R i g g i n g 1 0 1 O u t o f t h e A s h e s T h e L i f e a n d Wo r k o f J o h n Wa u g h

Dearest Readers of The Bowside,

We’re back with a bang (in more ways than one) Perhaps the overconfidence resulting from managing to pull together 3 issues parallels Icarus, perhaps it’s simply that time of year. This issue is months, and simultaneously just a week or two, in the making Hard and soft deadlines were grossly overshot, and it almost seemed like we wouldn’t make it What’s a girl to do without some reckless ambition?

This final issue of the year features a reworked and slightly updated article that I have some attachment to It is the very same one discussed in the first issue of 2025, which originally appeared in the Boat Race themed issue produced last year for the WUBC centenary dinner (how intertextual) The timeline of the creation of that issue may have foreshadowed this one.

It’s been restructured for a more general audience (sort of), I (unconvincingly) attempted to get lastminute commentary from UCT alumni of 1980, and hope the result is a decent patchwork history of the South African Universities’ Boat Race. Andy Pike’s column is a complement to the 1980s season of WUBC with the tortuous [full of twists and turns] but ultimately redemptive story of a terrible accident in 1981 on the way to Buffalo Regatta As a point of interest, Andy wrote this through a combination of speech-to-text and slow onehanded typing while recovering from a shoulder operation – potentially related to the injuries he’d

Mr Saloojee is training us up in Rigging 101, while Mr Moore trains us up to read dense reviews of training science (I attempted a glossary of sorts, for myself and everyone who isn’t regularly chomping down on academic human physiology and exercise science papers).

The main feature of this issue is “The Life and Work of John Waugh,” quite a hefty story Robert Waugh and I have been corresponding since the start of the year, and a journey it has been It’s hard not to like Rob, he’s enthusiastic about rowing in a way that only a man whose father hand-made boats could be. An absolute delight, and a wealth of knowledge – it seems his mother instilled her meticulous record-keeping in him I must profusely thank Rob for the time he has so generously given me to put this together I hope we do your dad justice, he must’ve been an incredible character

Each and every contributor makes this magazine what it is, thanks to Rebecca for making the amazing articles pretty in an outrageous timeline, thanks to Jenna and Lesedi for sifting through thousands and thousands of words with me to get them in line, and thank you to everyone who writes, photographs, draws, and proofreads this project into existence. Special thanks to our readers for letting our stories live on in your hearts and minds

sustained 44 years ago.

It’s that time again, Therese has reminded me that my Bowside article is running late (as usual) Honestly, I should have paid more attention in Mr Mitchell’s and Mr Broderick’s English classes, or maybe I should be outsourcing this to the far more erudite (biggest word I know) Paul Marketos, Trevor Dedlow or Warwick Van Breda

Truthfully, it is a pleasure to add my odd story to this wonderful initiative I now keep my hard copies of The Bowside lined up in a special spot in my study, realising how special it is to be reminded about the various characters who have and do make up our community

Amid the many interwoven stories being shared through this wonderful magazine celebrating South African rowing, there are individuals whose contributions we must remember One such person is John Waugh, the master boat builder whose legacy continues to be seen across our waters In fact, Mr Skinner has been winning in his JW for many years (he writes through gritted teeth)

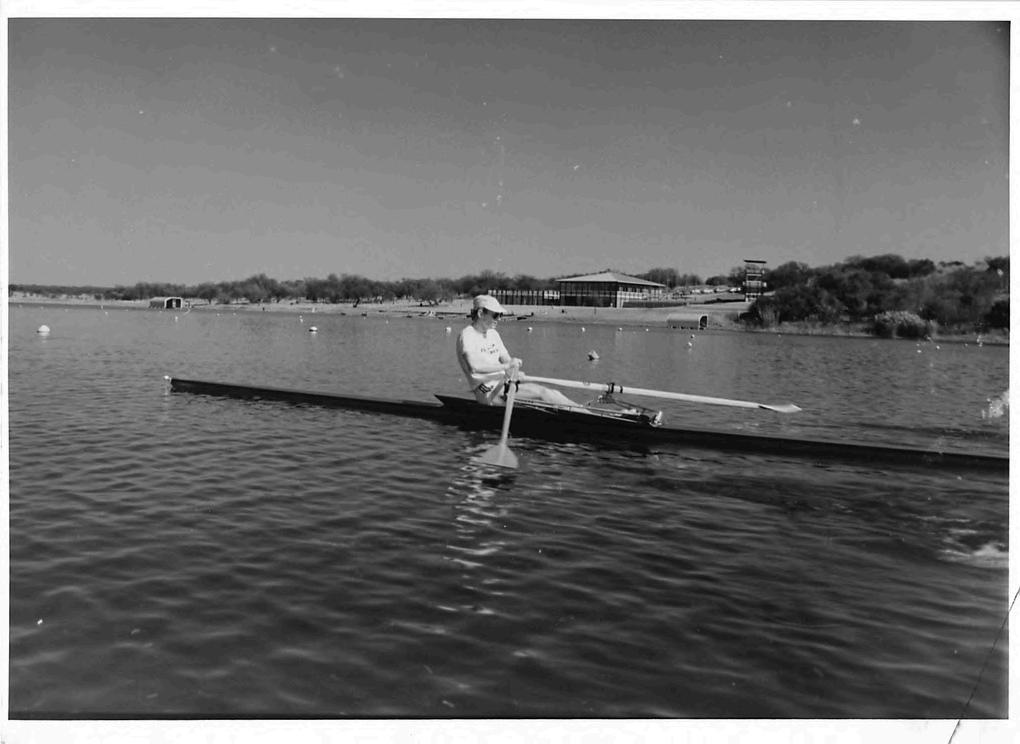

John was a boat builder, and so also an artist, a craftsman, and a quiet guardian of the sport’s soul He loved sculling, often seen on a winter morning out on Roodeplaat, rowing impeccably (although with his trademark, bent back) in one of his beautifully restored wooden skiffs

But his true passion lay in building sculls His iconic J-shape single scull (If anyone knows the story behind that shape, please share it. I did hear once that it was a collaboration between John and Phil Johnson, and hence the name ‘J-Shape’) remains, in my view, one of the fastest and most elegant designs ever built.

I remember being twenty-four, having finally saved enough money (by working night shift at Woolworths with Sean Kerr and Wayne Severin) to buy my own boat, a rare feat at the time Few schools had top-tier sculls, and owning one often meant your parents really loved you I approached John, only to find that prices had just risen due to Kevlar import duties He took me aside, asked how much I had, and told me he would build the boat for that amount (R12,500), but under no circumstances should I tell his wife, who managed the commercial side of the business

When I came to collect the boat, John was beaming (those who knew John know what that almost cheeky, maniacal smile looked like) It was not a commercial transaction, but rather a moment of passing on his craft, his passion, and his belief in the next generation. With resin wrinkled hands, he had infused the shell with purpose and pride I genuinely loved that boat, and it had a significant impact on my rowing career and, consequently, my life I remain forever indebted to him. His generosity is a testament to the kind of people who make our rowing community so special

How I started: I started rowing when I was 13, as my elder sister rowed I just fell in love with the sport and knew that I wanted to continue

Their answers remind us how the sport continues to shape, teach, and connect us

How I started: I was 14, and had moved to St Dunstans in grade 8 I really wanted to try a sport my previous school hadn’t offered, so it was between waterpolo and rowing On my first day I happened to make friends with a rower and my fate was decided!

What I’d tell my younger self: Don’t worry about how big an athlete looks or what school/club/country they row for You have to believe you belong on the start line.

What I’d tell my younger self: to keep training hard because it’s all worth the effortThe early mornings, hard sessions and tough races pay off in the end Rowing opens doors for me and creates unforgettable memories

How I started: I started rowing at 12, during a Learn-to-Row camp at Somerset College I used to watch my dad row at Roodeplaat on the weekends when we lived in JHB, and I wanted to row like him

What I’d tell my younger self: when I made the A final this year, it was a different experience, I was used to being filled with pressure and overwhelmed by the task. But this year I was excited I would tell my younger self to enjoy it more, and that my result doesn’t define who I am as a person, nor how worthy I am of other’s approval Big lesson for a kid, but an important one that I wish I learned sooner

How I started: I was 15 when I first started rowing I decided to start after a running injury that limited the sports I was able to participate in

What I’d tell my younger self: rowing would take me further than I ever imagined That every early morning and tough session would lead to amazing races, great teammates, unforgettable moments, and lifelong friends

How I started: I started rowing at 13 years old because my older brother rowed and I would often come along to all the regattas anyway, so it gave me a soft launch into understanding the sport

What I’d tell my younger self: trust the process, even when things feel tougher than ever And always find a reason to want to race, whether it's for a greater cause or, more importantly, for yourself This gives you something to fight for and a reason to love what you do.

Traditional endurance training theory suggests that long bouts of rhythmic, low-to-moderate intensity work gradually stresses oxidative metabolism , enhances capillarisation , and upregulates mitochondria production . In endurance sports, high volumes of mitochondria in the cells are associated with higher V02 max scores in elite athletes 1 2 3 4

In simpler terms: long, low-intensity, steady pieces are widely believed superior in generating the more endurance-forward components of physiology, the primary ones being more mitochondria, more capillaries and more oxidative enzymes. [In actually simpler terms: steady state is considered the most effective way to help your body adapt to become a high-endurance machine by improving its ability to use oxygen and produce energy]

The “80/20 rule” (or “polarised training”) has become a dominant heuristic [rule-of-thumb] in endurance sport: ~80% of training time at low (Zone 1/2) intensity and ~20% at high (Zone 3+) intensity (or sometimes high + threshold) Originally observed in elite endurance athletes, many coaches and athletes now apply it broadly, even to sub-elite, amateur, or recreational rowers But is it always appropriate?

Higher intensity pieces have been thought to only contribute to other components such as lactate buffering and hydrogen ion tolerance This difference in energy system function has led many to believe that higher intensity training is inferior in producing the endurance components (ie mitochondria, capillaries and enzymes) in comparison to lower intensity training 5 6

A recent systematic review [a study that compiles and analyses all prior research on a question] and meta-regression of human training interventions reported that low/moderate continuous (endurance) training (ET) increases markers of mitochondrial content by about 23% on average. At the same time, high-intensity interval or continuous training (HIT) yielded about 27% increases, and sprint interval (SIT) also 27% (ie relatively similar gross gains) 7

However, when normalised per hour of training, SIT was found to be ~2 3× more efficient than HIT, and 39× more efficient than ET; HIT itself was 17× more efficient than ET.

