Texas Wildlife Extra

E-MAGAZINE OF THE TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION

Nothing showcases the amazing beauty of our great outdoors more than autumn. I love this time of year! Just as green gives way to yellow and red, we see the abundance of wildlife all around us during hunting season. But more importantly, it is that time of year that brings family and friends together to enjoy fellowship and shared values whether in a dove field or a deer blind (or around a Thanksgiving table).

In fact, I just got back from West Texas where I got to watch my eldest daughter, Marcella, go after her first Texas Slam. She harvested a beautiful pronghorn and created a meaningful memory that will last forever as her parents, husband and children all got to share the experience with her. And that’s what it’s all about. Getting the gear on, watching the sun come up, seeing firsthand the beauty of this state far away from city limits. Learning, persevering and enjoying the unique and truly special legacy that our hunting heritage affords us. And now as a grandfather, getting to pass it down from one generation to another is priceless. My daughter inspired me to go after a Texas Slam this year and I hope you consider it too. Recognizing that achievement at the Texas Big Game Awards presented at the TWA Convention every year is just one of the many ways TWA supports our hunters and landowners to continue the legacy.

Another great way to share this treasured pastime with the next generation is through the TWA’s Texas Youth Hunting Program. Just by opening your ranch for a weekend to a group of kids eager to learn about wildlife and conservation can start a ripple effect for years to come. The Maxwell family of ranches was excited to host its seventeenth youth hunt in October at our ranch in Melvin. Six youngsters arrived with their parents with the goal of harvesting their first deer. After a great time making new friends, they left with not only having achieved their goal, but also with a solid understanding of the importance of hunter safety, wildlife habitats, and why conservation matters. Being able to enjoy our great outdoors is now something they think about without taking it for granted. Personally sharing that experience and feeling that reward of making a difference to a child is as easy as contacting the TWA office to become a host ranch.

And these opportunities aren’t just for our youth. It is never too late to enroll in our Adult Learn to Hunt Program which provides an educational experience like none other. For three days and two nights, you have the full attention of a personal guide and mentor who will share all the skills necessary for a successful and meaningful hunt. From firearms training and safety to cooking techniques for wild game, you will be able to learn and apply those skills on the spot and hopefully start what will be a rich tradition of hunting for years to come.

There are so many good reasons to get out there and experience all that Texas offers us, and TWA makes it easy. And so do the ranch and landowners who participate in these programs. I’d like to recognize again the Cargile Family who recently won the TWA Foundation San Angelo Conservationist of the Year award they—were honored last month at the Bentwood Country Club in San Angelo. Many thanks to everyone who applies best practices that enable our rich hunting heritage to continue for generations to come. We are grateful for it.

Wishing everyone a Happy Thanksgiving and happy hunting!

Texas Wildlife Association MISSION STATEMENT

Serving Texas wildlife and its habitat, while protecting property rights, hunting heritage, and the conservation efforts of those who value and steward wildlife resources.

OFFICERS

Nyle Maxwell, President, Georgetown Parley Dixon, Vice President, Austin

Dr. Louis Harveson, Second Vice President for Programs, Alpine

Spencer Lewis, Treasurer, San Antonio

For a complete list of TWA Directors, go to www.texas-wildlife.org

PROFESSIONAL STAFF/CONTRACT ASSOCIATES

ADMINISTRATION & OPERATION

Justin Dreibelbis, Chief Executive Officer

TJ Goodpasture, Director of Development & Operations

Denell Jackson, Controller

Becky Alizadeh, Office Manager

OUTREACH & MEMBER SERVICES

Sean Hoffmann, Director of Communications

Karly Bridges, Membership Manager

Nicole Vonkrosigk, Regional Development Coordinator

CONSERVATION LEGACY AND HUNTING HERITAGE PROGRAMS

Kassi Scheffer-Geeslin, Director of Youth Education

Andrew Earl, Director of Conservation

Amber Brown, Conservation Education Specialist

Gene Cooper, Conservation Education Specialist

Sarah Hixon Miller, Conservation Education Specialist

Megan Pineda, Conservation Education Specialist

Lisa Allen, Conservation Educator

Kay Bell, Conservation Educator

Denise Correll, Conservation Educator

Christine Foley, Conservation Educator

Yvonne Keranen, Conservation Educator

Terri McNutt, Conservation Educator

Jeanette Reames, Conservation Educator

Louise Smyth, Conservation Educator

Marla Wolf, Curriculum Specialist

Noelle Brooks, CL Program Assistant

Matthew Hughes, Ph.D. Director of Hunting Heritage

COL(R) Chris Mitchell, Texas Youth Hunting Program Director

Bob Barnette, TYHP Field Operations Coordinator

Taylor Heard, TYHP Field Operations Coordinator

Briana Nicklow, TYHP Field Operations Coordinator

Kim Hodges, TYHP Program Coordinator

Kristin Parma, Hunting Heritage Program Specialist

Jim Wentrcek, Adult Learn to Hunt Program Coordinator

Loryn Calderon, Hunting Heritage Administrative Assistant

TEXAS WILDLIFE ASSOCIATION FOUNDATION

Justin Dreibelbis, Chief Executive Officer

TJ Goodpasture, Director of Development & Operations

Denell Jackson, Development Associate

ADVOCACY

Joey Park, Legislative Program Coordinator

MAGAZINE CORPS

Sean Hoffmann, Managing Editor

Publication Printers Corp., Printing, Denver, CO

Texas Wildlife Association

6644 FM 1102

New Braunfels, TX 78132

(210) 826-2904

FAX (210) 826-4933

(800) 839-9453 (TEX-WILD) www.texas-wildlife.org

Texas Wildlife Extra

NOVEMBER

November 1

White-tailed deer general, wild turkey, quail and goose season opener, statewide.

November 6

Tex-I-Que night with Brandon Hurtado and Hank Shaw, 5-7 p.m., Sitka Gear Dallas, 4438 McKinney Ave. #200, Dallas, 75205. https:// secure.qgiv.com/for/twengeve/event/texiquebash/

November 13

Landowner Workshop: Diversifying Land Use in the Trans-Pecos, 9 a.m.-3:30 p.m., Morgan University Center, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, 79832. https://secure. qgiv.com/for/landownerworkshops/event/ alternativelandusealpine2025/

NOVEMBER

November 15

Texas A&M Tailgate Party with Capital Farm Credit, 3 hours prior to kickoff, Creamery & Premiere Lawn, Space P8, College Station, 77840.

