A “bridge space” between individuals, nature and our experiences

Social bench designs for Ladywell Fields, London

by Zijue WEI0.0 Introduction and contents

Following the essay about the “bridge” spaces in the city, this portfolio illustrates an attempt of intervening in the urban green space: Ladywell Fields, in order to increase the connections built between individual city dwellers, humans and nature, and different information from a variety of sources.

Starting with the analysis of the urban fabric and the visitors’ behaviours, followed by several experimentations with data collection systems and modular units, I could create a set of modular architectural interventions, named social benches, in this area.

1.1 A green space between the hustle and bustle

Initial site analysis: site location 4

1.2 The history of human mobility

Initial site analysis: site history 5

1.3 A retained urban green space

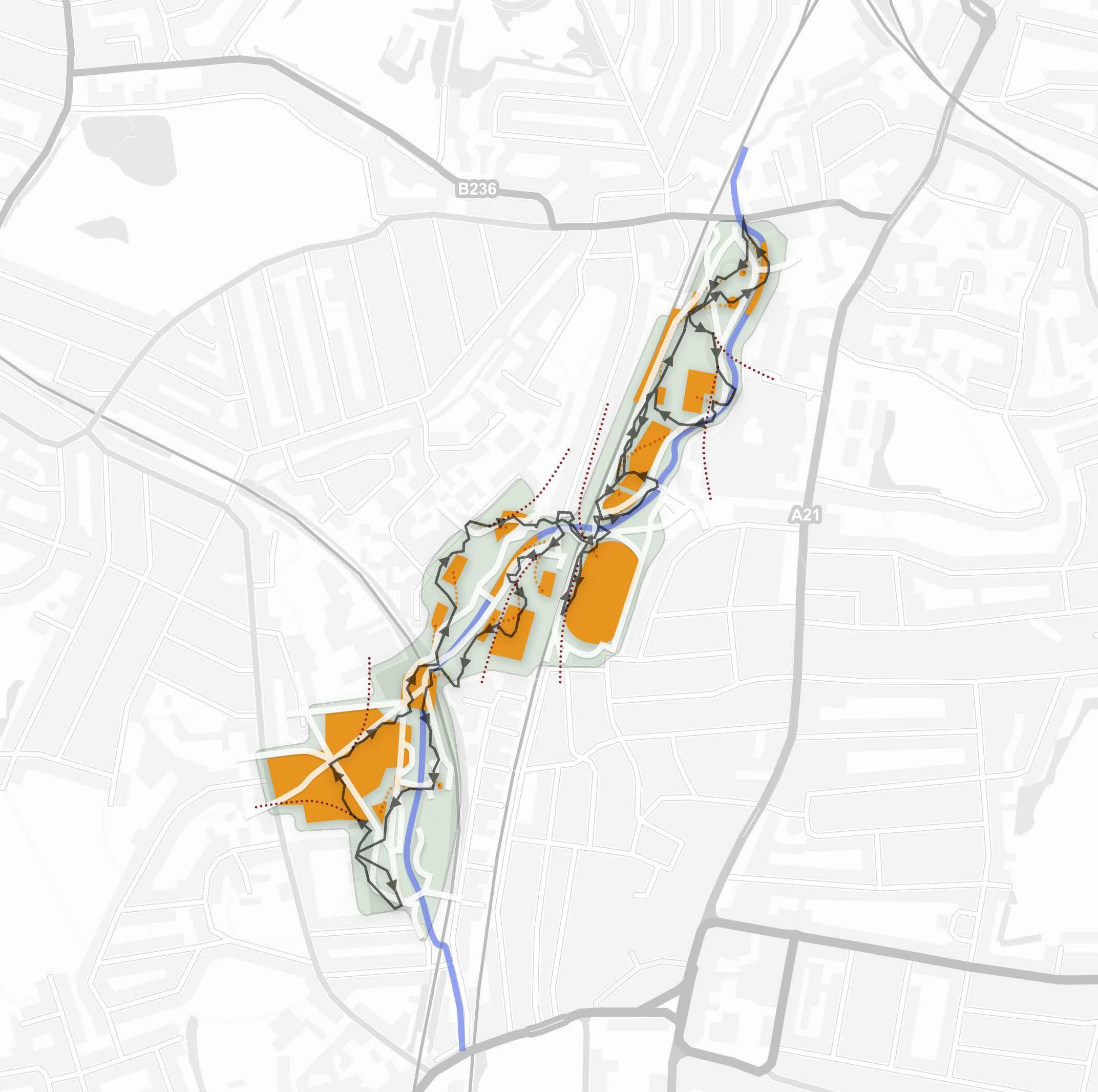

Site analysis: the urban fabric with urban green spaces 6

1.4 From macroscopic to microscopic: what makes people move?

Initial inspiration: the moving pattern of human, as individuals and as groups 8

2.1 The classification of urban spaces and the metaphor of “bridges”

Conceptualization: the methodology of deconstruction towards the urban fabric 10

2.2 Further investigation and classification of the “bridge spaces”

Conceptualization: the abstracted forms of “bridges” in urban areas and in urban green spaces 11

2.3 How does urban green spaces as “bridges” facilitate exploration?

Site analysis: first-hand experience of exploring through “bridge” spaces 12

2.4 The “bridges” inside Ladywell Fields

Site analysis: dissecting the site into a web of “bridges” 14

2.5 Points of reference in “bridge spaces”

Precedent: Parc de la Villette / Bernard Tschumi Architects 16

2.6 In a busier urban context

Precedent: Trafalgar Square 17

3.1 The barriers to the “green bridges”

Site analysis: insufficiencies and possible solutions for the site to be used as a “bridge space” 18

3.2 Risks and rewards trade-off

Site analysis: possible solutions to turn the meadow into circulation spaces 19

3.3 Comforting interactions with the natural surroundings

Precedent: Peak-A-Boo Installation / i.thee 20

3.4 Bringing people to the sceneries

Precedent: Path of Perspective / Snohetta 21

4.1 Constructing bridges in 3 realms

Initial design conceptualization 22

4.2 Integrating people’s experiences through data collection

Experimenting data collection with Pyhon coding 24

4.3 Information exchange in modular systems

A more achievable and practical substitution of data collection: modular structures 26