Further support comes from the “Effects of Exercise Training on Mitochondrial and Capillary Growth” review, which also noted that training load (volume × intensity) is a predictor of mitochondrial adaptation; but importantly, the gains per unit time differ across intensity modalities [types of training]

8

In addition, Yamada et al (2021) showed that highintensity training with intense contractions produced larger improvements in fatigue resistance and mitochondrial function than more modest workloads in animal muscle preparations9

A more recent controlled human/animal molecular study (Jahangiri et al. 2025) reported that HIIT increased expression of PGC-1α, mitofusin-2, OPA1 , and down-regulated fission genes, demonstrating favourable mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics changes in response to intermittent high-intensity stimuli

10 11

The 80/20 prescription emerged from observational data in elite endurance sports (cycling, running, cross-country skiing) where athletes already sustain high weekly volumes Drew Ginn, from the famous Australian “awesome foursome” is quoted as saying that most elite rowers spend 30 hours per week training (which is more than four hours per day!) This means a total of 6 hours per week is dedicated to high-intensity-only work for these athletes In such contexts, allocating ~80% to low-intensity can help manage fatigue while still accumulating the volume necessary for adaptation But applying that same ratio to lower-volume, time-constrained athletes may be misaligned

If a recreational rower is doing 6–8 hours per week (compared to 20–30+hrs) with 80% low-intensity, this leaves less than 2 hours a week for high-intensity That high-intensity quota might not be enough to sufficiently stress mitochondrial adaptation in welltrained muscle In contrast, elite athletes might invest 4–5+hrs at high intensity (20 % of 20–25 h), which produces greater cumulative stimulus [overall training effect on the body over time].

Amateur rowers spend significantly lower time training per week (6-10 hours) and therefore it could be hypothesised that applying an 80/20 principle to these lower volumes could risk losing important gains that are facilitated with the high-intensity training already described

Dr Ross Tucker (through Real Science of Sport) is a thoughtful voice in the intersection of rigorous exercise science and athletic pragmatism While he does not offer a one-size-fits-all prescription, his commentary often emphasizes:

Scepticism of dogmatic “golden rules” (eg that 80/20 is sacrosanct [untouchable or beyond question, sacred]).

The necessity of adapting “optimal” trainingintensity distributions to athlete context, volume, and goals

Moreover, Li et al (2025) provided direct evidence that HIIT (versus moderate continuous work) is superior for mitochondrial biogenesis and volume density in skeletal muscle 12

These findings do not imply that low-intensity work is useless – it likely remains essential for capillarisation, structural remodelling, recovery, and fat-oxidation efficiency – but they do challenge the notion that most adaptation is best driven via vast volumes of low-intensity in all contexts

13

The idea that time-efficient strategies (i.e. more high-intensity per limited available time) often outperform slavish adherence to low-intensity quotas

The importance of internal load, recovery, context, and periodisation (ie how one layers intensity over training blocks)

For example, in several episodes Tucker and Finch critique overemphasis on “Zone 2 only” ideology, arguing that context (athlete level, training history, available time) must guide balance of intensity domains.

Start from your volume.

Determine the realistic weekly training volume (in hours) that you can sustain over months (not just ideal) Let that be your constraint

If 80/20 is the distribution of intensity for an elite 30 hour training week, then change the ratio according to your training week hours The lower the hours, the more intensity that body can likely handle and adapt to

Maintain a “durability base” but don’t overdo low-volume steady-state

Keep low-intensity sessions (Zone 1/2) for recovery, fat oxidation, capillarisation, technique, and mitochondrial “tuning,” but don’t treat them as the lion’s share if volume is low

As the evidence for an 80/20 training distribution only comes from elite athlete programs, research suggests that it is worth trying out different/more high-intensity session distributions in non-elite training volumes (which tend to be significantly lower than elite programs) in order to benefit from, and maximise, training adaptations for performance

Richard has written separately in his book “Tangled Toes, Pins and Needles” about the accident and his miraculous recovery from his debilitating injuries. Our recollections differ on a few points, but we have no real way of determining whose version is more correct, given that both of us had taken a physical hammering and were probably verging on delusional. Suffice it to say that the situation was chaotic and memories blurred, both with the trauma and the passing of more than 40 years. *Editor’s note: the oldest sibling is always (the most) right, in my (not) unbiased opinion.

It was January 1981, the start of the new rowing season, filled with hope and some mild anxiety Quo vadis, Wits?

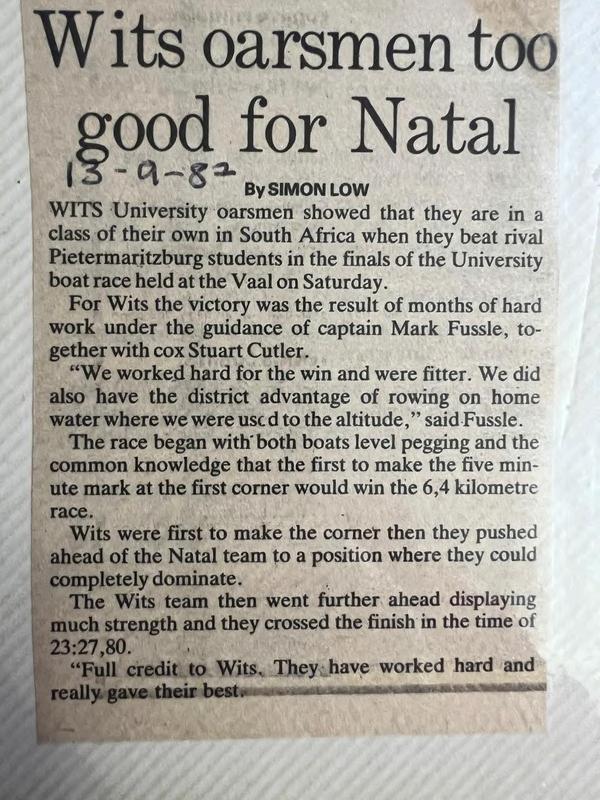

Wits had slain all comers the year before, winning all major championships In addition, our senior eight had been runners-up in the Henley Ladies Plate finals, bronze medallists in the British national championships and collected a few other pots along the way on our UK tour The eight went on to be awarded Springbok colours en masse on our return from the UK

We could not have asked for a better season, but most of the senior rowers left at the end of the season to continue their careers, and some to emigrate or go to the army I had been appointed as Club Captain for the coming year and was faced with developing and executing a strategy to rebuild the club.

We still had quite a bit of underlying junior strength and a selection of what I would call “senior-juniors” with whom we could crew the more senior boats, but probably not at the level necessary to be truly competitive in Senior A

We decided to call up my younger brother, Richard (who was just completing his national service) and pull him into the boat early in the season, before he had technically enrolled at Wits We filled the senior eight with a number of other oarsmen showing a lot of promise, but who had never raced at Senior A level From what I recall, I was the only remaining member of the 1980 crew

The Buffalo Regatta was always held a week or so before we went back to university, meaning quite a bit of training in December and January. In preparation for our trip to East London, we agreed that Jeremy Nichol, one of our oarsmen coming through the ranks, would (with me) co-drive the truck pulling the trailer and entire fleet of boats to East London Guy Muller and I gave him a few lessons in towing before we left I remember us discussing whether the trailer brakes were working properly at the time. I’m not sure that we resolved any doubt we may have had. In the end it seems

likely that our doubt had been justified Be that as it may, we set out early on the Thursday morning before the weekend’s regatta

Richard, Jeremy and I occupied the front seats of the truck. Hamilton Wende, Gary Stanley and Coenie Wesselink were in the canopy section of the truck, sharing it with luggage and mattresses

The route to East London in those days took us through Villiers and on through the Free State, skirting the Transkei and Ciskei and finally ending up in what is now Buffalo City.

After topping up for fuel at Villiers, I suggested that Jeremy should take the wheel for a while The Free State was relatively flat, and it would give a novice driver a good feel for towing the boats

As we trundled quietly through the flat Free State mielie fields, all seemed idyllic. Eventually, we started going down a hill – straight and not particularly steep, but a good km or two in length

I was sitting next to Jeremy on the front seat so that I could give him instructions if necessary Richard was sitting next to the passenger door, and none of us were strapped in, principally because the truck did not have seatbelts (they were not mandatory in those days) Fortuitously, our lack of seatbelts probably saved our lives*

As we rolled down the hill, I noticed the nose of the truck starting to sway from left to right and back again in rhythmic fashion. I remember saying to Jeremy, “Take it easy,” which he took to mean “Put the brakes on” In any event, he did put the brakes on, and what had started as a gentle sway turned into a massive swinging of the tail of the truck to the left and to the right, building in oscillation Jeremy was desperately turning the wheel this way and that, and probably still had his foot on the brake As the nose of the vehicle swung to the right for what would be the last time, I saw the tail end of the trailer jack-knifed out of Jeremy‘s window

With that, the truck flipped over on its left front corner, rolling several times I left the vehicle first, catapulted through the windscreen at around 70–80 km/h Richard followed close behind me, but without the benefit of a windscreen to slow his flight. Jeremy was somehow tossed out of the driver’s window

I don’t remember hitting the ground or picking myself up My main recollection was walking around, surveying debris and mayhem all around me: broken pieces of rowing boats, a truck with its roof flattened to dashboard level, glass, baggage, mattresses, an unrecognizable trailer. I could hear someone yelling in the background – it turned out to be Richard, who had broken his spine and pelvis I was hunting around vaguely for my identity book (all I could think of was how hard it is to get a new one) As I walked, I bumped into Hamilton Wende, who, shocked, said: “Look at your face And your arms!” I had no idea what he was talking about, but I could see that I was covered in blood. More blood was gushing out of my left arm For some reason I found I couldn’t lift my right arm to look It turned out that the windscreen had slashed me open in a few places and my crash-landing on the side of the road had caused some structural damage

Hamilton went to see what he could do for Richard. He soon realized that Richard was in real danger: firstly because he had figured out that he had broken his back and secondly, because fuel was pouring out of the vehicle very close to Richard Hamilton then crouched down and held Richard stationary for several hours before a helicopter could arrive and evacuate him from the scene. I have no doubt that the reason Richard can walk today is because of what Hamilton did for him on that dreadful day

I continued wandering aimlessly through the debris until a passing farmer stopped, took one look at me and loaded me into the back of his bakkie. I suppose I must’ve been with someone, but I can’t remember who We then did this open-air dash to the closest provincial hospital in the village of Reitz, some 40 km away

By then, I was feeling pretty sore, with a number of broken bones and bleeding from many sources. An intern at the hospital gave me a huge dose of pethidine or morphine, which helped numb me down and moved me into the matrix He then looked at my face, said that he had done a rotation in plastic surgery, and he would have a go at the repair job. I really didn’t care at that moment. I clearly needed something done. He stitched the gash in my face with 30 to 40 small stitches: not exactly invisible mending He also set about repairing the various other puncture wounds and removing what gravel he could No one checked for broken bones

At some time around midnight, John Stark arrived from Johannesburg in his Kombi, loaded me in the back, and drove me the four or five hours back to Garden City Clinic Richard arrived around the same

time by helicopter I have no idea how the other four guys in the van got back home: what a mess!