FOR INFORMATION ON HUNTING SEASONS, call the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department at (800) 792-1112, consult the 2025-2026 Texas Parks and Wildlife Outdoor Annual, or visit the TPWD website at: https://tpwd.texas.gov/

TWA MEMBER PHOTO CONTEST

EMAIL US YOUR BEST PHOTOS, TWA! We’ll accept them from current members through Dec. 31, 2025 and publish the best ones in upcoming issues to Texas Wildlife Extra. One entry per member per category, must be a current TWA member when photo is entered. Categories are landscape, wildlife, humor and game camera. Also, an open youth division for photographers who are 17 and under. Photos must be taken in Texas! Email your high resolution, unedited and unenhanced picture to TWA@texas-wildlife.org

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

TWA LETTER TO THE EDITOR POLICY: Texas Wildlife Association members are encouraged to provide feedback about issues and topics. The CEO and editor will review letters (maximum 400 words) for possible publication. Email letters to

Land, Water & Wildlife on the Ballot in November

ARTICLE BY ANDREW EARL, TWA DIRECTOR OF CONSERVATION

PHOTO BY PAUL K. STAFFORD

Standing at the polls on November 4, Texans will weigh 17 amendments to the Texas Constitution. Each of these were approved by no less than two-thirds of the Texas House & Senate and subsequently signed by the Governor. However, ultimate veto power lies with the voter.

In total, TWA’s legislative team has identified five items that advance the organization’s mission of keeping Texas wild. We hope you’ll consider supporting them while at the voting booth.

PROP 4

ANNUALLY DEDICATES $1 BILLION IN SALES TAX REVENUES TO THE TEXAS WATER FUND FOR DEVELOPMENT AND MAINTENANCE OF WATER SUPPLY & CONVEYANCE INFRASTRUCTURE

Paired with worsening drought conditions, residential and industrial growth are widening Texas’ water deficit.

The 2022 State Water Plan projects that over the next half century water demand will increase by roughly 10%, and available supply will decline by nearly twice that.

Prop 4 sets in motion a 20-year, $20 billion investment in water supply and conservation projects ranging from desalination, water storage and reuse to municipal water and wastewater improvements. Leveraged with private, local and federal investment, this represents a downpayment on a water-secure future for future generations of Texans.

PROP 5 CREATES A PROPERTY TAX EXEMPTION FOR ANIMAL FEED HELD FOR RETAIL SALE

Broadly speaking, animal feed in Texas is not subject to sales tax. However, feed intended for sale is taxed as property under current law, leaving feed stores with a hefty bill that is ultimately passed along to consumers.

In eliminating the property tax on animal feed being sold, Prop 5 would relieve this burden and help ensure animal agriculture and wildlife management operations have access to affordably priced feed as other prices continue to rise.

PROP 8

PROHIBITS IMPOSITION OF A STATE INHERITANCE TAX, ANY ADDITIONAL TAX ON THE TRANSFERENCE OF AN ESTATE/INHERITANCE/ETC.

Texas is at the outset of the greatest generational land transfer in our history. Consequently, intact tracts of working lands are being fractured and sold at record rates.

The federal estate or “death” tax adds fuel to the fire, disproportionately confronting land-rich, cash-poor heirs with the impossible decision to liquidate property assets to cover inheritance tax.

While not changing the federal tax, Prop 8 prohibits the imposition of an estate tax at the state level. Its passage would be a win for family farms, ranches, and everyday businesses throughout the state.

PROP 9

INCREASES THE TAX EXEMPTION FOR INCOMEPRODUCING PERSONAL PROPERTY TO $125,000

Like everything else, the price of tractors, trailers, irrigation, fencing and all other necessities of an agricultural operation has increased in recent years. Slim profit margins

have gotten slimmer, and any relief to the cost of doing business is welcome.

Prop 9 affords up to $125,000 of income-producing property to be exempt from ad valorum taxes. In turn, helping rightsize operational costs and encouraging reinvestment into one’s business.

PROP 17

EXEMPTS BORDER-RELATED INFRASTRUCTURE FROM THE TAXABLE VALUE OF A PROPERTY IN

BORDER COUNTIES

South Texas landowners shoulder an outsized burden in protecting our southern border, often working alongside law enforcement to quell the trafficking of drugs and migrants into the United States.

Prop 17 would ensure that border-related infrastructure (border wall, roads, cattle fencing, radio towers, etc.) placed on private property in assistance to law enforcement will not increase their property tax burden.

Voters are encouraged to get acquainted with each of the ballot measures up for consideration. To check your voter registration and confirm your polling place, visit www. votetexas.gov

Let’s Talk Turkey

Let’s Turkey

Get into the holiday spirit with this FREE, TEKS-aligned youth Distance Learning program as we discuss Wild Turkey anatomy, adaptations, and habitat as well as the various “calls” or vocalizations that turkeys make to communicate. We will also discuss life cycle and diet.

Get into spirit with this FREE, Distance Learning as we discuss adaptations, the or that to communicate. discuss cycle and

Aerial capture of a tractor and roller chopper managing Triadica sebifera trees and Rosa bracteata in an East Texas rangleand. Monitoring with a drone was performed by the ranch manager to assess the success or failure of roller chopping.

When Research and Practicality Converge Drones in Rangelands and Wildlife Habitat

ARTICLE & PHOTOS BY SILVERIO AVILA, BRI AND TEXAS A&M AGRILIFE EXTENSION

For ranchers, range practitioners, and natural resource researchers, time and money are always in short supply. Drones offer a new way to cover more ground, gather reliable information, and make quicker, more informed management decisions. When most people think of drones, they might picture them being used for recreation, law enforcement, military operations, or even package deliveries. But drones, also called Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), have become an important tool for studying and managing rangelands. From monitoring grazing distribution, checking water availability or evaluating brush treatments, these “eyes in the sky” are becoming practical, everyday tools to support rangeland and wildlife habitat stewardship.

