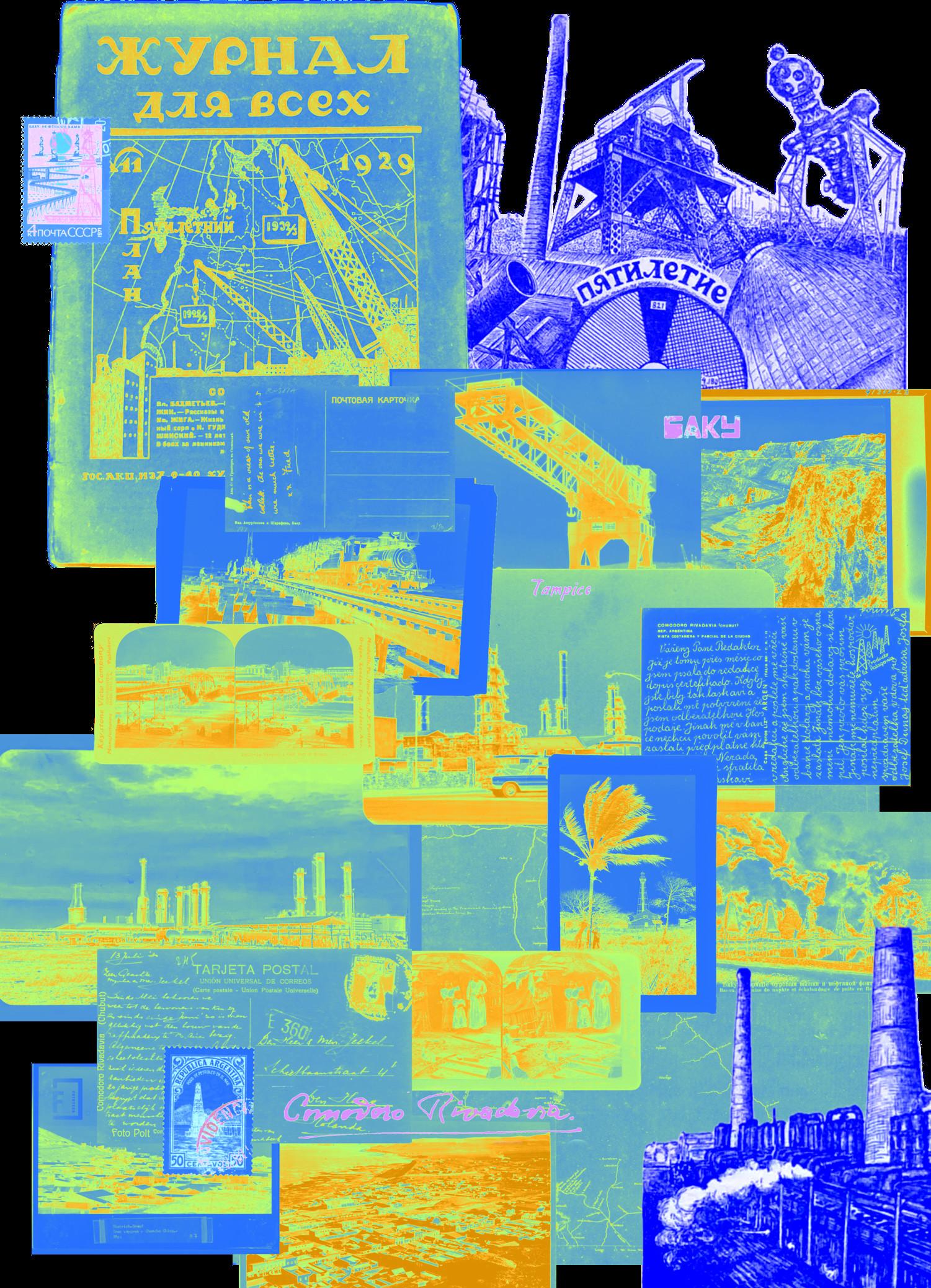

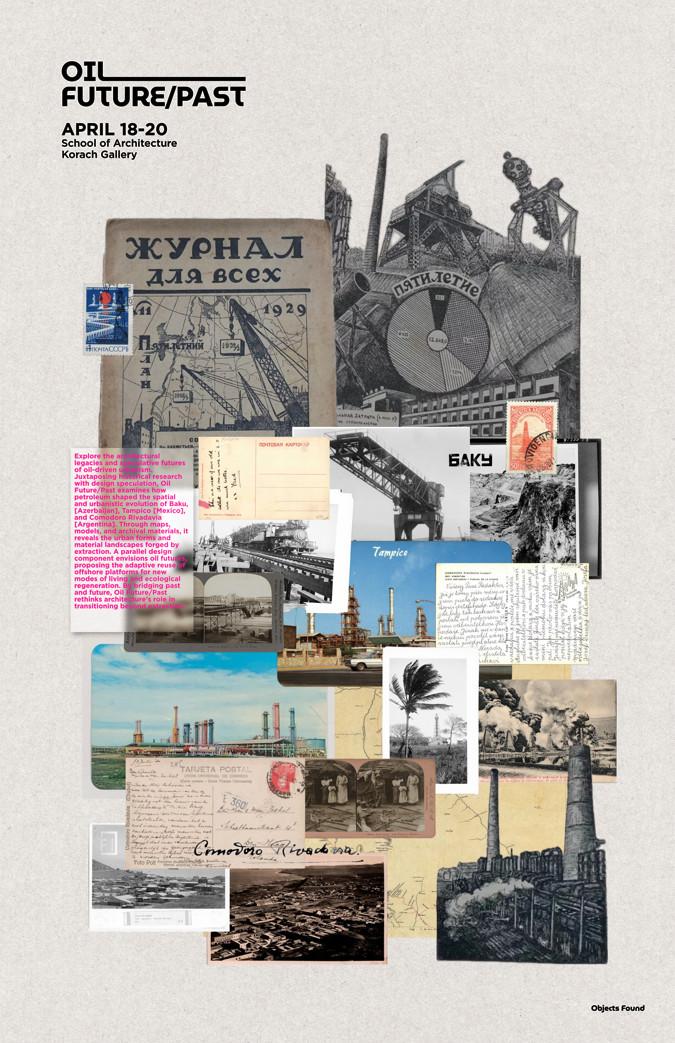

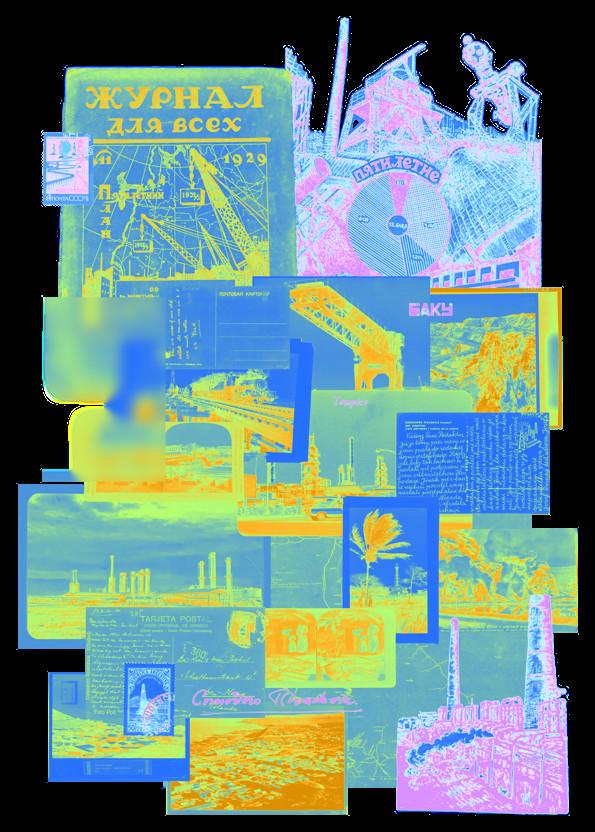

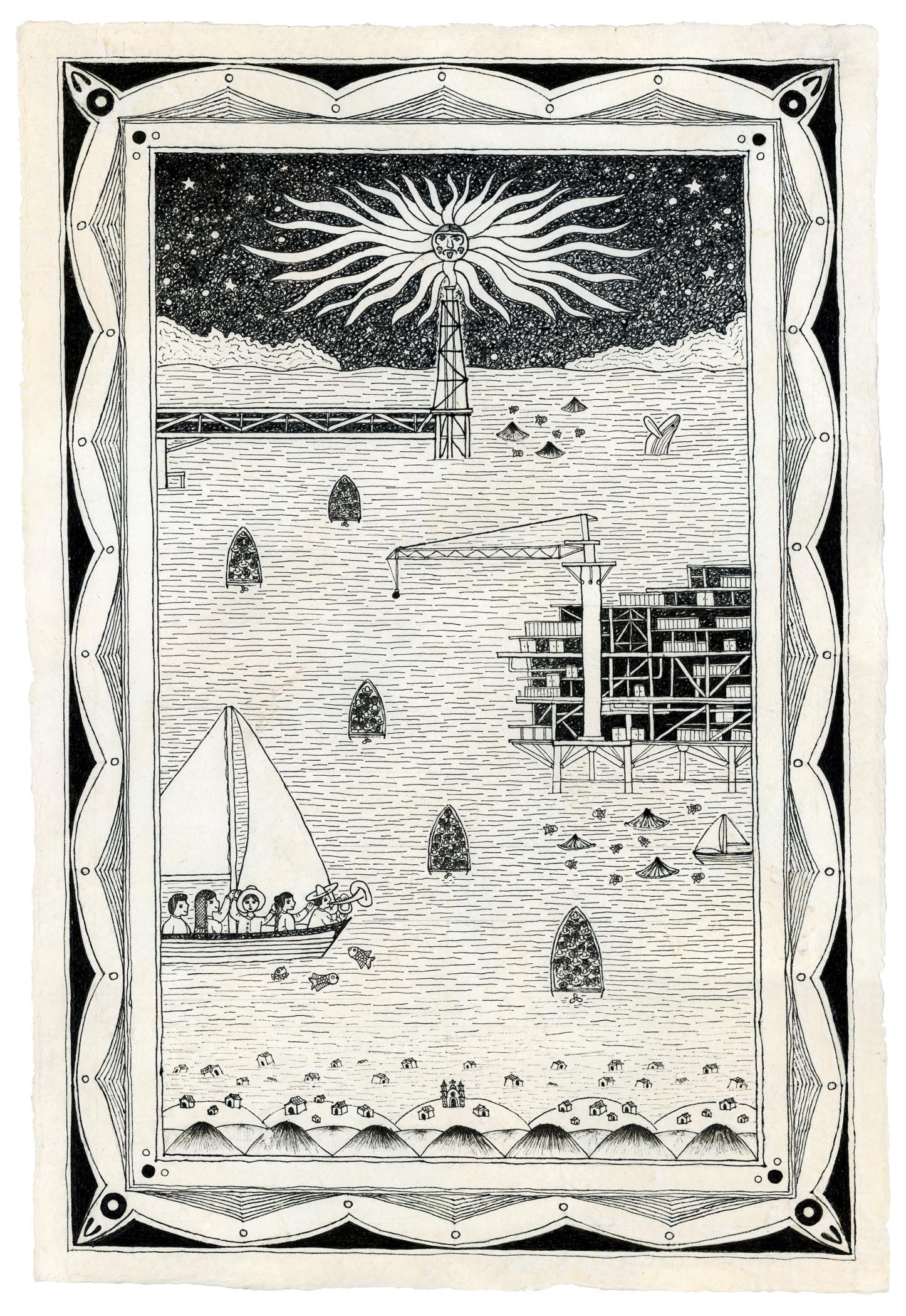

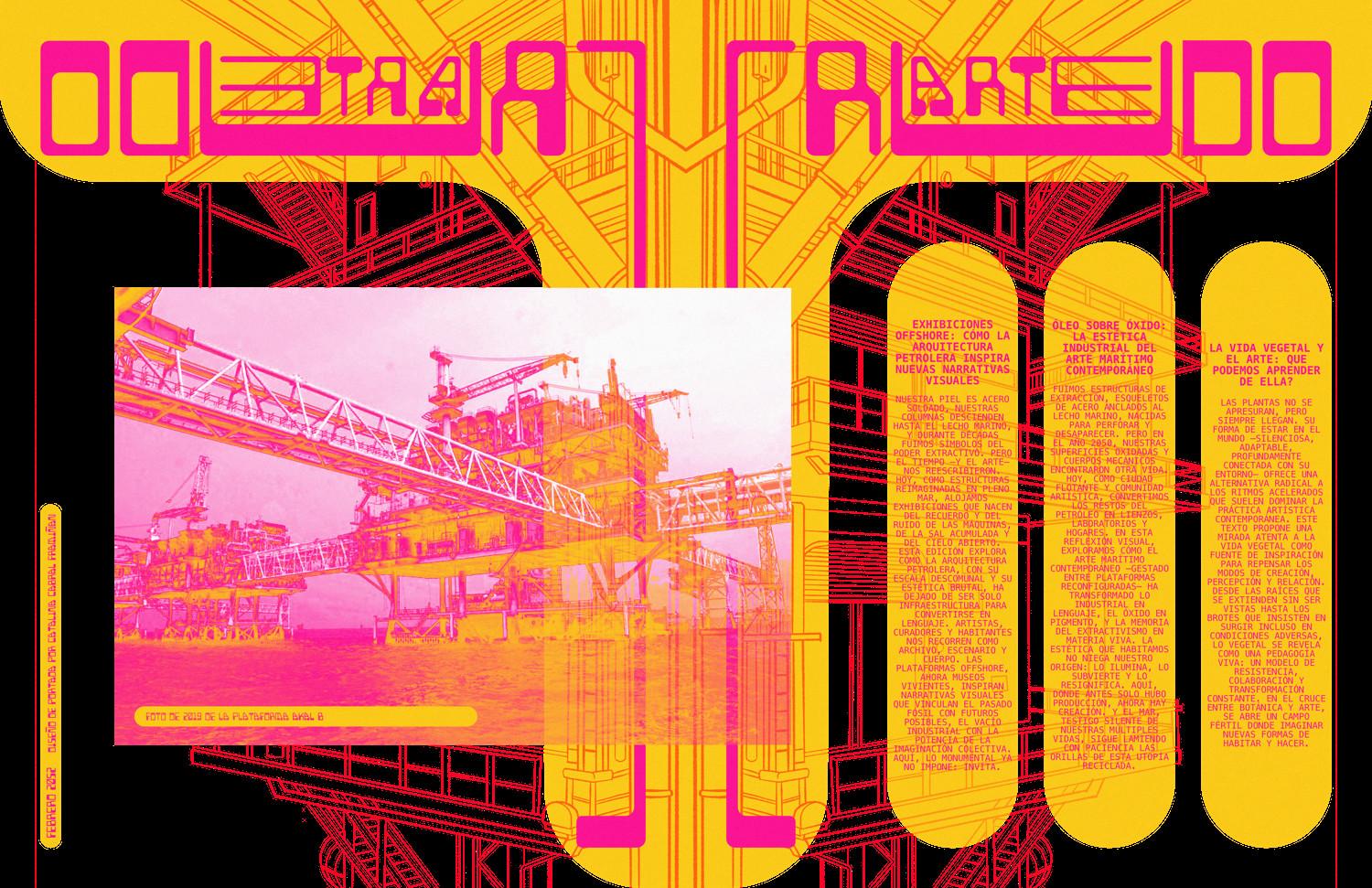

OIL AND CITY

Or A Comparative Study of Three “Petro-polis”:

Baku, Comodoro Rivadavia, and Tampico

Or A Comparative Study of Three “Petro-polis”:

Baku, Comodoro Rivadavia, and Tampico

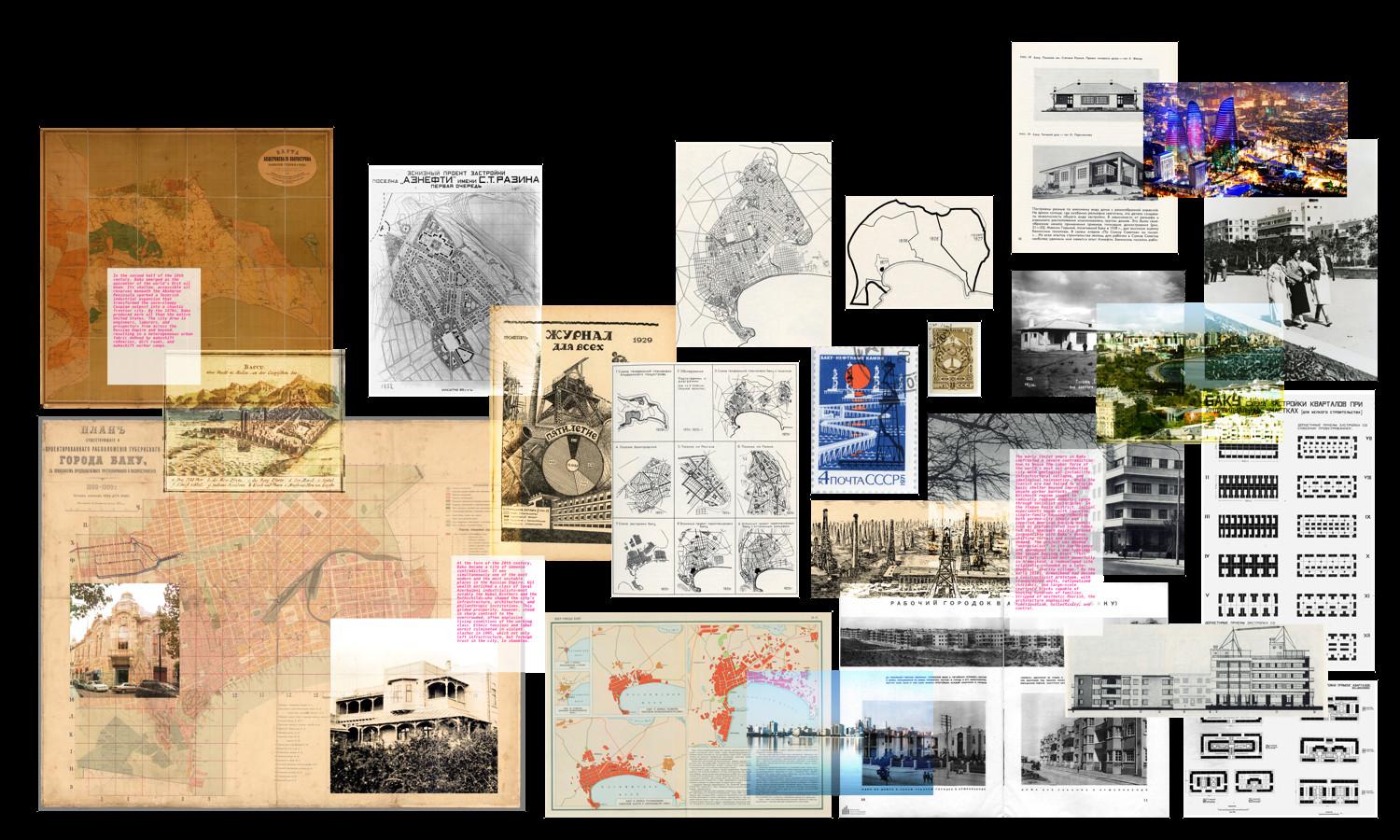

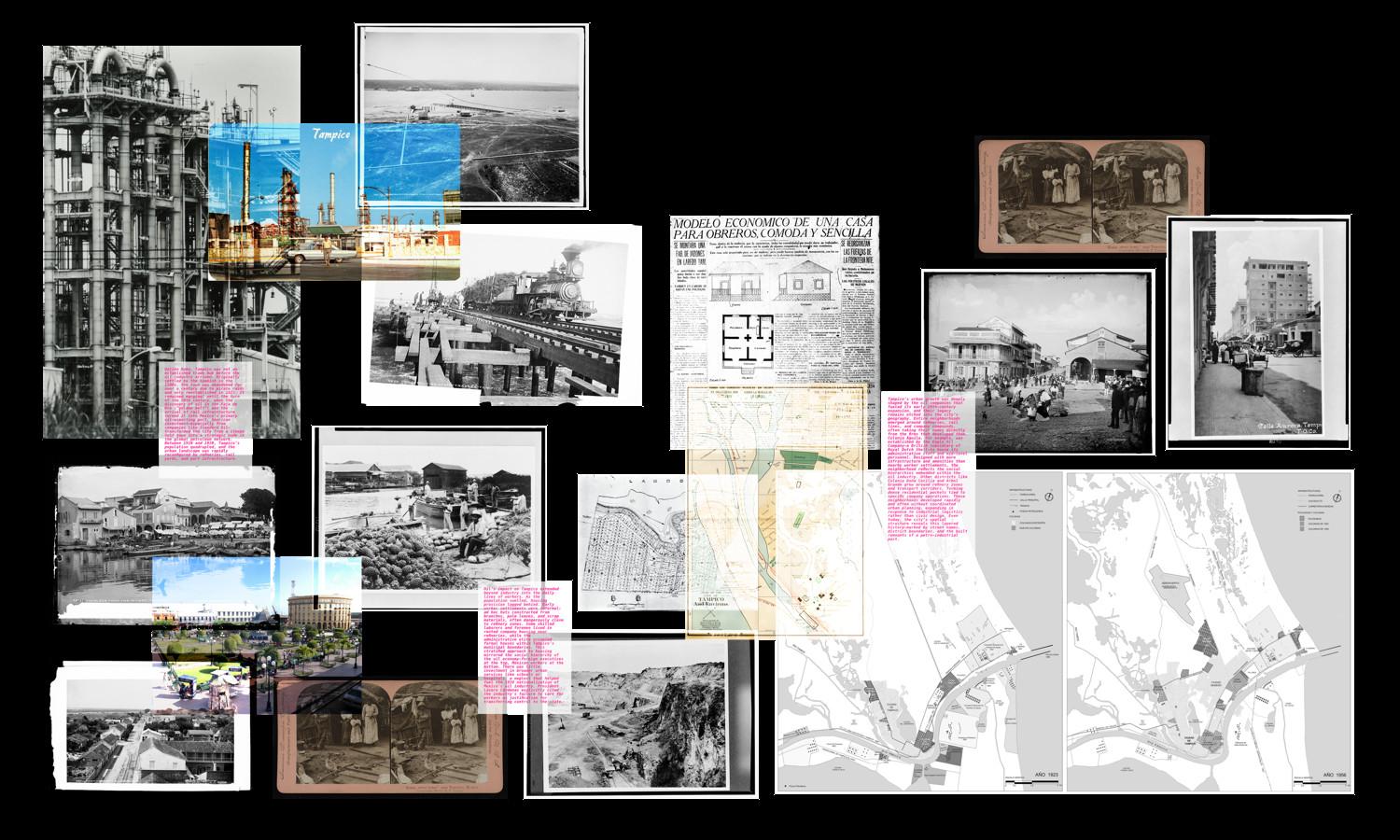

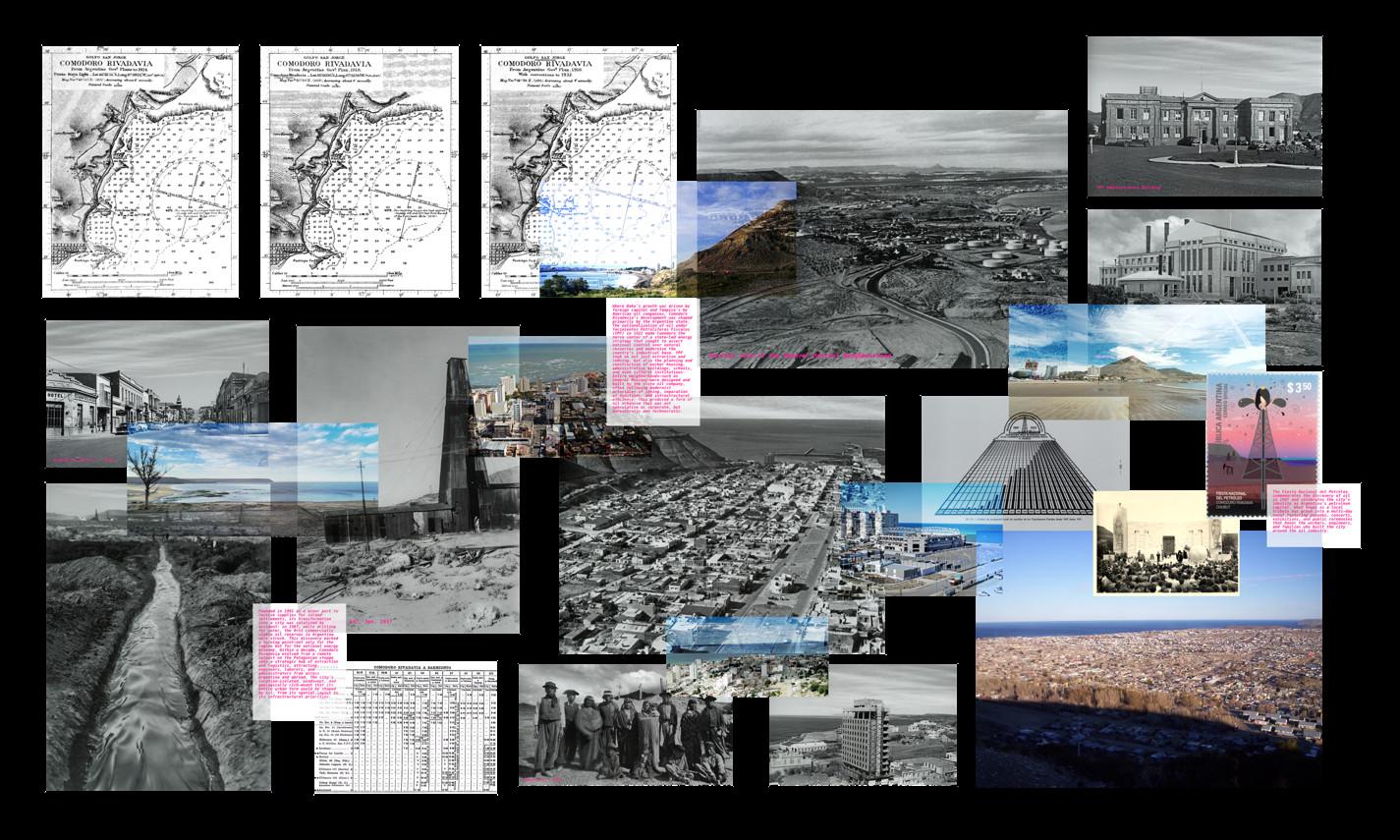

This thesis examines the complex relationship between oil-based industry and urban development through a comparative analysis of three cities: Baku (Azerbaijan), Comodoro Rivadavia (Argentina), and Tampico (Mexico).Thisstudychallengestheprevailingviewofthe “resource/oil curse” by exploring how oil urbanism is shaped by the intersection of industrial governance, geographic specificity, and cultural-political ideology. Rather than treating petro-cities as a single prototype, the research investigates the layered trajectories of each through five thematic lenses: pre-industrial urban form, geological constraints, industrial governance models, labor and housing strategies, and the role of migrationinshapingurbanidentity.

