Preface: P.S.A.

BLACK SPECULATIVE FICTION IS NOT SCIENCE FICTION OR FANTASY

In a 2021 interview, Reynaldo Anderson makes it clear that Black speculative production is not science fiction, or even a subgenre of science fiction. Rather, he argues that Black speculative production is “its own thing.” For Anderson, it is not merely a lexical difference marked by a name, but a qualitative difference marked by the emergence of thought and the imagination. In full, Anderson argues, “These traditions emerge separate from the European project of science fiction. That’s why the black speculative tradition is not science fiction. European science fiction emerges in the context of the Industrial Revolution and in the wake of Enlightenment, whereas the black speculative tradition emerges as a response to antebellum slavery, scientific racism, imperialism and colonialism over the last 150 years.”1

If we define science fiction as Enrico Terrone does in his article “Science Fiction as a Genre” as a genre principally concerned with the presentation and examination of “empirical times, places and characters,”2 but in a way that is different in nature or kind [thus, genre] from the mimetic or naturalistic elements of traditional fiction, then we see that what marks science fiction as unique and different from fiction is its capacity to render reality or ordinary experience “foreign” or estranged.3 For Terrone, science fiction accomplishes this “impression of ‘estrangement’ ” not through completely diverging from reality or ordinary experience itself, but through what Terrone terms “cognitive validation.”4 It is in this detail and this critical term that we can begin to get a sense of Anderson’s resistance to including Black speculative production within the genre of science fiction.

xii Preface: P.S.A.

P.1 Nola Hatterman, Op het terras (On the Terrace), oil on canvas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1930.

What Terrone writes next seals in Anderson’s resistance: A work of science fiction requires “cognitive validation” in the sense that the things constituting the novum are nonetheless simultaneously perceived as not impossible within the cognitive (cosmological or anthropological) norms of the author’s epoch.5 This is what we should slow down and focus on: the connection between the idea—that is, the experience—of estrangement and the idea of cognitive validation. What Terrone is arguing is that in order to reimagine the world, which science fiction as a genre does, there must first be an agreed-on baseline of what constitutes this world, or reality—that is, the cosmological and anthropological structuring order. It is this baseline, though, that distinguishes Black speculative production and Euro-modern science fiction.

Preface: P.S.A. xiii

To state it more directly, Euro-modern science fiction begins with baseline cosmological and anthropological assumptions of the nature of reality or ordinary experience that are themselves white. It is this baseline reality that science fiction alters to create in the reading audience—which is assumed to emerge from this same cosmological and anthropological order—a sense of an altered state of reality—which Terrone refers to as “estrangement.” What Anderson is telling us is that Black speculative producers and the audience of this production do not share this same assumption.6 That is, the baseline cosmological and anthropological structure of the Black world, and thus Black reality or ordinary experience, is radically different from that of Euro-modernity.7 In this way, Black speculative production cannot be a subgenre of science fiction because it does not assume the same starting points and the same cosmological or anthropological order.8

Anderson is not only pointing out this difference in the earlier quotation but is also establishing a critical argument: that what Black speculative production is really about is not a critique of Euro-modernity and the Euro-modern project; rather, Black speculative production is concerned with its own origins 9

What does this other, Black origin look like? What are its cosmological and anthropological assumptions? How do these assumptions manifest in Black speculative production? In order to answer these questions, we have to look more closely at what Anderson tells us in his interview. If we focus our attention on two key phrases in this interview, his argument becomes clear.

The first key phrase occurs in the first sentence of his interview, quoted earlier, where he says that science fiction is a European project. Project here has a double meaning: on the one hand, it refers to the site of a constructed object. Thus, building a house is a project. The house, though, is not itself the project per se, but the result of a project—that is, the physical expression of a shared or collected effort of individuals organized around a singular activity, bringing forth the concrete reality of an object from an abstract principle or plan of action. On the other hand, project also refers to a worldview, what is projected as the normative element of reality or ordinary experience itself. In this sense, project refers to a collection of beliefs and values shared within a group that constitutes not only their identity but also how they view and construct the world for themselves. This sense of project includes the cosmological and anthropological assumptions but also the philosophical systems and folklore, of which science fiction is one expression.10

xiv Preface: P.S.A.

