We find ourselves in the third quarter of 2025: The start of School Rowing Season is upon us, University rowing season is on its way out, and we’re all a little confused about how quickly the year has gotten away from us You’d think the run club trend would’ve helped everyone keep pace (not that I run)

This third issue marks a milestone. When I first sought advice about this endeavour from various generations of WUBC alumni, a lovely ex-rower (who, despite being incredibly busy, always seems to have a moment to spare me some sensible advice) told me that his crew had tried something of the sort in the 80s or 90s Despite a lot of initial buzz, it had, sadly, fizzled out after 2 issues, “so all you’ve got to do is aim for 3!” And here we are at the intersection between life and rowing (how dramatic!)

While extensively time-consuming, and torridly all-consuming, this magazine is not our job, and getting this together in the margins of our already bursting-at-the-seams busy lives is a mission and a half. And so, yet again, I must express my immense gratitude to all our contributors and supporters! Most especially to my friend, Jenna, who has so kindly volunteered to edit, and taken the time to dabble in some brilliant copyediting in the gap between attaining a distinction in her MPhil in

Theoretical and Applied Linguistics (from Cambridge, an institution she describes as “terrific” ie invoking terror), and the world of work She has done a decent job at it, and I might ask her back (I have already offered her a – currently unpaid – recurring role and hope she will take me up on it ) I have admired her intelligence and diligence since we met during the final year of our undergrad and secretly feel that she is much too cool for me

All this to say, Jenna’s presence meant that I could better shape this edition into what we are envisioning for The Bowside over the longer term (having two copy-editors who are not me is, unsurprisingly, quite helpful) That is, a lot more narrative styling, an emphasis on distinct voices for writers allowing their personalities to come through, delightfully packaged information that is profoundly, fundamentally focused on connecting with our readers. As we develop this magazine, our writers improve, and so does our editing. In addition, we’ve taken some more advice from real-life editors and designers and revamped our design process significantly; it’s gone a lot smoother and there’s a strong chance we’ll be sticking with and refining this new process.

I hope this issue inspires the rowers ending their high school careers and those entering their final season of high school rowing not only

to keep at it during their university years, but also to grow with the sport through their early working years, into masters, and on through retirement – like many of the fantastic lifelong rowers I’ve met over the past year.

Now, allow me to commit a terrible sin, like a mother verbalising that she has a favourite child (thankfully our writers are adults so they can write me strongly worded emails, rather than paying for years of intensive therapy):

Our best work this issue lies in Driving Practice’s submission by Liam Fortuin If you read nothing else, read that

Some other honourable mentions:

In Keeping it Simple with Saloojee, Moh did a great job letting his voice come through in the true-to-column-name advice he gives.

Part 3 of Andy Pike’s 1980 Henley tour leaves us with some good life lessons.

Lifa’s Corner, with a special thank you to Dieter Rosslee, for patiently working with us to turn this into another worthwhile read.

The Umpire Strikes Back for a lively conversation with Gaynor du Toit and Anne Killian about Umpiring both universities’ and schools’ Boat Race.

Enjoy issue 3, learn the dam traffic rules, wave at the jetty ducks, warm up for your sessions (looking at you, masters), and – as always –remember your sunblock!

shanks for kindly g e Kowie River course from his killer book (that I’d recommend all the matriculating rowers read over the December holidays, before starting university): Pangolin Crew.

Every now and then, I get the chance to sit quietly on the bank at Roodeplaat and just watch Crews gliding across the dam in perfect rhythm, a truly beautiful thing And, while I’m a self-confessed rowing nerd who loves debating what makes an Olympic champion, those quiet moments remind me that rowing is so much more than a sport It’s a floating classroom A masterclass in life

As we kick off a new season, I wanted to share a few thoughts especially for the new parents, their kids, and the coaches and teachers shaping their experience.

If you’re just starting out, strap in. Rowing is tough It demands early mornings, many aches and pains, many many blisters, and a lot of your time But trust me, the rewards far outweigh the sacrifices.

From the very first camp, your child will be expected to wake up before sunrise, carry and clean boats, and, eventually, push off from the safety of the bank for their first solo row.

In the process, they’ll learn some of life’s most valuable lessons: resilience, commitment, and teamwork And you, dear parents (whether you like it or not), will be pulled into the cult You’ll become “rowing parents”. Embrace it. As John Bellis, Tow Master at one of our schools, once said: “In this sport, you get what you give.” (He may have stolen that from the New Radicals) And just as “rowing parents” are pulled into the sport, the rowers themselves are often pulled further along its path, into university

On a serious note, yes, rowing takes time at university. But being part of a club is one of the best ways to make friends and find your people Parents, if you’re worried about academics, don’t be Universities, including overseas institutions, actively recruit rowers because they know what we know: rowers are disciplined, resilient, and know how to go the distance. And as athletes grow, many discover there’s another way to give back, finding themselves at the other end of the oar

For those finishing up with school rowing, it’s always a bit strange not heading off to preseason camp After five years, it’s almost hardwired into you But don’t worry, you’ve been well prepared for what comes next

Some of my best memories are from rowing after high school Like racing in the Wits Beight, where our tradition was to swim in whatever waterway we’d just raced in if we won (there’s more to that story, but I’m the President now, so you’ll have to ask Charles Thompson for the details), or fundraising with Old Eds – with everything from Tom Price’s Once Were Warriors bus-trip to the infamous Eds Full Monty crew (for the full story, speak to Mr. McDonald or Mr. Turvey).

Rowing’s educational value doesn’t stop when you ‘hang up your oars’ Many young athletes transition into coaching, and so their learning continues Coaching teaches patience, empathy, working with various personalities, and leadership – working hard to foster an environment where athletes thrive Never underestimate the power of encouragement and the role clubs play in shaping young lives

Let me leave you with two stories that show where a rowing “PhD” can take you Because rowing’s lessons don’t end at the water’s edge, the same values carry through, whether you become an Olympian or a corporate leader

The first story is about Imogen Grant. She’s the kind of person you want to hate – Olympic gold medallist, medical doctor, MBE But then you meet her, and she disarms you with humility and genuine interest in others Her journey wasn’t smooth; she battled injuries, intense academic pressure, and missed an Olympic medal by 0.01 seconds. Instead of quitting, she used this as a learning opportunity. She adapted and came back stronger. That’s rowing. When you fall short, you look inward, take ownership, pick up the pieces, and grow.

The other story comes from a local legend, Donk, from my Wits days Always rowing, Donk gave 110% to the sport When it was time to “get a real job,” someone asked him what he’d say in an interview His answer?

“I’ve spent over 12 years waking up before

sunrise, training hundreds of hours per year, working with teams of equally crazy people, and doing it all for no money, just the love of the pursuit Now imagine what I can do for your company”

Today, he’s the COO of one of South Africa’s major companies

Rowing teaches you how to show up, how to push through, how to work with others, and how to become intensely reliable to yourself and your crewmates. It’s a sport and a lifelong learning journey And we’re lucky to be part of it

