The first case of LSD in Europe was diagnosed on 21 June in Sardinia (Italy). It involved a farm with 131 animals, seven of which exhibited clinical signs consistent with LSD. A second case was confirmed in Lombardy in northern Italy on 25 June, at a farm that had purchased cattle from the farm where the first infection had occurred. Eight further outbreaks were then reported in Sardinia through to the end of June. On 29 June, the

first case of LSD infection in France was also confirmed, in the Savoie département. At the time of writing, several further suspected cases of LSD infections at cattle farms in that region are awaiting confirmation. Both France and Italy have implemented the measures required by the EU: the animals have been or are being culled and various control zones have been set up (source: WAHIS, BSHVI-SA).

According to information from the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA), no new clinical suspicions of BTV infections were reported in the second quarter of 2025. There were no positive PCR results indicating recent infections. Blood tests will no longer be reimbursed from 1 July 2025 onwards, but the obligation to notify suspected BTV cases will remain in effect (via www.nvwa.nl/ onderwerpen/blauwtong).

It was previously reported that the Veekijker had received numerous reports since the first week of January of calves exhibiting neural symptoms, ranging from abnormal behaviour (“stupid” or “slow” calves) to an arched-back head (opithotonus or “star-gazing”) and nervous signs like twitching and falling over. On top of that, it was noticeable that hydrocephalus or hydranencephaly was diagnosed more often in the first quarter of 2025 than in either the same quarter of the previous year or the fourth quarter of 2024.

In response to this increase, a pilot study has been launched to investigate the number of post-mortem cases of congenital brain abnormalities in calves. A literature review is also being conducted into the gestational period during which these abnormalities can develop, the medical history of the calves in question, and background information on their farms of origin.

The total number of confirmed cases of congenital brain abnormalities has been increasing since October 2024, with the biggest increase happening in January and February 2025, of 23 and 13 confirmed cases respectively. In particular, diagnoses of hydranencephaly have increased, a condition that was not diagnosed the previous years. Congenital brain abnormalities caused by a BTV infection occur when the calf is infected in the womb while its central nervous system (CNS) is developing. The CNS of cattle develops between days 65 and 125 of gestation. All the calves that were part of this pilot were in this high-risk period of gestation during the BTV outbreak.

Royal GD has been responsible for animal health monitoring in the Netherlands since 2002, in close collaboration with the veterinary sectors, the business community, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food Security and Nature, veterinarians and farmers. The information used for the surveillance programme is gathered in various ways, whereby the initiative comes in part from vets and farmers, and partly from Royal GD. This information is fully interpreted to achieve the objectives of the surveillance programme – rapid identification of health issues on the one hand and monitoring trends and developments on the other. Together, we team up for animal health, in the interests of animals, their owners and society at large.

The farms participating in the pilot study have a variety of backgrounds; dairy, veal and suckler cow farms were contacted. The clinical signs of live calves with abnormalities were highly variable: visible physical abnormalities at birth, “stupid” or “slow” calves, inability to drink, stand or walk, staring into space, trembling, falling over, blue eyes, blindness,

pushing, chewing without food, walking in circles, poor coordination, unsteady gait and trembling eyes. Eight animals were tested for BTV antibodies, which were detected in all of them. Six other animals were tested for the BTV virus using PCR and it was detected in five of those. No additional testing for BTV was carried out on six animals. In 2024, 85

per cent of farms in the pilot study had animals exhibiting clinical signs consistent with a BTV outbreak. The percentage of cattle with clinical symptoms varied widely, from 1 to 99 per cent. It was striking that only 10 per cent of the farms that sent calves in for pathological examination had vaccinated their cattle against BTV in 2024.

For animal health monitoring purposes, data from bulk milk deliveries is analysed weekly through bulk milk syndrome surveillance. For each region, this data is compared with the previous four years to identify clusters with lower milk production than expected. If one or more clusters with lower milk production are found in two consecutive weeks, the Veekijker veterinarians will proactively contact veterinary practices in the region concerned to gather more information from the field.

