Encountering nature on the way A study into the navigation experiences in cities, and the definition of urban green spaces Zijue Wei Unit 7 Year 2 University of the Arts London 2.2023 - 4.2023

By Zijue Wei

Introduction

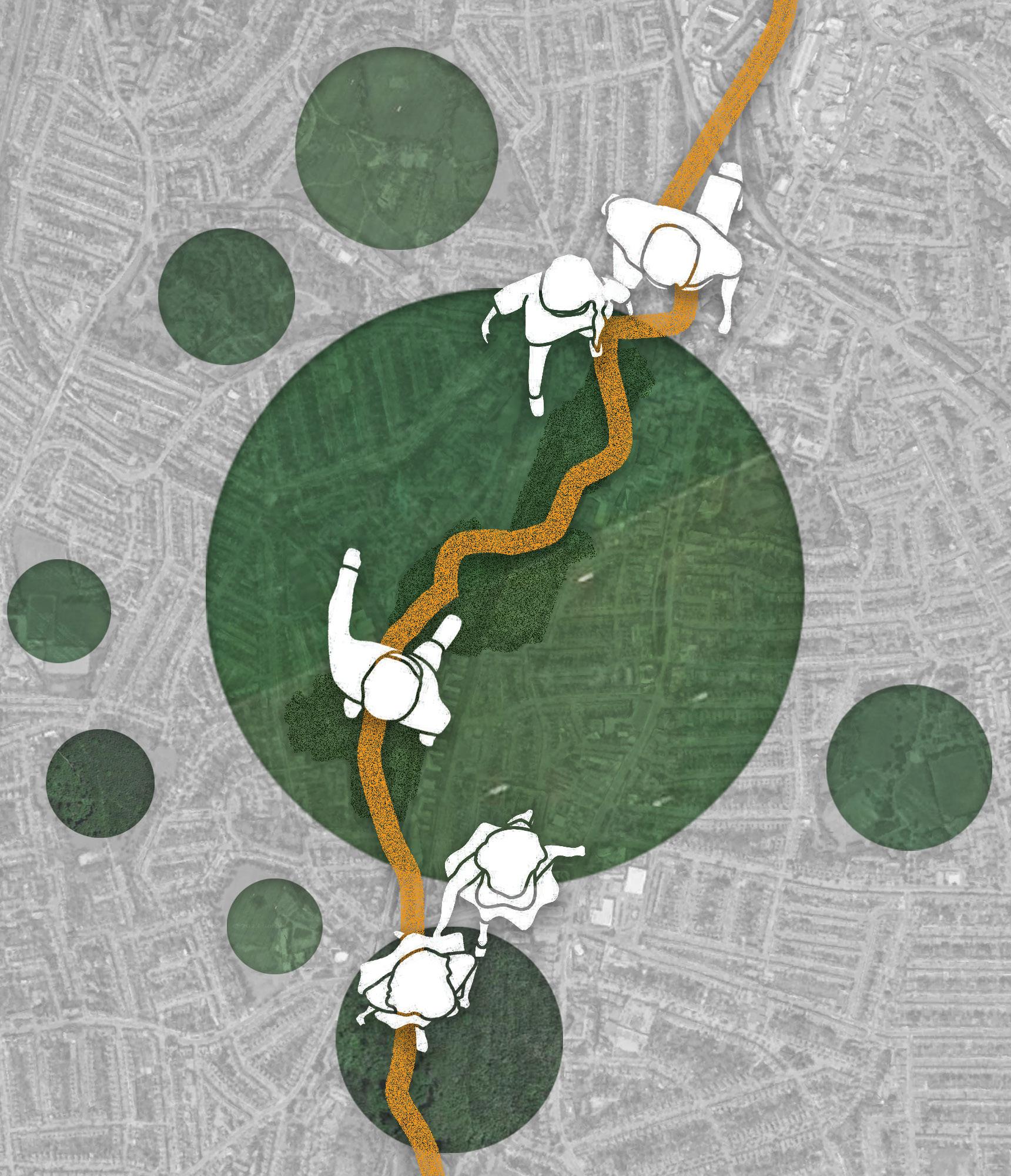

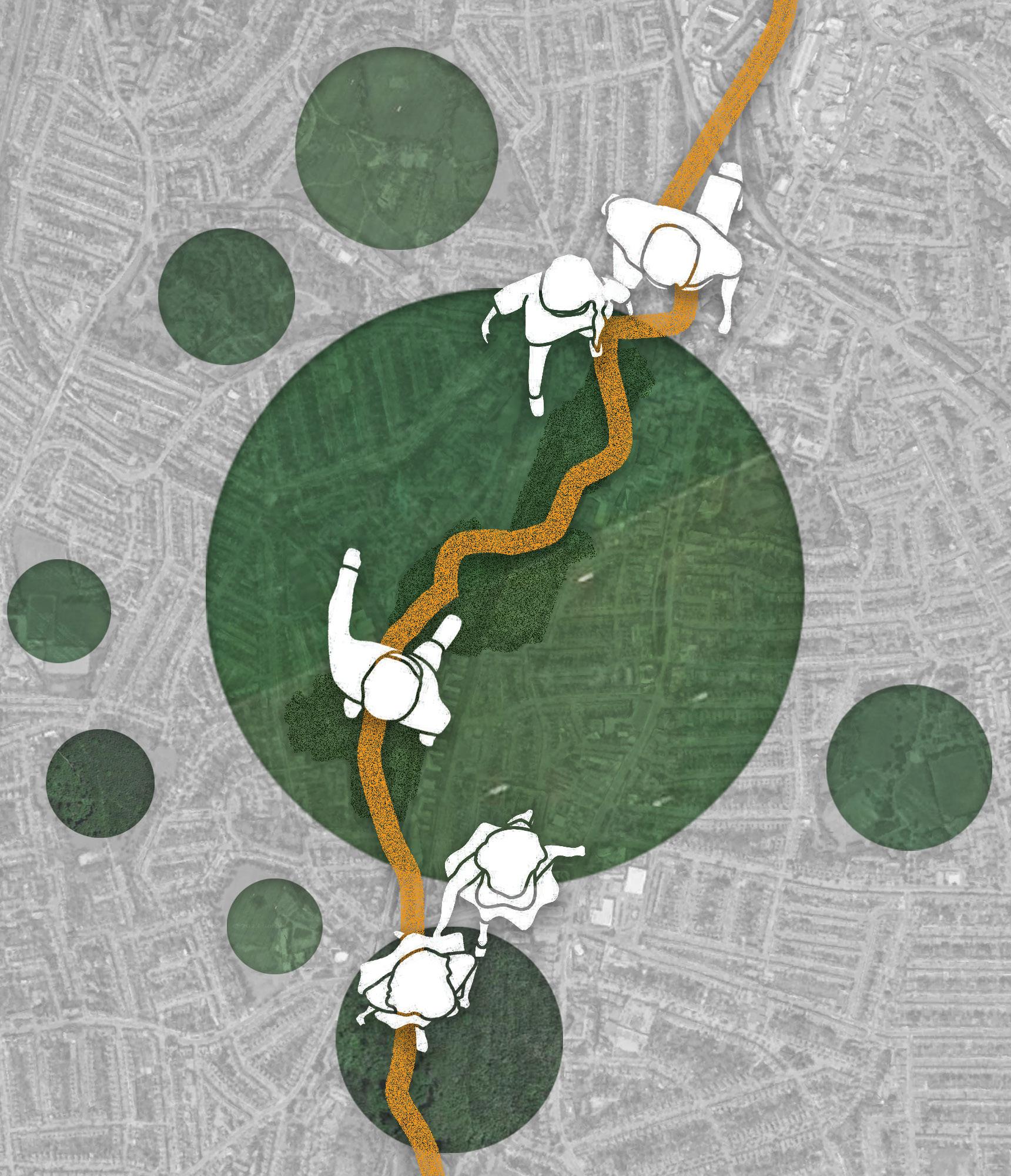

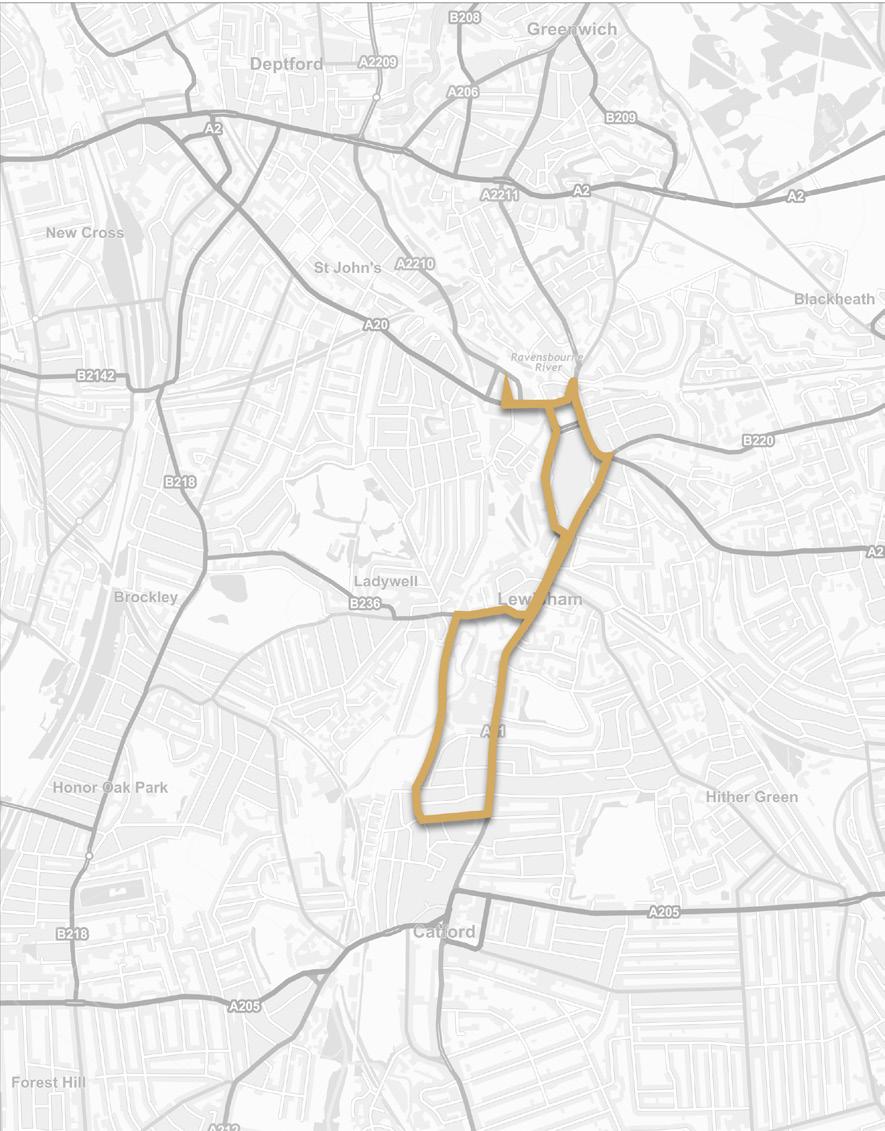

Inspired by the historical developments of Ladywell, and observations towards the moving pattern of people, I endeavoured to redefine urban green spaces as spatial connectors named “bridges”, an element integrating nature into the urban fabric. Consequently, we could strive to harmonize the nature and urbanization, and integrate nature into our daily experiences.

2

By Zijue Wei

1.1 Inspiration: the explorations of humans and individuals

Humans are on an unceasing expedition physically and spiritually.

Ordinary individuals as city denizens, decide where to go, which bus or tram to take, etc. We take detours by cutting into street forks, dropping by the new places and seeing fresh sceneries. As human beings, we migrate, reclaim wastelands, enhance science and technologies, and delve into the mysteries of the universe and humanity.

We are on a perpetual movement. As individual mortalities, we follow the paths of the pioneers and search for our own way, fueled by an insatiable thirst for exploration.

In the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, we see the establishment, upheaval, turmoil and collapse of the town of Macondo, like we see the ebb and flow of countless nations. Contemplating our past, present, and future, I want to probe into our origins and destinations in the lengthy history of human movements.

Looking at ourselves and our surroundings, a glimpse into our world was offered.

3

By Zijue Wei

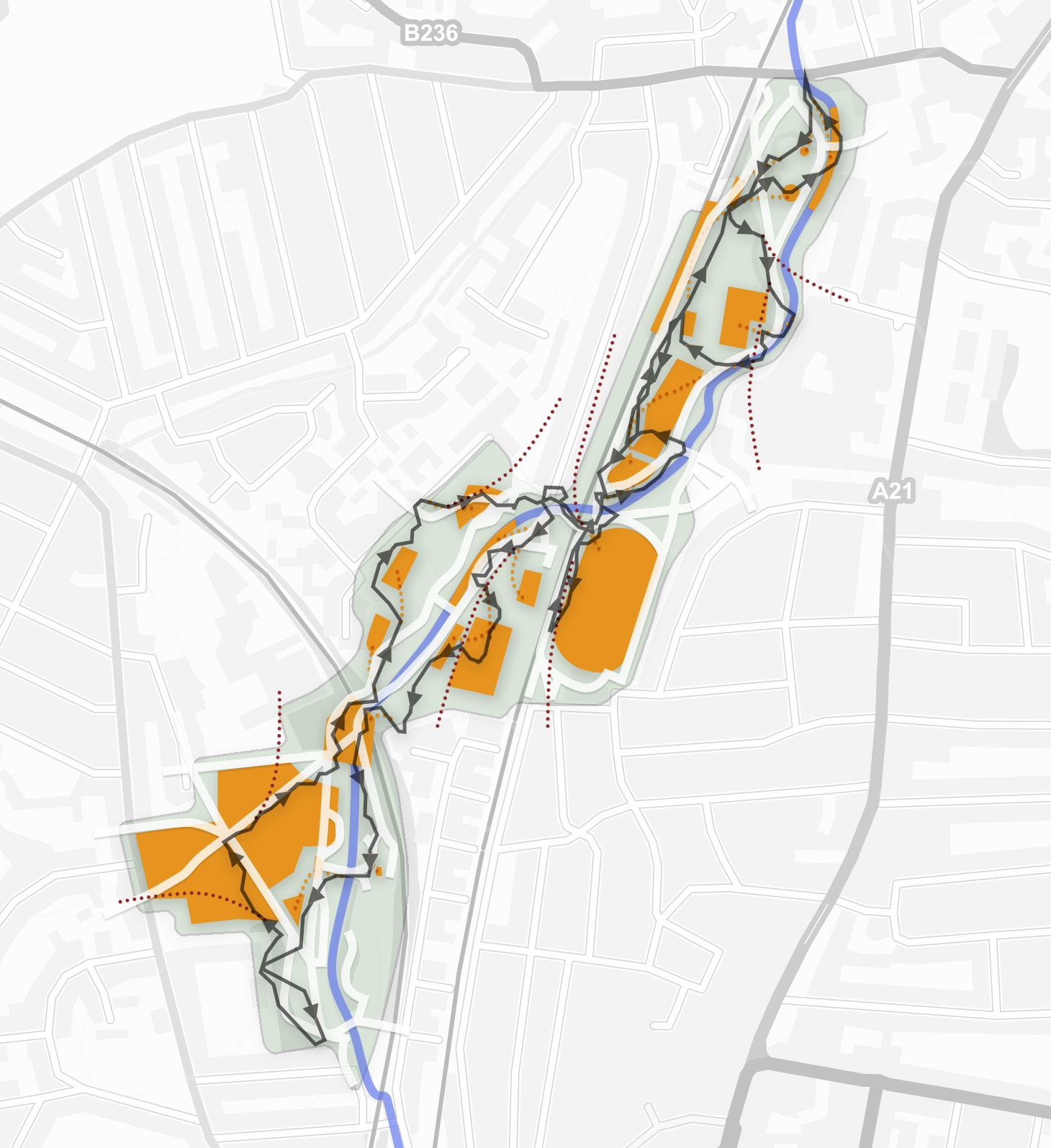

2.1 Site analysis: Ladywell Fields

Ladywell Fields is a common destination to unwind and access nature. It is between two busy streets along with large residential areas, and sheltering a variety of wildlife. The open and vast fields serve a place with the least physical barriers.

