September 9 November 4 2025 with special thanks to the Architectural League of NewYork and the Deborah J. Norden Travel Fund

September 9 November 4 2025 with special thanks to the Architectural League of NewYork and the Deborah J. Norden Travel Fund

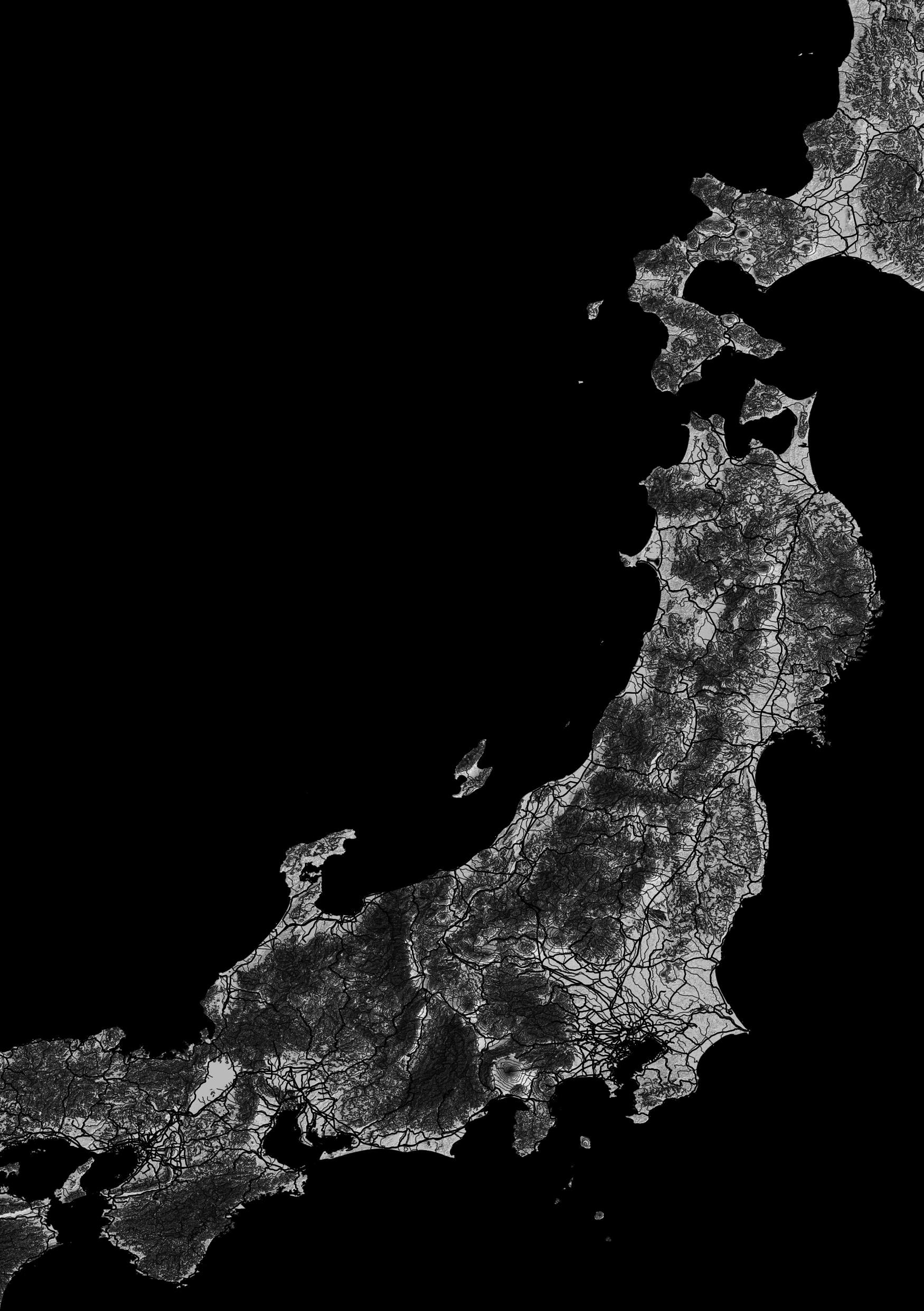

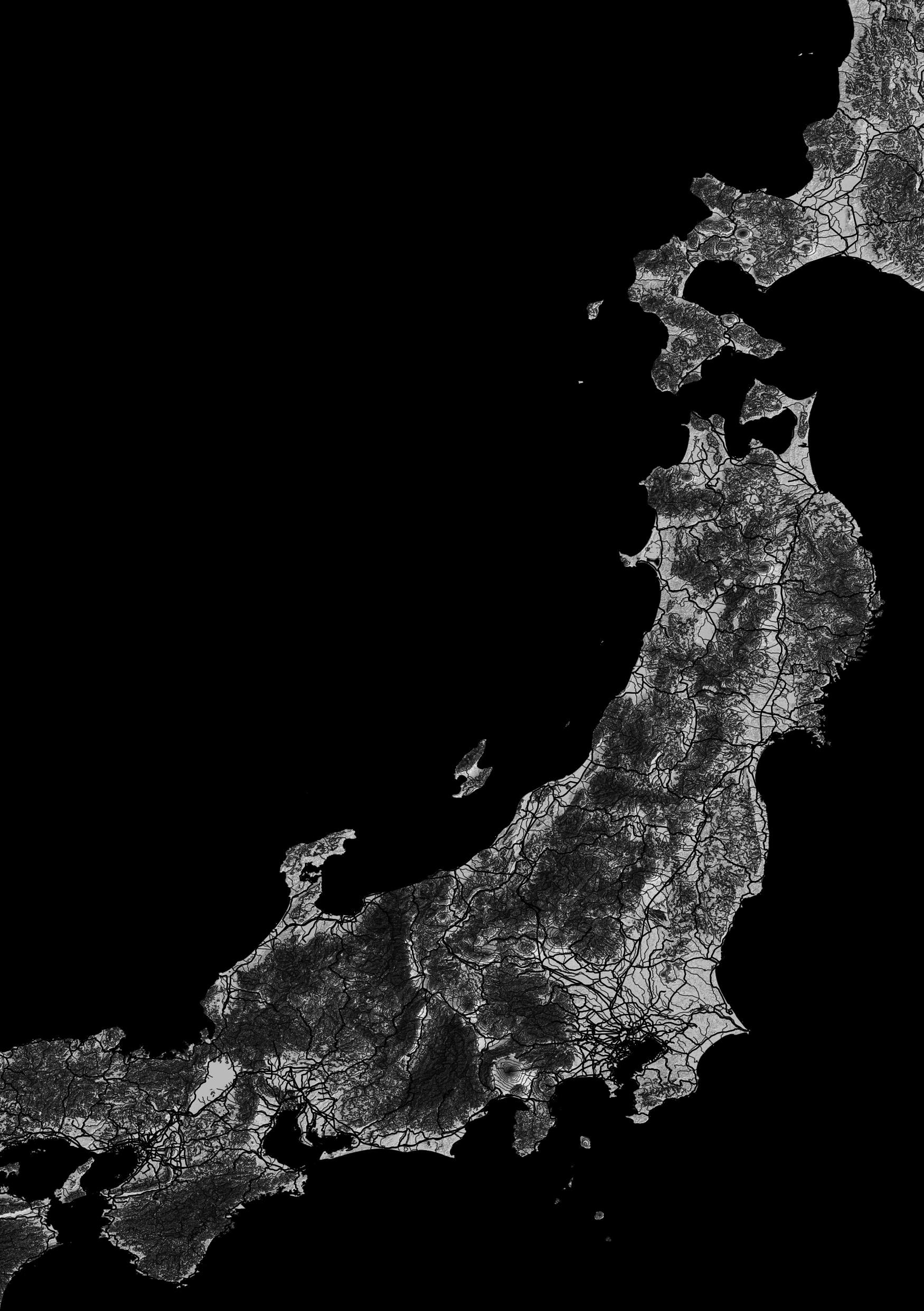

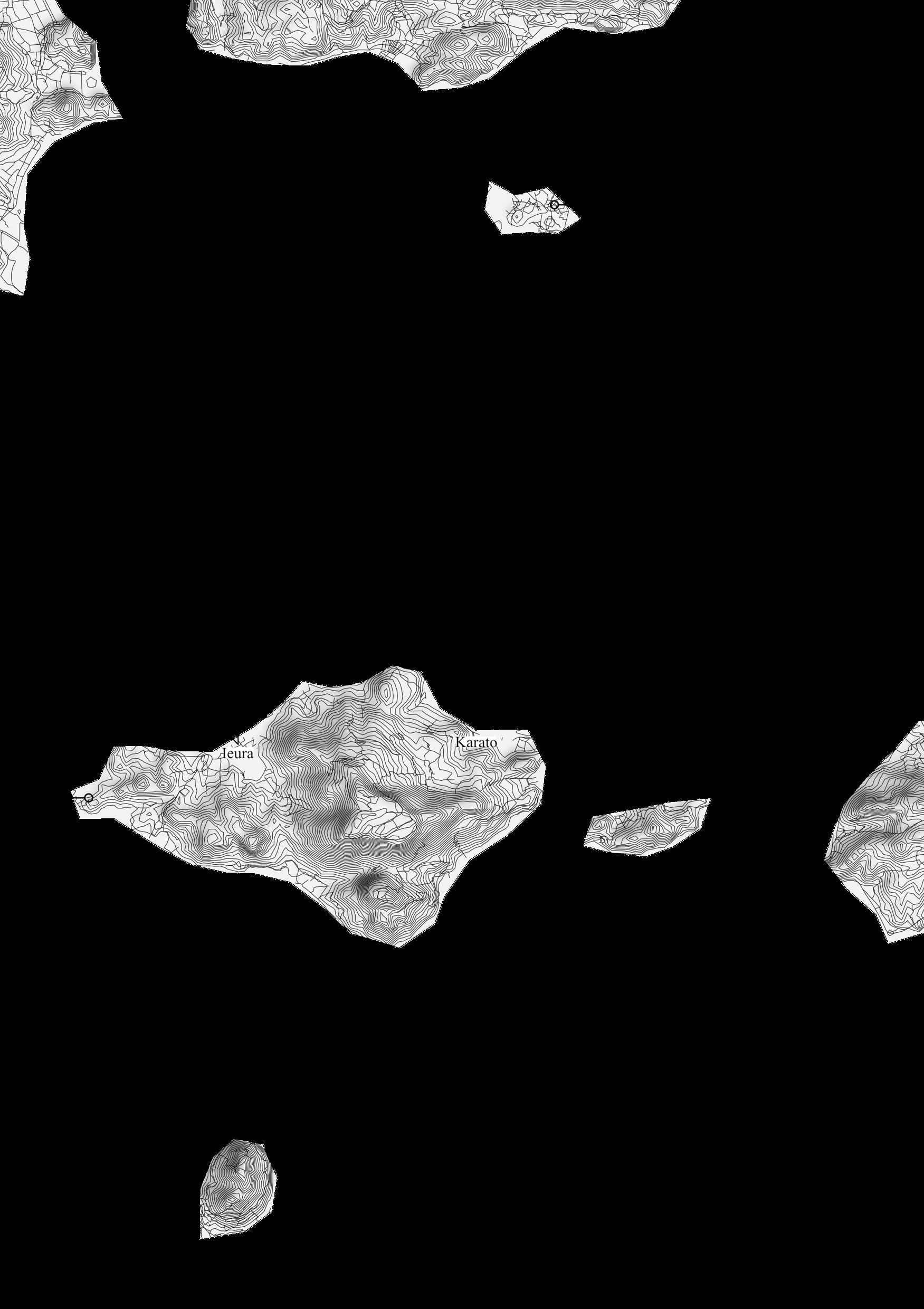

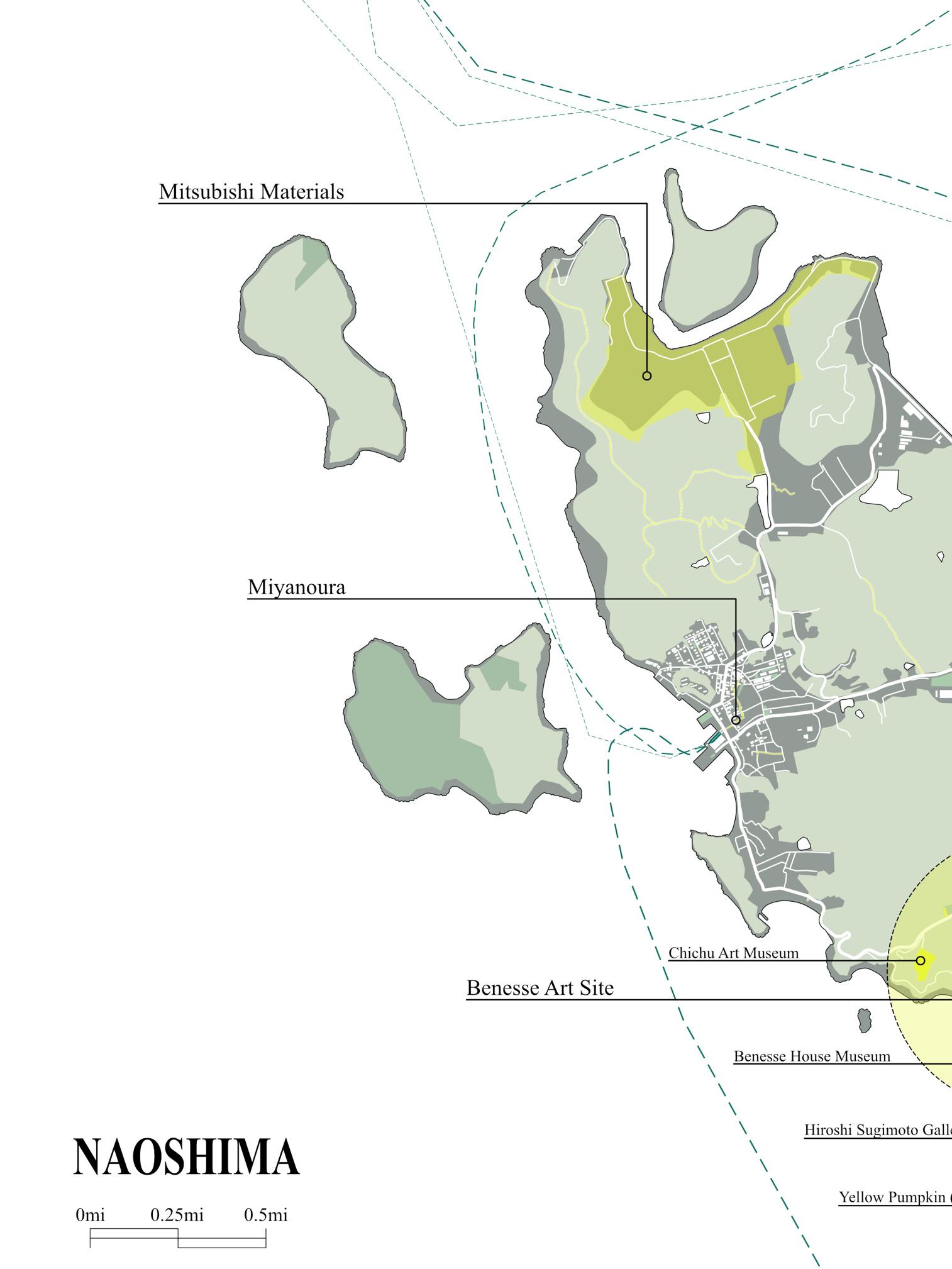

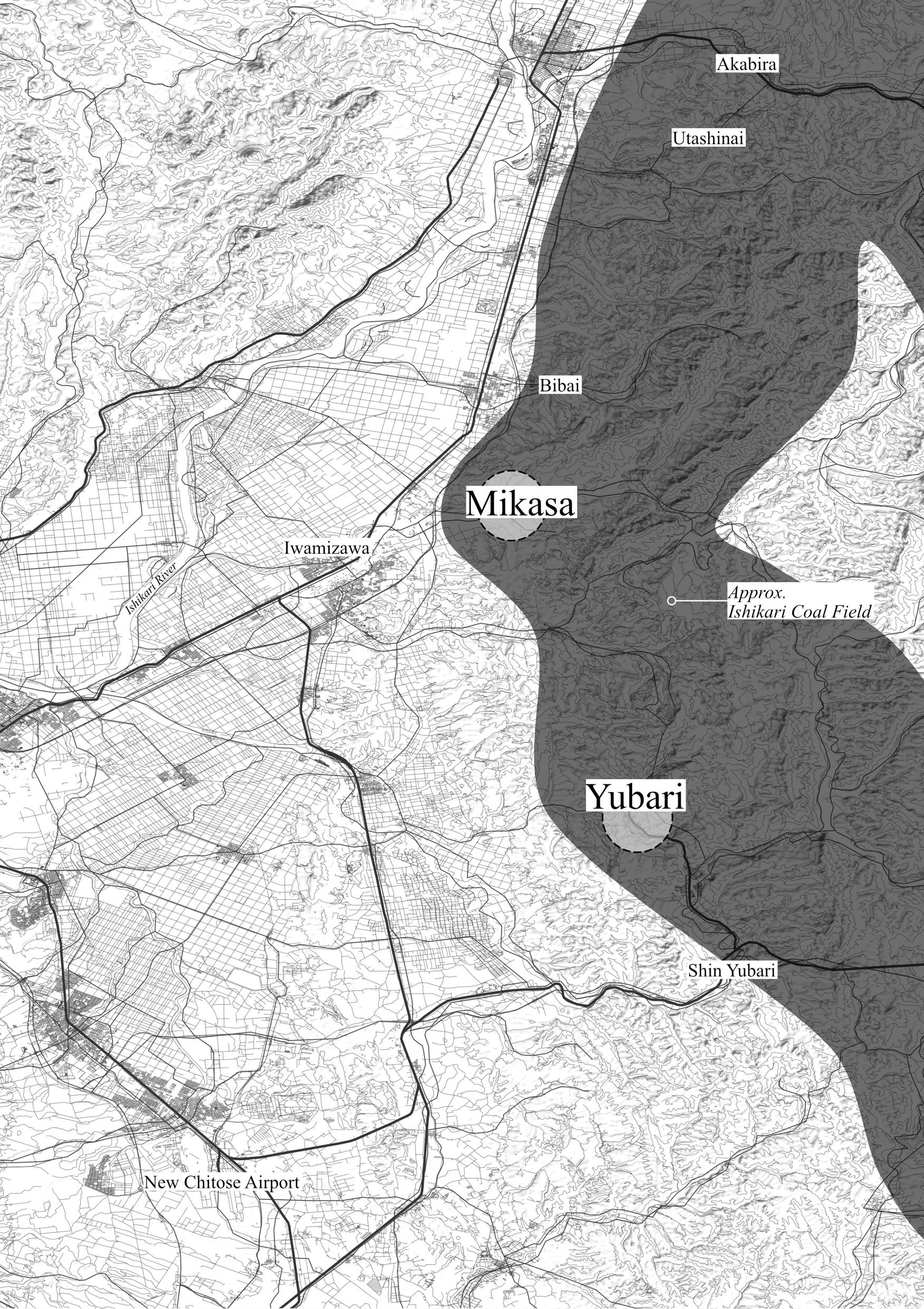

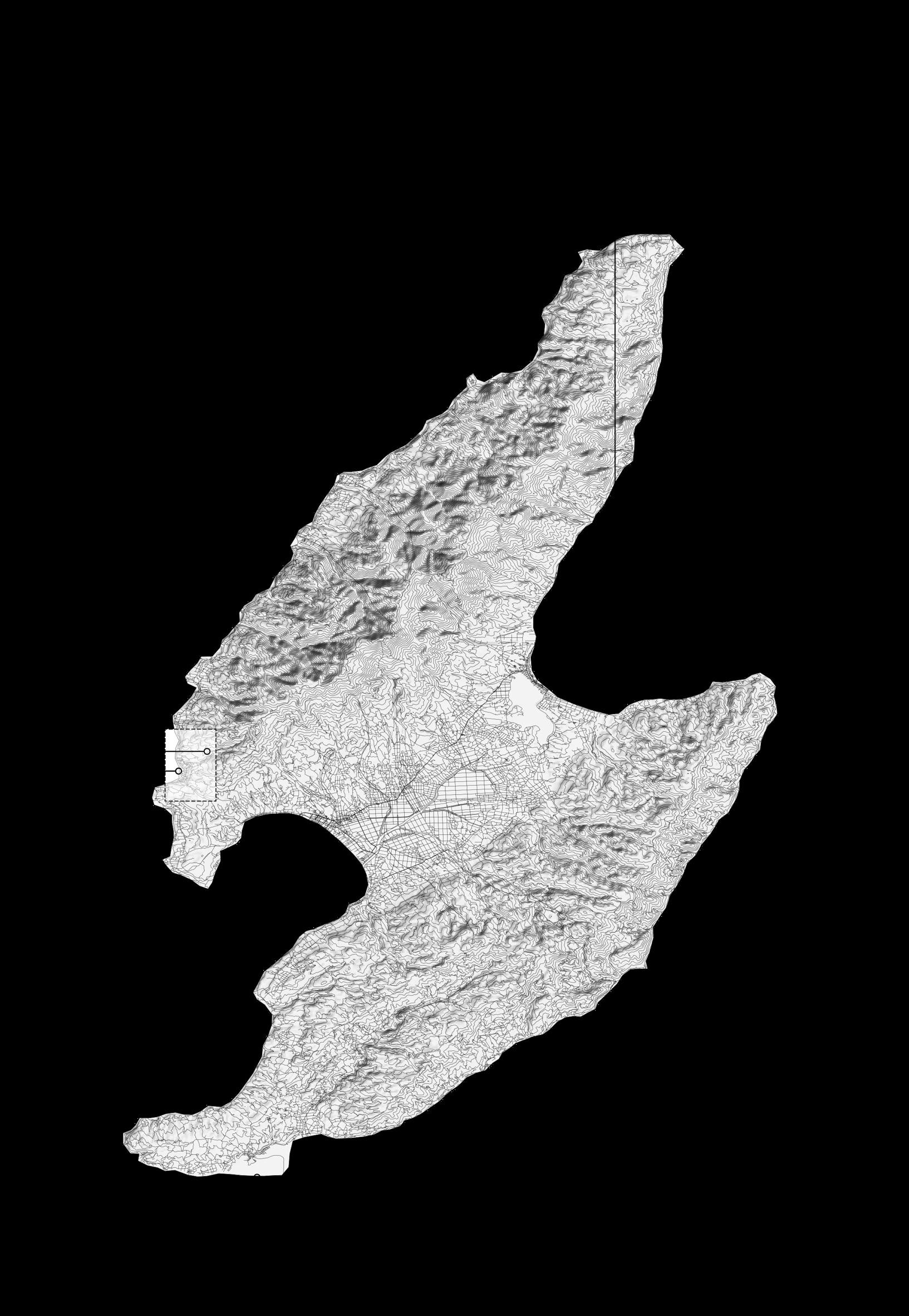

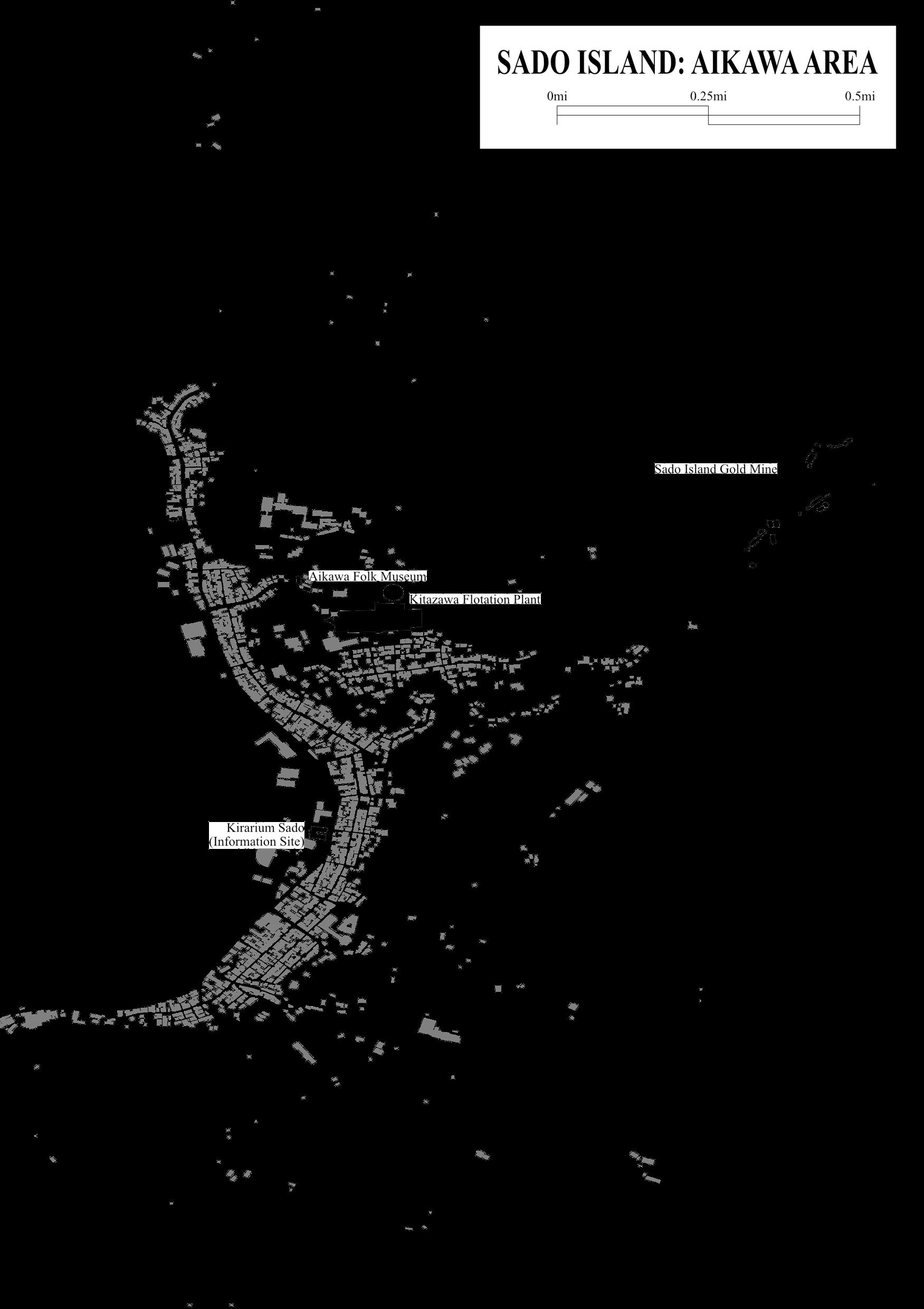

The following map shows all the locations visited during my research trip from September 9th to November 4th 2025. For this travelogue/report, only three areas will be discussed in detail: the Setouchi Art Islands, the Ishikari Coal Basin in Hokkaido, and Sado Island.

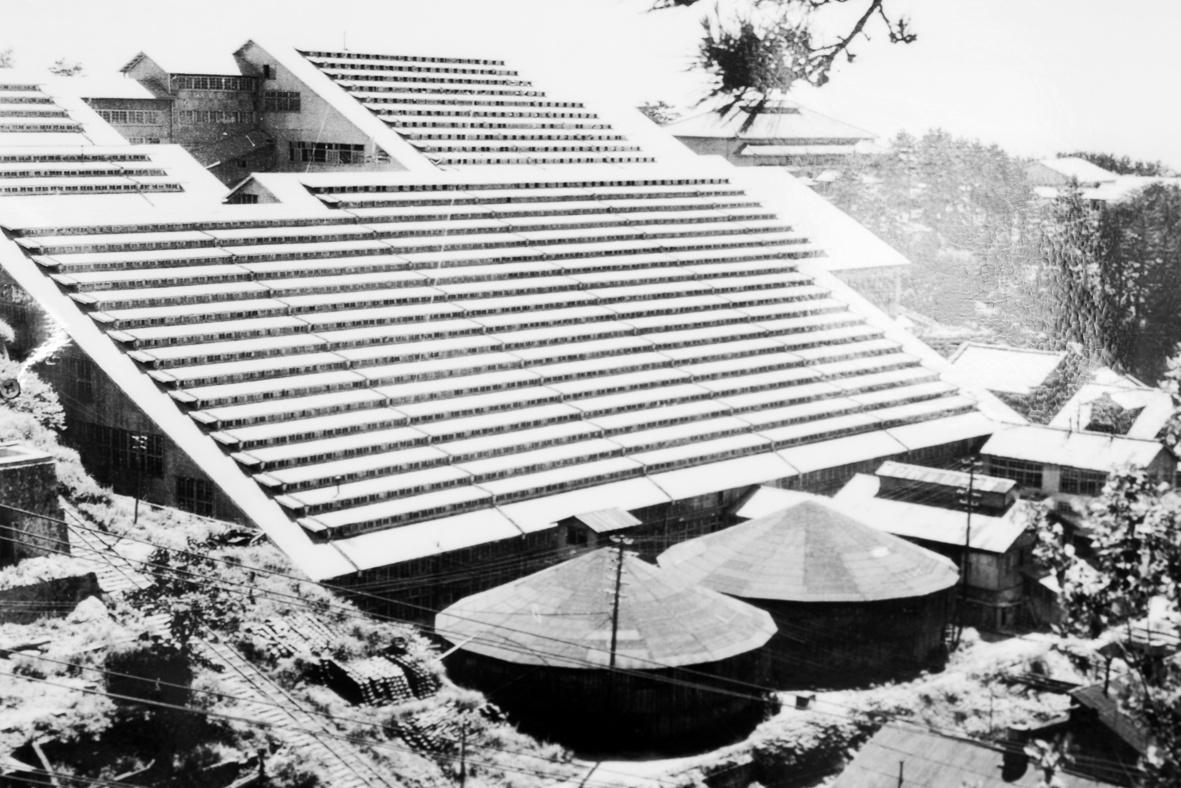

Overlooking the Kitazawa Flotation Plant, well known for its ruinous beauty and similarity to the fictional floating

