Hofstra University

Model United Nations Conference 2026

Special Political and Decolonization Committee (SPECPOL)

Jacob Bass, Co-Chair

Dayanna Rubio-Chacon, Co-Chair

Dear Participants of the Hofstra University Model United Nations Conference,

My name is Jacob Bass and I am a senior History and Social Studies Education major, as well as one of the Co-Chairs of the United Nations Special Political and Decolonization Committee (SPECPOL) committee for this year's HUMUNC conference. It will be great to meet all of you soon!

I have been involved with Model UN ever since ninth grade in high school. Model United Nations is a concept that has always fascinated me, combining my love for global affairs with a great opportunity to practice speech and debate in a unique way. Now in college, I had my first experience with the Hofstra Model United Nations Conference (HUMUNC) two years ago as a backroom member of a crisis committee. I served as Co-Chair for the NATO committee last year, and throughout my experience over those days, I was able to see just how this conference can be eventful, fun, productive, and educational. I have come back to lead a committee at HUMUNC 2026 for you all.

For a long time, I have loved history; it is my favorite subject in school, with math close behind. I have found my love for it growing in various ways over the years, and becoming a teacher is something I truly desire to do. I want to make learning history more interesting and not the stereotypical "boring" subject in school. We are living history every day- even if we are not thinking about it - and the study of global affairs can be our way of studying history as it is happening. In this committee, you will be doing just that, involving yourself and making history in the present!

But be aware that this will not be an easy task to complete, as a case we are looking at involves Kurdistan, a word that describes a place, a people, and an idea that, unlike the states represented on our own committee, does not show up as a nation on world maps. The Kurdish people have long been estimated as the largest ethnic group in the world without their own country. Kurdish autonomy and rights have been subject of referendums, protests over cultural expression, armed resistance, and decades of oppression. Several questions remain: what will be the fate of the Kurds? Will Kurdistan ever become a recognized state? Will Kurds be able to function in semiautonomous regions of existing states? How will Kurds continue to thrive in the center of the churning geopolitics of the Middle East?

In this committee topic, it will be up to you to come together and represent the international community's response to the Kurdish question while balancing issues of human rights and cultural preservation at the heart of your challenge.

Stay excited,

Jacob Bass Co-chair, SPECPOL HUMUNC2026

Greetings and salutations HUMUNC Delegates,

It is a great pleasure and honor to personally welcome you all to the Hofstra University Model United Nations Conference (HUMUNC) 2026, located on our very own campus. My name is Dayanna Rubio-Chacon and I will be serving as one of your co-chairs for the United Nations Special Political and Decolonization (SPECPOL) committee.

I have been debating in Model UN for only over a year, but it has been one of the greatest decisions I have ever made. From the moment I walked into the first meeting, I fell in love with the art of debate and diplomacy. Model UN has changed me so much that I even switched my major from what was originally Computer Science, to now Political Science with a concentration in International Relations (but still a Computer Science minor!). I was once an individual that was afraid to speak my mind, but now I am as open and loud as a diplomat without a filter.

Delegates, you are all up for a great challenge that cannot go through a filter: understanding the complex historic, cultural, ethnic, and political background of the Kurds, a group of people who, for decades, have fought through oppression of various government to achieve autonomy and to have a homeland that is recognized across the globe. The greatest difficulty you all will face as a diplomat is to advocate for your positions and find compromise when necessary, especially in times of crisis where human rights are at stake. The question of sovereignty and selfdetermination for Kurdistan lies in your hands.

Though I am still a novice delegate, Model UN has taught me the meaning of serious discussion, negotiation, strategy, and public speaking. It is with great joy and hope for you all to experience and learn these important skills in this year’s HUMUNC as I have within the club. On top of everything, I am incredibly honored and grateful to have this committee as my first experience as Co-Chair.

Wishing the best and most incredible debates to you all!

With great Pride,

Dayanna Rubio-Chacon Co-Chair, SPECPOL HUMUNC2026 drubiochacon1@pride.hofstra.edu

Introduction to the Special Political and Decolonization Committee (SPECPOL)

The Fourth Committee of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly is the Special Political and Decolonization Committee (SPECPOL). It was founded in 1990 when the Special Political Committee and the Decolonization Committee merged in a greater United Nations effort to end colonialism during its “International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism”.1 It is one of the four committee of the United Nations General Assembly and accomplishes some of its work though sub-committees, such as the Special Committee on Decolonization (C-24).2

The committee is responsible for the annual supervision of the UN’s response to topics focused on how decolonization has affected certain countries and regions. These topics include:

…the effects of atomic radiation, questions relating to information, a comprehensive review of the question of peacekeeping operations as well as a review of special political missions, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), the Report of the Special Committee on Israeli Practices and International cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space.3

To illustrate SPECPOL’s mandate, the committee’s 2025 sessions resulted in a call for commitments from administering powers to address decolonization in the seventeen remaining colonial territories monitored by SPECPOL, reaffirming the mandate of UNRWA, and the establishment of an “International Day against Colonialism in All Forms and Manifestations”, as well as other topics.4

Topic 1: The Kurdish Question

The motivations of SPECPOL came out of decolonization at the end of the Cold War, in line with principles stated in the UN Charter. SPECPOL today aims to continue this work on

behalf of regions where colonization continues. The Kurdish people have garnered attention in the context of nations like Türkiye, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Armenia — and whether they are a “colonized” people. The goal of the committee, as members of SPECPOL, will be to debate amongst each other in the framework of special political and decolonization themes, how, if at all, should the Kurdish situation apply within the context of colonization, and what, if anything, should be done, while reflecting on the past efforts of the Kurds to define their political status.

