Advance praise for From Risk to Resilience

Poor people are poor because markets fail them and governments fail them. Governments intervene to correct market failures, such as externalities or public goods, but these, in turn, create government failures, such as unaccountable service providers or elite capture of public resources. The challenge of poverty reduction is to design actions that correct government failures without recreating the market failures the policies were meant to address, and vice-versa.

These principles underpin this remarkable and refreshing book on climate adaptation in South Asia, the most vulnerable region on the planet. The book starts by asking how the private sector— households and firms—is adapting to higher temperatures and more frequent extreme-weather events. The authors’ motivation, namely that all South Asian governments lack fiscal space and, therefore, the private sector should undertake adaptation, is not necessary. Even if these governments had fiscal surpluses, the private sector should lead because there is no obvious market failure in adaptation. When a firm installs a ceiling fan or a household reinforces its walls, the firm or household benefits. As the report shows, firms and households are undertaking such adaptation measures. But these people may not have access to the most up-to-date information about rising heat or storm frequency. This information is a public good and so there is a case for the government to provide it at this stage. However, once this information becomes mainstreamed, there is no need for the government to be involved, just as financial investors get their information from non-government sources. Information is not the only constraint to better adaptation by the private sector.

The report documents how firms lack access to credit in order to purchase expensive technologies for adaptation. Although most surveyed firms—around the world—claim they lack credit, the solution of subsidizing credit should be treated with care. Usually, the lack of credit stems from a distortion in the banking sector, and unless that is addressed, a subsidy could even make matters worse. The report likewise points out that distortions in other markets, such as labor and land, impede firms’ adaptation. Again, the solution should be to reform these markets, not take them as given and subsidize adaptation. The latter is politically tempting, but it risks locking the country in a policy that is hard to reverse—the 50-year-old policy of free power to farmers in south India is a case in point. Incidentally, the detrimental effect of this free-power policy on groundwater supply, exacerbating the effects of climate change on agriculture, is another case of government failure undermining climate adaptation.

After examining the potential for the private sector, with better information and fewer regulatory constraints, to undertake adaptation, the report concludes that public investment in core public goods such as roads, bridges, and health systems, as well as in social protection, will be necessary. But these are sectors in which South Asian countries have historically underperformed. Maintenance of roads, which is the key to resilience, is chronically under-funded; doctors and nurses in primary health centers in India are absent 40 percent of the time; Sri Lanka’s flagship social protection program, Samurdhi, only reaches 40 percent of the poor (and is subject to political capture). The complementary public investments should build on these lessons, promote greater accountability, and minimize government failures in fulfilling the legitimate role of government.

By providing an analytically rigorous, evidence-based, and comprehensive treatment of climate adaptation in South Asia, this book is a model for how to use economics to help poor people. It will definitely feature in my syllabus, as well as in many others.

Shanta Devarajan

Professor of the Practice of International Development, Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University

This is a timely report for at least two reasons. First, recent disaster events and longer-run environmental changes across South Asia, ranging from massive floods in Pakistan and heat waves across India to an increase in water and soil salinity in the coastal areas of Bangladesh, West Bengal, and Orissa, imply that the climate crisis is already affecting millions of lives. It has become urgent to give private and public sector decision-makers in the region some ideas for policy tools to deal with these crises. Second, because households and firms have already started experiencing these changes, social scientists can finally observe how people mitigate and adapt to these shocks. This implies that the new insights that are now emerging from research studies based on actual empirical observations of people’s reactions to shocks are more robust and dependable than past studies that relied on counterfactual modeling of future climate scenarios. Social science research is on a much more solid footing when we analyze observations of actual changes rather than make predictions of future changes. It is important for the World Bank to use its considerable convening power and analytical capabilities to summarize and highlight these new insights for decision-makers in the region.

Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak

Jerome Kasoff ’54 Professor of Management and Economics, Yale University

From Risk to Resilience

This book, along with any associated content or subsequent updates, can be accessed at https://hdl.handle.net/10986/43230

Scan to see all the titles in this series. Data associated with this book have been deposited in the World Bank Open Data Repository (https://data.worldbank.org/).

South Asia Development Matters

From Risk to Resilience

Helping People and Firms Adapt in South Asia

Megan Lang, Jonah Rexer, Siddharth Sharma, and Margaret Triyana, Editors

© 2025 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433

Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org

Some rights reserved

1 2 3 4 28 27 26 25

This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent.

The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the data included in this work and does not assume responsibility for any errors, omissions, or discrepancies in the information, or liability with respect to the use of or failure to use the information, methods, processes, or conclusions set forth. The boundaries, colors, denominations, links/footnotes, and other information shown in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The citation of works authored by others does not mean The World Bank endorses the views expressed by those authors or the content of their works.

Nothing herein shall constitute or be construed or considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved.

Rights and Permissions

This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org /licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions:

Attribution —Please cite the work as follows: Lang, Megan, Jonah Rexer, Siddharth Sharma, and Margaret Triyana, eds. 2025. From Risk to Resilience: Helping People and Firms Adapt in South Asia. South Asia Development Matters. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-2152-3. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

Translations —If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation.

Adaptations —If you create an adaptation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This is an adaptation of an original work by The World Bank. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author or authors of the adaptation and are not endorsed by The World Bank.

Third-party content —The World Bank does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. The World Bank therefore does not warrant that the use of any third-party-owned individual component or part contained in the work will not infringe on the rights of those third parties. The risk of claims resulting from such infringement rests solely with you. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images.

All queries on rights and licenses should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org.

ISBN (paper): 978-1-4648-2152-3

ISBN (electronic): 978-1-4648-2260-5

DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-2152-3

Cover design: David Spours (Cucumber Design).

The cutoff data for the data used in the report was April 10, 2025.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2025928191.

South Asia Development Matters

This regional flagship series serves as a vehicle for in-depth synthesis of economic and policy analysis on key development topics for South Asia. It aims to promote dialogue and debate with all of the World Bank’s partners—from policymakers to civil society organizations, academic institutions, development practitioners, and the media—and to contribute toward building consensus among all those who care about stimulating development and eradicating poverty in South Asia.

Titles in the Series

2025

From Risk to Resilience: Helping People and Firms Adapt in South Asia (2025), Megan Lang, Jonah Rexer, Siddharth Sharma, and Margaret Triyana (eds.)

2023

Striving for Clean Air: Air Pollution and Public Health in South Asia (2023), World Bank

2021

Hidden Debt: Solutions to Avert the Next Financial Crisis in South Asia (2021), Martin Melecky

2018

South Asia’s Hotspots: Impacts of Temperature and Precipitation Changes on Living Standards (2018), Muthukumara Mani, Sushenjit Bandyopadhyay, Shun Chonabayashi, Anil Markandya, and Thomas Mosier

2016

Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability (2016), Peter Ellis and Mark Roberts

South Asia’s Turn: Policies to Boost Competitiveness and Create the Next Export Powerhouse (2016), Gladys Lopez-Acevedo, Denis Medvedev, and Vincent Palmade

2015

Addressing Inequality in South Asia (2015), Pradeep K. Mitra, Martin Rama, John Lincoln Newman, Tara Béteille, and Yue Li

2012

More and Better Jobs in South Asia (2012), Reema Nayar, Pablo Gottret, Pradeep Mitra, Gordon Betcherman, Yue Man Lee, Indhira Santos, Mahesh Dahal, and Maheshwor Shrestha

All books in the South Asia Development Matters series are available for free at https://hdl.handle.net/10986/2149

Weifeng Larry Liu, Warwick McKibbin, Franziska Ohnsorge, and Siddharth

Ademola Braimoh, Harideep Singh, and Ashesh Prasann

Ashley Charlotte Pople, Dhriti Pathak, Hagen Kruse, and Thomas Michael Kerr

Zhang, Capucine Riom, and Asmita Tiwari

5.7

5.8

6.6

S.1

2B.3

2B.4

3B.1

3B.7

3B.8

3C.5

4C.1

B5.1.1

5B.2

5B.3

5B.4

5B.6

Acknowledgments

This volume, a product of the World Bank’s Office of the Chief Economist for South Asia, represents the collective effort of far more individuals than the names that appear on its cover. First and foremost, we extend our deep gratitude to Martin Raiser, Vice President for South Asia at the World Bank, who has supported and championed this project from inception and whose vision has been central to shaping this book.