Traditionally, rangeland monitoring research relied on ground-based methods: walking or riding pastures, measuring plants, and recording observations by hand. Later, satellites and airplanes allowed scientists to see

Aerial footage of a planned drone flight over a pasture in the Trans-Pecos. The objectives of this flight were to map and assess the current conditions, and to later assess the effects of herbicide application on invasive brush species.

Quantum systems Trinity Pro fixed wing vertical take off and landing (VTOL) drone. With this drone and payload (a camera), we are able to fly and map up to 2,000 acres in six hours.

Advances

in drone imagery collection have also advanced the kinds of research questions we can ask about habitat.

larger landscapes and measure changes in vegetation, land cover, and wildlife habitat. These images are helpful, but their resolution is limited. Imagine a giant quilt covering a field, where each square is a pixel. Widely available satellite platforms may capture images with pixels as large as two basketball courts (9,680 sq ft) or as small as a kingsized bed (43 sq ft) in a single pixel. With satellites you can capture the “big picture,” but you’ll miss the finer details. Drones, on the other hand, allow us to zoom in much closer. Flying below the legal altitude limit of 400 feet, they can capture images with a pixel resolution as fine as half an inch, about the size of a blueberry. This gives researchers the ability to see and monitor habitat changes in far greater detail than ever before.

Advances in drone imagery collection have also advanced the kinds of research questions we can ask about habitat. Drones let us look at vegetation more precisely and objectively, detecting how grasses and other plants respond to different management practices. For example, drones can measure how vegetation responds to livestock under different grazing systems; monitor the success or failure of brush management projects; evaluate fine-scale habitat preferences of grassland birds and upland gamebirds; track patterns of soil erosion; monitor forage production; and even assess vegetation structure for small mammals. With the addition of thermal sensors or specialized cameras, drones have even been used worldwide to estimate populations of large mammals in areas that are otherwise difficult to access.

In my own dissertation research, I used drones to explore how cattle grazing could be managed to improve nesting habitat for bobwhite quail in South Texas. By mapping and evaluating the 3D structure of vegetation (including brush, grasses, and forbs) between grazed and ungrazed sites, we found that appropriate grazing could help maintain grass heights around 12 inches, creating the preferred nesting conditions for bobwhites. This work highlights how drones can bridge scientific research and real-world management to benefit both livestock and wildlife.

range practitioners. In general, drones are most useful for reaching areas that are inaccessible or time-consuming to visit in person. Ranchers have used drones to monitor water levels in tanks, troughs, creeks, and lakes. They can search for, monitor, and count livestock; track management practices such as seeding, prescribed burning, brush control, or grazing distribution; detect and manage invasive species like feral hogs; monitor wildlife populations and health; and even train cattle to move into working pens. In short, drones are becoming versatile everyday tools that help ranchers and landowners save time, reduce labor, and keep a closer eye on the land they depend on.

Still, there are rules and challenges when it comes to flying drones. Operators must follow Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations, which are designed to protect public safety, manned aircraft, and drone pilots themselves. For example, anyone using drones for research or financial purposes must obtain a remote pilot license, fly below 400 feet, keep the drone within visual line of sight, and avoid restricted areas such as critical infrastructure, Department of Defense facilities, or crowded public spaces, and must always give way to manned aircraft. Weather also plays a role. Rain, high winds, and limited access to land can all affect flight operations. In Texas, anyone using drones to survey or count wildlife, including exotic species, must also obtain an Aerial Wildlife Management Permit (AWM) from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. These requirements create a safer work environment but can also limit when, where, and how drones can be used for monitoring or research.

Ultimately, drones provide ranchers and landowners with sharper eyes in the sky, helping them manage their operations more efficiently while also caring for the rangelands and wildlife they steward. What once seemed like futuristic technology is now within reach, offering practical ways to improve management and decisionmaking. Just as research has shown how drones can track soil erosion, evaluate brush management, or even guide grazing to improve quail nesting habitat, these same tools are becoming accessible for everyday use. By blending new technologies with on-the-ground practices, drones are helping to ensure healthier rangelands, stronger operations, and better wildlife habitat across Texas.

Of course, analyzing and interpreting drone data takes training, but how does it really apply to the real and everyday life of a rancher or landowner? Today, there are many commercially available drones that are relatively inexpensive and offer multiple uses for ranchers and CENTER

Why Feral Pig Management Is Essential for New Landowners

ARTICLE BY BRITTANY WEGNER AND JAY LONG

Texas faces a threat that is adaptable, pervasive, and alarmingly expensive: the feral pig (Sus scrofa), known variously as wild hogs, wild boars, or razorbacks. This invasive exotic species has populations estimated in the millions, and the damage they inflict can be severe. A new publication, “Managing Feral Pigs on Small Acreage Properties and Metropolitan Areas,” underscores the urgent necessity of modernized feral pig management strategies, especially as Texas rapidly urbanizes.

The importance of control cannot be overstated when considering the sheer scale of the harm. In 2024 alone, agricultural losses in Texas exceeded a staggering $670 million due to feral pig activity. Furthermore, landowners across the state are currently spending over $130 million annually just on control costs. Beyond the financial destruction, feral pigs are known to cause water quality impacts, compete with native animals and livestock, and pose a serious disease threat to humans, livestock, and wildlife. Their ecological impact is visibly devastating, marked by rooting, the upturning of soil used to find subterranean food, which causes massive damage across pastures, rangelands, and forests, slowing the ability of these disturbed areas to recover. Additionally, their wallowing behavior loosens soil, leading to increased sedimentation and impairment of water quality and aquatic life.

A CHANGING LANDSCAPE DEMANDS NEW APPROACHES

While landowners in rural areas have dealt with these resilient animals for decades, the current challenge is amplified by Texas’s unprecedented population boom. Texas is experiencing rapid metropolitan growth, from 19 million to 29 million people in 20 years, with a projected growth to over 40 million by 2050. Over 86 percent of this growth has occurred in just 25 counties, according to Texas Land Trends data, leading to land ownership fragmentation and pushing metropolitan areas into formerly rural working lands.

This shifting landscape means that feral pig encounters and incursions into developed areas are on the rise. Landowners on small-acreage properties (less than 100 acres) and those residing in metropolitan areas face unique hurdles. For example, city codes, county ordinances, or Homeowners Associations (HOAs) often restrict the discharge of firearms or the setting of traps.

