AMERICAN MOVIE 1930s -1970s

SILVER SCREEN

by Peter Bosch

by Peter Bosch

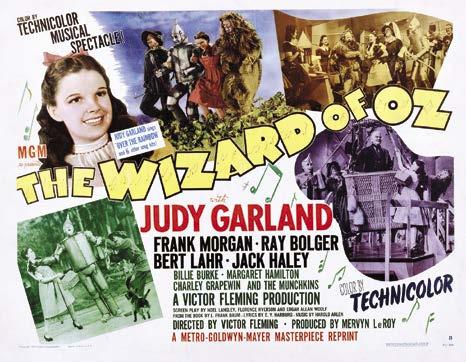

The Wizard of Oz (1939) wrapped up one of the greatest decades in motion picture history.

The world was in turmoil in the 1930s, brought on by the Wall Street stock market crash of 1929. At one point, almost 25% of the American populace was out of work. Herbert Hoover was President of the United States when the Depression started and shanty town areas that sprang up, where the poorest lived in poverty and in unsanitary conditions, were derisively nicknamed “Hoovervilles.” Bread lines existed even in the heart of Times Square.

The plight of the era was well expressed in the Warner Bros. movie musical Gold Diggers of 1933. The opening of the film had Ginger Rogers singing the glories of the end of the Depression in “We’re in the Money” during a rehearsal for a lavish Broadway stage production, but reality interceded with bill collectors barging in and shutting it down for lack of payment.

In 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt won an overwhelming majority of votes over Hoover and in 1933 began what would turn out to be an unprecented 12 years as President. Belief in him rescuing the country from despair was demonstrated in Warner Bros.’ Footlight Parade (1933) during a Busby Berkeley musical number in which his image filled the screen using multiple sections held together by dancers and extras underneath.

Footlight Parade (1933) featured a Busby Berkeley musical number in which multiple sheets are put together to form a picture of the new President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

© Warner Bros. Discovery

FDR’s “New Deal” government programs provided work for millions and helped get the country back on its feet, but it took time and people went to the movies for escapism. And motion picture studios presented it in amazing quantity.

Grand Hotel, Dracula, City Lights, Frankenstein, 42nd Street, King Kong, Mutiny on the Bounty, The Adventures of Robin Hood, Gunga Din, The Wizard of Oz, and Gone With the Wind were just a few of the films released in the 1930s.

It was also the decade in which comic books first appeared!

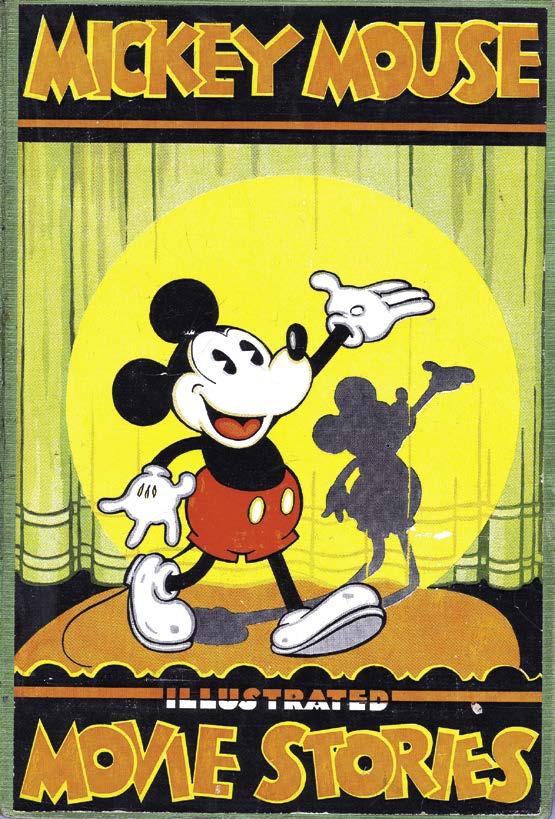

MICKEY MOUSE: Like Charlie Chaplin, Mickey Mouse was a skyrocket of a success in movies. Debuting in Walt Disney’s 1928 cartoon, Steamboat Willie, the mouse quickly went on to become the studio’s top star. A hardcover collection in 1931 of text and black-and-white film screen images adapting 11 early Mickey Mouse cartoons formed the basis for the book Mickey Mouse Illustrated Movie Stories (David McKay Co.). (In 1934, a second volume adapted 12 more cartoons.)

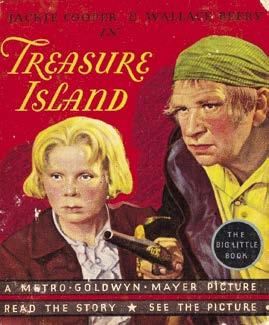

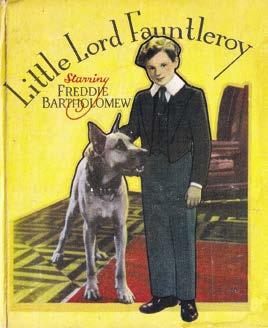

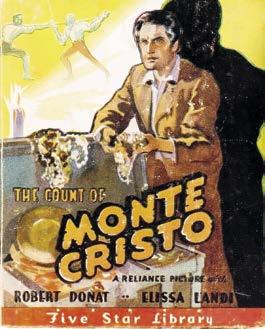

BIG LITTLE BOOKS: Created for children, and only costing a dime, Whitman’s Big Little Books (aka “BLBs”) were so named because of their pocket-size dimensions. The interiors had drawings on one page and story text on the opposite. The first was in 1932 with a Dick Tracy Big Little Book, but

by 1933 they added the first Hollywood tie-in, The Story of Jackie Cooper, a popular child actor at the time, replacing the drawings with photographs. In the following year, Shirley Temple, Laurel and Hardy, Tom Mix, and other stars would have BLBs of their own – as well as movie adaptations, including Alice in Wonderland, The Count of Monte Cristo, and Treasure Island

SEEIN’ STARS: In 1933, newspapers were still the greatest opportunity for studios to promote their films and contract players to the public on a regular basis. And one of the most popular ways was with Hollywood trivia comic panels and strips. One of the first was Twinkling Stars in 1927 by Ray Hoppman. Over the next few years, various newspaper syndicates came up with similar strips, including Star Dust and Screen Oddities (later renamed Star Flashes). However, the very best of the trivia strips arrived in 1933 when King Features Syndicate responded with its own daily Hollywood trivia comic panel and Sunday strip, the absolutely stunning Seein’ Stars by Feg Murray.

Murray’s lovely lines capturing the popular movie stars of the 1930s and 1940s were especially amazing to see on the Sunday page because of the added color. The daily strip ran until 1941, while the Sunday continued on until 1951. In addition, Seein’ Stars strips would be reprinted regularly

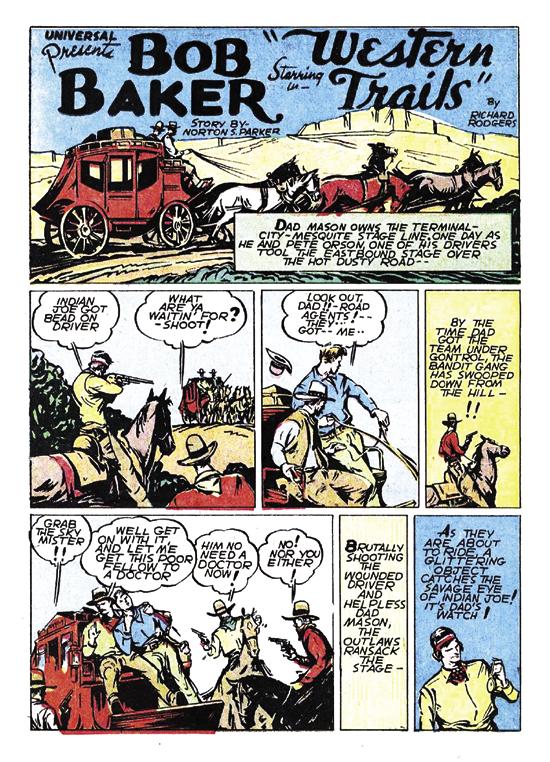

(left) Splash page for Western Trails (1938) in The Funnies #26 (Dell, Nov. 1938).

(right) Though the adaptation was only 3 pages in length – and in black and white – Letter of Introduction (1938) did grab the cover spot of Jumbo Comics #2 (Oct. 1938). Hollywood was on the move. Western Trails and Letter of Introduction © NBCUniversal. Cover scan courtesy of Heritage.

Introduction (1938), which featured Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy in supporting roles. Though the presence of the pair might lead one to believe it was a “laff-riot” as the comic book cover stated, the film was a showbiz soap opera about an actor discovering he has a daughter he never knew about.

Charlie McCarthy was also the first film celebrity to receive his own comic book, Edgar Bergen Presents Charlie McCarthy in Comics (1938). (See sidebar for this and other movie star comics.)

MR. DOODLE KICKS OFF : For the next issue of Jumbo Comics (#3, Nov. 1938), a four-page adaptation in black and white was included of Mr. Doodle Kicks Off (1938), a weak comedy about a rich man sending his bandleader son (Joe Penner) back to college to be a football star, which he unexpectedly becomes.

MOVIE COMICS (DC) : “Here, it is, boys and girls, the newest idea in Comics and Movie Books – a combination of both, which we believe you will like very much. We hope that it will give you many, many hours of interesting fun and pleasant reading. Movie Comics will present each month, an idea of the outstanding pictures to be shown in your neighborhood theatre so that you will better enjoy them when you see them on the screen. It will also serve as a permanent record of the pictures you have enjoyed, which you can refer to again and again with pleasure and entertainment.” – Editorial, Movie Comics #1 (Apr. 1939).

While other publishers inserted a movie item such as a gossip page or a trivia page here and there within their anthology comic books, DC Comics took the bold step of creating Movie Comics, the very first newsstand comic book fully dedicated to motion pictures, using photo stills in a comic page format to tell the story. Movie Comics #1 adapted five films, two of which (Gunga Din and Son of Frankenstein) would become classics of the silver screen. Lesser-known films of 1939 completed the roster of pictures, plus there were filler items that included a Screen Oddities -type trivia page called “Screen Scoops” and a page on the makeup used in Son of Frankenstein

CHAPTER 2: The 1930s 17

In the movie Stage Door Canteen (1943), Broadway legend Katharine Cornell (left) played herself, reflecting what she and many other well-known actors did at the real New York establishment, helping to serve enlisted men. © the respective holders. Image courtesy of

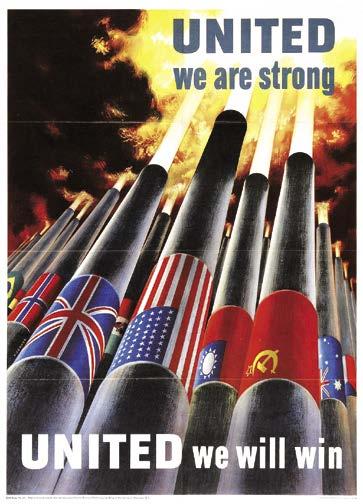

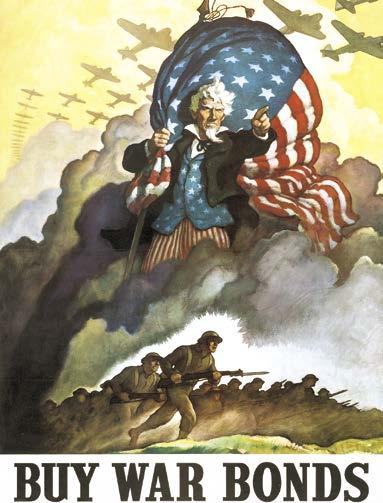

The world changed again on December 7, 1941. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, America was at war with the empire of Japan. Four days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. And we were in it until it was over, along with every country that opposed the would-be conquerors of free people.

Life changed. Men lined up to enlist, while others were drafted; and women joined various branches of military service. Even Hollywood saw its stars and behind-thecamera talent leave the safety of the soundstages where they engaged in pretend war to join up for the real thing. Clark Gable, James Stewart, Tyrone Power, John Ford, Frank Capra, Burgess Meredith, and many more were on the way.

The same, too, happened in the comic book and comic strip industries, with Jack Kirby, Will Eisner, Alex Raymond, Curt Swan, Robert Kanigher, and Dick Ayers among them.

It also meant a different lifestyle for those here in America. Alongside the founding of our country, it was probably the most patriotic four years anyone has ever experienced. Women were doing the jobs that men had left behind. Food and gas were rationed. War bond drives were everywhere to support the soldiers who fought on and on to defeat the hated Axis powers.

In 1940, the Chicago Tribune’s comic book section published a photo preview each week of the serial Drums of Fu Manchu (Republic, 1940).

© Paramount or the respective holders.

The war continued on for nearly four years, but one day it was all over. In May 1945, Germany surrendered. Four months later, Japan did likewise. It had been a time of unsurpassed courage from the collective countries of the world to fight for every person’s liberty – and soldiers started returning home by the end of the year. The Oscar-winning Best Picture of 1946, The Best Years of Our Lives, summed up the feeling of many of the men, not just taking up from where things left off prior to the war but, in many cases, having to start from scratch or readjust to a new world.

But before that happened…

DRUMS OF FU MANCHU / OVERLAND WITH KIT CARSON : In March of 1940, the Chicago Sunday Tribune introduced a 16-page horizontal comic giveaway called “Comic Book Magazine” within the newspaper. The weekly comic measured 8 by 10.5 inches and contained some old and some new comic strips, as well as photo adaptations of two movie serials, Drums of Fu Manchu (1940) and Overland with Kit Carson (1939), with each chapter getting three pages. Starting with the June 2, 1940 issue, the chapters were artistdrawn instead of photo-illustrated.

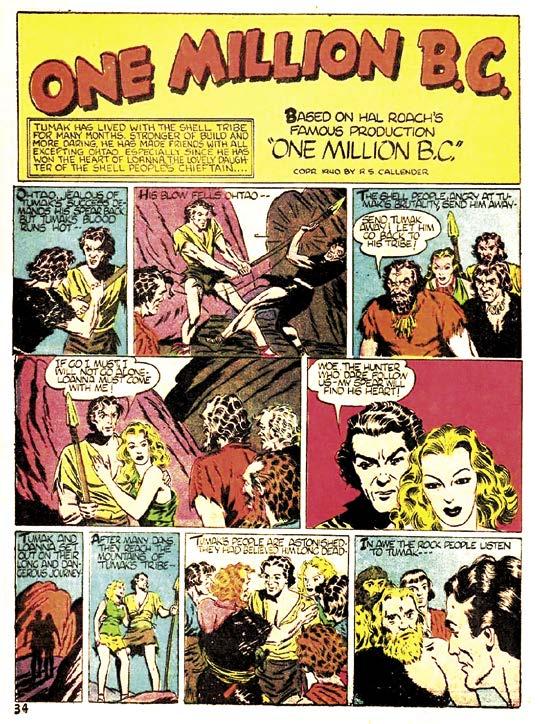

ONE MILLION B.C.: An early special effects film, One Million B.C. (1940) starred Victor Mature and Carole Landis as cave people of opposing tribes. The Stone Age Romeo and Juliet fantasy brought together dinosaurs and humans, something science says should be millions of years apart, but it was fun, nonetheless. Mature and Landis looked less like Neanderthals, though, and more like movie stars who crash-landed in the time period.

Dell published an eight-page adaptation of One Million B.C. (1940), split in two over Crackajack Funnies #s 25 and 26 (above) .

© the respective holders.

Dell published the film adaptation over two issues of Crackajack Funnies (#25, July 1940, and #26, Aug. 1940) with a four-page chapter in each. The illustrations by an unidentified artist were fair, much better depicting a Tyrannosaurus Rex than humans.

THE SEA HAWK : It can be argued that the very best Errol Flynn swashbuckling movie (after The Adventures of Robin Hood , of course) is The Sea Hawk (1940). Stylistically filmed in crisp black and white, the movie had Flynn at the height of his athletic prowess as Captain Geoffrey Thorpe, a sea captain serving Queen Elizabeth I (the magnificent Flora Robson). Spain was working on a secret plan to destroy England’s floating armada while appearing to be friendly to England, and Thorpe set out to capture Spanish gold in order to build more English ships. The film ended with a powerful speech from Elizabeth that warned war was coming and preparations must be made by free people to stop the ruthless ambition of a man seeking to engulf the world. Everyone in the audience knew it was a call-to-arms about Adolf Hitler. Two months after The Sea Hawk was released, Germany began bombing England.

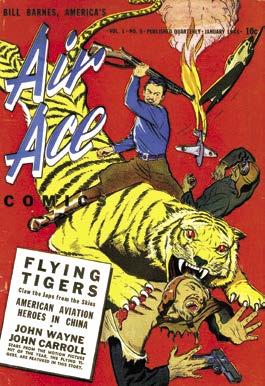

Flying Tigers in Bill Barnes, America’s Air Ace Comics Vol. 1 No. 9 (Jan. 1943).

© Paramount. Cover scan courtesy of Heritage.

In 1942, Fawcett published Jungle Girl #1 but instead of adapting the like-named serial in that first issue, they chose to do the sequel, Perils of Nyoka, and did so with great fidelity. The cover added a photo of Kay Aldridge.

FLYING TIGERS: John Wayne climbed out of the saddle and into a cockpit of a U.S. P-40 fighter aircraft in Flying Tigers (1942). The story focused on the real volunteer group of heroic American pilots who fought Japanese aircraft in China just prior to the start of World War II.

Street and Smith’s Bill Barnes, America’s Air Ace Comics Vol. 1 No. 9 (Jan. 1943) published a 12-page adaptation of the movie with good art by Jack Binder. New “Flying Tigers” stories appeared in subsequent issues of the comic book title.