Taken together, project refers to both the cosmological and anthropological assumptions that ground a world and the physical or material expressions that reflect and sustain these assumptions. Significant to these are the stories that we tell ourselves about our world, its meaning, and its values—not as one of many beliefs, but as what is manifestly true and reflective of something real about the world itself. As such, our projects, though flexible and swiftly changing, are also rigid. This is what Anderson is referencing when he argues that Black speculative production “is its own thing”: namely, that it is the expression of a unique set of beliefs and values, a unique set of axiological projects wherein cosmologies and anthropologies are developed and supported.

The other key phrase occurs in Anderson’s interview where he notes that “the black speculative tradition emerges as a response to antebellum slavery, scientific racism, imperialism and colonialism over the last 150 years.” This is an important point for two reasons. The first and most obvious reason is that it works to establish the Black speculative tradition as generating its own cosmology and anthropology—as already noted. Second, Anderson’s claim works to situate the foundation of the Black speculative tradition not just outside but also parallel to the Euro-modern project. That is, Anderson situates the Black project and the Euro-modern project not as twins or two sides of the same coin, but in parallel dimensional spaces that may overlap while largely existing side by side. Alongside of the Industrial Revolution, there are also critiques of antebellum slavery; alongside of the Enlightenment, there are also critiques of scientific racism. This alongside-of is also what establishes Black speculative thought as “its own thing,” operating on its own terms, on its own ground.11

Rather than being a continuation of a meditation on the angst and the emergence of the imaginative renderings of the future in the wake of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, Black speculative production emerges alongside these traditions as formative critiques of them and as imaginative renderings of a future that are not tied up with these. This alongside-of is the critical phrase—not just in response or subservience to , but also as an and or an Other that marks the alternate origin of the Black imaginative. This will be critical for this project: as other-to and otherwise-alongside and parallel-to Western modernity, the Black imagination as a way of rendering identity and politics revolves around another origin of cosmology and anthropology—not just in terms of lineage, but also in terms conceptual beginnings of the lines of descent.

Preface: P.S.A. xv

Black speculative production, then, reveals that origin is not an empirical idea wherein we can point to some specific moment as the beginning. Rather, Black speculative theory reveals that the very idea of origin refers to a constructed project of identity and chosen lineage as a project.

But what does this mean? That I am writing a book about Black speculative fiction? Yes, but no. Yes, it is a book of Black speculative fiction, but, no, it is not a book about speculative fiction. That is, it is not a book about the ideas of Octavia Butler or Samuel Delany revolving within the realm of Afrofuturism or what can be called Black science fiction or fantasy. Instead, this is a book that explores the inherent meaning of speculative production for thinking and writing and living and enacting concepts of Black freedom and why this production is and has always been so critical for understanding Black sociality and politics. That is to say, this is a book about Black politics, Black social science, and Black philosophy as viewed through a rendering of the Black imagination and the Black imaginary.12

HOW TO READ THIS BOOK

How, then, should you read this book? As just a book of speculative fiction stories? As a book on and about Black political and intellectual thought? As a form of alternative history? All of these—and yet none of them. What I mean by that is that it is a book centered on speculative fiction, or what some might term Afrofuturism; it is also a book about Black political thought and intellectual lineage. But what is more, Dark Delight is a book that explicitly and implicitly argues that Black speculative thought is Black political thought, that what some might call Afrofuturism is the foundation for and beginning of Black intellectual lineage, and that alternative Black history is itself Black history. This is what is meant by all of these—but also none of them. And this is what you will find throughout Dark Delight. It will not be a traditional text of traditional writings on and about Black political thought; it will also not be a work of speculative fiction divorced from the analyticity of Black political thought. Rather, it will be an admixture of these—what I will be terming analytical fiction. Different from and other than what musicology has termed analytical fiction, this book is not a debate over tradition itself and contemporary interpretation—especially for the aesthetically informed politics of musicology

xvi Preface: P.S.A.

and ethnomusicology. Rather, this book will use both fictional narrative and philosophical analysis at the same time. Each story, for the most part, will begin with philosophical prose, or the theory that necessitates speculative fiction, in that the speculative fiction picks up where theory wains or falls short of a full critical explanation. What you will also find in each of these stories along with the prose and fiction are robust endnotes that help to situate the stories and theories historically and intellectually. These endnotes function as another site of engagement and another mode in the communication of ideas. In short, what you have before you is an experiment in form and in content. Hopefully, it is an experiment that will work.