TAILORING MANAGEMENT TO RESTRICTED SPACES

Given these legal and physical constraints, management plans must be adapted. Fortunately, the state classifies feral pigs as “exotic livestock,” not as wildlife, meaning there is generally no hunting season or bag limit, and on private property, no hunting license is required. This regulatory framework allows for flexibility, but urban restrictions still necessitate careful choices among control methods:

• Trapping is a proven and effective method suitable for nearly all landowners. Options include animal-activated, human-activated, and continuous traps. Neighbors can collectively purchase and utilize an advanced smart trap across a neighborhood to manage populations and reduce the cost burden. Furthermore, commercial companies often offer trapping services and handle the removal and extermination of feral pigs where firearm use is prohibited.

• Fencing, though costly, is more feasible on small acreage compared to large ranches. While exclusion fences are expensive (up to $13,251 per mile), electric fencing offers a less permanent, psychological barrier at a fraction of the cost ($1,243 per mile).

• Toxicants offer a non-firearm alternative, gaining traction. Kaput®, the only legal toxicant in Texas, was legalized in February 2024. While highly compelling for areas restricting firearms, its use requires an applicator’s license through the Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA) and careful communication with neighbors, as poisoned pigs may die on adjacent properties.

THE PATH FORWARD: EDUCATION AND COLLABORATION

Feral pig management will only succeed if wildlife professionals, local officials, and landowners commit to working together.

Landowners, especially new and beginning landowners (those with less than 10 years of experience), have multiple resources available, including County Extension Agents (CEAs), Extension Specialists, and the Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute (NRI), which has developed dozens of resources specifically to assist with managing feral pigs. However, greater systemic change is necessary. City and county officials must examine existing rules and regulations to allow for better management alternatives on acreage under their restrictions. Ultimately, neighbors joining together, whether to implement management across larger areas or to share the financial burden of hiring professional services, will likely be the best way forward to reduce the destructive tide of this invasive species. Without aggressive and tailored action, the biological success of the feral pig will continue to compromise the economy and environment of the rapidly evolving Texas landscape.

In the Season of the Painted Leaves

ARTICLE BY LARRY WEISHUHN

“That red and black plaid shirt you’re wearing, really? You trying to look like a flaming sumac bush?” chided my friend. “You look like a red fireplug! Haven’t many of those out here on the ranch!” I smiled, nodded, and tried to remind him research had demonstrated deer did not see red as we do; they perceive it as a neutral gray. While he had heard me, I doubt he had actually listened, because he kept pointing at the latest designer camo he was wearing.

We live in a dynamic world and have come a long way when it comes to how we dress when hunting. I can remember years ago as a young wildlife biologist making fun of “hunters” who showed up in camp donning the latest camo patterns.

Times change as did my opinion. I came to understand there is value in camo in breaking up the human form and blending with one’s background. Those were some of the reasons we developed Bushlan Camo years ago, primarily designed by Steve Warner, with a little help from Bobby Parker and me. Bushlan was the first open area camo on the market that truly broke up the human form.

I wear camo, but have not abandoned what hunters wore before Treebark, Realtree and Mossy Oak became the uniform of hunters.

Years later, sitting around a late November campfire telling tales, I was again asked about the red and black plaid shirt I was wearing. “A bit off the subject, a few years back I was scheduled to be a guest on a popular outdoor television

PHOTO BY PAUL E. STAFFORD

show. The host requested that I wear traditional Texas camo. The next morning, I arrived wearing a silver belly western felt hat, a white shirt complimented by a red neckerchief, under a brown brush-popper jacket and starched blue-jeans worn inside tall western boots,” I said.

Upon seeing me, the laughing show host quipped, “You can’t kill a deer wearing that!” I smiled and explained that many thousands of deer had been taken by Texas hunters who had hunted in that same outfit. “Well, if you insist!”

Later that day after rattling in more than 20 bucks I shot an impressive 10-point whose antlers were twice the size of the bucks taken by the show’s deer expert “star.”

Most of today’s camo clothing is indeed worth wearing. In addition to offering patterns that effectively break up the human form, materials are extremely quiet and quite comfortable. I frequently wear camo when hunting and even

Above: November is prime time to rattle in a buck across much of Texas.

Right: This picture serves as a comparison of how whitetail deer, which are colorblind, supposedly see red and black plaids.

PHOTO COURTESY OF LARRY WEISHUHN OUTDOORS

PHOTO COURTESY OF LARRY WEISHUHN OUTDOORS

in public, but I never go to a hunting camp without my red and black plaid shirts.

To me, red and black plaid shirts, along with the latest Realtree, Mossy Oak, Kryptek and other camo, are the official uniforms of serious hunters. I wear all of it with pride, be it November or any other time of the year.

While MLD and archery hunting seasons have been open in Texas since September and October, November has long been the traditional opening of our white-tailed deer season. As a youngster, that meant November 16, long the traditional opening day to whitetail hunting season across our great state. Over time, opening day was changed to early November to allow more people to hunt.

Regardless of the date, Texas’ whitetail opener has always been a revered day to me, one I have now looked forward to for over 70 years. It continues to be a truly mystical and magical moment.

I plan to spend the season opener near Nocona, not far south of the Red River, hunting with Luke Clayton and Jeff Rice. We co-host our weekly “A Sportsman’s Life” digital television series on CarbonTV.com and YouTube channel. I will be with them the night before opening day, another truly magical time. After the Sunday morning hunt I will head east of Dallas to hunt the following week with Edgar and David Cotton on their property not far from the Trinity River. We have been working on their management program for a little over three years and it has made some great advances in both

quantity and quality. Their low-fenced property is one of my favorite places on Earth. I love hunting their big woods and the challenge such habitat creates and provides. One never knows what deer might show. It could be a young forkhorn, a massively antlered mature buck, or even a doe.

The first week of November is one of my favorite times to hunt northeastern Texas. Namely because that is when bucks there come to rattling.

Last year on the Cotton property I lured in several bucks to the delight of Edgar and David, as well as our mutual friend, Rick Lambert, whose daughter happens to be an entertainer of great renown. I rattled and had bucks walk within mere feet rather than yards of where I had them positioned. Two of the bucks I rattled in last year—should they respond this year--will be taking a ride back to camp with us in our side-by-side.

