Generosity

Housing and Urbanism 2023-24

HU005 Design Workshop

Tutors:Lawrence Barth, Dominic Papa

Students: Yasmina Arafat, Sharan Goppenahalli, Xuechen Guo, Luz Magali

Ibarrola Aguilar, Xinyuan Ji, AthanasiaMarina Neochoriti, Almitra Roosevelt

Evolving Ways of Living as Drivers of Urban Transformation

Associational Living Through Generosity

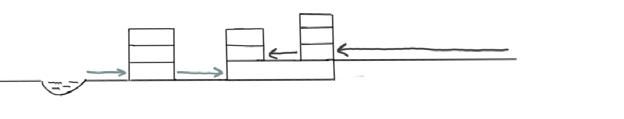

Indeterminacy

Privacy

Interactivity

Exteriority

Assemblage

Re-qualifying Primary Urban Elements

Transformative Value of Territorial Infrastructures

Dominating Structures as Collective Urban Accelerators

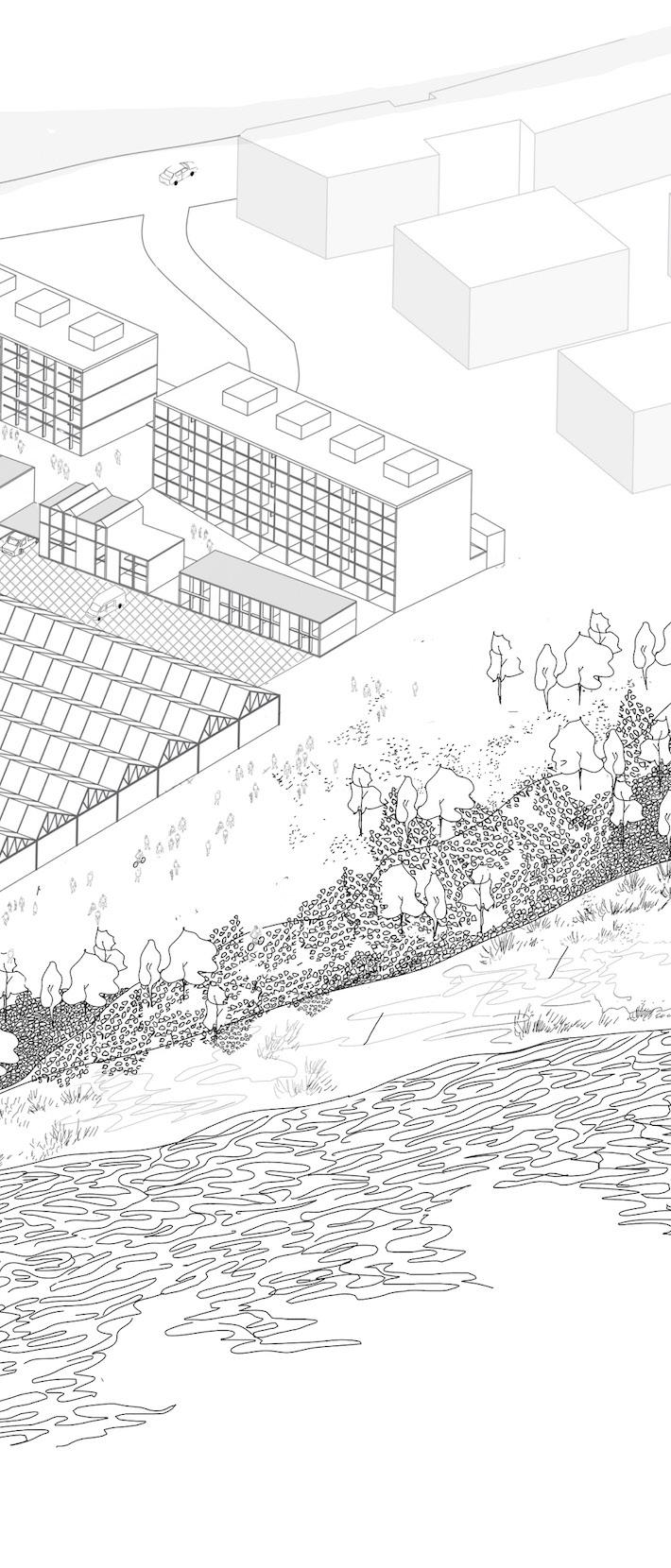

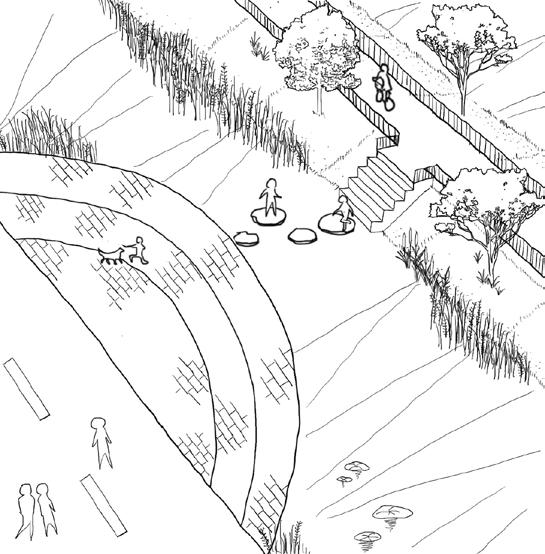

Waterfront, Wetlands and the Lea River System

The Railroads : Connectors and Disruptors

Blackhorse Lane and the Terraced Housing Blocks

Primary Urban Elements as Mobility Systems

Re-qualifying the Uplands

Resistance of the shed: Adaptability and Quality of space

Segmentation and Variation of linear type: Living and Working

Linear Blocks and the Definition of the Edge

Thickened Ground & Layered Movement: Active Civic Life

Exploring Linearity as a Threshold

Form as a Means of Connecting

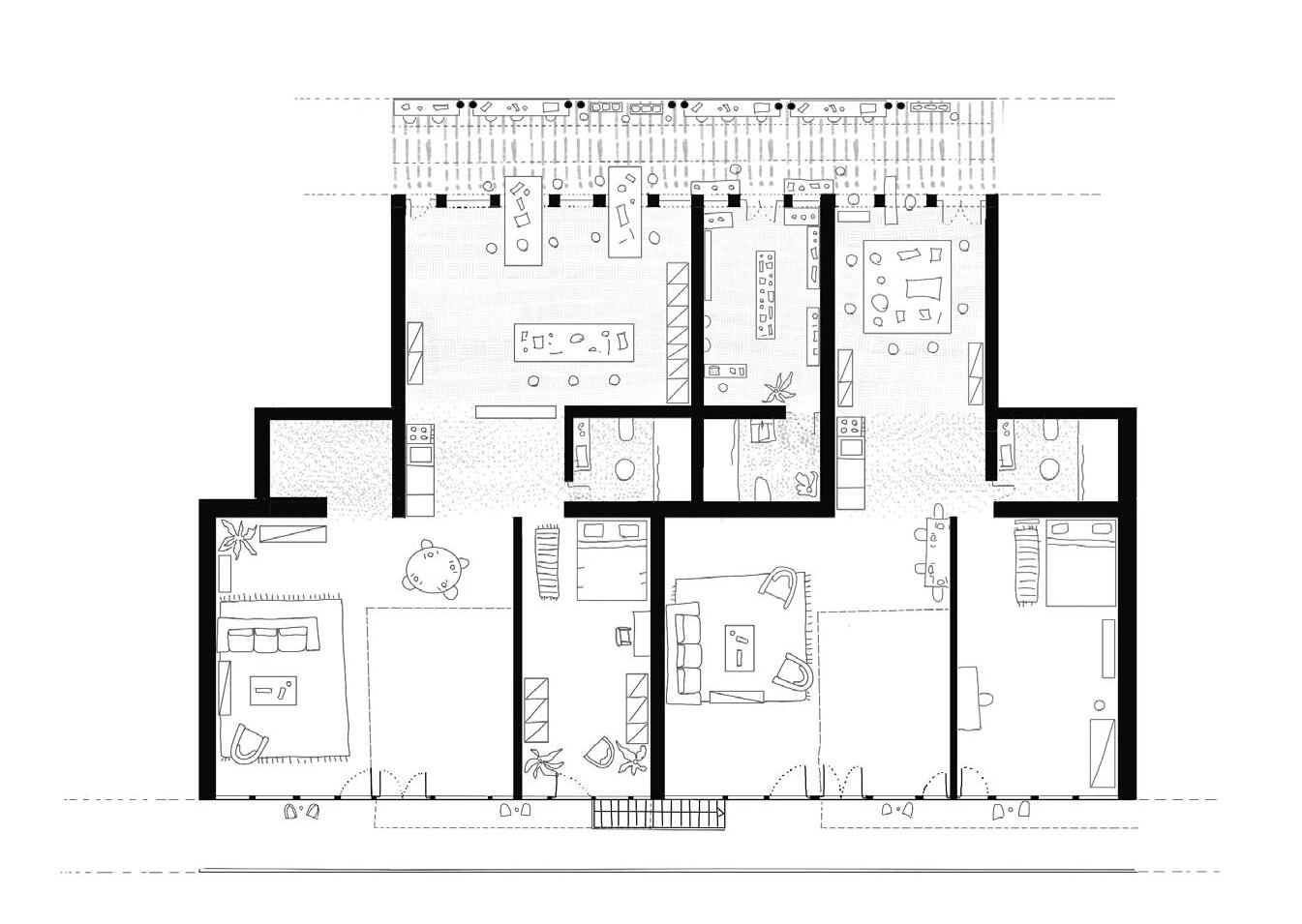

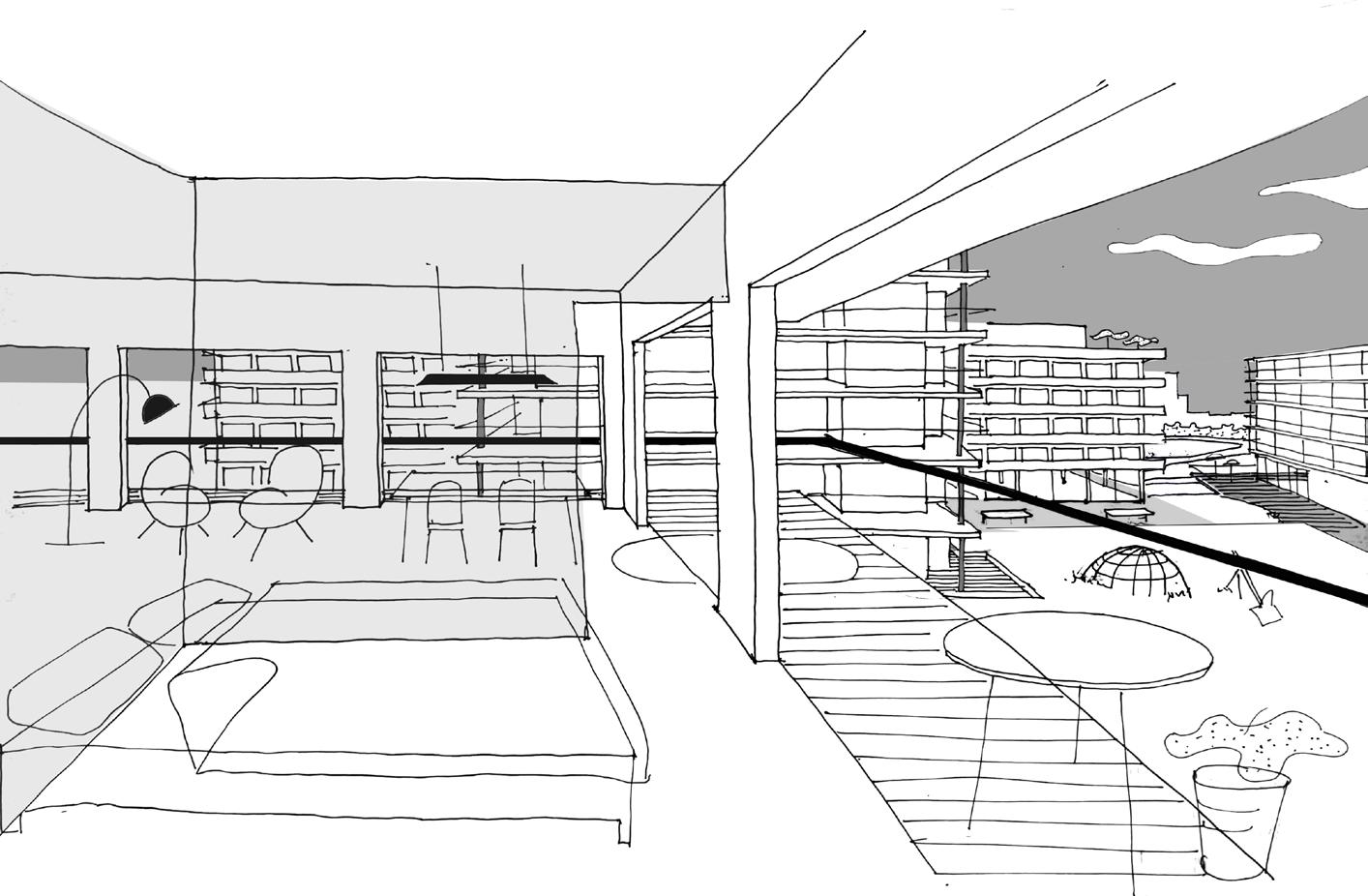

Same Volume- Different Uses: Accommodating Living and Working Separately Working and Living Brought Together: Generous Spaces Extending to the Exterior The Ateliers: Sharing Workshop Spaces with your Neighbours

The Extensive Gallery: When exteriority Accommodates Working Life

Structuring a Fluid Ground

Re-imagining the Periphery from the Inside Out

City Villa: One Type, Multiple Roles

Generating Civic Life Through Variation

Topography as a medium of differentiation

Re-qualifying the Existing

An Inventive Approach Towards the Perimeter Block Connecting to the Wetlands

Introducing collective spaces

Achieving Urban integration

The waterfront as a unifying factor

Reinventing the street as an extended surface

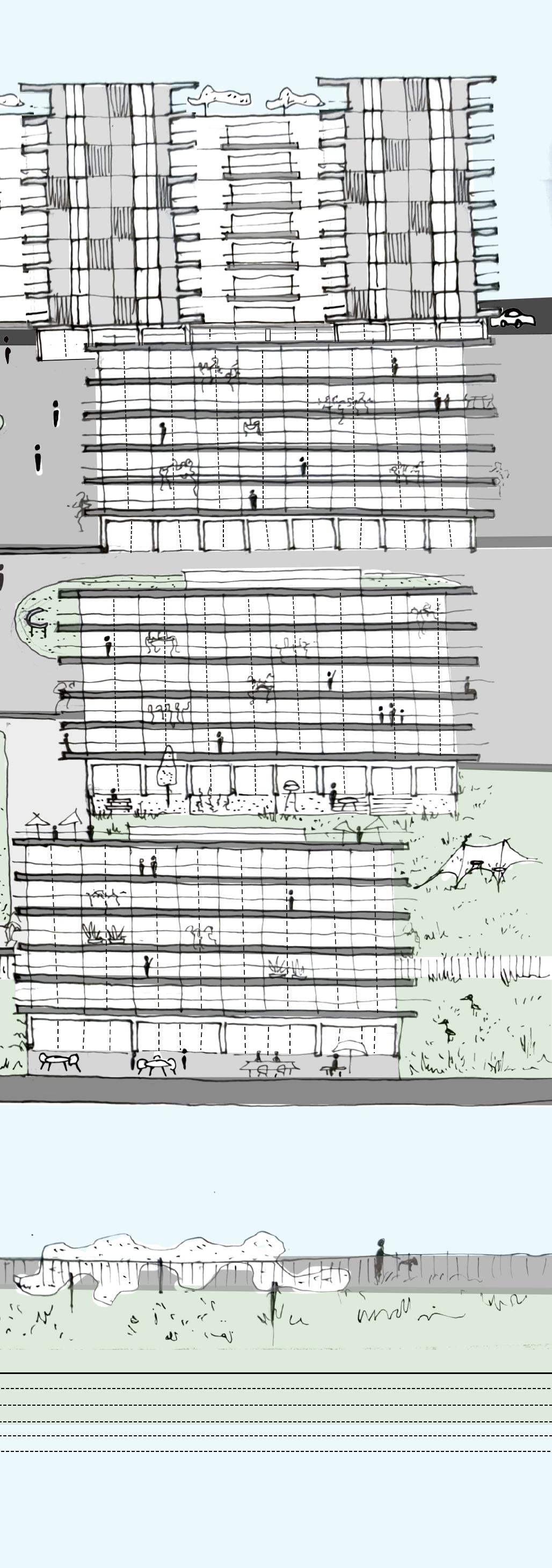

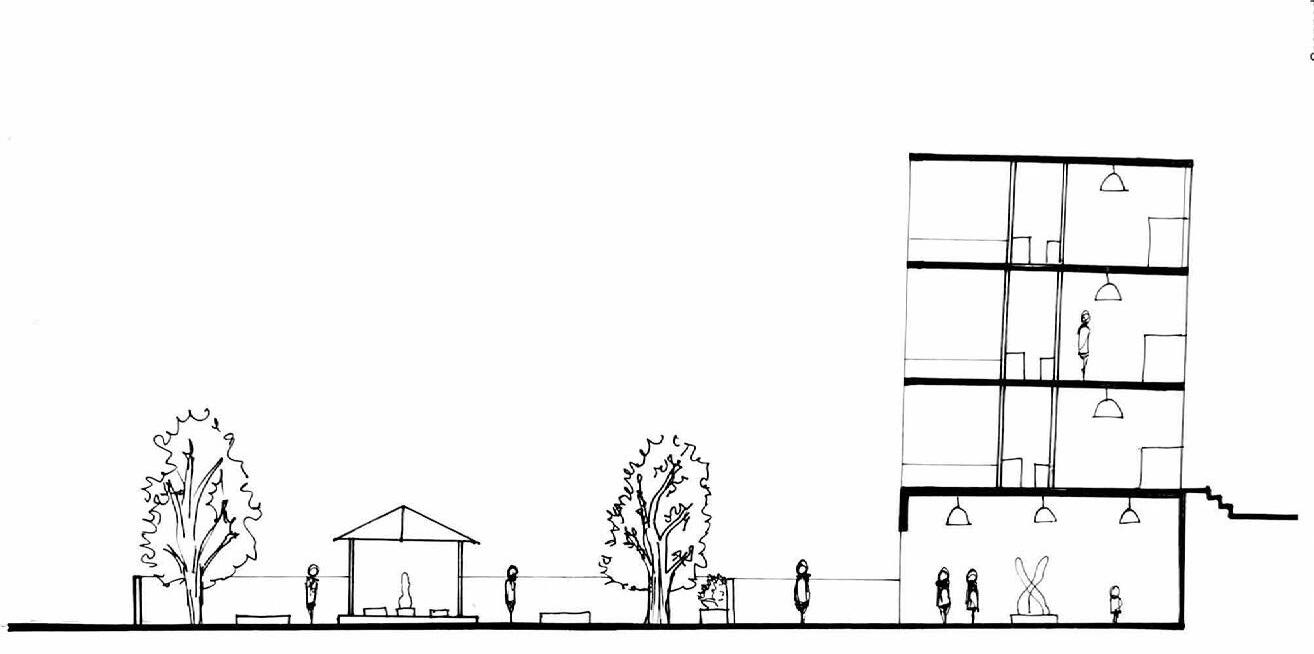

Generosity and Opportunity Explored through the Elevation

Housing +

Integration of living and working in a single environment, Kolner Brett

Housing as a place of civic interaction, House for Artists

I. Evolving Ways of Living as Drivers of Urban Transformation

Housing typology has been the seat of an incredible amount of innovation and change in recent years. These innovation are a direct response to emerging ways of living that demand a complete rethinking of housing from the inside out. One such primary driver is the increasing impulse for living environments that can support a range of working conditions. For instance, the Kolner Brett, a linear housing building in Germany allows professionals to live and work in the same unit through its generous dimensions and sectional segregation. The House for Artists in London provides housing for Artists where they could live, work and associate, both amongst each other and with the neighbourhood through

a range of civic activities facilitated by its transparent and generously dimensioned ground floor. Housing thus becomes the generator of civic life.

One can also observe the emergence of a range of innovative types that respond to emerging ways of collective living. Take for instance, the La Borda, a co-operative housing in Barcelona. The typological response of an indeterminate structure with an atrium, collective spaces and galleries support shared ways of living and fosters a strong sense of neighbourliness through which one can begin to re imagine the urban realm.

Collective Living, La Borda

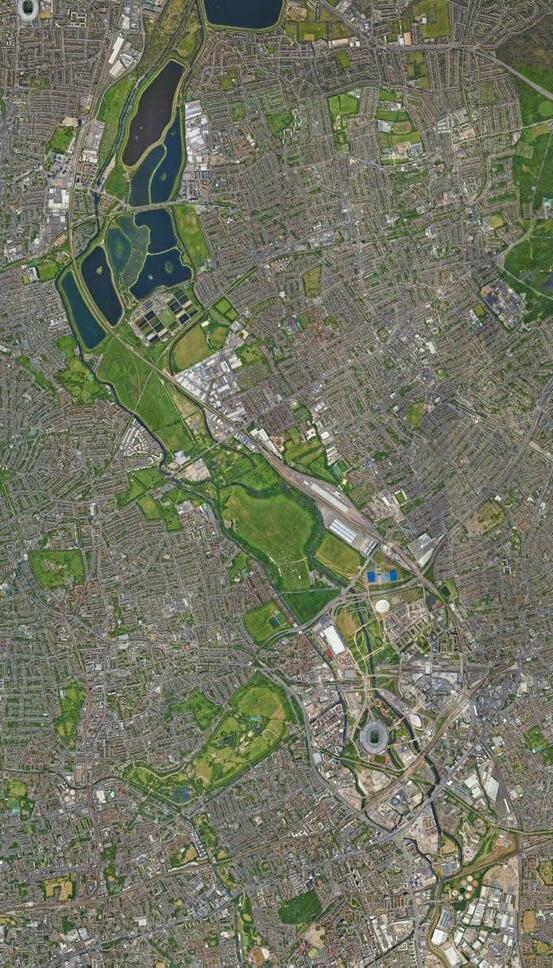

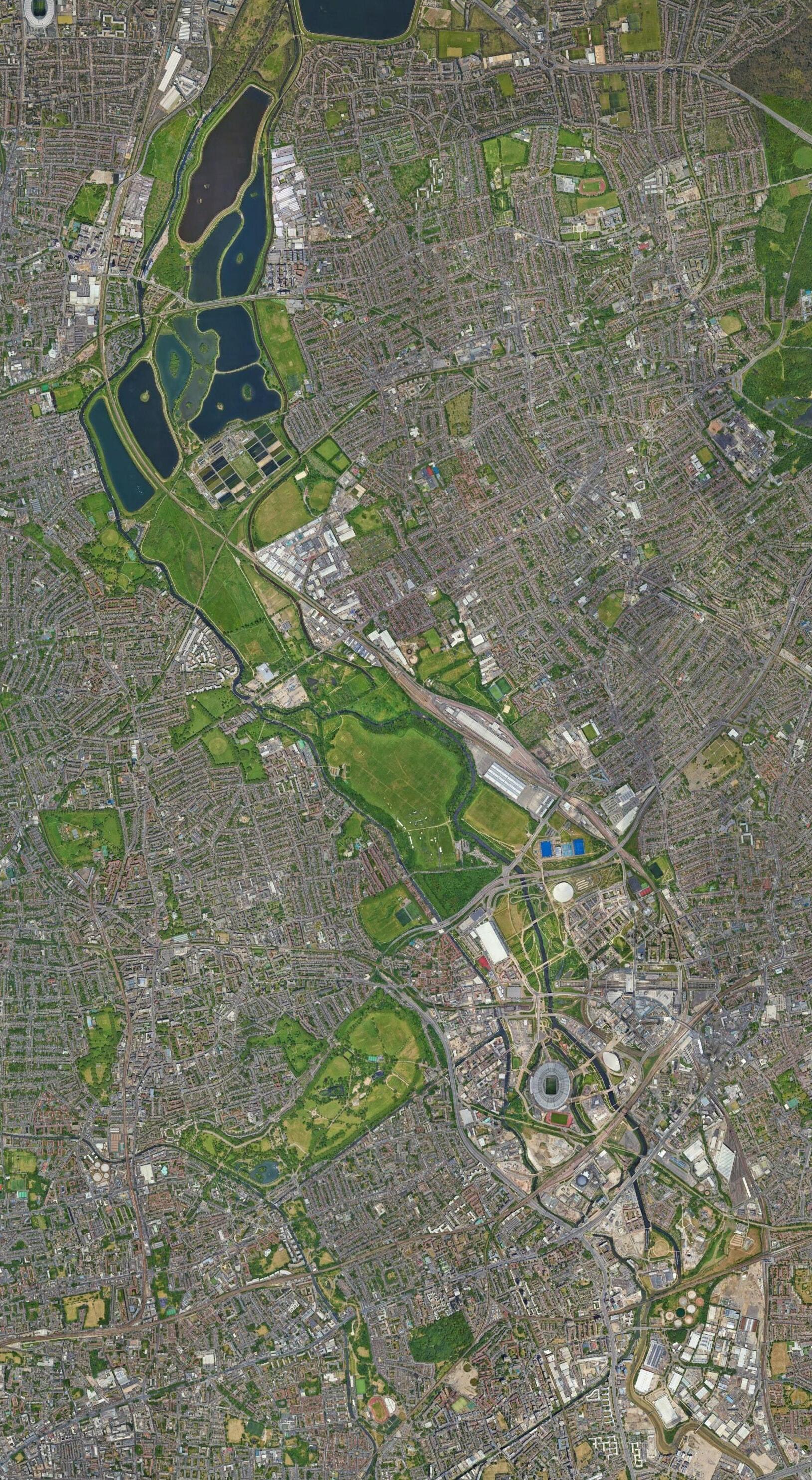

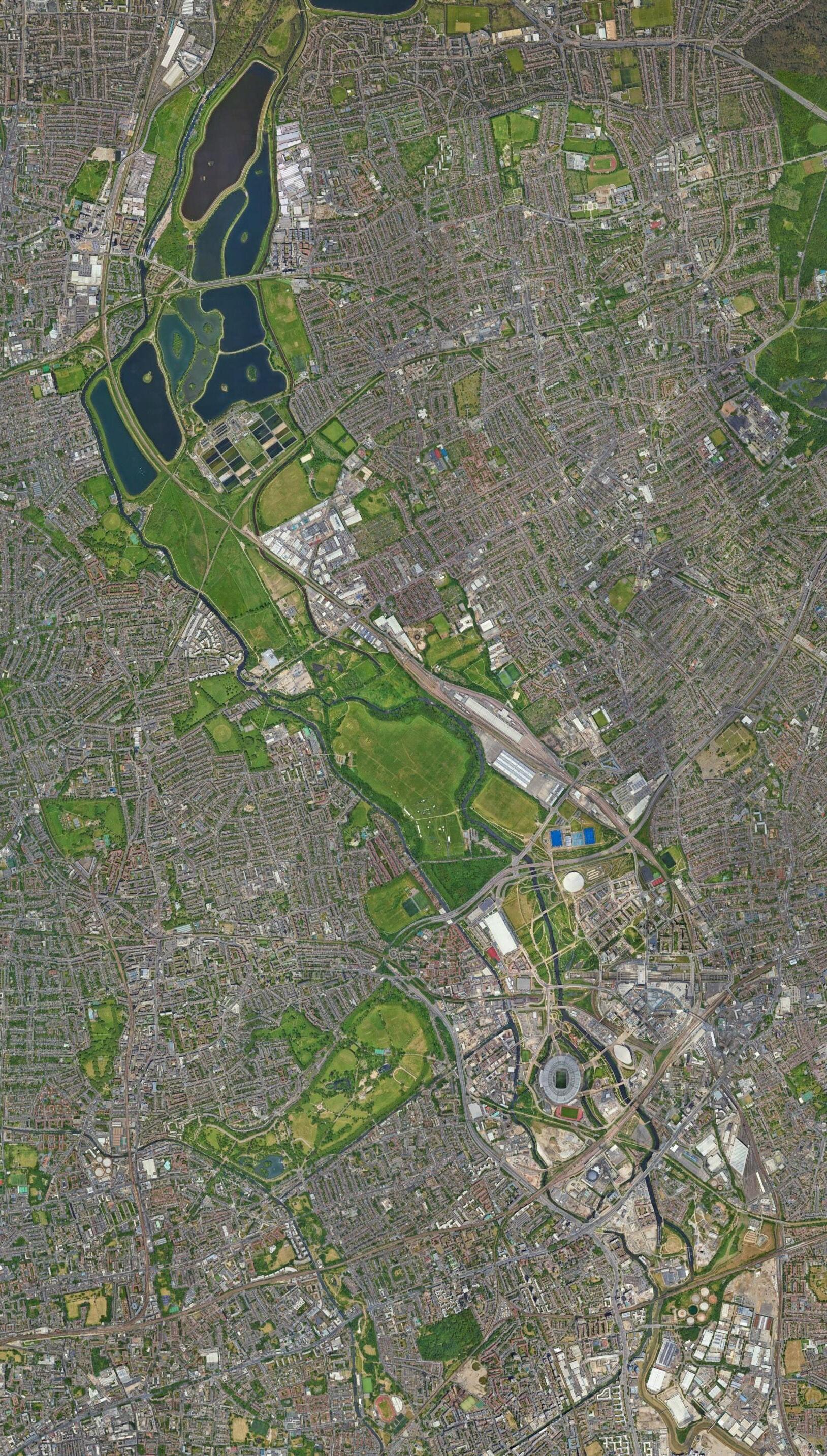

The Lee Valley as an opportunity area

Emerging creative industry in Lee Valley

A lost opportunity : The emerging high density developments along Blackhorse Lane

A large portion of our cities and urban areas is composed of housing and one could potentially rethink developmental models for urban areas that are supposed to offer both housing and employment through such innovative housing typologies that have the potential to offer much more than housing.

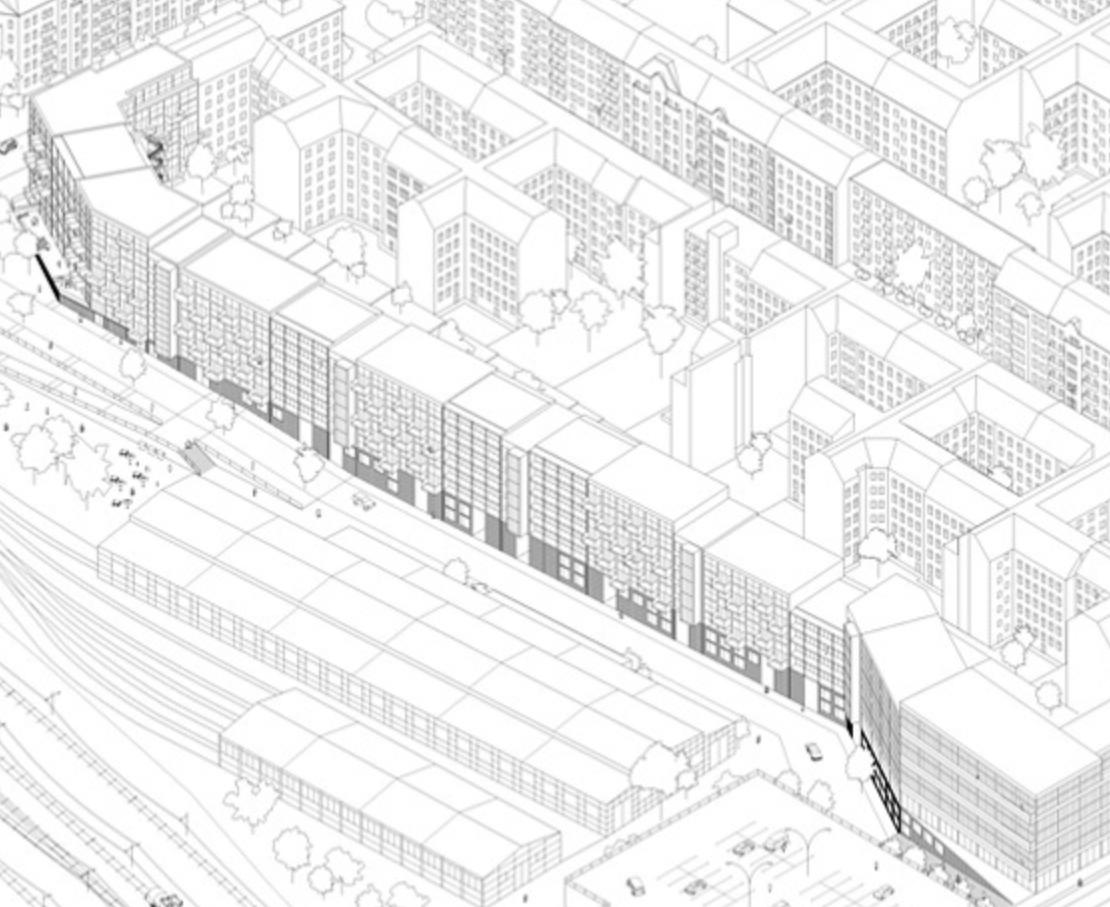

Consider for instance, the Lee Valley. The Lee Valley forms a distinctly recognisable urban armature in the fabric of London. It is dotted by industrial areas that are beginning to support a range of light creative industries and small businesses as opposed to the formerly heavy industrial uses. The sheer volume and diversity of blue- green infrastructure also adds to its distinctiveness. The blue green infrastructure and the industrial areas create a powerful break in the monotonous inner peripheral fabric of terraced hous-

ing. This rapidly transforming armature is increasingly viewed by the city of London as an opportunity area that can support both the employment and housing needs of London city. As a result one can see a great intensity of development along the Lee Valley, that stems from the Olympic Park and extends north up to areas like Blackhorse Lane and Tottenham Court Road.

The emerging developments are predicated on quantity and offer high density housing that fulfils the need. They follow the prevailing norm of perimeter blocks that one observed throughout London. In doing so , the developments fail to capitalise on the opportunities offered by the distinctiveness of the Lea Valley. Neither do they respond to the emerging ways of living along the Lee.