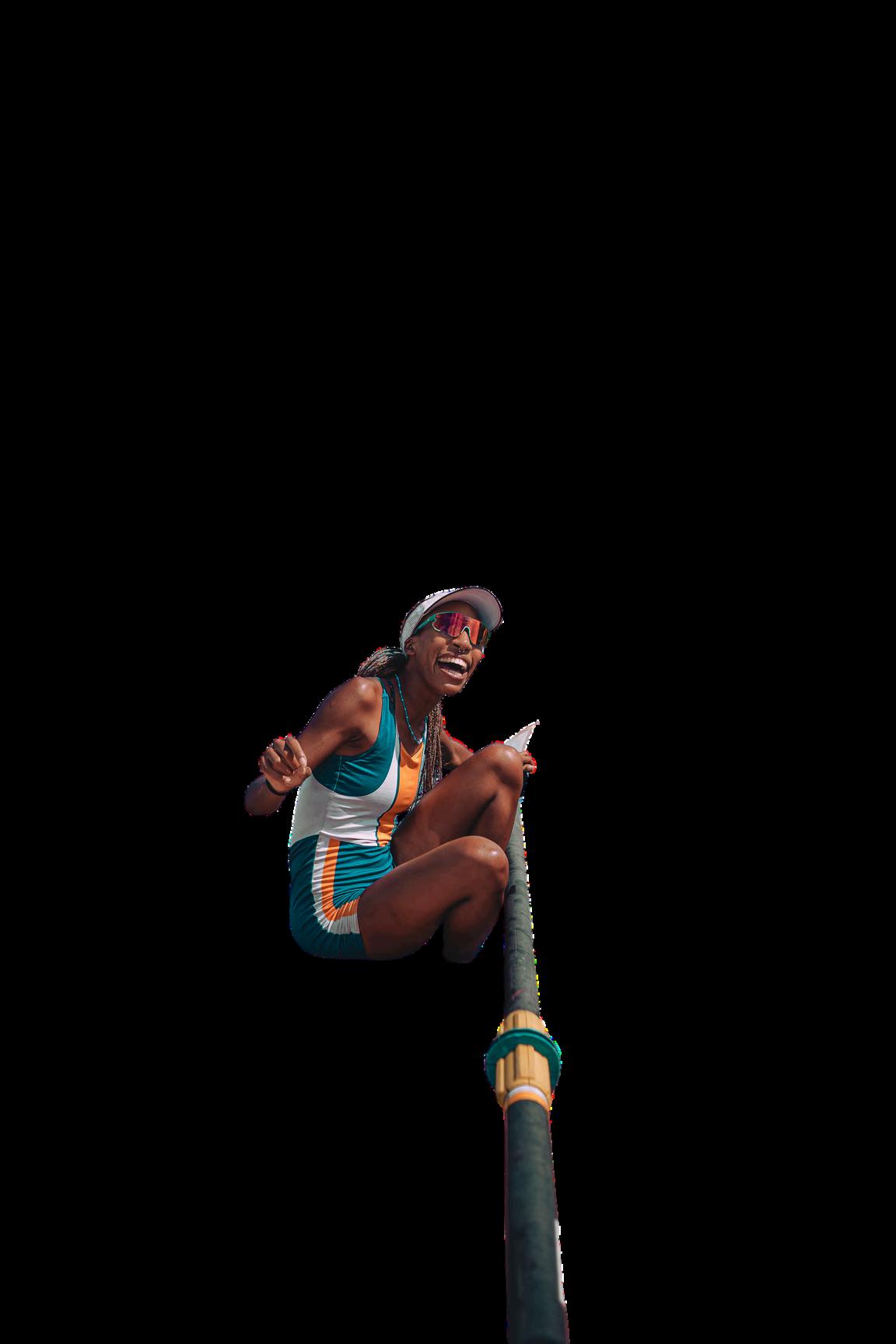

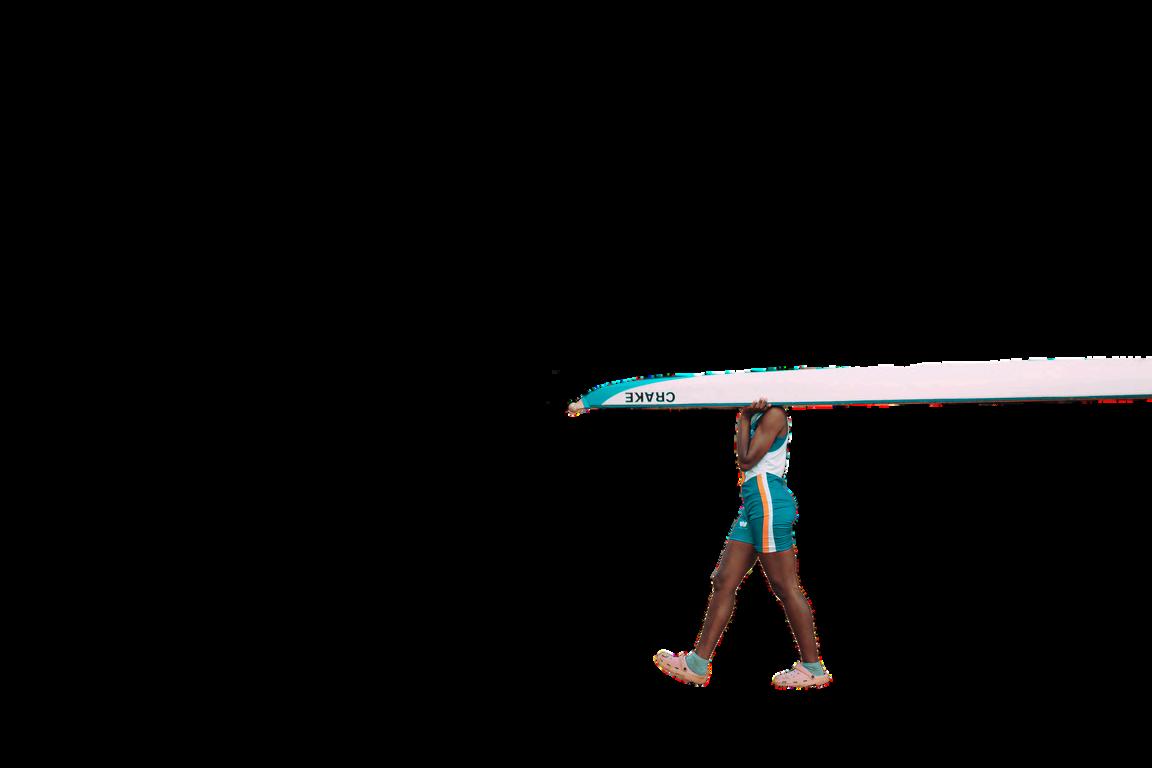

Over the past few weeks, I’ve had the privilege of speaking with female rowers from Rhodes, UWC, UCT, Wits, and Madibaz From novices who learned to swim so they could row, to seasoned athletes who’ve raced at Boat Race and beyond, one thing is clear: Rowing is a space where women are building something powerful. If you’ve seen a group of women with blistered hands, sock tans, and a quiet fire in their eyes, you’ve already

witnessed the spirit of women’s university rowing in South Africa. It’s a sport that demands focus, resilience, and a deep connection to both self and community. These women show up not just to race, but to grow together

This process reminded me why I agreed to write this column. These passionate women, and those who have come before them, deserve to have their voices heard and stories told.

Rowing is often the first place you feel truly seen. It offers a space to grow, to belong, and to be part of something bigger than yourself, whether you’re an elite athlete or have never touched a boat

before One novice that I spoke to, from Madibaz, told me how she placed second in the USSA 500m Indoor Sprints, before she was water-safe, and it inspired her to take the next steps into a boat Her club helped her find a learn-to-swim program, and now she’s confidently rowing on the water. These teams are defined by this unbridled support.

Some common themes in all the women’ rowing stories seem to be friendships forged in the erg room, the laughter during early morning training, and the deep trust built in boats. “Rowing hurts,” one athlete said, “but so does being away from the crew.”

I find the rise of women in leadership roles especially exciting At many universities, women are chairing clubs, managing logistics, and shaping the culture. From organising camps to sorting race-day snacks (a sacred duty, apparently), these women are proving that legacy is built through examples of genuine leadership. Shannon Reid (president of Wits Rowing Club and the backbone of its revival) is a standout example. This year, she served as the Rowing Manager at the Student World Games, and so represented South African university rowing on an international stage

Although we now have new female leadership across the clubs, the women who have represented their universities in the past still have an important role to play By sharing their stories through alumni network future crews, by setting th keeping the legacy alive!

Of course, it’s not all smooth gliding: Towing boats, long travel times to dams, and constant repairs plague every club. Equipment is often borrowed or shared, and fundraising is a challenge when everyone’s already stretched thin Rowing isn’t cheap, and that financial barrier keeps many from even trying

There’s also a lack of clarity around how to progress from university rowing to national teams. Athletes want to dream bigger, but the pathway’s murky As one rower put it, “You work so hard to get to Blues and Grudge crews, and to win a Boat Race, but the question is almost always ‘What next?’” Maybe a challenge for Rowing South Africa is creating a performance pathway, where everyone can stay informed on the standards required to represent the country

Despite all this, the women I spoke to just keep showing up For each other, for their clubs, for the sport They’re rebuilding clubs from scratch, creating inclusive spaces, and proving that rowing can be a place for anyone, regardless of background, body type, or athletic history

For these women, rowing has improved their academics, boosted their confidence, and opened doors they never expected. It’s given them life skills, leadership experience, and a second home.

Rowing is for the girl who wants more than just a sport. It’s for the girl who wants to feel strong, seen, and supported. It’s for the girl who doesn’t mind a few blisters or a sock tan if it means finding a crew that lifts her up and pushes her forward. You only need to follow these university rowing clubs on Instagram to see what I am talking about

No matter what crew you were in at school, university rowing offers a space to grow your confidence, sharpen your focus, and connect with a larger community that celebrates every version of you. Join a club, and you’ll discover just how far you can go, on the water and in life

Thank you to every woman who took time out of her busy schedule to chat rowing with me Your stories are the heartbeat of this column. To the captains and presidents of university clubs: I encourage you to connect, collaborate, and share ideas on recruitment and retention Together we’re growing the future of South African Rowing

In rowing, the blade (or oar) is a critical component of performance. It’s what turns your effort into boat speed (and, you know, let’s you actually move the boat forward) serving as a biomechanical lever and hydrodynamic interface between athlete and water, ie both a lever that transfers your power and a paddle that interacts with the water to push you along

Blade technology has evolved thanks to advances in physics, physiology, and materials engineering Today, rowers and coaches are faced with a range of blade shapes (with distinct performance characteristics) such as the Concept2, Fat2, or Smoothie2 Vortex Edge (VE)

