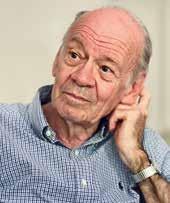

Jean-François Monnard

Jean-François Monnard

The texts in this publication are based on the prefaces to the Ravel editions edited by Jean-François Monnard and have been partly revised or expanded in this context.

PB 5299 Bolero

PB 5374 La Valse

PB 5530 Rapsodie espagnole

PB 5539 Valses nobles et sentimentales

PB 5540 Le Tombeau de Couperin

PB 5532 Tableaux d’une exposition

PB 5650 Daphnis et Chloé

PB 5716 L’Heure espagnole

PB 5753 L’Enfant et les Sortilèges

BV 515

ISBN 978-3-7651-0515-9

© 2025 by Breitkopf & Härtel KG

Walkmühlstraße 52

65195 Wiesbaden / Germany info@breitkopf.com www.breitkopf.com

All rights reserved

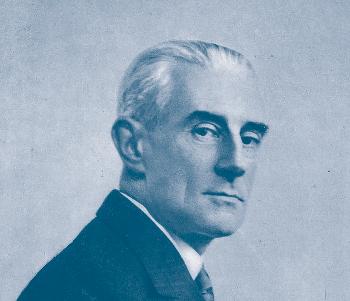

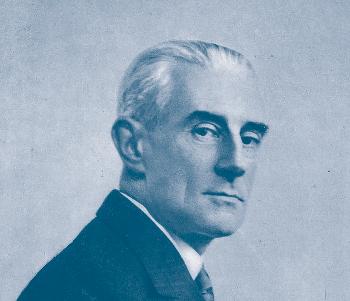

Cover photos: Portrait M. Ravel © picture alliance / Heritage Images / Lipnitzki Portrait J.-F. Monnard © Breitkopf & Härtel / Arthur Mildner

Cover design: Tankred Steinicke (Breitkopf & Härtel)

Layout and Typesetting: Tankred Steinicke (Breitkopf & Härtel)

Printing: Plump Druck & Medien GmbH, Rheinbreitbach

Printed in Germany

Jean-François Monnard of Lausanne (Switzerland), conductor, musicologist, and Ravel specialist, is the editor of Breitkopf & Härtel’s Urtext editions of works by Maurice Ravel. The collaboration between Breitkopf & Härtel and Monnard began in 1997 with a new critical edition of La Valse and was followed by further editions of the composer’s orchestral and stage works until this day.

For the 2025 Ravel anniversary, we interviewed Jean-François Monnard about his editorial work and his relationship to Ravel’s music.

Breitkopf & Härtel: Mr. Monnard, what for you is special about the composer Maurice Ravel?

Jean-François Monnard: First and foremost is Ravel’s work of always the same high caliber. But also fascinating is Ravel, the man, how he slips, intellectually sovereign, into the role of magician and illusionist. And finally, his modernity making him a forerunner of our time, while at the same time remaining a contemporary of his own time.

B&H: How did you approach Ravel’s work in your role as editor?

JFM: The adventure began in the 1990s, when Breitkopf & Härtel approached me, suggesting that I edit a critical edition of La Valse, “from the viewpoint of a conductor concerned with the reliability of the music text and the resulting performancepractice consequences.”* The first step was then a visit to the French National Library in Paris to obtain a copy of the first printed score, continued thereafter by ordering from the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York a photocopy of the autograph score authorized by Ravel. This was followed by a thorough examination and analysis of the documents, leading to a search for further sources. This research wasn’t always easy, but I was fortunate in being supported by experienced editors.

B&H: The work on the individual editions took several years. Have your goals changed during this time?

JFM: My aim was not so much to better understand Ravel’s works, but rather to be better able to listen to the music text, immersing myself in it and recognizing all its subtleties in order to be better able to respect the composer’s intention and to grasp the ideas underlying it. Such an aim calls for a step-by-step approach, in which a discipline characterized by objectivity and freed of emotional states must be just as important as the necessary modesty to deal with masterpieces.

