Hofstra University

Model United Nations Conference 2026

World Health Organization (WHO)

Nish Arumugam, Co-Chair

Aadi Gadekar, Co-Chair

Dear Delegates,

Welcome to HUMUNC and the WHO committee! My name isAadi Gadekar, and I am one of your chairs for the WHO committee. I am from northern New Jersey and am a second-year student at Hofstra. I am a double-major in Biology and Global Studies, while also enrolled in Hofstra’s BS/MD program in the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine.

I have always loved geography, so I was encouraged to join Model UN in high school. Even though my first MUN conference in my freshman year was virtual due to COVID-19, I had a great time and was encouraged to continue. I did GAthrough most of high school, although recently, I’ve chosen to participate in more crisis and specialized committees. For Hofstra’s MUN conference (HUMUNC) last year, I had the opportunity to help out with one of the specialized committees, so I’m looking forward to co-chairing the WHO committee this year.

In my free time, I enjoy reading and learning new languages. I’m currently reading The Lumumba Plot, a book about the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Patrice Lumumba, and how his government was taken down by various groups both inside and outside of the country. For the past few years, I’ve been focusing on learning three languages: Marathi, Hindi, and Spanish. I developed my passion for learning languages while improving my ability to speak my mother tongue, Marathi, and now, I’m committed to becoming fluent in all of the languages I’ve chosen to study. Other than that, I recently started baking, and I love listening to J. Cole; I think that 4 Your Eyez Only is his best album by far.

I’m very excited to be your Co-chair for the WHO committee and am looking forward to reading all of your committee papers! The goal that I and the rest of us at HUMUNC have for this year is to create a welcoming environment for everyone to learn from each other. As most of you know, global health initiatives around the world have been severely impacted by funding cuts and other challenges. Therefore, we hope that you all walk away from this committee with a better understanding of the vital work of agencies like the WHO and the challenges that they face. If you have any questions about the committee or if you just want to talk in general, you can always send me an email! If you have any questions about the conference itself, you can also email hofstramodelun@gmail.com. Good luck researching, and I can’t wait to meet all of you!

Best of luck,

Aadi Gadekar WHO Co-Chair HUMUNC 2026 agadekar1@pride.hofstra.edu

Hello Distinguished Delegates,

Welcome to the World Health Organization! My name is NishanthArumugam and it is my absolute pleasure to be one of your Co-Chairs for the WHO.

HUMUNC 2026 for me is quite special because it officially marks my 10th year of participation in Model United Nations. This decade-long involvement has genuinely been one of the most formative experiences of my life and I hope that you are all able to reap the same benefits that I still feel.

Outside of Model UN, I am a third-year pre-medical student with a major in Biochemistry and a minor in Sociology. I am also a student researcher and a Resident Assistant on campus. While the premedical path is not the field typically associated with Model United Nations, the research, communication, and leadership skills I developed here definitely are. I hope that this conference is the exciting and fun experience that Model UN is for me and your participation in the WHO committee will inspire you all to look deeper at how healthcare systems function.

Good luck with your research and preparation! I look forward to meeting you all in February and seeing what you accomplish at HUMUNC!

Best

Regards,

Nish Arumugam WHO Co-Chair HUMUNC 2026

Topic 1: Behind the Curtain of Life: Manipulating the Genome

What makes you, you? For most of humanity’s existence, this question could not be answered. Selective breeding of crops and animals thousands of years ago shows that early societies knew that traits could be inherited (passed down from parent to offspring), and they were able to harness this understanding for their benefit. However, the mechanism behind inheritance remained unknown for millennia.1 Even by the time Charles Darwin published his theory of natural selection in 1859, the basis for inheritance was not understood, but an explosion of scientific advances would soon shed light on this mystery.2

In the 1860s, Gregor Mendel unveiled the laws governing inheritance. His findings allowed mathematical predictions of heredity, and they provided a basis for traits “skipping” a generation. Repetition of Mendel’s pea plant experiments in fruit flies in the early 1900s produced a deeper understanding of inheritance patterns.3 Armed with new findings on inheritance patterns and advances in research capabilities, scientists began to peer into the cell to find its genetic material. So, what makes you, you? We now know that the answer lies (mostly) in your DNA. The color of your eyes. Your susceptibility to various diseases and responsiveness to treatments. The markers on red blood cells that circulate throughout your body. All these traits are encoded in your genome.4

In 1944, scientistsAvery, MacLeod, and McCarty first demonstrated that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, encodes a cell’s genetic information (Hershey and Chase provided more definitive proof in 1952).5 Six years later, Erwin Chargaff described how nucleotides (the building blocks of DNA) interact with each other. Using these base pair rules and an X-ray crystallography image of DNAcaptured by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, James Watson and Francis Crick were able to discover the structure of DNA.6,7 The pair

simultaneously predicted the mechanism for DNAreplication for transmission, and this pathway (called the semiconservative model) was proven in 1958 by Meselson and Stahl.8

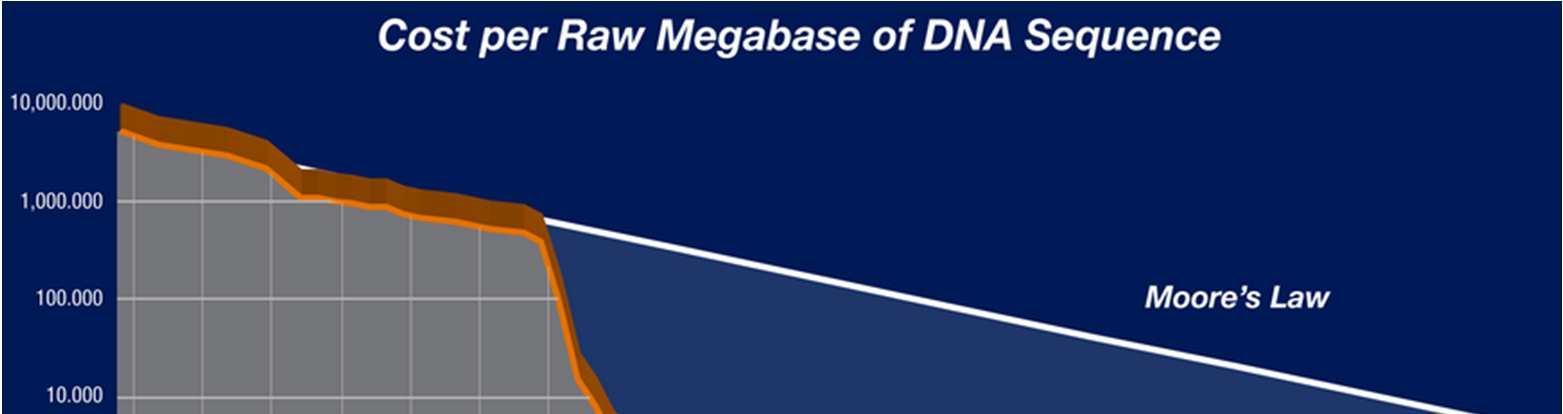

Figure 1: DNA double helix undergoing semi-conservative replication to transmit genetic info9

These discoveries heralded the dawn of a new age. The field of genetics barreled through the back half of the twentieth century with the discovery of the universal genetic code (the cipher to convert DNA/RNAinto protein), profiling of various genetic diseases, and development of recombinant DNA(a combination of genetic material from two or more different organisms).10 Progress has only continued, epitomized by the plummeting cost of DNAsequencing (see Figure 2). The WHO began to officially “examine the scientific, ethical, social and legal challenges associated with human genome editing” in 2018 and published an initial framework on gene editing shortly after.11 However, our ability to manipulate the genome has grown since the report, and the framework only focused on editing, not sequencing or screening. Thus, as the World Health Organization has not yet created protocols for member states on sequencing or screening, it has decided to revisit its preliminary guidelines.

Figure 2: Cost per raw megabase of DNA sequence throughout the twenty-first century12

Non-Human Genetic Manipulation

The manipulation of non-human genetics is by no means a new practice. As previously established, the advent of agriculture over 10,000 years ago meant that human societies were beginning to manipulate the genome of both plants and animals. Ancient farmers did not know what they were doing on a molecular or genetic level (let alone, what molecules or DNAare), but their efforts led to small genetic changes that steadily accumulated. This drift generated, at times, major shifts in phenotype (observable traits).13

While genetic manipulation is a practice nearly as old as human civilization, modern genetic engineering dramatically altered the method. In 1973, a group of four scientists published a paper detailing the successful introduction of exogenous DNAinto bacteria to alter their genome.14 This process allowed such a significant degree of control over bacterial genomes that the Supreme Court of the United States ruled such modifications could be patented in the landmark Diamond v Chakrabarty case (1980).15 In 1978, a similar process was used to engineer

bacteria to produce human insulin, and the purified compound was used to treat patients with diabetes by 1982.16 The 1990s saw an explosion in engineered crops to augment food production, and livestock were being engineered by the 2010s.17 Adeliberation over GMOs for food might be best suited for the UN’s Food andAgriculture Organization (FAO), but the engineering of microorganisms offers several questions relevant to the WHO.