4

Ladywell Fields and its surroundings

Lewisham High St.

Brockley Rd.

Ladywell Fields

Ravensbourne River

By Zijue Wei

5

By Zijue Wei

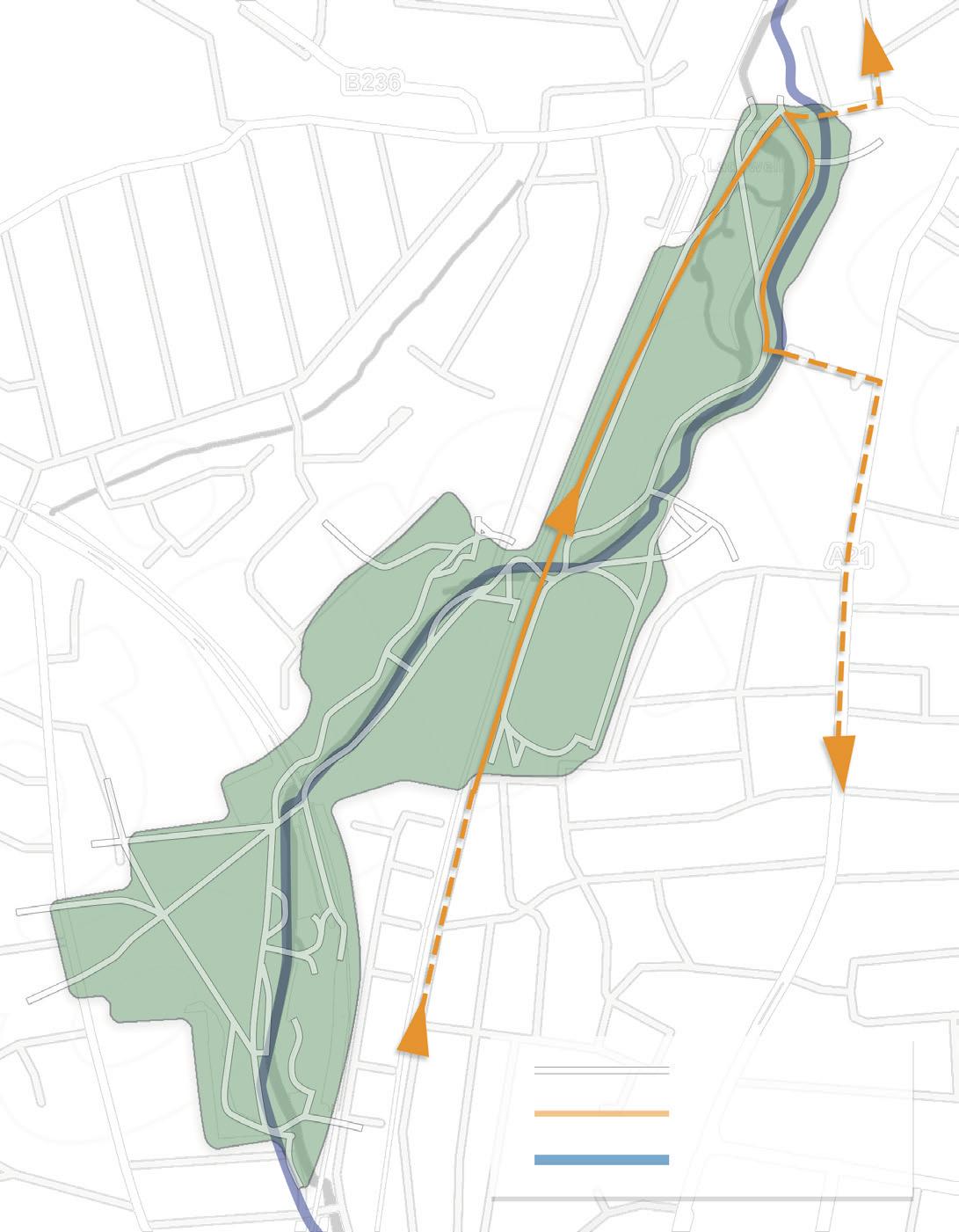

2.2 Site analysis: behaviours of park users

Though, something peculiar was noticed during my observations towards the park users. Distinctively, most dog walkers stick on the hard pavements, differing from those who play on the lawns in Greenwich Park, for example. Meanwhile, the lawns are damper and slippery in the south part, lasting for days after rain. Relatively, the lawn in the north part is more welcomed by dogs, kids and ball game players.

The reason can be the differences between each season and the weather, but still, the observation proves the lack of popularity on the lawns

6

Hard pavements

Relatively dry areas (north and middle)

Wet lawns (south)

By Zijue Wei

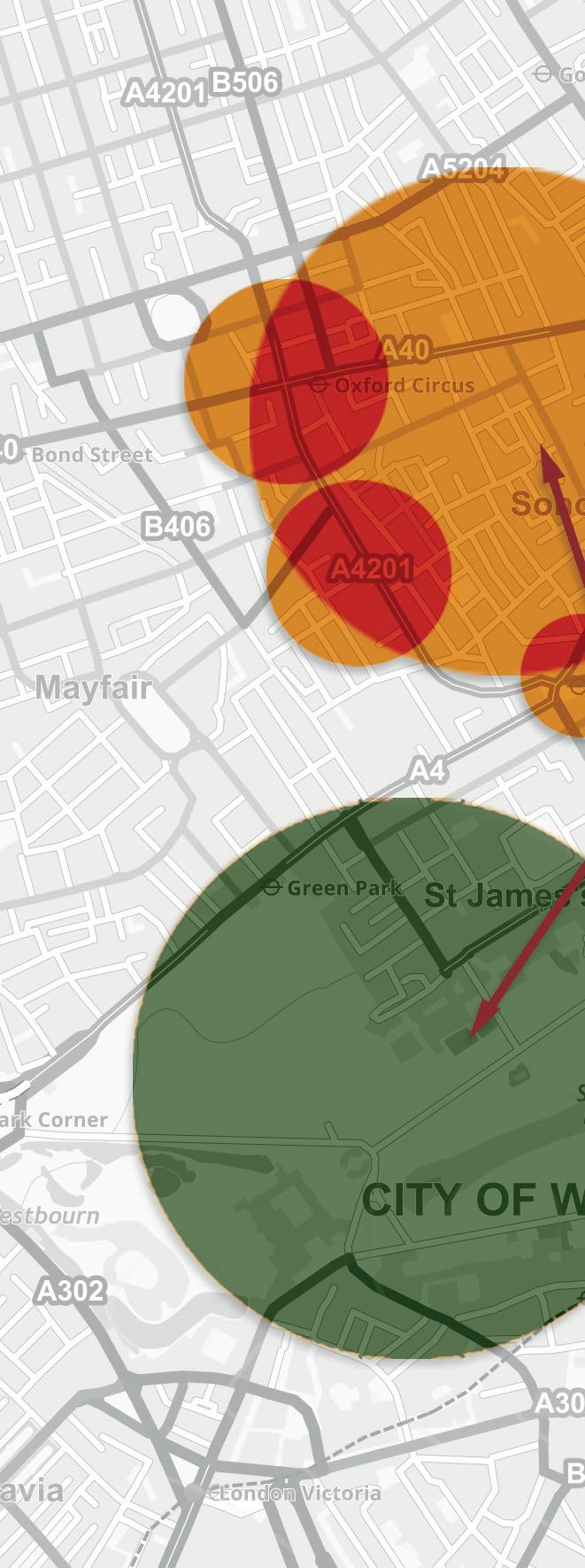

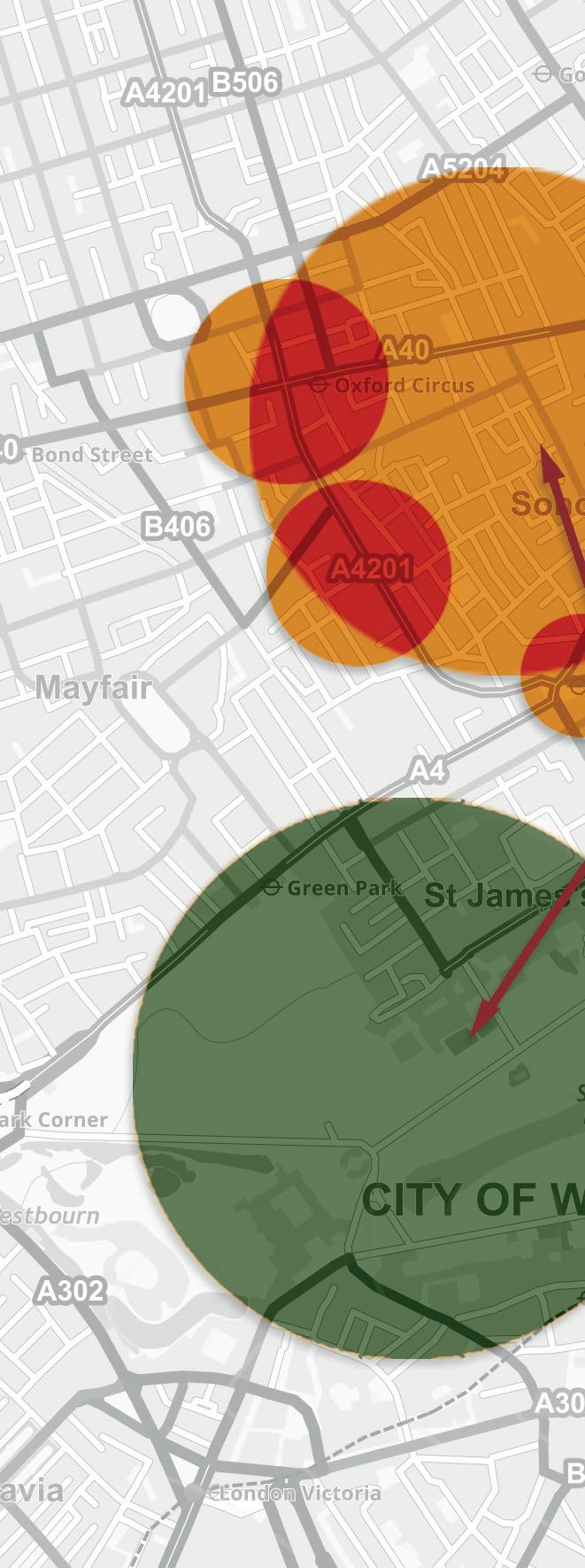

2.3 Site analysis: insufficiencies and improvements made in QUERCUS

A few years ago, a project named QUERCUS (Quality Urban Environments for River Corridor Users and Stakeholders), was carried out. The project successfully increased the number of visits and enjoyment by turning the nature feature into a major attraction: “... the landscape and river itself provide enjoyment, amusement and a focus for the park. “ (QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation

2008)

However, the project left some unresolved problems. The park users think the visibility of the park is poorer, although during the project, some trees were removed to open up the space. (QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation Report, 2008).

This project exemplified an approach which reshaped the natural space to benefit all living beings, differing from the traditional way of land reclamation. Humans are gaining more awareness about retaining the harmonious urban fabric.

