QUEENS at WAR ALISON WEIR

ENGLAND’S MEDIEVAL QUEENS

ALISON WEIR

Alison Weir is one of Britain’s top-selling historians. She is the author of numerous works of history and historical fiction, specialising in the medieval and Tudor periods. Her bestselling history books include The Six Wives of Henry VIII, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Elizabeth of York and The Lost Tudor Princess. Her novels include Innocent Traitor, Katherine of Aragon: The True Queen and Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession. She is an Honorary Life Patron of Historic Royal Palaces and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. She lives and works in Surrey.

Also by Alison

Weir

Non-fiction

Britain’s Royal Families

The Six Wives of Henry VIII

Richard III and the Princes in the Tower

Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses

Children of England: The Heirs of King Henry VIII

Elizabeth the Queen

Eleanor of Aquitaine, By the Wrath of God, Queen of England

Henry VIII: King and Court

Mary, Queen of Scots and the Murder of Lord Darnley

Isabella, She-Wolf of France, Queen of England

Katherine Swynford: The Story of John of Gaunt and his Scandalous Duchess

The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn

Mary Boleyn: ‘The Great and Infamous Whore’

Elizabeth of York: The First Tudor Queen

The Lost Tudor Princess: The Life of Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox

Queens of the Conquest: England’s Medieval Queens 1066–1167

Queens of the Crusades: Eleanor of Aquitaine and her Successors 1154–1291

Queens of the Age of Chivalry: Five Consorts in Turbulent Times 1299–1409

As co-author

The Ring and the Crown: A History of Royal Weddings 1066–2011

A Tudor Christmas

Fiction

Innocent Traitor

The Lady Elizabeth

The Captive Queen

A Dangerous Inheritance

The Marriage Game

Katherine of Aragon: The True Queen

Anne Boleyn: A King’s Obsession

Anna of Kleve: Queen of Secrets

Katheryn Howard: The Tainted Queen

Katharine Parr: The Sixth Wife

In the Shadow of Queens: Tales from the Tudor Court

Elizabeth of York: The Last White Rose

Henry VIII: The Heart and the Crown

Mary I: Queen of Sorrows

The Cardinal: The Secret Life of Thomas Wolsey

Quick Reads

Traitors of the Tower

Queens at War

England’s Medieval Queens

1403–1485

Alison Weir

Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London s W 11 7b W penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published by Jonathan Cape in 2025

Copyright © Alison Weir 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Typeset in 11.5/13.5pt Bembo Book MT Pro by Six Red Marbles UK, Thetford, Norfolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 y H 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

H b isbn 9781910702130

TP b isbn 9781910702147

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

This book is dedicated, with all my love, to the cherished memory of my dear husband, Rankin Alexander Lorimer Weir (1948–2023)

PART FIVE: ANNE NEVILLE, QUEEN OF RICHARD III

List of Illustrations

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be happy to acknowledge them in future editions.

Church roof boss depicting Joan of Navarre. (St Andrews Church in Sampford Courtenay; © Lionel Wall, greatenglishchurches.co.uk)

Joan’s father, Charles II ‘the Bad’, King of Navarre. (© Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Joan of Navarre with her first husband, John IV, Duke of Brittany and their children. (© Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Manuscript. Garrett MS 40)

