Biostimulant Applications in Watermelon Production

Evan Ch ristensen, Milena M. T. de Oliveira , Youping

Introduction

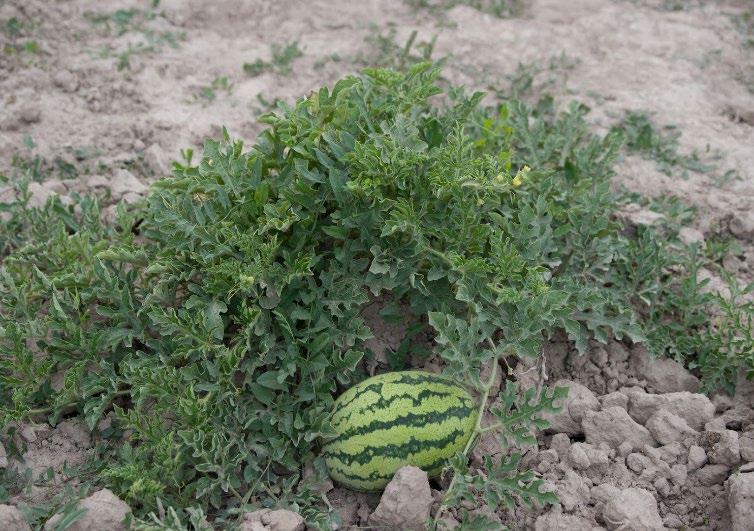

Watermelon is a water-intensive vegetable crop that is sensitive to drought and requires an adequate supply of nutrients for good yield and fruit quality. It is an important vegetable crop grown on 142,000 acres in the United States and 586 acres throughout Utah.

Utah experienced its driest year on record in 2020 during a five-year drought (2019 to 2023). This affected local ecosystems, such as the Great Salt Lake, which suffered recordlow water levels. The drought also negatively affected the agricultural sector, including watermelon growers. Higher-than-average fertilizer prices in recent years have also threatened watermelon production. Growing awareness of agriculture's water use and its contribution to nutrient pollution in waterways has prompted investigations into reducing water and fertilizer applications to achieve more sustainable watermelon production in Utah. Plant biostimulants have been shown to increase drought tolerance and enhance nutrient efficiency and may be a novel method to combat these challenges.

What Are Biostimulants?

Highlights

• Producers grow watermelon on 586 acres in Utah.

• Drought and high fertilizer prices have affected watermelon production.

• Biostimulants are microorganisms or substances applied to seeds, plants, or the soil

• Non-biological biostimulants include seaweed extracts and humic products.

Plant biostimulants are any microorganism or substance applied to seeds, plants, or the soil that stimulates natural processes to enhance or benefit nutrient efficiency or uptake, tolerance to stress, or crop quality and yield (Gedeon et al., 2022). Many substances and microorganisms can be considered biostimulants. Similar substances and microorganisms are grouped into major categories (du Jardin, 2015). These include beneficial bacteria and

• Adding biostimulants to seeds, plants, or the soil can enhance nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and crop quality and yield.

• Short-term applications may be insufficient to show biostimulant benefits according to trials run in Utah.

• More research is needed before commercial recommendations for watermelon production.

Sun, Grant Cardon, and Dan Drost

fungi, seaweed extracts (and botanicals), humic products, protein hydrolysates and other nitrogen compounds, chitosan and other biopolymers, and some inorganic compounds. Another useful way to classify them is biological or nonbiological biostimulants.

Biological Biostimulants

Biological biostimulants aim to foster relationships between plants and microbes that have evolved over millions of years. Bacteria and fungi are abundant in soil with around 108 and 105 individuals per gram of soil, respectively. The rhizosphere, which is the zone of soil influenced by plant roots, has a greater number of organisms, increased microbial activity, and altered microbial diversity from the bulk soil. Plants influence soil microbial diversity through changes in molecules excreted by roots. These “root exudates” serve as nutrition and attractants for microbes. Exudates are composed of amino acids, carbohydrates, enzymes, organic acids, phenolics, proteins, and sugars. Plants can recruit specific microbes to manage environmental stress, like drought, and satisfy nutrient needs based on plant growth stage. While many microbes associate with plants (actinomycetes, algae, archaea, bacteria, and fungi), biological biostimulants are primarily beneficial bacteria and fungi.