Global attention often gravitates towards the hyper-dense fabric that makes up tokyo, yet much of the country is defined instead by absence; with ever-shrinking populations and the physical ghosts an increasingly aging population leaves behind. Many of these rural territories also hold industrial histories which further exacerbated the issue, adding another driver to their decline. These places now exist in a state of liminality, with histories often too charged to be treated as neutral heritage, and yet too spatially significant to be ignored; too new to be ancient ruins and yet lacking programatic restructuring that could breathe new life into them.

This travelogue aims to act as a collection of musings, of observations, of photographs, of sketches, of maps, of drawings, of found objects, and an interview connected together by a continuous narrative report detailing my research and journey through these three regions and their relationship with their respective industrial resources of copper, coal, and gold.

Rather than proposing design solutions, I’d like to ask questions instead through the act of observation and documentation. What does it mean to preserve an industrial structure that can no longer be safely occupied? When does adaptive reuse honour history and when can it obscure it. Can a ruin be left intentionally ruinous to serve as a form of cultural memory?And how do communities negotiate the often conflicting identities that these former industrial structures hold?

Naoshima Teshima Inujima

My first stop on my itinerary was the Seto inland sea, the body of water between the main island of Honshu and the smaller island of Shikoku. It was the region I first focused on back in summer of 2023 for my final project during my school’s Open City Studio study abroad programme which I participated in following the third year of my B.Arch. Back then I studied the connection of water in the region, reimagining the inland sea as a traditional rock garden following the lessons of famous garden’s visited during the programme. This focus is what led to my first visit of the so-called ‘art islands’following the end of the official study abroad period, where I decided to journey to Naoshima in the few days I had before returning home to Miami.