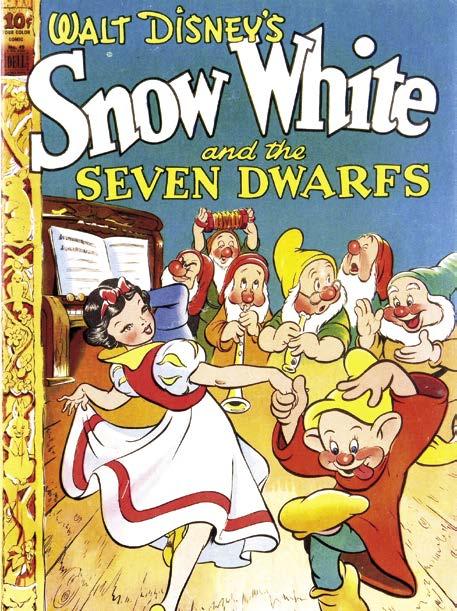

(bottom left) The cover for Four Color #49 (1944) featured new art by Walt Kelly. The interior story, though, was reprinted from the Sunday newspaper adaptation from 1937-1938.

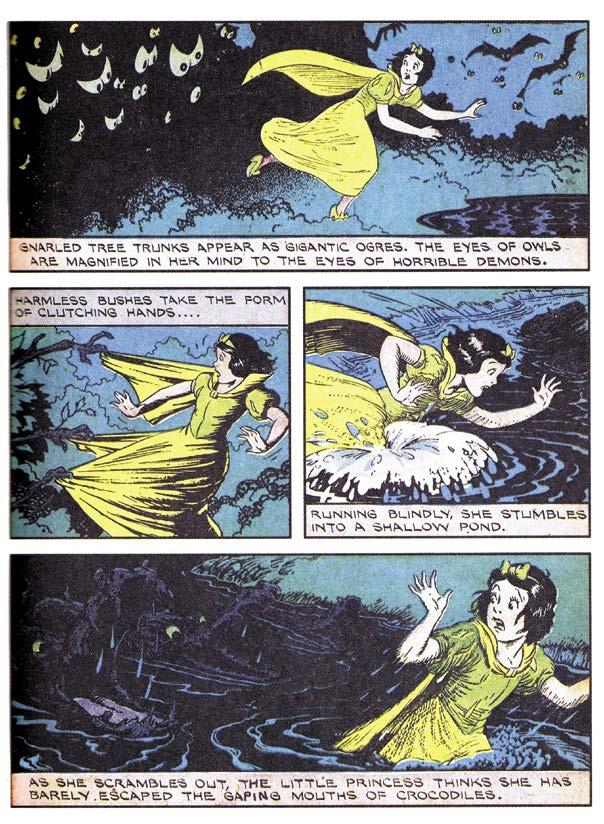

(bottom right) One of the intense Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs story pages in Four Color #49 that was cut from appearing in later reprints.

© Disney. Cover scan courtesy of Heritage.

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS : In 1937, the entire Hollywood industry was discussing (and some were looking forward to) how Walt Disney was going to lose everything in his ambition to release America’s first-ever fully-animated movie, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs . However, the film was an enormous success and earned Disney an Honorary Academy Award for screen innovation.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs set the storyline for many future Disney animated films by putting a young lady at the mercy of a fiery, malicious older woman. The motives of the villainesses varied, but all were pure evil through and through, and Snow White’s stepmother, the Queen, set the bar high right from the beginning.

is now responsible to take care of Hawkins’ cantankerous wife (Main) and her several brats. The hilarity truly starts when Chester is made sheriff and everyone backs down from killing him because then they would get stuck with the terrifying widow.

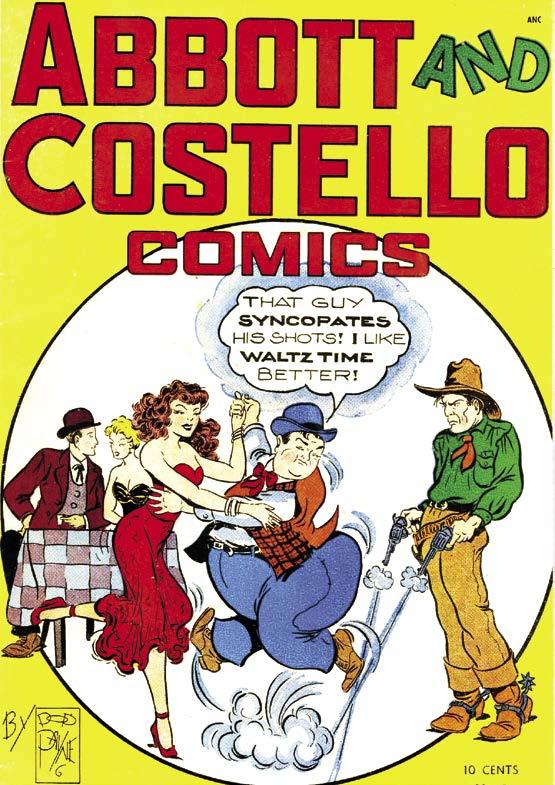

Abbott and Costello Comics #1 (Feb. 1948, St. John) adapted the movie, with excellent art by Charles “Pop” Payne. With this issue, St. John published the very first full-length, live-action movie adaptation in a regular-size color comic book.

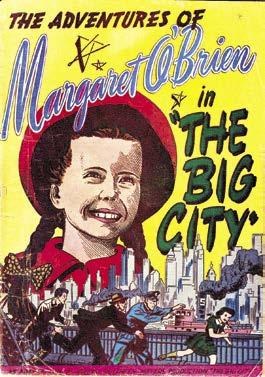

BIG CITY: Even with a trio of likeable male stars (Robert Preston, George Murphy, and Danny Thomas), the real star of the M-G-M film Big City (1948) was child actress Margaret O’Brien. She played a young girl that had been abandoned when she was a baby and found by a Jewish cantor (Thomas), a Protestant minister (Preston), and an Irish Catholic policeman (Murphy). The three men raised the child with the help of the cantor’s mother, and a court decreed whichever man marries first will become her legal father.

The 20-page comic book adapted from the film was published as The Adventures of Margaret O’Brien In “The Big City” and was a giveaway by Bambury Fashions, a maker of children’s clothes. The tale within was a fairly straightforward version of the film, but with a major religious censorship surprise on page one. Of the three men, only the policeman’s occupation stayed the same. The Protestant minister of the film was changed to a director of an east side settlement house and the cantor was now a storekeeper. The artwork for the issue was not signed but it resembles the work of a number of artists of the period, including Sheldon Mayer.

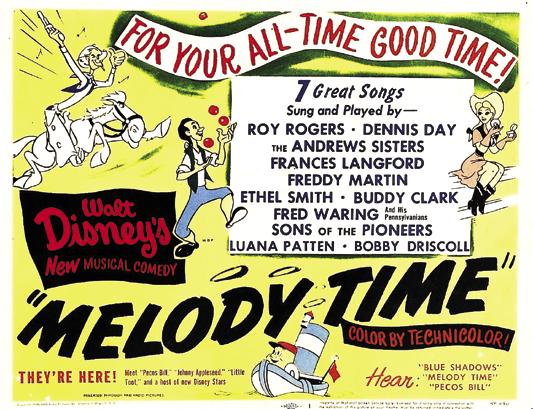

MELODY TIME : Melody Time (1948) was another multisegment animated/live-action movie from Walt Disney. There were a total of eight sections, with each set to music. Standouts were cartoons featuring legendary Pecos Bill (sung offscreen by Roy Rogers), Johnny Appleseed (Dennis Day) and Little Toot (the Andrews Sisters), the latter about a small tugboat trying to help his father, a New York harbor tugboat, but resulting in a series of comical errors.

While there was no full comic adaptation of the film this time, two segments were recreated in comics: Little Toot’s

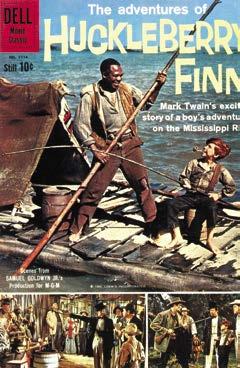

The world saw many transitions in the 1950s. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama. Princess Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor became Queen Elizabeth II. An orange grove in Anaheim, California, was converted into “the happiest place on Earth,” Disneyland. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was signed into law. Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, and Jerry Lee Lewis were part of the rock and roll revolution. Plus, there was a new generation of movie stars: Marilyn Monroe, Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Paul Newman among them. Unfortunately, for everything good that happened, so too were there bad times: McCarthyism and the House Un-American Activities Committee, the Cold War, the Korean War, and the start of the Vietnam War.

The 1950s also had the greatest anxiety ever seen in Hollywood, even more than the coming of sound in the 1920s, the Great Depression in the 1930s, and World War II in the 1940s. And it was all from a little box in people’s living rooms called “television.”

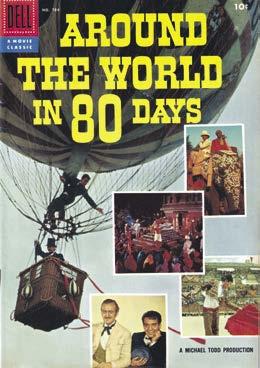

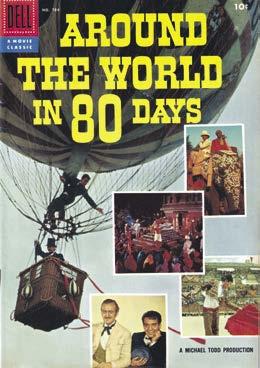

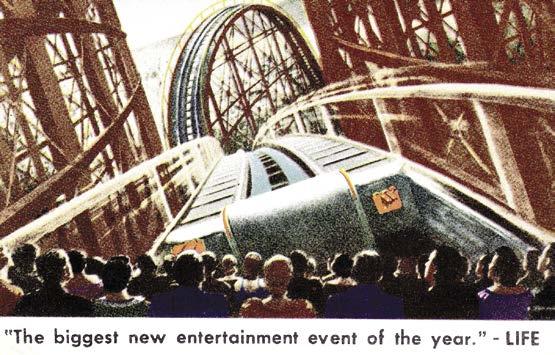

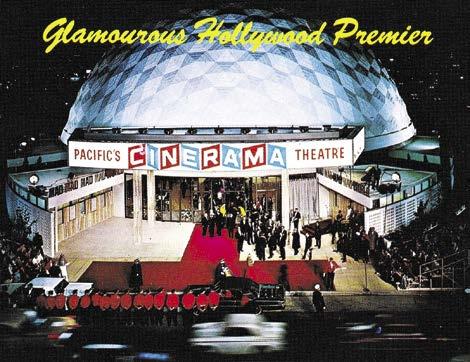

Families had already started moving to the suburbs, away from major city movie theaters, and now TV was keeping them entertained. People staying home was the worst thing that could happen to the movie industry. So, before many of the studios realized it was better to expand into television series production themselves, they tried new screen and sound gimmicks to get audiences back to the movies: Cinerama, CinemaScope, Panavision, VistaVision, Todd-AO, stereophonic sound, WarnerColor, Metrocolor, 3-D, and more. And some of the biggest films

Advertising postcard promoting the 1952 movie, This is Cinerama, the most dynamic of the decade’s screen gimmicks.

ever created, that could only be seen inside a movie theater, were The Ten Commandments , Around the World in 80 Days , Ben-Hur , and The Bridge on the River Kwai . (However, films also reflected a new cynicism across the land: Sunset Blvd. , All About Eve , Sweet Smell of Success , Blackboard Jungle , The Wild One , Rebel Without A Cause , On the Waterfront , and High Noon .)

Studio publicity departments went into high gear in promoting their films and contract actors everywhere, including in comic books. By comparison, the 1930s and the 1940s had been mere testing and learning periods. In the 1950s, movie promotion exploded in every direction, with nearly 190 movie-to-comic adaptations!

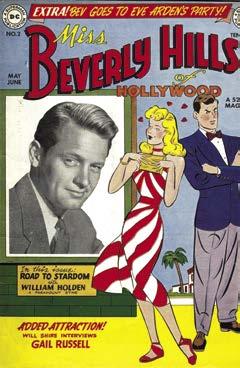

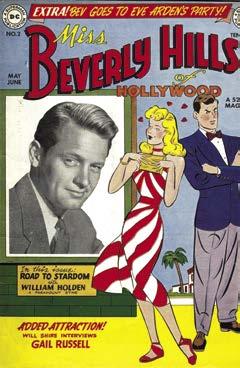

And 1950 itself was the year that started it all, with four anthology series dedicated to adapting films, plus 17 movie stars getting their own comic book titles (see the “Movie Star Comic Books” sidebar in Chapter 2). There were even more appearing within stories where comic book characters interacted with the elite of Hollywood. On top of this, there were countless comics with photos of actors on the cover without ever having a tie-in reason inside.

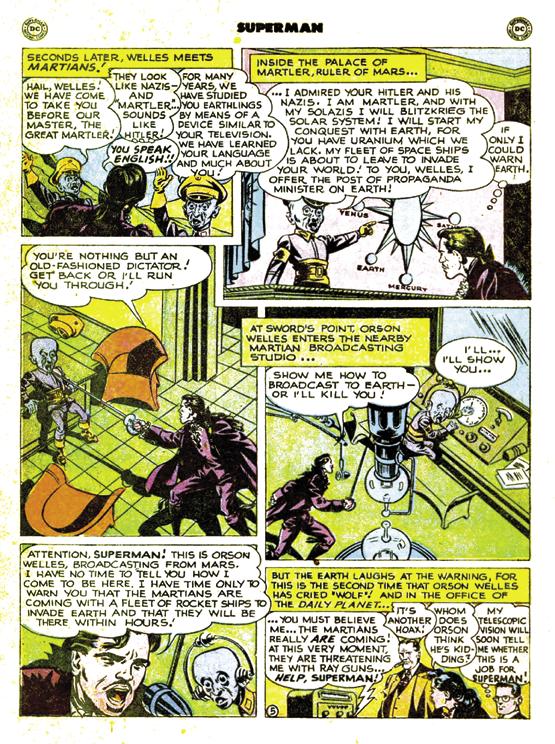

BLACK MAGIC: One of the more enjoyable “comic book character meets real-life movie star” stories appeared in Superman #62 (Jan.-Feb. 1950), with the Man of Steel meeting

actor Orson Welles. In the tale, fresh from filming his 1949 movie Black Magic, and still in costume, Welles accidentally got trapped aboard a rocket destined for Mars, where he discovered the red planet had a Hitler-like monarch about to attack Earth. Welles broadcast to Earth about the impending doom but he wasn’t believed because of his The War of the Worlds radio broadcast in 1939 (which really did fool a lot of people into believing that Mars had invaded Earth). Only Superman, using his telescopic vision, could see that Welles was telling the truth. Together, the superhero and the movie star defeated the Martian tyrant. Wayne Boring drew a fun tale, even though he didn’t capture Welles’ looks.

MOVIE LOVE: The best of the movie adaptation anthologies

– excepting Dell’s Four Color series as a whole, of course –was Eastern Color’s Movie Love, with 22 issues from 1950 to 1953. Movie Love followed the same publisher’s Personal Love to the newsstand by one month, and side-by-side the covers were very similar. Both had photo covers of movie actors and almost matching logos; however, it was the insides that told the difference. While Personal Love’s covers showed film stars and inside included a single-page text-and-photo bio for each actor, there was no other Hollywood content, just love stories. Movie Love, on the other hand, loved movies.

The stories in all issues were quite faithful to the movie they came from, especially in the illustration phase with heavy photo reference by artist Morris Weiss and others. For the first 15 issues, there were two movie adaptations in each, but starting with #16 it was changed to just one. The films they adapted were from several studios, the most notable title being the classic musical Singin’ in the Rain , starring Gene Kelly, from M-G-M. (A list of films adapted by Movie Love can be located in the end Appendix.)

Frank Frazetta was born on February 9, 1928, and showed his artistic talent very quickly. While other kids of 7-8 years old were in elementary school, he was enrolled in the Brooklyn Academy of Fine Arts!

He started his professional career in 1944 at age 16, working for funny animal and other humor comics. This lasted until he drew several Western stories that showed what he could do. But the true high points were Thunda, White Indian, and working with Al Williamson on sci-fi tales at E.C. Comics.

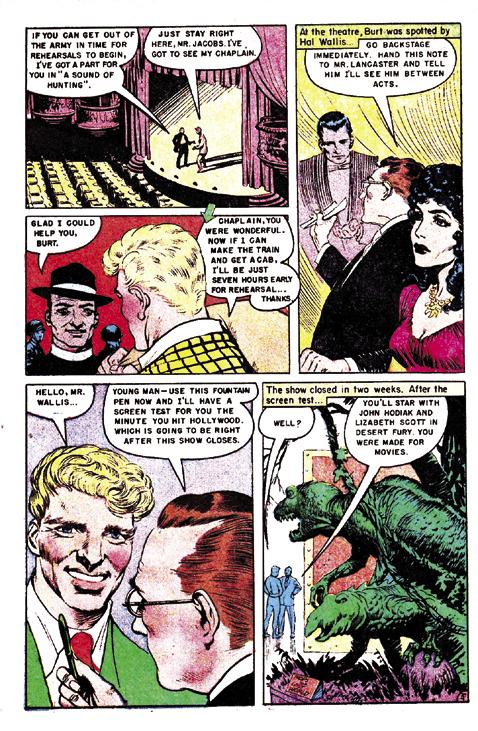

A fine Frazetta page from a bio of Burt Lancaster in Movie Love #10 (Aug. 1951).

© the respective holders.

In the early issues, there were also six-page illustrated biographies of film stars drawn by well-known comic book artists. One of these was Bill Everett’s history of star Dana Andrews in the sixth issue (Dec. 1950) and another being Fred Guardineer depicting the rise-to-stardom tale of Montgomery Clift in #11 (Oct. 1951). However, the actor bios that were truly amazing to see were those

In 1952, when he was 24, he accomplished something that more experienced and older artists only dreamed of achieving — he had his own newspaper comic strip, Johnny Comet. He also assisted Al Capp on Li’l Abner for several years.

In the 1960s, he was painting stunning covers for Warren magazines, as well as doing similar work for pocket book reprints of stories of Tarzan, Conan, and other fantasy characters. These, as much as anything, truly earned him a legion of fans.

The next phase of his career happened when he was asked to draw the humorous movie poster of What’s New Pussycat? (1965). Others followed, including After the Fox, Hotel Paradiso, The Night They Raided Minsky’s, and Yours, Mine and Ours

Art books, prints, record album covers, and much more continued to appear for the rest of his life. His fame as one of the greatest artists of the 20 th century never ceased, even when it was difficult for him to work because of ill health.

