Master of Landscape Architecture Thesis

Advisor: Behnaz Assadi

university of toronto

daniels faculty of architecture, landscape & design

printed by Omazzii Printing, Toronto

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

~ everything is subject to change ~

Atlas of Unsettling Ecologies

Kiran Khurana 2023

1 Slowing Down

Ubiquity of Plastics

Unsettling Lagosian Ecologies

Plasticization of West A ica

Plasti-pelagos

‘Sitting On a Mans Head’

2 Coming Alive

Waste Mismanagement

Living on Plastics In Praise of Soil

Archipelago of Belonging

3 Imagining Otherwise Lost in Lagos Agency of Plastics More than Human The ‘Plastisphere’ Seeing Places Without Being There Bibliography

Acknowledgments

In another iteration of this book these pages will express my endless graditute to my ancestors, to every one I have learned om, to the ground where my feet are.

commodo massa ex ut purus. Donec nec lectus ligula. Ut pellentesque fermentum mauris ac iaculis. Duis mauris velit, aliquam a finibus at, pharetra nec sapien. In ornare tellus eros, sollicitudin tincidunt quam ultricies quis. In eu justo lorem. Donec aliquam, nunc eget scelerisque semper, elit orci faucibus diam, non blandit ante neque ut elit. Aliquam volutpat arcu ut tellus ullamcorper, in iaculis odio sodales. Phasellus vulputate libero a justo congue imperdiet. Cras luctus risus in velit tincidunt sagittis. Aenean quis ligula.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In ingilla, dolor ac venenatis malesuada, tortor enim cursus felis, at commodo massa ex ut purus. Donec nec lectus ligula. Ut pellentesque fermentum mauris ac iaculis. Duis mauris velit, aliquam a finibus at, pharetra nec sapien. In ornare tellus eros, sollicitudin tincidunt quam ultricies quis. In eu justo lorem. Donec aliquam, nunc eget scelerisque semper, elit orci faucibus diam, non blandit ante neque ut elit. Aliquam volutpat arcu ut tellus ullamcorper, in iaculis odio sodales. Phasellus vulputate libero a justo congue imperdiet. Cras luctus risus in velit tincidunt sagittis. Aenean quis ligula.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. In ingilla, dolor ac venenatis malesuada, tortor enim cursus felis, at commodo massa ex ut purus. Donec nec lectus ligula. Ut pellentesque fermentum mauris ac iaculis. Duis mauris velit, aliquam a finibus at, pharetra nec sapien. In ornare tellus eros, sollicitudin tincidunt quam ultricies quis. In eu justo lorem. Donec aliquam, nunc eget scelerisque semper, elit orci faucibus diam, non blandit ante neque ut elit. Aliquam volutpat arcu ut tellus ullamcorper, in iaculis odio sodales. Phasellus vulputate libero a justo congue imperdiet. Cras luctus risus in velit tincidunt sagittis. Aenean quis ligula.

Ubiquity of Plastics

Plastics are ubiquitous in our lives and in our landscapes. Over the last century and a half, humans have introduced and rapidly streamlined the production of synthetic polymers. Plastics were conceived as a substitute for Ivory, due to the dwindling numbers of elephants. And during the first world war in the United States, uses for plastic and the mechanization of plastic production continued to develop, and to some intelligences, were perfected. There are certainly some good uses for plastics, Dr. Max Liboron, who studies marine ecosystems and plastic pollution, makes the case that if we banned plastics, then airplanes would just fall out of the sky, the economy would fail. This is to say there may be some places where it makes sense to value the rigidity and strength of plastics, but it is not even these types of plastics that leave systems and make their way into oceans -. It is absolutely mainly packaging, not so useful plastics, like some of the objects drawn that may be recognizable. And while we may not have participated in the ideation of ‘disposability’, we are all most likely complicit in how this global plastic addiction has continued to spiral and reach new heights.

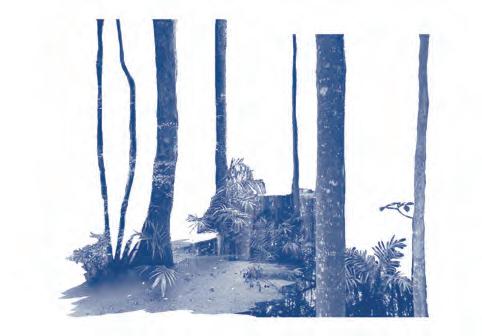

Along a series of alluvium plains and sandbars along the Atlantic coastline is a part of the city once known as Eko, by the Yoruba Aworis who lived (and still live) among these waters. Water occupies a central place in the folklore and the everyday sphere of the Yoruba cosmology just as it might be to other peoples around the world, and has long been an intrinsic part of spiritual beliefs, rites, and rituals (Water Symbolism in Yorùbá Folklore and Culture, George Olusola Ajibade).