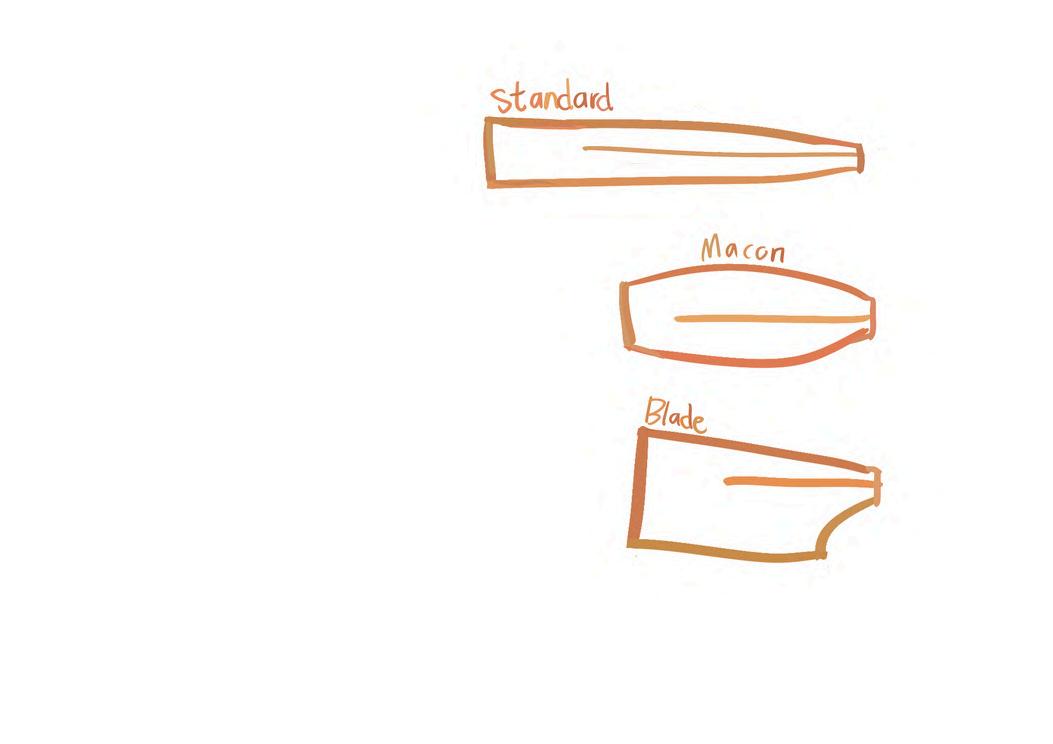

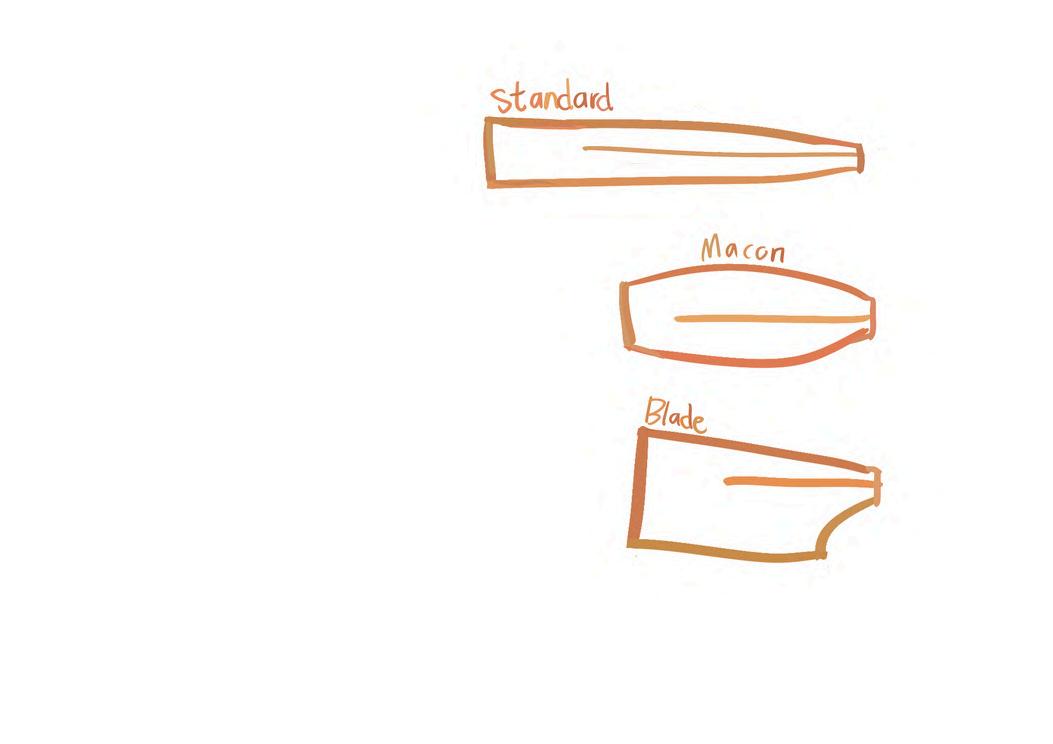

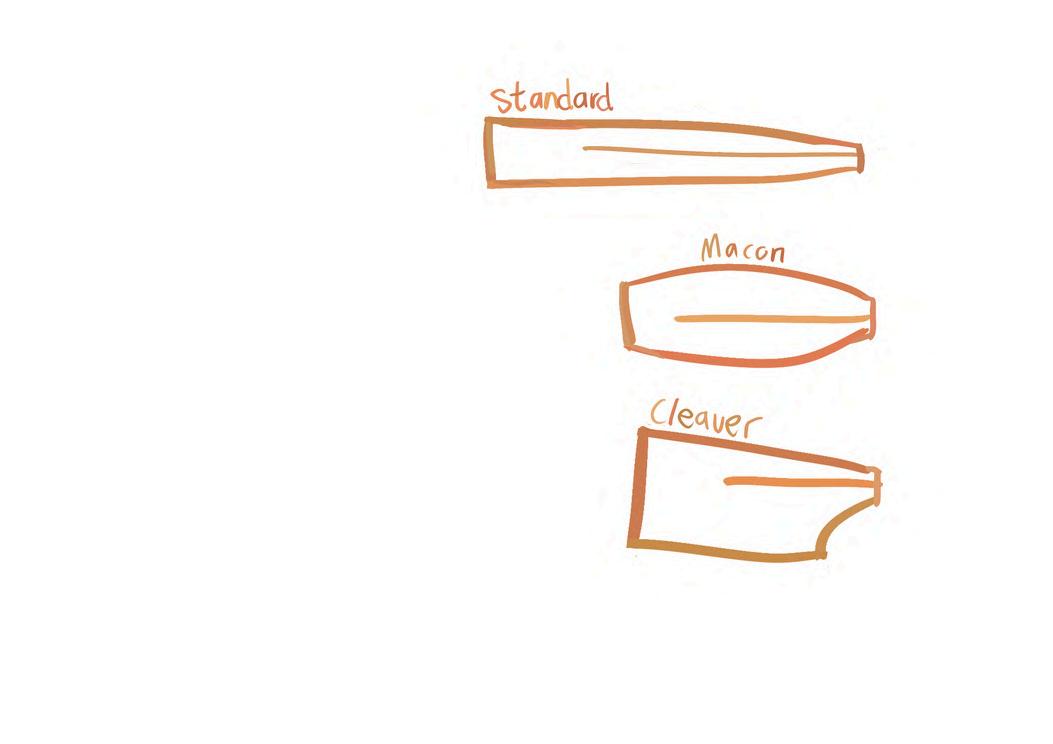

Early days – Standard Blade: Oars were long, thin, and made of wood They worked, but were heavy and inefficient by modern standards (Nolte, 2011)

Understanding the science behind these choices is essential for optimising racing and training outcomes, in order to choose the blade that suits your strength and technique

1950s – Macon: Aka the “spoon” or “tulip” blade This blade was wider and shorter than its predecessor, the “square” or “standard” blade It marked a significant hydrodynamic improvement, allowing for better water displacement without increasing drag, meaning rowers had a smoother and more efficient stroke (Baudouin & Hawkins, 2004)

1992 – The “Big Blade": Concept2 introduced the “Big Blade”, also known as the Cleaver or Hatchet It has a larger surface area with a more vertical edge for faster and more stable water-anchoring (Nolte, 2011)

Since then: Blade shapes have become more specialised to cater to different race types and physiological demands.

The oar acts as a first-class lever, where force generated by the rower is transferred through the gate blade (Kleshnev, 2006) ie your muscles create the force and the blade transfers to the water Larger blades offer more potential propulsion but require greater muscular force (more strength) and better technique to avoid premature fatigue or an inefficient catch. Smaller or more moderate blades are thus easier to handle, especially if you’re still developing your strength and technique.

Slip refers to the movement of the blade in the water without gaining full traction, ie when your blade moves through the water without grabbing it fully, almost like a car wheel spinning on an icy surface A welldesigned blade minimizes slip and maximizes lock-on during the catch (Baudouin & Hawkins, 2002) Overly large blades may lead to overloading if not matched to athlete strength.

Stronger rowers could benefit from wider blades like the Fat2 due to their ability to handle higher peak loads (Kleshnev, 2006)

Developing rowers may perform better with blades like the Smoothie2 VE, which are more forgiving of any errors during the catch

Masters Sprint (500–1000m): Larger, aggressive blades yield faster acceleration (Baudouin & Hawkins, 2004).

Endurance (2000–5000m): Moderate surface area reduces fatigue and may improve stroke consistency

The blade is just one part of the rowing system Rigging is hugely relevant to how the blade performs:

1 Inboard & Outboard Lengths: A longer outboard with a large blade increases “gearing” which can overload smaller rowers

2 Pitch and Spread: Ideal pitch sits between 3–5°; and affects how quickly the blade locks on and exits the water cleanly (Nolte, 2011)

3 Span and Gate Height: These affect the rower’s stroke arc and entry angle, and need to be optimised alongside blade size for efficient force application.

There is no universally “best” blade. The best blade is the one that delivers the most boat speed with the least wasted energy for you or your specific crew. Scientific evaluation should consider:

The athlete’s strength, technique, and fatigue tolerance

The race type and distance

Technical data from telemetry and ergometer trials

Crew synchronization and boat class

What one should aim for in an optimal blade selection is delivery of maximal propulsive efficiency with minimal biomechanical strain and energy loss, this should be customised to the athlete’s strengths and the competition's demands

We had beaten the mighty Ridley College to force our way into a semi-final on Sunday at Henley, a decent enough achievement, still, we didn’t want to just make up the numbers on Finals Day.

Our next race was against Harvard University, the East Coast sprint champions of the United States. We knew they would also be fast out of the start. Having been left behind in Ridley’s spray at the start on Saturday, we were determined not to have to try and come from behind again

On Saturday afternoon, after we had recovered from the Ridley race, we took our boat out again as we particularly wanted to practise some starts, given Harvard’s reputation as speed merchants and our dodgy start earlier that morning The boat was flying and we declared ourselves ready. Our coach, Peter Jones, thought we were in with a shout. He told us to keep our heads and do what we knew best.

had the Berkshire lane, which was thought to have the quicker start that year, though lane choices at Henley are always a bit of a lottery involving some guesswork

The umpire, resplendent as always, in his blazer and umpire’s launch, lifted his flag, and the starter boomed out:

Despite our best intentions, within 200 metres Harvard had taken 1½ boat lengths off us So much for practising our starts! Harvard was out of sight, and we realised we would have to repeat our previous day’s feat, but this time with even more ground to make up Having lived through the Ridley race, not one of us doubted that it was possible at that moment Though not one of us was deluded about what it was going to take

Finals Day was on Sunday morning, and after negotiating our way past the daily reception party of mildly abusive antiapartheid protestors, we put the boat onto the water to warm up before the Harvard race An hour later, we lined up on the Henley stake buoys, nervously confident For the first time during the regatta, we

followed a similar pattern, except this time we steadily clawed back water all the way down the course, with Stuart (cool, calm, professional and unpanicked) talking us through it

Stuart called for a final push as we approached the Stewards’ Enclosure, again with all of us dying a bit due to the oxygen shortage and lactic acid overload

Seeing us coming, Harvard panicked, lost their rhythm, and caught a crab We beat them by three feet in the dying yards of the race.

