On The Cover

Kian Benson Bailes, Weather Statue, 2025, ceramic, installation view, ‘Staying with the Trouble’; photograph by Ros Kavanagh, courtesy of the artist and IMMA.

First Pages

6. Roundup. Exhibitions and events from the past two months.

8. News. The latest developments in the arts sector.

9. Secret Painters. Cornelius Browne considers the secret life of working-class artist Eric Tucker. Time Crystal Disintegration. Pádraic E. Moore chronicles the life, work, and legacy of Irish painter Michael Ashur.

10. Stewardship, Care, and Collaboration. Eamon O’Kane and Chelsea Canavan outline their socially engaged project in care homes across Sligo.

Attuning to the Intelligence of the Body. Aoibheann Greenan outlines a holistic model for the creative process, rooted in four interdependent principles.

11. The Transition to Bedbound Art. Aine O’Hara outlines how she maintains an art practice while managing a chronic condition. A Creative Encounter. Jody O’Neill outlines research focusing on the cultural participation of neurodivergent people.

Exhibition Profile

12. The Iron Gates. Miguel Amado interviews Barbara Knežević about her new touring exhibition.

14. To Whom It May Concern. John Graham reviews an exhibition by Mohammed Sami currently showing at the Douglas Hyde Gallery.

16. Staying with the Trouble. Sadbh O’Brien reviews a large group exhibition at IMMA.

18. Beuys in Belfast. Emma Campbell reports on ‘Beuys 50 Years Later’ at the Ulster Museum.

Critique

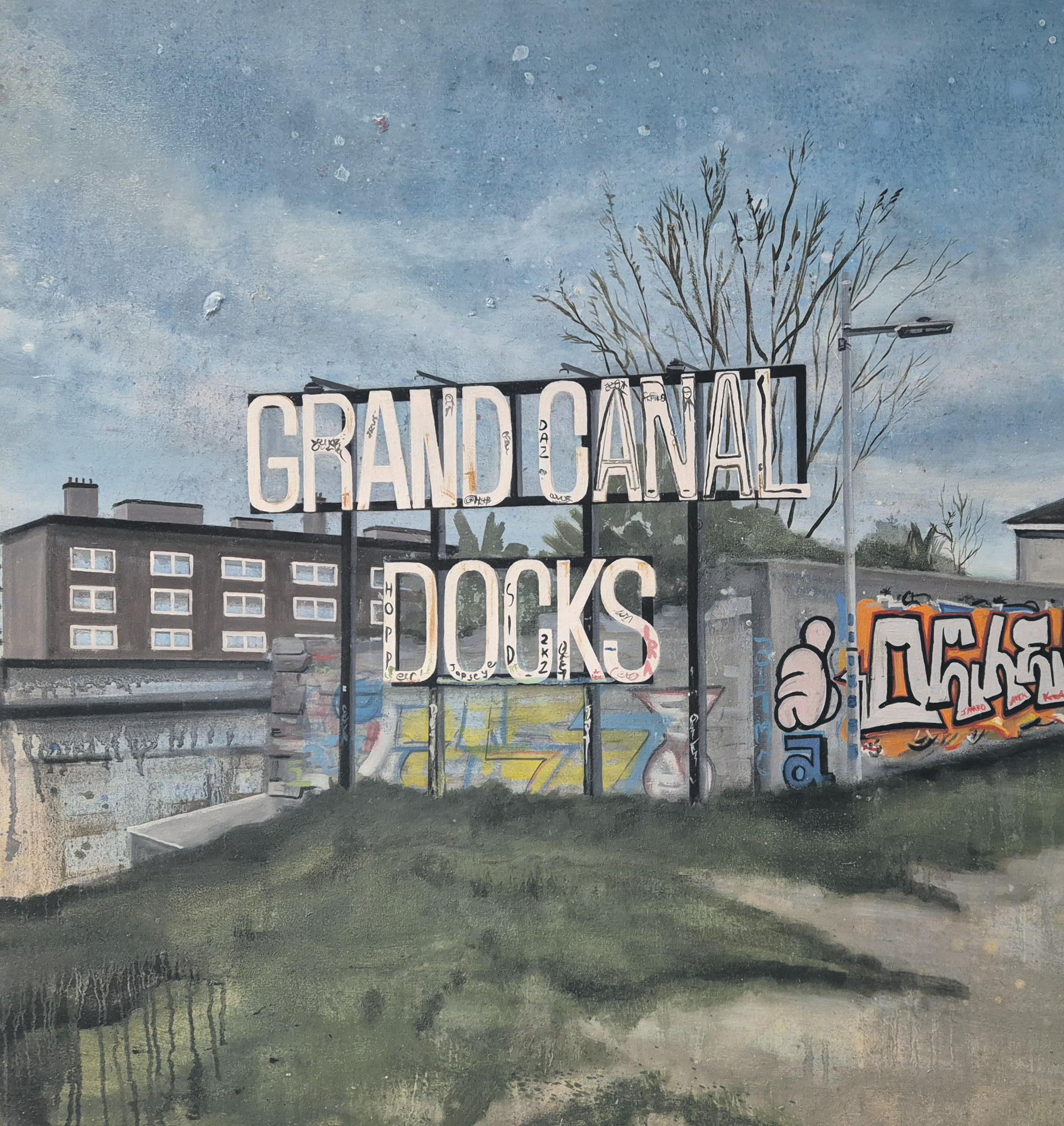

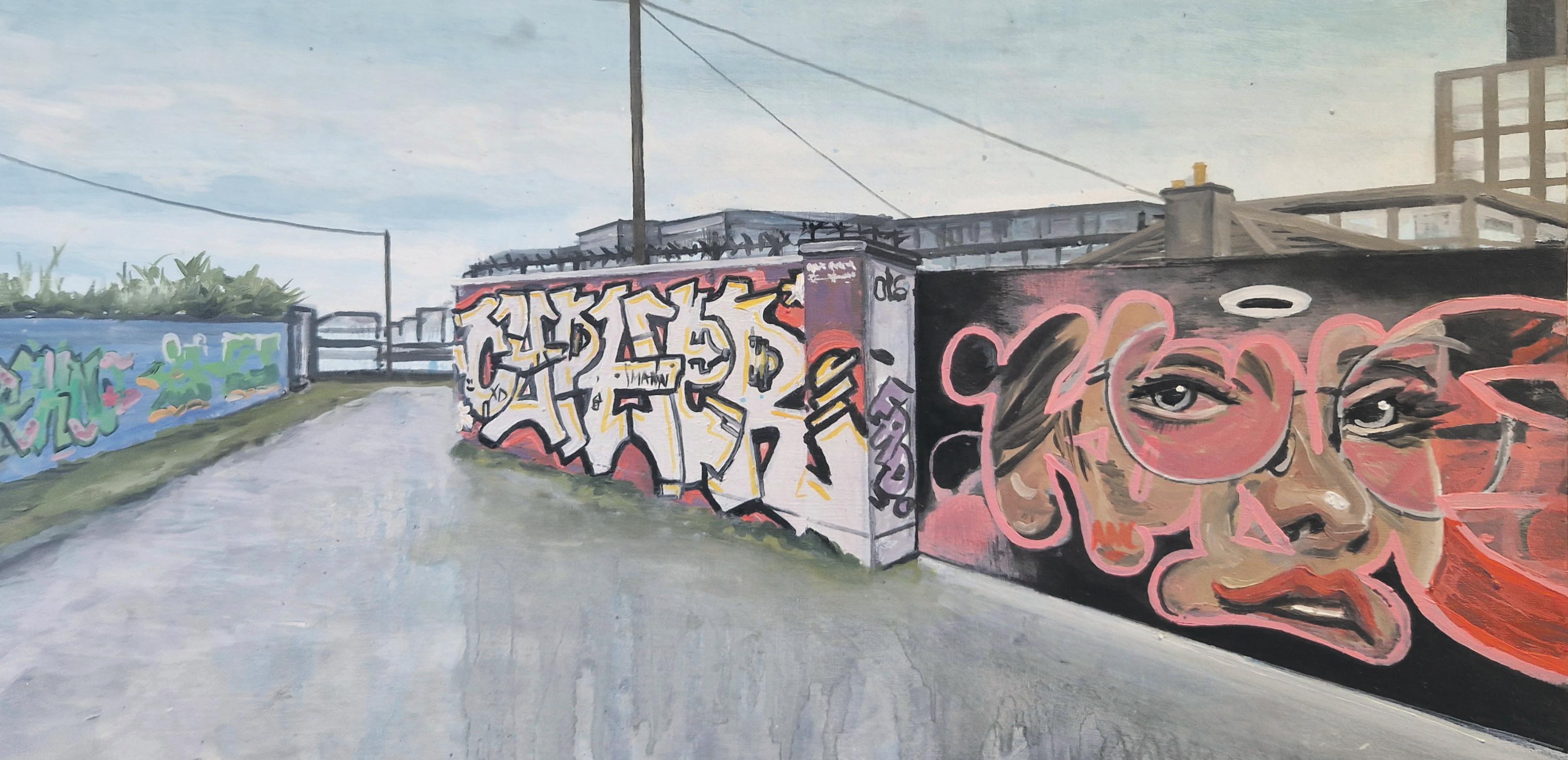

19. David Fox, Grand Canal Docks, 2024, oil on board.

20. Sharon Murphy and Emma Spreadborough at Photo Museum Ireland

22. Doireann O’Malley and STRWÜÜ at Goethe-Institut Irland

23. Mark Cullen at the Regional Cultural Centre

24. John Rainey at Golden Thread Gallery

26. David Fox at GOMA Waterford

Seminar Report

27. Opacities. Clodagh Assata Boyce reports on the Opacities seminar, workshop, and screening event at NCAD.

28. Sustain and Grow. Jane Morrow reports on a conference on artist-led models organised by Arts & Business NI.

Project Profile

29. Shared Histories. Ben Malcolmson outlines a recent cross-border community project funded by Creative Ireland.

Member Profile

30. Ar an Imeall / On the Edge. Pamela de Brí discusses the evolution of her artistic research. Haunted By Silence. Danny McCarthy discusses his sound art practice and new limited-edition CD, released by Farpoint Recordings.