We are immensely grateful to all our contributors, without whom this volume would not exist. The six chapters were prepared by Megan Lang, Weifeng Larry Liu, Warwick McKibbin, Franziska Ohnsorge, Jonah Rexer, Siddharth Sharma, and Margaret Triyana. Seema Jayachandran co-authored box 5.1. The authors of the deep dives were Ademola Braimoh, Ashesh Prasann, and Harideep Singh (deep dive 1); Thomas Michael Kerr, Hagen Kruse, Dhriti Pathak, and Ashley Charlotte Pople (deep dive 2); Sarah Coll-Black and Javier Sanchez-Reaza (deep dive 3); and Capucine Riom, Asmita Tiwari, and Yan Zhang (deep dive 4). We are grateful for their substantial expertise and for their patience and insightful responses to our frequent queries. By commenting on each other’s work, the authors and contributors have collectively improved the quality of this volume.

In addition to the core authors, many colleagues contributed inputs to the deep dives: Maha Ahmed, Md Mansur Ahmed, Amadou Ba, Olivier Durand, Andrew Goodland, Chris Jackson, Sabina Karki, John Keyser, Manivannan Pathy, Alreena Renita Pinto, Tomás Rosada, Sheu Salau, Joachim Vandercasteelen, and Shijie Yang (deep dive 1); Randa El-Rashidi, Tehreem Fatima, Catherine Fitzgibbon, and Martha Hobson (deep dive 3); and Chandan Deuskar, Ross Eisenberg, Tjark Gall, Natsuko Kikutake, Jolanta Kryspin-Watson, Jun Rentschler, Bachir Sabo, Zoe Trohanis, and Ayush Yadav (deep dive 4).

This book has benefited from the expert advice of many people, including peer reviewers, participants in the authors’ workshop, and attendees at numerous seminars and conferences. We especially thank Stephane Hallegatte and Richard Damania, and their respective teams, for helpful comments during the seminars.

Teevrat Garg and Anant Sudharshan served as external academic reviewers to the chapters. Patrick Behrer, Miki Khanh Doan, Jia Li, Viviana Perego, Sumati Rajput, and Mark Roberts served as peer reviewers. Charles Collyns, Graham Heche, Graeme Littler, Jim Rowe, and Chris Towe provided technical and editorial suggestions. Francesca de Nicola, Ebad Ebadi, Jia Li, Claudia Ruiz Ortega, and Marc Schiffbauer served as discussants at the authors’ workshop. Additional inputs and advice were received from Gayatri Acharya, Ana Goicoechea, Mehul Jain, Abhas Jha, Abedalrazq Khalil, and Cem Mete.

A special thanks is owed to Achyuta Adhvaryu, Teevrat Garg, and the 21st Century India Center at the University of California, San Diego, with whom we organized the joint 2024 World Bank–UC San Diego Workshop on Climate Adaptation in South Asia and who have served as fantastic intellectual partners from the beginning of this endeavor. Through many conversations, they have sharpened our thinking on climate adaptation, helped refine the firm surveys behind this report, and pushed our inquiries into new directions.

Issac Yurui Hu, Isabella Masetto, and Xinyi Wang provided excellent research assistance. Additional research assistance was provided by Kaihao Cai, Ahnaf Rafid Bin Habib, Andy Weicheng Jiang, Mehria Saadat Khan, MD Shah Naoaj, Muhammad Ahmed Nazif, Laura Heras Recuero, Saloni Taneja, Astha Vohra, and Nolan Ander Young Zabala.

The South Asia Climate Adaptation (SACA) Household Survey was conducted in collaboration with Mehul Jain, Ashley Charlotte Pople, Satya Priya, and Deepak Singh (Bihar, India) and Bramka Arga Jafino, Swarna Kazi, and Tom Schwantje (Bangladesh). The SACA Firm Survey was conducted in collaboration with Ana Goicoechea and Hosna Ferdous Sumi (Bangladesh); Mehul Jain, Nicholas Jones, and Deepak Singh (India); and Guillermo Carlos Arenas, Tobias Akhtar Haque, and Rafay Khan (Pakistan). The surveys would not have been possible without these close partnerships.

We are grateful for financial support for the book and the SACA survey from the World Bank’s Resilient Asia Program, funded by the UK government’s Foreign Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO). This funding is delivered through Climate Action for a Resilient Asia (CARA), the United Kingdom’s flagship regional program to build climate resilience in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific islands. The SACA Household Survey in Bangladesh received financial support from the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery’s (GFDRR) Japan–World Bank Program for Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Management in Developing Countries, which is financed by the Government of Japan and receives technical support from the GFDRR’s Tokyo Disaster Risk Management Hub. The SACA Firm Survey in Pakistan received financial support from the FCDO through the Pakistan@100 Partnership Trust Fund.

The dedication and professionalism of the production team converted the manuscript into a finished book. Rana Al-Gazzaz contributed to the report’s production and dissemination. Quinn David Spours designed the graphics and layout, and Sutton Austin was responsible for the layout and typesetting of the Advance Edition. Kathie Porta Baker, Talia Greenberg, Graeme Littler, Peter Milne, and Erin Rice edited the report. Elena Karaban and Mehreen Arshad Sheikh coordinated dissemination with support and advice from Shilpa Banerji, Diana Ya-Wai Chung, and Sudip Mozumder. Ahmad Khalid Afridi provided administrative support.

We thank Hans Timmer, former Chief Economist for South Asia at the World Bank, who sparked this book’s initial ideas and guided us in the early stages of the project.

Finally, we are deeply indebted to Franziska Ohnsorge, Chief Economist for South Asia at the World Bank, whose unwavering support and insightful guidance have been instrumental in driving our climate adaptation research program, which has culminated in this volume.

Foreword

People in South Asia are familiar with the intense heat and sudden downpours of monsoon season. The monsoon rains bring life to the crops and relief from the summer heat. But monsoons can also be powerful and destructive, especially as weather patterns in the region become increasingly unpredictable and extreme. Last year’s monsoon caused severe flooding in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. This year’s monsoon is expected to arrive early and again bring above-normal rainfalls.

South Asia is one of the most climate-vulnerable regions in the world, with its high population density, already high temperatures, and exposed geography. Since 2010, natural disasters have affected an average of about 67 million people each year. The situation is worsening: By 2030, nearly 90 percent of the region’s population will be at risk of extreme heat, and nearly 25 percent will be at risk of severe flooding.

The most dramatic weather shocks can destroy assets and livelihoods. Displaced households face lost incomes, and firms must address lost revenues and supply chain disruptions. Weather shocks can be damaging even when they are not dramatic; high temperatures can reduce worker productivity and crop growth.

South Asia’s households and firms are not helpless in the face of these shocks. Indeed, to the extent they can, they adapt. Households dig drainage ditches or plant trees to protect and shade their homes. They move to areas that are less vulnerable to weather shocks. Similarly, firms adjust and shift production locations or diversify suppliers to reduce their risks. Many firms invest in fans and air conditioning in response to higher temperatures.

But the autonomous actions of households and firms are often not enough. To date, most households and firms in South Asia take only basic adaptation measures that leave them vulnerable to climate shocks. More advanced adaptations, such as planting climate-resilient crop varieties and subscribing to index-based weather insurance products, are uncommon, especially among poor households.

