ORO Editions

Acknowledgments 8 Introduction 1 2

CHAPTER 1: Designing-Women’s Worlds 16 Draperies, My Mother, and Me 16 Herstory of Place-making 18 Julia Morgan, FAIA 24

CHAPTER 2: The Heroines’s Journey 30 A Woman’s Search for Meaning 30 Finding Your Woman’s Voice 34 Margo Grant Walsh 40

CHAPTER 3: Women on Fire 50 Igniting Design Psychology 50 Smoldering: Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and #MeToo 56 Denise Scott Brown, RIBA, Int. FRIBA, Hon. FAIA 63

PART II: USING LIVED EXPERIENCE TO TRANSFORM PLACES, PRACTICE, AND YOU

CHAPTER 4: Transcendent Liberating Design 76 T ranscendent Design 77 Liberating Design 87 Gloria Steinem 90

CHAPTER 5: Healing by Design Psychology 94 The Road to Wellness 94 The “Neuros,” Women, and Metaphoria 98 Esther Sternberg, MD 104

PART III: APPLYING DESIGN PSYCHOLOGY: CASE STUDIES

CHAPTER 6: Women Make Space 11 2 “One Woman’s Journey from Oppression to Self-Realization” by “Katya” 113

Transformation by Design 1 28

BECOMING 1 29 My Environmental Autobiography by Olga Strużyna 1 29

NESTING 132 Helping My Client Achieve a “Cultural Oasis” by Sarah Seung-McFarland, Ph.D. 132

MOVING 134 Finding Connection Globally and Within by Suzan Ahmed, Ph.D. 134

STANDING STRONG ALONE 138 The Morgan Residence by Toby Israel, Ph.D. 138

GRIEVING 142 The Thom Residence by Toby Israel, Ph.D. 142

CHAPTER 7: Conclusion 146 Appendix 149 Endnotes 155 Bibliography 167

This will be a conversation just between the two of us about how design of depth and connection between self and place can be a form of personal transformation. In 2003, with a similar goal in mind, in my book, Some Place Like Home,1 I introduced Design Psychology, “the practice of architecture, planning, and interior design in which psychology is the principal design tool.” Back then, rather than answering questions like, “Would my blue chairs look good against my yellow walls?”

I wanted readers to ask the deeper question, “How can I use my past, present, and future story of place and self to create emotionally fulfilling environments?”

Interestingly, I’ve noticed that it is mostly women who’ve approached me to learn about Design Psychology. Why mostly women? I thought maybe it was because the field was something new: Design Psychology’s digging through the emotional bedrock of one’s life/environment is so different from the objectively oriented, traditionally male-dominated field of architecture that’s master-minded our built world.

Over the years, I’ve watched women struggle to fit into that world. Given their struggle, I thought about the landmark book, Women’s Ways of Knowing: The Development of Self, Voice, and Mind.2 I wondered, “Is there a ‘women’s way of knowing’ crucial to place-making that’s been discounted?” My speculation about women and Design Psychology led me to ask a bigger question, “Is there, in fact, a whole realm of human experience that needs to be laced back into the built world?” If so, rather than struggle to fit in, shouldn’t women, especially, be pioneering a new way of making environments?

My questions about women and Design Psychology nagged at me, since I suspected that answers to them might have wider implications for creating place. I turned to writing this book as my quest to find answers and gain insight about designing-women, the psychology of design, and myself.

As you’ll see in Part I here, I first dug deeply into feminist design literature to understand the challenges facing designing-women. I define “designing-women” in this book, as “women who make place” including, especially, female architects and interior designers. My literature review gave me an overview of the challenges faced by female place-makers. Still, I wanted to dig down further to examine the

lived experience, the personal stories, of key designing-women pioneers. Was there something about their journeys or their sensibilities that led them so successfully to ride (and sometimes make) feminist waves?

With a historical overview in mind, I began to examine the life/work of architect Julia Morgan (1872–1957), now recognized for the amazing 700+ buildings she designed. Yet, since lived experience inevitably is a perspective told first-hand, I then reached out to interior architect Margo Grant Walsh, whose illustrious career at the Gensler design firm began in 1973. She broke the glass ceiling when she became managing principal there. Similarly, my search for insight led me to the door of architect/planner/icon Denise Scott Brown who won the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal in 2016 at the end of her amazing career. You’ll read here how these women not only helped transform their professions—they navigated their own personal transformations.

In fact, since my training is in environmental psychology, a field that studies how people affect environments and environments affect people, I examined their stories through that psychological lens. To do so, I took Grant Walsh and Scott Brown through the same Design Psychology series of exercises I’d previously used with famous design world men.3 As a result of excavating the “environmental autobiography,” the personal history of place of both of these females, I unearthed the fuller tale of how Grant Walsh triumphed over the oppression of the Chippewa reservation of her childhood and Scott Brown navigated through anti-Semitism in her South African homeland. Most relevant to my research was that I learned how their lived experience could be “read” in the design of their public projects and in their private homes.