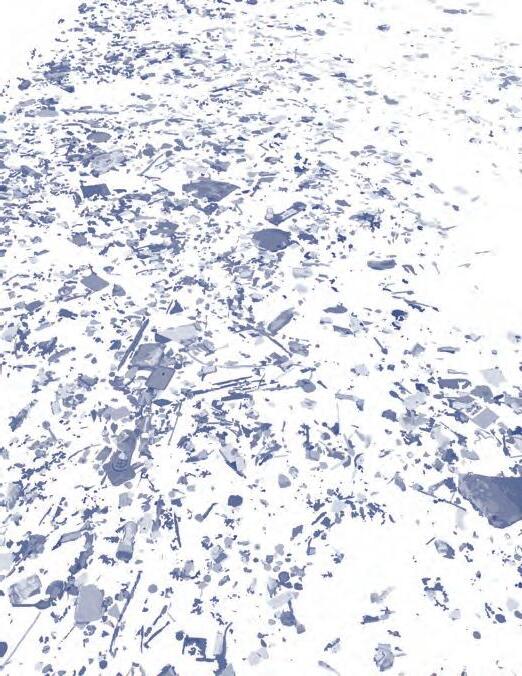

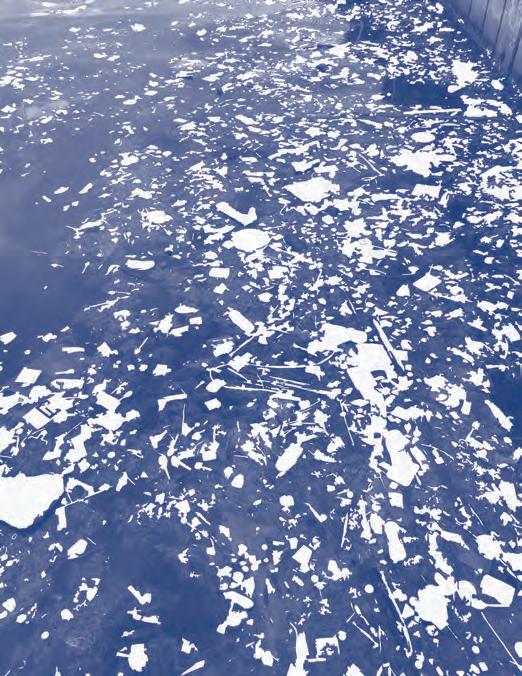

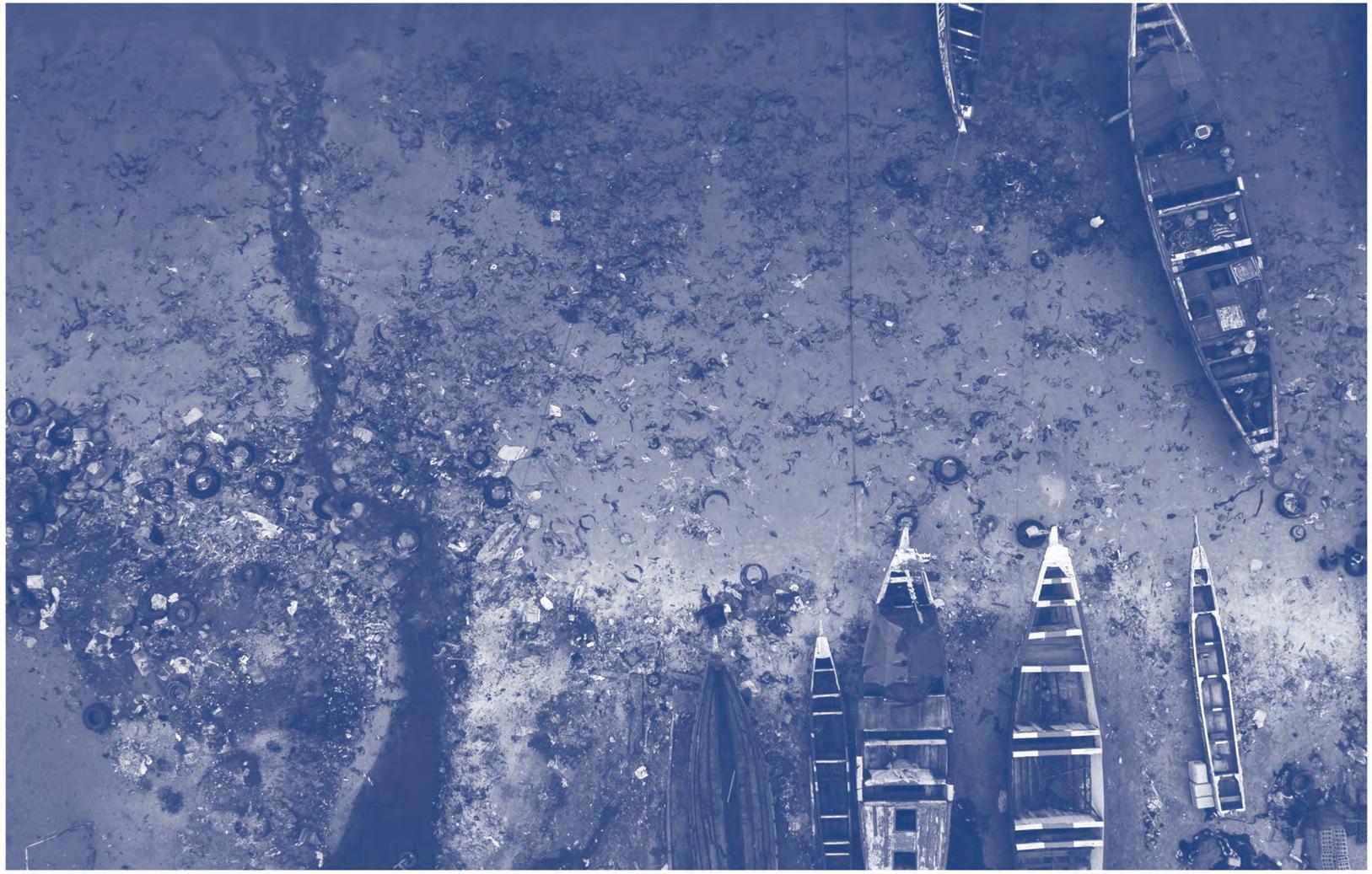

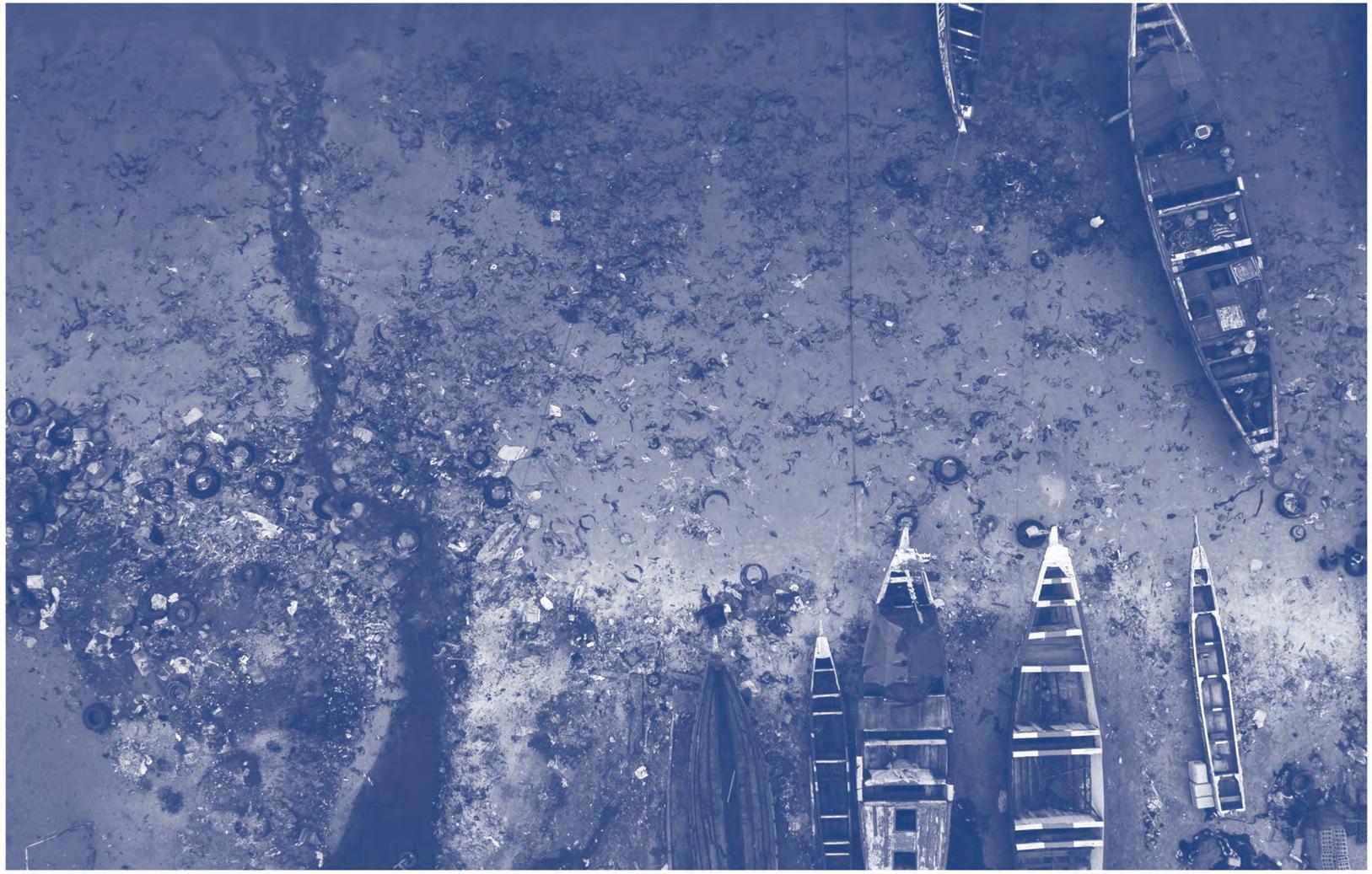

the Lagoon, a er the rains 30 04 2021

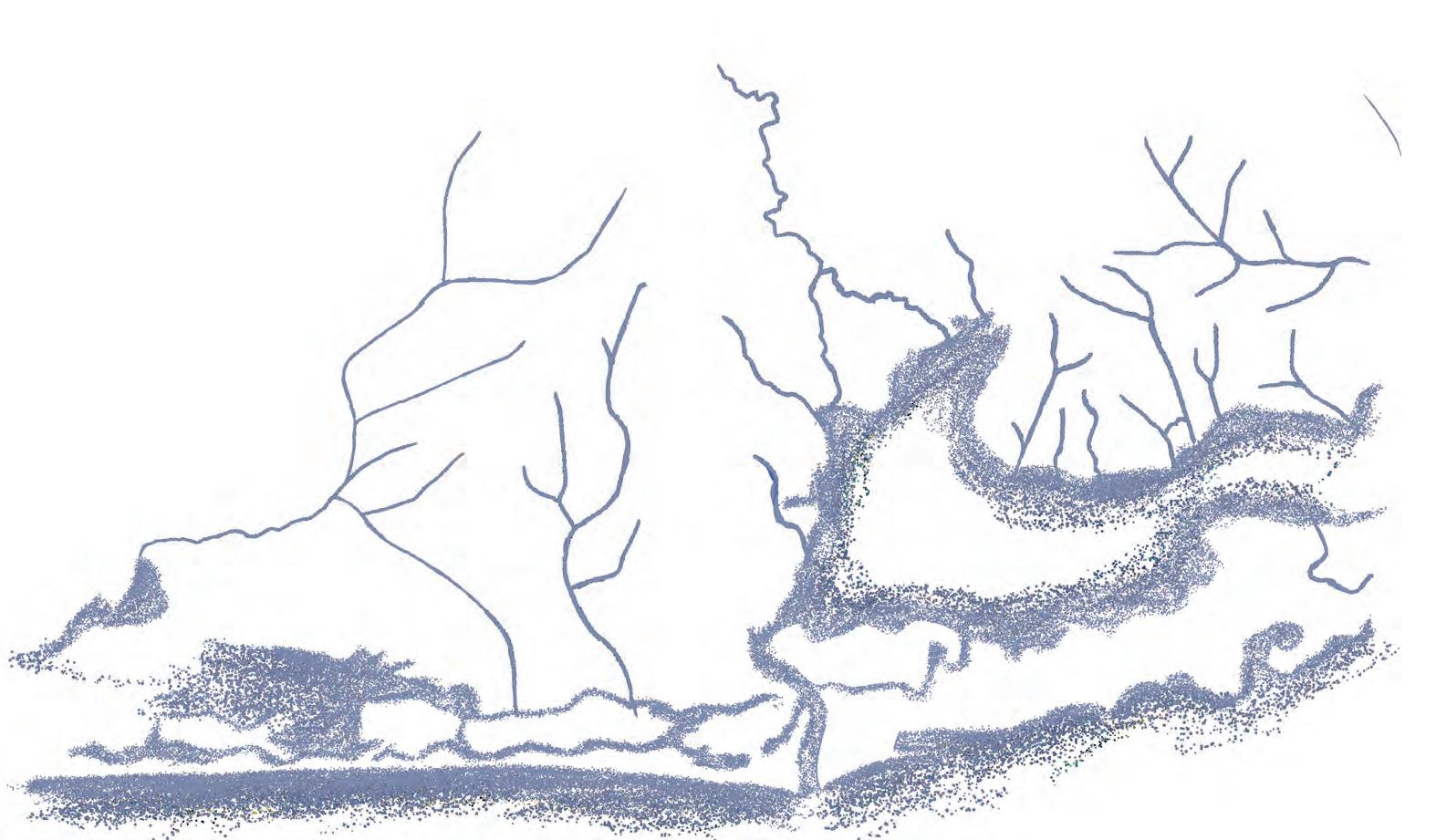

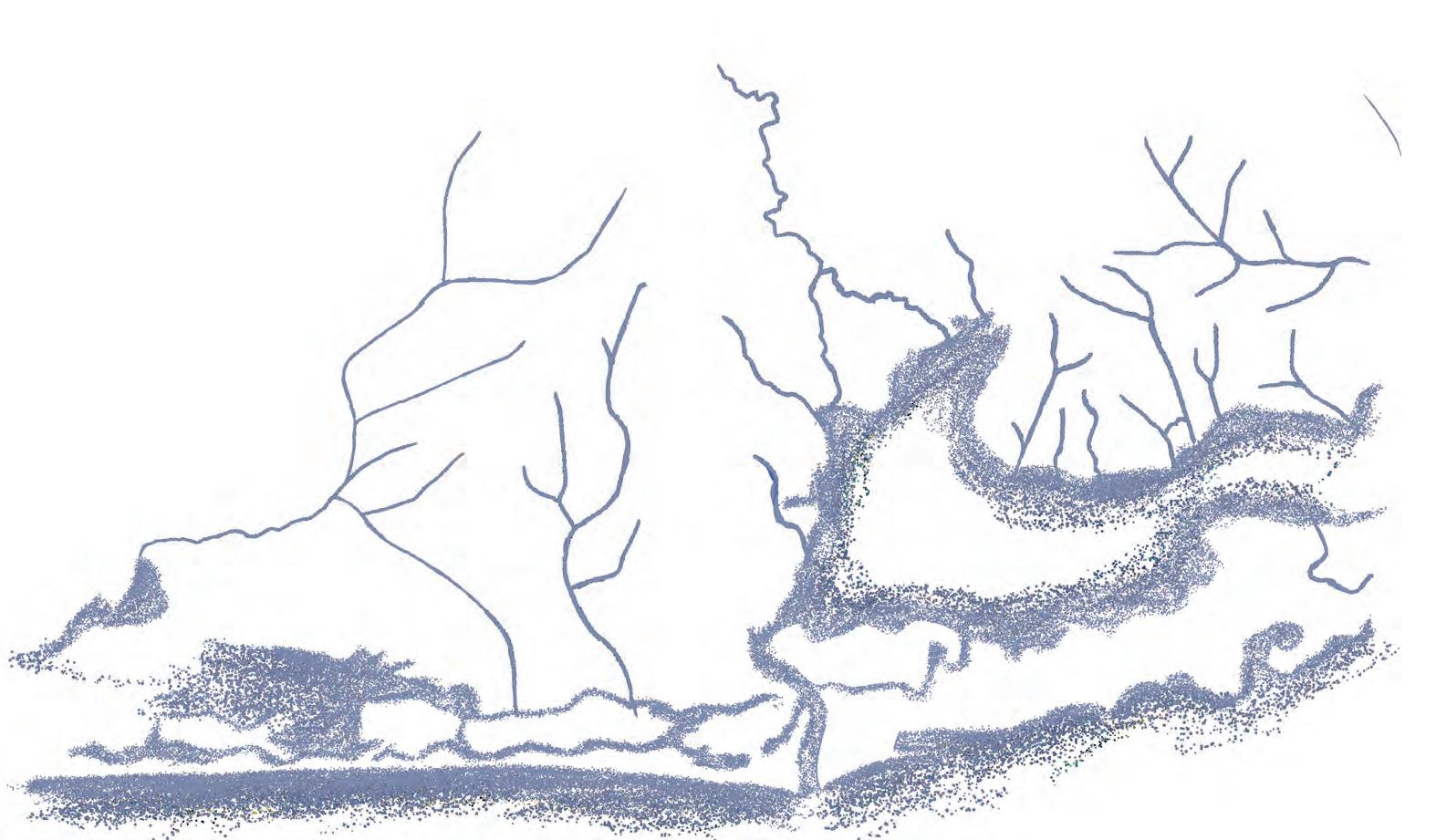

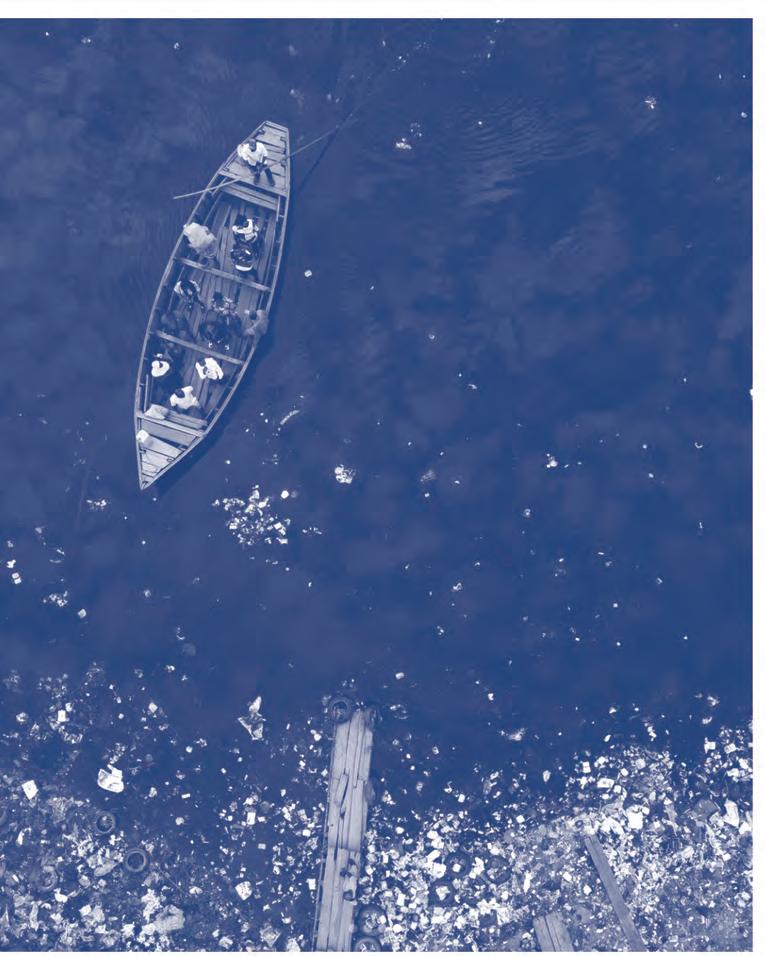

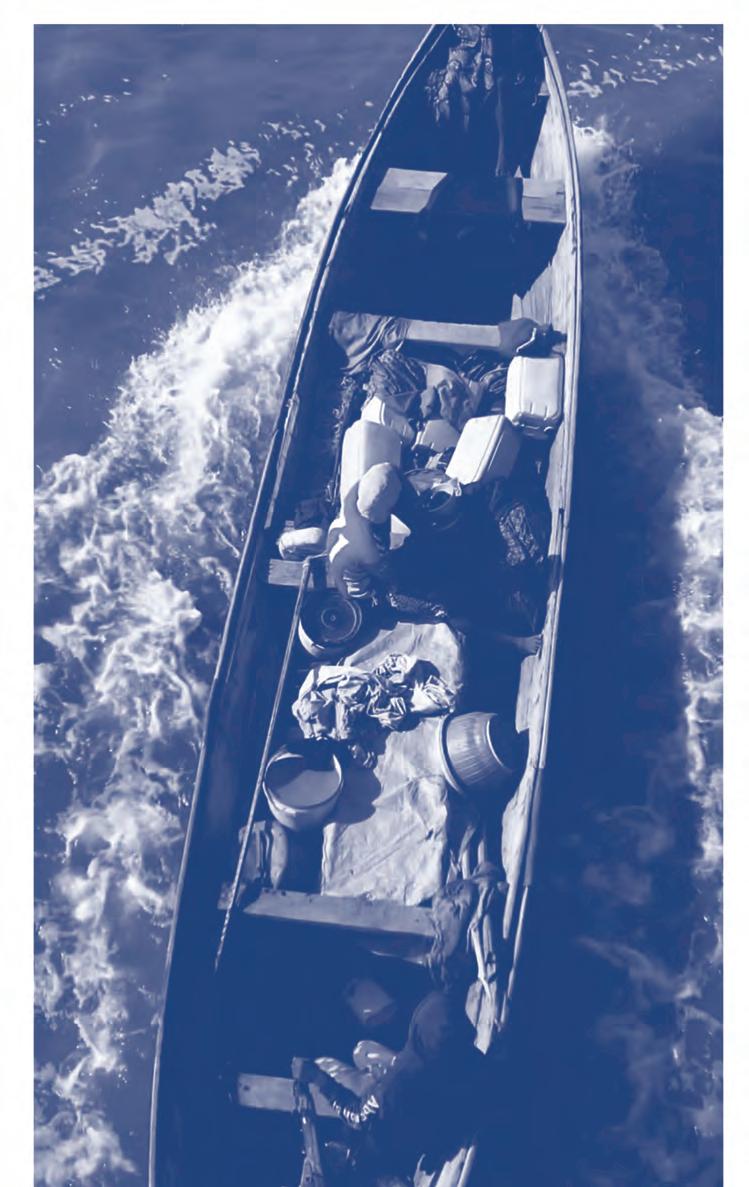

One of the first things I noticed when I moved back to Lagos, was the ubiquitous plastics, and the rivers of plastics emerging when the waters in the Lagoon are high. Let us now arrive in Lagos, Nigeria, the first city I called home, and attempt to slow down in urgent times.

An Atlas, is an intellectual construction, which stands in place as a reality.Even the most simple curation of an atlas is already a manipulation. It is already infused with the politics of the person. In thinking about how a landscape architect can arrive in an A ican context without being an agent, however unwittingly for the extension of colonialism. I wanted my contribution to enrich the stories we tell about Lagos, and maybe even the continent at