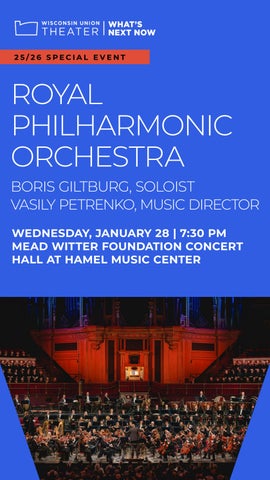

25/26 SPECIAL EVENT

25/26 SPECIAL EVENT

BORIS GILTBURG, SOLOIST

VASILY PETRENKO, MUSIC DIRECTOR

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 28 | 7:30 PM

MEAD WITTER FOUNDATION CONCERT

HALL AT HAMEL MUSIC CENTER

Please silence all devices while viewing this program. We also invite you to reduce your screen brightness if you are able.

We appreciate your help in maintaining a quiet hall that is conducive to music-making and listening.

In an effort to increase our sustainability efforts, the Wisconsin Union Theater is now utilizing digital programs.

Printed PDFs of the program and large print copies are available upon request. Please ask an usher.

The Wisconsin Union Directorate Performing Arts Committee (WUD PAC) is a student-run organization that brings world-class artists to campus by programming the Wisconsin Union Theater’s annual season of events.

WUD PAC focuses on pushing range and diversity in its programming while connecting to students and the broader Madison community.

In addition to planning the Wisconsin Union Theater’s season, WUD PAC programs and produces studentcentered events that take place in the Wisconsin Union Theater’s Play Circle. WUD PAC makes it a priority to connect students to performing artists through educational engagement activities and more.

WUD PAC is part of the Wisconsin Union Directorate’s Leadership and Engagement Program and is central to the Wisconsin Union’s purpose of developing the leaders of tomorrow and creating community in a place where all belong.

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Béatrice et Bénédict Overture

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15 Allegro con brio Largo Rondo: Allegro scherzando

Symphony No. 10 in E Minor, Op. 93

Moderato Allegro Allegretto—Largo—Più mosso Andante—Allegro—L’istesso tempo

Béatrice et Bénédict Overture (1862)

In the middle of the 19th century, a joke about the “three Bs” of music started to spread. They were Bach, Beethoven, and Berlioz—such was the widespread acclaim and influence of the French composer and music critic. For many, he became the voice of the generation immediately following Beethoven; his Symphonie fantastique, which launched him to fame, premiered in 1830, only three years after Beethoven’s death. By the end of his life, he was one composer Wagner pointed to as a forebear of the “Music of the Future.”

Starting with Symphonie fantastique, Berlioz became known as an exponent of so-called program music, which is instrumental music that depicts imagery, conveys a narrative, or communicates extra-musical ideas. But his larger aesthetic aim was to unify music and words—a central preoccupation of the Romantics. Berlioz believed that music should communicate meaning or ambience to an audience, and the pursuit of that idea propelled the musical structure forward (rather than, he claimed, any preconceived form). Operas were a unique point of inspiration for his genius; five survive today, though only three were performed in his lifetime. His final opera, and, indeed, final major composition, was Béatrice et Bénédict, a mercurial and multi-shaded work that Berlioz himself adapted from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing.

The origin story of Béatrice et Bénédict (completed in 1862) may be said to start as early as the 1830s, when Berlioz first tinkered with the idea of a work based on Shakespeare’s play. His decision to return to it came after thetrials and tribulations of trying to bring his previous opera, the epic Les Troyens, to the stage in Paris. Béatrice and Bénédict was written as a comic opera for the theater in Baden-Baden, known primarily as a tourist spa and resort town, where the work’s lighter mood would be welcome. After the difficulties

with Les Troyens, Berlioz scaled down and, by his standards, simplified his approach, while maintaining his fundamental commitment to emotional content and character. The result is a work he described as a “caprice written with the point of the needle,” featuring light textures and moments of transcendent serenity.

