SOCIALIST

REALISM

“Wemustceaseonceandforalltodescribetheeffectsofpowerinnegativeterms:it‘excludes’,it‘represses’,it‘censors’,it‘abstracts’,it‘masks’,it ‘conceals’.Infact,powerproduces;itproducesreality;itproducesdomainsofobjectsandritualsoftruth.” 1

--------- Michel Foucault, DisciplineandPunish:TheBirthofThePrison , 1975

TABLE OF CONTENTS

序 Foreword

國家意志與大基建主義捆綁 Integrating Technology and Nationalist Discourse China 2098 , Wennan Fan, 2020

虛假的想像共同體 Fake Imagined Communities

“ Our people will definitely accomplish the mission.”

Wandering Earth 2 , Fan Guo, 2022

對個人價值否定的神聖化 Canonizing Depersonalization

First Emperor of Qin’s supercomputer

Three-body Prolem , Cixin Liu, 2023

向外指涉的極權主義架空宇宙 Totalitarian Universe’s Outward Reference

Starship Troopers Paul Vanhoven, 1997

Adapted from the novel of the same title by Robert Heinlein

技術非我 Technological Nonself

They Live , John Carpenter, 1988

Homogenous Futurist Narrative 高度同質的未來主義敘事

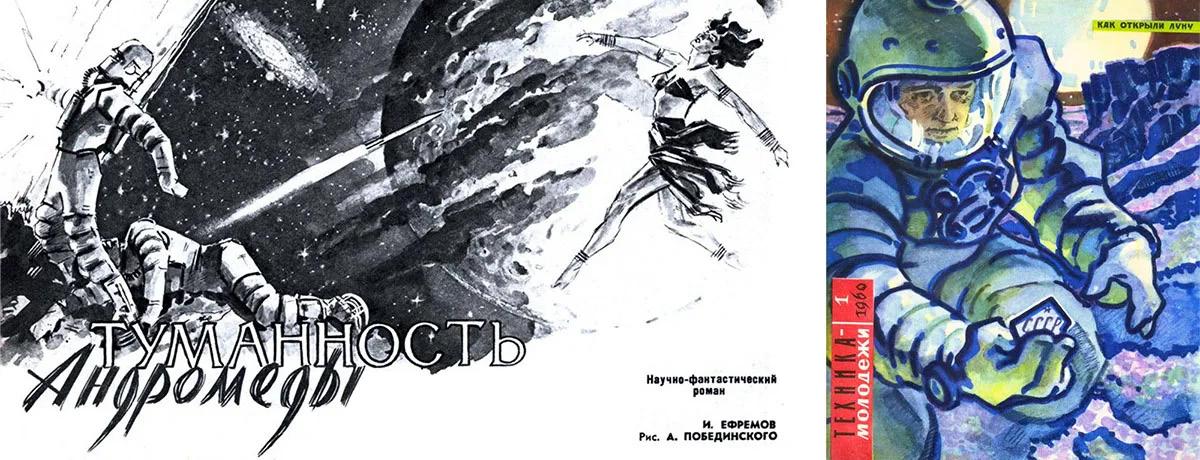

The Technology for the Youth Magazine

Entry illustration for Ivan Yefremov’s novel The Andromeda Nebula , Alexander Pobedinsky, 1957

A Futurism That Undoes Itself 自我消解的未來主義

”Zukunftsfilme (Films for The Future)”

Die Welt Der Gespenster (The World of Ghosts) , min. 01.25.19, Gottfried Kolditz and Joachim Hellwig, 1976