The reasons households and firms do not adapt effectively are the same as the ones that limit their livelihoods. They lack access to credit, affordable technology, and information and are trapped in high-risk locations by a lack of jobs elsewhere. They lack weather-resilient roads needed to access markets and inputs, even during weather shocks. They lack the piped water that can be safe to drink, even during floods.

What can governments in South Asia with limited fiscal resources do to boost the resilience of their economies and societies? This report offers some solutions, focused on ensuring that markets work better, thereby helping poor households and small firms adapt more effectively. Information is often helpful on its own, such as providing early warnings about impending storms, droughts, or floods. Governments can also help by removing obstacles to autonomous adaptation, such as increasing access to credit or removing labor and land market distortions that lock people and firms in vulnerable places. Targeted public investments in physical and social infrastructure—such as access roads, drainage systems, and primary health facilities—and adaptative social protection systems can complement market-based measures to protect those who are most vulnerable.

The people of South Asia have always found ways to adapt and thrive in difficult circumstances. As worsening weather shocks pose a serious challenge, simple yet effective adaptation strategies can help bolster the ingenuity and resilience of the people in the region to overcome such challenges.

Martin Raiser Vice President, South Asia Region

Executive Summary

South Asia is the most climate-vulnerable region among emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). With governments having limited room to act because of fiscal constraints, the burden of climate adaptation will fall primarily on households and firms. Awareness of climate risks is high; more than 75 percent of households and firms expect a weather shock in the next 10 years. Climate adaptation is widespread, with 63 percent of firms and 80 percent of households having taken action. However, most rely on basic, low-cost solutions rather than leveraging advanced technologies and public infrastructure. Market imperfections and income constraints limit access to information, finance, and technologies needed for more effective adaptation. If these obstacles were removed, private sector adaptation could offset about one-third of the potential damage from rising global temperatures to South Asian economies. The policy priority for governments is, therefore, to facilitate private sector adaptation through a comprehensive policy package. The package includes climate-specific measures such as improving weather information access, promoting resilient technologies and weather insurance, and investing in protective infrastructure in a targeted manner. Equally important are broader developmental initiatives with resilience co-benefits: in other words, policies that generate double dividends. These include strengthening core public goods like transportation, water systems, and health care; addressing barriers to accessing markets, inputs, and finance without causing unintended responses that increase vulnerabilities; and supporting vulnerable groups through shock-responsive social protection.

Chapter 2. Under the Weather: Household Climate Risk. South Asia is expected to face more frequent and more severe weather shocks over the coming decade. By 2030, 1.8 billion people (89 percent of the region’s population) are projected to be exposed to extreme heat, while 462 million people (22 percent) are projected to be exposed to severe flooding. Poor and agricultural households in the region are more exposed to, and affected by, weather shocks. Weather shocks cause damage to human capital and assets, as well as income losses. However, when households receive early warnings, nearly 90 percent take preemptive action to reduce damages. Households’ access to early warning systems is uneven: In vulnerable coastal and riverine areas,

most households have access to early warnings for cyclones, but fewer than half of them have access to early warnings for floods and other shocks. These findings call for better early warning systems, targeted programs to assist vulnerable households during shocks in a timely fashion, and policies to help households adapt to the growing risk of extreme weather shocks.

Chapter 3. Prepared for the Worst: Building Household Resilience. Rising exposure to climate risk in South Asia has increased pressure on households to adapt, but current adaptation strategies among rural households are inadequate for the scale of the problem. Although 80 percent of surveyed households in South Asia have adapted to climate change in some way, 80 percent of these adapting households rely on accessible, low-technology methods, with limited use of more advanced tools such as weather insurance or climate-resilient agricultural inputs. Limited access to credit, land, and information all constrain household adaptation. Extreme weather events lead to short-lived adaptations whose longer-term effectiveness may be limited, and underestimation of future climate risk leads to inadequate investment in adaptation. Protective public infrastructure tends to substitute for private adaptation. This removes some of the burden on households, but it carries a risk of investing in places rather than people, generating lock-in, and forestalling necessary reallocations. Policies to alleviate financial and land market failures and information constraints can help households adapt in place, and faster job creation in non-agricultural sectors and urban areas would help them move to more productive sectors and locations.

Chapter 4. Shutters Down: Firm Climate Risk. Increasingly frequent and severe weather shocks reduce revenues; damage physical assets; and require costly shifts in products, markets, and labor practices for South Asian firms. Firm managers in the region expect that increasingly frequent and severe weather shocks will cause damages in 2025–29 that are three times as great as those experienced from 2019 to 2024. More experienced and more highly skilled managers tend to have expectations about future weather shocks that are more aligned with consensus forecasts. They also expect lower damages, possibly because better managers tend to be better able to adapt to extreme weather.

Chapter 5. Back to Business: Building Firm Resilience. South Asian firms are acting to mitigate the impact of weather-related shocks on their business, with 63 percent of them having undertaken at least one such action in the past five years. But these firms have largely relied on low-cost upgrades to buildings and equipment for adapting to the growing risk of weather shocks rather than major upgrades to capital, technologies, or business practices. Firms that have experienced, or expect, more weather shocks have been more likely to undertake adaptations, while firms with less-advanced management practices and firms facing greater financial and regulatory obstacles have adapted less. These results suggest that there is scope for policies to encourage adaptation by improving access to information about adaptation options, by helping firms to strengthen managerial capabilities, and by easing regulatory burdens and expanding access to finance.

Chapter 6. Returns to Resilience: Aggregate Impacts of Adaptation. Because of South Asia’s already-high average temperature and reliance on rain-fed agriculture, rising global temperatures could lead to aggregate output and per capita income losses by 2050 that are larger than those in

the average EMDE. Higher temperatures would cause significant damage in the most vulnerable sectors, such as agriculture, but more limited damage in the most resilient sectors, such as services. About one-third of the total climate damage could be reduced if the private sector could flexibly shift resources across activities and locations in response to these climate-induced changes in relative prices and incomes. Even South Asia’s fiscally constrained governments have scope to facilitate these shifts, including by expanding access to finance, improving transport and digital connectivity, and providing well-targeted and flexible social benefit systems.

Spotlight. Who Bears the Burden of Climate Adaptation and How? A Systematic Review.

South Asia’s high vulnerability to rising global temperatures and increasingly common weather shocks, combined with constrained fiscal positions limiting public adaptation measures, means the burden of adaptation will fall disproportionately on firms and households—particularly poor households, which are more vulnerable to weather shocks. A comprehensive and systematic review of research identifies a variety of adaptation strategies used by households, firms, and farmers. These strategies have reduced the damage from weather shocks by 46 percent, on average, in the examples covered by the literature. Adaptations that involve new resilient technologies or public support—typically in the form of core public goods such as roads and health systems that help access jobs and protect human capital—tend to be the most effective in reducing the damage from weather shocks. Compared with households and farmers, firms have access to more effective adaptation strategies, typically technology-related. The analysis suggests that policy should be guided by three principles: (1) implementing a comprehensive package of policies, (2) prioritizing policies that generate “double dividends,” and (3) designing policies that target broader developmental goals in a manner that does not set back adaptation-related goals.

Deep Dive 1. Climate Adaptation and Agriculture in South Asia. South Asian agriculture faces significant challenges from rising global temperatures, compounded by the sector’s existing constraints, including the predominance of smallholder farming and low productivity. Rising temperatures, water scarcity, irregular rainfall patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events such as droughts and floods threaten to reduce South Asia’s agricultural output by 7.5 percent by 2050, considerably more than in other EMDE regions. The key strategies needed to build agricultural resilience are the promotion of climate-smart farming practices, expansion of weather insurance markets, redirection of inefficient input subsidies, modernization of irrigation infrastructure, and leveraging of digital technologies to deliver weather information and advisory services to farmers.

