Lisboa 5 vales

Encontro de Urbanismo 2023

Lisboa, A Cidade dos Vales

Urban Planning Meeting 2023 Lisbon, The City of Valleys Lisbon 5 valleys

FICHA TÉCNICA

Promotor: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Editora: Have a Nice Day

Título: “Lisboa – 5 Vales”

Textos: Fátima de Sousa – Have a Nice Day e Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Fotos: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Coordenação editorial:

Ana Rita Ramos – Have a Nice Day

Revisão editorial: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Paginação e design: Eva Vinagre e Maria Amorim – Have a Nice Day

Tradução: WordAholics

Impressão e acabamento: VRBL

Depósito legal: 541590/24

CREDITS

Promotor: Lisbon City Council

Editor: Have a Nice Day

Title: “Lisboa – 5 Vales” / Lisbon “5 Valleys”

Texts: Fátima de Sousa – Have a Nice Day and Lisbon City Council

Photography: Lisbon City Council

Editorial coordinator:

Ana Rita Ramos – Have a Nice Day

Revisor: Lisbon City Council

Pagination and design: Eva Vinagre and Maria Amorim – Have a Nice Day

Translation: WordAholics

Printing and finishing: VRBL

Legal deposit: 541590/24

índice contents

Estratégia Strategy

Uma visão estratégica para Lisboa

A strategic vision for Lisbon

Carlos Moedas

Presidente da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Mayor of the City of Lisbon

Pensar o futuro de uma cidade com mais de dois milénios de história tem tanto de desafiante como de motivador. Trata-se de um exercício que exige visão estratégica, reflexão técnica e audácia política. Essencialmente, exige que identifiquemos oportunidades e apresentemos soluções. Foi com base nesta abordagem que desenvolvemos o Programa 5 Vales.

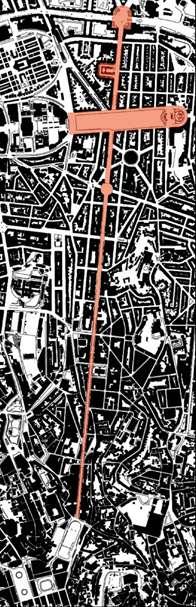

Tendo como ponto de partida o ciclo de conferências “Encontro de Urbanismo” de 2023, este programa nasce de uma abordagem inovadora e integrada de requalificação urbana, assumindo-se como uma resposta estratégica aos desafios de mobilidade, sustentabilidade e coesão social em Lisboa. A ideia de “Lisboa como cidade das sete colinas” inspira o plano de intervir nos vales situados entre essas colinas. Os cinco vales selecionados — Almirante Reis, Alcântara, Ajuda, Chelas e Santo António — representam áreas com características e necessidades distintas, mas partilham o potencial de integração social e requalificação urbanística.

Cada vale é objeto de uma abordagem personalizada e em linha com a Estratégia Lisboa 2040, para projetarmos uma cidade mais inclusiva, moderna e resiliente. Propomos uma abordagem estrutural, que vá desde a requalificação do espaço público no Vale da Avenida Almirante Reis – tornando a área mais verde, mais acessível e mais segura – até à construção de 2.400 habitações no Vale de Santo António.

No contexto de uma visão integrada do território, o Programa 5 Vales representa o compromisso deste Executivo com uma urbanização inclusiva e orientada para o futuro, colocando sempre o bem-estar das pessoas no centro das suas prioridades.

Reflecting upon the future of a city with more than two millennia of history is as challenging as it is motivating. This reflection requires strategic vision, technical consideration and political boldness. Essentially, it requires us to identify opportunities and deliver solutions. It was based on this approach that we developed the 5 Valleys Programme.

Using the 2023 “Urban Planning Meeting” series of talks as a stepping stone, this programme is the result of an innovative and integrated approach to urban regeneration as a strategic response to the challenges of mobility, sustainability and social cohesion in Lisbon. The idea of “Lisbon as a city of seven hills” inspired the plan to take action in the valleys nestled between these hills. The five selected valleys – Almirante Reis, Alcântara, Ajuda, Chelas and Santo António – are areas with different characteristics and needs, but all share the potential for social integration and urban regeneration.

A personalised approach will be followed for each valley, in line with the 2040 Lisbon Strategy to design a more inclusive, modern and resilient city. We propose a structural approach, ranging from the renewal of the public space in the Avenida Almirante Reis Valley – making it greener, more accessible and safer – to the construction of 2,400 homes in the Santo António Valley.

Taking an integrated view of the territory, the 5 Valleys Programme embodies the City Council’s commitment to inclusive and forward-thinking urban planning, putting people’s well-being at the heart of its priorities.

Pensar Cidade Think City

Joana Almeida

Vereadora com o pelouro do Urbanismo

na Câmara Municipal de Lisboa

Councillor for Urban Planning at the Lisbon City Council

Lisboa é, frequentemente, associada à imagem da cidade das sete colinas. São na verdade bem mais do que sete, mesmo considerando apenas a sua área histórica central, mas o facto é que esta topografia desafiadora define a imagem única da cidade e contribui para a sua identidade muito própria. No entanto, se são as “colinas” que mais visibilidade têm, é nos vales, entre elas, que muitos dos espaços vitais da cidade se desenvolvem. Os vales da cidade albergam todos os principais corredores de mobilidade, das avenidas à rede de metropolitano, a rede de drenagem e boa parte da estrutura verde da cidade.

Alguns estão completamente consolidados, como o Vale da Avenida da Liberdade, mas outros apresentam ainda problemas de compatibilização de usos, uma rede viária incompleta, ou estão ainda por consolidar ou requalificar. É nestes espaços, que atuam frequentemente como barreiras e descontinuidades no território, que paradoxalmente estão as maiores oportunidades de consolidar, equilibrar e dar mais verde e coesão social à cidade.

Foi precisamente por reconhecermos a importância deste desafio, e oportunidade, que estabelecemos o “5 Vales” como um dos programas estratégicos do Urbanismo da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Este programa tem como dois principais objetivos eliminar barreiras (melhorando a conectividade entre os vales) e promover a coesão territorial e social (ligando o tecido urbano, completando a estrutura verde e criando novas ligações pedonais e cicláveis).

Lisbon is often associated with the image of the city of seven hills. There are in fact far more than seven, even when only its historic centre is considered. Indeed, this challenging topography is what shapes the city’s unique image and gives it its very own identity. All the same, while it is famous for its “hills”, many of the city’s living spaces occupy the valleys between them. Lisbon’s valleys are home to all major mobility corridors, from avenues to the metro network, the sewer system, and much of the city’s green structure.

Some are fully consolidated, such as the Avenida da Liberdade Valley, while others still face functional incompatibilities, an unfinished road system or have yet to be consolidated or overhauled. It is these areas, which often act as barriers and discontinuities in the territory, that paradoxically offer the greatest opportunities to consolidate, balance, create more green spaces and achieve social cohesion in the city.

It was precisely because we recognise the importance of this challenge, and opportunity, that we established “5 Valleys” as one of the Lisbon City Council’s strategic urban planning programmes. The two main goals of this programme are to remove barriers (by improving connectivity between valleys) and to promote territorial and social cohesion (by stitching together the urban fabric, completing the green structure and creating new foot and cycle paths).

Para estes cinco vales, que representam espaços fundamentais na estrutura funcional da cidade, o Programa 5 Vales define estratégias e implementa projetos integrados para melhorar/ /requalificar/reconstruir os vales e a sua envolvente:

Vale de Chelas

O grande vale da zona oriental da cidade caracteriza-se pela incompleta articulação entre malhas, que geram isolamento e afastamento entre bairros. Urge completar ligações através, e ao longo, do vale. Muito em breve, a área central receberá o novo Hospital de Lisboa Oriental, que será o motor de regeneração urbanística da envolvente, no que designamos de uma nova “Cidade da Saúde”. Estamos a trabalhar numa estratégia integrada, suportada por uma Operação de Reabilitação Urbana que promova a melhor articulação entre os bairros, a conclusão da estrutura verde e requalificação ambiental do bairro e permita a coordenação de intervenções de entidades da administração central, local e de privados na produção de habitação e alojamentos estudantis, reforço da oferta de equipamentos e serviços de proximidade.

The 5 Valleys Programme sets out strategies for the five valleys, which are vital spaces in the city’s functional structure, and implements integrated projects to improve/ renew/rebuild the valleys and their surroundings.

This large valley in the eastern part of the city has unfinished connections between networks, which isolate and create distance between neighbourhoods. Completion of connections through and along the valley is urgently required. The downtown area will soon see construction of the new Lisboa Oriental Hospital, the driving force behind the urban regeneration of the surrounding area, which we call a new “City of Health”. We are working on an integrated strategy, underpinned by an Urban Renewal Operation promoting improved connection between the neighbourhoods, completion of the green structure and environmental renewal of the neighbourhood, and enabling coordination of actions by central and local government entities and private companies for the production of housing and student accommodation, increasing the supply of local amenities and services.

