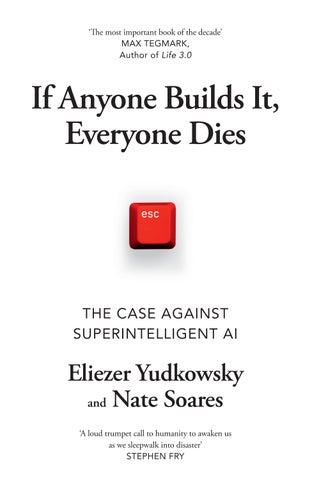

‘The most

important book of the decade’ MAX TEGMARK, Author of Life 3.0

‘The most

important book of the decade’ MAX TEGMARK, Author of Life 3.0

THE CASE AGAINST SUPERINTELLIGENT AI

Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares

‘A loud trumpet call to humanity to awaken us as we sleepwalk into disaster’ STEPHEN FRY

“If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies makes a compelling case that superhuman AI would almost certainly lead to global human annihilation. Governments around the world must recognize the risks and take collective and effective action.”

— Jon Wolfsthal, former special assistant to the president for national security a airs

“Yudkowsky and Soares lay out, in plain and easy-to-follow terms, why our current path toward ever-more-powerful AIs is extremely dangerous.”

— Emmett Shear, former interim CEO of OpenAI

“Essential reading for policymakers, journalists, researchers, and the general public. A masterfully written and groundbreaking text, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies provides an important starting point for discussing AI at all levels.”

— Bart Selman, professor of computer science, Cornell University

“While I’m skeptical that the current trajectory of AI development will lead to human extinction, I acknowledge that this view may reflect a failure of imagination on my part. Given AI’s exponential pace of change, there’s no better time to take prudent steps to guard against worst-case outcomes. The authors offer important proposals for global guardrails and risk mitigation that deserve serious consideration.”

— Lieutenant General John N.T. “Jack” Shanahan (USAF, Ret.), inaugural director, Department of Defense Joint AI Center

“If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies isn’t just a wake-up call; it’s a fire alarm ringing with clarity and urgency. Yudkowsky and Soares pull no punches: unchecked superhuman AI poses an existential threat. It’s a sobering reminder that humanity’s future depends on what we do right now.”

— Mark Ru alo

“A serious book in every respect. In Yudkowsky and Soares’s chilling analysis, a super-empowered AI will have no need for humanity and ample capacity to eliminate us. If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies is an eloquent and urgent plea for us to step back from the brink of self-annihilation.”

— Fiona Hill, former senior director, White House National Security Council

“A clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity. Recommended.”

— Ben Bernanke, Nobel laureate and former chairman of the Federal Reserve

“You’re likely to close this book fully convinced that governments need to shift immediately to a more cautious approach to AI, an approach more respectful of the civilization-changing enormity of what’s being created. I’d like everyone on Earth who cares about the future to read this book and debate its ideas.”

— Scott Aaronson, Schlumberger Centennial Chair of Computer Science, University of Texas at Austin

“An incredibly serious issue that merits — really demands — our attention. You don’t have to agree with the prediction or prescriptions in this book, nor do you have to be tech or AI savvy, to find it fascinating, accessible, and thought-provoking.”

— Suzanne Spaulding, former undersecretary, Department of Homeland Security

“The most important book I’ve read in years: I want to bring it to every political and corporate leader in the world and stand over them until they’ve read it. Yudkowsky and Soares sound a loud trumpet call to humanity to awaken us as we sleepwalk into disaster.”

— Stephen Fry

“The most important book of the decade.”

— Max Tegmark, professor of physics, MIT

“Claims about the risks of AI are often dismissed as advertising, intended to sell more gadgets. It would be comforting if true, but this book disproves that theory. Yudkowsky and Soares are not from the AI industry, and they’ve been writing about these risks since before AI existed in its present form. Read their disturbing book and tell us what they get wrong.”

— Huw Price, Bertrand Russell Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, Trinity College, Cambridge, UK

“Everyone should read this book. I’m 70 percent confident that you — yes, you reading this right now — will one day grudgingly admit that we all should have listened to Yudkowsky and Soares when we still had the chance.”

— Daniel Kokotajlo, OpenAI whistleblower and executive director, AI Futures Project

“If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies may prove to be the most important book of our time. Yudkowsky and Soares believe we are nowhere near ready to make the transition to superintelligence safely, leaving us on the fast track to extinction. Through the use of parables and crystal clear explainers, they convey their reasoning, in an urgent plea for us to save ourselves while we still can.”

