Migration

Africa’s Untapped Potential

Mohamed Abdel Jelil, Samik Adhikari, Quy-Toan Do, Heidi Kaila, Federica Marzo, Olive Nsababera, Ganesh Seshan, and Maheshwor Shrestha

Migration

This book, along with any associated content or subsequent updates, can be accessed at https://hdl.handle.net/10986/42534.

Scan to access all books in the Africa Development Forum series copublished by Agence française de développement and the World Bank.

Migration Africa’s Untapped Potential

Mohamed Abdel Jelil, Samik Adhikari, Quy-Toan Do, Heidi Kaila, Federica Marzo, Olive Nsababera, Ganesh Seshan, and Maheshwor Shrestha

A copublication of the Agence française de développement and the World Bank

© 2025 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433

Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org

Some rights reserved

1 2 3 4 28 27 26 25

This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent, or the Agence Française de Développement. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the data included in this work and does not assume responsibility for any errors, omissions, or discrepancies in the information, or liability with respect to the use of or failure to use the information, methods, processes, or conclusions set forth. The boundaries, colors, denominations, links/footnotes, and other information shown in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The citation of works authored by others does not mean The World Bank endorses the views expressed by those authors or the content of their works.

Nothing herein shall constitute or be construed or considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved.

Rights and Permissions

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions:

Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Abdel Jelil, Mohamed, Samik Adhikari, Quy-Toan Do, Heidi Kaila, Federica Marzo, Olive Nsababera, Ganesh Seshan, and Maheshwor Shrestha. 2025. Migration: Africa’s Untapped Potential. Africa Development Forum series. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-2168-4. License: Creative Commons

Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

Translations—If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation

Adaptations—If you create an adaptation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This is an adaptation of an original work by The World Bank. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author or authors of the adaptation and are not endorsed by The World Bank.

Third-party content—The World Bank does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. The World Bank therefore does not warrant that the use of any third-party-owned individual component or part contained in the work will not infringe on the rights of those third parties. The risk of claims resulting from such infringement rests solely with you. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images.

All queries on rights and licenses should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org

ISBN (paper): 978-1-4648-2168-4

ISBN (electronic): 978-1-4648-2169-1

DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-2168-4

Cover image: © World Bank. Pacita Abad (1946–2004), “Call My Name,” 1999. Paint on wood, 173 cm by 118 cm. World Bank Group Art Permanent Collection, object 462096. Further permission required for reuse.

Cover design: Bill Pragluski, Critical Stages, LLC

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024919328

Africa Development Forum Series

The Africa Development Forum Series was created in 2009 to focus on issues of significant relevance to Sub-Saharan Africa’s social and economic development. Its aim is both to record the state of the art on a specific topic and to contribute to ongoing local, regional, and global policy debates. It is designed specifically to provide practitioners, scholars, and students with the most up-to-date research results while highlighting the promise, challenges, and opportunities that exist on the continent.

The series is sponsored by Agence française de développement and the World Bank. The manuscripts chosen for publication represent the highest quality in each institution and have been selected for their relevance to the development agenda. Working together with a shared sense of mission and interdisciplinary purpose, the two institutions are committed to a common search for new insights and new ways of analyzing the development realities of the Sub-Saharan Africa region.

Advisory Committee Members

Agence française de développement

Thomas Mélonio, Executive Director, Research and Knowledge Directorate

Hélène Djoufelkit, Director, Head of Economic Assessment and Public Policy Department

Adeline Laulanié, Head, Publications Division

World Bank

Andrew Dabalen, Chief Economist, Africa Region

Cesar Calderon, Lead Economist, Africa Region

Chorching Goh, Lead Economist, Program Leader, Africa Region

Aparajita Goyal, Lead Economist, Africa Region

Titles in the Africa Development Forum Series

2025

Inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa: Multidimensional Perspectives and Future Challenges (2025), Anda David, Murray Leibbrandt, Vimal Ranchhod, Rawane Yasser (eds.)

*Migration: Africa’s Untapped Potential (2025), Migration : le potentiel inexploité de l’Afrique (2025), Mohamed Abdel Jelil, Samik Adhikari, Quy-Toan Do, Heidi Kaila, Federica Marzo, Olive Nsababera, Ganesh Seshan, Maheshwor Shrestha

2024

*Migrants, Markets, and Mayors: Rising above the Employment Challenge in Africa’s Secondary Cities (2024), Migrants, marchés et maires : répondre aux défis de l’emploi dans les villes secondaires africaines (2024), Luc Christiaensen, Nancy Lozano-Gracia (eds.)

2023

*Africa’s Resource Future: Harnessing Natural Resources for Economic Transformation during the Low-Carbon Transition (2023), Les ressources naturelles, un enjeu clé pour l’avenir de l’Afrique : ressources naturelles et transformation économique dans un contexte de transition vers des économies décarbonées (2023), James Cust, Albert Zeufack (eds.)

*L’Afrique en communs : tensions, mutations, perspectives (2023), The Commons: Drivers of Change and Opportunities for Africa (2023), Stéphanie Leyronas, Benjamin Coriat, Kako Nubukpo (eds.)

2021

Social Contracts for Development: Bargaining, Contention, and Social Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa (2021), Mathieu Clouthier, Bernard Harborne, Deborah Isser, Indhira Santos, Michael Watts

*Industrialization in Sub-Saharan Africa: Seizing Opportunities in Global Value Chains (2021), L’industrialisation en Afrique subsaharienne : Saisir les opportunités offertes par les chaînes de valeur mondiales (2022), Kaleb G. Abreha, Woubet Kassa, Emmanuel K. K. Lartey, Taye A. Mengistae, Solomon Owusu, Albert G. Zeufack

2020

*Les systèmes agroalimentaires en Afrique : repenser le rôle des marchés (2020), Food Systems in Africa: Rethinking the Role of Markets (2021), Gaëlle Balineau, Arthur Bauer, Martin Kessler, Nicole Madariaga

*The Future of Work in Africa: Harnessing the Potential of Digital Technologies for All (2020), L’avenir du travail en Afrique : exploiter le potentiel des technologies numériques pour un monde du travail plus inclusif (2021), Jieun Choi, Mark A. Dutz, Zainab Usman (eds.)

2019

All Hands on Deck: Reducing Stunting through Multisectoral Efforts in Sub-Saharan Africa (2019), Emmanuel Skoufias, Katja Vinha, Ryoko Sato

*The Skills Balancing Act in Sub-Saharan Africa: Investing in Skills for Productivity, Inclusivity, and Adaptability (2019), Le développement des compétences en Afrique subsaharienne, un exercice d’équilibre : Investir dans les compétences pour la productivité, l’inclusion et l’adaptabilité (2020), Omar Arias, David K. Evans, Indhira Santos

*Electricity Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: Uptake, Reliability, and Complementary Factors for Economic Impact (2019), Accès à l’électricité en Afrique subsaharienne : adoption, fiabilité et facteurs complémentaires d’impact économique (2020), Moussa P. Blimpo, Malcolm Cosgrove-Davies

2018

*Facing Forward: Schooling for Learning in Africa (2018), Perspectives : l’école au service de l’apprentissage en Afrique (2019), Sajitha Bashir, Marlaine Lockheed, Elizabeth Ninan, Jee-Peng Tan

Realizing the Full Potential of Social Safety Nets in Africa (2018), Kathleen Beegle, Aline Coudouel, Emma Monsalve (eds.)

2017

*Mining in Africa: Are Local Communities Better Off? (2017), L’exploitation minière en Afrique : les communautés locales en tirent-elles parti? (2020), Punam Chuhan-Pole, Andrew L. Dabalen, Bryan Christopher Land

*Reaping Richer Returns: Public Spending Priorities for African Agriculture Productivity Growth (2017), Obtenir de meilleurs résultats : priorités en matière de dépenses publiques pour les gains de productivité de l’agriculture africaine (2020), Aparajita Goyal, John Nash

2016

Confronting Drought in Africa’s Drylands: Opportunities for Enhancing Resilience (2016), Raffaello Cervigni, Michael Morris (eds.)