The Dream of Kurdistan and Geopolitical Reality

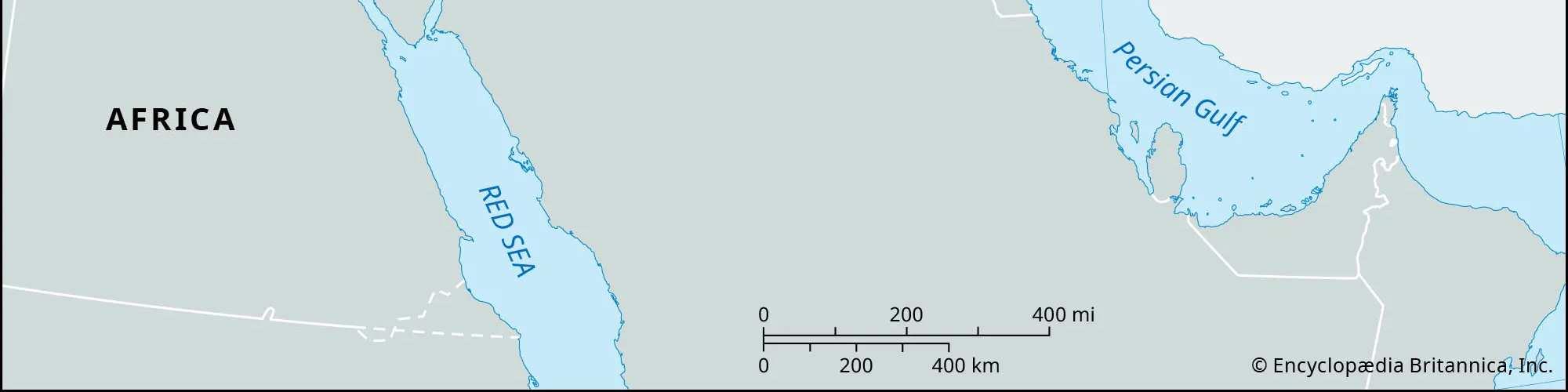

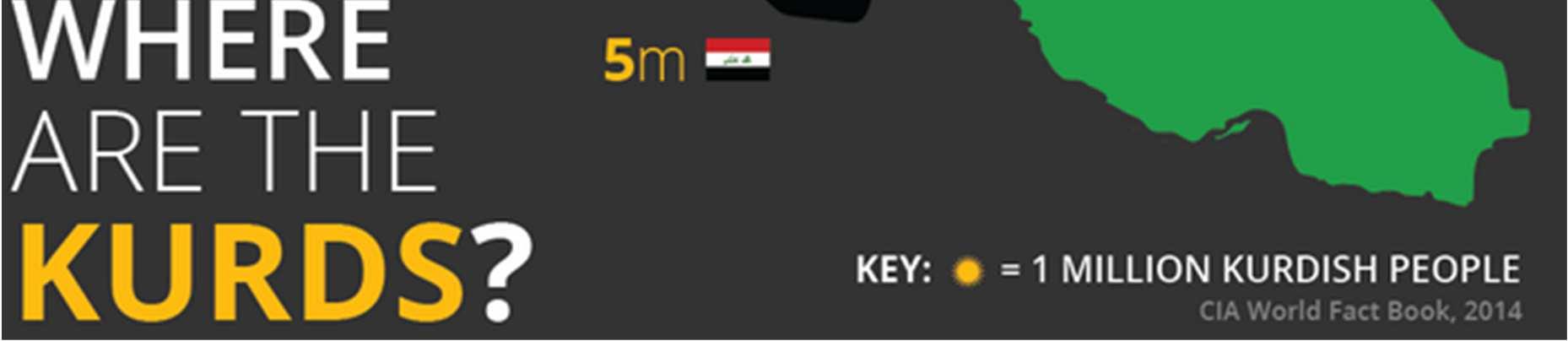

Kurdish people live in several countries across territory in southeastern Türkiye, northeastern Syria, northern Iraq, southern Armenia, and western Iran. The Kurdish people are ethnic group whose members mostly practice Sunni Islam and, in contemporary history, are the largest ethnic group who do not have a home country of their own. With an estimated population of approximately thirty million people,5 they have populated the Middle East and Asia Minor for over a thousand years.6 Their recorded history stretches back as far as approximately 990 AD, when they were citizens of many larger empires that dominated in the Middle East. Since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, they have asserted their right to selfdetermination and statehood, despite never having a traditional territory of their own.7

The fact that Kurds have never had their own state, and that their current population is spread across several countries, has presented challenges in their ability to make a case for an independent homeland, today. In the countries where they reside, there is strong resistance to the idea of giving up territory to create a new neighbor, especially since many of these countries are governed by authoritarian or nationalist regimes that see Kurdish claims as a threat to their power or the founding ideas of their country.

This committee will be charged with discussing the status of the Kurdish people and their desire to gain an independent state. But is this viable? How does it affect the rights of other UN Member States? Are there alternate arrangements that can meet the goals of Kurdish independence with less disruption? Or is the creation of an independent Kurdistan ultimately in line with the goals of the United Nations?

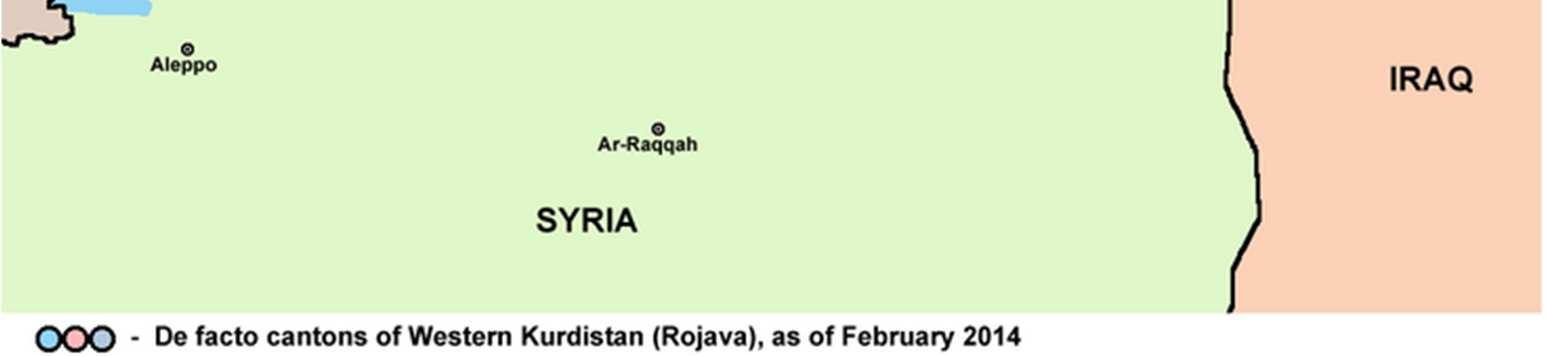

Figure 1: Kurdistan layered over national borders8

Due to the results of various conflicts throughout the 21st century, most notably the War in Iraq, the Kurdish people have had fluctuating control over in some of the regions where they live. What is the current status of Kurdish populations in the countries they inhabit? Because Iraqi Kurdish militias allied themselves with the United States against Saddam Hussein, they earned official recognition for their semi-autonomy in Iraqi Kurdistan region, representing the closest the Kurds have come to gaining an official territory and political control over their

affairs, to date.9 More recently, neither the Kurds in Iraq nor those based in other countries have been able to expand on their goal of an independent Kurdish homeland. What are the obstacles, inside and outside the Kurdish community, which might stand in the way of this goal?

Türkiye

The campaign for an independent Kurdistan has been especially fraught in Türkiye; a country whose founding principles aim to reduce the influence of various identities inside its borders in order to forge national unity. The idea of Kurdish autonomy, and especially any sense of nationalism, has been bitterly opposed by succeeding Turkish governments.

Formed from the former territory of the Ottoman Empire, Türkiye had its borders settled by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which nullified the 1920 The Treaty of Sevres which initially

outlined the post-war borders for Türkiye and proposed an autonomous Kurdish territory. After the Treaty of Lausanne, the Kurdish people found themselves divided by new international borders, with pockets of Kurds living inside several neighboring countries, including mountainous southeastern Türkiye.

The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) formed in 1974 by Abdullah Ocalan for Kurds living in Türkiye to fight an independent Kurdish state, after more loosely organized rebellions had failed in previous years. Because of its Marxist origins, it was opposed by the United States, but welcomed by Syria, which gave Ocalan a base of operations across the border from southeastern Türkiye. The PKK resorted to terrorist attacks to achieve its aims starting in 1984, which led to military reprisals by Türkiye that has cost the life of an estimated 40,000 Turks and Kurds.11

The PKK’s actions showed a different side of the struggle for independence, one that did not gain many international allies. In 1997, the United States, siding the wishes of its NATO ally Türkiye, designated the PKK as a terrorist organization. Türkiye achieved another diplomatic victory in 1998, when it signed the Asana Accords with Syria, which called on Syria to end support for the PKK. As a result, Ocalan was forced to flee his refuge in Syria and was arrested by U.S. forces in Kenya in 1999. Returned to Turkish authorities, Ocalan stood trial and was sentenced to life imprisonment.12

Türkiye’s military actions against the Kurds were balanced by their attempts to increase their prestige. In 2003, to improve its chances to gain European Union membership, Türkiye passed reforms to “expand Kurdish political and cultural rights, such as permitting the use of the Kurdish language in national television broadcasts.”13 Additional reforms announced in 2009 by then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan were soon reversed after a “nationalist backlash”.14

Türkiye began talks with the PKK in 2009 to end their decades-long conflict. Following the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, Türkiye sought to assert itself as a regional power.

Türkiye also aimed to weaken the PKK’s stature among other Kurdish groups by improving relations with Iraq’s Kurdish Regional Government (KRG). Now president, Erdogan travelled to the KRG and made an agreement to import oil and gas from KRG territory.15

During the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS (the Islamic State) which began in 2014, Türkiye did not want the conflict spilling over into its territory from northern Syria, the center of ISIS strength. Türkiye not only launched airstrikes against ISIS but also used the opportunity to attack PKK targets in Iraqi Kurdistan and Syria. When Türkiye saw Syrian Kurds gain control over cantons (districts) in northern Syria, they sent in troops to support Syrian Arab forces and limit the territory that Kurds could control. Türkiye was angered when the U.S. supported the Syrian Defense forces, composed mostly of a Syrian Kurdish militia called YPD, allowing them to seize the ISIS capital, Raqqa. In 2018, Türkiye continued its competition with YPD, working with its favored militias to secure Afrin in northern Syria to block Kurdish control.16

The struggle-within-the-struggle between Türkiye and Kurdish forces in Syria led to a scathing UN report on the conflict “alleging that the [Türkiye ]-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) committed war crimes in northern Syria…that the SNA carried out murder, torture, and arbitrary detention, as well as coerced primarily Kurdish residents to flee their homes. The UN team also accuses Kurdish forces of unlawful detention and recruitment of children.”17

In 2020, Türkiye further attacked PKK targets based in the KRG in response to alleged attacks on Turkish bases. Iraq’s Kurdish government did not block its ally Türkiye, despite reports of civilian casualties, and even granted additional rights to Turkish bases on its territory.