Unrestricted Technocracy 不受約束的技術專制

DAU. Degeneratsiya Ilya Khrzhanovsky, 2005 ~ 2013

Alienation by Instrumental Reason 工具理性對個體的異化

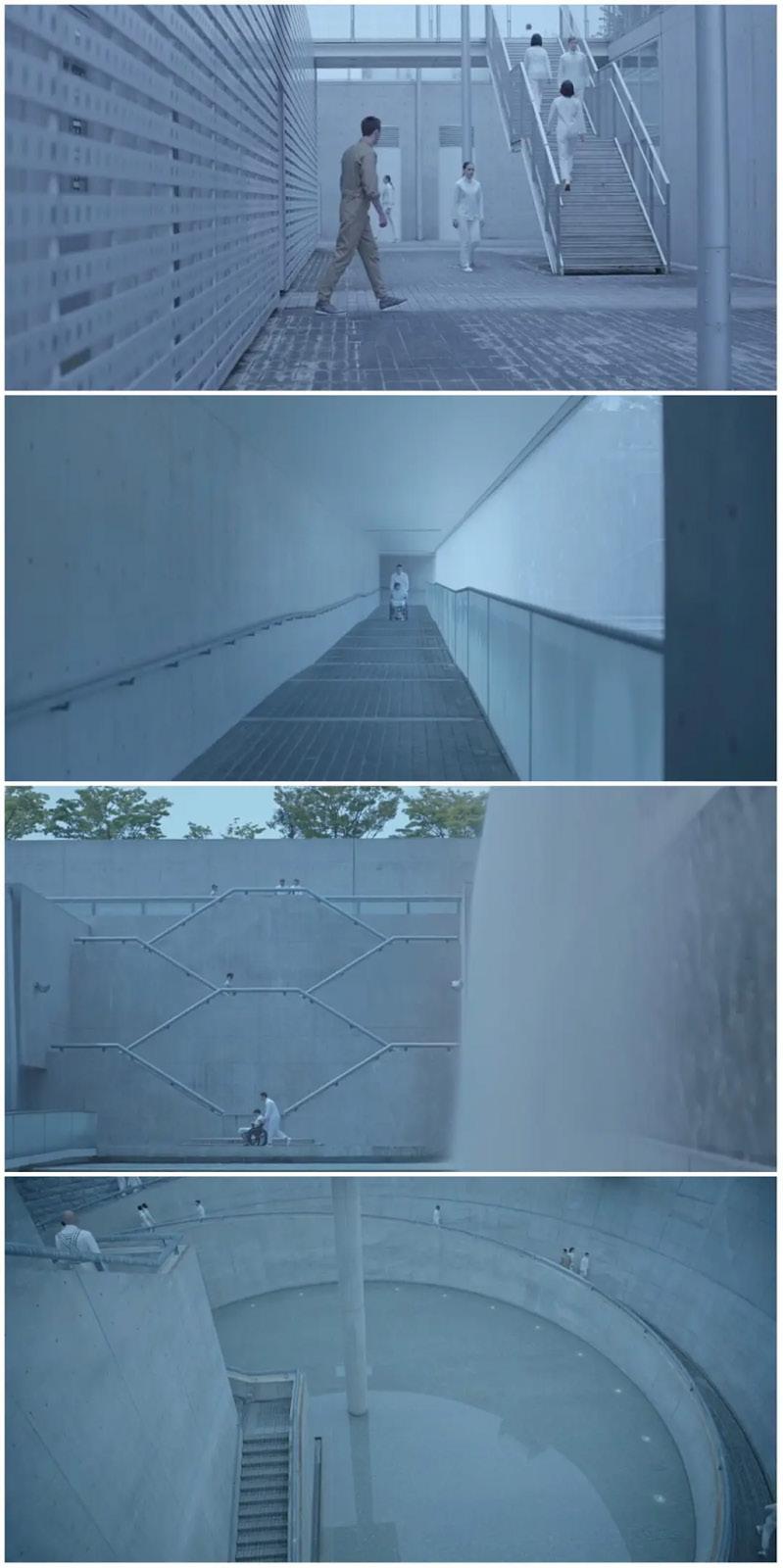

Equals , Drake Doremus, 2015

A Counterexample 寫在最後:一個反例

Солярис (Solaris) , Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972

Adapted from the novel of the same title by Stanisław Lem

Bibliography 參考書目

Endnotes 尾註

TABLE OF CONTENTS

“Beatthesquareswiththetrampofrebels!

Higher,rangesofhaughtyheads!

We’llwashtheworldwithaseconddeluge, Now’sthehourwhosecomingitdreads.

Tooslow,thewagonofyears.

Theoxenofdays—tooglum.

Ourgodisthegodofspeed, Our heart — our battle-drum.

Istheregolddivinerthanours?’

Whatwaspofabulletuscansting?

Songsareourweapons,ourpowerofpowers, Ourgold—ourvoices;justhearussing!” 1 ---------

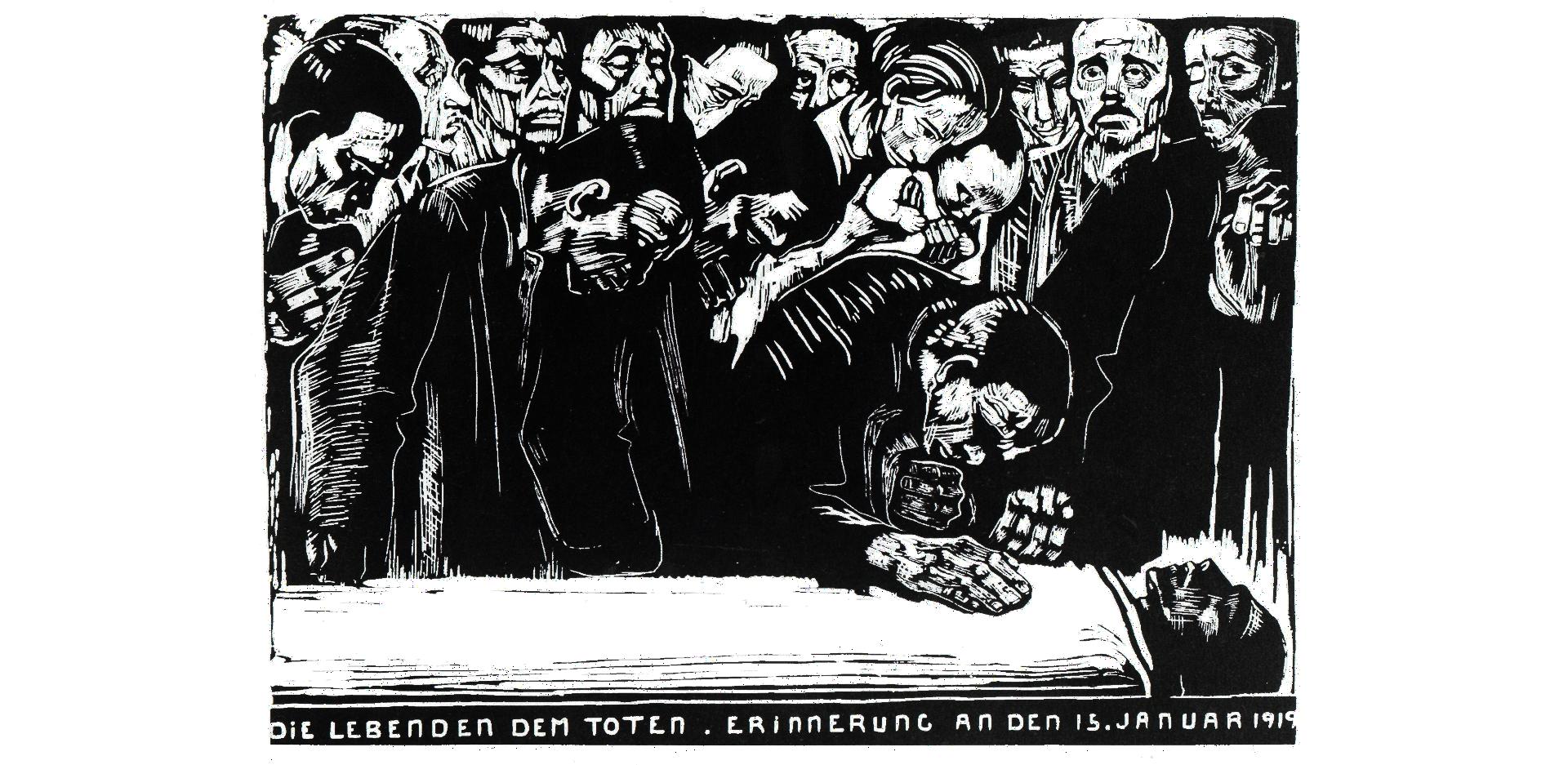

Expressionism?

Socialist Realism?

Or just one of the two sides?

