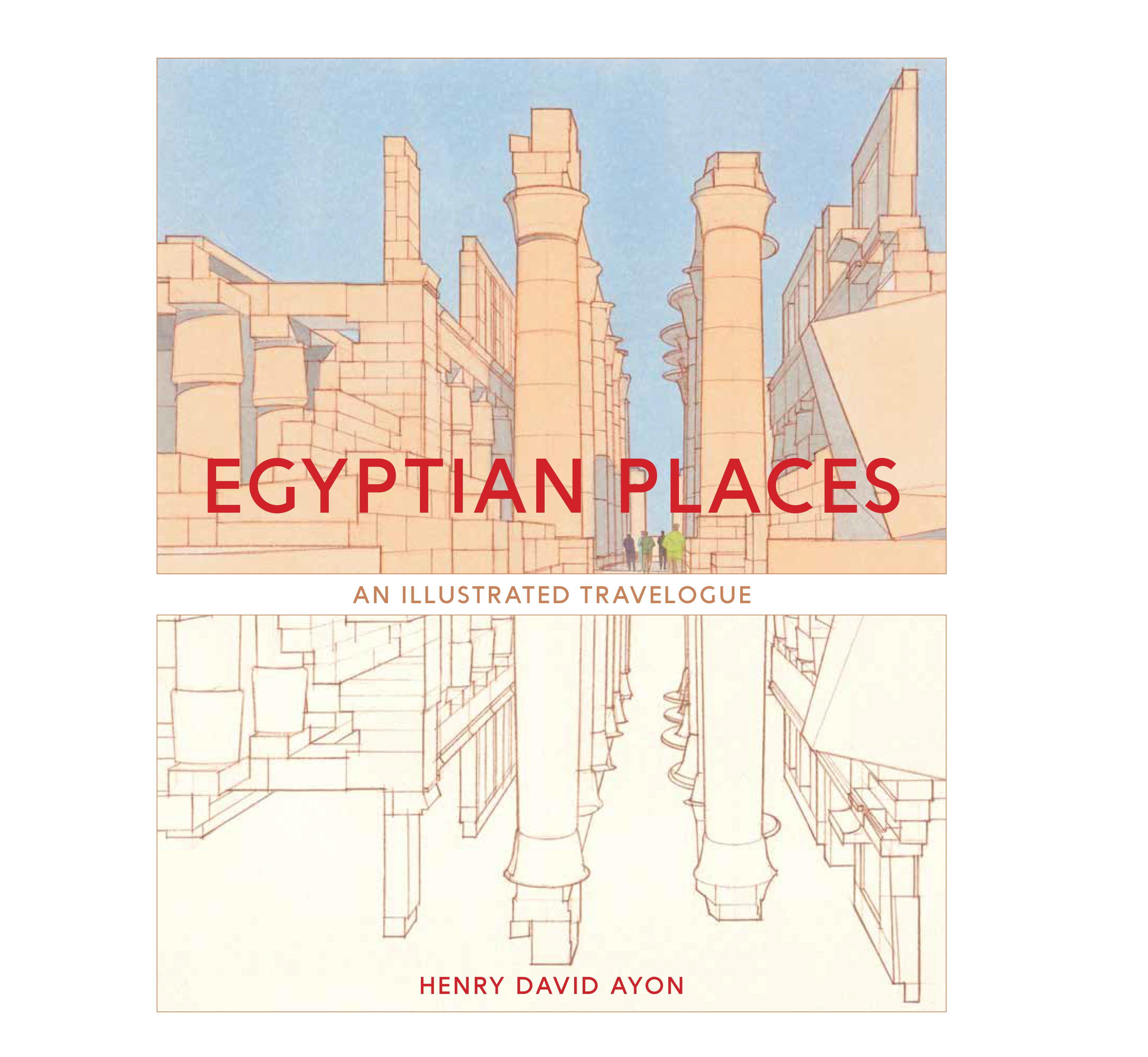

Foreword

TEMPLE OF DENDUR

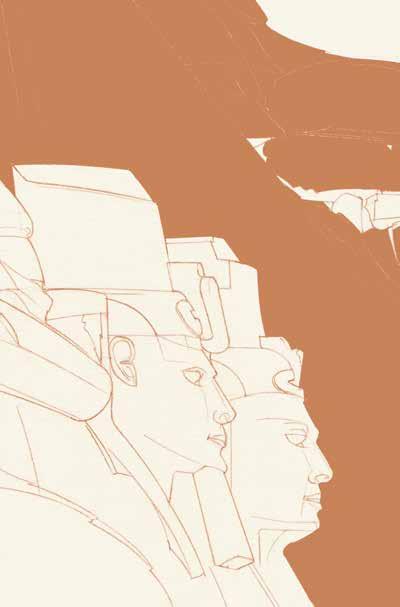

AS A RECENT GRADUATE employed at the office of Roche Dinkeloo Architects in the mid 1970s, I was part of a team building a model of the Temple of Dendur (completed 10 BC), a gift from Egypt to the United States for its assistance in saving various sites threatened by the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The temple and a freestanding stone entry gate were to be reassembled and featured in a new wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, as part of its Egyptian Collection. This relatively minor structure, exquisite in detail and scale, was my first direct contact with the wonders of ancient Egyptian architecture.

Although small, this temple is laid out with many of the same pieces, in miniature, as the massive temples I was to visit decades later:

• Entry Gate (Pylon) with Cavetto Fascia

• Courtyard

• Pronaos (Vestibule)

• Antechamber

• Sanctuary

• Battered Walls

• Ashlar Stone Blocks

This was an unusual assignment to be working on in the office of a well-known modern architect near the end of the 20th century. I never expected to make contact with an artifact so ancient and so exotic in the context of our work environment. Everything about this ancient edifice was, for me, new: the antiquity of the structure, the exotic iconography, and, stylistically, the non-Classical (Greek or Roman) ornament.

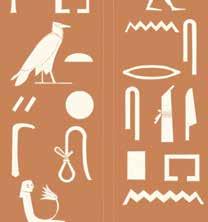

