Texas Wildlife Extra

E-MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION

Real estate transactions in Texas are like Texas rivers. Some are shallow and narrow; others are deep and wide, but all rivers are murky with hidden obstacles to navigate. Our real estate attorneys are a guide and trusted partner who understand your goals and help you navigate the Texas Real Estate landscape with confidence.

Legal Roadmap to Buying, Selling, and Subdividing Land in Texas

Texas is a landowner’s state. Whether you’re purchasing acreage for investment, preparing to sell a long-held family ranch, or subdividing land for development, it’s essential to understand the legal landscape. Every stage of a land transaction carries important legal implications that can affect property values, compliance with state and local regulations, and most importantly, your peace of mind. At Braun & Gresham, we’re advocates for you and your land. Our team is here to guide you through these complexities with clarity and confidence.

This legal roadmap for buying, selling, or subdividing land outlines the key considerations our team evaluates to protect your interests and help you realize your goals. Because these transactions often involve intricate legal details and significant financial consequences, we strongly recommend speaking with one of our Real Estate Attorneys to ensure your decisions are informed, strategic, and secure.

LEARN MORE

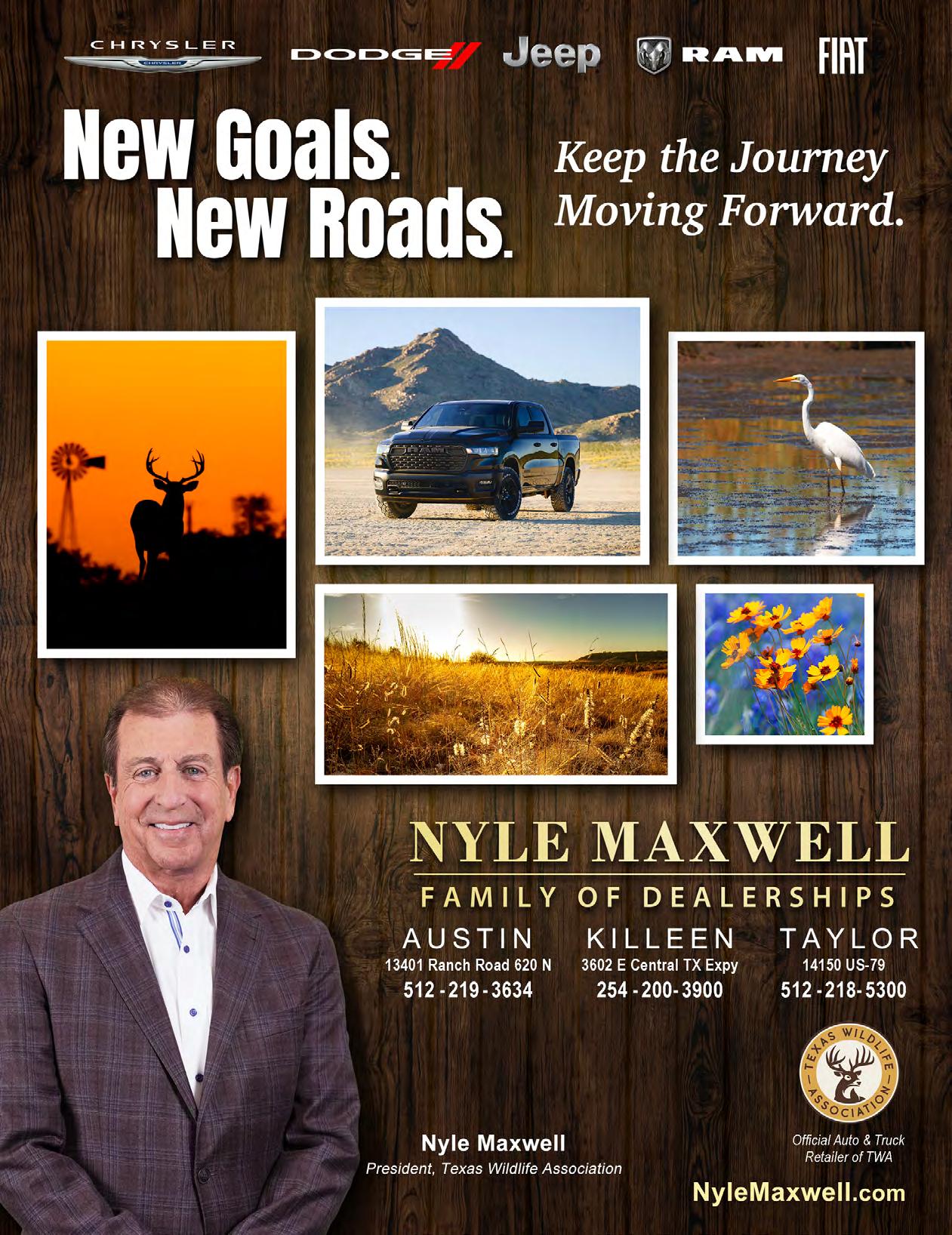

Greetings from TWA headquarters here in New Braunfels. We are coming off a highly successful 2025 across all three phases of the organization, and our team is energized and focused on serving and our membership in a big way in 2026.

With only a few remaining hog and turkey hunts scheduled through late winter and spring for the Texas Youth Hunting and Adult Learn to Hunt programs, our Hunting Heritage team is shifting its attention to the Texas Big Game Awards (TBGA). Once again, TBGA will host eight regional banquets across the state this summer. The deadline for entries is March 1, so I encourage everyone to submit scored, youth and first harvest entries as soon as possible.

We are also excited to share that TBGA is entering the development phase of a new interactive system that will strengthen the program in several important ways. Planned features include electronic entry submissions for official scorers, simplified trophy searches and the ability for hunters to submit photos and stories directly. Working alongside our partners at Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), we are confident this modernization effort will increase the quality of our data, decrease costs, decrease staff time and help grow and enhance this important R3 program well into the future.

Our Conservation Legacy team is equally busy planning and delivering education programs for youth and adults across Texas. At the start of the year, we launched our new lesson website, which provides teachers with free access to hundreds of TEKS-aligned natural resource lessons for classroom use statewide. Meanwhile, our adult education team is working with partners to finalize plans for a full slate of programs, including Water in the Desert in Alpine, Women of the Land at multiple locations, and the Trans-Pecos and South Texas wildlife conferences.

