November – December 2025

On The Cover

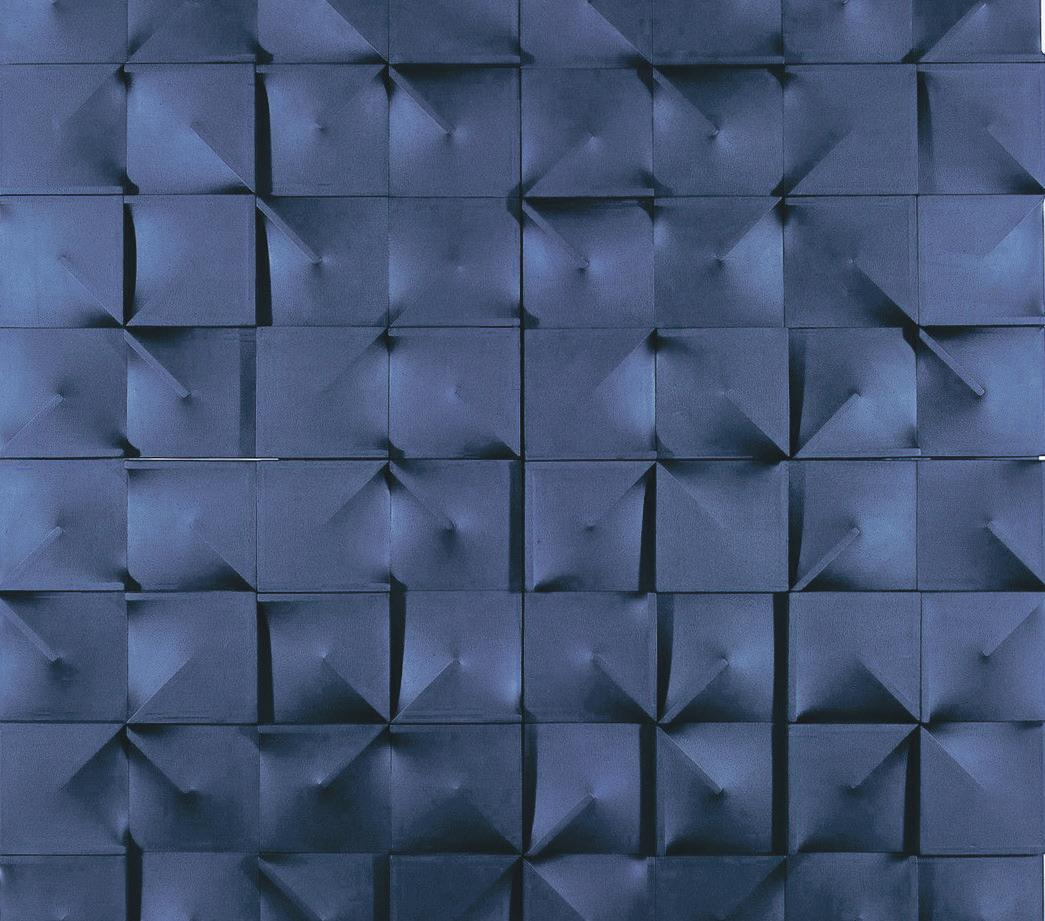

Mair Hughes, Spoil Shelter, 2025, from The Borderlands / Y Gororau project; photograph by Mair Hughes, courtesy of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts.

First Pages

5. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

8. Piering Eyes. Cornelius Browne recalls the mystery and lore of Atlantis House in Burtonport, County Donegal. Dublin Gallery Weekend. John Daly gives details of Dublin Gallery Weekend 2025, taking place from 6 to 9 November.

9. Art Made By Walking. Lian Bell outlines the importance of walking as creative practice and a refusal of productivity. Dreaming Disability Futures. Alex Cregan discusses a recent disability justice workshop at Void Art Centre.

10. Flock. Guest Curator Dr Selina Guinness outlines programme highlights for Dublin Art Book Fair in December.

11. A Greener Future. Stephen Beggs outlines the activities of Green Arts NI – a sustainability network for Northern Ireland. Issues of Our Time. Niamh O’Malley discusses the 2025 RDS Visual Art Awards at the RHA.