Four of the oarsmen involved in the accident were members of the senior eight and, naturally, couldn’t row because of injuries and the inconvenient aftermath of our Free State debacle. The remainder of the club made it to East London, but, of course, sans boats On race day they borrowed boats and competed as best they could If I’m not mistaken (my brain was somewhat addled over that period), somehow or another, four rowers were found to fill the empty seats in the senior eight. In a borrowed boat, they went on to win. Nothing short of extraordinary!

Richard underwent 10 complicated hours of surgery, months of rehab, and finally, somehow, learned to walk again about 6 months later His spinal cord had been all but severed, so some mobility could be restored, but it took at least two years before the damage was more or less healed

I had an easier healing path: I had lost patches of skin over a fair area of my body, but those healed over time A broken right collarbone put paid to any rowing for the next two months. Aggravating this were a couple of broken ribs (together with the rest of my ribs, which had detached themselves from my sternum), all of which made coughing, sneezing, and general physical activity a major challenge for the next six months

During my downtime, I decided to coach a senior D crew, comprising eight remarkably enthusiastic and athletic individuals I spent hours in the cox‘s seat, steering with one hand (frequently into the bulrushes) as I taught them whatever I knew To cut a long story short, we set ourselves some targets for the season and massively exceeded them From rank novices, they went on to win senior B eights at the SA national championships.

We had a pretty competent senior A four who carried on after the accident They competed well for the season, given the low base they were coming off

As Captain, I set a target for the club which was to win inter-varsity that season I wasn’t exactly sure how we were going to do it given how thinly

stretched we were, but I knew it was realistic and that the club needed some purpose

Two months after the accident, I got into a sculling boat for the first time ever, did a good amount of swimming, paddled in circles with my weak arm, but eventually became vaguely competitive in senior C or D I also managed to get into an eight Although I was not exactly in prime condition, I think I made some contribution

When inter-varsity came round, I encouraged members of the club to aim to win the event. However, the only way we could do so was to row in as many events as we could possibly enter Even if there was little hope of winning, at least we could accumulate points in the lesser positions On race day, every Club member to a man rowed his heart out, typically competing in three or four events in the day, some of which included heats. Astonishingly, at the end of the day, Wits had won the inter-varsity

You might be wondering what we did for boats, given that we had written off the entire fleet in the accident We were dismally under-insured: the insurers paid out somewhere between 10 and 20% of what we needed to restock the club.

Heartwarmingly, the entire rowing community clubbed together to raise funds for a new fleet of boats for the students Overnight we migrated from tired and flexing wooden boats to a new Kevlar eight and several other high-spec smaller wooden boats.

In the 1982 season, we had rebuilt the club, drawing on everyone we had (including those awesome novices whom I had the privilege of coaching) At the Buffalo Regatta, we won the senior eight and a number of other pots For the rest of the season, we were competitive, setting the base for the club renaissance.

is a candidate attorney, and an on-and-off freelance digital artist using Procreate She drew for PDBY while

Digital artwork by Rayna Naidoo

Rayna

at Tuks.

“If your boat is correctly rigged your technique should follow naturally” – Hamish Bond

“Rig Boats when it is sunny, and have a bottomless toolbox.” – Jurgen Grobler

Boat strap (for securing the hull)

2 x 10mm spanners

1 x 13mm

2 x 17mm

2 x 19mm

2m spirit level

Star and flat Screwdrivers

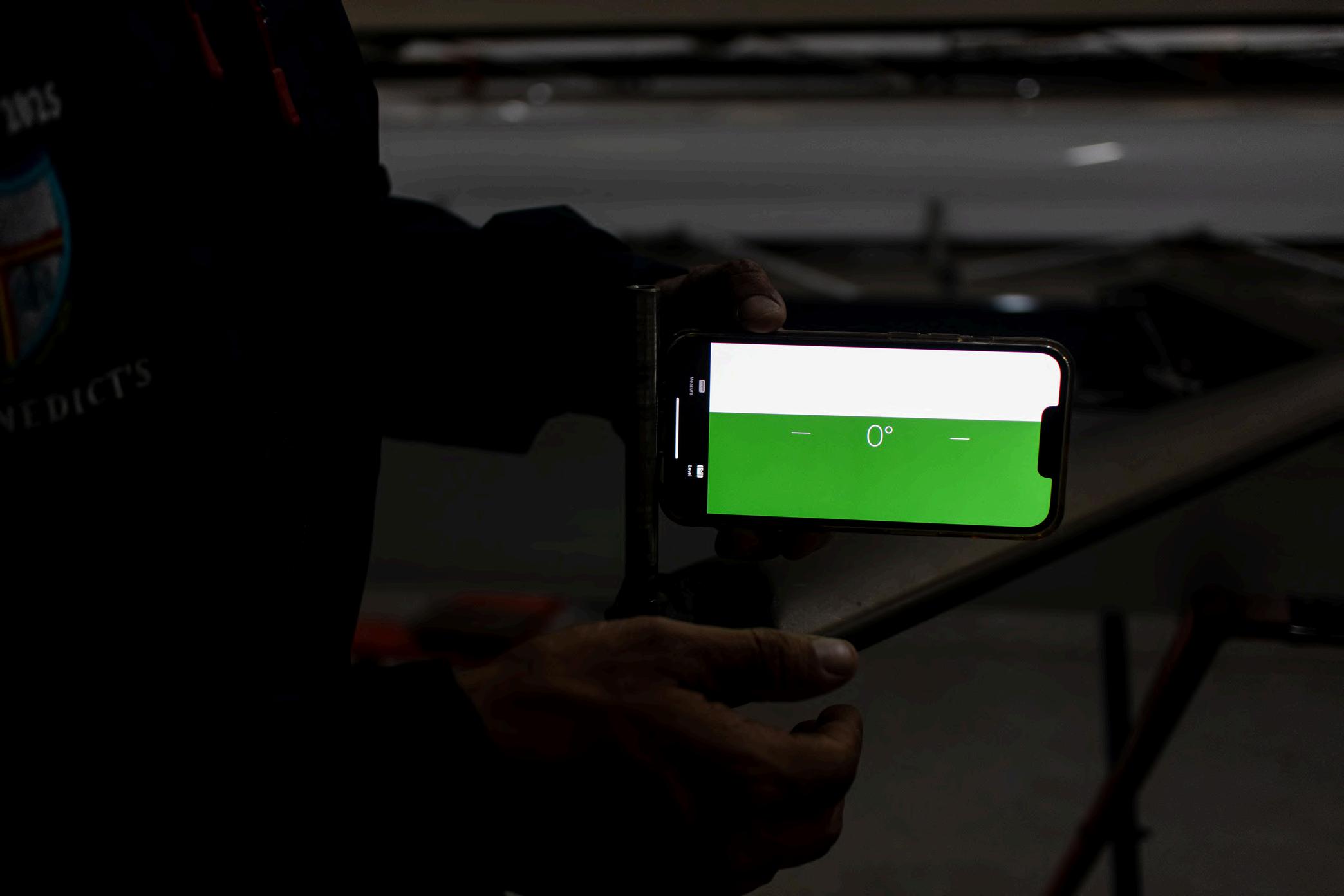

iPhone or pitch gauge

Hammer

Insulation tape

Scissors

Allen keys

A well rigged boat allows the athlete to easily and more naturally execute correct technique For junior rowers, a well rigged boat ensures that the athlete is limited only by their own ability, as the only variable directly under the influence of the coach has already been controlled for Having your finish angles set makes it easier to balance the boat; a correctly set boat provides a good platform to coach from

Poor rigging on the other hand, can ruin good rowing:

Incorrect Pitch → blades dig into the water or wash out

Uneven span in sculling → the boat to pulls to one side

Incorrect footboard height and angle → restricts athletes from properly compressing and pushing their legs

Incorrect gate height → excessive knucklescraping and difficulty getting blades out and off the water easily and comfortably.

That being said, rigging is not a silver bullet Still, good rigging makes for a far more comfortable, enjoyable and biomechanically correct experience A more comfortable athlete is a happy athlete and a happy athlete is a fast athlete

There’s nothing worse than trying to set a boat that’s rocking like a metallica concert you’re trying to set the span when the spirit level crashes to the ground, closely followed by your tools and every single nut, bolt and washer you’ve ever laid eyes on. So, tie the boat down first, your spirit level will thank you later

Now that the boat’s stable, it’s time to make sure everything’s tight and level.

Start with the small spanners and systematically work through the boat: Take the 2 x 10mm spanners and firmly (but not forcefully) tighten every rigger until it is secure If you’re getting a workout, it’s probably too tight Save your strength for the pins

Then grab a 2 x 17mm and/or 2 x 19mm spanner (the Big Boys) and tighten all the pins Make it “vas vas”

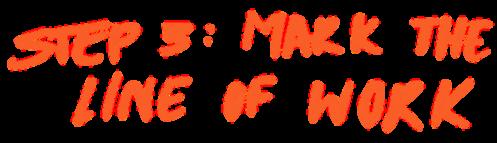

The line of work marks where the oar is perpendicular and the work is being applied directly in the direction we want the boat to go The line of work should line up with the face of the gate This is crucial for understanding where the 90° point is and where the most effective part of the stroke is

Simply explained, at the catch you're pushing out and at the finish you're pushing in, there's only a short period where you're applying the force in the most effective way and understanding and seeing that makes it easier to coach the athlete about how to take advantage of that point It also provides a marked and consistent measurement point for you to use when setting everything else (more on that later)

1 Place the spirit level perpendicular to the gunwale If you have a front or side rigger, get it flush against the back of the rigger

2 Apply insulation tape along the gunwale in front of the spirit level.

3. Place the spirit level in the gate, holding it flush against the gate like the oar would sit Looking straight down, align the back edge of the level with the front edge of the tape

4 Front of tape = Line of work

Your pin should be at zero laterally and zero stern/bow In general, all pins should be zero with 4/4 inserts All that means is that the pin should be zero and the gate should have a pitch plug with a 4 on both sides

If your pin isn’t at zero, you may need to bend the pin to get the lateral to zero To do this, use a nice solid trestle or pole with a hole and bend it If getting the stern pitch on the pin to zero isn’t happening, try to get it to at least -3 or +3 If you have -3 stern pitch and use a 7/1 insert with the 7 facing toward the stern on the top and the 7 facing toward the back on the bottom, your pitch on the gate will be 4. For -2 use a 6/2, -1 use a 5/3 and 0 use a 4/4 (reference table below)

After you’ve successfully performed advanced transfiguration on the pins, you can shift to the span.

Lateral (On Pin)

Stern (On Pin)

Insert (1st number faces forward on the top and back on the bottom)

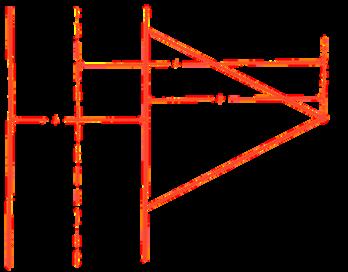

SCULLING BOATS

2 Calculate the gunwale-to-pin (GP) Write it on the tape (you’ll use this later for finish angles)

3 Span(3) = M + GP

The handle should sit at about sternum height and the athlete should be able to sit with their wrist and elbow level when the blade is square and buried.