In addition to closely monitoring several high-profile primary races, the Issues and Advocacy team is actively engaged on key policy matters, including New World screwworm response, transmission line routing, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s mountain lion management efforts, among others.

Finally, please mark your calendars for the 2026 TWA Convention, taking place July 9–11 in San Antonio. Registration information will be available soon, and we look forward to seeing you there.

Thanks for being a member of TWA.

Texas Wildlife Association MISSION STATEMENT

Serving Texas wildlife and its habitat, while protecting property rights, hunting heritage, and the conservation efforts of those who value and steward wildlife resources.

OFFICERS

Nyle Maxwell, President, Georgetown Parley Dixon, Vice President, Austin

Dr. Louis Harveson, Second Vice President for Programs, Alpine

Spencer Lewis, Treasurer, San Antonio

For a complete list of TWA Directors, go to www.texas-wildlife.org

PROFESSIONAL STAFF/CONTRACT ASSOCIATES

ADMINISTRATION & OPERATION

Justin Dreibelbis, Chief Executive Officer

TJ Goodpasture, Director of Development & Operations

Denell Jackson, Director of Finance & Administration

Becky Alizadeh, Office Manager

OUTREACH & MEMBER SERVICES

Sean Hoffmann, Director of Communications

Karly Bridges, Membership Manager

CONSERVATION LEGACY AND HUNTING HERITAGE PROGRAMS

Kassi Scheffer-Geeslin, Director of Youth Education

Andrew Earl, Director of Conservation

Amber Brown, Conservation Education Specialist

Gene Cooper, Conservation Education Specialist

Sarah Hixon Miller, Conservation Education Specialist

Megan Pineda, Conservation Education Specialist

Lisa Allen, Conservation Educator

Kay Bell, Conservation Educator

Denise Correll, Conservation Educator

Christine Foley, Conservation Educator

Yvonne Keranen, Conservation Educator

Terri McNutt, Conservation Educator

Jeanette Reames, Conservation Educator

Louise Smyth, Conservation Educator

Marla Wolf, Curriculum Specialist

Noelle Brooks, CL Program Assistant

Matthew Hughes, Ph.D. Director of Hunting Heritage

Mason Huffman TYHP Program Manager

Bob Barnette, TYHP Field Operations Coordinator

Taylor Heard, TYHP Field Operations Coordinator

Briana Nicklow, TYHP Field Operations Coordinator

Kim Hodges, TYHP Program Coordinator

Kristin Parma, Hunting Heritage Program Specialist

Jim Wentrcek, Adult Learn to Hunt Program Coordinator

Abbye Shattuck, Hunting Heritage Administrative Assistant

TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION FOUNDATION

Justin Dreibelbis, Chief Executive Officer

TJ Goodpasture, Director of Development & Operations

Denell Jackson, Director of Finance & Administration

ADVOCACY

Joey Park, Legislative Program Coordinator

MAGAZINE CORPS

Sean Hoffmann, Managing Editor

Publication Printers Corp., Printing, Denver, CO

Texas Wildlife Association

6644 FM 1102

New Braunfels, TX 78132

(210) 826-2904

FAX (210) 826-4933

(800) 839-9453 (TEX-WILD) www.texas-wildlife.org

Texas Wildlife Extra

E-MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION

FEBRUARY 2026 | VOLUME 41 | NUMBER 10

David K. Langford

FEBRUARY

February 1

Kids Gone Wild at Ft. Worth Stock Show & Rodeo, 11 a.m.-6 p.m., Cattle Arena. Visit our TWA booth! Details at https://www.fwssr.com/ events/2026/kids-gone-wild

February 11-13

Water in the Desert Conference, Sul Ross State University, Alpine. For details and registration information visit https://bri.sulross.edu/events/ water-in-the-desert-2026/

February 25

Wild at Work Webinar: Texas Big Bend Archaeological Initiative, 12-1 p.m., online at https://www.texas-wildlife.org/waw/

MARCH

March 2-7

Houston Rodeo Ranching & Wildlife Expo, Houston. Visit our TWA booth! Details at https://www.rodeohouston.com/plan-your-visit/ ranching-wildlife-expo/

MARCH

March 20-22

Women of the Land Workshop, Mason Mountain Wildlife Management Area, Mason. For details and registration information visit https://www. texas-wildlife.org/wotl/

March 25

Wild at Work Webinar: The Role of Joint Ventures in Habitat Restoration in Texas, 12-1 p.m., online at https://www.texas-wildlife.org/ waw/

March 27

Women of the Land Workshop, East Foundation El Sauz Ranch, Port Mansfield. For details and registration information visit https://www.texaswildlife.org/wotl/

JULY

July 9-11

41st Annual TWA Convention, J.W. Marriott Hill Country Resort & Spa, San Antonio.

FOR INFORMATION ON HUNTING SEASONS, call the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department at (800) 792-1112, consult the 2025-2026 Texas Parks and Wildlife Outdoor Annual, or visit the TPWD website at: https://tpwd.texas.gov/

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

TWA LETTER TO THE EDITOR POLICY: Texas Wildlife Association members are encouraged to provide feedback about issues and topics. The CEO and editor will review letters (maximum 400 words) for possible publication. Email letters to shoffmann@texas-wildlife.org

REGISTER TODAY

Easement Rights Being Wronged

ARTICLE BY ANDREW EARL, TWA DIRECTOR OF CONSERVATION

The third branch of government, the Judicial, is designed and intended to be a grounding force. The courts interpret laws, protect rights and administer justice on disputes that range from small claims to constitutional matters. Their impartiality is essential to our faith in governance.

TWA was founded over four decades ago to serve as a levee against the slow drainage of property rights arbitrated in the courts. Particularly in recent decades, the pressures of development have resulted in more frequent claims by municipalities, utilities, corporations and lawmakers challenging these foundational rights under the vague guise of “progress.”

