© 2025 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank

1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433

Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org

Some rights reserved

1 2 3 4 28 27 26 25

This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the data included in this work and does not assume responsibility for any errors, omissions, or discrepancies in the information, or liability with respect to the use of or failure to use the information, methods, processes, or conclusions set forth. The boundaries, colors, denominations, links/footnotes and other information shown in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The citation ofworks authored by others does not mean the World Bank endorses the views expressed by those authors or the content of their works.

Nothing herein shall constitute or be construed or considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all ofwhich are specifically reserved.

Rights and Permissions

=5

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions:

Attribution-Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2025. Global Economic Prospects, June 2025. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-2193-6. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

Translations-If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation.

Adaptations-If you create an adaptation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This is an adaptation ofan original work by The World Bank. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author or authors of the adaptation and are not endorsed by The World Bank.

Third-party content-The World Bank does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. The World Bank therefore does not warrant that the use of any third-party-owned individual component or part contained in the work will not infringe on the rights of those third parties. The risk of claims resulting from such infringement rests solely with you. If you wish to reuse a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images.

All queries on rights and licenses should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org.

ISSN: 1014-8906

ISBN (paper): 978-1-4648-2193-6

ISBN (electronic): 978-1-4648-2195-0

DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-2193-6

Cover design: Bill Pragluski, Critical Stages LLC.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025912134.

The cutoff date for the data used in the report was June 3, 2025.

This World Bank Flagship Report is a product of the Prospects Group in the Development Economics (DEC) Vice Presidency. The project was managed by M. Ayhan Kose and Carlos Arteta, under the general guidance of Indermit Gill.

The preparation of the analytical chapters was overseen by Dana Vorisek. The report was prepared by a team that included Amat Adarov, Marie Albert, Francisco Arroyo Marioli, Mirco Balatti, Samuel Hill, Phil Kenworthy, Jeetendra Khadan, Gitanjali Kumar, Dawit Mekonnen, Valerie Mercer-Blackman, Alen Mulabdic, Hayley Pallan, Edoardo Palombo, Peter Pedroni, Nikita Perevalov, Dominik Peschel, Peter Selcuk, Shijie Shi, Naotaka Sugawara, Takuma Tanaka, Garima Vasishtha, and Collette Wheeler.

Research assistance was provided by Sergiu Dinu, Jiayue Fan, Mario Guillen Salvatore, Matias Urzua, Shiqing Hua, Fuda Jiang, Nikola Evgeniev Kolev, Maria Hazel Macadangdang, Nikita Makarenko, Rafaela Martinho Henriques, Sadhna Naik, Vasiliki Papagianni, Juan Felipe Serrano Ariza, Kaltrina Temaj, Canran Zheng, and Juncheng Zhou. Modeling and data work was provided by Shijie Shi.

Online products were produced by Graeme Littler, with assistance from the Open Knowledge Repository. Adriana Maximiliano handled design and production. Joe Rebello managed communications and media outreach with a team that included

Kristen Milhollin, Mariana Lozzi Teixeira, and Leslie Yun, with extensive support from the World Bank's media and digital communications teams. Graeme Littler provided editorial support, with contributions from Adriana Maximiliano and Christina Davis.

Regional projections and write-ups were produced in coordination with country teams, country directors, and the offices of the regional chief economists.

Many reviewers provided extensive advice and comments. The analysis also benefited from comments and suggestions by staff members from World Bank country teams and other World Bank Vice Presidencies as well as Executive Directors in their discussion of the report on June 3, 2025. However, both forecasts and analysis are those of the World Bank staff and should not be attributed to Executive Directors or their national authorities.

The Prospects Group gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Policy and Human Resources Development (PHRD) Fund provided by the Government of Japan, which helped underpin some of the analytical work in this publication.

Only six months ago, a "soft landing" appeared to be in sight: the global economy was stabilizing after an extraordinary string of calamities both natural and man-made over the past few years That moment has passed. The world economy today is once more running into turbulence. Without a swift course correction, the harm to living standards could be deep.

International discord-about trade, in particular-has upended many of the policy certainties that helped shrink extreme poverty and expand prosperity after the end of World War II. This year alone, our forecasts indicate the upheaval will slice nearly half a percentage point off the global GDP growth rate that had been expected at the start of the year, cutting it to 2.3 percent. That's the weakest performance in 17 years, outside of outright global recessions By 2027, global GDP growth is expected to average just 2 5 percent in the 2020s-the slowest pace of any decade since the 1960s

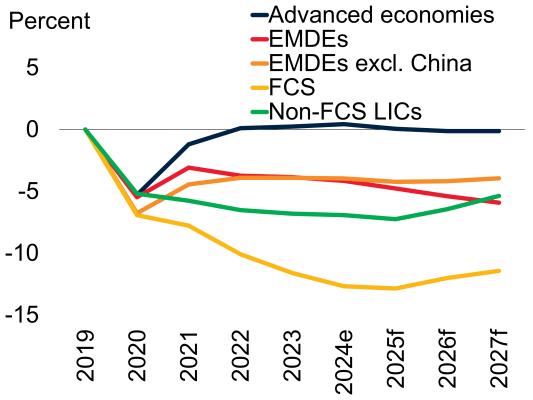

As this edition of Global Economic Prospects makes clear, the poorest countries will suffer the most. By 2027, the per capita GDP of high-income economies will be roughly where it had been expected to be before the COVID-19 pandemic. But developing economies would be worse off, with per capita GDP levels 6 percent lower. Except for China, it could take these economies about two decades to recoup the economic losses of the 2020s.

This grim predicament did not arrive by stealth. It has been advertising itself for at least a decade. Growth in developing economies has now been ratcheting downward for three decades in a row-from an average of 5.9 percent in the 2000s to 5.1 percent in the 2010s to 3.7 percent in the 2020s. That happens to track the declining trajectory of growth in global trade-which has fallen from an average of 5.1 percent in the 2000s to 4.6 percent in the 201 Os to 2.6 percent in the 2020s. Investment, meanwhile, has been growing at a progressively weaker pace. But debt is piling up.

In short, many of the forces behind the great economic miracle of the last 50 years-when per capita GDP in developing countries nearly quadrupled and more than 1 billion people escaped extreme poverty-have swung into reverse. Conditions that might have facilitated relatively painless policy corrections have come and gone-the record-low interest rates that prevailed in the first two decades of this century, for example, are now a thing of the past. Through it all, policymakers mostly stood still, hoping that conditions would somehow improve on their own. That was a false hope, but it is never too late to do the right thing. This report outlines three priorities:

First, rebuild trade relations. The evidence is clear: economic cooperation is better than any of the alternatives-for all parties. Our analysis suggests that if today's trade disputes were resolved with agreements that halve tariffs relative to their levels in late May, 2025, global growth could be stronger by about 0.2 percentage point on average over the course of 2025 and 2026.

Most developing economies today tend to have far higher tariffs than high-income economies. If their goal is to accelerate growth, their best course of action will be to lower tariffs with respect to all trading partners. Converting preferential trade agreements-mainly involving tariffs-into "deep trade agreements" that span the full range of cross-border regulatory policies could also juice GDP growth. Developing economies also have a crucial role to play in restoring a fully functional, rules-based trade system, specifically through the World Trade Organization (WTO). Predictability cuts trade costs, which in turn boosts GDP growth

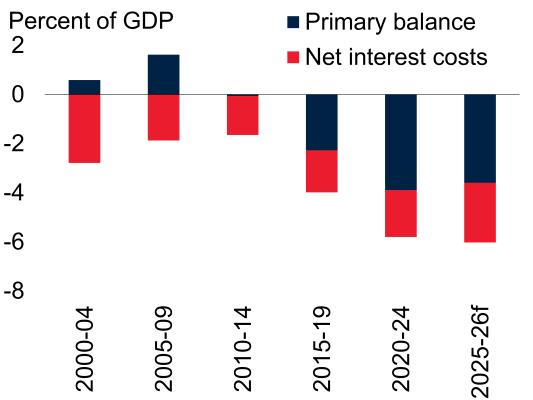

Second, restore fiscal order. It's fair to say that the succession of economic shocks in the 2020s has made a mess of government finances in many developing economies. But they were hardly the sole cause: in the era of easy money that preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, governments opted to take too many risks for far too long. The bill is

now due: fiscal deficits so far in the 2020s have averaged nearly 6 percent in developing economies, the highest level of this century. Interest costs alone account for about a third of the deficits. In low-income countries, the budget squeeze has been intensified by a drop in foreign aid, which finances a big share of critical needs such as health care. It should be no surprise that more than half of low-income countries are now either in debt distress or at high risk ofit.

Developing economics need to expand their fiscal room to maneuver. They have a lot of work to do in this regard, because they collect far less in revenues than high-income economies do-about 25 percent of GDP compared with nearly 40 percent of GDP in the wealthiest economies. They should seep up efforts to mobilize greater domestic resources-by broadening the tax base and strengthening tax administration and collection to reduce tax avoidance and proficshifring. They can also reap significant gains by narrowing the focus of costly food and fuel subsidies, channeling them simply toward lowincome households.

Third, accelerate job creation. Across the world, a historic demographic shift is underway-one that

is intensifying the need for jobs in many of the poorest countries. Sub-Saharan Africa's workingage population is forecast to almost double by 2050, growing by more than 600 million, more than any region has ever experienced over a 25year period. South Asia's working-age population is expected to expand by nearly 300 million over the same timcframe, and the Middle East and North Africa's by more than 100 million.

Whether these regions succeed or fail in tackling the challenge will determine the outlook for longterm global peace and prosperity. They will need to accelerate economic growth, upgrade the workforce's education and skills, and set the stage for labor markets to function efficiently.