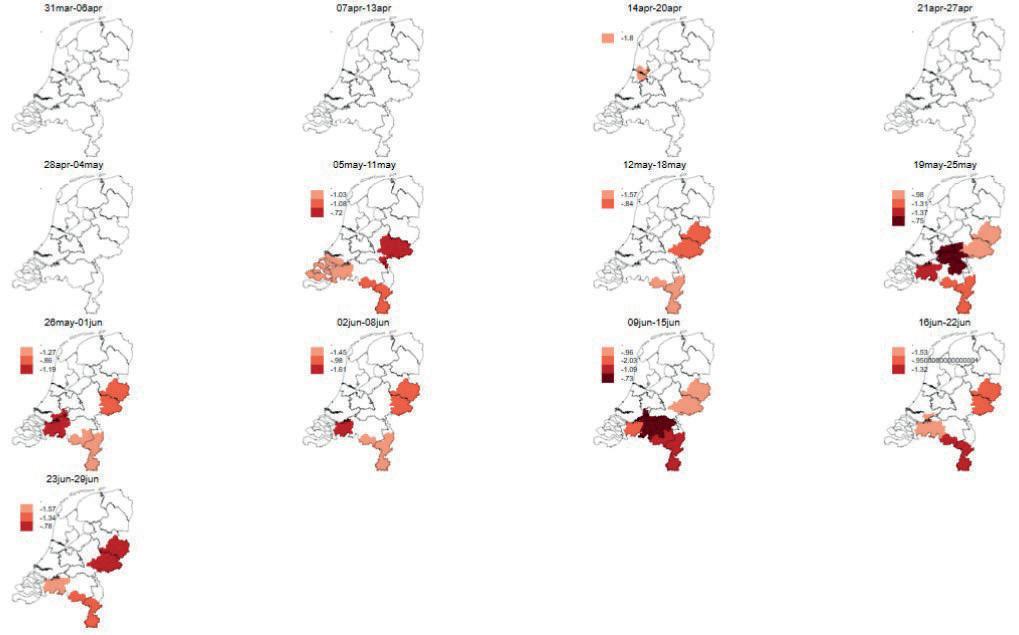

Early in May, syndrome surveillance noted a drop in milk production by 0.72 to 1.08 kilograms per cow per day in various regions of the Netherlands. In the fortnight that followed, milk production kept declining in Twente and Northeast Gelderland (cluster 1) and in Limburg and Southeast Brabant (cluster 2) (see Figure 1). The other observed clusters were only present for a single week. Because of the continuing decline in milk production, the Veekijker veterinarian

contacted three veterinary practices in each region. Initially, general questions were asked during this conversation about anything unusual, and then about specific symptoms such as abnormal milk (in terms of consistency or colour) or a clinical picture that could be consistent with bluetongue. None of the veterinarians had heard anything from farmers about unusual occurrences or clinical disease. All veterinarians, however said that many farms had a large number of cows with a lactation length of 400 days or more because of the reduced fertility and early embryonic mortality during the BTV-3 outbreak of 2024. The clusters found were in the parts of the Netherlands that had been relatively severely affected by the bluetongue outbreak of 2024. According to the veterinarians, the statement that there were more cows with a longer lactation length was supported by farm MPR (Milk Production Registration) data, fewer visits for transitionrelated conditions and a relatively high demand for vaccinations administered during

the dry period. Another explanation frequently given for the poor milk production was the poor grass supply due to drought, forcing livestock farmers to resort to using old, suboptimal grass silage. When a third cluster arose around Western Brabant and the south of Zuid-Holland, the Veekijker also contacted several veterinary practices in that region. They made the same suggestions as possible reasons for the drop in milk production. Although the sizes of these three clusters varied from week to week, they persisted until the end of the second quarter. In the third quarter, the clusters disappeared and milk production returned to normal in all regions.

This case study shows how important it is for the veterinarians at the Veekijker and in practices to be able to contact each other easily. Thanks to its contacts with veterinary practitioners, the Veekijker was able to gather information quickly and explain the signal from syndrome surveillance.