The Overture to Béatrice et Bénédict puts on display hallmark moments from the opera, especially Act I’s duonocturne, which was an immediate sensation among his aristocratic German audience. Following in the footsteps of Glück and his 18th-century opera reform, Berlioz believed the overture must convey the mood of the coming opera rather than act as mere exciting titillation for the audience. The Overture, which he composed last, shows remarkable atmospheric unity. He alludes to some six themes from the opera, which he also subjects to transformations in mood and emotion. Notably, the Overture opens with the opera’s final theme, creating a bookend.

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15 (1797, rev. 1800)

Still 21 years old in 1792, Beethoven left his hometown of Bonn for the imperial capital of Vienna. Officially, he came to study with Haydn, who, late in his life, was enjoying the status of cultural icon for his homeland. Unofficially, he also was fleeing his abusive alcoholic father, whose derelict behavior forced him to petition the court to become the head of his family at age 19, supporting his brothers, and garnishing half of his father’s salary to do so. By the end of the year, Beethoven turned 22, started lessons with Haydn, and became an orphan when his father died in December.

In his early years in Vienna, Beethoven focused primarily on making a name for himself as a performer. He quickly became known for his fiery piano improvisations, raising his profile with unusual speed. His success in Vienna, which financially sustained him later in his life as well, came from his connections to the aristocracy: He was court organist and pianist for the emperor’s brother Maximilian, who was the imperial representative overseeing Bonn, and he had already won over Count Waldstein, who had started to commission

the composer in Bonn. Beethoven also surrounded himself with the musical elite of the city, initially through Haydn, but also through lessons with Vienna’s best-known teacher, Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, and very likely with the imperial Kapellmeister himself, Antonio Salieri. Through a combination of personal motivations, remarkable talent, and professional and social connections, Beethoven ascended to the top of the Viennese musical scene.

The secular part of that musical scene consisted mainly of private concerts among the nobility, benefit concerts (events in support of a charitable cause), and eventually, after 1800, public concerts (meaning anyone who could afford it could buy a ticket). It was at a benefit concert in December 1795 that Beethoven gave the premiere of what is now called his First Piano Concerto. (What we call his Second Piano Concerto, based on the publication date, premiered nine months earlier at a different benefit concert.)

The repertoire at these concerts consisted of a mix of previously composed works and improvisations, and the importance of improvisation cannot be overstated. In fact, although it is unclear exactly which of the first two concertos he was referring to, Beethoven’s friend Franz Gerhard Wegeler, who was at rehearsals, remarked that Beethoven only completed the last movement a day before its premiere. In the same year, Beethoven also was pitted against pianist Joseph Wölfl in a widely publicized musical duel, where both improvised on themes handed to them. (Wölfl would later recall that even Beethoven’s improvisations tended toward darker emotions.)

The duality of (previously) composed music and improvisation pervades the First Piano Concerto. Aligning to the Enlightenment ideal of rationalism, composed music was often compared to rhetoric and understood as discursive: It needed a clear beginning, middle, and end (or exposition, development, and recapitulation in music’s sonata-allegro form). While Beethoven’s early music—known as his Classical period—upheld the formal conventions to satisfy such rationalist tastes, his improvisational impulses inevitably pop out.

The first movement, for example, opens with the orchestra laying out the two main themes after which the piano joins to repeat them both (a formal norm for Mozart as well). When the piano enters (keeping in mind it was originally the composer—a renowned improviser—as soloist), the pianist immediately begins to ornament the themes of the exposition, adding virtuosic excitement as well as color and interest. Confirming Wölfl’s observation, the piano part is also moodier out of the gate than the extraverted orchestra. The first movement also features a long (approximately five-minute) cadenza—Beethoven published three for this work in his lifetime. Growing out of an operatic tradition for singers, the cadenza was a staged moment of improvisation coming before the final phrase of the work, where soloists put their technical prowess on display. Beethoven’s cadenzas, however, broke new ground not just in length, but also by resembling so-called fantasias, an improvised genre marked by a freer, stream-of-consciousness flow of ideas that contrasts with rationalist desire for formal order. As it proceeds, the movement dramatizes the tension between form and freedom.