Vale de Santo António

Este vale situa-se bem no centro da cidade e representa a última grande oportunidade de desenvolvimento nesta área de 48 ha, sendo o município proprietário da quase totalidade. Trata-se de um território como uma configuração desafiante, mas como uma localização excecional e vistas privilegiadas sobre o Estuário. A CML, através da alteração ao Plano de Urbanização, está a planear um bairro sustentável, inovador, e que dá resposta à carência de oferta habitacional acessível, dirigida a famílias e jovens da cidade, com oportunidade de criação de cerca de 2.400 fogos. No centro do bairro situar-se-á um novo parque urbano, com área equivalente a dois jardins da Estrela, que vem dar resposta de oferta de espaços verdes numa das áreas da cidade com maior carência a este nível. Estão previstos mais de 15 novos equipamentos públicos, distribuídos pela área, e uma rede de apoio à mobilidade suave, os quais contribuem para a criação de um bairro próximo e acessível.

This valley is located right in the heart of the city and represents the last major development opportunity in this 48-hectar area, almost all of which is owned by the City. It presents a challenging landscape but is in a prime location and has privileged views over the Estuary. The Lisbon City Council, through the amendment of the Urbanisation Plan, is planning the (re)development of a sustainable, innovative neighbourhood to address the shortage of affordable housing for families and young people in the city, opening up an opportunity to create around 2,400 homes. A new city park, spanning an area the size of two Jardim da Estrela parks, will be implemented in the centre of the neighbourhood, providing green spaces in one of the areas of the city where they are sorely needed.

More than 15 new public amenities are planned for the area, as well as a soft mobility support network, all of which will help create an accessible and coalescent neighbourhood.

Vale da Almirante Reis

Este eixo fundamental da cidade está a ser objeto de um estudo aprofundado e integrado. O processo participativo, concluído em 2023, foi o mais participado de sempre para um espaço público da cidade, contando com mais de 2.500 contributos. Os lisboetas querem uma avenida mais amiga do peão, com mais espaço de convívio e maior segurança, mais arborizada e fresca. A proposta em desenvolvimento procura harmonizar os diferentes modos de transporte, criando mais espaço para os transportes públicos e bicicletas, sem comprometer a circulação automóvel, e revê toda a lógica de organização do perfil, prevendo um corredor arborizado contínuo, do Martim Moniz à Praça do Areeiro – o novo Passeio Verde de Lisboa.

This major artery of the city is currently the focus of an in-depth and integrated study. The participatory process, which concluded in 2023, saw the most engagement ever for a public space in the city, with over 2,500 contributions. The people of Lisbon want a more pedestrian-friendly avenue, with more space for socialising and a safer, cooler city, with more trees. The draft proposal seeks to harmonise the different modes of transport, creating more space for public transport and bicycles, without impeding motor traffic, and reworks the organisation of the area, envisaging a continuous tree-lined corridor from Martim Moniz to Praça do Areeiro squareLisbon’s new Green Promenade.

Vale de Alcântara

Estamos a desenvolver um plano integrado para este vale, focado na harmonização das intervenções sobre o espaço público, na melhoria da conectividade pedonal e na conclusão de um corredor verde contínuo. Na extremidade inferior, o vale terá uma nova estação de metro, em torno da qual se criará um dos principais interfaces de transportes da cidade que que integrará, no futuro, uma nova estação ferroviária na ligação direta entre a linha de Cascais e a linha de Cintura e a linha de transporte coletivo, em sítio próprio, que servirá a Ajuda e Belém. Toda a área será objeto de um projeto de redesenho do espaço público, que dotará de coerência e harmonia um conjunto de intervenções na zona baixa de Alcântara e permitirá unir e cerzir malhas urbanas hoje desconexas, através da criação de uma rede contínua de espaços públicos requalificados. Assim, se promoverá o reforço da acessibilidade pedonal e ciclável entre os bairros que se desenvolvem ao longo da Avenida de Ceuta e ambas as encostas do vale, bem como a consolidação do corredor verde do Vale de Alcântara.

We are developing an integrated plan for this valley, focused on harmonising works involving public space, improving pedestrian connectivity, and completing a continuous green corridor. At the lower end, the valley will have a new metro station, around which one of the city’s main transport hubs will be created. This hub will include a new railway station with a direct connection between the Cascais line and the Cintura line, and a public transport line, on a dedicated site, serving Ajuda and Belém. The entire area will be the focus of a project to redesign public space, ensuring consistency and harmony in a series of works in the lower end of Alcântara and connecting and joining urban networks that are currently disconnected by creating a continuous network of renewed public spaces. This will improve pedestrian accessibility and cycle paths between the neighbourhoods that line Avenida de Ceuta and both slopes of the valley, as well as consolidate the green corridor of the Alcântara Valley.

Vale da Ajuda

Este vale, ou melhor, vales, é repositório de um conjunto patrimonial e arqueológico único. No entanto, entre monumentos nacionais e museus de enorme qualidade e relevância, persistem vazios urbanos, fruto de sucessivas intervenções urbanísticas incompletas ou descontextualizadas. O resultado é uma malha urbana desestruturada, onde ligações entre bairros permanecem incompletas. O “remate” do Palácio Nacional da Ajuda, que apenas recentemente se concluiu, é espelho do tipo de ferida que persiste nesta área da cidade, onde bairros de diferentes épocas e tipologias nos surgem incompletos, com quarteirões por rematar, vias de ligação que terminam em impasses e uma certa ausência de espaços públicos qualificadores e unificadores. A estratégia de intervenção passa, assim, pelo estudo conjunto das malhas e intenções urbanísticas e preparação de uma rede coerente de espaços públicos e ligações viárias, com vista à qualificação urbanística e valorização patrimonial, ambiental e paisagística desta área da cidade, bem como do conjunto monumental ímpar que alberga.

This valley, or rather valleys, is home to a unique heritage and archaeological site. However, between national monuments and impressive and important museums, urban voids persist as a consequence of successive incomplete or haphazard urban works. The result is an unstructured urban environment, where connections between neighbourhoods are frayed. The “finishings” of the Ajuda National Palace, which were only recently completed, personify the still gaping wound in this area of the city, where neighbourhoods from different eras and various types appear incomplete, with unfinished city blocks, connecting roads that lead to nowhere, and a lack of quality and unifying public spaces. The intervention strategy thus involves a joint study of the urban networks and aspirations, and the preparation of a coherent network of public spaces and transport connections, with a view to the urban regeneration and enhancement of the heritage, environment and landscape of this area of the city, and that of the unique monuments and museums it houses.

Para dinamizar e dar voz a este programa, promovemos o ciclo de conferências

Encontro de Urbanismo dedicado ao tema “5 Vales”, realizado no CIUL – Centro de Informação Urbana de Lisboa, em 2023. Assistimos a um conjunto de intervenções de enorme qualidade, que nos estimularam a aprofundar ainda mais esta aposta.

Neste sentido, e dada a enorme qualidade das intervenções, a dedicação dos participantes e a relevância de divulgarmos o programa de requalificação destes vales, decidimos fazer uma edição destas conferências, perpetuando em palavras, memórias, ideias e conceitos.

É muito bom “Pensar Cidade” e poder deixar escrito o fantástico trabalho que desenvolvemos juntos.

To make this programme more dynamic and give it a voice, in 2023 we held the Urban Planning Meeting series of talks on the theme “5 Valleys”, at the Lisbon Urban Information Centre (CIUL). The quality of the talks was outstanding, encouraging us to pursue this endeavour even further. Accordingly, and given the excellent talks, the dedication of the participants and the importance of publicising the redevelopment programme for these valleys, we decided to create a publication relating to these talks, recording in words memories, ideas and concepts. It’s great to “Think City” and to be able to document the amazing work we’ve done together.

Vale de Chelas

20 de abril de 2023 20 April 2023

Moderador Moderator

José Correia

Divisão de Planeamento Territorial, CML

Spatial Planning Division, CML

Oradores Speakers

João Pedro Falcão de Campos

Falcão de Campos, Arquitecto Architect

José Veludo

Npk – Arquitectos Paisagistas Associados

Álvaro Fernandes

Divisão de Reconversão de Áreas Urbanas de Génese Ilegal, CML Division for the Conversion of Illegally Built Urban Areas, CML

Vale de Chelas e seu entorno: um valor (incomum) da cidade

Chelas Valley and its surroundings: an (exceptional) city

asset

O chão da cidade define-se pelos cambiantes geográficos e geomorfológicos, que dão estrutura e marca distintiva à paisagem e imagem da cidade. O vale de Chelas e seu entorno têm a marca do seu chão: um vale com uma bacia extensa (7 km2), de natureza complexa – topográfica e ecológica/ /ambiental –, que ao longo de séculos foi sendo ocupado, apropriado, modelado, construído e habitado. Estes processos densificaram a matriz do seu chão, que as dinâmicas e constrangimentos societais cimentaram numa estratificação de estruturas e infraestruturas, no seguinte encadeamento cronológico:

• Até ao início do séc. XIX, enquanto arrabalde da cidade, fixa-se uma primeira camada que deriva da relação natural e sistémica do vale com a frente ribeirinha. Esta paisagem rústica é pontuada pelas estruturas notáveis do convento e dos mosteiros;

• Com as vagas de industrialização do séc. XIX, dá-se o incremento do eixo ribeirinho Santa Apolónia - Braço de Prata (Rua do Açúcar) e consequente valorização portuária, que vão “fechando” a relação natural e sistémica entre vale e frente ribeirinha. Implantam-se, neste eixo, complexos fabris e vilas operárias. Em paralelo, a ferrovia impõe-se e progressivamente,

The city floor is shaped by the geographic and geomorphological changes that give structure and distinctive features to the city’s landscape and image.