Doing what we did to Ridley was unusual at Henley Doing it on consecutive days was almost unheard of We had become the darlings of the crowd.

The final that afternoon was against Yale University – a crew of giants Peter Jones told us to go out and do our best, but he had a pretty good idea of what was coming, even if the rest of us naively thought we could recover from two testing races and then take on a crew that was man for man probably 5kg and several cm bigger than each of us

Yale hadn’t been pushed in any of their previous

Remenham Club, which is up the tow path towards the start He had clearly started to drown his sorrows well before the starter dropped his flag for our race

All that was left for us to do was some serious partying at the hallowed Leander Rowing Club that night. In fact, so seriously did we take our partying that

Christopher Dodd,

races, while we were pretty spent from our last two When they dropped us off at the start, we had no real answer. They beat us by 2½ boat lengths, idling in over the finish line, and so, Henley racing was over for us Unlike in all of the other races, Peter Jones was nowhere to be seen at the finish when we came in After gasping our way (as we had every other day of the past 10 days or so) through the freezing boat house showers after our row, we went in search of Peter We found him wasted at the

book Henley Royal

in his great Regatta which spans at history, made an honourable mention in the 1980 chapter of least 150 years of the race’s

“…Witwatersrand students … celebrating their defeat in the garden.”

The rest of our tour was an overwhelming success (possibly to be covered in future columns), with us returning to South Africa with a number of trophies and medals from other regattas and hailed by the thenPresident of the South African Amateur Rowing Union as ‘the finest [crew] ever to represent South Africa’

None of our crew was left unaffected by that experience, and it has served every one of us at different times in our lives over the past 45 years For my own part, I have drawn on the learnings from the Ridley

race time and time again in my life, most especially when the chips have been down and life has called on me to lift my game

The understanding that life will, from time to time, if not from moment to moment, deliver to us moments of choice and possibility.

We may not want, ask for, or like the things that life delivers, but it will deliver them anyway

In those moments, we are free to choose which road we will take along our path: whether to choose a high road or a low road Each is a possibility, and each will take us in a different direction

When we take the high road, at that moment, we say ‘Yes’ to the thing that life has delivered and grasp it with both hands

Conversely, when we say ‘No’ to what life has placed before us, we are choosing a low road.

The high road is typified by acts and behaviour which reveal conscious and purposeful living Whilst the low road is lined with acts of unconsciousness and purposelessness

When we take the high road, we have learnt the lesson that Life delivered for us and are ready to take the next step on our journey

When we take the low road, life will continue to deliver the same sort of challenges until we have learnt how properly to deal with them

The way we choose to live our lives is entirely up to each of us as individuals. No matter how much we may try and blame others (or life) for our circumstances or predicaments, ultimately, we choose for ourselves how to live life when it presents itself in its numerous forms.

There is nothing that happens in our lives which is not a gift, that does not deliver some sort of learning and calling us forward to be the very best we can be. No exceptions.

There were other pieces I learnt from the Ridley race, such as not giving up (not ever) and also understanding that there are other human beings on whom I can count unreservedly to do their bit. It was only then that I discovered that the possibilities for my own life are limited only by the limitations I place on myself That I am 100% reliable and that I can do most anything to which I set my mind

We all have seminal or defining moments in our lives, and they offer the possibility of bringing out the best in every one of us, whether it be our authenticity, courage

Let's get the basics right this season.

You can feel it: The weather is warming up beautifully, VLC is getting busier in the afternoons, and Roodeplaat is gaining a few more visitors over weekends. Walking through schools, you can hear the hum of the ergo and the music turned all the way up, thumping into the distance like some type of fitness rave

It's an exciting time for coaches – getting to know your new rowers while reacquainting yourself with others you've coached before The ol’ faithful start-of-season team-talks being dusted off: "Boys, this year is a clean

slate...." followed swiftly by some variation of "This year we're just going to focus on doing x right" In the last few years I’ve realised that we, as coaches, need to have that chat with ourselves, and I’ll be the first to admit that getting The Basics right is my definite focus this season.

We see it in all sports after a blowout loss –the double DNF, the 6 love, by 10 wickets then the coach sits in front of the media and says: “We've got to go back to the basics.” Conversely, when teams win, they often attribute it to their commitment to the fundamentals, getting the little things right This begs the question: Why did they ever get away from them? How do we veer off course, straying from the basics?

A great phrase I came across a while ago was from Sir Ian McGeechan on the High Performance podcast: “World Class Basics”. And it really resonated with me as "bars" as the kids would say.

For me, “world class basics” means being on time, no breakages, no missed races. It also means making sure we're improving throughout the season (not just our crews but ourselves as well) Evaluating after every session and asking the queston: “Did I

get better today", "Did I help someone improve today" and if we do that, I think we'll all find things go a lot smoother.

Another fundamental we can get right: take our time making sure everyone is holding the handle properly If you want to debate "speed in, speed out", "Pause, no pause", "spin and float" by all means: meet each other in the beer tent and have it out.

All I'm saying is that we get everyone to "sit up and sequence," to "connect and drive," to "use our legs and let the boat run," we'll get where we need to go. It'll truly be good, but only for the last 2-3 weeks before SA Champs We'll need to be patient. We'll need to pay attention.

Let’s keep that boat stable, get them fit, get them excited to accelerate he shit out of it

and let it run Let's get them to enjoy rowing, and then, to love rowing. Carry some shoes, some blades, give a high 5, an "I saw you just shift there!". Let's get the basics done and have a helluva jol. Because that's why we do it

While some people remember who won at Buffalo or SA Champs, others can tell you the exact 2nd VIII seat racing times, 16 races and 3 days later and a final one to check When such and such had a blister on his bum, and so and so missed the jetty when he pushed off and fell in, that sunset session when water was like glass, that misty morning when the water was like glass (seeing the trend here?)

The point is: enjoy every moment and make it lekker – that might just be someone's go-to memory when they think of rowing

Get the basics right and have a jol, I'll see you at the dam.

This edition we continue our exploration of what makes rowing better than swimming i.e., the views! And the boats and the people and the and and and We’re carrying on with sharing some of the lesser known rowing (or at least rowable) sites around the country, and today that takes us to Bethlehem and Groot Marico, two towns famously not famous for rowing

There's always something magical about paddling an unfamiliar stretch, pushing your boat through territory that feels untouched by other rowers The experience brings a mix of excitement and caution, staying alert for hidden hazards beneath the surface or unexpected obstacles jutting from the water that you somehow missed during the safety talk This is particularly crucial

for today’s article. Do not miss The Safety Talk™ when rowing at a new venue! Even though your senses become sharper as you take in the fresh landscape, and a profound sense of gratitude washes over you for the privilege of pursuing this remarkable sport, there may be old telephone poles sticking up out of the dam which will break an oar in your pair, leaving you stranded, cold, and filled with complex emotions

Bethlehem, for those who don’t know it, is a small but surprisingly fast-growing town in the eastern Free State, about three hours from Johannesburg, five hours from Durban, and absolutely-not-worth-it hours from Cape Town. The Wikipedia page doesn’t feel the need to go into the tourism or attractions of the town, and we think that’s about all you need to know If you do feel like a beer, some art, or some seasonal cherries, though, Clarens is only twenty minutes down the drag

Bethlehem actually has two rowable dams, with the roughly 2km long Loch Athlone to the south, and the better rowing venue of Sol Plaatjie Dam to the east of the town

Focussing on Sol Plaatjie, The v-shaped dam presents a theoretical 12km lap, but the weekend we were there the wind kept most of us to one arm, which was about a 6km lap Still plenty to keep you happy, and it’s a surprisingly scenic paddle

Accommodation at Petronella Guest House is very comfortable for a rowing camp, and easily housed the 40 odd masters who camped with us there in 2021. There are plenty of rooms, and a large communal kitchen and dining hall. There is a bridge about 1.5km from the launching area which requires rowers to either lie down in the boat, or be very short to get under, but frankly it adds to the experience The launch area itself is a wee bit dicey, both in terms of getting boat trailers down a steep and

unprepared-for hill, and actually getting into the water which has very little hard shoreline It’s tricky but doable for sculls and pairs or doubles, but we’d avoid taking anything much larger.

Wikipedia describes Groot Marico as a hamlet, which feels quaint Herman Charles Bosman described it thusly: “There is no other place I know that is so heavy with atmosphere, so strangely and darkly impregnated with that stuff of life that bears the authentic stamp of South Africa”, which feels far more accurate You’re not going there for the giggles

Finally (not to overemphasise or anything), pay attention in the safety talk. Because the dam was flooded recently enough that old infrastructure still sticks out at certain places, and hitting a pole with your oar often offends

The dam we rowed on is Marico-bosveld Dam, just a few minutes north of the main town It’s a lovely 35km top to tail, with just enough steering needed to keep it interesting Established in 1933, it was built for the surrounding farms to provide irrigation water

We probably wouldn’t drink straight from the dam, but the water is definitely clean enough to paddle on The sunsets are particularly good, and rowing along while a flock of flamingos flies low overhead into the setting sun is a special memory that’s going to last for a long long time

For accommodation, rent a property or camp at Rickertsdam on the north-east of the dam. The cottages are clean and comfortable, and we had ten people between a cottage and a tent with no problems at all. Launching is an easy wade into the water, and there were no major obstacles that we came across, even with a couple of late-night paddles

It’s not an area with a ton of obvious activities outside of rowing, but if you’ve got bikes there are plenty of farm roads to explore. If you don’t have bikes, Groot Marico is famous for its mampoer, and tours to the various backyard distilleries are available. Approach with caution, though. If there’s rugby showing, make sure to watch it at Madikwena Croc Inn, where engelse people wearing red overalls and screaming Yahtzee in the corner are not unwelcome

The crocodile farm is located, thankfully, about 5km downstream of the dam, so any crocs that do end up in the dam are probably pretty tired by that point

Once more, if you do this amazing sport for fun and adventure rather than only boring old racing, get out there and try some new venues You won’t regret it – just listen to the safety brief!

