EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Roger

PUBLISHER

John

DESIGNER

EDITOR

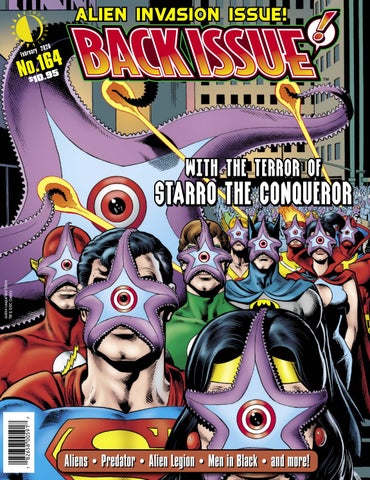

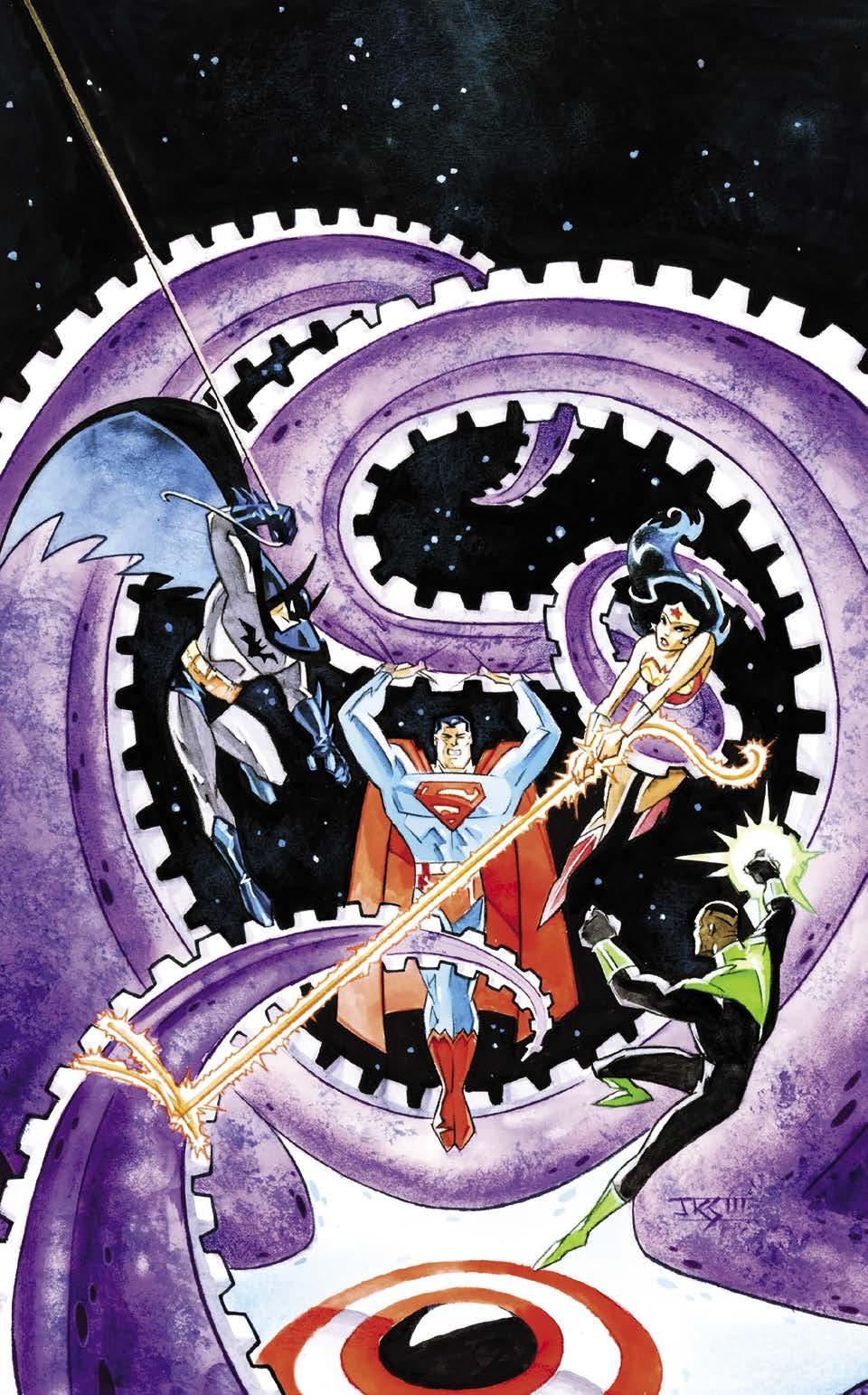

COVER

Brian

(Originally appeared as the cover of Justice League of America #190. Scan courtesy of Karim Elrafei.) COVER

Glenn

PROOFREADER

Kevin

SPECIAL

Terry

Tony

Sandy

Stephan

Grand

James

Paul

Ed

Alissa

BACK ISSUE ™ issue 164, February 2026 (ISSN 1932-6904) is published monthly (except Jan., March, May, and Nov.) by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Back Issue, c/o TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614.

Michael Eury, Editor Emeritus. Roger Ash, Editor-In-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. Editorial Office: BACK ISSUE , c/o Roger Ash, Editor, 2715 Birchwood Pass, Apt. 7, Cross Plains, WI 53528. Email: rogerash@hotmail.com. Eight-issue subscriptions: $108 Economy US, $128 International, $39 Digital. Please send subscription orders and funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial office. Cover artwork by Brian Bolland. TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. All editorial matter © TwoMorrows and Roger Ash, except Terry’s Toons © Terry Austin. Printed in China. FIRST PRINTING

by James Heath Lantz

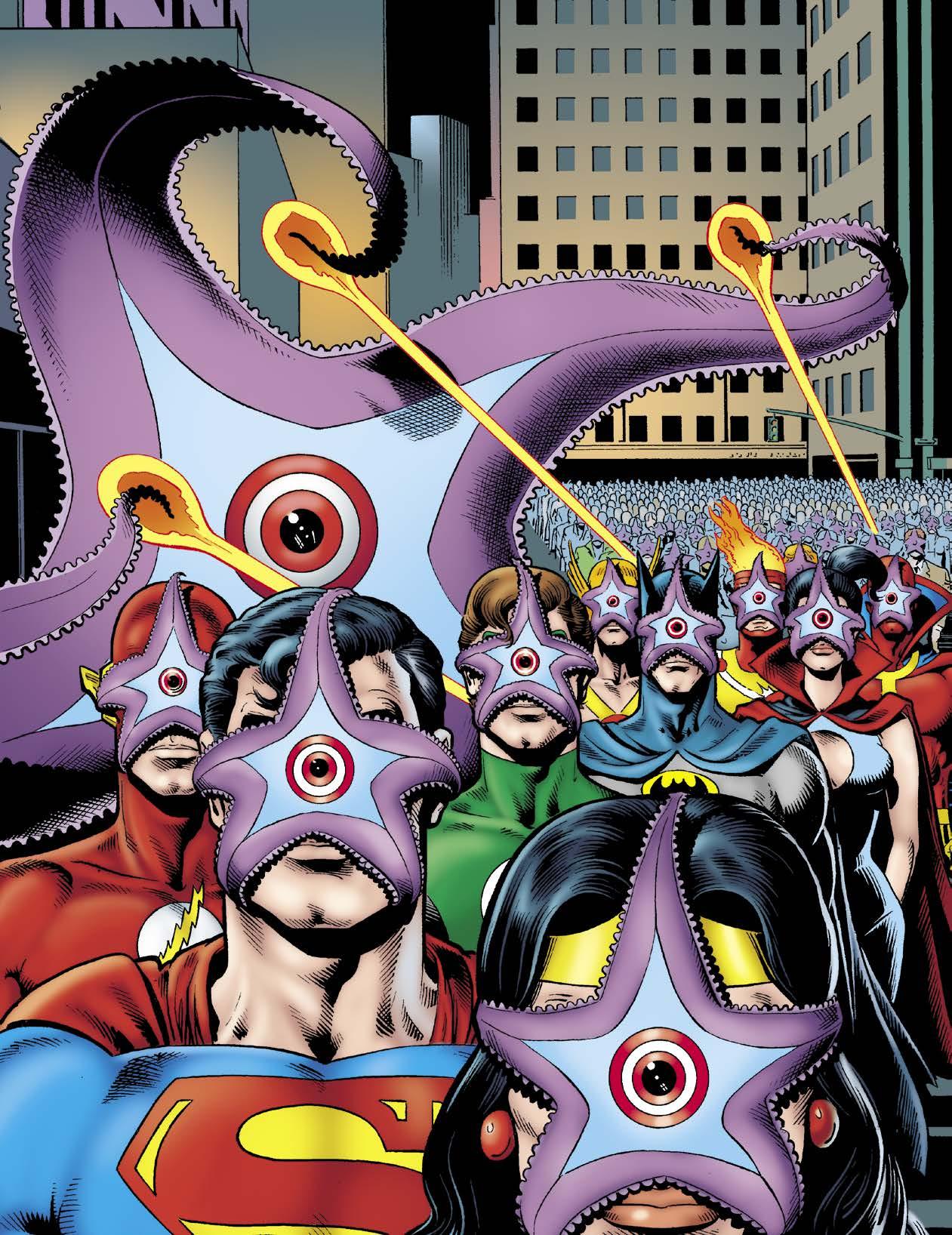

Painted art for the cover to Dark Horse’s 1995 one-shot Aliens vs. Predator: Booty by Den Beauvais. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com). TM & © 20th Century Studios.

Both the Alien and Predator film franchises have given lovers of science fiction and horror cinema action, thrills, chills, and a body count that rivaled those of many of the iconic characters of both genres. In the late 1980s, Dark Horse Comics went beyond the movies and began publishing Aliens, Predator , and Aliens vs. Predator comics. The fact that no film budget was needed allowed the publisher and creators to explore aspects that went beyond celluloid. The popularity of the Aliens and Predator comics led to the birth of the Aliens vs. Predator spin-off that would spawn its own video game and film series. Aliens vs. Predator would bring two series together, creating more fear and bloodletting than each extraterrestrial character could create on their own. BACK ISSUE will travel the cosmos to look at Dark Horse’s adaptation of Aliens , Predator , and both species’ interstellar slugfests. Just watch out for Face Huggers before you read this article, Bronze Age fans.

XENOMORPHIC PANELS

“In space, no one can hear you scream.”

That tagline introduced 1979 moviegoers to a new kind of terror that blended science fiction and horror. Ellen Ripley, portrayed by Sigourney Weaver, and the crew of the Nostromo must face off with the chest bursting, acid blood dripping, Xenomorph designed by H.R. Giger in Ridley Scott, Dan O’Bannon, and Ronald Shusett’s Alien. There is a claustrophobic atmosphere of terror, with every human and the treacherous android Ash, played by Ian Holme, becoming cannon fodder for the title character.

In Terminator director James Cameron’s 1986 sequel, Aliens , Ripley, the sole survivor of the Nostromo, is awakened from hypersleep, the Alien franchise’s name for suspended animation, fifty-seven years after her confrontation with the Xenomorph. This more action-oriented movie teams Ripley with a new crew of Colonial Marines, and Lance Henriksen as a friendlier android named Bishop, to battle more of these vicious creatures, including an Alien Queen. Ripley, Bishop, a young girl nicknamed Newt, and Corporal Dwayne Hicks live through the entire ordeal, going into a much earned hypersleep.

