About Us: Penn State Health is a multi-hospital health system serving patients and communities across central Pennsylvania. We are the only medical facility in Pennsylvania to be accredited as a Level I pediatric trauma center and Level I adult trauma center. The system includes Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State Health Children’s Hospital and Penn State Cancer Institute based in Hershey, Pa.; Penn State Health Hampden Medical Center in Enola, Pa.; Penn State Health Holy Spirit Medical Center in Camp Hill, Pa.; Penn State Health Lancaster Medical Center in Lancaster, Pa.; Penn State Health St. Joseph Medical Center in Reading, Pa.; Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute, a specialty provider of inpatient and outpatient behavioral health services, in Harrisburg, Pa.; and 2,450+ physicians and direct care providers at 225 outpatient practices. Additionally, the system jointly operates various healthcare providers, including Penn State Health Rehabilitation Hospital, Hershey Outpatient Surgery Center and Hershey Endoscopy Center.

We foster a collaborative environment rich with diversity, share a passion for patient care, and have a space for those who share our spark of innovative research interests. Our health system is expanding and we have opportunities in both academic hospital as well community hospital settings.

Benefit highlights include:

• Competitive salary with sign-on bonus

• Comprehensive benefits and retirement package

• Relocation assistance & CME allowance

• Attractive neighborhoods in scenic central Pennsylvania

Orlando, FL | March 26 - 29 | Pre-Day: March 25

We are excited to publish the 11th issue of the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine (WestJEM) Special Issue in Educational Research & Practice (Special Issue). Over a decade ago a unique relationship was formed between WestJEM, the Council of Residency Director for Emergency Medicine and the Clerkship Directors of Emergency Medicine to develop a publication that disseminates educational scholarship which impacts our communities while promoting the growth, as authors, of our junior faculty. The structure of the Special Issue provides a diversity of submission categories such as original research, educational advances, best practices, reviews and scholarly perspectives. This selection provides an opportunity for all scholars and scholarly approaches to have a voice. A successful Special Issue requires the courage of the authors to submit their work for peer review. In turn, we do our best to provide detailed feedback regardless of the final decision. Publication of the issue requires the commitment and hard work of the publication staff, leadership of the organizations, editors, and peer reviewers. We want to thank them all for their efforts and professionalism. The topics of this year’s education issue reflect many of the current issues in medical education today. We have begun receiving and reviewing submissions for next year’s Special Issue. The editorial staff review every submission on a rolling basis. Once accepted, the articles are available on PubMed in an expedited process. There are also no processing fees when accepted to the Special Issue. This is a great opportunity to submit your educational scholarship, thereby enhancing your professional development while disseminating your work to others. We are delighted that this initiative has flourished and look forward to seeing your work on display in this, our 11th issue.

Jeffrey Love, MD

Georgetown University School of Medicine

Co-Editor of Annual Special Issue on Education Research and Practice

Douglas Ander, MD

Emory University

Co-Editor of Annual Special Issue on Education Research and Practice

The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health would like to thank The Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) and the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) for helping to make this collaborative special issue possible.

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Emergency medicine is a specialty which closely reflects societal challenges and consequences of public policy decisions. The emergency department specifically deals with social injustice, health and economic disparities, violence, substance abuse, and disaster preparedness and response. This journal focuses on how emergency care affects the health of the community and population, and conversely, how these societal challenges affect the composition of the patient population who seek care in the emergency department. The development of better systems to provide emergency care, including technology solutions, is critical to enhancing population health.

Best Practices

1 Resident-as-Teacher Curriculum: An Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine

J Jordan, M Gottlieb, M Estes, ME Parsons, K Goldflam, A Grock, BJ Long, S Natesan

Original Research

10 A Qualitative Study of Senior Residents’ Strategies to Prepare for Unsupervised Practice

M Griffith, A Garrett, BK Watsjold, J Jauregui, M Davis, JS Ilgen

19 Characteristics and Educational Support Resources Available to Emergency Medicine Core Faculty: A National Survey

J Jordan, LR Hopson, F Gallahue, JA Cranford, JC Burkhardt, KE Kocher, DL Robinett, M Weizberg, T Murano

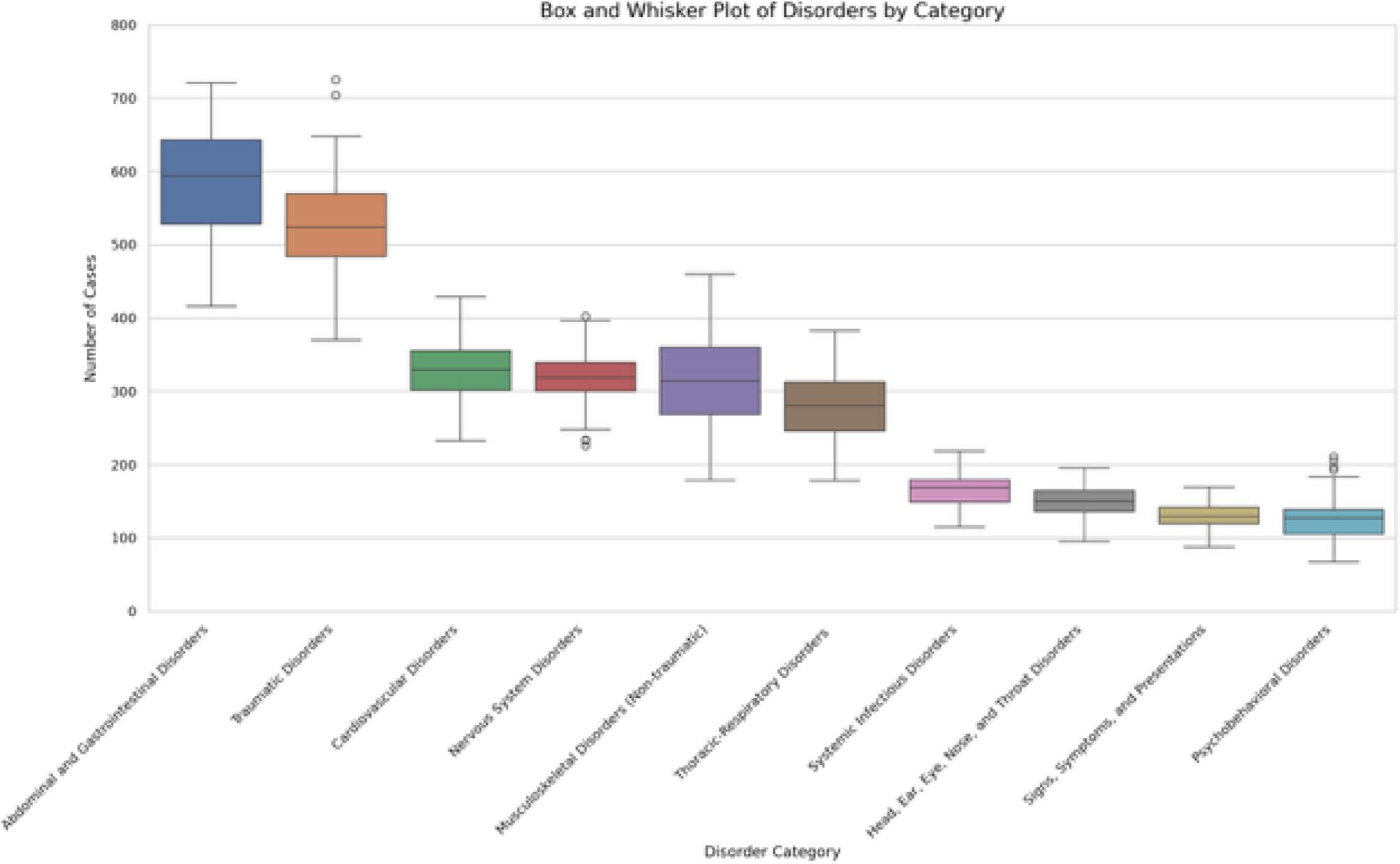

27 Substantial Variation Exists in Clinical Exposure to Chief Complaints Among Residents Within an Emergency Medicine Training Program

CM.Jewell, AT Hummel, DJ Hekman, BH Schnapp

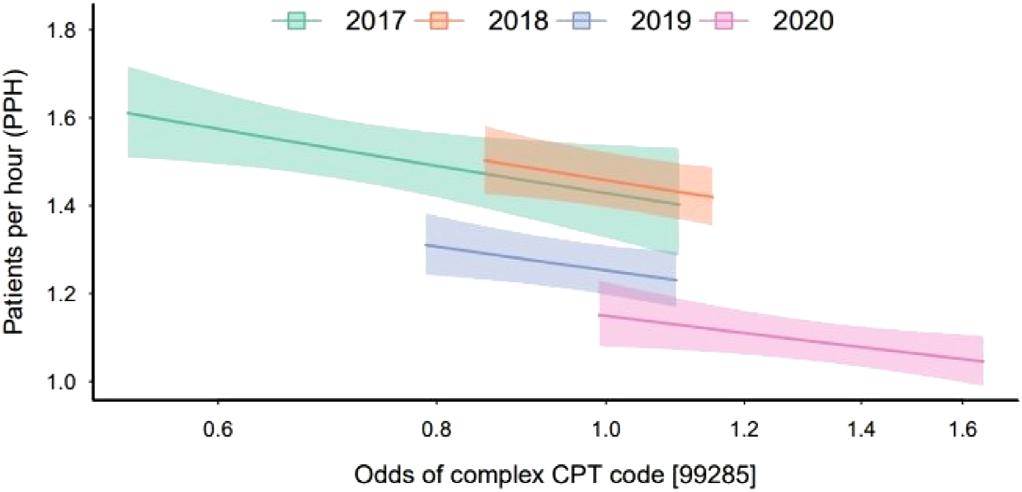

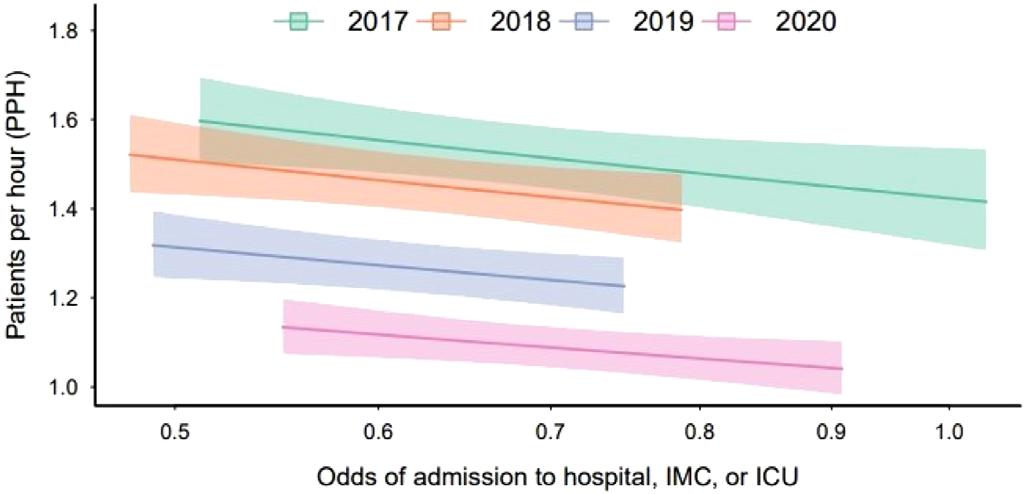

33 Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger? Residents Seeing More Patients Per Hour See Lower Complexity

