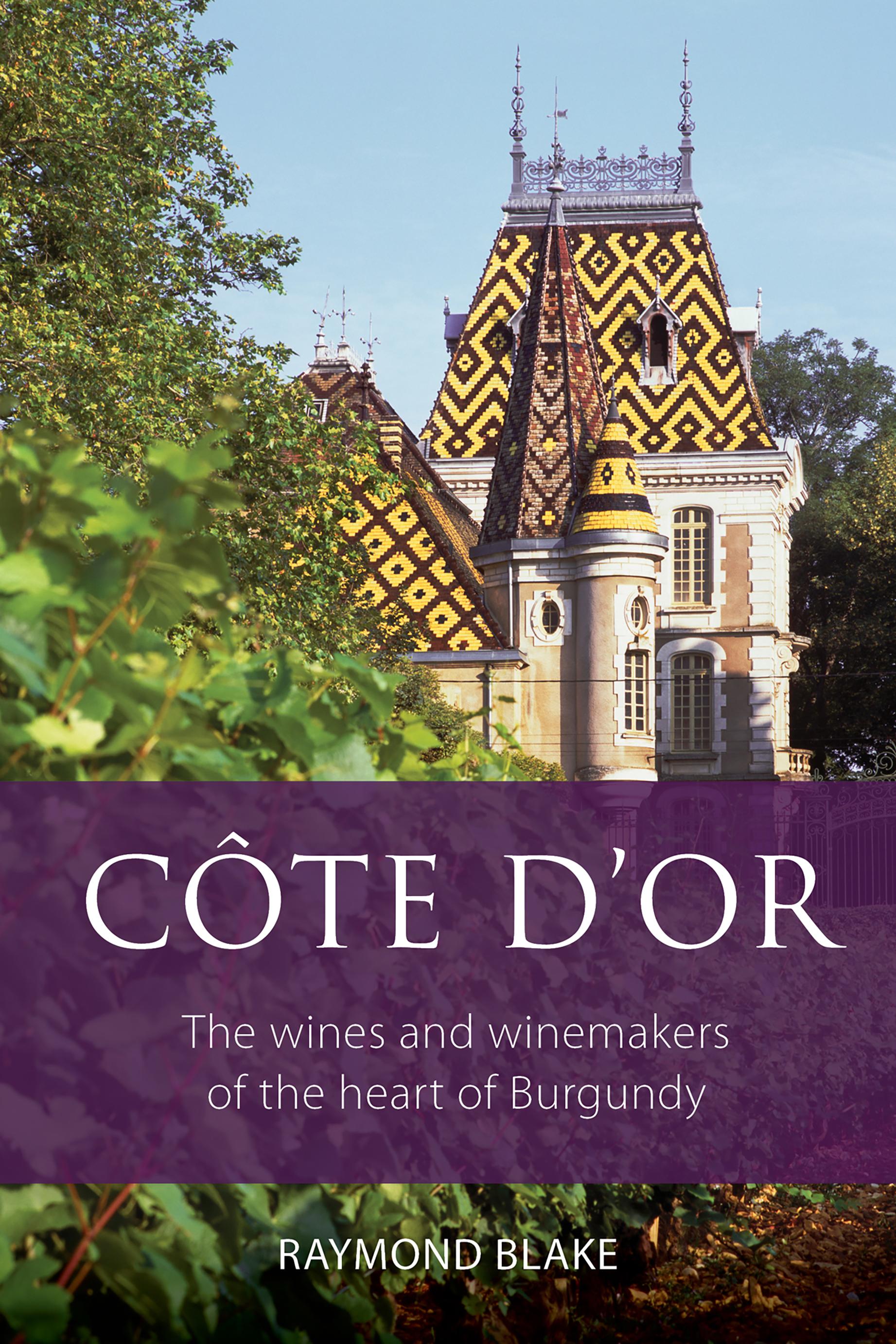

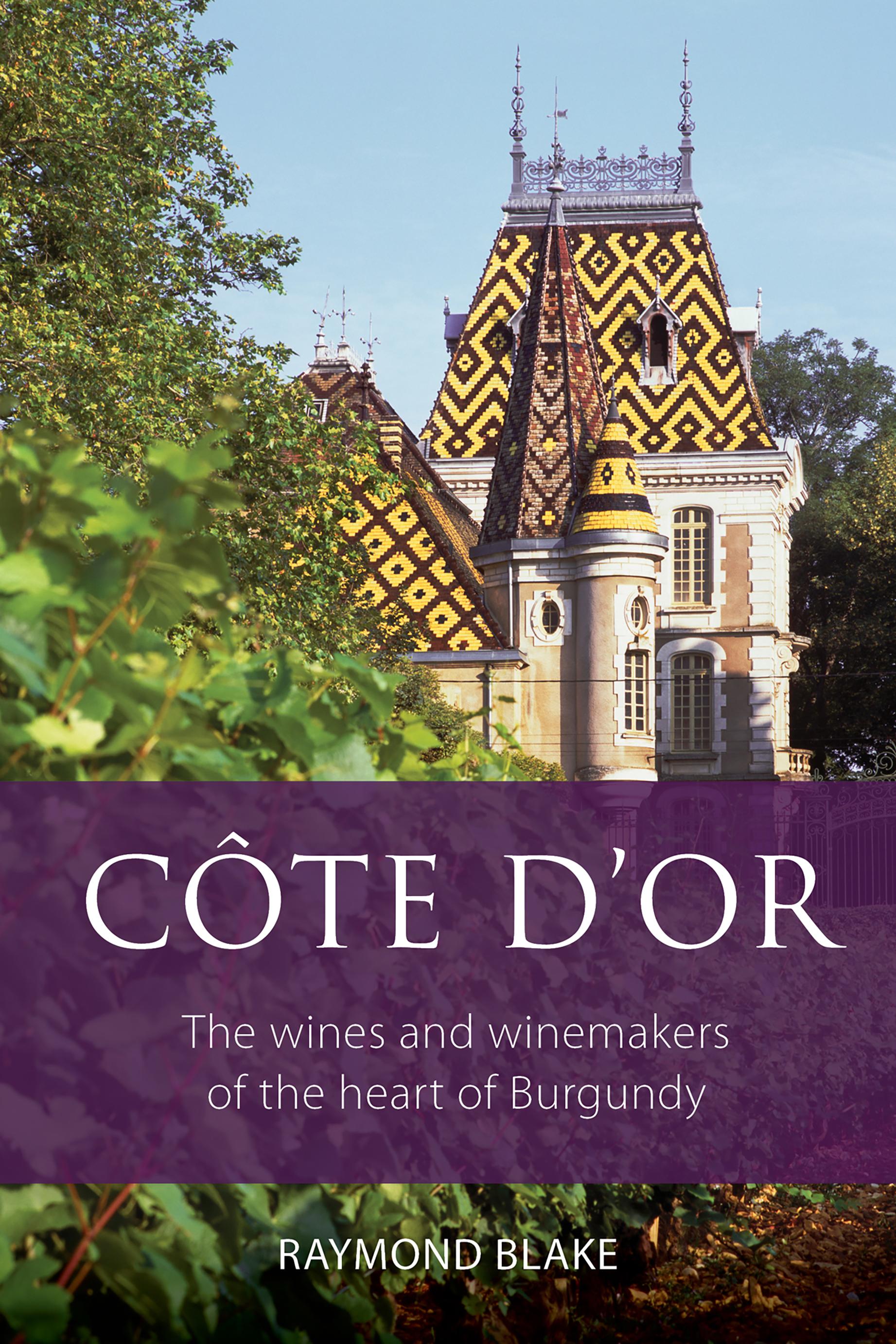

CÔTE D’OR

The wines and winemakers of the heart of Burgundy

Second edition

RAYMOND BLAKE

4: Chambolle-Musigny and Vougeot

Map 5: Vosnée-Romanée and Flagey-Echézeaux

Map 6: Nuits-Saint-Georges

10: Meursault

11: Puligny-Montrachet

12: Chassagne-Montrachet

INTRODUCTION

Te Côte d’Or, the Golden Slope, enjoys a reputation and exerts an infuence in the wine world out of all proportion to its size. It possesses none of the grandeur of the Douro Valley, for instance, nor the picture-postcard beauty of South Africa’s winelands. It is not majestic; its beauty is serene, and what strikes the observer time and again is the tiny scale. From north to south it is about 50 kilometres long, is sometimes less than a kilometre wide, and can be driven in little more than an hour. At a push it could be walked in a day. Yet for a thousand or more years this favoured slope has yielded wines that have entranced and delighted wine lovers, with a fair measure of frustration and disappointment thrown in too.

Avoiding hyperbole when writing about the Côte d’Or is a problem, for it has held people in thrall for centuries, frequently prompting poetic fights of prose: ‘Te Pathetic Fallacy resounds in all our praise of wine … Tis Burgundy seemed to me, then, serene and triumphant … it whispered faintly, but in the same lapidary phrase, the same words of hope.’ Tus wrote Evelyn Waugh in Brideshead Revisited eighty years ago. Literary critics might cavil at such prolixity, and Waugh himself tamed it severely in later editions, but it was enough to intrigue me decades ago and engender a love for the region and its wines that has never waned.