31. Lady Lazarus. Lara Quinn reflects on the evolution of her emerging practice.

Last Pages

34. Public Art Roundup. Site-specific works beyond the gallery.

36. Opportunities. Grants, awards, open calls and commissions.

37. VAI Lifelong Learning. Upcoming VAI helpdesks, cafés and webinars.

The Visual Artists’ News Sheet:

Editor: Joanne Laws

Production/Design: Thomas Pool

News/Opportunities: Thomas Pool, Mary

McGrath

Proofreading: Paul Dunne

Visual Artists Ireland:

CEO/Director: Noel Kelly

Office Manager: Grazyna Rzanek

Advocacy & Advice: Oona Hyland

Advocacy & Advice NI: Brian Kielt

Membership & Projects: Mary McGrath

Services Design & Delivery: Emer Ferran

News Provision: Thomas Pool

Publications: Joanne Laws

Accounts: Grazyna Rzanek

Special Projects: Robert O‘Neill

Impact Measurement: Rob Hilken

Shared Island Advocacy: Brian Kielt

Board of Directors:

Deborah Crowley, Michael Fitzpatrick (Chair), Lorelei Harris, Maeve Jennings, Gina O’Kelly, Deirdre O’Mahony (Secretary), Samir Mahmood, Paul Moore, Ben Readman.

Republic of Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

First Floor

2 Curved Street

Temple Bar, Dublin 2

T: +353 (0)1 672 9488

E: info@visualartists.ie

W: visualartists.ie

Northern Ireland Office

Visual Artists Ireland

109 Royal Avenue

Belfast

BT1 1FF

T: +44 (0)28 958 70361

E: info@visualartists-ni.org

W: visualartists-ni.org

LexIcon

Vanessa Donoso López’s ‘A rock can hurt you, a rock can open a nut’ ran from 13 April to 22 June. This collection, comprising over 1,000 pieces, includes archaeological artefacts and a series of marbled shapes that echo the intricate patterns found on petrified objects and rocks. These re-imagined artefacts are presented in wire caged structures, creating an archaeological like installation. Some clay pieces have been hand-moulded by local communities and schools, both in Spain and Ireland, using locally sourced clay.

dlrcoco.ie

‘À bientôt, j’espère…’ presents an array of archetypal abstract works by Liam Gillick, alongside a revisiting of his work relating to the French film collective, Groupe Medvedkine. Since the 1990s, Gillick’s abstract work has drawn upon the visual language of renovation, recuperation and re-occupation. He absorbs the aesthetics of neo-liberalism, which restage the remnants and surfaces of modernism as in the production of false ceilings, cladding systems and wall dividers. On display from 24 May to 28 June.

kerlingallery.com

The Complex

Lee Welch’s exhibition, ‘Oedipus’, spans painting, printmaking, and installation, offering an arresting meditation on how we see, remember, and relate to the world. His visual language is spare but loaded with figures, gestures, and fragments reduced to essentials that carry emotional weight. Paintings in the exhibition feature references from art history, popular culture, and the mundane rituals of daily life. In the myth of Oedipus, the act of seeing is both literal and symbolic: only in blindness does he come to understand the truth. On display from 24 May to 14 June.

thecomplex.ie

Pearse Museum

‘Lost Moments’ by Lorraine Whelan is an archive of memory. Both Whelan’s personal life and the museum’s exploration of the life of Patrick Pearse often deal with children, the relationships between children and adults, and the relationships between people, places, and things. The specifics of identity and memory are of interest to everyone. These works are based on drawings created from snapshots of people, places, and moments that are no longer in Whelan’s life. On display from 24 March to 22 June.

heritageireland.ie

Solomon Fine Art

‘Fathom: outstretched arms’ by Rachel Joynt is the result of her exploration and intervention with the marine reserve of Lough Hyne in West Cork. On observing the lake’s activity and the stillness that occurs in the moments before the turning of the tide at the narrow passage where the lake opens to the sea, Joynt was reminded of a respiratory system, of human lungs, and so a connection was made. On display from 29 May to 21 June.

solomonfineart.ie

TØN Gallery

‘Sheela / Sansun(a): Bridging Islands’ is the first solo show of Maltese artist Gabriel Buttigieg in Ireland. In the spirit of cultural diplomacy between Malta and Ireland, this exhibition fuses the stories of two powerful figures in Irish and Maltese history: the mysterious Irish mythological figure, Sheela na gig, and the prehistoric Maltese giantess, Sansuna. Adopting a new vibrant expressionistic style in his paintings, Buttigieg embodies his ardent and profound interest in the human condition through the Sheela and Sansuna. On display from 5 to 26 June.

tondublin.com

ArtisAnn Gallery

‘Human Chain’ is an exhibition of new artworks by Leah Davis in which the artist confronts the complexities of the human form through both drawing and painting. Since graduating in 2021 with a degree in Fine Art from Belfast School of Art, Leah has been chosen for several prestigious shows and commissions. In 2022 she was commissioned to paint the official portrait of the Lord Mayor of Belfast, currently displayed in the Belfast City Hall, the youngest artist to be so honoured. On display from 4 to 28 June.

artisann.org

Golden Thread Gallery

Currently showing at Golden Thread Gallery, ‘Beyond the Gaze – Shared Perspectives’ by Sophie Calle presents video works (Voir la Mer, 2011) and photographic pieces (L’Hôtel, 1981-1983). For Voir la Mer, Calle invited inhabitants of Istanbul, who often originated from central Turkey, to see the sea for the first time. Calle is one of the most celebrated and influential conceptual artists in the world, and this is the first time her work has been shown to audiences in Northern Ireland. The exhibition continues until 27 August.

goldenthreadgallery.co.uk

University of Atypical ‘Reliquary, As Oubliette’ by Eibh Gordon is a body of work which explores the materialisation of mortality and pain through sculptural offerings and ensorcelled amulets. These corporeal objects parallel ancient votives and sorceries to manifest wellness but also act as a memento mori: a reminder that inevitably, the flesh will die. Eibh Gordon is a queer visual artist practicing in Bangor. In 2024 she graduated from Ulster University with a MA in Fine Art. The exhibition ran at University of Atypical from 1 May to 26 June.

universityofatypical.org

Cultúrlann Mc Adam Ó Fiaich

‘Silent Conversations’ by Niamh Mooney presents portraits of friends, reflecting personal connections and draws inspiration from figurative painters like Vermeer, Manet, Hopper, and Matisse, with a focus on light, texture, composition, and the interplay of pattern and colour. The figures are absorbed in their surroundings, often unaware of the viewer, creating a psychological charge. These works evoke themes of privacy, intimacy, and the complexities of human experience. The exhibition continues until 31 July.

culturlann.ie

The MAC

Aisling O’Beirn’s ‘We Lose Sight of the Night’ was the first in a series of exhibitions which address climate and environmental change. O’Beirn (born in Galway) is a Belfast-based artist, whose practice explores the relationship between art and science, manifesting variously as sculpture, installation, animation and site-specific projects. This exhibition brought together new works and reworked older pieces. An interest in the wonders and political importance of the night sky characterised much of the exhibition, which ran from 17 April to 22 June. themaclive.com

Vault Artist Studios

The group exhibition ‘Cult: An Art Exhibition’ ran at Vault Artist Studios from 16 to 20 June. The exhibition included visceral artworks exploring the grotesque, ethereal, and macabre through dream space, heightened reality, and dark fantasy. Thirteen local and international artists were invited to respond to these themes in their own medium. The result was a curated gallery of paintings, illustration, making and sculpture. There was also a public programme to accompany the exhibition with workshops running each day.

vaultartiststudios.com

18th Street Arts Center

The group exhibition ‘The Irish Contemporaries {iv}’ was on display from 7 to 27 June in Los Angeles, California. CIACLA and partners, presented the dynamic group visual arts exhibition, featuring Brenda Welsh, Brendan Holmes, Christopher O’Mahony, Colleen Keough, Jerry McGrath, Julie Weber, Sionnan Wood, Tom Dowling. CIACLA’s annual exhibition brought together a compelling selection of LA-based and Irish artists exploring themes of identity, cultural memory and social engagement.

mart.ie

Droichead Arts Centre

‘Between Worlds’ featured artists Orlaith Cullinane, Patrick Dillon, Daria Ivanishchenko, Sallyanne Morgan, which ran from 6 May to 21 June. Cullinane’s high energy bronze figures transcend animal-human boundaries; Ivanishchenko’s paintings and video convey the reality of living between two places that are both ‘home’; Morgan’s women don a delicate external armour that speaks to unpredictable currents of change; and Dillon’s paintings explore television as a persistent presence in our lives and as a portal to and from another world. droichead.com

Luan Gallery

Luan Gallery presented ‘VASSALDOMS UNITED’ by Eimear Walshe. The exhibition launched on 26 April and ran until 22 June. This is Walshe’s first solo exhibition in Ireland, following their national representation at the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024. Born in Longford in 1992, Walshe’s work has long focused on representations of Ireland, and the local and international politics at play behind those representations, including questions of external optics and internal incoherencies.

luangallery.ie

Centre Culturel Irlandais

‘Nature Morte’ by Brian Maguire runs until 6 July. Maguire has committed the last 40 years to revealing the impact of war, corruption, and oppression on the human condition. Working in this case from photographs of unidentified remains, taken between 2017 and 2019, he compares the act of painting to a furious cry of love and remembrance. In stark yet beautiful terms, Maguire renders visible the fate of forgotten individuals. Two short documentaries presented in the exhibition further contextualise the artist’s deeply invested approach. centreculturelirlandais.com

Galway Arts Centre

‘Love, Rage & Solidarity’ by Treasa O’Brien was on display from 24 May to 29 June,.