The reason for this approach is twofold. On the one hand, there is a genuine interest in and concern over form and the relationship between theory and presentation. The question of the aesthetic of politics and political aesthetics has always been central to Black cultural and ritualistic life and is something I wish to highlight in Dark Delight as a central thematic. On the other hand, it, too, must be realized that Black politics and Black philosophical traditions find themselves, explicitly or not, searching for grounding, searching for origin, and, like all intellectual and cultural productions, are inherently speculative. Speculative fiction, it seems, as much as or perhaps more than other forms of production, is a natural direction for Dark Delight, in that it offers Black people the capacity, or at least an opportunity, to rearticulate themselves and the world in an explicitly and tangibly political way, and along-the-way, it reorients the very idea of origin and lineage.

This is what Tim Fielder means when he writes, “As an afrofuturist, I can’t always, all-the-time operate as a futurist. An afrofuturist is forced to deal in the past, present, and future simultaneously because you’re trying to reconcile all this information, misinformation, missing information—trying to fill in the blank. And that’s what makes it speculative in the real world sense and speculative in the fictional sense.”13 In other words, speculative fiction, or what some might call Afrofuturism, is really about human reality and human relations as a way of orienting the world as the place of and for human existence.

In the history of blackness in the modern Western world, this relation has been denied and obscured. As such, the issue of origin is one that has to be explicitly stated and argued for. This poses a problem, as Rinaldo Walcott notes: “The very basic terms of social human engagement are shaped by anti-Black logics so deeply embedded in various normativities that they resist intelligibility

Preface: P.S.A. xvii

as a mode of thought. Yet we must attempt to think them.”14 Walcott is defining thought or the activity of thinking in two ways: as the object that is thought about and as the process through which the thinking itself occurs. Thinking in this dual sense is not merely conceptualizing: if Anderson is correct in his assessment of Black speculative production as its own thing, the first step in thinking blackness is reconceptualizing it outside of enslavement or the white gaze. For Anderson, this means rescripting notions of Black origins and Black lineage. If we are not able to give blackness its own origin story or mythos of being, then, when we think blackness, it will be only in terms of a mythos or story form normative to white life.

This is why Black speculative production is so critical: it helps us to see that thinking itself, mythology itself, narrativity itself, and imagination itself are all political and that the creation of one’s own origin or lineage is itself a political act. This is why in Dark Delight Black speculative production and Black philosophical introspection and Black political thought are intertwined: in order to think Black life or think Black freedom or liberty/liberation, we have to first recode blackness itself at the level of mythology.

Walcott continues that “the idea of freedom cannot be divorced from the idea of what it means to be human,” so for Black people in an antiblack world, “the very idea of the human requires rethinking in order for an authentic freedom to emerge for Black people.”15 In other words, Black life and those elements concomitant with it are speculative or fictive. This is not to say that they are not real, but rather that their reality is inherently outside of Western modernity, in another world with another origin. Dark Delight argues that to rethink this world we must engage the very order of things to reorient the world itself, which requires a robust mythology rather than a reformulated ontology: that is, a mythology that functions as an ontology so as to engage the order of things at their origin, as a cosmogenesis

This is what Dark Delight is attempting to do via the Black speculative arts: to simultaneously uncover and recover a past as it also creates one. Following the footsteps of these figures, who themselves were equally committed to creation and recovery/discovery, this book attempts to situate itself as a kind of productive eruption.

The difficulty of Dark Delight is uncovering and recovering a past that is mired in an antiblack world. How does one create if one finds difficulty in the excavation itself? Does one make up a past in order to reengineer a future? In short,

xviii Preface: P.S.A.

no. Dark Delight argues that Black people have always already created an alternate world, one that is often equally dismissed, but also equally hidden. The task, then, of recovery is to locate a history both erased and hidden—that is, existing invisibly in plain sight. Dark Delight argues that speculative fiction, rather than a made-up past, helps to provide points of access to this past.

As points of entry, Black speculative production provides a new language, a new logic, a new form of thinking so as to allow for new forms of exploration, ones that recognize that a new origin and a new cosmology must begin with this exploration of blackness that is not solely tied to race—that is, the social, historical, and political process of racialization. Instead, blackness must be recoded as a set of practices, modes of existence, and sets of both outer and inner relations (of space and time) that we discover along-the-way to our understanding of those historical forces and traditional concepts that we account for with race and attach to Black flesh, Black mannerism, Black culture, Black reaction, Black beliefs and concepts and Black modes of existence and relation—to the very essence of Black time and space itself.