Once installed, the remarkable physical presence of battered walls, entry portal, hieroglyphic display, and the subtle tension of the spatial “cube” between portal and temple were inspiring and moving.

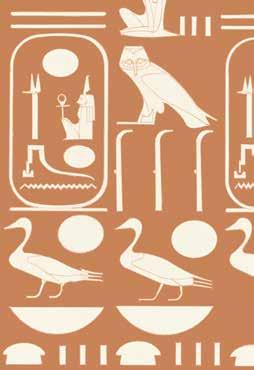

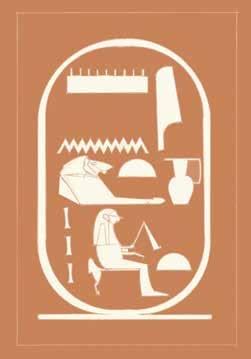

Decades later, on an excursion that would take us from congested present-day Cairo to the majestic temples along the Nile and then on to remote Abu Simbel, my point of reference was always the tiny Temple of Dendur: its stones were the stones we would encounter at Karnak and Edfu, its hieroglyphics were the same images we would see displayed on numerous sacred buildings, and its mysteries drew their inspiration from the same ancient land in the Sahara Desert of North Africa.

This volume is a combination of illustrations (colored drawings and sepia variations), factual information, and architectural commentary regarding the twelve Egyptian sacred sites we visited on our journey to temples and pyramids along the Nile.

Temple of Dendur: Metropolitan Museum / New York

Introduction: PRIMAL IMAGININGS

The essential qualities of Egyptian works are prodigious solidity and wonderful magnitude. These are the leading objects and prominent features in their architecture and sculpture. Indeed, in all their works everything seems calculated for eternity; and if solidity, quantity, mass, and breadth of light and shadow were the only requisites in architecture, we should find all that could be desired in the works of the Egyptians.