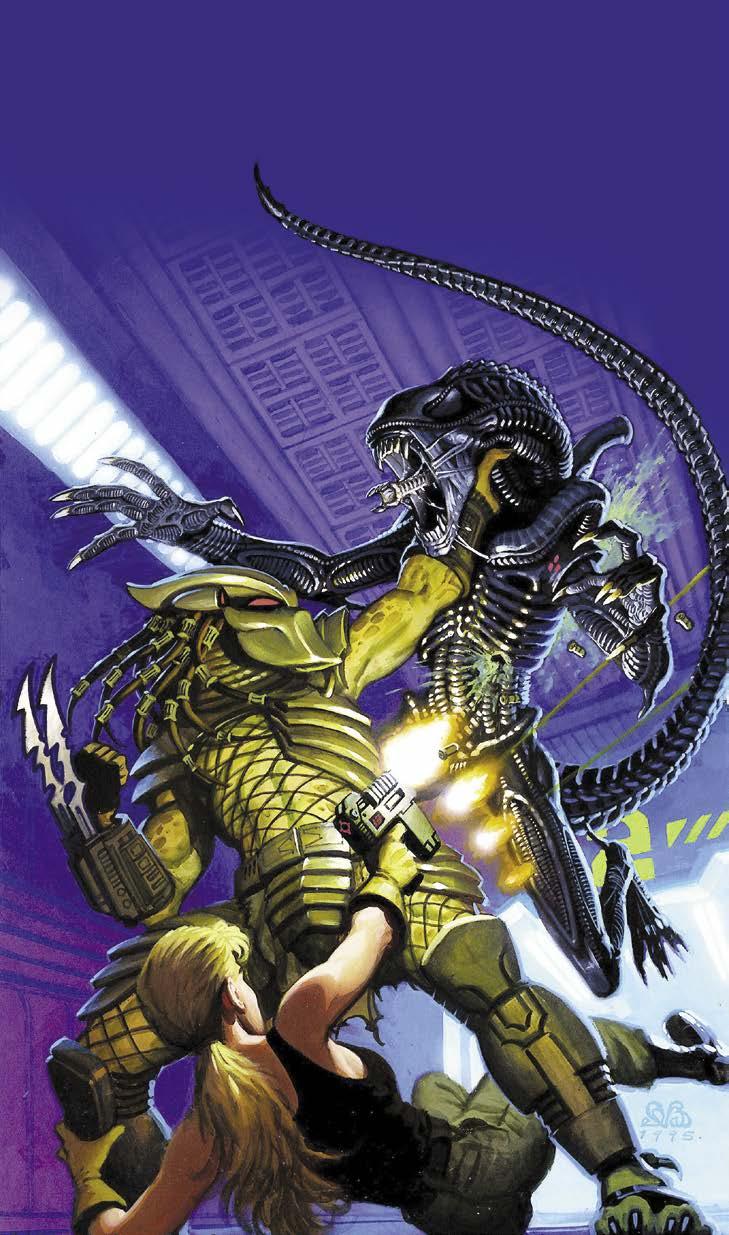

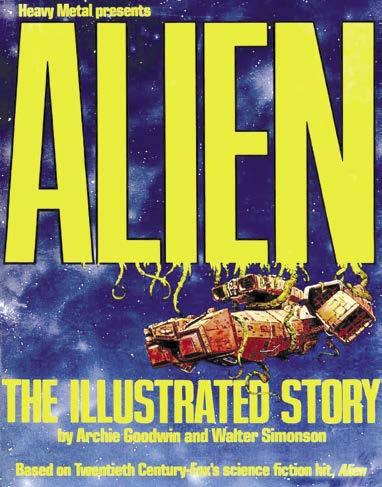

The Aliens comic series technically made its debut in Archie Goodwin and Walter Simonson’s adaptation of the first film in Heavy Metal Presents Alien: The Illustrated Story. Yet, the material released by Dark Horse Comics truly took Xenomorphs and Face Huggers beyond the silver screen. Common themes of the series included humanity’s survival in a universe dealing with corporate corruption and a vicious extraterrestrial lifeform.

Mike Richardson, in his introduction to the Aliens: Outbreak trade paperback that was later re-published in Marvel’s Aliens: The Original Years Volume One omnibus, stated that he and Randy Stradley set out to produce comic book sequels of their favorite motion picture properties. While not unheard of at the time, comics based on film, television shows, and/or

toys were not held by Marvel or DC in as high regard as Spider-Man or Superman. Yet, the staff at Dark Horse Comics had but one goal, to make comics they themselves would want to read. The first issue of Dark Horse Comics Presents proved they could do exactly that with the debut of Paul Chadwick’s Concrete and Chris Warner’s Black Cross. Sales exceeded expectations. This is perhaps due to the direct marketing to comic book shops in the 1980s which allowed for a wider variety of titles and genres compared to the spinner racks found in supermarkets, pharmacies, and department stores.

Dark Horse Comics acquired the rights to publish Godzilla comic books in 1987. Their success led to Aliens being next on Dark Horse’s agenda. Richardson and Stradley, according to the former’s introduction from the Aliens: Outbreak trade paperback and Marvel’s Aliens: The Original Years Volume One omnibus, decided to go beyond merely adapting the films (though Dark Horse would do that masterfully over the years) and produce miniseries, one-shots, and short stories, rather than a less reader-friendly monthly periodical. These stories would expand on the Aliens universe much like Star Wars and Star Trek novels and comics would do for those science fiction giants.

The six issue Aliens (June 1988-July 1989), later titled Aliens Book I and Aliens: Outbreak, was published in black-and-white, giving Nelson’s art done on Duoshade board the more horrific atmosphere of Ridley

Scott’s Alien mixed brilliantly with the action of Cameron’s Aliens. Dark Horse’s first miniseries, written by Mark Verheiden, is set several years after the second movie. Newt is a patient at the Feildcrest Home mental institution, Hicks, whose face was scarred by the Xenomorph’s acidic blood in the Aliens film, is avoided by his fellow Colonial Marines who fear he is infected with the Alien. Both Hicks and Newt must fight their own personal demons as they voyage to the Aliens’ homeworld. The insidious creatures, however, are much closer than Hicks and Newt believe as a captured Alien Queen is on Earth.

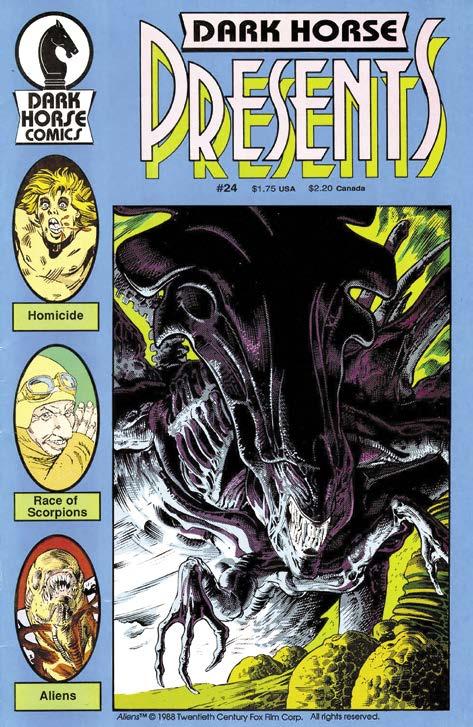

It should be noted that between the releases of Aliens #2 and 3 (Sept. 1988 and Jan. 1989), Verheiden and Nelson provided a short story in Dark Horse Presents #24 (Nov, 1988) that serves as a prologue for Aliens Book I . “Theory Of Alien Propagation” uses Nelson’s stunning visuals and narration captions with excerpts from Book I’s Doctor Waidslaw Orona’s research. The eight-page tale shows the life and habitat of the famous

Mark A. Nelson’s original art for a poster promoting the original Aliens miniseries. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com).

TM & © 20th Century Studios.

cinematic extraterrestrials created by H.R. Giger brilliantly and provides readers who are new to Aliens with a taste of what awaits them in the science fiction and horror classic.

Aliens Book I is fairly faithful to Aliens canon. Yet, it is not without some goofs here and there. The most obvious of these are Hicks’ nightmare and his conversation with the aforementioned Orona in issue #1. Hicks’ dreams force him to relive the events on Acheron depicted in Cameron’s film. However, Hicks is carrying young Newt. Ripley was holding the girl in the movie. The reason for this will be explained later, but other characters from celluloid met alternate fates in the comic. It could also be surmised that Hicks’ Post Traumatic Stress Disorder could have altered how his subconscious saw things. Later in issue #1 during Hicks’ meeting with Orona, Acheron is mistakenly referred to as a planet. The film Aliens stated that Acheron was a moon. There are also conflicting chronicles of the years in which Cameron’s movie, Dark Horse’s Aliens Book I, and its 1992

TM & © 20th Century

novelization Aliens: Earth Hive by Steve Perry occur. Cameron’s Aliens takes place in 2179, fifty-seven years after Scott’s Alien . Aliens Book I’s Operation: Outreach is erroneously set in 2154, and Perry’s prose dates events in April 5, 2092. When one considers basic math and the age of Hicks and Newt in Aliens Book I and Earth Hive, they are chronologically on April 5, 2192.

The success of Dark Horse’s first Aliens comic book led to six reprintings of each issue and Verheiden’s Aliens Book II, also known as Aliens: Nightmare Asylum. Newt, Hicks, and the damaged synthetic named Butler have survived the mission to the Aliens’ home planet in the previous miniseries, only to find out Earth has been overrun by Xenomorphs. They join forces with the insane General Spears, who is attempting to train the monsters to fight their own kind, in an effort to free the third planet from the sun.

Aliens Book II was released as a color series featuring art by Beauvais and Casselman. Beauvais provided covers for each chapter. The back covers formed the image of an Alien Queen when placed together. Beauvais and Casselman’s styles are obviously different from that of Nelson. Yet like Nelson’s pages of the first book, they combined the action and horror genres atmosphere and visuals contained in the first two films of the Alien franchise. Some elements from this comic would

later be used in the fourth movie Alien: Resurrection , and the hives on Earth are inspired by H.R. Giger’s egg silo concept, which was not shown in 1979’s Alien. Beauvais discussed working on Aliens: Book II with AVP Galaxy in 2018. While he didn’t have any input on the script, he did occasionally express concerns and opinions. Beauvais also would have liked to bring in his own new concepts to Aliens. However, 20th Century Fox did not wish to deviate too much from what had been established in the two films released at the time. Beauvais did manage to add something to Aliens Book II #2. That is the hammock sack the Face Huggers use as refuge until they fully mature.

Verheiden concluded his sequel trilogy to Cameron’s Aliens film with The Maxx creator Sam Kieth and covers provided by John Bolton. This time, the protagonist of most of the movie series, Ellen Ripley, joins Hicks and Newt after her cameo in Book II #4’s last page. Aliens: Earth War, later re-released as Aliens: Female War, continued the battle to save Earth from the vicious extraterrestrials where Book II left off. Now, BACK ISSUE readers are most likely asking, “Where was Ripley during the majority of first two installments of the Aliens comic books?” Behind the scenes, the character could not be used in the comic books until Book II’s finale and Earth War were in production.