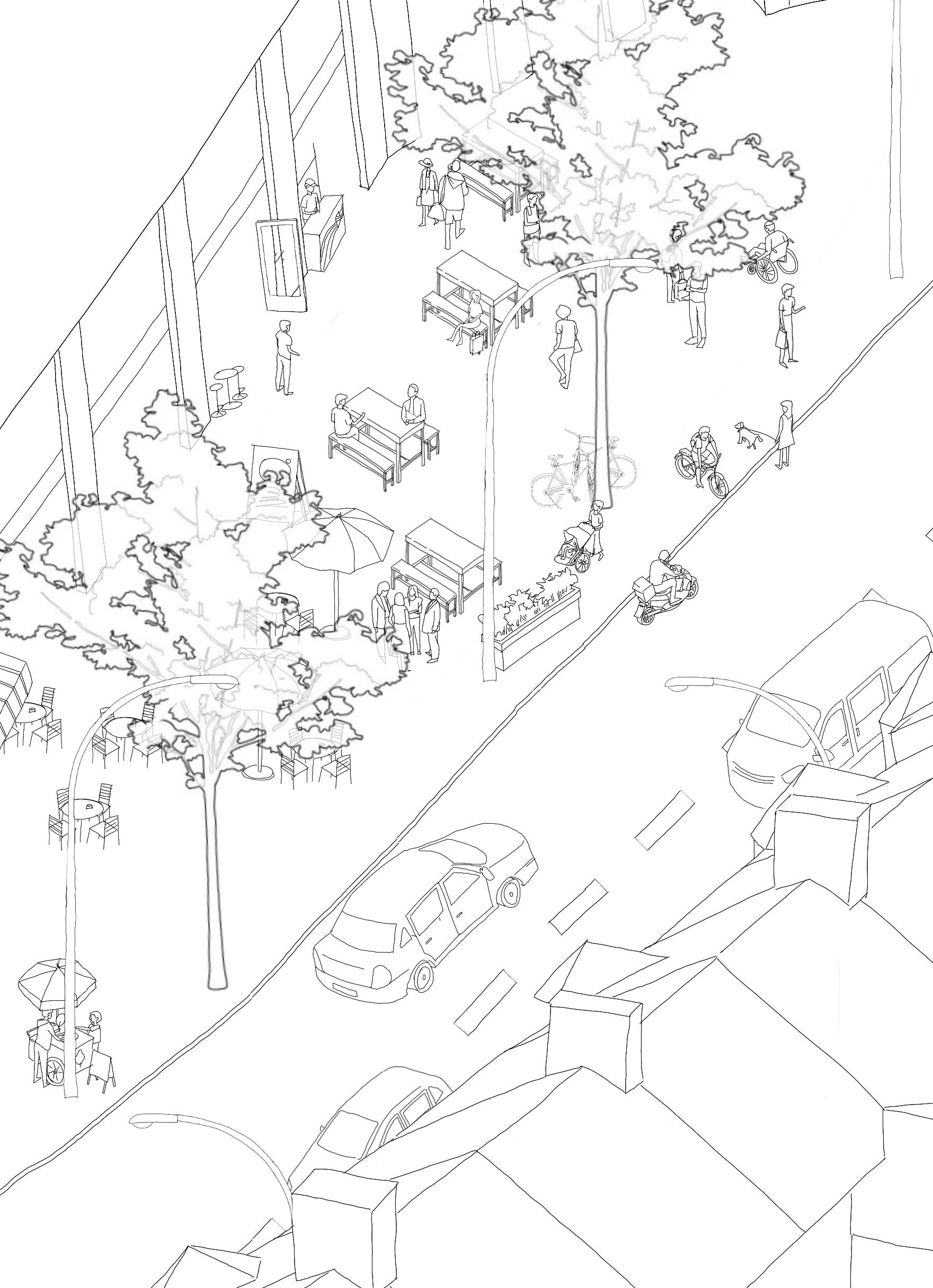

Emerging Craft and Culinary industries generating a rich public and civic space along Blackhorse Lane

Waterfront as both a mobility system and public realm,

A strong interrelationship between form and landscape, King’s Cross

Lea Valley as a place for leisure and biodiversity

King’s Cross

One could potentially conceive a completely different alternative, one that is informed by evolving ways of living and the resulting typological innovations in housing. Housing types that offer hybrid environments for working and living could capitalize on the emerging creative industry and offer the possibility of structuring a rich civic realm.

In addition, one could also build on the emerging trends of an expanded and biodiverse waterfront. But rather that just a mono functional green buffer, one could imagine a completely different landscape based on relationships between housing and the water that emerge from the inside out. The waterfront itself could potentially be a rich public and civic realm through the relationship between housing and the increased active mobility. The King’s Cross is a perfect case in

point that demonstrates the potential of the waterfront to act as a rich public and civic realm through the interaction of form and mobility.

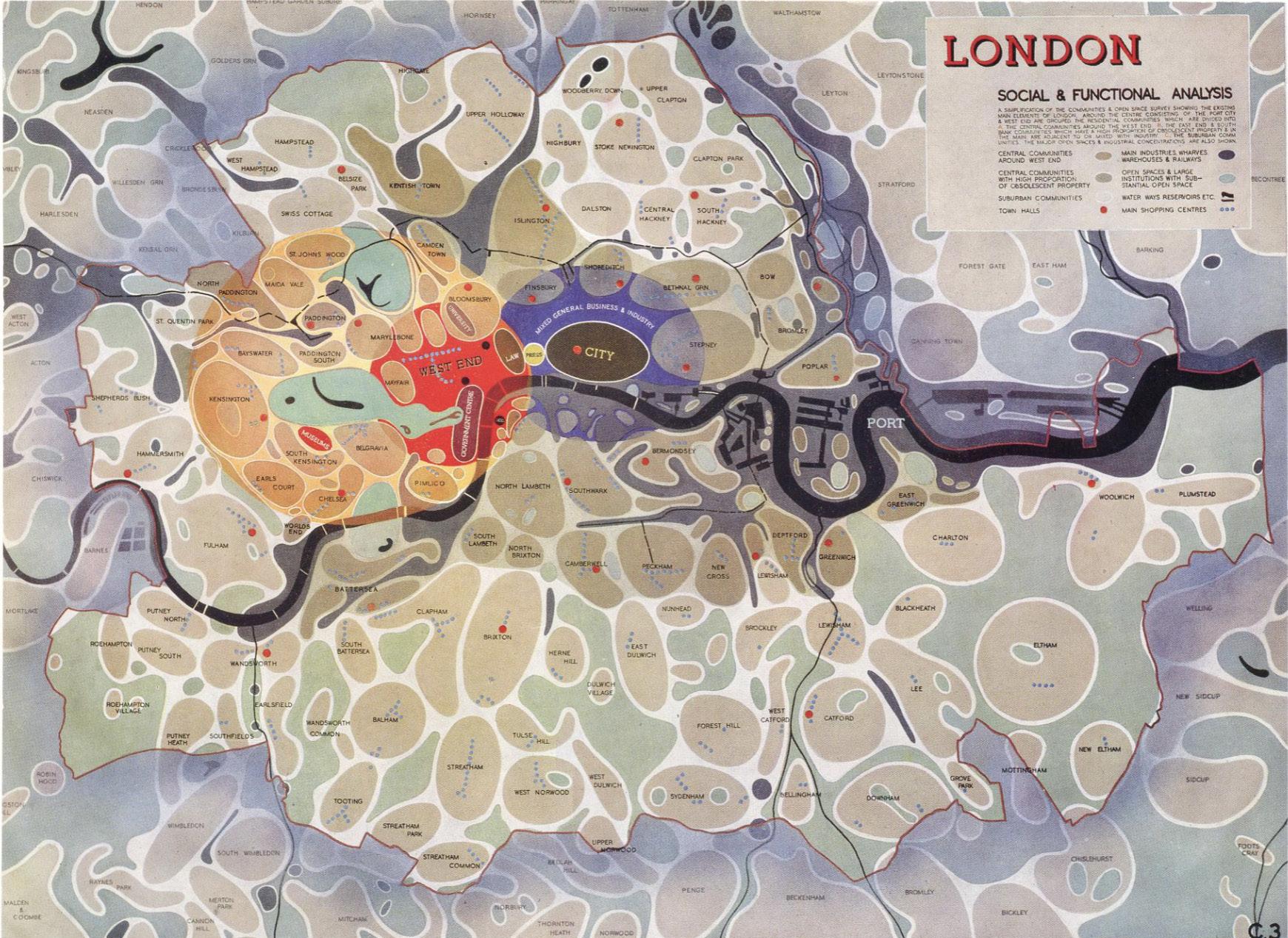

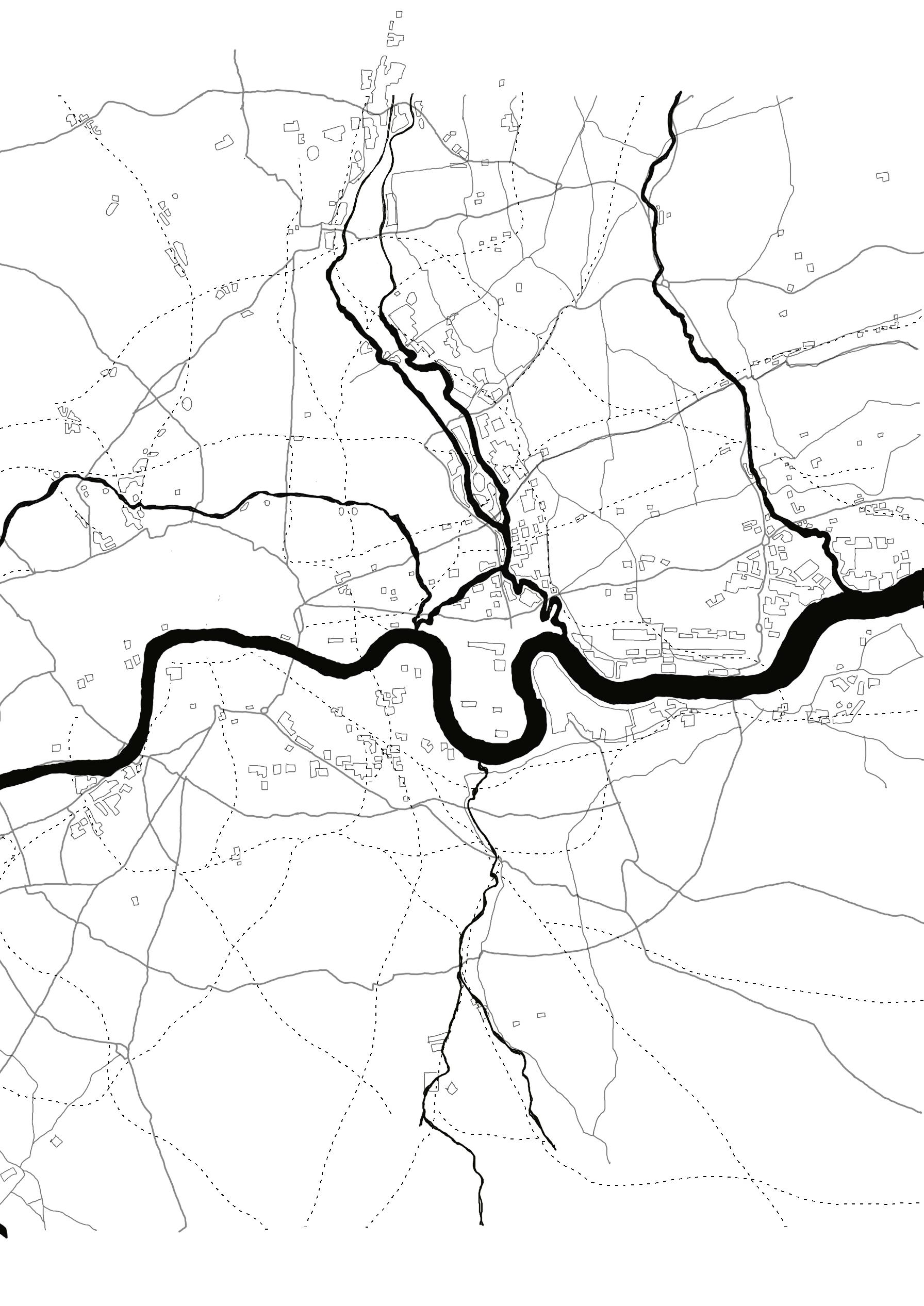

An increased active mobility and a civic realm that both structures mobility and feeds off it is of particular importance to a city like London. The Abercrombie Plan illustrates London as a poly-centric city composed of a collection of villages. A poly-centric network of public transportation system and urban centres coupled with intensive active mobility builds on London’s inherent morphology and helps create capacity and efficiency in the functioning of the city. New housing typologies can potentially become crucial in structuring these relationships that could create new active centres for the city of London.

London as a poly-centric aggregation of villages, The Abercrombie Plan of London

II. Associational Living Through Generosity

The narrative of collective housing and the search for new typologies have been shaped by the imperative to provide adequate housing for all, often driven by the demands and needs of society. One of the aspects of collective housing usually forgotten, as Anne Lacaton and Jean-Phillipe Vassal01 remind us, is the quality of housing and the need for ‘extraordinary’ attitude towards the transformation of cities through it since the urban unit of measure is housing. Thus vigorously dismissing the notion of housing as a “financial product” associated with social and financial classifications in order to match supply and need is what might be required to steer the narrative of collective dwelling and city building to qualitative well-being and associational living. According to them, the living space must be generous, comfortable, easily

appropriated, economical, fluid, flexible, bright, scalable, “luxurious” even.

Elucidating on this further, A+T magazine, in its series of publications on ‘Generosity’, define certain aspects essential for collective living that “transform the conditions of the built volume and make it liveable, generating comfort and wellbeing”. These strategies are grouped in four sections as Indeterminacy, Exteriority, Privacy and Interactivity strategies. These strategies work in congruence with one another to enhance flexibility in use, promote interaction between residents and improve the relationship with the surrounding whilst preserving the sanctity of one’s private dwelling.

01 Anne Lacaton, Jean-Philippe Vassal “The City from and by Housing” in a+t 45 Design Techniques. SOLID Harvard GSD Series, a+t architecture publishers, 2015. Pp 56-61.

Collective life in Mehr als Wohnen

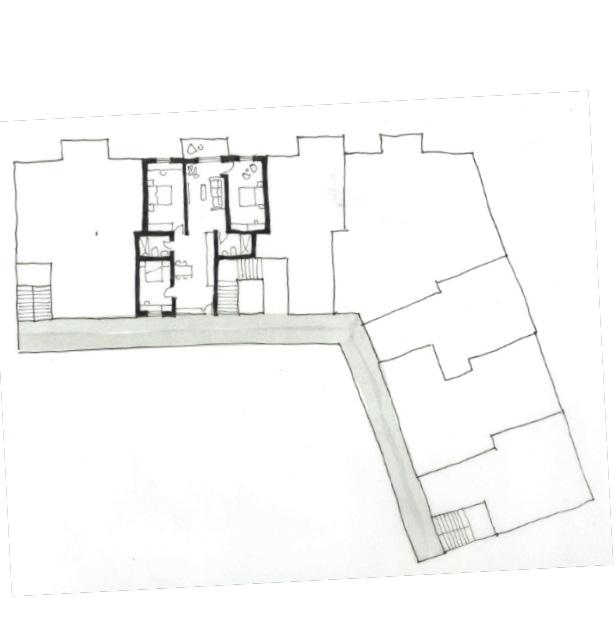

The house for artists by Apparata is a building that successfully combines living and working for a group of 14 artists. It encapsulates the aspects of generosity previously mentioned to foster interaction between the artists and also between the artists and the neighbourhood. The plan allows for various configurations of spaces and therefore enables multiple ways of living and associating – both within the flat and between the flats. The same space could potentially support multiple uses.

Associational life at the House for artists, Apparata

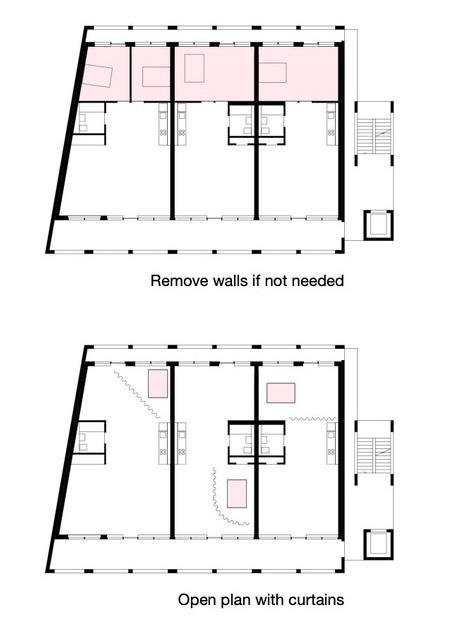

Indeterminacy

The plan of the House for Artists allows for various configurations of spaces and therefore enables multiple ways of living both within the flat and between the flats One floor of apartments has double doors in the party walls, creating optional and flexible shared living possibilities, such as parties, childcare, or co-working. Residents are invited to add to and adapt their apartments during their tenancy, removing or adding walls to meet their needs. Fundamentally, indeterminacy goes against the specialisation of space. In the post-pandemic times, the necessity of ease for working from one’s home has challenged the typical idea of a dwelling. And our increasingly diverse and changing

The indeterminacy and flexibility offered at the

ways of living calls for a re-imagination of housing as well. Charles Eames reflects on this in his article “What is a house?” by outlining the unexpected activities that he would like to carry out in a house such as “playing music, dancing, playing cowboys and indians, working out, playing cards, reading, projecting films, resting, flirting on a sofa, playing with planes, all should be possible…” Thus a structure that is robust and allows for adaptability and flexibility over time as needs arise, where one can work, cook, becomes highly favourable.

Such flexibility can be attained through a range of approaches. For example, in KNSM, the flexibility is achieved by making

House for Artists

the bedrooms generous in its dimensions thus allowing it to do more. But perhaps this attitude towards non-hierarchical spaces might be reductive in the range of qualities offered. In Unité(s) Experimental Housing by Sophie Delhay, it is attained through the repetition of an optimal size that can house multiple functions where housing is considered as a “collection of identical size, freely networked, without hierarchy and without assignment, leads to an emancipated vision of living and human relationships”. This in turn raises the question of whether there can be an optimal size at all. Likewise, in La Borda every unit has an opportunity to adapt two

similar rooms that are flexible in use by adding or eliminating partitions.

In the house for artists, the flexibility that it offers is reinforced by the dual gallery providing accessibility to the flat from both the ends and dissolves hierarchy enabling all spaces to be equally important in theory. However through the slight variation in the depth of the gallery, nuanced hierarchy is created. Though functions could be interchanged, particular activities that are more social tend to cluster along the deeper gallery as opposed to more private activities reserved for the other alternative route.

KNSM

La Borda

House for artists

Privacy

As seen in the house for artists, architectural refinement and the subtle characterization of spaces can serve as effective tools of negotiation between private and shared domains. Even with the same architectural element, in this case a gallery, depending on the way of life intended the architectural articulation changes. For example, in Kolner Brett, the gallery is separated from the units suggesting a way of life where collective interaction exists but one can choose to participate or not. And alternatively, in Bruchner Bründler housing in Basel , the sheer of the walls in the plan of the units allows one to benefit from the extended space of the gallery as one’s own living, cooking, dining or working space without the compromise of revealing the interiority of own private dwelling to all the passersby. The degree to which one’s privacy is compromised to benefit from a shared

collectivity varies across projects. A house is fundamentally understood as an individual or a family’s protected environment which facilitates tranquillity, privacy, withdrawal and concentration. As Christopher Alexander emphasises, “an urban anatomy must provide special domains for all degrees of privacy and all degrees of community living, ranging from the most intimately private to the most intensely communal. To separate these domains and yet allow their interaction, entirely new physical elements must be inserted between them”. There is thus created a hierarchy of domains and strategies of negotiation. At the same time, these gradual thresholds become opportunities to socialise, zones of miscellaneous activities and spaces that break away from mundane spatiality indifferent to their interior-exterior duality.

The separated gallery at Kolner Bret

The sheer of walls in Bruchner Bründler

Interactivity

The thresholds of private-shared duality such as corridors, galleries, staircases, front and back yards have commonly been treated as mere elements of functional connectivity prescribed by the minimum standards and regulations. But the recognition of such space to act beyond that to create spontaneous association amongst its residents have led

to different interpretations of such spaces. In Wohnprojekt, the staggered cut-outs in the floor plates create visual interaction between various levels of the circulatory spine. In IBEB, the corridor or ‘rue interior’ is naturally well-lit by a series of courts and is generous in dimension to facilitate common gathering that can transform it into an event space. In Machu Picchu

by Sophie Delhay, the kitchen is placed adjacent to the gallery that brings the most active part of everyday life to the perimeter of the dwelling while the private spaces are pulled into the depths of the plan.

A program is a determinate set of expected occurrences, a list of required utilities, often based on social behaviour, habit, or custom. In contrast, events occur as an indeterminate

set of unexpected outcomes. Events foster unprecedented bonds amongst people and thus the relationships between inside and outside become critical.

The thresholds becoming areas of potential interaction. From left to right, the rue interior of IBEB, Machu Pichu and Wohnprojekt

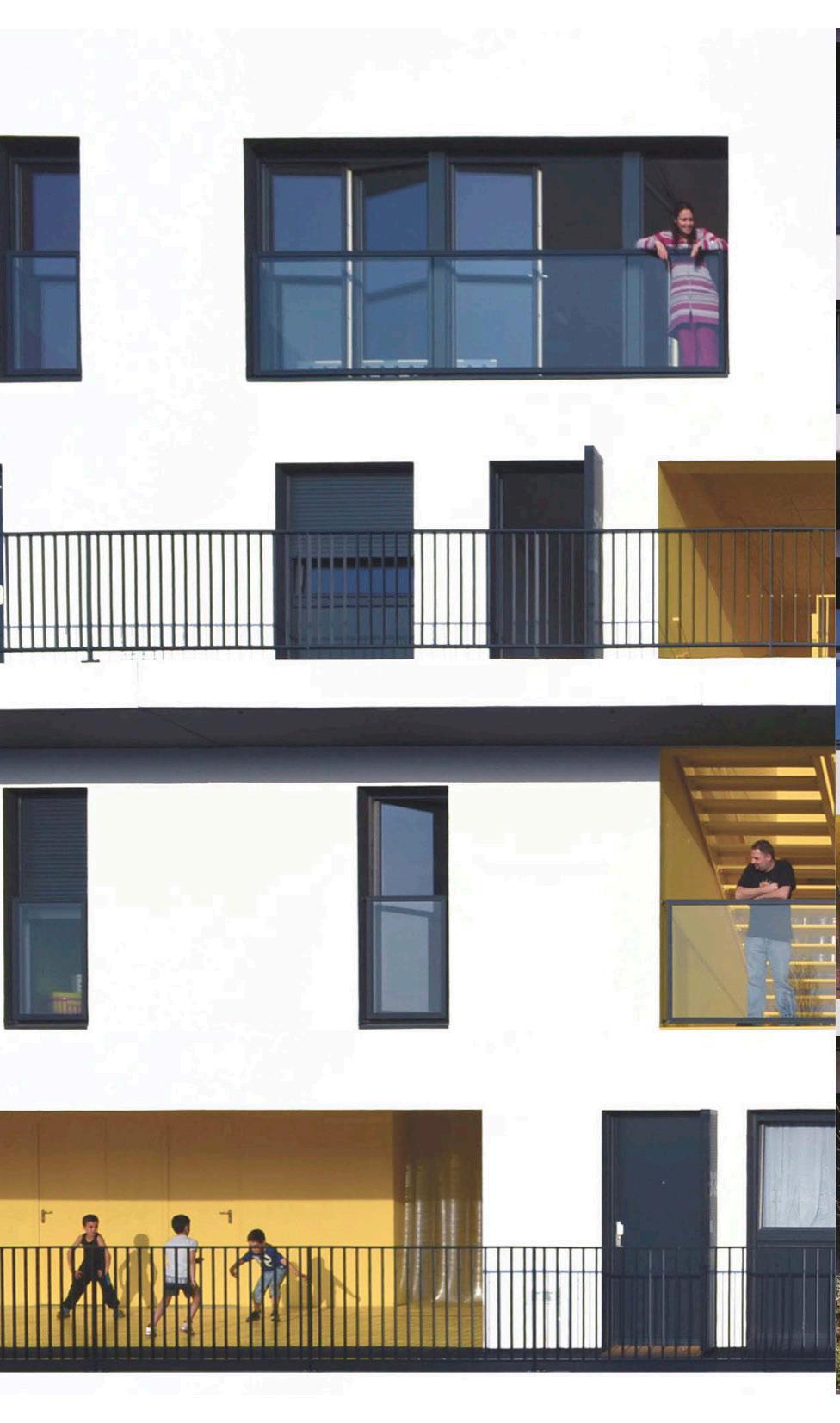

Exteriority

The relationship between the enclosure and the support has changed throughout different paradigms to an extent that Le Corbusier wrote that “the history of the window is also the history of architecture”. The exteriority of the dwelling enables its residents to enjoy daylight, space and vegetation. Achieving generosity in

collective dwelling is thus concerned with the creation of a livable domain outside the envelope of a building and improving the relationship with the surrounding. Such as in the case of Wohnprojekt, the generous balconies that overlook each other serve as another living domain where one can pursue interests such as gardening, pottery,

The extension of the dwelling into the exterior at Lacaton and Vassal’s housing project in Bordeaux, France

etc. and also facilitate interactivity amidst the neighbours. Whereas in Lacaton and Vassal, the addition to the existing facade serves as an extension of the dwelling space in itself demarcated by the belongings of each household. The three-dimensionality of the envelope facilitates the construction of liveable spaces within a thick facade. A ‘generous’ house, through all its aspects, cultivates neighbourliness and mutual respect amongst the people by encouraging a sense of togetherness.

However, how much more fruitful would it be if everyday conversations can lead to a potential creative collaboration, business opportunity, or pursuit of hobbies of similar interests. The relationships and associations become more enriching when work becomes part of living, and can start impacting change at a larger scale in the urban area.

Life at the balconies of Wohnprojekt

Association and Craftsmanship

Much like every other aspect of our lives, the notion of ‘work’ has also evolved through time and culture. There has been a shift in the way we work and it is no longer valued as a mere exchange of commodities based in large corporations subject to global economic and political trends but has made way for the emergence of small scale entrepreneurs, skill based creative industries and collaborative enterprises. They do not demand for large infrastructure

but are sometimes even run from the comfort of one’s home.

Imagine if one could practise music at one’s home, pursue their passion for gardening at the comfort of one’s backyard or balcony, or run a ceramic studio in their living room. When people with different expertise live collectively, it can open up a window to learn and teach a particular skill or craft, collaborate across different

Printmaking

Painting

Pottery

fields, invite the neighbourhood around by providing a place to convene thereby resulting in various scales of associations. Integration of work spaces into housing not only provides one with freedom with the way they live and work but also renders it affordable. The endless possibilities that blurring the boundaries between working and living bring about to our everyday lives driving the change in our idea of housing.

The modern day entrepreneur in a way is an atavism of the craftsman. In his book on ‘craftsmanship’, Richard Sennett states that all of us have an ‘enduring, basic human

impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake’. To him all skills even the most abstract begin as bodily practices and the duties when performed again and again cultivate the conduct of working independently and collectively. It is inherent to humans and commonly practised as long as relationship, community, and working together remains possible as he points out that “an ancient ideal in craftsmanship is the joined kill in community”.