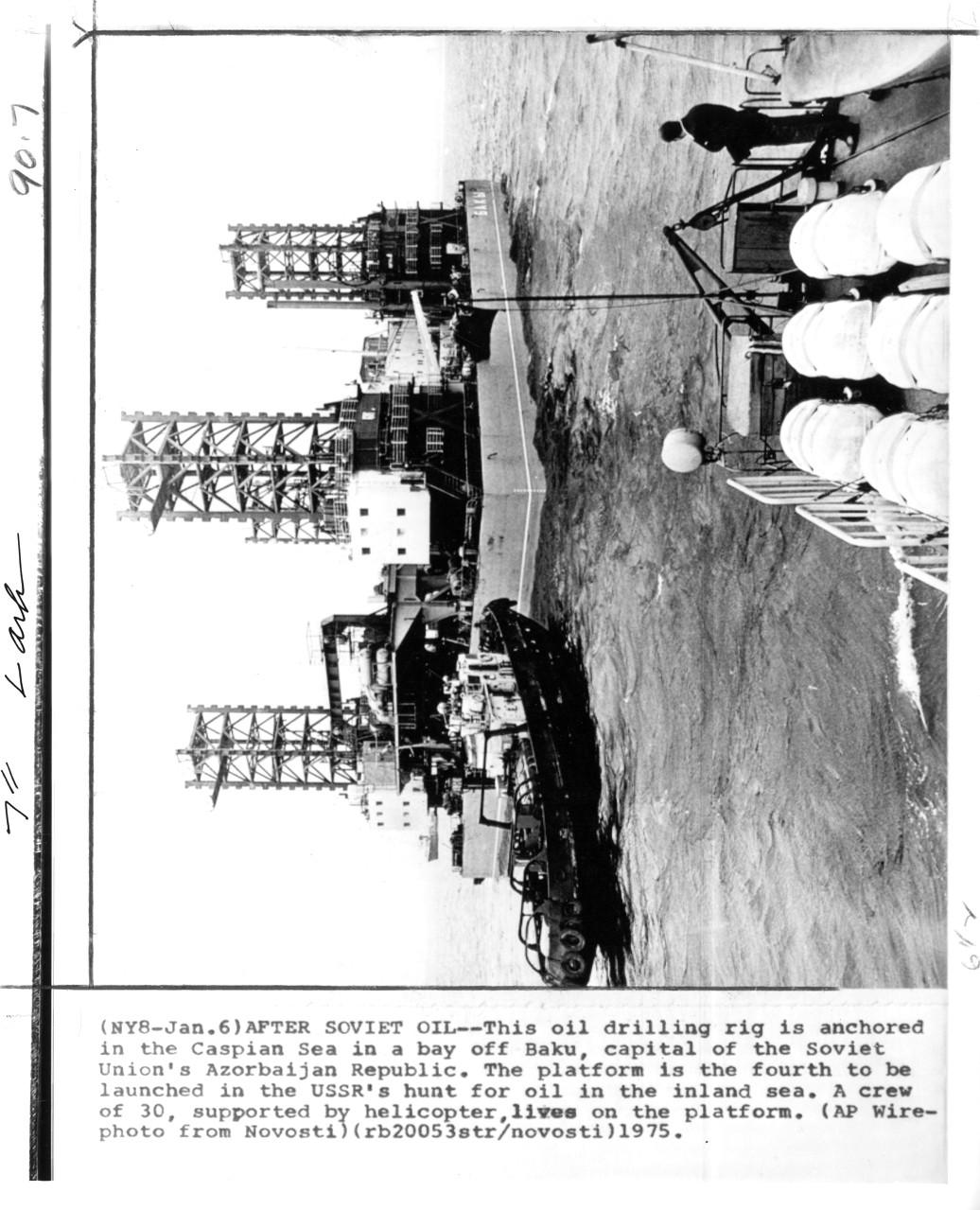

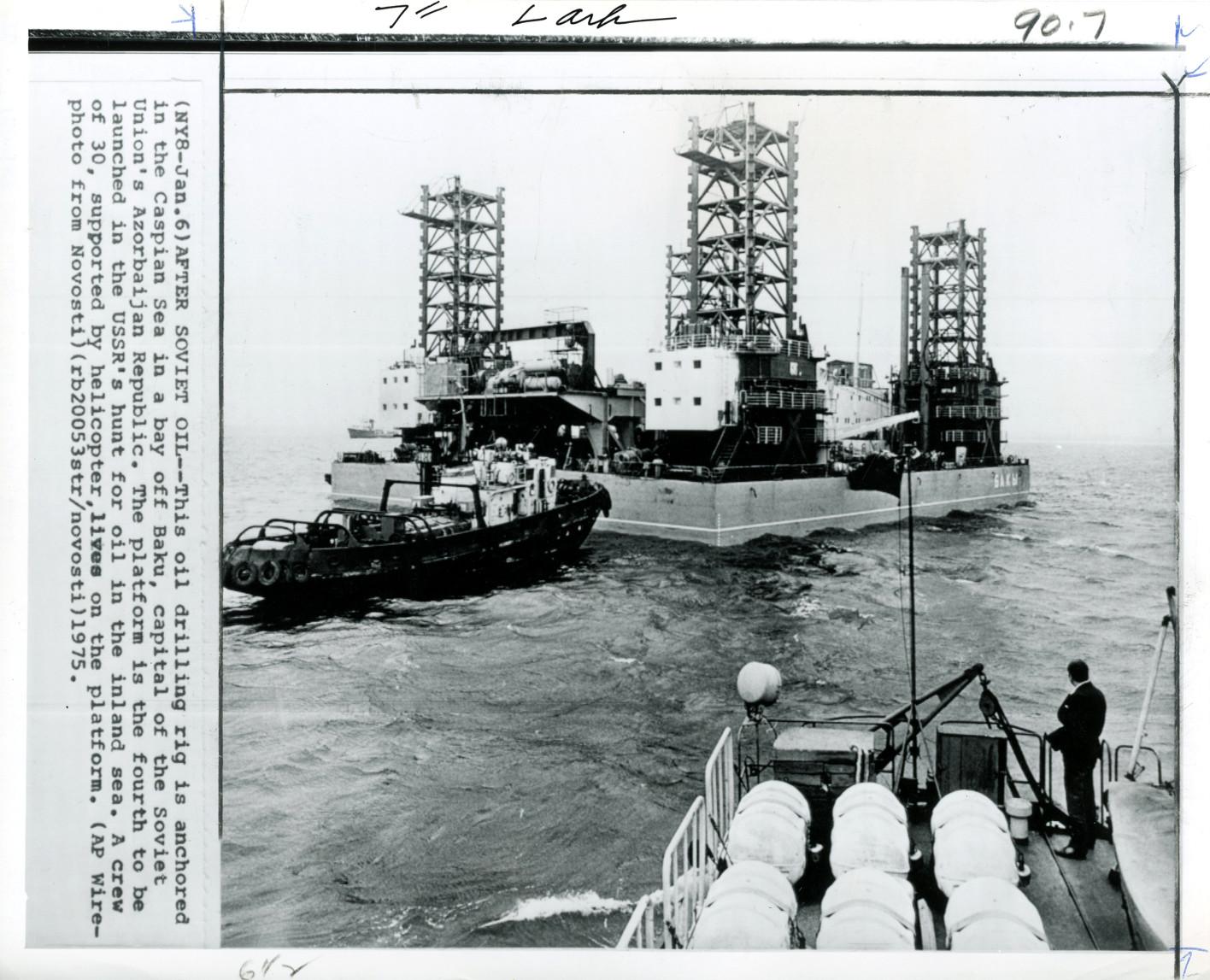

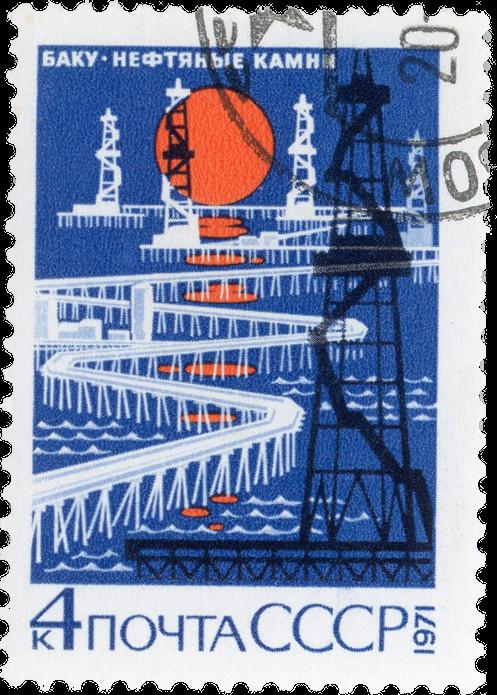

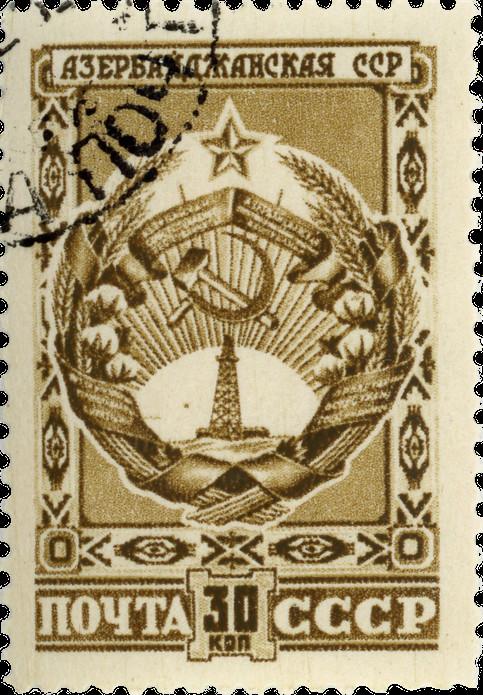

Baku emerges as both archetype and outlier—marked by its early industrialization, hyper-dense extraction zones,influentialoilbarons,andeventualtransformation intoaSoviettestinggroundforhousingexperimentation. Comodoro Rivadavia, by contrast, developed under conditionsofnationalistterritorialintegration,withYPF’s early state-led planning shaping both urban form and social policy from the outset. Tampico in contrast represents the volatility of speculative oil capitalism: rapidlyconstructedunderforeigncontrol,itexperienced infrastructural booms and busts that left lasting marks onitsurbanfabricandlaborhierarchy.

Through archival research, cartographic analysis, and spatial reading, this thesis offers a more nuanced understandingofhowoildoesnotmerelyfundcities,but produces them—shaping infrastructure, housing typologies,andsocialorganization.Ultimately,thestudy proposes oil urbanism not as a fixed model but as a condition—spatial, political, and cultural—whose consequences continue to resonate as cities face the post-oilfuture.

1. Pratt, Joseph A, Martin V Melosi, and Kathleen A Brosnan. Energy Capitals: Local Impact, Global Influence. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014.

2. Wiedmann, Florian. Building Migrant Cities in the Gulf : Urban Transformation in the Middle East, edited by Salama, Ashraf M. A., ProQuest (Firm). London: London : I. B. Tauris, 2019.

Therelationshipbetweenindustryandurbanizationhas shaped the development of cities across the globe,with resource-based industries playing a central role in the formationofmodernurbanlandscapes.Citiesthathave grown up around industries such as coal mining, steel production, and more recently, oil extraction, represent uniquecasestudiesinhowindustrialprocessesdrivenot only economic growth but also profound transformations in the built environment. While coalbasedindustrieshavealwaysbeenhistoricallycentralto thestudyofindustrialurbanizationandtherearedozens of case studies throughout the globe, the rise of oilbased industries have generally been considered detrimental to the generation of urban centers.¹ Even though the oil industry has massive capital flows, global connections, and high energy returns, it is rarely consideredtohavespurredurbandensificationthrough its industry. While there are several modern cases that can be considered to have been built through oilbased-wealth(ie.modernGulfcities)²therearefewthat grew through means of industry in addition to that of wealth. This disconnect between industry and development is what many consider as part of the “resource curse," a term often used to describe the negative economic, political, and social outcomes associatedwithsuchresource-dependenteconomies.

3. Ross, Michael L. “Will Oil Drown the Arab Spring? Democracy and the Resource Curse.” Foreign Affairs 90, no. 5 (2011): 2–7.

Peck, Sarah, and Sarah Chayes. “The Oil Curse: A Remedial Role for the Oil Industry.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2015.

4. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018, 24

The notion of a “resource” or “oil curse” suggests that countries and cities heavily reliant on oil extraction face a significantly higher risk of economic volatility, corruption, inequality, and environmental degradation.³ This narrative often assumes that oil wealth leads to underdevelopment in key areas such as governance, social welfare, and long-term economic sustainability. However, the implications of this reliance on oil are not straightforward, and the complex relationship between resource wealth and urbanization often reveals a more nuanced picture.4 While oil industrialization has undeniably led to the creation of infrastructure regarding the extraction, refining, and transportation of oil, lack of density regarding extraction combined with different geological and geographical considerations

regarding location of the industry has generally been considered counter-productive to the creation of an urban center. In addition, the extractive nature of the industry through foreign investment has also created disconnect between the creation of industry related infrastructureandthatrelatedtotheotherelementsofa holistic urban center. Such a “curse” suggests that an over reliance on oil wealth fosters economic instability, weak government structures due to foreign dependence and encouraged corruption, and an unsustainable development model that is inherently vulnerable to global oil price fluctuations and environmental degradation due to a lack of diversificationinindustry.

Yet much of this view overlooks the influence the presence of industry can have for other economic aspects of a city, as well as the possibility of local retentionofoilwealthforfurtherinvestmentinthecity.In many cases it also fails to properly examine the case studieswithinthelensofindustrynationalizationandthe reasons for such nationalization. In the Soviet model, it would be against Soviet ideology to focus on extraction without at least maintaining an image of caring for the living conditions of the proletariat, leading to the creation of housing estates to house the low level workersthathadpreviouslymainlylivedindeteriorating slums prior to nationalization with only a few exceptions5, even with the presence of local oil barons whoinvestedintheurbancity.

Additionally,theliteratureonoil-drivenurbanizationand economic case studies has a tendency to fall short of addressing the diversity of experiences across different global regions, especially outside of the Middle-Eastern field. Gulf cities such as Dubai, Riyadh, Doha, etc6, have received much of the scholarly attention due to their rapid urban growth fueled by locally retained oil money inthelastfewdecades.However,examplessuchasBaku or Latin American oil cities remain underrepresented in these discussions and rarely have much international attentionoutsideoftheirrespectivecountries.Moreover, the few studies that do examine oil cities outside the Middle East often treat them in isolation, without

5. Crawford, Christina E. “Part I. Oil City: Baku, 1920-1927” Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2022.

6. Salama, Ashraf M. A. Demystifying Doha : On Architecture and Urbanism in an Emerging City, edited by Wiedmann, Florian, Ebooks Corporation. Farnham, Surrey: Farnham, Surrey : Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2013.

7. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018

8. Crawford, Christina E. “Part I. Oil City: Baku, 1920-1927” Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union

considering possible comparative dynamics between different urban centers and the roles each has in influencing the other. By examining several case studies through the same methodology there is an opportunity to bridge the gap by creating an intersection between different disciplines and geographical conditions in an effort to view how industry can affect the urban fabric, and the urban fabric thus affect the life and living conditionsofthepeoplelivingwithin.

Thisthesisthusexaminestheroleofoil-basedindustryin urban infrastructural development through a lens of intersectionality. Focusing on three cities: Baku (Azerbaijan), Comodoro Rivadavia (Argentina), and Tampico (Mexico); they were selected due to the shifted phasesindevelopmentaswellasthepresenceofapreand-post-nationalizedindustrialdevelopment.

Baku, as one of the oldest oil cities, provides a historical lens through which the early development of industry relatedinfrastructurecanbestudied,aswellasconsider the relation of oil wealth to urban generation through a comparison of both foreign vs. local and pre-and-post soviet nationalization. The initial development through foreign European and American companies in the midto-late 19th century came at the hand of early idealized urban planning practices emerging in Europe.7 In addition,some of the earliest examples of Soviet worker housing and housing blocks were developed in Baku as an effort to house the ethnically diverse and impoverishedindustrylabourers.8 Throughthiscase,one can study both idealized versions of how industry can shapethecityaswellastheimpactoflocalvoicesinthe creation of a holistic urban model which develops beyond its industrial constraints to provide the workings of not only a city of industry but a cosmopolitan metropolis.

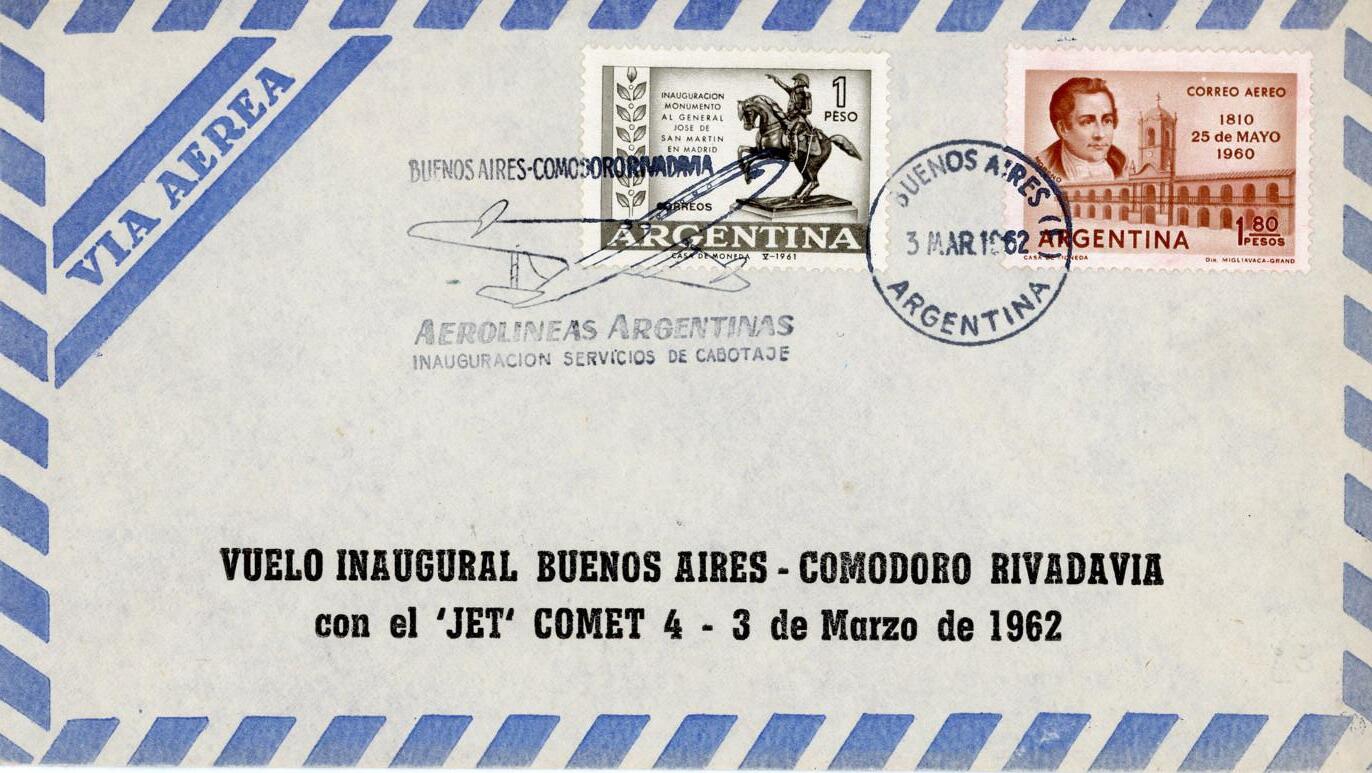

Comodoro Rivadavia provides an interesting example that settles comfortably between the development of Baku and Tampico through how early into its industrial development the industry became nationalized. Unlike Tampico, which was heavily shaped by foreign investment pre-nationalization, Comodoro Rivadavia’s

oil industry was largely controlled by the Argentine government, especially after the establishment of the YacimientosPetroliferosFiscales(YPF)in19229,oneofthe world’s first state owned oil companies and the first outside the Soviet Union. This meant it had less private development than Baku and Tampico, and combined with its remote location (even less connected than Tampico,whichatleastisconnectedtothelargerregion of the Gulf of Mexico through its port) provides a more isolated example of nationalized industrial urban development.