4.4 Customizing the experience

Precedent: Photograph series “One” / Pierre Sernet 27

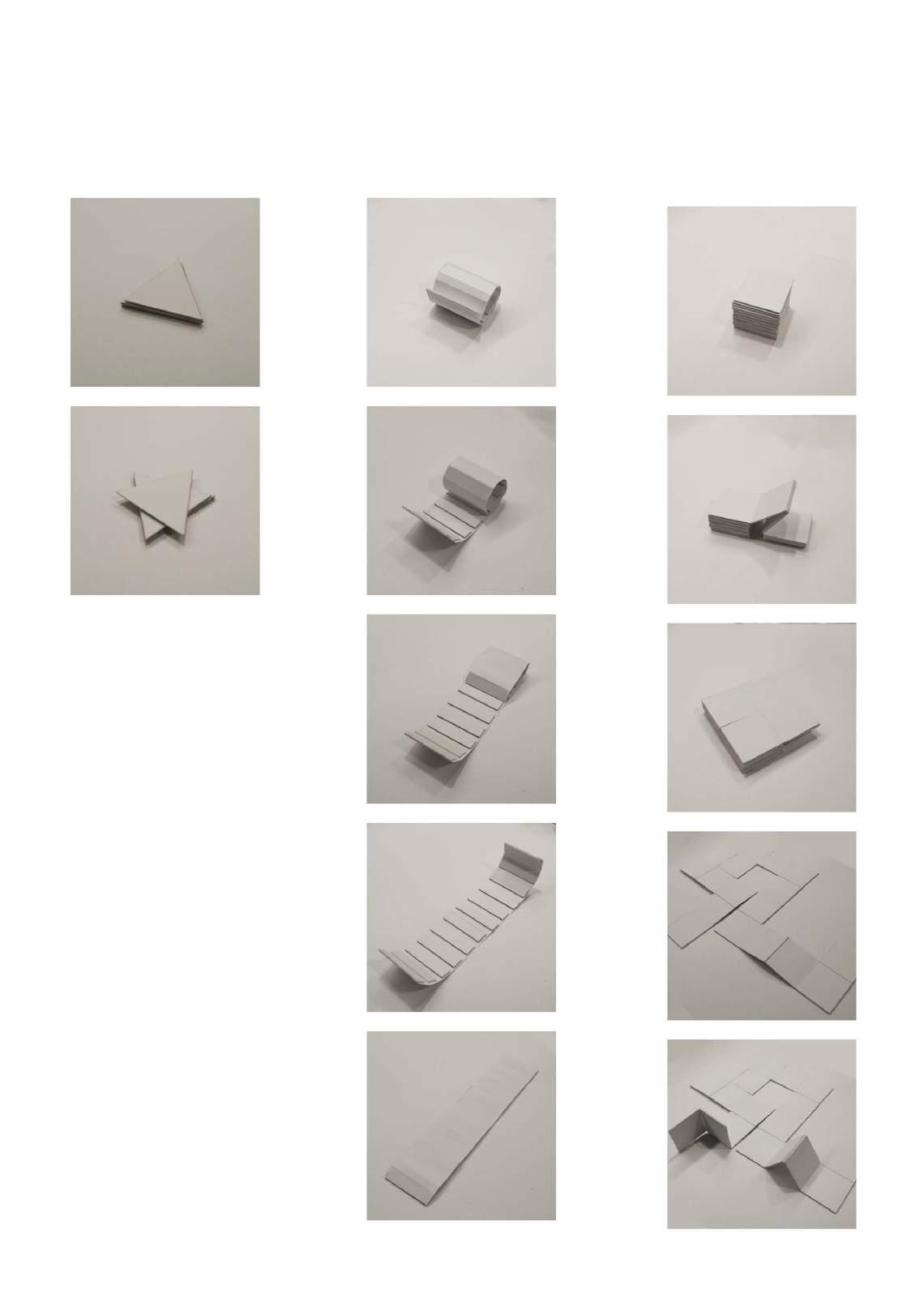

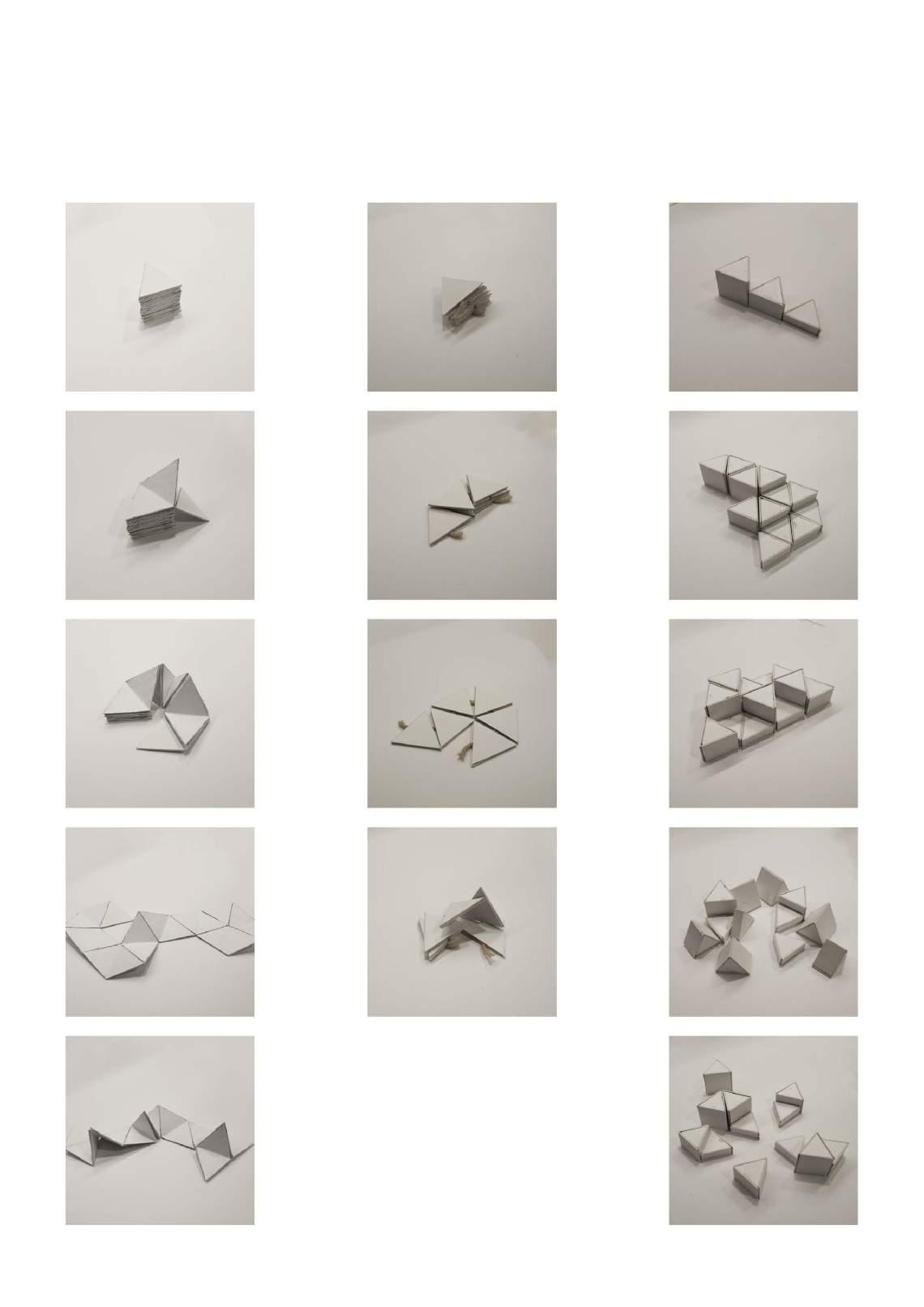

5.1 Build a space with geometrical forms

Experimenting with different shapes 28

5.2 Variable triangles in practical uses

Using triangles as the basic modular system 30

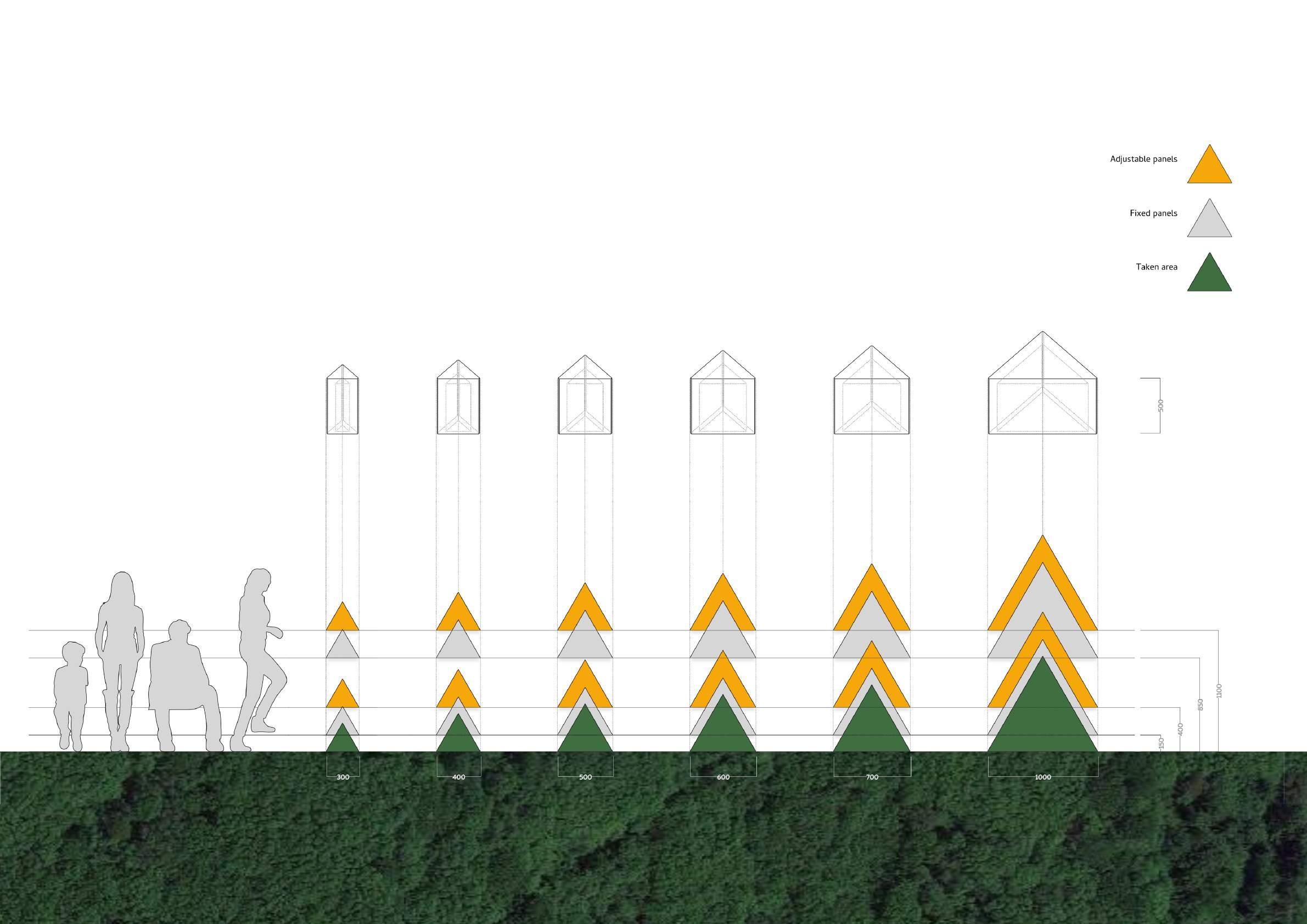

5.3 An appropriate size

Finding the best size for the modular system 32

5.4 Stacks of triangles

Installing the modular system in a small scale 34