Tie & Die

Gardening

Fashion designing

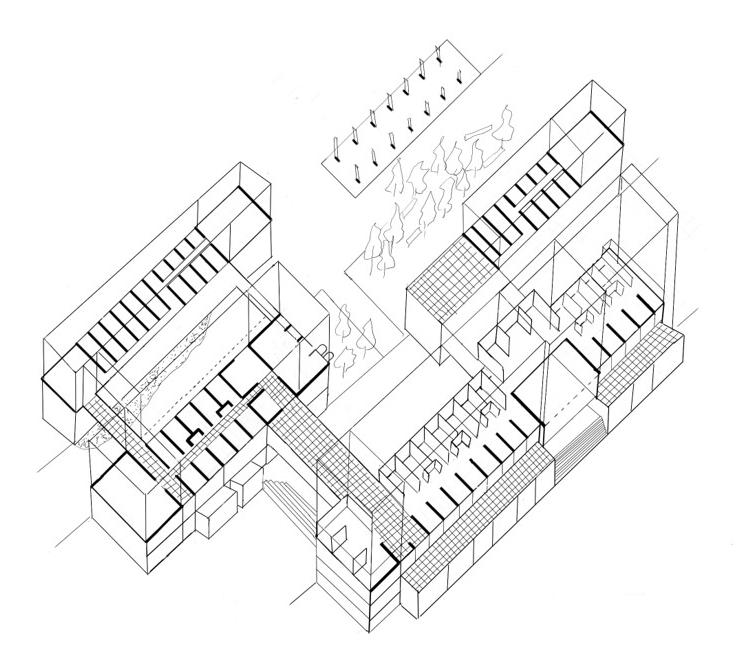

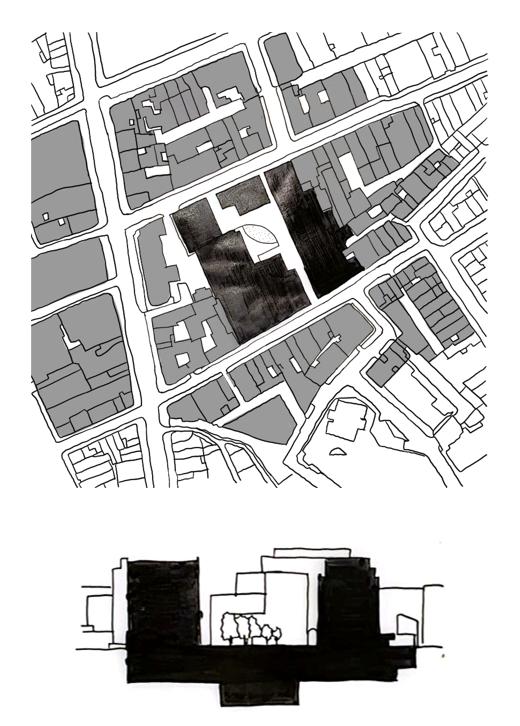

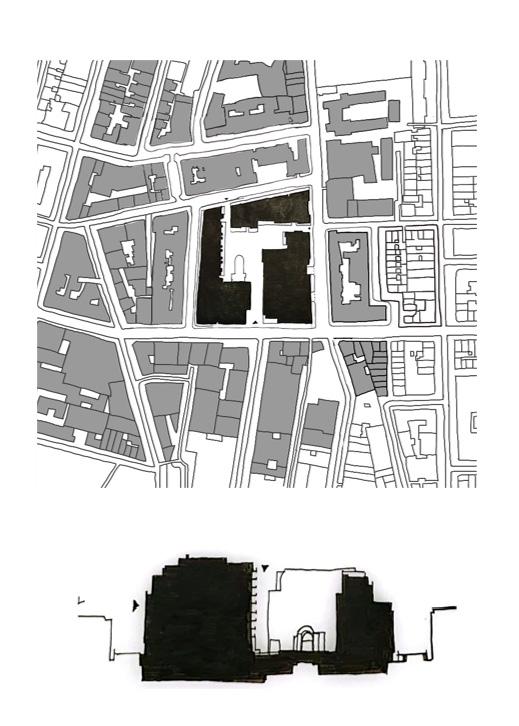

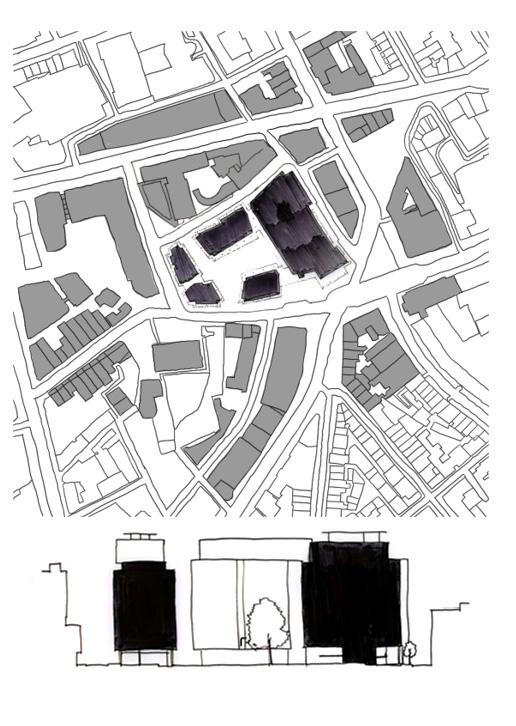

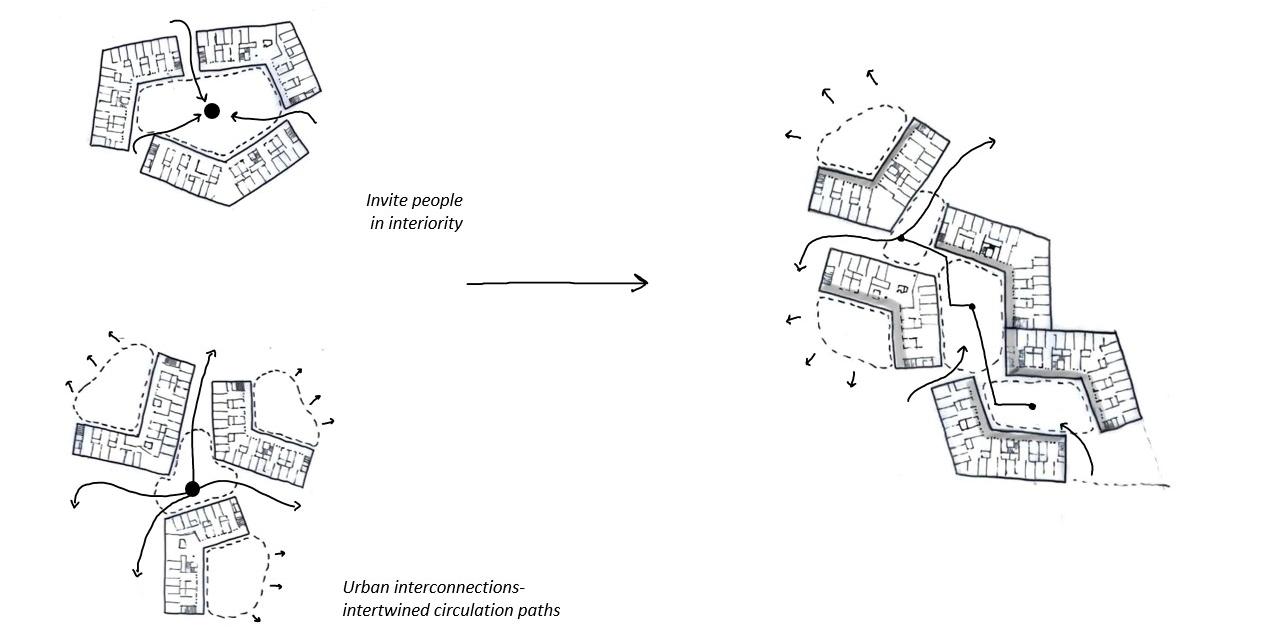

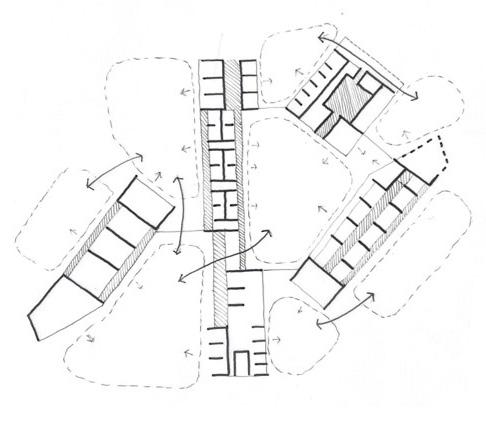

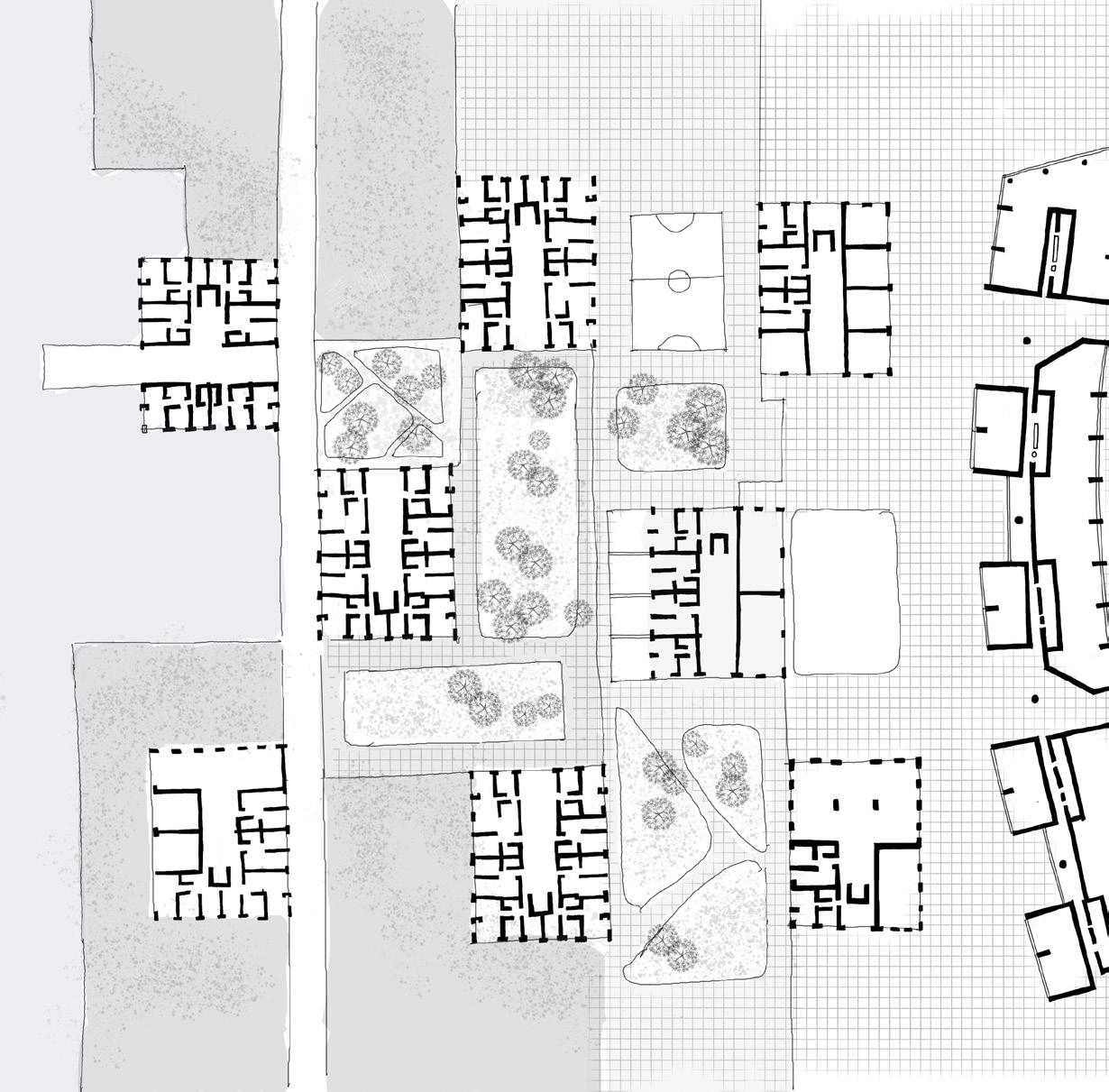

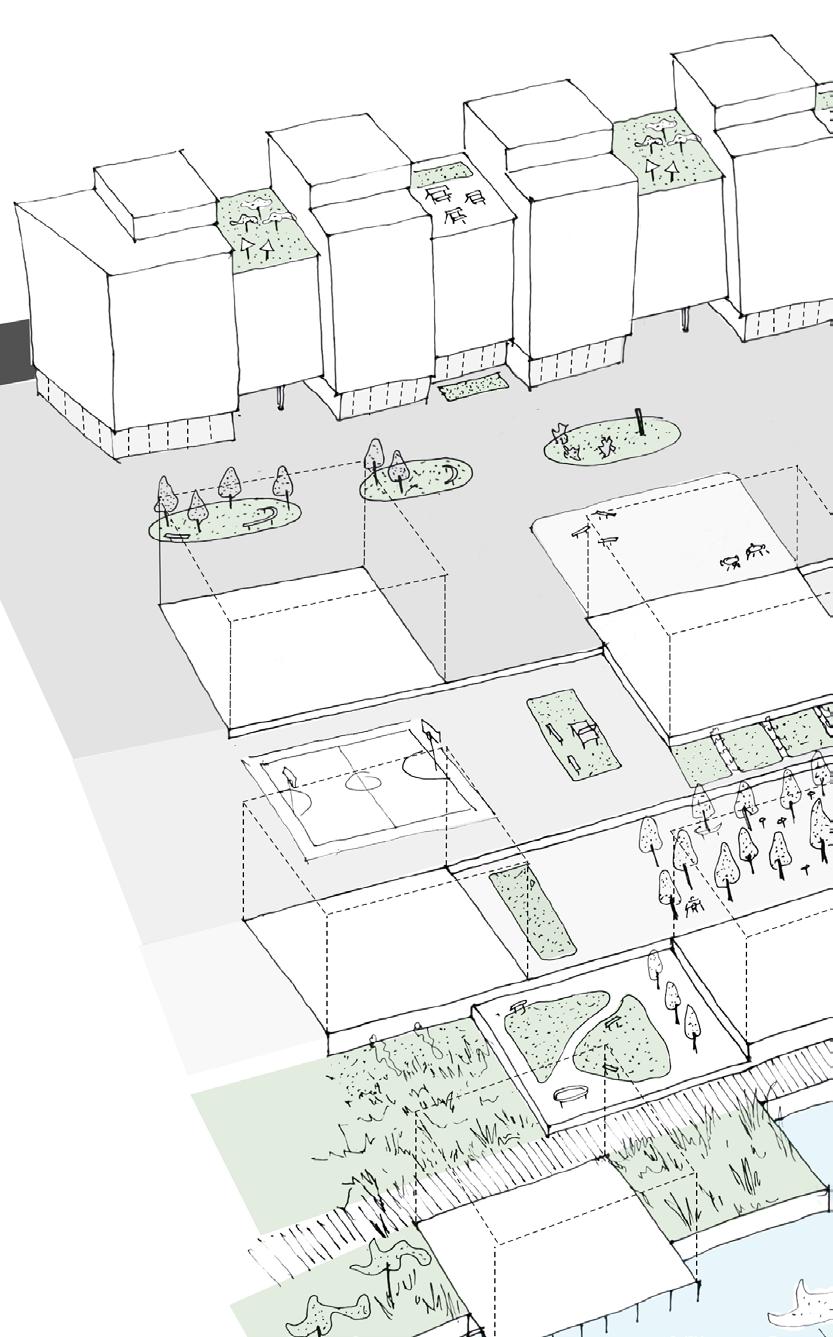

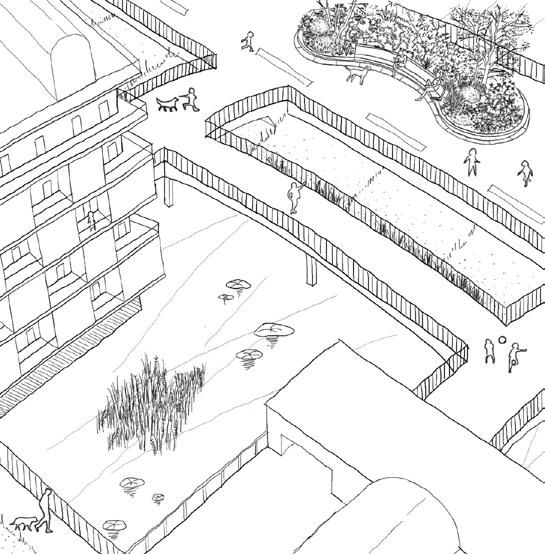

Assemblage

An enriching neighbourhood is one that allows for multiple associations of different ways of life to take place, where exchange of skills and knowledge, formation of civic groups around shared interests, discovery of services and businesses happens at ease. An Assemblage of 2-3 hectares acts as a tool of transformation of the urban area around, capable of driving change in the immediate surrounding. When the building blocks form an assemblage and work in synergy to create a shared civic landscape, the impact of the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. It derives its identity from the relation of the buildings with each other and the inside-out relationship

of every building. As lifestyles become diverse there is a need to conceptualise our neighbourhoods as vital pieces of the city rather than enclaves of homogenous lives. As Rossi rightly says the ‘type’ is associated with a particular way of life. And an assemblage arises out of a set of prescribed relations in the everyday lives of its residents. Typologies vary in depth, density, orientational characteristics and segmentation and the understanding of layering, structural flexibility and servicing can be leveraged to create patterns of continuity and sequence of spaces. Depending on the articulation of the assembly, they tend to perform differently

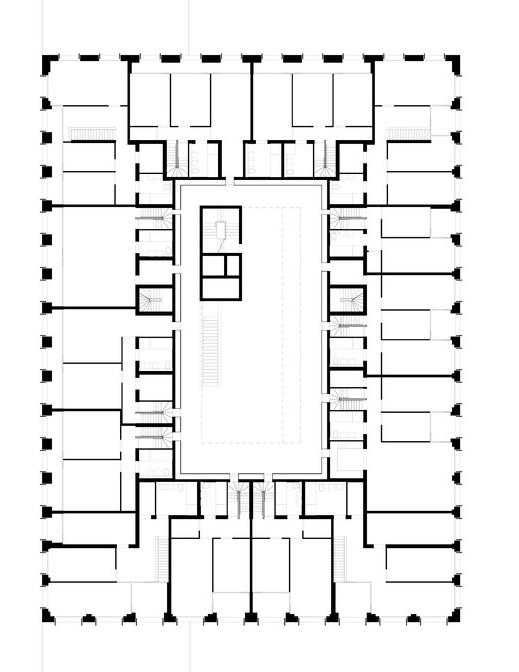

in different urban environments. Rathbone Square, Fitzroy Place, and Central Saint Giles are central city clusters, each spanning 1-2 hectares and developed with multiple building types arranged around a courtyard. While all three share the concept of a courtyard at their core, the character of each courtyard and its interaction with the urban context vary significantly. Rathbone Square features a well-defined internal courtyard with diverse building typologies. A diagonal access path cuts through the block, creating a court that maintains its own vibrant life distinct from the surrounding streets, yet remains wellconnected to them. In contrast, Fitzroy Place

presents a more fragmented and tranquil courtyard, fostering a sense of privacy. Predominantly residential, this courtyard is quieter and includes the historic presence of an old church, contributing to its serene atmosphere. Central Saint Giles offers a less confined courtyard with multiple access points, seamlessly integrating into the urban fabric. The courtyard lacks a strong sense of enclosure, feeling more like an extension of the surrounding streetscape. The edges of the surrounding blocks define its boundaries rather than the buildings within the block itself, resulting in a space that is highly interactive and economically vibrant.

From left to right, assemblages at Rathbone Square, Fitzroy Place and Central Saint Giles

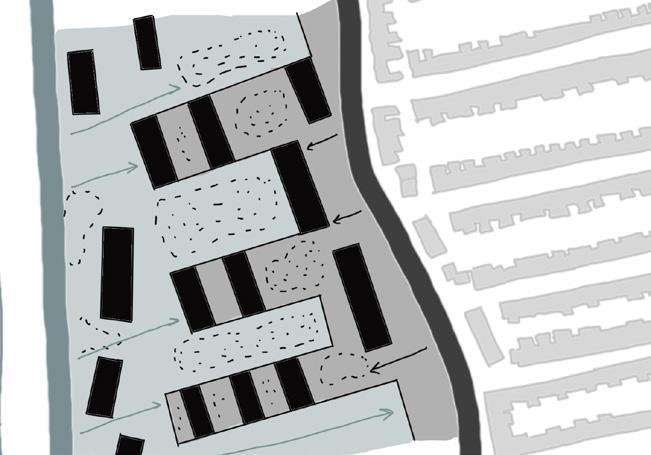

An assemblage of linear types can be organised into different sets to realise a range of open spaces and connections. The orientational bias and the staggered organisation of variations of the same type form the logic of grouping. Here, working and living can come together at the scale of the building by incorporating various generous aspects like indeterminacy and privacy. The porosity of the ground converts the spaces into collective urban environments. The terraces, loggia and balconies are domains of exteriority that are shared with various scales of people. The ends of the blocks are differentiated

to have a range of work spaces becoming part of the surrounding block. When linear blocks bend as a response to conditions of the surrounding, it can begin to act as a generative idea.It offers multiple orientations and pockets of introverted enclosures that can act as shared work spaces at every level.

In contrast to linear typologies, atrium buildings create a protected inner space that fosters an active communal environment for residents. By shearing atrium blocks, a variety of collective spaces emerge, each with its unique character and identity, further defined by the surrounding

structures. Rotating one of the atrium buildings can align with the extended city grid, generating movement axes and distinct spaces along the assemblage. This approach allows diverse building types to coexist, creating varied open spaces while maintaining a unified identity.

The coexistence of diverse building types establishes a hierarchy within the environment, shaping the relationships between blocks and fostering diversity within each one. Each block develops its own unique depth and orientation. This well-defined hierarchy between protected

and open spaces creates a spectrum of collective environments. The design can feature a public corridor that facilitates public functions and guides people towards the project, an inward-facing void for leisure, and additional corridors serving as collective working spaces. All of these contribute to an inclusive communal area within the atrium building itself and exploring varying levels further introduces additional layers of interactivity, enriching both individual blocks and the entire assembly.

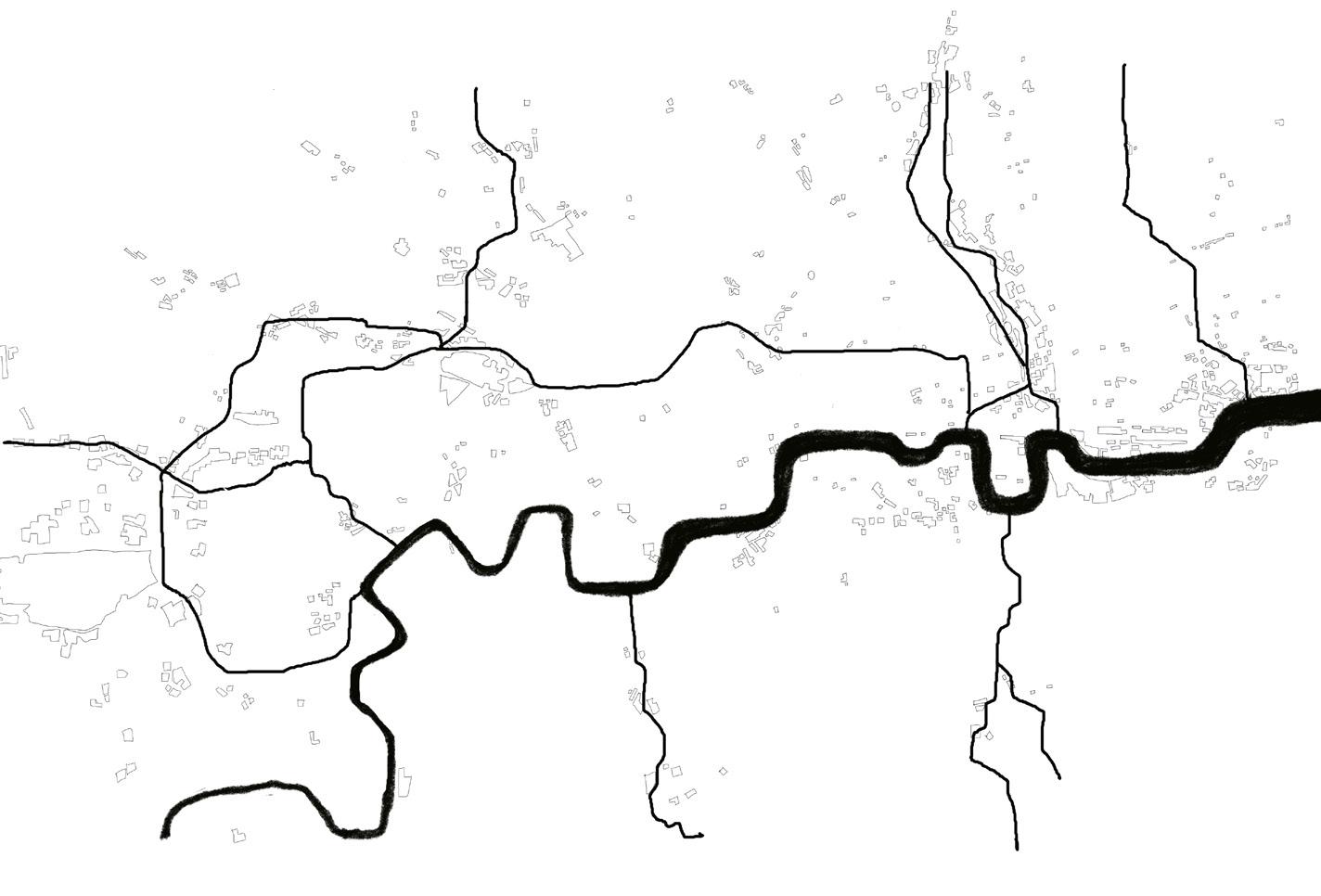

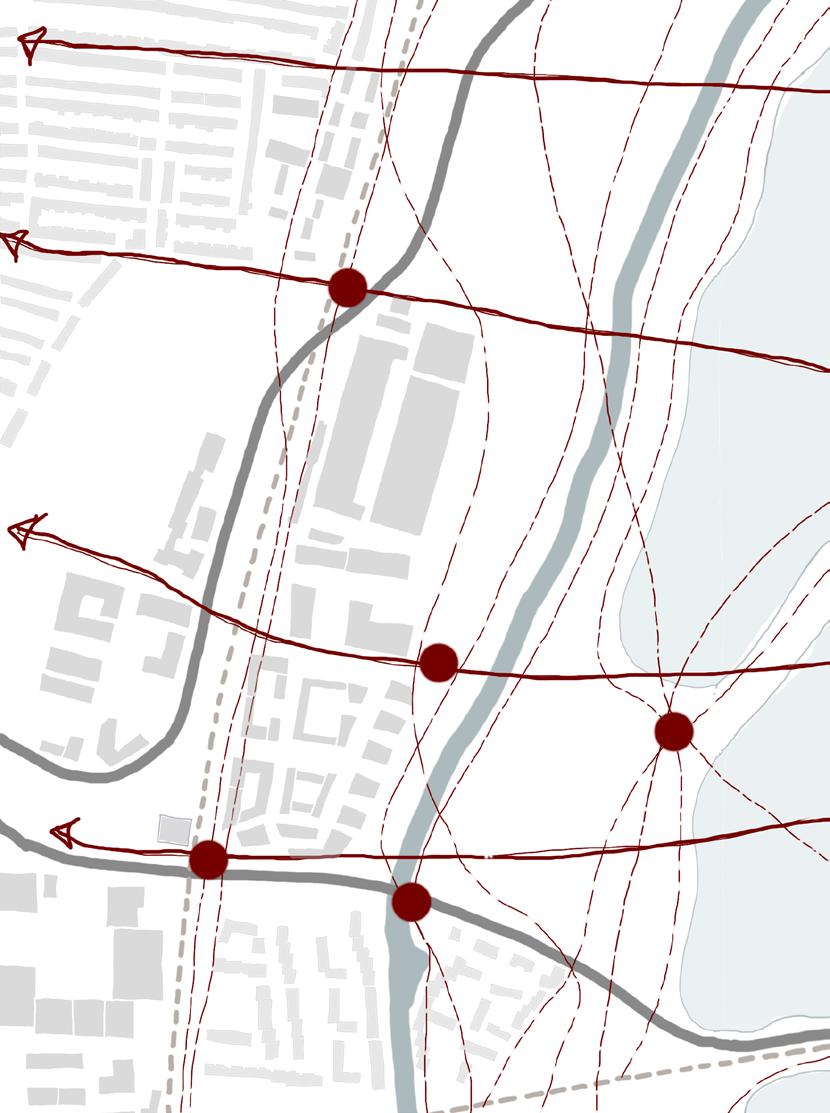

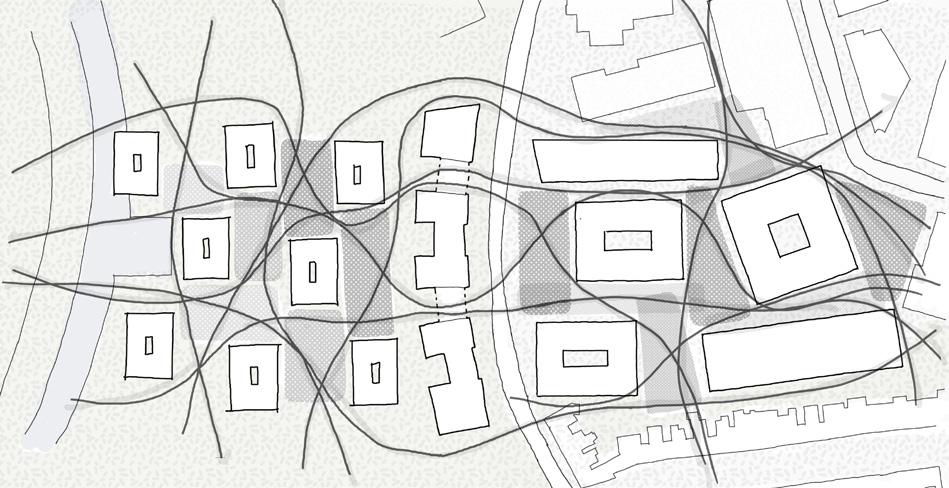

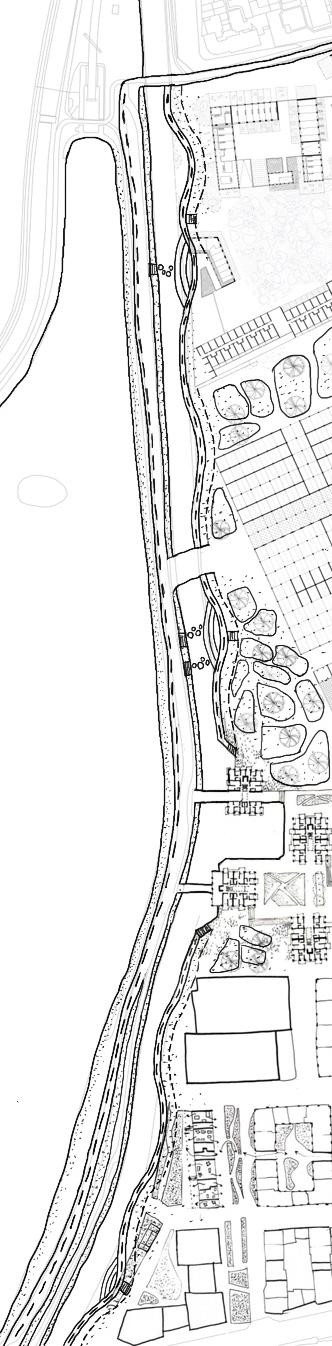

On a territorial scale, one perceives that the natural flow of the river is followed by the green infrastructure too, creating a braided system together with highways and railways. The loose urban industrial fabric that is interwoven with this system presents flexibility and wider opportunities for urban transformation than the extremely tight and rigid fabric of terraced housing that can be seen dominating the rest of the landscape

III. Re-qualifying Primary Urban Elements

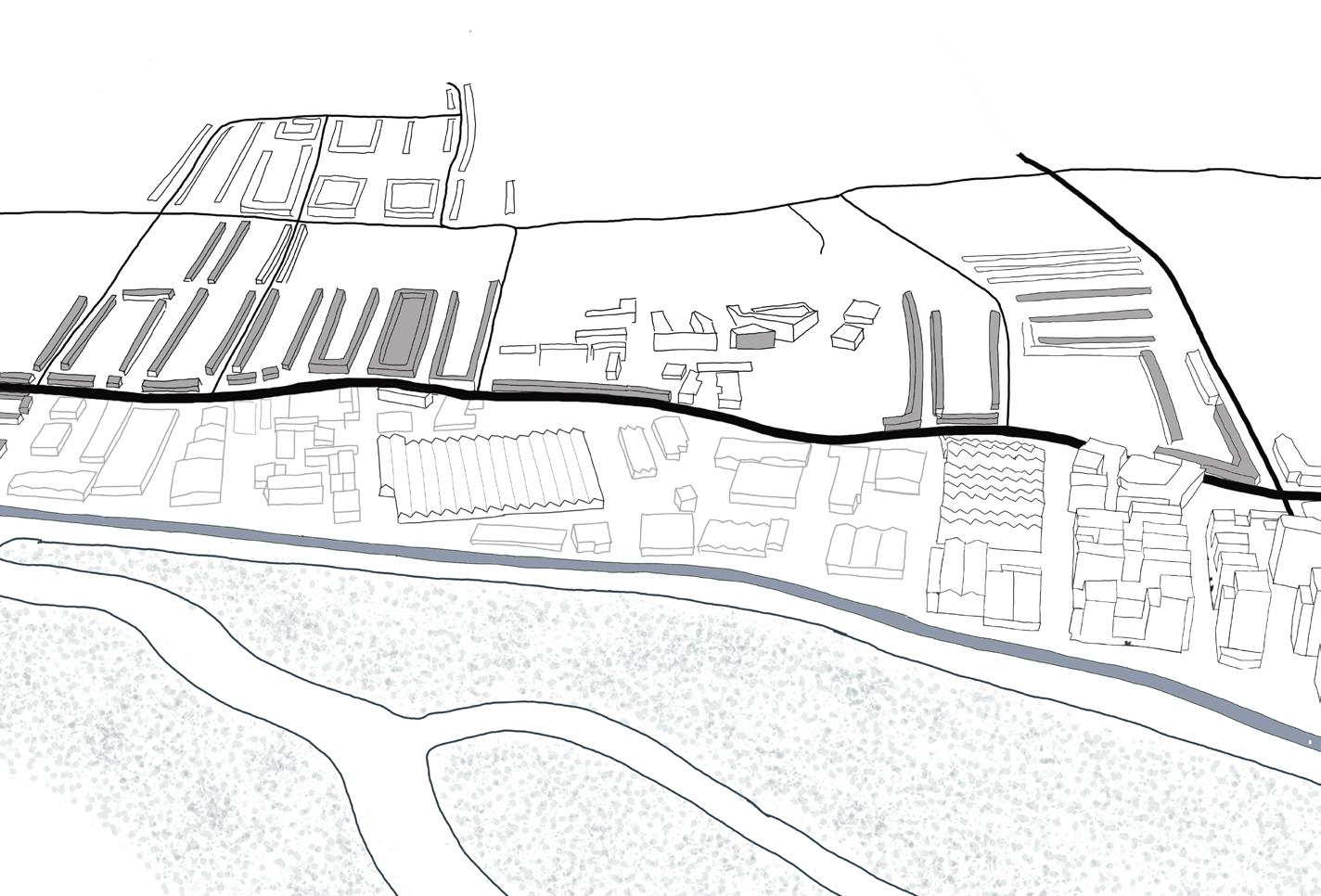

Transformative Value of Territorial Infrastructures

As illustrated earlier, there is a shift in the approach towards the periphery and its qualities. Former industrial areas like Blackhorse Lane start to be seen differently. The once industry-related qualities of them, seen from a different scope, appear as attractive traits for residential/working/leisure activities, distinguishing them from other peripheral residential districts. This is mostly happening because they provide an urban framework that is characterized by variety and malleability. Hence, they can easily accommodate new urban patterns and facilitate their integration to the existent grid without affecting or changing enormously the current elements. One can therefore understand that a mixed use development can easily be placed in a former industrial site rather than in the middle of a town-house strict residential grid. At the same time, the value of these former industrial areas is also linked with the

bigger scale elements that function as mediating elements across a wider urban area, such as the transport system, the waterfront or other elements of particularly large size that used to serve the industrial/ manufacturing purposes. One such example of using bigger territorial elements to the advantage of connectivity can be seen in the example of the Lee Valley area, whose value, since the Olympics started increasing drastically. Going back to the idea of London as a poly-centric city, one can easily understand and imagine how, under such types of expanding schemes, inner periphery areas such as Lea Valley could quickly grow and be developed into attractive places to live and work in proximity to the city centre. Consequently, even at a distance, they can function as providers of all necessary amenities one normally finds close to centre areas.

Primary Urban elements have affected the way industrial areas where dispersed around the London area in the past. It is by their grouping that we understand how territorial human-made or natural infrastructure affect their location , as they tend to gather around the intersections of primary infrastructural elements like rivers and rail.

RAILWAY

INDUSTRIAL FABRIC

Each primary element affects and imposes its characteristics on different parts of the site; by treating them as unique opportunities they can create distinctive qualities along their thresholds with the site

Dominating Structures as Collective Urban Accelerators

According to Rossi, the factors that affect and determine the urbanity and activity of an area can be grouped in three distinct categories: “housing, fixed activities and circulation”01. Within them, there are elements that can be considerably important, as they “have the power to retard or accelerate the urban process”02 and therefore should be the first to locate and study. If one looks at an instance of periphery, like Lea Valley’s former industrial site in Blackhorse Lane, the initial structural elements are the waterfront and lea river system, the railway and road system,the shed found in the middle of the site and

01 Rossi, Aldo. Architecture of the City , 1982. p.86

02 ibid. p.62

dominating with its size and location, as well as the grid of terraced housing. These elements,even though considered “unchangeable”, can bring value when treated in a sensible way. Some of them, as results of the former human activity have left noteworthy traces to the area. This raised questions on how the urban ”leftovers“ we inherit, could be used in an inventive way by virtue of their transforming capacities and respond actively to any urban regeneration scheme. The others, currently existing and in misuse can find the opportunity under such schemes to be revitalised and to improve their impact on the wider urban area.

TOWNHOUSES

Focusing on the Uplands Site one can understand the importance of the primary elements: The railway defines the southern limit; Blackhorse Lane and the waterfront run North- South along the site enforcing

its edges; the terraced housing forces a strict and dense urban grid on the east side; the wetlands become imposing with their size and volume on the west side

RAILWAY

WATERFRONT

BLACKHORSE LN.

The vast size of the reservoirs along with their location can provide the ideal framework to reinforce active mobility patterns in the area and offer better opportunities for leisure and well-being

Waterfront, Wetlands and the Lea River System

Historically, the distribution of industrial areas has been governed by blue infrastructure- both natural and artificial- as manufacturing and transport were heavily dependent on water. With the city’s expansion, heavy industry got relocated to the outer periphery, leaving these vast water structures heavily under-used. In the Lee Valley, one can find multiple former industrial sites, accommodating currently lighter industrial uses. The blue infrastructure that was previously serving as a means of connectivity, transport and supply, is functioning as a spatial barrier that only limits the sites.

Similarly, if we focus on the water reservoirs

located in the valley,they were originally created to supply water to the eastern part of London. As a result of the direct supply of water power, the area gradually developed into a concentration of industrial activity, particularly for water-related industries such as textiles, paper and chemicals. Currently, the reservoirs are used as a flood control system for the city and the resorvoirs that hold substantial amounts of water start attracting leisure activities. Being considered as a considerable green space in the proximity to the city centre, they provide the ideal framework to start functioning as such, bringing different qualities to the area and transforming its

Primary and secondary water elements affect not only the density of industry but also the urban expansion

The Blackhorse Lane site with the water canal functioning as a barrier- there is currently no opening towards the water

industrial caracteristics in more visitorfriendly ones. Their vast surface and the huge volume of water they carry, make them a distinctive part of the urban tissue. This highlights their imortance as elements that can affect not only the urban morphology but also the entirety of mobility systems functioning in the area. In Blackhorse lane, the waterfront, running along the site’s east limits, present no current connection to it, functioning as a restricting armature. By reshaping its past role, the former industrial mobility networks can be transformed into active mobility’s ones. By integrating the water system into the mobility network, it could provide the threshold between the site and the wetlands, creating braided system between water, green space and human activity that is not only extending along the primary elements’ orientation but would potentially reinforce the east-west connections too.

elements passing by/affecting

The Railroads : Connectors and Disruptors

Given it’s direct consequences in mobility networks, the railway can be considered the most important element affecting transformation, giving the option for transport based development. The revitalisation of Tottenham Hale into a mobility hub connecting London with further Northern areas, particularly with Stansted Airport and Cambridge, indicates an effort to create intermediate interest areas in the periphery that could function as a mediator between London and the northern cities, in an effort to decompress the city centre. If one looks at Blackhorse Lane, other than the proximity with Tottenham Hale, there is a direct underground connection with the city centre via Victoria Line and additional overground ones. All the above prove

that future projections for the area envisage something more than a former industrial site: accessibility brings potential for residential and civic uses, transforming the neighbourhood into a place with suburban qualities, while maintaining the positive traits of urban life.

As for the railway infrastructure, it currently functions as a barrier for accessibility and permeability for the area, particularly for any kind of east-west movement. Hence, local connectivity is obstructed, affecting urban fluidity and neighbourhood life. Finding a way to braid successfully these barriers in the urban fabric and allow for flexibility in the flow of movement could substantially improve the quality of life and the connectivity between adjacent districts.

Key Train connectivity

the Lee Valley area

Rail infrastructure creating a barrier and imposing a north to south mobility system with no capacity for an east-west connection

Blackhorse Lane and the Terraced Housing Blocks

The terraced housing block formation, following the typical town-house gridded pattern, has been seen, for a long time, as the ideal one for residential peripheral neighbourhoods. Proven effective as a spacial mechanism through which land had been appropriated-through subdivision, it prioritised car dependency and individual space over communal interaction, resulting in fragmented communities and limited access to essential services.

Currently, one can clearly see the limitations of such an urban grid, not only in terms of plot sizes, but also considering ownership

and change of use. The grid orientation and small size, as well as the interaction with transport infrastructure, can be seen as obstacles in any kind of urban change. The parcel division makes it almost impossible to rethink typology and land use.

At the same time, the primary road, Blackhorse Lane, in direct contact with the terraced houses’ urban grid, is setting the limits of the site up to now, by clearly defining the eastern edge. Because of the value attributed to it, the road mostly functions as a blocking armature. The incoherence in the way it channels different types of mobility,

By looking at the map of the eastern part of the site it is clear that the grid of the terraced houses dominate as an urban pattern with formations that can not be considered flexible for any future transformation.

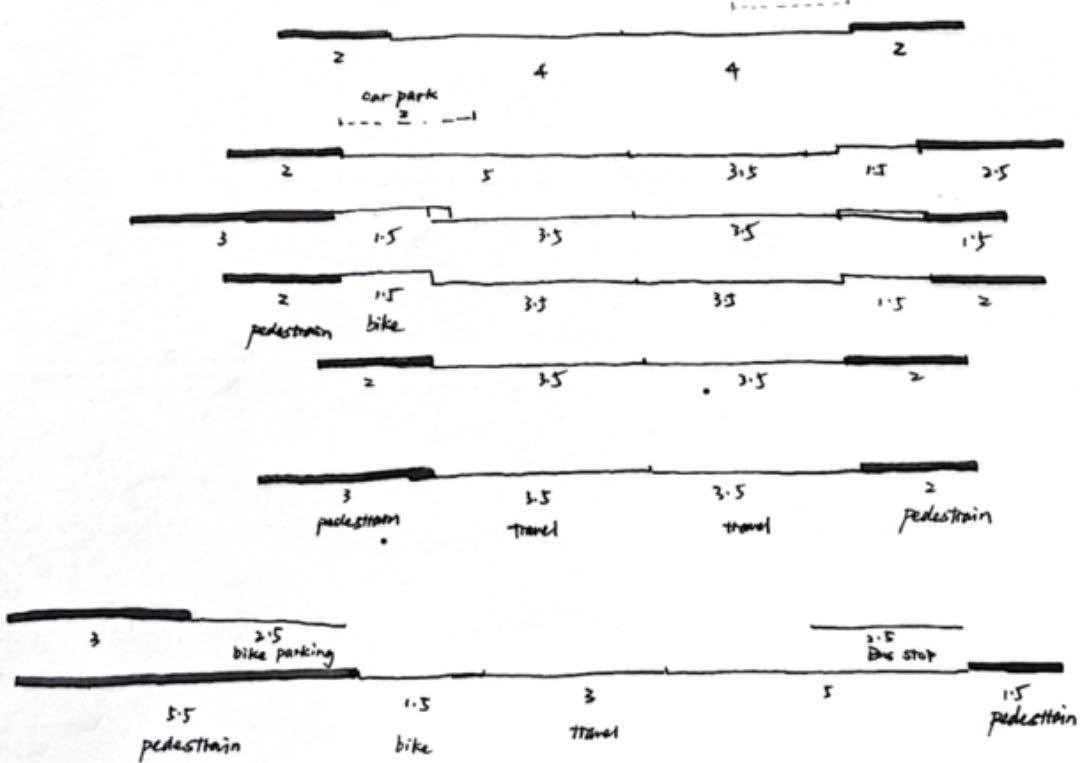

Variation in the section of Blackhorse Lane (up)- The existing inconsistency between elements can be used to bring variety in the its use, transforming it into a flexible threshold between the new development and the terraced houses.

