University College Ghent

Specialization in Environmental and Sustainability Management

Quy Nhơn University

University College Ghent

Specialization in Environmental and Sustainability Management

Quy Nhơn University

“How can a support base for reducing SUPs at Quy Nhon University be established by raising awareness and by offering reusable alternatives?”

GIL HEYMAN and INDY LAPLASSE

Bachelor thesis submitted with an eye on obtaining a bachelor’s degree in business management, specialization in Environmental and Sustainability Management

Mentor: Vo Van Chi

Supervisor: Sara Lieveld

2024-2025

Dear reader

We are conducting this thesis for two primary reasons: (1) to obtain our degree in Environment and Sustainability Management at HOGENT, and (2) to explore and highlight potential strategies for reducing single-use plastics (SUPs) and raising awareness of waste problems at Quy Nhon University (QNU).

We chose this topic because sustainable change is something we are deeply passionate about. Moreover, Vietnam still developing in terms of environmental awareness and sustainability offers both significant challenges and exciting opportunities.

Through this research, that was carried out from the end of March until the end of May 2025, we hope to provide valuable insights for future students involved in the SP7 subproject. This subproject is part of VLIR-UOS, a leading funding organization that supports scholarships and academic partnerships between institutions in Flanders and Asia, with a strong focus on global sustainable development.

We would like to sincerely thank the entire SP7 team (Tuong Vi, Tran Thi Thu Hien, Chi Vo Van, Dang Thi To Nu, Lieu, Tam Truong, Trang, Trang Phan) for their warm welcome, continuous support, and for always being there when we needed them. And also, the Belgian side of the team (Els Van Mechelen, Linde Raport, Yves Ronsse).

A very special thanks goes to Mister Chi, for organizing everything and making this internship possible; to Miss Vi, for her guidance and support throughout the entire stay; and to Miss Hien, for helping us roll out our survey with care and dedication.

We also want to thank Xander Bell and Jasper Ooghe for their valuable insights on our topic and their active involvement in several internship-related tasks. Alongside them, we gratefully acknowledge the visiting lecturers Miss. Gert Hooft, Miss. Ann Messens, and Miss. Nena Baeyens for their engagement and support during their visit.

And last but certainly not least, we would like to thank Miss. Sara Lieveld, who has been our most important support throughout this bachelor’s thesis. Her guidance, openness to questions, and thoughtful, constructive feedback were incredibly helpful and motivating every step of the way.

A special thanks to all students and staff at QNU who welcomed us in Vietnam, especially the members of the Green Club, who became friends as our internship progressed.

We hope you enjoy reading our thesis and that it may offer new insights or inspiration.

Kind regards

Indy Laplasse & Gil Heyman

May 23, 2025

This thesis explores the issue of single-use plastics (SUPs) at the Quy Nhon University (QNU) in Vietnam. While there is a growing interest in sustainability among students and staff, both awareness and sustainable alternatives for SUPs are still limited The widespread use of SUP items on campus contributes significantly to environmental problems and reflects a broader challenge in Vietnam’s waste management practices.

Our main research question is:

“How can a support base for reducing SUPs at Quy Nhon University be established by raising awareness and by offering reusable alternatives?”

To answer this question, we used different kinds of methods. First, we conducted a literature study to better understand the environmental and behavioural dimensions of plastic use, as well as current policies and practices in Vietnam. In annex you can find a report that provides further insights into the environmental and sustainability context in Vietnam.

We then carried out a large-scale survey with 605 respondents to know what the existing knowledge and attitudes towards SUPs within the university were This was followed by an on-campus experiment in which reusable bottles and cups were distributed to a selected group of students and staff. Their usage patterns were monitored over time, with short surveys to assess behavioural change.

Throughout the project, we worked closely with QNU’s Green Club to organize awareness-raising activities such as guest lectures, poster campaigns, and a beach clean-up

Next, the methodology section details the research design, explaining how both quantitative and qualitative methods including surveys were employed to gather insights. The results chapter then presents the key findings from this fieldwork, supported by data analysis and observations.

Our results show that while knowledge on SUPs varies widely between faculties, there is a clear willingness among students and staff to adopt reusable alternatives when properly informed and engaged. However, knowledge about single-use plastics (SUPs) and broader environmental issues is still limited among students. Therefore, continued efforts in awareness-raising and environmental education remain essential.

The results of the experiment have shown us that people use less SUPs when they received a reusable cup/bottle. Nevertheless, we think a solution with reusable cups and bottle will be more effective when working with a deposit system in the canteen at QNU.

Finally, the thesis ends with recommendations. These are primarily focused on improving waste management by the installation of color-coded bins, providing educational lessons, and creating awareness posters.

2.1.1

2.1.2

2.1.3

3.2

3.2.2

3.2.3

3.2.4

3.2.5

3.2.7

3.2.8

3.2.9

3.2.10

Abbreviation

EoL End-of-life

Meaning

EPR Extended Producer Responsibility

GWP Global Warming Potential

HU Heavy users (of disposable plastic cups)

ISW Industrial solid waste

LCA Life Cycle Assessment

MC Multiple Choice

MPs Microplastics

MSW Municipal solid waste

OU Occasional users (of disposable plastic cups)

OVAM Openbare Vlaamse Afvalstoffen Maatschappij

PE Polyethylene

PET Polyethylene Terephthalate

PP Polypropylene

PS Polystyrene

QNU Quy Nhon University

SUP Single-use plastics

UNEP United Nations Environment Programme

USD United States dollar

WtE Waste-to-Energy

WWF World Wide Fund for Nature

List of Figures

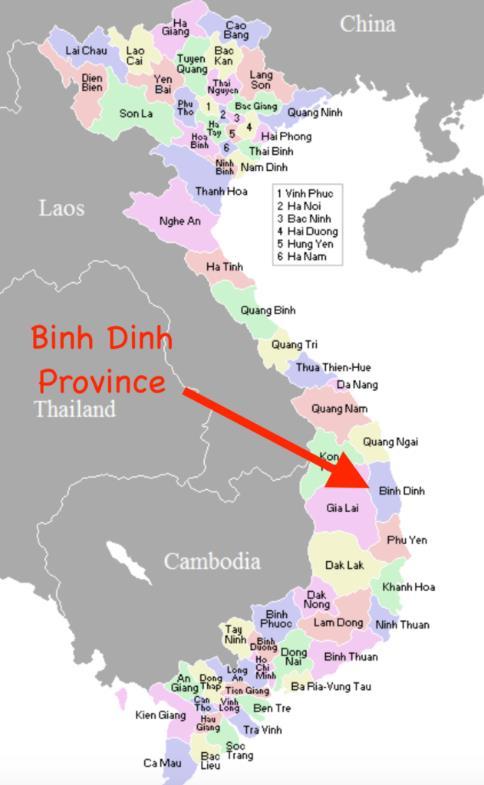

Figure 1: Vietnam, On World Map (2015). 13

Figure 2: Ha Long Bay, Wall Paper Cave (2011)....................................................................13

Figure 3: Local Festival for the celebration of the liberation of the Bin Dinh province - Quy Nhon. Photo by the author, March 2025. 14

Figure 4: Binh Dinh Province, Motormaps, (2022) .................................................................15

Figure 5: TMS Tower Quy Nhon, C. Trang, (2024). 16

Figure 6: Vietnamese delegation of the SP7 project and us. Photo by T. V. Nguyen, personal communication, April 2, 2025. Used with permission. 17

Figure 7: Landfill Quy Nhon. Photo by the author, April 2025. 18

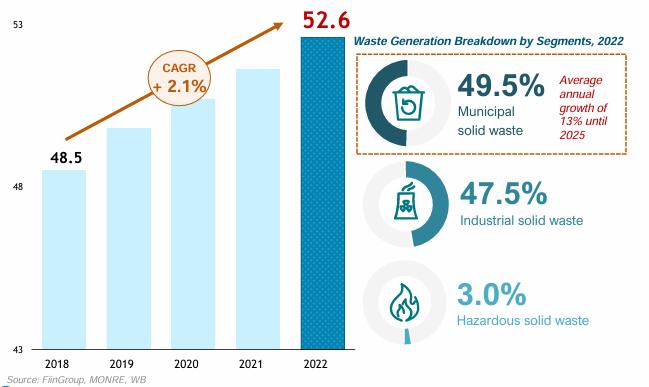

Figure 8: Solid Waste in Vietnam, FIIGroup (2024)...............................................................18

Figure 9: PET recycling line Quy Nhon. Photo by the author, April 2025. 19

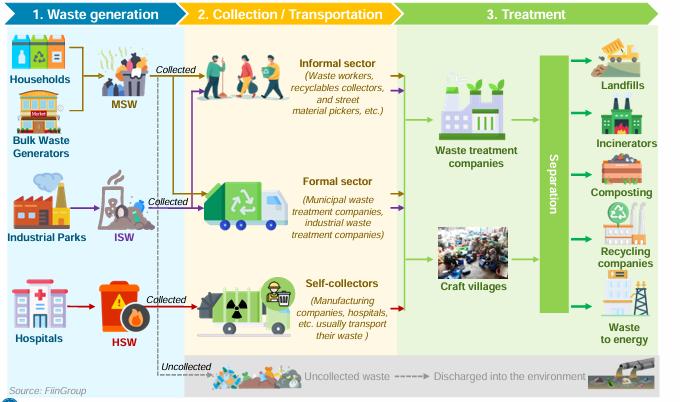

Figure 10: The Value Chain of Waste in Vietnam, FIIGroup (2024)......................................20

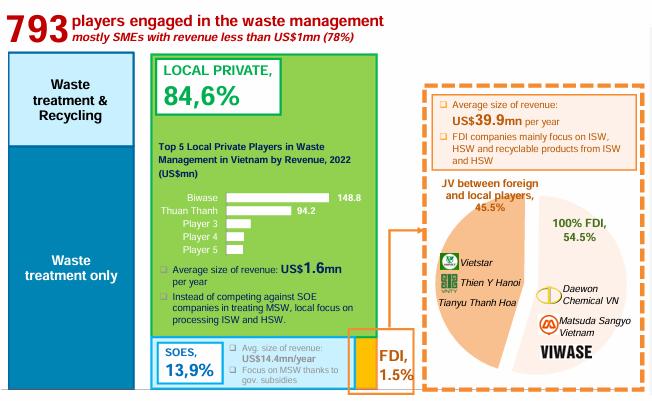

Figure 11: Waste Management Actors, FIIGroup (2025). 21

Figure 12: Ladder of Lansink, Nv E (n.d.). 22

Figure 13: Waste Management in the Future, FIIGroup (2024). .............................................23

Figure 14 : Global Plastic Cycles in 2022, adapted from Houssini, Li, & Tan, 2025. 24

Figure 15 : Global plastic production with projections (Business-as-usual scenario), adapted from Our World in Data, 2023.

Figure 16 : Plastic leakage into the Ocean (BAU), adapted from Pew Charitable Trusts (2020).

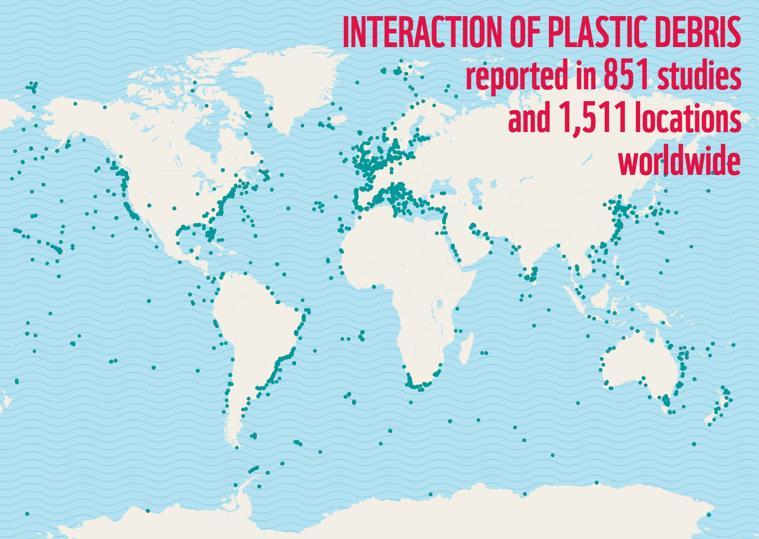

Figure 17 : Map of encounters between plastic pollutants and marine life, originates from Litterbase, adapted from Wold Wide Fund for Nature (2020).................................................