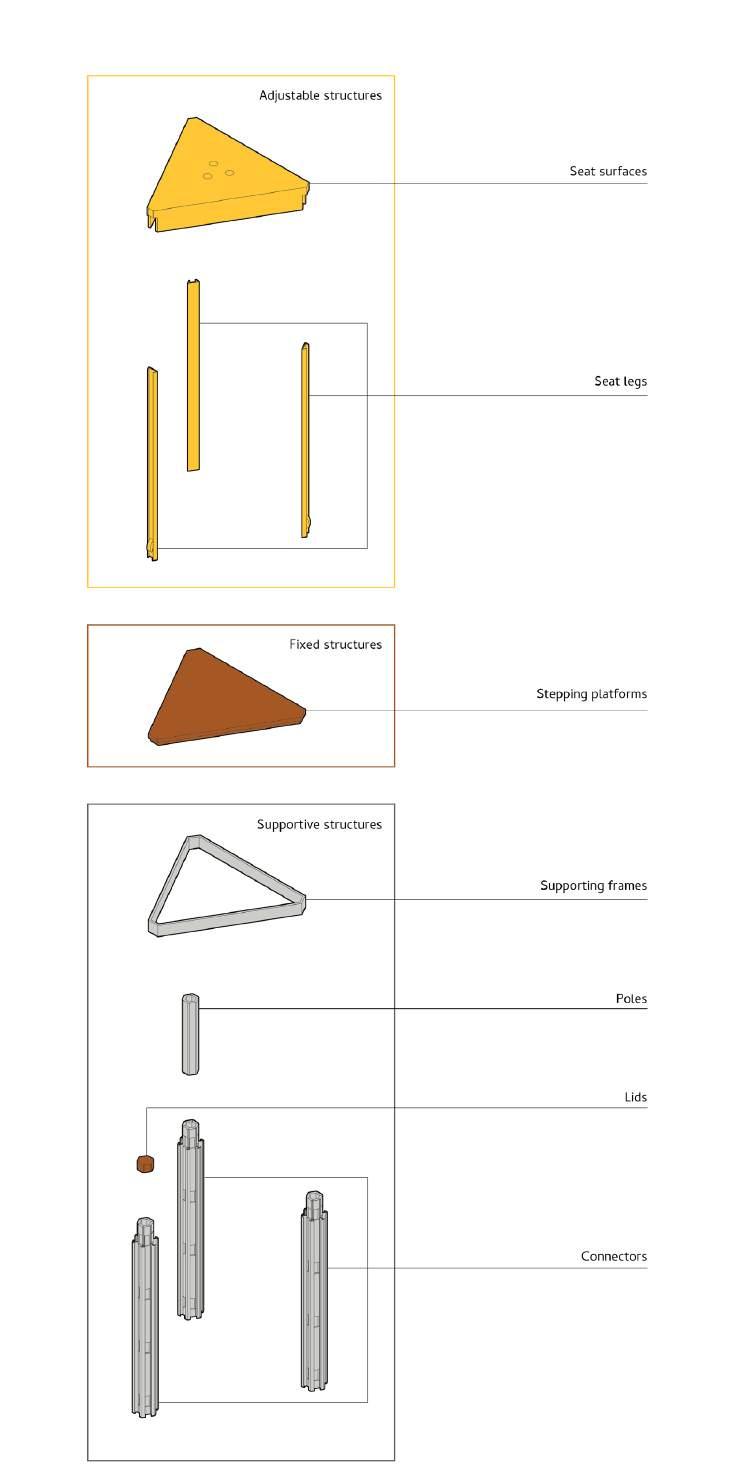

5.5 Modular units mix-and-match

Different configurations of triangular panels and frames 36

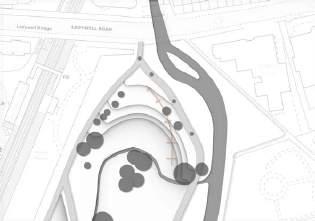

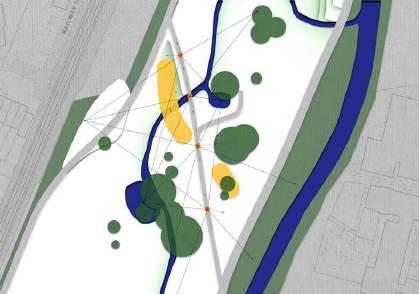

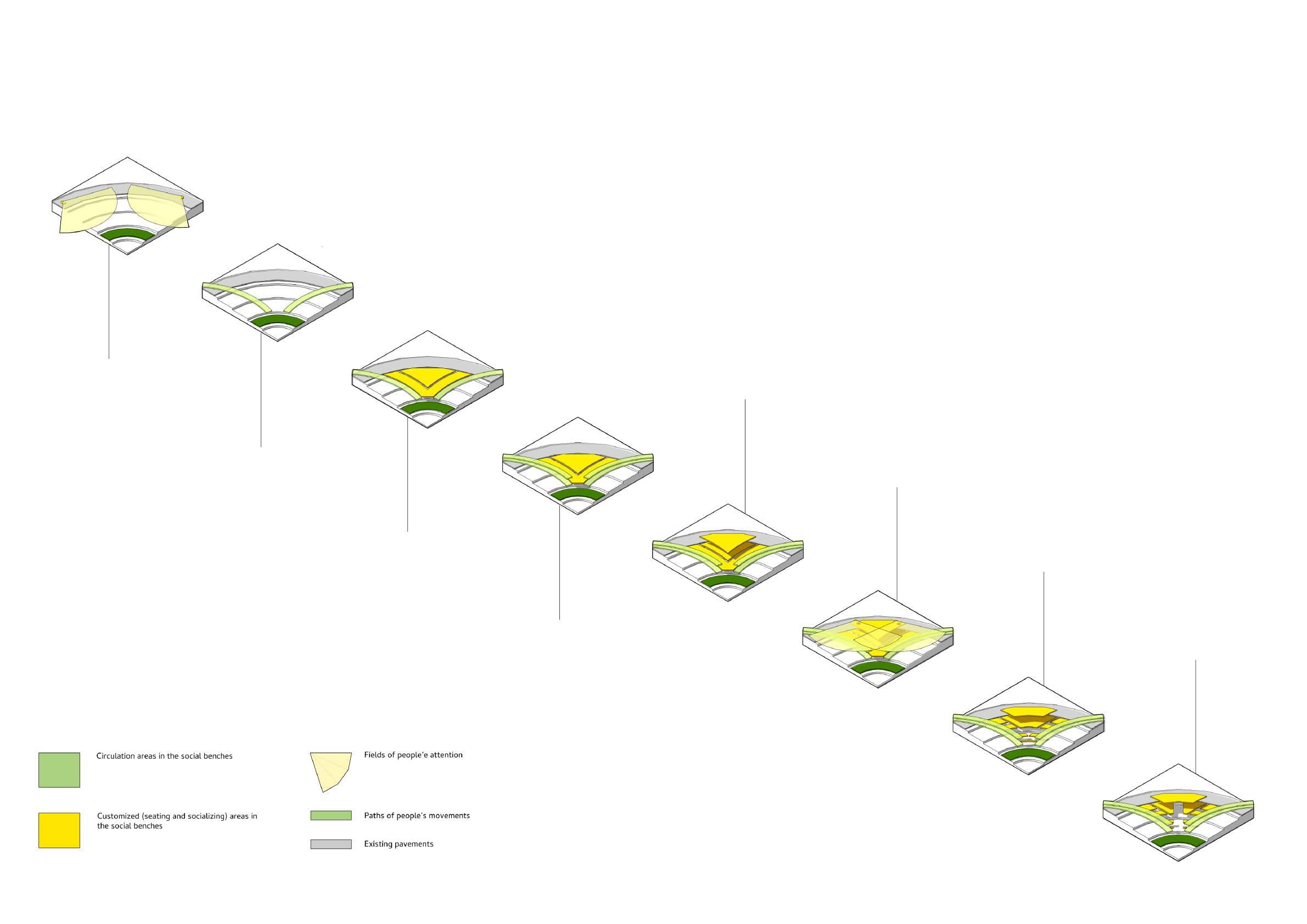

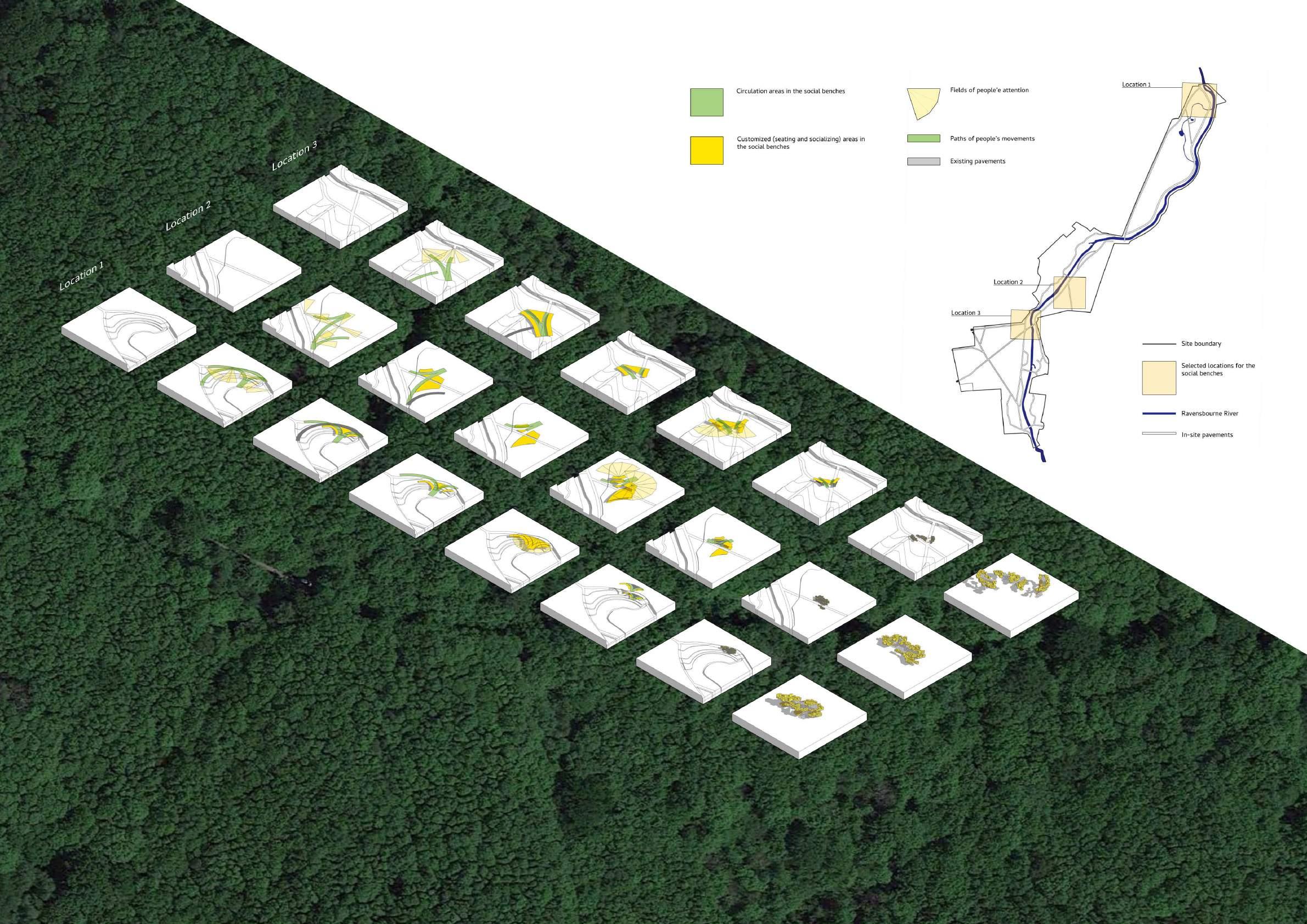

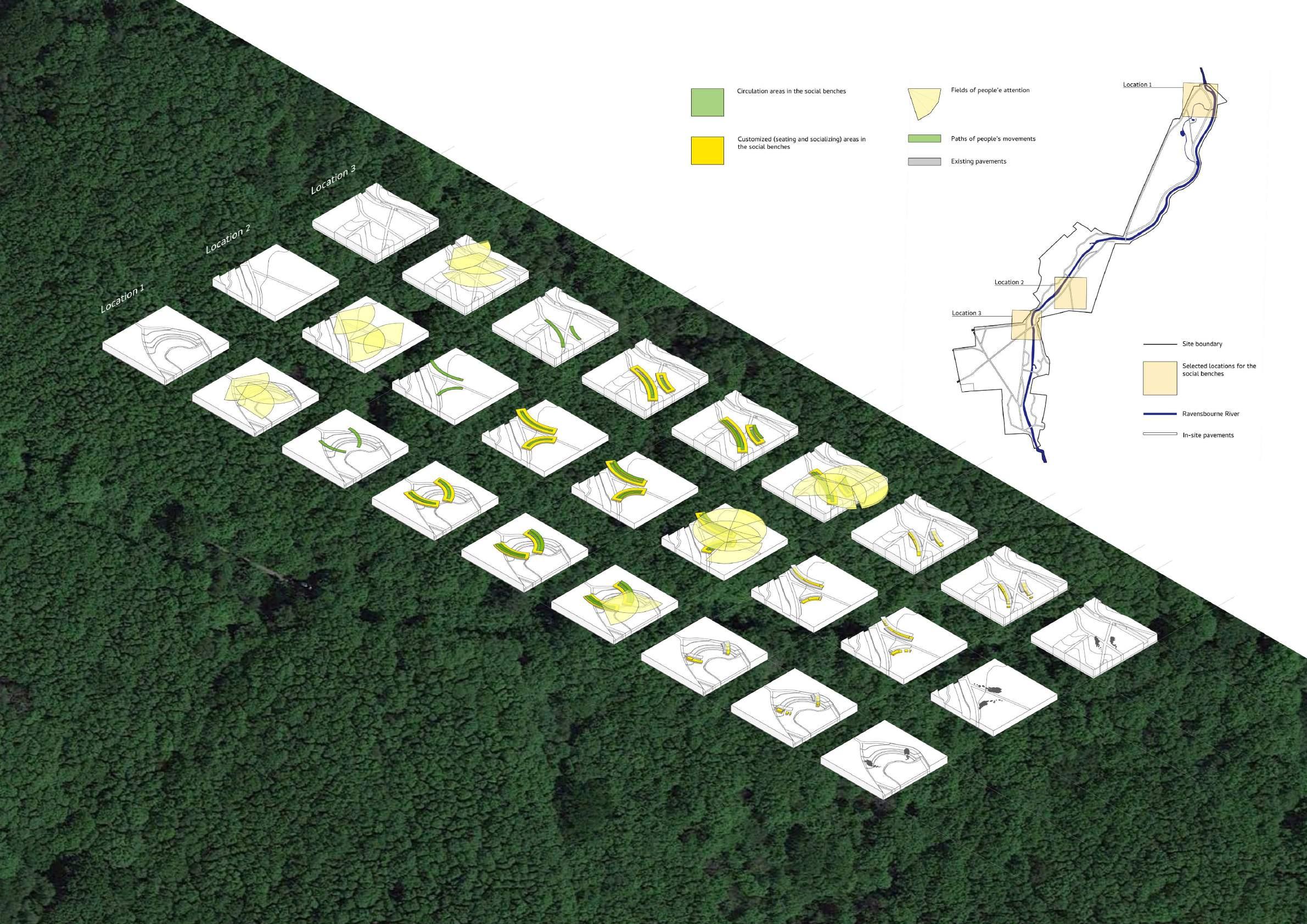

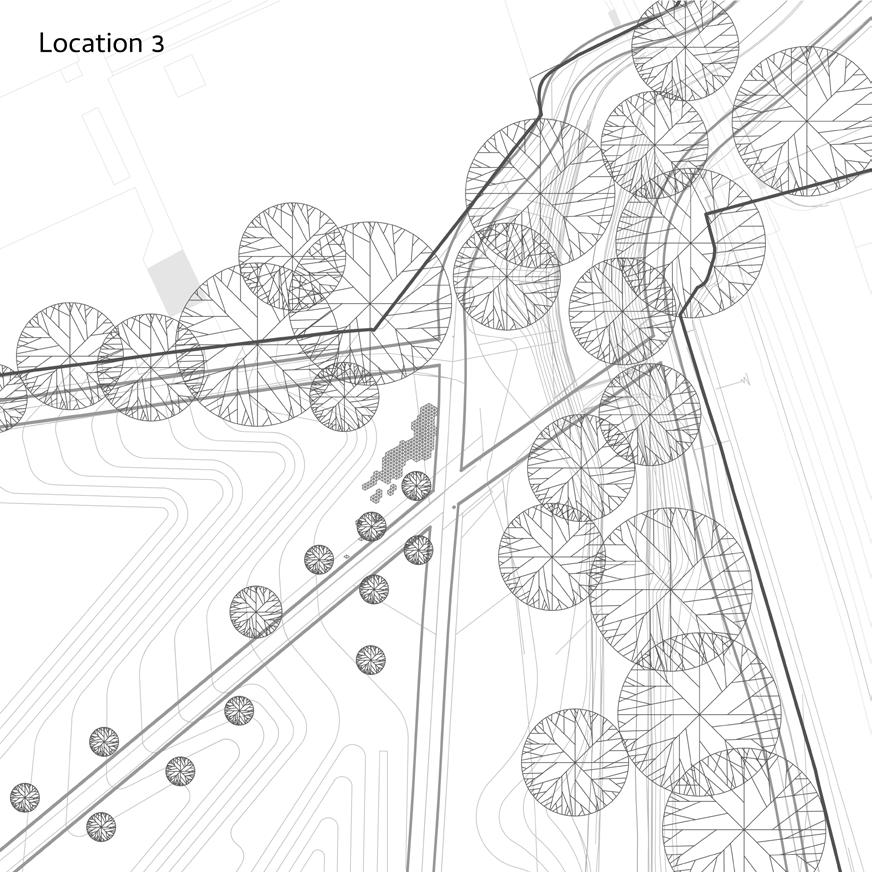

6.1 The rationale behind selecting possible locations Dissecting people’s attention, routes and experience to find the potential location for the designs 38

