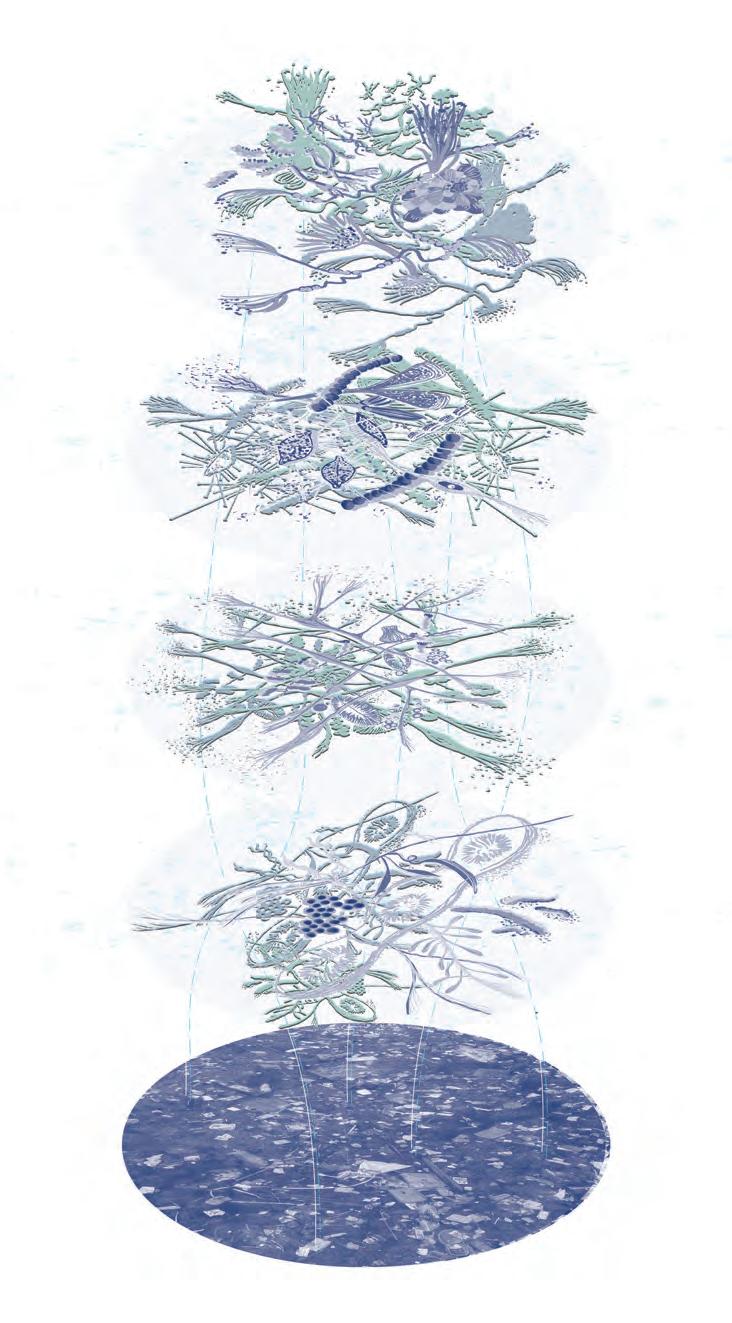

In getting lost, I started to think about the scales of plastics, and plastics as powerful agents in the landscape that shape and are simultaneously shaped in the environment. At their largest scale, they are in landfills, in gutters, in our streets, our waters. As they get smaller they find their way into the bellies of larger marine animals. Smaller, they are in the bellies of fish. Smaller, in the soil, in our blood, in the air

So now what do we do if we are becoming more plastic everyday. Are we any less Human?

In considering how the Human is really a static figure, and perhaps a product of a colonial imperial order. Being human is a way of acting, thinking, and believing.But our bodies are changing everyday - all live is evolving. So in some senses - we are not as Human - as we think we are. Perhaps we can find some solace there - knowing that there is the possibility that over time our thresholds to microplastics may grow. And we will always be more than Human.

It turns out there is another process of colonization in store for us, Polymeric Colonization. Max Liboroin talks about how plastics may have tricked us, and within these landscapes of waste, there are signs of life This constitutes the plastisphere, where there exists a whole strata of microbes that aggregate to form the plastisphere - that have evolved to live in human-made plastic environments.