As I became more and more engrossed in examining ways women know, design, and struggle in the world, I then went on the road to conferences to listen to more tales. Paying attention to our female stories seemed particularly vital since, when it comes to affecting real change, as author Elena Ferrante points out, “Power Is a Story Told by Women”:

There is one form of power that has fascinated me ever since I was a girl, even though it has been widely colonized by men: the power of storytelling. …Storytelling…gives us the power to bring order to the chaos of the real under our own sign, and in this, it isn’t very far from political power… The female story, told with increasing skill, increasingly widespread and unapologetic, is what must now assume power.4

When I sat back from this road I traveled, I understood that designing-women often have repressed their culturally nurtured “women’s way of knowing” (their feeling sensibility, for example) in order to achieve “success”: Females so often struggle to assume their professional as well as personal power.

Thus, in Part II, I suggest how, rather than struggle to fit in, women can break new ground by tapping into their lived experience to find their liberated, even transcendent voice. To show you what I mean, I write about how, despite her rootless childhood, even famous feminist activist Gloria Steinem created her home as a catalyst helping her achieve a healthier sense of self. Then, too, I tell of creating my

Women can break new ground by tapping into their lived experience to find their liberated, even transcendent voice.

Over the years, like a rapt archeologist, I’ve unearthed the past-place stories of famous design-world men. I’ve delicately examined each detail of their childhood homes and hangouts until I saw the full picture of how these fragments fit together to form the foundation of their famed male-made designs. Now that I’ve stepped back from my digging, I feel guilty as I realize I haven’t actually examined the environmental stories of women.

Curious about female place-makers whose stories I may have left unheard, I began to read the literature about feminism and design while on my back porch. Ah! But then a blue jay in a nearby tree began sweetly chirping on and on. Its song lulled me into musing about my mother, born in 1923. Mother became an interior decorator. She really wanted to be an actress before she married and had children. That creative fire was doused by her stern, hard-working immigrant mother, the family breadwinner, who heard “actress,” and thought “fallen woman.” Still, women with passionate hearts like my mother need to find avenues of expression.

So, my mother struggled to find a path for herself. She became the first family member to go to college. She went on to teach and do set design at Douglass College. By her mid-twenties, my mother left behind teaching and set designing, married, and gave birth to my older brother and to me. In her early homemaker years, she made all of my little lace dresses, directed the school plays, and helped my father at his paint and wallpaper store. But it wasn’t enough. She felt stifled and so she parlayed the advice she had been giving at the family store into a decorating business run out of our home.

Most female homemakers of that generation weren’t expected to work except within the home where the dictum was: MAKE WARM HEARTH = HAPPY HOME. Most men were out doing the “real work.” For my beloved father, the man-burden of real work at “the store” meant he had two heart attacks and died by the time he was fifty-four, when I was only sixteen.

My mother continued to work, and from an early age I can remember tagging along with her from designer showroom to showroom as she chose fabrics

and furniture that transformed her clients’ lackluster homes. Via these outings I learned to carry any color in my head, to arrange furniture in a space, imagining people within it, and soon I could spot a beautiful, jaunty lamp or a cushion with a tale to tell.

At first the world of interior decorating provided a creative outlet for my mother and many other marginalized homemakers to both express and transform their psychic and home interiors. As time progressed, however, the idea that “just anyone”1 could decorate a home became denigrated and was seen as trivial by those wanting interior “designers” to be viewed as professionals like architects or lawyers. In this new wave, designers were in and decorators were out

Such a push to put interior design on equal footing with male-dominated design professions seemed a step in the right direction in an era where women rightfully were demanding equal rights. Yet the push to professionalize also had a boomerang effect of re-marginalizing some women for whom home was the only canvas on which they could paint their most colorful selves. My mother, for example, began to feel she was a fraud despite her creative talent and professional success since she did not possess any “real” interior design credentials. What were the real credentials? Look closely and you’ll realize that even those women who became the standard-bearers of the profession, like former debutante Dorothy “Sister” Parish, had no formal design training. Interestingly, Parish wrote about how her interior design philosophy was influenced by childhood experience of place:

As a child, I discovered the happy feelings that familiar things can bring—an old apple tree, a favorite garden, the smell of a fresh-clipped hedge, simply knowing that when you round the corner, nothing will be changed, nothing will be gone. I try to instill the lucky part of my life in each house that I do. Some think a decorator should change a house. I try to give permanence to a house, to bring out the experiences, the memories, the feelings that make it a home.2

Yet Parish was no psychologist of design. Hers was nostalgia decorating where “chintzes, overstuffed armchairs, and brocade sofas with such unexpected items as patchwork quilts, four-poster beds, knitted throws, and rag rugs led to her being credited with ushering in what became known as American country style during the 1960s.”3

Right there laid a schism because these messages, like waves, went back and forth: Housewives should create the ideal home! Look to the high styles of the past! Search for your own unique expression! Meanwhile women entering place design professions were hearing, “Just find a way to join the exclusive, male place-maker’s club!”

