This edition © Kulturalis Ltd, 2026

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the author and publisher.

Published to accompany the What is the Meaning of Life? season at the Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Norfolk:

Living by the Rule: Contemporary meets Medieval

16 May – 4 October 2026

Play Power

16 May – 4 October 2026

Joy Like Time

20 June – 15 November 2026

New Commissions:

Life in the Multiverse: Libby Heaney

CATKINS FOREVER: Ruth Ewan

https://www.sainsburycentre.ac.uk

First published in 2026 by Kulturalis Ltd 14 Old Queen Street, London SW1H 9HP United Kingdom www.kulturalis.com

ISBN 978 1 83636 043 8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Series Editor: Tania Moore

Project Manager: Lizzy Silverton Design: James Alexander, Jade Design Reproduction by Opero, Verona Printed and bound in Czech Republic by PB Tisk, Příbram

EU GPSR Authorised Representative: EASY ACCESS SYSTEM EUROPE OÜ, Mustamäe tee 50, 10621, TALLINN, Estonia email: info@easproject.org

Front cover: Tacita Dean, Paradise: Thrones (detail), 2021, colour screenprint with a satin seal varnish on Somerset Satin Tub 410g Page 2: Gillian Wearing, Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say: EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED IN LIFE THE POINT IS TO KNOW IT AND TO UNERSTAND IT., 1992–3, c-type print on aluminium

Page 3: Gillian Wearing, Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say: MY GRIP ON LIFE IS RATHER LOOSE!, 1992–3, c-type print on aluminium

FOREWORD

Jago Cooper

WHAT IS THE MEANING OF LIFE?