Foreword

Aestheticization

Socialist Realism has been recognized as a cultural phenomenon that took place in the 1920s Soviet Union after Joseph Stalin assumed leadership. It denotes a specific style of art and literature that was officially endorsed by the Communist Party as the dominant form of artistic expression in the socialist state. In terms of political agenda, the style aims to engender forms of art and eventually an authoritative paradigm that would promote Marxist-Leninist ideals on proletariat dictatorship and the Soviet way of life, and that would inspire the masses to work towards the building of a socialist society. As part of the Stalinist political-aesthetic project, socialist realism doesn’t anchor itself on aestheticism, but on “aestheticization.” Aesthetics didn’t beautify reality; it is reality. On the other hand, socialist realism, if still qualifies as an aesthetics, presented a radically transformed world based on the idealist appeal, while everything outside of that proposed “realism” was awaiting reinterpretation by the artificial narrative. The alleged founder of Socialist realism, Maxim Gorky, defended the product of such aestheticization with the notion of projected reality. He famously stated in the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1935 that “reality doesn’t let itself be seen. So then we need not only know two realities-the past and the present one but a third reality-the reality of future,” which proletariats (artists) must include and portray in everyday practice or otherwise become traitors of the revolution who submit to the “force of facts.”3

Socialist realism refuses to “observe things statically-” a common failing of bourgeois realism. Bourgeois realism simply presents its objects as they are, without accounting for the strong developmental momentum that functions under real conditions, and it does not wish to actively participate in this process as a positive force.4 Resistance to a “static perspective” under Stalinist governance was partly out of desperation, though, if we factor in the republic’s numerous predicaments at that special juncture. Setbacks in collectivization and the Ukrainian Famine between 1932 and 1933 raised serious questions in the capitalist bloc about Russian socialism’s sustainability. For Stalin, feeling grave pressure both within and without, a means for stability was pressingly needed. As Anatoly Lunarcharsky, Ministry of Education of the

3 Dobrenko Evgenij Aleksandroviď, PoliticalEconomyofSocialistRealism (Yale University Press, 2007), 75.

4 Anatoly Vasilievich Lunacharsky, OnLiteratureandArtbyAnatolyLunacharsky (Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1965), 486.

GELI KORZHEV, BEFORE A LONG JOURNEY , 1970–1976. OIL ON CANVAS

3 Dobrenko Evgenij Aleksandroviď, PoliticalEconomyofSocialistRealism (Yale University Press, 2007), 75.

4 Anatoly Vasilievich Lunacharsky, OnLiteratureandArtbyAnatolyLunacharsky (Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1965), 486.

GELI KORZHEV, BEFORE A LONG JOURNEY , 1970–1976. OIL ON CANVAS

Soviet People’s Commissar, identified at the 1935 conference, “There are still, as is evident, many unresolved issues on our construction sites, all kinds of unsatisfactory and even outrageous things; all kinds of heartbreaking details are everywhere.”5 Indeed, artists couldn’t remain silent before these misdeeds, but had they treated them as different stages of development that should be overcome and were actually being overcome, they would find themselves contented with revolutionary optimism. Such was the substance of constructing an alternative dimension of socialist realism. On the contrary, if they viewed these instances as independent phenomena with little prospective implication, they shall criticize and condemn the entire struggle, hence the doomsday of Socialism.

5 Anatoly, 487.

6 Boris Grojs, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 30.

7 Petre M. Petrov, Automatic for the Masses: The Death of the Author and the Birth of Socialist Realism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), 7.

8 Petrov, 8.

Demiurgic Passion

The mimetic nature or anti-reality tendency of socialist realism, better called a demiurgic passion, owes an intellectual debt, as much as people wish to disavow that association, to the Russian Avant-Garde around the 1910s. As far as their ambitions for life-building and entering the broad arena of civil life, Stalin and Malevich/Mayakovsy find their intersection within the modernist framework. In the 1992 book The Total Art of Stalinism by Boris Grojs, a distinguished scholar of Russian and Slavic studies at NYU, a radical departure from traditional studies of Soviet culture was undertaken to dispel the myth “of an innocent avant-garde falling prey to the crudely concocted artistic orthodoxy of Stalinism,”6 In fact, from where modernism found an insurmountable limit to its aesthetic-political capacity of recreating the existing reality, Stalinism took over with its powerful executive organ-a party in full control of the state. And such collusion, according to Grojs, is actually what took place in the Soviet Union in the early 1930s: socialist realism inherited the unfinished project from the left avant-garde, the former “artists without talent,” and the latter “dictators without power.”7

As the proverb goes, “To create also means to destroy.” Demiurgic passion comes at the cost of the effacement of artistic authorship. Malevich, in his 1920 diary, cited that the attainment of perfection is conditioned by the annihilation of self. “Just as religious fanatics annihilate themselves in the face of the divine,” the modern saint must renounce his individuality before the “collective.”8 Sarcastically, on the one hand, avant-garde/modernism is established on hyperinflated subjectivity, as one needs to be quite egotistical to posit a topdown explanation for the universal state of affairs (modern saint’s demiurgic license); on the other hand, the avant-garde draws its legitimacy, at least outwardly, from the suppression

of artists’ absolute power over the objects/material to an extent of disentitling artists from their creations (death of the author). This leads to a serious desynchronization between the avant-garde’s intention and practice. To put it rather crudely, the authors of modernism/avant-garde pretend not to be authorially self-conscious, and such pretense, or the tug-o-war between subjectivity and universality considerably informs the ideological construct of socialist realism. Likewise, socialist realism presupposes an intrinsic dynamic for objects based on Thomas Hobbes’ mechanical materialism (see the non-static lens mentioned in previous paragraphs), while the human agentthe artistic subject-becomes only one of the extrinsic instruments that will find little pertinence to the constitution of the object.9 The human subject simply obeys or executes what the object’s volition mandates. Meanwhile, nevertheless, socialist realism, as one political device of Stalinism, assumes an aesthetical dictatorship-clearly an explosion of authorship-by posing the singular, exclusive narrative of aestheticization.

Dream for Universality

On the opposite half of the political spectrum, nationalism provides an analogous example of an ideological construct’s creativity-perhaps no less artificial than socialist realism. To this day, not a single account of the spontaneous formation of nations can draw a universal consensus, despite that “the phenomenon has existed and exists.” Indeed, the scientific definition of national identity isn’t accessible because all communities larger than primordial villages of face-to-face contact are imagined rather than engineered.10 As though an allusion to the chicken-and-egg problem, Ernst Gellner, in his Nations and Nationalism, rules that “nationalism is not the awakening of nations to self-consciousness: it [re]invents nations where they do not exist.”11 Nationalism, in itself an imagination for universality or all-encompassing group identification, invents an alternative dimension for human self-observation which incurs a panoramic effect powerful enough to relieve any concerns for individual differences. The nation is then imagined as a community since, “regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each,” it is always conceived to be a shared bottom line, a “horizontal comradeship.”12 Like socialist realism, nationalism is about depersonalizing while playing innocent. It guarantees the synchronous flourishment of individual potential within the imagined community but endows grandeur to one’s unconditional sacrifice for national sovereignty.