Arecent review of the field byAri et al. highlights the promises and concerns behind the use of genetically engineered microbes (GEMs) to improve human health. Cancer, autoimmune inflammatory conditions, and infection have all been pointed to as targets for GEM therapy. However, bacteria are living organisms, so treatment including GEMs cannot be sterilized in a traditional fashion.At the same time, a “potential risk of genetic information escape, i.e., horizontal gene transfer” exists. The tendency of engineered bacteria to include genes for antibiotic resistance compounds this issue; the proliferation of resistance genes across bacterial populations would be incredibly harmful.18 In response to these concerns, researchers have recently begun to make bacteria reliant on synthetic chemicals to prevent escape from the lab or follow a slightly different genetic code to prevent harmful gene transfer,19 but these techniques are still in their infancy. With a wider scope than the WHO’s focused foray into gene editing, this committee will have the opportunity to begin addressing these questions.

Human Genetics

The WHO’s main framework for human genetics focuses on editing, but the organization has offered some guidance on genomics overall. In 2022, for example, the WHO Science Council published a report titled “Accelerating access to genomics for global health”, which outlined a series of recommendations to accomplish the following goals:

1. Promote the adoption or expanded use of genomics by Member States;

2. Identify and overcome the practical issues that impede the implementation of genomics through local planning, financing, training of essential personnel, and the provision of instruments, materials, and computational infrastructure;

3. Foster commitments to collaborative activities to promote all aspects of national and regional programs that advance genomics in Member States;

4. Promote ethical, legal, and equitable use and responsible sharing of information obtained with genomic methods through effective oversight and national and international rules and standards in the practice of genomics.20

The set of recommendations in the WHO Science Council’s report are augmented by a review of the field by representatives of the Science Council, indicating that “progress has been made in genomic education and training.”21 One of the main hurdles that still limits access in low- and middle-income nations “is the lack of direct access to materials, services and support from major providers of genomic equipment, reagents and analytical tools, which are primarily situated in high-income regions.”22

Unlocking equitable access to genomic capabilities has the potential to significantly improve human health across the world. From improved risk analyses and diagnostic accuracy to rational drug development and targeted treatment selection, genomics has a wide range of applications.23 Next-generation sequencing in newborns, for example, can improve detection of rare and dangerous congenital disorders,24 but its use for fetal screening is much more controversial because of ethical concerns.25 In adults, gene sequencing has improved outcomes for cancer patients,26 cardiovascular disease patients,27 and more through precision medicine. At the same time, the legal responsibility of private corporations that offer gene sequencing products presents concerns over data privacy, as epitomized by the bankruptcy of 23andMe.28 Questions about access and privacy will be up to the committee to address.

Manipulating the Human Genome

Gene editing can take place in somatic cells (this category includes all cells except gametes), or the genome of all cells can be altered via germline editing. Because germ cells are precursors to gametes,29 they have a unique ability to pass on their genome to an organism’s offspring. In this regard, germline editing presents an inherent “risk of perpetuating unexpected and undesired changes through generations.”30 There are also serious ethical concerns regarding the engineering of babies to have “designer DNA” via germline editing which, in addition to creating irreversible errors introduced into the human germ line, could perpetuate discrimination against those with an “imperfect” genetic code.31

At the same time, germline editing during in-vitro fertilization (IVF) holds the promise of preventing genetic diseases before the onset of any symptoms and ensuring that the disease is not passed on to future generations.32 While the Oviedo Convention binds the members of the Council of Europe from germline editing and laws passed individually in the United Kingdom and Canada prohibit the practice in their countries,33 the World Health Organization has only mulled a temporary moratorium on germline editing for all countries in response to the concerns,34 which this committee should take up in debate.

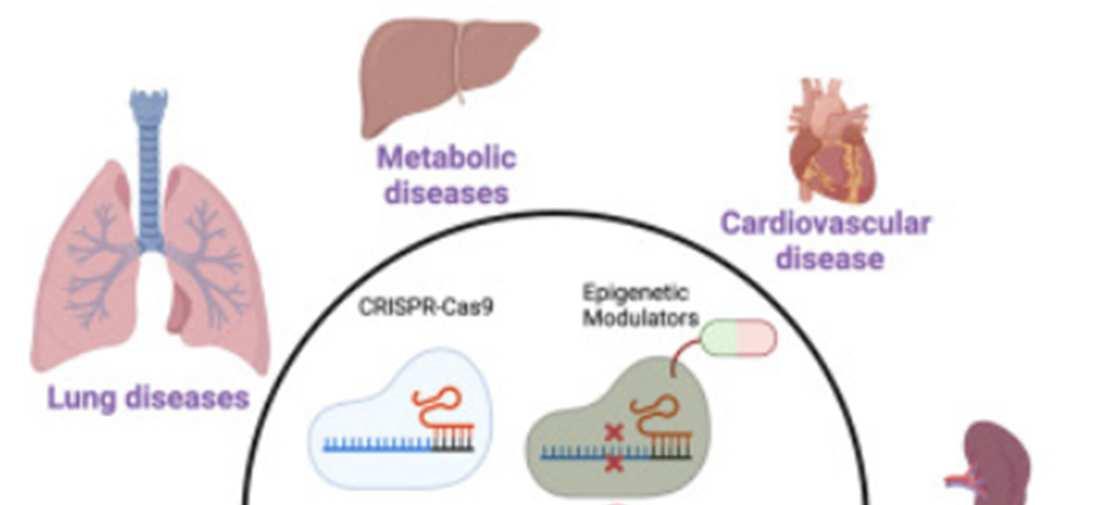

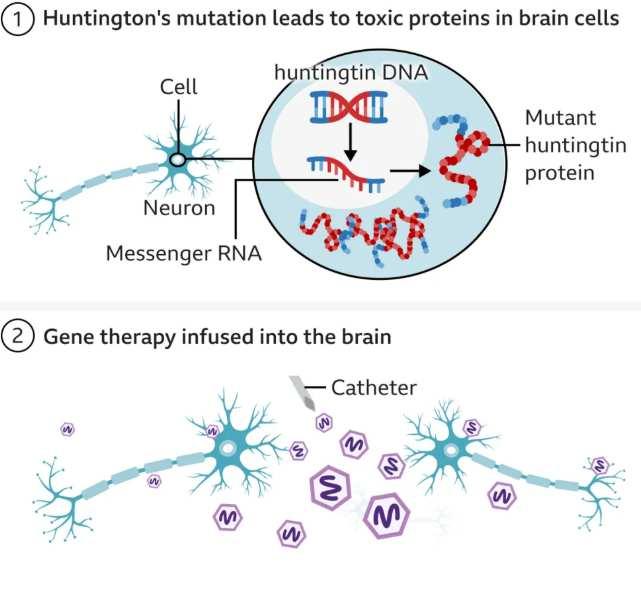

Regardless of decisions on germline editing, there are countless opportunities for somatic gene editing. The CRISPR-Cas9 system, which harnesses DNAcleavage enzymes from bacteria, is able to knock out (silence) target genes based on the sequence of a complementary guide RNA, and the tool is currently in clinical trials for treatment of various cancers, keratitis (eye inflammation), sickle cell disease, thalassemia (a form of anemia), HIV, and more. Base editors, with a more precise ability to edit individual nucleotides, are currently in trials to treat

hyperlipidemia (high fat levels in the blood), cardiovascular disease, and other conditions. The use of prime editors and epigenetic modulators offers even more treatment opportunities.35