Deep Dive 2. Bridging the Adaptation Financing Gap in South Asia. Dedicated adaptation finance meets only a fraction of South Asia’s needs for climate adaptation. This gap stems from limited fiscal space for public funding and financial market imperfections that limit private financing. To help finance public goods for adaptation, governments can mobilize resources by eliminating distortions like fossil fuel subsidies, scaling up innovative instruments like blended finance, and strengthening institutional capacity to access concessional sources of climate finance. Credit and insurance market failures that limit access to adaptation financing can be overcome through standardized metrics to improve lending decisions, the strategic use of public finance for de-risking private credit, emergency credit guarantee schemes, and expanded markets for weather index insurance.

Deep Dive 3. Adaptive Social Protection in South Asia. Social protection systems can help strengthen resilience, before a shock strikes, by reducing poverty and, once a shock strikes, by supporting those who are the most vulnerable. These programs can also help build resilience to climate change by encouraging adaptation, asset accumulation, and income diversification. However, although South Asia’s social protection systems have good coverage at 77 percent of the population, they are underfunded, with expenditures at only 4 percent of gross domestic product, less than half the EMDE average. These programs are also generally not well-targeted and not rapidly scalable, which could be addressed with investments in information systems and program design. Case studies from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan show that well-targeted social assistance programs, combined with up-to-date information, can be rapidly scaled up to respond to shocks and provide support for poor and vulnerable individuals.

Deep Dive 4. Urban Policy for Climate Adaptation in South Asia. Just like South Asia’s rural population, its urban population is also highly exposed to extreme weather shocks, and this exposure is projected to grow. By 2030, 322 million (24 percent of the urban population) are projected to be exposed to flooding, while 1.2 billion (92 percent) are projected to be exposed to extreme heat. Large and growing concentrations of vulnerable population groups in cities add to the region’s challenge of building urban resilience to extreme weather. South Asian cities can build climate resilience by better integrating climate risk data into urban planning and regulation, further investing in early warning systems and resilient infrastructure, supporting targeted interventions for vulnerable populations, and strengthening the technical capacity of city governments to implement resilience-related programs.

Abbreviations

acronyms definitions

AC air conditioner

ADB Asian Development Bank

AE advanced economy

AfDB African Development Bank

ATAI Agricultural Technology Adoption Initiative

AIIB Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

ASPIRE Atlas of Social Protection Indicators of Resilience and Equity

BAMIS Bangladesh Agro-Meteorological Information System

BDM Becker-DeGroot-Marschak

BISP Benazir Income Support Programme

BKBDP World Bank Bihar Kosi Basin Development Project

CAT catastrophe

CBI Climate Bonds Initiative

CCDR Country Climate and Development Report

CEB Council of Europe Development Bank

CEGA Center for Effective Global Action

CIAT International Center for Tropical Agriculture

CLP Chars Livelihood Program

COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV2)

CPI Climate Policy Initiative

CRAFT Climate Resilience and Adaptation Finance and Technology Transfer Facility

CREWS Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems

CSA climate-smart agriculture

DBT direct benefit transfer

DDO deferred drawdown option

acronyms definitions

DFI development finance institution

DFO Dartmouth Flood Observatory

EAP East Asia and Pacific

EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

ECA Europe and Central Asia

EIB European Investment Bank

EMDE emerging market and developing economy

ER enhancing resilience

EWS early warning system

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

FDI foreign direct investment

FFS farmer field school

GARI Global Adaptation & Resilience Investment Group

GCA Global Center on Adaptation

GCF Green Climate Fund

GDP gross domestic product

GFD Global Flood Database

GFDRR World Bank Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery

GHG greenhouse gas

GSDMA Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority

HH household

HSC Higher Secondary Certificate

IAAS Integrated Agrometeorological Advisory Service

ID identification document

IDB Inter-American Development Bank

IFPRI International Food Policy Research Institute

ILO International Labour Organization

IMF International Monetary Fund

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

IsDB Islamic Development Bank

J-PAL Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab

KAIP Kenya Agriculture Insurance Program

KLIP Kenya Livestock Insurance Program

KPI key performance indicator

LAC Latin America and the Caribbean

LDC least developed country

LVC land value capture

acronyms definitions

MARD Viet Nam Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

MDB Multilateral Development Bank

MGNREGS Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme

MNA Middle East and North Africa

MNAIS Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme

NAP National Adaptation Plan

NBS nature-based solution

NDB New Development Bank

NDCs Nationally Determined Contribution

ND-GAIN University of Notre Dame’s Global Adaptation Initiative

NGO non-governmental organization

NSER National Socio-Economic Registry

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OLS ordinary least squares (regression)

PIPIP Punjab Irrigated-agriculture Productivity Improvement Project

PKR Pakistani Rupee

PMFBY Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana

PMT proxy means test

PPPs public-private partnerships

R&D research and development

RCP representative concentration pathway

RHS Right-Hand Side

RWI Relative Wealth Index

SACA South Asia Climate Adaptation

SAR South Asia Region

SARCE Office of the Chief Economist for the South Asia Region (World Bank)

SCERs Sri Lankan Certified Carbon Reductions

SD standard deviation

SHRUG Socioeconomic High-resolution Rural-Urban Geographic Platform for India

SIDS Small Island Developing States

SLCCS Sri Lanka Carbon Crediting Scheme

SLCF Sri Lanka Climate Fund

SME small and medium-sized enterprise

SMS short message service

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

SSP Shared Socioeconomic Pathways

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

acronyms definitions

UNDRR United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction

UNEP United Nations Environment Programme

UNESCAP United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

WASH water, sanitation, and hygiene

WDI World Development Indicators

WMO World Meteorological Organization

WRD-GOB Water Resources Department-Government of Bihar

All dollar amounts are US dollars unless otherwise indicated.

Part 1 Household and Firm Climate Adaptation

Part 1 comprises six chapters and a spotlight that examine the impact of climate shocks and growing exposure to extreme weather on households and firms in South Asia, how households and firms in the region adapt to these growing risks, and how governments can support climate adaptation in South Asia. It presents new empirical insights on households’ and firms’ beliefs about climate risk and their adaptation strategies, as well as aggregate impacts of adaptation.

From Risk to Resilience: Overview of the Report

Siddharth Sharma

South Asia is the most climate-vulnerable region among emerging market and developing economies (EMDE’s). With governments having limited room to act because of fiscal constraints, the burden of climate adaptation will fall primarily on households and firms. Awareness of climate risks is high; more than 75 percent of households and firms expect a weather shock in the next 10 years. Climate adaptation is widespread, with 63 percent of firms and 80 percent of households having taken action. However, most rely on basic, low-cost solutions rather than leveraging advanced technologies and public infrastructure. Market imperfections and income constraints limit access to information, finance, and technologies needed for more effective adaptation. If these obstacles were removed, private sector adaptation could offset about one-third of the potential damage from rising global temperatures to South Asian economies. The policy priority for governments is therefore to facilitate private sector adaptation through a comprehensive policy package. The package includes climate-specific measures such as improving weather information access, promoting resilient technologies and weather insurance, and investing in protective infrastructure in a targeted manner. Equally important are broader developmental initiatives with resilience co-benefits: in other words, policies that generate double dividends. These include strengthening core public goods like transportation, water systems, and healthcare; addressing barriers to accessing markets, inputs, and finance without causing unintended responses that increase vulnerabilities; and supporting vulnerable groups through shock-responsive social protection.