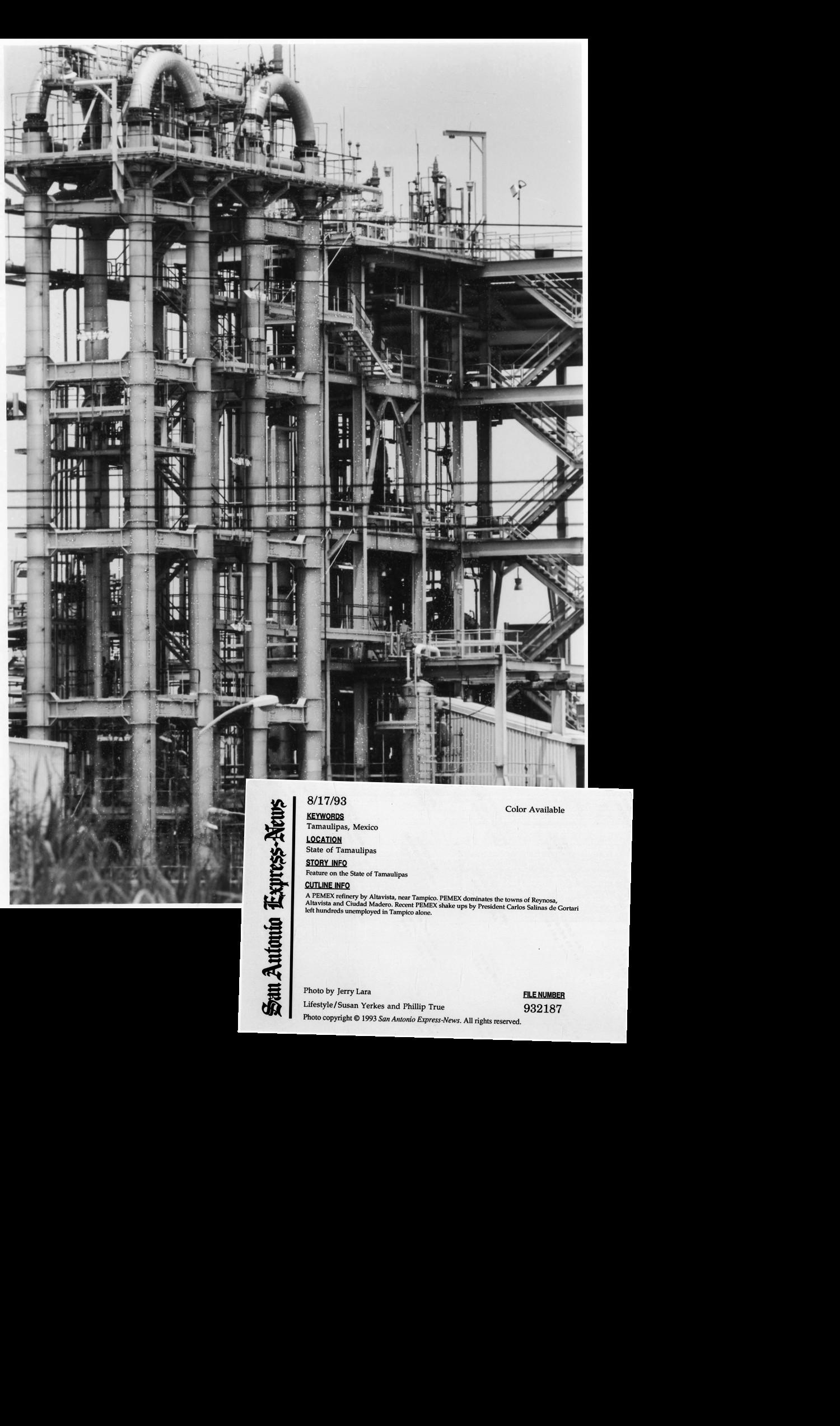

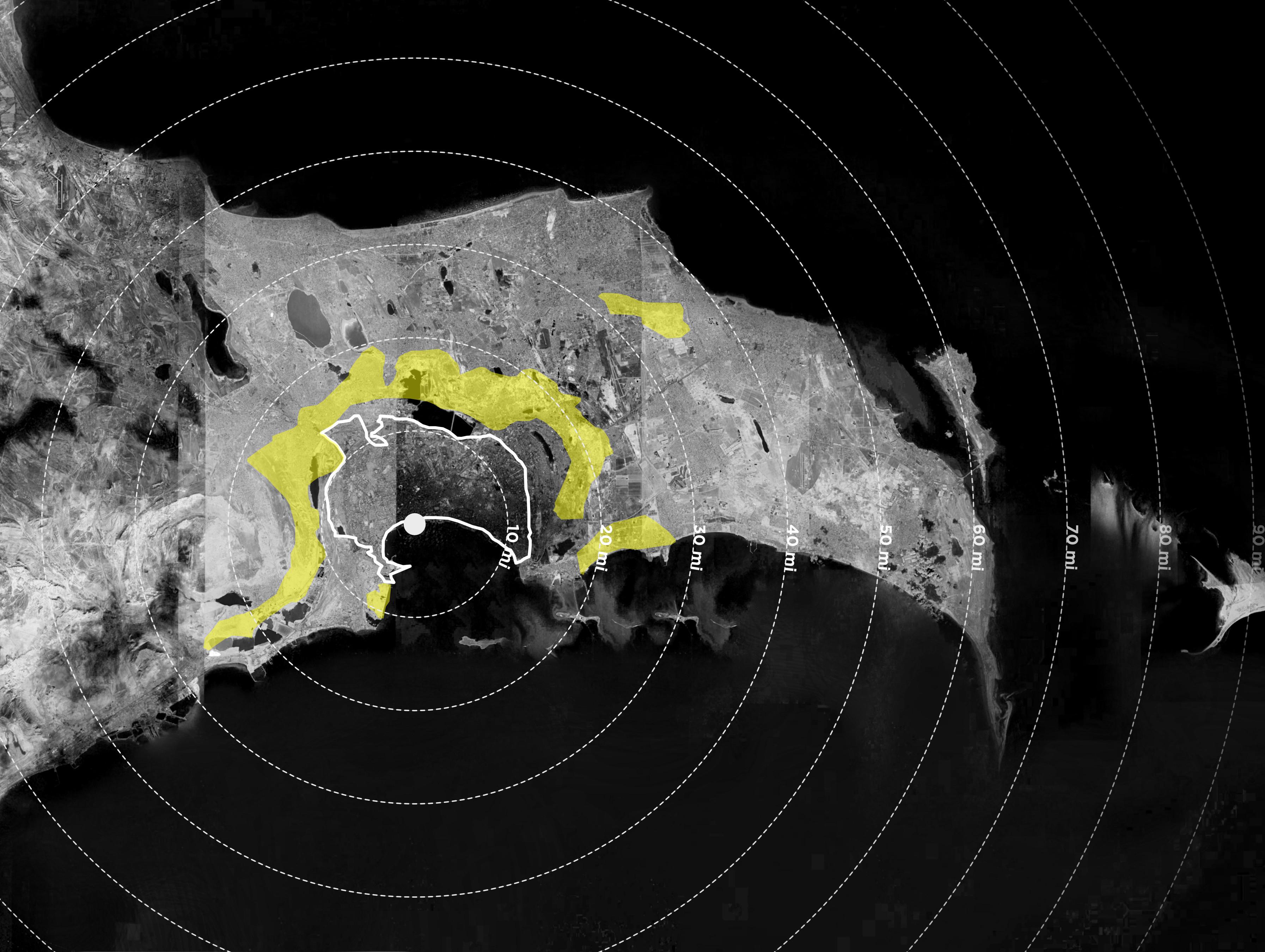

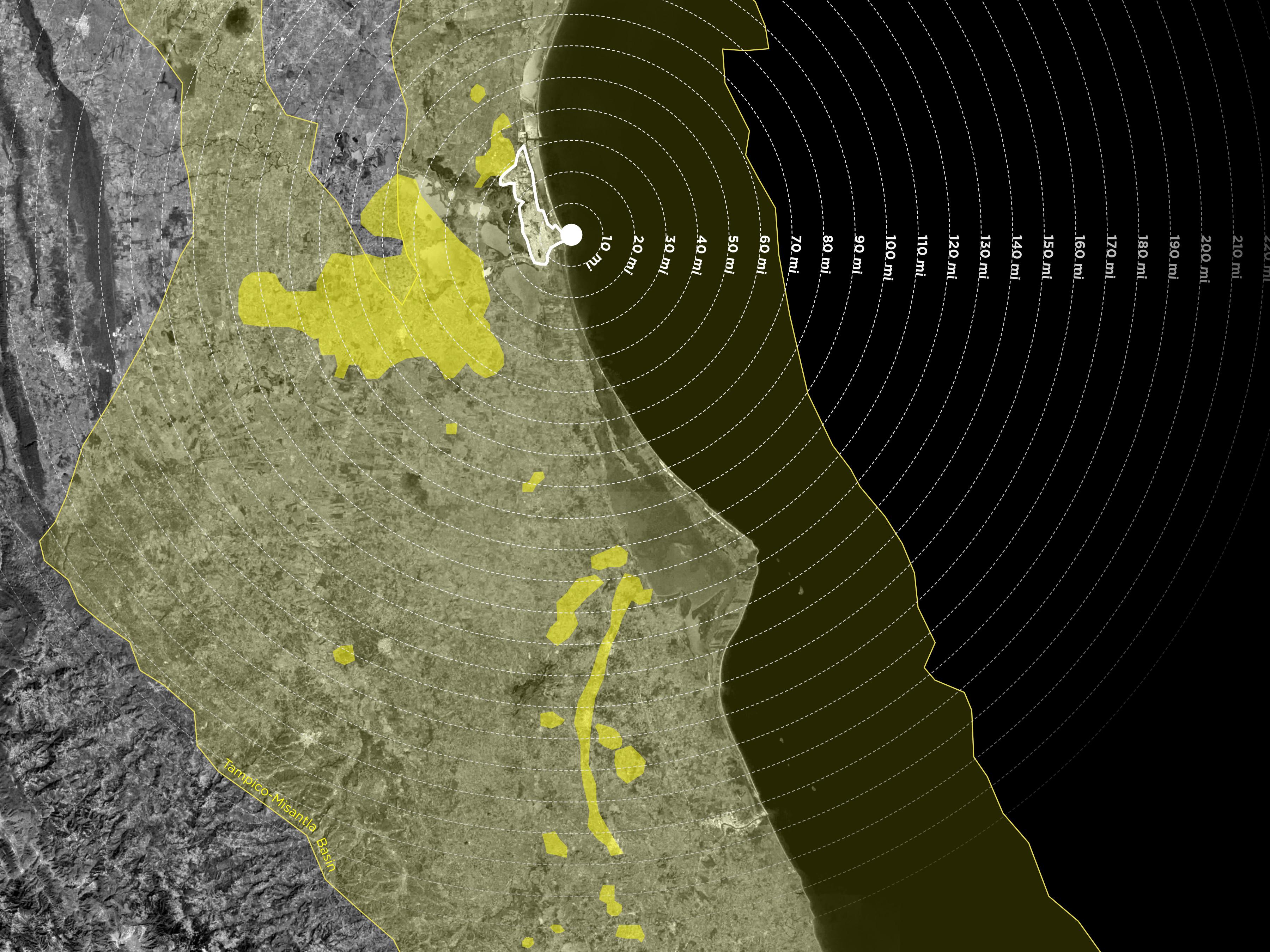

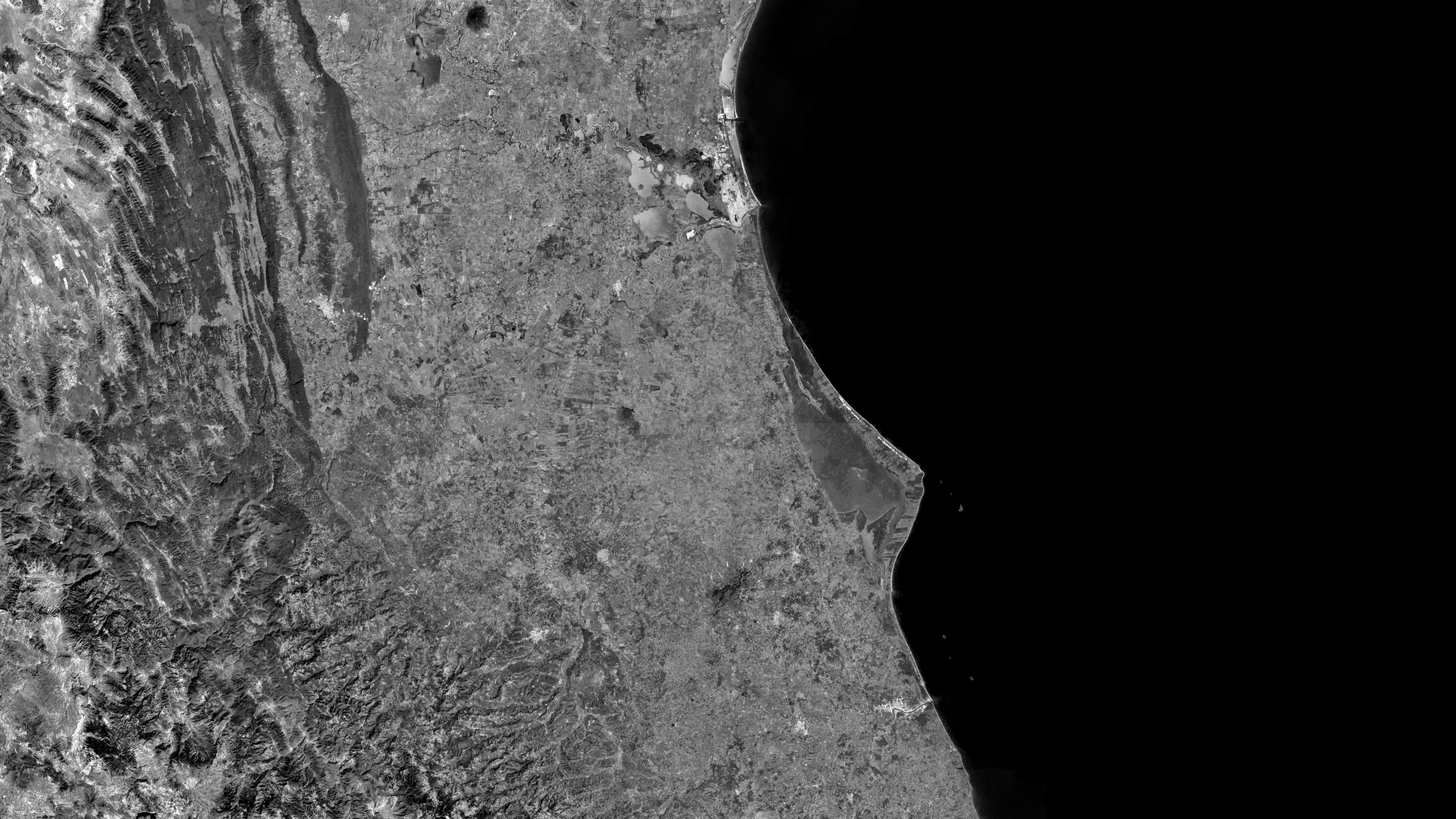

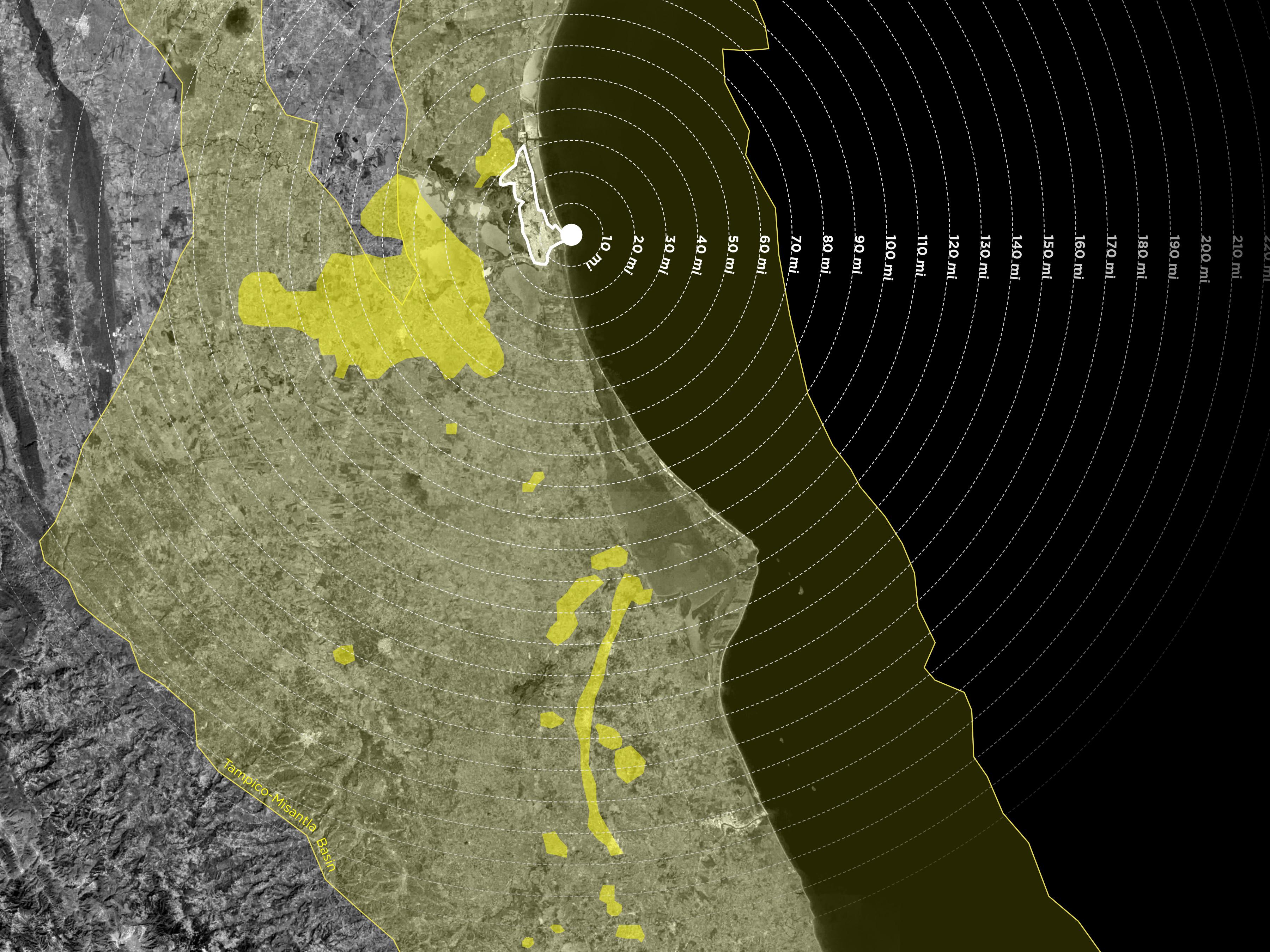

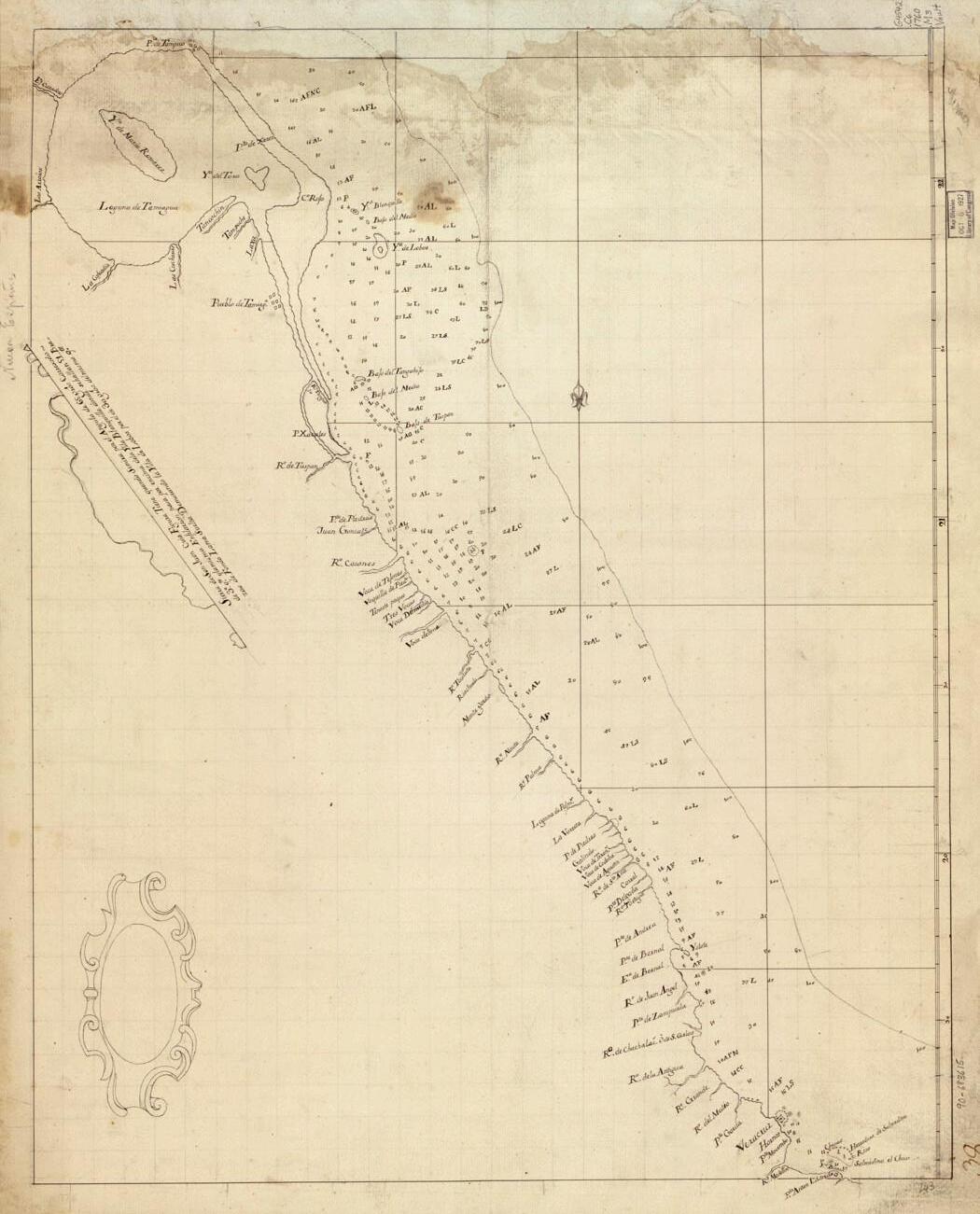

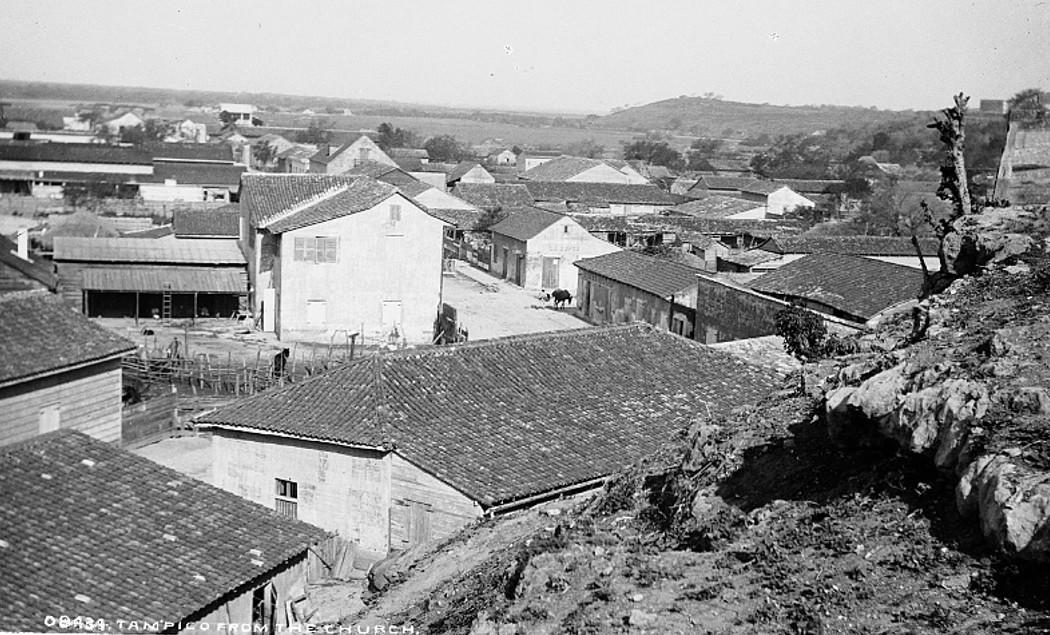

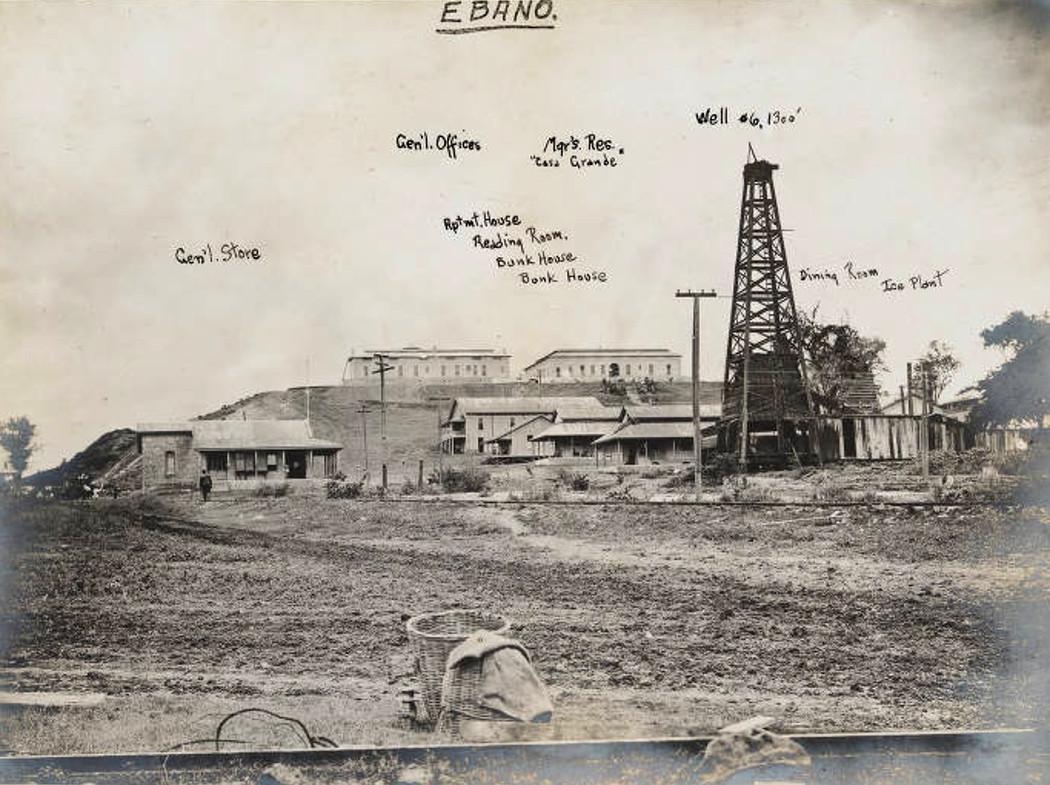

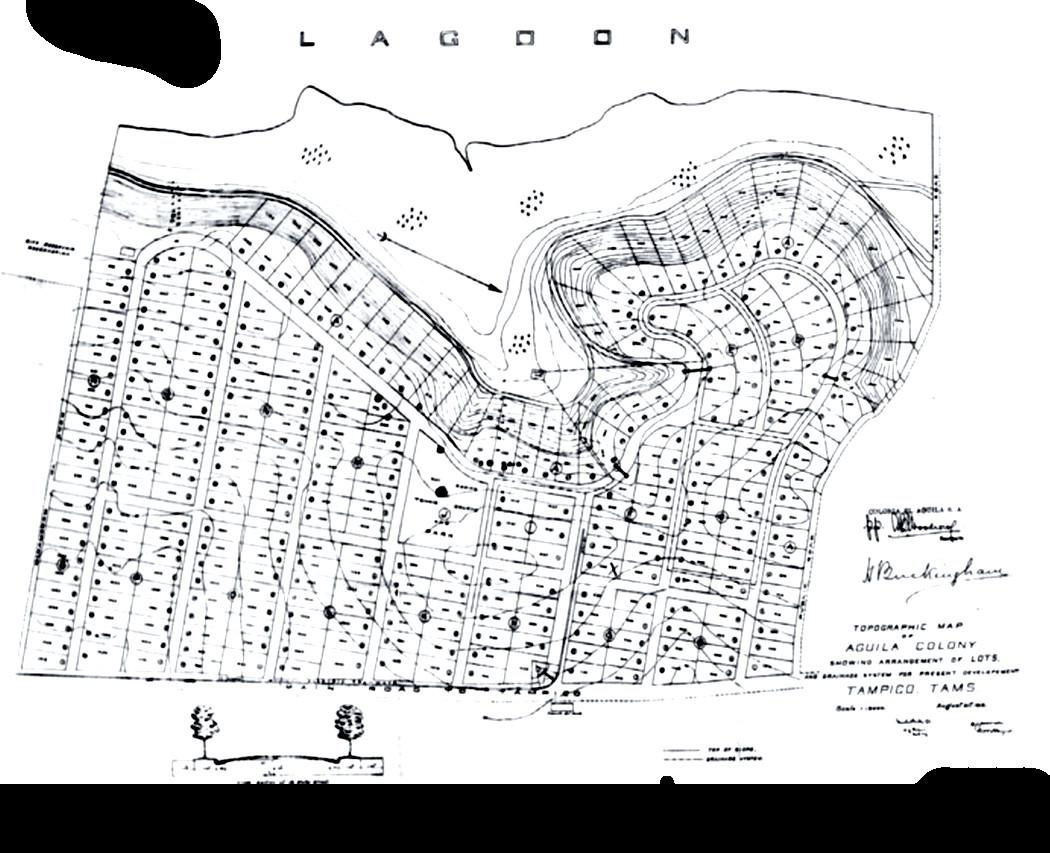

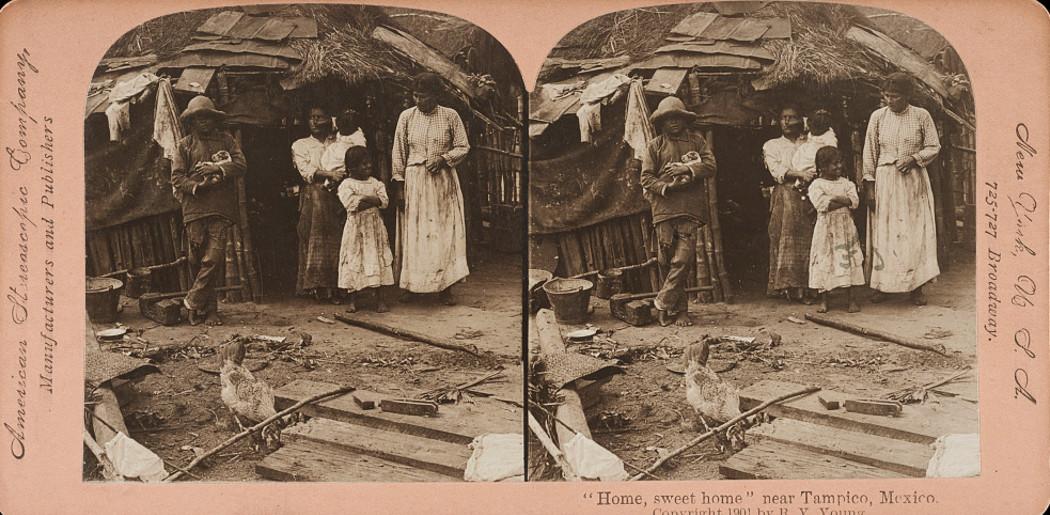

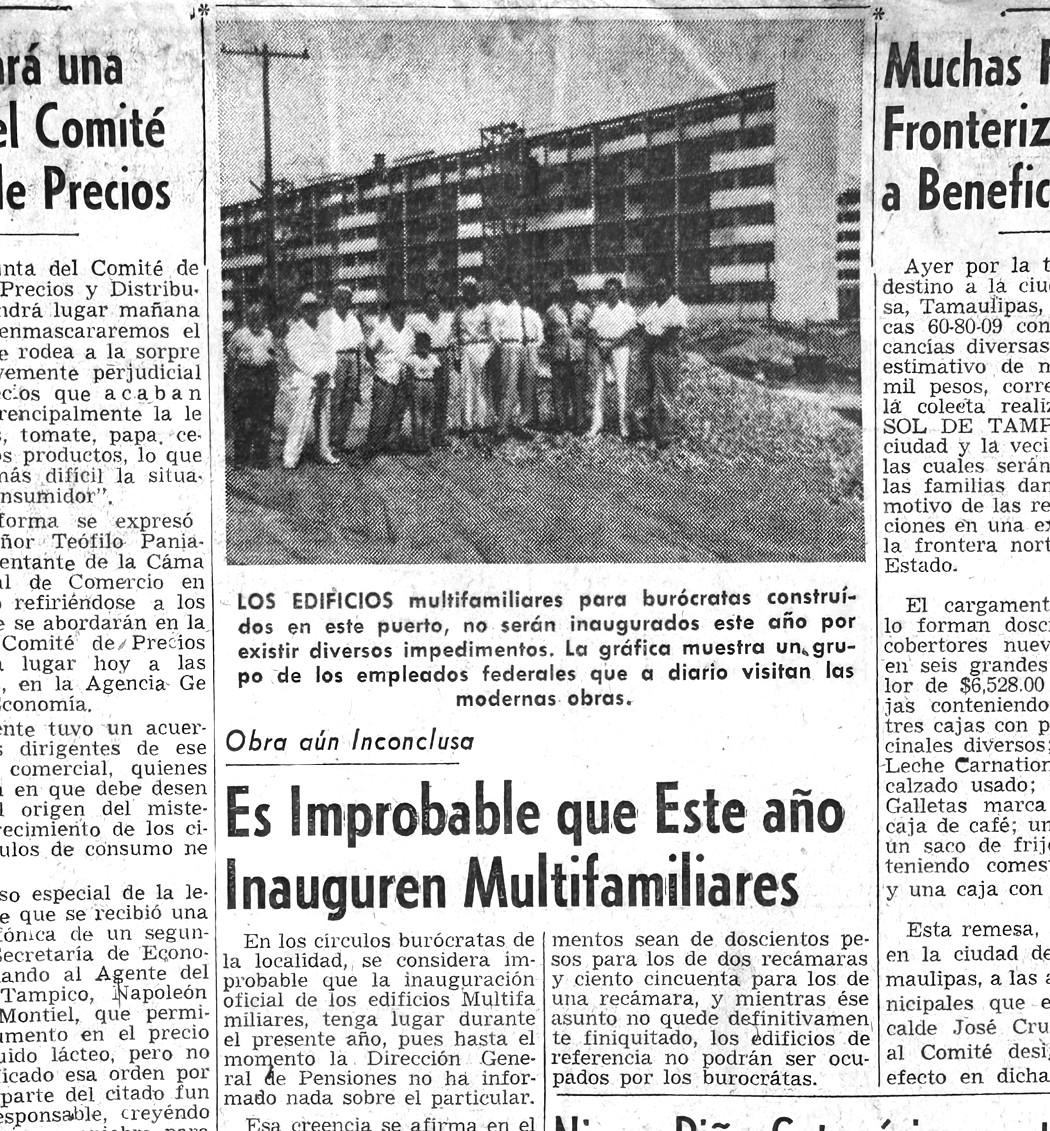

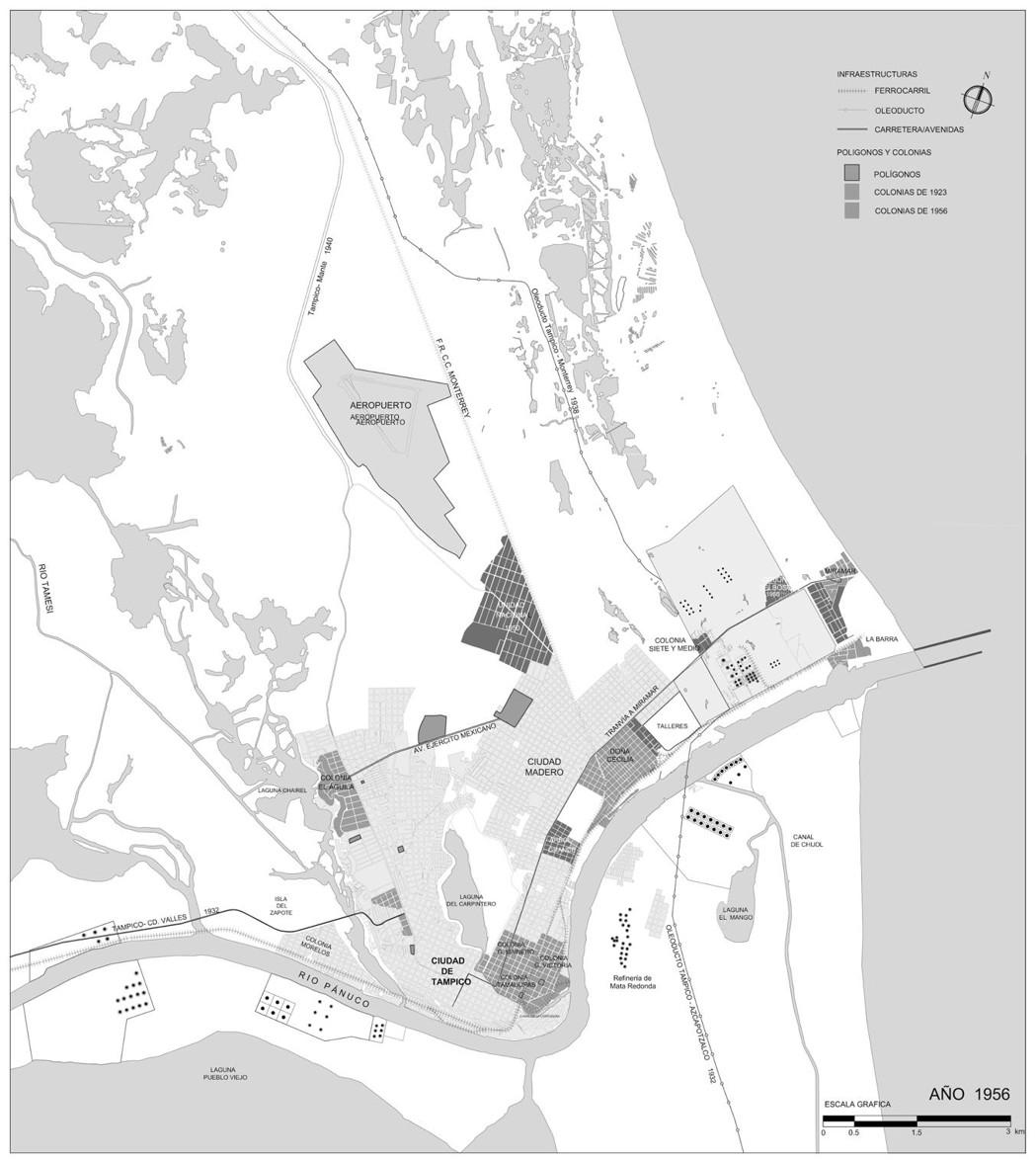

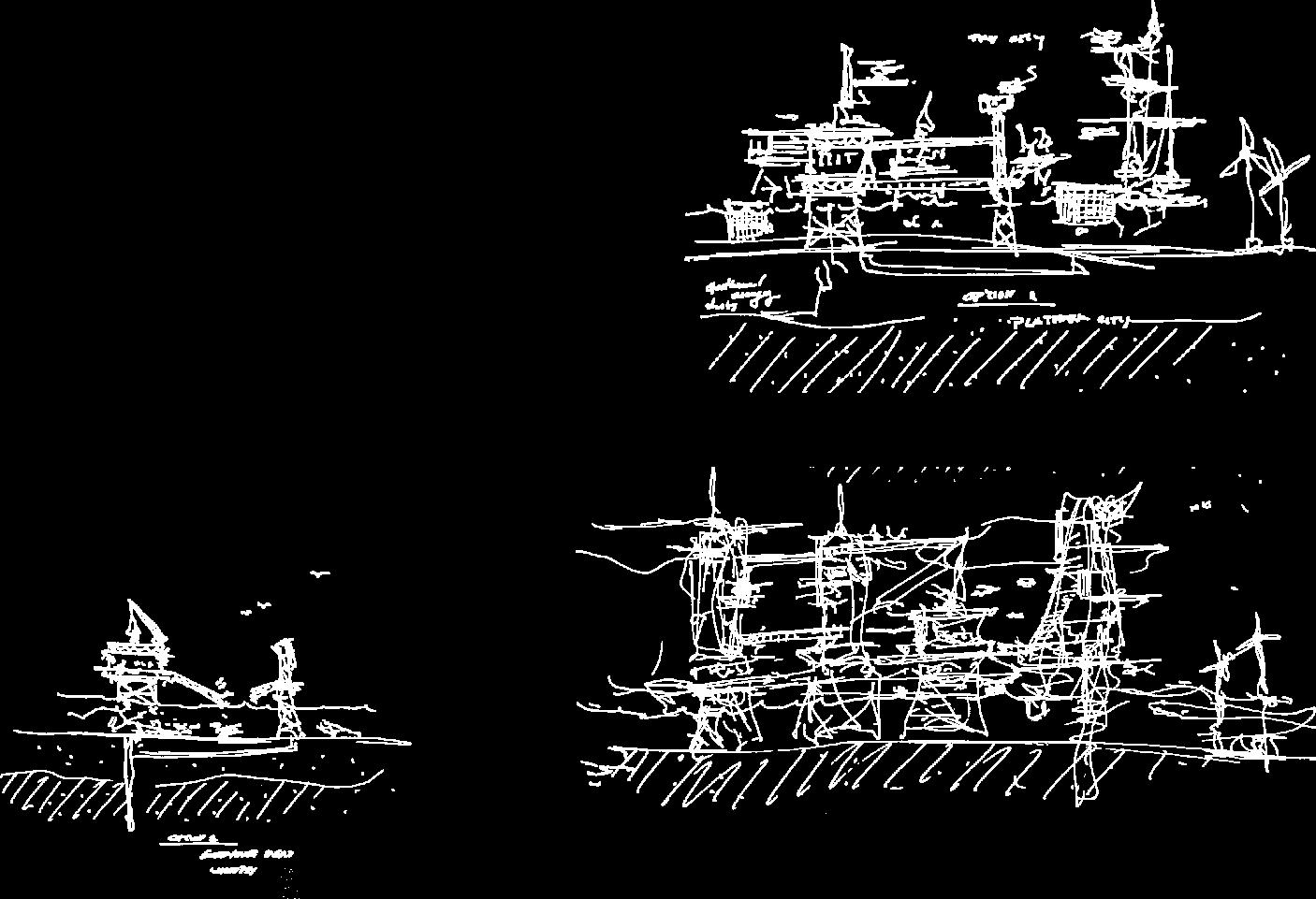

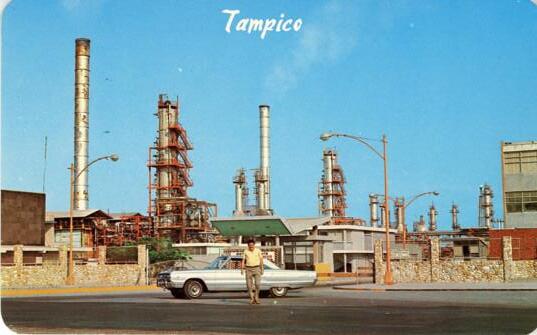

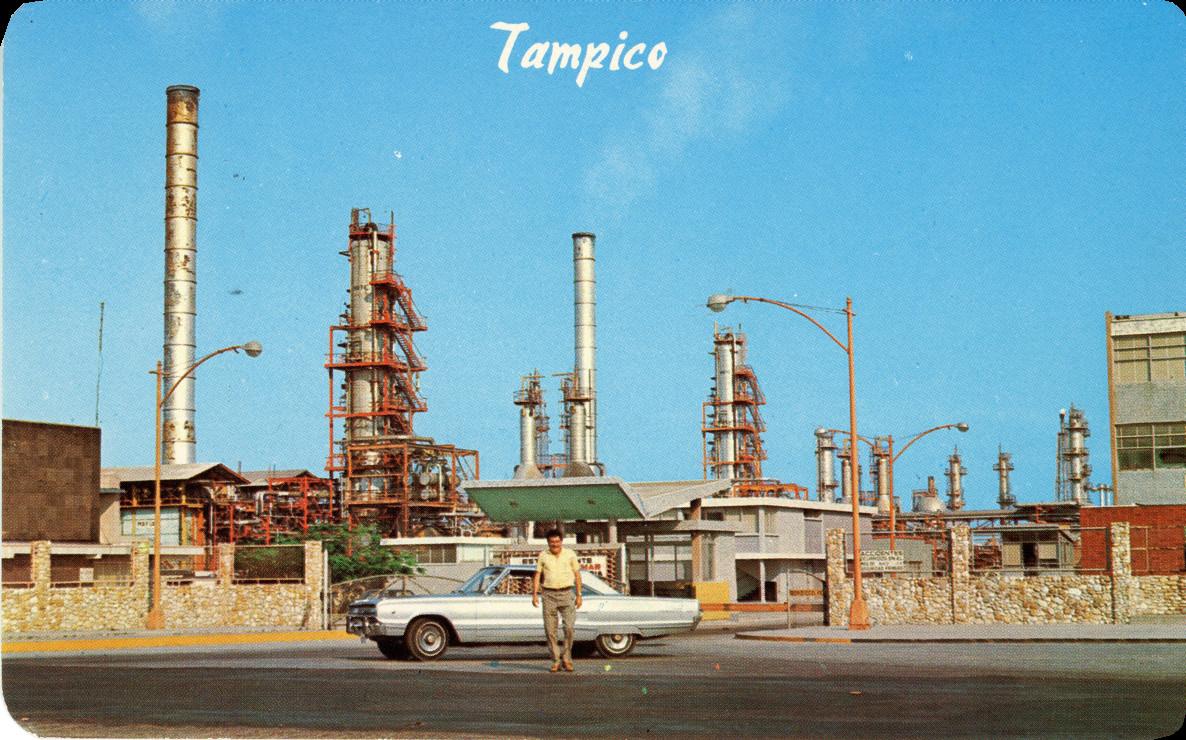

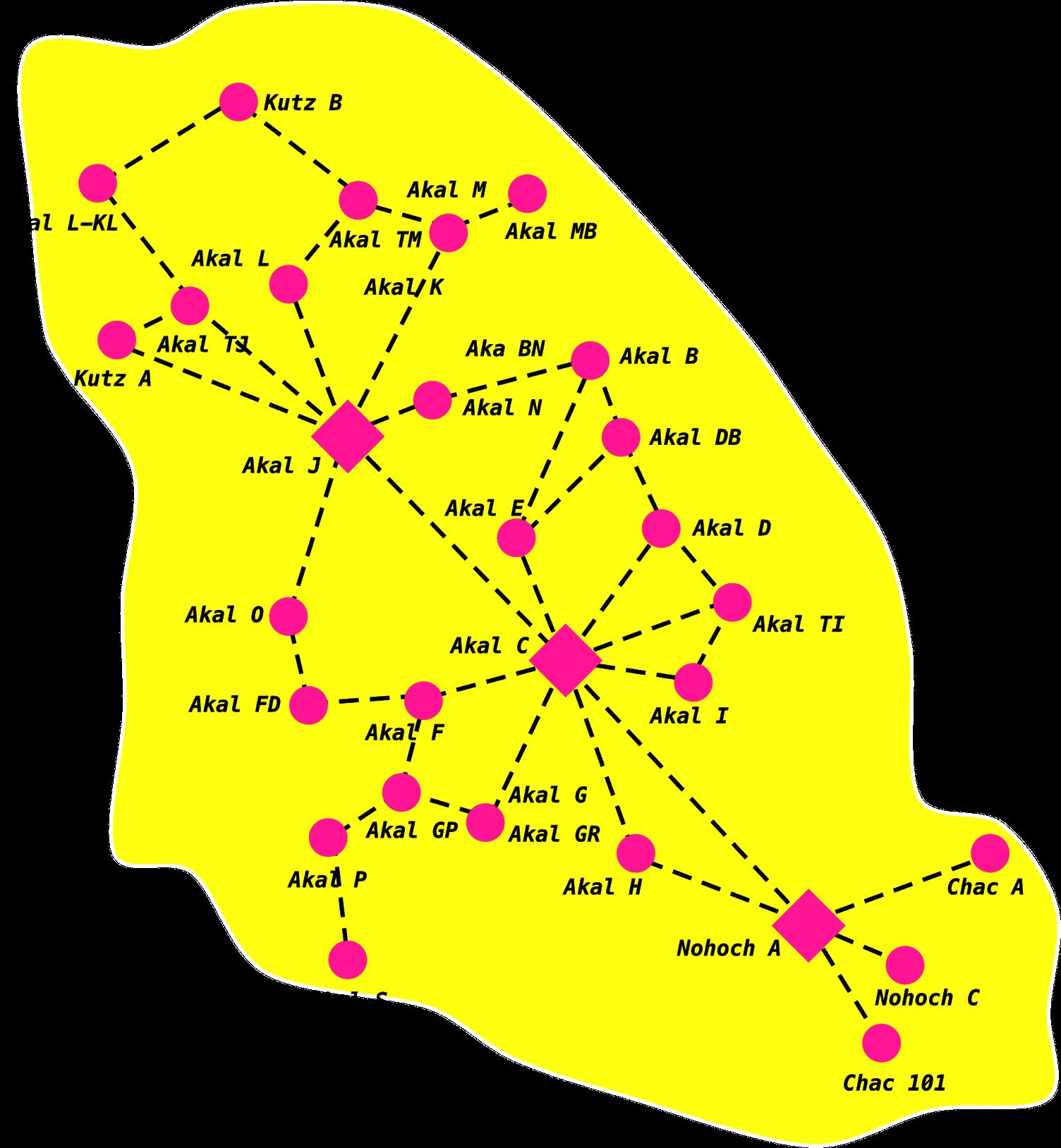

Tampico held a pivotal role in the early to mid 20th century oil boom in Mexico, and retains much of its importance in the industry today. As the center of Mexico’s petroleum industry through the majority of the 20th century, Tampico attracted substantial foreign investment, particularly from British and American oil companies, which played a crucial role in shaping its urbanfabric.10 Thecity’srapidindustrialexpansionasthe nexusofindustryintheregion ledtothedevelopmentof port facilities, rail connections, and several administrative and industrial districts. A steep social hierarchy and abysmal worker housing played a part in the nationalization of the industry in 1938, and while the urban development of the city continued,the latter20th century saw a shift in the epicenterof the industry in the country towards an offshore model of extraction, leading to a local decline in production.11 The city, however, remains critical in the industry, maintaining the port and many means of fabrication. Tampico’s experience thus serves as a lens to examine a city that grew solely due to the oil industry, and can thus provide insight into how can such cities prepare for the loss of thatindustry.