Digging deeper now to understand, I realize that such mixed messages sent mixed signals to my mother and to women in general about what it meant to be a successful homemaker, designer, or just a fulfilled woman in the world. It was confusing. Now I am wondering what messages you and I got from our homemakers about how to create a home oasis, places, or a life.

The push to professionalize had a boomerang effect of re-marginalizing some women for whom home was the only canvas on which they could paint their most colorful selves.

When Margo Grant Walsh opened the door to her Sutton Place, NYC apartment. I recognized her as the slender, striking woman with distinctive black glasses I’d seen featured in design magazines. Gracious, she put me at ease when inviting me into her entry foyer. It was the end of a long day for this woman who paved the way for women when she became the managing principal/vice chairperson of Gensler, a major commercial design firm often rated the number one design firm in the U.S. Inducted into the Interior Design magazine Hall of Fame in 1987, Grant Walsh has been described as “one of the most powerful and influential women in American architecture and interior design. She not only pioneered the way for woman in her field, but helped establish the profession as it is defined today.”1 She did this in a male- dominated corporate world. Together Grant Walsh and I walked through her dimly lit hallway and sat down in her elegant living room with its deep red walls. Now, if you think I am going to recount to you the environmental autobiography of a high society, silver-spoon-in-her-mouth woman and thereby tell a story that obscures the “structural inequalities of Western society,” 2 you couldn’t be more wrong. While Julia Morgan faced daunting challenges as a woman in architecture, Grant Walsh faced the intersectional obstacles of gender, class, and race. Nevertheless, she claimed her voice and power.

Once we sat down together, Grant Walsh’s fascinating story didn’t just tumble out. Her story emerged gradually as I took her through my Design Psychology Toolbox of Exercises, 3 by then a more formal version of the exercises I’d devised at Hull School of Architecture. Grant Walsh, born during the Great Depression (almost sixty-five years after Morgan), was alive and well before me. Thus, unlike Julia Morgan, I could interact with her by using the exercises from the Design Psychology Toolbox to explore the psychological foundation upon which her sense of place + self might rest. Thereby, too, I might gather further clues to see if this woman’s way of knowing may have helped her achieve such success.

Grant Walsh began our conversation: “You may notice that my apartment is very dimly lit. That might seem strange to you. It seems very familiar to me. I grew up on a Native American reservation where there was no electricity so we lived by the dim light of candles.”

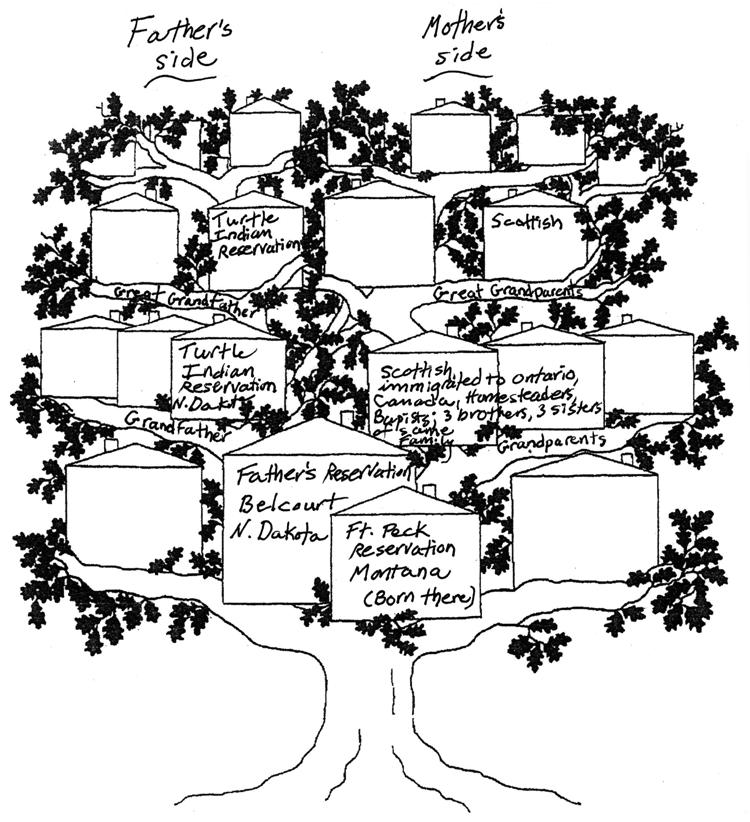

As Grant Walsh completed my first Environmental Family Tree exercise, I learned about the very different branches of her tree. The daughter of a Scottish/Canadian mother and a Native American father, Grant Walsh was born on a Blackfoot Native

American reservation in Montana and grew up in a Chippewa reservation in North Dakota. Such reservations were places of profound deprivation, lacking both electricity and plumbing. The only furniture the family owned was one green couch. Not only was the reservation a place of complete deprivation, it was a place of complete oppression. It was ruled with an iron hand by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and under their thumb no one had any say about anything.