large. And while some of its contents may seem counter-intuitive, my shi s away om the normative are instrumental in figuring out how we might consider landscapes of waste, not as marginal spaces but as designed landscapes, where we can critically layer subtle shi s in our thinking, to honor the ruins we live amongst.

In grappling with the existential urgencies that arise in this moment of planetary transformation, this atlas looks to mapping the spontaneous economies and ecologies of plastics and landscapes of waste to reveal the underlying power structures, material culture, and impossible dilemmas that are engaged in unsettling Lagosian ecologies.

how might we arrive at waste landscapes through a grammar of thinking otherwise, and noticing plastics as landscape agents?

How might we devise a way of looking and belonging in the wake of the destruction that we have propagated, and to honor the vulnerable ecologies that live among our ruins?

Unsettling Lagosian Ecologies

Pure Water is King

Orisha(s)

Idejohs Aworis

14th c.

COLONIAL

Interruptors

18th c.

wasting is a learned behaviour network of water distribution systems abandoned and allowed to decay

United Nations Britain George V Frederick Lugard

Lago de Curamo

Royal Niger Company

United A ica Company

Southern Nigeria Protectreate

Nigeria launches pilot brand of bottled water, Swan Table Water Water

1985

World Bank implemented a structural adjustment programme that recommended a cut back in spending on water and sanitation in astructure

Lagos, Nigeria

“Nigeria is not a nation. It is a mere geographical expression. There are no ‘Nigerians’ in the same sense as there are ‘English,’ ‘Welsh,’ or ‘French,’ The word ‘Nigeria’ is a mere distinctive appellation to distinguish those who live within the boundaries of Nigeria and those who do not”

Chief Obafemi Awolowo, 1947

“Water Crisis”

“The public sector in Nigeria has woefully failed in its responsibility at providing clean and affordable water”

Due to advancements in machinery, the same amount of plastic input can be produce up to 6x the amount of pure water sachets

88% of plastic waste is mismanaged

2018

China implements ban on importing plastic waste

UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals Introduced

Federal Government

Ministry of Environment

Extended Producers Responsibility (EPR)

2007 National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) sand filtration

Although there is no available record of pure water sachets collected, judging by the fact that plastic waste collectors are usually paid per kilogram, it is likely that many of them would opt to collect heavier items like glass bottles, PET bottles, plastic chairs and kegs, aluminum cans or cartons, rather than lightweight items like pure ware sachets with little economic incentive

closest working government policy tackling plastic waste in Nigeria lack of clarity on the policy is to be implemented due to inadequate communication between government and industry

Nigerians consumer 10 million sachets of pure water daily

Most successful method for mass distribution of potable water in Nigeria

I wonder if the world has ended many times, if every time we’ve lost our language, our placefulness, everytime we draw a line and call it a border, a world has ended.