Dark Delight argues that along-the-way to our traditional history and concepts, we discover that blackness inhabits another reality (in sets of practices and other held beliefs, concepts, and modes of relation of space and time), one that at times intersects and overlaps with the reality of traditional history and concepts and that at other times is independent of it altogether.

Dark Delight is a text of exploration and a book of discovery. It is a long meditation on what is discovered in our exploration into thinking and our living along-the-way to thinking about and theorizing about Black freedom. It is a book concerned with what is underaccounted for and undermined. It is a book that ultimately argues that Black life is not located in the spectacular—that is, in spectacular death, in spectacular social or political alienation, or in the spectacular overcoming of spectacular odds. It is a book about the mundane. It is a book about the spectacular nature of the mundane. It is a meditation on these details, one that allows us, calls for us, and at times demands for us to slow down and sit with the mundane, to investigate beyond the immediate into what not only constitutes a life but also holds it together and gives it meaning. In doing so, we not only may be granted access to this other world and its lives up close, but also may come to understand that what was thought to be straightforward is more nuanced and complex than we previously imagined and often involves mysterious or invisible elements.

Preface: P.S.A. xix

Dark Delight is a book that understands that as it investigates these details, they will emerge not in pure form but as fundamental entanglements—that is, moments of intersection, overlap, seeming contradiction, ambiguity, and opacity. It is a book that understands that blackness stands at these intersections, emergent within these entanglements, and that it is this fact of intertwinement that allows blackness to generate its own gravitational field around which theory emerges, concepts emerge—what we take to be life emerges—revealing that blackness is less concerned with history or historical accuracy per se and is instead a meta term—Blackness—one that marks historical continuity and undergirds historical interpretation. It is a point of departure, a gathering heuristic of contradictions that both unites and divides humanity with and from itself, humanity with and from the natural world of things and animals, and humanity with and from the earth itself; that both unites and divides the human terrestrial world with and from the metaphysical world, the extraterrestrial world, and also the intraterrestrial inner world of this planet; of both those visible elements of human relation and those invisible elements of force and dimensionality.

Dark Delight is an attempt to show us that blackness as a fundamental entanglement is not a limit (of the human, of freedom) and does not delimit these either. Instead, it is a path to something else, to somewhere else: it is a kind of surrealism that reveals the “magnificent now” and the prophetic vision that blackness is anywhere—and not just in those expected locations and in those anticipated objects. Rather, it is everywhere one looks—even in those places where it is said not to exist. Dark Delight is an examination of these unexpected moments, these unanticipated upsurges, and attempts to make sense of them.

Dark Delight is an attempt to create a language and a logic to introduce and account for this upsurge and unexpected everythingness—a language of excess, of spillage, of leakage, of that which cannot be contained, of the collapse of form and structure under the weight of the coalescence of all-at-once

In this way, Dark Delight tries to embody Arthur Jaffa’s answer to Saidiya Hartman’s provocation:

Let’s start out with a question about dreams and I guess I’m struck by two things, I mean it’s not simply like a document review recording, you know, a range of thinkers about what the meaning of blackness is as much as it is you curating and trying to, I guess, assemble . . . a certain set of propositions around blackness and those propositions are actually very very different. So,

xx Preface: P.S.A.

I want you to say more about the statement that is created through this various set of propositions on the one hand; and, then, the second part of the question: in making this, you were involved in a critical practice and a critical practice that was challenging the centrality of the white gaze and the cinematic apparatus and trying to grasp, to illuminate, to record other expressive modalities and I want you to talk about the relationship between these other expressive modalities and the kinds of things that can be said and imagined about blackness.16

Simply put: “Create, Curate as a way to translate or decode what is ambiguous or illegible from within a certain framework. In a sense, it is creating a language, a discourse, a syntax, or a regional dialect. A way of knowing, a manner of speaking that is revealed from within the curation itself.”17 Dark Delight is a space that curates all those details of Black life that fall outside of the normative gaze. It is a place that explores the creative possibility of speculative fiction and the role of the imagination in rendering as real another world and other modes of living outside of this normative view. Dark Delight argues in both form and content that it is through the effect of speculative fiction and other forms of storytelling that we gain access and entrance to this other world and learn how to create and curate within this repository that is blackness.