Beneficial Bacteria

Beneficial bacteria have been used on watermelon in greenhouse transplant production and field production, with reported increased growth and drought tolerance.

Bacteria can live in the bulk soil, the soil around the root, on the root surface, or within plant tissue Some bacteria are beneficial to the plant, many are harmless, and others can cause disease. Beneficial bacteria, also called plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, have been shown to promote growth through many modes of action, including nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and the production of plant growth regulators. A well-known example of this class of biostimulant is Rhizobium bacteria that are associated with legumes and fix atmospheric nitrogen that then becomes available to the plant. The modes of action differ by bacterial species and plant host. Beneficial bacteria have been used on watermelon in greenhouse transplant production and field production, with reported increased growth and drought tolerance.

Beneficial Fungi

Another category of biological biostimulants is beneficial fungi. Mycorrhizae are the most prominent type, although nonmycorrhizal fungi have also been shown to transfer nutrients to plant roots and may have an application in agricultural systems (du Jardin, 2015). Mycorrhizal fungi are classified as ectomycorrhiza (outside) and endomycorrhiza (inside). Ectomycorrhizal fungi grow in the intercellular space between plant root cells and are mostly associated with woody plants. This makes them important in forestry and nursery applications. Ectomycorrhizal fungi have been shown to have an association with pecan trees and may be useful in some orchard settings.

Multiple species of mycorrhizal fungi have been shown to infect watermelon roots

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are endomycorrhizal fungi that have associations with 78% of vascular plants (Gentry et al., 2021). AMF have been shown to help plants increase nutrient efficiency and acquisition (especially phosphorus) and aid in stress protection (du Jardin, 2015), either directly or through changes to the gene expression of host plants (Ma et al., 2024). AMF grow inside of plant root cells and form structures called arbuscules, and most form vesicles that are filled with lipids (Gentry et al., 2021). AMF are sensitive to biological, chemical, and physical disturbances (Verzeaux et al. 2017) In high disturbance agricultural systems, AMF products could supplement the native soil population. AMF can form tripartite interactions with plants and rhizobacteria (du Jardin, 2015), and multiple species of AMF can infect the same host plant (Verzeaux et al., 2017). Multiple species of mycorrhizal fungi have been shown to infect watermelon roots

Non-Biological Biostimulants

Non-biological biostimulants are an important portion of the biostimulant market. Products containing seaweed extracts and humic substances are popular non-biological biostimulants. Substances such as chitosan, protein hydrolysates, plant extracts, and inorganic compounds are also considered biostimulants and are widely used. While some non-biological biostimulants may be derived from living organisms, they are not alive when applied and cannot propagate.

Seaweed Extract

Seaweed extract products are popular biostimulants. Seaweed has a long history of use in agriculture as a source of organic matter and fertility in coastal regions (Battacharyya et al., 2015). Seaweed extract products are derived from brown, green, or red seaweed through multiple extraction processes that aim to keep active molecules intact. Carbohydrates, amino acids, limited quantities of phytohormones, osmoprotectants, and proteins are the proposed mechanisms for the biostimulant effect (Lefi et al., 2023), although there is evidence that regulating hormone synthesis genes may be the true mechanism (du Jardin, 2015).

Humic Substances

Humic substances are another popular biostimulant. Humic substances naturally occur as part of soil organic matter, but humic and fulvic acid products are extracted from peat, soils, compost, and mineral deposits for application to crops (Ampong et al., 2022). Historically, humic substances were broken down into three subclasses based on molecular weight and solubility (du Jardin, 2015). These include humic acids, fulvic acids, and humins which are characterized by their solubility in water, acidic, or alkaline solutions (Ampong et al., 2022). Humic acids are widely used in agriculture and can improve soil water holding capacity and structure, increase microbial populations, and enhance soil nutrient availability (Ampong et al., 2022). A precipitation reaction can occur between humic acids and heavy metals in the soil, reducing metal uptake by plants and toxicity (Ampong et al., 2022).