While not a formal regatta, The Long Row is a staple on the South African rowing calendar. This year, the frigid morning brought a couple of fun (and not-so-fun) detours, with Viking and VLC Masters W2x Anna Fisher and Sam Johnson taking the wrong path at a misty fork – only realising their error when beachy sand and confused cows had them checking their GPS and turning around, adding a “not-so-fun” 14 966km to the 29km row (and finishing their Extra Long Row in an exhausting 4 hours, 2 minutes and 23 seconds)

St John’s College Rowing and Viking Rowing Club kindly provided some lovely photos of the occasion (minus the cows, unfortunately)

This year marked the first organised entry of South African crews at Henley Royal Regatta since 2017, when the University of Pretoria made it to the semifinals of the Stewards’ Challenge Cup (Open Men’s Four)

Bonhage-Koen and Baxter lost to Meijssen and Ruiken, racing for Hollandia Roeiclub from the Netherlands, by a canvas in the first round of racing of the Silver Goblets and Nickalls’ Challenge Cup (the Elite Men’s Pairs) on Thursday, 3 July

Paige Badenhorst finished second to Denmark’s Frida Nielsen in her heat of the Women’s Single Sculls, qualifying for the semifinal, where she finished 5th in a close race She finished 2nd in the petit-final, losing out to Brazilian Beatriz Tavares by just over a second

Damien Bonhage - Koen and Chris Baxter qualified 2nd to the New Zealand pair of Oliver Welch and Benjamin Taylor in their heat on June 27th, before finishing in the same order the next day during semi-final 1. The gutsy South Africans rowed to an impressive 4th place in the medal final on the 29th, kicking off a special European summer for the Saffas

Badenhorst easily beat H.L. Wake of the City of Oxford Rowing Club in the first race of the Princess Royal Challenge Cup (Elite Women’s Single Scull) on Thursday, before losing by 2 lengths to eventual finalist F.S. Nielsen from Denmark on Friday.

Chaotic scenes ensued at the KwaZulu Natal Beach Sprints and Head of the Bay over the weekend of 11-13 July – hitting us with a cold front, unusual for Durban's seemingly foreversummer, bringing the rain, wind and WAVES.

On Friday, the juniors did time trials on a shortened course due to rolling swells Flailing limbs, capsized boats and broken oars set the scene for senior time trials, as weather worsened the next day Organisers ultimately had to make the difficult decision to cancel the rest of the races on Sunday out of concern for safety and equipment

And so, medals were awarded based on results from previous days’ time trials Buffalo Rowing Club excelled in the junior events, achieving gold across all 5 categories! Anna Fisher from Viking Rowing Club won the senior women's category George du Plooy from Cape Coastal Rowing Club won senior men’s, and Murray Bales-Smith and Alexa Kneale won the mixed 2x event The latter of the two teams managed sub-3-minute times in conditions meant for big boat sailing

Traditionally held in fine rowing boats, Head of the Bay switched to coastal boats which had, thankfully, been towed over earlier for the Beach Sprints. Medallists achieved incredible times in spite of the dubious conditions – one glance at the results show that all the rowers who bravely dared to venture out and complete the course were all winners in their own right!

Braden Howard returned to international rowing with a bang, coming third in his heat of the Men’s Single Sculls and qualifying for the quarterfinals. Scheduled for the next day, these went similarly well, with Braden finishing 3rd and qualifying for the A/B semifinals The chips did not fall for Braden at the third time of asking, as he finished 4th in the semi-finals, thus missing qualification for the medal race He ended with a hard-fought 5th place in the petitfinal, successfully earning himself 11th place in the world!

Adopted South African, Zimbabwe’s own Doné Erasmus, who does a lot of her rowing at the University of Pretoria, raced brilliantly to secure 3rd place in Heat 1 of the Lightweight Women’s Single Sculls and thus her progression into the finals of that event Her partner-in-crime at UP, South African dynamo Chloe Cresswell, raced in the second heat, winning a three-way slugfest to progress to the final as the event’s fastest qualifier

Doné and Chloe were exceptional again in the finals, with Chloe coming second to Italian sculler Melissa Schincariol, and Done securing 6th place

Danelia Price-Hughes, one of the most exciting athletes in South Africa’s rowing scene, returned to international racing in Heat 1 of the Women’s Single Sculls, from which she qualified for the petit-final with a 3rd- place finish. Danelia closed off her regatta with a strong second half of the final, securing 2nd in the B-final and 8th in the world.

Smith, Hirschson, Engelbrecht and Thomson, representing the South Africans in the Men’s Four, raced to third place in their heat, which sent them to the semifinal A tight semifinal saw the crew finish fourth (missing out on the medal final), before they bounced back to finish third in the B-final and 9th globally

Stefan Breytenbach and Ryan Dellbridge roared to third place in their heat of the Men’s Double Sculls, which was not enough to qualify for the medal finals, but was good enough for the C-final, where the South Africans finished 18th

South Africa’s brightest and best university athletes touched down in the Rhine-Ruhr region, aiming to dominate the student sporting world The rowers took to this task with gusto from the off

Phumelele Tshabalala and Jordan Craig blazed into the semifinals of the Men’s Pair, hunting down the Kazakhstani pair to finish in second place They made it into the B-final following a tough race, before winning the petit-final and finishing 7th in the world showpiece.

Katherine Williams and Courtney Westley used their international experience to blow the field apart in Heat 3 of the Women’s Pair, winning by a massive 15 seconds. True to form, Williams and Westley won the semifinal by 4 seconds, setting up an enticing final for their supporters watching back home The pair took a very well-earned silver medal in the final, losing narrowly to the Lithuanian pair of Juzenaite and Kralikaite

Warrick Kyriazis and Matthew Jasson, racing in the Men’s Pair, started their campaign strongly, finishing second to the Serbian pair of Cvetkovic and Stevanovic in the second heat, and qualifying for the semifinal. The semifinal didn’t go as well, with the Saffas coming 6th and qualifying for the B-final, where they raced to a well-earned 4th place (and 10th in the world).

The Men’s Double Sculls, made up of the van der Vyver twins, qualified to the D-final from the heats. Their narrow win over Georgia in that final – by a mere 0,22 seconds – earned Nicholas and Matthew 19th spot in the incredibly competitive boat class.

The Men’s Four, stroked by Germiston athlete Obinna Nnamani, qualified for the C-final of their event, winning the event from the Canadians in a miniscule 0,02 second margin of victory The crew – Nnamani, Matthew de Vos, George Cronje, and Liam Batley – earned 13th place in style, as well as an honourable mention on the World Rowing website’s “Race of the Day”

S T R I K E S

aynor du Toit is an administrative force to be reckoned with. Described by some as a “swiss army knife” and the “everything [rowing] lady”, she is the one person who will somehow make things work to let your club keep rowing. Not that she’d ever admit to it, in fact, she is rather prone to underplaying her admirable devotion to the sport, her skills in umpiring and admin-ing, and her unwavering ability to get (impossible) things done. Anna Fisher and I met Gaynor at a coffee shop, along with her partner in crime rowing, Anne Killian, for an umpiring-related conversation (Gaynor claims that she writes terribly. I’m sure she’s underselling herself) Gaynor got down to business quickly, with Anne’s sprightly interjections providing clarity when Gaynor downplayed her abilities, and adding some fun twists and turns to the already enjoyable umpiring-onthe-Kowie journey Gaynor was taking us on.

The following is written by Therese – based on that conversation, with editing for clarity.

B A C K

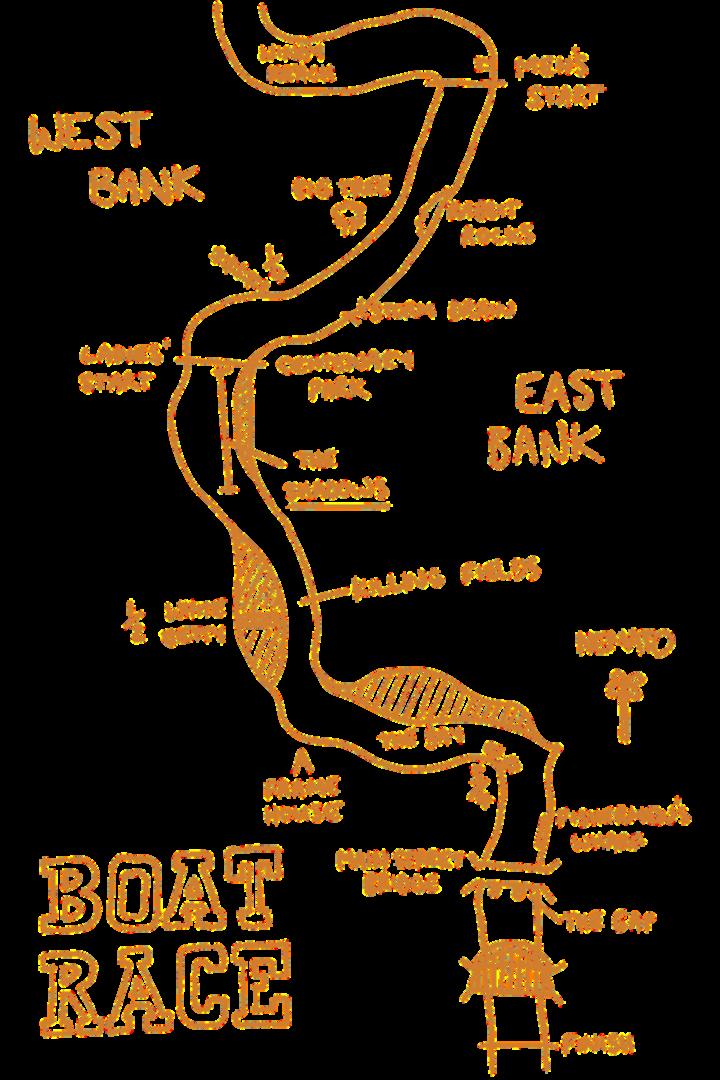

Umpiring Boat Race on the Kowie in Port Alfred is an experience distinct from anything else on the South African rowing calendar The race format, the distance, the winding saltwater course of the tidal river Gaynor had first gotten into umpiring around 2008, when her kids were at Bishop Bavin during its rowing peak There was a drive to recruit umpires from every school Kevin McNeice asked her to umpire, and even showed Anne the ropes when she got into it, too Gaynor just never managed to shake the rowing bug Interestingly, one of Gaynor’s sons had started rowing early on age 10), spending 4 years in u/14, and going on to

compete in Schools’ Boat Race 4 times (u/15, u/16, and in both his 1 and 2 year of Opens) She initially spent a lot of time assisting Wimpie du Plessis, Ian McFarlane, Kevin McNeice, and Selwyn Jackson – names synonymous with rowing The first time she umpired at Schools’ Boat Race was either in 2012 or 2013 (‘maybe even later’), and Carol Muirhead and Chris Barret taught her a ton st nd

The first day brings the Head race, where umpiring is static (no umpires follow the boats down at all) The starting order is based on results from the previous year’s finals and involves setting boats off with a running start in intervals of about 30 seconds. There is a marshall lining the boats up, umpires sending them off towards the start with a “turn your boat, get ready to row!”, a 10 second countdown, and “ROW!” – umpires on the

start line lower the flag while the timekeeper starts the clock Since this first day of racing uses only static umpiring, umpires are posted all along the course to make calls on the right of way when one boat overtakes another, and on whether the faster crew has the right to overtake on the inside or the outside of the corner

One such post lies after The Killing Fields – at an unnamed corner going into the Bay of Biscay –where umpires plop their feet firmly in the mud, after helping push the motorboat out due to how shallow the water is.

