INTRODUCTION

ON EMERGENCE

Sounding Beyond the Womb Abyss

Now and then a black man has risen above the debased condition of his people. . . . But no such fortune fell to the lot of the plantation woman. The black woman of the South was left perpetually in a state of hereditary darkness and rudeness. . . . Her entire existence from the day when she first landed, a naked victim of the slave-trade, has been degradation in its extremest forms.

—ALEXANDER CRUMMELL, “THE BLACK WOMAN OF THE SOUTH: HER NEGLECTS AND HER NEEDS”

The South in her, the land and salt-winds, moved her through Charleston’s streets as if she were a mobile sapling, with the gait of a well-loved colored woman whose lover was the horizon in any direction. . . . She made herself, her world, from all that she came from. . . . she made up what she needed. What she thought the black people needed.

—NTOZAKE SHANGE, SASSAFRASS, CYPRESS AND INDIGO

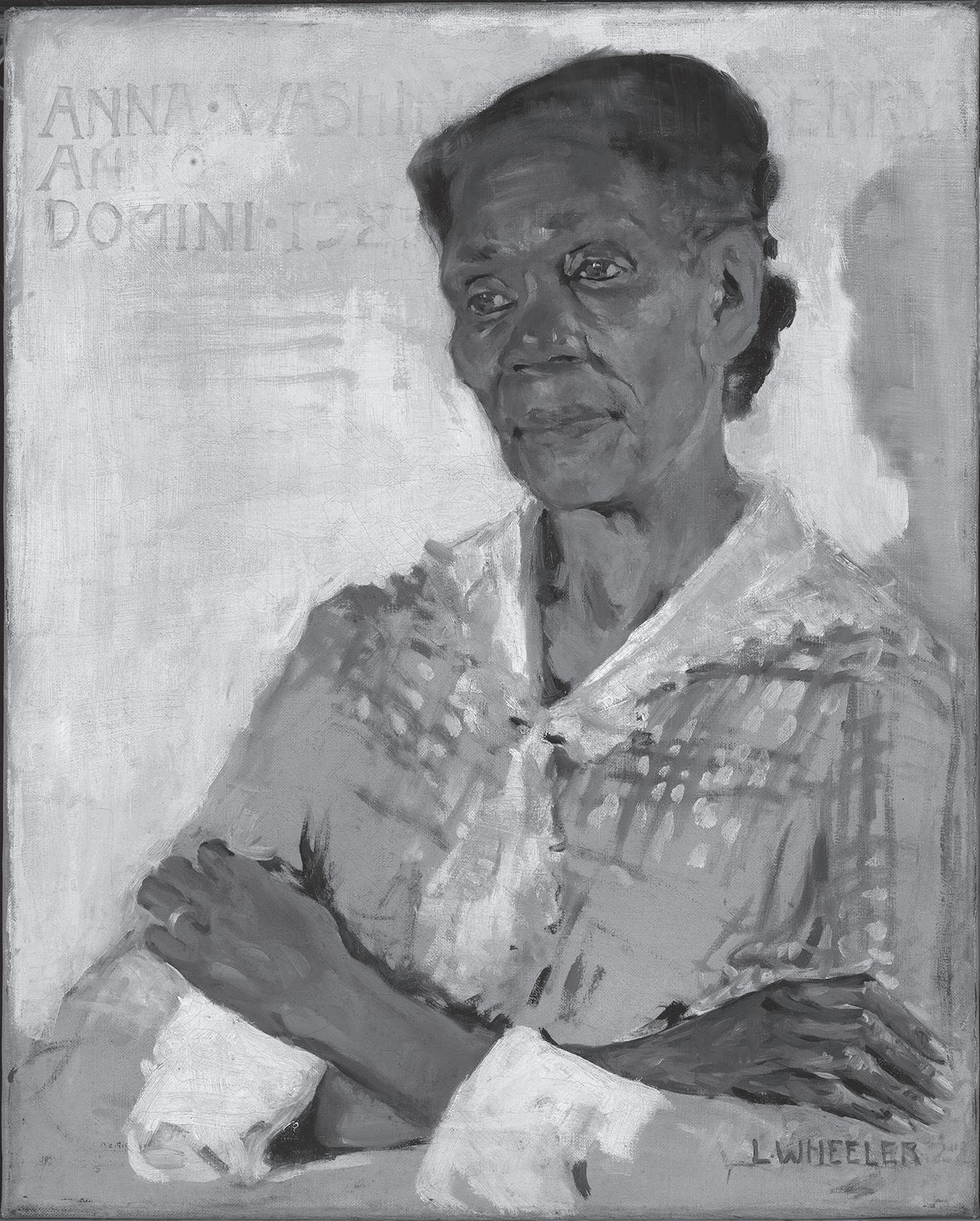

In the March 27, 1926, entry for her Pittsburgh Courier column “A Woman Speaks” (later “Une Femme Dit”), Alice Dunbar Nelson lauds the ability of the visual artist Laura Wheeler Waring to capture “the sorrow-laden heart” of the Black race in her portrait of Annie Washington Derry.1 By the mid-1920s, Waring had become widely known for her

portraits of influential African Americans as well as for her illustrations for the NAACP’s Crisis magazine. Waring’s oeuvre mainly features portraits of the Black middle class, but Dunbar Nelson is particularly enchanted by the painter’s 1925 portrait of the working-class Derry. Whereas her column typically showcases the author’s sharp wit, Dunbar Nelson’s solemn tone in her profile of Waring’s work aligns more closely with that of her short fiction. For Dunbar Nelson, Waring’s subject is an “age-old sorrow-lined, calm-after-storm of the aged colored woman. An epitome of a race. Summing up in her weather-beaten countenance three centuries of making bricks without straw under the hissing coil of the whip-lash. Envisioning a future of a people out of bondage, but still wandering in the wilderness.”2 Although located in the US North and painted by a northerner, Derry is interpreted as being inextricably tethered to a degraded enslaved past that is generally associated with the antebellum plantation South. Dunbar Nelson’s interpretation endows Derry with an ability to visualize a future beyond slavery and its afterlives, but, in a somewhat contradictory manner, she does not read the subject as possessing the ability to move toward it. While a movement into a more promising future may begin with her, it will not include her.