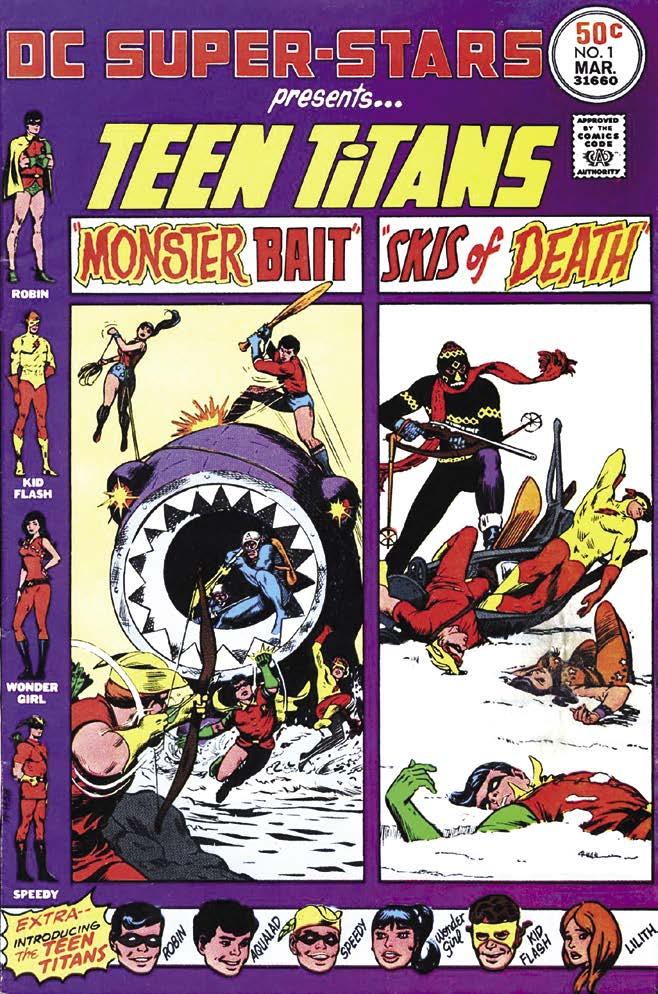

DC Super-Stars had it all: reprints, originals, sci-fi, fantasy, sports, war, good old-fashioned superheroes, and the list goes on. There were some landmark issues, too–the introduction of the Star Hunters in DCSS #16 for one, and Helena Wayne’s iconic debut as the Huntress in issue #17 for another. For eighteen issues and two years, DC Super-Stars was a bombshell of a book on both newsstands and those first stirrings of the early direct market, treating Bronze Age readers to a variety of stories rarely found elsewhere.

EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN

Initially starting out life in March 1976 as a themed reprint series under the editorship of E. Nelson Bridwell, DCSS eventually transitioned to all-new content over the course of its run. The first of the reprints featured the Teen Titans in a couple of Bob Haney-penned tales with art by Nick Cardy and Gil Kane, but it was its sophomore issue that became DCSS ’ raison d’etre. If the Titans could be seen back in their own ongoing team book in a matter of six months, then the

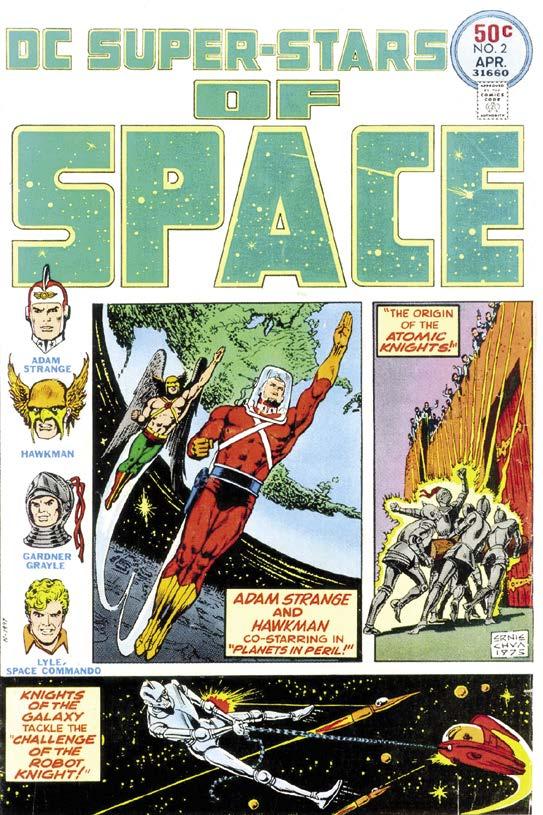

DC Super-Stars of Space began in issue #2 (left) and was a theme that the series returned to on a regular basis. Cover by Ernie Chan.

“DC Super-Stars of Space” showcased in that pivotal second issue were a sight for sore eyes indeed, more so for readers who had been too young to catch them as new releases over ten years prior.

With a classic Hawkman and Adam Strange story originally published in Mystery in Space #90 (Mar. 1964) by the evergreen team of Gardner Fox and Carmine Infantino, DC SuperStars had undertaken the theme it would return to over and over: heroes of space. The story saw the beginning of Hawkman’s friendship with Adam Strange, the pair teaming up in order to prevent Earth from colliding with Rann. The other features were both built around the same concept of medieval knights in a sci-fi setting; first with John Broome and Murphy Anderson’s apocalyptic Atomic Knights from Strange Adventures #117 (June 1960), then with Robert Kanigher and Infantino’s unexpected new recruit to the Knights of the Galaxy from Mystery in Space #7 (Apr. 1952).

The next two issues followed much the same trajectory. Superman traveled to the 30th Century to meet an adult version of the Legion of SuperHeroes in issue #3, and Adam Strange returned in #4 with a dilemma featuring a double of his beloved Alanna. The pattern was only interrupted by a Flash issue revolving around three generations

of speedsters, and featuring a genuine oddity–“Deal Me from the Bottom!”, Jay Garrick’s story, isn’t a reprint at all but rather a shot-by-shot remake by artist Rico Rival; the title card proclaims that the art in the original Golden Age story from All-Flash Comics #22 (Apr. 1946) was “too far below modern standards” and Rival had been asked to redraw the whole thing.

DCSS ’ space adventures continued in issue #6, reprinting much more obscure fare this time around with the likes of Captain Comet, Tommy Tomorrow, and Space Cabby taking center stage alongside Adam Strange. The real standout is Tommy Tomorrow’s tale of time travel by Jack Miller and Jim Mooney; initially appearing in World’s Finest #113 (Nov. 1960), the superbly drawn story has Tomorrow stranded in the then-present day and seeking help from his great-grandfather as a young child.

Briefly interrupted by Aquaman in #7, the ‘Super-Stars of Space’ were back in action in issue #8 (Oct. 1976) with a mind-controlled Adam Strange from Mystery in Space #89 (Feb. 1964) and the exciting origin of the Space Ranger from Showcase #15 (Aug. 1958). This was also Bridwell’s final issue as editor, and a sense of change seemed to come upon the series.

Jack C. Harris was briefly handed the editorial reins with DCSS #9, a collection of “man behind

by Stephan Friedt

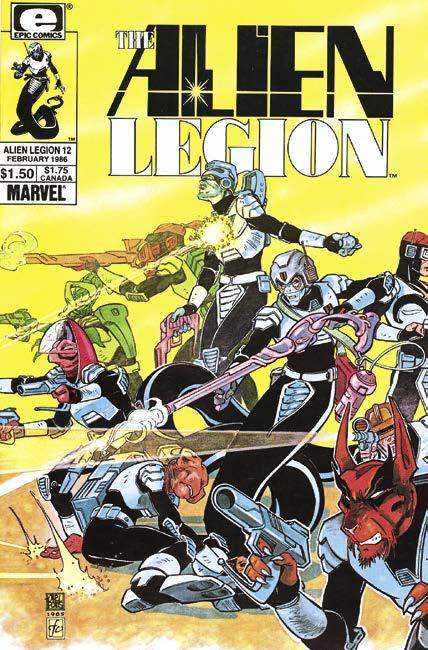

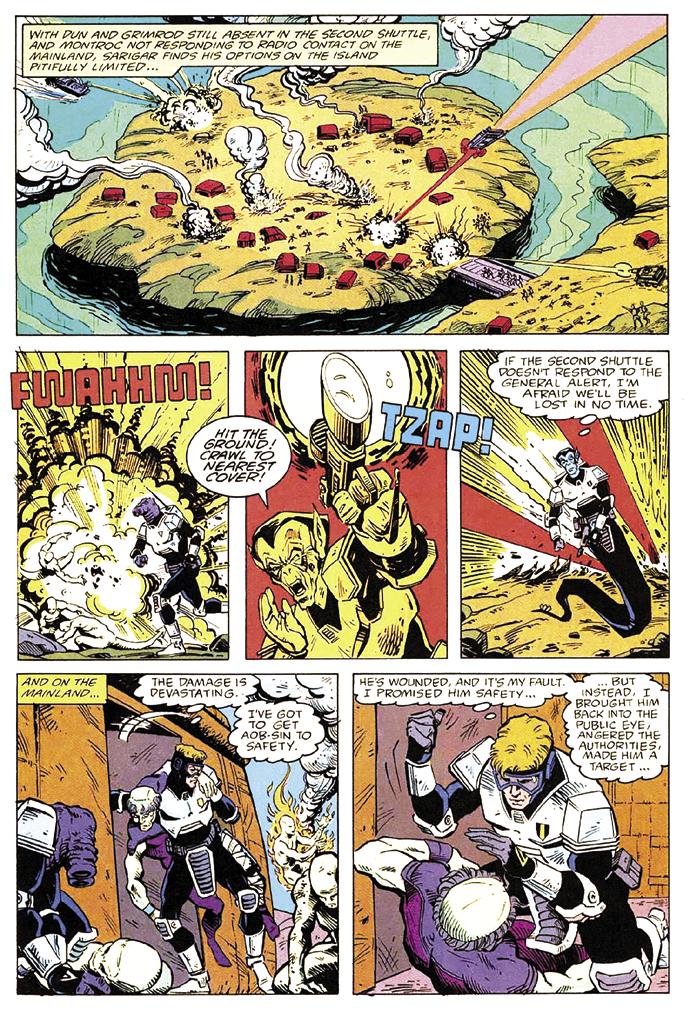

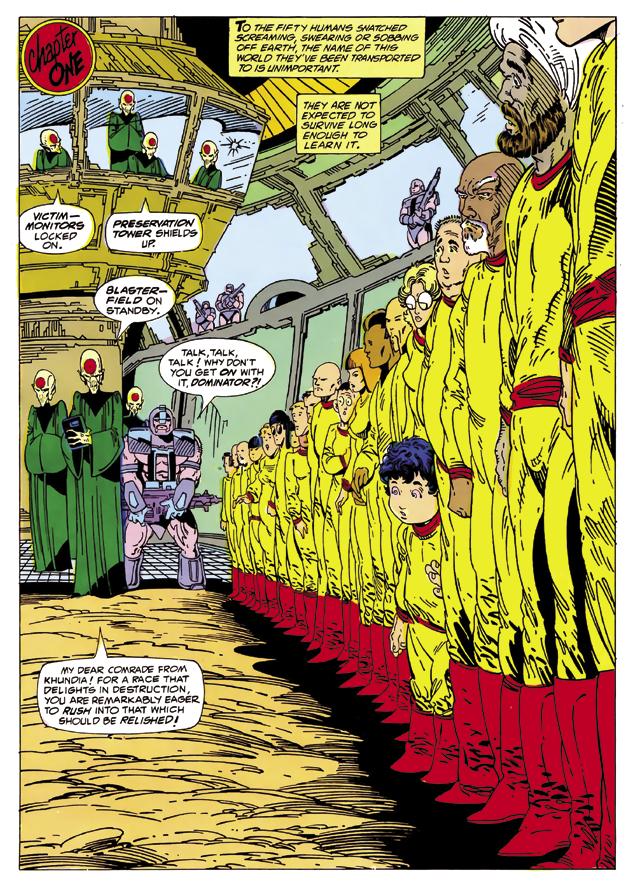

“Foot Sloggers and Soldiers of Fortune” Marvel/Epic’s Alien Legion debuted in April of 1984, ran for 38 issues until 1990 (and several offshoots), but the concepts and influences that spurred Carl Potts, Alan Zelenetz, and Frank Cirocco to build the universe, were much, much older.