Through these three cities, this thesis takes a comparative historical approach to examine the relationship between oil-based industry and urban development. By analyzing the urban fabrics and their respective histories, with each representing distinct geographical, economic, and political contexts, this study seeks to identify patterns and divergences in how the two are related through both their tangible

9. Gutiérrez, Ramón, Liliana Lolich, Liliana Carnevale, y Patricia Méndez. Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina: un siglo de vida petrolera. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Fundación YPF, 2007.

10. Hernández Elizondo, Roberto. Empresarios extranjeros, comercio y petroleo en Tampico y la Huasteca (1890-1930).

México D.F: Plaza y Valdés, S.A. de C.V., 2006.

11. Cardenas, Lazaro, “1938 Discurso con motivo de la Expropiacion Petrolera," 18 March 1938

environment and through the intangible aspects of economics and culture. The methodology combines archival research, geological considerations, architectural/urban analysis, and consideration of the different parties involved in order to reconstruct the development of these cities and assess the long-term impact of oil wealth (and who controls it) on their infrastructureandsocio-economicdiversity.

This study relies on a combination of primary and secondary sources, from archival documents and newspapers,fictionalliteratureandfirst-handaccounts, to spatial analysis through cartographical evidence such as historical maps and GIS analysis. All of this includes government reports, urban planning documents, chronological cartographical comparison, evidence of infrastructure development, housing projects, and newspaper reports of contemporary events to determine both the physical developments as wellastheasthelocalperception.

Toguidetheanalysisandprovideaframeworkforwhich each case study city can be compared, the research was structured around five key research considerations. Through this distillation of the different variables available into separate categories, the diverging experiencesofeachcitycanbestudiedinamoreholistic way.

The first set of research questions considers the preexisting urban context. What were the demographic, economic, and infrastructural characteristics of Baku, Tampico, and Comodoro Rivadavia prior to the discovery of oil? How connected were they to their surrounding regions? Was there a pre-existing urban fabric or population? How did these pre-existing conditionsinfluencethewaythatthecitiesdevelopedin responsetooilextraction?

The second reviews the geological and geographic contexts. Geographical context greatly influences the development of cities, seen in urban development and planning since ancient times. However, how did the physical characteristics of oil extraction shape the

spatial development of each city? How does industrial density affect the development of residential neighbourhoods? What areas were considered untouchableduetofutureextractionandthuscouldnot beused?

The third revolves around the industry itself. How did the different models of industry governance (foreigncontrolled, state-led, mixed, etc.) impact the development of urban infrastructure, labour policies, priorities, and architectural characteristics? Where was the wealth based or exported to? Was it purely local, semi-regional, foreign? How did broader political stability and geopolitics directly and indirectly affect developmentinthecityandregion?

The fourth set of questions looks at the relationship between labour, city, and industry. How did the past factorsinfluencethecreationofhousingdevelopments? What social stratification became prevalent in the city? Whatwerethelivingconditionsandhousingpoliciesfor oil workers? How did the difference between nationalizedvsprivatizedindustryaffecttheconditions? How did these all impact long-term urbanization throughinformalvs.formalsettlements?

The final cluster looks at the intersection between culture, migration, labour, and the built environment. What were the influences that generated the different ideas of urbanization in each city? How did migration of populations affect this? Were there cultural and ethnic stratificationsinadditiontotheeconomicones?Howdid immigrantvslocalpopulationsaffectdecisionstakenon the administrative and worker levels? How did these migration patterns influence the social composition and spatialorganization?

Byemployingthiscomparativeframeworkanattemptis made to draw broader conclusions about the relationship between industry and urban development. By integrating the element of pre-and-post nationalizationtothecomparativediscussion,thisthesis aims to contribute to the broader debate on resourcedriven development, studying how the influence of

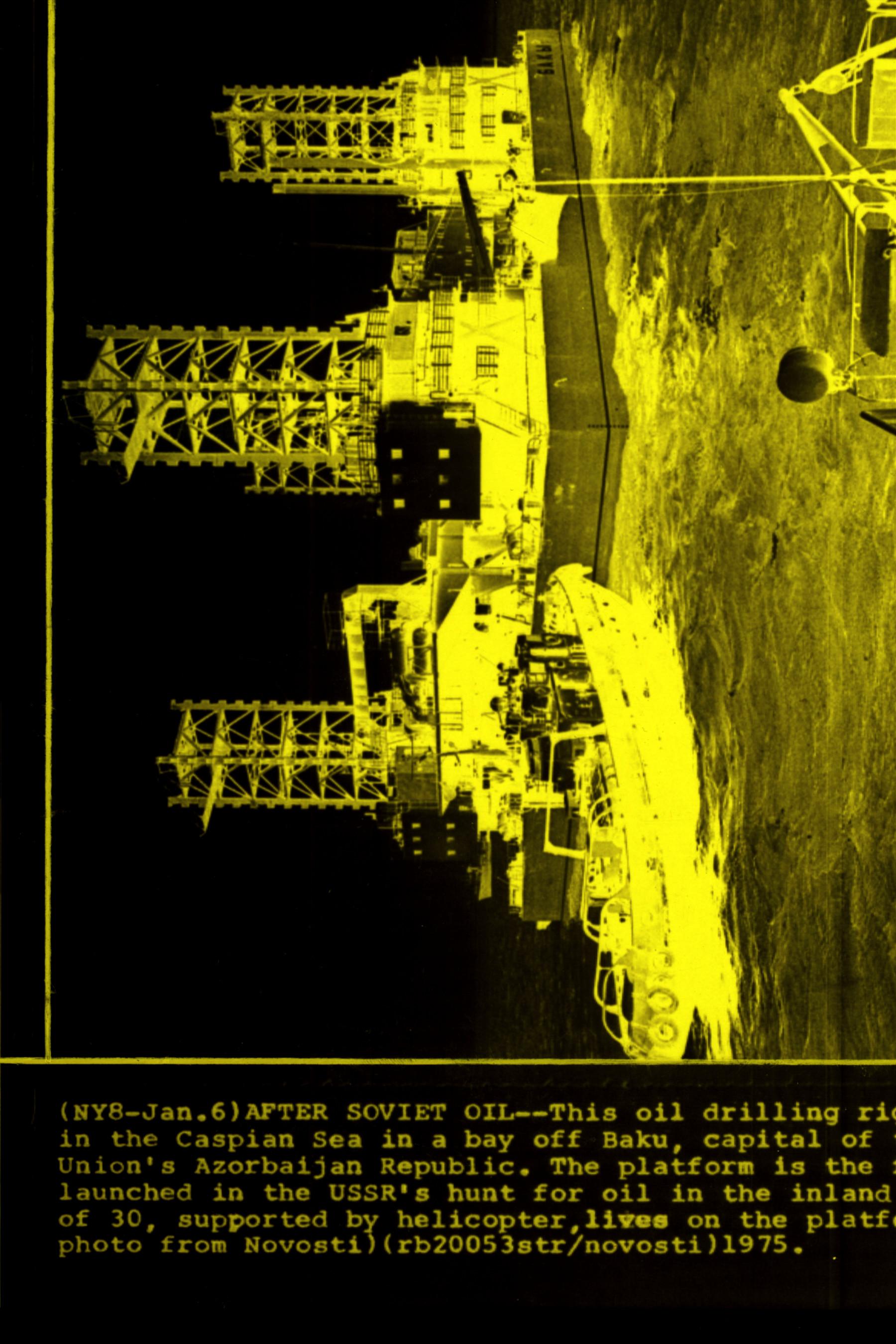

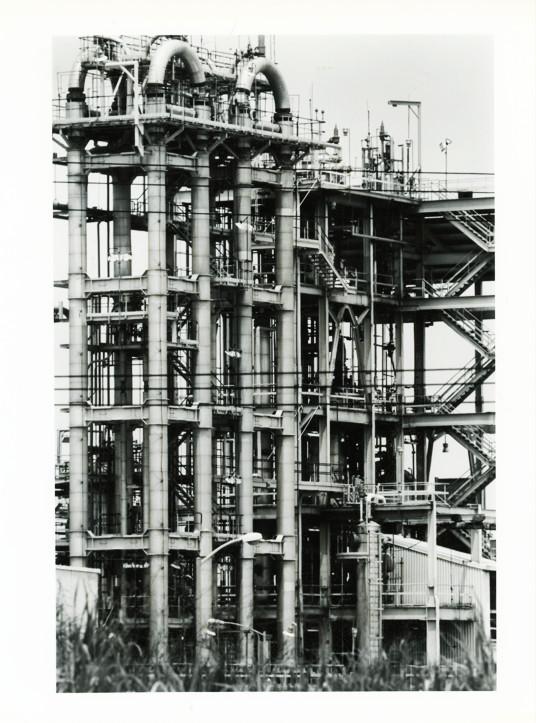

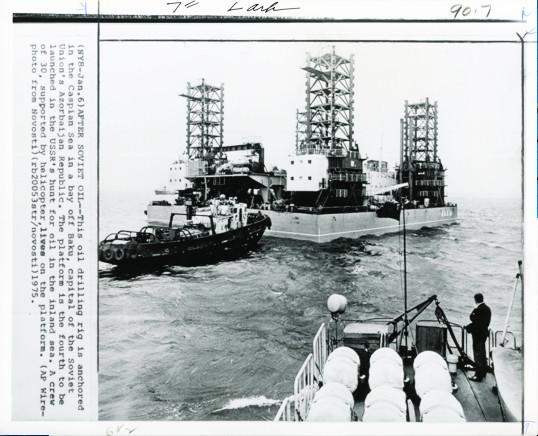

View of a refinery on the Baku coastline, now under construction as part of the current White City urban renewal plan. c. 2017

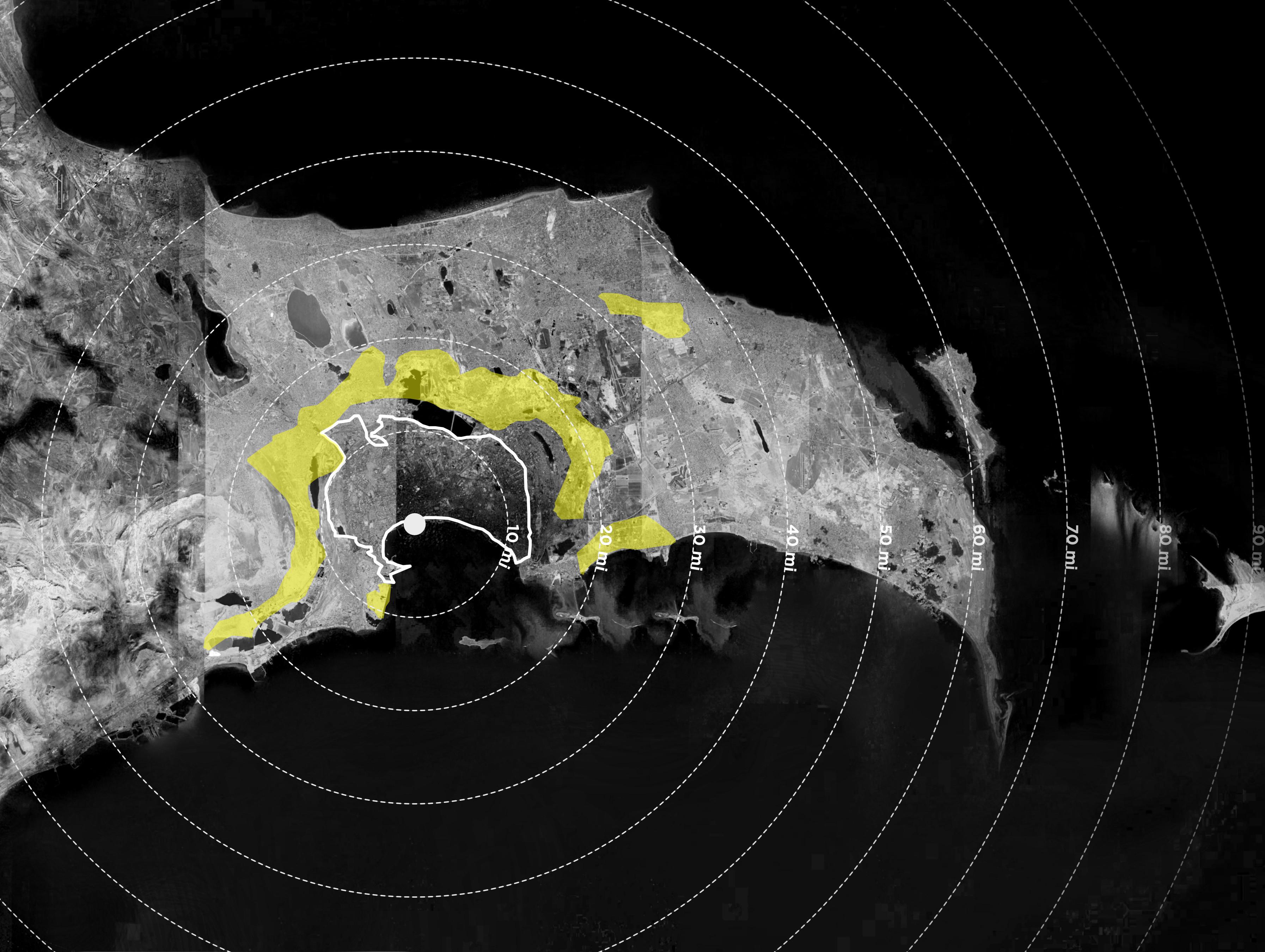

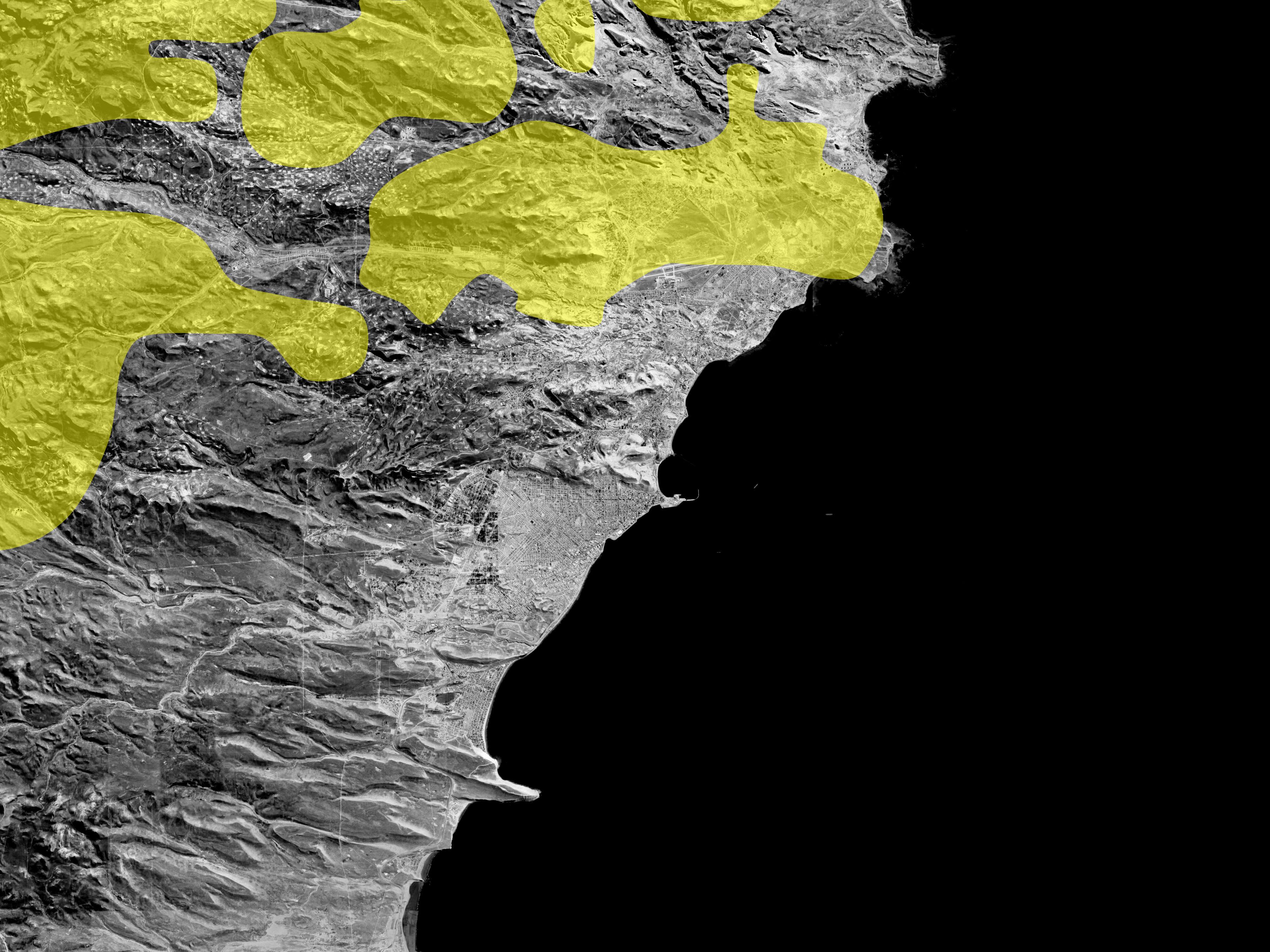

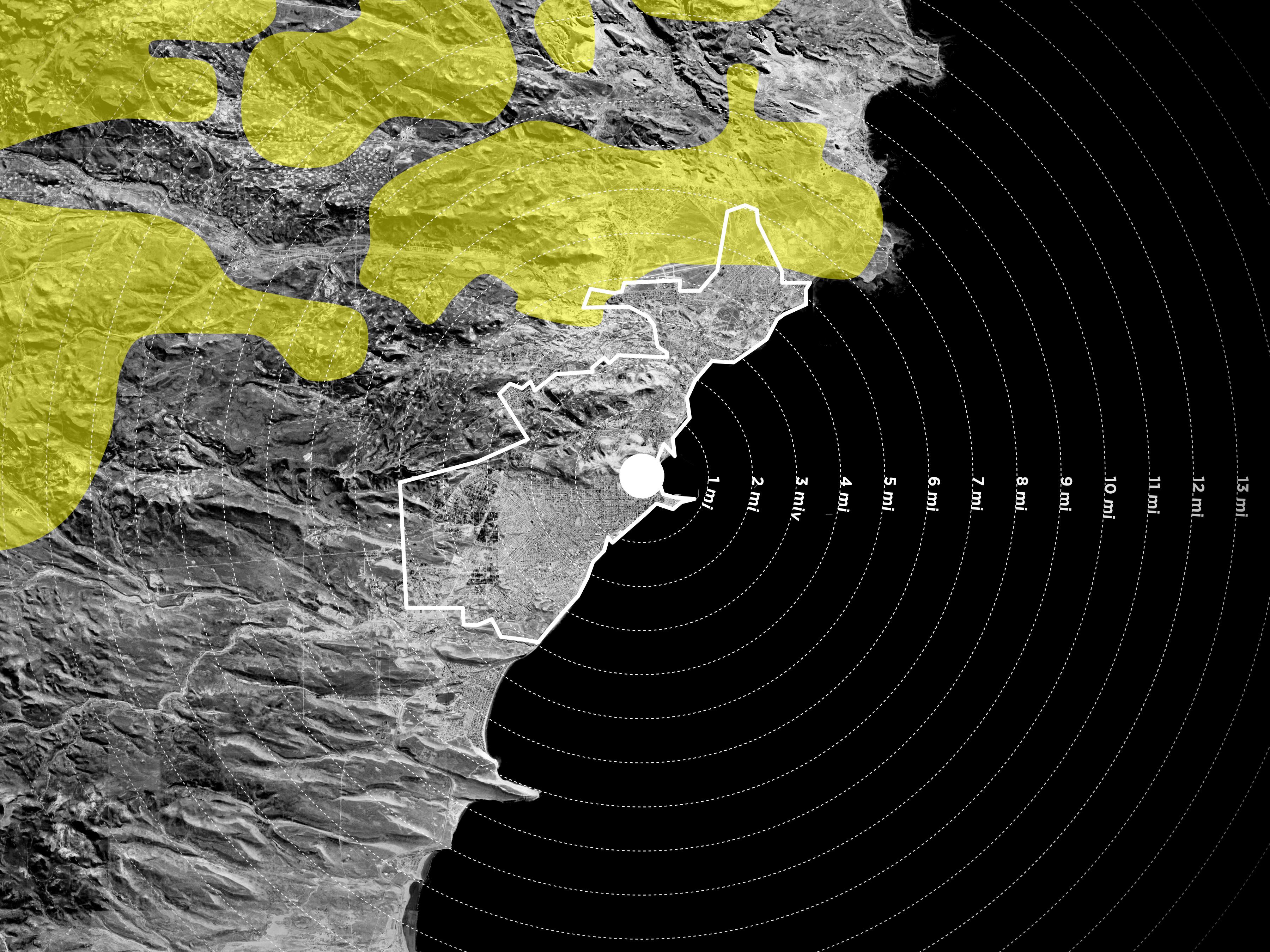

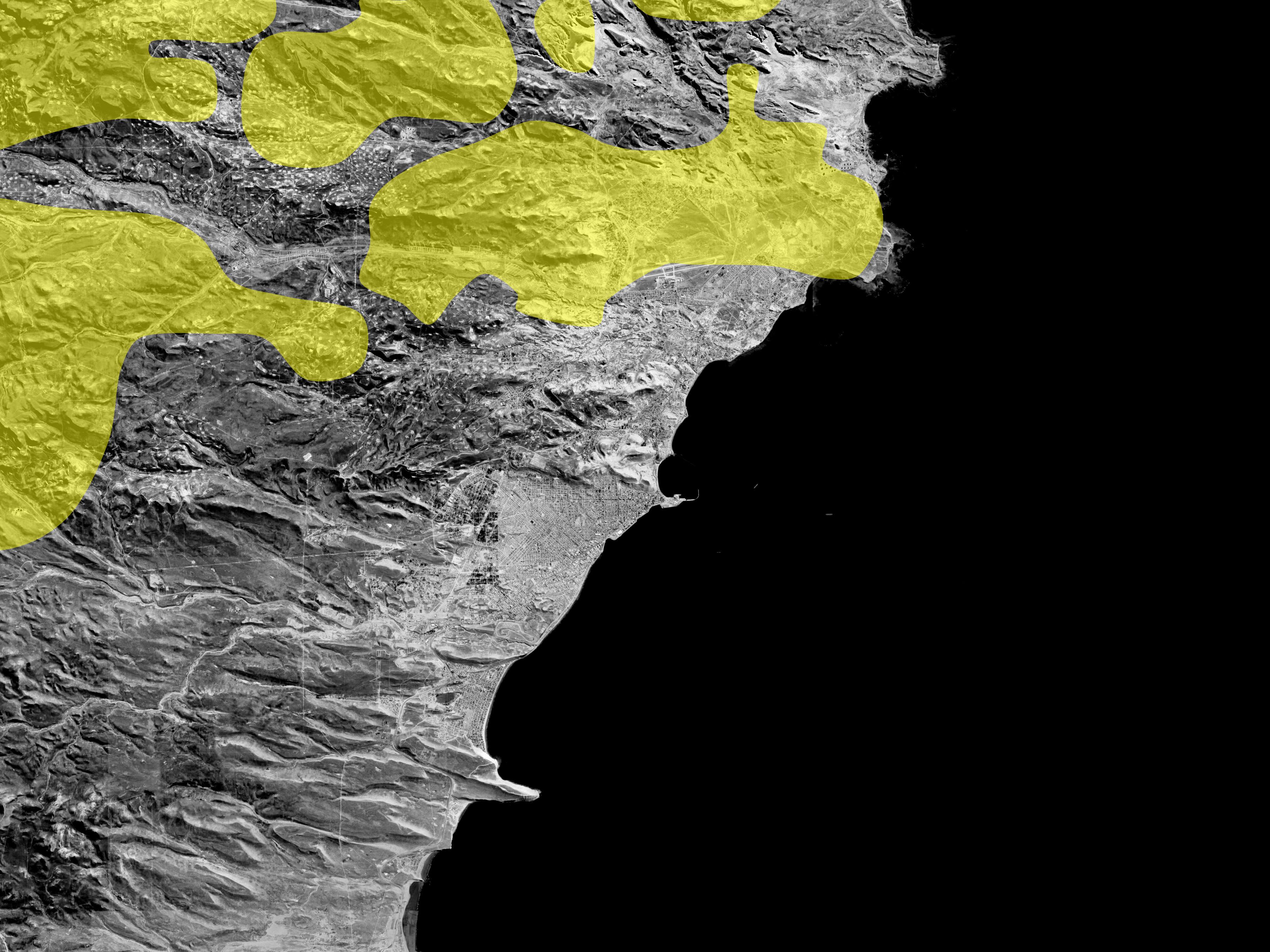

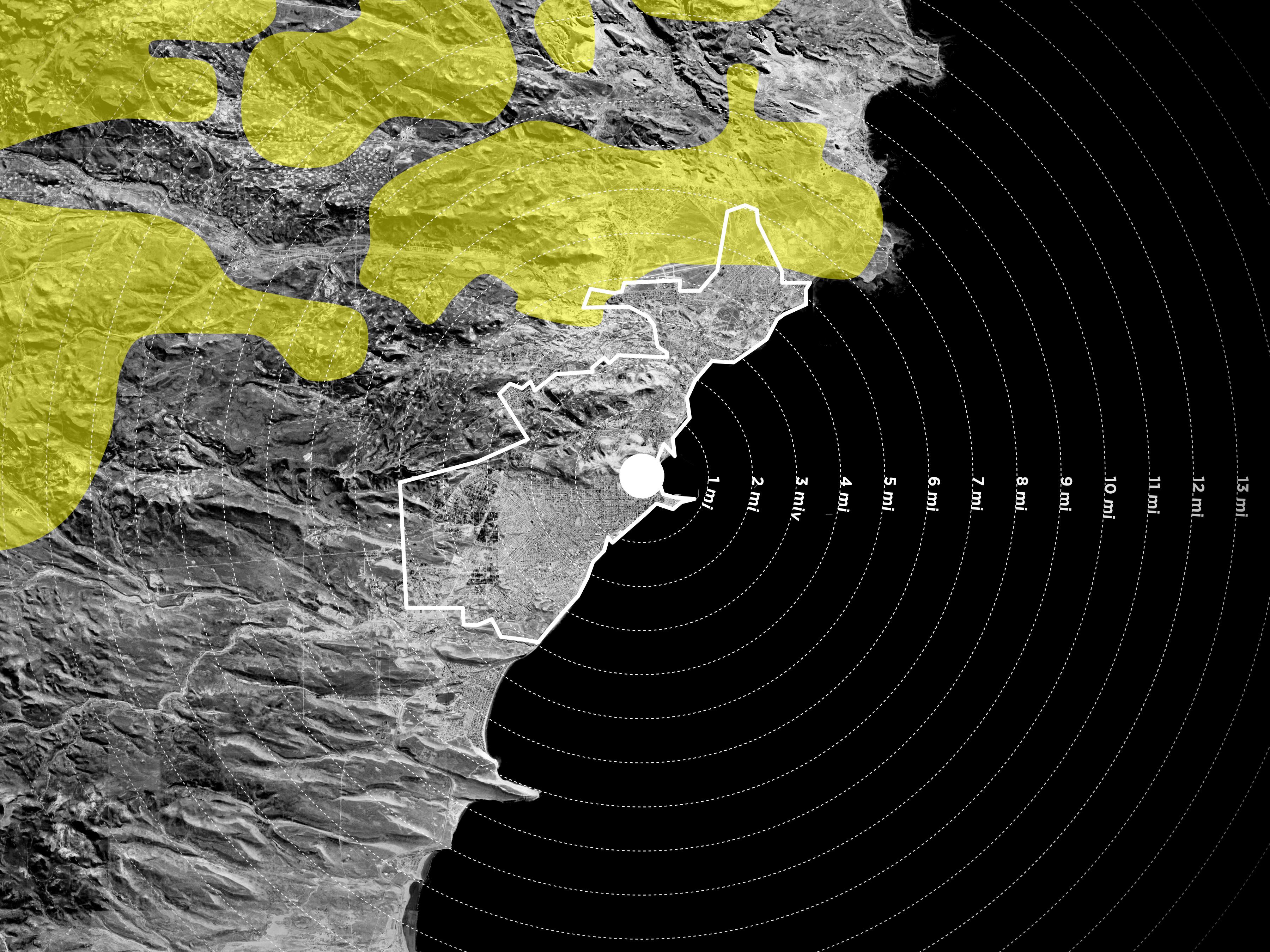

Satellite

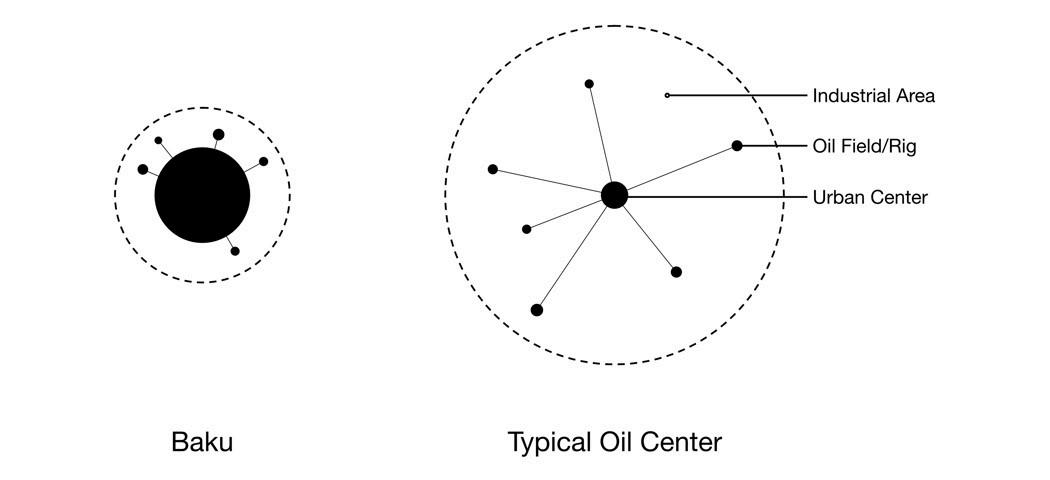

BakucanperhapsbebestdescribedasanOutlierCity.It serves as an exceptional case study within the broader examination of resource-driven urbanization, and paradoxically as the exemplary petro-city. While numerous cities globally have developed in response to the economic opportunities afforded by natural resource extraction, because of labour-based immigration, industrial investment, and local interests, many of these drivers are considered more indicative of extraction industries such as coal rather than that of oil. However, in Baku, all of them are present and more. Specifically, Baku stands apart from many oil-based urban centers due to four primary factors: the extraordinary density of its extractive areas, its notably early transition to industrial scale oil production, the significant presence and influence of local Azerbaijani oil barons, and its later role as a Soviet experimental ground for housing design and urban development strategies.