On the other hand, if you’re placed near Men’s Start, you’ll find yourself climbing up and standing on a rock-face with the loudhailer and flag, like Gaynor did with Brendan Gliddon (an international umpire, who has been coaching in the UK). At this station, you can be left stranded on Rabbit Rocks as the umpire follows the last boat – unless you have the foresight to specify that you will need to be fetched from the Rocks once the umpire boat starts following the final crew, as Gaynor and Brendan learned when having to radio for a motorboat to fetch them

Of course, overtaking on the straight of the river is simple, as the slower crew gives way by moving over and letting the faster crew overtake on the inside lane of an upcoming bend But that’s no fun Instead, umpires again play their starring roles at two other “defining corners”: The Bay of Biscay (where the wind comes in, and you’ve got to make sure you don’t end up on the sandbank losing a skeg or needing to hop out and push your beached boat), and Wreck Corner (aka Shipwreck’s Corner, which has a very sharp elbow bend and umpires standing on the jetties –Gaynor says that really good coxing will usually result in the crew’s blades missing the jetty by just a few cm). If a faster crew wants to overtake on one of these corners, but there is no contact between the crews when the slower crew’s bow ball reaches the corner’s marker, the faster crew has to overtake in the outside lane. On the other hand, if there is contact between the crews before the corner-marker, the faster crew has the right to the inside lane. The stationed umpires instruct the crews when they need to give way to another crew, and the coxes must raise their hands and respond immediately.

At this point in the conversation, we went off on quite the tangent about composite crews and catching crabs, which ended in Anne sharing a story about a rower who, while racing at VLC sprints, caught such an aggressive crab, he got ejected by the boat.

Anywho, the Finals are determined by the said Head-race-time-trial, with two boats racing headto-head this time. Occasionally, these have started as early as 6:30 am on the Friday morning. The static umpiring of the Head race is history, and the Umpire Boat follows the crews down the course during finals The ski boat has a pilot, an umpire and an assistant umpire on board – with the umpire taking over the starter role – and a marshall aligning the boats Because there is an East and a West bank (rivers are rather prone to having two banks),

a coin toss determines which crew gets to pick the station they prefer.

The East Bank is preferred by some as it gives you the inside line on the first corner. For the schools, who still use Ladies’ Start, it gives you the inside line through the Brierley’s Bog corner into the Bay of Biscay. The West Bank is a far more popular choice as it gives you the inside line through the Dog’s Leg, meaning you can gain a length if you’re quick enough and move across to take the inside line into the old Ladies’ Start corner Having the West Bank from Ladies’ Start makes your line slightly shorter through the first bend, paired with shallower water (preferred on an incoming tide)

Once the marshall determines that the boats are aligned, with a familiar “Hold it all crews!”, the umpire takes over with “ATTENTION! GO!”, and the East Bank boat starts pushing the West Bank boat over to get their line The majority of umpiring is done here, trying to keep those two boats apart Weirdly, a restart can be done at any point without returning to the start

On the odd occasion, a race will be close the whole way down Gaynor and Anne agree that it’s an extremely exciting and nerve-wracking prospect for an umpire – you’ve got to have your wits about you. For all her modesty, Gaynor embodies a blend of improvisation, grit, and a deep care for the sport. The truth is simple: Without people like Gaynor, there would be no race.

We must ask ourselves one important question at the start of every new cycle: Can we turn potential into performance?

The Lucerne World Cup gave us our answer.

Beyond being a race, it was confirmation that the spark we had earlier in the year had, without question, caught fire.

South Africa didn’t return to Lake Rotsee empty-handed this year, we brought precision, grit, and unwavering belief in each other.

In the Women’s Single Scull, Paige Badenhorst unflinchingly lined up against some of the world’s most renowned rowers She rowed with a huge amount of poise, resilience, and raw speed; you would be shocked to learn this was her senior World Cup debut as a single sculler Badenhorst held her own through every round When it was all said and done, she bagged a proud (and respectable) 8th-place finish For a country rebuilding its women’s team from the ground up, Paige showed us how potential translates into speed on the water

On the men’s side, the Coxless Pair of Chris Baxter and Damien Bonhage-Koen returned to international waters for the first time since their U23 World Championship title, and they did not disappoint Wading the waters in a fiercely competitive field, they raced with maturity and aggression, resulting in a 4th place finish in the A Final For two young men who have grown through the system together, this was a coming-of-age moment and well-earned validation that U23 success can lay the foundation for results on the biggest stages in the sport.

On the surface, you might mistake this as just the tale of two crews However, these results are proof of concept. They’re the outcome of a deliberate strategy A strategy that empowers athletes, supports coaches, and lets performance speak for itself Instead of chasing medals without process, we are laying the foundation and backing those who are willing to build with us

Across South Africa, clubs and universities are beginning to believe again Coaches are coaching with precision and determination because that’s what it takes We are now past the days of waiting to be selected and have entered an era where you build your way in

The U23 and Student seasons have come to a close with encouraging results Crews stood tall, raced with courage, and walked away with experience that can’t be coached It’s a reminder that our pipeline is alive and paddling strong

Equally exciting is the 2025 Junior Squad Theirs is a campaign brimming with promise, and I want to say to every single athlete involved: keep going and keep rowing. There is no doubt in my mind that your future is bright. Set your sights on U23s. Set your compass for LA 2028. The journey has already begun.

With the Shanghai 2025 Championships on the horizon, the goal is straightforward: row faster than you think is possible. Set a new standard. That’s what we want to see and what we’ll keep showing up for

One of the most exciting parts is that we’re beginning to return to a place where other countries look at the racing draw and think twice when they see a South African crew We are becoming fiercely competitive at every level

This tour also included the unforgettable experience of the Henley Royal Regatta – a venue steeped in tradition. We lined up amongst the world’s finest. Through this experience, we learned, adjusted, readjusted, and came home sharper, more connected, and hungrier than ever. The great news is we aren’t the only hungry ones in the rowing community.

Let’s keep going!

The very second I climbed into a boat, I knew. I was not a particularly active or sporty kid, but my parents received an email about a rowing open day at St Andrew’s, and we thought it would be interesting to check it out

Coming into the new cycle, the way we train has changed, and with that, I have a new favourite session

If you had asked me just last year what my favourite session was, I’d probably tell you it was our threshold pieces on the ergo Being able to really test yourself and see the results from all the hard days of training we had put in was incredibly rewarding

We have moved to a mileage-based program (where we spend 80% of our time rowing long steady kilometres, and 20% of the time doing what every athlete lives for – the racing), and so, my favourite session has changed I now look forward to the long steady rows, between 20km to 26km The shift came from confidently knowing we don’t always have to increase the pace to make us fast. Seeing the results at a lower intensity, and being able to hold form and technique has been just as, if not more, rewarding. We know that once we crank up to pace, it’s only going to get better!

Having grown up doing various water activities, I was immediately drawn to being out on the water I loved the idea of being outside and in nature I was also encouraged by the fact that everyone was starting on a level playing field – we were all new to the sport We were all starting on a level playing field I liked the challenges that came with rowing and I learnt early on that with hard work I would see progress

Funny story, we actually showed up to the open day a year early as I was in grade 6, but you can only start rowing in grade 7 I had to wait a whole year before I could actually get started Despite this, there was no question: Rowing was for me Little did I know that it would be the beginning of the most magical journey that would take me to the most incredible places.

Reflecting on our recent tour to Lucerne and Henley Royal Regatta has been such a sobering realisation of how far I’ve come in the last 8 months! I arrived in Lucerne with a childish naiveté with regards to the senior Men’s Pair event My teammate, Chris, kept telling me, “Dames, the world is fast!” and yes, it most certainly is, but from my perspective, “Why can’t we give them a run for their money?”

Racing the heat in Lucerne made me believe we could do it Our entire campaign filled me with the confidence to push on and believe in myself, the pair, and the training program All the physical work we were doing was proving to be (at least somewhat) in the right direction.

Notable technical changes include distinct work needed on our finish as a crew, recovery plains and, ultimately, the catch Now, I’m aware that I’ve just described the entire rowing stroke, but to my credit, the deeper each objective is unpacked, the more nuanced it becomes.

Competing at two of my bucket list rowing events has exposed how hard what we are trying to do in the RMB National Squad Men’s Pair truly is

My family, friends, fellow rowers, and even I believed, at one stage, that the hardest thing about this comeback story would be building the physical engine. Oh boy, were we wrong! I have been pushed to almost my breaking point physically; multiple times in the last 8 months To fully recover from that (and feel like myself again), I had to get a good night’s sleep, a healthy helping of dinner and a protein shake After that, I am all good, ready for the next physically debilitating task my coach can throw at me.