The global economy today is at an inflection point. The forces that once drove economic convergence and lifted billions out of poverty are now in retreat. But chis moment offers a chance to reset the agenda- with renewed global cooperation, restored fiscal responsibility, and a relentless focus on creating jobs. With decisive action, governments across the world can still regain the momentum of poverty reduction-and deliver rising living standards for the next generation.

lndermit Gill Senior Vice President and ChiefEconomise The World Bank Group

After a succession of adverse shocks in recent years, the global economy is facing another substantial headwind, with increased trade tension and heightened policy uncertainty. This is contributing to a deterioration in prospects across most of the world's economies. For emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) , the ability to narrow per capita income gaps with richer countries, boost job creation, and reduce extreme poverty remains insufficient. Downside risks to the outlook predominate, including an escalation of trade barriers, persistent policy uncertainty, rising geopolitical tensions, and an increased incidence of extreme climate events Conversely, policy uncertainty and trade tensions may ease if major economies succeed in reaching lasting agreements that address ongoing trade disputes. The challenging global context faced by EMDEs is compounded by the fact that foreign direct investment inflows into these economies have fallen to less than half of their peak level in 2008 and are likely to remain subdued. Global cooperation is needed to restore a more stable and transparent global trade environment and scale up support for vulnerable countries grappling with conflict, debt burdens, and climate change. Across EMDEs, domestic policy action is also critical to contain inflation risks, strengthen fiscal resilience through improved revenue mobilization, and reprioritize spending. To unlock job creation and long-term growth, structural reforms must focus on raising institutional quality, attracting private investment, and strengthening human capital and labor markets. In particular, countries in fragile and conflict situations (FCS) face daunting development challenges that will require tailored domestic policy reforms, underpinned by well-coordinated multilateral support.

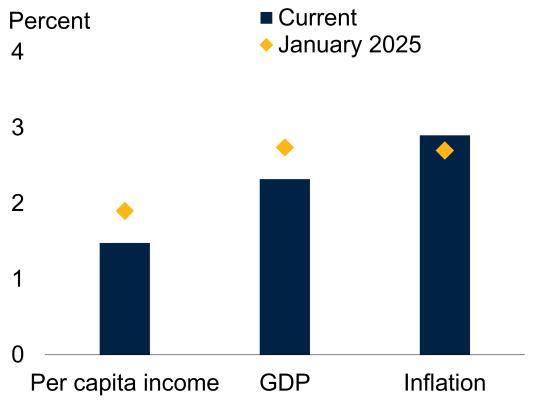

Global Outlook. Global growth is slowing due to a substantial rise in trade barriers and the pervasive effects of an uncertain global policy environment. Growth is expected to weaken to 2.3 percent in 2025, with deceleration in most economies relative to last year. This would mark the slowest rate of global growth since 2008, aside from outright global recessions. In 2026-27, a

tepid recovery is expected, leaving global output materially below January projections. Progress by emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) in closing per capita income gaps with advanced economies and reducing extreme poverry is anticipated to remain insufficient. The outlook largely hinges on the evolution of trade policy globally. Growth could turn out to be lower if trade restrictions escalate or if policy uncertainty persists, which could also result in a build-up of financial stress Other downside risks include weaker-than-expected growth in major economies with adverse global spillovers, worsening conflicts, and extreme weather events On the upside, uncertainty and trade barriers could diminish if major economies reach lasting agreements that address trade tensions. The ongoing global headwinds underscore the need for determined multilateral policy efforts to foster a more predictable and transparent environment for resolving trade tensions, some of which stem from macroeconomic imbalances. Global policy efforts are also needed to confront the deteriorating circumstances of vulnerable EMDEs amid prevalent conflict and debt distress, while addressing long-standing challenges, including the effects of climate change. National policy makers need to contain risks related to inflation as well as strengthen their fiscal positions by raising additional domestic revenues and reprioritizing spending. To facilitate job creation and boost long-term growth prospects in EMDEs, reforms are essential to enhance institutional quality, stimulate private investment growth, develop human capital, and improve labor market functioning.

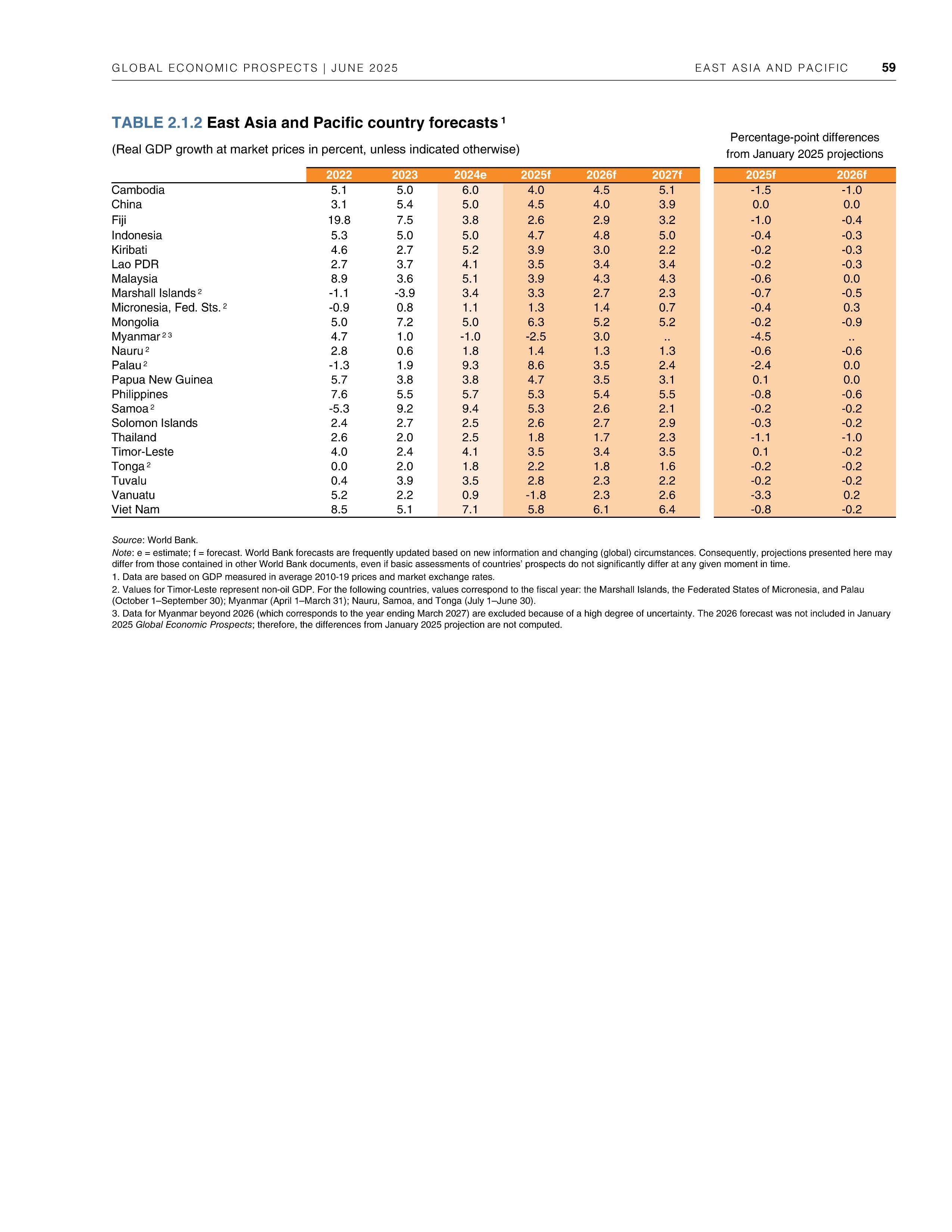

Regional Prospects. All EMDE regions face a challenging outlook amid the rise in trade tensions and heightened global uncertainty In 2025, growth is projected to slow in East Asia and Pacific as well as in Europe and Central Asia-both regions that are highly reliant on global trade-and, to a lesser extent, in South Asia. In Latin America and the Caribbean, growth is projected to be the lowest among

EMDE regions over the forecast horizon, as activity is held back by high trade barriers and long-standing structural weaknesses. In regions with a large number of commodity exporters, including in the Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, growth is anticipated to

face drags from the weakening outlook for external commodity demand. Against the backdrop of a deteriorating global environment, growth forecasts for 2025 have been downgraded in all EMDE regions relative to January projections.

AE

AI

CFA

CPI

EAP

ECA

EM7

EMBI

EMDEs

EU

FCS

FOi

FY

GCC

GDP

GNI

GVCs

IDA

IMF

KNOMAD

LAC

LIC

LNG

M&A

MNA

MNEs

NDVls

ODA

OECD

OPEC+

PMI

PPP

PVAR

R&D

SAR

SSA

SVAR

TFP

UN

UNCTAD

VAR

WDI

WTO

advanced economy

artificial intelligence

African Financial Community

consumer price index

East Asia and Pacific

Europe and Central Asia

Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, the Russian Federation, and Tiirkiye

Emerging Markets Bond Index

emerging market and developing economies

European Union

fragile and conflict-affected situations

foreign direct investment

fiscal year

Gulf Cooperation Council

gross domestic product

gross national income

global value chains

International Development Association

International Monetary Fund

Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development

Latin America and the Caribbean

low-income country

liquefied natural gas

mergers and acquisitions

Middle East and North Africa

multinational enterprises

normalized difference vegetation indices

official development assistance

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and other affiliated oil producers

purchasing managers' index

purchasing power parity

panel vector autoregression

research and development

South Asia

Sub-Saharan Africa

structural vector autoregression

total factor productivity

United Nations

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

vector autoregression

World Development Indicators

World Trade Organization

Global growth is slowing due to a substantial rise in trade barriers and the pervasive effects of an uncertain global policy environment Growth is expected to weaken to 2.3 percent in 2025, with deceleration in most economies relative to last year. This would mark the slowest rate of global growth since 2008, aside from outright global recessions. In 2026-27, a tepid recovery is expected, leaving global output materially below fanuary projections. Progress by emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) in closing per capita income gaps with advanced economies and reducing extreme poverty is anticipated to weaken The outlook largely hinges on the evolution of trade policy globally. Growth could turn out to be lower if trade restrictions escalate or ifpolicy uncertainty persists, which could also result in a build-up offinancial stress. Other downside risks include weaker-than-expected growth in major economies with adverse global spillovers, worsening conflicts, and extreme weather events. On the upside, uncertainty and trade barriers could diminish if major economies reach lasting agreements that address trade tensions. The ongoing global headwinds underscore the need for determined multilateral policy efforts to foster a more predictable and transparent environment for resolving trade tensions, some of which stem from macroeconomic imbalances. Global policy efforts are also needed to confront the deteriorating circumstances of vulnerable EMDEs amid prevalent conflict and debt distress, while addressing long-standing challenges, including the effects of climate change. National policy makers need to contain risks related to inflation as well as strengthen their fiscal positions by raising additional domestic revenues and re-prioritizing spending. To facilitate job creation and boost long-term growth prospects in EMDEs, reforms are essential to enhance institutional quality, stimulate private investment growth, develop human capital, and improve labor market functioning.