Chelas Valley and its surroundings are a hallmark of its floor: a valley with an extensive (7 km2) and (topographically and ecologically/environmentally) complex basin which, over the centuries, has been occupied, appropriated, shaped, built and inhabited. These processes increased the density of the soil matrix, which social dynamics and constraints cemented into a stratification of structures and infrastructures, in the following chronological sequence:

up until the beginning of the 19th century, as a city suburb, a first layer is deposited derived from the natural and systemic relationship between the valley and waterfront. This rural landscape is dotted with the remarkable structures of the convent and monasteries;

the waves of industrialisation in the 19th century ushered in the expansion of the Santa Apolónia - Braço de Prata (Rua do Açúcar) waterfront area and consequent port development, which “terminated” the natural and systemic relationship between the valley and the waterfront. Factory

até aos dias de hoje, vai rasgando o vale: primeiro transversalmente (junto ao rio) e depois prolongando-se para montante, impactando fortemente esta paisagem;

• Já no séc. XX, a partir das décadas de 50 e 60, o que foi o arrabalde, perante uma cidade em forte expansão, projeta-se agora como periferia de primeira linha: o entorno do vale absorve modelos e políticas direcionadas para a habitação; são planeados e edificados bairros e grandes ensembles de habitação, em contextos de grande pressão demográfica e política. Paralelamente, o impulso industrial perde vigor, criando bolsas, mais ou menos contínuas, de espaços vacantes em toda a frente ribeirinha, que se mantêm até aos dias de hoje.

Indelevelmente marcado que está este chão por estas sobreposições, é lugar comum olhar este extenso trecho de cidade como fragmentado, desconexo e até disruptivo.

No entanto, é imperativo (re)pensar este chão igualmente como lugar incomum: de valor na relação habitar e habitat; de valor enquanto centralidade; de valor na relação da cidade com o rio e seu estuário; de valor na relação entre a cidade compacta e a cidade “jardim”; de valor da(s) identidade(s) e pertença; de valor multicultural e plural; de valor de ecossistemas (água e solo); de valor da caminhabilidade e da mobilidade sustentável; e de valor na transição alimentar e na economia circular.

Pensar o fazer cidade desafia e convoca a (re)pensar este chão como um mosaico incomum de identidades de lugar (Tópos), impregnado de energia potencial regenerativa (Utopos) que é a energia vital de mobilização de utopias reais, para assim reconhecer o valor incomum deste território para a cidade, que “não tem só sete colinas, nem cinco vales”.

José Correia Divisão de Planeamento Territorial, CML

complexes and workers’ villages were erected along this axis. In parallel, the railway took root and progressively, and to this day, tears through the valley. First transversely (along the river) and then extending upstream, forever altering the landscape;

in the 20th century, from the 1950s and 1960s onwards, what had been a suburb is now projected as a prime area on the outskirts of a rapidly expanding city: the area surrounding the valley takes up housing models and policies; neighbourhoods and large housing estates are planned and constructed under great population and political pressure. At the same time, the industrial momentum waned, creating somewhat continuous pockets of vacant areas all along the waterfront, which remain to this day.

Despite the indelible mark left on the city floor by these overlaps, it is commonplace to see this vast stretch of city as fragmented, disconnected and even disruptive.

That said, one must (re)think this city floor as an exceptional place, one offering value in the relationship between habitation and habitat; as a centrality; in the city’s relationship with the river and its estuary; in the relationship between the compact city and the “garden” city; in identity(ies) and the sense of belonging; multicultural and plural value; ecological value (water and soil); walkability and sustainable mobility; in food transition and the circular economy.

Reflecting on building a city challenges and invites us to (re)think this floor as an exceptional mosaic of place-based identities (Topos), impregnated with potential regenerative energy (Utopos), the life force for mobilising real utopias, so as to recognise the exceptional value this territory adds to the city, which “doesn’t just have seven hills or five valleys”.

verde green

Verde é o futuro que se antecipa e se ambiciona para o Vale de Chelas.

Green is the future and what Chelas Valley aspires to.

Verde é o futuro que se antecipa e se ambiciona para o Vale de Chelas, o segundo vale mais expressivo de Lisboa na sua dimensão. É um território emoldurado pela principal linha de água de Lisboa – o rio Tejo – e por três conventos – o de Chelas, na sua centralidade interior, e os de Xabregas e da Madre de Deus, ambos na boca do vale. E que sofreu, historicamente, dois cortes abruptos: a construção do Porto de Lisboa e a edificação da linha ferroviária, com Santa Apolónia como ponto nevrálgico, os quais, nas palavras de José Correia, moderador da sessão, constituem “uma profunda barreira no contacto com a frente ribeirinha”. Também as sucessivas ações de urbanização imprimiram marcas de uma indelével descaracterização e disfuncionalidade, com a expansão da zona oriental, nos anos 90, a acentuar a incoerência territorial.

Green is the envisaged future and the one aspired to for Chelas Valley, Lisbon’s second largest valley. The area is enveloped by Lisbon’s main waterway – the Tagus River – and by three convents – Chelas, at its inner centre, and Xabregas and Madre de Deus, both at the mouth of the valley. Historically, the land saw two abrupt reductions: the construction of the Port of Lisbon and the laying down of the railway line, with Santa Apolónia as its central station, which, in the words of José Correia, moderator of the session, created “a profound barrier to contact with the riverfront”. Successive urban works also left indelible marks, stripping the area of its character and causing dysfunction, with the expansion of the eastern part of the valley in the 1990s accentuating the territorial disjointedness.

harmonia harmony

O vale carece, pois, de uma visão qualificadora, para a qual contribuíram os dois arquitetos convidados para esta sessão, ambos com pensamento e trabalho sobre este que é o segundo maior dos cinco vales que imprimem as suas marcas na topografia e na demografia de Lisboa.

O olhar de João Pedro Falcão de Campos começou por recuar no tempo, até às tentativas de urbanização do vale, nos anos 60, para se fixar nas repercussões dessas medidas sobre a atualidade. Repercussões ao nível da pobreza e, muitas vezes, da ausência de equipamentos, “introduzidos de forma avulsa e de má qualidade”, muitos ainda com muros e arame farpado à volta. A título de exemplo, mencionou o Bairro da Flamenga, com 8 mil habitantes servidos por um único café. Exemplificativa é, igualmente, a ausência de calçada à portuguesa, com o cimento a ser o revestimento de eleição. Do mesmo modo, também os espaços verdes foram alvo da ausência de planificação: “Foram-se fazendo umas intervenções”, sintetizou.

Nesses anos, em que o zonamento – delimitação de áreas de solo homogéneas, quase sempre com segregação espacial dos usos – estava na ordem do dia, o vale enfrentava um desafio anunciado: “Já se previa um novo grande hospital, que se anunciou em 2008, 2009, mas não aconteceu”. Mais tarde, novo desafio anunciado e também por concretizar: a terceira travessia do Tejo.

No entretanto, “o que ficou por construir foram os equipamentos”: “Não se construíram escolas, não se construíram zonas comerciais. Ficou a habitação, normalmente circundada por grandes vias, como que uma gola com quatro faixas, se bem que fizesse parte do esquema rodoviário uma cintura periférica e um atravessamento automóvel numa via principal. Ao não se fazerem equipamentos, tudo ficou completamente descosido”, sublinhou.

An enhanced and holistic approach is thus needed, to which the two architects invited to this session have contributed, both of whom have reflected and worked on this, the second largest of the five valleys that shape Lisbon’s topography and demography.

João Pedro Falcão de Campos began by contemplating the past, the attempts to urbanise the valley in the 1960s, focusing on the repercussions of these measures on the present. Repercussions on poverty and, often, the lack of amenities, “desultory and of poor quality”, many still surrounded by walls and barbed wire. By way of example, he mentioned the Flamenga neighbourhood, with 8,000 inhabitants served by a single café.

The absence of traditional cobblestone pavements is also illustrative, with cement being the coating of choice. Similarly, the green spaces also lacked planning. “Works were carried out here and there,” he summarised.

In the 1960s, when zoning – delimitation of homogeneous areas of land, almost always with spatial segregation of uses – was the order of the day,

the valley faced a notorious challenge. “A large new hospital was planned, announced in 2008/2009, but it didn’t happen.” Later, a new challenge was announced, which is also yet to materialise: the third Tagus River crossing.