What is striking in Dunbar Nelson’s focus on Derry’s face is how Derry signifies metonymically as “an epitome of a race”—as being representative of Black womanhood as a whole through three centuries of slavery and into the contemporary moment. Even though Derry lived in Pennsylvania, her body bears the history of southern plantation labor through generations of toil within a brutal system of surveillance and violence. For Black middle-class women of a younger generation such as Dunbar Nelson, Derry represents a moment of recognition, an acknowledgment of a cultural inheritance linked to Black women’s labor on the southern plantation. To acknowledge this inheritance was perhaps a difficult thing to do because Dunbar Nelson, who was born in Reconstruction Louisiana, was writing in the shadow of what Alexander Crummell described as Black women’s shame, as representing the most debased condition of Black people in the South.

In his 1883 speech, “The Black Woman of the South: Her Neglects and Her Needs,” Crummell casts Black rural women as obstacles to Black progress, as stuck in the past and unable to acquire the skills necessary to rise in the modern world.3 Whereas many Black men had certain opportunities

FIGURE 0.1 Laura Wheeler Waring, Anna Washington Derry, 1927, oil on canvas, 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.5 cm).

Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation, 1967.91.1.

for education and mobility, Black women of the South “were left perpetually in a state of heredity darkness and rudeness.” Black women, for Crummell, became the repository for all that was debased among the race; they alone carried the burden of primitivism in the age of uplift and modernity. Crummell’s understanding of Black progress rests on a series of dualisms, such as men/women, civilized/primitive, city/country, and North/South. At the center of this dualistic understanding of progress is the juxtaposition of Black male development versus the primitivism and rudeness of Black women. Whereas one travels, the other is static, stuck in the past as well as on the land. By 1926, as the implied relationship between northern-based Derry and the South in Dunbar Nelson’s review illustrates, the positioning of the Black woman as primitive appears to have extended beyond the geographical borders of the South. It is as if the notion of “hereditary darkness” that Crummell speaks of—a notion that has its origins in the Middle Passage and the plantation—ensures that Black women are perceived to be, as Dunbar Nelson suggests of Derry, “wandering in the wilderness” but unable to emerge and participate in the contemporary moment regardless of their location.4