While there were imitators of his style, all knew there was only one Frank Frazetta. And the world lost that one on May 10, 2010.

found in Movie Love #8 and #10. That eighth issue (Apr. 1951) had the regular two film adaptations, as well as miscellaneous trivia pages, but buried squarely in the middle was a six-page life-story of William Holden with artwork by Al Williamson and Frank Frazetta! Two issues later, Movie Love #10 (Aug. 1951) had a six-page history of Burt Lancaster, beautifully rendered by Frazetta.

CHAPTER 4: The 1950s 43

In Fawcett Movie Comic, Westerns like (left) The Thundering Trail (1951) (issue #11) were a staple, but the series also adapted the sci-fi cult film (right) The Man from Planet X (1951) (issue #15).

FAWCETT MOVIE COMIC : Fawcett Movie Comic was a 13-issue series that ran from 1950 to 1952, from #8 to 20. Just prior to that, though, Fawcett had published seven standalone full-issue movie adaptations. The seventh issue, which featured the Allan Lane film Gunmen of Abilene (1950), did have “A Fawcett Movie Comic No. 7” on its cover but the indicia and the tops of each page showed only “Gunmen of Abilene.” It was the next issue, #8, that actually had the new cover logo of Fawcett Movie Comic, as well as the indicia identifying it as such and also at the top of every interior page.

Below are those seven individual issues:

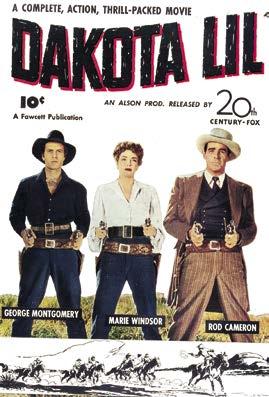

DAKOTA LIL: George Montgomery played a government agent in the Western Dakota Lil (1950), going undercover to stop a counterfeiting ring led by a crooked saloon owner (Rod Cameron) and Lil (Marie Windsor), an expert forger. The film failed to live up to its potential as the script was cliché with the bad girl falling for the good guy infiltrating the gang. The Dakota Lil adaptation (1949/p) featured tolerable art (said to have been by Pete Riss) and a straightforward retelling of the motion picture.

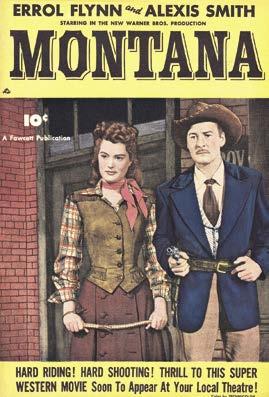

MONTANA: Not exactly dry-as-dust but Montana (1950) came close. Errol Flynn starred as a sheep farmer, someone considered a human target by cattlemen. Not admitting to what he was, Flynn’s romantic inclinations towards a female landowner (Alexis Smith) blinded her into thinking he was a cattleman and she leased him a piece of her land. Discovering the truth about him, she was torn between wanting to shoot him or to love him (she ended up doing both). The comic adaptation (1950/p) did well with the script and the art.

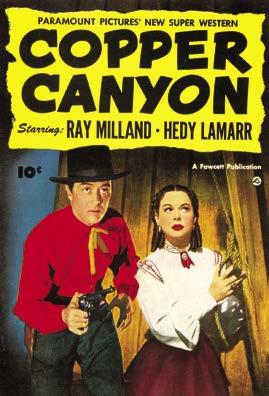

COPPER CANYON : Despite having A-list actors Ray Milland and Hedy Lamarr as the stars of Copper Canyon (1950), the story was hackneyed, with an ex-Confederate officer (Milland) traveling under a fake name, helping a small group of townspeople free themselves from the rule of a corrupt mayor and his murdering deputies. The Fawcett adaptation (1950/p) had weak art (unofficially credited to Clem Weisbecker).

RIVER RUSTLERS : Allan “Rocky” Lane starred in the 1949 Western, Powder River Rustlers , as a railroad agent who discovered a fellow employee had been replaced as part of a criminal plan to swindle the townspeople of El Dorado out of $50,000. The film was a typical shoot-’em-up B-picture. The Fawcett adaptation (1950/p) stayed almost word-for-word to the film script, and the artist (likely Pete Riss again) drew it in a very clean and fluid style, with accurate representations of the actors.

art, especially in capturing the pure evil grin of Cinderella’s stepmother. The issue took 48 pages to tell its story, but 13 of those were cut when Dell reprinted it in Four Color #786 (1957) and in the 1965 Gold Key edition.

CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS : Cody of the Pony Express (1950), a 15-chapter serial from Columbia, starred Jock O’Mahoney (aka Jock Mahoney aka Jack Mahoney) as an undercover Army lieutenant set on trapping a gang of outlaws who were robbing the Pony Express. Dickie Moore played Bill Cody – later known as Buffalo Bill Cody – in his teenage days.

Fox’s Colossal Features Magazine #s 33 (May 1950) and 34 (July 1950) adapted the 15-chapter movie serial Cody of the

Fox published Cody of the Pony Express over two issues of Colossal Features Magazine (#33, May 1950/p, and #34, July 1950/p), but the adaptation was poorly drawn. (Charlton picked up the rights and reprinted Colossal Features Magazine #33 in their Cody of the Pony Express issue #8, Oct. 1955.)

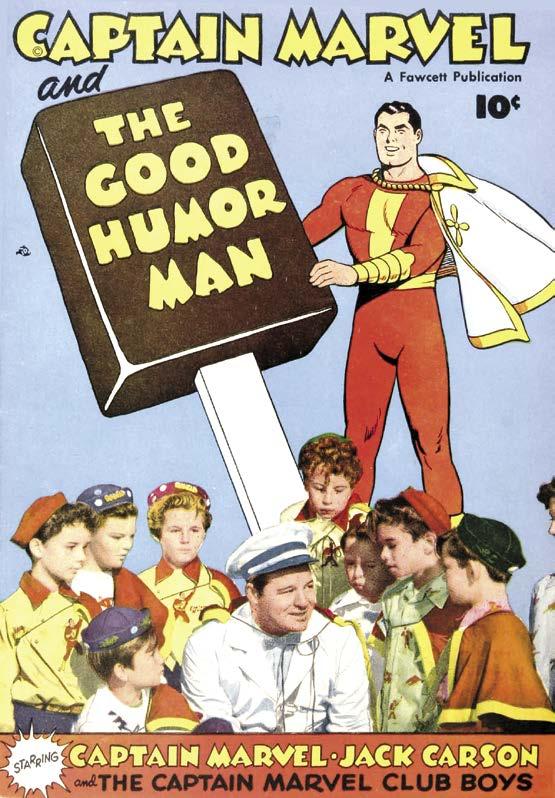

THE GOOD HUMOR MAN : Jack Carson often played a lovable goof in movie comedies, and one of these was as an ice cream truck driver in The Good Humor Man (1950). In the film, he ran afoul of criminals employed by a secret boss (George Reeves), who also happened to be his girlfriend’s employer and on the make for her. The only real charming part of the film was that Carson’s character was a member of a club of Captain Marvel fans who swore to do good.

Proving to be an ideal movie tie-in, Fawcett published Captain Marvel and The Good Humor Man (1950). The cover featured a drawing of Marvel, along with a photo of Carson and the boys of the club. The story inside told a behind-the-scenes tale of the making of the movie with Captain Marvel on the studio lot as a technical adviser, where he discovered that crooks who committed a robbery were disguised as bad guys in the movie being filmed. The 32-page comic tale was drawn by C.C. Beck.

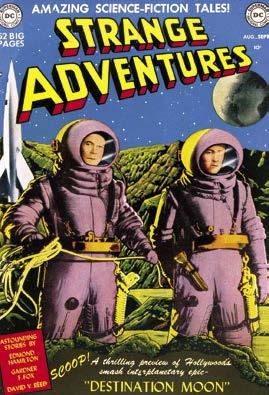

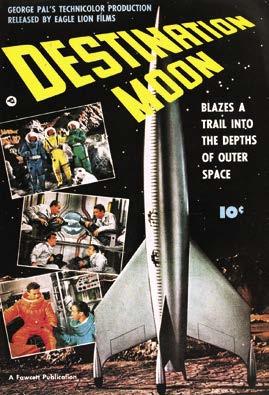

MOON : Destination Moon (1950) was the first feature-length motion picture about traveling to the Moon (Georges Méliès’ 1902 Le voyage dans la lune – aka A Trip to the Moon – was a film short). The movie started with test rockets and then a plan was made to

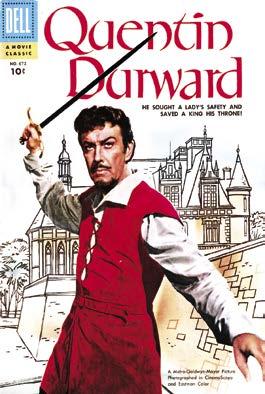

(top left and bottom) In Quentin Durward (1955), Robert Taylor was still a dashing hero, and Kay Kelland was never lovelier. Ralph Mayo’s art was excellently done throughout the Dell adaptation (Four Color #672).

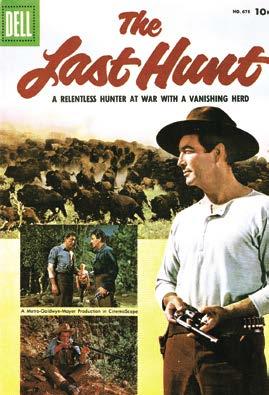

(top right) Robert Taylor broke from his good guy roles to play a cold-blooded hunter out to kill buffalos for profit in The Last Hunt (1956). Four Color #678.

© Warner Bros. Discovery.

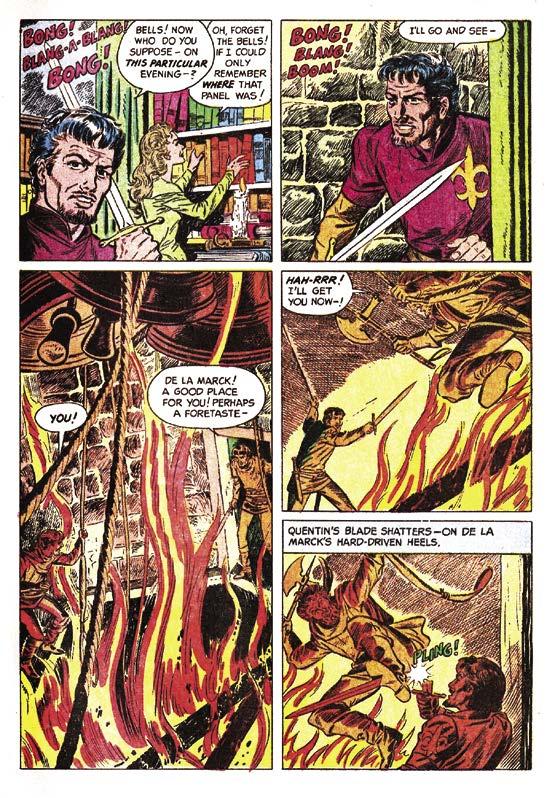

at the end had Durward and the villain (superbly played by Duncan Lamont) swinging from rope to rope over a raging fire while trading blows with axe and sword.

Gaylord Du Bois’ writing for the Dell comic ( FC # 672, 1955/p) told the story well, though it left out the more adult-themed sections of the movie. Ralph Mayo’s art (inked by Mike Peppe) was excellent throughout, especially in the end battle and in drawing Taylor and Kendall.

THE LAST HUNT : Robert Taylor and Stewart Granger teamed up for The Last Hunt (1956), a Western about buffalos and the men who slaughtered them for profit. Set in late 1800s South Dakota, Granger played a peaceable man who had enough of buffalo killing but got roped into it one more time by a ruthless hunter (Taylor). The film, directed by Richard Brooks, had a good supporting performance by Lloyd Nolan as a too-experienced skinner and featured an up-and-coming young player named Russ Tamblyn.

The Dell adaptation (FC #678, 1955/p) was poorly illustrated by Bob Jenney, but the excellent script carried over the film’s story.

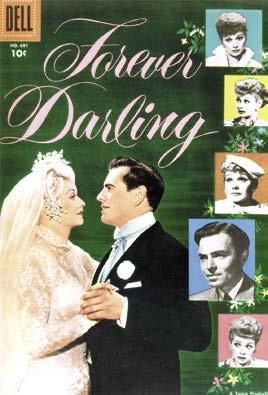

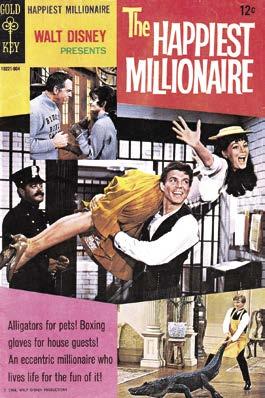

FOREVER, DARLING : Real-life married couple and TV superstars Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz starred in the film Forever, Darling (1956), a generally unfunny comedy of marital strife, with James Mason as a guardian angel trying to help her save their marriage.

Hy C. Rosen captured the looks of Lucy and Desi in a cartoonish way but that and ten photos of her on the cover and inside were the best things about the adaptation (FC #681, 1956/p).

Lucy and Desi starred in Forever, Darling (1956). Four Color #681.

© Warner Bros. Discovery. Courtesy of Heritage.

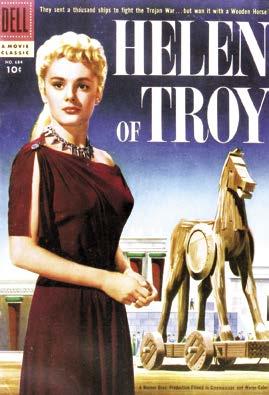

HELEN OF TROY: Helen of Troy (1956), Warner Bros.’ epic film directed by Robert Wise about the Queen of Sparta (played by Rossana Podestà) falling in love with Troy’s Prince Paris (Jacques Sernas) was filled with many attractive values, including full-length galleons and stunning costumes — plus Brigitte Bardot in a supporting role as Helen’s servant girl.

The artwork for the Dell realization (FC #684, 1956/p) of the movie was done with a lovely grace of line by future Marvel Comics giant John Buscema for his first movie adaptation. At the time, Buscema was drawing Roy Rogers Comics , so Helen of Troy with its ancient settings and costumes was entirely different than his norm but he did it with startling beauty. Paul S. Newman handled the scripting.

(top and bottom) Rossana Podestà played Helen of Troy in the 1956 sword-andsandals movie. In Four Color #684, John Buscema drew the adaptation with a clean line and elegance.

© Warner Bros. Discovery. Courtesy of Heritage.

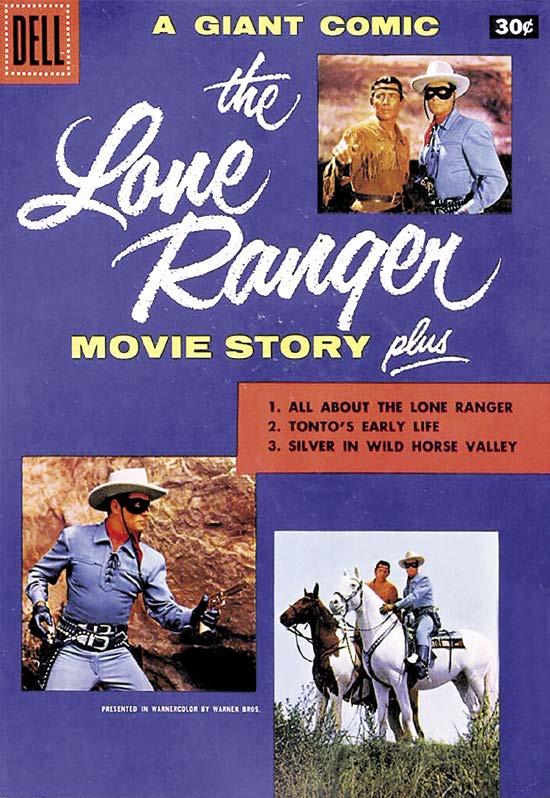

THE LONE RANGER : Towards the end of The Lone Ranger TV series, stars Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels appeared in the 1956 theatrical movie of the same name. The plot involved a rich ranch owner trying to frame Indians for crimes in order to drive them from their reservation. The Lone Ranger and Tonto discover that what he is really after is the mountain on the Indians’ land because it contains a mine of silver. The film was entertaining but was not much different than watching a couple of episodes of the television program.

The Dell adaptation was appropriately called The Lone Ranger Movie Story (1956/p) with good art by Tom Gill (the regular artist for The Lone Ranger comic book series) and a script that was accurate to the film. (Two years later, there was a second film with Moore and Silverheels, The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold , but there was no comic adaptation of it.)

As the TV series was coming to a close, Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels appeared in the The Lone Ranger movie. The story was adapted into a Dell Giant comic (later reprinted by Gold Key).

© NBCUniversal or the respective holders.

While films live and die based on casting the right actors, the production of The Story of Mankind (1957) deliberately sought the wrong actors. Dell’s Four Color #851.

©

THE STORY OF MANKIND:

It’s difficult to totally disparage Irwin Allen’s The Story of Mankind (1957), an all-star revue. In the film, humanity’s successes and failures were played out in a single court case in Limbo being fought between the Spirit of Man (Ronald Colman) and the Devil (Vincent Price), with the existence of all the people on the Earth at stake. It was a bad movie, to be sure, but the guest stars miscast as famous figures of history were a treat, including Peter Lorre as Nero, Harpo Marx as Sir Isaac Newton, and Edward Everett Horton as Sir Walter Raleigh.

The Dell comic ( FC # 851, 1957/p), however, went back to the book by Hendrik Willem van Loon and played it straight. The script for the comic version was by Gaylord Du Bois, and the art was handled competently by Bob Jenney but his figures were stiff and it felt like walking through a history exhibit in a wax museum. On the positive side, the front cover had photos of Colman and Price, as well as Hedy Lamarr as Joan of Arc, Agnes Moorehead as Queen Elizabeth I, Helmut Dantine and Virginia Mayo as Marc Anthony and Cleopatra, and Dennis Hopper as Napoleon.