Greater Burgundy is a bigger, more geographically diverse, region than might frst be supposed, stretching from Chablis, south-east of Paris, to Beaujolais, north of Lyon. Te subject matter of this book, however, is Burgundy’s heart, the Côte d’Or. Tere is no more celebrated stretch of agricultural land on earth. It has been pored over and

analysed, feted and cosseted, obsessed about and sought after for centuries and today, if anything, it exerts a greater pull on wine lovers than ever before. ‘Astronomical’ does not begin to describe the prices now being paid for prized patches of grand and premier cru vineyard, and for the wines produced from them by the top domaines. Such prices hog the headlines and paint a dazzling, though severely one-dimensional, picture of the Côte d’Or today. In the early years of the twenty-frst century they are part of the story but they are not the only part.

Tis book aims to get behind the dazzle and fesh out the story, to add some nuance and extra dimension. Te Côte d’Or cannot be captured in a sound bite nor, it must be admitted, in a book of this scope – but my hope is that it may add another chapter to the ever-unfolding tale, setting it in the early years of the twenty-frst century, a period that may come to be considered by future historians as a golden age for Burgundy but which has brought its own challenges in the shape of those ludicrous prices, the scandal of premature oxidation in the white wines, and the increasing challenge of dealing with extreme weather events such as hail and spring frost.