The PKK was blamed for additional attacks against Turkish targets in 2021 and 2022, inviting retaliatory campaigns by the Turkish military.18

The pressure applied by Türkiye turned the tide, as the PKK announced it was disbanding in February 2025, claiming it achieved it goals. The PKK underscored its new political mission by declaring a unilateral ceasefire against Türkiye in March 2025, announcing plans to continue to work within Türkiye’s political system to achieve “greater democratization in [Türkiye ]”.19

Iraq

Some of the strongest seeds for Kurdish nationalism were planted in 1946, in the Republic of Mahabad, a short-lived independent territory in Iran where Mustafa Barzani “considered the father of Kurdish nationalism”, formed the movement soon to be known as the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which continues to function as “the dominant Kurdish party” today. By 1961, Barzani used his growing organization to launch a rebellion against the Iraqi government for what it felt were broken commitments on Kurdish autonomy.20

The fighting paused when the Baath party took over Iraq in 1970 and made new commitments to the Kurds. The KDP resumed fighting the Iraqi government in 1974 when those commitments were not realized. The Baathists attempted to reduce the power of the Kurds in their stronghold in northern Iraq, the location of vast oil holdings, by moving in Arab Iraqis to displace Kurds. However, the United States and Iran supported the KDP’s continued conflict with Iraq’s Baathist regime. This support ended in 1975 when Iraq and Iran signed an agreement to settle territorial disputes, and the KDP’s revolt ended. Dissatisfaction with the KDP led to the formation of a new Kurdish party, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), led by Jalal Talabani. The KDP faced another transition when Mustafa Barzani died in 1979 and was replaced by his son, Masoud.21

During the Iran-Iraq War that churned from 1980 until 1988, the Kurds, whose historical territory overlapped the border area contested by both Iran and Iraq, found themselves on the front lines of the conflict. Kurdish groups on the Iranian side of the border were empowered by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein to attack inside Iran, while Iraqi Kurds were enlisted by Iran for attacks against the Saddam’s regime. Rather than using their role in the conflict to a strong sponsor for their goals of autonomy, the Kurds were further divided by factionalism.22

In September 1988, at the end of the Iran-Iraq War, the Kurds experienced one of the great catastrophes suffered by their people, as:

Saddam carries out the al-Anfal (‘the spoils’) campaign, known as the Kurdish Genocide, which includes mass killings, the destruction of thousands of villages, and the use of chemical weapons against civilians. An estimated 50,000 to 180,000 Iraqi Kurds are killed and tens of thousands displaced. On March 16, as many as five thousand Kurds are killed in a sarin and mustard-gas attack on the town of Halabja.23

Following Iraq’s defeat at the end of the Gulf War in 1991, Saddam Hussein aimed to attack Iraqi Kurdish forces battling his forces. “In response, a U.S.-led coalition carries out Operation Provide Comfort and the subsequent Operation Northern Watch, supplying humanitarian aid and enforcing a no-fly zone over Iraqi Kurdistan, allowing the Kurds to return.”24 As a result, Iraq’s Kurds had the protection of the international community to practice “de facto autonomy” and governance, forming the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and National Assembly in 1992 to govern Iraqi Kurdistan separately from the national government in Baghdad.25

Factional fighting that broke out in 1996 between the two major parties in Iraqi Kurdistan, Jalal Talabani’s PUK and Barzani’s KDP, saw the strange bedfellows of Barzani asking Saddam Hussein to help defeating the Iranian-sponsored PUK. “The conflict [ended] with the U.S.-brokered Washington Peace Agreement on September 17, 1998.”26

The U.S. relied on its relationship with the KRG in 2003 during the War in Iraq, when it enlisted the Kurds to secure the north of the country. As a result, Kurdish parties were part of the post-war landscape on the national level, joining in the drafting of a new constitution that enshrined semi-autonomy for KRG into law. Jalal Talabani was appointed president of the transitional Iraqi government. Kurdish representation in the national government also included positions in the new Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s government.27

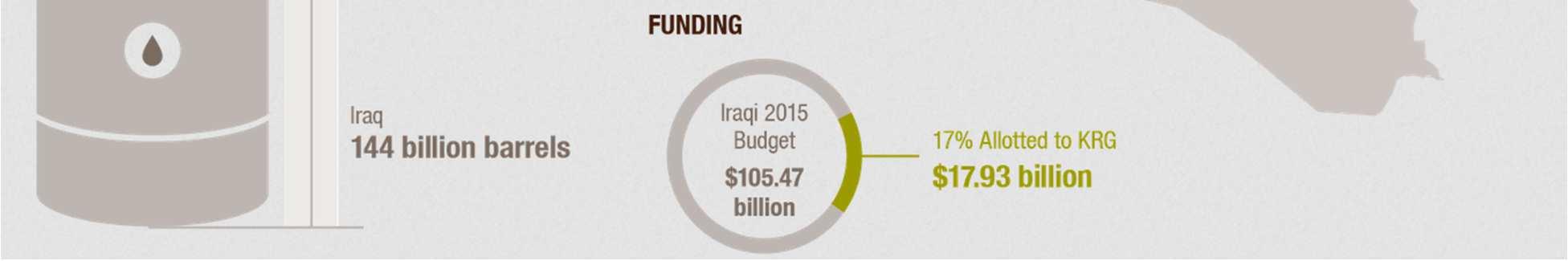

The KRG faced challenges in consolidating or maintaining its power in the post-Iraq war era. The KRG government sought to make direct sales of oil in 2013, rather than having sales coordinated with the national government. Fearing these oil sales were an attempt to establish funding to create an independent Kurdish state, the Iraqi national government threatened to cut other funding, leading to the KRG backing off.28

Figure 3: Iraqi Kurdistan’s key assets29

The once battle-tested Kurdish forces (peshmerga) were put on their heels in 2014, when ISIS took control of parts of Syria and then crossed the border into Iraq. Initially, ISIS secured some of the KRG’s territory, including the oil production center of Kirkuk. The peshmerga reconstituted and retook control of Kirkuk in June 2014. Iraqi Kurdish forces coordinated with

Kurdish groups from Syria and Türkiye, in league with U.S. forces, to battle ISIS across Iraq and Syria, even though Türkiye was apprehensive about the PKK gaining credibility for its role.30

One of the noteworthy events in modern Kurdish history took place in 2017, when the Iraqi Kurdish region voted on a referendum for independence from Iraq. The referendum resulted in ninety-three percent of the population voting for independence from Iraq. Although they had been warned not to secede, the nature of Kurdish politics made it necessary for leaders to hold the vote and show its people that independence was still a goal of their political movements. However, the Iraqi government’s rejection of the results led governments in Iran and Türkiye to close their borders to Iraqi Kurdistan and the Iraqi government to send troops to assert its control over the region. It also revealed political weaknesses between the leading Iraqi Kurdish factions the KDP and the PUK, which had mobilized its supporters to vote in the referendum.31

Iran

Kurds living in Iran have had a mostly adversarial relationship with various Iranian governments. In January 1946, Iranian Kurds formed an independent Republic of Mahabad in territory occupied by the Soviet Union in World War II that overlapped with areas where Kurds lived. When the Soviet forces pulled out in December 1946, Iranian forces moved in, forcing the end of the republic.32

The Iranian regime of Shah Reza Pahlavi supported a revolt in 1974 by Iraqi Kurds who were displaced by Saddam Hussein’s forces in northern Iraq. The following year, when Iraq and Iran signed an agreement to exchange territory on their border and end their conflict, Iran (and its ally, the United States) withdrew support from the Iraqi Kurds.33

Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the Kurdish populace of Iran has faced difficulties in asserting their rights as a minority in a Shiite Muslim, ethnically Persian Iran. Based mostly in western Iran, they constitute an estimated ten percent of Iran’s population.34 As Iran’s revolutionary government solidified control, it did not tolerate rights for Kurdish groups.