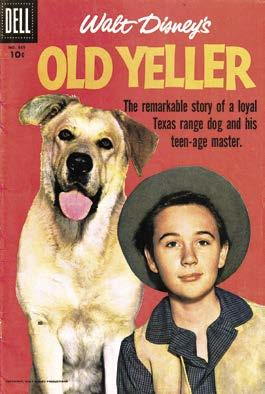

OLD YELLER: Walt Disney’s Old Yeller (1957) is known for bringing tears, the reason for which can’t be mentioned here. However, what can be said of this homespun story set in 1860s Texas is that Old Yeller is a fine picture, with excellent performances from humans and dogs alike. Dorothy McGuire and Fess Parker headed the cast (though Parker appears only at the beginning and end of the film) and Kevin Corcoran

The wonderful Walt Disney film, Old Yeller, was released on Christmas Day in 1957 and it was a great present to all. © Disney.

played the youngest son, with Tommy Kirk as the eldest, giving a great performance, far removed from some of the characters he would play later. Special mention must also be made of Spike, the dog picked to be Old Yeller. He was mischievous, happy, strong, protective, and so easy to love because he was every boy’s dog.

Dan Spiegle did moderately well with drawing Kirk and Corcoran for the Dell adaptation (FC #869, 1958/p), but not so much with the rest of the cast. It didn’t really matter much in this case because he captured the atmosphere so well and a lot of emotion that didn’t require words.

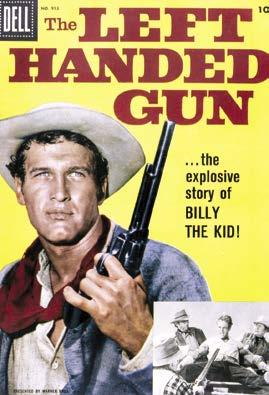

THE LEFT HANDED GUN : Years before he played Butch Cassidy, Paul Newman was Billy the Kid in the 1958 film, The Left Handed Gun . (The title derived from a belief that William Bonney was left-handed due to a tintype of him, which is now believed to have been accidentally reversed.) The movie was based on the TV play by Gore Vidal, The Death of Billy the Kid, which also starred Newman. The film, directed by Arthur Penn, was not well received when it first came out but has been reevaluated in more recent years as an exciting psychological Western.

The Dell adaptation ( FC # 913, 1958/p) carried over a number of the major plot points in this take on William Bonney, casting him as a psychotic avenger. The artwork was good, believed to have been by Mike Roy.

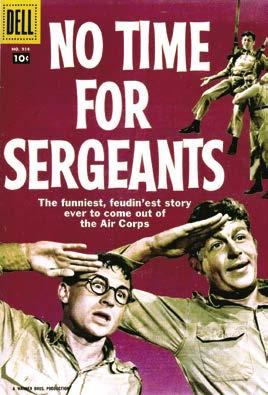

NO TIME FOR SERGEANTS: No Time For Sergeants was one of the funniest films of the late 1950s. It was originally a novel, then a teleplay in 1955, followed by a successful

© Warner Bros. Discovery. Scans courtesy of Heritage.

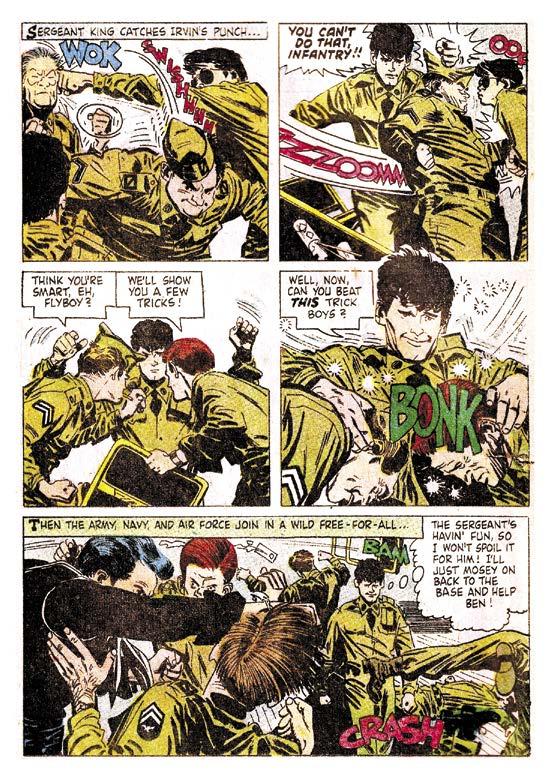

Alex Toth’s art for the No Time for Sergeants adaptation (Four Color #914, 1958) was an incredible free-for-all of fights, wacky flights, and just plain ol’ incredible fun!

© Warner Bros. Discovery.

two-year run on Broadway, and then to the big screen in 1958. The main character was Will Stockdale, a good-natured but none-too-bright young man from the hills drafted into the Air Force and who became the bane of his master sergeant’s life during basic training. Andy Griffith originated the role of Stockdale on TV, then on Broadway, and in the movie.

Even though Alex Toth was unable to render Griffith’s visage with any success for the Dell adaptation (FC #914, 1958/p), he did carry over the joy of the movie. Fight scenes became free-for-alls that exploded out of the panels. This was definitely one of Toth’s best.

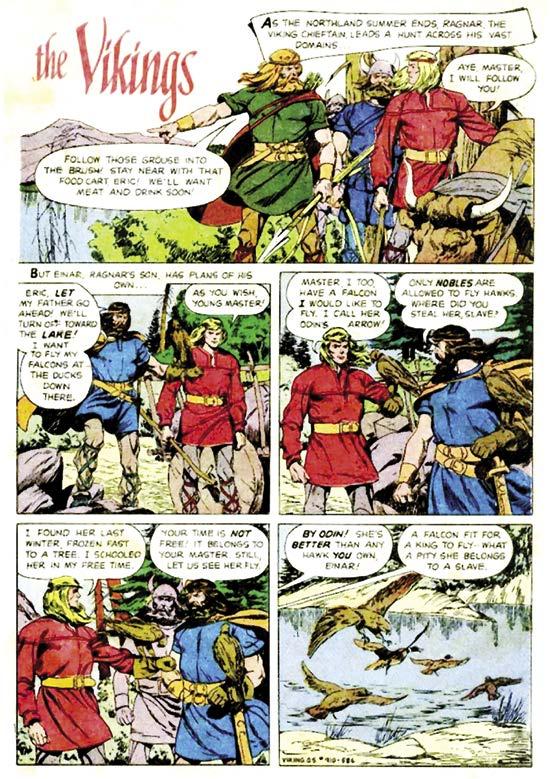

THE VIKINGS: The Vikings (1958) starred Kirk Douglas as the rough son of a Viking chief (Ernest Borgnine), not knowing his father sired another son through the rape of an English queen. That son (played by Tony Curtis) became a slave and turned up as such in the Viking camp with no one but an English traitor knowing the connection. Battles ensued between the sons, including fighting over the same woman (Janet Leigh).

The movie script is only slightly in evidence in the Dell Four Color issue (#910, 1958/p) here, and John Buscema’s artwork bears absolutely no resemblance to the film or its stars. The comic he drew was completely from his imagination — and it stands more than well on its own. His pencil and inks were extremely detailed and powerful. When Buscema drew Vikings, he drew genuine barbarians that could give Conan pause.

LAST OF THE FAST GUNS : Universal’s Western, Last of the Fast Guns (1958) told the story of an American gunslinger (Jock Mahoney) being sent to Mexico to find a dying businessman’s long-separated brother in order to bring him home so he will receive his fortune. The film has very good moments, mostly in the characterization of its players and Mahoney was good as the gunfighter. Gilbert Roland, Lorne Greene, and Linda Cristal also did well by the script.

The Dell adaptation (FC #925, 1958/p) followed the film’s plot, but the art was poorly done.

The Sixties saw a revolution in American homes. The Vietnam War would quickly crop up at dining room tables and the topic would divide loving fathers from their adoring sons who were now draft age. The Greatest Generation could not understand that Vietnam was different.

It was also a decade of revolution in every other area. Clothes, hair, and music, all a great rebellion compared to the decade before. It was the era of civil rights and some who had fought for freedom in World War II were averse to letting the Civil Rights Act pass Congress. It was the decade of the Cuban Missile Crisis and – very painfully – the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

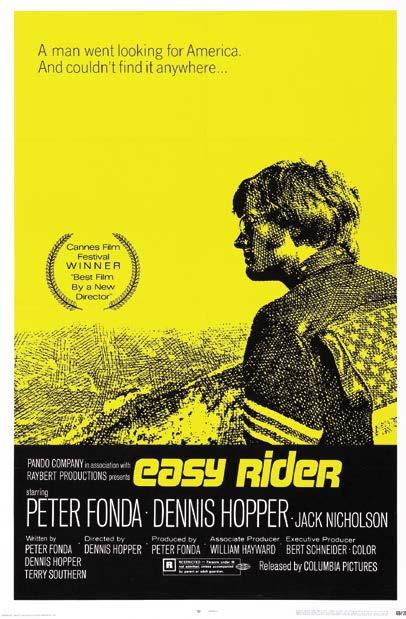

The cinema, as it always does, reflected the change felt in the nation. Escapist musicals like My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, and Camelot made way for controversial films like In the Heat of The Night, Easy Rider, and Midnight Cowboy

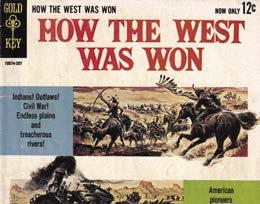

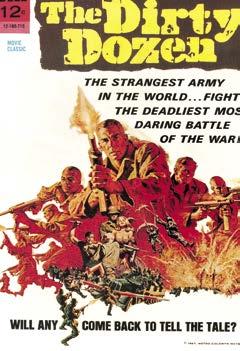

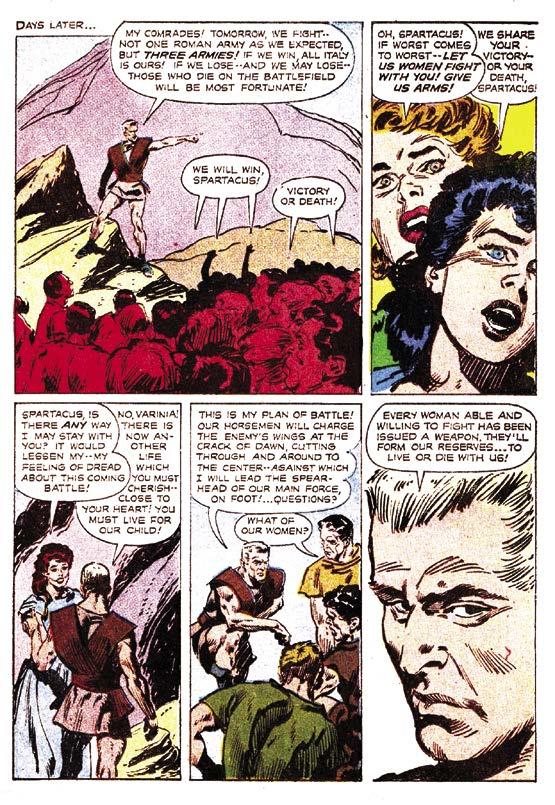

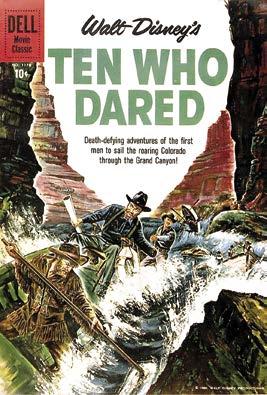

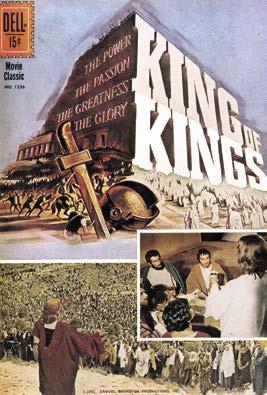

However, there were still many, many movies during those ten years where people got some of the greatest value their money could buy. The Time Machine, Spartacus, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, King of Kings, Dr. No, How the West Was Won, Mary Poppins, The Dirty Dozen, and The Love Bug, to name a few. (All of which, by the way, were adapted to comics.)

In the world of comic books, there were changes, too. The first was industrywide as comic publishers increased the price of their comics from 10 cents to 12 cents. Today, that is nothing. But children in 1961 had to cut back on how many comic books they could afford. As said, it was industry-wide, except for one company: Dell Comics, which had already increased its price a year before from 10 cents to 15 cents, a 50% increase! That, as much as anything, caused a major loss in sales. And in 1962, as will be seen, that decision would have drastic consequences for Dell.

Still, movie comic books would have an incredible decade, with over 160 films adapted.

After years of supporting parts, Kevin Corcoran finally got to play a starring role. Four Color #1092 (1960).

© Disney.

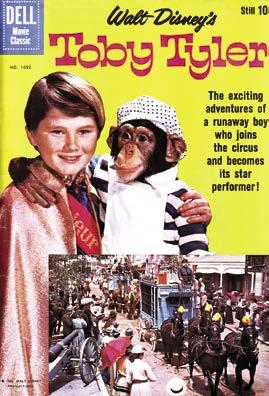

TOBY TYLER OR TEN WEEKS WITH A CIRCUS:

Walt Disney’s Toby Tyler or Ten Weeks With A Circus (aka Toby Tyler) (1960) was a delightful family movie set in the 1800s with Kevin Corcoran as Toby. The young boy ran away from his farm home to join a traveling circus because he felt unappreciated and unloved by his uncle and aunt (actually, a couple who took him in when his parents died so he wouldn’t be sent to an orphanage). A shifty concessionaire saw him as a good moneymaker. However, the circus strong man (Henry Calvin) and one of the clowns (Gene Sheldon) looked out for the protection of Toby. (Calvin and Sheldon had both been in Disney’s Zorro TV series.)

Dell’s adaptation (FC #1092, 1960/p) was true to the screenplay, and Nat Edson’s art caught the feeling of the circus as well as the actors, especially Calvin who could just stand around and still dominate a panel’s space. Gold Key reprinted the issue in 1964 to tie in to the TV airing of the film in two parts on Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color for November 22 and 29, 1964.

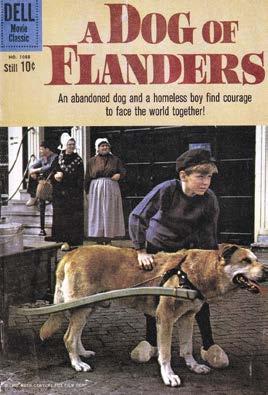

A DOG OF FLANDERS: Alan Ladd’s son, David, starred in 20th Century-Fox’s A Dog of Flanders (1960), a touching movie of a Flemish boy who is captivated by art and wants to be an artist himself. However, living in an old cottage with his poor grandfather and the dog he befriended, plus his daily work of gathering milk in containers from neighboring farmers to sell in the city, did not lend itself to the cost of a formal art training. (Spike, who played the title character, was also Old Yeller in the Disney film.)

The artwork for the Dell version (FC #1088, 1960/p) by Bill Ziegler (and possibly aided by Dan Spiegle) was very good on the whole; however, for a movie about art, the Rubens’ painting “The Elevation of the Cross” (also called “The Raising of the Cross”), shown in its full majesty in the final scene of the film, is barely rendered in the comic.

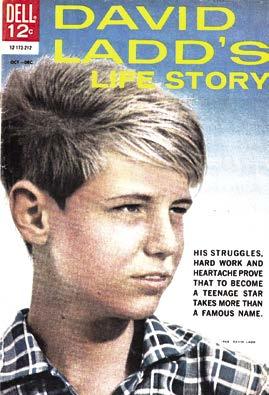

David Ladd was also the subject of another Dell comic, David Ladd’s Life Story (Oct.-Dec. 1962), even though he was only 15 at the time. (In his adult life, he would become an executive at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.)

(left) The Dell comic adaptation ( Four Color #1088, 1960) for A Dog of Flanders carried over the feeling of the filming locations in Belgium and Holland.

(right) Two years later, Dell published a separate comic about the film’s star, David Ladd, who was the son of Alan Ladd.

© Disney.

KIDNAPPED: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1960) got a handsome film production from Disney with James MacArthur as David Balfour, whose father had just died and he was told to take a letter to his father’s younger brother at his estate. The uncle quickly arranged with a corrupt sea captain (Bernard Lee) to take David away by force and have him sold into indentured servitude so that the young man could not rightfully inherit the property. Escaping this fate with the help of Scottish rebel Alan Breck (Peter Finch), David fought his way back to claim his estate.

The Dell adaptation ( FC #1101, 1960/p) was solid with a good script that followed the film, and the art by Nat Edson was competent. The comic was reprinted under the Gold Key imprint in 1963 when Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color aired the movie as a two-parter on March 17 and 24, 1963 (at which time, TV audiences could enjoy spotting new superstar Peter O’Toole in an early role in his career).

Walt Disney’s Kidnapped Four Color #1101 (1960).

© Disney.

THE BOY AND THE PIRATES: The Boy and the Pirates (1960) was a case of “be careful what you wish for” as a youngster (Charles Herbert), with a desire to escape the

(right) While it had a Western bent and John

was essentially a two-hour

The comic script for the Dell adaptation ( FC #1178, 1960/p) followed the movie very closely, so there was not much chance for improvement in the comic. The art by Sparky Moore did well when he was drawing close-ups of the characters/actors, but less so with the boating action.

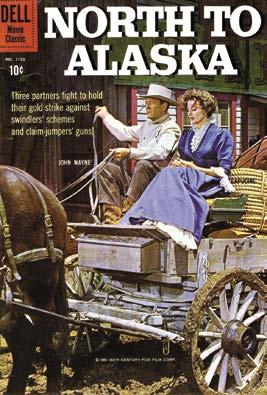

NORTH TO ALASKA : North to Alaska (1960) was a very enjoyable farce starring John Wayne as Sam McCord, a gold prospector in Alaska who strikes it rich with his partner, George Pratt (Stewart Granger). George sends Sam to Seattle to bring back George’s fiancée, a French maid, but she has already married someone else. He brings back Michelle Bonet (Capucine), a courtesan, hoping George can love her instead because she is also French, but Michelle went along on the trip thinking it was Sam who wants her and she had already fallen in love with him. Realizing Sam is secretly in love with her, too, George teams up with Michelle to make him jealous. Meanwhile, the men battle a gambler (Ernie Kovacs) who lays claim to their gold mine.