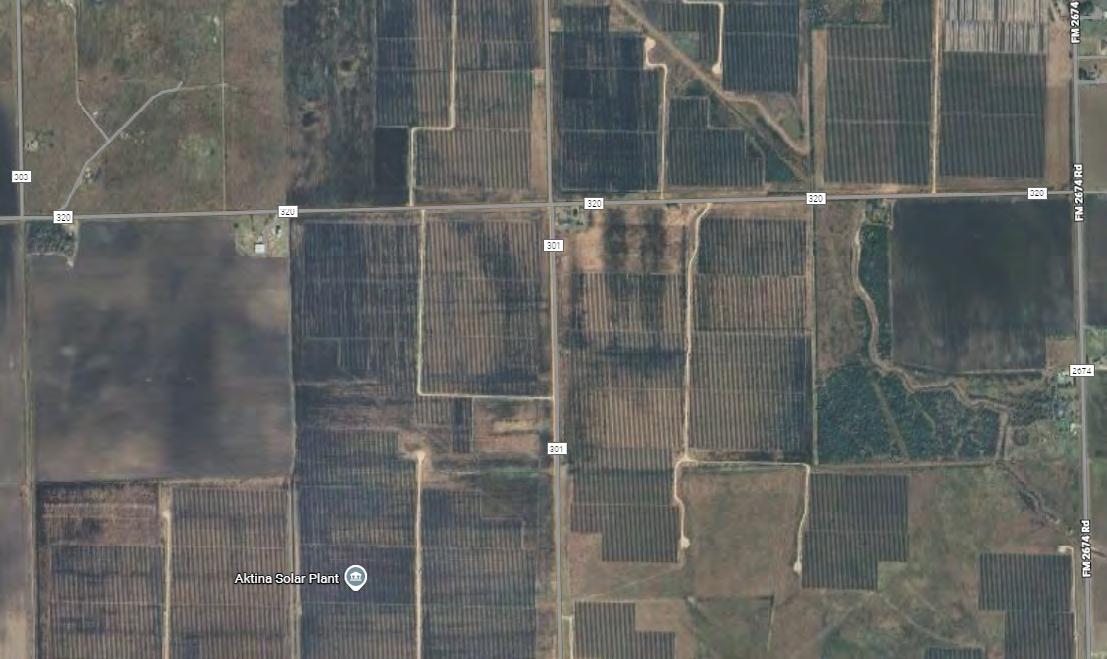

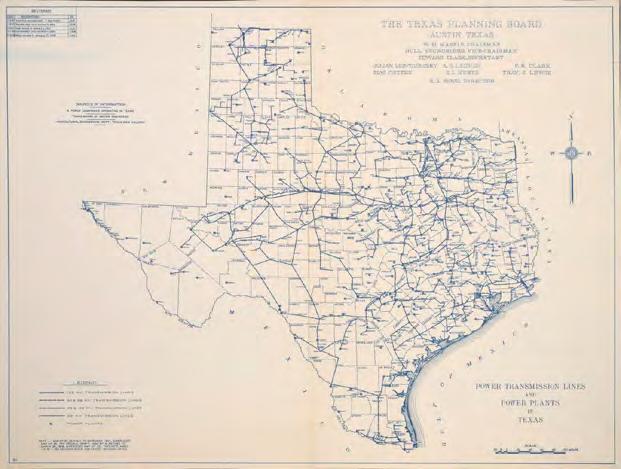

Examples of energy development, such as oil and gas near (near Barnhart) and solar (near El Campo), are readily viewable across Texas on free applications such as Google Maps.

Perhaps chief among the legal pressures facing property owners in Texas is energy development. Meeting the demands of Texas’ immense growth is an important ground for utilities being permitted to build, operate and maintain our electrical infrastructure. There are certainly instances where the need for new and upgraded power delivery infrastructure is justifiable, and in those cases the Landowner’s Bill of Rights and Chapter 21 of the Texas Property Code should guide condemnation proceedings.

There is, however, a concerning trendline of property rights being whittled away in the courts when trial judges are summarily granting

“implied” rights to utility providers leaning on the basis of ballooning energy demands as a justification for the involuntary taking of property.

the property owner caused the lines to collapse, killing a cow. The family demanded all remaining lines on the property be disconnected, given that the oil and gas activity receiving the power had concluded and that lease language had specified the utility no longer held rights to the lines. The provider had previously maintained several electric lines to service those operations and the family home.

The utility sued the family in 2018, alleging they held prescriptive easements (historical use) and easements by estoppel (promise) on the property. The utility did not provide the court any written account of the easements beyond an initial application for electrical service submitted in 1950.

There is, however, a concerning trendline of property rights being whittled away in the courts when trial judges are summarily granting “implied” rights to utility providers leaning on the basis of ballooning energy demands as a justification for the involuntary taking of property. These implied rights, which do exist in easement law should only be granted in rare cases and only after a full trial on the merits where the property owners can assert their rights.

Recently, TWA proudly joined partners at the Texas Farm Bureau, Texas & Southwestern Cattle Raisers, and Texas Forestry Association in pushing back on one such case emblematic of this pattern of granting overbroad and unnecessary rights to a utility.

Outside San Angelo in Irion County, a multi-generational family ranch is engaged in a decade-long battle with an electric cooperative over easement rights that were never granted in writing.

In 2015, the weight of icy broadband cables installed on old historic poles by a utility provider without consent of

Subsequently, the court issued a summary judgment in favor of the utility provider disregarding efforts by the family to receive a full jury trial. The judge with the stroke of a pen declared that the utility owned all lines it had constructed on the property, held valid easements to them, and required that the landowners pay roughly $800,000 of the utility’s attorney fees.

The family appealed the court’s ruling in 2025 and proceedings are ongoing. TWA and our partners filed an amicus brief on their behalf and are confident the case will be remanded to a lower court.

This broad decision carries significant implications beyond this family’s century-old ranching operation. It upsets the partnered relationship between landowners and utility providers, signaling that good faith negotiation and explicit agreement are optional, rather than compelled. At any time, a valid utility in Texas can exercise the powers granted to them to condemn valid and necessary easements and in that case the utility must pay just compensation. However, where utilities are granted implied rights, the owner in many cases will not receive any compensation.

Power transmission lines and power plants are indicated on this 1938 map created by the Texas Planning Board. Courtesy University of TexasArlington Library.