2015

*Africa’s Demographic Transition: Dividend or Disaster? (2015), La transition démographique de l’Afrique : dividende ou catastrophe? (2016), David Canning, Sangeeta Raja, Abdo Yazbech

Highways to Success or Byways to Waste: Estimating the Economic Benefits of Roads in Africa (2015), Rubaba Ali, A. Federico Barra, Claudia Berg, Richard Damania, John Nash, Jason Russ

Enhancing the Climate Resilience of Africa’s Infrastructure: The Power and Water Sectors (2015), Raffaello Cervigni, Rikard Liden, James E. Neumann, Kenneth M. Strzepek (eds.)

The Challenge of Stability and Security in West Africa (2015), Alexandre Marc, Neelam Verjee, Stephen Mogaka

*Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities: The Example of Bamako, Mali (2015), Le système d’approvisionnement en terres dans les villes d’Afrique de l’Ouest : L’exemple de Bamako (2015), Alain Durand-Lasserve, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, Harris Selod

*Safety Nets in Africa: Effective Mechanisms to Reach the Poor and Most Vulnerable (2015), Les filets sociaux en Afrique : méthodes efficaces pour cibler les populations pauvres et vulnérables en Afrique (2015), Carlo del Ninno, Bradford Mills (eds.)

2014

Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods (2014), Iain Christie, Eneida Fernandes, Hannah Messerli, Louise Twining-Ward

*Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa (2014), L’emploi des jeunes en Afrique subsaharienne (2014), Deon Filmer, Louise Fox

2013

*Les marchés urbains du travail en Afrique subsaharienne (2013), Urban Labor Markets in Sub-Saharan Africa (2013), Philippe De Vreyer, François Roubaud (eds.)

Enterprising Women: Expanding Economic Opportunities in Africa (2013), Mary Hallward-Driemeier

Securing Africa’s Land for Shared Prosperity: A Program to Scale Up Reforms and Investments (2013), Frank F. K. Byamugisha

*The Political Economy of Decentralization in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Implementation Model in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal (2013), Bernard Dafflon, Thierry Madiès (eds.)

2012

Empowering Women: Legal Rights and Economic Opportunities in Africa (2012), Mary HallwardDriemeier, Tazeen Hasan

*Financing Africa’s Cities: The Imperative of Local Investment (2012), Financer les villes d’Afrique : l’enjeu de l’investissement local (2012), Thierry Paulais

*Structural Transformation and Rural Change Revisited: Challenges for Late Developing Countries in a Globalizing World (2012), Transformations rurales et développement : les défis du changement structurel dans un monde globalisé (2013), Bruno Losch, Sandrine Fréguin-Gresh, Eric Thomas White

*Light Manufacturing in Africa: Targeted Policies to Enhance Private Investment and Create Jobs (2012), L’industrie légère en Afrique : politiques ciblées pour susciter l’investissement privé et créer des emplois (2012), Hinh T. Dinh, Vincent Palmade, Vandana Chandra, Frances Cossar

*The Informal Sector in Francophone Africa: Firm Size, Productivity, and Institutions (2012), Les entreprises informelles de l’Afrique de l’ouest francophone : taille, productivité et institutions (2012), Nancy Benjamin, Ahmadou Aly Mbaye

2011

Contemporary Migration to South Africa: A Regional Development Issue (2011), Aurelia Segatti, Loren Landau (eds.)

Challenges for African Agriculture (2011), Jean-Claude Deveze (ed.)

L’économie politique de la décentralisation dans quatre pays d’Afrique subsaharienne : Burkina Faso, Sénégal, Ghana et Kenya (2011), Bernard Dafflon, Thierry Madiès (eds.)

2010

Gender Disparities in Africa’s Labor Market (2010), Jorge Saba Arbache, Alexandre Kolev, Ewa Filipiak (eds.)

*Africa’s Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation (2010), Infrastructures africaines : une transformation impérative (2010), Vivien Foster, Cecilia Briceño-Garmendia (eds.)

*Available in French

All books in the Africa Development Forum series that were copublished by Agence française de développement and the World Bank are available for free at http://hdl.handle.net/10986/2150.

B1.2.1

2.2

2.3

Foreword

Migration has long played a crucial role in shaping Africa’s social, economic, and cultural landscape. At the World Bank, we recognize the immense potential of migration to drive economic development, reduce poverty, and enhance social cohesion across the continent. Migration is a powerful force for change, propelled by individuals and families seeking economic opportunities, safety, and improved living conditions both within Africa and beyond its borders.

Despite this transformative potential, the benefits of migration for Africa’s development remain largely untapped. It is essential to shift our perspective and view migration not merely as a challenge but as an opportunity to mobilize Africa’s vast human resources for the continent’s growth and prosperity—and for the global community as well.

Africa stands at a pivotal moment in its development journey, with a young and rapidly growing population poised to become a significant part of the global workforce. By 2050, one in three young working-age individuals will be born in Africa, offering an unprecedented opportunity to drive economic growth and innovation. To fully realize this potential, African countries, in partnership with the global community, must create environments that support and enhance the contributions of migrants to the prosperity of both origin and destination countries.

This companion report to World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies underscores the need for policies that facilitate safe, orderly, and regular migration while providing protection to the forcibly displaced. It calls for concerted efforts by policy makers, communities, and stakeholders in origin, transit, and destination countries to implement strategies that leverage the economic potential of migrants and refugees. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of providing alternatives to distressed movements, which too often result in human tragedies during transit.

The World Bank is committed to supporting African countries in this endeavor. We believe that, by investing in education, infrastructure, and governance and by promoting regional integration, Africa can unlock the full potential of its human capital. Our role is to provide the necessary resources, research, and partnerships to help African countries harness the power of migration for economic growth and development.

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of African migration patterns and offers actionable recommendations for policy makers. It highlights the need to protect the rights and dignity of migrants and refugees, ensuring that migration is a safe and beneficial process for all involved. By embracing the potential of migration, Africa can address its development challenges and build a brighter future for its people.

The World Bank remains a steadfast partner in this journey, committed to working with African governments, regional bodies, and international partners to achieve a future where migration is a catalyst for sustainable development. Together, we can turn the promise of migration into a reality that benefits Africa and the world.

Ousmane Diagana Vice President Western and Central Africa World Bank

Victoria Kwakwa Vice President Eastern and Southern Africa World Bank

Ousmane Dione Vice President Middle East and North Africa World Bank

Acknowledgments

Migration: Africa’s Untapped Potential was prepared by a World Bank team comprising Mohamed Abdel Jelil, Samik Adhikari, Quy-Toan Do, Heidi Kaila, Federica Marzo, Olive Nsababera, Ganesh Seshan, and Maheshwor Shrestha. Overall guidance was provided by Andrew Dabalen. The report was sponsored by the Office of the Chief Economist of the Africa Region. The analysis in the report was supported by the following background papers and case studies:

• “Do Bilateral Labor Agreements Increase Migration? Global Evidence from 1960 to 2020,” by Samik Adhikari, Narcisse Cha’ngom, Heidi Kaila, and Maheshwor Shrestha

• “A Profile of Migrants in North Africa: Background, Intentions, and Labor Market Outcomes,” by Marian Atallah and Federica Marzo

• “Effectiveness of Mass Regularization Policies in South Africa: Evidence from the Dispensation of Zimbabwean Project (DZP),” by Narcisse Cha’ngom

• “Climate Change and Mobility,” by Viviane Clement and Kanta Kumari Rigaud

• “Migration to and through North Africa: An Overview,” by Michele Di Maio, Valerio Leone Sciabolazza, and Federica Marzo

• “Population Aging and International Migration,” by Toan Do, Andrei Levchenko, Sebastian Sotelo, and Román D. Zárate

• “Migration Policies in Africa’s Regional Economic Communities,” by Blaise Gnimassoun and Assi Okara

• “Overview of Methods for State Collaboration on African Migration beyond the Continent,” by Michelle Leighton

• “Forced Displacement in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Stocktaking of Evidence,” by Zara Sarzin and Olive Nsababera

Kèneth Omondi provided administrative support. Narcisse Cha’ngom provided research assistance. Pascal Jaupart contributed to the box on health care worker migration. The report was edited by Sandra Gain. Bruno Bonansea, Brenan Gabriel Andre, Patricia Anne Janer, and Ryan Francis Kemna from the Cartography team provided the maps.