Biostimulants in Watermelon: USU Trials

To investigate the possibility of using biostimulants to reduce water and fertilizer applications, Utah State University (USU) researchers conducted trials on watermelon. Researchers used seven commercially available biostimulant products and investigated the efficacy of using biostimulant products in watermelon transplant production. Those showing promising performance were applied to field-grown watermelon under reduced applications of water and fertilizer. Experiments were conducted in 2023 and 2024 in North Logan, Utah. And finally, outreach trials were established on grower-cooperator fields throughout Utah using the same seven commercially available biostimulant products that were tested in the greenhouse

Greenhouse Transplant Production Case Study

Most watermelon production in the U.S. uses seedless cultivars, which are typically grown in greenhouses and transplanted due to poor seed germination and slow establishment in the field. The objectives were to: (1) evaluate commercially available biostimulants to improve watermelon transplant production, and (2) select superior products for

later field applications. Researchers selected and tested seven biostimulant products on watermelon seedlings (cv. ‘Crimson Sweet ’) to evaluate their effects on seedling emergence and growth:

• Three bacterial products (Continuum™, Spectrum DS™, and Tribus® Original)

• Two mycorrhizal products (Mighty Mycorrhizae and MycoApply® Endo).

• One seaweed extract product (Kelpak®).

• One humic product (Huma Pro® 16)

Products, except Kelpak, were incorporated into a peat-based soilless potting media. Seeds were sown into the inoculated media, and plants were grown for 30 days after emergence. Three trials were performed. Kelpak was applied at the first true leaf stage, so no conclusions can be drawn on this product’s effect on seedling emergence. Generally, applying biostimulant products had little effect on watermelon seedling emergence. After 30 days of growth, researchers weighed the seedlings’ shoots and roots (Table 1) and measured the leaf area. No differences in shoot growth or leaf area were noted between biostimulant-treated seedlings and the untreated control. In two trials we noted no difference in root weight between untreated and biostimulant treated seedlings. In one trial, a root rot affected the seedlings. Differences between treated seedlings and the control occurred, suggesting that these products may help plants manage biotic stress. While no differences in growth were noted, three products (Continuum, Spectrum DS, and Mighty Mycorrhizae) had numerically higher shoot weight and were selected for field studies.