1 Bow side should be 1 cm higher than stroke

2 Hook your measuring tape on the groove on the gate and measure to the bottom edge of the level (gateto-gunwale)

3 Seat-to-gunwale + gate-to-gunwale = Gate Height

My personal favourite, and the most underrated setting This strongly impacts comfort and the ability to slide forward and engage the legs. Too little and you can’t compress comfortably, too little and you’re overcompressing and feel like you’re pushing down A steeper angle means more horizontal force which is good but that require good mobility. A less steep angle means easier compression but less horizontal force As with all things, use the Goldilocks method

Use this as an opportunity for some maintenance. Remove the footplate so the screws can be tightened and the angle easily measured Once you’ve set the angle, put the shoes back on and then set heel/footboard height.

The athlete should be able to comfortably get to vertical shins and it should relatively restrict overcompression.

1 Secure footboard

2 Place spirit level directly over the point you’re measuring from

3. Push the heel flat

4 Measure from the inside of the heel to the bottom edge of the spirit level (heel to gunwale)

5 Heel-to-gunwale - seat-to-gunwale = Heel/Footboard Height

There’s no perfect setting and usually it’s best to be somewhere in the middle Adjust up or down after testing for a week

For example, if the recommended range is 83 to 85cm span, then you should start at 84cm and adjust based on your observations and research The manual recommends 38-42 degrees, start at 40 rows for a week and then adjust, decrease for those struggling and increase for those overcompressing or easily compressing

For school rowers 370 to 373 is the recommended range, I’d suggest not going longer than 370 and not longer than 373

Adjust the length by 1cm and assess its effect by measuring their ease with which they can generate speed and how much longer they can sustain it.

Ask for help and read the manual – it has 99% of what you need (https://worldrowing.com/document/coaching-manual-level-2/)

Ideally have someone come and help you by showing you while you’re doing it

Strip everything down and clean it before you start working on it

Write everything down.

Mark everything clearly, so you can easily see when things have moved

Write it all down! If you change something and go faster, you’ll know why.

Be accurate and do it right the first time

There’s a scene in the movie Burnt where the hotshot chef explains why people pay more for his food than for Burger King, and he talks about consistency: consistency is death Of course, in rowing, we know that’s not true Consistency counts, wins races, and sells boats If you buy a Filippi, a Hudson or an Empacher you know exactly what you’re getting, and you can row one here in South Africa and a different one in Europe And as long as they’re the same model and roughly the same age, they’ll give you the same feel and outcome. This is obviously better for the sport and for high performance

But I can’t help feeling that we’ve lost some of the pleasure and joy of boats with individual personalities.

The first time I really understood the unique personalities of boats was in the mid-nineties, when I rowed winters with a guy from

KES (I was at Jeppe) They had a pair and we had a pair, and Adin and I swapped between the boats depending on where we were.

Both boats were the same shape, same material, and same weight But the KES pair (I think the name might have been Ares?) was like rowing a couch – pure comfort all the way. You could row 70 km in a weekend, and it wouldn’t have given you a single blip Not fast, not slow, not rocky, not anything other than smooth like butter You really had to work to get the boat to do anything, and you had to properly mess up a stroke to get it to go wrong. Jeppe’s boat, Albion, was the complete opposite, like a twitchy racehorse, raring to go, ready at every stroke to spring out of the water and fly along Until you did something it didn’t like, such as blinking wrong, and then it firmly let you know

We had a single at Jeppe called Skien Du, and rowing in it ten years later was like a trip down memory lane: the acceleration, the places you pushed and didn’t push to get the best out of it

Sam Hudson has a single that I rowed a winter in, and it’s the same – completely different to any other single I’ve rowed

All of that comes before you start getting into the customisations that were so popular in John’s boats He was always spending time with crews and clubs to work out where something could change, something could be done that just might make the boat a little better Sometimes those changes worked, sometimes they didn’t (anybody who rowed the KES eight, Raka, about 3 years after they removed ribs throughout the boat to make it lighter, will know all about things that didn’t work!)

The point is, you don’t get that anymore, because boat builders (and I say this with respect, I completely understand why this is the case) are boat builders. They’re following a template and putting the bits together like a very complicated and precise LEGO set

I can’t help but feel that for all we’ve gained in boat technology, we’ve lost some of the pleasure of needing to really get to know your boat – your personality-filled craft

ohn Waugh’s career as a boatmaker started as a hobby in his garage in response to a problem he needed to solve Indeed, an appropriately South African response (well, I’ll just make my own!), resulting in a brilliant and unexpected career that is woven into the very fabric of rowing in South Africa

Thank you to Robert Waugh for your efforts in compiling all we needed to put this together, we could honestly write a book with all you provided (but I hope this will do, for now), and to Zak Wood and Wig Dreyer for your corrections and additions And, naturally, to John Waugh himself, for living a thoroughly good life

Born Arthur John Barrow Waugh to rigorously educated parents, John entered the world as a pre-empted legacy on the 25th of May 1945 in Cape Town to Harold (“Wuff”) Waugh and his wife Margaret (née Donald), a family already steeping in rowing-adjacent territory; boasting Cambridge and Oxford degrees left and right, and his mother’s medical degree from the Royal Free Hospital in London centre. Not to mention John’s uncle, Prof Dr Ian Donald CBE, the father of ultrasound in medicine

Along with his sister Liz, John spent much of his childhood growing up along the banks of the Lunga River. Great bushveld stories of big game, tiger fishing, fierce snakes under the bed at night, hornbills swooping to steal butter from the dining table, and a leopard cub as a childhood pet abound.

Although a bush baby, John was also an English public school boy, educated at Whitestone School in Bulawayo, and Blundell’s School in Devon After their mother’s early death, John and Liz’s aunt, Dame Alison Munro DBE took charge of their care in England Previously Britain’s Minister for Aviation, and high mistress of St Paul’s School, Aunt Alison was a formidable family matriarch More than that, she was always right* . Not just as a parental figure, but also about a boy band that she thought had promise, and a mum at her school that she thought could well become Prime Minister

The Beatles and Margaret Thatcher certainly didn’t let her down

Often staying at her beach cottage for summer holidays, John and his cousins were administered a few healthy doses of terror It is difficult to say who the real tyrant in that dynamic was, especially on the occasion when John and his cousin Robert managed to ground Aunt Alison’s beloved sailing boat on a sandbar directly in front of the sailing club clubhouse for which Alison was commodore

Whilst doing his Masters in Durban, John often supervised undergraduate students in their field work, particularly on trips to inspect beach rock pools for molluscs (John’s field of research). With a dashing young John Waugh arriving at the beach in a red convertible Alfa Spider, and the students typically arriving with their surfboards, more fun than research took place!

He later returned to England and married Barbara in 1972

Barbara June Bishop, born 9 April 1946 to Sheila (née Porteous) and George Bishop, near Hampton Court Palace, had attended boarding school in England, initially at St Mary’s in Horsell near Woking. She often stayed with her grandmother, Mary-Lee Porteous (née Dunn), at 6 Netherton Road near Twickenham stadium, where her grandfather William Porteous had been the “engineer in charge” of the delivery of the “new East Stand” in 1925

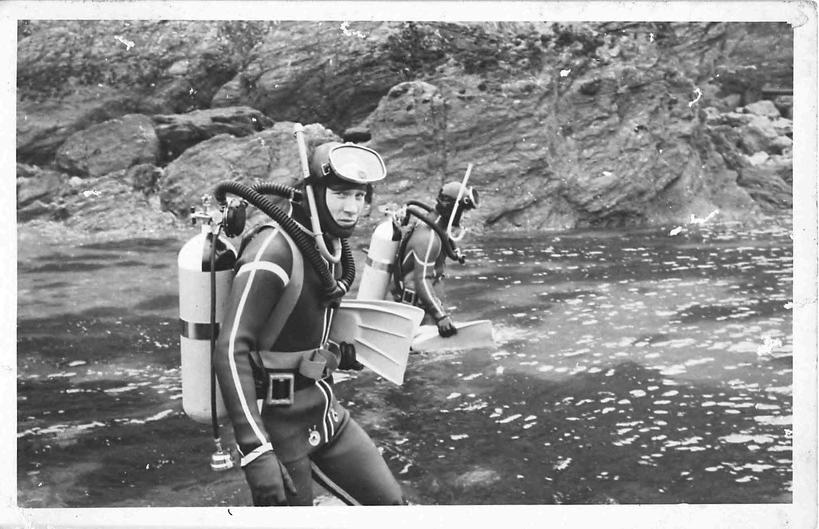

As a student in England, John often holidayed at his uncle Ian Donald’s cottage on Loch Fyne in Scotland. In those days, wet suits were not widely available commercially, so John had to make his own! Not much stopped him. Whilst at Loch Fyne, he and a friend dived on the wreck of an abandoned grain barge. Unfortunately, once through the hatch into the dark cargo hold, the sediment they kicked up blocked any light and any way to find the exit. John, cool-headed as ever, followed the perimeter of the hold in the deep pitch dark with rapidly reducing air until they found the exit hatch, and their way out

Barbara took a secretarial course at Brooklands Technical College, before working in London, initially for a marketing agency, and later for a city lawyer.

As newlyweds, Barbara and John lived in Twickenham, where John was quickly elected captain at Twickenham Rowing Club While he was keen to learn to scull, the long-standing head coach, George Plumtree, had other ideas He immediately put John in the stroke seat of the eight for a highly successful Tideway regatta season: winning at Kingston, Putney, Metropolitan and Mortlake regattas, and culminating in racing at Henley in the Thames Cup in 1973, where they were sadly knocked out by Brown USA

Later on, John (who was always up for a challenge) sculled his Sims wooden single upriver from Twickenham to Eton (via a number of locks and roughly 25 miles or 40 km upriver!) Upon arriving exhausted in Eton, the kindly boatman quietly remarked to a very tired looking John, “Been a long way then have you sir?”

In 1976 the family moved to Pretoria, where John joined the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) Although by all accounts one of the more productive scientists, he spent most of his time in the library researching hull shapes and boat construction technology, with a view to building a replacement for his faithful Simms

In 1974 John and Barbara moved to Durban along with a sculling boat and a new Triumph TR6 sports car John joined Durban Rowing Club and was immediately elected Captain and put back into the stroke seat for yet another successful regatta season While in Durban, John built the extension to the DRC boathouse, and his first son, Robert, was born in 1975.