The team relied on the guidance and inputs from an internal advisory committee, which comprised Patrick Barron, Himdat Bayusuf, Kathleen Beegle, Nazmul Chaudhury, Xavier Devictor, Johannes (Hans) Hoogeveen, Manjula Luthria, and Kanta Rigaud. Pablo Ariel Acosta, Tom Bundervoet, Aline Coudouel, Ugochi Daniels, Manuela Tomei, and Jackie Wahba served as peer reviewers.

The team is grateful for all the inputs received during consultations with government agencies, development partners, embassies, civil society organizations, academia, and think tanks in Algeria, Belgium, the Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Ethiopia, France, Ghana, the Holy See, Italy, Kenya, Morocco, Senegal, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Key Messages

Chapter 1: The State of African Mobility

1. Africans rarely migrate out of the continent.

Less than 1 percent of the region’s population leaves the continent, well below the global average.

2. Africans who leave the continent are increasingly heading to North America and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries rather than Europe.

Three-fourths of African migrants who left the continent used to go to Europe. Slightly more than one-half do so today.

3. Many African countries are becoming destinations for migrants.

Northern African countries are increasingly emerging as destinations rather than merely transit points for migrants heading to Europe. Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and South Africa receive at least twice as many migrants as they send.

4. Irregular migration across the continent is the most dangerous in the world.

Close to 5,000 deaths of African migrants were reported in 2023, more than twice the number of recorded deaths of migrants from Asia and around four times that of migrants from Latin America.

5. Africa hosts one-fourth of the world’s refugee population.

Most refugees move to neighboring countries, with nearly 90 percent hosted in just 10 countries.

Chapter 2: Overlapping Megatrends in Africa

1. By 2050, one in three youths (ages 15–34) will be African.

Africa is expected to add 600 million to its working-age population, while the working-age population in high- and upper-middle-income countries is expected to reduce by 200 million.

2. Africa’s economic growth has been stagnating, failing to create enough jobs for its expanding youthful population.

Economic growth continues to lag population growth, with 9 out of 10 Sub-Saharan African children in learning poverty.

3. By 2050, an estimated 1.3 billion Africans will live in countries that are currently fragile or in conflict.

Nearly half of Africa’s population lives in countries affected by persistent fragility, with instances of both conflict and violence and forced displacement rising sharply since 2010.

4. More than half a billion Africans are exposed to severe weather events, including floods, droughts, cyclones, or heat waves.

Climate change is an increasing threat to rural agricultural livelihoods and coastal areas, while African urban centers are struggling to cope with an expanding population and stresses on basic service provision.

Chapter 3: The Untapped Potential of Migration

1. African migration, as a source of prosperity for the continent, has been largely untapped.

Africans migrate in smaller numbers compared to other regions of the world, and a limited number move to countries where potential wage gains are significant.

2. The Great Demographic Divergence opens a window of opportunity for Africa to give greater prominence to migration in its development policy.

Key destination countries outside Africa face a shrinking workforce and will need to increase immigration from 14 percent to 77 percent of their existing population by 2050 to maintain their current working-age-to-elderly ratios.

3. Strategic management of migration enables both origin and destination countries to tailor migration to their mutual benefit.

Bilateral labor migration agreements are instruments to align skill development with destination needs, yet Africa lags in their use despite enduringly facilitating migration flows between countries.

4. Harnessing the economic potential of refugees and internally displaced people safeguards their dignity while lowering costs for host communities.

Economic integration, such as granting work rights and freedom of movement, empowers refugees and internally displaced people to become more self-reliant, thereby reducing the cost of hosting them.

Chapter 4: Harnessing the Productive Potential of African Mobility

1. Higher walls demand larger doors.

Fostering regular migration while disincentivizing irregular movements necessitates increasing the number of legal migration pathways.

2. Build and further strengthen migration systems in African countries.

Policies and systems are needed to support migrants and their origin and destination communities from departure, through transit, to destination, and eventually upon return.

3. Promote the regional mobility of Africans.

Lower barriers to free movement within regional economic communities, including for refugees, and improve the efficiency of regional labor markets by harmonizing skill acquisition and recognition.

4. Strengthen Africa’s ability to leverage the Great Demographic Divergence.

Africa will increase the benefits from international migration by reinforcing mechanisms of collective action and investing in globally demanded skills both domestically and in coordination with destination countries.

Glossary

This glossary provides general descriptions, not precise legal definitions, of terms used in this report. However, the descriptions include legal and policy elements that are relevant to how the terms are understood and applied in practice. The glossary is adapted from World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies.

Africa’s geographical core Countries in the West, Central, and East regions of Africa: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Africa’s geographical periphery Countries in the North and Southern regions of Africa: Algeria, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Libya, Mauritius, Morocco, Namibia, the Seychelles, South Africa, and Tunisia.

asylum or refugee status A legal status arising from judicial or administrative proceedings that a country grants to a refugee in its territory. This status confers on refugees international refugee protection by preventing their return (in line with the principle of non-refoulement), regularizing their stay in the territory, and providing them with certain rights while there.

asylum seeker A person outside their home country who is seeking asylum. For statistical purposes, it is a person who has submitted their application for asylum but has not yet received a final decision.

complementary (international) protection Forms of international protection provided by countries or regions to people who are not refugees but who still may need international protection. Countries use various legal and policy mechanisms to regularize the entry or stay of such individuals or prevent their return (in line with the principle of non-refoulement).

destination country/society The country to which a migrant moves.

diaspora The population of a given country that is scattered across countries or regions that are separate from its geographical place of origin.

distressed migrant A migrant who moves to another country under distressed circumstances but who does not meet the applicable criteria for refugee status. Their movements are often irregular and unsafe.

economic migrant A migrant who crosses an international border motivated not by persecution or possible serious harm or death but for other reasons, such as to improve their living conditions by working or reuniting with family abroad. This term encompasses labor migrants or migrant workers who move primarily to work in another country.

emigrant A person who leaves their country of habitual residence to reside in another country. This term is used from the perspective of the person’s country of origin.

host country/society The country to which a refugee moves, temporarily or permanently.

immigrant A person who moves to a country to establish habitual residence. This term is used from the perspective of the person’s destination country.

internally displaced persons (IDPs) People who have been displaced within a state’s borders to avoid persecution, serious harm, or death, including through armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights, or natural or human-made disasters.

international protection Legal protection granted by countries to refugees or other displaced people in their territory who cannot return to their home countries because they would be at risk there and because their home countries are unable or unwilling to protect them. International protection takes the form of a legal status that, at a minimum, prevents their return (in line with the principle of non-refoulement) and regularizes their stay in the territory.

irregular migrant A migrant who is not legally authorized to enter or stay in a given country (also called an undocumented migrant).

migrant In this report, those who change their country of habitual residence and who are not citizens of their country of residence. Such changes of country exclude short-term movement for purposes such as recreation, business, medical treatment, or religious pilgrimage.

non-refoulement The legal principle prohibiting countries from returning people to places where they may be at risk of persecution, torture, or other serious harm.

origin country/society The country from which a migrant or refugee moves.

refugee A person who has been granted international protection by a country of asylum because of feared persecution, armed conflict, violence, or serious public disorder in their origin country. The international protection granted by countries to refugees takes the form of a distinct legal status (refer to asylum or refugee status) preventing their return (in line with the principle of non-refoulement), regularizing their stay in the territory, and providing them certain rights while there, under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol or other international, regional, or national legal instruments.

regular migrant A migrant who is legally authorized to enter or stay in a given country.

stateless person A person who is not a citizen of any country.