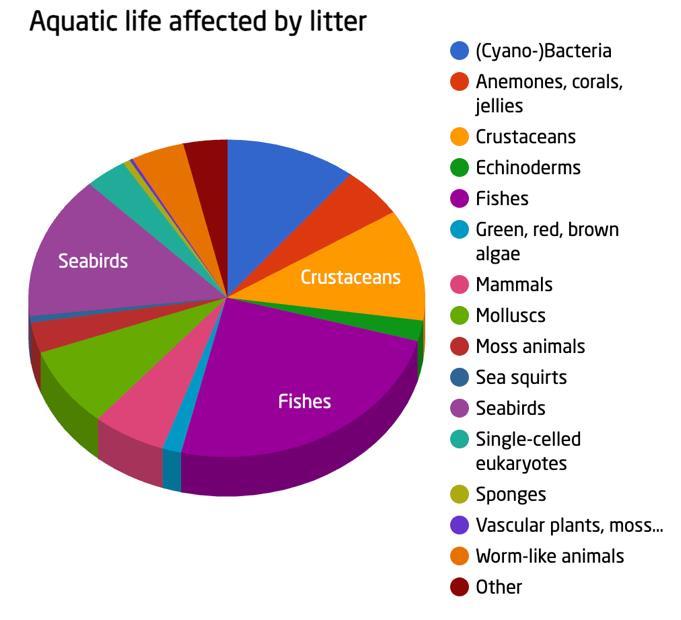

Figure 18 : Aquatic species affected by marine litter (Alfred Wegener InstituteLITTERBASE, n.d.).................................................................................................................

24

25

26

27

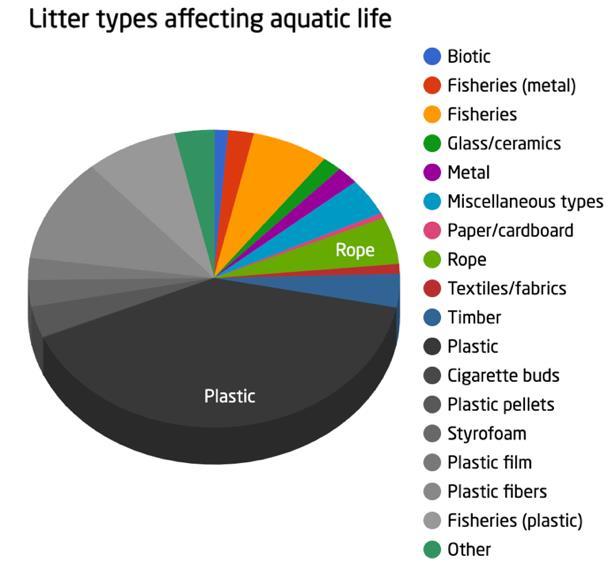

Figure 19: Different types of litter affecting aquatic life (Alfred Wegener InstituteLITTERBASE, n.d.) 27

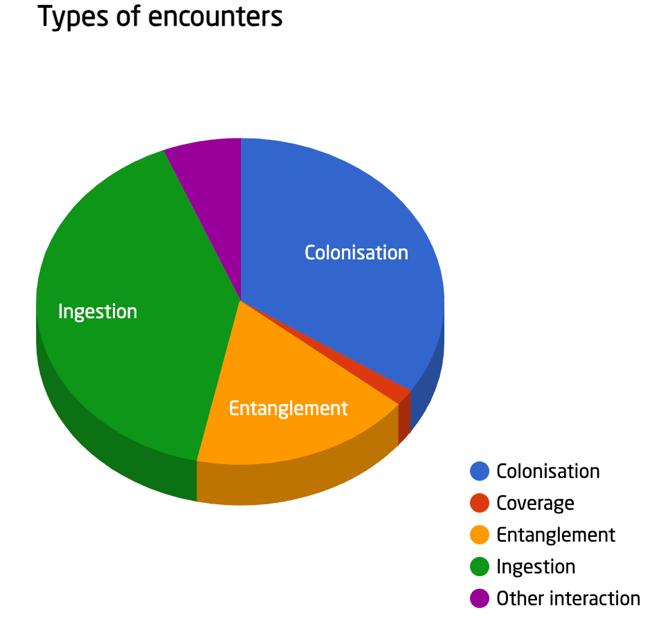

Figure 20: Types of plastic encounters with marine animals (Alfred Wegener InstituteLITTERBASE, n.d.).

Figure 21 : Image credits: Bird’ stomach with marine debris image – NOAA; Sea turtle balloon ingestion image – Blair Witherington, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Figure 22: Plastic debris entangled in a coral reef. Photograph by Lalita Putchim, originally published in Science, reproduced via The Guardian (2018).

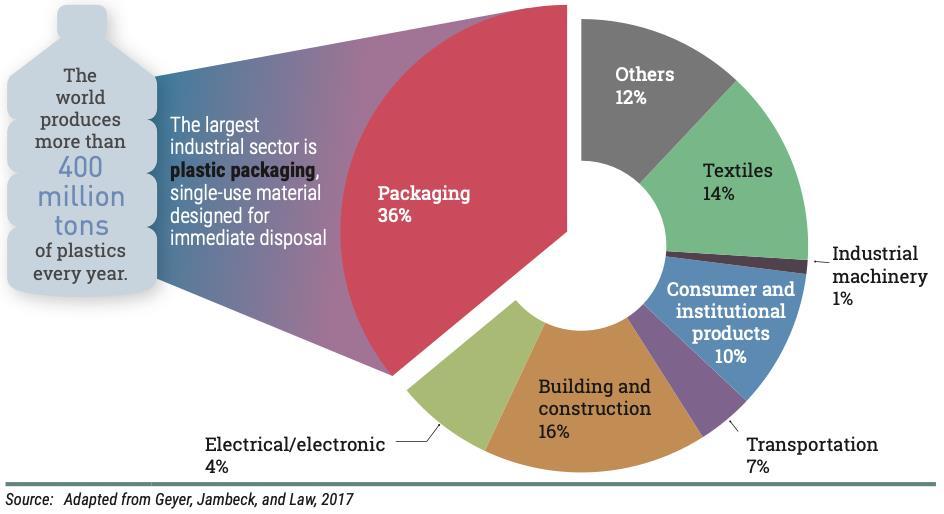

Figure 23: Global plastic production by industry in 2015, adapted from United Nations Environment Programme (2018).

Figure 24: Information about single-use plastic bottles. Data from Euromonitor International (2017), adapted from BBC News (2017). ................................................................................

28

28

29

30

31

Figure 25: Scenario analysis for GWP per Functional Unit (one use of a container) with EoL: (R) Recycling, (I) Incineration, Yadav et al. (2024)................................................................

Figure 26: Microplastics in take-out food containers, Du et al. (2020). ..................................

Figure 27: Analysis of reusable cups against paper cups, Anand et al. (2024)

Figure 28: An edible coffee cup. Image credit: Cupffee (2023), adapted from FoodNavigator (2023).

Figure 29: Blue Dopper water bottle. Image from HOGENT Shop (n.d.)...............................

Figure 30: Billie XXL reusable coffee cup. Image from Billie Cup (n.d.)..............................

Figure 31: Incentive Coupon for 10% reduction week 4. Created by T. V. Nguyen, using ChatGPT and Canva, personal communication, May 5, 2025. Used with permission............

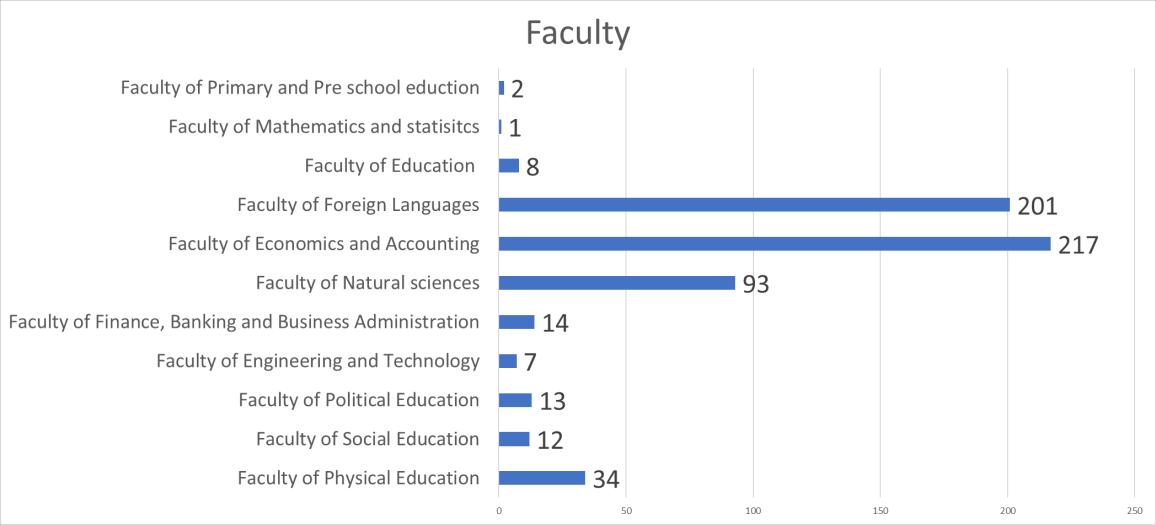

Figure 32: Faculty distribution. Source: own results.

32

33

34

34

38

38

40

42

Figure 33: Compilation of six images illustrating single-use and reusable products used in the survey. Images sourced from Shutterstock, CNN, product websites, and stock photo providers (see figure references). Compilation created by the author, March 2025. Copyright remains with the original image owners................................................................................................

Figure 34: Current usage of reusable bottles. Source: own results.

Figure 35: Current usage of straws. Source: own results.

43

49

50

Figure 36: Potential use of sustainable straws. Source: own results........................................51

Figure 37: Current usage of reusable bags. Source: own results.

51

Figure 38: Potential use of reusable bags. Source: own results. ..............................................52

Figure 39: Current usage of reusable cutlery. Source: own results.

Figure 40: Potential use of reusable cutlery. Source: own results.

Figure 41: Current usage of disposable cups. Source: own results..........................................

Figure 42: Potential use of reusable cups. Source: own results.

Figure 43: Potential ease of bringing reusable cup to QNU. Source: own results...................

Figure 44: Best reusable cup system. Source: own results.

Figure 45: Plastic bottle usage after 3 weeks in our project. Source: own results.

Figure 46: Plastic cup usage after 3 weeks in our project. Source: own results. .....................

53

53

54

55

56

56

59

62

Figure 47: Billie cup and HOGENT bottle in the canteen. Photo by T. T. V. Dinh, personal communication, May 5, 2025. Used with permission. 63

Figure 48: Billie cup in the canteen. Photo by T. V. Nguyen, personal communication, May 5, 2025. Used with permission 63

Figure 49: HOGENT bottle on the University. Photo by H. Hoang, personal communication, May 6, 2025. Used with permission.........................................................................................63

Figure 50: Plastic bottle usage, week 4 into our project. Source: own results. 65

Figure 51: Plastic bottle usage, week 4 into our project, taking the incentive into account. Source: own results. 66

Figure 52: Preferability of a deposit system for bottles, week 4 into our project. Source: own results. ......................................................................................................................................66

Figure 53: Plastic cup usage, week 4 into our project. Source: own results. 69

Figure 54: Plastic cup usage, week 4 into our project, taking the incentive into account. Source: own results. 70

Figure 55: Preferability of a deposit system for cups, week 4 into our project. Source: own results. ......................................................................................................................................70

Figure 56: Evolution in the use of reusable bottles through 4 weeks. Source: own results. 71

Figure 57: Evolution in the use of reusable cups (OU and HU) through 4 weeks. Source: own results…………………………………………………………………………………………72

Figure 58: Evolution in the use of reusable cups (HU) through 4 weeks. Source: own results. ..................................................................................................................................................73

Figure 59: Evolution in the use of reusable cups (OU) through 4 weeks. Source: own results.