This timeline begins in acknowledging the Yoruba Aworis who lived and still live among these waters. Following the arrival of the colonial interrupters on the West A ican coastal ecosystem, the dynamics of these waters were heavily altered. The interrupters came with a mission of kidnapping A icans, of destroying spiritual connections to ecological forces, channelizing rivers, and introducing in astructures of disposability and waste, to trick people into being complicit in the destruction of their worlds. This is perhaps an end of the world for these waters.

Even a er Nigeria was granted its “independence”, the colonial interrupters by way of the United Nations, still made decisions to cut back public spending, crushing incentives to invest in the in astructures needed to provide clean water and sanitation in the modern country they le behind. This water crisis eventually gave way into the everyday practice of plastic production and the making of an unlivable world.

It was in 1994, that Pure Water was introduced. Pure Water is purified water, most o en collected om boreholes, and purified, and then packaged in a polyethylene bag.

It was highly successful in being the first mode to distribute potable water on a massive scale across the country, and to significantly reduce the amount of people across the country suffering om waterborne illnesses. Nigerians consume over 10 million bags of pure water a day, and channels of accountability in the governing structure of the country continued to fail, this gave way to a new crisis - a crisis of plastics.

This bag of water is where my inquiry began about how we may navigate into new intelligences that reconsider how, in a place where there is an ongoing failure in government to support in astructures of potable water, how is plastic the bad guy? In order to slow down the urgency of this “war” on plastics, this project aims to invite new conversation around the matter of plastic pollution. And it is very much a language of war, just as with climate change - we are going to “fight” climate change, climate change is something we have to “beat”.