Te Côte d’Or has been the subject of forensic scrutiny for centuries, generating a library of books, so why another one now? For the simple reason that it is ever changing. Every year sees new names added to the producers’ roster and old ones slipping away, and thanks to this ongoing evolution the infant domaine of today can be the superstar of tomorrow. Te core of the book comprises about a hundred producer profles. Many fne domaines and négociants whose wines I am happy to purchase and drink have not found a place here. It is important to stress that they have not been included, rather than excluded, simply for reasons of space. Te aim was to feature a representative collection of producers, not a top-down selection of the most celebrated names in descending order of renown. As a consequence this book is not, nor was it ever intended to be, a comprehensive A to Z of producers.

I write as an amateur du vin, an enthusiast whose admiration for the wines of Burgundy stretches back over four decades, and who has been visiting the region and writing about the wines for some thirty years. I do not trade in wine. I try to see beyond the wine to get something of the backstory, the story of people and place that makes the Côte d’Or so fascinating. To examine the wines in isolation is to dislocate them from that, and not knowing something of the backstory precludes a full understanding of them. A broad lens must be brought to bear on the

côte. Too narrow, and the wood will never be seen for the trees. I have learned much by coming across things serendipitously rather than dashing hither and thither, seeing a lot but noticing little. Without time for assimilation and refection, subtlety and shade are missed.