..................................................................................................................................................74

Table 1: Wrongly identified SUPs. Source: own results.

44

Table 2: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1) and the question about the best incentive to use their reusable cup (Table 19). Source: own results.

44

..................................................................................................................................................

Table 3: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1) and the question about the ease to bring a reusable cup to QNU (Figure 43). Source: own results.

45

..................................................................................................................................................

Table 4: Question about post-treatment of SUPs. Source: own results.

45

Table 5: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1), the question about the post-treatment of SUPs (3.2.4), and the question about the best incentive to use their reusable cup (Table 19). Source: own results.

46

Table 6: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1), the question about the post-treatment of SUPs (3.2.4), and the question about the ease to bring a reusable cup to QNU (Figure 43). Source: own results. ..........................................................

Table 7: Most effective way to learn about SUPs. Source: own results. .................................

Table 8: Reasons to use a reusable bottle. Source: own results.

Table 9: Reasons not to use a reusable bottle. Source: own results.........................................

Table 10: Potential use of a reusable bottle. Source: own results.

Table 11: Reasons to use disposable straws. Source: own results.

Table 12: Reasons to use more sustainable straws. Source: own results.................................

Table 13: Reasons to use reusable bags. Source: own results.

Table 14: Reasons to use plastic bags. Source: own results.

46

48

49

49

49

50

51

52

52

Table 15: Reasons to use reusable cutlery. Source: own results..............................................53

Table 16: Reasons to use plastic cutlery. Source: own results. 54

Table 17: Reasons to use a reusable cup. Source: own results.................................................55

Table 18: Reasons to use plastic cups. Source: own results. 55

Table 19: Incentives to use reusable cups. Source: own results...............................................56

Table 20: Reasons, in general, to use reusable products. Source: own results. .......................57

Table 21: Places where they used the reusable bottle, results from week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results................................................................................................................................57

Table 22: Four forces model applied on bottle users, results week 1,2 and 3. Source: own results. 58

Table 23: How to encourage the use of reusable bottles, results week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results. 59

Table 24: Places where OU used the reusable cup, results from week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results. 59

Table 25: Places where HU used the reusable cup, results from week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results. ......................................................................................................................................59

Table 26: Four forces model applied on OU, results week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results. 60

Table 27: Four forces model applied on HU, results week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results....60

Table 28: How to encourage the use of reusable cups, results week 1, 2 and 3. Source: own results. 62

Table 29: Places where they used the reusable bottle, week 4. Source: own results...............64

Table 30: Four-forces model applied on reusable bottle users, results week 4. Source: own results. ......................................................................................................................................64

Table 31: How to encourage students to use the reusable bottle, results week 4. Source: own results. 65

Table 32: Places where OU used the reusable cup, results week 4. Source: own results........67

Table 33: Places where HU used the reusable cup, results week 4. Source: own results. 67

Table 34: Four-forces model applied on OU, results week 4. Source: own results.................67

Table 35: Four-forces applied on HU, results week 4. Source: own results............................68

Table 36: How to encourage students to use the reusable cup, results week 4. Source: own results. ......................................................................................................................................69

Table 37: Usage numbers of the reusable bottle, results week 1,2 and 3. Source: own results. ..................................................................................................................................................71

Table 38: Usage numbers of the reusable bottle, results week 4. Source: own results............71

Table 39: Usage numbers of the reusable cup (OU and HU), results week 1,2 and 3. Source: own results................................................................................................................................72

Table 40: Usage numbers of the reusable cup (OU and HU), results week 4. Source: own results. 72

Table 41: Usage numbers of the reusable cup (HU), results week 1,2 and 3. Source: own results. 73

Table 42: Usage numbers of the reusable cup (HU), results week 4. Source: own results......73

Table 43: Usage numbers of the reusable cup (OU), results week 1,2 and 3. Source: own results. 74

Table 44: Usage numbers of the reusable cup (OU), results week 4. Source: own results......74

Plastic pollution is one of the most urgent environmental challenges of our time. We do not only see plastic pollution in Belgium but also in Vietnam it is continuously present.

Each day, as we walk along the beach on our way to the Quy Nhon University, we are confronted with that sad reality. The entire shoreline of the beach is scattered with waste (Plastic bags; straws; food waste, plastic packaging and many more). Even when we go for a swim in the evening, it often feels like your swimming trough a sea of plastic These experiences make it painfully clear that urgent action is needed.

This bachelor thesis is only a small part of a bigger project with a collaboration of Quy Nhon University and several Flemish educational institutions: the VLIR-UOS project. This multi-year project is aiming to solve local problems by means of education and research.

This bachelor's thesis is part of Subproject 7 (SP7), which aims to develop a more effective waste management system at Quy Nhon University. Through the successful implementation of this system, the university hopes to serve as a model and inspire surrounding communities to adopt sustainable waste practices. Subproject 7 began in September 2022 and is planned to continue over a period of ten years.

Three students of HOGENT were sent to QNU in 2023 and provided an inventory of the waste streams present at QNU. One of their conclusions was that single-use plastics were the second biggest waste stream. In 2024 four students of the HOGENT were sent to QNU, where they further looked into the different types of SUPs that could be found on campus, and formulated possible solutions. For this reason, the goal of our thesis is to try to see if there is a support base for reducing SUPs and if there is awareness about the problems of SUPs.

In our thesis we tried to find an answer to the following research question: “How can a support base for reducing SUPs at Quy Nhon University be established by raising awareness and by offering reusable alternatives?”

This research is valuable for several reasons. First, it contributes to the global search for solutions to a reduce plastic. Secondly, it supports Quy Nhon University in making informed decisions about how best to invest in awareness campaigns and sustainable alternatives.

And finally, we hope that our efforts from guest lectures to the introduction of reusable bottles and cups have encouraged interest, inspired change, and planted the seeds for a more sustainable future at QNU.

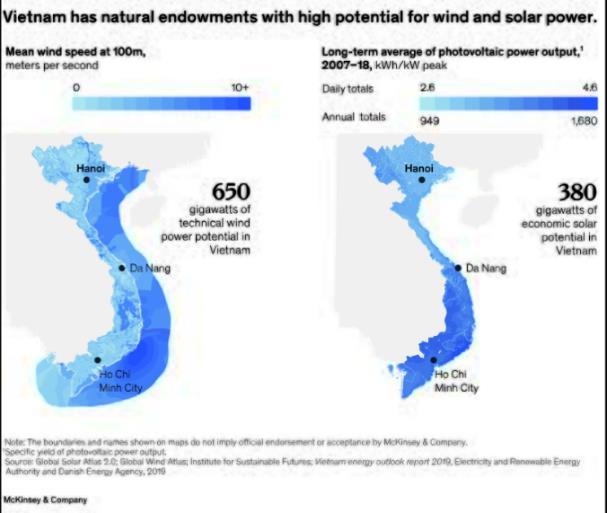

2.1.1 Vietnam

Vietnam, located in Southeast Asia, has a rich history shaped by its resilience and long struggle for independence. From ancient kingdoms to French colonization and the Vietnam War, the country has experienced significant transformation (Koops, 2023). Today, it is a socialist republic with a rapidly growing economy, though its political leadership remains firmly committed to a communist direction (Hickey et al., 2025).

The country is also known for its diverse landscapes, including Ha Long Bay, recognized as one of the seven natural wonders of the world by UNESCO (UNESCO World Heritage Centre, n.d.).

Economically, Vietnam has emerged as one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies in recent years. The rapid growth in sectors like textiles and electronics has strengthened its position as a key player in the global market (BNNVARA, 2021).

Looking towards 2030, Vietnam aims for a 7% gross domestic product growth, a $7,500 per capita gross domestic product, and a reduction in its agricultural workforce, while emphasizing industrialization and modernization (Nguyen, 2024). The country seeks to shift from processing to innovation and research, focusing on digital transformation and high-tech industries, with the goal of becoming one of the top three Asian nations in industrial competitiveness, with over 40% of its gross domestic product derived from industry. Policies will foster investment in technology, human resources, and infrastructure (Tuan, 2022).

In Vietnam, particularly in smaller towns and rural areas, life tends to unfold at a much slower pace compared to the fast-paced environments common in many Western countries. Here, meals are enjoyed with the whole family, conversations are held everywhere, daily routines often follow the natural rhythms of the environment (Mrowiński, 2023).

This slower pace of life is not just a reflection of tradition but also serves as a means for individuals to nurture strong family and community bonds, placing relationships at the forefront rather than the pressures of modern life (Cao, 2021). It shows a sense of calm and deep connection to the land, offering a contrast to the fast and hard line of urban living (Mrowiński, 2023).

However, in larger cities such as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, society is different. The streets are often filled with people in a rush, and the pace of life feels much faster, mirroring the demands of a rapidly growing economy This illustrates the tension between rural life and urban hustle and the tensions between tradition and modernity that are playing out across the country (Nguyen et al., 2020).

Despite Vietnam’s economic growth and increasing urbanization, traditional cultural practices remain an integral part of daily life. Practices like ancestor worship, tea ceremonies, and the celebration of various cultural festivals continue to hold great significance (Festivals Are Vital to Cultural Development, n.d.). These traditions not only shape the values of the Vietnamese people but also act as a counterbalance to the rapid changes driven by industrialization (Nguyen et al., 2020). They represent a means of preserving cultural identity and reinforcing community connections amidst the challenges and transformations of modern life (Claire & Beel, 2022).

Binh Dinh is a province located in central Vietnam. The province is known for its rich history and beautiful coastal landscapes. The capital of the province is Quy Nhon, where we are going to do our internship (Portal, 2022). Binh Dinh was an important centre of the Champa Kingdom, which was an ancient Indochinese kingdom lasting from the 2nd to the 17th century CE and extended over the central and southern coastal region of Vietnam. The influence of this kingdom is still visible in Vietnam and in Bin Dinh province, through, for example, the temples scattered across the country, but also through the influence that civilization now has on the country of Vietnam (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1998). The province is also famous for its traditional craft industries, including weaving and pottery (Portal, 2022).

The province also experienced a significant economic growth in recent years. The economy in the province is diverse, but the main sector is agriculture, especially rice, fruit and spice farming. Because of the coastal beauty and the historical sites in the province, tourism is also rapidly growing (Vietnam Investment Review, 2025).

Quy Nhon, is a coastal city in central Vietnam, located in the province of the Binh Dinh in Central Vietnam. Quy Nhon offers a mix of traditional Vietnamese culture and modern development. It has a growing role in the Vietnam’s tourism industry, as well as a very important economic role. This is because of the strategic position as a hub for trade and culture (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019).

The city has a lot of potential to grow into one of the biggest tourist destinations in Vietnam, but for now it lacks the supply of luxury properties and activities that can support tourists in the future (Cổng Ty Cổ, 2022).

Quy Nhon University (QNU) is the university where the internship and bachelor thesis will be executed QNU is located in the coastal city of Quy Nhon and is a prominent educational institution in the wide region but ranked lower as the universities in the big cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh. The university was founded in 1977 and plays a key role in higher education, research, and community development in Vietnam. As it continues to grow, the university remains committed to producing skilled graduates who contribute to the advancement of Vietnamese society (Quy Nhon University Ranking & Overview 2024, n.d.).

The university also fosters international cooperation, through partnerships with universities around the world, enhancing its academic and cultural exchanges, an example is the collaboration with the KU Leuven, UAntwerpen and HOGENT (A Message From The Rector Of Quy Nhon University, n.d.).

For a deeper insight into Vietnam’s environmental and sustainability initiatives, as well as the broader context of current policies, section 9.1Sustainabilityandtheenvironment in Vietnam is definitely worth reading. It provides a comprehensive overview of the strategies, legislation, and efforts being made by the government and other stakeholders to create a more sustainable Vietnam.