9 Petrov, 10.

10 E.J Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism (Cambridge: Cambrdige University Press, 1991), 98.

11 Ernest Gellner and John Breuilly, Nations and Nationalism (Blackwell Publishing, 2013), 76.

12 Anderson Benedict R O’G, ImaginedCommunities:ReflectionsontheOriginandSpreadofNationalism (London: Verso, 2016), 7.

Upon the arrival of modernity, technology and the innovative agents propelling its growth served a more decisive role in national security and subsequently took on a symbolic character for the imagined communities. The two world wars and the arms race facilitated, on a global scale, the authority’s intervention in the innovative process, as “nation-states [began to] represent centers of reference for the innovative agents.” At its height, the social extension of technology gave rise to such notions as techno-sovereignty, techno-territoriality, techno-citizenship, and the synthesis of three, techno-nationalism.13 Ultimately, techno-nationalism symbolizes not so much the absorption of technology into a nationalist corpus as the imagined community’s continuance in a technocratic medium.

...

Techno-nationalism’s Subdivisions

In an etymological sense, despite being an inextricable part of the post-iron-curtain global landscape, techno-nationalism, at its outset, described an American diplomatic policy shift with its Asian ally in the late Cold War. In 1987, Robert Reich, a Harvard professor who later served as Labor Secretary under the Clinton government, proposed this concept in an article in The Atlantic. Back then, the U.S.-Japan technological competition was turning white-hot, to which the democratic party responded by issuing a substantial cutback on numerous cooperative projects, adjusting the way technology was being shared to safeguard its advantage in the key areas. Reich referred to this transition as a challenge from techno-nationalism to techno-globalism.14

A number of studies have emerged in academic circles following Reich that sought to differentiate non-western techno-nationalisms from that of the Americans. The term’s connotation changed accordingly because these case-study countries, many still third-world, bore utterly distinct cultural/political/religious soils than the U.S., thus engendering a variety of techno-nationalist expressions. For instance, during the Iran-Iraq War, Iran’s technological achievements in stem cell research and therapy were regarded as the greatest “national glory” by its people. The Khomeini administration, therefore, struck a balance between maintaining religious/national communality and embracing technological progress, with its international image amended.15 After World War II, Japan shifted its technology strategy from militarism to a consumption-oriented economy, thus bringing about a new medium for national pride in daily space: buying and selling Japanese home appliances was the most widespread secular expression of patriotism.16 In the early 21st century, after achieving a certain level of primitive wealth accumulation, South Korea and India also gradually found their ways around technological self-sufficiency under the aid of overseas compatriots.17

As addressed earlier, different socio-political contexts precipitate various techno-nationalist expressions, as different political systems point to different forms of imagined communities. Specifically, communitarianism found in the U.S. and South Korea/Japan, to which Protestant republicanism and Confucianist morals are the cornerstones, leads to the pragmatic integration of mercantilist and liberal policies. The pursuit of national technological goals is, ergo, driven by the synergy between state activism and openness toward foreign capital. On the contrary, collectivism innate to autocratic regimes, from Nazi Germany’s state-centric capitalism to Putin’s oligarchy, demands way more extreme solidarity within the imagined community. Here, the overpowering presence of authority causes the alienation of technology itself-what people pay for probably at the cost of diversity or economy isn’t merely a technological entity, but the political institution’s precarious credibility.

To visualize the latter, contemporary China makes an excellent point of entry. In this land where the proletariats once sustained the imagination for a

13 Sandro Montresor, “Techno-Globalism, Techno-Nationalism and Technological Systems: Organizing the Evidence,” Technovation 21, no. 7 (2001): pp. 399-412, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-4972(00)00061-4, 400.

14 Robert B. Reich, “The Rise of Techno-Nationalism,” The Atlantic, July 8, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1987/05/the-rise-of-techno-nationalism/665772/, 64.

15 Tahereh Miremadi, “The Role of Discourse of Techno-Nationalism and Social Entrepreneurship in the Process of Development of New Technology: A Case Study of Stem Cell Research and Therapy in Iran,” Iranian Studies 47, no. 1 (2014): pp. 1-20, https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2013.825507, 14.

16 Morris Low, “Displaying the Future: Techno - Nationalism and the Rise of the Consumer in Postwar Japan,” History and Technology 19, no. 3 (2003): pp. 197-209, https://doi.org/10.1080/0734151032000123945, 202.

17 David Kang and Maurice R Greenburg, “The Siren Song of Technonationalism,” ESocialSciences, March 7, 2006, http://www.esocialsciences.org/Articles/show_Article.aspx?qs=bGp0Ut9EHmCw%2FEpGtd%2FDaLZRIw3TQoQPEnk8KyXd9n4, 54.

shared identity, although the collective exists only in name for generations born after the “reform and opening up,” collectivity managed to find its renaissance in the new political idioms of Xi Jinping. Throughout the term, Xi and his staff attempted to attribute China’s mortification over the past century to backwardness in the domains of economy and science, which doesn’t sound too fresh to Mao’s remnants but surprisingly tempting for their descendants.

Now, with China placed 2nd in the global GDP and people’s living conditions generally improved, it must strive at all costs for high grounds in cutting-edge fields against the West. The Xi administration envisions a future where little is unexpendable along the path to domestic technological advancement, be it justice or individual freedom, and preconceives every citizen’s accountability to the forging of a techno-nationalist identity. Most essentially, the thought derives self-efficacy from a make-believe premise that “the world has entered a new era of systemic rivalry between competing geopolitical powerhouses” that differ markedly in ideological values, political systems, and economic models. To take the initiative in this century-long campaign ( ) means the enactment of state-directed, top-down machinery for scientific innovations.19 Lastly, happiness is directly correlated to national/technocratic might, whereas just as imperialists cannot provide a definitive answer to how winning a war of aggression on the other end of the globe will increase the amount on one’s payroll, so can’t techno-nationalists convince people, by means of reason, of the connection between localized lithography machine and improvements on the treatment of grassroots scientific workers.

If anything, the commonality between socialist realism and techno-nationalism lies in their fabrication of a symbolic “reality” external and superior to the cognitive reality, their simultaneous affirmation and negation of the author/individuality, and their indivisibility with the state power. When these elements converge in the literary and artistic territory of futurism, they generate some sort of monstrous existence that many marvel as a dystopia or “something punk.”

I call it a totalitarian fictional universe.

...

18 Yadong Luo, “Illusions of Techno-Nationalism,” Journal of International Business Studies 53, no. 3 (2021): 550–67, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00468-5, 553.