7

Park users concerns pre and post QUERCUS

Report,

After QUERCUS, 2008

Current situation, February 2023

By Zijue Wei

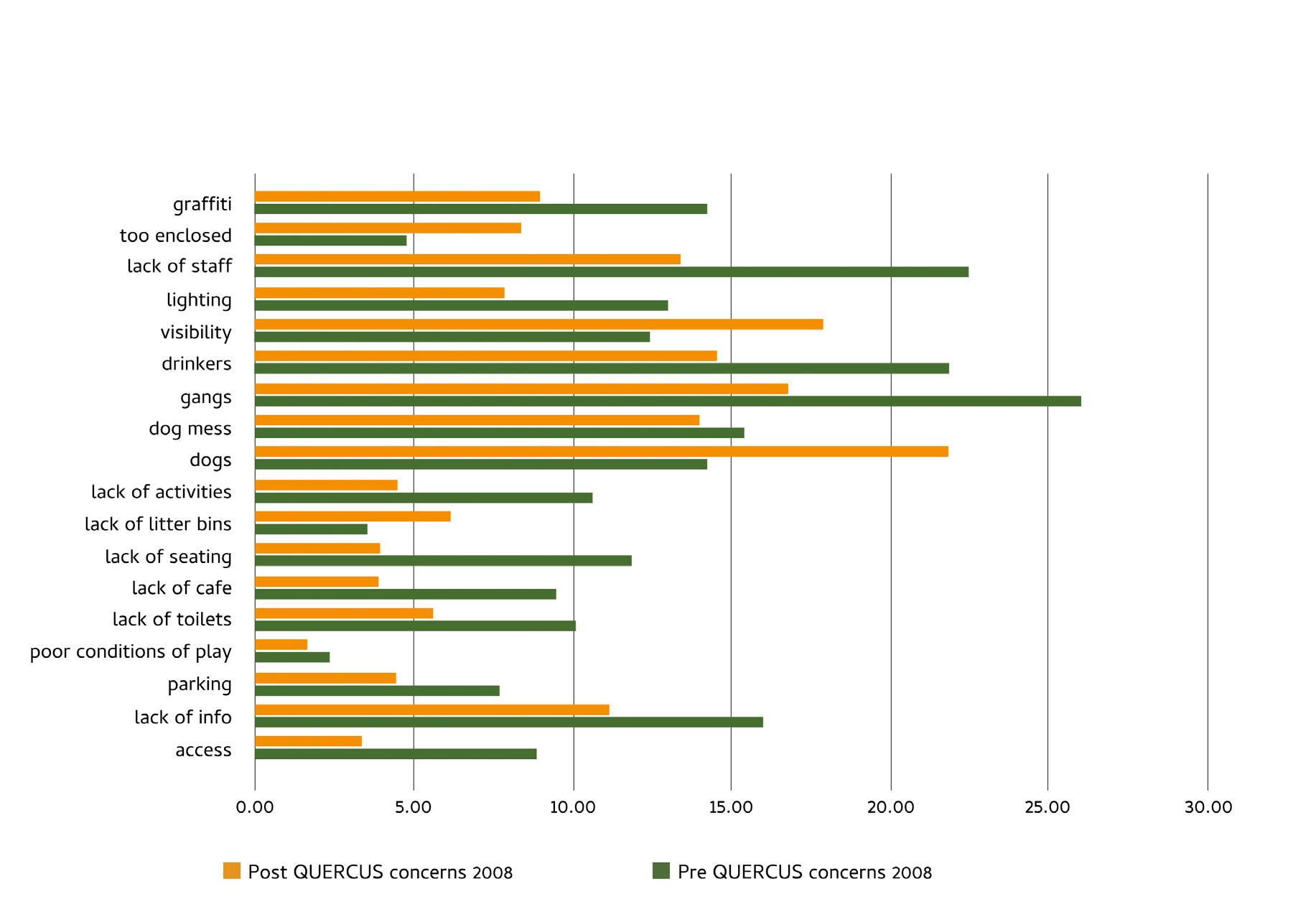

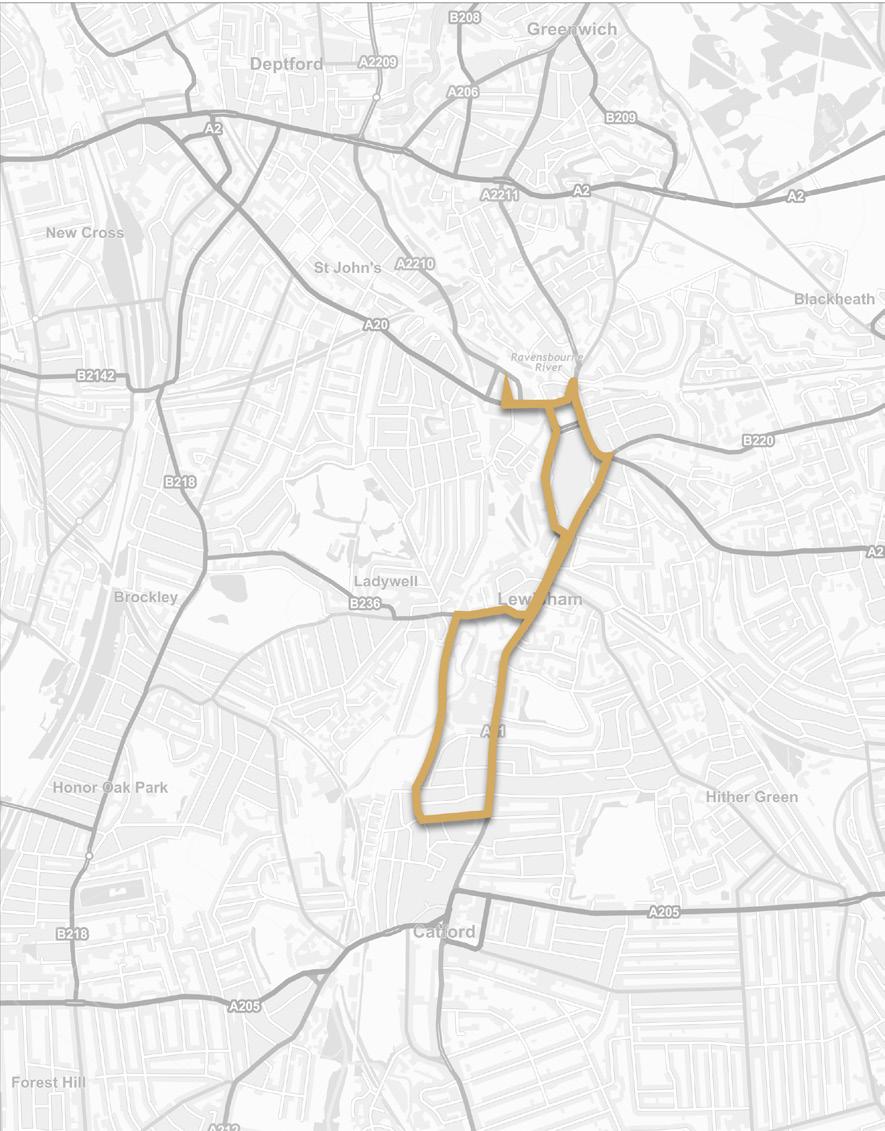

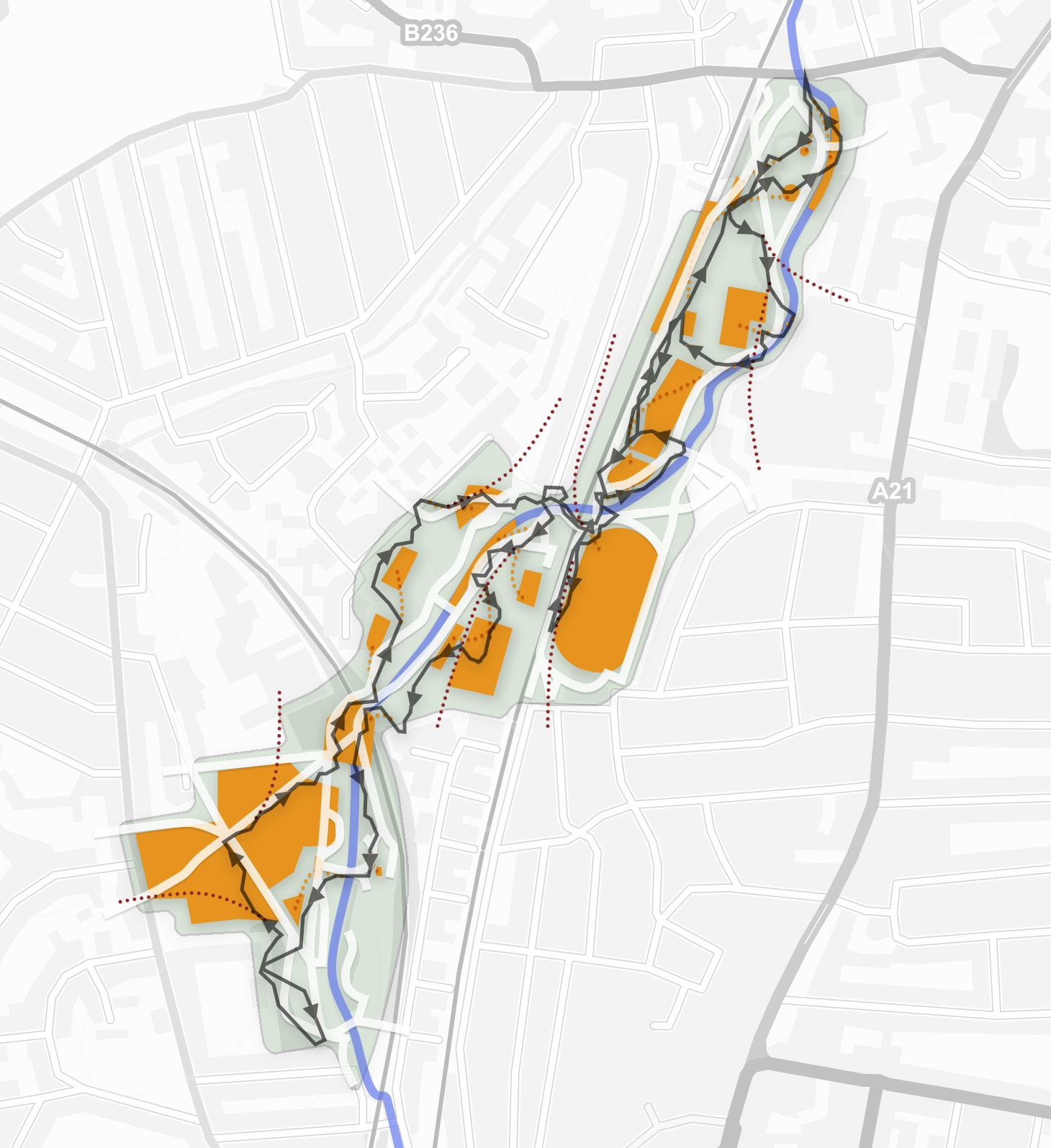

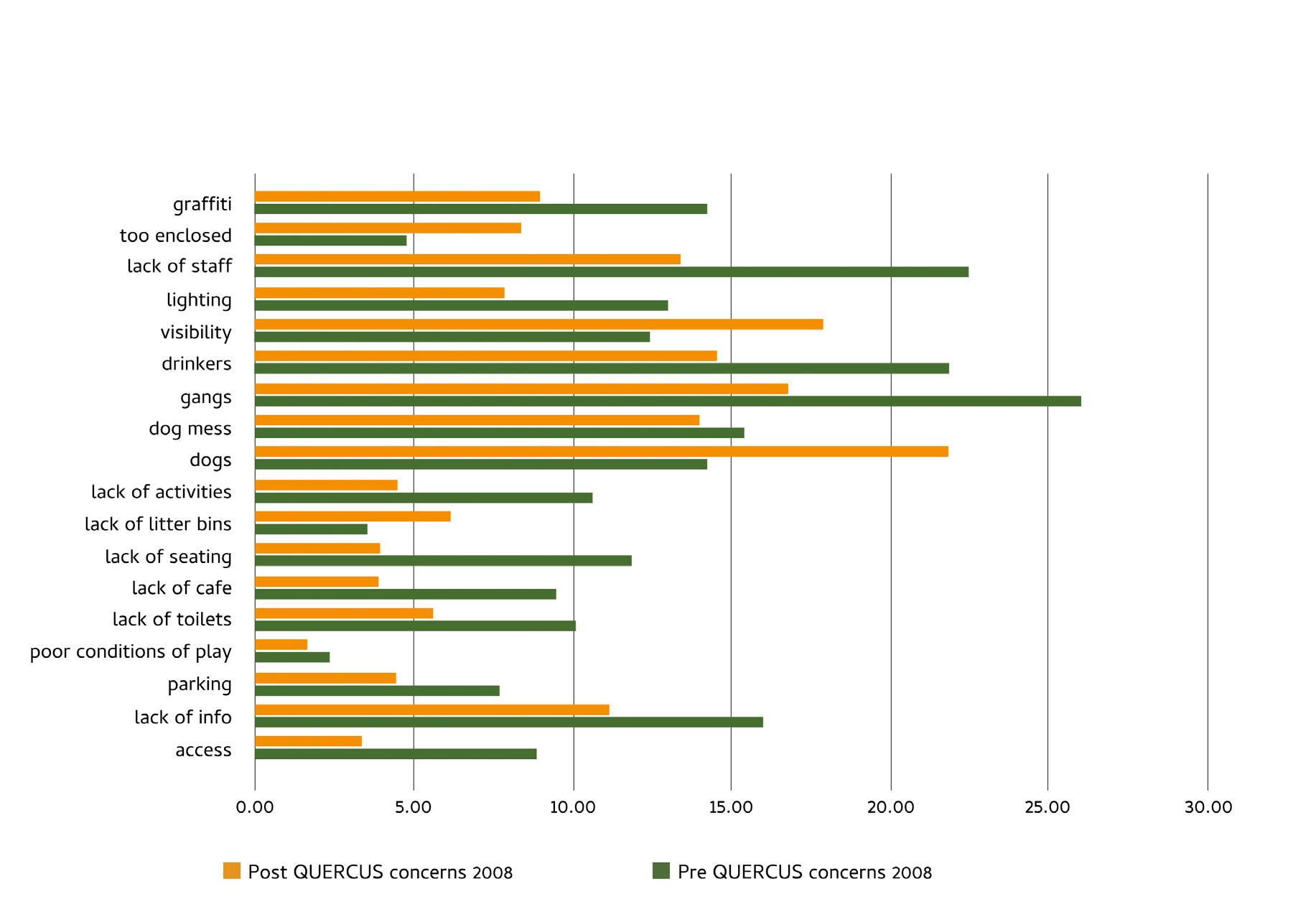

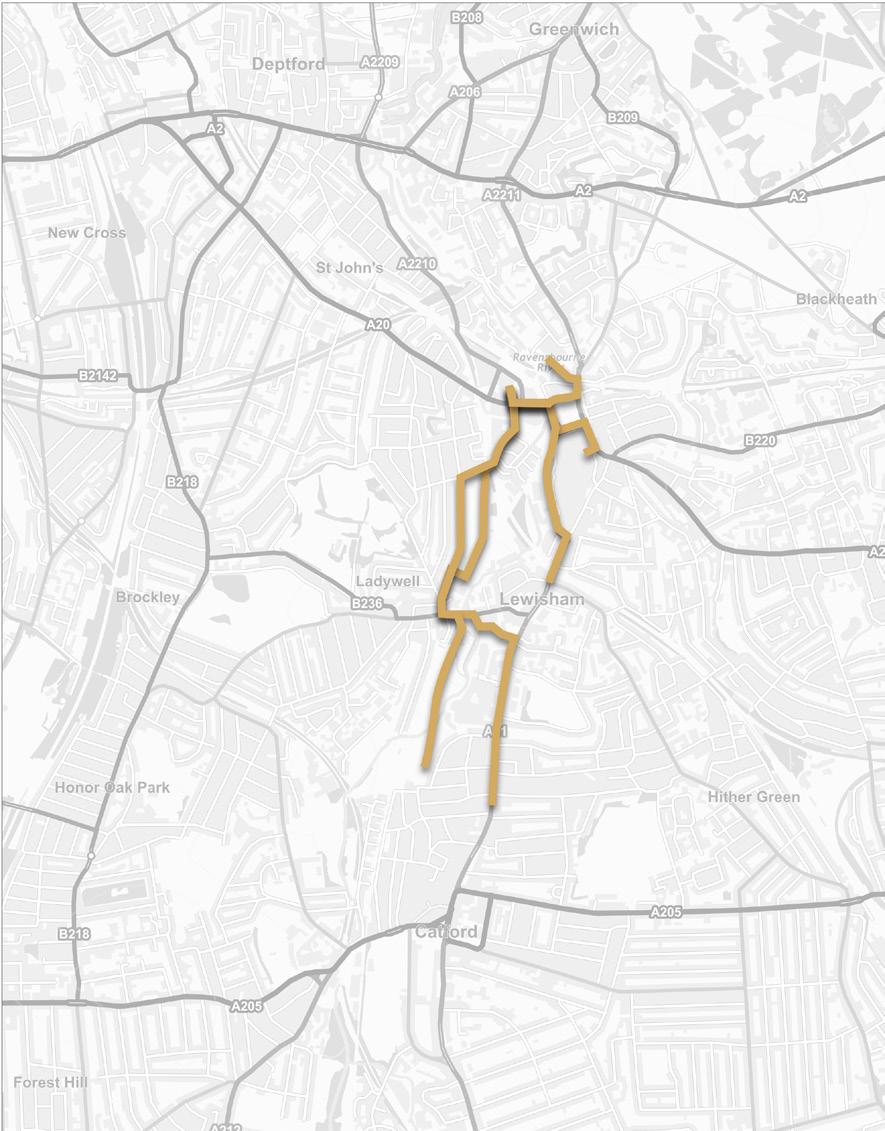

2.4 Site analysis - historical movements of people

Apparently, the history of the area mirrors the evolution of human society. Usually, human habitats originate from the watersides with agriculture and grazing, forming the earliest tribes. Prior to 1700, a few dwellings were located on the east bank of the River, surrounded by crop fields.