The Cambridge dictionary defines a “legion” as a large group of soldiers who form a part of an army, especially the ancient Roman army. Roman legions were often volunteers but were conscripted in times of conflict. They received no pay other than any spoils of war they could collect. Most comic book fans’ exposure to the Roman Legion is from films like Spartacus (1960), or Gladiator (2000) and Gladiator 2 (2024).

According to established histories, the “French Foreign Legion” (French: Légion étrangère, also known simply as la Légion, “the Legion”) is a corps of the French Army that was created to allow foreign nationals into French service. The Legion was founded in 1831 and still operates today. It was always known as a place that a person could “restart” their life, as it was originally required that you register under a new name. Many people know of the Foreign Legion through books and movies like Beau Geste, an adventure novel by P.C. Wren that was made into several films over the years. Outpost in Morrocco (1949), a George Raft film, was about the Legion itself. Or maybe even Abbot and Costello in the Foreign Legion (1950), which may have been my first exposure.

I should also mention the Japanese samurai or bushi. Originally provincial warriors who served imperial court in the late 12th century, later periods would find them as mercenaries. Samurai eventually came to play a major political role until their end in the late 1870s. Akira Kurosawa’s film Seven Samurai (1954) has been influential in much of popular culture as being the basis for The Magnificent Seven (1960). Seven Samurai is also listed as the favorite movie of creator Carl Potts and writer Alan Zelenetz in their bios printed in Alien Legion #1. Kurosawa’s films would also influence popular culture through George Lucas and many other film directors. The way of the samurai would also surface in the TV series Power Rangers Samurai and the popular animated series Afro-Samurai , originally created as a manga by Takashi Okazaki

Creator Carl Potts was born in Oakland California on November 12, 1952, and because his dad was in the Navy, he was raised in the San Francisco Bay Area of California, as well as in Hawaii. He earned an associate degree in commercial art from Chabot College in Hayward, California, and bachelor’s degree in creative writing and

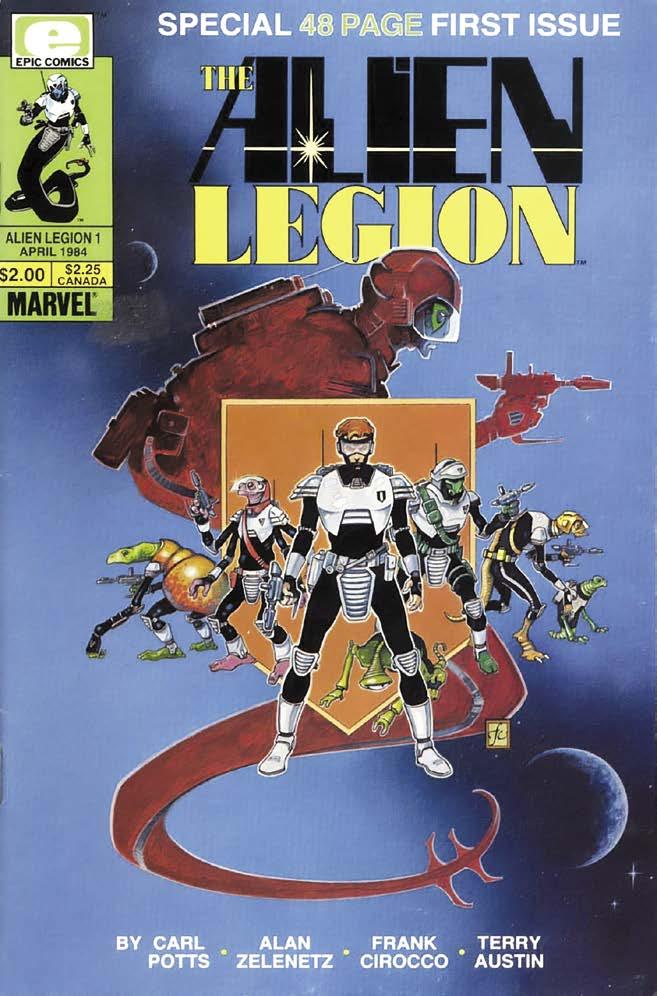

The adventure begins in The Alien Legion #1. Cover by Frank Cirocco.

Alien Legion TM & © Carl Potts.

editing from Empire State College, a part of the State University of New York (SUNY) system.

Carl’s Lambiek Comiclopedia entry notes that he started his comics career in fanzines, contributing to titles such as Venture in 1976. Carl contributed to several DC comics in the mid1970s, most of the jobs thanks to his fellow Bay Area friends, Jim Starlin and Alan Weiss. He went on to work briefly at Continuity Studios when they were producing Charton’s black-and-white TV tie-in magazines Six Million Dollar Man and Space: 1999 . Space: 1999 #7 has one of his stories in it. From there he slid over to the Marvel staff in the early 1980s as an editor. He has worked as an editor, writer, and sometimes penciler and inker on numerous titles. Besides being instrumental in the defining and growth of the Punisher as a major Marvel character, he also oversaw the first Rocket Racoon miniseries.

Legion should include a wide variety of species. This was in the early ‘70s. By the time I got around to developing the idea further in the early ‘80s, Star Wars obviously became an influence.”

Potts went on to add:

As detailed by Carl Potts in his interview for the website Popimage in May of 2000, The Alien Legion began as a concept when he was first trying to break into comics. Potts notes: “The original concept was the ‘foreign legion in space’ and all the legionnaires were human. It was inspired by true foreign legion history where the best and the worst of all the world’s cultures/ races are put into pressure cooker situations. Then I created the humanoid/serpentine design that later became Sarigar and decided that the

“The Alien Legion universe is a giant extrapolation of the American democratic melting pot society… dealing with the pluses and problems that the nation’s diversity creates. In the Legion universe, the differences are even more dramatic since we have wildly different species instead of just different cultures and races. The Legion is a microcosm, the best and the worst, of the diverse universe.”

According to the podcast interview conducted in 2019 by Alex Grand and Jim Thompson for their series Comic Book Historians , in 1983 when Carl joined Marvel, he pitched the series to Jim Shooter under their new creator participation program. Shooter okayed it, then later withdrew it. Archie Goodwin jumped on it and had Carl bring it to the new Epic Line.

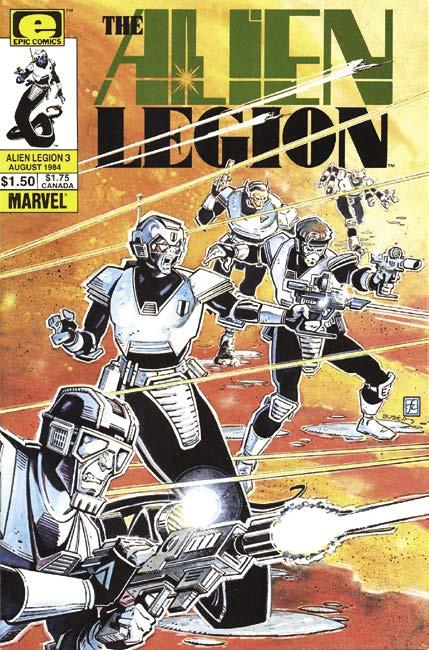

(left) The Alien Legion doing what they do best on the cover of issue #3. Art by Frank Cirocco and Terry Austin. (right) A portrait of the serpentine Major Sarigar by Chris Warner. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com).

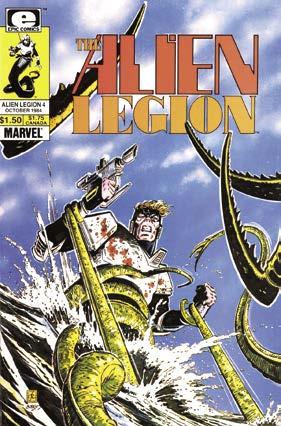

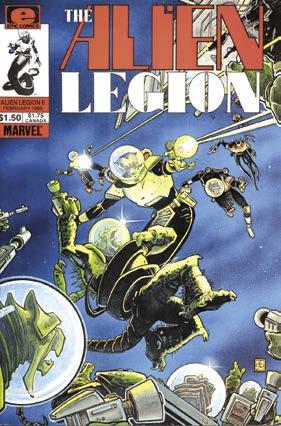

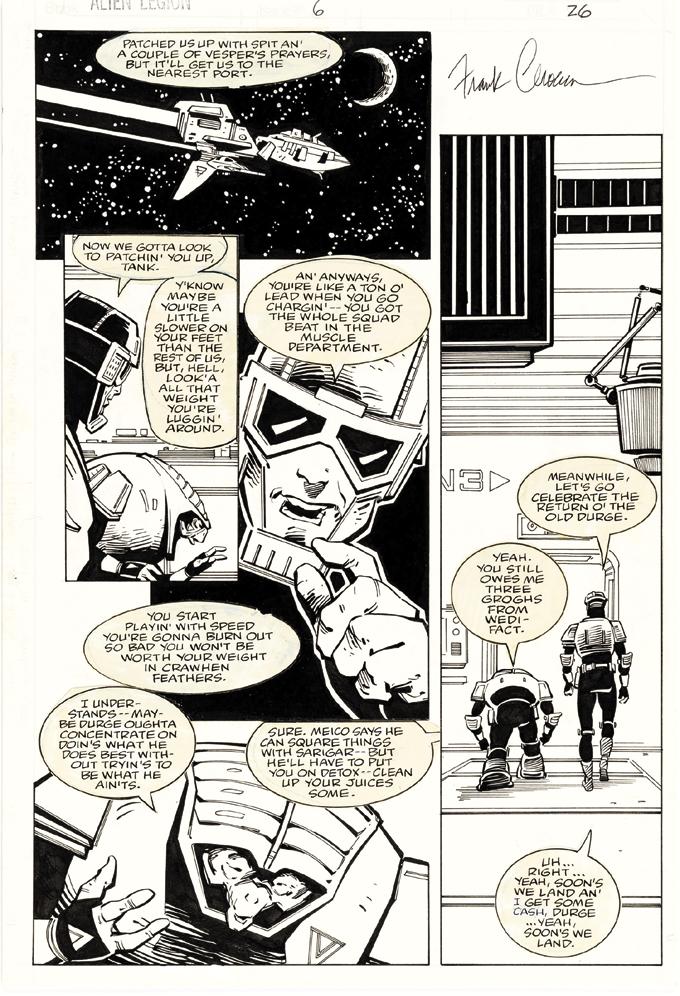

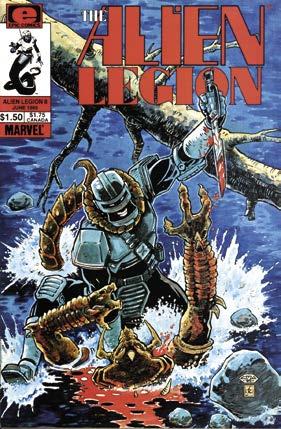

(top row) The gang battles for their lives on the covers of The Alien Legion #4, 6, and 8. Art by Frank Cirocco and Terry Austin. (bottom) Future star Whilce Portacio inked Frank Cirocco in The Alien Legion #6. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com).