Organisation Profile

12. A Crazy Vocation. Aengus Woods interviews John Daly about the 30-year evolution of Hillsboro Fine Art.

Festival / Biennial

14. Strange Lands Still Bear Common Ground. Clodagh Assata Boyce interviews Beulah Ezeugo, curator of TULCA 2025.

16. A Borderless Romance. Rachel Macmanus reports on Convergence Festival presented by Live Art Ireland in August.

Exhibition Profile

17. Ends and Infinity. Aengus Woods reviews a recent exhibition at Solstice Arts Centre.

18. Hometown. Dorothy Smith discusses Jason McCarthy’s recent exhibition at Droichead Arts Centre.

Critique

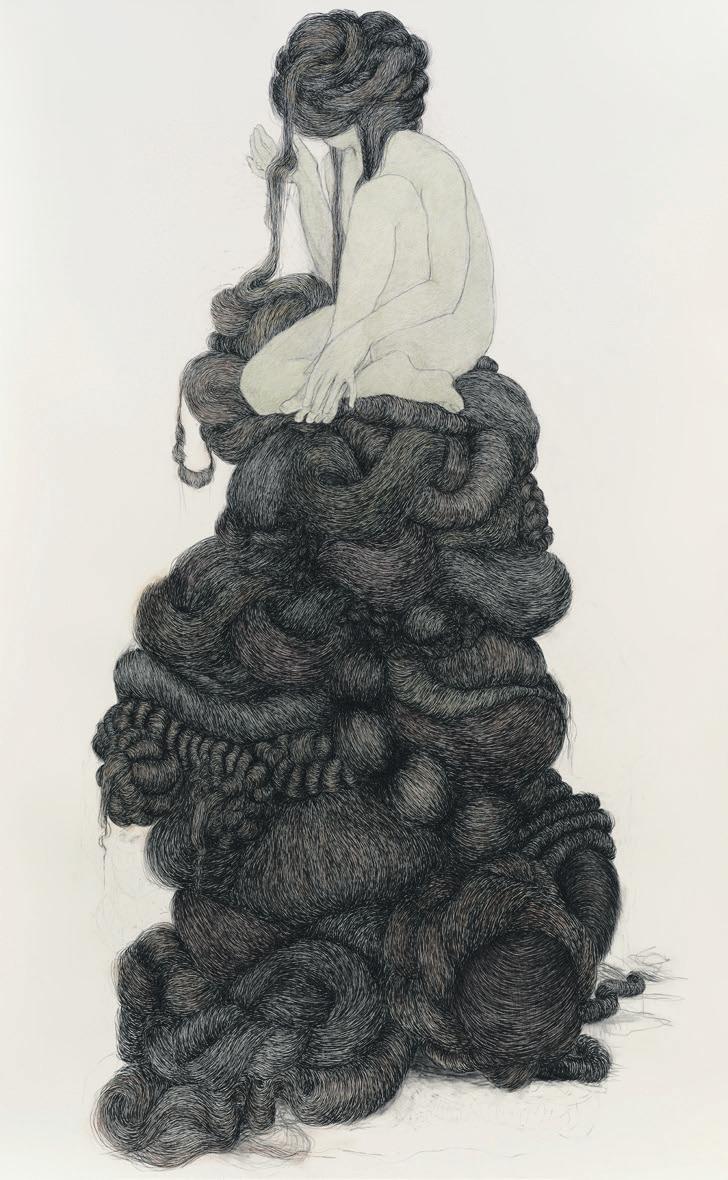

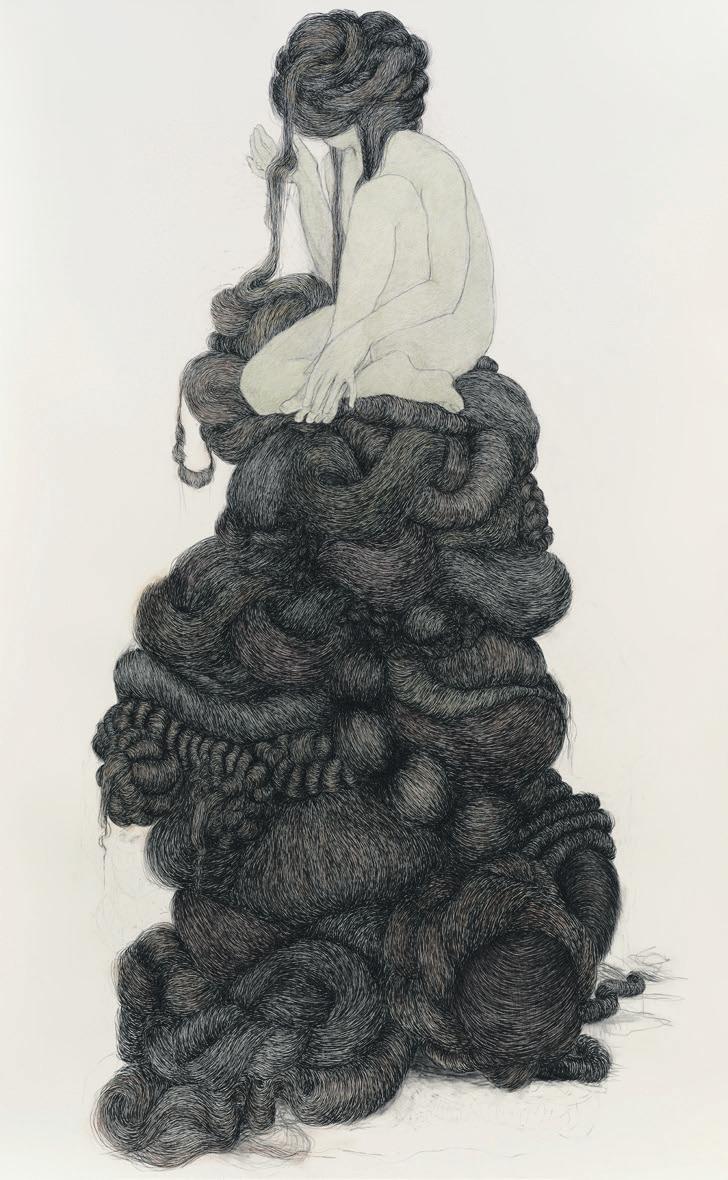

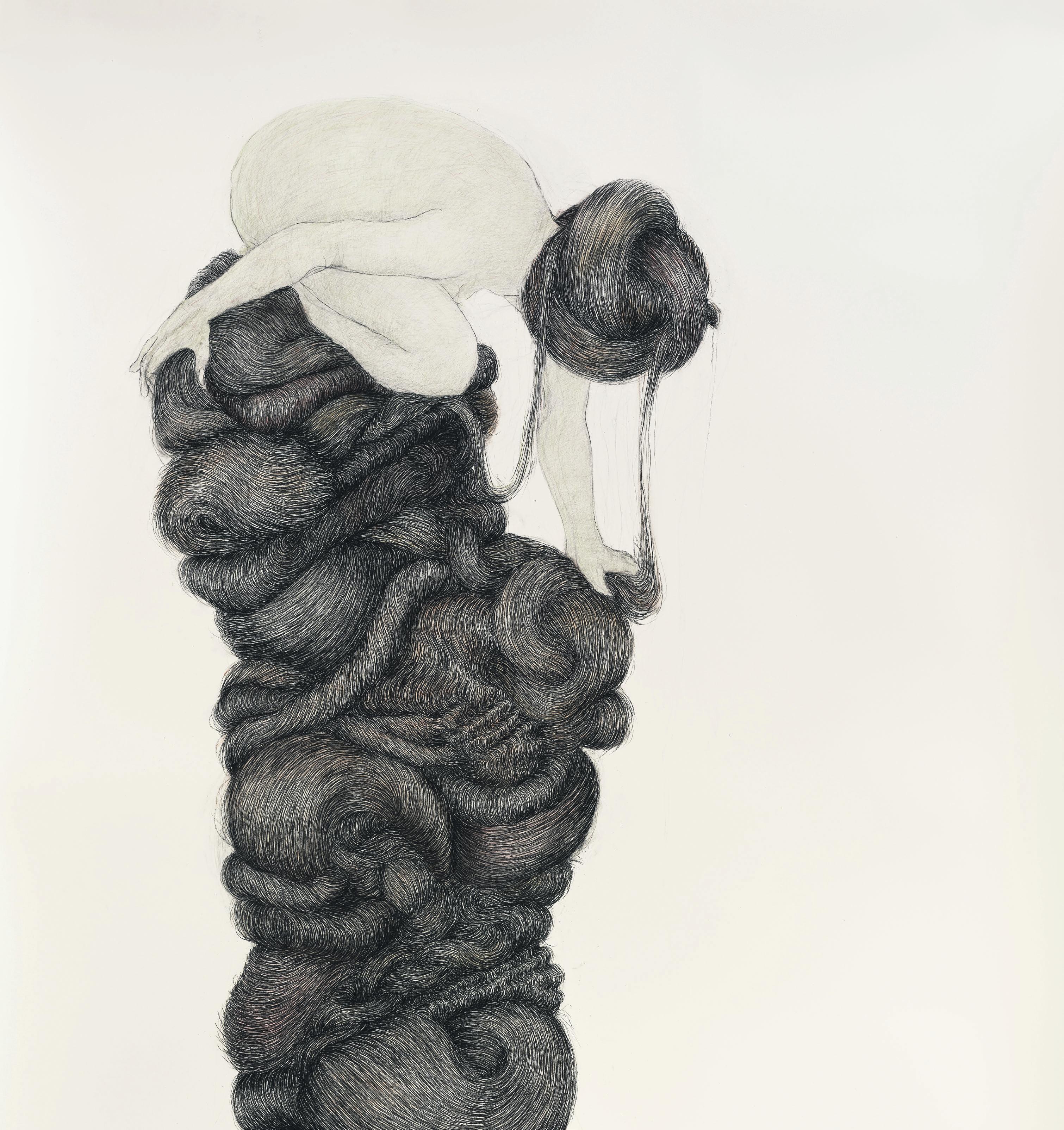

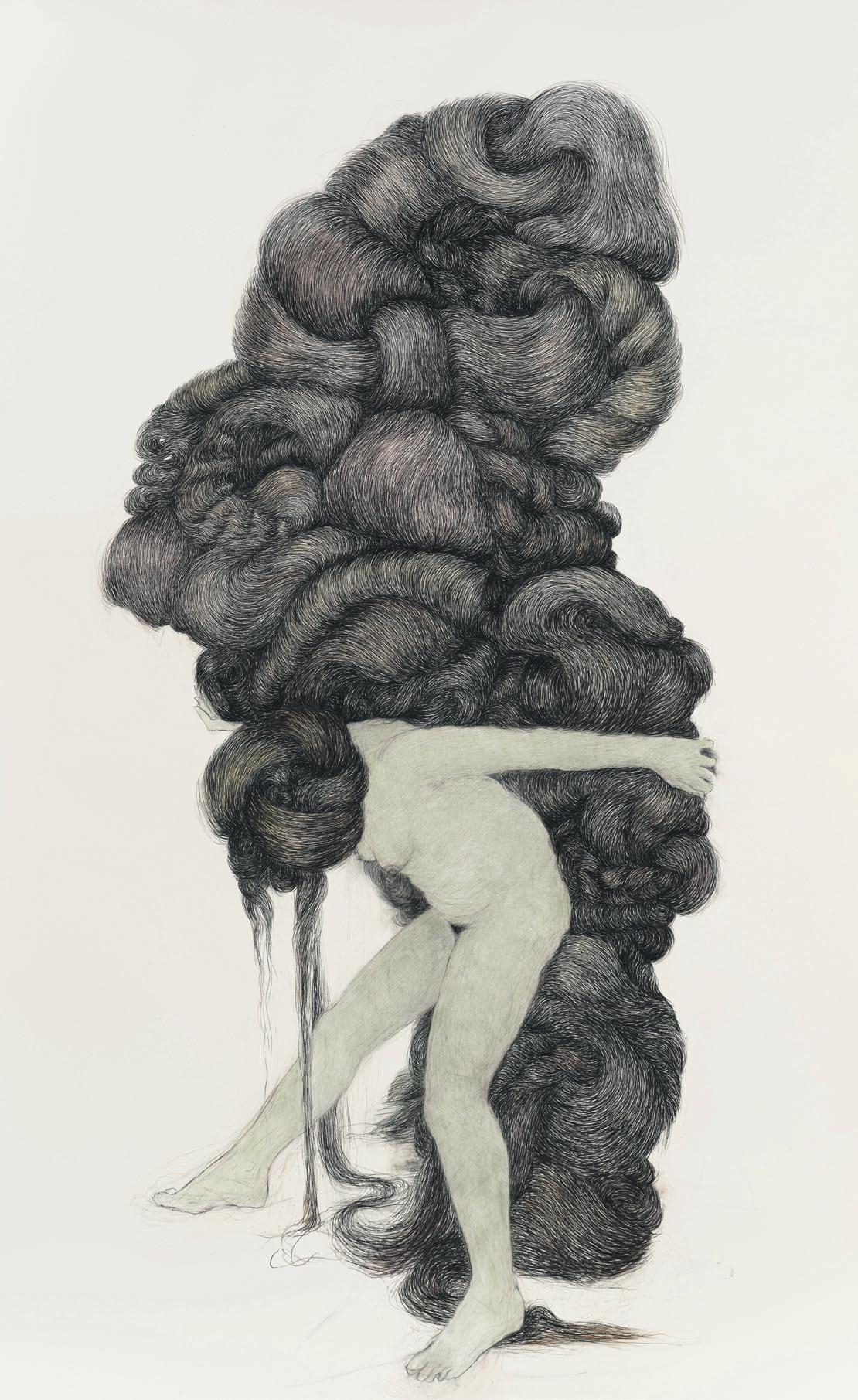

19. Alice Maher, Sibyl I, 2025.

20. Alice Maher at Kevin Kavanagh

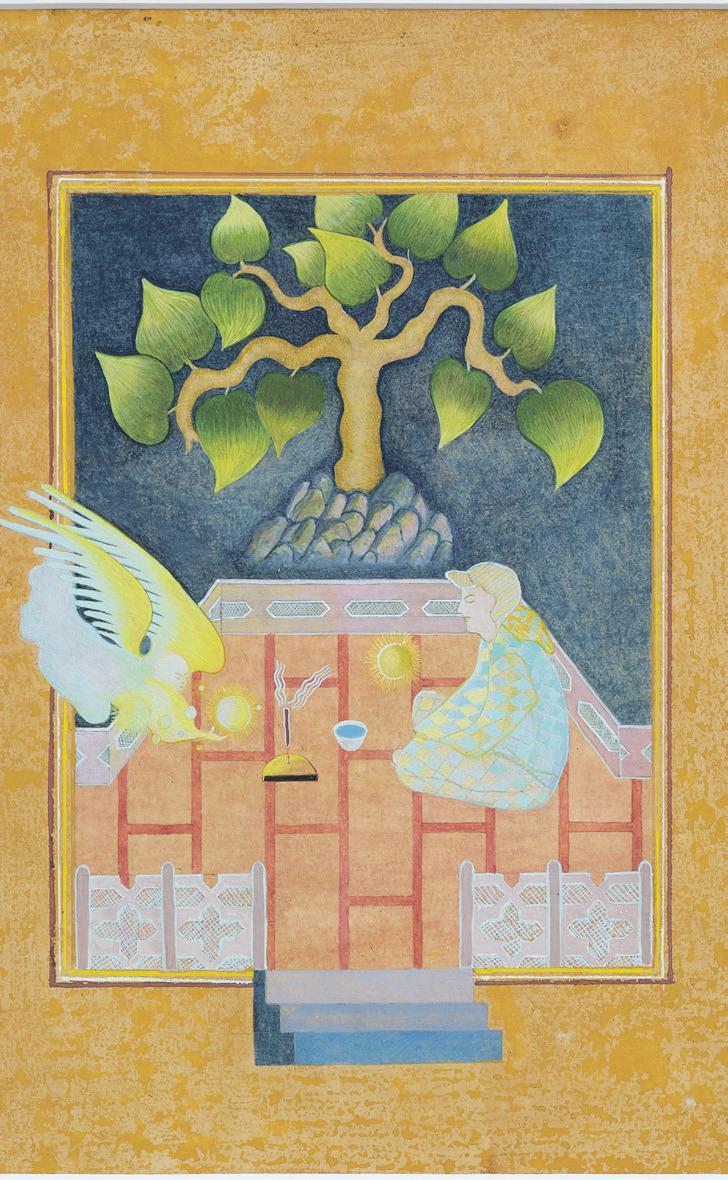

21. ‘SYSTEM ARMING’ at Luan Gallery

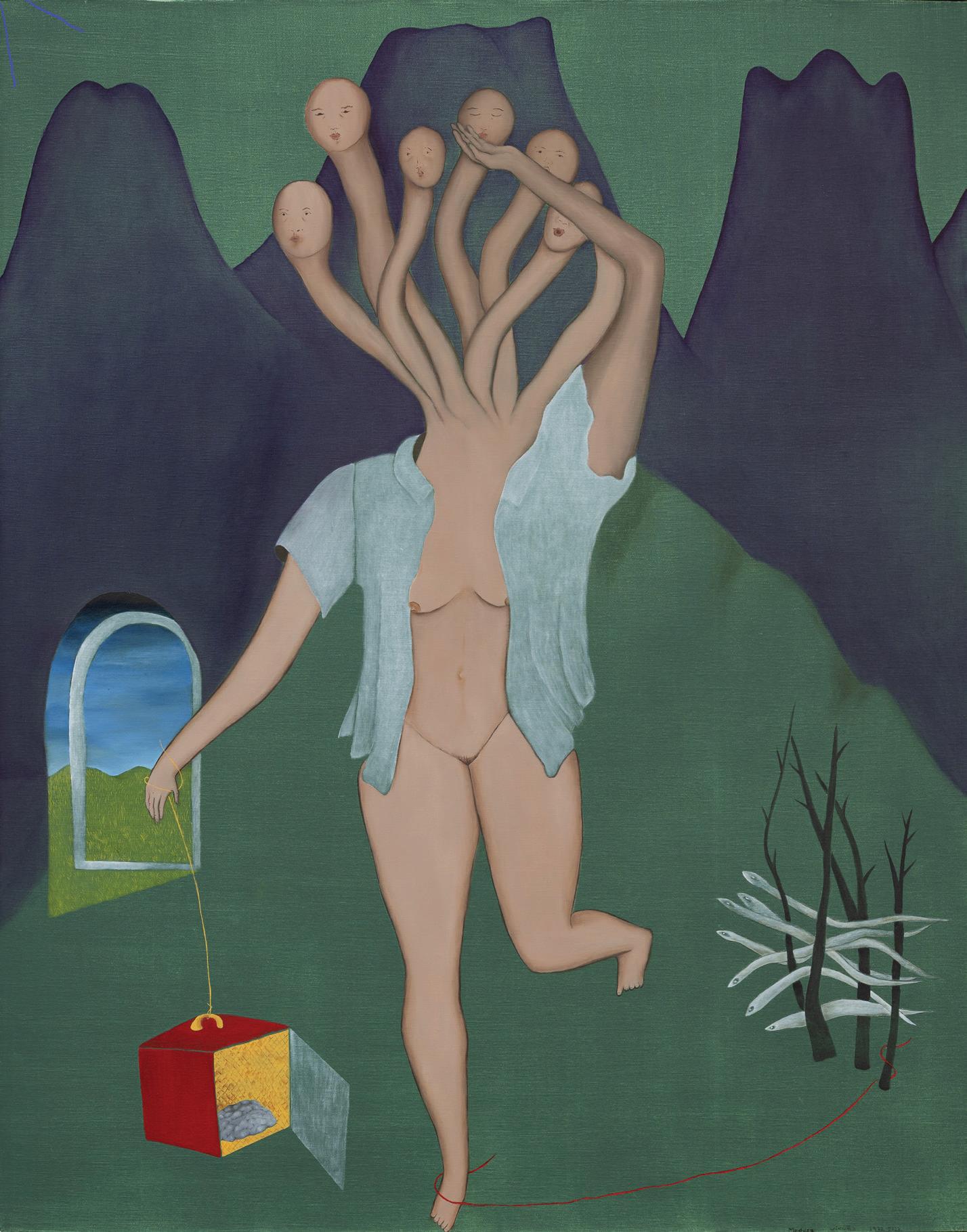

22. ‘New Irish Art’ at Lavit Gallery

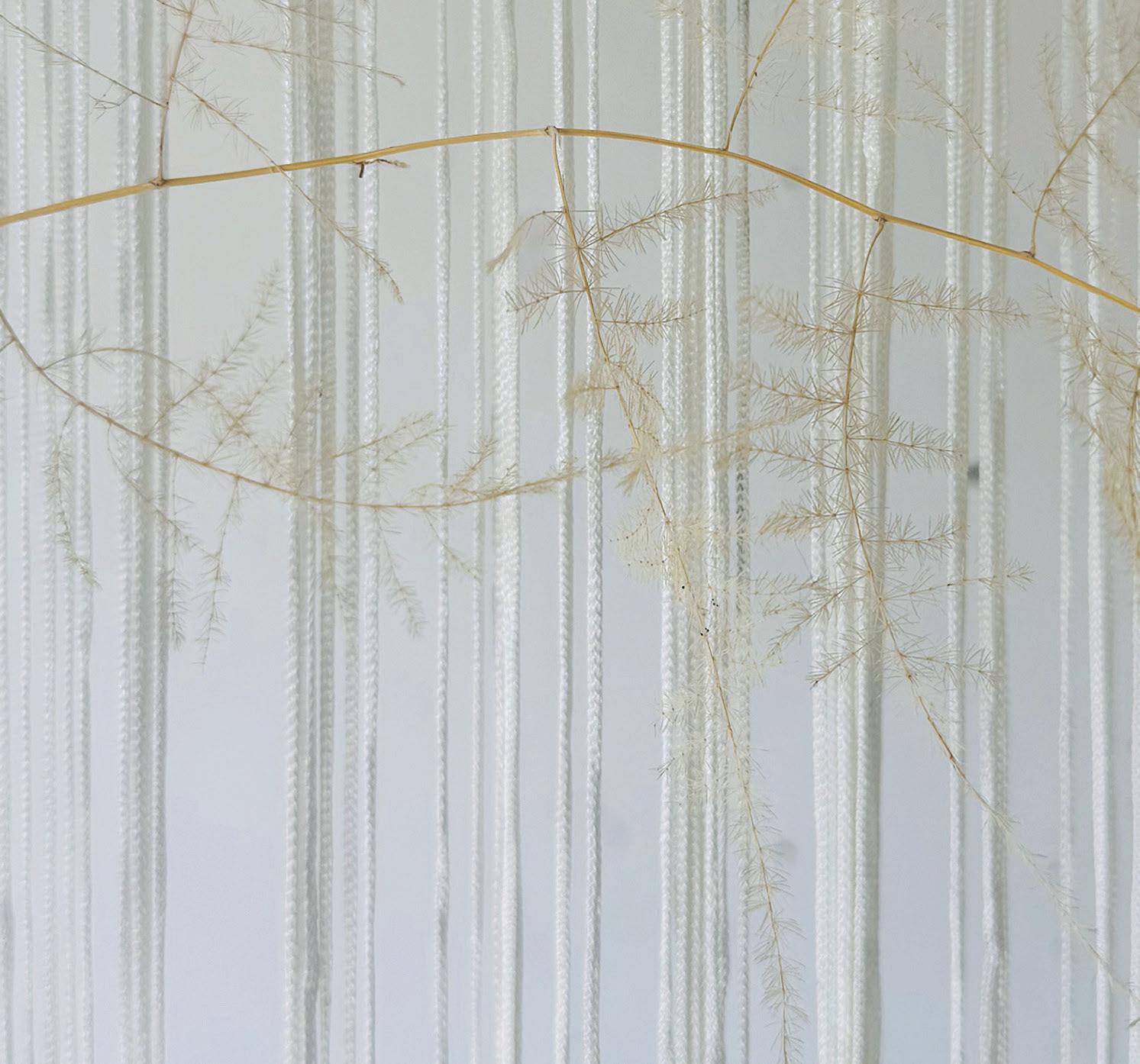

24. ‘Bíodh Orm Anocht’ at Ormston House

VAI Event

25. Connected Horizons. Brian Kielt reports on VAI’s ongoing Connected Horizons programme.

26. Get Together 2025. Joanne Laws and Thomas Pool report on Ireland’s annual networking event for visual artists.

29. New Institutional Approaches to Curating. Joanne Laws and Thomas Pool report on VAI’s inaugural curatorial presentation.

