Love, Desire, and Sorrow

Artworks from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation

Love, Desire, and Sorrow

Artworks from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation

Artists

vanessa german

Louise Bourgeois

Wangechi Mutu

Rufino Tamayo

Sanford Biggers

Enrique Chagoya

Tracey Emin

Kiki Smith

Alison Saar

Wendy Red Star

Malia Jensen

Edward Kienholz

Nancy Reddin Kienholz

Silvia Levenson

James Luna

Love, Desire, and Sorrow

Artworks from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation

Love, Desire, and Sorrow: Artworks from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation examines notions of house, home, and the body to explore the personal conditions and social entities that define them. As Gaston Bachelard observes in The Poetics of Space, an ideal house is a site of intimacy and solitude, a space for creativity. Bachelard writes, “If I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” As he envisions, a house can provide shelter and protection for our bodies, as well as inspiration, thereby becoming a home.

Love, Desire, and Sorrow foregrounds the notion of home, broadly defined, to ponder the economic, social, and political structures and policies that shape our current existence. Artists in the exhibition investigate colonialism, slavery, and the diaspora, evoking or representing subjects under duress in situations where the home and body exist in a state of threat. Other artists comment on family relationships and their complex nature, such as Louise Bourgeois’s spider, a visual metaphor for her mother, or by reclaiming old linens to safeguard memories. As artists explore the nation, or the environment, as a home, some portray bodies as hybrid creatures or stylized motifs. Others, such as Tracey Emin and Silvia Levenson, focus on seduction and intimacy. In sculptures, prints and textiles, artworks in the exhibition contest normative representations of home and body as the artists consider notions of belonging, justice, and healing.

Love, Desire, and Sorrow is presented in partnership with the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation. Funding for education and outreach programs has been provided by the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation. The exhibition is curated by Dr. Adriana Miramontes Olivas, Curator of Academic Programs and Latin American and Caribbean Art.

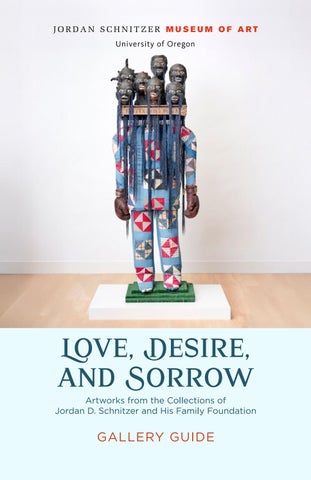

vanessa german (b. 1976 Milwaukee, WI). 7 Beautiful Ni$$As Awe-Struck in the Glory of An Appalachian Sunset, 2022. vintage quilt top, Astro turf, old farm picking fruit basket, getting caught up in the moment, foam tar, black pigment, cowrie shells, seeing your own self reflected in the open evening sky and wondering how anything could be so consistently beautiful and amazing as a sunset, love, gold thread, beaded rhinestone cloth, epoxy, boxing gloves, being speechless in wonder and delight and not having the police f*ck with you at all because they are too busy weeping by your side and clutching their own breast bones to wonder at how the rhythm of their own pattering hearts could match so perfectly the sound of light falling golden out of the sky and into their own open, stupefied maws, rhinestones, yes, yes, yes, 7 muscular wonders, 88 x 30 1/2 x 20 inches. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

Amor, deseo y pena

Obras de arte de las colecciones de Jordan D. Schnitzer y su fundación familiar

Amor, deseo y pena: Obras de arte de las colecciones de Jordan D. Schnitzer y su fundación familiar examina las nociones de casa, hogar y cuerpo para explorar las condiciones personales y las entidades sociales que definen estos conceptos. Como observa Gaston Bachelard en La poética del espacio, una casa ideal es un sitio de intimidad y solitud, un espacio para la creatividad. Bachelard escribe: “Si me pidieran que nombrara el beneficio principal de la casa, yo diría que la casa refugia el soñar despierto, la casa protege al soñador, la casa permite que podamos soñar en paz.” Como él visualiza esto, una casa puede proveer un refugio y protección para nuestros cuerpos y una inspiración, convirtiéndose así en un hogar.

Amor, deseo y pena destaca la noción de hogar definida ampliamente para reflexionar sobre las políticas y estructuras económicas y sociales que conforman nuestra existencia actual. Los artistas de la exposición investigan el colonialismo, la esclavitud y la diáspora representando a los sujetos bajo coacción en situaciones donde el hogar y el cuerpo existen en un estado de amenaza. Otros artistas comentan sobre las relaciones familiares y su naturaleza compleja, tales como la comparación que Louise Bourgeois hace de su madre con una araña o reclamando sábanas viejas para salvaguardar los recuerdos. Cuando los artistas consideran la nación o el medio ambiente como un hogar, ellos representan los cuerpos como criaturas híbridas o motivos estilizados. Sin embargo, otros artistas como Tracey Emin y Silvia Levenson se enfocan en la seducción y la intimidad. En esculturas, grabados y textiles, las obras de arte de la exposición cuestionan las representaciones normativas del hogar y el cuerpo mientras los artistas consideran las nociones de pertenencia, justicia y sanación.

Amor, deseo y pena es presentada en colaboración con Jordan Schnitzer y su fundación familiar. Los programas educativos y académicos cuentan con una subvención de la fundación de la familia Jordan Schnitzer. La exposición está curada por la Dra. Adriana Miramontes Olivas, curadora de Programas Académicos y Arte Latinoamericano y Caribeño.

Wangechi Mutu (nacida en 1972 en Nairobi, Kenia). De regreso a casa, 2010. Impresión en pigmento de archivo con serigrafía en colores sobre papel de archivo, edición 10/45, 25 x 19 3/8 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

Love, Desire, and Sorrow

Collector’s Statement

Love, Desire, and Sorrow: Artworks from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation invites us to reflect on the profound connections between house, home, and body. As a collector, I am drawn to works that illuminate the spaces where intimacy, solitude, and creativity converge. This exhibition reminds us that the house is not merely a structure, but a vessel for memory, imagination, and protection.

The French writer and philosopher, Gaston Bachelard’s words ring true in my own life: “the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” I have found that art does the same. Each piece in this exhibition invites us to dream, to confront desire and sorrow, and to discover how the body and the home are intertwined in shaping our humanity.

I am reminded that collecting art has always been, for me, about more than objects; it is about the spaces they create within us. A house may shelter the body, but art shelters the spirit. The eighteen works in this show, from established artists like Louise Bourgeois and Kiki Smith, to emerging talent like vanessa german and Wangechi Mutu, affirm my belief that art is itself a kind of dwelling: a place where we find shelter, where we confront longing, and where we are free to imagine new worlds. In these works, I see reflections of intimacy, solitude, and longing, the very emotions that make a house into a home.

As a collector, I feel a responsibility to share these works so that others may find their own shelter in them. My hope is that this exhibition offers not only protection for the dreamer, but also inspiration for the dream itself.

Jordan D. Schnitzer President

Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

Amor, deseo y pena

Declaración del coleccionista

Amor, deseo y pena: Obras de arte de las colecciones de Jordan D. Schnitzer y su fundación familiar nos invita a reflexionar sobre las conexiones profundas entre la casa, el hogar y el cuerpo. Como coleccionista, me siento atraído por las obras que iluminan los espacios donde convergen la intimidad, la soledad y la creatividad. Esta exposición nos recuerda que la casa no es simplemente una estructura, sino un vehículo para la memoria, la imaginación y la protección.