—Sir John Soane, Royal Academy Lectures I, 1819

Silence + Eternity / Time

A PALPABLE, AT TIMES SPELLBINDING, aura of both pervasive and profound mystery surrounds the desert culture of ancient Egypt, its various ritualistic practices, and its curious polytheism. We sensed this singular ambiance in the silent remains of each site visited on our journey. All Egyptian ruins are adorned with the hermetic notations of this antique civilization whose obsession was conjuring the magical means of extending life and establishing a path to eternity. This aura is a phantom presence that can be felt when stepping into the myth-centered ethos that occupies a dark temple chamber, bisected by a single sliver of sunlight, such as we gazed upon in the temple at Dendera, or sensed in the arcane carvings of deities and supernatural encounters animating the walls of a narrow, subterranean crypt, once sealed for millennia. The vacant temples and pyramids that once beheld a ritualized

conjuring of occult forces, the air resounding with prayers amid sacrificial burnings to their gods, are now mute—the silence sharpened and the enigmas further deepened by the obfuscation of distant, lost time.

Travelers journey to Egypt to be awed and even overwhelmed by the richness and scale of the ancient constructions. To enter that world, it is necessary to welcome a certain amount of credulity (as I have done in my comments) about the divinity of the pharaohs and the existence of Egyptian gods. True or not, these pagan beliefs inspired the entire culture and guided its efforts into the various artistic manifestations that have shaped its remarkable legacy.

For us, the remains of ancient dynasties proved to be the means and the media of our time travel, a complex shifting in multiple directions through the accreted layers of 4,500 years of history and art in a land of infinite contrasts: In the center of

a 21st-century metropolis, we studied the blackened flesh of mummies cocooned in sepia-stained wrappings, thousands of years old, now enshrined in a climate-controlled gallery; then, air-conditioned transport carried us to the edge of the Sahara desert to photograph the Pharaoh Khufu’s wooden “solar boat” now suspended in a futuristic, multifaceted metal and glass pavilion adjacent to the Great Giza Pyramid.

In every artifact or ruin, from diminutive, cultic figurines to the mammoth sculptures of Ramesses II at Abu Simbel, we experienced a unique, personal engagement that created an emotional connection to a particular point in time, an association that was artistic, historic, and cultural, all at once. Who would not respond to the endearing naiveté of two painted eyes on the side of General Sepi’s 12th-century wooden coffin, positioned to allow him to look east to the rising sun and the birth of the god AmunRa from the afterlife? And who would not be moved by the poignancy in the benign smile of King Tut-ankh-amun’s burial mask (the Egyptians had presumably conquered death, after all), or the four sculpted winged goddesses at his golden sarcophagus, arms outstretched to embrace and protect the king for all time? In each discovery, as interpreted by our collective conscience and our individual experience, a resonant vibration echoes upward from remote, distant time, through silence, into the light of the present where our own imaginings again bring it to life.