Shortly after arriving, John was appointed as the inaugural captain of Roodeplaat Rowing Club He had placed the first boat in the empty boathouse and personally tried out every rack before settling on the one that today bears his memorial plaque He also selected and declared the club’s founding colours: Claret and Old Gold

John and Barbara settled happily into the big, thatched house on Thelma Avenue in Clubview, where they would live for many years. Alison, their daughter, was born in Pretoria in January 1978

John had brought his trusty Simms wooden single from England, but as it aged, replacing it became unavoidable Since importing a new boat from Europe was prohibitively expensive, he decided to build one in his garage

As a scientist at the CSIR, he had the government's finest scientific library at his disposal Convenient for researching hull shapes, boat technology and construction techniques (and for the occasional power nap after some late night boat building) This quickly became an all-consuming passion

Not long after joining CSIR, and ably assisted by Barbara, he built his first wooden sculling boat around 1978

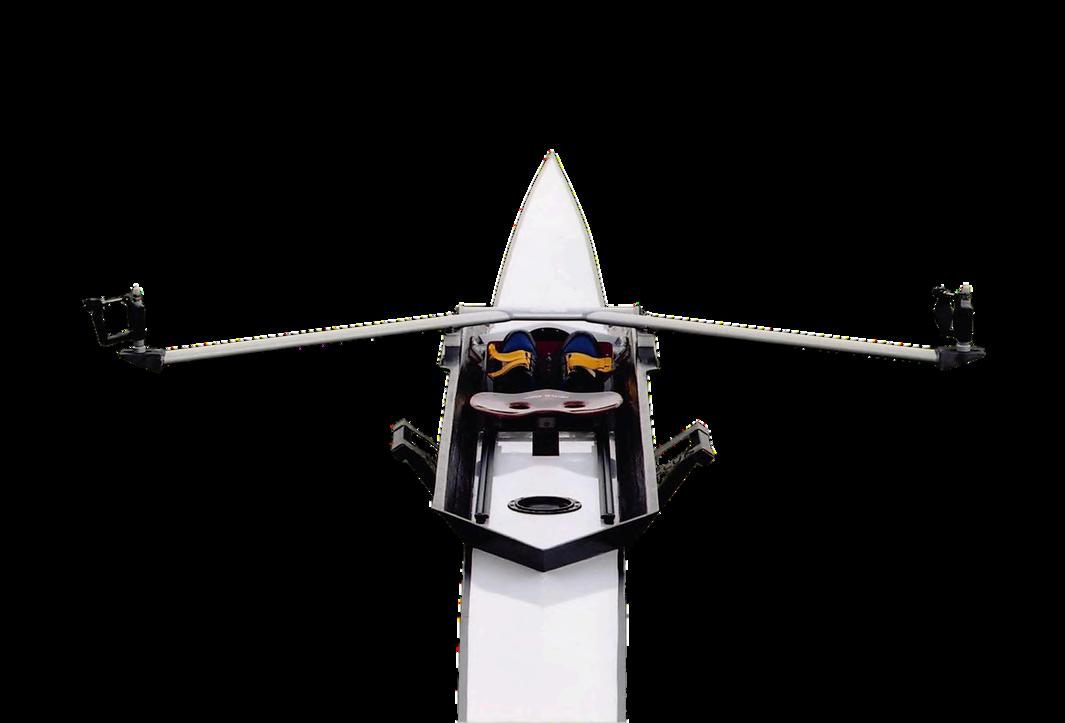

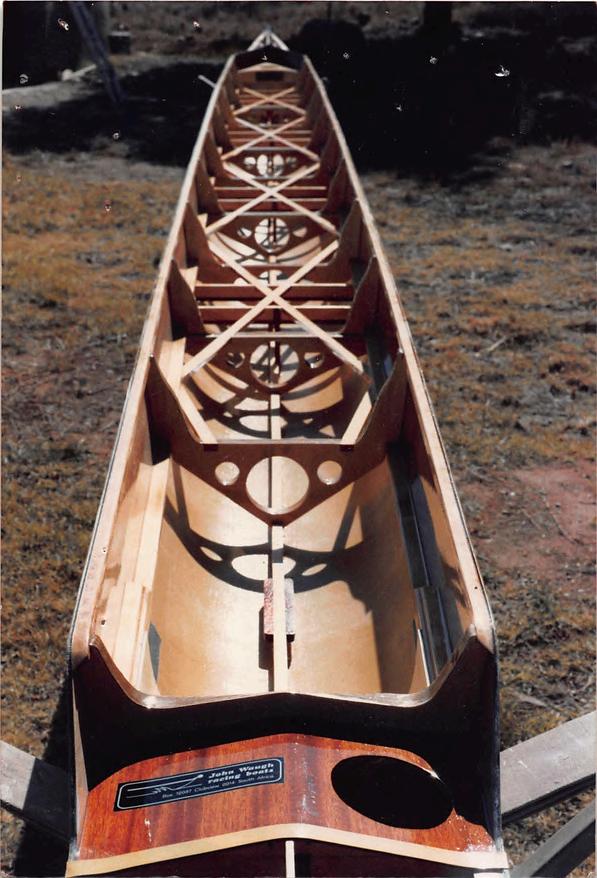

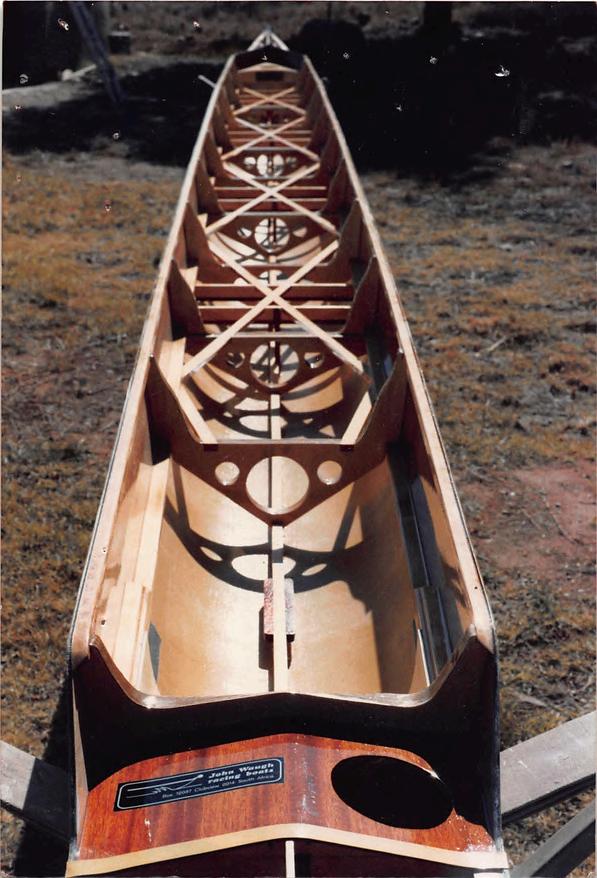

He’d set up “the singles bench” in the back of his double garage knocking through a storeroom to widen the space Good as John was on a bench in the gym, this was more of a precision engineering rig: a long timber plank, firmly mounted at chest height, with sturdy legs spaced at four foot intervals, meticulously checked for straightness and stability Above it was a pair of horizontal sight lines made from fishing line, arranged one above the other, to ensure everything below remained symmetrical.

Next came the formers: like ribs along a ribcage, cross-sections providing the shape around which the thin plywood shell would be formed Around the top and sides of the formers, he threaded the timber keel and side “inwales” to create the spine of the boat. Because the hull was built upside down, the keel was on top Delicate cross-bracing was crafted to link the inwales to one another and to the keel, locking the structure into a stiff lattice skeleton, and wooden saxboards were added to be trimmed to line later

The thin plywood skin was then steamed and formed around the skeleton Once shaped and trimmed, the hull was released from the bench, flipped right-side up, and the formers (excluding the main shoulders) were removed Foredecks, stern decks and a V-shaped breakwater then needed to be formed. One of the trickier components was the diagonally sloped sluice, which was patterned by using a light source to project the shadow of a former onto a piece of wood at a sloped angle Voila! This difficult pattern was revealed, ready for tracing and cutting

After hand-sanding the woodwork, the hull received perhaps seven coats of marine varnish bringing the finish to a high gloss The finest available wood was used: airgrade Sitka spruce for the frame (light, stiff and strong), marine ply for the shell, and beautiful mahogany or cedar for fine finishes in the exposed cockpit Even the sliding seats were individually carved by hand from a solid billet of mahogany. The fittings were equally premium: white leather calfskin Adidas rowing shoes; Len Neville, Neaves or Carl Douglas riggers; and Empacher or Stӓmpfli hardware

These wooden boats were beautiful masterpieces, a true labour of love and craftsmanship, each taking nearly three months to complete John’s own boat, Windrush* , was the third he made; others included those for John Reid, Colin Graham, Ivan Pentz, Phil Johnson, Bernard Janisch, Doug Munton, Bob Tucker, Keith Maybery, Henry Watermeyer, Ernest Gearing, Mark Shuttleworth (now owned by Wig Dreyer) and many others Custom wooden singles included Steve Lockwood’s ‘lunch box’ boat, which included a compartment below the runner deck, sized to snugly fit two long-tom beer cans, and Phil Johnson’s early wooden single used a custom rigger design that skipped the middle shoulder to allow a narrower, faster hull shape A handful of

wooden pairs followed (c.1982), including Dan and Derek for Wits and Wemmer

By this time John had left his day job, as his boatbuilding “hobby” started taking up more and more of his time A longer bench was built under a lean-to along the garden wall for constructing pairs, including Dan and Derek He produced over 30 wooden singles but only a handful of these wooden pairs.