Las palabras del escritor y filósofo francés Gaston Bachelard resuenan en mi propia vida: “la casa alberga el soñar despierto, la casa protege al soñador, la casa permite soñar en paz.” He encontrado que el arte hace lo mismo. Cada pieza de esta exposición nos invita a soñar, a confrontar el deseo y el dolor, y a descubrir cómo el cuerpo y el hogar se entrelazan para dar forma a nuestra humanidad.

Me recuerda que coleccionar arte siempre ha sido para mí algo más que objetos; es sobre los espacios que estos crean dentro de nosotros. Una casa puede albergar el cuerpo, pero el arte alberga el espíritu. Las dieciocho obras de esta exposición, desde artistas establecidas como Louise Bourgeois y Kiki Smith, hasta el talento emergente como vanessa german y Wangechi Mutu, afirman mi creencia de que el arte es en sí mismo una especie de morada: un lugar donde encontramos refugio, donde confrontamos la añoranza y donde somos libres para imaginar mundos nuevos. En estas obras, veo reflexiones de la intimidad, la soledad y la añoranza, las mismas emociones que hacen de una casa un hogar.

Como coleccionista, siento la responsabilidad de compartir estas obras para que otros puedan encontrar en estas su propio refugio. Mi esperanza es que esta exposición ofrezca no solamente una protección para el soñador, sino también una inspiración para el propio sueño.

Jordan D. Schnitzer Presidente

Fundación Familiar Jordan Schnitzer

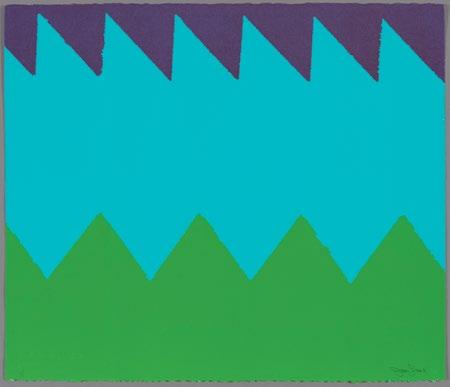

Sanford Biggers

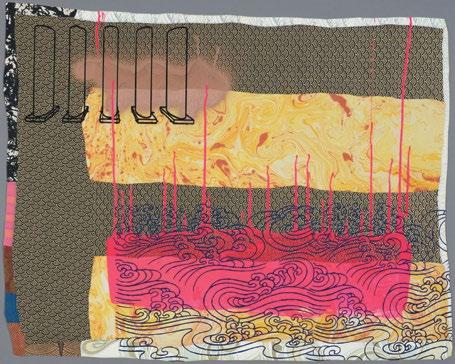

Sanford Biggers (b. 1970 Los Angeles, CA). Seven Heavens, 2013. Paper collage and silkscreen with hand-coloring, edition of 30 plus 10 AP, 21 3/4 x 27 3/8 inches. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation ©Sanford Biggers

Sanford Biggers’s prints evoke a tradition of quilting that extends across cultures. Quilts are commonly seen in homes as bed coverings and have also been used to share stories, preserve knowledge, and build community. In the U.S. the Black story quilt tradition foregrounds visual imagery for social activism and the representation and visibility of Black history and culture. Highly ornamental and textured, intricate motifs at the bottom of Seven Heavens suggest whirlpools and sea waves conveying a sense of movement and freedom.

Biggers’s artwork also references spirituality from Buddhism and Islam, as in Muhammad’s ascent to the “Seven Heavens” on his miraculous Night Journey. As such, Seven Heavens features Biggers’s characteristic “code-switching” that assembles, as curator Antonio Sergio Bessa explains, “a stock of cultural-historical references not as linear narratives but rather as dynamic combinations of clashing signs.”

Sanford Biggers (nacido en 1970 en Los Ángeles, CA). Siete cielos, 2013. Collage en papel y serigrafía con coloreado a mano, edición de 30 más 10 AP, 21 3/4 x 27 3/8 pulgadas. Colección de la Fundación Familiar Jordan Schnitzer ©Sanford Biggers

Los grabados de Sanford Biggers evocan una tradición de acolchado que se extiende a través de las culturas. Las colchas comúnmente se ven en los hogares como cubrecamas y también se han usado para compartir historias, preservar el conocimiento y crear comunidad. En los Estados Unidos, destaca la tradición de las colchas para el activismo social y la representación y visibilidad de la historia y la cultura negras. Muy ornamentales y texturizados, los intrincados motivos en la parte inferior de Siete cielos sugieren remolinos y olas marinas que transmiten una sensación de movimiento y libertad.

La obra de Biggers también hace referencia a la espiritualidad del budismo y el islam, como en el ascenso de Mahoma a los “Siete Cielos” en su milagroso Viaje Nocturno. Como tal, Siete cielos presenta el característico “cambio de códigos” de Biggers que ensambla, como lo explica el curador Antonio Sergio Bessa, “un acervo de referencias culturales-históricas no como narrativas lineales, sino más bien como combinaciones dinámicas de señales chocando”.

Louise Bourgeois

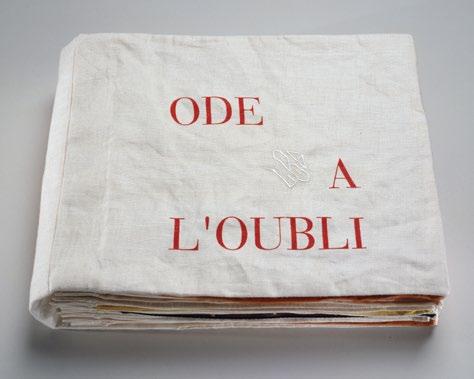

Louise Bourgeois (b. 1911 Paris, France - 2010). Ode à l’Oubli, 2004. Fabric and color lithograph book, with detachable cover with snap and buttonhole binding, edition BAT, 10 5/8 x 13 1/4 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

In 1951 Louise Bourgeois wrote in her diary, “To really work and produce, there must be integration of your work in your life, or the integration of your life in your work.” Ode à l’Oubli, or ode to forgetfulness, represents these beliefs. Bourgeois compiled and manipulated linens and clothes from her wardrobe to create works of art.

In Ode à l’Oubli her bridal clothes serve both as surfaces for artistic representation and as memory aides. Her trousseau and other garments embody her experiences in the domestic sphere, thus blurring the line between private and public affairs. This bon á tirer (BAT) edition, the first perfect impression of the work authorized by the artist, allows a unique and intimate encounter between viewer and artist. It is a window into her past and an entryway into her home, as well as her personal and artistic persona.

Louise Bourgeois (nacida en 1911 en París, Francia - 2010). Ode à l’Oubli, 2004. Libro de tela y litografía en color, con cubierta separable con encuadernación a presión y de ojal, edición BAT, 10 5/8 x 13 1/4 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

En 1951, Louise Bourgeois escribió en su diario: “Para realmente trabajar y producir, debe haber una integración de tu trabajo en tu vida o la integración de tu vida en tu trabajo.” Ode à l’Oubli (Oda al olvido) representa estas creencias. Bourgeois recopiló y manipuló las sábanas y ropa de su armario para crear obras de arte.