Residency

30. Jump Cuts & Tree Judgements. Joanne Laws interviews Katie Breckon and Kate O’Shea about THE IMMA Fremantle Residency Exchange.

Member Profile

32. The Spirit of the Place. Cristín Leach reflects on the Brigid’s Well paintings of Mary Fahy.

33. The Dysphoric Age. Stephen Doyle outlines their evolving practice and recent exhibition at Highlanes Gallery.

34. Echolocations. Sorcha McNamara outlines the evolution of her artistic practice.

Last Pages

36. VAI Lifelong Learning. Upcoming VAI helpdesks, cafés and webinars.

37. Opportunities. Grants, Awards, Open Calls, and Commissions.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary McGrath, Lewis Olivier

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Member & Artists Advice, Advocacy & Development: Mary McGrath

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Services Design & Delivery: Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Special Projects: Robert O‘Neill

Impact Measurement: Rob Hilken

Shared Island Advocacy: Brian Kielt

Board of Directors:

Deborah Crowley, Michael Fitzpatrick (Chair), Lorelei Harris, Maeve Jennings, Gina O’Kelly, Deirdre O’Mahony (Secretary), Samir Mahmood, Paul Moore, Ben Readman.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

First Floor

2 Curved Street

Temple Bar, Dublin 2

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie

W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

109 Royal Avenue

Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

The Kiosk Project Art Space is a new interdisciplinary arts venue established in late 2024 by artist and producer Brian Hegarty (thirtythree-45) in collaboration with the Droichead Arts Centre and its partners. Rita Hynes has since joined this curation team to assist with their 2026 programme.

The aim of The Kiosk Project Art Space is to showcase and support the work of artists and groups at any stage of their practice, by invitation or open call, cultivating a creative environment with an artist-led approach. The physical space of The Kiosk is tiny, versatile and adaptable, providing a dynamic setting that can accommodate temporary exhibitions, projects, residencies and events.

The Minister for Culture, Communications and Sport, Patrick O’Donovan TD, and the Minister of State for Sport and Postal Policy, Charlie McConalogue TD, announced details of €1,514,678,000 in funding allocated to the Department in Budget 2026, which will see increases across all areas with a total 9.5% rise across the Department. Funding for 2026 is increasing for all areas under the Department while supports for agencies in sectors continue to grow. Budget 2026 will enable the continuation of key supports in the Arts and Media sectors, while allowing for the delivery of ambitious projects across Communications, Sports and in our National Cultural Institutions.

The Department’s Arts and Culture programme aims to support and develop engagement with, and in arts, culture and creativity by individuals and communities thereby enriching lives through cultural and creative activity; to promote Ireland’s arts, culture and creativity globally; and to drive a more vibrant and diverse Night-Time Economy.

• Provision made, subject to Government approval, for a successor scheme to the Basic Income for the Arts Pilot, which will finish in February 2026. The research proves that the BIA successfully sustains artists careers and reduces the income precarity which is a feature of a career in the arts

• Completion of the repository project in the National Archives in 2026

• Commencement of the major redevelopment of the Crawford Art Gallery

• Commence redeveloping the National Concert Hall with the Discover Centre project (a music learning and engagement centre) in the old Pathology block

• A new €6m capital works scheme will be developed to fund arts capital projects in line with the commitment in the Programme for Government, providing support for communities across the country

• Screen Ireland 2026 allocation increased by €2.1m to develop new

In just over a year, The Kiosk Project Art Space has delivered an exciting programme as a gallery, residency space, and community hub. Recent highlights include exhibitions by Gee Vaucher, Helen McDonnell, Boz Mugabe, and Cathal Carolan; a pop-up radical bookshop called Cailleach Books; and creative residencies with Conor McMahon and Oksana So.

The year’s end will bring a new small press imprint called Paraphrase, and two exhibitions: ‘Cartomania’ – presenting nineteenth-century photographic portraits from Drogheda by historian Dr Orla Fitzpatrick – and ‘SWEAT, SOUNDS & STORIES’, a love letter to old band t-shirts, curated by Cliona Murphy and Brian Hegarty.

strategies to grow the gaming and special effects sectors in Ireland and for increased support to the indigenous and incoming screen industry

• An additional allocation of €600,000 to Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann who celebrate their 75th Anniversary in 2026

• €1m in funding, double the 2025 allocation, for the 2026 round of the Grassroots Music Venue Support scheme to support independent music venues and artists across the country.

• Culture Ireland 2026 allocation increased by €800k, to help develop and sustain Irish artists’ international careers

Ballinamore Public Art Commission

Leitrim County Council announced that artist Fiona Murphy has been awarded The Junction – Ballinamore Public Art Commission for her proposal, Hand to Land and Thread in Hand, following a nationwide open call and a highly competitive two-stage selection process. The commission is funded under the council’s Per Cent for Art programme.

Rooted in Ballinamore’s flax-growing and linen-making heritage, Murphy’s site-specific design takes the form of an undulating, fabric-like seating structure at The Junction in Ballinamore, County Leitrim. Drawing upon twists of linen for its form, its surface features mosaic in warm ochres, yellows, browns, flecks of gold, and accents of flax-flower blue, with the artwork harmonising with the surrounding architecture. The sculpture’s organic form, evoking the twists and folds of linen fabric, invites visitors to rest, explore, and interact. Community collaboration is central to the artwork’s creation, and as part of this approach, Murphy has been delivering a series of workshops with Transition Year students at Ballinamore Community School and is working with a local craft group, selected through a separate open call earlier this year. The group is developing a companion project as part of the Creative Ireland programme, building on social engagement and the participatory ethos at the heart of the artist’s design and concept.

Ardú Street Art Returns

Ardú Street Art, the open-air gallery that has transformed Cork city since 2020, returned in September with an exciting new programme of large-scale murals and artistic talent. Supported by Creative Ireland, Cork City Council Arts Office, Pat McDonnell Paints, and Cork Airport, this year’s project once again brought colour, conversation, and creativity to the streets of Cork.

The first mural of 2025, The Wonder of Travel, was recently unveiled at Cork Airport. A collaboration between Cork-based artists Peter Martin and Shane O’Driscoll, the work celebrates the history of air travel through Cork Airport since 1961, while looking forward to its bright future and development.

In addition, Ardú announced two new large-scale murals for Cork city centre by artists Kone.one (at Water Street) and Hixxy (at Liberty Street).

IMMA Wins 2025 Art Museum Award

The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) has won the 2025 Art Museum Award, presented by the European Museum Academy (EMA). This prestigious honour recognises IMMA as one of Europe’s leading cultural institutions, celebrated for its pioneering, inclusive, and socially engaged approach to contemporary museology. The award was presented to IMMA’s Director, Annie Fletcher, at a ceremony in Budapest on Saturday 27 September 2025, where cultural leaders from across Europe gathered to celebrate excellence in museum practice.

The EMA Art Museum Award which is supported by the A.G. Leventis Foundation, highlights institutions that use art in innovative and creative ways to address pressing social issues. It champions museums as ‘social arenas’, spaces for civic dialogue, inclusion, and community building. The Award recognises museums that explore themes such as participation, inclusion, accessibility, gender equality, migration, racial justice, decolonisation, sustainability, climate change, and public health.

IMMA was selected from a highly competitive shortlist of outstanding institutions, including the Centre Pompidou-Metz (France), Reykjavik Art Museum (Ice-

land), Lithuanian National Museum of Art (Lithuania), Museum of Contemporary Art of Montenegro (Montenegro), State Ethnographic Museum (Poland), Museum of Naïve and Marginal Art (Serbia), and Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery (United Kingdom).

Reel Art 2025

The Arts Council announced Éanna Mac Cana and Yvonne Mc Guinness are the recipients of the Reel Art 2025 awards, while Jesse Jones is the successful recipient of the Authored Works 2025 award.

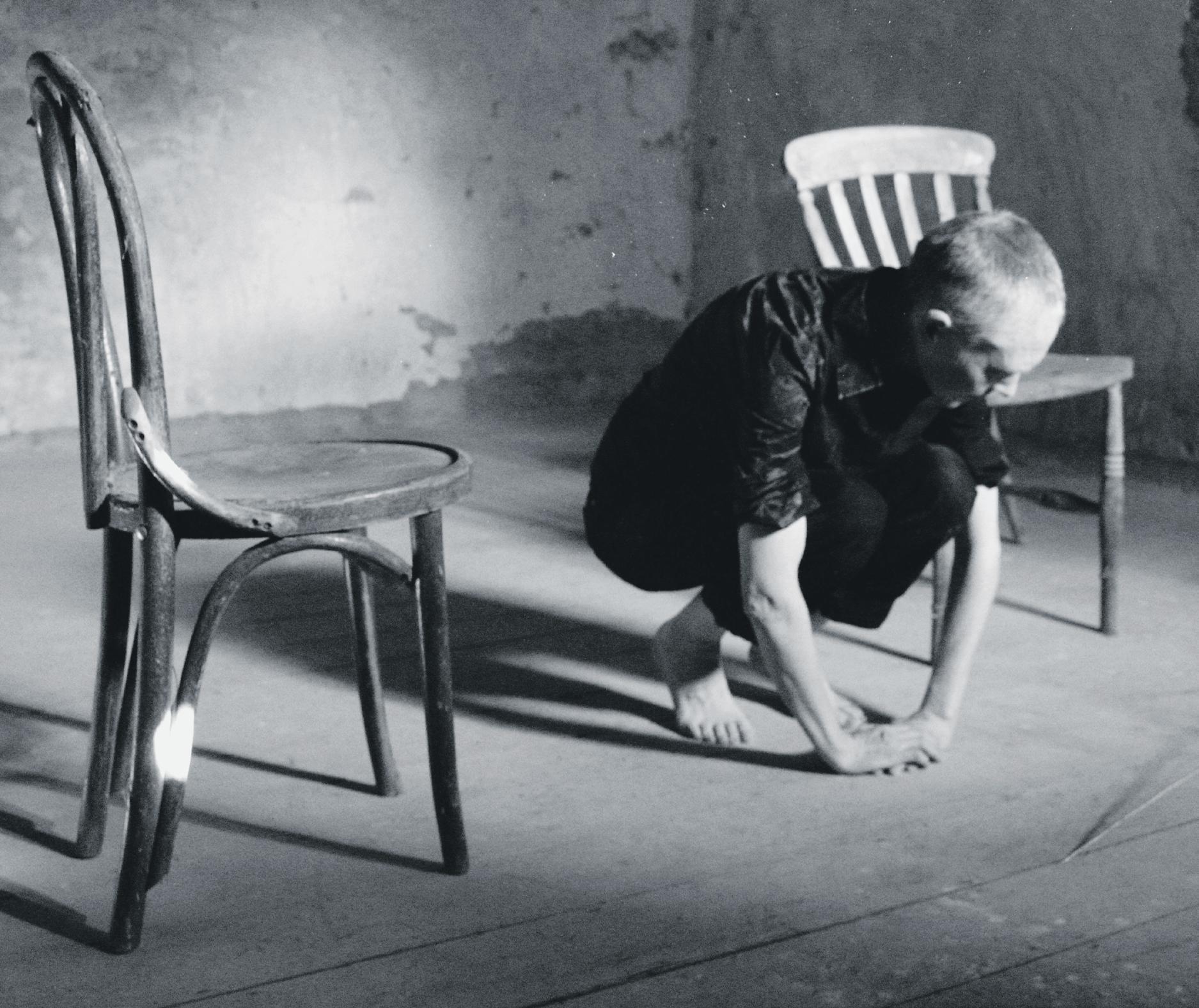

Éanna Mac Cana is a successful recipient of the Reel Art 2025 award for his film Sink a Death Stop which is a close look at the life, artistry and worldview of pioneering performance artist Alastair MacLennan. At the forefront of the Belfast art scene for a number of decades, the resonance of MacLennan’s work has led him to being considered one of Ireland’s leading and most influential performance artists. This film will move between Alastair’s one-of-akind archive and new recordings, revealing a deeply insightful and delicate portrait of a highly acclaimed performance artist.

Yvonne McGuinness is also a recipient of the Reel Art 2025 award for her film

The Buildings are Listening. The Buildings are Listening is a poetic, playful, and politically resonant journey through Ireland’s beloved but threatened cultural buildings told through the voices of the buildings themselves. Mixing vérité, archival footage, re-staged memory, and magical realism, the film is about presence, absence, legacy and the power of place.