© Disney. Cover scans courtesy of Heritage.

The basic plot of the movie was in the adaptation by Dell (FC #1155, 1960/p) but Gaylord Du Bois’ comic book script lacked the spark of the film and also its comedy. Mo Gollub’s art was adequate but not distinctive.

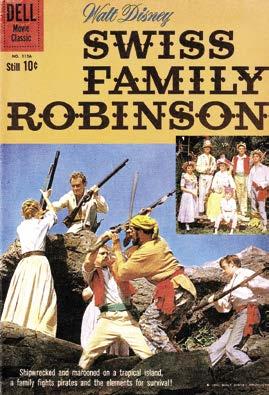

SWISS FAMILY ROBINSON : John Mills and a bunch of Disney regulars (Dorothy McGuire, James MacArthur, Kevin Corcoran, Janet Munro, and Tommy Kirk) starred in Swiss Family Robinson (1960), an adaptation of Johann David Wyss’ novel of a shipwrecked family trying to survive on a desert island. It was a grand adventure filmed on location on the island of Tobago, north of Trinidad, and the movie was the better for it. The cast had chemistry and looked to have fun, including a race with the actors seated variously on a zebra, a donkey, an ostrich, and a baby elephant. A battle against pirates (led by Sessue Hayakawa) provided a great wrap-up.

Swiss Family Robinson (1960) was a high mark in Disney movies, but the comic’s adaptation art by John Ushler made it a poor tie-in. Four Color #1156. © Disney.

Dan Spiegle would have been a perfect choice for Dell’s Swiss Family Robinson adaptation (FC #1156, 1960/p), but it went to John Ushler, whose art was too cartoony for this. The issue was reprinted under the Gold Key imprint in 1969.

In Dell’s Four Color #1199 (1961/p), John Ushler did the art but he was not the right illustrator for it. Dan Spiegle would have been perfect but he would have to wait for the sequel to get his turn.

CONTINENT: Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961) was a quick, not very good film from producer/director George Pal, using sets from The Time Machine and footage from the M-G-M epic, Quo Vadis . In it, Demetrios (Anthony Hall), a Greek fisherman, rescues a woman who turns out to be the Princess of Atlantis (Joyce Taylor). Along the way to taking her back to her people, the two fall in love. When they arrive, he is sent to be a slave in the pit by the king’s evil adviser (John Dall), who plans to subjugate the world with a secret weapon. Demetrios escapes from his prison, defeats him, and regains the princess.

Art for the Dell adaptation (FC #1188, 1961/p) was by Dan Spiegle and it was good but the inking was scratchy. The script was by Robert Schaefer and Eric Freiwald.

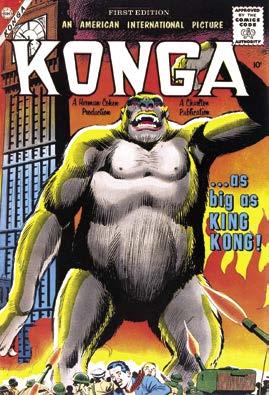

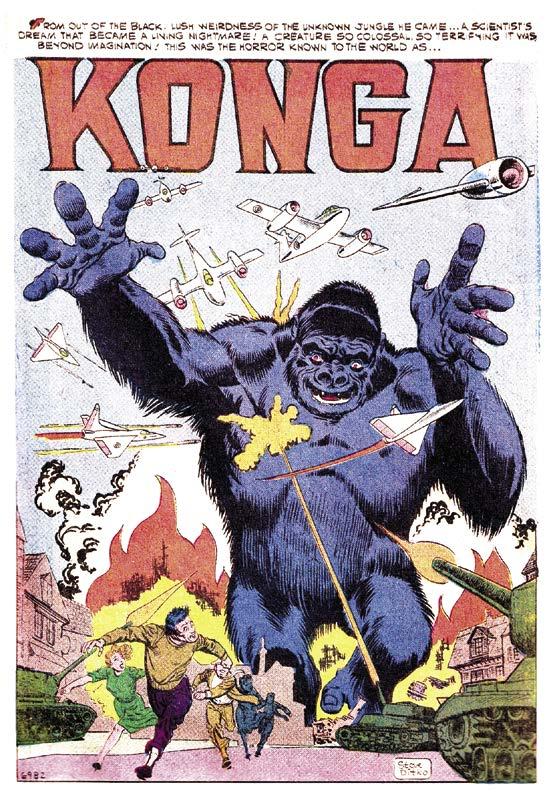

KONGA: Konga (1961) featured a scientist (Michael Gough) discovering the secret of enlarging living things to enormous proportions, including a chimpanzee he turns into a gorilla. However, as often is the case in this type of film, the scientist goes nuts and sends the gorilla to kill those standing in his way. Konga was a badly-made movie, including scenes that rarely flowed into another and a gorilla of the Three Stooges variety with a man in an ugly costume.

Steve Ditko’s art in the comic adaptation (Charlton, 1961/p), on the other hand, was magnificent. He tossed away the look of the movie, which was smart to do, and created his own Konga world. Every panel was Ditko at the top of his game. Also, Dick Giordano drew a standout cover. A regular comic book series followed, from #2 to #23 (Aug. 1961 to Nov. 1965). There were also three “special edition” issues: The Return of Konga (1962), Konga’s Revenge #2 (Summer 1963), and Konga’s Revenge #3 (Fall 1964).

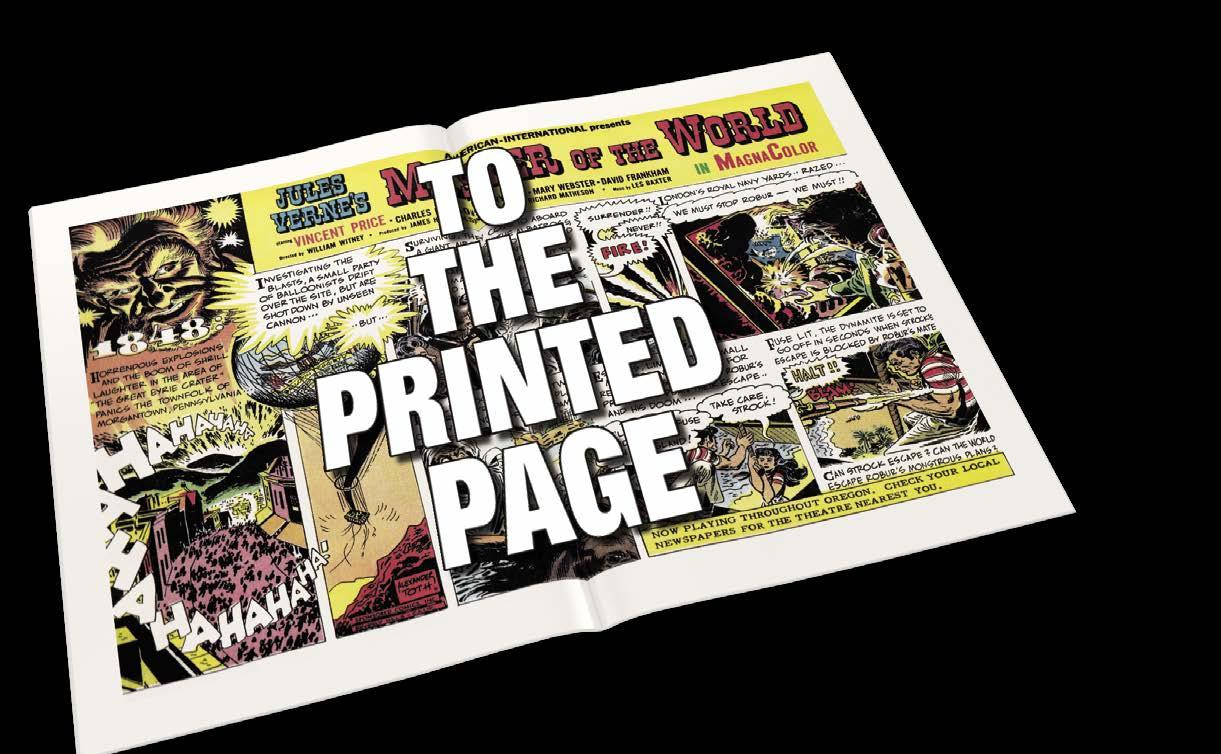

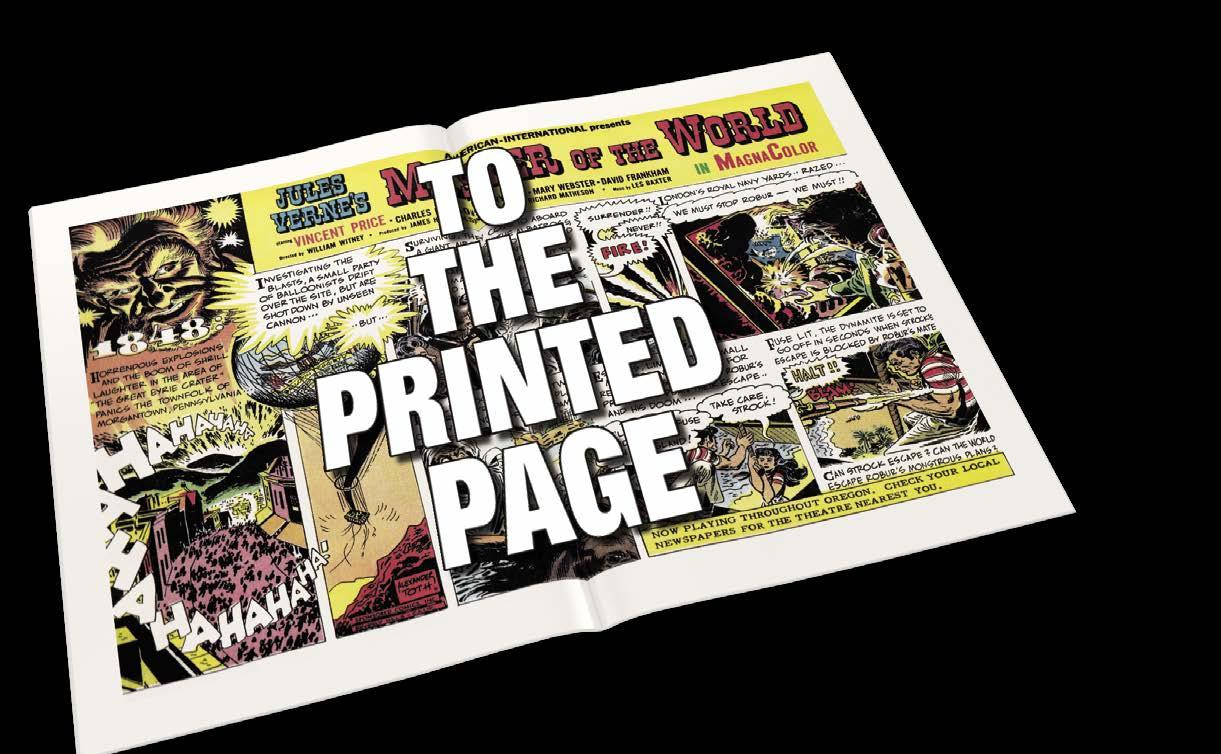

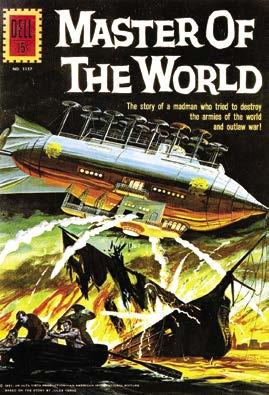

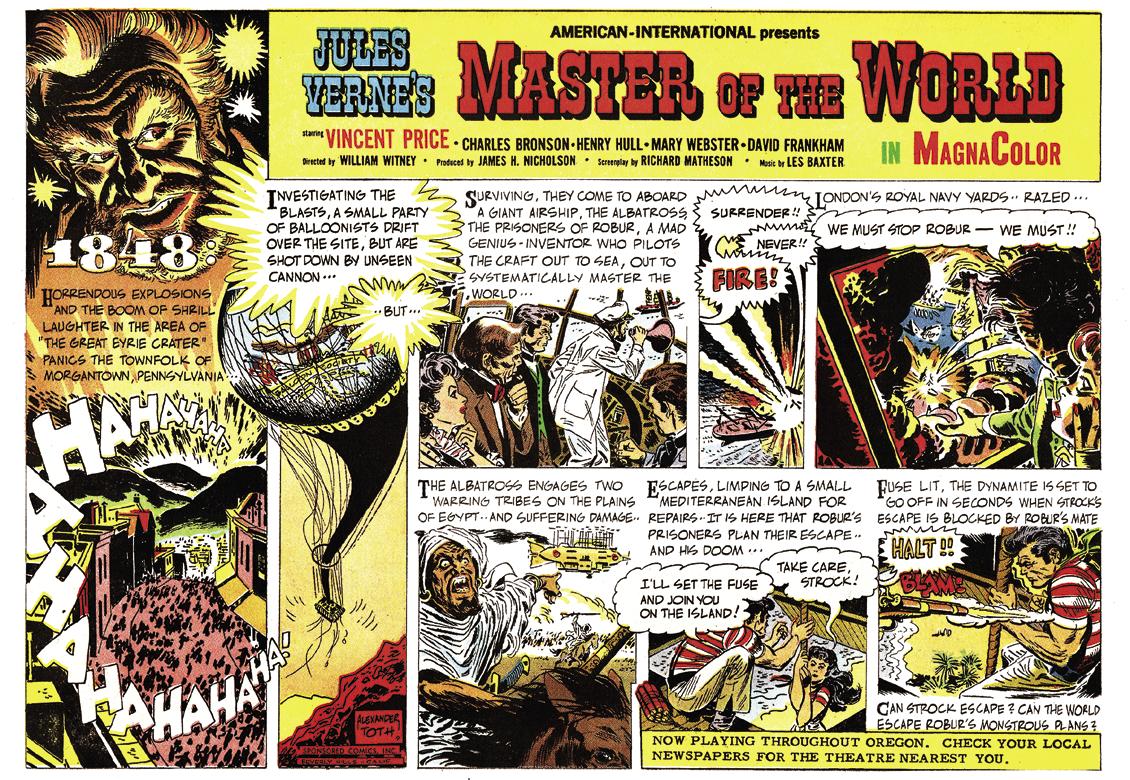

MASTER OF THE WORLD: Jules Verne’s Master of the World (1961) had Vincent Price as a madman who believed the only way to get rid of war was by waging war on every country

(top left) The Konga movie adaptation by Charlton had an amazing cover by Dick Giordano. (top right) Master of the World (Four Color #1157, 1961).

(below) Steve Ditko’s dynamic splash page for the Konga film adaptation.

(top) Master of the World Sunday comic supplement ad with art by Alex Toth. Scan provided by Ger Apeldoorn.

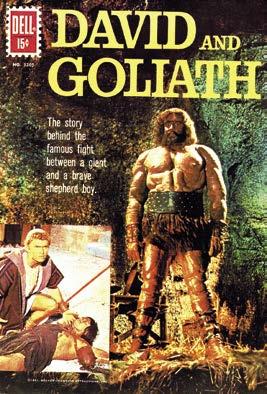

(bottom) David and Goliath (Four Color #1205, 1961).

in the world, threatening to destroy them if they did not give up all their weapons. His futuristic airship, the Albatross, contained great power and he would use it to kill anyone who stood in the way of his message of peace. Receiving second billing in the film’s screen credits was Charles Bronson as a U.S. government agent out to stop him. It was a good film and well-paced, though it contained a large amount of stock footage in its second half.

The Dell adaptation ( FC # 1157, 1961) was written by Gaylord Du Bois and contained an opening sequence that varied from the film but, ultimately, he did well by the Richard Matheson screenplay. Jack Sparling’s art was good, but his renditions of Price were likely from old photos because his appearance was vastly different in the film. There was also a Sunday comic section ad promoting the film, with dramatic Alex Toth art.

DAVID AND GOLIATH: David and Goliath (released in Italy in 1960 and in the U.S. in 1961) was yet another entry into the sword-and-sandals run of films produced in Italy, this time with a “Screenplay Freely Adapted from The Bible” opening credit. However, after 80 tedious minutes of court politics and very little else of interest, David (Ivo Payer) finally squared off against Goliath (Kronos). Four spears, one “Hey, look over there” (seriously), a stone, and it was all over. The only thing that kept it from being completely boring was Orson Welles as King Saul.

Jack Sparling didn’t make much of an effort with the art of the Dell adaptation ( FC # 1205, 1961/p), though he did provide a good two-page centerspread of David speaking before temple on the left side of the spread and the bulk of Saul/Welles filling the right side as he watched.

touching performance from Alex Mackenzie at the beginning of the film as Auld Jock. Plus, naturally, the incredibly adorable terrier that played Bobby.

The Dell adaptation (FC #1189, 1961/p) did an excellent job of retelling the film, and the art by Jesse Marsh was a nice match for the story and atmosphere of the Scottish village in that time.

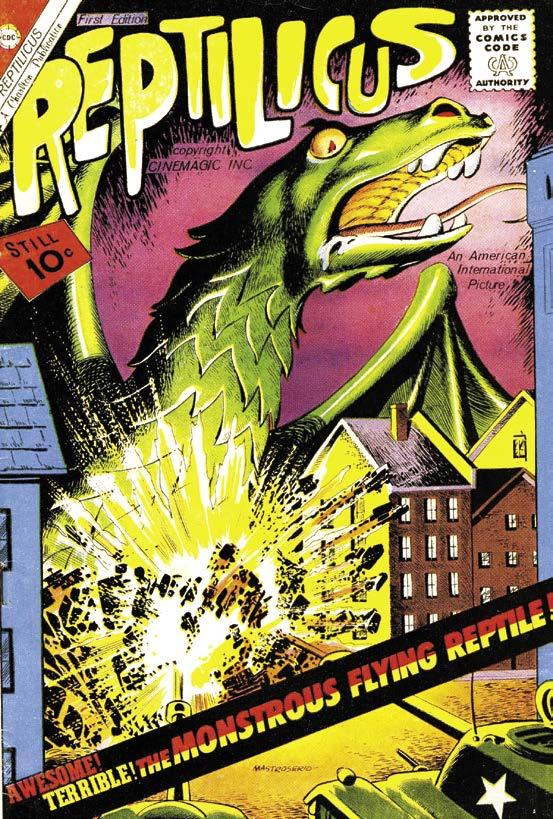

REPTILICUS : A monster movie is in trouble when the opening narration tells the audience that the tale of terror began in Lapland, which was not exactly New York City or London or Tokyo. Reptilicus was Denmark’s 1961 entry into the movie monster market and it was greatly formulaic. The story had an oil-drilling team finding the tail of a prehistoric lizard, still with its flesh intact, and scientists discovered that it being part of the lizard family it could regrow itself entirely. Of course, the rejuvenated creature destroyed everything in its path.