Where I have truly struggled the most (both mentally and emotionally) is coping with the training load whilst away from my support structure A solid foundation is so vital to what we are doing here in the RMB National Squad. We have an amazing team behind us in coaches, ROWSA, Planet Fitness, Biogen, physios, sponsors, WeRow supporters, the list goes on and on!

True greatness for me as an athlete lies in the pillar, the rock and the foundation that I can turn to when times are tough. Chris’s hugs can only comfort me so much and Coach’s wise words can only get me through so many sessions My true motivation lies at home, in those I leave to watch me live my dream on a computer screen It lies in those who never complain, who never make me feel guilty, who never ask for anything in return.

I thank God for putting them in my life I am well and truly blessed Thank you, Mouse, Mom, Dad and Shanny. I could not ask for a better group of people to be constantly cheering me on.

You know whats coming: 5:00 AM training on a freezing cold winter morning. Trekking to the gym for yet another round of lifting things, pulling things and attempting to get marginally better than you were the week before Muscles ache, backs hurt, sweat drips, and the sting of blisters on a dirty barbell becomes all too frequent. But there are 7 other people doing exactly the same thing, so you have to put your shift in all the same

Even so, there were days I felt like crying instead of waking up at that ungodly hour, preferring to promptly roll over and snooze my alarm for another 10 minutes, and another, until an hour passes – something I do now that I’ve got the choice.

My personal gripes with waking up early aside, how do you go from being able to endure intense physical stress to being unable to climb a flight of stairs without sweating? Or the other way around? It’s just a matter of how you use your time.

Exercise can feel weirdly complicated: Barbells, kettlebells, Crossfit, functional training, resistance bands. Rep ranges can span from 5 to 500 reps of a movement in one go (depending on your program), and you could sit on an ergo for 10 minutes or 100 if you were so inclined. I remember those days of lifting heavy, jumping over hurdles, doing burpees

and kipping pull-ups, kettlebell snatches or even just straight up doing jump squats until you felt sick (both literally and figuratively.) Sometimes, in the interest of “science,” we’d use giant therabands and some squat racks to catapult a swiss ball across the gym (miraculously, no coxes were ever hurt in these “highly scientific” gym experiments).

Having done all of this (and more!) at some point in my rowing training, getting to look at things now as someone who deals with sports in a professional capacity I can confidently say we got a lot wrong. Yet, somehow, we still got a lot right. Training without a perfect programme still taught me the value of discipline and effort, was far better than doing nothing, and laid the foundation for better, smarter training later on.

probably not the ideal recovery strategy Now that one can indulge in YouTube and Instagram reels for hours into the night, sleep can’t be any easier.

It’s great to know which training you should do and when Still, the most important part is actually training Of course, there are many factors involved in how we approach training from a scientific perspective, but doing something is always better than doing nothing The consistency of and compliance to a weekly program will differ between world-class athletes and casual paddlers (myself included). That said, if you want to be competitive, there is no way around commitment: training, diet, and recovery are paramount

Many of us fall into the trap of thinking that the more competitive your goal is, the more you should train, right? Well yes and no While I recall regularly training to the point that I couldn’t even move my body the next day, performing to the desired intensity sort of requires your muscles to be functional… Unfortunately, this poor periodisation (too much training combined with too little recovery) is far too common and totally unsustainable There is a science to programming, and it matters.

Working hard is good Working hard and smart is better If I could go back, I’d vary my training and rest more. Staying up until midnight texting on my Blackberry, at the cost of sweet, glorious sleep, was

To be practical, ask yourself: How many days can I realistically train? Do I have access to gym equipment or just my bodyweight? Am I training to compete or for health and enjoyment? Answering honestly should already start to give you a framework for your planning

There is research to show that twice weekly resistance training can improve your overall health. Even for higher level athletes, resistance training twice a week can be greatly beneficial Strength and conditioning coaches may look at specific types of work like strength, strengthendurance, power, endurance, and hypertrophy While this sounds very complicated, these terms are just different ways of defining how we use our muscles to reach certain performance goals

To improve your cardiovascular capacity and endurance, longer lower loads (like in steady state ergos) will do the job, allowing you to tolerate exercise for longer Unfortunately, it’s unlikely you’ll get faster through exclusively doing steady state sessions.

To address this, we incorporate shortduration, high-resistance training (low reps, heavy weight for example) leading to greater strength gains, ultimately, getting more power into the water each stroke. It’s best to combine these approaches, as only doing 10 hard strokes and subsequently coughing up a lung isn’t ideal either

Hypertrophy is a nice way of saying you’re training to grow your muscles. Usually in the form of a couple more reps at a moderate weight, to reach those rep ranges (before fatigue sets in and you have to put the weight down). This is the bodybuilder's delight.

Of course, each of these training variables needs time, consistent effort, and repetition to have any effect.

A professionally designed periodisation program should consider every variable, purposefully calculated down to the last rep, over the course of a sporting season. Pro athletes will know exactly how many reps, sets and for how long they will train on any given day, experiencing a variety of training demands over the season

These days I’m more than happy just rowing up and down and maybe doing some sprints here and there So I aim for a session or two of varied upper and lower body weight training per week, aiming to

fatigue on each set but still having enough in the tank to do it all over again on the next set, after briefly resting. Pulling some 20-40 minute bore snore ergo steady state will complement those strength gains nicely when I’m 1km into the course and don’t need to stop and wipe my tears, but can finish a full lap and then some.

Competition and participation in something makes it far easier to be fitter and healthier. It can get a little more difficult to stay on track when you’re trying to do everything on your own.

The main consideration is this: you need to figure out what’s appropriate for you right now Are you planning to race at world championships, or enjoy a quiet paddle at Roodeplaat on Sunday morning? In essence, how much time do you want to dedicate to this fitness goal to enjoy the sport in your own way? Whatever your answer, exercising in any capacity is a HUGE win. Whether it’s 4:30 am in the dead of winter or a more reasonable hour on a casual Sunday morning, showing up is what matters most.

Rowing in South Africa has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past two decades. Once confined to elite schools and urban centres, the sport now boasts a presence in all nine provinces, thanks to strategic development initiatives led by Virginia Mabaso, Development Coordinator of Rowing South Africa (RowSA). The expansion has been driven by indoor rowing programmes, school partnerships, provincial stakeholders and municipal collaborations that have introduced rowing to communities previously excluded from water-based sports.

Through these programmes, rowing is stretching its (welltrained) reach across South Africa, making its way into villages through development hubs in Limpopo, the North West, Mpumalanga, and the Eastern Cape. Every year, annual onboarding means that new districts are added to RowSA’s Learn to Row programme, where even under-resourced schools in provinces with no Roodeplaat-esque access now offer rowing as an indoor sport, with mass participation

Spear-heading (or should we say coxing) this transformation is Virginia Mabaso, a tireless advocate for equity in sport. Since joining RowSA in 2007, Mabaso has designed and implemented the national development strategy to promote rowing, from scratch, while championing inclusivity in terms

Establishment of development hubs in Limpopo, North West, Mpumalanga, and the Eastern Cape.

Annual provincial onboarding, with new districts added to the Learn to Row Rural Programme.

Integration of indoor rowing as a mass participation sport, enabling access in arid regions and underresourced schools.

of women’s participation and para-rowing. As a result, over 10,000 South Africans have been introduced to rowing through a number of rowing-related activities. In return for her troubles, Mabaso has been repaid in accolades, including SA Sports Administrator of the Year (2015, 2018), the Ministerial Award at the Gsport Awards (2017) and Women of the year at the Gsport Awards (2020).

Mabaso’s grassroots approach, as she travels to remote districts to engage educators and mentor coaches, has lent a hand in redefining what rowing can mean for South African youth. While certainly impressive, Mabaso’s medals and milestones are not the measure of her success That can instead be weighed up from the communities she’s empowered and the futures she’s helped shape.

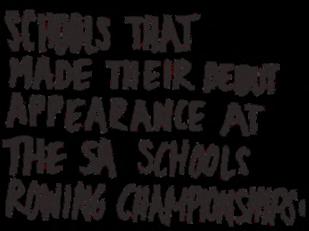

As an indicator of this success, the SA Schools Rowing Championships, held at Roodeplaat Dam in April 2025, marked a watershed moment for inclusive competition in rowing With representation from every province, the regatta reflected RowSA’s commitment to transformation and equitable access.

With the debut participation of schools like Phayizane High (Limpopo) and Nkwanca Secondary School (Eastern Cape), more than 78 students competed in the regatta Through the competition, rowers from rural districts were not only enabled to compete for the first time, but also received support and visibility as part of an inclusive and multicategory rowing community While the event was, in name, a competition, the enthusiastic participation of the rowers and the opportunities afforded to them meant that it was also a celebration of diversity and resilience. More than ever, rowing exercised its power to unite.

Phayizane High (Giyani, Limpopo)

Leonard Ntshuntshe Secondary School (Mpumalanga)

Elukhanyisweni Secondary School (Mpumalanga)

Khaiso sec (Seshego, Limpopo) Lingelihle (Komani, Eastern Cape)

Thembeni Rowing Club (Ilembe, KZN)

Shayamoya Rowing Club (Ilembe,KZN)

Nkwanca Secondary School (Eastern Cape)

Beyond the success of the event in itself, it has also upheld the real, though lofty, goals of RowSA’s development programmes Participation at the national-level competition has meant that new rowers from under-served areas have been scouted to receive rowing scholarships at the University of Johannesburg (big ups team UJ!) It has also fostered a sense of pride among provincial teams, as they work towards something that allows recognition, at the same time igniting the unavoidable competitive spirit of rowing. The programme has, then, fostered a cross-cultural exchange of spirit and athleticism that stands to dismantle the barriers that have fenced the arid provinces out of rowing for so long And how exciting it is to invite more people to dip their toes in the water

As this journey continues, the next chapter (stay tuned for issue 4 of The Bowside) lies in the villages themselves, where rowing is changing lives in real time. A special acknowledgement goes to the RowSA coaches and mentors whose dedication makes this transformation possible

Months of driving eights around in circles at VLC, and straight lines at Plaat, culminate in the ultimate challenge for a coxswain – The Boat Race. A tricky, tactical and turbulent regatta, hosted on one of the most stunning courses in the country. Tides, sand banks, crowds, wind,

clashes, The Boat Race on the Kowie River has it all.