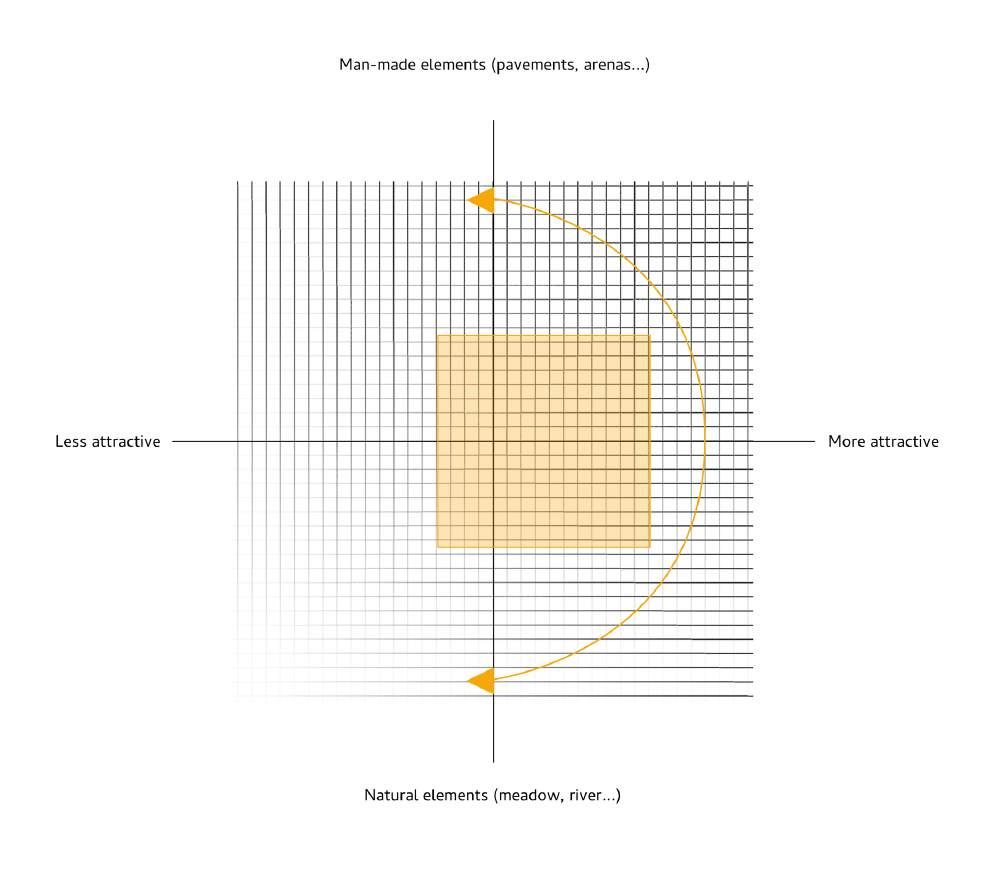

6.2 Bridging the man-made spaces and the nature

Location selections for the designs 40

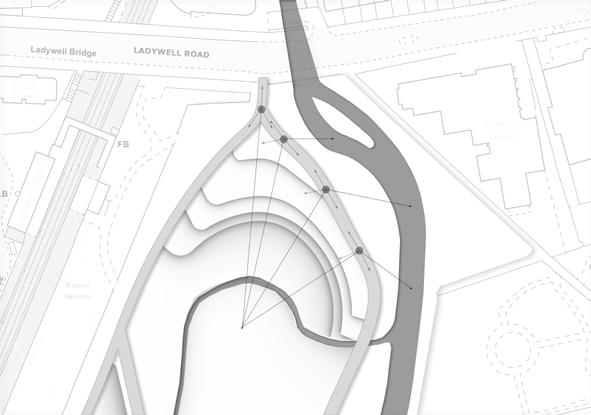

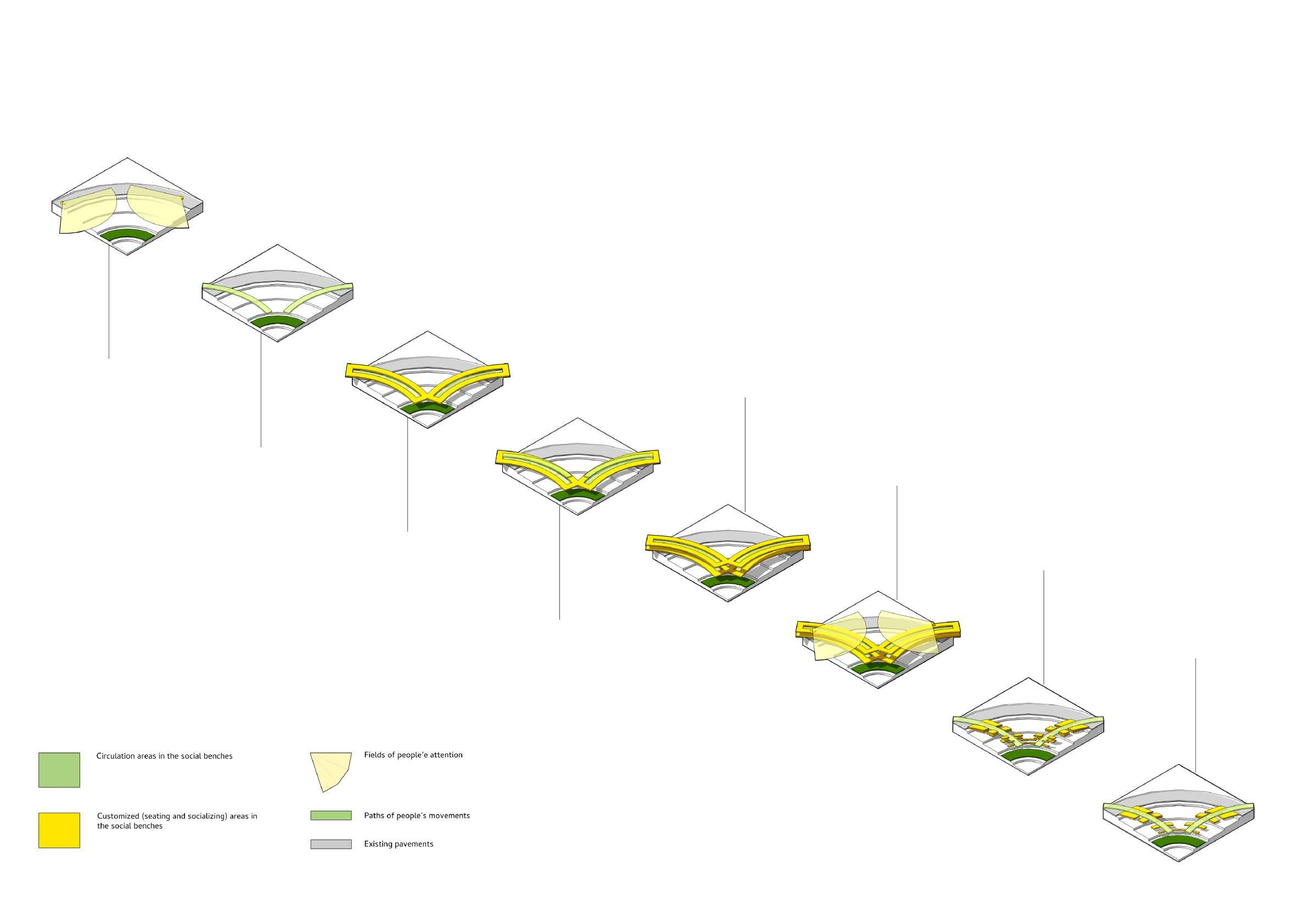

7.1 Building the “bridges”

First attempt of structuralize the “bridging” social benches 42

7.2 An initial attempt

First attempting to structure the design based on the method above 44

7.3 The logic underlying the structures

Identifying the basic rationale behind the space and people’s experiences 46

7.4 Following the paths of pedestrians

Second attempt to structuralize the “bridging” social benches 48

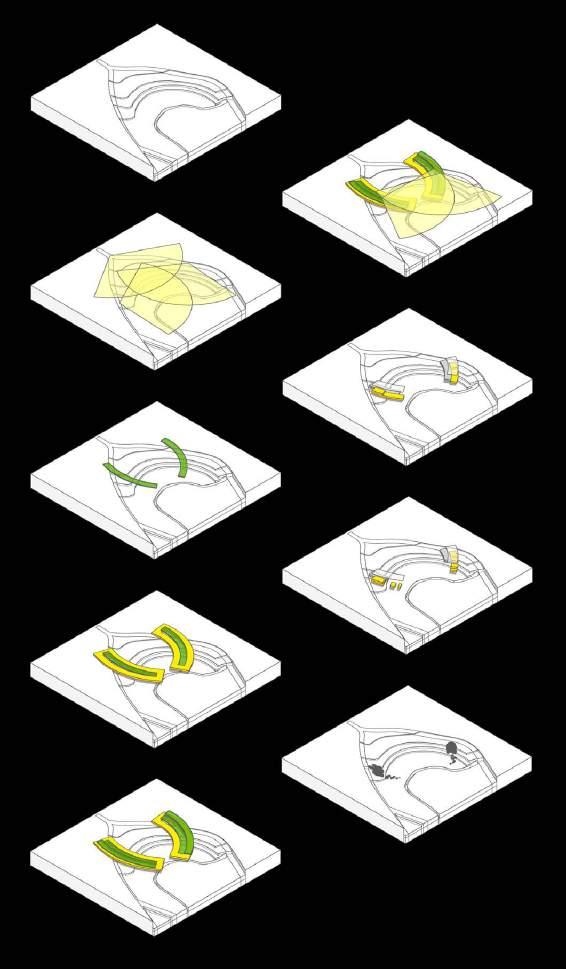

7.5 Into the site step by step

Second attempting to structure the design 50

7.6 First sample from the second attempt 52

7.7 Second sample from the second attempt 54

8.1 Flexible and adjustable structure Testing technical details 56

8.2 Mortise and tenon

8.3 A combination of the two

technical details 58

9.1 Light, strong and supportive Research: materials for outdoor light structures 60

9.2 Rattan, acrylic and aluminum Material selection for the light structure 61

10.1 Plan and elevation: Connectors and adjustable chair legs 62

10.2 Plan: Connectors and adjustable chair legs 64

10.3 Section: Adjustable structure in the chair legs 65

10.4 Plan and elevation: Vertical connectors A-E 66

10.5 Plan and elevation: Adjustable panels F-I 67

10.6 Elevation: Joined connectors and adjustable chair legs 68

10.7 Plan and elevation: Configurations of platforms at different levels (1) 70

10.8 Plan and elevation: Configurations of platforms at different levels (2) 71

10.9 Plan and elevation: Configurations of platforms at different levels (3) 72

11.1 Plan: Locations of the social benches 74

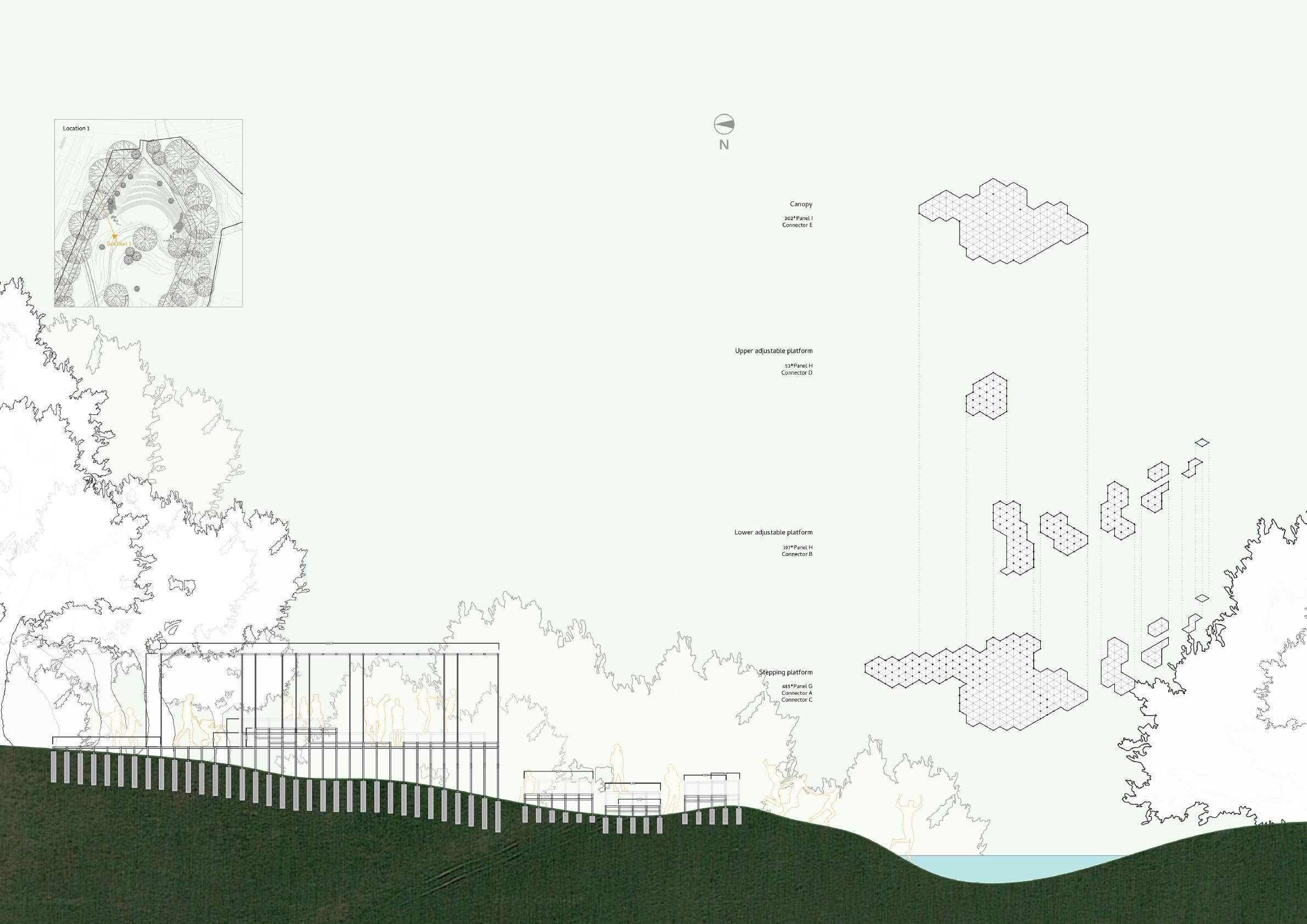

11.2 Section: Social bench design at Location 1 (West) 76

11.3 Plan: Social bench design at Location 1 (West) 77

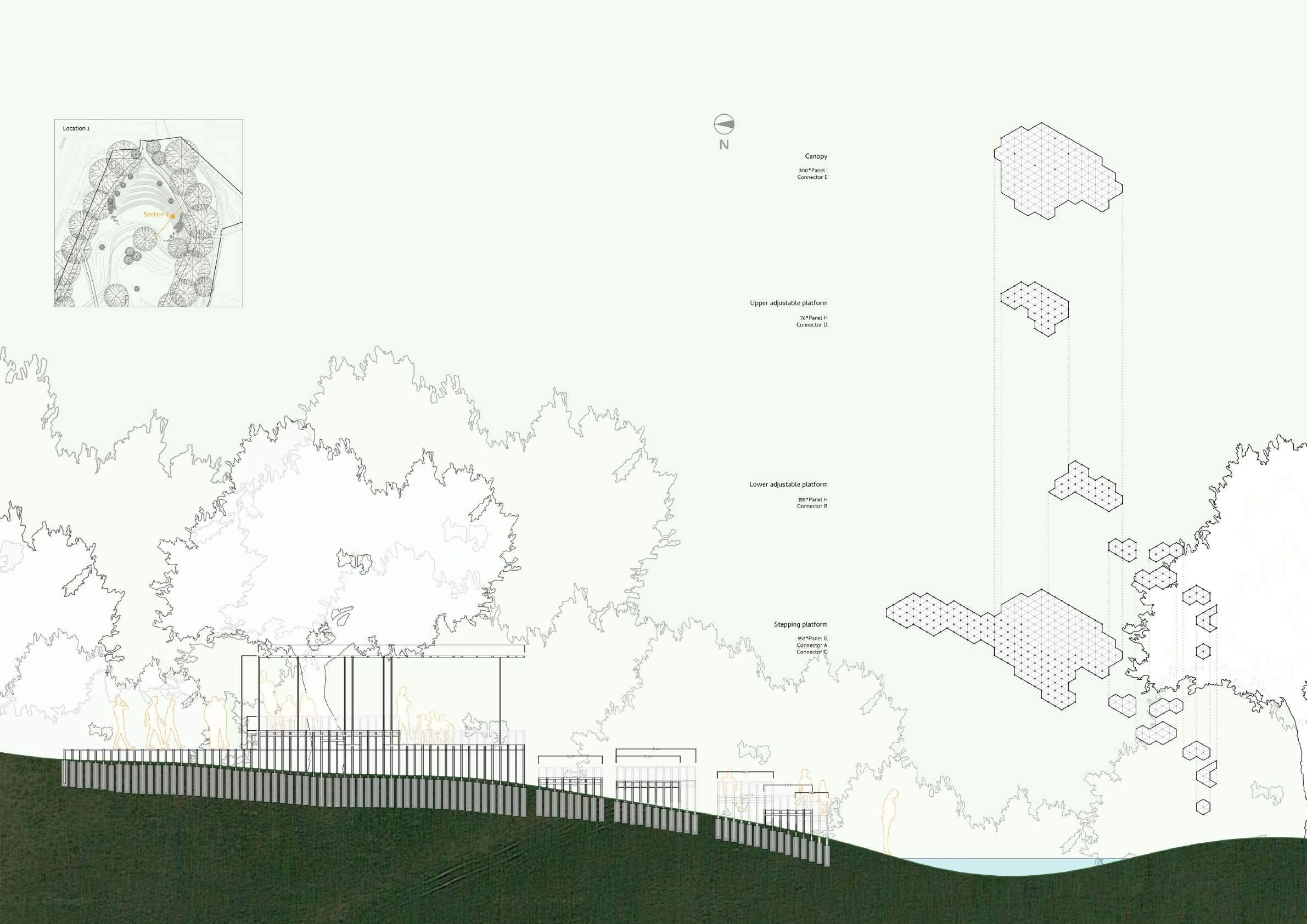

11.4 Section: Social bench design at Location 1 (East) 78

11.5 Plan: Social bench design at Location 1 (East) 79

11.6 Section: Social bench design at Location 2 80

11.7 Plan: Social bench design at Location 2 81

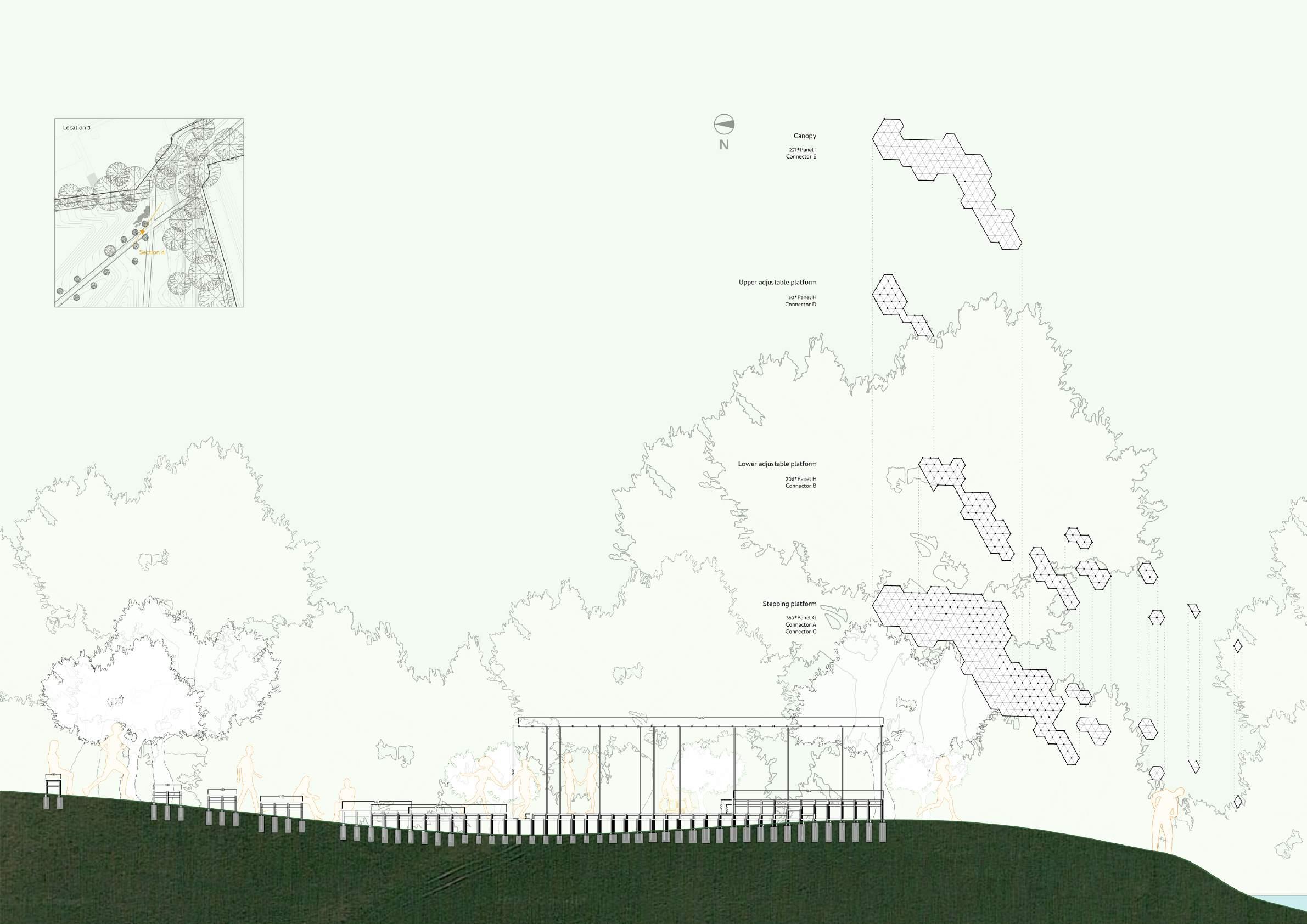

11.8 Section: Social bench design at Location 3 82

11.9 Plan: Social bench design at Location 3 83

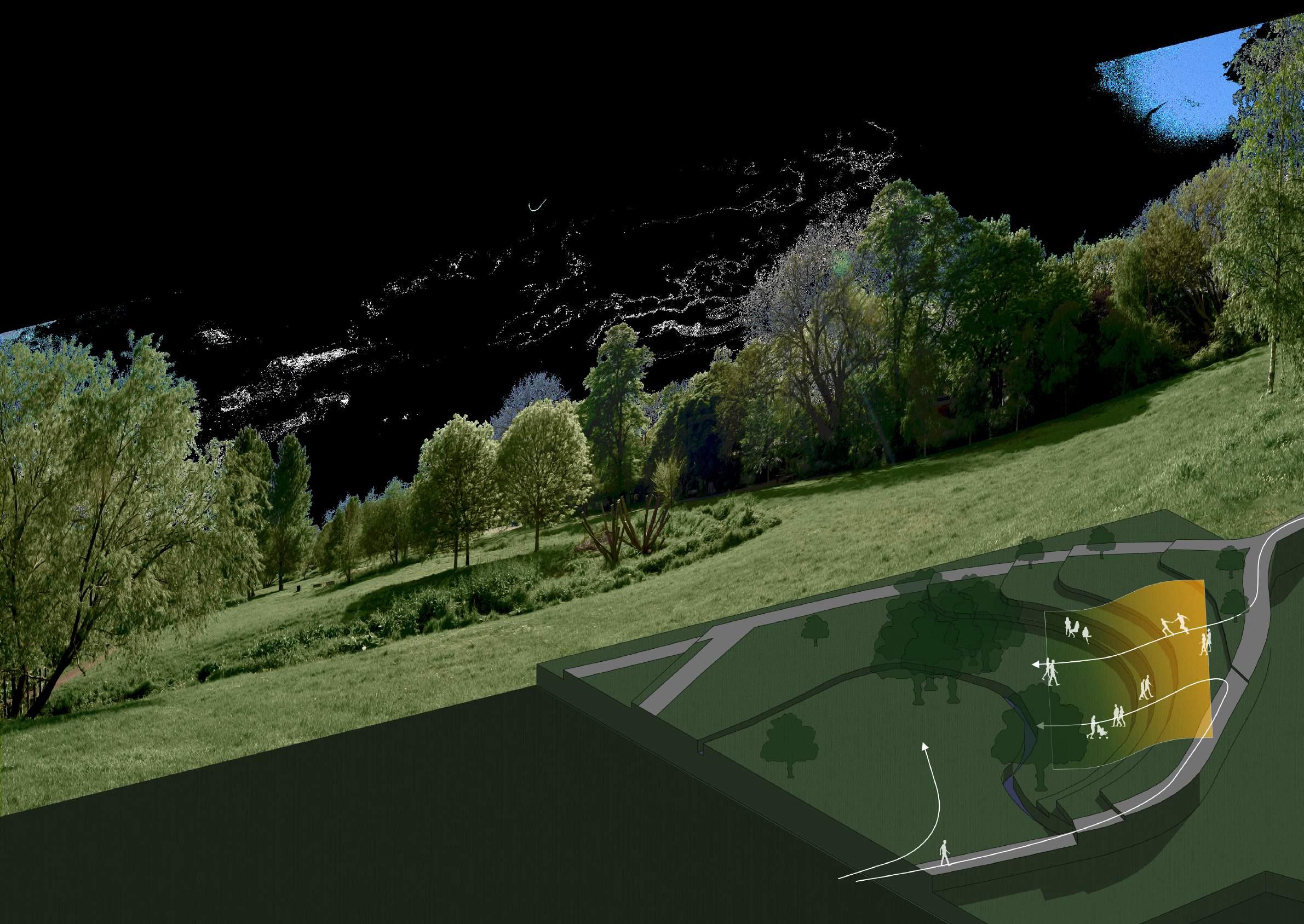

12.1 Rendering - Social bench 1 84

12.2 Rendering - Social bench 2 87

12.3 Rendering - Social bench 3 88

12.4 Rendering - Social bench 4 91

13 Reflection 92

14 Bibliography 93

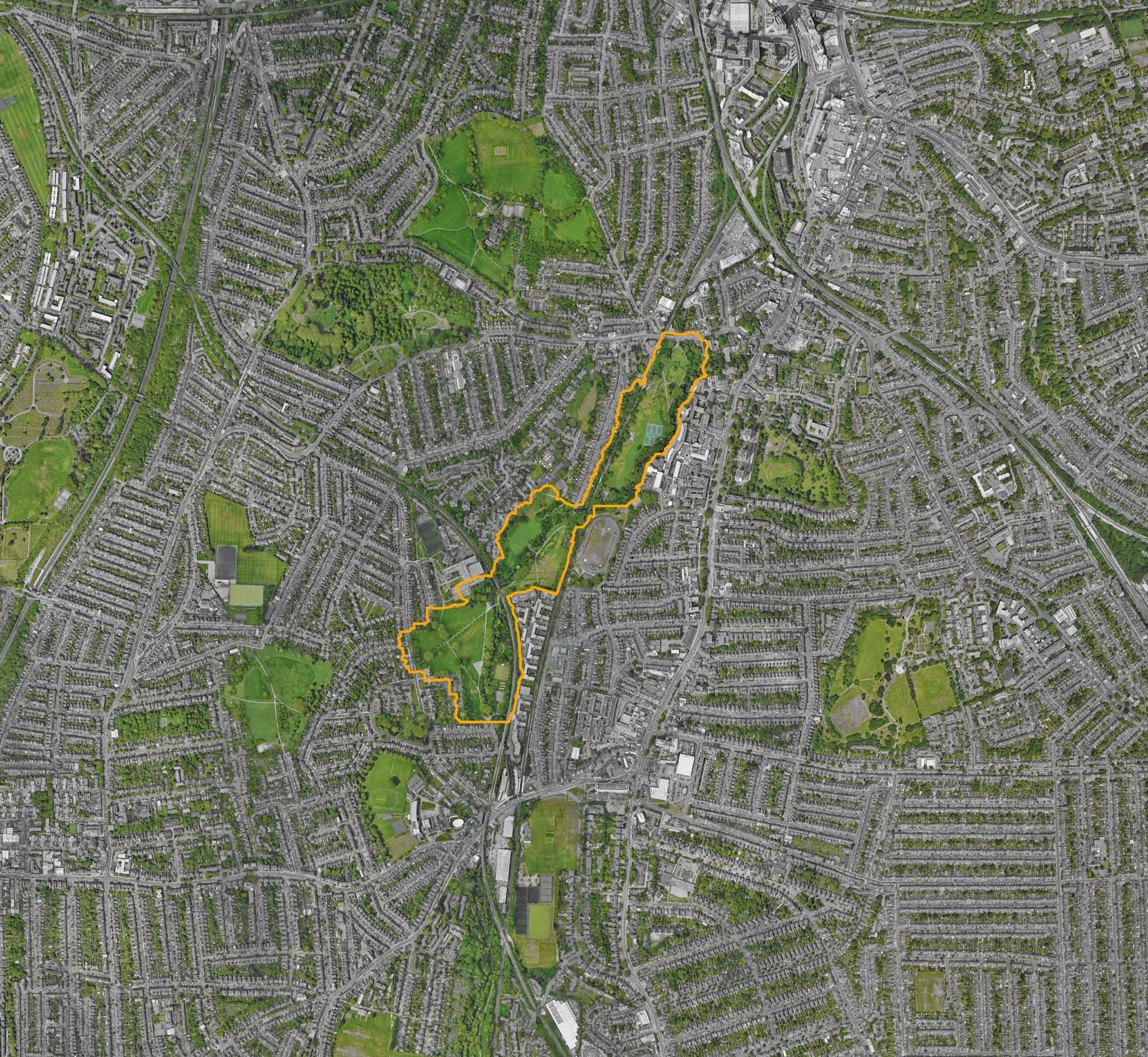