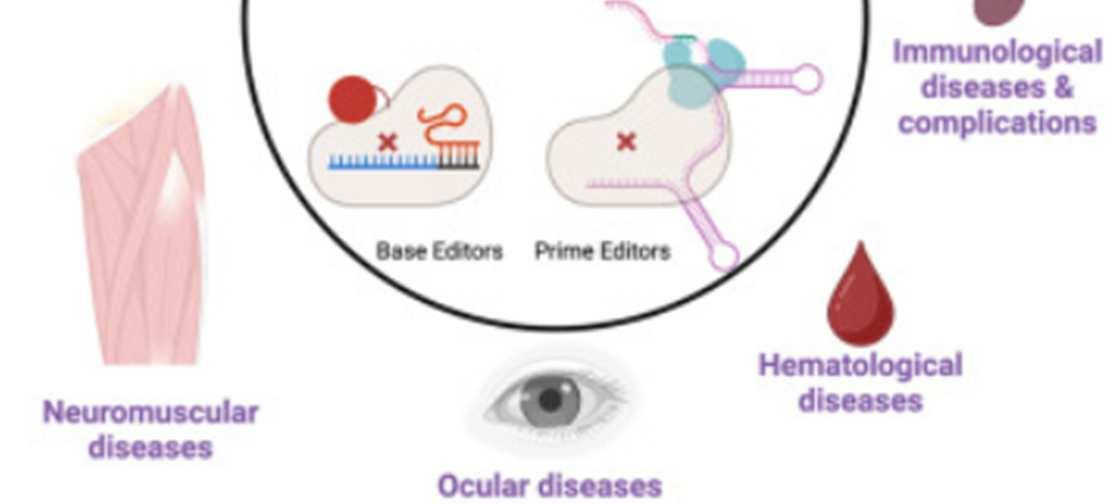

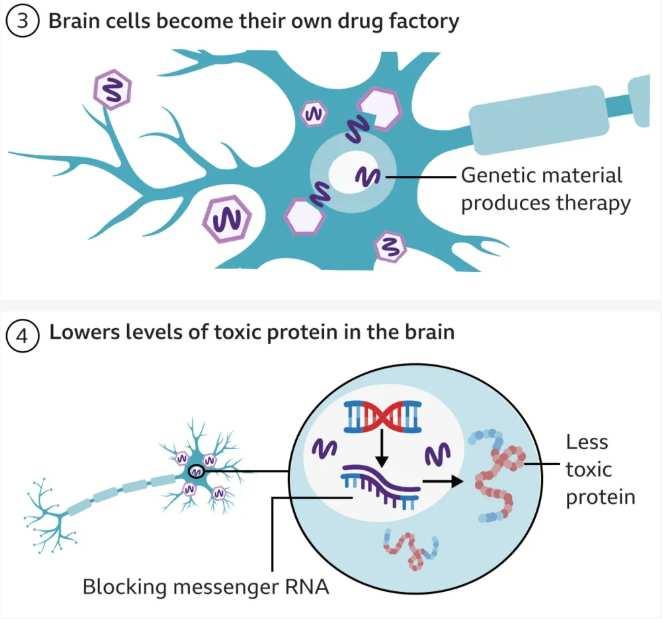

Figure 3: Tools and applications for somatic gene editing in humans36

However, treatment of genetic diseases may not always require the genome itself to be edited. The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology is a theory that explains that the flow of information runs from DNAto RNAto protein.37 Thus, treatment may be able to act on the RNA level to block translation into protein without directly modifying the DNA. This may seem farfetched, but it was recently accomplished in a landmark study that slowed Huntington’s disease progression by seventy-five percent. The disease revolves around excessive accumulation of Huntington protein that cannot be degraded, so treatment must block the buildup of the protein. Since mRNAcan be silenced when complementary miRNAbinds it, the team developed an adenoviral vector that transmitted DNAcoding for miRNAto silence Huntington and block translation (Figure 4).38,39,40 This method cannot yet be applied to all genetic diseases, but it offers a promising direction for those wary of directly manipulating the genome.

Bloc Positions

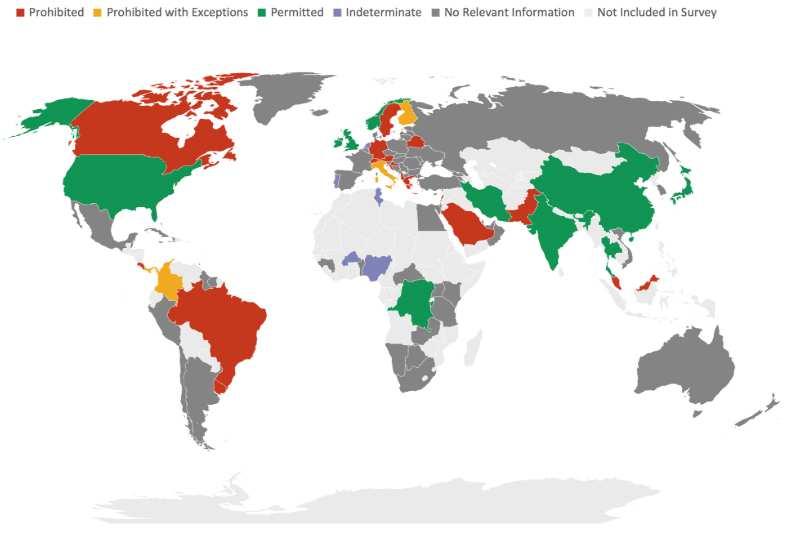

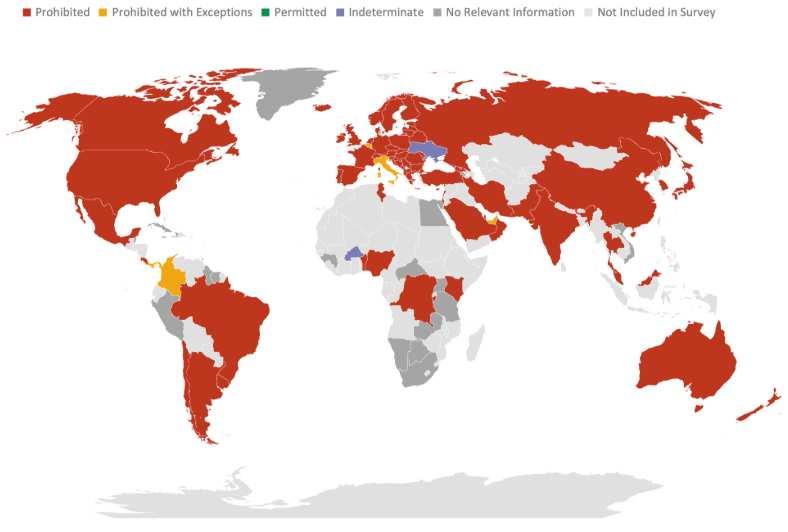

As pointed out in the previously described 2022 WHO Science Council report on genomics, technological capabilities related to the field vary highly across the world.42 Mid- and low-income nations will likely prefer focusing on building up access across the world. Wealthier nations with established programs may want to focus on funding research efforts and (for microbial genetic research) the prevention of outbreaks unless they can be made to see the benefits of expanded access. Current national policies on germline editing, however, show much more variation. The maps below depict country-by-country policies on germline editing for reproductive and non-reproductive intent (view the referenced source to look up your assigned country if you have trouble finding it on either map).43

5: Policies on human germline genome editing (not for reproduction)44

Figure 6: Policies on heritable human genome editing (for reproduction)45

Guiding Questions

1. Should the WHO encourage new research on the use of genetically engineered microbe therapies? If so, how can the WHO implement safe standards to prevent the escape of genes in recombinant DNAthat are harmful to public health?

2. How can genomic capabilities be expanded to more nations for equitable access?

3. What is the role of private corporations in DNAanalysis?

4. What can the WHO do to support development of new cures for genetic diseases? Is CRISPR the answer? miRNA?

5. What ethical responsibilities must be considered in the context of human genetics?

6. Should the moratorium on germline editing be implemented? If so, for reproductive uses specifically or for all uses?

Topic 2: The Tropics: The Next Pandemic Incubator?

In the contemporary era, forty percent of the world’s population is found in the tropics, which traditionally refers to the land found in between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. Stretching across much of Central America, the Caribbean, SouthAmerica, Africa, Asia, and Australia, the share of the world’s population living in the tropics is projected to increase to fifty percent within a few decades.46 Tropical diseases, which are diseases affecting people living in tropical and subtropical regions, include numerous diseases with various etiologies. Aspecific category of tropical diseases is neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), which is a list of twenty-two diseases classified by the WHO as diseases prevalent in tropical areas which have a substantial impact on the health of millions of people across the world yet receive little attention in mainstream global health discussions. The impact of these diseases cannot be understated; it is estimated that one billion people worldwide are currently affected by at least one NTD.47 As a result of globalization and increased population growth in tropical regions, tropical diseases, especially NTDs, cannot be ignored from global health agendas any longer.

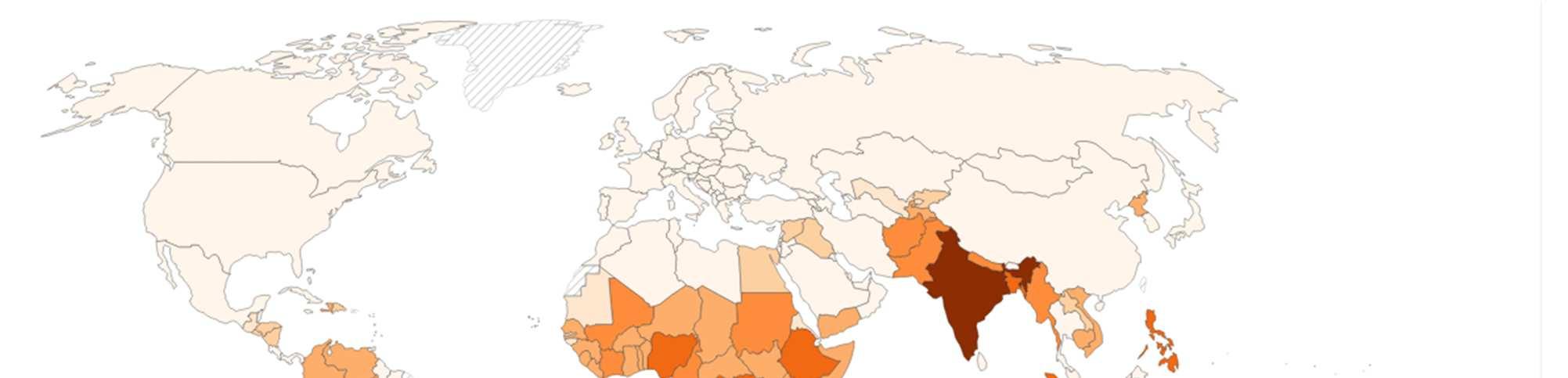

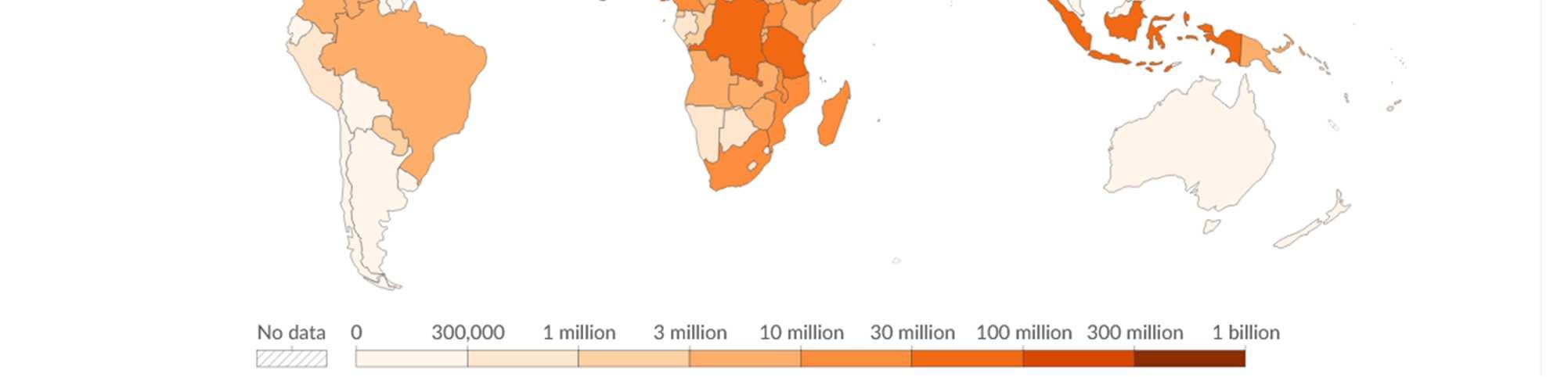

Figure 1: Number of people requiring treatment against NTDs, 202348

Overview of the Various Categories of NTDs

Mosquito-Borne Diseases (MBDs)