People cultivated, hunted, married, and reproduced, establishing a society where all movements were interwoven, enabling further

development. The UK began its industrial revolution in the latest 18th century, fostering urbanization.

In 1857, following the arrival of a railway, the local residents started to move towards the north, getting connected with other human habitats.

In 1890, the Ladywell Fields was established.

Present

Urbanization

Industrialization

Trade and migration

Ruling and religions

Agriculture and grazing

1922

Migrating towards the North

1864

Around North Kent Railway

1760

Around Ravensbourne River

6th - 8th century

St. Mary’s Church and King Alfred

8

Historical trend: expansion to the north

By Zijue Wei

3.1 How are urban green spaces retained in urban areas?

To some extent, our society is built upon human interactions, and developed through exploration, which catalyses the gaining and exchange of knowledge, currency, materials, etc. Everyone rely on each other for survival. Automatically, we are attracted by the places with more social interactions, just like being attracted by food and water.

Although urbanization strengthens the bonds between individuals, it also brought environmental and social issues including pollution and work stress, such as the Great Smog of London, which caused thousands of deaths before 1953 (Martinez, 2019). People realized the importance of environmental protection, and urban green spaces were recognized as an indispensable part of a city. (Lin et al., 2023)

The current map shows that natural spaces are more dispersed, including larger spaces consisting of woods and lawns, and smaller elements like solitary trees and bushes. Now the nature are more approachable in daily lives.

9

The map of Lewisham after highlighting green spaces

By Zijue Wei

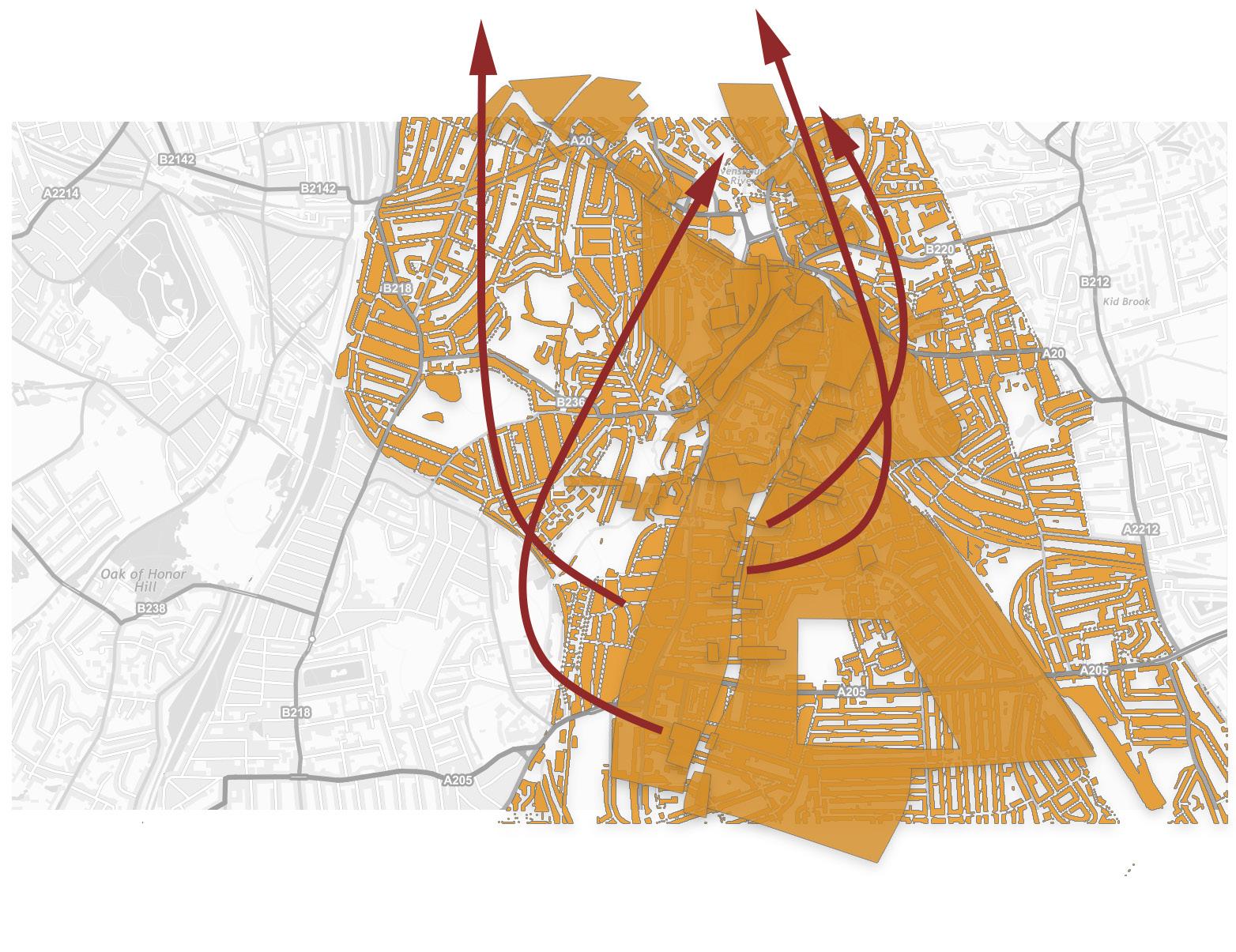

3.2 From macroscopic to microscopic: what makes people move?

Social interactions and nature in the area, appling “pulling” and “pushing” forces on people

Considering the history of the site and the moving patterns of people, there are two factors motivating people to move, with their attraction forces, and are still impacting people’s behaviours nowadays:

1. Man-made factors:

(1) Traffic webs

(2) Social interactions (churches, business, etc.)

(3) Political and economic divisions

(4) …

2. Natural factors:

(1) Vegetation

(2) Water

(3) Wildlife

(4) Terrain

(5) …

Attractions from man-made factors

Attractions from natural factors

10

By Zijue Wei

Now social interactions are not the only things that facilitate human movements, but also natural spaces are. Humans have a passion for getting closer to nature and living things, due to the subconscious desire. (Fromm, 1992)

These factors are not equally attractive at different times. In the age of agriculture and grazing, the river was the main attraction. But after the development of traffic webs, the roads offering effective communication with the outer world, caught people’s attention.

After the shift took place after the construction of the railway, the effects of the river remained but went weaker, compared to the railway and high streets.

This impulse towards nature is magnified in an environment of a fully urbanized city. Since the urban population is climbing, the enthusiasm towards nature will be inflating.

The two factors are motivating people’s exploration into the outer world, by applying “pulling forces” and “pushing forces” (Dolan et al., 2021) which make people move, playing significant roles in people’s decision-making at navigation

11

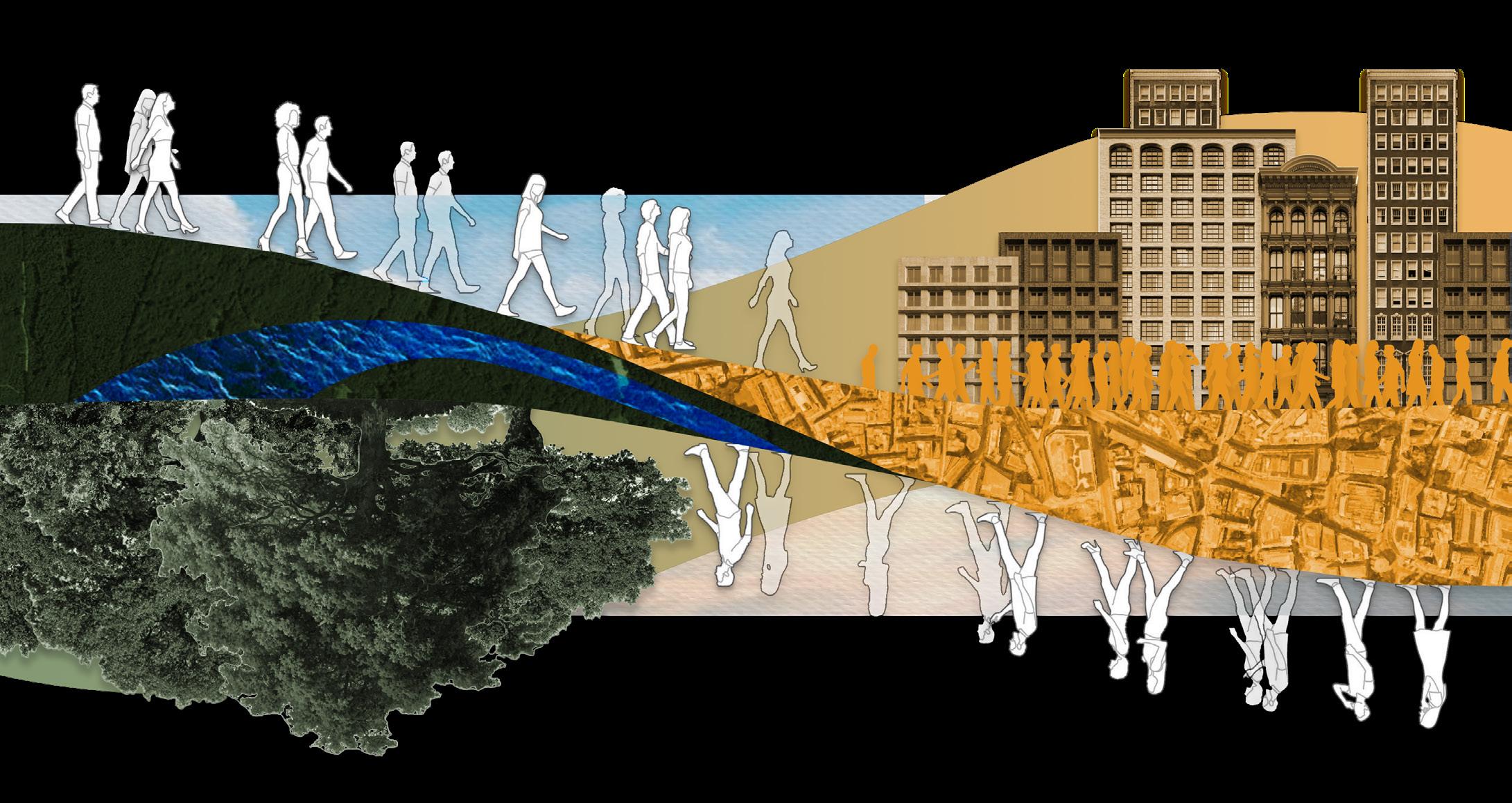

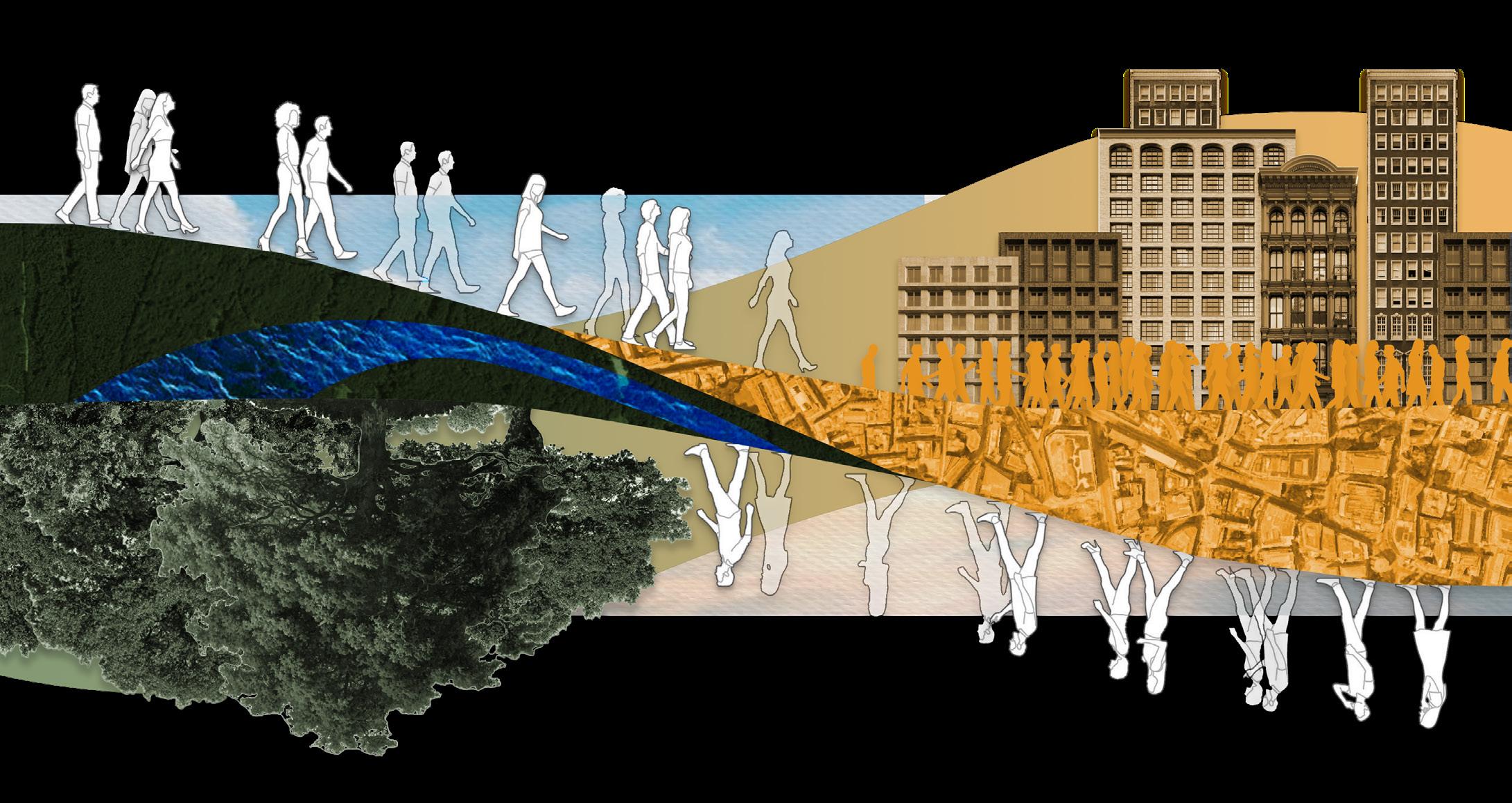

Digital collage: Mobius strip - Nature and human society finally came together in modern cities.

