ORO Editions

Construction of Kapiʻolani Boulevard began in 1931 to connect downtown Honolulu to Waikīkī, but it wasn’t until the conclusion of WWII that the humble stretch of road genuinely developed as a commercial corridor.

Retail stores began lining either side, with individual store parking lots on the front, side, or rear, catering more to automobile customers rather than pedestrian traffic. The thoroughfare quickly became labeled “The Miracle Mile” because of its similarities to the highly successful two-mile stretch of Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. Stores typically were designed with extended buildings oriented towards the street to appeal to the vehicular traffic, with simple signage and ornamentation easily recognized by those passing by at a higher rate of speed.

These low-rise buildings were a change from the typical vertical orientation of the downtown retail stores.

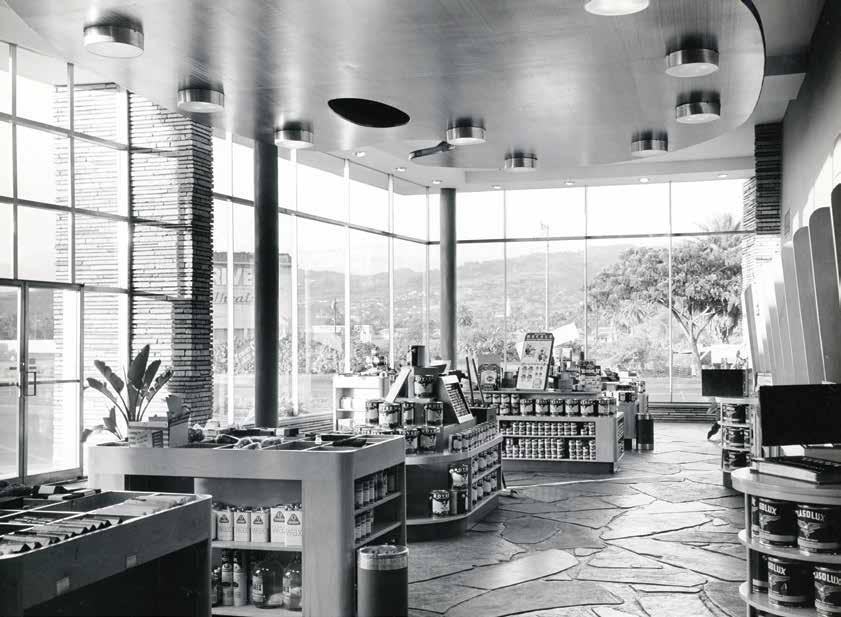

In 1949, the firm built its first significant commercial building along this newly thriving commercial corridor. Designed by Cy Lemmon, the building’s tall vertical feature wall created a striking element that became a significant landmark for customers driving by along Kapiʻolani Boulevard. Lemmon appreciated the roughness of the surface of Arizona sandstone and the effect created with the horizontal cut of the stone and used it on the finish of the building. The exterior embodies strong vertical and horizontal contrasts, comprising the flat horizontal roof supported by heavy vertical elements, and the prominent vertical feature wall dividing the building. The full-height windows along the street side and

Kamehameha III established free public schools in Hawaiʻi in 1840. It is the only educational system in the United States founded by a sovereign monarch and the oldest educational system west of the Mississippi.

Teachers initially taught their students in Hawaiian, but as foreign influence in economics and politics increased, English became the primary language of instruction

In the late 1960s and early 70s, there was concern that the culture of the Hawaiian people was at risk of disappearing. This fear sparked a major movement of local support for Hawaiian music, hula, and language. In 1978 the State constitution was amended to officially recognize Hawaiian as one of the two official state languages in Hawaiʻi.

Leading up to this movement was Honolulu’s accelerating growth during the 1950s and 60s. This growth created an equally urgent demand for new public schools. The City & County appointed Lemmon, Freeth & Haines, and its affiliate Belt, Lemmon & Lo to develop a comprehensive master plan for the future of education in the new state. The plan included elementary, intermediate, and high schools; athletic fields; parks and recreation areas; and future faculty housing. The City & County selected Belt, Lemmon & Lo as architects-engineers for four new major public schools: Wai‘anae High School, Wai‘anae Intermediate School, Kalani High School, and James Campbell High School.

The Wai‘anae campus design included multiple low-rise concrete buildings with elongated, rectangular massing. Wai‘anae’s frequently dry, hot climate required the orientation of all buildings to take full advantage of the northeast trade winds. The design of the wide overhanging eaves and continuous bands of louvered windows keep the buildings cool. Despite restrictive design

King

COMPLETED 1962

The 1950s began with Honolulu’s historic retail center in Downtown.

By the end of the decade, retail’s “center of gravity” had shifted.