En Ode à l’Oubli, su ropa de novia sirve como superficie de representación artística y también como ayuda para la memoria. Su ajuar y otras prendas representan sus experiencias en la esfera doméstica, difuminando así la línea entre los asuntos privados y públicos. Esta edición bon á tirer (BAT), la primera impresión perfecta de la obra autorizada por la artista, permite un encuentro único e íntimo entre el espectador y la artista. Es una ventana a su pasado y una entrada a su hogar, así como también a su identidad personal y artística.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois (b. 1911 Paris, France - 2010). Ode à Ma Mère: Untitled, plate 1 - 9, 1995. Drypoint, monotype, and embossing; also drypoint with selective wiping, edition 17/45, 12 x 12 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Louise Bourgeois’s family ran a tapestry restoration shop, and this has been commonly associated with the artist’s interest in the arachnids and their weaving-centered practice. As predators, spiders are often portrayed as aggressive and feared, and these themes, along with entrapment and trauma, captivated the artist’s attention.

In Ode à Ma Mère, Untitled spiders are a dominant motif revealing the artist’s deep admiration. As Bourgeois explains, “…my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider…. The spider is a very lonely creature. They hang by thread, meaning that her position is very fragile. Of course, she is very strong, and she can invade. She has an invading power. She has taken hold of the whole house. So, there is a similarity between the spider and my mother.”

Louise Bourgeois (nacida en 1911 en París, Francia - 2010). Ode à Ma Mère: Sin título, placa 1-9, 1995. Punta seca, monotipo y gofrado también punta seca con frotado selectivo, edición 17/45, 12 x 12 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

La familia de Louise Bourgeois tenía un taller de restauración de tapices, y esto comúnmente se ha asociado con el interés de la artista por los arácnidos y su práctica centrada en el tejido. Como depredadores, las arañas con frecuencia se representan como agresivas y temidas, y estos temas, junto con el atrapamiento y el trauma, cautivaron la atención de la artista.

En Ode à Ma Mère (oda a mi madre): Sin título, las arañas son un motivo omnipresente que revela la gran admiración de la artista. Como explica Bourgeois: “...mi mejor amiga era mi madre y ella era deliberada, inteligente, paciente, calmante, razonable, delicada, sutil, indispensable, pulcra y tan útil como una araña... La araña es una criatura muy solitaria. Ella se cuelga de un hilo, lo cual significa que su posición es muy frágil. Por supuesto, ella es muy fuerte y puede invadir. Tiene un poder invasor. Ella se ha apoderado de toda la casa. Entonces, hay una similitud entre la araña y mi madre.”

Enrique Chagoya

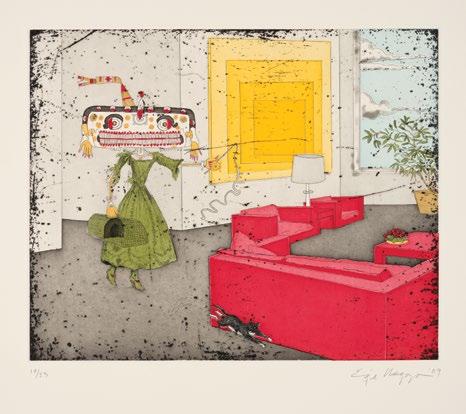

Enrique Chagoya (b. 1953 Mexico City, México). Homage to the Un-Square and My Cat Frida, 2009. Etching with aquatint and drypoint with hand-coloring, edition 17/23, 20 x 22 inches. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

Enrique Chagoya appropriates modernist and Mesoamerican iconography to engage with decolonial epistemologies and question the ways art, language, and knowledge are produced and circulated. In Homage to the Un-Square and My Cat Frida, Chagoya incorporates Josef Albers’s Homage to the Square IV (1967). The predominantly yellow composition, a formal study on color and shape, is juxtaposed with a woman whose face and headdress incorporate circular stylized motifs and feathers that echo Aztec and Maya imagery similar to the goddess Coatlicue, whose necklace is made of severed hands.

In Homage to the Un-Square and My Cat Frida, the figure’s unsettling expression, and the cat’s escape, signal a disturbing atmosphere within this domestic setting. Chagoya mentions, “I don’t want to be didactic with my imagery at all. My art just helps me to exorcise my anxieties in my best possible creative mood.”

Enrique Chagoya (nacido en 1953 en la Ciudad de México, México). Homenaje al no cuadrado y a mi gata Frida, 2009. Aguafuerte con aguatinta y punta seca con coloreado a mano, edición 17/23, 20 x 22 pulgadas. Colección de la Fundación Familiar Jordan Schnitzer

Enrique Chagoya se apropia de la iconografía modernista y mesoamericana para involucrarse en epistemologías decoloniales y cuestionar las maneras en que el arte, el lenguaje y el conocimiento se producen y circulan. En Homenaje al no cuadrado y a mi gata Frida, Chagoya incorpora Homenaje al cuadrado IV (1967) de Josef Albers. La composición predominantemente amarilla, un estudio formal sobre el color y la figura, se yuxtapone a una mujer cuyo rostro y tocado incorporan motivos circulares estilizados y plumas que evocan los diseños aztecas y mayas similares a los de la diosa Coatlicue, cuyo collar está hecho de manos amputadas.

En Homenaje al no cuadrado y a mi gata Frida la expresión inquietante de la figura y la señal de escape del gato crean una atmósfera perturbadora en este entorno doméstico. Chagoya menciona: “No quiero ser didáctico con mis imágenes en absoluto. Mi arte simplemente me ayuda a exorcizar mis ansiedades en mi mejor estado de ánimo creativo posible.”

Tracey Emin

Tracey Emin (b. 1963 Croydon, UK). Wanting You, 2015. Embroidered linen handkerchief, Edition of 50, 15 31/4 x 16 1/4 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

This intimate and embroidered linen handkerchief embodies Tracey Emin’s body of work, which often focuses on love and sex. Personal relationships are central to her artistic practice—creating installations with beds, condoms, and pregnancy tests. While not confined to the home, Emin’s imagery and subjects reveal a commitment to what many relegate to the private sphere. Her artworks become like diary entries in which the artist announces her adventures and misfortunes, and through this act of vulnerability, she connects with the viewer. As Emin explains, “There’s nothing cynical about my paintings. All the things that we live through life, all the things that we go through and experience, I put into my painting.”