After being buffeted by a series of adverse shocks over 2020-24, the global economy is facing another significant headwind this year, with increased trade barriers and heightened policy uncertainty leading to a notable deterioration of the outlook relative to January (figure L LA). In particular, global output is expected to grow at its weakest pace since 2008, aside from outright global recessions (figure LLB). The sharp increase in tariffs and the ensuing uncertainty are contributing to a broad-based growth slowdown and deteriorating prospects in most of the world's economies (figure L LC). Subdued global growth prospects are unlikely to improve materially without policy actions to address increasing trade restncttons, geopolitical tensions, heightened uncertainty, and limited fiscal space.

The global outlook is predicated on tariff rates close to those of late May prevailing throughout the forecast horizon. Accordingly, pauses to previously announced tariff hikes between the

Note: This chapter was prepared by Carlos Arteta, Phil Kenworthy, Nikita Perevalov, Peter Selcuk, Garima Vasishcha, and Collette Wheeler, with contributions from Micco Balatri, Jongrim Ha, Samuel Hill, Gicanjali Kumar, Dawit Mekonnen, Ale n Mulabdic, Edoardo Palombo, Shijie Shi, Naocaka Sugawara, and Takuma Tanaka.

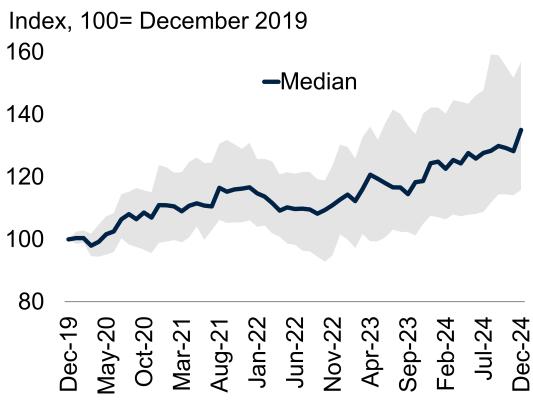

United States and its trading partners are assumed to persist. This baseline nonetheless entails the highest U S average effective tariff rate in nearly a century. In addition, in view of recent rapid shifts in trade policies and the potential for a return to even higher tariffs, consumers and businesses continue to grapple with unusually elevated uncertainty (figure LLD). In this context, a prospective recovery in global trade and investment-two important drivers of long-term development that have been relatively subdued in recent years-has been disrupted.

Commodity prices plunged in early April in response to deteriorating growth prospects. Oil prices posted an especially large decline, with the effects of a notable hike in oil production by OPEC+ nations compounded by a muted outlook for oil demand growth (figure L LE). Base metal prices also dropped as markets priced in substantial headwinds to global manufacturing and industrial activity but have since partially recovered. Overall commodity prices are forecast to decline by 10 percent in 2025, softening further in 2026-mainly due to falling oil prices.

Global headline inflation generally remains elevated relative to central bank targets and prepandemic averages and has even risen in some advanced economies since late last year. Slower

M emorandu m item s: Real GDP 1

Source : World Bank

Note : e= estimate;f= forecast. EM? = Brazil,China,India,Indonesia,Mexico,the Russian Federation,and TOrkiye WBG = World Bank Group World Bank forecasts are frequently updated based on newinformation Consequently, projectionspresented here may differfrom those contained in otherWorld Bank documents,even if basic assessments of countries' prospects do not differat any given date For the definition of EMDEs, developing countries,commodity exporters,and commodity importers,please refer to table 1.2 The World Bank is currently not publishing economic output, income,orgrowth data for Turkmenistan and Reptlblica Bolivariana de Venezuela owing to lack of reliable data of adequate quality. Turkmenistan and Reptlblica Bolivariana de Venezuela are excluded from cross-country macroeconomic aggregates.

1 Headline aggregate growth rates are calculated using GDP weights at average 2010-19prices and market exchange rates.

2 GDP growth rates are on afiscalyear(FY) basis. Aggregates thatinclude these countries are calculated using datacompiled on acalendar yearbasis. For India and the Islamic Republic of Iran,the column for 2022 refers to FY2022/23 For Bangladesh,the Arab Republicof Egypt,and Pakistan,the column for 2022 refers to FY2021/22. Pakistan'sgrowth rates are basedon GDP atfactorcost.

3 World growth rates are calculated using average 2010-19purchasing powerparity (PPP) weights,which attribute agreater share of global GDP to emerging market anddeveloping economies (EMDEs) thanmarketexchange rates.

4 World trade volume of goods and nonfactorservices.

5 Indexes are expressed in nominal US. dollars (2010 = 100). Oil refers to theBrent crude oil benchmark For weightsand composition of indexes,see https://worldbank org/commodities

disinflation globally over the last six months has largely reflected continuing inflationary pressures from services prices. The recent rise in consumer inflation expectations has been influenced by the implementation of trade restrictions. In addition, core inflation in some economies is expected to remain high due to persistent services price increases. In all, GDP-weighted global inflation is projected to average 2.9 percent in 2025 and 2026-still a little above the average inflation target-but with notable heterogeneity across economies.

Global financial conditions have been tighter this year, on average, relative to late 2024, principally reflecting trade policy uncertainty Volatility in financial markets spiked and equity markets plunged globally as trade tensions escalated in early April; however, asset prices largely recovered after an initial 90-day tariff pause was announced and following the rollback in U.S.-China tariffs in May (figure 1.1.F). Long-term government bond yields in major advanced economies have increased since late last year, albeit with pronounced volatility. EMDE financial conditions are also somewhat tighter, on average, relative to late last year. In early April, many EMDEs saw sharp declines in equity markets amid a surge in capital outflows. Sovereign spreads rose, albeit to differing degrees based on economies' exposure to announced trade barriers Nevertheless, EMDE equity markets regained ground and spreads narrowed again following the partial de-escalation in trade tensions

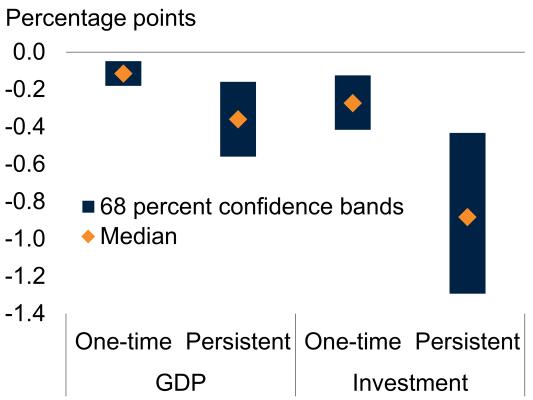

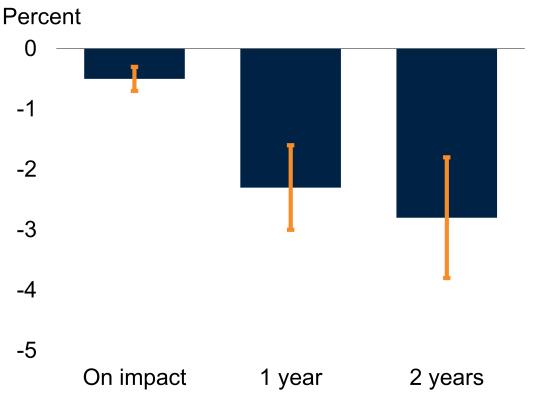

Against this backdrop, global growth is set to slow this year, to 2.3 percent-substantially weaker than previously projected amid the impact of higher trade barriers, elevated uncertainty, increased financial volatility, and weakened confidence. Thereafter, growth is forecast to firm to about 2.5 percent over 2026-27, as trade flows continue adjusting to higher tariffs such that global trade edges up, while policy uncertainty moderates from record-high levels. The downgrade to global growth this year is principally driven by advanced economies (figure 1.2.A). This slowdown is projected to be concentrated on investment, including foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio flows-which tend to respond