By Zijue Wei

4.1 Deciding routes: Marginal Value Theorem

However, deciding on the destinations is not the only thing we do when planning our schedules. People either follow their past experiences or rely on navigation apps like Google Maps, and usually follow the Marginal Value Theorem to find a more precise route. (Dolan et al., 2021)

“...areas of higher ‘mass’ attract more people. This higher mass can be considered in terms of attractiveness or some other factor that pulls people in.“ (Dolan et al., 2021) The places with the two factors: natural factors and man-made factors, have higher “mass”, due to their stronger forces of attraction.

One by one

“Roundabout way”

Going to places with higher “mass” help to improve efficiency as well. For example, if I plan to visit Ladywell Fields, the park will not be my only destination: I may take a roundabout way, to drop by nearby places with higher “mass”, such as shopping centres and grocery stores, to save around 2 hours. It is a common tactic performed by most people unconsciously.

12

Aldi Ladywell Arena Oriental Shop Lewisham Shopping Centre Tesco Superstore Aldi Ladywell Arena Oriental Shop Lewisham Shopping Centre Tesco Superstore 166 min walk 49 min walk

By Zijue Wei

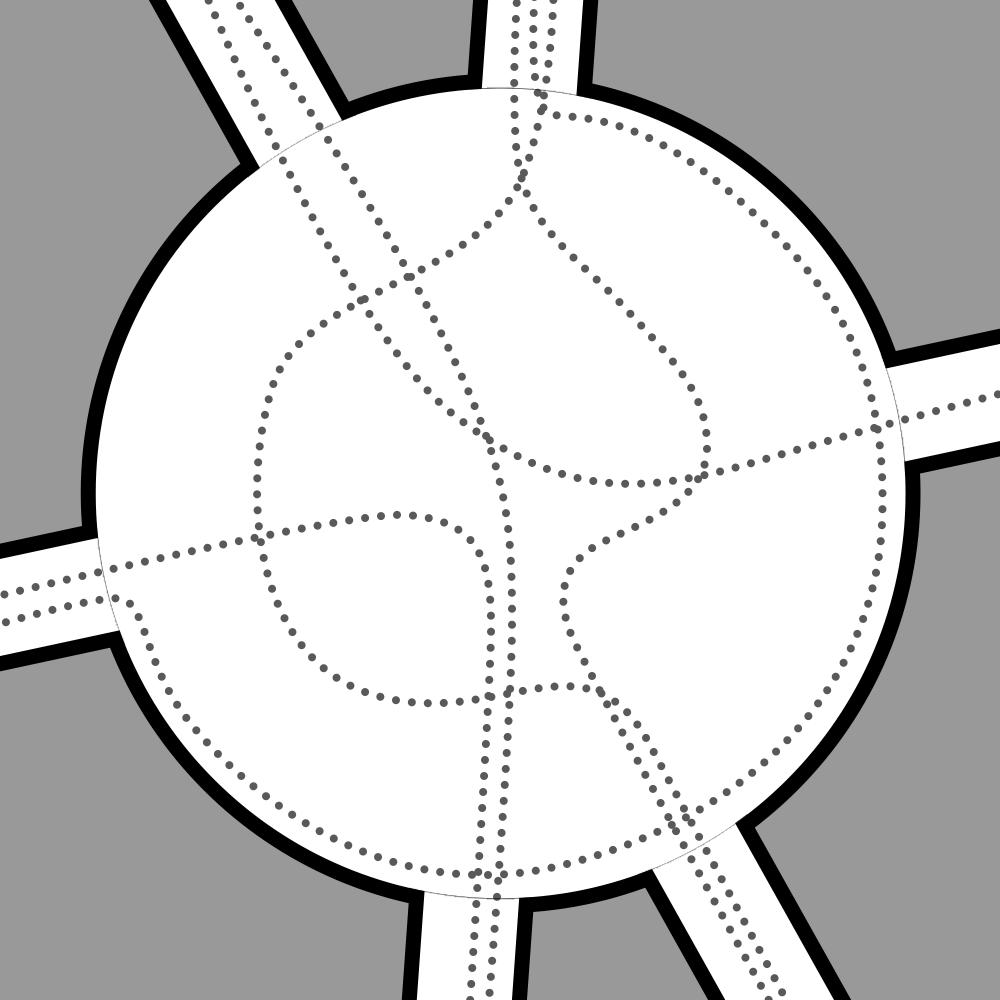

4.2 The classification of urban spaces and the metaphor of “bridges”

My experiences in the city gave me further insights into the city’s structure and the navigation’s decision-making. How do we get attracted by those places with higher “mass”? How do we plan our routes towards these destinations?

To better understand these, I tried to divide different places in the city into several types:

1. Endpoints: These spaces can only be entered and left through one threshold. Usually, what we do here is to turn back and head towards where we set out. For example, in an ordinary shop by the street, customers can only enter and leave the shop through the main entrance.

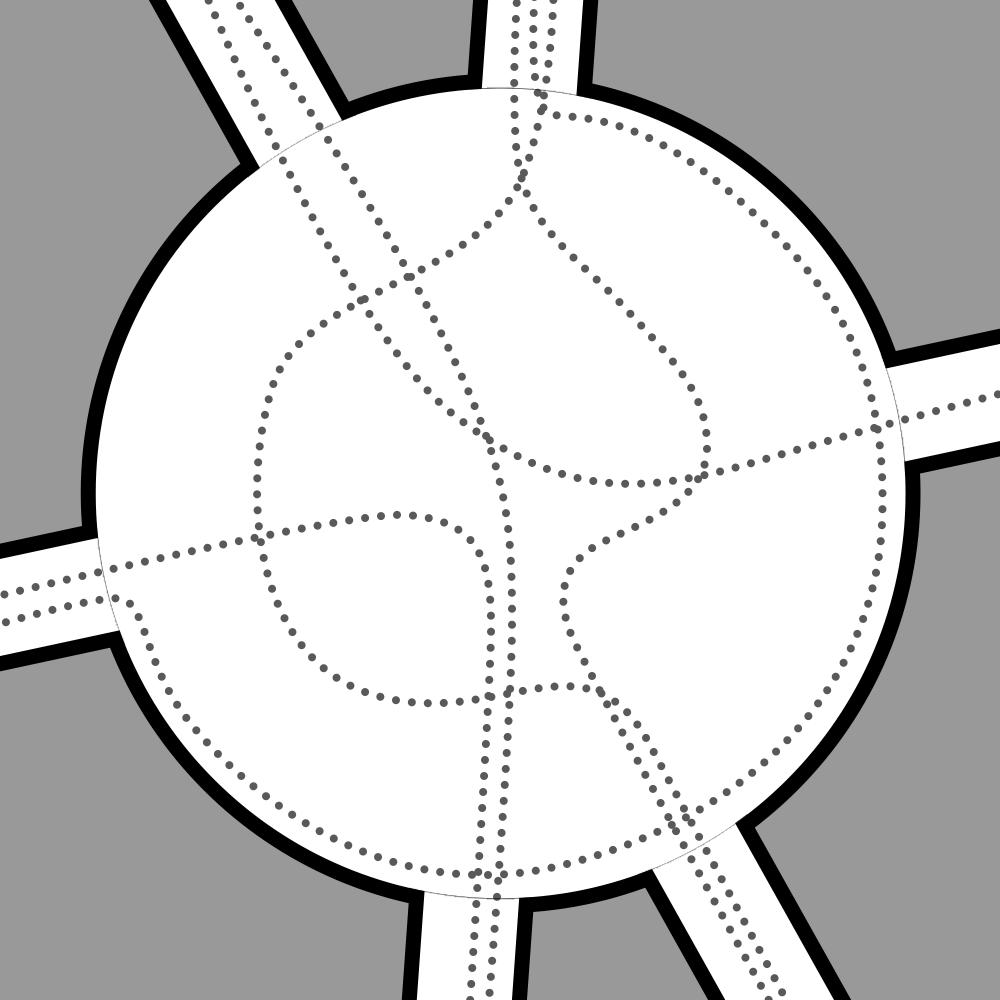

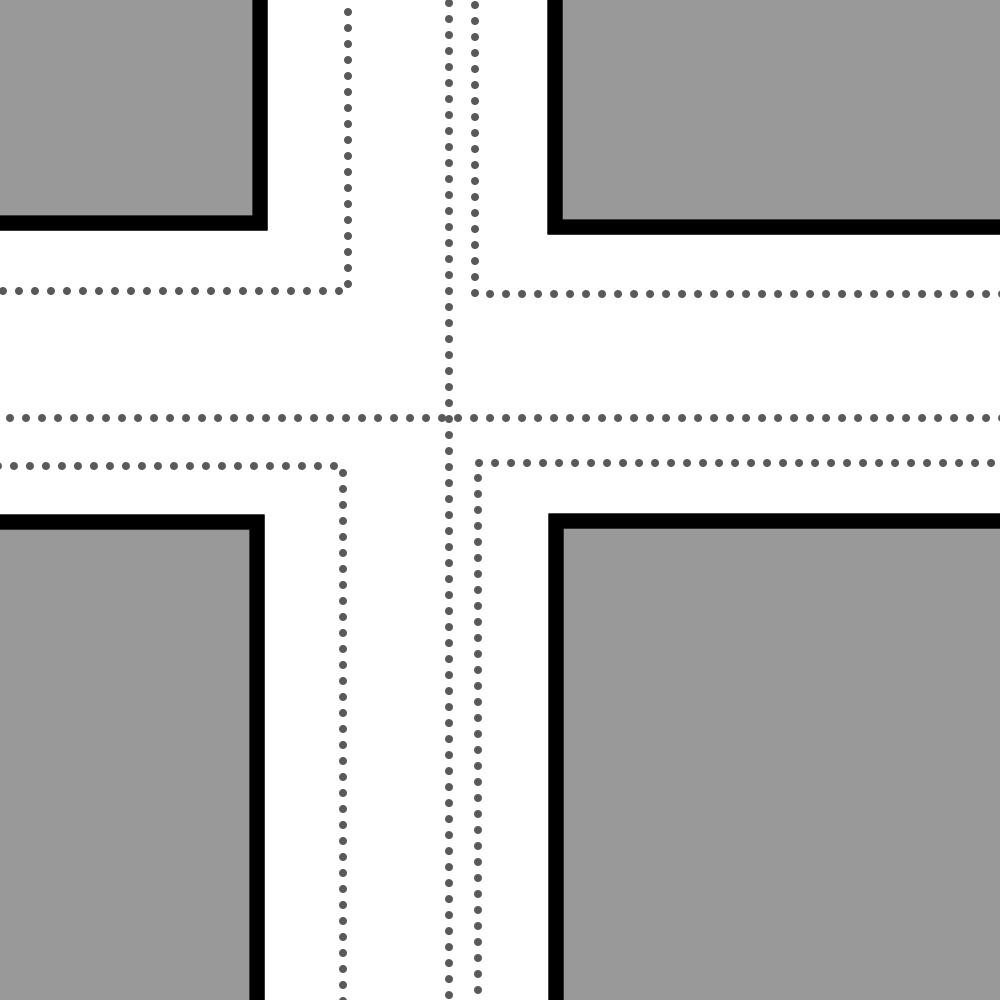

2. Bridges: For those places that join other places together spatially, they are performing the functions of a “bridge” – a metaphoric term. When a place attracts people, the force it applies is not always straight, to bring people to the destination directly, but more usually goes through these “bridges”, which make people go across more places. They might be streets, footbridges, tunnels, or even an interior space with multiple entrances.

The two types of space are both commonly seen in our cities. They differ mainly according to the type of movements happening in these places: entering an “endpoint” means that this part of the trip ends here. But in “bridge spaces”, we are always free to leave from the multiple openings, which link the space to other places. In “bridge spaces”, people get attracted easier due to the openness of bridges, and consequently, further movements are facilitated.

13

Examples of “bridges” in a city

Examples of “endpoints” in a city

By Zijue Wei

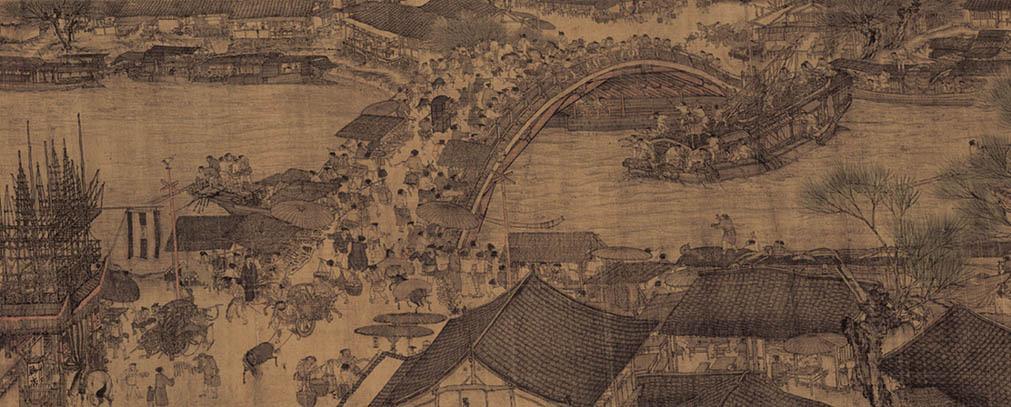

4.3 Multifunctional “bridges”

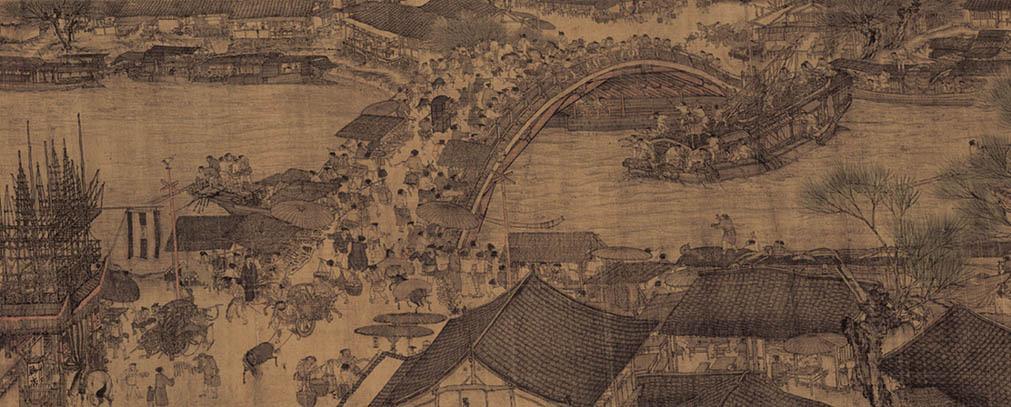

The “bridges” usually carry more functions than only traffic. In ancient ink paintings, we see people set up retailing stalls on arch bridges.