— Tim Urban, creator, Wait But Why

“A stark and urgent warning delivered with credibility, clarity, and conviction, this provocative book challenges technologists, policymakers, and citizens alike to confront the existential risks of artificial intelligence before it’s too late. Essential reading for anyone who cares about the future.”

— Emma Sky, senior fellow, Yale Jackson School of Global A airs

“This book offers brilliant insights into history’s most consequential standoff between technological utopia and dystopia. It shows how we can and should prevent superhuman AI from killing us all.”

— George Church, founding core faculty, Wyss Institute at Harvard University

“A sober but highly readable book on the very real risks of AI. Both skeptics and believers need to understand the authors’ arguments and work to ensure that our AI future is more beneficial than harmful.”

— Bruce Schneier, author of A Hacker’s Mind

“This is our warning. Read today. Circulate tomorrow. Demand the guardrails. I’ll keep betting on humanity, but first we must wake up.”

— R.P. Eddy, former director, White House National Security Council

“A compelling introduction to the world’s most important topic. Superhuman AI could be here in a few short years. This book takes the implications seriously and explains, without mincing words, what could be in store.”

— Scott Alexander, creator, Astral Codex Ten

“You will feel actual emotions when you read this book. We are currently living in the last period of history where we are the dominant species. Humans are lucky to have Yudkowsky and Soares in our corner, reminding us not to waste the brief window that we have to make decisions about our future.”

— Grimes

“The best no-nonsense, simple explanation of the AI risk problem I’ve ever read.”

— Yishan Wong, former CEO, Reddit

The Bodley Head, an imprint of Vintage, is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies

Vintage, Penguin Random House UK, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

penguin.co.uk/vintage global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain by The Bodley Head in 2025

First published in the United States of America by Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group in 2025

Copyright © Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares 2025

The moral right of the author has been asserted

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HB ISBN 9781847928924

TPB ISBN 9781847928931

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

To all the humans who ever died, in the process of our species coming this far;

To all those who are still among the living; And to all the children that could someday be.

Chapter 1: Humanity’s

Chapter

“MITIGATING THE RISK OF EXTINCTION FROM AI SHOULD BE A global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

In early 2023, hundreds of Artificial Intelligence scientists signed an open letter consisting of that one sentence. These signatories included some of the most decorated researchers in the field. Among them were Nobel laureate Geoff rey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio, who shared the Turing Award for inventing deep learning.

We — Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares — also signed the letter, though we considered it a severe understatement. It wasn’t the AIs of 2023 that worried us or the other signatories. Nor are we worried about the AIs that exist as we write this, in early 2025. Today’s AIs still feel shallow, in some deep sense that’s hard to describe. They have limitations, such as an inability to form new long-term memories. These

IF ANYONE BUILDS IT, EVERYONE DIES

shortcomings have been enough to prevent those AIs from doing substantial scientific research or replacing all that many human jobs.

Our concern is for what comes after: machine intelligence that is genuinely smart, smarter than any living human, smarter than humanity collectively. We are concerned about AI that surpasses the human ability to think, and to generalize from experience, and to solve scientific puzzles and invent new technologies, and to plan and strategize and plot, and to reflect on and improve itself. We might call AI like that “artificial superintelligence” (ASI), once it exceeds every human at almost every mental task.

AI isn’t there yet. But AIs are smarter today than they were in 2023, and much smarter than they were in 2019. AI research has yielded jump after jump after jump in AI capability, in 2012* and 2016† and 2020‡ and 2022§ and 2024.¶ We don’t know whether progress will peter out, causing these jumps to halt for a time until new methods and technologies are invented. We don’t know how many jumps are left before AI becomes the extinction-level threat that the letter’s signatories warned about. But history has shown time and time again that AI researchers invent new methods and overcome old obstacles. Progress is often surprisingly fast. Most computer scientists in 2015 would have told you that ChatGPT-level artificial conversation wouldn’t be in reach for another thirty or fi ft y years.

We didn’t know when artificial superintelligence would arrive, but we agreed it should be a global priority. In fact, we think the open letter drastically undersells the issue.

* In 2012, AlexNet cracked open the problem of recognizing objects in images.