Reel Art is the Arts Council’s long-running arts documentary scheme which provides film artists with the creative and editorial freedom to make highly creative, imaginative and experimental documentaries on an artistic theme for cinema exhibition. The Dublin International Film Festival is the Arts Council’s exhibition partner for Reel Art and Sink a Death Stop and The Buildings are Listening will premiere at DIFF in 2027.

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council presents ‘An Outer Reflection of an Inner Reality’, showing new work by Karen Ebbs. The exhibition featured large, colourful oil paintings, mirrored plexiglass, and sculptures. Ebbs’s work invites viewers to explore themes of reflection, perception, and the nature of reality. At the heart of the work is colour – life-affirming and transformative – which the artist uses as a quiet rebellion against grey apathy, to offer hope. The exhibition continues until 9 November 2025.

dlrcoco.ie

National Botanical Garden

‘Sculpture in Context’, celebrated its 40th anniversary at the National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin, Dublin, from 4 September to 10 October this year. As part of the anniversary celebration, the exhibition also welcomed several distinguished invited artists. Among them were Eilis O’Connell, Alison Kaye, Ken Drew, Ana Duncan, Seamus Gill, Beatrice Stewart, Ciaran Patterson, Penelope Lacey, Michelle Maher, and Richard Healy, whose contributions further enriched this 40th anniversary exhibition.

opw.ie

REDS Gallery Dublin

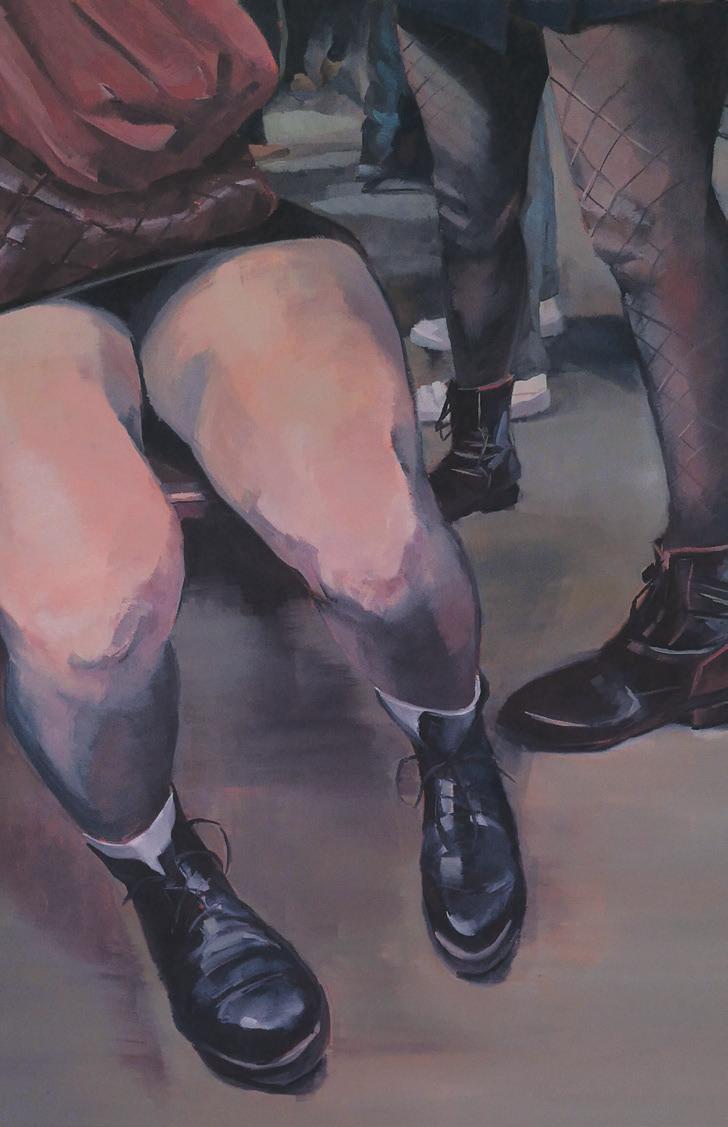

‘In Transit’ by Maria Ginnity ran from 9 to 15 October at REDS Gallery Dublin on Dawson Street. The exhibited works capture the choreography of public transport. Ginnity turned the daily ritual of commuting into a quiet theatre of human behaviour, navigating intimate proximity with strangers – with glances avoided, elbows angled, phones in hand, and bags clutched like protective armour. An emerging artist, Ginnity has recently qualified with a Diploma in Painting and Drawing (Distinction) from the RHA School.

@reds_gallery_dublin

mother’s tankstation

Christopher Steenson’s ‘They haven’t gone away you know’, comprises a series of artworks that explore power struggles between the individual and the state, from both human and more-than-human perspectives. This body of work, collectively titled ‘The Long Grass’ (2022-24), was borne through an extensive period of research surrounding the corncrake – a bird that is now almost extinct, with the bird’s call now only heard in remote sections of Ireland’s west coast. On display from 25 September to 22 November.

motherstankstation.com

Pallas Projects/Studios

Gary Farrelly’s first solo exhibition in Ireland in fifteen years, ‘Quasi-Autonomous Stitch’, takes its name from a sewing procedure devised as a method of overwriting and absorbing images and surfaces. The works here are restless, shifting between seams, carbon traces, labels, blueprints, photographs, and logbooks. At stake are languages of construction, obsolescence, staging, and transmission – creased, overwritten, redacted, repaired, forced into proximity. On display from 9 to 25 October.

pallasprojects.org

Slane Castle

Named after the Irish word for sanctuary, ‘CAIM’ is Slane Castle’s new art programme, dedicated to exploring nature and sanctuary through contemporary art. In September, ‘CAIM’ launched its inaugural exhibition at the 18th-century estate, fostering dialogues between international contemporary art and Ireland’s cultural heritage. The exhibition brought together 19 Irish and international contemporary artists working across various mediums, generations, and cultural backgrounds, including Niamh O’Malley, Lee Welch, Kathy Tynan, and Fergus Martin. On display from 12 to 30 September. caimatslane.com

Belfast Exposed presents three concurrent exhibitions, showcasing the work of four seminal Polish photographers: Zofia Rydet, Anna Beata Bohdziewicz, Teresa Gierzyńska, and Aneta Grzeszykowska. Each artist explores how photography has been used across generations to question identity, memory, and the visibility of women’s lives. They each turn the camera into a tool for self-definition, resistance, and storytelling, reclaiming image-making as a way of shaping how women are seen, and how they see themselves. Runs until 20 December. belfastexposed.org

Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich

Rónán Ó Raghallaigh’s exhibition ‘Turais Taibhsí’ was on display at Culturlann in Belfast from 7 August to 11 September. Each painting in this exhibition is the result of a personal pilgrimage to a sacred place within the Irish landscape. The titles of the paintings are in Irish, honouring the original names of these places and the memories they hold. Ó Raghallaigh spent time researching the folklore imbued in these places, their logainmneacha (Irish place names), and archaeology.

culturlann.ie

PS²

‘Meeting The Lough On Its Own Terms’ (4 to 27 September) by artist Ami Clarke, delivered in partnership with Friends of the Earth, Digital Art Studios, Sonic Arts Research Centre and PS2, and Banner Repeater (London). Expanding upon her previous work on complex systems, and informed by a collective writing project with Friends of the Earth NI, Clarke worked with many local people to record something of the multiple scales and temporalities of Lough Neagh, combining 4K drone footage with cinematography, underwater filming, and microscopic footage. pssquared.org

Alex Keatinge and Niamh Hannaford presented ‘non-stick frying pan’ from 2 October to 6 November. The non-stick pan is a mass-produced household staple. Practical and easy to clean, its non-stick coating makes cooking and cleaning more efficient than stainless steel alternatives. Using the non-stick frying pan as a vehicle for discussion, this exhibition and public programme positioned the western domestic space as an active site, where socio-political, economic and imperial systems are perpetuated and sustained.

catalystarts.org.uk

‘Radical Hope’, a group exhibition developed in collaboration with Arsenal Gallery in Białystok, Poland. The exhibition is curated from ‘Collection II’, one of Poland’s most significant collections, which traces the evolving landscape of contemporary art in Poland and Eastern Europe over the past three decades. The collection is a living archive: dynamic, growing, and responsive to the shifting narratives of our time. ‘Radical Hope’ reflects on uncertainty, resilience, and the transformative potential of art. On display from 13 September to 8 November. goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

‘Glimpses’ by Jennifer Alexander ran from 4 September to 31 October. In her exhibition, which launched on 4 September for Late Night Art Belfast, Alexander interpreted Aristotle’s imagining the cosmos as 56 celestial spheres by creating a series of acrylic sketches on linen. Each fragment invited a shift in perspective, exploring in-between spaces, identity beyond the body, and our place in the universe – a constellation of moments that ask who we are, and how we find meaning.

flaxartstudios.org

Butler Gallery

‘Cities of the World’ by Kathy Prendergast and Chris Leach was on display from 9 August to 27 October. Although the two artists have never met, they are intrinsically linked by their subject matter, which they realise in different ways. The juxtaposition of their work prompted wider discussion on geography, architecture and politics – what cities say about us, and what they don’t. Additionally, a film programme, ‘City as Character’, aimed to highlight iconic cities in both mainstream and art house cinema.

butlergallery.ie

Munster Technological University

‘COLLECTED EXPRESSION: MTU Alumni in the Arts Council Collection’ ran from 15 September to 15 October. The exhibition was a multi-venue exhibition, showcasing selected artworks from the Arts Council Collection by national and international artists who are alumni of MTU Crawford College of Art & Design. It was presented by MTU Arts Office supported by the Arts Council Collection. The main exhibition took place at the James Barry Exhibition Centre, MTU Bishopstown Campus, in Cork.

arts.mtu.ie

Solas Art Centre

Two concurrent exhibitions ran from 5 September to 3 October at Solas Art Centre: Senga Sharkey’s ‘Somewhere Between Two Extremes’ and Sylvia Thirlway’s ‘Elemental Spaces’. Sharkey, a Fermanagh-based artist, explores a delicate artistic balance between the abstract and the familiar, with her latest exhibition emphasising the power of storytelling. Sylvia Thirlway’s exhibition is inspired by the state of the planet, and the ways in which many societies have forgotten how to value the natural world and all its wonders.

solasart.ie

Clifden Arts Festival

Clifden Arts Festival is Ireland’s longest-running community arts festival. What began in 1977 as a small school-based event has grown into an 11-day celebration of creativity that transforms the town each September. At its core, Clifden Arts Festival remains deeply rooted in community. The people of Clifden and the wider region are not only the audience but active participants. The festival ran from 17 to 28 September, delivering an extensive programme of exhibitions, workshops, and events.

clifdenartsfestival.ie

Lavit Gallery

‘A kind of dark’ by Ciara Roche and Daniel Coleman was on display from 2 to 25 October at Lavit Gallery. Roche’s paintings are all about the places we like to imagine ourselves living, and places in which we wish to be seen, all relating to things we assign value to, such as glamourous homes, gardens, fancy cars, high-end hotels, restaurants and bars. Daniel Coleman explores the impermanence of life and the significance of the everyday. His work is steeped in symbolism and meaning, in relation to his rural Irish upbringing. lavitgallery.com

The Model ‘Inheritance’ runs from 11 October to 31 December. The group exhibition features artists: Marcus Coates, Miriam de Búrca, Susan Hiller, Anna Maria Maiolino, Kathy Prendergast, Cornelia Parker, and Selvagem – Cycle of Studies. In the mid-2020s, we live in the aftermath of a pandemic, widening social polarisation, the threat of climate collapse, and geopolitical instability. The exhibition brings together a constellation of artworks that confront the legacies that shape our present moment, and ask how we can create a better future for humanity. themodel.ie

Grilse Gallery

‘In Search of Presence’ by Dorota Borowa, ran from 19 September to 12 October. Rather than depicting nature, Borowa sought to collaborate with it, exploring her relationship with the natural world. The process is central to her inquiry, seen as lessons in humility, openness, attentiveness, mindfulness, patience, determination, and forgiveness. Dorota works with water as an active collaborator in the creation of an image. Mixing it with oil paint, watercolour, or ink, she allows the materials to interact organically on paper or board.

grilse.ie

Palazzo Provana di Collegno

Thomas Brezing’s exhibition in Turin, ‘I Think I Made You Up Inside My Head’, confronted the viewer with a meditation on the fragile architecture of identity and memory. The architecture of the palazzo, a space where history, education, and ideology converge, becomes the ideal stage for an inquiry into the human face as both mask and mirror, portrait and vanitas. The building’s dual legacy as a theatre of power and education echoes the artist’s own inquiry into how the human face becomes a vessel for change, reflection, and impermanence. museoschneiberg.org

Wexford Arts Centre

‘Siren’ by Ursula Burke is an expansive exhibition that incorporates ceramic sculpture, textile sculpture, tapestry and mosaic sculpture. Greco-Roman inspired, surrealist mosaic sculptures take centre stage, framed by major new monumental tapestry work. Having lived for over 20 years in post-conflict Belfast, during and after the peace process, Burke has developed a unique continuum of exploration between political and aesthetic inquiries into trauma, wounding and repair in her practice. Continues at until 6 December. wexfordartscentre.ie

Island Arts Centre

‘Common Threads’ is the second edition of the Northern Ireland Linen Biennale’s headline exhibition, where flax and linen serve as the common thread, across a range of art practices. Curated by artist and creative producer Meadhbh McIlgorm, the exhibition ran from 21 August to 13 September, celebrating the slow, considered, and skilful labour of artist-makers. This year, an undercurrent of weaving ran through much of the presented works, highlighting interdependence over fragmentation: as in a weave, no thread stands alone.

linenbiennalenorthernireland.com

Rubin Foundation NYC

‘Romance, Regret, and Regeneration in Landscape’, a group exhibition, ranging from the poetic to the political, is on display until 9 December at the Rubin Foundation in NYC. The featured artists – Francis Alÿs, Joseph Beuys, Boyle Family, Chagos Research Initiative, Anya Gallaccio, Michele Horrigan, Sanam Khatibi, Ishmael Marika, Megs Morley and Tom Flanagan, Richard Mosse, Winfred Rembert, Alexis Rockman, Clement Siatous, and Yang Yongliang – engage with the environment through a range of approaches. the8thfloor.org

Wexford County Council

‘Sidelong Glances: An Oblique Look at the Sea’ is a group exhibition, curated by Catherine Bowe, which runs from 13 October to 21 November. The exhibition features work from IMMA’s National Collection and invited Irish and international artists. It draws inspiration from a poem, written by Marianne Moore in 1921, titled The Grave, which stems from Moore’s personal experience of observing the sea with her mother. The exhibition extends Moore’s examination of the sea as a powerful, indifferent force – a place of both beauty and death.

wexfordcoco.ie

CORNELIUS BROWNE RECALLS THE MYSTERY AND LORE OF ATLANTIS HOUSE IN BURTONPORT, COUNTY DONEGAL.