CM Jewell, G (Anthony) Bai, DJ Hekman, AM Nicholson, MR Lasarev, R Alexandridis, BH Schnapp

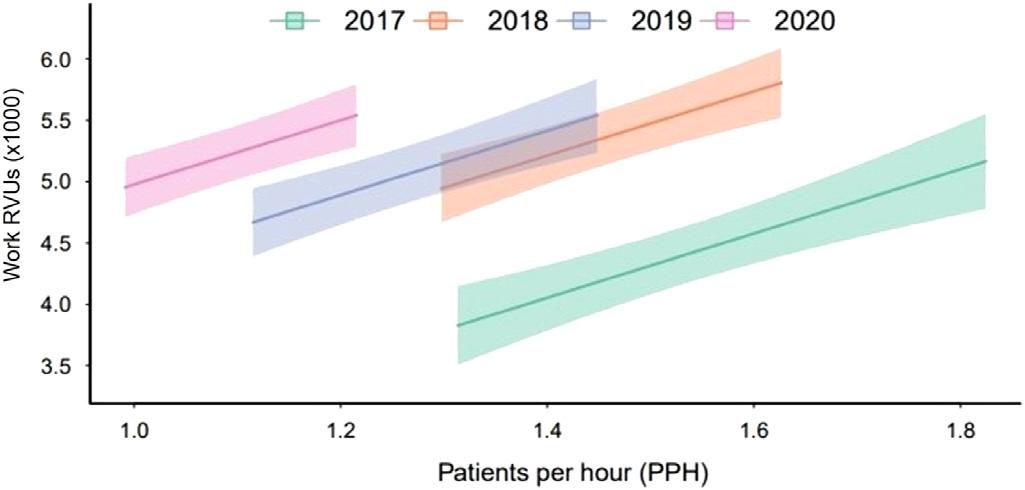

40 The Effect of Hospital Boarding on Emergency Medicine Residency Productivity

P Moffett, A Best, N Lewis, S Miller, G Hickam, H Kissel-Smith, L Barrera, S Huang, J Moll