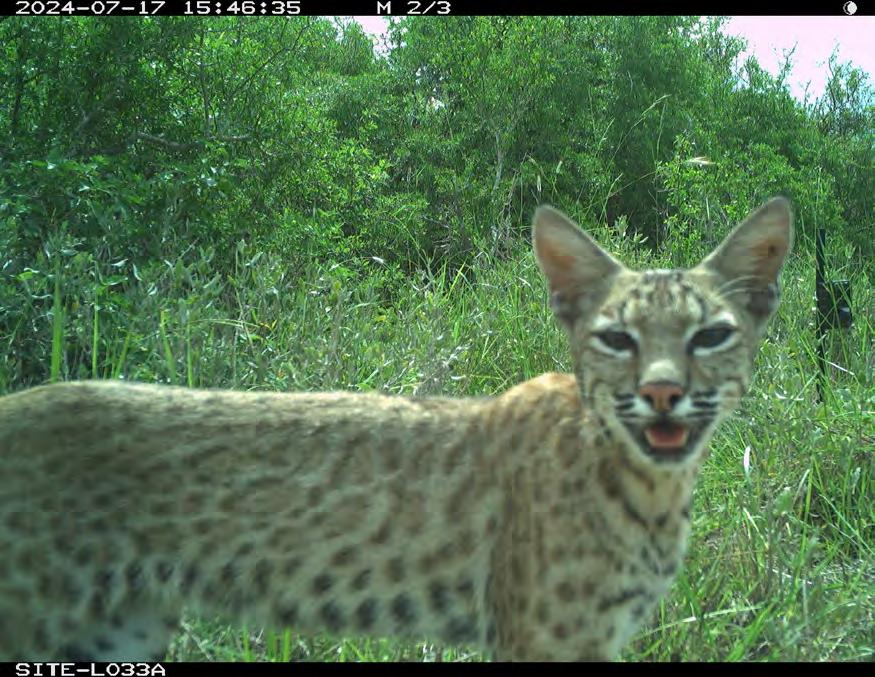

An ocelot in South Texas with rodent prey. Ocelots are federally endangered in Texas, with as few as 120 individuals remaining in the United States. Ocelots are at risk to anticoagulant rodenticide exposure due to small rodents being their primary prey items. PHOTO

Could Use of Rat Poisons Be Affecting Non-target Wildlife in South Texas?

ARTICLE BY LISANNE PETRACCA, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF CARNIVORE ECOLOGY, CAESAR KLEBERG WILDLIFE RESEARCH INSTITUTE, TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY – KINGSVILLE

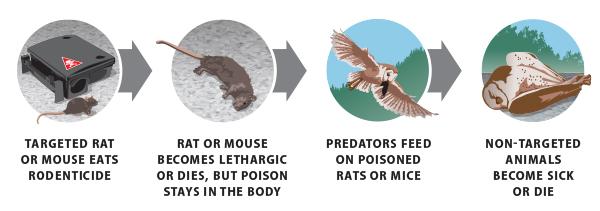

If you were looking to contain a pervasive rat or mouse problem, what would you do? Many Texans, as well as businesses and local governments, will turn to the deployment of rodent baits to get rid of the problem once and for all. These baits are commonly sold in pellet or block form or even as bait stations, which are designed to keep out domestic animals such as cats and dogs and only allow

entry to animals that are rat-sized or smaller. The rodents will ingest the poison-laced bait and, over the course of hours or days, will hopefully be a problem no longer.

Sounds like an open and shut case, right? Well, scientific studies are popping up all over the United States that suggest that, while the targets of rodent baits are rats and mice, the poisons used in these baits can impact other species in the

food web. And we have new research from South Texas that sheds a bit more light on these potential risks.

First, let’s talk about how rodent baits work. The products sold at places like Tractor Supply, Lowe’s, and Home Depot generally contain food that is attractive to rodents but also come laced with lethal compounds. These compounds are called “anticoagulant rodenticides,” also referred to by the acronym ARs, and work by preventing the body from forming clots, leading to internal hemorrhaging and death.

Importantly, there are two levels of AR potency: firstgeneration, which are less potent and therefore require multiple feedings to be effective, and second-generation, which are lethal from a single dose and designed in response to rodents developing a tolerance to the first-generation compounds. The high lethal dosage of the second-generation compounds makes them particularly effective at fulfilling their purpose (killing rodents!), but linger at high doses longer in the rodent’s body.

Most research into unanticipated impacts of ARs has involved avian scavengers, particularly raptors. A review led by researchers at Hokkaido University, Japan, found that at least 60% of individuals of various raptor species globally, including bald eagles, golden eagles, great horned owls, barred owls, long-eared owls, and turkey vultures here in the United States, had detectable levels of ARs in their tissues. Only more recently has attention shifted to mammals.

A recent global review of anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in wild carnivores, led by Meghan Keating at Clemson University, showed that eight families of carnivores had been exposed to ARs. The three families most exposed were mustelids (e.g., weasels, badgers, and martens), canids (e.g., wolves and coyotes), and felids (e.g., bobcats, lynx, and large-bodied wild cats such as jaguars and African lions). In addition, they found that ARs caused death to at least one individual in about one-third of studies.

If you use rodenticides and are curious about whether the products you use are first-generation or second-generation, check out the label. Common first-generation compounds include warfarin and diphacinone, while common secondgeneration compounds include brodifacoum, bromadiolone, and difethialone.

A key thing to understand about the second-generation rodenticides is that, because they persist longer in rodent tissues, they also expose predators, such as bobcats, coyotes, and ocelots, and scavengers, such as vultures and caracara, that consume these rodents to that same high dosage of lethal compounds. These non-target wildlife species can die from eating poisoned rodents, or experience sublethal effects such as liver damage, internal hemorrhaging, poor immune response, and reproductive complications. As an example, work led by Dr. Seth Riley in California showed that exposure to ARs, in conjunction with mange, led to a decline in bobcat survival.

Given the growing evidence that anticoagulant rodenticides represent a pervasive issue among carnivores that feed on rodents, we at the Spatial and Population Ecology of Carnivores (SPEC) Lab, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University – Kingsville, decided to launch new research to investigate this issue. This research was led by me and master’s student Tori Locke, who successfully defended her thesis this past fall and will be continuing her studies in my lab as a Ph.D. student.

Tori’s work answered two questions: (1) Have carnivores in South Texas, namely bobcats, coyotes, and endangered ocelots, been exposed to anticoagulant rodenticides? And (2) If yes, are the levels detected in bobcats, coyotes, and ocelots of concern? We mainly tested exposure to ARs via liver tissue, as that is the tissue where AR compounds accumulate. We collected liver samples from deceased animals that were roadkills, harvested by participating landowners, or died as part of our long-term monitoring efforts.

Overview of how anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs) can impact species in other parts of the food web, such as mammalian and avian predators and scavengers.