The Road currently functions as a barrier between the industrial area and the terraced housing elements, providing no other quality than its transport use

is also limiting, as various mobility elements such as pedestrian space or bike lanes appear and disappear randomly, creating a rather chaotic situation incapable to accommodate any kind of public elements. Its permanent existence along the site though, creates the opportunity of functioning as an intermediate urban space, in the future, an active access point connecting the existent residential fabric of the terraced houses with the new one within the site’s limits. The juxtaposition of detached town-houses, on the other side, introduces the residential character of the area within the street’s facade reinforcing identity, functioning as an interesting starting point for the formal exploration of the street’s elevation.

As part of the ring road that services the whole area and connects it with the railway, congestion might be a problem at Blackhorse Lane if the traffic is not treated correctly. Envisaging a development that increases density and accommodates different life environments would require a well organised inside system to manage traffic flows

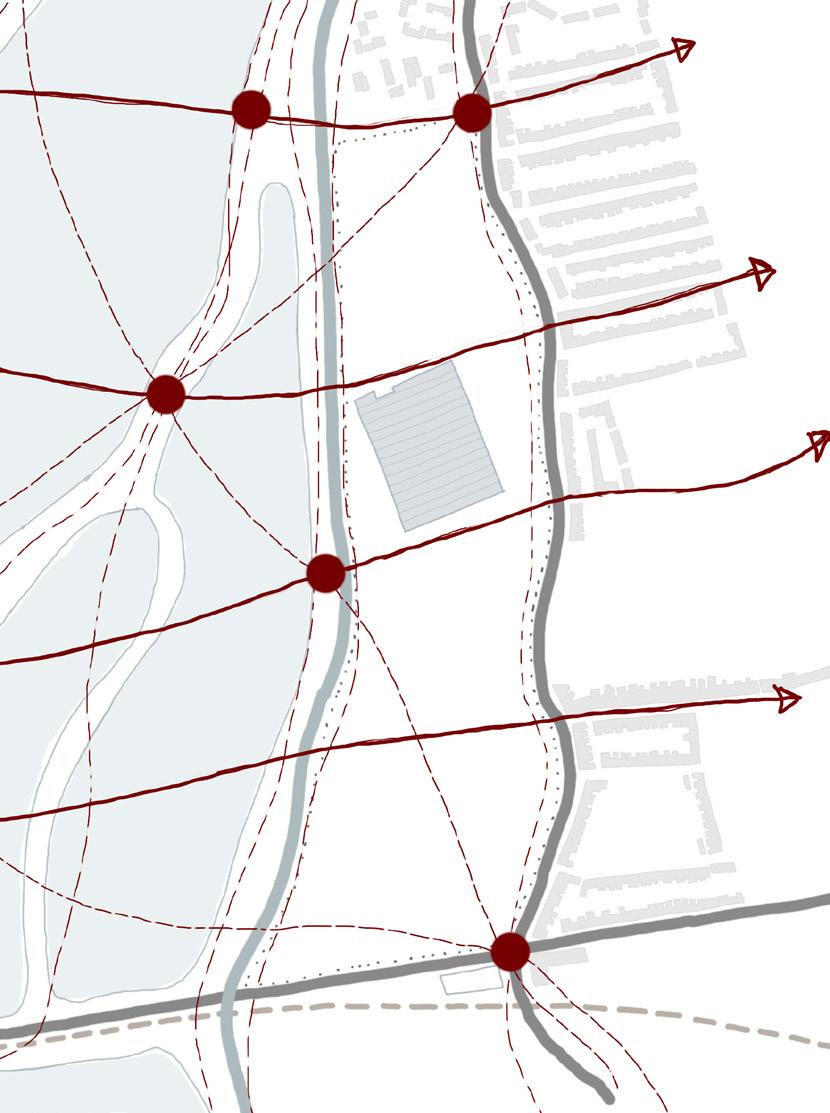

Primary Urban Elements as Mobility Systems

In terms of traffic and transport system resolution, the current status of Blackhorse Lane is to function as part of a wider ring road connecting the NE area with the Railway Station therefore its role for the larg-

er area in term of traffic control becomes important. As far as the site is concerned, whilst the current systems is serving the distinct industrial islands well, access is based on roads that function as vectors and do

Blackhorse Lane accommodating the terraced housing road system on the right and a few roads on the west that provide access to the industrial clusters. We see clearly the island and vector system with roads crossing the site but not having any connection whatsoever between them

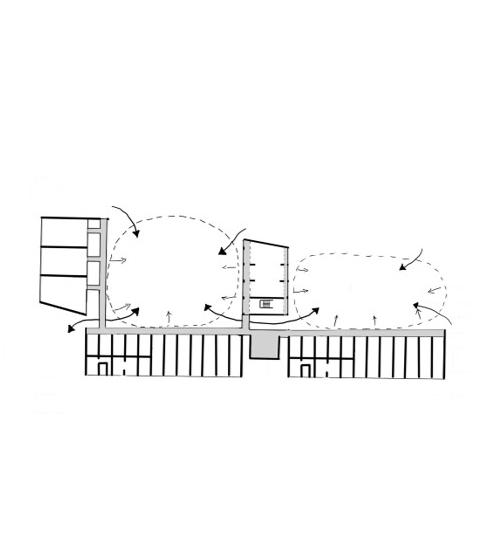

not provide any interconnection or fluidity in circulation within the site. For now, all the above mentioned urban elements bring an even more negative impact to the overall traffic-mobility system, as their importance and vast size are functioning more as a limiting armature and not as a means of connectivity. As primarily elements that affect urban structure, their impact in mobility and traffic system is sub-

stantial. Acknowledging that the current transport network is based on a dysfunctional system of vectors and islands, the purpose would be to make use of the urban elements to achieve a more homogeneous system that creates an amalgamation of various modes of mobility that brings together the multiple layers and directions the existent patters with the new ones.

The current limiting situation- waterfront and street elevation underused-no connection between site-wetlands-terraced housing blocks.

Interaction with the waterfront and Blackhorse Lane could improve the quality of the site.

That can potentially expand furthermore in a more complex network of various intertwined mobility patterns

That could be achieved with a dynamic braiding of multiple elements.

network bringing together various urban elements in a complex system

Creating opportunities for an extended network of various kinds of mobility, interacting with the elements of the wider urban area.