Grant Walsh’s mother, a schoolteacher in the reservation’s one-room schoolhouse, wasn’t paid. Instead she got “scrip” she could use in the company store. Her father delivered gravel, drove trucks, painted houses, and played in a local band. Interestingly, Grant Walsh’s mother seemed to be the driving force in her family. Her father played the role of caretaker. She explained:

I glance up and see geese flying against the blue sky in “V”ictorious formation. Did one generation show the next how to use their wings to fly? Victorious, Margo Grant Walsh, too, ascended great heights. I wish she’d been my mentor when I moved back from England to New Jersey in the early 1990s.

By then, environmental psychology had sparked interest, but hadn’t caught fire since its founding in 1969. Architecture magazines still lauded beautiful buildings by (mostly male) starchitects. Universities courses rarely offered psychology courses along with design courses, despite calls for interdisciplinary learning. I wasn’t sure what path to go down next.

Upon my return I was supposed to write a book about environmental psychology. “Personal Space,” “Noise,” and “Crowding” would be my worthy topics about this research field. Yet my fingers refused to type about those topics. Instead, I kept remembering back to ways I’d tapped into my students’ memories of a warm kettle’s whistle on a cold day, of slithering from rocky bank to pristine lake, of the scent of heather on hills. I felt sure it wasn’t just a fluke that such echoes kept unconsciously reappearing in their designs. Such design elements seemed pastplace signposts of those students’ evolving self.

Then, too, apropos of my sessions with Margo Grant Walsh, I felt driven to uncover ways such environmental memories hidden beneath the surface, re-surface in the design of our homes and the spaces that even famous designers create. I felt certain that such insight could be applied to help professionals and all of us “design from within” our deepest selves. Grant Walsh found her self/home voice intuitively. Design Psychology might provide a method to do so consciously and, perhaps, more quickly.

Was my desire to write about using environmental autobiography as a catalyst when making place fueled by burning curiosity? By my own desire to heal my childhood wounds that kept forcing me to find how best to express authentic soul in space? Regardless, for months I dove into books by theorists who suggested

ways to achieve a sense of wholeness. This led to my grounding Design Psychology in the well-known, classic theory of humanist psychologist Abraham Maslow who believed that we all can achieve a sense of wholeness and fulfillment via “self-actualization.”

According to Maslow, self-actualized people are able to “appreciate again and again freshly and naively, the basic good of life with awe, pleasure, wonder and even ecstasy.”1 To reach this pinnacle of healthy selfhood, Maslow theorized that we have to satisfy a hierarchy of needs from ‘physiological’ to ‘esteem’ needs. For the purpose of Design Psychology I transposed Maslow’s theory into a theory of

“Place as Self-Actualization”:

According to the Design Psychology version of Maslow’s hierarchy, to have a truly fulfilling place, one has to meet basic needs such as the need for shelter yet also meet psychological, social, and aesthetic needs. Typically, architects and interior designers necessarily are trained to focus on the bottom of the pyramid, i.e., shelter: buildings must stand up and the roof can’t leak. They’re also educated to focus on aesthetics. Often, however, the middle pieces—the emotional/psychological and social aspects of design are like less-valued (female?) children who’ve been left behind.

Alternatively, the actualized place-self pyramid offers a more holistic basis for design. With this in mind, each of the exercises in the Design Psychology Toolbox 2 , like the Environmental Tree Exercise that I administered to Margo Grant Walsh, systematically explores and analyzes each level of the “Place as Self-Actualization” pyramid to assess if that client’s environment is fulfilling. Yet this isn’t simply a rigorous, objective process: apropos of women’s ways of “knowing,” it’s a subjective, consciousness-raising process wherein the exercises subtly unfold not only one’s past but one’s present and future self/place story.

Driving back to New Jersey that cold, dark night after meeting with Denise Scott Brown, I felt warmed by her heroine’s journey. As with each of the designing-women I’ve discussed, she blazed a trail for other women.