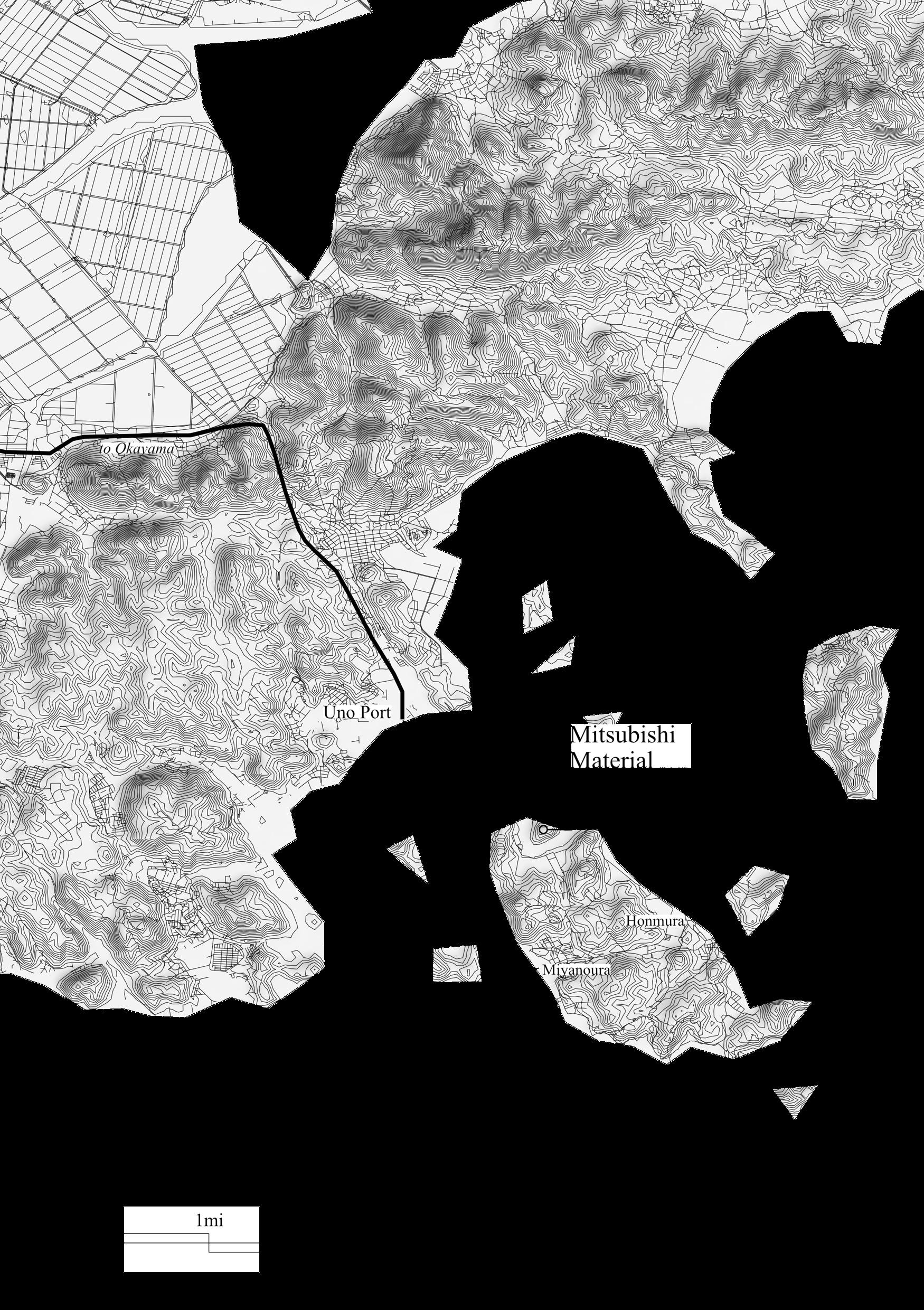

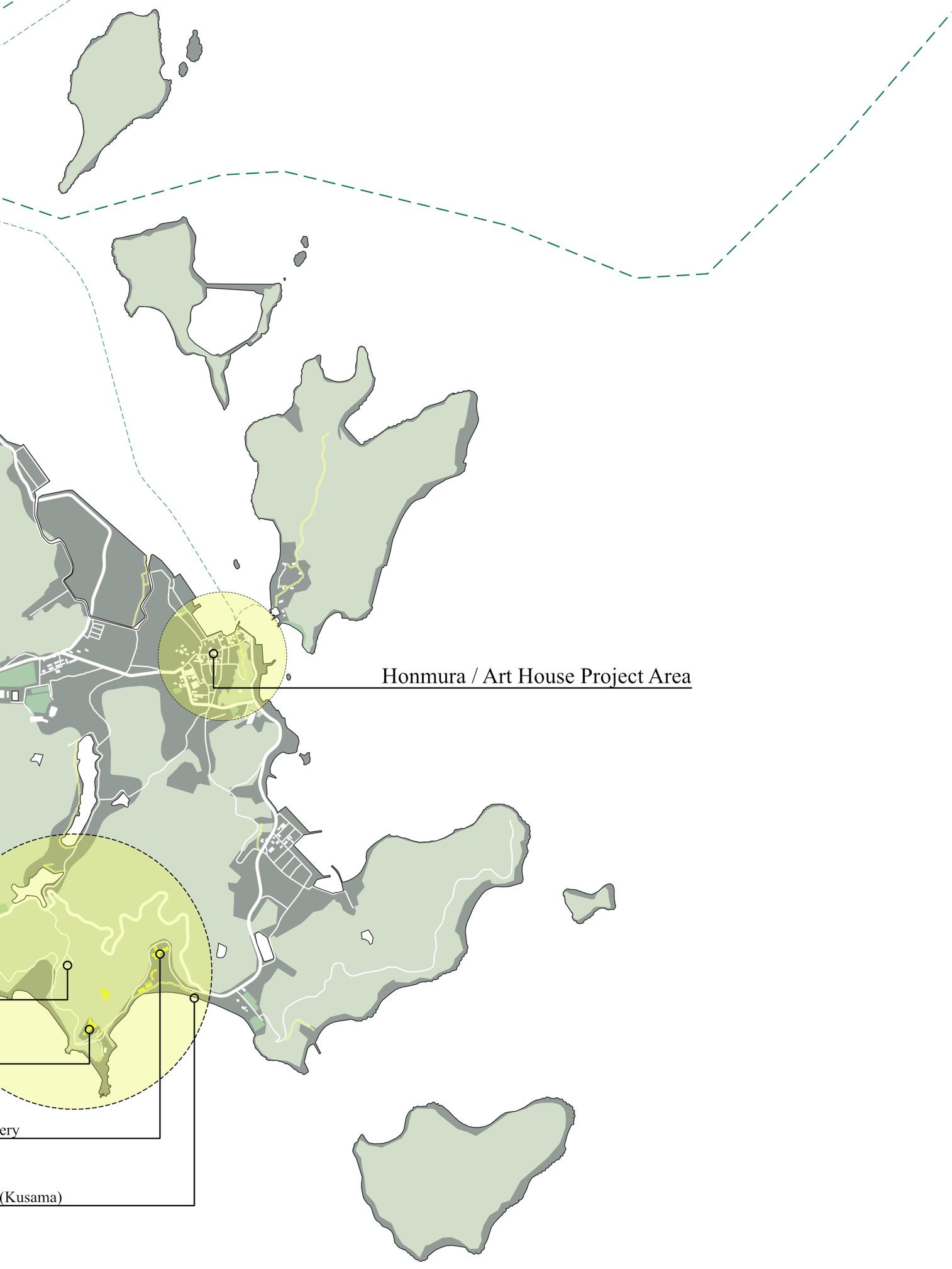

Naoshima is the most well known of the three main ‘art islands’by a decent margin, and with a significantly higher yearly visitor count to match, welcoming around a million visitors a year with higher numbers during the Setouchi Triennale (an art festival spanning the art islands and surrounding areas every three years). This imbalance in popularity compared to the other islands is probably due to it housing the most amount of projects as well as being better connected both internally and through ferry connections to Uno Port (Okayama), Takamatsu, and the other islands. While Teshima also has ferries to Uno Port and Takamatsu, they are fewer in frequency and are less transited by tourists.

Naoshima is also where the vision for the ‘art islands’ began back in the 80s, with a collaboration between Tetsuhiko Fukutake, the founder of the company which would later become the Benesse Corporation, and Naoshima’s mayor at the time, Chikatsugu Miyake, who aimed to open a campground for children in the southern portion of the island. Naoshima had acquired a bad reputation by this time due to general pollution from the copper refinery on its northern tip, leading to a need for revitalization in order to save the island from complete decline. Tetsuhiko Fukutake’s vision for a campground, however, wouldn’t come to fruition before he passed, but his broader mission would be taken up by his son, Soichiro Fukutake. He saw a grander vision for the island and the land purchased in the southern half of the island for the campground, seeing it as a place redeveloped towards contemporary art that would draw visitors from across Japan in order to revive the local economy. He sought the help of TadaoAndo to design the museums and a high-end hotel that became the new heart of the island in the area now known as the Benesse art site.

What was considered a far-fetched idea at the time evidently worked. The islands are no known worldwide, with Naoshima consistently named one of the world’s top destinations and drawing people from around the world. Over half of visitors are from abroad, and you can tell simply from the amount of French, Spanish, and German you hear on the ferry there, and with most of the domestic tourists being on the younger, perhaps more ‘trendy’side.

Accessibility was a primary concern when the project was first underway. Who would even go out of their way to go there just for art?After all, even forty years later and at a

View from the entrance to the gallery spaces in the Naoshima New Museum of Art, the newest addition to Naoshima’s impressive roster of art museums, holding work from several artists and designed by Tadao Ando. Opened only a few months before visiting it in May of 2025.

peak of interest, it’s around a three-hour Shinkansen ride from Tokyo to Okayama, then an hour on a local train to get to the small port of Uno, and then another ferry ride just to get to Naoshima, not to mention the other islands. Yet, the journey itself feels like an accomplishment. Fukutake’s vision for the island was distinctly antimetropolitan in a decade where everything in the country revolved around Tokyo. “Tokyo was supposedly building Japan, yet Tokyo was destroying Japan.” He stated in an interview series withAndo a few years ago. I described the journey to my friend when I first visited Naoshima three years ago as a pilgrimage of architecture.At the time it felt even longer of a journey than it was, having taken a sleeper train from Tokyo to Okayama the day after the final review for my course (admittedly, not my finest idea), but the length of the trip made the destination that much sweeter.

When you land on the island, you don't really see any of the contaminated history, per se. You’re immediately faced with pieces of architecture set in pristine landscape and within two towns that feel as removed from the chaos of the city as one can be.And it is in the destination that Fukutake’s genius vision is really seen, with getting architects the caliber ofAndo, Fujimoto, SANAA.As impressive as the permanent collections containing work from Hiroshi Sugimoto, Walter de Maria, Lee Ufan, and James Turrell (among others) are, they don't feel center stage in the island, at least not as much compared to the museums themselves. Even Yayoi Kusama’s famous yellow pumpkin becomes only a stop along the way between the several museums in Naoshima. In every one you go to, it’s impossible not to notice the visitors focusing on the architectural spaces as much (if not more)

as the artworks themselves.Ando himself is the main artist of the island, creating incredible sculptures of concrete inset into the rocky coastline. Some, like the ChichuArt Museum, are beautiful in how hidden they are, and some, like the BennesseArt House, are visible from afar, with massive protruding linear forms on the lush landscape.

Yet within the entire experience of Naoshima, you never realise that less than an hour bike ride away on the northern tip of the island still stands the same smelter and refinery that gave the island a bad reputation forty years ago, which has been operating since 1918 as a copper refinery on the island and which later turned to other related industry as copper production declined, currently focused on waste recycling. Specifically, the around 600,000 tons of toxic waste that was illegally dumped on nearby Teshima from the 70s to the late 80s, and which was a national scandal as Japan’s worst case of illegal dumping of industrial waste, with cleanup operations only beginning in 2003. The effects of industry are more evident in Teshima, where the story of the dumping scandal and ongoing cleanup efforts are present in every history in every museum on every one of the “art islands.” Yet, apart from the story itself, the presence of industry isn't as apparent in either Naoshima or Teshima as a visitor. You only really get a glimpse of it when on the passenger boat or ferry shuttling between Miyanoura in Naoshima and Teshima as you pass by the northern tip of the island and see the pale yellow of the deforested area and a mountain of black material marring what seemed like a pristine island from the other side.

Industry is most present in Inujima, the smallest island by far, and the most difficult to reach, with only three ferries a

day from Naoshima/Teshima and no actual accommodation. It first became known for its granite, with its quarries providing the stone for several castles in the region, including in Osaka and Tokyo. Later, during the Meiji and Taisho periods, the island prospered with a copper smelting industry when the refinery opened in 1909. Yet, the refinery was forced to close its doors only 10 years after it opened.At its peak of industry, the island had about 5000 people living there, but now the island has a population of less than 50, and an average age demographic of 75.

Approaching the island, the effect of the refinery is immediately evident. From the relatively flat landscape, several brick towers jut out visible from afar like chimneys on a skyline. On closer approach, you can tell they are in various stages of decay, some more complete, while others are Kudzu-covered nubs and barely identifiable as brick chimneys. Disembarking, there is a small ticket center and cafe, more low-key than the ferry terminal and information center in Naoshima, and the small village, with the same yukisugi-clad houses present in the other islands in various states of disrepair or straight up abandonment. Here, the houses take on an even greater relationship between art and disrepair; some fully fixed to be integrated into the “Art house project,” and others integrated through the relationship of nature’s encroachment and painted interiors.

