İçindekiler | Table of Contents

Giriş | Introduction, Ceren Erdem

Sürekli Dönüşümler | Constant Transformations, Jörg Heiser

Dünyayı Yeniden Düzenlemek | Reordering the World, Banu Karaca

Yakıcı Buzlar | Burning Icicles, Erden Kosova

Yapıtlar | Works

Özlem Günyol ve Mustafa Kunt hakkında, Jakob Sturm ile Felix Ruhöfer arasında geçen, anekdotlara dayalı bir sohbet

An anecdotal conversation between Jakob Sturm and Felix Ruhöfer about Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt

Biyografiler | Biographies

Yapıtlar Dizini | Index of Works

Yazarlar hakkında | About authors 6-9 12-31 34-41

Bildiğimizi bilmediğiniz şeyler var, detay There are things you don’t know that we know, detail

Constant Transformations on the Materials

and Techniques of

Özlem Günyol & Mustafa Kunt

Jörg Heiser

What Drives the Work

The underlying tension that drives the work of Özlem Günyol and Mustafa Kunt is one that can potentially best be approached by identifying four kinds of materials that the artist duo apply to their practice, using four kinds of techniques. By focusing on these eight parameters I do not want to reject the importance of the subject matters that Günyol and Kunt deal with —but I want to shed light on what exactly they bring to these subject matters by making art with and about them. Or in other words, I think there is no point in taking the artist duo’s work as a mere pretext to express one’s critical awareness of the political and social issues they address, while ignoring how exactly they transform, translate, conceptualize and abstract these very issues into something that becomes an artwork. Instead, the term “underlying tension” delineates that the very point of their work is arguably to make it hard or even impossible to neatly separate subject matter from form, material presence from symbolic meaning, or the ethical and the political from aesthetics.

I will expand on the often mixed or overlapping relationships between the four materials and the four techniques I have tried to identify in their oeuvre from the last fifteen years or so, in order to come closer to a characterization of that underlying tension: my hypothesis is that it has do with social and historic trauma —often the result of economic or political rifts within or between nation states— as expressed through repetition, translation and abstraction. But what kinds of traumas are these, and what exactly does it mean to repeat or translate them in abstracted ways?

Wide Apart, at First

Let’s start with two early works, which seem wide apart, at first. One is a piece called 354512 cm2 of 2003 (see p. 272), the other is a video titled Section 1 from 2005 (see p. 264). Günyol and Kunt created the former when they were still in the midst of studying fine arts at Städelschule in Frankfurt, after they had studied at the Sculpture Department of Hacettepe University in Ankara. The work involved spending three months in the spacious rooms of Frankfurt’s former Customs Office building, which a few years later, in 2007, became a part of the city’s Museum of Modern Art. During those three months, working continuously nearly every day, the two meticulously measured and indicated the distances between almost each and every point of the room —its corners, doors and windows as much as its light fixtures or water pipes— by applying ruler-like signage using permanent marker straight onto the wall. They only indicated horizontal and vertical distances, not diagonal ones, which makes the result feel all the more like a perfect mixture

between studiously applied rationality and idiosyncratic insanity: why would you make all these measurements and apply them painstakingly onto the wall, when it was already clear that the building would undergo bottom-up refurbishment to prepare for its new purpose? That is the point of this piece, and one could say of art in general: to do something which on the surface level has no value, no use, to the point that it might seem insane that someone has put any energy into it. But exactly because art is something useless, in vein, it gains a sort of relative autonomy that allows the artist and the viewer to engage —separately or reciprocally— with something that you thought you knew but didn’t really, opening up your mind and your senses if you’re inclined to allow that to happen.