Finally, no gustatory experience can match the thrill of a great Côte d’Or red drunk at its peak. Te colour, crimsoned by age; the heavenly scent, perfumed with notes of sweet decay; a sauvage edge, the palate lively and tingling, managing to be so many things at once, oscillating between fruit and spice and meat and game, a merry-go-round of favour, spiralling on the palate, refusing to be pinned down by anything so prosaic as a tasting note. All the primary components melded by age and yielding up new ones, unsignalled when the wine was young. Everything cohesive and in harmony, like a great orchestra playing at its best. Above all, vital and living, endlessly enchanting and intriguing, engaging the palate and the spirit like no other wine.

SOME NOTES

Te terms ‘village’ and ‘commune’ are sometimes used interchangeably. In general I use ‘commune’ to indicate the vineyard area surrounding a village, and ‘village’ for the urban heart of the commune, but they tend

The author collecting wine by wheelbarrow

to overlap and there isn’t a rigid distinction between them. In common parlance, village is more widely heard than commune. When written in italics, village is used to indicate the rank of a vineyard and its wine, so that in the hierarchy of vineyard classifcation village comes below premier cru and grand cru. A wine labelled simply Gevrey-Chambertin or Chambolle-Musigny is a village wine.

Te Côte d’Or runs in a south-south-west direction from Dijon but for simplicity’s sake when, for example, describing the relative positions of diferent villages to one another I use the cardinal compass points.

Tus Pommard is ‘north’ of Volnay and Vosne-Romanée is ‘south’ of Vougeot. Te same applies to east and west. Greater accuracy is employed when mentioning the orientation of a specifc vineyard or slope.

Each producer profle includes a ‘try this’ note about one of their wines. It could be their greatest wine, their simplest one, or something in between; the criteria for selection were loose and purely personal. Each stands as an individual, and should be seen as such: the wines do not form a homogeneous group, nor is it a parade of fagship wines. Te wines represent the house style and ethos of each producer and in many cases they punch above their weight in terms of price or appellation. ‘Try this’ is not a formal tasting note, it is meant to highlight distinctive and characterful wines that I believe are worth seeking out.

Note to the second edition

Almost all the material in the producer profles in Chapters 4 and 5 is new, while other sections of this second edition have been updated and modifed where necessary. Tus the profles form the core of the book, in each case giving a snapshot of a domaine’s or a négociant’s philosophy and practices. In describing how scores of winemakers go about their work the risk is that the profles can read repetitively so, to combat this, I have sought to highlight distinctive features that mark out one winemaker from another, what sets each apart from the other. Because so much is new in Chapters 4 and 5 this second edition can be used as a companion volume to the frst.

1 A BRIEF HISTORY TO 1985

Beneath the streets of Beaune, in the cellars of Joseph Drouhin, the twelfth-century section dubbed the ‘Cellar of the Kings of France’ is built on the foundations of a Roman fort. Nearby is La Collégiale, a cellar that dates from the thirteenth century and which is classifed as a historical monument. It is built above the source of a stream named Belena, from which the name Beaune is derived. More importantly for the citizens, it was the original source of their drinking water. History runs deep in Burgundy’s Côte d’Or.

Te vine has been planted in the Burgundy region, if not specifcally on the narrow hillside strip that constitutes the Côte d’Or, for about two millennia. Vine cultivation in Roman times was widespread but probably scattered. It shared the land with other forms of agriculture and the blanket monoculture of today, with the vines intensively tended and trained, had yet to take hold. What is worth noting is that the vineyards were planted on fat ground that was not well drained. Ease of tending probably prompted this, with quantity rather than quality as the ultimate goal.