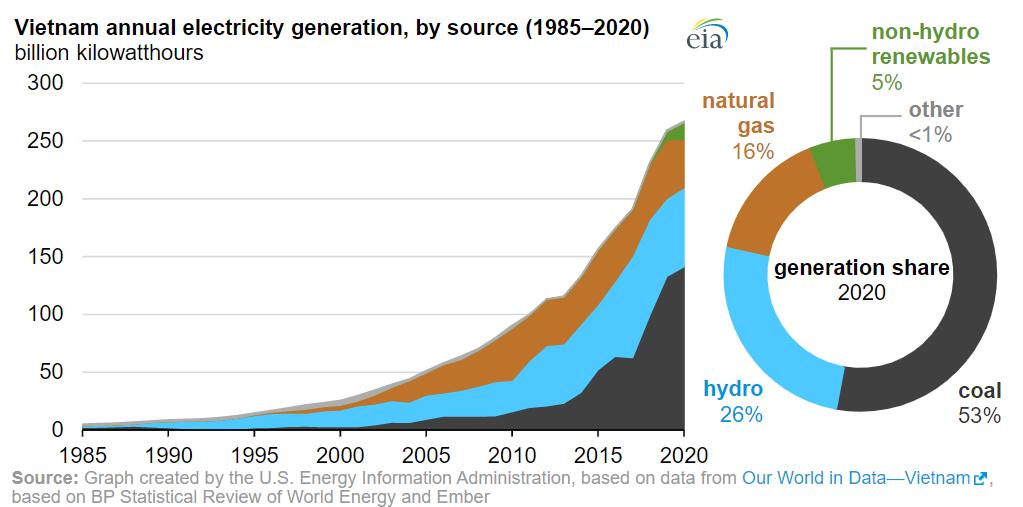

2.1.7.1 The Current Waste Situation in Vietnam

Vietnam is facing increasing pressure on its waste management system. In 2022 alone, Vietnam produced 26.1 million tons of solid waste, of which 49.5% was municipal waste (MSW), 47.5% industrial waste (ISW), and 3% hazardous waste (HSW) (FiinGroup, 2024). SUPs in Vietnam count as solid waste (VietnamPlus, 2024).

As of 2024, the country generates approximately 65,000 tons of solid waste daily, of which urban areas and industrial zones remain the major contributors. This growing waste volume is largely driven by rapid urbanization, industrial expansion, and rising consumption patterns (FiinGroup, 2024; Pham, 2024; Ngan, 2018).

As a response to this problem, Vietnam has made several commitments to design smart solutions for preserving the environment (Cho et al., 2018). Since 2007, the Vietnamese government has made several attempts to implement waste separation at source. However, it was not until 2020 that these efforts were formally codified into legislation (WasteSortingAtSourceRemainsUnimplementedinManyAreas, z.d.). The law officially came into effect on December 31, 2024, with the aim of reducing the volume of waste sent to landfills and promoting recycling (Waste Sorting At Source Remains UnimplementedinManyAreas, n.d.).

Despite various policy efforts, landfilling remains the dominant disposal method, accounting for more than 85% in 2022 and still over 70% in 2024. This also applies to single-use plastics, as they are considered a significant component of solid waste due to their widespread use and limited recyclability (FiinGroup 2024; Pham, 2024).

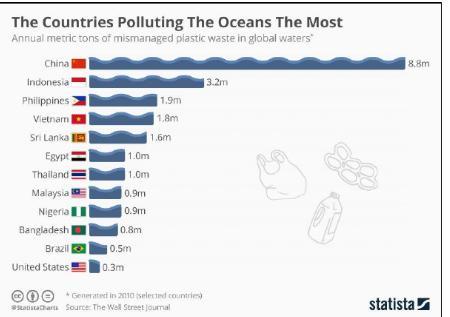

Recycling and reuse are still limited, with only 15% of solid waste being recycled, largely through informal networks. This limited capacity, combined with insufficient sorting at the source, reduces recycling efficiency and adds to environmental strain. Vietnam is also among the top five contributors to ocean plastic pollution, releasing an estimated 280,000 to 730,000 tons of plastic into the ocean annually (Reuters, 2024; Expert Market Research, 2024).

Vietnam’s waste management system follows a structured value chain that includes three key stages: waste generation, collection and transportation, and treatment. Each stage involves a range of actors and processes that reflect the country’s blend of formal and informal management practices (FiinGroup, 2024)

The process begins with waste generation from several main sources. Households and bulk generators such as restaurants and markets contribute to municipal solid waste (MSW). Industrial parks are responsible for industrial solid waste (ISW), while hospitals generate hazardous solid waste (HSW) (Pham, 2024) However, not all waste is properly collected. Some remains uncollected or is discharged directly into the environment, adding to pollution concerns (FiinGroup, 2024).

Once generated, waste moves into the collection and transportation phase. Here, three key groups are involved The first one is the informal sector, including waste pickers and street collectors (Harafadli et al, 2024).

The first sector plays a vital role in collecting recyclables from households and public spaces. The second, the formal sector comprising municipal and industrial waste management companies handles organized waste collection and transportation services. Lastly, there are the self-collectors, such as manufacturing companies and hospitals, which often manage their own waste transport, particularly when dealing with hazardous materials (FiinGroup, 2024).

Waste separation at the source remains minimal, and in most cases, all types of waste are mixed together. While pilot programs in large cities aim to improve household sorting, these are still in early stages and not yet widely implemented (FiiGroup, 2024).

In the treatment stage, waste is delivered to different facilities where it is sorted and processed. Waste treatment companies and craft villages - many of which operate informally - carry out the separation of materials. Depending on the type of waste and treatment method, the waste is sent to landfills, incinerators, composting sites, recycling companies sometimes it is also converted into energy through Waste-to-Energy (WtE) technology (ESCAP, 2015). A side note to this is that the majority of all the waste gets dumped in a landfill (Fiingroup, 2024).

Many landfill sites such as Nam Son in Hanoi are nearly full, with utilization rates of up to 99.9% (FiinGroup, Pham, 2024). Incineration is primarily used for hazardous and medical waste, although energy is not typically recovered. Composting remains limited to rural areas, and recycling is largely informal and inefficient. As a response, Vietnam has begun investing more heavily in Waste-to-Energy (WtE) solutions, which offer both environmental and energy benefits (Ngan, 2018).

The lack of modern treatment infrastructure, combined with low government spendingonly 0.23% of GDP in 2023 compared to a global average of 0.5% further (World Bank, 2023) - complicates the country’s ability to handle rising waste volumes effectively (FiinGroup, 2024).

To address Vietnam’s growing waste challenge, improved coordination and targeted investment are required at every stage of the complex yet essential collaboration between the formal waste management systems and the informal labor sector. Every stem in the value chain holds the potential to support a more sustainable waste management future (FiiGroup, 2024).

Vietnam’s government has recognized these challenges and is actively shaping a more sustainable future through policy reforms, investments, and international commitments. The country has set clear targets: by 2030, at least 50% of municipal waste should be treated through Waste-to-Energy technologies, and by 2050, 100% of waste should be treated without landfilling. (Vietnamese Government, 2023; FiinGroup, 2024).

To support this transition, the government has introduced a number of strategic policies. To make WtE plants more financially viable the Vietnamese government took Decision 31/QD-TTg it offers tax incentives, low-interestloans, andimport duty exemptions forWtE projects. Circular 32/TT-BCT sets standards for electricity pricing to make them higher (Vietnamese Government, 2023). Additionally, the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policy requires manufacturers to manage the waste created by their packaging and products, encouraging more sustainable production and better waste recovery systems (FiinGroup, 2024).

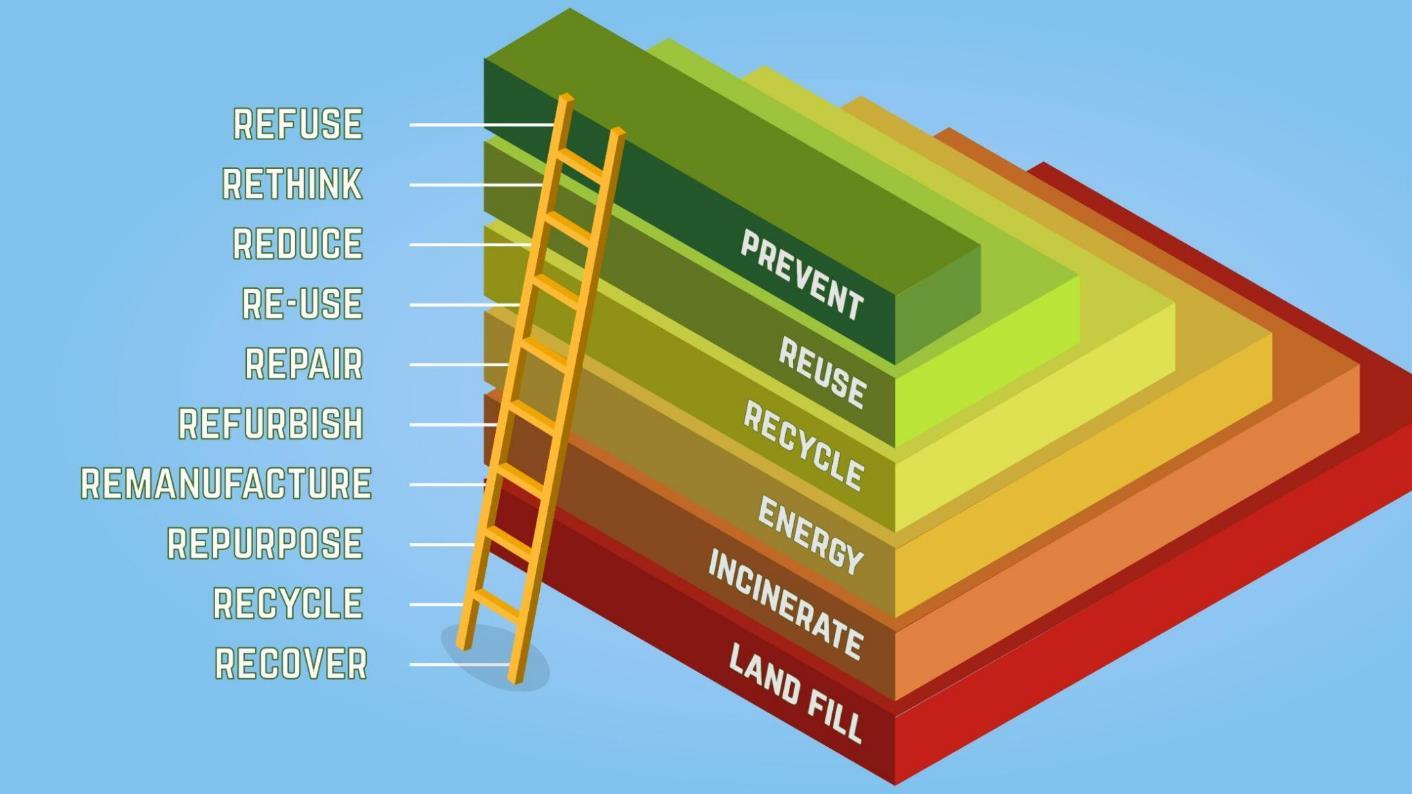

However, these targets must be assessed with a critical eye. When you look at Lansink's ladder you see that getting energy from waste is at the bottom of the ladder. The Vietnamese government actually needs to do a better job on refuse, rethink and all the other levels on the ladder of Lansink (FiinGroup, 2024).

Alongside policy, market potential is also growing. The Vietnamese waste management market is expected to grow from approximately USD 6.42 billion in 2024 to over USD 11.4 billion by 2034, with an annual growth rate of 6.6% (Expert Market Research, 2024). This opens major opportunities for both local and foreign investors in infrastructure, technology, and recycling services (Ngan, 2018).

Vietnam’s efforts also align with its commitment to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, as announced at the COP27 summit. Modern waste treatment, especially WtE, will play a crucial role in achieving this goal (FiinGroup, 2024).