But the Inujima Seirensho Museum is where the relationship between industry and art is most well done in all the islands. It was the product of a collaboration between artist Yukinori Yanagi and architect Hiroshi Sambuichi, and weaves the story of copper and industry

through the entire design and exhibition. Beginning with the material, the path to approach the museum is a somewhat labyrinthine path of black stone ruins.At first glance, they just seem like any other dark stone, yet they aren’t. Sambuichi used the copper slag bricks that littered the island to create the main walls of both the craggy exterior path as well as parts of the museum itself. In addition to this, the Inujima granite that first made the island well known form grander slanted walls that seem to act as retaining walls to the sunken-like volume that forms the main section of the museum, and seem to evoke the great slanted retaining walls of the castles the stone was used for hundreds of years ago. It is these three materials that make up the palette of the museum: karami (copper slag), Inujima stone, and the brick of the crumbling towers. Thus, the very materials of the copper industry on the island are present in the materials of the museum, connecting the design of the museum with the island and its history in a way not really present in Naoshima or Teshima.

The interior of the museum or its exhibition isn't any different. Yukinori Yanagi designed the path and exhibit through the lens of the history of the industry of the island. You first enter through dark sheet pile tunnels with twoway mirrors on either end, always showing you a burning sun on one side and light on the other. It feels like a mineshaft, meant to disorient until you finally reach the end, where all you see is a light well with a mirror showing the sky. The rest of the exhibit follows this line, until you reach the end, where a path takes you through the ruins of the actual refinery, the crumbling towers and free-standing walls nestled in the forest as much part of the exhibit as the artwork inside.

Thus, as Naoshima seems to mask its heritage of industry and contamination underneath beautiful concrete minimalism and Teshima lives with it as a cautionary tale present in the memories of residents, Inujima wears it openly, creating an architecture and exhibition that could not exist anywhere else, refusing to erase or minimize its legacy. Perhaps this is due to the short lifespan of the refinery itself, as it didn’t have a chance to gain a bad reputation due to contamination before external economic forces forced its closure. Yet all three show a way that art can revitalize old histories of industry and breathe new life into aging communities.

While not allowed to take photos inside the museum, my camera was still turned on and I accidentally caught this light trail while turning it off.

(In my defence, the shutter is on the same dial as the on/off switch)

Abandoned houses in the village area of Inujima. The combination of artistic interventions and the complete disrepair and abandonment of surrounding houses create a contrasting dialogue between them.

Decaying Torii gate in the higher part of the village area in Inujima.

Remnants of mining structures, in the parking/entrance area of the Yubari Coal Mine Museum.

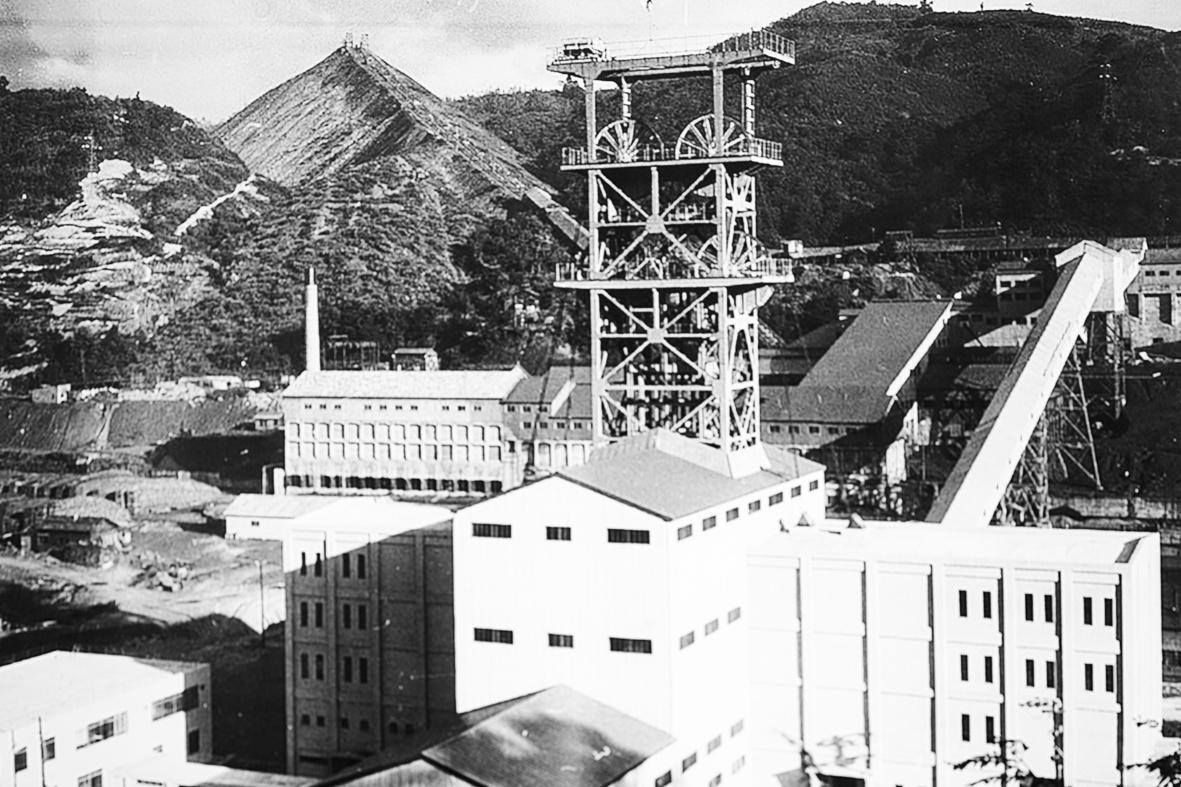

The Ishikari coal field in Hokkaido presents another landscape shaped by extraction, but on a scale far larger and far harsher than the islands of the Seto Inland Sea. It stretches across the western portion of Hokkaido, in the mountains alongside the Ishikari River basin. The entire region embodies a different type of industrial ambition, one marked by the forces of rapid industrialization of the Meiji era that must also grapple with the contentious history of colonization of the island itself, which both enabled and justified Japanese development in the region.

The extraction of coal in Hokkaido came just as the Kaitakushi (the Hokkaido Development Commission tasked with the administration and development of the northern island) was disbanded. Instead, development of the industry fell to different private entities that would thus drive the industrial revolution of Northern Japan. Once one of Japan’s most productive coal regions, Ishikari coal helped fuel the rapid industrialization of the country, which would characterize the Meiji era. The nature of extractive economies would also come to be the region’s downfall. With the energy revolution in the mid-1900s and transition to other forms of energy, mines began to close, with the final one stopping production in 1990, only a hundred years after production began, leaving remnants of industry dotting the landscape by the dozens.As is the case with such extraction economies, the towns that were created to support the mines and once prospered began to decline. Yubari, one of the worst hit, was once home to 24 mines and a population of nearly 120,000. In 2007, the

city was forced to declare bankruptcy, and as of 2024, the estimated population lies at 6,374. The city tried to diversify with multiple efforts, but ultimately failed in each.

One such effort which nonetheless failed and closed by 2006 was a vast Coal History Village theme park (an attempt to be part of an 80s and 90s boom in Japanese theme parks).Another effort to turn towards tourism was to look towards the region’s famous cantaloupes, even creating a mascot to promote it called Melon Bear, which was just as cuddly as it was downright creepy (the plush version followed the rules of the typical kawaii mascot, yet the actual mascot is a terrifying black bear with a melon for a head with bulging bright green veins and human like teeth that jutted out of bright red gums), and didn't truly work with the same expressway visible in Shin-Yubari station taking the city out of the standard roadside destination catalog. The railway line that once ran further into the mountain to support the main portion of the city also closed, with the nearest rail stop being ShinYubari station, an hour bus ride away.

Shin-Yubari station itself is already a small station by Japanese standards. Perhaps it was the day I went, where only a few lines were running due to storm-caused damage further down the line, resulting in the cancellation of most of the trains that week, but as I waited both before and after, most of the trains I saw pass were cargo ones.An hour train ride from Sapporo, yet it felt worlds away. People were scarce, with locals having a car as their main choice of transportation and tourists nowhere to be seen. I was the only one on the bus for the majority of the ride, with only an older lady to share the bus until she got off a

few stops away. The area around Shin-Yubari station was already sparse, dominated by a nearby expressway and with only a few shops, houses, and a roadside station as signs of urban life.As the bus went on, houses lined the route, yet the farther from Shin-Yubari the bus went, the more forgotten the air felt. Standardized housing blocks lined the way further into the mountains, yet they all lay on a spectrum ranging from taken care of but evidently under-utilized to clearly abandoned. It was midday on a Monday, yet signs of life were sparse save for the occasional cars passing by. The closer to the coal mine area, the more signs of former industry could be seen until you reached the car park next to the Yubari Coal Mine Museum where the bus terminated.

The Yubari Coal Mine Museum is the main museum regarding the coal industry in the area, and one of the few in the country. It originated as part of Yubari’s efforts to diversify away from coal mining towards coal-based tourism. It acts as a repository of mining artifacts, with two stories of exhibition dedicated to the history of the city and coal mining in the Ishikari coal field. Its main attraction, however, is the renovated mining shaft of the former Yubari mine (opened in 1900), which was prepared for a tour by the Emperor Hirohito and Empress Kojun in 1954. When I went, there was a decent number of visitors, all Japanese, who had all evidently come by car as a weekend day trip.

It was here that I was able to get the contact information of the director of the museum and was later able to interview him as part of my research.

by Catalina Cabral-Framiñan

Translated by Xinrong “Cindy”Ye from the original Japanese

Catalina Cabral Framiñan {CCF}: Is there an estimate of how much money would be required to digitize/scan all the material?Additionally, beyond digitization, what would you think is the most urgent next step for the museum? If sufficient resources were available, how would you like to expand the museum’s role in documenting or revitalizing Yubari’s industrial heritage? Essentially, what would the ideal vision for the museum be and what it could bring to Yubari.

Shigeaki Ishikawa {SI}: The vast amount of paper materials (books, photographs, drawings, etc.) to be digitized are stored in repositories and archives in the same state as when our NPO took them over. In order to promote the utilization of these materials, it is essential to first make a list of the materials, but this task is outside the scope of designated management, and the volume is too large to be carried out independently.

From a medium- to long-term perspective, we believe that maintaining and continuing the museum is extremely important for passing down to future generations the image of Yubari, which prospered through coal, mining, and related industries in the history of our nation’s modernization. On the other hand, since our NPO has undertaken the designated management of the facility under a five-year contract, we have not considered longterm expansion of the museum’s functions or planning based on sufficient resources (funding).

CCF: How do you feel about preservation vs. adapting industrial structures? Would you rather see structures be maintained as they were to show how they were originally used or adapted towards other uses in order to be able to preserve the building but perhaps not the complete memory of it?Alternatively, is there an inherent beauty in the ruin of the structure in itself and do you think that could be useful?An example being the Kitazawa Floatation Plant in Sado Island.

SI: Unlike small cultural properties, the preservation of industrial structures involves risks that threaten people's safety, such as collapse due to aging. In particular, for most coal mining facilities that have been closed for more than half a century, even maintaining their current condition is extremely difficult, and in many cases, restoring them to their original operational state is considered highly challenging.

That said, we believe that especially valuable facilities (such as cultural properties) must be subject to appropriate preservation measures. However, for structures where conservation measures are difficult, socalled “watchful preservation” (minimal intervention conservation) can be one possible approach. In addition, when multiple structures of the same type exist, it may be necessary to make selective choices, such as preserving a representative example.

When renovation of structures is possible, we believe that assigning them new roles and promoting initiatives for regional sustainability (including economic activities, if

feasible) is an effective approach. However, in coalproducing areas facing population decline, there are concerns that even the operation and management of renovated facilities may become difficult in the short term. In particular, in Hokkaido, heavy snow and cold weather pose a major obstacle to year-round use.