IN THE LATE seventies, sometime around the death of Elvis Presley, my parents bought a bottle-green car that they managed to keep on the road until sometime around the shooting of John Lennon. Unspooling along the routes of Donegal brought a hitherto unknown and short-lived freedom, for never again would we own a car. A short run, made often, carried us to a weathered mobile home that housed a family of eight on Burtonport Pier. Through the cacophony of children, I zeroed in on my cousin and her fisherman husband, whenever they mentioned The Screamers.

Drives to ‘The Port’ in those days meant navigating a hallucinatory interlude. Vehicles slowed passing the Georgian mansion. Necks craned. Nose pressing against chilly glass, my gaze gobbled baffling symbols. Above the gaily-coloured doorway, large letters spelled ATLANTIS. My eyes climbed to the second-storey windows to meet the stare for which this house was infamous. The pair of enormous red eyes watched, unblinkingly, the dogged tides and mortals clinging to these penurious shores.

During one visit, I left behind the caravan chatter and pelted up the hill from the pier with my sketchbook. An overnight snowfall had left the ground patchy white. Christmas trees twinkled in windows. Upon reaching Atlantis House, already fumbling a pencil out of my gaberdine pocket, I froze at the sight of a Screamer perched atop a long ladder. Balancing a paint tin, she was adding another zodiac sign to her constellation.

The Beatles sang from an eye, painted around an open window. Just as I was about to turn and flee, the muralist peeked over her shoulder and raised her paintbrush in greeting. She went back to painting, and I began drawing. Might this have been Jenny James, founder of the Atlantis Primal Therapy Commune? As my icy fingers conjured onto paper the house and its matriarch, the squall of all I knew of the cult blew through my brain: kidnappings, violence, and the padded room where the 30 inhabitants thrashed and screamed to exorcise inner

demons. Fresh snowflakes beginning to fall, I titled my drawing in scrawly pencil, piering eyes. Whether this was a misspelling of ‘peering’ or ‘piercing’, or wordplay, the pier being so near, I can no longer recall.

During the first summer of the nineties, my girlfriend and I fell into wintry homelessness. Both art students, about to embark on our final year, that autumn we failed to return to college, instead seeking refuge under my parents’ roof. By November, my childhood home finally became uninhabitable. The old slates were letting in so much rain that the electricity company cut our supply. Christmas was celebrated in darkness. In the New Year, my parents and younger siblings moved into a caravan. Paula and I settled into a rat-infested outbuilding in Burtonport, within the grounds of a once-grand house filled with echoes of its illustrious past. Many mornings, we roved the pier with our easels, sometimes painting side by side within sight of Atlantis House. The Screamers had long since sailed to Colombia, their tale ending amid blood and beheadings.

Rechristened St. Bride’s and transformed into a boarding school for adult women, where canings were commonplace, the house now belonged to the Silver Sisterhood. In their full-length dresses, shawls, and bonnets, the maids, as they termed themselves, were a familiar sight in town throughout my teenage years. Recreating a Victorian household, these women lived without electricity by choice, their evenings bathed in the glow of oil lamps and candles, as they listened to records on a windup gramophone.

Painting Atlantis House today, the jigsaw of its history is more complete. Jack the Ripper stalked the imaginations of the maids, leading them to design the first ever ‘18’ certificate video game. The murals of Jenny James lie buried under hefty layers of paint, yet her ‘piering’ eyes have never fully closed.

Cornelius Browne is a Donegal-based artist.

JOHN DALY GIVES DETAILS OF DUBLIN GALLERY WEEKEND 2025, TAKING PLACE ACROSS THE CITY FROM 6 TO 9 NOVEMBER.

DUBLIN GALLERY WEEKEND (DGW) was started by Ireland’s Contemporary Art Gallery Association (CAGA) a few years ago with a mission to support visual artists, expand audiences, deepen public engagement, foster a culture of collecting, and elevate the profile of contemporary art in Ireland. CAGA’s core belief is around the primacy of the artist; when artists thrive, so does the entire arts ecosystem.

So, in many ways, DGW is more than just a visual arts festival; it’s a catalyst for a stronger, more vibrant art scene in Ireland. This year’s DGW takes place from Thursday 6 November to Sunday 9 November and is set to be our largest showcase yet. There are over 60 free events, offering opportunities to experience the ambition, quality and creative energy of Irish contemporary art.

More than 40 galleries, cultural institutions, creative spaces, and artist studios across Dublin will present brand new exhibitions, featuring work from over 100 of Ireland’s most exciting contemporary artists. From painting to sculpture, installation to performance, digital art to street art, the programme spans the full spectrum of artistic practice.

For the first time, Dublin’s leading contemporary galleries will join forces with the major public institutions – including the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Douglas Hyde Gallery, and National Gallery of Ireland – in a city-wide programme of exhibition launches, live demonstrations, film screenings, concerts, artist talks, panel discussions, tours, studio visits, workshops for children and families, and much more. There are also studio tours and gallery brunches, curated art trails, and late-night socials, talks, workshops and neighbourhood art events.

The weekend kicks off with an opening reception in the Grand Hall at IMMA, bringing together artists, collectors, supporters, sponsors, and key stakeholders for an evening of artistic celebration and exchange. Within the public institutions, I am thrilled that Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña will present her first exhibition in Ireland, ‘Reverse Migration, a Poetic Journey’ at IMMA, while Dublin-based

Japanese artist Atsushi Kaga will have a much-anticipated show at the Douglas Hyde Gallery.

The National Gallery of Ireland presents ‘Pablo Picasso: From the Studio’, an exhibition that includes paintings, sculptures, ceramics, and works on paper, as well as photographic and audiovisual works –sure to be a cultural highlight of the year. Sinéad Ní Mhaonaigh exhibits a new series of paintings entitled ‘Snáithe’ at The LAB Gallery, while at Temple Bar Gallery + Studios, Frank Sweeney’s film, Go Ye Afar (2025), follows an Irish-Nigerian taxi driver on a miraculous voyage through the streets of Dublin and Calabar.

Ahead of her representation of Ireland at the 61st Venice Biennale next year, Isabel Nolan’s ‘Look at the Harlequins!’ at Kerlin Gallery offers insights into the artist’s practice across a range of media. ‘Patrick Graham: Gilboa Iris’ at Hillsboro Fine Art sees the artist, now in his 80s, making his strongest work ever. Sculptor Corban Walker is at the Solomon Gallery, David Eager Maher’s hyper-detailed landscapes, rendered in vibrant colour, are on show at Oliver Sears Gallery, and there are very interesting group exhibitions at both the Taylor Galleries and at Olivier Cornet.

At the Guinness Storehouse, ‘Rising Conversations: These Walls’ brings together artists Hazel O’Sullivan and Niall de Buitléar to revisit a pivotal chapter in Irish art history: the ROSC exhibitions of 1984 and 1988, which introduced contemporary Irish and international art to Dublin, while platforming the industrial architecture of the former hop store as a site for cultural exchange.

Many renowned contemporary curators and members of the international art press will be attending this year’s event, so hopefully their presence and engagement will help to shine a global spotlight on Dublin as a leading cultural capital on the European stage. Programme details can be found at: dublingalleryweekend.ie

John Daly is Director of Hillsboro Fine Art and Chair of the Contemporary Art Gallery Association (CAGA). hillsborofineart.com

LIAN BELL OUTLINES THE IMPORTANCE OF WALKING AS CREATIVE PRACTICE AND A REFUSAL OF PRODUCTIVITY.

White supremacist, capitalist, (post-)colonial, ableist, patriarchy*

WALKING WITH THESE women, together and apart, has given me a way to think about what walking means for me as a part of a creative practice. Walking as art itself. That’s a frustrating, slippery, and liberating thought. It’s that slippiness that draws me back, and that is where I think the art is. If it were just frustrating or just liberating, I don’t think I would call it art.

The structure for this project was created in the doing. We decided to meet. We decided to walk together. We took it from there. There was a great deal of not knowing. We refused to be rushed.

There is a great deal of NO in our walking. There is a great deal of refusal. We are refusing productivity, busy-ness, the guilt-making pull of what work should look like. We are refusing to be certain and we are refusing to be overwhelmed by uncertainty. We let the walking itself, the being together while walking, guide us, rather than structuring something from the outset. In January, as we walk together almost each week, my father emails me to tell me about the term ‘negative capability’, used by the poet John Keats in 1817. Wikipedia says it is “the capacity of artists to pursue ideals of beauty, perfection and sublimity even when it leads them into intellectual confusion and uncertainty... the ability to perceive and recognise truths beyond the reach of what Keats called ‘consecutive reasoning’.” I add my definitions: the capacity to refuse the rational and still function. The capacity to do something that seems non-sensical, but through the doing of it, grows a sense. We are refusing to forget the layers some of us can see under what a landscape looks like now. We are sharing our knowledge of these layers. We are talking about the village that died when the peat industry stopped, as well as talking about the sculptures in the rewilded bog around us. We are talking about the trees that are missing from the beautiful bare hills and the flats that are missing from the beautiful city fields. We are talking about the urban infrastructure hidden under the grassy skin of those fields and the homes that were once in those patches of sky. We are talking about what used to be in place of the student accommodation, how the roads used to run in our childhood. We are talking about how our dead aunt’s belongings passed through this particular charity shop. We are talking about the places where the fairies cross over into our world, and the places where we touch theirs. We are talking about the light that will be lost when the next hotels are built. We are talking about poor people on rich land, and rich people on our land. We don’t talk about it much, but we wear green, black and red badges that feel heavier than they are.

There is also a great deal of kindness. The walking is not always easy. Our bodies are changing and getting older. One body gives birth to another during our time together. One body loses the body that gave birth to it. We are worrying about others, and we are taking care of them. We are overworked, or underworked. We drink tea and coffee and eat together, we seem to drift in our conversations, we laugh. In the context of Art Made By Walking, this is all the work that doesn’t look like work.

I use my Art Made By Walking time to develop a personal practice called Municipal Walker that is something about walking with intent for the good of the city. Or is something about civic responsibility at times of overwhelm. The conversations we have as a group help clarify my thinking about the practice, so that I am able to talk about it in the world, although it’s still slippery, and frustrating, and liberating.

I remember the term ‘mitching’, and because I am pleased with it as a small regular act of refusal, on a walk in Birr we talk about it, and I begin to use it more in my own work. I begin to invite others to mitch. I invite you to mitch. Remember these words of refusal and kindness in the coming days. Step away from something, even at a point where you don’t think it’s possible. Tell no one. Go outside. Start to walk.

* with gratitude to bell hooks

This text was read aloud on 22 April at the opening of an exhibition in Axis Ballymun; the culmination of a long and slow research process called Art Made By Walking. Four artists, who use walking in different ways in their practice, were commissioned by Axis to take part. Maeve Stone (project instigator, in her capacity as lead artist for the Green Arts Department at Axis), Shanna May Breen, Veronica Dyas, and I were joined by creative producer Niamh Ní Chonchubhair. We walked together in Dublin, Offaly, and Clare. To mark the end of a year and a half of walking (and talking about walking), the group collectively assembled an exhibit – a kind of loose scrapbook of ideas and experiences that had emerged – traces of which are now available on my website.

Lian Bell is an artist and arts worker based in Dublin. lianbell.com

ALEX CREGAN DISCUSSES A RECENT DISABILITY JUSTICE WORKSHOP IN OCTOBER AT VOID ART CENTRE IN DERRY.

DREAMING DISABILITY FUTURES was a workshop I ran on Saturday 4 October at Void Art Centre in Derry as part of Bounce Arts Festival 2025. The workshop ran for four hours, with a one-hour break. It is based on the book, Care Work (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018) by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha – a collection of essays, lists, and personal notes around the topic of disability justice and collective care.

The book highlights disability justice as a model coined by QTBIPOC activists and artists in the face of an ever-growing disability rights movement that did not represent them.1 They pushed for a more radical model that foregrounded the most marginalised, taking an intersectional, non-curative approach, and borrowing from the social model of disability.

The workshop had two distinct parts, the first being a discussion around concepts explored in the book – most notably care webs, disability justice, care as a form of work, and what to do if the medical system of care lets us down. The second part was a free-writing and creating session, based on these discussions. While free-writing was my original plan, I didn’t want to restrict the creative output of participants, so I provided space for sound-making, mark-making, and visual art.

The motivation behind this workshop was simple: the growing inequality for d/ Deaf, disabled, and neurodivergent people, not only on the island of Ireland, but beyond. Examples of inequality in the UK include proposed reform of the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) and removal of the Limited Capability for Work-Related Activity (LCWRA) group from state benefits, as well as the increasing privatisation of the NHS. Many disabled people are facing insurmountable questions: What do we do when all our resources are stripped from us? Who do we turn to when the government won’t protect us?