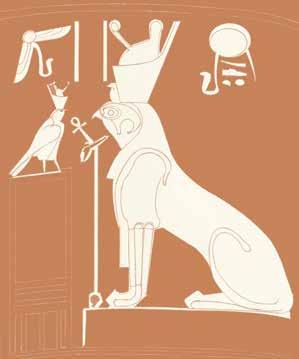

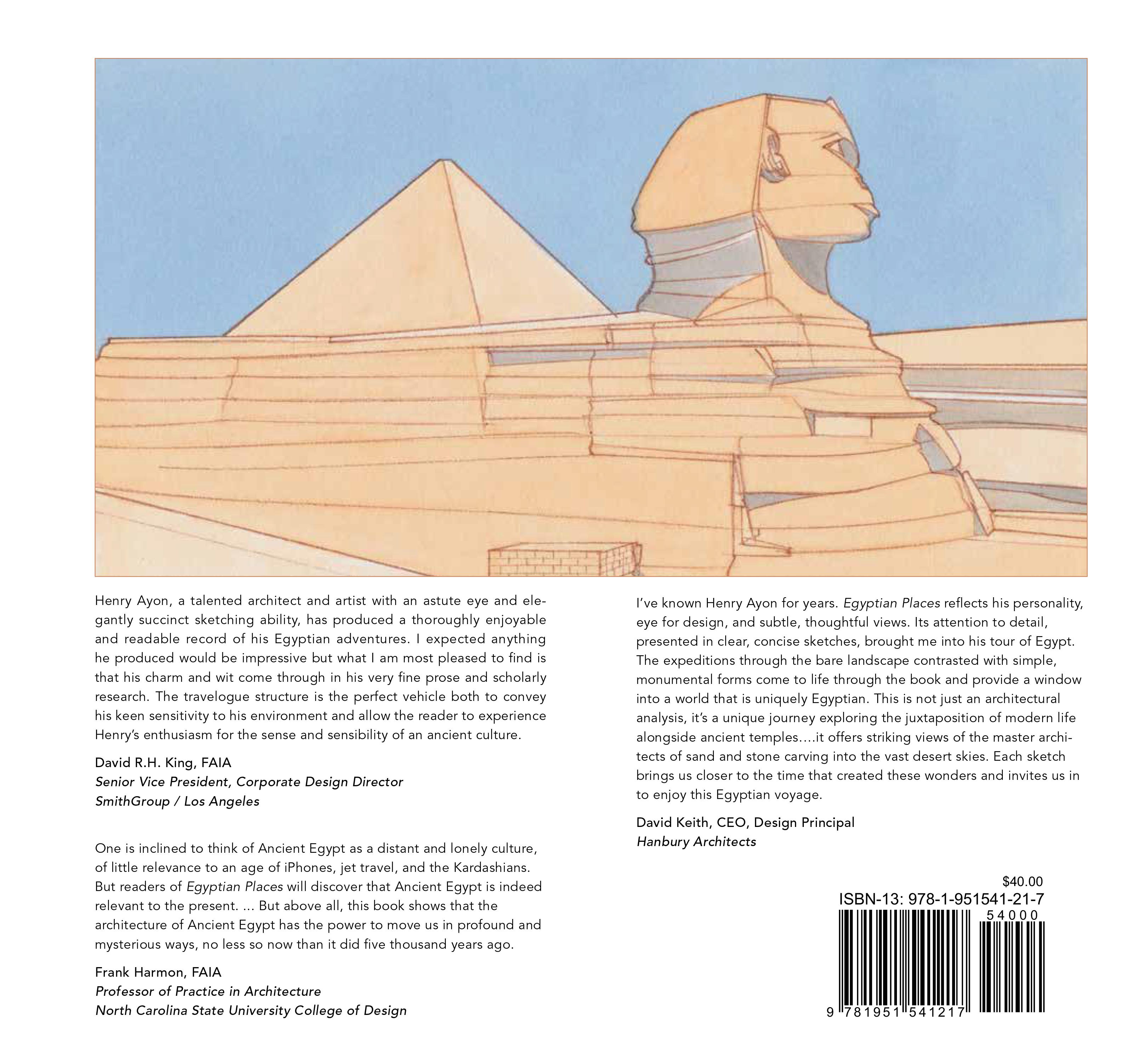

Ancient Egypt’s remarkable oddities and monuments have inspired and sustained a centuries-old, universal fascination with the land and history of the pharaohs that shows no sign, either in scholarly research or in popular culture, of abating. We were drawn to Egypt by the mythic attraction and opulent exoticism of the land of the pharaohs, its evocative structures and splendid iconography as represented by the Giza pyramids and Sphinx, the flooded Nile cutting through the Sahara Desert, bizarre symbology and pictographs, and a wild phantasmagoria of imagined (at least as far as we know), animal-headed, human-bodied deities