But three months per boat was not sustainable and modern technology was on the march

In the interim, John continued to race competitively with fierce rivalry in the masters singles against Keith Mayberry, Bernard Janisch (BJ), Brian Chrisite, Derek Read, Phil Johnson and many others

With the help of his friend Jack White (a highperformance glider pilot with an industrial fibreglass factory), John started exploring composite materials He acquired two moulds for fibreglass trainer singles (a standard and a smaller “mini” version) and used them to build his initial fibreglass training boats while learning this new technology and skill. He produced over 70 fibreglass trainer singles

Many rowers started off in these boats South African Olympian Rogan Clarke learnt in one of the full-size sculls, while John’s son Robert started off in a yellow mini-scull that Barbara named Starlight. Phil Johnson collaborated with John during this period, producing riggers and other fittings for these early fibreglass boats

Whilst John endeavored to optimise these designs, fibreglass technology of the day was seldom as light or stiff as the best wooden singles, hardly the stuff of hi-tech, high-performance dreams, still a crucial step towards the composite era that followed

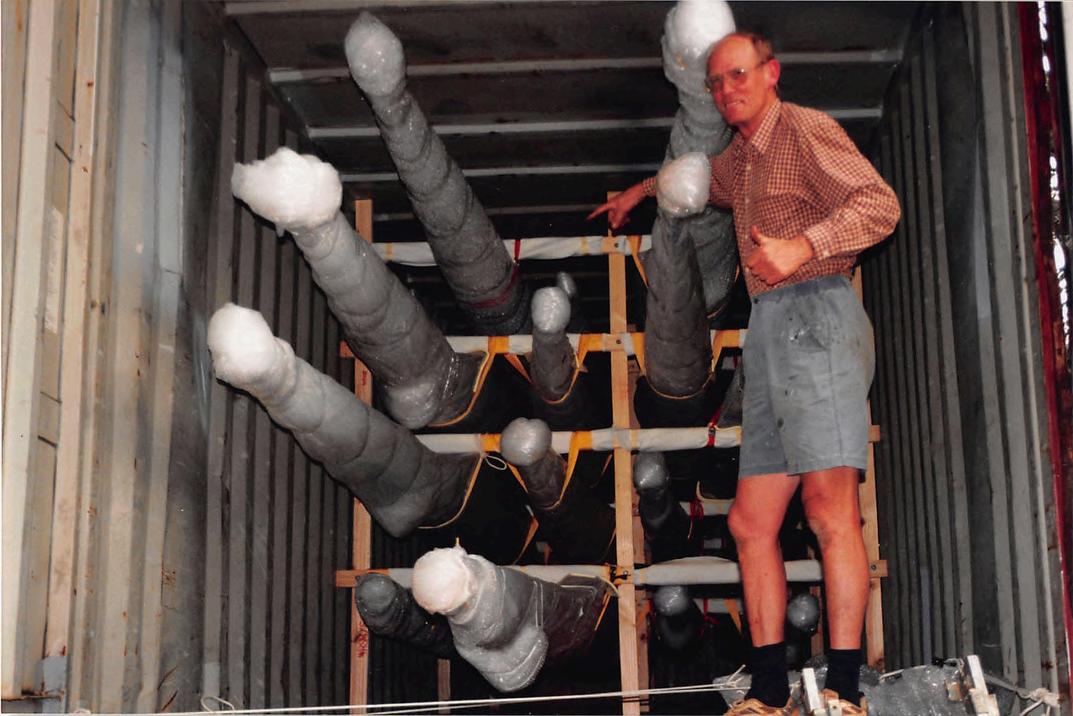

The next evolution in John’s boatmaking came with the shift from fibreglass to Kevlar and carbon fibre, laying thin shells over traditional wooden frames to create hybrid composite boats that combined the stiffness of wood with the speed and responsiveness of modern materials (the best of the old and new) The new process dramatically reduced construction time, and orders skyrocketed. Although he started out making only singles this way, John quickly began to dabble in doubles, which became fours and quads, and eventually the first composite eight produced in South Africa

To keep pace with international developments and fast-track his learning, John visited the workshops of Europe’s builders – Empacher, Stämpfli and even Janousek He also spent many happy hours in deep technical discussion with Klaus Filter, the legendary East German designer whose work for Berlin Bootsbau (BBG) helped shape modern racing shells and contributed to their success against their West German rivals and Empacher Filter, a founding member and longserving head of FISA’s Materials Commission, was also one of the forefathers of modern composite boat technology as he designed the world’s very first composite rowing hull in 1960

John initially designed his own single hull shape, but as he moved into larger boats, he adopted hull shapes from the best international brands. This culminated in the mould for the Empacher eight used to build a new boat for St Stithians

The resulting boat (the first eight ever built in Africa!) was christened Cormorant by John’s beloved aunt, Dame Alison Munro DBE, who flew out from London for the ceremony There were many fabled eights from this variant including the second of type, AngloVaal for Wits Boat Club (WUBC) as well Strenue for KES/Eds, Isis for St Andrews and many others.

Advances in aerospace materials soon made monocoque construction possible: hulls where the skin itself carries the structural load, eliminating the need for an internal frame Lightweight cores such as Nomex honeycomb, sandwiched between layers of carbon or Kevlar, produced stiffer and far lighter boats

John quickly adopted these radical new technologies He used Nomex honeycomb as the core between a sandwich of carbon fibre of Kevlar, or combinations of the two Production rates catapulted again, and John managed to make several new moulds including Empacher and BBG shapes for singles, lightweight sizes for pairs and fours from Filippi and others, and a big heavyweight eight from the latest Empacher of the day recently acquired by the national squad

Of course there were also risks Standard practice in composite construction was to spray a forgiving gel coat into the mould first; to avoid air pockets and allow for easier finishing. Many builders also waited to spray the hull with its final paint finish only after it was released from the mould

John radically rejected both steps. In his fanatical quest for the minimum weight and maximum performance, he sprayed the final paint finish directly into the mould and laminated the outer layer of the sandwich (carbon/Kevlar skins) directly onto this Whilst still wet, he then laid the honeycomb core down before securing the entire structure under a vacuum bag to cure

This incredibly high-stakes, high-precision process meant that even one small part of the process failing could ruin the entire hull – a heavy gamble Working from an agricultural shed in Irene, John jury-rigged a set of heating lamps overnight to help accelerate curing He was known to sleep under the boat through cold winter nights to monitor the cure due to frequent power failures that would affect both the vacuum pump and the array of heating lamps

Once successfully cured, the second skin layer was applied to complete the sandwich, and the hull could be released from the mould – a truly nervewracking moment, with any sticking or trapped air pockets potentially proving catastrophic Hopefully, the only minor blemishes were on the fine bow or stern tips, which could be easily repaired and small cosmetic bow and stern tip paint trim applied Foredecks, stern decks and runner platforms were made using the same two-stage vacuum process, then trimmed and bonded to the hull to complete the monocoque

Shoulders evolved from wood to wood-faced with carbon to fully carbon components Fittings were drawn from the best international suppliers, while stainless-steel hardware like nuts and bolts were sourced locally Shoes first came in the form of track shoes from local sports shops, then, as demand increased, had to be imported (it’s tough to supply eight pairs of identical size 12 middle distance spikes on short notice!)

John rapidly mastered the new technologies and produced every class of boats (from singles to eights) in multiple configurations (although never a coxed pair!), steadily increasing his production speed Amongst many of the rigger suppliers, Neaves alone produced at least 72 different rigger configurations for his boats.

John’s scientific training made him an expert in hull shapes and hydrodynamics He developed several designs, including:

the J-type (with Phil Johnson) the E-type (Empacher shape) the M-type, based on the boat Swedish Olympian and heavyweight world champion sculler Maria Brandin brought to Roodeplaat for altitude training

He constantly sought input from South Africa’s highest performing athletes to get their feedback, aiming to be at the cutting edge of design, innovation and technology He was passionate about ensuring his boats delivered the highest possible performance, working with clients to push the performance envelope

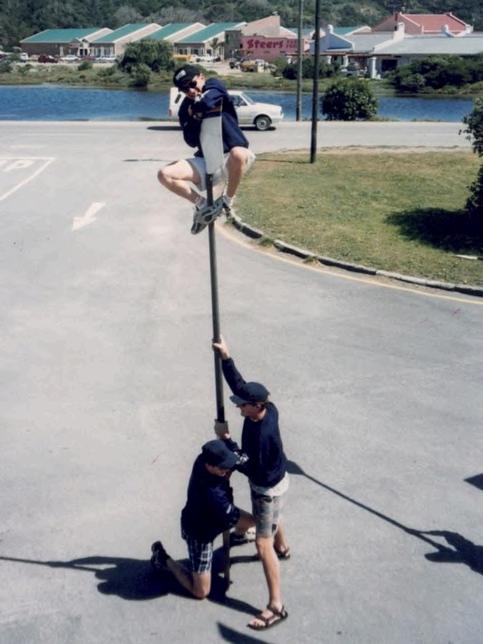

One of his most ambitious projects was the Viking eight, Odin: a sectionless eight (to reduce weight and increase stiffness) that had wide wing riggers that skipped the middle shoulder at each seat It was unbelievably advanced for its time, but was also so long that the trailer had to be modified to allow it to extend forward over the towing vehicle (something of this length would be illegal to tow today) Awesome for racing but not exactly practical (or safe) to transport, particularly when maneuvering around tight corners with lamp posts involved

Later boats also adopted the latest wing riggers as John continued to evolve in the pursuit of performance

Another standout of the era was AngloVaal, built for Wits Boat Club. Known for its exceptional stiffness and speed, it became one of the most admired boats John ever produced Other notable boats included Cormorant, of course, Strenue (Eds), Challis (for KES and named after Chris Challis’s son), Isis (St Andrews under Oxford Blue, Martin “Machine” Kennard)

As John’s business grew, so did his workspace. From the garage loft, he moved to a lean-to “pair oar bench,” then to Mountain Hiney Farm in Irene, first occupying the large shed and later an even bigger one Finally, he relocated closer to home to “the plot” on End Road, also known as “the office”

Key staff over the years included Philemon, Lucas, and David, along with short-term rower assistants such as Rod McKinnon, Andy Mac, and Wayne Sevrin

Precisely how many hundreds or thousands of boats John made is unknown, but their impact on South African rowing has been profound. John’s boats have probably carried nearly every South African Olympian at some point in their careers and have probably held every single major South African rowing record

John Price, who knew John Waugh well, reminisced that in the 1990s, when South Africa hosted the African Championship, the Egyptian crew complained that they had been allocated the John Price (a local John Waugh boat), while the SA crew had the Empacher South Africa offered to swap and consequently won while setting a new course record.

The supply of John Waugh boats underpinned the explosive growth in South African schools rowing, which grew into a three-day regatta with endless racks of boats – mostly John Waughs, hundreds of them! John would proudly mark the results sheets each year, highlighting the winners and course records won in John Waugh boats. For many years it was almost a clean sweep at both seniors and schools’ levels, from first eights down to first singles, and throughout much of the field too

John’s youngest son, Geoffrey, was born in Sandton in August 1984, shortly after John’s long European study tour through Empacher and other boatyards

Unsurprisingly, both sons went on to win the Youngest Oarsman Trophy at Wemmer Sprint: Robert in 1986 (age 11) and Geoffrey in 1994 (age 10)

John proudly watched Robert row for Wits in the 1995 Boat Race final. Despite a fierce race, Wits was ultimately beaten by Rhodes (with a magnificent photo taken by John!) In the Wits boat were: Sean Kerr (cox), Iain “Iron” Macualay (stroke), Guy du Sautoy, Richards Ehlers, Vaughan “Magnum” Adnams, Tristan Bergh, EJ Scott, Rory Hudson and Robert Waugh (bow) The Rhodes crew comprised: Andrew Grant (stroke), Andrew MacLachlan, Luke Hartley, Rich Steele Grey, Barry Banks, Gregor Calderwood, Richard Dickerson and Warren Bolttler (bow)

Over the years, John was also a keen Viking and later a member of the Vikings Beefeaters Society Outside of rowing, he was a passionate collector of classic sculling boats, vintage Mercedes Benz’s, fine English antiques and silver And grandsons (amassing a total of six)

In 2011 John and Barbara survived a violent home invasion from which John never fully recovered They left their beloved thatched house in Thelma Avenue, but found new happiness at Heritage Hill where they lived together blissfully for many years

John passed away peacefully on 18 July 2018 with family at his side and his sixth grandson having just arrived that very same day

John’s contribution to South African rowing is immeasurable His boats supported the rise of school rowing, dominated SA Schools and Champs podiums for decades, and helped build the foundation for South Africa’s modern international success

His wooden single remains on display at St Alban’s College, where his memorial service was held (and both of his sons were educated). His ashes were scattered at sunset on the Thames near Twickenham Rowing Club and on the waters of Roodeplaat Dam

A collection of his wooden singles is displayed at the Blades Hotel, on the banks of Roodeplaat Dam, courtesy of Bruce Turvey, Paul Backes and Ramon DiClemente, including a wooden Stӓmpfli akin to that used by Olympic champion Pertti Karpinnen, and a custom three-section Max Schellenbacher single*

Further memorial items include:

a London-style blue plaque at Roodeplaat Rowing Club

a brass plaque marking his favourite rack

a memorial bench under the trees overlooking the dam (as Barbara always wished for) trophies at SA Schools Champs named in his honour (including the John Waugh Trophy for Boys U14 Octuples, Waugh Trophy for Boys U14 Single Sculls, and the John Waugh Plate for Girls U14 Octuples)

the “John Waugh Rock the Boat” regatta series launched by Olympic champions James Thompson and Matthew Brittain

Outside of South Africa, St Edmund Hall, Oxford, has an eight built by John. A container shipment of John's boats was also exported to Ireland and several still appear on the Thames Tideway His work has been featured in Forbes Magazine and documented on Wikipedia

Above all, John Waugh was a loving husband and father to his family, and a master craftsman whose boats shaped a nation’s rowing heritage.