From there I’ll be headed to a lease that borders the Red River northwest of Fort Worth. The week before Thanksgiving is generally prime rattling time in this area. I plan on rattling a buck across the Red River from Oklahoma to Texas.

All that said, don’t try calling me during November. My message will state, “I’m probably out hunting”

I suspect November is special to you regardless of whether you wear the latest designer camo or traditional red or green plaid. Thankfully the “season of the painted leaves” is upon us. Enjoy and make memories!

Get Your Holida y Gifts Here!

Nothing says Mer r y Christmas quite like a limited edition TWA ha t. Get ‘em before they’re gone, your choice, $30! Click Yellow and Brown to place your order--we’ll mail them to your door.

Deer, Decoys and Dummies

ARTICLE BY JON BRAUCHLE

BY

PHOTO

RYAN JOHNSON

Picture yourself in the driver’s seat of a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department game warden patrol vehicle. You, the game warden, are sitting back in the brush just off a desolate road in the wee hours of the morning. As your head bobs in a battle to stay awake, you catch the first flitter of distant headlights methodically moving towards you. Bolting upright, you grab your binoculars, step out into the cold night air, and climb up onto the toolbox of your patrol truck, all the while hoping the 10-point buck you saw grazing in the bar ditch as you pulled in behind the gate of your hidey-place is still there.

Standing on that toolbox, you watch and wait. Then, as the headlights swing, and the vehicle stops about 200 yards away…POP! You jump down, get into your truck, and race towards the dummy-locked gate on the roadside. Of course, you’re running dark with no lights whatsoever. When you pull onto the road, you see taillights in the distance, so you speed up and concentrate on keeping your eyes right and staying in the roadway. You’re driving way faster than you should with your lights off, but that’s just what you have to do if you plan on catching anyone. When you get close, you turn the kill switches back on and hit the red and blues. Maybe the suspect vehicle stops and maybe it doesn’t.

Indeed, from that point on, it’s like that box of chocolates Forrest’s mom talked about—you never know what you’re going to get. Maybe it’s just a bunch of good ol’ boys who saw a nice buck and just couldn’t help themselves, or maybe it’s some methed-up thug who’ll do just about anything to keep from going back to prison. Every law enforcement officer knows the feeling and the stress of approaching the unknown.

For many game wardens, catching someone in the act of shooting a deer off the road at night is the ultimate adrenaline rush...

For many game wardens, catching someone in the act of shooting a deer off the road at night is the ultimate adrenaline rush and the currency by which they count coup when they gather around a campfire, under a bridge at the county line, or at a table in the local café. In fact, back in the day, whenever a warden caught someone shooting a deer at night, they would get on their patrol radio and broadcast to every warden within a 100-mile radius that they were “10-95 with the meat,” meaning that they had caught someone with an illegally taken deer and were taking them to jail. Nowadays, wardens use a text thread to extol their achievements—usually with a picture to boot.

It has been a time-honored tradition, and like everything else in our lives, it’s constantly evolving. At some point along the way, some game warden somewhere figured they

When you’re a decoy deer in South Texas, your job is to take bullets to help get road hunters off the road. Even if it means taking a bullet to your antlers.

PHOTO BY RYAN JOHNSON

PHOTO BY RYAN JOHNSON

A South Texas daytime set. The need for realism is compounded when dummies are used during daylight hours.

could make the whole process easier by making a full-body mount of a dead deer, putting it out on the side of the road, and waiting for the fun to begin. It’s not as easy as it sounds, but God bless whoever that game warden was, because the stories that have accumulated over the years of some folks’ determination to kill a decoy deer have added some high entertainment value to wildlife conservation lore.

Retired game wardens Neal McCarn and Garland Burney have certainly done their part to add to that lore. In the mid-to-late 1990s, Neal and Garland were kind of the mad scientists of deer decoy innovation in South Texas. Though decoys had already been used for years, getting the funds to have one made and put into use wasn’t always in the district budget. So, Neal, who was stationed in Mathis (San Patricio County), and Garland, who was stationed in George West (Live Oak County), pooled their personal funds together and made their own.

Garland had some taxidermy experience. In fact, he’d been somewhat of an innovator in dummy deer design years before teaming up with Neal. He and Game Warden James Connally, a master taxidermist, used a life-sized deer archery target as the basic form to apply a hide and some antlers and made a decoy that was convincing enough to get shot a few times. Garland and James were winging it, but it worked.

When Neal arrived on the scene, things kicked up a notch. Neal and Garland ordered a full-body form that they got a deal on because it was unusually large for a white-tailed deer. The hide they had wouldn’t cover the belly, but that really didn’t matter. They fitted it together as best they could, screwed on some antlers, and gave it the name “Bullwinkle.”

Bullwinkle, one of the first South Texas decoy deer, was pieced together by game wardens Neal McCarn and Garland Burney. Here he is, on the job.