B&H: After the editing of Ravel’s major symphonic orchestral works, you prepared the first critical edition of the ballet music for Daphnis et Chloé. It is generally known that the first edition contained many errors. What did you do to correct these errors?

JFM: Detecting errors is a real sport, and since in my first life I was a conductor, I practiced that! In addition to the wrong notes, there are carelessly omitted nuances,

Having played the role of conductor in my first life, I continue to question the notes. In a different way, but with the same passion. Examining Ravel ’s manuscripts is a quest for truth. “The manuscript is the original source, through which we are placed in direct proximity to the work and its character.” 1 (András Schiff). The task is to decipher it with almost maniacal meticulousness, to question it relentlessly. By consulting the manuscript, we are fortunate to have access to details – erasures, corrections, scratches, stains – that disappear when the text is edited. In most cases, however, the manuscript cannot serve as an absolute reference. Indeed, a comparison between the manuscript and the first printed version often reveals numerous differences. It is therefore necessary to search, through painstaking and patient investigation, for the composer’s true intentions. This requires constant to-ing and fro-ing between sources, in order to gather well-established facts that can then be used to propose a reference version. It is always a lengthy process, involving trial and error before being able to transform a hypothesis into certainty. Intuition guides the research (even if it has to be challenged later), and the motive is that of rigor

Often, Ravel ’s notation raises questions about missing accidentals, missing slurs or nuances that lead into the void, where the musician in the orchestra is unaware of the dynamics required. Sometimes, even when doubt paralyzes our thinking, we are relieved and grateful for the advice of seasoned musicians, such as Charles Dutoit, who remains an incomparable interpreter of Ravel ’s work.

The study of Ravel ’s manuscripts also allows us to appreciate the excellence of the execution, the craftsmanship, the plastic beauty and the precision of the writing –traits common to most great creators, and always exemplary in the eyes of Henri Dutilleux. We know that Ravel made sketches and drafts that he corrected, but the fair copy is impeccable and offers us great aesthetic pleasure. I like to imagine the hand that traced the signs on the paper, to decipher the ideas of sound, to auscultate the promise of resonance that takes its rightful place in immobility, and to decant a little soul between the notes and the silences.

Although the object is not the same, the musicologist’s approach is similar to that of the archaeologist who, after clearing away the accumulated sand, discovers a treasure which he studies carefully before restoring it and freeing the resources hidden within. He puts nothing of himself into it, especially no subjectivity that might steal the work from its author. It is like bringing water out of the ground, a virtue proper to the dowser who, for his part, senses things.

Jean-François Monnard

1 András Schiff, Musik kommt aus der Stille. Gespräche mit Martin Meyer. Essays, Kassel 2017, p. 225.

1875 March 7: birth of Maurice Ravel in Ciboure.

1878 June 13: birth of brother Édouard in Paris.

1882 First piano lessons with Henry Ghys.

1888 Friendship with Ricardo Viñes.

1891 Admitted to Charles de Bériot’s piano class at the Paris Conservatoire.

1893 Acquaintance with Erik Satie.

1897 First contract with publisher Enoch (Menuet antique dedicated to Ricardo Viñes).

1898 Admitted to Gabriel Fauré’s composition class.

March 5: premiere of Sites auriculaires for 2 pianos by Ricardo Viñes and Marthe Dron, Salle Pleyel.

April 18: premiere of Menuet antique for solo piano by Ricardo Viñes, Salle Érard.

1899 May 27: premiere of Shéhérazade, Ouverture de féerie for orchestra under the direction of the composer, Nouveau-Théâtre.

1902 April 5: premiere of Pavane pour une infante défunte and Jeux d’eau for solo piano by Ricardo Viñes, Salle Pleyel.

1903 Acquaintance with Maurice Delage who became Ravel’s pupil and closest friend.

1904 March 5: premiere of the Quartet dedicated to Gabriel Fauré by the Quatuor Heymann, Schola Cantorum.

May 17: premiere of Shéhérazade for voice and orchestra by Jane Hatto under the direction of Alfred Cortot, Nouveau-Théâtre.