Kurdish uprisings in Iran in the 1980s and 90s were met with heavy repression. Key Kurdish parties were pushed out of their strongholds, and many of their leaders and fighters relocated across the border to bases in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. Civilian communities were also forced into Iraq, although large Kurdish communities remained inside Iran.35

During the Iran-Iraq War from 1980-1988, the Kurdish population, which lived in the border areas of each country, found itself in the middle of the conflict. Iran once again supported Iraqi Kurds to attack in Iraq, while Iraq sponsored Kurds living in Iran to revolt against its government. The Kurds suffered on two fronts, as a result; divisions grew among Kurdish groups on either side of the border. Also, both Iraq and Iran viewed “their Kurdish populations as collaborating with the enemy and retaliate against civilians, destroying villages and carrying out summary executions.”36 The most notorious reprisals conducted during the war were the al-Anfal campaign (Kurdish Genocide) by Saddam Hussein’s forces against Iraqi Kurds.37

Most recently, Kurdish Iranians formed the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK) in 2004 in the wake of the War in Iraq, using bases in the mountainous border region between Iraq and Iran to conduct armed attacks against Iranian targets.38 PJAK’s ties to the Turkish Kurds of the PKK meant it was designated a terrorist organization by the United States, leaving it without international support. PJAK signed a ceasefire with Iran in 2011 after suffering heavy losses in an Iranian retaliation campaign.39

During a wave of anti-government protests in Iran in 2022 resulting from the death of a Kurdish-Iranian woman detained by police, the government launched drone strikes and missiles

against Iraqi Kurish groups for allegedly backing the protests. The attacks “[killed] at least twenty people within two months and injure dozens more; the casualties include civilian women, refugees, and children.”40

Syria

Kurds have also faced major repression in Syria throughout the country’s history. After a government census in 1962, “Kurds who [could not] prove their residence in Syria prior to 1945 and those who [failed] to participate are stripped of their citizenship, rendering them stateless and unable to travel. These Kurds and their descendants are unable to vote, own property or businesses, or legally marry.”41 In 1973, the Arab-nationalist Syrian government further aimed to dilute Kurdish influence along Syria’s northern border with Türkiye, which falls within an area rich in natural resources, by displacing Kurds living there and moving in Arab Syrians.42

Despite the Syrian Kurdish population facing official repression, the Syrian government permitted Abdullah Ocalan and his Turkish Kurd PKK to use Syria as a base after the military took power in Türkiye. This continued until 1998, when Türkiye and Syria signed an agreement ending Syia’s support for PKK, eventually leading to Ocalan’s arrest.

In 2003, the Kurdish Democratic Union (PYD) formed, seeking “recognition of Kurdish rights and regional autonomy”. By aligning with the more militant approach of the PKK, it was at odds with other Syrian-Kurdish parties. In 2004, a funeral procession for nine Kurdish youths killed in a brawl with Arab teenagers was attacked by Syrian government forces, setting off protests by Syrian Kurds in Qamishli and abroad. To quell the conflict, Bashar al-Assad offered citizenship to some Kurds who were forced to register as foreigners in the 1962 census.43

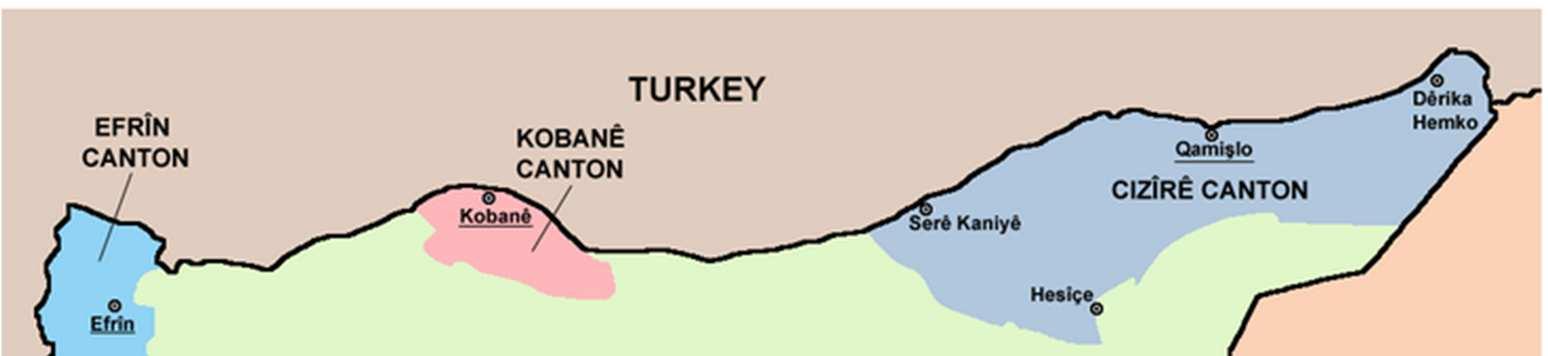

After Syria’s Civil War began in 2011, Syrian-Kurds joined the opposition to the alAssad regime. In 2013, The PYD declared that three cantons (districts) in northern Syria would now be known as “Rojava”, or Western Kurdistan. However, by the time ISIS began to rise in 2014, it attacked Kobani, a city in Western Kurdistan that bordered Türkiye. The U.S. bombed ISIS forces to support PYD forces on the ground. Although Türkiye opposed ISIS, they objected to U.S. support for any group allied with the PKK, revealing the complex dynamics of the position of Kurds in the region.

Figure 4: Cantons controlled by Syrian Kurds, February 202444

The Kurdish forces have been the main group backing behind the Syrian Democratic Forces, which also supported by the United States. They have been a controversial body, mainly in the eyes of the Turkish, who see it as just as much a threat as the PKK.45 As the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS continued through 2016, Türkiye would attack the PKK in Syria and Iraq and back Syrian-Arab rebels, fulfilling a dual objective of fighting ISIS while limiting the growth of Kurdish territory and influence in northern Syria. This dynamic continued after ISIS was defeated in 2019, with Türkiye replacing U.S. forces on the ground and shifting priorities to reducing the influence of Syrian-Turkish groups.46 Since the end of the Syrian Civil War, there

have been talks about integrating the Kurdish region into a more federalized Syrian state, however, negotiations are still tense.47

Armenia

Kurdish people arrived in Armenia in 1828, after fleeing some of the intermittent conflicts known as the Russo-Turkish wars. More Kurds arrived in significant numbers in 1918. When Armenia was part of the Soviet Union, Kurds were counted among the Yazidi (Yezidi) population, until reforms of the 1980s allowed them to distinguish themselves as their own group. Still, they were otherwise not restricted from participating in Armenian society.48 One Armenian-Kurdish leader explained that Armenian Kurds, unlike Kurds in other parts of the Middle East, have “enjoyed freedom regarding practicing one’s culture, language and traditions” while living in Armenia.49

Armenian Kurds represent the group living the furthest north and also count as the largest ethnic minority in Armenia, estimated at nearly 1,700 in 2022. The teaching of Kurdish language is permitted by Armenia at the primary and secondary level, although there is no significant data on how many Kurds pursue learning the language there. Since 1998, Armenian Kurds have sought greater representation in the Armenian political system, which does not provide any special representation for minority groups. Despite having the first Kurdish member of Parliament elected in 2017, there is still debate about whether special seats or positions in government should be set aside for Kurds and other minorities in Armenia.50