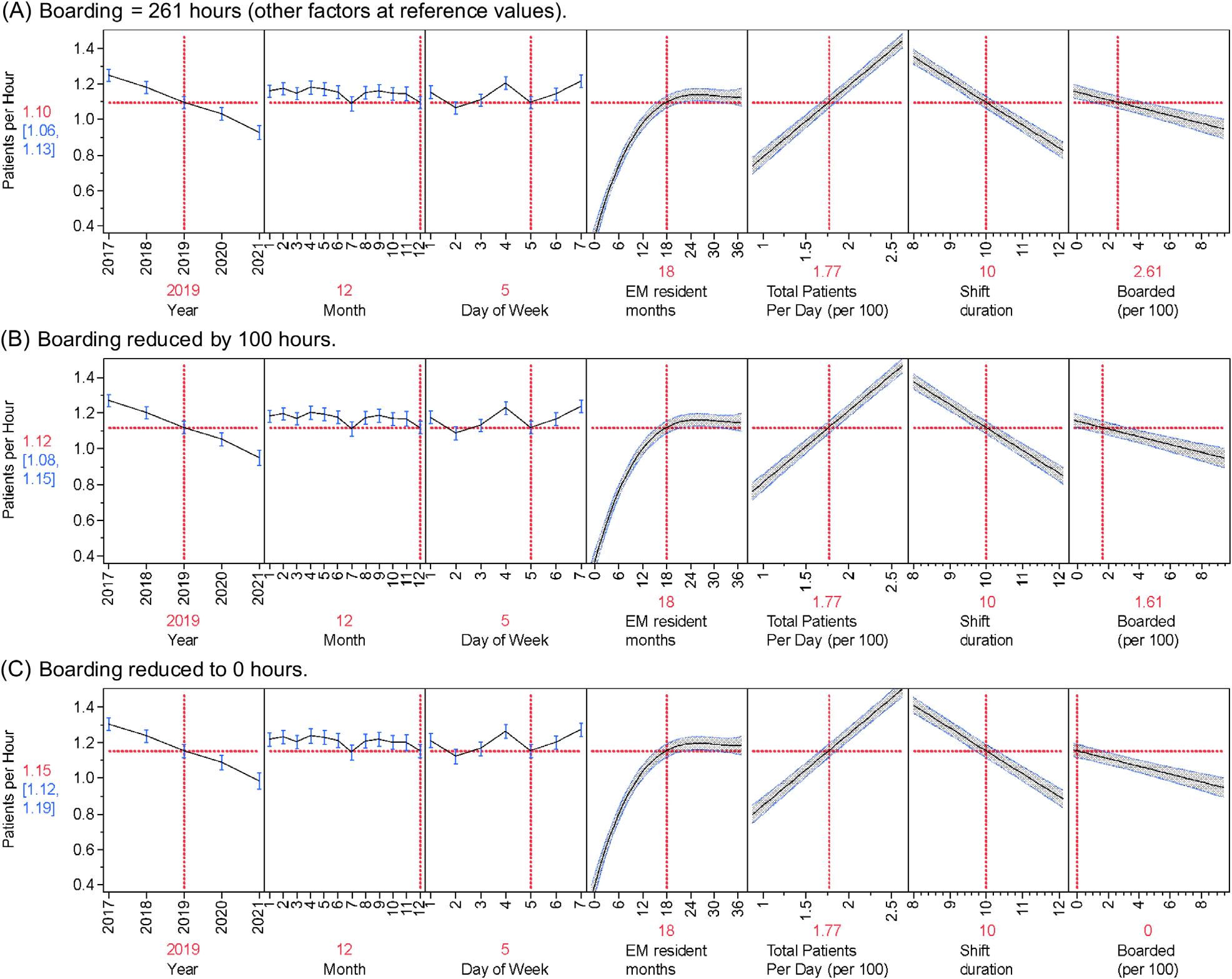

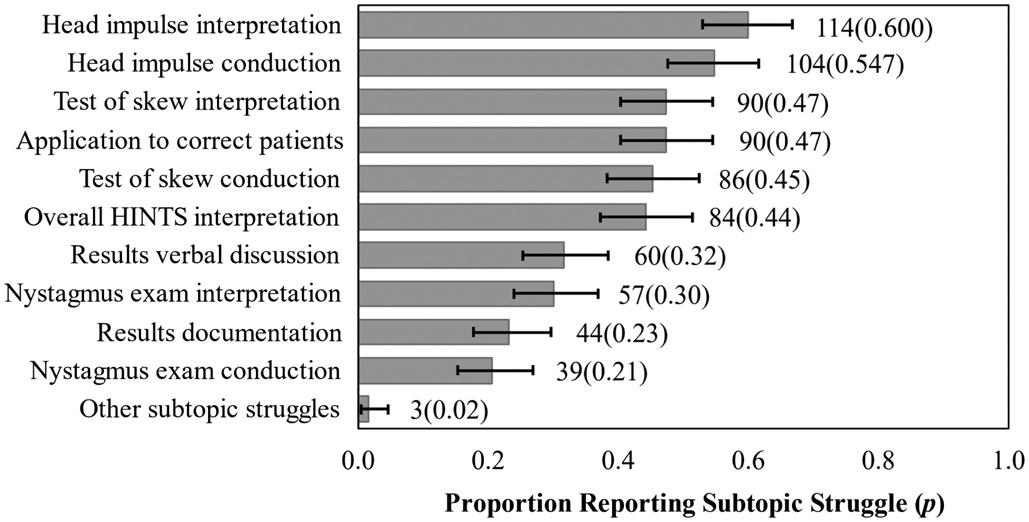

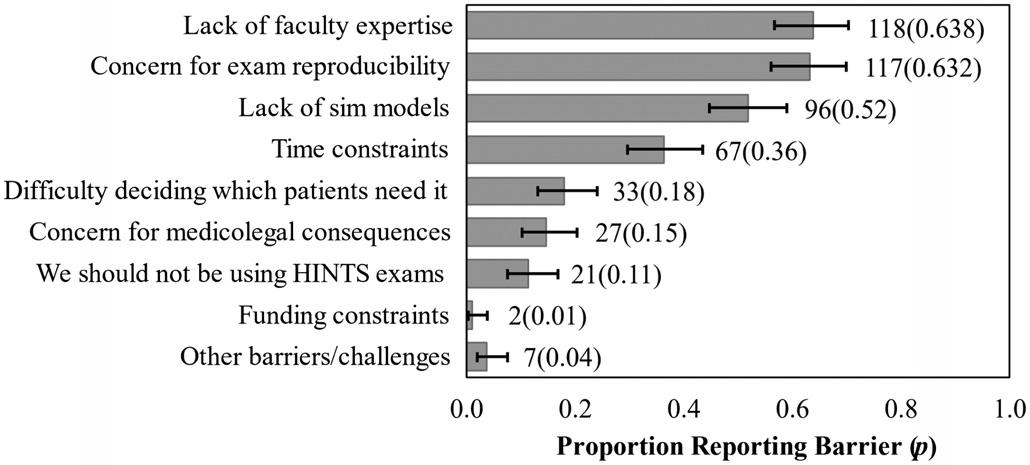

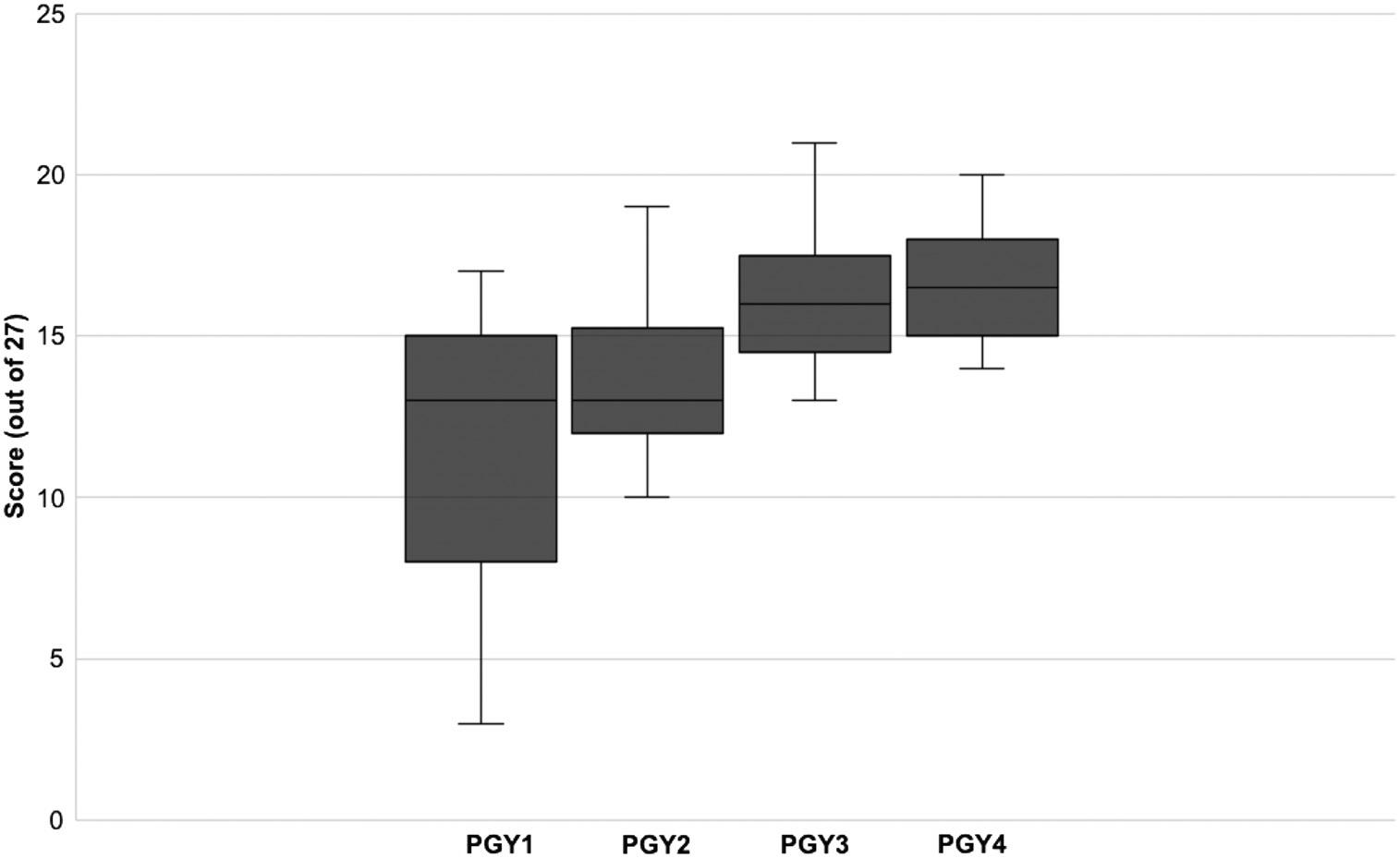

49 Leadership Perceptions, Educational Struggles and Barriers, and Effective Modalities for Teaching Vertigo and the HINTS Exam: A National Survey of Emergency Medicine Residency Program Directors

M McLean, J Stowens, R Barnicle, N Mafi, K Shah

57 Push and Pull: What Factors Attracted Applicants to Emergency Medicine and What Factors Pushed Them Away Following the 2023 Match

M Kiemeney, J Morris, L Lamparter, M Weizberg, A Little, B Milman

67 Emergency Medicine Residency Website Wellness Pages: A Content Analysis

A Sappington, B Milman

74 Inequities in the National Clinical Assessment Tool for Medical Students in the Emergency Department

BZ Amin, CJ Dine, ER Tabakin, M Trotter, JK Heath

Policies for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found online at www.westjem.com.

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Brief Research Reports

84

Program Director Perspectives on the Impact of the Proposed 48-Month Emergency Medicine Residency Requirement: A National Survey R Austin, C Patel, K Delfino, S Kim

90 Virtual Interviews Correlate with Home and In-State Match Rates at One Emergency Medicine Program C Motzkus, C Frey, A Humbert

Edcuational Advances

95 Development of a Reliable, Valid Procedural Checklist for Assessment of Emergency Medicine Resident Performance of Emergency Cricothyrotomy DE Loke, AM Rogers, ML McCarthy, MK Leibowitz, ET Stulpin, DH Salzman

Brief Educational Advances

101 A Taste of Our Own Medicine: Fostering Empathy in Medical Learners Through Patient Simulation RP Peña, W Weber

105 Effectiveness of a Collaborative, Virtual Outreach Curriculum for 4th-Year EM-bound Students at a Medical School Affiliated with a Historically Black College and University C Brown, R Carter, N Hartman, A Hammond, E MacNeill, L Holden, A Pierce, L Campbell, M Norman

Editorial

111 A 30-year History of the Emergency Medicine Standardized Letter of Evaluation JS Hegarty, CB Hegarty, JN Love, A Pelletier-Bui, S Bord, MC Bond, SM Keim, K Hamilton, EF Shappell

Policies for peer review, author instructions, conflicts of interest and human and animal subjects protections can be found online at www.westjem.com.

The WestJEM Special Issue in Educational Research & Practice couldn’t exist without our many reviewers. To all, we wish to express our sincerest appreciation for their contributions to this year’s success. Each year a number of reviewers stand out for their (1) detailed reviews, (2) grasp of the tenets of education scholarship and (3)efforts to provide feedback that mentors authors on how to improve. This year’s “Gold Standard” includes:

• Max Berger (UCLA Medical Center)

• April Choi (Rutgers New Jersey Medical School)

• Anna Darby, Jeff Riddell (Keck School of Medicine-USC)*

• Zoe Fisher, Jenna Paul Schultz, Linda Regan (Johns Hopkins)*

• Max Griffith (University of Washington)

• Kirlos Haroun, Katie Lorenz, Kathryn Ritter, Linda Regan (Johns Hopkins)*

• Arman Hussain, Claudia Ranniger (George Washington University)*

• Carlos Jaquez, Daniela Ortiz (Baylor College of Medicine)*

• Corlin Jewell (University of Wisconsin)

• Chelsea Johnson, Anne Messman (Wayne State University)*

• Justine McGiboney (University of AlabamaBirmingham)

• Vivek Medepalli, Avirale Sharma, Larissa Valez (UT Southwestern)*

• Joe-Ann Moser (University of Wisconsin)

• Collyn Murray (University of North Carolina)

• Elspeth Pearce (University of Kansas Medical Center)

• Jessica Pellitier (University of Missouri)

• Monica Shah, Patrick Felton, Bryanne McDonald, Lucienne Lutfy-Clayton (University of Massachusetts)*

• Emily Straley, Vicki Zhou, Richard Bounds (University of Vermont)*

• NeelouTabatabai, Samual O Clarke (UC Davis)*

• Thadeus Schmitt (Medical College of Wisconsin)

• Juhi Varshney, Michael Zdradzinski (Emory University)*

• Kalen Wright, Eric Shappell (HarvardMassachusetts General Hospital)*

• Chris Yang, Tim Koboldt, Chelsea Broomhead, Margaret Goodrich (Missouri Health)*

• Ivan Zvonar, Jon Ilgen (University of Washington)*

• Ivan Zvonar (University of Washington)

*Mentored Peer Reviews from Emergency Medicine Education Fellowship Programs

We would also like to recognize our guest consulting editors who assisted with pre-screening submissions during our initial peer-review stages.

Thank you for all of your efforts and contributions.

CDEM

• Christine Stehman

• Eric Shappell

• Sharon Bord

• Andrew Golden

CORD

• Jenna Fredette

• Danielle Hart

• William Soares III

• Jamie Jordan

• Anne Messman

• Logan Weygandt

Consulting Statistician/ Psychometrician

• David Way

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

Jeffrey N. Love, MD, Guest Editor Georgetown School of Medicine- Washington, District of Columbia

Danielle Hart, MD, MACM, Associate Guest Editor Hennepin Healthcare-Minneapolis, Minnesota

Benjamin Schnapp, MD, MEd, Associate Guest Editor University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin

Wendy Macias-Konstantopoulos, MD, MPH, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Danya Khoujah, MBBS, Associate Editor University of Maryland School of Medicine- Baltimore, Maryland

Patrick Joseph Maher, MD, MS, Associate Editor Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai- New York, New York

Yanina Purim-Shem-Tov, MD, MS, Associate Editor Rush University Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Gayle Galletta, MD, Associate Editor University of Massachusetts Medical SchoolWorcester, Massachusetts

Section Editors

Behavioral Emergencies

Bradford Brobin, MD, MBA Chicago Medical School

Marc L. Martel, MD Hennepin County Medical Center

Ryan Ley, MD Hennepin County Medical Center

Cardiac Care

Sam S. Torbati, MD Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

Rohit Menon, MD University of Maryland

Elif Yucebay, MD Rush University Medical Center

Mary McLean, MD AdventHealth

Climate Change

Gary Gaddis, MBBS University of Maryland

Clinical Practice

Casey Clements, MD, PhD Mayo Clinic

Murat Cetin, MD

Behçet Uz Child Disease and Pediatric Surgery Training and Research Hospital

Patrick Meloy, MD Emory University

Carmine Nasta, MD Università degli Studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”

David Thompson, MD University of California, San Francisco

Tom Benzoni, DO Des Moines University of Medicine and Health Sciences

Critical Care

Christopher “Kit” Tainter, MD University of California, San Diego

Joseph Shiber, MD University of Florida-College of Medicine

David Page, MD University of Alabama

Quincy Tran, MD, PhD University of Maryland

Dan Mayer, MD, Associate Editor Retired from Albany Medical College- Niskayuna, New York

Julianna Jung, MD, Associate Guest Editor Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland

Douglas Franzen, MD, Associate Guest Editor Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, Washington

Gentry Wilkerson, MD, Associate Editor University of Maryland

Michael Gottlieb, MD, Associate Editor Rush Medical Center-Chicago, Illinois

Sara Krzyzaniak, MD Associate Guest Editor Stanford Universtiy-Palo Alto, California

Susan R. Wilcox, MD, Associate Editor Massachusetts General Hospital- Boston, Massachusetts

Donna Mendez, MD, EdD, Associate Editor University of Texas-Houston/McGovern Medical School- Houston, Texas

Taku Taira, MD, EDD, Associate Guest Editor LAC + USC Medical Center-Los Angeles, California

Antonio Esquinas, MD, PhD, FCCP, FNIV Hospital Morales Meseguer

Dell Simmons, MD Geisinger Health

Disaster Medicine

Andrew Milsten, MD, MS UMass Chan Medical Center

John Broach, MD, MPH, MBA, FACEP University of Massachusetts Medical School UMass Memorial Medical Center