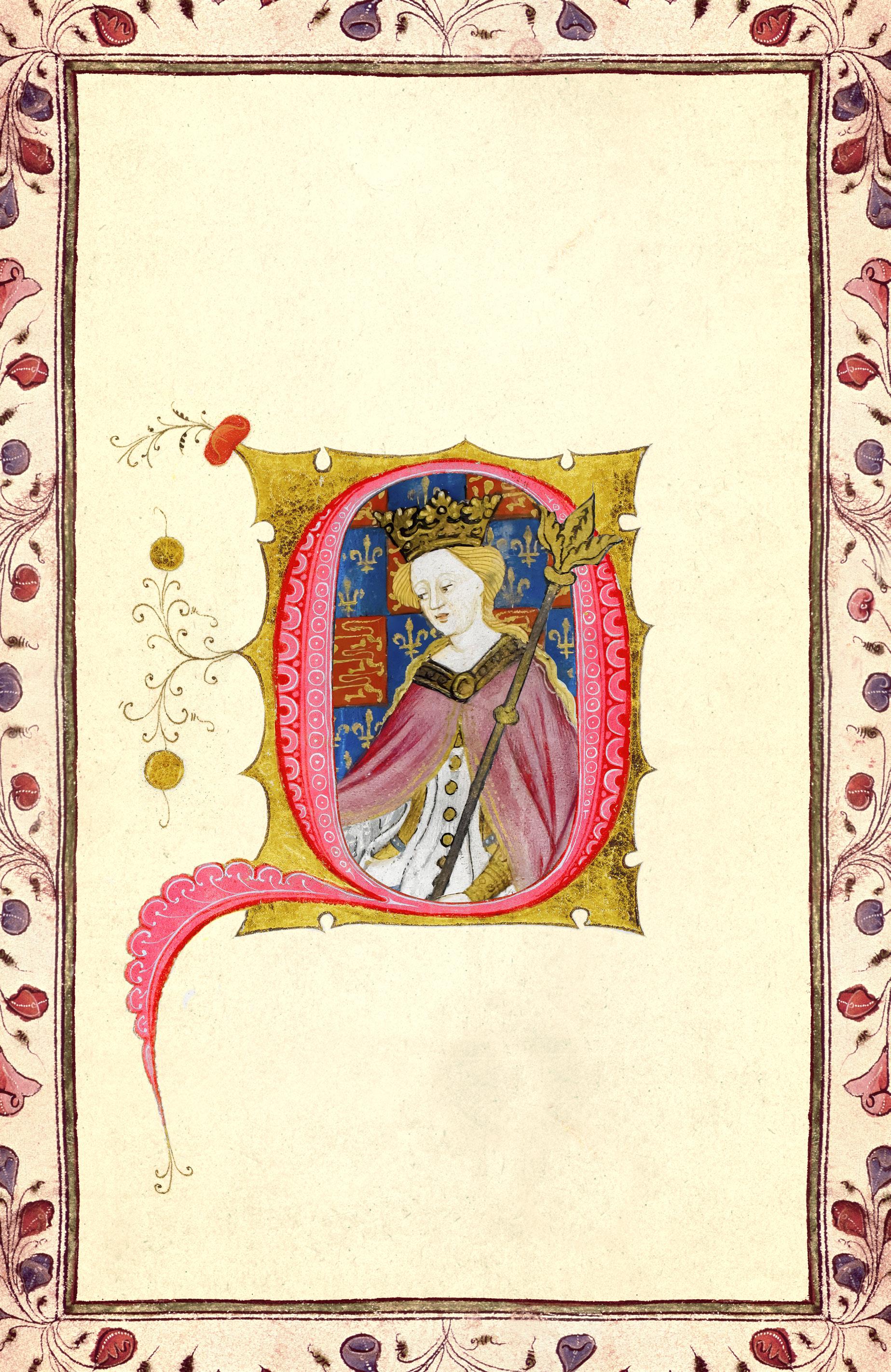

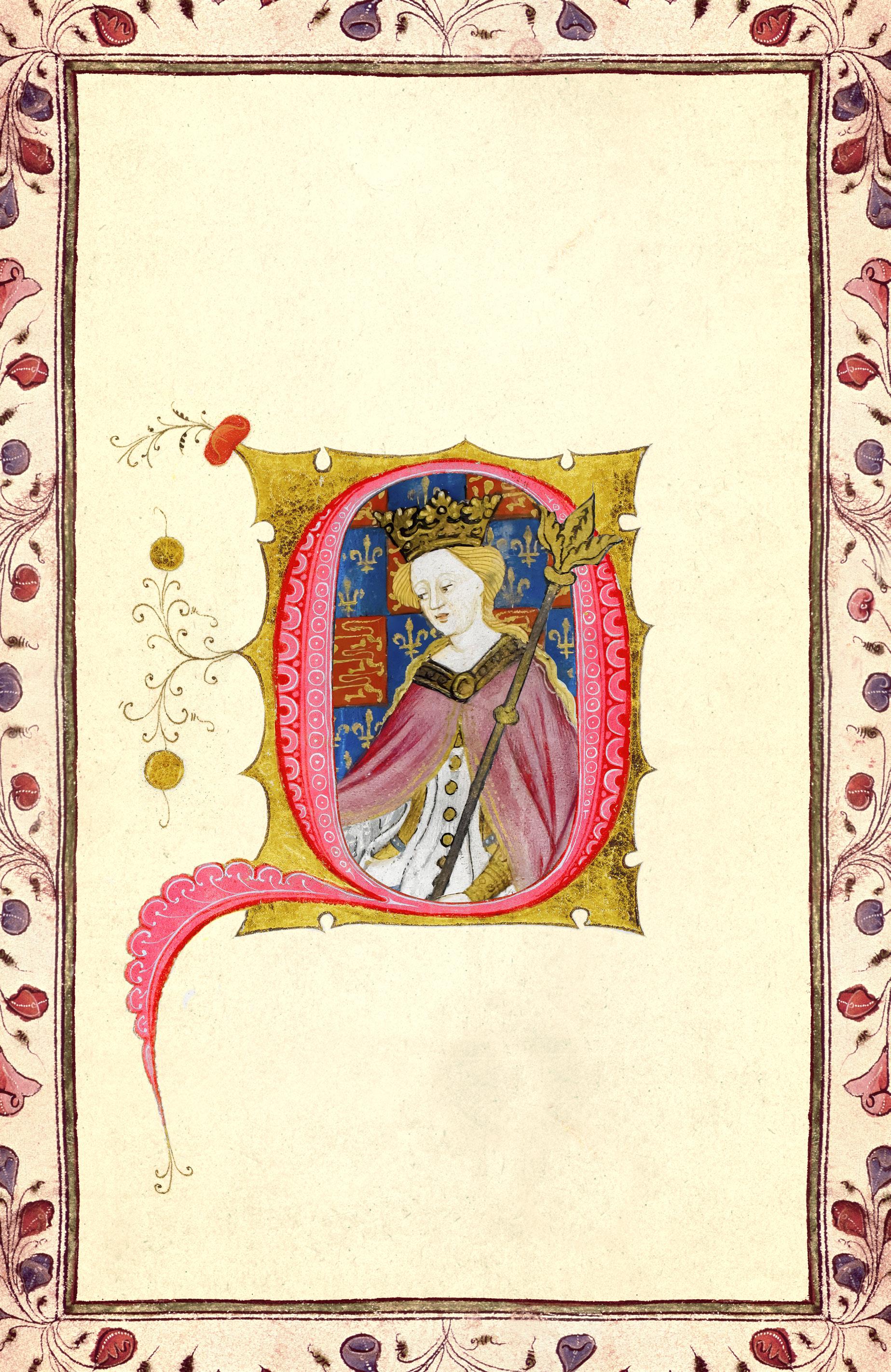

Historiated initial ‘H’(enry) of Henry IV, with a full foliate border, at the beginning of his Statutes. (Yates Thompson 48, folio 147; © British Library archive/Bridgeman Images)

An imaginary portrait of King Henry IV. (Anglesey Abbey, National Trust; © National Trust Photographic Library/Bridgeman Images)

The coronation of Joan of Navarre, wife of King Henry IV of England, 26 January 1403, c. 1483 (ink on vellum). (Pageant IV from Cotton Julius E. IV, art. 6, from the ‘Beauchamp Pageant’ © British Library archive/Bridgeman Images)

Pevensey Castle, where Joan was imprisoned for witchcraft. (© john/ Alamy Stock Photo)

Leeds Castle, owned by several medieval queens of England. (© Ian Dagnall/Alamy Stock Photo)

List

of Illustrations xi

Tomb of Henry IV and Joan of Navarre. (Canterbury Cathedral © Angelo Hornak/Alamy Stock Photo)

Tomb effigy of Charles VI , King of France. (Basilica of Saint-Denis, fifteenth century © Photo Josse/Bridgeman Images)

Tomb effigy of Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France. (Basilica of SaintDenis © Bridgeman Images)

Portrait of Henry V (oil on panel). (National Portrait Gallery © Bridgeman Images)

The marriage of King Henry V of England and Katherine of Valois. (British Library Royal MS . 20 E VI folio 9v © British Library archive/Bridgeman Images)

Katherine of Valois, Queen to Henry V, giving birth to Henry VI at Windsor. (© Smith Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Statue of King Henry V. (Part of the Kings Screen inside the historic York Minster in York, England, on 19 July 2017 © Chris Dorney/ Alamy Stock Photo)

Bermondsey Abbey, where Katherine of Valois died. (The History of London by Walter Besant, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1892 © The Library of Congress)

Katherine of Valois: funeral effigy. (Westminster Abbey © Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

The tomb of Katherine of Valois. (Westminster Abbey © Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

Portrait of King René of Anjou (1409–1480), also called René I of Naples or René of Sicily, 1475 (oil on canvas). (Detail of triptych, Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur, Aix-en-Provence © Photo Josse/Bridgeman Images)

Margaret of Anjou, medal by Pietro da Milano, 1463. (Victoria and Albert Museum © Jimlop collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

King Henry VI . (National Portrait Gallery © CBW /Alamy Stock Photo)

The ruins of Titchfield Abbey, Hampshire, where Henry VI married Margaret of Anjou. (© Kevin Allen/Alamy Stock Photo)

The marriage of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. (Illuminated manuscript entitled ‘Mariage d’Henri VI et de Marguerite d’Anjou c. 1484, Bibliotèque Nationale, Paris, MS . Français 5054, folio 126v © IanDagnall Computing/Alamy Stock Photo)

List of Illustrations

Margaret of Anjou, drawing of lost window in the church of the Cordeliers, Angers. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France as part of the collection of Roger de Gaignières, who assembled a large collection of drawings of monuments nationwide during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The drawings of the Gaignières collection were published in 1729–33 in Les Monuments de la Monarchie Françoise by Bernard de Montfaucon, Volume 3, Plate LXIII ; © Photo Vault/Alamy Stock Photo)

John Talbot, Early of Shrewsbury, presenting the Talbot Shrewsbury Book to Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. (Illustration from ‘Shrewsbury Talbot Book of Romances’, c.1445 (ink, colour and gold on vellum) British Library Royal MS . 15 E. VI , folio 2v © British Library archive/Bridgeman Images)

The prayer roll of Margaret of Anjou. (Bodleian Library, Jesus College, Oxford MS . 124 © Jesus College, Oxford)

The château of Amboise, where Margaret of Anjou was reconciled to Warwick, and Anne Neville married Edward of Lancaster. (Loire Valley, Touraine, France © Ian G Dagnall/Alamy Stock Photo)

Margaret of Anjou, from the Roll of the Fraternity of Our Lady, of the Skinners Company of London. (From Some Account of the Worshipful Company of Skinners of London, by James Foster Wadmore, 1902 © by kind permission of the Worshipful Company of Skinners)

The marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville. (Illuminated manuscript page from Volume 6 of the Anciennes chroniques d’Angleterre by Jean de Wavrin, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, MS . Français 85, folio 215 © The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Elizabeth Widville (c.1437–1492). (Portrait in oil on panel, Queens’ College, Cambridge © incamerastock/Alamy Stock Photo)

Edward IV. (© With the kind permission of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge)

Elizabeth Widville, from the guild book of the London Skinners’ Fraternity, of the Assumption of the Virgin. (Guildhall Library MS . 31692 © Bridgeman Images)

Frontispiece of the Luton Guild Book showing the Holy Trinity, the founders of the Guild, and Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville. (From the frontispiece of the Luton Guild Register, Wardown Park Museum © Courtesy of the Culture Trust)

List of Illustrations xiii

King Edward IV of England (1461–1483), and Queen Elizabeth Widville. (Royal Window, North-West Transept, Canterbury Cathedral © GRANGER – Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Anne Neville and her two husbands, Edward of Lancaster, Prince of Wales, and Richard III ; and Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales. (Cotton Julius E. IV, art. 6, folio 28, Descendants of Countess Anne of Warwick, from the ‘Beauchamp Pageant’, c.1483 (ink on vellum) © British Library archive/Bridgeman Images)

Anne Neville, Richard III and their son Edward of Middleham. (Section of the ‘Rous Rolls’, an illustrated armorial roll-chronicle by John Rous, British Library, Additional MS . 48976, folios 62–65 © World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Portrait of King Richard III (oil on panel. (National Portrait Gallery © Bridgeman Images)

King Henry VII (1457–1509). (Hardwick Hall © National Trust Images)

Elizabeth of York. (East window at Little Malvern Priory, Worcs, 1480s, depicting King Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville © G. P. Essex/ Alamy Stock Photo)

The tomb of Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville in St George’s Chapel, Windsor (© By permission of the Dean and Canons of Windsor)

Falkland

Dunfermline

Linlithgow

Edinburgh

SCOTLAND

Dumfries Lincluden

Kirkudbright

ANGLESEY

Pembroke

Penmynydd

Denbigh

Harlech

Dunstanburgh

Alnwick

Workworth

Hexham

Wark

Newcastle

Durham

Barnard Castle

Middleham

Sheriff Hutton

Towton

York

Wakefield Sandal

Doncaster

E N G L A N D

Chester

Sheen

Eccleshall Tutbury

Shrewsbury

WALES

Brecon

Carnarthen

Hereford

Gupshill

Abergavenny

Chepstow Raglan

Lincoln

Nottingham

Bosworth Leicester Groby

Kenilworth

Warwick Worcester

Tewkesbury

Berkhamsted Coventry

Wallingford

Bristol

Bath

Heytesbury

Reading

Southampton

Cerne

Exeter

Plymouth

Britain

Ravenspur

Stamford

Fotheringhay

Northampton

Stony Stratford

Walsingham

King’s Lynn

Norwich

Cambridge Bury St Edmunds

Hertford Ware St Albans

Pleshey

Barnet Blackheath Havering Eton Ewelme

London

Windsor

Bermondsey

Winchester Titchfield

Portsmouth

Dartmouth

Rochester

Eltham Greenwich

Leeds

Maidstone

Ightham

Pevensey

Sandwich

Canterbury Dover

France and the Low Countries

B R I T A I N B a y o f

Caen

B R I T T A N Y

Vannes

Rennes

Nantes

Boulogne

Harfleur

Honfleur

Rouen

Flushing

Bruges

Calais Saint-Omer

Lille

Agincourt

Saint-Polde-Ternoise

Picquigny

Paris

Senlis

Rheims

Koeur-la-Petite

L O R R A I N E

N O R M A N D Y A N J O U A N J O U

Angers Tours Amboise

Saumur

Bar Louppy-le-Château

Seine

Troyes

Dijon

Pont-aMousson `

Toul

Nancy

Dampierre

Q U I T A I N E

i s c a y

N A V A R R E

Pamplona

Toulouse S P A I N F R A N C E

Bordeaux

Castillon

Tarascon

Edward Prince of Wales 1330–76

Richard II 1367–1400

Roger Mortimer Earl of March d. 1398

Anne d. 1411

Lionel Duke of Clarence 1338–68

Philippa 1355–81

Blanche of Lancaster 1342–68

Mary de Bohun 1. Joan of Navarrez 2. 1368?–1437

Henry V 1387–1422

Richard Earl of Cambridge ex 1415

Richard Plantagenet Duke of York 1411–1460

Edward IV 1442–83

m.

m.