Dark Delight invites us to imagine and reimagine history and memory and how—that is, the process by which—we remember, understand, and deal with the past; how we engage and deal with the meaning of the past for the present and future; and what our imagination, memory, and recollection have to do with the places we create for ourselves and our identity in those places and the manner in which we carve those places out of space and, with it, time

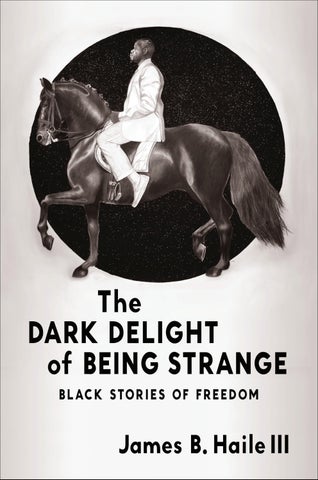

In terms of the structure of the book itself, each chapter is comprised of four elements: the image, philosophical prose, a fictive story, and a set of endnotes. Each of these elements speaks to the others, providing the reader with a fuller, synoptic experience inherent to blackness and Black lifeworlds. The image that begins each chapter sets the conceptual tone, the philosophical prose announces the history and meaning of the concept, the fictional story sets forth the world in which the concept lives and tries to find itself, and the endnotes function as a

Preface: P.S.A. xxi

kind of metanarrative or the omniscient narrator that places all of the elements within a particular intellectual, social, and historical context.

In this way, the endnotes act as “a site of memory” for each story, the philosophical prose as the moment of recall, and the story itself as a kind of truth telling beyond “facts” balancing the “liminal space between fiction and non-fiction” so as to “expose a truth about the interior life of person.”18

Part I, titled “Of the Door of No Return to the Stars,” tackles the ideas of history and memory and the roles they play within our construction and understanding of blackness. The chapters in this part explicitly argue that our construction of time and space within the colonial framework negatively affects our capacity to think and understand not only blackness but also our construction of history and also of space and place.

This part begins with a chapter/story on Henry “Box” Brown. Rather than offering a traditional story and analysis of the nature of enslavement and its existential torment, it challenges the historical and existential frames of knowledge of the past and the present. It is concerned with memory and the act of remembering, with how this act is informed by and informs our relationship to facts and evidence, and with how we understand, articulate, and think of blackness more generally—and Black people in particular. This chapter/story, like the others in part I, begins by interrogating what are taken to be quotidian or everyday truths, only to reconsider them not through a traditional lens but from a Black speculative viewpoint. It is argued herein that a Black speculative perspective will offer what appears to be a radical and novel reading of memory, remembering, history, and the existentiality of blackness and of Black life.

Specifically, this chapter/story offers a rereading of enslavement and an alternate history of enslavement through the figure of Henry Box Brown as it analyzes his famed escape. Taken by many historians and social theorists as a moment of emotional and existential collapse, Brown’s escape was not thought to be a technological innovation. This chapter/story, though, argues through archival research and Black speculative fiction that Brown, in fact, participated in a larger mystical school of enslaved persons, where he learned skills such as “electro-biology,” or the ability to place himself in a state of animated suspension (like a bear in hibernation), and hypnotism, which he demonstrated frequently in the performances and lectures he gave throughout England and in parts of New England. The realization of an unknown set of skills is important because it forces us to rethink our past and, more precisely, to rethink the history of enslavement and

xxii Preface: P.S.A.

the role of technology in this history. It places figures such as Harriet Tubman— who was known as the Black ghost for her capacity to “disappear” in plain sight— and Frederick Douglass—who situated the technological process of photography as central to abolitionism, as even more central than the laws themselves—in relief against this new perspective.

The second chapter/story is centered on a mythological figure, HLG, and is a play on the science fiction writer H. G. Wells, and his book The Time Machine, as well as Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, but rather than going to the center of the earth, this chapter/story hypothesizes interdimensional travel to a Black lifeworld. Utilizing Black speculative fiction rather than Wells’s or Verne’s science fiction, it argues for a hollow earth theory, which claims that advanced persons moved underground to avoid colonial expansion. But instead of going inside the earth per se, these people travel to an alternate dimensional space altogether—a parallel Black time/space.