PHOTO BY NEAL MCCARN

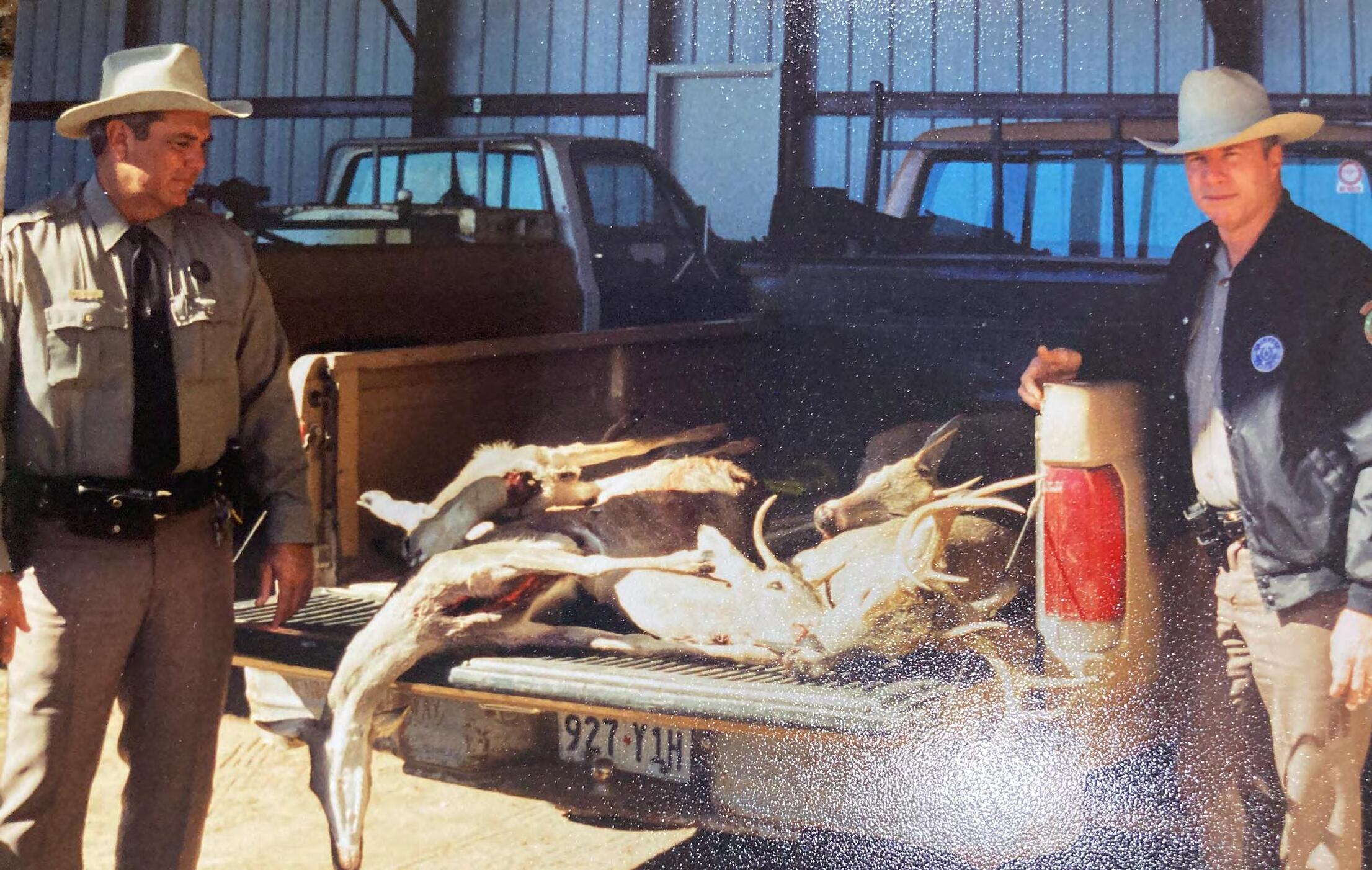

Texas game wardens Neal McCarn and Garland Burney with a truckload of ill-begotten venison that was illegally harvested.

PHOTO BY NEAL MCCARN

Close up pictures of the reflector eyes used in Neal and Garland’s nighttime sets.

A pair of reflector eyes, engineered by wardens McCarn and Burney, that were used to add realism to their nighttime sets.

PHOTO BY NEAL MCCARN

PHOTO BY NEAL MCCARN

PHOTO BY NEAL MCCARN

...and of course, it’s not really fair to the poacher to put a big ol’ Boone and Crockett set of antlers on a decoy.

Bullwinkle was a nice 10-pointer, but not too nice. Deer decoys, or dummies, vary according to the antler size of the deer in the area they are used, and of course, it’s not really fair to the poacher to put a big ol’ Boone and Crockett set of antlers on a decoy. Anyway, Bullwinkle worked well and was shot many times, but Neal and Garland, like all mad scientists do, kept tinkering.

When they received their official Texas Parks and Wildlife issued decoy, complete with detachable plastic antlers and various and sundry remote-controlled parts, they used it in a dual-deer setup where Bullwinkle was the buck and the unnamed TPWD deer was the doe. The wardens even experimented with reflectors they got from the Texas Department of Transportation to create a realistic eye reflection at night. They eventually came up with a setup that used small white reflectors wrapped in green cellophane recessed into PVC pipe that they painted black. These reflectors were then placed onto rebar stakes and set off to the side of the decoys just enough – maybe six to eight feet away - to convincingly reflect off the headlights of any vehicles that passed by.

After the first Bullwinkle was retired, Neal and Garland kept manufacturing new versions as needed. They even branched out with a couple of wild hog decoys. But on those, instead of using a stinky hog hide to cover it, they used some black, furry-looking artificial material that looked pretty good. Unfortunately, nobody ever took a shot at their hog decoys.

On a typical decoy night, Neal and Garland would set up around 10 p.m. and then pick everything up right before daylight. It made for long nights, but they had some interesting encounters. One night, a guy took a shot at Bullwinkle, and when they stopped him, Neal asked, “What were you shooting at?” The man said, “You know, I shot one of those ‘statue

Another South Texas daytime set.

PHOTO BY RYAN JOHNSON

PHOTO BY NEAL MCCARN

A Texas Game Warden cadet transporting a decoy deer.

deers’ I’ve been reading about in the newspaper.” Then the man said, “You know what, sir? Those things really work!”

On another night, another man got out of his vehicle with a .22 and started shooting at Bullwinkle as he walked towards him. Neal and Garland got to the guy while he was still shooting and announced themselves, “State game wardens – STOP shooting!” But the man ignored them and kept on until he ran out of bullets. When the wardens finally got to the visibly perplexed guy, he said, “You know, I shot him about 5 or 6 times, and he just wouldn’t go down!”

Then again, there was a night when Neal and Garland were joined by Game Warden Steve Woodmansee in December 2019 for a night of babysitting Bullwinkle. It was around 1 a.m. when a truck stopped. A shot rang out. After a pause, the truck sped off. Neal and Steve were on them in no time and stayed in pursuit for several miles until the driver of the truck finally gave up. The vehicle was occupied by three individuals who were headed home to Freer from a wedding in Corpus Christi. Still in their wedding attire, the bride and groom were in the back seat, and the best man/Bullwinkle shooter was in the front.