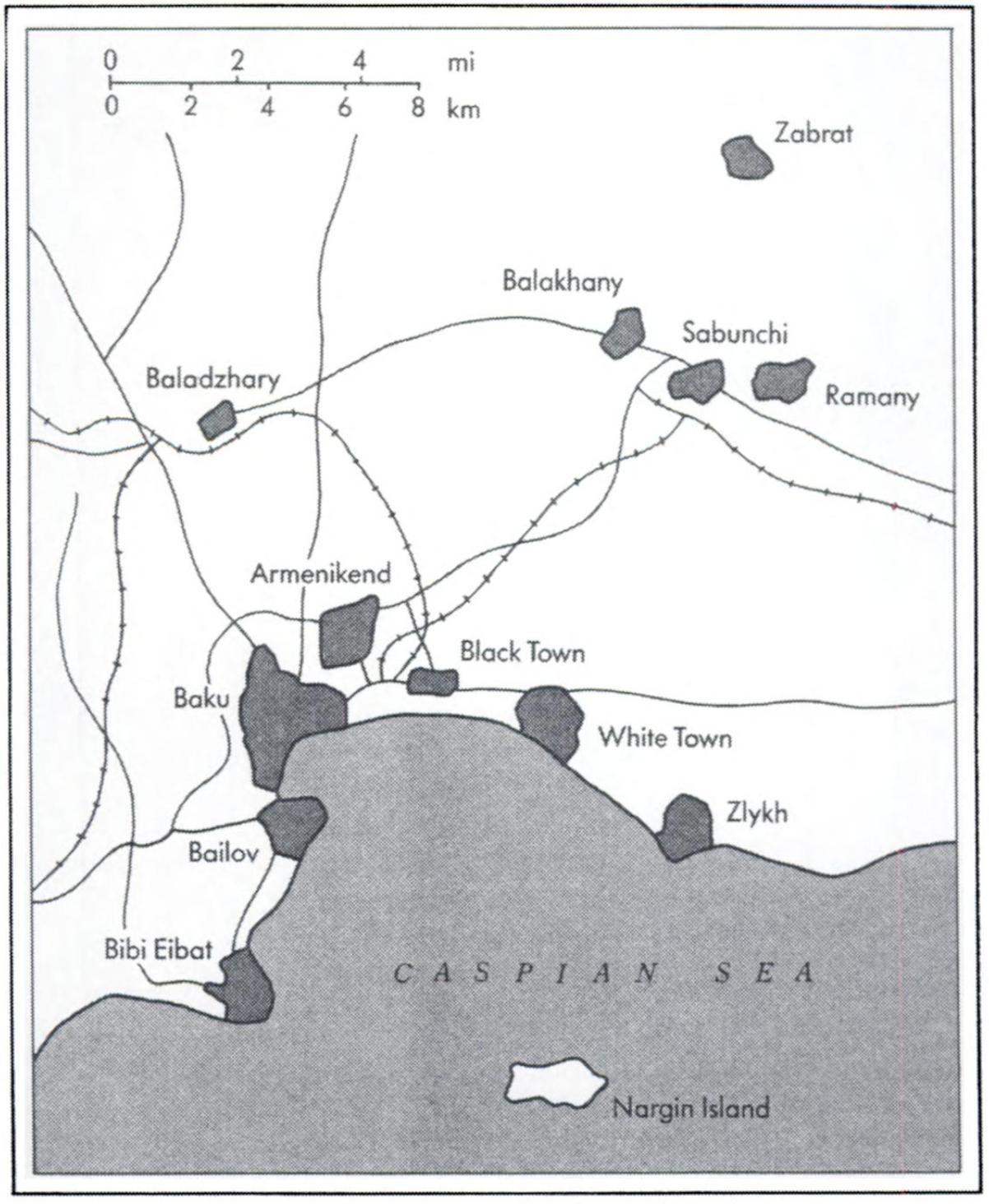

Baku’s urban fabric was profoundly influenced by the unprecedented density of its oil fields and industrial infrastructure. Unlike other oil regions characterized by massive and decentralized extraction areas (typically connected by sprawling networks of oil pipelines), Baku’s oil extraction, refining, and transportation infrastructure were concentrated in an exceptionally compact area of approximately 20 sq. kilometers (or 7.2 sq.miles).1 Thisconcentratedextractionfootprintnotonly facilitated a remarkably dense industrial landscape for

refining within the city limits. Additionally, the lack of overallopenareaavailableinBakuduetoitslocationon theAbsheronPeninsula(onlyabout2110sq.km,or810sq. miles) and the present terrain meant the city did not have much area available to contribute to sprawl for anypurpose.

Bakuishistoricallysignificantasoneof,ifnottheearliest global center to industrialize specifically around fuel oil, decades ahead of other major oil-producing regions. Whileotherplacesaroundtheworlddrilledoilmainlyfor theproductionofkerosene,Bakustartedproducing fuel oil about 30 years before its competitors (whose conversion from producing kerosene to fuel oil was mainly spurred by World War 1)2, mainly for use in powering Peter the Great’s Russia’s Caspian Fleet and the Transcaucasian Railway,3 thus giving Baku an immense advantage when focus started shifting towards fuel oil, setting the stage for its rapid growth, further integrating the city into the broader imperial economic and military networks, and thus introducing it tothegeneralEuropeansphereofinfluence.

Baku’s urban development is also uniquely marked by the significant involvement and influence of local Azerbaijani oil barons, who emerged alongside the influx of foreign capital. This local entrepreneurial class played a crucial role in the economic and cultural developmentofthecity.Enabledbytheeconomicboom knownlocallyasthe“GoldenBazaar”whichallowedthe local purchase of oil-producing lands, Azerbaijani barons invested heavily in urban infrastructure and monumental architecture, actively participating in shaping Baku’s built environment. Their ambitious developments, such as the expansive boulevard, ornate public buildings, and private palatial residences, paralleled the contemporary European urban and architectural models,earning Baku the title “Paris on the Caspian.” Thus, unlike other petro-cities dominated exclusively by foreign capital, Baku experienced significant reinvestment of oil profits into the local urban sphere, creating an enduring legacy of civic (and later national)prideandurbansophistication.

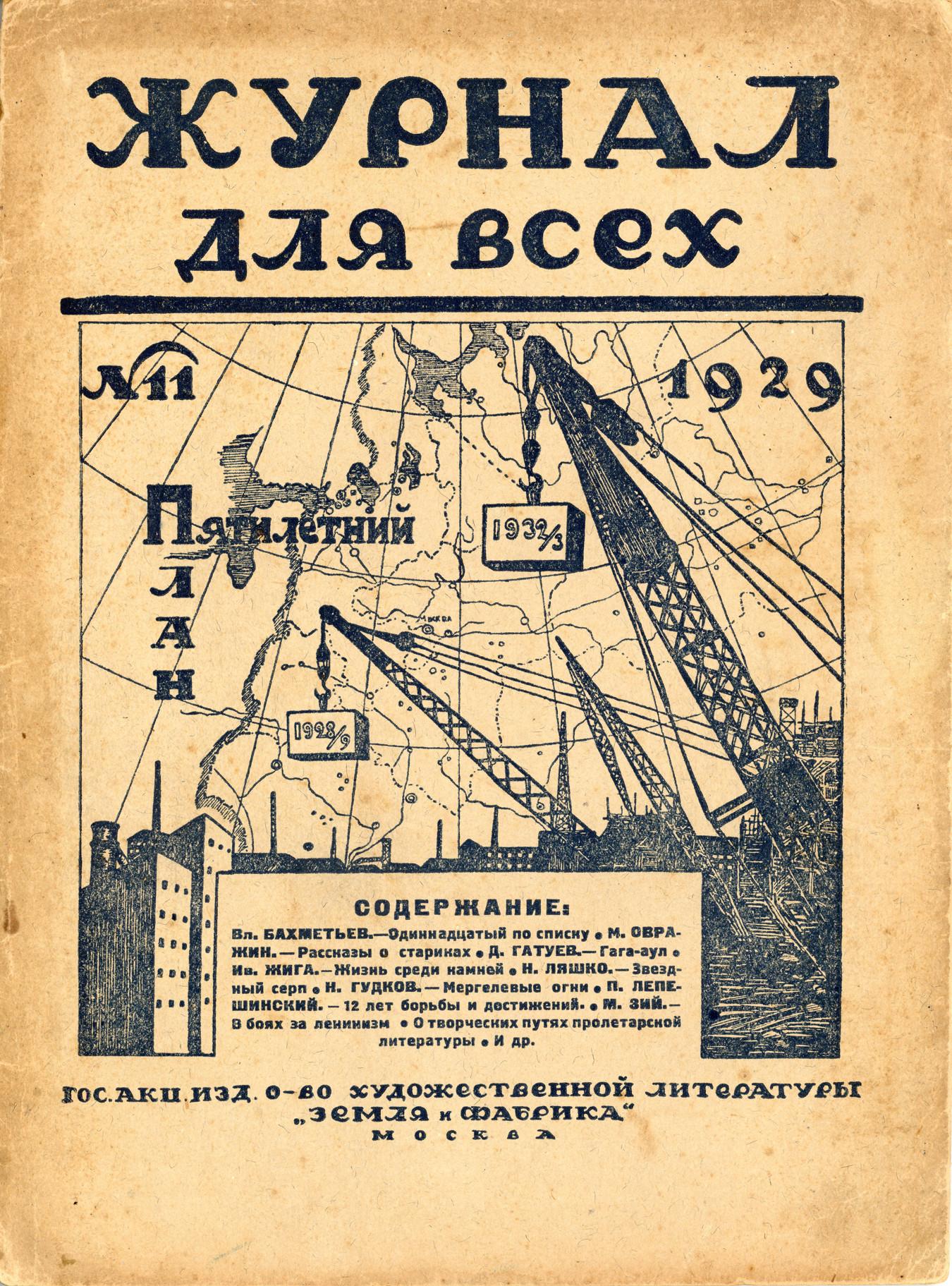

Finally, Baku’s urban narrative extends into the Soviet era, when the city became an experimental laboratory for Soviet urban planning and housing policies, prototyping the model of proletariat-focused architectureandcivicinfrastructure.Thecity’seconomic presence and the need for labourer housing developmentoutsideofthepre-existingdensemedieval urban fabric made it a key site for experimenting with socialist urban ideals and modernist architecture, inclusively producing some of the earliest models of the infamous Soviet housing block. Throughout the 20th century, Baku experienced rigorous Soviet-led urban interventions aimed at addressing housing shortages, improving living standards, and promoting ideological goalsofthenewSovietgovernment.Thisphaseofurban experimentation included extensive implementation of standardized housing typologies, the creation of large residential districts, and innovative communal living models designed to reflect socialist values. The Soviet interventions added a further distinctive layer to Baku's urban complexity, showcasing the city’s ability to continuously evolve and serve as a testing ground for evolvingurbanideologies.

Collectively, these four factors—density of oil infrastructure, early industrialization, presence of influential local barons, and the city's role as a Soviet experimental site—position Baku as an outlier within studies of oil-based urbanism, and a perfect starting pointforthiscomparativestudy.

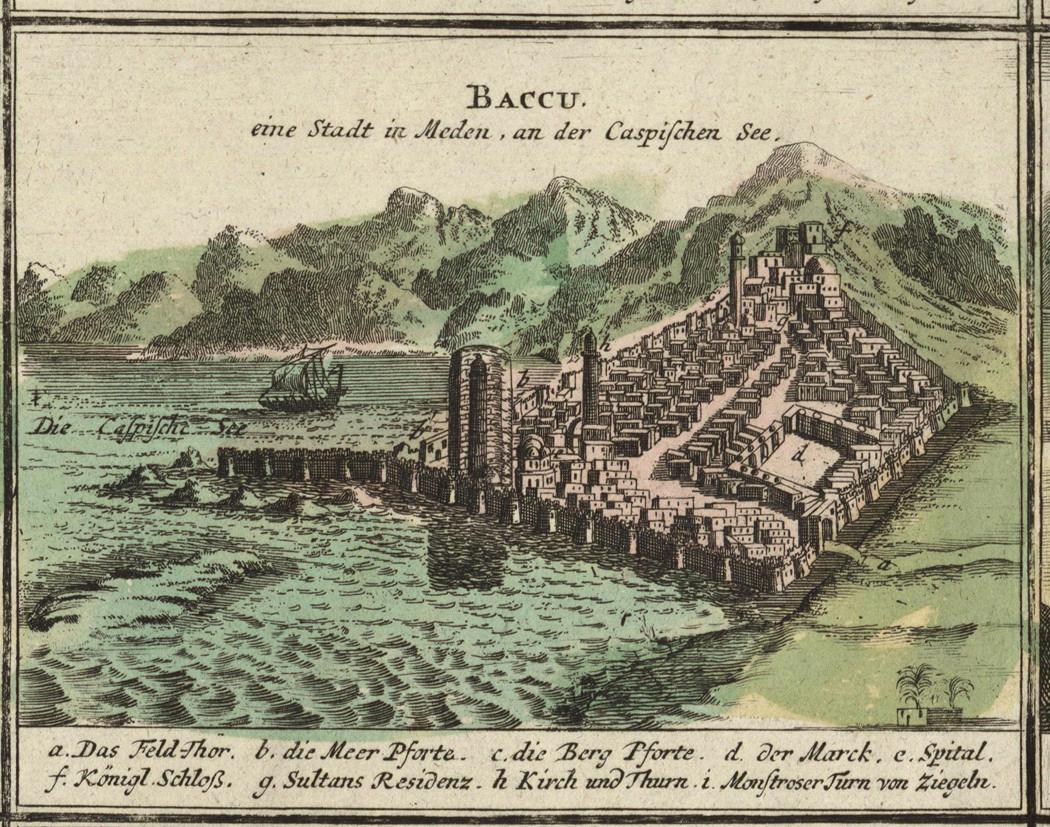

From the earliest mentions of Baku in classical and islamic texts, the city has been inextricably tied to the presence of oil—its scent, its fire, and its spirituality. Unlike many other resource-based cities whose industrialization emerged from colonial extraction and/or foreign investment, Baku’s relationship with hydrocarbons predates both the imperial conquest and thetechnologiesthatwouldlaterdefinethelaterperiod of its history. On the Absheron Peninsula, oil and gas were not just a commodity, it was the landscape’s condition.Theywerenothiddenwithintheearth,onlyto

be reached after discovery through drilling as happened in Comodoro Rivadavia or only visible if one knew where to look as was the case in Tampico. They quite literally bubbled from the earth,was soaked in the sand,andgasburnedinperpetualflamesinthehillsides outside of the city (such as in the Ateshgah of Baku and Yanar Dagh). This presence of oil would define the early pre-industrialized urban identity of Baku as much as its strategiclocationontheCaspianSea.

Archaeological traces in the Absheron region point to continuous habitation since the Paleolithic era, but it is

not until the early Islamic period that Baku emerges as an identifiable node in the written records. Arab geographers and writers in the 9th and 10th centuries such as Al-Muqaddasi, Ibn Hawqal refer to Baku as a site of flammable oil springs, describing an area with rudimentary oil use. By the 12th century, the fire worshipping temples that dotted the peninsula (most notably the Ateshgah in the outskirts of Baku) had become pilgrimage destinations for Zoroastrians, their flames sustained not by man-made intervention but by subterranean gas that seeped through cracks in the earth and spontaneously combusted. In this sense, the earliesturbanformofBakucanbereadnotonlythrough itsobviousconnectiontotradingroutesintheregionbut alsothroughitsrelationshipwithoil.

It would not be until the rise of the Shirvanshahs that Baku began to be formalized as a city. They ruled over much of what is now Azerbaijan from the 9th to 16th centuries, initially governed from the inland city of Shamakhi but later forced to move to Baku following a devastatingearthquake,Baku’sdefensivequalitieslayin its geography, a natural harbour surrounded by rocky hills on a contained peninsula. It was during this period that the first substantial urban fabric began to emerge, including the construction of the emblematic Maiden Tower and, later, the palatial complex of the ruling Shirvanshahs;allhousedwithinacontainedwalledcity.

Yet, even during this early industrial period, oil remained materially embedded in the city’s atmosphere rather than in its economy. Surrounding Baku were manually dug oil wells—some of them gushers—but extraction remained primarily for local use. Foreign travelers from the 14th century onwards described Baku as a city marked by fire and oil. Marco Polo is believed to have also visited Baku, with a passage from his Travels believed to have been referring to the city. “Near the Georgian border there is a spring from which gushes a stream of oil, in such abundance that a hundred ships may load there at once. This oil is not good to eat; but it is good for burning and as a salve for men and camels affected with itch or scab. Men come from a long distance to fetch this oil, and in all the neighbourhood

no other oil is burnt but this.”4 Thisconceptofaresource inthiscontextdidnotyetimplyrefinementbutwasonits waytobeingusedasanaccumulatedresource.

The Safavid conquest in the early 16th century integrated Baku more formally into the Persian imperial system, but it nevertheless remained a relatively minor coastaloutpost.Itsoilcontinuedtobecollectedforlocal andregionaluse,buttherewasnoinfrastructuralscaling of industry. What changed was not the scale of productionbutthegeopoliticalawarenessofthecity.By the 17th century, as maritime empires expanded their territorial ambitions into the Caspian inland sea, Baku’s resource landscape began to attract strategic interest. Peter the Great’s temporary conquest of Baku in 1723 as part of a broader campaign to assert Russian dominance in the Caspian basin as a response to Ottoman incursions in Persia, was less about the city’s urban form or trading abilities than it was about its mineral potential. The Russian commissioned accounts oftheregionandcityemphasizeitsresourcewealthand industrial capacity, and the ease from which oil can be extracted from the earth. While the city returned to Safavid control in 1735 with the Treaty of Ganja, its identity had already begun to crystallize into more than just a local town with commercial ties,the industrial age

was beginning to emerge and with it the interest in fuelbasedresources.

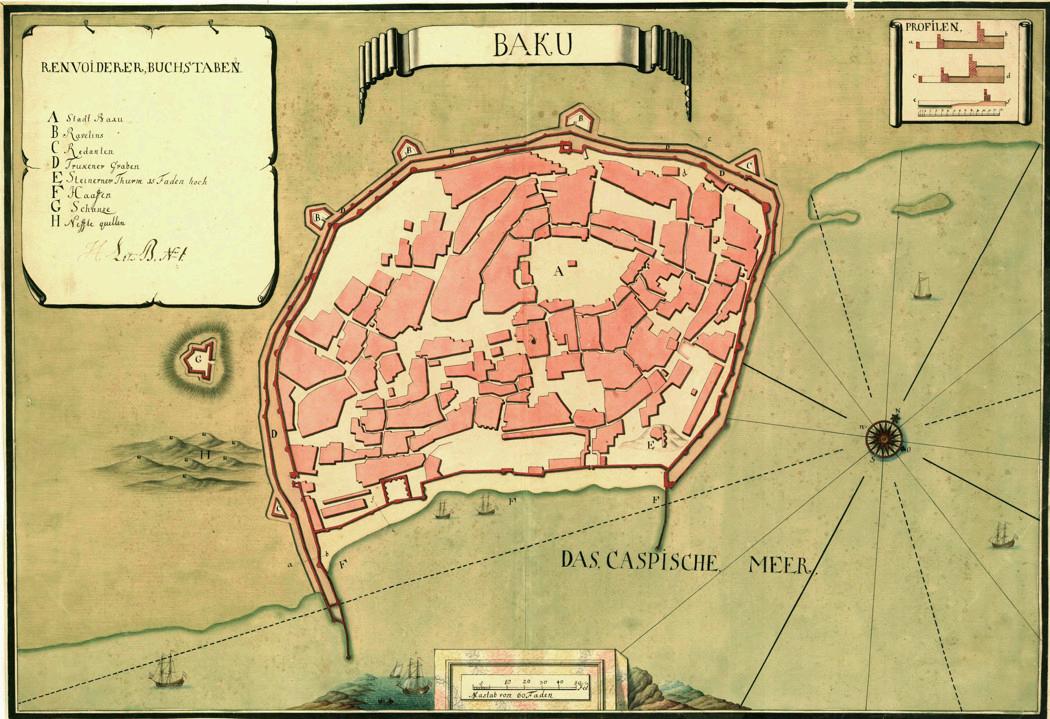

Following the death of Nader Shah in 1747 and the consequent fragmentation of Persian authority, Baku entered a period of semi-autonomous rule under the Baku Khanate. While the khanate lacked the technologicaloradministrativeresourcestoindustrialize extraction, it did oversee the larger scale commercialization of oil in the region. It was sold regionally, sent across the Caspian to Astrakhan or transported inland via caravan. The khans taxed the resource, built rudimentary infrastructure around it mainlybasedonkeroseneuse,andmaintainedthecity’s defensive capacities. The urban form of Baku remained little changed in this period from that of the Shirvanshahs or early Safavids, remaining primarily centeredaroundthewalledIcherisheher(Innercity),but did expand outwards for the purpose of a rudimentary industry.

What distinguished Baku from other regional oil sites was not simply the abundance of its resources, but also its spatial compression. Everything was within immediate proximity. When Russian forces finally captured Baku in 1806 and formalized control under the TreatyofGulistanin1813,theyinheritednotatabularasa butacityalreadyconditionedbyhydrocarbons.Yet,the

infrastructure remained modest with only an initial industrial scale infrastructure created by Peter the Great: oil was still extracted from manually dug shallow pits that relied on collected seepage, transported in skins, and mainly burned in household lamps as kerosene. It was not yet the petroleum capital it would become in the following century, but it was always unmistakablyacityofoil.

WhattheRussianEmpirewasabletodowithBakuinthe decades to come depended in part on the legacy that was inherited. Unlike oil centers in other regions such as the American continent that emerged overnight from speculative or even accidental drilling, Baku had centuries of interaction with oil. Its culture, religious history, and spatial contradictions were all shaped by the long presence of oil and gas—not as industry but as environment.

Peter the Great’s brief occupation of the city during his Persian campaign was not motivated solely by resources, but by a broader territorial vision to project Russian power into the Caspian Sea and carve a southernmaritimefrontieragainstPersianandOttoman influence. However, it was during this campaign that Baku’s worth as resource rich was officially recorded and recognized for its military utility. Russian commissioned engineers and surveyors would send backreportsoftheabundanceofoilthatcouldbefound in the area. In this moment of transition, Baku ceased to be a place of spiritual fire temples and primitive local extractiontooneofamilitaryoutpostfueledbyimperial ambition. Though the Russian military withdrew after 1735,theencounterwiththerichresourcelandscapehad left a lasting impression and the its usefulness was beginning to be viewed through the lens of imperial extraction.

The strategic presence of the Caspian fleet—especially after Baku returned to Russian hands in 1813—reinforced the military importance of Baku’s oil.5 As Russia consolidated its power in the region in the early to mid 19thcentury,Bakubecameacrucialhubandwouldlater

5. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018

6. McKay, John P. “Baku Oil and Transcaucasian Pipelines, 1883-1891: A Study in Tsarist Economic Policy.” Slavic Review 43, no. 4 (1984): 604–23. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2499309.

house the headquarters of the fleet from 1867 onwards. The fleet required maintenance, fuel, and provisioning, and the proximity of oil wells—however primitive— providedararelogisticaladvantage.

At this stage, however, oil extraction remained limited. Manually dug pits and animal skin containers defined much of the material reality of production, and it would not be until the mid 19th century that the resource landscape was reshaped by emergent technologies. Nonetheless, the recognition of oil as a strategic fuel resource and economic boon meant that imperial engineers and industrialists began to imagine this Caspianfrontiernotjustasasitefordefense,butalsoas alaunchingpointforindustrialandeconomicexpansion.

Perhaps the single most transformative piece of infrastructure in Baku’s early industrialization was not the creation of oil drilling infrastructure, but that of its transportation in the Transcaucasian Railway, which was completed in stages during the mid to later 19th century, and which reached Baku in 1883.6 It connected BakutotheBlackSeaportofBatumi,therebylinkingthe oil fields to be transported to otherRussian cities via the Black Sea and from there to European markets. Prior to the railway, oil transport had been limited to coastal trade or caravan routes, neither of which could accommodate the scale needed for such industrial expansion. With the introduction of rail infrastructure, however, Baku’s oil could be exported in massive volumes, thus serving as a critical hinge from the transitionoflocalizedmarkettothecontinentalstage.

7. Mir-Babayev, Mir Yusif. "The Bibi-Heybat Oil Field." AAPG Explorer, August 2021.

While the railway only connected Baku to external markets from 1883, what distinguished Baku from other emergingoilfieldsinthesametimewasitschronological advantage. The first modern oil well in the world was drilled in Baku in 1848 in the Bibi Heybat Oil field— a decade before the Titusville well in Pennsylvania (1859) which is often miscredited as the first.7 While American fields would quickly scale to enormous volumes, Baku’s early head start allowed it to create a more developed infrastructure relating to extraction, refining, and transportbeforeothercitieshadevenbeguntodevelop

theirs. By the 1880s, Baku was producing over half of the world’soil.

ThisearlytransitiontoindustrialoilgaveBakuaposition of dominance that shaped not only its own urban development but the global architecture of petroleum extraction. The city became a laboratory for the spatial organization of industry: pipelines, derricks, and refineries were laid out according to new European principles of urban design, and grafted onto a city whosehistoricallayerswerealreadycomplex.Itwasthis interaction of resource abundance, imperial interest, and industrial experimentation that allowed Baku to emergeasthefirsttrueoilmetropolis.

Therapidityofthistransformationcannotbeoverstated. Inthespanof25years,thepopulationofthecitygrewby morethan700%,outpacingalmosteveryothercityinthe Russian Empire.8 This extraordinary pace and density of industrial growth in the city during the mid to late 19th century produced not a unified urban fabric, but rather a fabric divided into a bifurcated industrial landscape. As foreign investment, imperial planning, and private speculation converged, the city’s spatial logic fractured into two distinct zones: the Black city and the newer White city. While both were products of the oil boom,

8. Audrey Altstadt Mirhadi and Michael Hamm. The City in Late Imperial Russia. (Baku: Transformation of a Muslim Town). 1st ed. 1986.

Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018

they represented divergent responses to the problem of industrialized growth. The Black City embodied the first wave: a tight, spatial grid which lacked the dimensional flexibilityneededforrefining.TheWhiteCitycameafter, more flexible and spatially expansive, and which grew from need rather than from measured planning. Together they offer a uniquely early example of industrialzoningandpetro-urbanism.

Just as oil itself was being transformed into a strategic commodity—extracted, refined, and exported—so too wasthecitybeingreshapedintodiscretezonesoflabor, capital,andcontrol.Thecity’sfirstencounterwithzoning was thus not in a cultural or civic context, but in one of extractive urgency. And while the grid of Black City and the irregularity of White City appear in opposition, they together represent the ideological contradictions of the industrialage:speedvsorder,andhygienevsdensity.

Baku’s geological geography—both above and below ground—amplifiedtheintensityofitsindustry.Thecitysits ontheeasternedgeoftheAbsheronPeninsula,atongue ofaridlandthatjutsintotheCaspianSea,hemmedinby saline flats and low hills. Its proximity to both shallow oil fieldsandmaritimeexportroutesmadeitanidealcenter for extraction. But this ideal was paradoxically also a constraint: everything—wells, refineries, housing, port facilities—had to be compressed into a tightly bounded area. Unlike American oil towns that sprawled outward across fields and plains, Baku’s oil economy developed vertically and concentrically, with each new layer of infrastructure built atop oradjacent to the previous one. The result was not only a highly densified industrial landscape, but also tensions between resource and residence,industrialgrimeandculturalrefinery.

This spatial compression heightened the urgency for urban planning. Fires broke out regularly. The air thickenedwithwastegases.Andasthecity’spopulation exploded basic services collapsed under pressure. Authorities, increasingly nervous about the emergent disorder and fire risk, saw in zoning a way to mitigate crisis without interrupting extraction. The Black City and the later White City were thus products not only of

ambition, but of necessity. They were industrial buffers, designed to shield the broader city from the consequencesofitsownsuccess.