19 Jun Zhang, ChineseTechno-NationalismMorethanMerePropaganda , 2022, https://doi. org/10.54377/94ee-51e0, 68.

EXHIBITION ARTIFACTS

TECHN & NATION DISCOURSE ALIST TING

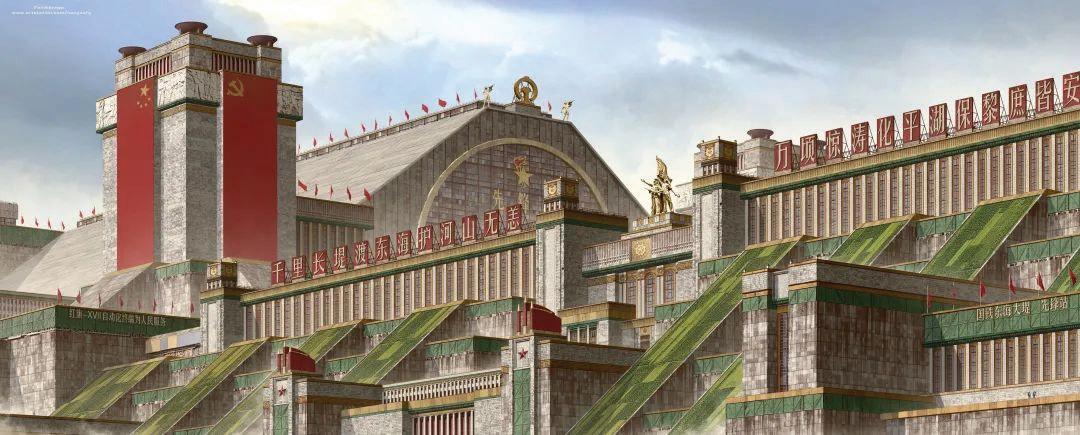

China 2098 , Wennan Fan, 2020 OLOGY INTEGRA

August 2020 was marked by two seemingly disjunctive yet politically tied events: China declaring its “institutional superiority” over the United States in the battle against the pandemic, and U.S. covid patients striking 1 million. Amid the ensuing perhaps most formidable outburst of Chinese national pride since the reform and opening up in the early 1980s, CAA (Central Academy of Arts) student Wennan Fan made public an illustration series he originally created for his degree project on Weibo (Chinese Twitter), to which he proudly titled “China 2098.” The work, distinctive with its genre “mega infrastructure punk,” is an outright eulogy to the then-prevailing idea “The East is Rising” propagated by Xi Jinping who aspires for contemporary China to reerect its bygone role as the third world’s spearhead against Western imperialism. It tells a storyline in which, with rising oceans inundating the Western hemisphere and everyone disillusioned with the American order, China, the only unaffected power, led the human race into Type II civilization on the Kardashev Scale. As part of Fan’s ambition, China and its Northeast allies built levees to enclose the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan only to pump water into the Loess Plateau, which improves the ecology of the northwest deserts. Meanwhile, land has been reclaimed in the East China Sea and the Sea of Japan to expand living space for mankind.

- ARTIFACT I8

... OLOGY INTEGRA TECHN & NATION DISCOURSE ALIST TING

WanderingEarth2, Fan Guo, 2022

“Our people will definitely accomplish the mission.”

In Wandering Earth 2, a sequel to the Chinese Sci-Fi movie Wandering Earth, our home planet is programmed to escape the dying sun with the assistance of numerous planetary rocket engines. A malfunction with the supercomputer causes the moon to fall to Earth, forcing mankind to detonate the moon using the entire nuclear stockpile to date. The operation requires all three global internet root servers (Beijing, Tokyo, and Dulles) to be back online to calculate the correct propulsion scheme out of lunar debris. However, with the Beijing task force remaining silent on the radio, the American mission director, knowing no alternatives, suggests detonating the moon after the countdown which at least would lend people some time to bid farewell to their families before erroneous propulsion rate tears the Earth’s core apart. The Chinese representative, as indicated in this movie shot, voices strongly against him by reiterating his unconditional confidence in the Chinese task force’s ability to reconnect the server.

In the fictional universe of the Wandering Earth series, the filmmaker tries, by all means, to avoid the single-perspective Chinese narrative in the hope of establishing an antithesis of Americentricism in mainstream Hollywood disaster movies. The series’ creative intention centers on the “common fate of mankind,” a political vision initially raised by President Xi in 2013 and hasn’t left the Chinese diplomatic lexicon ever since. As if a result of the overexertion of a political gesture, though, every second of the movie is swarmed with suspicious exclusivist expressions. Milder examples include the flattening portrayal of foreign astronauts and governments. In the space elevator crisis early on, when Wu Jing fought with the villain, a part of the spaceship inscribed “Made in China” flew out. The part was later handed to the character’s wife as a gift, along with the red rose, which had been used as a symbol of cosmopolitanism a few minutes before.21 In the final moon detonation scene, the imagined human entity completely dissolved as the Chinese spokesman redivided “us” into “you” and “we” so that the unswerving belief in “our people” becomes the foremost and exclusive reason for “everyone”’s survival.

IMAGINED COMMUNITY TING

POLITICIZING DEPERSONALIZATION

Three-bodyProblem , Cixin Liu, 2022

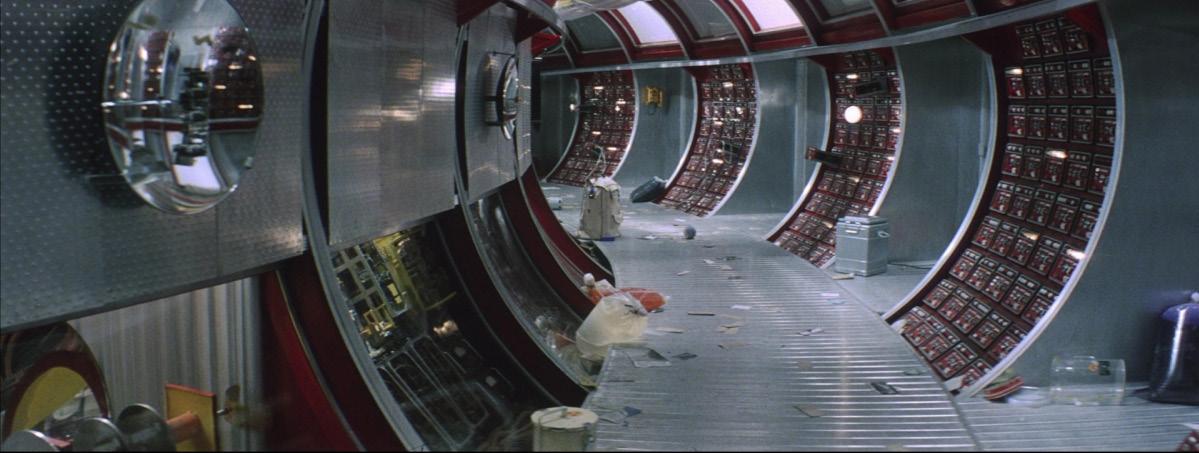

First Emperor of Qin’s supercomputer

In Three Body Problem, a Chinese TV show based on Liu Cixin’s novel, the main character logged into a game that allows players to role-play famous historical figures from different times. In this episode, he and three other players acted as Newton, Leibniz, and von Neumann. Together they were teleported to the Qin dynasty to convince the First Emperor of China to solve the three-body problem (a calculus-based mathematical approach to predict star movements in a three-star system) using the massive human resource at his disposal. The emperor ordered the construction of a human supercomputer run by hundreds of thousands of men holding double-color lanterns (to represent 1s and 0s in binary language). The algorithm was expected to run for years and involved a literal “debugging” mechanism-or simply put-the physical elimination of individuals who made mistakes.