Vietnam is moving away from landfilling towards modern waste treatment, like composting and anaerobic digestion. These methods reduce environmental impact and generate renewable energy from organic waste (B-Company, 2024)

With rising urbanization, the government is investing in better infrastructure, promoting waste separation at source, and improving recycling practices. Combined with stronger regulations and public education, these steps aim to build a more circular economy focused on sustainability and resource recovery (Ngan, 2018)

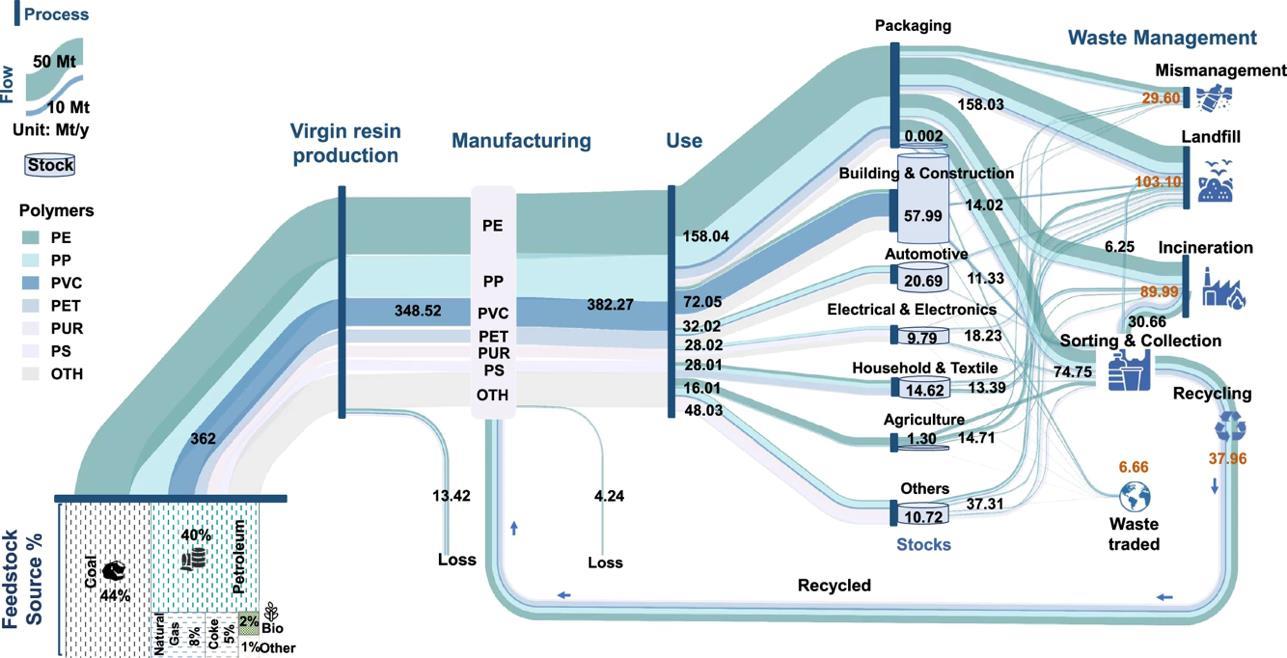

Plastic is one of the most widely used materials globally, with an annual production of approximately 400 million tons (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2018), a number also supported by a recent study published in the Nature journal Communications Earth & Environment. The study also highlights that in 2022, 98% of global plastic production was derived from fossil fuels, which contribute to higher greenhouse gas concentrations, thereby driving global warming (Liu & Liu, 2023). The full plastic lifecycle, including production, trade, and waste, is illustrated in Figure 14 (Houssini et al., 2025).

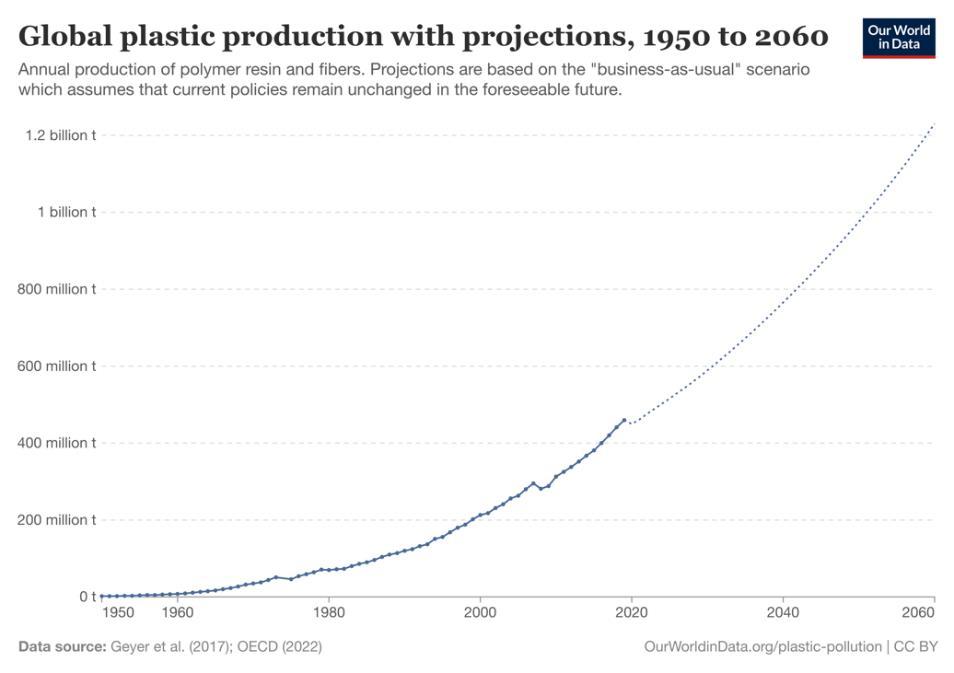

As shown in Figure 15, plastic production has consistently risen over the years. If current trends continue, it is projected to increase even further (Our World in Data, 2023).

15 :Global plastic production with projections (Business-as-usual scenario), adapted from Our World in Data, 2023.

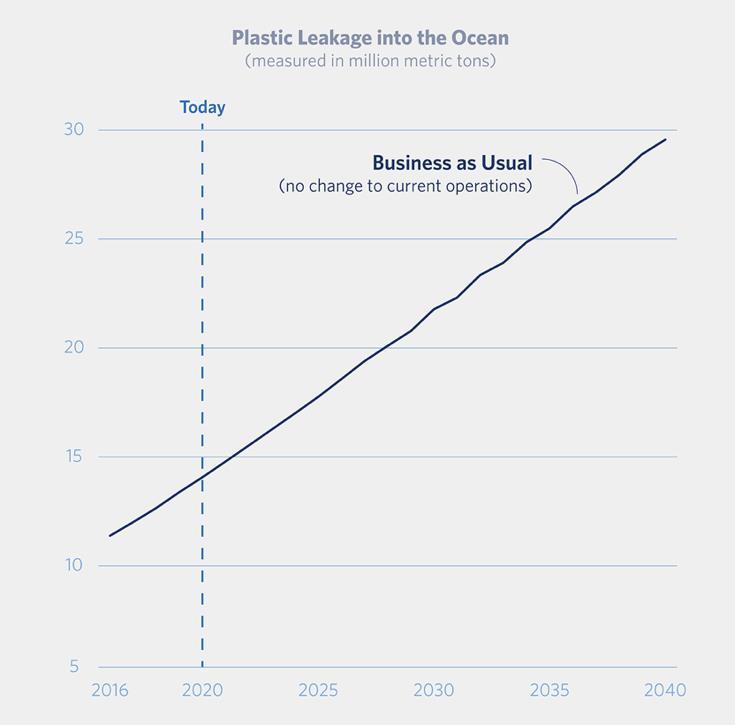

Each year, an estimated 11 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean, with projections ranging from 9 to 14 million metric tons annually in 2016, increasing to 29 million metric tons by 2040 (Pew Charitable Trusts & Systemiq, 2020).

16: Plastic leakage into the Ocean (BAU), adapted from Pew Charitable Trusts (2020).

These are small pieces of plastic (ranging from 5mm to 500 µm) that can originate from various plastic items like bags, cups, and bottles (Allemann et al., 2024). In 2021, Isobe et al. estimated that there were approximately 24.4 trillion (10¹²) pieces of microplastics (MPs) in the upper layer of the world’s oceans, equivalent to around 30 billion 500milliliter plastic water bottles.

Microplastics typically form through the fragmentation of plastic due to abrasion or UV degradation caused by sunlight (Allemann et al., 2024) and often contain polymers and additives, which, when released, can cause toxicity. Thus, they are inherently toxic and act as carriers for numerous pollutants, especially heavy metals, enabling them to enter the organs of organisms (Li et al., 2023).

MPs can enter the human body in several ways. One major route is through the air, where MPs - mainly from traffic and tire wear - can be inhaled. Another pathway is through skin contact. Microplastics can settle on the skin through the use of facial products like creams, and even handling items such as phone cases can lead to the absorption of harmful chemicals attached to these particles. The third route is through food and drinks. MPs have been found in common items like drinking water, seafood, salt, sugar, tea, milk, and take-out food containers. They can even enter the water transport systems of plants, moving into roots, stems, leaves, and fruits (Li et al., 2023). According to Cox et al. (2019), adult men are estimated to consume around 52,000 MPs particles per year, while women consume approximately 46,000 MPs per year.

Humans are increasingly exposed to microplastics on a daily basis. According to a study by Nihart et al. (2024), the proportion of microplastics found in the brains of deceased individuals increased by approximately 50% in 2024 compared to 2016. This trend underscores the rising concentrations of both microplastics and nano plastics in various parts of the human body, with the brain showing levels 7 to 30 times higher than those found in the liver or kidneys. (As a side note, the study also included nano plastics in its analysis, alongside microplastics). The researchers stress the need for further studies to reach definitive conclusions, as it remains unclear whether this level of exposure has negative health effects. Determining such impacts requires epidemiological data, which is currently lacking (Danopoulos et al., 2023). These concerns are echoed in other scientific studies, including Bao et al. (2024).

A total of 2,141 marine species have been identified as affected by plastic pollution in their natural habitats. Figure 17 provides an overview of the locations where interactions between aquatic life and marine litter occur. This figure is based on a 2022 WWF report that utilized ‘Litterbase’, an online portal for marine litter. The report indicated that there were 1,511 locations with interactions with marine litter, based on 851 studies (Tekman et al., 2022). As of today, three years later, the number has risen to 4,076 marine species, documented in 1,956 scientific studies (Alfred Wegener Institute, n.d.).

Of the 4,076 species known to be affected by marine litter, 23.74% are fishes, 14.3% are seabirds, 11.16% are crustaceans, 10.53% are (cyano-)bacteria, 7.99% are molluscs, 5.85% are mammals, and 5,04% are coral reefs, among others, with numerous other groups making up the remainder (Figure 18) (Alfred Wegener InstituteLITTERBASE, n.d.).

Using a risk model based on multiple studies, Wilcox, Van Sebille, and Hardesty (2015) predicted that by 2050, 99% of all seabird species will have ingested plastic. While evidence of ingestion and/or entanglement has been documented in all species of marine turtles (Tekman et al., 2022).

Most of the litter impacting aquatic life is plastic, accounting for 68.24% of all litter types. In addition, other materials also contribute to the problem: fishing-related waste (non-plastic) makes up 6.68%, rope 5.13%, timber 3.63% of all litter types, along with various other types of debris (Figure 19) (Alfred Wegener Institute-LITTERBASE, n.d.).

The primary types of plastic encounters are ingestion, which accounts for 40.42%, followed by colonization at 34.29%, and entanglement at 17.44%. The remaining small percentage is attributed to coverage and other interactions, as shown in Figure 20 (Alfred Wegener Institute-LITTERBASE, n.d.)

All marine species ingest plastic, leading to several harmful effects. These include a false sense of fullness, which reduces food intake and negatively impacts growth. Additionally, plastic can cause blockages in the digestive system or severe internal injuries. It also affects immune response, fertility, and reproduction (Tekman et al., 2022). Also, microplastics are ingested by animals, leading to bioaccumulation within food chains and amplifying their impact on the entire food web (Li et al., 2023).