And so, in my case, even though I didn’t experience the piece in situ, I first of course have to think of the function of the building as a customs office: for isn’t it a kind of monument to, of course, the rationality-cum-insanity that customs actually are? A huge building in the middle of a city, dedicated to securing the control of incoming and outgoing goods according to their weight, measurements, and value —something as seemingly rational as it is random (random in the sense that local political turns may dictate the preference of protectionism over free trade or vice versa), and historically a kind of legalization of nationalist chauvinism and highway robbery in the guise of law & order. Nevertheless, devoid of its former function, the building, with its rationalist clarity mixing modernism and classicism (imposing stair cases and brick columns in otherwise unadorned spaces, a boxy, grid-like building with a strangely steep saddle roof on top), takes on a new contemplative air. With their process of measuring and indicating, it’s as if Günyol and Kunt perform a three month séance conjuring the building’s former function as a ghost: no goods anymore to measure and control, so you resort to the naked walls. The result, in more sternly art-historic terms, is reminiscent of minimalist-conceptual works of mainly two artists, namely Mel Bochner’s Measurement Room of 1969 —which does what it says in the gallery’s white cube, using black tape and Letraset numbers to delineate the widths and heights— and Stanley Brouwn’s Door of 1989, which reconstructs —in an artist book, but also as a reproduction in art spaces in the form of a recess in a wall— the outline and measurement of a small door of a residential building on Reguliersgracht 27 in Amsterdam, using Brouwn’s very own system of measurement, the SB-foot, SB-elle, and SB-step —a measurement system derived from the artists own body. Günyol and Kunt’s work, in comparison, is neither overtly about the white cube like Bochner’s, nor the artist’s body like Brouwn, but instead brings the functional transformation of a building into play.

That said, Brouwn’s emphasis on the body as a literal yardstick leads us straight to the second aforementioned piece by Günyol and Kunt. In the short video of 2005 titled Section 1, we see a couple in a kitchen, in black and white, through a door slightly ajar, like we are an eavesdropper hiding in the dark of the corridor. The couple are the artists themselves, which is not unimportant. In any case, the scene starts like a banal

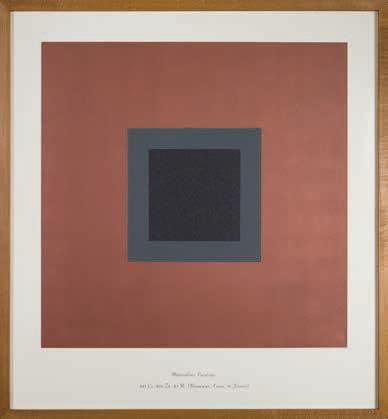

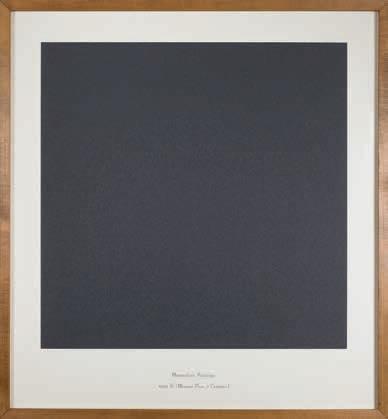

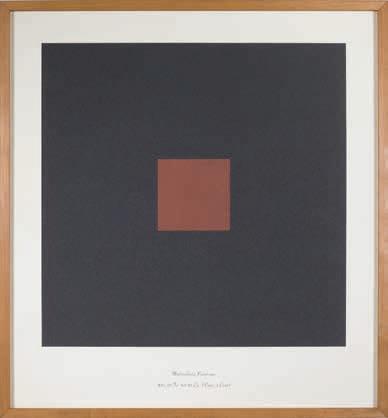

Maddesel Resimler

2018, devam eden seri resim

metal tozu, 300 gr/m² Hahnemühle yapımı baskı kâğıdı her biri 76x82 cm

%97 Cu %2,5 Zn %0,5 Sn (Avustralya Doları, 1 Cent)

%81 Cu %10 Zn %9 Ni (Norveç Kronu, 10 Kroner)

%65 Cu %29 Zn %6 Ni (Türk Lirası, 5 Kuruş)

%76,6 Cu %12,1 Ni %11,3 Zn (Turk Lirası, 1 Lira)

%75,1 Cu %14,7 Zn %10,2 Ni (Avro, 2 Avro)