Carl would add a bit more to the beginnings of the series in the Critical Blast interview by Jeff Ritter (2014): “After we’d worked on the book for a few months, the editor-in-chief decided to change the terms of the deal we’d agreed on before beginning work on the series. I gave back the money that Marvel had paid us so far in order to retain ownership and control over the property. I was approached by Archie Goodwin. Archie was starting up the new Epic Comics line of creator-owned titles. He wanted Alien Legion to be the third title in his new line ([Jim Starlin’s] Dreadstar and [Steve Englehart & Marshall Rogers’] Coyote were the first two titles).”

In April 1984, the new Epic comic, The Alien Legion, premiered, co-created from Carl‘s original ideas and fleshed out by writer Alan Zelenetz and artist Frank Cirocco. The first run of 20 issues (1984-1987) would be thanks to the same team, along with inker Terry Austin, as well as Marvel Graphic Novel #25 with the stand-alone story “A Grey Day to Die” (1986).

Alan Zelenetz, the original writer and cocreator, started as a junior high school principal at the Yeshiva of Flatbush, an Orthodox Jewish school in Brooklyn, and Solomon Schechter High School of New York. Zelenetz then decided it wasn’t what he wanted to do with his life and worked his way up the ladder at Marvel, from doing free proofreading (and “groveling on his knees before Tom DeFalco and Mark Gruenwald”) to becoming the writer of Alien Legion , as well as working on issues of Moon Knight (establishing Moon Knight’s Jewish origins), Thor, and King Conan. Alan was also the author and researcher for Marvel’s Official Handbook of the Conan Universe. When comic writing was no longer interesting to him, he became a film producer. The fan favorite/cult film Darkon is thanks to Alan.

Frank Cirocco, the original artist and cocreator, first appeared in fandom when he published his fanzine, Venture in the 1970s. Frank was born in New Jersey and moved with his family to California. Frank met Neal Adams in 1973 at SDCC, commissioned a cover from him

for Venture in 1975, and moved to work for him at Continuity Studios in New York in 1976 as a member of the “Crusty Bunkers” team.

Terry Austin, the original inker, was born in Detroit, Michigan and according to the bio in Alien Legion #1, he credits Al Milgrom, Neal Adams, and Dick Giordano for bringing him into the comics business.

In 1977, Frank returned to California to start a commercial art studio called Horizon Zero Graphiques with longtime friend Gary Winnick and create illustrations for the booming video game industry.

In the 1990s, Frank did work with Marvel for Samurai Cat and Defenders of Dynatron City, as well as covers for a number of Marvel titles.

From 1996 to 2012, Frank would reunite with Gary Winnick to create Lightsource Studios, a content development studio.

Frank is married to fellow artist Lela Dowling.

The first run of the series was a favorite of mine, waiting patiently for each new issue.

The first issue not only had the initial story “Survival of the Fittest,” but it also included a background text piece explaining the relationship between “The Union and the Legion.” The stories took place in the TOPHAN Galactic Union, comprised of three galaxies; Thermor, Ophides, and Auron, commonly known as TGU and using a form of government they call a “Galarchy.”

From the first issue: “Alien Legion ranks are comprised of bio forms from countless far-flung Union worlds. Some have joined to serve their government or flee oppression, others seek adventure and fortune, still others are criminals in hiding, wandering poets seeking inspiration, or frontier preachers in search of new souls.

“Footsloggers and soldiers of fortune, priests and poets, killers and cads—They fight for a future Galarchy, for cash, a cause, for the thrill of adventure. Legionnaires live rough and they die hard, tough as tungsten and loyal to the dirty end.”

We are also given excellent background info on our main characters.

Torie Montroc III…Humanoid native of the planet Arat in the Solus star system of the Ophidian galaxy. Joined at the insistence of his father to develop him into a “real man.” A sports jock and a compassionate idealist and a diplomat of unusual tact. Your basic comic book hero.

Sarigar …Serpentine native of the planet Jantek in the Belgar II-star system of the Auron galaxy. He’s a descendant of ancient slave stock and holds degrees in cosmology and military history. He’s a pragmatist, a perfectionist, and a consummate professional rarely permitting emotion to obstruct logic and sound judgement. Mr. Spock in the body of a human-sized cobra.

Under a cover (left) by creator Carl Potts and inker Frank Cirocco, Larry Stroman would become the penciler for the rest of the series with issue (right) #12.

“Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck;” (Shakespeare, Sonnet 14).

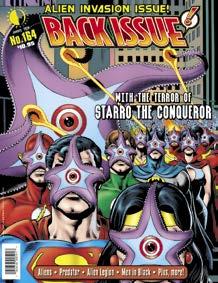

A starfish is not all that threatening upon initial glance. A giant one, sure that’s potentially problematic, but not necessarily something that would arouse widespread panic or despair. However, a conqueror from another planet that will sap all free will and individuality from a species that it parasitically controls while continuously spawning mass quantities of itself–well, that is absolutely something to be terrified of!

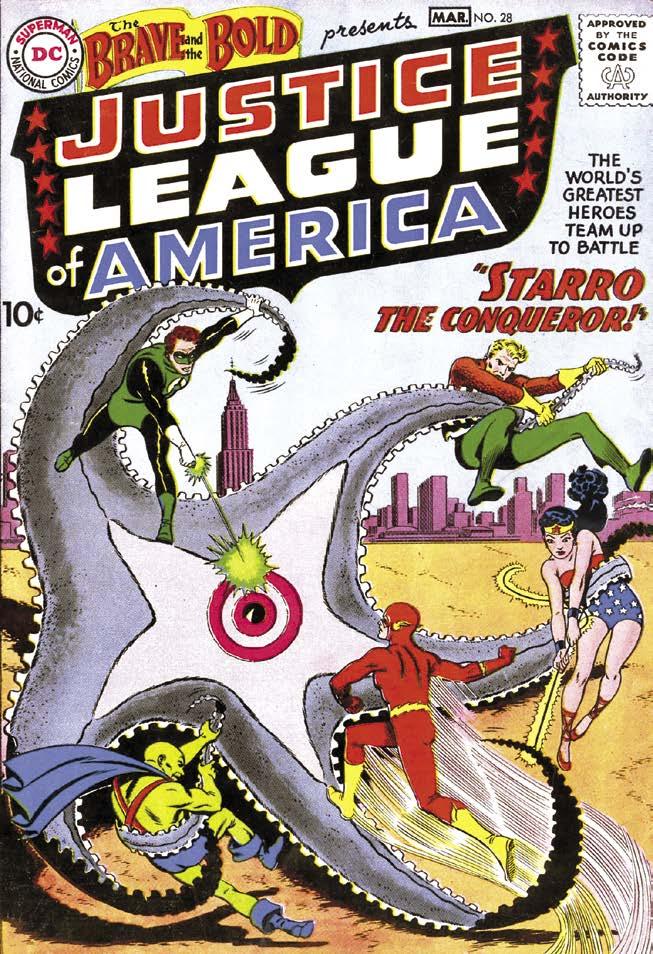

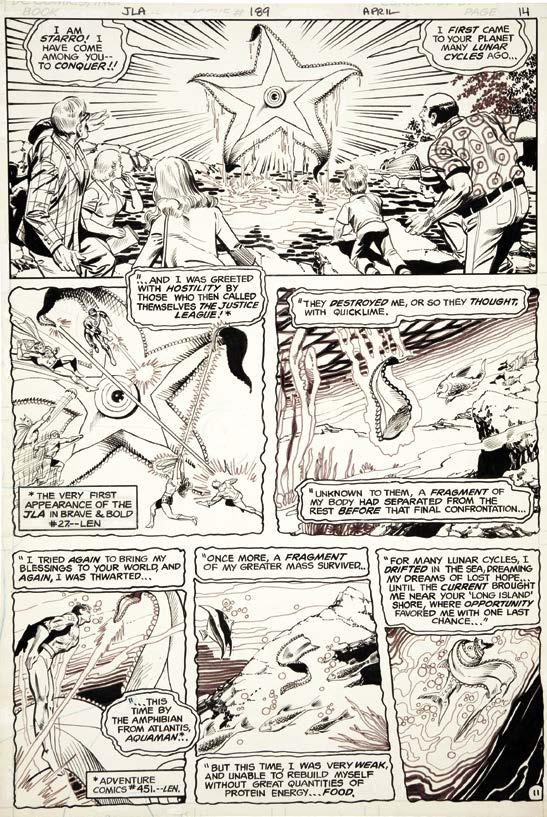

Starro is a singular Silver Age nemesis that evolved during the Bronze Age into one of DC’s greatest super villains. Starro is equal parts visual spectacle, intellectual inspiration, and mild absurdity. However, the conceptual basis of what Starro represents is something humanity has feared for centuries: the loss of free will and individual agency. The fact that this phobia has been wrapped in a seemingly harmless sea animal is not quite moot. It’s the juxtaposition of this quaint, calm creature contrasting with the threat of an indomitable conquering force that creates an unforgettable character. Plus, starfish have radial symmetry, giving many artists much to experiment with. Few, if any, knew back in 1960 that the first appearance of the Justice League of America (in The Brave & The Bold #28, Mar. 1960) would also contain a Kaiju-esque despot that would menace DC comics for decades to come. We will explore Starro’s origin, history, and the legacydefining story strands which continue to reverberate today. Join us, BI readers, as we consider how this 1960s concept not only cuts to the core of what a despot really represents but may also provide us with some insight into how individuals can inadvertently contribute to their own subjugation!

WARNING FROM SPACE

One look at the imagery for Warning From Space (1956), and you may notice the concept designs of these Kaiju alien invaders and Starro the Conqueror are eerily similar. This film was released in Japan two years after the original Godzilla (1954), riding the wave of sci-fi, alien, and monster (Kaiju) films that post WWII Japan was famous for. Possibly, these extraterrestrial sea stars that disguised themselves as humans had something to do with the eventual existence of Starro. Although never considered a hit, perhaps someone working for DC Comics saw this film. Industry veteran and San Diego Comic-Con co-founder Scott Shaw shared with BI his theory on the possibility. “Julie Schwartz, Mort Weisinger, and other DC editors were also sci-fi editors and agents. In1956, there weren’t that many new sci-fi movies at the time, and it’s likely that NYC had one or more Japanese movie theaters (we’ve had a few in Los Angeles for decades), so it’s

(top) Starro debuts in The Brave and The Bold #28, along with the Justice League of America. Art by Mike Sekowsky and Murphy Anderson. (bottom) Did the Japanese movie Warning From Space inspire Starro?

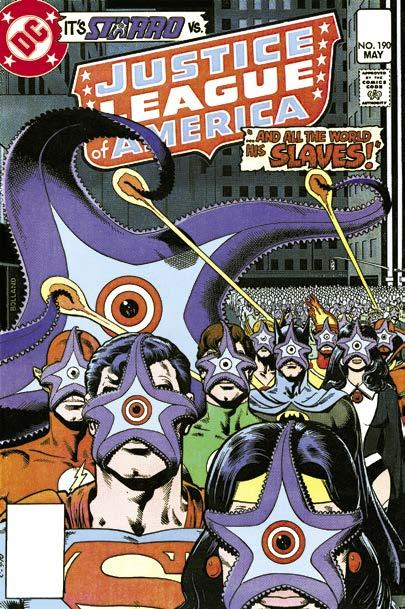

(top) Brian Bolland’s classic cover to Justice League of America #190, which you can also see on our cover. (bottom left) Starro waxes nostalgic in Justice League of America #189. (right) It’s dawning on our heroes just what they are up against. Original art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com). Art by Rich Buckler.