The next day I sat down to contemplate the tales of all of the female place-makers I’d heard. I imagined myself chatting with Julia Morgan, Margaret Grant Walsh and Denise Scott Brown albeit sitting inside in winter without a roaring fire to inspire dialogue (and with spring’s birds still so far away). Nevertheless the warp and weft of these women’s wise words, my readings, and all our lived experience resulted in my own fabric of beliefs– my answers to the questions I raised at the beginning of this book:

Is there a “woman’s way of knowing” crucial to place-making that’s been discounted?

I believe:

• Women in general are culturally conditioned to be more emotionally expressive than men.

• Often, women especially have had to mute this “feeling side” and other subjective ways they know in order to succeed in the objectively oriented, traditionally male field of architecture

• As sometimes reflected in space design, hiding one’s full persona can create a disjoint between public image and deeper self.

Is there a whole realm of human experience that needs to be laced back into the built world?

I believe:

• Rather than experience a disjoint, we can create places that integrate both our deeper subjective/feeling as well as our objective/thinking sides.

• To create such whole, human-centered places we can use our lived experience as the basis for design.

• Design Psychology’s “design from within” process brings such personal environmental experience to the fore so fulfilling design elements can be used to create actualized self/place.

Rather than struggle to fit in, shouldn’t women, especially, be pioneering a new way of making environments?

I believe:

• Since women have been given greater cultural “permission” to speak personally about their lives, they are particularly well-positioned to break new ground by using lived experience as the basis for design.

• Thus, as well as using their voices to challenge bias, women can champion human-centered place-making processes that help overcome oppressions.

• As part of this humanistic wave, the Design Psychology process can be used by anyone to transform places, practice, and one’s very sense of self.

Having reached these conclusions, in Part II of this book I want to tell you more about how women and men have turned to using personal experience to shift toward such transformative, what I call “transcendent liberating design” (TLD). Moreover I want to show you how such vital feelings of transcendence and liberation can be released by the Design Psychology process and, ultimately, applied when making place. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Denise Scott Brown wasn’t the first to challenge modernism’s tight hold. As early as 1929, Eileen Gray1, a then famed (yet now, too-little known) designer, declared, “Modern designers have exaggerated the technological side. …Intimacy is gone, atmosphere is gone. …Formulas are nothing. …Life is everything. And life is mind and heart at the same time.”2 Gray’s was a clarion call to bring back the human element in place-making. Her warning was so different from that of architectural modernist Adolph Loos who in 1910 famously (now infamously?) linked ornament with crime, declaring Art Nouveau-type ornament (like that on Scott Brown’s dresser?) “immoral and degenerate.”3

Perhaps Gray’s call fell on deaf ears: While post-modernism and other architectural isms have come and gone over the years, the pervasive grip of modernism remains strong. As writer/editor Leilah Stone observed in 2020:

Driven by the heroic male architect, Modernist dictates of good design, functionalism, truth to materials, purity of form quickly took over and continue to be the dominant ideology today in the way architecture and interiors are taught and practiced.

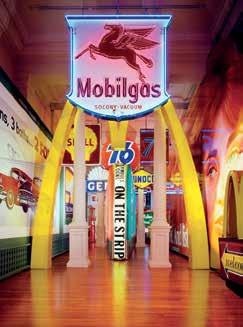

Signs of Life Exhibition, Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC, 1976.

Photograph by Tom Bernard.

If Modern architecture was rational, masculine, and structural, then decoration was considered emotional, feminine, and shallow.4

Renowned architect/theorist Christopher Alexander places blame on our ubiquitous culture. He decries what he sees as society’s rational, objective ways of knowing, a way so different from the women’s ways of knowing I’ve been discussing here. Alexander declares:

I believe that we have in us a residue of a world-picture which is essentially mechanical in nature—what we might call the mechanist-rationalist world-picture. …Like an infection it has entered us, it affects our actions, it affects our moral, it affects our sense of beauty. It controls the way we think when we try to make buildings and— in my view—it has made the making of beautiful buildings all but impossible.5

Alternatively, Alexander champions a more subjective, personal—even spiritual approach that aims to create transcendent design. He states, “To reach the ultimate I, the transcendent ground of all existence, you have to reach yourself.”6 Rather than thus calling for a narcissistic “self”absorption when designing, what Alexander refers to here, is “This self, this ‘something’ which lies in me and beyond me7 is nameless, without substance, without form—and yet is also intensely personal”8 that “is necessary as an underpinning for a successful art of building.”9

As with Design Psychology, rather than look toward superficial decoration, Alexander’s (feminist?) stance turns to deep emotion as luminous, something to be celebrated, not white-washed. In fact, for Alexander, what makes a good place or building is if it seems “alive”:10

Only a deliberate process of creating being-like (and self-like) centers in buildings throughout the world will encourage the world to become more alive. By this I mean that the successful maker consciously moves towards those things which most deeply reflect or touch his own self, his inner feelings, and consciously moves away from those which do not.”11