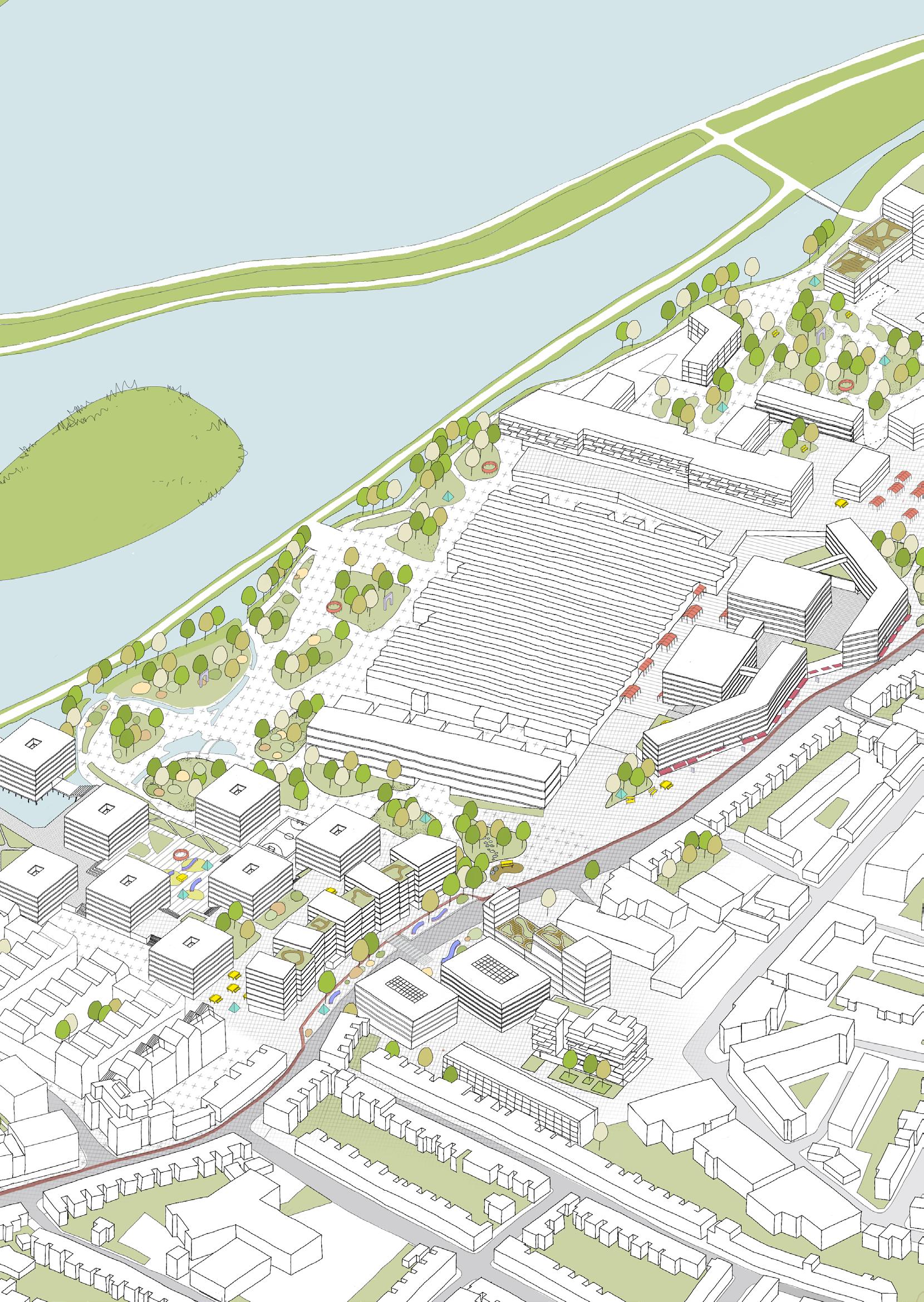

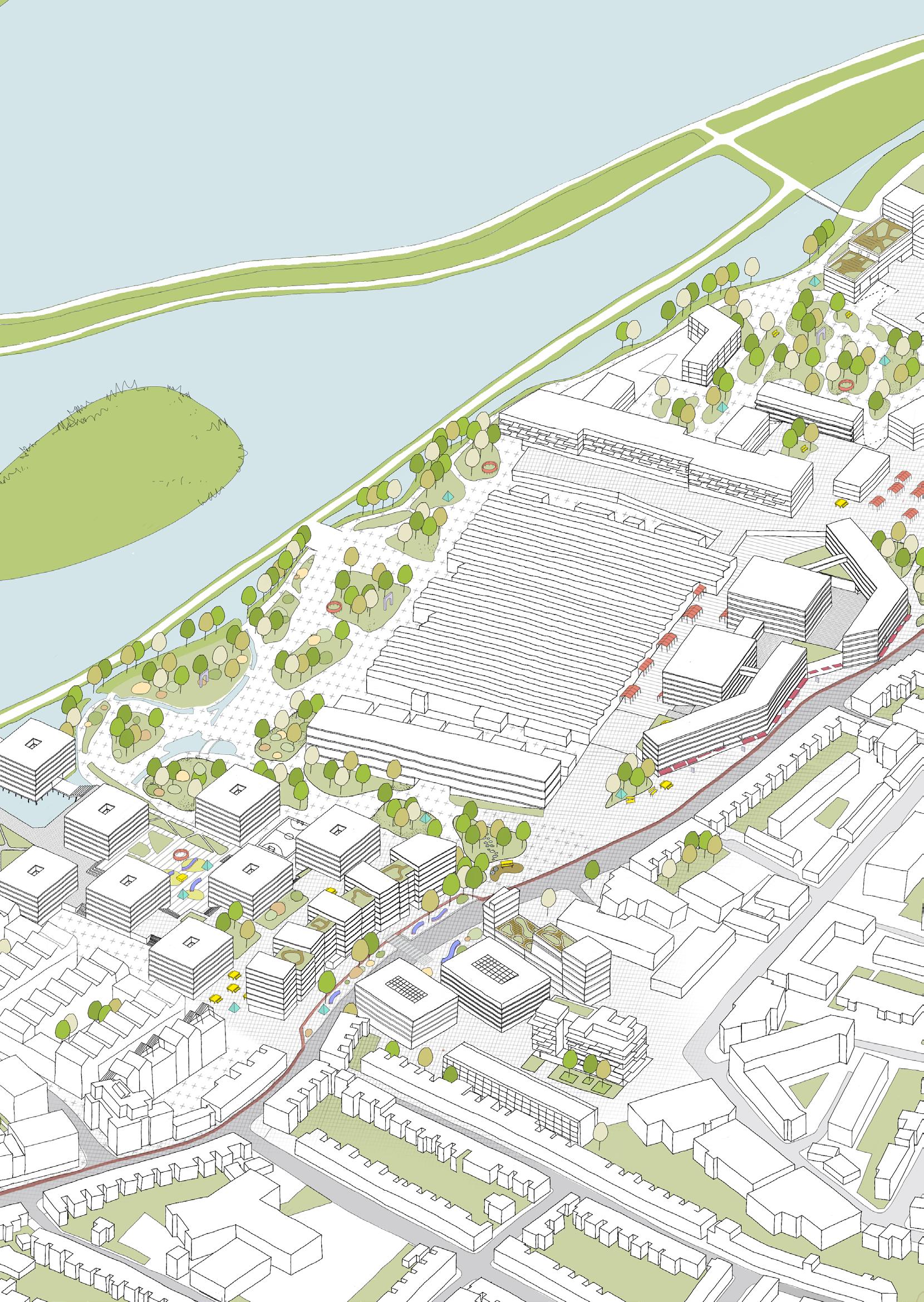

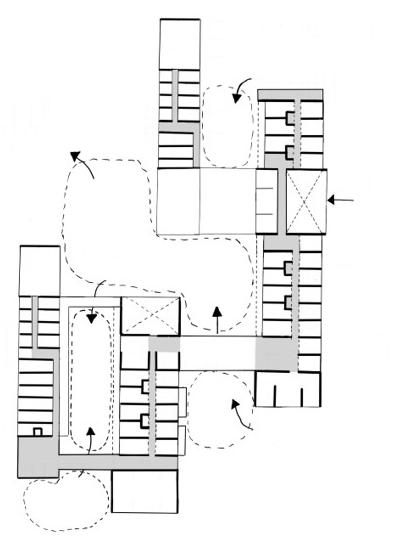

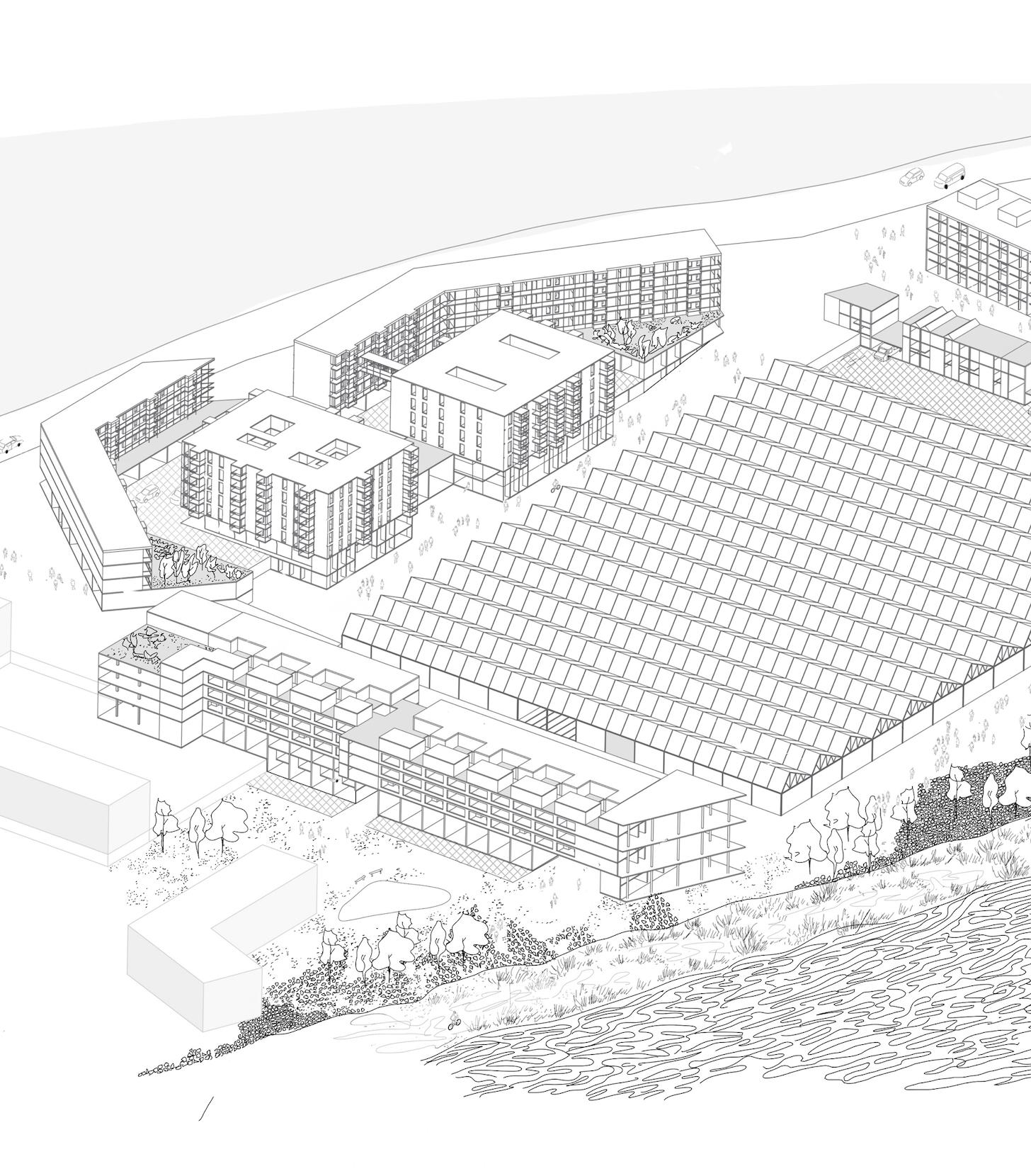

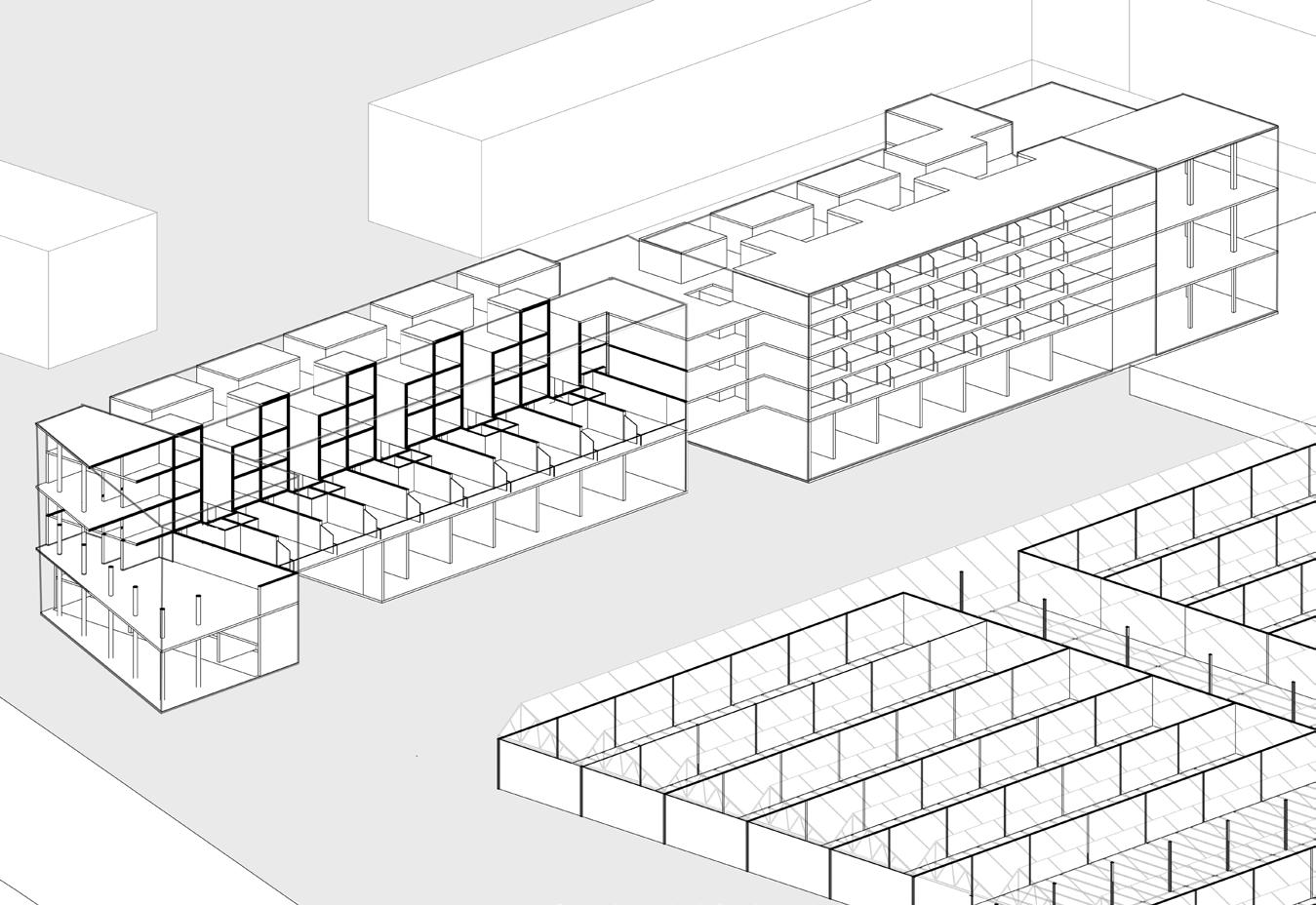

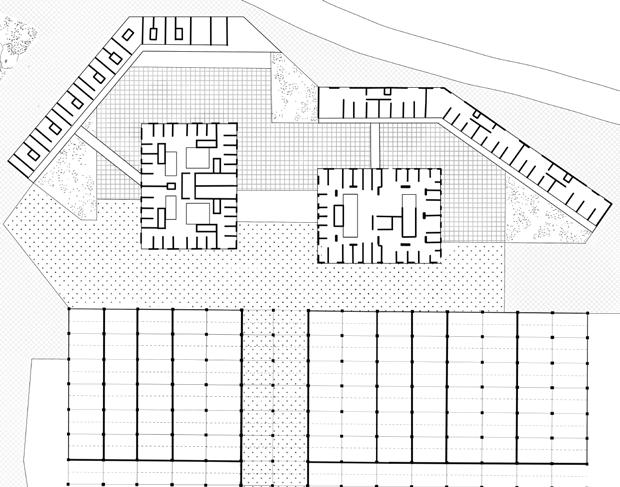

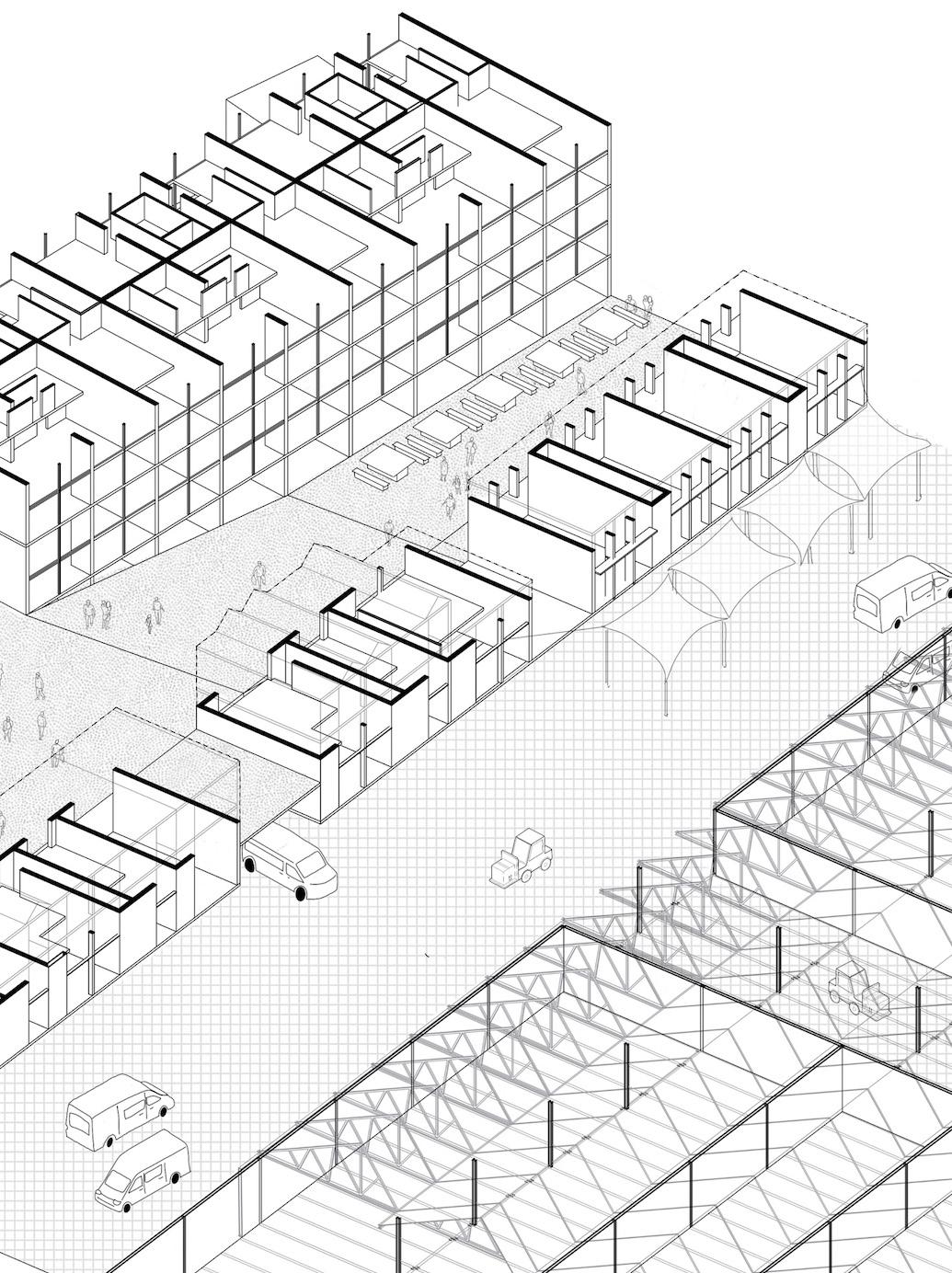

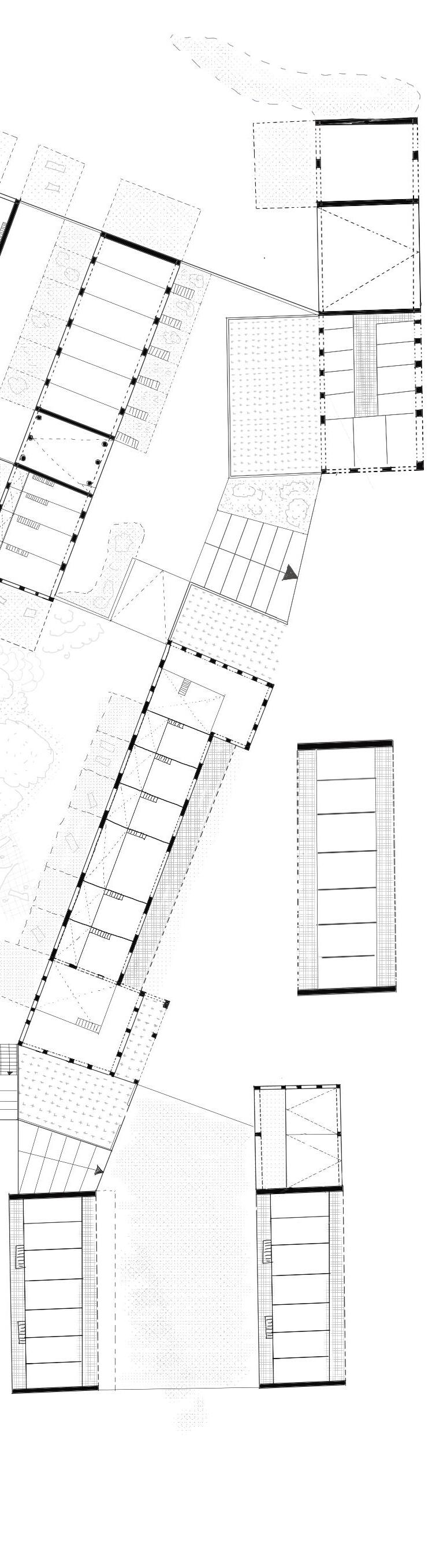

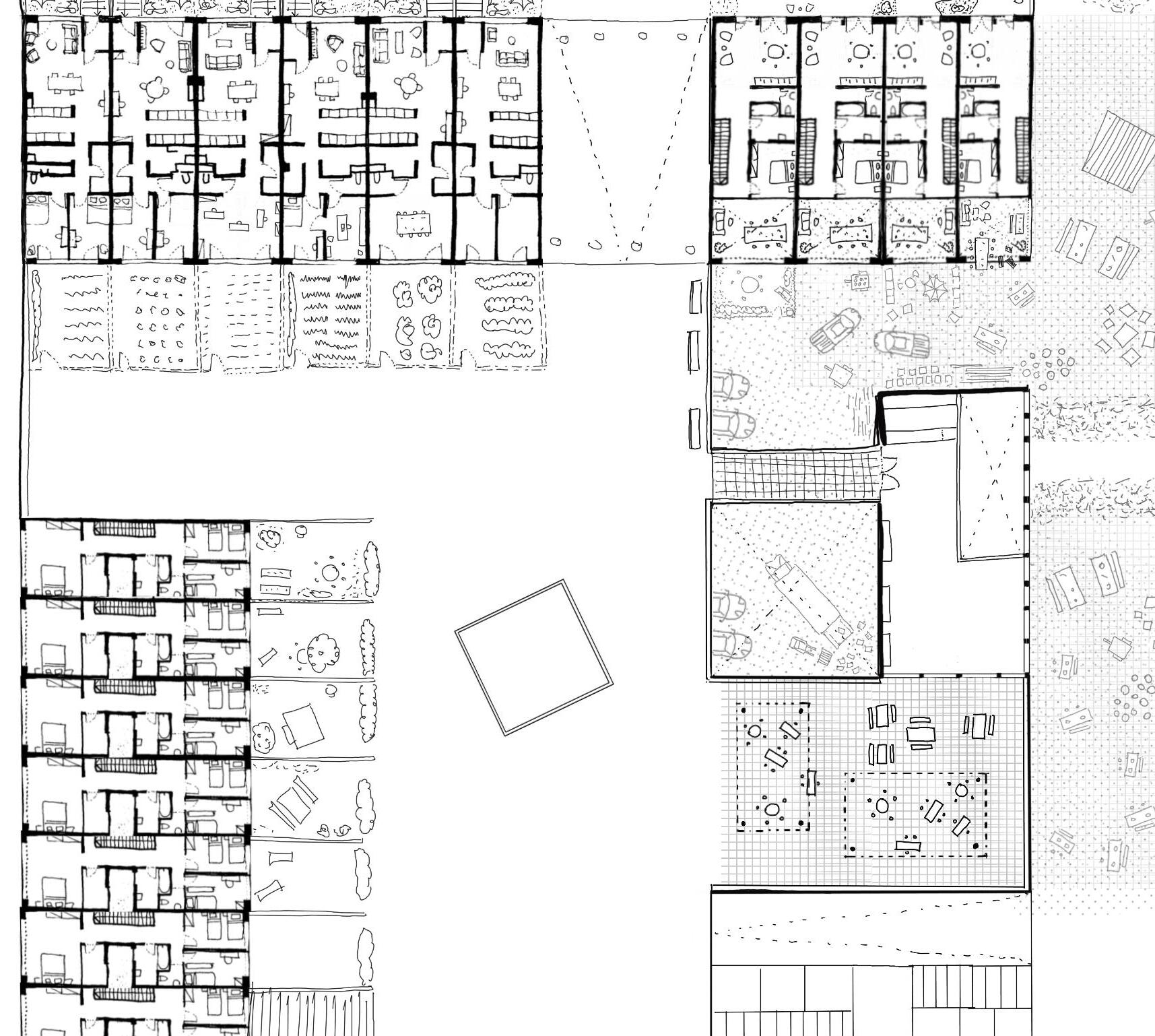

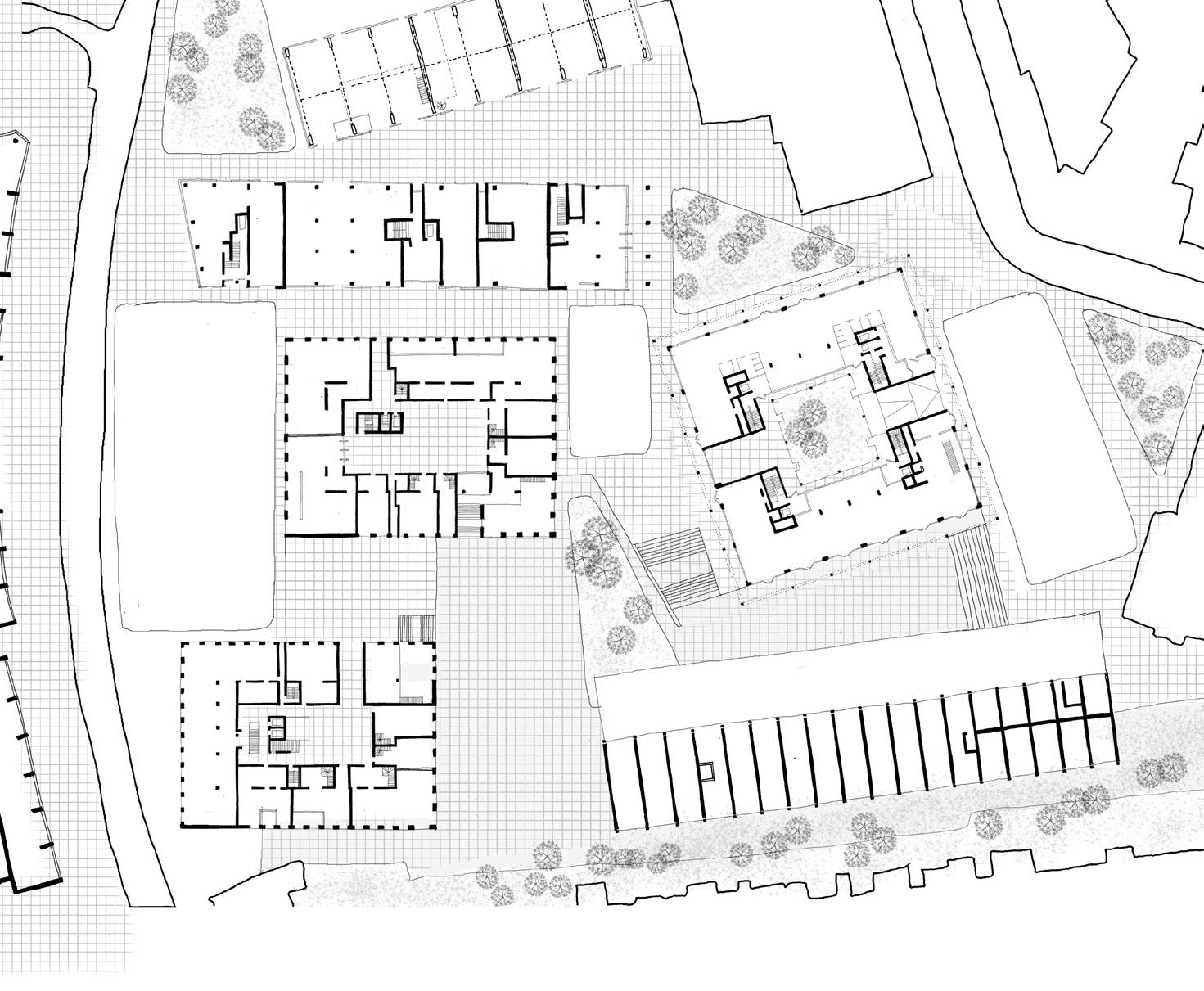

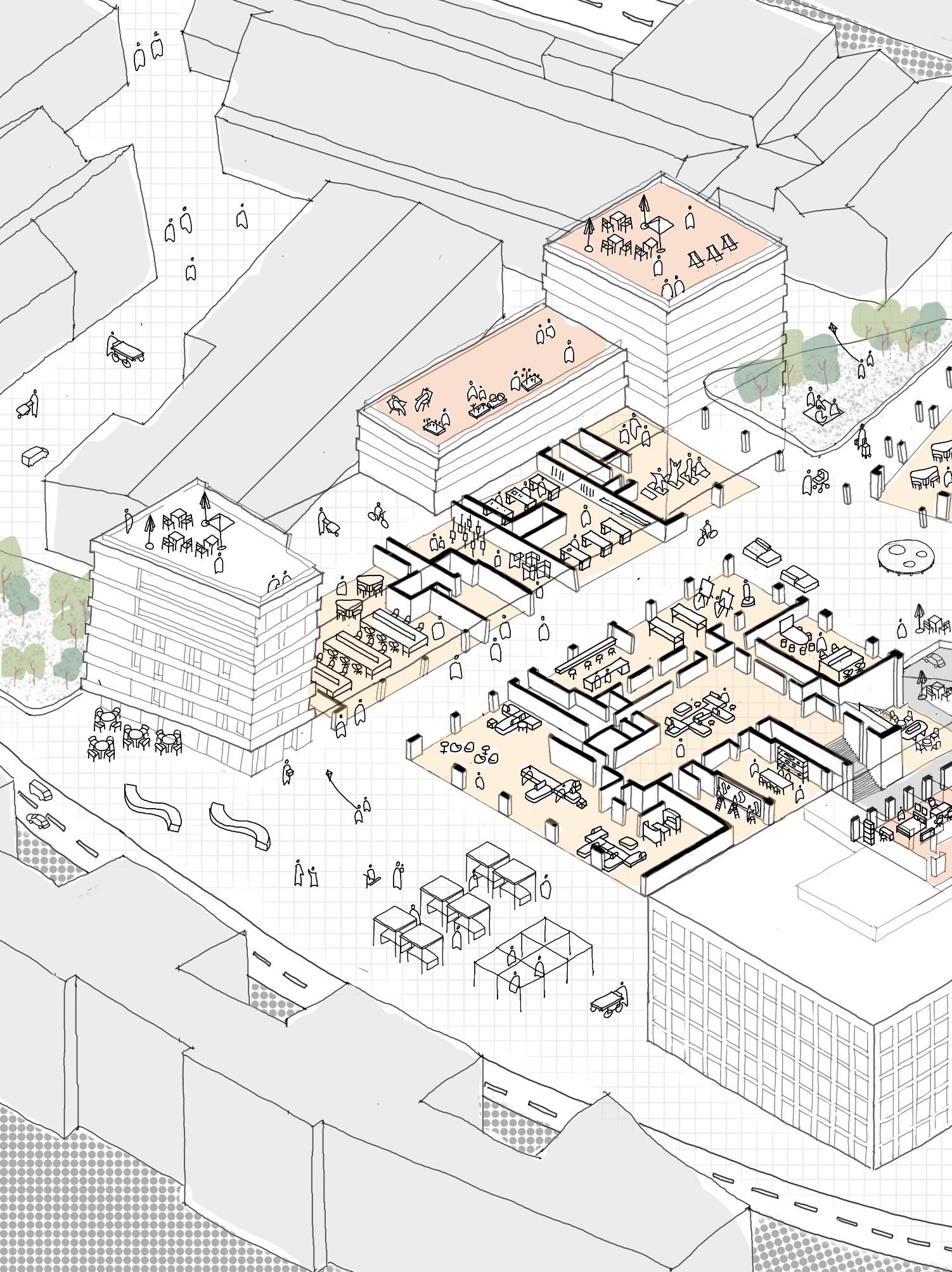

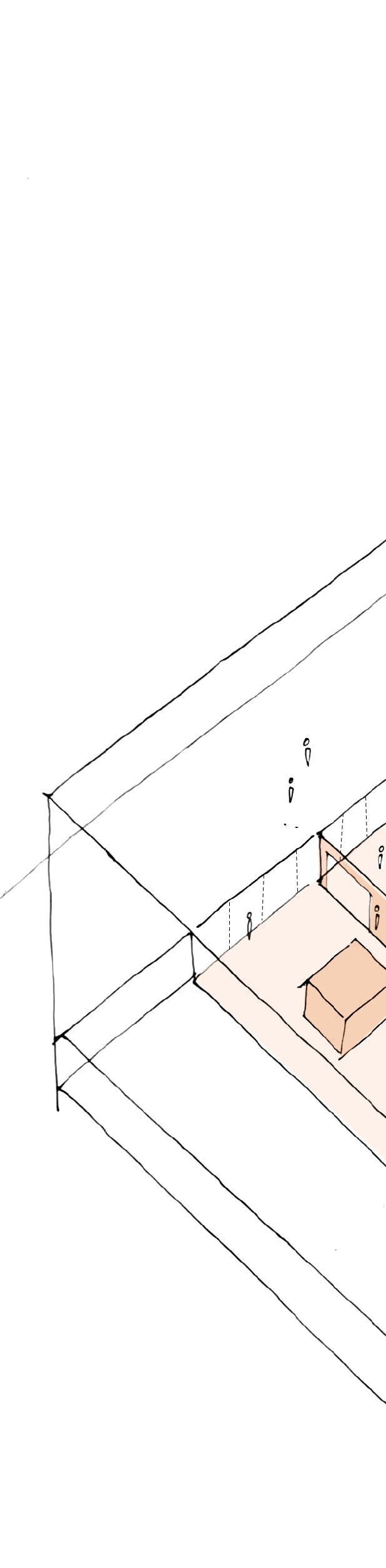

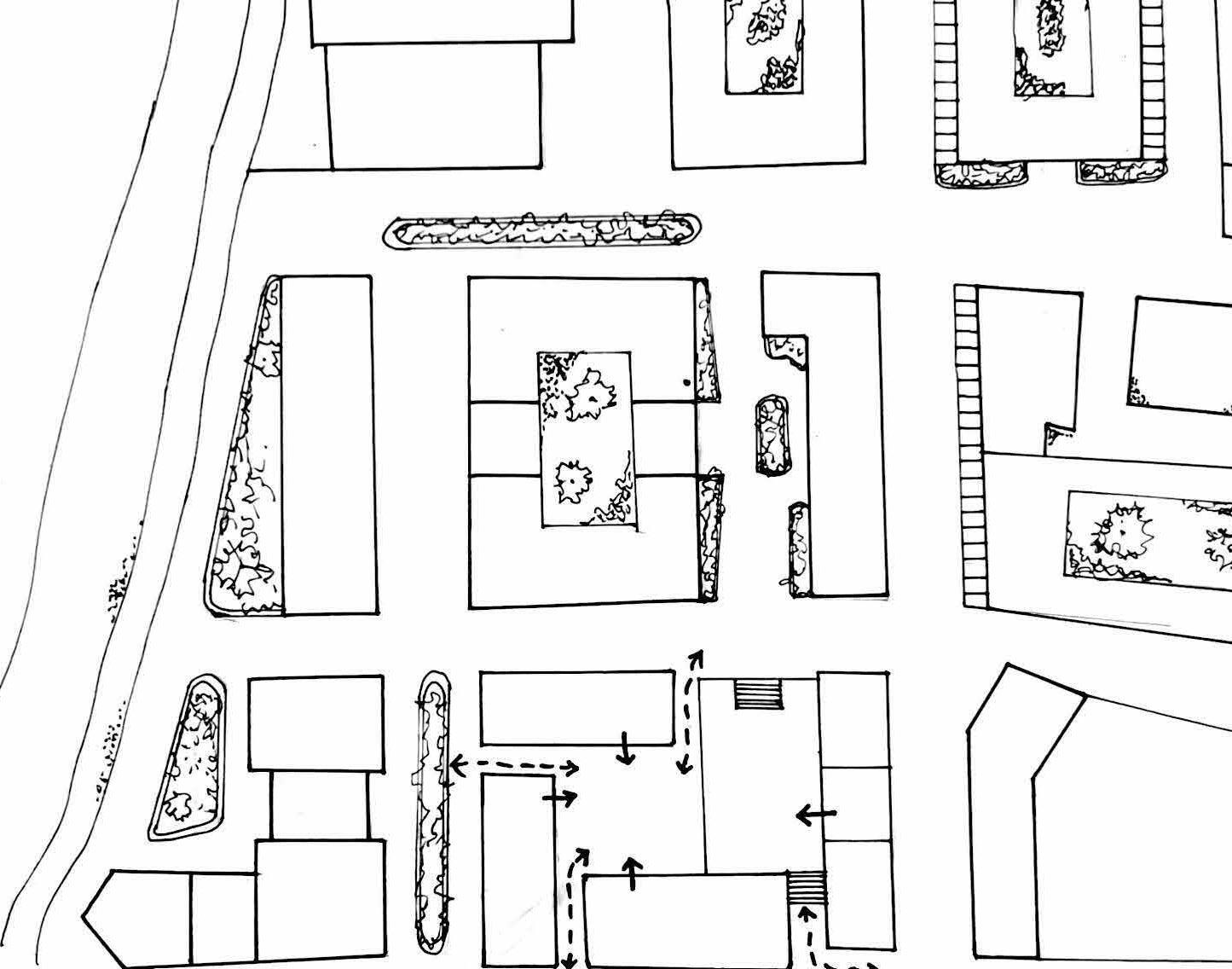

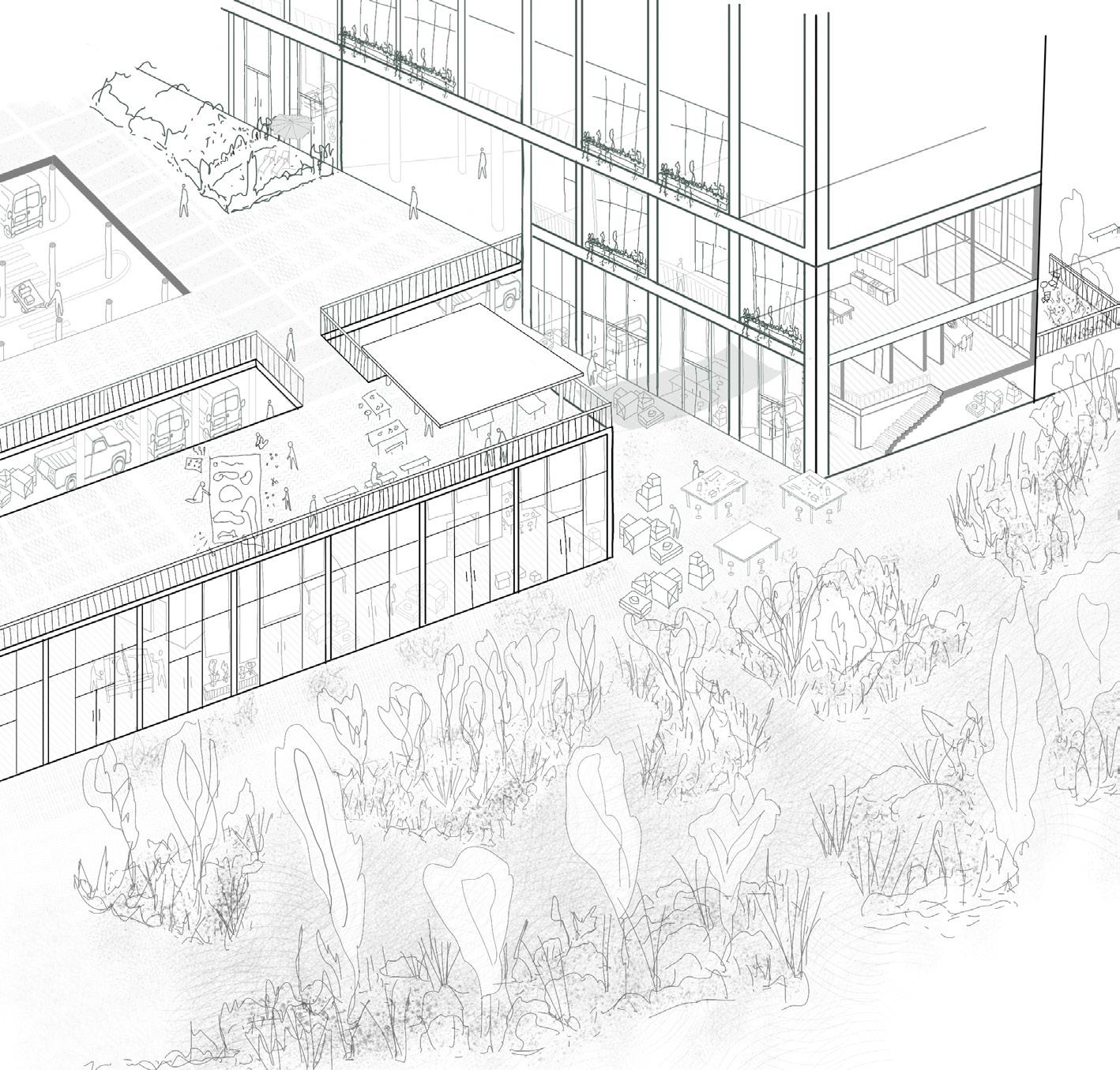

Assemblage of living and working typologies around the shed that re-qualifies the shed and its surrounding environment.

IV. Requalifying the Uplands

The Uplands in Blackhorse Lane is a significant industrial cluster that qualifies as one of the primary elements as seen earlier not merely because of its physical presence but also owing to the paradigm shift in its usage and potential brought about by the emerging light and creative industries. Retention of the shed can be viewed as the begin of the re-qualification of the uplands and in extension, the entire Black Horse Lane by inviting the necessary actors and drivers of change. As the first stage of development, the area around the shed can be transformed into an intensive mixed development that brings living and working together and retaining some of the traditional industries already existing. In this way, the civic regeneration is brought to its neighbourhood increasing the value and investment potential for the rest of the development.

Resistance of the Shed: Adaptability and Quality of Space

The Uplands of the Lee Valley was traditionally occupied by large industrial sectors similar to other industrial clusters in the city. Whilst some more uses remain in the last ten years, there has been a shift towards artisan manufacturing on site with the arrival of businesses like Square Mile Roasters, Wildcard Brewery, Replica, Minor Figures and Signature Brewery. It is notable that this later wave of development demonstrates a change in typology and unit size, away from large-scale warehouses

towards smaller units and multi-storey buildings. The Shed accommodates several industries such as breweries, gelato manufacturers, coffee roasters, packaging, etc. allowing for small scale light industries to coexist with larger industries that is often a reflection of growing interest in self-initiated small businesses in the periphery. In congruence, the existing large warehouse has been subdivided into much smaller units inviting various range of industries and actors together making

it fundamentally urban in nature. The small businesses support the local entrepreneurs. Overtime the shed has been adapted and modified owing to its structural robustness and the abundance of natural light that flows through. Thus retaining the shed in recognition of the shift happening in the industrials clusters becomes core to how the development unravels around it. And as the value around the area is heightened, the shed can attain a new life and can be removed and redeveloped in the future.

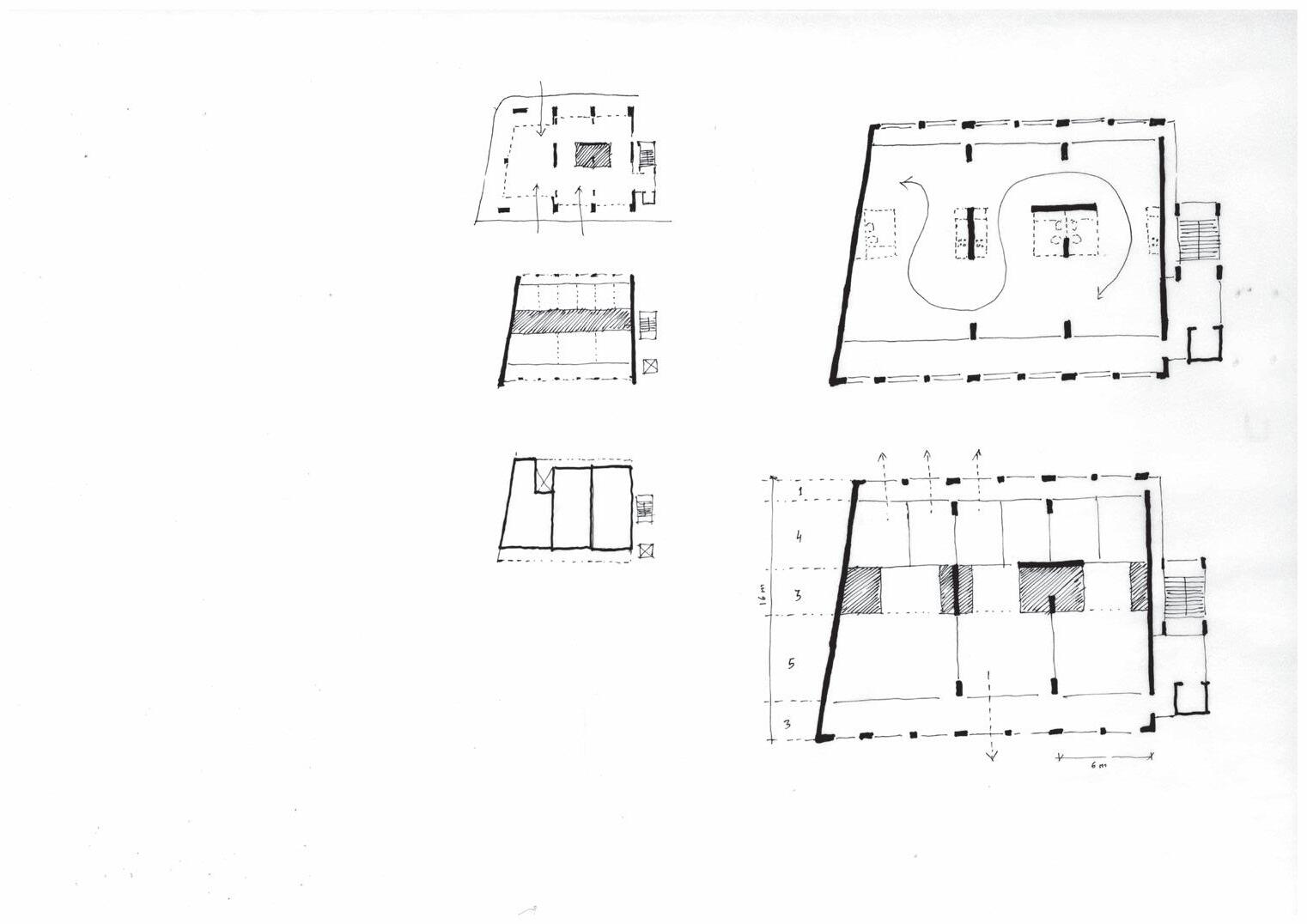

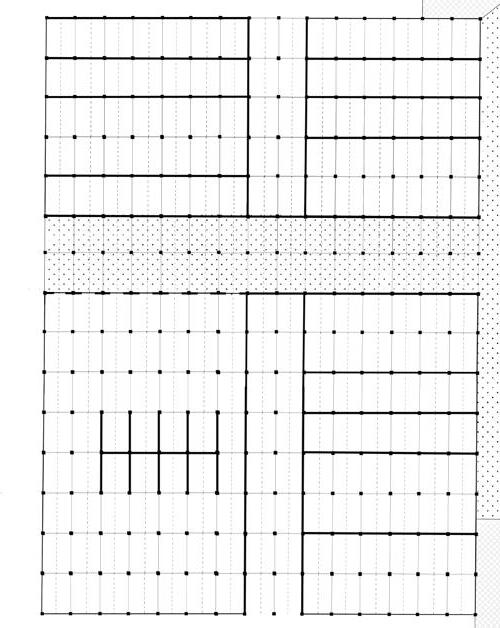

Structural grid of the shed

180 m

120 m

The high volume and the well-lit interior of the shed becomes ideal for workspaces and

The Uplands shed acting as a primary element that drives the development around

The vertical segmentation of Frizz 23 bring housing, working and civic functions together

Horizontal tripartite where the ground is differentiated

Modular repetition of units that are flexible to be working of living spaces

Another case of vertical segmentation of a long linear building defining the edge

Frizz 23, Berlin

IBEB, Berlin

Lokdepot, Berlin

Superlofts, Amsterdam

Highly segmented linear block accommodating a range of living and working

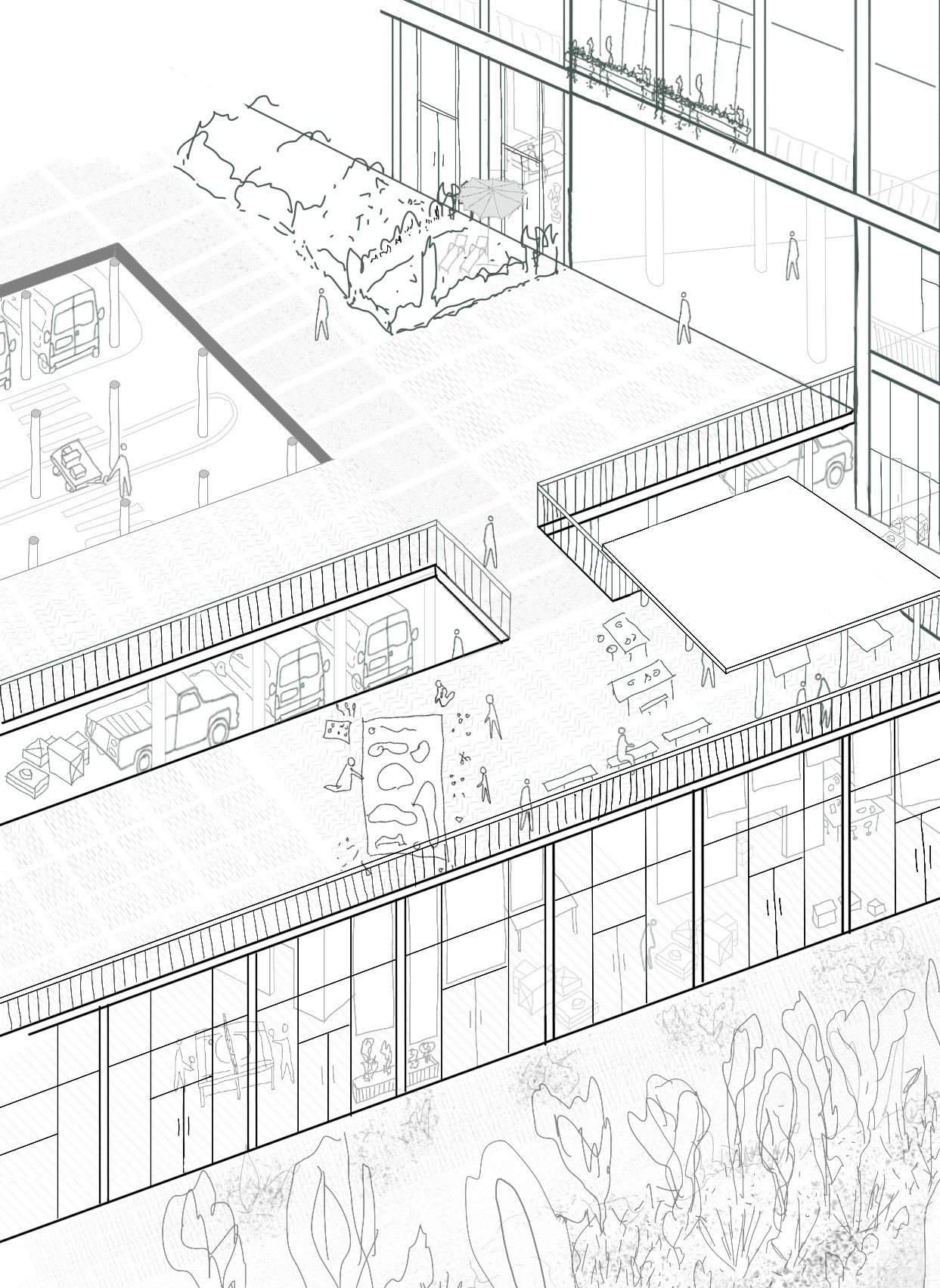

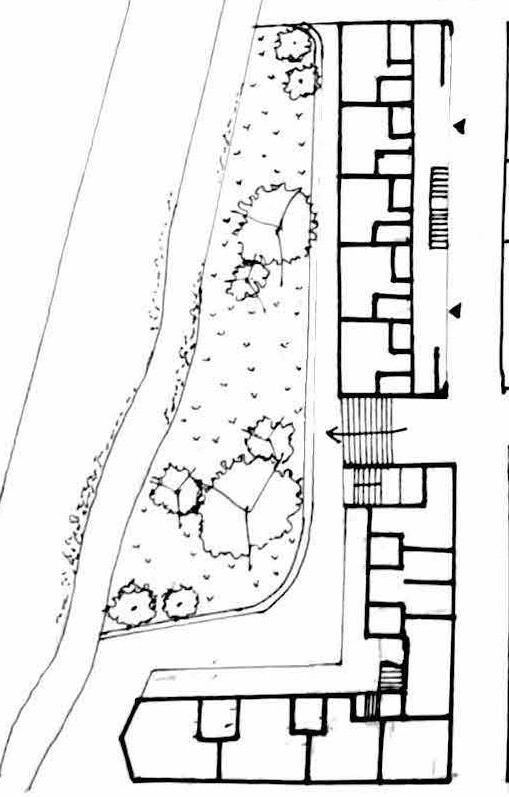

Segmentation and Variation of linear type: Living and Working

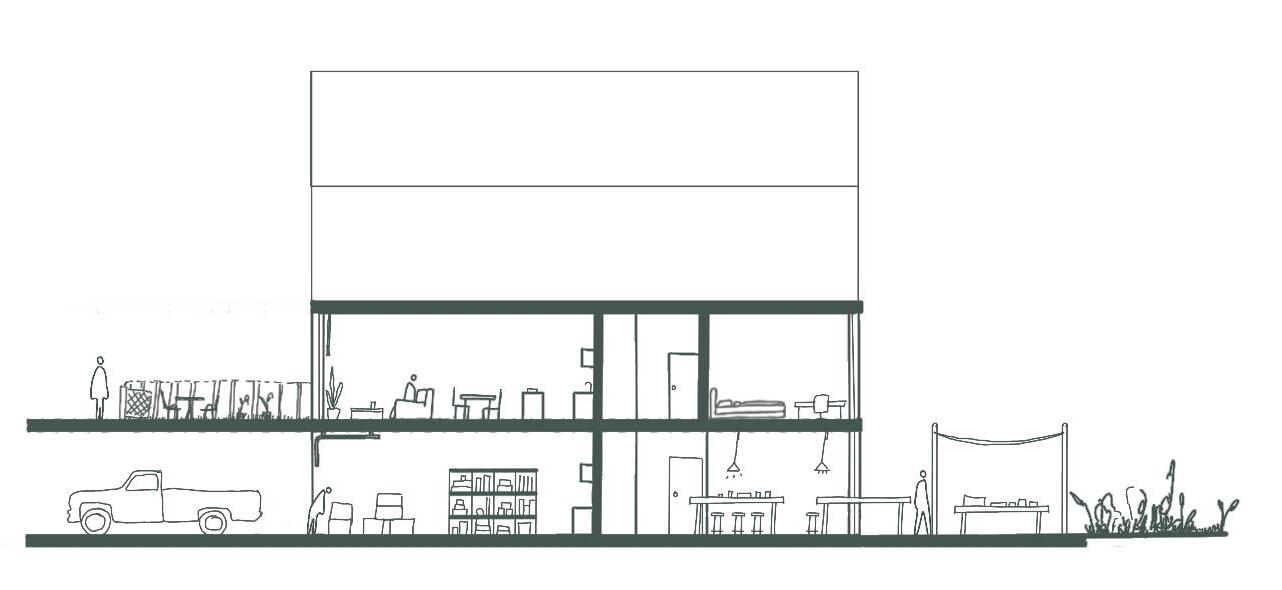

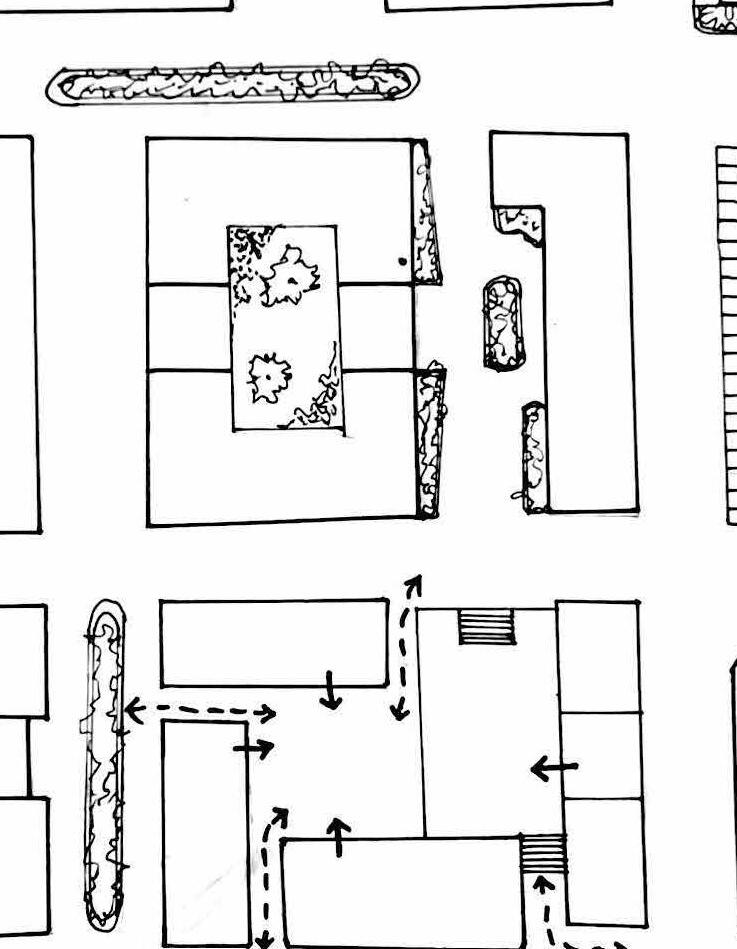

Linear blocks can be segmented vertically and horizontally to accommodates a range of living and working types intensely that is suitable for the upland re-qualification. Typologies such as IBEB that is segmented vertically into living and working sandwiched together where its ground is differentiated in relation to its immediacies is suitable to be built around the shed. The long deep linear block allows it to have a definite and highly differentiated nature of relations with the face of the shed on one side and the residential part on the other side. The dual aspect flats bring qualities of south and north light to the dwelling and generous views towards the wetlands.

The typology of Superlofts offers a different type of work-life integration. The modular unit system consisting of units of 18m x 6m and 5m in height offers the possibility for multiple configurations that can be modified according to one’s needs. The prefabrication method of construction and centrally located service shafts facilitates the units to be either studios or dwelling units that can be serviced from the basement and the shared yard space by the shed. The double height units between the shed and the Superloft’s units create a buffered pedestrian access above and services space below.

The linear blocks are used to separate the servicing of the shed from the civic realm and allows for multiple interactions at the thresholds

The segmented linear block that accommodates working and living units become a shared entity for the public side to the south and the quiet residential side to the north

Linear Blocks and Definition of the Edge

The linear blocks work together to striate and different the spaces in between and each space becomes characteristic whose definition arrives from the articulation of the edges of the buildings. Currently the shed is serviced from all four sides hindering or rather conflicting with the civic nature that it could possibly create. Thus the linear blocks are articulated to define the nature of its frontage. The dual aspect flats bring qualities of south and north light to the dwelling and generous views towards the wetlands. The south facing balconies and terraces become grounds for individual and communal leisure.

The linear blocks act as a buffer for the civic realm creating a shared protected environment and creates an active edge towards Blackhorse Lane.

Movement pattern around and through the shed. The servicing of the shed is limited to its north and south faces and run through internally in such a way that the units can be serviced both internally and peripherally depending upon its location

The striation of spaces created by the linear building acting in congruence with the differentiated levels to facilitate different nature of public and civic activities. The double height units between the shed and the Superloft units create a buffered pedestrian access above and services space below.

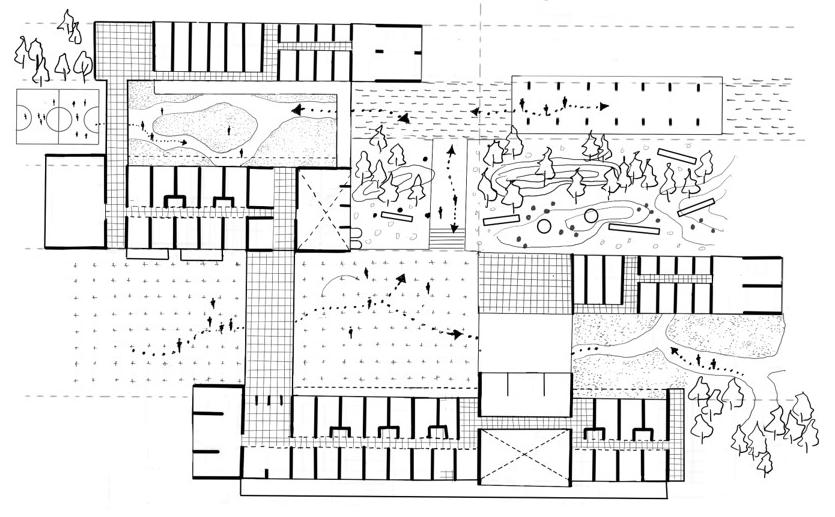

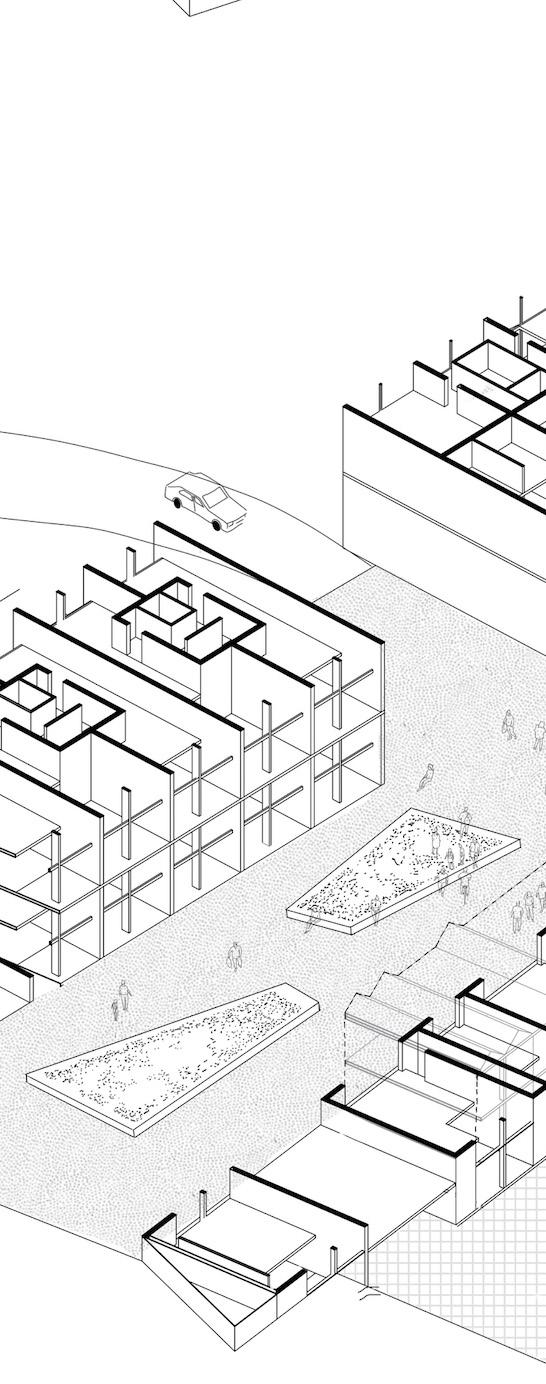

Thickened Ground & Layered Movement: Active Civic Life

Something valuable to the city is created when a set of such buildings form an assemblage i.e, its manipulation of the ground. The thickened ground accommodates shared services such as parking, bicycle storage, storage and other utilities freeing the pedestrian level to become active grounds. The level difference is negotiated at the threshold allowing double volume work spaces that can be accessed from both levels i.e. the shared yard and serving level of the shed and the pedestrian alley that leads to the water edge.