Christopher Kang, MD Madigan Army Medical Center

Scott Goldstein, MD Temple Health

Education

Danya Khoujah, MBBS University of Maryland School of Medicine

Jeffrey Druck, MD University of Colorado

Asit Misra, MD University of Miami

Cameron Hanson, MD The University of Kansas Medical Center

ED Administration, Quality, Safety

Gary Johnson, MD Upstate Medical University

Brian J. Yun, MD, MBA, MPH Harvard Medical School

Laura Walker, MD Mayo Clinic

León D. Sánchez, MD, MPH Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Robert Derlet, MD

Founding Editor, California Journal of Emergency Medicine University of California, Davis

Tehreem Rehman, MD, MPH, MBA Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Anthony Rosania, MD, MHA, MSHI Rutgers University

Neil Dasgupta, MD, FACEP, FAAEM Nassau University Medical Center

Emergency Medical Services

Daniel Joseph, MD Yale University

Douglas S. Ander, MD, Guest Editor Emory University School of Medicine-Atlanta, Georgia

Edward Ullman, MD, Associate Guest Editor Harvard University-Cambridge, Massachusetts

Abra Fant MD, MS, Associate Guest Editor

Northwestern Medicine-Chicago, Illinois

Kendra Parekh, MD, MS, Associate Guest Editor Vanderbilt University-Nashville, Tennessee

Matthew Tews, DO, MS, Associate Guest Editor Indiana University School of Medicine, Augusta, Georgia

Rick A. McPheeters, DO, Associate Editor Kern Medical- Bakersfield, California

Niels K. Rathlev MD, MS, Associate Editor Tufts University School of Medicine-Boston, Massachusetts

Shahram Lotfipour, MD, MPH, Managing Associate Editor University of California, Irvine School of Medicine- Irvine, California

Mark I. Langdorf, MD, MHPE, Editor-in-Chief University of California, Irvine School of Medicine- Irvine, California

Joshua B. Gaither, MD University of Arizona, Tuscon

Julian Mapp University of Texas, San Antonio

Shira A. Schlesinger, MD, MPH Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

Tiffany Abramson, MD University of Southern California

Jason Pickett, MD University of Utah Health

Geriatrics

Stephen Meldon, MD Cleveland Clinic

Luna Ragsdale, MD, MPH Duke University

Health Equity

Cortlyn W. Brown, MD Carolinas Medical Center

Faith Quenzer

Temecula Valley Hospital San Ysidro Health Center

Victor Cisneros, MD MPH Eisenhower Health

Sara Heinert, PhD, MPH Rutgers University

Naomi George, MD MPH University of Mexico

Sarah Aly, DO Yale School of Medicine

Lauren Walter, MD University of Alabama

Infectious Disease

Elissa Schechter-Perkins, MD, MPH Boston University School of Medicine

Ioannis Koutroulis, MD, MBA, PhD

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Stephen Liang, MD, MPHS Washington University School of Medicine

Injury Prevention

Mark Faul, PhD, MA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Wirachin Hoonpongsimanont, MD, MSBATS Eisenhower Medical Center

International Medicine

Heather A.. Brown, MD, MPH Prisma Health Richland

Taylor Burkholder, MD, MPH Keck School of Medicine of USC

Christopher Greene, MD, MPH University of Alabama

Chris Mills, MD, MPH Santa Clara Valley Medical Center

Shada Rouhani, MD

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Legal Medicine

Melanie S. Heniff, MD, JD Indiana University School of Medicine

Statistics and Methodology

Shu B. Chan MD, MS Resurrection Medical Center

Soheil Saadat, MD, MPH, PhD University of California, Irvine

James A. Meltzer, MD, MS Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Monica Gaddis, PhD University of Missouri, Kansas City School of Medicine

Emad Awad, PhD University of Utah Health

Musculoskeletal

Juan F. Acosta DO, MS Pacific Northwest University

Neurosciences

Rick Lucarelli, MD Medical City Dallas Hospital

William D. Whetstone, MD University of California, San Francisco

Antonio Siniscalchi, MD Annunziata Hospital, Cosenza, Italy

Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Muhammad Waseem, MD Lincoln Medical & Mental Health Center

Cristina M. Zeretzke-Bien, MD University of Florida

Jabeen Fayyaz, MD The Hospital for Sick Children

Available in MEDLINE, PubMed, PubMed Central, CINAHL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, eScholarship, Melvyl, DOAJ, EBSCO, EMBASE, Medscape, HINARI, and MDLinx Emergency Med. Members of OASPA. Editorial and Publishing Office: WestJEM/Depatment of Emergency Medicine, UC Irvine Health, 3800 W Chapman Ave Ste 3200, Orange, CA 92868, USA. Office: 1-714-456-6389; Email: Editor@westjem.org.

Volume 27, No. 1.1: January 2026

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians California ACEP

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

Alameda Health System-Highland Hospital Oakland, CA

Ascension Resurrection Chicago, IL

Arnot Ogden Medical Center Elmira, NY

Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Winston-Salem, NC

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX

Baystate Medical Center Springfield, MA

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Boston, MA

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA

Brown University-Rhode Island Hospital Providence, RI

Carolinas Medical Center Charlotte, NC

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Los Angeles, CA

Cleveland Clinic Cleveland, OH

Desert Regional Medical Center Palm Springs, CA

Eisenhower Health Rancho Mirage, CA

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine

Emory University Atlanta, GA

Franciscan Health Carmel, IN

Geisinger Medical Center Danville, PA

Healthpartners Institute/ Regions Hospital Minneapolis, MN

Hennepin Healthcare Minneapolis, MN

Henry Ford Hospital Detroit, MI

Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital Wyandotte, MI

Howard County Department of Fire and Rescue Marriotsville, MD

Icahn School of Medicine at Mt Sinai New York, NY

Indiana University School of Medicine Indianapolis, IN

INTEGRIS Health Oklahoma City, OK

Kaweah Delta Health Care District Visalia, CA

Kent Hospital Warwick, RI

Kern Medical Bakersfield, CA

Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

Loma Linda University Medical Center Loma Linda, CA

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Louisiana State University Shreveport Shereveport, LA

Massachusetts General Hospital/ Brigham and Women’s Hospital/ Harvard Medical Boston, MA

Mayo Clinic in Florida Jacksonville, FL

Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester Rochester, MN

Mayo Clinic in Arizona Phoeniz, AZ

Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospital Milwaukee, WI

Mount Sinai Medical Center Miami Beach Miami Beach, FL

Mount Sinai Morningside New York, NY

New York University Langone Health New York, NY

North Shore University Hospital Manhasset, NY

NYC Health and Hospitals/ Jacobi New York, NY

Ochsner Medical Center New Orleans, LA

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Columbus, OH

Oregon Health and Science University Portland, OR

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA

Poliklinika Drinkovic Zagreb, Croatia

Prisma Health/ University of South Carolina SOM Greenville Greenville, SC

Rush University Medical Center Chicago, IL

Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School New Brunswick, NJ

St. Luke’s University Health Network Bethlehem, PA

Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Springfield, IL

Stony Brook University Hospital Stony Brook, NY

SUNY Upstate Medical University Syracuse, NY

Temple University Philadelphia, PA

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, TX

American Academy of Emergency Medicine Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia Thai Association for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive print and copies for all faculty and electronic for faculty/residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health

Indexed in MEDLINE, PubMed, and Clarivate Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded

This open access publication would not be possible without the generous and continual financial support of our society sponsors, department and chapter subscribers.

Professional Society Sponsors

American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians

California ACEP

Academic Department of Emergency Medicine Subscriber

The University of Texas Medical Branch Galveston, TX

UT Health Houston McGovern Medical School Houston, TX

Touro University College of Osteopathic Medicin Vallejo, CA

Trinity Health Muskegon Hospital Muskegon, MI

UMass Memorial Health Worcester, MA

University at Buffalo Program Buffalo, NY

University of Alabama, Birmingham Birmingham, AL

University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson Little Rock, AR

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Galveston, TX

University of California, Davis Medical Center Sacramento, CA

University of California San Francisco General Hospital San Francisco, CA

University of California San Fracnsico Fresno Fresno, CA

University of Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Cincinnati Medical Center/ College of Medicine Cincinnati, OH

University of Colorado Denver Denver, CO

University of Florida, Jacksonville Jacksonville, FL

University of Illinois at Chicago Chicago, IL

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Iowa City, IA

University of Kansas Health System Kansas City, IA

University of Louisville Louisville, KY

University of Maryland School of Medicine Baltimore, MD

University of Miami Jackson Health System Miami, FL

University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI

University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences Grand Forks, ND

University of Southern Alabama Mobile, AL

State Chapter Subscriber

Arizona Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Florida Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

International Society Partners

Emergency Medicine Association of Turkey Lebanese Academy of Emergency Medicine Mediterranean Academy of Emergency Medicine

California Chapter Division of American Academy of Emergency Medicine

University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA

University of Vermont Medical Cneter Burlington, VA

University of Virginia Health Charlottesville, VA

University of Washington - Harborview Medical Center Seattle, WA

University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Madison, WI

UT Southwestern Medical Center Dallas, TX

Franciscan Health Olympia Fields Phoenix, AZ

WellSpan York Hospital York, PA

West Virginia University Morgantown, WV

Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Fairborn, OH

Yale School of Medicine New Haven, CT

Great Lakes Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Tennessee Chapter Division of the

Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine Sociedad Argentina de Emergencias

American Academy of Emergency Medicine Uniformed Services Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Virginia Chapter Division of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine

Sociedad Chileno Medicina Urgencia Thai Association for Emergency Medicine

To become a WestJEM departmental sponsor, waive article processing fee, receive print and copies for all faculty and electronic for faculty/residents, and free CME and faculty/fellow position advertisement space, please go to http://westjem.com/subscribe or contact:

Stephanie Burmeister

WestJEM Staff Liaison

Phone: 1-800-884-2236

Email: sales@westjem.org

Jaime Jordan, MD, MAEd*†

Michael Gottlieb, MD‡

Molly Estes, MD§

Melissa E. Parsons, MD||

Katja Goldflam, MD#

Andrew Grock, MD*

Brit J. Long, MD¶

Sree Natesan, MD**

David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California Los Angeles, Department of Emergency Medicine, Los Angeles, California

Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Emergency Medicine, Portland, Oregon

Rush University Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, Chicago, Illinois

Northwestern University, Department of Emergency Medicine, Chicago, Illinois

University of Florida College of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jacksonville, Florida

Yale School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

Brooke Army Medical Center, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Antonio, Texas

Duke University, Division of Emergency Medicine, Durham, North Carolina

Section Editor: Kendra Parekh, MD, MHPE

Submission history: Submitted December 14, 2024; Revision received May 17, 2025; Accepted May 17, 2025

Electronically published September 24, 2025

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

DOI: 10.5811/westjem.41493

Improving resident teaching skills is an expectation of training. Despite the recognized importance of resident-as-teacher (RaT) curricula, variability indicates the need for evidence-based guidelines to inform best practices. This paper outlines expert guidelines for the development, implementation, and evaluation of RaT curricula from the members of the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine Best Practices Subcommittee, based on a critical review of the literature. It is important to perform a needs assessment prior to creating and implementing a RaT curriculum. The RaT curricula should include instruction on adult learning theory, feedback, and classroom and bedside teaching techniques. Outcomes of RaT curricula should be assessed using multiple sources including direct observation and incorporate both knowledge and skill retention, as well as acquisition. [West J Emerg Med. 2025;26(5)1135–1143.]