1

Introduction

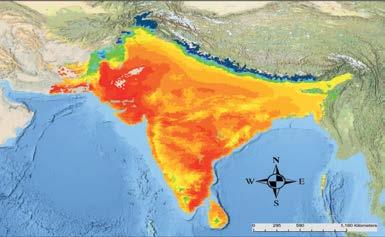

Growing exposure to heat in South Asia. Exposure to extreme heat, already high in much of South Asia, is predicted to grow as the global mean temperature rises (Watts et al. 2017). Maximum daily temperatures in South Asia during 2017–21 averaged 30°C, about 6° above the average for other EMDE regions (refer to figure 1.1a). Temperature projections indicate that by 2030, approximately 89 percent (1.8 billion) of South Asia’s population will face extreme heat risk (refer to figure 1.1b). In 2021, an average of six hours a day were too hot to safely work outside in four South Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka); this is expected to increase to seven or eight hours a day by 2050 (refer to figure 1.1c).

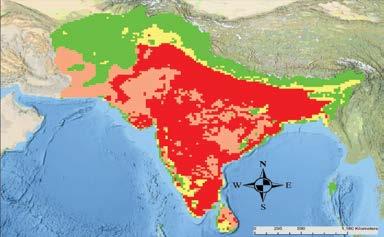

Rise in natural disasters. On average, about 67 million people per year have been affected by natural disasters in South Asia since 2010, more than in any other region in the world (refer to figure 1.1d). Flooding is a particularly common weather-related hazard in the region, with 40 percent of land area having been flooded during 2000–18, a share above the EMDE average (refer to figure 1.1e). Extreme rainfall and flooding are expected to become more frequent and intense with rising global temperatures, with 22 percent (462 million) of the population projected to face floods exceeding 15 centimeters in depth by 2030 (refer to figure 1.1b). In sum, given its combination of exposed geography and dense population concentrations, South Asia’s vulnerability to rising global temperatures and associated developments exceeds that of all other EMDE regions, as is shown by the University of Notre Dame’s (2024) Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) vulnerability index (refer to figure 1.1f).

Aggregate Exposure of South Asia

South Asia is particularly vulnerable to rising global temperatures. It is the EMDE region with the largest number of people affected by natural disasters and one of the highest incidences of floods and extreme temperatures. The region’s exposure to heat and floods is rising.

FIGURE 1.1 Aggregate Exposure of South Asia (Continued)

c. Number of hours when it is too hot to work outside

d. Number of people affected by natural disasters, 2015–24 average

average

Share of population (RHS) Number of people (LHS)

f. Vulnerability to climate risk, 2017–21 average

Sources: Fathom; Flood Observatory; International Disaster Database ( https://www.emdat.be/ ); Romanello et al. 2023; Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/ ); Schiavina, Melchiorri, and Pesaresi 2023; Observed Climate Data Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series 4.07 0.5-degree (University of East Anglia); World Bank. Note: Panel a: Average maximum daily temperature in SAR countries, 2017–21. “Other EMDEs” are EMDEs excluding SAR countries. Panel b: Population exposed to flooding (>15 cm water depth in one-in-100-year floods) and heat (two-day heatwaves >30°C) in 2020, with projections for 2030 and 2050 under moderate emissions scenario (SSP2-4.5). Panel c: Average daily hours per person with at least moderate heat stress risk faced during light outdoor activity, based on Sports Medicine Australia’s 2021 Extreme Heat Policy criteria. This includes 2050 projections for 2°C warming scenarios. Panel d: Population affected by natural disasters, total number (bars) and share (diamonds), averaged over 2015–24. Sample includes 144 EMDEs (22 in EAP, 20 in ECA, 31 in LAC, 18 in MNA, 8 in SAR, and 45 in SSA). Panel e: The proportion of total land mass flooded in South Asia compared with the rest of EMDEs excluding SAR countries. Panel f: Regional aggregates computed using 2015 gross domestic product as weights. Values shown are an average over 2017–21. Sample includes 148 EMDEs (22 in EAP, 22 in ECA, 31 in LAC, 18 in MNA, 8 in SAR, and 47 in SSA). AFG = Afghanistan; BGD = Bangladesh; BTN = Bhutan; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; IND = India; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; LHS = left-hand side; LKA = Sri Lanka; MDV = Maldives; MNA = Middle East and North Africa; NPL = Nepal; PAK = Pakistan; RHS = right-hand side; SAR = South Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; SSP2-4.5 = Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2, with a radiative forcing level of 4.5 W m-2 by 2100.

Impacts of rising global temperatures. The rise in the global mean temperature is projected to reduce agricultural yields, industrial output, labor supply, productivity, and human capital.1 The agricultural sector, in which almost half of South Asia’s working-age population works, is expected to experience the most acute impacts. For example, by 2050, almost half of the Indo-Gangetic Plain—South Asia’s primary food-producing region—may become unsuitable for wheat cultivation because of warming (Ortiz et al. 2008). Rising temperatures and heat stress are projected to reduce staple crop yields—including wheat, rice, and maize—by 5–25 percent in the coming decades (IFPRI 2022). Nonfarm enterprises are not immune, either. For example, in South Asia, on average, each cyclone reduces the value of firm-level physical assets by 2.2 percent, and every degree Celsius of warming reduces the annual output of manufacturing factories by 2 percent (Pelli et al. 2023; Somanathan et al. 2021).

Adaptation for development. Continued growth and poverty reduction progress will depend on South Asia’s ability to adapt to the growing risk of extreme weather. Evidence is growing that households, farmers, and firms worldwide are adapting to rising temperatures and the accompanying increase in extreme weather conditions. These adaptations include protective investments in buildings, shifts to less vulnerable economic activities, and the adoption of more resilient technologies, and they have had some success in reducing the adverse impacts of rising global temperatures and associated developments (Ohnsorge and Raiser 2024; Rexer and Sharma 2024).

Fiscal constraints on adaptation options in South Asia. Recognizing the threats from rising global temperatures, governments in the region are preparing national adaptation plans and have embarked on large-scale programs to build resilient infrastructure and disaster preparedness systems (World Bank 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). However, their ability to invest in climate adaptation is severely constrained by a lack of fiscal space. On average, South Asia’s government debt (relative to gross domestic product [GDP]) and its government interest spending (relative to revenues) are the highest among EMDE regions (refer to figures 1.2a and 1.2b). The heavy lifting needed to build climate resilience in South Asia may need to be done by firms and individuals, facilitated by complementary public investments and policy reforms.

Questions addressed in this report. In the face of these policy challenges, this report addresses the following questions:

• How do rising global temperatures and growing exposure to extreme weather affect people and firms?

• How are people and firms in South Asia adapting to rising global temperatures?

• How can governments support climate adaptation in South Asia?

Key Contributions

This report contributes to the understanding of adaptation to rising global temperatures in South Asia through systematic literature reviews, analysis of new household and firm surveys, geospatial data analysis, original macroeconomic modeling, and policy case studies. Although recent literature

FIGURE 1.2 Fiscal Constraints

Fiscal pressures, including high debt, severely constrain governments’ ability to support climate adaptation.

a. Government debt b. Government interest spending

Sources: World Economic Outlook database, IMF (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook -databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending); World Bank.

Note: Unweighted averages. Panel b: Interest spending is defined as the difference between primary and overall net lending or borrowing. EAP = East Asia and Pacific (21 economies); ECA = Europe and Central Asia (22 economies); GDP = gross domestic product; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean (32 economies); MNA = Middle East and North Africa (18 economies); SAR = South Asia (7 economies); SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa (46 economies).

and policy reports have examined climate resilience and adaptation globally, this report is the first to comprehensively examine adaptation in South Asia by analyzing both the adaptation behavior of households and firms and the evidence on adaptation and its effects at the macro level.2 Among the report’s contributions are the following.