Importantly, although Alexander’s emphasis is on places that elicit feeling, he draws a distinction between everyday emotion—happiness, sadness, or anger, for instance, and “emotion” as he defines it: “this feeling as the inward aspect of life.12 … in which my vulnerable inner self becomes connected to the world.”13

Interestingly, too, Joseph Campbell wrote:

The goal of life is rapture

And art is the way we experience it.14

I believe that the making of transcendent places can be ‘the way we experience’ rapture, as well. To achieve such transcendent environments/rapture for ourselves, we can use Design Psychology to “design from within” our very personal lived experience, especially childhood experience of transcendent environments. Long ago, after all, I remember how my elementary school students ‘fell in love with the universe’ when building their playground and ways my architecture students rediscovered their magical symbiosis with past places while going through Design Psychology’s exercises.

Thus it’s not modernist design per se to which I object. In fact, I love the design of my own mid-century modern home so reminiscent of my favorite cousins’ home of my childhood. My home’s simple exterior, angled roof, and huge windows always let in light that uplift me. What Alexander and I critique is modernist buildings devoid of spirit and emotion. For instance, what gripped my own community to construct a high school addition that seems more dead than “alive”? What messages do such structures send to current and future generations about the meaning of architecture—or even the meaning of life?

Similarly, author Annie Murphy Paul asks, “What thoughts are inspired, what emotions are stirred by a row of beige cubicles, or a classroom housed inside a windowless trailer? This is not simply a question of aesthetics; it is a question of what we think, how we act, who we are.”15

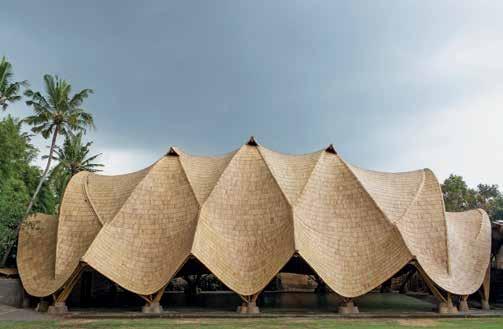

For example, compare the “dead” gym above right, with the one on next page, built under the direction of Elora Hardy for the Green School in Bali. Rather than follow in modernism’s footsteps, that structure “wraps around”16 students, “holds them, inspires them and nourishes them.”17 It’s a space that’s alive, transcendent.

Hardy, trained in fine art rather than architecture, is the founder and creative director of “Ibuku,” a word that connotes “My Mother Earth” in Balinese. As recommended here, she’s brought her personal, environmental, lived experiences to the fore. Consciously or not, she drew from her environmental autobiography when founding Ibuku. Hardy’s use of bamboo echoes back to her childhood experience of place growing up in Indonesia.18 She recalls, “My earliest memory of Bali was my fifth birthday party. I remember making scarecrows together out of thatch,

High School Front (left), High School Rear Auditorium (center), & Gymnasium Addition (right).

Photographs by the author.

Gymnasium, The Arc at Green School, Bali, designed by IBUKU.

Photograph by Tommaso Riva.

Gymnasium, The Arc at Green School, Bali, designed by IBUKU.

Photograph by Tommaso Riva.

Entrance Tunnel, Bali, designed by IBUKU.

Photograph by Rio Helmi.

Sharma Springs, Bali, designed by IBUKU.

Photography by Errol Vaes.

The case studies I present next are shorter snapshots of ways Design Psychology worked for other women wishing to transform their interior space. Of particular interest is that each woman was experiencing a different life-passage while on her self/place journey:

• Olga, a home-style writer whom I mentored, was separating from her childhood environment and creating her first home.

• Sarah, a clinical psychologist and a student in my Design Psychology training program, writes about a case study she completed during her mentorship. She worked with Maribel, a single parent, who wished to make a solid, cozy nest for herself and her young girls.

• Jennifer, my client, was about to become an empty nester. She completed a home addition using Design Psychology as a way of welcoming in her wider community.

• Suzan, also a clinical psychologist, enrolled in my training program. She worked with “Nary,” a second-generation immigrant seeking to move house and find home. Of special interest is that Suzan embedded the Design Psychology process in her therapeutic, not design, practice.

• Binnie, my client, needed a new place to grieve, recover, and make a new life after the death of her beloved husband.

After going through the Design Psychology Toolbox, 1 some of these women went on to make design choices on their own. They selected interior design elements— colors, furniture, special objects, etc., as recommended in their Design Psychology Blueprint. Others hired architects or interior designers who used their client’s Design Psychology Blueprint of recommendations as a guide for making place. A few hired me to help them carry out their place-making plan. No matter what the final design route, every one of these Transformation by Design stories highlights how these women used Design Psychology to become more aware of their own lived experience and of ways they could translate that experience into transcendent, liberating space.