Along the River During the Qingming Festival, ZHANG Zeduan. 1145

“Bridges” are still commonly seen in cities today. For example, the space in front of Westfield Stratford City also served a place for socialization, traffic and retailing, similar to other places around shopping centres and traffic junctions.

14

Westfield Stratford City

By Zijue Wei

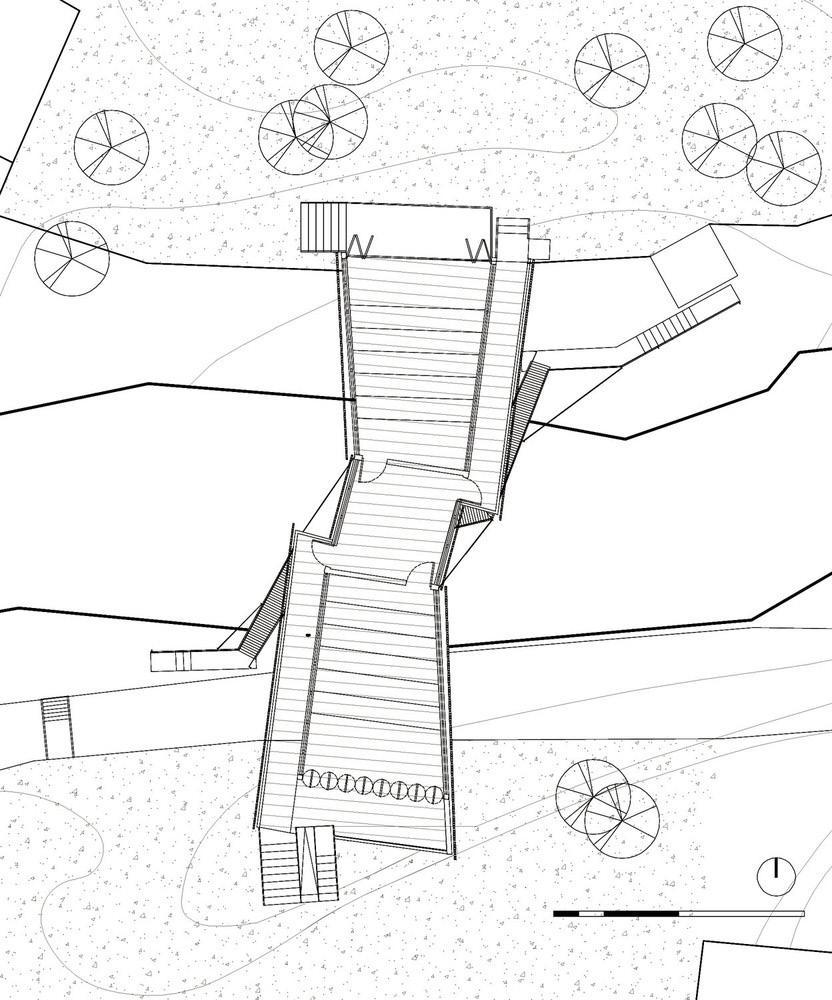

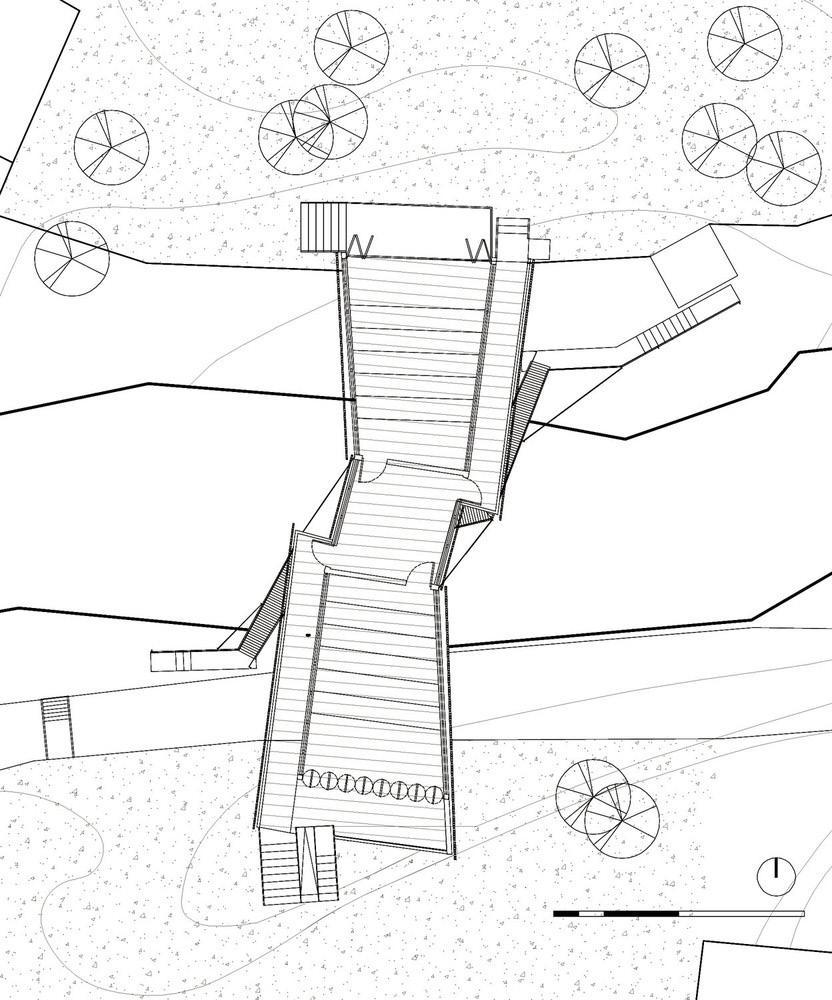

The concept of “bridge” was seen in contemporary architectural designs as well. School Bridge combines the functions of transport and education. While the architecture bridges the inside and outside of the village physically, it also helps to link the students with the knowledge, giving the building deeper symbolistic and humanistic values.

15

Case study: School Bridge / Li Xiaodong Atelier

Top view of School Bridge (ArchDaily, 2010)

School Bridge

By Zijue Wei

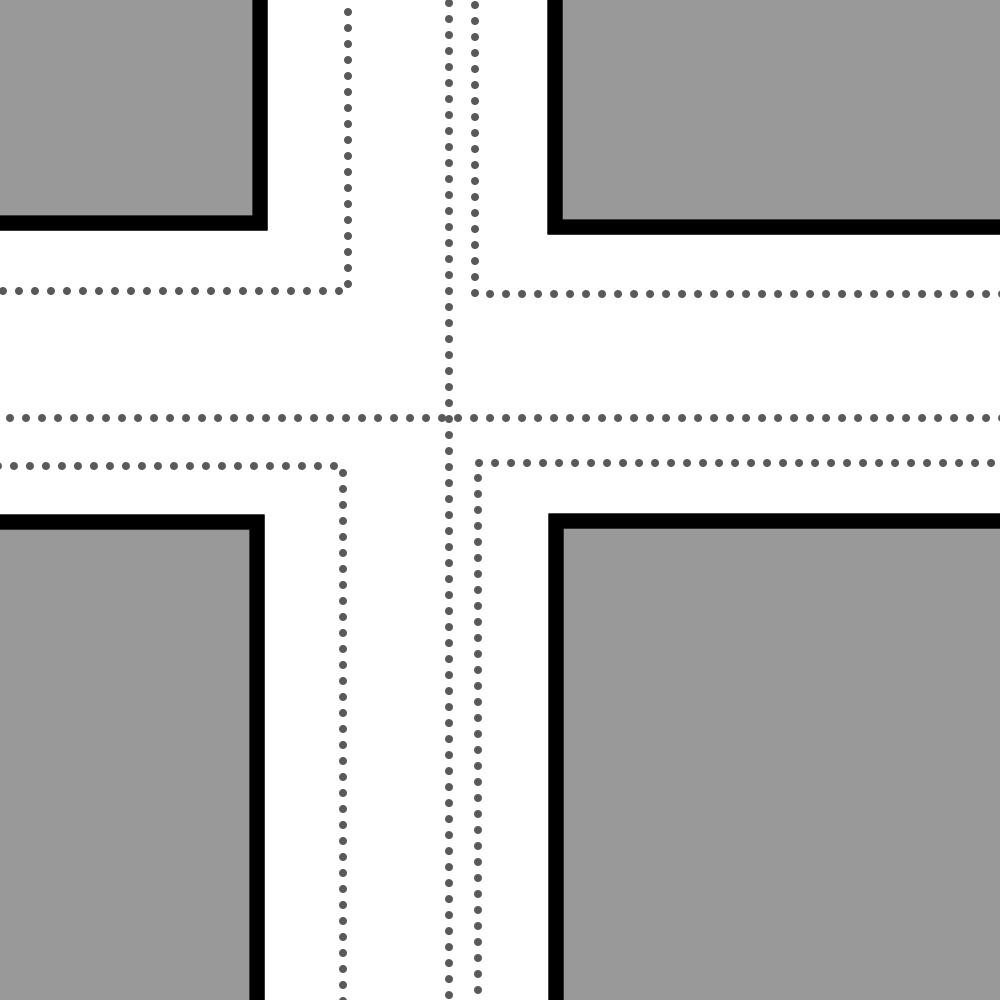

4.4 Further investigation and classification of the “bridge spaces”

However, it is unnecessary to narrow down the range of “bridges” into spaces like roads and interior spaces. The “bridges” can be any place with multiple openings and do not have to be linear

Most of the urban green spaces with open edges, are naturally “bridges”. Urban green spaces are wide and open, unlike the constraint city roads limited by traffic and width. The spaces easily become sites for social and cultural events due to their approachability. It is common to see weekend markets and music events taking place in the parks in London, such as Camberwell Green, thriving and energizing.

16

Urban green spaces

Linear roads

By Zijue Wei

4.5

The

“bridges” inside Ladywell Fields

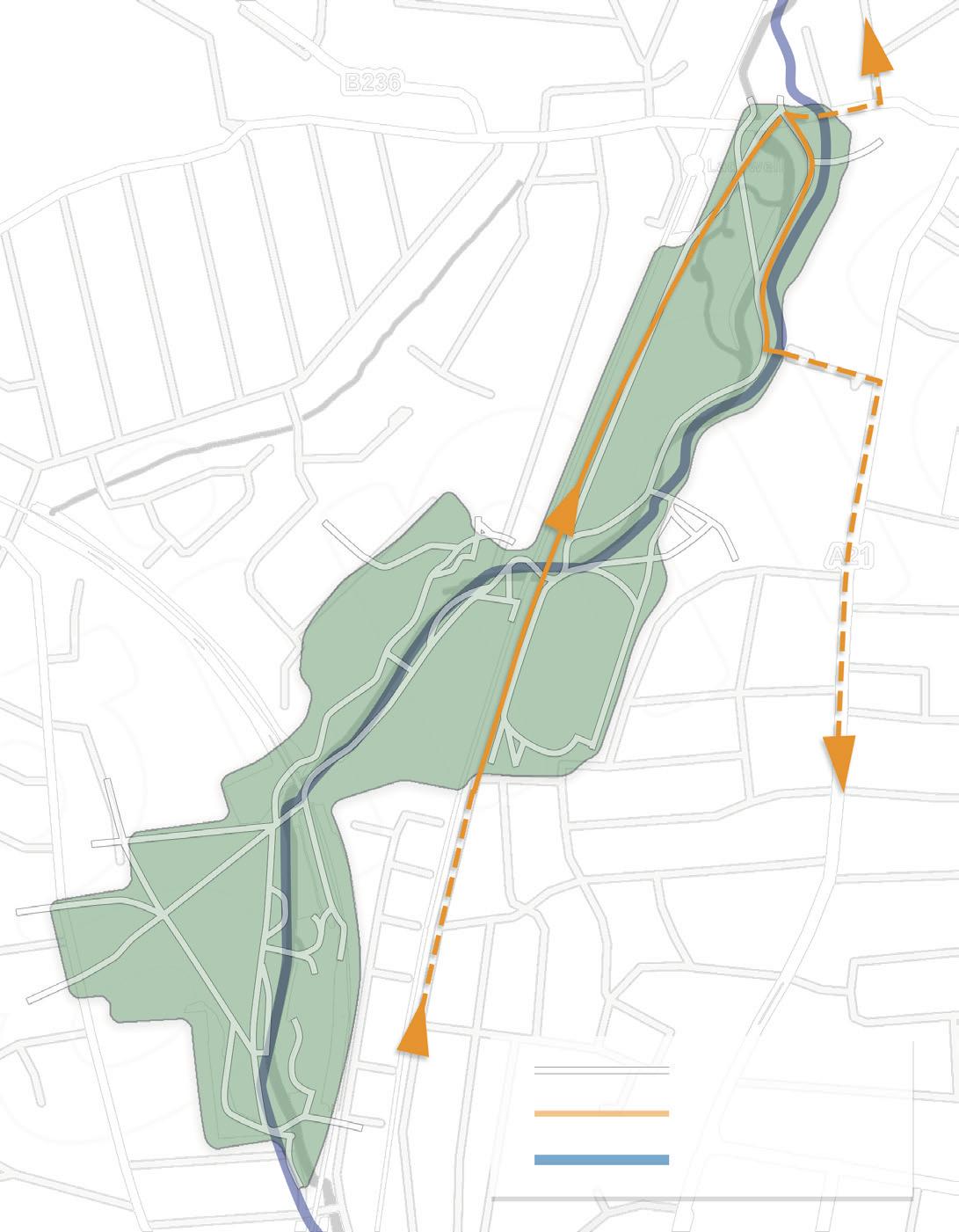

There are mainly two types of “bridges” at the site: hard pavements and lawns. By focusing on the routes on lawns that people take to reach their destinations, based on my empirical judgements and observations towards the footprints on lawns, I identified how green spaces act as “bridge spaces” inside Ladywell Fields, and how the attraction forces are applied on the audiences

Starting and ending point

The forces of attraction can be applied in many ways:

1. Visual: seeing an obvious symbol or landmark

2. Acoustic: hearing other users or the environment

3. Aware: knowing the place from experiences or other information sources

4. ...