Colonization is the process by which marine organisms - such as bryozoans, barnacles, and other small species - attach themselves to plastic waste and use it as a means of transport. Unlike ships, which move quickly, plastic debris drifts slowly and remains in the ocean for extended periods. This prolonged exposure increases the chances of survival and spread for these colonizing species. As a result, colonization via plastic waste has become one of the most significant threats to global biodiversity (Barnes, 2002). A more recent study conducted along the Indian coastline highlights similar concerns. This region receives significant amounts of plastic waste, partly due to international shipping activity from Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam. The study emphasizes the threat posed by plastic debris as a transport medium, enabling invasive species to spread to new habitats. These invasions can disrupt ecosystem functions and diminish the valuable services those habitats provide (Kannan et al., 2023).

Abandoned, lost, or discarded fishing gear - such as ropes, nets, monofilament lines, and many others - can entangle marine animals, leading to strangulation, injury, restricted movement, and even death (Tekman et al., 2022).

In 2018, Lamb et al. conducted a large study across 159 coral reefs in the Asia-Pacific region, revealing that approximately 11.1 billion plastic items were entangled on these reefs. They projected a 40% increase by 2025, although current data to confirm this is unavailable. The study also found that plastic significantly raises the risk of coral diseases - by a factor of 20 - due to stress, such as light deprivation, tissue damage, release of toxic chemicals, and lack of oxygen, allowing pathogens to invade. Over time, this increased susceptibility could contribute to the death of coral reefs.

Given their ecological and economic importance, the vulnerability of coral reefs to plastic entanglement is especially concerning. Coral reef ecosystems support at least 25% of all marine species and are estimated to contribute approximately 2.7 trillion USD per year in ecosystem service value. However, global data show that between 2009 and 2018, the world lost around 14% of its coral, highlighting a significant decline in these vital ecosystems (Souter et al., 2021).

When it comes to terrestrial animals, less has been documented compared to marine species. However, Thrift et al. (2023), through a study utilizing data from rescue centers and population modeling, have identified the impact of plastic entanglement on the hedgehog population in Great Britain. Their model estimates that between 4,000 and 7,000 hedgehogs die each year as a result of plastic entanglement

2.1.8.3 Single-use-plastics (SUPs) & their negative impact

With approximately 144 million tons of plastic produced annually as single-use plastics (SUPs), they represent the largest share of plastic production, as shown in Figure 23. SUPs are designed to be used once and then discarded. These include, among other items, cups, food packaging, bags, bottles and straws (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2018). This section explores the main types of single-use plastics

and their environmental, health, and social impacts. The effects on animals and ecosystems, which were discussed in the previous section, will therefore not be addressed in detail here.

2.1.8.3.1

Plastic bags are widely used because they are lightweight, strong, inexpensive, and convenient for transporting goods. They require less energy and water to produce than alternatives like paper bags and occupy less space in landfills. However, the same traits that make them appealing - such as durability and low cost - also contribute to environmental problems when they're mismanaged. Their resistance to breakdown and difficulty to recycle means plastic bags can persist in the environment for decades (up to 1000 years), posing threats to ecosystems and contributing to long-term pollution (see 2.1.7.2Harmtowildlife). Due to their lightweight nature, plastic bags are easily carried by the wind, often ending up in the ocean or scattered across the land (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2018).

2.1.8.3.2

Foamed plastics, often referred to as ‘Styrofoam’, are widely used in food packaging due to their rigidity, light weight, and insulating properties that help keep food warm. They also make food easier to transport. However, a major concern with this material is that it contains toxic and potentially carcinogenic chemicals, such as benzene and styrene, which are known to harm the respiratory, nervous, and reproductive systems. These substances can leach into food during use. Moreover, when foamed plastics are burned, these toxic compounds are released in greater quantities, increasing both health and environmental risks (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2018). Styrofoam is frequently found on beaches and along shorelines, where it makes up a significant portion of marine litter. Wildlife is particularly affected, as Styrofoam breaks down into small particles that can obstruct airways, cause digestive issues, and even lead to cancer. These particles also contaminate the animals’ food and water sources, further threatening their survival (Miller et al., n.d.).

2.1.8.3.3

Disposable cups are commonly used in various settings, including offices, take-away restaurants and shops, parties, and schools. They are convenient because they’re inexpensive, require no maintenance, and are easy to use (van der Harst & Potting, 2013).

On a global scale, around 500 billion single-use beverage cups are consumed annually. These cups are among the most frequently littered items found on beaches worldwide. Like other mismanaged plastic waste, they play a major role in marine pollution, harming marine ecosystems and disrupting economic activities that depend on healthy oceans (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2021).

2.1.8.3.4

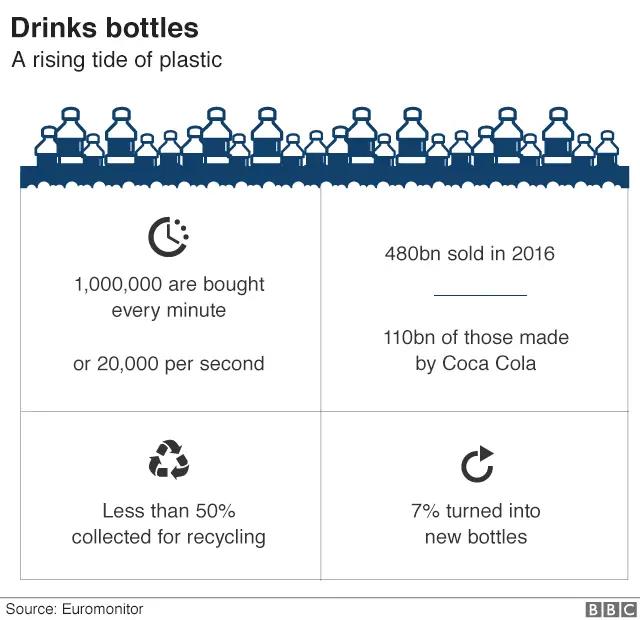

Every minute, one million plastic bottles are sold worldwide; as a result, they are among the most commonly found single-use plastic items on beaches (United Nations Environment Programme, 2020). The following figure shows information related to the consumption, sale, and recycling of plastic bottles.

2.1.8.3.5

An estimated 4 billion pieces of plastic cutlery are used annually in England alone. Of these, only 10% are recycled (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2023). Global usage data has yet to be reported.

2.1.8.4

There are many alternatives to the use of SUPs. For instance, recycled paper, bamboo, and corn-based plastics -which are biodegradable materials when composted- are available for food packaging. Additionally, reusable packaging options offer a practical and sustainable solution (Miller et al., n.d.).

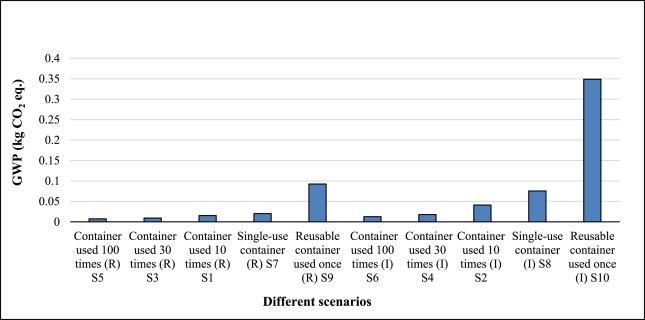

Yadav et al. (2024) conducted a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment focusing on reusable packaging, made of polypropylene (PP). Their study found that after just six uses, with recycling included, reusable packaging has a lower global warming potential (GWP) than disposable alternatives. This also means that if reusable packaging is only used once, its global warming potential (GWP) would be 315% higher than that of singleuse packaging in the recycling scenario, and 363% higher in the incineration scenario.

As seen in Figure 25, the results from the end-of-life (EoL) incineration option showed a different environmental impact compared to recycling. The analysis indicated that, in all scenarios, a reusable container used once had a higher global warming potential (GWP) than the single-use container. However, as the number of uses of the reusable container increased, the GWP decreased significantly. After 10 uses, the GWP of the reusable container was 46% lower than that of the single-use container. With 30 uses, the GWP decreased by an additional 56%, and with 100 uses, the GWP was 83% lower compared to a single-use container in the EoL incineration scenario (Yadav et al., 2024).

The study highlights that several factors, such as user behaviour, transportation method, and travel distance, can significantly influence the environmental outcomes. The authors emphasize the importance of promoting reusable food packaging systems and recommend establishing pick-up and return stations within walking distance to maximize sustainability benefits (Yadav et al., 2024).

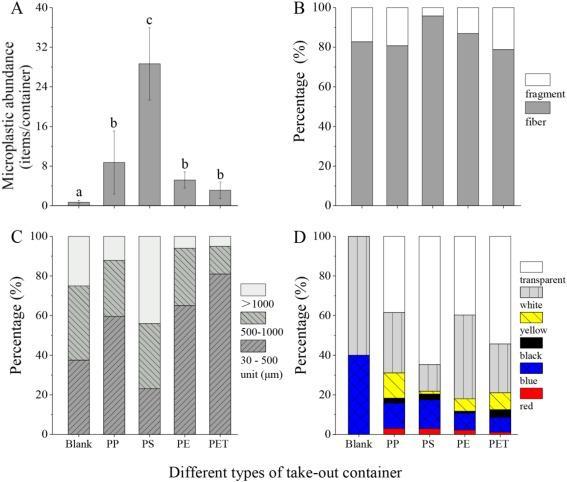

Although PP has a lower GWP when used multiple times, it does not necessarily release fewer microplastics. A study by Du et al. (2020) analysed the abundance of microplastics in food containers made from polystyrene (PS), PP, polyethylene (PE), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). The results (Figure 26) showed that PS released the most microplastics, followed by PP, then PE, and PET with the least.

Although less research is available on reusable cups, Garrido and Alvarez del Castillo (2007) conducted a comparable study during a large-scale event in Barcelona, evaluating both reusable and single-use cups made of polypropylene (PP), though differing in design and weight. Their findings showed that reusable cups need to be used more than 10 times to achieve a lower environmental impact than single-use alternatives. The majority of the environmental burden was attributed to the production of PP. It should be taken into account that the study by Garrido and Alvarez del Castillo (2007) is 18 years old, while the study by Yadav et al. (2024) is more recent and focuses on a different type of product. However, both studies examine reusable products made of PP, which makes the comparison still relevant despite the differences in time and application.

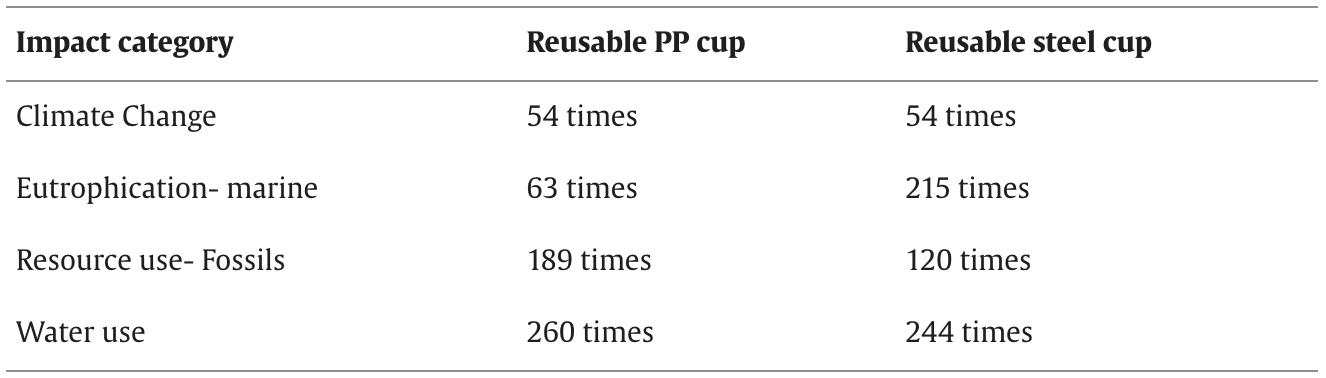

A more recent study by Anand et al. (2024) examined different reusable cup options in comparison to single-use paper cups. The authors found that a PP cup must be used at least 54 times to match or reduce the climate change impact of paper cups. In terms of water consumption, the PP cup would need to be used at least 260 times to have an equivalent or lower impact. An overview of these findings is presented in Figure 27.