Yep, Neal and Garland had a lot of fun dealing with dummies shooting dummies over the years, but they are both happily retired now and out of the biz. But don’t you worry, there are still guys like Neal and Garland out there, tinkering. The possibility of running into a Bullwinkle or Bucky on a desolate road on a cold winter’s night is still very real. Just don’t be a dummy, and it’s no big deal.

A South Texas daytime set.

PHOTO BY RYAN JOHNSON

Block Creek on the Laurels Ranch.

Proposition 4 Can Help Texas Water Infrastructure Keep Pace With Rapid Growth

ARTICLE & PHOTO BY DAVID LANGFORD

The following op-ed was published in the San Antonio ExpressNews on October 16, 2025. David Langford served as CEO of Texas Wildlife Association from 1990-2002 prior to retiring.

Since 1887, when my great-grandfather founded Hillingdon Ranch in the Texas Hill Country, our family’s way of life has depended on the flow of the spring-fed creeks that run through our land.

For nearly a century, the main creeks flowed year-round, nourishing livestock, supporting native vegetation and helping to recharge aquifers that serve Texans near and far. But what once sustained us is no longer guaranteed.

These days, instead of flowing steadily, much of our surface water stands in stagnant pools. Even after a good rain, creek beds can stay dry. While this scarcity threatens our ability to run a working ranch, the implications go far beyond our fence line.

I’ve spent my life working to protect Texas’ natural resources. As a founding member of the Texas Wildlife Association — now representing thousands of landowners across 35 million acres — I’ve seen the quiet, extraordinary work rural Texans put into caring for their land. But even the best conservation efforts can’t succeed without a statewide strategy that treats water as a cornerstone of our future.

What’s happening in the Texas Hill Country is a warning sign for the entire state.

As a rural landowner, I’ve seen firsthand the strain on our water system. The demands brought by explosive population growth, aging infrastructure and unchecked development are converging in ways we can no longer afford to ignore.

This is why I’m urging my fellow Texans to vote yes on Proposition 4 this November.

Proposition 4 represents the largest investment in water infrastructure in Texas history, and it would give Texas the tools to invest more wisely in infrastructure, conservation and long-term planning that can keep pace with our growth.

It’s a once-in-a-generation opportunity to fund meaningful action, not just for ranchers and farmers but for every Texan who turns on a tap, irrigates a field or depends on a healthy environment.

At Hillingdon Ranch, our extended family raises Angus cattle, Angora goats and fine wool sheep, rotating them across our pastures to protect the land and preserve vegetative diversity.

This helps guard our thin Hill Country soils by enabling better rainfall capture that slows runoff. Well-managed grasslands act like a sponge, filtering water as it percolates into the ground and recharges the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer, the groundwater source that sustains life across this region.

Without dependable water, we can’t raise livestock. And without livestock, we can’t produce the beef, wool and mohair that feed and clothe Americans — or generate the income needed to care for our families, support our community and steward this land.

This isn’t just a rural concern. Our state’s environmental and economic futures are more intertwined than ever.

Block Creek, which runs through the northern end of our ranch, eventually joins the Guadalupe River as a major tributary. That river flows south as a lifeline, supplying water for millions of Texans and providing critical habitat for the endangered whooping crane.

Proposition 4 recognizes this reality.

It takes a broader view, recognizing that rural and urban water challenges are part of the same story. Fixing the billions of gallons lost each year to leaking city pipes is part of the answer. So is supporting the landowners who protect the land those waters run through.

Water is not just a resource. From Hill Country creeks to city taps, from family ranches to booming metro areas, our prosperity depends on it. With Proposition 4, we can take an overdue step toward securing the future of this state for all of us.

TPWD Biologists Predict Favorable Season for Waterfowl Hunters

ARTICLE BY TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT

Abundant population numbers and above average rainfall during the summer months is a confidence booster for hunters preparing for the start of the new waterfowl hunting season.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) biologists indicated that teal, gadwall, wigeon, pintails, shovelers and redheads, key duck species for Texas hunters, are collectively plentiful and showed population increases this past summer.

“Texas hunters can anticipate another strong waterfowl season, though overall success will depend on local water availability and the timing of cold fronts,” said Kevin Kraai, TPWD Waterfowl Program Leader. “Hunters who scout actively and find fresh shallow water will have the best opportunities this season.”

Hunters will also benefit from the new three-bird daily bag limit for pintails. A recent analysis confirmed that pintails

PHOTO BY SEAN HOFFMANN

The National Weather Service

outlook calls for a developing La Niña this winter which usually means warmer and drier conditions are more likely.

are more numerous than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) May Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey detected. The new fall flight models also indicate the potential for a greater sustainable harvest compared to previous models.

On the weather front, the above average summer rainfall resulted in numerous reservoirs and stock ponds holding more water than last year. The increased water levels have expanded habit for migrating ducks, but hot and dry conditions during the month of September have begun to reduce shallow wetlands, playa lakes and other surface water. Hunters can expect birds to concentrate in areas where rainfall or active management has maintained fresh habitat.

On the coast, irrigation restrictions tied to low Highland Lake levels last year have resulted in fewer flooded rice fields this fall. Rice acreage across the state is slightly lower than last year and continues to trail the long-term averages. The upshot are habitats in coastal marshes and large reservoirs are in good condition. Most High Plains playas are also still holding water, but new rainfall is needed to prevent them from drying out.

The National Weather Service outlook calls for a developing La Niña this winter which usually means warmer and drier conditions are more likely. However, individual cold fronts will continue to drive waterfowl migrations into Texas and hunters should be prepared to take advantage of these weather events as they occur.

In addition to ducks, TPWD biologists denote that goose hunting prospects are strong due to a second year of improved productivity that could send more juvenile birds south. Those factors typically lead to better decoy response and higher harvest success for Texas hunters.

The special youth-only, veteran and active-duty military duck season, occurs Oct. 11-12 in the High Plains Mallard Management Unit. Closely followed by youth-only/activeduty military duck season Oct. 25-26 in the South Zone and Nov. 1-2 in the North Zone. Regular duck season in the High Plains Mallard Management Unit opens Oct. 18, Nov. 1 in the South Zone and Nov. 8 the North Zone.

More information regarding duck seasons and daily bag limits can be found in the Outdoor Annual

Light and dark goose season starts Nov. 1 in the East Zone and West Zone. More information regarding goose seasons and daily bag limits can be found in the Outdoor Annual.