Case Study: 2017 Kurdistan Independence Referendum and Kirkuk Crisis

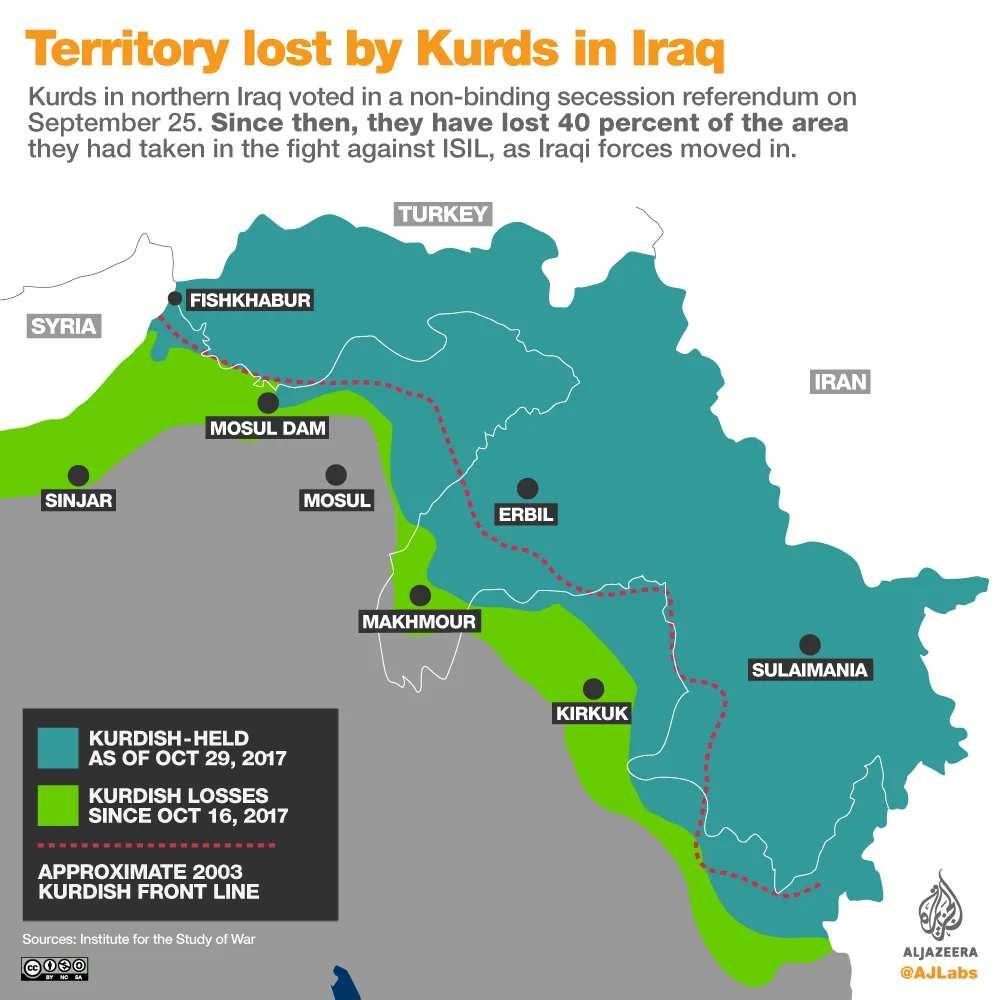

On September 25, 2017, the regional government of Iraqi Kurdistan held a referendum, initiated by regional president Masoud Barzani and the KDP, for the Kurdish people in the region to decide whether or not they should be independent of Iraq. The PUK, however, was not in favor of using a referendum to push for independence, creating a rift between the two major Kurdish parties. Overwhelmingly, the result of the referendum was in favor of independence and autonomy, and it seemed as if the Kurds were finally taking a step forward. However, in response to this referendum’s results, the Iraqi government militarily intervened to suppress the formation of an independent Iraqi Kurdistan.51

Figure 5: Territory lost by Kurds in Iraq (2017)52

The ensuing conflict would come to be known as the Kirkuk Crisis. Iraqi prime minister Haider Al Abadi had asked Kurdish parties to postpone any referendum until greater stability in the region was established after the defeat of ISIS. Barzani’s KDP felt that Kurdish aid in fighting ISIS provided it with the greatest leverage with the international community that it

might ever have and pushed for the referendum. However, the United States and other countries sided with the Iraqi government and did not support the timing. Israel, which shares historical ties with the Kurdish people going back to ancient times, and more recently have worked together in opposition to Saddam Hussein, supported the Kurdish referendum in hopes of strengthening ties with a potential new ally in the Middle East.53

Disorganization among Kurdish parties and the overwhelming attacks from the Iraqi troops caused Kurdish resistance to Iraqi forces to fall in just over a week. As a result, Iraqi Kurdistan lost almost half of its territory and a large degree of autonomy within Iraq. It was considered a humiliating defeat for the Kurdish struggle.54

The Kurdistan Question at the United Nations

Despite the lack of statehood for the Kurdish people, there have been dialogues between the United Nations and Kurdish groups over the years involving many topics, from humanitarian rights to questions of autonomy. According to Stephane Dujarric, current spokesperson for the United States Secretary-General, “The Secretary-General has been very much aware of the Kurdish issues, and I think when he was High Commissioner for Refugees, he dealt with it and was very close to it as well.”55 During the 2017 Kirkuk Crisis, the United Nations expressed concerns over violence against Kurds and human rights violations after analyzing the violence used by Iraqi troops to displace the Kurdish people. They have since urged the Iraqi government to cease all violence against the Kurdish people.56

The United Nations does not have any active plans to address the idea of an independent Kurdish state. Given the continued struggle between the Kurdish and the other national governments in the region, as well as the lack of solid efforts by the United Nations on helping

the Kurdish people, how can the assembled SPECPOL delegates confront the questions of the future of the Kurdish people?

Bloc Positions

The situation in Kurdistan is complex, and as can be expected, many nations may have a nebulous policy on the topic. However, there are some patterns that will likely guide bloc formation. Western democracies like the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Germany have relied on the Kurds over the years for conflicts with authoritarian regimes in Iraq and Iran, as well as in the fight against the Islamic State, leading many to become among the Kurd’s strongest supporters.57 The United States recently opened the world’s largest consulate in Erbil (Iraqi Kurdistan) and discussed strengthened economic ties with the U.S., including new business partnerships with American companies like Google, IBM, Visa, PepsiCo, and CocaCola58 Indeed, few nations, aside from Israel have supported Kurdish independence. Nations that host large Kurdish populations, including Türkiye, Iraq, and Iran, strongly oppose Kurdish independence — responding in various ways over the years to limit Kurdish nationalism by banning language and cultural expression, to diluting Kurdish populations, opposing political rights, and engaging in military conflict with Kurdish groups.59 The rest of the Middle East/North Africa, including Egypt,60 Saudi Arabia,61 and the United Arab Emirates62 have held dialogue with top Kurdish officials to strengthen diplomatic and economic ties with Iraqi Kurdistan as a regional government, but have not overtly supported an independent Iraqi Kurdistan or a greater independent Kurdistan.

The following nations/groups currently host representatives from Iraqi Kurdistan, though this does not necessarily indicate support for independence:63

● Commonwealth of Australia

● Republic of Austria

● European Union

● Republic of France

● Federal Republic of Germany

● Islamic Republic of Iran

● Republic of Italy

● Republic of Poland

● Russian Federation

● Kingdom of Spain

● Kingdom of Sweden

● Swiss Confederation

● United Kingdom

● United States of America

Discussion Questions

1. How does SPECPOL’s mandate to supervise decolonization apply to the unique circumstances of the Kurdish people?

2. What exact measures should SPECPOL take, if any, to call for greater human rights protections for the Kurdish people?

3. What types of interventions can SPECPOL engage in within nations like Türkiye or Iraq to supervise or evaluate referendums related to Kurdish populations in their borders?

4. How will the varying interests of the member states be managed as an organization while assessing the future of the Kurdish people?

5. For countries based outside of the region, how can they assess their own viewpoint on various options for the Kurdish people?

