Birmingham, 1989, Ben Coseley studies his latest issue of RAD magazine

Photo courtesy Ben Coseley

Birmingham, 1989, Ben Coseley studies his latest issue of RAD magazine

Photo courtesy Ben Coseley

Birmingham, 1989, Ben Coseley studies his latest issue of RAD magazine

Photo courtesy Ben Coseley

Birmingham, 1989, Ben Coseley studies his latest issue of RAD magazine

Photo courtesy Ben Coseley

I’ve always had pangs of envy at the people in punk documentaries who were lucky with timing—the ones who were the ‘right’ age when punk broke. The energy must’ve been amazing — that feeling of being a part of something exciting and new, actively participating in a golden era.

But I recently realised something that I hadn’t considered at the time—I had experienced some perfect timing too. I was an enthusiastic participant in a different golden era; I was part of the Read And Destroy generation. I was just perfectly ready for it and effortlessly part of it. In fact, I felt as though I had been waiting for it. And though skateboarding was a tiny subculture (and the British proponents of it therefore formed an exponentially tinier subculture) RAD magazine has always had huge significance for those of us who were of the right age and mindset. Ripples still felt, and all that.

The magazine entered my life subtly. Growing up in the New Forest, it made sense to ride BMX when that first entered my psyche in the early 1980s; there were lots of bumps and jumps around. It was fun. Oh, and there, on the shelves of the newsagent—a magazine—BMX Action Bike? Cool. Perhaps a bit dry, a bit ‘sporty’, what with all those races and things, but then along came the freestylers. They started out innocuously enough. Routines and such. But soon, something interesting started to happen. A new breed of freestyler. They didn’t wear the regulation jerseys and helmets, and they did tricks in unregulated places, places where surely it must be illegal? A subversive feel was building… And then, slowly at first, the skateboarders appeared in the pages. Not the long-haired, bare-footed kind. No short-shorts or hang-tens here. Neon shirts, ripped jeans, chequered canvas shoes, wild hair, these big wide boards with skulls on! And they weren’t gliding round the slopes at skateparks, they were in the streets — wild in the streets. They were jumping off benches!

Something happened to the magazine then. It entered its golden era. It became edgy, it became exciting. It became RAD. I devoured that mag every month. Growing up in the middle of nowhere, it was—cliché imminent— my Bible. I still remember captions from 35 years ago. That’s ridiculous. The energy was bursting out of that thing every issue. Boneless ones off planters, BMX wallrides, punkish collages. The jarring juxtaposition of neon berets and shorts with drab British car parks. This was a unique moment.

In the mid-1980s, street skating was just blossoming. The first street pro-model skateboards were coming out; it was Gonz and Natas over Hosoi and McGill. And frankly, there was no contest. It seems so obvious in retrospect. Of course street skating would take over—it’s accessible. No vert ramp required. All it did require was imagination. Skateboard culture was exploding and evolving and RAD was right there, all the way, documenting the UK scene and fuelling the fire. The American skaters undeniably led the way at this point, and so the US magazines were hugely important. They portrayed an idyllic far-off land. One with sun! One where skaters seemed to be an accepted—or at least acknowledged—part of life. Things were different on our drizzly isles

though. Skating seemed somehow more surreal in these environs. And we may not have had the smooth sidewalks of SoCal, but as a nation, we’ve always been good at ‘making-do’, at adapting. So while the US magazines did dictate, they didn’t quite translate. Not only did RAD speak to this curious breed, the British skater, it was also, significantly, much easier to find, and much cheaper than the American magazines.

At the time, skate magazines—and later, but much less frequently, skate videos—were hugely important for communication. Skateboarding has always progressed very fast— much faster than most things by comparison. Monthly magazines could barely keep up. And I don’t suppose I need to outline the progression of skateboarding since that era —presumably you already know all about it if you are holding this book in the first place. And if you don’t, I suppose you could just flip through the pages and get a good general idea. Because RAD was always on top of things. From a how-to on cutting down your skate shoes, to the rave-era ‘Get a Clue’ sticker, to those dreadful-quality video-grab sequences of dreadful triple-pressure-flips or whatever; RAD always knew what was up. And then, quite suddenly it changed. The original editorial staff left, making way for the all-too-brief Phat magazine which, if pressed, I would describe as a British Big Brother, only less deliberately controversial. And then, that… was that.