1905 June-July: cruise aboard Alfred and Misia Edwards’ yacht Aimée November: publication of Sonatine by Durand, who became the exclusive publisher of Ravel’s works.

* Sources:

Marcel Marnat, Maurice Ravel, Paris, 1986.

Maurice Ravel, Lettres, Ecrits, Entretiens, presented and commented by Arbie Orenstein, Paris, 1989. Roger Nichols, Ravel, New Haven, 2011.

Maurice Ravel, L’intégrale. Correspondance (1895–1937), écrits et entretiens, ed. by Manuel Cornejo, Paris, 2018.

“Dance,” wrote André Suarès, “holds sway over all of Ravel’s music ...” 1. This statement also applies perfectly to the Rapsodie espagnole (without h), although the work is not a ballet. Contrary to Bolero and La Valse, the Rapsodie espagnole is a symphonic work of absolute music, which was originally conceived for piano four-hands. It is a “rhapsody” in the broadest sense of the term. According to the ancient Greeks, the word “rhapsody” derives from rhápsôdos, which is put together of rháptein (sew, patch) and odè (song, poem) and means the patching together of various elements in song. In ancient Greece, the rhapsodist performer was a kind of traveling bard who recited epic poems, above all the verses of Homer. In time, the rhapsody freed itself from its textual references and evolved into an independent musical genre. It was later adapted to the orchestra by Franz Liszt in a development that was inspired by popular works with themes that were either national or regional, real or imaginary. His goal was to preserve the local color and the epic character of the rhapsody. In this sense, Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole most certainly deserves its name; one could compare it with a patchwork of Andalusian clichés.

Ravel sketched the four movements of the Rapsodie espagnole during a stay of four weeks aboard the yacht Aimée of Misia and Alfred Edwards in the summer of 1907. Three autograph pages (Source K) are preserved in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York; they contain a complete first draft of the Prélude à la nuit. They have neither tempo markings nor dynamic nuances save for a p expressif. Many accidentals are also missing. Ravel finished the complete version of the Rapsodie espagnole for piano duet in his residence in Levallois in October of that year, contemporaneously with the piano-vocal score of L’Heure espagnole. He completed the orchestration in February 1908, at which time he dedicated the work to Charles de Bériot, whose piano class Ravel had attended at the Paris Conservatoire from 1891 on. A letter to Ida Godebska 2 confirms that he corrected the proofs of the orchestral parts in late May/early June, which clearly shows that the changes in the autograph were entered during the rehearsals or even after the first performance of the piece, which took place at the Châtelet in Paris on 15 March 1908 conducted by Édouard Colonne. The rather grab-bag concert program began with the overture to Le roi d’Ys, which was followed by Schubert’s “Unfinished,” an excerpt from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Night Before Christmas, sung by Mme de Wieniawski, and Fauré’s Ballade for piano and orchestra played by Alfred Cortot. Then came the Rapsodie espagnole, followed by excerpts from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Snow Maiden, the Variations symphoniques by César Franck, again performed by Cortot, and finally the march from the second act of Tannhäuser. “The audience greeted

1 André Suarès, Pour Ravel, in: La Revue musicale, April 1925, p. 7.

2 Letter from Ravel to Ida Godebska of 22 May or 5 June 1908, see Maurice Ravel, Lettres, Ecrits, Entretiens, presented and commented by Arbie Orenstein, Paris, 1989, pp. 96f.

the work warmly – and very spontaneously, one might add.” 3 Only the Malagueña provoked a certain disquiet and was finally repeated at the behest of the public in the upper balcony, from where the thunderous voice of Florent Schmitt boomed out, demanding that it be played “once again for those down below who didn’t understand a thing.”