However, a major shift transpires between the literary and artistic approaches shared by the formerly enslaved and first generations of emancipated southern Black women and those of their literary and creative progeny. Impressions such as those shared by Crummell that linked the South and the Black female body together as landscapes of abject primitivity—impressions shaped by what I call womb abyss framing— began to come under scrutiny as early as 1928, when Zora Neale Hurston shuns sentiments like Dunbar Nelson’s celebration of the “sincere elevation of tragedy in the artistic life of the race” and the idea of sorrow being linked to the Black South in particular.5 This shift continues fifty-six years after Dunbar Nelson’s review, when the writer Ntozake Shange presents a contrasting portrait of the relationship between Black womanhood and the South. In a 1982 Today show interview, Jane Pauley poses the following question regarding characters in Shange’s debut novel, Sassafrass, Cypress and Indigo: “One of your characters is a little girl who has quote ‘too much south in her.’ What’s that mean?”6 Pauley is referring to an exchange between a lovingly exasperated Hilda Effania and her youngest daughter, Indigo. Although perhaps made mildly nervous by the audacity of her daughter’s generation, Hilda is not unfamiliar with the Black southern

women’s heritage and is indeed largely responsible for teaching her girls about its power. Shange responds: “Oh, ‘too much south in her.’ It’s like she is never losing contact with whatever it was that the slaves contributed to American culture. She’s never lost sight of how we look in the sunset or how we cook or how gorgeous we are when we are being friendly with one another. If you think about what makes New Orleans gorgeous what makes Charleston beautiful or some sections of Paris even, it is . . . people of color and how strange we are in a European environment.” As Shange explains, the phrase refers to Black girls and women who have maintained contact with African contributions to the cultures of the Americas.

Shange’s South is a tool that enables mobility and that authorizes the defining of self and world, and it is Shange’s notion of the “South in her” that inspires the title for this study. Shange’s explanation of Black women’s relationship to the South disrupts the logic of “hereditary darkness” that formerly linked the two. Taking up Shange’s notion of both the South and the strange as representing not abjection but possibility, The Souths in Her tells the story of the writing and choreographic practices of twentieth-century Black women artists and the ways they move between artforms and geographies.7 This study constitutes a diasporic genealogy that indexes key expressive shifts in the life writing, choreography, and fiction produced by, among others, Zora Neale Hurston, Katherine Dunham, Dianne McIntyre, Ntozake Shange, Maryse Condé, and Jamaica Kincaid. Hailing from diverse geographical and temporal locations, these artists share a history of confrontations with the multiple tensions that Souths as idiom present. Their varied positions enable an examination of the ways that these tensions play out between Black women artists and a number of intellectual and artistic movements, including the New Negro, Négritude, and Black Arts Movements. As their oeuvres show, each artist’s movement across and encounters with various Africana southern cultures lead to significant transformations in her experimental relationship to artistic form. Each artist’s shifts issue challenges to intellectual and expressive frameworks that understand modernity as determined by the symbols that emerged from the slave ship, the plantation, and masculinity, and they impel us to investigate the assumptions and narratives that inform these frames.

The Souths in Her illustrates the central role that Souths have played in the formation of a poetics of transmutation generated by Black women artists. I argue that this poetics represents the disruption and reconfiguration

of creative and cultural organizing principles informed by notions of “hereditary darkness and rudeness”—notions that emerge from a point of origin that I call the womb abyss—affixing the Black female to static notions of the South.8 Through their travels across Black Souths, the authors and choreographers featured in this study encounter strange sounds, relationships to body and spirit, creation myths, relationships to inheritance, and modes of expression that catalyze this transmutation, and these encounters directly affect each artist’s expressive horizons: their perceptions of the stories that can be told and their potential for telling them. Following these encounters, each artist casts new sites of emergence: The storytelling that follows the encounter with a strange South provides a model of expressive form and strategy undergirded by more expansive creative principles.

I analyze each artist’s transformative negotiations with the narrative afterlives of the plantation by engaging both their writing and their choreography, since it is precisely at the nexus of the written word and the Black woman’s moving body that plantation-based narratives of primitivity accrue, situating Black women as primitive sites of extraction that exist not to contribute to a broader cultural archive but rather to aid the formation of others’ subjectivity. In locating this nexus, The Souths in Her makes key theoretical and methodological interventions: The Black female body becomes sutured to the word, and this union becomes codified in expressive forms. To understand the history of this fusion and Black women’s maneuvers around it, we must examine written and embodied forms. Therefore, to most fully understand Black women’s aesthetic maneuvers, we are required to examine the correspondence among movement, writing, and their formal innovations.