At one point, the First Emperor explained, as though through the author’s tone, the ideological significance of his practice: “Europeans accuse me of tyranny and stifling the creativity of society, but great wisdom can come out of large numbers of people under strict discipline.” Here, the denial of personal rights is elevated from the domain of pure technical ethics to the antagonistic narrative between Eastern and Western cultures. Therefore, not only are individuals kidnapped by the algorithm per se but also by the totalizing discourse system to which that algorithm is entitled. Such is an example of politicizing/canonizing depersonalization in a totalitarian fictional world.

StarshipTroopers , Paul Vanhoven, 1997

Adapted from novel of the same title by Robert Heinlein

Starship Troopers is perhaps one of the most easily overlooked dystopian movies of all time. Apart from the parodic referencing of fascist aesthetics and narratives, the setting of Arachnids (alien bugs) and the demonstration of military technologies weave into a very authentic totalitarian paradigm that is equally worthy of interpretation.

The Arachnids are a kind of otherness to Earth Union’s iron discipline. Morphologically, they are ugly, barbaric, and crafty; in terms of sociological attributes, they are deprived of individual consciousness and moral conscience. It seems as though their appearance communicates a message to soldiers that “we are born to be killed in bundles without any questions and at no remorse.” Now, since movies are a made-up world of the director’s will, why can’t we reasonably speculate that the message has an outward reference, too: that it’s trying to absolve viewers of ethical dilemmas with the slaughtering of a conscious being? Only in hindsight would audiences wake up to the fact that they were all bound up in the director’s design and shared complicity in energizing a totalitarian discourse.

Military technologies in Starship Troopers puncture the sophistry in techno-nationalism’s myth about imagined community. Techno-nationalists often preconceive a transcendental linkage by default between the prosperities of individuals and collectivity. However, watching the movie, one couldn’t help but ask why the Earth Union doesn’t equip each soldier with better armor to reduce casualty when it has enough resources to encircle the moon with a single space station. Likewise, it could have chosen much shrewder tactics against the Arachnids than throwing six million men into positional warfare of no return.

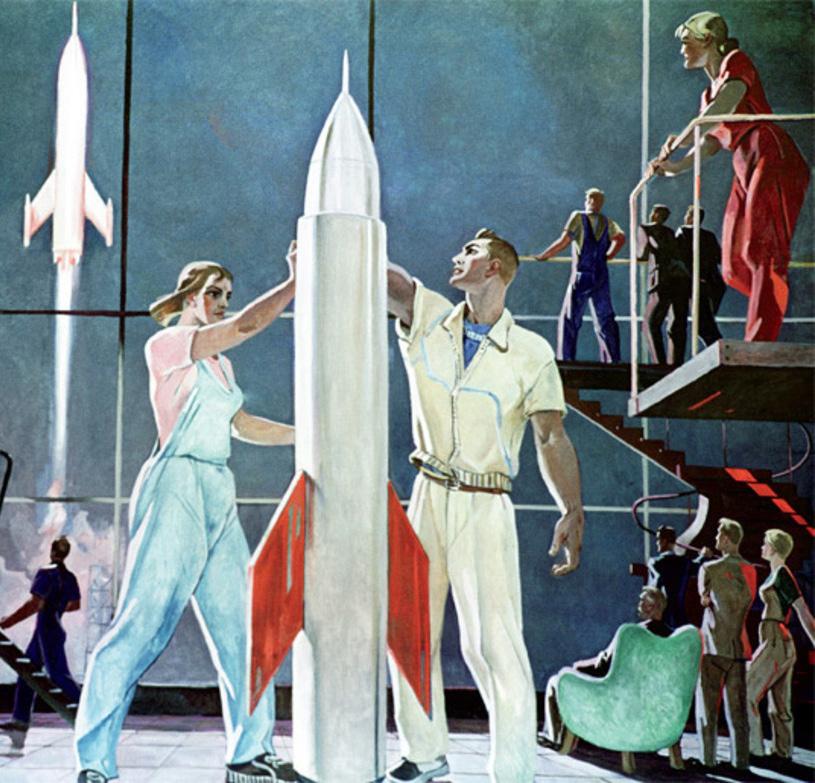

Entry illustration for Ivan Yefremov’s novel The Andromeda Nebula, Alexander Pobedinsky, 1957

TheTechnologyfortheYouth

magazine

In USSR, the very idea of futurism was an extension of socialist realism and the propaganda organ. Magazines such as T-M played a crucial role in the process of indoctrination by effectively spreading this new definition to a large audience. In 1934, the first All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers was held, and at this event, science fiction drawings were specifically defined as an “art form of the youths.” The genre was expected to concentrate on providing “scientific and technological education” to the masses while adhering to the principles of socialist realism. This turn towards socialist realism brought an end to the avant-garde experiments of the 1910s and 1920s, giving rise to a more practical yet homogeneous form of futurist art, which often lacked a traditional plot and thereby the author’s distinguished character. The sci-fi illustrators of the period generally had a background in engineering, allowing them to create intricate and engaging depictions of the socialist future. Their primary focus was on futuristic technologies per se, rather than inquiring into the nature of their relationship with humanity, that could enable the communist state to gain control over Earth’s natural resources and establish colonies on other planets. Extraterrestrial civilizations were often conceived as friendly to the Soviets, whereas foreign spies, imperialists, and capitalists were typically depicted as threats and adversaries.22

Technology, introduced as an invisible TV signal, plays a crucial part in the process of surrogation, as it exerts an all-pervasive but impalpable influence on human subjects, making discipline a painless and even enjoyable ritual. The intermarriage of technology and ideology (techno-nationalism counts as one) has been thus so destructive due to its tacitness, and the way to disenchantment, as Zizek remarks, is easy: just punch yourself right in the face.24

What is the price of disillusionment? They Live by horror movie maestro John Carpenter explains in an explicit, almost dorky way: it takes some serious wrestling.

In a fictional world infinitely approximate to our consumerist society, the deep government adopts a hypnotic signal transmitted through television waves to control people’s cognitions. However, some unwilling to be ruled develop a pair of special sunglasses that can reveal the true skeletal form of those seemingly righteous officials in television programs. John Nadda, a bum from L.A. wanting to show his friends the world as it really is through glasses, is met with great resistance.