Using documentary and narrative forms, essay film, sci-fi, and DIY tactics, O’Brien investigated the potential of video and filmmaking as both an artist and an activist. The works explored (de)colonialism, social politics, climate change and migration, with an intersectional, queer, and feminist approach. Many of the works explored their own making as part of the work and challenge ideas of authorship and collaboration.

galwayartscentre.ie

Solstice Arts Centre

Cecilia Danell’s solo exhibition, ‘These Magnetic Magnitudes’ opened on 14 June and continues until 16 August. In a practice which is rooted in materiality and process, the starting point for Danell’s work is a first-hand engagement with the landscape in the area of Sweden where she grew up. The experience of traversing the landscape, along with the physical process of engaging with materials in the studio, results in works that exist between realism and abstraction, utilising fiction and the imaginary to speak about the present and possible futures. solsticeartscentre.ie

Cork Midsummer Festival

Amanda Coogan returned to Cork Midsummer Festival with an extraordinary new durational work, presented from 14 to 21 June. Caught In The Furze was a seven-day performance within an immersive installation of furze (gorse) bushes. Drawing on ancient folk traditions and contemporary performance, Coogan navigated the spaces between history and memory, myth and modernity. Evolving and shifting each day, the work invited audiences to step in and out, and to witness moments of stillness, transformation, and physical endurance. corkmidsummer.com

Leitrim Sculpture Centre

Simon Browne’s ‘a workshop for everyday technology’ runs from 20 June to 19 July. His practice is based around nurturing convivial conditions for working and learning together and publishing through whatever means available, with a preference for Free/ Libre Open-Source Software (F/LOSS). The artist’s research and experimental publishing projects produce outcomes such as drawings, workshops, work sessions, meetups, graphic diagrams, plastic diagrams, digital tools, archives, libraries and more.

leitrimsculpturecentre.ie

Waterford Gallery of Art

‘You couldn’t make it up’ by Dungarvan-based, award-winning artist, Catherine Barron. This mid-career retrospective features paintings made by Barron between 2010 and 2025. Salvaged metal plates, vintage 78rpm records, book covers, and playing cards serve as the artist’s canvas to reveal a deeply personal, as well as allegorical, biographical journey. Barron was born in County Carlow, lives and works in Dungarvan, County Waterford since 2017, and is represented by the Molesworth Gallery, Dublin. Runs until 16 August. waterfordgalleryofart.com

Custom House Studios & Gallery

Judy Carroll Deeley’s research into gold mining in South Africa began with a trip to Gauteng Province, part of the international study, ‘Post-extractivist Landscapes and Legacies: Humanities, Artist and Activist Responses’. Deely said: “The area around Johannesburg is pitted by underground mines, some of which are flooded and leak toxic minerals into waterways and rivers. This mining legacy, known as Acid Mine Drainage, is an ongoing problem for the city, its inhabitants.” ‘Gold Mine, Gauteng, South Africa’ ran from 1 to 25 May. customhousestudios.ie

Linenhall Arts Centre

‘Domestic Bodies’ was on display from 24 May to 28 June. Featuring video screenings and photographic images by Áine Phillips and collaborators Vivienne Dick, Ella Bertilsson, and Emily Lohan. Embedded with Ella Bertilsson explores comfort, shelter and safe resting place. Vivienne Dick’s Robing Room considers the struggles of women’s bodies in Irish social history. Red Couch/ Archeology with performer Emily Lohan enacts, with humour and transcendence, the symbolic immersion of a woman into the underbelly of domesticity. thelinenhall.com

Wexford Arts Centre

‘Sync Shift’ by artist Órla Bates, opened in Wexford Art Centre’s lower and upper galleries on 14 June. In 2023, Órla Bates was invited to take part in the MAKE/ curate programme, a partnership initiative between Wexford Arts Centre and partners. The aim of the programme is to provide artists working regionally with an opportunity to work with a national curator. Orla worked with curator Ann Mulrooney towards her solo exhibition at Wexford Arts Centre. The exhibition continues until 26 July.

wexfordartscentre.ie

Temple Bar Gallery + Studios (TBG+S) recently announced Rachel Enright Murphy as the recipient of the TBG+S Recent Graduate Residency Award in 2025.

The Recent Graduate Residency Award offers a unique and substantial professional development opportunity to an emerging artist on an annual basis. The award includes a large free studio for one year, an artist bursary, and a variety of institutional supports to an artist who has graduated from an undergraduate degree in the past three years. TBG+S looks forward to welcoming Rachel Enright Murphy to its creative community of artists, and supporting her practice as it develops.

Rachel Enright Murphy’s work

Maureen Kennelly Steps Down

The Board of the Arts Council announced, with deep regret, that Maureen Kennelly stepped down as Director of the Arts Council in June. Maureen concluded her five-year term on 4 May and has generously agreed to remain in her role to represent the Arts Council at upcoming Public Accounts Committee and Oireachtas hearings.

Maureen was appointed Director in April 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. She led the organisation through an exceptionally challenging time, guiding it with strength and vision. Under her leadership, the Arts Council underwent a period of significant cultural change, with a strong focus on organisational development and staff wellbeing.

She successfully resolved longstanding legacy challenges and brought renewed strategic clarity to the Council’s work. Together with the Council, she secured unprecedented increases in state funding for the arts – enabling artists and organisations across the country to create and present work of outstanding quality. She also championed higher professional standards and fostered a climate of trust and respect across the wider arts sector.

Maureen’s contribution to the arts in Ireland has been transformative and is recognised both nationally and internationally. Throughout her tenure, Maureen has demonstrated the highest levels of integrity and commitment to public service. Her principled approach to leadership and unwavering dedication to the arts community have been defining hallmarks of her directorship.

In the latest edition of the miniVAN, artists Annie West, Elisa Beli Borrelli, and Will Sliney discuss their work and practice as comic illustrators and graphic novelists in a series of essays exclusively for Visual Artists Ireland!

The miniVAN is the online magazine published by Visual Artists Ireland. With uniquely commissioned content, The miniVAN explores the visual arts with an accessible view of all aspects of careers and practice that make up our visual community. Please visit: visualartistsireland.com

combines moving image, sound, performance, and printed material with text and explores error and ambiguity as an artistic practice, confronting the boundaries and inadequacies of written language. Her work often creates intimate narratives within impersonal or bureaucratic structures. Examples include romantic poetry as a stock photo watermark, spelling mistakes in the trial of a fifteenth-century homosexual nun, and a never-ending horse racing commentary. She appropriates from a range of documentary sources such as scientific papers, historical and legal testimony, reconfiguring linguistic forms to examine the production of identity, objective truth and collective experience.

Gibson Travelling Fellowship Award

Crawford Art Gallery recently announced visual artist Basil Al-Rawi as the recipient of the inaugural Gibson Travelling Fellowship Award.

Basil Al-Rawi will become the first Gibson Travelling Fellow, following a highly competitive open-call selection process, which sought to identify a clear vein of innovation, experimentation and impact.

Al-Rawi’s practice explores the landscapes of personal and cultural memory, hybrid identity, and the digital mediation of reality. He will use the award to support an extended period of self-determined enquiry across Lebanon, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and France.

Basil Al-Rawi is an Irish-Iraqi multidisciplinary artist working across photography, film, VR, and sculptural installation. His practice explores the landscapes of memory, identity, and the digital mediation of experience – often drawing from personal and collective archives to reimagine how memory can be spatialised and shared. His recent work engages participatory methods to reconstruct photographic and mnemonic moments from Iraqi diaspora, resulting in projects such as the Iraq Photo Archive and the immersive VR experience House of Memory. Basil holds degrees in English, sociology, cinematography, a Masters in photographic studies, and completed a practice-based PhD at The Glasgow School of Art in 2023. He has exhibited widely, including at IMMA, The Photographers’ Gallery, The LAB, and the Lahore Biennale, and his work is held in public and private collections. He is currently supported by the Arts Council of Ireland and continues to explore memoryscapes through hybrid forms of storytelling and digital media.

The Cork-based Irish-Iraqi artist was selected from a shortlist by a panel of experts working in the field of contemporary art: Dragana Jurišić (Artist and Educator), Megs Morley (Director and Curator, Galway Arts Centre), Paul McAree (Curator, Lismore Castle Arts), and chaired by Mary McCarthy (Director, Crawford Art Gallery). Impressed by the high quality of applicants, they ultimately determined that Al-Rawi’s proposal most closely articulated the spirit and scope of the Gibson Travel-

ling Fellowship Award and has the potential for significant personal and professional transformation for the artist.

Basil Al-Rawi was selected from a shortlist of six artists including Chloe Austin, Ursula Burke, Amanda Dunsmore, Niamh McCann, and Deirdre O’Mahony.

RHA Director Steps Down

At the President’s Dinner, held at the Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts on 23 May to mark the opening of the 195th Annual Exhibition, in association with McCann FitzGerald, the President of the Academy, Dr Abigail O’Brien, announced that Patrick T. Murphy, the Director of the RHA, will step down from his post at the end of the year, bringing to a close his 28-year tenure as the first Director of the RHA.

In 1998, Murphy returned from a decade at the helm of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, to assume his position with the RHA. Murphy said:

“It’s been a marvellous three decades at the RHA, a period that has seen the Academy completely transform as an organisation at all levels. My mantra at the beginning was to make the RHA relevant to all artists at each stage of their career – emerging, established and senior and to curate an exhibition programme that was truly diverse and reflected the many strategies now available to artmaking”.

Murphy acknowledged the support of Academy members and colleagues in the achievement over these years, and he praised the continuing and fundamental support of the Arts Council to the Academy’s annual operations.

Under Murphy’s leadership, the Academy’s annual budget grew tenfold and now nears €1.5 million annually. He oversaw the €9.5m refurbishment of the Academy’s premises, the Gallagher Gallery in 2007, and negotiated the troubled economic waters just after that re-build during the financial collapse of 2008/9.

He has curated many exhibitions at the RHA, working with Ireland-based artists from all generations and curating such thematic exhibitions as ‘I not I – Beckett, Nauman and Guston’, ‘SKIN an Atlas’, ‘A Growing Enquiry – Art and Agriculture’, ‘In and Of Itself – Contemporary Abstrac-

tion’ and most recently ‘BogSkin – Myth and Science’.

The RHA will commence its search for a new Director towards the end of the summer with a view to making an appointment by the end of the year.

ACNI Annual Funding Programme

The Arts Council of Northern Ireland announced that 86 arts organisations will benefit from a public investment of approximately £13.97m from their Annual Funding Programme (AFP 2025-26).

The AFP awards will support the core and programming costs of organisations which are central to the arts infrastructure in Northern Ireland today.

With £8.15m exchequer funding from the Department for Communities allocation, and £5.82m from Arts Council’s National Lottery sources, the total public investment offered is £13.97m.