Abbreviations

ACE Africa Higher Education Centers of Excellence

BLMA bilateral labor migration agreement

BSSA bilateral social security agreement

ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States

EU European Union

GCC Gulf Cooperation Council

GDP gross domestic product

GSP global skills partnership

ICL income contingent loan

IDP internally displaced person

IOM International Organization for Migration

MOU memorandum of understanding

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

REC regional economic community

SADC Southern African Development Community

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

WHR Window for Host Communities and Refugees

introduction

Overview

African migration is a story of movement spurred by the pursuit of economic opportunities near and far, the quest for safety and security, the urgent need to escape environmental hardships, and the pull of familial bonds. Migration, both voluntary and forced, reveals the continent’s resilience and adaptability, delineating pathways extending across Africa and reaching regions as distant as Europe, the Americas, and the Middle East. Yet, the transformative potential of migration to improve the lives of Africans remains largely untapped. Realizing the benefits of migration for Africa’s development challenges calls for policy makers and communities in origin, transit, and destination countries to implement strategies to achieve the economic potential of mobility, while safeguarding the dignity and rights of all migrants and refugees.

The key to securing Africa’s future lies in its ability to prepare its burgeoning youth population to tackle the continent’s development challenges. Migration, a largely underutilized response, can greatly benefit the region. With nearly 60 percent of its population younger than age 25, youth are at the heart of the continent’s economic, social, and political transformation. To harness its demographic dividend, Africa needs to confront the overlapping development challenges of an economic transformation that has yet to deliver on anticipated productivity gains, along with the impacts of climate change and the pervasive issues of fragility, conflict, and violence.

Africa, especially Sub-Saharan Africa, is poised to become home to a significant portion of the global workforce. By 2050, one in three young working-age individuals (ages 15–34) will have been born on the continent. The challenge for Africa—and the world—is to create viable jobs by attracting capital and other resources to Africa’s abundant labor or by facilitating African labor

movement to areas with these resources. This requires fostering and utilizing the productive potential of the labor force. Addressing these challenges will shape Africa’s development. This report on Africa’s cross-border migration explores how the continent can harness the potential of migration for economic opportunities within and beyond Africa.

The State of African Migration

To date, the rate of outmigration of Africans—in particular, citizens of countries in West, Central, and East Africa—has been limited compared to that of other regions of the world. Although African migrants make up close to 15 percent of the world’s migration stock, less than 1 percent of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa migrates to a country outside Africa. The bulk of migration from Sub-Saharan African countries occurs between member countries in the same regional economic communities. For countries in North Africa, the rate of migration outside the subregion is closer to 5 percent.

Additionally, when it occurs, migration typically yields low economic returns for the migrants and the origin societies. Since outmigration is largely toward a neighboring country, West, Central, and East Africa receive the lowest remittances per capita among all regions. Relatedly, as of 2020, forced movements constitute 30 percent of total cross-border migration flows in Africa. Moreover, distressed and irregular movements put migrants, especially women, in vulnerable situations and test the resilience of host communities. Although irregular sea crossings to Europe are a small share of total entries, they impose significant human costs in terms of casualties at sea and human rights abuses along the route.

Yet, this retrospective view of Africa’s migration hides a dynamic phenomenon wherein the destinations and compositions of the flows of migrants are changing. Although they traditionally moved to other countries in the continent or Europe, African migrants are increasingly diversifying their destination countries, with North America and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries gaining prominence. Moreover, the profile of migrants is also changing, as they are more educated and the share of female migrants has increased, reaching 45 percent across the continent. Meanwhile, countries such as Kenya, Morocco, and Tunisia are following the footsteps of others, such as the Arab Republic of Egypt and South Africa, by becoming destinations for a rising number of migrants, mostly from other African countries.

At the same time, the African continent hosts over a third of the global forcibly displaced population and over a quarter of refugees worldwide. An estimated 32.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), 8.2 million refugees, and 1.1 million asylum seekers live in Africa. Chronic political instability and the effects of a warming climate put an increasing number of Africans at risk of being forcibly displaced, internally or across country borders. It is crucial to recognize that displacement situations are likely to be protracted and, therefore, require leveraging the economic potential of refugees and IDPs toward building sustainable protection systems and developing pathways for faster integration into current or future host societies.

Migration: Tapping Africa’s Potential

Africa is at the confluence of global megatrends: a youth bulge paired with limited economic opportunities, increasing climate hazards, and state fragility. The consequences of the Great Demographic Divergence between the countries in West, Central, and East Africa and highincome and upper-middle-income countries is exacerbated by slow structural transformation, severe climate change effects, and chronic political instability plaguing many African countries.

Conversely, populations in high-income and upper-middle-income countries are aging rapidly. To maintain the current ratio of working-age population to the elderly in 2050, more than 130 million additional workers will be needed in the European Union, with an otherwise estimated loss of 12 percent of gross domestic product. Alternative policies, like raising retirement ages, increasing female labor force participation, and automation, cannot fully address the shortfall, especially in nontradable service sectors, where the scope for automation and offshoring is limited.

Yet, African workers face obstacles in their quest to seize the opportunities generated by the Great Demographic Divergence. Chief among these is the skill level of African youth, which is significantly lower than that of retiring workers in high-income and upper-middle-income countries. For instance, the average learning-adjusted years of schooling in countries in West, Central, and East Africa is 4.8, compared to 10.7 in key European destinations. Additionally, highly educated African migrants already in high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries often work in low- or middle-skilled sectors or occupations due to a lack of recognition of their qualifications or a deficiency in language or sociobehavioral skills beyond formal education.

Moreover, immigration, especially from Sub-Saharan Africa, faces strong opposition from various constituencies in many destination countries. Immigration regularly tops the list of citizens’ concerns, and recent national or European elections saw the rise of parties with strong anti-immigration platforms. While racism and xenophobia may drive some attitudes toward immigration, policies formulated by both origin and destination countries can harness African migration for the net benefit of both origin and destination societies.

Policies to Foster Better Migration: From Pre-Migration to Post-Return

For origin and destination countries, better migration implies ensuring a strong match between the migrant and the destination society. The gains from cross-border migration are the highest when migrants’ skills respond to the demand in the labor markets of destination countries. Not only do migrants need to acquire skills and credentials prior to departure, they also need to be recognized in the destination country. However, information frictions are an important impediment to effective matching between supply and demand, and the regulation of private recruitment agencies and other intermediaries plays a critical role in ensuring that information is transparent for both migrant workers and their employers. Moreover, in destination countries, opening or expanding legal pathways that correspond to the needs of

the labor market helps to overcome current and expected skills shortages. Student migration offers potential solutions to several policy challenges, including skill recognition and social integration.

The match can be improved by providing alternatives to migration. Providing alternative coping mechanisms and labor market opportunities can improve the outside options for those considering cross-border migration, especially those contemplating irregular pathways. Although identifying the set of development policies that could generate attractive domestic alternatives to migration is beyond the scope of this report, targeting these to specific population groups or areas experiencing higher rates of emigration could have stronger impacts on the resulting composition of migration flows. Furthermore, agreements on labor mobility that facilitate movement between countries in the same regional economic community give migrants access to regional hubs where economic opportunities offer an alternative to irregular movements.

Complementary policies play a crucial role in ensuring that the migration experience is rewarding for migrants and beneficial for both origin and destination societies. The advantages of migration are maximized when migrants are granted the right to work, face no labor market discrimination, and enjoy decent working conditions and wages. This allows them to contribute to their fullest productive potential. However, integrating migrants into the destination society incurs certain costs, which can be mitigated by implementing policies that facilitate social integration, promote social cohesion, and address any distributional impacts on native populations. For origin countries, the benefits of migration are amplified by reducing remittance costs, creating mechanisms and incentive schemes for diaspora investment, and enacting social policies that support families left behind and prepare for the migrants’ eventual return.

Making migration gains sustainable requires creating a policy environment that promotes reintegration and incentivizes returns. Temporary legal pathways are sustainable when all parties abide by the return provisions. Otherwise, the enforcement of immigration laws and provision of financial incentives are instruments available to policy makers in destination countries. For origin countries, promoting the reintegration of returnees into their origin communities entails recognizing the skills, credentials, and experiences acquired abroad and providing technical, administrative, and financial support to leverage returnees’ economic potential, foster social cohesion, and ultimately incentivize returns.