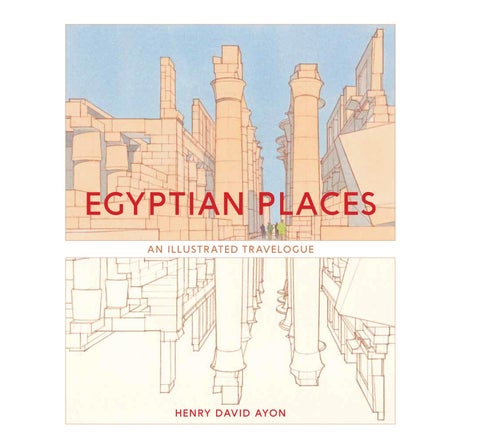

Seven Doors: Temple of Osiris Hek-Djet / Karnak

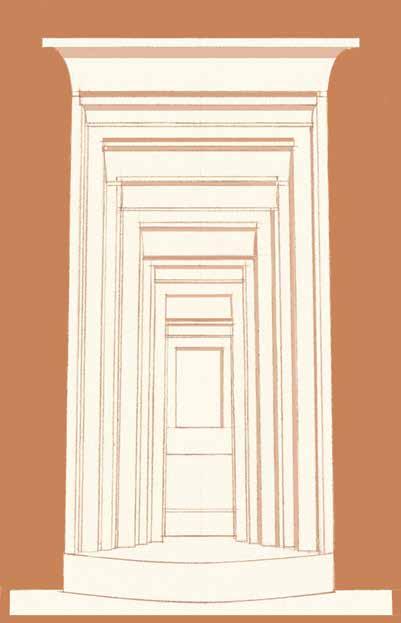

Sphinx of Memphis / Memphis

DAY 2

TODAY WE ARE TRAVELING WEST, moving away from the sad disorder of present-day Cairo, passing dusty townscapes, dry canals, and railway tracks, crossing over the “green ribbon” of the Nile into the Sahara and a vista defined only by the flat horizon line between desert and sky. Our destination is the site of the first true pyramid to be constructed in Egypt. Turning south into the pyramid field at Dahshur, driving through a sandy plateau on a paved stretch of road curving subtly in an elongated S-shape, we pass the Red Pyramid on our left, and moving on in a gentle arc, we then see the Black Pyramid to the east before arriving at the parking area closest to the provocatively titled Bent Pyramid, its slanted shape in the distance, as our initial destination.

This is the desert setting of Egypt’s first true pyramidal mausoleum. King Menes and a future line of pharaohs established their royal necropolises in this place, running north/south on the west bank of the Nile and just outside the natural line currently delineating verdant agriculture from barren desert.

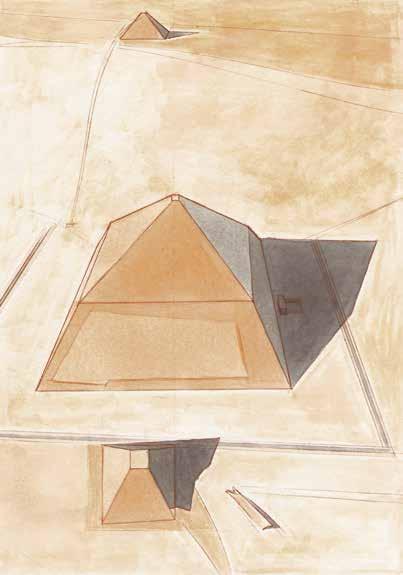

Known as the Memphite Necropolis, this swath of desert includes, moving south from Giza, the great Pyramid of Khufu and its satellite structures, including the Great Sphinx; Saqqara, among the oldest burial sites with the revolutionary Step Pyramid of Djoser; and the pyramid field here at Dahshur.

Although we are not very far from the greenish flow of the Nile (just over a mile), the setting is a lunar landscape of barren aridity: a desiccated Saharan setting of compacted earth, sand, and clay, devoid of visible life as far as the eye can see (although near the Red Pyramid is an abandoned rusted-out kiosk surrounded by trash, Coke bottles, and a gas can, left unattended in the sun).

A panoramic view of the site, moving from north to south, as seen through a haze of pollution and sand hanging in the