In the second movement, the piano takes the lead, engaging with the orchestra in a more interactive manner. In this case the improvisatory element is that of an openended dialogue, where the responses are linked by the conversation’s theme, but the voices have their own slant. The prominent clarinet solo, acting like the orchestra’s leader, heightens the sense of a dialogue between independent voices.

Marked Rondo, the highly rhythmic final movement follows the older Baroque ritornello concerto structure, on which Mozart also leaned: The orchestra returns intermittently with a memorable theme (the ritornello) that is interspersed with free episodes by the soloist. In Beethoven’s hands, each episode becomes increasingly improvisatory (and based on Wegeler’s account, was potentially improvised the day before and maybe on the spot, too). Like a microcosm of the larger concert experience, the movement ultimately alternates between the composed music and improvisation.

Completed in 1953 and premiered in December of that year, Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony appeared after an eightyear hiatus from the genre and some nine months after the death of Joseph Stalin. His break from symphonic writing was partly a result of cultural politics: In 1948, for a second time, he (along with Myaskovsky, Popov, Prokofiev, Shaporin, and Shebalin) was reprimanded in an official party decree for leading Soviet music astray. (Andrei Zhdanov, the party bureaucrat responsible for the arts, wanted to suppress Western influences in the wake of East-West wartime alliances.) Shostakovich lost his teaching position at the Leningrad Conservatory and, as a result, his housing. Several former friends openly denounced him, and a handful of works were placed on the blacklist.

By 1950, he had already gone through his second rehabilitation, officially apologizing in a public address written by a friend. Shostakovich also wrote several dutiful works conforming to official political agendas as well as the aesthetic ideology of socialist realism, like his oratorio Song of the Forests, which won him the Stalin Prize and 100,000 rubles. After a personal phone call from Stalin, he was assured his works would be removed from the blacklist, and he agreed to travel to the US in 1951 as part of a peaceseeking conference. He also received a governmentsponsored apartment.

Although back in the party’s good graces, he remained gun-shy about his next big statement piece. Indeed, his gloomy Fourth Symphony, which he withdrew days before the scheduled premiere in 1936, after his first public condemnation, would not receive its premiere until 1961. With his Tenth Symphony, then, Shostakovich accomplished something monumental: a work that met the grand Romantic symphonic tradition and breathed new relevance into it with a healthy dose of 20th-century anxiety, grotesquerie, and sarcasm. As such, the work is not simplistically triumphant, although the final movement shifts to a warm major key for moments of truly festive celebration. Instead, the symphony is full of contrasts and contradictions, recurring themes across the movements,

and, for the first time, his musical signature, DSCH (D, E-flat, C, B, but spelled in the German system). The symphony marks a significant shift in his style toward quotation (including self-quotation), personal references, and autobiography that ultimately culminated in his well-known Eighth String Quartet from 1960.

The large-scale first movement follows a sonata-allegro form in the Romantic tradition, but rather than feature motivic development and transformation, it tends toward discrete musical scenes. An extended, ominous introduction slowly ascends from the depths giving way to a slow, lyrical first theme introduced by the solo clarinet. The second theme, introduced by the solo flute, features a folk dance in a loosely Jewish style (over time, Shostakovich came to identify with the oppressed Jewish people of the USSR as a fellow marked man). With an ambiguous, unresolved ending, the movement provides no Romantic narrative of triumph, but rather a sense of stasis through struggle.

Following this open-ended first movement, the brief second movement, a raging scherzo, starts at a sprint and continues to ramp up to a wild and reckless conclusion. Despite its brevity, it features prominently across the work, introducing themes that reappear in the following two movements.

The third movement is the crux of the whole symphony. It picks up the lyrical clarinet theme from the first movement and one section from the second movement, bringing them into dialogue with statements of Shostakovich’s musical signature. The DSCH motive appears first in the high strings (not yet at the correct pitch) and becomes increasingly pervasive: It appears like desperate shouts, meek whispers, and even a fatalistic dirge in the low brass, but never as selfconfident affirmation.