Chair of the Arts Council, Liam Hannaway, said: “Today’s formal announcement of the Annual Funding Programme awards is welcome news and I want to thank the Minister for the Department for Communities, Gordon Lyons, for securing an extra £500,000 for the Arts Council’s baseline allocation for this year. This allows us to give a modest uplift from standstill funding to 80 hard-pressed organisations dealing with the inescapable pressures from increased core costs. We are grateful for the Minister’s recognition of the positive value of the arts in our society and for his help in securing this additional investment. I also want to thank The National Lottery, who this year marked 30 years of supporting good causes, and the game-changing impact that National Lottery funding brings to so many of our arts organisations, who simply couldn’t do without it.”

The AFP awards are the single biggest funding announcement made by ACNI in any one year. The Arts Council makes other funding announcements throughout the year which benefit many organisations and communities across NI. This particular announcement is not a reflection of overall arts funding invested by ACNI.

CORNELIUS BROWNE CONSIDERS THE SECRET LIFE OF WORKINGCLASS BRITISH ARTIST ERIC TUCKER ( 1932–2018 )

PAINTING THE ADVENT of hawthorn blossoms, I hear the post van reversing down our dirt road to deliver a book. My hands hastily wiped, and the package ripped open, I breathe in fresh print. This hardback joins a family of thousands. Within view are two roomy bookcases, absorbing sunlight after another winter in a mouldy log-cabin. Mildew-spotted books sunbathe on beds of wild grasses. How they must envy their distant cousins, newer books allowed to live in the house. Many of these sunbathers came into my life when I was a book-hungry teenager in the 1980s. Evidently, this appetite hasn’t abated. I set aside my paintbrushes to steal an hour with this new arrival.

My sylvan open-air studio dissolves, and I find myself in the place judged Britain’s worst town for culture by the Royal Society of Arts: Warrington. This was the hometown of an uneducated and unskilled labourer, named Eric Tucker (1932–2018), who never left home. Upon his impending death, Tucker’s family discover that his small council house harbours a secret. Voicing for the first time in his life that he’d like to have an exhibition, the dying man initiates a search. Lodged in every nook and cranny are artworks, so many that it takes the family two years to complete cataloguing: 540 paintings and drawings too copious to count.

Hidden from the world for 60 years, Tucker had been painting in his front room, commemorating the working-class sphere to which he belonged with a dedication scarcely glimpsed by close relatives. The Secret Painter (Canongate, 2025), written by Tucker’s nephew, Joe Tucker, charts the life and afterlife of an artist who did not live to see his talent recognised. An inner sun of love warms these pages, delivered to readers from the bosom of a family.

In 1983, the year that I, the child of longterm unemployed parents, began painting daily in earnest, the renowned economist Professor J.K. Galbraith visited London to deliver a lecture on Economics and the Arts for the Arts Council of Great Britain: “It is only when other wants are satisfied that

people and communities turn generally to the arts; we must reconcile ourselves to this unfortunate fact. In consequence, the arts become part of the affluent standard of living. When life is meagre so are they.” Galbraith’s lecture ignores the rich tradition of working-class art, dating from at least the Industrial Revolution. Works of art by people who knew want intimately, germinated outside the opulent radiance of academies, art schools or galleries, and their history remains under-illuminated. Home-made art that rarely left home.

Tellingly, as the Tucker family scrambled to honour a final wish, rebuffed by officialdom, they converted Eric Tucker’s home into a gallery for his first posthumous exhibition. By dint of sweat, they managed to wrench the cultural spotlight towards Warrington. Major exhibitions followed, one of which saw a leading London gallery transformed into a replication of Tucker’s humble painting room.

My parents’ lives in Glasgow, working on building sites, in factories, and cleaning hospitals, dovetailed with the world of Eric Tucker. Fresh from the experience of battling for his uncle’s art, Joe Tucker observed that less than eight percent of creative workers currently come from a working-class background. On the last page of this poignant story that never overlooks the humorous side of life, Tucker reaches a supportive hand, offering his book to all artists who, faced with systemic unfairness and exclusion, think: “What’s the point in trying?”

Upon graduating from art college, abloom with youthful vigour, I set aside my paintbrushes for over 20 years. What’s the point in trying? When I resumed painting, a decade had passed since I’d last set foot inside an art gallery. Circumstances of birth plant working-class artists into north-facing gardens that receive no direct sunlight. Over a meagre life, I’ve grown to cherish my place among secret painters, who flower in the shade.

Cornelius Browne is an artist based in County Donegal.

MICHAEL ASHUR AND his paintings had already drifted into obscurity long before the artist died in the spring of 2024. By then, it had been decades since he had been included in any exhibitions in Ireland. Although opportunities to view his work in the flesh are few, his legacy is worthy of consideration. Aside from the aesthetic merits of his paintings, the vagaries of his career reveal much about the vicissitudes of cultural production in Ireland over the past 50 years.

Born in Dublin in 1950, Michael Byrne commenced his studies at NCAD in the late 1960s. Upon graduation, Byrne assumed the pseudonym, ‘Ashur’, after a Babylonian sky god. His early work shows an awareness of international painting, and he is one of the only Irish representatives of the shaped canvas movement, proponents of which Ashur would have seen at the Rosc exhibitions.1 Encountering works by Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely at the Hendriks Gallery in Dublin was also a formative experience for the artist.

With their luminous hues and angular, crystalline compositions, Ashur’s paintings appear backlit and prefigure much of what we see today on digital screens. But what makes this artist distinctive and idiosyncratic are the non-art influences that shaped his output. Ashur came of age in the late 1960s – a period suffused with science fiction and space exploration. Technological progress and pop culture merged; Kubrick’s classic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, was released in 1968, the year before the lunar landings.

That era was also fundamentally shaped by aesthetics that evoked altered states of consciousness – fantastical and galactic imagery, often containing optical and perceptual illusions. Crucially, this was propagated via popular artforms: poster art, science fiction novels, album sleeves, product and fashion design. Ultimately, Ashur’s work represents the last gasps of visual culture, spawned by the psychedelic revolution.

Ashur enjoyed considerable success in Ireland and Europe from the early 1970s but as the 1980s progressed, his currency waned. The doom-laden atmosphere per-

vading Ireland in that era was conducive to tendencies typified by Neo-expressionism. That movement and all it represented was anathema to Ashur’s creations, characterised by an excess of airbrush, fastidiousness and procedural detachment. Instead, directness, muscular authenticity, and existential angst was embraced by artists who sought to sidestep an excessively cerebral and etiolated approach to making art.

As Ashur honed his aesthetic, his images grew in scale and became more complex and baroque. But as several critics noted at the time, his modus was ultimately one of repetition. For an artist operating mainly in the context of Ireland, this proved detrimental. The closure of his Dublin gallery extinguished possibilities for engaging new collectors, and consequently, Ashur ceased making art.

By the mid-90s, his work had receded from view. Crucially, this was a period in which contemporary Irish art moved rapidly forward, falling in step with other European countries, whilst also focusing upon post-colonial discourse. Initially considered valid, his works eventually came to be seen as anachronistic and were relegated to institutional basements and storage units.

Ashur’s meteoric progression was typical of an age when a succession of movements flourished and superseded one another. Technological advancement and an appetite for novelty led to rapid cycles of change in which the visual arts played an integral part. The fate of Ashur’s oeuvre demonstrates more universal realities. Early commercial success and critical acclaim are no guarantee of a place within the canon, and the fate of an artist is often shaped by factors that are arbitrary and capricious.

Pádraic E. Moore is an art historian, curator, and Director of Ormston House. padraicmoore.com

1 International exhibitions included ‘The

EAMON O’KANE AND CHELSEA CANAVAN OUTLINE THEIR SOCIALLY ENGAGED PROJECT IN CARE HOMES ACROSS SLIGO.

IN OCTOBER 2023, Eamon O’Kane was approached by Marie-Louise Blaney and Emer McGarry at The Model in Sligo to develop a proposal for an Arts Participation Project Award. The Model houses O’Kane’s interactive installation, Froebel Studio: A History of Play (2010 – ongoing) in the Niland Collection, and they were interested in his previous interactive commission at a dementia care home in Bristol. From this invitation, Eamon conceived The School for Generational Storytelling and invited Chelsea Canavan to join the application as a support artist.

At its core, the project aimed to create spaces of encounter shaped by care, participation, and transformation. Rooted in action research and public engagement, it was structured around residencies in six care homes across Sligo, exploring how creative practice supports wellbeing, memory, and intergenerational exchange. It asked how we might share knowledge across time and how art can nurture relationships –between individuals, disciplines, and institutions.

Our collaboration drew on a long-standing creative rapport, first sparked during the pandemic in 2020 when Chelsea initiated a series of ‘Creative Resonance Conversations’ during her work on Folding Worlds The reconnection of our practices formed the conceptual and practical foundation for The School for Generational Storytelling

A central question emerged: How can an ethics of care be practiced through collaboration? For us, this meant structuring our time with flexibility, responding attentively to participant feedback, and co-developing processes that valued mutual respect. The dynamics we witnessed – caregivers and residents in moments of exchange – mirrored our own collaborative process. It was a dialogue shaped by listening, openness, and transformation.

The collaborative model we developed was not about blending disciplines into one voice but amplifying each other’s strengths. Eamon’s architectural and visual language shaped the aesthetics and spatial logic of

the project, while Chelsea’s background in participatory arts and healthcare ensured a socially engaged, responsive methodology. Our combined experience in education informed a shared pedagogical approach, with each residency generating insights and artifacts through co-created toolkits, tailored to the context of each care home.

A major influence on our thinking was the systems-based ecological work of The Harrisons, whose pioneering framework for collaborative practice offered ways of understanding social and institutional systems as dynamic and interconnected. We embraced this perspective in our roles as stewards – of spaces, relationships, and processes. The project was less about delivery and more about co-shaping environments that honored the contributions of all participants.

Each care home was not just a venue but a collaborator. As artists, we responded to the specific needs and rhythms of each place, developing tools and strategies that reflected the lived realities of residents and staff. These toolkits – now housed in a permanent archive and resource library at The Model and in the care homes themselves –serve as vessels for shared meaning, memory, and imagination, facilitating further engagement beyond the life of the project.

In this sense, The School for Generational Storytelling becomes more than a project: it is a living framework that encourages others to think differently about creative collaboration. Beyond co-creation, it models co-learning and even co-healing. In a time when ecological systems and infrastructures of care are increasingly under pressure, the work gestures toward alternative futures, rooted in empathy, dialogue, and sustained attention.