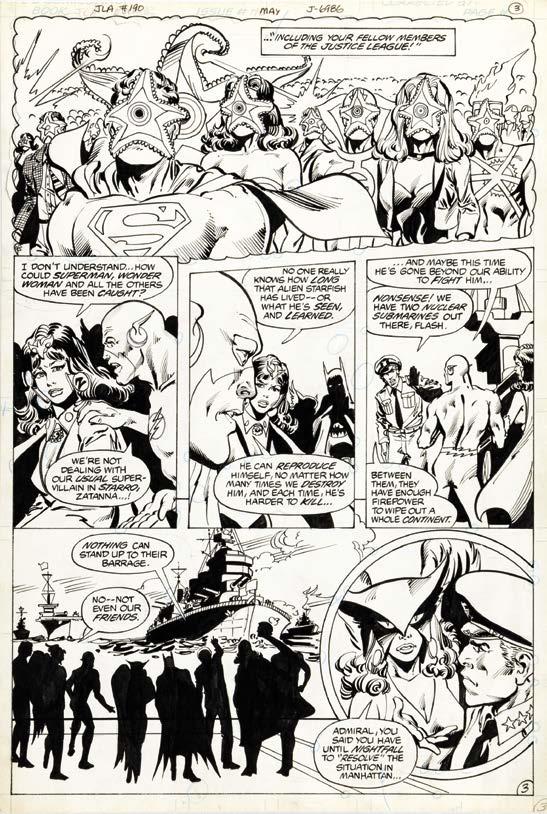

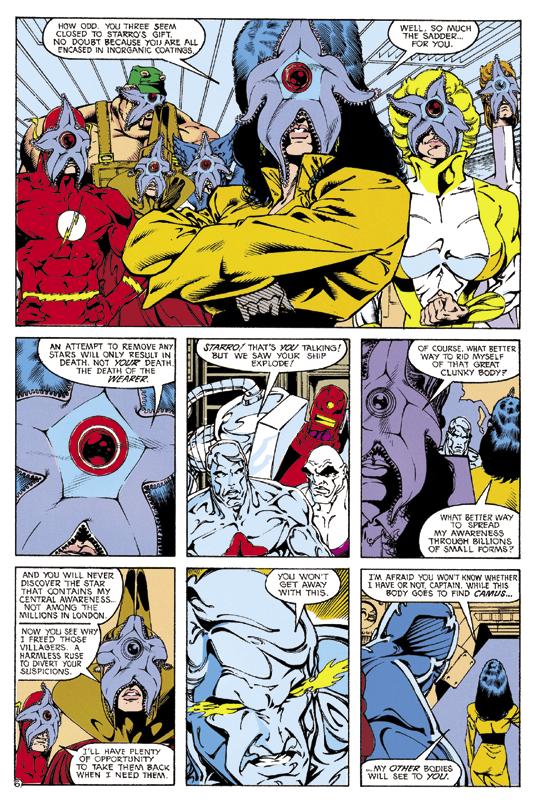

Firestorm, and new readers, they headed out to confront the would-be conqueror. They were not aware however, that he had some new tricks up his sleeve…er, arms. We are talking about the quadruple threat of regeneration, replication, infiltration, and mass subjugation.

Starro could now emit a multitude of miniature versions of itself that attached to a host’s face while overtaking their central nervous system! Starro led its replica army to New York’s Grand Central Station for maximum effect. The Flash mansplained to Zatanna, “We’re not dealing with our usual supervillain in Starro…he can reproduce himself (itself?), no matter how many times we destroy him, and each time he’s harder to kill!”

Several powerful JLA members fell under this control, including Superman, Green Lantern, Firestorm, and even Wonder Woman. It ended up being an unlikely hero that saved the rest of the team and planet: Red Tornado, who survived due to his android sentience being incompatible with Starro’s biological brain dominance. He was able to decommission the power grid that supplied Starro with food access and light source, disarming the creature for the final attack. Terry Watson was coincidentally released from Starro’s sway while gathering food in a restaurant freezer. With Hawkman and Hawkgirl finding Terry and discovering the probable Achilles’ heel, the JLA combined science and magic (alchemy?) to defeat

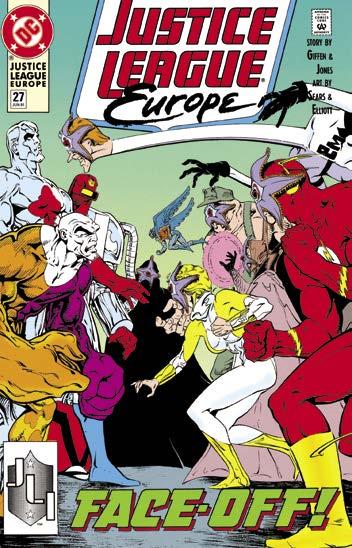

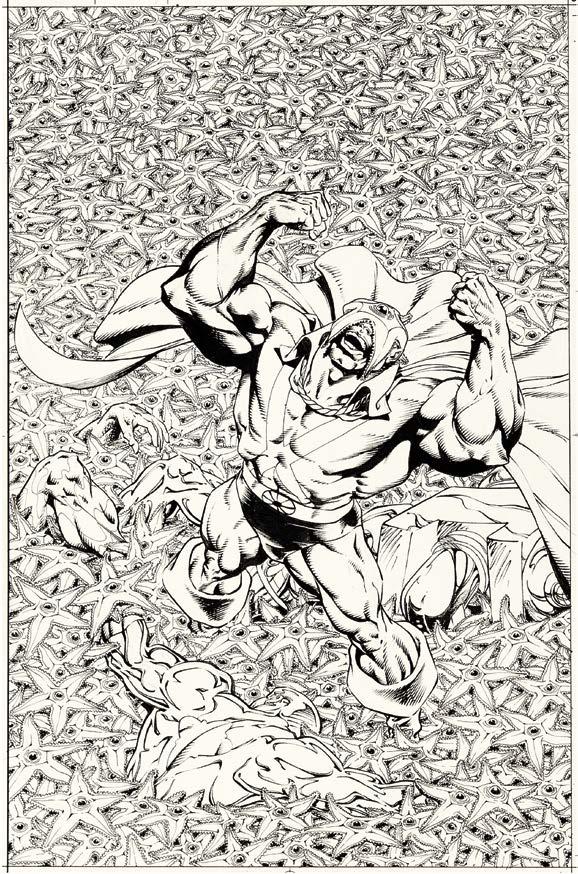

(top) Guess who’s back in Justice League

Europe #27? Art by Bart Sears. (bottom left) Bart Sears draws more Starros than you can shake a stick at, if that’s your idea of fun, on the cover of Justice League Europe #28. (bottom right) How do you convey emotion when a starfish is covering most of a character’s face? Art by Bart Sears and Randy Elliott.

(eyes, mouth, forehead, etc.) to nail that expression behind the starfish. And pair that with body language (head tilt, pose, etc.). Not easy, but FUN!”

Starro falls in JLE #28 (July 1991) in an anticlimactic fashion. In a nod to his defeat in Justice League of America #190 (May 1981), Ice uses her powers to freeze the prime Starro on Martian Manhunter’s head, thus severing the connection to the rest of the horde. Recurring villain and intergalactic trader Manga Khan was then given Starro for safekeeping, while the JLE lived to squabble another day.

IT IS AMONG US

Six years later, in JLA: Secret Files and Origins #1 (Sept. 1997), Starro reunites the Justice League in the now modern classic run by Grant Morrison. The Flash was face-hugged by a Starro spawn in Blue Valley and required the immediate assistance of his teammates. Due to a warning provided by the Spectre to not act in haste, the team temporarily surrenders their super-powers in order to smuggle Batman in undetected, avoiding alarms and triggering a universal conquest. The Dark Knight uses one of the oldest tricks in the book of alien echinoderm disruption, hijacking the air conditioning systems in order to drop the temperature to below zero conditions. This negated Starro’s functionality, which oddly seems to be just fine when travelling through the sub-zero conditions of outer space!? Nevertheless, the day is saved, and the Spectre returns the JLA to their previously fully powered status.

Starro crossed paths with Sandman in the two-part storyline “It” and “Conquerors.” In JLA #22 (Sept. 1998), a young boy named Michael Haney inadvertently reaches

by Ian Millsted

How many times have you laughed out loud at something you’ve read in a comic book? For me, truth be told, not that often. Lots of things have produced a wry smile, but the ones that have extracted spontaneous laughter are more rarified: Groo, Lucky Luke, early Cerebus, and on more than one occasion, “D.R. and Quinch.” This comparatively early work from writer Alan Moore and artist Alan Davis was always a bit unique, whether in its original home in the British weekly comic 2000AD or in US reprint monthlies or the various book collections. So, just who were D.R. and Quinch and what were Messrs Moore and Davis thinking? BACK ISSUE travels back in time to the days when a couple of young aliens could have good clean fun by, like, blowing stuff up.

“D.R. and Quinch” was never intended as a series. The first episode was published as a standalone and could easily have remained so. In fact, it was actually written as part of another series of short time travel stories, which were being written by Alan Moore for 2000AD. The science fiction anthology, 2000AD, had been (and still is) published every week since February 1977 and the various editors were often on the lookout for good new writers. Alan Moore had been submitting one-off twist-in-the-tale stories and was someone the editor, Steve MacManus, saw as one such “good new writer.” The format was five or six different stories each week, one of which was “Judge Dredd,” running to five or so pages each. By 1983 most of the sub-genres of science fiction had been explored: future war (“Rogue Trooper,” “The VCs”), future cops (“Judge Dredd”), space western (“Strontium Dog”), comedy robots (“Robo-Hunter”), cosy catastrophe (“Disaster 1990”), space opera (“Dan Dare”), and much else besides. What most of these had in common was the main protagonist being something of an anti-hero. For the Time Twisters series of short stories, Alan Moore wrote “D.R. and Quinch Have Fun on Earth.”

At this point in his career, Alan Moore had written (and drawn) comic strips for his local newspaper ( Maxwell the Magic Cat ) and a music paper (The Stars My Degradation”), comic scripts for Marvel UK based in the worlds of Doctor Who and Star Wars, and revisionist superheroes Captain Britain and Marvelman (published as Miracleman in the US). He was currently writing his first full series for 2000AD in Skizz, a British take on the recent E.T. the Extra Terrestrial. Alan Davis had formed a partnership with Moore on Captain Britain, which Davis had been drawing before Moore joined as writer. He, in turn, joined Moore on Marvelman after original artist Garry Leach departed. Davis had recently joined the 2000AD team where he had drawn the prison-in-space serial Harry 20 on the High Rock.