Training future physicians to be teachers is an important curricular component of residency programs and supported by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), which states that residents are expected to participate in the education of patients, families, students, residents, and other health professionals and should be encouraged to teach using a scholarly approach.1 Residentas-teacher (RaT) curricula hold the potential to provide numerous benefits to residents, medical students, and patients by enhancing teaching skills that allow for transfer of knowledge.2-17 Benefits of RaT programs across medical specialties include improved teaching skills, self-reflection,

self-efficacy in teaching, and improved educational outcomes for both residents and their learners, as well as better outcomes for patient care.2-17

Despite recommendations to provide this training in residency and a substantial body of literature on the topic, there is no standard approach to RaT curricula.1 This deficit can lead to variability in education skill development for resident trainees. It also leaves education leaders uncertain about how to best provide this important training in their programs. While a few prior reviews have sought to address this topic, they include only a small number of papers, are narrow in scope (focusing on the benefits and effectiveness of RaT curricula rather than how to best deliver this type of

instruction), and may be outdated and not reflect the current literature available.6,9,13,17 Therefore, a critical need exists to develop best practices and evidence-based guidelines to optimize RaT curricular content, implementation, and evaluation in graduate medical education training programs.

Based on the best available evidence through a critical review of the literature, we offer expert guidelines on RaT curricular content, implementation, and evaluation from members of the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) Best Practices Subcommittee. This paper provides readers with recommendations on the content, educational strategies, curricular implementation, and program evaluation for RaT curricula.

This is the 11th paper in a series of evidence-based best practice reviews from the CORD Best Practices Subcommittee.18-27 The author group consists of expert emergency medicine (EM) educators and education researchers with experience in residency program education and leadership. We conducted a literature search in conjunction with a medical librarian using MEDLINE with a combination of Medical Subject Heading terms and keywords focused on RaT curricula searching for papers published from inception to December 31, 2023 (Supplemental Appendix 1). We also reviewed the bibliographies of all included papers. Two authors (JJ and SN) independently screened and included papers that addressed RaT curricula development, implementation and evaluation. We excluded papers that were not related to RaT curricula development, implementation, or evaluation. We also excluded papers that were not in English, were abstracts only, or did not have full text available. Papers were included based on agreement of the two screeners. The two screeners resolved discrepancies through in-depth discussion and negotiated consensus.

The search yielded 1,486 papers, of which 89 were deemed to be directly relevant to this review (Supplemental Appendix 2). The author group derived their best practice recommendations based on the literature review and discussion among the expert author group. The level and grade of evidence were provided for each best practice statement implementing the Oxford Center for EvidenceBased Medicine criteria (Tables 1 and 2).28 When supporting data were not available, recommendations were made based upon the authors’ combined experience and consensus opinion. Prior to submission, the manuscript was reviewed by the CORD Best Practices Subcommittee and posted to the CORD website for two weeks for peer review by the entire CORD medical education community. Upon completion of the review period, there was general agreement, and no substantial changes to the guideline were recommended.

What do we already know about this issue? Resident-as-teacher (RaT) curricula are an important part of residency training and have many potential benefits.

What was the research question? What are best practices for RaT curricular content, implementation, and evaluation in graduate medical education training programs?

What was the major finding of the study? This paper offers expert recommendations for best practices on RaT curricular content, implementation, and evaluation.

How does this improve population health? Improving teaching skills ultimately leads to better education outcomes for residents and better care of their patients.

1a

1b

2a

2b

3a

3b

4

5

Systematic review of homogenous RCTs

Individual RCT

Systematic review of homogenous cohort studies

Individual cohort study or a low-quality RCT*

Systematic review of homogenous casecontrol studies

Individual case-control study**

Case series/Qualitative studies or lowquality cohort or case-control study***

Expert/consensus opinion

*Defined as <80% follow up; **includes survey studies and crosssectional studies; ***defined as studies without clearly defined study groups.

RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Of the reviewed papers, few included a formal needs assessment beyond a review of the literature. Residents’ responsibility to teach students, other residents, and other

Table 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine grades of recommendation.28

Grade of Evidence Definition

A Consistent Level 1 studies

B Consistent Level 2 or 3 studies or extrapolations* from Level 1 studies

C Level 4 studies or extrapolations* from Level 2 or 3 studies

D Level 5 evidence, or troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive studies of any level

*“Extrapolations” refers to data being used in a situation that has potentially clinically important differences than the original study situation.

staff is well recognized, as is the need to provide training to prepare residents for their roles as teachers.29 Reasons for implementing RaT curricula include the following: to teach a skill important to the resident role; meet residents’ desire for formal training in education; address regulatory requirements; and prepare trainees for future career roles.1,30 General curricular goals included improving resident formal and informal teaching skills in both classroom and clinical settings and increasing resident confidence in teaching skills.29,31 The RaT curricula reviewed contain diverse components. The topics most consistently included in RaT curricula were adult learning theory, creating a positive learning environment and setting objectives, clinical or bedside teaching techniques, classroom teaching techniques, and how to give feedback.10-12,14,15,29-60

Adult learning theory—which describes how adults learn best when material is problem-centered, relevant to their work, and when they are involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction—was a major component of RaT curricula, both as a framework for the curricular development and a topic of instruction for learners.10,29,31-42 Adult-learning theory was often considered in how RaT curricula was applied.34,35,61 For example, RaT leaders factored this in for determining the length, frequency, and formatting of these educational sessions within the curricula. 34,35,61

Many curricula also include adult learning principles as part of their educational content.11,29, 33,35-42,49,56 Berger et al provided a primer for anesthesiology residents about adult learning principles by having the learners discuss effective and ineffective teaching moments that they remembered in their education.11 They also had learners review literature on adult learning principles and watch a video demonstration.11 Similarly, Chee et al had residents identify effective and ineffective teaching strategies observed in video clips to better understand adult learning theory.35 Choski et al had learners review two papers on adult learning theory to better understand adult education principles.36 Another group used formal lectures on adult learning theory followed

by debriefing.29 Tang Girdwood et al revised a previous curriculum by removing the PowerPoint lecture on adult learning theory and instead having residents teach the principles of adult learning theory to one another with a faculty facilitator present.42

Many RaT curricula sought to teach residents how to set the stage for learning.11,12,15, 31,32,34-36,38,43-49 Curricular content included how to create a positive learning environment and recognize behaviors that can lead to an environment of harassment or learner mistreatment.12,31,35,43,44 Understanding how to set goals and expectations with learners to facilitate knowledge and skill acquisition was also an important topic included in RaT curricula.11,15,31,32,34,36,38,44-49

Clinical or bedside teaching techniques and tools was another commonly included topic in RaT curricula.10,14,15,29-31,33,37-42,44,46-48,50-55 One survey study in EM found that 84% of programs reported bedside teaching to be a major focus of their educational curriculum.32 One of the most frequently included teaching tools was the One-Minute Preceptor.31,32,37,44,47,51,52.54,57,62 Ahn et al found that 45% of RaT programs in a single specialty incorporated training on the One-Minute Preceptor.32 In another example, curricula learners were asked to describe the elements of this model, apply the model to a simulated learner’s patient presentation, and use the model to assess the learner’s knowledge level and identify educational points.31 Content specific to procedural teaching was included in many curricula. 5,10,11,15, 29,32,33,35-37,41,46,53,55,57,59

In addition to the clinical setting, many RaT curricula also seek to prepare residents for teaching in the classroom by including content on didactic, small group, and case-based instruction.11,15,31,32,38,41,42, 45,46,48,50,53,54,56-58 While these content areas were often listed as topics or titles of educational sessions included in curricula, there was little additional description in the included studies as to what these content areas were comprised of. Many curricula also included content on the use of simulation in education.14,32,42,53,55,57,63

Feedback was also consistently included in RaT curricula.8,10-12,14,15,29,31-38,40-44,46-48,50,52,53,55,59,60 One study found that 96% of EM residency programs that had RaT curricula included feedback as a major focus.32 Specific content areas related to feedback included techniques and components of effective feedback, optimizing the environment for feedback, and how to receive feedback.33 Curricula often included interactive activities, during which the learners could practice feedback interactions via role-play and debrief with the other learners.30,33 Other RaT curricular content included education to augment teaching such as communication skills, professionalism, and how to deal with difficult learning situations.32,46,50,57,58 Some curricula also included content that could help prepare residents as education professionals such as mentorship and role modeling, curricular design, time management, and learner assessment.15,32,40,46,57,60,64 We provide a summary of RaT curricular content and educational strategies in Tables 3 and 4.

Resident-as-Teacher Curriculum: Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices

Table 3. Summary of content in resident-as-teacher curricula.

Curricular Content

Adult learning theory

Number of Papers

14 8, 10, 29, 31, 33-42

Assessment of learners 1 60

Case-based instruction

Clinical/bedside instruction

7 8, 11, 42, 46, 54, 57, 58

References

23 10, 14, 15, 29, 30, 31, 33, 37-42, 44, 46-48, 50-55

Communication skills 4 8, 46, 57, 58

Creating a positive learning environment 5 12, 31, 35, 43, 44

Curriculum design 2 8, 46

Didactic instruction 10 11, 15, 31, 38, 42, 45, 48, 50, 53, 54

Difficult learning situations

2 8, 50

Feedback 28 8, 10-12, 14, 15, 29, 31, 33-38, 40-44, 46-48, 50, 52, 53, 55, 59, 60

Mentorship 2 8, 40

Procedural instruction

16 5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 29, 33, 35-37, 41, 46, 53, 55, 57, 59

Professionalism and role modeling 5 8, 15, 46, 57, 64

Setting goals and expectations

13 8, 11, 15, 31, 34, 36, 38, 44-49

Simulation instruction 7 8, 14, 42, 53, 55, 57, 63

Small group instruction 7 8, 41, 46, 50, 53, 56, 57

Time management 2 8, 46

Table 4. Summary of educational strategies in resident-as-teacher curricula.