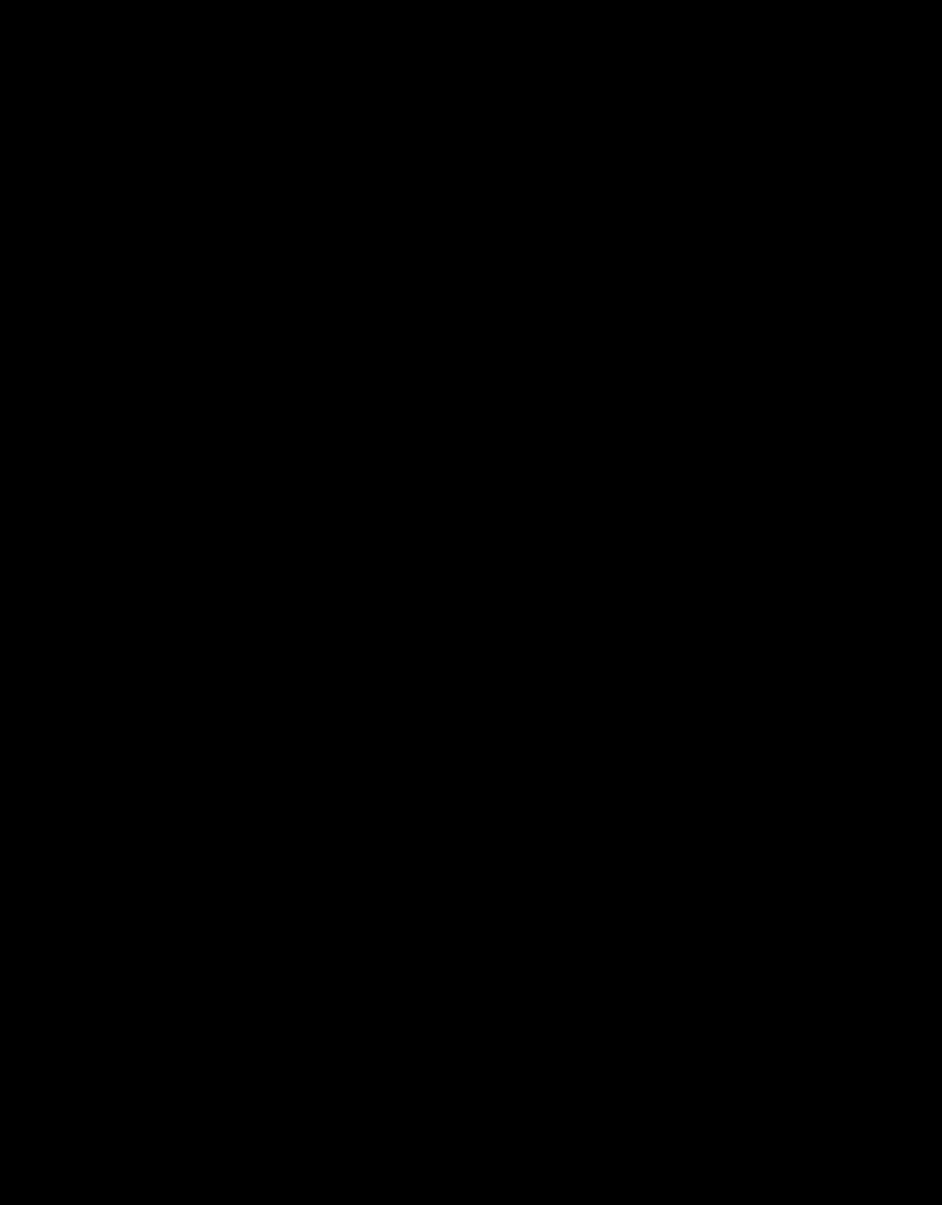

Table 1. Shoot and Root Fresh Weight (g) of Greenhouse-Grown Watermelon Seedlings (cv ‘Crimson Sweet’)

Biostimulant

(g)

A, B, C Different letters within a column indicate significant differences at α = 0.05 using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test.

Notes. Trials were conducted three times in 2023. Seedlings were untreated (control) or treated with: bacterial biostimulants (Tribus Original, Continuum, or Spectrum DS); mycorrhizal biostimulants (MycoApply Endo, or Mighty Mycorrhizae); seaweed extract Kelpak; or humic acid Huma Pro 16.

Field Production Case Studies

Three products selected from greenhouse trials were tested in the field. The two bacterial biostimulants, Continuum and Spectrum DS, and the mycorrhizal biostimulant, Mighty Mycorrhizae, were incorporated into soilless growth media, and watermelon transplants were produced. ‘Crimson Sweet’ (seeded) and ‘Fascination’ (seedless) were planted in 2023 and 2024. Seedlings were transplanted into raised beds with drip tape and plastic mulch in late May. Water and fertilizer were applied through the drip tape throughout the season.

Irrigation applications were based on evapotranspiration (ET) models, soil texture, and the use of soil moisture sensors. Water was applied at 100% ET (recommended irrigation) or 75% ET (water stressed) in the late season during fruit sizing. Fertilizer applications were based on soil test results and recommendations from the Utah Vegetable and Pest

Management Guide (Volesky et al., 2020). Plants were fertilized at 100% (recommended fertilizer) or 67% (nutrientstressed) levels over the entire growing season.

No differences were observed in vine growth, yield, or fruit quality based on biostimulant treatments (Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Reducing irrigation from 100% ET to 75% ET in the late season did not reduce yield in either year but did increase soluble solids content. Reducing fertilizer applications by 1/3 had no effect on yield or fruit quality in 2023, although a reduction in vine growth was observed. In 2024, the recommended fertility treatment had a higher yield and fruit number per meter squared than the reduced fertility treatment.

A Different letters within a column indicate significant differences at α = 0.05 using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test.

Notes. Watermelon plants were subjected to standard management practices (control), added bacterial biostimulants (Continuum or Spectrum DS), or added fungal biostimulant (Mighty Mycorrhizae). Plants were fertilized at 100% or 67% levels of fertility or irrigated at 100% or 75% (in the late season) of evapotranspiration on top of biostimulant treatments.