Living or working

work & storage units

shared workshop and servicing yard

The differentiated and modulated ground allows for a range of civic and public life to flourish. The typology of deep floor plates of 40m x 30m blocks in the eastern development that is volumetrically carved to create atria of light is highly conducive to accommodate work environments in the lower levels and cluster flats above. Common facilities such as vehicular parking, bike storage, restaurants and other service industries are accommodated in the basement and the ground level.

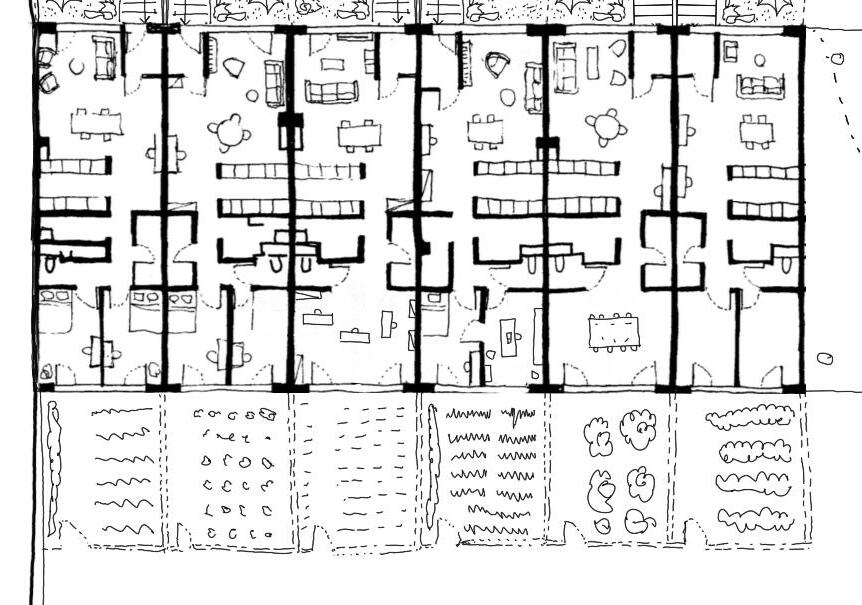

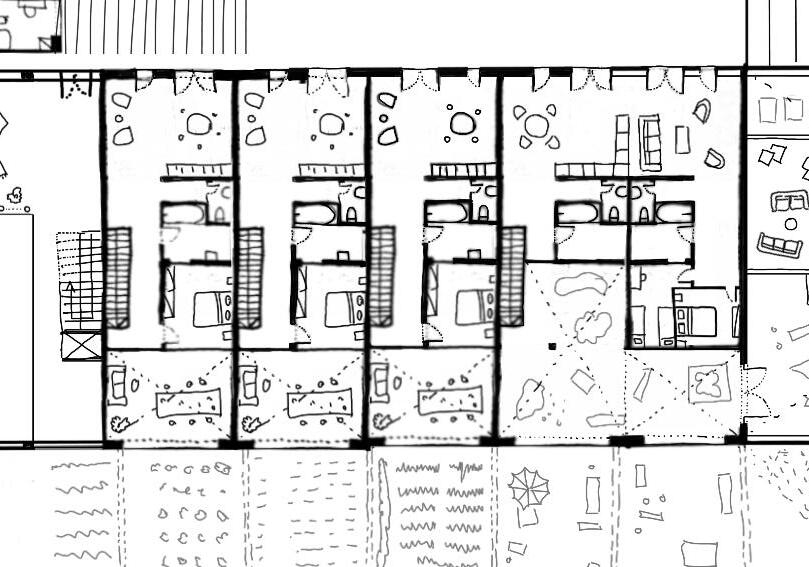

Same volume-different uses: buildings accommodating living and working separately

Bringing working life together with living: generous spaces extending to the exterior

Shared workshop spaces or creating together with our neighbours (and others!)

The extensive gallery: using exteriority to accommodate working life

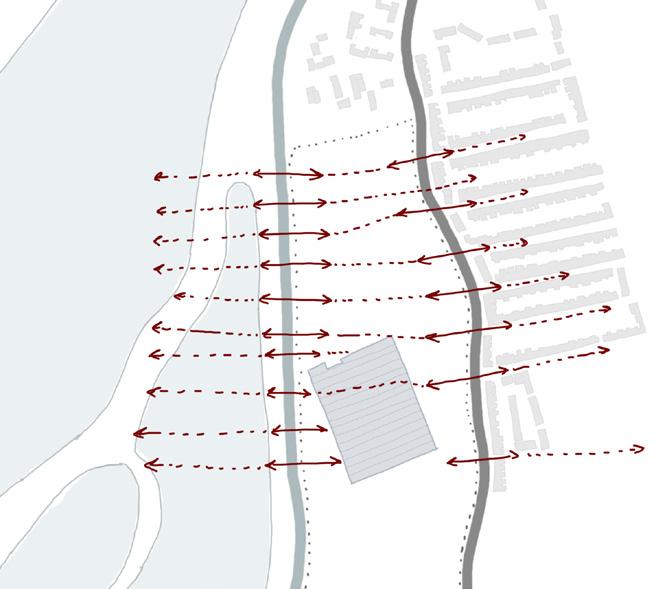

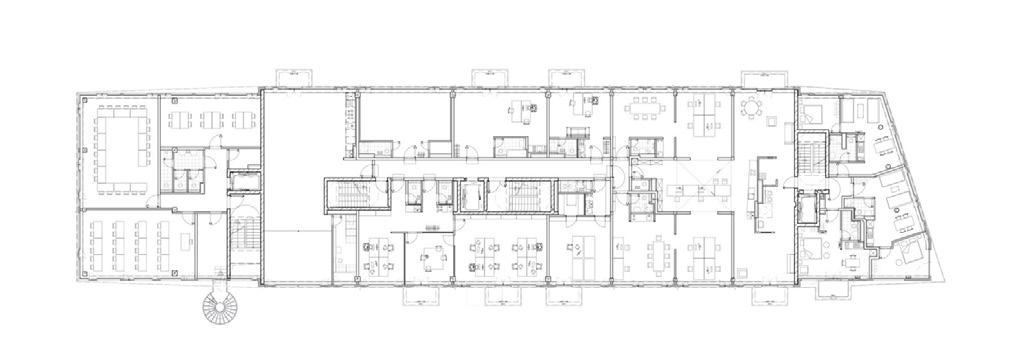

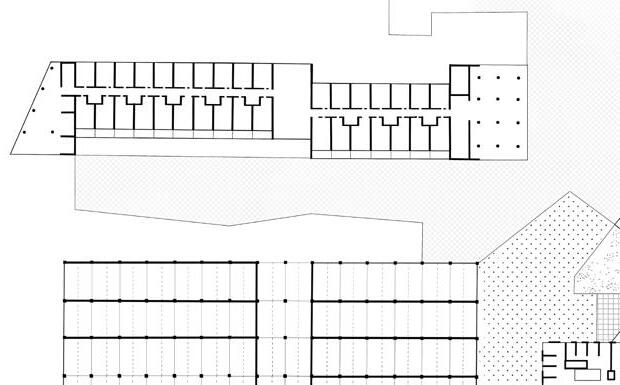

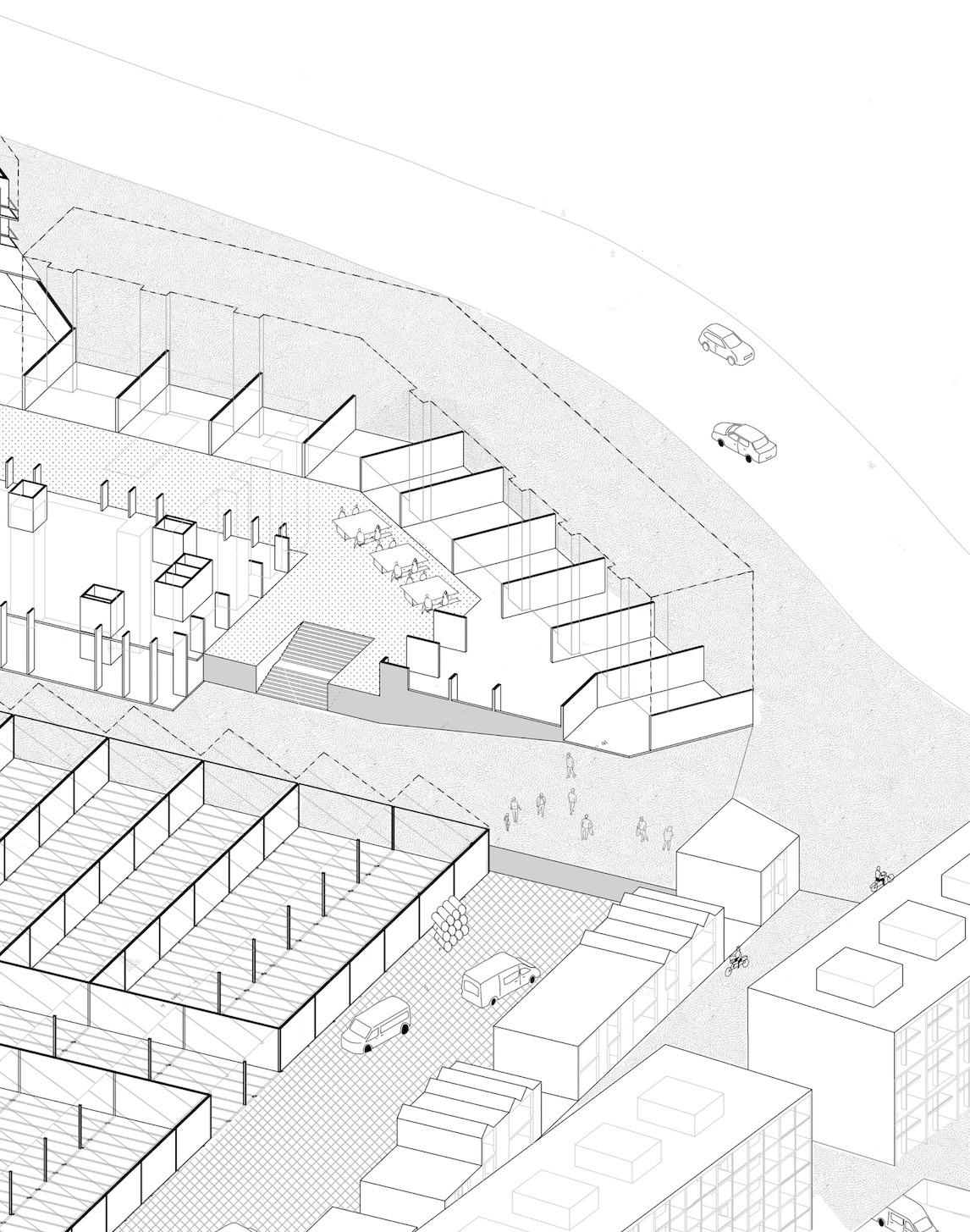

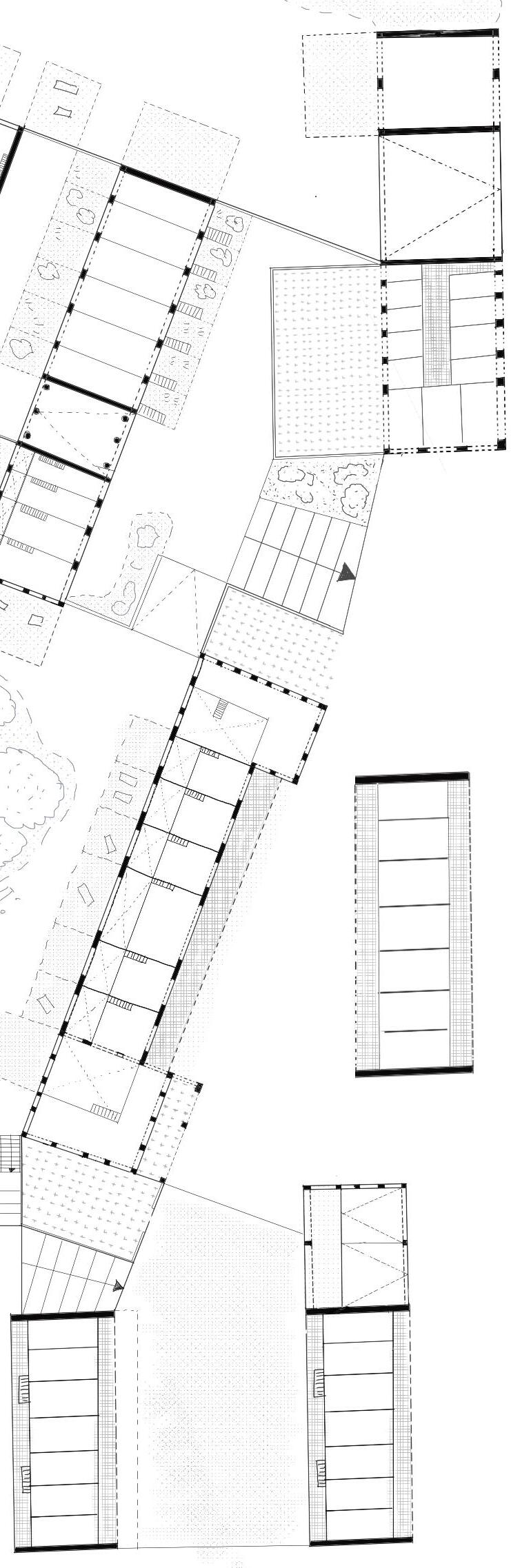

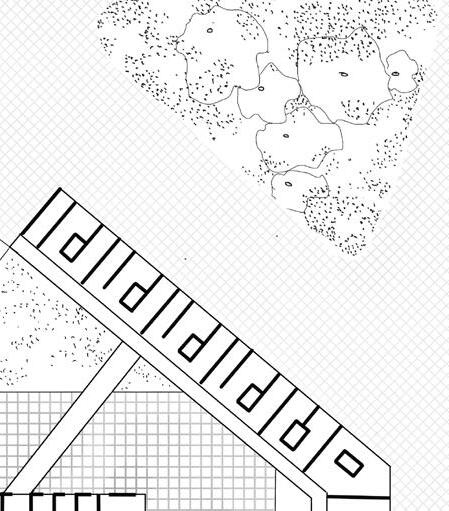

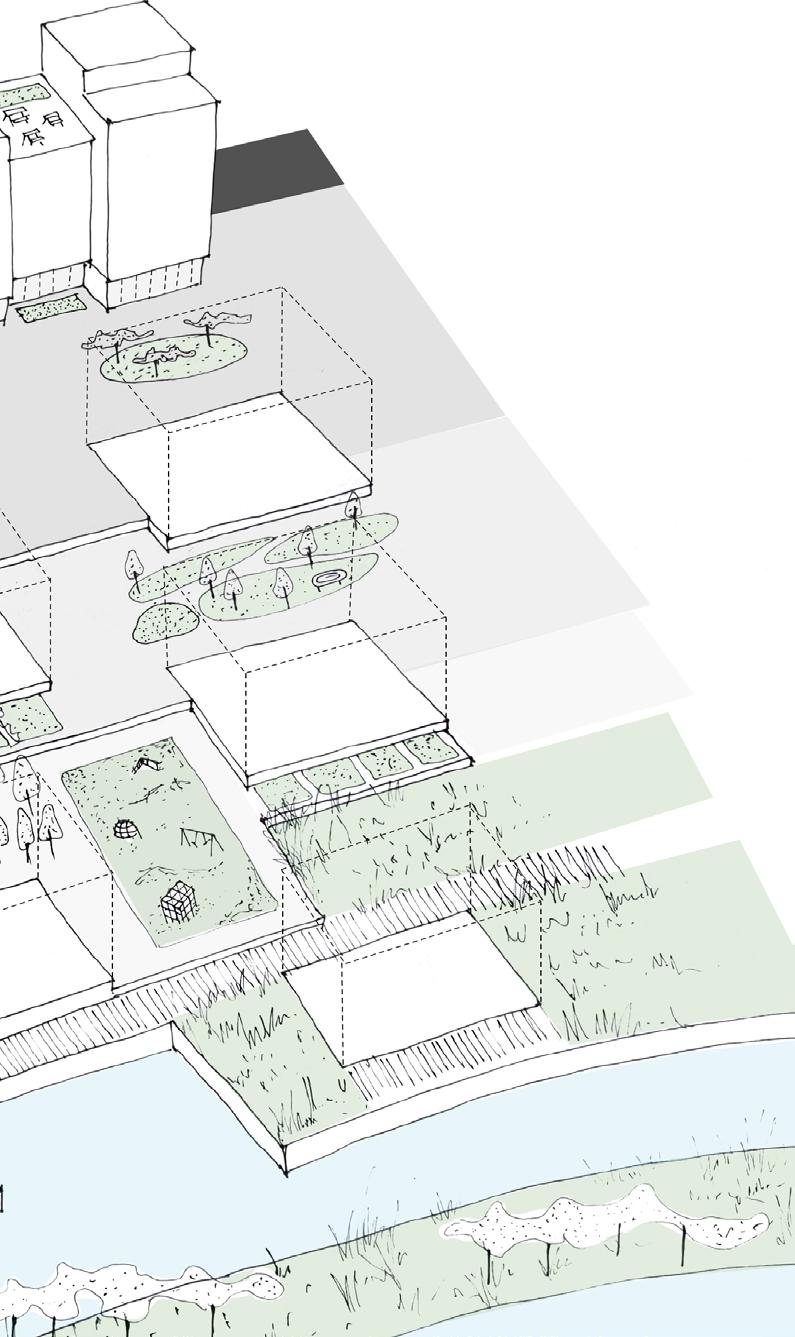

V. Exploring Linearity as a Threshold

If the Shed works as the core of the site, accommodating bigger-scale industrial activity, the role of the northern part of the site is to facilitate the crossovers between industrial and residential elements. Working primarily with linear buildings, there is a gradual shift in the typology of working spaces provided. Size, accessibility and connection with residential life vary , in an effort to explore different ways of living and working in addition to the changing relationships with the external environment. A spectrum of opportunities are then created in relation to the variety of overlapping elements. Options vary from closeness to the nature and the green environment, to working spaces in direct connection with the neighbourhood or a direct access from the street. A series of open public spaces is also accommodated, in various scales, enclosed by the linear buildings . Their form, size and sequence give to each building assemblage different qualities, bringing variety to the way the open space is experienced.

Form as a Means of Connecting

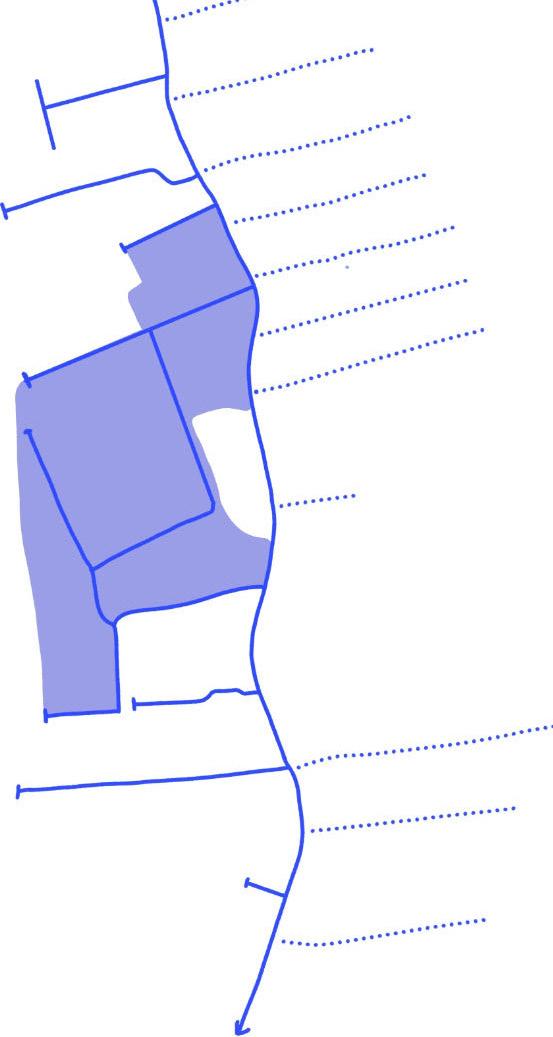

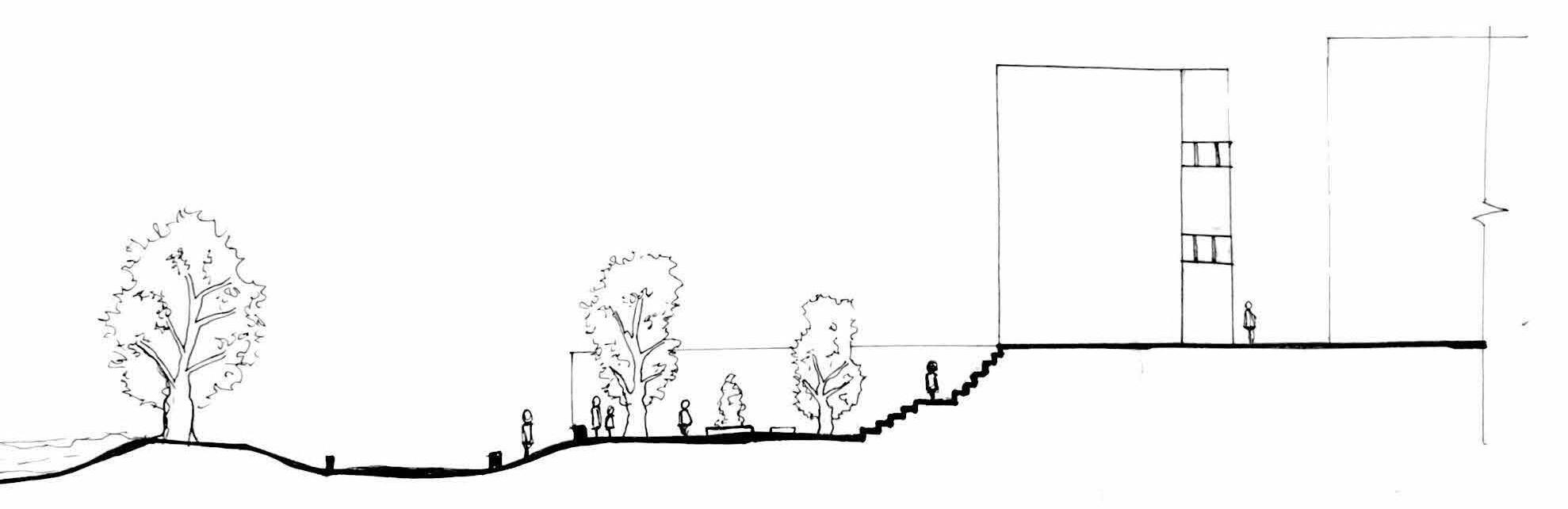

As formerly explained, the site is compressed between two, primary urban elements that run along it. On one side there is Blackhorse Lane and the terraced housing fabric, highlighting the residential aspect of the area. On the other side one can find the wetlands, serving both for leisure activities and as a natural reserve, providing habitats for animals and having an impact on the biodiversity of the area. The absolute segregation of the armatures is highlighted by the level difference between them. An initial effort was made to understand how these two levels could come together with the help of urban elements, in order to improve their interaction by respecting at the same time their fundamental differences. Focusing on the edges of the two areas, a

set of propositions were made, examining how the upper-urban”surface” and the lower “green”one can interact, coexist or even pile up. By experimenting with buildings’ organisation and orientation it was decided that linear buildings, when put along the edges of the two levels, could bring them together in a subtle way, providing a layered, protected interaction between the two. In addition, by extending the urban surface, the area underneath can be used for the vehicular mobility, leaving the whole upper area for active mobility. Accessed by ramps in direct connection with Blackhorse Lane, the vehicular circulation runs along the basement of the buildings facilitating service and serving storage spaces more efficiently.

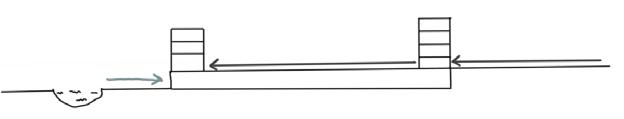

Option 1.

Extending the street level towards the waterfront with the creation of an elevated ground floor that functions as a service level. Buildings are placed along the limits following loose patterns allowing for permeability. Creation of a sequence of open public spaces playing with levels and openness.

Option 2.

Extending the green level towards the street level. Separation becomes more rigid with the position of linear buildings along the limits of the two, functioning as a threshold.

Option 3.

Extending the green level towards the street level. Separation becomes however more malleable with openings and variety in length and scale of the buildings, as well as flexibility of the ground floors’ configuration.

Option 4.

Equal extensions from both sides intertwined to create a series of level differentiations. Buildings are put either parallel and at the end of the elevated platform to profit from level differentiation. Or, buildings are offset from that edge, therefore functioning as a second threshold and creating more private open spaces.

The street-green levels can be used separately allowing for an upper level providing generous double-sided housing and a lower one accommodating workshops with additional open spaces and direct connection to service areas and vehicular mobility system

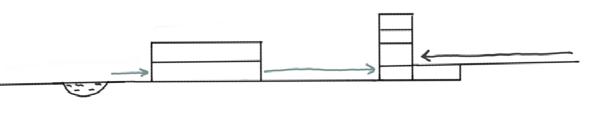

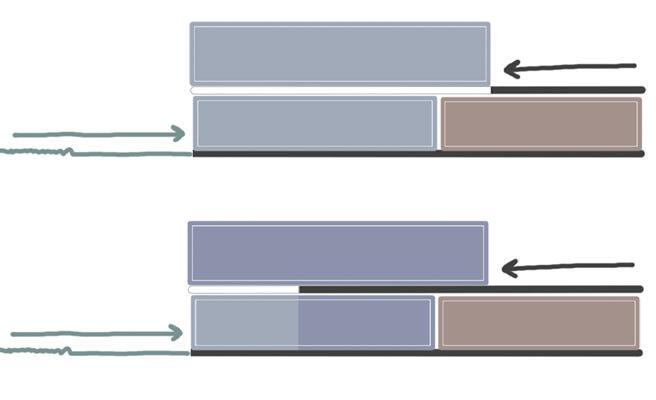

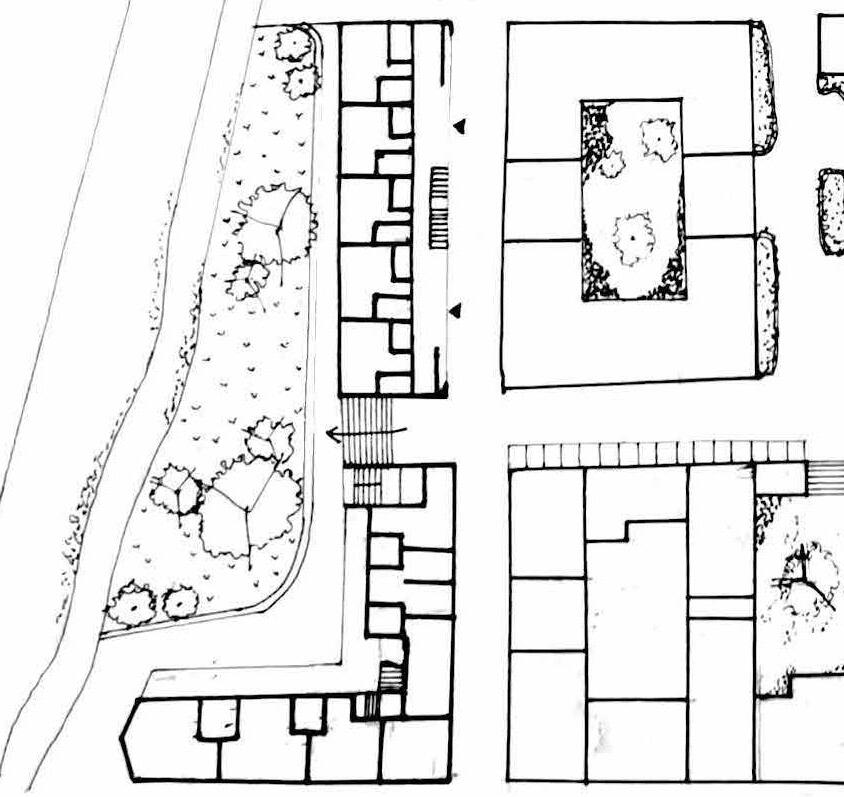

Same Volume- Different Uses: Accommodating Living and Working Separately

One can use level differentiation that structures the proposal at the scale of the unit to arrange spaces in generous ways so as to provide opportunities for different uses. One begins to explore then a set of crossovers between working, living and service spaces that can start interacting in various ways, depending on their priorities of connections. Having access to the street level on one side, the vehicular mobility and servicing underground and the green level on the other side gives the opportunity for a wide range of working and living environments that interact with different levels With an east to west orientation, a width of 5m and lenghs that vary from 10 to 16m lin-

ear units can provide generous qualities as they are double oriented and they can provide double sided access on the ground floor. Using the central part for services, each unit mirrors two generous spaces, that can be used in various ways according to need. At the same time, the lineal stacking allows for flexibility in any potential merging of multiple units, in order to create variety in living conditions. The dimensional patterns allows flexibility to working spaces too ,providing variety in depth for generous open spaces capable of extending to the outside, whether that is the green zone or the internal courtyards of the blocks.

housing

workshop

service & storage

street level

green level

Diagram explaining multiple ways of stacking or putting aside uses to provide different options of accessing from the level of Blackhorse Lane or from the waterfront

green level

housing service & storage

housing& workshop

street level

The street-green levels can be used separately allowing for an upper level providing generous double-sided housing and a lower one accommodating workshops with additional open spaces and direct connection to service areas and vehicular mobility system