First, the report presents comprehensive findings on exposure to extreme weather in South Asia from new quantitative analysis and by updating existing reviews (Hallegatte, Bangalore, et al. 2016; Hallegatte, Vogt-Schilb, et al. 2016; Triyana et al. 2024). The World Bank’s new South Asia Climate Adaptation (SACA) surveys allow a comprehensive assessment of vulnerability to multiple weather hazards among households and firms. Using recent global wealth estimates on a 2.4-kilometer grid, the report also provides a detailed geographical analysis of the incidence of exposure to both heat and floods. Past household and firm studies have largely examined specific shocks in isolation and in specific contexts (Goicoechea and Lang 2023; Triyana et al. 2024).

Second, this report comprehensively examines households’ and firms’ beliefs about future extreme weather events and their impacts, and it shows that these beliefs are central to adaptation by households and firms (Carleton et al. 2024). Here, these beliefs are assessed using direct measures rather than inferring beliefs indirectly, as done in most prior research (see, for example, Balboni, Boehm, and Waseem 2024; Burlig et al. 2024; Ding and Deng 2024; Kala 2017; Kelly, Kolstad, and Mitchell 2005; Lemoine and Kapnick 2024; Lin, Schmid, and Weisbach 2019; Pankratz, Bauer, and Derwall 2023; Pankratz and Schiller 2024; Rosenzweig and Udry 2014; Shrader 2021; Taraz 2017).

Third, the report presents the first comprehensive analysis of adaptation methods and prevalence in South Asia using the SACA surveys Defining climate adaptation as household or firm actions that attempt to reduce the economic losses from weather shocks, the surveys provide uniquely granular and comparable data on adaptation strategies in three South Asian countries. This goes beyond existing research, which has typically been context specific or focused on a limited set of adaptations (see, for example, Aragon, Oteiza, and Rud 2021; Branco and Féres 2021; Chaijaroen 2019; Taraz 2017).

Fourth, this report comprehensively examines factors influencing adaptation, including market conditions, institutions, beliefs, information, managerial skills, and behavioral biases. Prior research has been constrained by much more limited information on households’ and firms’ adaptation responses and their determinants and their expectations about weather and climate than the SACA surveys provide (Rexer and Sharma 2024).

Fifth, this report explores the aggregate effects of climate adaptation in a global dynamic general equilibrium model, advancing beyond a small, growing literature that is generally not global and does not account for sectoral linkages and dynamic effects (Wei and Aaheim 2023; World Bank 2022c). It distinguishes between autonomous and directed adaptation. The former is the spontaneous market-based response of individuals and firms to the impacts of rising temperatures, whereas the latter consists of investments explicitly aimed at offsetting the expected impact of rising temperatures.

Sixth, this report identifies the main policy options for facilitating climate adaptation in South Asia, drawing on lessons from empirical research and case studies of policy initiatives in South Asia and other EMDE regions.

Data and Methods

The report uses a combination of econometric analysis of microdata, macroeconomic modeling, and systematic literature reviews to examine climate adaptation in South Asia.

Econometric analysis of novel microdata. The report’s core analysis of the impacts of weather shocks and adaptation to them among households and firms is based on descriptive statistics and regressions using new microdata. The main data sets are as follows:

• The SACA household surveys, which provide comprehensive data on climate impacts and adaptation patterns across 9,451 households in the Kosi River region in India’s Bihar state and coastal Bangladesh in 2024, capturing experiences with weather shocks, expectations and perceived risks of future weather shocks, adaptation behaviors, and socioeconomic characteristics. Although covering multiple climate hazards, the surveys focus particularly on flooding-related adaptations because of the high vulnerability of the surveyed areas to floods.

• The SACA firm survey, which collected data from a broadly representative sample of about 3,019 manufacturing and services firms across Bangladesh, Pakistan, and three industrialized Indian states (Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu) in 2024, capturing information on past and expected exposure to weather shocks, associated damages, and adaptation measures.

• Geospatial data from multiple sources, which are used to analyze extreme weather exposure and incidence throughout South Asia. The temperature data combine historical daily maximum temperatures (Copernicus Climate Change Service 2019) with projections from the Climate Impact Lab (O’Neill et al. 2016), and the flood exposure data come from the Global Flood Database (https://global-flood-database.cloudtostreet.ai/), using satellite imagery and machine learning at 250 meters resolution (Tellman et al. 2021). The new Relative Wealth Index provides detailed spatial information on relative wealth in 2011–19 (Chi et al. 2022).

Macroeconomic modeling of adaptation impacts. The report uses a variant of the dynamic general equilibrium G-Cubed model with detailed economic disaggregation for Asian countries, including South Asia, to analyze climate adaptation impacts (Liu and McKibbin 2022; McKibbin and Wilcoxen 2013). The model is used to examine two adaptation strategies: adaptation by households and firms in response to market signals—often termed autonomous adaptation—and government investment in agricultural resilience.

Systematic literature review. Microdata analysis of exposure to, and impacts of, weather shocks is complemented by a systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 70 empirical economic studies of the exposure to, and impact on, poor households of weather shocks. The spotlight on the effectiveness of adaptations by households, farmers, and nonagricultural firms is based on a metaanalysis of more than 80 empirical studies of climate adaptation.

Main Findings

Several new findings emerge from this report.

First, as in other EMDE regions, poor and agricultural households in South Asia are disproportionately exposed and vulnerable to weather shocks. Region-wide, places with lower wealth are significantly more exposed to heat. In the riverine and coastal SACA household survey regions, agricultural households experience 5 percent more shocks and a 10 percentage point greater likelihood of flood damage than others. In these locations, 40 percent of households experience shocks at an annual frequency, with negative impacts on human capital, income, and assets.

Second, South Asian firms face significant and growing challenges from extreme weather. Threequarters of firms have experienced at least one weather shock in the past five years, with average damages from all shocks totaling 17 percent of revenues annually. More than three-quarters of firms expect their exposure and damage to rise.

Third, people and firms are already adapting to rising global temperatures. Nearly 80 percent of households and 63 percent of firms have adapted in some form in the past five years. However, households tend to rely on basic adaptations, such as reinforcing housing structures to protect against cyclones. Firms have also typically relied on low-cost investments in cooling and building upgrades.

Fourth, the types of adaptations that are most effective in reducing damages from weather shocks are still uncommon in South Asia. A meta-analysis shows that adaptations can offset nearly half of

damages from weather shocks on average, although with sizable variation across methods and contexts. The most effective adaptations involve new technology or the use of core public goods, such as roads and local clinics, to protect livelihoods and health. Such adaptations are uncommon in South Asia, in part because they are not widely available. For example, apart from minor upgrades, fewer than 5 percent of firms have adopted energy-efficient technology.

Fifth, household and firm beliefs about exposure to weather shocks are a key driver of adaptation. For example, firms that expect a weather shock in the next five years have a 30 percent higher level of adaptation than those not expecting a shock. Beliefs vary widely and often deviate from expert predictions, suggesting that providing people with more accurate, science-based climate information could improve adaptation.

Sixth, adaptation by people and firms faces obstacles arising from credit and other market imperfections. For example, greater access to credit from formal institutions is associated with more household and firm adaptation. Among rural households, adaptation is constrained by land market frictions. Among firms, adaptation is constrained by a prevalence of weak management practices and behavioral biases in decision-making, which stem partly from weak human capital but also from legal and regulatory constraints.

Seventh, in aggregate, a continuation of recent trends in global temperatures could reduce South Asia’s output by nearly 7 percent below baseline by 2050, a loss more than 50 percent larger than in other EMDEs on average. Market-driven autonomous adaptation could offset approximately one-third of climate damage in South Asia, an impact larger than the EMDE average, provided that enabling policies are enacted to facilitate such actions. Directed public investment, such as that in more resilient agricultural crops and practices, could offset a significant portion of the remaining damages.