Bent Pyramid + Red Pyramid / Dahshur

Entrance of Queen Meresankh III Tomb / Giza

Solar Boat Pit / Giza

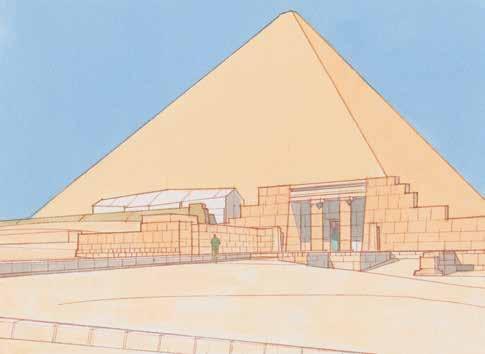

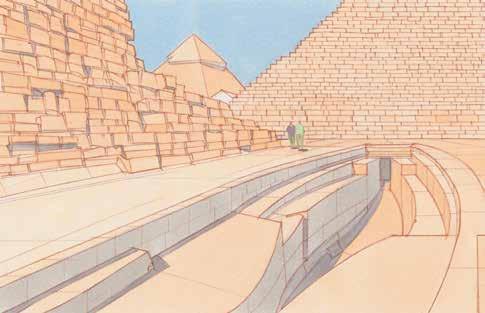

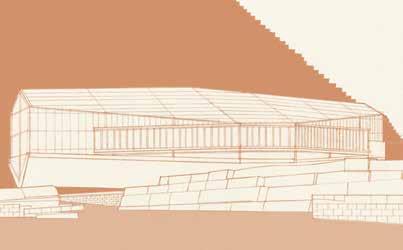

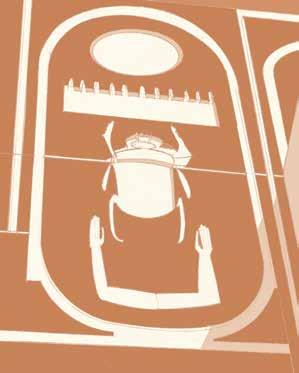

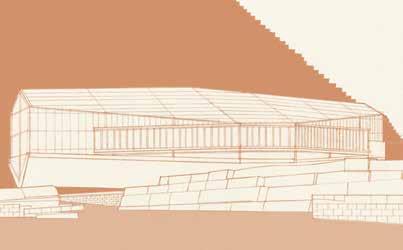

YET ALL IS NOT MASSIVE ABSTRACTION AT GIZA. As a contrast, Khufu’s delicately fashioned wooden “solar boat” is on display in an ultra-modern, 20th-century pavilion of faceted metal and glass (curiously resembling a futuristic spacecraft, which may be intentional). The pavilion sits somewhat awkwardly adjacent to the Great Pyramid, parallel to one triangular face. In 1954, the unassembled boat (in over 1,200 pieces), meant for Khufu’s journey through the afterlife, was discovered almost by chance in a pit outside the pyramid. It took over twelve years to reassemble.

Upon entering the pavilion, every visitor must place coverings over each shoe to reduce floor wear. After passing through some galleries of models and exhibits, we enter a multistory open space with the now assembled boat positioned in the middle, supported on metal columns. Within the space, walkways are suspended as “bridges,” so it is possible to have views of the entire vessel. It is an impressive and beautiful example of superb Egyptian craftsmanship.

Additional structures, constructed on a smaller scale, include other tombs and numerous eroded mastabas set in rows. The mastaba tomb of Queen Meresankh III, located southeast of the Great Pyramid, is graced with an entry porch that is especially beautiful in its simplicity and ideal in proportion. The battered stone façade, at least what is left of it, is interrupted by an indented entrance, headed above with a simple lintel and a shallow cavetto molding. Supporting the lintel are two round columns with block capitals and short, round bases; the whole, still beautiful and inspiring in its ruined state.

At nearly any time of day, the Giza Plateau is vibrant with activity: hundreds of tourists emptying out of buses and autos and then moving in all directions. As is typical of such sites, there are numerous vendors (the descendants of pharaohs and priests) with wares strung out along the sand in ragged lines of carpets and merchandise, selling Egyptian mythic trinkets, camel rides, and cold drinks and posing with travelers for a fee, all beneath the eye of the Great Sphinx.

Solar Boat Pavilion / Giza

Solar Boat / Giza

DAY 4

FOR THE TRAVELER, the word “Karnak” invokes images of Egyptian exotica and desert mysteries: temples of great mass and darkened chambers of incantations and magic. It stands among the largest religious complexes ever built, a dramatic mise-enscène populated with huge freestanding columns, the statuary of men and gods and animal figures arrayed as lines of sphinxes: a magnificent backdrop for pageantry, festival, and the worship of their deities.

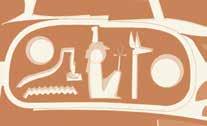

Starting with a single structure and ending with a massive precinct of worship constructed over a period of approximately 1,300 years, Karnak Temple was dedicated to the greatest of the deities: Amun; Muut, his consort; and their son Khonus.