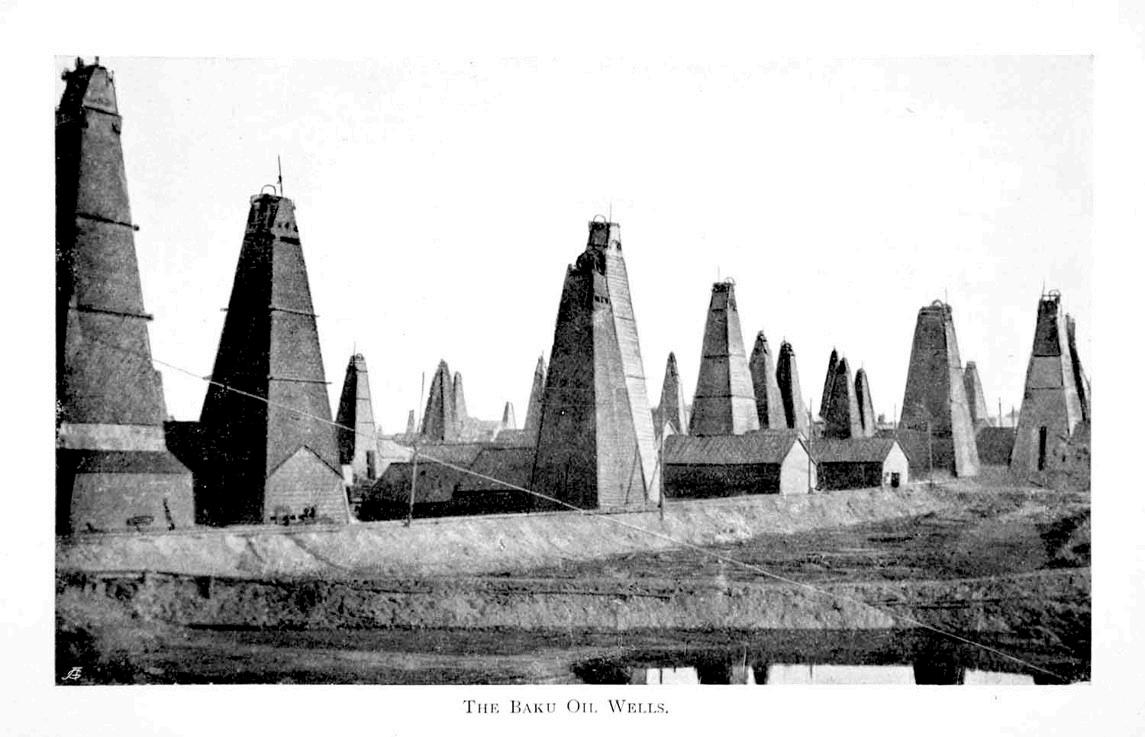

The earliest of these industrial spatial experiments was the Black City, which was planned in 1876 using some of the farms and pastures in a neighboring village and followed imported European ideas on urban planification. This made Black City the first deliberately planned industrial zone in the Russian Empire, anticipating the functionalist zoning of the early 20th century. It was separated from the original residential and commercial zones by a two-kilometer buffer zone.9 It included a dense 80 sq. meter block grid would be created, designated for flexible factory-based use. It showedanattempttocombineideasofurbanplanning with an experiment of how to house a burgeoning industryintoapre-existingdensifiedurbanrealm.

and its

c.

from

book

9. Sh. S. FatullayevFigarov, Arkhitekturnaia Entsiklopediia Baku (The Architectural Encyclopedia of Baku), trans. Dimitry Doohovskoy (Baku/ Ankara: Mezhdunrodnaia Akademiia Arkhitektury stran Vostoka, 1998), 31. Retrieved from Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism, 62

Tadeusz Swietochowski, Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community, 1985, p.xiii

10. Fatullayev, Shamil. “Gradostroitel’stvo Baku XIX – Nachala XX Vekov” Urban Development of Baku in the 19th – Early 20th Centuries

By1880,thereweresome118businessesoperatingoutof the Black City, and the district also accommodated the administrative offices, workshops and housing for those working in both administrative and labor capacities.10 Living conditions were abysmal compared to those in the city proper, where industry was prohibited. The spatialregularityinthedistrictdidnottranslatetoorder. Air quality was toxic, and the ground contaminated. Observers described the soil as slick with residue, the skyline jagged with derricks and black smoke.The city, while gridded and functional, had no real infrastructure forhealthorhygiene.Asoilproductionincreased,sotoo didtherisks.Thegrid,ratherthanmitigatinghazard,had effectively intensified it—packing more refineries into tighter spaces without corresponding regulation.

11. Charles Marvin, The Region of Eternal Fire, Reprint, Hyperion Press, 1976, Originally Published 1883, 234-235

Charles Marvin, an English writer and traveler would describe the district in his 1883 Book The Region of Eternal Fire, “All day long dense clouds of smoke, possessing the well-known attributes of oil-smoke, rise from hundreds of sources… The buildings are black and greasy, the walls are black and greasy; the roads between consist of jutting rock and drifting sand, interspersed with huge pools or oil-refuse, and forming a vast morass of mud and oil.”11 It was this “blackness” that would give this industrial district its name: Baku’s BlackCity.

“All day long dense clouds of smoke, possessing the wellknown attributes of oilsmoke, rise from hundreds of sources… The buildings are black and greasy, the walls are black and greasy; the roads between consist of jutting rock and drifting sand, interspersed with huge pools or oil-refuse, and forming a vast morass of mud and oil.”

THE REGION OF ETERNAL FIRE

Charles Marvin, p.234-235

“There is a very marked difference between the appearance of the Black and White [cities]; in the second, no smoke, or hardly any, is seen to come out of the refinery chimneys, while in the former, with a few exceptions, volumes of black smoke are vomited forth.”

BAKU, AN EVENTFUL HISTORY

James Henry, p.14

12. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018, 67

TheWhiteCity’snamereflectedarelativecomparisonto the Black City, not an absolute. The newer technology present in the refineries it housed meant that there was less visible pollution than that present in the older Black City, and the lack of density distributed what was created. Its creation in the late 1880s was characterized by its lack of a block structure, instead opting to have larger blocks (about 500x300 meters on average), irregular in shape, which would accommodate to the shape taken by the factories rather than the other way aroundaswellasallowingforfutureexpansion.Itwasa more “organic” development, mainly focused around a main access street which connected to the Black City in the east and which the blocks expanded perpendicularly from. The White City grew to mainly house only select new refineries, which were cleaner thanthoseusedintheBlackCity,andwashometosome of the workers’ housing developments created by the ownersofthefactoriesandrefineries.12

13. Henry, James. Baku an Eventful History. London: London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd, 1905. p. 14

Yet this spatial reordering was as much about optics as it was about functionality. By the 1890s, Baku had become a global name in oil production. Foreign dignitaries, investors, and engineers visited the city regularly, and companies began to compete not only in production but in presentation. Some of the facilities in White City included manicured gardens, neoclassical office buildings, and worker quarters styled after European model towns. The Rothschilds and Nobels in particular used their compounds to stage a narrative of technological advancement and benevolent paternalism. Refineries were painted white. Public amenities were installed. And yet, the labor conditions remained deeply unequal. Only a few years after the development of the two cities in 1886, a British Colonel called James Henry would write, “There is a very marked difference between the appearance of the Black and White; in the second,no smoke,orhardly any, is seen to come out of the refinery chimneys,while in the former, with a few exceptions, volumes of black smoke are vomited forth.” 13

While the Russian Empire provided the geopolitical framework for Baku’s industrialization, it was foreign capital—particularly Scandinavian and Western European—that provided the financial and technological backbone of its oil boom. Foremost among these were the Nobel Brothers, whose arrival in the 1870s marked a turning point in the scale and organization of the city’s petroleum economy. Founded by Ludwig and Robert Nobel, Branobel (The Petroleum ProductionCompanyNobelBrothers,Limited)pioneered techniques in refining, pipeline transport, and vertical integration that revolutionized oil extraction in the Caucasus.

The Nobels played a central role in the establishment of Black City, securing blocks of land within the newly gridded industrial district and building some of the most productive and advanced refineries in the region. Their operations pushed the need for zoning, as fire risk and fumes made proximity to the central city increasingly dangerous. At the same time, the Nobels recognized the instability caused by rapid labor migration and

inadequate housing. In response, they developed a model workers’ village known as Villa Petrolea in what would later become part of White City. The village included schools, hospitals, gardens, and worker housingbuiltataremovefromthenoxiousindustrialgrid. In form and ethos, Villa Petrolea bore striking similarities to contemporary English Garden City experiments— separated zones of labor and leisure, manicured green space, and a logic of moral and hygienic uplift. Though still hierarchically structured and closely surveilled, the development reflected a new corporate paternalism, one that used space as a means of labor control and socialprojection.14

Beyond the Nobels, Baku attracted a wide range of international investors—French (Rothschilds), Belgian, German, Swedish, and British capital flowed into the city’s oil fields during the last quarter of the 19th century. The Rothschilds, for instance, invested heavily in infrastructure and built company headquarters within Baku (now the General Prosecutor’s Office). As demand foroilgrewglobally,Bakubecamelessaremoteimperial outpost and more a node in a globalized energy economy.

The single most important event in creating Baku’s oil aristocracy was the 1873 land auction later nicknamed the “Golden Bazaar," when the Russian government openedlargetractsofoil-richlandforprivatepurchase. While much of this land was snapped up by foreign companies, a significant portion was acquired by local Azeris. This locally owned segment of the oil economy became a powerful counterweight to foreign dominance. Figures like Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, Murtuza Mukhtarov, Shamsi Asadullayev, Agha Musa Nagiyev, and others, not only grew immensely wealthy, but invested directly in the urban development of Baku beyond the industrial landscape, funding schools, theaters, and other cultural and civic landmarks as a formofphilanthropiccompetition.

These families often modeled themselves after their European counterparts. Their profits were poured into extravagantmansions,manyofwhichstilllinethestreets

ofcentralBakutoday(thoughwereinmostcasesturned intocivicadministrativebuildingsintheSovietera),most notably along what is now called Neftchilar (literally “oil worker”) Avenue. These structures reflected a hybrid architectural vocabulary: Beaux-Arts and Neo-Baroque facades coupled with local materials, traditional motifs, and environmental adaptations suited to the dry, windy climate. Stone sourced from local quarries was cut to mimic French styles, but windows were recessed, courtyards internalized, and rooflines adjusted for solar exposure.

They would model the urban area after the great European cities of the time, with wide canopied boulevards, a seaside esplanade, monumental civic buildings, and all the new technologies in communication and transportation.15 The oil barons competed with each other to donate the most lavish and monumental civic buildings, but the initial construction was spearheaded by Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev (1823?-1924), one of the most philanthropic of the industrialists.16 The first Azerbaijani National Theater was founded in 1873, as well as another theater built in 1882. Parks and educational centers such as vocational schools were given great importance during this time, including Baku's first school for Muslim girls in 1910,

15. Ibid. 82-83,

Pirouz Khanlou, “Baku’s Architecture: A Fusion of East and West” Azerbaijan International, Winter 1994

16. Blau, 80

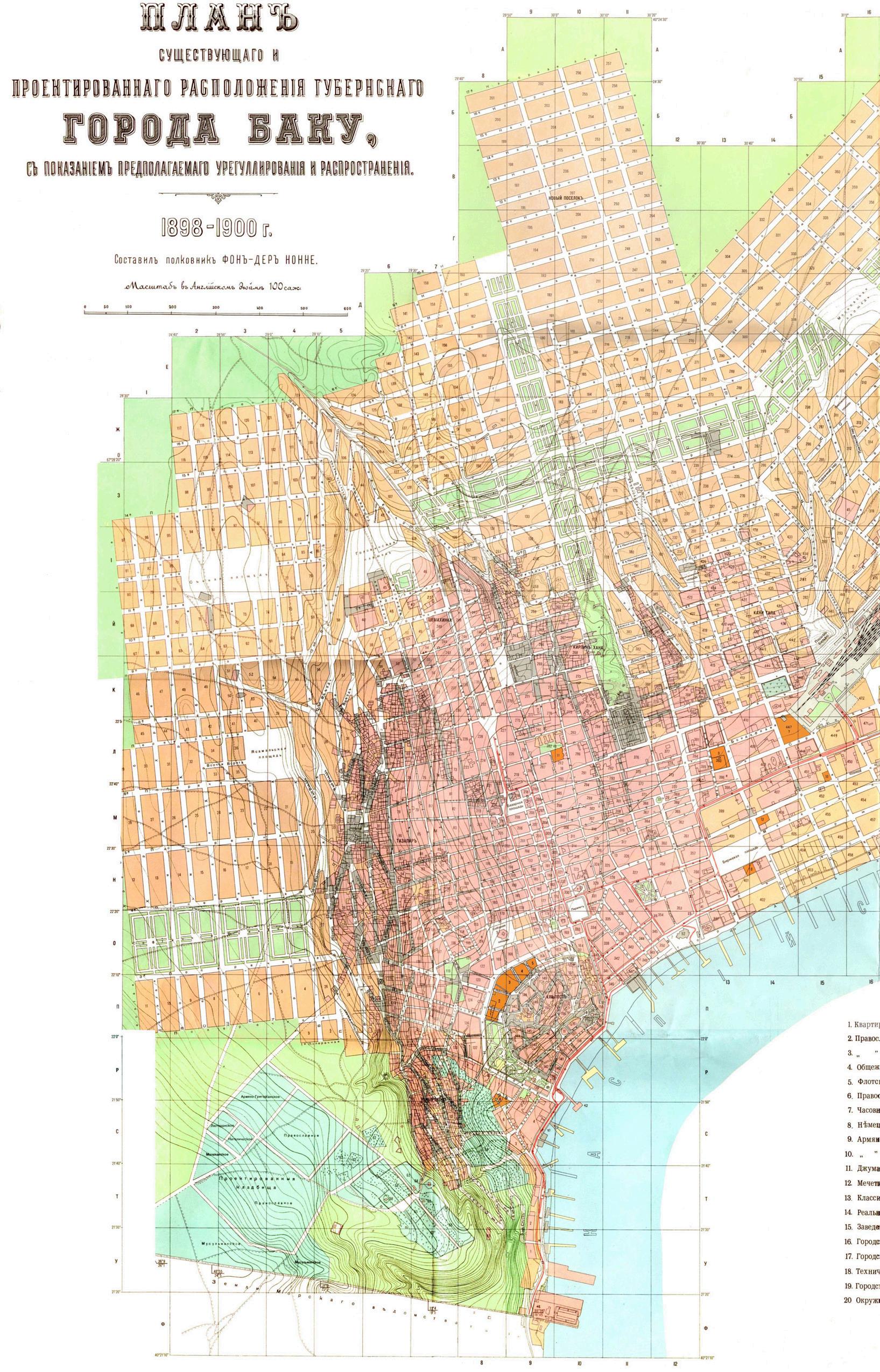

plan

Red represents existing urban blocks, orange is proposed.

17. Pirouz Khanlou, “Baku’s Architecture: A Fusion of East and West” Azerbaijan International, Winter 1994

18. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018, 80-83

19. Ibid. 78-79

20. Charles Marvin, The Region of Eternal Fire, Reprint, Hyperion Press, 1976, Originally Published 1883, 155

designed by Josef Goslavsky, who was then the Chief Architect of Baku.17 Soon more of the wealthy industrialists followed and competed in a philanthropic battle of donating towards the development of the city, such as Musa Naghiyev and Shamsi Asadullaev.18 Many of the hallmarks of a thriving cosmopolitan city were constructed during this time. The Baku City Duma was built from 1900-1904, also designed by Goslavsky in an Italianate renaissance style on the northern edge of the medieval walled city.19 In the same 1883 book, Charles Marvin would write, “What was ten years ago a sleepy Persian town is today a thriving city. There is more building activity visible at Baku than in any other place in the Russian Empire.”20

21. Luigi Villari, Fire and Sword in the Caucasus, 181

22. Plan of Baku 18981900, Nikolaus Von Der Nonne

And yet, amid this architectural flourish and grandiosity which set Baku apart from other oil boomtowns, the city’s infrastructure was no outlier to the boomtown norm. Roads were often unpaved outside of elite neighborhoods; water systems failed to reach the labor districts; waste disposal was ad hoc at best. This would be commented on by an Italian diplomat in 1905 who wrote, “Baku, considering its wealth, is one of the worst managed cities in the world. The lighting is inadequate, the wretched horse-tram service is pitiable, the sanitaryarrangementsappalling;vastspacesareleftin the middle of the town, drinking water is only supplied by sea water distilled.”21 Suchlackinthedevelopmentof facilitiesneededinawell-functioningcityisindicativeof bothitsrapidgrowthandrapiddevelopmentwithalack of government oversight, both things indicative of its industrial character. This deficiency led to the urban proposalinthe1890sspearheadedbythelocaloilbaron Zeynalabdin Taghiyev and designed by the German engineer Nikolaus von Der Nonne.22 The plan itself is clearly derived from European models of city planning thathadbecomeprevalentinthepriordecades(vonDer Nonne was well versed in the Hobrecht Plan for Berlin from a few decades earlier and which also featured a similar expansion of urban layout and infrastructure which avoided full scale demolition such as in Haussmann’s plan of Paris) and thus clearly drew inspiration from these precedents. In it, it proposed a seriesofgridlayoutstobegraftedontotheemptybuffer

“What was ten years ago a sleepy Persian town is today a thriving city. There is more building activity visible at Baku than in any other place in the Russian Empire.”

Charles Marvin, p.155

“Baku, considering its wealth, is one of the worst managed cities in the world. The lighting is inadequate, the wretched horse-tram service is pitiable, the sanitary arrangements appalling; vast spaces are left in the middle of the town, drinking water is only supplied by sea water distilled.”

Luigi Villari, p.181

23. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018, 87

24. Ibid 94

25. Robert Tolf, Russian Rockefellers, p. 152-153

zones between the different districts, with clearly definedblocklayoutsthatwouldthenbesoldforprivate development. 23

The result would be a plan that aimed to connect the different fragments that constituted Baku’s urban and industrialcenters,creatingapatchworkquiltofdifferent stylesofurbanfabric—rangingfromthemedievalwalled Icherisheher to the tightly gridded Black City to the expansive blocks of the White City to the oil fields and informal settlements that currently surrounded it all. Between it all it had to deal with the existing railway lines, oil pipelines, and all the inherent issues that came with an industrialized petro-city. Grant linear parks would split certain areas, serving as organizational devices to separate different areas.This plan, however, would only partially be constructed, and some parts suchastheplannedseasideesplanadewouldnotcome into being until the Soviet period, when there was no more different private industrial ownership to contend withwhenexpropriatinglandsforcivicuse.24

By the early 20th century, Baku stood as the most productiveoilcityintheworld,apatchworkofmedieval fabric,beaux-arts palaces,derricks,refineries,and both ad-hoc and planned labour housing that stretched acrosstheAbsheroncoast.Yetbeneaththespectacleof industrial modernity, deep social fissures were creating cracksinitsfabric.In1905,thesetensionswouldexplode.

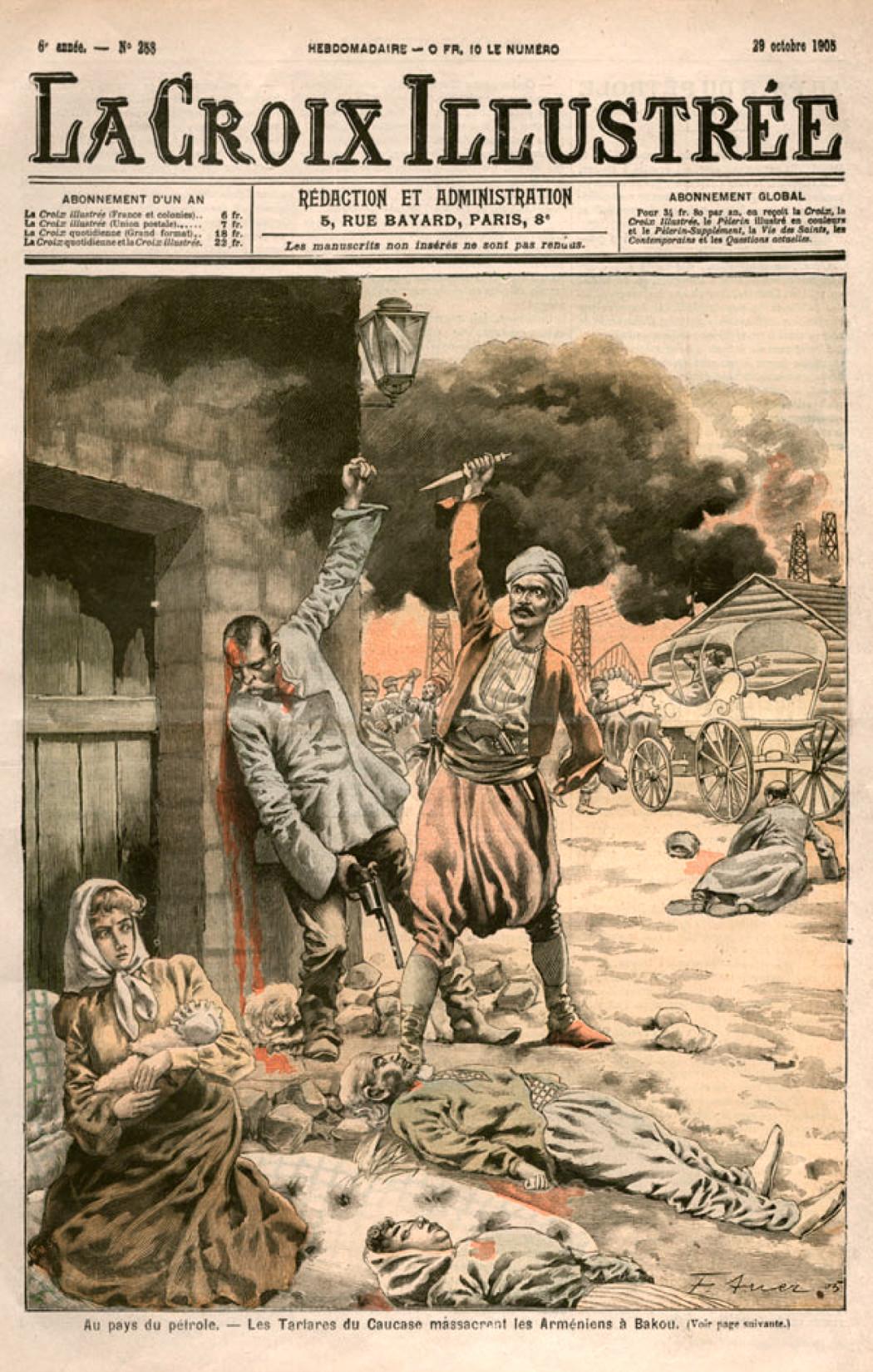

A series of ethnic riots and class-based uprisings destabilizedthecity,revealingthefragilityoftheexisting societalstructurethathadproducedsuchacosmopolis. They had been brewing for several years prior to their explosion, with the appalling working and living conditions of the oil workers having already led to large scale strikes in 1903 and 1904, all of which were suppressed by force. The city had already been a hotbed of revolutionary thought, with pamphlets by Lenin, Trotsky, and Marx’s manifesto being disseminated through the same network as the Nobel’s industrial channels.25

While not limited to any one sector in particular, oil

companies (most of which employed mixed workforces of Azeris, Armenians, and Russians, among others) saw their production sites become targeted by the rioters. Out of the 200 derricks in the oil fields of Bibi Heybat,118 weredestroyedandmostofthebuiltsurroundingslayin ruins.Villari describes it in his accounts, “The whole area was covered with debris and wreckage, thick iron bars snapped asunder like sticks, or twisted by the fire into the shape of coiled up serpents and fantastic monsters; great sheets of iron torn to shreds as though they had

been paper, broken machinery, blackened beams, fragments of cogged wheels, pistons, burst boilers, miles of steel wire ropes, all piled up in the wildest confusion, workmen’s Baracks, offices, and engine houses razed to the ground. Everywhere streams of thick-oozing naphtha flowed down to channels, or formed slimy pools of dull greenish liquid; the whole atmosphere was charged with the smell of oil.”26 Among everything, one thing was clear: the dense concentration of the industry and living was proving counter-productive to efficiency as the hallmarks of metropolis—flowing thought, dissension, among other things—was interfering with the authoritarian control requiredforindustrialscaleproduction.

TheresponsefromtheRussianimperialgovernmentwas slow and contradictory, with the pleas of the local Azeri oilbaronsforgreaterhelpinsuppressingtheriotslargely ignored. The riots themselves also had an ethnic component, with mutual pogroms being instigated between the local Azeri and Armenian populations and often encouraged by the Russian officials who would rather see the two local groups fight between each other than united against themselves. The local economic dynamic which had created a vibrant cosmopolitan urban center was proving detrimental in the face of colonial imperial authorities. What resulted was not only violence, but a reconfiguration of trust in the city.Foreign investors,once excited about the city as a great investment began to reconsider the long-term stability of their ventures. Much of the cosmopolitan, industrial optimism of the final decades of the 19th centurybegantogivewaytoaseeminglycontradictory combination of defensive nationalism and socialist thought.

The immediate aftermath was that foreign investment stalled. The large-scale destruction of industry—both extractive and administrative— led to the rather correct perception of Baku as an unpredictable and unstable investment and which prompted a withdrawal or consolidation of foreign capital, including among those who had invested the most with the transnational companies of the Nobels, Rothschilds, and Royal Dutch/

“The whole area was covered with debris and wreckage, thick iron bars snapped asunder like sticks, or twisted by the fire into the shape of coiled up serpents and fantastic monsters; great sheets of iron torn to shreds as though they had been paper, broken machinery, blackened beams, fragments of cogged wheels, pistons, burst boilers, miles of steel wire ropes, all piled up in the wildest confusion, workmen’s Baracks, offices, and engine houses razed to the ground. Everywhere streams of thickoozing naphtha flowed down to channels, or formed slimy pools of dull greenish liquid; the whole atmosphere was charged with the smell of oil.”

Luigi Villari, p.205-206

27. Van der Leeuw, Oil and Gas, p. 72

28. Blau, p.95-97

29. Harry Luke, Cities and Men, An Autobiography, (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1953), p. 105

Shell.27 While the city was granted greater autonomy after 1905, unrest continued, with strikes happening againlessthanadecadelater.28

Nevertheless,thelocalcapitalistextensionofthecitydid resume, albeit at a slower pace than a few decades prior. One traveler to Baku would describe the city in 1920 as deeply cosmopolitan, though bearing the hallmarks of unplanned boomtown growth such as having lavish civic buildings existing side-by-side with shantytowns. He likened the local Azeri oil barons to the American millionaires who made their money from oil, andwouldpaintanimageoraratherEuropeancitywith aCaspianflavour. 29

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent incorporation of Azerbaijan into the Soviet sphere in 1920 following a brief period of autonomy would fundamentallyrestructureBaku’soileconomy.Whathad once been a mosaic of private companies, foreign investors, and local elites was replaced with a state-run monopoly under what would become Azneft. The city’s industrial landscape was thus nationalized, with refineries, pipelines, and transportation infrastructure broughtundercentralplanning.

The period between 1905 and 1920 represented a transitional moment in Baku’s urban and industrial identity. Ethnic and class violence revealed the fragility of cosmopolitanism under capitalist extractive pressure, foreign capital retracted as volatility increased, and the Sovietstatesteppedintothevoidwithpromisesoforder and planned development. Yet, much of what was did not change, the city did not become something else. Many of the contradictions of the oil city remained, however, a change in investment—now focused on education, housing and other socialist programs created a new mode of urban life, one no longer oriented openly around private accumulation but around the socialist ideal. Oil remained central in the city’sworld—butnowasanemblemoftheproletariat,of theoilworkerratherthantheoilbaron.

As Baku’s oil economy expanded rapidly in the mid to late 19th century, its housing infrastructure remained persistentlyinadequate.Despitethecityproducingover half of the world’s oil alone, its urban landscape was marked by stark inequality: opulent mansions and villas for the oil elite on one hand, and overcrowded, unsanitary ad-hoc settlements for workers on the other. Unlikecitiesthatgrewundermunicipalregulation,Baku’s expansion was largely speculative, driven by local oil profits and/or foreign capital who generally had little interest in the local urban realm, both with little coordinated planning to accommodate the ever growinglabourforce.

Housing was one of the first—and most visible—domains where the contradictions of Baku’s “modernity” played out. Workers in Black City often lived within or adjacent to refinery compounds, in hastily constructed wooden barracks, sheds, or mud-brick hovels. These units were typically shared by multiple families, with no access to plumbing,sanitation,orevenconsistentelectricity.These conditions were not incidental but structural: oil companiesrarelyinvestedinlaborhousingbeyondwhat wasnecessaryforimmediateproductivity.Theproximity of housing to the refinery zone exposed workers to toxic fumes, noise, and industrial accidents, but also reduced transportation costs and facilitated surveillance. These living conditions, often compared to those of mining camps or factory towns in the American Midwest, were compounded by a chronic lack of water infrastructure, as Baku’s arid geography and overburdened municipal systems failed to meet the demands of a rapidly expanding population. Disease outbreaks were common, and housing-related grievances became a major source of labor unrest and ethnic tension, particularly as different ethnic groups were informally segregated into specific districts. Some efforts were madetotrytomitigatethis,namelytheoriginalmodelof garden city style worker’s housing in the Nobel’s Villa Petrolea,andthenthedesignationoflandtothenorthof the city for a “Charity Village” by the City Duma in 1897. However, the area that had been set aside lacked vital

30. Crawford, Christina E. “Part I. Oil City: Baku, 1920-1927” Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2022.

infrastructure and became filled with small ad hoc settlements.

The Soviet seizure of power in Baku in 1920 brought with it new ideals—and new contradictions—around the question of housing. Guided by Marxist principles and earlyBolshevikpoliciesoncommunalproperty,thestate embarked on a campaign to reorganize domestic life along socialist lines. In theory, this meant the end of private real estate ownership, the redistribution of elite residences, and the construction of new proletarian housing that reflected the collective ethos of the socialist city. In practice, two major pieces of legislation in the new Soviet state would pave the way for this: the “Decree on the Nationalization of the Land” in February 1918andthe“DecreeontheAbolitionofPrivateProperty in Cities” in October 1918. After the introduction of Baku into the Soviet realm, both of these went into effect and thus led to the dismantling of the existing norm of capitalist land speculation in the city which divided the realmintoprivateandpublicspace.