Hard pavements

Directions of the attention out the site

Directions of the attention in the site

Routes

17

Railway

Hospital Chimney Residence Residence Residence Residence School Residence Large trees Pool River

Skate field Tennic court Open field Children playground Arena Cherry blossoms River Wood field Wood field Open field Children playground River Benches Benches Sport fields Open field Cafe

By Zijue Wei

Case study: Parc de la Villette / Bernard Tschumi Architects

Parc de la Villette, a famous precedent of transforming urban green space into facilities with cultural and social purposes, successfully utilized the green spaces as “bridge spaces”. The most inspiring part is how the red buildings are aligned in a grid pattern, which “gives the visitors points of reference” (Souza, 2011). The design illustrated how a spatial design facilitates movements, by giving buildings the ability to apply attraction forces with cultural and political values (higher mass).

18

Aerial view of Parc de la Villette

A singular building in the park

By Zijue Wei

4.6 How does urban green spaces as “bridges” facilitate exploration?

Residing in a city for a long time, it is pragmatic to stay on the familiar routes, to minimize the likelihood of encountering possible dangers and unknowns.

The reason people insist on familiarity is not only about the collective empirical judgements, but also about the route planned by municipal administrations. In most urban green spaces, hard pavements are built on top of the natural surfaces, to enhance accessibility and landscape aesthetics. These roads are designed strategically in order to utilize the terrains and sceneries better. Indeed, the paved roads make the walking experience more comfortable without dirtiness and rugged grounds.

Nonetheless, excessive familiarity may also lead to counteractive behaviours, that prompt people to explore unknown areas. This is usually “risky” but rewarding.

In urban contexts, the “bridges” offer opportunities for explorations into the surroundings.

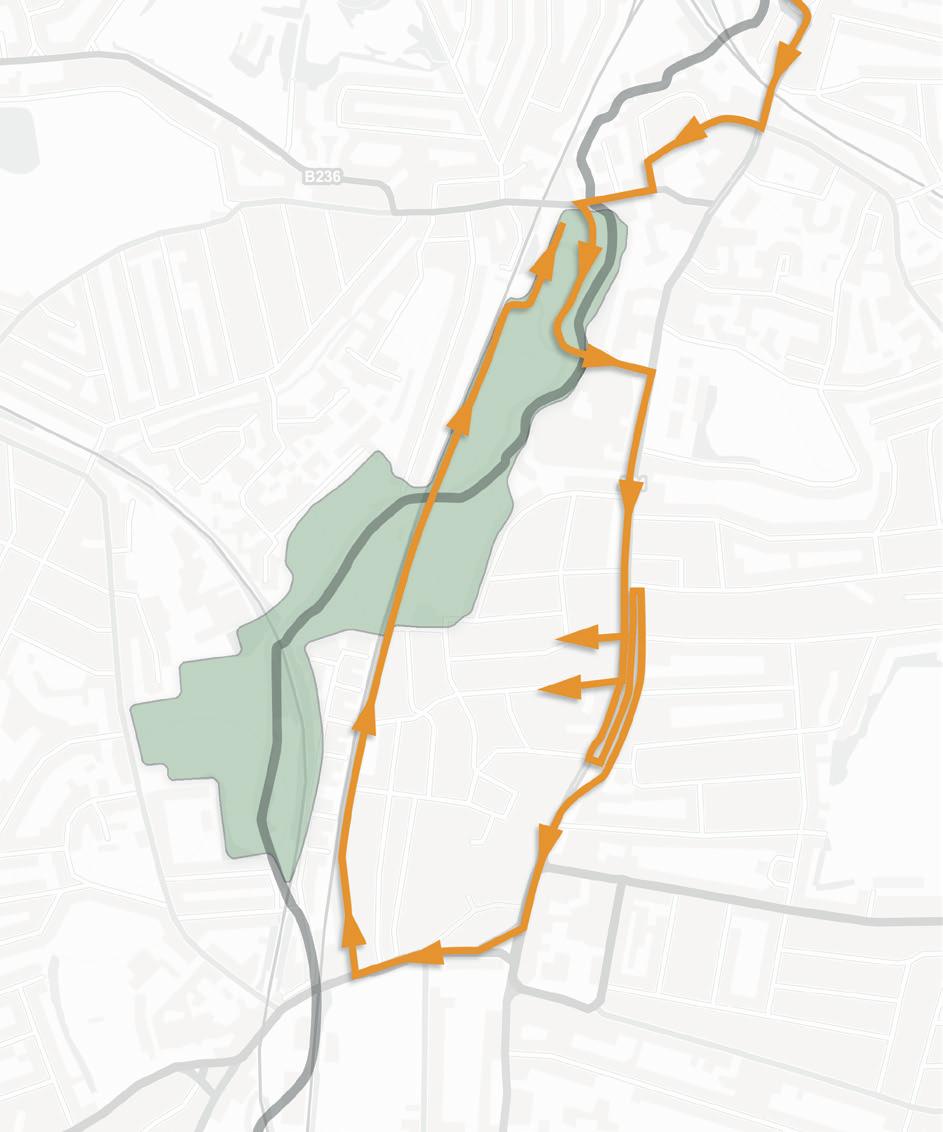

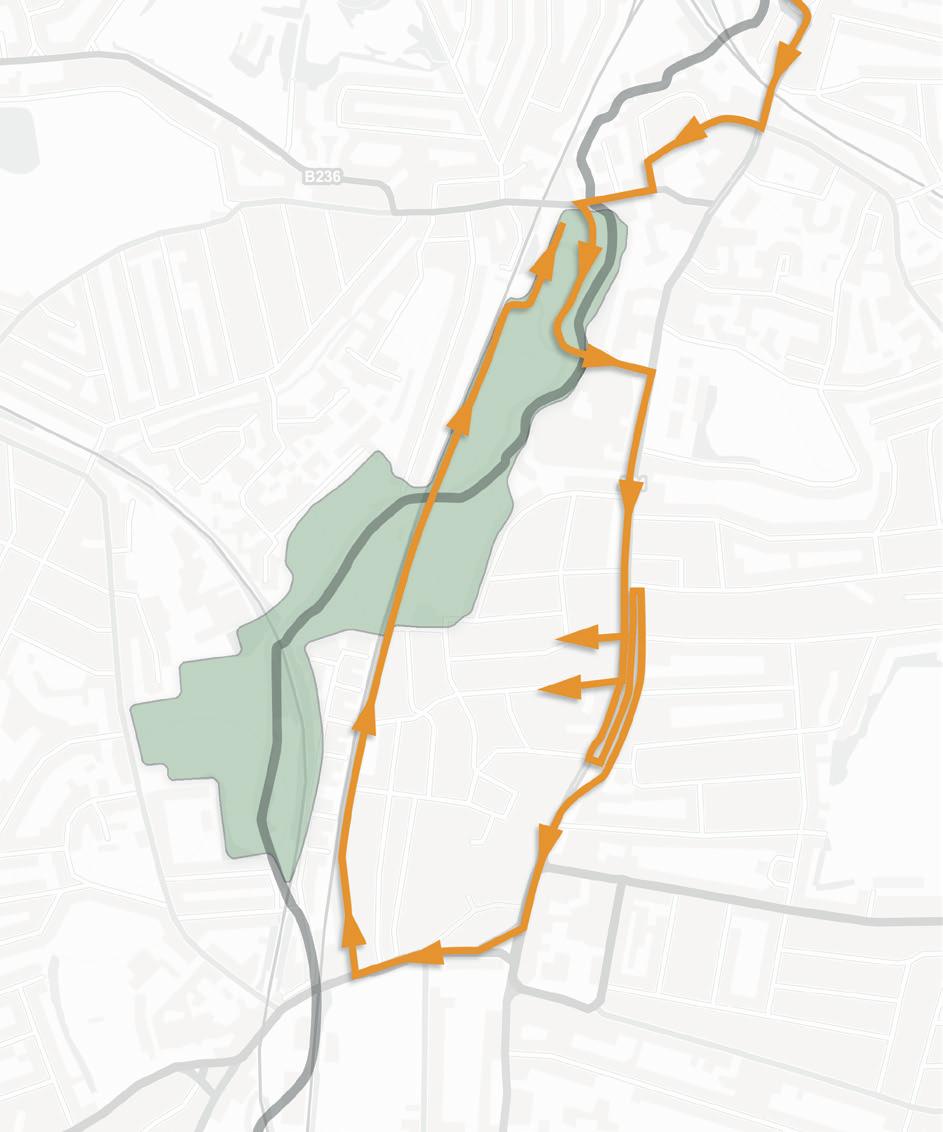

At another site visit, I embarked on a trip through Ladywell Fields, by leaving the park through an attractive entrance intentionally, to see where it took me to. I chose to enter the park through the north entrance and exit through the opening next to the hospital, which brought me to Catford.

19

River Taken routes Built roads

How did the park lead me to the places nearby?

By Zijue Wei

During my trip, I captured everything that caught my attention. These sceneries might keep me on the planned route, or take me into street forks connected to new areas. The map indicates me deviating when noticing something intriguing, and returning to the planned route after satisfying my curiosity.

The trip to Catford left me some positive impressions towards the behaviour of exploration: it can be very rewarding and satisfying, making me feel “connected” to the society.

20

My route and my “photo trophies”