According to Slavoj Zizek’s comment in The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, in modern post-ideological society, we are interpolated by the authority not as subjects who submit to imperative discipline,

but as subjects of pleasure. In other words, ideology/counterfeited reality is no longer something imposed around us; it is part of us, a body snatcher.23 This accounts for all the defiance received by John in the movie because, to exorcise this built-in nonself (step out of ideology), self-harming is inevitable.

DieWeltDerGespenster(TheWorldofGhosts) , Gottfried Kolditz and Joachim Hellwig, 1976

Zukunftsfilme (Films for The Future) of DEDA-Futurum

Zukunftsfilme was a late-1960s experimental cinematic project presided over by the artistic working group Futurum of the East German state film production DEFA, a.k.a. Defa-futurum. Its main driving force, ex-political documentary director Joachim Hellwig, characterized his project as providing a socialist counter-dystopian narrative directly contesting the pessimistic futurism of the capitalist sector. Zukunftsfilme openly disparaged the West German literary works of Perry Rhodan magazine series which depicts a dystopian future of war, greed, and battles for domination25-all deemed a capitalist bias that couldn’t stand up to the scrutiny of Marx’s scientific socialism. By contrast, Hellwig’s socialist future contributes effectively and artistically to “building socialism in the GDR and educating citizens.” As shown in the snapshot of DieWeltDerGespenster, “the west is negatively distorted, turning GDR into a positive counter-image-both accounting for the current situation and with a view to the future.”26

However, while our story seems to steer toward a common (almost hackneyed) confrontation between totalitarian brainwashing and liberalism’s disenchantment of the former, Hellwig never framed Zukunftsfilme’s objective an outright exposition of the communist utopia. We can credibly deduce that defa-futurum reserved an equal distance to dystopia and utopia synchronously since, on a closer look, orthodox Marxism prohibits the possibility of an immaculate society. In his theorization, Marx made a conscious effort to differentiate his scientific socialism from early utopian socialists, albeit a significant precursor of socialism. Historical materialism was an esteemed scientific methodology that does not purport to predict the future in detail; instead, it only offers an understanding of the principles governing historical events.27

To avoid ideological inconsistency, Defa-futurum had no choice but to go for eclecticism, which Hellwig branded as a “non-fiction/documentary science fiction.” It’s a form of inter-genre film emphasizing the “scientific” representation of the future, or simply speaking, an act of excluding all unverified scientific speculations from the realm of sci-fi. In the same way that socialist realism undoes what we perceive as reality, Zukunftsfilme’s veto on the hypothetic and imaginative nature of fiction, best described as an anti-fiction tendency, annuls the notion of futurism.

25

27

TECH

The camera crew, better-called experimenters, purchased a 120-square-mile land outside of Kharkiv, Ukraine only to hold up a 1:1-scale 1960s Soviet town (tourists needed a visa to visit the set) of 1.4 million residents. The 1.4 million non-professional actors were subsequently asked to live like old-time Soviets, partake in numerous roles ranging from KGB secret agent to humble waitress, and trade in Soviet Rubles.

DAU.Degeneratsiya, Ilya Khrzhanovsky, 2005-2013

T he DAU. series is an anthropological experiment/performance art directed by Russian filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky between 2005 and 2013. Describing the DAU project precisely is difficult. Initially, it was intended to be a simple biopic about Lev Landau, a Soviet quantum physicist who won a Nobel Prize in 1962 (referred to as “Dau” in the films). However, the project quickly evolved into an artistic experiment that aimed to reflect and distort the concerns of the Soviet elite and those who served them within the imaginary Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics. The project functioned as some sort of Stalinist Trumen’s show within a closed-off environment.

Out of the 12 movies edited from thousands of footage captured over the span of eight years, the final episode, named DAU.Degeneration focuses on the gruesome practice at the nation’s covert scientific facility. Occult experiments were carried out on animals and infants at that institution with the ultimate goal of breeding the “perfect human being” for communism. The distinguished scientists employed disturbing and gnarly research methods, while the KGB general and his associates turned a blind eye to their misdeeds. However, their world became disrupted when a radical youth group (whose casts are real-life Russian skinheads) posing as test subjects infiltrated the facility, whose mission was to eliminate the dissolute act of the intelligentsia and, by any means, to obliterate every trace of their crime.28 The failed experiment, as much as the tragic finality of the fabricated totalitarian universe itself, metaphors the homogeneity between utopism and fascism under unrestricted technocracy.

TheEquals, Drake Doremus, 2015

The 2015 film TheEquals critiques a world of techno-totalitarianism under the guise of peace, advancedness, and rationality. The story settles in a distant future when a race called the “Equals” has become the primary workforce in a quasi-Nordic society. Compared to the discriminated “peninsular” who are in fact ordinary humans, the Equals are more perfect and possess noble morals, stable mentality, and intelligent minds.

However, their excessive perfection is attained at the expense of losing basic empathy-something that the collectivity reverse-advertises as the leading destabilizing factor in their society, or a disease named SOS. Those who contract SOS become sensitive, sad, and impulsive, and if discovered, they are banished from the collectivity to concentration camps to get cleansed of any emotions.

In essence, the “Equals” doesn’t tolerate any outliers to the imagined community that is erected on the totemization of technology-of the instrumental reason manifested through technology. In the main character’s recount of his childhood education lies the evidence: all members have been indoctrinated since a very young age that the ultimate answer to humanity lies in space exploration, thus the only noteworthy existential problem. Whereas the character realizes after being infected with SOS and undergoing an intimate relationship that the true answer resides in the complexity of humans per se-an ensemble of conflicting forces-nuanced, vulnerable, yet housing unlimited energy. Humans needn’t instrumentalize themselves, as taught by the power machine, to abridge their distance from the truth. Instead, sensitivity and compassion are sufficient for the voluntary formation of a shared community: of the real “Equals.”

ALIENATION BY INSTRUMENTAL REASON

COUNTER EXAMPLE

...

Солярис(Solaris) , Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972

Adapted from the novel of the same title by Stanisław Lem

In some respect, Solaris, a sci-fi movie directed by Andrei Tarkovsky who is the representative personage of the Soviet film poetry movement, describes a state of being that the abstract symbolic worlds of techno-nationalism and socialist realism cannot supply. Hence, including his work in this discussion is meant for thematic expansion and retrospection.

The story arc is incredibly simple. Psychologist Chris Kelvin is dispatched to a space station orbiting planet Solaris to investigate an incident. Upon arrival, he noticed that everyone onboard are either suicided or freaked out. Bewildered at the many inexplicable phenomena, Kelvin encountered his deceased wife only to learn that all humanoid beings on the station are probes of the Solaris’ ocean-a living and breathing life form-who produces copies of the station’s organisms by scanning their cerebral cortex. Finally, after scanning him, Solaris stops sending new probes as Kelvin’s old love takes action to self-eradicate.