Depending on the type of industrial structure and the degree of deterioration, the following kinds of selective approaches will need to be taken (and in fact are already being taken):

1. Preserve the facility and repurpose it for new uses (e.g., commercial use) → Example: Ebetsu City’s brick factory converted into the commercial facility “EBRI”

2. Preserve or restore the facility and utilize it in its original function or appearance → Example: The simulated mining tunnel at the Yubari Coal Museum

3. Temporary use (such as for artistic activities or special openings that require entry permission) → Example: The Shimizusawa Thermal Power Plant in Yubari City

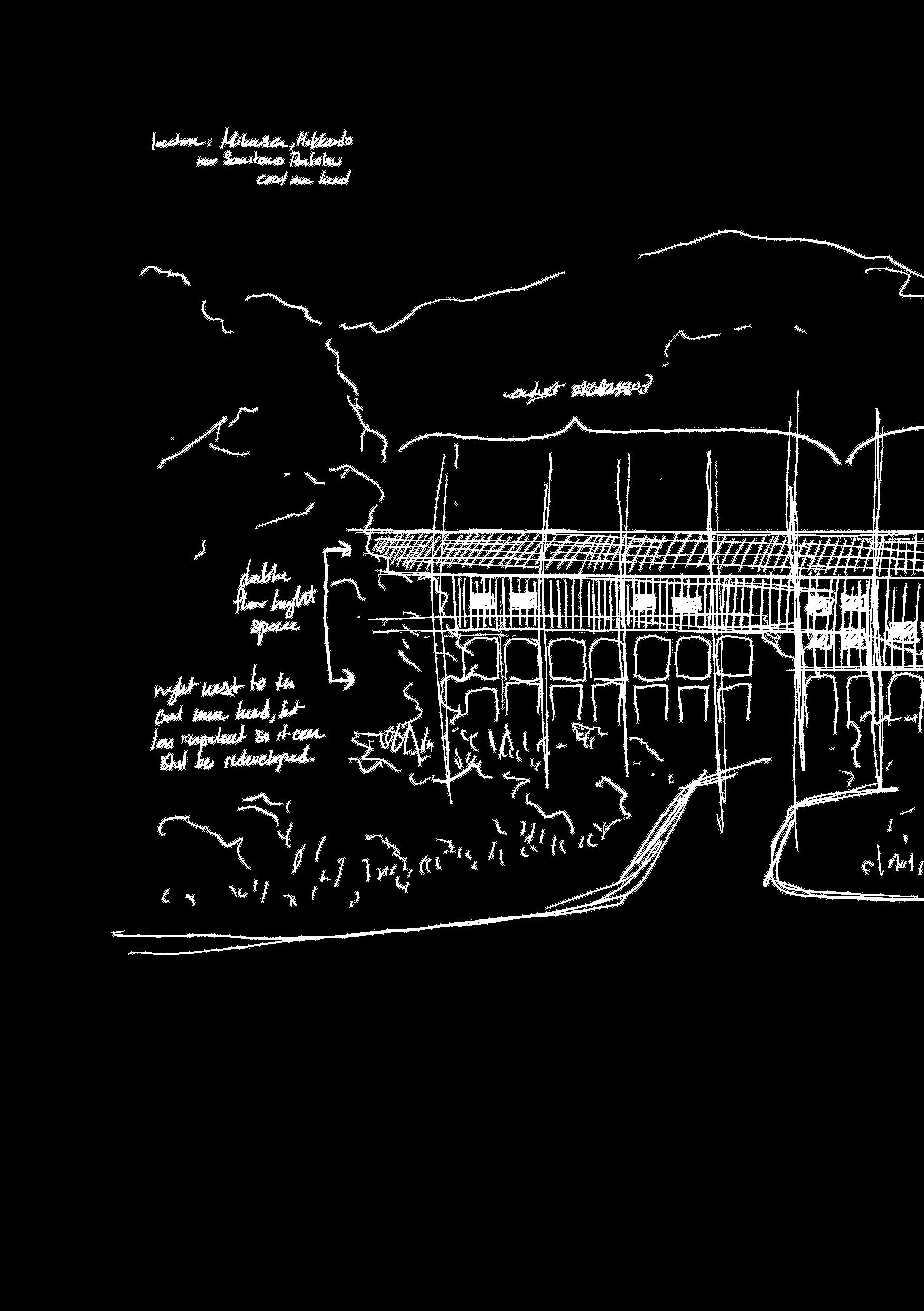

4. Watchful preservation (no maintenance or management possible) → Example: The hopper at the Ponbetsu Coal Mine in Mikasa City, which is valued for its presence (scenic, design, and scale).

CCF:Are you familiar with the Inujima Seirensho Museum or the Setouchi Triennale?As a case study in my project I am trying to see how art and architectural intervention has managed to bring new life to the original structure through new use rather than as a museum of industry. I am, for instance, drawing a comparison to the Sado Island Gold Mine model of bringing tourism to the area.

SI: I am familiar with both the Inujima case and the Setouchi Triennale. I understand them both as good examples of utilizing existing facilities and working with companies that support artistic activities genres closely attuned to those structures and facilities.

In the Sorachi region, including Yubari, various artistic activities are being carried out at coal mining heritage sites, although they are not well known nationwide. As with other areas across the country, this initiative makes use of the affinity between coal mining facilities and art.

The Sado Gold Mine, as a consolidated subsidiary of Mitsubishi Materials, manages the mining facilities and operates tourism-related businesses. Meanwhile, the Osarizawa Mine in Akita Prefecture, also operated by the company, will shift to a business model limited to group reservations starting in the spring of 2026 due to staff shortages and aging personnel.

It is clear that there is a significant difference in the level of effort devoted to utilization between the Osarizawa Mine, which has been open to the public for decades, and

the Sado Gold Mine, which gained novelty after being registered as a World Heritage Site in 2024. Just as visitor numbers at the World Heritage Site of Iwami Ginzan dropped by half within a few years, attention should also be paid to how long the popularity of the Sado Gold Mine can be sustained, as well as to the extent of the company’s efforts—together with the local community of Sado City— in maintaining the facility through its ability to attract visitors, disseminate information, and provide financial resources.

In terms of sustaining popularity and building relationships with people who have no direct connection to mining heritage (through outreach efforts), I believe that interaction with different industries—beyond just artistic activities—is important.

CCF: In relation to the previous question, if an artist or architect proposed a project within Yubari’s industrial landscape, what conditions or principles would you insist on preserving? If what they proposed kept the original structure but greatly changed the look of it and kept little of the original history would it still be acceptable if it could bring something new to the city?

SI: This year in Yubari City, an organization that runs cosplay events recruited participants and, with permission, held a one-day event in which photos and videos were taken at several facilities in the city. About

200 people took part, providing an opportunity for individuals who normally would not visit Yubari or its coal mining heritage sites to come.

When accepting such activities at our museum, we conveyed the following points of caution:

1. Do not engage in actions that would diminish the dignity of the museum or cultural properties.

2. Do not provide explanations or comments in works that disparage Yubari.

3. Do not interfere with ordinary visitors.

Although we received a few opinions saying that the event was “not suitable for Yūbari,” I felt that participants taking photos in cosplay within the extraordinary setting of the underground mining tunnels could represent a new form of value and possibility.

In this way, even people who have no particular interest in coal mines or industrial heritage can become fans of the region through combinations with other interests. While from the perspective of strict preservation and transmission of coal mining heritage this may feel somewhat incongruous, I believe it is nevertheless an important initiative for the future.

CCF: Is there organization between the different cities and museums (for instance perhaps the Mikasa City Museum) of the Ishikari region and could greater regional organization and promotion of the area’s heritage aid in outside interest rather than individual groups and cities acting independently?

SI: I think the distinctive feature of the Japan Heritage “Coal, Iron, Ports” initiative is that, unlike the typical government-led approach often seen in our country’s tourism and community development, it has become natural for public and private sectors to collaborate and work together.

Six years have passed since “Coal, Iron, Ports” was designated as a Japan Heritage site in 2019, and I feel that regional cooperation has advanced. This is not only in terms of collaboration among museums, but more significantly in the sense of cooperation across both the public and private sectors as a whole.

The target area of “Coal, Iron, Ports” covers roughly 100 square kilometers. About ten years ago, events were promoted and held individually, but through the overarching story of “Coal, Iron, Ports,” a sense of unity has gradually been fostered. Among the most significant effects is that it has become easier for people to reach out to one another.

Building on that effect, we held the “Coal, Iron, Ports 3Days” for the first time this year. During the three-day holiday in October, facilities that are normally closed to

the public were opened and special guided tours were offered, encouraging circulation across the wider region and attracting many participants to explore it.

Unlike World Heritage sites, which are intended for strict preservation, Japan Heritage places greater emphasis on practical utilization. For that reason, I feel it is an effective initiative for connecting the scattered coalrelated industries and their remains to the future.

CCF:Are you from Yubari? If so, do you have any memories or anecdotes about how the city and region has changed over your lifetime? Or, do you have any that you’ve heard from other people from the city?

SI: I am from Tokyo.

Carrying out work across a wide range of fields in various regions means gaining an understanding of the lives and needs of local residents, as well as the technologies and economic conditions that can be applied there. Therefore, my interest was not limited to coal mining areas alone; rather, I have been viewing regions from a multifaceted, overarching perspective. I became directly involved with Yubari eight years ago. At present, there are people at the museum who worked in the coal mines until their closure, and although their knowledge is limited to what they know, I am expanding my understanding by listening to their accounts of the conditions during the period when the mines were in operation.

CCF: Do you think that Yubari’s decline was inevitable the moment it grew around a single industry and didn’t diversify or can there also be urban planning choices that were made that accelerated it?

SI: As for the changes in the Yubari region, I believe they were not the result of autonomous local transformation, but rather changes unique to a region that was inevitably dependent on national policy and global energy circumstances—namely, the decline of the coal industry and the resulting population decrease.

CCF: Is there anything that personally drew you to the museum from working in a different field?

SI: I became interested in the unique history and geography of Hokkaido within Japan and decided to move there. Because my parents were frequently transferred for work, I lived in four different places from childhood until graduating from university, and I enjoyed observing the characteristics, changes, and folk traditions of each region. Although I was interested in geography and history up through high school, I went on to pursue the field of transportation engineering.

After graduating from university, I worked for five years in ski resort development, and then joined a construction consulting company where I was involved in regional planning, transportation planning (roads, railways, ports), and projects for the preservation of historic structures. In

the course of this work, members who were committed to sustaining various memories of coal mines and mining regions came together to form an NPO, and I became deeply engaged in its activities.

Three years ago, the former NPO director and museum director suddenly passed away, and I was asked to take on the role of director because of my expertise in Hokkaido’s history, geography, and industrial heritage. As mentioned earlier, the museum’s designated management does not include curatorial duties, nor does it require curator qualifications, so I accepted the position of director.

CCF: From my experience when I visited, the grand majority of people in the museum seemed to be visiting from Japan. Does the museum get much foreign visitors?

SI: Because the region is inconvenient to access, visitors from overseas are extremely few—probably around 0.5% (about 150 people) per season. Still, compared to a few years ago when it was only about 0.1%, I feel the number has been increasing. Since there are coal mines near Taipei and Keelung in Taiwan, it seems that more people there are becoming interested.

CCF:Are most of the Japanese visitors from Hokkaido or is there interest from other areas as well?

SI: As a characteristic of residents in coal mining regions, many people have little interest in (or even dislike) coal mines. Although we hold a free admission day for citizens once a month, attendance remains at only about 20 visitors each time.

I estimate that around 50–60% of visitors come from within Hokkaido, while about 40% come from outside the prefecture. Despite being such an inconvenient location, people from all over the country visit out of interest, and in that sense I believe this is an important place for Japan.