1.1 A green space between the hustle and bustle

Initial site analysis: site location

Ladywell Fields is a common destination to unwind and access nature. It is between two busy streets along with large residential areas, and sheltering a variety of wildlife. The open and vast fields serve a place with the least physical barriers.

1.2 The history of human mobility

Initial site analysis: site history

Apparently, the history of the area mirrors the evolution of human society. Usually, human habitats originate from the watersides with agriculture and grazing, forming the earliest tribes. Prior to 1700, a few dwellings were located on the east bank of the River, surrounded by crop fields.

People cultivated, hunted, married, and reproduced, establishing a society where all movements were interwoven, enabling further

development. The UK began its industrial revolution in the latest 18th century, fostering urbanization.

In 1857, following the arrival of a railway, the local residents started to move towards the north, getting connected with other human habitats.

In 1890, the Ladywell Fields was established.

Historical trend: expansion to the north

Urbanization

Industrialization

Trade and migration

1760

1922

1864

Present Ruling and religions

Migrating towards the North

Around North Kent Railway

Around Ravensbourne River

6th - 8th century

St. Mary’s Church and King Alfred

Agriculture and grazing

Ladywell Fields and its surroundings Lewisham High St. Brockley Rd. Ladywell Fields Ravensbourne River1.3 A retained urban green space

Site analysis: the urban fabric with urban green spaces

To some extent, our society is built upon human interactions, and developed through exploration, which catalyses the gaining and exchange of knowledge, currency, materials, etc. Everyone rely on each other for survival. Automatically, we are attracted by the places with more social interactions, just like being attracted by food and water.

Although urbanization strengthens the bonds between individuals, it also brought environmental and social issues including pollution and work stress, such as the Great Smog of London, which caused thousands of deaths before 1953 (Martinez, 2019). People realized the importance of environmental protection, and urban green spaces were recognized as an indispensable part of a city. (Lin et al., 2023)

The current map shows that natural spaces are more dispersed, including larger spaces consisting of woods and lawns, and smaller elements like solitary trees and bushes. Now the nature are more approachable in daily lives.