From Policies to Results: National and Regional Migration Systems

Building migration systems is central for origin countries to collect information and formulate and implement policies to regulate market actors, both private and public. Coordination mechanisms are needed to alleviate the fragmentation of migration policy competencies across government agencies. These mechanisms help to identify statistical, financial, and human resource capacity needs to identify, formulate, and implement policies that promote better migration.

In addition, effective regulation of cross-border movement requires coordination between origin and destination countries, facilitated by policy instruments such as bilateral labor migration agreements (BLMAs). Policies to maximize the match between migrants and their destination countries and address the potential negative externalities of cross-border movements require specific investments, for example, in adequate training in origin countries and social integration policies in destination countries, which will take time to materialize. To incentivize both origin and destination countries to undertake such investments, instruments such as BLMAs offer a framework for such bilateral coordination to take place. Yet, although there has been a recent uptick in this type of coordination, countries in West, Central, and East Africa have engaged in few such arrangements.

Collective action mechanisms ensure that bilateral agreements fairly distribute the economic benefits of migration between origin and destination countries. By negotiating as a unified group rather than individually, African nations prevent a race to the bottom, thus achieving objectives like improved salaries and working conditions for migrant workers, greater involvement of destination countries in funding education and training in origin countries, and overall enhanced assistance from destination countries toward the development goals of origin countries. These collective action mechanisms can be integrated into existing regional institutions, such as the African Union and regional economic communities, or formed through ad hoc coalitions of countries, and can focus on specific sectors like health care or be more comprehensive. Although they are intergovernmental in nature, these mechanisms should involve worker and employer organizations and receive technical assistance from development partners.

Forced Displacement: Harnessing the Economic Potential of Refugees and IDPs

Africa has been a pioneer in the adoption of legal frameworks governing protection and assistance for refugees and IDPs. The 1969 Organisation of African Unity Convention was the first regional instrument on refugees, introducing several important innovations in international law, and it remains the only legally binding regional instrument on refugees. Similarly, the Kampala Convention was the first and only legally binding instrument on internal displacement globally. It provides a comprehensive legal framework for addressing internal displacement in the Africa region. However, access to socioeconomic opportunities for the displaced is weak in practice. About 54 percent of the refugees in Africa still live in camps, and over 80 percent reside in rural areas with limited access to markets and restrictions on their mobility.

With an increasing number of refugees and IDPs in protracted situations and diminishing resources from host countries and the international community, promoting self-reliance among these populations offers a sustainable path forward. Creating conditions that leverage the economic potential of forcibly displaced people helps to preserve their dignity, safeguard their well-being, and enable them to contribute to the host economy. Policies aimed at sustainable protection systems strive to maximize refugee and IDP self-reliance while addressing relevant security and political economy issues. Humanitarian and development

assistance should focus on fostering self-reliance among refugee and IDP communities. This involves building their skills to meet the demands of host labor markets, mitigating any negative impacts on local workers, creating conditions for the private sector to employ these skills locally, or allowing forcibly displaced populations to move to opportunities within the country or even region, provided there are legal protections in place to ensure their continued safety.

1

The State of African Mobility

FIVE FACTS ABOUT AFRICAN MOBILITY

Fact 1. Africans rarely migrate out of the continent.

Less than 1 percent of the region’s population leaves the continent, well below the global average.

Fact 2. Africans who leave the continent are increasingly heading to North America and the Gulf Cooperation Council countries rather than Europe.

Three-fourths of African migrants who left the continent used to go to Europe. Slightly more than one-half do so today.

Fact 3. Many African countries are becoming destinations for migrants.

Northern African countries are increasingly emerging as destinations rather than merely transit points for migrants heading to Europe. Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and South Africa receive at least twice as many migrants as they send.

Fact 4. Irregular migration across the continent is the most dangerous in the world.

Close to 5,000 deaths of African migrants were reported in 2023, more than twice the number of recorded deaths of migrants from Asia and around four times that of migrants from Latin America.

Fact 5. Africa hosts one-fourth of the world’s refugee population.

Most refugees move to neighboring countries, with nearly 90 percent hosted in just 10 countries.

Africans Rarely Migrate Out of the Continent

The proportion of Sub-Saharan Africans who migrate out of the continent is low compared to global averages. Despite Sub-Saharan Africa accounting for 85.3 percent of the continent’s population, less than 1 percent of its residents migrate beyond Africa, which is below the world average of 1.7 percent for intercontinental migration. In contrast, regions like

Latin America and the Caribbean and South Asia have higher rates, with 5 and 2 percent of their populations, respectively, relocating to other parts of the world. North African countries, unlike the rest of Africa, have about 5 percent of their populations living abroad, reflecting historical migration trends from Mediterranean countries to Europe and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. In 2020, approximately 60 percent of migrants from North Africa resided in European countries, around 30 percent in the GCC and other Middle Eastern countries, and about 7 percent in North America. In addition, while low in the aggregate, intercontinental migration from Sub-Saharan Africa masks considerable diversity. Some small island nations have experienced significant emigration over recent decades. In Cabo Verde, the Comoros, and São Tomé and Príncipe, the ratio of citizens living abroad to those residing domestically stands at 130 percent, 22 percent, and 18 percent, respectively; among the 700,000 Cabo Verdeans living overseas, the majority are in the United States and or in Europe (IOM 2024).

Despite evolving over time, most migration from Sub-Saharan Africa remains within the continent. As of 2020, 66 percent of people who had left a country in Sub-Saharan Africa moved within Africa, and three-fourths of those migrated to a neighboring country (figure 1.1). The degree of intracontinental migration is significantly higher in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to North Africa, where such migration is almost nonexistent, and other regions: only 26 percent of migration in Latin America and the Caribbean and 20 percent in South Asia remains within the region. Intracontinental mobility in Sub-Saharan Africa persists despite changing migration patterns, with an increasing share of migrants heading outside the continent.

Figure 1.1 Share of Migrants Staying in Their Region of Origin, 2020

Africans Who Leave the Continent Are Increasingly Heading to North America and the GCC, rather than Europe

Among Africans leaving the continent, their destinations have become increasingly diverse, moving away from a focus on Europe. The share of African migrants settled in European countries decreased from 73 percent in 1960 to 55 percent in 2020 (figure 1.2). In the 1960s and 1970s, two-thirds of African intercontinental migrants moved to Belgium, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. This share fell below 40 percent by 2020.

Conversely, the proportion of African migrants in North America increased from 2 to 17 percent over the same period. This shift reflects a broader pattern with the emergence of new migration corridors: between 2010 and 2020, the number of African migrants to the GCC countries increased by 50 percent, exceeding 3.5 million. The GCC now hosts 20 percent of African migrants outside the continent, with increasing numbers, especially from East Africa. For example, in 2020, Ethiopians represented 18 percent of all migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa in the GCC, up from 7 percent in 2000. The extent of migration to the GCC countries is likely underestimated given data limitations (box 1.1).

Figure 1.2 Africa’s Outmigration Destinations, 1960–2020

BOX 1.1

Migration Data and Limitations

Population censuses are the primary source of data for measuring global migration stocks. Yet, timeliness, comparability, and accessibility limit their effectiveness. In origin countries, censuses often underestimate emigration since they fail to capture emigrants when entire households have left. Additionally, with censuses typically conducted once every 10 years, they are insufficient for monitoring rapid changes in migration flows. Moreover, irregular migrants and refugees are frequently excluded from census counts. Despite these constraints, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Bank, and International Migration Institute’s Database on Immigrants in OECD and non-OECD Countries and the International Labour Organization’s Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers are examples of global migration databases.a

Discrepancies in census methodology and timing across countries hinder accurate measurement. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only 17 of the 41 countries covered by the 2010 round of censuses included questions about household emigration, and 30 included a question about country of birth.b This means that international migrants are mostly recorded at their destination rather than at their origin. Additionally, some censuses report country of birth while others report country of citizenship. The census year can also vary significantly, complicating cross-country comparisons, especially when significant migration events have occurred. For example, Mozambique conducted its census in 2007, while South Africa did so in 2011, creating statistical differences between these two countries in data on migration. Nonetheless, recent regional statistics projects in East, West, and Southern Africa aim to harmonize data across groups of countries (World Bank 2021, 2023a, 2023b).