Cecily Neville 1415–95

Elizabeth Widville 1437–92

John Earl of Lincoln d.1487

Elizabeth of York 1466–1503

Arthur Prince of Wales 1486–1502

Henry IV 1367–1413

Katherine of Valois 1401–37

Henry VI 1421–71

Richard Neville Earl of Salisbury d. 1460

Richard Neville Earl of Warwick d. 1471

Elizabeth 1444–1503

m.

John de la Pole Duke of Su olk

Edmund Earl of Su olk ex 1513

Richard ‘Earl of Su olk’ d. 1525

Henry VII 1457–1509

m. Katherine of Aragon 1485–1536

Edward III 1312–77

John of Gaunt Duke of Lancaster 1340–99

Owen Tudor ex 1461

Margaret of Anjou 1429–82

Edmund Tudor Earl of Richmond 1430–56

Margaret 1446–1503

m.

Charles the Bold Duke of Burundy

Margaret 1473–1541

m.

Mary 1467–82

Cecily 1469–1507 m.1 John, Viscount Welles m.2 Thomas Kyme

Edward V 1470–83

Margaret b. & d. 1472

Margaret 1489–1541 (married

m. James IV King of Scots 1473–1513

m. 3

Katherine Swynford 1350–1403

John Beaufort Marquess of Somerset d. 1410

Edmund Duke of York 1341–1402

Joan Beaufort d. 1440

m. Ralph Neville Earl of Westmorland d. 1425

Thomas Duke of Gloucester 1355–97

John Beaufort Duke of Somerset d. 1444

Margaret Beaufort 1443–1509

m. 2 Sir Henry Sta ord d. 1471

m. 3 Thomas Stanley Earl of Derby d. 1504

George Duke of Clarence 1449–78

Sir Richard Pole d. 1505

m. Isabel Neville 1451–76

Richard III 1452–85

m. 2

Jasper Tudor Earl of Pembroke Duke of Bedford d. 1495

m. 21 m.

Katherine Widville

1 m. Henry Sta ord Duke of Buckingham ex 1483

Anne Neville 1456–85

m.1

Edward of Lancaster 1453–71

Edward Earl of Warwick 1475–99

Richard Duke of York 1473–83

Henry VIII 1491–1547 (married six times)

m. Anne Mowbray 1472–81

Elizabeth 1492–5 Mary 1496–1533

Edward of Middleham Prince of Wales d. 1484

Lord Thomas Howard Anne m. 1475–1513?

George Duke of Bedford 1477–9

m. 1. Louis XII, King of France 2. Charles Brandon Duke of Su olk

Katherine 1479–1527 m. William Courtenay Earl of Devon

Edmund Duke of Somerset 1499–1500

Bridget, nun at Dartford 1480–?

Katherine b. & d. 1503

Preface

On 13 October 1399, the coronation of Henry IV, first sovereign of the House of Lancaster, took place at Westminster. His accession heralded almost a century of dynastic conflict, for up to 1485 and beyond, as will be related in this book, the English crown was to be the object of feuds, wars and conspiracies – not because of a dearth of heirs, but because there were too many powerful magnates with a claim to the throne. During this period, might would largely prevail over right in determining who should be king. Alliances were made and broken, or shifted bewilderingly in the wake of events. Strength and success were what counted: an effective ruler was more likely to hold on to the throne and bring stable government, however dubious his title.

English queenship did not change significantly during this period; consorts were still expected to produce heirs, exercise charity and patronage, play a ceremonial role and be the very mirror of the Virgin Mary: virtuous, submissive, yet regal. Nevertheless, England’s queens would be caught up in the dynastic conflicts and wars. The fifteenth century was a turbulent age that witnessed the latter stages of the Hundred Years War between England and France and the English civil wars between the royal houses of Lancaster and York, known as the Wars of the Roses, which dragged on intermittently from 1455 to 1487.

Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, English kings had chosen brides from European royal and noble houses in the interests of forging dynastic connections and political alliances. But the fifteenth century was to witness a radical change in that respect, for in 1464, Edward IV married Elizabeth Widville for love, which scandalised his subjects because it brought no material benefits, while Richard III wed an heiress from the English nobility, although he did gain a great landed inheritance.

Each of the five queen consorts who lived in this period was involved in one way or another in the Hundred Years War or the Wars of the Roses. The marriage of Joan of Navarre to Henry IV was meant to give England an advantage against France; those of Katherine of Valois, to Henry V, and Margaret of Anjou, to Henry VI , were supposed to bring about a peace, while Margaret of Anjou, Elizabeth Widville and Anne Neville were all deeply involved in the Wars of the Roses. It was a perilous time for queens, and all, in one way or another, were overtaken by tragedy.

The sources for the period are rich and give more insights into the personal lives and personalities of these women than those written in earlier centuries. Yet good as the sources are, they lack the personal detail of those documenting, for example, the wives of Henry VIII , in the 1530s, so my approach to the book, as in earlier volumes, is to focus on what information we do have and infer what I can from that, which means that the narrative may not always be chronological.

Aside from Edward IV marrying for love, there is good evidence that the marriages of all the Lancastrian monarchs, Henry IV, Henry V and Henry VI , were love matches too, even if they were contracted for political reasons. We know too little about the marriage of Richard III and Anne Neville to draw many conclusions, yet there are pointers to its being the least successful of royal marriages in this period.

Her fierce loyalty to the weak Henry VI drove Margaret of Anjou to be fiercely proactive in the Lancastrian cause and to fight for her son’s rights, but she was criticised and slandered for her unfeminine assumption of leadership, and Edward IV thought her more a threat than any Lancastrian general, while Shakespeare later called her a ‘she-wolf’. Elizabeth Widville wielded considerable power as queen, but was ruthlessly deprived of any influence when Edward died. Foreign-born consorts were at a disadvantage from the outset because the insular English had long memories of extravagant queens who had brought no dowry or secured the aggrandisement of greedy kinsfolk; with the exception of Katherine of Valois and, perhaps, Anne Neville, none of these queens was very popular, and most suffered some disparagement of their reputations, creating a mythology that has sometimes endured for centuries.

I should like to acknowledge the fantastic support and creative input that I have received from my brilliant editor, Anthony Whittome, my commissioning editors, Bea Hemming and Susanna Porter, and the amazing publishing teams at Jonathan Cape in the UK and Ballantine

Preface

in the USA . Huge thanks also go to Lucy Chaudhuri of Cape, for managing the publication process, Mary Chamberlain, for the copy-edit, Louise Navarro-Cann for sourcing the many images I asked for, and Jessica Spivey for publicity.

I wish also to express my warmest thanks and appreciation to my agents, Julian Alexander, Ben Clark, Abby Koons and Sarah Stamp. You’re the best, and I feel very privileged as an author to have such a great team behind me.

Lastly, but never least, I am indebted to my family and friends for all their love and support, especially my daughter Kate and her husband Jason, my cousin Christine, who has been like a sister to me, my uncle and aunt, John and Joanna Marston, my brother-in-law Kenneth, and my cousins David and Peter and their families, and Wendy and Brian. You’re all stars!

Introduction

In 1340, Henry IV ’s grandfather, Edward III , had laid claim to the crown of France, asserting that he was the true heir by virtue of descent from his mother, the sister of the last king of the House of Capet. The French held that the Salic law prevented a woman from succeeding to their throne, or transmitting a claim, in consequence of which the House of Valois was now ruling France.

Edward’s defiant quartering of the lilies of France with the leopards of England on his coat of arms had led to what later became known as the Hundred Years War. When he died in 1377, all that remained of the territories he had wrested from the French were the duchy of Aquitaine, five towns and the land around Calais known as the Pale.

Edward had provided for his sons by marrying them to English heiresses and creating them dukes. Their descendants would one day challenge each other for the throne itself. The eldest son, Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales (known from the sixteenth century as the ‘Black Prince’), had predeceased his father, and it was his son, Richard II , who succeeded Edward III , but remained childless. Edward’s second son, Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, had sired one daughter, Philippa, who married Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March. The House of York would one day claim the throne on the basis of its descent from Edward III through Philippa of Clarence.