Could Use of Rat Poisons Be Affecting Non-target Wildlife in South Texas?

An ocelot killed by vehicle strike. Our research found that one roadkilled male ocelot had a concentration of one anticoagulant rodenticide compound that was about four times higher than that detected in a bobcat in California that had died from exposure.

BY

PHOTO

RECONECTA PROJECT

Game camera images of coyote and bobcat obtained by the Spatial and Population Ecology of Carnivores (SPEC) Lab, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University – Kingsville. Both coyotes and bobcats are exposed to anticoagulant rodenticides through consumption of rodents.

PHOTO COURTESY

Could Use of Rat Poisons Be Affecting Non-target Wildlife in South Texas?

Our data collection area spanned approximately 400,000 acres in South Texas and included private rangelands and public lands and roadways. We tested liver tissue from 39 individuals: 18 bobcats, 16 coyotes, and 5 ocelots. Anticoagulant rodenticides were present in 60% (n=3/5) of ocelots, 5.5% (n=1/18) of bobcats, and 25% (n=4/16) of coyotes. The compounds detected were largely second-generation (brodifacoum, bromadiolone, and difethialone), with only one first-generation compound detected (diphacinone). Of concern is that two of the three AR-positive ocelots had all four compounds detected in their liver samples.

Given the above, we knew that all three of our target species (ocelots, bobcats, and coyotes) had been exposed to anticoagulant rodenticides. But were the levels of compounds in these individuals something to worry about? Tori’s work suggests that the answer is “maybe”, given that the liver sample from one male ocelot had about four times the amount of a second-generation compound found in a bobcat in California that died from toxin exposure. The ocelot in Texas was killed by vehicle strike rather than ARs, but we still don’t know what role AR exposure may have played in the animal’s death. For example, ARs could increase an animal’s susceptibility to injuries that cause internal bleeding.

Thus, we have evidence from South Texas that non-target species such as ocelots, bobcats, and coyotes are exposed to anticoagulant rodenticides. We do not know if this exposure has led to mortalities in South Texas, nor whether the use of ARs will have a negative effect on the populations of these three carnivore species. Tori’s work is continuing this year as we try to collect more samples across a wider geographic area. If you are located in South Texas, employ predator control, and are interested in providing tissue samples, please get in touch with us victoria.locke@students.tamuk.edu. Importantly, our primary goal is to better understand anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in South Texas carnivores. However, we understand that scientific research can also provide new information that may assist with future decision-making. If you are a user of rodent baits, we encourage you to investigate the compounds used and to deploy them judiciously to reduce harm to non-target wildlife. We understand that there are benefits and tradeoffs to everything we do, and that there are often unintended consequences of well-intended actions.

If you are interested in the work that we do on the carnivores of Texas, please visit our research group’s website at https://thespeclab.weebly.com/ and the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute website.

Measuring River Health Through Mussels

NRI researchers advance water quality study on the Trinity River

ARTICLE BY BRITTANY WEGNER

PHOTOS BY NRI

Trinity River Basin

Measuring River Health Through Mussels

On a cool morning along the West Fork of the Trinity River, NRI researchers waded carefully through flowing water to check a series of mussel silos submerged along the riverbed. These silos, concrete domes with a central opening that houses juvenile mussels and allows water to flow through, are a part of a project examining how water quality influences mussel growth and survival. The field team is led by research associate Rachel Carpenter and supported by Dr. Charles Randklev, research scientist and head of NRI’s freshwater mussel program.

This project is part of a long-standing partnership with the Trinity River Authority (TRA), the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Together, these organizations are collaborating to better understand the ecological conditions shaping mussel populations in the Trinity River basin, which is home to several of Texas’s most imperiled species.

WHY MUSSELS ARE KEY TO UNDERSTANDING RIVER HEALTH

Freshwater mussels are among the most reliable biological indicators of ecosystem health. Their sensitivity to pollutants, shifts in water chemistry, and changes in sediment loads make them early-warning sentinels for river systems. At the same time, mussels are ecological

powerhouses filtering water, stabilizing sediment, and contributing to overall aquatic diversity. We often refer to them as the “liver of the river.”

Yet, across North America, mussel species are disappearing at an unprecedented rate. Habitat fragmentation, water quality degradation, altered hydrology, and land-use change have contributed to steep declines. Conservation scientists, including those at NRI, now face a critical challenge: species declines are outpacing the research needed to protect remaining populations.

Randklev’s lab focuses on closing this gap. By studying unionid mussels as long-lived, highly sensitive species, the team evaluates river health and tests ecological theories that can inform more effective conservation strategies.

“This research will provide us much needed information on how mussels respond to changes in water quality, helping guide conservation and management actions that strengthen the overall health of the Trinity River,” Randklev shared.

A MULTI-YEAR RESEARCH PROGRAM WITH REAL IMPACT

NRI’s mussel program has grown into one of the leading applied research efforts in integrating mussel ecology with hydrologic science to evaluate risks to stream and river

The Texas A&M NRI team of freshwater mussel researchers has been carefully wading through the flowing waters of the Trinity River and examining how water quality influences mussel growth and survival.

ecosystems and to guide efforts that safeguard and protect aquatic species. Under Dr. Randklev’s leadership, the team has conducted basin-wide assessments, rediscovered populations of species believed to be rare or declining, and worked closely with state and federal agencies to inform listing decisions and recovery planning. “This silo study is the critical first step for mussel conservation and recovery efforts in the upper Trinity River basin and will provide valuable information on next steps for the conservation of these species”, said Clint Robertson, TPWD freshwater mussel conservation coordinator.

For TRA, understanding mussels is part of understanding basin-wide ecological integrity. “As indicators of both quality habitat and good water quality, native mussels provide a piece of the puzzle in understanding the current and future water quality challenges within the Trinity Basin,” said Ryan Seymour, TRA environmental scientist. TRA staff routinely assist in research, provide access to reach-specific data, and coordinate mussel relocation efforts during major construction projects, all with the goal of ensuring the best available science underpins conservation decisions.

LINKING WATER QUALITY TO MUSSEL GROWTH

While NRI has long focused on documenting distribution, abundance, and habitat characteristics, Carpenter’s project adds a new dimension by testing how water quality, an essential component of mussel habitat, shapes growth directly in a natural river system.