The final movement offers an optimistic ending, but like the second movement, it goes over the edge, when liberty becomes libertine and excitement turns manic. Ultimately in the context of the Romantic symphonic tradition, Shostakovich’s Tenth undercuts the idea of some unscathed hero, but at the same time suggests, perhaps, that survival is its own victory.

Vasily Petrenko is music director of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, a position he assumed in 2021, and which ignited a partnership that has been praised by audiences and critics worldwide. The same year, he became conductor laureate of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, following his hugely acclaimed 15-year tenure as their chief conductor from 2006 to 2021. He is the associate conductor of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Castilla y León, and has also served as chief conductor of the European Union Youth Orchestra (2015–2024) and Oslo Philharmonic (2013–2020), and principal conductor of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain (2009–2013). He stepped down as artistic director of the State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia “Evgeny Svetlanov” in 2022, having been its principal guest conductor from 2016 and artistic director from 2020.

Petrenko has worked with many of the world’s most prestigious orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Czech Philharmonic, and NHK Symphony Orchestra, and in North America has led The Philadelphia Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, and the Boston and Chicago symphony orchestras. He has appeared at the Edinburgh Festival, Grafenegg Festival, and BBC Proms. Equally at home in the opera house, and with over 30 operas in his repertoire, Petrenko has conducted widely on the operatic stage, including at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, the Opéra National de Paris, Opernhaus Zürich, Bayerische Staatsoper, and the Metropolitan Opera, New York.

Recent highlights as music director of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra have included tours across Europe, China, Japan, and the US. In London, recent acclaimed performances have included Mahler’s choral symphonies and concerts with Yunchan Lim and Maxim

Vengerov at the Royal Albert Hall, performances at the BBC Proms, and the Icons Rediscovered and Lights in the Dark series. In the 2025–26 season, the orchestra will perform three mighty Mahler symphonies alongside Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms and Korngold’s Violin Concerto. At the Royal Festival Hall, highlights include Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 10, Messiaen’s TurangalîlaSymphonie, orchestral music from Wagner’s Parsifal, and Scriabin’s Symphony No. 3, “The Divine Poem.”

Petrenko has established a strongly defined profile as a recording artist. Among a wide discography, his Shostakovich, Rachmaninov, and Elgar symphony cycles with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra have garnered worldwide acclaim. With the Oslo Philharmonic, he has released cycles of Scriabin’s symphonies and Strauss’s tone poems, and an ongoing series of the symphonies of Prokofiev and Myaskovsky. In autumn 2025, he launched a new partnership between the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Harmonia Mundi label, with Elgar’s Falstaff and Rachmaninov’s The Bells, to be followed by subsequent releases of Strauss, Bartók, and Stravinsky.

Born in 1976, Petrenko was educated at the St. Petersburg Capella Boys Music School and St. Petersburg Conservatory. He was Gramophone Artist of the Year (2017), Classical BRIT Male Artist of the Year (2010), and holds honorary degrees from Liverpool’s three universities. In 2024, he launched a new academy for young conductors, co-organized by the Primavera Foundation of Armenia and the Armenian National Philharmonic Orchestra. Learn more at vasilypetrenkomusic.com.

Boris Giltburg is lauded across the globe as a deeply sensitive, insightful and compelling interpreter for his narrative-driven approach to performance. Critics have praised his “interplay of spiritual calm and emphatic engagement” as “gripping ... one could not wish for a more illuminating, lyrical or more richly phrased interpretation”(Süddeutsche Zeitung).