Chelsea Canavan is an interdisciplinary artist and educator. chelseacanavan.com

Eamon O’Kane is a visual artist based in Denmark and Norway. eamonokane.com

AOIBHEANN GREENAN OUTLINES A HOLISTIC MODEL FOR THE CREATIVE PROCESS, ROOTED IN FOUR KEY PRINCIPLES

AS ARTISTS, WE intuitively understand that creativity moves in cycles, much like the seasons. A burst of inspired output is often followed by a quieter, more fallow phase. This isn’t a failure of discipline; it’s a vital part of the process – a time when experiences and ideas compost, becoming fertile ground for the next creative surge.

Trouble arises when cultural expectations clash with these natural and intuitive rhythms. Conditioned to constantly produce, we interpret inevitable slowdowns as ‘procrastination’ or ‘creative block.’ But what if these moments aren’t a deficiency, but a misalignment – between the pace we’ve internalised and the pace we actually need?

Our creative cycles are no different from the rhythms of growth, rest, decay, and renewal found in nature. It’s only our disconnection from this perennial wisdom that distorts the process. In recent years, I’ve been leaning into the intelligence of the body, which is attuned to the pulse of life in ways that we can’t always grasp intellectually.

Through this act of listening, I’ve begun to embrace a more holistic model for the creative process, rooted in four interdependent principles: curiosity, creation, curation, and connection. Each principle relates to a classical element and its corresponding season, as honoured in many ancient cultures and traditions, thereby offering a potent metaphor for the creative life cycle, with all its ebbs and flows.

Curiosity (Air | Spring): Air is light, mobile, and expansive. It represents intellect, inspiration, and the circulation of ideas. You know you’re in this phase when you’re following threads of interest without knowing where they’ll lead – reading widely, diving into rabbit holes, making unlikely connections. You may feel more sociable, hungry for input, and open to new perspectives.

The key here is to stay untethered. Your only job is to follow the sparks and gather what you find. Keep a notebook or digital folder for scattered thoughts. The dots don’t have to connect yet – just let them accumulate. Slowly, a landscape begins to form. Without this phase of expansion, future work may lack depth and vitality.

Creation (Fire | Summer): Fire is radiant, transformative, and energising. It represents passion, will, and creative force. This is the phase of decisive action – moving from potential to form. You’ll know you’re here when collecting ideas no longer satisfies; you feel compelled to make. Where before your perspective was wide-ranging, it now sharpens into focused intention. You feel lit up with inspiration and drive.

This stage calls for discernment. You’ll need to let go of certain ideas to fully commit to the one that feels most alive. Can you articulate your intention in one clear sen-

tence? Paradoxically, this narrowed focus creates greater freedom to experiment. All that’s required is your commitment. As momentum builds, the idea will evolve in surprising ways.

Curation (Earth | Autumn): Earth is solid, grounding, and integrative. It represents stability, discipline, practicality, and structure. This is the time to harvest the fruits of your labour and shape them into a coherent whole. It’s about bringing clarity and refinement to what you’ve created. You may find yourself editing, organising, and pruning. Your pace slows; your rhythm becomes more methodical.

You’re envisioning the work beyond the studio – experimenting with arrangement and how the pieces speak to one another. This phase requires gentle ruthlessness. Not everything will make the final cut – but even the cuttings can seed future work. This is an ideal time for studio visits or feedback. As you reflect on what you’ve made, outside perspectives can help illuminate what has now emerged.

Connection (Water | Winter): Water is fluid, receptive, and purifying. It represents intuition, wisdom and emotional depth. With enough distance from the work, this is the moment to reflect on the full arc of the cycle and tend to your relational web. Connection flows outward and inward.

This is a potent time for sharing through presentations, interviews, or casual conversations sparked by your work. It’s also a time for receiving – by witnessing the creations of others, attending shows, and engaging with your creative community. After intense output, there is deep nourishment to be found in stillness, if you can invite it.

All four principles weave through every stage of the creative process. The aim isn’t to isolate them, but to notice where you are in the cycle and tend to that moment with care. What matters most is being present and gently attuned to your body’s capacity. Rather than pushing past your natural rhythm, can you sense where your energy most wants to go?

Ultimately, this can be part of a decolonial practice: resisting extractive systems that demand constant output and remembering that creativity – like life – moves in cycles. Reattuning to the body’s wisdom is one way we begin to unlearn these inherited pressures and allow your process to breathe.

Aoibheann Greenan is an Irish artist and the founder of Rodeo Oracle, a creative coaching and mentoring service for artists.

rodeoracle.com

ÁINE O’HARA OUTLINES HOW SHE MAINTAINS AN ART PRACTICE WHILE MANAGING A CHRONIC CONDITION.

I HAVE ALWAYS been unwell. I’ve always spent a lot of time in bed. Throughout my childhood, I had endless symptoms that no one could really explain. My twenties were a constant search for answers as my health steadily declined. For years, I endured crash after crash – brief collapses that forced me into bed for days at a time. Eventually, I’d come back out and the cycle would start all over again, though each time it was harder and harder to resume.

The cycle changed dramatically in the autumn of last year. Following a severe allergic reaction, my body entered complete collapse. My symptoms escalated overnight. I couldn’t eat or drink. Light, sounds, smells, even miniscule attempts at communication were dangerous and caused tachycardia, allergic reactions, severe pain, nausea, vertigo, migraines and flu-like symptoms, to name only the worst. I needed to lie in complete silence and darkness. Making it to the bathroom once a day became the most physically brutal effort I’d ever faced.

I lived like that for months – minute by minute – telling myself: “If it just gets 2% better, I can survive this.” I had previously heard of M.E. (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) and even suspected I might have it in a mild form. But with so few specialists and the reality of the illness seeming so terrifying, I pushed it to the background when I was more functional. Sometimes known by its less revealing name, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, M.E. is a chronic, neuroimmune disease, marked by a range of debilitating symptoms. 25% of people with M.E. experience it in its severe or very severe forms – confined to dark rooms, trapped in our bodies, often for years.

One of its most defining and torturous features is PESE – Post-Exertional Symptom Exacerbation – often called a ‘crash’. For me, exertion meant anything from rolling over in bed to reading a single text message. Any activity, no matter how minor, could cause a sharp, prolonged worsening of all symptoms.

Everything collapsed: hygiene, creative projects, communication, friendships. I knew enough from advocates and the M.E. community to recognise what was happening. This was severe M.E. – not the most extreme form, but severe enough to dismantle my life. I was already living with several comorbidities: POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome), MCAS (Mast Cell Activation Syndrome), Endometriosis, and a rare heart condition. Those minutes, hours, days, and months were unbearable. Just months earlier, I had been able to periodically visit my studio, cook for myself, go for short walks, collaborate with other artists. That life may be much more limited than many of you reading this, but to me, it was truly abundant. Suddenly, then slowly, all of that slipped away. I became 99% bedbound, barely able to manage the daily

battle of descending six steps to the bathroom. I became completely dependent on my partner for everything – food, care, and communication with the outside world.

I was surprised by what I missed most. I could barely eat, speak, or move, but more than anything, I missed people. And I missed art. My ability to connect was gone. My ability to express was gone. But in the worst moments, my mind gave me something to hold onto: images, memories, ideas. I wasn’t dreaming. I was awake, in pain, in stillness. But, behind closed eyes, scenes came to the surface – places, colours, shapes of things I had seen or imagined in the past. Some part of me was still making but production wasn’t the goal; I was just trying to survive.

Over time, when I had small windows of clarity, I found ways to record them – a note on my now dim phone, a short voice message, a passing thought I repeated in my head. In January I got a notebook. In March I was lucky enough to sketch for an hour or so in the dim light before needing to lie back down. My perspective on time, on everything, was altered. Urgency looks different here. The deadline can wait; the exhibition can wait. There are no art emergencies.

My art practice has always interrogated concepts of ‘rest’ and what it means to live outside of the accepted structures of ‘productivity’ in our capitalist society. I didn’t fully grasp just how much further away I could be pushed from those norms. Sickness forces a new relationship with time. Rest is now a survival strategy. Silence isn’t absence – it’s preservation. I am lucky, at the moment, to be able to write this and create in any way.

I’ve never thought of myself as a particularly sincere person – my work, and the work I love, usually leans into mess, irreverence, dark humour. But if I’m being honest, the practice I built – the part of me that makes things, that thinks in images, that sees the world in layers – is what carried me through. Even when everything else fell away, being an artist was the one identity that stayed. I hope to keep sharing this practice with you as it develops – in fragments, ideas, and survival from bed.

Áine O’Hara is a visual artist, designer, and disability advocate based in Ireland. aineohara.com

JODY O’NEILL OUTLINES RESEARCH ON THE CULTURAL PARTICIPATION OF NEURODIVERGENT PEOPLE.

THE IDEA FOR ‘IMMA Perspectives – a Creative Encounter’ began last December. IMMA and Dublin City Council had allocated funding towards making IMMA more neurodiversity inclusive. Our main collaborators were Melissa Ndakengerwa (IMMA Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Executive Officer) and Liz Coman (DCC Assistant Arts Officer). In engaging with DCC’s ambitions to make Dublin an Autism Inclusive City, their key question was: “How can neurodivergent people fully participate in and enjoy cultural experiences?”

Rather than designing a workshop programme for visitors, my impulse was to embed neurodivergent artists at IMMA to conduct an informal, experiential, sensory audit of the institution. I approached Dee Roycroft, who I collaborate with regularly, and we proposed a facilitated, weeklong, paid engagement for neurodivergent artists. The artists would have the opportunity to interact with the space, the visitor engagement programme, and each other. They would be supported in developing their artistic practice through workshops, conversations, and individual research. At the end of the week, they would offer a responsive workshop to IMMA and DCC staff, reflecting their experiences as neurodivergent artists at the museum.

Dee and I designed the programme, identifying key artistic and access priorities. We felt it was crucial for participants to have opportunities for new engagements and provocations as well as space and time for individual practice. We also wanted to tailor it specifically to the needs and desires of the selected participants, so developed an overarching vision with flexibility to adapt.