During their sampling trip, Carpenter and the team collected water-quality data, including temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity, and conductivity, as well as growth measurements of mussels at selected Trinity River sites. By pairing these datasets, the project aims to answer a few questions:

• Which water quality parameters most strongly influence juvenile and adult mussel growth?

• How do shifts in river conditions affect mussel health?

• Can growth patterns be used to predict long-term population viability?

Understanding these relationships is essential for assessing river health, understanding threats to aquatic species and forecasting how mussel populations may respond to future environmental change.

“Growth is a powerful measure of ecological stress,” Carpenter explained. “By linking growth rates to water quality trends, we can better understand how mussels are experiencing and responding to conditions in the river.”

LOOKING AHEAD

As the project continues, the research team will analyze growth trends across different environmental conditions, building models that link mussel physiology to river health. Their findings will contribute to a growing body of work positioning mussels as essential indicators of broader ecosystem function.

For Carpenter, Randklev, and their partners, this research underscores the value of long-term collaboration. By combining expertise in ecology, water management, and conservation policy, they are charting a clearer path forward for protecting Texas’s freshwater biodiversity.

Texas Hornshell freshwater mussels.

Cleaning Up?

ARTICLE BY LARRY WEISHUHN

BY LARRY WEISHUHN OUTDOORS

PHOTOS

As a youngster playing baseball, I did not bat in the cleanup position. My hand-eye coordination was okay, but not great. What I lacked in skill however I made up in “want to” and “try.” But that was baseball and not hunting. When it comes to hunting, particularly on properties under our Texas Managed Land Deer Permit, I have often played a cleanup role in a last-ditch effort to remove the suggested number of does and even bucks.

It is a role I appreciate and enjoy. My family and I really like prime venison, and late season does certainly fit into that category, as do management bucks. With the latter they are trying to repair from the rigors of the rut and are again putting on weight. Within any deer herd there are always management bucks. What constitutes management bucks? My criterion is bucks at least four years old or older than have 6 or less points, some short tined 8 and larger bucks, and bucks with misshaped antlers (meaning a good antler

one one side and a single spike or odd shaped antler on the other side).

I do not consider most 8-point bucks as management bucks unless they lack mass, tine and/or main beam length for at least two-years in a row. Over the many years I have been involved in managing whitetail deer on private property, I have seen many high scoring 3- and 4-year-olds after chasing really hard during the rut get so run down they do not recover to produce the same huge antlers the following year. I have seen numerous 150 B&C or better scoring bucks as 3 or 4-years old, which I could readily identify, revert to 120 B&C class bucks the following year. Something to seriously consider if you are culling 8-point bucks on your property or lease.

I am not concerned about these bucks passing on their genes to offspring they may sire. Buck to doe ratios on the properties I’ll be hunting late or early in the year have a

LEFT: Late season MLDP hunts often deliver some to the coldest temperatures of hunting season. Deer tend to hit food sources hard as winter transitions into early spring. Here, Larry is with David Cotton and an older deer that he considered a management buck.

ABOVE: Playing cleanup creates opportunities to experiment with a variety of firearms, including handguns, that might not be used quite as often during the regular season.

The other thing I really like about playing cleanup is the chance to hunt with a variety of firearms.

fairly narrow buck to doe ratio. The chance of any one buck breeding more than two or more does is pretty slim. My concern comes from a nutritional perspective. The bucks with apparent poor antlers that lack potential to produce larger antlers eat just as much as those bucks with great antler potential. If range conditions become less than ideal because of an extended drought, I would rather the bucks with impressive or potentially impressive antlers eating what forage is available.

The other thing I really like about playing cleanup is the chance to hunt with a variety of firearms. In my gun safe I have a couple of old Savage Model 99 lever-actions which I have used over the years. Both are chambered in .300 Savage. One I am having laser-engraved and embellished, which I will donate to our annual Grand Auction fundraiser at our TWA Convention in July. Both have served me well in the past. I have several other lever-actions, including a Winchester Model 1895 chambered in .30 Gov’t ‘06, Rossi lever-actions in both .30-30 Win and .45-70 Govt, as well as several Ruger Number 1s which I intend to use on deer during February. These include an early production .270 Win, a 9.3x62 in RSI, .275 Rigby and possibly a couple of others. Too, I intend to take at least one or more deer during late January and February with my .454 Casull and .44 Mag Taurus Raging Hunter revolver. Thanks to the Texas MLDP I will have those opportunities.

I also have an extremely accurate 7mm PRC with a Thunder Valley Precision (Tom Sarver) Avient Rapid Heat Releasing Barrel Technology rifle topped with a Stealth Vision 5-20x50 scope shooting Hornady loads that I plan on using to take late season whitetails. This one may see second duty as a longer range “hog-taker.”

One of the reasons for mentioning the different calibers, rounds and guns is because usually there are several places where you might be able to hunt during the extended MLDP season, especially for does. That season, which extends through the last day of February, is a great time to try different guns, scopes and loads, or, to break in that new rifle (conventional, air rifle or muzzleloader), or possibly bow and arrow or crossbow that you got for Christmas.

February is also a great time to plan upcoming hunting trips, and a perfect place to do that will be at the DSC Convention in Atlanta, GA at the World Congress Center Feb. 6-8. In recent year TWA and DSC have worked together on numerous projects that benefit our TWA members. I have long proudly served as an Ambassador for DSC and continue to connect our two organizations whenever and wherever possible.

Management bucks taken during the extended MLDP season are a great way to top off the freezer until the season cranks back up in the fall.

Even adults enjoy goin g o utsi d e to play.

There’s nothing like being out in nature It’s where you can forget about the everyday, while reintroducing you to yourself. And the one thing that could make all this even

to hunt, fish, or do any other outdoor activity, Capital Farm Credit is here for you. We have the knowledge, guidance and expertise in financing recreational land with loans that have competitive terms and rates. Which is helpful because it’s time you reconnect to the land, and to the person you see in the mirror every day.

THEPOSSUM CO P CHRONICLES

The four-laned Chiltipin Creek bridge on Hwy 281 as it appears today.

Heads You Win, Tails You Lose

ARTICLE BY JON BRAUCHLE

If there is a natural disaster in the state of Texas, you can bet Texas Game Wardens will be there. In fact, even if there is a disaster in some other state and a call for assistance is made, there’s a good chance Texas Game Wardens will be there too. Why? Because they are an elite

group of law enforcement professionals with the equipment and know-how to operate in dangerous situations where there are people in need of rescue, whether it be flood, fire, hurricane, tornado or other disaster. And with specialized units that have been created and have evolved in the past

25 years or so, like the dive team, search and rescue, K-9, aerial, swift water boat and forensic mapping units, Texas Game Wardens are ready for anything.