CCF: Lastly, have you or the staff noticed any differences between how visitors from different areas engaged with the museum and its content?

SI: I feel that people with ties to Yubari (such as ancestors or relatives there) are often interested in learning about the city’s changes and its past. Those without such connections tend to be drawn to the coal mining facilities and remains that cannot be found in other regions, or they visit with the specific purpose of experiencing the mock mine tunnel that reopened this year. Although our museum is located in an inconvenient place, domestic travelers generally perceive it as a spot that can be easily reached while touring Hokkaido by car or rental car—since it is just over an hour’s drive from New Chitose Airport.

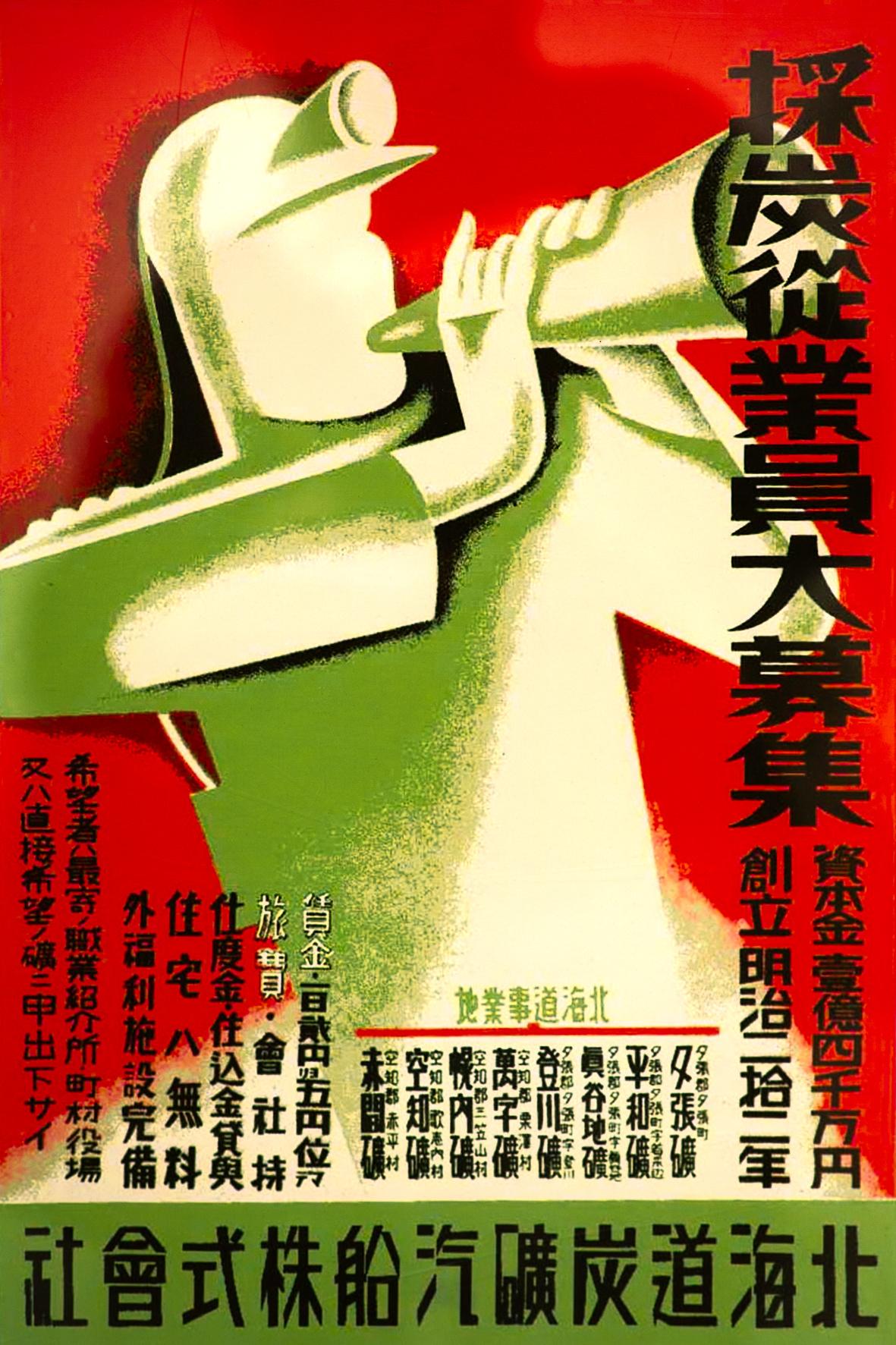

Recruitment poster for coal mines in the area, with Yubari listed as one. Benefits listed include accomodation, loaned preparation fees, travel expenses covered, and external welfare facilities that are fully equipped. Early 20th century.

Recruitment poster for coal mines in the area, with Yubari listed as one. Benefits listed include accomodation, loaned preparation fees, travel expenses covered, and external welfare facilities that are fully equipped. Early 20th century.