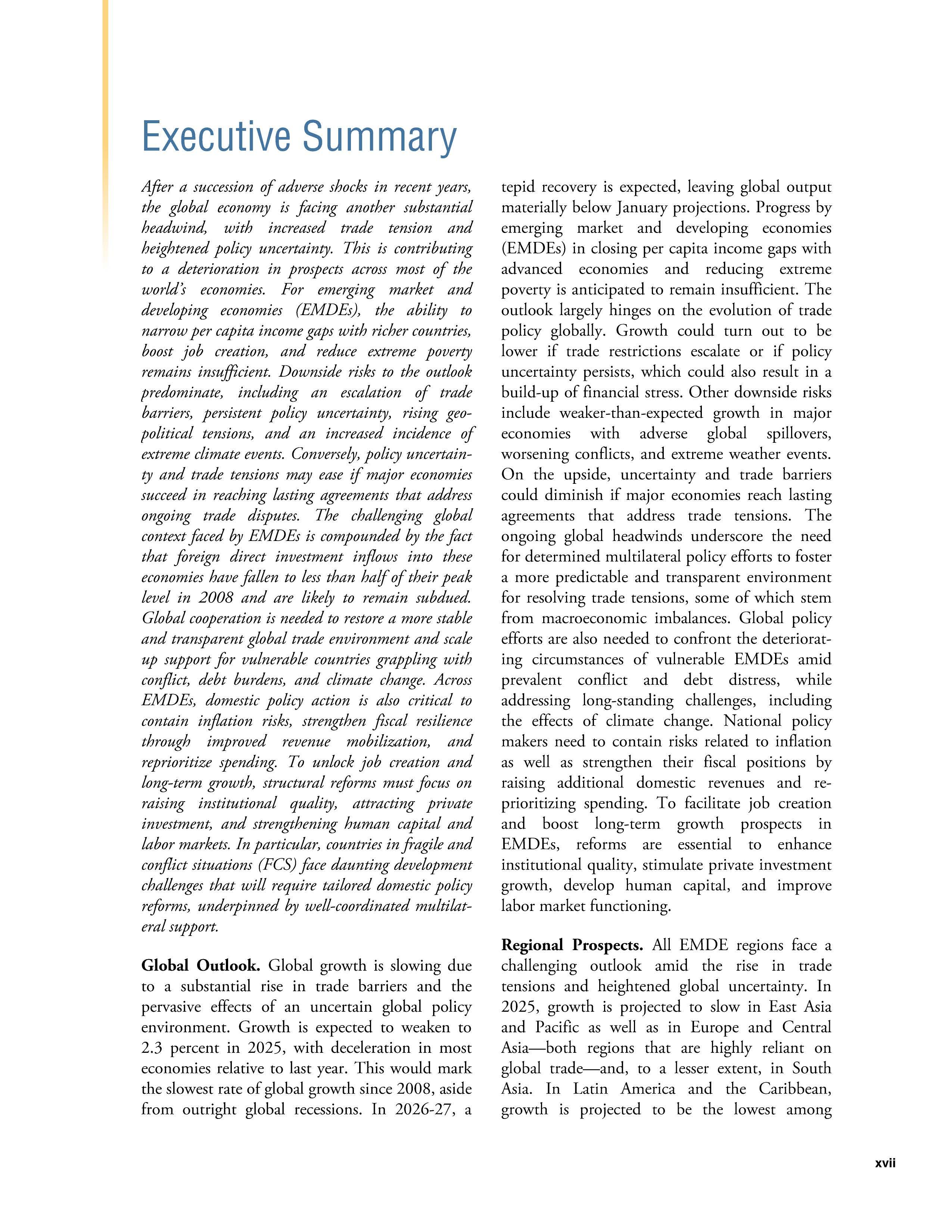

The global outlook has deteriorated substantially relative to January, with global growth in 2025 expected to register its weakest pace since 2008, aside from outright global recessions. This deterioration is broad-based across the world's economies and follows sharp increases in trade tensions and policy uncertainty. The slowdown in global growth will erode demand for oil and various other commodities, weighing on the outlook for many EMDE commodity exporters. Following U.S. tariff announcements, financial markets experienced substantial turbulence, with a spike in equity market volatility and a rise in EMDE sovereign bond spreads, although these subsequently subsided. A. Global growth, per capita income growth, and inflation in 2025

F. Equity market volatility and EMDE bond spreads

Sources: Caldara et al. (2020); Haver Analytics; International Energy Agency (IEA); J.P. Morgan; UN World Population Prospects;World Bank.

Note: f =forecast. AEs =advanced economies; ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations; EMDEs =emerging marketand developing economies;mb/d = million barrels perday;GDP aggregates calculated using real U.S. dollar GDP weights at

prices and market exchange rates.

A. Blue bars "current''correspond to the current edition of the Global Economic Prospects (GEP) report and yellow diamonds "January 2025" correspond to the January 2025 edition of the GEP.

B. Data for 2024 are estimates;data for 2025-27 are forecasts.

C. Panel shows the share of economies with slowing growth and with growth outlook downgraded relative to January 2025 forecasts. Horizontal line shows 50 percent.

D. Trade Policy Uncertainty Index based on automated text searchesof the electronic archives of seven newspapers. A highervalue indicates higher trade policy uncertainty. Last observation is May 2025.

E. Bars indicate the average change in annual oil demand in mb/d for the selected periods. Data based on IEA's Oil Market Report,May 2025 edition. 2025 and 2026 are projections

F. Blue line represents the daily CBOE Volatility Index, which measures marketexpectations of nearterm volatility conveyed by stock index option prices. Red line represents the median sovereign bond spread for a sample of up to 71 EMDEs. Lastobservation is May 30 2025.

The deterioration in the global outlook has largely emanated from trade shocks, with forecasts for advanced economies downgraded markedly. These shocks are set to weigh on EMDEs via trade, financial, and investment flows with major economies. Risks are tilted to the downside. Global growth could be even lower if an escalation of trade tensions and uncertainty further weakens investment, trade, and confidence. Geopolitical fragmentation could accelerate if trade or geopolitical tensions worsen. In EMDEs, a higher incidence of conflict could lead to lasting output losses. A downside scenario of renewed trade tensions could push the world economy into an extended period of anemic growth.

A Contributions to global growth downgrades in 2025 and 2026

C. Probability distribution around global growth forecast

B Trade and financial linkages between major economies and EMDEs excluding China

D. Geopolitical Fragmentation Index

more to demand shifts than aggregate outputand trade, with widespread adverse spillovers to other economies (figure 1.2.B).

Growth in EMDEs is expected to slow in 2025, to 3.8 percent, before edging up a touch over 202627, to 3.9 percent. China's economy is projected to decelerate across the forecast horizon, as a nearterm boost from fiscal policy fades amid slowing potential growth. Meanwhile, near-term growth in many other EMDEs is anticipated to decelerate amid weakening investment, which is likely to more than offset any possible benefits from trade diversion during the forecast period Against the backdrop of a deteriorating external environment, progress by EMDEs in closing sizable per capita income gaps with advanced economies, spurring job creation, or reducing extreme poverty rates is anticipated to slow further, leaving poverty rates above pre-pandemic levels in many poorer or fragile EMOEs At the same time, many of these economies are set to face a looming jobs challenge in the coming decades, especially if employment growth continues to be outstripped by population growth

Sources : BIS (database); Bloomberg; Consensus Economics; Fernandez-Villaverde, Mineyama, and Song (2025); IMF Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (database); Ohnsorge, Stocker, and Some (2016); Uppsala Conflict Data Program; Oxford Economics; World Bank (WITS; KNOMAD)

Note: e = estimate; f = forecast. EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; FDI = foreign direct investment; GDP aggregates calculated using real U S. dollar GDP weights at average 201019 prices and market exchange rates.

A Contributions to the global growth downgrade between the current and the January 2025 editions of Global Economic Prospects.

B Bars show, for EMDEs excluding China, the share of total exports (total inward FDI positions, remittance inflows, and portfolio liabilities) that are to (from) China, the euro area, and the United States. See figure 1.11.Cfor details.

C. The dashed line is the global recession threshold (below zero per capita growth). Probabilities use the range and skewness implied by oil and equity price derivatives, and term spread forecasts Last observation is May 2025

D. Last observation is 2024Q1. See figure 1.13.Bfor details

E. Lines show the cumulative gap between forecasted and actual percapita GDP following highintensity conflict. Sample includes 14conflicts in 14 EMDEs (3 not currently FCS) from 2006-23 See figure 1.12 E for details

F Panel shows the deviation of aggregate growth in the upside and downside scenarios,using Oxford Economics' Global Economic Model.

Risks to the global outlook remain tilted decidedly to the downside (figure 1.2.C). High and persistent policy uncertainty-particularly related to trade-could lead to greater-than-expected weakening in investment, trade, and confidence. Renewed increases in trade restrictions could push inflation higher in key economies, magnifying real income losses and limiting the scope for major central banks to support flagging growth by lowering policy rates. This backdrop also implies several potential triggers for a souring of financial risk appetite, which could reverberate globally and amplify downside surprises to growth. Even with efforts to resolve some major conflicts, geopolitical tensions and regional conflict risks persist in many parts of the world and could contribute to further geopolitical fragmentation (figure 1.2.D). Moreover, worsening conflict could generate lasting, concentrated output losses, particularly in EMDEs (figure 1.2.E). Natural disasters, the frequency and intensity of which have increased over time, pose another ever-present threat in many economies.

Nonetheless, there are also some notable upside risks to growth. A cooling of trade tensions on the back of recent and ongoing negotiations-for instance, through further trade agreements between large economies that secure lower tariffs-would curb uncertainty, limit trade disruptions, and strengthen business and consumer confidence. A synchronous loosening of fiscal policy in several large economies could mitigate the downward pressures on demand, albeit while also exerting upward pressure on inflation, government debt levels, and interest rates. Efforts to widely employ recent advances in technology-notably artificial intelligence (Al)could give rise to stronger-than-anticipated global investment growth and start to feed into broad productivity improvements.

To quantify downside risks concerning trade policy, a scenario is modeled in which U.S. weighted average tariffs increase by about 10 percentage points relative to the baseline, with proportional retaliation from trading partners. This sudden escalation in trade barriers results in global trade seizing up in the second half of this year and is accompanied by a widespread collapse in confidence, surging uncertainty, and turmoil in financial markets. The combination of these multiplying shocks reduces global growth, by 0.5 and 0.4 percentage point in 2025 and 2026, relative to the baseline, tipping the world economy into an extended period of anemic growth (figure 1.2.F). In contrast, an upside scenario features further trade agreements that halve tariffs relative to the baseline and reduce trade-related uncertainty. Under these conditions, global growth would be higher compared with the baseline by 0.1 and 0 3 percentage point in the next two years.