† AlphaGo beat the top human Go player in 2016.

‡ The (purely predictive) language model GPT-3 was released in 2020.

§ The (widely useful) ChatGPT arrived in 2022.

¶ In 2024, reasoning models began solving math, coding, and visual puzzles.

We were invited to sign that one-sentence open letter in our capacity as co-leaders of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI), a nonprofit institute. MIRI had been working on questions relating to machine superintelligence since 2001, long before these issues got much publicity or funding. To oversimplify: Among the few who have been following this matter for decades, MIRI is acknowledged as having worked on it the longest. One of us, Yudkowsky, is the founder of MIRI; the other, Soares, is its current president.

MIRI was the first organized group to say: “Superintelligent AI will predictably be developed at some point, and that seems like an extremely huge deal. It might be technically difficult to shape superintelligences so that they help humanity, rather than harming us. Shouldn’t someone start work on that challenge right away, instead of waiting for everything to turn into a massive emergency later?”

We did not start out saying that. Yudkowsky began by trying to build machine superintelligence, in the year 2000. But in 2001, he realized that it would not necessarily turn out friendly. And in 2003, he realized that problem would be hard.

For its first two decades, MIRI was a technical research institute, without much involvement in policy. The organization mostly held workshops for interested scientists and housed a few promising researchers. We tried to figure out the math for understanding and shaping superhuman machine intelligence, and for predicting how it might go wrong.

MIRI also had some downstream effects that we now regard with ambivalence or regret. At a conference we organized, we introduced Demis Hassabis and Shane Legg, the founders of

IF ANYONE BUILDS IT, EVERYONE DIES

what would become Google DeepMind, to their first major funder. And Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, once claimed that Yudkowsky had “got many of us interested in AGI”* and “was critical in the decision to start OpenAI.”†

MIRI’s history is complicated, but one way of summarizing our relationship to the larger field might be this: Years before any of the current AI companies existed, MIRI’s warnings were known as the ones you needed to dismiss if you wanted to work on building genuinely smart AI, despite the risks of extinction.

More recently, as AI has begun to take off, we watched with concern as some of the newer people starting AI companies began talking about artificial superintelligence as a source of vast, wonderful powers. Powers that they assumed they’d control. The main danger, according to many of these founders, was that the wrong people might “have” ASI. They talked of the need to win an “AI arms race.” As for the possibility that you don’t “have” an ASI, the ASI has an ASI — that the only winner of an AI arms race would be the ASI itself — well, these founders didn’t talk about that.

We saw that AI capabilities were growing very fast.

We saw that the research field in which we were involved — the one aimed at understanding AIs and having them maybe not go wrong — was progressing much, much slower.

The AI companies’ headlong charge toward superhuman AI — their efforts to build it as quickly as possible, before their competitors could do it — started looking to us like a race to

* “AGI” stands for “Artificial General Intelligence,” a term to distinguish AI that is intuitively “actually smart” from the single-purpose sorts of AIs of yesteryear. We avoid the term in this book, because of how much people disagree about what it means in the wake of AIs like ChatGPT.

† If true, this is despite Yudkowsky objecting that OpenAI was a terrible, terrible idea.

the bottom. The industry was careening toward disaster: the sort that would get into textbooks as an example of how not to do engineering — except no one would be left alive to write the analysis.

It no longer seemed realistic to us that humanity could engineer and research its way out of catastrophe. Not under conditions like these. Not in time.

We wrote off our previous efforts as failures, wound down most of MIRI’s research, and shifted the institute’s focus to conveying one single point, the warning at the core of this book:

If any company or group, anywhere on the planet, builds an arti cial superintelligence using anything remotely like current techniques, based on anything remotely like the present understanding of AI, then everyone, everywhere on Earth, will die.

We do not mean that as hyperbole. We are not exaggerating for effect. We think that is the most direct extrapolation from the knowledge, evidence, and institutional conduct around artificial intelligence today.

In this book, we lay out our case, in the hope of rallying enough key decision-makers and regular people to take AI seriously. The default outcome is lethal, but the situation is not hopeless; machine superintelligence doesn’t exist yet, and its creation can still be prevented.

How can anyone be confident of what will happen with regard to AI? “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future,” goes the aphorism. Most of what we’d like to know about the future is not actually predictable. We can’t tell you next week’s winning

IF ANYONE BUILDS IT, EVERYONE DIES

lottery numbers, for example. One set of numbers seems just as likely as any other.