Mosquito-borne diseases (MBD) are some of the most common tropical disorders. It is estimated that 700 million people annually contract a mosquito-borne illness, and of those people, one million will die because of their infection.49 Malaria is arguably the most widelyknown MBD, with 282 million people contracting malaria annually. The plasmodium parasite, which is commonly found in the Anopheles genus of mosquitoes, is responsible for spreading malaria. While the initial symptoms of malaria may mirror those of a fever, serious cases could potentially lead to jaundice, difficulty breathing, and convulsions (seizures). While the disease can be found in numerous countries across the tropics, approximately ninety-five percent of malaria cases and deaths originate in African countries. Among the countries in this region, the majority of malaria deaths occur in children under five years old, with especially high mortality

in three sub-SaharanAfrican countries: Nigeria (31.9%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (11.7%), and Niger (6.1%), respectively.50

Another category of mosquito-borne diseases includes those diseases caused by arboviruses. While arbovirus is an umbrella term referring to all viruses spread by arthropods, numerous arboviruses, such as dengue and Zika, are recognized as NTDs and present a major global health threat. While dengue is found throughout the tropics, Zika, which was initially discovered in the East African nation of Uganda, is most notable for spreading throughout Central and SouthAmerica in an outbreak from 2015 to 2017. While most people infected by these diseases are asymptomatic, serious complications from dengue and Zika include hemorrhagic shock and birth defects such as microcephaly, respectively.51

Parasitic NTDs

Parasitic NTDs encompass a wide variety of diseases spread by parasites. While diseases such asAfrican trypanosomiasis and Chagas disease are spread by vectors such as the tsetse fly or the triatomine (“kissing bug”), respectively, other diseases, such as hookworm infections or Guinea-worm disease, originate from individuals interacting with environments where the parasite is found. Parasitic NTDs are common throughout the tropics, with diseases such as hookworm infections impacting 470 million people annually.52 While many parasitic NTD infections lead to symptoms such as diarrhea and joint pain, other diseases, such as Chagas disease, can have lifelong impacts. Chagas disease can specifically cause cardiovascular damage that, in some cases, could lead to heart failure.53

Bacterial NTDs

Out of the twenty-two NTDs, very few of them are caused by bacteria. Hansen’s disease, formerly known as leprosy, is a bacterial NTD whose incidence has gone down dramatically since the twentieth century. Nevertheless, roughly 250,000 people globally get diagnosed with Hansen’s disease each year. Annually, India has the most cases of Hansen’s disease, followed by Brazil, Indonesia, and Bangladesh.54 Yaws, another bacterial NTD, can cause skin ulcers and eventually lead to bone disfigurations. As many as 300,000 annual cases were reported worldwide between 2008 and 2012. Yaws is endemic to “Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Togo, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu.”55 Incidence of Yaws is not as widespread, with over eighty-four percent of current cases concentrated in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Ghana. Additionally, countries like India and Ecuador have succeeded at eradication efforts.56

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (VHF)

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHF) are an especially worrisome group of tropical disorders given the high transmissibility and lethality of the diseases. Ebola is the most well-known VHF following the 2013-2016 West African Ebola outbreak that killed over 11,000 people, totaling to an approximate forty percent fatality rate.57 Apart from Ebola, outbreaks of other VHFs, such as Lassa virus and Marburg virus, have also been reported throughout theAfrican continent in the past few years. While some VHF infections initially produce mild symptoms such as fever, muscle aches, and a loss of strength, more severe infections can result in convulsions, neurological damage, hemorrhagic shock, and death. These diseases are incredibly transmissible

through insects or rodents initially but can also be spread through contact with an infected human’s body fluids.58

Economic and Social Consequences of Tropical Diseases

The economic burden of tropical diseases on the economies of tropical countries is substantial. To fight diseases such as Chagas disease and dengue, countries around the world spend annually $7.2 billion59 and nearly $9 billion,60 respectively. However, on a family level, the economic burden of tropical diseases is even more significant. For instance, it was found that in Cameroon, the costs associated with treating hospitalized cases of Buruli ulcer, a tropical bacterial disease, amounted to nearly one-fourth of a household’s annual income. Furthermore, in Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia and Vietnam, more than half of households where dengue was present were forced to take on debt to pay for treatment.61 Yet, the costs associated with tropical diseases are not just limited to the cost of medical treatment. If the breadwinner of a family is unable to work due to an infection, the financial security of the entire family is jeopardized. On top of that, much of the costs associated with treating tropical diseases come from the costs that family members incur while caring for their relatives. The cost of transportation to and from healthcare centers and the cost of food and other daily necessities all contribute to the economic burden of tropical diseases.

Alongside the economic burden of tropical diseases, the social implications of these conditions cannot be ignored. When measuring the social cost of disease, one of the most commonly used metrics are disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which take into account the amount of healthy years of an individual’s life that were lost due to a disability or early death caused by a disease. The loss of DALYs associated with NTDs is staggering; in 2019, it is

estimated that twelve million DALYs were lost by East African countries alone due to neglected tropical disease.62

In addition, individuals suffering from certain tropical diseases may be subject to social stigma as a result of their illness. For instance, people with Hansen’s disease were historically confined to places such as leper colonies because the disease was thought to be highly contagious and the disfiguration it caused in some cases exacerbated fear of transmission. Despite greater understanding of how it spreads and available treatments, discrimination against people with the disease still persists. In India, over ninety laws which are considered discriminatory against people with Hansen’s disease are still part of the country’s legal code.63 Another example can be seen with the disease lymphatic filariasis, a disease that can result in the condition elephantiasis, in which certain body parts, such as the legs, may become swollen. As a result of their condition, many patients face social exclusion and isolation, resulting in poorer mental health outcomes and the development of disorders like depression and anxiety and “contributing to disability, stigma, and economic hardship.”64

Current and Emerging Challenges in Fighting Tropical Diseases

In the past fifty years, great strides have been made towards eliminating tropical diseases. The WHO has played a major role in this fight through various initiatives, such as the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF),65 which have been instrumental in building care guidelines and donating supplies to fight tropical diseases. Furthermore, a publicprivate partnership between the WHO and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation66 has worked to eliminate diseases like malaria. The Mectizan Donation Program, a public-private venture between the pharmaceutical company Merck, theWHO, and numerous other nonprofits, is the

longest-running drug-donation program for NTDs in the world. Since its inception in 1987, the program has donated medicine to millions of people in sixty-two countries across the tropics, helping in the fight against diseases such as lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis.67

However, in spite of all of this progress, much work still needs to be done in order to fight tropical diseases. Additionally, in the coming years, new challenges will complicate preexisting frameworks and necessitate the creation of new strategies.

Challenge 1: Increased Geographical Range and At-Risk Populations for Tropical Diseases

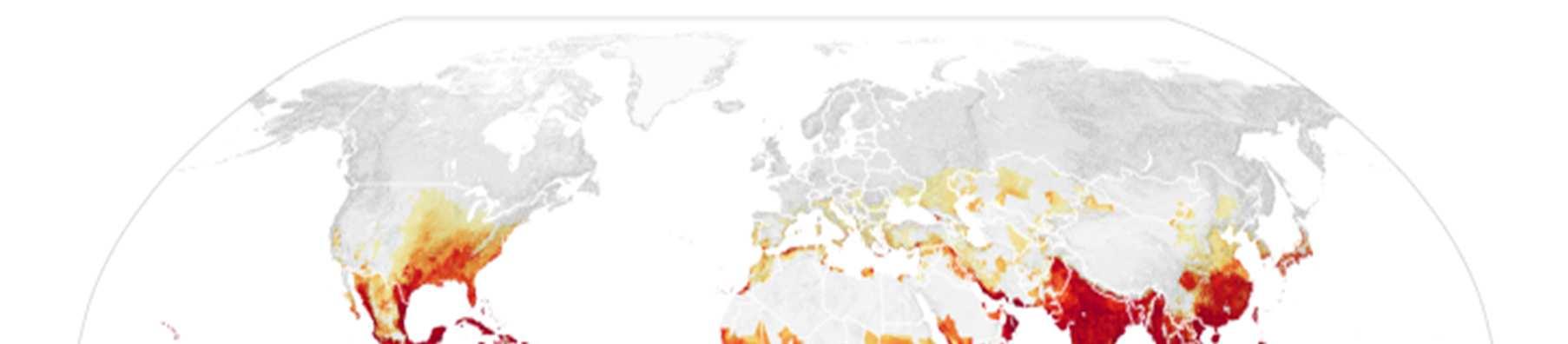

One of the most pressing challenges in controlling the spread of tropical diseases is that the number of people globally who are at risk of tropical diseases is projected to increase in the coming years. Climate change is one of the main contributing factors behind this problem. This is most evidently displayed with MBDs such as dengue. While dengue has historically been confined to tropical regions of the world, in recent years, dengue outbreaks have occurred in regions that were historically unaffected by the disease. This is in part due to the fact that climate change has expanded the habitat range of the mosquito Aedes aegypti, which is the main vector for dengue. Increased precipitation levels and temperatures in subtropical and temperate regions of the world have made more places around the world suitable for Aedes aegypti, resulting in once-unaffected populations now being at risk for the disease.68 The map below illustrates how areas once unaffected by dengue, including areas like the contiguous United States and southern Europe, will be at an increased risk of dengue.