An increase in Salmonella Enteritidis (SEN) infections has been observed on dairy farms since September 2024. Between September 2024 and June 2025, SEN was isolated from 41 samples originating from 26 dairy farms, whereas it was in total isolated from only 134 samples between 1999 and September 2024. Increases in SEN infections have also been observed since 2023 in both humans and poultry. Approximately 39 per cent of human salmonella infections are caused by SEN (source: RIVM). In the Netherlands and Europe as a whole, eggs and egg products are seen as the main source of human SEN infections.

The cause of the increase on dairy farms is unknown. A pilot study was started that aims to characterise dairy farms with SEN infections better and to investigate possible relationships between SEN isolates. This pilot study consisted of three parts:

1. A survey of 19 dairy farms with SEN infections about observed clinical signs and possible risk factors for introduction.

2. Sending five anonymised SEN isolates from five dairy farms (located close to poultry farms or where the symptoms seemed consistent with human salmonellosis) to the RIVM for whole genome sequencing (WGS).

3. Investigating a possible association between the first isolate from each dairy farm and the salmonella vaccine strain for poultry; the potential for that strain spreading to cattle has been described in the literature.

The outcome of the survey shows that SEN was mainly isolated from samples taken from adult cattle. Various risk factors were identified for salmonella being introduced to dairy farms, such as cattle purchase and using surface water for their drinking water. The relative

importance of these risk factors could not be determined, though. None of these dairy farms kept poultry for commercial purposes. At three of the farms, the dairy farmer and/or family members and/or employees described symptoms consistent with salmonella infections, which was confirmed at one farm through additional diagnostics.

WGS demonstrated a close genetic relationship between two of the five cattle isolates, and these also had close genetic relationships with several human isolates from 2022–2025. This suggests a possible link between the infections in cattle and the human cases. The isolates from cattle were not related to any single attenuated poultry vaccine strain (the most commonly occurring one) for which spreading to cattle has been described. Associations with other attenuated SEN poultry vaccines were not studied in this pilot.

VETERINARY DISEASES SITUATION IN THE NETHERLANDS

Category (AHR)

Highlights, second quarter of 2025

Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1882 of Animal Health Regulation (AHR) 2016/429 (category A disease)

Lumpy Skin Disease (LSD) Viral infection.

The Netherlands is officially disease-free.

Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) Viral infection.

The Netherlands has been officially diseasefree since 2001.

A, D, E Infections never detected in the Netherlands. Outbreaks in France and Italy.

A, D, E No infections detected In the Netherlands, some outbreaks in Europe.

Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1882 of Animal Health Regulation (AHR) 2016/429 (categories B to E)

Bluetongue (BT)

Bovine genital campylobacteriosis

Bluetongue serotype 3 outbreak in the Netherlands since September 2023 (see §3.2.1).

Bacterium.

The Netherlands has been disease-free since 2009. Monitoring of AI and embryo stations and of animals for export.

Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (BVD) Viral infection.

Control measures are compulsory for dairy farms but voluntary on beef cattle farms.

C, D, E New infections are not suspected; pilot study of congenital brain abnormalities.

D, E Campylobacter fetus spp. veneralis not detected.

C, D, E The status* of 91.1 per cent of dairy farms is ‘BVD-free’ or ‘BVD not suspected’.

The status of 20.7 per cent of all non-dairy farms is favourable (BVD-free or BVD not suspected).

* The BVD status as determined according to the GD programme.

Brucellosis (zoonosis, infection through animal contact or inadequately prepared food)

Bacterium.

The Netherlands has been officially diseasefree since 1999. Monitoring via antibody testing of blood samples from aborting cows.

Enzootic bovine leukosis Viral infection.

The Netherlands has been officially diseasefree since 1999. Monitoring via antibody testing of bulk milk and blood samples from slaughtered cattle.

Epizootic Haemorrhagic Disease (EHD) Viral infection.

Detected since 2022 in cattle in Europe (Spain, Italy, Portugal and France).

Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR) Viral infection. Control measures are compulsory for dairy farms but voluntary on beef cattle farms.

Anthrax (zoonosis, infection through contact with animals)

Bacterium. Not detected in the Netherlands since 1994. Monitoring through blood smears from fallen stock.

B, D, E No infections detected.

C, D, E No infections detected.