The challenging global context highlights the need for policy action at both global and national levels. To mitigate the adverse impact of elevated trade barriers and policy uncertainty on global growth, a key priority is to foster dialogue and cooperation to address global imbalances and restore a more predictable, transparent, and rules-based approach to resolving trade tensions and avoiding escalation. The global community also needs to confront the worsening circumstances of many vulnerable

EMDEs amid debt distress, acute food insecurity, and prevalent conflict. Tackling these severe headwinds to growth and development has become more challenging considering declining aid flows from key donors Meanwhile, reinvigorating global efforts toward climate change adaptation and mitigation is vital to limit the future economic and social costs of increasingly frequent natural disasters.

Policy action at the domestic level is critical. Some EMDE central banks will face a difficult balancing act between addressing continuing price pressures, on the one hand, and seeking to moderate the contractionary effects of trade restrictions and policy uncertainty, on the other. This will require careful calibration of monetary policy tailored to each economy's circumstances At the current juncture, some EMDEs may be especially prone to financial volatility and capital outflows, underscoring the importance of central bank credibility With respect to fiscal policy, many EMDEs are not well positioned for the expected slowdown in growth, with fiscal deficits remaining above pre-pandemic averages and debt levels rising in many economies. To build fiscal space, EMDEs need to raise additional domestic revenues, especially where other sources of financing are drying up, while reprioritizing spending toward growth-enhancing measures and protecting vulnerable populations

In the long run, the most sustainable solution to the wide range of challenges facing EMDEsincluding insufficient job creation, slow poverty reduction, debt-related challenges, and scarce fiscal resources-is to foster stronger environments for private investment and raise potential growth. Reinvigorating FDI deserves particular attention, given its historical role as a vector of technology diffusion and productivity gains. Doing so would require improving institutions and safeguarding political, regulatory, and socioeconomic stability

To help EMDEs create productive employment for growing working-age populations, measures to strengthen foundational infrastructure, address structural bottlenecks, and enhance private sector dynamism are critical. Priorities could include

policies that encourage upskilling workers, ease access to finance, and promote labor markets that better match workers and employers. Moreover, policy makers need to consider not only aggregate job creation but also the quality of jobs-for instance, by seeking to improve productivity, ensure good working conditions, and reduce barriers to firms expanding and formalizing. For EMDEs recently or currently embroiled in conflict, attaining durable peace and stability is paramount not only for limiting the human toll but also as a prerequisite for raising employment, human capital, and income levels.

Against the backdrop of heightened policy uncertainty and increased trade barriers, the global economic context has become more challenging, with the risk of further adverse policy shifts materializing, particularly with respect to trade relations among the largest economies. The rise in trade restrictions clouds the near-term trade outlook-despite solid trade growth earlier this year, which partly reflected the front-loading of imports by some large economies in anticipation of tariff hikes. Beyond the direct impact of higher tariffs, the potential for further rapid shifts in the timelines and magnitudes of trade-restrictive measures is a source of sentiment-sapping policy uncertainty. Commodity prices have fallen substantially, reflecting new headwinds to global manufacturing and broader industrial activity. With re-emerging pressures in core inflation globally, the pace of global disinflation has slowed, while survey-based inflation expectations in key countries have risen alongside tariff-related developments. Trade policy shifts and the associated increase in uncertainty weighed substantially on financial markets earlier this year, although risk appetite has largely recovered in recent weeks.

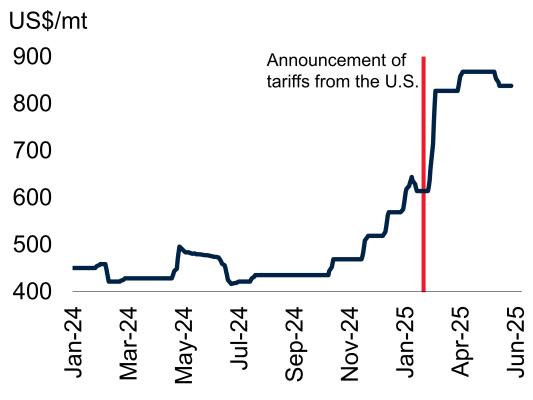

Global trade conditions experienced a large shock in early April when the United States announced prospective tariffs on most trading partners, with rates proportional to bilateral goods trade deficits, in addition to previously announced tariffs. A sharp escalation of trade barriers between China

and the United States followed. Subsequently, country-specific tariffs were reduced to a universal 10 percent-including in the case of China, with initially prohibitively high tariff rates being rolled back sharply in May. However, other tariff increases remain on China and other large trade partners. As a result, the effective U.S. tariff rate has been brought to levels not seen in almost a century (figure 1.3.A). Tariff rates in effect as of May 27 are assumed to prevail throughout the forecast period, but there is notable uncertainty in this regard. The baseline projections for global trade also incorporate important carve-outs for USMCA-compliant goods, pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, bullion, energy, copper, and other critical minerals, as well as retaliatory measures in place as of late May

Shifting policy announcements have led to heightened global trade policy uncertainty, measures of which reached historical highs over the past few months (figure 1.3.B). This reflects uncertainty over whether current tariff rates will endure, their implementation, and the scale and timing of potential retaliatory responses. New tariff measures mark an intensification of the upward trend in trade-restrictive measures seen in recent years, with a significant risk of further escalation in trade barriers, as announced policies could generate substantial spillovers to third markets These markets may respond by adopting protectionist measures to shield domestic industries from a surge in imports

Prior to the recent tariff announcements, growth in global goods trade had accelerated at the turn of the year, partly reflecting inventory build-ups in anticipation of changes in trade policy in major economies (figure 1.3.C). The growth in goods trade has been relatively widespread, albeit with the pace of expansion in advanced economies exceeding that in EMDEs. Likely driven by the rush to front-load imports before tariffs took effect, the global new export orders manufacturing PMI subindex briefly entered expansionary territory in March, signaling temporary improvements in goods trade, before falling in April to its lowest level in 20 months. Global services trade growth has flattened out after several years of recovery from the pandemic, with travel activity approaching pre-pandemic levels. The

stabilization in services trade is also reflected in the continued softening of the expansion in the global services PMI.

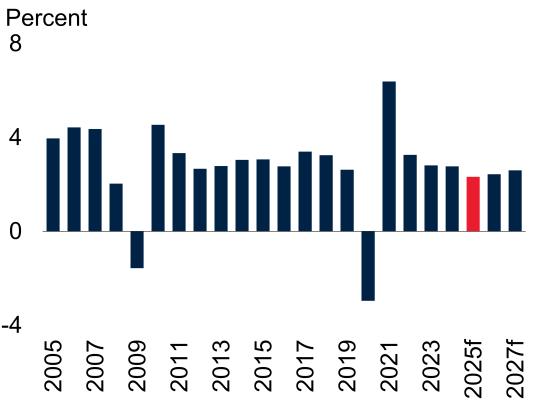

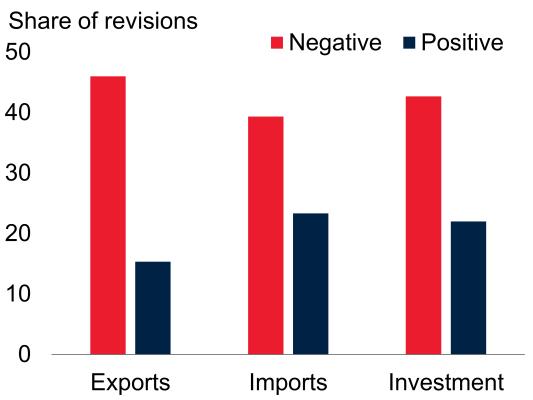

Global trade growth in goods and services is projected to slow sharply in 2025, to 1 8 percent, from 3.4 percent in 2024 (figure 1.3 D). The forecast has been revised down by 1.3 percentage points since January, reflecting changes in trade policies in key economies and higher trade policy uncertainty. Increased tariffs are expected to weigh on global trade over the forecast horizon. In tandem with the projected pickup in global growth, trade growth is nonetheless forecast to firm from a feeble pace this year, reaching 2.4 percent in 2026 and 2.7 percent in 2027-still well below its pre-pandemic average of 4.6 percent. The forecast for global trade growth masks significant heterogeneity. Countries with greater export exposure to EMDE markets are projected to recover more rapidly than those more reliant on advanced economies, though elevated policy uncertainty and weakening demand could weigh on the recovery more broadly.

The outlook for global trade is subject ro substantial downside risks, notably a renewed escalation of trade restrictions. Even absent further escalation, a related risk is that uncertainty about trade and other policies could slow investment, an import-intensive component of GDP, dampening trade more than anticipated.

Commodity prices have fallen since February, largely owing to weaker growth prospects amid increased trade barriers and policy uncertainty (figure 1.4 A). Largely reflecting these movements, annual average commodity prices are expected to decline by 10 percent in 2025 (figure 1.4.B). In 2026, commodity prices are projected to soften further, by 6 percent, as production of some energy and metals commodities expands and supply constraints on several agricultural commodities ease Thereafter, commodity prices are projected to edge up as global growth continues to recover, supporting commodity consumption. Risks to the commodity price projections are tilted to the downside, as a renewed escalation of trade tensions between

The effective U.S. tariff rate has risen sharply in 2025 to its highest level in almost a century Trade policy uncertainty, which has reached record-high levels, could further weaken trade prospects. Global goods trade growth had firmed at the turn of the year, partly reflecting inventory build-ups ahead of new tariff announcements Global trade growth is projected to slow substantially in 2025 and then firm in 2026-27, in line with the projected pickup in global growth.

Sources : Caldara etal. (2020); CPB Netherlands Bureau of Economic Analysis; IMF;The Budget Lab;World Bank.

Note : e = estimate; f = forecast. AEs = advanced economies: EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies. Trade in goods and services is measured as the average of export and importvolumes.

A. Panel shows historical and projected customs duty revenues based on tariffs in force as of May 12,2025,as a share of goods imports,without accounting for potential shifts in consumerand business purchasing behavior in response to tariff increases.

B. Trade Policy Uncertainty index based on automated text searches of the electronicarchives of seven newspapers: Boston Globe Chicago Tribune, Guardian, Los Angeles Times New York Times, Wall Street Journal , and Washington Post. A higher value indicates highertrade policy uncertainty. Last observation is May2025.