During the 2025–26 season, Giltburg appears with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Frankfurt

Radio Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic, Salzburg Mozarteum, Warsaw Philharmonic, Essen Philharmonic, Basque National Orchestra, and Taipei Symphony Orchestra. This season, Giltburg is artist-in-residence at the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra and returns to the orchestra on three occasions, and embarks on a tour to Italy. This season also sees Giltburg collaborate with leading conductors, including Jukka-Pekka Saraste, Krzysztof Urbański, Dima Slobodeniouk, Dalia Stasevska, Kahchun Wong, Jun Märkl, and Anja Bihlmaier. Giltburg’s long list of orchestral collaborators includes the Czech Philharmonic, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Finnish Radio Symphony, Orchestre National de France, Oslo Philharmonic, Philharmonia Orchestra, NHK Symphony, and Seoul Philharmonic, among others.

Giltburg regularly gives recitals in the world’s most prestigious halls, including the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam; BOZAR, Brussels; Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg; Southbank Centre and Wigmore Hall, London; Carnegie Hall, New York; Rudolfinum, Prague; and Konzerthaus, Vienna. Following the success of his Beethoven Piano Sonatas cycle across eight sold-out concerts at the Wigmore Hall, he continues the project at the Flagey (Brussels), Palau de la Música (Valencia) and Teatro Municipal (Santiago). In recent years, Giltburg has also engaged in a series of in-depth explorations of other major composers, such as Ravel and Chopin.

Giltburg is widely recognized as a leading interpreter of Rachmaninov: “His originality stems from a convergence of heart and mind, served by immaculate technique and motivated by a deep and abiding love for one of the 20th century’s greatest composer-pianists” (Gramophone). This season, Giltburg performed the complete Rachmaninov Preludes during the opening weekend of the Southbank Centre’s 25/26 season and the Third Piano Concerto with the Philharmonia Orchestra at Bold Tendencies. In 2025, Giltburg released an album of Rachmaninov’s landmark Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 and 2 alongside his own version of Isle of the Dead based on Kirkor’s arrangement, which received the Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik / German Record Critics’ Award.

A consummate recording artist, Giltburg has recorded exclusively for Naxos since 2015. He was awarded

the Opus Klassik Award for Best Soloist Recording of Rachmaninov’s concertos and Études-Tableaux and a Diapason d’Or for Shostakovich concertos and his own arrangement of Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet. Among others, he has won a Gramophone Award for the Dvořák Piano Quintet on Supraphon with his regular collaborators, the Pavel Haas Quartet, as well as a Diapason d’Or and Choc de Classica for their joint release of the Brahms Piano Quintet. Giltburg feels a strong urge to engage audiences beyond the concert hall. His blog Classical Music for All is aimed at a non-specialist audience, which he complements with articles in publications such as Gramophone, BBC Music Magazine, The Guardian, and The Times.

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO), with music director Vasily Petrenko, is on a mission to bring the thrill of live orchestral music to the widest possible audience. The RPO’s musicians believe that music can—and should—be a part of everyone’s life, and they aim to deliver on that belief through every note. Based in London and performing around 200 concerts per year worldwide, the RPO brings the same energy, commitment and excellence to everything it plays, be that the great symphonic repertoire, collaborations with pop stars, or TV, video game and movie soundtracks. Proud of its rich heritage yet always evolving, the RPO is regarded as the world’s most versatile symphony orchestra, reaching a live and online audience of more than 70 million people each year.

Founded in 1946 by Sir Thomas Beecham, live performance has always been at the heart of what the RPO does, and through its thriving artistic partnership with Vasily Petrenko, the RPO has reaffirmed its status as one of the world’s most respected and in-demand orchestras. In London, that means flagship concert series at Cadogan Hall, the Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall, and the iconic Royal Albert Hall, where the RPO is proud to be Associate Orchestra. The orchestra is also thrilled to be resident in four areas of the UK: Crawley, Hull, Northampton, and Reading. And around the world, the RPO flies the flag for the best of British music-making.

The RPO remains true to its pioneering, accessible roots. Now in its fourth decade, the RPO Resound community and education program continues to thrive as one of the UK’s—and the world’s—most innovative and respected initiatives of its kind. Passionate, versatile and uncompromising in its pursuit of musical excellence, the orchestra looks to the future with a determination to explore, share, and reaffirm its reputation as an orchestra with a difference: open-minded, forward-thinking and accessible to all. Discover more online at rpo.co.uk.