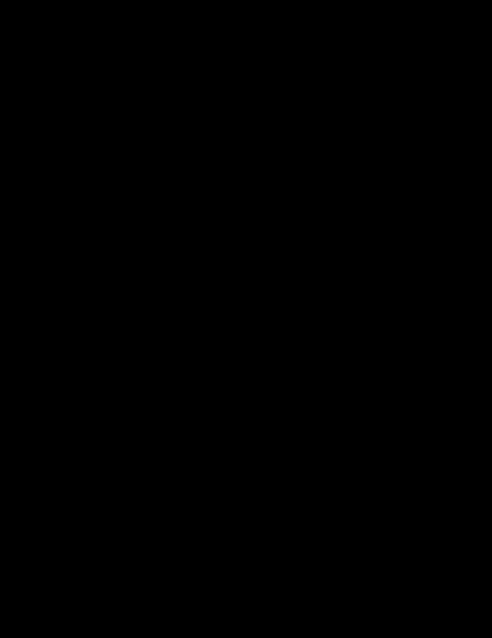

Table 3. Fertility Trial: Total Yield (lb∙acre-1) and Soluble Solids Content (SSC in °Brix) of Watermelon Fruits Grown in 2023 and 2024

Biostimulant

A, B Different letters within a column from the same factor indicate significant differences at α = 0.05 using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test.

Notes. Watermelon plants, seeded ‘Crimson Sweet’ and seedless ‘Fascination’, were subjected to standard management practices (control), added bacterial biostimulants (Continuum or Spectrum DS), or added fungal biostimulant (Mighty Mycorrhizae). Plants were fertilized at 100% or 67% levels of fertility rate on top of biostimulant treatments.

Table 2. Length of Watermelon Vines (m) Grown in 2023 and 2024

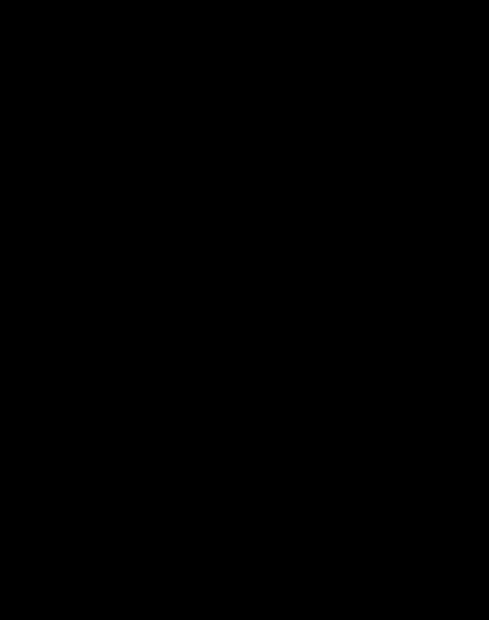

Table 4. Irrigation trial: Total Yield (lb∙acre-1) and Soluble Solids Content (SSC in °Brix) of Watermelon Fruits Grown in 2023 and 2024

Biostimulants

A, B Different letters within a column from the same factor indicate significant differences at α = 0.05 using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference test.

Notes. Watermelon plants, seeded ‘Crimson Sweet’ and seedless ‘Fascination’, were subjected to standard management practices (control), added bacterial biostimulants (Continuum or Spectrum DS), or added fungal biostimulant (Mighty Mycorrhizae). Plants were irrigated at 100% or 75% (in the late season) of evapotranspiration on top of biostimulant treatments.

Grower Cooperator Case Study

Studies were established in watermelon fields in Cache, Emery, and Utah counties (Table 5). Products were applied as a soil drench at manufacturer recommended rates to watermelon seedlings before transplanting into the field. Cultivars used were chosen by the grower, and treated plants were spaced according to each grower’s specification. Products were reapplied to the soil at one-month intervals throughout the growing season. Field variability is likely a large contributor to the overall performance variability and may not be related to treatments.