Tracey Emin (nacida en 1963 en Croydon, Reino Unido). Queriéndote, 2015. Pañuelo de lino bordado, edición de 50, 15 31/4 x 16 1/4 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

Este pañuelo de lino íntimo y bordado representa los intereses de investigación de Tracey Emin, cuyo cuerpo de trabajo con frecuencia se enfoca en el amor y el sexo. Las relaciones personales son centrales en su práctica artística que incluye instalaciones con camas, condones y pruebas de embarazo. Aunque no están relegadas al hogar, sus imágenes y sujetos revelan un compromiso con lo que muchos asocian con la esfera privada. Sus obras de arte se convierten en entradas de diario en las cuales la artista anuncia sus aventuras y desgracias y, a través de este acto de vulnerabilidad, ella se conecta con el espectador. Como explica Emin: “No hay nada cínico sobre mis pinturas. Todas las cosas que vivimos en la vida, todas las cosas por las que pasamos y experimentamos, yo las pongo en mi pintura.”

vanessa german

vanessa german (b. 1976 Milwaukee, WI). 7 Beautiful Ni$$As Awe-Struck in the Glory of An Appalachian Sunset, 2022. vintage quilt top, Astro turf, old farm picking fruit basket, getting caught up in the moment, foam tar, black pigment, cowrie shells, seeing your own self reflected in the open evening sky and wondering how anything could be so consistently beautiful and amazing as a sunset, love, gold thread, beaded rhinestone cloth, epoxy, boxing gloves, being speechless in wonder and delight and not having the police f*ck with you at all because they are too busy weeping by your side and clutching their own breast bones to wonder at how the rhythm of their own pattering hearts could match so perfectly the sound of light falling golden out of the sky and into their own open, stupefied maws, rhinestones, yes, yes, yes, 7 muscular wonders, 88 x 30 1/2 x 20 inches. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

vanessa german’s sculpture features a seven-headed individual decapitated by an old farm fruit basket. Each head has a distinct hair style, but the figures are united by a single body and a collective cry of shared pain. Yet despite their suffering, the heads and their detached body remain standing and ready to fight. Together they offer a poignant reminder of an ongoing struggle, and a tragic history lived and witnessed in this country as well as throughout colonies across the Americas, where slavery was institutionalized, and freedom was (and is) a hard-won battle. As german explains, “the past is not dead, it is not even past. It exerts constant pressure on the present & can be mined for strategic ingredients to be used for intentional & creative future making. All of this is Love.”

vanessa german (nacida en 1976 en Milwaukee, WI). 7 hermosas Ni$$As deslumbradas por la gloria de un atardecer en los Apalaches, 2022. colcha vintage, AstroTurf, vieja canasta para recoger fruta en las granjas, dejándose llevar por el momento, alquitrán de espuma, pigmento negro, conchas de cauri, viendo tu propio yo reflejado en el cielo abierto del atardecer y preguntándose cómo algo puede ser tan consistentemente bello y asombroso como una puesta de sol, amor, hilo de oro, tela de pedrería, epoxi, guantes de boxeo, quedarse mudo de asombro y deleite y que la policía no se meta contigo porque están demasiado ocupados llorando a tu lado y agarrándose sus propios esternones para preguntarse cómo los latidos de sus propios corazones pueden coincidir tan perfectamente con el sonido de la luz cayendo dorada del cielo y en sus propias fauces abiertas y estupefactas, pedrería, sí, sí, sí, 7 maravillas musculares, 88 x 30 1/2 x 20 pulgadas. Colección de la Fundación Familiar Jordan Schnitzer

La escultura de vanessa german presenta un individuo de siete cabezas decapitado por una vieja canasta de frutas para granjas. Cada cabeza tiene un estilo de pelo distinto, pero las figuras están unidas por un cuerpo compartido y un grito colectivo de dolor. Sin embargo, a pesar de su sufrimiento, el cuerpo permanece de pie y dispuesto a pelear, ofreciendo un recordatorio conmovedor de una lucha continua y de una historia trágica vivida y presenciada en este país, así como también en todas las colonias de las Américas, donde la esclavitud estaba institucionalizada y la libertad era (y es) una batalla ganada con esfuerzo. Como explica german: “el pasado no está muerto, ni siquiera es pasado, sino que ejerce una presión constante sobre el presente y puede extraerse de ingredientes estratégicos que se usen en la creación intencional y creativa del futuro. Todo esto es Amor.”

Malia Jensen

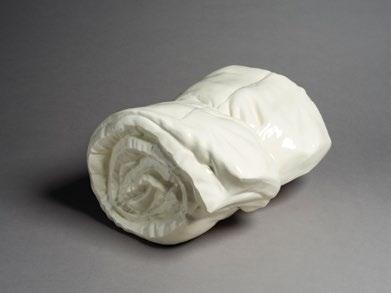

Malia Jensen (b. 1966 Honolulu, HI). Bedroll, 2005. Slip-cast ceramic, edition 2/2, 10 x 16 x 14 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Malia Jensen’s artworks question our relationship to nature and notions of belonging. While the natural world remains a dominant theme in her artistic practice, the artist also examines sexuality, desire, and vulnerability through her animal repertoire or ordinary everyday objects as seen here. Blankets provide protection and warmth. Their portability promises rest wherever one might go. Yet, the word “bedroll” also defines a list of deeds or even a list of one’s sexual partners. As such, Jensen’s Bedroll connotes not only sleep but an active sexual life. As the artist explains, “I like to simplify and complicate the work in ways that allow it to contain multiple meanings but also assert itself as conceptually intentional.”

Malia Jensen (nacida en 1966 en Honolulu, HI). Bedroll (Colchoneta), 2005. Cerámica moldeada con barbotina, edición 2/2, 10 x 16 x 14 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

Las obras de arte de Malia Jensen cuestionan nuestra relación con la naturaleza y las nociones de pertenencia. Aunque el mundo natural sigue siendo un tema dominante en su práctica artística, la artista también examina la sexualidad, el deseo y la vulnerabilidad a través de su repertorio de animales o de objetos cotidianos, como puede verse aquí. Las mantas proveen protección y calor. Su portabilidad promete un descanso dondequiera que vayamos. Sin embargo, la palabra “bedroll” en inglés también define una lista de actos o incluso una lista de las parejas sexuales de una persona. Como tal, la obra Bedroll de Jensen connota no solamente dormir, sino también una vida sexual activa. Como explica la artista: “Me gusta simplificar y complicar la obra de maneras que le permitan contener múltiples significados, pero también afirmarse como conceptualmente intencional.”

Edward Kienholz

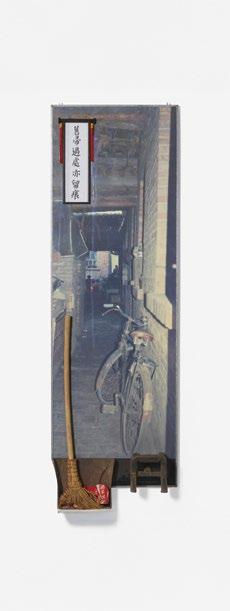

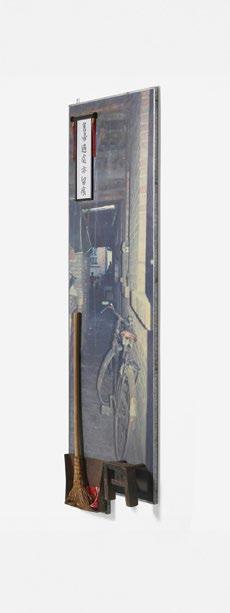

Edward Kienholz (b. 1927 Fairfield, WA - 1994) and Nancy Reddin Kienholz (b. 1943 Los Angeles, CA - 2019). Yip Monoseries #14, 1991. Mixed media assemblage, 81 1/2 x 25 1/2 x 6 1/2 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

The artistic duo, Edward Kienholz and Nancy Redding Kienholz, created largescale installations and sculptures that focused on industry, the urban landscape, and technology. They were also motivated to examine questions about aging and prostitution. In Yip Monoseries #14, their signature style is evident in the inclusion of a mélange of found objects, such as a Coca Cola can or an old broom. Through their artistic lens, and aesthetic strategies, the duo places the viewer within a small corridor, raising questions about our whereabouts and destination. The scene becomes more intimate through the bicycle nearby that invites viewers on a journey or perhaps suggests we have arrived at our journey’s end. Through precarious objects and everyday items, their artwork embodies mobility and consumption, as well as an interest in time and the housekeeping of the spaces we occupy.