Edward III ’s third surviving son was John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, whose marriage to Blanche, the heiress of Lancaster, made him a fabulously wealthy magnate with vast estates throughout England. Blanche was the mother of his heir, Henry of Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV. After her death in 1368, Lancaster wed Constance of Castile, in an unsuccessful attempt to claim the crown of Castile. When she died in 1394, he

married his mistress, Katherine Swynford, who had borne him four bastards, all surnamed Beaufort after a lordship he had once owned in France. The Beauforts would dominate English politics for the next century. From the eldest, John Beaufort, were descended the Beaufort dukes of Somerset. The only daughter, Joan, was married to the powerful Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, and would become matriarch of the prolific Neville family.

Edward III ’s fourth surviving son was Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, the founder of the male line of the royal House of York. He fathered two sons: Edward, his heir, who was killed in 1415 in the Battle of Agincourt, and Richard, Earl of Cambridge, who married Anne Mortimer, the great-granddaughter of Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence.

Edward III ’s youngest son was Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, whose descendants became the dukes of Buckingham. Gloucester was Henry of Bolingbroke’s brother-in-law. At thirteen, Henry had been married to eleven-year-old Mary de Bohun (pronounced Boon), younger daughter and co-heiress of Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Hereford, Essex and Northampton. The Bohuns were of ancient Norman stock, one of England’s great noble families. Eleanor de Bohun, Mary’s elder sister and co-heiress, was married to Gloucester.

Not being content with his share of the Bohun inheritance, Gloucester was determined to lay his hands on the rest, and put relentless pressure on Mary to give it up and take the habit of a Poor Clare nun. But, in July 1380, with the connivance of Lancaster, Mary’s aunt kidnapped her while Gloucester was campaigning in France and spirited her away to Arundel Castle in Sussex. That month, Lancaster obtained from Richard II a grant of Mary’s marriage, thus thwarting his brother’s ambitions. A furious Gloucester ‘never after loved the Duke as he had hitherto done’.1 By March 1381, Henry and Mary had been married with great ceremony and rejoicing at Rochford Hall in Essex.

Afterwards, Mary remained there with her mother, with Lancaster paying for her maintenance; it had been agreed that the consummation of the marriage should be delayed until Mary reached fourteen on 15 February 1382. But the young couple breached this rule and in April 1382, Mary bore a son who lived for four days.

The young couple were finally given their own establishment and began cohabiting in November 1385. On 16 September 1386, at Monmouth Castle, Mary gave birth to the future Henry V. Thomas followed in 1387, John in 1389, Humphrey in 1390 and Blanche in 1392. The marriage appears to have been happy, with the couple sharing a love of chess, dogs, parrots and music. Mary, who came from a cultivated family,

played the harp and cithar, Henry the recorder. His faithfulness to her was commented on throughout the courts of Europe, and he was assiduous in sending gifts of food to satisfy her cravings during pregnancy.

Mary de Bohun did not survive the birth of her last child, Philippa, in 1394, and Henry sincerely mourned her death.

By then, a deadly enmity had flared between Henry and Richard II Alienated by the King’s high-handed misgovernment and his unpopular favourites, Henry had united in opposition with Gloucester and the earls of Arundel, Nottingham and Warwick. Because they were appealing to Richard to restore good government, they called themselves the ‘Lords Appellant’. In the ‘Merciless’ Parliament of 1388, they had purged the court of favourites and curbed the King’s autonomy. Two years later, Richard had wrested the reins of government from the Lords Appellant, and for the next eight years ruled England himself.

In 1396 he signed a truce with France and sealed it by marrying Isabella, the six-year-old daughter of Charles VI . Both peace and marriage were unpopular with his subjects, who would have preferred to see England’s claim to France reasserted, but Richard’s resources could not support another war.

In the face of vociferous opposition from his magnates, he was anxious to retain Lancaster’s loyalty and in 1396, he persuaded Pope Boniface XI to issue a bull confirming the Duke’s marriage to Katherine Swynford and legitimising the Beauforts. In 1397, Richard issued letters patent declaring the Beauforts legitimate under English law, which was afterwards confirmed by Act of Parliament.

That year, Richard showed himself determined to be an absolute monarch and rule without Parliament. He ordered the murder of his uncle, Gloucester, then moved against the other former Lords Appellant. When Henry and Nottingham fell out and accused each other of treason, the King ordered that the issue should be settled according to trial by combat, an ancient European custom whereby God was invited to intervene by granting a victory to the righteous party. But, just as the combat was about to begin, the King threw down his baton, halted the proceedings and sentenced both men to exile. Henry sought refuge in Paris.

Grieved by the exile of his son, Lancaster died in 1399. In Paris, Henry learned that Richard had sequestered the vast estates he should have inherited, and immediately returned to England, burning with a desire for vengeance. In July, he landed in Yorkshire, claiming that he had come to safeguard his inheritance and reform the government. There was a huge tide of popular feeling against Richard, especially in

London, where Henry was well liked. As he progressed south, nobles and commons flocked to his banner and he quickly gathered a large army, meeting little resistance. Richard was unable to rouse much support and many of his followers deserted him. At Conwy Castle, he surrendered to a deputation sent by Henry.

In September, Henry entered London to a tumultuous reception, while Richard, a prisoner in his train, was greeted with jeers, pelted from the rooftops with rubbish, and confined in the Tower of London. Henry now appointed a commission to consider who should be king. Many magnates were unhappy at the prospect of his seizing the throne, yet there were reasons enough for setting Richard aside. Henry, it seemed, was the only realistic alternative, for the legitimate heir, the Earl of March, was just a child.

Henry used every means in his power to force Richard to abdicate. Knowing that his own claim was precarious, the official line was to be that Richard’s misgovernment justified his deposition. Coercion and threats were used to persuade the King to co-operate and on 29 September 1399, he signed an instrument of abdication, in which he requested that he be succeeded by his cousin of Bolingbroke, who took the crown as Henry IV.

Some believed that Henry IV was a usurper who had gained a crown by deposing England’s lawful, anointed sovereign. The legitimacy of his title would remain a sensitive issue. His claim to rule by right of blood was a bald lie, for he had falsely asserted that his ancestor, Edmund Crouchback, Earl of Lancaster, had been the eldest son of Henry III , not the second son, and had been overlooked because of bodily deformity in favour of his ‘younger’ brother, Edward I. This deceived no one. Henry’s title really derived from his already being de facto king of England, having taken the throne by force. Yet, his birth, wealth, abilities and four strapping sons had made him the only viable candidate for the throne, the only man capable of restoring law, order and firm government.

No one had supported the superior claim of the legitimate heir, the Earl of March. Indeed, Archbishop Arundel took it upon himself to preach a sermon stating that England would from now on be ruled by men, not boys. As a result, the claim of the rightful heirs to the throne would remain dormant for sixty years.

Henry IV soon discovered that it was less easy to hold on to the crown than to usurp it. He had promised to provide good and just government

but the first decade of his reign would be troubled by conspiracies to overthrow him. He did his best to demonstrate that he was ruling with the advice and support of Parliament, sanctioning laws giving it unprecedented powers, establishing the privileges of free debate, and the immunity of members from arrest, leaving them free to criticise him as they pleased.

Yet the charisma that had attracted people to his cause, and the heady burst of popularity that had greeted his accession, were not so much in evidence after it, especially when people realised that the evils of Richard’s misgovernment could not be put right overnight. Henry might be an industrious man of business and ruthless when it came to dealing with rebels; he might have enjoyed the support of the Church, having authorised the passing of the statute De Heretico Comburendo, which condemned heretics to be burned to death. But the distrust of various magnates and a permanent shortage of money, exacerbated by the cost of putting down rebellions, were problems he could not surmount; consequently, his reign was a time of continual tension.

In France, the government of the mad Charles VI steadfastly refused to recognise Henry as king, denouncing him as a traitor to his lawful sovereign and referring to him, when addressing English envoys, as ‘the lord who sent you’. This would lead, in 1401, to the resumption of the Hundred Years War. The Valois court was at that time riven by opposing factions led by Charles VI ’s powerful relatives, the dukes of Burgundy and Orléans, whose followers were called Burgundians and Armagnacs. Henry became adept at playing these two nobles off against each other, but little military action was seen in France during his reign.

Parliament had condemned the former King Richard to perpetual imprisonment in a secret place from which no one could rescue him, and he was taken north to Pontefract Castle. The order for his murder was probably sent there in January 1400. The chronicler Adam of Usk stated that death came miserably to the former King as ‘he lay in chains in the castle of Pontefract, tormented with starving fare’.

By the spring of 1400, Henry IV may have felt more secure on his throne, but he was shortly to be disabused of that comfortable illusion. Impersonations of his dead rival were not all that he had to contend with. Shakespeare called the first decade of his reign ‘a scrambling and unquiet time’ because it witnessed a series of rebellions. In Wales, Owen Glendower, a descendant of the princes of Powys, inspired the Welsh people to revolt against English rule. Then hostilities erupted between the King and the Percy family, who were a great power in the North. This was the situation when Henry decided to take a second wife.

Part One

Joan of Navarre, Queen of Henry IV

‘Mutual affection and delight’

The story of fifteenth-century English queenship began in February 1400, when Joan of Navarre, Dowager Duchess of Brittany, was residing at De La Motte, her château at Vannes, and received a proposal of marriage from Henry IV

Henry had then been a widower for six years. In Paris, he had considered marrying Lucia, daughter of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, or Marie, Countess of Eu, a niece of Charles VI , but Richard II had scuppered those plans. Now, as king, Henry needed a great marriage alliance with political advantages, and he saw Joan as the ideal choice. He was hoping for an ally against Charles VI . Brittany seemed ideal, as it enjoyed virtual independence from France, while owing fealty to its King, and dynastic blood ties between Brittany and England were close.