The map of Lewisham, green spaces highlighted

The map of Lewisham, green spaces highlighted

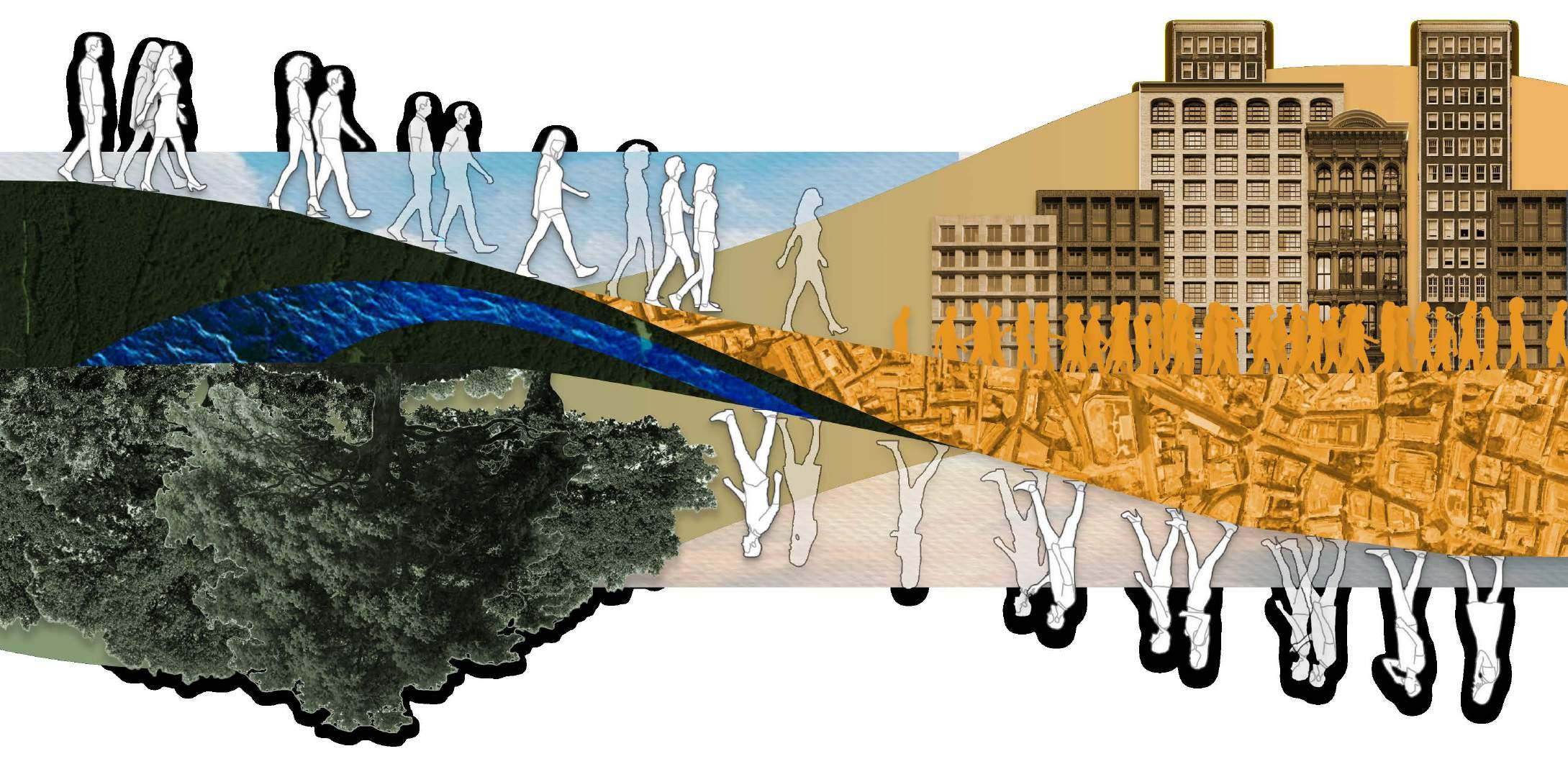

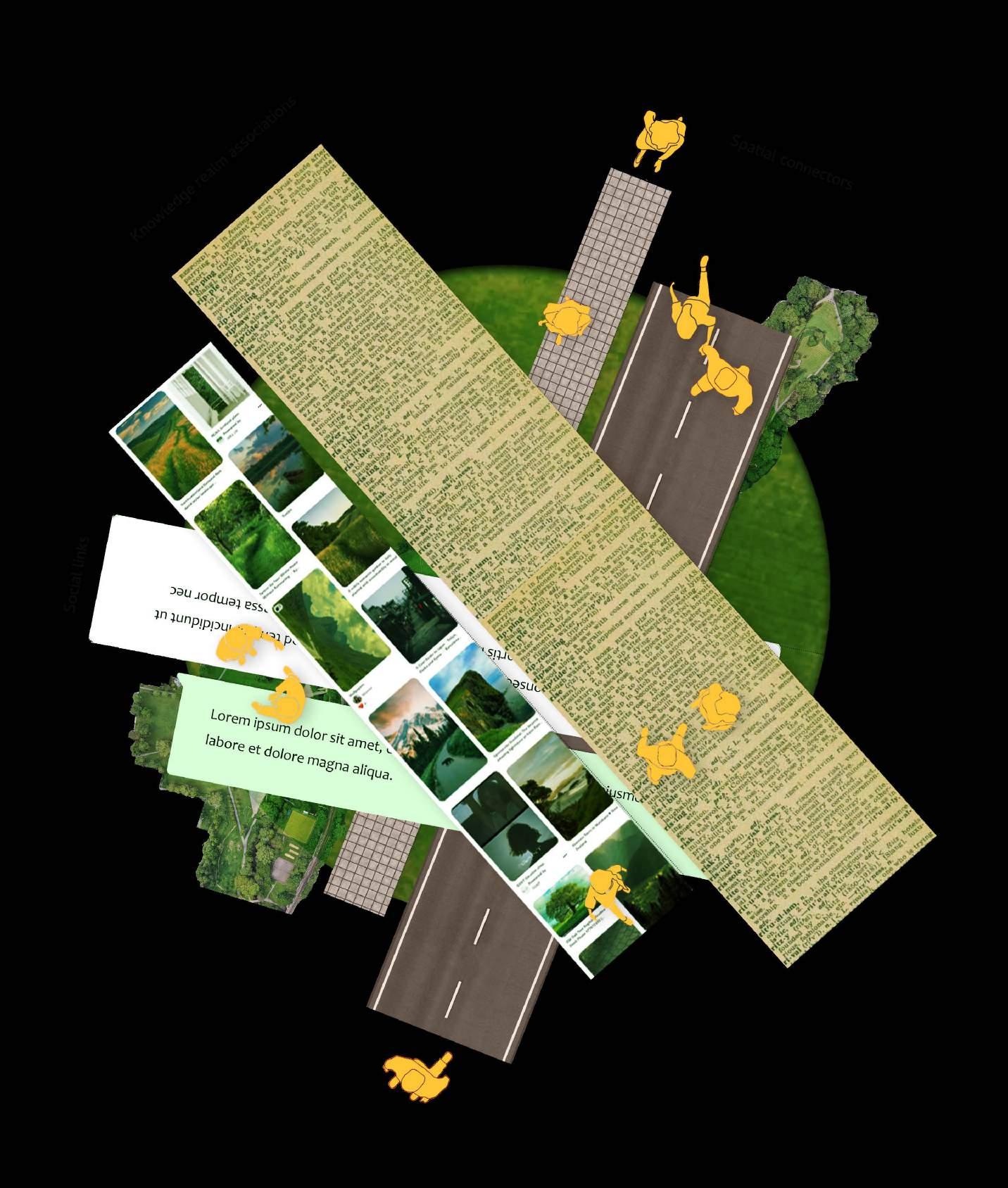

1.4 From macroscopic to microscopic: what makes people move?

Initial inspiration: the moving pattern of human, as individuals and as groups

Now social interactions are not the only things that facilitate human movements, but also natural spaces are. Humans have a passion for getting closer to nature and living things, due to the subconscious desire. (Fromm, 1992)

These factors are not equally attractive at different times. In the age of agriculture and grazing, the river was the main attraction. But after the development of traffic webs, the roads offering effective communication with the outer world, caught people’s attention. After the shift took place after the construction of the railway, the effects of the river remained but went weaker, compared to the railway and high streets.

This impulse towards nature is magnified in an environment of a fully urbanized city. Since the urban population is climbing, the enthusiasm towards nature will be inflating.

The two factors are motivating people’s exploration into the outer world, by applying “pulling forces” and “pushing forces” (Dolan et al., 2021) which make people move, playing significant roles in people’s decision-making at navigation.

Digital collage: Mobius strip - Nature and human society finally came together in modern cities.

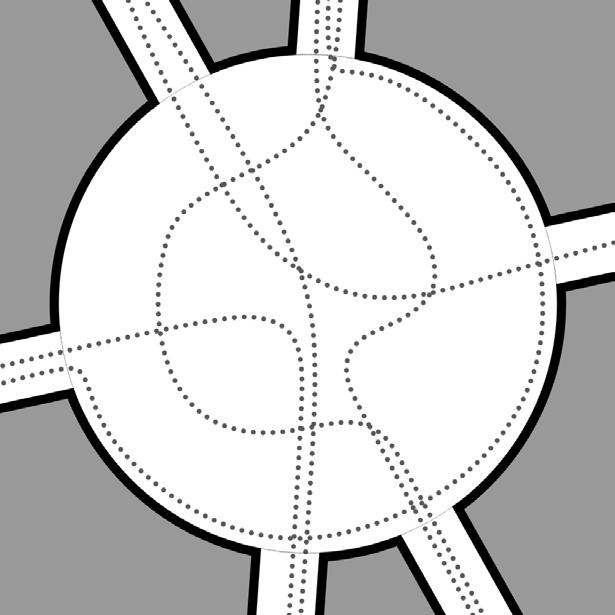

2.1 The classification of urban spaces and the metaphor of “bridges”

Conceptualization: the methodology of deconstruction towards the urban fabric

How do we get attracted by those “attractive” places? How do we plan our routes towards these destinations?

To look into the current urban fabric, I tried to classify different places in the city into several types:

2.2 Further investigation and classification of the “bridge spaces”

Conceptualization: the abstracted forms of “bridges” in urban areas and in urban green spaces

1. Endpoints: These spaces can only be entered and left through one threshold. Usually, what we do here is to turn back and head towards where we set out. For example, in an ordinary shop by the street, customers can only enter and leave the shop through the main entrance.

2. Bridges: For those places that join other places together spatially, they are performing the functions of a “bridge” – a metaphoric term. When a place attracts people, the force it applies is not always straight, to bring people to the destination directly, but more usually goes through these “bridges”, which make people go across more places. They might be streets, footbridges, tunnels, or even an interior space with multiple entrances.

The two types of space are both commonly seen in our cities. They differ mainly according to the type of movements happening in these places: entering an “endpoint” means that this part of the trip ends here. But in “bridge spaces”, we are always free to leave from the multiple openings, which link the space to other places. In “bridge spaces”, people get attracted easier due to the openness of bridges, and consequently, further movements are facilitated.

Urban green spaces

The “bridges” can be any place with multiple openings and do not have to be linear

Most of the urban green spaces with open edges, are naturally “bridges”. Urban green spaces are wide and open, unlike the constraint city roads limited by traffic and width. The spaces easily become sites for social and cultural events due to their approachability. It is common to see weekend markets and music events taking place in the parks in London, such as Camberwell Green, thriving and energizing.

Linear roads

Examples of “bridges” in a city Examples of “endpoints” in a city2.3 How does urban green spaces as “bridges” facilitate exploration?

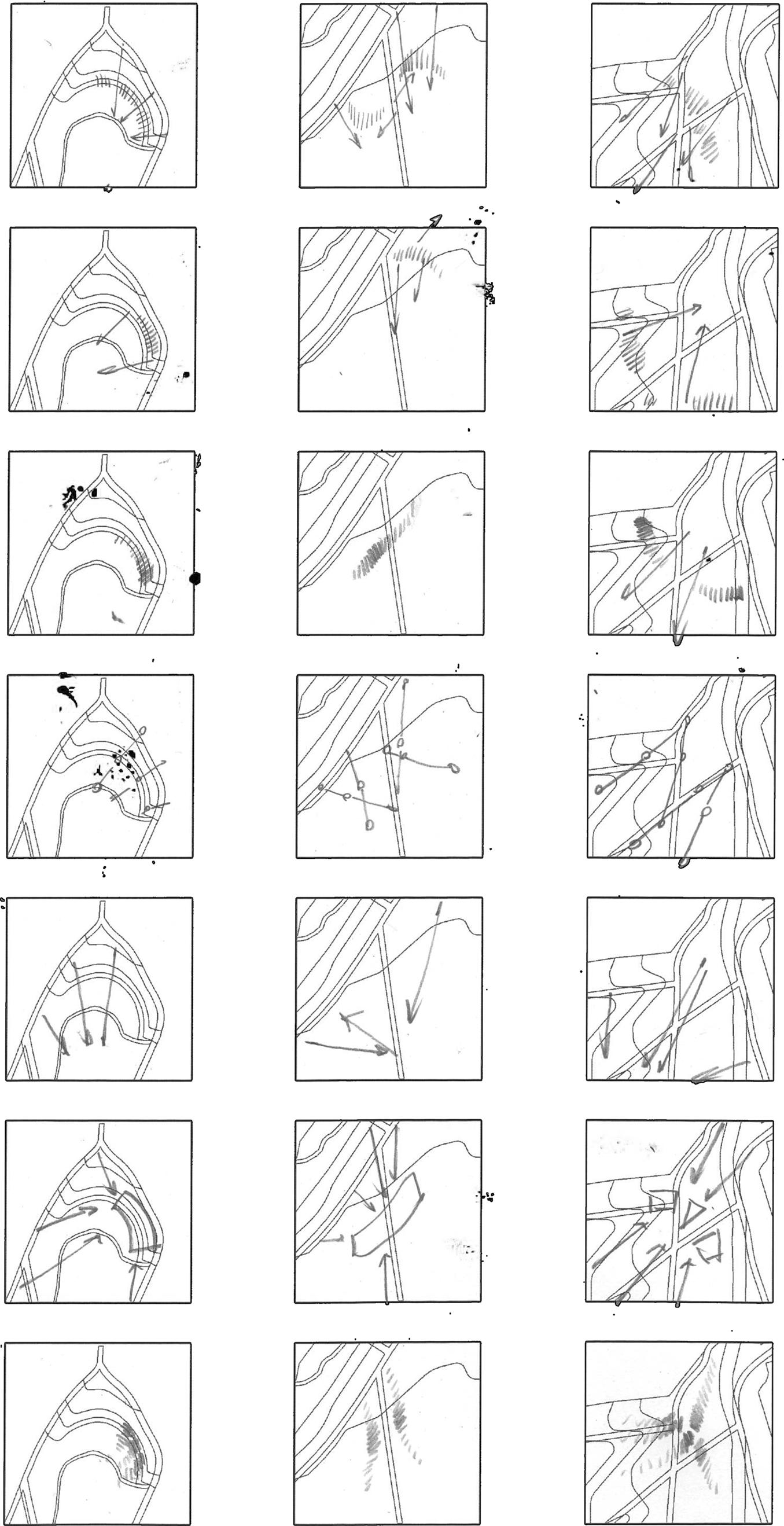

Site analysis: first-hand experience of exploring through “bridge” spaces

Residing in a city for a long time, it is pragmatic to stay on the familiar routes, to minimize the likelihood of encountering possible dangers and unknowns.

In most urban green spaces, hard pavements are built on top of the natural surfaces, to enhance accessibility and landscape aesthetics. Indeed, the paved roads make the walking experience more comfortable without dirtiness and rugged grounds.

Nonetheless, excessive familiarity may also lead to counteractive behaviours, that prompt people to explore unknown areas. This is usually “risky” but rewarding.

In urban contexts, the “bridges” offer opportunities for explorations into the surroundings.

At another site visit, I embarked on a trip through Ladywell Fields, by leaving the park through an attractive entrance intentionally, to see where it took me to.

The map indicates me deviating when noticing something intriguing, and returning to the planned route after satisfying my curiosity.

The behaviour of exploration was rewarding and satisfying, making me feel “connected” to the society.

2.4 The “bridges” inside Ladywell Fields

Site analysis: dissecting the site into a web of “bridges”

While the site itself is performing as a “bridge” space, smaller bridges spaces, such as pavements and meadows, consist Ladywell Fields as well.

There are mainly two types of “bridges” at the site: hard pavements and lawns. By focusing on the routes on lawns that people take to reach their destinations, based on my empirical judgements and observations towards the footprints on lawns, I identified how green spaces act as “bridge spaces” inside Ladywell Fields, and how the attraction forces are applied on the audiences

The forces of attraction can be applied in many ways:

1. Visual: seeing an obvious symbol or landmark

2. Acoustic: hearing other users or the environment

3. Aware: knowing the place from experiences or other information sources

4. ...

Hard pavements

Directions

Directions

Routes

Cafe

Starting and ending point

2.5 Points of reference in “bridge spaces”

Precedent: Parc de la Villette / Bernard Tschumi Architects

de la Villette, a famous precedent of transforming urban green space into facilities with cultural and social purposes, successfully utilized the green spaces as “bridge spaces”. The most inspiring part is how the red buildings are aligned in a grid pattern, which “gives the visitors points of reference” (Souza, 2011).