It is interesting to think that maybe plastics are just finding ways to put up with the messes we’ve made.I think of the humility required to understand that even if we eradicate humans, the landscapes keep on living, if a government fails its people, Lagosians find a way to struggle and to live. I think I need to be able to arrive in Lagos as a landscape activist, architect, and to have a sense of belonging.

Consider what you know - or knowledge you think you know. And consider that how you move through the world creates the world and creates knowledge. Knowledge is not some stable objective view that concludes a scientific inquiry.

Knowledge is how you meet the world and how the world meets you. And perhaps we will meet the world in plasticized landscapes like this. And I don’t mean for this to evoke some kind of apocalypse. For ‘Apocalypse’ is a colonial concept that believes that the world will end when colonialism fails to hold our bodies anymore. If this is true - then because of this project - i am more optimistic about our impending doom.

And it is true what they say about Lagos - only the strong will survive.

Bibliography

Acey, Charisma. 2019. “Rise of the Synthetic City: Eko Atlantic and Practices of Dispossession and Repossession in Nigeria.” In Disassembled Cities: Social and Spatial Strategies to Reassemble Communities, edited by Elizabeth L. Sweet, 51-61. N.p.: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315104614-5.

Achebe, Chinua. 1994. Things Fall Apart. N.p.: Penguin Publishing Group.

Achebe, Chinua. 2013. There Was a Country : a Memoir. New York: Penguin Press.

Adedinni, Ayobami. “Meet the Brands Turning A ica's Plastic Trash into Treasure.” Adweek, July 25, 2022.

“A ica Region – Plastic Pollution and Marine Litter Law and Policy.” A ica Region – Plastic Pollution and Marine Litter Law and Policy | UNEP Law and Environment Assistance Platform, n.d.https://leap.unep.org/countries/case-studies/a ica-region-plastic-pollution-and-marine-litter-law-and-policy.

“A ica's Plastics Bans Are Pitting the Environment against the Economy.” Quartz, May 16, 2021. https://qz.com/a ica/2007658/why-western-style-plastic-bans-arent-working-in-a ica.

Aït-Touati, Frédérique, Alexandra Arènes, and Axelle Grégoire. Terra forma : manuel de cartographies potentielles. Paris: Éditions B42, 2019.

Ajibade, Idowu. 2017. “Can a Future City Enhance Urban Resilience and Sustainability? A Political Ecology Analysis of Eko Atlantic City, Nigeria.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 28:85-92.

Akindele;Alimba. “Plastic Pollution Threat in A ica: Current Status and Implications for Aquatic Ecosystem Health.” Environmental science and pollution research international. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Accessed April 17, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33398755/.

Akindele, Emmanuel O. “Nigeria's Plastic Pollution Is Harming the Environment: Steps to Combat It Are Overdue.” The Conversation, February 21, 2023. https://theconversation.com/nigerias-plastic-pollution-is-harming-the-environment-steps-to-combat-it-are-overdue-177839.

Akomolafe, Bayo. 2017. These Wilds Beyond Our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity's Search for Home. N.p.: North Atlantic Books.

Akomolafe, Bayo. 2020. “Coming Down to Earth.” https://www.bayoakomolafe.net/post/coming-down-to-earth.

Akomolafe, Bayo, and Alnoor Ladha. 2017. “Perverse Particles, Entangled Monsters and Psychedelic Pilgrimages: Emergence as an Ontoepistemology of Not-Knowing.” Ephemera 17, no. 4 (November): 819-839. http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fperverse-particles-entangled-monsters-psychedelic%2Fdoc view%2F1988414392%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D14771.

Akunyili, Dora. “The Role of Pure Water and Bottled Water Manufacturers in Nigeria.” 29th WEDC International Conference. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://wedc-knowledge.lboro.ac.uk/resources/conference/29/Akunyili.pdf.

Anikwe, Martin A.N., and Ejike E. Ikenganyia. “Ecophysiology and Production Principles of Cassava (Manihot Species) in Southeastern Nigeria.” Cassava, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70828.

Basel Academy of Art and Design. “Educating Otherwise: From Design Educator to Design Fugitive by Tanveer Ahmed.” Vimeo, March 23, 2023. https://vimeo.com/545390741.

Bassett, Thomas J. “Indigenous Mapmaking in Intertropical A ica,” n.d.. https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V2_B3/HOC_VOLUME2_Book3_chapter3.pdf.