D, E No infections detected. Vaccine has temporary authorisation In the Netherlands.

C, D, E The status of 83.5 per cent of dairy farms is ‘IBR-free’ or ‘IBR not suspected’.

The status of 21.8 per cent of all non-dairy farms was favourable (IBR-free or IBR not suspected).

D, E No infections detected.

VETERINARY

Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/1882 of Animal Health Regulation (AHR) 2016/429 (categories B to E)

Paratuberculosis

Bacterium.

In the Netherlands, the control programme is compulsory for dairy farms. 99 per cent take part.

Rabies

(zoonosis, infection through bites or scratches)

Bovine tuberculosis (TB) (zoonosis, infection through animal contact or inadequately prepared food)

Viral infection.

The Netherlands has been officially diseasefree since 2012 (an illegally imported dog).

Bacterium.

The Netherlands has been officially diseasefree since 1999. Monitoring of slaughtered cattle.

Trichomonas Parasite.

The Netherlands has been disease-free since 2009. Monitoring of AI and embryo stations and of animals for export.

E The status of 83 per cent of dairy farms is A (‘not suspected’) in the PPN (Paratuberculosis Programme Netherlands) or 6 in the IPP (Intensive Paratuberculosis Programme).

B, D, E No infections detected.

B, D, E No infections detected.

C, D, E Tritrichomonas foetus not detected.

Q fever (zoonosis, infection through dust or inadequately prepared food)

Bacterium.

In the Netherlands, this is a different strain to the one found on goat farms with no established relationship to human illness.

From the first quarter of 2023 onwards, this is once again part of the aborter pathology protocol.

E Two infections detected in aborted foetuses.

Article 3a.1 Notification of zoonoses and disease symptoms, ‘Rules for Animal Husbandry’ from the Dutch Animals Act Leptospirosis

(zoonosis, infection through animal contact or inadequately prepared food)

Listeriosis

(zoonosis, infection through inadequately prepared food)

Salmonellosis

(zoonosis, infection through animal contact or inadequately prepared food)

Yersiniosis (zoonosis, infection through animal contact or inadequately prepared food)

Bacterium.

Control measures are compulsory for dairy farms but voluntary on beef cattle farms.

Bacterium. Infections are occasionally detected in adult cattle and aborted foetuses.

Bacterium.

Control measures are compulsory for dairy farms but voluntary on beef cattle farms.

Bacterium.

Infections detected occasionally in cattle.

- The status of 97.9 per cent of dairy farms is ‘leptospirosis-free’.

The status of 29.5 per cent of non-dairy farms is ‘leptospirosis-free’.

No new leptospirosis infections.

- Six infections detected in cattle or aborted foetuses presented for necropsy.

- The bulk milk results of 96.8 per cent of dairy farms are favourable (the nationwide Qlip programme).

- Two infections detected.

Royal GD P.O. Box 9, 7400 AA Deventer

T. +31 (0)88 20 25 575

info@gdanimalhealth.com www.gdanimalhealth.com

VETERINARY DISEASES

Regulation (EC) no. 999/2001

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE)

Prion infection. The OIE status for the Netherlands is ‘negligible risk’. Monitoring has not revealed any further cases since 2010 (total from 1997 to 2009: 88 cases).

Other infectious diseases in cattle

Malignant Catarrhal Fever (MCF)

Viral infection. There are occasional cases in the Netherlands of infection with type 2 ovine herpes virus.

Liver fluke Parasite.

Liver flukes are endemic in the Netherlands, particularly in wetland areas.

Neosporosis Parasite.

In the Netherlands, this is an important infectious cause of abortion in cows.

Tick-borne diseases

External parasite that can transmit infections. Ticks infected with Babesia divergens, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Mycoplasma wenyonii can be found in the Netherlands.

- No infections detected.

Table continuation

- Three infections confirmed upon necropsy.

- Infections were detected at seventeen farms and in five animals presented for necropsy.

- No infections detected in aborted foetuses submitted for necropsy.

- Microscopic examination of blood smears is no longer possible; a PCR test is available for Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Four infections with Anaplasma phagocytophilum detected by PCR.