Figure 2: Areas of the world projected to become suitable for dengue transmission by 2050. 69

However, alongside the changes that increase the areas where infections can occur, the increased movement of people from regions where tropical diseases are prevalent to regions where they are not prevalent is contributing to the increased geographical range of populations infected by tropical diseases. For instance, the movement of infected individuals from areas of high, endemic dengue transmission to areas with little to no dengue transmission has contributed to the introduction of dengue into regions where the disease was once not found.70 While most Chagas disease cases occur in Central and South America, increased migration from those regions to the United States has resulted in an estimated 300,000 people living in the United States with the disease. While in some U.S. states, especially those in theAmerican South, may experience local transmission of Chagas due to the parasite naturally occurring within

triatomines or “kissing bugs” found within those states, the vast majority of those found in the region to already have Chagas disease can be attributed to immigration from endemic regions.71 While the movement of people already infected may not be a factor in spreading the disease further, healthcare systems may need to adapt to understand the complications faced by those infected.

While the migration of humans to new regions or countries could result in the introduction of new diseases, the way that humans interact with their environment may increase their likelihood of contracting a tropical disease. Specifically, the encroachment of human settlements into habitats such as rainforests have increased the number of human-wildlife interactions, thus increasing the risk of populations from these communities from contracting zoonotic diseases such as Ebola and Nipah virus.

Challenge 2: Difficulty in Accessing Communities Affected by Tropical Diseases

While great strides have been made in fighting tropical diseases, one of the challenges in eradicating some tropical diseases is that the communities in which these diseases persist are in remote places that are difficult to access. For example, while the Indian government has made great strides in fighting malaria, such as through the creation of task forces dedicated to eradicating the disease and working with the World Bank to implement anti-malaria programs, it is still not eliminated, particularly in the eastern and northeastern parts of the country. While these regions have a favorable climate for the development of malaria and the presence of drugresistant strains of malaria, other issues, like the remoteness of these regions and poor healthcare infrastructure in these regions, have hindered efforts to fight the disease.72

Moreover, the area most heavily impacted by malaria are inhabited byAdivasi communities in the northeastern part of India. This community is considered to be the indigenous inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent and have historically struggled with poor healthcare access and low socioeconomic status.73 As a result, in their fight to eradicate malaria, the Indian government will need to address the underlying socioeconomic factors that have contributed to the disease having a strong foothold in this community and the parts of the country they inhabit. The volatile political situation of some communities has impaired global health efforts to eradicate tropical diseases. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a country found in Central Africa, has struggled with political instability ever since it gained independence in 1960. Currently, an armed insurgency in the eastern part of the country has further destabilized the nation, and previous United Nations peacekeeping efforts, such as the MONUSCO mission, have failed to improve the security situation.74 This has also complicated recent efforts to fight Ebola outbreaks there. The volatile security situation in the region has decimated local public health infrastructure and has left aid organizations struggling to operate. Moreover, capitalizing off of the fear sparked by Ebola, “rumors are spread by clerics, traditional healers, men, women, and even healthcare professionals” have fomented fear and mistrust of public health authorities among the people of the region.75 Along with Ebola, the relatively high prevalence of NTDs such asAfrican trypanosomiasis can also be attributed to the DRC’s poor security situation.