It was these questions that I found addressed by Care Work, and it was these questions I wanted to discuss. They are not easily answered. However, the talks that unfolded, as well as the creation that happened, was a beautiful jumping-off point.

The attendees of the workshop were a diverse group: all were of marginalised genders (transgender people and cis women); most of us were queer; all of us were neurodivergent and/or had invisible disabilities; and all of us had had greatly different experiences with care and our own disabilities. These differences and marginalisations greatly influenced our conversations.

Immediately, when introducing ourselves, the elephant in the room became clear: most, if not all, of us had experienced or witnessed harm within the mainstream care model and were desperately seeking an alternative.

Most of us are afraid of our autonomy

being called into question, or of having care forced upon us, in the form of institutionalisation, especially given the harm we had observed or experienced in the past. For a variety of reasons, many of us feel the spectre of autonomy loss hanging over us, whether due to aging (leading to presumed incompetence), worsening mental health (in the face of worsening living conditions), or a variety of other factors.

Most of us want care, but want it on our own terms, at our own pace, in our own capacities. We don’t want to be forced into a one-size-fits-all model that the medical model of care often adopts – one that may not understand our specific quirks, identities, needs, wants, or desires.

Care webs were explored as an alternative to, or accompaniment to, the medical or government-issued healthcare model. Care webs are formed when a collective of people get together and support a disabled person. Often (but not always), these webs are reciprocal to some degree, with care being passed back and forth along the strands. Different people have different capacities, and a perfectly divided 50/50, in giving and receiving, simply isn’t possible for a lot of people. More often, things are fluid. We discussed communication within these webs, boundary setting, and knowing our own abilities.

Some of us, no matter the time, place or desire, would never be able to provide some kinds of physical care, such as lifting someone out of their wheelchair. Some care is messy, vulnerable, even scary, and above all, care webs rely on the community around you to show up.

Further questions emerged: What does a person do if they fall out with their care web? What does a person do if they feel ostracised from their community? How does a person build a care web from scratch? What if you, genuinely, have no one who can support you?

These situations aren’t easily resolved or magically fixed; however, movement has begun in our own lives and practices to dream and create something better than a system that harms us. The connections made between disabled people of different backgrounds, showing solidarity and care to one another, felt like something necessary in the face of hopelessness. This workshop felt more like the beginning of something than a one-off. It feels as though these dreams will grow beyond the confines of the workshop, for its participants and beyond.

Alex Cregan is a writer, poet, and creative facilitator from Derry.

@flo.raldisaster

1 Queer, Trans, Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (QTBIPOC) communities advocate for disabled people who experience intersectional forms of marginalisation. See, for example: Care Work pp 20–21.

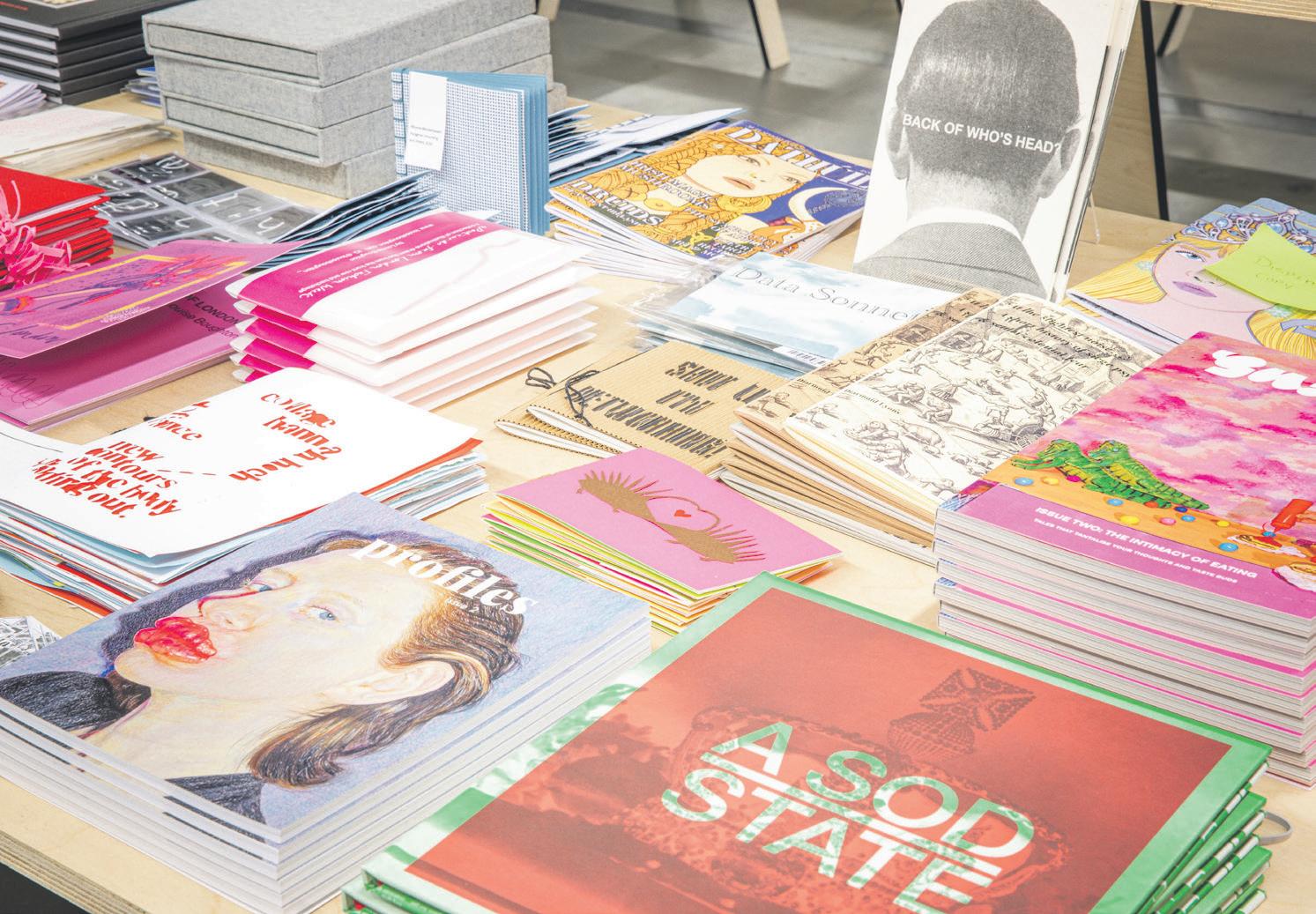

GUEST CURATOR DR SELINA GUINNESS OUTLINES PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS FOR DUBLIN ART BOOK FAIR IN DECEMBER.

EACH YEAR, DUBLIN Art Book Fair (DABF) is produced by Temple Bar Gallery + Studios and presents a wide range of unique artist books and titles from creative, small, and independent publishers alongside an events programme of talks, tours, workshops and book launches. As part of the wider DABF programme, a Guest Curator is invited to create their own programme of events and selection of titles under a chosen theme.

As DABF 2025 Guest Curator, my theme ‘Flock’ examines all thing pastoral. This includes topics such as humans and beasts as herding creatures; the relational arts of shepherding; the impact of flocks on habitats, and how wary scapegoats, too, may flock together to combat predation. Two decades of farming sheep in the Dublin Mountains while teaching at IADT have focused my mind on the kinds of habitat required to sustain different flocks – when one ewe fails to thrive, the whole flock needs to move onto better pasture.

In September, my first event for DABF was a successful preview at Philip Maguire’s farm on Newtown Hill, Glencullen. This farm walk and herding demonstration introduced a small group to the farming community who work to make a living from grazing animals in full view of the city. Returning to TBG+S, the remaining events I have curated for the DABF 2025 programme aim to provide a creative commons, where human flocks can meet, graze and find sustenance in mutual regard and a shared commitment to collective welfare.

DABF 2025 launches on Thursday 4 December in TBG+S main gallery with a Guest Curator’s Talk to discuss ten titles chosen to expand on this theme, with the opening reception to follow.

On Friday 5 December is Cowboys & Shepherds, Fieldwork & Studio, a curatorial panel discussion with acclaimed artists and farmers, Miriam O’Connor and Orla Barry, about what counts as work in art and agriculture, co-moderated with Adam Stead (SETU). When wool is worthless, and farming beef-cattle barely viable, how do we value pastoral lives? What does it mean to breed, feed and mind the sheep and cows we send to slaughter? We will focus on the work of raising flocks and explore the lives of shepherds and cowherds as disruptive pinch-points in late-stage capitalism, as they tend to people, place, produce and practice in the contested rural environment.

On Friday 12 December, the second of my curatorial panel talks, Of Human Flocks & Other Species, sees acclaimed artist, Isabel Nolan, and two exceptional writers, Darran Anderson and Cathy Sweeney, discuss the complexities of their relations with particular flocks, human and non-human. How do other species instruct us in what counts as work and care? The conversation will explore the ambivalence of artists and

writers as shepherds and sheep in negotiating real and creative habitats, drawing on Nolan’s dynamic practice, and two literary works sparked by a compulsive desire for perspective: Darran Anderson’s Derry memoir, Inventory (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2020), and Cathy Sweeney’s debut novel, Breakdown (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2024). We will take a hard look at flock dynamics, and the new habitats formed by strays, scapegoats and outcasts, while questioning how artists fare when penned up individually.

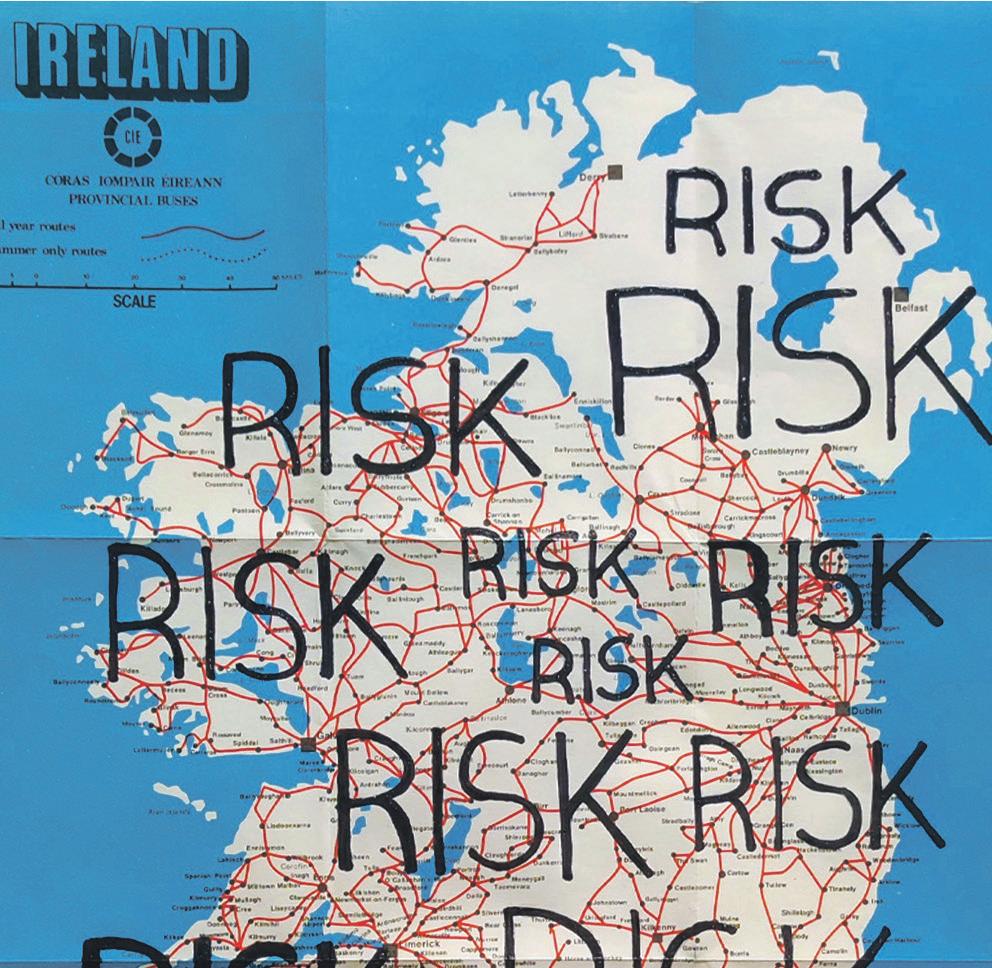

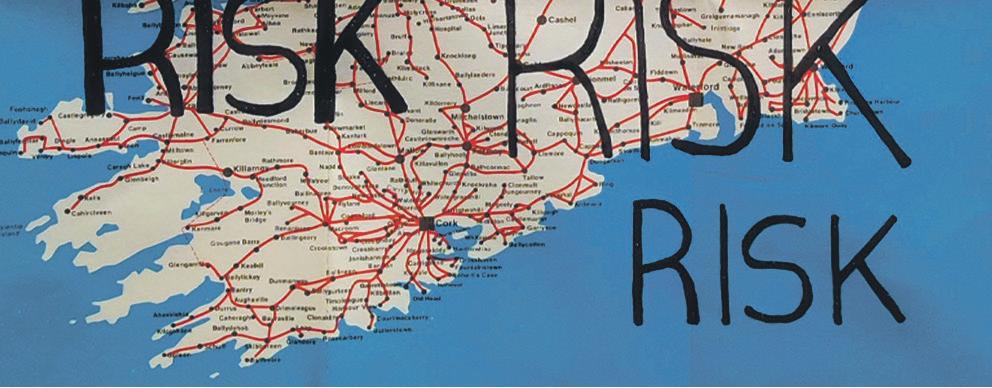

A highlight of DABF 2025 is a new Publisher’s Series made possible through a partnership with the Culture Office of the Creative Europe Desk (Ireland). For this, we are inviting acclaimed Palestinian author, Adania Shibli, and her Fitzcarraldo Editions publisher, Tamara Sampey-Jawad, to discuss her astonishing novel, Minor Detail (2017). A Palestinian woman sets out to locate the site of a war crime committed in 1948, only to find the familiar maps to be of no use in navigating disputed territories. Minor Detail vividly enacts the experience of military surveillance, violent dispossession, and land confiscation suffered under occupation.