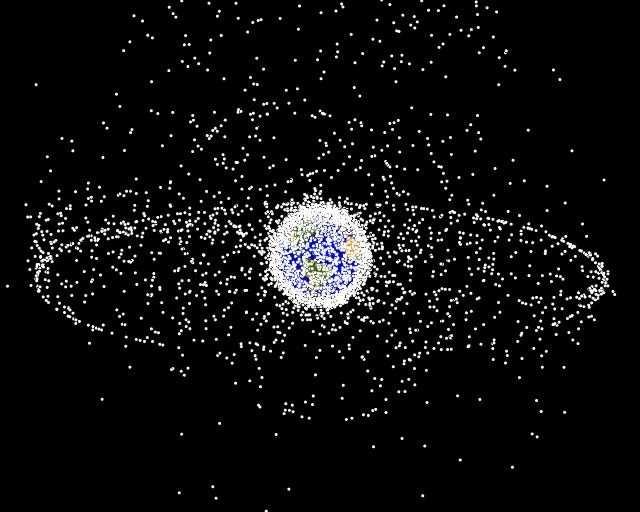

Topic 2: The Dangers Caused by Space Debris

The many discoveries and achievements in the realm of space travel have been accompanied by the difficult and often ignored problem of the “space junk” left behind. Much of the debris cluttering the skies above Earth comes from both countries and private companies leaving waste from space travel (decommissioned satellites, waste from the International Space Station, and remnants of spacecraft) in orbit instead of bringing it back to Earth for disposal.64 Since the beginning of space exploration in 1957, with the launch of the Sputnik I satellite, the incidence of this space junk has only grown.65 As the amount of space junk in orbit increases, the potential for dangerous collisions with this debris rises, as well.

In the past, the majority of space junk was purposely left in orbit, but as the amount increases, collisions between pieces of junk contribute to a positive feedback loop of increasing debris. Stijn Lemmens, Senior Space Debris Mitigation Analyst at the European Space Agency (ESA) explained that “[currently], most space debris comes from [planned] explosive break-up events; in the future, we predict collisions will be the driver. It's like a cascade event: Once you have one collision, other satellites are at risk for further collisions.”66

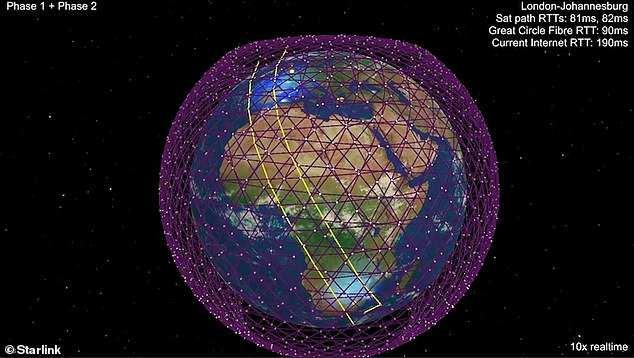

With more and more countries, and more concerningly, private companies, launching satellites, participating in space travel, and exploring space, the threat of collisions and increasing debris has become more of a pressing issue. One of the most prominent private companies is Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which has its own satellite program called Starlink, a network of linked satellites.68 The goal of the Starlink satellite program is to provide low latency, broadband internet access globally through a series of satellites “bouncing signals to orbit before returning them down to earth.”69 As of January 2026, Starlink has more than 9,400 satellites in orbit,70 worrying some astronomers that they will begin to block the view of some existing telescopes.71

Beginning in 2026, Starlink will begin to move half of their satellites, about 4,400, to a lower orbiting altitude, in large part because of the collision risk they face at higher altitudes. In addition to Starlink, whose satellites make up about two-thirds of operational satellites currently in orbit, China has also begun rolling out plans for two major satellite constellations to provide internet to its country. Although they remain just plans, the two constellations would add a combined 20,000 satellites to low-earth orbit, dramatically increasing collision risks with existing satellites and other space junk.72

Figure 7: SpaceX model of Starlink satellites (as of July 2020).73

Despite dangers associated with ever-growing clouds of satellites around planet Earth, none of the five major international treaties regarding space mention space debris in any form.74

The issue of space junk is instead handled by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), which was established in 2002 as an inter-governmental body of ten space agencies, as well as the European Space Agency (ESA).75 The IADC has since expanded and is currently comprised of twelve space agencies, including NASA, ROSCOSMOS (Russia), CSNA (China), JAXA (Japan), KARI (South Korea), ISRO (India), the UK Space Agency, CSA (Canada), and SSAU (State Space Agency of Ukraine), as well as the ESA.76 Although these agencies work together under the IADC, they lack the ability to regulate what other countries, especially private companies like Starlink, launch into the low-earth orbit (LEO). The LEO is defined as the top of earth’s atmosphere, about 180 km above Earth, up to about 2,000 km and contains the pathways for many earth-imaging satellites, as well as the International Space Station (ISS).77

In 2007, discussion of mitigating space debris moved to the United Nations. The Scientific and Technical Subcommittee (STSC), which is under the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), built on the regulations agreed upon by IADC for mitigation guidelines. Both COPUOS and the UN General Assembly accepted and endorsed the proposed regulations in 2007.78

With Starlink’s constellation, along with all of the other satellites in the LEO, both coordination among countries and the space junk problem are heightened. Countries within the IADC will need to make plans accounting for the Starlink constellation, but only the United States, where Starlink is based — and not the IADC as a whole — can regulate Starlink’s activities. In addition, debris or fragments of past satellites are not guaranteed to stay within their

known orbit, posing a threat to individual satellites, as well as such a large constellation like Starlink.

The dangers of such a high density of satellites hoping to dodge existing space junk straying from known orbits is best explained by the Kessler Syndrome theory. According to NASA, there are “‘more than 20,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball orbiting the Earth,’” as well as “‘500,000 pieces of debris the size of a marble or larger. There are many millions of pieces of debris that are so small they can’t be tracked.’”79 They can travel up to 17,500 miles per hour, carrying more than enough speed to damage or destroy satellites upon impact. The Kessler Syndrome postulates that once a single collision occurs, it will produce hundreds of additional pieces of space junk through the fracturing of the two pieces.80 In theory, once the density of both satellites and space debris are high enough, their collisions will trigger a spiraling cascade of never-ending collisions, threatening the entire space ecosystem and any human lives in space.

Because of this, the Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), under the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, created a set of guidelines for space debris mitigation, which were adopted by the committee in 2007.81

Table 1: Details of the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS).82

Limit Debris Released During Normal Operations

Spacecraft and orbital stages should be designed not to release debris during normal operations. Where not feasible, any release of debris should be minimized in number, area, and orbital lifetime.

Any program, project or experiment that will release objects in orbit should not be planned unless an adequate assessment can verify that it does not produce long-term danger to future spacecraft or tethered systems.

Minimize the Potential All space systems should be built and operated with the intention

for On-Orbit Break-ups of minimizing the potential of break ups or explosions, whether accidental or intentional. Purposeful destruction to spacecraft should be avoided and not planned at all.

Minimize the Potential for Post Mission Breakups Resulting from Stored Energy

Minimize the Potential for Break-ups During Operational Phases

To reduce post-mission dangers, all on-board sources of stored energy that are no longer needed, such as residual propellants, batteries, high-pressure vessels, self-destructive devices, flywheels and momentum wheels, should be stored safely as soon as this operation does not pose an unacceptable risk to the payload.

During the design of spacecraft or orbital stages, each program or project should demonstrate through models that there is no probable failure mode leading to accidental break-ups or that there are procedures to minimize the probability of their occurrence.

Spacecraft should be periodically monitored while operating to detect malfunctions that could lead to a break-up or loss of control function.

Adequate recovery measures should be planned and conducted; otherwise, disposal and passivation measures for the spacecraft or orbital stage should be planned and conducted.

Avoidance of Intentional Destruction and other Harmful Activities

Intentional destruction of a spacecraft or orbital stage, (selfdestruction, intentional collision, etc.), and other harmful activities that may significantly increase collision risks to other spacecraft and orbital stages should be avoided. For instance, intentional break-ups should be conducted at sufficiently low altitudes so that orbital fragments are short-lived.

Then, in early 2025, the IADC adopted its own guidelines, a revised version of past documents based on the COPUOS guidelines.83 The similarities and differences between these two sets of guidelines are listed in Table 2, below.

Table 2: Debris Mitigation Guidelines from the Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) and the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC).

COPUOS84 IADC85

Guideline Description

1 Limit debris released during normal operations.

2 Minimize the potential for break-ups during operational phases.

3 Limit the probability of accidental collision in orbit.

4

Avoid intentional destruction and other harmful activities.