Duncan Riddell

Tamás András

Janice Graham

Esther Kim

Lauren Bennett

Savva Zverev

Andrew Klee

Kay Chappell

Anthony Protheroe

Erik Chapman

Adriana Iacovache-Pana

Imogen East

Momoko Arima

Judith Choi-Castro

Joanne Chen

Izzy Howard

Andrew Storey

Alexandra Lomeiko

Charlotte Ansbergs

Jennifer András

Peter Graham

Stephen Payne

Manuel Porta

Inês Soares Delgado

Sali-Wyn Ryan

Charles Nolan

Leonardo Jaffe

Susie Watson

Clare Wheeler

Susan Evans

VIOLAS

Abigail Fenna

Wenhan Jiang

Liz Varlow

Joseph Fisher

Ugne Tiškuté

Esther Harling

Jonathan Hallett

Pamela Ferriman

Gemma Dunne

Raquel Lopez Bolivar

Kate Correia De Campos

Annie-May Page

CELLOS

Rosie Biss

Jonathan Ayling

Chantal Woodhouse

Roberto Sorrentino

Jean-Baptiste Toselli

Rachel van der Tang

Naomi Watts

Anna Stuart

Emma Black

George Hoult

DOUBLE BASS

Jason Henery

Alice Durrant

David Gordon

Ben Wolstenholme

Joe Cowie

Martin Lüdenbach

Lewis Reid

Guillermo Arevalos

FLUTES

Amy Yule

Joanna Marsh

Diomedes Demetriades

PICCOLOS

Diomedes Demetriades

Joanna Marsh

OBOES

Tom Blomfield

Hannah Condliffe

Patrick Flanaghan

COR ANGLAIS

Patrick Flanaghan

CLARINETS

Sonia Sielaff

Katy Ayling

James Gilbert

E-FLAT CLARINET

James Gilbert

BASSOONS

Richard Ion

Ruby Collins

Fraser Gordon

CONTRABASSOON

Fraser Gordon

HORNS

Alexander Edmundson

Ben Hulme

Finlay Bain

Zoë Tweed

Paul Cott

TRUMPETS

Matthew Williams

Kaitlin Wild

Mike Allen

Toby Street

TROMBONES

Roger Cutts

Ryan Hume

BASS TROMBONE

Josh Cirtina

TUBA

Kevin Morgan

TIMPANI

James Bower

PERCUSSION

Stephen Quigley

Martin Owens

Gerald Kirby

Richard Home

MANAGEMENT TEAM

Managing Director

Sarah Bardwell

Business Development

Director / Deputy Managing Director

Huw Davies

Finance Director

Ann Firth

Director of Artistic Planning and Partnerships

Tom Philpott

Concerts Director

Frances Axford Evans

Tours Manager

Rose Hooks

Tours Coordinator

Victoria Webber

Director of Community and Education

Chris Stones

Senior Orchestra Manager

Kathy Balmain

Orchestra Manager

Rebecca Rimmington

Librarian

Patrick Williams

Stage Managers

Dan Johnson

Toni Abell

Sam Swift

Anonymous

Margaret Alferi & Eugene Kim

Robin Axel & Jacob Axel

Mohamed Bacchus

Martin Baggott & Jennine Baggott

Robert Bell & Jeanne Bell

Bennett Berson & Rebecca Holmes

James Bigwood & Jay Cha

Diane Bless

Cassandra Book

Michael Brody & Elizabeth Ester

Daniel Burrell Jr & Jenice Burrell

James Carlson

Peggy Chane

Janet Cohen

Charles Cohen & Christine Schindler

Mary Crosby

George Cutlip

Heather Daniels & Alan Hiebert

Kelly Dehaven & David Cooper

André De Shields

Mark Dettmann & Cathleen Dettmann

Jaimie Dockray & Brian Dockray

Elizabeth Douma

Margaret Douma & Wallace Douma

James Doyle Jr & Jessica Doyle

Rae Erdahl

Deborah Fairchild

Hildy Feen

Marlene Fiske