Preparation is simple: four cold winter months of training at VLC, with the occasional break at Roodeplaat. If you're lucky, you end up on a warm, windless 10to 14-day camp And as luck would have it, amidst the COVID-induced cancelling of the 2021 USSA Sprints, UJ redirected funds, landing me on a 14-day camp in The Land of Speed, Tzaneen Beautiful 12km stretches in either direction, with just enough turns to keep things interesting, and the rumoured hippo on the banks keeping things exciting.

Coxing in Tzaneen wasn’t all smooth sailing. Isolated from the city, our two weeks of nonstop rowing meant that there were, inevitably, complex crew dynamics. As a cox, driving both the Men's and Women's A Eights (and occasionally the Men’s B), 70% of my challenges were on land: crew management, conflict resolution, and emotional control Take that for a big learning curve

That season taught me an important lesson about managing my own emotions and learning when and how to show them I quickly realised that what the crew needed from me was to be the best, most confident version of myself – composed yet excited, loud but not boisterous As a cox, your panic ignites distrust in the crew, and your apathy leaves way for complacency. So, as a great cox, you have to be approachable, respectable, and in total control of your headspace The most overlooked and underappreciated value of a cox? Regulating yourself before worrying about the rest of the crew Air hostesses aren’t lying when they tell you to secure your own mask before attempting to help others

Fast forward to arriving on the Kowie River in early September. I had raced the river twice before, so like any other 20-year-old KES old boy, I naturally thought I knew it all. After

sessions, while the rest of the crew rested, I would head down the course in the motorboat with our coaches, Athi and Lebo, taking videos and photos of the course, and scribbling notes about markers and what to aim for. I’d carefully note which banks were at what tide, try to remember where one specific tree was from about one and a half kilometres away, and then rehearse my lines for every session

I’ll never forget the Tuesday evening, when we were visualising the race in a sort of dress rehearsal I was in my element, thinking I was hitting every line perfectly, only to be creatively crushed by Athi at every point along the Kowie

“That line was disastrous”, “What are you doing?”, “Liam, did you leave your brain on the bank?”, “You are so far over, it’s ridiculous”

The ultimate roast session, two days before the (then) biggest race of my life

In my defence, coxing is a bit like trying to drive a bus while 80% of the windscreen is covered by a big picture of some guy But Athi’s epic roasting wasn't about humiliating or embarrassing me. It was all a lesson in humility. I had been too hyped up, and my head was getting a little too big for the boat. I had to humble myself and remember I was in

a constant state of learning.

My advice? Don’t ever believe the hype

On the Thursday morning, I raced with the Women’s A, landing in the B-Final against Rhodes The midday race with the Men’s A went perfectly, earning us a place in the AFinal against Tuks for the first time since 2011, when our coaches were in the boats, with Athi in the UJ Men’s A-Eight and Sieze stroking the SA National Squad Domestic Eight (otherwise known as “Tuks Men’s A”) Messages flooded in Though we were UJ’s only A-Final crew, it felt like a club victory. It was never just about the 9 guys in the boat. That race laid the foundation for our USSA–Sprints win six months later, not to mention the rise of future UJ stars like Lebone and Murray, who both raced at World Champs the following year. That AFinal made us visible again. And it again proved that, as a cox (even at Boat Race), it’s not about you There’s always a bigger picture

My two finals of that campaign are easily two of my favourite races of all time UJ’s Saturday started with the Women’s A lined up against a tough, physical and wickedly experienced Rhodes crew, driven by one of the most decorated coxes the Kowie River has ever seen – Andrew Meikeljohn. I’d be lying to say I wasn’t a little intimidated by Andrew In my opinion, he’s one of the greatest coxes to have been on the Kowie.

We lined up on the East Bank, getting the first advantage of the bowside corner, but

with the disadvantage of rowing in the channel first Barry insisted that we keep it clean – no clashes, just skill, and the fight to win it. Out the blocks, we managed to get ahead, holding a narrow advantage as we passed the poles in the Killing Fields Andrew tried to push me into the channel early, where we would’ve battled a stiff head wind and incoming current. Luckily the Umpire, the legendary Carol Muirhead, called him over to his station I tracked him across, trying to delay eventually crossing the channel

About 10 strokes after we entered the channel, Rhodes came back at us, drawing level into the bowside corner We had the advantage of being on the inside, and I managed to push Rhodes out just enough, around the bend. The corner gave us a length, and we kept the race tidy from there to secure the bronze Knowing the course and clean racing is what allowed me to give my crew the best possible opportunity. Note to coxes: Deliberately clashing is not worth it! Andrew and I definitely understood that After all, if your driving is good enough, and your crew is quick enough, you should be winning fairly Intentional clashing, something I’ve seen a little more frequently now as a coach, just doesn’t pay.

Finally, the last race of the day was upon us. The men’s A Division A-Final. UJ vs Tuks. We drew the West Bank in the coin toss, getting the advantage early on in the race as we had the Dog Leg on the inside However, this meant we had to try to break Tuks early on to get an advantage when going into Ladies’ Corner. Likewise, Tuks knew they had to go out hard in the start to try and mitigate any advantage we gained coming out of the Dog Leg Ultimately, and unknowingly, the race would be won and lost in the first 2km before Ladies Corner

We anticipated Tuks pulling their classic “1-minute” tactic, pushing for 1 minute until they caught a lead. Our counter was to push hard in 30-second intervals, timed to give us the advantage around corners, when crossing channels, or wherever I believed we could use it Athi told me to trust my gut, saying that I’ll know when to go. I’ll never forget Murray telling me before the race, “Don’t let us feel like we could have done more”.

Going into the Dog Leg, we were down about half a length. As we came out, we were about a quarter of a length down Then Tuks dropped the hammer and took a whole length in about 30 strokes, going into Ladies’ Corner In the approach, Teal Alves took the Tuks men wide around the corner to avoid catching weeds, like they did in the Head Race This is where I called the first 30-second push I called the second one through the kink in The Killing Fields, when the famous Kowie River Cruises barge was coming straight down the course Teal swerved around it, and I played a game of chicken until it veered off to the side I called another one through The Killing Fields just before Bowside Corner, and then again straight after it when I saw Teal swerve again, reaching her hand into the water I thought she had lost

her skeg. I called two more pushes in a row, and we made up some water, bringing us back a bit closer By Shipwreck Corner, Tuks still had about a length lead, but we refused to allow them to take any more ground. Belief until the end, the ultimate lesson. No matter where, and no matter how many opportunities the Kowie threw at us, we pushed to get back in front. The whole time I had to just trust my gut and give it my all, not wanting to ever look back and think I could have done better or given more

In keeping with the spirit of giving it my all, the afterparty was particularly special I paraded the Ian Maxwell Trophy around everywhere I went that night, dipping it into various clubs’ punches. But no accolades, no finals, no medal could mean as much as those lessons. They continue to shape my career and lifestyle More importantly, they are truly what makes university rowing and The Boat Race so special, because they can’t really be taught in classrooms and lecture halls. Especially not the most epic experiences with your mates

There is no right line on the Kowie, only the line you trust after honing it time after time.

Refusing to live in the moment and obsessing over the future is a trait most of us (unfortunately) share While this anxious impulse is likely inherited through our evolutionary need to survive, it also manifests in far less life-anddeath arenas, such as sports

Sport-trauma often hits much harder than it should, but deeply-invested fans and athletes typically try to take comfort in the belief that better days are coming: “Sure, we lost today, but we’ve got some great youngsters coming through 2030 is our year!” It’s a beautiful and hopeful instinct, but one that all too often overlooks the many things that have the capacity to stop us from reaching our potential, like inadequate coaching, inaccessible facilities, and tight finances.

Rowing, like many sports, thrives on this kind of optimism. But behind the (occasionally) calm waters and (mostly) synchronised strokes lies a tougher question: What does growth actually mean in rowing, and how does its unique challenges shape its sustainability?

There’s a good reason why RowSA lists ‘medalwinning’ alongside ‘transformation’ and ‘development’ as key goals on their website They aim to win medals “across all disciplines”, with a focus on “the sustainability of rowing from one Olympic cycle to another” Besides the bragging rights, the drive to win hints at a deeper challenge (for niche sports like rowing): performance is directly tied to funding

The Summer Olympics represent the biggest and best window for lesser-followed sports to attract marketing attention, gain prestige, and prove their worth to both government and private funders But between Olympic cycles, these sports often struggle for visibility, which makes every competition, even at the junior level, high-stakes

Of course, elite athletes aren’t ones to shy away from pressure, but when the sustainability of an entire sport depends on athletes constantly performing, it becomes an inherently fragile model. Athletes are human, after all (shocker, I know), and life inevitably throws challenges their way, making placing all your chips on individuals and teams a risky bet.

Federations try to control this risk by developing better athletes On its face, this is a simple solution: better athletes equal better performances The dilemma we face is that

developing athletes is complex and highly dependent on funding.

If a country has a larger pool of natural talent to choose from, it makes unearthing and developing world-class talent more likely. Rowing wants (and needs) more rowers, but barriers abound Rowing requires specific (expensive) equipment, which can be said for many other sports, yet rowing pairs this with some unique geographical prerequisites You need a body of water, and on top of that, must sit a boat. There’s no way around it This makes our sport’s constraints more stringent than sports like rugby, football, or cricket

In the previous issue of The Bowside, I detailed my first trip out onto the water Thinking back on the experience made me realise just how lucky I was, in contrast to most novices who have no guidance whatsoever If you Google “rowing lessons”, the first thing that pops up is Superprof, a worldwide tutoring website where you can purchase lessons for prices that vary wildly, from R100 per hour to more than R1000 per hour Many of these tutors seem competent and experienced, but unless you’re getting the lessons in person, I imagine it would be quite challenging to recreate the experience in the comfort of your home.