Edward Kienholz (nacido en 1927 en Fairfield, WA - 1994) y Nancy Reddin Kienholz (nacida en 1943 en Los Ángeles, CA - 2019). Monoseries Yip #14, 1991 Ensamblaje en técnica mixta, 81 1/2 x 25 1/2 x 6 1/2 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

El dúo artístico de Edward Kienholz y Nancy Redding Kienholz creó instalaciones y esculturas de gran escala que se enfocaban en la industria, el paisaje urbano y la tecnología. Ellos también estaban motivados para examinar cuestiones sobre el envejecimiento o la prostitución. En Monoseries Yip #14, su estilo característico es evidente en la inclusión de una mezcla de objetos encontrados como una lata de Coca Cola o una escoba vieja. A través de su lente artístico y sus estrategias estéticas, el dúo coloca al espectador dentro de un pequeño corredor que plantea preguntas sobre nuestro paradero y destino. La escena se vuelve más íntima a través de la bicicleta cercana que invita a los espectadores a una travesía o quizás sugiere que hemos llegado al final de un paseo. Por medio de objetos precarios y motivos cotidianos, sus obras representan la movilidad y el consumo, así como también el interés por el tiempo y el mantenimiento de los espacios que ocupamos.

Silvia Levenson

Silvia Levenson (b. 1957 Buenos Aires, Argentina). I Want to be Happy and Gorgeous, 2009. Kiln cast glass, 8 1/8 x 14 x 3 5/8 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Silvia Levenson migrated to Italy during Argentina’s Dirty War (1976-1983) when dictator Jorge Rafael Videla embraced a politics of state terror in the country. Migration and the “disappeared” play a dominant role in Levenson’s artistic practice. Here, however, the artist turns her attention to other ways in which bodies remain the focal point.

In I Want to be Happy and Gorgeous, a series of glass bottles alludes to the kind of self-care that can take place at home, as well as to the excessive use of commercial products. Levenson’s feminist agenda references the beauty industry and consumer society. Yet, all the glass containers remain seemingly empty (and fragile), thus speaking of the impossibility of fulfilling the dream “to be happy and gorgeous” as a critique of commodity culture and the beauty standards imposed upon bodies.

Silvia Levenson (nacida en 1957 en Buenos Aires, Argentina). Quiero ser feliz y hermosa, 2009. Vidrio fundido en horno, 8 1/8 x 14 x 3 5/8 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

Silvia Levenson emigró a Italia durante la Guerra Sucia de Argentina (1976-1983), cuando el dictador Jorge Rafael Videla adoptó una política de terror del estado en el país. La migración y los “desaparecidos” desempeñan un papel dominante en la práctica artística de Levenson. Aquí, sin embargo, la artista dirige su atención hacia otras maneras en las cuales los cuerpos siguen siendo el punto focal.

En Quiero ser feliz y hermosa, una serie de botellas de vidrio aluden al tipo de cuidado personal que puede realizarse en casa, así como también al uso excesivo de los productos comerciales. La agenda feminista de Levenson hace referencia a la industria de la belleza y la sociedad de consumo. Sin embargo, todos los envases de vidrio aparentemente se mantienen vacíos (y frágiles), hablando así de la imposibilidad de cumplir el sueño de “ser feliz y hermosa” como una crítica a la cultura de las mercancías y los cánones de belleza impuestos a los cuerpos.

Silvia Levenson (b. 1957 Buenos Aires, Argentina). Still Life, 2011. Kiln cast glass, 6 3/4 x 14 1/2 x 8 3/4 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Silvia Levenson (nacida en 1957 en Buenos Aires, Argentina). Naturaleza muerta, 2011. Vidrio fundido en horno, 6 3/4 x 14 1/2 x 8 3/4 . Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

James Luna

James Luna (b. 1950 Orange, CA; Payómkawichum, Luiseño, Ipi, and Mexican-American - 2018). Indian Edge, 2011. Monotype, edition 1/1, 22 1/4 x 26 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

James Luna (Payómkawichum) used his body as an artistic medium to address colonialism and objectification of people in science and art. In Indian Edge, Luna disrupts the history of landscape painting to reclaim and reinvent it. The artwork suggests mountains and rivers as well as a sense of movement and rhythm. Yet, Luna does not depict a specific location or place. As art historian and UO Associate Vice Provost Kate Morris explains, many Indigenous artists have adopted denying as a way to critique colonial practices that have led to the destruction of the environment. In its abstraction, Indian Edge invites viewers to consider landscape more broadly and to reflect on the spaces we inhabit, the land and sites we call “home,” and our relationships to nature and our non-human companions.

James Luna (nacido en 1950 en Orange, CA; Payómkawichum, ipi, luiseño y mexicano americano - 2018). Borde indio, 2011. Monotipo, edición 1/1, 22 1/4 x 26 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

James Luna (Payómkawichum) usa su cuerpo como medio artístico para abordar el colonialismo y la objetivación de los cuerpos en la ciencia y el arte. En Borde indio, Luna trastorna la historia de la pintura de paisaje para reclamarla y reinventarla. La obra evoca montañas y ríos, así como también el sentido de movimiento y ritmo. Sin embargo, Luna no representa un lugar específico. Como explica la historiadora de arte y vicerrectora de la UO, Kate Morris, los artistas indígenas adoptan la negación para criticar las prácticas colonialistas que condujeron a la destrucción del paisaje. En Borde indio, Luna invita a los espectadores a considerar el paisaje más ampliamente y reflexionar sobre los espacios que habitamos, la tierra y los lugares que llamamos “hogar”, así como también sobre nuestra relación con la naturaleza y nuestros acompañantes no humanos.

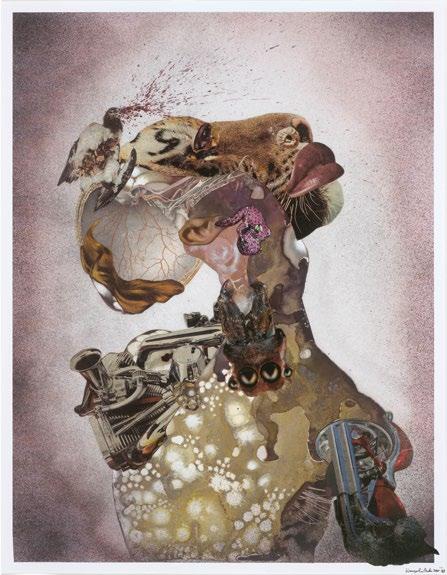

Wangechi Mutu

Wangechi Mutu (b. 1972 Nairobi, Kenya). Fish Mother, 2014. Lithograph, edition 16/60, 27 1/2 x 39 1/4 inches. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

Wangechi Mutu’s iconography relates to womanhood, Black femininity, and Kenyan mythology to challenge colonial discourses. She deconstructs images through montage, collage, and bricolage, reimagining the body and where we come from. As Mutu explains, “I create as a way of reinvigorating myself by replacing and reworking images and ideas that never fully represented me and the women and the people I was born from and who made me—the women who worked so hard to feed me and guide me and to give me space to exist…. How significant it is that we are all from the same family in Africa.”