But some facts about the future are predictable. If you, personally, buy a lottery ticket tomorrow, we don’t know what complicated theories or whims you’ll use to pick your numbers, and we don’t know what numbers will come up, but all that uncertainty adds up to a very strong prediction that you will not win the lottery. Similarly, if you drop an ice cube into a glass of hot water, it’s impossibly complicated to predict where each molecule will end up ten minutes later — but all that uncertainty adds up to a near-certain prediction that the ice cube will melt. Half of physics is like that: We can’t calculate which exact path gets taken, but we know where almost all paths lead.

Some aspects of the future are predictable, with the right knowledge and effort; others are impossibly hard calls. Competent futurism is built around knowing the difference.

History teaches that one kind of relatively easy call about the future involves realizing that something looks theoretically possible according to the laws of physics, and predicting that eventually someone will go do it. Heavier-than-air fl ight, weapons that release nuclear energy, rockets that go to the Moon with a person on board: These events were called in advance, and for the right reasons, despite pushback from skeptics who sagely observed that these things hadn’t yet happened and therefore probably never would. People who strapped wings to their arms and jumped off hills looked all sorts of foolish, and were mocked by their contemporaries, and in fact hurt themselves and failed — but that didn’t stop the Wright brothers from figuring out how to fly.

Conversely, predicting exactly when a technology gets developed has historically proven to be a much harder problem.

People say that a technology is two years off when it’s really fi ft y years, or say fi ft y years when it’s really two years and they themselves will build that technology. “Man will not fly for a thousand years,” Wilbur Wright said to Orville Wright in 1901, fed up with the unpowered glider they were testing at the time. Two years later, in 1903, the Wright brothers flew.

Successful forecasting is not about being clever enough to predict the sort of details that usually can’t be predicted. It is not about inventing a complete story about what will happen and then being magically correct. Rather, it’s about finding aspects of the future that become easy calls when viewed from the right angle.

We don’t know when the world ends, if people and countries change nothing about the way they’re handling artificial intelligence. We don’t know how the headlines about AI will read in two or ten years’ time, nor even whether we have ten years left. Our claim is not that we are so clever that we can predict things that are hard to predict. Rather, it seems to us that one particular aspect of the future — “What happens to everyone and everything we care about, if superintelligence gets built anytime soon?” — can, with enough background knowledge and careful reasoning, be an easy call.

Humanity’s extinction by superhuman AI might not seem like an easy call at first glance. But that’s what the rest of this book is for. Just as it takes some arithmetic to calculate the chance of winning a lottery, just as it takes some ideas from thermodynamics to say why an ice cube predictably melts, so does it take some background to understand why artificial intelligence poses an imminent extinction risk to humanity. Once those foundations are in place, though, predicting the outcome of our present trajectory starts to look grimly, horribly straightforward.

Even in the face of superhuman machine intelligence, it can be tempting to imagine that the world will keep looking the way it has over the last few decades of our relatively short lives. It is true, but hard to remember, that there was a time as real as our own time, just a few short centuries ago, when civilization was radically different. Or millennia ago, when there was no civilization to speak of. Or a million years ago, when there were no humans. Or a billion years ago, when multicellular colonies had no specialized cells.

Adopting a historical perspective can help us appreciate what is so hard to see from the perspective of our own short lifespans: Nature permits disruption. Nature permits calamity. Nature permits the world to never be the same again.

Once upon a time, 2.5 billion years ago, an event occurred that biologists call the Oxygen Catastrophe: A new life form learned to use the energy of sunlight to strip valuable carbon out of air. That life form exhaled a dangerously toxic and reactive chemical as waste, poisonous to most existing life: a chemical we now call “oxygen.” It began to build up in the atmosphere. Most life — including most of the bacteria exhaling that oxygen — could not handle its reactivity, and died. A lucky few lines of cells adapted, and eventually evolved into organisms that use oxygen as fuel. But things never went back to the old normal. The world was never the same again.

Once upon a time, the continents were barren rock. Then in the blink of an evolutionary eye, they were carpeted in vegetation. Soon after, forests were teeming with life. The world was never the same again.

Once upon a time, some humans domesticated wheat and barley. In a tinier fraction of an evolutionary eye-blink, they started building civilizations. The world was never the same again.