Skateboarding is on television now. Most human beings in the Western world under 60 years old have heard of Tony Hawk. Today you’ll walk past a dozen people wearing ‘skate shoes’ but never give them a second glance because you already know they aren’t skaters. Paradoxically, you may well actually skate in shoes made by a major sports brand. Things have changed, of course. It’s the 2020s for goodness’ sake; we all live in ‘the future’ now. The golden era I speak of is long, long gone. But—and another cliché races towards us—its influence is still being felt.

Such is the generational nature of things (and especially of skateboarding), that those kids who were pictured in the pages of RAD doing boneless ones off Tesco shopping trolleys and chink-chinks on suburban mini-ramps, some of them anyway, now own the skate shops, run the board companies, or have been absorbed into the Californian skateboarding industry. Or not. Some have gone on to do other things entirely—some of them exceptional. Because to be a skater then, especially in a small place like England, meant that you probably were exceptional in some way. A black sheep maybe; a weirdo probably; a free-thinker definitely. I’ve always maintained that skateboarding doesn’t ‘matter’ in the grand scheme of things, but how much richer it has made some of our lives. RAD magazine was, for a few golden years, a lifeline for the outsider skaters of the UK. Thank you Tim Leighton-Boyce and everyone else. We really appreciate it.

RICHARD HART Photographer and Editor, Push Periodical

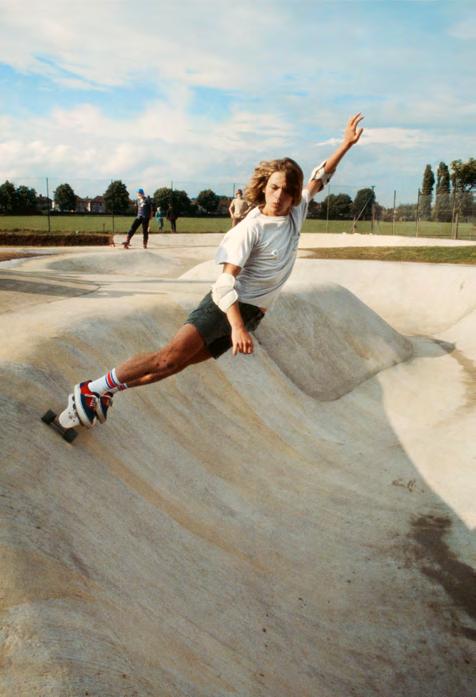

Opposite: John Sablosky in the legendary 14-foot-deep Harrow skatepark performance bowl, 1979 Above: Jules Gayton, Harrow skatepark, 1979

Opposite: John Sablosky in the legendary 14-foot-deep Harrow skatepark performance bowl, 1979 Above: Jules Gayton, Harrow skatepark, 1979

‘During the ’80s, skateboarding outgrew the sanitised confines of commercial skateparks and was looking to lay claim to any shreddable surface that presented itself. The magazines’ infectious enthusiasm for skate culture and “what if…?” approach to graphic design captured skaters’ imaginations and hot-wired a street-skating revolution across the UK. Staffed by the very same skaters, riders and “vandals” the magazine celebrated, RAD adopted a partisan DIY skate zine aesthetic in a bid to replicate the exhilaration of a grinding truck or bike frame along a concrete edge.’

Joel LardnerIn 1987, the building blocks finally fell into place. The long-awaited opportunity to publish a full-colour magazine with British skateboarding at its heart, had arrived. As TLB remembers: ‘In the “dark ages” of skateboarding, nobody would have believed that you could release a magazine about skateboarding. That really wasn’t on anyone’s radar. But as soon as it was offered I grabbed at the chance.’ Fortuitously, TLB had been given an opening to allow him to continue the job of documenting and promoting the British skate scene, now via a prominent, full-colour platform.