This chapter/story, though, is not a mode of escapism from the antiblack world. Instead, it argues for a parallel Black time/space, always already in existence and constituted by a kind of technological intervention. Utilizing the lesser known Paris exhibit in 1900 where Black Americans were given a separate space to exhibit their technological innovations and contributions to industrialization, the chapter/story argues this as a kind of evidence for how we should read Black lifeworlds. In particular, it theorizes that figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois, who attended the Paris exhibit by invitation from Booker T. Washington, forwarded a spiritual technology to travel interdimensionally, a technology that HLG accidentally stumbles on to travel to parallel Black time/space.

The third and final chapter/story in this part follows the work of Henry Dumas, a master storyteller of Black grief and sorrow but also of Black joy and freedom. He knew well the power of the speculative imagination for understanding Black political consciousness and also for developing a philosophical and aesthetic understanding of Black freedom and liberty. Blending speculative fiction with African American, West African, East Asian, and Indigenous folklore, Dumas was able to tell a rich and complex story of Black life.

Utilizing Dumas’s own intuitions on the role of the speculative imagination in rendering Black life visible, this chapter/story explores the very notion of time itself and the effects of trauma on the construction of the past, present, and future, arguing that time is not only a temporal or psychic structure, but also an embodied or phenomenological reality. As such, trauma that occurs in the mind

Preface: P.S.A. xxiii

and in the body disrupts the experience of time: in this case, the experience of colonialism in chattel enslavement disallows the past to be what is past or the future to be what is to come. Instead, the past emerges simultaneously within the present—but in a way that often feels contradictory and in conflict with a notion of the future. This is what I call the “haunt,” or the haunting at the center of this chapter/story.

This story mines Dumas’s poem “Take This River” and his historical fiction story “Ark of Bones” and blends the results with insights from Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech on the significance of language and the imagination to create the setting for a Black speculative fictional story about memory, rememory, and time travel.

Part II of this book, “On the Transformation of the Spirit,” picks up where the first part ends—with the dilemma of time and space of/for blackness and the possibility of an alternate space/time and history for Black existence. In this part though, the chapters/stories center on one question: What kind of person or being needs to be enacted, and what transformation of the spirit is needed to exist within Black time/space? That is, just who or what can inhabit this reality? What was it about Brown or Tubman, Du Bois or Dumas that allowed for this transition?

The fourth chapter/story, “Theft,” is ostensibly about the global pandemic, Covid-19, and its influence on Black people—in particular, on Black men, who found themselves also in a kind of racial pandemonium. It asks the question, How does one already in a pandemonium of state violence survive a pandemic? I say ostensibly because this historical moment provides the context for another kind of conversation—one on the nature of endurance and survival that asks, What kind of change, internal and external, is required to endure and to survive blackness in an antiblack world? What must one become in their blackness—and what must blackness itself be—in order to survive blackness? As a mode of analysis, this chapter/story traces the unlikely figure of the mimic octopus and its ability to blend into any environment as the pretext for how we could think about the strategies that Black people—in particular, Black men—utilize to exist as Black. It questions whether this capacity for endurance and survival by way of internal and external alteration—in Black people, code switching and in mimic octopi, camouflage—is a gift or a curse and whether it is enough for freedom.

The fifth chapter/story, “Tathāgata,” is the only story in the collection that does not have philosophical prose or companion endnotes. It is principally

xxiv Preface: P.S.A.

concerned with social alienation and its influence on memory and asks, Is our memory—that is, our capacity for recollection—reliable within the context of social alienation, or does social alienation itself cause us to misremember the events of our own lives? Yet because the context for social alienation in this case is racialization—that is, blackness within an antiblack context—memory and the act of remembering are equally a metaphysical and ontological wanting, making it difficult to tell fact from fiction, actual events from those constructed in our consciousness.

This chapter/story raises the question of how much of social alienation we— the alienated—are responsible for. How much of our condition do we enact in ourselves as a mode of fitting in or trying to camouflage ourselves in gentility or professionalism that is itself antiblack?

The last chapter/story of this collection is perhaps the most charged. It questions if there is an outside at all—a place where blackness can be free. It takes place within the shadow of the death of Trayvon Martin and traces through the death of George Floyd and all the pitfalls that came from these bookended deaths—from the very desire and demand of white people to be forgiven and to be absolved of this condition of death called democracy.