By Zijue Wei

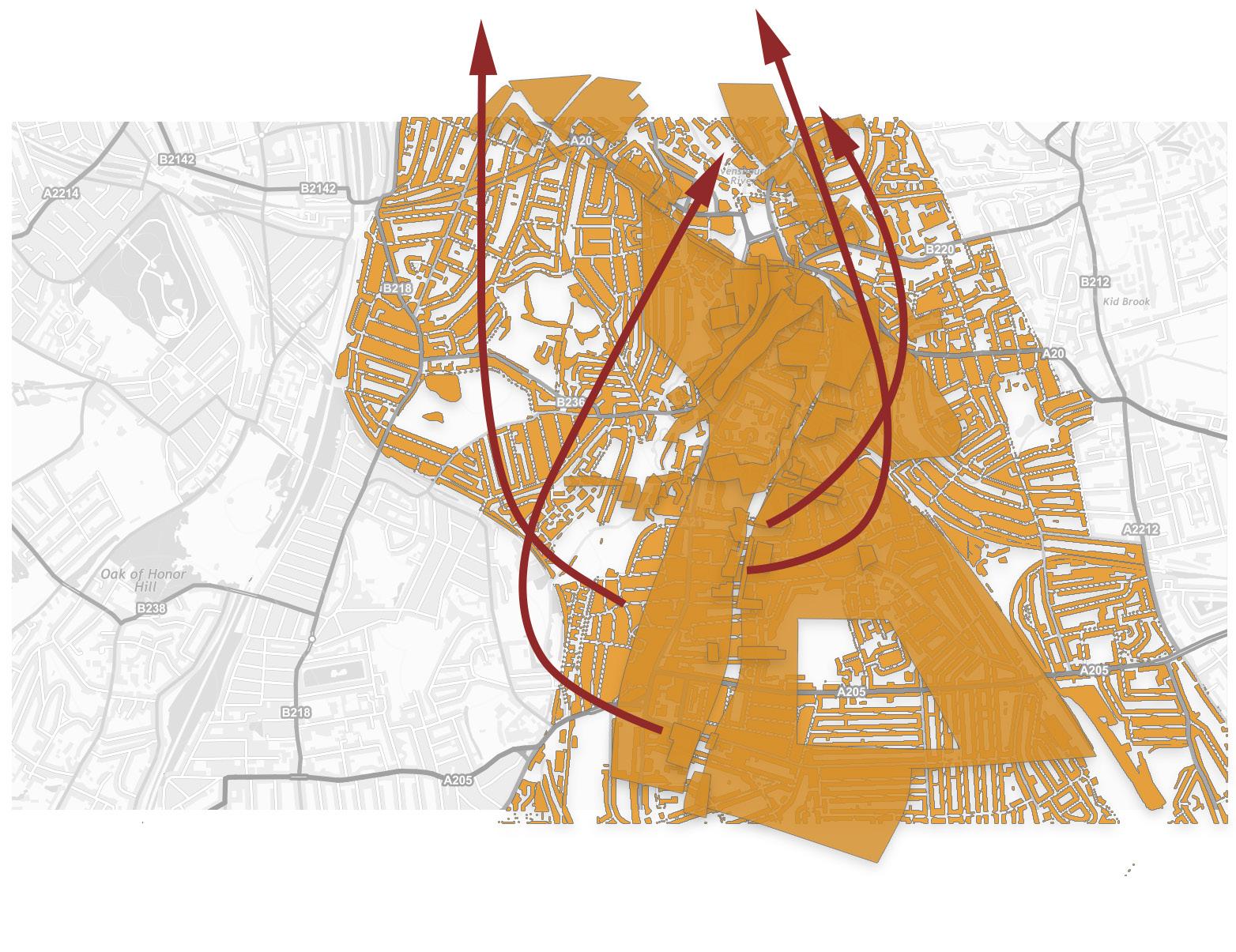

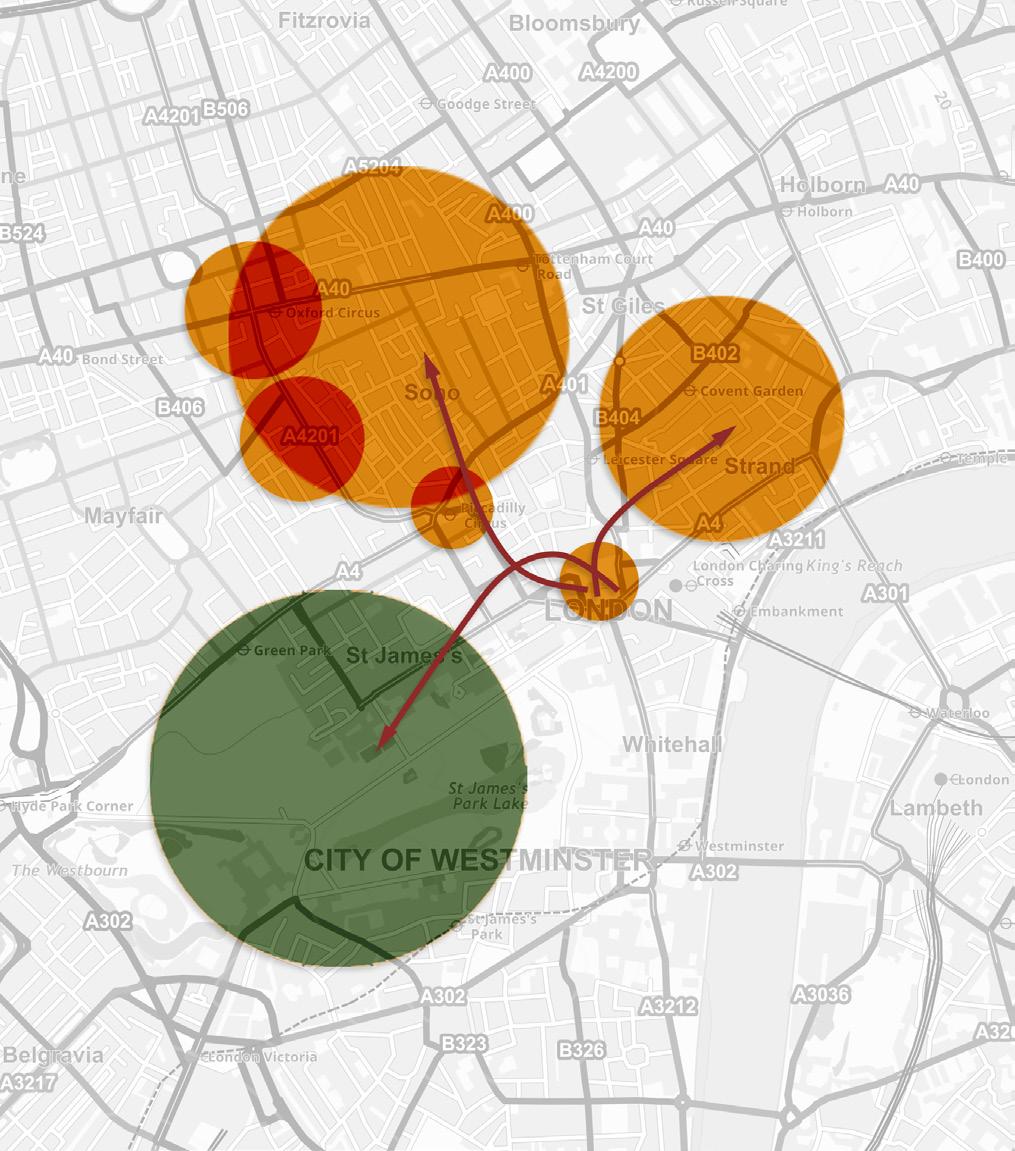

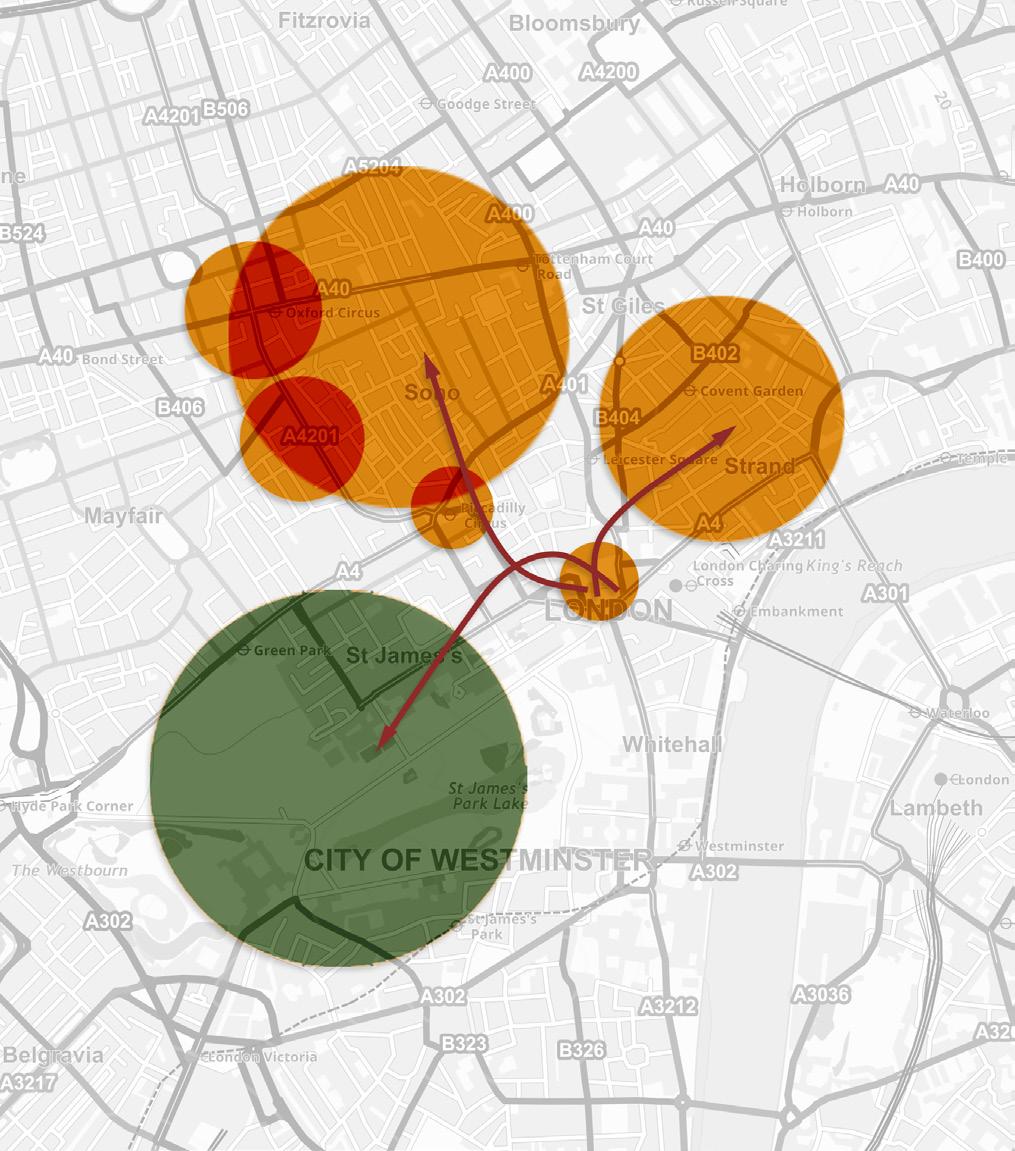

Case study: Trafalgar Square, London

Central London

be compared to a special “bridge”: the landmark Nelson’s Column and the fountains make the square iconic, and turn the square into a “reference point”, similar to the design of Parc de la Villette but in a larger scale.

When the surrounding places of interest, such as the National Gallery and Chinatown, are applying their “attraction forces” onto the tourists, the forces will possibly go through Trafalgar Square, which guides people to these destinations. Similarly, these places of interest act the same role when guiding people to the square.

21

Trafalgar Square in

can

Trafalgar Square: The Heart of London

The surroundings of Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square

Covent Garden

Soho

Piccadilly Circus

Regent Street

Oxford Street

St James’s Park

By Zijue Wei

4.7 Value judge towards going off the beaten path: risks and rewards

Recalling the discussion of the factors which facilitate movements and explorations, and the experiences and observations about going through “bridge spaces”, we get an inference into how people balance the risks and rewards of their possible exploration:

Knowledge expansion

1. Rewards:

(1) Fulfilling curiosity

(2) Gaining cultural enrichment

(3) Building social connections

(4) Meeting materialistic needs

(5) …

2. Risks:

(1) Physical barriers on the route: terrain, distances…

(2) Possible consumption of other resources: time, stamina…

(3) Navigation challenges

(4) Safety concerns

(5) …

People usually make a move when they perceive the rewards to outweigh the risks.

Although the movements of people crossing Ladywell Fields were witnessed, the space cannot be regarded as a successful “bridge space” at present. The wet lawns and other factors are stopping people from going across them, increasing the “risk” on the way.

The QUERCUS project, as an successful example, boosted access to the river and lawns by reshaping the landscape, which made the way to the river less “risky”. Following building a “self-policing space” through opening up the space, the site rewards people with better protection and visibility. (QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation Report, 2008)

If the actions of exploration are to be motivated, the simplest way is to increase the “rewards” and reduce the “risks”.

22

Getting in touch with nature Social connections

Tranquility

Dirtiness

Enclosed space

Muddy road

Rugged surface

By Zijue Wei

5.1 Conclusion: encountering nature on the way

Through the investigation into the structure and the navigation experiences in a city, I extracted a special metaphoric term: “bridges”, describing the places as connections and found out how they facilitate explorations into the surroundings. Throughout history, “bridge spaces” played a vital role, making humans connect to the objects of their curiosity, and providing chances for further exploration. For individuals nowadays, “bridge spaces” strengthen our bonds with society, and enhance people’s mobility.

By redefining urban green spaces such as Ladywell Fields, I saw how these places can function as special “bridges”.

When urban green spaces are “bridges” as a part of the route, instead of a set-up destination, we see how nature is integrated into our lives seamlessly. For the city, the sensory boundaries between urban green spaces and other spaces are weakened, forming an ecologically harmonious urban fabric

23

By Zijue Wei

6.1 Reflection: my thoughts and my life

My analysis made me rethink my mindset, and gave me a lesson about my lifestyle “unconnected to the bridges”.

I started the study with my idealistic impression towards population migration, which misled me at the early stage since I underestimated the number of people entering big cities. This experience reminded me of avoiding subjective judgements through making observations and identifying reliable sources of information.

The study into the idea of facilitating exploration also reflected my self-enclosed lifestyle.

“The individual becomes autonomous when he is able to recognize himself as a unique entity, when he can appreciate his own particular strengths and limitations, and when he can distinguish his own experiences from those of others.” (Kazimierz Dabrowski, 2015) By making connections with other individuals and the surroundings, and getting information through the tangible world, I realized how to improve my lifestyle, by experiencing the real world instead of gaining information from books and the Internet solely.

24

By Zijue Wei

Bibliography

admin (2016). Trafalgar Square: The Heart of London | London Airport Transfers. [online] London Airport Transfers. Available at: https://londonairportransfers.com/ trafalgar-square-the-heart-of-london/.

ArchDaily. (2010). School Bridge / Li Xiaodong Atelier. [online] Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/45409/school-bridge-xiaodong-li [Accessed 2 Mar. 2023].

atlasofurbanexpansion.org. (n.d.). Atlas of Urban Expansion - Cities. [online] Available at: http://atlasofurbanexpansion.org/data [Accessed 23 Feb. 2023].

Barbosa, H., Hazarie, S., Dickinson, B., Bassolas, A., Frank, A., Kautz, H., Sadilek, A., Ramasco, J.J. and Ghoshal, G. (2021). Uncovering the socioeconomic facets of human mobility. Scientific Reports, [online] 11(1), p.8616. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598021-87407-4.

Bayly, C.A. (2004). The birth of the modern world, 1780-1914 : global connections and comparisons. Malden, Ma: Blackwell Pub.

Boyd, B. (2019). Urbanization and the Mass Movement of People to Cities | Grayline Group. [online] Grayline Group. Available at: https://graylinegroup.com/urbanizationcatalyst-overview/.

Chen, J. (2020). Risk-Return Tradeoff. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https:// www.investopedia.com/terms/r/riskreturntradeoff.asp.

Crafts, N.F.R. (2002). Understanding the Industrial Revolution. The English Historical Review, 117(471), pp.489–490. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/117.471.489.

Dimensions.com (n.d.). 230 Humans ideas | human, built environment, human body. [online] Pinterest. Available at: https://www.pinterest.de/dimensionscom/humans/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2023].

Dolan, R., Bullock, J.M., Jones, J.P.G., Athanasiadis, I.N., Martinez-Lopez, J. and Willcock, S. (2021). The Flows of Nature to People, and of People to Nature: Applying Movement Concepts to Ecosystem Services. Land, 10(6), p.576. doi:https://doi. org/10.3390/land10060576.

Fromm, E. (1992). The anatomy of human destructiveness. New York: Henry Holt And Comp.

Gabriel García Márquez (2014). One hundred years of solitude. London: Penguin Books.

Jagannath, T. (2020). City Life - Why people prefer to live in cities? [online] planningtank.com. Available at: https://planningtank.com/city-insight/advantagesliving-cities?utm_content=cmp-true.

Kazimierz Dabrowski (2015). Personality-shaping through positive disintegration. Red Pill Press.

Knight, C. (1842). Kent ....

Leese, M. and Stef Wittendorp (2017). Security/Mobility. Manchester University Press. Lewisham Card. (n.d.). A Brief History Of The Lewisham Borough. [online] Available at: http://www.lewishamcard.co.uk/latest/2016/4/6/a-brief-history-of-lewisham-

borough [Accessed 6 Mar. 2023].

Lin, B.B., Chang, C., Andersson, E., Astell-Burt, T., Gardner, J. and Feng, X. (2023).

Visiting Urban Green Space and Orientation to Nature Is Associated with Better Wellbeing during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), p.3559. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043559.

Martinez, J. (2019). Great Smog of London | Facts, Pollution, Solution, & History. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/ Great-Smog-of-London.

Pew Research Center (2018). Demographic and economic trends in urban, suburban and rural communities. [online] Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/05/22/ demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/. QUERCUS in Lewisham Evaluation Report. (2008).

Ritchie, H. and Roser, M. (2018). Urbanization. [online] Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization.

Ross, P. and Maynard, K. (2021). Towards a 4th industrial revolution. Intelligent Buildings International, [online] 13(3), pp.1–3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17508975.20 21.1873625.

Souza, E. (2011). AD Classics: Parc de la Villette / Bernard Tschumi Architects. [online]

ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/92321/ad-classics-parc-de-lavillette-bernard-tschumi.

Tschumi, B. (1987). Parc de la Villette.

Tschumi, B. (2001). Architecture and disjunction. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press.

tschumi.com. (n.d.). Bernard Tschumi Architects. [online] Available at: http://tschumi. com/projects/3/.

World Bank (2022). Urban Development. [online] World Bank. Available at: https:// www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview.

Zhang, Z. (1145). Along the River During the Qingming Festival. [Ink and color on silk; handscroll].

25