Educational Strategy Number of Papers

Didactic lectures

Direct observation and feedback

Iterative reminders / staged repetition

Simulation/role playing

Small groups

Virtual sessions/electronic handouts

Workshops

References

22 5, 7, 8, 12, 17, 29, 33, 37, 38, 42, 47, 57, 58, 64, 71, 75, 86, 87, 93, 95, 103, 104

13 29, 31, 49, 56, 57, 59, 66, 69, 71, 87, 88, 94, 104

4 29, 31, 61, 71

12 12, 14, 31, 37, 57, 64, 69, 70, 75, 87, 88, 91

6 12, 36, 37, 56, 69, 93

7 5, 41, 43, 61, 71, 86, 97

21 4, 15, 17, 31, 33, 37, 38, 44, 48, 52, 54, 57, 59, 62, 64, 65, 66, 83, 87, 98, 104

Best Practices Recommendations

Resident-as-teacher curricula should include the following:

1. Teaching techniques applicable to both classroom and bedside settings (Level 1, Grade A).

2. Effective feedback techniques that educators can use to provide feedback to learners (Level 1, Grade B).

3. Adult learning theory as part of the framework of the curriculum and its delivery, as well as an educational component of the curriculum. (Level 2, Grade B).

RESIDENT-AS-TEACHER CURRICULAR LOGISTICS AND IMPLEMENTATION

Timing, duration, and frequency of interventions varied greatly among studies and specialties, with no overarching consensus on ideal approaches. The most common

approach included single interventions, usually early in intern year or during residency orientation, with most one-day curricula ranging from 4-8 hours.44, 47, 59, 60, 62, 65-67

According to a landmark paper published by Morrison et al in 2004, the average total time for a RaT curriculum was 11 hours, with their institutional published curriculum lasting for 13 total cumulative hours of longitudinal instruction.68, 69 Some longitudinal curricula had longer durations including those that spanned the entire length of resident training.12, 29, 31, 38, 42, 49, 54, 55

Staffing of the educational sessions was largely by general residency faculty who participated in didactics, mentorship, or evaluations of resident teaching.56, 58, 59, 62, 69, 70 Sometimes faculty with additional training or specialization in education led or designed the curricula, which included

“educational experts,” designated education faculty, and education fellows.12, 15, 70 Additionally, residents themselves often contributed, including chief residents and teach-theteacher models.47, 58

Several barriers were identified in the implementation of RaT curricula, with the most frequently mentioned being the balance of workload on faculty and residents.71, 48, 58 Both the total time required for participation and instruction as well as real-time balancing responsibilities of patient care with teaching while working clinically were noted. 37, 57, 72, 73 Additionally, many residents felt it was challenging to teach topics that they themselves still did not feel quite familiar with, even for the sake of experiential learning. 37, 43, 57 Lastly, despite ACGME supportive program requirements, some program directors felt that RaT curricula were not a priority among other competing educational demands.1, 58,74

A needs assessment before creating and implementing a RaT curriculum can help confirm interest, elucidate clear, specific program goals for participants, and secure buy-in from faculty and leadership.37, 56, 58, 75 Buy-in from residents was less challenging, with many residents confirming that they lacked self-confidence in their own teaching abilities, wanted mentorship in this area, and were willing to spend time to gain this experience.5, 59, 76 Medical students, who along with junior residents, were frequently the recipients of the outcomes of RaT, identified residents as more approachable than faculty and appreciated near-peer teaching.73, 77-79

Administration of RaT curricula may be challenging due to the resources required for successful implementation. This includes the number of faculty needed and time for residents to participate in curricular sessions, as well as time to learn and practice these skills while working clinically.58,70 Through an online survey of 47 residency programs and iterative expert consensus building, McKeon et al proposed the following key components to a successful RaT curriculum: required trainee participation; evaluations and feedback of resident teaching; recognition of excellence through teaching awards; and faculty teaching evaluations

Best Practices Recommendations:

1. General residency faculty can teach, provide mentorship, and evaluate participants in RaT curricula (Level 2a, Grade B).

2. Perform a needs assessment prior to implementing a RaT curriculum (Level 3a, Grade B).

3. Identify and address barriers such as time limitations for residents and faculty when implementing a RaT curriculum (Level 4, Grade C).

When evaluating a RaT program, it is critical to use a robust model, accounting for various inputs, outputs, and outcomes. Examples of relevant program evaluation frameworks include the Kirkpatrick framework, the Logic Model, and CIPP (Context, Input, Process, Products).81,82 Despite this, most studies did not explicitly state the program evaluation framework they used.

While many studies included only a single or limited number of outcome measures individually, when assessed as a whole, there were a wide range of potential outcomes assessed (Table 5). The most common form of learner assessment was self-surveys of perceived effectiveness after a RaT program.4-7, 9-12, 14, 31, 33, 35, 39, 42, 44, 48, 49, 51, 54-56, 58, 61, 62, 65, 66, 71, 74, 83-97 A few studies also conducted delayed self-assessments at 3-12 months following RaT course completion.11,44, 51 One study assessed differences in attitude toward teaching after the course, while others performed knowledge assessment tests.36, 43, 44 Another study assessed actual use of the skills in subsequent teaching.52

Skill assessments were performed using either direct observation or structured assessments in a simulated environment. Several studies directly observed resident teaching, while others video-recorded resident teaching for delayed assessments.6, 49, 71, 72, 74, 87 Other measures included end-of-shift teaching evaluations completed by faculty.56, 58, 74 The most common assessment, using simulation, was the Objective Structured Teaching Exercise (OSTE).6, 9, 36, 38, 41, 46, 49, 54, 63, 71, 74, 84, 87, 92, 96, 98 The OSTEs were incompletely reported; they often ranged from 6-8 stations and were 2-4 hours in length. One study used the Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare (DASH) instrument instead of the OSTE.14 Another assessed both initial and delayed OSTE as part of a randomized trial.75

Additional measures were obtained via learners (eg, students, junior residents). Learner assessments used a variety of measures of teaching effectiveness, although most had limited validity evidence.4, 6, 9, 10, 14, 39, 47, 48, 62, 66, 71, 74, 84-89, 97, 99, 100

One study used the Stanford Faculty Development Program—a 25-item tool assessing learning climate, control of teaching sessions, communicating goals, promoting understanding and retention, evaluation, feedback, and promoting self-directed learning.47 Another study evaluated the effect of the intervention by comparing course/rotation evaluations from students.48

linked to annual faculty review but not to salary or promotion.80 Finally, a RaT curriculum should be iteratively refined to ensure optimization of its content.42

One study focused on the feasibility to inform broader implementation.38 A few other select studies assessed organizational changes and broader outcomes. Two studies found that the RaT program led to substantive changes, which resulted in residency programs converting to this model going forward.60,101 Others assessed downstream effects on student learning by comparing student Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) or Objective Structured Assessments of Technical Skills (OSATS) between those taught by residents completing the RaT program vs those who did not.63, 102

Resident-as-Teacher Curriculum: Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices

Table 5. Summary of methods of outcome assessments in resident-as-teacher curricula.

Educational Strategy

Observed Structured Teaching Evaluation

Survey of faculty

Survey of learners

Semi-structured interview

Best Practices Recommendations:

Number of Papers

References

12 14, 15, 17, 37, 41, 49, 54, 69, 70, 75, 87, 98

4 7, 17, 54, 58

36 4, 7, 8, 12, 14, 17, 29, 31, 33, 37, 38, 42, 44, 47, 48, 51, 54, 56, 57, 58, 61, 62, 65, 66, 71, 73, 83, 86, 91, 94, 96, 97, 100, 103-105

1 59

1. RaT outcomes should be assessed using multiple sources of data (Level 1b, Grade B).

2. Use OSTE or direct observation to directly assess RaT outcomes (Level 1b, Grade B).

3. Incorporate delayed assessment for skill retention (Level 1b, Grade B).

4. Use higher level outcome assessments, such as learner evaluations or assessments (Level 3b, Grade B).

RaT, resident as teacher; OSTE, Observed Structured Teaching Evaluation.

Although we performed a comprehensive search guided by a medical librarian in conjunction with a bibliographic review and expert consultation to augment content when needed, we used a single search engine, and it is possible that we may have missed some pertinent papers. In instances where evidence in the form of high-quality data was limited or lacking, we relied upon expert opinion and group consensus for the best practice recommendations. Finally, in areas where evidence was not available, we used the consensus from the expertise of our authorship group. While our author group possesses experience in research and scholarship in both RaT curricula and medical education, there was a potential for bias to have been introduced during this process. Therefore, we also sought peer review from the CORD Best Practices Subcommittee and posted it online for open review feedback by the CORD community.

Resident-as-teacher curricula are a vital component of graduate medical education training programs. This paper provides guidance on best practices for developing, implementing, and evaluating RaT curricula.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the members of the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) and the members of the CORD Best Practice Committee for their review and feedback of this manuscript. The authors would also like to acknowledge Samantha

Kaplan, PhD, Medical Librarian, Duke University, Durham, NC, for her contributions.

Address for Correspondence: Jaime Jordan, MD, MAEd, Oregon Health & Science University, Department of Emergency Medicine, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR 97239. Email: jaimejordanmd@gmail.com.

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. No author has professional or financial relationships with any companies that are relevant to this study There are no conflicts of interest or sources of funding to declare.

Copyright: © 2025 Jordan et al. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) License. See: http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). 2022. Accessed December 5, 2024. Available at chrome-extension:// bdfcnmeidppjeaggnmidamkiddifkdib/viewer.html?file=https:// www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/ cprresidency_2023.pdf

2. Bordley DR, Litzelman DK. Preparing residents to become more effective teachers: a priority for internal medicine. Am J Med 2000;109(8):693‐696.

3. Julian KA, O’Sullivan PS, Vener MH, Wamsley MA. Teaching residents to teach: the impact of a multi‐disciplinary longitudinal curriculum to improve teaching skills. Med Educ Online 2007;12(1):4467.

4. Nejad H, Bagherabadi M, Sistani A, Dargahi H. Effectiveness of resident as teacher curriculum in preparing emergency medicine residents for their teaching role. J Adv Med Educ Prof 2017;5(1):21‐25.

5. Kobritz M, Demyan L, Hoffman H, Bolognese A, Kalyon B, Patel V. “Residents as teachers” workshops designed by surgery residents for surgery residents. J Surg Res. 2022;270:187-194.

6. Wamsley MA, Julian KA, Wipf JE. A literature review of “resident‐as‐

Jordan et al.

Resident-as-Teacher Curriculum: Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices

teacher” curricula: Do teaching courses make a difference? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 2):574‐581.

7. Ratan BM, Johnson GJ, Williams AC, Greely JT, Kilpatrick CC. Enhancing the teaching environment: 3‐year follow‐up of a resident‐led residents‐as‐teachers program. J Grad Med Educ 2021;13(4):569‐575.

8. Ahn J, Golden A, Bryant A, Babcock C. Impact of a dedicated emergency medicine teaching resident rotation at a large urban academic center. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(2):143‐148.

9. Post RE, Quattlebaum RG, Benich JJ 3rd. Residents‐as‐teacher curricula: a critical review. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):374‐380.

10. Geary AD, Hess DT, Pernar LI. Efficacy of a resident-as-teacher program (RATP) for general surgery residents: an evaluation of 3 years of implementation. Am J Surg. 2021;222(6):1093-1098.