With the opening of America’s largest shopping mall in 1959, Ala Moana Shopping Center accelerated the growth of personal automobile transportation throughout O‘ahu. Ala Moana’s central location between Downtown and Waikīkī shifted O‘ahu’s retail core toward the east, enabling greater focus on Downtown’s professional and office development moving forward.

Landlocked between Chinatown to the west and the State Capitol District to the east, Honolulu’s government and civic leaders considered many means of providing more urban, high-density development opportunities in the nascent State. Bishop National Bank of Hawaiʻi (renamed to First Hawaiian Bank in 1969) engaged Lemmon, Freeth, Haines & Jones in 1959 to design their modernist Downtown office building, envisioned as matching Aloha Tower’s ten-story height. Planning and design discussions resulted in the City’s approval for Bishop National Bank of Hawaii’s office building well exceeding Aloha Tower’s height at 18 stories, and Downtown Honolulu’s building boom was erupted.

Bishop National Bank of Hawaii’s 225-foot office tower was Hawai‘i’s first modern high-rise. The tower, set in a landscaped sidewalk plaza, was equipped with high-speed elevators, drive-in tellers, and a multi-level parking garage with a service station. The concrete tower structure set a precedent in Hawai‘i, utilizing highly efficient driven piles into Downtown’s deep subterranean coral shelf to support the tower; a practice later applied on numerous other Downtown high-rises yet to come.

Bishop National Bank of Hawaii had long inhabited the historic low-rise Damon Building. The new modern tower design respected the Damon Building’s façade. It maintained the bank’s downtown branch therein, while preserving open space at the pedestrian level through tower setbacks along Bishop Street and King Street. The tower’s modern design expressed functionality and order while featuring extensive city view. The top-floor penthouse featured executive meeting and dining facilities for 45 persons, a president’s room displaying historical items from the bank’s opening in 1858, and guestroom accommodations.

With the Hawai‘i State Capitol under construction concurrent with the Bishop National Bank of Hawaii Tower, Lemmon, Freeth, Haines & Jones founder CY Lemmon chose to relocate the firm’s offices from Kapiʻolani Boulevard’s Kenrock Building to the new Bishop National Bank of Hawaii Tower. Lemmon, Freeth, Haines & Jones moved to the 15th Floor in 1963, and the firm has remained in Downtown Honolulu thereafter. The office moved into its newer Bishop Street office high-rises, then to American Savings Bank Tower in the 1970s, and its present location in Pacific Guardian Center in 2012.

COMPLETED ONGOING

The Queen’s Medical Center is the first hospital in the US established by royalty. In King Kamehameha IV’s opening speech to the legislature in 1855, the King proposed creating a hospital for the people of Hawaiʻi.

The smallpox epidemic of 1853 seriously threatened the continued existence of the Hawaiian race, killing thousands of people in the already dwindling population. In 1859 Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV raised $13,530, which, together with $6,000 of legislature funding, was used to build Hawai‘i’s first modern medical facility. The King laid the cornerstone for the two-story 124-bed facility named “House of Kalākaua” in 1860, and Queen Emma herself became its chief volunteer.