C. Panel shows the annual percentage change in goods trade volume and industrial production. Last observation is March 2025.

D. Panel shows the growth of global trade volume in goods and services. "Exporting to AEs" refers to trade growth for countries with over 50 percent of exports to advanced economies during the 201519 period;"Exporting to EMDEs"refers to trade growth for countries with over 50 percentofexports to EMDEs during the 2015-19 period.

major economies could further weaken global trade and investment, undermining commodity demand.

Oil prices declined precipitously in early April, as worries about the effect of rising trade tensions on demand coincided with OPEC+ pivoting toward relatively rapid increases in oil production. Brent oil prices are projected to average $66 per barrel this year and $61 per barrel next year, with demand growth set to remain well below 2015-19

Commodity prices have fallen, partly reflecting deteriorating growth prospects due to increased trade tensions and policy uncertainty. Annual average prices are expected to decline markedly in 2025 and soften further in 2026. Energy prices are forecast to decrease by 15 percent this year, reflecting increases in oil production from OPEC+ and weakening demand growth, which is set to remain well below 2015-19 levels From early in 2025, the front-running of new trade-restrictive measures buoyed aluminum prices to well above global benchmarks.

=

=

Sources : Bloomberg; International Energy Agency (IEA); World Bank. Note: AEs = advanced economies; ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations; IEA = International Energy Agency; mb/d = million barrels per day.

A B. "Commodity prices"/"Commodities" line refers to the World Bank Commodity Price Index, excluding precious metals.

A Monthly prices. Last observation is May 2025.

B Dashed lines indicate forecasts.

C. Bars indicate the average change in annual oil demand in mb/d for the selected periods Data based on IEA's Oil Market Report, May 2025 edition 2025 and 2026 are projections ASEAN includes the following members: Brunei Darussalam,Cambodia, Indonesia,Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines,Singapore, Thailand,and Viet Nam. Data for Lao PDR is excluded from the calculations due to its unavailability.

D Five-day moving average of July 2025 futures contract for aluminum Midwest premium Premium reflects the additional cost above the London Metal Exchange price for aluminum delivered to U.S. Midwest. Last observation is June 3 2025.

Agricultural commodity prices are forecast to be little changed this year and decrease slightly in 2026-27. In 2025, a surge in beverage pricesreflecting weather-related supply shocks to coffee and cocoa-is expected to be offset by a decline in food commodity prices, partly owing to mounting rice stocks and record-high soybean production In addition, maize prices are projected to edge down, in part due to lower oil prices reducing demand for maize-derived ethanol. In 2026-27, beverage prices are expected to start normalizing, with food prices broadly holding steady, such that overall agricultural prices are forecast to soften slightly.

Metal prices (excluding precious metals) fell sharply in early April as global growth prospects deteriorated, before partially recovering as trade tensions cooled somewhat. From earlier in the year, copper and aluminum prices were bolstered by the front-running of prospective tariff increases, with U.S. aluminum prices substantially exceeding the global benchmark (figure 1.4.D). In all, the metals index is projected to drop by 5 percent in 2025 and drift lower in 2026 before stabilizing. Prices for most base metals are set to decline this year, reflecting trade-related headwinds to global manufacturing. The precious metals price index-reflecting principally gold but also silver and platinum-is projected to buck the broader trend, increasing by more than 30 percent in 2025. Annual average gold prices are expected to reach a record high this year, supported by safe haven flows, before plateauing in 2026-27.

levels (figure 1.4.C). In contrast, annual average natural gas prices are set to climb markedly this year, due mainly to a more than 50 percent jump in U.S. natural gas prices. While European natural gas prices have generally fallen in recent months due to mild weather and adequate inventories, U.S. prices have been buoyed by the ongoing structural expansion of LNG exports. In all, energy prices are projected to decrease by 15 percent in 2025 and 7 percent in 2026, before increasing somewhat in 2027 as oil prices firm.

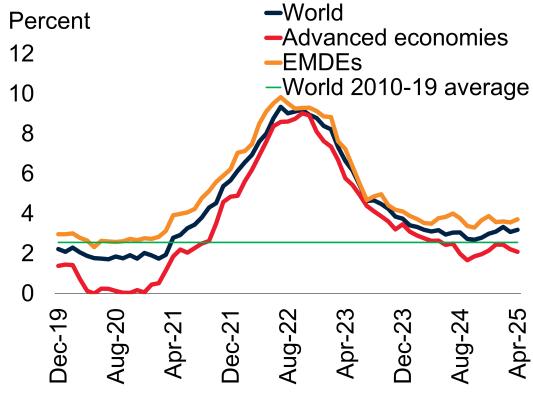

Global headline consumer price inflation has remained elevated above pre-pandemic norms over the past year, briefly edging higher in some advanced economies in early 2025 (figure 1.5.A). Continued tightness in labor markets has kept core inflation at a somewhat elevated level in many economies. In EMDEs, monthly headline inflation readings were volatile earlier this year, with a pickup in core inflation partly reflecting rising services prices and wage pressures.

The outlook for global inflation has become more uncertain since last year due to a combination of shocks. Most notably, substantial tariff hikes are

set to exert upward pressure on consumer inflation in key economies by raising prices for imported consumer goods and inputs into production and redirecting demand toward domestic production that is relatively inelastic in the short run (Barbiero and Stein 2025). Indeed, manufacturing purchasing managers in advanced economies have already reported accelerating input and output prices so far this year (figure 1.5.B). Even so, outside economies where import duties have significantly increased, higher trade barriers are likely to be generally deflationary as they weaken external demand. There may nevertheless be other upside risks to inflation in these economies that are indirectly associated with trade restrictions. These include the potential for damage to global supply chains to push up prices in unpredictable ways, and the possibility of sizable currency depreciations.

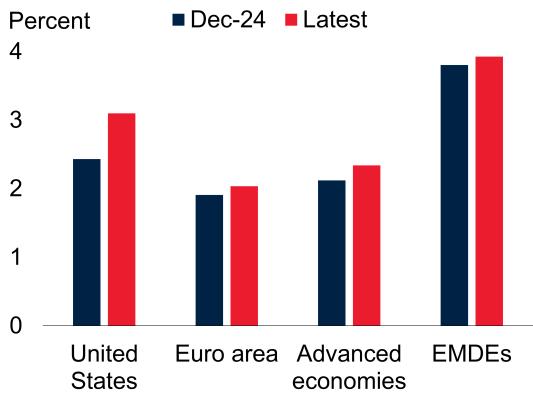

Inflation expectations, particularly at the shorter horizon, have picked up in 2025, mainly in some major economies (figure 1.5.C). This is likely explained by the expected impact of tariff increases on consumer prices, even as trade tensions weigh on economic activity and commodity prices. Persistent underlying inflationary pressures, coupled with the impact of rising tariffs and tradeprotectionist measures, are anticipated to delay the normalization of global inflation to levels broadly consistent with inflation targets. On a GDPweighted basis, global inflation is projected to average 2.9 percent in both 2025 and 2026, before easing to 2.5 percent in 2027-about in line with the average inflation target. However, there is significant heterogeneity across countries, with inflation projections revised slightly lower in EMDEs in 2025 due to the impact of weaker demand for traded goods, while being revised significantly higher in advanced economies, primarily the United States (figure 1.5.D).

Global financial conditions have been tighter this year, on average, compared to late 2024, due to financial market volatility and some decline in risk appetite, fueled by elevated trade policy uncertainty (figure 1.6.A). The surge in and then partial de-escalation of trade tensions in the second quarter led to marked financial market turbulence,

Global headline inflation has remained somewhat elevated over the past year, briefly edging higher in advanced economies in early 2025 . Tariffinduced upward pressure on prices has begun to build along supply chains, particularly in advanced economies, with manufacturing surveys pointing to rising input and output prices Inflation expectations have picked up in 2025, especially in some major economies Inflation projections in 2025-26 have been revised slightly lower in EMDEs on account of weaker demand for traded goods, while being revised notably higher in advanced economies, primarily the United States

Sources: Consensus Economics;Haver Analytics; Oxford Economics; World Bank.

Note: CPI = consumer price index; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; PMI = purchasing managers' index;ytd = year to date.

A. Aggregates are calculated as medians. Sample includes up to 36 advanced economies and 99 EMDEs. Last observation is April 2025.

B. Aggregated by source. PMI readings above (below) 50 indicate expansion (contraction). Last observation is April 2025.

C. Panel shows median inflation expectations. Latest survey is May2025.

D. Model-based GDP-weighted projections ofconsumer price inflation using Oxford Economics' Global Economic Model. Sample includes 69countries,out of which 35 are EMDEs, and excludes Argentina and Republica Bolivariana deVenezuela.

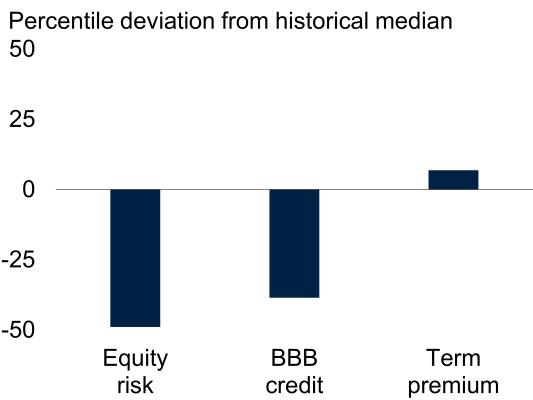

including in core government bond markets. Global equity markets plunged in early April, followed by a recovery driven by the postponement of some tariffs and the partial rollback of tariffs between the United States and China. Risk premia in U.S. equity and corporate credit markets, as gauged by cyclically adjusted equity earnings relative to the risk-free rate and highyield spreads, have increased this year, albeit from very low levels (figure 1.6.B).