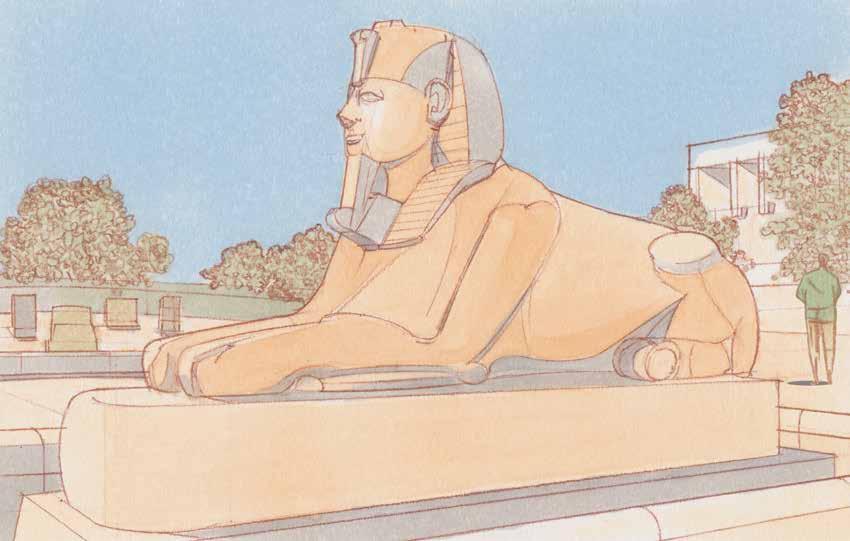

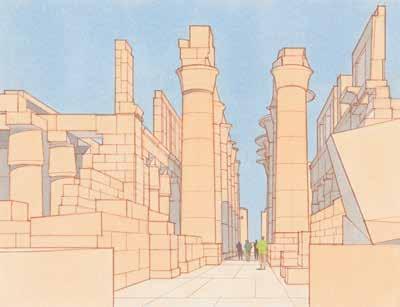

WE WALK FROM OUR TRANSPORT into the expansive paved plaza and turn ninety degrees to face the majestic entrance into what is one of the greatest achievements of the pharaohs: Karnak Temple. The time is near midday under a cloudless sky, and, as we approach the wide portal opening, flanked by a pair of pylons, the massive façade seems afloat on the vaporous, heated waves of air shimmering off the reflective pavement. With a crowd of hundreds descending on the site, the foreground is a plane of constantly shifting, multicolored patterns moving toward the slot between the unfinished towers at its entry point. Approaching the threshold to the complex, the converging crowds coalesce in the last 100 feet of a sphinx-bordered allée, axial with the sanctuary beyond. Each massive, unfinished pylon towers above the site, and the surge forward, of which we are willing participants, has the biblical sweep and the visual incident of Noah loading the Great Ark.