Eighth, given fiscal constraints, a policy priority for governments should be to facilitate private sector adaptation with both climate-specific measures and broader developmental measures with resilience cobenefits. Priorities for resilience-specific public investments include improving weather information access, promoting resilient technologies and weather insurance, and investing in protective infrastructure in a targeted manner, with rigorous cost-benefit analyses that consider undesirable lock-in effects that delay transitions out of vulnerable locations or jobs. Priorities for broader developmental measures with resilience cobenefits include strengthening core public goods, like transportation, water systems, and health care; addressing barriers to accessing markets, inputs, and finance; and supporting vulnerable groups through shock-responsive social protection.

Structure of the Report

Part I uses novel microdata and systematic literature reviews to analyze how people and firms in South Asia are being affected by rising global temperatures and adapting to them. Chapter 2 examines household climate impacts. Chapter 3 studies household climate adaptation. Chapter 4 examines firm climate impacts. Chapter 5 studies firm adaptation. Chapter 6 presents the results of a macroeconomic analysis of the aggregate impacts of climate adaptation in South Asia.

The spotlight examines the effectiveness of adaptation methods. Part II draws on sector expertise, reviews of the literature, and case studies to present options for building resilience in four domains: social protection, adaptation financing, agriculture, and urban development.

Impact of Extreme Weather on People and Firms in South Asia

Vulnerability to rising global temperatures and associated developments in South Asia is uneven, with exposure and impacts positively correlated with poverty. Poor households not only experience more shocks but also suffer more severe and persistent impacts on income, human capital, and assets. Dependence on agricultural activity also increases exposure and vulnerability. In vulnerable coastal and riverine locations, 98 percent of households have faced at least one weather shock in the past five years, with 40 percent having experienced a shock in each of those years. Firms in the nonfarm sector also report widespread and growing exposure to weather shocks, with 80 percent of firms having experienced a shock in the past five years, resulting in substantial financial costs.

Household Vulnerability to Extreme Weather

Poverty and exposure to extreme weather. A systematic review of past research shows that globally, poor households have generally been found to have suffered more exposure to extreme weather than affluent households, with statistically significant higher exposure among poor households in 68 percent of studies, potentially because of limited residential mobility (refer to figure 1.3a; Cattaneo and Peri 2016). This report finds, through its analysis of regionwide geospatial data, that this unevenness also applies in South Asia. Thus, during 2014–18, locations with a lower Relative Wealth Index were significantly more exposed to higher temperatures, particularly in urban areas. Furthermore, projected warming trends are steeper in poorer rural locations, suggesting that inequality of exposure is likely to worsen more in rural areas. During 2000–18, poorer households were also more exposed to floods in urban areas, where locations with repeated flood exposure had lower wealth on average (refer to figure 1.3b).

The SACA household surveys zoom in on rural parts of South Asia that are poorer than average and face a higher-than-average flood risk because of their coastal and riverine locations. They suggest that people residing in such poor, vulnerable locations experience frequent and multiple types of extreme weather shocks (refer to figure 1.3c).

Poverty and the impacts of extreme weather. A meta-analysis of 61 studies shows that, globally, extreme weather has also tended to have a disproportionately large impact on poor households, with 80 percent of studies finding that income effects have been worse among poorer households (refer to figure 1.3a). These disproportionate effects can be long-lasting, with three-fourths of the estimates finding that poor households still experienced impacts more than one year after a shock.

Agricultural dependence and vulnerability to shocks. Among surveyed households in coastal Bangladesh and riverine Bihar, the most important predictor of exposure was found to be a dependence on agriculture, with agricultural households being exposed to 5 percent more climate shocks than nonagricultural households in the past five years (refer to figure 1.3d). Households that depend on agriculture are not just more exposed to weather shocks, but also experience greater damage from them (refer to figure 1.3e).

Multiple channels of household impact. In line with the literature, the surveys suggest that weather shocks damage household human capital, income, and assets. Among the surveyed households that experienced a weather shock in the past five years,

• 45 percent reported illness due to the shock, and 50 percent reported damage to water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure;

• 40 percent reported a decline in earnings and damage to crops;

• 35 percent reported damage to local infrastructure and roads; and

• 30 percent also experienced damage to their homes, their main private asset (refer to figure 1.3f).

Although not captured in the survey, another channel of impact on human capital is that on children’s test scores and educational outcomes—effects that persist into adulthood.

Poor and agricultural households are disproportionately exposed to and affected by weather shocks, with adverse impacts on

and

a. Share of studies that report the poor to be disproportionately vulnerable to weather shocks: Exposure, income loss, and human capital loss

b. Relative wealth and exposure to temperature extremes and floods in urban and rural areas

(continued)

FIGURE 1.3 Poverty, Agricultural Dependence, and Vulnerability (Continued)

c. Hazard exposure in the past five years

e. Agricultural dependence and disproportionate impact of weather shocks

d. Agricultural dependence and disproportionate exposure to weather shocks

f. Channels of impact

Illness Crop Earnings WASH

Infrastructure

Sources: ERA5-Land; Flood Observatory; Li 2019; RWI; South Asia Climate Adaptation Survey; World Bank.

Note: SSP2-4.5, with a radiative forcing level of 4.5 watts per square meter by 2100. Estimates based on ordinary least squares regressions. Orange whiskers show 95 percent confidence intervals. Panel a: The bar for exposure shows the share of studies (n = 33) that document greater exposure of poor households to shocks. The other bars show the share of studies ( n = 61) documenting that poor households have larger income and human capital losses. Panel b: Blue bars = estimated relationship between RWI and an increase in the average daily maximum temperature from 30°C to 32°C; urban estimates are for 2014–17 temperatures and rural estimates are for 2050 SSP2-4.5 temperature projections. Red bars = relationship between RWI and flooding during 2000–18. Estimates are provided in annex table 2A.2. Panel c: Percentage of households experiencing at least one shock (left), annual shock occurrence averaged across shock types (middle), and average exposure to multiple weatherrelated shocks (right). All figures represent unweighted averages. Panel d: Estimated relationship of household shock exposure to agricultural dependence (annex table A2.2.2). Panel e: Estimated relationship of the probability of negative shock impacts to agricultural dependence (annex table A2.2.3). Panel f: Share of households reporting being affected by each channel due to shocks, averaging across all shocks. RWI = Relative Wealth Index; SSP2-4.5 = Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2; WASH = water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Firm Vulnerability to Extreme Weather

Widespread and rising exposure and impacts. The SACA firm survey covers a broadly representative cross-section of manufacturing and services firms in Bangladesh, three states of India (Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu), and Pakistan. The survey results indicate that South Asia’s nonfarm sectors have increasingly been exposed to extreme weather. Three-quarters of the firms in the survey have been exposed to at least one weather shock in the past five years, and an even larger share expect to be affected by such a shock in the next five years (refer to figure 1.4a). The three most common shocks have been excessive rainfall with waterlogging, extreme heat, and floods. Average annual damage to firms from all shocks has been a sizable 17 percent of annual revenues. Firms expect such damages to rise substantially in the next five years, partly because of greater exposure and partly because each shock is expected to be more damaging, on average (refer to figure 1.4b).

Multiple channels of impact. The literature suggests that extreme weather affects firms in several ways. For example, it can disrupt access to markets or lead to local income losses and therefore depress sales. It can lead to higher rates of absenteeism, adjustments in working hours, and damage to capital and inventory. In line with the literature, declining sales; costs of adjusting labor, products, or marketing practices; and damaged capital and inventory were found to have contributed significantly to the total damage from shocks among SACA survey firms (refer to figure 1.4c).