5 Minimize potential for post-mission break-ups resulting from stored energy.

6

7

8

9

Limit the long-term presence of spacecraft and launch vehicle orbital stages in the low-Earth orbit (LEO) region after the end of their mission.

Limit the long-term interference of spacecraft and launch vehicle orbital stages with the geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO) region after the end of their mission.

Limit debris released during normal operations.

Minimize the potential for on-orbit explosive break-ups.

Minimize the potential for post-mission break-ups resulting from stored energy.

Minimize the potential for break-ups during operational phases.

Avoidance of intentional destruction and other harmful activities.

Avoid the long-term presence of launch vehicle orbital stages and spacecraft in the geosynchronous region .

Objects that pass through the LEO Protected Region, or have the potential to interfere with the LEO Protected Region, should be de-orbited through direct re-entry or by appropriate maneuver into a decay orbit within twenty-five years.

Space programs or projects should incorporate probability of accidental collision estimates into disposal timelines, and design craft to limit collision probability.

Constellations should be planned, designed, and operated to minimize the likelihood of on orbit collisions during operations and disposal stages.

As with many guidelines created by the United Nations and other international bodies, it is difficult to provide any real method of enforcement without the full commitment of Member States, particularly with the influx of private companies like SpaceX participating in space travel. Despite both of these international efforts to combat space junk, the problem has only continued to grow. With the recent addition of satellite constellations, the threat to all existing spacecraft is ever-increasing, and it will be up to the committee to create new solutions to combat these issues.

Case Study

Originally barred from participation on the International Space Station (ISS) due to national security concerns from the United States, China’s space program launched the Tiangong space station, which rotates crews of three people approximately every six months.86 On November 5, 2025, China’s Shenzhou-20 mission to return three of its astronauts to Earth was delayed more than a week after the spacecraft was hit with a piece of space junk.87 While the Chinese space program did not share publicly many of the details of the collision, it is clear that the Shenzhou-20 sustained enough damage on impact that it became unsafe for the crew to return home on that spacecraft.

The three astronauts — mission commander Chen Dong, mission operator Chen Zhongrui, and flight engineer Wang Jie — were eventually able to make a safe return, using the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft that brought the next mission of astronauts to Tiangong.88 While China did have the capability to send emergency spacecraft into orbit for rescue missions and has had to postpone the transfer of space crews for various reasons in the past, this is the first known incident of space junk interfering with a crewed mission into space.

In another incident from September 2020, a large piece of space junk came within a single mile of the ISS, forcing the crew to take emergency measures for the safety of both themselves and the space station.89 The three astronauts aboard the ISS at the time were forced to seal themselves in the Soyuz spaceship, the “safe haven” attachment to the ISS, which would have allowed them more flexibility should the piece of space debris had made contact with the ISS. Between 1999 and 2020, the ISS had to take emergency action nearly thirty times to avoid space debris, with three of those incidents occurring in 2020 alone. Along with the close calls, 2020 also saw three high-risk collisions occur.90 These collisions, along with the space junk that impacted the Shenzhou-20 mission, indicate that the risks of space junk are always present and need to be accounted for in mission planning.

Bloc Positions

Because of the growing concern of space debris mitigation and its possible effect on all nations, this issue will require collective action. Not all countries have space programs, but the threats of space debris and its effects can affect them, as well, since they rely on functioning satellites launched by other countries and private companies to provide them with government and commercial services. However, as more and more countries develop space programs, there has been an increase in applications to both COPUOS and IADC. In addition, many countries with and without space programs have become signatories to COPUOS initiatives like Net Zero Space and the Artemis Accords with the joint goal of ensuring the “long-term sustainability of space activities.”91

The United States was the first country to set its own standards for the mitigation of space debris, with NASA creating its own, and the United States government following suit in 1997.92

Since then, many other nations with the earliest space programs also committed to the mitigation of space debris, which ultimately led to the creation of the IADC in 2002. As evidenced above by Table 2, the mitigation guidelines eventually adopted by the IADC and those of COPUOS are very similar in their goals.

Both the COPUOS and IADC treaties include provisions for mitigation that require additional engineering and inclusions to spacecraft that may not otherwise be added. Although no countries are explicitly against the mitigation of space debris, space agencies that are significantly more active in the use of space technology — like the United States, European Union, Russia, and China — are much more likely to be involved in the creation of space debris.93 While countries like these are party to the COPUOS and IADC treaties for mitigation, private companies are not bound by the same rules (unless regulated by their home country), and the costs of adhering to such treaties may make companies attempt to avoid them because they would prove very costly.

Questions to Consider:

1. What are some improvements that can be made on current guidelines and regulations?

2. Has your country had any difficulties with their space programs due to space debris?

3. Is space debris a priority to your country and its space program?

4. What are your country’s views on private companies becoming more involved in outer space?

Endnotes

1 “SPECPOL: Special Political & Decolonization Committee.” National High School Model United Nations. https://imuna.org/nhsmun/nyc/committees/specpol-special-political-decolonization-committee/

2 “Special Committee on Decolonization.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/dppa/decolonization/en/c24/about

3 United Nations - General Assembly: Special Political and Decolonization (Fourth Committee). https://www.un.org/en/ga/fourth/.

4 United Nations Fourth Committee: Meetings Coverage and Press Releases (Page 1). https://www.un.org/press/en/content/fourth-committee.

5 “Where is Kurdistan?” The Kurdish Project. https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map/

6 Britannica Editors. "Kurd". Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 Jan 19, 2026. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kurd

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 “Where is Kurdistan?” The Kurdish Project. https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map/

11 Ariav, Hargit. “The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness.” The Council on Foreign Relations. Last Updated December 7, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/timelines/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

12 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 “Iraq (Bashur or Southern Kurdistan).” The Kurdish Project. https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map/iraqikurdistan/

30 Ariav, Hargit. “The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness.” The Council on Foreign Relations. Last Updated December 7, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/timelines/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

31 Degli Esposti, N. (2021). The 2017 independence referendum and the political economy of Kurdish nationalism in Iraq. Third World Quarterly, 42(10), 2317–2333. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2021.1949978

32 Ariav, Hargit. “The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness.” The Council on Foreign Relations. Last Updated December 7, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/timelines/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

33 Ibid.

34 Shamim, Sarah. “What do we know about the Kurdish groups in the Middle East?.” Al Jazeera. Jan 19, 2026. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/1/19/who-are-the-kurds-2

35 Ariav, Hargit. “The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness.” The Council on Foreign Relations. Last Updated December 7, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/timelines/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Shamim, Sarah. “What do we know about the Kurdish groups in the Middle East?.” Al Jazeera. Jan 19, 2026. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/1/19/who-are-the-kurds-2

39 Ariav, Hargit. “The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness.” The Council on Foreign Relations. Last Updated December 7, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/timelines/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 “Syria (Rojava or Western Kurdistan).” The Kurdish Project. https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-map/syriankurdistan/

45 Aftandilian, Gregory. "Kurdish Dilemmas in Syria." Arab Center Washington, DC. January 13, 2021. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/kurdish-dilemmas-in-syria/

46 Ariav, Hargit. “The Kurds’ Long Struggle With Statelessness.” The Council on Foreign Relations. Last Updated December 7, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/timelines/kurds-long-struggle-statelessness

47 "Syria merges Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces into state institutions." Al Jazeera. March 10, 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/3/10/syria-merges-kurdish-led-syrian-democratic-forces-into-stateinstitutions

48 “Kurds in Armenia.” Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/communities/kurds-kurdmanzh/

49 Hovhannisyan, Harmik. “Kurds in Armenia.” Fondation-Institut kurde de Paris. https://www.institutkurde.org/en/info/kurds-in-armenia-1192617209.html. October 15, 2007.

50 “Kurds in Armenia.” Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/communities/kurds-kurdmanzh/

51 “After Iraqi Kurdistan’s Thwarted Independence Bid.” International Crisis Group. Report 199. March 27, 2019. https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/iraq/199-after-iraqi-kurdistans-thwarted-independencebid#:~:text=A%20mere%20two%20weeks%20following,lifeline%20to%20the%20outside%20world

52 Chughtai, Alia, et. al. “Territory lost by Kurds in Iraq.” Al Jazeera. November 1, 2017. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/1/territory-lost-by-kurds-in-iraq

53 Halbfinger, David M. “Israel Endorsed Kurdish Independence. Saladin Would Have Been Proud.” The New York Times. September 22, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/world/middleeast/kurds-independenceisrael.html.