Batta Box. “Inside Nigeria's ‘Pure Water’ Factories.” YouTube, July 29, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3pc4JD6zXg.

Bermúdez, J.R., and P.W. Swarzenski. “A Microplastic Size Classification Scheme Aligned with Universal Plankton Survey Methods.” MethodsX 8 (2021): 101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2021.101516.

Boeri, Stefano., Rem. Koolhaas, Sanford. Kwinter, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Nadia. Tazi. Mutations. Barcelona: ACTAR, 2000.

Borges, Jorge L. 2007. Labyrinths. Edited by James E. Irby and Donald A. Yates. N.p.: New Directions. Calvino, Italo. 1978. Invisible Cities. Translated by William Weaver. N.p.: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Campt, Tina M. 2021. A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See. N.p.: MIT Press.

Correa, Leo. “AP Photos: 'Plastic Man' in Senegal on Mission against Trash.” AP NEWS. Associated Press, November 10, 2022. https://apnews.com/article/a ica-business-senegal-dakar-pollution-ec56cfdb4eb6f82cd3348fc7bbf0acfc.

Dada, Olanrewaju. 2022. “Waste pickers in Lagos tell their stories about a dangerous existence.” The Conversation.

Dada, Olanrewaju Timothy, Gbemiga Bolade Faniran, Deborah Bunmi Ojo, and Amos Oluwole Taiwo. “Waste Pickers’ Perception of Occupational Hazards and Well-Being in a Nigerian Megacity.” International Journal of Environmental Studies, 2022, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2022.2055344.

Daston, Lorraine, and Peter. Gailson. Objectivity. New York: Zone Books, 2007.

Dipeolu, Adedotun Ayodele, Eziyi Offia Ibem, and Joseph Akinlabi Fadamiro. 2021. “Determinants of Residents’ Preferences for Urban Green In astructure in Nigeria: Evidence om Lagos Metropolis.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 57.

Ekrem, Erica. “Dr. Bayo Akomolafe on Slowing down in Urgent Times [Encore] /285.” FOR THE WILD. FOR THE WILD, May 6, 2022. https://forthewild.world/podcast-transcripts/dr-bayo-akomolafe-on-slowing-down-in-urgent-times-encore-285.

Ekrem, Erica. “Dr. Max Liboiron on Reorienting within a World of Plastic /156.” FOR THE WILD. FOR THE WILD, May 23, 2022. https://forthewild.world/podcast-transcripts/dr-max-liboiron-on-reorienting-within-a-world-of-plastic-156?rq=max.

Fadamiro, Joseph Akinlabi, and Joseph Adeniran Adedeji. 2016. “Cultural Landscapes of the Yoruba of South-Western Nigeria Demystified as Solidified Time in Space.” Space and Culture 19 (1): 15-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331215595751.

Farhat, Georges. 2022. Worldviews: Natures, Environments, Landscape.

Folayan, Bolu J., and Oluwaseun Dokunmu. 2019. “Participatory Communication as a tool in all-inclusive grassroots governance: A study of Selected Community Development Associations (CDAs) in Lagos and Ogun States.” Nigerian Communications and Information Technology Journal 1 (1).

Foster, Jeremy. 2018. “Landscape Criticism: Between Dissolution and Objectification.” Journal of Landscape Architecture 13 (3): 8-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2018.1589116.

Galison, Peter, and Lorraine Daston. 2010. Objectivity. N.p.: Zone Books.

Gandy, Matthew. 2005. “Learning om Lagos.” New Le Review 33 (June): 37-53. https://newle review-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/issues/ii33/articles/matthew-gandy-learning- om-lagos.

Gundaker, Grey. 2016. “Design on the World: Blackness and the Exclusion of Sub-Saharan A ica om the ‘Global’ History of Garden and Landscape Design.” In Cultural Landscape Heritage in Sub-Saharan A ica, edited by John Beardsley, 15-60. Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Haber, Alejandro F. 2009. “Animism, Relatedness, Life: Post-Western Perspectives.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19 (3): 418-430. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774309000602.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. N.p.: Minor Compositions.

Heinrich Boll Sti ung. 2020. The Plastic Atlas. Nigeria ed.

Hutton, Jane E. 2020. Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements. N.p.: Taylor & Francis Group.

Ikioda, Faith Ossy. 2013. “Urban Markets in Lagos, Nigeria: An Examination of Complex Urban Retailing Environments.” Geography Compass 7 (7): 517-526.