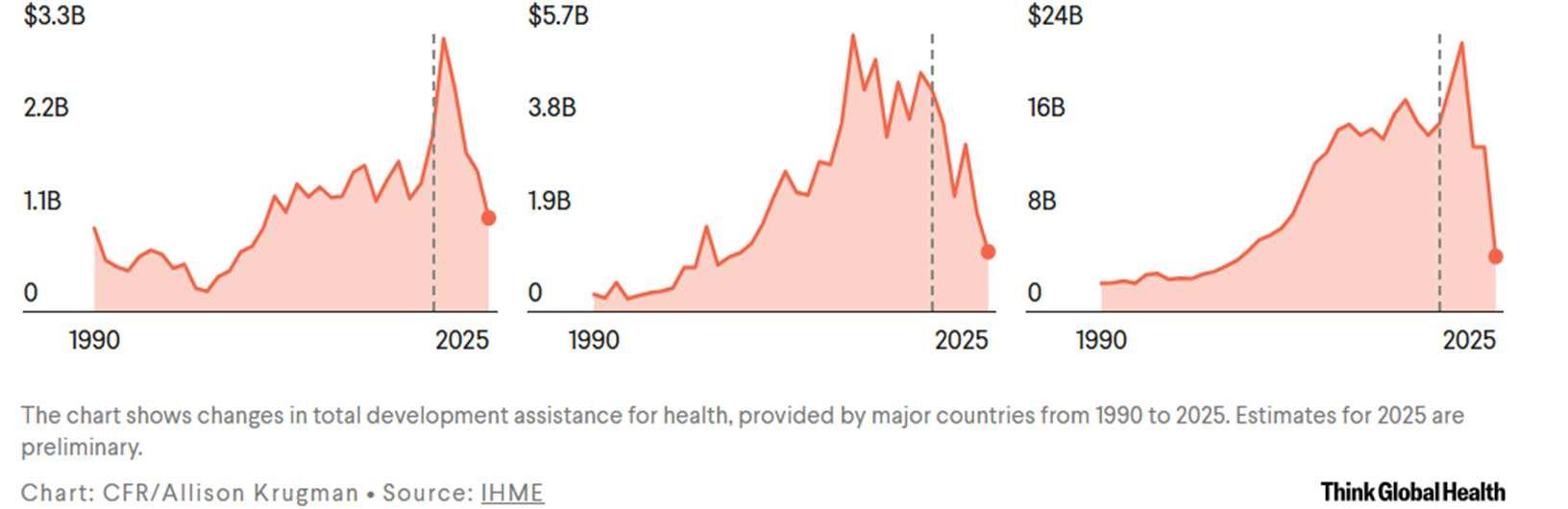

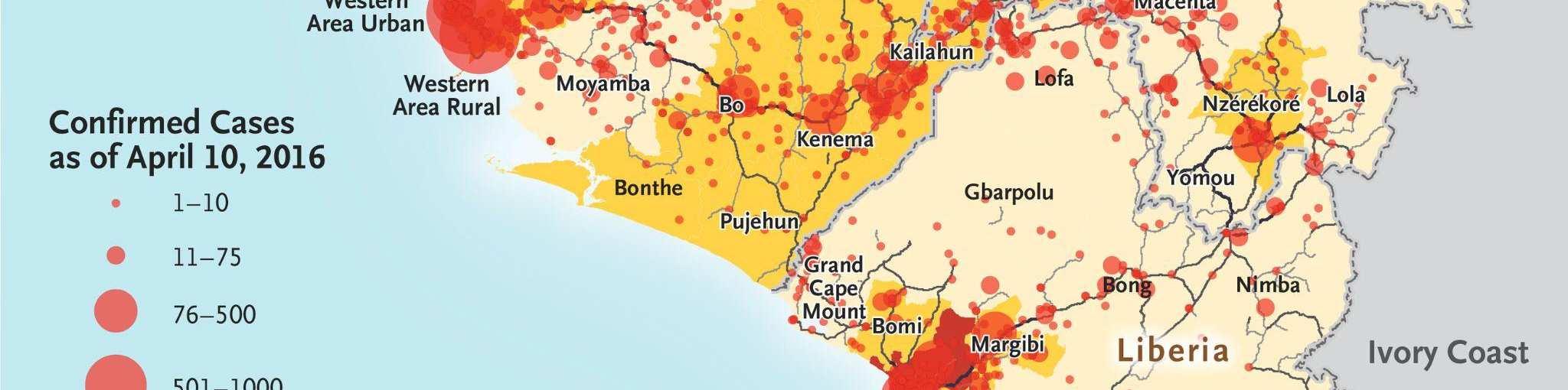

Challenge 3: Decreased Funding for Fighting Tropical Diseases

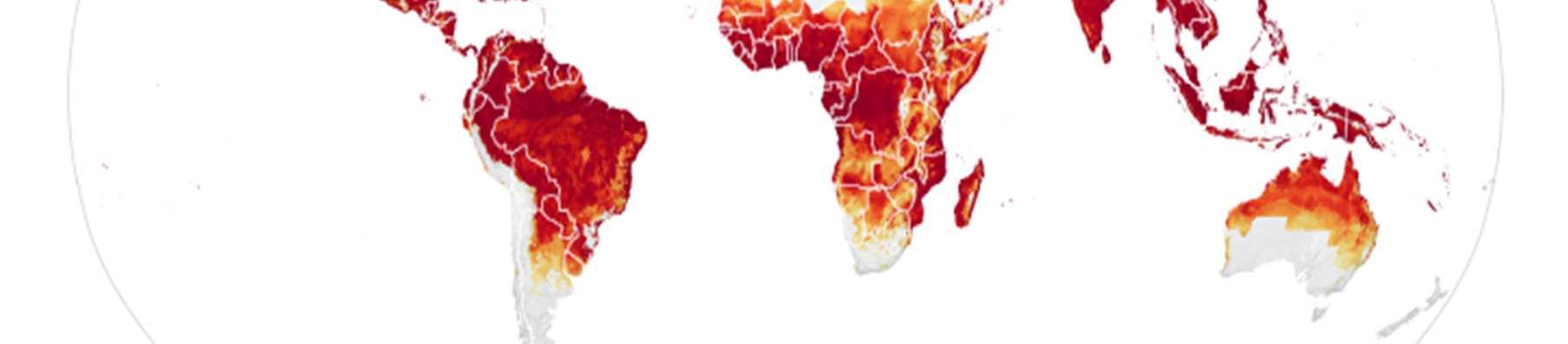

The biggest threat to global health programs in the present day and in the next few years is the financial security of global health agencies, such as the WHO. Funding for the WHO comes from two major sources. The first source is the member dues paid by WHO members,

whose share is determined by assessing their GDP and population size. These contributions constitute twenty percent of the organization’s budget. The second source is the voluntary contributions made by member states or by private organizations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Historically, the United States was the WHO’s main funder through significant voluntary contributions.76 Yet, in January 2025, it announced that it would be officially withdrawing from the WHO in January 2026, signaling the end of anyAmerican financial commitments to the organization. This is significant because the United States combined share from assessed contributions plus voluntary contributions made up twenty percent of the WHO’s total budget.77

Accompanying the withdrawal from the WHO came a flurry of funding cuts for numerousAmerican global health programs, such as USAID’s NTD program, established in 2006 to “control and eliminate five of the most prevalent NTDs – lymphatic filariasis (LF), trachoma, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and soil transmitted helminths (hookworm, roundworm, and whipworm)”.78 This program played an integral role in the procurement of medicine needed to treat patients of various NTDs. One major feature of this program was its partnership with pharmaceutical companies that enabled each dollar invested in the program to yield twenty six dollars’worth of treatments. However, following the dismantling of USAID in 2025, such programs are no longer operating, resulting in millions of people across the world at risk of NTDs and other tropical diseases.79

While dramatic, the global health cuts by the United States are not unique. Other major donors for global health programs, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, have also reduced their global health contributions following the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar cuts have occurred by NGOs which have previously donated to the WHO. As a result of all of these funding cuts,

the WHO is projected to undergo a severe budget deficit in 2026-2027. Despite raising membership dues for its remaining members, theWHO is projected to fall short $1.9 billion of its $4.2 billion budget. This dramatic shortfall guarantees that the organization’s ability to respond to global health threats will be impaired.80

Figure 3: Funding pledged to global health efforts by leading contributors.81

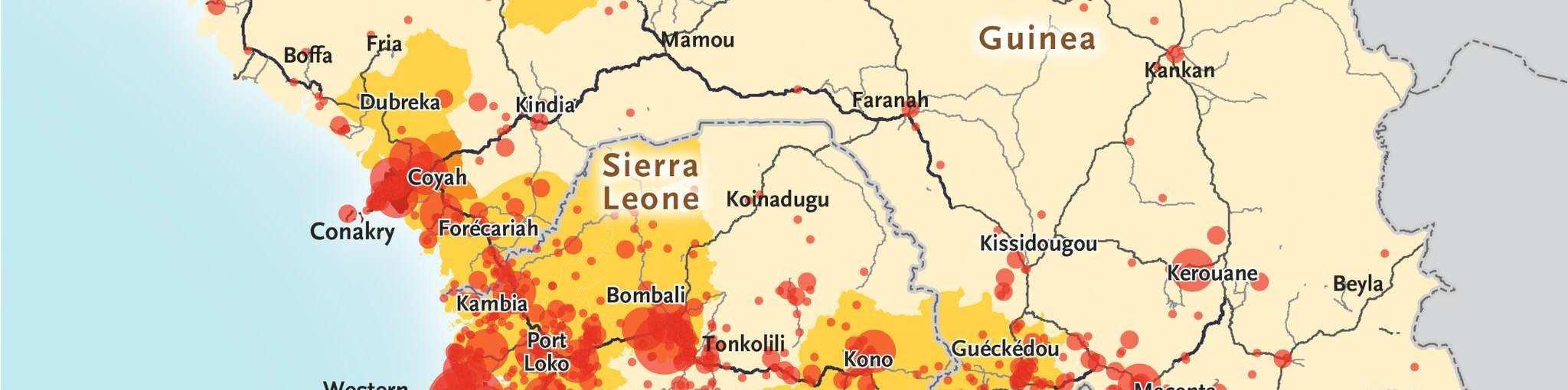

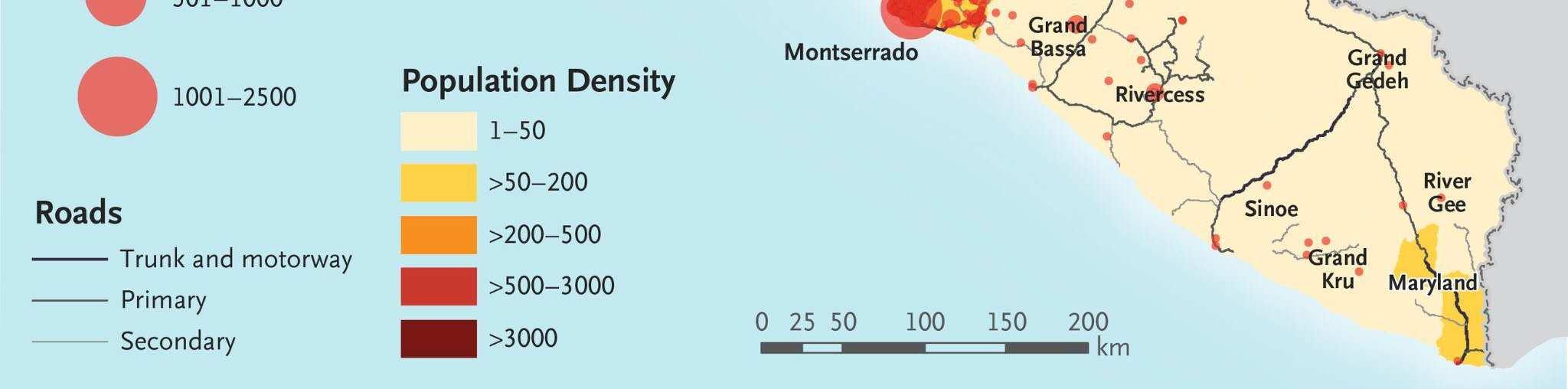

Case Study: Management of the 2013-2016 West African Ebola Outbreak

The 2013-2016 West African Ebola outbreak originated at the end of December 2013 when a two-year old child from a village in rural Guinea, suspected of encountering food infected by bat droppings, inadvertently carried Ebola back to his village. Ebola then spread through the boy’s village, and soon, many individuals died from the disease. Traditional burial practices from the region, which involve bathing the body of the deceased, brought more people in contact with infected bodies and contributed to the spread of Ebola. Furthermore, the porous

borders between neighboring Sierra Leone and Liberia, contributed to the spread of the disease as people frequently traveled across these borders as part of their day-to-day lives.82

While Ebola was left to spread throughout the region for months, many national governments downplayed the risk of Ebola or communicated messages that confused local leaders, leading to denial of Ebola’s presence in vulnerable communities. However, by the time the public acknowledged the danger at hand, Ebola had spread rapidly, entering into the cities from more rural communities. By July 2014, Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, became full of Ebola patients seeking treatment in overcrowded hospitals. The government instituted a quarantine of the neighborhoods in Freetown most affected by the disease as a measure to contain the outbreak. However, the quarantine, along with misinformation regarding the virus, brewed resentment among the neighborhood’s inhabitants, culminating in anti-government riots rocking the neighborhood.83

Figure 4: Distribution of Ebola cases in the 2013-2016 West African Ebola outbreak.84

In light of the unprecedented scope of the outbreak, nations from around the world and international organizations such as the United Nations mobilized a response that included donating medical supplies, training medical personnel, and financing containment and treatment efforts within the most-affected nations. By 2016, the outbreak had been contained and was declared to be over. However, the international response against Ebola had been criticized as being slow, with many NGOs, such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) taking the lead in the beginning stages of the outbreak to fight against the disease.