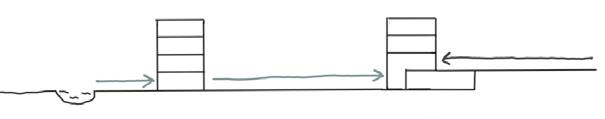

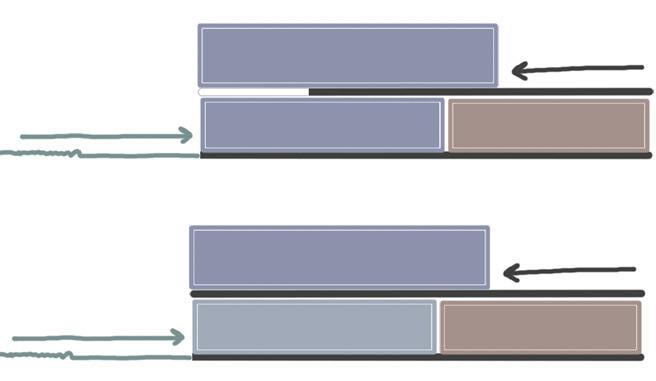

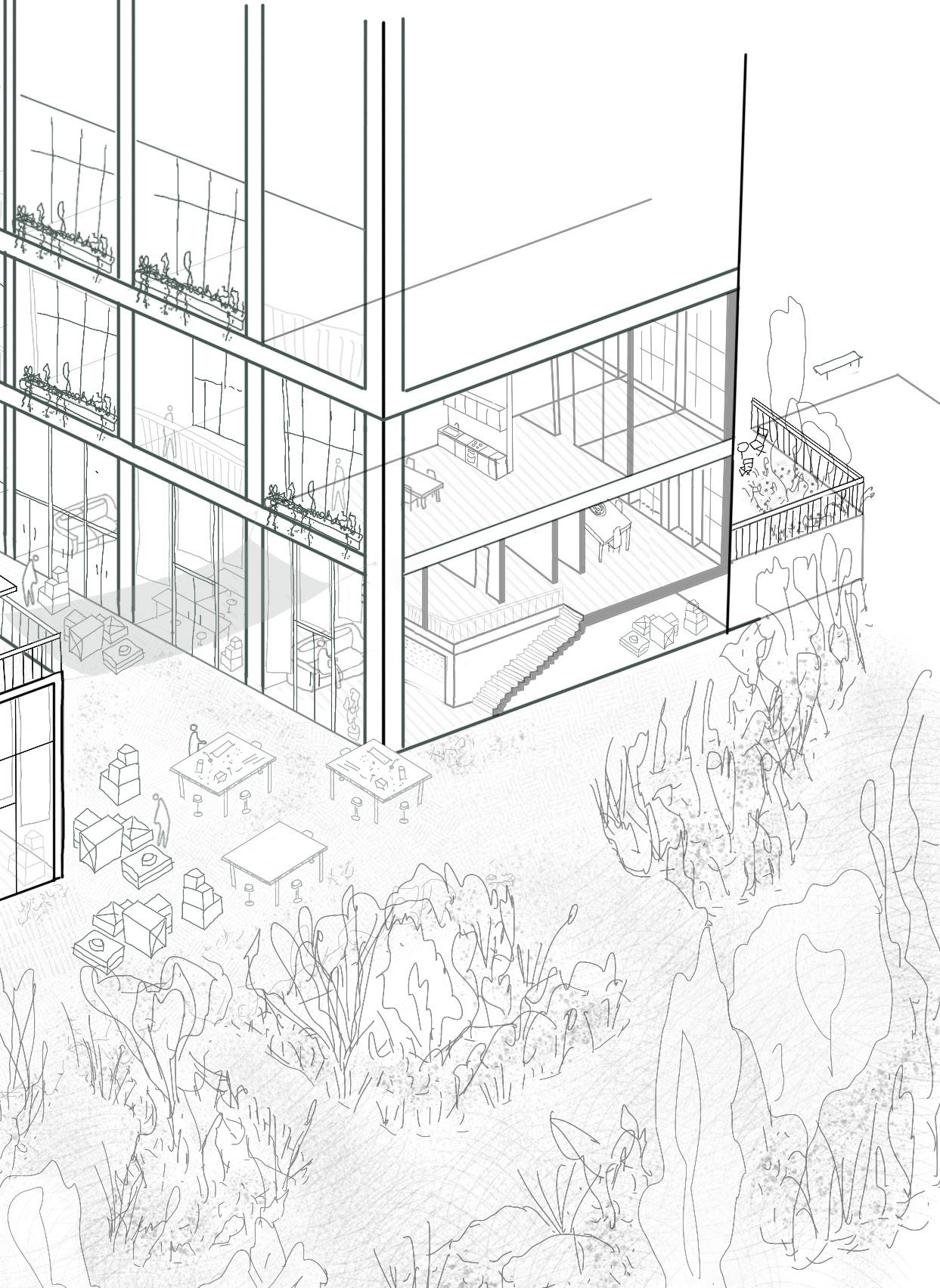

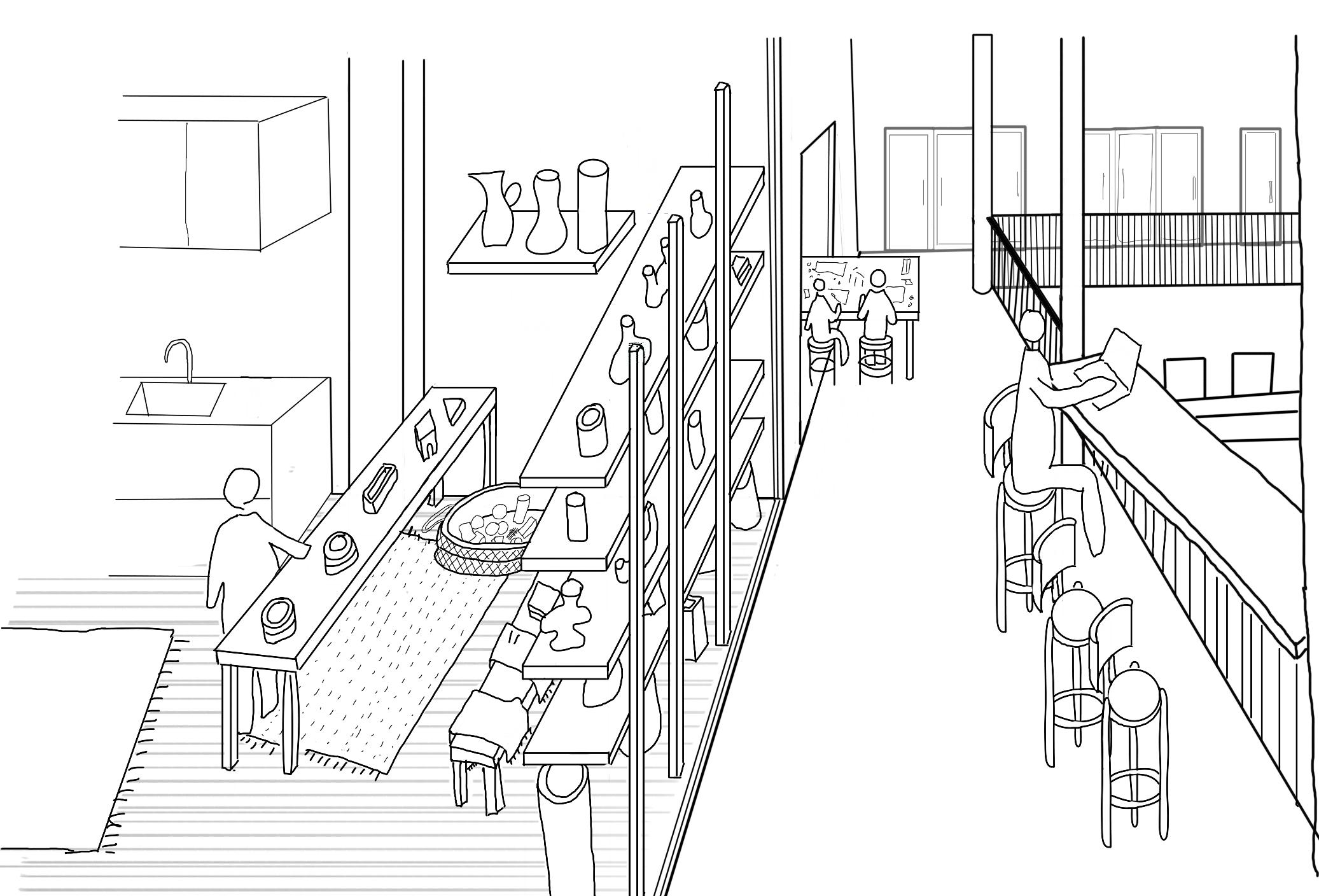

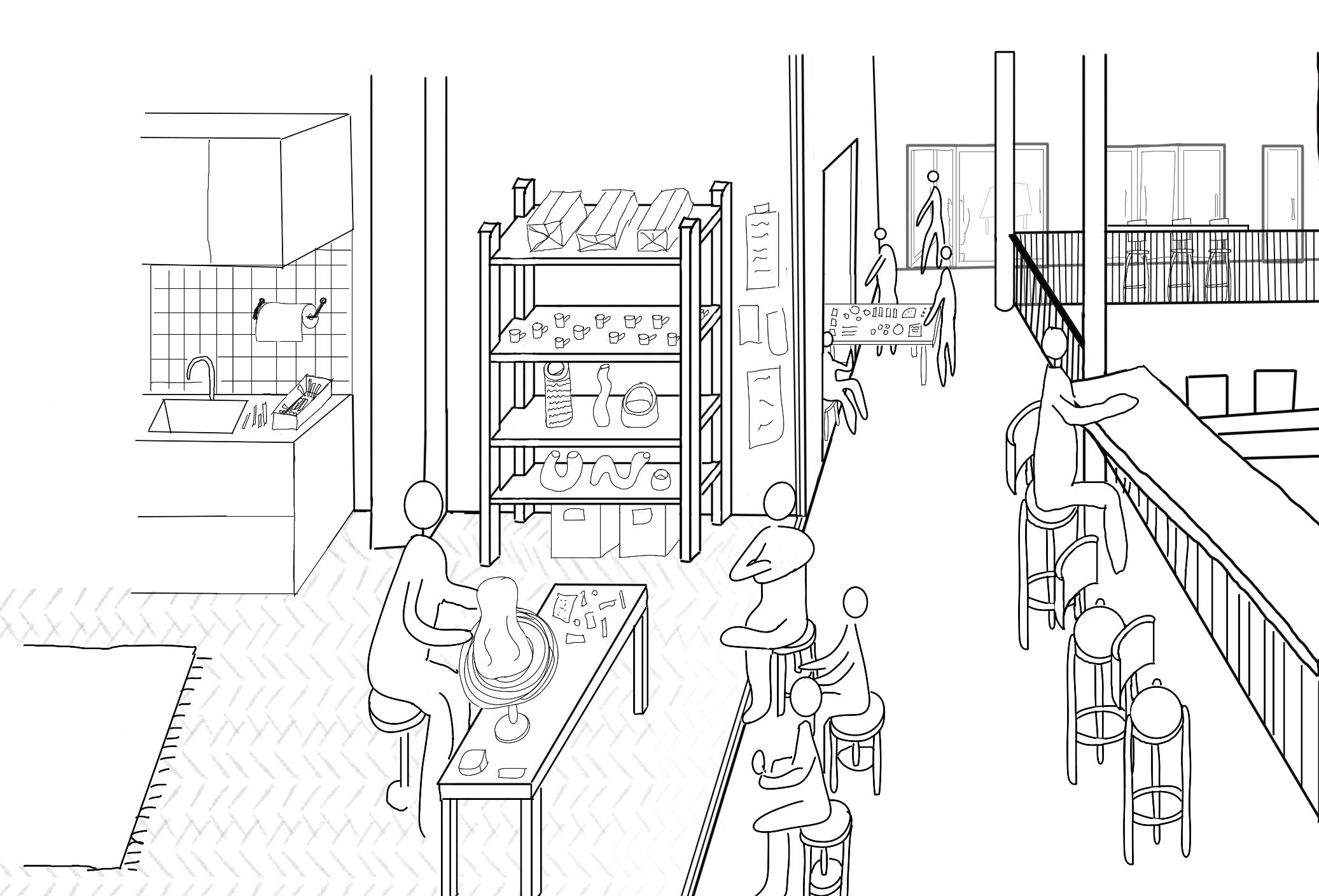

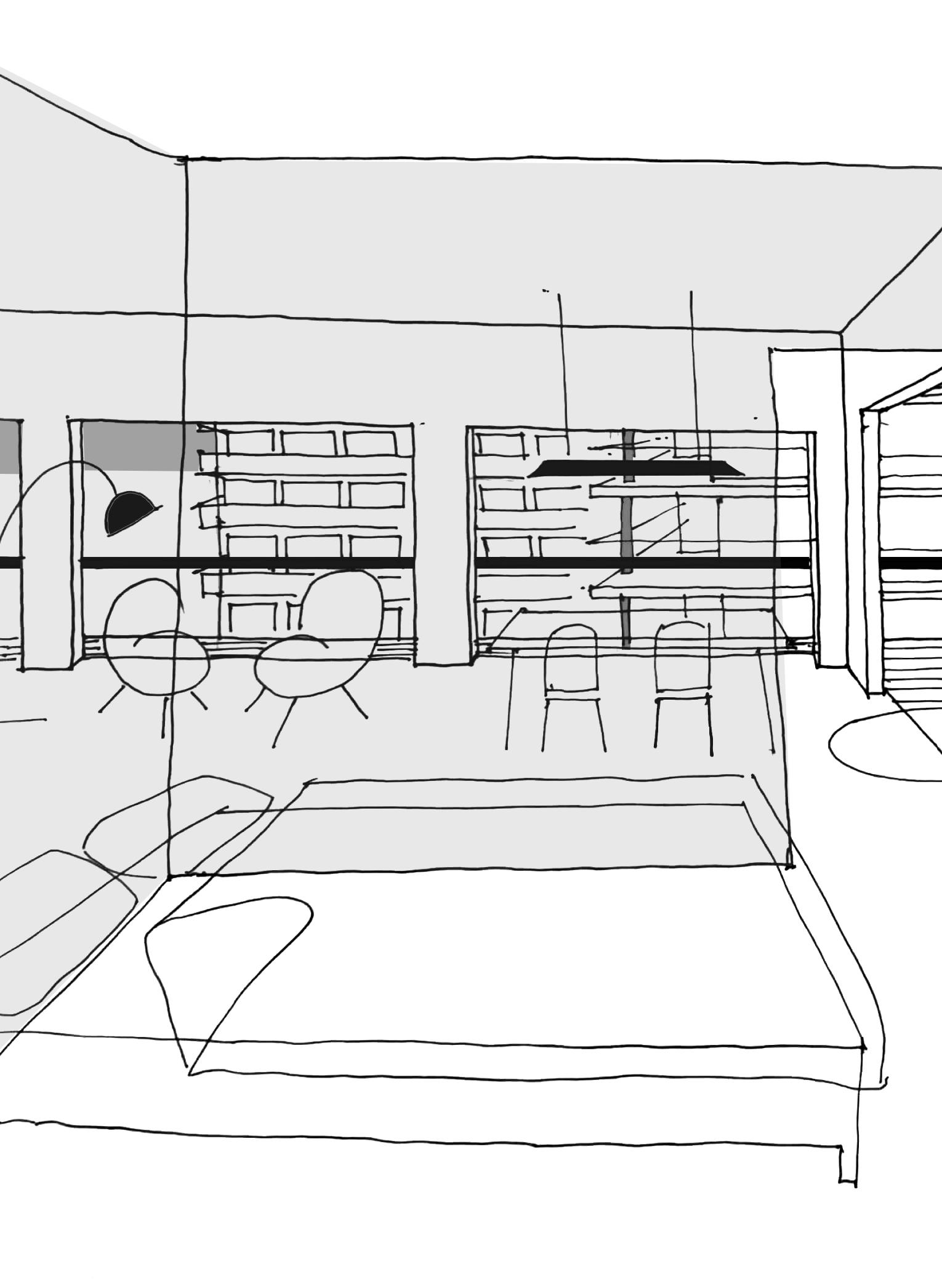

Working and Living Brought Together: Generous Spaces Extending to the Exterior

The flexibility of the linear typology can be explored furthermore on the ground level, in cases of connection between multiple levels, so as to provide one part of the unit with generous double height facilitating working conditions that need light, extra height etc. The double height space can function as a threshold between the life accommodated at the depth of the unit and the working life provided there as well as to the outdoor extension of the unit. Following the edges of the thicker extended urban ground one can then find qualities in the crossover between outdoors working spaces and service/circulation ones,

bringing together a wider range of activities. Semi enclosed courtyards can be then created to function as the common open area between living spaces, workshops, service areas as well as the green-zone allowing transparency and interactivity between the various activities and facilitating their interaction(zone 1).As an alternative option, the connection between the levels combined with a potential merging of units can initiate the beginning of different ways of living combined with bigger scale working environments ideal for collective housing or collectivities working together etc.

Workshop and Residential Units brought together through shared open spaces- Visual connection between upper-civic level, service area and lowerworkshop level

Workshop spaces occupy part of the linear buildings or develop their own volumes, creating generous spaces available to inhabitants as well as the public. The visual and movement connections between the workshops, the green and street levels and the storage/ service areas allow for a better interactivity and mix of uses.

The Ateliers: Sharing Workshop Spaces with your Neighbours

The ends of the linear buildings can be used differently, changing their orientation in order to interact with all three edges instead of only with the two long axes. The dimension of the spaces created can be used to accommodate workshops , using the double height to interact with the street level as well as the green one . More private rooms with mezzanines above them can be accommodated inside the volumes to bring variety in the working spaces. Bring-

ing together in the same buildings residential units with shared workshops can initiate a better interaction between the two, creating lively environments throughout the day and exploring new possibilities of sharing common spaces within the building as well. The aspect of learning can then be integrated, under the scope of collective seminars or events or even by pure visual connection between the different environments.

Stacking volumes bring variety in the quality of environments created, whether they are used to house living, working or public activities. The way they interact and are held together brings up the liveliness of the space , allowing for varied possibilities .

By adding a secondary access gallery to the plan, the bigger one works at the same time as one’s personal balcony providing exteriority qualities while keeping in touch, if wanted, with the neighbours.

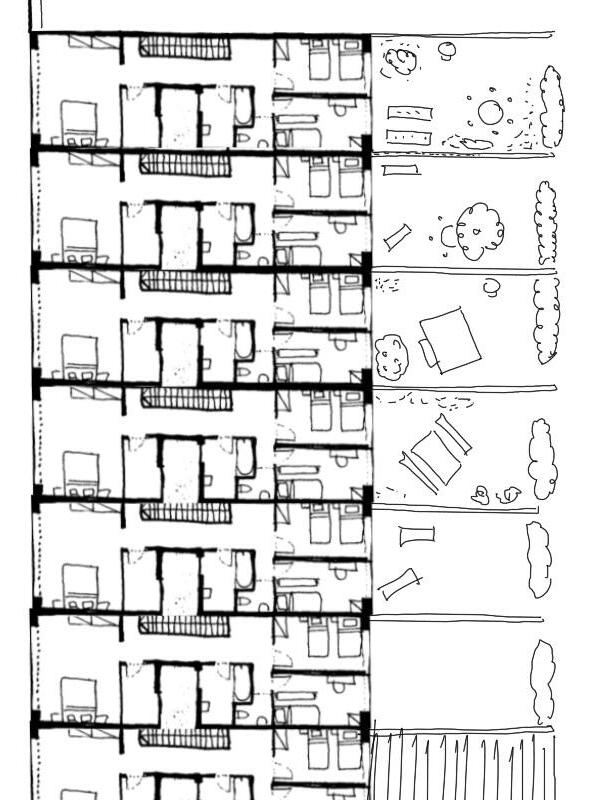

The Extensive Gallery: When Exteriority Accommodates Working Life

One can consider the gallery access as an interesting option regarding the creation of generous spaces at the upper levels of the linear buildings. Architectural projects such as the House for artists by Apparata and Lacaton and Vassal’s projects treat the gallery as an extension of the unit, rather than a secondary space, attributing to it qualities of communicating with the neighbours, working outdoors or using it to create more generous living spaces. To secure a certain level of privacy , at the scale of the

unit, the spaces interacting with the exterior can slightly shift to create more private corners. With the use of two galleries, one dedicated to circulation and access and the second one to the various uses further privacy is achieved and mobility is facilitated. The orientation of the second one towards the interior of the block can provide better interaction between the various uses accommodated there, such as the workshop extensions, public spaces, civic or collective spaces etc.

Apparata - House for Artists: The Gallery is used as an extension of the Artists’ studios and houses providing a common space for exchange between them.

Lacaton & Vassal - Transformation of 530 apartments in Bordeaux: The Gallery as an extension of the living room, creating more generous living environments

Buchner Bründler - Cooperative Building Stadterle:The communal gallery is used between neighbours to host events for the community and accommodate civic life.

Propositions showing how the gallery’s space can be used as an extension of the unit, to accommodate various uses and bring together living, working and civic activities. The sketches demonstrate how the same space can be used as 1. Exhibition and retail space for creative makers, 2. Collective workshop space or 3. Educational purposes, ateliers etc.

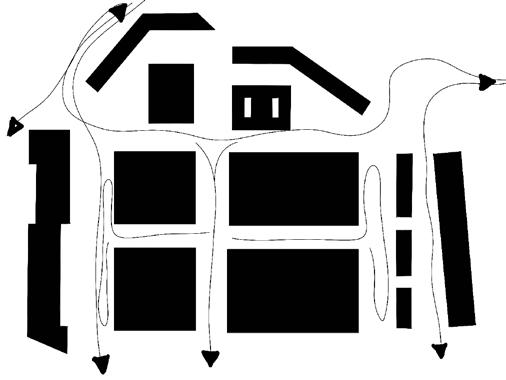

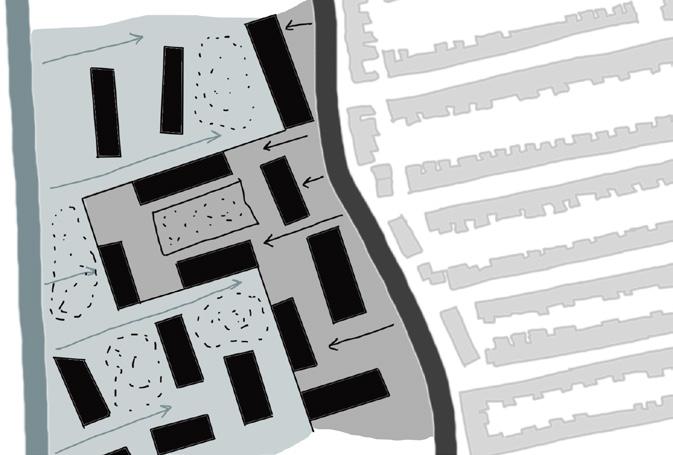

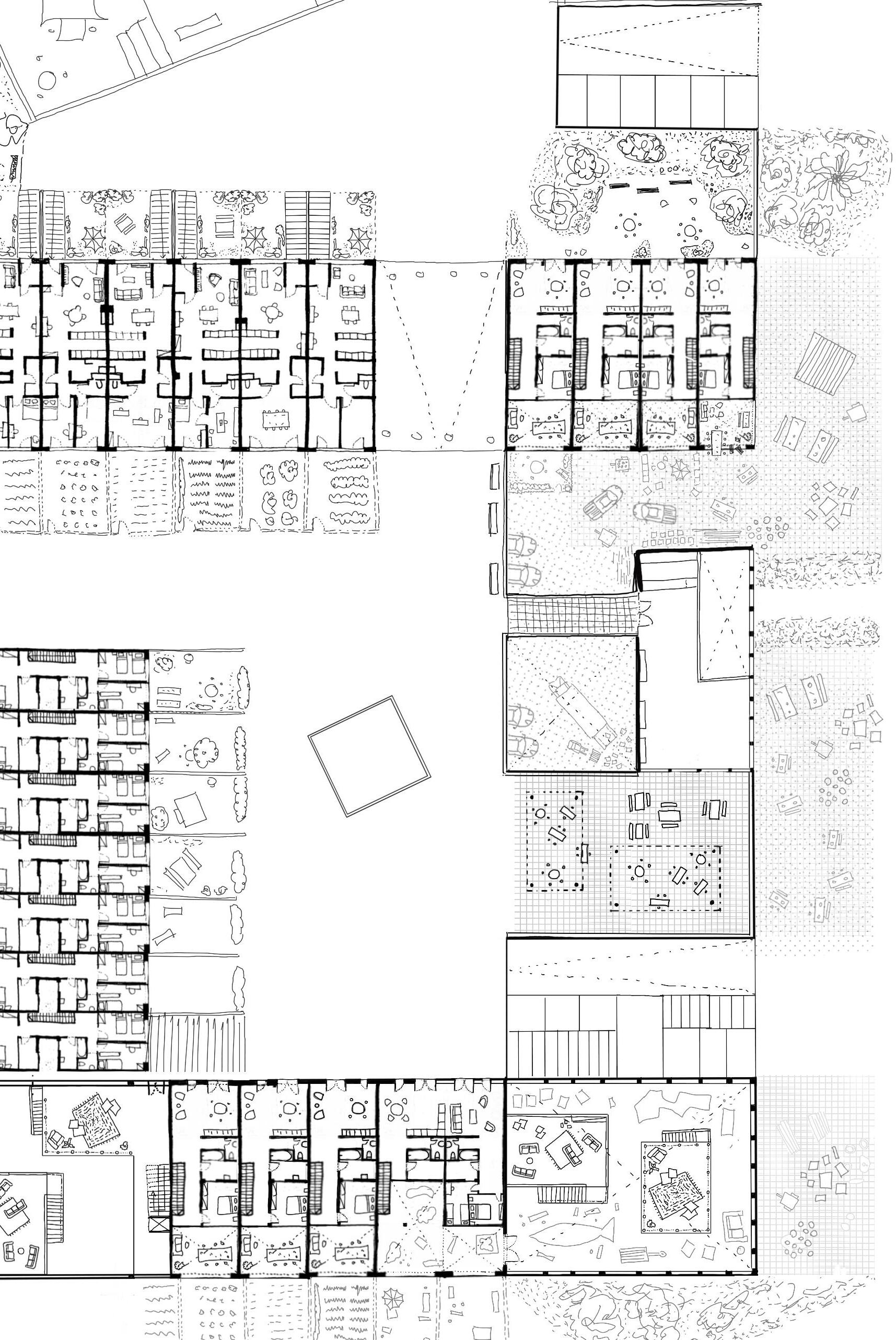

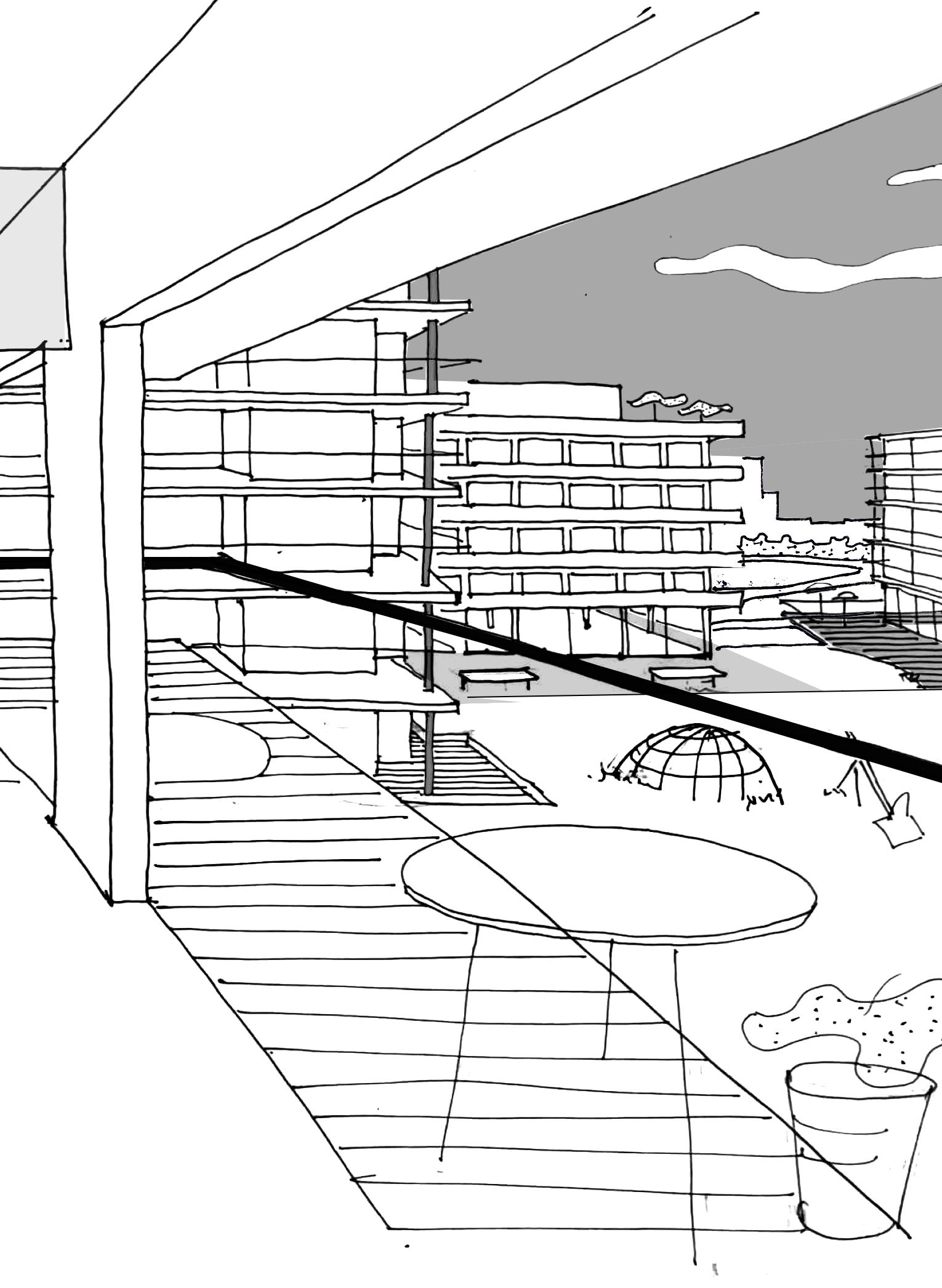

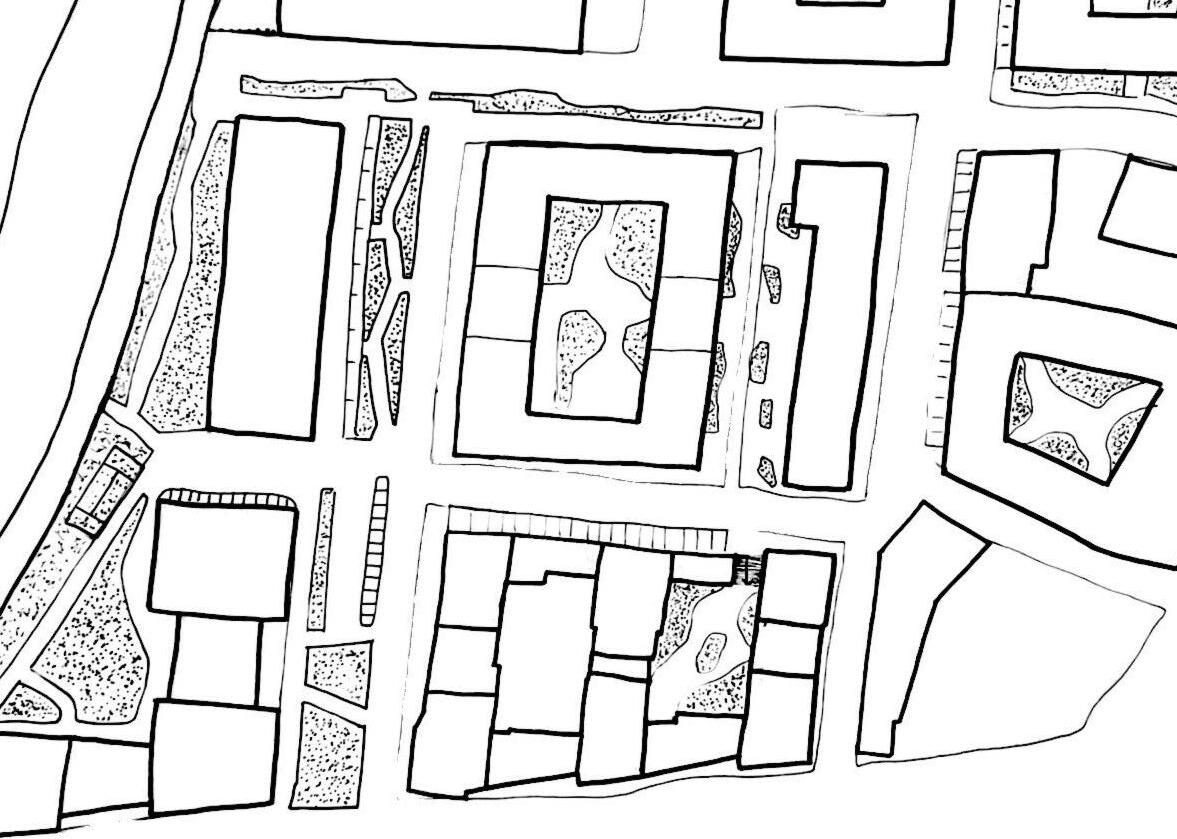

VI. Structuring a Fluid Ground

The re-qualification of Blackhorse Lane is a substantial developmental effort that would span over a long period of time. The re-qualification of the shed and the rich and diverse civic realm offered by the proposed assemblage of linear blocks in the northern part of the site are substantial preliminary moves that add value and interest to the site. A value that can then potentially

drive developments with substantial high quality housing and working environments towards the south of the shed. In addition to meeting the demand for high quality housing, the development in this portion offers a particularly unique opportunity as the potential developmental parcels extend across Blackhorse Lane, into the east, up to Sutherland Road.

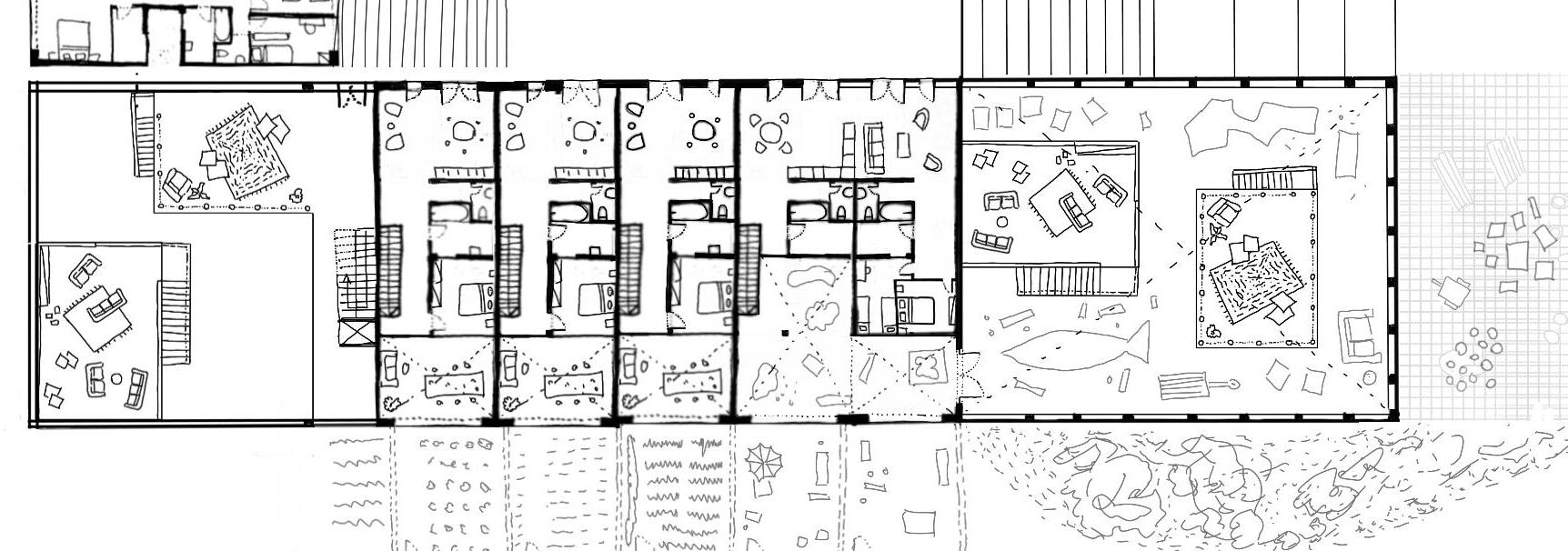

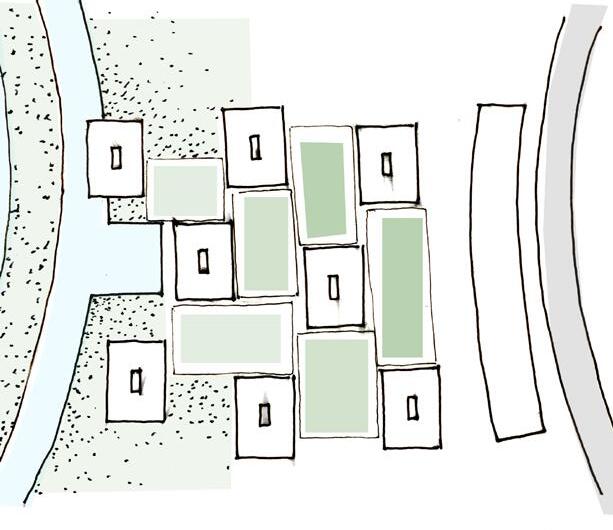

A layered and porous assemblage of differentiated staggered city villa blocks cutting across Blackhorse Lane structuring a dynamic and fluid civic realm. Linear blocks with deep floor plates help overcome the limitation of city villa blocks to define edges.

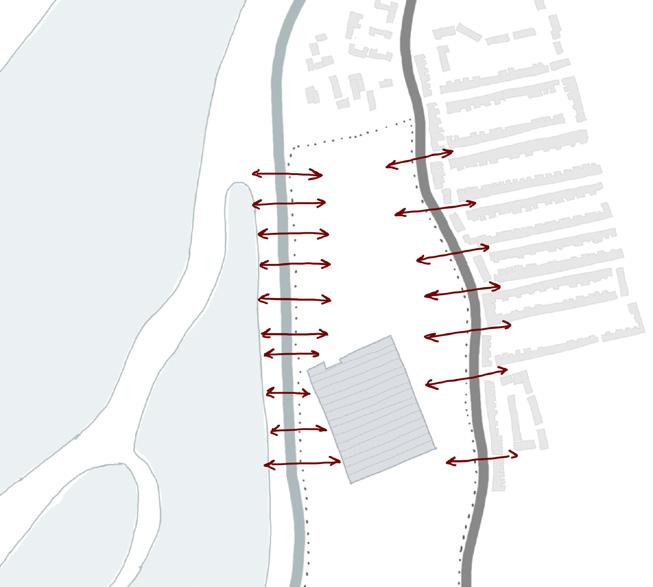

This lateral extension can potential help bridge the divide that exists between the waterfront and the eastern terraced fabric. Therefore, the permeability through the development becomes increasingly important. In addition to fostering a fluid east- west movement across Blackhorse Lane, the parcel would also carry the burden of carrying and building on the north- south

mobility that would be generated from the proposed northern developments up to the station in the south. Therefore, structuring a fluid ground, through forms that can offer distinctive qualities by capitalising on the qualities of the site becomes key to developing this portion. Staggered arrangements of city villas could be an effective model to achieve the same.

Re-imagining the Periphery from the Inside Out

The re-qualification of industrial areas in the urban periphery, like Blackhorse Lane, opens up a potential opportunity for a diverse range of formal arrangements that could capitalise on the distinctiveness of such a site. The potential for a strong relationship with the natural landscape and the access to considerably large portions of land, unconstrained by a tight street and block system are the main characteristics that define the distinctiveness of

the condition. However, the current developments along Blackhorse Lane and Tottenham Hale do very little to capitalize on these opportunities. They impose a system of tight streets and perimeter blocks with densities comparable to central urban areas. One could argue that the inwardlooking nature of the perimeter blocks may well be suited for urban centres, but is clearly a misfit in peripheral conditions as they fail to create meaningful relationships

A modulated and serviced balcony fostering life and interaction through the assemblage, Tulestrasse

with the opportunities offered by the ground and the outside.

On the contrary, the city villa block could be an effective alternative. Unlike the courtyard/perimeter block, the city villa is predominantly oriented outward. The city villa blocks are compact and offer an interface with the exterior on all four sides, maximising prospect and the visual connection that units have with the exterior. The building envelope, its transparency and extensions, thus become crucial in capitalising on the fundamental advantage of the type. The R50 and Tulestrasse blocks

clearly illustrates this. Through generous glazing and a continuous external gallery/ balcony, the type allows the life of the interior to effectively extend out physically to the galleries and visually much beyond. The modulations in the galleries can also offers some generous external spaces that one could inhabit and use in multiple ways as observed in the Tulestrasse. These galleries not only serve as extensions of the interior, but are the fundamental elements of a city villa block that fosters associations between the residents of units within a floor of the block and also between blocks.