‘There was a strong desire to try and do a proper skate mag—it was totally a goal, right the way through. This was a mission to get a skateboard magazine. We subverted that magazine [BMX Action Bike]. And I do feel awkward—because I knew what it felt like as a skater in the skateboard community when a magazine disappeared. But then I did that to another community, I stole their magazine I suppose. It feels bad; that’s the way it’s described at least.’ TLB

This move had not been a calculated, pre-meditated overthrow of any existing order—trying to force the hand of an unwilling audience. The evolution of the magazine came about in many ways by accident, but the change also captured the zeitgeist:

‘Everyone saw the BMX industry beginning to contract and BMX Action Bike were sensing this because advertising revenue was drying up. One of their biggest advertisers, Shiner Distribution in Bristol, knew that a resurgence in skateboarding’s popularity was happening in America. They wanted to fund a skateboarding supplement for the BMX mag (to advertise the skate products that they were selling). The SK8 Action magwithin-a-mag was the result and it went down relatively well, encouraging further skate coverage in BMX Action Bike during that period.’ TLB

It was not just industry insiders who could see change on the horizon. The established die-hard skate community was dumbfounded when, seemingly out of the blue, Hollywood delivered two movies—Back To The Future in 1985 and Thrashin’ in 1986—with skateboarders as the main protagonists. Who could predict that the jokey teen adventure movie Back To The Future would be the spark to ignite the passions of a whole new generation of skate enthusiasts, discovering fun on four wheels instead of two. By 1987, commercial and media interests had skateboarding firmly fixed in their sights and joined Hollywood in introducing skateboarding to a whole new audience.

Two key events in ’87 clearly illustrated that major changes in the fortunes of British skateboard culture were underway. London’s annual commercial BMX extravaganza, Holeshot, chose for the first