Temple Entrance / Karnak

Hypostyle Hall / Karnak

Kom Ombo

DAY 8

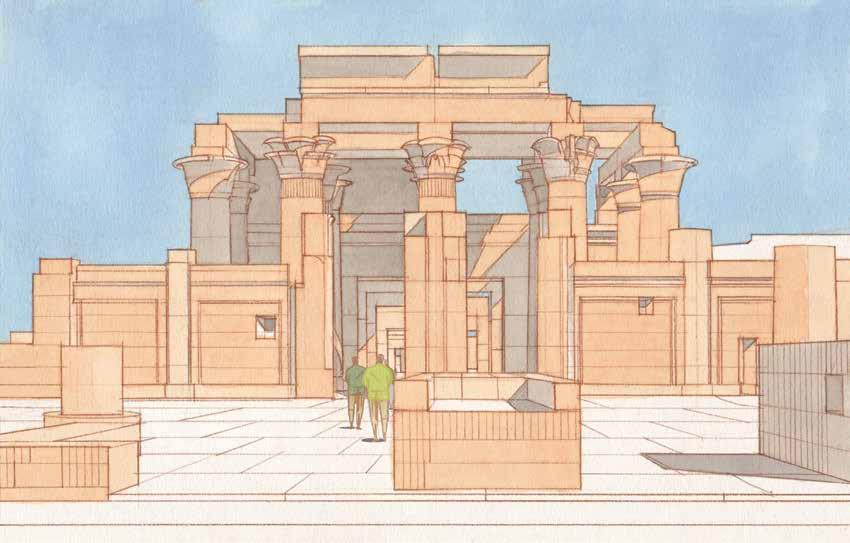

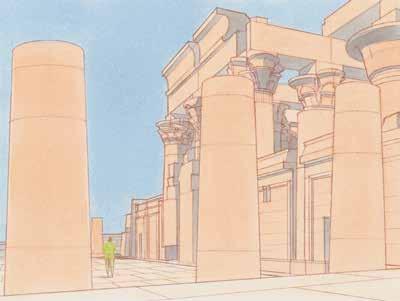

FROM OUR ELEVATED BOAT DECK, we descend on Kom Ombo much as the gods, Horus the Elder and Sobek, approached their temple: the falcon in flight and the crocodile skimming the surface of the Nile. Set on elevated ground within a few hundred feet of the river, the superstructure of the rare dual temple at Kom Ombo emerges majestically above the tree line, its mirrored image shimmering in shallow undulations on the waters of the river’s surface. Seen from this vantage point as we near the dock, the hulking stone mass, impressively modeled in deep shadow, gives the impression of a magnificent, god-sized brow rising from this perennially dust-covered terrain to survey the latest legion of visitors, as it has for over 2,000 years.

AS A TWO-DEITY TEMPLE, one might expect Kom Ombo to be twice the size of a standard temple, but such is not the case—the building is simply bisected down the center, each half being the mirror image of the other. In this polytheistic religion, this juxtaposition was apparently acceptable, and the structure has been designed around this accommodation.

Kom Ombo is atypical in several other respects: one conjectural reconstruction shows the Nile as situated adjacent to the outer walls of the complex, precluding pedestrian access directly on axis with the sanctuary chamber. If correct, the approach was from the north, parallel to the Nile, entering through the Gate of Ptolemy XII, which is located on the eastern face of the perimeter masonry wall.

Today, an impressively wide set of modern stairs links the dock level with the temple entrance, a very different perspective from that seen by a Kom Ombian in 40 BC. On the slow ascent from

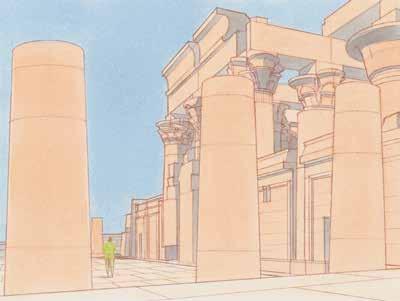

Court + Gate of Ptolemy XII / Kom Ombo

Entrance Court / Kom Ombo

Entrance

Entrance Façade / Kom Ombo

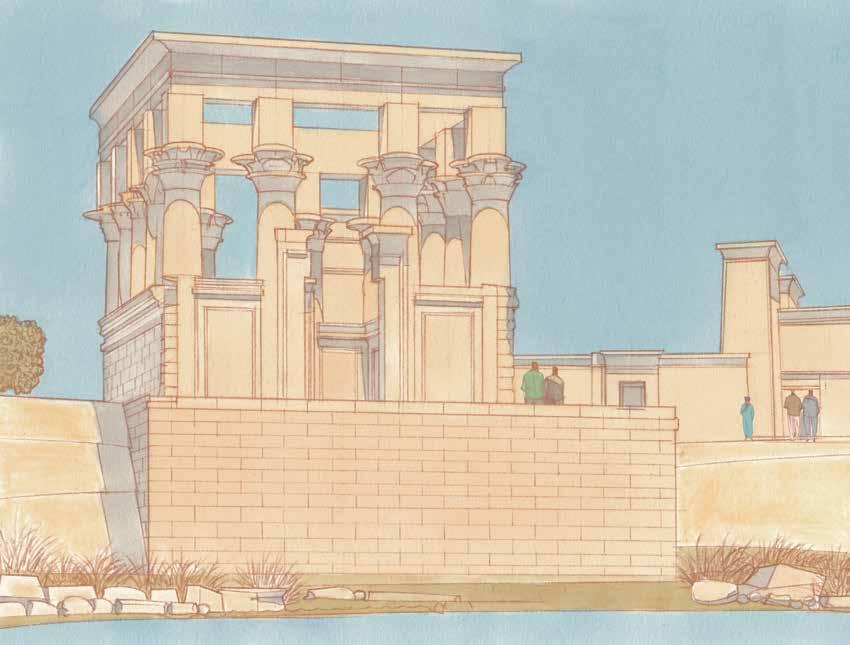

View from Nile River / Philae Island