There were large yield differences between farms. The low yield at Farm 3 was likely due to high plant mortality on edge rows of the field. Due to scheduling conflicts, some fruits were harvested by growers before data was taken, further contributing to the data variability. While some differences are observed from treatment to treatment, the responses are not consistent from farm to farm. While no conclusions can be drawn from these trials, they aided in improving our techniques, providing preliminary data, and strengthening relationships between researchers at USU and melon growers throughout the state.

Table 5. Yield (lb∙acre-1) of W

From Three Farms Across Utah

Pro 16

,500

Notes. Plants were subjected to standard management practices (control) or the addition of the bacterial biostimulants Tribus Original, Continuum, or Spectrum DS, mycorrhizal biostimulants MycoApply Endo or Mighty Mycorrhizae, the seaweed extract Kelpak, or the humic acid Huma Pro 16.

Conclusion

No significant difference in greenhouse-grown seedlings (size, weight) was observed between plants treated with biostimulant products and the untreated control. We found that biostimulant applications had no effect on plant growth, fruit yield, or fruit quality in the field. Biostimulants hold promise in improving crop productivity, and their long-term applications in the field may offer robust benefits that our short-term greenhouse or field work could not fully capture. This warrants further investigation before recommending their use for commercial melon production.

References

Ampong, K., Thilakaranthna, M. S., & Gorim, L. Y. (2022). Understanding the role of humic acids on crop performance and soil health. Frontiers in Agronomy, 4. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fagro.2022.848621

Battacharyya, D., Babgohari, M. Z., Rathor, P., & Prithiviraj, B. (2015). Seaweed extracts as biostimulants in horticulture. Scientia Horticulturae, 196, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.012

du Jardin, P. (2015). Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Scientia Horticulturae, 196, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.021

Gentry T J , Fuhrmann, J J , Zuberer, D A (Eds.). (2021) Principles and applications of soil microbiology (3rd ed). Elsevier https://doiorg.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1016/C2018-0-05260-3

Gedeon, S., Ioannou, A., Balestrini, R., Fotopoulos, V., & Antoniou, C. (2022). Application of biostimulants in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) to enhance plant growth and salt stress tolerance. Plants, 11(22).

Impello® Biosciences. (2025). Continuum™ https://impellobio.com/

Lefi, E., Badri, M., Hamed, S. B., Talbi, S., Mnafgui, W., Ludidi, N., & Chaieb, M. (2023). Influence of brown seaweed (Ecklonia maxima) extract on the morpho-physiological parameters of melon, cucumber, and tomato plants. Agronomy, 13(11), 2745. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13112745

Ma, J , Zhao, Q , Zaman, S , Anwar, A , & Li, S. (2024) The transcriptomic analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) inoculation in watermelon. Scientia Horticulturae, 332, 113184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113184

Verzeaux, J., Hirel, B., Dubois, F., Lea, P. J., & Tétu, T. (2017). Agricultural practices to improve nitrogen use efficiency through the use of arbuscular mycorrhizae: Basic and agronomic aspects. Plant Science, 264, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.08.004

Volesky, N , Murray, M , Olds, A , & Carey, B. (2024) Utah vegetable production guide (5th ed ). Utah State University Extension. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/2460

In its programs and activities, including in admissions and employment, Utah State University does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination, including harassment, based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy, Title IX, or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University is an equal opportunity employer and does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination including harassment in employment including in hiring, promotion, transfer, or termination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University does not discriminate in its housing offerings and will treat all persons fairly and equally without regard to race, color, religion, sex, familial status, disability, national origin, source of income, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Additionally, the University endeavors to provide reasonable accommodations when necessary and to ensure equal access to qualified persons with disabilities. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the application of Title IX and its implementing regulations and/or USU’s non-discrimination policies: The Office of Equity in Distance Education, Room 400, Logan, Utah, titleix@usu.edu, 435-797-1266. For further information regarding non-discrimination, please visit equity.usu.edu, or contact: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 800-421-3481, ocr@ed.gov or U.S. Department of Education, Denver Regional Office, 303-844-5695 ocr.denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L. White, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University. July 2024 Utah State University Extension

The authors used no generative AI in the creation of this content, and it is purely the work of the authors. This content should not be used for the purposes of training AI technologies without express permission from the authors.

January 2026

Utah State University Extension

Peer-reviewed fact sheet