The Rapsodie espagnole consists of four sections. The Prélude à la nuit depicts the “weariness at the end of a hot day,” wrote Vladimir Jankélévitch.4 A motif consisting of the four notes F–E–D–Ck that returns in Malagueña and Feria actually does suggest the idea of a place where torpor and nonchalance give rise to a feeling of unending languor. This feeling is underscored by the binary rhythm which Ravel inserts into the triple meter. The cadencing entry of the clarinets and bassoons has an improvisatory feel and reveals the influence of Rimsky-Korsakov. Nevertheless, it is undeniable that Ravel favors an economy of means.

The Malagueña is a kind of Scherzo that evokes a dance in triple meter from the Costa Brava. The tempo of this dance is usually rather moderate. Ravel prescribes “Assez vif” and replaces the 3/8 time by a 3/4 time. The dynamics, which did not exceed a mf in the Prélude, become more explosive, and the entire percussion stands in sharp contrast to the suave melody of the English horn, which, through its melodic arc, singularly recalls the languid song of the bassoon solo in Alborada. And how can we not point out that Ravel chose the form of the malagueña for Gonzalve’s arietta in L’Heure espagnole

The third movement, the Habanera, is also a dance which recalls the young Ravel’s fascination with a Spain that was popularized and idealized in the stories told to him by his mother. “Whenever he wanted to portray Spain in music,” wrote Manuel de Falla, “he tended to use the rhythm of the habanera, the song which his mother had often heard in the Madrid ‘tertulias’ of times long past …” 5 This languorous scene is actually the orchestration of a piece for two pianos written in November 1895 and first performed with Entre Cloches under the joint title Sites auriculaires by Marthe Dron and Ricardo Viñes at the Société Nationale, the former Salle Pleyel, in Paris on 5 March 1898. “As the performers had rehearsed only little or not at all, there emerged such a grandiose mess that one completely forgot the calm Habanera that preceded it. Only Debussy paid close attention to the Habanera, this brilliant stroke of pianistic genius, by keeping it alive for posterity […]. Five years later, the master felt that he could adapt this little gem to his own purposes [Soirée dans Grenade].” 6 This led to a conflict between Debussy and Ravel about which Manuel Rosenthal reported to Marcel Marnat in his Souvenirs: “La Soirée dans Grenade from Debussy’s Estampes (1903) seems modeled upon the music of Ravel’s Habanera (1895), which had fallen into oblivion after its disastrous first performance in March 1898. Debussy had asked the young musician for a copy of the piece, as it interested him a great deal. Upon witnessing the encomiums lavished upon the Soirée dans Grenade, however, Ravel felt obliged to publicly announce that his piece was the earlier of the two. This prompted

3 Jean d’Udine, in: Le Courrier musical, 1 April 1908.

4 Vladimir Jankélévitch, Ravel, Paris, 1959, p. 44.

5 Manuel de Falla, in: La Revue musicale, March 1939.

6 Marcel Marnat, Faux-jours et pleine lumière: Ravel, in: Cahiers Maurice Ravel, no. 12, Séguier, 2009, p. 10.

Debussy to sever relations definitively with the younger man. Legend has it that a short while later, when Debussy was moving, the copy of the Habanera reappeared; it had fallen behind the piano … Ravel avoided throwing oil on the fire by orchestrating his work and inserting it – with its date of origin – into his Rapsodie espagnole as the third movement.” The author adds: “He [Ravel] never directly accused Debussy in front of me. Instead, he was elusive and said: ‘He [Debussy] kept it [the Habanera] longer than it was planned. I should have asked him more often to give it back to me.’” 7 It seems, moreover, that Debussy also “cast a sidelong glance” at the Jeux d’Eau as well, when he wrote Les Jardins sous la pluie two years later. In 1913 he spoke of the “phenomenon of autosuggestion” upon learning that Ravel had written Soupirs and Placet futile at the very same time.