11. Berger JS, Daneshpayeh N, Sherman M, et al. Anesthesiology residents-as-teachers program: a pilot study. J Grad Med Educ 2012;4(4):525-528.

12. Santini VE, Wu CK, Hohler AD. Neurology Residents as Comprehensive Educators (Neuro RACE). Neurologist 2018;23(5):149-151.

13. Busari JO, Scherpbier AJ. Why residents should teach: a literature review. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50(3):205‐210.

14. Miloslavsky EM, Sargsyan Z, Heath JK, et al. A simulation-based resident-as-teacher program: the impact on teachers and learners. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(12):767-772.

15. Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, et al. A pilot randomized, controlled trial of a longitudinal residents-as-teachers curriculum. Acad Med. 2003;78(7):722-729.

16. Snell L. The resident‐as‐teacher: It’s more than just about student learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):440‐441.

17. Hill AG, Yu T, Barrow M, Hattie J. A systematic review of resident‐as‐teacher programmes. Med Educ. 2009;43(12):1129‐1140.

18. Chathampally Y, Cooper B, Wood DB, et al. Evolving from morbidity and mortality to a case-based error reduction conference: Evidencebased Best Practices from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(6):231–41.

19. Wood DB, Jordan J, Cooney R, et al. Conference didactic planning and structure: an Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):999–1007.

20. Parsons M, Bailitz J, Chung AS, et al. Evidence-based interventions that promote resident wellness from the Council of Emergency Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(2):412–22.

21. Parsons M, Caldwell M, Alvarez A, et al. Physician pipeline and pathway programs: an evidence-based guide to best practices for diversity, equity, and inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. West J Emerg Med 2022;23(4):514–24.

22. Davenport D, Alvarez A, Natesan S, et al. Faculty recruitment, retention, and representation in leadership: an Evidence-Based Guide to Best Practices for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. West J

Emerg Med. 2022;23(1):62–71.

23. Gallegos M, Landry A, Alvarez A, et al. Holistic review, mitigating bias, and other strategies in residency recruitment for diversity, equity, and inclusion: an Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(3):345–52.

24. Natesan S, Bailitz J, King A, et al. Clinical teaching: An Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):985–98.

25. Estes M, Gopal P, Siegelman JN, et al. Individualized Interactive Instruction: a Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(2):363–8.

26. Gottlieb M, King A, Byyny R, et al. Journal club in residency education: an Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(4):746–55.

27. Natesan S, Jordan J, Sheng A, et al. Feedback in medical education: An Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices from the Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine. West J Emerg Med 2023;24(3):479-494.

28. Phillips R, Ball C, Sackett D. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence. CEBM: Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2021. Accessed December 5, 2024. Available at: https:// www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-ofevidence

29. Nguyen S, Cole KL, Timme KH, Jensen RL. Development of a residents-as-teachers curriculum for neurosurgical training programs. Neurosurgical focus. 2022;53(2):E6.

30. Al Achkar M, Hanauer M, Morrison EH, Davies MK, Oh RC. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:299-306.

31. Rowat J, Johnson K, Antes L, White K, Rosenbaum M, Suneja M. Successful implementation of a longitudinal skill-based teaching curriculum for residents. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):346

32. Ahn J, Jones D, Yarris L, Fromme H, Yarris LM, Fromme HB. A national needs assessment of emergency medicine resident-asteacher curricula. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12(1):75-80.

33. Anderson MJ, Ofshteyn A, Miller M, Ammori J, Steinhagen E. “Residents as teachers” workshop improves knowledge, confidence, and feedback skills for general surgery residents. J Surg Educ 2020;77(4):757-764.

34. Bensinger LD, Meah YS, Smith LG. Resident as teacher: the Mount Sinai experience and a review of the literature. Mt. Sinai J Med 2005;72(5):307-311.

35. Chee YE, Newman LR, Loewenstein JI, Kloek CE. Improving the teaching skills of residents in a surgical training program: results of the pilot year of a curricular initiative in an ophthalmology residency program. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(5):890-897.

36. Chokshi BD, Schumacher HK, Reese K, et al. A “Resident-asteacher” curriculum using a flipped classroom approach: Can a model designed for efficiency also be effective? Acad Med. 2017;92(4):511514.

Resident-as-Teacher Curriculum: Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices

37. Cullimore AJ, Dalrymple JL, Dugoff L, et al. The obstetrics and gynaecology resident as teacher. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32(12):1176-1185.

38. Friedman S, Moerdler S, Malbari A, Laitman B, Gibbs K. The Pediatric Resident Teaching Group: the development and evaluation of a longitudinal resident as teacher program. Med Sci Educ 2018;28(4):619-624.

39. Langer AL, Bernard S, Block BL. Two-week resident-as-teacher program may improve peer feedback and online evaluation completion. Med Sci Educ. 2018;28(4):633-637.

40. Mendoza D, Peterson R, Ho C, Harri P, Baumgarten D, Mullins ME. Cultivating future radiology educators: development and implementation of a clinician-educator track for residents. Acad Radiol. 2018;25(9):1227-1231.

41. Ricciotti HA, Freret TS, Aluko A, McKeon BA, Haviland MJ, Newman LR. Effects of a short video-based resident-as-teacher training toolkit on resident teaching. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36S-41S.

42. Tang Girdwood S, Treasure J, Zackoff M, Klein M. Implementation, evaluation, and improvement of pediatrics residents-as-teachers elective through iterative feedback. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(2):375-378.

43. Bettendorf B, Quinn-Leering K, Toth H, Tews M. Teaching when Time Is Limited: a Resident and Fellow as Educator Video Module. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(3):631-635.

44. Tipton AE, Ofshteyn A, Anderson MJ, et al. The impact of a “residents as teachers” workshop at one year follow-up. Am J Surg. 2022;224(1 Pt B):375-378.

45. Gaba ND, Blatt B, Macri CJ, Greenberg L. Improving teaching skills in Obstet Gynecol residents: evaluation of a residents-as-teachers program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):87.e1-7.

46. Messman A, Kryzaniak SM, Alden S, Pasirstein MJ, Chan TM. Recommendations for the development and implementation of a residents as teachers curriculum. Cureus. 2018;10(7):e3053.

47. Moser EM, Kothari N, Stagnaro-Green A. Chief residents as educators: an effective method of resident development. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(4):323-328.

48. Ostapchuk M, Patel PD, Hughes Miller K, Ziegler CH, Greenberg RB, Haynes G. Improving residents’ teaching skills: a program evaluation of residents as teachers course. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):e49-e56.

49. Zackoff M, Jerardi K, Unaka N, Sucharew H, Klein M. An Observed Structured Teaching Evaluation demonstrates the impact of a resident-as-teacher curriculum on teaching competency. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(6):342-347.

50. Achkar MA, Davies MK, Busha ME, Oh RC. Resident-as-teacher in family medicine: a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):452-458.

51. Burgin S, Zhong CS, Rana J. A resident-as-teacher program increases dermatology residents’ knowledge and confidence in teaching techniques: A pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;83(2):651-653.

52. Burke S, Schmitt T, Jewell C, Schnapp B. A novel virtual emergency medicine residents-as-teachers (RAT) curriculum. J Educ Teach Emerg Med. 2021;6(3).

53. Farrell SE, Pacella C, Egan D, et al. Resident-as-teacher: a

suggested curriculum for emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13(6):677-679.

54. Liang JF, Cheng HM, Huang CC, Yang YY, Chen CH. Lessons learned from a novel 3-year longitudinal stepwise “residents-asteachers” program. J Chin Med Assoc. 2023;86(6):577-583.

55. Seelig S, Bright E, Bod J, et al. Educating future educators-resident distinction in education: a longitudinal curriculum for physician educators. West J Emerg Med. 2021;23(1):100-102.

56. Frey-Vogel A. A resident-as-teacher curriculum for senior residents leading morning report: a learner-centered approach through targeted faculty mentoring. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10954.

57. Fromme HB, Whicker SA, Paik S, et al. Pediatric resident-as-teacher curricula: a national survey of existing programs and future needs. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):168-175.

58. Pien LC, Taylor CA, Traboulsi E, Nielsen CA. A pilot study of a “resident educator and life-long learner” program: using a faculty train-the-trainer program. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):332-336.

59. McKinley SK, Cassidy DJ, Sell NM, et al. A qualitative study of the perceived value of participation in a new department of surgery research residents-as-teachers program. Am J Surg 2020;220(5):1194-1200.

60. Roberts KB, DeWitt TG, Goldberg RL, Scheiner AP. A program to develop residents as teachers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1994;148(4):405-410.

61. Watkins AA, Gondek SP, Lagisetty KH, et al. Weekly e-mailed teaching tips and reading material influence teaching among general surgery residents. Am J Surg. 2017;213(1):195-201.e3.

62. Ofshteyn A, Bingmer K, Tseng E, et al. Effect of “residents as teachers” workshop on learner perception of trainee teaching skill. J Surg Res. 2021;264:418-424.

63. York-Best C, Bengtson J, Stagg A. A Simulation-Based Resident as Surgical Teacher (RAST) program. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):382384.

64. Patocka C, Meyers C, Delaney JS. Residents-as-teachers: a survey of Canadian emergency medicine specialty programs. CJEM 2010;12(3):249.

65. Aiyer M, Woods G, Lombard G, Meyer L, Vanka A. Change in residents’ perceptions of teaching: following a one day “residents as teachers” (RasT) workshop. South Med J. 2008;101(5):495-502.

66. Ryg PA, Hafler JP, Forster SH. The efficacy of residents as teachers in an ophthalmology module. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(2):323-328.

67. Wipf JE, Pinsky LE, Burke W. Turning interns into senior residents: preparing residents for their teaching and leadership roles. Acad Med. 1995;70(7):591-596.

68. Morrison EH, Friedland JA, Boker J, Rucker L, Hollingshead J, Murata P. Residents-as-teachers training in U.S. residency programs and offices of graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 Suppl):S1-4.

69. Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, et al. The effect of a 13-hour curriculum to improve residents’ teaching skills: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):257-263.

70. Ricciotti HA, Dodge LE, Head J, Atkins KM, Hacker MR. A novel

Jordan et al. Resident-as-Teacher Curriculum: Evidence-based Guide to Best Practices

resident-as-teacher training program to improve and evaluate Obstet Gynecol resident teaching skills. Med Teach. 2012;34(1):e52-7.

71. Geary A, Hess DT, Pernar LIM. Resident-as-teacher programs in general surgery residency - a review of published curricula. Am J Surg. 2019;217(2):209-213.

72. Ilgen JS, Takayesu JK, Bhatia K, et al. Back to the bedside: the 8-year evolution of a resident-as-teacher rotation. J Emerg Med 2011;41(2):190-195.