This chapter/story begins with an analysis and comparison of the surrealism in the film Sorry to Bother You and what is taken to be realism in the film Queen & Slim and argues that these films are, in fact, twins—both tackling and engaging with the very idea of the legacy of blackness and the lineage of the Black subject. Utilizing James Baldwin’s infamous letter to his nephew—and the very idea of the “open letter” as a format of examination and communication by those colonized with those colonizing—the chapter/story wonders out loud about such a strategy—wonders what strategy, if any at all, could lead to racial healing, given the white need and demand for forgiveness and absolution.

The epilogue of this book is not so much a conclusion—in the sense that a conclusion brings together and synthesizes each of the elements into a coherent whole. Rather, it is a conclusion understood as a further meditation on what went before it, centering on a specific historical figure who embodies all of the elements of confluence, Frederick Douglass, who constitutes blackness inherent in this text, but also foregrounds the aesthetic, political, and philosophical ideas around structure and form inherent in Dark Delight. In this way, Douglass, as a forefather of the Black speculative tradition,19 grounds but does not dominate the epilogue. A principal figure in the abolitionist movement, he is also a beguiling

Preface: P.S.A. xxv

figure who both reveals and obscures his thoughts on violent resistance, constitutionalism, democracy, lynching, and antiblack violence. This epilogue, reflecting back on the book in total, leans into this ambiguity as a pretext for meandering through the questions of Black freedom and liberty and the kind of Black being who can be free and liberated.

But this is not the full significance of Douglass’s impact for Dark Delight. In addition to these ideas, Douglass alongside his grandson becomes a catalyst for thinking about the nature of the nation itself—the very idea of what constitutes the Constitution, what constitutes reconciliation and reconstruction—and questions aloud whether reconciliation and reconstruction—that is, redemption itself—must also somehow involve tearing down the present to its foundation rather than ameliorating or attempting to reconcile ourselves with the past.

AGENRE-CROSSING EXPLORATION of Black speculative imagination, The Dark Delight of Being Strange combines fiction, historical accounts, and philosophical prose to unveil the extraordinary and the surreal in everyday Black life. James B. Haile III traces how Black speculative fiction responds to enslavement, racism, colonialism, and capitalism and how it reveals a life beyond social and political alienation. He reenvisions Black technologies of freedom through Henry Box Brown’s famed escape from slavery in a wooden crate, fashions an anticolonial “hollow earth theory” from the works of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, and considers the octopus and its ability to camouflage itself as a model for Black survival strategies. Through the lens of speculative fiction, this book invites us to reimagine history and memory, time and space, our identities and ourselves.

“This book is a true trickster, changing forms every few pages and doing so with deep intellectual certitude and winking hilarity. It’s a critical and deep reflection on Blackness that takes on the ever-changing formlessness of Blackness. Now that I have read The Dark Delight of Being Strange, I’m looking forward to reading it again.”

—RION AMILCAR SCOTT, AUTHOR OF THE WORLD DOESN’T REQUIRE YOU: STORIES

“The Dark Delight of Being Strange is a thought-provoking, creative meditation on Black freedom. Not only does Haile explore the ‘what if’ of the speculative imagination, he also situates his reflections in the time-honored space where philosophy and storytelling meet. The result is a gift for all readers.”

—CHARLES JOHNSON, AUTHOR OF MIDDLE PASSAGE: A NOVEL

“This book is a kaleidoscopic fever dream of thinking and creativity, of analytical experiment and diligence. Using stories as case studies, Haile reflects on the illogic of Blackness’s constitutive ironies. It is a meditation—a mediation—that tethers together philosophy and art, magic and physics, memoir and manifesto and prayer. It is a Black male song cycle, a dark delight indeed.”

—KEVIN QUASHIE, AUTHOR OF BLACK ALIVENESS, OR A POETICS OF BEING

JAMES B. HAILE III is an Afrosurrealist and Afrofuturist writer who is an associate professor of philosophy with a joint appointment in English at the University of Rhode Island. He is the author of The Buck, the Black, and the Existential Hero: Refiguring the Black Male Literary Canon, 1850 to Present (2020).

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover art: Tylonn J. Sawyer, Embellished Study: Man on a Horse, 2022