Thereality,however,wasoneofoverlappingcrises.Early attempts to address the problem were mired by a multitude of problems such as lack of proper data, lack ofabaseinfrastructure,lackofmaterials,lackofproper budget, and perhaps most relating to oil itself were geological concerns themselves. The consideration of geological folds, which much like veins in mineral extraction are lines of oil concentration and results in an “anticline axis” which is essentially an untouchable line duetothepossibilityoffutureoildrilling.Thesesweeping areas unavailable for development coupled with the hyper-densification of the industry of extraction, refinery, transportation, and metropolitan life resulted in a territorial catch-22 when it came to worker’s housing. On the one hand, you want workers to be housed near the area of drilling for ease of transportation. On the other hand, having worker settlements near oil fields meansyouhavetodisplacethemassoonasyouwantto expand the drilling area, as well as the added problem of having to create separate infrastructure for worker settlementsfarfromtheindustrialzones.30

31. Crawford, Christina E. “Part I. Oil City: Baku, 1920-1927” Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2022.

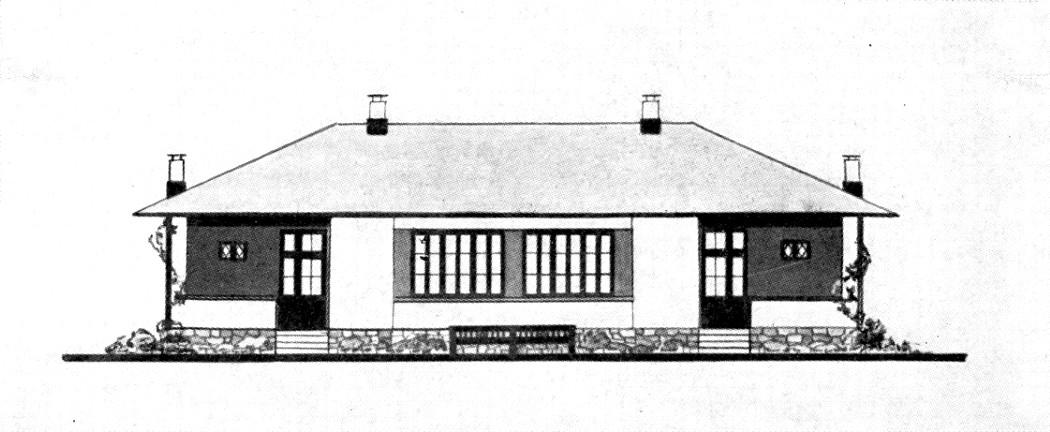

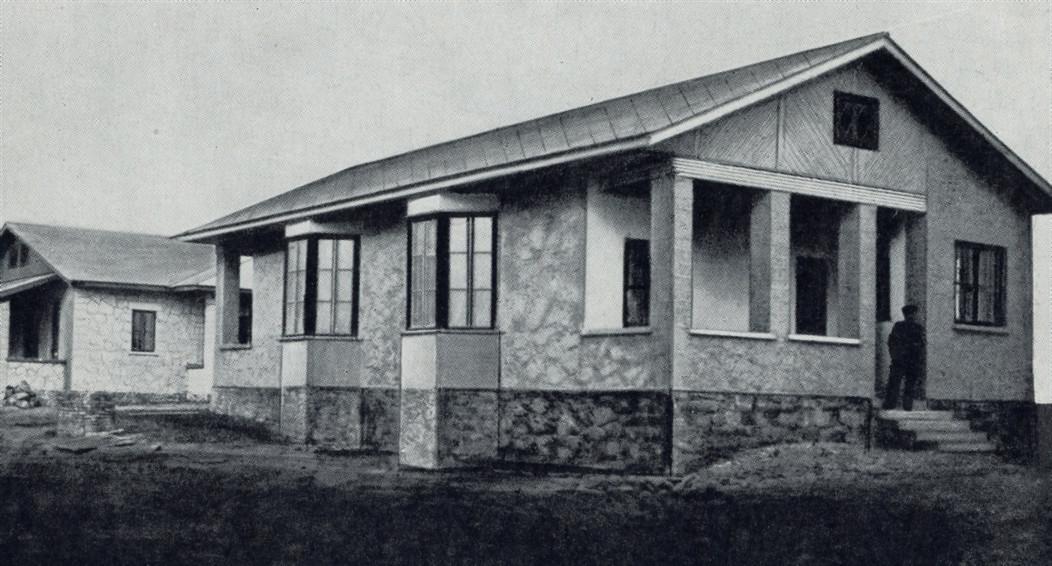

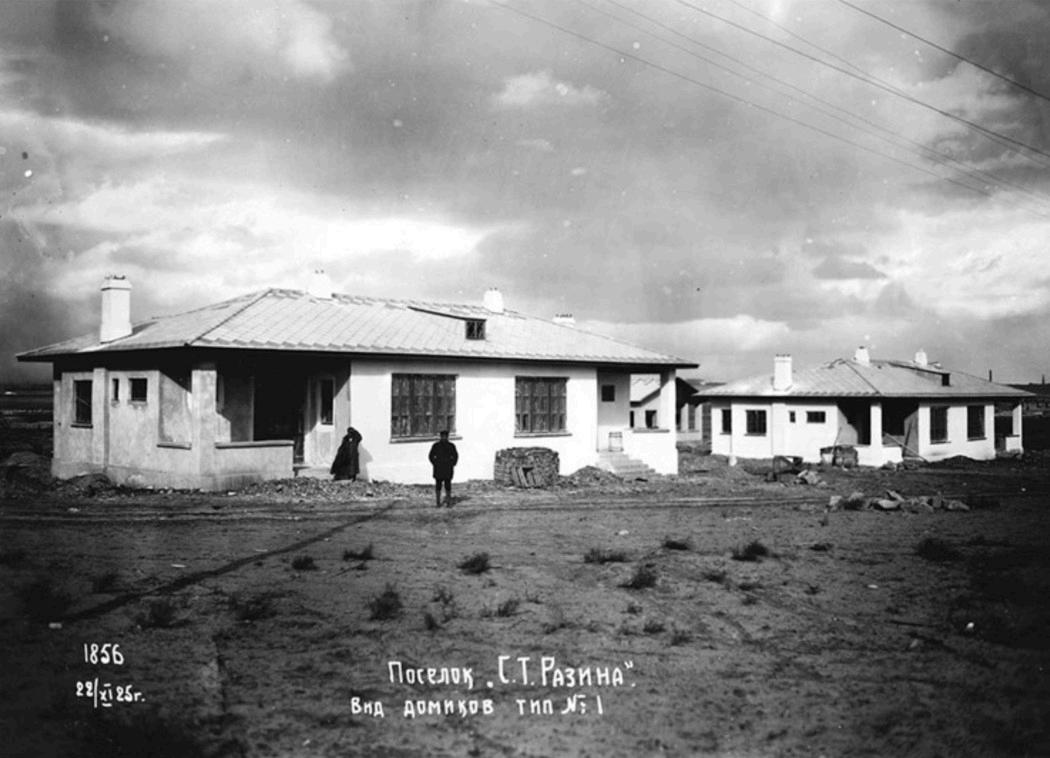

To address this shortfall, the new Soviet administration encouraged experimental interventions, attempting to create new models of socialist housing. Among one of the more unexpected links was the attempt to import American-style housing typologies—most famously the Sears catalog houses, pre-fabricated wooden homes shippedacrossoceansandrailwaysandassembledonsite. There are reports of a few of such homes arriving in Baku in the 1920s and early 30s, intended as experimental models for rational housing in a modern socialist city, bought through an accord in which Standard Oil in the US would serve as the sole creditor for the newly created Azneft.31 Whether or not these houses were widely adopted, they underscore the transnational circulation of housing ideas, even within the Soviet context which we now consider to be extremely insular. Through study of other international models and precedents of labour housing, Baku’s administratorsdecidedonamiddlegroundofdensityto quality of housing by settling on a general garden-city style grid for the new settlements, and initially constructingsingle-familyhousingtypologies.

One such settlement was Stepan Razin. The first phase constituted standardized single story housing prototypes which were economical and yet maintained the idea of the individual home. While these prototypes

were completed in the hundreds of units during this initial phase, they soon became troublesome. The low density of the resulting settlement proved costly and inadequate to house the sheer volume of families. Considered by some to be a “prime example of a nonsocialist housing type”32, the low density housing was soon abandoned in favor of denser multi unit housingblocks.33

The site for the new model of the soviet, constructivist housing block was actually the original plot of land set asideforthecharityvillagesomethirtyyearsearlier,and became the Armenikend settlement and illustrated the way in which housing functioned both as an architectural and political project, merging the two in order to envision a new purely socialist mode of designing (as opposed to the patron-artist mode of architectural design). Rather than considering single story stand-alone housing as a model, parti diagrams show variations of a living block instead. In these early experiments of what would become the famous Soviet housing super blocks, one can see the abstract considerationsoftheporosityoftheblockaswellasthe formation of densified living units inside the generated massing.Theresultingtestblockhad174totallivingunits and served 300 families, with some of the apartments designed to be co-living units.34 The aesthetic was not a priority, only the pure functionality and efficiency, a proper proletariat-oriented architecture, a constructivist rationality. The original courtyard typologies were expanded, unified, and scaled to accommodate hundreds. Units were standardized, elevations simplified, and access corridors rationalized. By the early 1930s,Armenikend had become a model for how the Soviet state could transform pre-revolutionary urban fragments into integrated infrastructures of socialism. This transformation was both symbolic and practical. It erased the ethnic branding of the original settlement and absorbed it into a universalist Soviet narrative of collective life. Yet in doing so, it preserved and scaled the very typology—the internal courtyard— that had been devised as a local response to the importedEuropeanbeauxartsaesthetic.

32. Ibid

33. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018, 114

34. Crawford, “Baku”

V.G. Davydovich, T.A. Chizhikova, “Aleksandr Ivanitskii”, 1973

Armenikend housing, panorama, Retrieved from http://electro.nekrasovka.ru/ books/3980/pages/12

Baku’s urban and industrial trajectory reveals a city as much by its contradictions as by its innovations. Its transformation from a windswept peninsula of flammable has vents and Zoroastrian fire temples into theworld’sfirstmodernoilmetropolisillustratesnotjusta chronological head start in global petroleum production, but also a deeper combination of factors: empire, capital, and ideology within a uniquely compressed geographical and geological environment. In every phase of its evolution—from medieval fortified capital to imperial outpost, from boomtown to urban experimental playground— the city demonstrated the capacity of oil to reshape space, society, and sovereignty in a way that is contradictory to the preconceived notion of a typical “resource cursed” region.

Few cities in the world so fully embody oil as condition, economy, symbol, and crisis. The city’s spatial dualities— Black and White City, industrial core and aristocratic boulevard, informal worker settlements and monumental civic architecture—mirror the deeper dualities of industrial modernity: between accumulation and exploitation, cosmopolitanism and ethnic tension, monumentalambitionandinfrastructuralneglect.

Baku’sroleinthehistoryofoilurbanismisthustwofold:it is both archetype and outlier. It anticipated many of the traits that would later define other oil cities—capital concentration, migrant labor surges, stratified housing, infrastructural contradictions—yet it did so earlier, and with far more dramatic spatial intensity. Unlike the sprawlinghorizontalgeographiesofAmericanoiltowns, Baku’s compact footprint necessitated density and greaterzoningexperimentation,producingacitywhere oil was not merely adjacent to urban life but deeply embeddedinitsspatiallogic.AndunlikeoilcapitalsLatin America such as Tampico and Comodoro Rivadavia, which were planned from the outset with industrial coherence in mind and had little to no urban centralization prior to industrial development, Baku developed through chaotic layering, accreted through

imperial and economic improvisation necessitated by the extreme density and compression inherent in the geographyofthepeninsula.

The four framing characteristics that mark Baku’s outlier status—its early industrialization, its unparalleled spatial density, its powerful class of local oil barons, and its role as a Soviet experimental ground—reverberate across the physical and political fabric of the city. Each contributes to a unique urban condition in which material extraction directly shaped urban form: roads paved to access derricks, housing dislocated to avoid anticlines, boulevards funded by extraction profits, neighborhoods created and architecturally developed in accordance to ideology. Whether as a space of speculative capitalism or as a site of socialist experimentation,Bakualwaysremainedacityofoil—not merelyanoiltown.

Yet, Baku’s contradictions also make it a powerful entry point for comparative study. In cities such as Tampico and Comodoro Rivadavia, we see echoes of Baku’s tensions—betweenforeigninvestmentandlocalagency, between industrial functionality and social precarity, between extractive logic and spatial design. But these cities, emerging later and within different administrative frameworks, responded to oil’s urban demands in markedly different ways. Baku, then, is not a blueprint but a historical fulcrum—a city whose lessons are not easilytransferable,butwhoselegacypersistsinhowwe understandtheurbanconsequencesofenergy.

In short, to study Baku is to study the city as resource: layered, combustible, extractive, and evolving. It is to confront the question of how oil doesn’t just fund cities, but produces them—through violence, labor, architecture, and ideology. And it is to begin thinking of oil urbanism not as a typology, but as a condition— unstable,transformative,andalwaysspatiallyinscribed.

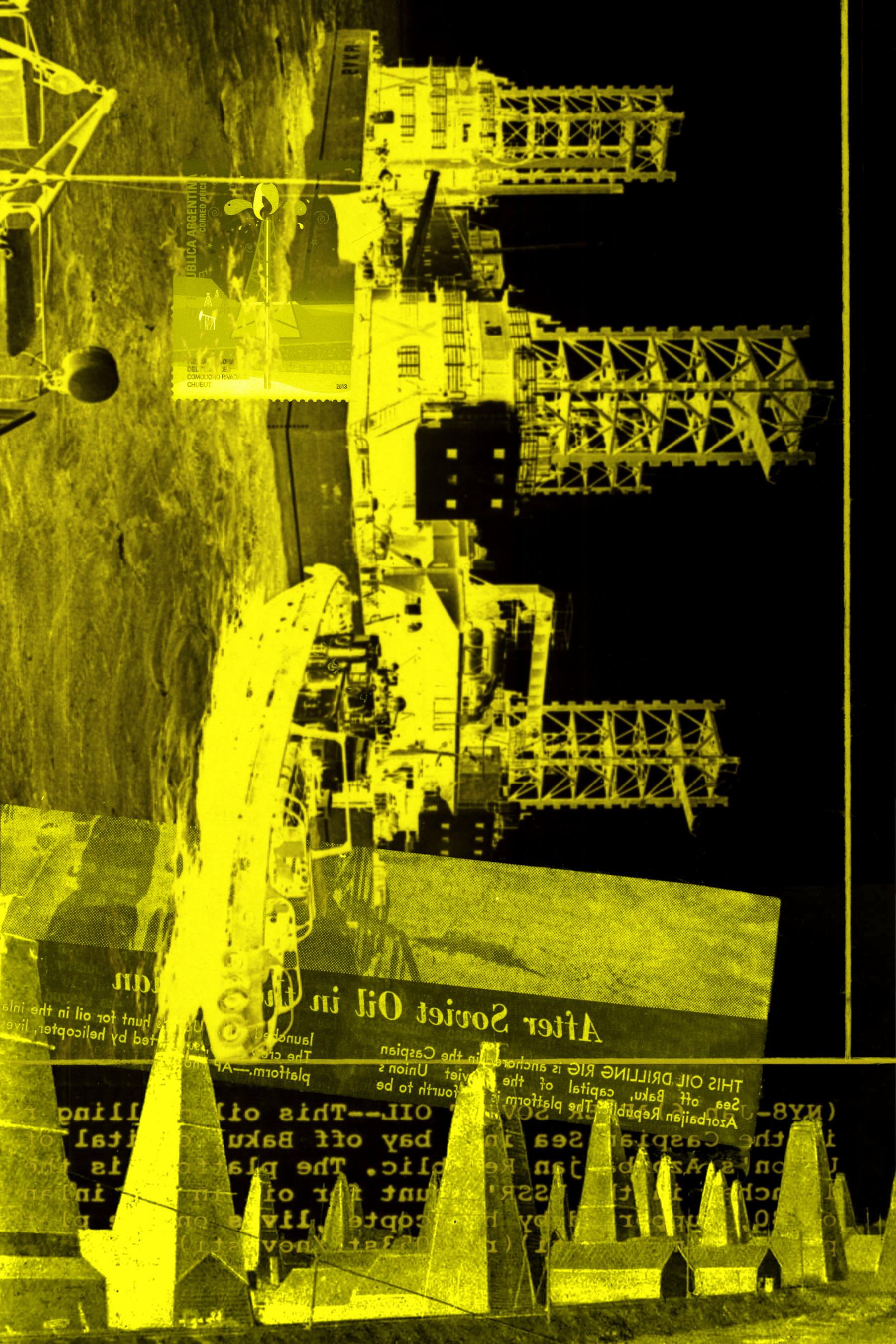

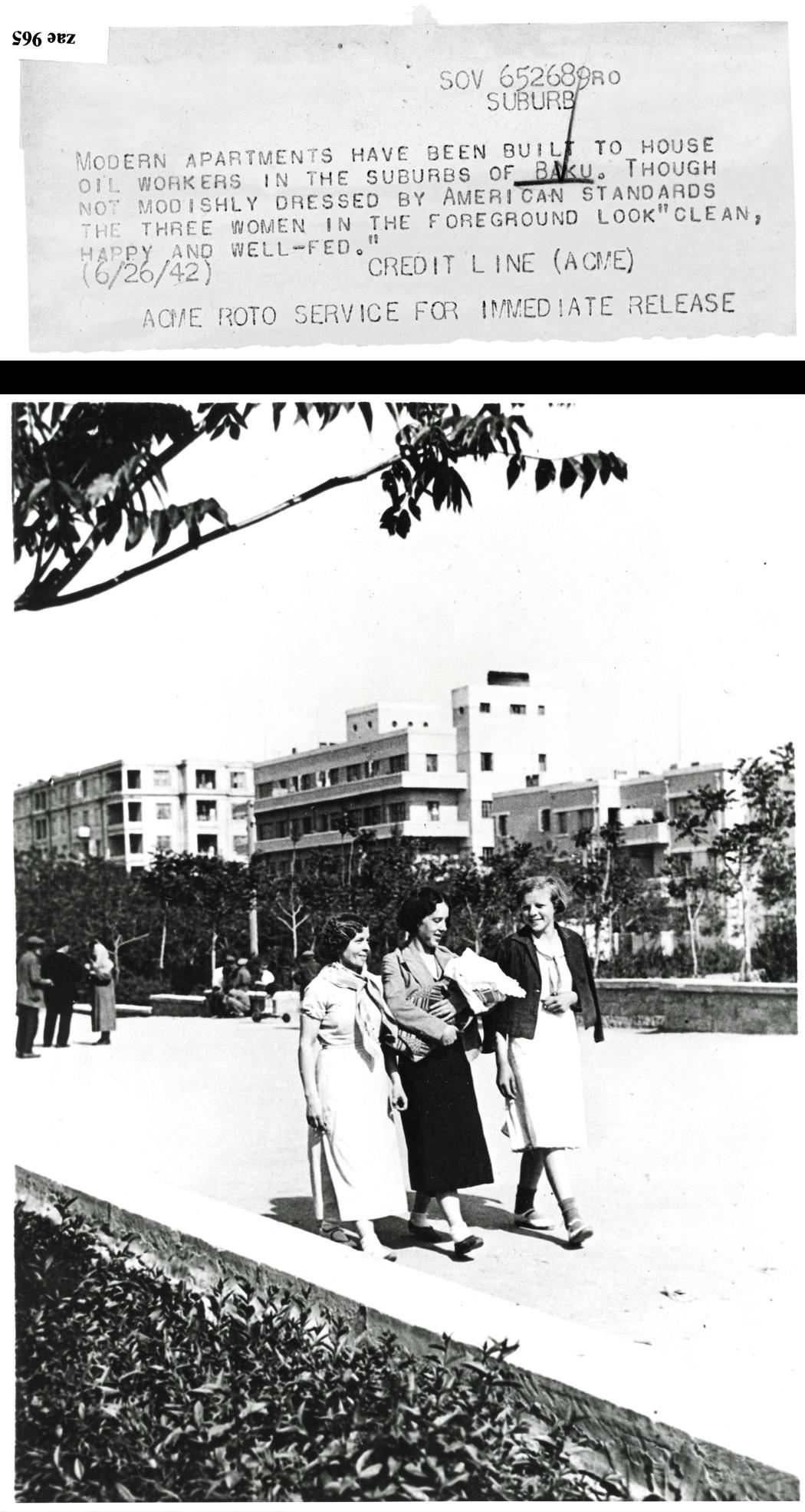

“Modern apartments have been built to house oil workers in the suburbs of Baku. Though not modishly dressed by American standards the three women in the foreground look ‘clean, happy, and well-fed’” [Credit line, ACME]

Photo Service, ACME Newspapers, New York, 26 June 1942

1. Asbrink, Brita. "The Nobels in Baku: Swedes' Role in Baku's First Oil Boom." (2002).

2. Audrey Altstadt Mirhadi and Michael Hamm. The City in Late Imperial Russia. Baku: Transformation of a Muslim Town. 1st ed. 1986.

3. “Architecture of the Oil Baron Period: Wedding Palace” Azerbaijan International, Winter 1998 6.4, https://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/ magazine/64_folder/64_articles/OilBarons/64.weddingpalace.html

4. “Architecture of the Oil Baron Period: Taghiyev Residence” Azerbaijan International, Winter 1998 6.4, https://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/ magazine/64_folder/64_articles/OilBarons/64.taghiyev.html

5. Bretanit︠ s ︡kiı̆ L. S. 1965. Баку; Архитектурно-Художественные Памятники. Leningrad: Исскуство.

6. Charles Marvin, The Region of Eternal Fire, Reprint, Hyperion Press, 1976, Originally Published 1883

7. Crawford, Christina E. “Part I. Oil City: Baku, 1920-1927” Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2022.

8. Dohrn, Verena. The Kahans from Baku: A Family Saga. Academic Studies Press, 2022.

9. Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism. Zurich: Park Books, 2018

10. Gökay, Bülent. “The Battle for Baku (May-September 1918): A Peculiar Episode in the History of the Caucasus.” Middle Eastern Studies 34, no. 1 (1998): 30–50.

11. Hastings, Rebecca Lindsay. "Oil Capital: Industry and Society in Baku, Azerbaijan, 1870-Present." Order No. 28000613, University of Oregon, 2020.

12. Henry, James. Baku an Eventful History. London: London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd, 1905.

13. Iljine, Nicolas V. Memories of Baku. Seattle: Marquand Books, 2013.

14. Khanlou, Pirouz. "The Metamorphosis of Architecture and Urban Development in Azerbaijan." Azerbaijan International (1998).

15. Leeuw, Charles van der. Oil and Gas in the Caucasus & Caspian: a History. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

16. Lund, N. (2013). At the center of the periphery: Oil, land, and power in Baku, 1905-1917 (Order No. 28122538). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2463715261).

17. McKay, John P. “Baku Oil and Transcaucasian Pipelines, 1883-1891: A Study in Tsarist Economic Policy.” Slavic Review 43, no. 4 (1984): 604–23.

18. Plan of Baku 1898-1900, Nikolaus Von Der Nonne (Retrieved from Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism, 87-90)

19. Sh. S. Fatullayev-Figarov, Arkhitekturnaia Entsiklopediia Baku (The Architectural Encyclopedia of Baku), trans. Dimitry Doohovskoy (Baku/ Ankara: Mezhdunrodnaia Akademiia Arkhitektury stran Vostoka, 1998), 31. Retrieved from Eve Blau, Baku: Oil and Urbanism, 62

20. V.G. Davydovich, T.A. Chizhikova, “Aleksandr Ivanitskii”, 1973

21. Villari, Luigi, 1876. Fire and Sword in the Caucasus. England: England: T. F. Unwin, 1906, 1906.

22. Seits, Irina. “From Ignis Mundi to the World’s First Oil-Tanker The Legacy of the Nobels’ Oil Empire in Baku.” Approaching Religion 13, no. 2 (2023): 57–76.

23. Tadeusz Swietochowski, Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community, 1985, p.xiii

24. Tolf, Robert, Russian Rockefellers,

25. Polo, Marco, and da Pisa Rusticiano. The Travels of Marco Polo

26. Swietochowski, Tadeusz. Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community. Vol. 42. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

27. Fatullayev, Shamil. Gradostroitel’stvo Baku XIX – Nachala XX Vekov [Urban Development of Baku in the 19th – Early 20th Centuries]. Accessed April 14, 2025.

28. Harry Luke, Cities and Men, An Autobiography, (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1953)

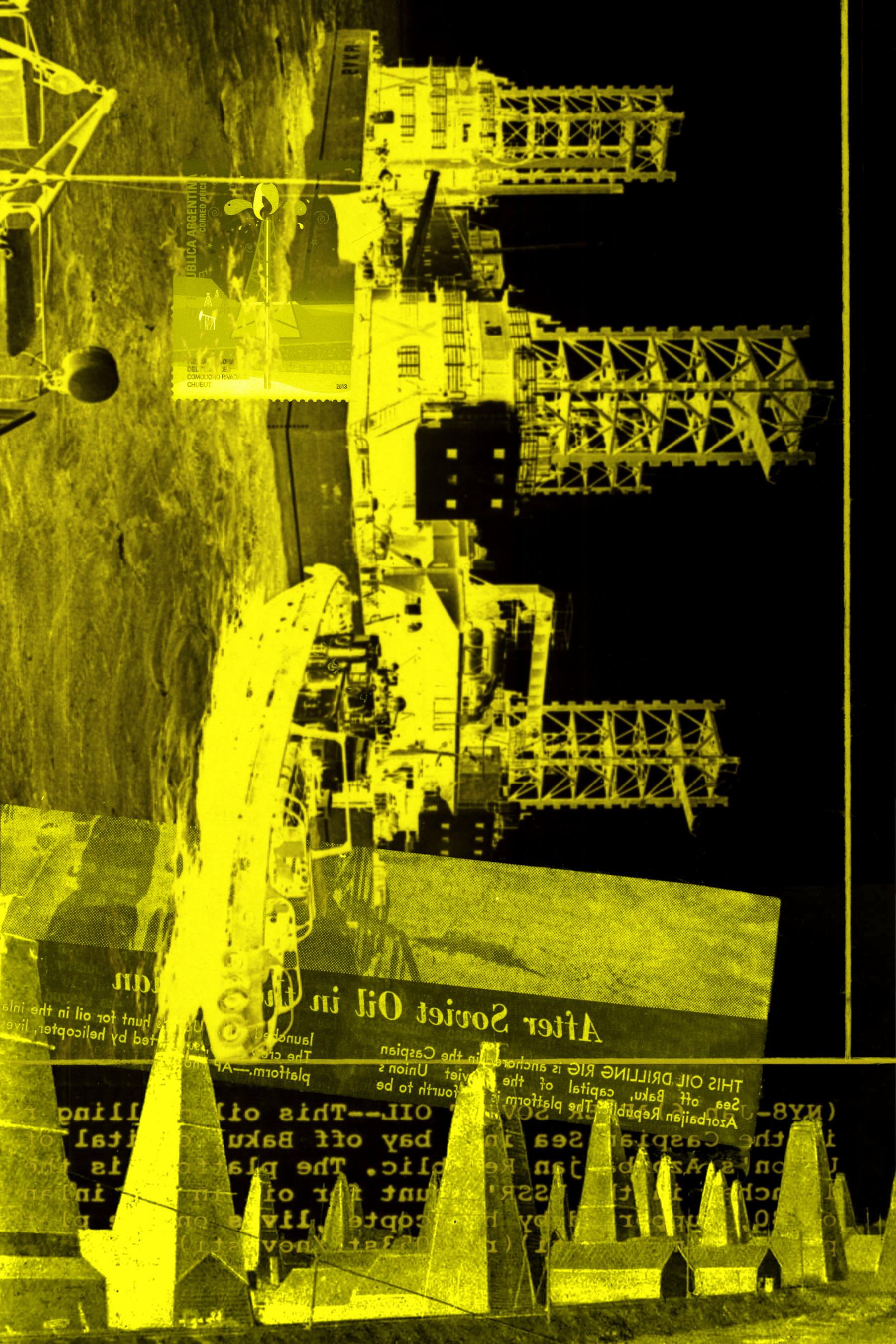

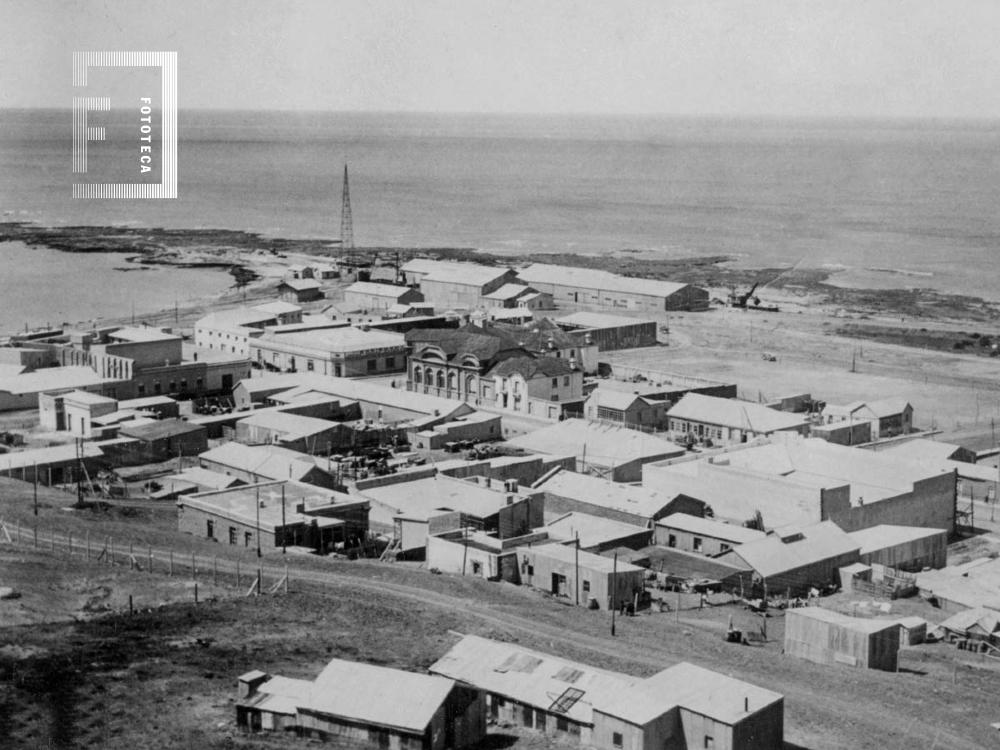

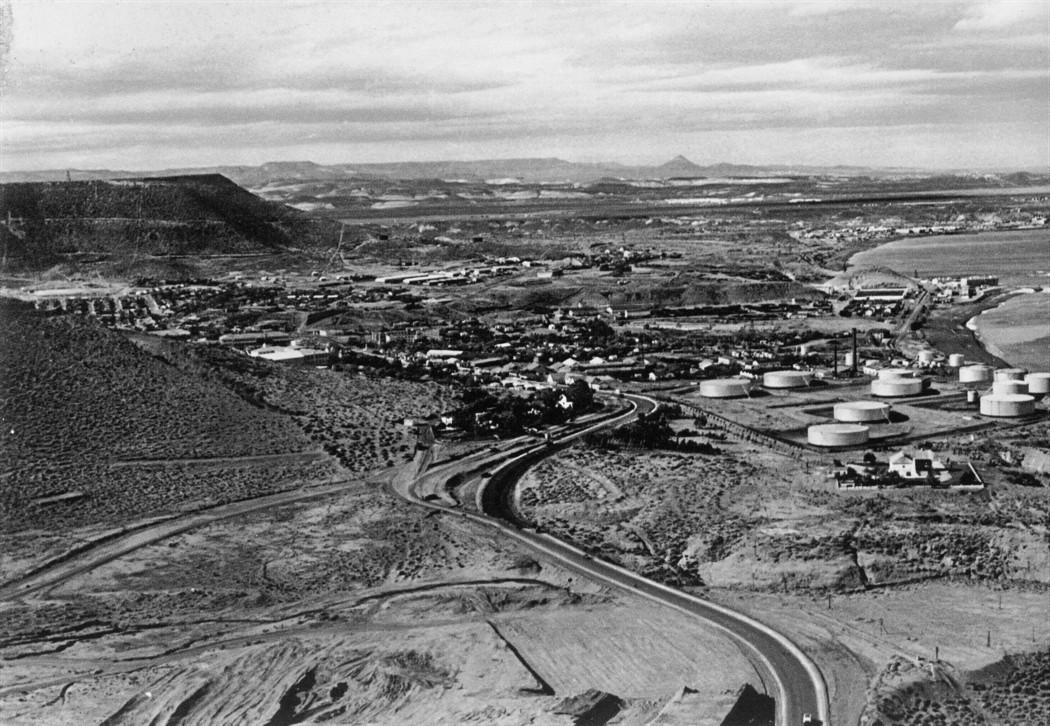

Panoramic view of Comodoro Rivadavia, looking South c. 2009

Satellite

1. Cabral Márquez, Daniel y Godoy, Mario (coords.): Distinguir y comprender. Aportes para pensar la sociedad y la cultura en Comodoro Rivadavia., Comodoro Rivadavia, Ediciones Proyección Patagónica, 1995.