We launched the initiative in March with a webinar supported by Cultural and Creative Skillnet. Neurodivergent artists and creators, Aideen Barry, Alan James Burns, Tierra Porter, and Maja Toudal participated in a conversation with Dee. With over 100 attendees, the webinar was a powerful public event, which, in itself, was of benefit to our community.

Following the webinar, ADHD Ireland generously offered to fund two additional places on the programme, which meant seven places in total. The open-call application process was simple and accessible with support available upon request. The selection criteria ensured a diversity of practice, background, ethnicity, levels of professional experience, and neurodivergent conditions. We were delighted with the quality of the applications, but noticed a lack of artists of colour, traveller artists, male artists, and older artists, which speaks to the systemic difficulties faced by intersectional artists.

All applicants were offered an online Access Rider workshop, facilitated by disability-led theatre company, Birds of Paradise. It felt important to acknowledge the

time and effort in making an application in this context, and we wanted to recognise that investment by offering something to all applicants in return.

The selected participants were: April Bracken, Natany de Souza Gomes, Megan Scott, Patrick Groenland, Maria McSweeney, HK Ní Shioradáin, and Nathan Patterson. The encounter took place at IMMA from 12 to 16 May, with an online briefing in advance. Beforehand, we created a visual guide for the artists, to try to make their journeys to IMMA and time there as accessible and easeful as possible.

The week was frontloaded with creative workshops, talks and tours, including: yoga, pathways and mapmaking, creative writing, performance, sound, a biodiversity tour, a slow art experience, a tour of the permanent collection, and guest workshops with Aideen Barry, Louis Haugh, Carl Kennedy, and Joanne King.

By midweek, the artists were beginning to structure the final workshop, with an emphasis on showcasing their practices as well as accessibility priorities. They each took ownership of a section of the workshop, but co-facilitated sections and were always assisted by the group. It was a highly impactful experience for the attendees, who are now looking at aspects of IMMA’s visitor engagement in new ways.

Throughout the week, we spoke about the importance of how we encounter a new space. Artists were encouraged to think about an objective experience of the institution as well as their own personal experience and internal narrative. This allowed them to more comprehensively evaluate access barriers, both as artists and visitors to IMMA. We then needed to articulate personal engagements with the environment in a way that was empathetic and meaningful to both neurotypical and neurodivergent stakeholders. Rather than simply pointing to access barriers, the artists created a workshop where participants could truly experience barriers, which elicited an empathetic, embodied response. They identified tangible areas where IMMA could improve access, including clear signage, maps, sensory considerations and supports, visitor visual guides, and certain aspects of communication.

From a development perspective, the artists highlighted several key benefits, including: the opportunity to learn from each other’s artistic and facilitation practices; having access needs met; having a defined end goal; being paid for their work; and a shared understanding and acceptance of neurodivergence. We are now evaluating the process and outcomes with IMMA and DCC, in order to shape future plans.

Jody O’Neill is an autistic writer, performer, producer and inclusion consultant.

Miguel Amado: Your exhibition ‘Gvozdene Kapije / The Iron Gates’ presents a film of the same title and a group of corresponding sculptures, influenced by Lepenski Vir – an ancient settlement on the banks of the Danube River in eastern Serbia. Your encounter with this culture has triggered reflection on your European heritage and upbringing in Australia. What is the framework that informs these works?

MIGUEL AMADO INTERVIEWS BARBARA KNEŽEVIĆ ABOUT HER NEW TOURING EXHIBITION.

Barbara Knežević: This is the first time that I am engaging with notions of identity in my practice. Yet I am not claiming to have a unique position – this is not a story specific to me, but an Australian story of displacement after the Second World War, a story of the Balkans and a story about migration. We live in an era defined by people migrating globally, and so my subjectivity is one that is shared widely. My focus is on what happens when people are forcibly relocated and re-establish themselves somewhere else. I am interested in the diaspora, namely in first and second generations of people born to migrants.

MA: You want to reclaim your diasporic experience?

BK: Yes. I made a couple of decisions – minor things, but nevertheless powerful – that helped me in that undertaking, for instance to put the diacritic marks on my surname and to learn the jezik (language or tongue), or what is now known as Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian.

MA: This is your first film – a feature, 48 minutes long. What led you to choose this medium? Was there a storytelling aspect that you felt was required to examine such complex themes?

BK: I wanted to explore the narrative potential of sculpture. I had been researching votive objects from Europe, mainly Greek,

Roman and Etruscan traditions, and then I cast my eye a bit further back and came across the sculptures of Lepenski Vir, which were found along a stretch of the border between Serbia (then Yugoslavia) and Romania during the construction of the Iron Gates, a dam on the Danube River, in the 1960s. There are three reasons why these sculptures interested me. Firstly, there is a claim by the archaeologist who discovered them, Dragoslav Srejović, that they are the first monumental sculptural forms in Europe. On the other hand, they are part of what archaeologist Marija Gimbutas conceptualises as a culture structured by matriliny. Finally, the inhabitants of Lepenski Vir lived alongside the sculptures in their dwellings, and there is some evidence that they produced them over a series of generations.

MA: Aesthetically, the sculptures are unique; they are carved in sandstone and express a hybrid of human and a certain fish that is common in the region. The fish (Moruna) is one of the five characters in the film. The others are one of the sculptures (Water Fairy), the mountain (Treskavac), the river (Danube) and the dam (Đerdap), who each materialise through voiceover.

BK: The characters were all written from a first-person perspective, describing their experiences and relationships to one another, in a polyphonic arrangement. I had accumulated a vast amount of visual and written material, and realised I could not ‘translate’ all this research through a single perspective, nor use a purely documentary approach. I had to employ the device of fiction, and these characters were what facilitated that.

MA: This fictional dimension is mainly complemented by three types of imagery: speeches-to-camera by experts, who offer explanations of the sculptures;

archival footage, associated with the construction of the dam by the Yugoslav and Romanian governments, which provides a political context; and the dance sequence, in a hotel situated in what became the Lepenski Vir archaeological site, interspersed with views of welded-steel-chain tapestries, specially produced for the site by artist Zvonimir Šutija, from which you got the inspiration to create a sculpture that the dancers manipulate.

BK: The archival footage, which includes former Yugoslav president, Josip Broz Tito, and ordinary citizens of both Yugoslavia and Romania, helps me navigate temporal shifts, in line with the methodology of the essay and experimental genres in cinema or journalism. The choreographed element is a way of articulating the link between people and matter via embodiment and, through that, feminist discourse.

MA: Is this why the performers are all women?

BK: Yes, in allusion to Gimbutas’s reading of the Lepenski Vir culture as matrilineal. Each performer embodies a character, whose voice is also female.

MA: The sculpture you created has a circular shape, referring to cyclicality, collectivity and spirituality.

BK: The sculpture evokes the whirlpools common in this part of the Danube River, as well as the dam’s turbines. This motif represents spinning into something one cannot escape. I fabricated and welded the piece myself. This was quite labour intensive and emotional, and related to the life of my grandmother, who was forced to make munitions in a German factory during the Second World War.

MA: The various registers are brought together in a

scene where you appear, reflected in a hotel room mirror, slamming down clay and speaking in jezik, like the other characters. The scene gives the impression of both dislocation and introspection, even psychological charge – there is a ‘fantastical’ atmosphere that suggests a spectral presence, which points towards memory and civilisation. This allows you to simultaneously insert yourself into the past and distance yourself from it –particularly concerning your grandmother, who was deported to Germany and a victim of forced labour.

BK: This scene is the punctum – it breaks the fourth wall (which also happens at the beginning and the end, with the crew and the cast for the characters) and empowers me to revisit and interpret the sculptures of Lepenski Vir through the lenses of my family’s condition and movement from Europe to Australia. My position as author is that of both insider and foreigner, a liminal space occupied by someone between geographies and histories.

Miguel Amado is a curator and critic, and director of Sirius Arts Centre in Cobh, County Cork. siriusartscentre.ie

Barbara Knežević is an artist based in Dublin. Gvozdene Kapije / The Iron Gates (2025) was commissioned by, and presented at, Solstice Arts Centre (29 March – 30 May 2025) as part of a tour that includes Sirius Arts Centre in 2025, and Wexford Arts Centre and Regional Cultural Centre in 2026. The tour is curated by Rayne Booth with support from Sirius Arts Centre. barbaraknezevic.com

THE ARTIST’S EYE programme at the Douglas Hyde Gallery invites exhibitors in Gallery 1 to select artists for Gallery 2. The Baghdad-born, London-based painter Mohammed Sami has chosen the Dutch artist Bas Jan Ader. Designed to show the importance of influence, the pairing is instructive, and even more so if you put the separate exhibition titles together. Suggesting a stymied address, ‘To Whom it May Concern – I’m Too Sad To Tell You’ offers a plaintive note that illuminates both practices.

JOHN GRAHAM REVIEWS THE CURRENT EXHIBITION BY MOHAMMED SAMI AT THE DOUGLAS HYDE

Sami makes very big paintings showing ostensibly very little, their outward appearance bristling with dark interiors. A painting called Law Books (2023) is almost three meters high and consists of a painted brick wall. The painstakingly modular surface has eruptions of red, a seeping wound or inferno. I wrote ‘blood shadow’ in my notebook, but that doesn’t have to mean anything. Unless the bricks are stacked volumes, the ‘Law Books’ of the title remain a mystery. We can speculate about analogies, but the only certainty is that Sami’s titles do a lot of work.

In a series of well-known short films, Bas Jan Ader rolls off rooftops and cycles into canals with an absurdist insouciance. In the wake of his final work, In Search of the Miraculous (1975), the artist’s corpus persisted but his corporeal presence disappeared. Projected onto a suspended screen in Gallery 2, his three-minute black and white film I’m too sad to tell you (1971) is formally similar to Andy Warhol’s 16mm Screen Tests but is their dramatic obverse. As though foreseeing his own cult, Ader’s ‘living portrait’ eschews studied nonchalance for performed emotion, an agitated close-up of weeping. In the absence of bodies – a feature of Sami’s work too – the human stain, the bodies’ leftover presence, seems everywhere. Directly opposite Ader’s work in Gallery 2, a vertical painting is called The Operations Room (2023). Rattan chairs are gathered

around a circular table. From the acutely downwards point of view, a patterned carpet is a scramble of brushy marks. With a title suggesting military planning, the painting’s sickly palette of violets and maroons is punctuated by a creeping lacunae, a shadow leeching across the table like the dark side of a forbidding moon.