Yet, “no public amenities were provided”. “No schools were built, no shopping centres. Only housing, usually engulfed by major thoroughfares, like a four-lane ring road, although the planned road network included a peripheral ring road and a crossing on a main road. By not including amenities, there was no cohesion at all,” he stressed.

urbanização

Municipal

Chelas: agosto de 1965 (agosto de 1965,

–

de referência PT/AMLSB/PAE/PURB/01/0015) | Chelas urban development plan: August 1965 (August 1965, Lisbon Municipal Archive – Photographic Archive, Reference code PT/AMLSB/PAE/PURB/01/0015)

Não houve consolidação desde os anos 60, não obstante uma tentativa no final dos anos 90, recordou, com a quadra (ou quarteirão), “com um propósito bondoso, que consistia em, num só gesto, juntar quatro bairros – Flamenga, Amendoeiras, Armador e Condado – e atrás deste grande centro comercial e da habitação vinha uma rede viária, com rails e túneis”. O propósito era “bondoso”, mas a diferença de cotas faz com que, muito dificilmente, os bairros consigam aceder à quadra, “com a agravante de que a passagem de um lado para o outro se faz através do supermercado e de uma pequena ponte”. “O resto é tudo desnivelado”, notou, descrevendo este cenário como “um autêntico rodilhão do ponto de vista urbano”. Neste contexto, e convidado a (re)pensar o vale, Falcão de Campos propõe a sua transformação no segundo grande pulmão da cidade. Uma proposta que vai beber ao plano original para Chelas: “Como, defendendo o vale, podíamos ter uma densificação e uma continuidade de verde, consolidando-o com uma grande massa arbórea”. A curto-médio prazo, é “uma solução de requalificação”, uma resposta, à semelhança da experiência do vizinho bairro de Alvalade, com a sua diversidade de tipologias de habitação, e, parcialmente, do bairro do Restelo, que conseguiu criar centralidade com baixa volumetria.

There has been little or no consolidation since the 1960s of the city block, despite an attempt in the late 1990s, Falcão de Campos recalled, “with good intent to, in one swoop, unite the four neighbourhoods –Flamenga, Amendoeiras, Armador and Condado – with a road network, including rails and tunnels, running behind this large shopping centre and housing”. Their intentions were “good”, but the difference in elevation makes access to the block by the neighbourhoods very difficult, “made worse by having to cross a supermarket and small bridge to get to the other side”. “The rest is all uneven,” he noted, describing it as “complete chaos from an urban point of view”.

Bearing this in mind, and invited to (re)think the valley, Falcão de Campos proposes to transform the valley into the city’s second major lung. A proposal that builds on the original plan for Chelas.,“since, by sustaining the valley, we could increase the density and create continuity of green space, consolidating it with a large mass of trees.” In the short to medium term, it is “a regeneration solution”, a response, similar to that implemented for the neighbouring Alvalade neighbourhood, with its housing diversity, and, partially, for the Restelo neighbourhood, which created low-volume centrality.

“O Vale de Chelas carece, precisamente, de coerência, de coesão, traduzidas em ligações transversais, ligações ao rio, maior profundidade de penetração em termos ecológicos e requalificação urbana. Carece, em suma, de uma visão qualificadora.”

“Indeed, Chelas Valley lacks congruence, cohesion, translated into transversal connections, connections to the river, greater depth of eco-penetration and urban regeneration. In short, it lacks an enhanced and holistic approach.”

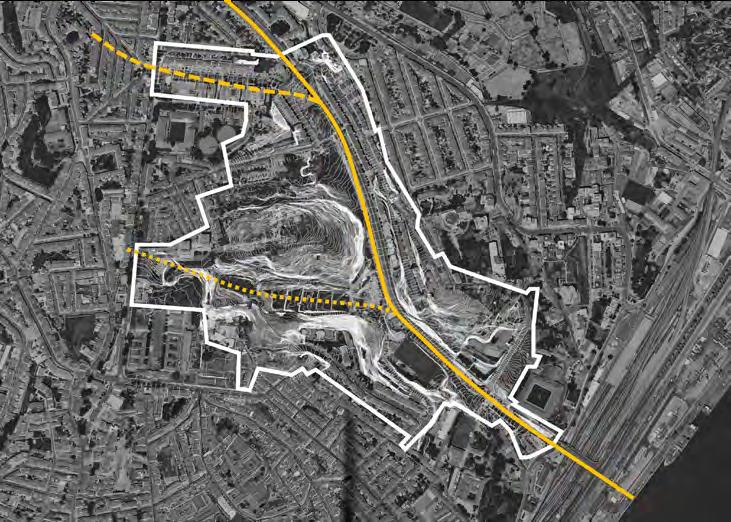

PLANTA GERAL DA PROPOSTA – ESTRATÉGIA

Planta Geral da Proposta – Estratégia (Falcão de Campos Arquitectos, LDA., NPK – Arquitectos Paisagistas Associados, LDA. e ABAP – Alçada Baptista Arquitectura Paisagista, LDA.) | General Layout included in the Proposal - Strategy (Falcão de Campos Arquitectos, LDA., NPK - Arquitectos Paisagistas Associados, LDA. and ABAP - Alçada Baptista Arquitectura Paisagista, LDA.)

São exemplos que demonstram que é “perfeitamente possível” harmonizar habitação e espaços verdes. O que implica planeamento: no caso concreto do Vale de Chelas, e antecipando que o novo Hospital de Todos os Santos será edificado na zona do Armador, impõe-se refletir sobre o impacto da circulação automóvel, com soluções de estacionamento que não minem o usufruto do bairro e com a criação de uma sequência de percursos de espaços públicos. É exatamente este o desafio subjacente à área atualmente ocupada com a designada “Feira do Relógio”, que Falcão de Campos encara como merecedora de um projeto dignificante. Afinal, são 1,5 km passíveis de disciplina, não apenas nos dias de feira, nomeadamente com o desenho de um passeio público até ao Metro e ao centro comercial.

O potencial existe, neste espaço e em todo o Vale de Chelas e nos seus bairros. O desígnio, esse, passa pela criação de novas centralidades, com equipamentos robustos – como bibliotecas ou espaços de utilização mista, para práticas sociais, culturais e desportivas – que aportem qualidade à população residente.

These examples demonstrate that it is “perfectly possible” to harmonise housing and green spaces. This, however, requires planning. Specifically in the case of Chelas Valley, and assuming that the new Todos os Santos Hospital will be built in the Armador area, the impact of motor traffic must be considered, offering parking solutions that do not frustrate enjoyment of the neighbourhood and creating a sequence of public pathways. This is exactly the challenge posed by the area currently occupied by the so-called Relógio Flea Market, which Falcão de Campos sees as deserving of a dignified project. After all, it encompasses the use of an area spanning 1.5 kilometres, not just on market days, including designing a public walkway to the Metro and the shopping centre.

This space and the entire Chelas Valley area and its neighbourhoods definitely have potential. The goal is to create new centralities with robust public amenities, such as libraries or mixed-use spaces for social, cultural and sporting activities, that improve the quality of life of the resident population.

equilíbrio balance

Estudo de Viabilidade do Corredor Oriental do Vale de Chelas (julho de 2016, NPK e Falcão de Campos Arquiteto) | Feasibility Study for the Chelas Valley Eastern Corridor (July 2016, NPK and Architect Falcão de Campos)

No cumprimento desse futuro, a coesão não está sozinha: o equilíbrio é também palavra-chave. E foi o fio condutor da intervenção de José Veludo, chamado a pensar o futuro parque hospitalar na zona oriental de Lisboa e que, neste encontro de urbanismo, se pronunciou sobre o corredor verde do Vale de Chelas. Deixou que algumas interrogações conduzissem a sua reflexão, a saber: “Com que peso e com que dimensão a construção deve estar no espaço vazio do vale? Vamos ter ou não mais construção?”. E, antes de partilhar a sua perspetiva, convidou a um primeiro olhar sobre a cidade no seu todo: “Não tenho dúvidas de que não existe equilíbrio entre o sistema natural e o sistema cultural. Não estamos numa situação em que, com pequenas correções, consigamos alcançar esse equilíbrio, no qual acredito”, comentou, defendendo “uma presença do sistema natural muito maior”.

Na sua opinião, esta maior convivência entre natural e cultural deve advir da existência de natureza de forma espontânea. “Não chega acrescentar mais um jardim, mais um parque, mais um corredor de arborização. É necessário acrescentar natureza de forma a que possa ter características suficientes para que seja espontânea, para que possa existir sem que se esteja a trabalhar sobre ela”. Monsanto é o exemplo desta premissa: “Tem uma dimensão tal que produz muito mais benefícios do que toda a energia que lá colocamos. Consegue ter dimensão para gerar uma espontaneidade natural que não depende de nós.” Alicerçou esta visão, afirmando que existem muitos sítios no parque florestal que as pessoas não conhecem, mas onde “a planta, o animal e a bactéria funcionam sem impacto da água de rega ou do corte”. “Funcionam por si só e a cidade precisa disso”, advogou.