%91,67 Cu %8,33 Ni (Amerikan Doları, 10 Cent)

%89 Cu %5 Al %5 Zn % 1 Sn (İsveç Kronu, 5 Kronen)

%97,5 Zn %2.5 Cu (ABD Doları, 1 Cent)

%100 Al (Japon Yeni, 1 Yen)

%94,35 Fe %5,65 Cu (Avro, 1 Cent)

%89 Cu %5 Al %5 Zn %1 Sn (İsveç Kronu, 5 Kronen)

%100 St (Meksika Pesosu, 5 Centavos)

%94 St %6 Cu (Pound Sterling, 1 Penny)

%92 Cu %6 Al %2 Ni (İsviçre Frankı, 5 Rappen)

Dünyada en yaygın kullanılan ABD Doları, Avro, Pound Sterling, Japon Yeni gibi para birimlerinden madeni para yapımında kullanılan metallerle yapılan resim serisi. Her bir resim, belirli bir para birimine ait bir madeni paranın yapımında kullanılan metallerle yapılmıştır. Bu metallerin resim yüzeyinde kapladıkları alanlar, ilgili madeni parada kullanıldıkları oranlarla orantılıdır.

Materialistic Paintings

2018, ongoing series painting metal powder, 300 g/m² Hahnemühle mould-made print making paper each 76x82 cm

%97 Cu %2,5 Zn %0,5 Sn (Australian Dollar, 1 Cent)

%81 Cu %10 Zn %9 Ni (Norwegian Krone, 10 Kroner)

%65 Cu % 29 Zn %6 Ni (Turkish Lira, 5 Kuruş)

%76,6 Cu %12,1 Ni %11,3 Zn (Turkish Lira, 1 Lira)

%75,1 Cu %14,7 Zn %10,2 Ni (Euro,2 Euro)

%91,67 Cu %8,33 Ni (American Dollar, 10 Cent)

%89 Cu %5 Al %5 Zn %1 Sn (Swedish Krona, 5 Kronen)

%97.5 Zn % 2.5 Cu (American Dollar, 1 Cent)

%100 Al (Japanese Yen, 1 Yen)

%94.35 Fe %5.65 Cu (Euro, 1 Cent)

%89 Cu %5 Al %5 Zn %1 Sn (Swedish Krona, 5 Kronen)

%100 St (Mexican Peso, 5 Centavos)

%94 St %6 Cu (Pound Sterling, 1 Penny)

%92 Cu %6 Al %2 Ni (Swiss Frank, 5 Rappen)

Series of paintings made with the metals used in the coin production of the most traded currencies such as the US Dollar, Euro, Pound Sterling, Japanese Yen etc. Each painting includes the metals that are connected to the specific coin of the related currency. Areas that are occupied by these metals on paintings’ surfaces are in proportion to the amount that are used in the corresponding coin.

Sayfa 90-91: Maddesel Resimler, sergi görünümü, Dirimart, İstanbul

Pages 90-91: Materialistic Paintings, installation view, Dirimart, Istanbul

Lır’nîng ey läng’gwîc îz riley’tıd nat on’li tu dhı ándırständ’îng áv ey sen’tıns strâk’çır änd dhı mi’nîng áv dhı wırds, bát ôl’so tu dhı ôrgınızey’şın áv let’ırs. Fır’dhırmôr, ît îz ôl’so kerîktırîs’tîk fôr en’i läng’gwîc dhät dhı pır’sın kôlîng dhı wırds wîdh ey sır’tın

saund änd rîdh’ım

dez’îgneyts dhı yu’sîc áv dhät läng’gwîc.

İ’vın ey pır’sın lır’nîng ey nu läng’gwîc stîl ıproç’s tu dhı fôr’în läng’gwîc hwît hîz/ hir on lîng.gwîs’tîk mel’ıdi änd rîdh’ım, änd dhîs finam’ınan sam’taymz kôzız mîs’ándırständ’îng.

AYRIAYRIBİRARADA