In this context, it should come as no surprise that the last tableau of the Rapsodie espagnole, Feria, also slightly anticipates Debussy’s Iberia, completed in 1908. As the name suggests, Feria conjures up a bustling musical market that prefigures the Bacchanale from Daphnis et Chloé and borrows several motifs from the jota, a popular Aragonese dance. The wealth of colors in this frenetic, diabolical dance also brings to mind Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio espagnol, even if it is not at all as gaudy. Here we can see particularly clearly the art of Ravel’s crescendo, which announces the unbridled finale of La Valse. Stravinsky might be suspected of having “copied” in 1910 the last two measures of the Rapsodie espagnole (with the woodwind’s p-fff-p on one breath) at the end of the Danse infernale in the Firebird. Be that as it may, this ultimately remains a creative rivalry that gave birth to masterpieces.

Rhythm and motion are the determinant stylistic characteristics of the Rapsodie espagnole score, which, next to an amazing gift for stimulating developments, manifests a great wealth of ideas and a variety of uncommon sounds. These compelling pages are so full of instrumental details that it is worth taking a closer look at a few of them: the division of the string desks (in the Prélude and the Habanera), which produces a wonderful transparency; the arpeggios in harmonics of the solo violin (Prélude, m. 54 → 1-01, p. 78); the repeated down-bows at the frog (Prélude, mm. 32–35); the effects produced by using the finger-board (Malagueña, mm. 40–45) or the bowstick (Feria, mm. 127–130 → 1-02, p. 78) and various kinds of glissando effects like the one in the double bass solo in the high register (Feria, mm. 75ff. → 1-03, p. 79) or the glissando instruction: “Slide the finger lightly over the string near the bridge.” (Feria, m. 6 → 1-04, p. 79). Ravel also makes virtuoso use of harmonics and does not shy from entrusting the harp with a high G (Feria, mm. 1–6, 14–16) and five-note flageolet chords (Feria, mm. 88, 139f. → 1-05, p. 79). Also noteworthy is the alternation between “muted” and “stopped without mute” at the horns (Prélude, mm. 56–60) and the challenge for the trumpets to mute while playing (Habanera mm. 57–60 → 1-06, p. 79). Among the instruments, one should note the sarrusophone, which, with its supple articulation and its full sonorities in the lower range, provides an enhancing alternative to the contrabassoon.

7 Ravel. Souvenirs de Manuel Rosenthal, compiled by Marcel Marnat, Paris, 1995, p. 75.

1-01 (Prélude, Solo-Vl., m. 54)

NB 01-02

1-03 (Feria, Cb. I solo, mm. 75–77)

1-06 (Habanera, Trp. I–III, mm. 57–60)

Nicht alle Seiten werden angezeigt.

This is an excerpt. Not all pages are displayed. Have we sparked your interest? We gladly accept orders via music and book stores or through our webshop at www.breitkopf.com. Dies ist eine Leseprobe.

Haben wir Ihr Interesse geweckt?

Bestellungen nehmen wir gern über den Musikalien- und Buchhandel oder unseren Webshop unter www.breitkopf.com entgegen.

Jean-François Monnard

was born in 1941 and studied music and law in his native city of Lausanne. He studied conducting with Heinz Dressel and theory with Krzysztof Penderecki at the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen (1968 artist diploma with a major in conducting).

Monnard’s theater career took him from Kaiserslautern via Graz, Trier, Aachen, Wuppertal to Osnabrück, where he worked as GMD. Numerous guest invitations in the opera sector and extensive concert activities. In 1998, he moved to the Deutsche Oper Berlin, first as Artistic Administrator, then as Opera Director.

2007 Return to Switzerland, where new tasks await him: Deputy Director of the “Septembre Musical Montreux-Vevey” festival, Head of Planning and Casting at the Geneva Opera and Artistic Advisor at the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.

Since 2013, increasingly active in musicology, in particular as editor of a critical edition of Ravel ʼ s orchestral and stage works for the publisher Breitkopf & Härtel (nine volumes) and as editor-in-chief of “Cahiers Ravel”, a publication of the Maurice Ravel Foundation in Paris. In addition, he has published several books with inFOLIO:

• Septembre Musical. 70 ans de festival, 2016

• L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. Un siècle en poche, 2018

• Markevitch. Musicien cosmopolite, 2021

• Magaloff. Prince des pianistes, 2023