After each of their vignettes, I provide specific suggestions to others going through a similar life-stage about how to use Design Psychology as a catalyst for well-being. Those tips are collectively based on the many other clients’ stories that I’ve heard over the years. No matter what stage you are passing through, feel free to use those suggestions in conjunction with doing the Design Psychology He/She/ They Oasis Exercises specific to this book, although adapted from the original Design Psychology Toolbox of Exercises. 2 Just go to www.designpsychology.net/DWL. pdf to access the adapted exercises. You can complete the exercises in the sequence indicated in the ‘Suggestions’ section after each of the case studies below.

I was born in Warsaw, the capital of Poland. I lived there with my twin sister and parents in an apartment until I was twenty-eight. When I think back to those years, I realize I had no privacy, since I shared my room with my sister. Even in my early childhood, for example, my only private place was my drawer in kindergarten. Then, too, my privacy often was disrupted by my mother and grandmother. Someone was always checking on me. I remember that one of them read my diary. Then, too, my mother didn’t have housekeeping skills. She was a collector, but had so many things in the house you couldn’t admire any of them.

Luckily, the district where I lived was away from the city center so I had places where I could wander. I remember small shops—ice cream, bakery, and shoe shops. In the nearby park we sunbathed in summer and went skiing or sledding downhill in the winter. Nearby, separating my house from railroad tracks, there was a green belt full of bushes and trees. Here my friends and I collected flowers or herbs for drying, or snails and ladybirds. I always felt free and ready for adventure there. From these experiences I gained a still-deep need to be with nature.

In fact, when I did the Design Psychology Guided Visualization Exercise, I vividly remembered a house in nature—the transcendent bungalow of my mother’s best friend, “Auntie Basia.” It was a bungalow in the middle of the forest. It was quite small with only about two rooms but had lots of books and paintings. I used to go there between the ages of seven to twelve. It had a wonderful atmosphere with lots of trees outside, old furniture inside, and lots of food. I felt happy when I went there. I felt freedom! For the first time, I really felt deeply that I wanted to live close to nature.

Later, since I’d lived so long with my family and my twin sister, I wanted to spend time by myself. I made my own, first mature decision when I took a break from my university and went abroad to Amsterdam. There I lived in a house with no curtains on the windows, a big greenhouse, with farmland in the back and a garden in the front. I felt very comfortable there: calm, free, happy, close to the water and nature. By spending time without my mom and sister, I found myself.

The next year, after being depressed, I went to Holland for a second time. I worked in a restaurant. The owners treated me as a part of their family. They noticed me, accepted me, cared about me. I felt more important. I didn’t need to play a role or be perfect.

Interior of Olga’s aunt’s house.

Photograph by Olga Strużyna.

When my grandmother died, she left me this apartment. I chose to live here because of what she represented to me: an honest, good person who liked things clean—not like in my mother’s house. My grandmother was more of a mother to me than my real mother. Nevertheless, when my grandmother lived here, I never liked this apartment. It felt too small and full of unnecessary things. Her old furniture also wasn’t very attractive. During our Design Psychology work, I realized that I didn’t want her old furniture anymore. I bought new furniture and mixed it with the old pieces. Now I only have the few things I really need.

Still, this present home doesn’t reflect my full personality. I do not feel free here, maybe because of the fact that it’s still a small space. There were only two rooms, but I kicked the walls out and created an open space. Similarly, although in my neighborhood there are small shops, a church, etc., I’m more in the city center than before. That’s not a good thing. I have no close contact with nature.

Wondering if I belong in this apartment, I thought I should become aware of what I was going through. I started to read Some Place Like Home1 and Cooper Marcus’s book. 2 Then, after one Design Psychology session, I realized that I still was stuck with “things.” I decided to make changes step by step. I was a little afraid, but I liked it. Doing the Ideal Place Exercise helped me realize what type of home I wanted:

My ideal home is warm, cozy with magical atmosphere including artwork, candles, glass or crystal dishes and furniture that doesn’t overcrowd. It has a garden where I can walk on the grass in my bare feet. Partly sunny, partly shady, it makes me and my guests feel that we never want to leave.

After writing this, while still sitting at my desk

I thought, “This isn’t my desk—it was my grandmother’s desk.” I had a lot of energy and couldn’t sleep, so I started to rearrange the space. The place was a mess, which didn’t make me feel good, but something kept me from changing it—from being open, free. I think it was an old part of myself, so I said to myself, “Can I clean out old papers and old junk? Yes! I can do this, but very slowly.”