2. Ibid.

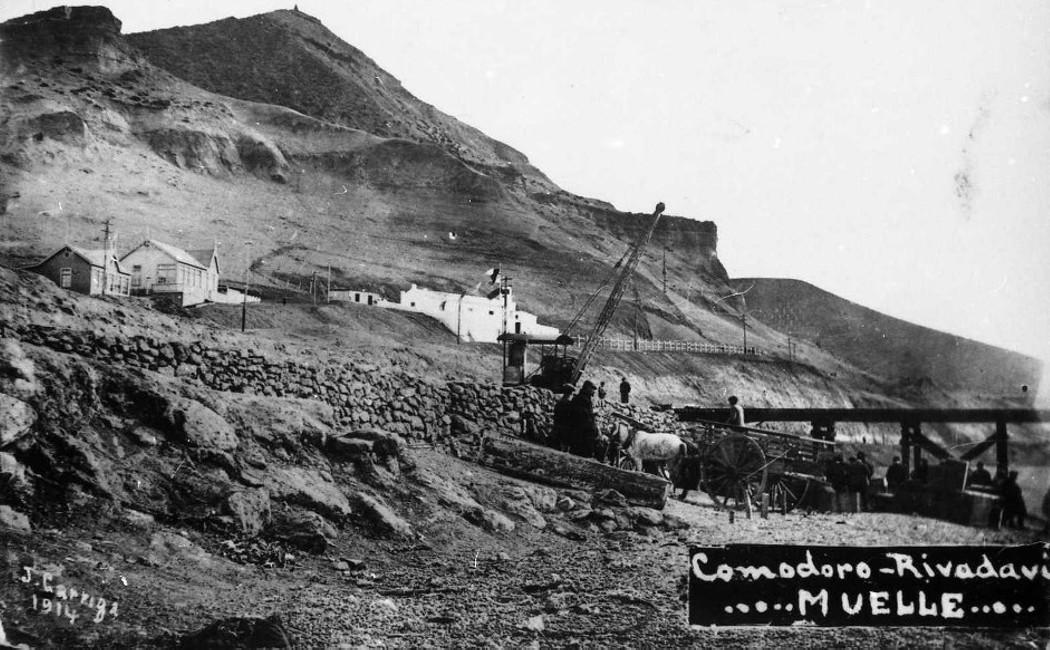

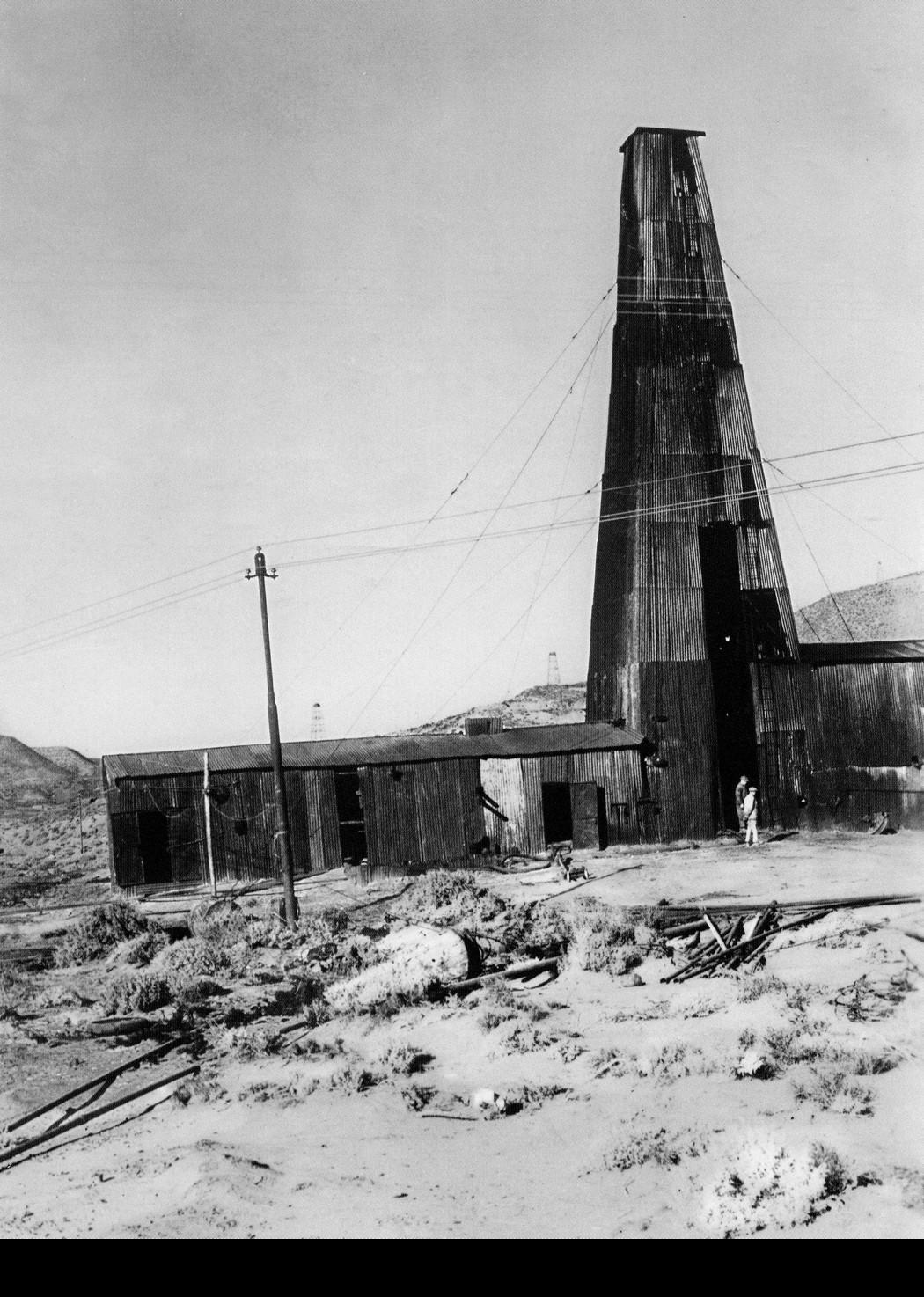

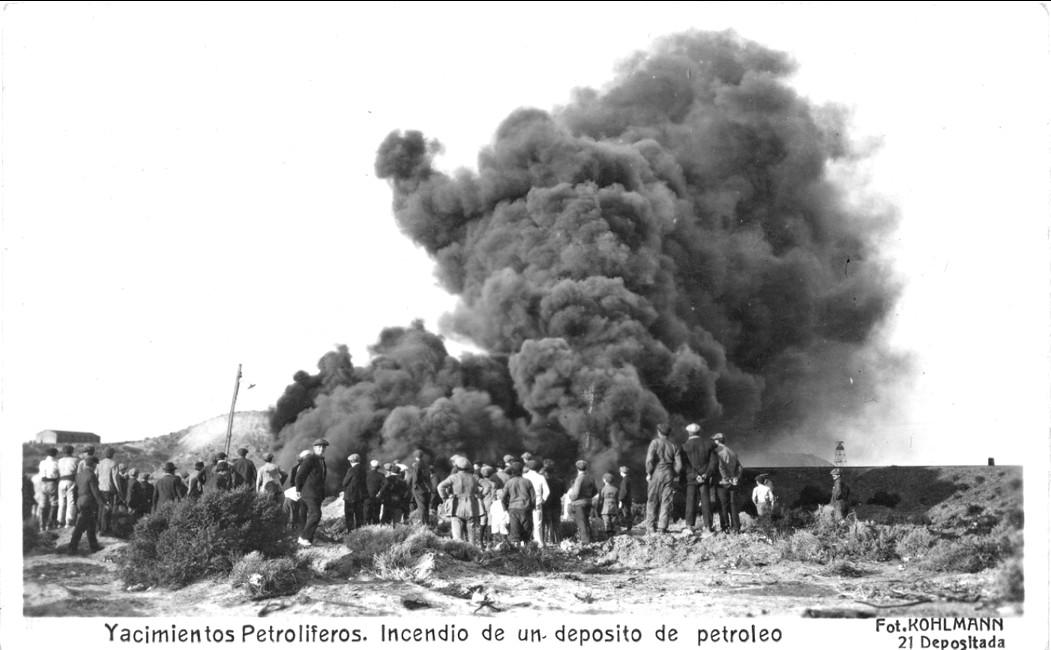

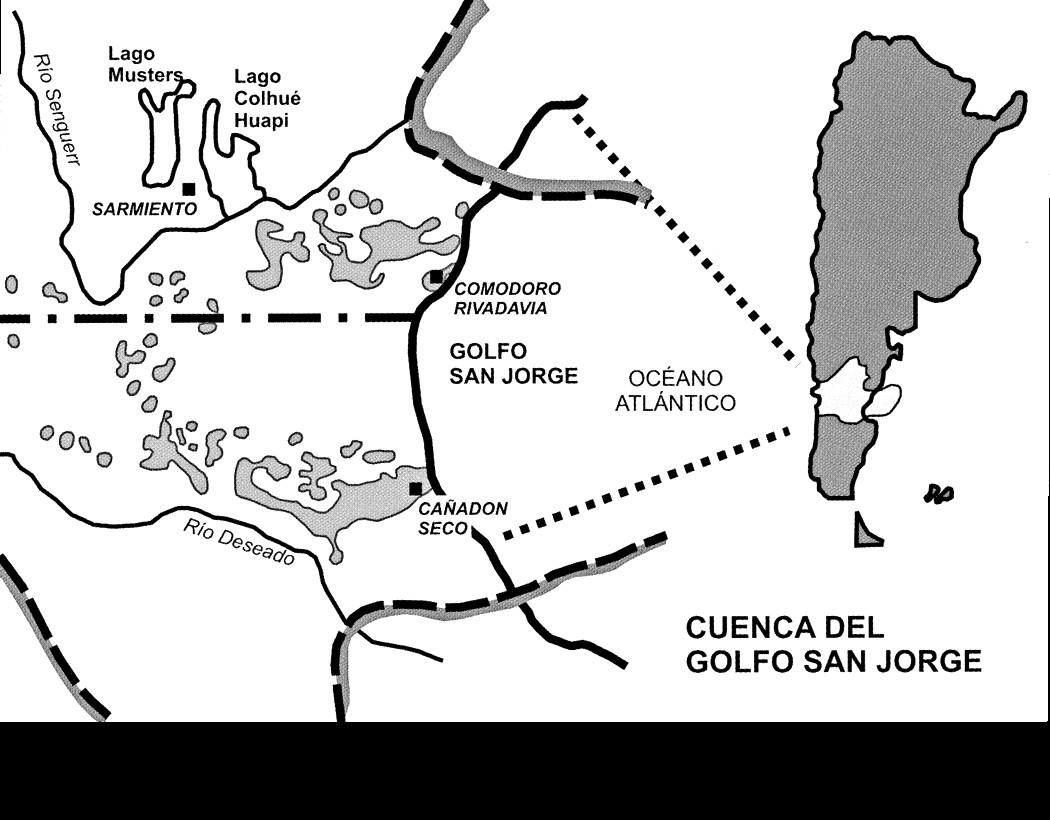

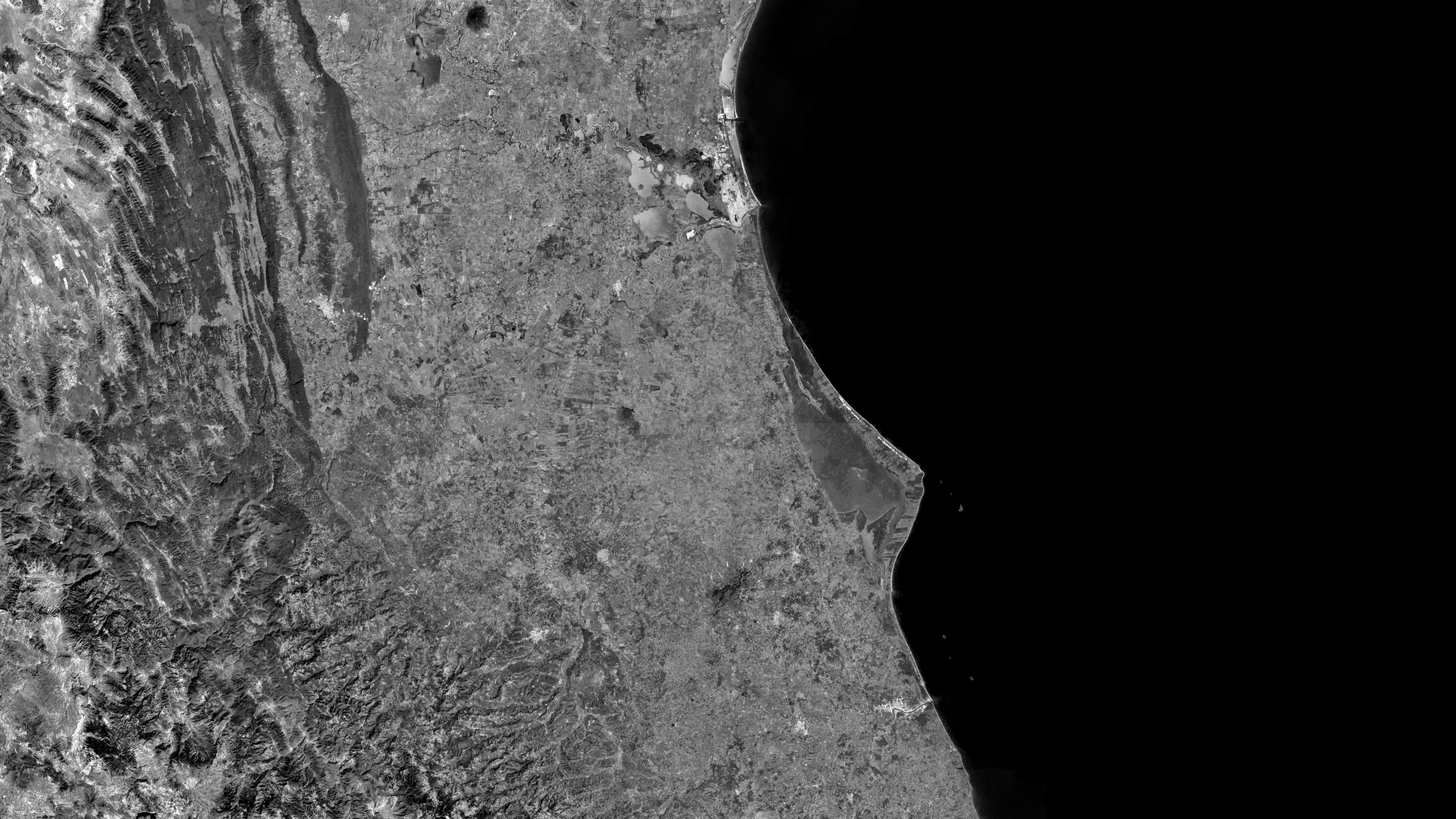

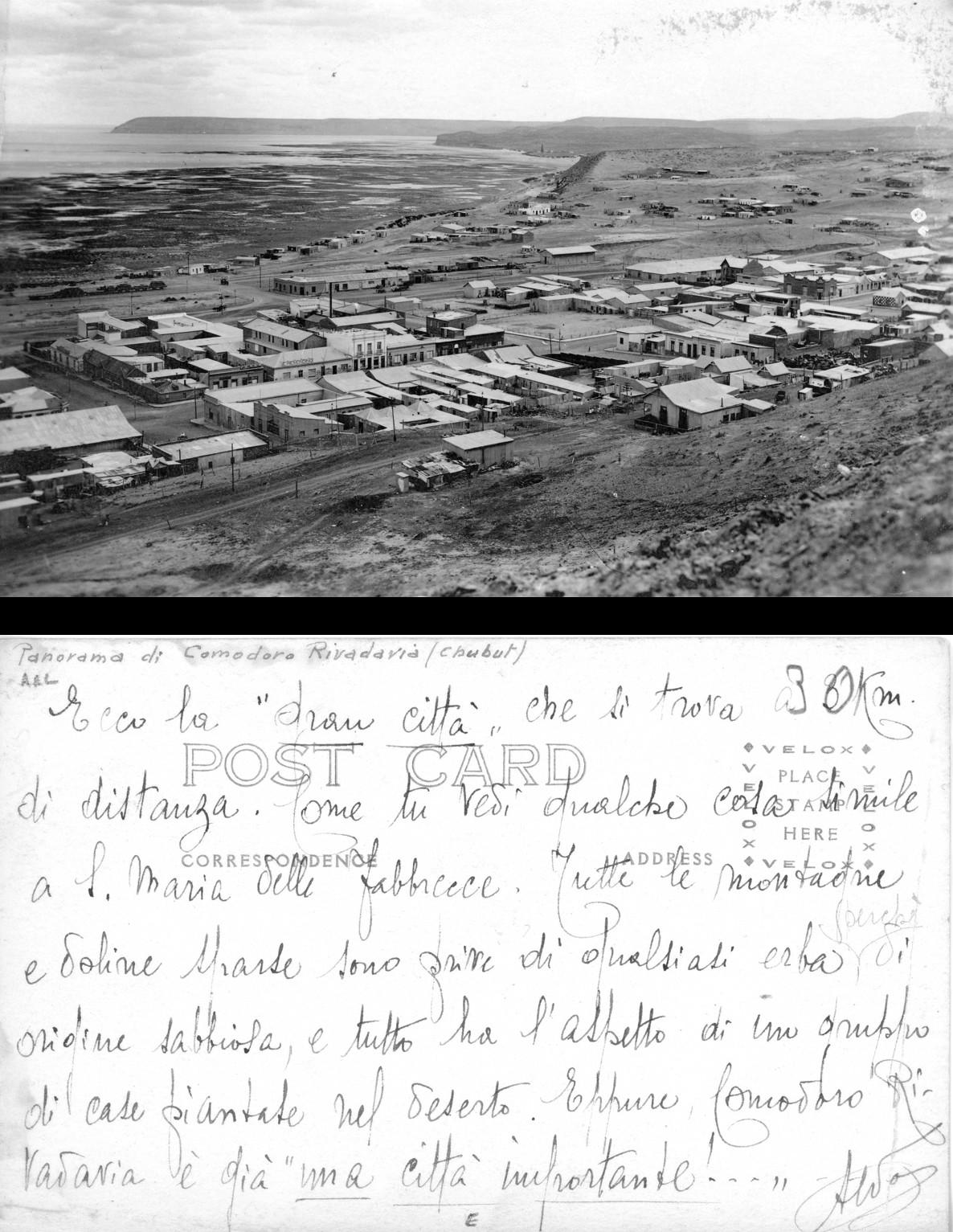

The formation of Comodoro Rivadavia did not emerge from a deliberate state project of industrial modernity norfromthespeculativeinitiativesofforeigncapital,but fromtheaccumulationofcircumstantialdecisionsmade at the margins of Argentine territorial consolidation. Initially conceived as a logistical node to connect the remote agricultural interior of southern Chubut to maritimeroutes,itsselectionasaportsiteowedmoreto geographical pragmatism than to any urban vision. It was the discovery of oil in 1907, during a routine search for potable water, that shifted the axis of development from pastoral economy to extractive industry, rapidly transforming the scale and meaning of the settlement. YetunlikeBakuorTampico,whereoilurbanismunfolded under the dominance of multinational companies and thefluctuatingdemandsofforeignmarkets,Comodoro’s industrial destiny was from the outset entangled with national sovereignty, territorial security, and the ideological project of integrating Patagonia into the Argentinenation-state.

3. Barrera, M., 2014, La entrega de YPF. Análisis del proceso de privatización de la empresa,Editorial Atuel, Colección Cara o Ceca, Buenos Aires.

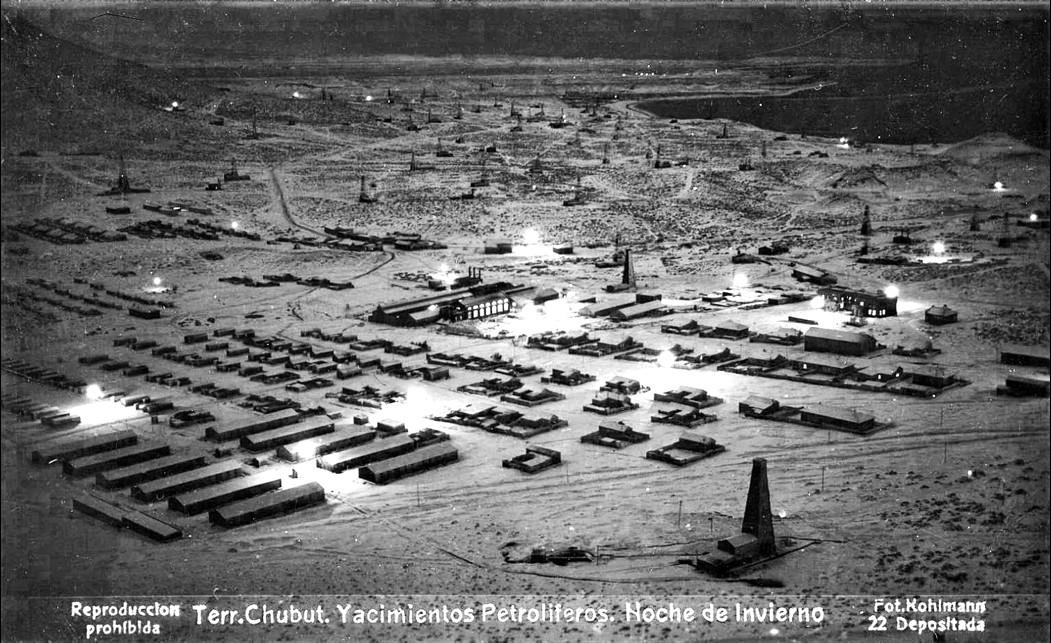

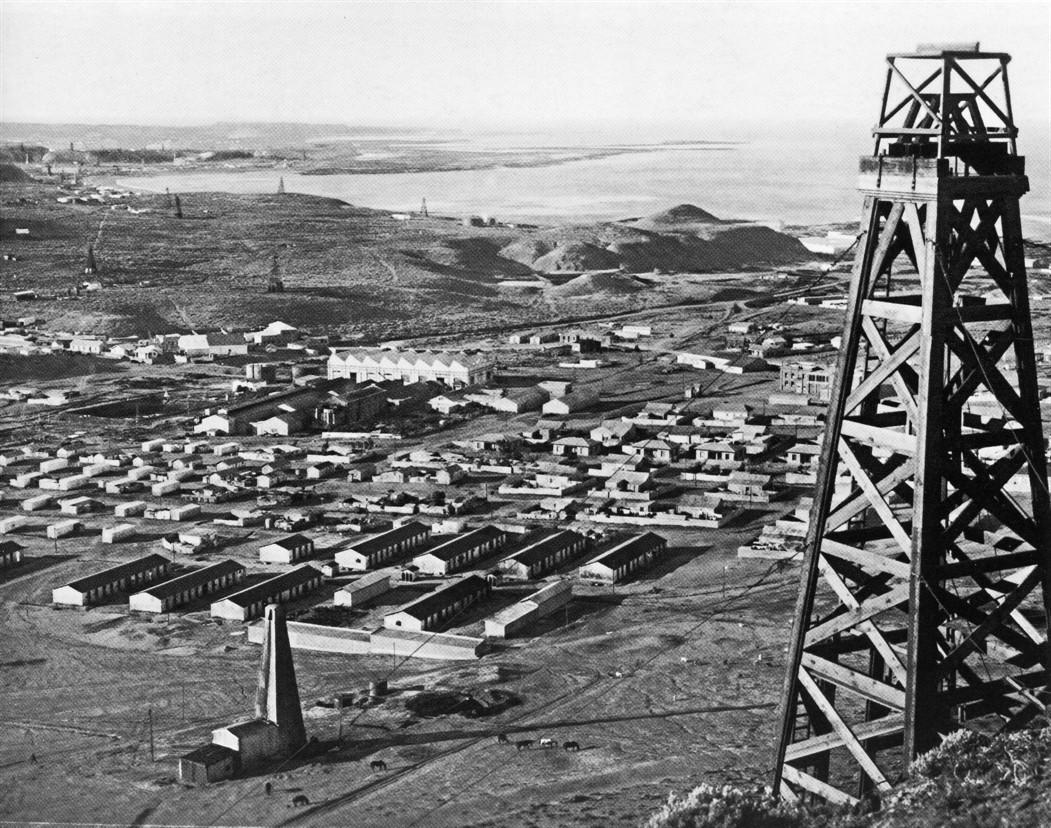

Thecity’searlystructurereflectedneithertheconcentric rationality of planned industrial cities nor the chaotic layering of speculative boomtowns. Instead, it developedasamultifocalandsegmentedterritory,with industrial enclaves, railway nodes, and provisional urban centers dispersed across a harsh landscape.1 The originalportuarysettlementcoexistedwithanemerging archipelago of oil camps established first by the state, and then by private companies such. Cerro Chenque, a physicalbarrierbetweenthecoastalsettlementandthe northernoilzones,becameasymbolicdemarcationofa deeperterritorialdivide:betweencivilmunicipallifeand the extraterritorial governance of industrial production.2 Unlike the colonial urban fabrics of Baku, where dense capitalist competition produced intricate residentialcommercial zones, or the disjointed foreign bubbles of Tampico,Comodorodevelopedasaspaceoffunctional zonescreatedonablankslate.3

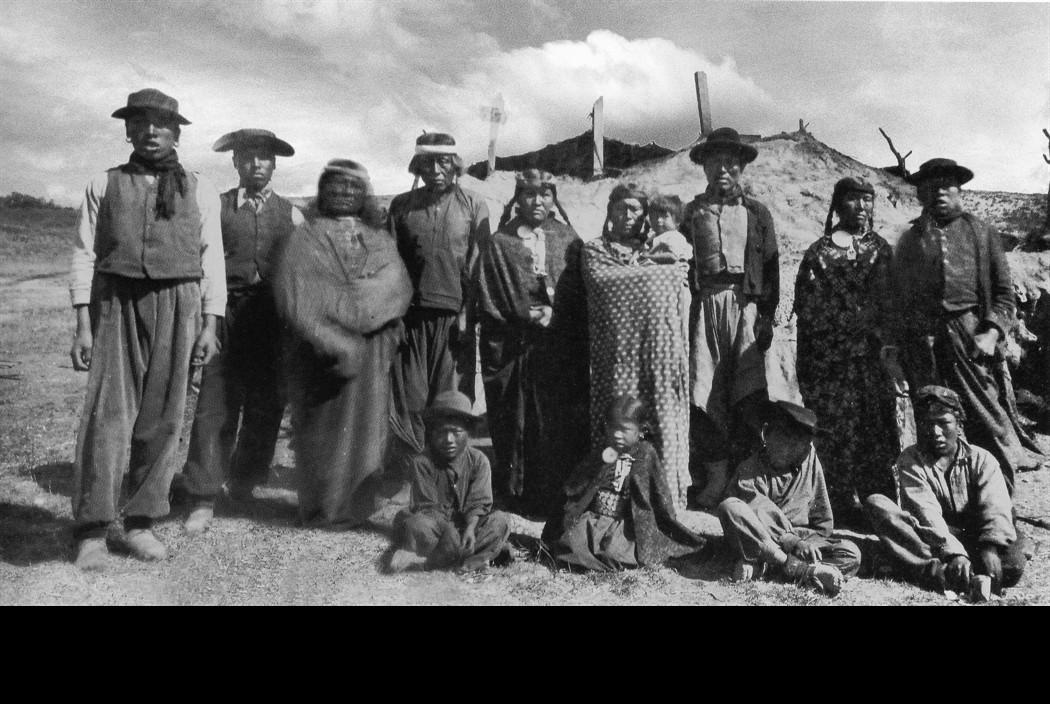

The discovery of oil coincided with a national ideological shift.In the aftermath of the Conquest of the

Desert (a late 19th-century military campaign led by the Argentine government to forcibly subjugate and displace indigenous populations in Patagonia), the Argentine state viewed the region less as a frontier of opportunity and more as a precarious, semi-integrated periphery vulnerable to foreign influence and internal disorder.4 The project of "argentinizing Patagonia," articulated especially during the administrations of Hipolito Yrigoyen5, positioned oil not merely as an economic asset but as a means of asserting political control. The creation of Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF) in 1922—the first vertically integrated state oil company outside the Soviet Union—was both a culmination of this ambition and a preemptive defense against the influx of foreign capital into a vital industry.6 Oil nationalization in Comodoro was not a belated reaction to multinational abuses, as elsewhere; it was embedded since the very start of industrialization, shaping the city's social, political, and urban fabric from itsinception.

UnderEnriqueMosconi’sleadership,YPFconstructednot only wells, pipelines, and refineries but also a totalizing social infrastructure: worker housing, schools, public baths, and hospitals.7 The state assumed a paternalistic role, regulating everyday life as much as production, framing labor not only as a technical necessity but as a patrioticduty.8

Migration patterns further complicated the demographicandsociallandscape.IncontrasttoBaku’s multiethnic proletariat or Tampico’s transient workforce drawn to volatile extractive booms, Comodoro’s labor base was composed largely of foreign migrants, mainly from Europe but also from South Africa, Chile, and internalArgentinemigrants.9 Settlementwasfragileand uneven:administratorsandskilledtechnicianstendedto reside in company-built neighborhoods with access to services, while temporary and low-wage laborers often occupied marginal spaces. The absence of a deeply rooted local population created a society that was at onceopentonewformsofidentificationandvulnerable to fragmentation through factionalization. Unlike cities with established oligarchies or municipal institutions,

4. Navarro Floria, Pedro: «La República Posible conquista el desierto. La mirada del reformismo liberal sobre los territorios del sur argentino», en Navarro Floria, Pedro (coord.): Paisajes del Progreso. La resignificación de la Patagonia Norte 18801916, Neuquén, EDUCO, 2007, 191-234.

5. Yrigoyen, Hipólito: Mi vida y mi doctrina, Buenos Aires, Leviatán, 1981 (1.ª edición 1923).

6. Bucheli, Marcelo. “Major Trends in the Historiography of the Latin American Oil Industry.” The Business History Review 84, no. 2 (2010): 339–62. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/ 20743908.

7. Gutiérrez, Ramón, Liliana Lolich, Liliana Carnevale, y Patricia Méndez. Comodoro Rivadavia, Argentina: un siglo de vida petrolera. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Fundación YPF, 2007.

8. Ester Elizabeth Ceballos (2005). “El primero de mayo en Comodoro Rivadavia durante el período 19011945”. X Jornadas Interescuelas/ Departamentos de Historia. Escuela de Historia de la Facultad de Humanidades y Artes, Universidad Nacional del Rosario. Departamento de Historia de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Rosario. Dirección estable:

9. Mármora, Lelio. Migración al Sur: argentinos y chilenos en Comodoro Rivadavia. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Libera, 1968.

Comodoro Rivadavia grew under the heavy hand of state and corporate administrators on a quite literal blankslate.