A much clearer picture of Roman viticulture emerged in 2008 when an ancient vineyard dating to the frst century AD was discovered near Gevrey-Chambertin. It covered an area of about 3 hectares with rows arranged in a regular, carefully measured pattern. Hollows were dug in each row, with a pair of vines planted in each, separated by stones so that their roots did not become entwined. It appears the vines were propagated by provignage or layering, whereby a shoot of the vine was bent and buried in the soil, there to take root, a method practised up until the time of phylloxera in the late nineteenth century. Later, in

AD 312, written evidence of vine cultivation is found in a submission to the emperor Constantine pleading for fscal leniency by way of reduced taxes. To back up the plea, the submission detailed a baleful litany of decline and adversity, outlining the problems faced by the wine growers. Drainage channels were blocked through neglect, rendering the good land swampy, the vines were untended and the vineyards chaotic. Te region of Arebrignus, today’s côte, was in a sorry state, abandoned in parts where it was populated by wild animals. Even allowing for a certain gilding of the lily to soften the emperor’s heart, these travails help to put today’s problems of frost, hail and the like into a more tolerable perspective.

It is not clear exactly when vines began to be planted on the hillsides of the Côte d’Or but the regimented symmetry of today’s vignobles with their ordered ranks of arrow-straight rows was still far in the future. Certainly, by the sixth century the vineyards had begun their creep up and away from the fat lands of the plain into less fertile areas. It was a logical move to plant vines where they could thrive and where cultivation of other crops would meet with poor results; land more suited to them was also freed up by this process.

Te name ‘Burgundy’ comes from the Burgondes, a people who moved westwards into the region from Germany in the ffth century. Apart from giving their name to the region, blame might also be laid at the Burgondes’ door for starting the process of regulation that has developed into the labyrinthine, bureaucrat’s dream of today. To be fair, they were only codifying the law, stipulating what was and was not permitted in the vineyards, and not concocting a Byzantine nomenclature. As the Romans abandoned their lands due to a shortage of labour to work them, the Burgondes moved in to plant them with vines. Te law in this respect was clear: if the legal owner did not immediately object then the newcomer only had to compensate him by way of gifting him another piece of land equal in area to the newly planted vineyard. If, however, the land was planted against the owner’s wishes then he could claim the new vineyard as his.

In 630 the abbey of Nôtre Dame de Bèze was founded by Duke Amalgaire who granted the monks a sizeable area of vines in Gevrey and elsewhere. Teir memory is preserved in the Clos de Bèze vineyard name, which, along with many others, acts as a historical marker in the story of the Côte d’Or. Indeed, a study of vineyard and place names, tracing their origins back over the centuries, makes for a revealing if

challenging investigation of the côte’s history. Corton-Charlemagne is the most resonant of all, recalling that the Holy Roman Emperor owned vines on the hill of Corton, reputedly having ordered they be planted there when he noticed winter snow melting earlier on the hill than elsewhere.

Moving towards the end of the frst millennium, the foundation of the Benedictine abbey at Cluny in 910 could justifably be regarded as the most signifcant date in Burgundy’s history. In time the abbey grew to be the largest Christian building in the world and despite the depredations it sufered after the French Revolution, when it was used as a handy source of stone for building, it is still worth visiting to gain an appreciation of its scale. Tanks to grants and donations of prime land from local lords, noblemen and less-exalted citizens, the Benedictine order assembled a massive landholding, much of which was vineyard. Cluniac monasteries spread across Europe. Te donors were motivated not by generosity but by a desire to atone for an indulgent lifestyle that ran contrary to the church’s teaching. Provided the donations were generous enough, being appropriate to the donors’ means, the monks would intercede with the Lord on their behalf and grant them a clean slate, allowing them to pursue their less-than-sacred lifestyle with a clear conscience. Te monks themselves were not immune to temporal pleasures and in time came to adopt the feasting habits of their benefactors, fuelled by the produce of their vineyards. Monastic asceticism and strict adherence to Benedict’s Rule of prayer and moderation gave way to excess and dissipation. Te good life took its toll and many monks grew forid of face and full of fgure.