Kraai reminds migratory bird hunters that they need to make sure they are Harvest Information Program (HIP)

certified and confirm the questions are answered correctly. HIP surveys allow biologists to get an accurate sample of hunters so the USFWS can deliver harvest surveys to a subsample of hunters during the hunting season.

Hunters should purchase their new 2025-26 Texas hunting license prior to hitting the field. In addition, waterfowl hunters will also need a migratory game bird endorsement, federal duck stamp and HIP certification. It’s also required by law that hunters have proof of their completion of a hunter education course.

The Duck Stamp Modernization Act of 2023 modified provisions of the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp, commonly referred to as the Duck Stamp, now allowing an individual to carry an electronic stamp (E-stamp) for the entire waterfowl hunting season. A physical Federal Duck Stamp will be mailed to each E-stamp purchaser after the hunting season between March 10 – June 30, 2026. Hunters can find waterfowl season dates, regulations, bag limits and more on this year’s Outdoor Annual. Hunters can also access digital copies of their licenses via the Outdoor Annual and Texas Hunt & Fish apps

Anyone hunting on Texas public hunting lands must purchase an Annual Public Hunting Permit. Texas has more than one million acres of land for public access. More information about these lands and locations can be found on the TPWD website. Hunters using public lands can complete their on-site registration via the Texas Hunt & Fish app

New World Screwworm Necessary Vigilance

ARTICLE BY SEAN HOFFMANN, TWA COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR

Texas’ one million-plus hunters taking to the field this fall are asked to proactively identify and report potential cases of New World screwworm (NWS), which have been confirmed in livestock 70 miles south of our border. In this particular case, the fly larvae were discovered in a cow at an inspection facility in Nuevo Leon. The cow had been transported from an active screwworm area in southern Mexico. The larvae were removed and killed, the cow was treated and sterile flies were released in the area. However, the possibility of NWS moving north is very real.

• Be vigilant for infestation on wildlife, livestock and pets. This includes open sores or wounds with maggots, animals shaking heads or exhibiting irritated demeanor and a foul, rotting flesh odor.

• Landowners, land managers and outfitters are encouraged to communicate NWS infestation characteristics and reporting information with lease hunters and guests.

• Closely review game camera photos and videos for sores or open wounds on animals.

• Examine harvested game for sign of NWS infestation.

• Commonly affected wildlife species include whitetailed deer, rabbits (cottontail and jackrabbits), small mammals and wild turkey. However, all warm-blooded animals can be infested.

• Suspected NWS wildlife infestation should be reported to Texas Parks & Wildlife Department at (512) 389-4505. For livestock, call the Texas Animal Health Commission at (800) 550-8242.

Screwworm infestations are weather dependent. They are possible year-round in temperate areas such as South Texas yet historically seasonal in areas to the north. Early detection is key and reporting is crucial to implement management and eradication efforts.

Keep tabs on the latest Texas NWS news at https:// screwwormtx.org/

New World Screwworm

WHAT ARE NEW WORLD SCREWWORMS?

New World screwworms (NWS) are parasitic flies (Cochliomyia hominivorax) that lay eggs in open wounds or mucous membranes such as the nostrils, eyes or mouths of live warm-blooded animals. These eggs hatch into a type of parasitic larvae (maggots) that only feeds on living tissue, while other species of fly larvae prefer dead or necrotic tissue. NWS larvae burrow or “screw” into living tissue with sharp mouth hooks, giving them a screw-like appearance. Infested wounds quickly become infected and, if left untreated, will kill the infested animals.

If you see LIVE animals with LIVE maggots, report to local biologists. Early detection is key. Do not delay if you suspect a NWS infestation. Reporting is crucial to the implementation of management actions and eradication of NWS.

COMMONLY AFFECTED WILDLIFE SPECIES

• White-tail deer

• Rabbits (jackrabbits, cottontails)

• Small mammals

• Turkey

Note: All warm-blooded animals can be infested

COMMON INFESTED AREAS

• Newborn animals’ umbilical stump/navel

• Mucous membranes — genitalia, eyes, nose, ears, mouth

• Damaged skin — cuts, scrapes, stings, tick bites, antler/velvet shedding

• Management-related — dehorning, ear tagging, castration, branding

INFESTATION MIGHT LOOK LIKE

• Open sores or wounds with maggots

• Animals shaking heads or irritated demeanor

• Foul rotted flesh odor

Screwworm infestations occur year-round in temperate regions such as South Texas but are generally seasonal (Spring through Fall) in other areas like the Panhandle and farther north.

USDA Shares New World Screwworm Response Playbook

Ensuring Preparedness and Coordination

Should NWS Spread to the United States

ARTICLE BY UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

The United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is announcing the availability of the New World Screwworm (NWS) Response Playbook. The playbook outlines key approaches, resources and tools to implement animal health response activities in the event of a U.S. detection of NWS.

“USDA continues to execute our five-pronged plan to keep NWS out of the United States,” said U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins.

“While we continue to aggressively protect the U.S. border and are working with Mexico to stop the pest from continuing to spread further north, we also have to ensure our domestic response plans are ready to activate if needed.”

The NWS Response Playbook outlines critical response strategies for federal, state, and local responders including how to:

• Effectively manage a coordinated response and communications with stakeholders and the public

• Reduce spread to non-infested animals and prevent NWS from establishing in new areas

• Manage NWS on infested premises

• Implement NWS surveillance and management strategies in wildlife

• Implement NWS fly surveillance and management strategies

• Maintain continuity of business

• Ensure information flow and management

• Identify and maintain resource requirements

APHIS incorporated initial input from state animal health officials, industry and veterinary organizations when developing the playbook. The activities outlined in the playbook will allow a flexible, science-based approach and data-driven decisions to allow responders to plan, act and adapt across all phases of an outbreak.

APHIS is posting the draft playbook to the NWS Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response website and will continue to gather feedback from states and industry to help ensure operational usability and alignment with field practices. This playbook, along with the accompanying preparedness materials, is a living, dynamic document. Feedback and suggestions can be provided to FAD.PReP.Comments@ usda.gov

Adult New World screwworm flies are rarely seen except when females are laying eggs on open wounds of warm-blooded animals.