This special event on Saturday 6 December will reflect on the work of Fitzcarraldo Editions, a staple at the Dublin Art Book Fair, and the vital importance of literary translation in protecting our intellectual commons against aggressive polarisation. In addition to Minor Detail, and in keeping with the DABF theme ‘Flock’, our honoured guest, Adania Shibli, will present selected works by Palestinian artists who have continued to create, and counter subjection, while living under colonial and genocidal conditions.

Full details of DABF 2025 (4 – 14 December), including the events I have curated and mentioned above, are available on the TBG+S website. DABF 2025 is proudly sponsored by Henry J Lyons and supported by Dublin UNESCO City of Literature.

Dr Selina Guinness is Guest Curator of Dublin Art Book Fair 2025. She is also Head of Teaching and Learning at IADT, where she works to promote transdisciplinary pedagogies across IADT’s provision. iadt.ie/about/staff/dr-selina-guinness

STEPHEN BEGGS OUTLINES THE ACTIVITIES OF GREEN ARTS NI –

IN SEPTEMBER THIS year, Green Arts NI was delighted to attend VAI’s Get Together in TU Dublin. For the first time, we were able to engage widely with artists from the Republic of Ireland and discuss the challenges of making sustainable work in a world where climate change and the ecological crisis are all around us. What we found so encouraging was the level of positivity at the event. In the face of a highly uncertain future, artists continue to present solutions – sounding alarms whilst celebrating the wonder in everyday life. We continue to welcome new members from across the island of Ireland.

Green Arts NI is a sustainability network, supported by Belfast City Council, covering all art forms. We have over 100 members across more than 50 organisations, ranging from freelance artists of many disciplines to venues, festivals, umbrella bodies, and production companies. We work collectively to reduce our environmental impact across Northern Ireland and use creativity to inspire our communities in relation to climate action. We have found that this collaborative approach across artforms and member types has enabled us all to work more effectively within small budgets and limited capacities, in terms of time and personnel.

To this end, our website was designed to be useful as well as informative. It features case studies on our members’ green projects; resources that can be used by individual creatives and companies of any size to make their practices more sustainable; and a section for signing up to be part of our growing community (greenartsni.org). Membership is free and is accessible to all. We also hold regular members meetings in Belfast and online, where everyone can come together, share the latest news, ask others for support, and plan for the various events in which we take part throughout the year.

In June, Green Arts NI members curated an event as part of the Summer Solstice celebrations at Brink! This amazing organi-

sation brings people together from all walks of life to think, play, discuss, and take action on climate-related issues. Our members delivered workshops, talks, an art exhibition, and film screenings. In previous years, we have also contributed to the Climate Craic festival in Belfast, and the next few months will see us presenting at IETM’s Focus Event in Bradford and Wild Belfast’s National Park City gathering.

In October, Green Arts NI launched its second round of ‘Good Green Ideas’. This micro-bursary scheme allows members, either individually or in collaboration, to try out an idea that they might not be in a position to explore otherwise. Once the proposals have been submitted, our members vote on which ones should go forward. Happily, last year we were able to make all three proposals happen. Ideas could include a study trip or exchange to improve knowledge that can then be applied or shared, supporting a community microproject, or buying items that can be shared by members to help everyone’s work. In the previous round, The Oh Yeah Music Centre established a bee colony on their roof in Belfast City Centre – a refuge and resource for pollinator insects. They installed two bee hives on the roof along with a range of planters filled with year-round flowering plants. Tinderbox Theatre Company delivered a project called ‘The Sustainable Storyteller’ in partnership with Professor John Barry of Queen’s University and supported by the university’s Centre for Sustainability, Equality, and Climate Action.

Maybe it’s because of its relatively small size, but the arts community in Northern Ireland is well connected, especially when it comes to combating environmental challenges. Green Arts NI epitomises this supportive artistic collaboration, in our collective action for a greener future. Join us!

Stephen Beggs is Co-Chair of Green Arts NI. greenartsni.org

NIAMH O’MALLEY, CURATOR OF THE RDS VISUAL ART AWARDS 2025, DISCUSSES THIS YEAR’S EXHIBITION AT THE RHA.

IT’S A COMPLICATED thing, the idea of selecting some of the ‘best’, when it comes to the vast number of excellent art graduates we have on our island every year. I have the privilege of being the 2025 curator of the RDS Visual Art Awards, opening in the RHA Gallery on 21 November. I’m hopeful that exhibitions like this can demonstrate the diversity and quality of practice being produced and allow us to consider how these new and innovative voices are speaking – and why.

A large, committed panel of curators and artists arrived at a shortlist this year that includes artists like Charlie Yris, who has used a process of photographic and video documentation to both compile and reimagine a list of derelict buildings in Limerick. In their work, these buildings shift in our consciousness by the simple placement of phrase on a ceramic plaque – an ode to home or its possibility. Their activism confronts vacancy and produces a poetic protest in a way that generates future thinking and vision.

The building blocks of materials that make a life, a home, a space – the functional and the aspirational – are also evident in the work of Vicky Ochala, who presents a fullscale steel frame of a room in her childhood home, where her grandparents still live. Her work considers post-communist Polish architecture but also smell and décor, furniture and floorplans. Her video, Come, let me tell you something (2025), blends archival footage of communist media propaganda with her own recordings.

Clara McSweeney allows the architecture itself to speak in her work, Now Listen Closely, Fellow Humans (2024), as she responds to the peculiarities of three vacant buildings in Dublin city centre. Monologues spoken by actors are played through speakers in a drainpipe, air vent and intercom. We are invited to eavesdrop on these recordings, which the artist describes as ‘confessions’, in which the buildings themselves are voicing their deepest fears, anxieties and confusions.

The sense that material realities support and distort our lives, as well as ‘speak’ in their own particular way, is also present in the work of Éile Medb Ní Fhiaich. In her sculptural assemblages, combinations of found and made forms, such as industrial plastic, metal and foam, connect and entangle with each other via handmade interventions of silicone, ceramic and stuffed fabric. Her works consider material adaptation, support and transformation as they elongate, hold, and rely on each other.

Lily Mannion’s delicate composition, Maybe if I sit and watch the sun fully set (2025), uses resin, steel, hair and skin cells, as part of her material and linguistic inquiry. This work is vulnerable in its fears, concerns and overwhelm. It positions its very physical compositions, which also include

ceramic, felt and steel, as a new kind of script – maybe even a spell – to reconnect and touch past and future.

The subject of touch is equally present in the work of Anastassia Varabiova as they reflect on the absurdity and odd behaviours of a screen-based lifestyle. Blending dread and humour, their iPhone installation, Try Normal Life Maxxing (2025), combines spirituality and wellness content with marketing footage from sex doll factories and snippets of the artist’s performance. This physically small yet potent video, played on a caged phone, questions the role of the algorithm in the construction of reality.

In a deliberate negation of the problematics of the digital, Charlie Dineen’s film, The City Beneath Me (2025), casts his analogue camera on the landscape of Kerry, examining ritual, ancestral memory and mythology. This stark and overt nod to our landscape and heritage summons an empathy of touch, rhythm, and reignites a relationship with the physical and divine land.

In a strikingly different but equally beautiful setting, Thais Muniz’s two-channel work, The Kite Ballet (2024), shows people flying kites in a semi-barren, white, sandy landscape with blue skies. Contested land and environmental issues are spoken directly to and with the wind. Thais presents this joyful activity, producing curiosity, community and solidarity by considering ‘play as a revolutionary act’. Alongside Charlie Dineen, she also harnesses indigenous knowledge systems, identity, traditions and ritual, as well as land and climate.

Exploring the physicality of the sensing and evolving human body, Susanne Horsch maps, sews and produces outsize cloths of touch and labour. Swimming in Space (2025) draws from autobiography as well as feminist and queer theories to realise an immersive installation of enlarged bodily shapes, torsos, breasts, sperm and genitalia as fabric, stitch, dyeing and quilting.

Billie Adele O’Regan flies the flag for the alchemy of painting. Billie describes exaggerated and amorphous bodily forms that sit within histories of horror, sci-fi and the occult. Strange beauty – equally monstrous and compelling – is generated through the messy truth of paint and puddle, brush mark and stain.

These ten innovative artists speak to many issues of our time, from housing and ecology to the relationship of our weighty, complicated bodies in the physical world. Come and see the work – it will do the speaking.

Niamh O’Malley is an artist based in Dublin. niamhomalley.com

The RDS Visual Art Awards 2025 exhibition runs at the RHA Gallery from 21 November 2025 to 25 January 2026. rds.ie

Aengus Woods: Tell me about your background and how you came into the world of visual arts.

AENGUS WOODS INTERVIEWS JOHN DALY ABOUT THE THIRTY-YEAR EVOLUTION OF HILLSBORO FINE ART.

John Daly: I’m from Dublin – my family have lived in the same house since 1882, and I have collected art since I was about 15. Most kids were trying to buy motorbikes, but my parents wouldn’t let me, so I bought a rare print at auction in Christie’s. That was the first artwork; it was by Victor Pasmore, an English artist. I don’t know what possessed me. We had no art in the house, and my parents had no interest really. I am very academic and if I like something, I aim to read every book by that person, and I do the same with art. I first learned about modern British art and that became my collecting focus. I read all about the artists, and their lives were fascinating.

AW: How did Hillsboro Fine Art get started?

JD: Well, Hillsboro is actually the name of my house. It’s a big old house and I would use the downstairs for exhibitions. I’d open on a Friday evening and weekends for a month or two, before changing shows around. I did the first solo show in my house with Terry Frost. We would meet people in London in the Arts Club and places, and he’d say, “Oh, do you not know John? You know, he’s got the best gallery in Ireland!” He was so supportive. And all of these guys, like Howard Hodgkin, because they’re so polite, they would say, “Oh, yes, that’s right, I remember him now!” And so, they all gave me their work, but I was showing it in my house! I first moved the gallery to Anne’s Lane, then later to Parnell Square, and kept up the relationships with those important international artists. Once you get the trust of one artist, particularly if they are already well-connected, then that trust spreads.

AW: Which gallery shows have stood out in your memory over the years?

JD: When I started, a lot of the big artists, like Basil Blackshaw, Patrick Graham and Gwen O’Dowd, were already showing with other galleries. I knew a lot about postwar British art and so I approached Terry Frost first and he introduced me to Anthony Caro. I asked him to do a show, and then also John Hoyland. The art world at that level is a small one. The major international sculptors and painters all know each other. So, if they saw your enthusiasm and passion and knew it was financially okay to give you work, it would all be fine. At that stage, I began to attract artists from other galleries. John Noel Smith would have been one of the first. He had exhibited for years in another gallery, but he was living in Berlin at the time. There’s also Michael Warren. I had already collected quite a bit of his work before I even met him, but later he became one of my closest friends.

AW: Michael sadly passed away in July 2025. Tell me more about your history with him.

JD: We both had a very international outlook on art. He was unusual for his time, in that he studied in the Brera Academy in Milan. When Michael went there, he was hoping that Marino Marini would be his tutor, but unfortunately Marini left just the semester before. Nonetheless, Michael ended up with Luciano Minguzzi as his tutor. All this just told me that Micheal wanted to pitch himself against these people and not be confined to a small parochial environment. I appreciated that.

AW: How, then, do you understand the role of the gallery? Is there a distinction between nurturing younger artists and showing more established figures?

JD: The reason for first bringing in the more established artists was to let people know I was serious about what I was doing. It’s not necessarily a commercial thing. I mean, it has to somehow pay its way, but the word ‘commercial’ is a misnomer for most galleries in Ireland. It’s more about showing work that you believe in. When selecting younger or newer Irish artists, you’re picking them on the basis that they can sit comfortably beside the best of what is out there already. Artist Gerald Davis once advised me to only show work that I love, because I’ll probably end up with most of it! And that’s true, in the sense that I don’t show anything that I wouldn’t want myself.

AW: Are the collectors an important part of the equation?

JD: Oh, very much so. Most of them have become lifelong friends. We’d be in each other’s houses, and they would ask advice, not just about work from my gallery, but in other spaces or at auction. The main eight to ten galleries in Dublin are all serving the function of showing art that they believe in. Most of the galleries have a mix of Irish and work from elsewhere. But having the personalities of each of those people gives a different curatorial flavour to each gallery.

AW: What are your plans for the future of the gallery?

JD: Onwards and upwards! Some galleries have a group of 20 artists, and they just show them in rotation forever and that’s fine. But I like to inject a bit of something

into it to keep myself interested. So, I will always be looking for artists. In a way, the previous exhibition, Karl Weschke ‘Painting Order Out of Chaos’, is probably the most important one I’ve done. Weschke has become a bit forgotten about, but he was a friend of Bacon and Auerbach and there are eight of his paintings in the Tate. I usually try to show at least one big international name each year. And I collect things as well with the idea of putting together thematic shows. I did that with Cecil King. I gathered a body of his work over the years, and then during his retrospective in IMMA, I exhibited those pieces. Similarly, when IMMA had their Alex Katz exhibition, I did a show with him here. I went to his studio and then carried the entire show in a plastic bag through customs – those are the fun bits!