Opposite: Ged Wells, Southsea skatepark, 1987

Opposite: Ged Wells, Southsea skatepark, 1987

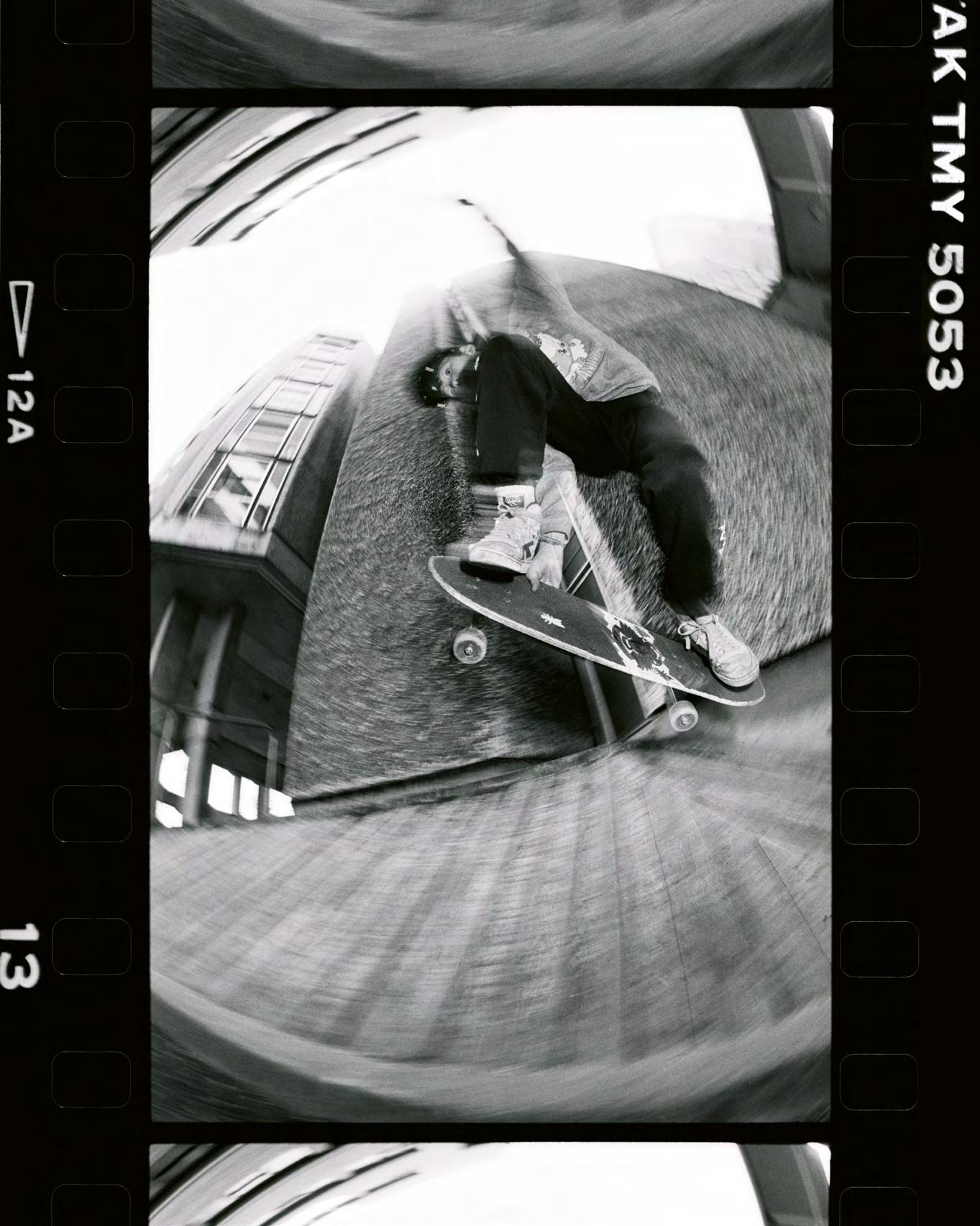

‘I remember sitting with Lee Ralph in Bod’s mum’s house looking at a Santa Cruz video of Tom Knox skating some curbs. Lee said “Imagine these guys talking in years to come about that concrete block they used to skate” and we were laughing but now that’s totally true. Street at that time wasn’t considered the thing you should be doing if you were pro, it was something you did for a laugh.’ Mike John

Opposite: Hugh ‘Bod’ Boyle, Chingford, London, 1989 Right: Steve Douglas

Opposite: Hugh ‘Bod’ Boyle, Chingford, London, 1989 Right: Steve Douglas

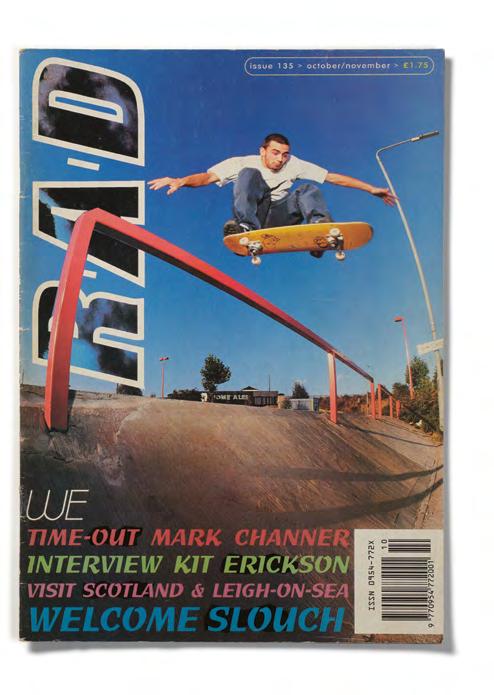

Clockwise from top left: Covers designed by Andy Horsley, 1994–95: Mark Channer, Kennington, 1994; Carl Shipman, Worksop, 1994; Danny Wainwright,

Clockwise from top left: Covers designed by Andy Horsley, 1994–95: Mark Channer, Kennington, 1994; Carl Shipman, Worksop, 1994; Danny Wainwright,

Skateboarding culture had a vibrant, messy energy as it emerged from the underground of the early 1980s and the photographers of Read And Destroy magazine were there to document it.

‘Skateboard culture was exploding and evolving and RAD was right there, all the way, documenting the UK scene and fuelling the fire.’ Richard Hart, editor of Push Periodical

For British skateboarders in the late-’80s, Britain’s seminal skateboard magazine RAD (aka Read And Destroy) was more than just a magazine. A whole generation of this once underground subculture relied on RAD to be their beacon, bringing them together in spirit and in person.

‘RAD … was everything. It captured the whole culture. Not just the skateboarding—what people were wearing, music, fashions. You go into the newsagent’s and it’s there—and you’re in it! You’re like, … this is crazy!’ Danny

WainwrightThe legacy of the magazine is an action-packed photo archive documenting a unique time, place and attitude, capturing the death and rebirth of skateboarding as it evolved into a mainstay of extreme sports and street culture the world over.

This book is the inspired and dedicated documentation of a vital subculture driven purely by passion, offering an inside view of skateboarding and youth culture in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s.