Charlton certainly had a lock on new movie monsters. Konga, Gorgo…and then Reptilicus (Aug. 1961). The comic adaptation had a powerfully-drawn cover by Rocco Mastroserio of army tanks firing on a spread-winged Reptilicus looming high over city buildings. The inside comic was written by Joe Gill, but with story art by Bill Molno and Vince Alascia that was not even close to the masterful work done by Steve Ditko on the previous monster titles.

KING OF KINGS : King of Kings (1961) was a remake of a classic silent film and in many ways improved upon it, though it never achieved the critical distinction of the original. Beautifully filmed, the remake starred Jeffrey Hunter, creating a Jesus Christ who had gentleness in every glance and body movement. This would be in great contrast to Max Von Sydow’s gaunt Jesus in The Greatest Story Ever Told four years later.

The trouble with Dell’s adaptation (FC #1236, 1961/p) was the stodgy art by Gerald McCann, and the comic read more like a Classics Illustrated issue.

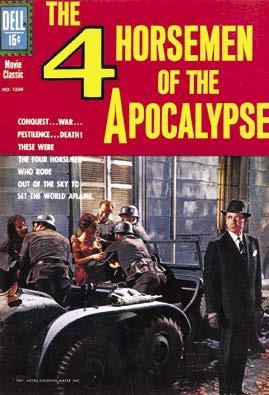

THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE: Upon its release in 1962, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was heavily panned. One of the main problems was Glenn Ford was no Rudolph Valentino, the star of the original silent version. Where Valentino had charisma, Glenn Ford had… um…well, he wasn’t Valentino. Ford played a reckless Argentinian playboy who had to see everyone he knew fall victim to the Nazis before he joined the Resistance. Looking at the film today, it holds up better than originally reviewed at the time, with a good script and fine production

© the respective holders.

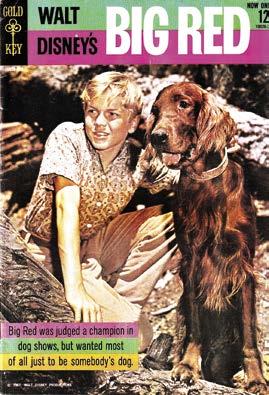

BIG RED : Walt Disney’s Big Red (1962) had Gilles Payant playing a young lad in Quebec who gets a job as keeper of the dogs at the home of a wealthy man (Walter Pidgeon), especially Big Red who was purchased for $5,000. Pidgeon plays his usual isolated and unemotional onscreen character, steering away from ties to any human or animal since the loss of his soldier son. Big Red to him was just a purchase to improve for future selling. Not so to the young man who bonded very quickly with the dog, and their relationship brought the rich man back to caring about others again.

Dan Spiegle’s artwork for the Gold Key adaptation (Nov. 1962/p) was detailed and showed accuracy in drawing the actors.

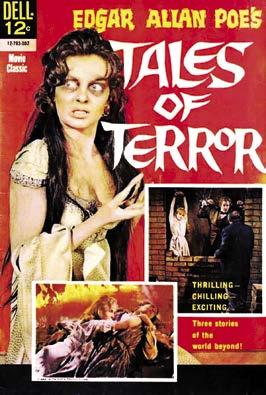

TALES OF TERROR : Richard Matheson’s screenplay for Tales of Terror (1962) adapted several Edgar Allen Poe stories. Roger Corman had great success in producing and directing the famed author’s various works for American International Pictures in the 1960s, and actor Vincent Price achieved a career resurrection starring in them. In Tales of Terror , Price starred in all three segments, teaming up with Peter Lorre in one and Basil Rathbone in another. The stories were good entertainment, some parts spooky, some funny, but the sum didn’t make a great whole.

The Dell adaptation (1962/p) had a script that captured the movie perfectly, and had the additional treat of very mesmerizing artwork by George Evans which carried over the film’s atmosphere and imagery.

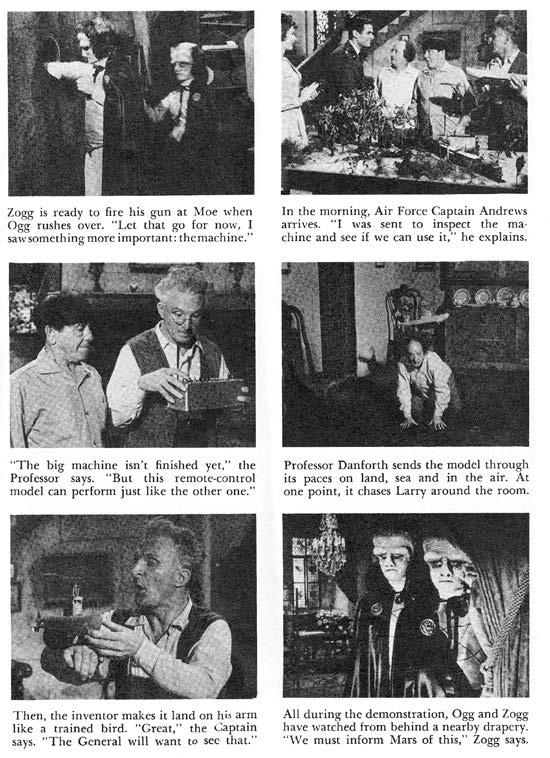

THE THREE STOOGES IN ORBIT: In The Three Stooges in Orbit (1962), Moe, Larry, and Curly Joe are in top form playing TV performers looking for a gimmick in order to have their show contract renewed. An inventor has an answer for a new way of filming them but they are wary because he also says Martians are planning to invade Earth. They quickly discover he is right and it falls to them to help save the Earth from takeover.

The Gold Key adaptation, The Three Stooges in Orbit Film Story (Nov. 1962/p), was completely photoillustrated in comic book

page in comic book format

young Fogg’s servants (Moe, Larry and Curly Joe) as they go with him on the journey. The film recreated the Stooges’ famous “Maharajah” routine and it was still a delight after two decades with Joe DeRita in place of original Stooge Curly Howard.

The adaption from Gold Key in The Three Stooges #15 (Jan. 1964/p) had art by Pete Alvarado.

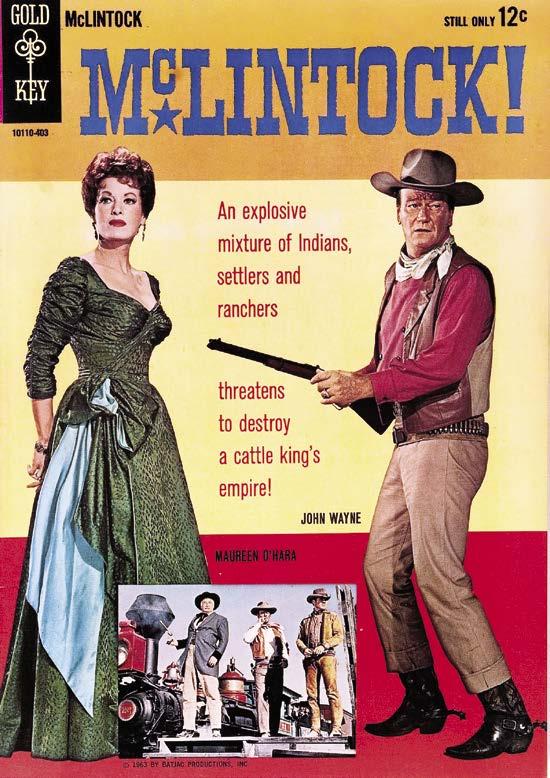

McLINTOCK! : McLintock! (1963) featured John Wayne as a wealthy rancher who was looking forward to the return of his daughter (Stephanie Powers) from school, but suddenly had to deal with the arrival of his estranged and antagonistic wife (Maureen O’Hara). Wayne and O’Hara were a joy to watch in this, with the plot being more than just a nod to The Taming of the Shrew (O’Hara’s character was even named Kate).

Mike Sekowsky’s artwork for the Gold Key movie adaptation (Mar. 1964/p) was good in many areas, but at other times his characters were incredibly stiff.

THE SWORD IN THE STONE : The trouble with Walt Disney’s The Sword in the Stone (1963), the story of

young Wart who would one day become King Arthur, was his training by Merlin. The ending is known of pulling the sword from the stone, but instead of working on a steady straight course to that end, it deals with Wart being turned into a fish, a bird, and a squirrel by Merlin as mentioned in the novel The Once and Future King by T.H. White. Most of The Sword in the Stone was devoted to those adventures and they were not that entertaining. (In the stage and film musical Camelot , a grown King Arthur mentions that teaching by Merlin in just a few lyrics.) When compared to the previous elaborate animated Disney films, The Sword in the Stone felt like filler before the release of Mary Poppins the following year.

The Gold Key adaptation was a 64-page issue (Feb. 1964/p), which had Carl Fallberg handling the script and Pete Alvarado doing the art (with Tony Di Paolo inking).

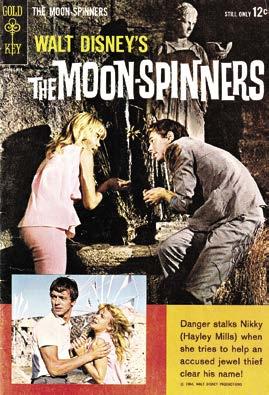

(left) Walt Disney’s The Moon-Spinners (1964) was an example of how the quality of graphics and printing of Gold Key’s covers outshone the competition from Dell Comics.

(right) McHale’s Navy (1964).

other side of the coin, female performances were very good: Mills, Irene Papas as the owner of the hotel, and Pola Negri portraying a mysterious rich woman.

The Gold Key comic adaptation (Oct. 1964/p) generally followed the film story. The artwork by Dan Spiegle was good but Mills, who was 19 at the time of the film, looked like a child of 14 in the comic.

McHALE’S NAVY: Spinning off of the TV series, the McHale’s Navy theatrical movie (1964) features a plot with McHale (Ernest Borgnine) trying to pay off a gambling debt of his crew, as well getting money necessary to repair a French port’s dock after Ensign Parker (Tim Conway) accidentally ran PT 73 aground. McHale devises a scheme to disguise an Australian champion horse they found and enter it into a race. To do so, however, they need to transport it on the bow of the PT cruiser and there is a Japanese sub operating nearby.

This sort of slapstick humor has grown tired over the years, and that carries over into the Dell comic adaptation (Oct.-Dec. 1964/p), which was drawn by Henry Scarpelli.

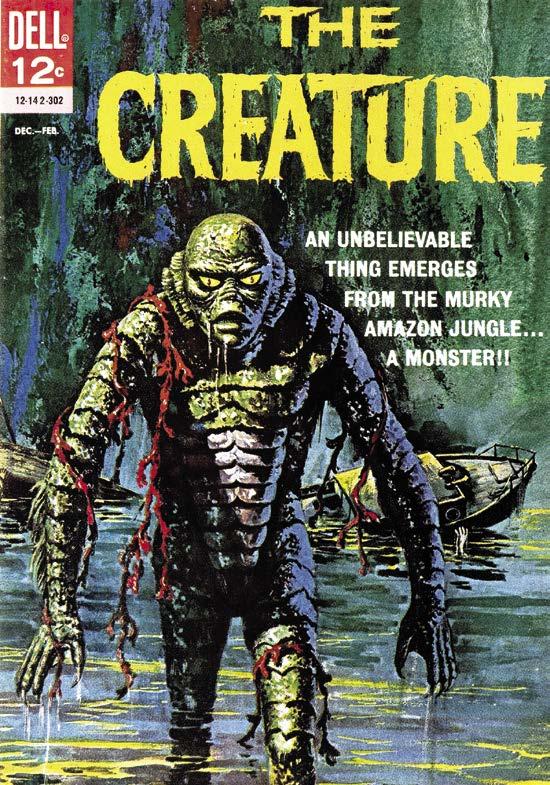

CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON / THE MUMMY / DRACULA / THE WOLF MAN / FRANKENSTEIN: In the early Sixties, Dell licensed five of Universal’s famous monsters for their comic books: the Mummy, Dracula, the Wolf Man, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, and the Frankenstein monster, but they weren’t film adaptations. Instead, Dell threw them into new stories. Even worse, a few years later, Dell created superheroes based on the Frankenstein creature, Dracula, and the Werewolf. On a positive note, though, legitimate comic adaptations of several of the great horror films did appear around that time:

CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON : The Creature (Dec. 1963-Feb. 1964, Dell) was the closest by Dell in adapting a Universal classic monster movie (in this case, Creature from the Black Lagoon from 1954). It even included an excellent representation of the Gill Man costume from the movie, which involved much more detail than just drawing a knockoff of the Mummy, Dracula, or the Frankenstein monster. Bob Jenney handled the artwork for the issue, which Dell reprinted a few months later (cover dated Aug.-Oct. 1964).

THE MUMMY: An actual retelling of the 1932 Boris Karloff horror film was a six-pager in Warren Magazines’ Monster World #1 (Nov. 1964), with story and art by Russ Jones and Wallace Wood. The art perfectly captured the likenesses of Karloff and several others in the original cast. (It was later reprinted in Eerie #11, September 1967.)

Monster World also published another Mummy movie adaptation, The Mummy’s Hand (1940), which had Tom Tyler as Kharis/the Mummy. The comic-illustrated version ran

The Creature was a fair representation of the Creature from the Black Lagoon movie story but used different character names. © NBCUniversal. Cover scan courtesy of Heritage.

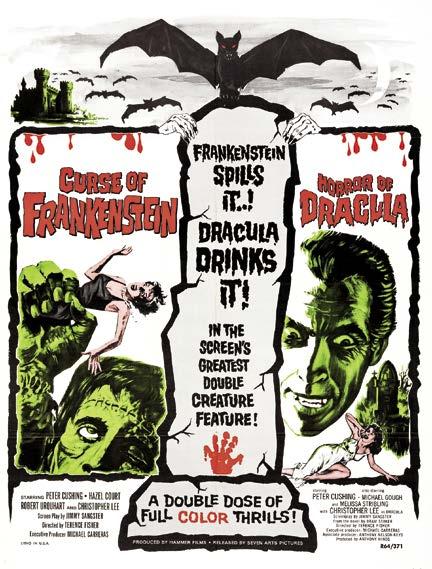

The Horror of Dracula and Curse of Frankenstein combination issue (1964) satisfied Peter Cushing/Christopher Lee fans with a total of almost 500 photographs and frame stills.

seven pages in Monster World #2 (Jan. 1965), with story and art by Russ Jones and Joe Orlando. (A reprint of the story could be found in Warren’s Famous Monsters of Filmland #40, August 1966, and in Creepy #17, October 1967.)

DRACULA: Warren also did a comic-illustrated adaptation of Hammer’s 1958 Horror of Dracula with Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee in Famous Monsters of Filmland #32 (Mar. 1965) (and reprinted in #50, July 1968), with story and art by Russ Jones and Joe Orlando.

FRANKENSTEIN : A seven-page comic adaptation of The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), which also starred Cushing and Lee, was published in Monster World #3 (Apr. 1965, Warren). The story and art had Russ Jones and Joe Orlando teaming up again.

WARREN FUMETTI: THE HORROR OF PARTY BEACH, THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN, HORROR OF DRACULA, AND THE MOLE PEOPLE : In 1964, Warren Publications tried the fumetti approach with photo magazines based on The Horror of Party Beach (1964), The Mole People (1956), and a double-bill of Horror of Dracula (1958) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). The magazines each contained approximately 500 photos.

A perfect double-bill for Drive-In movie theaters in 1964! © Warner Bros. Discovery. Poster image courtesy of Heritage.

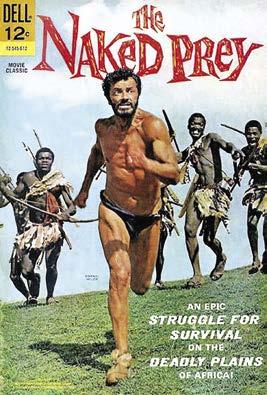

including the guide. For amusement, the chief ordered the death of the party in different ways, but the guide –stripped of all clothes and protection – was seen as sport for his ten greatest hunters to chase across the land and kill. However, the naked prey was more dangerous than they expected.

Dell’s comic book adaptation (1966) had art by Dick Giordano, but here he was ill-matched with inker Vince Colletta who again lost what good there was in Giordano’s pencils.

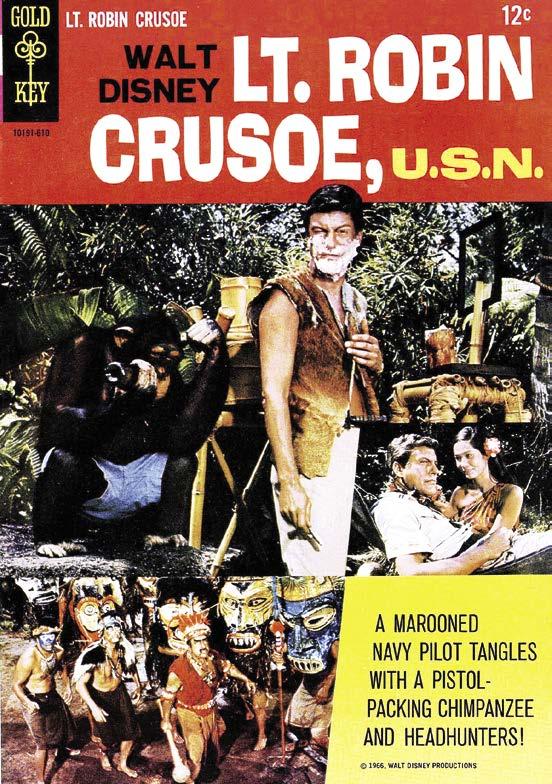

LT. ROBIN CRUSOE, U.S.N. : Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. (1966) was based on a story by Walt Disney (credited backwards onscreen as “Retlaw Yensid”) about a modernday Robinson Crusoe, in this case a Navy flyboy who had to bail out of his plane when it caught fire. He drifted at sea, then found an abandoned island…or so he thought. Even with the presence of the very talented Dick Van Dyke, the film headed into boredom until the arrival of beautiful and funny Nancy Kwan as a native girl whom he named “Wednesday.”