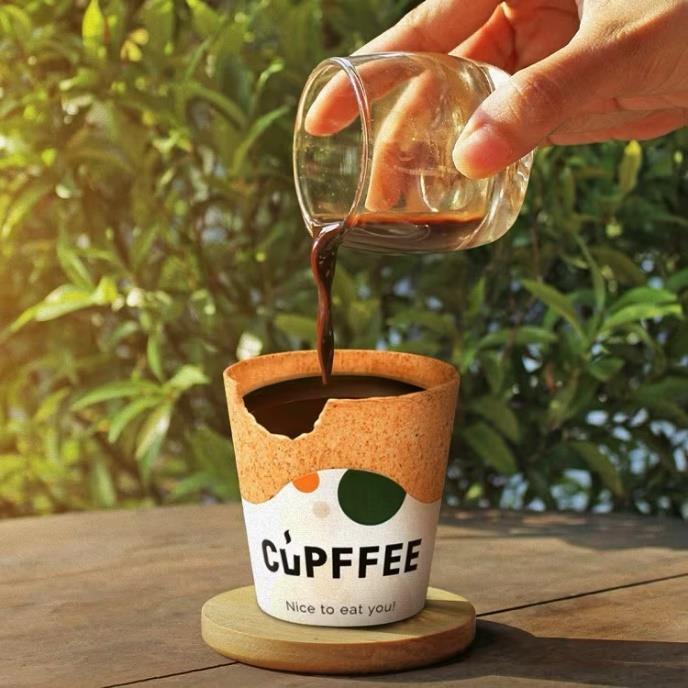

The study also conducted a life cycle assessment (LCA) of edible coffee cups (Figure 28). These cups were found to have production impacts that are 10 times greater than those of paper cups, primarily due to land use changes associated with the cocoa beans used for flavouring. However, it was noted that if the edible cups replace other edible products, such as cookies, their environmental impact would be minimal. Additionally, it was highlighted that edible cups could help reduce plastic litter, which could be particularly beneficial at festivals or outdoor cafes. The study concludes that further research is needed, and that in most cases, reusable cups remain the more sustainable option (Anand et al., 2024).

Biodegradation can also apply to plastic cutlery alternatives. For example, cutlery made from water hyacinth, reinforced with cellulose-rich materials such as banana fibre, sugarcane leaf, and waste paper, offers an environmentally friendly and functional option. These materials improve strength and moisture resistance. The cutlery demonstrated rapid biodegradation, with most samples disintegrating completely or losing 90% of their weight within 20 days (Harikrishnan et al., 2023).

Vietnam has recently introduced several legislative measures to tackle plastic waste pollution, particularly in the marine environment. In October 2018, the Vietnamese government passed Resolution No. 36-NQ/TW, which outlines the country’s strategy for sustainable marine development and includes objectives like reducing ocean plastic pollution. This resolution laid the groundwork for the development of the Law on Environmental Protection (2020) and the National Action Plan on Marine Litter (Van Daelen, 2024).

The Law on Environmental Protection, implemented in 2020, marked a significant step by introducing an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system, requiring producers to manage the lifecycle of their products, including packaging and plastic waste. It also mandates the classification of household waste and sets a target for a 22% recycling rate for rigid PET packaging in its first three years (Van Daelen, 2024).

Further, Decree No. 08/2022/ND-CP, an elaboration of the Environmental Protection Law, establishes a roadmap for reducing and eventually banning non-biodegradable plastic bags and single-use plastics by 2031. The government is also focusing on educating the public, particularly students, about waste reduction through campaigns and information initiatives (Van Daelen, 2024).

The World Bank’s "Toward a National Single-Use Plastics Roadmap in Vietnam" report outlines a comprehensive strategy to reduce plastic pollution through a three-pillar approach: reducing plastic waste, improving waste collection, and creating value from waste reuse. These efforts are complemented by Vietnam’s National Action Plan for Marine Litter, which aims to significantly reduce marine plastic litter by 2030 (Van Daelen, 2024).

2.1.10.1 Four-forces model

To switch from disposable cups to reusable cups, behaviour will have to change. During a workshop organized by OVAM (Openbare Vlaamse Afvalstoffen Maatschappij), information was given about how to encourage the necessary societal transition regarding packaging. There are four forces that will play a role in the change towards a more sustainable alternative.

The first force is the gains you get from using the more sustainable product. The second force involves what the frustrations (pains) are with the reusable product. The third force relates to what causes you to stay with the current product (comforts). The final, fourth force is the anxieties/ barriers at the sustainable alternative (J. Craeghs, personal communication, 25 February 2025; De Bruyne, n.d.-b).

A good method can be “chunking”. This is a method for getting people to successfully change behavior. It tells you in very small steps how to get to the end, where the first step is so easy that you are much more likely to start the action. A trigger is hit in the brain that makes people want to finish what they started after the first step. This is one way that can help shift to more sustainable behaviors (J. Craeghs, personal communication, 25 February 2025; Groenewegen, n.d.).

According to Sun and He (2023), several factors influence people's intention to purchase SUPs. One of the most significant is normative social influence, which involves the pressure to meet others’ expectations in order to be accepted by a group. This means that if some individuals choose to stop buying SUPs, others may do the same to avoid feeling left out.

The study also highlights the role of informational social influence, where people rely on the opinions and advice of others to guide their choices. Friends and family, in particular, can have a strong impact on decisions about sustainable behaviour, like avoiding SUPs. If someone close recommends buying a product, the likelihood of purchase increases. Conversely, if they advise against buying SUPs, the individual’s intention to purchase them tends to decrease (Sun & He, 2023).

Third, positive anticipated emotions also influence consumer behaviour. When consumers recognize the environmental harm caused by purchasing SUPs, they may feel hesitant to buy them. Although these emotions may not lead to immediate behavioural change, they can gradually deepen as consumers reflect on the broader impact on society. Nevertheless, the research shows that informational social influence has a more significant and lasting effect. The behaviours and opinions of important others, such as friends and family, often outweigh environmental concerns. As a result, individuals may still choose to buy SUPs if those around them do, even when they are aware of the negative environmental impact (Sun & He, 2023)

2.1.10.3

A study conducted in the United States on the willingness to use reusable cups under financial incentives found that individuals with higher environmental involvement - for example, awareness of the resources used to produce disposable cups - were less influenced by financial incentives. In contrast, individuals with lower environmental involvement were more likely to be motivated by such incentives (Nicolau et al., 2022).

Another study by Sheppard et al. (2025) found that probabilistic rewards, such as a 10% chance to win a free coffee or a 5% chance to win a $5 gift card, can encourage greater use of reusable cups. However, it is worth noting that the study only collected data from cafés offering the rewards, not from those that did not.

Promoting social awareness is essential to changing consumer behaviour. Sustainable habits must become an integral part of daily life, supported by a variety of activities that raise awareness and educate individuals. Isolated campaigns or minimal changes in cultural attitudes toward environmental issues are insufficient to address the scale of the problem. Education plays a critical role in this process. Children, in particular, should be introduced to environmental topics from an early age and taught about them in an objective and engaging manner (United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2018)

This research project aims to explore the potential for introducing reusable alternatives to single-use plastics (SUPs) at Quy Nhon University. The primary objective is to assess whether there can be a support base among students and staff for reducing SUPs by replacing them with reusable products, which aligns with the second level of Lansink’s ladder: reuse. Additionally, the study investigates the general level of awareness and knowledge regarding SUPs what they are, how they are used, and what happens to them after disposal.

To address the central research question “How can a support base for reducing SUPs at Quy Nhon University be established by raising awareness and offering reusable alternatives?”, we employed a mixed-method approach. The study combines quantitative data collection through surveys with qualitative insights obtained via informal discussions, guest lectures and green club activities. This approach allows us to measure certain behaviours and attitudes, as well as gain deeper understanding of the motivations, challenges, and perceptions related to plastic use and sustainability on campus.

2.1.1 Subquestion: What do participants already know about SUPs, and how do they perceive reusable alternatives?

As previously mentioned in order to better understand the attitudes, behaviours and challenges related to the use of reusable bottles and cups, a survey was conducted among the students and lecturers of QNU. 36 questions were initially prepared in English (Attachment 9.2.1 General survey in English). The survey questions varied and were divided into three sections: one focusing on personal information, another on general knowledge about SUPs, and a third assessing both awareness of and willingness to use reusable products. After that the survey was then translated into Vietnamese by “Vertaalbureau Perfect” (Attachment9.2.2GeneralsurveyinVietnamese).

After receiving the translation, the text was fine-tuned and clarified in collaboration with the Vietnamese team. The finalized survey was put into a Google form and was sent out to all students and staff at Quy Nhon University. A total of 605 responses of both students and staff members, such as lecturers were received.

The primary aim of this survey was to gather data on current practices concerning plastic consumption, as well as to assess the willingness of the university community to adopt more sustainable alternatives. This so that we could answer the research question “How can a support base for reducing SUPs at Quy Nhon University be established by raising awareness and offering reusable alternatives?”. Furthermore, the survey results were analysed using Excel to identify a target group to distribute reusable bottles and cups to

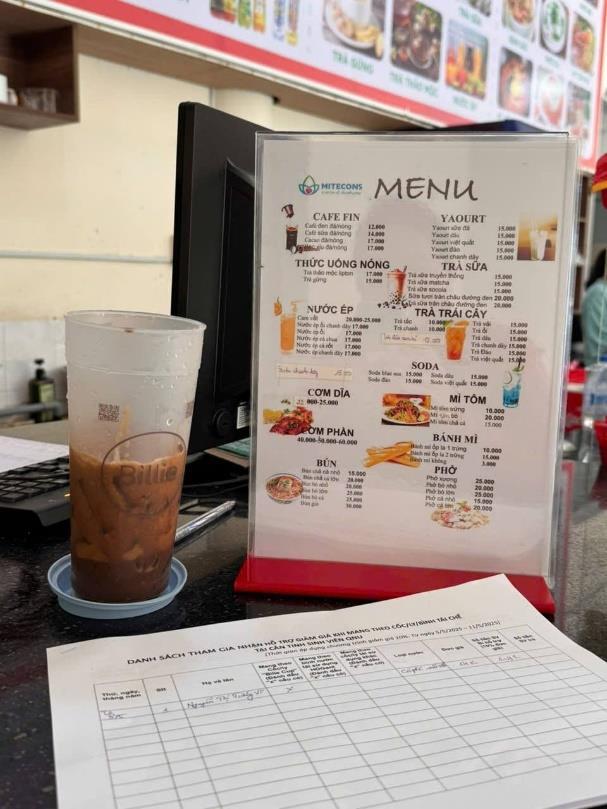

For the reusable bottles, Dopper bottles with the HOGENT logo were chosen. They are suitable for both hot and cold drinks. Additionally, they have a special feature that allows them to also be used as cups (Figure 29).

For the cups, the XXL Billie cups were chosen. These cups have a capacity of 650 ml and come with a lid. They are easy to clean and can be used for both hot and cold drinks. The decision to go with these cups was also influenced by the practice in Vietnam of adding a lot of ice to drinks, making a larger cup size necessary (Figure 30).

For the bottles: 30 participants who indicated that they did not currently own a reusable bottle but would be willing to use one if they had it, were selected.

For the cups: The distinction between occasional users (OU), who use a cup up to 5 times per week, and heavy users (HU), who use a cup at least 5 times per week was made. From these groups, 15 OU and 15 HU participants were selected. Their comfort using a reusable cup was also taken into consideration.