The transparent and extended envelope that articulates the relationship between inside and out, R50

The life of a high quality dual aspect interior extending out into the balconies and beyond to the open spaces and the Lea reservoir

The City villa is a highly flexible type that can support a range of living and working conditions through small changes to its structure and size

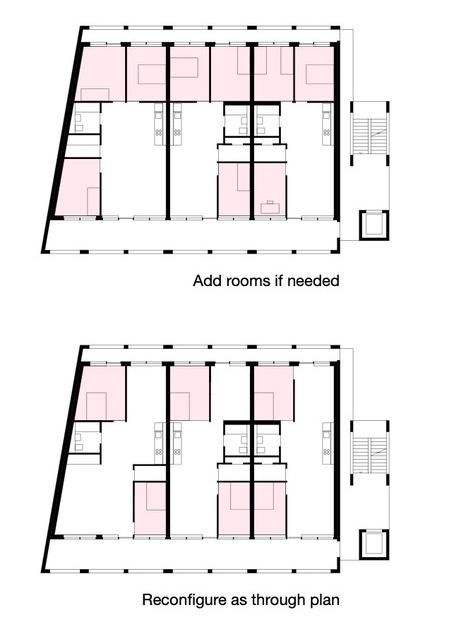

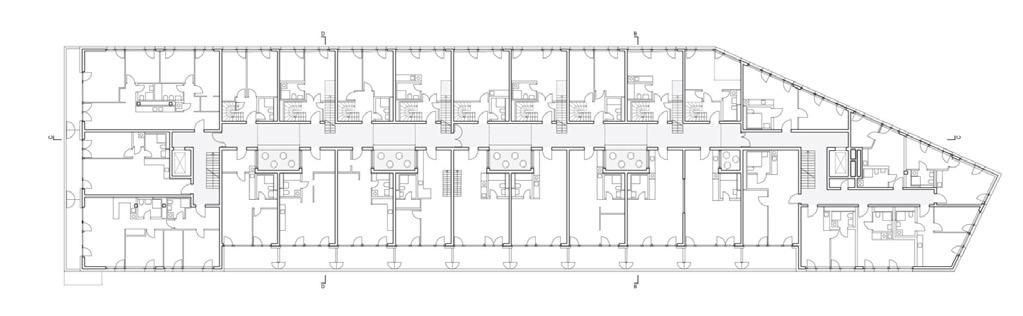

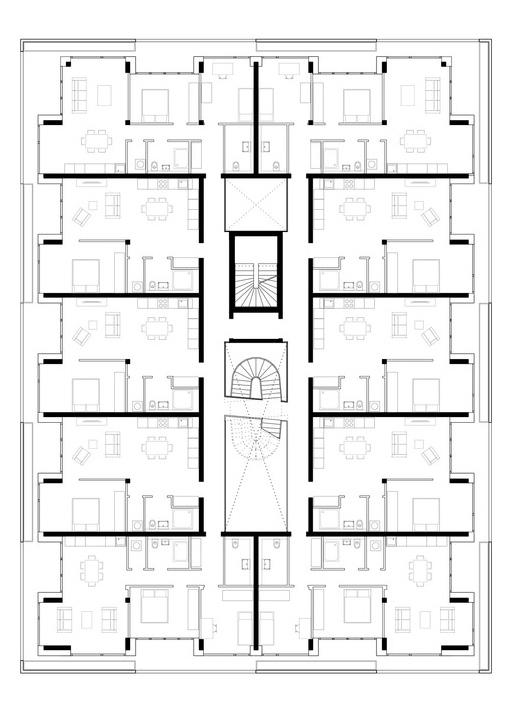

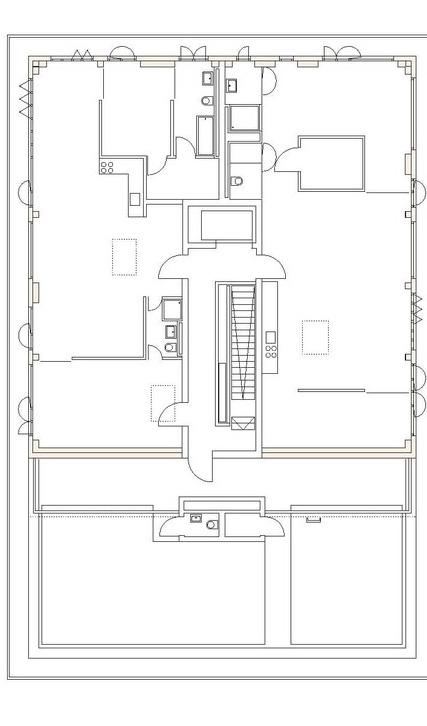

City Villa: One Type, Multiple Roles

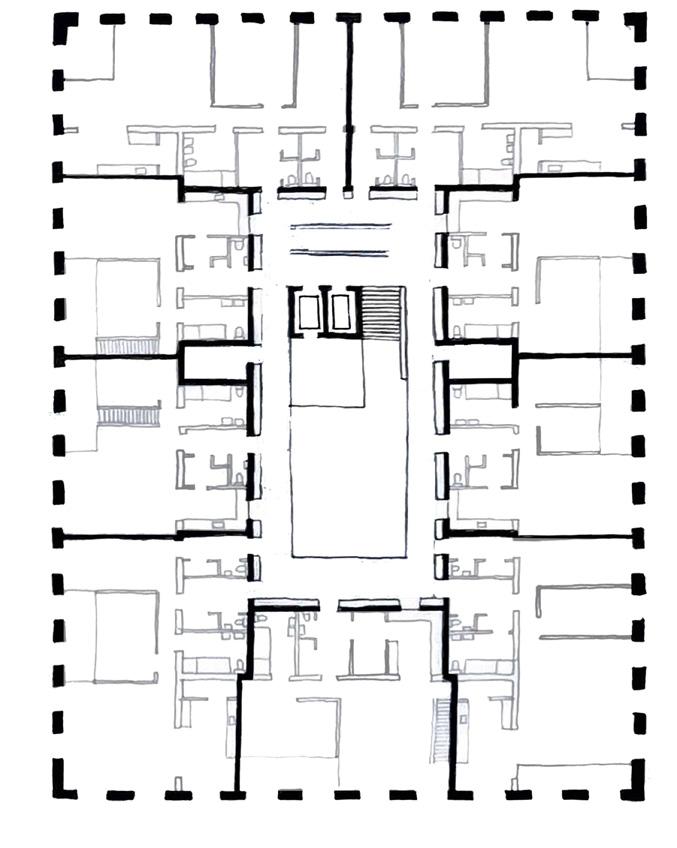

The city villa type is compact and efficient. A trait that makes it a preferred choice in terms of environmental and economic terms. However, its major strength could be attributed to its versatility and ability to support a diverse range of living and working environments through small changes to its dimensions and structure. One could look at a series of city villa blocks of increasing dimensions to illustrate the idea. The R50 represents the city villa block at its most compact form

of around 20m X30m. It consists of a tight circulation core that directly opens into dual or triple aspect units that can extend out by virtue of the continuous strip of external gallery. It demonstrates the ability of the city villa block to offer high quality residential environments in extremely tight and economic conditions. One could then look at the Tulestrasse block as a larger version of the city villa block with similar characteristics as that of R50. At about 25m X35m, the Tulestrasse the central core

Piazza Ceramique

Tulestrasse

transforms into a narrow, yet substantial atrium that could support some interactions. The block is also deep enough to support two dual aspect units along the ends. The dimensions also offer more generous and differentiated balcony conditions.

The nature of the city villa, truly begins to transform at around 30m X40m with an atrium that could potentially function as a meaningful and intense internal environment. The Piazza Ceramique demonstrates this ability of the city villa to support hybrid environments which could support both living and working. Its structure is also fundamentally different

from Tulestrasse, with structure on the periphery, allowing immense flexibility with the internal arrangement. The City Palace by Kempe Thill at Brussels pushes the dimensions of the city villa to the extreme, where the atrium takes the role of a small courtyard. Though close to a courtyard/ perimeter block, the city palace could be characterised as a city villa as it still retains its outward orientation. The City Palace’s generous dimension of around 50m X 50m allows it to house substantial work environments at ground and first floors and offers a range of different residential units at the higher levels.

R50

Atrium limited to a circulatory core, R50

A substantially large atrium that can support larger communion and working life, Piazza Ceramique

An atrium that is transformed into a courtyard, City Palace

A well lit, yet tight atrium facilitating occasional interactions between residents, Tulestrasse

Piazza Ceramique’s Load-bearing exterior façade and the structural ‘shell’ with services and installations surrounding the atrium allows for a wide range of floor plans. Within the rings of structure along the periphery and core, non-load-bearing walls and partitions can be shifted to achieve different layout arrangements.

The range of variations in Piazza Ceramique Left. Stacked/vertical working and living unit. Access to (a) working and (c) living in different levels. Hori-

zontal/semi-detached workspace (b) adjacent to the dwelling unit. Protection of the domestic environment through differentiating access points.

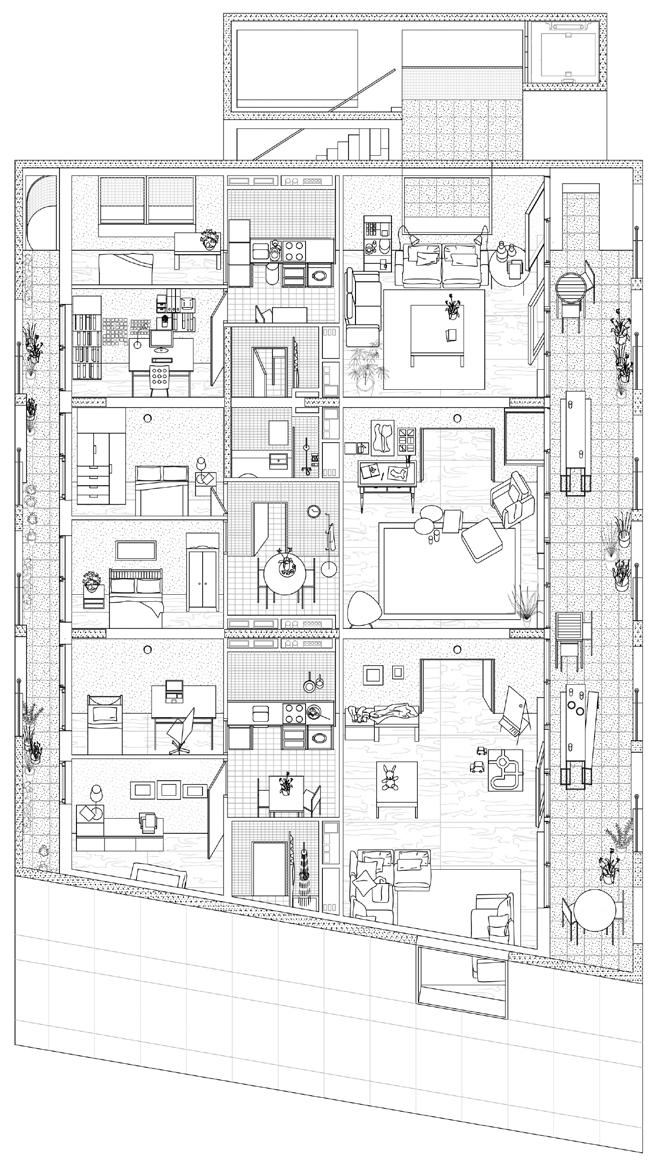

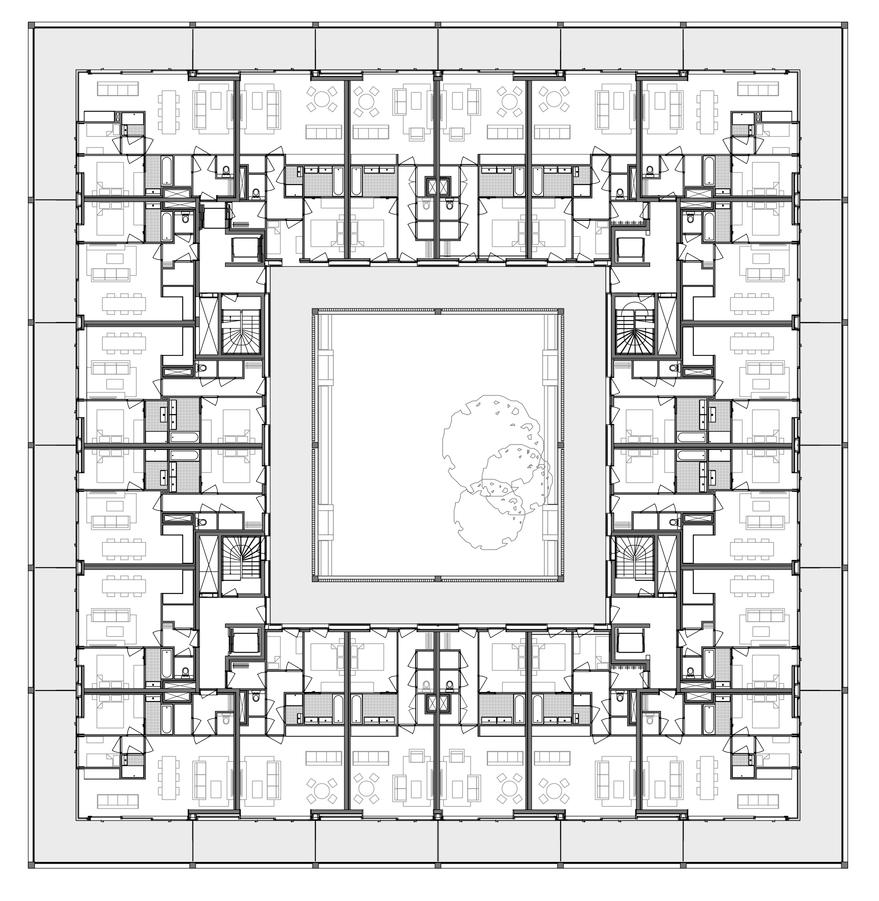

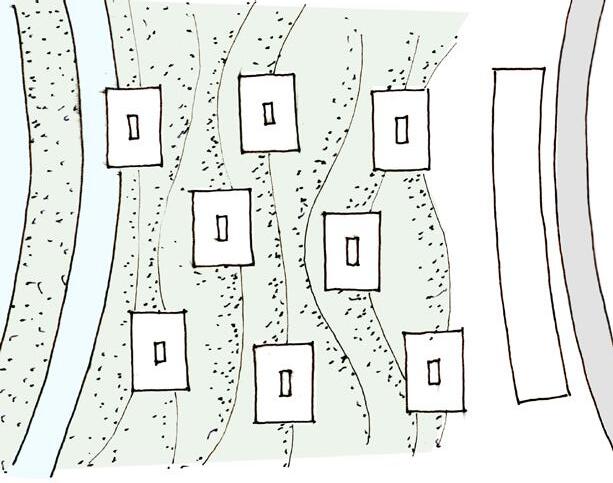

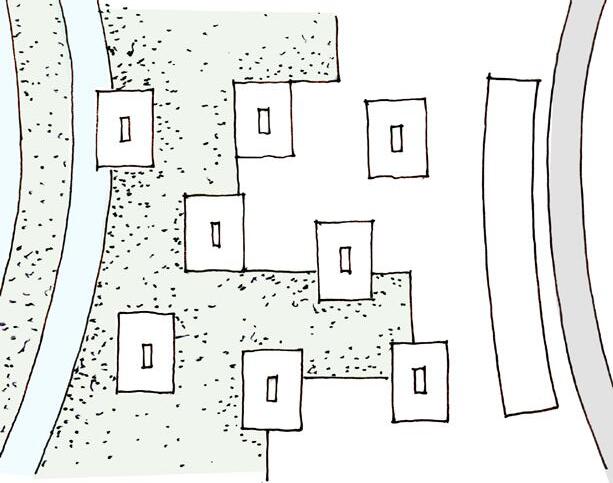

Generating Civic Life Through Variation

One can also truly understand the versatility of the city villa block through Mehr als Wohnen, which pushes the malleability of the city villa blocks to the extreme. Each of the 13 city villa blocks offer radically different takes on the type with variations in structure, dimensions and orientations. Most of the blocks are chunky enough to hold substantially large spaces on the ground that could contribute to the civic and working life of the assemblage. The assemblage also offers a range of different atrium environments. Some are quite compact and predominantly circulatory

in nature. Some are linear and extended and often sheared giving rise to set of differentiated conditions within a single atrium. One also encounters a block with a dual atrium. The Block A and its fluid shared space wedged in between the private pods could be arguably the most generous and unique atrium of them all. In addition to demonstrating the formal versatility of the city villa, the Mehr als Wohnen also demonstrates the ability of the city villa types to support different models of collective living and associational practices.

A set of differentiated city villa blocks structuring a fluid and rich civic ground, Mehr als Wohnen

side of the proposal leverages the adaptability of the floor plate in large city villa blocks The composition of the volumes creates a porous civic environment that allows the hybrid living and working environments.

Similar models like Mehr als Wohnen have the potential to be applied in the Blackhorse Lane area with an assemblage of city villa blocks of varying sizes. Larger city villa types are preferred as a way to capitalise from its wide spatial versatility that promotes hybrid environments of living and working. The assemblage of more than one villa type block with surrounding buildings encourage a porous civic environment. The structural flexibility of types such as Piazza Ceramique allows to set larger spaces that provide assorted workspaces, meeting, and offices areas to support and strengthen the already existing associational practices, workshops and light industries in the area. The same structural logic permits to set a wide range of dimensions of dwelling units. The load bearing envelope of the buildings and the structural ring around the atrium protects the interior of the domestic environments. The ensemble then negotiate different levels of interactivity and exteriority. A juxtaposition of intense civic realm along with protected domestic and living spaces are possible through the exploration of what the type offers.

East

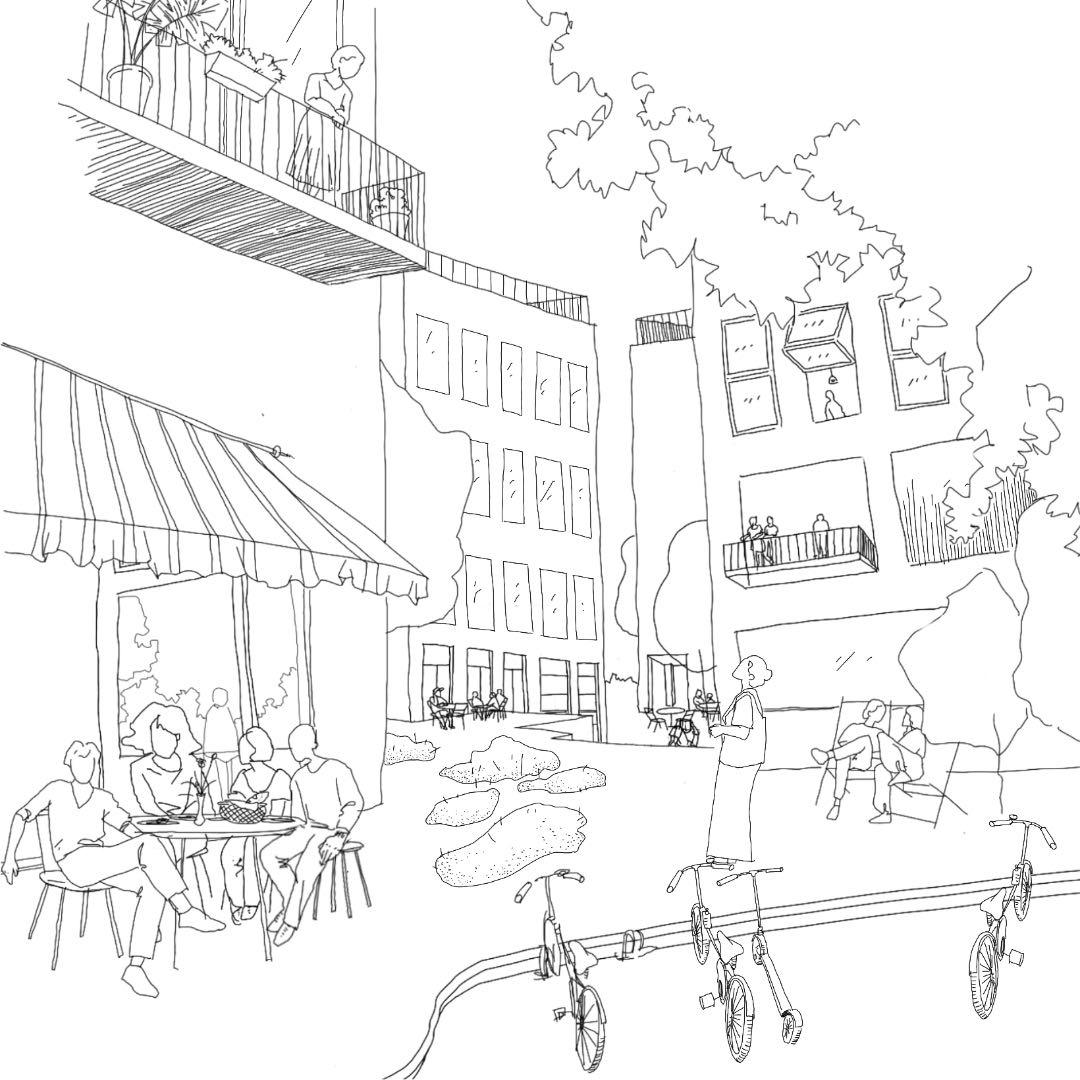

A fluid, yet structured civic realm is created through the interaction between a city villa block and the linear building defining the western edge of Blackhorse Lane. The civic realm is composed of the open spaces structured by the positioning of the blocks and the ground floor of the buildings. The assemblage effectively expands the surface of the Blackhorse Lane and pull the life of the street inward.

The proposal sets up a multi-directional permeability that cuts across Blackhorse Lane. The ground is porous, fostering different types of association and activities.

A contoured sloping natural ground that extends the biodiverse landscape along the waterfront into the assemblage

The natural topographic variation rationalised into two levels, a lower natural level and a formal upper level. The profile of the threshold provides an opportunity to create multiple conditions of overlap with the city villa blocks

A formal terraced treatment of the ground where formal landscaped gardens and a variety of public spaces step down to eventually meet the biodiverse waterfront

A series of differentiated terraced gardens creating a fluid and striated transition from Blackhorse Lane into a zone dominated by active which the life of the city villa blocks could extend onto.

Topography as a medium of differentiation

The city villa block is no doubt versatile and the Mehr Als Wohnen demonstrates the potential of this versatility to define and support a fluid and rich civic ground. Such an approach could potentially transform parts along Blackhorse Lane that extend across the street, bringing

striated ground. The linear building hold the edge and marks the mobility. The striated ground offers a variety of conditions onto

in much needed muti-directional fluidity and diversity. However, the repetition of city villa blocks could also be conceived along different lines as illustrated by the Tulestrasse model. The Tulestrasse model is a developmental model predicated on procurement and efficiency, thereby leading to the repetition of identical blocks throughout the assemblage. It’s ability to support a hybrid work- life environments and a rich civic realm is limited. The ground too is quite monotonous in character and follows the natural topography. However,

A set of identical city villa blocks structuring a quiet, yet fluid residential ground, Tulestrasse

one could imagine a potential scenario where a differentiated ground could offer diversity to such an identical repetition of city villa blocks.

The natural contour of the site could act as a potential instrument for creating differentiation. There could be multiple ways of conceiving the same. Unlike the Tulestrasse model of an monotonous contour, one could consider options where the contour is rationalised into 2 or more formal levels through which one can create a striated and differentiated ground.

Interaction of the city villa blocks with their transparent and extended envelopes with the layered landscape

Street and Block approach towards Blackhorse Lane

VII. Re-qualifying the Existing

The re-imagination of Tottenham Hale masteplan, by Allies and Morrison , demonstrates the increasing emphasis of densification around transportation nodes. Tottenham Hale is part of lower lee valley opportunity area. The buildings were carried out by different architects and they all claimed that this design approach creates a sense of identity for the local community.

Peter Chmiel, director at Grant Associates

says the following01, regarding their approach:

‘Our aim is to breathe new life into the area, providing attractive and functional public spaces for existing residents and future resident to enjoy. We aim to improve access to Tottenham Hale Station, and maximise the opportunity for active frontages to enliven the public spaces by creating an attractive south and west facing public square. In addition to creating a

01 Damian Holmes, “Tottenham Hale Redevelopment Plan Features Landscape Design by Grant Associates,” World Landscape Architecture, August 28, 2019, https://worldlandscapearchitect.com/grant-associ-

focal point for Tottenham, this scheme is set to create employment opportunities, as well as deliver much needed affordable housing and amenities for the community. We’re very excited to be part of Tottenham’s transformational plans.’

This approach is also seen in the new developments occurring close to Blackhorse Road Station. The new development is occurring from the station area upwards. According to Assael Architecture02, one of the firms responsible for the development plan, this design connects to the wetland area and celebrates the reservoirs promoting health and well-being through design and fosters inclusivity.

In order to answer the previous question ates/?v=3a1ed7090bfa.

on whether this design approach fosters a sense of neighbourhood, one should clearly study the reality of these developments post their execution.

The perimeter block creates rational streets that lack any sense of differentiation and hierarchy. There is no place that we can call a collective plaza, and no place that has a secondary relationship to a place that has a primary sense of grouping. Through reliance on these standard planning models, urbanists often miss the opportunity of innovative typologies which mix living and working, leading to vibrant inclusion instead of units separated spatially and institutionalized into monotypes.

02 “Blackhorse Mills,” Assael, accessed June 12, 2024, https://www.assael.co.uk/portfolio/list/blackhorse-mills/.

Street and Block approach towards Tottenham Hale

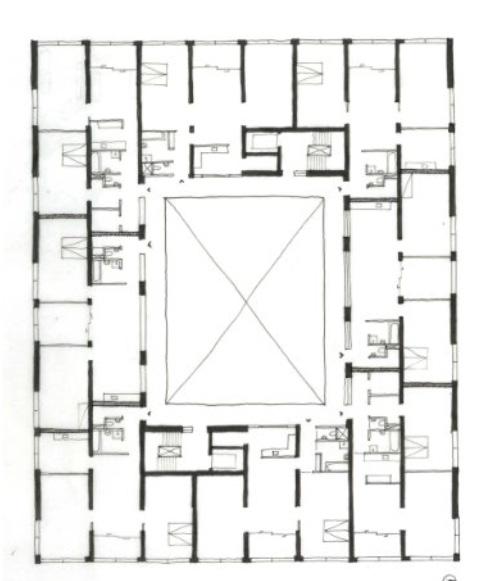

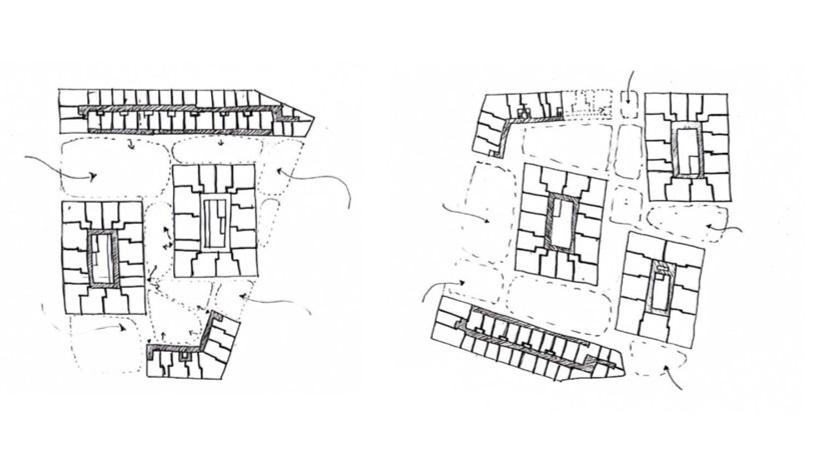

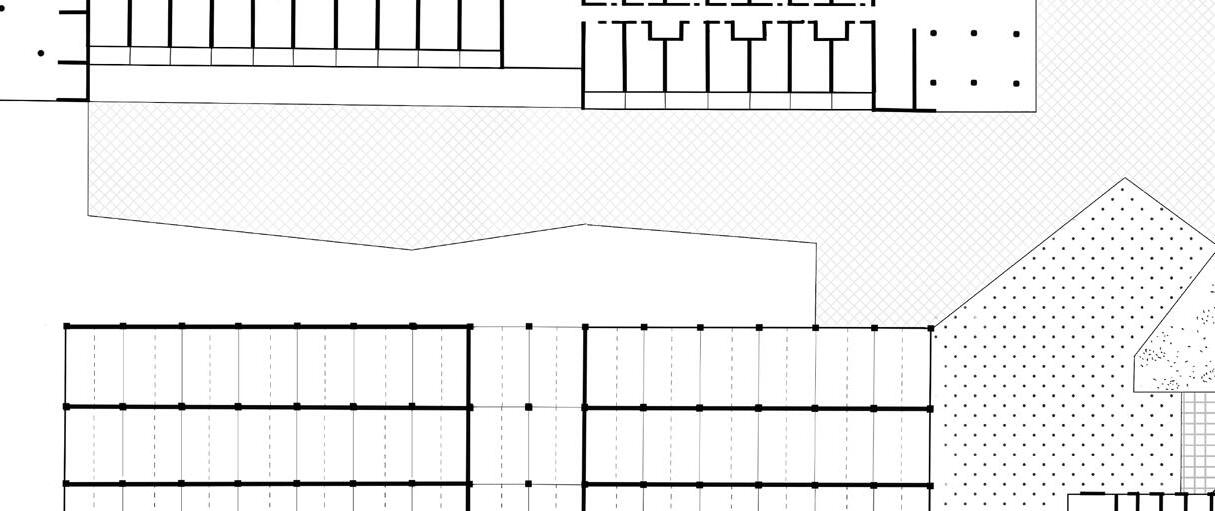

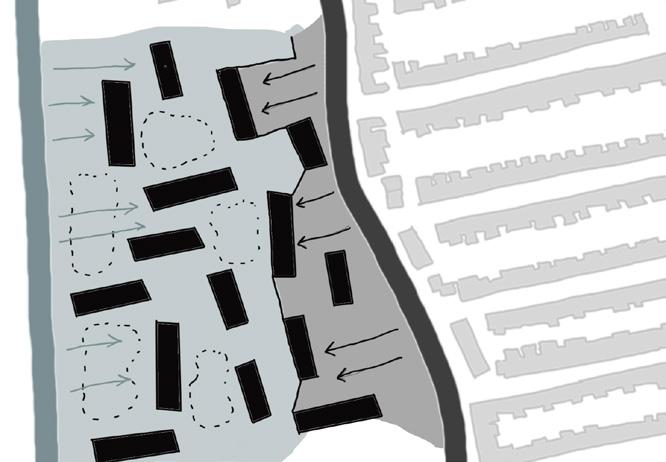

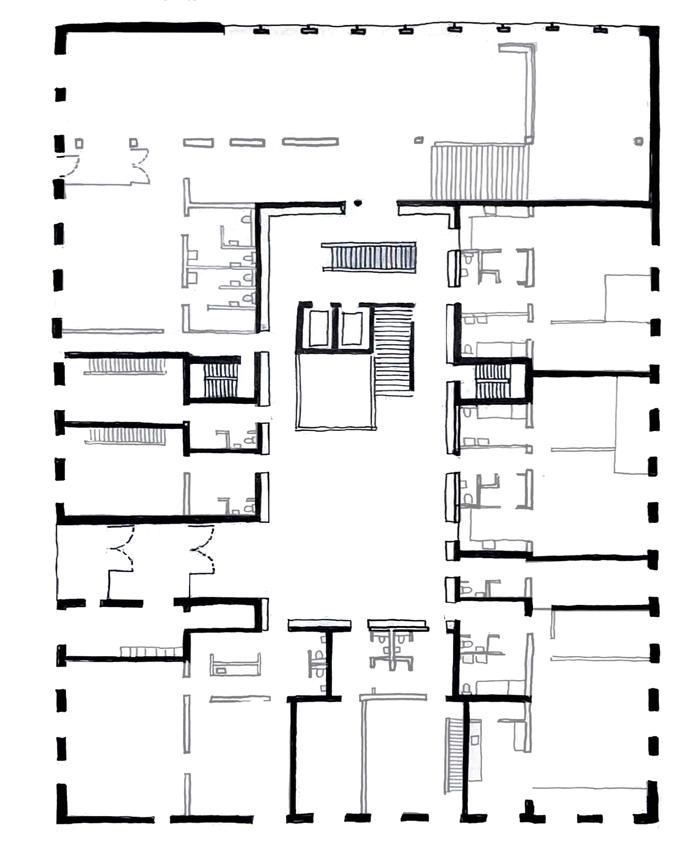

An Inventive Approach Towards the Perimeter Block

The new development of Black Horse Lane site, represents an example of a monotonous approach to urban planning. Although each one of them is developed by a different developer, all had a similar perimeter block organization with commercial use on the ground floor and living units above with double loaded corridors. Although this potential is marketed as a solution that fosters community engagement, it works in an opposite way. Perimeter blocks, while commonly utilized, pose several challenges. They lack communal gathering spaces like plazas, resulting in a non-hierarchical layout

with uniform streets and a lack of diversity in the built environment. Moreover, each block operates independently, leading to a neutral urban fabric, devoid of secondary relationships between spaces.

Despite these limitations, if we’re constrained to this planning stage, there are minimal changes that could be implemented. These might include introducing varied streetscapes, creating pocket parks or plazas, implementing mixed-use development, enhancing connectivity to activate underutilized spaces within the block and foster a sense of community.

Creating a gated community by closing off the courtyards undermining any sense of neighbourhood cohesion.

The rational streets, devoid of any sense of hierarchy, as a result of placing residential units on the ground floor that are closed off for privacy.

Failing to connect to the wetlands and creating a border between the built environment and the natural landscape, limiting the connection to mere visual access from the upper floors while the lower levels remain disconnected and obscured.

Interaction across levels between existing buildings and green infrastructure facilitated by the intermediate communal plaza

Connecting to the Wetlands

The new developments in Black Horse Lane fail to connect to the wetlands physically

By reconsidering the building typologies and incorporating linear blocks, we can seamlessly integrate living and working spaces, thereby breaking away from the restrictive perimeter block design. One could imagine different scenarios happening in the ground floor units within a linear block, such as double-height units

that offer varied living arrangements or workshop spaces. This formal organization allows for the creation of common open spaces where workshops could expand outdoors, fostering transparency and interactivity between the working spaces and the community. The typology offers views towards the open space and wetlands. The galleries created also offer a second layer of interactivity among the residents.

Opening up the building to the plaza to create a dialogue between workshops accommodated on the ground floor and the public space.

Transformation of the urban fabric: from obstacle to threshold. Using linear building’s ground floor to access the green zone and facilitate accessibility

The public plaza acts as a mediating environment that offers a place to which the activities of the linear building on the ground floor to extend into and connect to the waterfront

Creating two interconnected open spaces: one at ground level and another on a podium or elevated courtyard. By linking these spaces, a larger and more interactive communal area is formed, enhancing the overall quality of the urban environment.

Introducing Collective Spaces

One of the problems with the current master plan is that it doesn’t provide a collective, central open space, for people to gather. One approach to address this issue is to break the central block to create two interconnected open spaces: one at ground level and another on a podium or elevated courtyard. By linking these spaces, a larger and more interactive communal area is formed, enhancing the overall quality of the urban environment.

The block thus could be reconfigured to allow adjacent buildings to access and utilize

both courtyards, fostering connectivity and encouraging interaction among residents and users. Introducing small streets or alleys between the blocks facilitates seamless movement and engagement with the inner courtyards, promoting a sense of community and shared ownership of the public realm. This transformation from a single small space to two equivalent spaces, with opportunities for utilization by adjacent buildings, enhances the accessibility, functionality, and social dynamics of the urban block, ultimately creating a more inclusive urban environment.

Structuring a multi- layered communal ground

The perimeter block is effectively opened up and the courtyard transforms into a scene of collective engagement

A permeable and active urban realm that ties Blackhorse Lane and the river-front

VIII. Achieving Urban Integration

The suggested proposals along Blackhorse Lane are quite varied in terms of their typology and morphology. However as a whole, they establish an integrated piece of the urban fabric by structuring a fluid ground. The proposal effectively brings together the major armatures of the waterfront and Blackhorse Lane. The erstwhile underperforming primary elements are now successfully re-qualified and integrated into the life of the urban fabric. The waterfront expands and flows into the industrial fabric