But it wasn’t always like that. Over the years, game wardens have had to do the best they could with what they’ve had. If, as a game warden, you were asked to go rescue someone in a flood and all you had was a little Jon boat with an outboard motor that took 10 pulls on the starter rope to get it to go, you made sure you brought along some Band-Aids or some gloves to take care of the inevitable rope blisters between your fingers and you went.

In the summer of 1980, Game Warden Adolph Castillo and his partner, Mitchell Pawlik, got a call around 2 a.m. to check on some people stranded in a trailer park north of Alice by the rising floodwaters of Hurricane Allen. Numerous first responders were already at the scene, but they were unable to get to the trailer park because it was surrounded by floodwater. They needed a boat, and game wardens have boats.

Adolph and Mitchell launched a small aluminum skiff in the calm water of the barrow ditch on the west side of Highway 281 about 75-100 yards away from the creek amid concerns that the water would soon overtake the two-lane

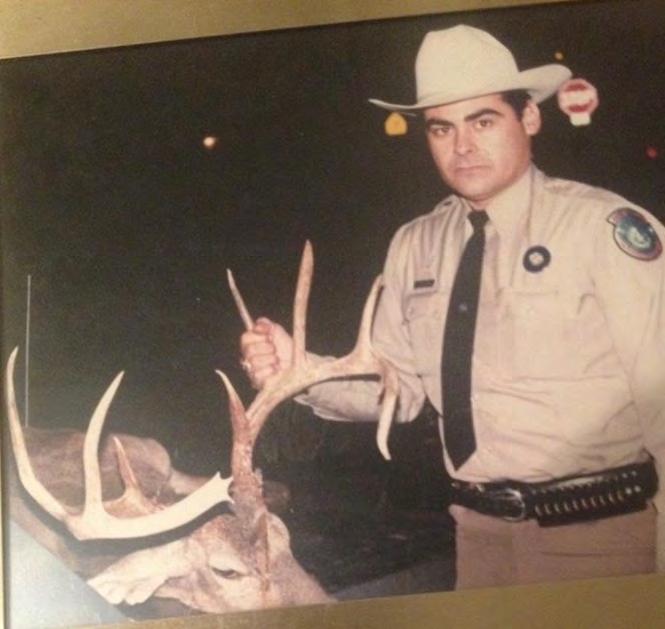

Adolph Castillo with an illegally taken buck.

highway bridge. Mitchell was operating the 9.9 horsepower tiller-drive motor at the stern of the boat and Adolph was at the bow. Neither one of them were wearing a lifejacket. At the time, there was no department policy mandating the wearing of a lifejacket while working in a boat, and for whatever reason, they chose not to that night.

After they launched, everything went as it should have until they hit the deceptively calm-looking main channel of the creek. The water was deep, and the current was much stronger than they expected. They should have brought a bigger boat.

But it was too late for that. The current took control and pushed their boat up against one of two large culverts under the bridge. Upon impact, the boat crinkled up like an aluminum can and capsized. A couple of guys ran out onto the bridge and grabbed Mitchell’s hand and pulled him out. Adolph was not as fortunate. He was sucked into one of the culverts.

In the swirling abyss of the tunnel underneath the highway, Adolph was first met by something violently crashing into the side of his head. He soon realized that there was nothing he could do about anything, except to try not to gasp for air.

When he came out of the culvert on the east side of 281, he was swept into a barbed-wire fence. He managed to grab the top wire, but the current kept pushing him under. As the fence barbs dug into his hands, he fought to get his head up to breathe. As he struggled, Adolph got a sick feeling that this was it. He was going to drown. He thought about his family and friends. Would he see them again? What would death feel like?

Adolph pulled with everything he had and finally got his head above water. Then, he took a moment to breathe and assess the situation. There wasn’t a whole lot to assess--just raging water and darkness. He knew he wouldn’t have the strength to hold on indefinitely.

So, he let go. Swept away immediately, he fought to keep his head above water as he looked for a way out. He crossed another fence but didn’t hang up. Finally, he hit a tree and managed to straddle himself around a low-hanging limb. Exhausted, he climbed up to a fork in the tree and got far enough out of the current to catch his breath. He knew he was in a tight spot, but there was nothing left to do but hold on and wait.

The other first responders at the scene had no idea where Adolph was or if he was even alive. Several of them fanned

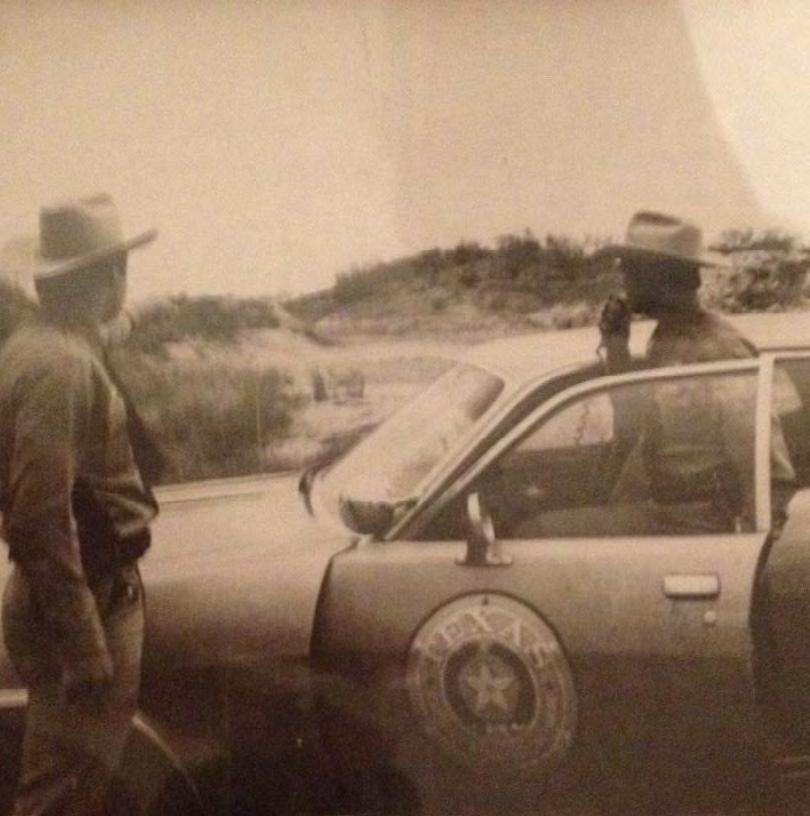

Adolph Castillo (L) and Mitchell Pawlik responding to a call in the late 1970s.