Jago Cooper and Tania Moore

GLORIOUS, CONVULSIVE FRIVOLITY: WILD PLAY

Ben Highmore

DEITIES, MIGHTY QUEENS AND HEROES AT PLAY: GAMES IN HUMAN SOCIETIES

Samuele Tacconi

LIVING BY THE RULE

Jessica Barker and Ed Krčma

JOY LIKE TIME

John Kenneth Paranada

LIFE IN THE MULTIVERSE: LIBBY HEANEY

Rosy Gray

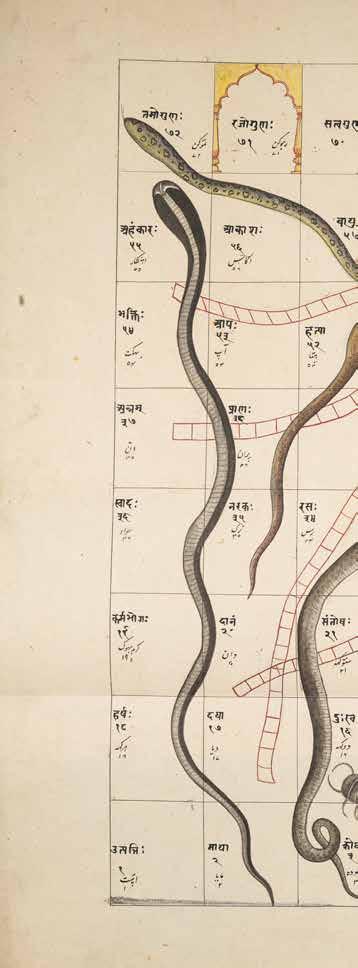

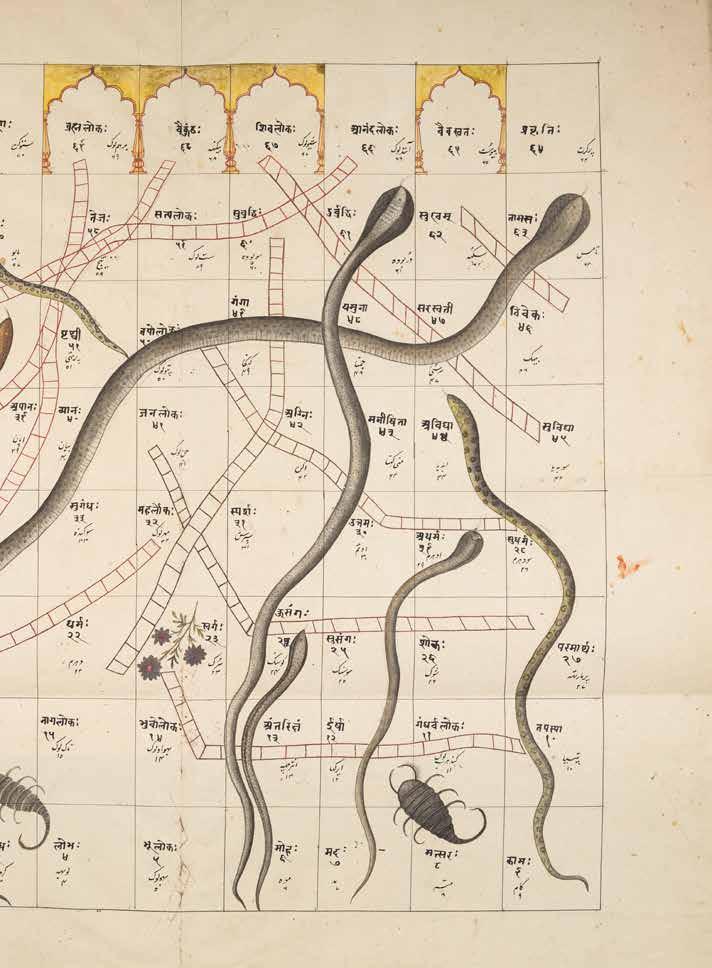

chaupar, commissioned by Richard Johnson in Lucknow, India, 1780–82, watercolour and pencil on paper.

British Library

building an independent city in Greenland, features deeply Eurocentric AI-generated images of its ideal city, a soaring mass of pinnacles and arches that is strongly reminiscent of a Gothic church – albeit in Lord of the Rings mode. Right-wing commentators on X post paired images of modern versus ‘traditional’ architecture, some with captions that bemoan the limitations of democracy and the Establishment’s inability to appreciate real beauty.13 Monasticism itself is often enlisted by wellness gurus, who promise that all the psychological demands of contemporary life can be overcome if one could simply ‘think like a monk’.14

In his bestselling ‘guide for Christians under siege today’, The Benedict Option (2017), American conservative Rod Dreher appeals to the ‘enchanted’ world of the Middle Ages as a route out of what he sees as our contemporary crisis.15 Here, apparently without effort, ‘medieval man’ experienced everything around him as an integrated divine reality, enjoying a perspective so radically divorced from our own that we moderns, sadly, are adrift on ‘a distant shore’, inhabiting a ‘blasted heath of atomization, fragmentation and unbelief’.16 Such romanticised versions of the medieval and/or the monastic widen the gulf between past and present: if medieval monks were spiritual superheroes, experiencing the world in an entirely different way, all they can offer us now is the wistful recognition of our own disenchantment and ineptitude. But what if the more valuable lessons are rooted in the difficulty, unevenness, failures and compromises that medieval monks experienced in forging a life

together? Rather than stripping medieval monasticism back to an imagined pristine ideal, considering the Rule in the light of its later accretions and corruptions offers something more approachable, and more valuable, for those of us living amidst the compromises and messiness of the present.

There is still something wild, and even scandalous, about the attempt to imagine and live out a different form of life, one that flies in the face of shared habits, assumptions and priorities. Our project does not pretend that the principles of Benedict’s Rule can simply be mapped onto contemporary social structures of an entirely different scale and composition. Our lives are far more mobile and technologically advanced than Benedict could ever have imagined. And yet, neither are they entirely unrecognisable: we still live in communities, even if they are digital; we still eat, sleep, work and rest; we still operate in relation to the rules and under the authority of others. And in our workplaces, schools and other sites, we are thrown together with relatively small groups of people, ones we did not choose and cannot necessarily leave, and we must find ways of rubbing along together – or even of thriving.17

Art, modernity and rule cultures

The unevenly distributed ruptures and transformations signalled by the term ‘modernity’ – and the emergence of industrial capitalism and of mass societies – nevertheless constitute a decisive shift in the nature of social relations.18 For art historian

T. J. Clark, modernity is fundamentally about contingency. Capitalism helped produce a social order that turned from the worship of ancestors and past authorities to the pursuit of projected futures, be it in the form of goods, pleasures, freedoms or forms of control. ‘Without ancestor-worship,’ Clark maintains, ‘meaning is in short supply – “meaning” here meaning agreed-on and instituted forms of value and understanding, implicit orders, stories and images in which a culture crystallizes its sense of the struggle with the realm of necessity and the reality of pain and death.’19 Further, the existential damage inflicted by the overhauls of modernity relate to its being overwhelmingly driven by material, statistical, ‘economic’ considerations.20

Markets operating according to laws of competition and exchange constituted one of the crucial mechanisms that enabled modernity’s development. They also served to transform the character and social function of art, especially from the late eighteenth century onwards. In particular, the expansion of markets unharnessed art from its traditional sites, forms of aristocratic and religious patronage, and rhetorical modes of address. 21 Without a specific patron there to determine production, or a particular functional context to serve, artists became increasingly self-possessed, producing work speculatively to serve their own purposes and patrons.22

This situation entailed both new kinds of freedom and new pressures and dependencies. The kind of nesting that held medieval art within the wider political, social and religious frameworks

narrative and no score, only the unqualified presence of another person and the courage to meet their gaze. Abramović turned duration into revelation, showing that presence itself can be an art form. Her stillness recalls Augustine’s insistence that the present exists only in vanishing, and Arendt’s claim that every encounter holds the potential for beginning. In a culture saturated with signals, this quiet reciprocity became rare value. Meaning here is crafted not through novelty but through endurance, the slow burn of being fully alive.