Firm characteristics associated with larger impact. Among the firms surveyed in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, location is the most important predictor of firms’ vulnerability to weather shocks. Adjusting for location, firms with better management practices and more skilled workers lose less revenue each year to weather-related damages than other firms (refer to figure 1.4d). This suggests that firms with better managerial and worker skills may be better placed to undertake adaptations to partially offset the effects of weather shocks.

Firms report high and rising exposure to weather shocks, with expectations of growing adverse effects on revenue, labor productivity, and capital.

a. Weather shocks: Exposure and damages

Costs associated with a single incident of each weather shock

FIGURE 1.4

Weather Shock Exposure and Damage among Firms (Continued)

c. Average damages across all weather shocks, by types of damages

d. Firm characteristics and expected damages

Correlation with expected damages

Percent of revenues

workers Management practices index

Regulatory burden Domestic inputs

Sources: South Asia Climate Adaptation Survey; World Bank.

Note: Estimates based on firm-level survey data. Weights are used to make data representative of firms in the survey districts. Rain refers to excessive rainfall, and heat refers to a period of abnormally high heat lasting at least two days. Panel a: Blue bars = share of firms that were affected by a weather shock in the past five years (2019–24) or expect to be affected by one in the next five years (2025–29). Red bars = average annual total costs associated with all shocks experienced in the past five years (2019–24) or expected in the next five years (2025–29) as a percentage of a firm’s annual revenues. Sample includes all firms, including those that did not experience a shock or did not expect to experience a shock. Panel b: Blue bars = the average per-shock cost associated with each type of shock experienced over the past five years (2019–24) as a percentage of a firm’s annual revenues. Red bars = the average per-shock costs associated with each type of expected shock event over the next five years (2025–29). Panel c: Means of the percent of annual revenue going to revenue loss, product adjustment costs, labor adjustment costs, and capital costs resulting from all types of weather shocks, 2019–24, among firms that experienced at least one weather shock during that time period. Panel d: Bars represent coefficients from ordinary least squares regressions of total expected damages in the next five years (2025–29) from all weather shocks on indicators for which shocks a firm expects to be exposed to and firm characteristics. Skilled workers are the percentage of the firm’s employees that have completed secondary school. The management practices index is an index of good management practices. Regulatory burden is an index of the burden a firm faces from labor, trade, and licensing regulations. Domestic inputs are the percentage of inputs that a firm sources from domestic markets. Orange whiskers show 95 percent confidence intervals. Coefficients for all continuous variables show the association between a 1-standard-deviation change in the variable and the error rate. Estimates are in annex table 4B.3. RHS = right-hand side.

Adaptation Strategies Used by People and Firms in South Asia

South Asian households and firms are adapting to rising global temperatures and extreme weather, but primarily through basic, low-cost measures. Households typically rely on measures such as small-scale rainwater harvesting and housing reinforcement, and technology-based solutions remain rare. Firms predominantly implement low-cost building and cooling equipment upgrades. A meta-analysis conducted for this report finds that adaptation efforts by households and firms globally reduce about half of weather-related damage on average and that, leaving costs aside, the most effective adaptations involve new technologies and the use of public goods, such as roads and health facilities, to access more resilient jobs and protect human capital. Such adaptations are uncommon in the region.

Anticipatory and reactive adaptation. There is growing global evidence that people and firms in EMDEs are undertaking measures to mitigate the losses from rising global temperatures. This adaptive behavior is often forward-looking, with people and firms choosing their best options to mitigate expected damages from extreme weather, based on their beliefs about the future climate (Bilal and Rossi-Hansberg 2023; Carleton et al. 2024; Hsiang 2016; Lemoine 2018). Examples of such anticipatory adaptations (also referred to as ex ante or directed adaptations) include firms diversifying suppliers to minimize future supply chain disruption from floods and farmers choosing when to plant seeds based on six-month forecasts of the onset of monsoon rains (Balboni, Boehm, and Waseem 2024; Burlig et al. 2024; Castro-Vincenzi et al. 2024). People and firms also respond to current or recent weather conditions, undertaking what is termed reactive (or autonomous) adaptation. For example, farmers facing dry years shift from high- to low-water-intensity crops (Taraz 2017).

New evidence on adaptation methods in South Asia. Although many specific instances of adaptation by households and firms have been examined in past studies, the literature has lacked comparisons across different adaptation strategies and systematic analysis of comprehensive evidence on adaptation strategies and their prevalence, especially in EMDEs. The data from the novel SACA surveys help fill this gap.

Household Adaptation

Prevalence of basic adaptations. The household-level SACA surveys suggest that although most households in especially vulnerable areas have taken action to build resilience to weather shocks, they have predominantly relied on basic, accessible measures. Thus, in the past five years, 77 percent of surveyed households have adapted in some form to the risks of weather shocks in general, the two most common adaptations being rainwater harvesting to cope with drought and housing reinforcement to cope with storms. Because these are flood-prone areas, an equally large share of households has also undertaken some form of flood-specific adaptation, usually through simple protective techniques like raising houses and planting trees to prevent erosion (refer to figure 1.5a).

Limited use of technology and market-based adjustment. The use of more sophisticated, technologically innovative adaptations, like climate-resilient crop varieties, has been rare among surveyed households, irrigation being a notable exception. Past research has shown that when land or labor markets have been sufficiently flexible, households have adapted by reallocating their labor or land use to less vulnerable activities; examples are moving labor to off-farm activities in response to long-run groundwater depletion and migration after a major flood (Blakeslee, Fishman, and Srinivasan 2020; Giannelli and Canessa 2022). However, there is limited evidence in the literature of such adaptations in South Asia, and the SACA surveys suggest that they are less common than more basic protective measures. The surveys do show, however, that exposure to heat has raised the share of households engaged in off-farm wage employment by 2.2 percentage points from a baseline of 36 percent while raising the migration rate from 10 to 20 percent (refer to figure 1.5b).

Low adoption of insurance. Index-based weather insurance—in which policyholders are paid when an extreme weather event causes a weather index to cross some threshold—has shown promise in encouraging agricultural investments by reducing risk, but its uptake remains low in EMDEs (Boucher et al. 2024; Hill et al. 2019; Karlan et al. 2014). Only 1.1 percent of surveyed households have used a weather insurance product as a climate adaptation (refer to chapter 3).

Firm Adaptation

Widespread adaptation through low-cost capital upgrades. The firm survey reveals that many South Asian firms are acting to adapt to the growing risk of extreme weather, with 63 percent having taken some measure for weather-related reasons in the past five years (refer to figure 1.5c). The adaptations typically involve upgrades to buildings and machinery, most commonly installation of fans, followed by air conditioners, building upgrades, and energy-efficient appliances. Many of the reported adaptations are low in cost (relative to the scale of the firm): if adaptation measures costing less than 1 percent of revenue annually are excluded, the share of firms that have adapted is just 31 percent. On average, among firms with at least one type of adaptation implemented in the past five years, the total adaptation spending per year has been a moderate 3 percent of revenue (refer to figure 1.5d).

FIGURE 1.5 Household and Firm Adaptation and Its Effectiveness

A large share of households and firms are adapting to the growing risk of extreme weather, but mainly through basic, lowcost approaches. Adaptations undertaken by firms and those involving technology adoption or basic public goods are most effective at offsetting shock damages.

a. Households: Adaptation in general and for flooding

b. Households: Impact of exposure to climate shocks on off-farm employment and migration

FIGURE 1.5 Household and Firm Adaptation and Its Effectiveness (Continued)

c. Firms that have undertaken adaptations d. Average expenditure on adaptation among adapters

2024

BuyACsBuildingupgradeEEappliancesHeatcontingencyplan

e. Mean adaptation ratio among households,

f. Mean adaptation ratio, by adaptation mechanism

Sources: Investment and Capital Stock data set, International Monetary Fund; Rexer and Sharma 2024; South Asia Climate Adaptation Survey; World Bank.