For both target groups, the aim was to select participants with diverse backgrounds in terms of gender, faculty, age, and role (student or staff member, such as lecturer, etc.). However, this turned out to be more challenging than expected. Despite several attempts to reach out, very few responses were received from the student population. As a result, many of our participants ended up coming from the Faculty of Natural Sciences, as the teachers supporting our project were familiar with these students and could contact them more easily. Given that around 79% of respondents of the survey were women, our target audience is mainly female. For the bottles group, the male-to-female ratio is 2:3. For the cups group, the ratio is 4:15.

In the bottles group, approximately 13% of participants are staff members, compared to around 17% in the cups group.

Our target audience was contacted and added to a Zalo group (a messaging platform). Two pickup times for the cups/bottles were then scheduled.

After the first three weeks, an initial survey for bottles (Attachment9.2.3Surveybottles: week1,2and3) and another one for cups (Attachment9.2.4Surveycups:week1,2and 3) was sent to gather feedback from participants on their experience. The survey aimed to identify potential barriers and success factors After the fourth week, a final survey was sent for bottles (Attachment9.2.5Surveybottles:week4) and cups (Attachment9.2.6 Surveycups:week4).

2.1.2 Subquestion: How do participants perceive reusable cups and bottles in terms of their positive and negative aspects, comforts, and anxieties?

To determine this, the four-forces model was used. Each week, the four factors were identified by distributing a short survey after the first three weeks and again after the fourth week, which included questions about pains, gains, comforts, and anxieties.

2.1.3 Subquestion: How effective is a 10% discount to increase the use of reusable cups/bottles?

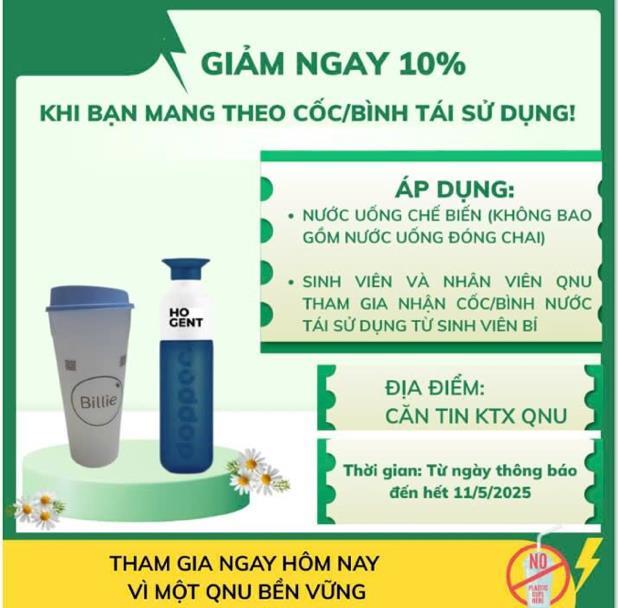

In the fourth week, an incentive was introduced in partnership with QNU's canteen employees. Participants received a 10% discount when ordering a drink with their reusable cup or bottle.

The use of the discount was monitored by QNU canteen employees. Additionally, a short survey was distributed after the incentive week to gain insight into participants' behaviour toward reusable products, and whether the incentive had influenced that behaviour. This enabled a cross-check of the data, using two independent sources

2.1.4 Subquestion: How can broader environmental awareness be promoted among students and staff at QNU?

Over several days, posters about the problem of SUPs were created in cooperation with the Green Club. In addition, several guest lectures on waste management and the SUPs issue were given to students. A beach clean-up involving students and teachers was also organized on May 17, covering an area approximately 500 meters long.

The results presented in this chapter provide valuable insights into the existing awareness, habits, and potential barriers related to the use of reusable materials at the university. These findings serve as the basis for further analysis and recommendations on how to effectively promote more environmentally friendly behaviour within QNU.

The first three questions of the questionnaire collected personal contact information, such as the respondent’s name and phone number. This information was gathered solely for the purpose of contacting participants in case they were selected for further involvement in the project. These personal details were not included in the data analysis

and have been treated with strict confidentiality. The actual analysis of the results is therefore based only on the substantive questions that followed.

When examining the gender distribution of the 605 respondents, it becomes clear that a large majority, accounting for 78,85%, were female, while 20.99% were men. 1 student selected “other” when asked about their gender.

When examining the work distribution of the 605respondents, we see that23participants were lecturers, 1 person was laboratory staff, 2 were cleaning staff, 4 were office staff, and 575 were students

Among the participating 572 students (3 students did not answered), 44.58% are firstyear students, while 24.30% are fourth-year students (final-year students). Additionally, 16.96% of the respondents are third-year students, and the remaining 14.16% are second-year students.

The survey responses were collected from students and staff across various faculties. 605 people answered this question. The distribution of participants is as follows: the Faculty of Economics and Accounting had the highest number of respondents, with 217 respondents completing the survey. This was followed by the Faculty of Foreign Languages with 201 participants, and the Faculty of Natural Sciences with 93 participants. Other faculties had fewer respondents: the Faculty of Social Education (12), Faculty of Political Education (13), Faculty of Finance, Banking and Business Administration (14), Faculty of Physical Education (34), Faculty of Education (8), Faculty of Engineering and Technology (7), Faculty of Primary and Pre-School Education (2), and the Faculty of Mathematics and Statistics, which had only 1 respondent. The other 3 respondents chose ‘Other’ because they were office and cleaning staff, so they are not assigned to a specific faculty.

Important note: by 'multiple choice' (MC), we mean that several answer options were provided, and respondents were allowed to select more than one.

3.2.1

In this question, respondents were asked to indicate which materials they believed to be SUPs. They were allowed to select as many options as they considered appropriate. This approach allowed for a broader understanding of their knowledge and perceptions regarding different materials associated with SUPs. The multiple-choice format provided valuable insights into how well respondents could distinguish between various types of materials commonly linked to single-use plastics.

Figure 33: Compilation of six images illustrating single-use and reusable products used in the survey. Images sourced from Shutterstock, CNN, product websites, and stock photo providers (see figure references). Compilation created by the author, March 2025. Copyright remains with the original image owners.

The image above presents several options that participants were asked to evaluate. The correct answers were A, B, and D. Option A was correct because it showed disposable plastic cutlery. Option B was correct as it showed a disposable plastic plate. Option D was also correct, illustrating plastic straws.

Options C, E, and F were not correct. Option C displayed reusable coffee cups, option E showed reusable containers, and option F showed a reusable bottle. As these items are

designed for repeated use and do not fall under the category of single-use plastics, they were not considered the correct choices.

Out of 605 respondents, 438 respondents were able to correctly identify all the SUP items. 167 responded incorrectly. The most common mistake was selecting option (A, B, C, D), which occurred 55 times. In addition, various other types of errors were made in different ways.

The following table represents the percentage of respondents who incorrectly selected certain items when asked to identify all SUPs. These respondents chose at least one incorrect item, meaning they did not correctly identify the SUP items.

Table 1: Wrongly identified SUPs. Source: own results.

Wrongly identified SUP’s (Multiple choice) Responses in % (167 responses)

C (reusable cup)

E (reusable food container)

F (reusable bottle) 21%

The results show that the most selected incorrect item was the reusable cup with 56%.

Correlation between participants’ understanding of SUPs and their incentive-driven behaviour

Table 2: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1) and the question about the best incentive to use their reusable cup (Table 19) Source: own results.

Multiple choice question Knows what SUPs are (438 participants) Doesn’t know what SUPs are (167 participants)

Reusable cup is already an incentive

when using reusable cup

drink when using the reusable cup

There appears to be a difference between participants who correctlyidentified what SUPs are and those who did not. Those with correct knowledge are more likely to view the reusable cup itself as an incentive and show less need for additional reductions. In contrast, participants who answered incorrectly tend to be more motivated by an immediate price reduction but are less influenced by other rewards such as receiving a free drink after ten uses.

3.2.3 Correlation between participants’ understanding of SUPs and perceived ease of bringing a reusable cup to QNU

Table 3: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1) and the question about the ease to bring a reusable cup to QNU (Figure 43) Source: own results.

No multiple choice questions Knows what SUPs are (438 participants) Doesn’t know what SUPs are (167 participants)

Yes, easy to bring reusable cup to QNU

No, not easy to bring reusable cup to QNU

When asked about the ease of bringing a reusable cup to QNU, only a slight difference was observed between participants who correctly identified what SUPs are and those who did not.

3.2.4 What do the respondents think that happens with SUPs in Vietnam?

Respondents were given three possible answer options: A = The SUPs are collected and then recycled; B = They are collected and burned; C = They are collected and then dumped in a landfill. Additionally, respondents had the option to provide their own answer. Respondents were allowed to choose more than one option.

In the open-ended responses, 6.77% of the students who answered indicated that they had no idea at all, while 54.71% answered that they were certain the SUPs were simply dumped on a landfill 605 people answered the question.

A (Collected and Recycled), B (Collected and Burned) and C (Collected and Dumped on a landfill) are all right answers.

Table 4: Question about post-treatment of SUPs Source: own results.

Answer possibilities (Multiple Choice) Responses in % (605 respondents)

A (Collected and Recycled) 48,01%

B (Collected and Burned) 30,58%

C (Collected and Dumped on a landfill) 54,71%

Open Response 6,77%

A, B, C (Right Answer) 11%

3.2.5 Correlation between participants’ understanding of SUPs and their post-use handling and their incentive-driven behaviour

Table 5: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1), the question about the posttreatment of SUPs (3.2.4), and the question about the best incentive to use their reusable cup (Table 19) Source: own results.

Multiple choice question

Knows what SUPs are, AND correctly knows what happens with SUPs in Vietnam (53 participants)

Doesn’t know what SUPs are, AND doesn’t know correctly what happens with SUPs in Vietnam (152 participants)

cup is already an

free drink when using the reusable cup 10 times

The total amount of participants (53 + 152) does not add up to 605 because some respondents were aware of what SUPs are but did not select all the correct options regarding their handling in Vietnam (A, B, C), and others selected those options without knowing what SUPs are.

Here, there is also a distinction between individuals with greater knowledge about SUPs and their post-use handling. Those who are more informed are more likely to view the reusable cup as a sufficient incentive. However, they still show a similar, or even greater, interest in additional rewards, such as a reduction or a free drink after 10 uses.

3.2.6 Correlation between participants’ understanding of SUPs and their post-use handling and perceived ease of bringing a reusable cup to QNU

Table 6: Correlation between the question where they had to select the SUP items (3.2.1), the question about the posttreatment of SUPs (3.2.4), and the question about the ease to bring a reusable cup to QNU (Figure 43) Source: own results.

No multiple choice questions

Knows what SUPs are, AND correctly knows what happens with SUPs in Vietnam (53 participants)

Doesn’t know what SUPs are, AND doesn’t know correctly what happens with SUPs in Vietnam (152 participants)

Yes, easy to bring reusable cup to QNU

No, not easy to bring reusable cup to QNU

There is also a slight difference between participants who understand what SUPs are and are aware of their post-use handling. These individuals find it easierto bring their reusable cup to QNU.

3.2.7 What do the respondents think Vietnam does to reduce SUPs?

The respondents primarily answered "yes" to the question “Do you think Vietnam tries the reduce the SUPs usage, give an example?”, either simply stating "yes" or providing an example. The examples given were diverse. This question had 605 respondents, 5.45% responded "yes" without providing any examples, 4.79% believed that nothing is happening, 4.22% did not know, and 1.48% did not answer at all.

A significant majority of 84.3% said "yes" with an example, indicating that they believe or are aware that Vietnam is taking action to reduce SUPs. However, many struggled to give concrete examples, which made it difficult to quantify their awareness accurately, especially given the open-ended nature of the question.

Among the examples provided, some participants mentioned recycling as a measure being taken. Others noted that the government appears to be promoting the use of reusable or eco-friendly alternatives, such as paper straws and reusable shopping bags.

3.2.8 What do the respondents think is the biggest negative effect of single-use plastics?

For this question there were 605 respondents

On a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating the most severe negative impact, respondents rated the environmental impact of single-use plastics at an average of 4.16.

The impact on human health was rated at 3.99, showing that this is also seen as a major concern among the respondents.