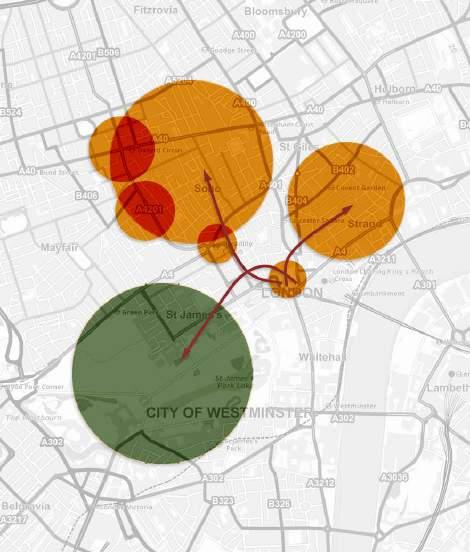

2.6 In a busier urban context

Precedent: Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square in Central London can be compared to a special “bridge”: the landmark Nelson’s Column and the fountains make the square iconic, and turn the square into a “reference point”, similar to the design of Parc de la Villette but in a larger scale.

Parc Fig.3 Aerial view of Parc de la Villette. (n.d.). Fig.4 Parc de la Villette. The surroundings of Trafalgar Square Trafalgar Square Covent Garden Soho Piccadilly Circus Regent Street Oxford Street St James’s Park3.1 The barriers to the “green bridges”

Site analysis: insufficiencies and possible solutions for the site to be used as a “bridge space”

Hard pavements

Relatively dry areas (north and middle)

Wet lawns (south)

Though, something peculiar was noticed during my observations towards the park users. Distinctively, most dog walkers stick on the hard pavements, differing from those who play on the lawns in Greenwich Park, for example. Meanwhile, the lawns are damper and slippery in the south part, lasting for days after rain. Relatively, the lawn in the north part is more welcomed by dogs, kids and ball game players. The observation proves the lack of popularity on the lawns

3.2 Risks and rewards trade-off

Site analysis: possible solutions to turn the meadow into circulation spaces

Getting in touch with nature Social connections

Knowledge expansion

Enclosed space Muddy road

Tranquility Dirtiness

Recalling the discussion of the factors which facilitate movements and explorations, and the experiences and observations about going through “bridge spaces”, we get an inference into how people balance the risks and rewards of their possible exploration:

1. Rewards:

(1) Fulfilling curiosity

(2) Gaining cultural enrichment

(3) Building social connections

(4) Meeting materialistic needs

(5) …

People usually make a move when they perceive the rewards to outweigh the risks.

Rugged surface

2. Risks:

(1) Physical barriers on the route: terrain, distances…

(2) Possible consumption of other resources: time, stamina…

(3) Navigation challenges

(4) Safety concerns

(5) Lack of rest spaces

(6) …

Although the movements of people crossing Ladywell Fields were witnessed, the space cannot be regarded as a successful “bridge space” at present. The wet lawns and other factors are stopping people from going across them, increasing the “risk” on the way.

If the actions of exploration are to be motivated, the simplest way is to increase the “rewards” and reduce the “risks”.

3.3 Comfortable interactions with the natural surroundings

Precedent: Peak-A-Boo Installation / i.thee

3.4 Bringing people to the sceneries

Precedent: Path of Perspective / Snohetta

Peak-A-Boo, an installation in the wood, illustrated a most common tactic of reducing the “risks” when approaching nature. The wood panel created comfortable platforms for more variable activities, making a distinctive scenery among the trees.

Fig.6 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation.

Fig.7 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation.

Fig.8 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation.

Path of Perspectives, different from Peak-A-Boo, strongly ascended the “rewards” gained during the trip. The extruding platforms provide perfect locations for looking out, bringing the beautiful landscape directly to the tourists’ sights.

Fig.9 Path of Perspectives.

Fig.10 Path of Perspectives.

Peak-A-Boo, an installation in the wood, illustrated a most common tactic of reducing the “risks” when approaching nature. The wood panel created comfortable platforms for more variable activities, making a distinctive scenery among the trees.

Fig.6 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation.

Fig.7 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation.

Fig.8 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation.

Path of Perspectives, different from Peak-A-Boo, strongly ascended the “rewards” gained during the trip. The extruding platforms provide perfect locations for looking out, bringing the beautiful landscape directly to the tourists’ sights.

Fig.9 Path of Perspectives.

Fig.10 Path of Perspectives.

4.1 Constructing bridges in 3 realms

Initial design conceptualization

After researching and analysing, three main purposes were identified.

In an exploration through “bridges”, we gain physical and mental benefits and strengthen our social connections with the outer world. The designs would be the architectural interventions that facilitate the bonds formed in the “bridges”. And ultimately, they are abstracted into the three metaphorical “bridges”, constructed not only in the physical world but also in the social webs and knowledge realms.

I planned to design several social benches, as the materialised forms of these “bridges”

4.2 Integrating personal experiences through data collection

Experimenting data collection with Pyhon coding

At a very early stage, I experimented with simple coding that summarize the use of benches, such as the staying time, locations and directions, indicating the factors that grab their attention, to provide real-time feedback to the users.

However, I moved away from this concept. Other than practical reasons such as the threats of theft, the program failed to include the most possible factors affecting the final results of the calculation. For example, people do not always face the sceneries attracting them but the people interacting with them. Also, the precise movement and behaviours of the users cannot be recorded and analysed.

import random

# Define constants

NUM_CHAIRS = 10

DISTANCE_RANGES = [(0, 100), (100, 200), (200, 300), (300, 400), (400, 500), (500, 600), (600, 700), (700, 800), (800, 900), (900, 1000)]

ANGLE_RANGES = [(0, 30), (30, 60), (60, 90), (90, 120), (120, 150), (150, 180), (210, 240), (240, 270), (300, 360)]

MASS_RANGE = (0, 150)

MIN_MASS_RECORD = 30

# Generate random data chair_data = []

for in range(NUM_CHAIRS):

distance = random.randint(0, 1000) angle = random.randint(0, 360) mass = random.randint(*MASS_RANGE) chair_data.append((distance, angle, mass))

# Record data for chairs with mass > 30kg time_distance = [[0] * len(DISTANCE_RANGES) for _ in range(NUM_CHAIRS)] time_angle = [[0] * len(ANGLE_RANGES) for _ in range(NUM_CHAIRS)]

for in range(NUM_CHAIRS):

distance, angle, mass = chair_data[i] if mass > MIN_MASS_RECORD: for j, (start, end) in enumerate(DISTANCE_RANGES):

time_distance[i][j] = random.randint(0, 100000)

if start <= distance < end: time_distance[i][j] += random.randint(0, 100000) for j, (start, end) in enumerate(ANGLE_RANGES):

time_angle[i][j] = random.randint(0, 100000) if start <= angle < end: time_angle[i][j] += random.randint(0, 100000)

# Calculate longest periods of time for each chair longest_distance = []

longest_angle = [] for i in range(NUM_CHAIRS):

max_distance_time = max(time_distance[i])

longest_distance.append(DISTANCE_RANGES[time_distance[i].index(max_distance_time)])

max_angle_time = max(time_angle[i])

longest_angle.append(ANGLE_RANGES[time_angle[i].index(max_angle_time)])

# Output results

for i in range(NUM_CHAIRS):

print(f”Chair {i+1}:”)

print(f”Longest period of time at distance: {longest_distance[i]}”)

print(f”Longest period of time at angle: {longest_angle[i]}”)

4.3 Information exchange in modular systems

A more achievable and practical substitution of data collection: modular structures

Moving forward, I thought of modular systems to be adjusted throughout time and by different groups. The modular system integrates people’s personalized experience indirectly: when they are adjusting the space for their personal experiences, they are also shaping these experiences with other users.

What is a part of “personalized experience”?

1. How people use the space (move, utilize...)

2. How people adjust the space (take away, put in, change...)

3. What people do with each other (socialization, playing...)

4. ...

4.4 Customizing the experience

Precedent: Photograph series “One” / Pierre Sernet

Recalling the analysis of Parc de la Villette, which exemplified the importance of building points of reference, linked it to the photograph series about an identical space in different locations. In this series, the same tearoom space indicates a certain area of tranquillity, relaxation, etc.

When an identical space takes place repetitively, it posts a clue of a certain vibe. This is the other reason to use the modular system with repeating units: the identical units scattered throughout the site would make the urban green space a whole while acting as “points of reference”, and give a subtle hint of mental relaxation.

Fig.13 Sernet, P. (2002). T-006,-Mr.-Noguchi-& Mr.Ueno, Sakai, Japan. Fig.14 Sernet, P. (2002). T016-Alice,-CDG-Airport, Paris, France. Fig.12 Sernet, P. (2003). T055-Mrs.-Watanabe,-Mt. Fuji, Shizuoka.5.1 Build a space with geometrical forms

Experimenting with different shapes

Spinning triangle panels Foldable panel rolls Foldable square panels Foldable triangular panels Foldable and rotatable triangular panels Height-adjustable triangular platforms

5.2

Using

Variable triangles in practical uses

Variable triangles in practical uses

5.3 An appropriate size

Finding the best size for the modular system

When trying to select a suitable size for all the identical units, I thought of the existing dimensions of chairs, tables and staircases. The units must be light and easily carried by any individuals.

And finally, 50 cm was considered an appropriate size.

5.4 Stacks of triangles

Installing the modular system in a small scale

In the social bench, there are fixed units for stepping and stabilisation, and units to be moved vertically. The structure of triangle stacks made this possible.

The structure consists of a few triangular panels, with poles made with 6 connectors, allowing free vertical movements of the adjustable structures, and fixing necessary fixed stepping panels at the bottom.

1 Installing base supporting structure.

2 Adding connectors to the level needing different triangular modular units.

3 Installing fixed units.

4 Installing movable units.

5 Installing canopy units.

5.5 Modular units mix-and-match

Different configurations of triangular panels and frames

Other than the initial configurations by the designer, the modular units catalyse users to personalise and “create” spaces on their own. Among the 4 modular units that are available for changes, the users can create infinite mix-and-matches.

6.1 The rationale behind selecting possible locations

Dissecting people’s attention, routes and experience to find the potential location for the designs

As spatial “bridges”, the architectural interventions should locate between the area where people stay, and the area attracting people but with barriers on the way. They act as spatial junctions and rest spaces.

6.2 Bridging the man-made spaces and the nature

Location selections for the designs

Potential areas selected for the architectural interventions

Existing pavements in the site

Vegetations other than meadows, such as trees and shrubs

Ravensbourne River

7.1 Building the “bridges”

First attempt of structuralize the “bridging” social benches

1

Identifying the sights of visitors on the pavements

2 Finding the routes taken by these visitors to the attractive places

This was the first attempt when I was trying to divide the selected areas into smaller zones. However, without thinking of the logic behind setting up rest spaces in parks, the initial design led to problems, such as excessive area taken, risks of falling from high places, etc.

5 Adding a second level above

6

Identifying the sights of the visitors on the second level

3

Extracting the space between the routes

4

Creating routes to a higher place

7

Removing the area too close to the natural elements such as rivers

8

Cutting the space to leave a route cutting through

7.2 An initial attempt

First attempting to structure the design based on the method above

Following the first attempt at an early stage, made the initial zoning for the 3 locations. After reflecting on the problems that emerged in these designs, I could fix them and restructure the rationale behind the zonings.

For instance, the sitting zone should be directly linked to the routes taken, instead of cutting out an area with the routes. Also, the second level was removed for safety concerns, and they are replaced with unaccessible canopies.

7.3 The logic underlying the structures

Identifying the basic rationale behind the space and people’s experiences

Before really starting to restructure the space, I went back to the logic behind these design iterations thoroughly. By understanding the relationships between the visitors, the natural environments, the man-made structures on the site and my design, I could make the design clearer and more effective.

The main purpose of these social benches is to intervene in the existing surroundings, by joining the pavement areas and the attractive natural elements, without posting too many effects on the original natural preserved areas.

Directions of attention

Possible directions of moving towards the attractive places

Locations for the social benches

Social benches joining pavements and natural elements

People moving through the social benches

Directions of attentions towards the social benches around the site

Height arrangements in the social benches (more intense, then higher)

Rough

7.4 Following the paths of pedestrians

Second attempt to structuralize the “bridging” social benches

1

Identifying the sights of visitors on the pavements

2 Finding the routes taken by these visitors to the attractive places

With different underlying logic, the results made in the second attempt were completely different. The areas allocated for the adjustable sitting spaces are smaller and more accessible. Meanwhile, the structures are scattered around the selected locations, giving more options for visitors.

5 Adding a second level above (but lower than in the first attempt)

6

Identifying the sights of the visitors on the second level

3

Arranging the sitting spaces around the routes

4

Creating routes to a higher place

7

Reducing the areas closer to the natural attractors

8

Removing some second-level platforms due to excessive height

7.5 Into the site step by step

Second attempting to structure the design

Following the page above, the zonings for each location were made. I was trying to adjust the height of the adjustable platforms according to the terrains around these locations, in order to provide convenience and better sights.

The location in the north part has a steeper slope, which means it is tougher to get close to the centre of the meadow and can be seen more easily.

With the social bench linking the highest point and the river bank, it is easier for people to get close to the river.

In the location in the south part, the pavement structure is more complex than in other places, while 5 pavements join here.

The social benches are placed between two pavements, with lush wood on the north. It makes sure that people from most directions can see the social bench, without blocking people’s sights towards the beautiful landscape.

8.1 Flexible and adjustable structure

Testing technical details

Considering the necessity of moving the sitting surfaces upwards and downwards freely, I conjured up several possible structures that can fix the chair legs to a certain level and can be altered as well.

In most of the initial concepts, the movability of the chairs is controlled by the buttons or handles at the sitting surface. However, these complicated structures might lead to challenges such as theft, corrosion, etc. Consequently, I was looking for a simpler and lighter structure, allowing better flexibility and controllability in these modular units.

8.2 Mortise and tenon Experimenting models

8.3 A combination of the two Designing technical details

On the first try, the rotatable tenon was inserted into the chair leg and was controlled by the thread connected to the seat surface.

Nonetheless, the structure consisted of too many small units, which increase the budget for production and maintenance. Meanwhile, the connectors for this structure were too big and unstable.