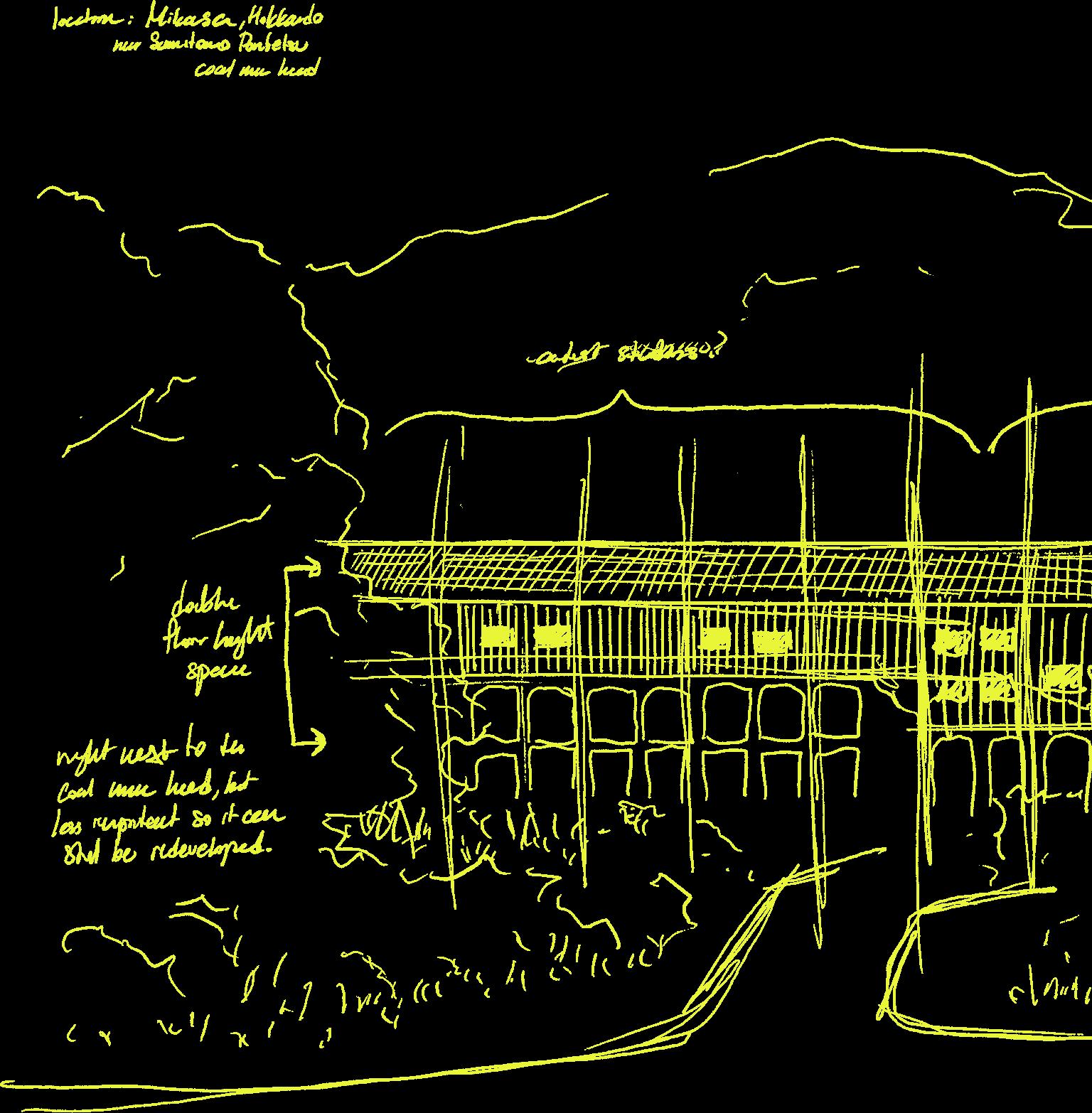

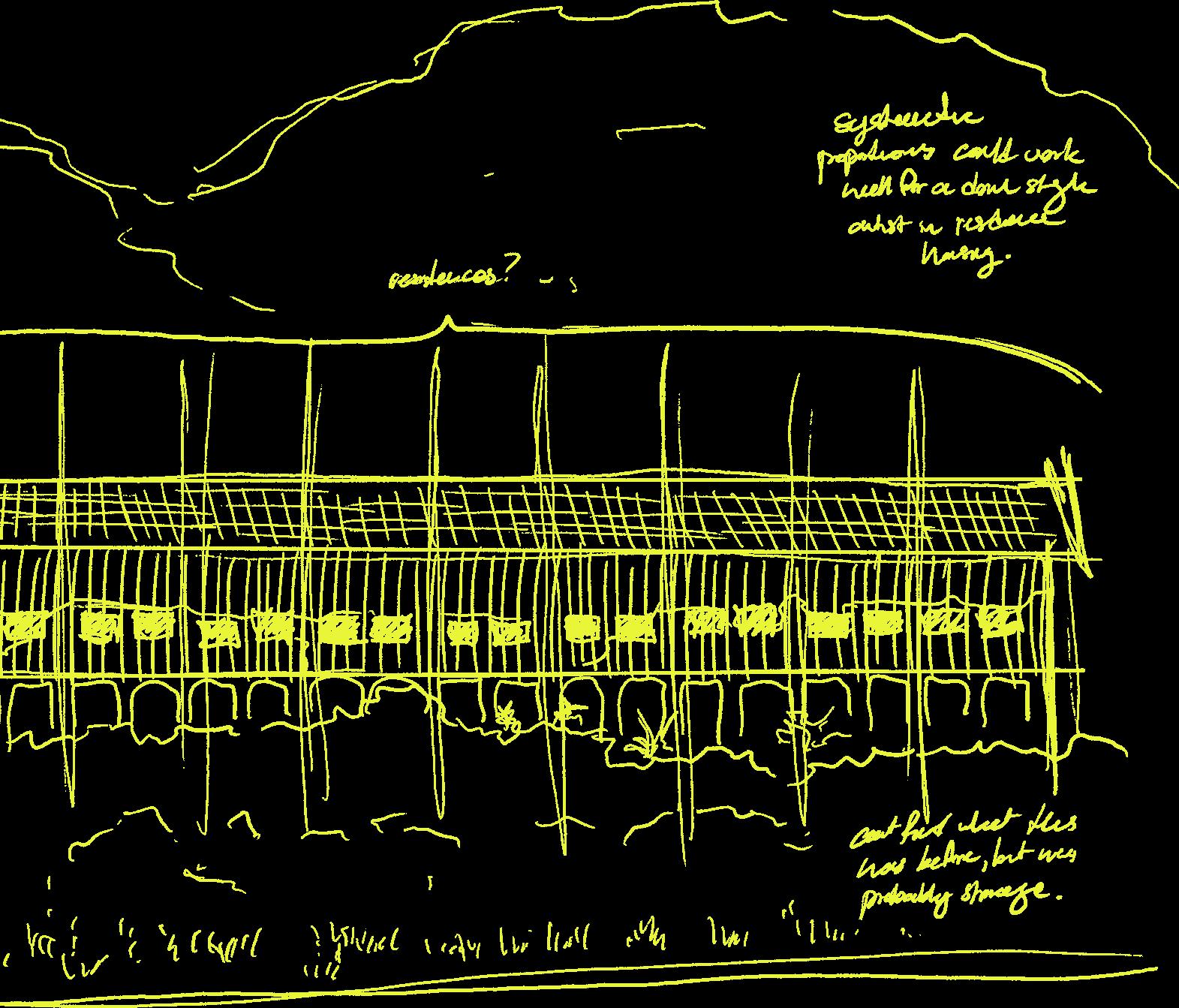

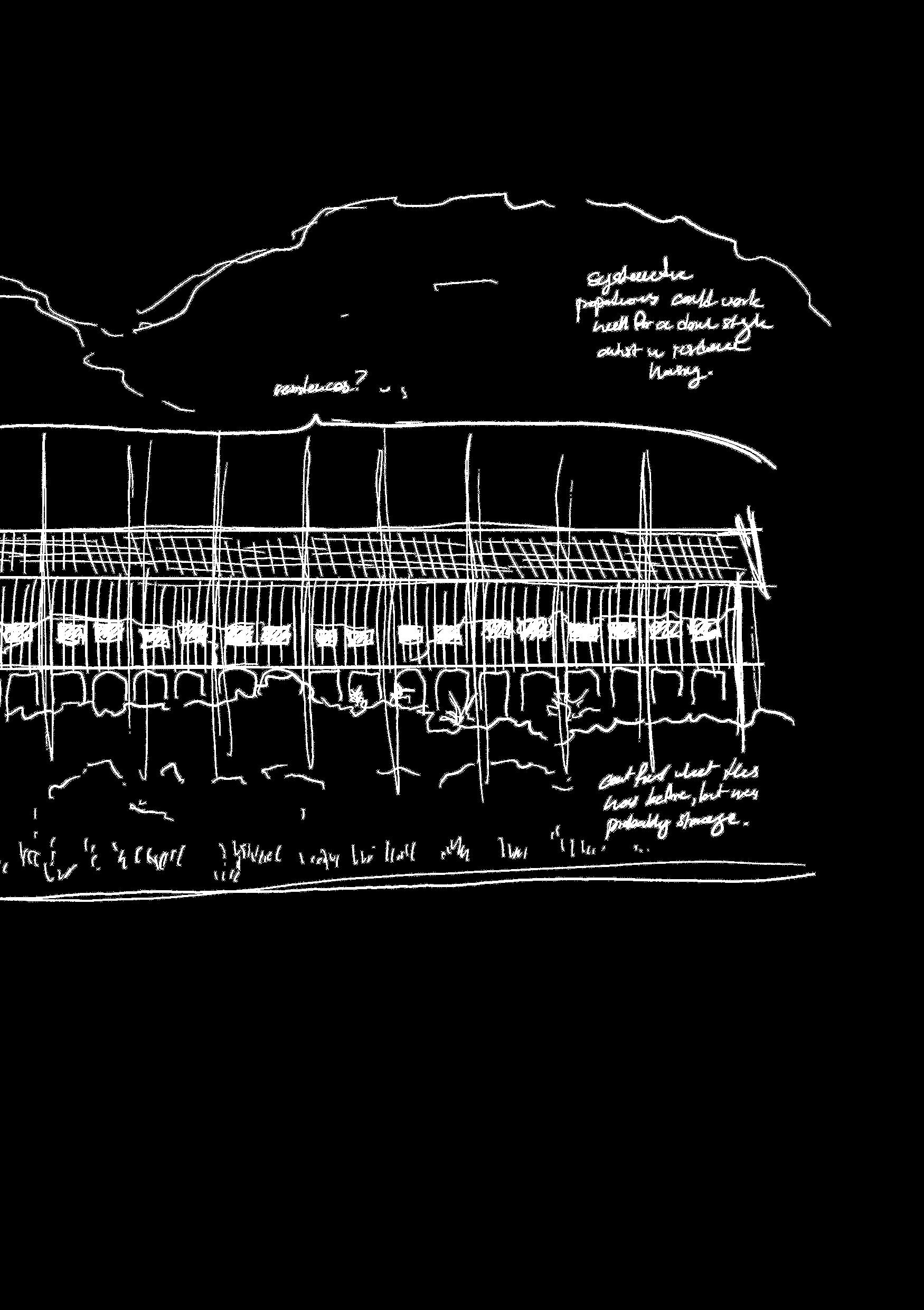

I also visited the coal town of Mikasa, which was also a victim of the boom and bust cycle of the coal industry. It was easier to reach compared to Yubari, the same hour train followed by an hour bus ride, yet the region seemed more populated in general than Yubari. The train stopped at Iwamizawa, which is a larger station, and the bus left from a large bus terminal that served the greater region. The route to Mikasa was also more transited, in a large part by motorcycle enthusiasts taking advantage of the beautiful day.

My reasons for going to Mikasa were two-fold. The Sumitomo Ponbetsu Coal Mine is there, one of the most famous abandoned sites in Japan (typically called Haikyo). While I was there, several people stopped by to take pictures before continuing along on their road trip. Mikasa is also home to a museum and a geo-park with several more industrial ruins, though when I went, the geo-park was closed off due to multiple bear sightings. The museum did have an area dedicated to coal mining history, but the main attraction was the massive collection of ammonites and marine dinosaur fossils that had been excavated in the area. The fossils were the main reason for visiting the museum, with lots of dinosaur statues and reliefs decorating the exterior of the building, and even a Pokémon manhole cover which every kid there wanted to take a picture with.

Across the region, the remnants of coal extraction form a constellation of abandoned industrial structures tied together by towns in decline. Yubari and Mikasa are only two points within the much larger area of mines, and show only two sides of the story present in the communities across the coal field. Some museums, memorial and geo-

parks, and notable haikyo show isolated efforts to preserve communities, but they exist alongside areas where nature is steadily reclaiming the abandoned structures. It is a landscape of incomplete erasure, where industrial heritage has not been condensed into a cohesive narrative through the region, and which lacks the large-scale self-promotion of the SetouchiArt Islands or the Sado Island Gold Mines. The Ishikari coal field thus shows how extractive economies can both make and destroy regions.

Abandoned structure next to the Ponbetsu Coal Mine head in Mikasa, sketched over digitally to see how it could look reconstructured. The standardised proportion system could lend itself well to a half artist studio half dorm or studio style residences program.

Sado Island’s gold mines present another landscape shaped by extraction, this time by gold. Its temporality, however, far exceeds that of Ishikari, stretching back at least around four centuries to the early Edo period. Here, the gold mines are one of, if not the main attraction of the rather massive island of Sado, recently named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2024, and currently promoted in train stations in every city I visited (even local subway stations in Tokyo and Nagoya had signs advertising the mines). The terrain is physically marked by the gold mining, most famously with the V-shaped cleft of Doyuno-Warito, which serves as the most emblematic view of the island.

The island is most accessible by a two-hour ferry or a 45minute jet-foil from Niigata, and the mines are an additional 45-minute bus ride from the ferry terminal in Ryotsu port to theAikawa area on the northwestern side of the island. The ferry and jet-foils are filled to the brim with tourists and day-trippers. Most visit the mines during their stay, though some are obviously locals from Niigata who traveled to the island for its fishing or to visit friends and family.

While known for its surface deposits of gold and silver since the Heian period, extraction of gold in Sado began in the 1600s during the Edo period when those mining silver discovered the deeper gold veins. In 1601 full-scale mining began under the Tokugawa Shogunate in what became theAikawa Gold and Silver Mine. Gold was

minted into “Koban” on the island as the largest gold mine in the country during operation and distributed through the country as coinage, even making its way to foreign ports in Europe. Mining would continue for centuries, though transferred to imperial holdings in the Meiji restoration and then released to Mitsubishi Goshi Kaisha (now Mitsubishi Materials, the same company which operates in Naoshima) in the 1890s. Production briefly continued to increase following the invasion of Manchuria and WWII, during which the mines began to conscript Korean workers from the Japanese occupied Korean Peninsula to fill in the shortage of Japanese workers, leading to a controversial history which continues to be discussed today (South Korea was against the naming of the mines as a UNESCO world heritage site due to lack of representation of the history of these conscripted workers in the exhibits). Production declined following WWII, and the mines eventually closed in 1989.

Apart from the modestly sized exhibit with dioramas showing the history of the mines in the site, the main attraction in the mining area are the tunnels themselves, around 300m of the original 400km which have been converted into a walkthrough with wax-figure miners, some machinery, and a newAR walk geared towards children where you are meant to help “charge” an adorable spirit on glowing crystals to help fight off the encroaching corrosion turning the once sparkly blue moss and crystal AR overlay into purple and red sludge.

However, what first drew me to the island is what perhaps draws a large part of my demographic and a good amount of families to Sado: The Kitazawa Flotation Plant. On paper, it’s an odd attraction, the ruins of the flotation plant

built in 1937 during peak production and investment in WWII to extract gold and silver using methods originally created for copper extraction. Most of the massive facilities were dismantled following the closure of the mine, leaving only its concrete carcass to be covered by ivy and other plants. It is well known for its obvious resemblance to the floating kingdom of Laputa in Studio Ghibli’s Castle in the Sky, something most evidenced by the amount of Ghibli figures hiding amongst the tableware in the cafe facing the site, the Castle in the Sky soundtrack playing on the speakers, and the amount of families with young children both excited to see the site and also slightly dejected due to the lack of friendly giant robots.

The mines and ruins of the flotation plant show that preservation of the mining heritage itself and the inherent beauty of ruins themselves can be enough to attract a large amount of tourists to the area, enough to power the economy of the island. The novelty of the site, however, is still apparent, as there has been a peak in tourism due to its recent UNESCO status. It is a novelty which Mr. Ishikawa noted during my interview with him, “Just as visitor numbers at the World Heritage Site of Iwami Ginzan dropped by half within a few years, attention should also be paid to how long the popularity of the Sado Gold Mine can be sustained, as well as to the extent of the company’s efforts—together with the local community of Sado City—in maintaining the facility through its ability to attract visitors, disseminate information, and provide financial resources.”

Across these three landscapes, the afterlives of the communities once built around industry reveal separate efforts to regenerate them. Some are top-down; the billionaire foundation backed development of Naoshima, Teshima, and Inujima into the now famous “art islands”. Some are more grassroots in a way, as communities try and struggle to reinvent themselves in order to survive, like in Ishikari’s former coal towns. Some seem to be working in preserving their heritage as is with help from international backing and diversifying tourist activities, like in Sado Island.

Studying, visiting, and engaging these three sites from a research point of view has helped me gain a deeper understanding of how extractive landscapes influence the communities that are built by them, as well as gaining a deeper viewpoint of rural Japan that I wasn’t able to get from living in Tokyo during my study abroad program and internship in years past. Industry and community is a topic I originally worked on for my undergraduate research thesis, albeit unable to visit the case study sites I had chosen. This opportunity finally allowed me to bridge the gap between research and field study, grounding my understanding in first-hand experience and gaining new contacts that I otherwise would’ve been unable to get.

Naoshima

Teshima

Inujima

Osaka

Sapporo

Otaru

Yubari

Mikasa

Niigata

Sado

Nagoya

Tokyo