Diaspora and spirituality as well as lineage remain dominant themes in Mutu’s artistic practice. In Fish Mother Mutu portrays a hybrid body—humanoid, mechanical, and animal, in coexistence, nurtured by each other, as they inhabit this white abyss.

Wangechi Mutu (nacida en 1972 en Nairobi, Kenia). Madre pez, 2014. Litografía, edición 16/60, 27 1/2 x 39 1/4 pulgadas. Colección de la Fundación Familiar Jordan Schnitzer

La iconografía de Wangechi Mutu se relaciona con la femineidad, la feminidad negra y la mitología keniana para desafiar los discursos coloniales. Mutu deconstruye las imágenes a través del montaje, el collage y el bricolaje para reimaginar el cuerpo y de dónde provenimos. Como explica Mutu: “Yo creo mi trabajo como una manera de revigorizarme a mí misma, reemplazando y reelaborando las imágenes y las ideas que nunca me representaron plenamente a mí ni tampoco a las mujeres y las personas de las que nací y que me hicieron, las mujeres que trabajaron muy duro para alimentarme y guiarme y para darme un espacio para existir... Qué significativo es que todos procedemos de la misma familia de África.”

La diáspora y la espiritualidad, así como también el linaje, siguen siendo los temas dominantes en la práctica artística de Mutu. En Madre pez, Mutu representa un cuerpo híbrido (humanoide, mecánico y animal) en coexistencia, nutriéndose mutuamente mientras habitan este abismo blanco.

Wangechi Mutu

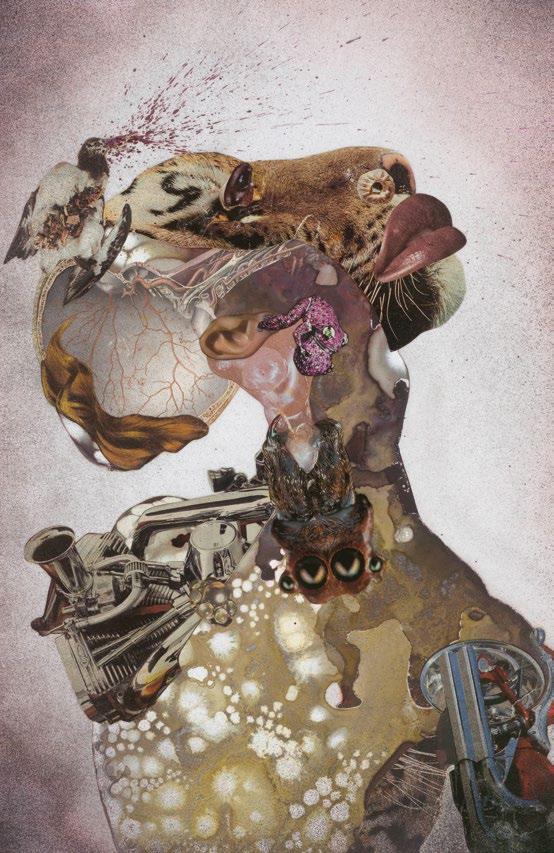

Wangechi Mutu (b. 1972 Nairobi, Kenya). Homeward Bound, 2010. Archival pigment print with screenprint in colors on archival paper, edition 10/45, 25 x 19 3/8 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Wangechi Mutu’s fantastical world consists of composite creatures extracted from fashion magazines, National Geographic, and everyday materials. In Homeward Bound, Mutu captures the stillness of a being whose traveling sack is made of motorcycle parts. Its head is made of a jeweled frog, a tiger’s fur, and human eyes and lips. Bloodlike spatters across the canvas, seemingly originating from the bird’s beak, suggest a tragic encounter. Yet the main subject’s eye, and overall expression, remains calm amidst the graphic details taking place in its head.

In her work, Mutu often addresses socio-political issues including overconsumption, war, and displacement. Homeward Bound raises questions about the subject’s whereabouts, their place of origin, and destination. By decontextualizing the figure, the artist grants her subject a universal character allowing those who are “homeward bound” to relate to it.

Wangechi Mutu (nacida en 1972 en Nairobi, Kenia). De regreso a casa, 2010. Impresión en pigmento de archivo con serigrafía en colores sobre papel de archivo, edición 10/45, 25 x 19 3/8 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

El mundo fantástico de Wangechi Mutu consiste en criaturas compuestas extraídas de las revistas de moda, National Geographic y materiales cotidianos. En De regreso a casa, Mutu captura la quietud de un ser cuyo saco de viaje está hecho de partes de motocicleta. Su cabeza está hecha de una rana enjoyada, piel de tigre y ojos y labios humanos. Las salpicaduras como de sangre del pico del pájaro a través del lienzo evocan un encuentro trágico. Sin embargo, la mirada y la expresión general del sujeto principal permanecen calmadas en medio de los detalles gráficos que tienen lugar en su cabeza.

En su obra, Mutu con frecuencia aborda cuestiones sociopolíticas, incluyendo el consumo excesivo, la guerra y el desplazamiento. De regreso a casa plantea preguntas sobre el paradero del sujeto, su lugar de origen y destino. Al descontextualizar la figura, la artista otorga a su sujeto un carácter universal, permitiendo que quienes están “de regreso a casa” puedan relacionarse con este.

Wangechi Mutu

Wangechi Mutu (b. 1972 Nairobi, Kenya). Mary & Magda, 2018. Variegated leather (pigskin), dyed and painted by hand, hand stitch–assembled with cotton thread, synthetic fiber fill and sand weights, in two parts; on welded steel bed with blackened wax finish, edition 1/4 unique variants, 18 x 60 1/8 x 38 inches (table), height varies with sculpture placement. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Wangechi Mutu’s artworks address decadence, disorientation, and hunger. Some of her works reflect on diseases, amputations, and war-related consequences. In Mary & Magda, a fragmented body is apparent. The touching limbs evoke intimacy and familiarity while the title, “Mary and Magda,” might reference a couple, friends, or family members.

According to artist Firelei Báez, Mutu creates “an illusion to sitting between another’s legs while her hair was getting done. They represent the comfort of the matriarch or feminine company, but they would always be severed limbs, so there’s a troubling aspect of this thing that brings comfort but has also been mechanized. Those thighs were something visceral.” Whether referencing the artist’s body or someone else’s, Mary & Magda provokes an uncanny effect that is simultaneously attractive and repulsive.

Wangechi Mutu (nacida en 1972 en Nairobi, Kenia). Mary y Magda, 2018. Cuero variegado (piel de cerdo), teñido y pintado a mano, cosido a mano, ensamblado con hilo de algodón, relleno de fibra sintética y pesos de arena, en dos partes; colocado sobre cama de acero soldado con acabado de cera ennegrecida, edición 1/4 variantes únicas, 18 x 60 1/8 x 38 pulgadas (mesa), la altura varia con la posición de la esculturas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

Las obras de arte de Wangechi Mutu abordan la decadencia, la desorientación y el hambre. Algunas de sus obras reflexionan sobre las enfermedades, las amputaciones y las consecuencias de la guerra. En Mary y Magda, un cuerpo fragmentado es aparente. Las extremidades tocándose evocan una intimidad y familiaridad, mientras que el título “Mary y Magda” podría referirse a una pareja, amigas o familiares.