Next, I experimented with the structure with 2 springs. By reducing the number of components, I made it to reduce the size and maintenance difficulties. The drawback of this design is the durability - the springs get tired after too many movements. By using tougher materials for the springs, the problem can be alleviated to some extent.

9.1 Light, strong and supportive

Research: materials for outdoor light structures

9.2 Rattan, acrylic and aluminum

Material selection for the light structure

When selecting materials, there are some key factors to be considered:

1. Light enough to be carried by human individuals

2. Strong enough to support the structure

3. Resisting erosion

4. Easily gained and replaced within the UK

While aluminum alloy acts the role of the supportive structure, the transparent acrylic panel makes the visual of the social benches lighter and less overwhelming, while allowing a stronger visual connection with nature, such as sunlight and vegetation. And instead of acrylic for seats, I chose synthetic rattan, which has a lighter density and warmer texture, while they can easily be obtained and replaced in the local country.

317.6 cm^2 (the volume of the rattan surface) *

1 g/cm^2 (the density of synthetic rattan)

+

511.0 cm^2 (the volume of the seat surface frame) *

2.63 g/cm^2 (the density of aluminum alloy)

+

3*24.9 cm^2 (the volume of the adjustable chair legs) * 2.63 g/cm^2 (the density of aluminum alloy) =1857.991 g

Considering of the weights of necessary other components such as screws, and the stains and dirt attached after being used, the total weight of the adjustable unit could still be less than 2.5 kg. While most of the stools without chair backs weigh from 2 kg to 6 kg, I made it to minimize the size and weight of these adjustable seats.

Foam board

Acrylic PVC

Stainless steel

Plywood Rubber

Synthetic ratten

Concrete Bamboo

Transparent acrylic Aluminum alloy

HDPE

Foam board

Acrylic PVC

Stainless steel

Plywood Rubber

Synthetic ratten

Concrete Bamboo

Transparent acrylic Aluminum alloy

HDPE

10.1 Plan and elevation: Connectors and adjustable chair legs

Scale 1:5

Unit: mm

Plan

10.2 Plan: Connectors and adjustable chair legs

Scale 1:1

Unit: mm

10.3 Section: Adjustable structure in the chair legs

Scale 1:1

Unit: mm

Plans of the 6 connectors as a group in a standing pole, and the 6 adjustable chair legs when in the connectors. The number of smaller components in each connector can be adjusted for special purposes, such as the junction area between higher and lower platforms.

The section of the adjustable chair legs, showing the movable small component as a part of the adjustable seat.

10.4 Plan and elevation: Vertical connectors A-E

Scale 1:20

Unit: mm

10.5 Plan and elevation: Adjustable panels F-I

Scale 1:20

Unit: mm

Different connectors as poles, for the adjustable surfaces at different levels specifically.

Different fixed frames and panels to be connected to the connectors, providing different functions such as flooring, sitting and sheltering.

10.6 Elevation: Joined connectors and adjustable chair legs

Scale 1:10

Unit: mm

Presenting how the panels at different levels are connected to the different connectors.

10.7 Plan and elevation: Configurations of platforms at different levels (1)

10.8 Plan and elevation: Configurations of platforms at different levels (2)

Plans and elevations of the 2 lower platforms consist of different panels and connectors.

Plans and elevations of the 2 upper platforms consist of different panels and connectors.

10.9 Plan and elevation: Configurations of platforms at different levels (3)

Scale 1:20

Unit: mm

Plans and elevations of the canopy consist of different panels and connectors.

11.1 Plan: Locations of the social benches

Site plan:

Scale 1:150000

Social bench plans:

Scale 1:50000

11.2 Section: Social bench design at Location 1 (West)

Scale 1:100

Unit: mm

11.3 Plan:

Scale 1:200

Unit: mm

The plan and section of the social bench locating in the northwest corner of Ladywell Fields. Since the north area is more popular, two social benches were placed. This page shows one of them. Social bench design at Location 1 (West)11.4

Scale 1:100

Unit: mm

Scale 1:200

Unit: mm

Section: Social bench design at Location 1 (East) The plan and section of the social bench locating in the north-east corner of Ladywell Fields. Due to the steep slope at the east, the scattered small benches are placed at different heights. 11.5 Plan: Social bench design at Location 1 (East)11.6 Section: Social bench design at Location 2

Scale 1:100

Unit: mm

11.7 Plan: Social bench design at Location 2

Scale 1:200

Unit: mm

The plan and section of the social bench locating in the middle part of Ladywell Fields. In the area without much height changes, the social bench provide chances for more direct connections with the natural surroundings in the area.

11.8 Section: Social bench design at Location 3

Scale 1:100

Unit: mm

11.9 Plan: Social bench design at Location 3

Scale 1:200

Unit: mm

The plan and section of the social bench locating in the south part of Ladywell Fields. The most popular part closer to the railway is at a lower altitude, leading to a different design logic, which is to increase the platform height at the lowest point, to create a better lookout.

13 Reflection

It was an extremely busy unit since I have been reworking so many ideas and designs, that I feel such satisfied when I am finally completing it. However, if this was a longer unit, I will think of structuring my initial ideas in a clearer way, in order to identify the problems existing in the site and my design target, which would save more time to improve my designs, since at the early stage I spent too much time to figure out what I wanted to do, instead of analysing for the design.

Meanwhile, there are still things to be improved in the technical drawings. For instance, I found it tough to draw the technical details, such as the movable units, since I could only rely on the experimental models to construct those details, but could not build a 1:1 model for experimentation. Also, with little former experience in building movable structures, the experimenting process was tough as well.

After the unit, I gained more experience in combining scientific theories into my design. I understood how to utilise them to analyse the site and my ideas, such as Marginal Value Theory when analysing visitor behaviours, and semantic links between abstract concepts when understanding the reasons behind confirmation bias on the Internet and in real life. The theories strongly support my conceptualization and design.

14 Bibliography

Reference list

Admin (2016). Trafalgar Square: the Heart of London | London Airport Transfers. [online] London Airport Transfers. Available at: https://londonairportransfers.com/ trafalgar-square-the-heart-of-london/.

Atlas of Urban Expansion (2016). Atlas of Urban Expansion - Cities. [online] atlasofurbanexpansion.org. Available at: http://atlasofurbanexpansion.org/data [Accessed 23 Feb. 2023].

Baldwin, E. (2019). Beatrice Bonzanigo Unveils Off-Grid Micro Home for Milan Design Week. [online] Beatrice Bonzanigo Unveils Off-Grid Micro Home for Milan Design Week. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/912987/beatrice-bonzanigo-unveils-off-grid-micro-home-for-milan-design-week?ad_source=search&ad_ medium=projects_tab&ad_source=search&ad_medium=search_result_all.

Barbosa, H., Hazarie, S., Dickinson, B., Bassolas, A., Frank, A., Kautz, H., Sadilek, A., Ramasco, J.J. and Ghoshal, G. (2021). Uncovering the socioeconomic facets of human mobility. Scientific Reports, [online] 11(1), p.8616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-021-87407-4.

Bayly, C.A. (2004). The Birth of the Modern world, 1780-1914 Global Connections and Comparisons. Malden, Ma: Blackwell Pub.

Bernard Tschumi Architects (n.d.). Bernard Tschumi Architects. [online] tschumi. com. Available at: http://tschumi.com/projects/3/.

Boyd, B. (2019). Urbanization and the Mass Movement of People to Cities | Grayline Group. [online] Grayline Group. Available at: https://graylinegroup.com/urbanization-catalyst-overview/.

Chen, J. (2020). Risk-Return Tradeoff. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https:// www.investopedia.com/terms/r/riskreturntradeoff.asp.

Crafts, N.F.R. (2002). Understanding the Industrial Revolution. The English Historical Review, 117(471), pp.489–490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/117.471.489.

Dimensions.com (2023). Browse Humans | Dimensions.com. [online] www.dimensions.com. Available at: https://www.dimensions.com/browse/humans.

Dolan, R., Bullock, J.M., Jones, J.P.G., Athanasiadis, I.N., Martinez-Lopez, J. and Willcock, S. (2021). The Flows of Nature to People, and of People to Nature: Applying Movement Concepts to Ecosystem Services. Land, 10(6), p.576. doi:https://doi. org/10.3390/land10060576.

Edwards, S. (2022). User Behavior Analytics: How to Track and Analyze. [online] Amplitude. Available at: https://amplitude.com/blog/user-behavior.

Florian, M.-C. (2022). ‘I Believe that Architecture is Never Finished’: In Conversation with FAR, Creator of the First Generative Project for the Metaverse. [online] ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/990862/i-believe-that-architecture-is-never-finished-in-conversation-with-far-creator-of-the-first-generativeproject-for-the-metaverse?ad_source=search&ad_medium=projects_tab&ad_ source=search&ad_medium=search_result_all [Accessed 1 May 2023].

Fromm, E. (1992). The anatomy of human destructiveness. New York: Henry Holt And Comp.

Hitch, N.L. (2022). sweeping arches and wood-laminate decks form i/thee’s stage at site of woodstock festival. [online] designboom | architecture & design magazine. Available at: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/arches-decks-wood-laminate-i-thee-stage-woodstock-festival-08-25-2022/ [Accessed 3 May 2023].

Kazimierz Dabrowski (2015). Personality-shaping through positive disintegration. Red Pill Press.

Leese, M. and Stef Wittendorp (2017). Security/Mobility. Manchester University Press.

Lin, B.B., Chang, C., Andersson, E., Astell-Burt, T., Gardner, J. and Feng, X. (2023). Visiting Urban Green Space and Orientation to Nature Is Associated with Better Wellbeing during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), p.3559. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043559.

Maguire, P. (2016). A Brief History Of The Lewisham Borough. [online] Lewisham Card. Available at: http://www.lewishamcard.co.uk/latest/2016/4/6/a-brief-history-of-lewisham-borough [Accessed 6 Mar. 2023].

Martinez, J. (2019). Great Smog of London | Facts, Pollution, Solution, & History. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/ event/Great-Smog-of-London.

Niantic, Inc (2023). Niantic, Inc. [online] Niantic. Available at: https://nianticlabs. com/.

Pew Research Center (2018). Demographic and economic trends in urban, suburban and rural communities. [online] Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/ social-trends/2018/05/22/demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/.

Pintos, P. (2022). Peak-A-Boo Installation / i/thee. [online] ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/988189/peak-a-boo-installation-i-thee?ad_source=search&ad_medium=projects_tab [Accessed 3 May 2023].

QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation Report. (2008).

Ritchie, H. and Roser, M. (2018). Urbanization. [online] Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization.

Ross, P. and Maynard, K. (2021). Towards a 4th industrial revolution. Intelligent Buildings International, [online] 13(3), pp.1–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508975. 2021.1873625.

Sernet, P. (2018). One. [online] Pierre Sernet. Available at: http://pierresernet.com/ one/.

Snøhetta (n.d.). Path of Perspectives. [online] www.snohetta.com. Available at: https://www.snohetta.com/projects/path-of-perspectives [Accessed 1 May 2023].

Souza, E. (2011). AD Classics: Parc de la Villette / Bernard Tschumi Architects. [online] ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/92321/ad-classicsparc-de-la-villette-bernard-tschumi.

Tschumi, B. (1987). Parc de la Villette. [Architecture Design].

Tschumi, B. (2001). Architecture and disjunction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press.

World Bank (2022). Urban Development. [online] World Bank. Available at: https:// www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview.

Images

Fig.1 Ladywell Fields after QUERCUS Project in 2008. (2008). [Photograph]. QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation Report.

Fig.2 Park users concerns pre and post QUERCUS. (2008). QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation Report.

Fig.3 Aerial view of Parc de la Villette. (n.d.). [Photograph]. Le Parc de la Villette est le plus grand centre de création artistique du Grand Paris Nord. Available at: https://www.tourisme-plainecommune-paris.com/decouvrir/aux-alentours/lavillette.

Fig.4 Tschumi, B. (n.d.). Parc de la Villette. [Photograph]. Available at: https:// www.tschumi.com/projects/104.

Fig.5 Admin (2016). Trafalgar Square. [Photograph]. Trafalgar Square: The Heart of London. Available at: https://londonairportransfers.com/trafalgar-square-theheart-of-london/.

Fig.6 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation 1. [Photograph]. Peak-A-Boo Installation / i/thee. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/988189/peak-a-boo-installation-ithee?ad_medium=gallery.

Fig.7 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation 2. [Photograph]. Peak-A-Boo Installation / i/thee. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/988189/peak-a-booinstallation-i-thee?ad_medium=gallery.

Fig.8 i/thee (n.d.). Peak-A-Boo Installation 3. [Photograph]. Peak-A-Boo Installation / i/thee. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/988189/peak-a-booinstallation-i-thee?ad_medium=gallery.

Fig.9 Snøhetta (n.d.). Path of Perspectives 1. [Photograph]. Path of Perspectives ‘Perspektivenweg’ at Innsbruck’s spectacular Nordkette mountain range. Available at: https://www.snohetta.com/projects/path-of-perspectives.

Fig.10 Snøhetta (n.d.). Path of Perspectives 2. [Photograph]. Path of Perspectives ‘Perspektivenweg’ at Innsbruck’s spectacular Nordkette mountain range. Available at: https://www.snohetta.com/projects/path-of-perspectives.

Fig.11 Snøhetta (n.d.). Path of Perspectives 3. [Photograph]. Path of Perspectives ‘Perspektivenweg’ at Innsbruck’s spectacular Nordkette mountain range. Available at: https://www.snohetta.com/projects/path-of-perspectives.

Fig.12 Sernet, P. (2003). T055-Mrs.-Watanabe,-Mt. Fuji, Shizuoka. [Photograph]. Pierre Sernet. Available at: http://pierresernet.com/one/.

Fig.13 Sernet, P. (2002). T-006,-Mr.-Noguchi-& Mr.Ueno, Sakai, Japan. [Photograph]. Pierre Sernet. Available at: http://pierresernet.com/one/.

Fig.14 Sernet, P. (2002). T016-Alice,-CDG-Airport, Paris, France. [Photograph]. Pierre Sernet. Available at: http://pierresernet.com/one/.

Fig.15 Sernet, P. (2004). T058-Malcolm,-Sunset-Beach, Hawaii, USA. [Photograph]. Pierre Sernet. Available at: http://pierresernet.com/one/.