Southern encounters begin to disrupt the Middle Passage– and plantation-informed logics embedded in expressive forms and traditions. These encounters expose the writers and choreographers featured in this study to unfamiliar and differently organized principles through which they may define anew themselves and the world around them. The relationship between geography and the writing and choreography of Black women is dynamic: as Aimee Meredith Cox argues, “Choreography suggests that there is a map of movement or plan for how the body interacts with this environment, but it also suggests that by the body’s placement in a space, the nature of that space changes,” and for Shange, geography

and movement coalesce in a manner that enables her written expression.9 The genealogy presented in this book does not lend itself to a teleological, linear story of progress; rather, it provides a snapshot of the recursive mappings full of irruption and shifts that collectively suggest another way of understanding Black women’s poetics in relationship to the South.

WOMB ABYSS AND HEREDITARY DARKNESS

Informed by Black studies, decolonial studies, and feminist and queer theorists, The Souths in Her understands the issue of “hereditary darkness” as an inheritance passed down from the transatlantic slave trade with implications that exceed genetic transfer. Most urgent for this study are the ways this inheritance has become embedded and reinforced in our structures of thinking and the implications of this transfer for Black women’s expression. As several theorists of African American and Caribbean studies have argued, the Middle Passage represents both a moment of unspeakable violent loss and a moment of emergence, with the latter true for the shaping of both Black culture and European modernity. Captive Africans’ emergence from the violent sites of enclosure referred to as “holds”—from the warehouses of Cape Coast Castle to what Édouard Glissant in “The Open Boat” (1990) calls the “belly of the boat”—was understood as a kind of birth.10 Following Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, Christina Sharpe explains that modernity “ ‘is sutured by this hold.’ The hold is the slave ship hold; is the hold of the so-called migrant ship; is the prison; is the womb that produces blackness.”11 This womb or belly into which Africans descended and were “dissolved,” as Glissant describes, served as a site of suffering doubling as a womb that constituted one of three abysses that kidnapped Africans encountered and sometimes emerged from en route to the Americas.12 He posits that “the unconscious memory of the abyss served as the alluvium” for the forging of new relation, or shared knowledge, from which new Afro-Creole cultures were born. If in this moment, as Glissant notes, captive Africans witness “language vanish, the word of the gods vanish, and the sealed image of even the most everyday object, of even the most familiar animal vanish,” then as semiotics and forms of expression are reconfigured, they

Nicole M. Morris Johnson shows how key Black women writers, artists, choreographers, and performers contested pervasive silencing and developed new forms of expression by drawing on creative visions of multiple Souths: the Southern United States and the Caribbean, as well as Africa. She analyzes the intertwined relationship between movement and writing in their works, examining how unexpected encounters with unfamiliar traditions catalyzed formal experimentation and movements for expressive liberation.

“The Souths in Her offers an important exploration of how Black women artists have used selfexpression to counter misperceptions about them and their legacies in the South. Through rich analysis of Black women writers and choreographers, including Zora Neale Hurston, Katherine Dunham, Maryse Condé, Ntozake Shange, and Jamaica Kincaid, alongside contemporary artists like Allison Janae Hamilton, Urban Bush Women, and Akwaeke Emezi, this book showcases how they achieve new ‘expressive horizons’ and chart new territory to move freely.”

SOYICA DIGGS COLBERT , author of Radical Vision: A Biography of Lorraine Hansberry

“Taking her title from Ntozake Shange, Nicole M. Morris Johnson explores various Souths: the worlds that Black women artists, primarily writers and choreographers, made to counter silencing. Authoritative and beautifully written, The Souths in Her understands Black women’s art as emancipatory in its broadest and bravest forms, delving into feminist cultural expression out of the Middle Passage to illuminate its creative power and impressive diasporic reach.”

THADIOUS M. DAVIS , author of Understanding Alice Walker

“The Souths in Her is a brilliantly conceptualized examination of women writers and artists of African descent from the Caribbean and the United States whose contributions boldly confront confining narratives that have typically centered Black masculinity. Morris Johnson’s beautifully written book refines and expands these methodologies to center Black women, Africa, and its diasporas. An outstanding and exciting achievement in Southern studies.”

RICHÉ RICHARDSON , author of Emancipation’s Daughters: Reimagining Black Femininity and the National Body

NICOLE M. MORRIS JOHNSON is an assistant professor of English at the University at Buffalo.

BLACK LIVES IN THE DIASPORA: PAST / PRESENT / FUTURE

COVER DESIGN : Julia Kushnirsky

COVER IMAGE : Allison Janae Hamilton, Floridawater II (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York and Aspen. © Allison Janae Hamilton

UNIVERSITY PRESS / NEW YORK cup.columbia.edu