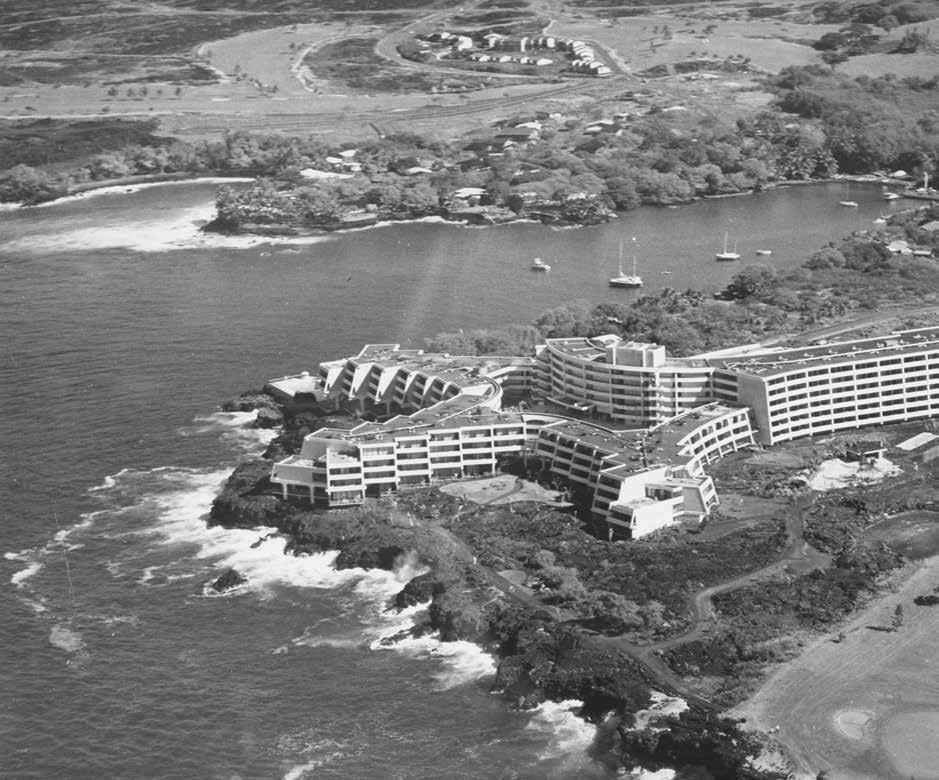

The hospital’s “Punchbowl” campus grew steadily from the 1950s on. In 1967 its name was changed to The Queen’s Medical Center. During that time, preliminary design studies focused on a coordinated Hawai‘i medical services growth strategy with The Queen’s Medical Center as its epicenter.

From the 1970s to the present, AHL has served as architect and master planner on selected commissions. The relocation of the radiation oncology facility in the late 1970s was the first step in AHL’s extensive medical center renovation master plan. Tight site constraints prompted a below-grade building design solution with an at-grade landscaped roof for patients and staff relaxation.

Immediately adjacent to the Radiation Oncology building is AHL’s fivestory exposed-aggregate concrete Cancer Center of Hawaii, completed in 1979. In the 2000s, the Cancer Center moved into AHL’s newly expanded

Kapi‘olani Boulevard and Ke‘eamoku Street is one of Honolulu’s most visible and bustling intersections, and some residents refer to it as “the corner of Main & Main.” Ala Moana Shopping Center’s pivotal main entrance is at this intersection along with one of Honolulu’s stations. Lively pedestrian activity and continuous vehicular traffic make this one of the most visible and active locations on O‘ahu.

Following the selection of this prominent site, AHL’s design team set about creating an architecturally significant and unique landmark rooted in Hawai‘i’s cultural traditions. A critical project objective was to redefine the Walgreens brand’s physical environment and product offerings in the context of Hawaiʻi’s diverse mosaic of people, cultures, and tastes. A related goal was improving and re-energizing the surrounding pedestrian environment by improving site visibility and strategically locating the entry point to create an active urban space on the main corner.

AHL’s overall design intent was to create a culturally inspired, publicly relevant, and architecturally significant building to express the Walgreens brand in Hawai‘i. The building structure was a modified version of the traditional Hawaiian Hale A-Frame, featuring transparent glass and metal cladding to create an inviting environment for customers and passersby. In Hawaiian, Ala Moana means “path to the sea,” and the Ala Moana area served as the source of inspiration for the design throughout the building.

"We wanted to create a space that would pay homage to Hawaiian culture in a modern, contextually appropriate way."

said AHL’s Director of Design & Sustainability, Lester Ng.

Walgreens entrusted AHL as the architect for its new flagship store, and together the team chose the corner of Kapi‘olani and Keʻeamoku for the project site.

Velocity Honolulu is much more than the average car dealership. A significant part of this development’s vision was to encourage each tenant to be part of the greater shared branding of Velocity. This vision put aside individual requirements in favor of a process that embraces the idea that “the whole exceeds the sum of its parts” in crafting a modern, luxurious, multi-functional events and arts space.

Velocity is a creative and entertaining retail anchor tenant in the LEED Certified Symphony Honolulu high-rise mixed-use development, located at Honolulu’s visible and high-trafficked crossroads intersection of Ward Avenue and Kapiʻolani Boulevard. Housed in the lower portion of Symphony’s 70-foot podium, Velocity’s three-story transparent glass façade provides interest and excitement to passers-by along both principal thoroughfares. Its glass floor displays unique cars 30-feet above street level and is itself a memorable urban design element. Special lighting effects add delight inside and out during evenings.

The design vision required redefining the “auto dealership” into a museum quality “auto galleria.” Fifteen exotic European car and cycle brands combine with niche boutique retail in a minimalistic setting to create an atmosphere that exudes sophisticated design and effortless luxury. As with a museum, the public is encouraged and invited to wander throughout. Trained in five-star hotel customer relations, staff focuses on extolling design and style rather than closing sales. Niche, boutique retail includes a café, auto paraphernalia, specialist clothing, a beauty salon, and fine Italian dining. In addition to sales,

Driven by the shared vision to reinvigorate Honolulu, Velocity Honolulu contributes to Live.Work.Play neighborhoods and encourages healthy lifestyles in Transit-Oriented development.