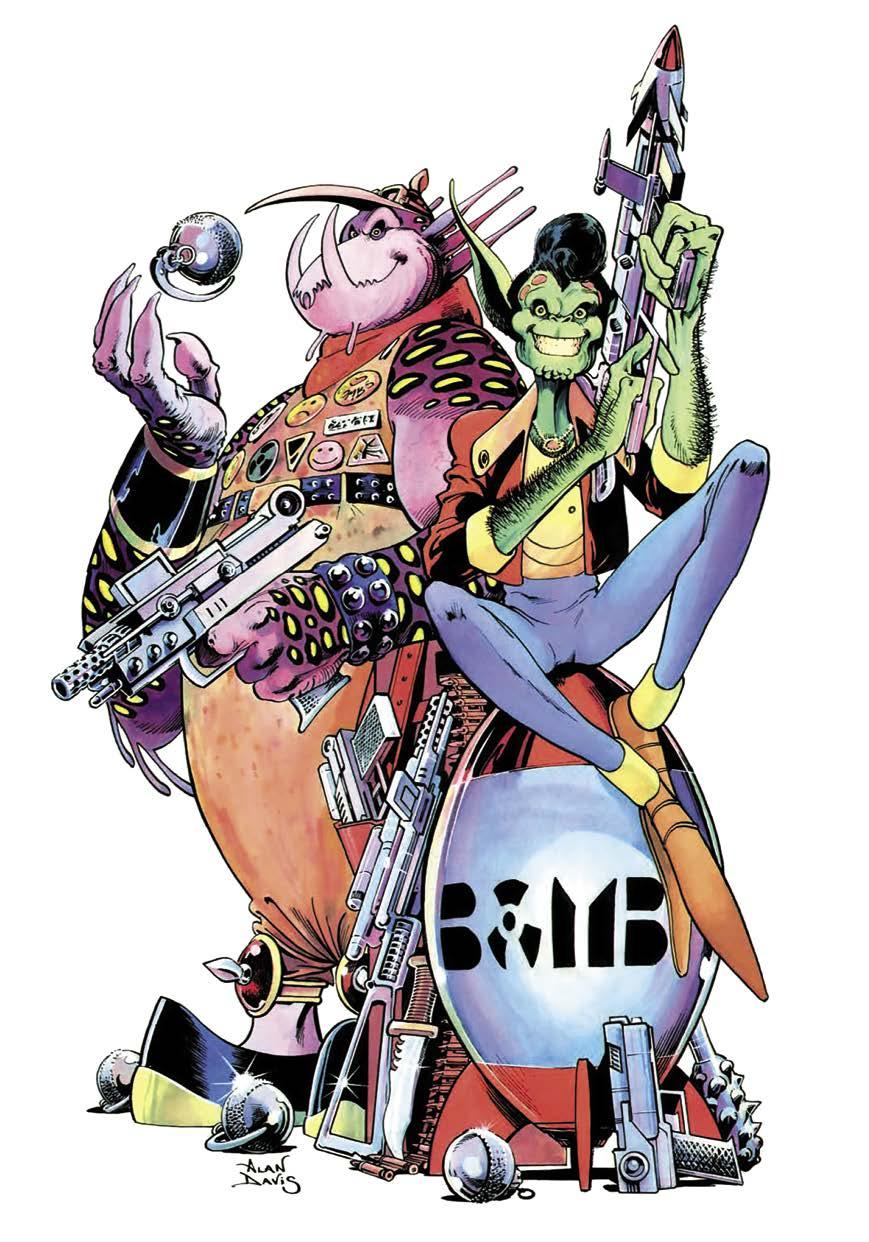

D.R. and Quinch are ready for some fun. Art by Alan Davis.

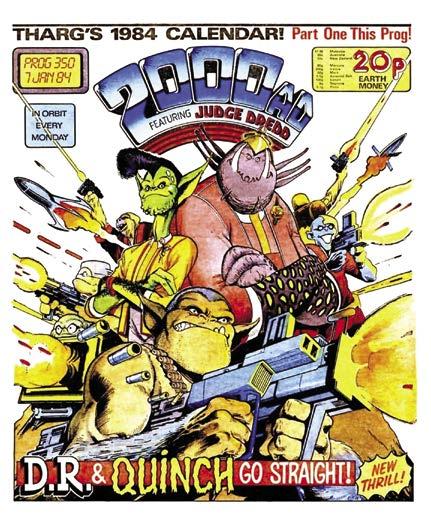

(left) The mayhem begins in the first D.R. and Quinch adventure. (right) D.R. and Quinch get the cover treatment in only their second appearance.

In 10 Years of 2000AD, Moore revealed some of the ideas behind “D.R. and Quinch.” “It was a short story that got out of hand. I did a short story about a couple of alien juvenile delinquents who are responsible for the creation of life upon Earth, and the destruction of Earth several thousand years later. It was not a terribly objectionable story. Then they (MacManus) said, hey, the readers really love this, do us a series. It didn’t last very long because there are only so many things you can do … where every episode ends with a huge explosion and limbs flying everywhere. That was the whole point of ‘D.R. and Quinch’. It was continuing the tradition of ‘Dennis the Menace,’ but giving him a thermonuclear capacity.”

It should be noted that the “Dennis the Menace” Moore refers to is the British comic series published in the weekly comic The Beano, not the US newspaper comic strip of the same name. The British Dennis was first published in issue 452 of The Beano cover dated 17 March 1951 but on sale from 12 March 1951. The original artist was David Law. The US Dennis was also first published on 12 March 1951. The two series were produced in isolation from each other with the respective creators unaware of the

other until sometime later. Where the US Dennis was a roguish grade schooler, the UK Dennis was an anarchic boy with dark, spiky hair who constantly challenged the ordered world around him. Moore was writing in a tradition of British comic characters which most 2000AD readers would have been fully aware of.

Steve MacManus recalled the genesis in his memoir The Mighty One: My Life Inside the Nerve Centre: “Alan’s Time Twisters had been popular with the readers, but D.R. and Quinch were far and away the most obvious candidates for a follow-up series… a comedy series to balance the drama of ‘Judge Dredd,’ ‘Rogue Trooper,’ ‘Slaine’ and ‘Strontium Dog.’ Alan, gentleman that he was, kindly agreed… and when Alan Davis came aboard to reprise his role as the artist/creator, D.R. and Quinch returned to 2000AD with the aforementioned thermonuclear impact.”

Davis has also related his memory of the creation process. “I obviously loved drawing them. When you’ve designed a character, it almost flows off the end of the pen. It was maybe the fastest work I ever drew. With D.R. and Quinch it didn’t take any real concentration in being consistent, drawing real people or anything like that. Anything you did was alright. I started having the characters break the fourth wall. Make eye contact with the reader and that made me laugh–the absurdity of it. Just completely wacky, the dafter the things you could do, the better.”

As part of the Time Twisters strand, “D.R. and Quinch Have Fun on Earth” was published in 2000AD #317 (21 May 1983) and introduced us to two aliens. Waldo Dobbs was a long eared, skinny kid with an exaggerated quiff hairstyle. He goes by the moniker of D.R. which stands for Diminished Responsibility. His almost-silent

by Joe Norton

Science Fiction as a literary genre has been around since, arguably, the epic tales of Gilgamesh, and the alien invasion plot point has been a cornerstone of science fiction since H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds . The notion of extra-terrestrial forces raining down on Earth to slaughter or enslave us has been a staple of comic books from day one. Comics are filled with aliens (Superman and Silver Surfer) and star-faring tales (“The Kree-Skrull War” and the adventures of the Legion of Super-Heroes) that make monthly space invaders the expected. Every comic book hero has encountered an alien or two on the streets of Manhattan, Metropolis, or farmland of Kansas in their career.

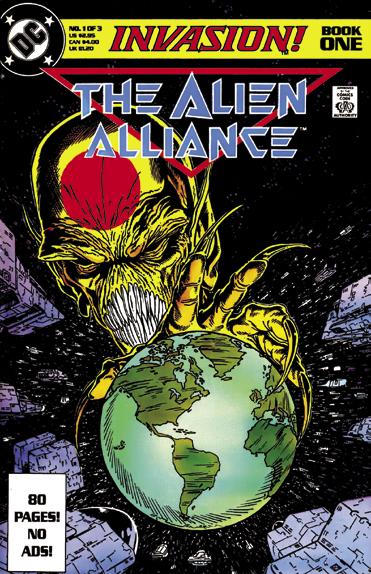

By the time DC published Invasion! in late 1988, the storyline was nothing unusual, all too familiar to readers. But what Keith Giffen and Bill Mantlo gave us was a truly epic and exciting, well-connected alien invasion, utilizing the entire cast of DC characters spread through 18 separate monthly titles, playing to the strengths of the individual heroes, and creating permanent aftereffects on characters that still resonate today. Invasion! may have sounded like a typical alien attack tale, but even a brief reading of the miniseries and crossovers shows Invasion!’s excellence shines through even the heavy tropes we had all come to expect.

PRELUDE TO INVASION!

Invasion! was an event series published in late fall of 1988 created by writer Keith Giffen and scripted by Bill Mantlo in his DC debut after a long and storied career at Marvel. Giffen and Mantlo had worked together at Marvel, highlighted by Rocket Raccoon’s debut in Marvel Preview #7 (June 1976). The main Invasion! title consisted of three 80-page, ad-free, giant-sized issues, harkening back to the early ‘70s when DC would publish these oversized books intermittently throughout their titles. The crossover event went line wide into 31 individual issues making stops in most of the major books at the time including Justice League International, Detective Comics, and Wonder Woman, to name a few. The main events had layouts by Giffen and interior artwork in the first two issues by artist Todd McFarlane (in early, and lesser regarded, DC work). Bart Sears handled all covers, and interiors for the third issue. Giffen and Mantlo, by that time, were absolute masters at their craft, both perfectly suited for this type of tale.

McFarlane talked about the Invasion! event, his pencils, and working with the two writers for a 2017 article on Comicbook.com . “I’d like to take credit, but let me place credit where credit is due. Keith Giffen and Bill Mantlo were writing the book, and Keith was doing rough thumbnails