73. Kaji A, Moorehead JC. Residents as teachers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):316-318.

74. Bree KK, Whicker SA, Fromme HB, Paik S, Greenberg L. Residentsas-teachers publications: What can programs learn from the literature when starting a new or refining an established curriculum? J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):237-248.

75. Dunnington GL, DaRosa D. A prospective randomized trial of a residentsas-teachers training program. Acad Med. 1998;73(6):696-700.

76. Benè KL, Bergus G. When learners become teachers: a review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):783-7.

77. Minor S, Poenaru D. The in-house education of clinical clerks in surgery and the role of housestaff. Am J Surg. 2002;184(5):471-5.

78. Weisgerber M, Flores G, Pomeranz A, Greenbaum L, Hurlbut P, Bragg D. Student competence in fluid and electrolyte management: the impact of various teaching methods. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(3):220–225.

79. Moore J, Parsons C, Lomas S. A resident preceptor model improves the clerkship experience on general surgery. J Surg Educ 2014;71(6):e16-8.

80. McKeon BA, Ricciotti HA, Sandora TJ, et al. A consensus guideline to support resident-as-teacher programs and enhance the culture of teaching and learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(3):313-318.

81. Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Med Teach. 2012;34(5):e288-e299.

82. Hosseini S, Yilmaz Y, Shah K, et al. Program evaluation: an educator’s portal into academic scholarship. AEM Educ Train 2022;6(Suppl 1):S43-S51.

83. Donovan A. Radiology resident teaching skills improvement: impact of a resident teacher training program. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(4):518-524.

84. Gill DJ, Frank SA. The neurology resident as teacher: evaluating and improving our role. Neurology. 2004;63(7): 1334-1338.

85. Johnson KM, Rowat J, Suneja M. A 3-year rolling teaching skills curriculum for all residents in the ambulatory block. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):675.

86. Tischendorf JS, MacDonald M, Harer MW, Pittner-Smith CA, Zelenski AB, Johnson SK. Bridging undergraduate and graduate medical education: a resident-as-educator curriculum embedded in an internship preparation course. Wis Med J. 2020;119(4):278-281.

87. Dewey CM, Coverdale JH, Ismail NJ, et al. Residents-as-teachers programs in psychiatry: a systematic review. Can J Psychiarty. 2008;53(2):77-84.

88. Chochol MD, Gentry M, Hilty DM, McKean AJ. Psychiatry Residents

as Medical Student Educators: a Review of the Literature. Acad Psychiatry. 2022;46(4):475-485.

89. James MT, Mintz MJ, McLaughlin K. Evaluation of a multifaceted “resident-as-teacher” educational intervention to improve morning report. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:20.

90. Haghani F, Eghbali B, Memarzadeh M. Effects of “teaching method workshop” on general surgery residents’ teaching skills. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:38.

91. Humbert AJ, Pettit KE, Turner JS, Mugele J, Rodgers K. Preparing emergency medicine residents as teachers: clinical teaching scenarios. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10717.

92. York-Best C, Bengtson J, Stagg A. Laparoscopic salpingectomy: a simulation-based resident as surgical teacher (RAST) program. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:63S.

93. Katzelnick DJ, Gonzales JJ, Conley MC, Shuster JL, Borus JF. Teaching psychiatric residents to teach. Acad Psychiatry 1991;15(3):153-159.

94. Marcus CH, Newman LR, Winn AS, et al. TEACH and repeat: Deliberate practice for teaching. Clin Teach. 2020;17(6):688-694.

95. Grady-Weliky TA, Chaudron LH, Digiovanni SK. Psychiatric residents’ self-assessment of teaching knowledge and skills following a brief “psychiatric residents-as-teachers” course: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(6):442-444.

96. Dannaway J, Ng H, Schoo A. Literature review of teaching skills programs for junior medical officers. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:25-31.

97. Geary AD, Hess DT, Pernar LIM. Resident-as-teacher programs in general surgery residency: context and characterization. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(5):1205-1210.

98. Zackoff MW, Real FJ, DeBlasio D, et al. Objective assessment of resident teaching competency through a longitudinal, clinically integrated, resident-as-teacher curriculum. Acad Pediatr 2019;19(6):698-702.

99. Hill AG, Srinivasa S, Hawken SJ, et al. Impact of a Resident-asteacher workshop on teaching behavior of interns and learning outcomes of medical students. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):34-41.

100. Loo BKG, Thoon KC, Tan JHY, Nadua KD, Chow CCT. Supporting paediatric residents as teaching advocates: changing students’ perceptions. Asia Pacific Scholar. 2020;5(3):62-70.

101. Litzelman DK, Stratos GA, Skeff KM. The effect of a clinical teaching retreat on residents’ teaching skills. Acad Med. 1994;69:433–4.

102. Thomas PS, Harris P, Rendina N, Keogh G. Residents as teachers: outcomes of a brief training programme. Educ Health. 2002;15:71–8.

103. Hoffman LA, Furman DT Jr, Waterson Z, Henriksen B. A novel resident-as-teacher curriculum to improve residents’ integration into the clinic. PRiMER. 2019;3:9.

104. Mann KV, Sutton E, Frank B. Twelve tips for preparing residents as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29(4):301-306.

105. Fakhouri Filho SA, Feijo LP, Augusto KL, Nunes M do PT. Teaching skills for medical residents: Are these important? A narrative review of the literature. Sao Paulo Med J. 2018;136(6):571-578.

Max Griffith, MD*

Alexander Garrett, MD*

Bjorn K. Watsjold, MD, MPH*

Joshua Jauregui, MD, MHPE*

Mallory Davis, MD, MPH†

Jonathan S. Ilgen MD, PhD*

Section Editor: Abra Fant, MD

University of Washington, Department of Emergency Medicine, Seattle, Washington University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Department of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Submission history: Submitted July 11, 2025; Revision received October 10, 2025; Accepted October 13, 2025

Electronically published November 26, 2025

Full text available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem DOI 10.5811/westjem.48914

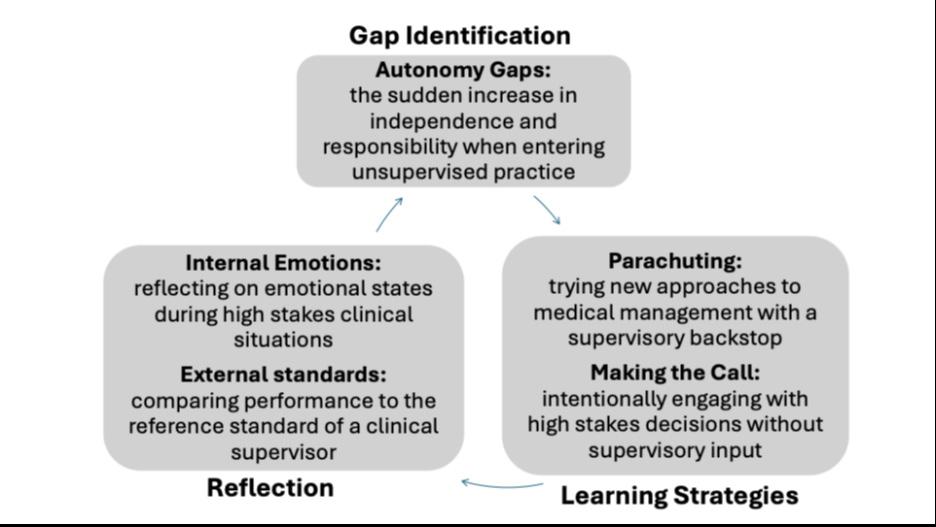

Introduction: As emergency medicine (EM) residents prepare for the transition into unsupervised practice, their focus shifts from demonstrating competencies within familiar training environments to anticipating their new roles and responsibilities as attending physicians, often in unfamiliar settings. Using the self-regulated learning framework, we explored how senior EM residents proactively identify goals and enact learning strategies leading up to the transition from residency into unsupervised practice.

Methods: In this study we used a constructivist grounded theory approach, interviewing EM residents in their final year of training at two residency programs. Using the self-regulated learning framework as a sensitizing concept for analysis, we conducted inductive, line-by-line coding of interview transcripts and grouped codes into categories. Theoretical sufficiency was reached after 12 interviews, with four subsequent interviews producing no divergent or disconfirming examples.

Results: We interviewed16 senior residents about their self-regulated learning approaches to preparing for unsupervised practice. Participants identified two types of gaps that they sought to address prior to entering practice: knowledge/skill gaps, and autonomy gaps. We employed specific workplace learning strategies to address each type of gap, which we have termed cherry-picking, case-based hypotheticals, parachuting, and making the call, and reflection on both internal and external sources of feedback to assess the effectiveness of these learning strategies. This study presents participants’ identification of gaps in their residency training, their learning strategies, and reflections as cyclical processes of self-regulated learning.

Conclusion: In their final months of training EM residents strategically leverage learning strategies to bridge gaps between their self-assessed capabilities and those they anticipate needing to succeed in unsupervised practice. These findings show that trainees have agency in how they use goal setting, strategic actions, and ongoing reflection to prepare themselves for unsupervised practice. Our findings also suggest tailored approaches whereby programs can support learning experiences that foster senior residents’ agency when preparing for the challenges of future practice. [West J Emerg Med. 2025;26(6)1510–1518.]

Competency-based medical education frameworks provide scaffolding and accountability to ensure that emergency medicine (EM) trainees develop the necessary

knowledge and skills for unsupervised practice.1,2 While competency-based medical education frameworks provide a roadmap for residents to deliberately practice the core elements of EM, graduates of EM training programs often

lament the inevitability of encountering new challenges when entering practice.3,4 This suggests that the training experiences that advance residents’ competencies (what a resident does to demonstrate their abilities) must be done in conjunction with efforts to advance residents’ capabilities (the things they can think or do in future practice.)5 While competencies are often embedded in the tools that training programs use to assess residents,1,6,7 capability development requires trainees to engage in dynamic self-assessment8 to consider what they can work on now to prepare themselves for future transitions. A capability approach looks beyond training residents who are simply competent, aiming instead to develop trainees who can self-diagnose their future learning needs and enact learning strategies to achieve their goals.9–11

Self-regulated learning (SRL) provides a framework to study how senior residents approach workplace learning to prepare for their transitions into unsupervised practice.12 The SRL theory proposes that individuals are “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process.”13 This provides a structure to consider how residents might assess their abilities and modulate their activities during training.14 These SRL behaviors are often depicted as a cycle whereby individuals set goals, employ learning strategies to attain these goals, and reflect on their progress.14 This cycle is context-dependent, shaped by learner characteristics (eg, knowledge, prior experiences, emotions, and confidence) as well as by the learning environment (structure, supports, and cultural expectations).15 Learnerrelated factors such as autonomy, efficacy, and accumulated experience have been shown to support engagement with SRL,16 suggesting that residents in the final months of training have nuanced and mature self-regulated learning habits.