Monetary policy in the United States remains restrictive, with policy rates unchanged so far this

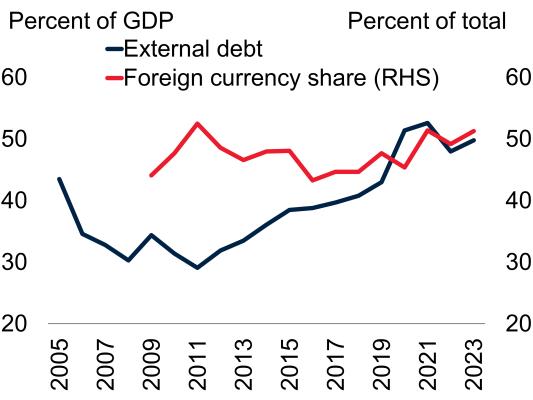

Global financial conditions have been tighter this year, on average, relative to late 2024 amid increased trade barriers, elevated trade policy uncertainty, and concerns of a slowdown in global growth. Risk premia in U.S. equity and high-yield bond markets have edged up, albeit from very low levels. Sovereign spreads have increased overall in EMDEs, although a spike in the spreads of countries exposed to higher U.S. tariffs largely unwound when tariffs were paused. A rise in borrowing costs would put pressure on vulnerable EMDEs with elevated levels of external debt and foreign-currency-denominated government debt, which have increased in recent years. A Financial conditions index

B Risk premia in the United States

EMDE financial conditions have been somewhat tighter, on average, relative to late last year. Tariff announcements in April led to portfolio outflows along with broad-based declines in EMDE equity markets, although these moves largely reversed after the pauses in tariffs were announced. Most EMDE currencies have appreciated against the U S dollar since the start of the year, except for some economies with pre-ex1stmg domestic vulnerabilities. EMDE sovereign spreads have increased overall in recent months, jumping in April among economies that faced higher prospective trade barriers (figure 1.6.C). However, this surge proved short-lived, with spreads generally retreating when trade tensions partially de-escalated. Despite this volatility, from a longerterm perspective, spreads have remained at manageable levels in most economies.

C. EMDE sovereign spreads, by announced U.S. tariff rate

D. EMDE external debt and foreigncurrency-denominated debt

PercentofGDP Percentoftotal -External debt

60 - Foreign currency share (RHS) 50

Sources : Barclays Investment Bank;Bloomberg; Federal Reserve Bankof St. Louis; Goldman Sachs; J.P Morgan; Kose et al. (2022); White House; World Bank.

Note: EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies.

A Higher index values represent tighter financial conditions. Last observation is May 30 2025

B "Shiller excess earnings yield" is the inverse of the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio minus the yield on 10-year U.S Treasury inflation-protected securities "High-yield corporate bond spreads" are measured by ICE BofA Option-Adjusted Spreads (OASs) These represent the calculated differences between a computed OAS index for all bonds rated below Baa/BBB and the spot U.S Treasury curve. Last observation is April 2025 for the yield and May 2025 for the bond spreads

C. Median spreads for 6 high-tariff EMDEs and 58 low-tariff EMDEs "Low tariff' is defined as a tariff rate of up to 30 percent as announced on April 2 Last observation is May 30 2025

D External debt (percent of GDP) is the median of up to 137 EMDEs. Foreign-currency share of government debt is the median of up to 36 EMDEs. Last observation is 2023.

year and anticipated to decline only gradually, despite expectations of a slowdown in growth. This partly reflects the Federal Reserve's communications regarding the need to ensure that near-term inflationary pressures do not become persistent and long-term inflation expectations remain anchored. Meanwhile, policy rates have been lowered in the euro area since January, with further cuts expected by the end of the year. Even so, long-term yields have risen, reflecting fiscal announcements earlier in the year.

Monetary policy in EMDEs has become more cautious, with many central banks easing or holding their policy rates unchanged as they assess the consequences for inflation and growth of higher trade barriers, elevated uncertainty, and potential shifts in investor appetite for EMDE financial assets. Policy rates may be kept higher for longer to ward off possible capital outflows and currency depreciations that could result from a renewed escalation of trade tensions. As a result, higher borrowing costs and weaker domestic currencies could put pressure on many EMDEs, especially those with weak credit ratings and large debt-refinancing burdens. External debt and the share of foreign-currency-denominated government debt in EMDEs have risen in recent years and are currently at elevated levels (figure 1.6.D).

Advanced economies

In advanced economies, growth forecasts for 2025 have declined substantially since January, driven by downgrades in some of the world's largest economies. This reflects the shock dealt by the increases in trade barriers-even with the partial 90-day pause in U S. tariff increases-and the associated policy uncertainty, financial volatility, and dampening effects on confidence As a result,

growth is expected to remain below potential growth estimates over the forecast horizon in some advanced economies, including in the United States and the euro area.

In the United States, the announcement of trade policy changes did not provide much-needed clarity or reduce policy uncertainty, given the scale and scope of new tariffs, shifting timelines for their implementation, and fluid lists of exemptions Furthermore, the implications of such large policy shifts, including potential steps that could be taken by other governments in response, remain highly unpredictable

Prior to recent tariffs coming into effect, U.S. activity had already begun to slow in early 2025 as spending on imports surged at the expense of domestically produced goods. Private consumption growth has eased somewhat, despite a brief pickup toward the end of the first quarter in anticipation of new tariffs in categories such as autos Consumer sentiment has fallen sharply amid declines in equity markets and risk appetite. In addition, U.S. consumer inflation expectations have risen markedly since the start of the year (figure 1.7.A) Treasury yields have increased, and corporate risk spreads have widened, while some corporate sectors faced the risk of disruption to tightly integrated supply chains, particularly in the U.S. auto industry. Policy uncertainty has remained high, with many firms highlighting concerns about the impact of trade policy changes on prices (Federal Reserve Board 2025). In tandem, the resilience in U S labor markets has continued to gradually diminish, with nonfarm payroll growth below the 2015-19 average and easing further, and other labor market indicators signaling reduced dynamism (figure 1.7.B).

The outlook for U.S. growth and inflation in 2025 has deteriorated relative to January forecasts. The rise in trade barriers, heightened uncertainty, and the spike in financial market volatility are set to weigh on private consumption, international trade, and investment. As a result, U.S. growth is expected to decelerate sharply in 2025, to 1.4 percent. Investment spending is projected to be particularly hard-hit following the earlier frontloading of imported investment goods

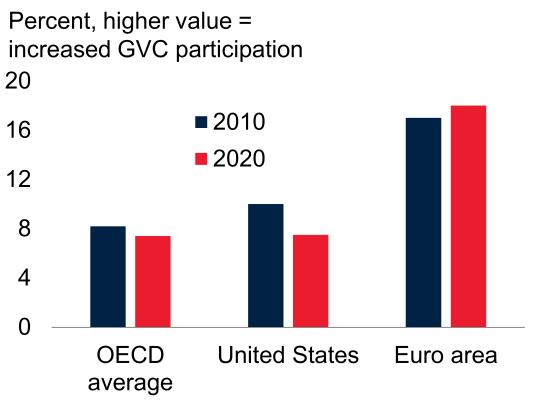

U.S. consumer inflation expectations have risen markedly this year amid escalating trade tensions. Increased trade restrictions, weak confidence, and the resulting slowdown in aggregate demand are expected to contribute to reduced dynamism in the U.S. labor market. In the euro area, activity is expected to remain anemic, particularly given its deep integration in global value chains, which leaves the bloc highly exposed to adverse shifts in trade policy. In China, goods exports expanded in early 2025, reflecting continued front-loading, but are expected to slow as the effects of rising trade restrictions and the associated policy uncertainty are felt.

C. Global value chain exposure:Share D Merchandise trade in China of foreign value added in gross exports

Sources: ECB; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Haver Analy1ics; Organisation of Economic Cooperationand Development (OECD);University of Michigan;World Bank

A Panel shows 12-month-ahead consumer inflation expectations from the Michigan Consumer Sentiment Survey and the European Central Bank (ECB) Consumer Expectations Survey. Last observation is April 2025

B. Hiring, layoffs, and quits and separations are shown as percent of employment. Payrolls are shown as year-over-year percent change. Panel shows simple averages for the indicated periods. Last observation is April 2025 y1d = year to date.

C Data measure the extent to which a country is a user of foreign inputs, which is considered as a measure of backward linkages in analyses of global value chains, as computed by the OECD Euro area aggregates exclude intra-regional trade. Due to data constraints, euro area excludes Croatia

D Lines indicate year-on-year percent change in goods exports and imports in US dollars Last observation isApril 2025

forward, the supply of investment goods is anticipated to be disproportionately impacted by tariffs due to their high import content, at the same time as investment demand cools due to record-high uncertainty, the rise in financing costs, and reduced domestic and external demand.

In 2026, growth is anticipated to edge up to 1.6 percent as the economy adjusts to higher trade barriers and policy uncertainty gradually declines.

Growth could prove to be stronger over the next few years if proposals to extend some expiring prov1s10ns of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and introduce other new fiscal measures clear the legislative process and are implemented. The resulting increase in the federal budget deficit would then be likely to broadly offset the budgetary impact of additional tariff-related revenues, with the latter estimated to reduce the primary deficit by $2.5 trillion over 10 years (CBO 2025).

In the euro area, the recent surge in policy uncertainty and financial volatility, as well as increases in tariffs on the European Union (EU), are set to prolong the bloc's economic weakness, holding back a recovery in investment and trade. The EU is exposed to adverse shifts in trade policies and related uncertainty given its high openness to trade, with extra-EU trade in value terms placing the bloc as the second largest exporter and importer of global goods in 2022 (ECB 2019; Eurostat 2024). The bloc is also vulnerable to these external shocks owing to its deep integration into global value chains (figure 1.7.C; Gunnella and Quaglietti 2019). Together, these developments are set to further dent exports, compounding the losses in competitiveness and global export market shares stemming from high energy prices in the past few years.