In their midst were some who found the dissolute lifestyle repellent, and in 1098 a breakaway group led by Robert de Molesme established a Novum Monasterium at Cîteaux, some 10 kilometres east of the Côte d’Or. It was an area of marshy woodland and the name derives from the old French cistels, meaning reeds, which grew in abundance there. In time the new Cistercian order took its name from Cîteaux. Te land for the new monastery was granted to Robert by the Viscount of Beaune, and other land was granted by the Duke of Burgundy, Eudes I, including a vineyard at Meursault. Fourteen years after its foundation Cîteaux was boosted by the arrival of Bernard de Fontaine, son of the lord of Fontaine, accompanied by a band of thirty followers. He rapidly became the driving force of the new order, instigating a fearsome work ethic that distinguished it from the Benedictines. Where the latter

administered and supervised their vineyards, the Cistercians worked the land themselves. To say they worked themselves to death is hardly an exaggeration – in the early years of the order a Cistercian was unlikely to live past his thirtieth birthday.

Te order expanded at an extraordinary pace. Daughter houses sprang up rapidly, including the abbey of Tart, whose cellar and vineyard still exist at Clos de Tart in Morey-Saint-Denis, and the Abbaye de la Bussière, which is now a luxury hotel. By the time of Bernard’s death in 1153 about 400 Cistercian monasteries had been established across Europe, and a hundred years later this fgure had increased to 2,000. As a consequence they enjoyed massive infuence even if they did not wield outright power – much like Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, TikTok and their ilk today. In vinous terms, however, the Cistercians’ most impressive legacy is the Clos de Vougeot, the remarkable 50-hectare block of vineyard they created over a period of centuries, starting in 1100.

Cistercian monasteries were required to be self-sufcient and wine was a basic necessity, a safe and nourishing drink at a time when a potable water supply wasn’t always easy to fnd. To go with their meals the monks were entitled to a hemina of wine per day, about half a pint, and wine was also required for sacramental purposes. But the swampy land at Cîteaux was unsuitable for vines so they moved westwards to Vougeot, where they were granted their frst lands in 1100. Other donations soon followed and gradually the roughly rectangular block of vineyard still in existence today took shape. Troughout the twelfth century the Cistercians were also acquiring vineyard land in many other Côte d’Or communes such as Chambolle, Vosne and Volnay. Tey built a winery in the heart of their Vougeot vineyard and quickly established a reputation as master winemakers. Tey brought a new rigour to winemaking, studying the land to see which plots yielded the best wines, working intensively and methodically. Because the monks could read and write they could keep records, gradually building a picture of the côte and developing the idea of a cru – a defned area of vineyard that yielded wine with an identity of its own, similar to those around it but observably diferent too. Vineyards that regularly ripened early or late were noted, as were ones that produced stronger or lighter wines, and so on and on, with all observations recorded. In modern parlance they assembled an ever-evolving database that was then used to inform and guide decisions and practices in vineyard and cellar. It was a Herculean task requiring manual labour on a scale that could not be met by their

name by both villages and, strictly speaking, the Chassagne section is Le Montrachet while the Puligny section does without the defnite article, though this distinction is not rigidly applied. It hardly needs stating that the frst ‘t’ is silent, thanks to the confation of two words, ‘Mont’ and ‘Rachet’, after which the pronunciation remained as if they were still two. Roughly speaking it means bare hill – it lacks the dense forest that runs along most of the Côte d’Or’s hilltops. Montrachet is the most celebrated white-wine vineyard on earth and when on song the wine is indubitably magnifcent but it can also leave expectations unfulflled, especially when the price is considered.