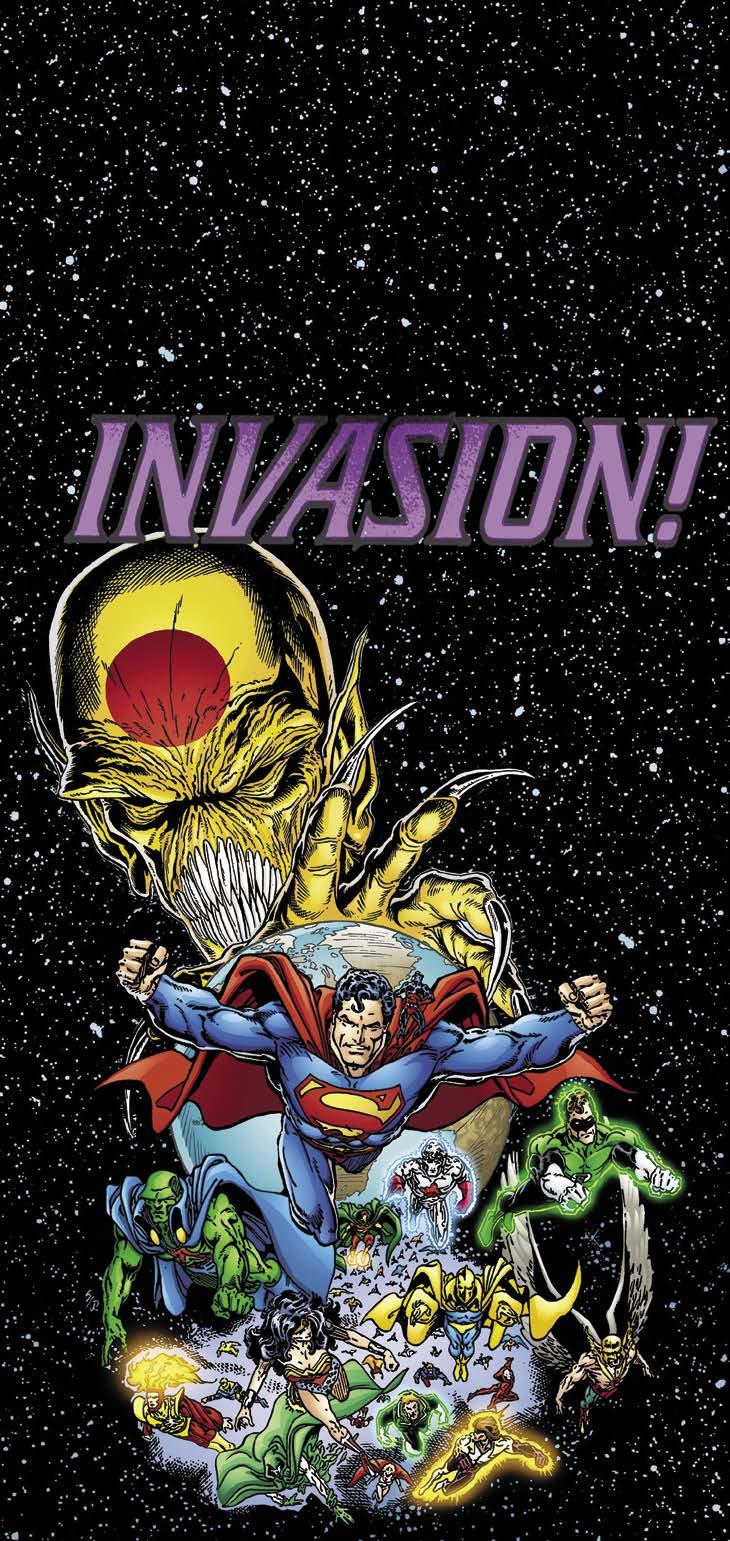

Cover from the 2008 Invasion! trade paperback, which reprinted the core storyline of the crossover event. Art by Bart Sears.

TM & © DC Comics.

(top) The invasion begins! Cover by Bart Sears. (bottom left) The invasion starts with a deadly test by the Dominators. Art by Giffen, McFarlane, and P. Craig Russell. (bottom right) The Omega Men’s ship is breached by Durlans in an action-packed battle. Art by Giffen, McFarlane, and Al Gordon.

for us, too, so that the book would have a sense of consistency to it. So, the early design in its generic sense was handed over to me when I got it. All I did was, once you get a silhouette of something, my job is to make it as sexy as possible.”

Sears tells BACK ISSUE of a similar experience with his work on Invasion! : “I had zero story input, which was more than fine with me. It was all decided upon and written before I even came onto the project. It was neither full script nor the Marvel plot method—Keith wrote in visual layouts, which was extremely helpful to a young, new comic penciler.”

Sears also remembers, “The saving grace was how Keith Giffen wrote his scripts. He basically did simple page layouts, with suggested dialogue and captions, so, instead of starting with a blank page, I had little thumbnails—simple layouts, crude drawings, but very clear storytelling—these really helped me do my layouts and storytelling for each page, which was probably the only way I could produce 80 pages in ten weeks of high-quality.”

THE ALIEN ALLIANCE Invasion! #1 (Dec. 1988), titled “The Alien Alliance,” was a pretty straightforward tale. A collection of alien races from all over the DC Universe led by the Dominators, a Jim Shooter creation from his work on the Legion of Super-Heroes, targeted Earth due to its outsized number of metahumans in the population. The Dominators believed they could conquer Earth and uncover its secret, something later identified as the “meta-gene.” Assisting with the invasion and all playing specific roles were Thangarians of Hawkman and Hawkwoman fame; from the Marv

by Ed Lute

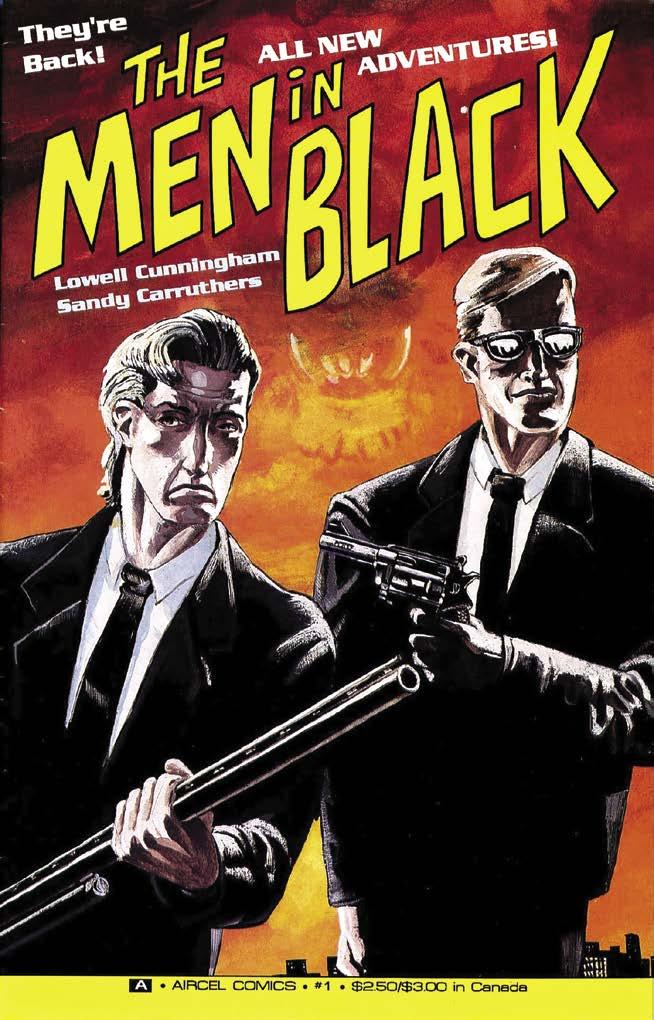

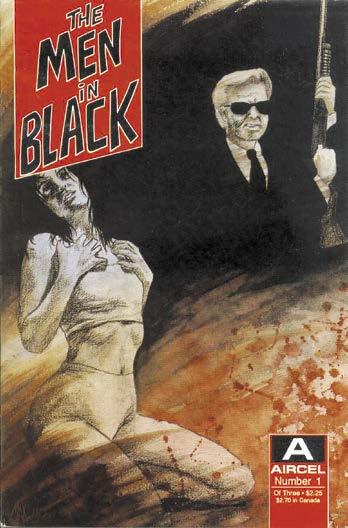

When most people think of Men in Black they think of the blockbuster films or even the popular animated television series. And why wouldn’t they? It was those things that really put Men in Black on the map. However, years before the franchise hit the big screen in 1997, there were two little-known black-and-white comic book miniseries published by Malibu Comics’ imprint Aircel Comics.

Come along, faithful BACK ISSUE readers, as we look at the history of those intrepid heroes who fight for the safety of Earth from the likes of aliens, demons, and more: The Men in Black.

MEN IN BLACK: THE COMICS

In 1990, a three-issue black-and-white miniseries called The Men in Black was published by Aircel Comics. The series featured agents in a secret organization uncovering mysteries of unexplained phenomena. This was even prior to the TV adventures of Fox Mulder and Dana Scully who did the same thing on The X-Files , which premiered in 1993. The comic book was created and written by Lowell Cunningham. In a 1997 interview in Marvel’s Men in Black movie adaption, Cunningham discussed the inspiration for the comic. “A friend of mine, Dennis Mathewson, is interested in UFO phenomena and he told me of various rumors and legends surrounding UFOs. The most fascinating stories involved mysterious men dressed in black who invariably appear after any UFO contact. I thought this would be a great idea for a television or comic book series. I have to admit I never really expected it to go straight to the big screen.

“Pretty much all I’ve kept from the UFO mythology are the clothes, the cars, and some of the MiB’s methods. In the popular folklore, Men in Black are interchangeable, robotic beings. I gave the agents distinct personalities, made them human.”

That’s where artist Sandy Carruthers came in. He had previously worked for Malibu. He tells BI, “I drew a couple of stories for Malibu Comics’ sci-fi imprint Eternity Comics. They published a black-and-white anthology called The Shattered Earth Chronicles where my ‘Twilight’s Last’ proposal ended up. After that they sent me another script and another script and another

The Men in Black open their second miniseries at Aircel Comics, this time with covers by Adam Adamowicz. Men in Black TM &

script. They kept sending them my way. And the best part was they paid. [Laughs] They didn’t pay a lot, but they paid. Unfortunately, a lot of the black-and-white guys weren’t doing that. For me, it fed my family. It was one of about 25 other things I was doing to make money, though. You want to eat every once in a while. I don’t know, it seems important to eat every now and then. [Laughs]”

Carruthers continues, “This was the first couple of years that I started drawing comics semi-professionally. Thank goodness for the whole black-and-white boom. It allowed artists like us who were on the edge of the industry to just see our work printed. It was a great time.”

Carruthers was sent the script for Cunningham’s The Men in Black . “So, I kind of was gearing towards a lot of the sci-fi stuff. [Creative director] Tom [Mason] called me up and asked if I’d look at the script. I said yes and he sent me the script for Men in Black I guess because I looked like I had an interest in U.F.O.s and monsters and stuff like this. They said you might like this. So, I read the script, and I did like it. I told them I’ll draw that, certainly,” he reveals.

Carruthers continues, “Lowell had provided a full script, panel by panel descriptions. I can work either way, though. I like the Marvel style because it gives me more freedom, but I’m perfectly fine with a full script like here. The visuals were all mine though. He described them and I brought them to life.”

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!

One of the standout aspects of the comics was the interaction between the two main characters, Jay and Kay. Although they were portrayed as more brutal in the comic books than in the movies, the basics of their camaraderie were there from the beginning. According to Cunningham in the 1997 interview, “I’ve always tried to make Jay and Kay as different as possible. Kay is a veteran; he’s seen and done it all. Jay learns something new every mission. The interplay between the characters is half of every story, and this comes across very strongly in the film. The film builds on the best aspects of the comic.”

While Cunningham developed the characters and story, Carruthers brought them to life. He tells BACK ISSUE , “Lowell gave descriptions, especially the look of Kay and Jay. I would think of an actor (I wasn’t looking for the likeness at all) just who would play that role in my head. You know, he would be perfect for that, and he would be perfect for that. These characters were just literally made up from my head.”

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99

https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_54&products_id=1837

However, character designs weren’t the only things that Carruthers brought to the comics. He even put his own stamp on the story for the first issue. “The script was all Lowell. The only thing that I changed was at the end of the first issue. I just basically added the fire at the end of that issue. That’s the only thing that I changed. Lowell asked why I did it and I said that I thought it just needed it. [Laughs] I thought they needed to all burn down.”

While the comics may seem similar to the movies, the tone of the books was vastly different than those of the films. The comics were darker and did not have much (if any) comedic touch. Both Jay and Kay were portrayed as ruthless killers in the comics but not so in the film. The comics also differ from the films in another important way. In the comics, the Men in Black not only safeguarded Earth from alien menaces, they also fought any threat to the planet including supernatural ones and even drug-dealing cults.

Carruthers states, “It’s just such an obscure little book. I remember [cartoonist] Ed Piskor told me that when he was a little kid, he opened up a comic and saw the ad for Men in Black and it just got him so excited to get the book because it was right up his alley.”