In April 2015, the WHO publicly acknowledged shortcomings in their response against the pandemic because of fears it could “antagonize” governments of affected countries. The insufficient response led the UN Secretary-General to “not only established the very first public health mission (the United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response or UNMEER ) to coordinate the response, he also appointed a high-level panel to review the international community’s capabilities for future health emergencies.”85 An internal draft document from the WHO cited numerous shortcomings, such as incompetent staff, unreliable information, and “most poignantly effecting an internal cultural change from its standard slow and methodical work of standard and agenda”.86

Bloc Positions

Most of the members of the United Nations, with the exceptions of Liechtenstein and the United States, are members of the WHO. As a result, all of these countries subscribe to the organization’s mission to “promote health, keep the world safe, and serve the vulnerable.”87 However, the countries that have traditionally shouldered the financial burden of global health initiatives, such as the United Kingdom and Canada, have begun to reduce their role in global health efforts. Nevertheless, this does not mean they would be entirely uninterested in assisting

the healthcare needs of the Global South. In light of attempts by both Russia and China to increase their influence in the Global South, these powers are still invested in the affairs of such countries and are eager to maintain their influence.88 As a result, while they may be reluctant to pledge more foreign aid money in support of such initiatives, they would still be interested in finding ways to support such efforts through business contacts and other partnerships.

As the traditional backers of global health initiatives are backing down, this has now left an opening for other countries to take the place. During the COVID-19 pandemic, China, Russia, and India engaged in vaccine diplomacy by mass-producing their COVID-19 vaccines and donating millions of doses to countries across the Global South.89 While the reduction in donations to the WHO represents a pressing challenge for the future of global health efforts, this vacuum may provide countries like China, Russia, and India an opportunity to expand their presence on the global stage and extend their direct connections across the Global South.

While countries across the Global South are eager to receive support for combatting tropical diseases and strengthening their healthcare systems, many nations may be wary of outside support. For instance, African nations such as Burkina Faso and Mali, which have been repudiated on the international level for coup-led governments, have begun to move away from the support and influence of regional bodies that criticize non-democratic governments.90 As a result, it is unlikely that these countries will be receptive to massive aid packages that would leave the healthcare systems of these countries reliant on “strings attached”, including democratic governance. Furthermore, while aid can be critical during times of crisis, long-term reliance on aid has been known to harm the economies of developing countries.91 Therefore, while it can be a lifeline during an acute crisis, simply donating massive amounts of aid will not be a sustainable solution to strengthening local health systems or tacking global health issues.

To learn more about your country’s position, research the various initiatives your country has taken on the international level regarding tropical diseases. Moreover, although COVID-19 was not classified as a tropical disease, learning more about the international relief efforts that your country contributed to, or received, would be a strong starting point to understand your country’s stance on ways to combat tropical diseases.

Guiding Questions

1. What interventions can the WHO implement to help reduce the financial burden of treating tropical diseases?

2. How can the WHO and its member states help curb the spread of diseases such as dengue while factoring in the effects of climate change on their spread?

3. Given the role of cross-border migration in spreading conditions such as Chagas disease and Ebola, should the WHO better monitor the movement of people across borders? Should Member States do so on their own? If so, how?

4. In light of misinformation and distrust surrounding disorders such as Ebola, how can the WHO fight such misinformation and boost the trust of populations in public health initiatives?

5. As global health initiatives face increasing budget cuts, how can the WHO stabilize funding to ensure its programs can continue to run?

Endnotes

1 Akre, Karin. "Selective Breeding". Encyclopedia Britannica. October 25, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/selective-breeding.

2 Horgan, John. “ABrief History of Genetics How Genetics Transformed Medicine and Identity.” World History.org. December 8, 2025. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2855/a-brief-history-of-genetics/

3 Naithani, Sushma. History and Science of Cultivated Plants. June 8, 2021. https://open.oregonstate.education/cultivatedplants/chapter/genetics/

4 “Genetics Basics.” Genonmics and Your Health. May 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics-andhealth/about/index.html

5 “1952: Genes are Made of DNA.” National Human Genome Research Institute. Last updatedApril 23. 2013. https://www.genome.gov/25520254/online-education-kit-1952-genes-are-made-of-dna

6 Kaplan, Judith. "Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins." Science History Institute Museum and Library. September 8, 2025. https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/franciscrick-rosalind-franklin-james-watson-and-maurice-wilkins/

7 Watson, J., Crick, F. “Molecular Structure of NucleicAcids:A Structure for Deoxyribose NucleicAcid.” Nature Pgs. 171, 737–738 (1953). https://www.nature.com/articles/171737a0

8 Pray, L. “Semi-conservative DNAreplication: Meselson and Stahl.” Nature Education. 2008. https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/semi-conservative-dna-replication-meselson-and-stahl-421/

9 "Semi-Conservative." BioNinja.com. https://old-ib.bioninja.com.au/standard-level/topic-2-molecular-biology/27dna-replication-transcri/semi-conservative.html

10 Wexler, Barbara. “Genetics and Genetic Engineering.” The History of Genetics. Information Plus. November 1, 2003. https://www.math.uci.edu/~brusso/The_History_of_Genetics.pdf

11 “Human genome editing: a framework for governance.” World Health Organization. 12 July 12, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030060

12 “DNASequencing Costs: Data.” National Human Genome Research Institute.https://www.genome.gov/aboutgenomics/fact-sheets/DNA-Sequencing-Costs-Data

13 “Evolution of Corn.” Learn.Genetics. https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/evolution/corn/

14 Cohen, Stanley N.; Chang, Annie C.Y.; Boyer, Herbert w.; Helling, Robert B. "Construction of Biologically Functional Bacterial Plasmids In Vitro." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. Vol. 70, No. 11, pp. 3240-3244, November 1973. https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.70.11.3240

15 SidneyA. Diamond, Commissioner of Patents and Trademarks, Petitioner v. Ananda M. Chakrabarty et al. 100 U.S. Supreme Court. 1980. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/447/303

16 "100 Years of Insulin." U.S. Food and DrugAdministration. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-historyexhibits/100-years-insulin

17 "Science and History of GMOs and Other Food Modification Processes." U.S. Food and DrugAdministration. https://www.fda.gov/food/agricultural-biotechnology/science-and-history-gmos-and-other-food-modificationprocesses

18 MahdizadeAri, Marzie et al. “Genetically Engineered Microorganisms and Their Impact on Human Health.” International journal of clinical practice vol. 2024 6638269. 9 March 9, 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10944348/

19Dolgin, E. GM microbes created that can’t escape the lab. Nature 517, 423 (2015). https://www.nature.com/articles/517423a

20 “Accelerating access to genomics for global health.“ WHO Science Council. July 12, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052857

21 Ambrosino, E., Abou Tayoun, A.N., Abramowicz, M. et al. The WHO genomics program of work for equitable implementation of human genomics for global health. Nat Med 30, 2711–2713 (2024). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03225-x)

22 Ibid.

23 “Genomics.” World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/genomics#tab=tab_2

24 Jiang, Shan, Wang, Haiyin, Gu, Yuanyuan. "Genome Sequencing for Newborn Screening—An Effective Approach for Tackling Rare Diseases." JAMA Network. September 1, 2023. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2809070

25 McDonough, Molly. “The Ethics of Prenatal Genetic Testing.” Havard Medicine. Summer 2024. https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/ethics-prenatal-genetic-testing

26 Ghoreyshi, Nima et al. “Next-generation sequencing in cancer diagnosis and treatment: clinical applications and future directions.” Discover oncology vol. 16,1 578. 20April 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12009796/

27 Landstrom, Andrew P., et. al. "Genetic and Genomic Testing in Cardiovascular Disease:APolicy Statement From theAmerican HeartAssociation." Circulation, Volume 152, Number 24. December 16, 2025. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001385

28 Capoot, Ashley. "23andMe bankruptcy under congressional investigation for customer data." CNBC. April 17, 2025. https://www.cnbc.com/2025/04/17/23andme-bankruptcy-investigation-genetic-datacongress.html?msockid=21661059f3c16c4f3e9d0499f2b36d8e

29 Maloy, Stanly and Kelly Hughes (eds.) Brenner's Encyclopedia of Genetics, Second Edition. 2013. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/germ-cell

30 “Human genome editing: ensuring responsible research.” The Lancet. Editorial. Volume 401, Issue 10380, page 877. March 18, 2023. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)00560-3/fulltext

31 Billauer, Barbara Pfeffer. "Designer DNA: Genetic Edits, Ethics, and Pseudo-Prophecy."American Council on Science and Health. July 17, 2025. https://www.acsh.org/news/2025/07/17/designer-dna-genetic-edits-ethics-andpseudo-prophecy-49617

32 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0015028223001735#sec3

33 Billauer, Barbara Pfeffer. "Designer DNA: Genetic Edits, Ethics, and Pseudo-Prophecy."American Council on Science and Health. July 17, 2025. https://www.acsh.org/news/2025/07/17/designer-dna-genetic-edits-ethics-andpseudo-prophecy-49617

34 Junghyun Ryu, Eli Y. Adashi, Jon D. Hennebold, “The history, use, and challenges of therapeutic somatic cell and germline gene editing.” Fertility and Sterility, Volume 120, Issue 3, Part 1, 2023, Pages 528-538, ISSN 0015-0282. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030060

35 Dongqi Liu, Di Cao, Renzhi Han. “Recent advances in therapeutic gene-editing technologies.” Molecular Therapy, Volume 33, Issue 6, 2025, Pages 2619-2644, ISSN 1525-0016. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S152500162500200X

36 Ibid

37 "Central Dogma." National Human Genome Institute. Updated January 17, 2026. https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Central-Dogma