Jones, Yinka, and Venessa Williams. 2022. “Achieving Affordable Public Transport in Lagos and NMT.” Lagos Urban Development Initiative.

Kadiri, Folashade. 2021. “Lagos and Community Development.” The Guardian Nigeria.

Kelum Palipane, Recorded Lecture Presentation, LAN2037. October 18 2021

Kobo, Kingsley. “A ica's Plastics Bans Are Pitting the Environment against the Economy.” Quartz, May 16, 2021. https://qz.com/a ica/2007658/why-western-style-plastic-bans-arent-working-in-a ica.

Kwinter, Sanford, Stefano Boeri, Nadia Tazi, Hans U. Obrist, and Rem Koolhaas. 2000. Mutations: Rem Koolhaas, Harvard Project on the City, Stefano Boeri, Multiplicity, Sanford Kwinter, Nadia Tazi, Hans Ulrich Obrist. N.p.: ACTAR.

Lama, Tsering Y. 2022. We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies: A Novel. N.p.: McClelland & Stewart.

Lerner, Sharon. “A ica's Exploding Plastic Nightmare.” Greenpeace A ica, January 9, 2022. https://www.greenpeace.org/a ica/en/blogs/11125/a icas-exploding-plastic-nightmare/.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. N.p.: Duke University Press.

Maier, Karl. 2000. This House Has Fallen Midnight in Nigeria. New York: Public Affairs.

Mendelsohn, Ben. 2018. “Making the Urban Coast: A Geosocial Reading of Land, Sand, and Water in Lagos, Nigeria.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, A ica, and the Middle East 38 (3): 455-472. https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201x-7208801.

Muhammad, Muhammad Bello and Dansabo, Muhammad Tasiu (2018) "“Pure Water” Sale and its Socio - Economic Implications in Nigeria.," Journal of Environmental Sustainability: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jes/vol6/iss1/3

Muriithi, Samuel. 2022. “List of 37 LCDA in Lagos State and their chairmen in 2022.”

“Nigeria: A Country of ‘Pure Water’ Cities.” Sahara Reporters. Accessed April 17, 2023. https://saharareporters.com/2011/03/28/nigeria-country-%E2%80%9Cpure-water%E2%80%9D-cities.

Ngozi Adichie, Chimamanda. 2019. “Still Becoming: At Home In Lagos.” Esquire.

Nzeadibe, Chidi, Chinedu Onyishi, Christian Ezeibe, Gerald Ezirim, and Peter Mbah in the Department of Political Science. “Informal Waste Management in Lagos Is Big Business: Policies Need to Support the Trade.” The Conversation, February 21, 2023. https://theconversation.com/informal-waste-management-in-lagos-is-big-business-policies-need-to-support-the-trade-151583.

Ogwu, Matthew Chidozie. 2019. The Geography of Climate Change Adaptation in Urban A ica. Edited by Michael Addaney and Patrick B. Cobbinah. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ojo, Adegbola A., Daniel Vickers, and Dimitris Ballas. 2012. “The Segmentation of Local Government Areas: Creating a New Geography of Nigeria.” Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy 5 (1): 25-49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-010-9058-0.

Okpokwasili, Okwui. 2018 Berlin Biennale. Sitting On a Man's Head, Peformance Piece. Orangotango+, Kollektiv, ed. 2018. This is Not an Atlas: A Global Collection of Counter-cartographies. N.p.: Transcript Verlag.

Osanyintuyi, Abiola John, YongHong Wang, and Nor Aieni Haji Mokhtar. 2022. “Nearly Five Decades of Changing Shoreline Mobility Along the Densely Developed Lagos Barrier-Lagoon Coast of Nigeria: A Remote Sensing Approach.” Journal of A ican Earth Sciences 194.

Phillips, Alexandra. 2014. “A ican Urbanization: Slum Growth and the Rise of the Fringe City.” Harvard International Review 35 (3): 29-31. https://go-gale-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/ps/i.do?p=CIC&u=utoronto_main&id=GALE|A364854933&v=2.1&it=r.

P.W. Swarzenski, J.R. Bermúdez. 2021. “A microplastic size classification scheme aligned with universal plankton survey methods.” MethodsX 8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2021.101516.

Robbins, Paul. 2015. “The Trickster Science.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by Gavin Bridge, Thomas A. Perreault, and James P. McCarthy, 89-101. N.p.: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://www-taylor ancis-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315759289-8/trickster-science-paul-robbins?context=ubx&refId=00562c b3-504e-4c9d-a974-b1ff198d232b.