A smaller painting from 2020 shows a trompe-l’oeil tabletop in a blood-red room. A potted monstera casts a shadow that looks more like a burn. The plant itself (named from the Latin word for monstrous or abnormal) has a sinister aspect too, its perforated leaves like spooky masks. Though the subject is cryptic – the painting is called Still Alive – Sami’s mark-making techniques are plain to see, with paint sprayed, smeared and dragged across the surface as though the material itself was unyielding.

A nominee for this year’s Turner Prize, the Iraqi painter’s work has become increasingly visible, with an accompanying narrative of trauma at once represented and repressed. A dichotomy of the visible and the invisible also plays out on the canvases themselves, a game of hide and seek, reflecting, perhaps, a culture of control being challenged by protean image making.

An exception to the embargo on human figures elsewhere, the familiar figure of Ruhollah Khomeini occupies the top half of a large painting on the back wall of the gallery. Supreme Leader of Iran from 1979 until his death ten years later, Khomeini became better known in the west as simply The Ayatollah. He appears here as a painted projection, an illuminated untouchable, looming over a vast assembly. That his audience is rendered by a loose brushing of liquid blacks testifies to Sami’s economic mark-making and my own willingness to see what isn’t there. Called Brick Game (2024), the title refers to a version of Tetris. An irregular host of white shapes could be bricks ascending in the manner of the outmoded video game but are more suggestive of mobile phones being held aloft. That reading is inconsistent with Khomeini’s era, but the era of painting is always now.

Born in 1984, Sami came of age in the presence of war. In the gallery setting, the raised hand of the Iranian leader could be understood as a welcome or a warning. The work by Ader conveys a similar ambivalence. As legacy and troubling continuance, both practices mine a difficult past to fashion an infinity of traces: Sami’s haunted surfaces, Ader’s exit ghost.

John Graham is a Dublin-based artist and writer.

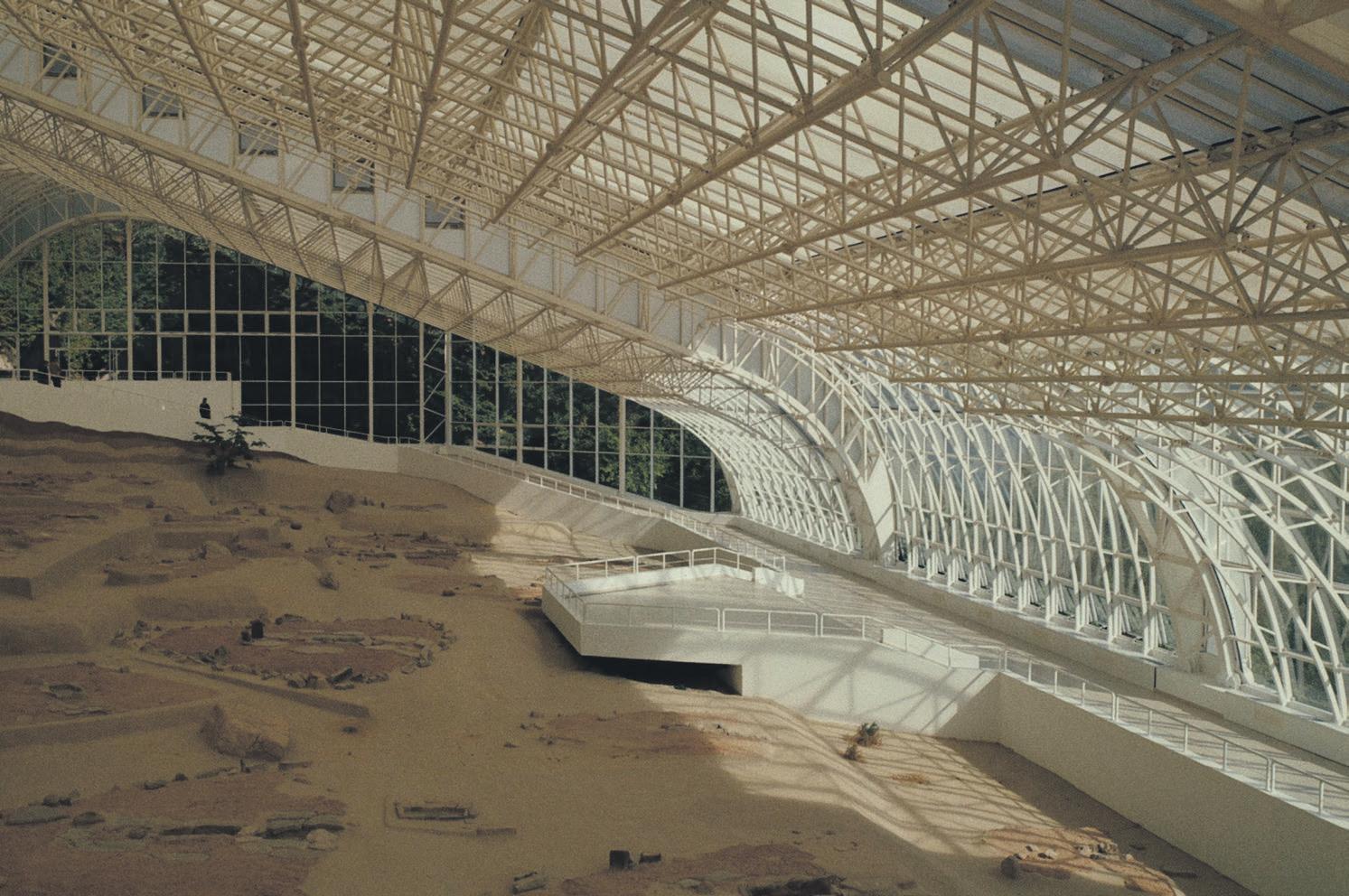

FEATURING OVER 40 Irish or Ireland-based artists, ‘Staying with the Trouble’ at IMMA feels especially important to the current moment. The exhibition is grounded in the research of Donna Haraway and is titled after her seminal text, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016).

SADBH O’BRIEN REVIEWS A CURRENT EXHIBITION AT IMMA.

A prominent figure in contemporary eco-feminism, Haraway offers reassuring perspectives on how we can respond to, and make sense of, troubling times. Where catastrophic events and seismic geopolitical shifts are triggering and can overwhelm us into inertia, Haraway gives us proactive methods to sit with, counteract, and think around these complex systems. Her expansive thesis conjures a biomorphic, multispecies space of storytelling, which denounces human exceptionalism and decentres capitalist viewpoints of the world.

This is a space of transmogrification in which genders and genres can be indeterminate, unresolved and of course, open to what she calls ‘Tentacular Thinking’. From this, the curators have used five propositions, as defined by Haraway: ‘Making Kin’, ‘Composting’, ‘Sowing Worlds’, ‘Critters’ and the ‘Techno Apocalypse’. However, strictly categorising each artwork into one of these is tricky, since most are multi-faceted and interwoven across multiple perspectives.

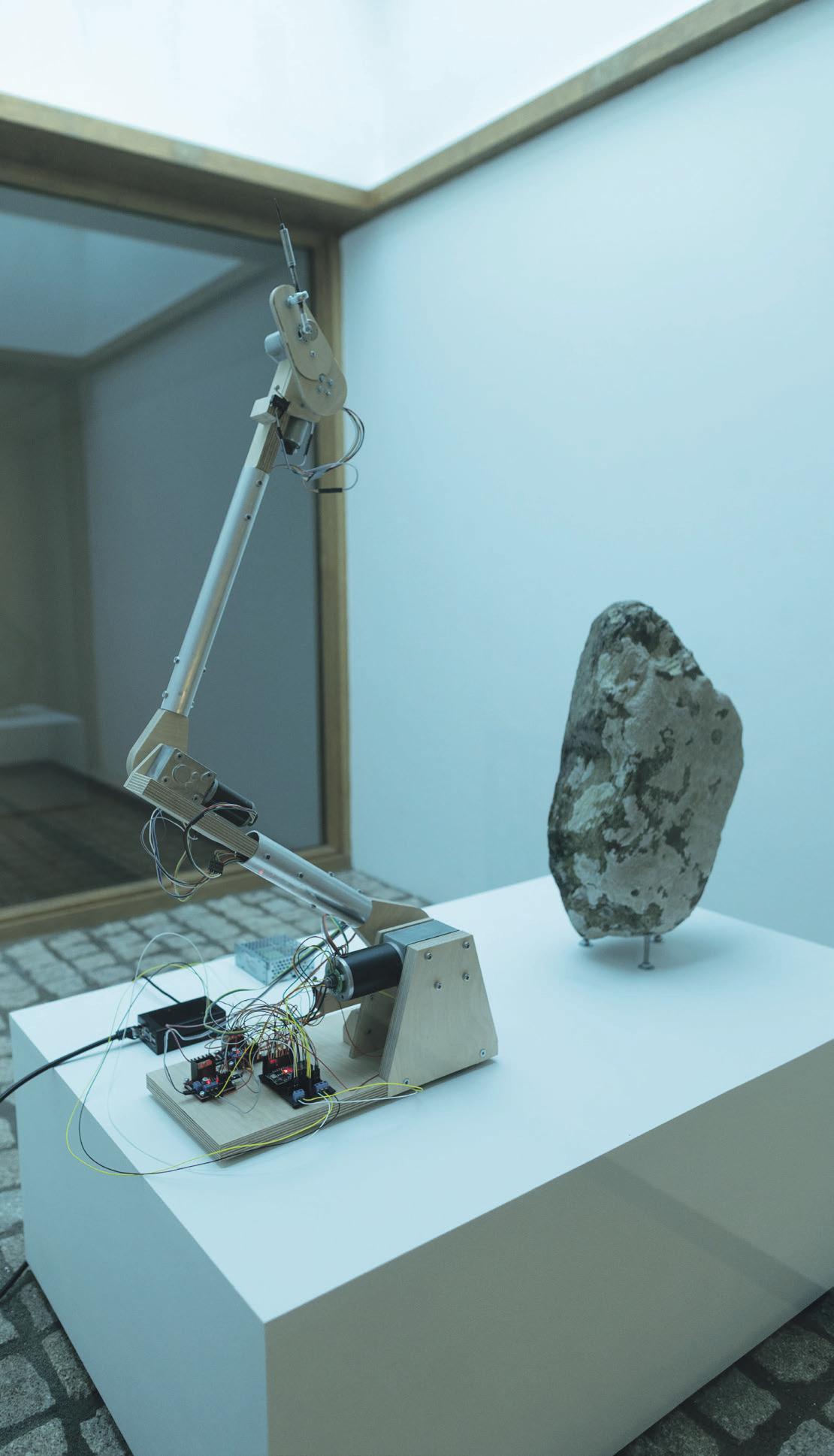

The first works encountered are rooted in a type of magic. In Kian Benson Bailes’s sculpture, Self Actualiser (2024), four spider-like creatures, playfully adorned with frills, phalluses, and bells, hang from coloured thread. Their knotted web evokes a playful and creative engagement – a woven dance. The multi-eyed faces are both mischievous and wise, evoking the supernatural, and alongside the small ceramic figurine, Weather Statue (2025), and textile creature, Archiver ii (2025), reflect the artist’s interest in folklore

customs and craft traditions.