A new alliance between England and Brittany would be advantageous in terms of enlisting Breton support against France and encircling that kingdom with Henry’s allies, while England could profit from the Breton salt trade. Doubtless the King also had his eye on Joan’s rich Breton dower, the financial settlement with which a man endowed his wife on marriage (as opposed to the dowry she brought to him). He believed that her illustrious dynastic connections would benefit him; being a usurper, he was in need of powerful allies, and may have felt that marriage with Joan would equate to recognition of his right to rule and his acceptance in European royal circles.

It is possible that they had met in the autumn of 1396 at a royal wedding at Calais, or in England in 1398, or in Brittany in 1399, when Henry was duke of Lancaster. At thirty-three, he would surely have made an impression on Joan, being a powerfully built man of five foot ten, always richly and elegantly garbed. He was handsome, with a curled moustache, good teeth, deep russet hair and the short, forked beard fashionable in that period, as was seen when his tomb was opened in 1832. He was well educated, and proficient in Latin, French and English, although, for preference, he spoke Norman French, the traditional language of the English court. A skilful jouster, he loved tournaments and

feats of arms, and his reputation as a knight was widespread. Devout and markedly orthodox in his religious views, he had been twice on crusade, first in 1390 with the German Order of Teutonic Knights against Lithuanian pagans in Poland, and then in 1392, to Jerusalem. He loved literature, poetry and music, and a consort of drummers, trumpeters and pipers accompanied him wherever he went, while he himself was a musician of note.

Joan might have detected that he was a man of great ability, energetic, tenacious, courageous and strong. He was popular and respected, having a charismatic personality, being humorous, courteous, eventempered, generous, reserved and dignified. People were impressed by his courtesy, chivalry and affability. He was conventional in outlook, staunch and devout. It may not have been apparent to Joan that he was also ambitious and restless, or that he could be a devious and calculating opportunist. But when the couple met, he was an exile, having been banished from the realm of England by Richard II . Attraction there may have been between the Dowager Duchess and her visitor, but his prospects were then uncertain.

The Infanta Joan of Navarre had already led a somewhat turbulent existence. She was the sixth of the seven children of Charles II ‘the Bad’, King of Navarre. She had been born around 1368–9, probably at Estella, where her mother, Jeanne of Valois, lived from 1368 to 1373. She was exceptionally well connected, being related to most of the ruling families of Europe. Queen Jeanne was the daughter of John II of France, and Joan’s grandmother, another Jeanne, who had died in 1349, had been the daughter of Louis X of France. Having been barred by the Salic law and the adultery of her mother from succeeding to the throne of France, the elder Jeanne had inherited only the small kingdom of Navarre, which bestrode the Pyrenees.

Joan was named for her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother, all reigning queens of Navarre. Her name is given variously in contemporary sources, but has been anglicised here to Joan. Her infancy coincided with an invasion of Navarre by the armies of Castile, and she was placed for safety with her cousin Jeanne de Beaumont in the monastery of Santa Clara at Estella, which had nurtured earlier Navarrese princesses and was now paid a florin a day for a teacher and a servant for the two girls. There, the young Joan grew up and received an elementary education befitting her sex and her rank.

Following the loss of a score of castles, King Charles had to make peace with the invaders. After her mother’s death in childbirth in 1373,

Joan returned to his court, where she and her sisters were looked after by their aunt, Agnes, Countess of Foix, and saw their father frequently. They kept dogs and birds, ate a lot of fish, meat and poultry, made offerings on feast days, enjoyed court entertainments, and were provided with new clothes and shoes as they outgrew their old ones. They were given writing materials, indicating that they were literate. They would have enjoyed visiting the King’s small menagerie at Pamplona, where he kept lions, a camel, an ostrich, monkeys and parrots.

Because he was descended from Louis X of France, the turbulent Charles the Bad considered he had a claim to the French throne, which inevitably set him at odds with the Valois kings, especially Charles V, who once claimed that his disreputable brother-in-law had used necromancy to attempt to murder him. Joan’s childhood was overshadowed by her father’s dangerous intrigues and the upheavals they caused, and in 1381, she and her brothers were placed in the castle of Breteuil in Normandy for their protection. But it wasn’t secure and, on the orders of the regents of France, their maternal uncles, the dukes of Berri and Burgundy, the children were captured by French soldiers and carried off to Paris, where they were held for five years as hostages for their father’s good behaviour. The regents looked after them well and they received honourable treatment until their father managed to procure their release in 1386.

In 1384, Berri and Burgundy had proposed a marriage between Joan, then about sixteen, and the widowed, childless John IV de Montfort, Duke of Brittany, who was a French vassal, but an autonomous ruler. He was forty-six, an irascible man with a long moustache who had strong links to England. He had been brought up at the court of Edward III , whose daughter Mary had been his first wife; his second was Joan Holland, half-sister to Richard II . Edward III had made John a Knight of the Garter, and he was then also earl of Richmond, his family having held the title since the thirteenth century. But there had been a coolness between John IV and Richard II since Brittany had made peace with France in 1381 and Richard had confiscated the earldom. John, however, was now inclining towards England again. Charles the Bad was eager to secure him as a husband for Joan because he needed allies against France, and Duke John was eager for the match because he desperately wanted an heir; if he failed to produce one, his duchy would pass to his dynastic rival and enemy, the Count of Penthièvre. Marriage to Joan might also bring about a rapprochement with her French relatives. John was so eager for the match that in November 1384, he entered into negotiations immediately after his second wife’s death.

Joan’s marriage was agreed upon in May 1386. Viscount and Viscountess de Rohan, her beloved paternal aunt and uncle, were instrumental in arranging the alliance, for which Joan was enduringly grateful. Years later, as a widow, she rewarded her aunt Jeanne with a pension of £1,000 (£936,380) ‘in remuneration of the good pains and diligence she used to procure our marriage with our very dear and beloved lord, whom God assoil, of which marriage it has pleased our Lord and Saviour that we should continue a noble line, to the great profit of the county of Bretagne and our other children, sons and daughters. And for this, it was the will and pleasure of our said very dear and beloved lord, if he had had a longer life, to have bestowed many gifts and benefits on our said aunt, to aid her in her sustenance and provision.’1 On 27 July, the marriage contract was signed at Pamplona. Under its terms, Charles the Bad promised an extravagant dowry of 120,000 gold livres (£73.5 million) in French coinage and 6,000 livres (£3.7 million) from rents due to him.

We have no record of Joan’s meeting with her future husband. She and John were married on 11 September 1386 in the chapel at Saillé, on the salt marches near Guérande, Brittany. A host of Breton nobles attended the ceremony. The wedding party then travelled to Nantes for the feasts and pageants that had been arranged in their honour.

Joan’s dowry was never paid in full. Her father, who had made superhuman efforts to raise just under 47,000 livres (£28.8 million) of it, was suffering a decline in health that caused paralysis in all his limbs, but seems not to have affected his propensity to make trouble. In December, from his sickbed at Pamplona, he dropped hints to Duke John that a powerful Breton warlord, Oliver de Clisson, who supported the House of Penthièvre, had conceived a criminal passion for Joan. John and the one-eyed Clisson had once been friends, but had recently fallen out after Clisson intrigued with the Duke’s enemies and made an unsuccessful attempt to invade England on behalf of the French. Fearing that Clisson was plotting to abduct Joan, John wrote a friendly letter inviting him to attend a parliament at Vannes, where the young Duchess would be holding court at her château of De La Motte.

Meanwhile, King Charles’s condition had deteriorated to the point where his doctor had felt bound to wrap him from neck to foot in linen cloth impregnated with brandy or aqua vitae. According to one source, the woman ordered to sew up the cloth knotted it at the top, but rather than cutting off the thread with scissors, she used a candle, which ignited the alcohol. Another contemporary, the chronicler Jean Froissart, stated that a brazier of coals was used to warm the bed and, ‘by the

pleasure of God, or of the devil, the fire caught to his sheets, and from that to his person, swathed as it was in matter highly inflammable, and the King was horribly burnt as far as his navel’. The fire was doused, but Charles lingered in agony for a fortnight before dying on 1 January 1387.

Some had seen his decay as a punishment for his dissolute life, but there was shock throughout Christendom at his horrific death. The Bretons, however, rejoiced that the world had been delivered from such a monster.

John’s suspicions of Clisson did not extend to Joan. Despite his being known as the most irascible prince in Europe, he and his bride were delighted with each other. In February 1387, ‘in token of their mutual affection and delight in their union, the Duke and Duchess exchanged gifts of gold, sapphires, pearls and other costly gems, with horses, falcons and various sorts of wines’.2 A child was quickly conceived, the first of nine children. In 1395, John would enlarge Joan’s dower handsomely.

Despite having had to fight off rival claimants to his duchy, John IV had brought peace to Brittany and made it prosperous. He favoured friendship with England over an alliance with France, which sometimes brought him into conflict with Charles VI and the French duke, who had been hoping for his support, not to mention powerful opponents like Oliver de Clisson. In consequence, Joan would soon suffer further upheavals in her life.