Dan Spiegle’s art for the Gold Key adaptation (Oct. 1966/p) featured excellent characterizations of Van Dyke and Akim Tamiroff playing the native girl’s tyrannical chieftain father, as well as superb layouts throughout. The story was reprinted in Walt Disney Showcase #26 (Dec. 1974).

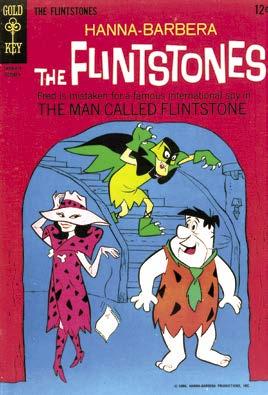

THE MAN CALLED FLINTSTONE : When dashing superspy Rock Slag is injured in a fight against foreign enemies working for an evil, would-be world conqueror called the

Green Goose, the government calls upon a lookalike to take Slag’s place. And the name of that exact twin is — The Man Called Flintstone . The 1966 feature animated film, released after the end of the TV program, was unfunny and had a series of forgettable musical numbers. The Flintstones #36 comic (Oct. 1966) adapted the movie with little changed. Art was by Pete Alvarado.

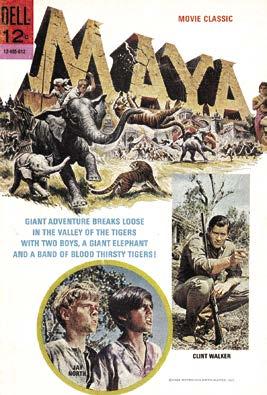

MAYA : In his first semigrownup role after appearing in the Dennis the Menace TV program, Jay North starred in a theatrical movie called Maya (1966) and then in the subsequent television series based on it. In the

exceptional job capturing the look of the film and the actors. When he drew MacMurray happily delivering a powerful punch to a Marine’s face, the reader truly felt the impact.

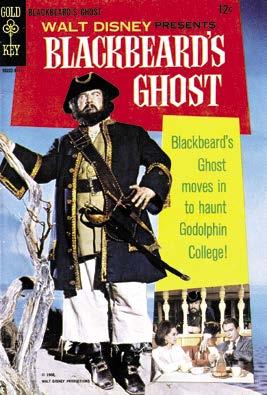

BLACKBEARD’S GHOST : Peter Ustinov absolutely delighted in Walt Disney’s Blackbeard’s Ghost (1968) as the title character (real name: Edward Teach) held trapped in limbo by a curse from his tenth wife, a witch, unless he did a good deed. That good deed, it turned out, was to help his little old lady descendants not get kicked out of the inn they lived in by a slimy gangster who wanted to build a gambling palace there. Dean Jones co-starred as the local college’s new coach and the person who unwittingly released the ghost from limbo temporarily.

The Gold Key comic (June 1968/p) did a very good job of carrying over the film. Of course, the giddiness of Peter Ustinov’s performance could not be captured in the adaptation, nor some of the movie’s hilarious moments. However, Dan Spiegle did exceptional work with it all.

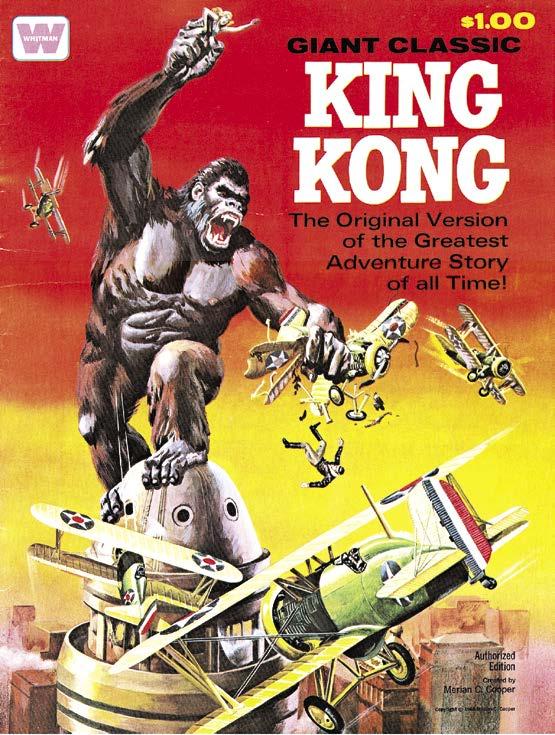

KING KONG : The greatest monster movie of all time was King Kong (1933). Though there have been remakes, the original is still unsurpassed in its own way: the giant gates, Ann (Fay Wray) struggling with the ropes that bind her to the platform, the noise of smashing trees and then the first appearance of Kong! And, later, inside the New York theatre with Kong busting loose from his chains and smashing up the city as he searched for Ann, leading to the climb to the top of the Empire State Building, the biplanes, and that famous ending. All in one film!

In 1968, Whitman issued a comic book adaptation worthy of such a great film to coincide with the 35 th anniversary rerelease of the film. The Whitman one-shot was tabloidsized, with art by Alberto Giolitti and a magnificent painted cover by George Wilson of Kong fighting the biplanes with one hand while holding Ann with his other. Gold Key published a regular comic-sized version, containing the same story and artwork.

Except for Kong, none of the comic’s characters resembled the actors, and Ann Darrow was updated with long hair and 1960s clothes. The edition is also notable for no mention of RKO Studios, which released the film. In actual fact, there is nothing mentioning the movie at all. The comic adaptation is listed as an authorized edition, with a credit of “Created by Merian C. Cooper.” The reason is that Cooper (the film’s co-producer, co-writer, and co-director) lost a court case involving rights to the movie but retained the rights to a novelization of the story, and it is that novelization the Whitman/Gold Key edition was based upon.

© the respective holders.

At a time when the world (and movies) needed it most, Star Wars (1977) gave everyone “a new hope.” © Lucasfilm/Disney.

When the 1960s came to an end, the U.S. was still embroiled in Vietnam. Nixon was still president. And the tension between the hawks and the doves was in the daily news, but never more so than on May 4, 1970, the day that the Ohio National Guard opened fire on anti-war protestors at Kent State University, killing four and wounding nine others.

It was also the decade that ended with the American embassy in Tehran overrun by Iranians and the American employees inside taken hostage, except for six workers who were secretly given refuge by Canadians at their embassy.

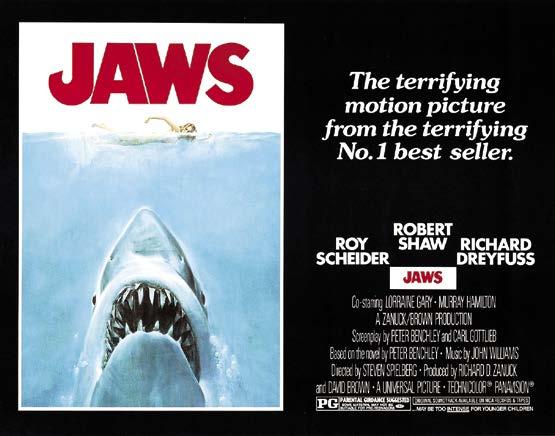

In the movies, escapism was what audiences wanted, just like in the 1930s. Among the biggest hits of the decade were Woodstock, The Godfather, Jaws, Superman the Movie, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Nostalgia for the past was also at an all-time high, with movies The Sting, That’s Entertainment, The Way We Were , Summer of ’42 , and American Graffiti becoming box office smashes. Even Star Wars was an update of 1930s swashbuckler films and movie serials.

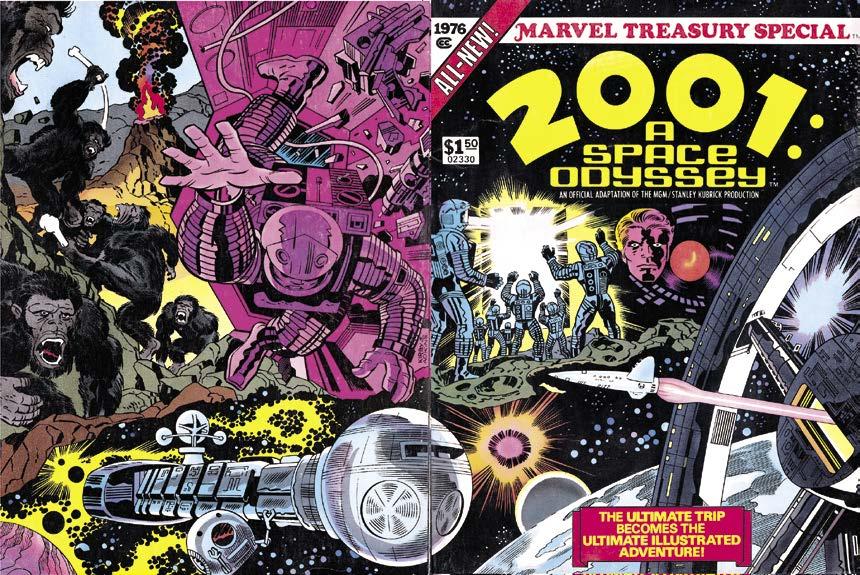

In comic books, Marvel entered the field for the first time, landing the rights to Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and the Planet of the Apes franchise, plus providing adaptations of The Wizard of Oz and 2001: A Space Odyssey

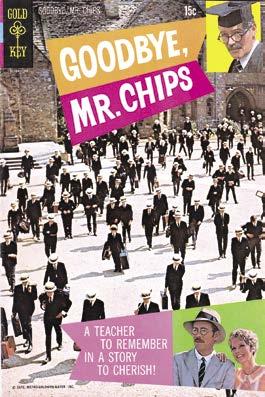

GOODBYE, MR. CHIPS: Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969) was the musical tale of a stiff English teacher, Mr. Chipping (Peter

Jaws (1975) was for audiences of the Seventies what King Kong (1933) was for those of the Thirties: an ultimate escapism movie.

© NBCUniversal. Poster image courtesy of Heritage.

O’Toole), at a private boys’ school. His life is changed when he meets the woman (Petula Clark) who will become his wife. That much was the same as the original 1939 non-musical film, which was based on a novella by James Hilton. However, the execution of the remake was entirely different, with the young woman he meets being a stage performer, which led to musical numbers in a theater and at wild parties in her home. All the songs were showstoppers — but in a bad way. They stopped the movie cold.

The Gold Key adaptation (June 1970/p) was an odd job. Whole sequences appear that are not in the film, while a lot of the movie fails to get more than a glance. The art by Giorgio Cambiotti was likewise a disappointment.

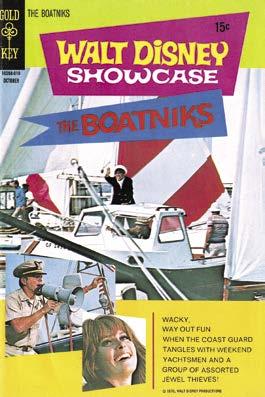

THE BOATNIKS : Robert Morse and Stefanie Powers led the cast in Disney’s The Boatniks (1970), a tale of a young, accident-prone Coast Guard ensign (Morse) taking command of a ship in California at the same time as three inept crooks try to slip away on a rented boat to Mexico with $2 million in stolen jewelry. The film was not fun and even Morse, the normally high-spirited, charming star of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying and TV’s Mad Men, looked like he was not interested.

The Boatniks was the first adaptation for Gold Key’s new comic book series, Walt Disney Showcase . The premiere issue (Oct. 1970) eliminated the dreary first 30 minutes of the film and jumped right to the ensign and the owner of the ketch (Powers) becoming suspicious of the three men. The art by Dan Spiegle, possibly aided by Bill Ziegler, was less than his best, but was good in the rendering of Morse.

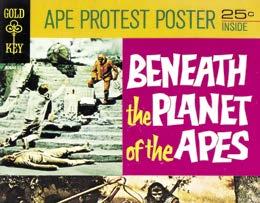

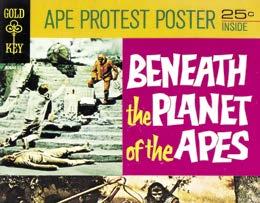

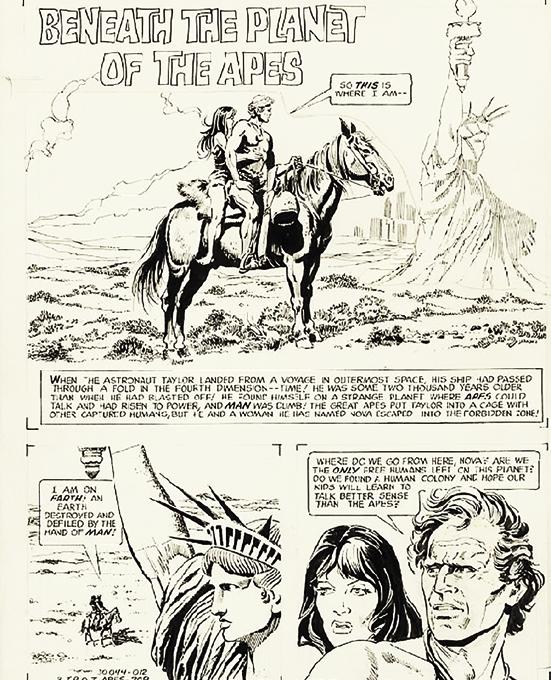

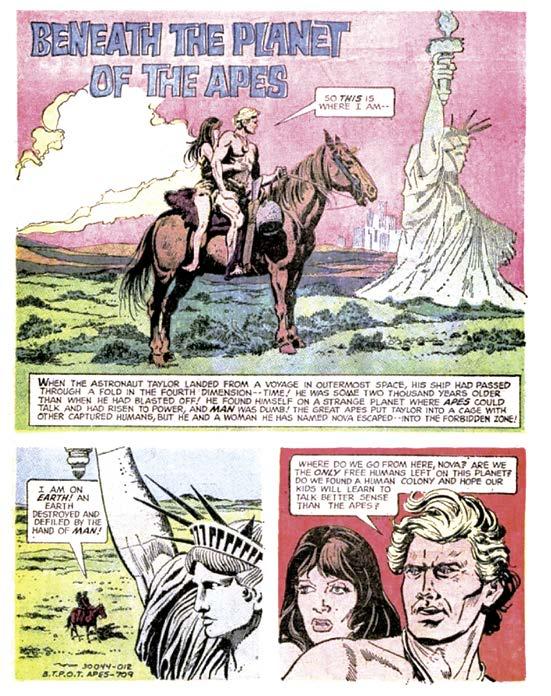

BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES : Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) took up where Planet of the Apes (1968) left off, with Taylor (Charlton Heston) and Nova (Linda Harrison) riding into the Forbidden Zone. Meanwhile, in yet another crash landing of a spaceship from Taylor’s time was Brent (James Franciscus), searching for Taylor and his crew. The sequel covered much of the same ground as the first movie, but it was the battle of apes vs. human beings that brought the audience back. Heston’s appearance in the movie was more of a guest shot, but his role as Taylor was important to the conclusion

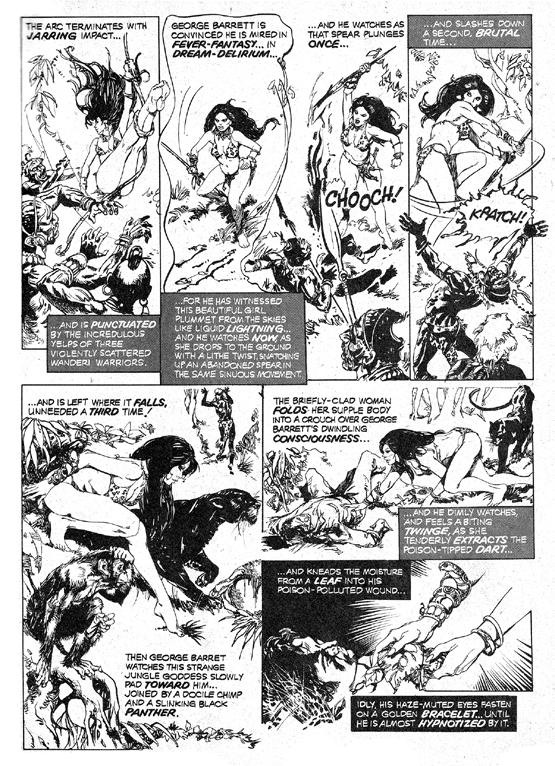

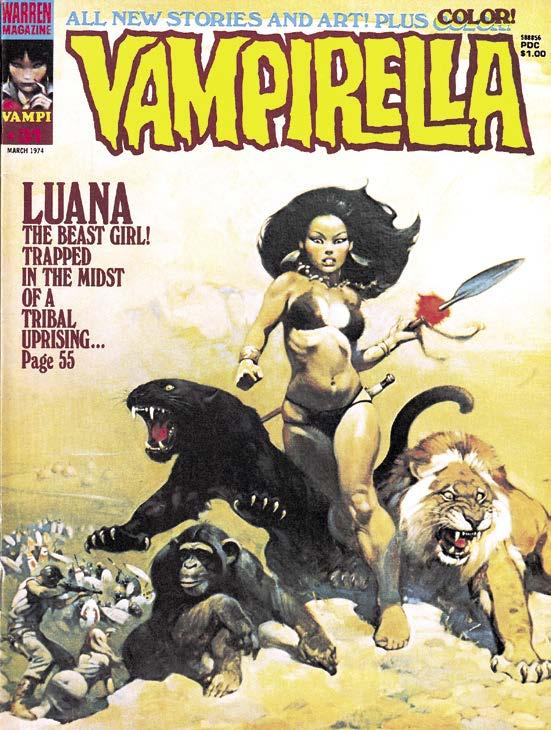

LUANA, THE GIRL TARZAN : The movie posters by Frank Frazetta made the heroine of the jungle movie Luana, the Girl Tarzan (1974, but released in Italy in 1968 as Luana la Figlia della Foresta Vergine ) look exciting; however, the most exciting thing that the picture’s star, Mei Chen, did during the movie was smile. She snuck through the jungle, stopped, and smiled. She watched two people kiss, and

© the respective holders.

smiled. She pulled poison darts out of the hero’s chest, and smiled. Looking pretty and cheery appeared to be the entire reason Chen was hired. Meanwhile, back in the movie where there was a script going on (actually straight out of King Solomon’s Mines ), a woman (Eva Marandi) goes to the African continent seeking to hire an explorer (Glenn Saxson) to help find her missing father. The film was low budget and looked it.