Jeffrey Fritsche & Carol Fritsche

Deirdre Garton

Neil Geminder & Joan Geminder

Jean Gessl & Douglas Gessl

Michelle Gregoire & Tim Gregoire

Mark Guthier & Amy Guthier

Kristine Hallisy

Justin Hein & Paige Hein

Brent Helt

John Hirsh & Lynnette Tenorio

Seth Hoff

Matthew Huston

Carol Hyland

Arnold Jacobson

Kelly Kahl & Kimberly Kahl

Elisabeth Kasdorf

Kate Kingery

Daniel Koehn & Mark Koehn

Diane Kostecke & Nancy Ciezkia

Kathleen Kotnour

Iris Kurman & Seth Dailey

Sandra Lee & Jun Lee

Christopher Louderback

Douglas Mackaman & Margaret O'Hara

Edward Manuel & Marian Holton-Manuel

Shibani Munshi

Eric Nathan

Glenda Noel-Ney & William Ney

Mitchell Nussbaum & Eugenia Ogden

Ann Pehle

David and Kato Perlman

Lisa Pfaff

Nicholas Pjevach

M Thomas Record Jr & Voula Kodoyianni

Sharon Rouse

Ralph Russo & Lauren Cnare

Peter Ryan

Joshua Rybaski

Morgan Sachs

J Gail Meyst Sahney & Vinod Sahney

Steven Schaffer & Beth Schaffer

Carol Schroeder

Daniel Schultz & Patricia Schultz

Sarah Schutt & Donald Schutt Jr

Margaret Shields

Elizabeth Snodgrass

Polly Snodgrass

Monica St Angelo & Mark Levandoski

Mark Stanley & Krista Stanley

Lynn Stathas

Jonathan Stenger

Jason Stephens & Ana Stephens

Andrew Stevens & Erika Stevens

Millard Susman & Barbara Susman

Kimberly Svetin & Todd Svetin

Thompson Investment Management

Elizabeth Van Ness

Daniel Van Note

Rachel Waner

Glenn Watts & Jane Watts

Shane Wealti

Kathleen Williams

Janell Wise

James Wockenfuss & Lena Wockenfuss

Debbie Wong

Donors as of July 31, 2025

COMING UP IN THEATER

JASON MORAN AND THE HARLEM HELLFIGHTERS

Saturday, February 7 7:30 PM

Shannon Hall at Memorial Union Jazz Event

JOYCE DIDONATO AND TIME FOR

THREE: EMILY - NO PRISONER BE

Thursday, February 12 7:30 PM

Shannon Hall at Memorial Union Classical Event

EMMET COHEN: “ MILES AND COLTRANE AT 100 ” FT. JEREMY PELT & TIVON PENNICOTT

Saturday, February 28 7:30 PM

Shannon Hall at Memorial Union Jazz Event

Elizabeth Snodgrass, Director

Kate Schwartz, Artist Services Manager

George Hommowun, Assistant Director of Theater Event Operations

Zane Enloe, Production Manager

Jeff Macheel, Technical Director

Heather Macheel, Technical Director

Sean Danner, Assistant Director of Ticketing and Patron Services

Ted Harks, Arts Ticketing Website Systems Administrator

Eric Henkes, Lead House Manager

Ava Conrad, Rentals Assistant

Kelsey Fleckenstein, Special Projects Assistant

Mandy Descorbeth, External Relations Intern

Paige Verbsky, Bolz Center for Arts Administration Intern

WISCONSIN

PERFORMING ARTS COMMITTEE

Jordan Waters, Director

Thomas Wieland, Programming Associate Director

Lucy Kenavan, Programming Associate Director

Sabrina Ortiz, Production Associate Director

Cosette Wildermuth, External Relations Associate Director

Kalia Gordon, Marketing Associate Director