Barbara lived a full and vibrant life at Heritage Hill, where she tended her beloved garden, joined her favourite clubs, and was cherished as the community’s English Rose (using the very administrative and organisational skills, vital to John’s boatmaking endeavours, in the clubs she joined). She travelled far and wide to visit her scattered family, carrying with her the wry smile and the spark of mischief in her eye that made her so loved. A devoted wife, mother and grandmother, she and John left behind three children and six grandchildren across England, Australia and beyond, all of whom carry their memory with deep affection.

This regatta recap will be different to any of the others that came before, because, for once, I was in the boat Will my experiences add some flavour to what is essentially a straightforward retelling of results? Hopefully

I’ll start the personal reflections right here: rowing is hard To get fit and strong as quickly as possible, training must align with school, work, sleep, relationships, and friendships It's relentless! I had always appreciated that rowing demands integration with every facet of one’s life, but I’d forgotten what it meant to fully embrace that In my role as “emergency fillin” for the 2025 Wits Boat Race men’s squad, I briefly – if you can call six weeks of punishing myself “brief” – felt the pressure of choosing between rest and training for the sake of eight other people chasing a goal weeks away from realisation I found myself taking naps between classes in the back seat of my car. I found myself wolfing down serving upon serving of pasta, much to my family’s dismay I even downloaded Strava The hard work and sacrifice excited me, reminding me about what I loved about this sport and about Boat Races: the community

This year’s Universities’ Boat Race, hosted on the Kowie River in Port Alfred by Rhodes University, took place from the 11th to the 13th of September. The weather leading up to the event was incredible, with warm temperatures, clear skies, and light winds Heats day, predictably, had none of that Judging by how wet my shoes were when I went to retrieve them from the balcony, it had rained overnight It was cold too Our shake-down row that morning was disrupted by gale-force winds between the Shipwreck Corner and the finish line Inside the Halyards breakfast buffet (highly recommended for people who suffer from tapeworms – we ate enough toast to cause a grain shortage in the Eastern Cape), the atmosphere was only slightly less frosty No one spoke Whenever I made eye-contact with one of the opposition rowers, their expressionless stares reminded me that we were about to watch the greatest test of strength on the rowing calendar I had never been keener

For the uninitiated: Heats Day is the most crucial day of the regatta Each crew races a time trial down the course, from the old Men’s Start, via the dogleg and old Women’s Start, through the Killing Fields, around Brierley’s Bog, through the Bay of Biscay and Shipwreck Corner, under the bridges, and all the way to the finish line In all, the distance is about five-and-a-half kilometres, although the best coxes with the best lines and best water conditions tend to shorten the course to around five kilometres

The crews are ranked according to their race time, then sorted into two-boat finals from the fastest to the slowest, with the first two (in the A-final) racing for the gold medal, the next two (the B-final) racing for the bronze medal, and so on Crews cannot change positions beyond their final, and so a successful regatta hinges on a solid performance during the Heats.

The first heats of the weekend were the Women’s B 8+ As has become tradition, the University of Pretoria recorded the fastest time of the trials by some margin They were followed into the gold medal race by the University of Stellenbosch, who are enjoying a successful season and showing immense strength-in-depth The Universities of Johannesburg and Cape Town finished third and fourth, respectively, qualifying for the bronze medal race. The University of the Western Cape ‘B’, another promising rowing program, finished fifth, beating UWC ‘C’ Nelson Mandela University put together a composite crew which, although qualifying fourth overall on time, rounded out the qualifying in seventh place

Conditions deteriorated as the day wore on, although the tide rushing out kept times quick. The Men’s Bdivision races largely stuck to the form guide

Pretoria’s “Beast Crew” and UCT’s “Pelican Crew” made up the Afinal, while the “Boets” from Stellenbosch, the University of Johannesburg, and the University of the Western Cape arranged a date for the bronze medal. There was drama in the early phases of the heats: UWC lost their skeg and found themselves turned perpendicular to the course, which, thankfully, had no effect on the result, as a UWC composite crew (with Wits, UJ, and Rhodes all sending athletes) was ineligible to race a higher final, and UCT ‘C’ was excluded

As the Women’s A crews launched, the race conditions were probably the worst they could possibly be The course had stretches of rolling waves more suited to Jeffrey’s Bay than the Bay of Biscay: the Boat Race challenge facing these athletes, already intense, now verged on formidable. The crew from the University of Pretoria (which I would argue is one of the best crews ever assembled for a Boat Race) steamrolled the opposition to win the time trial, beating runners-up UCT by over two minutes, and cementing their status as favourites for the gold medal Stellenbosch and a resurgent University of the Witwatersrand prepared themselves to battle for bronze, while last season’s silver medalists, the University of Johannesburg, qualified for the C-final, where they would face UWC

Both lower finals were all-Eastern Cape affairs, with Nelson Mandela University facing Walter Sisulu University for seventh, while hosts Rhodes would race the University of Fort Hare for ninth place.

The last of the heats saw the Men’s A-crews take to the water The University of Cape Town beat Pretoria by a mere seven seconds to set up a tantalizing gold medal race – perhaps less tantalizing was the bronze medal match-up, in which an unbelievable Stellenbosch crew (which narrowly missed out on the top two) would line up against a University of Johannesburg crew which qualified three-and-a-half minutes adrift of their opponents Wits would face Fort Hare in the C-final; Nelson Mandela University would take on UWC for seventh Rhodes and Walter Sisulu University would clash for ninth place

As the sun (finally) shone again at midday on Friday, the first finals of the regatta were raced Nelson Mandela University’s composite crew dominated the C-final of the Women’s B-division, beating both UWC crews by a three-minute margin The bronze medal in the Men’s B-division went to Stellenbosch, who beat UJ by just under two minutes The first Adivision final, the Women’s 9 & 10 race, saw Fort Hare beat Rhodes by a minute, while the corresponding Men’s final saw Walter Sisulu beat Rhodes by a minute-and-a-half, closing out the day

UJ dominated their final against UWC to finish fifth, while Fort Hare came back from a length down to beat Wits to fifth place in the Men’s event The University of Pretoria won their first gold medal of the weekend in the Women’s Bdivision event, beating Stellenbosch by five lengths UCT narrowly came third, beating UJ for the second time, after the race had to be re-rowed following an appeal the previous day. The Men’s B-division title also returned to Pretoria, after the TUKS men easily beat UCT to close out the division

Excitement built on the bank in anticipation of the A-division medal races. Each corner was crowded and buzzing, adding to the feeling that we were about to witness history Neither bronze medal race in the A-division was particularly close: Stellenbosch’s women beat Wits by just over two minutes, while the Stellenbosch men beat UJ by just under two minutes

Oh well The gold medal races would have to deliver the excitement, then

Finals Day (during which 11 medals would be awarded in several closerun races) began with a series of tight finals in the non-medal races WSU beat NMU for seventh place in the Women’s A event, while NMU beat UWC in the Men’s equivalent

In front of a fiercely partisan crowd, the TUKS women won the A-division by the largest gap of the day, beating UCT by nearly twoand-a-half minutes and extending their winning streak into its midteenage years The faithful crowd, desperate by now for some excitement, were finally repaid for our patience as we watched UCT overturn a two-length deficit at Ladies Corner to beat an unbelievable Pretoria crew – for a third consecutive year – by four lengths to claim the Men’s Boat Race title

September to November marks the opening half of the school rowing calendar And so far so good! A massive thank you to everyone who has made the incredible regattas so far, possible In Gauteng, there has been some super exciting racing across all age groups and divisions The Western Cape is also in full swing, as their calendar format focuses on their preparation for the big Schools Boat Race in December Eastern Cape is also a province to keep your eye on, especially with the return of a cult favourite regatta –Settler Sprints

and turns Clarendon came out on top in the girls 1st Quads, trumping DSG St Andrews College proved triumphant in the coxed and coxless fours, beating Grey and Selborne At the epic Settler Sprints Regatta, Selborne were dominant in the Open scull, winning the 500m and the 3000m events Overall, a strong start for the Eastern Cape schools, especially as the Schools Boat Race looms over the horizon in Port Alfred

of school girl rowing by winning the 1st Quad, Double and Scull at the St Stithians Regatta and Gauteng Champs St Stithians Girls are a force to be reckoned with this season, winning the quad at the St John’s Regatta At the same regatta, St Dunstans won the scull, and St Marys won the double St Benedicts claimed the boys overall, and St Andrews won the girls overall club

In the Western Cape, the big rivalry between Bishops, SACS and Rondebosh heats up again At the Cape Peninsula Champs on the 18th and 19th of October, the three shared the spoils in the fours, Bishops winning the quad, SACS winning the coxless four and Bosh winning the coxed four Rondebosh picked up the gold in the eight, followed quite closely by SACS in second and Bishops in third They went at it again at the Western Cape Champs on the 25th and 26th of October, with the 1st 8+ results staying the same, but a turn around for Rondebosh winning the quad and Bishops taking the coxed four On the girls side, it’s a two club clash between PGRC and Somerset; PGRC won the quad at Cape Peninsula while Somerset won at WC

The Eastern Cape has begun ramping up its regatta season with the Head of the Z Regatta on the 27th of September An epic 35 km boat-race-style regatta on the Zwartkopps River, where Clarendon, DSG, Grey High, St Andrews and Selborne all competed in winds, sandbanks

Gauteng has had a strong spread of regattas so far, culminating in Gauteng Schools Champs and Africa Champs There has been interesting developments in the boys 1st 8+s, with St John’s College claiming gold at the St John’s and St Stithians Regattas in September and October, with KES and St Stithians Boys not far behind them The small boats have been a challenge for the blue side of Houghton, with their red neighbours proving quite capable in the pairs and sculls, winning both events at the St Stithians Regatta. The Red Army’s kept up the pressure at the highly anticipated The Mile Regatta, winning the 1st 8+ against Saints Boys, while hosts St Andrews beat Saints Girls in the 1st 4x+ St Benedict's first full outing came at the Gauteng Schools Champs, where they flexed their dominance, winning the eight, coxless four, and pair St Andrews Girls are still carrying their momentum from the previous season, cementing their place as the top girls program in the province, scoring the hat-trick of

The recap would not be complete without mentioning the racing at the African Continental Championships, hosted over the same weekend as Gauteng Schools Champs African Champs was a phenomenal event, with a number of school athletes representing the country. Matthew Keus (SJC) raced in the Senior Men’s Quad alongside Olympian Chris Baxter, and finished second to Egypt Gabby Manson (SASG) won the Junior Women’s Scull, and fellow St Andrew’s teammate Jade Burnand won the Under 23 Women’s Scull South Africa also won the Junior Men’s Double, composed of King Edward boys Andrew van der Zee and Matthew van der Vyver The medal pile was topped with a silver medal performance in the Junior Women's Double, Robyn Moore (SASG) and Hannah Webb (HRS) Overall, school athletes contributed to 7 of the 11 medals South Africa won at the regatta

Hello!