The early performance Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975) clarifies the stakes of that endurance. For an hour, Abramović brushed her hair with relentless force while repeating the work’s title, an action that produced pain, extracted hair and exposed the coercive grammar of beauty as labour. The later project, Red Period and Blue Period (2025) reimagines two videos from 1998 as 1,200 photographic stills, a serial archive of micro-gestures and shifting affect. In the red sequence, the face seduces, warns and frays; in

the blue sequence, a small, compulsive action becomes a choreography of unease. Together they test how colour codes feeling, how repetition transforms impulse into form, and how the camera can score time as a register of attention.

As a reference point, Narcissus Garden (1966) and DOTS OBSESSION [RDLAT] (2018) by Yayoi Kusama (b.1929) show how repetition becomes a way of feeling time. Mirrored spheres and serial polka dots translate duration into pattern and return, drawing the viewer into an ever-renewing present. Kusama’s dot emerges from childhood hallucinations and from a sustained project of

self-obliteration, a practice of repeating the motif until the boundary between self and world softens. Seriality here is a temporal ethics that prepares the ground for other artists who pace the gaze and educate attention.

Bridget Riley, by contrast, locates duration in perception. Her Op art canvases arrange stripes of colour and intervals of white in rhythmic ascent. The eye cannot take them in at once; it must travel, pause, and travel again. The white bands function like breaths or rests in music, shaping attention and pacing the gaze. As the eye moves, the field seems to lift, settle, and lift once more, as if the canvas

the body. As with Please Don’t Cry, this footage is layered and interwoven, with the artist describing their ‘opacity and transparency determined by the intricate relationships formed within the quantum realm’.11 This layering, suggests Heaney, symbolises how emotion is held in the body ‘as one experiences different feelings and sensations simultaneously. The result is a blurry, indeterminate aesthetic, which symbolises the self.’12

In Heartbreak and Magic (2024), Heaney develops this approach, combining quantum computing and virtual reality technologies for the first time in her work. Presented at Somerset House, London, and HEK Basel in 2024, the work places particular emphasis on the notion of telepresence – being present in another world or another space without physically existing there. As Heaney describes:

Virtual reality felt like the best medium for the work because it really allows me to change reality in magical and unusual ways. For instance, some objects can morph and spread out in space and time, and the viewer can occupy a different body or experience things in ways that you couldn’t in the physical world.13

For Heaney, this notion of embodiment is fundamental to how people experience Heartbreak and Magic . Combining virtual reality and multimedia drawings, the installation is an intuitive and embodied experience – an approach that extends to the physical environment in which the work is presented, as much as the work itself. The

Dom Sylvester Houédard standing in his cream robes washing up at a sink, date unknown. Featured in the exhibition Living by the Rule: Contemporary Meets Medieval

The curatorial team expanded on the ideas within the season in illuminating new texts for this publication and we thank them all: Jessica Barker, Jago Cooper, Rosy Gray, Ben Highmore, Ed Krčma, Tania Moore, John Kenneth Paranada and Samuele Tacconi. The season was brainstormed by a group of artists, academics, life coaches and thinkers to help us conceive how to approach the theme. We are grateful to everyone who attended this creative think-in, generating a lively discussion, particularly the speakers Aribiah Attoe, Fiona Buckland and Libby Heaney.

The season’s ideas were transformed into reality by a team of designers including Simon Leach and Symeon Banos at Simon Leach Design, who carried out the 3D exhibition design for Living by the Rule and Play Power, and David Sudlow Designers who conceived and executed the graphic identity for the season. George Sexton Associates executed the lighting design for the season and Paul Kuzemczak carried out the 3D design for Joy Like Time. This book was expertly designed by James Alexander at Jade Design and project managed by Lizzy Silverton. We thank everyone at Kulturalis, our publishing partner on the book.

We are grateful to our regular funders, including, but not limited to, the Gatsby Charitable Foundation and UKRI. John Kenneth Paranada’s post is generously funded by the John Ellerman Foundation. Finally, these exhibitions and publications would not take place if it weren’t for all the staff at the Sainsbury Centre who work incredibly hard to create and run these seasons for our visitors’ enjoyment and enrichment, and we thank them all.