To achieve this future, cohesion is not enough. Balance is also key. This was the leitmotiv of José Veludo’s talk, who was asked to contemplate the future hospital complex in the eastern part of Lisbon and who, at this urban planning meeting, shared his thoughts about the Chelas Valley green corridor. In his reflection, he posed several questions, in particular “How important is and how big should the building be in the empty space of the valley? Will there be more construction?”. Before sharing his views, he invited us to first look at the city as a whole. “Obviously, there is no balance between the natural and the cultural systems. We are not in a situation where, with small corrections, we can strike this balance, which I believe is needed,” he commented, championing “a much greater presence of the natural system”.

In José Veludo’s opinion, this greater coexistence between nature and culture should emerge spontaneously from the existence of nature. “It’s not enough to just add another garden, another park, another corridor of trees. We need to add enough nature so that it thrives spontaneously, so that it can exist without intervention.” Monsanto is an example of this premise. “It is so big that it produces far more benefits than all the energy we put into it. Its size enables natural spontaneity that doesn’t depend on us.” He consolidated his perspective by saying that there are many places in the forest park that people are unfamiliar with, but where “flora, fauna and bacteria survive and thrive without irrigation or mowing”. “They flourish on their own and the city needs that,” he argues.

A propósito, José Veludo alertou que se vive uma fase de emergência em que é necessário acelerar esta coexistência. De volta ao Vale de Chelas, manifestou a convicção de que se impõe assumir que “este é o último espaço com dimensão suficiente e com continuidade que pode criar características que permitam à natureza existir com espontaneidade e sem intervenção humana”. Não obstante, chamou a atenção para o risco de se distorcer a lente com que se olha para este futuro: “O vale não é um espaço que sobra, não podemos olhá-lo como um grande vazio. O natural é o elemento identitário e de coesão entre os bairros, se as margens forem bem tratadas e se as ligações estiverem acauteladas com equipamentos da vida social e urbana”. São 285 ha com potencial de valorização como corredor verde.

A questão das margens não é um pormenor. O arquiteto lembrou que, historicamente, o centro do vale foi ocupado com construções, submetido a um processo de transformação, drástico em termos ambientais, desencadeado com a introdução do tecido industrial, um tema inicialmente abordado pelo moderador da sessão, José Correia. À medida que se instalavam fábricas de maior dimensão, mais pessoas eram atraídas para trabalhar e maior a intervenção sobre a paisagem. A linha de caminho de ferro veio protagonizar novo conflito com o sistema natural, com a ligação a Santa Apolónia a “soterrar”, de certa forma, dois dos

hectares

com potencial de valorização como corredor verde

In this regard, José Veludo warned that we are in a state of emergency in which we need to speed up this coexistence. Bringing his focus back to Chelas Valley, he expressed the belief that “this is the last space of sufficient size and continuity that can create characteristics that allow nature to exist spontaneously and without human intervention”. Nevertheless, he pointed out the risk of distorting the lens through which we look at this future: “The valley is not useless space, one must not look at it as a large void. The natural environment is the identity and cohesive element between neighbourhoods, if the riverbanks are well cared for and the connections are furnished with amenities for social and urban life.” There are 285 hectares with potential for redevelopment as a green corridor.

The issue of boundaries is not a detail. The architect recalled that, historically, the centre of the valley was occupied by buildings and saw a drastic transformation from an environmental perspective, brought about by the introduction of industry, a topic initially touched upon by the moderator of the session, José Correia. As larger factories were set up, the more people flocked to work in the area and the greater the impact on the landscape. The railway line brought a new conflict with the natural system, with the connection to Santa Apolónia, in a sense, “burying” two of the convents that lined

hectares

with potential for redevelopment as a green corridor

conventos que demarcam o vale, o de Xabregas e o da Madre de Deus. A construção da ETAR implicou uma nova apropriação do território, acentuando a desconexão.

Em consequência, há “uma profundidade em relação ao Tejo que está a ser desperdiçada”. E só as encostas, onde é difícil construir, travaram a urbanização. Porém, também eles se afirmam como elementos de desconexão, na medida em que, entre os bairros a nascente e os bairros a poente, a ligação só é possível através de pontes pedonais, porquanto 100 metros de distância correspondem, na prática, a um quilómetro. Focando-se na mobilidade, defendeu que o olhar devia ter sido transferido das ligações longitudinais, entre norte e sul, através do vale, para as ligações transversais, dentro do vale.

the valley, Xabregas and Madre de Deus. The construction of the wastewater treatment plant also ate away the land, deepening the divide.

Consequently, “the depth of the Tagus is being wasted”. Only the hillsides, which are difficult to build on, halt

urban development. That said, they are also elements of disconnection, in that between the neighbourhoods to the east and the neighbourhoods to the west connection is only possible via pedestrian bridges, where a distance of 100 metres in practice corresponds to one kilometre. Turning to mobility, José Veludo argued that the focus should shift from longitudinal connections between north and south, through the valley, to transversal connections within the valley.

E, dentro do vale, retomou a questão do espaço público, para subscrever a necessidade de o parque verde funcionar como elemento de coesão, fazendo o remate dos bairros e acrescentando os equipamentos que faltam, incluindo largos de encontro entre as pessoas e zonas de atravessamento.

Nesta coesão, “a grande ambição” que, porventura, é também “a grande utopia” envolve a demolição de uma parte das construções.

“Tudo criteriosamente selecionado, no sentido de perceber quais as zonas habitacionais coesas, conservando os bairros que funcionam bem”, advogou, notando que grande parte das demolições propostas constituem edifícios camarários em ruínas. A reorganização da ETAR integra este portefólio de soluções, de modo a “não ocupar tanto o vale” e a permitir trazer de novo a ribeira à superfície.

Esta é uma questão que se prende com o sistema hídrico da cidade. O arquiteto especificou que a entrega das propostas para o corredor verde de Chelas coincidiu com a apresentação do plano de drenagem de Lisboa. “Não temos dúvida de que vai resolver alguma frequência das cheias, mas a custo de enorme investimento e de mais uma infraestrutura de que vamos ter de cuidar no futuro”, comentou, contrapondo com a criação de pequenas bacias com capacidade para, numa situação de chuva intensa, armazenar 28 mil m3, “o que é relevante, pois equivale aos depósitos que o plano de drenagem tinha preparados”. Ora, com esta solução, além de atrasar as cheias na entrada do vale, potencia-se a infiltração de água que vai ser o suporte da natureza espontânea.

“Para o sistema natural voltar a funcionar no Vale de Chelas, não há outra maneira. O urbanismo não faz milagres”: foi o comentário final que partilhou, resumindo as propostas elencadas.

And, within the valley, the architect returned his focus to the issue of public space, agreeing that the green park should serve as a cohesive element, connecting the neighbourhoods and adding the needed amenities, including meeting places for people, and crossings.

In this cohesion, “the great ambition”, which is perhaps also “the great utopia”, involves tearing down some of the buildings. “Everything has been carefully selected for an understanding of which housing areas are cohesive, preserving the neighbourhoods that work well,” he said, noting that most of the proposed demolitions are of dilapidated municipal buildings. The restructuring of the wastewater plant is included in the solutions put forward, so as to “not take up so much of the valley” and to bring the stream back to the surface.

This is an issue that relates to the city’s water system. The architect specified that the submission of the proposals for the Chelas green corridor coincided with the presentation of Lisbon’s drainage plan. “This will without a doubt reduce flood frequency, but requires significant investment and other infrastructure that will have to be maintained in the future,” he commented, suggesting the creation of small basins with the capacity to store 28,000 cubic metres during heavy rainfall, “which is relevant because it is equivalent to the collection tanks envisaged in the drainage plan.”

Besides delaying flooding at the entrance to the valley, this solution increases water infiltration to help nurture spontaneous nature.

“This is the only way for the natural system to flourish again in Chelas Valley. Urban planning can’t perform miracles”. This was the final comment he shared, summarising the proposals made.

identidade identity

As pessoas são incontornáveis na transformação, pela impressão digital que deixam no território, mas também pelo modo como a sua vivência é impactada pela própria transformação.

People are elements that cannot be ignored in this transformation, because of the digital imprint they leave on the land, and because of the way their lives are impacted by the transformation itself.

E foi sobre o modo como pessoas e território se têm moldado, ao longo do tempo, no Vale de Chelas que interveio Álvaro Fernandes. E fê-lo com base no conhecimento acumulado enquanto membro da equipa multidisciplinar da Unidade de Intervenção Territorial Oriental que, em 2015, assumiu a missão de promover um diagnóstico que fundamentasse um conjunto de eixos para intervenção em Chelas. A saber: regeneração da habitação existente, renaturalização do vale, restruturação da rede de acessibilidades e mitigação do impacto das infraestruturas.

eixos para intervenção

axes of intervention

It is precisely on how people and the land have adapted over time in Chelas Valley that Álvaro Fernandes focused his talk. And he did so using the knowledge he accumulated as a member of the multidisciplinary team of the Eastern Territory Task Force, which, in 2015, conducted an assessment that would inform a set of axes of intervention in Chelas. These include regeneration of existing housing, renaturalisation of the valley, restructuring of the accessibility network, and mitigating the impact of infrastructure.