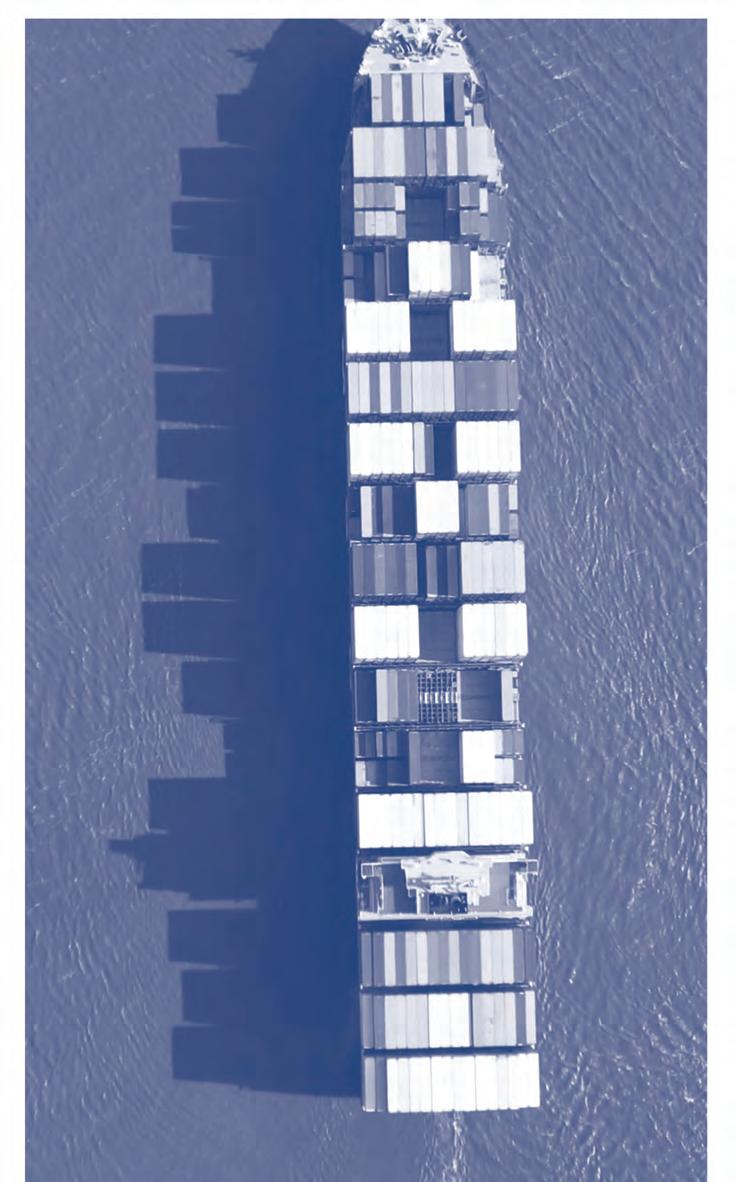

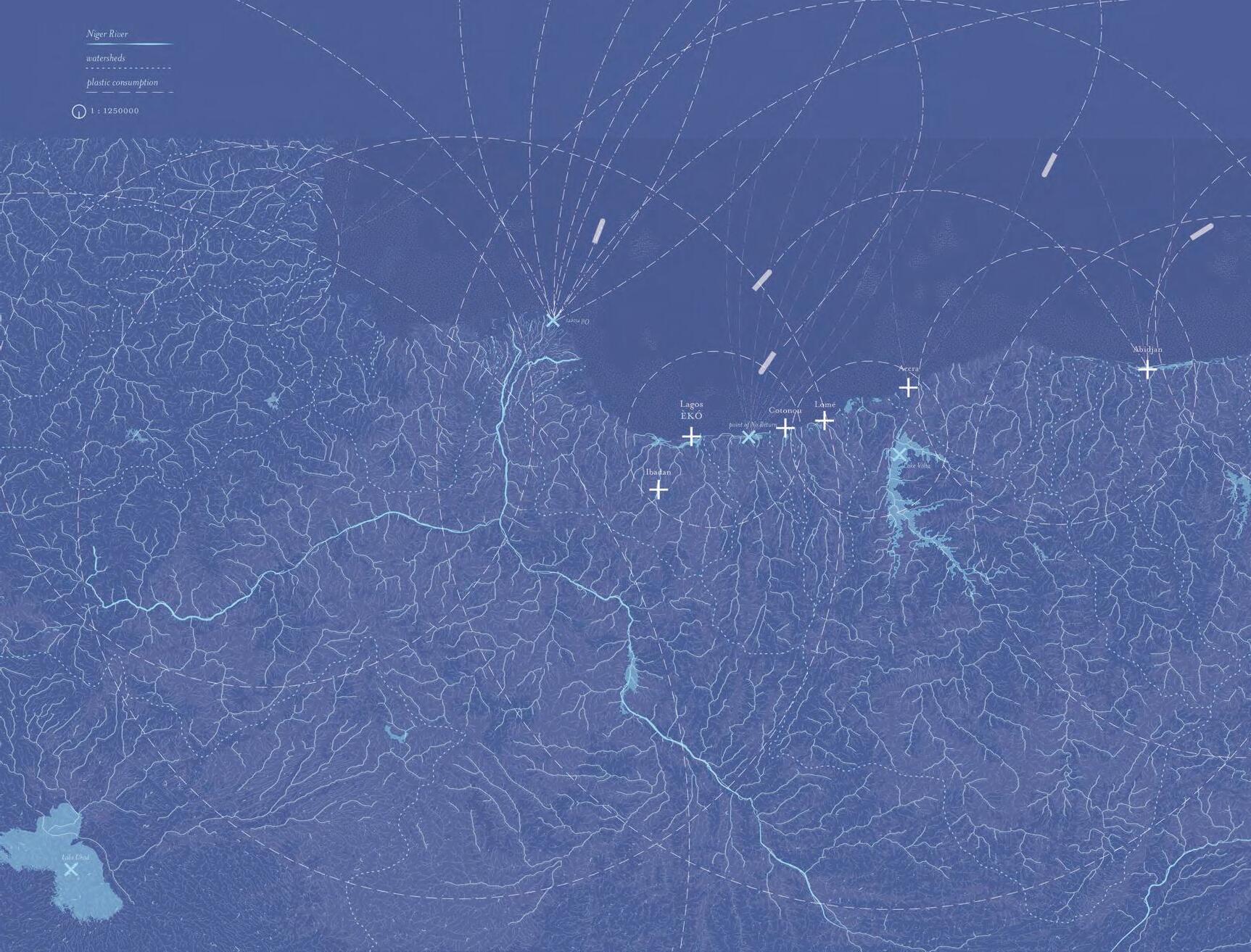

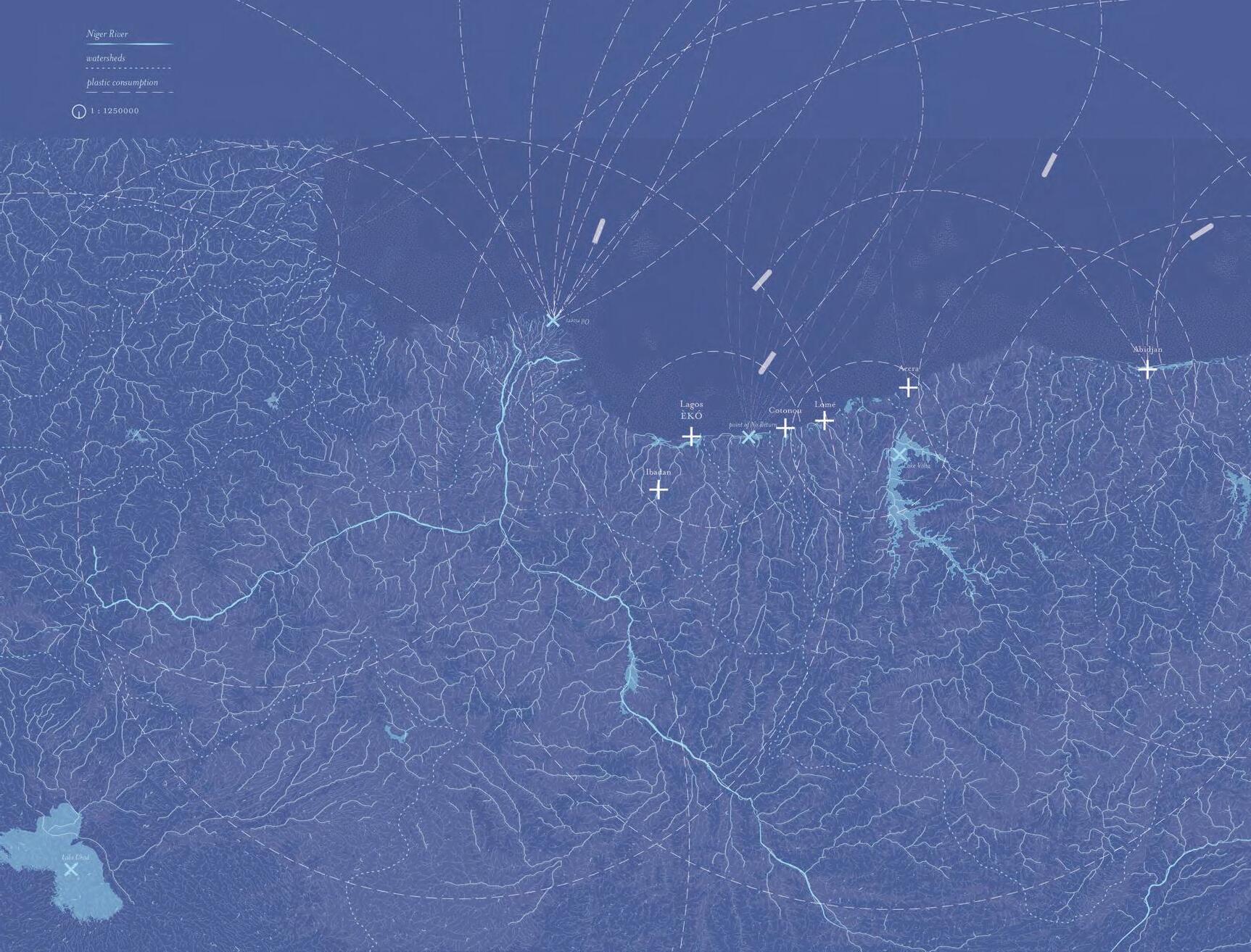

Plasticization of West A ica

At the scale of West A ica, considering the volumes of plastic waste produced by major cities along the coast. Rather than divide up the region through modern political borders, I've represented the watersheds, and honed in on the region that historically has been Yorubaland.