Anna from Viking here! You may have seen bits of my commentary in previous issues of The Bowside, and hopefully you found them interesting, as this is now my official bid to become a regular writer!!

Though it has been a flurry of school regattas since September, it’s awesome to see masters rowing gaining momentum. More and more masters rowers are diving back into competition for the thrill (and they’re pretty great at it!) Juniors might be interested to know that masters don’t just race each other, they also measure themselves against junior times!

Having a look at the St. Andrew’s Indoor Regatta (13 September)

Thirty men’s masters rowers from Category A (minimum 27 years old) through to Category E+ (55+ years old) raced 1000m individually Leading the pack was Luca Bezzi from Viking, who won Category A (and fastest overall time) with a quick 3:084

In second place for overall time was Category C’s (44-50 years old) champion Thomas Van Der Zee from Old Ed’s who clocked in 3:16 2 Meanwhile, we had a tie for thirdplace between Category C’s silver medalist Andrew Miller (also Old Ed’s), and Category E’s champion Philip Da Costa from Ravens, who both achieved exactly 3:16 8!

The oldest men’s entry, Keith Bradley from Wemmer Pan finished with a respectable 4:01 3 and was actually faster than four of his younger counterparts. There were lots of masters’ entries throughout all the age categories, meaning the older masters rowers showed the whippersnappers what’s what

On the ladies’ side, we had 14 entries across Categories A to Category D (51-55 years old). Darcy Carpenter from Old Ed’s won Category A in a time of 3:527 – her first indoor race after only four months of rowing. Category D’s Dimitra Sikiotis from Ravens, claimed the fastest overall lady in a time of 3:520 (faster than seven of her younger counterparts!)

Two brave souls, Steven Wilkins and Pavel Dabrytski, both from Viking, opted to face off against Seniors in the 2000m rather than the 1000m, winning silver and bronze with times of 6:491 and 6:52 2, respectively Both are 13 years older than 25-year-old Seniors champion Sebastian Prince from Old Ed’s who won in 6:473!

In case you missed it, masters and seniors events are now available at school regattas Sculls are always the first event of the day, and then there are certain 2x/- and 4x/events available I’d like to give a shoutout to the dedicated competitors Terence Temlett from Ravens, and Pavel Dabrytski from Viking, who compete in virtually every available sculling event Their support for the school regattas is inspiring Keep an eye out for them at the next one!

Each regatta typically sees 10-20 entries from masters, with entries in both 1000m and 2000m Terence Temlett remains undefeated over 1000m in the masters 1x across all regattas, with other rowers beating him over 2000m – Rob Riccardi from Ravens at St. John’s Regatta (27 September), and Anna Fisher from Viking at St. Stithian’s Regatta (18 October), who respectively achieved third and first place in their senior 1x events

One unforgettable sculling race was the masters 1x of St. Mary’s Regatta (4 October) – it was tip defying, adrenaline-fueled, and more about surviving than competing (unless you’re Terence, who managed to sub-5 whilst the rest of us fought the tough conditions to finish the race) My home ground is a tidal river, often with strong winds from typhoons that blow by the area, and I can confidently say this race was one of the most harrowing experiences of my rowing career! I stuck to 18=20spm for fear of tipping, finishing in 6:35 29 for 1000m (2:30ish slower than usual!)

Moving onto crew boats, the Viking men’s quad with Luca Bezzi, Sean Cloete, Sean Croxford, and Gregory Kent (Category B, average age 36–42) came first in their heat, and third overall in a time of 3:5998 against JM15A 4x at the St. Benedict’s Regatta (20 September). Meanwhile, a composite ladies quad from Viking, VLC, and Old Ed’s with Anna Fisher, Tracey Goodwin, Sam Johnson, and Karen King (Category D, average age 5025) matched the high standard set by the Viking quad and came first in their final against JW19 2nd 4x+ in a time of 8:32.44, gapping second place by 38 seconds!

It was exciting to see a number of masters competing in the senior events for The Mile Regatta (11–12 October), with many advancing to the finals before ultimately facing crews from the University of Pretoria Well done to Old Ed’s, Viking and VLC crews who showed fighting spirit in the Senior finals across M4-, M4x, and W4x! In the masters events, the doubles had a wild ride; what began as a helpful tailwind morphed into a fierce headwind halfway down the course Sam Johnson from VLC and Karen King from Old Ed’s raced against Jacqueline Lundberg and Dimitra Sikiotis from Ravens,

emerging victorious to claim The Tusks trophy Rob Holness from VLC and Terence Temlett from Ravens then went head-to-head against Andrew Craig and Tom Price from Old Ed’s in the finals, with Rob and Terence ultimately winning The Horns trophy

Masters came out in full force for the St. Dunstan’s Regatta (25 October) with the largest contingent of the school regattas thus far. Racing in every available category: M1x, W1x, M2x, W2x, M4x, W4x The 2x events were riveting, with both ladies and men facing off against the younger JM/W15 2x competitors Thanks to the high number of entries, everyone had their own heats Out of six ladies’ masters 2x, three clocked the fastest overall times: Sam Johnson from VLC and Karen King from Old Ed’s (again!), Toni Wadley and Elmari Verhage from VLC, and Alexa Marketos and Tracey Williams from VLC In the men’s masters 2x, five masters crews challenged six JM15B 2x boats, and all five finished at the top of the overall times The fastest boat was rowed by Rob Holness and Ian Johnson from VLC, who crossed the line in 3:51.73. In fifth place, we had Wig Dreyer from Viking and Andy Schlict from Wemmer Pan (Category G, average age 67) with a time of 4:2114 (they beat the next boat by 19 seconds!)

Kudos to all our masters for showing us how it’s done I hope you enjoy my regatta recap and stay tuned for more updates in the next issue!

When and where did you start rowing?

I started rowing at General Smuts High School, Vereeniging during Standard Eight During Standard Nine, our crew went from the 4th to the 1st division in one season.

When was your first time representing South Africa internationally?

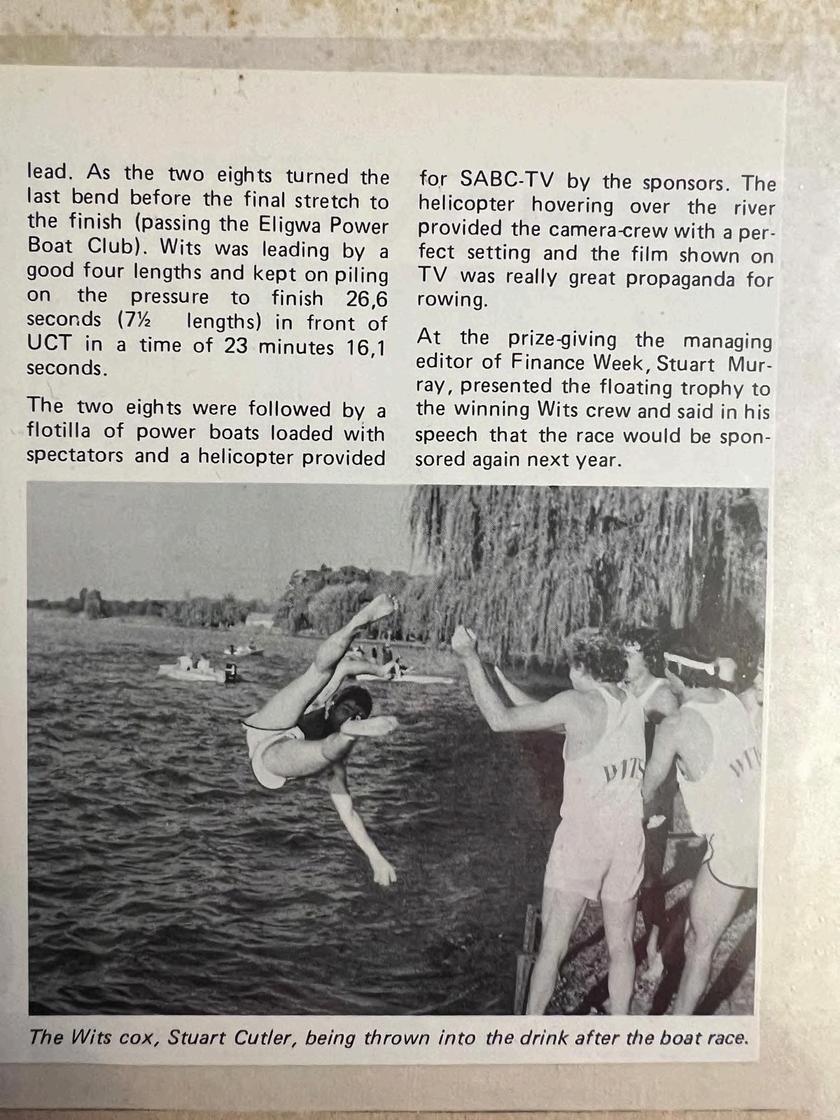

My first international trip was during 1980 with the Wits Crew to The Henley Royal Regatta We raced as WUBC in the Ladies Plate where we beat Harvard in the Semi-final and lost to Yale in the Final.

We then raced as Trident at the Bedford Regatta where we didn’t lose a race

After that, we went on to race as Thames Rowing Club at the British National Champs on Holme Pierrepont outside Nottingham where we won a Bronze.

The crew were awarded Springbok Colours upon our return to SA

Our Cantabrigian crew (1984):