For data on irregular migration and refugee populations, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) provide valuable supplementary sources, but with their own limitations. IOM uses Displacement Tracking Matrixes to monitor irregular and distressed mobility for humanitarian purposes, but these are not collected at the individual level and lack coverage in many countries, affecting representativeness. Some countries, like Libya, have multiple monitoring points, while many others do not. The information collected also varies by country and time period. UNHCR systematically collects data on refugees and other “persons of concern” but does not cover populations outside its mandate. Overlap between different data sources further complicates accuracy and consistency.

(continued next page)

Box 1.1 Migration Data and Limitations (continued)

Reconciling different data sources, when they are available, is challenging, and most countries lack dedicated surveys, especially surveys that collect longitudinal and geo-localized data (Di Maio, Marzo, and Sciabolazza 2024). The Maghreb region in North Africa, which experiences diverse and rapidly evolving migration patterns, exemplifies such complexity. Most countries conducted a new census round between 2020 and 2024, but the new data are not yet available. Tunisia is organizing a census now. Although Morocco has provided some information on foreign-born individuals, which is currently publicly accessible, this is not the case for other countries in the region. Furthermore, Displacement Tracking Matrix points are only available in Libya, making it difficult to estimate and monitor the total migrant stock in the subregion over time.

a. Organisation for economic co-operation and Development (OecD) (https://www.oecd.org/migration/mig /oecdmigrationdatabases.htm) and international labour Organization (ilO) (https://www.ilo.org/publications/ilo -global-estimates-international-migrant-workers-results-and-methodology), respectively.

b. united Nations Statistics Division (uNSTAT) (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/sconcerns /migration/) and uNSTAT (accessed June 19, 2024, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/census /censusdates/), respectively.

Many African Countries Are Becoming Destinations for Migrants

Until recently, migration within Africa primarily occurred between countries with economic ties and legal agreements for free movement. In 2020, there were 22 million African migrants on the continent, with more than 21 million from Sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly 95 percent of these migrants moved within their regional economic communities (RECs). Africa’s eight RECs all consider the free movement of nationals a fundamental principle for regional integration, but limited implementation means that most movements remain informal. For instance, in 2020, about 7.6 million international migrants resided in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with over 89 percent coming from within ECOWAS (figure 1.3). This figure is likely an underestimate due to high levels of temporary and seasonal migration that are not fully captured in the data (box 1.1). Key destinations include Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria, which attract migrants from Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Mali (map 1.1). In the Southern African Development Community (SADC), migrants increasingly use informal and unregulated routes, later legalizing their movement through various practices. Migrants make up 2.1 percent of the SADC population, but only 1.0 percent when considering only migrants from within SADC. South Africa (7.1 percent), Botswana (4.7 percent), and Namibia (4.2 percent) have the highest shares of immigrants per capita.

Figure 1.3 Share of Migrants within an REC Who Originate from the REC’s Member Countries, 2020

Source: calculations based on bilateral matrix data from world Bank 2023c.

Note: AMu = Arab Maghreb union; ceN-SAD = community of Sahel-Saharan States; cOMeSA = common Market for eastern and Southern Africa; eAc = east African community; eccAS = economic community of central African States; ecOwAS = economic community of west African States; iGAD = intergovernmental Authority on Development; rec = regional economic community; SADc = Southern African Development community.

Many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are already attracting more migrants than they send out. Today Kenya receives twice as many migrants as it sends, primarily from neighboring countries, including a significant number of refugees and asylum seekers. Similarly, Côte d’Ivoire and South Africa attract twice as many migrants from neighboring countries as they send out. In Côte d’Ivoire, 9.7 percent of the population consists of cross-border migrants, one of the highest proportions on the continent (ICMPD 2022). South Africa has seen a growing share of the intraregional migrant stock, hosting about 77 percent of all Namibian migrants. The country now accommodates 60 percent of migrants from SADC countries, up from 31 percent in 1995 (Crush et al. 2022). Furthermore, Djibouti has increasingly become a transit as well as destination country for movements across the Gulf of Aden and beyond. In 2023, migratory movements increased by 25 percent compared to 2022, with a total of 278,272 migratory movements recorded in the country of 1.12 million inhabitants, the majority from Ethiopia (IOM 2023).

Map 1.1 Patterns of Mobility within Africa, 2020

Stock of migrants

100,000–249,000

250,000–499,000

500,000–1,000,000

1,000,000–1,400,000

Regional economic communities

ECOWAS IGAD SADC

Total migration received by country 100,000

Source: calculations based on bilateral matrix data from world Bank 2023c.

Note: The map reflects the latest data available in 2020. in January 2024, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger announced their withdrawal from ecOwAS. ecOwAS = economic community of west African States; iGAD = intergovernmental Authority on Development; SADc = Southern African Development community.

North Africa is gradually transitioning from a sending and transit subregion to a destination for more migrants. Traditionally a major source of emigrants, it still remains so today. By some estimates, the Arab Republic of Egypt hosted 9 million migrants in 2022 (8.7 percent of the population), while also having 10 million to 14 million nationals abroad (IOM 2022b). Although estimates by different sources can vary (refer to box 1.1), Egypt hosts the highest number of immigrants in the region, owing to its historical openness to migrants. A significant portion of Egypt’s foreign-born population consists of refugees from Sudan, who account for almost half of the total immigrant stock according to the latest estimates. In other North African countries, except Libya, the number of immigrants represents a much smaller share of the population. In 2020, Morocco hosted 103,000 migrants and refugees (0.3 percent of the population), while 8.8 percent of Moroccans were expatriates (ETF 2021a). Tunisia had 7.6 percent of its population abroad, compared to only 0.5 percent of its residents being foreign-born (ETF 2021b).1 Yet, between 2015 and 2020, the number of international migrants in North Africa grew by more than 1 million,

reaching 3.2 million international migrants—1.3 percent of the total population—with 61 percent coming from the African continent.2 As North Africa’s economy evolves and its youth population remains large, labor markets will become more segmented, increasing both immigration and the emigration of highly educated nationals (De Haas 2006).

Irregular Migration across the Continent Is the Most Dangerous in the World

Migration routes within Africa are evolving rapidly, often involving irregular migration and high risks of violence. These routes respond to legal restrictions and border controls imposed by transit and destination countries. Routes from Sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa include distinct paths across the Sahara Desert from West and East Africa. Migrants often start their journey using legal means but turn to smugglers when faced with increased law enforcement, legal restrictions, or lack of commercial transport (Di Maio, Marzo, and Sciabolazza 2024). This exposes them to significant hardship and human rights abuses, including kidnapping, trafficking, sexual violence, and exploitation. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has documented severe abuses, through 16,000 interviews in 2018 and 2019, reporting 1,395 deaths; 2,008 episodes of sexual and gender-based violence involving more than 6,000 people; and 4,468 incidents of physical violence along migration routes (UNHCR 2020).

Irregular sea crossing is particularly perilous, with alarmingly high numbers of human losses. There are three main sea crossing points from North Africa to Europe: the Central Mediterranean route, with departure points in Libya and Tunisia; the Western Mediterranean route to Spain, mainly from Morocco; and the Canary Islands route. The relative significance of these routes has shifted over time, with some becoming more prominent and others becoming more difficult or hazardous. Almost 50,000 migrants are believed to have died worldwide while in transit since 2014 (IOM 2022a). Data on missing migrants show that in 2023, Africa had the worst outcomes compared to other regions (figure 1.4), with half of the fatalities occurring during attempts to cross the Mediterranean Sea. Additionally, about 45 percent of those arriving in Italy in 2018 reported experiencing physical violence while in transit through African countries (Black and Sigman 2022; Busetta et al. 2021; IOM 2020; World Bank 2018).