Según la artista Firelei Báez, Mutu crea “una ilusión de estar sentada entre las piernas de otra persona mientras le peinan su cabello. Estas representan el confort de la matriarca o la compañía femenina, pero siempre serían extremidades amputadas, por lo que hay un aspecto inquietante de esta cosa que trae confort pero que también ha sido mecanizada. Esos muslos eran algo visceral.” Ya sea haciendo referencia al cuerpo de la artista o de alguien más, Mary y Magda provoca un efecto inquietante que es a la vez atractivo y repulsivo.

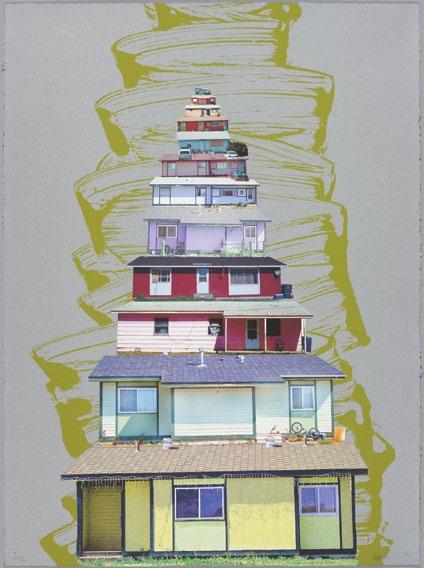

Wendy Red Star

Wendy Red Star (b. 1981 Billings, MT; Native American, Crow). The (HUD), 2010 Lithograph and archival pigment print, edition 12/12, 30 x 22 3/8 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Native Americans have been dispossessed from their lands and ancestral homes. They have endured substandard housing, poverty, and discrimination. From 2007-2008, Wendy Red Star photographed a series of houses and cars on the Crow reservation in Montana. As Red Star explains, “The series started with the simple questions ‘why are there so many broken down cars in front yards here?’ and ‘why are the HUD houses painted such bizarre colors?’” The brightly colored houses exemplify oppression and resilience as the U.S. government selected the colors, while inhabitants chose to keep them. The artwork alludes to agency while exposing government policies.

In The (HUD), Red Star stacks houses on top of each other, rendering them inaccessible. At the same time bicycles, trash cans, and automobiles remind viewers of the houses’ inhabitants. Red Star adds, “My work often looks at the normalcies of everyday Crow life. The mundane that connects Crow people to all people, and connects all people to a common humanity.”

Wendy Red Star (nacida en 1981 en Billings, MT; nativa americana, crow). El (HUD), 2010. Litografía e impresión con pigmento de archivo, edición 12/12, 30 x 22 3/8 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

Los nativos americanos han sido desposeídos de sus tierras y hogares ancestrales. Ellos han soportado viviendas precarias, pobreza y discriminación. Entre el 2007 y 2008, Wendy Red Star fotografió una serie de casas y coches en la reserva crow en Montana. Como explica Red Star: “La serie comenzó con las preguntas sencillas de ‘¿Por qué hay tantos coches descompuestos en los patios delanteros aquí?’ y ‘¿Por qué las casas del HUD están pintadas de colores tan extraños?’”. Las casas de colores brillantes ejemplifican la opresión y la resiliencia, ya que el gobierno estadounidense seleccionó los colores, pero los habitantes eligieron dejarlos así. La obra de arte alude a la agencia personal mientras expone las políticas gubernamentales.

En El (HUD), Red Star apila las casas una sobre otra para hacerlas inaccesibles, mientras las bicicletas, los botes de basura y los automóviles recuerdan a los espectadores sobre los habitantes de las casas. Red Star añade: “Mi trabajo con frecuencia observa las normalidades de la vida cotidiana de la gente crow. Lo mundano que conecta a la gente crow con toda la gente, y que conecta a toda la gente a una humanidad común.”

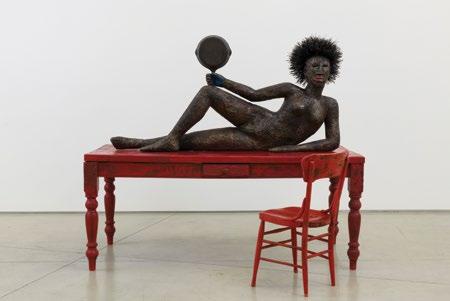

Alison Saar

Alison Saar (b. 1956 Los Angeles, CA). Set to Simmer, 2019. Wood, ceiling tin, enamel paint, wire, found table, chair, and skillet, 65 x 74 x 35 1/2 inches (table with figure), 34 1/8 x 16 3/4 x 17 1/2 inches (chair). Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Alison Saar’s oeuvre examines African diasporic identities and motherhood, often centering women and frying pans as a way to study gender and race. In the series, “Chaos in the Kitchen,” Set to Simmer features a body made of nails and metal. The body reveals flowers and other organic shapes that allude to tattoos or scars.

In Set to Simmer an intimate scene is apparent—a black woman lies naked on a kitchen table in a gesture that is both sensual and confrontational. She wears red lipstick while holding a skillet in her hand as a tool for self-defense. As Saar mentions, black women have been “revolting against our circumstances by using the only weapons we had, which were our tools… And this idea that you kind of turn scythes and sickles and hoes and machetes into weapons for freedom.”

Alison Saar (nacida en 1956 en Los Ángeles, CA). Poner a fuego lento, 2019. Madera, lámina de techo, pintura esmaltada, alambre, mesa encontrada, silla y sartén 65 x 74 x 35 1/2 pulgadas (mesa con figura), 34 1/8 x 16 3/4 x 17 1/2 pulgadas (silla). Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

La obra de Alison Saar examina las identidades de la diáspora africana y la maternidad. El conjunto de trabajos de Saar se centra en las mujeres y las sartenes para estudiar el género y la raza. En la serie “Caos en la cocina”, Poner a fuego lento presenta un cuerpo hecho de clavos y metal. El cuerpo revela flores y otras formas orgánicas que aluden a los tatuajes o las cicatrices.

En Poner a fuego lento, una escena íntima es aparente: Una mujer negra yace desnuda sobre una mesa de cocina con un gesto que es a la vez sensual y de confrontación. Ella usa un lápiz labial rojo mientras sostiene una sartén en su mano como una herramienta de autodefensa. Como menciona Saar, las mujeres negras han estado “rebelándose contra nuestras circunstancias usando las únicas armas que teníamos, las cuales eran nuestras herramientas... Y esta idea de que tú puedes convertir las guadañas y las hoces y las azadas y los machetes en armas para la libertad.”