The theme of ‘Composting’ arises in Bea McMahon’s ‘low-tech’ biomorphic breathing sculptures, Ierse Stoofpot/ Irish Stew (2024). The paper structures are stained with organic matter, such as beetroot, turmeric, coffee, and cabbage – a potent concoction influenced by Macbeth’s witches’ brew. Earthly, human, and cyborg, the work’s continuous inflation and deflation is controlled by exposed mechanical apparatus. Aoibheann Greenan’s compelling film, The Ninth Muse (2023), combines moving image, performance, and sculpture. A witch-like husky whisper conflates sinew with cables, skin with plastic, creating a speculative narrative on techno-human experience. It highlights looped technological systems and sits at the intersection of neuroscience, techno-feminism, myth, and magic.

Storytelling is central to the proposal of ‘Sowing Worlds’, focusing on planting ideas, relationships and stories that can influence potential futures. Visually striking works by Samir Mahmood and Sam Keogh expand this allegorical approach with colourful, figurative scenes, informed by the Mughal miniature painting tradition and sixteenth-century Flemish tapestries, respectively.

Venus Patel’s enrapturing film, Daisy: Prophet of the Apocalypse (2023), confronts and dismantles the heteronormative and transphobic preaching of religious indoctrination. Patel plays a self-proclaimed transexual Texan preacher who is attempting to convert the public to an LGBTQ cult, baptising her followers, who emerge from biblical waters as hybrid queer creatures. In this way, Patel flips abusive anti-trans and homophobic sentiments back towards heteronormative constructs in a truly effective manner.

Companionship and cohabitation between the humans and non-humans that share this planet are central to ‘Making Kin’, which proposes forming bloodlines to other planetary organisms. Alice Rekab uses their mixed-race heritage to consider identity through familial connections across two distinct places. In nest of tables (Red): together in difference (2022), Rekab blends the domestic and familial to highlight the symbolic influence of animals within cultural history.

Given that agriculture forms part of Irish heritage and contributes significantly to the country’s economy, it’s unsurprising that several works deal with farming practices and its by-products. For example, Watchorn’s sculpture, Surrogate II (field) (2021), a bevelled block of beef fat and leather rosette, mechanically bolted by gate clamps to a weathered fragment of a shipping pallet, demonstrates the artist’s clever and intuitive use of materials. Here, a tension occurs between life, death, and the stark inhumanity of systems designed to extract maximum value from livestock.

McKinney’s Drumgold Holly Embryo Transfer (2021) is a curiously striking sculpture comprising a crescent-shaped, galvanised, steel cattle feeder, flipped on its side and weighed down by sandbags. Hanging from this is a brightly coloured sculpture, woven from artificial insemination straws. Inspired by a protective talisman, made from a bunch of holly found in a Wexford farm, the woven straws form clusters of berries, from which pointed cat-

tle horns emerge. It calls to mind the very real grief and suffering in Andrea Arnold’s film, Cow (2021), showing the life of a dairy cow through the animal’s eyes, beginning with a heart-breaking postnatal separation. Like the film, McKinney’s work exposes stark systems of physical and psychological control, built into the engineering of farming apparatus, and questions the impact of bioengineering on our bovine counterparts.

Bridget O’Gorman also examines systems of power, specifically how civil infrastructure excludes those of us who have access or mobility issues. Highlighting a world rife with barriers, her installation, Support | Work (2023), forms a system of precarious, suspended pulleys, made from haphazard parts of mobility aids and fragments of mosaic flooring. The combination provokes a sense of phantom pain, as one imagines the brittle sculptures falling to the floor.

‘Techno Apocalypse’ draws on religion’s preoccupation with the end of the world; however, the presented works aim to variously subvert or dismantle end-stage capitalism. Both Austin Hearne and Luke van Gelderen focus on patriarchal systems of identity from a queer perspective. Hearne’s Curtains of Celibacy and Glory Box (both 2023) reference church interiors and confessionals, while alluding to institutional hypocrisy and oppression within the Catholic Church. Employing interior design techniques, including hand-painted wallpaper, the artworks subvert ‘divine’ authority by building an opulent, ecclesiastical den of secrecy and queer desire.

Van Gelderen’s film, HARDCORE FENCING (2023), examines the influential tropes of contemporary masculine identity emerging from digital culture and far-right politics. The film exposes the deep fault lines of insecurity, unpredictable anger, and violence – forces that have recently been seen on the nation’s streets. This is further evident in clips of riots, fires, and protests in Eoghan Ryan’s Circle A (2024). The film records a group discussing the term ‘anarchy’ and its role in contemporary society, unravelling its place within academia and lived experience in an increasingly polarised political landscape. In the face of accelerating global conflict, Diaa Lagan’s paintings offer reflection on political upheaval. Arabic calligraphy is laser-cut from Perspex, framing imagery of ancient Islamic architecture, designed for peace and tranquillity.

Continuing at IMMA until September, ‘Staying with the Trouble’ takes time for viewers to navigate, since the featured artists (too many to mention here) variously pull from complex material, digital, and metaphysical realms. Returning to Haraway’s argument for expansive ways of thinking about the world right now, the exhibition illustrates how humans are deeply woven into systems of interconnectedness, to which we have a profound and urgent responsibility.

Sadbh O’Brien is an artist and writer based in Dublin.

ON ‘BEUYS

AS PART OF the exhibition tour, ‘A Secret Block for a Secret Person’, Joseph Beuys visited Belfast on 18 November 1974, during a time of unending violent crises in Northern Ireland. In the Fine Art Gallery of the Ulster Museum, a coterie of interested artists, performers, and thinkers gathered to witness a legendary performance lecture or ‘action’ from Beuys, a mythic and monumental figure of great charisma and intellect.

Amidst the post-war decades of geo-political upheaval, the conceptual artist became a central figure of the Fluxus movement, expanding performance art to activist happenings and live debates. His absurdist methods coloured subsequent performance art and socially engaged practices for much of the twentieth century. Beuys advocated for “unity in diversity” and once stated that “discarded hope breeds violence” – which remains as presciently relevant today as it was 50 years ago.

What a febrile opportunity, then, amid our current poly-crisis, for the Ulster Museum to commemorate the 1974 Irish lecture tour and its reverberations with an exhibition titled ‘Beuys 50 Years Later: Action, Society, Performance and Change’. His famous performance blackboards, together with audio clips and black and white photographs from the action, were exhibited in a small room on the fourth floor of the

museum, curated by Anna Liesching.

Arguably, the practice and pedagogy of many performance artists and collectives in Northern Ireland might not have gained momentum without his high-profile visit to Belfast. As part of the exhibition, artists, curators, writers, and poets – many of whom continue to make work that could tangibly be threaded back to Beuys – took part in the accompanying performances, workshops, and events.

The museum co-hosted several events which re-considered the process and aims of ‘art for all’. On 18 November 2024, a symposium, titled ‘Root to Crown’, was curated by Thomas Wells on behalf of the Belfast International Festival of Performance Art, inviting responses from artists across Ireland who encapsulate Beuys’s ideas on ecology, pedagogy, and time.

Ulster Museum’s invited artists for other events firmly situate themselves within queer, feminist, and progressive practices, long fomented in Northern Ireland. One of these was Sally O’Dowd, who has been delving into the museum archives to identify women performance artists who were active in Ireland during the time of Beuys’s visit. O’Dowd ran experimental art sessions with physical movement and art exercises, inspired by Jane Fonda, in which each participant created a series of drawings, followed by a collective ‘dance-off’ drawing.

O’Dowd was playing with the Fluxus-inspired process of ‘creative action’ rather than fixating on outcomes. In a playful take on the changeable blackboards, she installed Drawing Machine (2025) – a lo-fi drawing apparatus to facilitate the collective enactment of large and chaotic drawings to music. There was also a display case of ‘Performance Documentation’ drawings and a selection of works exploring the ‘Transformative Line’ of drawing, selected by O’Dowd from the Ulster Museum’s paper archive.

On Saturday 12 April, Emma Brennan’s performance, Girls Who Like Beuys (2025), incorporated the materials of chalk and peat, channelling Celtic mythology and pre-colonial presence in Irish performance art. Brennan presented members of the audience with peat from a latex creation, in a continuation of themes awakened in her previous performance, It is I am (2024) at Belfast Exposed. Girls Who Like Beuys demonstrated a neat lineage, from the interdependent concerns of Beuys to Belfast’s burgeoning contemporary, queer, feminist practice.

Presented in the main exhibition was an intriguing short film by Amanda Coogan, Gnawing on the Bones – Reflections on Beuys (2022), originally commissioned by the Hugh Lane Gallery and first screened in conjunction with the exhibition, ‘Joseph

Beuys: From the Secret Block to Rosc’. Coogan delivered a five-hour durational performance on Saturday 17 May during the exhibition’s closing weekend. Embodying Beuys by wearing his ‘uniform’ (white shirt, waistcoat, trousers), Coogan’s performance also incorporated the Beuys-like props of black hat and walking stick (or ‘action cane’) alongside stereotypical artist accoutrements (easels, canvas, paint) and Beuys’s conceptual materiality (felt and fat). Often, she would emerge from the detritus with a new absurd or shiny object, her playful movements trying to disrupt and escape the conventions of classical art education.