Figure 1.4 Number of Dead and Missing Migrants, by Region of Incident, 2014–23 01,0002,0003,0004,0005,000 Number of dead and missing migrants

Mediterranean Africa Asia Europe Latin America and the Caribbean North America

Source: international Organization for Migration Missing Migrants projects data (https://missingmigrants.iom.int/data).

Yet, most migration from Africa to other continents happens through legal pathways, with irregular border crossings remaining relatively constant over time at a small fraction of total movements. In the European Union, the number of irregular arrivals has been largely constant since 2014, with the exception of the peak caused by the Syrian conflict in 2015. Although the data show a modest increase in irregular arrivals since 2020, with a 29 percent rise in irregular sea crossings in 2022 alone, these entries (both by sea and land) accounted for only 12.4 percent of total border crossings to Europe by African migrants in 2021 and 2022. North African nationals are disproportionately represented among irregular migrants, making up 1.8 times the number of irregular migrants from the rest of Africa and 60.8 percent of total irregular border crossings by all African nationals (figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Irregular Cross-Border Movements into Europe

a. Cumulative crossings from North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, 2021 and 2022

Crossings Crossings North Africa

b. Total quarterly irregular border crossings, 2014–23

Sub-Saharan Africa Regular Irregular 0

Sources: Data on regular entries (first residence permits) are from eurOSTAT; data on the number of irregular entries in europe are from united Nations High commissioner for refugees.

Note: North Africa includes Algeria, the Arab republic of egypt, libya, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia; Sub-Saharan Africa includes all the other African countries.

Africa Hosts One-Fourth of the World’s Refugee Population

African countries host more than 41 million forcibly displaced individuals, the highest number in any region globally (figure 1.6, panel a). Refugees constitute a large share of migrants within Africa, accounting for one-third of the continent’s migrant stock (figure 1.6, panel b). By the end of 2023, 8.2 million of the 31.6 million refugees worldwide under the UNHCR’s mandate were in Africa. Over 70 percent of the current refugees originate from just five source countries: the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan, as documented in Sarzin and Nsababera (2024). Conflicts have also affected some 32.6 million internally displaced persons facing specific challenges (box 1.2).

Nearly 90 percent of the refugees in Africa are concentrated in 10 countries, with Chad, Ethiopia, and Uganda hosting almost half. Over 60 percent of the refugees are in fragile and conflict-affected regions (Sarzin and Nsababera 2024). Since 2010, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and South Sudan have been

Figure 1.6 Refugees Make Up a Large Share of the Migrant Flows in Africa

a. Forcibly displaced, by region, 2023

b. Proportion of forced displacement in total cross-border movements, 2020

Refugees Asylum seekers IDPs

Source: united Nations High commissioner for refugees and united Nations Department of economic and Social Affairs (https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock).

Note: iDps = internally displaced persons.

the main sources of Sub-Saharan Africans settling in North Africa. In 2021 and 2022, the primary countries of origin were Chad, Mali, and Niger. In 2023, the UNHCR registered 254,300 new asylum seekers in North Africa, primarily from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mali, South Sudan, and Sudan (UNHCR 2024). The crisis in Sudan has displaced more than 2 million people to Chad, Egypt, and South Sudan. Sub-Saharan Africa has a high proportion of child refugees, impacting child protection, health and education services, as well as self-reliance efforts (Sarzin and Nsababera 2024). Additionally, while many refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa live in planned or self-settled camps, an increasing number reside in individual accommodations (Sarzin and Nsababera 2024). BOX 1.2

High Levels of Internal Displacement

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) constitute the majority of forcibly displaced people in Africa but often receive less support and attention compared to refugees. Over the past decade, IDPs have represented between 67 and 79 percent of the forcibly displaced population in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly 80 percent of current IDPs have been displaced by conflict in just five countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Somalia, and Sudan (Sarzin and Nsababera 2024) (figure B1.2.1). Assisting this vulnerable

(continued next page)

Box 1.2

Figure

High Levels of Internal Displacement (continued)

B1.2.1 Significant Levels of Internal Displacement Are Concentrated in a Few Countries

Eritrea

Cameroon

Central African Republic

Burkina Faso

Ethiopia

South Sudan

Nigeria

Somalia

Congo, Dem. Rep.

Sudan

Source: Sarzin and Nsababera 2024.

Displaced people (millions)

Refugees Asylum seekers IDPs

Note: The figure shows the number of iDps by country of origin. iDps = internally displaced persons.

population is hindered by several factors, including the lack of legal status that mandates governments and international bodies to protect them, reluctance among some governments to acknowledge the presence of IDPs, restricted access to conflict-affected regions where many IDPs live, insufficient monitoring of rapid population movements, and limited media coverage (Sarzin and Nsababera 2024).

Climate-related disasters have emerged as a source of internal displacement.a The longest and most severe drought on record triggered 2.1 million internal displacements in 2022 in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia, with Somalia alone accounting for 1.1 million displacements.b In 2023, floods hit the Horn of Africa after years of drought and triggered 1.7 million displacements in Somalia and 550,000 displacements in Ethiopia (IDMC 2023). Flood displacement has also affected other countries, with 2.4 million displacements in Nigeria in 2022, and 640,000 displacements in Kenya in 2023 (IDMC 2024). Tropical storms in Southern Africa triggered nearly 700,000 displacements across Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe in 2022 (IDMC 2023, 2024). In some instances, consecutive extreme weather events contribute to protracted displacement. For example, by the end of 2022, around 127,000 people were living in displacement in Mozambique as a result of three tropical cyclones and two tropical storms that hit Southern Africa earlier in the year, some of them previously displaced due to cyclones Idai in 2019 and Eloise in 2021 (IDMC 2023).

a. while displacement caused by conflict overlaps with demographic and economic forces, the internal Displacement Monitoring centre estimates that in 2023, conflict accounted for 13.5 million internal displacements, and disasters for 6.2 million (iDMc 2023).

b. “internal displacements” correspond to the estimated number of movements over a given period. As such, the estimates do not represent the total number of people because the same individuals could have been displaced several times.

Notes

1. According to the Higher Council for Tunisians Abroad, the share of registered Tunisians living outside Tunisia amounted to 12.8 percent in 2022.

2. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock

References

Black, J., and Z. Sigman. 2022. “50,000 Lives Lost during Migration: Analysis of Missing Migrants Project Data 2014–2022.” Global Migration Data Analysis Centre, International Organization for Migration, Geneva.

Busetta, A., D. Mendola, B. Wilson, and V. Cetorelli. 2021. “Measuring Vulnerability of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (3): 596–615.

Crush, J., V. Williams, A. Dakhal, and S. Ramachandran. 2022. Labour Migration in the Southern African Region: A Stocktaking. Southern African Migration Management Project. Pretoria, South Africa: International Labour Organization, Pretoria.

De Haas, H. 2006. “Trans-Saharan Migration to North Africa and the EU: Historical Roots and Current Trends.” Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article /trans-saharan-migration-north-africa-and-eu-historical-roots-and-current-trends

Di Maio, M., F. Marzo, and L. Sciabolazza. 2024. “Migration to and through North Africa: An Overview.” Background paper prepared for this report. World Bank, Washington, DC.

ETF (European Training Foundation). 2021a. “Skills and Migration Country Fiche Morocco.” ETF, Torino, Italy. https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-05/ETF%20Skills%20and%20Migration%20 Country%20Fiche%20MOROCCO_2021_EN%20Final.pdf.

ETF (European Training Foundation). 2021b. “Skills and Migration Country Fiche Tunisia.” ETF, Torino, Italy. https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-11/etf_fiche_pays_competences_et _migration_tunisie_2021_fr.pdf

ICMPD (International Centre for Migration Policy Development). 2022. “Migration Outlook 2022: West Africa.” ICMPD, Vienna. https://www.icmpd.org/file/download/57218/file/ICMPD_Migration Outlook_WestAfrica_2022.pdf

IDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre). 2023. “2023 Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID).” IDMC, Geneva. https://www.internal-displacement.org/publications/2023-global -report-on-internal-displacement-grid/.