Today, West A ica is actually one the fastest growing regions in the world, and its coastal ecosystems are some of the most plasticised. The Niger River that runs through this region, is one of the 10 major rivers that pollute the oceans to plastics - or rather those of us that have lived in the Niger River watershed are some of the largest contributors to ocean plastics. This also means that this region - and Nigeria more so than the other country - is a major contributor to the South Atlantic Ocean Patch.

Plasti-pelagos

95% of plastics polluting the worlds oceans come om 10 rivers

There are five such islands forming the larger islands of this earth's plastic archipelago. The Great Pacific Patch - which lies here - and is the most intensely studied, reveals that dozens of species of coastal invertebrate organisms have been able to survive and reproduce on plastic garbage that’s been floating in the ocean for years. It’s even been reported that “Quite a large percentage of the diversity that we found were coastal species and not the native pelagic open ocean species that we were largely expecting to find - but rather 80% were normally found in coastal habitats. As plastic pollution has become particularly unprecedented since 2005, we are bound to see more and more plastic agments, more pollution, more turtles tangled by fishing nets. But oddly enough, also more life.

‘Sitting

On a Mans Head’

Field Notes : Berlin Biennale 2018

I remember when it dawned on me that this isn’t all that there is. I was invited to participate in Sitting on a Man’s Head, a performance installation in Berlin by Igbo artist, Okuwi Okpokwasili. It was an invitation to be guided on a slow walk across the floor, and then to simply to take up space, humming so ly, moving eely. To sit on a man’s head was a form of protest practiced by women in Igboland, singing and dancing for hours in the courtyards of British colonial officials. As “a collective invasion of seats of power, it was a strategy used to speak back, air grievances, and effect change” marking opposition to British imperialism by women which transcended territories and class.

I felt heavy and nervous about the interaction, because it seemed to be an invitation into a kind of heightened self awareness that would be severely uncomfortable - but in reality, it was simultaneously peaceful and strained. The interaction moved inwards, into a silent revolution, outwards, intertwined in a collective utterance. Together, we sang in service of our resistance, our self preservation, calling out that which holds us outside of our bodies. A erwards, in the margins of my notebook, I wrote ‘stretch, more. you forgot how your body moves. you’ve become two lines’.

I find this notion of looking towards a space for “self preservation” to be an interesting one. The Biennale itself “explores the political potential of the act of self-preservation, refusing to be seduced by unyielding knowledge systems and historical narratives that contribute to the creation of toxic subjectivities”. Head Curator, Gabi Ngcobo, amed it in an interview as such: “we are all postcolonial”, and self preservation seems to be the work of “postcolonial” artists. This nods to asking questions about who created knowledge and systems of power that define our world order.

Thus, self preservation not only through questioning our identities, but also questioning the system of power in which we create ourselves. She says it is important to take positions that are outside of the grand narratives and add them to what we consider knowledge and challenge constructions of history. She points to the quest for decolonisation - acknowledging and creating new configurations of knowledge and power.

Thinking that we are all postcolonial feels a little turbulent to me because it ames our position today as not just a product of the passage of time. Rather, it scatters us across the globe. It points to the way space has changed and people have moved as the order of the world has changed. By deeming ourselves as postcolonial, our bodies become a site of this turbulence. Maybe then the work of self preservation, by way of rethinking systems of knowledge and power, becomes key to our postcolonial form.

Like Sitting on a Man’s Head, it is stretching so to not forget how our bodies can move. A safe space for a silent revolution. This Biennale calls on the creative manifestations that come of this revolution. WE DON’T NEED ANOTHER HERO is artists speaking to, and complicating our collective identities. What are your identities? Where are they?

When we sat down with Thiago de Paula Souza, a member of the Curatorial Team, he said that part of curating the Biennale was “taking an interest in how people are thinking about art, but also how they are not thinking about it” And that they aimed to open up the discussion to people outside of this artworld.

It had always been most interesting to me to visit and observe the nature of the cultural institutions that are available to the public in different parts of the world. I have been able to realize how art education and appreciation can be starkly different globally. In seeking to ponder the greater ways in which art can intersect with politics, economics, globalization, and identity, the Biennale prioritizes voices om artists that are more remote - not om the Western world.

I find that it spoke to the nature of the contemporary art shows I’ve experienced in Lagos and Dubai. Where art o en isn’t thought of, artists are collecting themselves in urban spaces and reflecting on how they have been shaped by history and dominant historical narratives. The result of this is what we see in Berlin. A new system of knowledge and a fabulous shi in power! It demands that art made outside of the Western world be looked at in terms of the individual, societal responsiveness, and aesthetic value, rather than as ethnographic objects.

Still, I am skeptical about how the Biennale will find success in its aims. Because these conversations that could only be happening in Berlin, would still largely be happening in Berlin. I do wonder what this Biennale could be if it happened in an urban center outside of the Western world. I appreciate the curatorial efforts that focus on artists om parts of the world that are not o en represented. But I don’t know that its sentiment will go the full length that it needs to go.

The record of it will surely mark it as part of the revolution that it serves. However, it speaks to me, to Berlin, and to the people who visit the exhibition in Berlin. Not to the people where we come om. Having been able to experience it, I wish that it could extend itself to more. It highlights that there is still much that is unsaid, and more stories to be told. There is a need for self preservation. As a young person, a hopeful artist, and literal byproduct of colonialism, the notion resonates with me.

We certainly are postcolonial. Where do we go om here?