54 Ching, Nike. “State Department: Kirkuk Crisis 'Not Over by Any means.” Voice of America. October 18, 2017. https://www.voanews.com/a/iraq-said-security-in-kirkuk-is-restored-but-conflict-not-over/4075477.html

55 “UN Stresses Need for Dialogue in Erbil-Baghdad Relations.” Kurdistan24. September 23, 2025. https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/story/865314/un-stresses-need-for-dialogue-in-erbil-baghdad-relations

56 “Iraq takes disputed areas as Kurds 'withdraw to 2014 lines’.” October 18, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41663350

57 Tawfiq, Hawraman Ali. “The International Status and Position of the Kurdistan Region.” The Kurdish Globe. August4, 2025. https://kurdishglobe.krd/the-international-status-and-position-of-the-kurdistan-region/

58 “United States Opens World’s Largest Consulate in Erbil, Marking a New Era in U.S.–Kurdistan Relations.” Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States. December 4, 2025. https://us.gov.krd/unitedstates-opens-worlds-largest-consulate-in-erbil-marking-a-new-era-in-u-s-kurdistan-relations/

59 Hubbard, Ben and Timur, Safak. “Kurdish Fighters Called a Truce, but Turkey Kept Up Lethal Strikes.” The New York Times. March 12, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/12/world/middleeast/turkey-kurds-deadlyairstrikes.html

60 “Egypt backs Kurdistan region as pillar of stability as Barzani meets Sisi.” December 12, 2025. https://www.middle-east-online.com/en/egypt-backs-kurdistan-region-pillar-stability-barzani-meets-sisi

61 Salami, Mohammad. "Saudi Arabia's Cautious Approach to the Syrian Kurds: Balancing Stability and Geopolitical Interests." Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. April 9, 2025. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/2025/04/saudi-arabias-cautious-approach-to-the-syrian-kurds-balancingstability-and-geopolitical-interests?lang=en

62 "Kurdistan Region Signs MoU with UAE to Enhance Governance and Administrative Capabilities." Kurdistan Regional Government. February 13, 2025. https://gov.krd/english/government/the-primeminister/activities/posts/2025/february/kurdistan-region-signs-mou-with-uae-to-enhance-governance-andadministrative-capabilities/

63 “KRG offices abroad.” Kurdistan Regional Government. https://gov.krd/dfr-en/krg-representations/

64 Hattenback, Jim. “Does Starlink Pose A Space Debris Threat? An Expert Answers.” Sky and Telescope. 3 June 2019. https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/starlink-space-debris/

65 “A Brief History of Space Debris.” Aerospace. 2 November 2022. https://aerospace.org/article/brief-historyspace-debris.

66 Hattenback, Jim. “Does Starlink Pose A Space Debris Threat? An Expert Answers.” Sky and Telescope. 3 June 2019. https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/starlink-space-debris/

67 Ibid.

68 Wall, Mike. “SpaceX Lowering Orbits of 4,400 Starlink Satellites for Safety’s Sake.” Space.com. 2 January 2026. https://www.space.com/space-exploration/satellites/spacex-lowering-orbits-of-4-400-starlink-satellites-for-safetyssake.

69 Koetsier, John. “Starlink Internet From Space: Faster Than 95% Of USA.” 1 November 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/11/01/starlink-internet-from-space-faster-than-95-ofusa/?sh=140c865d1bb0.

70 Wall, Mike. “SpaceX Lowering Orbits of 4,400 Starlink Satellites for Safety’s Sake.” Space.com. 2 January 2026. https://www.space.com/space-exploration/satellites/spacex-lowering-orbits-of-4-400-starlink-satellites-for-safetyssake.

71 Hattenback, Jim. “Does Starlink Pose A Space Debris Threat? An Expert Answers.” Sky and Telescope. 3 June 2019. https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/starlink-space-debris/

72 Wall, Mike. “SpaceX Lowering Orbits of 4,400 Starlink Satellites for Safety’s Sake.” Space.com. 2 January 2026. https://www.space.com/space-exploration/satellites/spacex-lowering-orbits-of-4-400-starlink-satellites-for-safetyssake

73 Liberatore, Stacy. “SpaceX files paperwork for 30,000 more Starlink satellites for high-speed internet - amid fears they will litter the night sky and make stargazing impossible.” 16 October 2019.https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-7577107/SpaceX-files-30-000-Starlink-satellites-approved12-000.html

74 Hattenback, Jim. “Does Starlink Pose A Space Debris Threat? An Expert Answers.” Sky and Telescope. 3 June 2019. https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/starlink-space-debris/.

75 Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science. “Debris Mitigation.” ARES: Orbital Debris Program Office. https://orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/mitigation/

76 IADC. “Member Agencies.” https://www.iadc-home.org/#none

77 European Space Agency. “Types of Orbits.” 30 March 2020. https://www.esa.int/Enabling_Support/Space_Transportation/Types_of_orbits#LEO.

78 Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science. “Debris Mitigation.” ARES: Orbital Debris Program Office. https://orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/mitigation/

79 “Advanced Technology to Remove Space Debris From Orbit.” Capitol Technology University. 1 June 2020. https://www.captechu.edu/blog/advanced-technology-remove-space-debris-orbit.

80 Kelvey, Jon. “Understanding the Misunderstood Kessler Syndrome.” University of Arizona. 8 March 2024. https://s4.arizona.edu/news/understanding-misunderstood-kessler-syndrome

81 United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. https://www.unoosa.org/pdf/publications/st_space_49E.pdf

82 IADC. “IADC Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines.” March 2020. https://orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/library/iadcspace-debris-guidelines-revision-2.pdf

83 IADC. “IADC Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines.” 3 February 2025. https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2025/aac_105c_12025crp/aac_105c_12025crp_9_0_html/AC1 05_C1_2025_CRP09E.pdf

84 United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. https://www.unoosa.org/pdf/publications/st_space_49E.pdf

85 IADC. “IADC Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines.” 3 February 2025. https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2025/aac_105c_12025crp/aac_105c_12025crp_9_0_html/AC1 05_C1_2025_CRP09E.pdf

86 Moritsugu, Ken. “Chinese Astronauts Return From Space Station After Delay Blamed on Space Debris Damage.” PBS News. 14 November 2025. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/chinese-astronauts-return-from-spacestation-after-delay-blamed-on-space-debris-damage

87 Baptista, Eduardo. “China's Shenzhou-20 Return Mission Delayed Due to Space Debris Impact.” Reuters. 5 November 2025. https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/chinas-shenzhou-20-return-mission-delayed-duespace-debris-impact-2025-11-05/

88 Beard, Stephen J. “Astronauts on Chinese Space Station Home After Being Stranded By Debris Impact.” USA Today. 15 November 2025. https://www.usatoday.com/story/graphics/2025/11/15/stranded-chinese-astronautsstuck-on-space-station/87212395007/

89 Business Insider. “‘Unknown’ space debris almost flew within 1 mile of the International Space Station. As junk builds up in orbit, the danger of collisions is growing.” https://www.businessinsider.com/nasa-unknown-orbitaldebris-narrowly-missed-striking-iss-avoidance-maneuver-2020-9

90 Ibid.

91 Smith, Jacqueline H., Minoo Rathnasabapathy, and Danielle Wood. “The Political and Legal Landscape of Space Debris Mitigation In Emerging Space Nations.” Science Direct. 18 December 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S246889672400123X.

92 Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science. “Debris Mitigation.” ARES: Orbital Debris Program Office. https://orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/mitigation/

93 Whittaker, Ian, and Lesley Masters. “Space Debris: Will It Take a Catastrophe For Nations to Take the Issue Seriously?” Space.com. 27 December 2025. https://www.space.com/space-exploration/space-debris-will-it-take-acatastrophe-for-nations-to-take-the-issue-seriously