One of Frazetta’s movie poster designs for Luana made it to the front cover of Vampirella #31 (Mar. 1974). The

of several

©

followed by Alfredo Alcala (#24, Sept. 1976), Sonny Trinidad (#25, Oct. 1976), Dino Castrillo (#26, Nov. 1976), and wrapped up by Virgil Redondo (#27, Dec. 1976, and #28, Jan. 1977). (The final issue, #29 – February 1977 – of the magazine series contained non-movie material.)

Power Records also adapted four of the movies in 1974 in their Book and Record Sets, missing only Conquest of the Planet of the Apes. “Arvid Knudsen and Associates” are credited in each with the story adaptation, comic art, and design. On a more individual basis, the art has been attributed to Ernie Chan for all four covers and Nestor Redondo for the interiors.

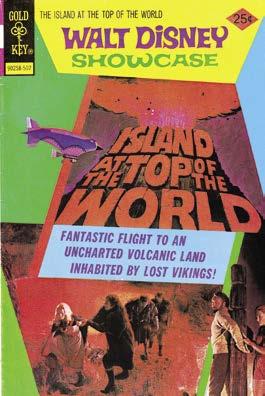

THE ISLAND AT THE TOP OF THE WORLD: Walt Disney’s production of The Island at the Top of the World (1974) was an adventure film set in the Arctic with Sir Anthony Ross (Donald Sinden) bankrolling a small expedition to find his missing son. The traverse over the frozen wasteland was by way of a huge zeppelin-like airship taking its members (including star David Hartman) into a hidden land that included an ancient race of Vikings. The movie was enjoyable, though the mattes with actors and special effects were not well combined.

The film’s 25-page comic book version was in Walt Disney Showcase #27 (Feb. 1975) with script by Mary Carey and art by Bill Ziegler. Though Ziegler’s drawing of people remained simplistic, his layouts were well done.

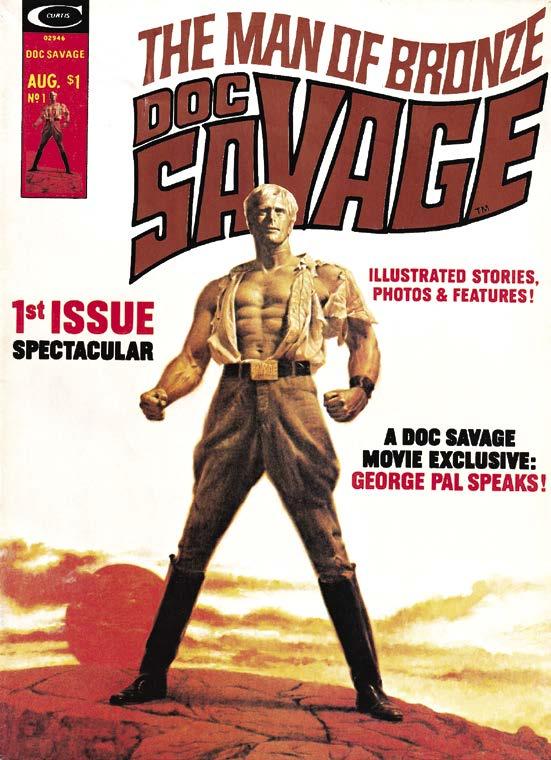

The use of the Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze movie poster art might lead one to think it was a film adaptation but it wasn’t. However, it did have an interview with producer/director George Pal. Doc Savage #1 (Aug. 1975). © Marvel or the respective holders.

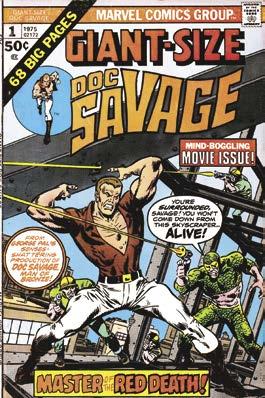

DOC SAVAGE: THE MAN OF BRONZE : The story of Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze (1975) involved wealthy adventurer Clark Savage, Jr. (aka Doc Savage) learning his father has been killed in Central America and setting out with his team to find out who did it. Based on the first Doc Savage story in March 1933, “The Man of Bronze,” the film’s use of the work was wobbly, to say the least. The casting of Ron Ely, former TV Tarzan, was not who many saw as Savage and the film was high camp.

(right) It says “movie issue” on the cover but it really wasn’t, just derived from the same source as the film…the original pulp story from 1933. Giant-Size Doc Savage #1 (1975). Cover art by John Buscema.

The Island at the Top of the World © Disney. Doc Savage © Marvel or the respective holders.

Though Marvel stated on its cover for Giant-Size Doc Savage #1 (1975) that it was a “Mind-Boggling Movie Issue!,” the actual stories inside were reprinted from the first two issues of Marvel’s already-running Doc Savage comic title adapting the pulp novels of Lester Dent (writing as Kenneth Robeson). The only tie-in was that it was “The Man of Bronze” storyline. Marvel also produced 8 issues of a Doc Savage black-and-white comic-illustrated magazine between August 1975 and Spring 1977.

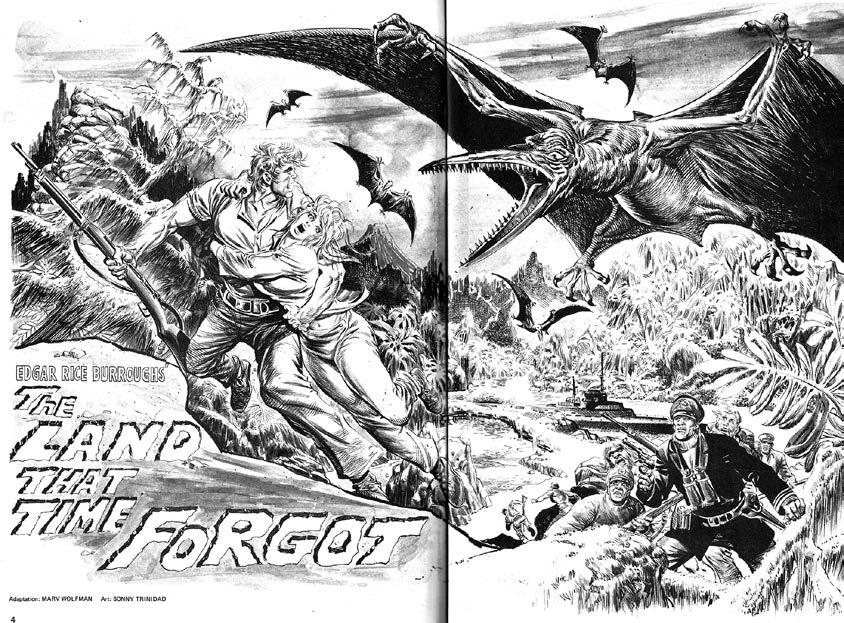

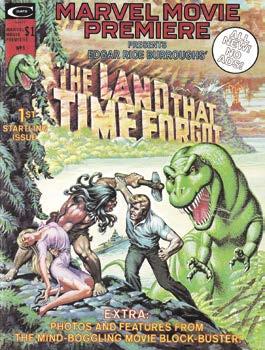

men. The movie starred Doug McClure as the hero and he was adequate enough, but the script was devoted to action and little towards characterization. By film’s end, it was just a monotonous piece with poor special effects. The adaptation in the black-and-white Marvel Movie Premiere #1 magazine (Sept. 1975) was better than the movie itself, with an excellent script by Marv Wolfman and art by Sonny Trinidad.

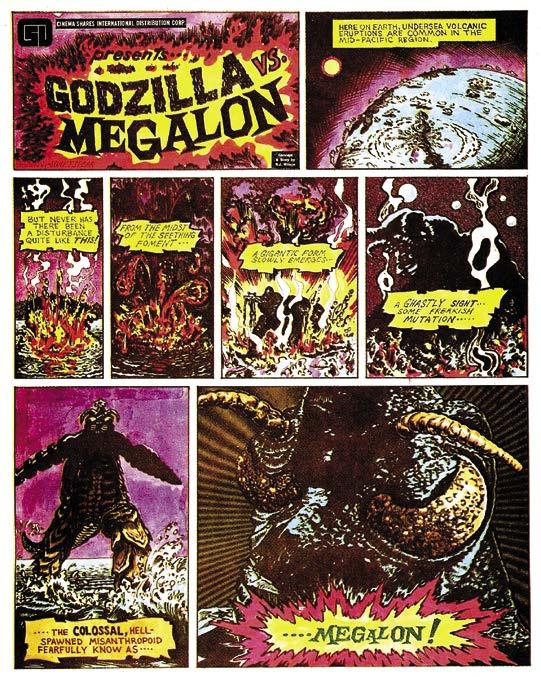

GODZILLA VS. MEGALON : Godzilla was absent for so much of Godzilla Vs. Megalon (1973, but released in the United States in 1976) it could have almost been almost forgotten he was in the movie. In the film, Godzilla went from being the monster who had a habit of stomping on Tokyo to becoming one of its heroes, aiding a giant robot called Jet Jaguar in defeating two ridiculous-looking monsters, Megalon and Gigan.

Upon its 1976 U.S. release, the film’s distributor (Cinema Shares) gave out a 4-page color comic adaptation. The art by Swiftspear was poor and the writing was limited to just a quick synopsis of the film’s story.

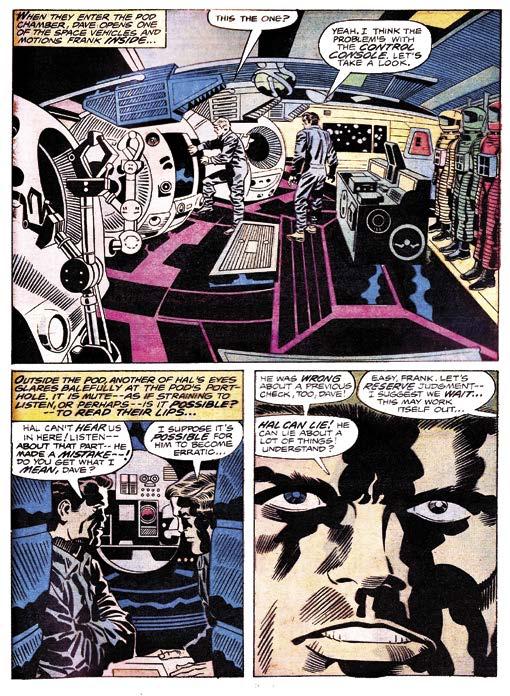

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY : 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) was a visual sensation with hardly any dialogue. The story focused on trying to solve the mystery of a black obelisk that had appeared during the primitive period

(above and left) Painted cover by Nick Cardy for the adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Land That Time Forgot (1975). Marvel Movie Premiere #1 (Sept. 1975). Marv Wolfman’s script, complemented by Sonny Trinidad’s action-packed art, was better than the film it was based on.

© the respective holder.

A page from the adaptation for Godzilla Vs. Megalon (1976 U.S. release).

© the respective holders. Scan courtesy of Heritage.

of Earth, then reappeared in 2001 AD on the moon. Later, a group is dispatched to Jupiter to discover why the obelisk sent out a signal to that planet.

It took eight years before the comic adaptation appeared. However, the Marvel Treasury-size special was worthy of going so large, featuring the company’s most important artist, Jack Kirby, drawing 70 pages of outstanding artwork (with exceptional inking by Frank Giacoia). Kirby also edited and wrote the comic’s script.

One of the least expected places to find an adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey was on a kids’ menu for Howard Johnson’s. Art by Al McWilliams.

There was one other comic adaptation of the film. It was part of a special children’s menu Preview Edition for Howard Johnson’s, with the title of Debbie And Robin Go To A Movie Premiere With Their Parents . The movie was 2001: A Space Odyssey – and the restaurant and hotel chain got to promote their brand in a scene in the film where “Howard Johnson Earthlight Room” appeared on a wall in an early scene in the space station. The art for the story was by Al McWilliams.

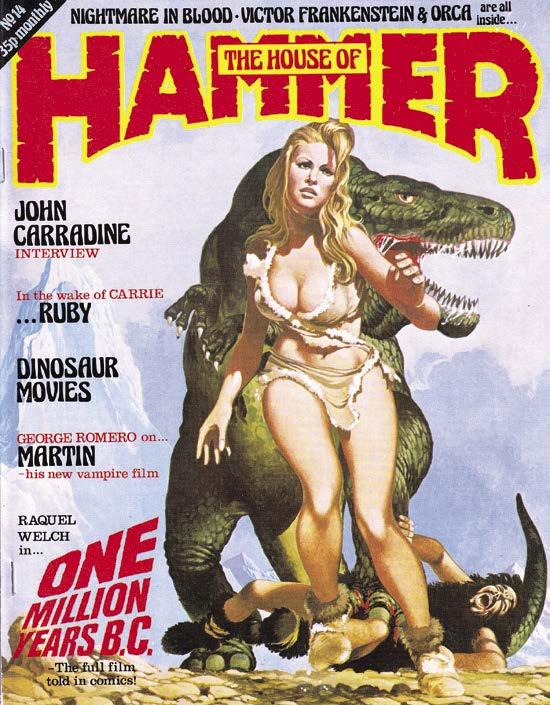

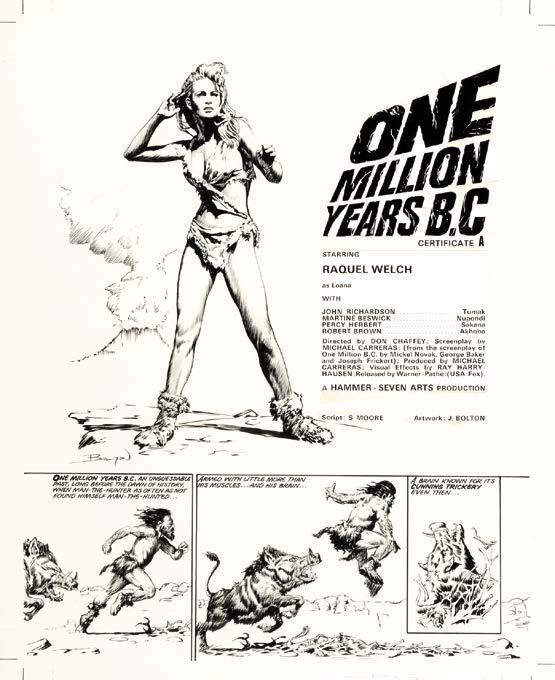

THE HOUSE OF HAMMER : The House of Hammer was a British magazine dedicated to the horror films produced by the Hammer studio. In addition to articles, the first issue (1976) featured an excellent 21-page black-and-white comicillustrated adaptation by Dez Skinn and Paul Neary of the 1958 movie Dracula (Horror of Dracula in the United States). A number of the following issues included other black-andwhite comic adaptations of classic and not-so-classic Hammer movies, among them The Mummy (1959), One Million Years B.C. (1966), Curse of the Werewolf (1961) and The Gorgon (1964) by some of the U.K.’s best writing and art talents, including Brian Clemens, David Lloyd, Brian Bolland, and John Bolton. The magazine changed its name to Hammer’s House of Horror with #19 and then to Hammer’s Halls of Horror with #21, lasting through #30 in 1979. (See Appendix for a full list of the movie adaptations.)

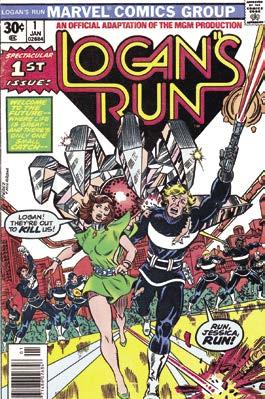

LOGAN’S RUN : Logan’s Run (1976) featured a pictureparadise city in which young people in the 23 rd Century lived and loved — until they reached their 30 th birthday

when the crystal attached to their palm flashed red and they were forced to go through a public display of “Renewal” in a coliseumround setting. Those who tried to escape (called “Runners”) were hunted down and killed by a police-like force, known as “Sandmen.” However, there was a “Sanctuary” where Runners who survived safely got to…and the computer controlling the city electronically stripped one Sandman, Logan (Michael York), of several years of his life until his own crystal flashed, and sent him out undercover to infiltrate Sanctuary.

The Marvel comic adaptation of Logan’s Run was published in the first five

The 1970s may have drawn to a close, but so much more was still to come. Disney entered a second Golden Age of animated movie musicals that were adapted to comic books. (A number of these films also went on to great success on Broadway, including Beauty and the Beast , Aladdin , and The Lion King ).

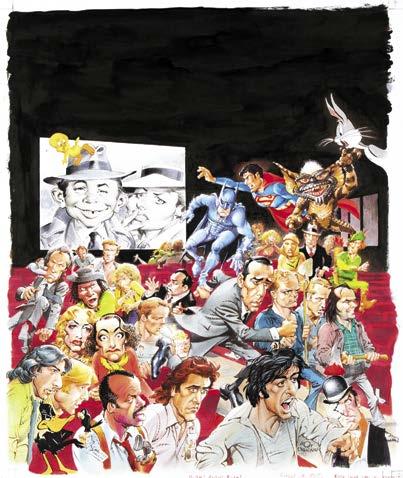

The franchises for Star Wars, Star Trek, and Indiana Jones got fine adaptations from DC, Marvel, and other publishers.