IDMC (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre). 2024. “2024 Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID).” IDMC, Geneva. https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2024/

IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2020. “Calculating ‘Death Rates’ in the Context of Migration Journeys: Focus on the Central Mediterranean.” GMDAC Briefing Series: Towards Safer Migration in Africa: Migration and Data in Northern and Western Africa. IOM, Geneva. IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2022a. “IOM Decries 50,000 Documented Deaths during Migration Worldwide.” IOM, Geneva. https://www.iom.int/news/iom-decries-50000 -documented-deaths-during-migration-worldwide.

IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2022b. “Triangulation of Migrants Stock in Egypt.” IOM, Geneva. https://egypt.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1021/files/documents/Migration%20Stock%20in%20 Egypt%20July%202022%20EN_Salma%20HASSAN.pdf

IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2023. “Djibouti, Country Overview.” IOM, Geneva. IOM (International Organization for Migration). 2024. “Cabo Verde, Country Overview.” IOM, Geneva. Sarzin, Z., and O. Nsababera. 2024. “Forced Displacement: A Stocktaking of Evidence.” Background paper prepared for this report. World Bank, Washington, DC.

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2020. “On This Journey, No One Cares If You Live or Die: Abuse, Protection, and Justice along Routes between East and West Africa and Africa’s Mediterranean.” UNHCR, Geneva. https://mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/127 UNHCR_MMC_report-on-this-journey-no-one-cares-if-you-live-or-die.pdf

UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2024. “Cartographie des services de protection: l’approche basée sur les routes pour les services de protection le long des routes de mouvements mixtes.” UNHCR, Geneva.

World Bank. 2018. “Asylum Seekers in the European Union: Building Evidence to Inform Policy Making.” World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank. 2021. “Eastern Africa Regional Statistics Program-for-Results.” Report P176371, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank. 2023a. “Harmonizing and Improving Statistics in West and Central Africa.” Project Appraisal Document PAD5154, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank. 2023b. “SADC Regional Statistics.” Project Appraisal Document PAD5178, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank. 2023c. World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies. Washington, DC: World Bank.

chapter 2

Overlapping Megatrends in Africa

Introduction

Africa is at a transformative juncture, where demography overlaps with low economic growth, conflict, and climate, factors known to drive the propensity to migrate.1 The continent’s population is set to grow from 1.5 billion in 2024 to 2.5 billion by 2050, with the working-age population increasing by more than 600 million. This substantial demographic shift contrasts sharply with high-income and upper-middle-income countries worldwide, where the working-age population will decrease by more than 200 million. However, Africa faces low productivity growth and declining relative incomes. Unless poverty reduction strategies alter the current trajectory, 89 million more people could fall into extreme poverty over the next three decades. Approximately 760 million people reside in countries that have been in a state of chronic fragility for over a decade, a figure that could nearly double by 2050. Additionally, two of every five people on the continent may face increasing severe heat risk by 2050.

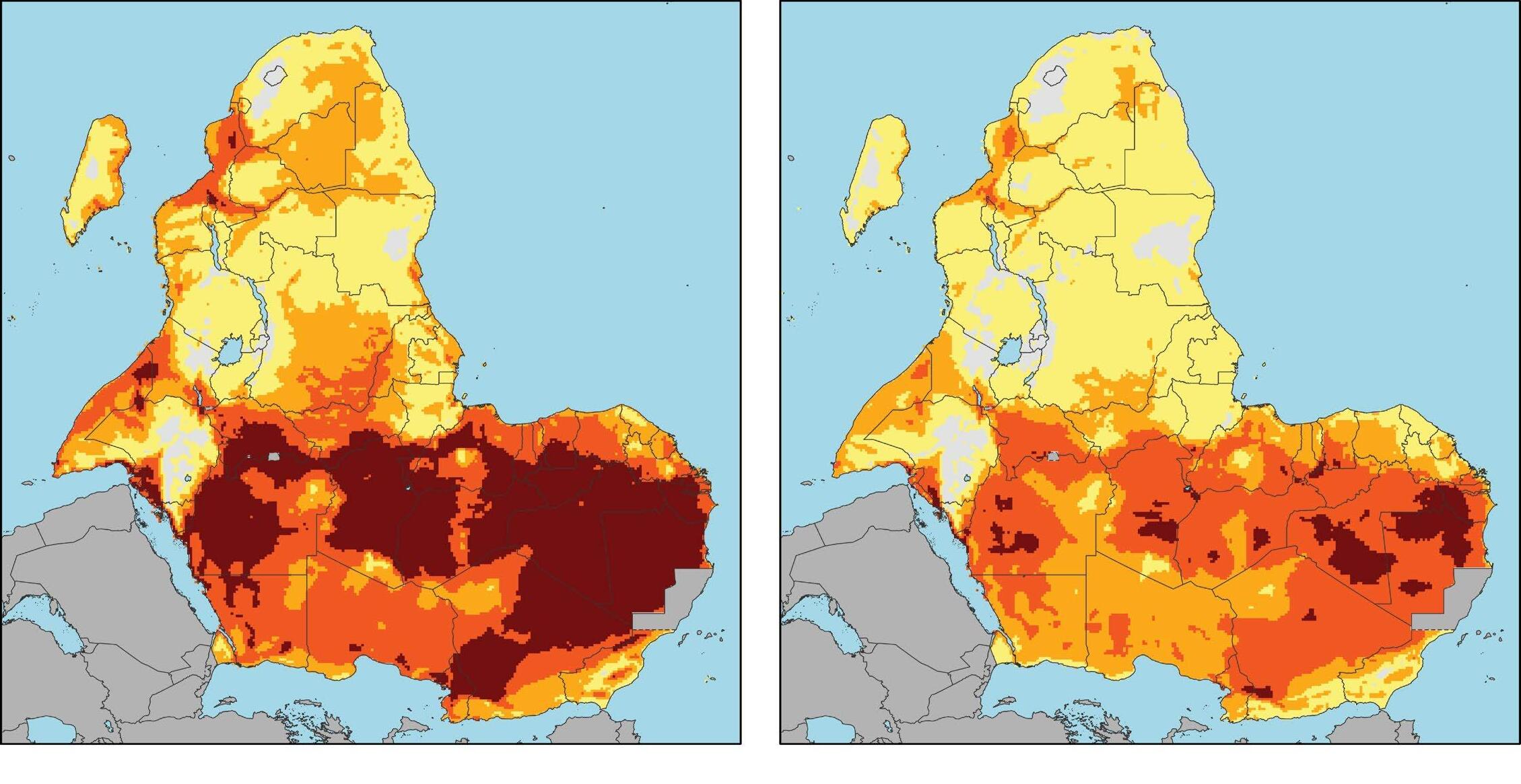

Africa’s Megatrends: A Tale of Two Subregions

There is considerable variation within the continent. Some of the highest fertility rates in the world are in Africa, particularly in countries in East, Central, and West Africa (map 2.1, panel a). Most of these countries also have lower levels of development (map 2.1, panel b); they are among the countries most exposed to climate change (map 2.1, panel c); and many of them have been plagued by chronic political instability (map 2.1, panel d). By contrast, the countries in North and Southern Africa are further into their demographic transitions; have higher incomes; are relatively less exposed to some of the consequences of climate change; and, except for Libya, are free of conflict. While recognizing the uniqueness of each country, this report henceforth refers to Africa’s geographical core, which includes the countries in the Central, East, and West subregions. These countries are home to 80 percent of the continent’s population. The remaining 20 percent live in North and Southern Africa, which form Africa’s geographical periphery.

Map 2.1 Confluence of Forces in Africa

a. Total fertility rate

Projected number of children per woman

IBRD 46666 | FEBRUARY 2025

b. GDP per capita

705.03

IBRD 46668 | FEBRUARY 2025

(continued next page)

2.1 Confluence of Forces in Africa (continued)

c. Climate vulnerability

ND-GAIN exposure score (higher score indicates higher exposure)

0.25

0.72

No data

46667 | FEBRUARY 2025

d. State fragility

Fragile and conflict-affected areas

High-intensity conflict

Medium-intensity conflict

High institutional and social fragility

No data

IBRD 46669 | FEBRUARY 2025