This is a crazy vocation. You don’t do it for the money, because you’d be disappointed. However, you end up meeting the most wonderful people. Every day is different. Even though one could say I am very tied to the gallery, it’s changing all the time; every month there’s a new exhibition. Every month for 30 years – that’s an awful lot of shows. The other thing that people don’t realise is that it’s quite tough physical work. I’m not getting any younger, so at some stage, I’m going to have to only show miniatures!

Aengus Woods is a writer and critic based in County Louth. @aengus_woods

John Daly is Director of Hillsboro Fine Art and current Chair of the Contemporary Art Gallery Association (CAGA). hillsborofineart.com

Clodagh Assata Boyce: TULCA Festival of Visual Arts 2025 is titled Strange lands still bear common ground. Can you explain why you chose this title?

CLODAGH ASSATA BOYCE INTERVIEWS BEULAH EZEUGO, CURATOR OF TULCA FESTIVAL OF VISUAL ARTS 2025.

Beulah Ezeugo: I chose this title because I enjoy a statement that can gather its own kind of energy. I also enjoy the trend of past editions of TULCA that lean into the poetic by using longer, slightly awkward titles. When a phrase is repeated enough, it can act like a shared refrain that shapes a shared language for that moment in time. This feels suitable for something as quick and celebratory as a festival.

The words in this title carry ideas that conjure very specific definitions that shift based on where you ask and who is speaking: the strange, the common, the land. When I am in Galway, the presence of the Atlantic feels significant. So, conceptualising the festival began with thoughts about Galway’s mercantile past, but also with the discourses taking place around migration now. Both of which make me wonder how arrival is felt on an island – a place that can feel protected by distance yet also vulnerable to outside forces. Earlier on, I came across an image of a medieval Burmese Map of the World. It depicts a teardrop-shaped island rising from the ocean, with smaller islands drifting below, detached from the mainland. Where the image shows up online it is captioned something along the lines of ‘The Himalayas are shown by a horizontal green line: above is the magical land of seven lakes and Mount Meru; below is where strangers come from.’ It suggested that to know the world is to expect strangeness, and that this encounter is not only inevitable but also vital. We meet the world through others, and in that sense, we are all strangers to someone else.

CAB: This exhibition sets out to chart new ways of relation. Can

you tell us a little bit about how this cartographical approach has shaped your curatorial and exhibition-building choices?

BE: Maps and borders hold a decisive place in contemporary art. For this exhibition, I was drawn to their paradoxes. Maps have long served as instruments of colonial power, but they can also act as anti-colonial tools, capable of encrypting, concealing, and revealing the limits of hegemonic knowledge.

In the curatorial process, I approached exhibition-making as a form of map-making: a search for pathways, a desire to document encounters, a projection of curiosity and intention across discrete spaces, and a pursuit of familiarity with the unknown alongside a willingness to be transformed by it. The exhibition follows this impulse, inviting audiences to navigate the worlds presented by the artists with openness and attentiveness.

The festival also borrows from cartographic methods to define its guiding themes. Much of the work begins from a specific historical or cultural vantagepoint and then from there, documents situated encounters with land, the sea, the creature, the stranger, and so on. So, re-orientation became a central theme and is understood as the act of unsettling assumed stances, turning again, and opening the possibility of encounter and contact.

CAB: How do you see the role of ‘the other’ and what is the role of art in shifting that?

BE: By evoking the idea of ‘the other’ I am evoking the ways of knowing and experiences that have been pushed aside or ignored by the dominant systems of power. The margin can also be an advantageous position. If every margin is someone else’s centre, then the task is to keep shifting our point of view toward the many centres that exist, noticing what becomes marginal from each new vantage point. Much of the work in the festival is a relational encounter with a powerful external presence, whether another person, another state, a non-human species, a mythical or spiritual figure. At times, the work itself shifts perspective from the margins, moving through overlooked or excluded positions to open new ways of seeing and being. Although art has the capacity to propose new considerations and ways of seeing, at the same time, it’s dif-

ficult to think of how exactly contemporary art makes significant shifts. I am aware that a festival, no matter how ambitious, cannot do that much. What it can do is create proximity and enable an artist or an audience into intimate relations with an idea, and then hopefully spark the impulse to act in a different way.

CAB: What can audiences expect from this year’s festival?

BE: The festival includes a performance, artist talks, various exhibitions in Galway and one in New York, a book, and several audio works shared online and broadcasted over radio. There are many films in the programme that move fluidly across different geographies, as well as cultural and historic points. I am particularly excited to share Kate Morrell’s film ...Y el barro se hizo eterno (...And the Mud Became Eternal) (2021), which explores ‘guaquería’, a type of political resistance that involves excavating the earth to loot archaeological treasures and indigenous cultural property.

I also look forward to the festival’s ephemerality. Many of the works are ongoing or exist as part of a larger continuum, so work in different states of completion will be able to converge and momentarily come into conversation with others. Marie Farrington’s Diagonal Acts (2025) appears here in its fourth, site-specific iteration, engaging with Galway’s Geology Museum and the knowledge embedded within it. There is also new work by Bojana Janković and Nessa Finnegan that brings together a living archive, related to crossing Ireland’s north-south border – a project that will continue to evolve during the festival and beyond.

CAB: Can you tell us about the accompanying publication?

BE: The publication extends the festival’s core questions around contact and proximity. It brings together several writers who explore the politics of place through poetry, prose, and experimental forms. Some of the writers involved in the festival also contribute to the publication, for example, the broader themes around Ireland’s revolutionary potential, presented in Caroline Mac Cathmhaoil’s film, Mirror States (2025), are extended through the publication in a more intimate register. Other contributors share writing that is rooted in research as well as personal experience, which

reflect on how lived histories and places intersect. The publication includes responses to a range of environments, with particular attention to architectural and natural landscapes.

CAB: To what extent does international collaboration play a critical role this year?

BE: Through the open call, the festival emphasised collaboration and cross-border exchange – not to showcase a particular kind of work, but to create conditions for a certain type of exchange. In much art-making, the focus is on the final outcome or exhibited work, so the life of thinking and making, including the negotiations and the frictions that led to it, often remains invisible. Artists who work collaboratively are especially compelling because of their ability to establish through shared systems that support this way of working. Considering global interconnectedness felt particularly important, in order to invite reflection on the kinds of relationships that sustain solidarity and those that do not.

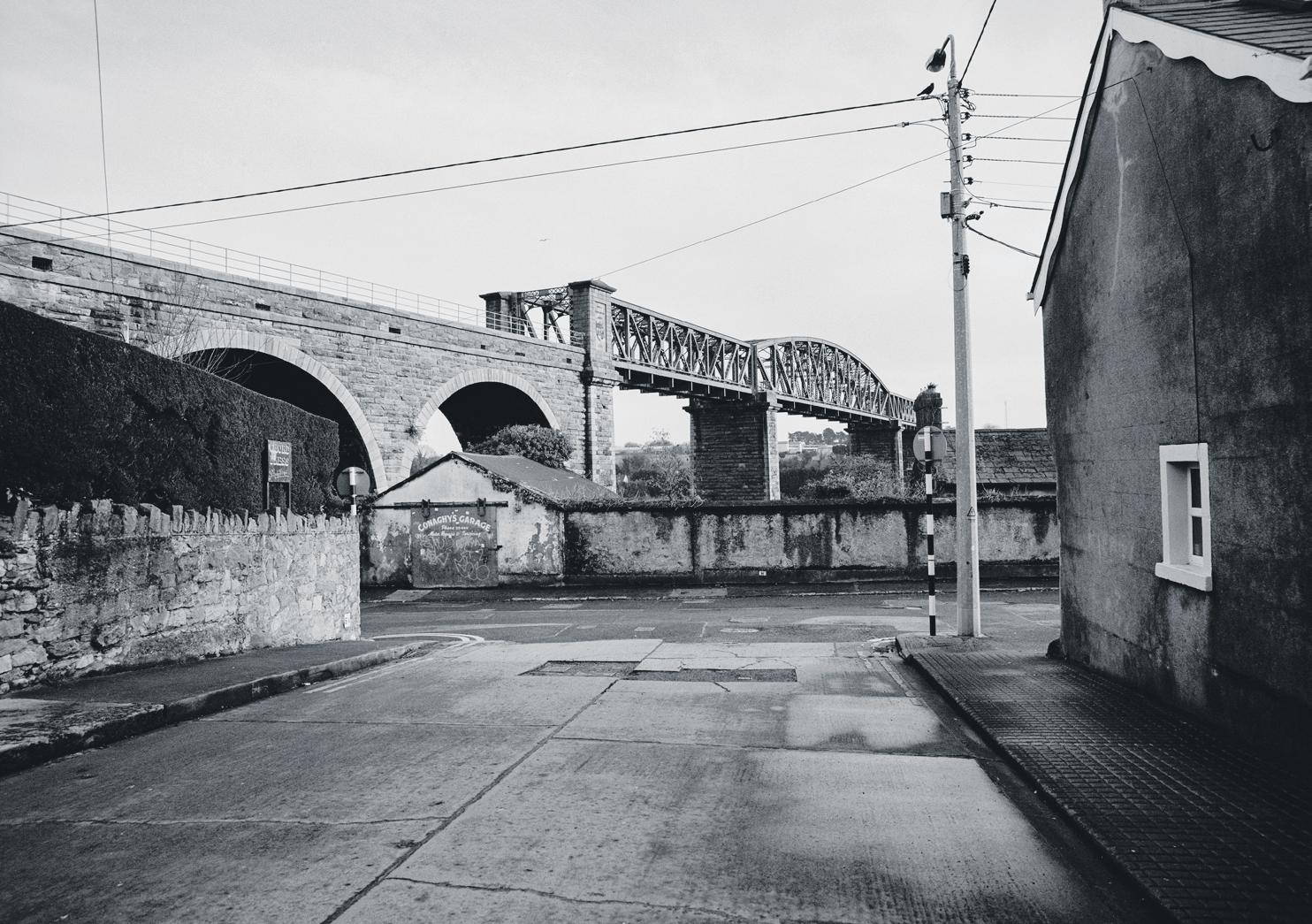

Some of the festival’s collaborative duos were already established, while others developed through the open call or expanded from individual practices. Mair Hughes, who has been exploring dual identity through excavations along the Welsh border, began with a solo project but invited collaborators Emily Joy and Durre Shahwar, who are now contributing artists in their own right. Peter Tresnan, a painter based in New York, has created a project which explores diasporic identity, drawing connections between Galway and New York. This has led to a secondary outpost of TULCA; an exhibition at 334 Broome Street in New York, organised by Peter, which will feature his work alongside contributions from other TULCA artists, and local artists working within similar themes.

Clodagh Assata Boyce is a Dublin-based independent curator and artist, who is influenced by the radical traditions of Black feminist thought. bio.site/Clodaghboyce

Beulah Ezeugo is curator of the 23rd edition of TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, which takes place across venues in Galway City from 7 to 23 November. tulca.ie

RACHEL MACMANUS REPORTS ON CONVERGENCE FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY LIVE ART IRELAND IN AUGUST.

CONVERGENCE FESTIVAL TOOK place in Milford House, North Tipperary, from 8 to 10 August. Since 2020, Live Art Ireland has carved out a hugely important role within the Irish performance art landscape, offering support, residential space, and opportunities to both international and Ireland-based artists. The mission of their biannual festival is to present the latest in live art practice alongside local and national musicians, complemented by workshops designed to foster creative exploration and cultural dialogue.

This year’s festival was curated by Deej Fabyc of Live Art Ireland and delivered in partnership with County Clare-based performance collective, p(art)y Here and Now, taking the theme, ‘A Borderless Romance’. Artists were selected through invitation and an international open call and were asked to consider borders and boundaries – of the body, of countries, of genders, of topography, or from an ecological perspective.

Arriving on Friday afternoon, in time for the opening processional performance by Monstera Deliciosa, I encountered the artist slowly moving through the wooded area behind Milford House, their long train of shiny fabric dragging behind them, reflecting the bright sunshine. This was a fitting launch for the weekend’s events. Mid-afternoon in the barn, there was a two-hour durational work by Sarajevo-born sound

and visual artist, Maja Zećo, who created a crackling, bubbling soundscape using their body attached to piano strings. This was an immersive, atmospheric, and highly constructed experience.

Next up was the first in a series of five performances from London-based artist, Katharine Meynell, whose witty, incisive works were interspersed over the three days of the festival. Shirani Bolle, a self-taught Limerick-based artist, then performed, Comfort Fruit (2025), a multi-layered work dealing with social media, apathy, and the modern paradox of caring from a distance. Rounding off Friday’s events was a performance talk by art historian and lecturer, Laura Leuzzi, offering an insightful exploration of the sonic, gendered body.

Saturday morning kicked off with Juliette Murphy, a multi-disciplinary artist based in Spain, who utilised giant dice and poetry for her outdoor performance. Dublin-based multimedia artist Fergus Byrne performed Vapour (2025) at midday – a high-octane piece with text, vocals, and mixed media. The afternoon featured a workshop facilitated by visual artist, Denys Blacker, incorporating martial arts techniques and breathwork, followed by a participatory performance outdoors in the sunshine.

The final performance of the day was from internationally renowned artist and

researcher, Sandra Johnston. Using the two adjoining rooms in the upper floor of the barn, Johnston worked with materials sourced onsite, creating an atmosphere so still that one could focus on the dust floating through beams of light coming through cracks in the window shutters. Her work was a masterclass in considered control and power, guiding the audience to pay attention to the smallest action and the force required to carry it out.

Sunday’s programme commenced with a high-energy workshop from p(art)y Here and Now, which finished with a participatory performance event for both artists and audience. At midday, Marie-Chantal Hamrock, an Irish artist based in Scotland, integrated seaweed and texts into their evocative piece on the use of laminaria digitata (a common seaweed) as a ‘backstreet abortion’ method until the mid-twentieth century.