In the same way that Chambertin has its satellites so too does Montrachet; in addition to Chevalier there’s Bâtard-Montrachet, Bienvenues-BâtardMontrachet and Criots-Bâtard-Montrachet. Chevalier is slightly smaller than Montrachet and the slope is slightly steeper, with leaner soil that gives racier, less substantial wine. Bâtard’s dozen hectares are shared almost equally between Puligny and Chassagne and it borders Montrachet on its western side, separated from it by a narrow road. Compared to Chevalier the soil is heavier, a distinction refected in the wines: Bâtard plush and plump, Chevalier more clearly etched. Bienvenues lies wholly within Puligny and Criots wholly within Chassagne; separated by about

Looking across Clos de la Perrières to Château du Clos de Vougeot, with a sliver of Musigny in the foreground

500 metres, there’s a yawning gulf between them in renown. Bienvenues comprises a block on the north-east corner of Bâtard with little to distinguish between them, and the wines are barely distinguishable also, while Criots slopes away from Bâtard on its southern side and is less favourably sited. Criots is the awkward child of the quintet and, for a grand cru, too often comes up short where it counts – on the palate.

Puligny is also home to some outstanding premiers crus, including Le Cailleret and Les Pucelles, both of which are contiguous with the block of grands crus and, in the right hands, capable of rivalling them for quality. A curiosity is the tiny amount of Puligny rouge that is produced, a distant echo from a time when Pinot Noir was widely planted in the commune. Indeed, with the exception of the grands crus, almost every premier cru and all but one of the ofcially recognized lieux-dits (over two dozen) are permitted to make red wine. If the vignerons chose to, they could convert nearly all of their vineyards to red and still call it Puligny.

Chassagne-Montrachet’s vineyards form a reasonably cohesive rectangle with the grands crus at the top, abutting Puligny. Tese and a few others stand apart, split from the bulk of Chassagne by the D906 road that leads to Saint-Aubin. Tis road feels like the Chassagne –Puligny boundary but nobody in Chassagne is complaining that it is not, for there would be no grands crus in the commune if it were. As a consequence they are part of the commune but stand separate, like a choir balcony in a church. Save for the grands crus, every scrap of village and premiers crus vineyard may produce red or white wine. Some, such as Clos Saint-Jean and La Boudriotte, produce both side by side, which makes for interesting comparative tasting and discussion as to whether this or that vineyard is better suited to Chardonnay or Pinot Noir.

Te stony Cailleret vineyard, beside the upper part of the village and facing south-east, is the leading premier, though Les Chaumées (not to be confused with Les Chaumes) on the boundary with Saint-Aubin can challenge it. And, in the right hands, Les Chenevottes can be excellent. To the south of the commune, Morgeot is a 54-hectare vineyard holdall that contains well-known lieux-dits such as La Boudriotte and Clos Pitois and others such as Guerchère and Ez Crottes, whose names only ever appear on detailed vineyard maps.

Saint-Aubin sits west of Puligny and Chassagne, and lacks their compactness, projecting away from the Côte de Beaune in a dog-leg

as the vineyards follow the varied slopes. Tanks to the jumble of those slopes the vineyards face in numerous directions, from northeast to south-west. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the two best premiers crus are found just around a turn in the hillside from the Montrachet grands crus. Tese are En Remilly and, above it at 350 metres, Les Murgers des Dents de Chien, the latter named for the murgers or heaps of stones piled at the edge of a vineyard, created by vignerons clearance work. Some are massive and prompt wonder at the toil that led to their creation.

South of Chassagne the Côte d’Or begins its long sweep westwards through Santenay to fnish with a rustic fourish in Maranges. Te frst vineyard you meet – Clos de Tavannes – vies for top spot with its neighbour Les Gravières and perhaps Beaurepaire, which sits above the village, rising steeply from 250 to 350 metres. All three wines can age well, especially Tavannes. One of Santenay’s biggest premiers crus, Clos Rousseau, sits on the commune’s southern boundary and changes its spelling to ‘Roussots’ in Maranges. Tis, along with other Maranges premiers crus such as Le Croix Moines and La Fussière, are vineyards with little recognition outside their immediate locality but, as with the best of Marsannay right at the other end of the Côte d’Or, they are likely to become better known in the future.

More stone than soil in Les Gravières vineyard, Santenay