Solaris ocean metaphorizes a mirror of humanity. It’s anonymous and a source of mystery, as if it were a materialization of the Hegelian “otherness.” So, Tarkovsky asks, do we, as humans, need an external space of meaning (like the universe we sought to understand, albeit vainly), when we are faced with an otherness that is essentially a reflection of our own-an otherness before which all artificial symbolic systems hitherto lose efficacy? There is this quote from Kelvin in the movie:

“...In this case, mediocrities and geniuses are equally worthless. We don’t have as much interest in exploring the universe as in stretching the earth’s frontier into its infinity; we don’t know how to deal with other worlds; we don’t need other worlds; we need a mirror. We strive for contact, but we never actually do. We are trapped in a stupid human situation, struggling for a goal he fears, struggling for a world he does not need. Humans need humans.”29

Solaris is an allegory of human introspection/consciousness that retains consistency outside the space of scientific imagination. For Tarkovsky, technology, let alone techno-nationalism is a nuisance as it denotes all the wrongs of modernity, a symbolic system already under decay. Mankind doesn’t need other worlds/symbolic dimensions to verify its existence from the exterior. And that “humans need humans” certainly doesn’t mean social connections, but a look inward, or a quest for truth through one’s subjective, ontological self. As one may have guessed, Tarkovsky was a fierce critic of socialist realism, not simply because it’s an autocratic power discourse, but because it repeats a kind of pseudo-objectivity. After all, in conceiving any symbolic dimension, one must acknowledge his anthropocentric position since he’s human and cannot contemplate beyond himself.

29 Solaris (Milano: Twentieth century fox home entertainment, 2003). P22-P23 https://ourculturemag.com/2019/07/12/thoughts-on-film-solaris-1972/.

Endnotes

1. “A Soviet Vision of the Future: The Legacy and Influence of Tekhikia – Molodezhi Magazine.” It’s Nice That, May 18, 2017. https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/tekinkia-molodezhi-russian-sci-fi-barbican-into-the-unknown-160517.

2. Dobrenko, Evgeniĭ Aleksandrovich. 2007. PoliticalEconomyofSocialistRealism. Yale University Press.

3. Foucault, Michel, and Alan Sheridan. DisciplineandPunish:TheBirthofthePrison. London: Penguin Classics, 2020.

4. Gellner, Ernest, and John Breuilly. Nations and Nationalism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2013.

5. Groys, Boris. ThetotalartofStalinism:Avant-garde,aestheticdictatorship,andbeyond. London: Verso Books, 1992.

6. Hobsbawm, E.J. Nations and Nationalism. Cambridge: Cambrdige University Press, 1991.

7. James, C. Vaughan. 1973. SovietSocialistRealism:OriginsandTheory. Springer.

8. Kang, David, and David Segal. n.d. “The Siren Song of Technonationalism.” Accessed April 8, 2023. http://www.esocialsciences.org/Articles/show_Article.aspx?qs=bGp0Ut9EHmCw/EpGtd/ DaLZRIw3TQoQPEnk8KyXd9n4=.

9. Low, Morris. n.d. “Displaying the Future: Techno-nationalism and the Rise of the Consumer in Postwar Japan: History and Technology: Vol 19, No 3.” Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0734151032000123945.

10. Lunacharsky, Anatoly Vasilievich. OnLiteratureandArtbyAnatolyLunacharsky. Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1965.

11. Luo, Yadong. 2022. “Illusions of Techno-Nationalism.” Journal of International Business Studies 53 (3): 550–67. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00468-5.

12. Mayakovsky, Vladimir. “Our March.” The poems of Vladimir Mayakovsky. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/mayakovsky/1917/our-march.htm.

13. Mende, Doreen. 2020. “The Time Lag of Defa-Futurum: A Socialist Cine-Futurism from East Germany.” In The Oxford Handbook of Communist Visual Cultures, edited by Aga Skrodzka, Xiaoning Lu, and Katarzyna Marciniak, 0. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190885533.013.11.

14. Miremadi, Tahereh. 2014. “The Role of Discourse of Techno-Nationalism and Social Entrepreneurship in the Process of Development of New Technology: A Case Study of Stem Cell Research and Therapy in Iran.” Iranian Studies 47 (1): 1–20.

15. Observer.com. “Socialist science fiction universe! The full version of “China 2098” is released.” Socialist science fiction universe! The full version of “China 2098” released | China_Sina News, April 29, 2022. https://k.sina.com.cn/article_1887344341_707e96d5020018z9h.html#/.

16. O’G, Anderson Benedict R. Imaginedcommunities:Reflectionsontheoriginandspreadofnationalism. London: Verso, 2016.

17. Petrov, Petre M. 2015. Automatic for the Masses: The Death of the Author and the Birth of Socialist Realism. University of Toronto Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt13x1qph.

18. Porton, Richard. “How a Soviet Experiment Became the Most Controversial Film in Years.” The Daily Beast, June 7, 2020. https://www.thedailybeast.com/inside-the-weird-world-of-dau-a-soviet-experiment-that-became-the-most-controversial-film-in-years.

19. Reich, Robert B. 1987. “The Rise of Techno-Nationalism.” The Atlantic. May 1, 1987. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1987/05/the-rise-of-techno-nationalism/665772/.

20. Solaris. Milano: Twentieth century fox home entertainment, 2003.

21. Spiegel, Simon. 2021. “Films for the Future: The Zukunftsfilme by Defa-Futurum.” In Utopias in Nonfiction Film, edited by Simon Spiegel, 123–47. Palgrave Studies in Utopianism. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79823-9_6.

22. Sun, Lin. n.d. “Techno-Nationalism: Constructing Nationalist Imaginaries through Digital Activism in China.” Ph.D. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/ docview/2451098740/abstract/11848EA300C34D2APQ/1.

23. “Techno-Nationalism: Constructing Nationalist Imaginaries through Digital Activism in China - ProQuest.” n.d. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/ docview/2451098740?pq-origsite=summon.

24. ThePervert’sGuidetoIdeology: Parts 1, 2, 3. Roma: Internazionale, 2008.

25. Thinking World. “Patriotic Globalism, Conservative Future Imagination: Has Wandering Earth 2 Progressed?: Jiemian News.” jiemian. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://m.jiemian.com/article/8801560.html.

26. Zhang, Jun. Chinese techno-nationalism more than mere propaganda, 2022. https://doi.org/10.54377/94ee-51e0.