Growth in the euro area is projected to slow in 2025, to 0.7 percent, and remain a touch below its trend of about 1 percent, averaging 0 9 percent over 2026-27. Substantial downgrades to growth forecasts relative to January projections reflect a combination of higher U.S. tariffs on imports from the EU, heightened uncertainty and financial market volatility, and weaker external demand, which are expected to more than offset newly legislated fiscal spending on defense and infrastructure-particularly in Germany. Although trade spillovers from higher spending in Germany to other euro area economies are expected to be positive, they are likely to be somewhat muted by the slow implementation of the package given Germany's capacity constraints.

The baseline is also predicated on additional policy rate cuts as inflation is expected to hover near the ECB's medium-term target. Although

possible price pressures could arise from increased trade barriers and additional government spending, they would likely be somewhat countered by weaker demand, softer commodity prices, and the potential redirection of exports from China to the EU (Attinasi et al. 2024; ECB 2025) The baseline assumptions include U.S. tariffs, including those on sectoral goods, as of late May and do not include any potential retaliatory trade measures

In Japan, growth is expected to firm from an estimated 0 2 percent in 2024 to 0 7 percent in 2025, underpinned by a rebound in consumption and the reopening of automobile plants after longer-than-expected shutdowns last year. However, the growth outlook has been downgraded by 0 5 percentage point this year relative to previous projections, largely due to slowing external demand amid increased trade barriers and weaker-than-expected real wage growth owing to elevated food inflation Over 2026-27, growth is forecast to average 0.8 percent, assuming a slow but continued recovery in consumer spending, as well as modest growth in capital investment, even if it is partly moderated by policy interest rate hikes as the Bank of Japan normalizes its policy stance.

In China, the imposition of tariffs by the United States, the ensuing retaliation, and the subsequent partial rollback will have notable implications for the outlook of trade and broader economic activity. Before these policy actions, China's growth remained resilient in the first quarter of 2025, driven by a front-loading of exports ahead of the implementation of tariffs (figure 1.7.D). In contrast, imports were sluggish, held back by continued tepid domestic demand amid the property sector downturn, now approaching the four-year mark. Resulting soft underlying price pressures, as well as falling food and energy prices, led to decreasing consumer prices earlier in 2025. Producer prices also continued to fall, reflecting declining global commodity prices and competition among firms for market share.

To help strengthen domestic demand and counter headwinds from trade tensions and heightened

trade policy uncertainty, additional fiscal support was announced in early 2025, implying an estimated consolidated fiscal deficit of 8.1 percent of GDP in 2025, wider than the 6.5 percent of GDP in 2024. 1 These measures are aimed at further boosting infrastructure-related spending and, to a much lesser extent, consumer spending. More recently, additional monetary policy easing and financial measures targeted at several sectors were announced to support domestic economic activity

Going forward, growth is forecast to slow from 5 percent in 2024 to 4.5 percent this year-in line with previous projections, as the impact of higher trade barriers and weaker external demand is assumed to be offset by the boost from additional fiscal policy support. Export growth is expected to slow as the impact of U.S. tariff increases materializes. A soft labor market and a subdued property sector are expected to weigh on consumption However, announced additional fiscal support will help buoy non-property-related investment, consumption, and industrial activity. Growth is projected to slow to 4 percent in 2026 and edge down to 3.9 percent in 2027, as the growth of potential ourpur decelerates, reflecting the effects of slowing productivity growth, an aging population, and high debt levels

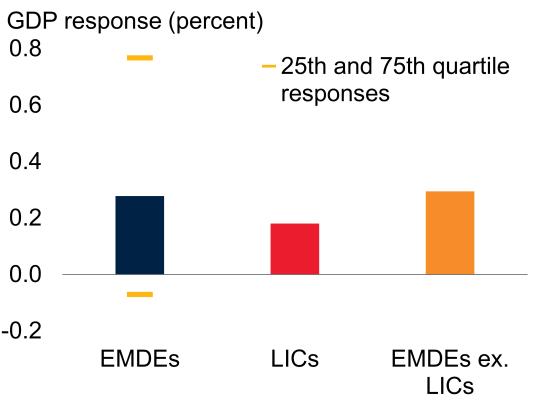

Against the backdrop of a more challenging external environment, EMDE growth is forecast to slow significantly in 2025, to 3.8 percent, with only a modest projected pickup in 2026-27 The expected rate of growth is well below prepandemic averages and the pace that is needed to create sufficient jobs to meet working-age population growth and make progress in closing large per capita income gaps with advanced economies. The deterioration in EMDE growth prospects is driven in large part by economies with a high degree of trade and investment openness. In these economies, large manufacturing sectors,

high global value chain participation, and reliance on global financial markets amplify the negative spillovers from the recent shocks to global trade and confidence and the sharp rises in uncertainty and financial market volatility. However, the softness in the EMDE outlook is anticipated to be broad-based, with growth expected to slow in nearly 60 percent of EMDEs in 2025. More generally, the capacity of many EMDEs to respond to negative shocks has diminished due to sharp pandemic-related increases in debt, elevated poverty rates, and waning official development assistance.

Prior to the recent deterioration in the external environment this year, activity in EMDEs had generally steadied over 2024, with domestic demand supported by generally benign financial conditions and solid credit growth (figure 1.8 A). Although domestic activity indicators remained relatively resilient over the first quarter of 2025, the rapid rise in uncertainty and slowdown in external demand have begun to act as a drag on acnv1ty. Gauges of manufacturing acnv1ty, including headline manufacturing PMis and goods trade indicators, have eased recently. Some trade-exposed EMDEs-such as Malaysia, Mexico, Romania, and Viet Nam-have seen the new export orders component of the manufacturing PMI weaken markedly since November amid increasing global trade policy uncertainty (figure 1.8.B).

On the services side, PMis have remained in expansionary territory bur nonetheless have trended lower this year (figure 1.8.C). Highfrequency consumption indicators also point to a similar dynamic, with both consumer confidence and retail sales losing some momentum in recent months. Nonetheless, the so-far generally resilient trends are expected to lose momentum amid the sharp rise in uncertainty following increases in trade restrictions and other policy shifts (figure 1.8.D).

1 For China, the World Bank uses a definition of the consolidated fiscal balance that allows for comparisons across countries. See chapter 2 for details

Growth has continued to diverge across EMDEs so far in 2025, with a slower pace of activity in some commodity-exporting EMDEs and somewhat more solid conditions across other

Before the recent deterioration in the external environment, activity in EMDEs had been supported by solid credit growth, in line with earlier domestic and global monetary policy easing. More recently, some tradeexposed EMDEs have seen a marked decline in new export orders, while services activity and other high-frequency indicators have trended lower Against the backdrop of a sharp rise in uncertainty, momentum across EMDEs is expected to ease further.

A EMDE credit impulse B. Manufacturing PMls: New export orders

the upside in some large energy-exporting EMDEs-including Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, and Nigeria-largely owing to domestic factors outside of the energy sector.

In commodity-importing EMDEs excluding China, activity had remained broadly steady before the sharp rise in trade tensions, supported by a pickup in private consumption and investment, with the latter benefiting from firm manufacturing acnv1ty. Despite overall solid performance, some economies have seen a material weakening in activity in recent quarters, largely reflecting an increase in uncertainty related to domestic developments or rising trade barriers.

C. Headline PMls: Manufacturing and services D. Overall World Uncertainty Index across EMDEs

Sources : Ahir, Bloom, and Furceri (2022); HaverAnalytics;World Bank.

Note: EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; PMI = purchasing managers' index.

A Sample includes up to 36 EMDEs Last observation is December 2024

B Blue line shows a 3-month moving average for a sample of select trade-exposed EMDEsthat includes Malaysia,Mexico, Romania and Viet Nam. Red line shows a 3-month moving average for a sample of 12 EMDEs. Last observation is April 2025. Shaded area indicates the interquartile range for all 16 EMDEs

C. PMI readings above (below) zero indicate expansion (contraction) Monthly readings are centered on 50, the expansionary threshold Last observation is April 2025

D Panel shows the 3-month moving average of the unweighted average of the country-specific measure of overall uncertainty based on the World Uncertainty Index (WUI). All indices have been computed by counting the frequency of the world uncertainty (or its variant) in EIU country reports The indices are normalized by total number of words and rescaled by multiplying by 1,000. A higher number means higher uncertainty and vice versa. Sample includes 49 EMDEs. Last observation is April 2025

In LICs, growth is estimated to have firmed to 4.6 percent in 2024, up from 2.8 percent a year earlier. The pickup in activity last year was driven mainly by major LICs facing fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS)-including the Democratic Republic of Congo, where mining activity surprised on the upside, and in Ethiopia, where mining and agriculture output was better than expected. Such positive momentum hinged on tailwinds from commodity markets and favorable financing conditions prevailing in 2024, which may give way to headwinds as global growth and trade slow, commodity prices weaken, and uncertainty dampens risk appetite. Moreover, pervasive violence and political instability have resulted in persistently challenging economic and humanitarian situations, particularly in the Sahel region and its adjacent countries. Sudan has continued to experience a deep contraction related to ongoing violent conflict, which has also hampered activity in neighboring South Sudan, leading to a steeper-than-anticipated decline in output.

economies. The weaker performance among the former was mostly concentrated in energyexporting economies and related to softness in global energy demand; ongoing OPEC+ production cuts; notable declines in commodity prices amid rising trade tensions, which weighed on net exports, revenues, and investment; and new sanctions on some oil-exporting economies. Prior to the deterioration in the external environment, earlier activity readings had modestly surprised to

Following the trade shocks that have rippled through the global economy, growth in EMDEs is forecast to slow to 3.8 percent in 2025, then edge up to an average of 3.9 percent over 2026-27, about 1.2 percentage points below the 2010-19 average (figure 1.9 A). In large part, the aggregate EMDE profile continues to be shaped by China's outlook, especially as the ongoing structural deceleration is exacerbated by the escalation in

trade tensions Nevertheless, the projected slowdown in EMDE growth this year is anticipated to be broad-based, affecting nearly 60 percent of EMDEs