Regeneração da habitação existente regeneration of existing housing

Renaturalização do vale renaturalisation of the valley

Restruturação da rede de acessibilidades restructuring the accessibility network

Mitigação do impacto das infraestruturas mitigating the impact of infrastructure

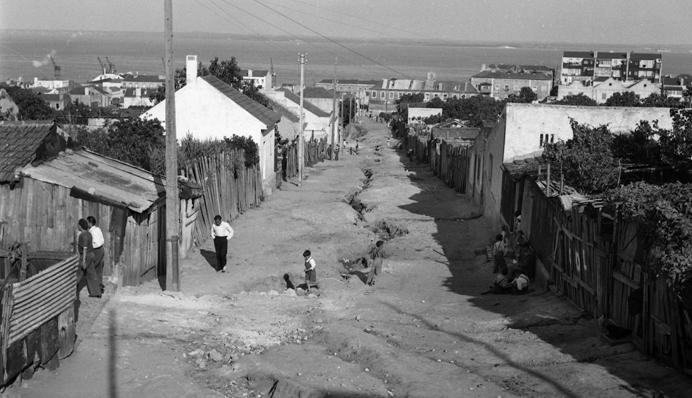

Um diagnóstico alavancado no espaço e no tempo, com a identificação de duas datas de referência no vale – 1885, ano da construção do caminho de ferro, e 1998, o ano da Expo98, que trouxe alterações tão profundas que se estendem à atualidade. Igualmente identificados foram dois espaços que marcam o território: a Estação de Santa Apolónia e a Fábrica de Gás da Matinha. A industrialização é, pois, um fenómeno decisivo, como já haviam assinalado os oradores anteriores, e os números atestam-no: em 1890, há registo de 156 fábricas, em 1942, ascendiam a 270. Em 1915, contavam-se cerca de 15 mil trabalhadores e em crescendo, o que impulsionou a criação de pátios e vilas – conjuntos habitacionais com uma estrutura social muito própria, que mimetizava a hierarquia das empresas. Com o êxodo rural, há um crescimento exponencial de toda a zona, alastrando pelas azinhagas e quintas a montante do vale, de que são exemplo a Curraleira, o Casal do Pinto e o Bairro Chinês.

Este movimento viria a conhecer uma face obscura, pois, entre 1980 e 2011, constata-se um esvaziamento do lugar, acompanhado da sua estigmatização. A decadência urbana acompanhou o declínio demográfico. Álvaro Fernandes sublinhou que, no estudo de 2015, foi possível identificar populações em situação limite, quase na exclusão, com atividades económicas muito desqualificadas. E isto devido a um aparente paradoxo: o vale oferecia alternativas de habitação, pelo facto de ser central, mas, como era isolado, em termos de sociologia urbana, constituiu-se como um espaço de exclusão ao centro.

As assessment conducted in space and time, pinpointing two reference dates in the valley: 1885, the year the railway was built, and 1998, the year Expo98 was held in Lisbon, both of which ushered in changes so profound that their effects are felt to this day. Two spaces that marked the territory were also identified, Santa Apolónia Station and the Matinha Gas Plant. Industrialisation was therefore a pivotal phenomenon, as previous speakers also pointed out, and the figures clearly attest to this. In 1890 a total of 156 factories were set up and in 1942 there were 270, and in 1915 there were around 15,000 workers, with the number progressively increasing, which led to the creation of courtyards and worker’s villages – housing estates with their own social structure mimicking the corporate hierarchy. With the rural exodus, the entire area saw exponential growth, spilling over into the alleyways and farms upstream of the valley, such as Curraleira, Casal do Pinto and Bairro Chinês.

This trend would bring with it a dark side. Between 1980 and 2011 the area would be abandoned and stigmatised. Urban decay accompanied population decline. Álvaro Fernandes pointed out that the 2015 study identified people living in extreme situations, in social exclusion, with highly unskilled economic activities, due to an apparent paradox: the valley offered housing alternatives because it was centrally located, but because it was isolated, in terms of urban sociology, it was a place of exclusion from the centre.

“Como é que chegamos ao estigma social e urbano daquele espaço?”,

questionou, sustentando que “há um conjunto de equipamentos que cria centralidade, mas isso não se reflete no vale. Os movimentos de entrada e saída fazem-se por portais, mas o fluxo de pessoas – estimado em 5 mil por dia, incluindo turismo – não influencia o vale. Não obstante, há oportunidades, como a localização do Ar.co [Centro de Arte & Comunicação Visual,

no antigo Mercado de Xabregas], a reabilitação das azinhagas e das antigas quintas para usos sustentáveis, bem como a divulgação da história do património material e imaterial do vale. Subsistem, contudo, algumas ameaças, em que pontua a terceira travessia do Tejo, com o risco de descaracterização e de perda de unidade e identidade.

São pontos de reflexão para o que Álvaro Fernandes preconizou como “linhas de orientação ética para uma intervenção” em Chelas. Para um território que se deseja regenerado, criativo, vibrante. E verde. Naturalmente.

“How did we arrive at this social and urban stigma?”,

he asked, arguing that “there are several public amenities that create centrality, but this is not reflected in the valley. Gateways facilitate inflows and outflows, but the flow of people (estimated to be 5,000 per day, including tourism) does not affect the valley. Nevertheless, there are opportunities to exploit, such as the location of Ar.co [Centre for Art & Visual Communication, housed in the old

Xabregas Market], the restoration of alleyways and farms for sustainable uses, as well as showcasing the history of the valley’s tangible and intangible heritage. Some threats remain, however, including construction of the third Tagus River crossing, with the risk of de-characterisation and the loss of unity and identity.

These are points of reflection on what Álvaro Fernandes recommended as “ethical guidelines for an intervention” in Chelas. For a regenerated valley, creative and vibrant. And green. Naturally.

Bairro chinês junto ao campo de futebol do Oriental (c. 1950, Judah Benoliel, Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa – Arquivo Fotográfico, Código de referência PT/AMLSB/ CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/JBN/004886) | Bairro Chinês shanty town near the Oriental football field (c. 1950, Judah Benoliel, Lisbon Municipal Archive - Photographic Archive, Reference code PT/AMLSB/ CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/JBN/004886)

Vale de Santo António

6 de julho de 2023 6 July 2023

Moderador Moderator

Paulo Pardelha

Departamento de Planeamento Urbano, CML

Urban Planning Department, CML

Oradores Speakers

João Veríssimo

Lisboa Ocidental SRU – Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana

João Sousa Morais

Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa

Faculty of Architecture, University of Lisbon

Paulo Torres

Associação Regador

O Vale de Santo António: uma oportunidade imperdível Santo António Valley: an

extraordinary opportunity

Nesta edição do Encontro de Urbanismo, em que se debateu a Cidade dos Vales, o Vale de Santo António gerou grande expectativa e curiosidade, tendo tido grande participação.

De facto, quando atravessamos o Vale de Santo António, através da Avenida Mouzinho de Albuquerque, ou quando espreitamos o vale, através do Alto da Eira ou do Alto do Varejão, somos invadidos por um sentimento de interrogação e inquietude perante a dimensão e aparente aridez que se vislumbra neste território.

Um território situado a menos de 2.000 m de distância do centro da histórica Baixa Pombalina, num percurso serpenteado onde encontramos o Castelo de São Jorge, São Vicente de Fora, o Panteão Nacional, Santa Clara e onde, logo após a Rua General Justiniano Padrel, nos deparamos com umas “ruínas modernas”, resquício do que esteve para ser o grande Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa.

Um vale que nos projeta, a norte, para o centro interior da Cidade, ligando-nos ao vale da Almirante Reis e que, a sul, encontra o rio numa relação tensa intermediada pela linha do norte e pela área portuária.

In this session of the Urban Planning Meeting, focusing on the City of Valleys, the Santo António Valley raised high expectations and aroused curiosity, with a large turnout.

Indeed, when crossing Santo António Valley via Avenida Mouzinho de Albuquerque, or when looking out over the valley from Alto da Eira or Alto do Varejão, we are overcome by a sense of puzzlement and unease at the size and seeming aridness of the area.

It is located less than 2,000 metres from Lisbon’s historic city centre, on a winding route along which one can find São Jorge Castle, São Vicente de Fora, the National Pantheon, Santa Clara and where, just after Rua General Justiniano Padrel, lie “modern ruins”, the remains of what was once the Lisbon Municipal Archive.

A valley that takes us north towards the inner centre of the city, connecting us to the Almirante Reis valley, and which, to the south, meets the river in a tense relationship mediated by the Northern Line and the port area.

Uma área expectante, mas não inoperativa, pois cumpre funções ecológicas importantes para a cidade como, por exemplo, a função de ventilação e de arrefecimento das áreas mais internas do território.

Um vale que apresenta algumas disfunções – rutura na malha urbana, efeito barreira, desencontros entre tecidos urbanos.

Um território que foi recebendo algumas intervenções com maior ou menor impacto urbanístico e social.

Uma área da cidade ainda por desenvolver, não porque não tenha havido planeamento, projetos, ações, vontades e um Plano de Urbanização em vigor.

O Vale de Santo António é… um território à procura da sua identidade, do seu futuro, à procura do seu encontro com as pessoas.