Roch, Samuel, Thomas Walter, Lukas D. Ittner, Christian Friedrich, and Alexander Brinker. “A Systematic Study of the Microplastic Burden in Freshwater Fishes of South-Western Germany - Are We Searching at the Right Scale?” Science of The Total Environment 689 (2019): 1001–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.404.

Rocheleau, Dianne, Barbara Thomas-Slayter, and Esther Wangari. 2013. “Gender and Environment: A feminist political ecology perspective.” In Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experience, edited by Dianne Rocheleau, Barbara Thomas-Slayter, and Esther Wangari, 3-23. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.4324/9780203352205.

Sadan, Z. and De Kock, L. 2021. Plastic Pollution in A ica: Identifying policy gaps and opportunities. WWF South A ica, Cape Town, South A ica.

Satrapi, Marjane. 2004. Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood. Translated by Marjane Satrapi. N.p.: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Shakiru Akin, Akinyemi. 2020. Understanding Factors That Increase Citizens’ Participation in Community Development Projects in Lagos, Nigeria. N.p.: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Simone, Nina. 1969. I Shall Be Released. To Love Somebody (Expanded Edition).

Sogbanmu, Temitope O. “Plastic Pollution in Nigeria Is Poorly Studied but Enough Is Known to Urge Action.” The Conversation, April 12, 2023. https://theconversation.com/plastic-pollution-in-nigeria-is-poorly-studied-but-enough-is-known-to-urge-action-184591.

Steff, Kevin. “The World Is Drowning in Ever-Growing Mounds of Garbage.” The Washington Post. WP Company, April 9, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/the-world-is-drowning-in-ever-growing-mounds-of-garbage/2017/11/21/cf22e4bd-17a4-473c-89f 8-873d48f968cd_story.html.

Tame Impala. 2015. The Less I Know The Better.

Tems. 2020. For Broken Ears.

The Ordinary : Recordings. Interview by Enrique Walker. New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2018.

“This Is Not an Atlas : a Global Collection of Counter-Cartographies.” 2018. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Tsering Yangzom, Lama. We Measure the Earth with Our Bodies : a Novel. First edition. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2022.

Tsing, Anna L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. N.p.: Princeton University Press.

“UNs New Task: Save A ica om Becoming World's Plastic 'Dustbin'.” Daily Sabah. Daily Sabah, February 26, 2022. https://www.dailysabah.com/world/a ica/uns-new-task-save-africa- om-becoming-worlds-plastic-dustbin.

“West A ica Is Drowning in Plastic. Who Is Responsible?” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2022-coca-cola-nestle-west-a ica-ghana-plastic-waste-recycling/#xj4y7vzkg.

Wolff, Jane. 2021. Bay Lexicon. N.p.: McGill-Queen's University Press.

The imagery on the following pages were taken by Nandini Mahbubani:

20 - 21, 28, 30 - 31, 60 - 63, 66 - 69, 72 - 73, 94 - 95

Nandini is an A o-Indian multitalented creative. She is a born drone artist, director, producer, photographer, dancer and idea generator with mastery over narrative conceptualisation. Passionate to the core she is a walking talking storyteller. She graduated om Emerson College with an undergraduate degree in Visual Media Arts in 2019. Subsequently, she moved back to Nigeria to fulfil her life's long dream to make a blockbuster movie fusing Indian and Nigerian culture as they have both been a major influence on her life. Her approach to a career in the entertainment industry has been unconventional, as she is a lone ranger and natural entrepreneur who thrives in bringing her ideas to life. Nandini has dedicated the last two years of her life towards researching and building momentum on these two films, by creating smaller pieces of work as proof of concept. She has also worked tirelessly to identify the right talent to showcase her vision and make up her dream team.

The images on the following pages were sourced om the articles listed:

38 - 41

Correa, Leo. “AP Photos: 'Plastic Man' in Senegal on Mission against Trash.” AP NEWS. Associated Press, November 10, 2022.

34 - 35

Lerner, Sharon. “A ica's Exploding Plastic Nightmare.” Greenpeace A ica, January 9, 2022.

36 - 37, 54 - 55

West A ica Is Drowning in Plastic. Who Is Responsible?” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, August 18, 2022.

The remaining images were taken by the author between October 2020 and August 2021.