Unaware of the insinuations made by Charles the Bad, Oliver de Clisson arrived at Vannes and was warmly welcomed by the Duke and the heavily pregnant Duchess. John invited him to view the massive new château of l’Hermine, which he had rebuilt for Joan on the city’s ramparts. But when Clisson arrived there on 27 June, he was suddenly arrested, imprisoned in chains and condemned to death. The Duke ordered that he be sewn into a sack and thrown in the river.

When his gaoler refused to comply, John relented and kept Clisson in prison, demanding a large ransom. The following year, the French King bought his freedom and Clisson fled to France, where he very loudly complained about the way he had been treated, and was later made Constable of France. The French believed that Joan had been behind a plot to get rid of him, yet there is no evidence to support that. In fact, she and the Duke were clearly unnerved by the affair because they shut themselves up at De La Motte, fearing a retaliatory ambush, and it was some time before they again ventured beyond Vannes.

Joan saw her marriage as a noble alliance and believed it to be the will of God that ‘we should continue a noble line, to the great profit of

the county of Bretagne’.3 Her eldest child, another Joan, was born on 12 August 1387 at Nantes, after the furore over Clisson had quietened. Isabella arrived in October 1388, in the midst of more political turmoil, but both she and her sister died in December that year. By then, on the advice of his council, John had reluctantly made peace with France and gone there to pay homage to Charles VI .

When Joan was nearing her time with her third pregnancy, she took up residence at the château of l’Hermine. Her palatial apartments were on the second floor of the central donjon, and included a bedchamber and two rooms for steam-bathing; a staircase ascended to John IV ’s suite above. The Breton council, concerned about potential threats from France or Oliver de Clisson, warned the Duke: ‘Your lady is now far advanced in her pregnancy and you should pay attention that she be not alarmed.’ But all went well and Joan gave birth to her first son on 24 December 1389, which ‘made the Duke very happy’.4 The baby was initially going to be called Peter, after Joan’s brother, but the Duke had him christened John after himself. In tribute to Joan, he created the Order of the Hermine in her honour and made her its first member.

In 1390, relations with France again became strained. Towards the end of 1391, Joan’s kinsman, John, Duke of Berri, visited Nantes at the behest of Charles VI to broker a peace between Duke John and his enemies, Oliver de Clisson and the House of Penthièvre. Attended by ‘a large cortège of illustrious ladies’, Joan ‘graciously welcomed her beloved uncle and gave him the kiss of peace’, telling him how much she welcomed his coming.5 She plied him with rich gifts and laid on entertainments. But Berri’s tactless, heavy-handed approach to the peace talks offended Duke John, who was about to pull out and hold the French envoys hostage when Joan’s brother Peter, Count of Mortmain, arrived at Nantes. Alarmed, he sought out the Duchess, who was again pregnant, and found her being washed by her attendants. She agreed to dissuade the Duke, being inclined – as King Charles’s cousin – to favour the French. ‘Setting aside her modesty,’ she ‘took her children in her arms, in spite of the encumbrance at the end of her term’, and, wearing her nightgown, with her hair loose, she ‘went that night, unexpected, to the room of the Duke, followed only by a few of her ladies. She went down on her knees before [him] and, in a voice broken by sobs, she begged him to take pity on her and her children and earnestly pleaded that he renounce his plans so as not to alienate himself by an act of felony towards his King and the princes of the blood, who might, after his death, protect his children.’

‘Lady,’ he replied, ‘how you come by your information I know not,

but rather than be the cause of such distress to you, I will revoke my order.’6

Joan persuaded him to meet the ambassadors the next day in Nantes Cathedral, and then to accompany them peaceably to Tours. The chronicler monk of Saint-Denis ‘heard this [tale] from the ambassadors themselves, who related to him the peril from which they escaped through the prudence of Joan’. At Tours, in February 1392, Charles VI received the Duke royally and offered the Duchess his two-year-old daughter Jeanne as a bride for her son John. Sadly, Jeanne died that year, but the King substituted his newborn infant of the same name in her place.

Joan’s daughter Marie was born on 18 February 1391 at Nantes. Marguerite followed in 1392, Arthur on 24 August 1393 at Château de Suscinio at Sarzeau, Gilles in 1394, Richard in 1395 at Château de Clisson, and Blanche in 1397. The Duchess’s frequent pregnancies and maternal responsibilities must have limited her influence at the Breton court, yet still she exercised a subtle agency, especially after she produced male heirs, which strengthened her position.

When Oliver de Clisson narrowly escaped assassination in France in June 1392, Duke John gave asylum to Peter de Craon, the man who had made the attempt. An angry Charles VI sent messengers to demand that he give him up. They were shocked to find Craon being treated as an honoured guest at Joan’s court at l’Hermine – as was Clisson, when he heard. Enraged, he incited a civil war in Brittany, and John, Joan and their children were again obliged to seek refuge at Vannes. Meanwhile, their jewels and plate were seized by their enemies. Urged on by Clisson, Charles VI himself marched on Brittany at the head of an army, but suffered the first attack of the madness that was to bedevil his life, and had to withdraw.

The rule of France was now entrusted to Joan’s uncle, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, who was friendly towards Brittany and broke the opposition to Duke John’s rule, obliging Clisson to renounce the office of Constable of France. At the plea of her cousin, Viscount de Rohan, who acted as her intermediary, Joan made efforts to win round those Breton nobles who had rebelled against the Duke. But, his heir being only four years old, John feared what might ensue if he was killed, and wrote to Clisson, offering peace terms. Clisson would only treat with him if he handed over his son as a hostage, but Joan protested, and it was some days before she could be persuaded to allow Rohan to take the child to Château Joscelin, where Clisson was under siege. To her great joy,

Clisson immediately sent her son back to her and agreed to make peace. Joan was praised by the Breton chroniclers for having brought it about through the good offices of Rohan. In 1393, she was further applauded when she prevailed on the Duke to raise the siege and extend concessionary terms to Clisson. The reconciliation, however, was only temporary.

In 1395, when Joan’s daughter Marie was three, her father offered her in marriage to Henry of Monmouth, son and heir of the newly widowed Henry of Bolingbroke. The castle of Brest was then in the possession of the English, but, ‘at the especial desire of the Duchess Joan’, it was ‘appointed for the solemnisation of the nuptials and the residence of the youthful pair. After the cession of this important town had been guaranteed by Richard II , who was against the Lancastrian marriage, the King of France contrived to break the proposed alliance by inducing the heir of Alençon to offer to marry the Princess with a smaller dower than the heir of Lancaster was to have received with her.’7 This strategy proved successful. In June 1396, Marie, now five, was betrothed to John of Perche, son of Peter, Duke of Alençon, at Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, Ille-et-Vilaine, near Fougères. The marriage took place in July. John succeeded his father as duke in 1404.

In March 1396, in the hope of restoring good relations and recovering the earldom of Richmond, of which Duke John still felt he had been unjustly deprived, Joan wrote to Richard II in the formal style then used in royal letters:

My most dear and redoubted lord,

I desire every day to be certified of your good estate, which God grant that it may ever be as good as your heart desires, and as I should wish it for myself. If it would please you to let me know of it, you would give me great rejoicings in my heart, for every time that I hear good news of you, I am most perfectly glad of heart. And if to know tidings from this side would give you pleasure, when this was written, my lord, I and our children were together in good health of our persons, thanks to our Lord, who, by His grace, ever grant you the same. I pray you, my dearest and most redoubted lord, that it would ever please you to have the affairs of my said lord well recommended, as well in reference to the deliverance of his lands as other things, which lands in your hands are the cause why he sends his people promptly towards you. So may it please you hereupon to provide him with your

gracious remedy, in such manner that he may enjoy his said lands peaceably, even as he and I have our perfect surety and trust in you more than in any other. And let me know your good pleasure, and I will accomplish it willingly and with a good heart, to my power. My dearest and most redoubted lord, I pray the Holy Spirit that He will have you in His holy keeping.

Written at Vannes, the 15th day of March, The Duchess of Brittany.8

That year, Joan and John travelled to Paris to see their eldest son John, Count of Montfort, married to Jeanne, the daughter of Charles VI . The wedding took place at the Hôtel de Saint-Pol, with the Archbishop of Rouen officiating. It was a splendid gathering of royalty, which included the King and Queen of France, the Queen of Sicily and Joan’s uncles, the dukes of Berri and Burgundy.

The Duke and Duchess travelled north to Saint-Omer, where they banqueted with a gathering of royalties who were on their way to Calais, where Richard II was to be married to Isabella of Valois. It was here that Joan probably met Henry of Bolingbroke for the first time. In November, John and Joan were among the congregation in the church of St Nicholas at Calais to witness the royal wedding.

Back in Vannes, on 15 February 1397, Joan wrote again to Richard II :

My very dear and most honourable lord and cousin,

Since I am desirous to hear of your good estate, which our Lord grant that it may ever be as good as your noble heart knows best how to desire, and indeed as I would wish it for myself, I pray you, my most dear and honoured lord and cousin, that it would please you very often to let me know the certainty of it, for the very great joy and gladness of my heart; for every time that I can hear good news of you, it rejoices my heart very greatly. And if, of your courtesy, you would hear the same from across here, thanks to you, at the writing of these presents, I and my children were together in good health of our persons, thanks to God, who grant you the same, as Johanna of Bavalen, who is going over to you, can tell you more fully, whom please it you to have recommended in the business on which she is going over.