Temos pela frente, nos próximos anos e gerações, o desafio de recuperar este vale e amplificar as suas valências ecológicas. Um desafio moldado por uma proposta urbanística sensível à orografia do vale e às populações da envolvente, que acrescente e some, através do desenvolvimento de políticas públicas de habitação municipal sustentável e acessível; bem como de políticas de mobilidade e acessibilidade transformadoras do paradigma ainda atual.

Temos pela frente o desafio de poder mobilizar esforços financeiros e competência para concretizar um novo Vale de Santo António, inclusivo, resiliente, ecológico, inteligente e acessível.

Estão todos convocados, pois a oportunidade é imperdível.

Paulo Pardelha Departamento de Planeamento Urbano, CML

A locality in limbo, but functional, as it fulfils important ecological functions for the city, such as ventilation and helping cool inner-city areas.

A valley plagued by some dysfunction – a break in the urban fabric, a barrier effect, inconsistency between urban surroundings.

A place that has seen several interventions with greater or lesser urban and social impact.

An area of the city that has yet to be developed, and not due to a lack of planning, projects, actions, willingness or an urban development plan.

Santo António Valley is... a place in search of its identity, its future, in search of its encounter with people.

In the coming years and generations, we face the challenge of recovering this valley and enhancing its ecological benefits. A challenge shaped by an urban design proposal that takes account of the valley’s orography and its populations, which multiplies and grows, with the development of public policies for sustainable and affordable municipal housing, as well as mobility and accessibility policies that transform the current paradigm.

We face the challenge of mobilising financial contributions and expertise to create a new Santo António Valley that is inclusive, resilient, environmentally friendly, smart and accessible.

We call upon everyone to join in this effort, as this is an extraordinary opportunity.

luz light

Iluminar. Renaturalizar.

Requalificar. São estes os verbos que guiam a vontade de intervir no Vale de Santo António, resgatando-o a um passado que o cognominou de “vale escuro”. Um vale onde, não obstante a secundarização e o quase esquecimento a que foi votado, germinam sementes de esperança na sua mutação em “vale claro”.

Brighten. Replant.

Redevelop. These are the goals that guide the desire for intervention in Santo António Valley, rescuing it from a past which saw it nicknamed the “dark valley”. A valley where, despite being relegated to an insignificant and forgotten area, seeds of hope have been planted to transform it into a “bright valley”.

Este é um território que, como sublinhou o moderador da sessão, Paulo Pardelha, surge, quase sempre, como uma área da cidade ainda por desenvolver: não – ressalvou – por ausência de vontades, projetos, ações, existindo, inclusivamente, um plano de urbanização em vigor. “É um vale ainda expectante, embora não completamente inoperativo”, na medida em que cumpre funções essenciais para a cidade, nomeadamente de ventilação e arrefecimento. Porém, nele subsistem disfunções do ponto de vista da ligação entre territórios – permanecem barreiras, desencontros entre tecidos urbanos, que as intervenções feitas ao longo dos anos não lograram terraplanar. E, por isso,

“é um espaço ainda à procura do seu espaço”.

The moderator of the session, Paulo Pardelha, pointed out that this locality is almost always seen as an area of the city that has yet to be developed – not, he stressed, due to a lack of willingness, projects and actions; there is even an urban development plan in force. “It is a valley in limbo, but functional” insofar as it fulfils essential functions for the city, in particular ventilation and cooling. However, there are still dysfunctions in terms of the connection between territories – there are still barriers, inconsistency between urban surroundings – which the interventions carried out over the years have not addressed. And so,

“it is a space still looking for its place”.

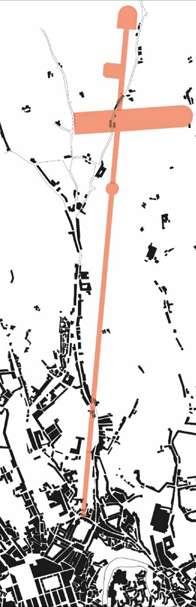

antecedentes background

Foi precisamente sobre o espaço que se debruçou o arquiteto João Veríssimo, coautor da proposta de alteração ao plano de urbanização do vale. O processo de desenhar novos eixos de intervenção fê-lo viajar no tempo, regressando ao que definiu como antecedentes de um plano e aos sucessivos momentos deste território em transformação. E nesta viagem pela cartografia e demais espólio documental, encontrou um território sulcado praticamente de norte a sul por uma avenida –a Mouzinho de Albuquerque – enquadrada por duas elevações geradoras de uma significativa mudança de cota em todo o vale. Um vale que não é apenas um, mas três. Dois subsidiários, escavados por linhas de água que, atualmente, são apenas teóricas, porquanto foram sendo anuladas com a evolução. E é pelo vale principal – o da avenida –que se desemboca no Convento de Santos-o-Novo e no Rio Tejo, “num percurso que aparenta ser luminoso, mas que é algo lúgubre, dada a estrutura de caminhos de ferro que tapava completamente” esse final – o atual Viaduto de Santa Apolónia.

It was precisely this space that was the focus of the talk by architect João Veríssimo, co-author of the proposal to amend the valley’s urban development plan. The design of new axes of intervention saw him travel back in time, returning to what he defined as the history of a plan and the ensuing events in this area in transformation. And on his journey through cartography and other documents, he found a locality plied by an avenue – Aveinda Mouzinho de Albuquerque – practically from north to south and framed by two slopes that cause a significant change in elevation across the valley. Not just one valley, but three. Two subsidiary valleys, carved out by theoretical water lines, erased by evolution. And it is through the main valley – plied by the avenue – that one reaches the Santos-o-Novo Convent and the Tagus River, “on a route that is bright but somewhat gloomy, because of the railway structure completely overshadowing” the destination – today the Santa Apolónia Viaduct.

João Veríssimo recordou, igualmente, como este era um território relativamente ocupado – com quintas e algumas residências desordenadas, mas, ainda assim, “uma ocupação bastante relevante”, nomeadamente na que viria a ser a Avenida General Roçadas. A população era, predominantemente, constituída por trabalhadores dessas quintas, que eram quintas de produção e muitas das quais sobreviveram quase até à atualidade. Mas o vale foi-se abrindo à indústria e novos habitantes chegaram – os operários. E é com eles que ganham forma as chamadas vilas – a Vila Gadanho e a Vila Cândida são vestígios desse fenómeno na atual freguesia da Penha de França. Tal como o bairro operário dos Barbadinhos, “desenhado e aprovado em tempo de Ressano Garcia”, em 1890, pela Companhia Comercial Construtora. Embora não sendo de génese municipal, é um bairro de estilo cooperativo, com habitação modular “de um rigor extremo”, tendo resultado de um movimento popular de trabalhadores fabris que se batiam por um bairro acessível. Contudo, este movimento viria a distorcer a razão de ser do projeto: ao gerar o interesse público, os preços aumentaram, tornando-o inacessível aos seus destinatários originais. Era atrativo: afinal, na descrição do arquiteto, era composto por habitações “extremamente cuidadas”, já com um corredor, o que era raro nas vilas do século XIX, com princípios higienistas, nomeadamente ventilação transversal, e um rigor modular extensível às fachadas, “na ótica de minimizar custos”. Acresce que era um bairro equipado – com escola e mercado –, mais uma vez algo inédito na Lisboa de 1890. Razões de sobra para se ter convertido num conjunto habitacional bastante valorizado.

João Veríssimo also recalled how this was a relatively busy area, with farms and a few haphazard dwellings, but nevertheless “a fairly significant occupation”, particularly along what would become Avenida General Roçadas. The population consisted predominantly of the workers of production farms, many of which have survived to the present day. But the valley gradually opened up to industry and new inhabitants arrived – labourers. This saw emergence of the so-called worker’s villages – Vila Gadanho and Vila Cândida are the remnants of this phenomenon in what is today the parish of Penha de França. Just as the Barbadinhos working-class neighbourhood, “designed and approved in the time of Ressano Garcia”, in 1890, by Companhia Comercial Construtora. Although not erected by the City, it is a co-op neighbourhood with “very robust” modular housing, the result of a popular movement of factory workers who were fighting for an affordable neighbourhood. This movement would, however, distort the raison d’être of the project: by generating public interest, prices increased, making it unaffordable for the original beneficiaries. It was an attractive estate, after all, in the architect’s description, it comprised “carefully crafted” homes, with a corridor, which was rare in 19th-century villages, principles of hygiene, namely cross ventilation, and a robust modular structure that extended to the façades, “with a view to minimising costs”. What’s more, the neighbourhood had public amenities – a school and a market –again something unheard of in 1890 Lisbon. It is thus not surprising that it became a highly sought-after housing estate.