It has been very difficult for me to cut out the old part of me—what my mum wanted me to be—and to look to the future to create my own new family that would care about me. Nevertheless, I threw out objects like small ceramic figures from my mum, my grandmother’s candlestick, etc., which reflected my family’s taste, not mine.

Now I see that everything has a connection. I want to visit my Auntie Basia’s house again. I want to take a photo of it because I think it’s really quite important. It’s so similar to what I want in the future. I’m not sure I can get a house like that, but, if I believe in that dream, why not? I have a piece of land. I am hoping to build a small summer house there. I now know how my future should look. I want to feel that my home is my place where people notice and respect me—where I can stand on my strong legs. I want to feel grass under my feet. It’s time to open next chapter of my life. I am ready for it.

Five years later Olga wrote to me:

Now I am pregnant and have moved with my husband to the home I always dreamed about. It’s a small house near the forest like the one where my auntie lived. (Do you remember it from the Guided Visualization Exercise?) This house is awesome. Maybe it’s not exactly like my auntie’s—but it’s quite in my style now.

I am continuing to do work with Design Psychology. Sometime I run workshops. More recently I completed a project for a cancer hospital designing two day-rooms for cancer patients and their families, as well as a small part of their lawn. It was really great for me.

Life’s circle comes around. As I re-read each one of these women’s stories, I think of the life passages I’ve been through. In truth, supporting Binnie also felt cathartic for me, too. Designing her healing space helped me further heal my sense of loss of my father still lingering from so long ago. Hopefully, these self/place tales also resonate, provide insight, and, maybe, comfort you.

Still, the overarching aim of this book has been to encourage all of us to retrieve the personal, subjective sense of self and place inherent in our lives. Yet, as I hope the designing-women’s stories and case studies here have shown, that sense of self, wrapped in emotional authenticity, often remains something women place-makers particularly have felt the need to hide. For most of us, in fact, the ways our self and environment are intertwined lies below the level of consciousness: it is raw, yet rich, material waiting to be mined to make ourselves and our places feel truly whole and alive!

With this in mind, my goal has been to get you feeling and thinking about ways you can use Design Psychology’s exercises as further tools in architecture, interior design, environmental psychology, design thinking, and even art therapy to transform places, practice, and you. I hope that, in the future, others will find new ways to incorporate and expand these and other human-centered tools. The Design Psychology process provides a comprehensive methodology that can be used, not just by women place-makers, but by anyone—non-professionals or professionals of any gender identity—to create transcendent, liberating space for others and/or for one’s self.

It’s not easy to get minds to shift toward using lived experience as the foundation for making a place more human. Pro forma place-making practice, mindless messages from mass media, patriarchal culture, and the design critics in our heads keep us from connecting the dots between our psyches and our front doors. As often happens when a vital part of our humanity is repressed, it is women who’ve experienced marginalization who step forward and call for change.

The almost all-female American Institute of Architects’ 2017 Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Commission has used their strong voice to declare: “Architecture

will go beyond physical, technical, and aesthetic distinction—it will reflect awareness and empathy. It will serve the best of humanity.”1 The architecture establishment is trying, and, in many ways, it is succeeding. “Architecture is no longer just a gentleman’s profession.” 2 The number of female architecture students continues to rise. The number of female deans of design schools keeps increasing. More and more women are creating spaces and public buildings in new and exciting ways. 3 Yet what remains to be seen, as designing-women climb bravely to the top, is if they’ve just scaled a mountain fogged in by the same old values and practices of patriarchal clubs. Time and distance will tell if, rather than fit in, the increasing numbers of diverse professionals (and non-professionals, too) will embrace the design of exterior and interior places that result in our most fully expressed landscapes, lives, and human selves.

Sometimes culture-shifts take time. In terms of EDI, for example, the AIA admits, “We have no illusions about the scope of the challenge. Fully living up to our highest ideals and values won’t happen overnight, but neither can it wait another day.”4

In the end, to muster my own woman’s voice and power, I make these final recommendations based on what I’ve learned about myself and from these stories of designing-women’s lives.

In terms of places, I advise that we:

• create transcendent places that make us feel alive and tuned into our human, rather than mechanistic, experience of the world

• base such transcendent design on our lived experience in a way that gives voice to our most liberated sense of self

• ensure that the places we create honor authentic people and place connections, not just trends

• make places sensitive to life passages and life cycles in ways that support positive growth and change

• consider using metaphoric design elements, especially in our homes, that act as inspiring symbols of self—catalysts to help us achieve emotional well-being

In terms of practice, I advise that we:

• integrate our thinking and feeling sides and express both of these aspects of our being in our designs

• tell our own and others’ personal stories in the places that we make such that design becomes a vehicle by which not only gender, but race and class identity can be expressed and celebrated, not obscured

• use our voices to challenge bias and champion empathetic, collaborative, participatory place-making processes that help overcome oppression