Kiki Smith

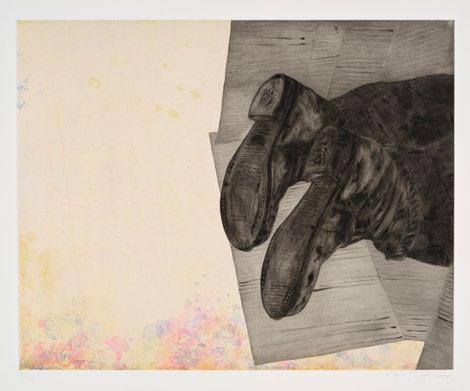

Kiki Smith (b. 1954 Nuremberg, Germany). Home, 2006. Color spitbite aquatint with flat bite, hardground and softground etching, and drypoint on gampi paper chine collé, edition 12/20, 26 1/2 x 31 inches. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer

Both unsettling and appealing, Kiki Smith’s artworks engage viewers with fictional scenes and characters in which humans and animals participate in sexual encounters or perform basic needs. Naked individuals lie helplessly on the floor or ask for redemption. Yet in other artworks by the artist, cartoon-like figures seemingly portray children’s narratives. In a series of prints such as Home and Still (2006), shoed and shoeless individuals have apparently fallen on the ground. Whether they rest there by accident or pleasure remains unknown, raising questions about their safety and wellbeing, as well as the artist’s intentions.

Kiki Smith (nacida en 1954 en Nuremberg, Alemania). Hogar, 2006. Aguatinta de spitbite en color con flat bite, aguafuerte con barniz duro y barniz blando, y punta seca sobre papel gampi chine collé, edición 12/20, 26 1/2 x 31 pulgadas. Colección de Jordan D. Schnitzer

A la vez inquietantes y atractivas, las obras de Kiki Smith involucran al espectador con escenas y personajes ficticios en los cuales los humanos y los animales participan en encuentros sexuales o desempeñan necesidades básicas. Individuos desnudos yacen indefensos en el suelo o piden redención. Sin embargo, en otras obras de la artista, las figuras como caricaturas parecen representar narrativas de niños. En una serie de grabados como Hogar y Quietud (2006), individuos calzados y descalzos aparentemente se han caído al suelo. Se desconoce si ellos descansan allí por accidente o por placer, planteando preguntas sobre su seguridad y bienestar y sobre las intenciones de la artista.

Rufino Tamayo

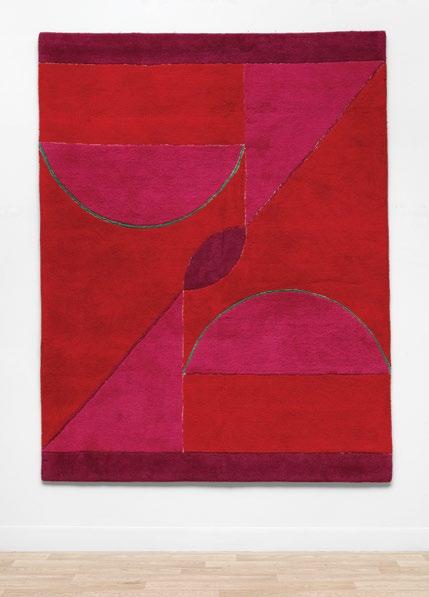

Rufino Tamayo (b. 1899 Oaxaca, México - 1991). Watermelon, c. 1970 . Wool tapestry, 97 1/2 x 75 3/4 x 1 1/2 inches. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

Rufino Tamayo’s Watermelon evokes a picnic blanket with fruit slices on their side in opposite directions. The compositional puzzle is geometrically rigid, highlighting Tamayo’s modernist aesthetic through a limited color palette, straight lines, and flatness. Tamayo’s modernist language further favors monumental figures and simplified forms.

Starting in the late 1920s, Tamayo increasingly turned his attention to watermelons, and their ubiquity within the artist’s oeuvre granted him the moniker Señor sandía (Mister Watermelon). The multivalent watermelon motif embodies notions of labor, globalization, and commerce.

Originally harvested in modern-day Sudan, and smuggled to the Americas by enslaved Africans, the fruit is symbolic of colonization and racism, but also of solidarity and freedom. In postrevolutionary Mexico, its hegemonic status in popular culture and visual arts made watermelon an icon of Mexican culture. As art historian Lesley A. Wolff comments, El fruto patrio (the national fruit) was integrated in paintings and depicted “…with other tropical fruits and popular motifs, like papel picado, which signified the domestic, vernacular, and visceral machinations of mexicanidad….”

Rufino Tamayo (nacido en 1899 en Oaxaca, México - 1991). Sandía, c. 1970 . Tapiz de lana, 97 1/2 x 75 3/4 x 1 1/2 pulgadas. Colección de la Fundación Familiar Jordan Schnitzer

Sandía de Rufino Tamayo evoca una manta de picnic con rodajas de fruta en su lado en direcciones opuestas. El rompecabezas compositivo es geométricamente rígido, destacando la estética modernista de Tamayo a través de una paleta de colores limitada, líneas rectas y planitud. El lenguaje modernista de Tamayo favorece además las figuras monumentales y formas simplificadas.

A partir de finales de la década de 1920, Tamayo dirigió cada vez más su atención hacia las sandías y su omnipresencia dentro de la obra del artista le valió el apodo de “Señor Sandía”. El motivo multivalente de la sandía representa las nociones de mano de obra, globalización y comercio.

Cosechada originalmente en lo que hoy es Sudán y traída de contrabando a América por los africanos esclavizados, esta fruta simboliza la colonización y el racismo, pero también la solidaridad y la libertad. En el México postrevolucionario, su estatus hegemónico en la cultura popular y las artes visuales, hizo de la sandía un icono de la cultura mexicana. Como explica la historiadora de arte Lesley A. Wolff, el fruto patrio (la fruta nacional) fue integrado a las pinturas y representado “...con otros frutos tropicales y motivos populares como el papel picado, los cuales significaban las maquinaciones domésticas, vernáculas y viscerales de la mexicanidad...”

Love, Desire, and Sorrow

Artworks from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation

Scan the QR code for a digital version of the Gallery Guide

Escanea el código QR para obtener copia digital de la guía de la galería

University of Oregon

The only academic art museum in Oregon accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) features engaging exhibitions, significant collections of historic and contemporary art, and exciting educational programs that support the university’s academic mission and the diverse interests of its off-campus communities. The JSMA’s collections galleries present selections from its extensive holdings of Chinese, Japanese, Korean and American art. Special exhibitions galleries display works from the collection and on loan, representing many cultures of the world, past and present. The JSMA continues a long tradition of bridging international cultures and offers a welcoming destination for discovery and education centered on artistic expression that deepens the appreciation and understanding of the human condition.

Translation to Spanish by Irene

El Museo de Arte Jordan Schnitzer (JSMA) de la Universidad de Oregón, único museo de arte académico de Oregón acreditado por la Alianza Estadounidense de Museos, presenta exhibiciones interesantes, colecciones significativas de arte histórico y contemporáneo y programas educativos interesantes que apoyan la misión académica de la universidad y los diversos intereses de sus comunidades fuera del campus. Las galerías de las colecciones del JSMA presentan selecciones de sus posesiones extensivas de arte chino, japonés, coreano y estadounidense. Las galerías de exhibiciones especiales muestran obras de la colección y en préstamo, que representan a muchas culturas del mundo pasadas y presentes. El JSMA continúa una larga tradición de vincular las culturas internacionales y ofrece un destino acogedor para el descubrimiento y la educación centrados en la expresión artística que profundiza la apreciación y el entendimiento de la condición humana.

Arce | Traducción

al

español por Irene Arce