This letter was misdated to 1400 by Mary Anne Wood, its Victorian editor, which has led many to suppose that it was sent to Henry IV, and

that Johanna of Bavalen was acting as a go-between in the brokering of a marriage between Joan and Henry. But it was sent on the same day, and expressed the same sentiments, as a letter from John IV to Richard II , and Johanna of Bavalen’s mission may have concerned the restitution of the earldom of Richmond. It has been suggested that she is to be identified with Joanna of Bavaria, Duchess of Austria, but there is no record of that lady visiting England in 1397, the year she bore her first child, so it is likely that Johanna was one of Joan’s ladies.

In April 1398, the Duke – and probably the Duchess – travelled to England to attend the annual feast of the Order of the Garter at Windsor. During this visit, Richard II restored the earldom of Richmond to John IV. This could have afforded Joan another opportunity to meet Henry of Bolingbroke.

Three contemporary sources – Froissart, Bouchart and Fernando de Ybarra – stated that in June 1399, just before his momentous invasion of England, the exiled Bolingbroke, who was staying in Paris, paid a brief visit to the court of Brittany at Nantes, where he was warmly welcomed by the Duke and the Duchess, to whom, according to Breton chroniclers, he was personally attracted from the first, for she was ‘a very beautiful princess’.9 Froissart states that John IV gave him arms and three warships and wished him well before he sailed away, while Ybarra claimed that Joan gave him a posy of forget-me-nots that inspired him to adopt his motto, ‘Souveignez’ or ‘Soverayne’ (‘Remember me’). But not three weeks elapsed between Henry leaving Paris and arriving at England on 30 June or 4 July (sources differ as to the date). Given that the distance from Paris to Nantes and then from Nantes to Boulogne, whence he sailed, was 810 miles, he would have had to ride a punishing forty miles a day to complete the journey; and Froissart was in error in stating that he landed at Plymouth, when he arrived at Ravenspur on the Yorkshire coast, so he may also have been wrong in claiming that Henry had visited Brittany. However, it is possible that Henry had done so earlier that year.

The autumn of 1399 saw Joan tending her husband in his final sickness. He died on 1 November. In a codicil to his will dated 26 October, he had confirmed Joan’s dower and ‘all his former gifts to his beloved companion’. He dictated it from his sickbed, in the absence of others and in the presence of the Duchess, and it was given under his seal in the castle tower near Nantes, about the hour of Vespers. He demonstrated his trust in Joan by appointing her and their son John, who now succeeded as John V, as chief executors. Because the new Duke was only

eleven, Joan was to rule as regent and have the entire care of him and her other children. She was present at her late husband’s funeral in Nantes Cathedral.

Peace was foremost on her list of priorities, and one of her first acts, in which she was aided by the clergy, was to stage a public reconciliation with Oliver de Clisson, Penthièvre and other rebel lords. This took place on 1 January 1400 at the château of Blein, where Clisson and his supporters all swore to obey Joan during her son’s minority. She also took oaths of loyalty on her son’s behalf from other prominent men and secured the fidelity of Brittany’s chief cities and towns.

On 22 March, accompanied by his mother, the young Duke made a state entry into Rennes, where, in the presence of a large gathering of nobles and prelates, he swore solemn oaths to govern righteously before keeping vigil all night before the altar of the cathedral. The next day, he was knighted by Clisson, after which he knighted his brothers Arthur and Gilles. He was then invested with the ducal regalia and borne in procession through the city before attending a feast hosted by Joan at the château of Rennes.

2

‘This blessed sacrament of marriage’

In February 1400, Joan had sent her trusted squire, Antoine Riczi (later her attorney and secretary), and one Nicholas Aldrewick, to London. They had been in England the previous year on business connected with the earldom of Richmond. Before February was out, they returned ‘by command of the King, with letters on his behalf addressed to the Duchess’1 and written by John Norbury, Henry IV ’s Treasurer, who addressed her as his ‘very dear and good friend’. These letters related to English and Breton pirates operating in the Channel, but there were almost certainly others in which Henry made discreet approaches to Joan.

Joan was interested. She may have felt attracted to Henry as a man, but that was not the prime consideration for a woman of her rank. As a monarch, he could offer her a crown, wealth and a new sphere of influence, whereas her role as regent of Brittany would soon be redundant

when her son reached his majority. Negotiations proceeded covertly and slowly, because both parties were aware that a marriage between them would not be popular in Brittany, France, Burgundy or England, and Joan, while keen on the prospect of becoming queen of England, may have stalled at the thought of what would happen to her children in her absence.

In November 1401, Joan’s envoys returned to England, sailing back to Brittany in December, bearing gifts for her (a bejewelled pax and costly rings that had been owned by Richard II ’s child bride, Isabella of Valois) and accompanied by English messengers. On 15 March 1402, Joan appointed Riczi and John Ruys as her proctors; John Norbury was to act for Henry. Soon afterwards, the Breton envoys crossed to England with letters under Joan’s signet empowering them to conclude the marriage treaty. A betrothal was secretly agreed upon, although Joan stipulated that she could not travel to England until she had set her affairs in order in Brittany.

She also needed to secure a dispensation, since she and Henry were third cousins twice over. Since 1378, the Church had been riven by what was known as the Great Schism, with rival pontiffs in Rome and Avignon. Joan supported Benedict XIII , who presided at Avignon. On 20 March 1402, he granted a dispensation permitting her to marry anyone she pleased within the fourth degree of consanguinity, a generous concession given that Henry IV supported the Roman Pope, Boniface IX . Joan had been warned by canon lawyers that marrying him would be a deadly sin, but Benedict assured her that this would be rendered void by the great benefits to be gained by her becoming queen of England. On 23 June, he would issue another dispensation that sanctioned her living with schismatics and receiving Holy Communion from them, as long as she remained loyal to him.

Joan instantly dispatched ambassadors, Anthony and John Rhys, to conclude the alliance. The marriage contract was signed on 2 April 1402, at Eltham Palace, the proxy wedding taking place the next day in the presence of Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, the Privy Council, the earls of Somerset and Northumberland and the latter’s heir, Sir Henry Percy, popularly known as ‘Hotspur’. Henry Bowet, Bishop of Bath and Wells, officiated, and Riczi stood in for Joan. The King placed a ring on his finger and the proxy bride vowed: ‘I, Antoine Riczi, in the name of my worshipful lady, Joan, the daughter of Charles, lately King of Navarre, Duchess of Brittany and Countess of Richmond, take you, Henry of Lancaster, King of England and Lord of Ireland, to my husband, and thereto I, Antoine, in the spirit of my said lady, plight you

my troth.’ It was the first recorded instance of the final sentence being used in a betrothal ceremony. Joan now began styling herself queen of England.

She brought no dowry to the marriage, but she had been left a large sum of money by Duke John and she had the income from her Breton dower lands; therefore, she was financially independent. After the proxy ceremony, she wrote to Henry to ask for compensation for the master of a Navarrese vessel that had been robbed of its cargo of wine by a captain in the Earl of Arundel’s fleet. ‘At the request of his dearest consort,’ the King enjoined his Admiral ‘to see that proper satisfaction be made to the master of the wine ship’,2 and warned that anyone who refused to obey him would be arrested.

The cat was now out of the bag. In May, rumour had it that the King intended to travel to Brittany to marry Joan, and there were fears that there would be an uprising in favour of Richard II in his absence. But on 25 June, the King directed Thomas, Lord Camoys, and other commissioners to safely conduct Queen Joan to England and paid him £100 (£76,200) in expenses, despite Parliament having insisted that Joan pay the cost of her journey from Brittany.

There was little enthusiasm for the marriage in England. It was highly unpopular in Brittany and – contrary to what Henry had evidently hoped – sparked a conflict with England, for the Breton lords feared that their duchy would be subsumed into the English Crown and were aghast when it became known that Joan wanted to take her children to England with her, to be brought up under the King’s tutelage. Outraged, they hastened to appeal to Burgundy, for support.

Joan’s forthcoming marriage set alarums ringing in France too, which now found itself surrounded by England and its allies. On 1 October 1402, Burgundy arrived at Nantes, intent on resolving matters to King Charles’s advantage. Joan welcomed him amiably and they dined together in great splendour. The Duke gave her costly crowns and sceptres, one set of crystal, the other of gold, pearls and precious stones, and he also had presents for her sons, her aunt Rohan, her ladies-in-waiting and the officers of her household. It was a clever ruse that soon had those ladies begging him to accept the guardianship of the duchy and the ducal princes.

The pleasantries disposed of, he put pressure on Joan to abandon her projected marriage, but she remained adamant. She did, however, allow herself to be persuaded that it would be better to leave her four sons under his guardianship than to alienate the Bretons by taking them abroad. He was, after all, her uncle and the boys’ kinsman. Joan agreed,

although it must have been with a heavy heart. Ceding control of the duchy to Burgundy, she required him to swear on the Holy Evangelists to protect her sons and respect the laws and privileges of Brittany, then made him put these promises in writing and herself signed the document and enjoined ‘the young princes to be obedient to him and to attend diligently to his advice’.3 She had to make protracted efforts to get the Bretons to agree to her taking her unmarried daughters Marguerite and Blanche, aged ten and five, to England, to which Henry had given his consent.