38 Parshall, Allison. "How Scientists Finally Found a Treatment That Slows Huntington’s Disease." Scientific American. October 1, 2005. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/first-treatment-that-slows-huntingtonsdisease-comes-after-years-of/

39 “Artificial miRNAslows Huntington’s.” Nat Biotechnol 43, 1746 (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587025-02910-7

40 Glynn, Niall. “Huntington's breakthrough 'amazing' but with 'caveats'.” BBC News. September 25, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c24r666ly3vo

41 Ibid

42 “Accelerating access to genomics for global health: Promotion, implementation, collaboration, and ethical, legal, and social issues .” WHO Science Council. 2022. https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/339d8866-fc5244bc-9759-484b9fbab1c4/content

43 Baylis, Francois, et. al. “Human Germline and Heritable Genome Editing: The Global Policy Landscape.” The CRISPR Journal. Vol. 3, NO. 5. October 20, 2020. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/crispr.2020.0082

44 Ibid

45 Ibid

46 Wilkinson, A. (2014). Expanding Tropics will play greater global role, report predicts | science | AAAS. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/expanding-tropics-will-play-greater-global-role-report-predicts

47 World Health Organization. (2025). Neglected tropical diseases -- global. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/neglected-tropical-diseases#tab=tab_1

48 “Number of people requiring treatment against neglected tropical diseases, 2023.” Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/interventions-ntds-sdgs

49 World Mosquito Program. (2025). World mosquito Day 2025 - A Global Health Crisis. World Mosquito Program. https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/news-stories/world-mosquito-day-2025-global-health-crisis

50 World Health Organization. (2025a). Fact sheet about malaria. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

51 Silva, N. M., Santos, N. C., & Martins, I. C. (2020). Dengue and Zika Viruses: Epidemiological History, Potential Therapies, and Promising Vaccines. Tropical medicine and infectious disease, 5(4), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed5040150

52 GhodeifAO, Jain H. Hookworm. [Updated 2023 Jun 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546648/

53 World Health Organization. (2025c, April 2). Chagas disease. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis)

54 Bhandari J, Awais M, Robbins BA, et al. Leprosy. [Updated 2023 Sep 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559307/

55 Maxfield L, Corley JE, Crane JS. Yaws. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526013/

56 Ibid.

57 Kyobe Bosa, Henry et al. “The westAfrica Ebola virus disease outbreak: 10 years on.” The Lancet Global Health. Volume 12, Issue 7, e1081 - e1083. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(24)001293/fulltext

58 Mangat R, Louie T. Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. [Updated 2023Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560717/

59 Lidani, K. C. F., Andrade, F. A., Bavia, L., Damasceno, F. S., Beltrame, M. H., Messias-Reason, I. J., & Sandri, T. L. (2019). Chagas Disease: From Discovery to a Worldwide Health Problem. Frontiers in public health, 7, 166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00166

60 World Mosquito Program. (2026). Sustainable methods to curb the economic toll of mosquito-borne diseases. World Mosquito Program. https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/en/news-stories/stories/sustainable-methodscurb-economic-toll-mosquito-borne-diseases

61 Fitzpatrick C, Nwankwo U, Lenk E, et al. An Investment Case for Ending Neglected Tropical Diseases. In: Holmes KK, Bertozzi S, Bloom BR, et al., editors. Major Infectious Diseases. 3rd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank; 2017 Nov 3. Chapter 17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525199/

62 Kirigia, J. M., & Kubai, P. K. (2023). Monetary Value of Disability-Adjusted LifeYears and Potential Productivity LossesAssociated With Neglected Tropical Diseases in the EastAfrican Community. Research and reports in tropical medicine, 14, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S382288

63 Bureau, T. H. (2025, December 2). Over 90 laws still discriminate against people with leprosy, NHRC tells Supreme Court. http://thehindu.com/news/national/over-90-laws-still-discriminate-against-people-with-leprosynhrc-tells-supreme-court/article70350860.ece#google_vignette

64 Goldin J, JuergensAL. Filariasis. [Updated 2025 Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556012/

65 World Health Organization. (2025b). Global Programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/lymphatic-filariasis/globalprogramme-to-eliminate-lymphatic-filariasis

66 "WHO welcomes US$ 140 million BMGF investment to end NTDs and malaria." World Health Organization. June 24, 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/24-06-2022-who-welcomes-us-140-million-bmgf-investment-to-endntds-and-malaria

67 Mectizan Donation Program. (2026, January 3). Mectizan Donation Program. https://mectizan.org/

68 Childs, Marissa Let al. “Climate warming is expanding dengue burden in theAmericas andAsia.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 122,37 (2025). https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2512350122

69 Patel, K. (2025, November 25). Of mosquitoes and models: Tracking disease by satellite - NASA science. NASA. https://science.nasa.gov/earth/earth-observatory/tracking-disease-by-satellite/

70 Gwee, X. W. S., Chua, P. E. Y., & Pang, J. (2021). “Global dengue importation: a systematic review.” BMC infectious diseases, 21(1), 1078. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34666692/

71 Montgomery, S. P., Parise, M. E., Dotson, E. M., & Bialek, S. R. (2016). What Do We KnowAbout Chagas Disease in the United States?. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 95(6), 1225–1227. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0213

72 Sarma, D. K., Mohapatra, P. K., Bhattacharyya, D. R., Chellappan, S., Karuppusamy, B., Barman, K., Senthil Kumar, N., Dash, A. P., Prakash, A., & Balabaskaran Nina, P. (2019). Malaria in North-East India: Importance and Implications in the Era of Elimination. Microorganisms, 7(12), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7120673

73 Deb Roy, A., Das, D., & Mondal, H. (2023). The Tribal Health System in India: Challenges in Healthcare Delivery in Comparison to the Global Healthcare Systems. Cureus, 15(6), e39867. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39867

74 The United Nations. (2026). Why have UN peacekeepers been in DR Congo for 65 years?. The United Nations Office at Geneva. https://www.ungeneva.org/en/news-media/news/2025/02/102924/why-have-un-peacekeepersbeen-dr-congo-65-years

75 Onyeneho, N. G., Aronu, N. I., Igwe, I., Okeibunor, J., Diarra, T., Diallo, A. B., Hamadou, B., Rodrigue, B., Djingarey, M. H., Yoti, Z., Yao, N. K. M., Fall, I. S., Chamla, D., & Gueye, A. S. (2023). Two Obstacles in Response Efforts to the Ebola Epidemic in the Provinces of North Kivu and Ituri in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Denial of and Rumors about the Disease. Journal of immunological sciences, Suppl 3, 44–57. https://doi.org/10.29245/2578-3009/2023/S3.1104

76 World Health Organization. (2025c). How WHO is Funded. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/about/funding

77 Aremu, S. O., Adamu, A. I., Obeta, O. K., Ibe, D. O., Mairiga, S. A., Otukoya, M. A., & Barkhadle, A. A. (2025) The United States withdrawal from the world health organization (WHO), its implications for global health governance. Globalization and health, 21(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-025-01137-0

78 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). Global NTD Programs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/neglected-tropical-diseases/programs/index.html

79 Ibid.

80 Fletcher, E. R. (2025, April 2). Who budget crisis bigger than previously thought - $2.5 billion gap for 2025-2027 Health Policy Watch. https://healthpolicy-watch.news/who-budget-crisis-bigger-than-previously-thought-2-5-billiongap-for-2025-2027/

81 Krugman, A. (2025). The State of Global Health Funding: August 2025. Think Global Health. https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/state-global-health-funding-august-2025

82 Alexander, K. A., Sanderson, C. E., Marathe, M., Lewis, B. L., Rivers, C. M., Shaman, J., Drake, J. M., Lofgren, E., Dato, V. M., Eisenberg, M. C., & Eubank, S. (2015). What factors might have led to the emergence of Ebola in WestAfrica?. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 9(6), e0003652. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003652

83 Hrdličková, Z., Macarthy, J. M., Conteh, A., Ali, S. H., Blango, V., & Sesay, A. (2023). Ebola and slum dwellers: Community engagement and epidemic response strategies in urban Sierra Leone. Heliyon, 9(7), e17425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17425

84 The New England Journal of Medicine. (2016). After Ebola in West Africa — Unpredictable Risks, Preventable Epidemics. The New England Journal of Medicine. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsr1513109

85 Kamradt-ScottA. (2017). What Went Wrong? The World Health Organization from Swine Flu to Ebola. Political Mistakes and Policy Failures in International Relations, 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68173-3_9

86 Ibid.

87 “About WHO.” World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/about

88 Matibe, P. (2025, May 27). Global Power Rivalry: Africom and Africa in the face of China and Russia’s influence Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2024/10/02/global-power-rivalry-africom-and-africa-in-the-faceof-china-and-russias-influence/

89 Suzuki, M., &Yang, S. (2023). Political economy of vaccine diplomacy: explaining varying strategies of China, India, and Russia’s COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy. Review of International Political Economy, 30(3), 865–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2074514

90 Haque, N. (2025, December 31). A marriage of three: Will Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso bloc reshape the sahel?. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2025/12/31/a-marriage-of-three-will-mali-niger-burkina-faso-blocreshape-the-sahel

91 Woldegiorgis, M.M., Omer, H.M., Taye, A.Y. (2025). Normative Consequences and Opportunities of DevelopmentAid inAfrica. In:Abourabi, Y., Durand de Sanctis, J., Ferrié, JN. (eds)African Continental Governance: Normative Trends andAgency Challenges. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3032-04431-0_9