Heads You Win, Tails You Lose

out with flashlights along the water’s edge on the east side of the highway. After a short search, Adolph was spotted in the tree. Right away, they could see he wasn’t going to be easy to reach. They considered calling in a helicopter or maybe using the ladder off one the fire trucks to attempt a rescue. While that discussion ensued, a DPS trooper, who himself had been in more than a few tight spots while serving his country in Viet Nam, was gathering up ropes and a couple of lifejackets. The trooper linked up the ropes, put on one of the lifejackets, and called everyone over to the water’s edge. He then handed one end of the linked ropes to several men and tied the other end to the other life jacket. Then, he put the coil of ropes on his shoulder and launched himself into the water.

The trooper made it as far as that first fence Adolph had hung up on. From there, he could see Adolph clinging to the tree. He shouted, “Okay, partner. We’re gonna get you out of here.” Indicating the lifejacket in his hand, the trooper said, “I’m going to throw this to you. When it comes by you, grab it, put it on, and hold on to the rope.”

The first two tosses didn’t go well, but the third time was a charm. Adolph grabbed the lifejacket and managed to get it on. As he held the rope, the trooper shouted, “OK – we’re gonna need you to come off that limb, and we’re gonna pull you all the way back.” Adolph shouted back, “No you’re not – there’s another barbed wire fence between me and the road and I’m not getting off this tree!” The trooper remained calm and hollered, “Hey partner – we’re not gonna let anything happen to you!”

In a leap of faith, Adolph held on tight to the rope and jumped down into the water. “Pull!” the trooper yelled to the men at the other end of the line. The water was running so fast and the men pulled so hard that Adolph skipped across the water like a flat rock hitting the water after spinning out of a side-armed throw, but it worked. When he was safely back to solid ground, he was quickly shuffled off to a waiting ambulance.

Adolph spent three days in the hospital but came out relatively no the worse for the wear, save for a big black bruise all around his right ear. After the water receded, he went back to the Chiltipin to try and make sense of what happened. The creek was low enough for him to walk down and look into the 10-foot in diameter culverts that passed under the highway. He could see clear to the other side of the highway in the one that he was swept through. When he looked at the adjacent culvert, he saw a large tree full of debris that was jammed up right in the middle of it. Indeed, in the “heads you win, tails you lose” proposition of fate that swept Adolph through one culvert instead of the other, Adolph was a winner.

Aug. 10, 2026 will mark 45 years since Hurricane Allen hit the Texas Coast. Adolph is 72 years old now and long retired from Texas Parks and Wildlife. He says he really doesn’t think about that night very much or what “tails” would’ve meant for him, but he has a grandson that’ll ask him about it every now and again when they’re enroute to go hunting or fishing somewhere together. Yep, Adolph has a lot to be thankful for. And so does his grandson.

.org

Purpose

O er rewards up to $1,000 for information leading to the arrest & conviction of natural resource crimes

Provide nancial aid to the families of game wardens & park peace o cers killed in the line of duty

Obtain technologically advanced equipment for game wardens, resulting in safer & more e cient operations

Outreach & educate all Texans in order to protect our natural resources and private property rights

If a violation is currently in progress, call 800 792-GAME or text to 847411 keyword TXOGT

Operation Game Thief is a 501(c)(3) nonpro t organization whose mission is to improve our quality of life by intentionally engaging individuals and communities across Texas to prevent theft and destruction of our natural resources through outreach, education, and a direct con dential link to report violators.

Big Bend National Park iPhone photo, December 2025.

BY TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT

PHOTO BY NATALIE NASH

PROOF OF RESIDENCY AMENDMENTS FOR HUNTING, FISHING LICENSE PURCHASE

On January 12, 2026, TPWD filed proposed amendments to the department’s rule regarding proof of residency requirements for issuance of recreational hunting and fishing licenses and permits with the Texas Secretary of State.

The proposed amendments would require a person to produce, at the time a license is purchased or obtained, a driver’s license or personal identification certificate issued by the state or territory of the United States of which the person is a resident that complies with the REAL ID Act of 2005.

Additional documentation options are provided for residents of a state or territory of the United States including a United States passport or passport card, United States military identification card, immigration-related documents issued by the United States Government, or a certified birth certificate; and for residents of Texas a concealed handgun license.

If the person is a resident of a foreign country, the person must produce a driver’s license or personal identification certificate issued by the person’s country of residence, accompanied by a valid foreign passport and other documents required for entry into the United States. The proposed rule amendments were scheduled to be published in the Jan. 23, 2026, issue of the Texas Register.

STATE PARK ADDED TO INTERNATIONAL DARK SKY LIST

Caprock Canyons State Park and Trailway is the latest Texas State Park to be designated as an International Dark Sky

Park by the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA). The designation will ensure the protection of the park’s dark skies not only for the park’s natural resources, but also for the local community and out-of-town visitors to enjoy.

To receive the dark sky park designation, parks are required to use quality outdoor lighting, effective policies to reduce light pollution, ongoing stewardship practices and more.

“I am very proud of the hard work and dedication that the park staff showed during this year’s long process to obtain the dark sky designation,” said Donald Beard, park and historic site superintendent for the Panhandle park. “It took each and every one of them to buy-in and work toward the ultimate goal of the certification.”

The Dark Sky designation for Caprock Canyons is something park staff can undoubtedly be proud of when they look back at their careers with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, added Beard.

Within the TPWD system, there are now two International Dark Sky Sanctuaries and four International Dark Sky Parks, including Big Bend Ranch State Park Complex, Copper Breaks State Park, South Llano River State Park, and Enchanted Rock State Natural Area, designated by the IDA. Devils River State Natural Area was designated as the first International Dark Sky Sanctuary in Texas in 2019.

To learn more about dark sky initiatives in state parks, visit the Dark Skies Program page on the TPWD website.