On 3 November, Joan bade farewell to her sons when Burgundy left with them for Paris. There, John V was required to pay homage to Charles VI . Joan would continue to keep in contact with the boys by letter.

At last, the way was clear for her to leave Brittany. In December, Henry sent his half-brothers, John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset, and Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Lincoln, with the earls of Worcester and Northumberland, Lord Camoys and many other lords to Brittany to receive Joan.

On 26 December, Joan left Nantes for Vannes with her daughters and their nurses, attended by a great retinue of Bretons and Navarrese. Plans for the assembly of a fleet to carry her to England had been afoot for months, and the Earl of Arundel ‘had provided, by royal command, a ship well-appointed with victuals, arms and thirty-six mariners for the service of bringing our lady the Queen from Brittany’.4 Sumptuous quarters had been prepared on board for her, hung with Imperial cloth of gold and containing a bed with curtains of crimson satin.

On 13 January, Joan and her daughters set sail from Camaret-sur-Mer near Brest for Southampton. The winter weather being atrocious, they endured a gruelling five-day voyage in storms that caused structural damage to the vessel and blew it off course to Cornwall. Joan was horribly seasick. Making land at Falmouth on 19 January 1403, she rested a while before being escorted by the lords across Bodmin Moor and via Okehampton to Exeter, arriving there on 27 January. She had come, observed the chronicler Thomas Walsingham, ‘from a smaller Brittany to a greater Britain, from a dukedom to a kingdom, from a fierce tribe to a peace-loving people’.

Apprised of Joan’s coming, Henry IV set out with a small retinue and rode for Exeter, where he welcomed her to England. They were lavishly entertained by the civic authorities, who provided them with a chariot and horses to take them to Bridport. While the King rode on towards Winchester, where they were to be married, Nicholas Aldrewick

Joan of Navarre, Queen of Henry IV 17 accompanied Joan via Dorchester and Salisbury to Winchester, where she met up again with Somerset, Worcester and Bishop Beaufort, who had had to race ahead to borrow money for the rest of the journey.

Joan had taken up residence in Wolvesey Castle, the Bishop of Winchester’s residence, by 5 February, when she and the King presided over a feast attended by a host of lords and ladies. In all, sixty-six dishes were served in three courses. It being Lent (the season when the devout were meant to abstain from meat, eggs and dairy produce), fish predominated, including roasted salmon, sturgeon, pike, bream, crab, lampreys, trout, eels and perch. Meat was also served: roast cygnets, capons, venison, griskins (pork tenderloin), rabbits, bitterns, pheasants, stuffed pullets, partridges, kid, woodcock, plover, quails, snipe, fieldfares, brawn and pottage; in addition cream of almonds, pears in syrup, custards, milk fritters and elaborate sugar sculptures, or ‘subtleties’, were presented to the high table after each course: a crowned panther breathing flames, and Lancastrian crowned eagles made of marzipan.

Henry’s chief wedding gift to Joan was a crown costing £1,313.6s.8d. (£1,133,550), which may have been the one Richard II had given Anne of Bohemia for their wedding in 1382. It had ten fleurons (flower-shaped ornaments) and was studded with emeralds, sapphires, rubies, pearls and diamonds. She also received a gem-encrusted cup and ewer of gold, ten armlets lavishly adorned with gems, a triangular clasp and a rich jewelled gold collar of linked S’s bearing Henry’s motto, ‘Souveignez’. Costing £333.6s.8d. (£287,490), the collar was delivered to Winchester in time for the wedding and is perhaps to be identified with the one on Joan’s tomb effigy. The King’s sons John and Humphrey gave her two gold tablets they had commissioned for her, although their father paid for them.5 The Prince of Wales was unable to attend the wedding, but wrote to Henry, ‘beseeching God in all wise, my sovereign lord, to send you in this blessed sacrament of marriage joy [and] prosperity, long to endure’.6

On 7 February, the marriage was solemnised with great ceremony in the priory of St Swithun (now Winchester Cathedral). The bride and groom processed along the striped cloth that had been laid down the nave, and Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Lincoln, officiated (he would become bishop of Winchester the following year, replacing William of Wykeham, who had been too infirm to officiate at the wedding). Among those present were the King’s children, John and Philippa. The celebrations continued for three days. The bill for the wedding itself came to £433.6s.8d. (£373,830), with an extra £522.12s. (£451,520) for the feast

that followed, at which meat and game were served in abundance, as well as fish for the clergy, followed by pears in syrup, cream of almonds and a subtlety in the form of a crowned eagle. The royal couple stayed in Winchester for three days before making their way in slow stages via Farnham Castle to Eltham Palace.

On 22 February, ‘messengers and couriers [were] sent to divers counties of England with letters to divers lords and ladies’, commanding them ‘to come to the coronation of the Lady Queen Joan, Queen of England’.7

Two days later, as the royal couple approached the capital, the Lord Mayor, aldermen and sheriffs, with members of the City’s guilds wearing liveries of brown and blue and hoods of scarlet, rode out in procession to Blackheath to welcome Joan and escort her into London. They were preceded by six minstrels who had been paid £4 (£3,450) each to play for her.

Joan spent that night in the royal palace of the Tower of London, where, by tradition, kings and queens stayed before their coronations. The next day, 25 February, she rode in procession to Westminster Abbey. As she passed through Cheapside, a band of minstrels played for her. She was crowned by Archbishop Arundel, with the diadem the King had given her. A manuscript drawing of her coronation in the Beauchamp Pageant,8 dating from c.1485–90, shows a queen enthroned on a raised platform beneath a canopy of estate bearing the royal arms, with two archbishops placing the crown on her head, and lords, ladies and damsels wearing chaplets of roses standing around the foot of the steps. She wears traditional ceremonial dress of a style dating back to the fourteenth century: a sideless surcoat – probably purple – with a kirtle beneath, and a mantle fastened across the upper chest with cords and tassels. In her hands – unusually for a queen consort, as they signify sovereignty – are a sceptre and an orb surmounted by a cross.

Her hair is loose, symbolic of queenly virginity. Only unmarried girls could wear their hair loose; it had to be covered after marriage, a custom that endured into the nineteenth century. But queens, who were supposed to be the mirror of the Virgin Mary in their piety and mercifulness, were the exception. As the Mother of Christ was the Queen of Heaven and mediatrix supreme, earthly queens exercised their influence through intercession.

Henry had outlaid £631 (£544,760) on a great feast and tournaments in celebration of the coronation. Joan’s champion, the Earl of Warwick, ‘kept joust on the Queen’s part against all other comers, and so notably and knightly behaved himself as redounded to his noble fame

Joan of Navarre, Queen of Henry IV 19 and perpetual worship’.9 A miniature in the Beauchamp Pageant shows Henry and Joan seated on a cushioned bench in an open gallery watching the tournament. Attended by her ladies, Joan appears in a close-fitting gown and a headdress with wired veiling that must have been two feet tall, and which may have looked slightly incongruous, given that she was petite in stature, like her effigy; when their tomb was opened in 1832, her leaden shroud – probably an anthropomorphic (body-shaped) coffin – was found to be much smaller than Henry IV ’s.

‘His beloved consort’

Whenthe celebrations were over, Henry moved with Joan, his sons and his daughter Philippa to Eltham Palace for Easter. On 8 March, at the petition of Parliament, Henry set Joan’s dower as queen of England at 10,000 marks (£5,754,920) annually, larger than that granted to most earlier consorts, making her one of the richest magnates – possibly the richest – in England. But Henry would struggle to maintain his Queen so lavishly; the Crown’s total annual income was just £56,000 (£48,346,200) – and the extra expense would cause financial problems that lasted the whole reign.

The sources are largely silent on the personal relationship between the King and Queen, but external evidence suggests that the marriage proved happy. The couple spent much time together, and Henry treated Joan well. Praised for his chaste life, he was faithful and generous and always solicitous in ascertaining that her needs and those of her household were met. They shared a love of music. Their stone heads can be seen on either side of the great east window of Naish Priory in Somerset.

Joan was lauded for her beauty, grace and majesty. Her tomb effigy at Canterbury shows her in a fashionable gown and surcoat with a low, gold-edged neckline leaving the shoulders bare, with gold buttons down the front. She wears her rich Lancastrian SS collar – the earliestsurviving example of one – and an elaborate crown. Her hair is confined in crespines on either side of her fashionably shaven forehead. Her impassive face has a slight double chin and a prominent pointed nose,

although this has been restored at some point and may not be the same shape as the original.

Joan was apparently welcomed by the King’s family. She established good relationships with his children and was to champion the Prince of Wales when he quarrelled with his father. Edward, Duke of York, the King’s thirty-year-old married cousin, was much taken with Joan and expressed his admiration for her in courtly verses extolling her beauty and virtues:

Excellent sovereign, seemly to see. Proved prudence, peerless of price; Bright blossom of benignity, Of figure fairest, and freshest of days! . . .

Your womanly beauty delicious Hath me all bent unto its chain; But grant to me your love gracious, My heart will melt as snow in rain.

If ye but wist my life and knew Of all the pains that I y-feel, I wis ye would upon me rue, Although your heart were made of steel . . .

And though ye be of high renown, Let mercy rule your heart so free; From you, lady, this is my boon, To grant me grace in some degree.

To mercy, if you will me take, If such your will be for to do, Then would I truly, for my sake, Change my cheer and slake my woe.