Quinta dos Peixinhos, vista do poente (abril de 1944, Eduardo Portugal, Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa – Arquivo Fotográfico, Código de referência PT/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/EDP/000594) | Quinta dos Peixinhos, view from the west (April 1944, Eduardo Portugal, Lisbon Municipal Archive - Photographic Archive, Reference code PT/AMLSB/ CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/EDP/000594)

Caminho que vai dar ao convento de Santos-o-Novo, onde atualmente existe a avenida Mouzinho de Albuquerque (1961, Artur João Goulart, Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa – Arquivo Fotográfico, Código de referência PT/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/AJG/000825) | Path leading to the Santos-o-Novo convent, currently Avenida Mouzinho de Albuquerque (1961, Artur João Goulart, Lisbon Municipal Archive - Photographic Archive, Reference code PT/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/AJG/000825)

No decurso da elaboração da revisão do plano de urbanização para o vale, muitos foram os planos que se ofereceram ao olhar investigador da equipa. A maioria nunca executada, mas alguns planos assinados por nomes de peso. E o que mais despertou a atenção – “Estudo Base para a Urbanização do Vale Escuro”, de 1957 –tem precisamente a chancela de dois desses nomes, o arquiteto Bartolomeu Costa Cabral e o arquiteto paisagista Francisco Caldeira Cabral. Não passou, porém, de um estudo, apresentando a particularidade de abranger um limite que “extravasa em muito” o do atual vale, o que, na ótica de João Veríssimo, “faz todo o sentido”, na medida em que está associado ao da Calçada das Lajes: “Só assim se consegue cerzir as malhas urbanas e viárias que estão interrompidas atualmente”, comentou, considerando que este é um plano de um “rigor enorme”, com a mais-valia de ter conseguido colar quase todas as implantações à orografia, com exceção da Avenida Machado Santos.

Esta avenida foi sendo lançada na imagem da cidade já no século XX, como eixo de atravessamento nascente-poente – uma diretriz a que este plano não pôde obstar, mas, ainda assim, introduzindo “implantações interessantes, que tentaram, e bem, não ocupar o vale”, evitando conjuntos habitacionais mais herméticos que pudessem erguer-se como barreiras visuais e, assim, libertando o vale para a sua permeabilidade e fertilidade. “É um plano excecional” que contrasta com outros dois identificados – um de 1932, que é de um “formalismo imenso”, com recurso a praças e outros símbolos de época, com vias lançadas em “inclinações tremendas”, e um outro da década de 1970, o “Plano de Urbanização do Vale Escuro”, apenas parcialmente executado.

Estes são antecedentes “extremamente interessantes e pouco conhecidos” e que ajudam a compreender a história do vale, agora sujeito a nova vontade de intervenção.

While revising the valley’s urban development plan, the team’s sharp eye looked over a myriad plans. Most never made it out of the drawer, but some were designed by respected architects. One in particular drew the most attention, the “Baseline Study for Urban Development of the Dark Valley”, conducted in 1957 by two such respected architects, Bartolomeu Costa Cabral and the landscape architect Francisco Caldeira Cabral. It was, however, only a study, but it included the detail of a boundary that “stretches far beyond” that of the current valley, which, in João Veríssimo says “makes perfect sense”, as it is associated with that of Calçada das Lajes. “This is the only way to seamlessly join the currently disconnected urban environments and road networks,” he remarked, adding that it is a “carefully thought-out” plan, enhanced by the fact that they were able to implement nearly everything into the orography, with the exception of Avenida Machado Santos.

This avenue became the hallmark of the city as early as the 20th century, as a major eastwest crossing – a guideline that this plan could not ignore, nevertheless introducing “interesting implementations, rightly attempting not to occupy the valley”, avoiding hermetic housing developments that could be erected as visual barriers and thus opening up the valley to a plethora of new and exciting projects. “It is a magnificent plan” that contrasts with the other two identified, one from 1932, which is “extremely formal”, replicating the squares and other symbols of the time, with roads implemented on “very steep slopes”, and another from the 1970s, the “Urban Development Plan for the Dark Valley”, which was only partially implemented.

This is “extremely interesting and little-known” background information that helps to understand the history of the valley, now the subject of a renewed desire for intervention.

exemplos examples

Uma outra viagem se seguiu a esta incursão pelo passado do Vale de Santo António, uma viagem por um passado mais recente e por outras geografias impulsionada pela visão de planeamento de João Sousa Morais.

Another journey followed this foray into the past of the Santo António Valley, one that explored the more recent past and foreign lands, fuelled by João Sousa Morais’s vision of planning.

Nesta digressão por projetos que identifica como emblemáticos, Paris foi a primeira paragem, mais propriamente o “Barriére La Villette”, que nasceu da intenção de reabilitar um edifício do século XVIII na vizinhança do Canal de Saint-Martin: um “projeto lindíssimo”, assinado por Claude Nicolas Ledoux, mas que viria a quedar-se pela parte edificada, com o espelho de água e a esplanada desenhada como abraço ao edificado a desaparecerem, deixando-o isolado e sem significado do ponto de vista do território. Seria preciso esperar até à década de 80 do século XX para nova abordagem, esta protagonizada pelo ateliê Apur e pelo arquiteto Bernard Tschumi. O resultado, mais do que um projeto urbano, é um projeto de arranjos exteriores, com a arborização a tapar o viaduto ali existente –um resquício da intervenção anterior – e o canal a recuperar o seu lugar central. E o que antes era uma zona marginal da cidade metamorfoseou-se num gerador urbano, fruto desta experiência totalmente financiada pela Mairie de Paris.

In this tour of what he refers to as iconic projects, Paris was the first stop, specifically the “Barriére La Villette”, born of the intention to restore an 18th century building near the Canal de Saint-Martin neighbourhood, a “sublime project”, signed by Claude Nicolas Ledoux, but which would ultimately be limited to the building, doing away with the water mirror and the esplanade embracing the building, leaving it isolated and rendering it meaningless, from a spatial perspective. Only in the 1980s would a new approach be followed, one led by Apur studio and architect Bernard Tschumi. More than an urban project, the result is an exterior design project, with trees covering the existing viaduct – a remnant of the previous intervention – and the canal once again being the centrepiece. And what was once a marginalised area of the city metamorphosed into an urban generator; the product of an experiment funded entirely by the City of Paris.

Estugarda Stuttgart

De França para a Alemanha, é Estugarda a cidade que acolhe o projeto Avenida 21, que ganhou corpo entre 1993 e 2000 pelas mãos do estúdio gmp Architekten. E, nesta paragem, um preâmbulo se impõe: é que, como atestou o orador, a Alemanha tem uma perspetiva “muito interessante” de planeamento, assente na premissa de que ao investimento deve corresponder retorno financeiro. O cenário da intervenção é a ferrovia, mais concretamente a estação central da cidade, e o seu impacto na malha urbana: uma estrutura pesadíssima, recordou, que constituía uma barreira muito relevante do ponto de vista urbano. A resposta encontrada envolveu a sua substituição por um monocarril elétrico, emoldurado por uma estrutura verde naturalmente diluidora do embate visual. Foram intervencionados 70 ha, com o plano de financiamento cumprido a 100% e o investimento a pagar-se a si próprio. E com o adicional de ter sido o pretexto para regenerar grande parte da cidade.

From France onto Germany, Stuttgart is home to the Avenida 21 project, which took shape between 1993 and 2000 at the hands of gmp Architekten studio. At this point, a foreword is in order. As the speaker pointed out, Germany has a “very interesting” view of planning, based on the premise that financial return should match the investment. The focus of the intervention was the railway, more specifically the city’s central station, and its impact on the urban fabric. A huge structure, he recalled, forming a significant urban barrier. The solution found involved replacing it with an electric rack railway, framed by a green structure, softening its visual impact. Works encompassed a total of 70 hectares, with the financing plan executed in its entirety and the investment paying for itself, with the added bonus of having served as the pretext to regenerate a large part of the city.

Nantes

Desfecho diferente teve o terceiro exemplo desta lição: de regresso a França, para conhecer as linhas mestras do Quartier Atlanpole, projeto de 1988 do arquiteto e urbanista francês Christian de Portzamparc, a cujo traço foram entregues 400 ha para construir uma cidade tecnológica num espaço rural junto a Nantes, parcialmente atravessado por uma autoestrada. “Corresponde à minha visão de planeamento expedito. É um projeto que é desenhado e tem uma metodologia própria”, sustentou, reconhecendo-lhe, como virtudes, a relação entre as várias tipologias de construção e o modo como os quarteirões absorvem a estrutura rural pré-existente. Não veria, porém, a luz do dia nesta localização, acabando por ser transferida para norte da cidade.

Lisboa

O Vale de Santo António é o ponto de chegada deste olhar sobre o planeamento urbano, com o estudo promovido por João Sousa Morais, no âmbito do Mestrado em Arquitetura na FAUL, visando perceber qual a relação com a envolvente, “complexa e diversa”. Constata-se que o vale foi sendo ocupado de forma muito distinta ao longo do tempo, resultando numa situação complexa do ponto de vista orográfico. “Tínhamos algumas perspetivas e a primeira foi tentar salvaguardar a estrutura viária, perceber o que poderia ser reutilizado”, descreveu, adicionando a esta leitura a análise dos vários bairros, nas suas diferentes dimensões, isto é, da morfologia urbana às tipologias construídas. Foi “uma ronda muito importante para se perceberem as ligações existentes no vale, até porque uma das funções fundamentais da arquitetura urbana e da arquitetura da cidade é garantir a continuidade com o tecido urbano pré-existente”.