Once upon a time in the 1930s, there were warning signs that certain families would no longer be safe in Germany. A few left early; most stayed. Then the Nazi government revoked their citizenship and their passports and made future escape much harder. A few years after that, German Jews and Romani and others were rounded up and sent to extermination camps. The survivors’ accounts say that many of those families had stayed, not because they hadn’t seen warning signs, but because they had believed life would go back to normal before matters went too far.

Once upon a time, humanity was on the brink of creating artificial superintelligence . . .

Normality always ends. Th is is not to say that it’s inevitably replaced by something worse; sometimes it is and sometimes it isn’t, and sometimes it depends on how we act. But clinging to the hope that nothing too bad will be allowed to happen does not usually help.

Humans have an ability to steer the future using our intelligence. But that ability only works if we use it — if we do the things we have to do, when we need to do them. Intelligence has no power apart from that. It works by changing our actions or not at all.

The months and years ahead will be a life-or-death test for all humanity. With this book, we hope to inspire individuals and countries to rise to the occasion.

ANYONE BUILDS IT, EVERYONE

In the chapters that follow, we will outline the science behind our concern, discuss the perverse incentives at play in today’s AI industry, and explain why the situation is even more dire than it seems. We will critique modern machine learning in simple language, and we will describe how and why current methods are utterly inadequate for making AIs that improve the world rather than ending it.

In Part I of this book, we lay out the problem, answering questions such as: What is intelligence? How are modern AIs produced, and why are they so hard to understand? Can AIs have wants? Will they? If so, what will they want, and why would they want to kill us? How would they kill us? We ultimately predict AIs that will not hate us, but that will have weird, strange, alien preferences that they pursue to the point of human extinction.

In Part II we draw together all of those points to tell a tale about an AI that ends a world much like our own. Th is story is not a prediction, because the exact pathway that the future takes is a hard call. The only part of the story that is a prediction is its fi nal ending — and that prediction only holds if a story like it is allowed to begin.

In Part III we evaluate the difficulty of the challenge facing humanity, and review the responses to date. How well are AI companies handling the problem? Why isn’t the world taking more note? What could society do differently, if enough of us decide not to die? What would it take for Earth to not build machine superintelligence?

An online supplement to this book is available at the website IfAnyoneBuildsIt.com. At the end of each chapter you’ll fi nd a URL and a QR code that links you to a supplement for that chapter. It will look like this:

IfAnyoneBuildsIt.com/intro

People have all sorts of confl icting intuitions about artificial intelligence, and we’ve heard a wide variety of questions and objections over the years, coming from a wide range of presuppositions and viewpoints. In our supplemental materials we cover more caveats, subtleties, and frequently asked questions, along with some of the principled theoretical foundations and extended arguments that would have made this book several times as long and much less accessible. If you fi nd objections springing to mind at the end of any chapter, we encourage you to continue reading online.

We open many of the chapters with parables: stories that, we hope, will help convey some points more simply than otherwise. They may also add a little levity to an otherwise heavy subject. Th is is in keeping with that most ancient tradition, perhaps older than the human species in its current form, to laugh in the face of death.

Th is book is not full of great news, we admit. But we’re not here to tell you that you’re doomed, either. Artificial superintelligence doesn’t exist yet. Humanity could still decide not to build it.

In the 1950s, many people expected that there would be a nuclear war between the major powers of the world. Given the history of human confl ict up until that point, there was reason to be pessimistic. Yet, to date, nuclear war has not happened.

ANYONE BUILDS IT, EVERYONE DIES

That’s not because nuclear bombs turned out to be pure science fiction that could never happen in real life; it’s because people have worked hard to build resilient systems around not starting nuclear wars. They did all that because world leaders knew that, in the event of a nuclear war, both they and the people of their countries would have a bad day.

They’d also have a bad day if anyone, anywhere on Earth, created a machine superintelligence. It is not in anyone’s interest to die along with all their family and friends, their country and its children.

Halting the ongoing escalation of AI technology, corralling the hardware used to create ever more powerful AI models — that is not something that would be easy to do in today’s world. But it would take much less work to stop further escalation of AI capabilities than it took, say, to fight World War II. Summoning the will to live only requires that some countries and leaders and voters realize that they are standing some hard-to-estimate, possibly-quite-short distance from the brink of death.

The job won’t be easy, but we’re not dead yet. Human dignity, and humanity’s dignity, demands that we put up a fight.

Where there’s life, there’s hope.